User login

CMS Puts Hospitalists in Holding Pattern Regarding Physician Payment Transparency

Hospitalists have little choice but to wait and see when it comes to the release by Medicare of information on how much it pays doctors, according to an SHM committee member.

The decision [PDF] by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service (CMS) to release the data starting in mid-March was long in the making and is aimed at "making Medicare data more transparent and accessible, while maintaining the privacy of beneficiaries," the agency notes on its website.

CMS will respond to individual Freedom of Information Act requests for physician-payment data and generate aggregate data sets regarding Medicare physician services for the public. The agency will make case-by-base decisions on whether to release data and will "weigh the balance between the privacy interest of individual physicians and the public interest in disclosure of such information," according to a notice [PDF] issued last January.

"It all boils down to how the information is released and how the information is going to be interpreted," says SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM. "Generally, most physician groups are supportive of improving access to information…but that's bounded by having context and privacy issues addressed."

In a letter to Congress [PDF], SHM, the American Medical Association, and others have cautioned that the balancing act is a tricky procedure that must take into account the privacy concerns of both patients and physicians. Dr. Lenchus adds that he is skeptical of creating rules to govern the release of information after announcing the intention to release it.

"It tends to make me feel like the horse is already out of the barn, and now we're going to try to corral him back in to some degree," he says. "The case-by-case standard with which they say they are evaluating the [requests] makes sense, but they haven't really defined what their balancing act will be…if there's fraud, waste, and abuse found, it should, of course, be rooted out, but it's tough to root out that abuse just based on the highest-paid cardiologist in your area."

Visit our website for more information on Medicare payment reform.

Hospitalists have little choice but to wait and see when it comes to the release by Medicare of information on how much it pays doctors, according to an SHM committee member.

The decision [PDF] by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service (CMS) to release the data starting in mid-March was long in the making and is aimed at "making Medicare data more transparent and accessible, while maintaining the privacy of beneficiaries," the agency notes on its website.

CMS will respond to individual Freedom of Information Act requests for physician-payment data and generate aggregate data sets regarding Medicare physician services for the public. The agency will make case-by-base decisions on whether to release data and will "weigh the balance between the privacy interest of individual physicians and the public interest in disclosure of such information," according to a notice [PDF] issued last January.

"It all boils down to how the information is released and how the information is going to be interpreted," says SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM. "Generally, most physician groups are supportive of improving access to information…but that's bounded by having context and privacy issues addressed."

In a letter to Congress [PDF], SHM, the American Medical Association, and others have cautioned that the balancing act is a tricky procedure that must take into account the privacy concerns of both patients and physicians. Dr. Lenchus adds that he is skeptical of creating rules to govern the release of information after announcing the intention to release it.

"It tends to make me feel like the horse is already out of the barn, and now we're going to try to corral him back in to some degree," he says. "The case-by-case standard with which they say they are evaluating the [requests] makes sense, but they haven't really defined what their balancing act will be…if there's fraud, waste, and abuse found, it should, of course, be rooted out, but it's tough to root out that abuse just based on the highest-paid cardiologist in your area."

Visit our website for more information on Medicare payment reform.

Hospitalists have little choice but to wait and see when it comes to the release by Medicare of information on how much it pays doctors, according to an SHM committee member.

The decision [PDF] by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service (CMS) to release the data starting in mid-March was long in the making and is aimed at "making Medicare data more transparent and accessible, while maintaining the privacy of beneficiaries," the agency notes on its website.

CMS will respond to individual Freedom of Information Act requests for physician-payment data and generate aggregate data sets regarding Medicare physician services for the public. The agency will make case-by-base decisions on whether to release data and will "weigh the balance between the privacy interest of individual physicians and the public interest in disclosure of such information," according to a notice [PDF] issued last January.

"It all boils down to how the information is released and how the information is going to be interpreted," says SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM. "Generally, most physician groups are supportive of improving access to information…but that's bounded by having context and privacy issues addressed."

In a letter to Congress [PDF], SHM, the American Medical Association, and others have cautioned that the balancing act is a tricky procedure that must take into account the privacy concerns of both patients and physicians. Dr. Lenchus adds that he is skeptical of creating rules to govern the release of information after announcing the intention to release it.

"It tends to make me feel like the horse is already out of the barn, and now we're going to try to corral him back in to some degree," he says. "The case-by-case standard with which they say they are evaluating the [requests] makes sense, but they haven't really defined what their balancing act will be…if there's fraud, waste, and abuse found, it should, of course, be rooted out, but it's tough to root out that abuse just based on the highest-paid cardiologist in your area."

Visit our website for more information on Medicare payment reform.

Colchicine may provide potent cardiac protection

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Evidence from three observational studies suggests colchicine has a strong protective effect against cardiovascular events in gout patients.

These data add to mounting evidence that the venerable 2,400-year-old medication also reduces the incidence of cardiac events in patients at elevated risk who don’t have gout, Dr. Michael H. Pillinger said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He was a coinvestigator in the three observational studies, two of which are ongoing with only interim results available.

The first of these observational studies was a retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study of 1,288 gout patients in the New York Harbor Healthcare System Veterans Affairs database. The demographics, baseline comorbidities, and cardiovascular risk factors in the 576 colchicine users and 712 nonusers were closely similar. The key finding in this snapshot study: the prevalence of a history of acute MI was 1.2% in the colchicine users, compared with 2.6% in the non-users with gout, for a significant 54% relative risk reduction (J. Rheumatol. 2012;39:1458-64).

"That degree of risk reduction seems too good to be believed, and it probably is," according to Dr. Pillinger, a rheumatologist and director of the crystal diseases study group at New York University.

But the next observational study showed a similar-size benefit. This was a retrospective cohort study of New York VA gout patients. It included only gout patients who met American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria as confirmed by manual chart review. There were 410 colchicine users with a collective 1,184 years of active use and another 682 years of lapse time, along with 234 colchicine nonusers with 1,041 years of follow-up time. Again, baseline demographics and comorbidities were remarkably similar for the two groups.

In an interim analysis, the incidence of acute MI was 0.7% among active users of colchicine, 2.0% in lapsed former users, and 3.1% in the nonuser controls. This translated to an incidence rate of 0.003 MIs per person-year in the colchicine users, 0.007 per person-year in the controls, and 0.009 MIs per person-year during a combined 1,723 person-years in the combined control group plus lapsed former users, for relative risk reductions of 57% and 67%, respectively. Still, the final results aren’t in yet, and this study is limited by a small number of events to date, its retrospective design, and the potential for confounding by indication, Dr. Pillinger noted.

Gout patients on colchicine in these two VA studies were on 0.6-1.2 mg/day rather than the now-standard 0.5 mg.

The latest observational study is a retrospective cohort study being conducted in collaboration with Dr. Peter Berger, chair of cardiology at the Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa. To date, it includes 3,064 gout patients. The MI incidence thus far is 6.3/100 person-years in the colchicine users and 11.2/100 person-years among lapsed users. After controlling for potential confounders such as age, hypertension, and diabetes in a logistic regression analysis, however, the trend for reduced MI risk in the colchicine users hasn’t yet reached significance. Stay tuned, Dr. Pillinger said.

The mechanistic rationale by which colchicine might reduce cardiovascular events in gout patients lies in the fact that it is an anti-inflammatory drug and atherosclerosis is a powerfully inflammatory process. Colchicine is known to suppress production of TNF-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and other inflammatory cytokines by neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells. These cell types are present in atherosclerotic plaque, the rheumatologist explained.

