User login

Team creates bone marrow on a chip

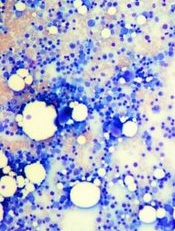

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic chip device mimics living bone marrow, according to research published in Tissue Engineering.

Experiments showed the engineered bone marrow responded in a way similar to living bone marrow when exposed to damaging radiation followed by treatment with compounds that aid in blood cell recovery.

The researchers said this new bone marrow-on-a-chip device holds promise for testing and developing improved radiation countermeasures.

Yu-suke Torisawa, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team used a tissue engineering approach to induce formation of new marrow-containing bone in mice. They then surgically removed the bone, placed it in a microfluidic device, and continuously perfused it with medium in vitro.

Next, the researchers set out to determine if the device would keep the engineered bone marrow alive so they could perform tests on it.

To test the system, the team analyzed the dynamics of blood cell production and evaluated the radiation-protecting effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI).

Experiments showed the microfluidic device could maintain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in normal proportions for at least 2 weeks in culture.

Over time, the researchers observed increases in the number of leukocytes and red blood cells in the microfluidic circulation. And they found that adding erythropoietin induced a significant increase in erythrocyte production.

When the researchers exposed the engineered bone marrow to gamma radiation, they saw reduced leukocyte production.

And when they treated the engineered bone marrow with G-CSF or BPI, the team saw significant increases in the number of hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid cells in the fluidic outflow.

On the other hand, BPI did not have such an effect on static bone marrow cultures. But the researchers pointed out that previous work has shown BPI can accelerate recovery from radiation-induced toxicity in vivo.

The team therefore concluded that, unlike static bone marrow cultures, engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic device effectively mimics the recovery response of bone marrow in the body. ![]()

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic chip device mimics living bone marrow, according to research published in Tissue Engineering.

Experiments showed the engineered bone marrow responded in a way similar to living bone marrow when exposed to damaging radiation followed by treatment with compounds that aid in blood cell recovery.

The researchers said this new bone marrow-on-a-chip device holds promise for testing and developing improved radiation countermeasures.

Yu-suke Torisawa, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team used a tissue engineering approach to induce formation of new marrow-containing bone in mice. They then surgically removed the bone, placed it in a microfluidic device, and continuously perfused it with medium in vitro.

Next, the researchers set out to determine if the device would keep the engineered bone marrow alive so they could perform tests on it.

To test the system, the team analyzed the dynamics of blood cell production and evaluated the radiation-protecting effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI).

Experiments showed the microfluidic device could maintain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in normal proportions for at least 2 weeks in culture.

Over time, the researchers observed increases in the number of leukocytes and red blood cells in the microfluidic circulation. And they found that adding erythropoietin induced a significant increase in erythrocyte production.

When the researchers exposed the engineered bone marrow to gamma radiation, they saw reduced leukocyte production.

And when they treated the engineered bone marrow with G-CSF or BPI, the team saw significant increases in the number of hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid cells in the fluidic outflow.

On the other hand, BPI did not have such an effect on static bone marrow cultures. But the researchers pointed out that previous work has shown BPI can accelerate recovery from radiation-induced toxicity in vivo.

The team therefore concluded that, unlike static bone marrow cultures, engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic device effectively mimics the recovery response of bone marrow in the body. ![]()

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic chip device mimics living bone marrow, according to research published in Tissue Engineering.

Experiments showed the engineered bone marrow responded in a way similar to living bone marrow when exposed to damaging radiation followed by treatment with compounds that aid in blood cell recovery.

The researchers said this new bone marrow-on-a-chip device holds promise for testing and developing improved radiation countermeasures.

Yu-suke Torisawa, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team used a tissue engineering approach to induce formation of new marrow-containing bone in mice. They then surgically removed the bone, placed it in a microfluidic device, and continuously perfused it with medium in vitro.

Next, the researchers set out to determine if the device would keep the engineered bone marrow alive so they could perform tests on it.

To test the system, the team analyzed the dynamics of blood cell production and evaluated the radiation-protecting effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI).

Experiments showed the microfluidic device could maintain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in normal proportions for at least 2 weeks in culture.

Over time, the researchers observed increases in the number of leukocytes and red blood cells in the microfluidic circulation. And they found that adding erythropoietin induced a significant increase in erythrocyte production.

When the researchers exposed the engineered bone marrow to gamma radiation, they saw reduced leukocyte production.

And when they treated the engineered bone marrow with G-CSF or BPI, the team saw significant increases in the number of hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid cells in the fluidic outflow.

On the other hand, BPI did not have such an effect on static bone marrow cultures. But the researchers pointed out that previous work has shown BPI can accelerate recovery from radiation-induced toxicity in vivo.

The team therefore concluded that, unlike static bone marrow cultures, engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic device effectively mimics the recovery response of bone marrow in the body. ![]()

Transparency doesn’t lower healthcare spending

Photo by Petr Kratochvil

Providing patients with a tool that enabled them to search for healthcare prices did not decrease their spending, according to a study published in JAMA.

Researchers studied the Truven Health Analytics Treatment Cost Calculator, an online price transparency tool that tells users how much they would pay out of pocket for services such as X-rays, lab tests, outpatient surgeries, or physician office visits at different sites.

The out-of-pocket cost estimates are based on the users’ health plan benefits and on how much they have already spent on healthcare during the year.

Two large national companies offered this tool to their employees in 2011 and 2012.

The researchers compared the healthcare spending patterns of employees (n=148,655) at these companies in the year before and after the tool was introduced with patterns among employees (n=295,983) of other companies that did not offer the tool.

Overall, having access to the tool was not associated with a reduction in outpatient spending, and subjects did not switch from more expensive outpatient hospital-based care to lower-cost settings.

The average outpatient spending among employees offered the tool was $2021 in the year before the tool was introduced and $2233 in the year after. Among control subjects, average outpatient spending increased from $1985 to $2138.

The average outpatient out-of-pocket spending among employees offered the tool was $507 in the year before it was introduced and $555 in the year after. In the control group, the average outpatient out-of-pocket spending increased from $490 to $520.

After the researchers adjusted for demographic and health characteristics, being offered the tool was associated with an average $59 increase in outpatient spending and an average $18 increase in out-of-pocket spending.

When the researchers looked only at patients with higher deductibles—who would be expected to have greater price-shopping incentives—they also found no evidence of reduction in spending.

“Despite large variation in healthcare prices, prevalence of high-deductible health plans, and widespread interest in price transparency, we did not find evidence that offering price transparency to employees generated savings,” said study author Sunita Desai, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

A possible explanation for this finding is that most patients did not actually use the tool. Only 10% of the employees who were offered the tool used it at least once in the first 12 months.

When patients did use the tool, more than half the searches were for relatively expensive services of over $1000.

“For expensive care that exceeds their deductible, patients may not see any reason to switch,” said study author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, also of Harvard Medical School. “They do not save by choosing a lower-cost provider, even if the health plan does.”

