User login

Hidden disparities: How language barriers reduce cancer care access

TOPLINE:

, a new study suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Language barriers between patients and physicians negatively affect the quality of care patients receive; however, less is known about how language barriers may affect patients’ access to cancer care.

- Researchers examined the impact of patients’ spoken language on their access to care for three types of cancer that disproportionately affect Hispanic and Asian populations (colon, lung, and thyroid cancer).

- Trained investigators who speak English, Spanish, or Mandarin called the general information line of 144 US hospitals in 12 states seeking an appointment.

- The primary outcome was whether the simulated patient caller was provided with next steps to access cancer care, defined as being given a clinic number or clinic transfer.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 1,296 calls made (432 in each language), 53% resulted in the caller receiving next steps to access cancer care.

- Spanish- and Mandarin-speaking callers were significantly less likely to receive information on next steps (37.7% and 27.5%, respectively), compared with English-speaking callers (93.5%).

- In multivariable logistic regression, non–English-speaking callers had lower odds of being given next steps to access cancer care (odds ratio, 0.04 for Spanish speakers; OR, 0.02 for Mandarin speakers).

- Compared with calls to teaching hospitals, calls to nonteaching hospitals were associated with lower odds of simulated callers receiving this next-step information (OR, 0.43).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study provides actionable insights into existing linguistic disparities in cancer care access due to systems-level barriers present prior to evaluation by a physician,” the authors concluded. It is essential to “engage in efforts to mitigate these communication barriers that disproportionately impact the health of vulnerable patient populations with cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Debbie Chen, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, was published online Sept. 5 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers only assessed responses from the hospital general information line, and the findings do not reflect the type or quality of cancer care a patient may have received once seen and treated. The study did not capture the complexities of hospital call center workflows, which limited the authors’ ability to discern the reasons behind the observed outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the University of Michigan’s Rogel Cancer Center and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . The authors have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a new study suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Language barriers between patients and physicians negatively affect the quality of care patients receive; however, less is known about how language barriers may affect patients’ access to cancer care.

- Researchers examined the impact of patients’ spoken language on their access to care for three types of cancer that disproportionately affect Hispanic and Asian populations (colon, lung, and thyroid cancer).

- Trained investigators who speak English, Spanish, or Mandarin called the general information line of 144 US hospitals in 12 states seeking an appointment.

- The primary outcome was whether the simulated patient caller was provided with next steps to access cancer care, defined as being given a clinic number or clinic transfer.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 1,296 calls made (432 in each language), 53% resulted in the caller receiving next steps to access cancer care.

- Spanish- and Mandarin-speaking callers were significantly less likely to receive information on next steps (37.7% and 27.5%, respectively), compared with English-speaking callers (93.5%).

- In multivariable logistic regression, non–English-speaking callers had lower odds of being given next steps to access cancer care (odds ratio, 0.04 for Spanish speakers; OR, 0.02 for Mandarin speakers).

- Compared with calls to teaching hospitals, calls to nonteaching hospitals were associated with lower odds of simulated callers receiving this next-step information (OR, 0.43).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study provides actionable insights into existing linguistic disparities in cancer care access due to systems-level barriers present prior to evaluation by a physician,” the authors concluded. It is essential to “engage in efforts to mitigate these communication barriers that disproportionately impact the health of vulnerable patient populations with cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Debbie Chen, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, was published online Sept. 5 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers only assessed responses from the hospital general information line, and the findings do not reflect the type or quality of cancer care a patient may have received once seen and treated. The study did not capture the complexities of hospital call center workflows, which limited the authors’ ability to discern the reasons behind the observed outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the University of Michigan’s Rogel Cancer Center and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . The authors have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a new study suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Language barriers between patients and physicians negatively affect the quality of care patients receive; however, less is known about how language barriers may affect patients’ access to cancer care.

- Researchers examined the impact of patients’ spoken language on their access to care for three types of cancer that disproportionately affect Hispanic and Asian populations (colon, lung, and thyroid cancer).

- Trained investigators who speak English, Spanish, or Mandarin called the general information line of 144 US hospitals in 12 states seeking an appointment.

- The primary outcome was whether the simulated patient caller was provided with next steps to access cancer care, defined as being given a clinic number or clinic transfer.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 1,296 calls made (432 in each language), 53% resulted in the caller receiving next steps to access cancer care.

- Spanish- and Mandarin-speaking callers were significantly less likely to receive information on next steps (37.7% and 27.5%, respectively), compared with English-speaking callers (93.5%).

- In multivariable logistic regression, non–English-speaking callers had lower odds of being given next steps to access cancer care (odds ratio, 0.04 for Spanish speakers; OR, 0.02 for Mandarin speakers).

- Compared with calls to teaching hospitals, calls to nonteaching hospitals were associated with lower odds of simulated callers receiving this next-step information (OR, 0.43).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study provides actionable insights into existing linguistic disparities in cancer care access due to systems-level barriers present prior to evaluation by a physician,” the authors concluded. It is essential to “engage in efforts to mitigate these communication barriers that disproportionately impact the health of vulnerable patient populations with cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Debbie Chen, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, was published online Sept. 5 in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers only assessed responses from the hospital general information line, and the findings do not reflect the type or quality of cancer care a patient may have received once seen and treated. The study did not capture the complexities of hospital call center workflows, which limited the authors’ ability to discern the reasons behind the observed outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the University of Michigan’s Rogel Cancer Center and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . The authors have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JNCCN

3D-printed meds customize the exact dose for sick children

Convincing kids to take their medicine could become much easier. Researchers at Texas A&M University are developing a new method of pharmaceutical 3D printing with pediatric patients in mind.

They hope to print precisely dosed tablets in child-friendly shapes and flavors. While the effort is focused on two drugs for pediatric AIDS, the process could be used to print other medicines, including for adults.

Researchers from Britain, Australia, and the University of Texas at Austin are also in the early stages of 3D-printed medication projects. It’s a promising venture in the broader pursuit of “personalized medicine,” tailoring treatments to each patient’s unique needs.

Drug mass production fails to address pediatric patients, who often need different dosages and combinations of medicines as they grow. As a result, adult tablets are often crushed and dissolved in liquid – known as compounding – and given to children. But this can harm drug quality and make doses less precise.

“Suppose the child needs 3.4 milligrams and only a 10-milligram tablet is available. Once you manipulate the dosage from solid to liquid, how do you ensure that it has the same amount of drug in it?” said co-principal investigator Mansoor Khan, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences at Texas A&M.

Most pharmacies lack the equipment to test compounded drug quality, he said. And liquified drugs taste bad because the pill coating has been ground away.

“Flavor is a big issue,” said Olive Eckstein, MD, an assistant professor of pediatric hematology-oncology at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, who is not involved in the research. “Hospitals will sometimes delay discharging pediatric patients because they can’t take their meds orally and have to get an IV formulation.”

Updating pharmaceutical 3D printing

The FDA approved a 3D-printed drug in 2015, but since then, progress has stalled, largely because the method relied on solvents to bind drug particles together. Over time, solvents can compromise shelf life, according to co-principal investigator Mathew Kuttolamadom, PhD, an associate professor of engineering at Texas A&M.

The Texas A&M team is using a different method, without solvents. First, they create a powder mixture of the drug, a biocompatible polymer (such as lactose), and a sheen, a pigment that colors the tablet and allows heat to be absorbed. Flavoring can also be added. Next, the mixture is heated in the printer chamber.

“The polymer should melt just enough. That gives the tablet structural strength. But it should not melt too much, whereby the drug can start dissolving into the polymer,” Dr. Kuttolamadom said.

The tablets are finished with precise applications of laser heat. Using computer-aided design software, the researchers can create tablets in almost any shape, such as “stars or teddy bears,” he said.

After much trial and error, the researchers have printed tablets that won’t break apart or become soggy.

Now they are testing how different laser scan speeds affect the structure of the tablet, which in turn affects the rate at which drugs dissolve. Slowing down the laser imparts more energy, strengthening the tablet structure and making drugs dissolve slower, for a longer release inside the body.

The researchers hope to develop machine learning models to test different laser speed combinations. Eventually, they could create tablets that combine drugs with different dissolve rates.

“The outside could be a rapid release, and the inside could be an extended release or a sustained release, or even a completely different drug,” Dr. Kuttolamadom said.

Older patients who take many daily medications could benefit from the technology. “Personalized tablets could be printed at your local pharmacy,” he said, “even before you leave your doctor’s office.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Convincing kids to take their medicine could become much easier. Researchers at Texas A&M University are developing a new method of pharmaceutical 3D printing with pediatric patients in mind.

They hope to print precisely dosed tablets in child-friendly shapes and flavors. While the effort is focused on two drugs for pediatric AIDS, the process could be used to print other medicines, including for adults.

