User login

Defect promotes CNS invasion of ALL in mice

Credit: Aaron Logan

Researchers say they’ve uncovered a genetic defect in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells that promotes their invasion of the brain.

The team believes the findings, recently published in Genes & Development, could lead to the development of therapies that specifically prevent ALL spread to the central nervous system (CNS).

Currently, curing children with ALL often requires injections of chemotherapy directly into the CNS to limit leukemia growth.

But these therapies can cause long-term health issues.

“If we can find therapies to prevent leukemia spread to the brain, instead of injecting chemotherapy into the brain, that would be huge,” said study author Cynthia Guidos, PhD, of The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada.

“Our findings suggest that drugs targeting the functions controlled by a gene called Flt3 could help block leukemic cell growth in the CNS and may be less toxic than current treatments.”

Using a mouse model, the researchers found that CNS-invading leukemias expressed higher levels of Flt3 than leukemias that did not spread to the CNS.

And the CNS-invading leukemias expressed a defective version of Flt3 that cannot be turned off, suggesting that Flt3 allows the leukemic cells to invade the CNS.

The researchers transferred the defective Flt3 gene into mouse leukemia cells that don’t usually invade the brain. And this endowed them with the ability to spread to the CNS.

The team also showed that a Flt3 inhibitor halted growth of the CNS leukemia cells in vitro.

Dr Guidos said the next step for this research will be to investigate whether Flt3 also plays an important role in promoting CNS invasion of human ALL.

She and her colleagues plan to use frozen cells from the SickKids leukemia cell bank, which contains frozen samples from more than 100 patients, to do just that. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

Researchers say they’ve uncovered a genetic defect in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells that promotes their invasion of the brain.

The team believes the findings, recently published in Genes & Development, could lead to the development of therapies that specifically prevent ALL spread to the central nervous system (CNS).

Currently, curing children with ALL often requires injections of chemotherapy directly into the CNS to limit leukemia growth.

But these therapies can cause long-term health issues.

“If we can find therapies to prevent leukemia spread to the brain, instead of injecting chemotherapy into the brain, that would be huge,” said study author Cynthia Guidos, PhD, of The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada.

“Our findings suggest that drugs targeting the functions controlled by a gene called Flt3 could help block leukemic cell growth in the CNS and may be less toxic than current treatments.”

Using a mouse model, the researchers found that CNS-invading leukemias expressed higher levels of Flt3 than leukemias that did not spread to the CNS.

And the CNS-invading leukemias expressed a defective version of Flt3 that cannot be turned off, suggesting that Flt3 allows the leukemic cells to invade the CNS.

The researchers transferred the defective Flt3 gene into mouse leukemia cells that don’t usually invade the brain. And this endowed them with the ability to spread to the CNS.

The team also showed that a Flt3 inhibitor halted growth of the CNS leukemia cells in vitro.

Dr Guidos said the next step for this research will be to investigate whether Flt3 also plays an important role in promoting CNS invasion of human ALL.

She and her colleagues plan to use frozen cells from the SickKids leukemia cell bank, which contains frozen samples from more than 100 patients, to do just that. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

Researchers say they’ve uncovered a genetic defect in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells that promotes their invasion of the brain.

The team believes the findings, recently published in Genes & Development, could lead to the development of therapies that specifically prevent ALL spread to the central nervous system (CNS).

Currently, curing children with ALL often requires injections of chemotherapy directly into the CNS to limit leukemia growth.

But these therapies can cause long-term health issues.

“If we can find therapies to prevent leukemia spread to the brain, instead of injecting chemotherapy into the brain, that would be huge,” said study author Cynthia Guidos, PhD, of The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada.

“Our findings suggest that drugs targeting the functions controlled by a gene called Flt3 could help block leukemic cell growth in the CNS and may be less toxic than current treatments.”

Using a mouse model, the researchers found that CNS-invading leukemias expressed higher levels of Flt3 than leukemias that did not spread to the CNS.

And the CNS-invading leukemias expressed a defective version of Flt3 that cannot be turned off, suggesting that Flt3 allows the leukemic cells to invade the CNS.

The researchers transferred the defective Flt3 gene into mouse leukemia cells that don’t usually invade the brain. And this endowed them with the ability to spread to the CNS.

The team also showed that a Flt3 inhibitor halted growth of the CNS leukemia cells in vitro.

Dr Guidos said the next step for this research will be to investigate whether Flt3 also plays an important role in promoting CNS invasion of human ALL.

She and her colleagues plan to use frozen cells from the SickKids leukemia cell bank, which contains frozen samples from more than 100 patients, to do just that. ![]()

Switch to nilotinib improves deep molecular response in CML

©ASCO/Phil McCarten

CHICAGO—Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) are more likely to achieve a deep molecular response if they switch to nilotinib rather than remain on imatinib, updated research suggests.

Patients with detectable disease who crossed over from imatinib to nilotinib after 24 months on the ENESTcmr study were able to achieve deep molecular responses (MR 4.5) by 36 months.

But none of the patients who remained on imatinib achieved undetectable BCR-ABL transcripts.

“Longer follow-up supports switching from imatinib to nilotinib to attain deep molecular responses,” said study investigator Nelson Spector, MD, of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil.

“Achievement of deeper molecular responses with nilotinib therapy may increase patient eligibility for treatment-free remission trials.”

Dr Spector presented these results—an update of the ongoing, phase 3 ENESTcmr study—at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7025).

The study included 207 patients with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase who were treated with imatinib for at least 2 years and achieved complete cytogenetic response but had detectable BCR-ABL transcripts.

With 36 months’ follow-up, rates of MR 4.5 remained higher with nilotinib vs imatinib (47% vs 33%). The median time to achievement of MR 4.5 was 24 months with nilotinib and was not reached with imatinib after the 36-month follow-up.

“Patients experienced a rapid reduction in median BCR-ABL levels within the first 3 months after crossover from imatinib to nilotinib,” Dr Spector said. “No patient with detectable BCR-ABL at 24 months who remained on imatinib achieved this response with another year of follow-up.”

MR 4.5 rates were higher by 12 months in patients randomized to nilotinib (33%) than patients who crossed over from imatinib to nilotinib (21%).

“Three years follow-up shows the ability to achieve undetectable BCR-ABL status with nilotinib as we strive to achieve deep molecular responses with the potential to stop therapy,” said ASCO discussant Michael Mauro, MD, of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

However, he questioned whether MR 4.5, “the last, deepest milestone of relevance, is enough to assess stopping.”

By 3 years of follow-up, 93 patients (92.1%) on nilotinib and 72 patients (69.9%) on imatinib had drug-related adverse events.

The most common events with nilotinib were headache, rash, and pruritus. With imatinib, the most common events were muscle spasms, nausea, and diarrhea. More cardiovascular events were reported in patients randomized to nilotinib compared with imatinib.

“Nilotinib-treated patients experienced adverse events early after switching from long-term imatinib therapy,” Dr Spector said. “These adverse events were expected and consistent with the safety profile of nilotinib observed in other studies.” ![]()

©ASCO/Phil McCarten

CHICAGO—Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) are more likely to achieve a deep molecular response if they switch to nilotinib rather than remain on imatinib, updated research suggests.

Patients with detectable disease who crossed over from imatinib to nilotinib after 24 months on the ENESTcmr study were able to achieve deep molecular responses (MR 4.5) by 36 months.

But none of the patients who remained on imatinib achieved undetectable BCR-ABL transcripts.

“Longer follow-up supports switching from imatinib to nilotinib to attain deep molecular responses,” said study investigator Nelson Spector, MD, of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil.

“Achievement of deeper molecular responses with nilotinib therapy may increase patient eligibility for treatment-free remission trials.”

Dr Spector presented these results—an update of the ongoing, phase 3 ENESTcmr study—at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7025).

The study included 207 patients with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase who were treated with imatinib for at least 2 years and achieved complete cytogenetic response but had detectable BCR-ABL transcripts.

With 36 months’ follow-up, rates of MR 4.5 remained higher with nilotinib vs imatinib (47% vs 33%). The median time to achievement of MR 4.5 was 24 months with nilotinib and was not reached with imatinib after the 36-month follow-up.

“Patients experienced a rapid reduction in median BCR-ABL levels within the first 3 months after crossover from imatinib to nilotinib,” Dr Spector said. “No patient with detectable BCR-ABL at 24 months who remained on imatinib achieved this response with another year of follow-up.”

MR 4.5 rates were higher by 12 months in patients randomized to nilotinib (33%) than patients who crossed over from imatinib to nilotinib (21%).

“Three years follow-up shows the ability to achieve undetectable BCR-ABL status with nilotinib as we strive to achieve deep molecular responses with the potential to stop therapy,” said ASCO discussant Michael Mauro, MD, of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

However, he questioned whether MR 4.5, “the last, deepest milestone of relevance, is enough to assess stopping.”