Still, the researchers said the tool does provide patients with valuable information, including their expected out-of-pocket costs, their deductible, and their health plan’s provider network.

“People might use the tools more—and focus more on choosing lower-priced care options—if they are combined with additional health plan benefit features that give greater incentive to price shop,” Dr Desai said. ![]()

Photo by Petr Kratochvil

Providing patients with a tool that enabled them to search for healthcare prices did not decrease their spending, according to a study published in JAMA.

Researchers studied the Truven Health Analytics Treatment Cost Calculator, an online price transparency tool that tells users how much they would pay out of pocket for services such as X-rays, lab tests, outpatient surgeries, or physician office visits at different sites.

The out-of-pocket cost estimates are based on the users’ health plan benefits and on how much they have already spent on healthcare during the year.

Two large national companies offered this tool to their employees in 2011 and 2012.

The researchers compared the healthcare spending patterns of employees (n=148,655) at these companies in the year before and after the tool was introduced with patterns among employees (n=295,983) of other companies that did not offer the tool.

Overall, having access to the tool was not associated with a reduction in outpatient spending, and subjects did not switch from more expensive outpatient hospital-based care to lower-cost settings.

The average outpatient spending among employees offered the tool was $2021 in the year before the tool was introduced and $2233 in the year after. Among control subjects, average outpatient spending increased from $1985 to $2138.

The average outpatient out-of-pocket spending among employees offered the tool was $507 in the year before it was introduced and $555 in the year after. In the control group, the average outpatient out-of-pocket spending increased from $490 to $520.

After the researchers adjusted for demographic and health characteristics, being offered the tool was associated with an average $59 increase in outpatient spending and an average $18 increase in out-of-pocket spending.

When the researchers looked only at patients with higher deductibles—who would be expected to have greater price-shopping incentives—they also found no evidence of reduction in spending.

“Despite large variation in healthcare prices, prevalence of high-deductible health plans, and widespread interest in price transparency, we did not find evidence that offering price transparency to employees generated savings,” said study author Sunita Desai, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

A possible explanation for this finding is that most patients did not actually use the tool. Only 10% of the employees who were offered the tool used it at least once in the first 12 months.

When patients did use the tool, more than half the searches were for relatively expensive services of over $1000.

“For expensive care that exceeds their deductible, patients may not see any reason to switch,” said study author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, also of Harvard Medical School. “They do not save by choosing a lower-cost provider, even if the health plan does.”

Still, the researchers said the tool does provide patients with valuable information, including their expected out-of-pocket costs, their deductible, and their health plan’s provider network.

“People might use the tools more—and focus more on choosing lower-priced care options—if they are combined with additional health plan benefit features that give greater incentive to price shop,” Dr Desai said. ![]()

Photo by Petr Kratochvil

Providing patients with a tool that enabled them to search for healthcare prices did not decrease their spending, according to a study published in JAMA.

Researchers studied the Truven Health Analytics Treatment Cost Calculator, an online price transparency tool that tells users how much they would pay out of pocket for services such as X-rays, lab tests, outpatient surgeries, or physician office visits at different sites.

The out-of-pocket cost estimates are based on the users’ health plan benefits and on how much they have already spent on healthcare during the year.

Two large national companies offered this tool to their employees in 2011 and 2012.

The researchers compared the healthcare spending patterns of employees (n=148,655) at these companies in the year before and after the tool was introduced with patterns among employees (n=295,983) of other companies that did not offer the tool.

Overall, having access to the tool was not associated with a reduction in outpatient spending, and subjects did not switch from more expensive outpatient hospital-based care to lower-cost settings.

The average outpatient spending among employees offered the tool was $2021 in the year before the tool was introduced and $2233 in the year after. Among control subjects, average outpatient spending increased from $1985 to $2138.

The average outpatient out-of-pocket spending among employees offered the tool was $507 in the year before it was introduced and $555 in the year after. In the control group, the average outpatient out-of-pocket spending increased from $490 to $520.

After the researchers adjusted for demographic and health characteristics, being offered the tool was associated with an average $59 increase in outpatient spending and an average $18 increase in out-of-pocket spending.

When the researchers looked only at patients with higher deductibles—who would be expected to have greater price-shopping incentives—they also found no evidence of reduction in spending.

“Despite large variation in healthcare prices, prevalence of high-deductible health plans, and widespread interest in price transparency, we did not find evidence that offering price transparency to employees generated savings,” said study author Sunita Desai, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

A possible explanation for this finding is that most patients did not actually use the tool. Only 10% of the employees who were offered the tool used it at least once in the first 12 months.

When patients did use the tool, more than half the searches were for relatively expensive services of over $1000.

“For expensive care that exceeds their deductible, patients may not see any reason to switch,” said study author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, also of Harvard Medical School. “They do not save by choosing a lower-cost provider, even if the health plan does.”

Still, the researchers said the tool does provide patients with valuable information, including their expected out-of-pocket costs, their deductible, and their health plan’s provider network.

“People might use the tools more—and focus more on choosing lower-priced care options—if they are combined with additional health plan benefit features that give greater incentive to price shop,” Dr Desai said. ![]()

FDA grants priority review for blinatumomab

and solution for infusion

Photo courtesy of Amgen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab (Blincyto) as a treatment for pediatric and adolescent patients with Philadelphia chromosome negative (Ph-) relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

To grant an application priority review, the FDA must believe the drug would provide a significant improvement in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of a serious condition.

The priority review designation means the FDA’s goal is to take action on an application within 6 months, rather than the 10 months typically taken for a standard review.

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act target action date for the supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab is September 1, 2016.

About blinatumomab

Blinatumomab is a bispecific, CD19-directed, CD3 T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibody construct that binds specifically to CD19 expressed on the surface of cells of B-lineage origin and CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells.

Blinatumomab was previously granted breakthrough therapy and priority review designations by the FDA and is now approved in the US for the treatment of adults with Ph- relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor ALL.

This indication is approved under accelerated approval. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in subsequent trials.

Blinatumomab is marketed by Amgen as Blincyto. The full US prescribing information is available at www.BLINCYTO.com.

‘205 trial

The supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab in pediatric and adolescent patients is based on data from the phase 1/2 '205 trial.

In this study, researchers evaluated blinatumomab in patients younger than 18 years of age. The patients had B-cell precursor ALL that was refractory, had relapsed at least twice, or relapsed after an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Treatment in this study has been completed, and subjects are being monitored for long-term efficacy. The data is being submitted for publication.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3703). ![]()

and solution for infusion

Photo courtesy of Amgen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab (Blincyto) as a treatment for pediatric and adolescent patients with Philadelphia chromosome negative (Ph-) relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

To grant an application priority review, the FDA must believe the drug would provide a significant improvement in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of a serious condition.

The priority review designation means the FDA’s goal is to take action on an application within 6 months, rather than the 10 months typically taken for a standard review.

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act target action date for the supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab is September 1, 2016.

About blinatumomab

Blinatumomab is a bispecific, CD19-directed, CD3 T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibody construct that binds specifically to CD19 expressed on the surface of cells of B-lineage origin and CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells.

