User login

Submit Proposals for VAM 2017

All SVS members may submit proposals for invited sessions for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting, set for May 31 to June 3 (plenaries and exhibits are June 1 to 3) in San Diego, Calif.

Previously, the process was open only to SVS committees; planners opened the process to all members this year, with any and all ideas for sessions to be reviewed for further development.

Invited sessions include postgraduate courses, breakfast and concurrent sessions and workshops. Initial submissions are due Sept. 16.

All SVS members may submit proposals for invited sessions for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting, set for May 31 to June 3 (plenaries and exhibits are June 1 to 3) in San Diego, Calif.

Previously, the process was open only to SVS committees; planners opened the process to all members this year, with any and all ideas for sessions to be reviewed for further development.

Invited sessions include postgraduate courses, breakfast and concurrent sessions and workshops. Initial submissions are due Sept. 16.

All SVS members may submit proposals for invited sessions for the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting, set for May 31 to June 3 (plenaries and exhibits are June 1 to 3) in San Diego, Calif.

Previously, the process was open only to SVS committees; planners opened the process to all members this year, with any and all ideas for sessions to be reviewed for further development.

Invited sessions include postgraduate courses, breakfast and concurrent sessions and workshops. Initial submissions are due Sept. 16.

Review Course Recordings Available

Just in time for the September recertification exam! Recordings of the 2015 Comprehensive Vascular Review Course are available for purchase. The 2015 intensive two-day course was led by vascular surgeons with extensive expertise in their respective fields.

The recordings include didactic lectures and review of essential VESAP questions. The recordings also provide a comprehensive update in all areas of vascular surgery.

No CME credit is available.

Purchase the recordings here.

Just in time for the September recertification exam! Recordings of the 2015 Comprehensive Vascular Review Course are available for purchase. The 2015 intensive two-day course was led by vascular surgeons with extensive expertise in their respective fields.

The recordings include didactic lectures and review of essential VESAP questions. The recordings also provide a comprehensive update in all areas of vascular surgery.

No CME credit is available.

Purchase the recordings here.

Just in time for the September recertification exam! Recordings of the 2015 Comprehensive Vascular Review Course are available for purchase. The 2015 intensive two-day course was led by vascular surgeons with extensive expertise in their respective fields.

The recordings include didactic lectures and review of essential VESAP questions. The recordings also provide a comprehensive update in all areas of vascular surgery.

No CME credit is available.

Purchase the recordings here.

Are You Up for the ‘Cardio’ Challenge?

SVS members who are researchers and clinicians have an opportunity to win $5,000 for study hypotheses in cardiovascular research.

The American Heart Association and PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) have announced a ‘crowdsourcing’ challenge, asking researchers and clinicians to suggest research questions that address difficult challenges identified by patients with cardiovascular diseases. Proposals should focus on questions that can be answered through comparative clinical effectiveness research with a precision medicine approach.

Submissions are due by Oct. 6. Four winners will each receive a $5,000 cash prize.

SVS members who are researchers and clinicians have an opportunity to win $5,000 for study hypotheses in cardiovascular research.

The American Heart Association and PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) have announced a ‘crowdsourcing’ challenge, asking researchers and clinicians to suggest research questions that address difficult challenges identified by patients with cardiovascular diseases. Proposals should focus on questions that can be answered through comparative clinical effectiveness research with a precision medicine approach.

Submissions are due by Oct. 6. Four winners will each receive a $5,000 cash prize.

SVS members who are researchers and clinicians have an opportunity to win $5,000 for study hypotheses in cardiovascular research.

The American Heart Association and PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) have announced a ‘crowdsourcing’ challenge, asking researchers and clinicians to suggest research questions that address difficult challenges identified by patients with cardiovascular diseases. Proposals should focus on questions that can be answered through comparative clinical effectiveness research with a precision medicine approach.

Submissions are due by Oct. 6. Four winners will each receive a $5,000 cash prize.

Highlights From the 2016 AHS Meeting

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Should clopidogrel be discontinued prior to open vascular procedures?

The continued use of perioperative clopidogrel is appropriate

Surgeons have always worried about bleeding risks for procedures we do. Complex vascular procedures are further complicated by the myriad of available antiplatelet agents designed to reduce ischemic events from cardiovascular disease burden at the expense of potential bleeding complications if antiplatelet medications are continued. Rather than relying on anecdotal reports by historical vignettes, let’s look at the evidence.

There probably is no other drug available in our vascular toolbox which has been studied more in the last 20 years than clopidogrel. Multiple randomized and double blinded studies such as CASPAR1 and CHARISMA2 have amplified what was known since the early CAPRIE trial in the 1990’s and that is that clopidogrel is safe when used as a single medication or as a dual agent with aspirin (duel antiplatelet therapy [DAPT]).

But not all our patients need DAPT. There is no level 1 evidence demonstrating the need for any antiplatelet therapy in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events for patients deemed at low or moderate risk of cardiovascular disease from a large meta-analysis review of six primary prevention trials encompassing over 95,000 patients.3

If our patients do present with vascular disease, current ACCP guidelines recommend single-agent antiplatelet medication (either ASA or clopidogrel) for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) whether planning LE revascularization with bypass or via endovascular means with grade 1A evidence.4 This works fine for single-focus vascular disease and each antiplatelet agent have proponents but either works well.

That’s great, but what about all those sick cardiac patients we see the most of? First, CHARISMA subgroup analysis of patients with preexisting coronary and/or cerebrovascular disease demonstrate a 7.1% risk reduction in MI, cerebrovascular events, and cardiac ischemic deaths when continuing DAPT over aspirin alone, and similar risk reduction is found in PAD patients for endpoints of MI and ischemic cardiovascular events. Second, there was no significant difference in severe, fatal, or moderate bleeding in those receiving DAPT vs. aspirin alone with only minor bleeding increased using DAPT. Third, real-life practice echoes multiple trial experiences such as the Vascular Study Group of New England study group confirmed in reviewing 16 centers and 66 surgeons with more than 10,000 patients. Approximately 39% underwent major aortic or lower extremity bypass operations.

No statistical difference could be found for reoperation (P = .74), transfusion (P = .1) or operative type between DAPT or aspirin use alone.5 This is rediscovered once again by Saadeh and Sfeir in their prospective study of 647 major arterial procedures over 7 years finding no significant difference in reoperation for bleeding or bleeding mortality between DAPT vs. aspirin alone.6

So can we stop bashing clopidogrel as an evil agent of bleeding as Dr. Dalsing wishes to do? After all, he has been on record as stating, “I don’t know if our bleeding risk is worse or better … something we have to do to keep our grafts going.” Evidence tells us the benefits for continuing DAPT as seen in risk reduction in primary cardiovascular outcomes far outweigh the risk of minor bleeding associated with continued use.

Let the science dictate practice. Patients with low or moderate risk for cardiovascular disease need no antiplatelet medication unless undergoing PAD treatment where a single agent, either aspirin or clopidogrel alone, is sufficient. In those patients having a large cardiovascular burden of disease, combination of aspirin and clopidogrel improves survival benefit and reduces ischemic events without a significant risk of reoperation, transfusion, or bleeding-related mortality. As many of our patients require DAPT for drug eluting coronary stents, withholding clopidogrel preoperatively increases overall risk beyond acceptable limits. Improving surgical skills and paying attention to hemostasis during the operation will allow naysayers to achieve improved patient survival without fear of bleeding when continuing best medical therapy such as DAPT.

Gary Lemmon, MD, is professor of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and chief, vascular surgery, Indianapolis VA Medical Center. He reported no relevant conflicts.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825-33

2. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:192-201

3. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-604. Chest. 2012;141:e669s-90s

5. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54: 779-84

6. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58: 1586-92

The continued use of perioperative clopidogrel is debatable!

