User login

Siponimod shows promise through 24 months in relapsing-remitting MS

Once-daily oral siponimod was associated with sustained effects on MRI outcomes at 24 months in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in a dose-blinded extension of the phase II study.

Disease activity was low, “with some evidence of greater benefit associated with siponimod at 10-mg, 2-mg, and 1.25-mg doses than with siponimod at 0.25-mg and 0.5-mg doses. No new safety signals emerged, and dose titration at treatment initiation mitigated cardiac effects,” Ludwig Kappos, MD, of University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), and his associates wrote in JAMA Neurology. “With similar efficacy but lower rates of lymphopenia relative to the 10-mg dose, siponimod 2 mg, has been chosen for further development,” they wrote.

Siponimod (BAF312) is a selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor (S1P1,5) modulator that was evaluated for up to 6 months at five doses in the phase II BOLD (BAF312 on MRI Lesion Given Once Daily) study. Patients with relapsing-remitting MS who received 10 mg siponimod had up to 80% reductions in MRI combined unique active lesions (CUALs, or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions and/or new and newly enlarging T2 lesions, without double counting), compared with the placebo group. The 2-mg and 0.5-mg dose cohorts had reductions of 72% and 50%, respectively. The current study was a 24-month, dose-blinded extension phase that included 185 participants (73% of 252 eligible patients), of whom 33 patients received 10 mg siponimod, 29 received 2 mg, 43 received 1.25 mg, 29 received 0.5 mg, and 50 received 0.25 mg (JAMA Neurol. 2016 July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1451).

Average reductions in gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesion counts were sustained in the 10-mg, 2-mg, 1.25-mg, and 0.5-mg dose groups at month 24, the researchers reported. The 1.25-mg and 2-mg doses yielded the highest proportions of patients free from new MRI activity (58% for both dose groups) and free from new or newly enlarging T2 lesions (61% and 58%, respectively). New or newly enlarging T2 lesions were numerically lower at doses exceeding 0.25 mg. “There were no clear changes in normalized brain volume within or between any of the treatment groups,” the investigators added.

Dose titration during the first 10 days of treatment mitigated bradycardia and atrioventricular conduction effects. Rates of adverse events within dose groups ranged from 84% to 97% and did not show a trend with dose size. Serious adverse events affected nine patients (5%) and included one case each of otosclerosis, gastritis, anaphylaxis, acute pyelonephritis, femoral and ankle fractures, basal cell carcinoma, cervical neoplasm, and abortion. Thirteen patients (7%) required treatment interruptions because of adverse events, of which seven consisted of lymphopenia or decreased lymphocyte count at the 10-mg dose. Other adverse events leading to dose interruptions or adjustments included neutropenia, upper respiratory tract infection, elevated hepatic transaminases, and hypertension.

Novartis is developing siponimod and funded the study. Coinvestigators employed by Novartis participated in all aspects of the study, including interpretation of the data and manuscript submission. Dr. Kappos disclosed financial ties to Novartis and numerous other pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and societies.

Dr. Kappos and colleagues acknowledged some limitations including the decreasing proportion of patients with evaluable MRIs and low numbers within each dosing group. Furthermore, the variable time between the end of the BOLD study and start of the extension phase, and the lack of a control group, limit conclusive evidence statements. Nonetheless, the current data may be the most relevant to report the safety and efficacy of long-term siponimod use in relapsing-remitting MS.

The full cumulative dose effect of siponimod beginning from the initiation of the BOLD study cannot be completely evidenced because of variable and prolonged times between the end of the BOLD study and initiating the extension phase, the dose-titration escalation procedure, and limiting reporting to the extension phase. The low numbers of participants do not allow an assessment of dose-related adverse events. The observed adverse events may be expected based on the pharmacokinetic profile of siponimod.

The extension phase of clinical trials performed without a reference treatment arm can result in challenges for interpreting and contextualizing findings. Where possible, a potential approach would be to rerandomize patients prior to the start of an extension phase and maintain a placebo or comparator arm.

Edward R. Hammond, MD, PhD, MPH, is with AstraZeneca’s Medical Evidence and Observational Research Center in Gaithersburg, Md. These comments are based on his accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2016 July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2284).

Dr. Kappos and colleagues acknowledged some limitations including the decreasing proportion of patients with evaluable MRIs and low numbers within each dosing group. Furthermore, the variable time between the end of the BOLD study and start of the extension phase, and the lack of a control group, limit conclusive evidence statements. Nonetheless, the current data may be the most relevant to report the safety and efficacy of long-term siponimod use in relapsing-remitting MS.

The full cumulative dose effect of siponimod beginning from the initiation of the BOLD study cannot be completely evidenced because of variable and prolonged times between the end of the BOLD study and initiating the extension phase, the dose-titration escalation procedure, and limiting reporting to the extension phase. The low numbers of participants do not allow an assessment of dose-related adverse events. The observed adverse events may be expected based on the pharmacokinetic profile of siponimod.

The extension phase of clinical trials performed without a reference treatment arm can result in challenges for interpreting and contextualizing findings. Where possible, a potential approach would be to rerandomize patients prior to the start of an extension phase and maintain a placebo or comparator arm.

Edward R. Hammond, MD, PhD, MPH, is with AstraZeneca’s Medical Evidence and Observational Research Center in Gaithersburg, Md. These comments are based on his accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2016 July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2284).

Dr. Kappos and colleagues acknowledged some limitations including the decreasing proportion of patients with evaluable MRIs and low numbers within each dosing group. Furthermore, the variable time between the end of the BOLD study and start of the extension phase, and the lack of a control group, limit conclusive evidence statements. Nonetheless, the current data may be the most relevant to report the safety and efficacy of long-term siponimod use in relapsing-remitting MS.

The full cumulative dose effect of siponimod beginning from the initiation of the BOLD study cannot be completely evidenced because of variable and prolonged times between the end of the BOLD study and initiating the extension phase, the dose-titration escalation procedure, and limiting reporting to the extension phase. The low numbers of participants do not allow an assessment of dose-related adverse events. The observed adverse events may be expected based on the pharmacokinetic profile of siponimod.

The extension phase of clinical trials performed without a reference treatment arm can result in challenges for interpreting and contextualizing findings. Where possible, a potential approach would be to rerandomize patients prior to the start of an extension phase and maintain a placebo or comparator arm.

Edward R. Hammond, MD, PhD, MPH, is with AstraZeneca’s Medical Evidence and Observational Research Center in Gaithersburg, Md. These comments are based on his accompanying editorial (JAMA Neurol. 2016 July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2284).

Once-daily oral siponimod was associated with sustained effects on MRI outcomes at 24 months in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in a dose-blinded extension of the phase II study.

Disease activity was low, “with some evidence of greater benefit associated with siponimod at 10-mg, 2-mg, and 1.25-mg doses than with siponimod at 0.25-mg and 0.5-mg doses. No new safety signals emerged, and dose titration at treatment initiation mitigated cardiac effects,” Ludwig Kappos, MD, of University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), and his associates wrote in JAMA Neurology. “With similar efficacy but lower rates of lymphopenia relative to the 10-mg dose, siponimod 2 mg, has been chosen for further development,” they wrote.

Siponimod (BAF312) is a selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor (S1P1,5) modulator that was evaluated for up to 6 months at five doses in the phase II BOLD (BAF312 on MRI Lesion Given Once Daily) study. Patients with relapsing-remitting MS who received 10 mg siponimod had up to 80% reductions in MRI combined unique active lesions (CUALs, or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions and/or new and newly enlarging T2 lesions, without double counting), compared with the placebo group. The 2-mg and 0.5-mg dose cohorts had reductions of 72% and 50%, respectively. The current study was a 24-month, dose-blinded extension phase that included 185 participants (73% of 252 eligible patients), of whom 33 patients received 10 mg siponimod, 29 received 2 mg, 43 received 1.25 mg, 29 received 0.5 mg, and 50 received 0.25 mg (JAMA Neurol. 2016 July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1451).

Average reductions in gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesion counts were sustained in the 10-mg, 2-mg, 1.25-mg, and 0.5-mg dose groups at month 24, the researchers reported. The 1.25-mg and 2-mg doses yielded the highest proportions of patients free from new MRI activity (58% for both dose groups) and free from new or newly enlarging T2 lesions (61% and 58%, respectively). New or newly enlarging T2 lesions were numerically lower at doses exceeding 0.25 mg. “There were no clear changes in normalized brain volume within or between any of the treatment groups,” the investigators added.

Dose titration during the first 10 days of treatment mitigated bradycardia and atrioventricular conduction effects. Rates of adverse events within dose groups ranged from 84% to 97% and did not show a trend with dose size. Serious adverse events affected nine patients (5%) and included one case each of otosclerosis, gastritis, anaphylaxis, acute pyelonephritis, femoral and ankle fractures, basal cell carcinoma, cervical neoplasm, and abortion. Thirteen patients (7%) required treatment interruptions because of adverse events, of which seven consisted of lymphopenia or decreased lymphocyte count at the 10-mg dose. Other adverse events leading to dose interruptions or adjustments included neutropenia, upper respiratory tract infection, elevated hepatic transaminases, and hypertension.

