User login

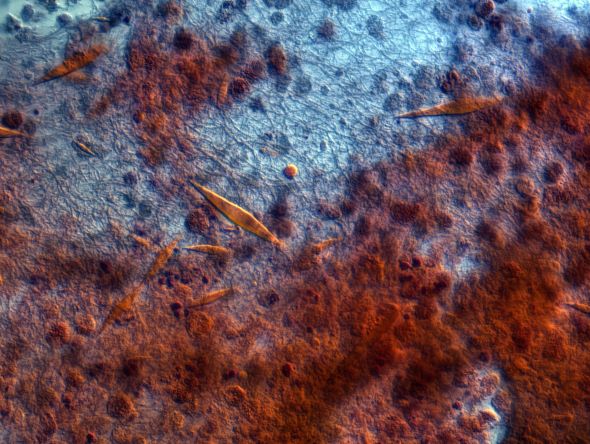

A 9-year-old male presents with multiple thick scaly plaques on scalp, ears, and trunk

Given the characteristic clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is characterized by well-demarcated thick scaly plaques on face, scalp, and intertriginous skin. Psoriasis is more common in adults than children, but the incidence of psoriasis in children has increased over time.1 Clinical presentation of psoriasis includes erythematous hyperkeratotic plaques, usually sharply demarcated. Pediatric patients may have multiple small papules and plaques less than 1 cm in size – “drop-size” – known as guttate lesions. Scalp and facial involvement are common in children. Chronic, inflamed plaques with coarse scale can involve ears, elbows, knees, and umbilicus, and nail changes can include pits, ridges, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis or “oil spots.” While the diagnosis is clinical, biopsy can sometimes be useful to distinguish psoriasis from other papulosquamous conditions. Psoriasis in children is associated with obesity, higher rates of cardiovascular disease over a lifetime, as well as arthritis and mental health disorders.2

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for psoriasis can include papulosquamous diseases such as nummular eczema, pityriasis rosea, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Tinea corporis may also be considered.

Nummular eczema, also known as “discoid eczema” is characterized by multiple pruritic, coin-shaped, eczematous lesions that may be actively oozing. The term “nummular” is derived from the Latin for “coin,” as lesions are distinct and annular. It is commonly associated with atopic dermatitis, and may be seen with contact dermatitis as well. Oozing, lichenification, hyperpigmentation and limited extent of skin coverage can help distinguish nummular dermatitis from psoriasis.

Pityriasis rosea is a common self-limited disease that is characterized by the appearance of acute, oval, papulosquamous patches on the trunk and proximal areas of the extremities. It usually begins with a characteristic “herald” patch, a single round or oval, sharply demarcated, pink lesion on the chest, neck, or back. Pityriasis rosea and guttate psoriasis may show similar clinical findings but the latter lacks a herald patch and is often preceded by streptococcal throat infection.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rarer inflammatory disease characterized by follicular, hyperkeratotic papules, thick orange waxy palms (palmoplantar keratoderma), and erythroderma. It can also cause hair loss, nail changes, and itching. The rash shows areas with no involvement, “islands of sparing,” which is a signature characteristic of pityriasis rubra pilaris. Skin biopsies are an important diagnostic tool for pityriasis rubra pilaris. In the case of circumscribed pityriasis rubra pilaris, it may look similar to psoriasis, but it can be differentiated in that it is often accompanied by characteristic follicular papules and involvement of the palms, which are more waxy and orange in color.

When evaluating annular scaly patches, it is always important to consider tinea corporis. Tinea corporis will commonly have an annular border of scale with relative clearing in the center of lesions. In addition, when topical corticosteroids are used for prolonged periods, skin fungal infections can develop into “tinea incognito,” with paradoxical worsening since the immune response is suppressed and the fungal infection worsens.