There are cases in which clopidogrel should not be discontinued for a needed vascular intervention. Delaying operation or maintaining clopidogrel during operation if your patient required a recent coronary stent is warranted unless you are willing to accept an acute coronary thrombosis.

However, in other cases, for example infrainguinal grafts, the risk of potential increased bleeding when adding clopidogrel to aspirin may outweigh potential improvements in graft patency. This is especially true of below-knee vein bypass grafts where data do not support improved patency. However, in the CASPAR trial, prosthetic graft patency did appear to be beneficial, but only in subgroup analysis.1

It is true that severe bleeding was not increased (intracranial hemorrhage, or hemodynamic compromise: 1 vs 2.7%, P = NS) but moderate bleeding (transfusion required: 0.7 vs 3.7%, P = .012) and mild bleeding (5.4 vs 12.1%, P = .004) was increased when this agent was used especially in vein graft surgery. This risk of bleeding was present even when clopidogrel was begun 2 or more days after surgery.1

To complicate this decision, a Cochrane review did not consider subgroup analysis as statistically valid and so the authors considered infrainguinal graft patency as not improved with clopidogrel but bleeding risk was increased. One might even question the use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for vein graft bypasses based on the results of this metanalysis.2 Carotid endarterectomy is a common vascular surgery procedure in which antiplatelet use has been evaluated in the real-world situation and with large cohorts. As is always the case when dealing with patient issues, the addition of one agent does not tell the entire story and patient demographics can have a significant influence on the outcome. A report from the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) database controlled for patient differences by propensity matching with more than 4,500 patients in each of the two groups; ASA vs. ASA + clopidogrel; demonstrated that major bleeding, defined as return to the OR for bleeding, was statistically more common with dual therapy (1.3% vs. 0.7%, P = .004).3

The addition of clopidogrel did statistically decrease the risk of ipsilateral TIA or stroke (0.8% vs. 1.2%, P = .02) but not the risk of death (0.2% vs. 0.3%, P = .3) or postoperative MI (1% vs. 0.8%, P = .4). Reoperation for bleeding is not inconsequential since in patients requiring this intervention, there is a significantly worse outcome in regard to stroke (3.7% vs. 0.8%, P = .001), MI (6.2% vs. 0.8%, P = .001), and death (2.5% vs. 0.2%,P = .001). Further drill down involving propensity score–matched analysis stratified by symptom status (asymptomatic vs. symptomatic) was quite interesting in that in only asymptomatic patients did the addition of clopidogrel actually demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in TIA or stroke, any stroke, or composite stroke/death. Symptomatic patients taking dual therapy demonstrated a slight reduction in TIA or stroke (1.4% vs. 1.7%, P = .6), any stroke (1.1% vs. 1.2%, P = .9) and composite stroke/death (1.2% vs. 1.5%, P = .5) but in no instance was statistical significance reached. The use of protamine did help to decrease the risk of bleeding.

Regarding the use of dual therapy during open aortic operations, an earlier report of the VQI database demonstrated no significant difference in bleeding risk statistically, but if one delves deeper the data indicate something different. In the majority of cases, vascular surgeons do not feel comfortable preforming this extensive dissection on dual therapy. Of the cases reported, 1,074 were preformed either free of either drug or only on ASA while 42 were on dual therapy and only 12 on clopidogrel only. In fact, in the conclusions, the authors note that they do not believe that conclusions regarding clopidogrel use in patient undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair can be drawn based on their results since the potential for a type II error was too great.4

It may be that our current level of sophistication is not sufficiently mature to determine the actual effect that clopidogrel is having on our patients. Clopidogrel, a thienopyridine, inhibits platelet activation by blocking the ADP-binding site for the P2Y12 receptor. Over 85% of ingested drug is metabolized into inactive metabolites while 15% is metabolized by the liver via a two-step oxidative process into the active thiol metabolite. Inter-individual variability in the antiplatelet response to thienopyridines is noted and partially caused by genetic mutations in the CP isoenzymes. Platelet reactivity testing is possible but most of the work has been conducted for those patients requiring coronary artery revascularization. Results of tailoring intervention to maximize therapeutic benefit and decrease the risk of bleeding have been inconsistent but, in some studies, appear to be promising.5 This approach may ultimately be found superior to determining how effective clopidogrel actually is in a particular case with some insight into the bleeding risk as well. With this determination, whether or not to hold clopidogrel perioperatively can be made with some science behind the decision.

Clearly, a blanket statement that the risk of bleeding should be accepted or ignored because of the demonstrated benefits of clopidogrel in patients requiring vascular surgery is not accurate. In some cases, there is no clear benefit, so eliminating the bleeding risk may well be the appropriate decision. The astute vascular surgeon understands the details of the written word in order to make an educated decision and understands that new information such as determining platelet reactivity may provide more clarity to such decisions in the future.

Michael C. Dalsing, MD, is chief of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He reported no relevant conflicts.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825-33

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000535

The continued use of perioperative clopidogrel is appropriate

Surgeons have always worried about bleeding risks for procedures we do. Complex vascular procedures are further complicated by the myriad of available antiplatelet agents designed to reduce ischemic events from cardiovascular disease burden at the expense of potential bleeding complications if antiplatelet medications are continued. Rather than relying on anecdotal reports by historical vignettes, let’s look at the evidence.

There probably is no other drug available in our vascular toolbox which has been studied more in the last 20 years than clopidogrel. Multiple randomized and double blinded studies such as CASPAR1 and CHARISMA2 have amplified what was known since the early CAPRIE trial in the 1990’s and that is that clopidogrel is safe when used as a single medication or as a dual agent with aspirin (duel antiplatelet therapy [DAPT]).

But not all our patients need DAPT. There is no level 1 evidence demonstrating the need for any antiplatelet therapy in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events for patients deemed at low or moderate risk of cardiovascular disease from a large meta-analysis review of six primary prevention trials encompassing over 95,000 patients.3

If our patients do present with vascular disease, current ACCP guidelines recommend single-agent antiplatelet medication (either ASA or clopidogrel) for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) whether planning LE revascularization with bypass or via endovascular means with grade 1A evidence.4 This works fine for single-focus vascular disease and each antiplatelet agent have proponents but either works well.

That’s great, but what about all those sick cardiac patients we see the most of? First, CHARISMA subgroup analysis of patients with preexisting coronary and/or cerebrovascular disease demonstrate a 7.1% risk reduction in MI, cerebrovascular events, and cardiac ischemic deaths when continuing DAPT over aspirin alone, and similar risk reduction is found in PAD patients for endpoints of MI and ischemic cardiovascular events. Second, there was no significant difference in severe, fatal, or moderate bleeding in those receiving DAPT vs. aspirin alone with only minor bleeding increased using DAPT. Third, real-life practice echoes multiple trial experiences such as the Vascular Study Group of New England study group confirmed in reviewing 16 centers and 66 surgeons with more than 10,000 patients. Approximately 39% underwent major aortic or lower extremity bypass operations.

No statistical difference could be found for reoperation (P = .74), transfusion (P = .1) or operative type between DAPT or aspirin use alone.5 This is rediscovered once again by Saadeh and Sfeir in their prospective study of 647 major arterial procedures over 7 years finding no significant difference in reoperation for bleeding or bleeding mortality between DAPT vs. aspirin alone.6

So can we stop bashing clopidogrel as an evil agent of bleeding as Dr. Dalsing wishes to do? After all, he has been on record as stating, “I don’t know if our bleeding risk is worse or better … something we have to do to keep our grafts going.” Evidence tells us the benefits for continuing DAPT as seen in risk reduction in primary cardiovascular outcomes far outweigh the risk of minor bleeding associated with continued use.