Blinatumomab was previously granted breakthrough therapy and priority review designations by the FDA and is now approved in the US for the treatment of adults with Ph- relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor ALL.

This indication is approved under accelerated approval. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in subsequent trials.

Blinatumomab is marketed by Amgen as Blincyto. The full US prescribing information is available at www.BLINCYTO.com.

‘205 trial

The supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab in pediatric and adolescent patients is based on data from the phase 1/2 '205 trial.

In this study, researchers evaluated blinatumomab in patients younger than 18 years of age. The patients had B-cell precursor ALL that was refractory, had relapsed at least twice, or relapsed after an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Treatment in this study has been completed, and subjects are being monitored for long-term efficacy. The data is being submitted for publication.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3703). ![]()

and solution for infusion

Photo courtesy of Amgen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab (Blincyto) as a treatment for pediatric and adolescent patients with Philadelphia chromosome negative (Ph-) relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

To grant an application priority review, the FDA must believe the drug would provide a significant improvement in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of a serious condition.

The priority review designation means the FDA’s goal is to take action on an application within 6 months, rather than the 10 months typically taken for a standard review.

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act target action date for the supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab is September 1, 2016.

About blinatumomab

Blinatumomab is a bispecific, CD19-directed, CD3 T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibody construct that binds specifically to CD19 expressed on the surface of cells of B-lineage origin and CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells.

Blinatumomab was previously granted breakthrough therapy and priority review designations by the FDA and is now approved in the US for the treatment of adults with Ph- relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor ALL.

This indication is approved under accelerated approval. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in subsequent trials.

Blinatumomab is marketed by Amgen as Blincyto. The full US prescribing information is available at www.BLINCYTO.com.

‘205 trial

The supplemental biologics license application for blinatumomab in pediatric and adolescent patients is based on data from the phase 1/2 '205 trial.

In this study, researchers evaluated blinatumomab in patients younger than 18 years of age. The patients had B-cell precursor ALL that was refractory, had relapsed at least twice, or relapsed after an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Treatment in this study has been completed, and subjects are being monitored for long-term efficacy. The data is being submitted for publication.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 3703). ![]()

Low fitness levels linked to platelet activation in women

Women with poor physical fitness may have an increased risk of thrombotic events due to increased platelet activation, according to research published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

In a study of 62 young women, those with poor cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) had significantly higher platelet activation than women with average to very good CRF.

However, the study also showed that women with poor CRF were able to achieve normal platelet function by increasing their physical fitness.

The women achieved platelet normalization via endurance training—running for a maximum of 40 minutes—3 times a week over a 2-month period.

“Latently activated platelets release a number of mediators that can encourage the development of atherosclerotic vascular changes,” said study author Stefan Heber, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria.

“If poor physical fitness is accompanied by a higher level of platelet activation, one can conclude that it also has an influence upon the early stages of this pathogenesis. The training effects we’ve found here are consistent with epidemiological data, according to which fit people have an approximately 40% lower risk of cardiovascular events than those who were physically inactive.”

To uncover their findings, Heber and his colleagues analyzed different aspects of platelet function in healthy, non-smoking women with low CRF, medium CRF, and high CRF.

The team assessed CRF using maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), which was determined by an incremental treadmill exercise test. VO2max criteria were:

- less than 45 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the low CRF group

- 45 to 55 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the medium CRF group

- more than 55 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the high CRF group.

The researchers assessed platelet activation state and platelet reactivity in these groups of women by evaluating basal and agonist-induced surface expression of CD62P and CD40L, as well as the intraplatelet amount of reactive oxygen species.

The team observed higher basal platelet activation and agonist-induced platelet reactivity in the low CRF group, when compared to the medium and high CRF groups. However, platelet activation and reactivity were roughly the same in the medium and high CRF groups.

For the low CRF group, the researchers assessed platelet function again after the women completed a supervised endurance training program that lasted 2 menstrual cycles. The team found this program was able to normalize platelet function. ![]()

Women with poor physical fitness may have an increased risk of thrombotic events due to increased platelet activation, according to research published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

In a study of 62 young women, those with poor cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) had significantly higher platelet activation than women with average to very good CRF.

However, the study also showed that women with poor CRF were able to achieve normal platelet function by increasing their physical fitness.

The women achieved platelet normalization via endurance training—running for a maximum of 40 minutes—3 times a week over a 2-month period.

“Latently activated platelets release a number of mediators that can encourage the development of atherosclerotic vascular changes,” said study author Stefan Heber, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria.

“If poor physical fitness is accompanied by a higher level of platelet activation, one can conclude that it also has an influence upon the early stages of this pathogenesis. The training effects we’ve found here are consistent with epidemiological data, according to which fit people have an approximately 40% lower risk of cardiovascular events than those who were physically inactive.”

To uncover their findings, Heber and his colleagues analyzed different aspects of platelet function in healthy, non-smoking women with low CRF, medium CRF, and high CRF.

The team assessed CRF using maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), which was determined by an incremental treadmill exercise test. VO2max criteria were:

- less than 45 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the low CRF group

- 45 to 55 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the medium CRF group

- more than 55 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the high CRF group.

The researchers assessed platelet activation state and platelet reactivity in these groups of women by evaluating basal and agonist-induced surface expression of CD62P and CD40L, as well as the intraplatelet amount of reactive oxygen species.

The team observed higher basal platelet activation and agonist-induced platelet reactivity in the low CRF group, when compared to the medium and high CRF groups. However, platelet activation and reactivity were roughly the same in the medium and high CRF groups.

For the low CRF group, the researchers assessed platelet function again after the women completed a supervised endurance training program that lasted 2 menstrual cycles. The team found this program was able to normalize platelet function. ![]()

Women with poor physical fitness may have an increased risk of thrombotic events due to increased platelet activation, according to research published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

In a study of 62 young women, those with poor cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) had significantly higher platelet activation than women with average to very good CRF.

However, the study also showed that women with poor CRF were able to achieve normal platelet function by increasing their physical fitness.

The women achieved platelet normalization via endurance training—running for a maximum of 40 minutes—3 times a week over a 2-month period.

“Latently activated platelets release a number of mediators that can encourage the development of atherosclerotic vascular changes,” said study author Stefan Heber, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria.

“If poor physical fitness is accompanied by a higher level of platelet activation, one can conclude that it also has an influence upon the early stages of this pathogenesis. The training effects we’ve found here are consistent with epidemiological data, according to which fit people have an approximately 40% lower risk of cardiovascular events than those who were physically inactive.”

To uncover their findings, Heber and his colleagues analyzed different aspects of platelet function in healthy, non-smoking women with low CRF, medium CRF, and high CRF.

The team assessed CRF using maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), which was determined by an incremental treadmill exercise test. VO2max criteria were:

- less than 45 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the low CRF group

- 45 to 55 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the medium CRF group

- more than 55 ml/min/kg bodyweight for the high CRF group.

The researchers assessed platelet activation state and platelet reactivity in these groups of women by evaluating basal and agonist-induced surface expression of CD62P and CD40L, as well as the intraplatelet amount of reactive oxygen species.

