User login

Inhibitor shows promise for hematologic disorders

Photo courtesy of EHA

MILAN—The IDH2 inhibitor AG-221 is well-tolerated and exhibits durable clinical activity in patients with hematologic disorders, results of a phase 1 study suggest.

The drug prompted responses in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).

Fourteen of 25 patients achieved a response, and 12 of those responses are ongoing.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2 in nature. However, 4 patients did have serious AEs that were possibly related to treatment.

Stéphane de Botton, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, presented these results at the 19th Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) as abstract LB2434.

Dr de Botton and his colleagues enrolled 35 patients who had a median age of 68 years (range, 48-81).

Twenty-seven patients had relapsed/refractory AML, 4 had relapsed/refractory MDS, 2 had untreated AML, 1 had CMML, and 1 had granulocytic sarcoma. Thirty-one patients had R140Q IDH2 mutations, and 4 had R172K IDH2 mutations.

The patients received AG-221 at 30 mg BID (n=7), 50 mg BID (n=7), 75 mg BID (n=6), 100 mg QD (n=5), 100 mg BID (n=5), or 150 mg QD (n=5). Patients completed a median of 1 cycle of treatment (range, <1-5+) and a mean of 2 cycles.

Safety data

“AG-221 was remarkable well-tolerated, and the [maximum tolerated dose] has not been reached,” Dr de Botton said. “The majority of adverse events were grade 1 and 2.”

Eighteen patients were evaluable for safety. AEs of all grades included nausea (n=4), pyrexia (n=4), thrombocytopenia (n=4), anemia (n=3), dizziness (n=3), febrile neutropenia (n=3), peripheral edema (n=3), sepsis (n=3), cough (n=2), diarrhea (n=2), fatigue (n=2), leukocytosis (n=2), neutropenia (n=2), petechiae (n=2), and rash (n=2).

Grade 3 or higher AEs included thrombocytopenia (n=3), anemia (n=1), febrile neutropenia (n=3), sepsis (n=3), diarrhea (n=1), fatigue (n=1), leukocytosis (n=2), neutropenia (n=1), and rash (n=1). Dr de Botton noted that diarrhea and rash were not expected events.

Four patients had serious AEs possibly related to treatment. One patient had grade 3 confusion and grade 5 respiratory failure. One patient had grade 3 leukocytosis, grade 3 anorexia, and grade 1 nausea. One patient had grade 3 diarrhea. And 1 patient had grade 3 leukocytosis.

Seven patients died within 30 days of study drug termination: 4 in the 30-mg cohort, 2 in the 50-mg cohort, and 1 in the 100-mg-BID cohort.

Five deaths were due to complications of disease-related sepsis (all in cycle 1), 1 complication of a humeral fracture, and 1 complication of a stroke.

Activity and response data

The researchers observed high AG-221 accumulation after multiple doses. And results were “really very similar” between the 30-mg-BID cohort and the 100-mg-QD cohort, Dr de Botton noted.

He also said AG-221 was “very efficient” at inhibiting 2-HG in the plasma. 2-HG was inhibited up to 100% in subjects with R140Q mutations and up to 60% in subjects with R172K mutations.

Twenty-five patients were evaluable for response. The remaining 10 patients did not have day-28 marrow assessments, either due to early termination (n=7) or receiving less than 28 days of treatment although they were still on the study (n=3).

In all, there were 6 complete responses (CRs), 2 CRs with incomplete platelet recovery (CRps), 1 CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi), and 5 partial responses (PRs). Five patients had stable disease (SD), and 6 had progressive disease (PD).

The most responses occurred in the 50-mg group, which had 3 CRs, 1 CRi, and 1 PR. This was followed by the 30-mg group, which had 2 CRs, 1 CRp, and 1 PR.

“The majority of responses occurred in cycle 1,” Dr de Botton noted, “except in the first cohort [30 mg], where responses occurred late, at the end of cycle 3 and cycle 4.”

Twelve of the 14 responses are ongoing. Of the 8 patients who achieved a CR or CRp, 5 have lasted more than 2.5 months (range, 1-4+ months). And the 5 patients with SD remain on study.

This study is sponsored by Celgene Corporation and Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc., the companies developing AG-221. ![]()

Photo courtesy of EHA

MILAN—The IDH2 inhibitor AG-221 is well-tolerated and exhibits durable clinical activity in patients with hematologic disorders, results of a phase 1 study suggest.

The drug prompted responses in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).

Fourteen of 25 patients achieved a response, and 12 of those responses are ongoing.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2 in nature. However, 4 patients did have serious AEs that were possibly related to treatment.

Stéphane de Botton, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, presented these results at the 19th Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) as abstract LB2434.

Dr de Botton and his colleagues enrolled 35 patients who had a median age of 68 years (range, 48-81).

Twenty-seven patients had relapsed/refractory AML, 4 had relapsed/refractory MDS, 2 had untreated AML, 1 had CMML, and 1 had granulocytic sarcoma. Thirty-one patients had R140Q IDH2 mutations, and 4 had R172K IDH2 mutations.

The patients received AG-221 at 30 mg BID (n=7), 50 mg BID (n=7), 75 mg BID (n=6), 100 mg QD (n=5), 100 mg BID (n=5), or 150 mg QD (n=5). Patients completed a median of 1 cycle of treatment (range, <1-5+) and a mean of 2 cycles.

Safety data

“AG-221 was remarkable well-tolerated, and the [maximum tolerated dose] has not been reached,” Dr de Botton said. “The majority of adverse events were grade 1 and 2.”

Eighteen patients were evaluable for safety. AEs of all grades included nausea (n=4), pyrexia (n=4), thrombocytopenia (n=4), anemia (n=3), dizziness (n=3), febrile neutropenia (n=3), peripheral edema (n=3), sepsis (n=3), cough (n=2), diarrhea (n=2), fatigue (n=2), leukocytosis (n=2), neutropenia (n=2), petechiae (n=2), and rash (n=2).

Grade 3 or higher AEs included thrombocytopenia (n=3), anemia (n=1), febrile neutropenia (n=3), sepsis (n=3), diarrhea (n=1), fatigue (n=1), leukocytosis (n=2), neutropenia (n=1), and rash (n=1). Dr de Botton noted that diarrhea and rash were not expected events.

Four patients had serious AEs possibly related to treatment. One patient had grade 3 confusion and grade 5 respiratory failure. One patient had grade 3 leukocytosis, grade 3 anorexia, and grade 1 nausea. One patient had grade 3 diarrhea. And 1 patient had grade 3 leukocytosis.

Seven patients died within 30 days of study drug termination: 4 in the 30-mg cohort, 2 in the 50-mg cohort, and 1 in the 100-mg-BID cohort.

Five deaths were due to complications of disease-related sepsis (all in cycle 1), 1 complication of a humeral fracture, and 1 complication of a stroke.

Activity and response data

The researchers observed high AG-221 accumulation after multiple doses. And results were “really very similar” between the 30-mg-BID cohort and the 100-mg-QD cohort, Dr de Botton noted.

He also said AG-221 was “very efficient” at inhibiting 2-HG in the plasma. 2-HG was inhibited up to 100% in subjects with R140Q mutations and up to 60% in subjects with R172K mutations.

Twenty-five patients were evaluable for response. The remaining 10 patients did not have day-28 marrow assessments, either due to early termination (n=7) or receiving less than 28 days of treatment although they were still on the study (n=3).

In all, there were 6 complete responses (CRs), 2 CRs with incomplete platelet recovery (CRps), 1 CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi), and 5 partial responses (PRs). Five patients had stable disease (SD), and 6 had progressive disease (PD).

The most responses occurred in the 50-mg group, which had 3 CRs, 1 CRi, and 1 PR. This was followed by the 30-mg group, which had 2 CRs, 1 CRp, and 1 PR.

