User login

Form of catheter-directed thrombolysis cured patients of submassive PEs

Ultrasound-accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis (USAT) was successful at treating acute submassive pulmonary embolisms, according to a retrospective study.

Acute pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction (RVD), on average, became significantly less severe in all of the study’s 45 participants. Specifically, main pulmonary artery pressure decreased to 31.1 mm Hg from 49.8 mm Hg. The improvement in RVD was demonstrated by a decreased right ventricle-to-left-ventricle ratio to 0.93 from 1.59.

Although no complications occurred as a result of catheter placement, six complications resulted from other causes. Those complications included four minor venous access-site hemorrhagic complications and two major bleeding complications: a flank hematoma and an arm hematoma.

“USAT is a safe and efficacious method of treatment of submassive PE to reduce acute pulmonary hypertension and RVD. Future studies should be aimed at examining the long-term effect of USAT on mortality, exercise tolerance, and pulmonary hypertension,” wrote Dr. Sandeep Bagla of the Inova Alexandria (Va.) Hospital and his colleagues.

Find the full study in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.12.017).

Ultrasound-accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis (USAT) was successful at treating acute submassive pulmonary embolisms, according to a retrospective study.

Acute pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction (RVD), on average, became significantly less severe in all of the study’s 45 participants. Specifically, main pulmonary artery pressure decreased to 31.1 mm Hg from 49.8 mm Hg. The improvement in RVD was demonstrated by a decreased right ventricle-to-left-ventricle ratio to 0.93 from 1.59.

Although no complications occurred as a result of catheter placement, six complications resulted from other causes. Those complications included four minor venous access-site hemorrhagic complications and two major bleeding complications: a flank hematoma and an arm hematoma.

“USAT is a safe and efficacious method of treatment of submassive PE to reduce acute pulmonary hypertension and RVD. Future studies should be aimed at examining the long-term effect of USAT on mortality, exercise tolerance, and pulmonary hypertension,” wrote Dr. Sandeep Bagla of the Inova Alexandria (Va.) Hospital and his colleagues.

Find the full study in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.12.017).

Ultrasound-accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis (USAT) was successful at treating acute submassive pulmonary embolisms, according to a retrospective study.

Acute pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction (RVD), on average, became significantly less severe in all of the study’s 45 participants. Specifically, main pulmonary artery pressure decreased to 31.1 mm Hg from 49.8 mm Hg. The improvement in RVD was demonstrated by a decreased right ventricle-to-left-ventricle ratio to 0.93 from 1.59.

Although no complications occurred as a result of catheter placement, six complications resulted from other causes. Those complications included four minor venous access-site hemorrhagic complications and two major bleeding complications: a flank hematoma and an arm hematoma.

“USAT is a safe and efficacious method of treatment of submassive PE to reduce acute pulmonary hypertension and RVD. Future studies should be aimed at examining the long-term effect of USAT on mortality, exercise tolerance, and pulmonary hypertension,” wrote Dr. Sandeep Bagla of the Inova Alexandria (Va.) Hospital and his colleagues.

Find the full study in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.12.017).

Two genes identified as VTE risk loci

A meta-analysis has identified two genes as susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism, according to Marine Germain of the Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris, and associates.

The identified risk loci were TSPAN15 and SLC44A2, with the odds ratios for VTE at 1.31 and 1.21, respectively. The most significant single-nucleotide polymorphism for the TSPAN15 loci was the intronic rs78707713; for SLC44A2, the most significant SNP was the nonsynonymous rs2288904, with ORs of 1.42 and 1.28, respectively. Although these associations are not strong, statistical evidence was much more convincing in the discovery and replication stages, the researchers reported.

“The identified VTE-associated SNPs map to genes that are not in conventional pathways to thrombosis that have marked most of the genetic associations to date, suggesting that these genetic variants represent novel biological pathways leading to VTE,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in the American Journal of Human Genetics (2015 April 2 [doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.019]).

A meta-analysis has identified two genes as susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism, according to Marine Germain of the Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris, and associates.

The identified risk loci were TSPAN15 and SLC44A2, with the odds ratios for VTE at 1.31 and 1.21, respectively. The most significant single-nucleotide polymorphism for the TSPAN15 loci was the intronic rs78707713; for SLC44A2, the most significant SNP was the nonsynonymous rs2288904, with ORs of 1.42 and 1.28, respectively. Although these associations are not strong, statistical evidence was much more convincing in the discovery and replication stages, the researchers reported.

“The identified VTE-associated SNPs map to genes that are not in conventional pathways to thrombosis that have marked most of the genetic associations to date, suggesting that these genetic variants represent novel biological pathways leading to VTE,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in the American Journal of Human Genetics (2015 April 2 [doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.019]).

A meta-analysis has identified two genes as susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism, according to Marine Germain of the Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris, and associates.

The identified risk loci were TSPAN15 and SLC44A2, with the odds ratios for VTE at 1.31 and 1.21, respectively. The most significant single-nucleotide polymorphism for the TSPAN15 loci was the intronic rs78707713; for SLC44A2, the most significant SNP was the nonsynonymous rs2288904, with ORs of 1.42 and 1.28, respectively. Although these associations are not strong, statistical evidence was much more convincing in the discovery and replication stages, the researchers reported.

“The identified VTE-associated SNPs map to genes that are not in conventional pathways to thrombosis that have marked most of the genetic associations to date, suggesting that these genetic variants represent novel biological pathways leading to VTE,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in the American Journal of Human Genetics (2015 April 2 [doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.019]).

Study: More DVTs than expected in patients who had varicose vein surgeries

A retrospective study of patients who underwent varicose vein surgeries with a tourniquet found a greater incidence of deep vein thromboses (DVTs) than previous studies.

Within the first 3 postoperative days, 113 (7.7%) of the 1,461 patients had DVTs. The researchers also found that DVTs occurred significantly more often in patients with gastrocnemius vein dilation (GVD). A total of 410 (28%) of the study’s participants had GVTs, and the incidence of DVTs was significantly greater in individuals with GVD compared to those without such a symptom. GVD had a higher predictive power for postoperative DVT than did all of the other risk factors examined in univariate and multivariate analyses.

The vast majority of the DVTs diagnosed were isolated distal. While 94 patients suffered from this kind of DVT, the remaining 19 DVTs were proximal. According to Dr. Chen Kai of Wenzhou (China) Medical University, and colleagues, proximal DVTs were nearly always asymptomatic and a larger percentage of them took more time to disappear than did the distal DVTs. Within 6 months following anticoagulant therapy, 94.3% of the distal DVTs exhibited thrombus resolution and 55.6% of the proximal DVTs were thrombus free. None of the study’s participants had died because of DVT or pulmonary embolus during the 6 months following their surgeries.

This study’s “present data reflect a higher incidence of postoperative DVT than previous studies, and we also identify GVD as a significant risk factor. Larger prospective studies will be needed to evaluate this issue precisely and to understand the clinical relevance of these results,” wrote the researchers.Find the full study in Thombosis Research (doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.008).

A retrospective study of patients who underwent varicose vein surgeries with a tourniquet found a greater incidence of deep vein thromboses (DVTs) than previous studies.

Within the first 3 postoperative days, 113 (7.7%) of the 1,461 patients had DVTs. The researchers also found that DVTs occurred significantly more often in patients with gastrocnemius vein dilation (GVD). A total of 410 (28%) of the study’s participants had GVTs, and the incidence of DVTs was significantly greater in individuals with GVD compared to those without such a symptom. GVD had a higher predictive power for postoperative DVT than did all of the other risk factors examined in univariate and multivariate analyses.