Let the science dictate practice. Patients with low or moderate risk for cardiovascular disease need no antiplatelet medication unless undergoing PAD treatment where a single agent, either aspirin or clopidogrel alone, is sufficient. In those patients having a large cardiovascular burden of disease, combination of aspirin and clopidogrel improves survival benefit and reduces ischemic events without a significant risk of reoperation, transfusion, or bleeding-related mortality. As many of our patients require DAPT for drug eluting coronary stents, withholding clopidogrel preoperatively increases overall risk beyond acceptable limits. Improving surgical skills and paying attention to hemostasis during the operation will allow naysayers to achieve improved patient survival without fear of bleeding when continuing best medical therapy such as DAPT.

Gary Lemmon, MD, is professor of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and chief, vascular surgery, Indianapolis VA Medical Center. He reported no relevant conflicts.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825-33

2. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:192-201

3. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-604. Chest. 2012;141:e669s-90s

5. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54: 779-84

6. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58: 1586-92

The continued use of perioperative clopidogrel is debatable!

There are cases in which clopidogrel should not be discontinued for a needed vascular intervention. Delaying operation or maintaining clopidogrel during operation if your patient required a recent coronary stent is warranted unless you are willing to accept an acute coronary thrombosis.

However, in other cases, for example infrainguinal grafts, the risk of potential increased bleeding when adding clopidogrel to aspirin may outweigh potential improvements in graft patency. This is especially true of below-knee vein bypass grafts where data do not support improved patency. However, in the CASPAR trial, prosthetic graft patency did appear to be beneficial, but only in subgroup analysis.1

It is true that severe bleeding was not increased (intracranial hemorrhage, or hemodynamic compromise: 1 vs 2.7%, P = NS) but moderate bleeding (transfusion required: 0.7 vs 3.7%, P = .012) and mild bleeding (5.4 vs 12.1%, P = .004) was increased when this agent was used especially in vein graft surgery. This risk of bleeding was present even when clopidogrel was begun 2 or more days after surgery.1

To complicate this decision, a Cochrane review did not consider subgroup analysis as statistically valid and so the authors considered infrainguinal graft patency as not improved with clopidogrel but bleeding risk was increased. One might even question the use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for vein graft bypasses based on the results of this metanalysis.2 Carotid endarterectomy is a common vascular surgery procedure in which antiplatelet use has been evaluated in the real-world situation and with large cohorts. As is always the case when dealing with patient issues, the addition of one agent does not tell the entire story and patient demographics can have a significant influence on the outcome. A report from the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) database controlled for patient differences by propensity matching with more than 4,500 patients in each of the two groups; ASA vs. ASA + clopidogrel; demonstrated that major bleeding, defined as return to the OR for bleeding, was statistically more common with dual therapy (1.3% vs. 0.7%, P = .004).3

The addition of clopidogrel did statistically decrease the risk of ipsilateral TIA or stroke (0.8% vs. 1.2%, P = .02) but not the risk of death (0.2% vs. 0.3%, P = .3) or postoperative MI (1% vs. 0.8%, P = .4). Reoperation for bleeding is not inconsequential since in patients requiring this intervention, there is a significantly worse outcome in regard to stroke (3.7% vs. 0.8%, P = .001), MI (6.2% vs. 0.8%, P = .001), and death (2.5% vs. 0.2%,P = .001). Further drill down involving propensity score–matched analysis stratified by symptom status (asymptomatic vs. symptomatic) was quite interesting in that in only asymptomatic patients did the addition of clopidogrel actually demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in TIA or stroke, any stroke, or composite stroke/death. Symptomatic patients taking dual therapy demonstrated a slight reduction in TIA or stroke (1.4% vs. 1.7%, P = .6), any stroke (1.1% vs. 1.2%, P = .9) and composite stroke/death (1.2% vs. 1.5%, P = .5) but in no instance was statistical significance reached. The use of protamine did help to decrease the risk of bleeding.

Regarding the use of dual therapy during open aortic operations, an earlier report of the VQI database demonstrated no significant difference in bleeding risk statistically, but if one delves deeper the data indicate something different. In the majority of cases, vascular surgeons do not feel comfortable preforming this extensive dissection on dual therapy. Of the cases reported, 1,074 were preformed either free of either drug or only on ASA while 42 were on dual therapy and only 12 on clopidogrel only. In fact, in the conclusions, the authors note that they do not believe that conclusions regarding clopidogrel use in patient undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair can be drawn based on their results since the potential for a type II error was too great.4

It may be that our current level of sophistication is not sufficiently mature to determine the actual effect that clopidogrel is having on our patients. Clopidogrel, a thienopyridine, inhibits platelet activation by blocking the ADP-binding site for the P2Y12 receptor. Over 85% of ingested drug is metabolized into inactive metabolites while 15% is metabolized by the liver via a two-step oxidative process into the active thiol metabolite. Inter-individual variability in the antiplatelet response to thienopyridines is noted and partially caused by genetic mutations in the CP isoenzymes. Platelet reactivity testing is possible but most of the work has been conducted for those patients requiring coronary artery revascularization. Results of tailoring intervention to maximize therapeutic benefit and decrease the risk of bleeding have been inconsistent but, in some studies, appear to be promising.5 This approach may ultimately be found superior to determining how effective clopidogrel actually is in a particular case with some insight into the bleeding risk as well. With this determination, whether or not to hold clopidogrel perioperatively can be made with some science behind the decision.

Clearly, a blanket statement that the risk of bleeding should be accepted or ignored because of the demonstrated benefits of clopidogrel in patients requiring vascular surgery is not accurate. In some cases, there is no clear benefit, so eliminating the bleeding risk may well be the appropriate decision. The astute vascular surgeon understands the details of the written word in order to make an educated decision and understands that new information such as determining platelet reactivity may provide more clarity to such decisions in the future.

Michael C. Dalsing, MD, is chief of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He reported no relevant conflicts.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825-33

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000535

The continued use of perioperative clopidogrel is appropriate

Surgeons have always worried about bleeding risks for procedures we do. Complex vascular procedures are further complicated by the myriad of available antiplatelet agents designed to reduce ischemic events from cardiovascular disease burden at the expense of potential bleeding complications if antiplatelet medications are continued. Rather than relying on anecdotal reports by historical vignettes, let’s look at the evidence.

There probably is no other drug available in our vascular toolbox which has been studied more in the last 20 years than clopidogrel. Multiple randomized and double blinded studies such as CASPAR1 and CHARISMA2 have amplified what was known since the early CAPRIE trial in the 1990’s and that is that clopidogrel is safe when used as a single medication or as a dual agent with aspirin (duel antiplatelet therapy [DAPT]).

But not all our patients need DAPT. There is no level 1 evidence demonstrating the need for any antiplatelet therapy in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events for patients deemed at low or moderate risk of cardiovascular disease from a large meta-analysis review of six primary prevention trials encompassing over 95,000 patients.3

If our patients do present with vascular disease, current ACCP guidelines recommend single-agent antiplatelet medication (either ASA or clopidogrel) for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) whether planning LE revascularization with bypass or via endovascular means with grade 1A evidence.4 This works fine for single-focus vascular disease and each antiplatelet agent have proponents but either works well.

That’s great, but what about all those sick cardiac patients we see the most of? First, CHARISMA subgroup analysis of patients with preexisting coronary and/or cerebrovascular disease demonstrate a 7.1% risk reduction in MI, cerebrovascular events, and cardiac ischemic deaths when continuing DAPT over aspirin alone, and similar risk reduction is found in PAD patients for endpoints of MI and ischemic cardiovascular events. Second, there was no significant difference in severe, fatal, or moderate bleeding in those receiving DAPT vs. aspirin alone with only minor bleeding increased using DAPT. Third, real-life practice echoes multiple trial experiences such as the Vascular Study Group of New England study group confirmed in reviewing 16 centers and 66 surgeons with more than 10,000 patients. Approximately 39% underwent major aortic or lower extremity bypass operations.

