User login

PSA screening: The USPSTF got it right

In his book, How We Do Harm: A Doctor Breaks Ranks About Being Sick in America, Otis Brawley1 writes, “I believe that a man should know what we know, what we don’t know, and what we believe about prostate cancer. I have been concerned that many patients and physicians have confused what is believed with what is known.” I agree.

Common sense is what we believe. Does common sense trump science? Did the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) get it wrong? I don’t think so.

The USPSTF bases its recommendations on an explicit assessment of the science that informs us of the benefits and harms of a preventive service, and a judgment about the magnitude of net benefit.

So what do we know about the benefits of prostate cancer screening? When attempting to answer the question of whether an intervention is beneficial, there is a hierarchy of evidence, from most likely to be wrong to most likely to be right. Relying on our personal stories is the former; relying on well-conducted randomized trials is the latter.

In the multicenter Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial2 conducted in the United States, there was a nonsignificant increase in prostate-cancer mortality in the screening group, while the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC)3 trial showed a statistically significant absolute reduction of 0.10 prostate-cancer deaths per 1000 person-years after a median follow-up of 11 years. In the ERSPC trial, all-cause mortality was 19.1% in the screened group and 19.3% in the control group, a difference that was not significant. What we know is that after 10 years, even with aggressive treatment of 80% to 90% of screen-detected cancers, very few, if any, men will have lived longer because they were screened.

What don’t we know about the benefits? We don’t know whether following screened and nonscreened men for 15 or 20 years or longer will demonstrate a larger difference in mortality. Competing causes of mortality make it progressively less likely that men who are screened will actually live longer. The average age of death from prostate cancer is 80 years, and 70% of all deaths occur after age 75.4 Contrast those statistics to breast cancer, for which the average age of death is 68 years and 63% of all deaths occur before age 75.5

What do we believe about the benefits? Some certainly believe the trials must be wrong; common sense tells us that early detection and treatment must provide more benefit than what the evidence has shown. Common sense tells us that the decline in prostate cancer mortality over the past 2 decades must be due to screening, although the ERSPC results clearly show that neither the magnitude nor the timing of the decline can be attributed to screening.

What do we know—and not know—about the harms?

We know that much of the suffering from prostate cancer is a consequence of the diagnosis and management of the disease, rather than the disease itself. Complications of both diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer are frequent and serious.6 We also know that many screen-detected cancers would never become apparent in a man’s lifetime without screening.

We don’t know the precise magnitude of overdiagnosis, although all estimates suggest it is substantial. In the ERSPC trial, 9.6% of the screened group received a prostate cancer diagnosis, vs 6.0% of the control group—a 60% increase in the rate of diagnosis. The recently published long-term results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial7 are enlightening. Finasteride reduced the incidence of screen-detected cancers by 30%, with no impact on all-cause mortality at 18 years. If those screen-detected cancers had been a significant threat to health, then after 18 years we would have expected some mortality benefit from finasteride.

What do we believe about the harms of screening?

We believe that by being more conservative about who gets treated, we shift the balance of benefits and harms of screening. There is no question that reducing the burden of overdiagnosis and overtreatment would provide a welcome reduction in the harms. But can we do it?8

In the United States 90% of men found to have prostate cancer are treated (including about 75% of men with low-risk cancers).6 And although we hope to be able to reduce harms without changing benefits, we do not know what impact more conservative management of screen-detected cancers would have on the already small effect of screening on prostate cancer mortality.

So what is the balance of benefit and harms? Should we make that judgment on what we know, or on what we believe?

Science trumps common sense. For every 1000 men screened, at most, one will avoid a prostate cancer death at 10 years. But 30 to 40 will have erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, or both due to treatment, 2 men will experience a serious cardiovascular event, one will have a venous thromboembolic event, and one in 3000 screened will die from complications of surgical treatment.6

The USPSTF concluded that the benefits of PSA screening do not outweigh the harms, but acknowledged that shared decision making is still appropriate when a physician feels obliged to offer the test or a patient requests it.

What does shared decision making look like? Just offering screening and answering any questions is not good enough. We do an enormous disservice to our patients if we pretend that this is just a blood test and that we can decide later what to do with the information. Men will get biopsies and there will be complications. Cancer will be detected, and men will be treated, many unnecessarily.

We need to tell our patients that the likelihood of avoiding a prostate cancer death over 10 years as a result of regular PSA screening is at most very small, and that many more men will suffer the harms of unnecessary treatment than will benefit. A few will die prematurely as a result of the complications of treating a screen-detected cancer.

If, with this knowledge, a patient places a higher value on the possibility of avoiding a prostate cancer death than he does on the known harms of diagnosis and treatment, he can still decide to be screened. He has made an informed decision. However, routine screening for prostate cancer in the absence of a truly informed decision is unacceptable.

1. Brawley OW, Goldberg P. How We Do Harm: A Doctor Breaks Ranks About Being Sick in America. NY: St. Martin's Press; 2011.

2. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grub III RL, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125-132.

3. Schröder FH, et al; ERSPC investigators. Prostate cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:981-990.

4. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Prostate. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. 2012. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed August 28, 2013.

5. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. 2012. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed August 28, 2013.

6. Chou R, Crosswell, JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: A review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:762-771.

7. Thompson IM Jr, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Long-term survival of participants in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:603-610.

8. Sartor AO. Surveillance for prostate cancer: are the proceduralists running amok? Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27:523, 589.

In his book, How We Do Harm: A Doctor Breaks Ranks About Being Sick in America, Otis Brawley1 writes, “I believe that a man should know what we know, what we don’t know, and what we believe about prostate cancer. I have been concerned that many patients and physicians have confused what is believed with what is known.” I agree.

Common sense is what we believe. Does common sense trump science? Did the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) get it wrong? I don’t think so.

The USPSTF bases its recommendations on an explicit assessment of the science that informs us of the benefits and harms of a preventive service, and a judgment about the magnitude of net benefit.

So what do we know about the benefits of prostate cancer screening? When attempting to answer the question of whether an intervention is beneficial, there is a hierarchy of evidence, from most likely to be wrong to most likely to be right. Relying on our personal stories is the former; relying on well-conducted randomized trials is the latter.

In the multicenter Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial2 conducted in the United States, there was a nonsignificant increase in prostate-cancer mortality in the screening group, while the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC)3 trial showed a statistically significant absolute reduction of 0.10 prostate-cancer deaths per 1000 person-years after a median follow-up of 11 years. In the ERSPC trial, all-cause mortality was 19.1% in the screened group and 19.3% in the control group, a difference that was not significant. What we know is that after 10 years, even with aggressive treatment of 80% to 90% of screen-detected cancers, very few, if any, men will have lived longer because they were screened.

What don’t we know about the benefits? We don’t know whether following screened and nonscreened men for 15 or 20 years or longer will demonstrate a larger difference in mortality. Competing causes of mortality make it progressively less likely that men who are screened will actually live longer. The average age of death from prostate cancer is 80 years, and 70% of all deaths occur after age 75.4 Contrast those statistics to breast cancer, for which the average age of death is 68 years and 63% of all deaths occur before age 75.5

What do we believe about the benefits? Some certainly believe the trials must be wrong; common sense tells us that early detection and treatment must provide more benefit than what the evidence has shown. Common sense tells us that the decline in prostate cancer mortality over the past 2 decades must be due to screening, although the ERSPC results clearly show that neither the magnitude nor the timing of the decline can be attributed to screening.

What do we know—and not know—about the harms?

