User login

Patients with severe mental illness can benefit from cognitive remediation training

Cognitive impairment seen in severely mentally ill people is well documented, and has been shown to affect as many as 98% of patients with schizophrenia.1 At this time, there are no FDA-approved medications for treating this cognitive impairment.2

Rusk State Hospital in Rusk, Texas, decided to put greater emphasis on improving cognitive impairment because of an increase in patients with a forensic commitment, either because of (1) not guilty by reason of insanity and (2) restoration of competency to stand trial, which typically require longer lengths of stay. Some of these patients experienced psychotic breaks while earning a college education, and one patient was a member of MENSA (an organization for people with a high IQ) before he became ill. Established programs were not adequate to address cognitive impairment.

How we developed and launched our program

Cognitive remediation is a new focus of psychiatry and is in its infancy; programs include cognitive remediation training (CRT) and cognitive enhancement therapy (CET) (Box3-9). CRT focuses more on practice and rote learning and CET is more inclusive, including aspects such as social skills training. These terms are interchangeable for programs designed to improve cognition. Because there is no standardized model, programs differ in content, length, use of computers vs manuals, social skills training, mentoring, and other modalities.

We could not find a program that could be adapted to our setting because of lack of funding and insufficient patient access to computers. Therefore, we developed our own program to address cognitive impairment in a population of individuals with severe mental illness in a state hospital setting.10 Our CRT program was designed for inpatient psychiatric patients, both on civil and forensic commitments.

The program includes >500 exercises and addresses several cognitive domains. Adding a facilitator or teacher in a group setting introduces an additional dimension to learning. Criteria to participate in the program included:

- behavior stable enough to participate

- ability to read and write English

- no traumatic brain injury that caused cognitive impairment

- the patient had to want to participate in the training program.

We tested each participant at the beginning and end of the 12-week training program, which consisted of 2 one-hour classes a week, with a target group size of 6 to 10 participants. As a rating tool, we used the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), which has been shown to be an efficient approach to screening for cognitive impairment across several domains.11

We offered 2 levels of training: basic and advanced. Referral was based on the patient’s level of education and current cognitive function. Materials for the advanced group were at a high school or college level; the basic group used materials that were elementary school or mid-high school in scope. Assignment to the basic or advanced training was based on the recovery team’s or psychologist’s recommendation. The training was ongoing, meaning that a participant could begin at any time and continue until he (she) had completed the 12-week training program.

The weekly sessions in the CRT program were based on 12 categories (Table).10

1. Picture Puzzles: Part 1, Odd Man Out. Participants receive a series of 4 pictures and are asked to select the 1 that does not share a common link with the other 3 items. Targeted skills include pattern recognition, visual learning, reasoning, and creativity (looking for non-obvious answers). This plays a role in global cognition and everyday activities that are sight-related.

2. Word Problems. Participants receive math exercises with significant background information presented as text. Targeted skills include calculation, concentration, and reasoning. This helps with making change, figuring out the tip on a bill, balancing a checkbook, and assisting children with homework.

3. Picture Puzzles: Part 2, Matching.Participants view an illustration followed by a series of 4 other pictures, where ≥1 of which will have a close relationship to the example. The participant selects the item with the strongest link. Targeted skills include determining patterns, concentration, visual perception, and reasoning.

4. Verbal Challenge. Participants are provided a variety of word-based problems that involve word usage, definitions, games, and puzzles. Targeted skills include vocabulary, reading comprehension, reasoning, concentration, and global cognition.

5. Picture Puzzles: Part 3, Series Completion. Participants receive a sequence of 3 pictures followed by 4 possible solutions. The participant selects the item that completes the series or shares a common bond. Targeted skills include visual perception, picking up on patterns, creativity, reasoning, and concentration.

6. Mental Arithmetic: Part 1, Coin Counting. Participants are presented math problems related to money that can be solved by simple mental or quick paper calculation. Targeted skills include basic math, speed, concentration, and counting money. This helps with making change and balancing a checkbook.

7. Picture Puzzles: Part 4, Ratio. Participants receive presented analogy questions where the participant has to determine the ratio or proportional relation of the items. Targeted skills include memory, creativity, and decision-making.

8. Mental Arithmetic: Part 2, Potpourri. Participants receive a hodgepodge of math problems, including number sequences and word problems. Targeted skills include reasoning and computation.

9. Visual/spatial. Participants are presented exercises that require them to think in 3 dimensions and see “hidden” areas behind folds or on the other sides of figures. Targeted skills include spatial perception, reasoning, and decision-making.

10. Reasoning. Participants receive problems that involve taking in information, processing the data, analyzing the options based on previous experiences, and coming up with a decision that is factual and rational. Targeted skills include reasoning and decision-making.

11. Memory Exercise, Listening. Participants are provided a reading selection. After the reading, there is 20-minute waiting period during which the participant is engaged in other exercises before returning to answer questions about the reading. Targeted skills include listening, retention, and memory.

12. Speed Training. Participants receive exercises that provide practice in gathering and processing information and making decisions based on the given information. Targeted skills include decision-making, speed, and concentration.

Preliminary results, optimism about good outcomes

In the past 12 months, 28 participants have completed the CRT program: 11 in the basic training class and 17 in the advanced class. Of those, 7 in the basic program and 11 in the advanced program showed significant improvement as measured by the pre- and post-training RBANS; 64% of the participants improved. The average pre-test score in the basic group was 63 and post-test score was 72 (t10 = 3.148, P < .05). The average advanced pre-test score in the advanced class was 75 and post-test score was 80 (t16 = 2.476, P < .05) (Figure 1).

Because this program was developed as a treatment intervention for psychiatric inpatients, not a research study, we did not establish a control group.

In addition to the overall increase in cognitive functioning, individual successes have been noted. One participant who experienced a psychotic break while pursuing a college degree in literature scored 73 on his initial RBANS, indicating moderate impairment. After completing the 12-week program, his RBANS score increased to 95 (Figure 2). One year after completing the CRT program without additional cognitive training, the participant achieved an RBANS score of 104. Since then, the patient has been observed reading the classics in Latin and Greek, as he did before his psychotic break, and has been noted to be making more eye contact and engaging in conversations.

Success also has been noted for participants who did not see an increase in their RBANS scores. One participant historically had shown little interest in any programming or classes, but attended every CRT class, participated, and asked for additional worksheets to take back to the unit. Based on this feedback, each session now includes a worksheet that participants can take back with them.

Further findings of success

Cognitive impairment can be a significant disability in patients with severe mental illness. Longer lengths of stay present an opportunity to provide a CRT program over 12 weeks. However, some increase in cognitive functioning, as measured by the RBANS, was seen with participants who would not or could not complete all 24 classes. In addition to increased cognitive functioning, clinicians have noted improvements in patients’ participation in treatment and self-esteem.

The program engaged patients who previously were uninvolved in activities, and provided a sense of purpose and hope for them. One participant stated that he felt better about himself and had a more optimistic outlook for the future.

This program offers the possibility for participants to clear the mental fog caused by their illness or medication. The exercises stimulate cognitive activity when the goal is not to get the correct answer, but to think about and talk about possible solutions.

CRT, we have found, can greatly increase the quality of life of people with severe mental illness.

1. Keefe R, Easley C, Poe MP. Defining a cognitive function decrement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):688-691.

2. Nasrallah HA, Keefe RSE, Javitt DC. Cognitive deficits and poor functional outcomes in schizophrenia: clinical and neurobiological progress. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(suppl 6):S1-S11.

3. Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):472-485.

4. Baharnoori M, Bartholomeusz C, Boucher A, et al. The 2nd Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference, 10-14 April 2010, Florence, Italy: summaries of oral sessions. Schizophr Res. 2010;124:e1-e62.