“The majority of responses occurred in cycle 1,” Dr de Botton noted, “except in the first cohort [30 mg], where responses occurred late, at the end of cycle 3 and cycle 4.”

Twelve of the 14 responses are ongoing. Of the 8 patients who achieved a CR or CRp, 5 have lasted more than 2.5 months (range, 1-4+ months). And the 5 patients with SD remain on study.

This study is sponsored by Celgene Corporation and Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc., the companies developing AG-221. ![]()

Photo courtesy of EHA

MILAN—The IDH2 inhibitor AG-221 is well-tolerated and exhibits durable clinical activity in patients with hematologic disorders, results of a phase 1 study suggest.

The drug prompted responses in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).

Fourteen of 25 patients achieved a response, and 12 of those responses are ongoing.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2 in nature. However, 4 patients did have serious AEs that were possibly related to treatment.

Stéphane de Botton, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, presented these results at the 19th Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA) as abstract LB2434.

Dr de Botton and his colleagues enrolled 35 patients who had a median age of 68 years (range, 48-81).

Twenty-seven patients had relapsed/refractory AML, 4 had relapsed/refractory MDS, 2 had untreated AML, 1 had CMML, and 1 had granulocytic sarcoma. Thirty-one patients had R140Q IDH2 mutations, and 4 had R172K IDH2 mutations.

The patients received AG-221 at 30 mg BID (n=7), 50 mg BID (n=7), 75 mg BID (n=6), 100 mg QD (n=5), 100 mg BID (n=5), or 150 mg QD (n=5). Patients completed a median of 1 cycle of treatment (range, <1-5+) and a mean of 2 cycles.

Safety data

“AG-221 was remarkable well-tolerated, and the [maximum tolerated dose] has not been reached,” Dr de Botton said. “The majority of adverse events were grade 1 and 2.”

Eighteen patients were evaluable for safety. AEs of all grades included nausea (n=4), pyrexia (n=4), thrombocytopenia (n=4), anemia (n=3), dizziness (n=3), febrile neutropenia (n=3), peripheral edema (n=3), sepsis (n=3), cough (n=2), diarrhea (n=2), fatigue (n=2), leukocytosis (n=2), neutropenia (n=2), petechiae (n=2), and rash (n=2).

Grade 3 or higher AEs included thrombocytopenia (n=3), anemia (n=1), febrile neutropenia (n=3), sepsis (n=3), diarrhea (n=1), fatigue (n=1), leukocytosis (n=2), neutropenia (n=1), and rash (n=1). Dr de Botton noted that diarrhea and rash were not expected events.

Four patients had serious AEs possibly related to treatment. One patient had grade 3 confusion and grade 5 respiratory failure. One patient had grade 3 leukocytosis, grade 3 anorexia, and grade 1 nausea. One patient had grade 3 diarrhea. And 1 patient had grade 3 leukocytosis.

Seven patients died within 30 days of study drug termination: 4 in the 30-mg cohort, 2 in the 50-mg cohort, and 1 in the 100-mg-BID cohort.

Five deaths were due to complications of disease-related sepsis (all in cycle 1), 1 complication of a humeral fracture, and 1 complication of a stroke.

Activity and response data

The researchers observed high AG-221 accumulation after multiple doses. And results were “really very similar” between the 30-mg-BID cohort and the 100-mg-QD cohort, Dr de Botton noted.

He also said AG-221 was “very efficient” at inhibiting 2-HG in the plasma. 2-HG was inhibited up to 100% in subjects with R140Q mutations and up to 60% in subjects with R172K mutations.

Twenty-five patients were evaluable for response. The remaining 10 patients did not have day-28 marrow assessments, either due to early termination (n=7) or receiving less than 28 days of treatment although they were still on the study (n=3).

In all, there were 6 complete responses (CRs), 2 CRs with incomplete platelet recovery (CRps), 1 CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi), and 5 partial responses (PRs). Five patients had stable disease (SD), and 6 had progressive disease (PD).

The most responses occurred in the 50-mg group, which had 3 CRs, 1 CRi, and 1 PR. This was followed by the 30-mg group, which had 2 CRs, 1 CRp, and 1 PR.

“The majority of responses occurred in cycle 1,” Dr de Botton noted, “except in the first cohort [30 mg], where responses occurred late, at the end of cycle 3 and cycle 4.”

Twelve of the 14 responses are ongoing. Of the 8 patients who achieved a CR or CRp, 5 have lasted more than 2.5 months (range, 1-4+ months). And the 5 patients with SD remain on study.

This study is sponsored by Celgene Corporation and Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc., the companies developing AG-221. ![]()

Engineered protein targets EBV lymphoma

Credit: Ed Uthman

Preclinical research suggests a newly engineered protein can suppress tumor growth and extend survival in a mouse model of lymphoma.

The molecule, called BINDI (BHRF1-inhibiting design acting intracellularly), was designed to trigger the self-destruction of cancer cells infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

EBV can disrupt the body’s clearance of old, abnormal, infected, and damaged cells. And BINDI works by overriding this interference.

Erik Procko, PhD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, and his colleagues described results observed with BINDI in Cell.

The researchers used computational design and experimental optimization to generate BINDI. The protein was designed to recognize and attach itself to an EBV protein called BHRF1 and to ignore similar proteins. BHRF1 keeps cancer cells alive, but, when bound to BINDI, it can no longer fend off cell death.

By examining the crystal structure of BINDI, the researchers saw that it nearly matched their computationally designed architecture for the protein molecule.

Furthermore, experiments showed that BINDI could prompt EBV-infected cancer cell lines to shrivel, disassemble their components, and burst into small pieces.

The researchers also tested BINDI in a mouse model of EBV-positive lymphoma. They delivered BINDI into cancer cells via an antibody-targeted nanocarrier designed to deliver protein cargo to intracellular cancer targets.

And BINDI behaved as ordered. It suppressed tumor growth and enabled the mice to live longer than control mice.

The researchers said this work demonstrates the potential to develop new classes of more effective, intracellular protein drugs, as current protein therapeutics are limited to extracellular targets. ![]()

Credit: Ed Uthman

Preclinical research suggests a newly engineered protein can suppress tumor growth and extend survival in a mouse model of lymphoma.

The molecule, called BINDI (BHRF1-inhibiting design acting intracellularly), was designed to trigger the self-destruction of cancer cells infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

EBV can disrupt the body’s clearance of old, abnormal, infected, and damaged cells. And BINDI works by overriding this interference.

Erik Procko, PhD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, and his colleagues described results observed with BINDI in Cell.

The researchers used computational design and experimental optimization to generate BINDI. The protein was designed to recognize and attach itself to an EBV protein called BHRF1 and to ignore similar proteins. BHRF1 keeps cancer cells alive, but, when bound to BINDI, it can no longer fend off cell death.

By examining the crystal structure of BINDI, the researchers saw that it nearly matched their computationally designed architecture for the protein molecule.

Furthermore, experiments showed that BINDI could prompt EBV-infected cancer cell lines to shrivel, disassemble their components, and burst into small pieces.

The researchers also tested BINDI in a mouse model of EBV-positive lymphoma. They delivered BINDI into cancer cells via an antibody-targeted nanocarrier designed to deliver protein cargo to intracellular cancer targets.

And BINDI behaved as ordered. It suppressed tumor growth and enabled the mice to live longer than control mice.

The researchers said this work demonstrates the potential to develop new classes of more effective, intracellular protein drugs, as current protein therapeutics are limited to extracellular targets. ![]()

Credit: Ed Uthman

Preclinical research suggests a newly engineered protein can suppress tumor growth and extend survival in a mouse model of lymphoma.

The molecule, called BINDI (BHRF1-inhibiting design acting intracellularly), was designed to trigger the self-destruction of cancer cells infected with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

EBV can disrupt the body’s clearance of old, abnormal, infected, and damaged cells. And BINDI works by overriding this interference.

Erik Procko, PhD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, and his colleagues described results observed with BINDI in Cell.

