User login

Hospital Mobility Program Maintains Older Patients’ Mobility after Discharge

Background: Older hospitalized patients experience decreased mobility while in the hospital and suffer from impaired function and mobility after they are discharged. The efficacy and safety of inpatient mobility programs are unknown.

Study design: Randomized, single-blinded controlled trial.

Setting: Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Alabama.

Synopsis: The study included 100 patients age 65 years and older admitted to general medical wards. Researchers excluded cognitively impaired patients and patients with limited life expectancy. Intervention patients received a standardized hospital mobility protocol, with up to twice daily 15- to 20-minute visits by research personnel. Visits sought to progressively increase mobility from assisted sitting to ambulation. Physical activity was coupled with a behavioral intervention focused on goal setting and mobility barrier resolution. The comparison group received usual care. Outcomes included changes in activities of daily living (ADLs) and community mobility one month after hospital discharge.

One month after hospitalization, there were no differences in ADLs between intervention and control patients. Patients in the mobility protocol arm, however, maintained their prehospital community mobility, whereas usual-care patients had a statistically significant decrease in mobility as measured by the Life-Space Assessment. There was no difference in falls between groups.

Bottom line: A hospital mobility intervention was a safe and effective means of preserving community mobility. Future effectiveness studies are needed to demonstrate feasibility and outcomes in real-world settings.

Citation: Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr, et al. Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):921-927.

Short Take

Topical NSAIDs Effective for Back Pain

Using ketoprofen gel in addition to intravenous dexketoprofen improves pain relief in patients presenting to the emergency department with low back pain.

Citation: Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexkeoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-1461.

Background: Older hospitalized patients experience decreased mobility while in the hospital and suffer from impaired function and mobility after they are discharged. The efficacy and safety of inpatient mobility programs are unknown.

Study design: Randomized, single-blinded controlled trial.

Setting: Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Alabama.

Synopsis: The study included 100 patients age 65 years and older admitted to general medical wards. Researchers excluded cognitively impaired patients and patients with limited life expectancy. Intervention patients received a standardized hospital mobility protocol, with up to twice daily 15- to 20-minute visits by research personnel. Visits sought to progressively increase mobility from assisted sitting to ambulation. Physical activity was coupled with a behavioral intervention focused on goal setting and mobility barrier resolution. The comparison group received usual care. Outcomes included changes in activities of daily living (ADLs) and community mobility one month after hospital discharge.

One month after hospitalization, there were no differences in ADLs between intervention and control patients. Patients in the mobility protocol arm, however, maintained their prehospital community mobility, whereas usual-care patients had a statistically significant decrease in mobility as measured by the Life-Space Assessment. There was no difference in falls between groups.

Bottom line: A hospital mobility intervention was a safe and effective means of preserving community mobility. Future effectiveness studies are needed to demonstrate feasibility and outcomes in real-world settings.

Citation: Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr, et al. Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):921-927.

Short Take

Topical NSAIDs Effective for Back Pain

Using ketoprofen gel in addition to intravenous dexketoprofen improves pain relief in patients presenting to the emergency department with low back pain.

Citation: Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexkeoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-1461.

Background: Older hospitalized patients experience decreased mobility while in the hospital and suffer from impaired function and mobility after they are discharged. The efficacy and safety of inpatient mobility programs are unknown.

Study design: Randomized, single-blinded controlled trial.

Setting: Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Alabama.

Synopsis: The study included 100 patients age 65 years and older admitted to general medical wards. Researchers excluded cognitively impaired patients and patients with limited life expectancy. Intervention patients received a standardized hospital mobility protocol, with up to twice daily 15- to 20-minute visits by research personnel. Visits sought to progressively increase mobility from assisted sitting to ambulation. Physical activity was coupled with a behavioral intervention focused on goal setting and mobility barrier resolution. The comparison group received usual care. Outcomes included changes in activities of daily living (ADLs) and community mobility one month after hospital discharge.

One month after hospitalization, there were no differences in ADLs between intervention and control patients. Patients in the mobility protocol arm, however, maintained their prehospital community mobility, whereas usual-care patients had a statistically significant decrease in mobility as measured by the Life-Space Assessment. There was no difference in falls between groups.

Bottom line: A hospital mobility intervention was a safe and effective means of preserving community mobility. Future effectiveness studies are needed to demonstrate feasibility and outcomes in real-world settings.

Citation: Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD Jr, et al. Comparison of posthospitalization function and community mobility in hospital mobility program and usual care patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):921-927.

Short Take

Topical NSAIDs Effective for Back Pain

Using ketoprofen gel in addition to intravenous dexketoprofen improves pain relief in patients presenting to the emergency department with low back pain.

Citation: Serinken M, Eken C, Tunay K, Golcuk Y. Ketoprofen gel improves low back pain in addition to IV dexkeoprofen: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1458-1461.

Daily Round Checklists in ICU Setting Don’t Reduce Mortality

Background: Checklists, goal assessment, and clinician prompting have shown promise in improving communication, care-process adherence, and clinical outcomes in ICUs and acute-care settings, but existing studies are limited by nonrandomized design and high-income settings.

Study design: Cluster randomized trial.

Setting: 118 academic and nonacademic ICUs in Brazil.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 6,761 patients to a quality improvement (QI) intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting. Analyses were adjusted for patient’s severity of illness and the ICU’s adjusted mortality ratio. There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.26). The QI intervention had no effect on 10 secondary clinical outcomes (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). The intervention improved adherence with four of seven care processes (e.g., use of low tidal volumes) and two of six factors of the safety climate. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only urinary catheter use remained statistically significant.

Strengths of this study are the large number of ICUs involved and a high rate of QI adherence. Limitations include the setting in a resource-constrained nation, limited success with adopting changes in care processes, and relatively short intervention period of six months.

Bottom line: In a large Brazilian randomized control trial, implementation of daily round checklists, along with goal setting and clinician prompting, did not change in-hospital mortality. It is possible that a longer intervention period would have found improved outcomes.

Citation: Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1480-1490.

Short Take

More Restrictions on Fluoroquinolones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended avoidance of fluoroquinolone drugs, which are often used for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, and uncomplicated UTI, due to the potential of serious side effects. Exceptions should be made for cases with no other treatment options.

Citation: Fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs: drug safety communication - FDA advises restricting use for certain uncomplicated infections. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

Background: Checklists, goal assessment, and clinician prompting have shown promise in improving communication, care-process adherence, and clinical outcomes in ICUs and acute-care settings, but existing studies are limited by nonrandomized design and high-income settings.

Study design: Cluster randomized trial.

Setting: 118 academic and nonacademic ICUs in Brazil.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 6,761 patients to a quality improvement (QI) intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting. Analyses were adjusted for patient’s severity of illness and the ICU’s adjusted mortality ratio. There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.26). The QI intervention had no effect on 10 secondary clinical outcomes (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). The intervention improved adherence with four of seven care processes (e.g., use of low tidal volumes) and two of six factors of the safety climate. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only urinary catheter use remained statistically significant.

Strengths of this study are the large number of ICUs involved and a high rate of QI adherence. Limitations include the setting in a resource-constrained nation, limited success with adopting changes in care processes, and relatively short intervention period of six months.