The vast majority of the DVTs diagnosed were isolated distal. While 94 patients suffered from this kind of DVT, the remaining 19 DVTs were proximal. According to Dr. Chen Kai of Wenzhou (China) Medical University, and colleagues, proximal DVTs were nearly always asymptomatic and a larger percentage of them took more time to disappear than did the distal DVTs. Within 6 months following anticoagulant therapy, 94.3% of the distal DVTs exhibited thrombus resolution and 55.6% of the proximal DVTs were thrombus free. None of the study’s participants had died because of DVT or pulmonary embolus during the 6 months following their surgeries.

This study’s “present data reflect a higher incidence of postoperative DVT than previous studies, and we also identify GVD as a significant risk factor. Larger prospective studies will be needed to evaluate this issue precisely and to understand the clinical relevance of these results,” wrote the researchers.Find the full study in Thombosis Research (doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.008).

A retrospective study of patients who underwent varicose vein surgeries with a tourniquet found a greater incidence of deep vein thromboses (DVTs) than previous studies.

Within the first 3 postoperative days, 113 (7.7%) of the 1,461 patients had DVTs. The researchers also found that DVTs occurred significantly more often in patients with gastrocnemius vein dilation (GVD). A total of 410 (28%) of the study’s participants had GVTs, and the incidence of DVTs was significantly greater in individuals with GVD compared to those without such a symptom. GVD had a higher predictive power for postoperative DVT than did all of the other risk factors examined in univariate and multivariate analyses.

The vast majority of the DVTs diagnosed were isolated distal. While 94 patients suffered from this kind of DVT, the remaining 19 DVTs were proximal. According to Dr. Chen Kai of Wenzhou (China) Medical University, and colleagues, proximal DVTs were nearly always asymptomatic and a larger percentage of them took more time to disappear than did the distal DVTs. Within 6 months following anticoagulant therapy, 94.3% of the distal DVTs exhibited thrombus resolution and 55.6% of the proximal DVTs were thrombus free. None of the study’s participants had died because of DVT or pulmonary embolus during the 6 months following their surgeries.

This study’s “present data reflect a higher incidence of postoperative DVT than previous studies, and we also identify GVD as a significant risk factor. Larger prospective studies will be needed to evaluate this issue precisely and to understand the clinical relevance of these results,” wrote the researchers.Find the full study in Thombosis Research (doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.008).

Are you a victim of the cognitive load theory?

My job recently changed to include some administrative responsibilities, so having done purely clinical work for my entire career as a physician, I thought it wise to begin broadening my horizons to learn how to best meet the new challenges ahead of me. Fortunately, not only was the Hospital Medicine 2015 conference just an hour’s drive away, it occurred just when I needed it most, within days of my taking on a new role.

Naturally, I opted for the Practice Management track this year since I will need a different skill set than I currently have. In the first session, called Case Studies in Improving Patient Experience, I learned about a patient named John, who had developed typical ischemic chest pain during a weekly tennis game with his wife. His doctors did everything right, or so they thought. They exceeded the national guidelines for each quality measure, including the time it took them to revascularize his blocked artery. John had no significant residual damage and within 2 weeks was back on the tennis courts.

But there had been a huge disconnect. His doctors practiced excellent medicine, yet John was displeased with his care. The hospital team had not communicated well with John during his hospital stay. A great success story seen through the eyes of his medical team was a great failure as seen through the eyes of John and his wife. The hospital team’s lack of communication trumped the fact that they had played a huge role in saving John’s life.

As a matter of fact, John and his wife were so distraught over their experience that they went to the hospital administration to express their concerns about how poorly they had been treated.

This story also was aired as part of a segment on National Public Radio. Some of the comments of listeners echoed the sentiments we hear often, such as “doctors don’t know how to communicate with patients” and “doctors don’t care.” While the former statement may be true in many cases, the latter couldn’t be further from the truth. We do care. Why else would we sacrifice so much of our lives to help others? There are certainly other careers that pay more than medicine, especially considering all the time and financial investment that go into becoming a physician.

So why is it that as intelligent as we are as a group, we often fall short of meeting the communication goals that are so important to our patients? Some believe – and I am one of them – that most physicians are examples of the cognitive load theory. Our brains are simply overloaded. This theory, developed by psychologist John Sweller in the 1980s, refers to the total amount of mental effort used in one’s working memory.

There are three types of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. Intrinsic cognitive load refers to how much effort goes into a particular topic, and in the field of medicine, the complexity of the information we deal with is very high, as is our intrinsic load.

Extraneous cognitive load refers to how this information is presented to us. When the pager is incessantly beeping, a line of nurses is waiting to ask a question, you desperately need to get to the ED to admit a potential stroke patient, and you eye a family member anxiously pacing the hallway and waiting for a chance to speak with you, your brain is bombarded with a variety of complex issues coming in all directions. In short, your extraneous load is through the roof.

The germane cognitive load refers to the work you put into processing information and creating a permanent store of that knowledge, creating a schema, so to speak. For instance, after much experience, it has become relatively simple to classify a patient as having heart failure if he presents with bilateral leg edema, progressive shortness of breath, and crackles on exam.

Experience helps us with our germane cognitive load and sometimes we have little control over our intrinisic load, but there are many potential opportunities to organize our extraneous cognitive load into chunks that flow more seamlessly, make our workday run more smoothly, and free up mental energy and time to deal effectively with other important issues. We all have our personal preferences for how we like our workday to flow. Chances are, with a little creativity, we can have a significant impact on our own extraneous loads.

Getting back to John, he is just one of many patients who feel emotionally neglected, not respected, or not kept up to date regarding their statuses. Considering his doctors, they were probably overwhelmed with the load they were carrying; the responsibility for a life is something only medical professionals can fully grasp. I know there have been times when I too felt simply overwhelmed and unable to do every single thing that would have been good, but not crucial, to the goal of curing the patient. Had I managed my intrinisic load better, perhaps I would have been better equipped to spend more time talking to patients and their family members. I suspect I am not alone.

My job recently changed to include some administrative responsibilities, so having done purely clinical work for my entire career as a physician, I thought it wise to begin broadening my horizons to learn how to best meet the new challenges ahead of me. Fortunately, not only was the Hospital Medicine 2015 conference just an hour’s drive away, it occurred just when I needed it most, within days of my taking on a new role.

Naturally, I opted for the Practice Management track this year since I will need a different skill set than I currently have. In the first session, called Case Studies in Improving Patient Experience, I learned about a patient named John, who had developed typical ischemic chest pain during a weekly tennis game with his wife. His doctors did everything right, or so they thought. They exceeded the national guidelines for each quality measure, including the time it took them to revascularize his blocked artery. John had no significant residual damage and within 2 weeks was back on the tennis courts.

But there had been a huge disconnect. His doctors practiced excellent medicine, yet John was displeased with his care. The hospital team had not communicated well with John during his hospital stay. A great success story seen through the eyes of his medical team was a great failure as seen through the eyes of John and his wife. The hospital team’s lack of communication trumped the fact that they had played a huge role in saving John’s life.

As a matter of fact, John and his wife were so distraught over their experience that they went to the hospital administration to express their concerns about how poorly they had been treated.

This story also was aired as part of a segment on National Public Radio. Some of the comments of listeners echoed the sentiments we hear often, such as “doctors don’t know how to communicate with patients” and “doctors don’t care.” While the former statement may be true in many cases, the latter couldn’t be further from the truth. We do care. Why else would we sacrifice so much of our lives to help others? There are certainly other careers that pay more than medicine, especially considering all the time and financial investment that go into becoming a physician.

So why is it that as intelligent as we are as a group, we often fall short of meeting the communication goals that are so important to our patients? Some believe – and I am one of them – that most physicians are examples of the cognitive load theory. Our brains are simply overloaded. This theory, developed by psychologist John Sweller in the 1980s, refers to the total amount of mental effort used in one’s working memory.

There are three types of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. Intrinsic cognitive load refers to how much effort goes into a particular topic, and in the field of medicine, the complexity of the information we deal with is very high, as is our intrinsic load.