The researchers used computational design and experimental optimization to generate BINDI. The protein was designed to recognize and attach itself to an EBV protein called BHRF1 and to ignore similar proteins. BHRF1 keeps cancer cells alive, but, when bound to BINDI, it can no longer fend off cell death.

By examining the crystal structure of BINDI, the researchers saw that it nearly matched their computationally designed architecture for the protein molecule.

Furthermore, experiments showed that BINDI could prompt EBV-infected cancer cell lines to shrivel, disassemble their components, and burst into small pieces.

The researchers also tested BINDI in a mouse model of EBV-positive lymphoma. They delivered BINDI into cancer cells via an antibody-targeted nanocarrier designed to deliver protein cargo to intracellular cancer targets.

And BINDI behaved as ordered. It suppressed tumor growth and enabled the mice to live longer than control mice.

The researchers said this work demonstrates the potential to develop new classes of more effective, intracellular protein drugs, as current protein therapeutics are limited to extracellular targets. ![]()

Tool may predict cancer patients’ risk of financial stress

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

A new questionnaire can measure a cancer patient’s risk for financial stress, according to a paper published in Cancer.

Researchers developed the 11-item questionnaire, called the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST), through conversations with more than 150 cancer patients.

The team used the term “financial toxicity” to describe the expense, anxiety, and loss of confidence confronting patients who face big, unpredictable costs of cancer treatment.

And the researchers said financial toxicity can be considered another side effect of cancer care.

“Few physicians discuss this increasingly significant side effect with their patients,” said study author Jonas de Souza, MD, of the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois.

“Physicians aren’t trained to do this. It makes them, as well as patients, feel uncomfortable. [However,] we believe that a thoughtful, concise tool that could help predict a patient’s risk for financial toxicity might open the lines of communication. This gives us a way to launch that discussion.”

Development of the COST questionnaire began with a literature review and a series of extensive interviews. Dr de Souza and his colleagues spoke with 20 patients and 6 cancer professionals, as well as nurses and social workers, and this produced a list of 147 questions.

The researchers pared the list down to 58 questions. Then, they asked 35 patients to help them decide which of the remaining questions were the most important. And the patients narrowed the list down to 30.

“In the end, 155 patients led us, with some judicious editing, to a set of 11 statements,” Dr de Souza said. “This was sufficiently brief to prevent annoying those responding to the questions but thorough enough to get us the information we need.”

All 11 entries are short and easy to understand, according to the researchers. For example, item 2 states, “My out-of-pocket medical expenses are more than I thought they would be.” And item 7 states, “I am able to meet my monthly expenses.”

For each question, patients choose from 5 potential responses: “not at all”, “a little bit,” “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “very much.”

Learning how a patient responds may help caregivers determine who is likely to need education, financial counseling, or referral to a support network. The quiz may also predict who is likely to have problems and require interventions.

All patients who helped develop the study had been in treatment for at least 2 months and had received bills. Excluding the top 10% and the bottom 10%, patients in the study earned between $37,000 and $111,000. The median annual income for these patients was about $63,000.

The researchers expected that financial toxicity would correlate with income.

“But, in our small sample, that did not hold up,” Dr de Souza said. “People with less education seemed to have more financial distress, but variations in income did not make much difference. We need bigger studies to confirm that, but at least we now have a tool we can use to study this.”

The researchers are now conducting a larger study to validate these findings and correlate the newly developed scale with quality of life and anxiety in cancer patients.

“We need to assess outcomes that are important for patients,” Dr de Souza said. “[T]his is another important piece of information in the shared-decision-making process.” ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

A new questionnaire can measure a cancer patient’s risk for financial stress, according to a paper published in Cancer.

Researchers developed the 11-item questionnaire, called the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST), through conversations with more than 150 cancer patients.

The team used the term “financial toxicity” to describe the expense, anxiety, and loss of confidence confronting patients who face big, unpredictable costs of cancer treatment.

And the researchers said financial toxicity can be considered another side effect of cancer care.

“Few physicians discuss this increasingly significant side effect with their patients,” said study author Jonas de Souza, MD, of the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois.

“Physicians aren’t trained to do this. It makes them, as well as patients, feel uncomfortable. [However,] we believe that a thoughtful, concise tool that could help predict a patient’s risk for financial toxicity might open the lines of communication. This gives us a way to launch that discussion.”

Development of the COST questionnaire began with a literature review and a series of extensive interviews. Dr de Souza and his colleagues spoke with 20 patients and 6 cancer professionals, as well as nurses and social workers, and this produced a list of 147 questions.

The researchers pared the list down to 58 questions. Then, they asked 35 patients to help them decide which of the remaining questions were the most important. And the patients narrowed the list down to 30.

“In the end, 155 patients led us, with some judicious editing, to a set of 11 statements,” Dr de Souza said. “This was sufficiently brief to prevent annoying those responding to the questions but thorough enough to get us the information we need.”

All 11 entries are short and easy to understand, according to the researchers. For example, item 2 states, “My out-of-pocket medical expenses are more than I thought they would be.” And item 7 states, “I am able to meet my monthly expenses.”

For each question, patients choose from 5 potential responses: “not at all”, “a little bit,” “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “very much.”

Learning how a patient responds may help caregivers determine who is likely to need education, financial counseling, or referral to a support network. The quiz may also predict who is likely to have problems and require interventions.

All patients who helped develop the study had been in treatment for at least 2 months and had received bills. Excluding the top 10% and the bottom 10%, patients in the study earned between $37,000 and $111,000. The median annual income for these patients was about $63,000.

The researchers expected that financial toxicity would correlate with income.

“But, in our small sample, that did not hold up,” Dr de Souza said. “People with less education seemed to have more financial distress, but variations in income did not make much difference. We need bigger studies to confirm that, but at least we now have a tool we can use to study this.”

The researchers are now conducting a larger study to validate these findings and correlate the newly developed scale with quality of life and anxiety in cancer patients.

“We need to assess outcomes that are important for patients,” Dr de Souza said. “[T]his is another important piece of information in the shared-decision-making process.” ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

A new questionnaire can measure a cancer patient’s risk for financial stress, according to a paper published in Cancer.

Researchers developed the 11-item questionnaire, called the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST), through conversations with more than 150 cancer patients.

The team used the term “financial toxicity” to describe the expense, anxiety, and loss of confidence confronting patients who face big, unpredictable costs of cancer treatment.

And the researchers said financial toxicity can be considered another side effect of cancer care.

“Few physicians discuss this increasingly significant side effect with their patients,” said study author Jonas de Souza, MD, of the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois.

“Physicians aren’t trained to do this. It makes them, as well as patients, feel uncomfortable. [However,] we believe that a thoughtful, concise tool that could help predict a patient’s risk for financial toxicity might open the lines of communication. This gives us a way to launch that discussion.”

Development of the COST questionnaire began with a literature review and a series of extensive interviews. Dr de Souza and his colleagues spoke with 20 patients and 6 cancer professionals, as well as nurses and social workers, and this produced a list of 147 questions.

The researchers pared the list down to 58 questions. Then, they asked 35 patients to help them decide which of the remaining questions were the most important. And the patients narrowed the list down to 30.

“In the end, 155 patients led us, with some judicious editing, to a set of 11 statements,” Dr de Souza said. “This was sufficiently brief to prevent annoying those responding to the questions but thorough enough to get us the information we need.”

All 11 entries are short and easy to understand, according to the researchers. For example, item 2 states, “My out-of-pocket medical expenses are more than I thought they would be.” And item 7 states, “I am able to meet my monthly expenses.”

For each question, patients choose from 5 potential responses: “not at all”, “a little bit,” “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “very much.”

Learning how a patient responds may help caregivers determine who is likely to need education, financial counseling, or referral to a support network. The quiz may also predict who is likely to have problems and require interventions.