Bottom line: In a large Brazilian randomized control trial, implementation of daily round checklists, along with goal setting and clinician prompting, did not change in-hospital mortality. It is possible that a longer intervention period would have found improved outcomes.

Citation: Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1480-1490.

Short Take

More Restrictions on Fluoroquinolones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended avoidance of fluoroquinolone drugs, which are often used for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, and uncomplicated UTI, due to the potential of serious side effects. Exceptions should be made for cases with no other treatment options.

Citation: Fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs: drug safety communication - FDA advises restricting use for certain uncomplicated infections. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

Background: Checklists, goal assessment, and clinician prompting have shown promise in improving communication, care-process adherence, and clinical outcomes in ICUs and acute-care settings, but existing studies are limited by nonrandomized design and high-income settings.

Study design: Cluster randomized trial.

Setting: 118 academic and nonacademic ICUs in Brazil.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 6,761 patients to a quality improvement (QI) intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting. Analyses were adjusted for patient’s severity of illness and the ICU’s adjusted mortality ratio. There was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.26). The QI intervention had no effect on 10 secondary clinical outcomes (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia). The intervention improved adherence with four of seven care processes (e.g., use of low tidal volumes) and two of six factors of the safety climate. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, only urinary catheter use remained statistically significant.

Strengths of this study are the large number of ICUs involved and a high rate of QI adherence. Limitations include the setting in a resource-constrained nation, limited success with adopting changes in care processes, and relatively short intervention period of six months.

Bottom line: In a large Brazilian randomized control trial, implementation of daily round checklists, along with goal setting and clinician prompting, did not change in-hospital mortality. It is possible that a longer intervention period would have found improved outcomes.

Citation: Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1480-1490.

Short Take

More Restrictions on Fluoroquinolones

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended avoidance of fluoroquinolone drugs, which are often used for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, and uncomplicated UTI, due to the potential of serious side effects. Exceptions should be made for cases with no other treatment options.

Citation: Fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs: drug safety communication - FDA advises restricting use for certain uncomplicated infections. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

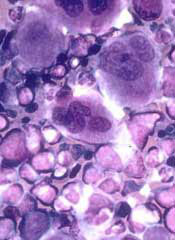

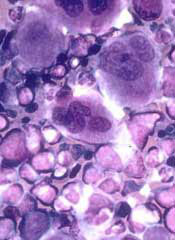

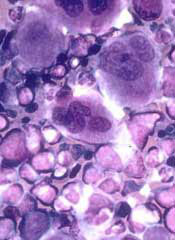

Long-Term Survival of a Patient With Late-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) a significant component of those deaths.1,2 Treatments for advanced-stage NSCLC, however, are limited. Erlotinib, a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has aided in advancing NSCLC therapy. Erlotinib has been shown to increase survival by 2 months compared with placebo in a phase 3, randomized controlled trial when used as second- or third-line therapy.3 The authors present a case of a man surviving almost 8 years with late-stage NSCLC on treatment with erlotinib at the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center (WLAMC).

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) a significant component of those deaths.1,2 Treatments for advanced-stage NSCLC, however, are limited. Erlotinib, a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has aided in advancing NSCLC therapy. Erlotinib has been shown to increase survival by 2 months compared with placebo in a phase 3, randomized controlled trial when used as second- or third-line therapy.3 The authors present a case of a man surviving almost 8 years with late-stage NSCLC on treatment with erlotinib at the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center (WLAMC).

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) a significant component of those deaths.1,2 Treatments for advanced-stage NSCLC, however, are limited. Erlotinib, a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has aided in advancing NSCLC therapy. Erlotinib has been shown to increase survival by 2 months compared with placebo in a phase 3, randomized controlled trial when used as second- or third-line therapy.3 The authors present a case of a man surviving almost 8 years with late-stage NSCLC on treatment with erlotinib at the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center (WLAMC).

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Note: Page numbers differ between the print issue and digital edition.

Potential therapeutic target for leukemia, other cancers

Photo by Thomas Semkow

Preclinical research indicates that a member of the Mediator protein complex plays a key role in hematopoiesis.

Investigators found that MED12 was required for the survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The team said this finding, along with the fact that MED12 mutations have been linked to leukemia and solid tumor malignancies, suggests that targeting MED12 hyperactivity might be a useful strategy for treating cancers.

“Because MED12 appears to be so essential to hematopoiesis, our study points to it as a possible target for future anticancer therapies for both chronic and acute forms of leukemia,” said Iannis Aifantis, PhD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York.

“Our study also suggests that MED12 hyperactivation or loss of control is a possible explanation for what factors may trigger these cancers and other solid tumors.”

Dr Aifantis and his colleagues described their study in Cell Stem Cell.

The investigators first analyzed the effects of MED12 deletion in mice. Mice bred to lack MED12 died within 2 weeks of birth and showed evidence of aberrant hematopoiesis—namely, a “severe reduction of bone marrow and thymus cellularity.”

Adult mice that were engineered to lose expression of MED12 after the injection of an activating molecule experienced a “rapid” reduction in bone marrow cellularity, as well as reductions in spleen and thymus size. These mice also had low white blood cell and platelet counts and died within 3 weeks of MED12 deletion.

Subsequent analyses of the animals’ bone marrow showed that estimates of HSPCs in each mouse fell from nearly 150,000 to 15,000 within 4 days of injection. Within 10 days, there were no HSPCs left.

Deleting MED12 was also lethal for human HSPCs. Colonies of CD34+ cells dropped from an average of 25 per plate to 5 per plate within 10 days of MED12 deletion.

On the other hand, MED12 did not affect the survival of other cell types. For example, MED12 deletion did not impact mouse embryonic fibroblasts, embryonic stem cells, or hair follicle stem cells.

In addition, deleting members of the Mediator kinase module besides MED12—MED13, CDK8, or CYCLIN C—did not have a significant effect on HSPCs and did not kill mice. The investigators said this provides further evidence that MED12—by loss of its function alone—is essential for hematopoiesis.

The team found that MED12 deletion destabilizes P300 binding at lineage-specific enhancers, which results in H3K27Ac depletion, enhancer de-activation, and the consequent loss of hematopoietic stem cell gene expression signatures.

As a next step, the investigators plan to screen blood samples from cancer patients for signs of MED12 mutations and uncontrolled HSPC development.

The team also hopes to determine the biological mechanisms involved in MED12 hyperactivation and identify drug molecules that could block MED12 hyperactivity and serve as potential MED12 inhibitors. ![]()

Photo by Thomas Semkow

Preclinical research indicates that a member of the Mediator protein complex plays a key role in hematopoiesis.

Investigators found that MED12 was required for the survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The team said this finding, along with the fact that MED12 mutations have been linked to leukemia and solid tumor malignancies, suggests that targeting MED12 hyperactivity might be a useful strategy for treating cancers.

“Because MED12 appears to be so essential to hematopoiesis, our study points to it as a possible target for future anticancer therapies for both chronic and acute forms of leukemia,” said Iannis Aifantis, PhD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York.