By the same rationale, colchicine might well be cardioprotective in individuals without gout. One strong piece of supporting evidence comes from a 3-year, randomized, observer-blinded clinical trial in which 532 Australian patients with stable coronary artery disease on background statin and antiplatelet therapy received 0.5 mg/day of colchicine or not. The composite primary endpoint comprised acute coronary syndrome, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke occurred in 5.3% of the colchicine group, compared with 16.0% of controls. That’s a 67% relative risk reduction, with a highly favorable number-needed-to-treat of 11 (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:404-10).

Dr. Pillinger reported being the recipient of research grants from Takeda, which markets colchicine (Colcrys), and Savient, which markets the gout drug pegloticase (Krystexxa).

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Evidence from three observational studies suggests colchicine has a strong protective effect against cardiovascular events in gout patients.

These data add to mounting evidence that the venerable 2,400-year-old medication also reduces the incidence of cardiac events in patients at elevated risk who don’t have gout, Dr. Michael H. Pillinger said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He was a coinvestigator in the three observational studies, two of which are ongoing with only interim results available.

The first of these observational studies was a retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study of 1,288 gout patients in the New York Harbor Healthcare System Veterans Affairs database. The demographics, baseline comorbidities, and cardiovascular risk factors in the 576 colchicine users and 712 nonusers were closely similar. The key finding in this snapshot study: the prevalence of a history of acute MI was 1.2% in the colchicine users, compared with 2.6% in the non-users with gout, for a significant 54% relative risk reduction (J. Rheumatol. 2012;39:1458-64).

"That degree of risk reduction seems too good to be believed, and it probably is," according to Dr. Pillinger, a rheumatologist and director of the crystal diseases study group at New York University.

But the next observational study showed a similar-size benefit. This was a retrospective cohort study of New York VA gout patients. It included only gout patients who met American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria as confirmed by manual chart review. There were 410 colchicine users with a collective 1,184 years of active use and another 682 years of lapse time, along with 234 colchicine nonusers with 1,041 years of follow-up time. Again, baseline demographics and comorbidities were remarkably similar for the two groups.

In an interim analysis, the incidence of acute MI was 0.7% among active users of colchicine, 2.0% in lapsed former users, and 3.1% in the nonuser controls. This translated to an incidence rate of 0.003 MIs per person-year in the colchicine users, 0.007 per person-year in the controls, and 0.009 MIs per person-year during a combined 1,723 person-years in the combined control group plus lapsed former users, for relative risk reductions of 57% and 67%, respectively. Still, the final results aren’t in yet, and this study is limited by a small number of events to date, its retrospective design, and the potential for confounding by indication, Dr. Pillinger noted.

Gout patients on colchicine in these two VA studies were on 0.6-1.2 mg/day rather than the now-standard 0.5 mg.

The latest observational study is a retrospective cohort study being conducted in collaboration with Dr. Peter Berger, chair of cardiology at the Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa. To date, it includes 3,064 gout patients. The MI incidence thus far is 6.3/100 person-years in the colchicine users and 11.2/100 person-years among lapsed users. After controlling for potential confounders such as age, hypertension, and diabetes in a logistic regression analysis, however, the trend for reduced MI risk in the colchicine users hasn’t yet reached significance. Stay tuned, Dr. Pillinger said.

The mechanistic rationale by which colchicine might reduce cardiovascular events in gout patients lies in the fact that it is an anti-inflammatory drug and atherosclerosis is a powerfully inflammatory process. Colchicine is known to suppress production of TNF-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and other inflammatory cytokines by neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells. These cell types are present in atherosclerotic plaque, the rheumatologist explained.

By the same rationale, colchicine might well be cardioprotective in individuals without gout. One strong piece of supporting evidence comes from a 3-year, randomized, observer-blinded clinical trial in which 532 Australian patients with stable coronary artery disease on background statin and antiplatelet therapy received 0.5 mg/day of colchicine or not. The composite primary endpoint comprised acute coronary syndrome, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke occurred in 5.3% of the colchicine group, compared with 16.0% of controls. That’s a 67% relative risk reduction, with a highly favorable number-needed-to-treat of 11 (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:404-10).

Dr. Pillinger reported being the recipient of research grants from Takeda, which markets colchicine (Colcrys), and Savient, which markets the gout drug pegloticase (Krystexxa).

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Evidence from three observational studies suggests colchicine has a strong protective effect against cardiovascular events in gout patients.

These data add to mounting evidence that the venerable 2,400-year-old medication also reduces the incidence of cardiac events in patients at elevated risk who don’t have gout, Dr. Michael H. Pillinger said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He was a coinvestigator in the three observational studies, two of which are ongoing with only interim results available.

The first of these observational studies was a retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study of 1,288 gout patients in the New York Harbor Healthcare System Veterans Affairs database. The demographics, baseline comorbidities, and cardiovascular risk factors in the 576 colchicine users and 712 nonusers were closely similar. The key finding in this snapshot study: the prevalence of a history of acute MI was 1.2% in the colchicine users, compared with 2.6% in the non-users with gout, for a significant 54% relative risk reduction (J. Rheumatol. 2012;39:1458-64).

"That degree of risk reduction seems too good to be believed, and it probably is," according to Dr. Pillinger, a rheumatologist and director of the crystal diseases study group at New York University.

But the next observational study showed a similar-size benefit. This was a retrospective cohort study of New York VA gout patients. It included only gout patients who met American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria as confirmed by manual chart review. There were 410 colchicine users with a collective 1,184 years of active use and another 682 years of lapse time, along with 234 colchicine nonusers with 1,041 years of follow-up time. Again, baseline demographics and comorbidities were remarkably similar for the two groups.

In an interim analysis, the incidence of acute MI was 0.7% among active users of colchicine, 2.0% in lapsed former users, and 3.1% in the nonuser controls. This translated to an incidence rate of 0.003 MIs per person-year in the colchicine users, 0.007 per person-year in the controls, and 0.009 MIs per person-year during a combined 1,723 person-years in the combined control group plus lapsed former users, for relative risk reductions of 57% and 67%, respectively. Still, the final results aren’t in yet, and this study is limited by a small number of events to date, its retrospective design, and the potential for confounding by indication, Dr. Pillinger noted.

Gout patients on colchicine in these two VA studies were on 0.6-1.2 mg/day rather than the now-standard 0.5 mg.

The latest observational study is a retrospective cohort study being conducted in collaboration with Dr. Peter Berger, chair of cardiology at the Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa. To date, it includes 3,064 gout patients. The MI incidence thus far is 6.3/100 person-years in the colchicine users and 11.2/100 person-years among lapsed users. After controlling for potential confounders such as age, hypertension, and diabetes in a logistic regression analysis, however, the trend for reduced MI risk in the colchicine users hasn’t yet reached significance. Stay tuned, Dr. Pillinger said.

The mechanistic rationale by which colchicine might reduce cardiovascular events in gout patients lies in the fact that it is an anti-inflammatory drug and atherosclerosis is a powerfully inflammatory process. Colchicine is known to suppress production of TNF-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and other inflammatory cytokines by neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells. These cell types are present in atherosclerotic plaque, the rheumatologist explained.

By the same rationale, colchicine might well be cardioprotective in individuals without gout. One strong piece of supporting evidence comes from a 3-year, randomized, observer-blinded clinical trial in which 532 Australian patients with stable coronary artery disease on background statin and antiplatelet therapy received 0.5 mg/day of colchicine or not. The composite primary endpoint comprised acute coronary syndrome, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke occurred in 5.3% of the colchicine group, compared with 16.0% of controls. That’s a 67% relative risk reduction, with a highly favorable number-needed-to-treat of 11 (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:404-10).