No statistical difference could be found for reoperation (P = .74), transfusion (P = .1) or operative type between DAPT or aspirin use alone.5 This is rediscovered once again by Saadeh and Sfeir in their prospective study of 647 major arterial procedures over 7 years finding no significant difference in reoperation for bleeding or bleeding mortality between DAPT vs. aspirin alone.6

So can we stop bashing clopidogrel as an evil agent of bleeding as Dr. Dalsing wishes to do? After all, he has been on record as stating, “I don’t know if our bleeding risk is worse or better … something we have to do to keep our grafts going.” Evidence tells us the benefits for continuing DAPT as seen in risk reduction in primary cardiovascular outcomes far outweigh the risk of minor bleeding associated with continued use.

Let the science dictate practice. Patients with low or moderate risk for cardiovascular disease need no antiplatelet medication unless undergoing PAD treatment where a single agent, either aspirin or clopidogrel alone, is sufficient. In those patients having a large cardiovascular burden of disease, combination of aspirin and clopidogrel improves survival benefit and reduces ischemic events without a significant risk of reoperation, transfusion, or bleeding-related mortality. As many of our patients require DAPT for drug eluting coronary stents, withholding clopidogrel preoperatively increases overall risk beyond acceptable limits. Improving surgical skills and paying attention to hemostasis during the operation will allow naysayers to achieve improved patient survival without fear of bleeding when continuing best medical therapy such as DAPT.

Gary Lemmon, MD, is professor of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and chief, vascular surgery, Indianapolis VA Medical Center. He reported no relevant conflicts.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825-33

2. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:192-201

3. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-604. Chest. 2012;141:e669s-90s

5. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54: 779-84

6. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58: 1586-92

The continued use of perioperative clopidogrel is debatable!

There are cases in which clopidogrel should not be discontinued for a needed vascular intervention. Delaying operation or maintaining clopidogrel during operation if your patient required a recent coronary stent is warranted unless you are willing to accept an acute coronary thrombosis.

However, in other cases, for example infrainguinal grafts, the risk of potential increased bleeding when adding clopidogrel to aspirin may outweigh potential improvements in graft patency. This is especially true of below-knee vein bypass grafts where data do not support improved patency. However, in the CASPAR trial, prosthetic graft patency did appear to be beneficial, but only in subgroup analysis.1

It is true that severe bleeding was not increased (intracranial hemorrhage, or hemodynamic compromise: 1 vs 2.7%, P = NS) but moderate bleeding (transfusion required: 0.7 vs 3.7%, P = .012) and mild bleeding (5.4 vs 12.1%, P = .004) was increased when this agent was used especially in vein graft surgery. This risk of bleeding was present even when clopidogrel was begun 2 or more days after surgery.1

To complicate this decision, a Cochrane review did not consider subgroup analysis as statistically valid and so the authors considered infrainguinal graft patency as not improved with clopidogrel but bleeding risk was increased. One might even question the use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for vein graft bypasses based on the results of this metanalysis.2 Carotid endarterectomy is a common vascular surgery procedure in which antiplatelet use has been evaluated in the real-world situation and with large cohorts. As is always the case when dealing with patient issues, the addition of one agent does not tell the entire story and patient demographics can have a significant influence on the outcome. A report from the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) database controlled for patient differences by propensity matching with more than 4,500 patients in each of the two groups; ASA vs. ASA + clopidogrel; demonstrated that major bleeding, defined as return to the OR for bleeding, was statistically more common with dual therapy (1.3% vs. 0.7%, P = .004).3

The addition of clopidogrel did statistically decrease the risk of ipsilateral TIA or stroke (0.8% vs. 1.2%, P = .02) but not the risk of death (0.2% vs. 0.3%, P = .3) or postoperative MI (1% vs. 0.8%, P = .4). Reoperation for bleeding is not inconsequential since in patients requiring this intervention, there is a significantly worse outcome in regard to stroke (3.7% vs. 0.8%, P = .001), MI (6.2% vs. 0.8%, P = .001), and death (2.5% vs. 0.2%,P = .001). Further drill down involving propensity score–matched analysis stratified by symptom status (asymptomatic vs. symptomatic) was quite interesting in that in only asymptomatic patients did the addition of clopidogrel actually demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in TIA or stroke, any stroke, or composite stroke/death. Symptomatic patients taking dual therapy demonstrated a slight reduction in TIA or stroke (1.4% vs. 1.7%, P = .6), any stroke (1.1% vs. 1.2%, P = .9) and composite stroke/death (1.2% vs. 1.5%, P = .5) but in no instance was statistical significance reached. The use of protamine did help to decrease the risk of bleeding.

Regarding the use of dual therapy during open aortic operations, an earlier report of the VQI database demonstrated no significant difference in bleeding risk statistically, but if one delves deeper the data indicate something different. In the majority of cases, vascular surgeons do not feel comfortable preforming this extensive dissection on dual therapy. Of the cases reported, 1,074 were preformed either free of either drug or only on ASA while 42 were on dual therapy and only 12 on clopidogrel only. In fact, in the conclusions, the authors note that they do not believe that conclusions regarding clopidogrel use in patient undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair can be drawn based on their results since the potential for a type II error was too great.4

It may be that our current level of sophistication is not sufficiently mature to determine the actual effect that clopidogrel is having on our patients. Clopidogrel, a thienopyridine, inhibits platelet activation by blocking the ADP-binding site for the P2Y12 receptor. Over 85% of ingested drug is metabolized into inactive metabolites while 15% is metabolized by the liver via a two-step oxidative process into the active thiol metabolite. Inter-individual variability in the antiplatelet response to thienopyridines is noted and partially caused by genetic mutations in the CP isoenzymes. Platelet reactivity testing is possible but most of the work has been conducted for those patients requiring coronary artery revascularization. Results of tailoring intervention to maximize therapeutic benefit and decrease the risk of bleeding have been inconsistent but, in some studies, appear to be promising.5 This approach may ultimately be found superior to determining how effective clopidogrel actually is in a particular case with some insight into the bleeding risk as well. With this determination, whether or not to hold clopidogrel perioperatively can be made with some science behind the decision.

Clearly, a blanket statement that the risk of bleeding should be accepted or ignored because of the demonstrated benefits of clopidogrel in patients requiring vascular surgery is not accurate. In some cases, there is no clear benefit, so eliminating the bleeding risk may well be the appropriate decision. The astute vascular surgeon understands the details of the written word in order to make an educated decision and understands that new information such as determining platelet reactivity may provide more clarity to such decisions in the future.