All patients who helped develop the study had been in treatment for at least 2 months and had received bills. Excluding the top 10% and the bottom 10%, patients in the study earned between $37,000 and $111,000. The median annual income for these patients was about $63,000.

The researchers expected that financial toxicity would correlate with income.

“But, in our small sample, that did not hold up,” Dr de Souza said. “People with less education seemed to have more financial distress, but variations in income did not make much difference. We need bigger studies to confirm that, but at least we now have a tool we can use to study this.”

The researchers are now conducting a larger study to validate these findings and correlate the newly developed scale with quality of life and anxiety in cancer patients.

“We need to assess outcomes that are important for patients,” Dr de Souza said. “[T]his is another important piece of information in the shared-decision-making process.” ![]()

Low-dose T-cell transfer can fight CMV

CMV infection

A new study indicates that transferring low doses of immune cells may be sufficient to protect against cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplant.

The researchers noted that the adoptive transfer of donor-derived, virus-specific, memory T cells is a promising strategy for treating and preventing CMV infection.

But transferring too many of these cells can increase the risk of graft-vs-host disease.

So Christian Stemberger, PhD, of Technische Universitaet Muenchen in Germany, and his colleagues set out to establish a lower limit for successful adoptive T-cell therapy.

The team reported their results—observed in mice and 2 human patients—in Blood.

The researchers first conducted low-dose CD8+ T-cell transfers in the murine Listeria monocytogenes infection model.

And they found these MHC-Streptamer-enriched, antigen-specific, CD62Lhi, CD8+ memory T cells proliferated, differentiated, and protected against Listeria monocytogenes infections.

“The most astonishing result was that the offspring cells of just 1 transferred donor cell were enough to completely protect the animals,” Dr Stemberger said.

Next, the researchers used virus-specific T cells to treat 2 critically ill pediatric patients—1 with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and the other with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

The patients had received allogeneic transplants and subsequently developed CMV infections.

The patients received low-dose transfers of Streptamer-enriched, CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells—3750 cells per kilogram of body weight for the SCID patient and 5130 cells per kilogram of body weight for the leukemia patient.

In both patients, the researchers observed “strong, pathogen-specific T-cell expansion.” The CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells proliferated, and the CMV viral load decreased. Furthermore, neither patient developed graft-vs-host disease.

“It is a great advantage that even just a few cells can provide protection [from CMV],” said study author Michael Neuenhahn, Dr med, also of Technische Universitaet Muenchen.

“This means that the cells can be used for preventive treatment in low doses that are gentler on the organism.”

The researchers are now testing the potential of the CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells in a clinical study. ![]()

CMV infection

A new study indicates that transferring low doses of immune cells may be sufficient to protect against cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplant.

The researchers noted that the adoptive transfer of donor-derived, virus-specific, memory T cells is a promising strategy for treating and preventing CMV infection.

But transferring too many of these cells can increase the risk of graft-vs-host disease.

So Christian Stemberger, PhD, of Technische Universitaet Muenchen in Germany, and his colleagues set out to establish a lower limit for successful adoptive T-cell therapy.

The team reported their results—observed in mice and 2 human patients—in Blood.

The researchers first conducted low-dose CD8+ T-cell transfers in the murine Listeria monocytogenes infection model.

And they found these MHC-Streptamer-enriched, antigen-specific, CD62Lhi, CD8+ memory T cells proliferated, differentiated, and protected against Listeria monocytogenes infections.

“The most astonishing result was that the offspring cells of just 1 transferred donor cell were enough to completely protect the animals,” Dr Stemberger said.

Next, the researchers used virus-specific T cells to treat 2 critically ill pediatric patients—1 with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and the other with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

The patients had received allogeneic transplants and subsequently developed CMV infections.

The patients received low-dose transfers of Streptamer-enriched, CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells—3750 cells per kilogram of body weight for the SCID patient and 5130 cells per kilogram of body weight for the leukemia patient.

In both patients, the researchers observed “strong, pathogen-specific T-cell expansion.” The CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells proliferated, and the CMV viral load decreased. Furthermore, neither patient developed graft-vs-host disease.

“It is a great advantage that even just a few cells can provide protection [from CMV],” said study author Michael Neuenhahn, Dr med, also of Technische Universitaet Muenchen.

“This means that the cells can be used for preventive treatment in low doses that are gentler on the organism.”

The researchers are now testing the potential of the CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells in a clinical study. ![]()

CMV infection

A new study indicates that transferring low doses of immune cells may be sufficient to protect against cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplant.

The researchers noted that the adoptive transfer of donor-derived, virus-specific, memory T cells is a promising strategy for treating and preventing CMV infection.

But transferring too many of these cells can increase the risk of graft-vs-host disease.

So Christian Stemberger, PhD, of Technische Universitaet Muenchen in Germany, and his colleagues set out to establish a lower limit for successful adoptive T-cell therapy.

The team reported their results—observed in mice and 2 human patients—in Blood.

The researchers first conducted low-dose CD8+ T-cell transfers in the murine Listeria monocytogenes infection model.

And they found these MHC-Streptamer-enriched, antigen-specific, CD62Lhi, CD8+ memory T cells proliferated, differentiated, and protected against Listeria monocytogenes infections.

“The most astonishing result was that the offspring cells of just 1 transferred donor cell were enough to completely protect the animals,” Dr Stemberger said.

Next, the researchers used virus-specific T cells to treat 2 critically ill pediatric patients—1 with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and the other with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

The patients had received allogeneic transplants and subsequently developed CMV infections.

The patients received low-dose transfers of Streptamer-enriched, CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells—3750 cells per kilogram of body weight for the SCID patient and 5130 cells per kilogram of body weight for the leukemia patient.

In both patients, the researchers observed “strong, pathogen-specific T-cell expansion.” The CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells proliferated, and the CMV viral load decreased. Furthermore, neither patient developed graft-vs-host disease.

“It is a great advantage that even just a few cells can provide protection [from CMV],” said study author Michael Neuenhahn, Dr med, also of Technische Universitaet Muenchen.

“This means that the cells can be used for preventive treatment in low doses that are gentler on the organism.”

The researchers are now testing the potential of the CMV-specific, CD8+ T cells in a clinical study. ![]()

Vascular reconstruction may have a role in pancreatic adenocarcinoma resection

BOSTON – In skilled hands, various vascular reconstructive methods used during pancreatic resections for adenocarcinoma result in early survival rates that are comparable to those in patients who undergo resection without vascular reconstruction, according to a retrospective review of cases.

This is important because up to 25% of cases in high-volume centers are borderline for resection using pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) because of vascular involvement. Resection is the only curative option for the disease, Dr. Michael D. Sgroi said at a meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Of 270 Whipple procedures and total pancreatectomy procedures performed from January 2003 to February 2013 at a single institution, 147 were for pancreatic adenocarcinoma that involved the surrounding vasculature (T3 lesions); 60 of these involved vascular reconstructions (including 49 venous and 11 arterial reconstructions) and 87 were Whipple procedures without reconstruction, The venous reconstructions included 37 primary repairs, four reconstructions with CryoVein, three repairs using an autologous vein patch, three autologous saphenous reconstructions, and two portacaval shunts. The arterial reconstructions included seven hepatic artery reconstructions, and four were superior mesenteric artery reconstructions.

All were performed by the vascular surgery service, said Dr. Sgroi of the department of surgery, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange.

Overall survival was greater than 18 months in the vascular reconstruction group, with no statistically significant difference seen between the various types of procedures or compared with the Whipple-only group. One perioperative death occurred (1.7%), and survival at 1 year for all reconstructions was 70.3% – a rate similar to the 72.6% survival among patients with T3 lesions who did not undergo vascular reconstruction.

Survival in the two groups remained similar at 3 years, but a survival advantage among those in the Whipple-only group emerged by year 4 and was statistically significant by year 5, Dr. Sgroi said.