“Our study also suggests that MED12 hyperactivation or loss of control is a possible explanation for what factors may trigger these cancers and other solid tumors.”

Dr Aifantis and his colleagues described their study in Cell Stem Cell.

The investigators first analyzed the effects of MED12 deletion in mice. Mice bred to lack MED12 died within 2 weeks of birth and showed evidence of aberrant hematopoiesis—namely, a “severe reduction of bone marrow and thymus cellularity.”

Adult mice that were engineered to lose expression of MED12 after the injection of an activating molecule experienced a “rapid” reduction in bone marrow cellularity, as well as reductions in spleen and thymus size. These mice also had low white blood cell and platelet counts and died within 3 weeks of MED12 deletion.

Subsequent analyses of the animals’ bone marrow showed that estimates of HSPCs in each mouse fell from nearly 150,000 to 15,000 within 4 days of injection. Within 10 days, there were no HSPCs left.

Deleting MED12 was also lethal for human HSPCs. Colonies of CD34+ cells dropped from an average of 25 per plate to 5 per plate within 10 days of MED12 deletion.

On the other hand, MED12 did not affect the survival of other cell types. For example, MED12 deletion did not impact mouse embryonic fibroblasts, embryonic stem cells, or hair follicle stem cells.

In addition, deleting members of the Mediator kinase module besides MED12—MED13, CDK8, or CYCLIN C—did not have a significant effect on HSPCs and did not kill mice. The investigators said this provides further evidence that MED12—by loss of its function alone—is essential for hematopoiesis.

The team found that MED12 deletion destabilizes P300 binding at lineage-specific enhancers, which results in H3K27Ac depletion, enhancer de-activation, and the consequent loss of hematopoietic stem cell gene expression signatures.

As a next step, the investigators plan to screen blood samples from cancer patients for signs of MED12 mutations and uncontrolled HSPC development.

The team also hopes to determine the biological mechanisms involved in MED12 hyperactivation and identify drug molecules that could block MED12 hyperactivity and serve as potential MED12 inhibitors. ![]()

Photo by Thomas Semkow

Preclinical research indicates that a member of the Mediator protein complex plays a key role in hematopoiesis.

Investigators found that MED12 was required for the survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The team said this finding, along with the fact that MED12 mutations have been linked to leukemia and solid tumor malignancies, suggests that targeting MED12 hyperactivity might be a useful strategy for treating cancers.

“Because MED12 appears to be so essential to hematopoiesis, our study points to it as a possible target for future anticancer therapies for both chronic and acute forms of leukemia,” said Iannis Aifantis, PhD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York.

“Our study also suggests that MED12 hyperactivation or loss of control is a possible explanation for what factors may trigger these cancers and other solid tumors.”

Dr Aifantis and his colleagues described their study in Cell Stem Cell.

The investigators first analyzed the effects of MED12 deletion in mice. Mice bred to lack MED12 died within 2 weeks of birth and showed evidence of aberrant hematopoiesis—namely, a “severe reduction of bone marrow and thymus cellularity.”

Adult mice that were engineered to lose expression of MED12 after the injection of an activating molecule experienced a “rapid” reduction in bone marrow cellularity, as well as reductions in spleen and thymus size. These mice also had low white blood cell and platelet counts and died within 3 weeks of MED12 deletion.

Subsequent analyses of the animals’ bone marrow showed that estimates of HSPCs in each mouse fell from nearly 150,000 to 15,000 within 4 days of injection. Within 10 days, there were no HSPCs left.

Deleting MED12 was also lethal for human HSPCs. Colonies of CD34+ cells dropped from an average of 25 per plate to 5 per plate within 10 days of MED12 deletion.

On the other hand, MED12 did not affect the survival of other cell types. For example, MED12 deletion did not impact mouse embryonic fibroblasts, embryonic stem cells, or hair follicle stem cells.

In addition, deleting members of the Mediator kinase module besides MED12—MED13, CDK8, or CYCLIN C—did not have a significant effect on HSPCs and did not kill mice. The investigators said this provides further evidence that MED12—by loss of its function alone—is essential for hematopoiesis.

The team found that MED12 deletion destabilizes P300 binding at lineage-specific enhancers, which results in H3K27Ac depletion, enhancer de-activation, and the consequent loss of hematopoietic stem cell gene expression signatures.

As a next step, the investigators plan to screen blood samples from cancer patients for signs of MED12 mutations and uncontrolled HSPC development.

The team also hopes to determine the biological mechanisms involved in MED12 hyperactivation and identify drug molecules that could block MED12 hyperactivity and serve as potential MED12 inhibitors. ![]()

NICE approves bosutinib for routine NHS use

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending that bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), be made available through the National Health Service (NHS).

This means patients will no longer have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain bosutinib.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

NICE previously considered making bosutinib available through the NHS in 2013 but decided the drug was not cost-effective. So bosutinib was made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. ![]()

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending that bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), be made available through the National Health Service (NHS).

This means patients will no longer have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain bosutinib.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

NICE previously considered making bosutinib available through the NHS in 2013 but decided the drug was not cost-effective. So bosutinib was made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. ![]()

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending that bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), be made available through the National Health Service (NHS).

This means patients will no longer have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain bosutinib.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

NICE previously considered making bosutinib available through the NHS in 2013 but decided the drug was not cost-effective. So bosutinib was made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. ![]()

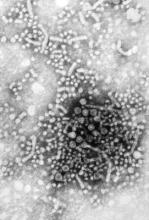

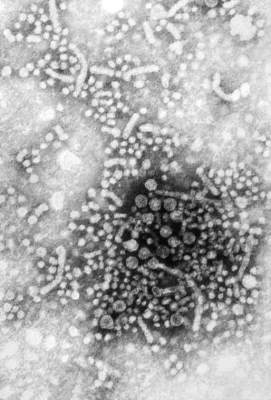

Patients with HBV inadequately monitored for disease activity

Chronic hepatitis B virus patients are insufficiently monitored for disease activity and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Philip R. Spradling, MD, and his associates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a cohort study of 2,992 patients with CHB, 2,338 were used for assessment. Researchers used alanine aminotransferase (ALT) monitoring, HBV DNA monitoring, assessment for cirrhosis, and HBV antiviral therapy for examination. For ALT monitoring, 1,814 (78%) of patients had at least one ALT level obtained per year of follow-up. Only 876 patients (37%) had at least one HBV DNA level assessment per year of follow-up and 1,037 (44%) had less than annual testing, and 18% of patients never had an HBV DNA level assessed. Among patients with cirrhosis, 297 (54%) had HBV DNA testing done at least annually, 189 (35%) had testing done but less frequently than annually, and 61 (11%) never had an HBV DNA test done. And of the 547 patients with cirrhosis, 305 (56%) were prescribed HBV antiviral therapy.

It was noted that patients were monitored during 2006-2013. Only 68% of patients had not been prescribed treatment, and 72% had received liver-related specialty care.