By 3 years of follow-up, 93 patients (92.1%) on nilotinib and 72 patients (69.9%) on imatinib had drug-related adverse events.

The most common events with nilotinib were headache, rash, and pruritus. With imatinib, the most common events were muscle spasms, nausea, and diarrhea. More cardiovascular events were reported in patients randomized to nilotinib compared with imatinib.

“Nilotinib-treated patients experienced adverse events early after switching from long-term imatinib therapy,” Dr Spector said. “These adverse events were expected and consistent with the safety profile of nilotinib observed in other studies.” ![]()

©ASCO/Phil McCarten

CHICAGO—Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) are more likely to achieve a deep molecular response if they switch to nilotinib rather than remain on imatinib, updated research suggests.

Patients with detectable disease who crossed over from imatinib to nilotinib after 24 months on the ENESTcmr study were able to achieve deep molecular responses (MR 4.5) by 36 months.

But none of the patients who remained on imatinib achieved undetectable BCR-ABL transcripts.

“Longer follow-up supports switching from imatinib to nilotinib to attain deep molecular responses,” said study investigator Nelson Spector, MD, of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil.

“Achievement of deeper molecular responses with nilotinib therapy may increase patient eligibility for treatment-free remission trials.”

Dr Spector presented these results—an update of the ongoing, phase 3 ENESTcmr study—at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7025).

The study included 207 patients with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase who were treated with imatinib for at least 2 years and achieved complete cytogenetic response but had detectable BCR-ABL transcripts.

With 36 months’ follow-up, rates of MR 4.5 remained higher with nilotinib vs imatinib (47% vs 33%). The median time to achievement of MR 4.5 was 24 months with nilotinib and was not reached with imatinib after the 36-month follow-up.

“Patients experienced a rapid reduction in median BCR-ABL levels within the first 3 months after crossover from imatinib to nilotinib,” Dr Spector said. “No patient with detectable BCR-ABL at 24 months who remained on imatinib achieved this response with another year of follow-up.”

MR 4.5 rates were higher by 12 months in patients randomized to nilotinib (33%) than patients who crossed over from imatinib to nilotinib (21%).

“Three years follow-up shows the ability to achieve undetectable BCR-ABL status with nilotinib as we strive to achieve deep molecular responses with the potential to stop therapy,” said ASCO discussant Michael Mauro, MD, of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

However, he questioned whether MR 4.5, “the last, deepest milestone of relevance, is enough to assess stopping.”

By 3 years of follow-up, 93 patients (92.1%) on nilotinib and 72 patients (69.9%) on imatinib had drug-related adverse events.

The most common events with nilotinib were headache, rash, and pruritus. With imatinib, the most common events were muscle spasms, nausea, and diarrhea. More cardiovascular events were reported in patients randomized to nilotinib compared with imatinib.

“Nilotinib-treated patients experienced adverse events early after switching from long-term imatinib therapy,” Dr Spector said. “These adverse events were expected and consistent with the safety profile of nilotinib observed in other studies.” ![]()

HCAHPS Patient Satisfaction Scores

Patient satisfaction surveys are widely used to empower patients to voice their concerns and point out areas of deficiency or excellence in the patient‐physician partnership and in the delivery of healthcare services.[1] In 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) led an initiative to develop the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questionnaire.[2] This survey is sent to a randomly selected subset of patients after hospital discharge. The HCAHPS instrument assesses patient ratings of physician communication, nursing communication, pain control, responsiveness, room cleanliness and quietness, discharge process, and overall satisfaction. Over 4500 acute‐care facilities routinely use this survey.[3] HCAHPS scores are publicly reported, and patients can utilize these scores to compare hospitals and make informed choices about where to get care. At an institutional level, scores are used as a tool to identify and improve deficiencies in care delivery. Additionally, HCAHPS survey data results have been analyzed in numerous research studies.[4, 5, 6]

Specialty hospitals are a subset of acute‐care hospitals that provide a narrower set of services than general medical hospitals (GMHs), predominantly in a few specialty areas such as cardiac disease and surgical fields. Many specialty hospitals advertise high rates of patient satisfaction.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] However, specialty hospitals differ from GMHs in significant ways. Patients at specialty hospitals may be less severely ill[10, 12] and may have more generous insurance coverage.[13] Many specialty hospitals do not have an emergency department (ED), and their outcomes may reflect care of relatively stable patients.[14] A significant number of the specialty hospitals are physician‐owned, which may provide an opportunity for physicians to deliver more patient‐focused healthcare.[14] It is also thought that specialty hospitals can provide high‐quality care by designing their facilities and service structure entirely to meet the needs of a narrow set of medical conditions.

HCAHPS survey results provide an opportunity to compare satisfaction scores among various types of hospitals. We analyzed national HCAHPS data to compare satisfaction scores of specialty hospitals and GMHs and identify factors that may be responsible for this difference.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional analysis of national HCAHPS survey data. The methods for administration and reporting of the HCAHPS survey have been described.[15] HCAHPS patient satisfaction data and hospital characteristics, such as location, presence of an ED, and for‐profit status, were obtained from Hospital Compare database. Teaching hospital status was identified using the CMS 2013 Open Payment teaching hospital listing.[16]

For this study, we defined specialty hospitals as acute‐care hospitals that predominantly provide care in a medical or surgical specialty and do not provide care to general medical patients. Based on this definition, specialty hospitals include cardiac hospitals, orthopedic and spine hospitals, oncology hospitals, and hospitals providing multispecialty surgical and procedure‐based services. Children's hospitals, long‐term acute‐care hospitals, and psychiatry hospitals were excluded.

Specialty hospitals were identified using hospital name searches in the HCAHPS database, the American Hospital Association 2013 Annual Survey, the Physician Hospital Association hospitals directory, and through contact with experts. The specialty hospital status of hospitals was further confirmed by checking hospital websites or by directly contacting the hospital.

We analyzed 3‐year HCAHPS patient satisfaction data that included the reporting period from July 2007 to June 2010. HCAHPS data are reported for 12‐month periods at a time. Hospital information, such as address, presence of an ED, and for‐profit status were obtained from the CMS Hospital Compare 2010 dataset. Teaching hospital status was identified using the CMS 2013 Open Payment teaching hospital listing.[16] For the purpose of this study, scores on the HCAHPS survey item definitely recommend the hospital was considered to represent overall satisfaction for the hospital. This is consistent with use of this measure in other sectors in the service industry.[17, 18] Other survey items were considered subdomains of satisfaction. For each hospital, the simple mean of satisfaction scores for overall satisfaction and each of the subdomains for the three 12‐month periods was calculated. Data were summarized using frequencies and meanstandard deviation. The primary dependent variable was overall satisfaction. The main independent variables were specialty hospital status (yes or no), teaching hospital status (yes or no), for‐profit status (yes or no), and the presence of an ED (yes or no). Multiple linear regression analysis was used to adjust for the above‐noted independent variables. A P value0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed on Stata 10.1 IC (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 188 specialty hospitals and 4638 GMHs within the HCAHPS dataset. Fewer specialty hospitals had emergency care services when compared with GMHs (53.2% for specialty hospitals vs 93.6% for GMHs, P0.0001), and 47.9% of all specialty hospitals were in states that do not require a Certificate of Need, whereas only 25% of all GMHs were present in these states. For example, Texas, which has 7.2% of all GMHs across the nation, has 24.7% of all specialty hospitals. As compared to GMHs, a majority of specialty hospitals were for profit (14.5% vs 66.9%).