Our patient had been previously treated with topical corticosteroids (medium to high strength) and topical calcineurin inhibitors without significant improvement. Other topical therapies for psoriasis include vitamin analogues, tazarotene, and newer therapies such as topical roflumilast (a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor approved for psoriasis in children over 12 years of age).3,4 In addition, as the indications for biological agents have been expanded, there are various options for treating psoriasis in children and adolescents when more active treatment is needed. Systemic therapies for more severe disease include traditional systemic immunosuppressives (for example, methotrexate, cyclosporine) and biologic agents. The four biologic agents currently approved for children are etanercept, ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Our patient was treated with ustekinumab, which is an injectable biologic agent that blocks interleukin-12/23, with good response to date.

Dr. Al-Nabti is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; Dr. Choi is a visiting research physician in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; and Dr. Eichenfield is vice-chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics, all at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. They have no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Tollefson MM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):979-87.

2. Menter A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161-201.

3. Mark G et al. JAMA. 2022;328(11):1073-84.

4. Eichenfield LF et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):170-81.

Given the characteristic clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is characterized by well-demarcated thick scaly plaques on face, scalp, and intertriginous skin. Psoriasis is more common in adults than children, but the incidence of psoriasis in children has increased over time.1 Clinical presentation of psoriasis includes erythematous hyperkeratotic plaques, usually sharply demarcated. Pediatric patients may have multiple small papules and plaques less than 1 cm in size – “drop-size” – known as guttate lesions. Scalp and facial involvement are common in children. Chronic, inflamed plaques with coarse scale can involve ears, elbows, knees, and umbilicus, and nail changes can include pits, ridges, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis or “oil spots.” While the diagnosis is clinical, biopsy can sometimes be useful to distinguish psoriasis from other papulosquamous conditions. Psoriasis in children is associated with obesity, higher rates of cardiovascular disease over a lifetime, as well as arthritis and mental health disorders.2

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for psoriasis can include papulosquamous diseases such as nummular eczema, pityriasis rosea, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Tinea corporis may also be considered.

Nummular eczema, also known as “discoid eczema” is characterized by multiple pruritic, coin-shaped, eczematous lesions that may be actively oozing. The term “nummular” is derived from the Latin for “coin,” as lesions are distinct and annular. It is commonly associated with atopic dermatitis, and may be seen with contact dermatitis as well. Oozing, lichenification, hyperpigmentation and limited extent of skin coverage can help distinguish nummular dermatitis from psoriasis.

Pityriasis rosea is a common self-limited disease that is characterized by the appearance of acute, oval, papulosquamous patches on the trunk and proximal areas of the extremities. It usually begins with a characteristic “herald” patch, a single round or oval, sharply demarcated, pink lesion on the chest, neck, or back. Pityriasis rosea and guttate psoriasis may show similar clinical findings but the latter lacks a herald patch and is often preceded by streptococcal throat infection.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rarer inflammatory disease characterized by follicular, hyperkeratotic papules, thick orange waxy palms (palmoplantar keratoderma), and erythroderma. It can also cause hair loss, nail changes, and itching. The rash shows areas with no involvement, “islands of sparing,” which is a signature characteristic of pityriasis rubra pilaris. Skin biopsies are an important diagnostic tool for pityriasis rubra pilaris. In the case of circumscribed pityriasis rubra pilaris, it may look similar to psoriasis, but it can be differentiated in that it is often accompanied by characteristic follicular papules and involvement of the palms, which are more waxy and orange in color.

When evaluating annular scaly patches, it is always important to consider tinea corporis. Tinea corporis will commonly have an annular border of scale with relative clearing in the center of lesions. In addition, when topical corticosteroids are used for prolonged periods, skin fungal infections can develop into “tinea incognito,” with paradoxical worsening since the immune response is suppressed and the fungal infection worsens.

Our patient had been previously treated with topical corticosteroids (medium to high strength) and topical calcineurin inhibitors without significant improvement. Other topical therapies for psoriasis include vitamin analogues, tazarotene, and newer therapies such as topical roflumilast (a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor approved for psoriasis in children over 12 years of age).3,4 In addition, as the indications for biological agents have been expanded, there are various options for treating psoriasis in children and adolescents when more active treatment is needed. Systemic therapies for more severe disease include traditional systemic immunosuppressives (for example, methotrexate, cyclosporine) and biologic agents. The four biologic agents currently approved for children are etanercept, ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Our patient was treated with ustekinumab, which is an injectable biologic agent that blocks interleukin-12/23, with good response to date.