Dr. Pillinger reported being the recipient of research grants from Takeda, which markets colchicine (Colcrys), and Savient, which markets the gout drug pegloticase (Krystexxa).

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Consensus Recommendations From the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the Management of Rosacea, Part 5: A Guide on the Management of Rosacea

What Does ICD-10 Mean for Dermatologists?

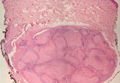

Myofibroma

CNS involvement doesn’t affect survival after allo-SCT

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS—Results of a large, retrospective study suggest that allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) can overcome the poor prognosis associated with central nervous system (CNS) involvement in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

By analyzing transplant outcomes in more than 5000 patients, researchers found that subjects with CNS AML had rates of relapse and survival that were similar to those of patients without CNS involvement.

The team also identified factors that can predict for survival in CNS AML, including cytogenetic risk group, the presence of chronic GVHD, and whether a patient was in complete response at transplant.

Jun Aoki, MD, of Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital in Japan, presented these findings at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings as abstract 68.

Dr Aoki pointed out that CNS involvement is rare in adult AML, occurring in about 5% of patients. However, these patients generally have poor prognosis. And although allo-SCT is one of the options used to treat CNS AML, exactly how CNS involvement impacts transplant outcomes remains unclear.

So Dr Aoki and his colleagues conducted a nationwide, retrospective study to gain some insight. They collected data from the registry database of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation.

Patients had to be older than 15 years of age, have their first allo-SCT between 2006 and 2011, and not have acute promyelocytic leukemia.

The researchers identified 5068 patients who met these criteria, and 157 of them had CNS AML. CNS involvement was defined as infiltration of leukemia cells into CNS or myeloid sarcoma in CNS that were identified at any time from diagnosis to transplant.

No difference in relapse, survival

There were no significant differences between CNS patients and controls with regard to the estimated overall survival (OS), leukemia-free survival, cumulative incidence of relapse, or non-relapse mortality at 5 years.

OS was 39.9% among controls and 38.5% among CNS patients (P=0.847). Leukemia-free survival was 41.2% and 41.5%, respectively (P=0.82).

The cumulative incidence of relapse was 29.8% among controls and 31.8% among CNS patients (P=0.418). And non-relapse mortality was 22.5% and 26.5%, respectively (P=0.142).

Factors predicting OS

To determine the impact of patient and treatment characteristics on OS, the researchers conducted a multivariate analysis. This confirmed that CNS involvement was not a risk factor for OS.

But it revealed a number of other factors that adversely affect OS, including age of 50 or older (P<0.001), lack of a complete response at allo-SCT (P<0.001), a donor source of unrelated cord blood (P=0.005), having a prognostic score of 2-4 (P<0.001), unfavorable cytogenetics (P<0.001), and the absence of acute or chronic GVHD (P<0.001 for both).

When the researchers analyzed only CNS patients, they discovered that not all of these factors retained significance. Only the absence of chronic GVHD (P=0.002), lack of complete response at transplant (P<0.001), and having either intermediate (P=0.003) or unfavorable cytogenetics (P=0.011) were adversely associated with OS in these patients. ![]()

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS—Results of a large, retrospective study suggest that allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) can overcome the poor prognosis associated with central nervous system (CNS) involvement in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

By analyzing transplant outcomes in more than 5000 patients, researchers found that subjects with CNS AML had rates of relapse and survival that were similar to those of patients without CNS involvement.

The team also identified factors that can predict for survival in CNS AML, including cytogenetic risk group, the presence of chronic GVHD, and whether a patient was in complete response at transplant.

Jun Aoki, MD, of Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital in Japan, presented these findings at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings as abstract 68.

Dr Aoki pointed out that CNS involvement is rare in adult AML, occurring in about 5% of patients. However, these patients generally have poor prognosis. And although allo-SCT is one of the options used to treat CNS AML, exactly how CNS involvement impacts transplant outcomes remains unclear.

So Dr Aoki and his colleagues conducted a nationwide, retrospective study to gain some insight. They collected data from the registry database of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation.

Patients had to be older than 15 years of age, have their first allo-SCT between 2006 and 2011, and not have acute promyelocytic leukemia.

The researchers identified 5068 patients who met these criteria, and 157 of them had CNS AML. CNS involvement was defined as infiltration of leukemia cells into CNS or myeloid sarcoma in CNS that were identified at any time from diagnosis to transplant.

No difference in relapse, survival

There were no significant differences between CNS patients and controls with regard to the estimated overall survival (OS), leukemia-free survival, cumulative incidence of relapse, or non-relapse mortality at 5 years.

OS was 39.9% among controls and 38.5% among CNS patients (P=0.847). Leukemia-free survival was 41.2% and 41.5%, respectively (P=0.82).

The cumulative incidence of relapse was 29.8% among controls and 31.8% among CNS patients (P=0.418). And non-relapse mortality was 22.5% and 26.5%, respectively (P=0.142).

Factors predicting OS

To determine the impact of patient and treatment characteristics on OS, the researchers conducted a multivariate analysis. This confirmed that CNS involvement was not a risk factor for OS.

But it revealed a number of other factors that adversely affect OS, including age of 50 or older (P<0.001), lack of a complete response at allo-SCT (P<0.001), a donor source of unrelated cord blood (P=0.005), having a prognostic score of 2-4 (P<0.001), unfavorable cytogenetics (P<0.001), and the absence of acute or chronic GVHD (P<0.001 for both).

When the researchers analyzed only CNS patients, they discovered that not all of these factors retained significance. Only the absence of chronic GVHD (P=0.002), lack of complete response at transplant (P<0.001), and having either intermediate (P=0.003) or unfavorable cytogenetics (P=0.011) were adversely associated with OS in these patients. ![]()

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS—Results of a large, retrospective study suggest that allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) can overcome the poor prognosis associated with central nervous system (CNS) involvement in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

By analyzing transplant outcomes in more than 5000 patients, researchers found that subjects with CNS AML had rates of relapse and survival that were similar to those of patients without CNS involvement.

The team also identified factors that can predict for survival in CNS AML, including cytogenetic risk group, the presence of chronic GVHD, and whether a patient was in complete response at transplant.

Jun Aoki, MD, of Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital in Japan, presented these findings at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings as abstract 68.

Dr Aoki pointed out that CNS involvement is rare in adult AML, occurring in about 5% of patients. However, these patients generally have poor prognosis. And although allo-SCT is one of the options used to treat CNS AML, exactly how CNS involvement impacts transplant outcomes remains unclear.

So Dr Aoki and his colleagues conducted a nationwide, retrospective study to gain some insight. They collected data from the registry database of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation.

Patients had to be older than 15 years of age, have their first allo-SCT between 2006 and 2011, and not have acute promyelocytic leukemia.

The researchers identified 5068 patients who met these criteria, and 157 of them had CNS AML. CNS involvement was defined as infiltration of leukemia cells into CNS or myeloid sarcoma in CNS that were identified at any time from diagnosis to transplant.

No difference in relapse, survival

There were no significant differences between CNS patients and controls with regard to the estimated overall survival (OS), leukemia-free survival, cumulative incidence of relapse, or non-relapse mortality at 5 years.

OS was 39.9% among controls and 38.5% among CNS patients (P=0.847). Leukemia-free survival was 41.2% and 41.5%, respectively (P=0.82).

The cumulative incidence of relapse was 29.8% among controls and 31.8% among CNS patients (P=0.418). And non-relapse mortality was 22.5% and 26.5%, respectively (P=0.142).