5. Antzoulatos EG, Miller EK. Increases in functional connectivity between prefrontal cortex and striatum during category learning. Neuron. 2014;83(1):216-225.

6. Hogarty G, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):866-876.

7. Medalia A, Freilich B. The neuropsychological educational approach to cognitive remediation (NEAR) model: practice principles and outcome studies. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2008;11(2):123-143.

8. Hurford IM, Kalkstein S, Hurford MO. Cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/schizophrenia/cognitive-rehabilitation-schizophrenia. Published March 15, 2011. Accessed March 3, 2016.

9. Rogers P, Redoblado-Hodge A. A multi-site trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: an Australian sample. Paper presented at: the 9th annual conference on Cognitive Remediation in Psychiatry; 2004; New York, NY.

10. Bates J. Making your brain hum: 12 weeks to a smarter you. Dallas, TX: Brown Books Publishing Group; 2016.

11. Hobart MP, Goldberg R, Bartko JJ, et al. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia, II: convergent/discriminant validity and diagnostic group comparisons. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1951-1957.

Cognitive impairment seen in severely mentally ill people is well documented, and has been shown to affect as many as 98% of patients with schizophrenia.1 At this time, there are no FDA-approved medications for treating this cognitive impairment.2

Rusk State Hospital in Rusk, Texas, decided to put greater emphasis on improving cognitive impairment because of an increase in patients with a forensic commitment, either because of (1) not guilty by reason of insanity and (2) restoration of competency to stand trial, which typically require longer lengths of stay. Some of these patients experienced psychotic breaks while earning a college education, and one patient was a member of MENSA (an organization for people with a high IQ) before he became ill. Established programs were not adequate to address cognitive impairment.

How we developed and launched our program

Cognitive remediation is a new focus of psychiatry and is in its infancy; programs include cognitive remediation training (CRT) and cognitive enhancement therapy (CET) (Box3-9). CRT focuses more on practice and rote learning and CET is more inclusive, including aspects such as social skills training. These terms are interchangeable for programs designed to improve cognition. Because there is no standardized model, programs differ in content, length, use of computers vs manuals, social skills training, mentoring, and other modalities.

We could not find a program that could be adapted to our setting because of lack of funding and insufficient patient access to computers. Therefore, we developed our own program to address cognitive impairment in a population of individuals with severe mental illness in a state hospital setting.10 Our CRT program was designed for inpatient psychiatric patients, both on civil and forensic commitments.

The program includes >500 exercises and addresses several cognitive domains. Adding a facilitator or teacher in a group setting introduces an additional dimension to learning. Criteria to participate in the program included:

- behavior stable enough to participate

- ability to read and write English

- no traumatic brain injury that caused cognitive impairment

- the patient had to want to participate in the training program.

We tested each participant at the beginning and end of the 12-week training program, which consisted of 2 one-hour classes a week, with a target group size of 6 to 10 participants. As a rating tool, we used the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), which has been shown to be an efficient approach to screening for cognitive impairment across several domains.11

We offered 2 levels of training: basic and advanced. Referral was based on the patient’s level of education and current cognitive function. Materials for the advanced group were at a high school or college level; the basic group used materials that were elementary school or mid-high school in scope. Assignment to the basic or advanced training was based on the recovery team’s or psychologist’s recommendation. The training was ongoing, meaning that a participant could begin at any time and continue until he (she) had completed the 12-week training program.

The weekly sessions in the CRT program were based on 12 categories (Table).10

1. Picture Puzzles: Part 1, Odd Man Out. Participants receive a series of 4 pictures and are asked to select the 1 that does not share a common link with the other 3 items. Targeted skills include pattern recognition, visual learning, reasoning, and creativity (looking for non-obvious answers). This plays a role in global cognition and everyday activities that are sight-related.

2. Word Problems. Participants receive math exercises with significant background information presented as text. Targeted skills include calculation, concentration, and reasoning. This helps with making change, figuring out the tip on a bill, balancing a checkbook, and assisting children with homework.

3. Picture Puzzles: Part 2, Matching.Participants view an illustration followed by a series of 4 other pictures, where ≥1 of which will have a close relationship to the example. The participant selects the item with the strongest link. Targeted skills include determining patterns, concentration, visual perception, and reasoning.

4. Verbal Challenge. Participants are provided a variety of word-based problems that involve word usage, definitions, games, and puzzles. Targeted skills include vocabulary, reading comprehension, reasoning, concentration, and global cognition.

5. Picture Puzzles: Part 3, Series Completion. Participants receive a sequence of 3 pictures followed by 4 possible solutions. The participant selects the item that completes the series or shares a common bond. Targeted skills include visual perception, picking up on patterns, creativity, reasoning, and concentration.

6. Mental Arithmetic: Part 1, Coin Counting. Participants are presented math problems related to money that can be solved by simple mental or quick paper calculation. Targeted skills include basic math, speed, concentration, and counting money. This helps with making change and balancing a checkbook.

7. Picture Puzzles: Part 4, Ratio. Participants receive presented analogy questions where the participant has to determine the ratio or proportional relation of the items. Targeted skills include memory, creativity, and decision-making.

8. Mental Arithmetic: Part 2, Potpourri. Participants receive a hodgepodge of math problems, including number sequences and word problems. Targeted skills include reasoning and computation.

9. Visual/spatial. Participants are presented exercises that require them to think in 3 dimensions and see “hidden” areas behind folds or on the other sides of figures. Targeted skills include spatial perception, reasoning, and decision-making.

10. Reasoning. Participants receive problems that involve taking in information, processing the data, analyzing the options based on previous experiences, and coming up with a decision that is factual and rational. Targeted skills include reasoning and decision-making.

11. Memory Exercise, Listening. Participants are provided a reading selection. After the reading, there is 20-minute waiting period during which the participant is engaged in other exercises before returning to answer questions about the reading. Targeted skills include listening, retention, and memory.

12. Speed Training. Participants receive exercises that provide practice in gathering and processing information and making decisions based on the given information. Targeted skills include decision-making, speed, and concentration.

Preliminary results, optimism about good outcomes

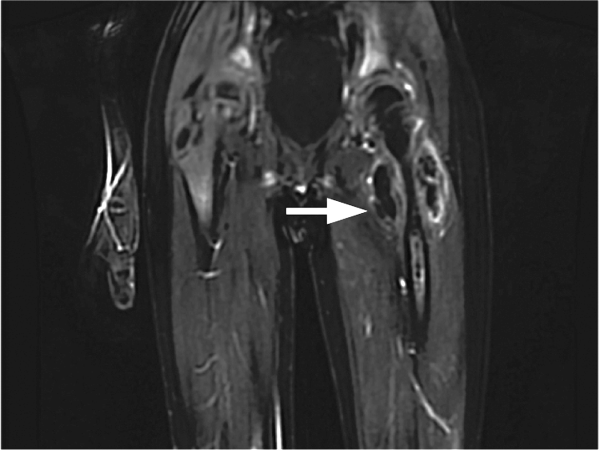

In the past 12 months, 28 participants have completed the CRT program: 11 in the basic training class and 17 in the advanced class. Of those, 7 in the basic program and 11 in the advanced program showed significant improvement as measured by the pre- and post-training RBANS; 64% of the participants improved. The average pre-test score in the basic group was 63 and post-test score was 72 (t10 = 3.148, P < .05). The average advanced pre-test score in the advanced class was 75 and post-test score was 80 (t16 = 2.476, P < .05) (Figure 1).

Because this program was developed as a treatment intervention for psychiatric inpatients, not a research study, we did not establish a control group.