“Our findings reiterate the need for clinicians who treat patients with [chronic HBV] to provide ongoing, continual assessment of disease activity based on HBV DNA and ALT levels, as well as liver imaging surveillance among patients at high risk for HCC,” researchers concluded. “As antiviral therapy for [chronic HBV] now includes potent and highly efficacious oral agents that have few contraindications and minimal side effects, as well as a high barrier to resistance, clinicians should be vigilant for opportunities to decrease the likelihood of poor clinical outcomes.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases here.

Chronic hepatitis B virus patients are insufficiently monitored for disease activity and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Philip R. Spradling, MD, and his associates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a cohort study of 2,992 patients with CHB, 2,338 were used for assessment. Researchers used alanine aminotransferase (ALT) monitoring, HBV DNA monitoring, assessment for cirrhosis, and HBV antiviral therapy for examination. For ALT monitoring, 1,814 (78%) of patients had at least one ALT level obtained per year of follow-up. Only 876 patients (37%) had at least one HBV DNA level assessment per year of follow-up and 1,037 (44%) had less than annual testing, and 18% of patients never had an HBV DNA level assessed. Among patients with cirrhosis, 297 (54%) had HBV DNA testing done at least annually, 189 (35%) had testing done but less frequently than annually, and 61 (11%) never had an HBV DNA test done. And of the 547 patients with cirrhosis, 305 (56%) were prescribed HBV antiviral therapy.

It was noted that patients were monitored during 2006-2013. Only 68% of patients had not been prescribed treatment, and 72% had received liver-related specialty care.

“Our findings reiterate the need for clinicians who treat patients with [chronic HBV] to provide ongoing, continual assessment of disease activity based on HBV DNA and ALT levels, as well as liver imaging surveillance among patients at high risk for HCC,” researchers concluded. “As antiviral therapy for [chronic HBV] now includes potent and highly efficacious oral agents that have few contraindications and minimal side effects, as well as a high barrier to resistance, clinicians should be vigilant for opportunities to decrease the likelihood of poor clinical outcomes.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases here.

Chronic hepatitis B virus patients are insufficiently monitored for disease activity and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Philip R. Spradling, MD, and his associates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a cohort study of 2,992 patients with CHB, 2,338 were used for assessment. Researchers used alanine aminotransferase (ALT) monitoring, HBV DNA monitoring, assessment for cirrhosis, and HBV antiviral therapy for examination. For ALT monitoring, 1,814 (78%) of patients had at least one ALT level obtained per year of follow-up. Only 876 patients (37%) had at least one HBV DNA level assessment per year of follow-up and 1,037 (44%) had less than annual testing, and 18% of patients never had an HBV DNA level assessed. Among patients with cirrhosis, 297 (54%) had HBV DNA testing done at least annually, 189 (35%) had testing done but less frequently than annually, and 61 (11%) never had an HBV DNA test done. And of the 547 patients with cirrhosis, 305 (56%) were prescribed HBV antiviral therapy.

It was noted that patients were monitored during 2006-2013. Only 68% of patients had not been prescribed treatment, and 72% had received liver-related specialty care.

“Our findings reiterate the need for clinicians who treat patients with [chronic HBV] to provide ongoing, continual assessment of disease activity based on HBV DNA and ALT levels, as well as liver imaging surveillance among patients at high risk for HCC,” researchers concluded. “As antiviral therapy for [chronic HBV] now includes potent and highly efficacious oral agents that have few contraindications and minimal side effects, as well as a high barrier to resistance, clinicians should be vigilant for opportunities to decrease the likelihood of poor clinical outcomes.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases here.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Summer flu? Think variant swine influenza virus infection

Two children presented with influenza, and both recovered without the need for hospitalization. This scenario would fail to pique the interest of any pediatrician in January. But what about when it happens in July?

In early August, public health authorities in Ohio announced that two children had tested positive for the variant swine influenza virus H3N2v. Both children had direct contact with pigs at the Clark County Fair in late July. Along with a handful of cases diagnosed in Michigan, these represent the first H3N2v cases in the United States in 2016.

Influenza viruses that normally circulate in swine are designated as “variant” when they infect humans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), human infections with H1N1v, H1N2v, and H3N2v have been identified in the United States. Influenza A H3N2v viruses carrying the matrix gene from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus were first detected in pigs in 2010, and in people in the summer of 2011. Since that time, 357 human cases have been reported from 14 states, with nearly 75% occurring in Indiana and Ohio. Most infections occurred after prolonged exposure to pigs at agricultural fairs.

Fortunately, most H3N2v infections have been mild: Since July 2012, only 21 individuals have required hospitalization and a single case resulted in death. Notably, though, many of the hospitalizations involved children.

On Aug. 15, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released Interim Guidance for Clinicians on Human Infections with Variant Influenza Viruses.

Because variant virus infection is indistinguishable from seasonal influenza or any other virus that cause influenzalike illness (think fever, cough, sore throat), physicians and other frontline providers need to maintain an index of suspicion. The key is eliciting a history of swine exposure in the week before illness onset. Practically, this means asking about direct contact with pigs, indirect contact with pigs, or close contact with an ill person who has had contact with pigs. Kudos to the astute clinicians in Ohio who thought to send the appropriate influenza testing in July.

When variant influenza virus is suspected, a nasopharyngeal swab or aspirate should be obtained for testing at a state public health lab or the CDC. Rapid antigen tests for influenza may be falsely negative in the setting of H3N2v infection, just as they may be with seasonal influenza infection. Molecular tests such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are likely more sensitive, but cannot distinguish variant influenza A viruses from seasonal influenza A viruses.

The Kentucky State Fair opened on Aug. 18, making the CDC guidance especially timely for health care providers in my area. I called a friend who is a pediatric emergency medicine physician to ask if she and her colleagues were routinely screening patients for encounters of the porcine kind.

“For example, are you asking, ‘Have you been showing, raising or feeding swine? Have you been to the pig barn at the fair?’ ”

When my friend quit laughing, I confessed to her that I had not been doing that routinely either. The exposure history is often the most interesting part of the infectious disease evaluation and in the last month, I’ve asked about exposure to sheep (a risk factor for Q fever), exposure to chickens (a risk factor for Salmonella infections), and exposure to beaver dams (a risk factor for blastomycosis). But I’ve not asked about exposure to pigs.

“The emergency medicine approach is to avoid a lot of viral diagnostic testing unless it is going to impact management,” she said. “Tell me how this changes management of my patient.”

From the patient perspective, making a presumptive diagnosis of H3N2v infection would open the door to empiric treatment with antivirals, at least for individuals who are hospitalized, have severe or progressive disease, or who at high risk for complications of influenza. Neuraminidase inhibitors, including oral oseltamivir, inhaled zanamivir, and intravenous peramivir, can be used for treatment of H3N2v infections.

From a societal perspective, making the diagnosis gives public health experts the opportunity to investigate and potentially prevent further infections by isolating sick pigs. Human to human transmission of H3N2v is rare, but has occasionally occurred in households and in one instance, a child care setting. Careful surveillance of each swine flu case in a human is important to exclude the possibility that the virus has developed the ability to spread efficiently from person to person, creating the risk for an epidemic.