Extraneous cognitive load refers to how this information is presented to us. When the pager is incessantly beeping, a line of nurses is waiting to ask a question, you desperately need to get to the ED to admit a potential stroke patient, and you eye a family member anxiously pacing the hallway and waiting for a chance to speak with you, your brain is bombarded with a variety of complex issues coming in all directions. In short, your extraneous load is through the roof.

The germane cognitive load refers to the work you put into processing information and creating a permanent store of that knowledge, creating a schema, so to speak. For instance, after much experience, it has become relatively simple to classify a patient as having heart failure if he presents with bilateral leg edema, progressive shortness of breath, and crackles on exam.

Experience helps us with our germane cognitive load and sometimes we have little control over our intrinisic load, but there are many potential opportunities to organize our extraneous cognitive load into chunks that flow more seamlessly, make our workday run more smoothly, and free up mental energy and time to deal effectively with other important issues. We all have our personal preferences for how we like our workday to flow. Chances are, with a little creativity, we can have a significant impact on our own extraneous loads.

Getting back to John, he is just one of many patients who feel emotionally neglected, not respected, or not kept up to date regarding their statuses. Considering his doctors, they were probably overwhelmed with the load they were carrying; the responsibility for a life is something only medical professionals can fully grasp. I know there have been times when I too felt simply overwhelmed and unable to do every single thing that would have been good, but not crucial, to the goal of curing the patient. Had I managed my intrinisic load better, perhaps I would have been better equipped to spend more time talking to patients and their family members. I suspect I am not alone.

My job recently changed to include some administrative responsibilities, so having done purely clinical work for my entire career as a physician, I thought it wise to begin broadening my horizons to learn how to best meet the new challenges ahead of me. Fortunately, not only was the Hospital Medicine 2015 conference just an hour’s drive away, it occurred just when I needed it most, within days of my taking on a new role.

Naturally, I opted for the Practice Management track this year since I will need a different skill set than I currently have. In the first session, called Case Studies in Improving Patient Experience, I learned about a patient named John, who had developed typical ischemic chest pain during a weekly tennis game with his wife. His doctors did everything right, or so they thought. They exceeded the national guidelines for each quality measure, including the time it took them to revascularize his blocked artery. John had no significant residual damage and within 2 weeks was back on the tennis courts.

But there had been a huge disconnect. His doctors practiced excellent medicine, yet John was displeased with his care. The hospital team had not communicated well with John during his hospital stay. A great success story seen through the eyes of his medical team was a great failure as seen through the eyes of John and his wife. The hospital team’s lack of communication trumped the fact that they had played a huge role in saving John’s life.

As a matter of fact, John and his wife were so distraught over their experience that they went to the hospital administration to express their concerns about how poorly they had been treated.

This story also was aired as part of a segment on National Public Radio. Some of the comments of listeners echoed the sentiments we hear often, such as “doctors don’t know how to communicate with patients” and “doctors don’t care.” While the former statement may be true in many cases, the latter couldn’t be further from the truth. We do care. Why else would we sacrifice so much of our lives to help others? There are certainly other careers that pay more than medicine, especially considering all the time and financial investment that go into becoming a physician.

So why is it that as intelligent as we are as a group, we often fall short of meeting the communication goals that are so important to our patients? Some believe – and I am one of them – that most physicians are examples of the cognitive load theory. Our brains are simply overloaded. This theory, developed by psychologist John Sweller in the 1980s, refers to the total amount of mental effort used in one’s working memory.

There are three types of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. Intrinsic cognitive load refers to how much effort goes into a particular topic, and in the field of medicine, the complexity of the information we deal with is very high, as is our intrinsic load.

Extraneous cognitive load refers to how this information is presented to us. When the pager is incessantly beeping, a line of nurses is waiting to ask a question, you desperately need to get to the ED to admit a potential stroke patient, and you eye a family member anxiously pacing the hallway and waiting for a chance to speak with you, your brain is bombarded with a variety of complex issues coming in all directions. In short, your extraneous load is through the roof.

The germane cognitive load refers to the work you put into processing information and creating a permanent store of that knowledge, creating a schema, so to speak. For instance, after much experience, it has become relatively simple to classify a patient as having heart failure if he presents with bilateral leg edema, progressive shortness of breath, and crackles on exam.

Experience helps us with our germane cognitive load and sometimes we have little control over our intrinisic load, but there are many potential opportunities to organize our extraneous cognitive load into chunks that flow more seamlessly, make our workday run more smoothly, and free up mental energy and time to deal effectively with other important issues. We all have our personal preferences for how we like our workday to flow. Chances are, with a little creativity, we can have a significant impact on our own extraneous loads.

Getting back to John, he is just one of many patients who feel emotionally neglected, not respected, or not kept up to date regarding their statuses. Considering his doctors, they were probably overwhelmed with the load they were carrying; the responsibility for a life is something only medical professionals can fully grasp. I know there have been times when I too felt simply overwhelmed and unable to do every single thing that would have been good, but not crucial, to the goal of curing the patient. Had I managed my intrinisic load better, perhaps I would have been better equipped to spend more time talking to patients and their family members. I suspect I am not alone.

VTE with transient risk factors is being overtreated

After a first episode of venous thromboembolism, more than 40% of patients with transient risk factors underwent anticoagulation therapy for 12 months or longer – a duration at least four times longer than the period recommended in guidelines, said authors of a large prospective cohort study.

Patients with VTE associated with surgery had about a 0.7% risk/patient-year of recurrence after 3 months of anticoagulation therapy. Patients with transient nonsurgical risk factors had about a 4% risk/patient-year of VTE recurrence.

Further, these patients were more likely to have major bleeding events than recurrent VTEs and were more likely to die of a fatal bleed than from a recurrent pulmonary embolism. Additionally, 38% of major bleeds among patients with transient risk factors occurred during the first 3 months of anticoagulation therapy.

“Our data suggest that in real life, physicians appear to be more concerned about the risk of recurrent VTE after discontinuing therapy than about the risk of bleeding,” said Dr. Walter Ageno at the University of Insubria in Varese, Italy, and his associates. “Clinicians base their treatment decisions on individual risk stratification, taking into account the location of VTE and the presence of additional risk factors for recurrence and bleeding. However, before adequately validated clinical prediction rules become available, this approach may expose a substantial proportion of patients, in particular those with VTE secondary to transient risk factors, to a possibly unnecessary risk of bleeding.”

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends 3 months of anticoagulation therapy for patients with VTE secondary to surgery or a transient, nonsurgical risk factor, and extended (possibly indefinite) anticoagulation for patients with unprovoked VTE or VTE caused by cancer. To look at real-world practice, the researchers carried out a prospective cohort study of 6,944 VTE patients in Italy, Spain, and Belgium. In all, 32% of patients had transient risk factors, 41% had unprovoked VTE, and 27% had cancer (Thrombosis Res. 2015;135:666-72). After excluding patients who died within a year after VTE, 42% of patients with transient risk factors such as recent surgery, pregnancy, or prolonged travel were treated with anticoagulants for more than 12 months, the researchers reported. Significant predictors of extended anticoagulation treatment including being older than 65 years old, having chronic heart failure, pulmonary embolism at presentation, and recurrent VTE during anticoagulation, the researchers also reported. Patients who weighed less than 75 kg, had anemia, or had transient risk factors for VTE were less likely to undergo prolonged treatment than were other patients.

“There is still uncertainty among experts on the optimal duration of secondary prevention of VTE,” concluded the investigators. “This decision should be taken by balancing the risk of recurrence after stopping treatment with the risk of bleeding if treatment is continued.”

Adequately validated clinical prediction rules are needed to make those decisions, the researchers said. Until such tools are validated, a substantial proportion of patients with transiet and secondary risk factors for VTE may be exposed to a possibly unnecessary risk of bleeding, they concluded.