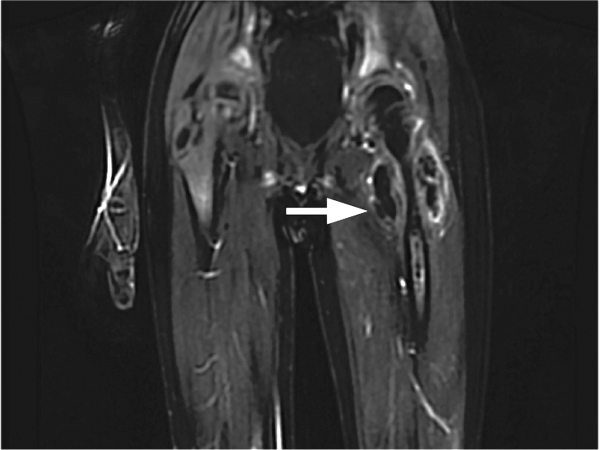

In addition to the overall increase in cognitive functioning, individual successes have been noted. One participant who experienced a psychotic break while pursuing a college degree in literature scored 73 on his initial RBANS, indicating moderate impairment. After completing the 12-week program, his RBANS score increased to 95 (Figure 2). One year after completing the CRT program without additional cognitive training, the participant achieved an RBANS score of 104. Since then, the patient has been observed reading the classics in Latin and Greek, as he did before his psychotic break, and has been noted to be making more eye contact and engaging in conversations.

Success also has been noted for participants who did not see an increase in their RBANS scores. One participant historically had shown little interest in any programming or classes, but attended every CRT class, participated, and asked for additional worksheets to take back to the unit. Based on this feedback, each session now includes a worksheet that participants can take back with them.

Further findings of success

Cognitive impairment can be a significant disability in patients with severe mental illness. Longer lengths of stay present an opportunity to provide a CRT program over 12 weeks. However, some increase in cognitive functioning, as measured by the RBANS, was seen with participants who would not or could not complete all 24 classes. In addition to increased cognitive functioning, clinicians have noted improvements in patients’ participation in treatment and self-esteem.

The program engaged patients who previously were uninvolved in activities, and provided a sense of purpose and hope for them. One participant stated that he felt better about himself and had a more optimistic outlook for the future.

This program offers the possibility for participants to clear the mental fog caused by their illness or medication. The exercises stimulate cognitive activity when the goal is not to get the correct answer, but to think about and talk about possible solutions.

CRT, we have found, can greatly increase the quality of life of people with severe mental illness.

Cognitive impairment seen in severely mentally ill people is well documented, and has been shown to affect as many as 98% of patients with schizophrenia.1 At this time, there are no FDA-approved medications for treating this cognitive impairment.2

Rusk State Hospital in Rusk, Texas, decided to put greater emphasis on improving cognitive impairment because of an increase in patients with a forensic commitment, either because of (1) not guilty by reason of insanity and (2) restoration of competency to stand trial, which typically require longer lengths of stay. Some of these patients experienced psychotic breaks while earning a college education, and one patient was a member of MENSA (an organization for people with a high IQ) before he became ill. Established programs were not adequate to address cognitive impairment.

How we developed and launched our program

Cognitive remediation is a new focus of psychiatry and is in its infancy; programs include cognitive remediation training (CRT) and cognitive enhancement therapy (CET) (Box3-9). CRT focuses more on practice and rote learning and CET is more inclusive, including aspects such as social skills training. These terms are interchangeable for programs designed to improve cognition. Because there is no standardized model, programs differ in content, length, use of computers vs manuals, social skills training, mentoring, and other modalities.

We could not find a program that could be adapted to our setting because of lack of funding and insufficient patient access to computers. Therefore, we developed our own program to address cognitive impairment in a population of individuals with severe mental illness in a state hospital setting.10 Our CRT program was designed for inpatient psychiatric patients, both on civil and forensic commitments.

The program includes >500 exercises and addresses several cognitive domains. Adding a facilitator or teacher in a group setting introduces an additional dimension to learning. Criteria to participate in the program included:

- behavior stable enough to participate

- ability to read and write English

- no traumatic brain injury that caused cognitive impairment

- the patient had to want to participate in the training program.

We tested each participant at the beginning and end of the 12-week training program, which consisted of 2 one-hour classes a week, with a target group size of 6 to 10 participants. As a rating tool, we used the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), which has been shown to be an efficient approach to screening for cognitive impairment across several domains.11

We offered 2 levels of training: basic and advanced. Referral was based on the patient’s level of education and current cognitive function. Materials for the advanced group were at a high school or college level; the basic group used materials that were elementary school or mid-high school in scope. Assignment to the basic or advanced training was based on the recovery team’s or psychologist’s recommendation. The training was ongoing, meaning that a participant could begin at any time and continue until he (she) had completed the 12-week training program.

The weekly sessions in the CRT program were based on 12 categories (Table).10

1. Picture Puzzles: Part 1, Odd Man Out. Participants receive a series of 4 pictures and are asked to select the 1 that does not share a common link with the other 3 items. Targeted skills include pattern recognition, visual learning, reasoning, and creativity (looking for non-obvious answers). This plays a role in global cognition and everyday activities that are sight-related.

2. Word Problems. Participants receive math exercises with significant background information presented as text. Targeted skills include calculation, concentration, and reasoning. This helps with making change, figuring out the tip on a bill, balancing a checkbook, and assisting children with homework.

3. Picture Puzzles: Part 2, Matching.Participants view an illustration followed by a series of 4 other pictures, where ≥1 of which will have a close relationship to the example. The participant selects the item with the strongest link. Targeted skills include determining patterns, concentration, visual perception, and reasoning.

4. Verbal Challenge. Participants are provided a variety of word-based problems that involve word usage, definitions, games, and puzzles. Targeted skills include vocabulary, reading comprehension, reasoning, concentration, and global cognition.

5. Picture Puzzles: Part 3, Series Completion. Participants receive a sequence of 3 pictures followed by 4 possible solutions. The participant selects the item that completes the series or shares a common bond. Targeted skills include visual perception, picking up on patterns, creativity, reasoning, and concentration.

6. Mental Arithmetic: Part 1, Coin Counting. Participants are presented math problems related to money that can be solved by simple mental or quick paper calculation. Targeted skills include basic math, speed, concentration, and counting money. This helps with making change and balancing a checkbook.

7. Picture Puzzles: Part 4, Ratio. Participants receive presented analogy questions where the participant has to determine the ratio or proportional relation of the items. Targeted skills include memory, creativity, and decision-making.

8. Mental Arithmetic: Part 2, Potpourri. Participants receive a hodgepodge of math problems, including number sequences and word problems. Targeted skills include reasoning and computation.

9. Visual/spatial. Participants are presented exercises that require them to think in 3 dimensions and see “hidden” areas behind folds or on the other sides of figures. Targeted skills include spatial perception, reasoning, and decision-making.

10. Reasoning. Participants receive problems that involve taking in information, processing the data, analyzing the options based on previous experiences, and coming up with a decision that is factual and rational. Targeted skills include reasoning and decision-making.

11. Memory Exercise, Listening. Participants are provided a reading selection. After the reading, there is 20-minute waiting period during which the participant is engaged in other exercises before returning to answer questions about the reading. Targeted skills include listening, retention, and memory.

12. Speed Training. Participants receive exercises that provide practice in gathering and processing information and making decisions based on the given information. Targeted skills include decision-making, speed, and concentration.

Preliminary results, optimism about good outcomes

In the past 12 months, 28 participants have completed the CRT program: 11 in the basic training class and 17 in the advanced class. Of those, 7 in the basic program and 11 in the advanced program showed significant improvement as measured by the pre- and post-training RBANS; 64% of the participants improved. The average pre-test score in the basic group was 63 and post-test score was 72 (t10 = 3.148, P < .05). The average advanced pre-test score in the advanced class was 75 and post-test score was 80 (t16 = 2.476, P < .05) (Figure 1).