Factors predicting OS

To determine the impact of patient and treatment characteristics on OS, the researchers conducted a multivariate analysis. This confirmed that CNS involvement was not a risk factor for OS.

But it revealed a number of other factors that adversely affect OS, including age of 50 or older (P<0.001), lack of a complete response at allo-SCT (P<0.001), a donor source of unrelated cord blood (P=0.005), having a prognostic score of 2-4 (P<0.001), unfavorable cytogenetics (P<0.001), and the absence of acute or chronic GVHD (P<0.001 for both).

When the researchers analyzed only CNS patients, they discovered that not all of these factors retained significance. Only the absence of chronic GVHD (P=0.002), lack of complete response at transplant (P<0.001), and having either intermediate (P=0.003) or unfavorable cytogenetics (P=0.011) were adversely associated with OS in these patients. ![]()

Palliative chemo can have undesired outcomes

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Palliative chemotherapy can negatively impact the end of life for terminally ill cancer patients, according to a paper published in BMJ.

Investigators found that patients who received palliative chemotherapy in their last months of life had an increased risk of requiring intensive medical care, such as resuscitation, and dying in a place they did not choose, such as an intensive care unit.

The researchers therefore suggested that end-of-life discussions may be particularly important for patients who want to receive palliative chemotherapy.

“The results highlight the need for more effective communication by doctors of terminal prognoses and the likely outcomes of chemotherapy for these patients,” said study author Holly Prigerson, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

“For patients to make informed choices about their care, they need to know if they are incurable and understand what their life expectancy is, that palliative chemotherapy is not intended to cure them, that it may not appreciably prolong their life, and that it may result in the receipt of very aggressive, life-prolonging care at the expense of their quality of life.”

Data have suggested that between 20% and 50% of patients with incurable cancers undergo palliative chemotherapy within 30 days of death. But it has not been clear whether the use of chemotherapy in a patient’s last months is associated with the need for intensive medical care in the last week of life or with the patient’s death.

So Dr Prigerson and her colleagues decided to study the use of palliative chemotherapy in patients with 6 or fewer months to live. The researchers used data from “Coping with Cancer,” a 6-year study of 386 terminally ill patients.

The patients were interviewed around the time of their decision regarding palliative chemotherapy. In the month after each patient died, caregivers were asked to rate their loved ones’ care, quality of life, and place of death as being where the patient would have wanted to die. The investigators then reviewed patients’ medical charts to determine the type of care they actually received in their last week.

Effects of palliative chemo

In all, 56% of patients opted to receive palliative chemotherapy. They were more likely to be younger, married, and better educated than patients not on the treatment.

Patients on chemotherapy also had better performance status, overall quality of life, physical functioning, and psychological well-being at study enrollment.

However, patients who received palliative chemotherapy had a greater risk of requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or mechanical ventilation (14% vs 2%), and they were more likely to need a feeding tube (11% vs 5%) in their last weeks of life.

Patients on chemotherapy had a greater risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit (14% vs 8%) and of having a late hospice referral (54% vs 37%).

They were also less likely to die where they wanted to (65% vs 80%). They had a greater risk of dying in an intensive care unit (11% vs 2%) and were less likely than their peers to die at home (47% vs 66%).

“It’s hard to see in these data much of a silver lining to palliative chemotherapy for patients in the terminal stage of their cancer,” Dr Prigerson said. “Until now, there hasn’t been evidence of harmful effects of palliative chemotherapy in the last few months of life.”

“This study is a first step in providing evidence that specifically demonstrates what negative outcomes may result. Additional studies are needed to confirm these troubling findings.”

Explaining the negative effects

Dr Prigerson said the harmful effects of palliative chemotherapy may be a result of misunderstanding, a lack of communication, and denial. Patients may not comprehend the purpose and likely consequences of palliative chemotherapy, and they may not fully acknowledge their own prognoses.

In the study, patients receiving palliative chemotherapy were less likely than their peers to talk to their oncologists about end-of-life care (37% vs 48%), to complete Do-Not-Resuscitate orders (36% vs 49%), or to acknowledge that they were terminally ill (35% vs 47%).

“Our finding that patients with terminal cancers were at higher risk of receiving intensive end-of-life care if they were treated with palliative chemotherapy months earlier underscores the importance of oncologists asking patients about their end-of-life wishes,” said Alexi Wright, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“We often wait until patients stop chemotherapy before asking them about where and how they want to die, but this study shows we need to ask patients about their preferences while they are receiving chemotherapy to ensure they receive the kind of care they want near death.”

Moving forward

The investigators stressed that the study results do not suggest patients should be denied palliative chemotherapy.

“The vast majority of patients in this study wanted palliative chemotherapy if it might increase their survival by as little as a week,” Dr Wright said. “This study is a step towards understanding some of the human costs and benefits of palliative chemotherapy.”

The researchers said additional studies should examine whether patients who are aware that chemotherapy is not intended to cure them still want to receive the treatment, confirm the negative outcomes of palliative chemotherapy, and determine if end-of-life discussions promote more informed decision-making and receipt of value-consistent care.

In a related editorial, Mike Rabow, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that although most patients with metastatic cancer choose to receive chemotherapy, evidence suggests most do not understand its intent.

He said Dr Prigerson’s study suggests the need to “better identify patients who are likely to benefit from chemotherapy near the end of life.” And he encouraged oncologists to discuss with patients the broader implications of chemotherapy when making decisions about treatment. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Palliative chemotherapy can negatively impact the end of life for terminally ill cancer patients, according to a paper published in BMJ.

Investigators found that patients who received palliative chemotherapy in their last months of life had an increased risk of requiring intensive medical care, such as resuscitation, and dying in a place they did not choose, such as an intensive care unit.

The researchers therefore suggested that end-of-life discussions may be particularly important for patients who want to receive palliative chemotherapy.

“The results highlight the need for more effective communication by doctors of terminal prognoses and the likely outcomes of chemotherapy for these patients,” said study author Holly Prigerson, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

“For patients to make informed choices about their care, they need to know if they are incurable and understand what their life expectancy is, that palliative chemotherapy is not intended to cure them, that it may not appreciably prolong their life, and that it may result in the receipt of very aggressive, life-prolonging care at the expense of their quality of life.”

Data have suggested that between 20% and 50% of patients with incurable cancers undergo palliative chemotherapy within 30 days of death. But it has not been clear whether the use of chemotherapy in a patient’s last months is associated with the need for intensive medical care in the last week of life or with the patient’s death.

So Dr Prigerson and her colleagues decided to study the use of palliative chemotherapy in patients with 6 or fewer months to live. The researchers used data from “Coping with Cancer,” a 6-year study of 386 terminally ill patients.

The patients were interviewed around the time of their decision regarding palliative chemotherapy. In the month after each patient died, caregivers were asked to rate their loved ones’ care, quality of life, and place of death as being where the patient would have wanted to die. The investigators then reviewed patients’ medical charts to determine the type of care they actually received in their last week.

Effects of palliative chemo

In all, 56% of patients opted to receive palliative chemotherapy. They were more likely to be younger, married, and better educated than patients not on the treatment.

Patients on chemotherapy also had better performance status, overall quality of life, physical functioning, and psychological well-being at study enrollment.

However, patients who received palliative chemotherapy had a greater risk of requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or mechanical ventilation (14% vs 2%), and they were more likely to need a feeding tube (11% vs 5%) in their last weeks of life.

Patients on chemotherapy had a greater risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit (14% vs 8%) and of having a late hospice referral (54% vs 37%).