We know that much of the suffering from prostate cancer is a consequence of the diagnosis and management of the disease, rather than the disease itself. Complications of both diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer are frequent and serious.6 We also know that many screen-detected cancers would never become apparent in a man’s lifetime without screening.

We don’t know the precise magnitude of overdiagnosis, although all estimates suggest it is substantial. In the ERSPC trial, 9.6% of the screened group received a prostate cancer diagnosis, vs 6.0% of the control group—a 60% increase in the rate of diagnosis. The recently published long-term results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial7 are enlightening. Finasteride reduced the incidence of screen-detected cancers by 30%, with no impact on all-cause mortality at 18 years. If those screen-detected cancers had been a significant threat to health, then after 18 years we would have expected some mortality benefit from finasteride.

What do we believe about the harms of screening?

We believe that by being more conservative about who gets treated, we shift the balance of benefits and harms of screening. There is no question that reducing the burden of overdiagnosis and overtreatment would provide a welcome reduction in the harms. But can we do it?8

In the United States 90% of men found to have prostate cancer are treated (including about 75% of men with low-risk cancers).6 And although we hope to be able to reduce harms without changing benefits, we do not know what impact more conservative management of screen-detected cancers would have on the already small effect of screening on prostate cancer mortality.

So what is the balance of benefit and harms? Should we make that judgment on what we know, or on what we believe?

Science trumps common sense. For every 1000 men screened, at most, one will avoid a prostate cancer death at 10 years. But 30 to 40 will have erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, or both due to treatment, 2 men will experience a serious cardiovascular event, one will have a venous thromboembolic event, and one in 3000 screened will die from complications of surgical treatment.6

The USPSTF concluded that the benefits of PSA screening do not outweigh the harms, but acknowledged that shared decision making is still appropriate when a physician feels obliged to offer the test or a patient requests it.

What does shared decision making look like? Just offering screening and answering any questions is not good enough. We do an enormous disservice to our patients if we pretend that this is just a blood test and that we can decide later what to do with the information. Men will get biopsies and there will be complications. Cancer will be detected, and men will be treated, many unnecessarily.

We need to tell our patients that the likelihood of avoiding a prostate cancer death over 10 years as a result of regular PSA screening is at most very small, and that many more men will suffer the harms of unnecessary treatment than will benefit. A few will die prematurely as a result of the complications of treating a screen-detected cancer.

If, with this knowledge, a patient places a higher value on the possibility of avoiding a prostate cancer death than he does on the known harms of diagnosis and treatment, he can still decide to be screened. He has made an informed decision. However, routine screening for prostate cancer in the absence of a truly informed decision is unacceptable.

In his book, How We Do Harm: A Doctor Breaks Ranks About Being Sick in America, Otis Brawley1 writes, “I believe that a man should know what we know, what we don’t know, and what we believe about prostate cancer. I have been concerned that many patients and physicians have confused what is believed with what is known.” I agree.

Common sense is what we believe. Does common sense trump science? Did the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) get it wrong? I don’t think so.

The USPSTF bases its recommendations on an explicit assessment of the science that informs us of the benefits and harms of a preventive service, and a judgment about the magnitude of net benefit.

So what do we know about the benefits of prostate cancer screening? When attempting to answer the question of whether an intervention is beneficial, there is a hierarchy of evidence, from most likely to be wrong to most likely to be right. Relying on our personal stories is the former; relying on well-conducted randomized trials is the latter.

In the multicenter Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial2 conducted in the United States, there was a nonsignificant increase in prostate-cancer mortality in the screening group, while the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC)3 trial showed a statistically significant absolute reduction of 0.10 prostate-cancer deaths per 1000 person-years after a median follow-up of 11 years. In the ERSPC trial, all-cause mortality was 19.1% in the screened group and 19.3% in the control group, a difference that was not significant. What we know is that after 10 years, even with aggressive treatment of 80% to 90% of screen-detected cancers, very few, if any, men will have lived longer because they were screened.

What don’t we know about the benefits? We don’t know whether following screened and nonscreened men for 15 or 20 years or longer will demonstrate a larger difference in mortality. Competing causes of mortality make it progressively less likely that men who are screened will actually live longer. The average age of death from prostate cancer is 80 years, and 70% of all deaths occur after age 75.4 Contrast those statistics to breast cancer, for which the average age of death is 68 years and 63% of all deaths occur before age 75.5

What do we believe about the benefits? Some certainly believe the trials must be wrong; common sense tells us that early detection and treatment must provide more benefit than what the evidence has shown. Common sense tells us that the decline in prostate cancer mortality over the past 2 decades must be due to screening, although the ERSPC results clearly show that neither the magnitude nor the timing of the decline can be attributed to screening.

What do we know—and not know—about the harms?

We know that much of the suffering from prostate cancer is a consequence of the diagnosis and management of the disease, rather than the disease itself. Complications of both diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer are frequent and serious.6 We also know that many screen-detected cancers would never become apparent in a man’s lifetime without screening.

We don’t know the precise magnitude of overdiagnosis, although all estimates suggest it is substantial. In the ERSPC trial, 9.6% of the screened group received a prostate cancer diagnosis, vs 6.0% of the control group—a 60% increase in the rate of diagnosis. The recently published long-term results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial7 are enlightening. Finasteride reduced the incidence of screen-detected cancers by 30%, with no impact on all-cause mortality at 18 years. If those screen-detected cancers had been a significant threat to health, then after 18 years we would have expected some mortality benefit from finasteride.

What do we believe about the harms of screening?

We believe that by being more conservative about who gets treated, we shift the balance of benefits and harms of screening. There is no question that reducing the burden of overdiagnosis and overtreatment would provide a welcome reduction in the harms. But can we do it?8

In the United States 90% of men found to have prostate cancer are treated (including about 75% of men with low-risk cancers).6 And although we hope to be able to reduce harms without changing benefits, we do not know what impact more conservative management of screen-detected cancers would have on the already small effect of screening on prostate cancer mortality.

So what is the balance of benefit and harms? Should we make that judgment on what we know, or on what we believe?

Science trumps common sense. For every 1000 men screened, at most, one will avoid a prostate cancer death at 10 years. But 30 to 40 will have erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, or both due to treatment, 2 men will experience a serious cardiovascular event, one will have a venous thromboembolic event, and one in 3000 screened will die from complications of surgical treatment.6

The USPSTF concluded that the benefits of PSA screening do not outweigh the harms, but acknowledged that shared decision making is still appropriate when a physician feels obliged to offer the test or a patient requests it.

What does shared decision making look like? Just offering screening and answering any questions is not good enough. We do an enormous disservice to our patients if we pretend that this is just a blood test and that we can decide later what to do with the information. Men will get biopsies and there will be complications. Cancer will be detected, and men will be treated, many unnecessarily.

We need to tell our patients that the likelihood of avoiding a prostate cancer death over 10 years as a result of regular PSA screening is at most very small, and that many more men will suffer the harms of unnecessary treatment than will benefit. A few will die prematurely as a result of the complications of treating a screen-detected cancer.

If, with this knowledge, a patient places a higher value on the possibility of avoiding a prostate cancer death than he does on the known harms of diagnosis and treatment, he can still decide to be screened. He has made an informed decision. However, routine screening for prostate cancer in the absence of a truly informed decision is unacceptable.

1. Brawley OW, Goldberg P. How We Do Harm: A Doctor Breaks Ranks About Being Sick in America. NY: St. Martin's Press; 2011.

2. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grub III RL, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125-132.