Because this program was developed as a treatment intervention for psychiatric inpatients, not a research study, we did not establish a control group.

In addition to the overall increase in cognitive functioning, individual successes have been noted. One participant who experienced a psychotic break while pursuing a college degree in literature scored 73 on his initial RBANS, indicating moderate impairment. After completing the 12-week program, his RBANS score increased to 95 (Figure 2). One year after completing the CRT program without additional cognitive training, the participant achieved an RBANS score of 104. Since then, the patient has been observed reading the classics in Latin and Greek, as he did before his psychotic break, and has been noted to be making more eye contact and engaging in conversations.

Success also has been noted for participants who did not see an increase in their RBANS scores. One participant historically had shown little interest in any programming or classes, but attended every CRT class, participated, and asked for additional worksheets to take back to the unit. Based on this feedback, each session now includes a worksheet that participants can take back with them.

Further findings of success

Cognitive impairment can be a significant disability in patients with severe mental illness. Longer lengths of stay present an opportunity to provide a CRT program over 12 weeks. However, some increase in cognitive functioning, as measured by the RBANS, was seen with participants who would not or could not complete all 24 classes. In addition to increased cognitive functioning, clinicians have noted improvements in patients’ participation in treatment and self-esteem.

The program engaged patients who previously were uninvolved in activities, and provided a sense of purpose and hope for them. One participant stated that he felt better about himself and had a more optimistic outlook for the future.

This program offers the possibility for participants to clear the mental fog caused by their illness or medication. The exercises stimulate cognitive activity when the goal is not to get the correct answer, but to think about and talk about possible solutions.

CRT, we have found, can greatly increase the quality of life of people with severe mental illness.

1. Keefe R, Easley C, Poe MP. Defining a cognitive function decrement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):688-691.

2. Nasrallah HA, Keefe RSE, Javitt DC. Cognitive deficits and poor functional outcomes in schizophrenia: clinical and neurobiological progress. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(suppl 6):S1-S11.

3. Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):472-485.

4. Baharnoori M, Bartholomeusz C, Boucher A, et al. The 2nd Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference, 10-14 April 2010, Florence, Italy: summaries of oral sessions. Schizophr Res. 2010;124:e1-e62.

5. Antzoulatos EG, Miller EK. Increases in functional connectivity between prefrontal cortex and striatum during category learning. Neuron. 2014;83(1):216-225.

6. Hogarty G, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):866-876.

7. Medalia A, Freilich B. The neuropsychological educational approach to cognitive remediation (NEAR) model: practice principles and outcome studies. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2008;11(2):123-143.

8. Hurford IM, Kalkstein S, Hurford MO. Cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/schizophrenia/cognitive-rehabilitation-schizophrenia. Published March 15, 2011. Accessed March 3, 2016.

9. Rogers P, Redoblado-Hodge A. A multi-site trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: an Australian sample. Paper presented at: the 9th annual conference on Cognitive Remediation in Psychiatry; 2004; New York, NY.

10. Bates J. Making your brain hum: 12 weeks to a smarter you. Dallas, TX: Brown Books Publishing Group; 2016.

11. Hobart MP, Goldberg R, Bartko JJ, et al. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia, II: convergent/discriminant validity and diagnostic group comparisons. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1951-1957.

1. Keefe R, Easley C, Poe MP. Defining a cognitive function decrement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):688-691.

2. Nasrallah HA, Keefe RSE, Javitt DC. Cognitive deficits and poor functional outcomes in schizophrenia: clinical and neurobiological progress. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(suppl 6):S1-S11.

3. Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):472-485.

4. Baharnoori M, Bartholomeusz C, Boucher A, et al. The 2nd Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference, 10-14 April 2010, Florence, Italy: summaries of oral sessions. Schizophr Res. 2010;124:e1-e62.

5. Antzoulatos EG, Miller EK. Increases in functional connectivity between prefrontal cortex and striatum during category learning. Neuron. 2014;83(1):216-225.

6. Hogarty G, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):866-876.

7. Medalia A, Freilich B. The neuropsychological educational approach to cognitive remediation (NEAR) model: practice principles and outcome studies. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2008;11(2):123-143.

8. Hurford IM, Kalkstein S, Hurford MO. Cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/schizophrenia/cognitive-rehabilitation-schizophrenia. Published March 15, 2011. Accessed March 3, 2016.

9. Rogers P, Redoblado-Hodge A. A multi-site trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: an Australian sample. Paper presented at: the 9th annual conference on Cognitive Remediation in Psychiatry; 2004; New York, NY.

10. Bates J. Making your brain hum: 12 weeks to a smarter you. Dallas, TX: Brown Books Publishing Group; 2016.

11. Hobart MP, Goldberg R, Bartko JJ, et al. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia, II: convergent/discriminant validity and diagnostic group comparisons. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1951-1957.

Genetic and related laboratory tests in psychiatry: What mental health practitioners need to know

What has been the history of the development of laboratory tests in the field of psychiatry?

During my almost-40-year academic medical career, I have been interested in the development and incorporation of laboratory tests into psychiatry.1 This interest initially focused on therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and the genetics of drug responsiveness, with an emphasis on drug metabolism. In addition to TDM—which I have long believed is vastly underutilized in psychiatry—there have been many failed attempts to develop diagnostic tests, including tests to distinguish between what were postulated to be serotonergic and noradrenergic forms of major depression in the 1970s2,3 and the dexamethasone suppression test for melancholia in the 1980s.4 Recently, a 51-analyte immunoassay test was marketed by Rules-Based Medicine, Inc. (RBM), as an aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia, but the test was found to suffer a high false-positive rate and was withdrawn from the market.5 Given this track record, caution is warranted when examining claims for new tests.

What types of tests are being developed?

Most tests in development are pharmacogenomic (PG)-based or immunoassay (IA)-based.

PG tests examine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in genes that code for pharmacokinetic mechanisms, primarily cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes responsible for drug metabolism and P-glycoprotein, responsible for drug transportation. The next most common type of test examines pharmacodynamic mechanisms, such as SNPs of specific receptor genes, including serotonin (or 5-hydroxytryptophan [5-HT] transporter [SET or 5-HTT]) or the 5-HT2A receptor.

The fact that CYP enzymes lead the list is not surprising: These enzymes and their role in the metabolism of specific drugs have been extensively studied since the late 1980s. Considerable data has been accumulated regarding variants of CYP enzymes, which convey clinically meaningful differences among individuals in terms of their ability to metabolize drug via these pathways. Individuals are commonly divided into 4 phenotypic categories: ultra-rapid, extensive (or normal), intermediate, and poor metabolizers. Based on these phenotypes, clinical consequences can be quantitated in terms of changes in drug concentration, concentration-dependent beneficial or adverse effects, and associated/recommended changes in dosing.

Research into the role of pharmacodynamic variants, however, is still in infancy and more difficult to measure in terms of assessing endpoints, with related limitations in clinical utility.

IA assays generally measure a variety of proteins, particularly those reflecting inflammatory processes (eg, various cytokines, such as interleukin-6).6 As with pharmacodynamic measures, research into the role of inflammatory biomarkers is in early stages. The clinical utility of associated tests is, therefore, less certain; witness the recent study5 I noted that revealed a high false-positive rate for the RBM schizophrenia panel in healthy controls. Nevertheless, considerable research is being conducted in all of these areas so that new developments might lend themselves to greater clinical utility.