Sanofi Spain and Bayer Pharma AG funded the study. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

After a first episode of venous thromboembolism, more than 40% of patients with transient risk factors underwent anticoagulation therapy for 12 months or longer – a duration at least four times longer than the period recommended in guidelines, said authors of a large prospective cohort study.

Patients with VTE associated with surgery had about a 0.7% risk/patient-year of recurrence after 3 months of anticoagulation therapy. Patients with transient nonsurgical risk factors had about a 4% risk/patient-year of VTE recurrence.

Further, these patients were more likely to have major bleeding events than recurrent VTEs and were more likely to die of a fatal bleed than from a recurrent pulmonary embolism. Additionally, 38% of major bleeds among patients with transient risk factors occurred during the first 3 months of anticoagulation therapy.

“Our data suggest that in real life, physicians appear to be more concerned about the risk of recurrent VTE after discontinuing therapy than about the risk of bleeding,” said Dr. Walter Ageno at the University of Insubria in Varese, Italy, and his associates. “Clinicians base their treatment decisions on individual risk stratification, taking into account the location of VTE and the presence of additional risk factors for recurrence and bleeding. However, before adequately validated clinical prediction rules become available, this approach may expose a substantial proportion of patients, in particular those with VTE secondary to transient risk factors, to a possibly unnecessary risk of bleeding.”

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends 3 months of anticoagulation therapy for patients with VTE secondary to surgery or a transient, nonsurgical risk factor, and extended (possibly indefinite) anticoagulation for patients with unprovoked VTE or VTE caused by cancer. To look at real-world practice, the researchers carried out a prospective cohort study of 6,944 VTE patients in Italy, Spain, and Belgium. In all, 32% of patients had transient risk factors, 41% had unprovoked VTE, and 27% had cancer (Thrombosis Res. 2015;135:666-72). After excluding patients who died within a year after VTE, 42% of patients with transient risk factors such as recent surgery, pregnancy, or prolonged travel were treated with anticoagulants for more than 12 months, the researchers reported. Significant predictors of extended anticoagulation treatment including being older than 65 years old, having chronic heart failure, pulmonary embolism at presentation, and recurrent VTE during anticoagulation, the researchers also reported. Patients who weighed less than 75 kg, had anemia, or had transient risk factors for VTE were less likely to undergo prolonged treatment than were other patients.

“There is still uncertainty among experts on the optimal duration of secondary prevention of VTE,” concluded the investigators. “This decision should be taken by balancing the risk of recurrence after stopping treatment with the risk of bleeding if treatment is continued.”

Adequately validated clinical prediction rules are needed to make those decisions, the researchers said. Until such tools are validated, a substantial proportion of patients with transiet and secondary risk factors for VTE may be exposed to a possibly unnecessary risk of bleeding, they concluded.

Sanofi Spain and Bayer Pharma AG funded the study. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

After a first episode of venous thromboembolism, more than 40% of patients with transient risk factors underwent anticoagulation therapy for 12 months or longer – a duration at least four times longer than the period recommended in guidelines, said authors of a large prospective cohort study.

Patients with VTE associated with surgery had about a 0.7% risk/patient-year of recurrence after 3 months of anticoagulation therapy. Patients with transient nonsurgical risk factors had about a 4% risk/patient-year of VTE recurrence.

Further, these patients were more likely to have major bleeding events than recurrent VTEs and were more likely to die of a fatal bleed than from a recurrent pulmonary embolism. Additionally, 38% of major bleeds among patients with transient risk factors occurred during the first 3 months of anticoagulation therapy.

“Our data suggest that in real life, physicians appear to be more concerned about the risk of recurrent VTE after discontinuing therapy than about the risk of bleeding,” said Dr. Walter Ageno at the University of Insubria in Varese, Italy, and his associates. “Clinicians base their treatment decisions on individual risk stratification, taking into account the location of VTE and the presence of additional risk factors for recurrence and bleeding. However, before adequately validated clinical prediction rules become available, this approach may expose a substantial proportion of patients, in particular those with VTE secondary to transient risk factors, to a possibly unnecessary risk of bleeding.”

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends 3 months of anticoagulation therapy for patients with VTE secondary to surgery or a transient, nonsurgical risk factor, and extended (possibly indefinite) anticoagulation for patients with unprovoked VTE or VTE caused by cancer. To look at real-world practice, the researchers carried out a prospective cohort study of 6,944 VTE patients in Italy, Spain, and Belgium. In all, 32% of patients had transient risk factors, 41% had unprovoked VTE, and 27% had cancer (Thrombosis Res. 2015;135:666-72). After excluding patients who died within a year after VTE, 42% of patients with transient risk factors such as recent surgery, pregnancy, or prolonged travel were treated with anticoagulants for more than 12 months, the researchers reported. Significant predictors of extended anticoagulation treatment including being older than 65 years old, having chronic heart failure, pulmonary embolism at presentation, and recurrent VTE during anticoagulation, the researchers also reported. Patients who weighed less than 75 kg, had anemia, or had transient risk factors for VTE were less likely to undergo prolonged treatment than were other patients.

“There is still uncertainty among experts on the optimal duration of secondary prevention of VTE,” concluded the investigators. “This decision should be taken by balancing the risk of recurrence after stopping treatment with the risk of bleeding if treatment is continued.”

Adequately validated clinical prediction rules are needed to make those decisions, the researchers said. Until such tools are validated, a substantial proportion of patients with transiet and secondary risk factors for VTE may be exposed to a possibly unnecessary risk of bleeding, they concluded.

Sanofi Spain and Bayer Pharma AG funded the study. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THROMBOSIS RESEARCH

Key clinical point: After venous thromboembolism, patients with transient or removable risk factors for VTE often underwent unneeded, prolonged anticoagulation therapy.

Major finding: Of patients with transient VTE risk factors, 42% underwent anticoagulation therapy for 12 months or longer.

Data source: Prospective cohort study of 6,944 patients with VTE.

Disclosures: Sanofi Spain and Bayer Pharma AG funded the study. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

RBC age doesn’t affect outcomes, trial suggests

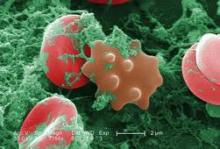

Photo by Elise Amendola

Results of the RECESS trial suggest the duration of red blood cell (RBC) storage does not affect clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Patients who received older RBCs (stored for 21 days or more) did not have significantly higher multi-organ dysfunction scores, mortality rates, or rates of serious adverse events, when compared to patients who received newer RBCs (stored for 10 days or fewer).

Marie E. Stein, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and her colleagues reported these results in NEJM. Dr Stein presented the same data last October at the AABB Annual Meeting 2014. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

Results of the RECESS trial suggest the duration of red blood cell (RBC) storage does not affect clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Patients who received older RBCs (stored for 21 days or more) did not have significantly higher multi-organ dysfunction scores, mortality rates, or rates of serious adverse events, when compared to patients who received newer RBCs (stored for 10 days or fewer).

Marie E. Stein, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and her colleagues reported these results in NEJM. Dr Stein presented the same data last October at the AABB Annual Meeting 2014. ![]()

Photo by Elise Amendola

Results of the RECESS trial suggest the duration of red blood cell (RBC) storage does not affect clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Patients who received older RBCs (stored for 21 days or more) did not have significantly higher multi-organ dysfunction scores, mortality rates, or rates of serious adverse events, when compared to patients who received newer RBCs (stored for 10 days or fewer).

Marie E. Stein, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and her colleagues reported these results in NEJM. Dr Stein presented the same data last October at the AABB Annual Meeting 2014. ![]()

How vitamin D fights lymphoma

to engulf two particles

Vitamin D can stimulate macrophages to kill lymphoma cells, according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that activation of the vitamin D signaling pathway activates the antitumor activity of tumor-associated macrophages and improves the efficacy of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

The team said these results support the use of vitamin D supplements to boost the effectiveness of existing lymphoma therapies.