The team observed higher basal platelet activation and agonist-induced platelet reactivity in the low CRF group, when compared to the medium and high CRF groups. However, platelet activation and reactivity were roughly the same in the medium and high CRF groups.

For the low CRF group, the researchers assessed platelet function again after the women completed a supervised endurance training program that lasted 2 menstrual cycles. The team found this program was able to normalize platelet function. ![]()

The Perfect Storm: Delivery system reform and precision medicine for all

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth and final installment of a five-part monthly series that will discuss the biologic, genomic, and health system factors that contribute to the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. The series was adapted from an article that originally appeared in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,1 a journal of the American Cancer Society.

As discussed in the last installment of this series, multifaceted interventions that address all stakeholders are needed to close the racial disparity gap in breast cancer. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) emphasizes delivery system reform with a focus on the triple aim of better health, better health care, and lower costs.2 One component of this reform will be accountable care organizations (ACOs). ACOs potentially could assist in closing the racial mortality gap, because provider groups will take responsibility for improving the health of a defined population and will be held accountable for the quality of care delivered.

In the ACO model, an integrated network of providers, led by primary care practitioners, will evaluate the necessity, quality, value, and accountable delivery of specialty diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, including cancer care.3 ACOs will also collect extensive patient data through the meaningful use of medical records.3 These detailed data can then be used to shape locoregional protocols for clinical decision making in oncology and evaluate physician performance. Intermountain Healthcare is an example of an organization that has had success with instituting these clinical protocols to highlight best practices and improve the quality of care.4 In breast cancer, oncologists will need to be prepared to develop and follow protocols tailored for their communities, which will lead to standardized, improved care for minority populations.

The oncology medical home is one example of an ACO delivery system reform that has the potential to reduce the racial mortality gap. The oncology medical home replaces episodic care with long-term coordinated care and replaces the fee-for-service model with a performance and outcomes-based system. A key trait of the oncology medical home is care that is continuously improved by measurement against quality standards.5 The model oncology home accomplishes this by incorporating software to extract clinical data as well as provider compliance with locoregional guidelines to give oncologists feedback regarding the quality of care that they are providing.6 Through this system reform, oncologists will be held accountable for the care they deliver, and it is hoped that this will eliminate the delays, misuse, and underuse of treatment. This could be especially important for optimizing use of hormone therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Trial oncology medical homes in North Carolina and Michigan have yielded promising results regarding improved care (fewer emergency department visits and inpatient admissions) and high adherence to national and practice-selected guidelines.7,8

PPACA also increases funding for community health centers and provides grants to support community health workers; this highlights again the importance of place in racial health care disparities.9 Encouraging collaboration between community health centers and academic institutions, this funding could build bridges between minority communities and high-quality health care institutions while also improving patient communication and education.9 As this series has discussed, a failure to provide culturally appropriate clinical information can lead to issues with follow-up and adjuvant treatment compliance and further widen the breast cancer racial mortality gap.

Delivery system reform has the potential to help close the disparity gap by improving the quality of care delivered to minority breast cancer patients. As Chin et al10 describe in their analysis of effective strategies for reducing health disparities, successful interventions are “culturally tailored to meet patients’ needs, employ multidisciplinary teams of care providers, and target multiple leverage points along a patient’s pathway of care.” ACOs have the financial incentive to meet these features of a successful intervention and improve quality across the continuum of breast cancer care. In addition, the PPACA “incentivized experimentation” with health care delivery, such as the oncology medical home and novel telemedicine interventions, to provide higher quality care outside of hospital settings, which could impact the disparity gap.11

In the face of this new era of organizational structures focused on coordinated, population-based care, oncology providers put themselves at financial risk if they do not position themselves for policy and reimbursement changes that reduce disparities.10 However, ongoing research will be needed to ensure that as these changes are implemented, the racial mortality gap in breast cancer decreases, and that no vulnerable patient populations are left out.

Precision medicine for all

In addition, as discussed earlier in this series, there are differences in the tumor biology and genomics of breast cancer in African American patients. Beyond quality interventions, initiatives to reduce the mortality gap should focus on precision medicine for all. These initiatives should allow researchers to better understand biologic and genomic differences among breast cancer patients and tailor treatments accordingly. The PPACA has taken steps in this direction and is the first federal law to require group health plans and state-licensed health insurance companies to cover standard-of-care costs associated with participation in clinical trials as well as genetic testing for prevention.12

The clinical trial regulations also expressly require plans to show that administrative burdens are not used to create barriers to cancer care for anyone who might benefit from participation in a clinical trial.9 The overarching goal of this push to eliminate financial and administrative barriers is to increase the enrollment of minority patients, especially those who do not live close to academic medical centers. In his April 2016 address at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Vice President Joseph Biden identified increased clinical trial participation as a key component of the administration’s cancer “moonshot” as well. Community medical oncologists will be called upon to facilitate and encourage clinical trial participation by their minority patients and should be supported in this endeavor by academic medical centers. With greater minority patient involvement, however, there also should be further research on how trial designs can better lead to clinically significant findings for minority patients. As Polite et al13 argue, at a bare minimum, basic sociodemographic and detailed comorbidity information should be prospectively collected and integrated with tumor and host biology data to better examine racial differences in cancer outcomes.

Initiatives also are needed to address the gap in referrals to cancer risk clinics so that more data are available on African American genetic variants, allowing the creation of more robust risk assessment models. Risk assessment relies on predictive statistical models to estimate an individual’s risk of developing cancer, and without accurate estimates of mutation prevalence in minority subgroups, these models’ reliability is compromised.14 As shown in a recent study at the University of Chicago’s Comprehensive Cancer Risk and Prevention Clinic using targeted genomic capture and next-generation sequencing, nearly one in four African American breast cancer patients referred to the clinic had inherited at least one damaging mutation that increased their risk for the most aggressive type of breast cancer.15

To identify damaging mutations only after a diagnosis of incurable breast cancer is a failure of prevention. As has been documented in Ashkenazi Jewish populations, there is evidence of high rates of inherited mutations in genes that increase the risk for aggressive breast cancers in populations of African ancestry. This is a fertile area for further research to better understand how these mutations affect the clinical course of breast cancer, what targeted interventions will increase the proportion of breast cancer diagnosed at stage 1, and what molecularly targeted treatments will produce a response in these tumors. Churpek et al15 also demonstrated the need for continued technological innovation to reduce the disparity gap, because next-generation sequencing is a faster and more cost-efficient way to evaluate multiple variants in many genes. This approach is particularly valuable for African Americans, who tend to have greater genetic diversity.16 The current administration is also heralding this approach to cancer care. In his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama announced a precision medicine initiative, including a request for $70 million for the National Cancer Institute to investigate genes that may contribute to the risk of developing cancer.17 African American women should no longer be left behind in the push for personalized medicine that caters to a patient’s tumor biology and genetic profile. As Subbiah and Kurzrock state, universal genomic testing is not necessarily cost prohibitive, as the cost to obtain a “complete diagnosis and to select appropriate therapy may be miniscule compared with the money wasted on ill-chosen therapies.”18

In conclusion, there is an opportunity in the current climate of health care reform ushered in by the Affordable Care Act to address many of the discussed elements leading to the persistent racial mortality gap in breast cancer. We have argued that two substantial factors lead to this eroding gap. One is differences in tumor biology and genomics, and the second is a quality difference in patterns of care. In describing the perfect storm, Sebastian Junger19 wrote of the collision of two forces – a hurricane’s warm-air, low-pressure system and an anticyclone’s cool-air, high-pressure system – that combined to create a more powerful and devastating meteorological force. Similarly, we argue that it is the collision of these two factors – tumor biology and genomics with patterns of care – that leads to the breast cancer mortality gap. The delays, misuse, and underuse of treatment that we have underscored are of increased significance when patients present with more aggressive forms of breast cancer. Interventions to close this gap will take leaders at the patient, provider, payer, and community levels to drive system change.