(Note that PG biomarkers are trait measures, whereas IA biomarkers are state measures, so that complementary use of both types of tests might prove useful in diagnosis and clinical management. Although such integrative use of these 2 different types of tests generally is not done today.)

What does it take to market these tests?

At a minimum, offering these tests for sale requires that the laboratory be certified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, according to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standards (www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/ivdregulatoryassistance/ucm124105.htm). CLIA-certified laboratories are required to demonstrate the analytical validity of tests that they offer—ie, the accuracy and reliability of the test in measuring a parameter of interest—but not the clinical validity or utility of those tests. The fact that a test in fact measures what it claims to be measuring in and of itself does not mean it has clinical validity or utility (see the discussion below).

Must the FDA approve laboratory tests?

No, but that situation might be changing.

Currently, only tests used in a setting considered high risk—eg, a test intended to detect or diagnose a malignancy or guide its treatment—requires formal FDA approval. The approval of such a test requires submission to the FDA of clinical data supporting its clinical validity and utility, in addition to evidence of analytic validity.

Even in such cases, the degree and quality of the clinical data required are generally not as high as would be required for approval of a drug. That distinction is understandable, given the type and quantity of data necessary for drug approval and the many years and billions of dollars it takes to accumulate such data. For most laboratory tests, providing the same level of data required to have a drug approved would be neither necessary nor feasible given the business model underlying most laboratories providing laboratory tests.

What do ‘clinical validity’ and ‘clinical utility’ mean?

These are higher evidence thresholds than is needed for analytic validity, although the latter is a necessary first step on the path to achieving these higher thresholds.

Clinical validity is the ability of a test to detect:

- a clinically meaningful measure, such as clinical response

- an adverse effect

- a biologically meaningful measure (eg, a drug level or a change in the electrocardiographic pattern).

Above the threshold of clinical validity is clinical utility, which is proof that the test can reliably be used to guide clinical management and thus meaningfully improve outcomes, such as guiding drug or dosage selection.

Is the use of PG testing recommended? If so, in what instances?

Specific types of PG testing is recommended by the FDA recommended. The FDA has been incorporating PG information into the labels of specific medications for several years; the agency has a Web site (www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm) that continuously updates this information. The involved drugs are in all therapeutic classes—from oncology to psychiatry.

More than 30 psychotropic drugs have PG information in their label; some of those drugs’ labels contain specific recommendations, such as obtaining PG information before selecting or starting a drug in a specific patient. An example is carbamazepine, for which the recommendation is to obtain HLA testing before starting the drug in patients of Han Chinese ancestry, because members of this large ethnic group are at greater risk of serious dermatologic adverse effects, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

In other instances, the recommendation is to do the testing before increasing beyond a specific dose. Examples of psychiatric drugs whose labels contain such PG information include pimozide and iloperidone as well as citalopram. In the FDA-approved label, guidance is provided that these drugs can be started without testing if prescribed at a reduced recommended starting dosage range, rather than the full starting dosage range. The guidance on these drugs further recommends testing for genetic CYP2D6 poor metabolizer (PM) status before dosing above that initial recommended, limited, starting dosage range.

The rationale for this guidance is to reduce the risk that (1) patients in question will achieve an excessively high plasma drug level that can cause significant prolongation of intracardiac conduction (eg, QTc prolongation) and thus (2) develop the potentially fatal arrhythmia torsades de pointes. Guidance is based on thorough QTc studies that were performed on each drug,7,8 which makes them examples of instances in which the test has clinical validity and utility as well as analytical validity.

To find PG labeling in the package insert for these drugs, visit: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm.

What about data for other tests that are marketed and promoted by developers?

Sometimes, there are—literally—no data on available tests beyond the analytical validity of the test; other times, the amount and quality of clinical data are quite variable, ranging from results of ≥1 small retrospective studies without controls to results of prospective, randomized, controlled studies. Even among the latter, the developer may conduct and analyze their studies without oversight by an independent agency, such as the FDA.

This situation (1) raises concern that study results are not independent of the developer’s business interests and, as one might expect, (2) leads to controversy about whether the data are compelling—or not.9-12

What is a critical difference between PG test results and results of most laboratory tests?

PG tests are, as noted, trait rather than state characteristics. That means that the results do not change except for a phenomenon known as phenocoversion, discussed below. (Of course, advances in gene therapy might make it possible someday to change a person’s genetic makeup and for mitochondrial genes that is already possible.)

For this reason, PG test results should not get buried in the medical record, as might happen with, say, a patient’s serum potassium level at a given point in time. Instead, PG test results need to be carried forward continuously. Results also should be given to the patient as part of his (her) personal health record and to all other health care providers that the patient is seeing or will see in the future. Each health care provider who obtains PG test results should consider sending them to all current clinicians providing care for the patient at the same time as they are.

Is your functional status at a given moment the same as your genetic status?

No. There is a phenomenon known as phenoconversion in which a person’s current functional status may be different from what would be expected based on their genetic status.

CYP2D6 functional status is susceptible to phenoconversion as follows: Administering fluoxetine and paroxetine, for example, at 20 or 40 mg/d converts 66% and 95%, respectively, of patients who are CYP2D6 extensive (ie, normal) metabolizers into phenocopies of people who, genetically, lack the ability to metabolize drugs via CYP2D6 (ie, genotypic CYP2D6 PM). Based on a recent study of 900 participants in routine clinical care who were taking an antidepressant, 4% of the general U.S. population are genetically CYP2D6 PM; an additional 24% are phenotypically CYP2D6 PM because of concomitant administration of a CYP2D6 substantial inhibitor, such as bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or terbenafine.13

That is the reason a provider needs to know what drugs a patient is taking concomitantly—to consider the possibility of phenoconversion and, when necessary, to dose accordingly.

What does the future hold?

Development of tests for use in psychiatric practice is likely to grow substantially, for at least 2 reasons:

- There is a huge unmet need for clinically meaningful tests to aid in the provision of optimal patient care and, therefore, a tremendous business opportunity

- Knowledge in the biological basis of psychiatric disorders is growing exponentially; with that knowledge comes the ability to develop new tests.

A recent example comes from a research group that devised a test that could predict suicidality.14 Time will tell whether this test or a derivative of it enters practice. Nevertheless, it is a harbinger of the likely dramatic changes in the landscape of clinical medicine particularly as it applies to psychiatry.

Given these developments, the syndromic diagnoses in DSM-5 will in the future likely be replaced by a new diagnostic schema that breaks down existing heterogenous syndromic diagnoses into pathophysiologically and etiologically meaningful entities using insights gained from genetic and biomarker data as well as functional brain imaging. Theoretically, those insights will lead to new modalities of treatment, including somatic treatments that target novel mechanisms of action, coupled to more effective psychosocial therapies—with both therapies guided by diagnostic tests to monitor response to specific treatment interventions.

During this transition from the past to the future, answers to the questions I’ve posed here about laboratory testing in psychiatry will, I hope, help the practitioner understand, evaluate, and incorporate these changes readily into practice.

1. Preskorn SH, Biggs JT. Use of tricyclic antidepressant blood levels. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(3):166.

2. Schildkraut JJ. Biogenic amines and affective disorders. Annu Rev Med. 1974;25(0):333-348.

3. Maas JW. Biogenic amines and depression. Biochemical and pharmacological separation of two types of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(11):1357-1361.

4. Carroll BJ, Feinberg M, Greden JF, et al. A specific laboratory test for the diagnosis of melancholia. Standardization, validation, and clinical utility. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(1):15-22.

5. Wehler C, Preskorn S. High false-positive rate of a putative biomarker test to aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. In press.

6. Savitz J, Preskorn S, Teague TK, et al. Minocycline and aspirin in the treatment of bipolar depression: a protocol for a proof-of-concept, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2x2 clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000643. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000643.