3. Schröder FH, et al; ERSPC investigators. Prostate cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:981-990.

4. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Prostate. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. 2012. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed August 28, 2013.

5. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. 2012. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed August 28, 2013.

6. Chou R, Crosswell, JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: A review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:762-771.

7. Thompson IM Jr, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Long-term survival of participants in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:603-610.

8. Sartor AO. Surveillance for prostate cancer: are the proceduralists running amok? Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27:523, 589.

1. Brawley OW, Goldberg P. How We Do Harm: A Doctor Breaks Ranks About Being Sick in America. NY: St. Martin's Press; 2011.

2. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grub III RL, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:125-132.

3. Schröder FH, et al; ERSPC investigators. Prostate cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:981-990.

4. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Prostate. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. 2012. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Accessed August 28, 2013.

5. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program Web site. 2012. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed August 28, 2013.

6. Chou R, Crosswell, JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: A review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:762-771.

7. Thompson IM Jr, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Long-term survival of participants in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:603-610.

8. Sartor AO. Surveillance for prostate cancer: are the proceduralists running amok? Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27:523, 589.

Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) affects almost half of all women in the United States.1,2 Estimates suggest that the prevalence of UI gradually rises during young adult life, comes to a broad plateau in middle age, and then steadily increases from that plateau after age 65. Therefore, over the next 40 years, as the elderly population expands in size, the number of women affected by UI will significantly grow.3

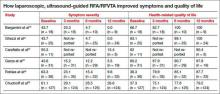

For patients with UI, a multitude of therapeutic options are available. Which option is the best for your patient? In this article, we aim to answer that question by interpreting the results of four randomized trials, each of which directly compare two available treatment options. The first study examines patients with stress urinary incontinence (SUI), comparing the patients’ subjective improvement in urinary leakage and bladder function at 12 months after randomization to treatment with physiotherapy or midurethral sling surgery.

The three other trials examine patients with overactive bladder (OAB) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Each trial directly compares the use of anticholinergic medications to an alternate treatment modality. Currently, anticholinergic medications and behavioral therapy are the recommended first-line therapies for OAB. Unfortunately, anticholinergic medications have poor patient compliance and significant systemic side effects.4 Caution should be used when considering anticholinergic medications in patients with impaired gastric emptying or a history of urinary retention. They also should be used with caution in elderly patients who are extremely frail. Additionally, clearance from an ophthalmologist must be obtained prior to starting anticholinergic medication in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma.5 Due to poor adherence and potential side effects, there is a growing effort to discover alternative treatment modalities that are safe and effective. Therefore, we chose to examine trials comparing: mirabegron versus tolterodine, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus tolterodine, and onabotulinumtoxinA versus anticholingeric medications.

UI defined

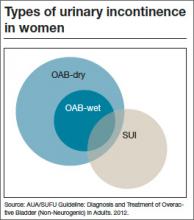

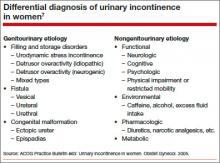

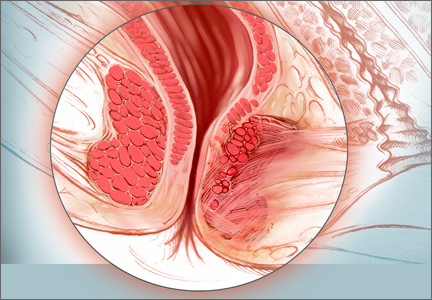

Before discussing treatment options, we want to clarify the main types of UI (FIGURE). UI is defined as the complaint of involuntary loss of urine. UI can be subdivided into SUI, OAB/UUI, or mixed urinary incontinence.6 While there are other less common genitourinary etiologies that can lead to UI, nongenitourinary etiologies are prevalent and can aggravate existing SUI or OAB (TABLE).

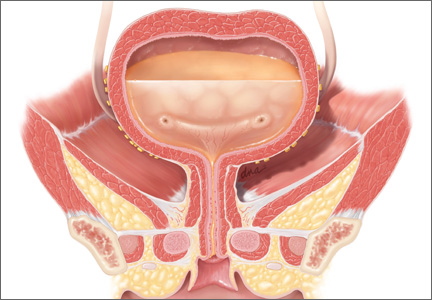

SUI is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion (such as during sporting activities) or on sneezing or coughing. Often, SUI can be diagnosed by patient report alone and surgery can be considered in symptomatic patients who demonstrate cough leakage on physical examination and normal postvoid residual volumes.

UUI is the involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency; it often occurs in the setting of OAB, which is defined as the syndrome of urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without UUI, in the absence of urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology (such as neurologic dysfunction, infection, or urologic neoplasm). OAB-dry is present when patients do not have leakage with urgency, but are bothered by urgency, frequency, and/or nocturia. OAB-wet occurs when a patient has urgencyincontinence.

The presence of both SUI and OAB/UUI is known as mixed urinary incontinence. Stress and urgency urinary symptoms often present together. In fact, 10% to 30% of women with stress symptoms are found to have bladder overactivity on subsequent evaluation.2,7 Therefore, it is important to take a good history and consider urodynamic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of SUI prior to surgery in women with mixed stress and urge symptoms, a history of a previous surgery for incontinence, or when there is a poor correlation of physical examination findings to reported symptoms.

Is surgery a first-line option for patients with SUI?

Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. NEJM. 2013;369(12):1124−1133.

Physiotherapy, including pelvic floor muscle training (“Kegel exercises”), is utilized as a first-line treatment option for women with SUI that carries minimal risk for the patient. Midurethral sling surgery is often recommended if an initial trial of conservative treatment fails.7 Up to 50% of women treated with pelvic floor physiotherapy will ultimately undergo surgery to treat their SUI.8

Related article: Does urodynamic testing before surgery for stress incontinence improve outcomes? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, December 2012)

Details of the study

This was a randomized, multicenter trial of women aged 35 to 80 years with moderate to severe SUI. After excluding women with previous incontinence surgery and stage 2 or higher pelvic organ prolapse, 460 participants were randomly assigned to undergo either a midurethral sling surgery or physiotherapy (pelvic floor muscle training). The primary outcome was subjective improvement in urinary leakage and bladder function at 12 months, as measured by the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “very much worse” to “very much better.”

In an intention-to-treat analysis, subjective improvement at 12 months was significantly higher in women randomized to midurethral sling surgery than in women randomized to physiotherapy (91% vs 64%, respectively).

Ten percent of patients had adverse events (AEs); all were related to surgery. The most common AEs were hematoma, vaginal epithelial perforation, and bladder perforation.

Notably, women had the option to cross over to the other treatment modality if they desired. In the physiotherapy group, 49% of women elected to cross over to surgery, while 11% of those who underwent midurethral sling surgery elected to cross over to physiotherapy during the 12-month follow-up period. When analyzing results by treatment received, the investigators found that the proportion of women who reported improvement was significantly lower among women who underwent physiotherapy only (32%), versus sling only (94%), or sling after physiotherapy (91%).

This randomized trial was well-designed and included a variety of treatment centers (university and general hospitals) with interventions performed by experienced surgeons (all of whom had performed at least 20 sling surgeries) and physiotherapists educated specifically in pelvic floor physiotherapy. The study population was limited to patients with moderate to severe SUI as defined by the Sandvik severity index.9 Therefore, these results may not be applicable to patients with milder symptoms, for whom physiotherapy has been recommended as first-line therapy with consideration of surgery if physiotherapy fails to sufficiently improve symptoms.7

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Women with moderate to severe SUI without significant prolapse or a history of prior incontinence surgery have significantly better outcomes at 12 months after undergoing midurethral sling surgery versus physiotherapy. Physiotherapy carries little to no risk of adverse effects. Women with moderate to severe SUI should be counseled regarding the risks and benefits of both physiotherapy and midurethral sling surgery as initial treatment options.