Seasonal influenza vaccine does not prevent infection with variant viruses, so avoidance is key. Those at high risk for complications from influenza infection, including children younger than 5 years of age and those with asthma, diabetes, heart disease, immunocompromised conditions, and neurologic or neurodevelopmental disorders, are urged to avoid pigs and swine barns when visiting fairs where the animals are present. Everyone else needs to follow common sense measures to prevent the spread of infection.

• Don’t take food or drink into pig areas; don’t eat, drink or put anything in your mouth in pig areas.

• Don’t take toys, pacifiers, cups, baby bottles, strollers, or similar items into pig areas.

• Wash your hands often with soap and running water before and after exposure to pigs. If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub.

• Avoid close contact with pigs that look or act ill.

• Take protective measures if you must come in contact with pigs that are known or suspected to be sick. This includes wearing personal protective equipment like protective clothing, gloves, and masks that cover your mouth and nose when contact is required.

• To further reduce the risk of infection, minimize contact with pigs in the pig barn and arenas.

It shouldn’t be surprising that flu viruses spread from pigs to people in the same way that regular seasonal influenza spread from person to person. An infected pig coughs or sneezes influenza-containing droplets, and these droplets are inhaled or swallowed by a susceptible human. That makes avoiding contact with pigs that look or act ill especially important. For the record, a pig with flu might have fever, depression, cough, nasal or eye discharge, eye redness, or a poor appetite.

On the bright side, you can’t get H3N2v or any other variant virus from eating properly prepared pork meat. Fairgoers can feel free to indulge in a deep-fried pork chop or one of this year’s featured food items: a basket of French fries topped with smoked pork, cheddar cheese sauce, red onions, jalapeño peppers and barbecue sauce.

Or maybe not. The CDC has a web page devoted to food safety at fairs and festivals. It notes that cases of foodborne illness increase during summer months, and usual safety controls “like monitoring of food temperatures, refrigeration, workers trained in food safety and washing facilities, may not be available when cooking and dining at fairs and festivals.”

The public is urged to seek out “healthy options” from fair vendors first. If healthy options aren’t available, we’re advised to consider bringing food from home to save money and calories.

Sigh. I remember when summer used to be more fun.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville, Ky. and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville.

Two children presented with influenza, and both recovered without the need for hospitalization. This scenario would fail to pique the interest of any pediatrician in January. But what about when it happens in July?

In early August, public health authorities in Ohio announced that two children had tested positive for the variant swine influenza virus H3N2v. Both children had direct contact with pigs at the Clark County Fair in late July. Along with a handful of cases diagnosed in Michigan, these represent the first H3N2v cases in the United States in 2016.

Influenza viruses that normally circulate in swine are designated as “variant” when they infect humans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), human infections with H1N1v, H1N2v, and H3N2v have been identified in the United States. Influenza A H3N2v viruses carrying the matrix gene from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus were first detected in pigs in 2010, and in people in the summer of 2011. Since that time, 357 human cases have been reported from 14 states, with nearly 75% occurring in Indiana and Ohio. Most infections occurred after prolonged exposure to pigs at agricultural fairs.

Fortunately, most H3N2v infections have been mild: Since July 2012, only 21 individuals have required hospitalization and a single case resulted in death. Notably, though, many of the hospitalizations involved children.

On Aug. 15, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released Interim Guidance for Clinicians on Human Infections with Variant Influenza Viruses.

Because variant virus infection is indistinguishable from seasonal influenza or any other virus that cause influenzalike illness (think fever, cough, sore throat), physicians and other frontline providers need to maintain an index of suspicion. The key is eliciting a history of swine exposure in the week before illness onset. Practically, this means asking about direct contact with pigs, indirect contact with pigs, or close contact with an ill person who has had contact with pigs. Kudos to the astute clinicians in Ohio who thought to send the appropriate influenza testing in July.

When variant influenza virus is suspected, a nasopharyngeal swab or aspirate should be obtained for testing at a state public health lab or the CDC. Rapid antigen tests for influenza may be falsely negative in the setting of H3N2v infection, just as they may be with seasonal influenza infection. Molecular tests such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are likely more sensitive, but cannot distinguish variant influenza A viruses from seasonal influenza A viruses.

The Kentucky State Fair opened on Aug. 18, making the CDC guidance especially timely for health care providers in my area. I called a friend who is a pediatric emergency medicine physician to ask if she and her colleagues were routinely screening patients for encounters of the porcine kind.

“For example, are you asking, ‘Have you been showing, raising or feeding swine? Have you been to the pig barn at the fair?’ ”

When my friend quit laughing, I confessed to her that I had not been doing that routinely either. The exposure history is often the most interesting part of the infectious disease evaluation and in the last month, I’ve asked about exposure to sheep (a risk factor for Q fever), exposure to chickens (a risk factor for Salmonella infections), and exposure to beaver dams (a risk factor for blastomycosis). But I’ve not asked about exposure to pigs.

“The emergency medicine approach is to avoid a lot of viral diagnostic testing unless it is going to impact management,” she said. “Tell me how this changes management of my patient.”

From the patient perspective, making a presumptive diagnosis of H3N2v infection would open the door to empiric treatment with antivirals, at least for individuals who are hospitalized, have severe or progressive disease, or who at high risk for complications of influenza. Neuraminidase inhibitors, including oral oseltamivir, inhaled zanamivir, and intravenous peramivir, can be used for treatment of H3N2v infections.

From a societal perspective, making the diagnosis gives public health experts the opportunity to investigate and potentially prevent further infections by isolating sick pigs. Human to human transmission of H3N2v is rare, but has occasionally occurred in households and in one instance, a child care setting. Careful surveillance of each swine flu case in a human is important to exclude the possibility that the virus has developed the ability to spread efficiently from person to person, creating the risk for an epidemic.

Seasonal influenza vaccine does not prevent infection with variant viruses, so avoidance is key. Those at high risk for complications from influenza infection, including children younger than 5 years of age and those with asthma, diabetes, heart disease, immunocompromised conditions, and neurologic or neurodevelopmental disorders, are urged to avoid pigs and swine barns when visiting fairs where the animals are present. Everyone else needs to follow common sense measures to prevent the spread of infection.

• Don’t take food or drink into pig areas; don’t eat, drink or put anything in your mouth in pig areas.

• Don’t take toys, pacifiers, cups, baby bottles, strollers, or similar items into pig areas.

• Wash your hands often with soap and running water before and after exposure to pigs. If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub.

• Avoid close contact with pigs that look or act ill.

• Take protective measures if you must come in contact with pigs that are known or suspected to be sick. This includes wearing personal protective equipment like protective clothing, gloves, and masks that cover your mouth and nose when contact is required.

• To further reduce the risk of infection, minimize contact with pigs in the pig barn and arenas.

It shouldn’t be surprising that flu viruses spread from pigs to people in the same way that regular seasonal influenza spread from person to person. An infected pig coughs or sneezes influenza-containing droplets, and these droplets are inhaled or swallowed by a susceptible human. That makes avoiding contact with pigs that look or act ill especially important. For the record, a pig with flu might have fever, depression, cough, nasal or eye discharge, eye redness, or a poor appetite.