7. Rogers HL, Bhattaram A, Zineh I, et al. CYP2D6 genotype information to guide pimozide treatment in adult and pediatric patients: basis for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s new dosing recommendations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(9):1187-1190.

8. Potkin S, Preskorn S, Hochfeld M, et al. A thorough QTc study of 3 doses of iloperidone including metabolic inhibition via CYP2D6 and/or CYP3A4 inhibition and a comparison to quetiapine and ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):3-10.

9. Howland RH. Pharmacogenetic testing in psychiatry: not (quite) ready for primetime. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52(11):13-16.

10. Rosenblat JD, Lee Y, McIntyre RS. Does pharmacogenomics testing improve clinical outcomes for major depressive disorder? A systematic review of clinical trials and cost-effectiveness studies. J Clin Psychiatry. In press.

11. Nassan M, Nicholson WT, Elliott MA, et al. Pharmacokinetic pharmacogenetic prescribing guidelines for antidepressants: a template for psychiatric precision medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. In press.

12. Altar CA, Carhart JM, Allen JD, et al. Clinical validity: combinatorial pharmacogenomics predicts antidepressant responses and healthcare utilizations better than single gene phenotypes. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15(5):443-451.

13. Preskorn S, Kane C, Lobello K, et al. Cytochrome P450 2D6 phenoconversion is common in patients being treated for depression: implications for personalized medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):614-621.

14. Niculescu AB, Levey DF, Phalen PL, et al. Understanding and predicting suicidality using a combined genomic and clinical risk assessment approach. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(11):1266-1285.

What has been the history of the development of laboratory tests in the field of psychiatry?

During my almost-40-year academic medical career, I have been interested in the development and incorporation of laboratory tests into psychiatry.1 This interest initially focused on therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and the genetics of drug responsiveness, with an emphasis on drug metabolism. In addition to TDM—which I have long believed is vastly underutilized in psychiatry—there have been many failed attempts to develop diagnostic tests, including tests to distinguish between what were postulated to be serotonergic and noradrenergic forms of major depression in the 1970s2,3 and the dexamethasone suppression test for melancholia in the 1980s.4 Recently, a 51-analyte immunoassay test was marketed by Rules-Based Medicine, Inc. (RBM), as an aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia, but the test was found to suffer a high false-positive rate and was withdrawn from the market.5 Given this track record, caution is warranted when examining claims for new tests.

What types of tests are being developed?

Most tests in development are pharmacogenomic (PG)-based or immunoassay (IA)-based.

PG tests examine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in genes that code for pharmacokinetic mechanisms, primarily cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes responsible for drug metabolism and P-glycoprotein, responsible for drug transportation. The next most common type of test examines pharmacodynamic mechanisms, such as SNPs of specific receptor genes, including serotonin (or 5-hydroxytryptophan [5-HT] transporter [SET or 5-HTT]) or the 5-HT2A receptor.

The fact that CYP enzymes lead the list is not surprising: These enzymes and their role in the metabolism of specific drugs have been extensively studied since the late 1980s. Considerable data has been accumulated regarding variants of CYP enzymes, which convey clinically meaningful differences among individuals in terms of their ability to metabolize drug via these pathways. Individuals are commonly divided into 4 phenotypic categories: ultra-rapid, extensive (or normal), intermediate, and poor metabolizers. Based on these phenotypes, clinical consequences can be quantitated in terms of changes in drug concentration, concentration-dependent beneficial or adverse effects, and associated/recommended changes in dosing.

Research into the role of pharmacodynamic variants, however, is still in infancy and more difficult to measure in terms of assessing endpoints, with related limitations in clinical utility.

IA assays generally measure a variety of proteins, particularly those reflecting inflammatory processes (eg, various cytokines, such as interleukin-6).6 As with pharmacodynamic measures, research into the role of inflammatory biomarkers is in early stages. The clinical utility of associated tests is, therefore, less certain; witness the recent study5 I noted that revealed a high false-positive rate for the RBM schizophrenia panel in healthy controls. Nevertheless, considerable research is being conducted in all of these areas so that new developments might lend themselves to greater clinical utility.

(Note that PG biomarkers are trait measures, whereas IA biomarkers are state measures, so that complementary use of both types of tests might prove useful in diagnosis and clinical management. Although such integrative use of these 2 different types of tests generally is not done today.)

What does it take to market these tests?

At a minimum, offering these tests for sale requires that the laboratory be certified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, according to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standards (www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/ivdregulatoryassistance/ucm124105.htm). CLIA-certified laboratories are required to demonstrate the analytical validity of tests that they offer—ie, the accuracy and reliability of the test in measuring a parameter of interest—but not the clinical validity or utility of those tests. The fact that a test in fact measures what it claims to be measuring in and of itself does not mean it has clinical validity or utility (see the discussion below).

Must the FDA approve laboratory tests?

No, but that situation might be changing.

Currently, only tests used in a setting considered high risk—eg, a test intended to detect or diagnose a malignancy or guide its treatment—requires formal FDA approval. The approval of such a test requires submission to the FDA of clinical data supporting its clinical validity and utility, in addition to evidence of analytic validity.

Even in such cases, the degree and quality of the clinical data required are generally not as high as would be required for approval of a drug. That distinction is understandable, given the type and quantity of data necessary for drug approval and the many years and billions of dollars it takes to accumulate such data. For most laboratory tests, providing the same level of data required to have a drug approved would be neither necessary nor feasible given the business model underlying most laboratories providing laboratory tests.

What do ‘clinical validity’ and ‘clinical utility’ mean?

These are higher evidence thresholds than is needed for analytic validity, although the latter is a necessary first step on the path to achieving these higher thresholds.

Clinical validity is the ability of a test to detect:

- a clinically meaningful measure, such as clinical response

- an adverse effect

- a biologically meaningful measure (eg, a drug level or a change in the electrocardiographic pattern).

Above the threshold of clinical validity is clinical utility, which is proof that the test can reliably be used to guide clinical management and thus meaningfully improve outcomes, such as guiding drug or dosage selection.

Is the use of PG testing recommended? If so, in what instances?

Specific types of PG testing is recommended by the FDA recommended. The FDA has been incorporating PG information into the labels of specific medications for several years; the agency has a Web site (www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm) that continuously updates this information. The involved drugs are in all therapeutic classes—from oncology to psychiatry.

More than 30 psychotropic drugs have PG information in their label; some of those drugs’ labels contain specific recommendations, such as obtaining PG information before selecting or starting a drug in a specific patient. An example is carbamazepine, for which the recommendation is to obtain HLA testing before starting the drug in patients of Han Chinese ancestry, because members of this large ethnic group are at greater risk of serious dermatologic adverse effects, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

In other instances, the recommendation is to do the testing before increasing beyond a specific dose. Examples of psychiatric drugs whose labels contain such PG information include pimozide and iloperidone as well as citalopram. In the FDA-approved label, guidance is provided that these drugs can be started without testing if prescribed at a reduced recommended starting dosage range, rather than the full starting dosage range. The guidance on these drugs further recommends testing for genetic CYP2D6 poor metabolizer (PM) status before dosing above that initial recommended, limited, starting dosage range.

The rationale for this guidance is to reduce the risk that (1) patients in question will achieve an excessively high plasma drug level that can cause significant prolongation of intracardiac conduction (eg, QTc prolongation) and thus (2) develop the potentially fatal arrhythmia torsades de pointes. Guidance is based on thorough QTc studies that were performed on each drug,7,8 which makes them examples of instances in which the test has clinical validity and utility as well as analytical validity.

To find PG labeling in the package insert for these drugs, visit: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm.

What about data for other tests that are marketed and promoted by developers?