Heiko Bruns, PhD, of the University Hospital Erlangen in Germany, and his colleagues knew that vitamin D plays a central role in regulating macrophages, and macrophages often fail to kill tumor cells, partly because of cancer’s ability to evade immune detection.

Previous research has shown that lymphoma patients with low vitamin D levels do not respond to chemotherapy or immunotherapy as well as their peers. And this prompted the recommendation that such patients should take vitamin D supplements before and during treatment.

To uncover the mechanism behind vitamin D’s potential benefits, Dr Bruns and his colleagues analyzed how the vitamin affects macrophages’ ability to fight lymphoma cells.

The researchers found that vitamin D stimulated macrophages to secrete a peptide called cathelicidin, which kills lymphoma cells by damaging their mitochondria.

Macrophages from lymphoma patients were unable to properly metabolize vitamin D. Therefore, the macrophages produced fewer cathelicidin peptides and failed to kill the lymphoma cells.

Treating the macrophages with vitamin D boosted the production of cathelicidin and, in turn, lymphoma cell death.

Similarly, the researchers found that, in healthy individuals with vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D supplements triggered macrophages to release more cathelicidin, making them more effective against cultured lymphoma cells.

Furthermore, treating macrophages from lymphoma patients with both vitamin D and rituximab killed lymphoma cells more effectively than treatment with rituximab alone.

The researchers said these results suggest vitamin D can potentially enhance immunotherapy to more effectively treat lymphoma. ![]()

to engulf two particles

Vitamin D can stimulate macrophages to kill lymphoma cells, according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that activation of the vitamin D signaling pathway activates the antitumor activity of tumor-associated macrophages and improves the efficacy of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

The team said these results support the use of vitamin D supplements to boost the effectiveness of existing lymphoma therapies.

Heiko Bruns, PhD, of the University Hospital Erlangen in Germany, and his colleagues knew that vitamin D plays a central role in regulating macrophages, and macrophages often fail to kill tumor cells, partly because of cancer’s ability to evade immune detection.

Previous research has shown that lymphoma patients with low vitamin D levels do not respond to chemotherapy or immunotherapy as well as their peers. And this prompted the recommendation that such patients should take vitamin D supplements before and during treatment.

To uncover the mechanism behind vitamin D’s potential benefits, Dr Bruns and his colleagues analyzed how the vitamin affects macrophages’ ability to fight lymphoma cells.

The researchers found that vitamin D stimulated macrophages to secrete a peptide called cathelicidin, which kills lymphoma cells by damaging their mitochondria.

Macrophages from lymphoma patients were unable to properly metabolize vitamin D. Therefore, the macrophages produced fewer cathelicidin peptides and failed to kill the lymphoma cells.

Treating the macrophages with vitamin D boosted the production of cathelicidin and, in turn, lymphoma cell death.

Similarly, the researchers found that, in healthy individuals with vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D supplements triggered macrophages to release more cathelicidin, making them more effective against cultured lymphoma cells.

Furthermore, treating macrophages from lymphoma patients with both vitamin D and rituximab killed lymphoma cells more effectively than treatment with rituximab alone.

The researchers said these results suggest vitamin D can potentially enhance immunotherapy to more effectively treat lymphoma. ![]()

to engulf two particles

Vitamin D can stimulate macrophages to kill lymphoma cells, according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that activation of the vitamin D signaling pathway activates the antitumor activity of tumor-associated macrophages and improves the efficacy of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

The team said these results support the use of vitamin D supplements to boost the effectiveness of existing lymphoma therapies.

Heiko Bruns, PhD, of the University Hospital Erlangen in Germany, and his colleagues knew that vitamin D plays a central role in regulating macrophages, and macrophages often fail to kill tumor cells, partly because of cancer’s ability to evade immune detection.

Previous research has shown that lymphoma patients with low vitamin D levels do not respond to chemotherapy or immunotherapy as well as their peers. And this prompted the recommendation that such patients should take vitamin D supplements before and during treatment.

To uncover the mechanism behind vitamin D’s potential benefits, Dr Bruns and his colleagues analyzed how the vitamin affects macrophages’ ability to fight lymphoma cells.

The researchers found that vitamin D stimulated macrophages to secrete a peptide called cathelicidin, which kills lymphoma cells by damaging their mitochondria.

Macrophages from lymphoma patients were unable to properly metabolize vitamin D. Therefore, the macrophages produced fewer cathelicidin peptides and failed to kill the lymphoma cells.

Treating the macrophages with vitamin D boosted the production of cathelicidin and, in turn, lymphoma cell death.

Similarly, the researchers found that, in healthy individuals with vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D supplements triggered macrophages to release more cathelicidin, making them more effective against cultured lymphoma cells.

Furthermore, treating macrophages from lymphoma patients with both vitamin D and rituximab killed lymphoma cells more effectively than treatment with rituximab alone.

The researchers said these results suggest vitamin D can potentially enhance immunotherapy to more effectively treat lymphoma. ![]()

Palliative Care and Last-Minute Heroics

4/8/15

HM15 Presenter: Tammie Quest, MD

Summation: Heroics- a set of medical actions that attempt to prolong life with a low likelihood of success.

Palliative care- an approach of care provided to patients and families suffering from serious and/or life limiting illness; focus on physical, spiritual, psychological and social aspects of distress.

Hospice care- intense palliative care provided when the patient has terminal illness with a prognosis of 6 months or less if the disease runs its usual course.

We underutilize Palliative and Hospice care in the US. Here in the US fewer than 50% of all persons receive hospice care at EOL, of those who receive hospice care more than half receive care for less than 20 days, and 1 in 5 patients die in an ICU. Palliative Care can/should co-exist with life prolonging care following the diagnosis of serious illness.

Common therapies/interventions to be contemplated and discussed with patient at end of life: cpr, mechanical ventilation, central venous/arterial access, renal replacement therapy, surgical procedures, valve therapies, ventricular assist devices, continuous infusions, IV fluids, supplemental oxygen, artificial nutrition, antimicrobials, blood products, cancer directed therapy, antithrombotics, anticoagulation.

Practical Elements of Palliative Care: pain and symptom management, advance care planning, communication/goals of care, truth-telling, social support, spiritual support, psychological support, risk/burden assessment of treatments.

Key Points/HM Takeaways:

1-Palliative Care Bedside Talking Points-

- Cardiac arrest is the moment of death, very few people survive an attempt at reversing death

- If you are one of the few who survive to discharge, you may do well but few will survive to discharge

- Antibiotics DO improve survival, antibiotics DO NOT improve comfort

- No evidence to show that dying from pneumonia, or other infection, is painful

- Allowing natural death includes permitting the body to shut itself down through natural mechanisms, including infection

- Dialysis may extend life, but there will be progressive functional decline

2-Goals of Care define what therapies are indicated. Balance prolongation of life with illness experience.

Julianna Lindsey is a hospitalist and physician leader based in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Her focus is patient safety/quality and physician leadership. She is a member of TeamHospitalist.

4/8/15

HM15 Presenter: Tammie Quest, MD

Summation: Heroics- a set of medical actions that attempt to prolong life with a low likelihood of success.

Palliative care- an approach of care provided to patients and families suffering from serious and/or life limiting illness; focus on physical, spiritual, psychological and social aspects of distress.

Hospice care- intense palliative care provided when the patient has terminal illness with a prognosis of 6 months or less if the disease runs its usual course.

We underutilize Palliative and Hospice care in the US. Here in the US fewer than 50% of all persons receive hospice care at EOL, of those who receive hospice care more than half receive care for less than 20 days, and 1 in 5 patients die in an ICU. Palliative Care can/should co-exist with life prolonging care following the diagnosis of serious illness.

Common therapies/interventions to be contemplated and discussed with patient at end of life: cpr, mechanical ventilation, central venous/arterial access, renal replacement therapy, surgical procedures, valve therapies, ventricular assist devices, continuous infusions, IV fluids, supplemental oxygen, artificial nutrition, antimicrobials, blood products, cancer directed therapy, antithrombotics, anticoagulation.