On the bright side, you can’t get H3N2v or any other variant virus from eating properly prepared pork meat. Fairgoers can feel free to indulge in a deep-fried pork chop or one of this year’s featured food items: a basket of French fries topped with smoked pork, cheddar cheese sauce, red onions, jalapeño peppers and barbecue sauce.

Or maybe not. The CDC has a web page devoted to food safety at fairs and festivals. It notes that cases of foodborne illness increase during summer months, and usual safety controls “like monitoring of food temperatures, refrigeration, workers trained in food safety and washing facilities, may not be available when cooking and dining at fairs and festivals.”

The public is urged to seek out “healthy options” from fair vendors first. If healthy options aren’t available, we’re advised to consider bringing food from home to save money and calories.

Sigh. I remember when summer used to be more fun.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville, Ky. and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville.

Two children presented with influenza, and both recovered without the need for hospitalization. This scenario would fail to pique the interest of any pediatrician in January. But what about when it happens in July?

In early August, public health authorities in Ohio announced that two children had tested positive for the variant swine influenza virus H3N2v. Both children had direct contact with pigs at the Clark County Fair in late July. Along with a handful of cases diagnosed in Michigan, these represent the first H3N2v cases in the United States in 2016.

Influenza viruses that normally circulate in swine are designated as “variant” when they infect humans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), human infections with H1N1v, H1N2v, and H3N2v have been identified in the United States. Influenza A H3N2v viruses carrying the matrix gene from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus were first detected in pigs in 2010, and in people in the summer of 2011. Since that time, 357 human cases have been reported from 14 states, with nearly 75% occurring in Indiana and Ohio. Most infections occurred after prolonged exposure to pigs at agricultural fairs.

Fortunately, most H3N2v infections have been mild: Since July 2012, only 21 individuals have required hospitalization and a single case resulted in death. Notably, though, many of the hospitalizations involved children.

On Aug. 15, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released Interim Guidance for Clinicians on Human Infections with Variant Influenza Viruses.

Because variant virus infection is indistinguishable from seasonal influenza or any other virus that cause influenzalike illness (think fever, cough, sore throat), physicians and other frontline providers need to maintain an index of suspicion. The key is eliciting a history of swine exposure in the week before illness onset. Practically, this means asking about direct contact with pigs, indirect contact with pigs, or close contact with an ill person who has had contact with pigs. Kudos to the astute clinicians in Ohio who thought to send the appropriate influenza testing in July.

When variant influenza virus is suspected, a nasopharyngeal swab or aspirate should be obtained for testing at a state public health lab or the CDC. Rapid antigen tests for influenza may be falsely negative in the setting of H3N2v infection, just as they may be with seasonal influenza infection. Molecular tests such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are likely more sensitive, but cannot distinguish variant influenza A viruses from seasonal influenza A viruses.

The Kentucky State Fair opened on Aug. 18, making the CDC guidance especially timely for health care providers in my area. I called a friend who is a pediatric emergency medicine physician to ask if she and her colleagues were routinely screening patients for encounters of the porcine kind.

“For example, are you asking, ‘Have you been showing, raising or feeding swine? Have you been to the pig barn at the fair?’ ”

When my friend quit laughing, I confessed to her that I had not been doing that routinely either. The exposure history is often the most interesting part of the infectious disease evaluation and in the last month, I’ve asked about exposure to sheep (a risk factor for Q fever), exposure to chickens (a risk factor for Salmonella infections), and exposure to beaver dams (a risk factor for blastomycosis). But I’ve not asked about exposure to pigs.

“The emergency medicine approach is to avoid a lot of viral diagnostic testing unless it is going to impact management,” she said. “Tell me how this changes management of my patient.”

From the patient perspective, making a presumptive diagnosis of H3N2v infection would open the door to empiric treatment with antivirals, at least for individuals who are hospitalized, have severe or progressive disease, or who at high risk for complications of influenza. Neuraminidase inhibitors, including oral oseltamivir, inhaled zanamivir, and intravenous peramivir, can be used for treatment of H3N2v infections.

From a societal perspective, making the diagnosis gives public health experts the opportunity to investigate and potentially prevent further infections by isolating sick pigs. Human to human transmission of H3N2v is rare, but has occasionally occurred in households and in one instance, a child care setting. Careful surveillance of each swine flu case in a human is important to exclude the possibility that the virus has developed the ability to spread efficiently from person to person, creating the risk for an epidemic.

Seasonal influenza vaccine does not prevent infection with variant viruses, so avoidance is key. Those at high risk for complications from influenza infection, including children younger than 5 years of age and those with asthma, diabetes, heart disease, immunocompromised conditions, and neurologic or neurodevelopmental disorders, are urged to avoid pigs and swine barns when visiting fairs where the animals are present. Everyone else needs to follow common sense measures to prevent the spread of infection.

• Don’t take food or drink into pig areas; don’t eat, drink or put anything in your mouth in pig areas.

• Don’t take toys, pacifiers, cups, baby bottles, strollers, or similar items into pig areas.

• Wash your hands often with soap and running water before and after exposure to pigs. If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub.

• Avoid close contact with pigs that look or act ill.

• Take protective measures if you must come in contact with pigs that are known or suspected to be sick. This includes wearing personal protective equipment like protective clothing, gloves, and masks that cover your mouth and nose when contact is required.

• To further reduce the risk of infection, minimize contact with pigs in the pig barn and arenas.

It shouldn’t be surprising that flu viruses spread from pigs to people in the same way that regular seasonal influenza spread from person to person. An infected pig coughs or sneezes influenza-containing droplets, and these droplets are inhaled or swallowed by a susceptible human. That makes avoiding contact with pigs that look or act ill especially important. For the record, a pig with flu might have fever, depression, cough, nasal or eye discharge, eye redness, or a poor appetite.

On the bright side, you can’t get H3N2v or any other variant virus from eating properly prepared pork meat. Fairgoers can feel free to indulge in a deep-fried pork chop or one of this year’s featured food items: a basket of French fries topped with smoked pork, cheddar cheese sauce, red onions, jalapeño peppers and barbecue sauce.

Or maybe not. The CDC has a web page devoted to food safety at fairs and festivals. It notes that cases of foodborne illness increase during summer months, and usual safety controls “like monitoring of food temperatures, refrigeration, workers trained in food safety and washing facilities, may not be available when cooking and dining at fairs and festivals.”

The public is urged to seek out “healthy options” from fair vendors first. If healthy options aren’t available, we’re advised to consider bringing food from home to save money and calories.

Sigh. I remember when summer used to be more fun.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville, Ky. and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville.

Proper treatment of herpes zoster ‘a work in progress’

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – In medical school you may have been taught that herpes zoster infection primarily impacts elderly patients, but the burden of disease is shifting – along with the understanding of herpes zoster itself.

“Herpes zoster is a disease that can lull us into a false sense of security because we see it all the time,” Iris Ahronowitz, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “But our understanding of how to manage this disease is still very much a work in progress.”