They were also less likely to die where they wanted to (65% vs 80%). They had a greater risk of dying in an intensive care unit (11% vs 2%) and were less likely than their peers to die at home (47% vs 66%).

“It’s hard to see in these data much of a silver lining to palliative chemotherapy for patients in the terminal stage of their cancer,” Dr Prigerson said. “Until now, there hasn’t been evidence of harmful effects of palliative chemotherapy in the last few months of life.”

“This study is a first step in providing evidence that specifically demonstrates what negative outcomes may result. Additional studies are needed to confirm these troubling findings.”

Explaining the negative effects

Dr Prigerson said the harmful effects of palliative chemotherapy may be a result of misunderstanding, a lack of communication, and denial. Patients may not comprehend the purpose and likely consequences of palliative chemotherapy, and they may not fully acknowledge their own prognoses.

In the study, patients receiving palliative chemotherapy were less likely than their peers to talk to their oncologists about end-of-life care (37% vs 48%), to complete Do-Not-Resuscitate orders (36% vs 49%), or to acknowledge that they were terminally ill (35% vs 47%).

“Our finding that patients with terminal cancers were at higher risk of receiving intensive end-of-life care if they were treated with palliative chemotherapy months earlier underscores the importance of oncologists asking patients about their end-of-life wishes,” said Alexi Wright, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“We often wait until patients stop chemotherapy before asking them about where and how they want to die, but this study shows we need to ask patients about their preferences while they are receiving chemotherapy to ensure they receive the kind of care they want near death.”

Moving forward

The investigators stressed that the study results do not suggest patients should be denied palliative chemotherapy.

“The vast majority of patients in this study wanted palliative chemotherapy if it might increase their survival by as little as a week,” Dr Wright said. “This study is a step towards understanding some of the human costs and benefits of palliative chemotherapy.”

The researchers said additional studies should examine whether patients who are aware that chemotherapy is not intended to cure them still want to receive the treatment, confirm the negative outcomes of palliative chemotherapy, and determine if end-of-life discussions promote more informed decision-making and receipt of value-consistent care.

In a related editorial, Mike Rabow, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that although most patients with metastatic cancer choose to receive chemotherapy, evidence suggests most do not understand its intent.

He said Dr Prigerson’s study suggests the need to “better identify patients who are likely to benefit from chemotherapy near the end of life.” And he encouraged oncologists to discuss with patients the broader implications of chemotherapy when making decisions about treatment. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Palliative chemotherapy can negatively impact the end of life for terminally ill cancer patients, according to a paper published in BMJ.

Investigators found that patients who received palliative chemotherapy in their last months of life had an increased risk of requiring intensive medical care, such as resuscitation, and dying in a place they did not choose, such as an intensive care unit.

The researchers therefore suggested that end-of-life discussions may be particularly important for patients who want to receive palliative chemotherapy.

“The results highlight the need for more effective communication by doctors of terminal prognoses and the likely outcomes of chemotherapy for these patients,” said study author Holly Prigerson, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

“For patients to make informed choices about their care, they need to know if they are incurable and understand what their life expectancy is, that palliative chemotherapy is not intended to cure them, that it may not appreciably prolong their life, and that it may result in the receipt of very aggressive, life-prolonging care at the expense of their quality of life.”

Data have suggested that between 20% and 50% of patients with incurable cancers undergo palliative chemotherapy within 30 days of death. But it has not been clear whether the use of chemotherapy in a patient’s last months is associated with the need for intensive medical care in the last week of life or with the patient’s death.

So Dr Prigerson and her colleagues decided to study the use of palliative chemotherapy in patients with 6 or fewer months to live. The researchers used data from “Coping with Cancer,” a 6-year study of 386 terminally ill patients.

The patients were interviewed around the time of their decision regarding palliative chemotherapy. In the month after each patient died, caregivers were asked to rate their loved ones’ care, quality of life, and place of death as being where the patient would have wanted to die. The investigators then reviewed patients’ medical charts to determine the type of care they actually received in their last week.

Effects of palliative chemo

In all, 56% of patients opted to receive palliative chemotherapy. They were more likely to be younger, married, and better educated than patients not on the treatment.

Patients on chemotherapy also had better performance status, overall quality of life, physical functioning, and psychological well-being at study enrollment.

However, patients who received palliative chemotherapy had a greater risk of requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or mechanical ventilation (14% vs 2%), and they were more likely to need a feeding tube (11% vs 5%) in their last weeks of life.

Patients on chemotherapy had a greater risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit (14% vs 8%) and of having a late hospice referral (54% vs 37%).

They were also less likely to die where they wanted to (65% vs 80%). They had a greater risk of dying in an intensive care unit (11% vs 2%) and were less likely than their peers to die at home (47% vs 66%).

“It’s hard to see in these data much of a silver lining to palliative chemotherapy for patients in the terminal stage of their cancer,” Dr Prigerson said. “Until now, there hasn’t been evidence of harmful effects of palliative chemotherapy in the last few months of life.”

“This study is a first step in providing evidence that specifically demonstrates what negative outcomes may result. Additional studies are needed to confirm these troubling findings.”

Explaining the negative effects

Dr Prigerson said the harmful effects of palliative chemotherapy may be a result of misunderstanding, a lack of communication, and denial. Patients may not comprehend the purpose and likely consequences of palliative chemotherapy, and they may not fully acknowledge their own prognoses.

In the study, patients receiving palliative chemotherapy were less likely than their peers to talk to their oncologists about end-of-life care (37% vs 48%), to complete Do-Not-Resuscitate orders (36% vs 49%), or to acknowledge that they were terminally ill (35% vs 47%).

“Our finding that patients with terminal cancers were at higher risk of receiving intensive end-of-life care if they were treated with palliative chemotherapy months earlier underscores the importance of oncologists asking patients about their end-of-life wishes,” said Alexi Wright, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“We often wait until patients stop chemotherapy before asking them about where and how they want to die, but this study shows we need to ask patients about their preferences while they are receiving chemotherapy to ensure they receive the kind of care they want near death.”

Moving forward

The investigators stressed that the study results do not suggest patients should be denied palliative chemotherapy.

“The vast majority of patients in this study wanted palliative chemotherapy if it might increase their survival by as little as a week,” Dr Wright said. “This study is a step towards understanding some of the human costs and benefits of palliative chemotherapy.”

The researchers said additional studies should examine whether patients who are aware that chemotherapy is not intended to cure them still want to receive the treatment, confirm the negative outcomes of palliative chemotherapy, and determine if end-of-life discussions promote more informed decision-making and receipt of value-consistent care.

In a related editorial, Mike Rabow, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that although most patients with metastatic cancer choose to receive chemotherapy, evidence suggests most do not understand its intent.

He said Dr Prigerson’s study suggests the need to “better identify patients who are likely to benefit from chemotherapy near the end of life.” And he encouraged oncologists to discuss with patients the broader implications of chemotherapy when making decisions about treatment. ![]()

Histones’ role in gene regulation

Credit: Eric Smith

Researchers say they’ve discovered how histones control PARP1’s ability to activate genes and repair DNA damage.

Their findings, published in Molecular Cell, appear to have implications for cancer treatment.

Specifically, the investigators found that chemical modification of the histone H2Av leads to substantial changes in nucleosome shape.

As a consequence, a previously hidden portion of the nucleosome becomes exposed and activates PARP1.

Upon activation, PARP1 assembles long branching molecules of Poly(ADP-ribose), which appear to open the DNA packaging around the site of PARP1 activation, thereby exposing specific genes for activation.