Practical Elements of Palliative Care: pain and symptom management, advance care planning, communication/goals of care, truth-telling, social support, spiritual support, psychological support, risk/burden assessment of treatments.

Key Points/HM Takeaways:

1-Palliative Care Bedside Talking Points-

- Cardiac arrest is the moment of death, very few people survive an attempt at reversing death

- If you are one of the few who survive to discharge, you may do well but few will survive to discharge

- Antibiotics DO improve survival, antibiotics DO NOT improve comfort

- No evidence to show that dying from pneumonia, or other infection, is painful

- Allowing natural death includes permitting the body to shut itself down through natural mechanisms, including infection

- Dialysis may extend life, but there will be progressive functional decline

2-Goals of Care define what therapies are indicated. Balance prolongation of life with illness experience.

Julianna Lindsey is a hospitalist and physician leader based in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Her focus is patient safety/quality and physician leadership. She is a member of TeamHospitalist.

4/8/15

HM15 Presenter: Tammie Quest, MD

Summation: Heroics- a set of medical actions that attempt to prolong life with a low likelihood of success.

Palliative care- an approach of care provided to patients and families suffering from serious and/or life limiting illness; focus on physical, spiritual, psychological and social aspects of distress.

Hospice care- intense palliative care provided when the patient has terminal illness with a prognosis of 6 months or less if the disease runs its usual course.

We underutilize Palliative and Hospice care in the US. Here in the US fewer than 50% of all persons receive hospice care at EOL, of those who receive hospice care more than half receive care for less than 20 days, and 1 in 5 patients die in an ICU. Palliative Care can/should co-exist with life prolonging care following the diagnosis of serious illness.

Common therapies/interventions to be contemplated and discussed with patient at end of life: cpr, mechanical ventilation, central venous/arterial access, renal replacement therapy, surgical procedures, valve therapies, ventricular assist devices, continuous infusions, IV fluids, supplemental oxygen, artificial nutrition, antimicrobials, blood products, cancer directed therapy, antithrombotics, anticoagulation.

Practical Elements of Palliative Care: pain and symptom management, advance care planning, communication/goals of care, truth-telling, social support, spiritual support, psychological support, risk/burden assessment of treatments.

Key Points/HM Takeaways:

1-Palliative Care Bedside Talking Points-

- Cardiac arrest is the moment of death, very few people survive an attempt at reversing death

- If you are one of the few who survive to discharge, you may do well but few will survive to discharge

- Antibiotics DO improve survival, antibiotics DO NOT improve comfort

- No evidence to show that dying from pneumonia, or other infection, is painful

- Allowing natural death includes permitting the body to shut itself down through natural mechanisms, including infection

- Dialysis may extend life, but there will be progressive functional decline

2-Goals of Care define what therapies are indicated. Balance prolongation of life with illness experience.

Julianna Lindsey is a hospitalist and physician leader based in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Her focus is patient safety/quality and physician leadership. She is a member of TeamHospitalist.

Melanoma incidence drops for U.S. children and teens

The incidence of melanoma among American children and teens decreased by approximately 12% from 2004 to 2010, with the decline most notable for adolescents. The findings were published online in the Journal of Pediatrics.

In a review of data from the period of 2000-2010, Dr. Laura Campbell of Stanford (Calif.) University and her colleagues at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland found an overall reduction in melanoma diagnoses of 11.58% per year for the period of 2004-2010 (J. Pediatr. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds. 2015.02.050]).

The study was conducted at Case Western Reserve University, and the researchers used the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER-18) registry to examine trends in the incidence of pediatric melanoma.

Of note, the number of new melanoma cases decreased significantly (approximately 11%) among 15- to19-year-olds between 2003 and 2010. In addition, the overall incidence of melanoma decreased significantly (7%) among boys between 2000 and 2010.

The data revealed significant decreases for the number of new cases of melanoma on the trunk (15% per year from 2004 to 2010) and upper extremities (5% from 2000 to 2010).

Dr. Campbell and her colleagues determined that a melanoma diagnosis was equally likely for male and female patients, and was more common in older than in younger patients. White patients had by far the greatest incidence of melanoma, with 97% of the overall diagnoses; 90% of the cases were in non-Hispanic whites. Superficial spreading melanoma was the most common type of melanoma, at 31%, though nodular histology was seen almost as frequently in the 0- to 9-year-olds. This younger group was more likely to have thicker tumors, ulceration, lymph node involvement, and distant metastases.

Drawing on this large registry allowed researchers more confidence that they were identifying true trends in melanoma incidence, Dr. Campbell noted.

The reasons for this decrease, which stands in contrast to earlier data showing increased incidence rates of pediatric melanoma, were not examined in this study. However, Dr. Campbell drew on these earlier studies, as well as some international studies, to identify the potential contribution of public health campaigns advocating sun protection. These campaigns began in the 1990s in the United States, and would have benefited the 15- to 19-year olds in the SEER-18 data, in whom melanoma incidence decreased beginning in 2003. Some Swedish and Australian studies showing decreased melanoma cases were confounded by an immigration-driven decrease in the highest risk light-skinned population, noted Dr. Campbell; however, the quality of the SEER-18 data allowed researchers to account for this variable, she said.

Although the widespread adoption of sun-protective behaviors (wearing hats and protective clothing, using sunscreen appropriately, and avoiding midday sun exposure) may have accounted for some of the reduction in pediatric melanomas, other societal changes may have been at play.

“We hypothesize that there has been a shift in youth participating increasingly in indoor activities, such as television/electronic devices, which may be decreasing their UVR exposure,” Dr. Campbell said.

The incidence of melanoma among American children and teens decreased by approximately 12% from 2004 to 2010, with the decline most notable for adolescents. The findings were published online in the Journal of Pediatrics.

In a review of data from the period of 2000-2010, Dr. Laura Campbell of Stanford (Calif.) University and her colleagues at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland found an overall reduction in melanoma diagnoses of 11.58% per year for the period of 2004-2010 (J. Pediatr. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds. 2015.02.050]).

The study was conducted at Case Western Reserve University, and the researchers used the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER-18) registry to examine trends in the incidence of pediatric melanoma.

Of note, the number of new melanoma cases decreased significantly (approximately 11%) among 15- to19-year-olds between 2003 and 2010. In addition, the overall incidence of melanoma decreased significantly (7%) among boys between 2000 and 2010.

The data revealed significant decreases for the number of new cases of melanoma on the trunk (15% per year from 2004 to 2010) and upper extremities (5% from 2000 to 2010).

Dr. Campbell and her colleagues determined that a melanoma diagnosis was equally likely for male and female patients, and was more common in older than in younger patients. White patients had by far the greatest incidence of melanoma, with 97% of the overall diagnoses; 90% of the cases were in non-Hispanic whites. Superficial spreading melanoma was the most common type of melanoma, at 31%, though nodular histology was seen almost as frequently in the 0- to 9-year-olds. This younger group was more likely to have thicker tumors, ulceration, lymph node involvement, and distant metastases.

Drawing on this large registry allowed researchers more confidence that they were identifying true trends in melanoma incidence, Dr. Campbell noted.

The reasons for this decrease, which stands in contrast to earlier data showing increased incidence rates of pediatric melanoma, were not examined in this study. However, Dr. Campbell drew on these earlier studies, as well as some international studies, to identify the potential contribution of public health campaigns advocating sun protection. These campaigns began in the 1990s in the United States, and would have benefited the 15- to 19-year olds in the SEER-18 data, in whom melanoma incidence decreased beginning in 2003. Some Swedish and Australian studies showing decreased melanoma cases were confounded by an immigration-driven decrease in the highest risk light-skinned population, noted Dr. Campbell; however, the quality of the SEER-18 data allowed researchers to account for this variable, she said.