1. Daly B, Olopade OI: A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Apr;65:221-38.

2. Fox J: Lessons from an oncology medical home collaborative. Am J Manag Care. 2013; 19:SP5-9.

3. Mehta AJ, Macklis RM: Overview of accountable care organizations for oncology specialists. J Oncol Pract. 2013 Jul; 9(4):216-21.

4. Daly B, Mort EA: A decade after to Err is Human: what should health care leaders be doing? Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun; 40(3):50-2, 54.

5. Dangi-Garimella S: Oncology medical home: improved quality and cost of care. Am J Manag Care. 2014 Sep.

6. McAneny BL: The future of oncology? COME HOME, the oncology medical home. Am J Manag Care. 2013 Feb.

7. Goyal RK, Wheeler SB, Kohler RE, et al: Health care utilization from chemotherapy-related adverse events among low-income breast cancer patients: effect of enrollment in a medical home program. N C Med J. 2014 Jul-Aug;75(4):231-8.

8. Kuntz G, Tozer JM, Snegosky J, et al: Michigan Oncology Medical Home Demonstration Project: first-year results. J Oncol Pract. 2014 Sep. 10:294-7.

9. Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Oct;29(28):3816-24.

10. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al: A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Aug; 27(8):992-1000.

11. Emanuel EJ: How Well Is the Affordable Care Act Doing?: Reasons for Optimism. JAMA 315:1331-2, 2016.

12. Zhang SQ, Polite BN: Achieving a deeper understanding of the implemented provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e472-7.

13. Polite BN, Sylvester BE, Olopade OI: Race and subset analyses in clinical trials: time to get serious about data integration. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Oct. 103(20):1486-8.

14. Hall MJ, Olopade OI: Disparities in genetic testing: thinking outside the BRCA box. J Clin Oncol. 2006 May; 24(14):2197-203.

15. Churpek JE, Walsh T, Zheng Y, et al: Inherited predisposition to breast cancer among African American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015 Jan;149(1):31-9.

16. Easton J: Genetic mutations more common among African American women with breast cancer: early testing could protect patients and their relatives. news.uchicago.edu/article/2013/06/03/genetic-mutations-more-common-among-african-american-women-breast-cancer. Published June 3, 2013. Accessed April 20, 2016.

17. Pear R: U.S. to collect genetic data to hone care. New York Times. January 30, 2015.

18. Subbiah V, Kurzrock R: Universal Genomic Testing Needed to Win the War Against Cancer: Genomics IS the Diagnosis. JAMA Oncol, 2016.

19. Junger S: The Perfect Storm. New York, NY: WW Norton and Co; 2009.

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, is the chief fellow in the section of hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. His clinical focus is breast and thoracic oncology, and his research focus is health services. Specifically, Dr. Daly researches disparities in oncology care delivery, oncology health care utilization, aggressive end-of-life oncology care, and oncology payment models. He received his MD and MBA from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Business School, both in Boston, and a BA in Economics and History from Stanford (Calif.) University. He was the recipient of the Dean’s Award at Harvard Medical and Business Schools.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, OON, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, and director, Center for Global Health at the University of Chicago. She is adopting emerging high throughput genomic and informatics strategies to identify genetic and nongenetic risk factors for breast cancer in order to implement precision health care in diverse populations. This innovative approach has the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce costs while saving more lives.

Disclosures: Dr. Olopade serves on the Medical Advisory Board for CancerIQ. Dr. Daly serves as a director of Quadrant Holdings Corporation and receives compensation from this entity. Frontline Medical Communications is a subsidiary of Quadrant Holdings Corporation.

Published in conjunction with Susan G. Komen®.

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth and final installment of a five-part monthly series that will discuss the biologic, genomic, and health system factors that contribute to the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. The series was adapted from an article that originally appeared in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,1 a journal of the American Cancer Society.

As discussed in the last installment of this series, multifaceted interventions that address all stakeholders are needed to close the racial disparity gap in breast cancer. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) emphasizes delivery system reform with a focus on the triple aim of better health, better health care, and lower costs.2 One component of this reform will be accountable care organizations (ACOs). ACOs potentially could assist in closing the racial mortality gap, because provider groups will take responsibility for improving the health of a defined population and will be held accountable for the quality of care delivered.

In the ACO model, an integrated network of providers, led by primary care practitioners, will evaluate the necessity, quality, value, and accountable delivery of specialty diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, including cancer care.3 ACOs will also collect extensive patient data through the meaningful use of medical records.3 These detailed data can then be used to shape locoregional protocols for clinical decision making in oncology and evaluate physician performance. Intermountain Healthcare is an example of an organization that has had success with instituting these clinical protocols to highlight best practices and improve the quality of care.4 In breast cancer, oncologists will need to be prepared to develop and follow protocols tailored for their communities, which will lead to standardized, improved care for minority populations.

The oncology medical home is one example of an ACO delivery system reform that has the potential to reduce the racial mortality gap. The oncology medical home replaces episodic care with long-term coordinated care and replaces the fee-for-service model with a performance and outcomes-based system. A key trait of the oncology medical home is care that is continuously improved by measurement against quality standards.5 The model oncology home accomplishes this by incorporating software to extract clinical data as well as provider compliance with locoregional guidelines to give oncologists feedback regarding the quality of care that they are providing.6 Through this system reform, oncologists will be held accountable for the care they deliver, and it is hoped that this will eliminate the delays, misuse, and underuse of treatment. This could be especially important for optimizing use of hormone therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Trial oncology medical homes in North Carolina and Michigan have yielded promising results regarding improved care (fewer emergency department visits and inpatient admissions) and high adherence to national and practice-selected guidelines.7,8

PPACA also increases funding for community health centers and provides grants to support community health workers; this highlights again the importance of place in racial health care disparities.9 Encouraging collaboration between community health centers and academic institutions, this funding could build bridges between minority communities and high-quality health care institutions while also improving patient communication and education.9 As this series has discussed, a failure to provide culturally appropriate clinical information can lead to issues with follow-up and adjuvant treatment compliance and further widen the breast cancer racial mortality gap.