Researchers from Britain, Australia, and the University of Texas at Austin are also in the early stages of 3D-printed medication projects. It’s a promising venture in the broader pursuit of “personalized medicine,” tailoring treatments to each patient’s unique needs.

Drug mass production fails to address pediatric patients, who often need different dosages and combinations of medicines as they grow. As a result, adult tablets are often crushed and dissolved in liquid – known as compounding – and given to children. But this can harm drug quality and make doses less precise.

“Suppose the child needs 3.4 milligrams and only a 10-milligram tablet is available. Once you manipulate the dosage from solid to liquid, how do you ensure that it has the same amount of drug in it?” said co-principal investigator Mansoor Khan, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences at Texas A&M.

Most pharmacies lack the equipment to test compounded drug quality, he said. And liquified drugs taste bad because the pill coating has been ground away.

“Flavor is a big issue,” said Olive Eckstein, MD, an assistant professor of pediatric hematology-oncology at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, who is not involved in the research. “Hospitals will sometimes delay discharging pediatric patients because they can’t take their meds orally and have to get an IV formulation.”

Updating pharmaceutical 3D printing

The FDA approved a 3D-printed drug in 2015, but since then, progress has stalled, largely because the method relied on solvents to bind drug particles together. Over time, solvents can compromise shelf life, according to co-principal investigator Mathew Kuttolamadom, PhD, an associate professor of engineering at Texas A&M.

The Texas A&M team is using a different method, without solvents. First, they create a powder mixture of the drug, a biocompatible polymer (such as lactose), and a sheen, a pigment that colors the tablet and allows heat to be absorbed. Flavoring can also be added. Next, the mixture is heated in the printer chamber.

“The polymer should melt just enough. That gives the tablet structural strength. But it should not melt too much, whereby the drug can start dissolving into the polymer,” Dr. Kuttolamadom said.

The tablets are finished with precise applications of laser heat. Using computer-aided design software, the researchers can create tablets in almost any shape, such as “stars or teddy bears,” he said.

After much trial and error, the researchers have printed tablets that won’t break apart or become soggy.

Now they are testing how different laser scan speeds affect the structure of the tablet, which in turn affects the rate at which drugs dissolve. Slowing down the laser imparts more energy, strengthening the tablet structure and making drugs dissolve slower, for a longer release inside the body.

The researchers hope to develop machine learning models to test different laser speed combinations. Eventually, they could create tablets that combine drugs with different dissolve rates.

“The outside could be a rapid release, and the inside could be an extended release or a sustained release, or even a completely different drug,” Dr. Kuttolamadom said.

Older patients who take many daily medications could benefit from the technology. “Personalized tablets could be printed at your local pharmacy,” he said, “even before you leave your doctor’s office.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Convincing kids to take their medicine could become much easier. Researchers at Texas A&M University are developing a new method of pharmaceutical 3D printing with pediatric patients in mind.

They hope to print precisely dosed tablets in child-friendly shapes and flavors. While the effort is focused on two drugs for pediatric AIDS, the process could be used to print other medicines, including for adults.

Researchers from Britain, Australia, and the University of Texas at Austin are also in the early stages of 3D-printed medication projects. It’s a promising venture in the broader pursuit of “personalized medicine,” tailoring treatments to each patient’s unique needs.

Drug mass production fails to address pediatric patients, who often need different dosages and combinations of medicines as they grow. As a result, adult tablets are often crushed and dissolved in liquid – known as compounding – and given to children. But this can harm drug quality and make doses less precise.

“Suppose the child needs 3.4 milligrams and only a 10-milligram tablet is available. Once you manipulate the dosage from solid to liquid, how do you ensure that it has the same amount of drug in it?” said co-principal investigator Mansoor Khan, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences at Texas A&M.

Most pharmacies lack the equipment to test compounded drug quality, he said. And liquified drugs taste bad because the pill coating has been ground away.

“Flavor is a big issue,” said Olive Eckstein, MD, an assistant professor of pediatric hematology-oncology at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, who is not involved in the research. “Hospitals will sometimes delay discharging pediatric patients because they can’t take their meds orally and have to get an IV formulation.”

Updating pharmaceutical 3D printing

The FDA approved a 3D-printed drug in 2015, but since then, progress has stalled, largely because the method relied on solvents to bind drug particles together. Over time, solvents can compromise shelf life, according to co-principal investigator Mathew Kuttolamadom, PhD, an associate professor of engineering at Texas A&M.

The Texas A&M team is using a different method, without solvents. First, they create a powder mixture of the drug, a biocompatible polymer (such as lactose), and a sheen, a pigment that colors the tablet and allows heat to be absorbed. Flavoring can also be added. Next, the mixture is heated in the printer chamber.

“The polymer should melt just enough. That gives the tablet structural strength. But it should not melt too much, whereby the drug can start dissolving into the polymer,” Dr. Kuttolamadom said.

The tablets are finished with precise applications of laser heat. Using computer-aided design software, the researchers can create tablets in almost any shape, such as “stars or teddy bears,” he said.

After much trial and error, the researchers have printed tablets that won’t break apart or become soggy.

Now they are testing how different laser scan speeds affect the structure of the tablet, which in turn affects the rate at which drugs dissolve. Slowing down the laser imparts more energy, strengthening the tablet structure and making drugs dissolve slower, for a longer release inside the body.

The researchers hope to develop machine learning models to test different laser speed combinations. Eventually, they could create tablets that combine drugs with different dissolve rates.

“The outside could be a rapid release, and the inside could be an extended release or a sustained release, or even a completely different drug,” Dr. Kuttolamadom said.

Older patients who take many daily medications could benefit from the technology. “Personalized tablets could be printed at your local pharmacy,” he said, “even before you leave your doctor’s office.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Fracture risk factors described in patients with ankylosing spondylitis

TOPLINE:

Opioid use, older age, and fracture history increase the risk for fractures in older adults with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) based on a review of registry and Medicare claims data.

METHODOLOGY:

- Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry data were linked to Medicare claims from 2016 to 2018; each patient had two AS International Classification of Diseases–9 and –10 codes at least 30 days apart.

- The study population included 1426 adults with AS (mean age, 69.4 years) who had continuous Medicare enrollment (Parts A and B) for the entire follow-up period but did not have Medicare Advantage Plan (Part C).

- The researchers used a logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with fractures including age, sex, and body mass index.

TAKEAWAYS:

- The overall incidence of fractures was 76.7 per 1,000 person-years.

- Older age, history of fracture, and opioid use at a morphine-equivalent dose > 30 mg (at least one prescription 30 or more days prior to the index date) were significantly associated with increased risk for fracture (odds ratios, 2.8, 5.24, and 1.86, respectively).

- Fracture risk was equally likely for men and women.

IN PRACTICE:

The study supports fracture risk-reduction strategies for men and women with AS and a fracture history, with added attention to opioid users.

SOURCE:

The first author of the study was Rachael Stovall, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco. The study was published Aug. 22, 2023, in Arthritis Care & Research.

LIMITATIONS:

The study does not include individuals younger than 65 years and references only first fractures. Some EHR data on variables including race, body mass index, national area deprivation index, and smoking status are incomplete.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by various grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Opioid use, older age, and fracture history increase the risk for fractures in older adults with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) based on a review of registry and Medicare claims data.

METHODOLOGY:

- Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry data were linked to Medicare claims from 2016 to 2018; each patient had two AS International Classification of Diseases–9 and –10 codes at least 30 days apart.

- The study population included 1426 adults with AS (mean age, 69.4 years) who had continuous Medicare enrollment (Parts A and B) for the entire follow-up period but did not have Medicare Advantage Plan (Part C).

- The researchers used a logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with fractures including age, sex, and body mass index.

TAKEAWAYS:

- The overall incidence of fractures was 76.7 per 1,000 person-years.

- Older age, history of fracture, and opioid use at a morphine-equivalent dose > 30 mg (at least one prescription 30 or more days prior to the index date) were significantly associated with increased risk for fracture (odds ratios, 2.8, 5.24, and 1.86, respectively).

- Fracture risk was equally likely for men and women.

IN PRACTICE:

The study supports fracture risk-reduction strategies for men and women with AS and a fracture history, with added attention to opioid users.

SOURCE:

The first author of the study was Rachael Stovall, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco. The study was published Aug. 22, 2023, in Arthritis Care & Research.

LIMITATIONS:

The study does not include individuals younger than 65 years and references only first fractures. Some EHR data on variables including race, body mass index, national area deprivation index, and smoking status are incomplete.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by various grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Opioid use, older age, and fracture history increase the risk for fractures in older adults with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) based on a review of registry and Medicare claims data.

METHODOLOGY:

- Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry data were linked to Medicare claims from 2016 to 2018; each patient had two AS International Classification of Diseases–9 and –10 codes at least 30 days apart.