Michael C. Dalsing, MD, is chief of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He reported no relevant conflicts.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:825-33

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000535

Painful Purple Toes

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

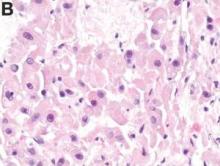

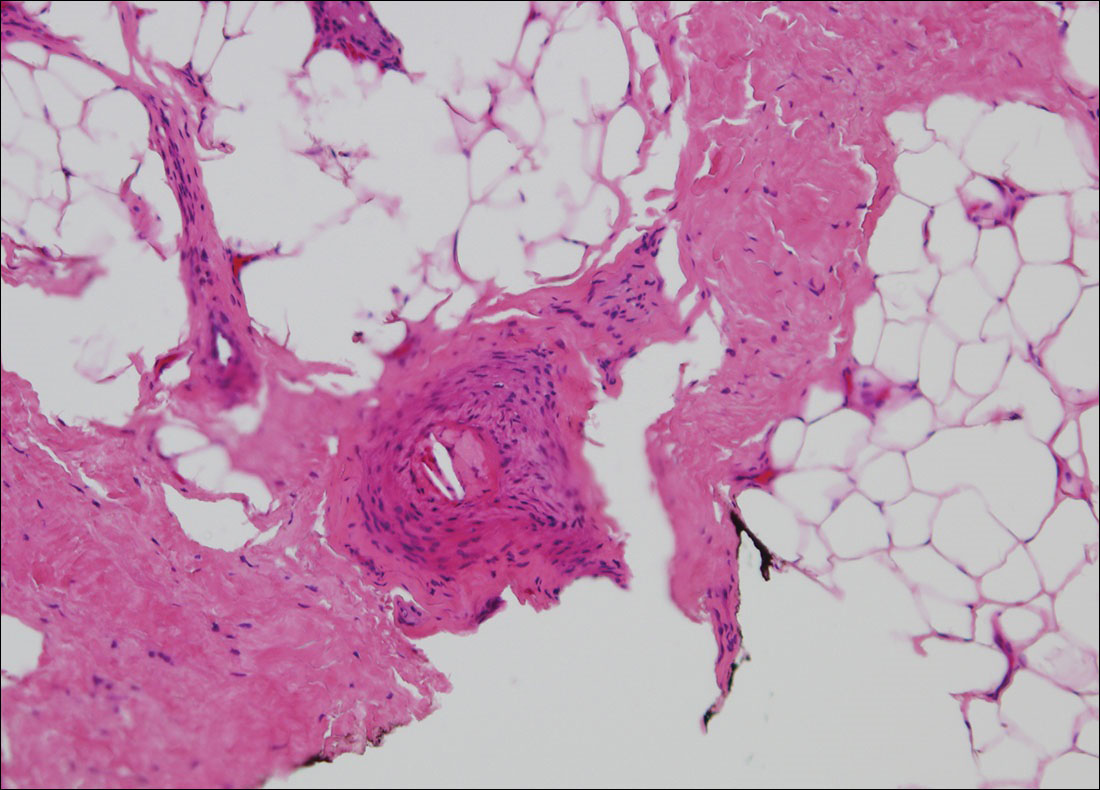

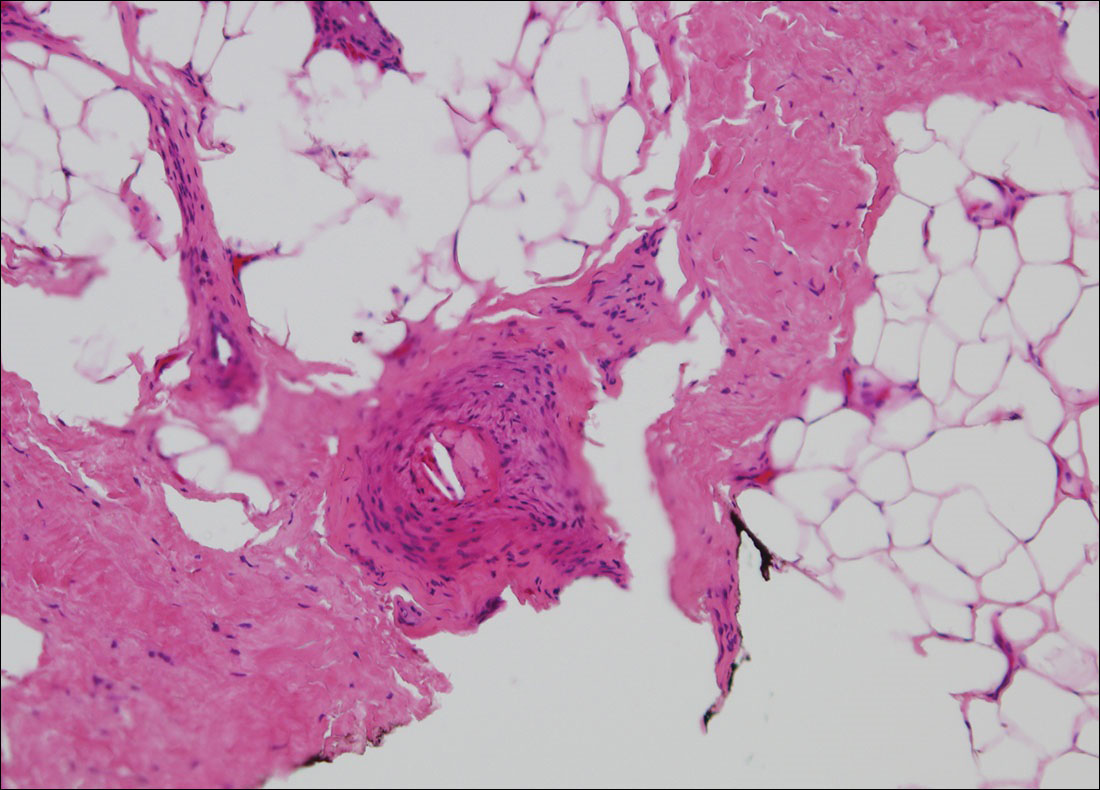

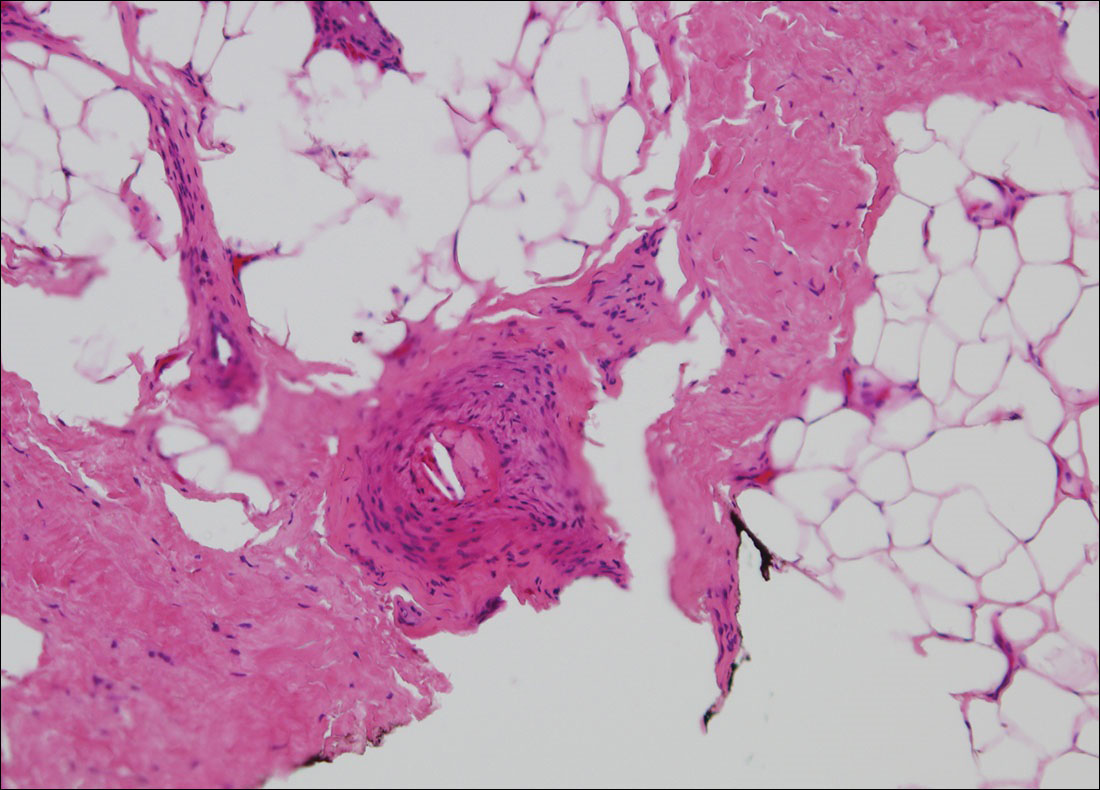

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

A 63-year-old man presented with sudden onset of severe pain in the right hallux and fifth toe of 3 days' duration. The patient had hypertension and hyperlipidemia with a 45-year history of smoking and had not undergone any vascular procedures. Physical examination revealed relatively well-defined cyanotic change with remarkable coldness on the affected toes as well as livedo reticularis on the underside of the toes. All peripheral pulses were present. Laboratory investigation revealed no remarkable changes with eosinophil counts within reference range and normal renal function. A biopsy taken from the fifth toe revealed thrombotic arterioles with cholesterol clefts.