Because stress and urgency urinary symptoms often present together, it is important to consider urodynamic evaluation to confirm SUI prior to surgery in women with:

• mixed stress and urge symptoms

• a history of a previous surgery for incontinence, or

• poor correlation of physical examination findings to reported symptoms.

Safety and tolerability of mirabegron versus tolterodine for OAB

Chapple CR, Kaplan SA, Mitcheson D, et al. Randomized double-blind, active-controlled phase 3 study to assess 12-month safety and efficacy of mirabegron, a beta(3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2013;63(2):296−305.

In the bladder, beta3-receptors located within the detrusor smooth muscle facilitate urine storage by relaxing the detrusor, enabling the bladder to fill.10 The activation of beta3-receptors is thought to increase the bladder’s ability to store urine, with the goal of decreasing urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urgency incontinence. An alternative to anticholinergic medications, mirabegron is a beta3-agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for clinical use in the treatment of OAB.

Details of the study

Chapple and colleagues aimed to assess the 12-month efficacy and safety of mirabegron in a randomized, double-blind active controlled trial. The primary outcome was incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs); the secondary outcome was the change in OAB symptoms from baseline to up to 12 months. Patients experiencing OAB symptoms for more than 3 months were eligible and were subsequently enrolled if they averaged 8 or more voids per day and 3 or more episodes of urgency with or without incontinence on a 3-day bladder diary. A total of 2,444 patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 fashion to mirabegron 50 mg daily, mirabegron 100 mg daily, or tolterodine extended release (ER) 4 mg daily.

There was a similar incidence (60% to 63%) of TEAEs across all three groups. The most common TEAEs were hypertension (defined as average systolic blood pressure [BP] >140 mm Hg or average diastolic BP >90 mm Hg at two consecutive visits), UTI, headache, nasopharyngitis, and constipation. The adjusted mean changes in BP from baseline to final visit were less than 1 mm Hg for both systolic and diastolic BP for patients taking both doses of mirabegron, as well as for patients taking tolterodine. The incidence of dry mouth was higher in the tolterodine group than the mirabegron groups. Mirabegron 50 mg daily and 100 mg daily improved incontinence symptoms within 1 month of starting therapy; the degree of improvement was similar to that seen in the patients taking tolterodine ER 4 mg daily.

Related article: New overactive bladder treatment approved by the FDA (August 2012)

Some caveats

This study was well-designed to assess the safety and tolerability of mirabegron versus tolterodine. The doses utilized in the study were at or above the FDA-approved dosage of 25 mg to 50 mg daily for OAB treatment. Although investigators found mirabegron to be a safe alternative to anticholinergic medication, the study was not designed or powered to examine the efficacy of mirabegron versus tolterodine. No formal comparison of efficacy was made between mirabegron or tolterodine, or between the 50-mg and 100-mg doses of mirabegron. Moreover, 81% of participants had been treated with mirabegron in earlier Phase 3 studies, so most were not treatment naïve, limiting the applicability of results.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Mirabegron should be considered as a potential treatment option for patients who demonstrate poor tolerance of or response to anticholinergic medications; however, caution should be used in patients with severe uncontrolled high BP, end-stage kidney disease, or severe liver impairment.

Consider percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation over tolterodine for OAB in select patients

Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, et al. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: Results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol. 2009;182(3):1055−1061.

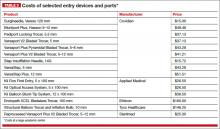

Neuromodulation utilizes electrical stimulation to improve bladder function and decrease OAB symptoms. First developed in the early 1980s by McGuire and colleagues, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) was approved by the FDA in 2000 as Urgent PC and provides an outpatient, nonimplantable neuromodulation alternative to medication therapy for patients with OAB.11,12 By directly stimulating the posterior tibial nerve, PTNS works via the S3 sacral nerve plexus to alter the micturition reflex and improve bladder function.

Details of the study

Patients were eligible for the study if they demonstrated 8 or more voids per day on a 3-day bladder diary (whether or not they had a history of previous anticholinergic drug use). A total of 100 ambulatory adults with OAB symptoms were enrolled and randomly assigned to PTNS 30-minutes per week or tolterodine ER 4 mg daily.

At 12 weeks, both groups demonstrated a significant improvement in OAB measures as well as validated symptom severity and quality-of-life questionnaire scores. Subjective assessment of improvement in OAB symptoms was significantly greater in the PTNS group than in the tolterodine group (79.5% vs 54.8%, respectively; P = .01). However, mean reduction of voids for 24 hours was not significantly different between the two groups.

Both treatments were well tolerated, with only 15% to 16% of patients in both groups reporting mild to moderate side effects. The tolterodine group did have a significantly higher risk of dry mouth; however, the risk of constipation was not significantly different between the groups.

Study limitations

The authors performed an important multicenter, nonblinded, randomized, controlled trial, which was one of the first trials to directly compare two OAB therapies. The generalizability of the findings were limited, as the cohort included mostly patients with dry OAB who had no objective measures on UUI episodes. In addition, this trial had a limited observation period of only 12 weeks. Information regarding the effect of treatment after cessation of weekly PTNS therapy was not examined. Therefore, we are not able to determine whether repeat sessions provide adequate maintenance in the long term.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

PTNS 30 minutes daily is as effective as tolterodine ER 4 mg daily for 12 weeks in reducing OAB symptoms. PTNS is a safe alternative that should be considered in patients with OAB who poorly tolerate or have contraindications to medication therapy.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is an effective therapy for OAB

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al. Anticholinergic therapy vs onabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. NEJM. 2012;367(19):1803−1813.

The newest therapy for OAB is onabotulinumtoxinA, or Botox, which was FDA approved this year for the treatment of OAB in adults who cannot use or do not tolerate anticholinergic medications. Recommended doses are 100 U onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with idiopathic refractory OAB and 200 U onabotulinumtoxinA for patients with neurogenic OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin that blocks synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction to cause muscle paralysis and atrophy.13 Injecting onabotulinumtoxinA into the detrusor smooth muscle should relax the bladder and decrease sensations of urgency and frequency to achieve a longer duration of time for bladder filling and reduce the risk of urgency incontinence.

Effects of onabotulinumtoxinA appear to wear off over time, and patients may require repeat injections. Side effects of onabotulinumtoxinA therapy include an increased risk of UTI and the potential for urinary retention requiring intermittent self-catheterization.

Related article: Update on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (October 2012)

Details of the study

The Anticholinergic Versus Botulinum Toxin Comparison (ABC) study was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-placebo–controlled trial conducted in women without known neurologic disease with moderate to severe UUI (defined as >5 UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary). Women were randomly assigned to a single intradetrusor injection of 100 U onabotulinumtoxinA plus oral placebo or to a single intradetrusor injection of saline plus solifenacin 5 mg daily (with the option of dose escalation and then switching to trospium XR if no improvement was seen).