Dr. Al-Nabti is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; Dr. Choi is a visiting research physician in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; and Dr. Eichenfield is vice-chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics, all at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. They have no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Tollefson MM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):979-87.

2. Menter A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161-201.

3. Mark G et al. JAMA. 2022;328(11):1073-84.

4. Eichenfield LF et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):170-81.

Given the characteristic clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is characterized by well-demarcated thick scaly plaques on face, scalp, and intertriginous skin. Psoriasis is more common in adults than children, but the incidence of psoriasis in children has increased over time.1 Clinical presentation of psoriasis includes erythematous hyperkeratotic plaques, usually sharply demarcated. Pediatric patients may have multiple small papules and plaques less than 1 cm in size – “drop-size” – known as guttate lesions. Scalp and facial involvement are common in children. Chronic, inflamed plaques with coarse scale can involve ears, elbows, knees, and umbilicus, and nail changes can include pits, ridges, hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis or “oil spots.” While the diagnosis is clinical, biopsy can sometimes be useful to distinguish psoriasis from other papulosquamous conditions. Psoriasis in children is associated with obesity, higher rates of cardiovascular disease over a lifetime, as well as arthritis and mental health disorders.2

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for psoriasis can include papulosquamous diseases such as nummular eczema, pityriasis rosea, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Tinea corporis may also be considered.

Nummular eczema, also known as “discoid eczema” is characterized by multiple pruritic, coin-shaped, eczematous lesions that may be actively oozing. The term “nummular” is derived from the Latin for “coin,” as lesions are distinct and annular. It is commonly associated with atopic dermatitis, and may be seen with contact dermatitis as well. Oozing, lichenification, hyperpigmentation and limited extent of skin coverage can help distinguish nummular dermatitis from psoriasis.

Pityriasis rosea is a common self-limited disease that is characterized by the appearance of acute, oval, papulosquamous patches on the trunk and proximal areas of the extremities. It usually begins with a characteristic “herald” patch, a single round or oval, sharply demarcated, pink lesion on the chest, neck, or back. Pityriasis rosea and guttate psoriasis may show similar clinical findings but the latter lacks a herald patch and is often preceded by streptococcal throat infection.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rarer inflammatory disease characterized by follicular, hyperkeratotic papules, thick orange waxy palms (palmoplantar keratoderma), and erythroderma. It can also cause hair loss, nail changes, and itching. The rash shows areas with no involvement, “islands of sparing,” which is a signature characteristic of pityriasis rubra pilaris. Skin biopsies are an important diagnostic tool for pityriasis rubra pilaris. In the case of circumscribed pityriasis rubra pilaris, it may look similar to psoriasis, but it can be differentiated in that it is often accompanied by characteristic follicular papules and involvement of the palms, which are more waxy and orange in color.

When evaluating annular scaly patches, it is always important to consider tinea corporis. Tinea corporis will commonly have an annular border of scale with relative clearing in the center of lesions. In addition, when topical corticosteroids are used for prolonged periods, skin fungal infections can develop into “tinea incognito,” with paradoxical worsening since the immune response is suppressed and the fungal infection worsens.

Our patient had been previously treated with topical corticosteroids (medium to high strength) and topical calcineurin inhibitors without significant improvement. Other topical therapies for psoriasis include vitamin analogues, tazarotene, and newer therapies such as topical roflumilast (a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor approved for psoriasis in children over 12 years of age).3,4 In addition, as the indications for biological agents have been expanded, there are various options for treating psoriasis in children and adolescents when more active treatment is needed. Systemic therapies for more severe disease include traditional systemic immunosuppressives (for example, methotrexate, cyclosporine) and biologic agents. The four biologic agents currently approved for children are etanercept, ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. Our patient was treated with ustekinumab, which is an injectable biologic agent that blocks interleukin-12/23, with good response to date.