Novartis is developing siponimod and funded the study. Coinvestigators employed by Novartis participated in all aspects of the study, including interpretation of the data and manuscript submission. Dr. Kappos disclosed financial ties to Novartis and numerous other pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and societies.

Once-daily oral siponimod was associated with sustained effects on MRI outcomes at 24 months in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in a dose-blinded extension of the phase II study.

Disease activity was low, “with some evidence of greater benefit associated with siponimod at 10-mg, 2-mg, and 1.25-mg doses than with siponimod at 0.25-mg and 0.5-mg doses. No new safety signals emerged, and dose titration at treatment initiation mitigated cardiac effects,” Ludwig Kappos, MD, of University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), and his associates wrote in JAMA Neurology. “With similar efficacy but lower rates of lymphopenia relative to the 10-mg dose, siponimod 2 mg, has been chosen for further development,” they wrote.

Siponimod (BAF312) is a selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor (S1P1,5) modulator that was evaluated for up to 6 months at five doses in the phase II BOLD (BAF312 on MRI Lesion Given Once Daily) study. Patients with relapsing-remitting MS who received 10 mg siponimod had up to 80% reductions in MRI combined unique active lesions (CUALs, or gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions and/or new and newly enlarging T2 lesions, without double counting), compared with the placebo group. The 2-mg and 0.5-mg dose cohorts had reductions of 72% and 50%, respectively. The current study was a 24-month, dose-blinded extension phase that included 185 participants (73% of 252 eligible patients), of whom 33 patients received 10 mg siponimod, 29 received 2 mg, 43 received 1.25 mg, 29 received 0.5 mg, and 50 received 0.25 mg (JAMA Neurol. 2016 July 5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1451).

Average reductions in gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesion counts were sustained in the 10-mg, 2-mg, 1.25-mg, and 0.5-mg dose groups at month 24, the researchers reported. The 1.25-mg and 2-mg doses yielded the highest proportions of patients free from new MRI activity (58% for both dose groups) and free from new or newly enlarging T2 lesions (61% and 58%, respectively). New or newly enlarging T2 lesions were numerically lower at doses exceeding 0.25 mg. “There were no clear changes in normalized brain volume within or between any of the treatment groups,” the investigators added.

Dose titration during the first 10 days of treatment mitigated bradycardia and atrioventricular conduction effects. Rates of adverse events within dose groups ranged from 84% to 97% and did not show a trend with dose size. Serious adverse events affected nine patients (5%) and included one case each of otosclerosis, gastritis, anaphylaxis, acute pyelonephritis, femoral and ankle fractures, basal cell carcinoma, cervical neoplasm, and abortion. Thirteen patients (7%) required treatment interruptions because of adverse events, of which seven consisted of lymphopenia or decreased lymphocyte count at the 10-mg dose. Other adverse events leading to dose interruptions or adjustments included neutropenia, upper respiratory tract infection, elevated hepatic transaminases, and hypertension.

Novartis is developing siponimod and funded the study. Coinvestigators employed by Novartis participated in all aspects of the study, including interpretation of the data and manuscript submission. Dr. Kappos disclosed financial ties to Novartis and numerous other pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and societies.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Siponimod was associated with sustained efficacy at 24 months among patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: The proportion of patients free from new MRI activity was highest (58%) in the 1.25-mg and 2-mg dose groups. There were no new safety signals, and dose reduction during initiation mitigated cardiac adverse effects. Lymphopenia was more common at the 10-mg dose than at lower doses.

Data source: A dose-blinded extension of 184 patients from the phase II BOLD study.

Disclosures: Novartis funded the study. Coinvestigators employed by Novartis participated in all aspects of the study, including interpretation of the data and manuscript submission. Dr. Kappos disclosed financial ties to Novartis and numerous other pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and societies.

Deutetrabenazine modestly reduces chorea of Huntington disease

A deuterated form of the vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitor tetrabenazine, called deutetrabenazine, modestly reduced chorea of Huntington disease over 12 weeks in a phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

First author Samuel Frank, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and his colleagues in the Huntington Study Group wrote that the observed treatment effect of 2.5 points on the primary end point of total maximal chorea score, “taken together with improvements in patient-centered end points, such as PGIC [Patient Global Impression of Change] and SF-36 [36-Item Short Form] physical functioning component scales, may be of clinical relevance, although this remains to be determined. The difference in total maximal chorea score associated with deutetrabenazine treatment that was observed in this study is notable given the progressive decline in total maximal chorea score and total motor score that has been previously described as part of the natural history of Huntington disease.”

The phase III trial is the first to use an active ingredient with deuterium substituted for hydrogen at key positions. The use of deuterium in the molecule, according to the investigators, prolongs “plasma half-life and reduce[s] metabolic variability, without changing target pharmacology,” and its “longer half-life and unique pharmacokinetic profile ... may enable less frequent and lower daily doses, thus achieving similar systemic exposure with lower peak concentrations and simplified dosing, compared with tetrabenazine.”

Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) is used worldwide and is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for treating chorea associated with Huntington disease.

The trial enrolled 90 patients with genetically diagnosed Huntington disease across 34 centers in the United States and Canada. The patients had a baseline total maximal chorea score of 8 or higher (range 0-28) and were randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive deuterated tetrabenazine (deutetrabenazine) or placebo. The deutetrabenazine group had a mean age of 55 years and 49% were male. The placebo group had a mean age of 52 years and 62% were men. Patients on the active drug were commenced at a total daily dose of 6 mg (divided into two doses) for the first week. Doses were then increased weekly by 6 mg daily until either chorea was adequately controlled or the maximum dose of 48 mg a day was reached. The final dose was maintained for an additional 4 weeks for a total of 12 weeks, followed by a 1-week washout (JAMA 2016;316[1]:40-50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8655).

The total maximal chorea score, in which higher scores represent worse chorea, that was measured from baseline to an average across the maintenance period during weeks 9 through 12 of therapy declined by a statistically significant 4.4 points – from a mean of 12.1 to 7.7 – in the deutetrabenazine group, compared with a decline of 1.9 points – from a mean of 13.2 to 11.3 – in the placebo group.

Improvements in secondary endpoints such as PGIC and SF-36 physical functioning component scales were also seen in the treatment group, although no improvement was seen in the Berg Balance Test.

Adverse events were similar between the deutetrabenazine and placebo groups, including depression, anxiety, and akathisia.

“Further research is needed to assess the clinical importance of the effect size, and to determine longer-term efficacy and safety,” the study authors concluded.

The study was supported by Auspex Pharmaceuticals, a wholly owned subsidiary of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Dr. Frank reported receiving grants from the Huntington Study Group, and many other authors in the group reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, including Auspex and Teva. Several authors are employees of Auspex.

The study demonstrated a proof of principle that deutetrabenazine, compared with placebo, provided improvement on chorea over 12 weeks and allowed less frequent drug dosing with fewer adverse effects, but it’s not possible to determine how the drug compares with tetrabenazine.

An ideal trial would involve three groups comparing deutetrabenazine, tetrabenazine, and placebo. A head-to-head, noninferiority comparison of deutetrabenazine against tetrabenazine, as was recommended by one of the developers of the compound, would also have been useful.

Nevertheless, tetrabenazine was approved by the FDA for the treatment of chorea in Huntington disease essentially based on efficacy data similar to the current study. Assuming deutetrabenazine was not priced significantly higher than tetrabenazine, its “favorable profile” would offer an additional option for patients and clinicians if and when the drug is approved.

The ongoing ARC-HD (Alternatives for Reducing Chorea in Huntington Disease) study is examining the safety and tolerability of patients with Huntington disease who switch from tetrabenazine to deutetrabenazine (and also includes patients from the current deutetrabenazine study who chose to switch to open-label deutetrabenazine). It should help to resolve whether the effect sizes are clinically meaningful and stable over a period longer than 12 weeks.

Michael D. Geschwind, MD, PhD, and Nick Paras, PhD, are in the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Geschwind reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging and from many sources in industry, including travel support from Teva. Dr. Paras reported receiving research support from Daiichi-Sankyo, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the Tau Consortium. Their comments are derived from an editorial accompanying the phase III trial’s paper (JAMA. 2016;316[1]:33-5).

The study demonstrated a proof of principle that deutetrabenazine, compared with placebo, provided improvement on chorea over 12 weeks and allowed less frequent drug dosing with fewer adverse effects, but it’s not possible to determine how the drug compares with tetrabenazine.

An ideal trial would involve three groups comparing deutetrabenazine, tetrabenazine, and placebo. A head-to-head, noninferiority comparison of deutetrabenazine against tetrabenazine, as was recommended by one of the developers of the compound, would also have been useful.