Of the 241 women included in the final analysis, approximately 70% in each group reported adequate control of symptoms at 6 months. Adequate control was defined as a response of “agree strongly” or “agree” to the statement: “This treatment has given me adequate control of my urinary leakage.” Women in the onabotulinumtoxinA group were significantly more likely than women in the anticholinergic medication group to report complete resolution of UUI at 6 months (27% vs 13%, P = .003). However, the mean reduction in episodes of UUI per day and the improvements in quality-of-life questionnaire scores were found to be similar. Interestingly, worse baseline UUI was associated with greater reduction in episodes of UUI for both therapies.

This was a rigorous and well-executed double-blind, double-placebo−controlled randomized trial. By utilizing broad inclusion criteria and enrolling patients both with and without previous exposure to anticholinergic medications, the generalizability of study findings are greatly improved. Because this study did not examine the effect or efficacy of repeat injections, these findings have limited applicability to patients undergoing multiple onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

When considering use in your patient population, keep the possible side effects in mind.There were important differences in the side effects experienced with each therapy. Specifically, while the anticholinergic group had a higher frequency of dry mouth (46% anticholinergic vs 31% onabotulinumtoxinA, P = .02), the onabotulinumtoxinA group demonstrated higher rates of incomplete bladder emptying requiring catheterization (peak of 5% at 2 months) and greater risk of UTI (33% onabotulinumtoxinA vs 13% anticholinergic, P <.001).

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This study showed that, among women with UUI, anticholinergic medication and onabotulinumtoxinA are equally effective in reducing UUI episodes and improving quality of life. It is important to consider the side effect profile, determine the patient’s preferences, and weigh the risks and benefits of each therapy when deciding what is the best treatment for your individual patient.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Anger JT, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling adult women: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2006;175(2):601–604.

- Dooley Y, Kenton K, Cao G, et al. Urinary incontinence prevalence: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2008;179(2):656–661.

- Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstetr Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1278–1283.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline. Americal Urological Association. http://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Overactive-Bladder.pdf. Published 2012. Revised June 11, 2013. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- Yu YF, Nichol MB, Yu AP, Ahn J. Persistence and adherence of medications for chronic overactive bladder/urinary incontinence in the California Medicaid program. Value Health. 2005;8(4):495–505.

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(1):5–26.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 63: Urinary incontinence in women. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetr Gynecol. 2005;105(6):1533–1545.

- Bo K, Kvarstein B, Nygaard I. Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic floor muscle exercise adherence after 15 years. Obstetr Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):999–1005.

- Sandvik H, Hunskaar S, Seim A, Hermstad R, Vanvik A, Bratt H. Validation of a severity index in female urinary incontinence and its implementation in an epidemiological survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1993;47(6):497–499.

- Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(6):453–466.

- Levin PJ, Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL. The efficacy of posterior tibial nerve stimulation for the treatment of overactive bladder in women: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(11):1591–1597.

- McGuire EJ, Zhang SC, Horwinski ER, Lytton B. Treatment of motor and sensory detrusor instability by electrical stimulation. J Urol. 1983;129(1):78–79.

- Schiavo G, Santucci A, Dasgupta BR, et al. Botulinum neurotoxins serotypes A and E cleave SNAP-25 at distinct COOH-terminal peptide bonds. FEBS Lett. 1993;335(1):99–103.

Urinary incontinence (UI) affects almost half of all women in the United States.1,2 Estimates suggest that the prevalence of UI gradually rises during young adult life, comes to a broad plateau in middle age, and then steadily increases from that plateau after age 65. Therefore, over the next 40 years, as the elderly population expands in size, the number of women affected by UI will significantly grow.3

For patients with UI, a multitude of therapeutic options are available. Which option is the best for your patient? In this article, we aim to answer that question by interpreting the results of four randomized trials, each of which directly compare two available treatment options. The first study examines patients with stress urinary incontinence (SUI), comparing the patients’ subjective improvement in urinary leakage and bladder function at 12 months after randomization to treatment with physiotherapy or midurethral sling surgery.

The three other trials examine patients with overactive bladder (OAB) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Each trial directly compares the use of anticholinergic medications to an alternate treatment modality. Currently, anticholinergic medications and behavioral therapy are the recommended first-line therapies for OAB. Unfortunately, anticholinergic medications have poor patient compliance and significant systemic side effects.4 Caution should be used when considering anticholinergic medications in patients with impaired gastric emptying or a history of urinary retention. They also should be used with caution in elderly patients who are extremely frail. Additionally, clearance from an ophthalmologist must be obtained prior to starting anticholinergic medication in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma.5 Due to poor adherence and potential side effects, there is a growing effort to discover alternative treatment modalities that are safe and effective. Therefore, we chose to examine trials comparing: mirabegron versus tolterodine, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus tolterodine, and onabotulinumtoxinA versus anticholingeric medications.

UI defined

Before discussing treatment options, we want to clarify the main types of UI (FIGURE). UI is defined as the complaint of involuntary loss of urine. UI can be subdivided into SUI, OAB/UUI, or mixed urinary incontinence.6 While there are other less common genitourinary etiologies that can lead to UI, nongenitourinary etiologies are prevalent and can aggravate existing SUI or OAB (TABLE).

SUI is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion (such as during sporting activities) or on sneezing or coughing. Often, SUI can be diagnosed by patient report alone and surgery can be considered in symptomatic patients who demonstrate cough leakage on physical examination and normal postvoid residual volumes.

UUI is the involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency; it often occurs in the setting of OAB, which is defined as the syndrome of urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without UUI, in the absence of urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology (such as neurologic dysfunction, infection, or urologic neoplasm). OAB-dry is present when patients do not have leakage with urgency, but are bothered by urgency, frequency, and/or nocturia. OAB-wet occurs when a patient has urgencyincontinence.

The presence of both SUI and OAB/UUI is known as mixed urinary incontinence. Stress and urgency urinary symptoms often present together. In fact, 10% to 30% of women with stress symptoms are found to have bladder overactivity on subsequent evaluation.2,7 Therefore, it is important to take a good history and consider urodynamic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of SUI prior to surgery in women with mixed stress and urge symptoms, a history of a previous surgery for incontinence, or when there is a poor correlation of physical examination findings to reported symptoms.

Is surgery a first-line option for patients with SUI?

Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. NEJM. 2013;369(12):1124−1133.

Physiotherapy, including pelvic floor muscle training (“Kegel exercises”), is utilized as a first-line treatment option for women with SUI that carries minimal risk for the patient. Midurethral sling surgery is often recommended if an initial trial of conservative treatment fails.7 Up to 50% of women treated with pelvic floor physiotherapy will ultimately undergo surgery to treat their SUI.8

Related article: Does urodynamic testing before surgery for stress incontinence improve outcomes? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, December 2012)

Details of the study

This was a randomized, multicenter trial of women aged 35 to 80 years with moderate to severe SUI. After excluding women with previous incontinence surgery and stage 2 or higher pelvic organ prolapse, 460 participants were randomly assigned to undergo either a midurethral sling surgery or physiotherapy (pelvic floor muscle training). The primary outcome was subjective improvement in urinary leakage and bladder function at 12 months, as measured by the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “very much worse” to “very much better.”

In an intention-to-treat analysis, subjective improvement at 12 months was significantly higher in women randomized to midurethral sling surgery than in women randomized to physiotherapy (91% vs 64%, respectively).

Ten percent of patients had adverse events (AEs); all were related to surgery. The most common AEs were hematoma, vaginal epithelial perforation, and bladder perforation.