In unadjusted analyses, specialty hospitals had significantly higher patient satisfaction scores compared with GMHs. Overall satisfaction, as measured by the proportion of patients that will definitely recommend that hospital, was 18.8% higher for specialty hospitals than GMHs (86.6% vs 67.8%, P0.0001). This was also true for subdomains of satisfaction including physician communication, nursing communication, and cleanliness (Table 1).

| Satisfaction Domains | GMH, Mean, n=4,638* | Specialty Hospital, Mean, n=188* | Unadjusted Mean Difference in Satisfaction (95% CI) | Mean Difference in Satisfaction Adjusted for Survey Response Rate (95% CI) | Mean Difference in Satisfaction for Full Adjusted Model (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nurses always communicated well | 75.0% | 84.4% | 9.4% (8.310.5) | 4.0% (2.9‐5.0) | 5.0% (3.8‐6.2) |

| Doctors always communicated well | 80.0% | 86.5% | 6.5% (5.67.6) | 3.8% (2.8‐4.8) | 4.1% (3.05.2) |

| Pain always well controlled | 68.7% | 77.1% | 8.6% (7.79.6) | 4.5% (3.5‐4.5) | 4.6% (3.5‐5.6) |

| Always received help as soon as they wanted | 62.9% | 78.6% | 15.7% (14.117.4) | 7.8% (6.19.4) | 8.0% (6.39.7) |

| Room and bathroom always clean | 70.1% | 81.1% | 11.0% (9.612.4) | 5.5% (4.06.9) | 6.2% (4.7‐7.8) |

| Staff always explained about the medicines | 59.4% | 69.8% | 10.4 (9.211.5) | 5.8% (4.7‐6.9) | 6.5% (5.37.8) |

| Yes, were given information about what to do during recovery at home | 80.9% | 87.1% | 6.2% (5.57.0) | 1.4% (0.7‐2.1) | 2.0% (1.13.0) |

| Overall satisfaction (yes, patients would definitely recommend the hospital) | 67.8% | 86.6% | 18.8%(17.020.6) | 8.5% (6.910.2) | 8.6% (6.710.5) |

| Survey response rate | 32.2% | 49.6% | 17.4% (16.018.9) | ||

We next examined the effect of survey response rate. The survey response rate for specialty hospitals was on average 17.4 percentage points higher than that of GMHs (49.6% vs 32.2%, P0.0001). When adjusted for survey response rate, the difference in overall satisfaction for specialty hospitals was reduced to 8.6% (6.7%10.5%, P0.0001). Similarly, the differences in score for subdomains of satisfaction were more modest when adjusted for higher survey response rate. In the multiple regression models, specialty hospital status, survey response rate, for‐profit status, and the presence of an ED were independently associated with higher overall satisfaction, whereas teaching hospital status was not associated with overall satisfaction. Addition of for‐profit status and presence of an ED in the regression model did not change our results. Further, the satisfaction subdomain scores for specialty hospitals remained significantly higher than for GMHs in the regression models (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that specialty hospitals had significantly higher overall satisfaction scores on the HCAHPS satisfaction survey. Similarly, significantly higher satisfaction was noted across all the satisfaction subdomains. We found that a large proportion of the difference between specialty hospitals and GMHs in overall satisfaction and subdomains of satisfaction could be explained by a higher survey response rate in specialty hospitals. After adjusting for survey response rate, the differences were comparatively modest, although remained statistically significant. Adjustment for additional confounding variables did not change our results.

Studies have shown that specialty hospitals, when compared to GMHs, may treat more patients in their area of specialization, care for fewer sick and Medicaid patients, have greater physician ownership, and are less likely to have ED services.[11, 12, 13, 14] Two small studies comparing specialty hospitals to GMHs suggest that higher satisfaction with specialty hospitals was attributable to the presence of private rooms, quiet environment, accommodation for family members, and accessible, attentive, and well‐trained nursing staff.[10, 11] Although our analysis did not account for various other hospital and patient characteristics, we expect that these factors likely play a significant role in the observed differences in patient satisfaction.

Survey response rate can be an important determinant of the validity of survey results, and a response rate >70% is often considered desirable.[19, 20] However, the mean survey response rate for the HCAHPS survey was only 32.8% for all hospitals during the survey period. In the outpatient setting, a higher survey response rate has been shown to be associated with higher satisfaction rates.[21] In the hospital setting, a randomized study of a HCAHPS survey for 45 hospitals found that patient mix explained the nonresponse bias. However, this study did not examine the roles of severity of illness or insurance status, which may account for the differences in satisfaction seen between specialty hospitals and GMHs.[22] In contrast, we found that in the hospital setting, higher survey response rate was associated with higher patient satisfaction scores.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was not possible to determine from the dataset whether higher response rate is a result of differences in the patient population characteristics between specialty hospitals and GMHs or it represents the association between higher satisfaction and higher response rate noted by other investigators. Although we used various resources to identify all specialty hospitals, we may have missed some or misclassified others due to lack of a standardized definition.[10, 12, 13] However, the total number of specialty hospitals and their distribution across various states in the current study are consistent with previous studies, supporting our belief that few, if any, hospitals were misclassified.[13]

In summary, we found significant difference in satisfaction rates reported on HCAHPS in a national study of patients attending specialty hospitals versus GMHs. However, the observed differences in satisfaction scores were sensitive to differences in survey response rates among hospitals. Teaching hospital status, for‐profit status, and the presence of an ED did not appear to further explain the differences. Additional studies incorporating other hospital and patient characteristics are needed to fully understand factors associated with differences in the observed patient satisfaction between specialty hospitals and GMHs. Additionally, strategies to increase survey HCAHPS response rates should be a priority.

- About Picker Institute. Available at: http://pickerinstitute.org/about. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- HCAHPS Hospital Survey. Centers for Medicare 45(4):1024–1040.

- , . Consumers' use of HCAHPS ratings and word‐of‐mouth in hospital choice. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 pt 1):1602–1613.

- , , . Improving patient satisfaction in hospital care settings. Health Serv Manage Res. 2011;24(4):163–169.

- Live the life you want. Arkansas Surgical Hospital website. Available at: http://www.arksurgicalhospital.com/ash. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Patient satisfaction—top 60 hospitals. Hoag Orthopedic Institute website. Available at: http://orthopedichospital.com/2012/06/patient‐satisfaction‐top‐60‐hospital. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Northwest Specialty Hospital website. Available at: http://www.northwestspecialtyhospital.com/our‐services. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- , , , et al. Specialty versus community hospitals: referrals, quality, and community benefits. Health Affairs. 2006;25(1):106–118.

- Study of Physician‐Owned Specialty Hospitals Required in Section 507(c)(2) of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, May 2005. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud‐and‐Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/Downloads/RTC‐StudyofPhysOwnedSpecHosp.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Specialty Hospitals: Information on National Market Share, Physician Ownership and Patients Served. GAO: 03–683R. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; 2003:1–20. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03683r.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- , , , . Insurance status of patients admitted to specialty cardiac and competing general hospitals: are accusations of cherry picking justified? Med Care. 2008;46:467–475.

- Specialty Hospitals: Geographic Location, Services Provided and Financial Performance: GAO‐04–167. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; 2003:1–41. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04167.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare 9(4):5–17.

- , , . The relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty: cross‐industry differences. Total Qual Manage. 2000;11(4‐6):509–514.

- , . Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum Relat. 2008;61:1139–1160.

- , . Survey, cohort and case‐control studies. In: Design of Studies for Medical Research. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley 2005:118–120.

- , , , , . A demonstration of the impact of response bias on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1403–1417.

- , , , et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix and nonresponse on CAHPS hospital survey scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:501–518.

Patient satisfaction surveys are widely used to empower patients to voice their concerns and point out areas of deficiency or excellence in the patient‐physician partnership and in the delivery of healthcare services.[1] In 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) led an initiative to develop the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questionnaire.[2] This survey is sent to a randomly selected subset of patients after hospital discharge. The HCAHPS instrument assesses patient ratings of physician communication, nursing communication, pain control, responsiveness, room cleanliness and quietness, discharge process, and overall satisfaction. Over 4500 acute‐care facilities routinely use this survey.[3] HCAHPS scores are publicly reported, and patients can utilize these scores to compare hospitals and make informed choices about where to get care. At an institutional level, scores are used as a tool to identify and improve deficiencies in care delivery. Additionally, HCAHPS survey data results have been analyzed in numerous research studies.[4, 5, 6]

Specialty hospitals are a subset of acute‐care hospitals that provide a narrower set of services than general medical hospitals (GMHs), predominantly in a few specialty areas such as cardiac disease and surgical fields. Many specialty hospitals advertise high rates of patient satisfaction.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] However, specialty hospitals differ from GMHs in significant ways. Patients at specialty hospitals may be less severely ill[10, 12] and may have more generous insurance coverage.[13] Many specialty hospitals do not have an emergency department (ED), and their outcomes may reflect care of relatively stable patients.[14] A significant number of the specialty hospitals are physician‐owned, which may provide an opportunity for physicians to deliver more patient‐focused healthcare.[14] It is also thought that specialty hospitals can provide high‐quality care by designing their facilities and service structure entirely to meet the needs of a narrow set of medical conditions.

HCAHPS survey results provide an opportunity to compare satisfaction scores among various types of hospitals. We analyzed national HCAHPS data to compare satisfaction scores of specialty hospitals and GMHs and identify factors that may be responsible for this difference.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional analysis of national HCAHPS survey data. The methods for administration and reporting of the HCAHPS survey have been described.[15] HCAHPS patient satisfaction data and hospital characteristics, such as location, presence of an ED, and for‐profit status, were obtained from Hospital Compare database. Teaching hospital status was identified using the CMS 2013 Open Payment teaching hospital listing.[16]

For this study, we defined specialty hospitals as acute‐care hospitals that predominantly provide care in a medical or surgical specialty and do not provide care to general medical patients. Based on this definition, specialty hospitals include cardiac hospitals, orthopedic and spine hospitals, oncology hospitals, and hospitals providing multispecialty surgical and procedure‐based services. Children's hospitals, long‐term acute‐care hospitals, and psychiatry hospitals were excluded.