Nevertheless, tetrabenazine was approved by the FDA for the treatment of chorea in Huntington disease essentially based on efficacy data similar to the current study. Assuming deutetrabenazine was not priced significantly higher than tetrabenazine, its “favorable profile” would offer an additional option for patients and clinicians if and when the drug is approved.

The ongoing ARC-HD (Alternatives for Reducing Chorea in Huntington Disease) study is examining the safety and tolerability of patients with Huntington disease who switch from tetrabenazine to deutetrabenazine (and also includes patients from the current deutetrabenazine study who chose to switch to open-label deutetrabenazine). It should help to resolve whether the effect sizes are clinically meaningful and stable over a period longer than 12 weeks.

Michael D. Geschwind, MD, PhD, and Nick Paras, PhD, are in the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Geschwind reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging and from many sources in industry, including travel support from Teva. Dr. Paras reported receiving research support from Daiichi-Sankyo, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the Tau Consortium. Their comments are derived from an editorial accompanying the phase III trial’s paper (JAMA. 2016;316[1]:33-5).

The study demonstrated a proof of principle that deutetrabenazine, compared with placebo, provided improvement on chorea over 12 weeks and allowed less frequent drug dosing with fewer adverse effects, but it’s not possible to determine how the drug compares with tetrabenazine.

An ideal trial would involve three groups comparing deutetrabenazine, tetrabenazine, and placebo. A head-to-head, noninferiority comparison of deutetrabenazine against tetrabenazine, as was recommended by one of the developers of the compound, would also have been useful.

Nevertheless, tetrabenazine was approved by the FDA for the treatment of chorea in Huntington disease essentially based on efficacy data similar to the current study. Assuming deutetrabenazine was not priced significantly higher than tetrabenazine, its “favorable profile” would offer an additional option for patients and clinicians if and when the drug is approved.

The ongoing ARC-HD (Alternatives for Reducing Chorea in Huntington Disease) study is examining the safety and tolerability of patients with Huntington disease who switch from tetrabenazine to deutetrabenazine (and also includes patients from the current deutetrabenazine study who chose to switch to open-label deutetrabenazine). It should help to resolve whether the effect sizes are clinically meaningful and stable over a period longer than 12 weeks.

Michael D. Geschwind, MD, PhD, and Nick Paras, PhD, are in the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Geschwind reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging and from many sources in industry, including travel support from Teva. Dr. Paras reported receiving research support from Daiichi-Sankyo, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the Tau Consortium. Their comments are derived from an editorial accompanying the phase III trial’s paper (JAMA. 2016;316[1]:33-5).

A deuterated form of the vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitor tetrabenazine, called deutetrabenazine, modestly reduced chorea of Huntington disease over 12 weeks in a phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

First author Samuel Frank, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and his colleagues in the Huntington Study Group wrote that the observed treatment effect of 2.5 points on the primary end point of total maximal chorea score, “taken together with improvements in patient-centered end points, such as PGIC [Patient Global Impression of Change] and SF-36 [36-Item Short Form] physical functioning component scales, may be of clinical relevance, although this remains to be determined. The difference in total maximal chorea score associated with deutetrabenazine treatment that was observed in this study is notable given the progressive decline in total maximal chorea score and total motor score that has been previously described as part of the natural history of Huntington disease.”

The phase III trial is the first to use an active ingredient with deuterium substituted for hydrogen at key positions. The use of deuterium in the molecule, according to the investigators, prolongs “plasma half-life and reduce[s] metabolic variability, without changing target pharmacology,” and its “longer half-life and unique pharmacokinetic profile ... may enable less frequent and lower daily doses, thus achieving similar systemic exposure with lower peak concentrations and simplified dosing, compared with tetrabenazine.”

Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) is used worldwide and is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for treating chorea associated with Huntington disease.

The trial enrolled 90 patients with genetically diagnosed Huntington disease across 34 centers in the United States and Canada. The patients had a baseline total maximal chorea score of 8 or higher (range 0-28) and were randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive deuterated tetrabenazine (deutetrabenazine) or placebo. The deutetrabenazine group had a mean age of 55 years and 49% were male. The placebo group had a mean age of 52 years and 62% were men. Patients on the active drug were commenced at a total daily dose of 6 mg (divided into two doses) for the first week. Doses were then increased weekly by 6 mg daily until either chorea was adequately controlled or the maximum dose of 48 mg a day was reached. The final dose was maintained for an additional 4 weeks for a total of 12 weeks, followed by a 1-week washout (JAMA 2016;316[1]:40-50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8655).

The total maximal chorea score, in which higher scores represent worse chorea, that was measured from baseline to an average across the maintenance period during weeks 9 through 12 of therapy declined by a statistically significant 4.4 points – from a mean of 12.1 to 7.7 – in the deutetrabenazine group, compared with a decline of 1.9 points – from a mean of 13.2 to 11.3 – in the placebo group.

Improvements in secondary endpoints such as PGIC and SF-36 physical functioning component scales were also seen in the treatment group, although no improvement was seen in the Berg Balance Test.

Adverse events were similar between the deutetrabenazine and placebo groups, including depression, anxiety, and akathisia.

“Further research is needed to assess the clinical importance of the effect size, and to determine longer-term efficacy and safety,” the study authors concluded.

The study was supported by Auspex Pharmaceuticals, a wholly owned subsidiary of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Dr. Frank reported receiving grants from the Huntington Study Group, and many other authors in the group reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, including Auspex and Teva. Several authors are employees of Auspex.

A deuterated form of the vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitor tetrabenazine, called deutetrabenazine, modestly reduced chorea of Huntington disease over 12 weeks in a phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

First author Samuel Frank, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and his colleagues in the Huntington Study Group wrote that the observed treatment effect of 2.5 points on the primary end point of total maximal chorea score, “taken together with improvements in patient-centered end points, such as PGIC [Patient Global Impression of Change] and SF-36 [36-Item Short Form] physical functioning component scales, may be of clinical relevance, although this remains to be determined. The difference in total maximal chorea score associated with deutetrabenazine treatment that was observed in this study is notable given the progressive decline in total maximal chorea score and total motor score that has been previously described as part of the natural history of Huntington disease.”

The phase III trial is the first to use an active ingredient with deuterium substituted for hydrogen at key positions. The use of deuterium in the molecule, according to the investigators, prolongs “plasma half-life and reduce[s] metabolic variability, without changing target pharmacology,” and its “longer half-life and unique pharmacokinetic profile ... may enable less frequent and lower daily doses, thus achieving similar systemic exposure with lower peak concentrations and simplified dosing, compared with tetrabenazine.”

Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) is used worldwide and is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for treating chorea associated with Huntington disease.

The trial enrolled 90 patients with genetically diagnosed Huntington disease across 34 centers in the United States and Canada. The patients had a baseline total maximal chorea score of 8 or higher (range 0-28) and were randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive deuterated tetrabenazine (deutetrabenazine) or placebo. The deutetrabenazine group had a mean age of 55 years and 49% were male. The placebo group had a mean age of 52 years and 62% were men. Patients on the active drug were commenced at a total daily dose of 6 mg (divided into two doses) for the first week. Doses were then increased weekly by 6 mg daily until either chorea was adequately controlled or the maximum dose of 48 mg a day was reached. The final dose was maintained for an additional 4 weeks for a total of 12 weeks, followed by a 1-week washout (JAMA 2016;316[1]:40-50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8655).

The total maximal chorea score, in which higher scores represent worse chorea, that was measured from baseline to an average across the maintenance period during weeks 9 through 12 of therapy declined by a statistically significant 4.4 points – from a mean of 12.1 to 7.7 – in the deutetrabenazine group, compared with a decline of 1.9 points – from a mean of 13.2 to 11.3 – in the placebo group.

Improvements in secondary endpoints such as PGIC and SF-36 physical functioning component scales were also seen in the treatment group, although no improvement was seen in the Berg Balance Test.

Adverse events were similar between the deutetrabenazine and placebo groups, including depression, anxiety, and akathisia.

“Further research is needed to assess the clinical importance of the effect size, and to determine longer-term efficacy and safety,” the study authors concluded.

The study was supported by Auspex Pharmaceuticals, a wholly owned subsidiary of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Dr. Frank reported receiving grants from the Huntington Study Group, and many other authors in the group reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, including Auspex and Teva. Several authors are employees of Auspex.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Use of a deuterated form of tetrabenazine resulted in modest reductions in chorea of Huntington disease over 12 weeks, compared with placebo.

Major finding: The total maximal chorea score measured from baseline to maintenance therapy was reduced by a statistically significant 4.4 points in patients taking deutetrabenazine, compared with 1.9 point in those taking placebo.

Data source: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 90 patients genetically diagnosed with Huntington disease.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Auspex Pharmaceuticals, a wholly owned subsidiary of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Dr. Frank reported receiving grants from the Huntington Study Group, and many other authors in the group reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, including Auspex and Teva. Several authors are employees of Auspex.