She noted that while 50% of people will acquire herpes zoster by the time they reach 85 years of age due to diminishing cell-mediated immunity, the major burden of disease impacts immunocompromised patients of all ages. HIV patients and solid-organ transplant recipients are well known to face an increased risk of acquiring herpes zoster, but the most overwhelming risk is seen in leukemia patients, who have rates as high as 100-fold that of the general population.

“More recent data on stem cell transplant patients show that about 50% of them will get zoster,” added Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Most of that’s happening within the first year and a half after their transplant.”

Several recent epidemiologic studies in the medical literature have reported herpes zoster in patients who are not traditionally believed to be immunosuppressed, such as those with lupus, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. “It begs the question: is it the disease or is it the treatment?” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “We don’t know the answer to that yet. In dermatomyositis and lupus, use of antimalarials has been found to be most associated with the risk of herpes zoster. Other studies looking at one disease are so heterogeneous, some saying that it’s one medication, some saying that it’s another. There’s no cohesive message yet about which medications cause the highest risk of zoster.”

Herpes zoster was originally believed to be far less transmissible than varicella. “Later it was thought that the only way that you can get VZV [varicella zoster virus] from a zoster patient was by direct contact with vesicle fluid,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “That turns out to be wrong as well.” One study of pediatric patients found similar rates of secondary varicella cases from varicella and herpes zoster cases (15% vs. 9%, respectively), regardless of anatomic location of zoster (J Infect Dis. 2012; 205[9]:1336-41).

Another report that called into question prevailing beliefs about the disease involved an immunocompetent patient in a long-term care facility who developed localized herpes zoster (J Infect Dis. 2008;197[5]:646-53). That individual turned out to be “patient zero” in a varicella outbreak in the facility, even though the person’s lesions had been covered by gauze and clothing at all times. “The next patient who got infected was one of the health care workers who had never been in the room at the same time as the patient but who had changed the patient’s bed linens,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, who was not involved with the study. “Environmental samples were collected from the patient’s room and were contaminated with VZV DNA.”

She went on to note that VZV DNA has been found in vesicle fluid, serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and saliva. One randomized, controlled trial found that hydrocolloid dressings are superior to traditional gauze and paper dressings in preventing the excretion of aerosolized VZV DNA from skin lesions of patients with localized herpes zoster (J Infect Dis. 2004;189[6]:1009-12). Using hydrocolloid dressings to cover lesions “does seem to make a difference,” she said. “Because of all this new data coming out, I think it’s time to reconsider isolation precautions in all hospitalized patients with herpes zoster, because the consequences of VZV transmission within a hospital where there are other patients nearby who have low immune systems could be absolutely devastating.”

The impact of herpes zoster infection on the central nervous system can be significant, including cranial nerve palsy, encephalitis, encephalopathy, and aseptic meningitis. “Patients can have long-lasting residual neurologic deficits from this at 6 months or longer despite appropriate treatment,” she said. “No correlation between CSF viral load and neurologic sequelae has been found at 3 months.”

More recent research has found an association between herpes zoster infection and an increased risk of stroke – up to threefold in some cases. “That risk doesn’t normalize until 6 months after the infection,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “We’re even seeing it in kids, who have two times the risk of stroke in the first 6 months after VZV infection.” MI risk also seems to be elevated as a secondary outcome (a 1.7-fold increase in the first week of infection).

“There have also been recent reports of VZV antigen/DNA found in the vessel wall of patients with giant cell arteritis and granulomatous arteritis of the aorta,” she said. “This is an evolving story about zoster that we never knew about.”

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) is also associated with CNS manifestations, but they resolve much faster, unlike those of CNS zoster. “As long as you take away the offending medication and put them on steroids they will recover very quickly,” she said. At least one case in the medical literature to date has reported DIHS in association with VZV (Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95[4]:503-4).

The zoster vaccine (Zostavax, Merck & Co.) is currently indicated in patients aged 60 years and older, but since it is a live attenuated vaccine, it is contraindicated in many patients who could most benefit from it, including those with primary immunodeficiency disorders, those with a hematologic malignancy, those who have had a hematopoietic stem cell transplant within the last 2 years, pregnant patients, and patients taking high-dose steroids or anti–tumor necrosis factor biologics.

“There is an inactivated vaccine in the works being tested, and that is showing good efficacy,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Hopefully we’ll be able to prevaccinate patients, even young patients, prior to immune suppression.”

She reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – In medical school you may have been taught that herpes zoster infection primarily impacts elderly patients, but the burden of disease is shifting – along with the understanding of herpes zoster itself.

“Herpes zoster is a disease that can lull us into a false sense of security because we see it all the time,” Iris Ahronowitz, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “But our understanding of how to manage this disease is still very much a work in progress.”

She noted that while 50% of people will acquire herpes zoster by the time they reach 85 years of age due to diminishing cell-mediated immunity, the major burden of disease impacts immunocompromised patients of all ages. HIV patients and solid-organ transplant recipients are well known to face an increased risk of acquiring herpes zoster, but the most overwhelming risk is seen in leukemia patients, who have rates as high as 100-fold that of the general population.

“More recent data on stem cell transplant patients show that about 50% of them will get zoster,” added Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Most of that’s happening within the first year and a half after their transplant.”

Several recent epidemiologic studies in the medical literature have reported herpes zoster in patients who are not traditionally believed to be immunosuppressed, such as those with lupus, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. “It begs the question: is it the disease or is it the treatment?” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “We don’t know the answer to that yet. In dermatomyositis and lupus, use of antimalarials has been found to be most associated with the risk of herpes zoster. Other studies looking at one disease are so heterogeneous, some saying that it’s one medication, some saying that it’s another. There’s no cohesive message yet about which medications cause the highest risk of zoster.”

Herpes zoster was originally believed to be far less transmissible than varicella. “Later it was thought that the only way that you can get VZV [varicella zoster virus] from a zoster patient was by direct contact with vesicle fluid,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “That turns out to be wrong as well.” One study of pediatric patients found similar rates of secondary varicella cases from varicella and herpes zoster cases (15% vs. 9%, respectively), regardless of anatomic location of zoster (J Infect Dis. 2012; 205[9]:1336-41).

Another report that called into question prevailing beliefs about the disease involved an immunocompetent patient in a long-term care facility who developed localized herpes zoster (J Infect Dis. 2008;197[5]:646-53). That individual turned out to be “patient zero” in a varicella outbreak in the facility, even though the person’s lesions had been covered by gauze and clothing at all times. “The next patient who got infected was one of the health care workers who had never been in the room at the same time as the patient but who had changed the patient’s bed linens,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, who was not involved with the study. “Environmental samples were collected from the patient’s room and were contaminated with VZV DNA.”

She went on to note that VZV DNA has been found in vesicle fluid, serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and saliva. One randomized, controlled trial found that hydrocolloid dressings are superior to traditional gauze and paper dressings in preventing the excretion of aerosolized VZV DNA from skin lesions of patients with localized herpes zoster (J Infect Dis. 2004;189[6]:1009-12). Using hydrocolloid dressings to cover lesions “does seem to make a difference,” she said. “Because of all this new data coming out, I think it’s time to reconsider isolation precautions in all hospitalized patients with herpes zoster, because the consequences of VZV transmission within a hospital where there are other patients nearby who have low immune systems could be absolutely devastating.”