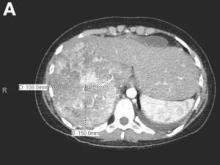

Clinical Challenges - September 2016: Fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

Histologic analysis was consistent with a fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient developed decerebrate posturing without cerebral edema on CT of the head. The patient was treated with mannitol, hyperventilation, and therapeutic hypothermia, as well as lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, and “empiric” sodium benzoate/sodium phenylacetate (Ammonul, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Ariz.) for the possibility of a urea cycle disorder. In hopes of decreasing blood flow to the tumor, the patient underwent embolization of the right hepatic artery with no clinical improvement. Given the persistently elevated ammonia level, a work-up for an underlying urea cycle disorder was performed, revealing trace citrulline and increased urine orotic acids and uracil, suggesting an ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. She was started on parenteral nutrition with arginine supplementation, after which her ammonia level normalized with subsequent improvement in her mental status.

Fibrolamellar-HCC is a rare, malignant, primary liver tumor predominantly affecting young adults with no underlying liver disease. This hypervascular tumor is radiographically characterized by a central scar.1 Most patients experience vague abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Fibrolamellar-HCC carries a better prognosis than HCC; in surgically resectable cases, the 5-year survival rates range between 37% and 76% vs. 12-14 months in nonresectable cases.2 Systemic chemotherapy has been used in case reports and the role of sorafenib remains unexplored and ill defined.

This is the second reported case of metastatic fibrolamellar-HCC with hyperammonemia.3 Although urea cycle disorders are more commonly diagnosed in newborns and infants, patients with partial enzyme deficiencies may present later in life and manifest in the setting of metabolic decompensation or stress. Our patient’s initial evaluation was consistent with a urea cycle deficiency, but OTC sequencing from the blood was negative. We hypothesize that the patient exhibited a “functional” OTC deficiency as a result of a combination of the massive tumor burden and portal vein thrombus, leading to a decreased expression of the OTC gene and insufficient enzyme production. The patient is doing well 3 months post resection and is being considered for a phase I clinical trial with a telomerase inhibitor, imetelstat.

References

1. Ichikawa, T., Federle, M.P., Grazioli, L., et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352-61.

2. Ward, S.C. Waxman, S. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: A review with focus on genetics and comparison to other malignant primary liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(1):61-70.

3. Sethi, S., Tageja, N., Singh, J., et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: A rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522-4.

The diagnosis

Histologic analysis was consistent with a fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient developed decerebrate posturing without cerebral edema on CT of the head. The patient was treated with mannitol, hyperventilation, and therapeutic hypothermia, as well as lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, and “empiric” sodium benzoate/sodium phenylacetate (Ammonul, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Ariz.) for the possibility of a urea cycle disorder. In hopes of decreasing blood flow to the tumor, the patient underwent embolization of the right hepatic artery with no clinical improvement. Given the persistently elevated ammonia level, a work-up for an underlying urea cycle disorder was performed, revealing trace citrulline and increased urine orotic acids and uracil, suggesting an ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. She was started on parenteral nutrition with arginine supplementation, after which her ammonia level normalized with subsequent improvement in her mental status.

Fibrolamellar-HCC is a rare, malignant, primary liver tumor predominantly affecting young adults with no underlying liver disease. This hypervascular tumor is radiographically characterized by a central scar.1 Most patients experience vague abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Fibrolamellar-HCC carries a better prognosis than HCC; in surgically resectable cases, the 5-year survival rates range between 37% and 76% vs. 12-14 months in nonresectable cases.2 Systemic chemotherapy has been used in case reports and the role of sorafenib remains unexplored and ill defined.

This is the second reported case of metastatic fibrolamellar-HCC with hyperammonemia.3 Although urea cycle disorders are more commonly diagnosed in newborns and infants, patients with partial enzyme deficiencies may present later in life and manifest in the setting of metabolic decompensation or stress. Our patient’s initial evaluation was consistent with a urea cycle deficiency, but OTC sequencing from the blood was negative. We hypothesize that the patient exhibited a “functional” OTC deficiency as a result of a combination of the massive tumor burden and portal vein thrombus, leading to a decreased expression of the OTC gene and insufficient enzyme production. The patient is doing well 3 months post resection and is being considered for a phase I clinical trial with a telomerase inhibitor, imetelstat.

References

1. Ichikawa, T., Federle, M.P., Grazioli, L., et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352-61.

2. Ward, S.C. Waxman, S. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: A review with focus on genetics and comparison to other malignant primary liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(1):61-70.

3. Sethi, S., Tageja, N., Singh, J., et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: A rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522-4.

The diagnosis

Histologic analysis was consistent with a fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient developed decerebrate posturing without cerebral edema on CT of the head. The patient was treated with mannitol, hyperventilation, and therapeutic hypothermia, as well as lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, and “empiric” sodium benzoate/sodium phenylacetate (Ammonul, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Ariz.) for the possibility of a urea cycle disorder. In hopes of decreasing blood flow to the tumor, the patient underwent embolization of the right hepatic artery with no clinical improvement. Given the persistently elevated ammonia level, a work-up for an underlying urea cycle disorder was performed, revealing trace citrulline and increased urine orotic acids and uracil, suggesting an ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. She was started on parenteral nutrition with arginine supplementation, after which her ammonia level normalized with subsequent improvement in her mental status.

Fibrolamellar-HCC is a rare, malignant, primary liver tumor predominantly affecting young adults with no underlying liver disease. This hypervascular tumor is radiographically characterized by a central scar.1 Most patients experience vague abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Fibrolamellar-HCC carries a better prognosis than HCC; in surgically resectable cases, the 5-year survival rates range between 37% and 76% vs. 12-14 months in nonresectable cases.2 Systemic chemotherapy has been used in case reports and the role of sorafenib remains unexplored and ill defined.

This is the second reported case of metastatic fibrolamellar-HCC with hyperammonemia.3 Although urea cycle disorders are more commonly diagnosed in newborns and infants, patients with partial enzyme deficiencies may present later in life and manifest in the setting of metabolic decompensation or stress. Our patient’s initial evaluation was consistent with a urea cycle deficiency, but OTC sequencing from the blood was negative. We hypothesize that the patient exhibited a “functional” OTC deficiency as a result of a combination of the massive tumor burden and portal vein thrombus, leading to a decreased expression of the OTC gene and insufficient enzyme production. The patient is doing well 3 months post resection and is being considered for a phase I clinical trial with a telomerase inhibitor, imetelstat.

References

1. Ichikawa, T., Federle, M.P., Grazioli, L., et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352-61.

2. Ward, S.C. Waxman, S. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: A review with focus on genetics and comparison to other malignant primary liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(1):61-70.