Specialty hospitals were identified using hospital name searches in the HCAHPS database, the American Hospital Association 2013 Annual Survey, the Physician Hospital Association hospitals directory, and through contact with experts. The specialty hospital status of hospitals was further confirmed by checking hospital websites or by directly contacting the hospital.

We analyzed 3‐year HCAHPS patient satisfaction data that included the reporting period from July 2007 to June 2010. HCAHPS data are reported for 12‐month periods at a time. Hospital information, such as address, presence of an ED, and for‐profit status were obtained from the CMS Hospital Compare 2010 dataset. Teaching hospital status was identified using the CMS 2013 Open Payment teaching hospital listing.[16] For the purpose of this study, scores on the HCAHPS survey item definitely recommend the hospital was considered to represent overall satisfaction for the hospital. This is consistent with use of this measure in other sectors in the service industry.[17, 18] Other survey items were considered subdomains of satisfaction. For each hospital, the simple mean of satisfaction scores for overall satisfaction and each of the subdomains for the three 12‐month periods was calculated. Data were summarized using frequencies and meanstandard deviation. The primary dependent variable was overall satisfaction. The main independent variables were specialty hospital status (yes or no), teaching hospital status (yes or no), for‐profit status (yes or no), and the presence of an ED (yes or no). Multiple linear regression analysis was used to adjust for the above‐noted independent variables. A P value0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed on Stata 10.1 IC (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 188 specialty hospitals and 4638 GMHs within the HCAHPS dataset. Fewer specialty hospitals had emergency care services when compared with GMHs (53.2% for specialty hospitals vs 93.6% for GMHs, P0.0001), and 47.9% of all specialty hospitals were in states that do not require a Certificate of Need, whereas only 25% of all GMHs were present in these states. For example, Texas, which has 7.2% of all GMHs across the nation, has 24.7% of all specialty hospitals. As compared to GMHs, a majority of specialty hospitals were for profit (14.5% vs 66.9%).

In unadjusted analyses, specialty hospitals had significantly higher patient satisfaction scores compared with GMHs. Overall satisfaction, as measured by the proportion of patients that will definitely recommend that hospital, was 18.8% higher for specialty hospitals than GMHs (86.6% vs 67.8%, P0.0001). This was also true for subdomains of satisfaction including physician communication, nursing communication, and cleanliness (Table 1).

| Satisfaction Domains | GMH, Mean, n=4,638* | Specialty Hospital, Mean, n=188* | Unadjusted Mean Difference in Satisfaction (95% CI) | Mean Difference in Satisfaction Adjusted for Survey Response Rate (95% CI) | Mean Difference in Satisfaction for Full Adjusted Model (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nurses always communicated well | 75.0% | 84.4% | 9.4% (8.310.5) | 4.0% (2.9‐5.0) | 5.0% (3.8‐6.2) |

| Doctors always communicated well | 80.0% | 86.5% | 6.5% (5.67.6) | 3.8% (2.8‐4.8) | 4.1% (3.05.2) |

| Pain always well controlled | 68.7% | 77.1% | 8.6% (7.79.6) | 4.5% (3.5‐4.5) | 4.6% (3.5‐5.6) |

| Always received help as soon as they wanted | 62.9% | 78.6% | 15.7% (14.117.4) | 7.8% (6.19.4) | 8.0% (6.39.7) |

| Room and bathroom always clean | 70.1% | 81.1% | 11.0% (9.612.4) | 5.5% (4.06.9) | 6.2% (4.7‐7.8) |

| Staff always explained about the medicines | 59.4% | 69.8% | 10.4 (9.211.5) | 5.8% (4.7‐6.9) | 6.5% (5.37.8) |

| Yes, were given information about what to do during recovery at home | 80.9% | 87.1% | 6.2% (5.57.0) | 1.4% (0.7‐2.1) | 2.0% (1.13.0) |

| Overall satisfaction (yes, patients would definitely recommend the hospital) | 67.8% | 86.6% | 18.8%(17.020.6) | 8.5% (6.910.2) | 8.6% (6.710.5) |

| Survey response rate | 32.2% | 49.6% | 17.4% (16.018.9) | ||

We next examined the effect of survey response rate. The survey response rate for specialty hospitals was on average 17.4 percentage points higher than that of GMHs (49.6% vs 32.2%, P0.0001). When adjusted for survey response rate, the difference in overall satisfaction for specialty hospitals was reduced to 8.6% (6.7%10.5%, P0.0001). Similarly, the differences in score for subdomains of satisfaction were more modest when adjusted for higher survey response rate. In the multiple regression models, specialty hospital status, survey response rate, for‐profit status, and the presence of an ED were independently associated with higher overall satisfaction, whereas teaching hospital status was not associated with overall satisfaction. Addition of for‐profit status and presence of an ED in the regression model did not change our results. Further, the satisfaction subdomain scores for specialty hospitals remained significantly higher than for GMHs in the regression models (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that specialty hospitals had significantly higher overall satisfaction scores on the HCAHPS satisfaction survey. Similarly, significantly higher satisfaction was noted across all the satisfaction subdomains. We found that a large proportion of the difference between specialty hospitals and GMHs in overall satisfaction and subdomains of satisfaction could be explained by a higher survey response rate in specialty hospitals. After adjusting for survey response rate, the differences were comparatively modest, although remained statistically significant. Adjustment for additional confounding variables did not change our results.

Studies have shown that specialty hospitals, when compared to GMHs, may treat more patients in their area of specialization, care for fewer sick and Medicaid patients, have greater physician ownership, and are less likely to have ED services.[11, 12, 13, 14] Two small studies comparing specialty hospitals to GMHs suggest that higher satisfaction with specialty hospitals was attributable to the presence of private rooms, quiet environment, accommodation for family members, and accessible, attentive, and well‐trained nursing staff.[10, 11] Although our analysis did not account for various other hospital and patient characteristics, we expect that these factors likely play a significant role in the observed differences in patient satisfaction.

Survey response rate can be an important determinant of the validity of survey results, and a response rate >70% is often considered desirable.[19, 20] However, the mean survey response rate for the HCAHPS survey was only 32.8% for all hospitals during the survey period. In the outpatient setting, a higher survey response rate has been shown to be associated with higher satisfaction rates.[21] In the hospital setting, a randomized study of a HCAHPS survey for 45 hospitals found that patient mix explained the nonresponse bias. However, this study did not examine the roles of severity of illness or insurance status, which may account for the differences in satisfaction seen between specialty hospitals and GMHs.[22] In contrast, we found that in the hospital setting, higher survey response rate was associated with higher patient satisfaction scores.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was not possible to determine from the dataset whether higher response rate is a result of differences in the patient population characteristics between specialty hospitals and GMHs or it represents the association between higher satisfaction and higher response rate noted by other investigators. Although we used various resources to identify all specialty hospitals, we may have missed some or misclassified others due to lack of a standardized definition.[10, 12, 13] However, the total number of specialty hospitals and their distribution across various states in the current study are consistent with previous studies, supporting our belief that few, if any, hospitals were misclassified.[13]

In summary, we found significant difference in satisfaction rates reported on HCAHPS in a national study of patients attending specialty hospitals versus GMHs. However, the observed differences in satisfaction scores were sensitive to differences in survey response rates among hospitals. Teaching hospital status, for‐profit status, and the presence of an ED did not appear to further explain the differences. Additional studies incorporating other hospital and patient characteristics are needed to fully understand factors associated with differences in the observed patient satisfaction between specialty hospitals and GMHs. Additionally, strategies to increase survey HCAHPS response rates should be a priority.

Patient satisfaction surveys are widely used to empower patients to voice their concerns and point out areas of deficiency or excellence in the patient‐physician partnership and in the delivery of healthcare services.[1] In 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) led an initiative to develop the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questionnaire.[2] This survey is sent to a randomly selected subset of patients after hospital discharge. The HCAHPS instrument assesses patient ratings of physician communication, nursing communication, pain control, responsiveness, room cleanliness and quietness, discharge process, and overall satisfaction. Over 4500 acute‐care facilities routinely use this survey.[3] HCAHPS scores are publicly reported, and patients can utilize these scores to compare hospitals and make informed choices about where to get care. At an institutional level, scores are used as a tool to identify and improve deficiencies in care delivery. Additionally, HCAHPS survey data results have been analyzed in numerous research studies.[4, 5, 6]

Specialty hospitals are a subset of acute‐care hospitals that provide a narrower set of services than general medical hospitals (GMHs), predominantly in a few specialty areas such as cardiac disease and surgical fields. Many specialty hospitals advertise high rates of patient satisfaction.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] However, specialty hospitals differ from GMHs in significant ways. Patients at specialty hospitals may be less severely ill[10, 12] and may have more generous insurance coverage.[13] Many specialty hospitals do not have an emergency department (ED), and their outcomes may reflect care of relatively stable patients.[14] A significant number of the specialty hospitals are physician‐owned, which may provide an opportunity for physicians to deliver more patient‐focused healthcare.[14] It is also thought that specialty hospitals can provide high‐quality care by designing their facilities and service structure entirely to meet the needs of a narrow set of medical conditions.