Erythema and Induration on the Right Ear and Maxilla

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) is a chronic, cutaneous, granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae or the newly discovered Mycobacterium lepromatosis, both acid-fast, intracellular, bacillus bacterium.1 Although decreasing in prevalence due to effective treatment with antimicrobials, LL continues to be endemic in warm tropical or subtropical areas in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America.1 The mode of transmission of infection is not well established.

The cutaneous manifestation of leprosy was previously classified based on the cell-mediated immune response of the patient, as described by Ridley and Jopling,2 ranging from tuberculoid leprosy (TT) to LL. In this spectrum of leprosy are the borderline lesions including borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous.2,3 Although this classification is popular, in 2012 the World Health Organization implemented a new 2-category classification system to standardize treatment regimens: paucibacillary (2–5 lesions or 1 nerve involvement) and multibacillary (>5 lesions or multiple nerve involvement).4

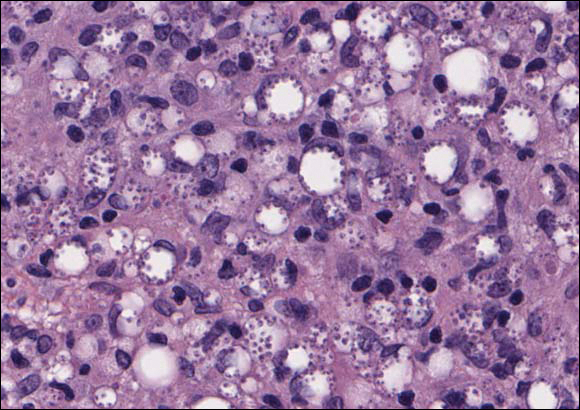

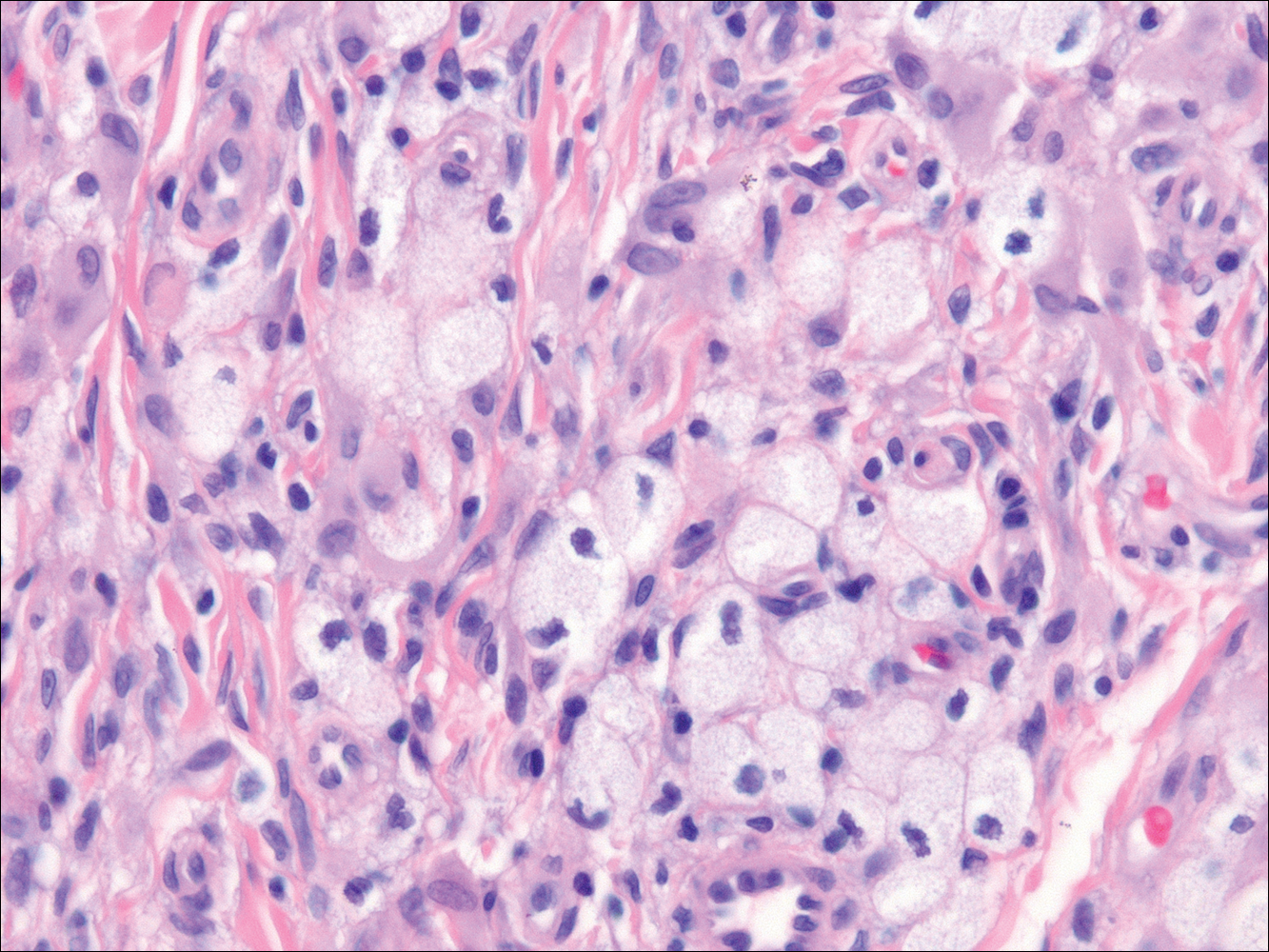

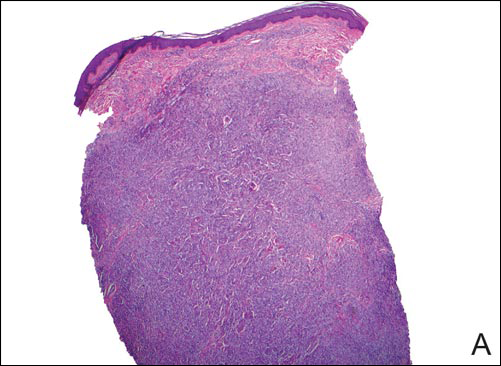

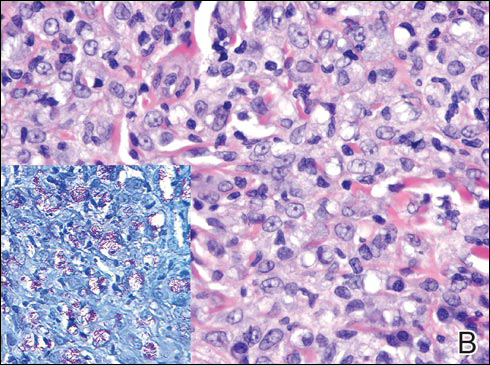

In LL, a cell-mediated immune response is not mounted against the infection in the patient. Clinically, the disease can manifest as macular and nodular erythematous cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders that are preferentially located on the face, earlobes, and nasal mucosa. Chronic infections are associated with sensory loss. Histologically, the dermis is densely infiltrated by foamy macrophages (Virchow cells or lepra cells), which do not form granulomas (quiz image A). The infiltrate may have varying accompanying lymphocytes and plasma cells, which can extend deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis is an uninvolved band of superficial dermis called the Grenz zone. The epidermis is flattened and atrophic. Nerves often are surrounded by macrophages with degrees of hyalinization but rarely are swollen. On acid-fast staining (Wade-Fite or Ziehl-Neelsen), numerous acid-fast bacilli are present within dermal cells in densely packed, intracellular collections called globi (quiz image B).2,3,5

In TT, the robust immune response causes epithelioid granuloma formation, similar to cutaneous sarcoidosis, and few, if any, organisms can be found on special stains. The remaining borderline lesions have varying numbers of bacilli and varying amounts of granuloma formation.3,6,7 Many cases of TT resolve without specific treatment. For most leprous diseases, the World Health Organization currently recommends a regimen of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine combination treatments for 6 to 12 months depending on the type of leprosy.8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients from LL endemic areas. Early lesions can have a histiocytic infiltration with associated mixed inflammation and prominent epidermal hyperplasia. These early lesions usually have parasitic organisms located within the periphery of the cytoplasm of macrophages (“marquee sign”) to help differentiate it from leprous diseases (Figure 1).9