Notably, women had the option to cross over to the other treatment modality if they desired. In the physiotherapy group, 49% of women elected to cross over to surgery, while 11% of those who underwent midurethral sling surgery elected to cross over to physiotherapy during the 12-month follow-up period. When analyzing results by treatment received, the investigators found that the proportion of women who reported improvement was significantly lower among women who underwent physiotherapy only (32%), versus sling only (94%), or sling after physiotherapy (91%).

This randomized trial was well-designed and included a variety of treatment centers (university and general hospitals) with interventions performed by experienced surgeons (all of whom had performed at least 20 sling surgeries) and physiotherapists educated specifically in pelvic floor physiotherapy. The study population was limited to patients with moderate to severe SUI as defined by the Sandvik severity index.9 Therefore, these results may not be applicable to patients with milder symptoms, for whom physiotherapy has been recommended as first-line therapy with consideration of surgery if physiotherapy fails to sufficiently improve symptoms.7

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Women with moderate to severe SUI without significant prolapse or a history of prior incontinence surgery have significantly better outcomes at 12 months after undergoing midurethral sling surgery versus physiotherapy. Physiotherapy carries little to no risk of adverse effects. Women with moderate to severe SUI should be counseled regarding the risks and benefits of both physiotherapy and midurethral sling surgery as initial treatment options.

Because stress and urgency urinary symptoms often present together, it is important to consider urodynamic evaluation to confirm SUI prior to surgery in women with:

• mixed stress and urge symptoms

• a history of a previous surgery for incontinence, or

• poor correlation of physical examination findings to reported symptoms.

Safety and tolerability of mirabegron versus tolterodine for OAB

Chapple CR, Kaplan SA, Mitcheson D, et al. Randomized double-blind, active-controlled phase 3 study to assess 12-month safety and efficacy of mirabegron, a beta(3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2013;63(2):296−305.

In the bladder, beta3-receptors located within the detrusor smooth muscle facilitate urine storage by relaxing the detrusor, enabling the bladder to fill.10 The activation of beta3-receptors is thought to increase the bladder’s ability to store urine, with the goal of decreasing urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urgency incontinence. An alternative to anticholinergic medications, mirabegron is a beta3-agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for clinical use in the treatment of OAB.

Details of the study

Chapple and colleagues aimed to assess the 12-month efficacy and safety of mirabegron in a randomized, double-blind active controlled trial. The primary outcome was incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs); the secondary outcome was the change in OAB symptoms from baseline to up to 12 months. Patients experiencing OAB symptoms for more than 3 months were eligible and were subsequently enrolled if they averaged 8 or more voids per day and 3 or more episodes of urgency with or without incontinence on a 3-day bladder diary. A total of 2,444 patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 fashion to mirabegron 50 mg daily, mirabegron 100 mg daily, or tolterodine extended release (ER) 4 mg daily.

There was a similar incidence (60% to 63%) of TEAEs across all three groups. The most common TEAEs were hypertension (defined as average systolic blood pressure [BP] >140 mm Hg or average diastolic BP >90 mm Hg at two consecutive visits), UTI, headache, nasopharyngitis, and constipation. The adjusted mean changes in BP from baseline to final visit were less than 1 mm Hg for both systolic and diastolic BP for patients taking both doses of mirabegron, as well as for patients taking tolterodine. The incidence of dry mouth was higher in the tolterodine group than the mirabegron groups. Mirabegron 50 mg daily and 100 mg daily improved incontinence symptoms within 1 month of starting therapy; the degree of improvement was similar to that seen in the patients taking tolterodine ER 4 mg daily.

Related article: New overactive bladder treatment approved by the FDA (August 2012)

Some caveats

This study was well-designed to assess the safety and tolerability of mirabegron versus tolterodine. The doses utilized in the study were at or above the FDA-approved dosage of 25 mg to 50 mg daily for OAB treatment. Although investigators found mirabegron to be a safe alternative to anticholinergic medication, the study was not designed or powered to examine the efficacy of mirabegron versus tolterodine. No formal comparison of efficacy was made between mirabegron or tolterodine, or between the 50-mg and 100-mg doses of mirabegron. Moreover, 81% of participants had been treated with mirabegron in earlier Phase 3 studies, so most were not treatment naïve, limiting the applicability of results.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Mirabegron should be considered as a potential treatment option for patients who demonstrate poor tolerance of or response to anticholinergic medications; however, caution should be used in patients with severe uncontrolled high BP, end-stage kidney disease, or severe liver impairment.

Consider percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation over tolterodine for OAB in select patients

Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, et al. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: Results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol. 2009;182(3):1055−1061.

Neuromodulation utilizes electrical stimulation to improve bladder function and decrease OAB symptoms. First developed in the early 1980s by McGuire and colleagues, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) was approved by the FDA in 2000 as Urgent PC and provides an outpatient, nonimplantable neuromodulation alternative to medication therapy for patients with OAB.11,12 By directly stimulating the posterior tibial nerve, PTNS works via the S3 sacral nerve plexus to alter the micturition reflex and improve bladder function.

Details of the study

Patients were eligible for the study if they demonstrated 8 or more voids per day on a 3-day bladder diary (whether or not they had a history of previous anticholinergic drug use). A total of 100 ambulatory adults with OAB symptoms were enrolled and randomly assigned to PTNS 30-minutes per week or tolterodine ER 4 mg daily.

At 12 weeks, both groups demonstrated a significant improvement in OAB measures as well as validated symptom severity and quality-of-life questionnaire scores. Subjective assessment of improvement in OAB symptoms was significantly greater in the PTNS group than in the tolterodine group (79.5% vs 54.8%, respectively; P = .01). However, mean reduction of voids for 24 hours was not significantly different between the two groups.

Both treatments were well tolerated, with only 15% to 16% of patients in both groups reporting mild to moderate side effects. The tolterodine group did have a significantly higher risk of dry mouth; however, the risk of constipation was not significantly different between the groups.

Study limitations

The authors performed an important multicenter, nonblinded, randomized, controlled trial, which was one of the first trials to directly compare two OAB therapies. The generalizability of the findings were limited, as the cohort included mostly patients with dry OAB who had no objective measures on UUI episodes. In addition, this trial had a limited observation period of only 12 weeks. Information regarding the effect of treatment after cessation of weekly PTNS therapy was not examined. Therefore, we are not able to determine whether repeat sessions provide adequate maintenance in the long term.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

PTNS 30 minutes daily is as effective as tolterodine ER 4 mg daily for 12 weeks in reducing OAB symptoms. PTNS is a safe alternative that should be considered in patients with OAB who poorly tolerate or have contraindications to medication therapy.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is an effective therapy for OAB

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al. Anticholinergic therapy vs onabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. NEJM. 2012;367(19):1803−1813.

The newest therapy for OAB is onabotulinumtoxinA, or Botox, which was FDA approved this year for the treatment of OAB in adults who cannot use or do not tolerate anticholinergic medications. Recommended doses are 100 U onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with idiopathic refractory OAB and 200 U onabotulinumtoxinA for patients with neurogenic OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin that blocks synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction to cause muscle paralysis and atrophy.13 Injecting onabotulinumtoxinA into the detrusor smooth muscle should relax the bladder and decrease sensations of urgency and frequency to achieve a longer duration of time for bladder filling and reduce the risk of urgency incontinence.

Effects of onabotulinumtoxinA appear to wear off over time, and patients may require repeat injections. Side effects of onabotulinumtoxinA therapy include an increased risk of UTI and the potential for urinary retention requiring intermittent self-catheterization.