HCAHPS survey results provide an opportunity to compare satisfaction scores among various types of hospitals. We analyzed national HCAHPS data to compare satisfaction scores of specialty hospitals and GMHs and identify factors that may be responsible for this difference.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional analysis of national HCAHPS survey data. The methods for administration and reporting of the HCAHPS survey have been described.[15] HCAHPS patient satisfaction data and hospital characteristics, such as location, presence of an ED, and for‐profit status, were obtained from Hospital Compare database. Teaching hospital status was identified using the CMS 2013 Open Payment teaching hospital listing.[16]

For this study, we defined specialty hospitals as acute‐care hospitals that predominantly provide care in a medical or surgical specialty and do not provide care to general medical patients. Based on this definition, specialty hospitals include cardiac hospitals, orthopedic and spine hospitals, oncology hospitals, and hospitals providing multispecialty surgical and procedure‐based services. Children's hospitals, long‐term acute‐care hospitals, and psychiatry hospitals were excluded.

Specialty hospitals were identified using hospital name searches in the HCAHPS database, the American Hospital Association 2013 Annual Survey, the Physician Hospital Association hospitals directory, and through contact with experts. The specialty hospital status of hospitals was further confirmed by checking hospital websites or by directly contacting the hospital.

We analyzed 3‐year HCAHPS patient satisfaction data that included the reporting period from July 2007 to June 2010. HCAHPS data are reported for 12‐month periods at a time. Hospital information, such as address, presence of an ED, and for‐profit status were obtained from the CMS Hospital Compare 2010 dataset. Teaching hospital status was identified using the CMS 2013 Open Payment teaching hospital listing.[16] For the purpose of this study, scores on the HCAHPS survey item definitely recommend the hospital was considered to represent overall satisfaction for the hospital. This is consistent with use of this measure in other sectors in the service industry.[17, 18] Other survey items were considered subdomains of satisfaction. For each hospital, the simple mean of satisfaction scores for overall satisfaction and each of the subdomains for the three 12‐month periods was calculated. Data were summarized using frequencies and meanstandard deviation. The primary dependent variable was overall satisfaction. The main independent variables were specialty hospital status (yes or no), teaching hospital status (yes or no), for‐profit status (yes or no), and the presence of an ED (yes or no). Multiple linear regression analysis was used to adjust for the above‐noted independent variables. A P value0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed on Stata 10.1 IC (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 188 specialty hospitals and 4638 GMHs within the HCAHPS dataset. Fewer specialty hospitals had emergency care services when compared with GMHs (53.2% for specialty hospitals vs 93.6% for GMHs, P0.0001), and 47.9% of all specialty hospitals were in states that do not require a Certificate of Need, whereas only 25% of all GMHs were present in these states. For example, Texas, which has 7.2% of all GMHs across the nation, has 24.7% of all specialty hospitals. As compared to GMHs, a majority of specialty hospitals were for profit (14.5% vs 66.9%).

In unadjusted analyses, specialty hospitals had significantly higher patient satisfaction scores compared with GMHs. Overall satisfaction, as measured by the proportion of patients that will definitely recommend that hospital, was 18.8% higher for specialty hospitals than GMHs (86.6% vs 67.8%, P0.0001). This was also true for subdomains of satisfaction including physician communication, nursing communication, and cleanliness (Table 1).

| Satisfaction Domains | GMH, Mean, n=4,638* | Specialty Hospital, Mean, n=188* | Unadjusted Mean Difference in Satisfaction (95% CI) | Mean Difference in Satisfaction Adjusted for Survey Response Rate (95% CI) | Mean Difference in Satisfaction for Full Adjusted Model (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nurses always communicated well | 75.0% | 84.4% | 9.4% (8.310.5) | 4.0% (2.9‐5.0) | 5.0% (3.8‐6.2) |

| Doctors always communicated well | 80.0% | 86.5% | 6.5% (5.67.6) | 3.8% (2.8‐4.8) | 4.1% (3.05.2) |

| Pain always well controlled | 68.7% | 77.1% | 8.6% (7.79.6) | 4.5% (3.5‐4.5) | 4.6% (3.5‐5.6) |

| Always received help as soon as they wanted | 62.9% | 78.6% | 15.7% (14.117.4) | 7.8% (6.19.4) | 8.0% (6.39.7) |

| Room and bathroom always clean | 70.1% | 81.1% | 11.0% (9.612.4) | 5.5% (4.06.9) | 6.2% (4.7‐7.8) |

| Staff always explained about the medicines | 59.4% | 69.8% | 10.4 (9.211.5) | 5.8% (4.7‐6.9) | 6.5% (5.37.8) |

| Yes, were given information about what to do during recovery at home | 80.9% | 87.1% | 6.2% (5.57.0) | 1.4% (0.7‐2.1) | 2.0% (1.13.0) |

| Overall satisfaction (yes, patients would definitely recommend the hospital) | 67.8% | 86.6% | 18.8%(17.020.6) | 8.5% (6.910.2) | 8.6% (6.710.5) |

| Survey response rate | 32.2% | 49.6% | 17.4% (16.018.9) | ||

We next examined the effect of survey response rate. The survey response rate for specialty hospitals was on average 17.4 percentage points higher than that of GMHs (49.6% vs 32.2%, P0.0001). When adjusted for survey response rate, the difference in overall satisfaction for specialty hospitals was reduced to 8.6% (6.7%10.5%, P0.0001). Similarly, the differences in score for subdomains of satisfaction were more modest when adjusted for higher survey response rate. In the multiple regression models, specialty hospital status, survey response rate, for‐profit status, and the presence of an ED were independently associated with higher overall satisfaction, whereas teaching hospital status was not associated with overall satisfaction. Addition of for‐profit status and presence of an ED in the regression model did not change our results. Further, the satisfaction subdomain scores for specialty hospitals remained significantly higher than for GMHs in the regression models (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this national study, we found that specialty hospitals had significantly higher overall satisfaction scores on the HCAHPS satisfaction survey. Similarly, significantly higher satisfaction was noted across all the satisfaction subdomains. We found that a large proportion of the difference between specialty hospitals and GMHs in overall satisfaction and subdomains of satisfaction could be explained by a higher survey response rate in specialty hospitals. After adjusting for survey response rate, the differences were comparatively modest, although remained statistically significant. Adjustment for additional confounding variables did not change our results.

Studies have shown that specialty hospitals, when compared to GMHs, may treat more patients in their area of specialization, care for fewer sick and Medicaid patients, have greater physician ownership, and are less likely to have ED services.[11, 12, 13, 14] Two small studies comparing specialty hospitals to GMHs suggest that higher satisfaction with specialty hospitals was attributable to the presence of private rooms, quiet environment, accommodation for family members, and accessible, attentive, and well‐trained nursing staff.[10, 11] Although our analysis did not account for various other hospital and patient characteristics, we expect that these factors likely play a significant role in the observed differences in patient satisfaction.

Survey response rate can be an important determinant of the validity of survey results, and a response rate >70% is often considered desirable.[19, 20] However, the mean survey response rate for the HCAHPS survey was only 32.8% for all hospitals during the survey period. In the outpatient setting, a higher survey response rate has been shown to be associated with higher satisfaction rates.[21] In the hospital setting, a randomized study of a HCAHPS survey for 45 hospitals found that patient mix explained the nonresponse bias. However, this study did not examine the roles of severity of illness or insurance status, which may account for the differences in satisfaction seen between specialty hospitals and GMHs.[22] In contrast, we found that in the hospital setting, higher survey response rate was associated with higher patient satisfaction scores.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was not possible to determine from the dataset whether higher response rate is a result of differences in the patient population characteristics between specialty hospitals and GMHs or it represents the association between higher satisfaction and higher response rate noted by other investigators. Although we used various resources to identify all specialty hospitals, we may have missed some or misclassified others due to lack of a standardized definition.[10, 12, 13] However, the total number of specialty hospitals and their distribution across various states in the current study are consistent with previous studies, supporting our belief that few, if any, hospitals were misclassified.[13]

In summary, we found significant difference in satisfaction rates reported on HCAHPS in a national study of patients attending specialty hospitals versus GMHs. However, the observed differences in satisfaction scores were sensitive to differences in survey response rates among hospitals. Teaching hospital status, for‐profit status, and the presence of an ED did not appear to further explain the differences. Additional studies incorporating other hospital and patient characteristics are needed to fully understand factors associated with differences in the observed patient satisfaction between specialty hospitals and GMHs. Additionally, strategies to increase survey HCAHPS response rates should be a priority.