- The study population included 1426 adults with AS (mean age, 69.4 years) who had continuous Medicare enrollment (Parts A and B) for the entire follow-up period but did not have Medicare Advantage Plan (Part C).

- The researchers used a logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with fractures including age, sex, and body mass index.

TAKEAWAYS:

- The overall incidence of fractures was 76.7 per 1,000 person-years.

- Older age, history of fracture, and opioid use at a morphine-equivalent dose > 30 mg (at least one prescription 30 or more days prior to the index date) were significantly associated with increased risk for fracture (odds ratios, 2.8, 5.24, and 1.86, respectively).

- Fracture risk was equally likely for men and women.

IN PRACTICE:

The study supports fracture risk-reduction strategies for men and women with AS and a fracture history, with added attention to opioid users.

SOURCE:

The first author of the study was Rachael Stovall, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco. The study was published Aug. 22, 2023, in Arthritis Care & Research.

LIMITATIONS:

The study does not include individuals younger than 65 years and references only first fractures. Some EHR data on variables including race, body mass index, national area deprivation index, and smoking status are incomplete.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by various grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From Breakouts to Bargains: Strategies for Patient-Centered, Cost-effective Acne Care

In the United States, acne affects 85% of adolescents and can persist into adulthood at a prevalence of 30% to 50% in adult women. 1,2 The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial and involves hyperkeratinization of the follicle, bacterial colonization with Cutibacterium acnes , and increased androgen-induced sebum production, which together lead to inflammation. 3,4 A wide range of treatment guideline–recommended options are available, including benzoyl peroxide (BPO), topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, antiandrogens, and isotretinoin. 5 However, these options vary widely in their clinical uses, effectiveness, and costs.

Why Cost-effective Acne Care Matters

Out-of-pocket spending by patients on acne treatments can be substantial, with surveys finding that acne patients often spend hundreds to thousands of dollars per year.6,7 In a poll conducted in 2019 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 3 in 10 patients said they had not taken their medicine as prescribed because of costs.8 A mixed methods study by Ryskina et al9 found that 65% (17/26) of participants who reported primary nonadherence—intended to fill prescriptions but were unable to do so—cited cost or coverage-related barriers as the reason. With the continued rise of dermatologic drug prices and increased prevalence of high-deductible health plans, cost-effective treatment continues to grow in importance. Failure to consider cost-effective, patient-centered care may lead to increased financial toxicity, reduced adherence, and ultimately worse outcomes and patient satisfaction. We aim to review the cost-effectiveness of current prescription therapies for acne management and highlight the most cost-effective approaches to patients with mild to moderate acne as well as moderate to severe acne.