Related article: Update on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (October 2012)

Details of the study

The Anticholinergic Versus Botulinum Toxin Comparison (ABC) study was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-placebo–controlled trial conducted in women without known neurologic disease with moderate to severe UUI (defined as >5 UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary). Women were randomly assigned to a single intradetrusor injection of 100 U onabotulinumtoxinA plus oral placebo or to a single intradetrusor injection of saline plus solifenacin 5 mg daily (with the option of dose escalation and then switching to trospium XR if no improvement was seen).

Of the 241 women included in the final analysis, approximately 70% in each group reported adequate control of symptoms at 6 months. Adequate control was defined as a response of “agree strongly” or “agree” to the statement: “This treatment has given me adequate control of my urinary leakage.” Women in the onabotulinumtoxinA group were significantly more likely than women in the anticholinergic medication group to report complete resolution of UUI at 6 months (27% vs 13%, P = .003). However, the mean reduction in episodes of UUI per day and the improvements in quality-of-life questionnaire scores were found to be similar. Interestingly, worse baseline UUI was associated with greater reduction in episodes of UUI for both therapies.

This was a rigorous and well-executed double-blind, double-placebo−controlled randomized trial. By utilizing broad inclusion criteria and enrolling patients both with and without previous exposure to anticholinergic medications, the generalizability of study findings are greatly improved. Because this study did not examine the effect or efficacy of repeat injections, these findings have limited applicability to patients undergoing multiple onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

When considering use in your patient population, keep the possible side effects in mind.There were important differences in the side effects experienced with each therapy. Specifically, while the anticholinergic group had a higher frequency of dry mouth (46% anticholinergic vs 31% onabotulinumtoxinA, P = .02), the onabotulinumtoxinA group demonstrated higher rates of incomplete bladder emptying requiring catheterization (peak of 5% at 2 months) and greater risk of UTI (33% onabotulinumtoxinA vs 13% anticholinergic, P <.001).

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

This study showed that, among women with UUI, anticholinergic medication and onabotulinumtoxinA are equally effective in reducing UUI episodes and improving quality of life. It is important to consider the side effect profile, determine the patient’s preferences, and weigh the risks and benefits of each therapy when deciding what is the best treatment for your individual patient.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence (UI) affects almost half of all women in the United States.1,2 Estimates suggest that the prevalence of UI gradually rises during young adult life, comes to a broad plateau in middle age, and then steadily increases from that plateau after age 65. Therefore, over the next 40 years, as the elderly population expands in size, the number of women affected by UI will significantly grow.3

For patients with UI, a multitude of therapeutic options are available. Which option is the best for your patient? In this article, we aim to answer that question by interpreting the results of four randomized trials, each of which directly compare two available treatment options. The first study examines patients with stress urinary incontinence (SUI), comparing the patients’ subjective improvement in urinary leakage and bladder function at 12 months after randomization to treatment with physiotherapy or midurethral sling surgery.

The three other trials examine patients with overactive bladder (OAB) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Each trial directly compares the use of anticholinergic medications to an alternate treatment modality. Currently, anticholinergic medications and behavioral therapy are the recommended first-line therapies for OAB. Unfortunately, anticholinergic medications have poor patient compliance and significant systemic side effects.4 Caution should be used when considering anticholinergic medications in patients with impaired gastric emptying or a history of urinary retention. They also should be used with caution in elderly patients who are extremely frail. Additionally, clearance from an ophthalmologist must be obtained prior to starting anticholinergic medication in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma.5 Due to poor adherence and potential side effects, there is a growing effort to discover alternative treatment modalities that are safe and effective. Therefore, we chose to examine trials comparing: mirabegron versus tolterodine, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus tolterodine, and onabotulinumtoxinA versus anticholingeric medications.

UI defined

Before discussing treatment options, we want to clarify the main types of UI (FIGURE). UI is defined as the complaint of involuntary loss of urine. UI can be subdivided into SUI, OAB/UUI, or mixed urinary incontinence.6 While there are other less common genitourinary etiologies that can lead to UI, nongenitourinary etiologies are prevalent and can aggravate existing SUI or OAB (TABLE).

SUI is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion (such as during sporting activities) or on sneezing or coughing. Often, SUI can be diagnosed by patient report alone and surgery can be considered in symptomatic patients who demonstrate cough leakage on physical examination and normal postvoid residual volumes.

UUI is the involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency; it often occurs in the setting of OAB, which is defined as the syndrome of urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without UUI, in the absence of urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology (such as neurologic dysfunction, infection, or urologic neoplasm). OAB-dry is present when patients do not have leakage with urgency, but are bothered by urgency, frequency, and/or nocturia. OAB-wet occurs when a patient has urgencyincontinence.

The presence of both SUI and OAB/UUI is known as mixed urinary incontinence. Stress and urgency urinary symptoms often present together. In fact, 10% to 30% of women with stress symptoms are found to have bladder overactivity on subsequent evaluation.2,7 Therefore, it is important to take a good history and consider urodynamic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of SUI prior to surgery in women with mixed stress and urge symptoms, a history of a previous surgery for incontinence, or when there is a poor correlation of physical examination findings to reported symptoms.

Is surgery a first-line option for patients with SUI?

Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. NEJM. 2013;369(12):1124−1133.

Physiotherapy, including pelvic floor muscle training (“Kegel exercises”), is utilized as a first-line treatment option for women with SUI that carries minimal risk for the patient. Midurethral sling surgery is often recommended if an initial trial of conservative treatment fails.7 Up to 50% of women treated with pelvic floor physiotherapy will ultimately undergo surgery to treat their SUI.8

Related article: Does urodynamic testing before surgery for stress incontinence improve outcomes? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, December 2012)

Details of the study

This was a randomized, multicenter trial of women aged 35 to 80 years with moderate to severe SUI. After excluding women with previous incontinence surgery and stage 2 or higher pelvic organ prolapse, 460 participants were randomly assigned to undergo either a midurethral sling surgery or physiotherapy (pelvic floor muscle training). The primary outcome was subjective improvement in urinary leakage and bladder function at 12 months, as measured by the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “very much worse” to “very much better.”

In an intention-to-treat analysis, subjective improvement at 12 months was significantly higher in women randomized to midurethral sling surgery than in women randomized to physiotherapy (91% vs 64%, respectively).

Ten percent of patients had adverse events (AEs); all were related to surgery. The most common AEs were hematoma, vaginal epithelial perforation, and bladder perforation.

Notably, women had the option to cross over to the other treatment modality if they desired. In the physiotherapy group, 49% of women elected to cross over to surgery, while 11% of those who underwent midurethral sling surgery elected to cross over to physiotherapy during the 12-month follow-up period. When analyzing results by treatment received, the investigators found that the proportion of women who reported improvement was significantly lower among women who underwent physiotherapy only (32%), versus sling only (94%), or sling after physiotherapy (91%).

This randomized trial was well-designed and included a variety of treatment centers (university and general hospitals) with interventions performed by experienced surgeons (all of whom had performed at least 20 sling surgeries) and physiotherapists educated specifically in pelvic floor physiotherapy. The study population was limited to patients with moderate to severe SUI as defined by the Sandvik severity index.9 Therefore, these results may not be applicable to patients with milder symptoms, for whom physiotherapy has been recommended as first-line therapy with consideration of surgery if physiotherapy fails to sufficiently improve symptoms.7

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Women with moderate to severe SUI without significant prolapse or a history of prior incontinence surgery have significantly better outcomes at 12 months after undergoing midurethral sling surgery versus physiotherapy. Physiotherapy carries little to no risk of adverse effects. Women with moderate to severe SUI should be counseled regarding the risks and benefits of both physiotherapy and midurethral sling surgery as initial treatment options.