“[T]he nucleosome is often portrayed as a stable, inert structure, or a tiny ball,” said study author Alexei V. Tulin, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

“We found that the nucleosome is actually a quite dynamic structure. When we modified one histone, we changed the whole nucleosome.”

In addition to revealing new information about how histones control gene activation, Dr Tulin’s research elucidated a new mechanism of PARP1 regulation.

“This mechanism of PARP1 regulation by histones is still very new,” Dr Tulin said. “People believe that PARP1 is mainly activated through interactions with DNA, but we have found that the main pathway of PARP1 activation is through interactions with the nucleosome.”

Previous research suggested that combining standard anticancer agents with drugs that inhibit PARP1 can more effectively kill cancer cells. But clinical trials testing PARP1 inhibitors in cancer patients have produced disappointing results.

“I believe that, to a large extent, the previous setbacks were caused by a general misconception of the role of PARP1 in living cells and the mechanisms of PARP1 regulation,” Dr Tulin said. “Now that we know this mechanism of PARP1 regulation, we can design approaches to inhibit this protein in an effective way to better treat cancer.”

Dr Tulin and his colleagues are now developing the next generation of PARP1 inhibitors. Designed to block the newly identified mechanism of PARP1 activation, these inhibitors will specifically target PARP1, in contrast to the PARP1 inhibitors currently being tested in clinical trials. ![]()

Credit: Eric Smith

Researchers say they’ve discovered how histones control PARP1’s ability to activate genes and repair DNA damage.

Their findings, published in Molecular Cell, appear to have implications for cancer treatment.

Specifically, the investigators found that chemical modification of the histone H2Av leads to substantial changes in nucleosome shape.

As a consequence, a previously hidden portion of the nucleosome becomes exposed and activates PARP1.

Upon activation, PARP1 assembles long branching molecules of Poly(ADP-ribose), which appear to open the DNA packaging around the site of PARP1 activation, thereby exposing specific genes for activation.

“[T]he nucleosome is often portrayed as a stable, inert structure, or a tiny ball,” said study author Alexei V. Tulin, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

“We found that the nucleosome is actually a quite dynamic structure. When we modified one histone, we changed the whole nucleosome.”

In addition to revealing new information about how histones control gene activation, Dr Tulin’s research elucidated a new mechanism of PARP1 regulation.

“This mechanism of PARP1 regulation by histones is still very new,” Dr Tulin said. “People believe that PARP1 is mainly activated through interactions with DNA, but we have found that the main pathway of PARP1 activation is through interactions with the nucleosome.”

Previous research suggested that combining standard anticancer agents with drugs that inhibit PARP1 can more effectively kill cancer cells. But clinical trials testing PARP1 inhibitors in cancer patients have produced disappointing results.

“I believe that, to a large extent, the previous setbacks were caused by a general misconception of the role of PARP1 in living cells and the mechanisms of PARP1 regulation,” Dr Tulin said. “Now that we know this mechanism of PARP1 regulation, we can design approaches to inhibit this protein in an effective way to better treat cancer.”

Dr Tulin and his colleagues are now developing the next generation of PARP1 inhibitors. Designed to block the newly identified mechanism of PARP1 activation, these inhibitors will specifically target PARP1, in contrast to the PARP1 inhibitors currently being tested in clinical trials. ![]()

Credit: Eric Smith

Researchers say they’ve discovered how histones control PARP1’s ability to activate genes and repair DNA damage.

Their findings, published in Molecular Cell, appear to have implications for cancer treatment.

Specifically, the investigators found that chemical modification of the histone H2Av leads to substantial changes in nucleosome shape.

As a consequence, a previously hidden portion of the nucleosome becomes exposed and activates PARP1.

Upon activation, PARP1 assembles long branching molecules of Poly(ADP-ribose), which appear to open the DNA packaging around the site of PARP1 activation, thereby exposing specific genes for activation.

“[T]he nucleosome is often portrayed as a stable, inert structure, or a tiny ball,” said study author Alexei V. Tulin, PhD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

“We found that the nucleosome is actually a quite dynamic structure. When we modified one histone, we changed the whole nucleosome.”

In addition to revealing new information about how histones control gene activation, Dr Tulin’s research elucidated a new mechanism of PARP1 regulation.

“This mechanism of PARP1 regulation by histones is still very new,” Dr Tulin said. “People believe that PARP1 is mainly activated through interactions with DNA, but we have found that the main pathway of PARP1 activation is through interactions with the nucleosome.”

Previous research suggested that combining standard anticancer agents with drugs that inhibit PARP1 can more effectively kill cancer cells. But clinical trials testing PARP1 inhibitors in cancer patients have produced disappointing results.

“I believe that, to a large extent, the previous setbacks were caused by a general misconception of the role of PARP1 in living cells and the mechanisms of PARP1 regulation,” Dr Tulin said. “Now that we know this mechanism of PARP1 regulation, we can design approaches to inhibit this protein in an effective way to better treat cancer.”

Dr Tulin and his colleagues are now developing the next generation of PARP1 inhibitors. Designed to block the newly identified mechanism of PARP1 activation, these inhibitors will specifically target PARP1, in contrast to the PARP1 inhibitors currently being tested in clinical trials. ![]()

Gabapentin for alcohol use disorder

Two-thirds of U.S. adults currently consume alcohol, according to the National Health Interview Survey. While most are infrequent or light drinkers, 8% are problem drinkers (more than 14 drinks per week for men and more than 7 drinks per week for women).

Alcohol consumption is the second-leading cause of preventable death and disability in the United States. Annually, excessive alcohol consumption costs us almost a quarter of a trillion dollars in lost productivity, health care, law enforcement, and motor vehicle collisions.

Alcoholism is a relapsing and remitting disease characterized by psychosocial impairment and drug craving and withdrawal. Challenged by access inequalities to formal treatment services, few alcoholics, when interacting with the medical setting for other reasons, are offered or receive treatment. Some patients may be open to receiving treatment by primary care providers, but few drugs are available (naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram). Clinicians may be unconvinced of their efficacy or uncomfortable with their use.

Gabapentin is an antiepileptic used commonly in primary care settings, mostly for neuropathic pain. Gabapentin is well tolerated, with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and a broad therapeutic index. Preclinical data suggest that gabapentin normalizes stress-induced GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) activation associated with alcohol use disorder. Human data suggest that gabapentin reduces alcohol craving and alcohol-associated sleep and mood problems.

Mason and colleagues published the results from a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of different doses of gabapentin for increasing alcohol abstinence and reducing heavy drinking, insomnia, dysphoria, and craving. Potential participants were eligible for enrollment if they were aged 18 years or older, met criteria for alcohol dependence, and were recently abstinent from alcohol (at least 3 days). Participants were randomized to gabapentin 900 mg/day, gabapentin 1,800 mg/day, or placebo. Treatment was received for 12 weeks with titration and tapering (JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:70-7).

A total of 150 patients were randomized, and the groups were similar at baseline. Abstinence rates were 17%, 11.1%, and 4.1% in the 1,800-mg, 900-mg, and placebo groups (P = .04 for linear dose effect), respectively. The no-heavy-drinking rates were 44.7%, 29.6%, and 22.5% (P = .02 for linear dose effect). A dose effect was also observed for reductions in mood disturbance, sleep problems, and craving. No serious adverse events were reported.

We need to try to meet patients where they are. Patients should be directed to alcohol treatment services if they are willing to go. In my experience, many of them are not. In these cases, recommending an Alcoholics Anonymous group, trying gabapentin, and following them up in a clinic is a harm-reduction strategy worth trying.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. He reports no conflicts of interest.