3. Sethi, S., Tageja, N., Singh, J., et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: A rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522-4.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Jana G. Hashash, MD, Kavitha Thudi, MD, and Shahid M. Malik, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143[5]:1157, 1401-2).

An 18-year-old white woman with no significant medical history was in good health until 2 days before admission, when she developed nausea, vomiting, and confusion. She was awake but lethargic and disoriented with asterixis. The remainder of her neurologic examination was nonfocal.

Laboratory data revealed white blood cell count of 13,000/L, hemoglobin of 13 g, and a platelet count of 300,000/L. A serum venous ammonia level was 342 micromol/L (normal range, 9-33). A urine drug screen was negative, as were her serum acetaminophen and aminosalicylic acid levels. Infectious work-up was unrevealing. Work-up for underlying chronic liver disease, including viral hepatitis serologies, autoimmune serologies, ceruloplasmin level, alpha-1 antitrypsin level, as well as hemochromatosis gene testing, was negative. An electroencephalography revealed burst suppression but no seizure activity. A lumbar puncture was negative.

An abdominal contrast-enhanced CT revealed an 11 × 15-cm heterogeneous, hypervascular mass replacing the majority of the right hepatic lobe (Figure A), right portal vein thrombosis, an enlarged hypervascular portocaval node measuring 2.0 × 2.0 cm, and an 8-mm left lower lobe lung lesion concerning for metastatic disease. Her liver was mildly enlarged, but was noncirrhotic. There was no radiologic evidence of portal hypertension or varices. There was no evidence of extrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Serum tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein, were within normal limits (1 ng/mL).

What is the cause of this young patient’s acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Updated: Federal Practitioner Submission Guidelines

Federal Practitioner welcomes submission of manuscripts on subjects pertinent to physicians, clinical pharmacists, physician assistants, advanced practice nurses, and medical center administrators currently working within the VA, the DoD, IHS, and the PHS. Authored features include clinical review articles, original research, case reports, evidence-based treatment protocols, and program profiles. The journal also publishes bylined editorials and columns. Manuscript submissions will be considered for publication only if the author has certified that the work is original, has not been published previously, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All manuscripts are subject to peer review.

Federal Practitioner welcomes submission of manuscripts on subjects pertinent to physicians, clinical pharmacists, physician assistants, advanced practice nurses, and medical center administrators currently working within the VA, the DoD, IHS, and the PHS. Authored features include clinical review articles, original research, case reports, evidence-based treatment protocols, and program profiles. The journal also publishes bylined editorials and columns. Manuscript submissions will be considered for publication only if the author has certified that the work is original, has not been published previously, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All manuscripts are subject to peer review.

Federal Practitioner welcomes submission of manuscripts on subjects pertinent to physicians, clinical pharmacists, physician assistants, advanced practice nurses, and medical center administrators currently working within the VA, the DoD, IHS, and the PHS. Authored features include clinical review articles, original research, case reports, evidence-based treatment protocols, and program profiles. The journal also publishes bylined editorials and columns. Manuscript submissions will be considered for publication only if the author has certified that the work is original, has not been published previously, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. All manuscripts are subject to peer review.

Study reveals barriers to accessing palliative care services

©ASCO/Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients may face challenges when trying to access palliative and supportive care services at cancer centers, a new study suggests.

Researchers took a “mystery shopper” approach and placed calls to cancer centers inquiring about palliative and supportive care services for a family member.

The callers sometimes had difficulty obtaining information about these services, even though all of the centers offer them.

“It’s sobering to hear that such services are not readily accessible at many centers,” said study investigator Kathryn Hutchins, a medical student at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“However, it provides an opportunity for cancer centers to empower their front-line staff, as well as the oncology care team, through education and training so that the entire enterprise has a common understanding of palliative care and how to access it.”

Hutchins and her colleagues presented this research at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 122).

The researchers placed 160 calls to 40 major cancer centers. The team chose to focus on National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers because they all provide palliative care services along with other supportive care services.

The researchers used the same script for every call, asking about services for a 58-year-old female who was recently diagnosed with inoperable liver cancer. The team called each center 4 times on different days.

In 38.2% of the calls, the researchers were not able to receive complete information about supportive care services.

In 9.5% of calls, cancer center staff gave an answer other than “yes” regarding the availability of palliative care services, even though such services were available.

The answers varied and included responses such as:

- Palliative care was for end-of-life patients only (n=2)

- No physicians specialized in symptom management (n=3)

- A medical record review would be needed first (n=2).

In addition, 10 staff members said they were unsure about the availability of palliative care, and 2 were unfamiliar with the term.

Overall, 37.6% of the callers were told that all 7 supportive care services they inquired about were offered.

“As oncologists, we like to believe that, when we refer patients to our institution’s helpline, they will get connected to the services they need, but that doesn’t always happen,” said study investigator Arif Kamal, MD, of Duke Cancer Institute.

“It’s important for oncologists to be aware of these barriers and to work to eliminate them.” ![]()

©ASCO/Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients may face challenges when trying to access palliative and supportive care services at cancer centers, a new study suggests.

Researchers took a “mystery shopper” approach and placed calls to cancer centers inquiring about palliative and supportive care services for a family member.

The callers sometimes had difficulty obtaining information about these services, even though all of the centers offer them.

“It’s sobering to hear that such services are not readily accessible at many centers,” said study investigator Kathryn Hutchins, a medical student at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“However, it provides an opportunity for cancer centers to empower their front-line staff, as well as the oncology care team, through education and training so that the entire enterprise has a common understanding of palliative care and how to access it.”

Hutchins and her colleagues presented this research at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 122).

The researchers placed 160 calls to 40 major cancer centers. The team chose to focus on National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers because they all provide palliative care services along with other supportive care services.

The researchers used the same script for every call, asking about services for a 58-year-old female who was recently diagnosed with inoperable liver cancer. The team called each center 4 times on different days.

In 38.2% of the calls, the researchers were not able to receive complete information about supportive care services.

In 9.5% of calls, cancer center staff gave an answer other than “yes” regarding the availability of palliative care services, even though such services were available.

The answers varied and included responses such as:

- Palliative care was for end-of-life patients only (n=2)

- No physicians specialized in symptom management (n=3)

- A medical record review would be needed first (n=2).

In addition, 10 staff members said they were unsure about the availability of palliative care, and 2 were unfamiliar with the term.

Overall, 37.6% of the callers were told that all 7 supportive care services they inquired about were offered.

“As oncologists, we like to believe that, when we refer patients to our institution’s helpline, they will get connected to the services they need, but that doesn’t always happen,” said study investigator Arif Kamal, MD, of Duke Cancer Institute.

“It’s important for oncologists to be aware of these barriers and to work to eliminate them.” ![]()

©ASCO/Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients may face challenges when trying to access palliative and supportive care services at cancer centers, a new study suggests.

Researchers took a “mystery shopper” approach and placed calls to cancer centers inquiring about palliative and supportive care services for a family member.

The callers sometimes had difficulty obtaining information about these services, even though all of the centers offer them.

“It’s sobering to hear that such services are not readily accessible at many centers,” said study investigator Kathryn Hutchins, a medical student at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“However, it provides an opportunity for cancer centers to empower their front-line staff, as well as the oncology care team, through education and training so that the entire enterprise has a common understanding of palliative care and how to access it.”

Hutchins and her colleagues presented this research at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 122).

The researchers placed 160 calls to 40 major cancer centers. The team chose to focus on National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers because they all provide palliative care services along with other supportive care services.

The researchers used the same script for every call, asking about services for a 58-year-old female who was recently diagnosed with inoperable liver cancer. The team called each center 4 times on different days.

In 38.2% of the calls, the researchers were not able to receive complete information about supportive care services.