No factors were found to be significantly associated with outcome, but there was a trend toward significance for positive lymph nodes and positive margins as predictors of survival. Positive margins were present in 22% of patients in the vascular reconstruction group, compared with only 11% of those in the Whipple-only group, he noted.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most deadly neoplasms, with 1- and 5-year survival rates for all stages being 25% and 5%, respectively," he said, noting that resection is associated with high rates of morbidity.

Currently the only curative option for this disease is a margin-negative resection, but because most cases are not detected until they are in later stages, only about 20% of patients undergo resection, he said.

"As the morbidity and mortality rates have declined postoperatively following Whipple operations, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have also changed to now consider borderline resectable or stage 2 tumors for resection. These are tumors that have portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, or confluence involvement as well as arterial involvement of less than 180 degrees of the common hepatic or right hepatic artery," he explained, adding that "in general, superior mesenteric artery or celiac access involvement is a contraindication to surgery, and these cases now account for about 25% of all Whipples performed in high-volume institutions."

The various approaches to reconstruction that can be performed have been used with acceptable patency rates and outcomes, and multiple single-institution reviews have demonstrated that both venous and arterial resections performed concomitantly with Whipple procedures have equivalent morbidity and mortality rates to Whipple performed without reconstruction.

"A flaw of these studies has always been that their sample size is small, diminishing the power of the study," Dr. Sgroi noted.

Further complicating the issue are two recent manuscripts demonstrating significantly increased morbidity and mortality with vascular reconstruction, while a review of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database showed that when vascular surgeons are involved, outcomes are comparable with and without reconstruction – with the exception of increased blood loss and time in the operating room with vascular reconstruction.

The findings of the current study support the latter finding.

Notably, with the advances in chemotherapy agents it is now protocol that all patients at the University of California, Irvine receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and survival was improved in those who received both vascular reconstruction and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those who received vascular reconstruction without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

"We believe that experience matters with this operation and that there is a learning curve," he said.

An example involves the need for packed red blood cells. The average number of units of packed red blood cells given with each case declined over time, and now less than one unit is used per case, he noted.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a dismal disease with poor long-term survival. Performing a Whipple on T3 lesions with vascular invasion will allow for an increased amount of surgical resections, and it is possible to achieve equivalent survival outcomes, compared with patients who receive a Whipple only," he said, adding that further study is needed to determine if any of the multiple vascular reconstruction options is superior to the others.

"It is our recommendation that a multidisciplinary team with surgeons experienced with vascular reconstruction perform these operations, and that, if possible, these patients be referred to a high-volume institution for the best outcome," he concluded.

Dr. Sgroi reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – In skilled hands, various vascular reconstructive methods used during pancreatic resections for adenocarcinoma result in early survival rates that are comparable to those in patients who undergo resection without vascular reconstruction, according to a retrospective review of cases.

This is important because up to 25% of cases in high-volume centers are borderline for resection using pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) because of vascular involvement. Resection is the only curative option for the disease, Dr. Michael D. Sgroi said at a meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Of 270 Whipple procedures and total pancreatectomy procedures performed from January 2003 to February 2013 at a single institution, 147 were for pancreatic adenocarcinoma that involved the surrounding vasculature (T3 lesions); 60 of these involved vascular reconstructions (including 49 venous and 11 arterial reconstructions) and 87 were Whipple procedures without reconstruction, The venous reconstructions included 37 primary repairs, four reconstructions with CryoVein, three repairs using an autologous vein patch, three autologous saphenous reconstructions, and two portacaval shunts. The arterial reconstructions included seven hepatic artery reconstructions, and four were superior mesenteric artery reconstructions.

All were performed by the vascular surgery service, said Dr. Sgroi of the department of surgery, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange.

Overall survival was greater than 18 months in the vascular reconstruction group, with no statistically significant difference seen between the various types of procedures or compared with the Whipple-only group. One perioperative death occurred (1.7%), and survival at 1 year for all reconstructions was 70.3% – a rate similar to the 72.6% survival among patients with T3 lesions who did not undergo vascular reconstruction.

Survival in the two groups remained similar at 3 years, but a survival advantage among those in the Whipple-only group emerged by year 4 and was statistically significant by year 5, Dr. Sgroi said.

No factors were found to be significantly associated with outcome, but there was a trend toward significance for positive lymph nodes and positive margins as predictors of survival. Positive margins were present in 22% of patients in the vascular reconstruction group, compared with only 11% of those in the Whipple-only group, he noted.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most deadly neoplasms, with 1- and 5-year survival rates for all stages being 25% and 5%, respectively," he said, noting that resection is associated with high rates of morbidity.

Currently the only curative option for this disease is a margin-negative resection, but because most cases are not detected until they are in later stages, only about 20% of patients undergo resection, he said.

"As the morbidity and mortality rates have declined postoperatively following Whipple operations, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have also changed to now consider borderline resectable or stage 2 tumors for resection. These are tumors that have portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, or confluence involvement as well as arterial involvement of less than 180 degrees of the common hepatic or right hepatic artery," he explained, adding that "in general, superior mesenteric artery or celiac access involvement is a contraindication to surgery, and these cases now account for about 25% of all Whipples performed in high-volume institutions."

The various approaches to reconstruction that can be performed have been used with acceptable patency rates and outcomes, and multiple single-institution reviews have demonstrated that both venous and arterial resections performed concomitantly with Whipple procedures have equivalent morbidity and mortality rates to Whipple performed without reconstruction.

"A flaw of these studies has always been that their sample size is small, diminishing the power of the study," Dr. Sgroi noted.

Further complicating the issue are two recent manuscripts demonstrating significantly increased morbidity and mortality with vascular reconstruction, while a review of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database showed that when vascular surgeons are involved, outcomes are comparable with and without reconstruction – with the exception of increased blood loss and time in the operating room with vascular reconstruction.

The findings of the current study support the latter finding.

Notably, with the advances in chemotherapy agents it is now protocol that all patients at the University of California, Irvine receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and survival was improved in those who received both vascular reconstruction and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those who received vascular reconstruction without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

"We believe that experience matters with this operation and that there is a learning curve," he said.

An example involves the need for packed red blood cells. The average number of units of packed red blood cells given with each case declined over time, and now less than one unit is used per case, he noted.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a dismal disease with poor long-term survival. Performing a Whipple on T3 lesions with vascular invasion will allow for an increased amount of surgical resections, and it is possible to achieve equivalent survival outcomes, compared with patients who receive a Whipple only," he said, adding that further study is needed to determine if any of the multiple vascular reconstruction options is superior to the others.

"It is our recommendation that a multidisciplinary team with surgeons experienced with vascular reconstruction perform these operations, and that, if possible, these patients be referred to a high-volume institution for the best outcome," he concluded.

Dr. Sgroi reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – In skilled hands, various vascular reconstructive methods used during pancreatic resections for adenocarcinoma result in early survival rates that are comparable to those in patients who undergo resection without vascular reconstruction, according to a retrospective review of cases.

This is important because up to 25% of cases in high-volume centers are borderline for resection using pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) because of vascular involvement. Resection is the only curative option for the disease, Dr. Michael D. Sgroi said at a meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Of 270 Whipple procedures and total pancreatectomy procedures performed from January 2003 to February 2013 at a single institution, 147 were for pancreatic adenocarcinoma that involved the surrounding vasculature (T3 lesions); 60 of these involved vascular reconstructions (including 49 venous and 11 arterial reconstructions) and 87 were Whipple procedures without reconstruction, The venous reconstructions included 37 primary repairs, four reconstructions with CryoVein, three repairs using an autologous vein patch, three autologous saphenous reconstructions, and two portacaval shunts. The arterial reconstructions included seven hepatic artery reconstructions, and four were superior mesenteric artery reconstructions.

All were performed by the vascular surgery service, said Dr. Sgroi of the department of surgery, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange.