Because stress and urgency urinary symptoms often present together, it is important to consider urodynamic evaluation to confirm SUI prior to surgery in women with:

• mixed stress and urge symptoms

• a history of a previous surgery for incontinence, or

• poor correlation of physical examination findings to reported symptoms.

Safety and tolerability of mirabegron versus tolterodine for OAB

Chapple CR, Kaplan SA, Mitcheson D, et al. Randomized double-blind, active-controlled phase 3 study to assess 12-month safety and efficacy of mirabegron, a beta(3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2013;63(2):296−305.

In the bladder, beta3-receptors located within the detrusor smooth muscle facilitate urine storage by relaxing the detrusor, enabling the bladder to fill.10 The activation of beta3-receptors is thought to increase the bladder’s ability to store urine, with the goal of decreasing urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urgency incontinence. An alternative to anticholinergic medications, mirabegron is a beta3-agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for clinical use in the treatment of OAB.

Details of the study

Chapple and colleagues aimed to assess the 12-month efficacy and safety of mirabegron in a randomized, double-blind active controlled trial. The primary outcome was incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs); the secondary outcome was the change in OAB symptoms from baseline to up to 12 months. Patients experiencing OAB symptoms for more than 3 months were eligible and were subsequently enrolled if they averaged 8 or more voids per day and 3 or more episodes of urgency with or without incontinence on a 3-day bladder diary. A total of 2,444 patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 fashion to mirabegron 50 mg daily, mirabegron 100 mg daily, or tolterodine extended release (ER) 4 mg daily.

There was a similar incidence (60% to 63%) of TEAEs across all three groups. The most common TEAEs were hypertension (defined as average systolic blood pressure [BP] >140 mm Hg or average diastolic BP >90 mm Hg at two consecutive visits), UTI, headache, nasopharyngitis, and constipation. The adjusted mean changes in BP from baseline to final visit were less than 1 mm Hg for both systolic and diastolic BP for patients taking both doses of mirabegron, as well as for patients taking tolterodine. The incidence of dry mouth was higher in the tolterodine group than the mirabegron groups. Mirabegron 50 mg daily and 100 mg daily improved incontinence symptoms within 1 month of starting therapy; the degree of improvement was similar to that seen in the patients taking tolterodine ER 4 mg daily.

Related article: New overactive bladder treatment approved by the FDA (August 2012)

Some caveats

This study was well-designed to assess the safety and tolerability of mirabegron versus tolterodine. The doses utilized in the study were at or above the FDA-approved dosage of 25 mg to 50 mg daily for OAB treatment. Although investigators found mirabegron to be a safe alternative to anticholinergic medication, the study was not designed or powered to examine the efficacy of mirabegron versus tolterodine. No formal comparison of efficacy was made between mirabegron or tolterodine, or between the 50-mg and 100-mg doses of mirabegron. Moreover, 81% of participants had been treated with mirabegron in earlier Phase 3 studies, so most were not treatment naïve, limiting the applicability of results.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Mirabegron should be considered as a potential treatment option for patients who demonstrate poor tolerance of or response to anticholinergic medications; however, caution should be used in patients with severe uncontrolled high BP, end-stage kidney disease, or severe liver impairment.

Consider percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation over tolterodine for OAB in select patients

Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, et al. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: Results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol. 2009;182(3):1055−1061.

Neuromodulation utilizes electrical stimulation to improve bladder function and decrease OAB symptoms. First developed in the early 1980s by McGuire and colleagues, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) was approved by the FDA in 2000 as Urgent PC and provides an outpatient, nonimplantable neuromodulation alternative to medication therapy for patients with OAB.11,12 By directly stimulating the posterior tibial nerve, PTNS works via the S3 sacral nerve plexus to alter the micturition reflex and improve bladder function.

Details of the study

Patients were eligible for the study if they demonstrated 8 or more voids per day on a 3-day bladder diary (whether or not they had a history of previous anticholinergic drug use). A total of 100 ambulatory adults with OAB symptoms were enrolled and randomly assigned to PTNS 30-minutes per week or tolterodine ER 4 mg daily.

At 12 weeks, both groups demonstrated a significant improvement in OAB measures as well as validated symptom severity and quality-of-life questionnaire scores. Subjective assessment of improvement in OAB symptoms was significantly greater in the PTNS group than in the tolterodine group (79.5% vs 54.8%, respectively; P = .01). However, mean reduction of voids for 24 hours was not significantly different between the two groups.

Both treatments were well tolerated, with only 15% to 16% of patients in both groups reporting mild to moderate side effects. The tolterodine group did have a significantly higher risk of dry mouth; however, the risk of constipation was not significantly different between the groups.

Study limitations

The authors performed an important multicenter, nonblinded, randomized, controlled trial, which was one of the first trials to directly compare two OAB therapies. The generalizability of the findings were limited, as the cohort included mostly patients with dry OAB who had no objective measures on UUI episodes. In addition, this trial had a limited observation period of only 12 weeks. Information regarding the effect of treatment after cessation of weekly PTNS therapy was not examined. Therefore, we are not able to determine whether repeat sessions provide adequate maintenance in the long term.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

PTNS 30 minutes daily is as effective as tolterodine ER 4 mg daily for 12 weeks in reducing OAB symptoms. PTNS is a safe alternative that should be considered in patients with OAB who poorly tolerate or have contraindications to medication therapy.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is an effective therapy for OAB

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al. Anticholinergic therapy vs onabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. NEJM. 2012;367(19):1803−1813.

The newest therapy for OAB is onabotulinumtoxinA, or Botox, which was FDA approved this year for the treatment of OAB in adults who cannot use or do not tolerate anticholinergic medications. Recommended doses are 100 U onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with idiopathic refractory OAB and 200 U onabotulinumtoxinA for patients with neurogenic OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin that blocks synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction to cause muscle paralysis and atrophy.13 Injecting onabotulinumtoxinA into the detrusor smooth muscle should relax the bladder and decrease sensations of urgency and frequency to achieve a longer duration of time for bladder filling and reduce the risk of urgency incontinence.

Effects of onabotulinumtoxinA appear to wear off over time, and patients may require repeat injections. Side effects of onabotulinumtoxinA therapy include an increased risk of UTI and the potential for urinary retention requiring intermittent self-catheterization.

Related article: Update on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (October 2012)

Details of the study

The Anticholinergic Versus Botulinum Toxin Comparison (ABC) study was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-placebo–controlled trial conducted in women without known neurologic disease with moderate to severe UUI (defined as >5 UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary). Women were randomly assigned to a single intradetrusor injection of 100 U onabotulinumtoxinA plus oral placebo or to a single intradetrusor injection of saline plus solifenacin 5 mg daily (with the option of dose escalation and then switching to trospium XR if no improvement was seen).

Of the 241 women included in the final analysis, approximately 70% in each group reported adequate control of symptoms at 6 months. Adequate control was defined as a response of “agree strongly” or “agree” to the statement: “This treatment has given me adequate control of my urinary leakage.” Women in the onabotulinumtoxinA group were significantly more likely than women in the anticholinergic medication group to report complete resolution of UUI at 6 months (27% vs 13%, P = .003). However, the mean reduction in episodes of UUI per day and the improvements in quality-of-life questionnaire scores were found to be similar. Interestingly, worse baseline UUI was associated with greater reduction in episodes of UUI for both therapies.