Although the widespread adoption of sun-protective behaviors (wearing hats and protective clothing, using sunscreen appropriately, and avoiding midday sun exposure) may have accounted for some of the reduction in pediatric melanomas, other societal changes may have been at play.

“We hypothesize that there has been a shift in youth participating increasingly in indoor activities, such as television/electronic devices, which may be decreasing their UVR exposure,” Dr. Campbell said.

The incidence of melanoma among American children and teens decreased by approximately 12% from 2004 to 2010, with the decline most notable for adolescents. The findings were published online in the Journal of Pediatrics.

In a review of data from the period of 2000-2010, Dr. Laura Campbell of Stanford (Calif.) University and her colleagues at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland found an overall reduction in melanoma diagnoses of 11.58% per year for the period of 2004-2010 (J. Pediatr. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds. 2015.02.050]).

The study was conducted at Case Western Reserve University, and the researchers used the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER-18) registry to examine trends in the incidence of pediatric melanoma.

Of note, the number of new melanoma cases decreased significantly (approximately 11%) among 15- to19-year-olds between 2003 and 2010. In addition, the overall incidence of melanoma decreased significantly (7%) among boys between 2000 and 2010.

The data revealed significant decreases for the number of new cases of melanoma on the trunk (15% per year from 2004 to 2010) and upper extremities (5% from 2000 to 2010).

Dr. Campbell and her colleagues determined that a melanoma diagnosis was equally likely for male and female patients, and was more common in older than in younger patients. White patients had by far the greatest incidence of melanoma, with 97% of the overall diagnoses; 90% of the cases were in non-Hispanic whites. Superficial spreading melanoma was the most common type of melanoma, at 31%, though nodular histology was seen almost as frequently in the 0- to 9-year-olds. This younger group was more likely to have thicker tumors, ulceration, lymph node involvement, and distant metastases.

Drawing on this large registry allowed researchers more confidence that they were identifying true trends in melanoma incidence, Dr. Campbell noted.

The reasons for this decrease, which stands in contrast to earlier data showing increased incidence rates of pediatric melanoma, were not examined in this study. However, Dr. Campbell drew on these earlier studies, as well as some international studies, to identify the potential contribution of public health campaigns advocating sun protection. These campaigns began in the 1990s in the United States, and would have benefited the 15- to 19-year olds in the SEER-18 data, in whom melanoma incidence decreased beginning in 2003. Some Swedish and Australian studies showing decreased melanoma cases were confounded by an immigration-driven decrease in the highest risk light-skinned population, noted Dr. Campbell; however, the quality of the SEER-18 data allowed researchers to account for this variable, she said.

Although the widespread adoption of sun-protective behaviors (wearing hats and protective clothing, using sunscreen appropriately, and avoiding midday sun exposure) may have accounted for some of the reduction in pediatric melanomas, other societal changes may have been at play.

“We hypothesize that there has been a shift in youth participating increasingly in indoor activities, such as television/electronic devices, which may be decreasing their UVR exposure,” Dr. Campbell said.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The overall incidence of melanoma in American children and teens decreased from 2004 to 2010.

Major finding: Researchers identified 1,185 patients younger than 20 years of age with melanoma diagnoses during the period of 2000-2010, and noted a significant decrease of 11.58% per year in melanoma diagnoses from 2004 to 2010.

Data source: The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER-18) registry for 2000-2010.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Individualized Care Plans

High utilizers of hospital services are medically complex, psychosocially vulnerable, and at risk for adverse health outcomes.[1, 2] They make up a fraction of the patient population but use a disproportionate amount of resources, with high rates of emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions.[1, 3, 4] Less than 1% of patients account for 21% of national healthcare spending, and hospital costs are the largest category of national healthcare expenditures.[2, 5] Many patients who disproportionately contribute to high healthcare costs also have high hospital admission rates.[6]

Interventions targeting high utilizers have typically focused on the outpatient setting.[7, 8, 9, 10] Interventions using individualized care plans in the ED reduced ED visits from 33% to 70%, but all have required an additional case management program or partnership with an outside nonprofit case management organization.[11, 12, 13] One study by a hospitalist group using individualized care plans reduced ED visits and admissions by 70%, 2 months after care‐plan implementation; however, all of their care plans were focused explicitly on restricting intravenous opiate use for patients with chronic pain.[14]

Given the current focus on cost‐conscious, high‐quality care in the American healthcare system, we designed a quality‐improvement (QI) intervention using individualized care plans to reduce unnecessary healthcare service utilization and hospital costs for the highest utilizers of ED and inpatient care. Our approach focuses on integrating care plans within our electronic medical record (EMR) and implementing them using the existing healthcare workforce. We analyzed pre‐ and postintervention data to determine its effect on service utilization and hospital costs across a regional health system.

METHODS

QI Intervention

We retrospectively analyzed data collected as part of an ongoing QI project at Duke University Hospital, a 924‐bed academic tertiary care center with approximately 36,000 inpatient discharges per year. The Complex Care Plan Committee (CCPC) aims to improve the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of care for medically, socially, and behaviorally complex adult patients who are the highest utilizers of care in the ED and inpatient medicine service. The CCPC is a volunteer, QI committee comprised of a multidisciplinary team from hospital medicine, emergency medicine, psychiatry, ambulatory care, social work, nursing, risk management, and performance services (system analysts). Individualized care plans are developed on a rolling basis as new patients are identified based on their hospital utilization rates (ED visits and admissions). To be eligible for a care plan, patients have to have at least 3 ED visits or admissions within 6 months and have some degree of medical, social, or behavioral complexity, for example, multiple medical comorbidities with care by several subspecialists, or concomitant psychiatric illness, substance abuse, and homelessness. Strict eligibility criteria are purposefully not imposed to allow flexibility and appropriate tailoring of this intervention to both high‐utilizing and complex patients. Given their complexity, the CCPC felt that without individualized care plans these patients would be at increased risk for rehospitalization and increased morbidity or mortality. The patients included in this analysis are the 24 patients with the most ED visits and hospital admissions at Duke University Hospital, accounting for a total of 183 ED visits and 145 inpatient admissions in the 6 months before the care plans were rolled out.

Each individualized care plan summarizes the patient's medical, psychiatric, and social histories, documents any disruptive behaviors, reviews their hospital utilization patterns, and proposes a set of management strategies focused on providing high‐quality care while limiting unnecessary admissions. They are written by 1 or 2 members of the CCPC who perform a thorough chart review and obtain collateral information from the ED, inpatient, and outpatient providers who have cared for that patient. Care plans are then reviewed and approved by the CCPC as a whole during monthly meetings. Care plans contain detailed information in the following domains: demographics; outpatient care team (primary care provider, specialists, psychiatrist/counselors, social worker, case manager, and home health agency); medical, psychiatric, and behavioral health history; social history; utilization patterns (dates of ED visits and hospitalizations with succinct narratives and outcomes of each admission); and finally ED, inpatient, and outpatient strategies for managing the patient, preventing unnecessary admissions, and connecting them to appropriate services. The CCPC chairperson reviews care plans quarterly to ensure they remain appropriate and relevant.

The care plan is a document uploaded into the EMR (EpicCare; Epic, Verona, WI), where it is available to any provider across the Duke health system. Within Epic, a colored banner visible across the top of the patient's chart notifies the provider of any patient with an individualized care plan. The care plan document is housed in a tab readily visible on the navigation pane. The care plan serves as a roadmap for ED providers and hospitalists, helping them navigate each patient's complex history and guiding them in their disposition decision making. We also developed an automated notification process such that when a high utilizer registers in the ED, a secure page is sent to the admitting hospitalist, who then notifies the ED provider. An automated email is also sent to the CCPC chairperson. These alerts also provide a mechanism for internal oversight and feedback by the CCPC to providers regarding care‐plan adherence.