Overall survival was greater than 18 months in the vascular reconstruction group, with no statistically significant difference seen between the various types of procedures or compared with the Whipple-only group. One perioperative death occurred (1.7%), and survival at 1 year for all reconstructions was 70.3% – a rate similar to the 72.6% survival among patients with T3 lesions who did not undergo vascular reconstruction.

Survival in the two groups remained similar at 3 years, but a survival advantage among those in the Whipple-only group emerged by year 4 and was statistically significant by year 5, Dr. Sgroi said.

No factors were found to be significantly associated with outcome, but there was a trend toward significance for positive lymph nodes and positive margins as predictors of survival. Positive margins were present in 22% of patients in the vascular reconstruction group, compared with only 11% of those in the Whipple-only group, he noted.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most deadly neoplasms, with 1- and 5-year survival rates for all stages being 25% and 5%, respectively," he said, noting that resection is associated with high rates of morbidity.

Currently the only curative option for this disease is a margin-negative resection, but because most cases are not detected until they are in later stages, only about 20% of patients undergo resection, he said.

"As the morbidity and mortality rates have declined postoperatively following Whipple operations, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have also changed to now consider borderline resectable or stage 2 tumors for resection. These are tumors that have portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, or confluence involvement as well as arterial involvement of less than 180 degrees of the common hepatic or right hepatic artery," he explained, adding that "in general, superior mesenteric artery or celiac access involvement is a contraindication to surgery, and these cases now account for about 25% of all Whipples performed in high-volume institutions."

The various approaches to reconstruction that can be performed have been used with acceptable patency rates and outcomes, and multiple single-institution reviews have demonstrated that both venous and arterial resections performed concomitantly with Whipple procedures have equivalent morbidity and mortality rates to Whipple performed without reconstruction.

"A flaw of these studies has always been that their sample size is small, diminishing the power of the study," Dr. Sgroi noted.

Further complicating the issue are two recent manuscripts demonstrating significantly increased morbidity and mortality with vascular reconstruction, while a review of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database showed that when vascular surgeons are involved, outcomes are comparable with and without reconstruction – with the exception of increased blood loss and time in the operating room with vascular reconstruction.

The findings of the current study support the latter finding.

Notably, with the advances in chemotherapy agents it is now protocol that all patients at the University of California, Irvine receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and survival was improved in those who received both vascular reconstruction and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those who received vascular reconstruction without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

"We believe that experience matters with this operation and that there is a learning curve," he said.

An example involves the need for packed red blood cells. The average number of units of packed red blood cells given with each case declined over time, and now less than one unit is used per case, he noted.

"Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a dismal disease with poor long-term survival. Performing a Whipple on T3 lesions with vascular invasion will allow for an increased amount of surgical resections, and it is possible to achieve equivalent survival outcomes, compared with patients who receive a Whipple only," he said, adding that further study is needed to determine if any of the multiple vascular reconstruction options is superior to the others.

"It is our recommendation that a multidisciplinary team with surgeons experienced with vascular reconstruction perform these operations, and that, if possible, these patients be referred to a high-volume institution for the best outcome," he concluded.

Dr. Sgroi reported having no disclosures.

AT THE 2014 VASCULAR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Performing a Whipple on borderline T3 lesions with vascular invasion may allow for an increased amount of surgical resections.

Major finding: One-year survival was 70.3% with Whipple plus reconstruction and 72.6% with a Whipple-only procedure, but a survival advantage among those in the Whipple-only group emerged by year 4 and was statistically significant by year 5.

Data source: A retrospective review of 147 cases.

Disclosures: Dr. Sgroi reported having no disclosures.

Renal denervation proceeds as U.S. trial’s flaws emerge

PARIS – At least three different factors undermined the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial that earlier this year did not show a significant difference in blood pressure lowering between renal denervation and a sham-control procedure, most notably the failure of the vast majority of operators in the study to follow ablation instructions and produce thorough and reliable interruptions of sympathetic innervation of the kidneys, according to new data released by the trial’s investigators.

As the full range of problems with the U.S.-based SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial, which had its main results reported in April (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1393-1401), became apparent in a report at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions, many top European practitioners and supporters of renal denervation voiced their belief that the treatment is an effective and safe option for many patients with true drug-resistant, severe hypertension.

The only qualifications they now add are that renal denervation is not easily performed and must be done carefully and in a more targeted way, with an ongoing need to find the patients best suited for treatment and the best methods for delivering treatment.

During the meeting, Dr. Felix Mahfoud, an interventional cardiologist at the University Hospital of Saarland in Homburg/Saar, Germany, joined with hypertension specialist Dr. Konstantinos Tsioufis of the University of Athens and Dr. William Wijns, codirector of EuroPCR, in an official statement from the meeting that despite the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results they continued to support renal denervation as a treatment option for selected patients with drug-resistant, severe hypertension.

Their sentiment echoed another endorsement made a few weeks earlier for continued use and study of renal denervation from the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) in reaction to the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results.

The ESH "sticks to its statement" from 2013 on using renal denervation in appropriate patients with treatment-resistant, severe hypertension (Eurointervention 2013;9:R58-R66), said Dr. Roland E. Schmieder, first author for the 2013 ESH position paper and a leader in European use of renal denervation.

"We need more studies to prove that renal denervation works, and in particular to get more precise information on which patients get the greatest benefit," Dr. Schmieder said in a separate talk at the meeting. For the time being, he said he was comfortable with routine use of renal denervation in patients with an office systolic BP of at least 160 mm Hg that remains at this level despite maximally tolerated treatment with at least three antihypertensive drugs, including a diuretic, the use endorsed by current European guidelines. It remains appropriate to investigate the impact of renal denervation on other disorders, such as heart failure, arrhythmia, metabolic syndrome, and depressed renal function, said Dr. Schmieder, professor and head of hypertension and vascular medicine research at University Hospital in Erlangen, Germany.

The problems with SYMPLICITY HTN-3

While much speculation swirled around what had gone wrong in the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial after researchers on the study gave their first report on the results early in the spring, the full extent of the study’s problems didn’t flesh out until a follow-up report during EuroPCR by coinvestigator Dr. David E. Kandzari. In his analysis, Dr. Kandzari highlighted three distinct problems with the trial that he and his associates identified in a series of post hoc analyses:

• The failure of a large minority of enrolled patients in both arms of the study to remain on a stable medical regimen during the 6 months of follow-up before the primary efficacy outcomes were measured.

• The inexplicably large reduction in BP among the sham-control patients, especially among African American patients, who made up a quarter of the trial’s population.

• The vastly incomplete nerve-ablation treatment that most patients received, treatments that usually failed to meet the standards specified in the trial’s protocol.

The background medical regimens that patients received proved unstable during SYMPLICITY HTN-3 even though the study design mandated that patients be on a stable regimen for at least 2 weeks before entering the study. Roughly 80% of enrolled patients in both the denervation and sham-control arms of the study had been on a stable regimen for at least 6 weeks before they entered. Despite that, during the 6 months of follow-up, 211 (39%) of patients in the study underwent a change in their medication regimen. The changes occurred at virtually identical rates in both study arms, and in more than two-thirds of cases were driven by medical necessity.

"The pattern of drug changes challenges the notion of maximally tolerated therapy," Dr. Kandzari said during his report. "Can this [maximally tolerated therapy] be sustained in a randomized, controlled trial?" It also raised the issues of how trial design can better limit drug changes.

Even though it remains unclear why blood pressure reduction was so pronounced among the African Americans in the sham-control group, the impact of this unexpected effect substantially upended the trial’s endpoints. Among the 49 African Americans randomized to sham treatment, office-measured systolic pressure dropped by an average of 17.8 mm Hg, far exceeding the 8.6–mm Hg decline seen among the non–African Americans in the control arm and even exceeding the average 15.5–mm Hg drop in office systolic BP among African Americans treated with renal denervation.