- About Picker Institute. Available at: http://pickerinstitute.org/about. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- HCAHPS Hospital Survey. Centers for Medicare 45(4):1024–1040.

- , . Consumers' use of HCAHPS ratings and word‐of‐mouth in hospital choice. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 pt 1):1602–1613.

- , , . Improving patient satisfaction in hospital care settings. Health Serv Manage Res. 2011;24(4):163–169.

- Live the life you want. Arkansas Surgical Hospital website. Available at: http://www.arksurgicalhospital.com/ash. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Patient satisfaction—top 60 hospitals. Hoag Orthopedic Institute website. Available at: http://orthopedichospital.com/2012/06/patient‐satisfaction‐top‐60‐hospital. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Northwest Specialty Hospital website. Available at: http://www.northwestspecialtyhospital.com/our‐services. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- , , , et al. Specialty versus community hospitals: referrals, quality, and community benefits. Health Affairs. 2006;25(1):106–118.

- Study of Physician‐Owned Specialty Hospitals Required in Section 507(c)(2) of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, May 2005. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud‐and‐Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/Downloads/RTC‐StudyofPhysOwnedSpecHosp.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Specialty Hospitals: Information on National Market Share, Physician Ownership and Patients Served. GAO: 03–683R. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; 2003:1–20. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03683r.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- , , , . Insurance status of patients admitted to specialty cardiac and competing general hospitals: are accusations of cherry picking justified? Med Care. 2008;46:467–475.

- Specialty Hospitals: Geographic Location, Services Provided and Financial Performance: GAO‐04–167. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; 2003:1–41. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04167.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare 9(4):5–17.

- , , . The relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty: cross‐industry differences. Total Qual Manage. 2000;11(4‐6):509–514.

- , . Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum Relat. 2008;61:1139–1160.

- , . Survey, cohort and case‐control studies. In: Design of Studies for Medical Research. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley 2005:118–120.

- , , , , . A demonstration of the impact of response bias on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1403–1417.

- , , , et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix and nonresponse on CAHPS hospital survey scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:501–518.

- About Picker Institute. Available at: http://pickerinstitute.org/about. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- HCAHPS Hospital Survey. Centers for Medicare 45(4):1024–1040.

- , . Consumers' use of HCAHPS ratings and word‐of‐mouth in hospital choice. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 pt 1):1602–1613.

- , , . Improving patient satisfaction in hospital care settings. Health Serv Manage Res. 2011;24(4):163–169.

- Live the life you want. Arkansas Surgical Hospital website. Available at: http://www.arksurgicalhospital.com/ash. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Patient satisfaction—top 60 hospitals. Hoag Orthopedic Institute website. Available at: http://orthopedichospital.com/2012/06/patient‐satisfaction‐top‐60‐hospital. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Northwest Specialty Hospital website. Available at: http://www.northwestspecialtyhospital.com/our‐services. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- , , , et al. Specialty versus community hospitals: referrals, quality, and community benefits. Health Affairs. 2006;25(1):106–118.

- Study of Physician‐Owned Specialty Hospitals Required in Section 507(c)(2) of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, May 2005. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud‐and‐Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/Downloads/RTC‐StudyofPhysOwnedSpecHosp.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Specialty Hospitals: Information on National Market Share, Physician Ownership and Patients Served. GAO: 03–683R. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; 2003:1–20. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03683r.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- , , , . Insurance status of patients admitted to specialty cardiac and competing general hospitals: are accusations of cherry picking justified? Med Care. 2008;46:467–475.

- Specialty Hospitals: Geographic Location, Services Provided and Financial Performance: GAO‐04–167. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; 2003:1–41. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04167.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare 9(4):5–17.

- , , . The relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty: cross‐industry differences. Total Qual Manage. 2000;11(4‐6):509–514.

- , . Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum Relat. 2008;61:1139–1160.

- , . Survey, cohort and case‐control studies. In: Design of Studies for Medical Research. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley 2005:118–120.

- , , , , . A demonstration of the impact of response bias on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1403–1417.

- , , , et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix and nonresponse on CAHPS hospital survey scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:501–518.

Penalties and Insurance Expansions

The goal of reducing hospital readmissions has received a lot of attention in recent years, because hospital readmissions are expensive and potentially preventable.[1] Medicare and some large private health insurers have instituted programs that impose penalties on hospitals with high readmission rates.[2, 3] However, using 30‐day readmissions as a quality metric is controversial because, among other reasons, readmissions can be significantly affected by factors unrelated to hospital care quality. In particular, hospitals that care for poorer and sicker patients tend to have higher readmission rates. Payers typically risk adjust their readmission metrics to try to take into account this variation, but the adequacy of this risk adjustment is disputed. For example, the risk adjustment methodology used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)'s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program does not account for patient socioeconomic status.[4]

One factor that has not previously been studied to our knowledge is the relationship between hospital readmission rates and major changes in population health insurance coverage. Over the next decade, 25 million Americans are expected to gain health insurance under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).[6] Across the country, hospitals vary significantly in the proportion of their patients who are uninsured. Depending on their baseline patient insurance status, some hospitals will face a major influx of newly insured patients.

The net impact of this insurance expansion on readmissions is difficult to predict, because it could in theory have various conflicting effects. Hospitals' readmission rates may increase or decrease depending on the health and socioeconomic status of the new patient populations that they serve. For instance, if hospitals face an influx of poorer and less healthy patients, then their readmission rates may go up. If, on the other hand, coverage gives previously uninsured patients the flexibility to seek care at other institutions, some hospitals may see lower readmission rates as their poorer and sicker patients seek care elsewhere. Expanding health insurance could also affect readmission rates through other channels: providing greater access to outpatient and preventive care might decrease readmissions, whereas reducing the out‐of‐pocket costs of inpatient care could increase readmissions because health care utilization tends to increase as patient cost‐sharing decreases.[7] Thus, there are a number of potential countervailing mechanisms and studying the impact of health insurance expansions on overall hospital readmission rates may lend us insight into patterns of patient and physician behavior. If any changes in readmission rates are not adequately accounted for by current risk‐adjustment algorithms, then readmission penalties may unfairly penalize hospitals as the ACA is implemented.

The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, which studied a population of uninsured patients who were randomly lotteried to Medicaid, provides the best empirical evidence to date about the behavior of patients who recently gain health insurance. In this study, newly insured patients were shown to have increased health care utilization across outpatient visits, prescription drugs, inpatient stays and emergency room (ER) use. The study found ambiguous results, however, regarding the relationship between patient‐level readmissions and gaining insurance coverage.[8] Moreover, there was no analysis of the change in readmissions at the hospital level. Because payers track readmission rates at the hospital level, it is necessary to examine hospital, rather than individual, readmission rates to understand the consequences of applying this metric in the midst of an insurance expansion.

To evaluate the impact of a large‐scale health insurance expansion on hospital‐level readmission rates, we took advantage of a natural experiment in Massachusetts, which in 2006 passed a health reform law that was a model for the ACA and reduced uninsurance rates by half among working‐age adults in its first year.[9] We used a time‐series analysis to study the relationship between the state's insurance expansion and the state's hospital readmission rates prior, during, and after their 2006 reform law. We stratified hospitals based on their percentage of patients who were uninsured prior to the reform law to determine whether the insurance expansion had a differential effect on hospitals depending on the magnitude of the change in their insured population. Given that the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment found increased utilization by patients who newly gain insurance, that previous research has shown that poorer and less healthy patients tend to have higher readmission rates, and that uninsured populations tend to be poorer and less healthy,[10] we hypothesized that an expansion of insurance might be associated with higher hospital readmission rates, particularly among those hospitals with the highest levels of uninsured patients prior to reform.

METHODS

We used a difference‐in‐difference time‐series analysis that incorporated data from 2004 to 2010, 2 years before and 2 years after the 2006 to 2008 Massachusetts insurance expansion. We first obtained administrative databases from the Massachusetts government consisting of patient‐level data from all hospitals in Massachusetts, reported on a quarterly basis for the fiscal year, starting on October 1. The data were collected pursuant to state regulation 114.1 CMR 17.00. Data submissions were edited, summarized, and returned to the submitting hospital by the division to verify accuracy of records. This project was exempted from institutional board review.