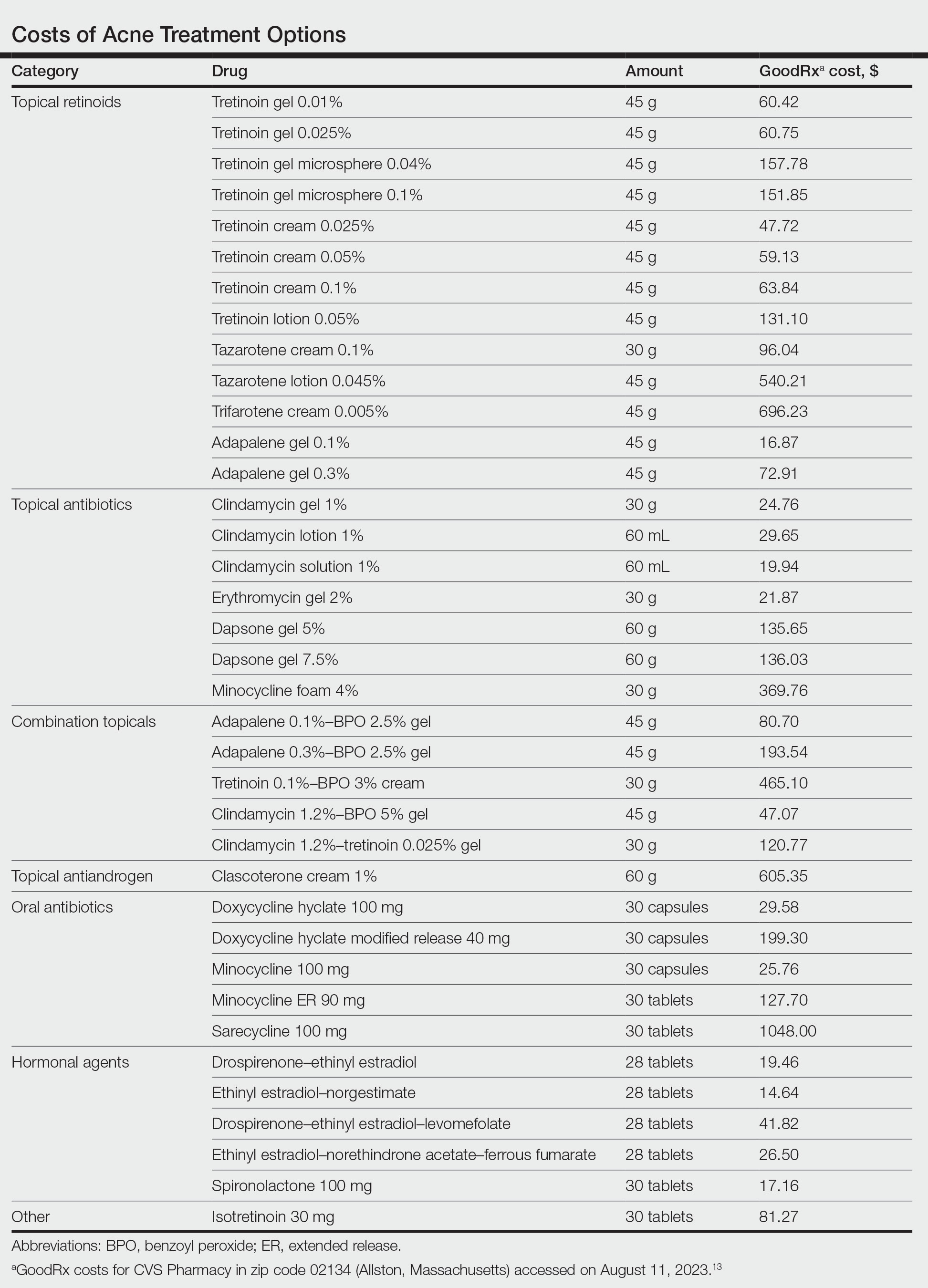

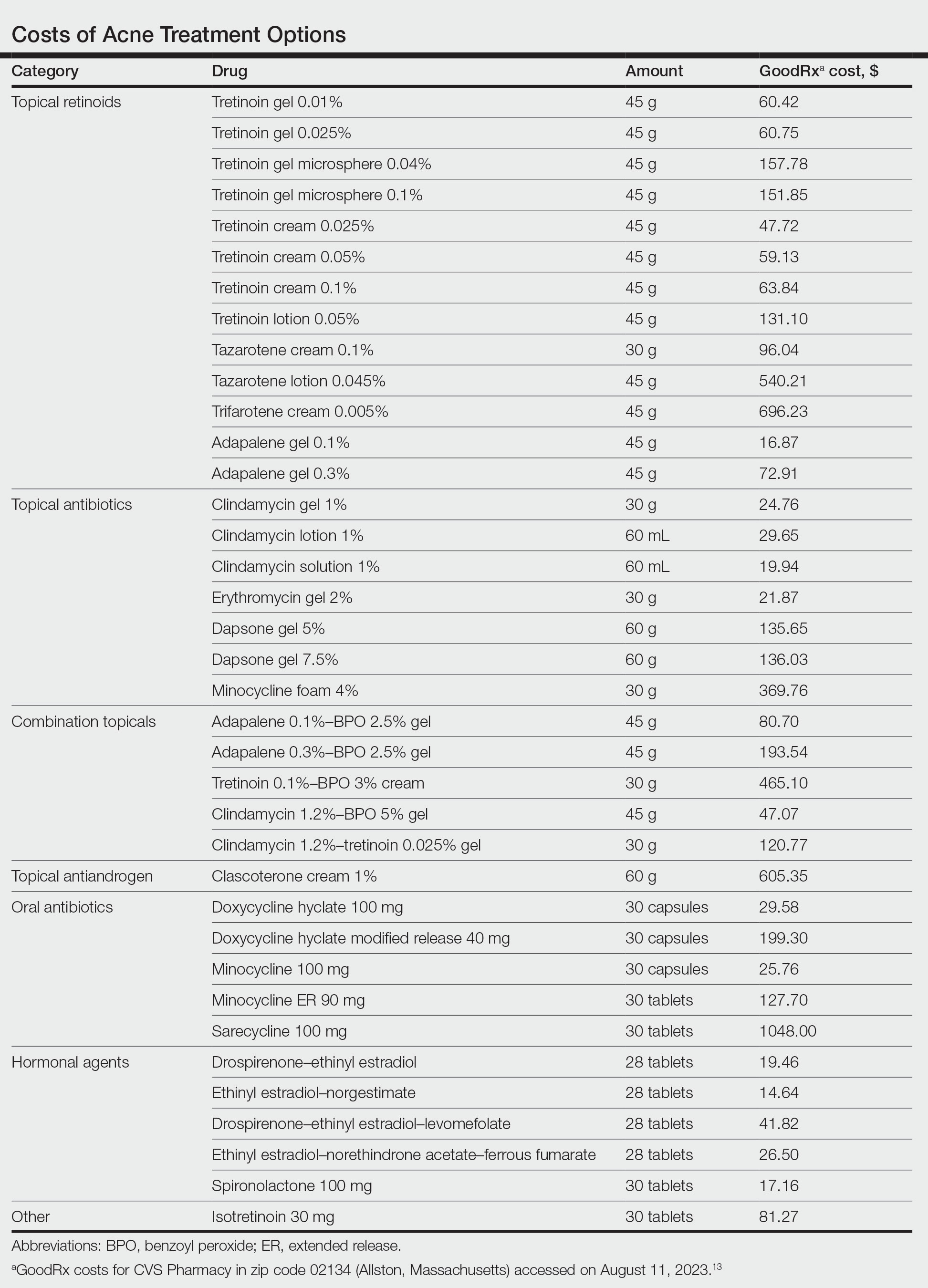

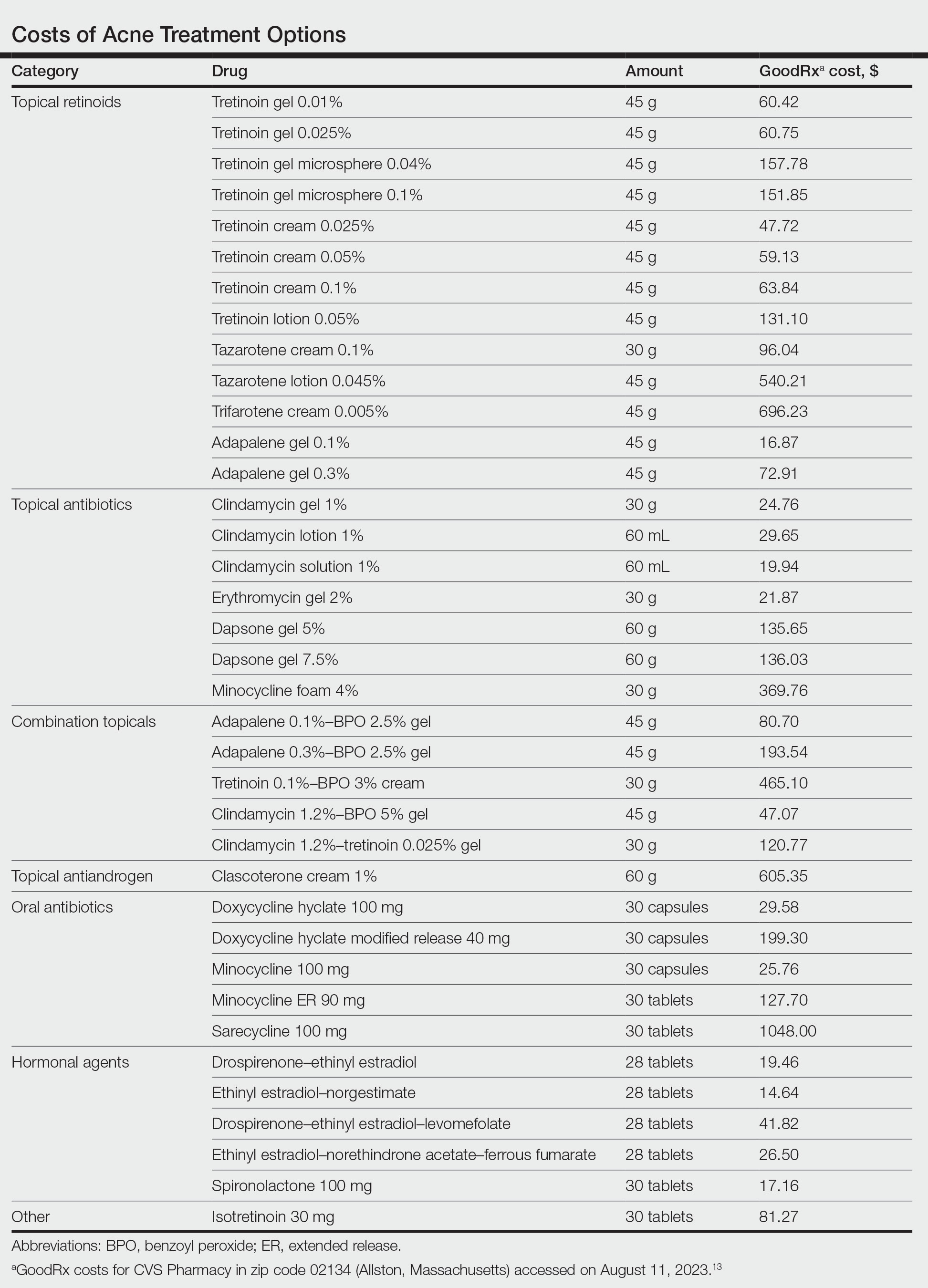

In this review, we will take a value-oriented framework.10 Value can be defined as the cost per outcome of interest. Therefore, a treatment does not necessarily need to be inexpensive to provide high value if it delivers outstanding clinical outcomes. In addition, we will focus on incremental cost-effectiveness relative to common alternatives (eg, a retinoid could deliver high value relative to a vehicle but still provide limited value compared to other available retinoids if it is more expensive but not more efficacious). When possible, we present data from cost-effectiveness studies.11,12 We also use recent available price data obtained from GoodRx on August 11, 2023, to guide this discussion.13 However, as comparative-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies rarely are performed for acne medications, much of this discussion will be based on expert opinion.

Treatment Categories

Topical Retinoids—There currently are 4 topical retinoids that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acne: tretinoin, tazarotene, trifarotene, and adapalene. These drugs are vitamin A derivatives that bind retinoic acid receptors and function as comedolytic and anti-inflammatory agents.5 In general, generic tretinoin and adapalene products have the lowest cost (Table).

In network meta-analyses, tretinoin and adapalene often are highly ranked topical treatment options with respect to efficacy.14 Combined with their low cost, generic tretinoin and adapalene likely are excellent initial options for topical therapy from the standpoint of cost-effectiveness.15 Adapalene may be preferred in many situations because of its better photostability and compatibility with BPO.

Due to the importance of the vehicle in determining retinoid tolerability, efforts have been made to use encapsulation and polymeric emulsion technology to improve tolerability. Recently, polymeric lotion formulations of tretinoin and tazarotene have become available. In a phase 2 study, tazarotene lotion 0.045% was found to have equivalent efficacy and superior tolerability to tazarotene cream 0.1%.16 Although head-to-head data are not available, it is likely that tretinoin lotion may offer similar tolerability improvements.17 Although these formulations currently are more costly, this improved tolerability may be critical for some patients to be able to use topical retinoids, and the additional cost may be worthwhile. In addition, as these products lose market exclusivity, they may become more affordable and similarly priced to other topical retinoids. It is important to keep in mind that in clinical trials of tretinoin and adapalene, rates of dropout due to adverse events typically were 1% to 2%; therefore, because many patients can tolerate generic tretinoin and adapalene, at current prices the lotion formulations of retinoids may not be cost-effective relative to these generics.14

Trifarotene cream 0.005%, a fourth-generation topical retinoid that is highly sensitive for retinoic acid receptor γ, recently was FDA approved for the treatment of acne. Although trifarotene is efficacious for both facial and truncal acne, there is a lack of active comparator data compared to other topical retinoids.18 In a 2023 network meta-analysis, trifarotene was found to be both less efficacious and less tolerable compared to other topical retinoids.19 Thus, it is unclear if trifarotene offers any improved efficacy compared to other options, and it comes at a much higher cost (Table). In a tolerability study, trifarotene was found to be significantly more irritating than tazarotene lotion 0.045% and adapalene gel 0.3% (P<.05).20 Therefore, trifarotene cream 0.005% is unlikely to be a cost-effective option; in fact, it may be overall inferior to other topical retinoids, given its potentially lower tolerability.