Outcome Variables and Data Analysis

Our analysis included the 24 patients with individualized care plans developed from August 1, 2012 to August 31, 2013. We analyzed utilization data 6 and 12 months before and 6 and 12 months after the individualized care‐plan intervention was initiated (August 1, 2011 to August 31, 2014). Primary outcomes were the number of ED visits and hospital admissions, as well as ED and inpatient variable direct costs (VDCs). Secondary outcomes included inpatient length of stay (LOS) and 30‐day readmissions. We analyzed outcome data across all 3 hospitals in the Duke University Health System. This includes the only 2 hospitals in Durham, North Carolina (population 245,475) and 1 hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina (population 431,746).

We also describe basic demographic data, payor status, and medical comorbidities for this cohort of patients. Payor status is defined as the most frequently reported payor type prior to care‐plan implementation. Variable direct costs are directly related to patient care and fluctuate with patient volume. They include medications, supplies, laboratory tests, radiology studies, and nursing salaries. They are a proportion of total costs for an ED visit or hospitalization, excluding fixed and indirect costs, such as administrator or physician salaries, utilities, facilities, and equipment.

Primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous outcomes are summarized with mean (standard deviation) and median (range), whereas categorical outcomes are summarized with N (%). LOS is calculated as the average number of days in the hospital per hospital admission per patient. The time periods of 12 months prior, 6 months prior, 6 months after, and 12 months after care‐plan implementation were examined. Only patients with 6 or more months of postcare‐plan data are included in the 6‐month comparison, and only patients with 12 or more months of postcare‐plan data are included in the 12‐month comparison. One patient in the 6‐month comparison group died very soon after care‐plan implementation, so that patient is included in Table 1 (N=24) but excluded from outcome analyses in Tables 2 and 3 (N=23). Differences between 6 months pre and 6 months postcare plan, and 12 months pre and 12 months postcare plan were examined using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for nonparametric matched data. Mean change is calculated as ([Post‐Pre]/Pre) for each patient, and then averaged across all patients. Mean percentage change is calculated as ([Post‐Pre]/Pre)*100 for each patient, and then averaged across patients. It was done this way to emphasize the effect on the patient level. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was granted exempt status by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

| Patients With Care Plans, N=24 | Patients With 12 Months PostCare Plan Follow‐up, N=12 | Patients With 6 Months PostCare Plan Follow‐up, N=23* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 38.5 (11.7) | 41.6 (9.2) | 37.3 (10.5) |

| Median (range) | 36 (2565) | 41 (2858) | 36 (2558) |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 11 (46%) | 5 (42%) | 11 (48%) |

| Female | 13 (54%) | 7 (58%) | 12 (52%) |

| Payor, N (%) | |||

| Medicare | 11 (46%) | 6 (50%) | 10 (43%) |

| Medicaid | 9 (38%) | 4 (33%) | 9 (39%) |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Private insurance | 2 (8%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (9%) |

| None | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Other | 1 (4%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | |||

| Asthma | 9 (38%) | 5 (42%) | 9 (39%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2 (8%) | 2 (17%) | 2 (9%) |

| Chronic pain | 20 (83%) | 12 (100%) | 20 (87%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (21%) | 4 (33%) | 5 (22%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (42%) | 6 (50%) | 9 (39%) |

| End‐stage renal disease | 4 (17%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (17%) |

| Heart failure | 5 (21%) | 2 (17%) | 4 (17%) |

| Hypertension | 13 (54%) | 6 (50%) | 12 (52%) |

| Mental health/substance abuse | 23 (96%) | 12 (100%) | 22 (96%) |

| Sickle cell | 10 (42%) | 5 (42%) | 10 (43%) |

| 6 Months Pre Care Plan | 6 Months Post Care Plan | 12 Months Pre Care Plan | 12 Months Post Care Plan | 6‐Month Change | 6‐Month P Value | 12‐Month Change | 12‐Month P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Admissions | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 145 | 56 | 131 | 58 | 56.0% (41.6%) | 50.5% (43.9%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.3 (3.8) | 2.4 (2.4) | 10.9 (6.3) | 4.8 (4.2) | 3.9 (3.76) | 6.1 (6.02) | ||

| Median (range) | 5 (114) | 2 (08) | 8 (320) | 3 (011) | ||||

| 30‐day readmissions | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 130 | 44 | 106 | 45 | 66.0% (32.4%) | 51.5% (32.0%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (4.1) | 1.9 (2.4) | 8.8 (7.0) | 3.8 (2.7) | 3.7 (3.79) | 5.1 (5.71) | ||

| Median (range) | 4 (013) | 1 (08) | 6 (019) | 3 (011) | ||||

| Inpatient LOS | 0.506 | 0.910 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 766 | 358 | 665 | 317 | 50.8% (51.4%) | 37.8% (78.8%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.0 (3.2) | 4.7 (4.3) | 4.7 (1.5) | 4.4 (3.1) | 0.3 (4.3) | 0.3 (2.27) | ||

| Median (range) | 4.3 (1.515.8) | 4 (016) | 4.8 (2.26.9) | 3.7 (09) | ||||

| ED visits | 0.836 | 0.941 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 183 | 198 | 185 | 307 | +42.9% (148.4%) | +48.4% (145.1%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.0 (11.5) | 8.6 (19.8) | 15.4 (14.7) | 25.6 (54.4) | 0.7 (11.92) | 10.2 (43.19) | ||

| Median (range) | 5 (050) | 3 (096) | 12 (150) | 7 (1196) | ||||

| 6 Months Pre Care Plan | 6 Months Post Care Plan | 12 Months Pre Care Plan | 12 Months Post Care Plan | 6‐Month Change | 6‐Month P Value | 12‐Month Change | 12‐Month P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Inpatient costs ($) | 0.001 | 0.052 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 686,612.43 | 358,520.42 | 538,579.90 | 299,501.03 | 47.7% (52.3%) | 35.8% (76.1%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 29,852.71 (21,808.22) | 15,587.84 (21,141.79) | 44,881.66 (30,132.26) | 24,958.42 (27,248.41) | 14,264.9 (19,301.75) | 19,923.2 (31,891.69) | ||

| Median (range) | 30,203.43 (1,625.1880,171.87) | 7,041.28 (086,457.05) | 39,936.05 (8,237.5382,861.11) | 13,321.56 (082,309.19) | ||||

| ED costs ($) | 0.143 | 0.850 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 80,105.34 | 60,500.38 | 82,473.86 | 98,298.84 | +12.5% (147.5%) | +48.0% (161.8%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3,482.84 (4,423.57) | 2,630.45 (4,782.56) | 6,872.82 (5,633.70) | 8,191.57 (13,974.75) | 852.4 (2,780.01) | 1,318.7 (10,348.89) | ||

| Median (range) | 2,239.19 (019,492.03) | 1,163.45 (022,449.84) | 5,924.31 (277.3019,492.03) | 3,002.70 (553.7250,955.56) | ||||

| Combined costs ($) | 0.002 | 0.129 | ||||||

| N | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 766,717.77 | 419,020.80 | 621,053.76 | 397,799.87 | 45.3% (48.3%) | 25.5% (76.9%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 33,335.56 (22,427.77) | 18,218.30 (21,398.27) | 51,754.48 (32,248.94) | 33,149.99 (31,769.40) | 15,117.3 (19,932.41) | 18,604.5 (35,513.56) | ||

| Median (range) | 32,000.42 (1,625.1880,611.70) | 9,088.88 (087,549.37) | 45,716.08 (10,874.0599,426.72) | 23,971.85 (553.7285,440.12) | ||||

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographics and comorbidities for the 24 patients with care plans included in this analysis. The average age of patients is 38.5 years (range, 2565 years) and a nearly even split between males (11) and females (13). Chronic disease burden is high. Furthermore, 83% of patients have chronic pain and 96% have mental health problems or substance abuse.