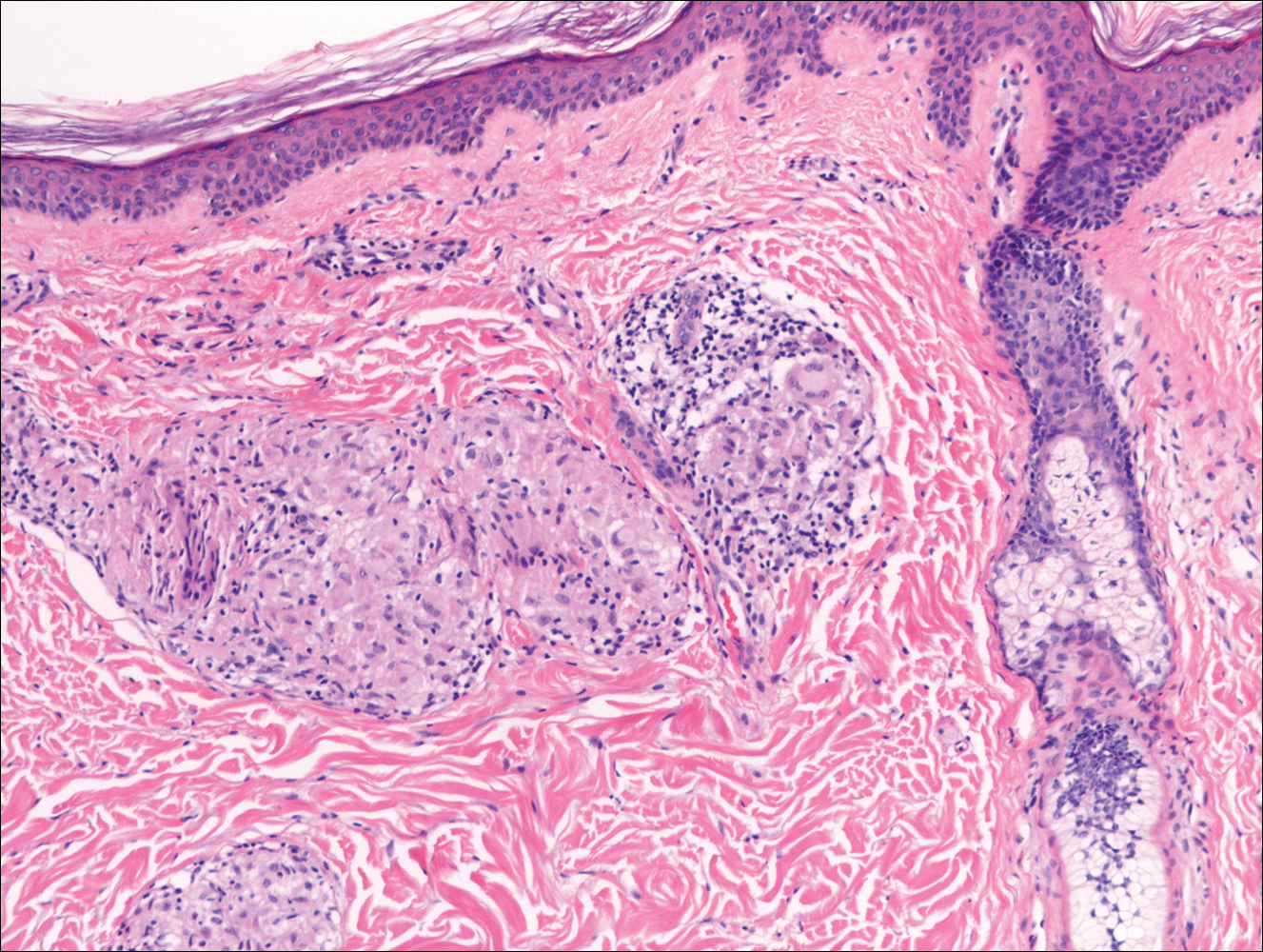

In nonendemic areas, leprous diseases often are mistaken for sarcoidosis, xanthomas, granular cell tumors, paraffinomas, or other histiocytic-rich lesions.10 Cutaneous sarcoidosis may be difficult to distinguish from TT, as both have noncaseating granulomas (Figure 2). Rare acid-fast bacilli may aid in the diagnosis, and sarcoid granulomas are not typically associated with cutaneous nerve involvement. New diagnostic tools such as polymerase chain reaction or genome sequencing can pick up rare organisms.

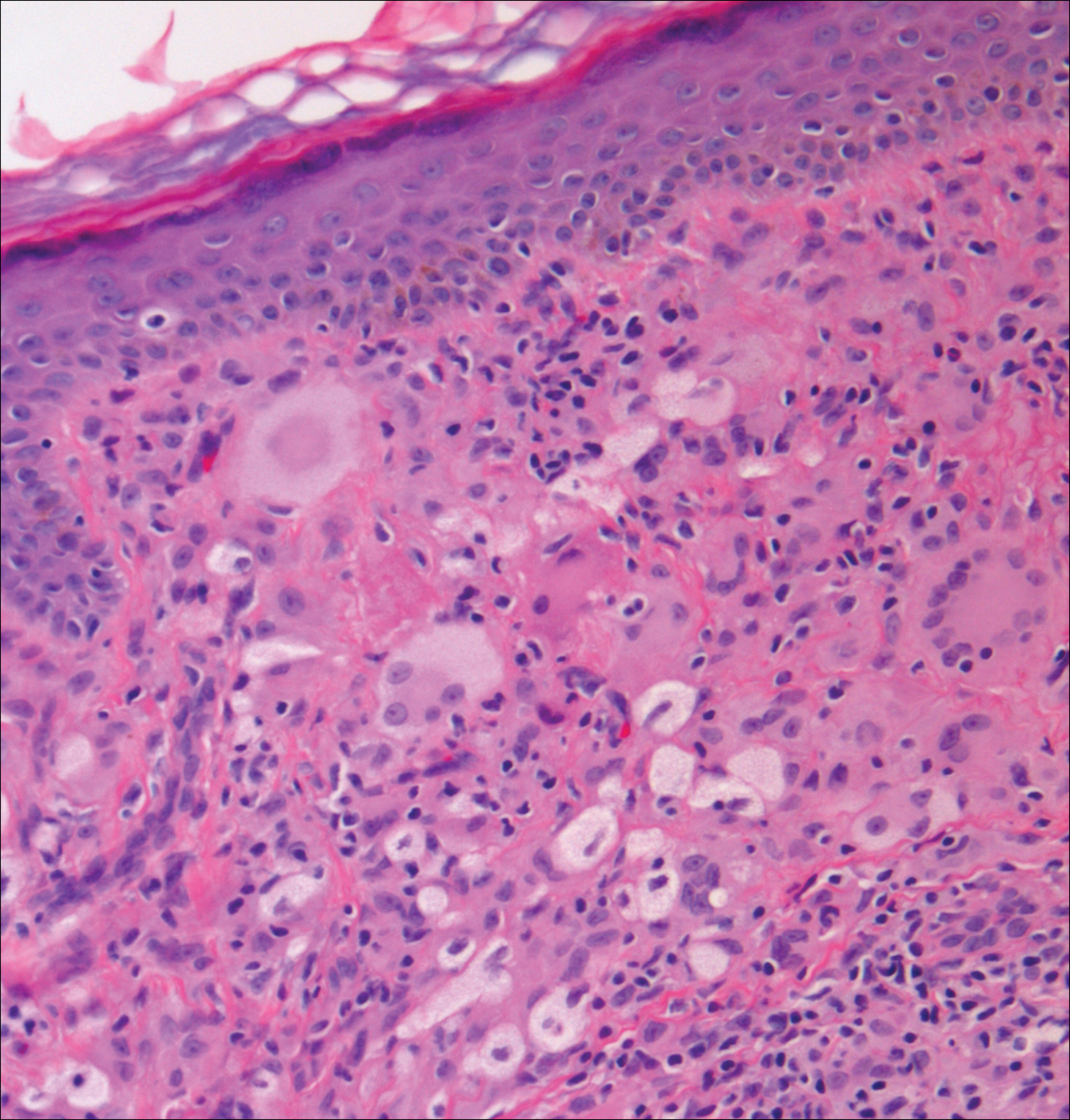

Xanthogranuolomas and xanthomas may histologically resemble LL with a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes. No organisms are found in the infiltrate. Histologically, xanthogranulomas (juvenile or adult) will be a mixed infiltrate with foamy histiocytes; giant cell formation, especially Touton giant cells; lymphocytes; and granulocytes (Figure 3). Touton giant cells have a wreathlike formation of nuclei and an outer vacuolated cytoplasm. Xanthomas have sheets of large histiocytes with a foamy, lipid-filled interior and mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

- Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, et al. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:856-864.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255-273.

- Ridley DS. Histological classification and the immunological spectrum of leprosy. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;51:451-465.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2012;968:1-61.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm M Jr. Treponemal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson Jr BL, et al. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:540-579.

- Dacso MM, Jacobson RR, Scollard DM, et al. Evaluation of multi-drug therapy for leprosy in the United States using daily rifampin. South Med J. 2011;104:689-694.

- Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-926.

- Massone C, Nunzi E, Cerroni L. Histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy in a nonendemic area. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:417-419.

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) is a chronic, cutaneous, granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae or the newly discovered Mycobacterium lepromatosis, both acid-fast, intracellular, bacillus bacterium.1 Although decreasing in prevalence due to effective treatment with antimicrobials, LL continues to be endemic in warm tropical or subtropical areas in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America.1 The mode of transmission of infection is not well established.