Topical Antibiotics—There are 4 commonly prescribed topical antibiotics that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne: clindamycin, erythromycin, dapsone, and minocycline. The American Academy of Dermatology guidelines for the treatment of acne recommend concomitant use of BPO to prevent antibiotic resistance.5 Clindamycin is favored over erythromycin because of increasing antibiotic resistance to erythromycin.21 Inexpensive generic options in multiple vehicles (eg, solution, foam, gel) make clindamycin a highly cost-effective option when antibiotic therapy is desired as part of a topical regimen (Table).

The cost-effectiveness of dapsone gel and minocycline foam relative to clindamycin are less certain. Rates of resistance to minocycline are lower than clindamycin, and minocycline foam may be a reasonable alternative in patients who have not had success with other topical antibiotics, such as clindamycin.22 However, given the absence of comparative effectiveness data to suggest minocycline is more effective than clindamycin, it is difficult to justify the substantially higher cost for the typical patient. Although dapsone gel has been suggested as an option for adult women with acne, there are no data to support that it is any more effective than other topical antibiotics in this patient population.23 As generic dapsone prices decrease, it may become a reasonable alternative to clindamycin. In addition, the antineutrophil properties of dapsone may be useful in other acneform and inflammatory eruptions, such as scalp folliculitis and folliculitis decalvans.24

Combination Topicals—Current combination topical products include antibiotic and BPO, antibiotic and retinoid, and retinoid and BPO. Use of combination agents is recommended to reduce the risk for resistance and to enhance effectiveness. Combination products offer improved convenience, which is associated with better adherence and outcomes.25 Generic fixed-dose adapalene-BPO can be a highly cost-effective option that can sometimes be less expensive than the individual component products (Table). Similarly, fixed-dose clindamycin-BPO also is likely to be highly cost-effective. A network meta-analysis found fixed-dose adapalene-BPO to be the most efficacious topical treatment, though it also was found to be the most irritating—more so than fixed-dose clindamycin-BPO, which may have similar efficacy.14,26,27 Generic fixed-dose tretinoin-clindamycin offers improved convenience and adherence compared to the individual components, but it is more expensive, and its cost-effectiveness may be influenced by the importance of convenience for the patient.25 An encapsulated, fixed-dose tretinoin 0.1%–BPO 3% cream is FDA approved for acne, but the cost is high and there is a lack of comparative effectiveness data demonstrating advantages over generic fixed-dose adapalene-BPO products.

Topical Antiandrogen—Clascoterone was introduced in 2020 as the first FDA-approved topical medication to target the hormonal pathogenesis of acne, inhibiting the androgen receptors in the sebaceous gland.28 Because it is rapidly metabolized to cortexolone and does not have systemic antiandrogen effects, clascoterone can be used in both men and women with acne. In clinical trials, it had minimal side effects, including no evidence of irritability, which is an advantage over topical retinoids and BPO.29 In addition, a phase 2 study found that clascoterone may have similar to superior efficacy to tretinoin cream 0.05%.30 Although clascoterone has several strengths, including its efficacy, tolerability, and unique mechanism of action, its cost-effectiveness is limited due to its high cost (Table) and the need for twice-daily application, which reduces convenience. Clascoterone likely is best reserved for patients with a strong hormonal pathogenesis of their acne or difficulty tolerating other topicals, or as an additional therapy to complement other topicals.

Oral Antibiotics—Oral antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed systemic treatments for acne, particularly tetracyclines such as doxycycline, minocycline, and sarecycline.31-34 Doxycycline and minocycline are considered first-line oral antibiotic therapy in the United States and are inexpensive and easily accessible.5 Doxycycline generally is recommended over minocycline given lack of evidence of superior efficacy of minocycline and concerns about severe adverse cutaneous reactions and drug-induced lupus with minocycline.35

In recent years, there has been growing concern of the development of antibiotic resistance.5 Sarecycline is a narrow-spectrum tetracycline that was FDA approved for acne in 2018. In vitro studies demonstrate sarecycline maintains high efficacy against C acnes with less activity against other bacteria, particularly gram-negative enterobes.36 The selectivity of sarecycline may lessen alterations of the gut microbiome seen with other oral antibiotics and reduce gastrointestinal tract side effects. Although comparative effectiveness studies are lacking, sarecycline was efficacious in phase 3 trials with few side effects compared with placebo.37 However, at this time, given the absence of comparative effectiveness data and its high cost (Table), sarecycline likely is best reserved for patients with comorbidities (eg, gastrointestinal disease), those requiring long-term antibiotic therapy, or those with acne that has failed to respond to other oral antibiotics.

Hormonal Treatments—Hormonal treatments such as combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and spironolactone often are considered second-line options, though they may represent cost-effective and safe alternatives to oral antibiotics for women with moderate to severe acne.38-41 There currently are 4 COCs approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate acne in postmenarcheal females: drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (Yaz [Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc]), ethinyl estradiol-norgestimate (Ortho Tri-Cyclen [Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Inc]), drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol-levomefolate (Beyaz [Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc]), and ethinyl estradiol-norethindrone acetate-ferrous fumarate (Estrostep Fe [Allergan USA, Inc]).5 Treatment with COCs has been shown to cause substantial reductions in lesion counts across all lesion types compared to placebo, and a meta-analysis of 24 randomized trials conducted by Arowojolu et al42 demonstrated no consistent differences in acne reduction among different COCs.43,44 Although oral antibiotics are associated with faster improvement than COCs, there is some evidence that they have similar efficacy at 6 months of therapy.45 Combined oral contraceptives are inexpensive and likely reflect a highly cost-effective option (Table).

Spironolactone is an aldosterone inhibitor and androgen receptor blocker that is used off label to treat acne. It is one of the least expensive systemic medications for acne (Table). Although randomized controlled trials are lacking, several large case series support the effectiveness of spironolactone for women with acne.38,46 In addition, observational data suggest spironolactone may have similar effectiveness to oral antibiotics.41 Spironolactone generally is well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and diuresis.47,48 Many of these adverse effects are dose dependent and less likely with the dosing used in acne care. Additionally, menstrual irregularities can be reduced by concomitant use of a COC.48

Although frequent potassium monitoring remains common among patients being treated with spironolactone, there is growing evidence to suggest that potassium monitoring is of low value in young healthy women with acne.49-51 Reducing this laboratory monitoring likely represents an opportunity to provide higher-value care to patients being treated with spironolactone. However, laboratory monitoring should be considered if risk factors for hyperkalemia are present (eg, older age, comorbidities, medications).51

Isotretinoin—Isotretinoin is the most efficacious treatment available for acne and has the unique property of being able to induce a remission of acne activity for many patients.5 Although it remains modestly expensive (Table), it may be less costly overall relative to other treatments that may need continued use over many years because it can induce a remission of acne activity. As with spironolactone, frequent laboratory monitoring remains common among patients being treated with isotretinoin. There is no evidence to support checking complete blood cell counts.52 Several observational studies and a Delphi consensus support reduced monitoring, such as checking lipids and alanine aminotransferase at baseline and peak dose in otherwise young healthy patients.53,54 A recent critically appraised topic published in the British Journal of Dermatology has proposed eliminating laboratory monitoring entirely.55 Reducing laboratory monitoring for patients being treated with isotretinoin has been estimated to potentially save $100 million to $200 million per year in the United States.52-54

Other Strategies to Reduce Patient Costs

Although choosing a cost-effective treatment approach is critical to preventing financial toxicity given poor coverage for acne care and the growth of high-deductible insurance plans, some patients may still experience high treatment costs.56 Because pharmacy costs often are inflated, potentially related to practices of pharmacy benefit managers, it often is possible to find better prices than the presented list price, either by using platforms such as GoodRx or through direct-to-patient mail-order pharmacies such as Cost Plus Drug.57 For branded medications, some patients may be eligible for patient-assistance programs, though they typically are not available for those with public insurance such as Medicare or Medicaid. Compounding pharmacies offer another approach to reduce cost and improve convenience for patients, but because the vehicle can influence the efficacy and tolerability of some topical medications, it is possible that these compounded formulations may not perform similarly to the original FDA-approved products.

Conclusion

For mild to moderate acne, multimodal topical therapy often is required. Fixed-dose combination adapalene-BPO and clindamycin-BPO are highly cost-effective options for most patients. Lotion formulations of topical retinoids may be useful in patients with difficulty tolerating other formulations. Clascoterone is a novel topical antiandrogen that is more expensive than other topical therapies but can complement other topical therapies and is well tolerated.

For moderate to severe acne, doxycycline or hormonal therapy (ie, COCs, spironolactone) are highly cost-effective options. Isotretinoin is recommended for severe or scarring acne. Reduced laboratory monitoring for spironolactone and isotretinoin is an opportunity to provide higher-value care.

- Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474-485. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149

- Collier CN, Harper JC, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:56-59. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.045

- Webster GF. The pathophysiology of acne. Cutis. 2005;76(2 suppl):4-7.