Two-thirds of U.S. adults currently consume alcohol, according to the National Health Interview Survey. While most are infrequent or light drinkers, 8% are problem drinkers (more than 14 drinks per week for men and more than 7 drinks per week for women).

Alcohol consumption is the second-leading cause of preventable death and disability in the United States. Annually, excessive alcohol consumption costs us almost a quarter of a trillion dollars in lost productivity, health care, law enforcement, and motor vehicle collisions.

Alcoholism is a relapsing and remitting disease characterized by psychosocial impairment and drug craving and withdrawal. Challenged by access inequalities to formal treatment services, few alcoholics, when interacting with the medical setting for other reasons, are offered or receive treatment. Some patients may be open to receiving treatment by primary care providers, but few drugs are available (naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram). Clinicians may be unconvinced of their efficacy or uncomfortable with their use.

Gabapentin is an antiepileptic used commonly in primary care settings, mostly for neuropathic pain. Gabapentin is well tolerated, with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and a broad therapeutic index. Preclinical data suggest that gabapentin normalizes stress-induced GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) activation associated with alcohol use disorder. Human data suggest that gabapentin reduces alcohol craving and alcohol-associated sleep and mood problems.

Mason and colleagues published the results from a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of different doses of gabapentin for increasing alcohol abstinence and reducing heavy drinking, insomnia, dysphoria, and craving. Potential participants were eligible for enrollment if they were aged 18 years or older, met criteria for alcohol dependence, and were recently abstinent from alcohol (at least 3 days). Participants were randomized to gabapentin 900 mg/day, gabapentin 1,800 mg/day, or placebo. Treatment was received for 12 weeks with titration and tapering (JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:70-7).

A total of 150 patients were randomized, and the groups were similar at baseline. Abstinence rates were 17%, 11.1%, and 4.1% in the 1,800-mg, 900-mg, and placebo groups (P = .04 for linear dose effect), respectively. The no-heavy-drinking rates were 44.7%, 29.6%, and 22.5% (P = .02 for linear dose effect). A dose effect was also observed for reductions in mood disturbance, sleep problems, and craving. No serious adverse events were reported.

We need to try to meet patients where they are. Patients should be directed to alcohol treatment services if they are willing to go. In my experience, many of them are not. In these cases, recommending an Alcoholics Anonymous group, trying gabapentin, and following them up in a clinic is a harm-reduction strategy worth trying.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. He reports no conflicts of interest.

Two-thirds of U.S. adults currently consume alcohol, according to the National Health Interview Survey. While most are infrequent or light drinkers, 8% are problem drinkers (more than 14 drinks per week for men and more than 7 drinks per week for women).

Alcohol consumption is the second-leading cause of preventable death and disability in the United States. Annually, excessive alcohol consumption costs us almost a quarter of a trillion dollars in lost productivity, health care, law enforcement, and motor vehicle collisions.

Alcoholism is a relapsing and remitting disease characterized by psychosocial impairment and drug craving and withdrawal. Challenged by access inequalities to formal treatment services, few alcoholics, when interacting with the medical setting for other reasons, are offered or receive treatment. Some patients may be open to receiving treatment by primary care providers, but few drugs are available (naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram). Clinicians may be unconvinced of their efficacy or uncomfortable with their use.

Gabapentin is an antiepileptic used commonly in primary care settings, mostly for neuropathic pain. Gabapentin is well tolerated, with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and a broad therapeutic index. Preclinical data suggest that gabapentin normalizes stress-induced GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) activation associated with alcohol use disorder. Human data suggest that gabapentin reduces alcohol craving and alcohol-associated sleep and mood problems.

Mason and colleagues published the results from a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of different doses of gabapentin for increasing alcohol abstinence and reducing heavy drinking, insomnia, dysphoria, and craving. Potential participants were eligible for enrollment if they were aged 18 years or older, met criteria for alcohol dependence, and were recently abstinent from alcohol (at least 3 days). Participants were randomized to gabapentin 900 mg/day, gabapentin 1,800 mg/day, or placebo. Treatment was received for 12 weeks with titration and tapering (JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:70-7).

A total of 150 patients were randomized, and the groups were similar at baseline. Abstinence rates were 17%, 11.1%, and 4.1% in the 1,800-mg, 900-mg, and placebo groups (P = .04 for linear dose effect), respectively. The no-heavy-drinking rates were 44.7%, 29.6%, and 22.5% (P = .02 for linear dose effect). A dose effect was also observed for reductions in mood disturbance, sleep problems, and craving. No serious adverse events were reported.

We need to try to meet patients where they are. Patients should be directed to alcohol treatment services if they are willing to go. In my experience, many of them are not. In these cases, recommending an Alcoholics Anonymous group, trying gabapentin, and following them up in a clinic is a harm-reduction strategy worth trying.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author. He reports no conflicts of interest.

Managing fever in the first month

Febrile neonates represent a challenge to clinicians as the risk for serious bacterial infections is highest at this age, the presence of discriminating clinical signs are often absent, and outcomes can be poor in the absence of early treatment. For this reason, most experts recommend that all neonates with a rectal temperature 38°C or higher have blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures regardless of clinical appearance (Ann. Emerg. Med. 1993;22:1198-1210). Such neonates should be admitted to the hospital and treated with empiric antibiotics.

In a study of 41,890 neonates (up to 28 days of age) evaluated in 36 pediatric emergency departments, 2,253 (5.4%) were febrile. Three hundred sixty-nine (16%) infants were seen, then discharged from the ED; the remaining 1,884 (84%) were seen and admitted.

As with prior studies, a high rate of serious infection (12%) was documented; urinary tract infection (27%), meningitis (19%), bacteremia and sepsis (14%), cellulitis and soft tissue infections (6%), and pneumonia (3%) were most common. Of the 369 infants discharged, 3 (1%) had serious infection; of the 1,884 admitted, 266 (14%) did.

The study demonstrated significant variability in the approach used to evaluate and treat febrile neonates, with 16% of infants being discharged from the emergency department, the majority of whom (97%) did not get antimicrobial therapy. Sixty-four (3%) of all febrile infants were discharged without any laboratory evaluation or treatment. Eighty-four percent of febrile infants were admitted to the hospital, and 96% of those admitted received antimicrobial treatment (Pediatrics 2014;133:187).

Prior studies reported that serious bacterial infection was uncommon in febrile neonates who met the following six low-risk criteria: 1. an unremarkable medical history, 2. a healthy, nontoxic appearance, 3. no focal signs of infection, 4. an erythrocyte sedimentation rate less than 30 mm at the end of the first hour, 5. a white blood cell count of 5,000-15,000/mcL, and 6. a normal urine analysis (Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F15-8).

Although it is unclear what criteria were used to discharge febrile neonates from the pediatric ED in the current study, only 1 of the 369 neonates discharged from the pediatric ED subsequently returned to the same pediatric ED and was diagnosed with serious infection; however, only 10 in total returned for evaluation. How many subsequently were diagnosed with serious infection at a different facility is unknown. These results were consistent with the initial studies of the "low-risk criteria," which indicates these criteria are not sufficiently reliable to exclude the presence of serious infection.

The study demonstrates that there remains disagreement about how febrile neonates should be evaluated and managed in the ED setting, and how much reliance should be placed on clinical and laboratory parameters. Unlike children older than 3 months of age, in whom immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines has dramatically reduced the incidence of invasive disease, serious infection in febrile neonates up to 28 days of age remains common.