"The absolute reduction in blood pressure by renal denervation in African Americans was identical to non–African Americans." The problem that arose "related more to what happened in the sham-control group of African Americans, who had a nearly 18–mm Hg reduction in blood pressure," said Dr. Kandzari, chief scientific officer and director of interventional cardiology at Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta.

The low rate at which patients assigned to receive renal denervation actually received the type of treatment spelled out in the study’s protocol may have been the biggest problem of all, although Dr. Kandzari stressed that, in his opinion "no single factor led to the neutral efficacy seen in the study."

The supplementary methods section of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 report published in April explicitly called for patients to receive "4-6 ablations" per side, delivering them in a spiral, circumferential pattern starting distally in each renal artery. That meant each patient was to receive a minimum of eight total ablations.

But analysis of data recorded independently by the research nurse and by the proctor during each procedure, as well as cineangiography films made and submitted by the operator for each ablation, clearly showed that many patients did not receive the treatment that the protocol spelled out. Synthesis of the data collected by the three methods showed that about half of the 364 patients randomized to renal denervation received at least eight ablations, while the other half did not receive this minimum number.

The three separate sets of ablation records also contained information on whether ablations occurred in the anterior, posterior, superior, or inferior quadrants of each renal artery. Full circumferential ablation, what the protocol prescribed, required an ablation in at least one of each of these quadrants per side. What actually happened was that 253 patients (70%) received no circumferential ablations, 68 patients (19%) received circumferential ablation on just one side, and 19 patients (5%) received the bilateral circumferential ablations that the protocol called for. Data for the remaining 24 patients treated with renal denervation were not amenable to analysis for this parameter.

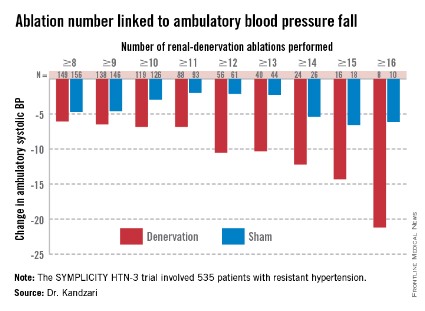

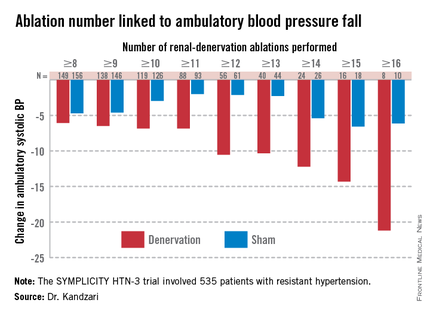

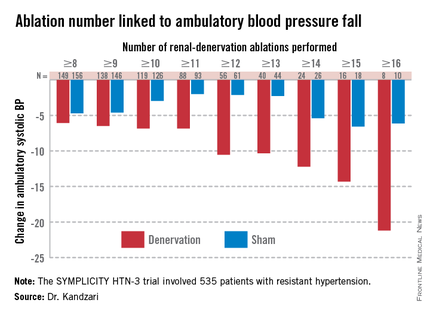

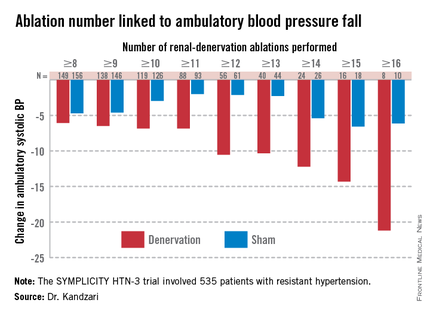

As might be expected, greater ablation number and completeness strongly linked with a robust blood pressure effect.

Among patients who received at least eight ablations, office systolic pressure fell by an average 13.1 mm Hg. But among the nine patients who received 16 or more ablations, the average systolic BP reduction at 6 months was 30.9 mm Hg. Among the 18 patients who received at least 15 ablations, the average systolic pressure reduction was 25.4 mm Hg. A very similar relationship occurred for BPs measured by ambulatory monitoring (see graphic), and the data also suggested a positive link between an increasing number of ablations and an increased effect on heart rate. The consistency of the association across all three measures lent further support to this as a real relationship, Dr. Kandzari noted.

Circumferentiality of the ablations showed a similar pattern. The average office systolic pressure fall in patients with no circumferential ablations was 14.2 mm Hg, and it was 16.1 mm Hg in patients who received just one circumferential ablation. But in the 19 patients who received circumferential ablations bilaterally, the average office systolic pressure reduction was 24.3 mm Hg, with a similar pattern seen for ambulatory measures as well as for home-based BP measurements.

"All patients randomized to renal denervation received renal denervation, but they may not have received it in a fashion that seemed to translate into a greater blood pressure reduction," Dr. Kandzari concluded.

Who to treat, where to treat, how to treat

"One result of the neutral HTN-3 result was a call to revisit the basic science behind renal denervation. The clinical enthusiasm had exceeded the science behind renal denervation," Dr. Kandzari observed.

Renal denervation’s many European advocates seem to agree, and have begun the process of determining characteristics of the best patients to receive renal denervation and where and how ablations are best delivered within the renal artery to achieve interruption of sympathetic innervation, although the targeting information they have right now is rudimentary.

"Probably most important is patient selection. You must be sure to get the right patient, one with high sympathetic activity, because the treatment lowers sympathetic activity," said Dr. Atul Pathak, an interventional cardiologist at Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse, France.

Some clues for patient selection have come from the Global SYMPLICITY Registry, which is enrolling patients treated with renal denervation at more than 200 experienced centers worldwide, many of them in Germany but also elsewhere in Europe, Australia, Canada, Korea, and other locations. Initial findings from the first 1,000 patients entered into the registry and followed for 6 months came out in March at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology, and Dr. Mahfoud presented new analyses of the data at EuroPCR.

"The major concern we had when we started renal denervation was its safety. I believe the safety issue is now answered," especially with the data collected in the global registry as well as in the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial, by far the largest trial completed for the procedure, said Dr. Thomas Zeller, professor and head of clinical and interventional angiology at the Heart Center in Bad Krozingen, Germany. "I was concerned that we might harm the renal arteries with long-lasting stenosis or embolic showers, but this does not happen, at least with the Symplicity catheter," he said during a talk at the meeting.

"The number of patients suitable for renal denervation is potentially much smaller than we initially expected. Real drug resistance is rare, poor adherence is common, and the Symplicity catheter is technically challenging and not effective in every patient. It is hard to rotate the catheter in the tortuous iliac arteries that some patients with hypertension have; the anatomic conditions of hypertension may not be suited to the Symplicity flex catheter," said Dr. Zeller, who added that he has performed renal denervations with the Symplicity catheter since 2009.

"We should focus on the patients that the HTN-3 trial identified as responders, including patients younger than 65, and patients on an aldosterone antagonist," he suggested in a talk at the meeting.

Finding the right patients and the right ablation targets

In the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial, 123 (23%) of the 535 patients remained severely hypertensive despite treatment with an aldosterone antagonist such as spironolactone at the time of entry into the study. In this subgroup, renal denervation produced an average 8.1–mm Hg additional reduction in office systolic BP compared with the average reduction seen among the sham-control patients, a much larger effect than the average 3.2–mm Hg incremental reduction by renal denervation over control seen in the patients who were not on an aldosterone antagonist at baseline, Dr. Manesh Patel reported in a talk at the meeting.

One possible explanation for this effect is that "these patients were resistant to an aldosterone antagonist and hence have a good chance of having high sympathetic activity," explained Dr. Patel, director of interventional cardiology at Duke University in Durham, N.C., and a coinvestigator on the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial. Another possibility is that "aldosterone antagonist use is a marker for patients who have been treated in a hypertension clinic to receive this fourth-line agent," and hence are more likely to have true drug-resistant hypertension, he added. More recent analyses of the HTN-3 results also showed that the 38% of patients who entered the study while on treatment with a vasodilator had absolutely no added benefit from renal denervation compared with the sham controls, while in the patients not on a vasodilator renal denervation produced an average 6.7–mm Hg reduction in office systolic BP compared with control patients, a statistically significant difference.