- Degitz K, Placzek M, Borelli C, et al. Pathophysiology of acne. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:316-323. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06274.x

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

- Felmingham C, Kerr A, Veysey E. Costs incurred by patients with acne prior to dermatological consultation and their relation to patient income. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:384-386. doi:10.1111/ajd.13324

- Perche P, Singh R, Feldman S. Patient preferences for acne vulgaris treatment and barriers to care: a survey study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1191-1195. doi:10.36849/JDD.6940

- KFF Health Tracking Poll—February 2019. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-Health-Tracking-Poll-February-2019

- Ryskina KL, Goldberg E, Lott B, et al. The role of the physician in patient perceptions of barriers to primary adherence with acne medications. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:456-459. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6144

- Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2477-2481. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1011024

- Barbieri JS, Tan JKL, Adamson AS. Active comparator trial designs used to promote development of innovative new medications. Cutis. 2020;106:E4-E6. doi:10.12788/cutis.0067

- Miller J, Ly S, Mostaghimi A, et al. Use of active comparator trials for topical medications in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:597-599. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0356

- GoodRx. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com

- Stuart B, Maund E, Wilcox C, et al. Topical preparations for the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate acne vulgaris: systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:512-525. doi:10.1111/bjd.20080

- Mavranezouli I, Welton NJ, Daly CH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of topical pharmacological, oral pharmacological, physical and combined treatments for acne vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2176-2187. doi:10.1111/ced.15356

- Tanghetti E, Werschler W, Lain T, et al. Tazarotene 0.045% lotion for once-daily treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: results from two phase 3 trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:70-77. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.3977

- Tyring SK, Kircik LH, Pariser DM, et al. Novel tretinoin 0.05% lotion for the once-daily treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: assessment of efficacy and safety in patients aged 9 years and older. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:1084-1091.

- Tan J, Thiboutot D, Popp G, et al. Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 μg/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1691-1699. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.044

- Huang CY, Chang IJ, Bolick N, et al. Comparative efficacy of pharmacological treatments for acne vulgaris: a network meta-analysis of 221 randomized controlled trials. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21:358-369. doi:10.1370/afm.2995

- Draelos ZD. Low irritation potential of tazarotene 0.045% lotion: head-to-head comparison to adapalene 0.3% gel and trifarotene 0.005% cream in two studies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34:2166346. doi:10.1080/09546634.2023.2166346

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in acne: epidemiological trends and clinical practice considerations. Yale J Biol Med. 2022;95:429-443.

- Gold LS, Dhawan S, Weiss J, et al. A novel topical minocycline foam for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: results of 2 randomized, double-blind, phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:168-177. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.020

- Wang X, Wang Z, Sun L, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapsone gel for acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11:611-620. doi:10.21037/apm-21-3935

- Melián-Olivera A, Burgos-Blasco P, Selda-Enríquez G, et al. Topical dapsone for folliculitis decalvans: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:150-151. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.004

- Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86:103-108.

- Ting W. Randomized, observer-blind, split-face study to compare the irritation potential of 2 topical acne formulations over a 14-day treatment period. Cutis. 2012;90:91-96.

- Aschoff R, Möller S, Haase R, et al. Tolerability and efficacy ofclindamycin/tretinoin versus adapalene/benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:295-301. doi:10.36849/JDD.2021.5641

- Rosette C, Agan FJ, Mazzetti A, et al. Cortexolone 17α-propionate (clascoterone) is a novel androgen receptor antagonist that inhibits production of lipids and inflammatory cytokines from sebocytes in vitro. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:412-418.

- Hebert A, Thiboutot D, Stein Gold L, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clascoterone cream, 1%, for treatment in patients with facial acne: two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:621-630. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0465

- Trifu V, Tiplica GS, Naumescu E, et al. Cortexolone 17α-propionate 1% cream, a new potent antiandrogen for topical treatment of acne vulgaris. a pilot randomized, double-blind comparative study vs. placebo and tretinoin 0·05% cream. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:177-183. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10332.x

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. Association of race/ethnicity and sex with differences in health care use and treatment for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:312-319. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818

- Guzman AK, Barbieri JS. Comparative analysis of prescribing patterns of tetracycline class antibiotics and spironolactone between advanced practice providers and physicians in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1119-1121. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.044

- Barbieri JS, James WD, Margolis DJ. Trends in prescribing behavior of systemic agents used in the treatment of acne among dermatologists and nondermatologists: a retrospective analysis, 2004-2013. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:456-463.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.016

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:290-297. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944

- Garner SE, Eady A, Bennett C, et al. Minocycline for acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012:CD002086. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002086.pub2

- Zhanel G, Critchley I, Lin LY, et al. Microbiological profile of sarecycline, a novel targeted spectrum tetracycline for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;63:e01297-18. doi:10.1128/AAC.01297-18

- Moore A, Green LJ, Bruce S, et al. Once-daily oral sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day is effective for moderate to severe acne vulgaris: results from two identically designed, phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:987-996.

- Garg V, Choi JK, James WD, et al. Long-term use of spironolactone for acne in women: a case series of 403 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1348-1355. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.071

- Barbieri JS, Choi JK, James WD, et al. Real-world drug usage survival of spironolactone versus oral antibiotics for the management of female patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:848-851. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.036

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.055

- Barbieri JS, Choi JK, Mitra N, et al. Frequency of treatment switching for spironolactone compared to oral tetracycline-class antibiotics for women with acne: a retrospective cohort study 2010-2016. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:632-638.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD004425. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub6

- Maloney JM, Dietze P, Watson D, et al. Treatment of acne using a 3-milligram drospirenone/20-microgram ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive administered in a 24/4 regimen. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:773-781. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318187e1c5

- Lucky AW, Koltun W, Thiboutot D, et al. A combined oral contraceptive containing 3-mg drospirenone/20-microg ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating lesion counts and participant self-assessment. Cutis. 2008;82:143-150.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:450-459. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.051

- Roberts EE, Nowsheen S, Davis DMR, et al. Use of spironolactone to treat acne in adolescent females. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:72-76. doi:10.1111/pde.14391

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.105557

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, et al. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:169-191. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0245-x

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5468

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.34

- Thiede RM, Rastogi S, Nardone B, et al. Hyperkalemia in women with acne exposed to oral spironolactone: a retrospective study from the RADAR (Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports) program. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:155-157. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.04.024

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, et al. The clinical utility of laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne and changes to monitoring practices over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.025

- Lee YH, Scharnitz TP, Muscat J, et al. Laboratory monitoring during isotretinoin therapy for acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:35-44. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3091

- Xia E, Han J, Faletsky A, et al. Isotretinoin laboratory monitoring in acne treatment: a Delphi consensus study. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:942-948. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.2044

- Affleck A, Jackson D, Williams HC, et al. Is routine laboratory testing in healthy young patients taking isotretinoin necessary: a critically appraised topic. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:857-865. doi:10.1111/bjd.21840

- Barbieri JS, LaChance A, Albrecht J. Double standards and inconsistencies in access to care-what constitutes a cosmetic treatment? JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:245-246. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.6322

- Trish E, Van Nuys K, Popovian R. US consumers overpay for generic drugs. Schaeffer Center White Paper Series. May 31, 2022. doi:10.25549/m589-2268

In the United States, acne affects 85% of adolescents and can persist into adulthood at a prevalence of 30% to 50% in adult women. 1,2 The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial and involves hyperkeratinization of the follicle, bacterial colonization with Cutibacterium acnes , and increased androgen-induced sebum production, which together lead to inflammation. 3,4 A wide range of treatment guideline–recommended options are available, including benzoyl peroxide (BPO), topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, antiandrogens, and isotretinoin. 5 However, these options vary widely in their clinical uses, effectiveness, and costs.

Why Cost-effective Acne Care Matters

Out-of-pocket spending by patients on acne treatments can be substantial, with surveys finding that acne patients often spend hundreds to thousands of dollars per year.6,7 In a poll conducted in 2019 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 3 in 10 patients said they had not taken their medicine as prescribed because of costs.8 A mixed methods study by Ryskina et al9 found that 65% (17/26) of participants who reported primary nonadherence—intended to fill prescriptions but were unable to do so—cited cost or coverage-related barriers as the reason. With the continued rise of dermatologic drug prices and increased prevalence of high-deductible health plans, cost-effective treatment continues to grow in importance. Failure to consider cost-effective, patient-centered care may lead to increased financial toxicity, reduced adherence, and ultimately worse outcomes and patient satisfaction. We aim to review the cost-effectiveness of current prescription therapies for acne management and highlight the most cost-effective approaches to patients with mild to moderate acne as well as moderate to severe acne.