Sometimes, there are—literally—no data on available tests beyond the analytical validity of the test; other times, the amount and quality of clinical data are quite variable, ranging from results of ≥1 small retrospective studies without controls to results of prospective, randomized, controlled studies. Even among the latter, the developer may conduct and analyze their studies without oversight by an independent agency, such as the FDA.

This situation (1) raises concern that study results are not independent of the developer’s business interests and, as one might expect, (2) leads to controversy about whether the data are compelling—or not.9-12

What is a critical difference between PG test results and results of most laboratory tests?

PG tests are, as noted, trait rather than state characteristics. That means that the results do not change except for a phenomenon known as phenocoversion, discussed below. (Of course, advances in gene therapy might make it possible someday to change a person’s genetic makeup and for mitochondrial genes that is already possible.)

For this reason, PG test results should not get buried in the medical record, as might happen with, say, a patient’s serum potassium level at a given point in time. Instead, PG test results need to be carried forward continuously. Results also should be given to the patient as part of his (her) personal health record and to all other health care providers that the patient is seeing or will see in the future. Each health care provider who obtains PG test results should consider sending them to all current clinicians providing care for the patient at the same time as they are.

Is your functional status at a given moment the same as your genetic status?

No. There is a phenomenon known as phenoconversion in which a person’s current functional status may be different from what would be expected based on their genetic status.

CYP2D6 functional status is susceptible to phenoconversion as follows: Administering fluoxetine and paroxetine, for example, at 20 or 40 mg/d converts 66% and 95%, respectively, of patients who are CYP2D6 extensive (ie, normal) metabolizers into phenocopies of people who, genetically, lack the ability to metabolize drugs via CYP2D6 (ie, genotypic CYP2D6 PM). Based on a recent study of 900 participants in routine clinical care who were taking an antidepressant, 4% of the general U.S. population are genetically CYP2D6 PM; an additional 24% are phenotypically CYP2D6 PM because of concomitant administration of a CYP2D6 substantial inhibitor, such as bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or terbenafine.13

That is the reason a provider needs to know what drugs a patient is taking concomitantly—to consider the possibility of phenoconversion and, when necessary, to dose accordingly.

What does the future hold?

Development of tests for use in psychiatric practice is likely to grow substantially, for at least 2 reasons:

- There is a huge unmet need for clinically meaningful tests to aid in the provision of optimal patient care and, therefore, a tremendous business opportunity

- Knowledge in the biological basis of psychiatric disorders is growing exponentially; with that knowledge comes the ability to develop new tests.

A recent example comes from a research group that devised a test that could predict suicidality.14 Time will tell whether this test or a derivative of it enters practice. Nevertheless, it is a harbinger of the likely dramatic changes in the landscape of clinical medicine particularly as it applies to psychiatry.

Given these developments, the syndromic diagnoses in DSM-5 will in the future likely be replaced by a new diagnostic schema that breaks down existing heterogenous syndromic diagnoses into pathophysiologically and etiologically meaningful entities using insights gained from genetic and biomarker data as well as functional brain imaging. Theoretically, those insights will lead to new modalities of treatment, including somatic treatments that target novel mechanisms of action, coupled to more effective psychosocial therapies—with both therapies guided by diagnostic tests to monitor response to specific treatment interventions.

During this transition from the past to the future, answers to the questions I’ve posed here about laboratory testing in psychiatry will, I hope, help the practitioner understand, evaluate, and incorporate these changes readily into practice.

What has been the history of the development of laboratory tests in the field of psychiatry?

During my almost-40-year academic medical career, I have been interested in the development and incorporation of laboratory tests into psychiatry.1 This interest initially focused on therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and the genetics of drug responsiveness, with an emphasis on drug metabolism. In addition to TDM—which I have long believed is vastly underutilized in psychiatry—there have been many failed attempts to develop diagnostic tests, including tests to distinguish between what were postulated to be serotonergic and noradrenergic forms of major depression in the 1970s2,3 and the dexamethasone suppression test for melancholia in the 1980s.4 Recently, a 51-analyte immunoassay test was marketed by Rules-Based Medicine, Inc. (RBM), as an aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia, but the test was found to suffer a high false-positive rate and was withdrawn from the market.5 Given this track record, caution is warranted when examining claims for new tests.

What types of tests are being developed?

Most tests in development are pharmacogenomic (PG)-based or immunoassay (IA)-based.

PG tests examine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in genes that code for pharmacokinetic mechanisms, primarily cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes responsible for drug metabolism and P-glycoprotein, responsible for drug transportation. The next most common type of test examines pharmacodynamic mechanisms, such as SNPs of specific receptor genes, including serotonin (or 5-hydroxytryptophan [5-HT] transporter [SET or 5-HTT]) or the 5-HT2A receptor.

The fact that CYP enzymes lead the list is not surprising: These enzymes and their role in the metabolism of specific drugs have been extensively studied since the late 1980s. Considerable data has been accumulated regarding variants of CYP enzymes, which convey clinically meaningful differences among individuals in terms of their ability to metabolize drug via these pathways. Individuals are commonly divided into 4 phenotypic categories: ultra-rapid, extensive (or normal), intermediate, and poor metabolizers. Based on these phenotypes, clinical consequences can be quantitated in terms of changes in drug concentration, concentration-dependent beneficial or adverse effects, and associated/recommended changes in dosing.

Research into the role of pharmacodynamic variants, however, is still in infancy and more difficult to measure in terms of assessing endpoints, with related limitations in clinical utility.

IA assays generally measure a variety of proteins, particularly those reflecting inflammatory processes (eg, various cytokines, such as interleukin-6).6 As with pharmacodynamic measures, research into the role of inflammatory biomarkers is in early stages. The clinical utility of associated tests is, therefore, less certain; witness the recent study5 I noted that revealed a high false-positive rate for the RBM schizophrenia panel in healthy controls. Nevertheless, considerable research is being conducted in all of these areas so that new developments might lend themselves to greater clinical utility.

(Note that PG biomarkers are trait measures, whereas IA biomarkers are state measures, so that complementary use of both types of tests might prove useful in diagnosis and clinical management. Although such integrative use of these 2 different types of tests generally is not done today.)

What does it take to market these tests?

At a minimum, offering these tests for sale requires that the laboratory be certified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, according to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standards (www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/ivdregulatoryassistance/ucm124105.htm). CLIA-certified laboratories are required to demonstrate the analytical validity of tests that they offer—ie, the accuracy and reliability of the test in measuring a parameter of interest—but not the clinical validity or utility of those tests. The fact that a test in fact measures what it claims to be measuring in and of itself does not mean it has clinical validity or utility (see the discussion below).

Must the FDA approve laboratory tests?

No, but that situation might be changing.

Currently, only tests used in a setting considered high risk—eg, a test intended to detect or diagnose a malignancy or guide its treatment—requires formal FDA approval. The approval of such a test requires submission to the FDA of clinical data supporting its clinical validity and utility, in addition to evidence of analytic validity.

Even in such cases, the degree and quality of the clinical data required are generally not as high as would be required for approval of a drug. That distinction is understandable, given the type and quantity of data necessary for drug approval and the many years and billions of dollars it takes to accumulate such data. For most laboratory tests, providing the same level of data required to have a drug approved would be neither necessary nor feasible given the business model underlying most laboratories providing laboratory tests.

What do ‘clinical validity’ and ‘clinical utility’ mean?

These are higher evidence thresholds than is needed for analytic validity, although the latter is a necessary first step on the path to achieving these higher thresholds.

Clinical validity is the ability of a test to detect:

- a clinically meaningful measure, such as clinical response

- an adverse effect

- a biologically meaningful measure (eg, a drug level or a change in the electrocardiographic pattern).