"We must accept that currently denervation is a ‘black box’ procedure. You deliver energy and you hope blood pressure goes down, but the main confounder is we are not sure if we have damaged the nerve fibers," Dr. Mahfoud said.

According to data he compiled, the depth of ablation penetration varies by device, with several devices including the Symplicity producing an ablation depth of 3 mm, while a few other systems produce ablation depths of 4 mm or even 6 mm.

Results from autopsy studies he analyzed suggested that afferent nerve density closer to the renal-artery lumen is highest in the distal section of the renal artery compared with the more proximal side, and that the posterior and anterior quadrants of the distal renal artery harbor a higher concentration of nerve fibers closer to the lumen than the superior and inferior quadrants.

This information begins to define the "sweet spot" for applying denervation energy, Dr. Mahfoud said. When he performs renal denervation today "we go even more distally, into the branches [off the distal renal arteries] if they are large enough" to accommodate the catheter. "Nerves are not equally distributed over the entire renal artery," and ideally this information should help guide ablation placements, he said.

The global divide in renal denervation use

The inability of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial to prove the treatment’s efficacy has further divided use of renal denervation by geography. The technology remains unapproved for U.S. use, and will remain that way until another large, sham-controlled trial finishes and shows a clear benefit for BP reduction. In contrast, the procedure’s use in Europe seems on track to continue and grow further, although European thought leaders urge caution and further research to identify the best denervation techniques and optimal patients.

European leaders such as Dr. Mahfoud and Dr. Schmieder also see great promise in using renal denervation for other types of patients, such as those with heart failure or arrhythmias. Just one example of the wide-ranging effects examined for renal denervation was a report Dr. Mahfoud cited published earlier this year that focused on changes in left ventricular mass in 55 patients with resistant hypertension who underwent renal denervation. The results collected by Dr. Mahfoud and his associates showed that even when patients experienced little or no change in their systolic BP they often had substantial reductions in left ventricular mass (Eur. Heart J. 2014 March 6 [doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu093]).

"Reducing systolic blood pressure by 10 mm Hg [in patients with severe, drug-resistant hypertension] would have a massive impact, so renal denervation remains an important tool for potentially benefiting patients with uncontrolled hypertension," Dr. Wijns, codirector of the Cardiovascular Center in Aalst, Belgium, said in an interview.

But the renal denervation tool that is increasingly seen as important by the cardiovascular disease leadership in Europe will remain beyond the reach of U.S. physicians for some time to come.

The SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial and the Global SYMPLICITY Registry were sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Symplicity catheter. All of the sources for this article have received speaker fees, consulting fees, and/or research grants from Medtronic and numerous other medical device, drug, or biotechnology companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – At least three different factors undermined the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial that earlier this year did not show a significant difference in blood pressure lowering between renal denervation and a sham-control procedure, most notably the failure of the vast majority of operators in the study to follow ablation instructions and produce thorough and reliable interruptions of sympathetic innervation of the kidneys, according to new data released by the trial’s investigators.

As the full range of problems with the U.S.-based SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial, which had its main results reported in April (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1393-1401), became apparent in a report at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions, many top European practitioners and supporters of renal denervation voiced their belief that the treatment is an effective and safe option for many patients with true drug-resistant, severe hypertension.

The only qualifications they now add are that renal denervation is not easily performed and must be done carefully and in a more targeted way, with an ongoing need to find the patients best suited for treatment and the best methods for delivering treatment.

During the meeting, Dr. Felix Mahfoud, an interventional cardiologist at the University Hospital of Saarland in Homburg/Saar, Germany, joined with hypertension specialist Dr. Konstantinos Tsioufis of the University of Athens and Dr. William Wijns, codirector of EuroPCR, in an official statement from the meeting that despite the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results they continued to support renal denervation as a treatment option for selected patients with drug-resistant, severe hypertension.

Their sentiment echoed another endorsement made a few weeks earlier for continued use and study of renal denervation from the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) in reaction to the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 results.

The ESH "sticks to its statement" from 2013 on using renal denervation in appropriate patients with treatment-resistant, severe hypertension (Eurointervention 2013;9:R58-R66), said Dr. Roland E. Schmieder, first author for the 2013 ESH position paper and a leader in European use of renal denervation.

"We need more studies to prove that renal denervation works, and in particular to get more precise information on which patients get the greatest benefit," Dr. Schmieder said in a separate talk at the meeting. For the time being, he said he was comfortable with routine use of renal denervation in patients with an office systolic BP of at least 160 mm Hg that remains at this level despite maximally tolerated treatment with at least three antihypertensive drugs, including a diuretic, the use endorsed by current European guidelines. It remains appropriate to investigate the impact of renal denervation on other disorders, such as heart failure, arrhythmia, metabolic syndrome, and depressed renal function, said Dr. Schmieder, professor and head of hypertension and vascular medicine research at University Hospital in Erlangen, Germany.

The problems with SYMPLICITY HTN-3

While much speculation swirled around what had gone wrong in the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial after researchers on the study gave their first report on the results early in the spring, the full extent of the study’s problems didn’t flesh out until a follow-up report during EuroPCR by coinvestigator Dr. David E. Kandzari. In his analysis, Dr. Kandzari highlighted three distinct problems with the trial that he and his associates identified in a series of post hoc analyses:

• The failure of a large minority of enrolled patients in both arms of the study to remain on a stable medical regimen during the 6 months of follow-up before the primary efficacy outcomes were measured.

• The inexplicably large reduction in BP among the sham-control patients, especially among African American patients, who made up a quarter of the trial’s population.

• The vastly incomplete nerve-ablation treatment that most patients received, treatments that usually failed to meet the standards specified in the trial’s protocol.

The background medical regimens that patients received proved unstable during SYMPLICITY HTN-3 even though the study design mandated that patients be on a stable regimen for at least 2 weeks before entering the study. Roughly 80% of enrolled patients in both the denervation and sham-control arms of the study had been on a stable regimen for at least 6 weeks before they entered. Despite that, during the 6 months of follow-up, 211 (39%) of patients in the study underwent a change in their medication regimen. The changes occurred at virtually identical rates in both study arms, and in more than two-thirds of cases were driven by medical necessity.

"The pattern of drug changes challenges the notion of maximally tolerated therapy," Dr. Kandzari said during his report. "Can this [maximally tolerated therapy] be sustained in a randomized, controlled trial?" It also raised the issues of how trial design can better limit drug changes.

Even though it remains unclear why blood pressure reduction was so pronounced among the African Americans in the sham-control group, the impact of this unexpected effect substantially upended the trial’s endpoints. Among the 49 African Americans randomized to sham treatment, office-measured systolic pressure dropped by an average of 17.8 mm Hg, far exceeding the 8.6–mm Hg decline seen among the non–African Americans in the control arm and even exceeding the average 15.5–mm Hg drop in office systolic BP among African Americans treated with renal denervation.

"The absolute reduction in blood pressure by renal denervation in African Americans was identical to non–African Americans." The problem that arose "related more to what happened in the sham-control group of African Americans, who had a nearly 18–mm Hg reduction in blood pressure," said Dr. Kandzari, chief scientific officer and director of interventional cardiology at Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta.

The low rate at which patients assigned to receive renal denervation actually received the type of treatment spelled out in the study’s protocol may have been the biggest problem of all, although Dr. Kandzari stressed that, in his opinion "no single factor led to the neutral efficacy seen in the study."

The supplementary methods section of the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 report published in April explicitly called for patients to receive "4-6 ablations" per side, delivering them in a spiral, circumferential pattern starting distally in each renal artery. That meant each patient was to receive a minimum of eight total ablations.