In 9.5% of calls, cancer center staff gave an answer other than “yes” regarding the availability of palliative care services, even though such services were available.

The answers varied and included responses such as:

- Palliative care was for end-of-life patients only (n=2)

- No physicians specialized in symptom management (n=3)

- A medical record review would be needed first (n=2).

In addition, 10 staff members said they were unsure about the availability of palliative care, and 2 were unfamiliar with the term.

Overall, 37.6% of the callers were told that all 7 supportive care services they inquired about were offered.

“As oncologists, we like to believe that, when we refer patients to our institution’s helpline, they will get connected to the services they need, but that doesn’t always happen,” said study investigator Arif Kamal, MD, of Duke Cancer Institute.

“It’s important for oncologists to be aware of these barriers and to work to eliminate them.” ![]()

Pregnancy screening lacking in girls with AML, ALL

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Many adolescent females are not being screened for pregnancy before beginning chemotherapy or undergoing computed tomography (CT) scans, according to research published in Cancer.

In this study, pregnancy screening was underused in adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), those with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and those who received CT scans of the abdomen or pelvis during visits to the emergency room (ER).

“We found that adolescent girls are not adequately screened for pregnancy prior to receiving chemotherapy or CT scans that could harm a developing fetus,” said study author Pooja Rao, MD, of Penn State Health’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“Adolescents with ALL, the most common childhood cancer, had the lowest rates of pregnancy screening of the patients we studied.”

Dr Rao and her colleagues examined pregnancy screening patterns among adolescent females newly diagnosed with ALL or AML, as well as adolescent females who visited the ER and received CT scans of the abdomen or pelvis. (In emergency medicine, pregnancy screening protocols exist for adolescents prior to receiving radiation due to the known teratogenic risks of radiation.)

The analysis included patients ages 10 to 18 who were admitted to hospitals across the US from 1999 to 2011. There were a total of 35,650 patient visits—127 for AML patients, 889 for ALL patients, and 34,634 ER admissions with CT scans of the abdomen/pelvis.

The proportion of visits with an appropriately timed pregnancy test was 35% for the ALL patients, 64% for the AML patients, and 58% in the ER group.

The researchers noted that ALL patients tended to be younger than the AML patients and the ER patients, and there was substantial variation in pregnancy screening patterns among the different hospitals.

However, in a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model adjusted for hospital clustering and patient age, patients with ALL were significantly less likely to have an appropriately timed pregnancy test when compared to patients in the ER cohort. The adjusted prevalence ratio was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.65-0.78).

And in a GEE model adjusted for hospital clustering, patients with AML were more likely to have an appropriately timed pregnancy test than patients in the ER cohort, but this difference was not statistically significant. The adjusted prevalence ratio was 1.12 (95% CI, 0.99-1.27).

The researchers also found that pregnancy screening continued to increase over time in the ALL cohort but remained “relatively stable” from 2008 onward in the AML and ER cohorts.

“Since nearly all chemotherapy agents used for childhood/adolescent acute leukemia can cause potential harm to a developing fetus, our findings indicate a need for standardized pregnancy screening practices for adolescent patients being treated for cancer,” Dr Rao said.

She also noted that the low rates of pregnancy screening observed in this study may indicate a reluctance on the part of pediatric oncologists to discuss sexual health practices with adolescent patients.

“While sexual health discussions and education may traditionally be thought to be the responsibility of the patient’s primary care provider, adolescents with cancer will often see their oncologist frequently over the course of their cancer treatment and afterwards,” Dr Rao said. “Oncologists therefore are well-positioned to initiate discussions about sexual health with their patients.” ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Many adolescent females are not being screened for pregnancy before beginning chemotherapy or undergoing computed tomography (CT) scans, according to research published in Cancer.

In this study, pregnancy screening was underused in adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), those with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and those who received CT scans of the abdomen or pelvis during visits to the emergency room (ER).

“We found that adolescent girls are not adequately screened for pregnancy prior to receiving chemotherapy or CT scans that could harm a developing fetus,” said study author Pooja Rao, MD, of Penn State Health’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“Adolescents with ALL, the most common childhood cancer, had the lowest rates of pregnancy screening of the patients we studied.”

Dr Rao and her colleagues examined pregnancy screening patterns among adolescent females newly diagnosed with ALL or AML, as well as adolescent females who visited the ER and received CT scans of the abdomen or pelvis. (In emergency medicine, pregnancy screening protocols exist for adolescents prior to receiving radiation due to the known teratogenic risks of radiation.)

The analysis included patients ages 10 to 18 who were admitted to hospitals across the US from 1999 to 2011. There were a total of 35,650 patient visits—127 for AML patients, 889 for ALL patients, and 34,634 ER admissions with CT scans of the abdomen/pelvis.

The proportion of visits with an appropriately timed pregnancy test was 35% for the ALL patients, 64% for the AML patients, and 58% in the ER group.

The researchers noted that ALL patients tended to be younger than the AML patients and the ER patients, and there was substantial variation in pregnancy screening patterns among the different hospitals.

However, in a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model adjusted for hospital clustering and patient age, patients with ALL were significantly less likely to have an appropriately timed pregnancy test when compared to patients in the ER cohort. The adjusted prevalence ratio was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.65-0.78).

And in a GEE model adjusted for hospital clustering, patients with AML were more likely to have an appropriately timed pregnancy test than patients in the ER cohort, but this difference was not statistically significant. The adjusted prevalence ratio was 1.12 (95% CI, 0.99-1.27).

The researchers also found that pregnancy screening continued to increase over time in the ALL cohort but remained “relatively stable” from 2008 onward in the AML and ER cohorts.

“Since nearly all chemotherapy agents used for childhood/adolescent acute leukemia can cause potential harm to a developing fetus, our findings indicate a need for standardized pregnancy screening practices for adolescent patients being treated for cancer,” Dr Rao said.

She also noted that the low rates of pregnancy screening observed in this study may indicate a reluctance on the part of pediatric oncologists to discuss sexual health practices with adolescent patients.

“While sexual health discussions and education may traditionally be thought to be the responsibility of the patient’s primary care provider, adolescents with cancer will often see their oncologist frequently over the course of their cancer treatment and afterwards,” Dr Rao said. “Oncologists therefore are well-positioned to initiate discussions about sexual health with their patients.” ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Many adolescent females are not being screened for pregnancy before beginning chemotherapy or undergoing computed tomography (CT) scans, according to research published in Cancer.

In this study, pregnancy screening was underused in adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), those with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and those who received CT scans of the abdomen or pelvis during visits to the emergency room (ER).

“We found that adolescent girls are not adequately screened for pregnancy prior to receiving chemotherapy or CT scans that could harm a developing fetus,” said study author Pooja Rao, MD, of Penn State Health’s Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“Adolescents with ALL, the most common childhood cancer, had the lowest rates of pregnancy screening of the patients we studied.”

Dr Rao and her colleagues examined pregnancy screening patterns among adolescent females newly diagnosed with ALL or AML, as well as adolescent females who visited the ER and received CT scans of the abdomen or pelvis. (In emergency medicine, pregnancy screening protocols exist for adolescents prior to receiving radiation due to the known teratogenic risks of radiation.)

The analysis included patients ages 10 to 18 who were admitted to hospitals across the US from 1999 to 2011. There were a total of 35,650 patient visits—127 for AML patients, 889 for ALL patients, and 34,634 ER admissions with CT scans of the abdomen/pelvis.

The proportion of visits with an appropriately timed pregnancy test was 35% for the ALL patients, 64% for the AML patients, and 58% in the ER group.

The researchers noted that ALL patients tended to be younger than the AML patients and the ER patients, and there was substantial variation in pregnancy screening patterns among the different hospitals.