Above the threshold of clinical validity is clinical utility, which is proof that the test can reliably be used to guide clinical management and thus meaningfully improve outcomes, such as guiding drug or dosage selection.

Is the use of PG testing recommended? If so, in what instances?

Specific types of PG testing is recommended by the FDA recommended. The FDA has been incorporating PG information into the labels of specific medications for several years; the agency has a Web site (www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm) that continuously updates this information. The involved drugs are in all therapeutic classes—from oncology to psychiatry.

More than 30 psychotropic drugs have PG information in their label; some of those drugs’ labels contain specific recommendations, such as obtaining PG information before selecting or starting a drug in a specific patient. An example is carbamazepine, for which the recommendation is to obtain HLA testing before starting the drug in patients of Han Chinese ancestry, because members of this large ethnic group are at greater risk of serious dermatologic adverse effects, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

In other instances, the recommendation is to do the testing before increasing beyond a specific dose. Examples of psychiatric drugs whose labels contain such PG information include pimozide and iloperidone as well as citalopram. In the FDA-approved label, guidance is provided that these drugs can be started without testing if prescribed at a reduced recommended starting dosage range, rather than the full starting dosage range. The guidance on these drugs further recommends testing for genetic CYP2D6 poor metabolizer (PM) status before dosing above that initial recommended, limited, starting dosage range.

The rationale for this guidance is to reduce the risk that (1) patients in question will achieve an excessively high plasma drug level that can cause significant prolongation of intracardiac conduction (eg, QTc prolongation) and thus (2) develop the potentially fatal arrhythmia torsades de pointes. Guidance is based on thorough QTc studies that were performed on each drug,7,8 which makes them examples of instances in which the test has clinical validity and utility as well as analytical validity.

To find PG labeling in the package insert for these drugs, visit: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm.

What about data for other tests that are marketed and promoted by developers?

Sometimes, there are—literally—no data on available tests beyond the analytical validity of the test; other times, the amount and quality of clinical data are quite variable, ranging from results of ≥1 small retrospective studies without controls to results of prospective, randomized, controlled studies. Even among the latter, the developer may conduct and analyze their studies without oversight by an independent agency, such as the FDA.

This situation (1) raises concern that study results are not independent of the developer’s business interests and, as one might expect, (2) leads to controversy about whether the data are compelling—or not.9-12

What is a critical difference between PG test results and results of most laboratory tests?

PG tests are, as noted, trait rather than state characteristics. That means that the results do not change except for a phenomenon known as phenocoversion, discussed below. (Of course, advances in gene therapy might make it possible someday to change a person’s genetic makeup and for mitochondrial genes that is already possible.)

For this reason, PG test results should not get buried in the medical record, as might happen with, say, a patient’s serum potassium level at a given point in time. Instead, PG test results need to be carried forward continuously. Results also should be given to the patient as part of his (her) personal health record and to all other health care providers that the patient is seeing or will see in the future. Each health care provider who obtains PG test results should consider sending them to all current clinicians providing care for the patient at the same time as they are.

Is your functional status at a given moment the same as your genetic status?

No. There is a phenomenon known as phenoconversion in which a person’s current functional status may be different from what would be expected based on their genetic status.

CYP2D6 functional status is susceptible to phenoconversion as follows: Administering fluoxetine and paroxetine, for example, at 20 or 40 mg/d converts 66% and 95%, respectively, of patients who are CYP2D6 extensive (ie, normal) metabolizers into phenocopies of people who, genetically, lack the ability to metabolize drugs via CYP2D6 (ie, genotypic CYP2D6 PM). Based on a recent study of 900 participants in routine clinical care who were taking an antidepressant, 4% of the general U.S. population are genetically CYP2D6 PM; an additional 24% are phenotypically CYP2D6 PM because of concomitant administration of a CYP2D6 substantial inhibitor, such as bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or terbenafine.13

That is the reason a provider needs to know what drugs a patient is taking concomitantly—to consider the possibility of phenoconversion and, when necessary, to dose accordingly.

What does the future hold?

Development of tests for use in psychiatric practice is likely to grow substantially, for at least 2 reasons:

- There is a huge unmet need for clinically meaningful tests to aid in the provision of optimal patient care and, therefore, a tremendous business opportunity

- Knowledge in the biological basis of psychiatric disorders is growing exponentially; with that knowledge comes the ability to develop new tests.

A recent example comes from a research group that devised a test that could predict suicidality.14 Time will tell whether this test or a derivative of it enters practice. Nevertheless, it is a harbinger of the likely dramatic changes in the landscape of clinical medicine particularly as it applies to psychiatry.

Given these developments, the syndromic diagnoses in DSM-5 will in the future likely be replaced by a new diagnostic schema that breaks down existing heterogenous syndromic diagnoses into pathophysiologically and etiologically meaningful entities using insights gained from genetic and biomarker data as well as functional brain imaging. Theoretically, those insights will lead to new modalities of treatment, including somatic treatments that target novel mechanisms of action, coupled to more effective psychosocial therapies—with both therapies guided by diagnostic tests to monitor response to specific treatment interventions.

During this transition from the past to the future, answers to the questions I’ve posed here about laboratory testing in psychiatry will, I hope, help the practitioner understand, evaluate, and incorporate these changes readily into practice.

1. Preskorn SH, Biggs JT. Use of tricyclic antidepressant blood levels. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(3):166.

2. Schildkraut JJ. Biogenic amines and affective disorders. Annu Rev Med. 1974;25(0):333-348.

3. Maas JW. Biogenic amines and depression. Biochemical and pharmacological separation of two types of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(11):1357-1361.

4. Carroll BJ, Feinberg M, Greden JF, et al. A specific laboratory test for the diagnosis of melancholia. Standardization, validation, and clinical utility. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(1):15-22.

5. Wehler C, Preskorn S. High false-positive rate of a putative biomarker test to aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. In press.

6. Savitz J, Preskorn S, Teague TK, et al. Minocycline and aspirin in the treatment of bipolar depression: a protocol for a proof-of-concept, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2x2 clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000643. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000643.

7. Rogers HL, Bhattaram A, Zineh I, et al. CYP2D6 genotype information to guide pimozide treatment in adult and pediatric patients: basis for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s new dosing recommendations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(9):1187-1190.

8. Potkin S, Preskorn S, Hochfeld M, et al. A thorough QTc study of 3 doses of iloperidone including metabolic inhibition via CYP2D6 and/or CYP3A4 inhibition and a comparison to quetiapine and ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):3-10.

9. Howland RH. Pharmacogenetic testing in psychiatry: not (quite) ready for primetime. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52(11):13-16.

10. Rosenblat JD, Lee Y, McIntyre RS. Does pharmacogenomics testing improve clinical outcomes for major depressive disorder? A systematic review of clinical trials and cost-effectiveness studies. J Clin Psychiatry. In press.

11. Nassan M, Nicholson WT, Elliott MA, et al. Pharmacokinetic pharmacogenetic prescribing guidelines for antidepressants: a template for psychiatric precision medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. In press.

12. Altar CA, Carhart JM, Allen JD, et al. Clinical validity: combinatorial pharmacogenomics predicts antidepressant responses and healthcare utilizations better than single gene phenotypes. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15(5):443-451.

13. Preskorn S, Kane C, Lobello K, et al. Cytochrome P450 2D6 phenoconversion is common in patients being treated for depression: implications for personalized medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):614-621.

14. Niculescu AB, Levey DF, Phalen PL, et al. Understanding and predicting suicidality using a combined genomic and clinical risk assessment approach. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(11):1266-1285.

1. Preskorn SH, Biggs JT. Use of tricyclic antidepressant blood levels. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(3):166.