The cutaneous manifestation of leprosy was previously classified based on the cell-mediated immune response of the patient, as described by Ridley and Jopling,2 ranging from tuberculoid leprosy (TT) to LL. In this spectrum of leprosy are the borderline lesions including borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous.2,3 Although this classification is popular, in 2012 the World Health Organization implemented a new 2-category classification system to standardize treatment regimens: paucibacillary (2–5 lesions or 1 nerve involvement) and multibacillary (>5 lesions or multiple nerve involvement).4

In LL, a cell-mediated immune response is not mounted against the infection in the patient. Clinically, the disease can manifest as macular and nodular erythematous cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders that are preferentially located on the face, earlobes, and nasal mucosa. Chronic infections are associated with sensory loss. Histologically, the dermis is densely infiltrated by foamy macrophages (Virchow cells or lepra cells), which do not form granulomas (quiz image A). The infiltrate may have varying accompanying lymphocytes and plasma cells, which can extend deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis is an uninvolved band of superficial dermis called the Grenz zone. The epidermis is flattened and atrophic. Nerves often are surrounded by macrophages with degrees of hyalinization but rarely are swollen. On acid-fast staining (Wade-Fite or Ziehl-Neelsen), numerous acid-fast bacilli are present within dermal cells in densely packed, intracellular collections called globi (quiz image B).2,3,5

In TT, the robust immune response causes epithelioid granuloma formation, similar to cutaneous sarcoidosis, and few, if any, organisms can be found on special stains. The remaining borderline lesions have varying numbers of bacilli and varying amounts of granuloma formation.3,6,7 Many cases of TT resolve without specific treatment. For most leprous diseases, the World Health Organization currently recommends a regimen of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine combination treatments for 6 to 12 months depending on the type of leprosy.8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients from LL endemic areas. Early lesions can have a histiocytic infiltration with associated mixed inflammation and prominent epidermal hyperplasia. These early lesions usually have parasitic organisms located within the periphery of the cytoplasm of macrophages (“marquee sign”) to help differentiate it from leprous diseases (Figure 1).9

In nonendemic areas, leprous diseases often are mistaken for sarcoidosis, xanthomas, granular cell tumors, paraffinomas, or other histiocytic-rich lesions.10 Cutaneous sarcoidosis may be difficult to distinguish from TT, as both have noncaseating granulomas (Figure 2). Rare acid-fast bacilli may aid in the diagnosis, and sarcoid granulomas are not typically associated with cutaneous nerve involvement. New diagnostic tools such as polymerase chain reaction or genome sequencing can pick up rare organisms.

Xanthogranuolomas and xanthomas may histologically resemble LL with a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes. No organisms are found in the infiltrate. Histologically, xanthogranulomas (juvenile or adult) will be a mixed infiltrate with foamy histiocytes; giant cell formation, especially Touton giant cells; lymphocytes; and granulocytes (Figure 3). Touton giant cells have a wreathlike formation of nuclei and an outer vacuolated cytoplasm. Xanthomas have sheets of large histiocytes with a foamy, lipid-filled interior and mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) is a chronic, cutaneous, granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae or the newly discovered Mycobacterium lepromatosis, both acid-fast, intracellular, bacillus bacterium.1 Although decreasing in prevalence due to effective treatment with antimicrobials, LL continues to be endemic in warm tropical or subtropical areas in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America.1 The mode of transmission of infection is not well established.

The cutaneous manifestation of leprosy was previously classified based on the cell-mediated immune response of the patient, as described by Ridley and Jopling,2 ranging from tuberculoid leprosy (TT) to LL. In this spectrum of leprosy are the borderline lesions including borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous.2,3 Although this classification is popular, in 2012 the World Health Organization implemented a new 2-category classification system to standardize treatment regimens: paucibacillary (2–5 lesions or 1 nerve involvement) and multibacillary (>5 lesions or multiple nerve involvement).4

In LL, a cell-mediated immune response is not mounted against the infection in the patient. Clinically, the disease can manifest as macular and nodular erythematous cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders that are preferentially located on the face, earlobes, and nasal mucosa. Chronic infections are associated with sensory loss. Histologically, the dermis is densely infiltrated by foamy macrophages (Virchow cells or lepra cells), which do not form granulomas (quiz image A). The infiltrate may have varying accompanying lymphocytes and plasma cells, which can extend deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis is an uninvolved band of superficial dermis called the Grenz zone. The epidermis is flattened and atrophic. Nerves often are surrounded by macrophages with degrees of hyalinization but rarely are swollen. On acid-fast staining (Wade-Fite or Ziehl-Neelsen), numerous acid-fast bacilli are present within dermal cells in densely packed, intracellular collections called globi (quiz image B).2,3,5

In TT, the robust immune response causes epithelioid granuloma formation, similar to cutaneous sarcoidosis, and few, if any, organisms can be found on special stains. The remaining borderline lesions have varying numbers of bacilli and varying amounts of granuloma formation.3,6,7 Many cases of TT resolve without specific treatment. For most leprous diseases, the World Health Organization currently recommends a regimen of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine combination treatments for 6 to 12 months depending on the type of leprosy.8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients from LL endemic areas. Early lesions can have a histiocytic infiltration with associated mixed inflammation and prominent epidermal hyperplasia. These early lesions usually have parasitic organisms located within the periphery of the cytoplasm of macrophages (“marquee sign”) to help differentiate it from leprous diseases (Figure 1).9

In nonendemic areas, leprous diseases often are mistaken for sarcoidosis, xanthomas, granular cell tumors, paraffinomas, or other histiocytic-rich lesions.10 Cutaneous sarcoidosis may be difficult to distinguish from TT, as both have noncaseating granulomas (Figure 2). Rare acid-fast bacilli may aid in the diagnosis, and sarcoid granulomas are not typically associated with cutaneous nerve involvement. New diagnostic tools such as polymerase chain reaction or genome sequencing can pick up rare organisms.

Xanthogranuolomas and xanthomas may histologically resemble LL with a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes. No organisms are found in the infiltrate. Histologically, xanthogranulomas (juvenile or adult) will be a mixed infiltrate with foamy histiocytes; giant cell formation, especially Touton giant cells; lymphocytes; and granulocytes (Figure 3). Touton giant cells have a wreathlike formation of nuclei and an outer vacuolated cytoplasm. Xanthomas have sheets of large histiocytes with a foamy, lipid-filled interior and mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

- Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, et al. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:856-864.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255-273.

- Ridley DS. Histological classification and the immunological spectrum of leprosy. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;51:451-465.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2012;968:1-61.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm M Jr. Treponemal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson Jr BL, et al. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:540-579.

- Dacso MM, Jacobson RR, Scollard DM, et al. Evaluation of multi-drug therapy for leprosy in the United States using daily rifampin. South Med J. 2011;104:689-694.

- Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-926.

- Massone C, Nunzi E, Cerroni L. Histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy in a nonendemic area. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:417-419.

- Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, et al. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:856-864.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255-273.

- Ridley DS. Histological classification and the immunological spectrum of leprosy. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;51:451-465.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2012;968:1-61.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm M Jr. Treponemal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson Jr BL, et al. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:540-579.

- Dacso MM, Jacobson RR, Scollard DM, et al. Evaluation of multi-drug therapy for leprosy in the United States using daily rifampin. South Med J. 2011;104:689-694.

- Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-926.

- Massone C, Nunzi E, Cerroni L. Histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy in a nonendemic area. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:417-419.

A 43-year-old man from Ghana presented with erythema and induration on the skin of the right maxillary region and right ear of several weeks’ duration.

The best diagnosis is:

a. cutaneous leishmaniasis

b. lepromatous leprosy

c. sarcoidosis

d. xanthogranuloma

e. xanthoma

Global Visits, 99024, and MACRA: 3 Things You Should Think About and Lose Sleep Over But Probably Do Not

How does the global period affect dermatologists?

Global period is a term used to describe what is included in the payment for performance of a procedure using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. These global periods can either be 0 (000), 10 (010), or 90 (090) days. In dermatology, we have all three. Most codes used by dermatologists fall under global periods of 0 and 10 days, while 90-day codes are used for all adjacent tissue transfers and split- and full-thickness grafts. In documents listing global periods for CPT codes,1 you also may see “XXX” when the global period concept does not apply to a particular code, “YYY” when the payer decides on whether a global period applies and what it will be, and “ZZZ” when a certain code is an add-on to another service and is therefore included in the global period for that service.

The contents of a service are defined by the global period. Although the procedure itself is an obvious component, CPT codes with a global period of 000 (eg, biopsy of a skin lesion, simple repairs) have no preoperative or postoperative periods, and an evaluation and management (E&M) service usually is not payable if it was done in relation to the procedure. If the patient returns the following day for any reason, including concerns about the procedure itself, these visits may be reported separately.