The current spectrum of pathogens and disease – gram-negative uropathogens, staphylococcal and streptococcal skin and soft tissue infections, group B Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, and CNS infection – have not been significantly impacted by efforts to prevent "early-onset" neonatal sepsis and by vaccine strategies that target primarily older children. Age remains a risk, with a decreasing incidence of serious bacterial infection as each week of life passes. However, in another study, the rate of serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates 15-21 days of age was found to be sufficiently high to warrant comparable management to that given younger neonates (Pediatr. Inf. Dis. J. 2012;31:455-8).

Thus, currently there seem to be few strategies that would protect febrile neonates from delays in therapy and preventable outcomes, other than the traditional practice of thorough medical evaluation, laboratory testing to include blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures, chest x-ray when respiratory tract signs/symptoms are present, and presumptive treatment with parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Office-based studies report greater reliance on clinical judgment with the belief that reliance on clinical guidelines would have only a small benefit, if any, but would result in greater hospitalization and laboratory testing (JAMA 2004;291:1203-12). Still the high rate of disease (14%) in those admitted to the hospital underscore the vulnerability of this age group, the significance of fever, and the potential for a poor outcome without thorough evaluation of each child and presumptive treatment for serious bacterial infection.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail him at [email protected].

Febrile neonates represent a challenge to clinicians as the risk for serious bacterial infections is highest at this age, the presence of discriminating clinical signs are often absent, and outcomes can be poor in the absence of early treatment. For this reason, most experts recommend that all neonates with a rectal temperature 38°C or higher have blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures regardless of clinical appearance (Ann. Emerg. Med. 1993;22:1198-1210). Such neonates should be admitted to the hospital and treated with empiric antibiotics.

In a study of 41,890 neonates (up to 28 days of age) evaluated in 36 pediatric emergency departments, 2,253 (5.4%) were febrile. Three hundred sixty-nine (16%) infants were seen, then discharged from the ED; the remaining 1,884 (84%) were seen and admitted.

As with prior studies, a high rate of serious infection (12%) was documented; urinary tract infection (27%), meningitis (19%), bacteremia and sepsis (14%), cellulitis and soft tissue infections (6%), and pneumonia (3%) were most common. Of the 369 infants discharged, 3 (1%) had serious infection; of the 1,884 admitted, 266 (14%) did.

The study demonstrated significant variability in the approach used to evaluate and treat febrile neonates, with 16% of infants being discharged from the emergency department, the majority of whom (97%) did not get antimicrobial therapy. Sixty-four (3%) of all febrile infants were discharged without any laboratory evaluation or treatment. Eighty-four percent of febrile infants were admitted to the hospital, and 96% of those admitted received antimicrobial treatment (Pediatrics 2014;133:187).

Prior studies reported that serious bacterial infection was uncommon in febrile neonates who met the following six low-risk criteria: 1. an unremarkable medical history, 2. a healthy, nontoxic appearance, 3. no focal signs of infection, 4. an erythrocyte sedimentation rate less than 30 mm at the end of the first hour, 5. a white blood cell count of 5,000-15,000/mcL, and 6. a normal urine analysis (Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F15-8).

Although it is unclear what criteria were used to discharge febrile neonates from the pediatric ED in the current study, only 1 of the 369 neonates discharged from the pediatric ED subsequently returned to the same pediatric ED and was diagnosed with serious infection; however, only 10 in total returned for evaluation. How many subsequently were diagnosed with serious infection at a different facility is unknown. These results were consistent with the initial studies of the "low-risk criteria," which indicates these criteria are not sufficiently reliable to exclude the presence of serious infection.

The study demonstrates that there remains disagreement about how febrile neonates should be evaluated and managed in the ED setting, and how much reliance should be placed on clinical and laboratory parameters. Unlike children older than 3 months of age, in whom immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines has dramatically reduced the incidence of invasive disease, serious infection in febrile neonates up to 28 days of age remains common.

The current spectrum of pathogens and disease – gram-negative uropathogens, staphylococcal and streptococcal skin and soft tissue infections, group B Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, and CNS infection – have not been significantly impacted by efforts to prevent "early-onset" neonatal sepsis and by vaccine strategies that target primarily older children. Age remains a risk, with a decreasing incidence of serious bacterial infection as each week of life passes. However, in another study, the rate of serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates 15-21 days of age was found to be sufficiently high to warrant comparable management to that given younger neonates (Pediatr. Inf. Dis. J. 2012;31:455-8).

Thus, currently there seem to be few strategies that would protect febrile neonates from delays in therapy and preventable outcomes, other than the traditional practice of thorough medical evaluation, laboratory testing to include blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures, chest x-ray when respiratory tract signs/symptoms are present, and presumptive treatment with parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Office-based studies report greater reliance on clinical judgment with the belief that reliance on clinical guidelines would have only a small benefit, if any, but would result in greater hospitalization and laboratory testing (JAMA 2004;291:1203-12). Still the high rate of disease (14%) in those admitted to the hospital underscore the vulnerability of this age group, the significance of fever, and the potential for a poor outcome without thorough evaluation of each child and presumptive treatment for serious bacterial infection.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail him at [email protected].

Febrile neonates represent a challenge to clinicians as the risk for serious bacterial infections is highest at this age, the presence of discriminating clinical signs are often absent, and outcomes can be poor in the absence of early treatment. For this reason, most experts recommend that all neonates with a rectal temperature 38°C or higher have blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures regardless of clinical appearance (Ann. Emerg. Med. 1993;22:1198-1210). Such neonates should be admitted to the hospital and treated with empiric antibiotics.

In a study of 41,890 neonates (up to 28 days of age) evaluated in 36 pediatric emergency departments, 2,253 (5.4%) were febrile. Three hundred sixty-nine (16%) infants were seen, then discharged from the ED; the remaining 1,884 (84%) were seen and admitted.

As with prior studies, a high rate of serious infection (12%) was documented; urinary tract infection (27%), meningitis (19%), bacteremia and sepsis (14%), cellulitis and soft tissue infections (6%), and pneumonia (3%) were most common. Of the 369 infants discharged, 3 (1%) had serious infection; of the 1,884 admitted, 266 (14%) did.

The study demonstrated significant variability in the approach used to evaluate and treat febrile neonates, with 16% of infants being discharged from the emergency department, the majority of whom (97%) did not get antimicrobial therapy. Sixty-four (3%) of all febrile infants were discharged without any laboratory evaluation or treatment. Eighty-four percent of febrile infants were admitted to the hospital, and 96% of those admitted received antimicrobial treatment (Pediatrics 2014;133:187).

Prior studies reported that serious bacterial infection was uncommon in febrile neonates who met the following six low-risk criteria: 1. an unremarkable medical history, 2. a healthy, nontoxic appearance, 3. no focal signs of infection, 4. an erythrocyte sedimentation rate less than 30 mm at the end of the first hour, 5. a white blood cell count of 5,000-15,000/mcL, and 6. a normal urine analysis (Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F15-8).

Although it is unclear what criteria were used to discharge febrile neonates from the pediatric ED in the current study, only 1 of the 369 neonates discharged from the pediatric ED subsequently returned to the same pediatric ED and was diagnosed with serious infection; however, only 10 in total returned for evaluation. How many subsequently were diagnosed with serious infection at a different facility is unknown. These results were consistent with the initial studies of the "low-risk criteria," which indicates these criteria are not sufficiently reliable to exclude the presence of serious infection.

The study demonstrates that there remains disagreement about how febrile neonates should be evaluated and managed in the ED setting, and how much reliance should be placed on clinical and laboratory parameters. Unlike children older than 3 months of age, in whom immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines has dramatically reduced the incidence of invasive disease, serious infection in febrile neonates up to 28 days of age remains common.