The first major piece of the Massachusetts health reform occurred in October 2006, when Commonwealth Care, a new set of state‐subsidized private insurance plans, opened for enrollment. By January 2008, adults in Massachusetts were required to have health insurance or face financial penalties, bringing into effect the last major reform provision. As in earlier work, we defined 3 study periods based on these dates: the prereform period as before October 2006, the reform period as October 2006 through December 2007, and the postreform period as beginning in January 2008.11

We excluded patients 65 years or older and those younger than 18 years to focus on the demographic that benefited most from Massachusetts's insurance expansion. We first calculated each hospital's prereform insurance status according to the percentage of all inpatient stays attributed to uninsured patients at each hospital during the prereform period from January 2004 to October 2006. Based on these results, hospitals were stratified into quartiles, consistent with how the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis, the state's health care analysis agency, groups hospitals to evaluate state‐wide health care trends.[12] Although quartiles were used for the primary unit of analysis, all regressions were also calculated with hospital deciles as sensitivity analysis.

The primary outcome was the hospital 30‐day readmission rate, calculated for each fiscal year quarter. Readmission rates were calculated as both unadjusted and risk adjusted. Risk adjustment was done using age, gender, and race as well as the Elixhauser risk‐adjustment scheme, a methodology that was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for use with administrative data.[13] The Elixhauser scheme has been widely used in the peer‐reviewed literature to risk adjust readmission rates based on administrative data and is accepted as having good predictive validity.[14, 15, 16, 17]

We tracked 30‐day readmissions using each patient's unique health identification number, which counts readmissions to all hospitals in the state, not only the same hospital as the index admission. This is similar to how Medicare counts readmissions under its readmissions reduction program. We used difference‐in‐difference multivariate regressions to compare the change in hospital readmission rates between hospital cohorts from the prereform period to the reform and postreform period, controlling for seasonality. Difference‐in‐difference regressions are based on linear regression models that compare the changes in the outcome variable over time of the population of interest (e.g., a hospital quartile) to that of a baseline population (e.g., comparison hospitals). The coefficients on our regression model provide an estimate of the difference between the changes of these 2 groups, thereby allowing us to estimate changes in an outcome variable among a population of interest beyond any baseline trends.

We also tested the statistical significance of changes in the readmission rate trend at the transition from the prereform to reform periods as well as reform to postreform periods, using spline regression models controlling for seasonality. Spline models construct a series of discrete, piecewise regressions (e.g., separate regressions for the prereform, reform, and postreform period), and we compared the outcomes of these regressions on readmission rates to determine whether the trend of the readmission rates differed between each time period. Spline regression models were calculated in natural log so that coefficients could be interpreted as changes in absolute percentage points (e.g., a coefficient of 0.001 is equivalent to an absolute increase in the readmission rate of 0.1 percentage points). We used a significance threshold of 0.05 using a 2‐sided test. All analyses were performed using Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The prereform patient population characteristics of each hospital quartile are listed in Table 1. Because of the large sample size, most of the demographic characteristics reached statistical significance, but not all were substantively different. Notably, the patient populations were similar by age but differed in their breakdown of race, gender, and average number of diagnostic codes. The higher uninsured hospital quartiles had more nonwhite patients and more males, as might be expected since males and minorities are more likely to be uninsured. The higher uninsured hospital quartile patients also typically tended to have fewer diagnostic codes, consistent with the possibility that they might have less access to medical attention and diagnostic testing.

| Quartile 1 (Lowest Uninsured Hospitals) n=313,917 | Quartile 2, n=385,256 | Quartile 3, n=212,948 | Quartile 4 (Highest Uninsured Hospitals), n=174,786 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, ya | 43.26 (7.20) | 43.23 (4.04) | 44.15 (4.37) | 44.19 (5.27) |

| 1924, % | 9.48 | 8.83 | 8.37 | 8.48 |

| 2534, %a | 19.58 | 19.58 | 17.78 | 16.26 |

| 3544, %a | 19.35 | 20.95 | 20.14 | 22.13 |

| 4554, %a | 21.96 | 23.94 | 24.79 | 25.14 |

| 5564, %b | 27.72 | 25.48 | 27.84 | 27.01 |

| Male, %a | 38.73 (17.29) | 43.33 (15.09) | 41.23 (13.96) | 47.15 (16.11) |

| White, %a | 81.16 (22.28) | 78.65 (22.35) | 74.45 (24.91) | 73.92 (24.92) |

| Death, %c | 1.84 (5.15) | 0.89 (.672) | 1.05 (1.41) | 0.88 (1.23) |

| Diagnosisa | 6.40 (2.80) | 6.30 (2.07) | 5.71 (1.67) | 5.49 (1.90) |

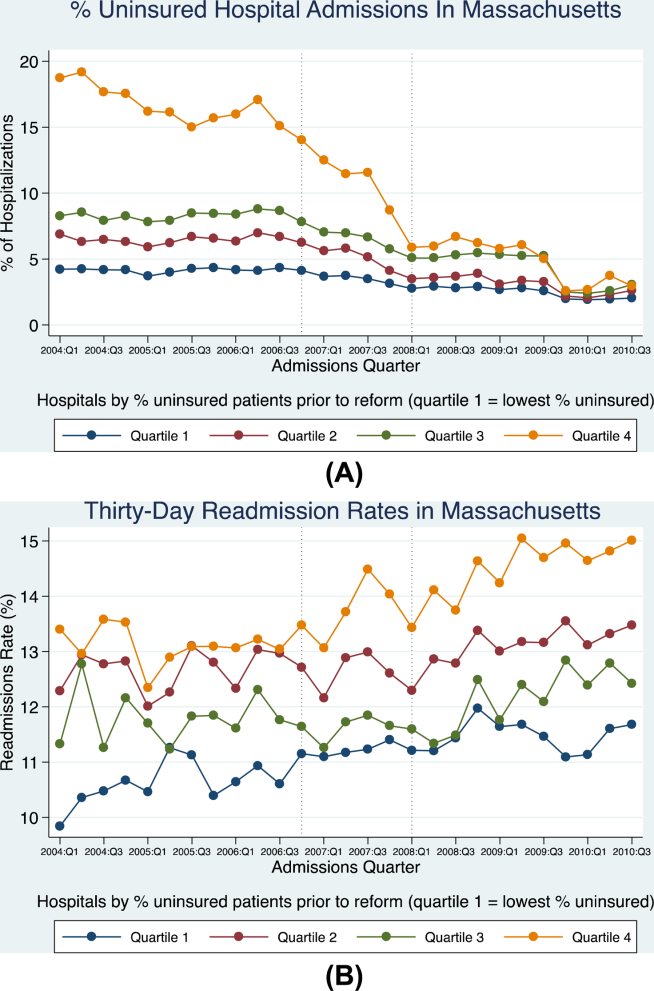

Decreases in uninsurance rates during and after the reform were significantly more pronounced in the hospital quartile with the highest prereform uninsurance rates (Figure 1A). Prior to the reform, uninsured patients were concentrated into this highest uninsured hospital quartile. These hospitals saw their uninsured population drop from approximately 14% of total admissions at the start of the reform period to 5.9% by the end of the reform period, and then decrease further to 2.9% by the end of the study period. The other 3 hospital quartiles collectively experienced smaller changes in patient insurance status: uninsured patients represented about 5.9% of their collective admissions at the beginning of reform, 3.6% at the end of the reform period, and 2.5% at the end of the study period. Because changes in insurance status were most pronounced in the highest uninsured hospital quartile, these hospitals were considered the primary cohort of interest (referred to as the highest uninsured hospital quartile).

Prior to reform, the highest uninsured hospital quartile started with a higher unadjusted readmission rate (13.4%) than the other 3 hospital cohorts (which together had an average of 11.2%) (Figure 1B). Rates remained steady for both groups throughout the prereform period until the beginning of reform in the fourth quarter of 2006, at which point the readmissions trend among the highest uninsured quartile had a statistically significant increase (P<0.001; Table 2), climbing to 15% by the end of the study period. The other 3 quartiles each had no statistically significant change in their unadjusted admissions rate at the beginning of reform compared to their peers, although there was a change from the reform to postreform periods (Table 2).

| Quartile 1 (Lowest Uninsured Hospitals), Percentage Points (SE) | Quartile 2, Percentage Points (SE) | Quartile 3 Percentage Points (SE) | Quartile 4 (Highest Uninsured Hospitals), Percentage Points (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Change in readmission rate in absolute percentage points from prereform to reform period (unadjusted) | +0.74% (0.36) | +0.048% (0.24) | 0.24% (0.44) | +1.3% (0.0032)a |

| Change in readmission rate in absolute percentage points from prereform to reform period (adjusted) | 0.13% (1.3) | 1.4% (0.58)b | 0.40% (0.88) | +0.52% (1.2) |

| Change in readmission rate in absolute percentage points from reform to postreform period (unadjusted) | +0.050% (0.16) | +0.58% (0.12)c | +1.0% (0.21)c | +0.69% (0.20)a |

| Change in readmission rate in absolute percentage points from reform to postreform period (adjusted) | 0.55% (0.58) | 0.62% (0.32) | +0.18% (0.39) | 0.54% (0.65) |