In this review, we will take a value-oriented framework.10 Value can be defined as the cost per outcome of interest. Therefore, a treatment does not necessarily need to be inexpensive to provide high value if it delivers outstanding clinical outcomes. In addition, we will focus on incremental cost-effectiveness relative to common alternatives (eg, a retinoid could deliver high value relative to a vehicle but still provide limited value compared to other available retinoids if it is more expensive but not more efficacious). When possible, we present data from cost-effectiveness studies.11,12 We also use recent available price data obtained from GoodRx on August 11, 2023, to guide this discussion.13 However, as comparative-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies rarely are performed for acne medications, much of this discussion will be based on expert opinion.

Treatment Categories

Topical Retinoids—There currently are 4 topical retinoids that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acne: tretinoin, tazarotene, trifarotene, and adapalene. These drugs are vitamin A derivatives that bind retinoic acid receptors and function as comedolytic and anti-inflammatory agents.5 In general, generic tretinoin and adapalene products have the lowest cost (Table).

In network meta-analyses, tretinoin and adapalene often are highly ranked topical treatment options with respect to efficacy.14 Combined with their low cost, generic tretinoin and adapalene likely are excellent initial options for topical therapy from the standpoint of cost-effectiveness.15 Adapalene may be preferred in many situations because of its better photostability and compatibility with BPO.

Due to the importance of the vehicle in determining retinoid tolerability, efforts have been made to use encapsulation and polymeric emulsion technology to improve tolerability. Recently, polymeric lotion formulations of tretinoin and tazarotene have become available. In a phase 2 study, tazarotene lotion 0.045% was found to have equivalent efficacy and superior tolerability to tazarotene cream 0.1%.16 Although head-to-head data are not available, it is likely that tretinoin lotion may offer similar tolerability improvements.17 Although these formulations currently are more costly, this improved tolerability may be critical for some patients to be able to use topical retinoids, and the additional cost may be worthwhile. In addition, as these products lose market exclusivity, they may become more affordable and similarly priced to other topical retinoids. It is important to keep in mind that in clinical trials of tretinoin and adapalene, rates of dropout due to adverse events typically were 1% to 2%; therefore, because many patients can tolerate generic tretinoin and adapalene, at current prices the lotion formulations of retinoids may not be cost-effective relative to these generics.14

Trifarotene cream 0.005%, a fourth-generation topical retinoid that is highly sensitive for retinoic acid receptor γ, recently was FDA approved for the treatment of acne. Although trifarotene is efficacious for both facial and truncal acne, there is a lack of active comparator data compared to other topical retinoids.18 In a 2023 network meta-analysis, trifarotene was found to be both less efficacious and less tolerable compared to other topical retinoids.19 Thus, it is unclear if trifarotene offers any improved efficacy compared to other options, and it comes at a much higher cost (Table). In a tolerability study, trifarotene was found to be significantly more irritating than tazarotene lotion 0.045% and adapalene gel 0.3% (P<.05).20 Therefore, trifarotene cream 0.005% is unlikely to be a cost-effective option; in fact, it may be overall inferior to other topical retinoids, given its potentially lower tolerability.

Topical Antibiotics—There are 4 commonly prescribed topical antibiotics that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne: clindamycin, erythromycin, dapsone, and minocycline. The American Academy of Dermatology guidelines for the treatment of acne recommend concomitant use of BPO to prevent antibiotic resistance.5 Clindamycin is favored over erythromycin because of increasing antibiotic resistance to erythromycin.21 Inexpensive generic options in multiple vehicles (eg, solution, foam, gel) make clindamycin a highly cost-effective option when antibiotic therapy is desired as part of a topical regimen (Table).

The cost-effectiveness of dapsone gel and minocycline foam relative to clindamycin are less certain. Rates of resistance to minocycline are lower than clindamycin, and minocycline foam may be a reasonable alternative in patients who have not had success with other topical antibiotics, such as clindamycin.22 However, given the absence of comparative effectiveness data to suggest minocycline is more effective than clindamycin, it is difficult to justify the substantially higher cost for the typical patient. Although dapsone gel has been suggested as an option for adult women with acne, there are no data to support that it is any more effective than other topical antibiotics in this patient population.23 As generic dapsone prices decrease, it may become a reasonable alternative to clindamycin. In addition, the antineutrophil properties of dapsone may be useful in other acneform and inflammatory eruptions, such as scalp folliculitis and folliculitis decalvans.24

Combination Topicals—Current combination topical products include antibiotic and BPO, antibiotic and retinoid, and retinoid and BPO. Use of combination agents is recommended to reduce the risk for resistance and to enhance effectiveness. Combination products offer improved convenience, which is associated with better adherence and outcomes.25 Generic fixed-dose adapalene-BPO can be a highly cost-effective option that can sometimes be less expensive than the individual component products (Table). Similarly, fixed-dose clindamycin-BPO also is likely to be highly cost-effective. A network meta-analysis found fixed-dose adapalene-BPO to be the most efficacious topical treatment, though it also was found to be the most irritating—more so than fixed-dose clindamycin-BPO, which may have similar efficacy.14,26,27 Generic fixed-dose tretinoin-clindamycin offers improved convenience and adherence compared to the individual components, but it is more expensive, and its cost-effectiveness may be influenced by the importance of convenience for the patient.25 An encapsulated, fixed-dose tretinoin 0.1%–BPO 3% cream is FDA approved for acne, but the cost is high and there is a lack of comparative effectiveness data demonstrating advantages over generic fixed-dose adapalene-BPO products.

Topical Antiandrogen—Clascoterone was introduced in 2020 as the first FDA-approved topical medication to target the hormonal pathogenesis of acne, inhibiting the androgen receptors in the sebaceous gland.28 Because it is rapidly metabolized to cortexolone and does not have systemic antiandrogen effects, clascoterone can be used in both men and women with acne. In clinical trials, it had minimal side effects, including no evidence of irritability, which is an advantage over topical retinoids and BPO.29 In addition, a phase 2 study found that clascoterone may have similar to superior efficacy to tretinoin cream 0.05%.30 Although clascoterone has several strengths, including its efficacy, tolerability, and unique mechanism of action, its cost-effectiveness is limited due to its high cost (Table) and the need for twice-daily application, which reduces convenience. Clascoterone likely is best reserved for patients with a strong hormonal pathogenesis of their acne or difficulty tolerating other topicals, or as an additional therapy to complement other topicals.

Oral Antibiotics—Oral antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed systemic treatments for acne, particularly tetracyclines such as doxycycline, minocycline, and sarecycline.31-34 Doxycycline and minocycline are considered first-line oral antibiotic therapy in the United States and are inexpensive and easily accessible.5 Doxycycline generally is recommended over minocycline given lack of evidence of superior efficacy of minocycline and concerns about severe adverse cutaneous reactions and drug-induced lupus with minocycline.35

In recent years, there has been growing concern of the development of antibiotic resistance.5 Sarecycline is a narrow-spectrum tetracycline that was FDA approved for acne in 2018. In vitro studies demonstrate sarecycline maintains high efficacy against C acnes with less activity against other bacteria, particularly gram-negative enterobes.36 The selectivity of sarecycline may lessen alterations of the gut microbiome seen with other oral antibiotics and reduce gastrointestinal tract side effects. Although comparative effectiveness studies are lacking, sarecycline was efficacious in phase 3 trials with few side effects compared with placebo.37 However, at this time, given the absence of comparative effectiveness data and its high cost (Table), sarecycline likely is best reserved for patients with comorbidities (eg, gastrointestinal disease), those requiring long-term antibiotic therapy, or those with acne that has failed to respond to other oral antibiotics.

Hormonal Treatments—Hormonal treatments such as combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and spironolactone often are considered second-line options, though they may represent cost-effective and safe alternatives to oral antibiotics for women with moderate to severe acne.38-41 There currently are 4 COCs approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate acne in postmenarcheal females: drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (Yaz [Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc]), ethinyl estradiol-norgestimate (Ortho Tri-Cyclen [Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Inc]), drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol-levomefolate (Beyaz [Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc]), and ethinyl estradiol-norethindrone acetate-ferrous fumarate (Estrostep Fe [Allergan USA, Inc]).5 Treatment with COCs has been shown to cause substantial reductions in lesion counts across all lesion types compared to placebo, and a meta-analysis of 24 randomized trials conducted by Arowojolu et al42 demonstrated no consistent differences in acne reduction among different COCs.43,44 Although oral antibiotics are associated with faster improvement than COCs, there is some evidence that they have similar efficacy at 6 months of therapy.45 Combined oral contraceptives are inexpensive and likely reflect a highly cost-effective option (Table).