The impact of herpes zoster infection on the central nervous system can be significant, including cranial nerve palsy, encephalitis, encephalopathy, and aseptic meningitis. “Patients can have long-lasting residual neurologic deficits from this at 6 months or longer despite appropriate treatment,” she said. “No correlation between CSF viral load and neurologic sequelae has been found at 3 months.”

More recent research has found an association between herpes zoster infection and an increased risk of stroke – up to threefold in some cases. “That risk doesn’t normalize until 6 months after the infection,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “We’re even seeing it in kids, who have two times the risk of stroke in the first 6 months after VZV infection.” MI risk also seems to be elevated as a secondary outcome (a 1.7-fold increase in the first week of infection).

“There have also been recent reports of VZV antigen/DNA found in the vessel wall of patients with giant cell arteritis and granulomatous arteritis of the aorta,” she said. “This is an evolving story about zoster that we never knew about.”

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) is also associated with CNS manifestations, but they resolve much faster, unlike those of CNS zoster. “As long as you take away the offending medication and put them on steroids they will recover very quickly,” she said. At least one case in the medical literature to date has reported DIHS in association with VZV (Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95[4]:503-4).

The zoster vaccine (Zostavax, Merck & Co.) is currently indicated in patients aged 60 years and older, but since it is a live attenuated vaccine, it is contraindicated in many patients who could most benefit from it, including those with primary immunodeficiency disorders, those with a hematologic malignancy, those who have had a hematopoietic stem cell transplant within the last 2 years, pregnant patients, and patients taking high-dose steroids or anti–tumor necrosis factor biologics.

“There is an inactivated vaccine in the works being tested, and that is showing good efficacy,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Hopefully we’ll be able to prevaccinate patients, even young patients, prior to immune suppression.”

She reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – In medical school you may have been taught that herpes zoster infection primarily impacts elderly patients, but the burden of disease is shifting – along with the understanding of herpes zoster itself.

“Herpes zoster is a disease that can lull us into a false sense of security because we see it all the time,” Iris Ahronowitz, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “But our understanding of how to manage this disease is still very much a work in progress.”

She noted that while 50% of people will acquire herpes zoster by the time they reach 85 years of age due to diminishing cell-mediated immunity, the major burden of disease impacts immunocompromised patients of all ages. HIV patients and solid-organ transplant recipients are well known to face an increased risk of acquiring herpes zoster, but the most overwhelming risk is seen in leukemia patients, who have rates as high as 100-fold that of the general population.

“More recent data on stem cell transplant patients show that about 50% of them will get zoster,” added Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Most of that’s happening within the first year and a half after their transplant.”

Several recent epidemiologic studies in the medical literature have reported herpes zoster in patients who are not traditionally believed to be immunosuppressed, such as those with lupus, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. “It begs the question: is it the disease or is it the treatment?” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “We don’t know the answer to that yet. In dermatomyositis and lupus, use of antimalarials has been found to be most associated with the risk of herpes zoster. Other studies looking at one disease are so heterogeneous, some saying that it’s one medication, some saying that it’s another. There’s no cohesive message yet about which medications cause the highest risk of zoster.”

Herpes zoster was originally believed to be far less transmissible than varicella. “Later it was thought that the only way that you can get VZV [varicella zoster virus] from a zoster patient was by direct contact with vesicle fluid,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “That turns out to be wrong as well.” One study of pediatric patients found similar rates of secondary varicella cases from varicella and herpes zoster cases (15% vs. 9%, respectively), regardless of anatomic location of zoster (J Infect Dis. 2012; 205[9]:1336-41).

Another report that called into question prevailing beliefs about the disease involved an immunocompetent patient in a long-term care facility who developed localized herpes zoster (J Infect Dis. 2008;197[5]:646-53). That individual turned out to be “patient zero” in a varicella outbreak in the facility, even though the person’s lesions had been covered by gauze and clothing at all times. “The next patient who got infected was one of the health care workers who had never been in the room at the same time as the patient but who had changed the patient’s bed linens,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, who was not involved with the study. “Environmental samples were collected from the patient’s room and were contaminated with VZV DNA.”

She went on to note that VZV DNA has been found in vesicle fluid, serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and saliva. One randomized, controlled trial found that hydrocolloid dressings are superior to traditional gauze and paper dressings in preventing the excretion of aerosolized VZV DNA from skin lesions of patients with localized herpes zoster (J Infect Dis. 2004;189[6]:1009-12). Using hydrocolloid dressings to cover lesions “does seem to make a difference,” she said. “Because of all this new data coming out, I think it’s time to reconsider isolation precautions in all hospitalized patients with herpes zoster, because the consequences of VZV transmission within a hospital where there are other patients nearby who have low immune systems could be absolutely devastating.”

The impact of herpes zoster infection on the central nervous system can be significant, including cranial nerve palsy, encephalitis, encephalopathy, and aseptic meningitis. “Patients can have long-lasting residual neurologic deficits from this at 6 months or longer despite appropriate treatment,” she said. “No correlation between CSF viral load and neurologic sequelae has been found at 3 months.”

More recent research has found an association between herpes zoster infection and an increased risk of stroke – up to threefold in some cases. “That risk doesn’t normalize until 6 months after the infection,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “We’re even seeing it in kids, who have two times the risk of stroke in the first 6 months after VZV infection.” MI risk also seems to be elevated as a secondary outcome (a 1.7-fold increase in the first week of infection).

“There have also been recent reports of VZV antigen/DNA found in the vessel wall of patients with giant cell arteritis and granulomatous arteritis of the aorta,” she said. “This is an evolving story about zoster that we never knew about.”

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) is also associated with CNS manifestations, but they resolve much faster, unlike those of CNS zoster. “As long as you take away the offending medication and put them on steroids they will recover very quickly,” she said. At least one case in the medical literature to date has reported DIHS in association with VZV (Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95[4]:503-4).

The zoster vaccine (Zostavax, Merck & Co.) is currently indicated in patients aged 60 years and older, but since it is a live attenuated vaccine, it is contraindicated in many patients who could most benefit from it, including those with primary immunodeficiency disorders, those with a hematologic malignancy, those who have had a hematopoietic stem cell transplant within the last 2 years, pregnant patients, and patients taking high-dose steroids or anti–tumor necrosis factor biologics.

“There is an inactivated vaccine in the works being tested, and that is showing good efficacy,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Hopefully we’ll be able to prevaccinate patients, even young patients, prior to immune suppression.”

She reported having no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT PDA 2016

Self-Administered Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation May Pose Serious Risks

Neuroscientists cautioned patients about the dangers of self-administered transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in an open letter published July 7 in Annals of Neurology. “We perceive an ethical obligation to draw the attention of both professionals and ‘do it yourself’ (DIY) users to some of these issues,” said Michael D. Fox, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston. The open letter, written by four neuroscientists and signed by 39 colleagues, addresses several less commonly recognized complications of self-administered brain stimulation.