For CPT codes with global periods of 010 (eg, excisions, intermediate and complex repairs, destructions), there also is no preoperative period and a visit on the day of the procedure generally is not payable as a separate service. The day of the procedure and the 10 days after are included in the global period, and any visits relating to the procedure on that day and the 10 days following the procedure are not payable separately. Typically, the value of one 99212 or 99213 E&M visit is included in the payment for the procedure.

For CPT codes with global periods of 090, the day before the procedure, the day of the procedure, and 90 days following the procedure are all included. Typically, more than one established patient visit along with hospital management and discharge planning where deemed necessary by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) are included, which seems straightforward, but there is a sort of paradox here. An initial evaluation by the surgeon who determines the need for the 090 code (by definition, 090 means major surgery and major surgery means 090) can be separately reported for E&M using modifier -57 (decision for surgery), which means the surgeon seeing the hot abdomen in the emergency department can report an E&M code in addition to the procedure, as can the surgeon who decides to repair a defect after removal of a skin tumor with a flap or graft. The same is not applicable if one performs a simple repair (included with benign or malignant excisions) following Mohs micrographic surgery or an intermediate or complex repair after any form of skin cancer removal. In any event, you are making a decision about what repair is best for the patient and sharing that with him/her while obtaining patient consent, but only 090 codes allow the capture of the decision to perform the procedure.

Which modifiers can you use on the same day as a procedure during the global period?

All is not lost if you perform other activities on the same day as the procedure or during the global period if those other activities are unrelated, which means complications of the procedure cannot be separately reported. If the unrelated cognitive work is reported on the day of a procedure with an E&M code, it should be accompanied by modifier -25 (significant, separately identifiable E&M service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service). If you have an E&M visit unrelated to the procedure within the global period, report it using modifier -24 (unrelated E&M service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during a postoperative period).

If you perform another procedure on the same day as the primary one, you can use modifier -51 (multiple procedures) to let the payer know you provided other services that are separately reportable. If you do multiples of the same procedure, use modifier -59 (distinct procedural service) to let the payer know that you indeed did multiple procedures and did not submit a typographical error. Modifier -59 also is used when you perform a pair of procedures on separate and distinct lesions that would be disallowed by Mutually Exclusive Edits if done on a single lesion. For example, if you perform a biopsy of a lesion and immediately curette it, you should wait for the pathology report; if the lesion is malignant, only the destruction should be reported, and if it is benign, the only medically necessary service was the biopsy. When biopsy and curettage are performed on 2 separate lesions on the same date of service, payer software will disallow the biopsy charge unless a -59 modifier is attached to indicate that the biopsy was performed on a separate lesion. Medicare has introduced the -XS modifier, which is planned to be phased in to replace the -59 modifier for Medicare patients,2 if and when the CMS sets up their systems to accept the modifier.

If you repeat a procedure during the global period (eg, reexcision for a positive margin), it is appropriate to use modifier -58 (staged or related procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during the postoperative period). If an unrelated procedure is performed during the global period, such as removing another lesion at a different site, modifier -79 (unrelated procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during the postoperative period) lets you report it.

There are 2 available modifiers that you might think twice before using. Modifier -76 (repeat procedure or service by same physician or other qualified health care professional) may be used if, for example, a wound opens and you have to sew it up again. The more common usage is more pedestrian; a second electrocardiogram reading on the same day is a common use.3 Modifier -78 (unplanned return to the operating/procedure room by the same physician or other qualified health care professional following initial procedure for a related procedure during the postoperative period) is used when something goes awry, such as an aneurysm repair that is bleeding postoperatively, necessitating a trip back to the operating room.4

How might these modifiers be used in dermatology? One example may be if a wound dehisces or needs to be seen for a bleeding issue that might necessitate opening and exploring the wound; if a patient has one of these problems after fixing the plumbing and hits himself with a wrench, use of these modifiers is reasonable. On the other hand, if the patient is waiting in your office to be picked up and the problem happens, using these modifiers may not be the wisest thing to do. Let common sense prevail!

What is CPT code 99024?

Likely a code you have never used in your private office, the descriptor for 99024 states “postoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an E&M service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure,” which translates to “here for an included visit so why am I billing this and having the cost of a claim with no reimbursement?” Why indeed. You may be using it as a space holder—one more check and balance so no patient leaves the office without a superbill or its electronic equivalent being submitted to your billing staff—or you may simply never use it. The CMS is interested in it as a way to see if the visits embedded in global periods actually take place. This is especially important as CMS is legally mandated under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA)5 to see if these visits actually take place.6 There are billions of dollars paid out for visits that are part of the global package and this code is one way the government may track them. If you are not using this code at all, you might consider it, even if you do not submit a claim. Your staff will know you did not forget to report a service and the reporting of the code by you internally and it lets you document for the billing side of the practice that they were there and a code report has been performed and not simply forgotten.

Final Thoughts

Following this discussion of global periods and CPT code 99024, you may be wondering why you get paid what you do and how the visits all link together. The buzzword is intensity, and we will explore that concept and IWPUT (intraservice work per unit of time), which I have coined as meaning “I Will Persevere Until Then,” in the next column.

- Revisions to Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2016. Addendum B—Relative Value Units and Related Information Used in CY 2016 Final Rule. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched?Downloads?CY2016-PFS-FC-Addenda.zip. Updated November 5, 2015. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- Modifier 59 article. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/NationalCorrectCodInitEd/downloads/modifier59.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- Modifier dictionary FAQ. American College of Emergency Physicians website. https://www.acep.org/Physician-Resources/Practice-Resources/Administration/Financial-Issues-/-Reimbursement/Modifier-Dictionary-FAQ/. Updated April 2014. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- Modifier 78 fact sheet. Wisconsin Physicians Service Insurance Corporation website. http://wpsmedicare.com/j8macpartb/resources/modifiers/modifier-78.shtml. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, HR 2, 114th Cong, 1st Sess (2015).

- Medicare Learning Network. Collecting data on global surgery as required by MACRA: listening session. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/2016-01-20-MACRA-Transcript.pdf. Posted January 20, 2016. Accessed June 2, 2016.

How does the global period affect dermatologists?

Global period is a term used to describe what is included in the payment for performance of a procedure using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. These global periods can either be 0 (000), 10 (010), or 90 (090) days. In dermatology, we have all three. Most codes used by dermatologists fall under global periods of 0 and 10 days, while 90-day codes are used for all adjacent tissue transfers and split- and full-thickness grafts. In documents listing global periods for CPT codes,1 you also may see “XXX” when the global period concept does not apply to a particular code, “YYY” when the payer decides on whether a global period applies and what it will be, and “ZZZ” when a certain code is an add-on to another service and is therefore included in the global period for that service.

The contents of a service are defined by the global period. Although the procedure itself is an obvious component, CPT codes with a global period of 000 (eg, biopsy of a skin lesion, simple repairs) have no preoperative or postoperative periods, and an evaluation and management (E&M) service usually is not payable if it was done in relation to the procedure. If the patient returns the following day for any reason, including concerns about the procedure itself, these visits may be reported separately.

For CPT codes with global periods of 010 (eg, excisions, intermediate and complex repairs, destructions), there also is no preoperative period and a visit on the day of the procedure generally is not payable as a separate service. The day of the procedure and the 10 days after are included in the global period, and any visits relating to the procedure on that day and the 10 days following the procedure are not payable separately. Typically, the value of one 99212 or 99213 E&M visit is included in the payment for the procedure.

For CPT codes with global periods of 090, the day before the procedure, the day of the procedure, and 90 days following the procedure are all included. Typically, more than one established patient visit along with hospital management and discharge planning where deemed necessary by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) are included, which seems straightforward, but there is a sort of paradox here. An initial evaluation by the surgeon who determines the need for the 090 code (by definition, 090 means major surgery and major surgery means 090) can be separately reported for E&M using modifier -57 (decision for surgery), which means the surgeon seeing the hot abdomen in the emergency department can report an E&M code in addition to the procedure, as can the surgeon who decides to repair a defect after removal of a skin tumor with a flap or graft. The same is not applicable if one performs a simple repair (included with benign or malignant excisions) following Mohs micrographic surgery or an intermediate or complex repair after any form of skin cancer removal. In any event, you are making a decision about what repair is best for the patient and sharing that with him/her while obtaining patient consent, but only 090 codes allow the capture of the decision to perform the procedure.

Which modifiers can you use on the same day as a procedure during the global period?

All is not lost if you perform other activities on the same day as the procedure or during the global period if those other activities are unrelated, which means complications of the procedure cannot be separately reported. If the unrelated cognitive work is reported on the day of a procedure with an E&M code, it should be accompanied by modifier -25 (significant, separately identifiable E&M service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service). If you have an E&M visit unrelated to the procedure within the global period, report it using modifier -24 (unrelated E&M service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during a postoperative period).