Spironolactone is an aldosterone inhibitor and androgen receptor blocker that is used off label to treat acne. It is one of the least expensive systemic medications for acne (Table). Although randomized controlled trials are lacking, several large case series support the effectiveness of spironolactone for women with acne.38,46 In addition, observational data suggest spironolactone may have similar effectiveness to oral antibiotics.41 Spironolactone generally is well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and diuresis.47,48 Many of these adverse effects are dose dependent and less likely with the dosing used in acne care. Additionally, menstrual irregularities can be reduced by concomitant use of a COC.48

Although frequent potassium monitoring remains common among patients being treated with spironolactone, there is growing evidence to suggest that potassium monitoring is of low value in young healthy women with acne.49-51 Reducing this laboratory monitoring likely represents an opportunity to provide higher-value care to patients being treated with spironolactone. However, laboratory monitoring should be considered if risk factors for hyperkalemia are present (eg, older age, comorbidities, medications).51

Isotretinoin—Isotretinoin is the most efficacious treatment available for acne and has the unique property of being able to induce a remission of acne activity for many patients.5 Although it remains modestly expensive (Table), it may be less costly overall relative to other treatments that may need continued use over many years because it can induce a remission of acne activity. As with spironolactone, frequent laboratory monitoring remains common among patients being treated with isotretinoin. There is no evidence to support checking complete blood cell counts.52 Several observational studies and a Delphi consensus support reduced monitoring, such as checking lipids and alanine aminotransferase at baseline and peak dose in otherwise young healthy patients.53,54 A recent critically appraised topic published in the British Journal of Dermatology has proposed eliminating laboratory monitoring entirely.55 Reducing laboratory monitoring for patients being treated with isotretinoin has been estimated to potentially save $100 million to $200 million per year in the United States.52-54

Other Strategies to Reduce Patient Costs

Although choosing a cost-effective treatment approach is critical to preventing financial toxicity given poor coverage for acne care and the growth of high-deductible insurance plans, some patients may still experience high treatment costs.56 Because pharmacy costs often are inflated, potentially related to practices of pharmacy benefit managers, it often is possible to find better prices than the presented list price, either by using platforms such as GoodRx or through direct-to-patient mail-order pharmacies such as Cost Plus Drug.57 For branded medications, some patients may be eligible for patient-assistance programs, though they typically are not available for those with public insurance such as Medicare or Medicaid. Compounding pharmacies offer another approach to reduce cost and improve convenience for patients, but because the vehicle can influence the efficacy and tolerability of some topical medications, it is possible that these compounded formulations may not perform similarly to the original FDA-approved products.

Conclusion

For mild to moderate acne, multimodal topical therapy often is required. Fixed-dose combination adapalene-BPO and clindamycin-BPO are highly cost-effective options for most patients. Lotion formulations of topical retinoids may be useful in patients with difficulty tolerating other formulations. Clascoterone is a novel topical antiandrogen that is more expensive than other topical therapies but can complement other topical therapies and is well tolerated.

For moderate to severe acne, doxycycline or hormonal therapy (ie, COCs, spironolactone) are highly cost-effective options. Isotretinoin is recommended for severe or scarring acne. Reduced laboratory monitoring for spironolactone and isotretinoin is an opportunity to provide higher-value care.

In the United States, acne affects 85% of adolescents and can persist into adulthood at a prevalence of 30% to 50% in adult women. 1,2 The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial and involves hyperkeratinization of the follicle, bacterial colonization with Cutibacterium acnes , and increased androgen-induced sebum production, which together lead to inflammation. 3,4 A wide range of treatment guideline–recommended options are available, including benzoyl peroxide (BPO), topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, antiandrogens, and isotretinoin. 5 However, these options vary widely in their clinical uses, effectiveness, and costs.

Why Cost-effective Acne Care Matters

Out-of-pocket spending by patients on acne treatments can be substantial, with surveys finding that acne patients often spend hundreds to thousands of dollars per year.6,7 In a poll conducted in 2019 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 3 in 10 patients said they had not taken their medicine as prescribed because of costs.8 A mixed methods study by Ryskina et al9 found that 65% (17/26) of participants who reported primary nonadherence—intended to fill prescriptions but were unable to do so—cited cost or coverage-related barriers as the reason. With the continued rise of dermatologic drug prices and increased prevalence of high-deductible health plans, cost-effective treatment continues to grow in importance. Failure to consider cost-effective, patient-centered care may lead to increased financial toxicity, reduced adherence, and ultimately worse outcomes and patient satisfaction. We aim to review the cost-effectiveness of current prescription therapies for acne management and highlight the most cost-effective approaches to patients with mild to moderate acne as well as moderate to severe acne.

In this review, we will take a value-oriented framework.10 Value can be defined as the cost per outcome of interest. Therefore, a treatment does not necessarily need to be inexpensive to provide high value if it delivers outstanding clinical outcomes. In addition, we will focus on incremental cost-effectiveness relative to common alternatives (eg, a retinoid could deliver high value relative to a vehicle but still provide limited value compared to other available retinoids if it is more expensive but not more efficacious). When possible, we present data from cost-effectiveness studies.11,12 We also use recent available price data obtained from GoodRx on August 11, 2023, to guide this discussion.13 However, as comparative-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies rarely are performed for acne medications, much of this discussion will be based on expert opinion.

Treatment Categories

Topical Retinoids—There currently are 4 topical retinoids that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acne: tretinoin, tazarotene, trifarotene, and adapalene. These drugs are vitamin A derivatives that bind retinoic acid receptors and function as comedolytic and anti-inflammatory agents.5 In general, generic tretinoin and adapalene products have the lowest cost (Table).

In network meta-analyses, tretinoin and adapalene often are highly ranked topical treatment options with respect to efficacy.14 Combined with their low cost, generic tretinoin and adapalene likely are excellent initial options for topical therapy from the standpoint of cost-effectiveness.15 Adapalene may be preferred in many situations because of its better photostability and compatibility with BPO.

Due to the importance of the vehicle in determining retinoid tolerability, efforts have been made to use encapsulation and polymeric emulsion technology to improve tolerability. Recently, polymeric lotion formulations of tretinoin and tazarotene have become available. In a phase 2 study, tazarotene lotion 0.045% was found to have equivalent efficacy and superior tolerability to tazarotene cream 0.1%.16 Although head-to-head data are not available, it is likely that tretinoin lotion may offer similar tolerability improvements.17 Although these formulations currently are more costly, this improved tolerability may be critical for some patients to be able to use topical retinoids, and the additional cost may be worthwhile. In addition, as these products lose market exclusivity, they may become more affordable and similarly priced to other topical retinoids. It is important to keep in mind that in clinical trials of tretinoin and adapalene, rates of dropout due to adverse events typically were 1% to 2%; therefore, because many patients can tolerate generic tretinoin and adapalene, at current prices the lotion formulations of retinoids may not be cost-effective relative to these generics.14

Trifarotene cream 0.005%, a fourth-generation topical retinoid that is highly sensitive for retinoic acid receptor γ, recently was FDA approved for the treatment of acne. Although trifarotene is efficacious for both facial and truncal acne, there is a lack of active comparator data compared to other topical retinoids.18 In a 2023 network meta-analysis, trifarotene was found to be both less efficacious and less tolerable compared to other topical retinoids.19 Thus, it is unclear if trifarotene offers any improved efficacy compared to other options, and it comes at a much higher cost (Table). In a tolerability study, trifarotene was found to be significantly more irritating than tazarotene lotion 0.045% and adapalene gel 0.3% (P<.05).20 Therefore, trifarotene cream 0.005% is unlikely to be a cost-effective option; in fact, it may be overall inferior to other topical retinoids, given its potentially lower tolerability.

Topical Antibiotics—There are 4 commonly prescribed topical antibiotics that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne: clindamycin, erythromycin, dapsone, and minocycline. The American Academy of Dermatology guidelines for the treatment of acne recommend concomitant use of BPO to prevent antibiotic resistance.5 Clindamycin is favored over erythromycin because of increasing antibiotic resistance to erythromycin.21 Inexpensive generic options in multiple vehicles (eg, solution, foam, gel) make clindamycin a highly cost-effective option when antibiotic therapy is desired as part of a topical regimen (Table).

The cost-effectiveness of dapsone gel and minocycline foam relative to clindamycin are less certain. Rates of resistance to minocycline are lower than clindamycin, and minocycline foam may be a reasonable alternative in patients who have not had success with other topical antibiotics, such as clindamycin.22 However, given the absence of comparative effectiveness data to suggest minocycline is more effective than clindamycin, it is difficult to justify the substantially higher cost for the typical patient. Although dapsone gel has been suggested as an option for adult women with acne, there are no data to support that it is any more effective than other topical antibiotics in this patient population.23 As generic dapsone prices decrease, it may become a reasonable alternative to clindamycin. In addition, the antineutrophil properties of dapsone may be useful in other acneform and inflammatory eruptions, such as scalp folliculitis and folliculitis decalvans.24