Delivery system reform has the potential to help close the disparity gap by improving the quality of care delivered to minority breast cancer patients. As Chin et al10 describe in their analysis of effective strategies for reducing health disparities, successful interventions are “culturally tailored to meet patients’ needs, employ multidisciplinary teams of care providers, and target multiple leverage points along a patient’s pathway of care.” ACOs have the financial incentive to meet these features of a successful intervention and improve quality across the continuum of breast cancer care. In addition, the PPACA “incentivized experimentation” with health care delivery, such as the oncology medical home and novel telemedicine interventions, to provide higher quality care outside of hospital settings, which could impact the disparity gap.11

In the face of this new era of organizational structures focused on coordinated, population-based care, oncology providers put themselves at financial risk if they do not position themselves for policy and reimbursement changes that reduce disparities.10 However, ongoing research will be needed to ensure that as these changes are implemented, the racial mortality gap in breast cancer decreases, and that no vulnerable patient populations are left out.

Precision medicine for all

In addition, as discussed earlier in this series, there are differences in the tumor biology and genomics of breast cancer in African American patients. Beyond quality interventions, initiatives to reduce the mortality gap should focus on precision medicine for all. These initiatives should allow researchers to better understand biologic and genomic differences among breast cancer patients and tailor treatments accordingly. The PPACA has taken steps in this direction and is the first federal law to require group health plans and state-licensed health insurance companies to cover standard-of-care costs associated with participation in clinical trials as well as genetic testing for prevention.12

The clinical trial regulations also expressly require plans to show that administrative burdens are not used to create barriers to cancer care for anyone who might benefit from participation in a clinical trial.9 The overarching goal of this push to eliminate financial and administrative barriers is to increase the enrollment of minority patients, especially those who do not live close to academic medical centers. In his April 2016 address at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Vice President Joseph Biden identified increased clinical trial participation as a key component of the administration’s cancer “moonshot” as well. Community medical oncologists will be called upon to facilitate and encourage clinical trial participation by their minority patients and should be supported in this endeavor by academic medical centers. With greater minority patient involvement, however, there also should be further research on how trial designs can better lead to clinically significant findings for minority patients. As Polite et al13 argue, at a bare minimum, basic sociodemographic and detailed comorbidity information should be prospectively collected and integrated with tumor and host biology data to better examine racial differences in cancer outcomes.

Initiatives also are needed to address the gap in referrals to cancer risk clinics so that more data are available on African American genetic variants, allowing the creation of more robust risk assessment models. Risk assessment relies on predictive statistical models to estimate an individual’s risk of developing cancer, and without accurate estimates of mutation prevalence in minority subgroups, these models’ reliability is compromised.14 As shown in a recent study at the University of Chicago’s Comprehensive Cancer Risk and Prevention Clinic using targeted genomic capture and next-generation sequencing, nearly one in four African American breast cancer patients referred to the clinic had inherited at least one damaging mutation that increased their risk for the most aggressive type of breast cancer.15

To identify damaging mutations only after a diagnosis of incurable breast cancer is a failure of prevention. As has been documented in Ashkenazi Jewish populations, there is evidence of high rates of inherited mutations in genes that increase the risk for aggressive breast cancers in populations of African ancestry. This is a fertile area for further research to better understand how these mutations affect the clinical course of breast cancer, what targeted interventions will increase the proportion of breast cancer diagnosed at stage 1, and what molecularly targeted treatments will produce a response in these tumors. Churpek et al15 also demonstrated the need for continued technological innovation to reduce the disparity gap, because next-generation sequencing is a faster and more cost-efficient way to evaluate multiple variants in many genes. This approach is particularly valuable for African Americans, who tend to have greater genetic diversity.16 The current administration is also heralding this approach to cancer care. In his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama announced a precision medicine initiative, including a request for $70 million for the National Cancer Institute to investigate genes that may contribute to the risk of developing cancer.17 African American women should no longer be left behind in the push for personalized medicine that caters to a patient’s tumor biology and genetic profile. As Subbiah and Kurzrock state, universal genomic testing is not necessarily cost prohibitive, as the cost to obtain a “complete diagnosis and to select appropriate therapy may be miniscule compared with the money wasted on ill-chosen therapies.”18

In conclusion, there is an opportunity in the current climate of health care reform ushered in by the Affordable Care Act to address many of the discussed elements leading to the persistent racial mortality gap in breast cancer. We have argued that two substantial factors lead to this eroding gap. One is differences in tumor biology and genomics, and the second is a quality difference in patterns of care. In describing the perfect storm, Sebastian Junger19 wrote of the collision of two forces – a hurricane’s warm-air, low-pressure system and an anticyclone’s cool-air, high-pressure system – that combined to create a more powerful and devastating meteorological force. Similarly, we argue that it is the collision of these two factors – tumor biology and genomics with patterns of care – that leads to the breast cancer mortality gap. The delays, misuse, and underuse of treatment that we have underscored are of increased significance when patients present with more aggressive forms of breast cancer. Interventions to close this gap will take leaders at the patient, provider, payer, and community levels to drive system change.

1. Daly B, Olopade OI: A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Apr;65:221-38.

2. Fox J: Lessons from an oncology medical home collaborative. Am J Manag Care. 2013; 19:SP5-9.

3. Mehta AJ, Macklis RM: Overview of accountable care organizations for oncology specialists. J Oncol Pract. 2013 Jul; 9(4):216-21.

4. Daly B, Mort EA: A decade after to Err is Human: what should health care leaders be doing? Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun; 40(3):50-2, 54.

5. Dangi-Garimella S: Oncology medical home: improved quality and cost of care. Am J Manag Care. 2014 Sep.

6. McAneny BL: The future of oncology? COME HOME, the oncology medical home. Am J Manag Care. 2013 Feb.

7. Goyal RK, Wheeler SB, Kohler RE, et al: Health care utilization from chemotherapy-related adverse events among low-income breast cancer patients: effect of enrollment in a medical home program. N C Med J. 2014 Jul-Aug;75(4):231-8.

8. Kuntz G, Tozer JM, Snegosky J, et al: Michigan Oncology Medical Home Demonstration Project: first-year results. J Oncol Pract. 2014 Sep. 10:294-7.

9. Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Oct;29(28):3816-24.

10. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al: A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Aug; 27(8):992-1000.

11. Emanuel EJ: How Well Is the Affordable Care Act Doing?: Reasons for Optimism. JAMA 315:1331-2, 2016.

12. Zhang SQ, Polite BN: Achieving a deeper understanding of the implemented provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e472-7.

13. Polite BN, Sylvester BE, Olopade OI: Race and subset analyses in clinical trials: time to get serious about data integration. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Oct. 103(20):1486-8.

14. Hall MJ, Olopade OI: Disparities in genetic testing: thinking outside the BRCA box. J Clin Oncol. 2006 May; 24(14):2197-203.

15. Churpek JE, Walsh T, Zheng Y, et al: Inherited predisposition to breast cancer among African American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015 Jan;149(1):31-9.