If you perform another procedure on the same day as the primary one, you can use modifier -51 (multiple procedures) to let the payer know you provided other services that are separately reportable. If you do multiples of the same procedure, use modifier -59 (distinct procedural service) to let the payer know that you indeed did multiple procedures and did not submit a typographical error. Modifier -59 also is used when you perform a pair of procedures on separate and distinct lesions that would be disallowed by Mutually Exclusive Edits if done on a single lesion. For example, if you perform a biopsy of a lesion and immediately curette it, you should wait for the pathology report; if the lesion is malignant, only the destruction should be reported, and if it is benign, the only medically necessary service was the biopsy. When biopsy and curettage are performed on 2 separate lesions on the same date of service, payer software will disallow the biopsy charge unless a -59 modifier is attached to indicate that the biopsy was performed on a separate lesion. Medicare has introduced the -XS modifier, which is planned to be phased in to replace the -59 modifier for Medicare patients,2 if and when the CMS sets up their systems to accept the modifier.

If you repeat a procedure during the global period (eg, reexcision for a positive margin), it is appropriate to use modifier -58 (staged or related procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during the postoperative period). If an unrelated procedure is performed during the global period, such as removing another lesion at a different site, modifier -79 (unrelated procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during the postoperative period) lets you report it.

There are 2 available modifiers that you might think twice before using. Modifier -76 (repeat procedure or service by same physician or other qualified health care professional) may be used if, for example, a wound opens and you have to sew it up again. The more common usage is more pedestrian; a second electrocardiogram reading on the same day is a common use.3 Modifier -78 (unplanned return to the operating/procedure room by the same physician or other qualified health care professional following initial procedure for a related procedure during the postoperative period) is used when something goes awry, such as an aneurysm repair that is bleeding postoperatively, necessitating a trip back to the operating room.4

How might these modifiers be used in dermatology? One example may be if a wound dehisces or needs to be seen for a bleeding issue that might necessitate opening and exploring the wound; if a patient has one of these problems after fixing the plumbing and hits himself with a wrench, use of these modifiers is reasonable. On the other hand, if the patient is waiting in your office to be picked up and the problem happens, using these modifiers may not be the wisest thing to do. Let common sense prevail!

What is CPT code 99024?

Likely a code you have never used in your private office, the descriptor for 99024 states “postoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an E&M service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure,” which translates to “here for an included visit so why am I billing this and having the cost of a claim with no reimbursement?” Why indeed. You may be using it as a space holder—one more check and balance so no patient leaves the office without a superbill or its electronic equivalent being submitted to your billing staff—or you may simply never use it. The CMS is interested in it as a way to see if the visits embedded in global periods actually take place. This is especially important as CMS is legally mandated under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA)5 to see if these visits actually take place.6 There are billions of dollars paid out for visits that are part of the global package and this code is one way the government may track them. If you are not using this code at all, you might consider it, even if you do not submit a claim. Your staff will know you did not forget to report a service and the reporting of the code by you internally and it lets you document for the billing side of the practice that they were there and a code report has been performed and not simply forgotten.

Final Thoughts

Following this discussion of global periods and CPT code 99024, you may be wondering why you get paid what you do and how the visits all link together. The buzzword is intensity, and we will explore that concept and IWPUT (intraservice work per unit of time), which I have coined as meaning “I Will Persevere Until Then,” in the next column.

How does the global period affect dermatologists?

Global period is a term used to describe what is included in the payment for performance of a procedure using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. These global periods can either be 0 (000), 10 (010), or 90 (090) days. In dermatology, we have all three. Most codes used by dermatologists fall under global periods of 0 and 10 days, while 90-day codes are used for all adjacent tissue transfers and split- and full-thickness grafts. In documents listing global periods for CPT codes,1 you also may see “XXX” when the global period concept does not apply to a particular code, “YYY” when the payer decides on whether a global period applies and what it will be, and “ZZZ” when a certain code is an add-on to another service and is therefore included in the global period for that service.

The contents of a service are defined by the global period. Although the procedure itself is an obvious component, CPT codes with a global period of 000 (eg, biopsy of a skin lesion, simple repairs) have no preoperative or postoperative periods, and an evaluation and management (E&M) service usually is not payable if it was done in relation to the procedure. If the patient returns the following day for any reason, including concerns about the procedure itself, these visits may be reported separately.

For CPT codes with global periods of 010 (eg, excisions, intermediate and complex repairs, destructions), there also is no preoperative period and a visit on the day of the procedure generally is not payable as a separate service. The day of the procedure and the 10 days after are included in the global period, and any visits relating to the procedure on that day and the 10 days following the procedure are not payable separately. Typically, the value of one 99212 or 99213 E&M visit is included in the payment for the procedure.

For CPT codes with global periods of 090, the day before the procedure, the day of the procedure, and 90 days following the procedure are all included. Typically, more than one established patient visit along with hospital management and discharge planning where deemed necessary by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) are included, which seems straightforward, but there is a sort of paradox here. An initial evaluation by the surgeon who determines the need for the 090 code (by definition, 090 means major surgery and major surgery means 090) can be separately reported for E&M using modifier -57 (decision for surgery), which means the surgeon seeing the hot abdomen in the emergency department can report an E&M code in addition to the procedure, as can the surgeon who decides to repair a defect after removal of a skin tumor with a flap or graft. The same is not applicable if one performs a simple repair (included with benign or malignant excisions) following Mohs micrographic surgery or an intermediate or complex repair after any form of skin cancer removal. In any event, you are making a decision about what repair is best for the patient and sharing that with him/her while obtaining patient consent, but only 090 codes allow the capture of the decision to perform the procedure.

Which modifiers can you use on the same day as a procedure during the global period?

All is not lost if you perform other activities on the same day as the procedure or during the global period if those other activities are unrelated, which means complications of the procedure cannot be separately reported. If the unrelated cognitive work is reported on the day of a procedure with an E&M code, it should be accompanied by modifier -25 (significant, separately identifiable E&M service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of the procedure or other service). If you have an E&M visit unrelated to the procedure within the global period, report it using modifier -24 (unrelated E&M service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during a postoperative period).

If you perform another procedure on the same day as the primary one, you can use modifier -51 (multiple procedures) to let the payer know you provided other services that are separately reportable. If you do multiples of the same procedure, use modifier -59 (distinct procedural service) to let the payer know that you indeed did multiple procedures and did not submit a typographical error. Modifier -59 also is used when you perform a pair of procedures on separate and distinct lesions that would be disallowed by Mutually Exclusive Edits if done on a single lesion. For example, if you perform a biopsy of a lesion and immediately curette it, you should wait for the pathology report; if the lesion is malignant, only the destruction should be reported, and if it is benign, the only medically necessary service was the biopsy. When biopsy and curettage are performed on 2 separate lesions on the same date of service, payer software will disallow the biopsy charge unless a -59 modifier is attached to indicate that the biopsy was performed on a separate lesion. Medicare has introduced the -XS modifier, which is planned to be phased in to replace the -59 modifier for Medicare patients,2 if and when the CMS sets up their systems to accept the modifier.

If you repeat a procedure during the global period (eg, reexcision for a positive margin), it is appropriate to use modifier -58 (staged or related procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during the postoperative period). If an unrelated procedure is performed during the global period, such as removing another lesion at a different site, modifier -79 (unrelated procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional during the postoperative period) lets you report it.

There are 2 available modifiers that you might think twice before using. Modifier -76 (repeat procedure or service by same physician or other qualified health care professional) may be used if, for example, a wound opens and you have to sew it up again. The more common usage is more pedestrian; a second electrocardiogram reading on the same day is a common use.3 Modifier -78 (unplanned return to the operating/procedure room by the same physician or other qualified health care professional following initial procedure for a related procedure during the postoperative period) is used when something goes awry, such as an aneurysm repair that is bleeding postoperatively, necessitating a trip back to the operating room.4

How might these modifiers be used in dermatology? One example may be if a wound dehisces or needs to be seen for a bleeding issue that might necessitate opening and exploring the wound; if a patient has one of these problems after fixing the plumbing and hits himself with a wrench, use of these modifiers is reasonable. On the other hand, if the patient is waiting in your office to be picked up and the problem happens, using these modifiers may not be the wisest thing to do. Let common sense prevail!

What is CPT code 99024?

Likely a code you have never used in your private office, the descriptor for 99024 states “postoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an E&M service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure,” which translates to “here for an included visit so why am I billing this and having the cost of a claim with no reimbursement?” Why indeed. You may be using it as a space holder—one more check and balance so no patient leaves the office without a superbill or its electronic equivalent being submitted to your billing staff—or you may simply never use it. The CMS is interested in it as a way to see if the visits embedded in global periods actually take place. This is especially important as CMS is legally mandated under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA)5 to see if these visits actually take place.6 There are billions of dollars paid out for visits that are part of the global package and this code is one way the government may track them. If you are not using this code at all, you might consider it, even if you do not submit a claim. Your staff will know you did not forget to report a service and the reporting of the code by you internally and it lets you document for the billing side of the practice that they were there and a code report has been performed and not simply forgotten.

Final Thoughts