The change in unadjusted readmission rates from before reform to after reform for each hospital quartile was then compared to those of their peers, using difference‐in‐difference regression analysis (Table 3). The first 2 hospital quartiles had no statistically significant change in their readmission rate from before or after reform, as compared to other hospitals, but the third quartile had a statistically significant decrease in readmissions (decrease of 0.6 percentage points [1.13 to 0.01]; P=0.05), whereas the fourth and highest uninsured quartile had a statistically significant increase in their unadjusted readmission rate of 0.6 percentage points (P=0.01; 95% confidence interval: 0.1%1.1%). This represented a relative decrease of 5.2% for the third quartile's readmission rate and a relative increase of 4.5% for the readmission rate of the highest uninsured quartile.

| Quartile 1 (Lowest Uninsured Hospitals), Percentage Points (SE) | Quartile 2, Percentage Points (SE) | Quartile 3, Percentage Points (SE) | Quartile 4 (Highest Uninsured Hospitals), Percentage Points (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Change in readmission rate in absolute percentage points (adjusted) | +1.099% (0.263) a | 0.096% (0.197) | 0.567% (0.198) b | +0.461% (0.260) |

| Change in readmission rate in absolute percentage points (unadjusted) | +0.145% (0.196) | 0.428% (0.267) | 0.572% (0.282)c | +0.604% (0.232)c |

This analysis was then repeated using risk‐adjusted readmission rates. In spline regression analysis, there was a statistically significant decline in readmissions for the second quartile at the start of reform (1.4% in absolute percentage points; standard error [SE]: 0.0058; P=0.0164), but otherwise no statistically significant change for each of the other 3 quartiles. In difference‐in‐difference analysis, the first quartile had an increase in its readmission rate (1.1 absolute percentage points; SE 0.26; P=0.0001), whereas the third quartile had a decrease in its readmission rate (0.57%; SE: 0.20; P=0.006). The highest uninsured quartile had an increase in the readmission rate that approached, but did not reach, statistical significance (0.5%; SE: 0.26; P=0.08).

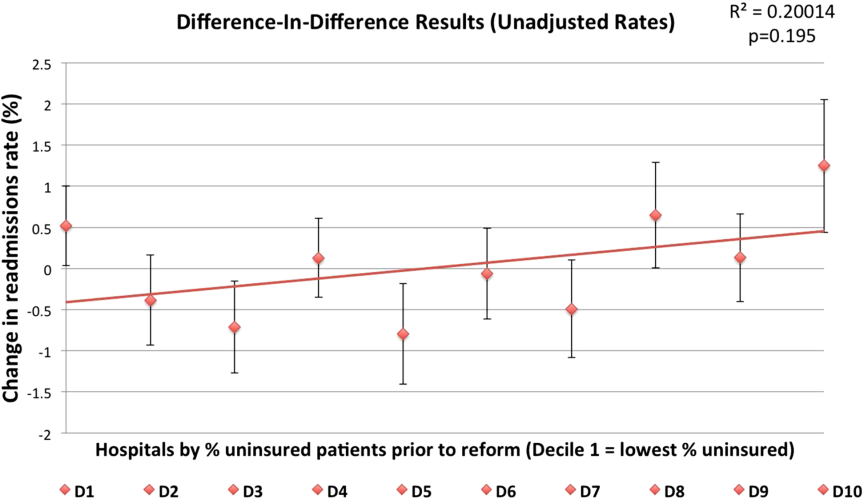

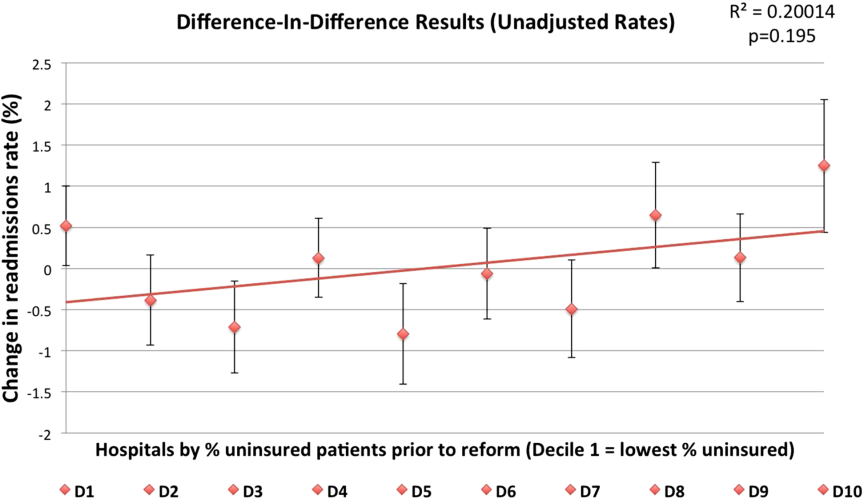

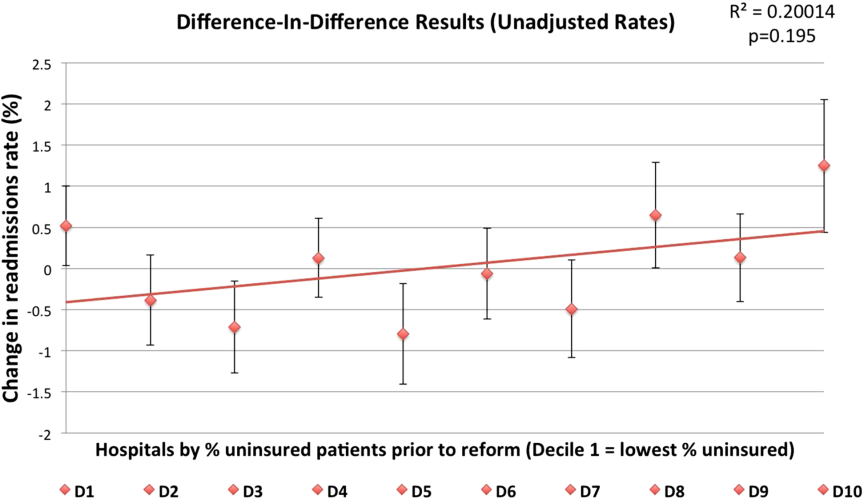

For sensitivity analysis, we also stratified hospitals by deciles and repeated the regressions. The results were less precise, given the relatively small sample size in each analysis group, but were consistent with the quartile results. In difference‐in‐difference analysis, there was a modest, nonsignificant tendency for the higher‐uninsured deciles to have small increases in their unadjusted readmission rates from the reform versus prereform period (best fit line r2=0.20; P=0.195) (Figure 2). There was no discernable pattern in the risk‐adjusted readmission rates. With spline regression models, there was no statistically significant change at the reform or postreform period for either risk‐adjusted or unadjusted readmission rates for any hospital decile.

DISCUSSION

Our results support a general trend that major changes in insurance status among a hospital's patient population may be associated with increases in unadjusted readmission rates. As illustrated in Figure 1, although all hospital quartiles experienced changes in their readmission rates, the highest uninsured quartile experienced a change in insurance status of much greater magnitude from the reform to postreform period. This highest uninsured hospital quartile had a significant increase in its readmission rate compared to its peers from the prereform to the reform and postreform period, whereas the other 3 hospital quartiles had no change in their readmission rate. When the readmission rate was risk adjusted, there was no clear relationship between uninsurance status and changes in readmission rate.

There are a few different mechanisms that could explain why health insurance expansions may be associated with increased hospital readmissions. First, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment found that patients who newly gain insurance were more likely to use health care resources across the boardoutpatient, prescribing drugs, inpatient care, and ER use.[8] Because health insurance reduces the out‐of‐pocket cost of a hospital readmission, just as with other types of health care (ER use, outpatient use), patients may be more willing to return to the hospital after they have been released. Second, increased readmissions among high‐uninsured hospitals could be driven not by the insurance expansion but by cuts to safety‐net hospital funding that were part of the Massachusetts reform law. The law cut block payments to safety‐net hospitals in anticipation of the expanded insurance coverage being sufficient to cover their costs, which has not necessarily proven to be the case. For example, Boston Medical Center, one of Boston's most prominent safety‐net hospitals, found itself in such financial straits after the passage of the health reform law that it sued the state Medicaid program for supplemental reimbursement.18 These funding cuts may have affected the ability of safety‐net hospitals to invest in care coordination resources or care quality, which could affect readmission rates. The ACA makes similar cuts to federal funding for safety‐net hospitals.[19]