16. Easton J: Genetic mutations more common among African American women with breast cancer: early testing could protect patients and their relatives. news.uchicago.edu/article/2013/06/03/genetic-mutations-more-common-among-african-american-women-breast-cancer. Published June 3, 2013. Accessed April 20, 2016.

17. Pear R: U.S. to collect genetic data to hone care. New York Times. January 30, 2015.

18. Subbiah V, Kurzrock R: Universal Genomic Testing Needed to Win the War Against Cancer: Genomics IS the Diagnosis. JAMA Oncol, 2016.

19. Junger S: The Perfect Storm. New York, NY: WW Norton and Co; 2009.

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, is the chief fellow in the section of hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. His clinical focus is breast and thoracic oncology, and his research focus is health services. Specifically, Dr. Daly researches disparities in oncology care delivery, oncology health care utilization, aggressive end-of-life oncology care, and oncology payment models. He received his MD and MBA from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Business School, both in Boston, and a BA in Economics and History from Stanford (Calif.) University. He was the recipient of the Dean’s Award at Harvard Medical and Business Schools.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, OON, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, and director, Center for Global Health at the University of Chicago. She is adopting emerging high throughput genomic and informatics strategies to identify genetic and nongenetic risk factors for breast cancer in order to implement precision health care in diverse populations. This innovative approach has the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce costs while saving more lives.

Disclosures: Dr. Olopade serves on the Medical Advisory Board for CancerIQ. Dr. Daly serves as a director of Quadrant Holdings Corporation and receives compensation from this entity. Frontline Medical Communications is a subsidiary of Quadrant Holdings Corporation.

Published in conjunction with Susan G. Komen®.

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth and final installment of a five-part monthly series that will discuss the biologic, genomic, and health system factors that contribute to the racial survival disparity in breast cancer. The series was adapted from an article that originally appeared in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,1 a journal of the American Cancer Society.

As discussed in the last installment of this series, multifaceted interventions that address all stakeholders are needed to close the racial disparity gap in breast cancer. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) emphasizes delivery system reform with a focus on the triple aim of better health, better health care, and lower costs.2 One component of this reform will be accountable care organizations (ACOs). ACOs potentially could assist in closing the racial mortality gap, because provider groups will take responsibility for improving the health of a defined population and will be held accountable for the quality of care delivered.

In the ACO model, an integrated network of providers, led by primary care practitioners, will evaluate the necessity, quality, value, and accountable delivery of specialty diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, including cancer care.3 ACOs will also collect extensive patient data through the meaningful use of medical records.3 These detailed data can then be used to shape locoregional protocols for clinical decision making in oncology and evaluate physician performance. Intermountain Healthcare is an example of an organization that has had success with instituting these clinical protocols to highlight best practices and improve the quality of care.4 In breast cancer, oncologists will need to be prepared to develop and follow protocols tailored for their communities, which will lead to standardized, improved care for minority populations.

The oncology medical home is one example of an ACO delivery system reform that has the potential to reduce the racial mortality gap. The oncology medical home replaces episodic care with long-term coordinated care and replaces the fee-for-service model with a performance and outcomes-based system. A key trait of the oncology medical home is care that is continuously improved by measurement against quality standards.5 The model oncology home accomplishes this by incorporating software to extract clinical data as well as provider compliance with locoregional guidelines to give oncologists feedback regarding the quality of care that they are providing.6 Through this system reform, oncologists will be held accountable for the care they deliver, and it is hoped that this will eliminate the delays, misuse, and underuse of treatment. This could be especially important for optimizing use of hormone therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Trial oncology medical homes in North Carolina and Michigan have yielded promising results regarding improved care (fewer emergency department visits and inpatient admissions) and high adherence to national and practice-selected guidelines.7,8

PPACA also increases funding for community health centers and provides grants to support community health workers; this highlights again the importance of place in racial health care disparities.9 Encouraging collaboration between community health centers and academic institutions, this funding could build bridges between minority communities and high-quality health care institutions while also improving patient communication and education.9 As this series has discussed, a failure to provide culturally appropriate clinical information can lead to issues with follow-up and adjuvant treatment compliance and further widen the breast cancer racial mortality gap.

Delivery system reform has the potential to help close the disparity gap by improving the quality of care delivered to minority breast cancer patients. As Chin et al10 describe in their analysis of effective strategies for reducing health disparities, successful interventions are “culturally tailored to meet patients’ needs, employ multidisciplinary teams of care providers, and target multiple leverage points along a patient’s pathway of care.” ACOs have the financial incentive to meet these features of a successful intervention and improve quality across the continuum of breast cancer care. In addition, the PPACA “incentivized experimentation” with health care delivery, such as the oncology medical home and novel telemedicine interventions, to provide higher quality care outside of hospital settings, which could impact the disparity gap.11

In the face of this new era of organizational structures focused on coordinated, population-based care, oncology providers put themselves at financial risk if they do not position themselves for policy and reimbursement changes that reduce disparities.10 However, ongoing research will be needed to ensure that as these changes are implemented, the racial mortality gap in breast cancer decreases, and that no vulnerable patient populations are left out.

Precision medicine for all

In addition, as discussed earlier in this series, there are differences in the tumor biology and genomics of breast cancer in African American patients. Beyond quality interventions, initiatives to reduce the mortality gap should focus on precision medicine for all. These initiatives should allow researchers to better understand biologic and genomic differences among breast cancer patients and tailor treatments accordingly. The PPACA has taken steps in this direction and is the first federal law to require group health plans and state-licensed health insurance companies to cover standard-of-care costs associated with participation in clinical trials as well as genetic testing for prevention.12

The clinical trial regulations also expressly require plans to show that administrative burdens are not used to create barriers to cancer care for anyone who might benefit from participation in a clinical trial.9 The overarching goal of this push to eliminate financial and administrative barriers is to increase the enrollment of minority patients, especially those who do not live close to academic medical centers. In his April 2016 address at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, Vice President Joseph Biden identified increased clinical trial participation as a key component of the administration’s cancer “moonshot” as well. Community medical oncologists will be called upon to facilitate and encourage clinical trial participation by their minority patients and should be supported in this endeavor by academic medical centers. With greater minority patient involvement, however, there also should be further research on how trial designs can better lead to clinically significant findings for minority patients. As Polite et al13 argue, at a bare minimum, basic sociodemographic and detailed comorbidity information should be prospectively collected and integrated with tumor and host biology data to better examine racial differences in cancer outcomes.

Initiatives also are needed to address the gap in referrals to cancer risk clinics so that more data are available on African American genetic variants, allowing the creation of more robust risk assessment models. Risk assessment relies on predictive statistical models to estimate an individual’s risk of developing cancer, and without accurate estimates of mutation prevalence in minority subgroups, these models’ reliability is compromised.14 As shown in a recent study at the University of Chicago’s Comprehensive Cancer Risk and Prevention Clinic using targeted genomic capture and next-generation sequencing, nearly one in four African American breast cancer patients referred to the clinic had inherited at least one damaging mutation that increased their risk for the most aggressive type of breast cancer.15

To identify damaging mutations only after a diagnosis of incurable breast cancer is a failure of prevention. As has been documented in Ashkenazi Jewish populations, there is evidence of high rates of inherited mutations in genes that increase the risk for aggressive breast cancers in populations of African ancestry. This is a fertile area for further research to better understand how these mutations affect the clinical course of breast cancer, what targeted interventions will increase the proportion of breast cancer diagnosed at stage 1, and what molecularly targeted treatments will produce a response in these tumors. Churpek et al15 also demonstrated the need for continued technological innovation to reduce the disparity gap, because next-generation sequencing is a faster and more cost-efficient way to evaluate multiple variants in many genes. This approach is particularly valuable for African Americans, who tend to have greater genetic diversity.16 The current administration is also heralding this approach to cancer care. In his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama announced a precision medicine initiative, including a request for $70 million for the National Cancer Institute to investigate genes that may contribute to the risk of developing cancer.17 African American women should no longer be left behind in the push for personalized medicine that caters to a patient’s tumor biology and genetic profile. As Subbiah and Kurzrock state, universal genomic testing is not necessarily cost prohibitive, as the cost to obtain a “complete diagnosis and to select appropriate therapy may be miniscule compared with the money wasted on ill-chosen therapies.”18

In conclusion, there is an opportunity in the current climate of health care reform ushered in by the Affordable Care Act to address many of the discussed elements leading to the persistent racial mortality gap in breast cancer. We have argued that two substantial factors lead to this eroding gap. One is differences in tumor biology and genomics, and the second is a quality difference in patterns of care. In describing the perfect storm, Sebastian Junger19 wrote of the collision of two forces – a hurricane’s warm-air, low-pressure system and an anticyclone’s cool-air, high-pressure system – that combined to create a more powerful and devastating meteorological force. Similarly, we argue that it is the collision of these two factors – tumor biology and genomics with patterns of care – that leads to the breast cancer mortality gap. The delays, misuse, and underuse of treatment that we have underscored are of increased significance when patients present with more aggressive forms of breast cancer. Interventions to close this gap will take leaders at the patient, provider, payer, and community levels to drive system change.

1. Daly B, Olopade OI: A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Apr;65:221-38.

2. Fox J: Lessons from an oncology medical home collaborative. Am J Manag Care. 2013; 19:SP5-9.

3. Mehta AJ, Macklis RM: Overview of accountable care organizations for oncology specialists. J Oncol Pract. 2013 Jul; 9(4):216-21.

4. Daly B, Mort EA: A decade after to Err is Human: what should health care leaders be doing? Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun; 40(3):50-2, 54.

5. Dangi-Garimella S: Oncology medical home: improved quality and cost of care. Am J Manag Care. 2014 Sep.

6. McAneny BL: The future of oncology? COME HOME, the oncology medical home. Am J Manag Care. 2013 Feb.

7. Goyal RK, Wheeler SB, Kohler RE, et al: Health care utilization from chemotherapy-related adverse events among low-income breast cancer patients: effect of enrollment in a medical home program. N C Med J. 2014 Jul-Aug;75(4):231-8.

8. Kuntz G, Tozer JM, Snegosky J, et al: Michigan Oncology Medical Home Demonstration Project: first-year results. J Oncol Pract. 2014 Sep. 10:294-7.

9. Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Oct;29(28):3816-24.

10. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al: A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Aug; 27(8):992-1000.

11. Emanuel EJ: How Well Is the Affordable Care Act Doing?: Reasons for Optimism. JAMA 315:1331-2, 2016.

12. Zhang SQ, Polite BN: Achieving a deeper understanding of the implemented provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e472-7.

13. Polite BN, Sylvester BE, Olopade OI: Race and subset analyses in clinical trials: time to get serious about data integration. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Oct. 103(20):1486-8.

14. Hall MJ, Olopade OI: Disparities in genetic testing: thinking outside the BRCA box. J Clin Oncol. 2006 May; 24(14):2197-203.

15. Churpek JE, Walsh T, Zheng Y, et al: Inherited predisposition to breast cancer among African American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015 Jan;149(1):31-9.

16. Easton J: Genetic mutations more common among African American women with breast cancer: early testing could protect patients and their relatives. news.uchicago.edu/article/2013/06/03/genetic-mutations-more-common-among-african-american-women-breast-cancer. Published June 3, 2013. Accessed April 20, 2016.

17. Pear R: U.S. to collect genetic data to hone care. New York Times. January 30, 2015.

18. Subbiah V, Kurzrock R: Universal Genomic Testing Needed to Win the War Against Cancer: Genomics IS the Diagnosis. JAMA Oncol, 2016.

19. Junger S: The Perfect Storm. New York, NY: WW Norton and Co; 2009.

Bobby Daly, MD, MBA, is the chief fellow in the section of hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. His clinical focus is breast and thoracic oncology, and his research focus is health services. Specifically, Dr. Daly researches disparities in oncology care delivery, oncology health care utilization, aggressive end-of-life oncology care, and oncology payment models. He received his MD and MBA from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Business School, both in Boston, and a BA in Economics and History from Stanford (Calif.) University. He was the recipient of the Dean’s Award at Harvard Medical and Business Schools.

Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, FACP, OON, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics, and director, Center for Global Health at the University of Chicago. She is adopting emerging high throughput genomic and informatics strategies to identify genetic and nongenetic risk factors for breast cancer in order to implement precision health care in diverse populations. This innovative approach has the potential to improve the quality of care and reduce costs while saving more lives.

Disclosures: Dr. Olopade serves on the Medical Advisory Board for CancerIQ. Dr. Daly serves as a director of Quadrant Holdings Corporation and receives compensation from this entity. Frontline Medical Communications is a subsidiary of Quadrant Holdings Corporation.

Published in conjunction with Susan G. Komen®.

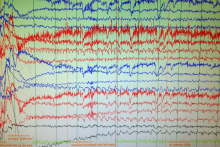

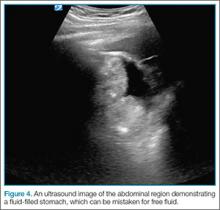

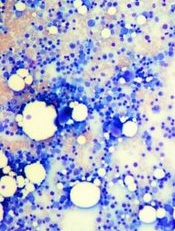

Case Study: Unclear Spells

Stephanie E. MacIver, MD

Dr. MacIver will graduate residency in July 2016 and will be starting her neurophysiology fellowship at the University of South Florida.

Selim R. Benbadis, MD

Dr. Benbadis is Professor and Director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at the University of South Florida and Tampa General Hospital in Tampa, Florida.

A 35-year-old right-handed woman with anxiety has a five-year history of possible syncopal events associated with pronounced tachycardia, which occur about twice a month. The events are preceded by palpitations, anxiety, and rarely a sense of déjà vu. The patient feels that if she is able to lie down and raise her legs above her head, she can prevent a full episode from happening. If she is unable prevent the spell, then she will have altered awareness for 1 to 3 minutes and will frequently bite her lower lip. The patient also reports an isolated episode of bladder incontinence. After a spell, she may feel confused for 2 to 10 minutes. As far as she can remember, these events only occur in the daytime.