Dr. Al-Nabti is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; Dr. Choi is a visiting research physician in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; and Dr. Eichenfield is vice-chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics, all at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. They have no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Tollefson MM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):979-87.

2. Menter A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161-201.

3. Mark G et al. JAMA. 2022;328(11):1073-84.

4. Eichenfield LF et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):170-81.

A 9-year-old male is seen in the clinic with a 1-year history of multiple thick scaly plaques on scalp, ears, and trunk. He has been treated with hydrocortisone 1% ointment with no change in the lesions. He had upper respiratory tract symptoms 3 weeks prior to the visit.

Examination reveals erythematous, well-demarcated plaques of the anterior scalp with thick overlying micaceous scale with some extension onto the forehead and temples. Additionally, erythematous scaly patches on the ear, axilla, and umbilicus were noted. There was no palmar or plantar involvement. He denied joint swelling, stiffness, or pain in the morning.

Wearable fluid sensor lowers risk of HF rehospitalizations: BMAD

NEW ORLEANS – A wearable device that monitors thoracic fluid and can signal elevated levels can improve outcomes after heart failure hospitalization, according to a comparative but nonrandomized trial.

In this study, management adjustments made in response to a threshold alert from the device led to several improvements in outcome at 90 days, including a significant 38% reduction in the primary outcome of rehospitalization, relative to controls (P = .02), reported John P. Boehmer, MD, at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

The same relative risk reduction at 90 days was observed for a composite outcome of time to first hospitalization, visit to an emergency room, or death (hazard ratio, 0.62; P = .03).

Quality of life, as measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), improved steadily in both the experimental and control arm over the 90-day study, but the curves separated at about 30 days, Dr. Boehmer reported. By the end of the study, the mean KCCQ difference was 12 points favoring the experimental arm on a scale in which 5 points is considered clinically meaningful.

70% report improved quality of life

“Responder analysis revealed that nearly 70% of patients in the arm managed with the monitor reported a clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life, compared to 50% of patients in the control arm,” said Dr. Boehmer, professor of medicine and surgery at Penn State Health, Hershey.

Fluid overload is an indication of worsening disease and a frequent cause of heart failure hospitalization. The Zoll Heart Failure Monitoring System (HFMS) that was tested in this study already has regulatory approval. It is equipped to monitor several biomarkers, including heart rate and respiration rate, but its ability to measure lung fluid through low electromagnetic radiofrequency pulses was the function of interest for this study.

In this nonrandomized study, called Benefits of Microcor in Ambulatory

Decompensated Heart Failure (BMAD), a control arm was enrolled first. By monitoring the initial patients enrolled in the control arm, the investigators established a threshold of thoracic fluid that would be used to trigger an alert in the intervention arm. This ultimately was defined as 3 standard deviations from the population mean.

Patients were eligible for this study if they were discharged from a hospital with heart failure in the previous 10 days. Of exclusion criteria, a short life expectancy (< 1 year) and a wearable cardiac defibrillator were notable. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was not considered for inclusion or exclusion.

All subjects participated in weekly phone calls and monthly office visits. However, both investigators and patients were blinded to the device data in the control arm. Conversely, subjects and investigators in the intervention arm were able to access data generated by the device through a secure website.

Of the 245 eligible patients in the control arm, 168 were available for evaluation at 90 days. Among the 249 eligible patients in the intervention arm, 176 were included in the 90-day evaluation. Of those who were not available, the most common reason was study withdrawal. About 20% died before the 90-day evaluation.

The majority of patients in both arms were in class III or IV heart failure. About half had LVEF less than 40%, and more than 40% of patients in each group had chronic kidney disease (CKD). Roughly 55% of patients were at least 65 years of age.

At 90 days, the absolute risk reduction in rehospitalization was 7%, producing a number to treat with the device of 14.3 to prevent one rehospitalization. In a subgroup stratification, the benefit was similar by age, sex, presence or absence of CKD, LVEF greater or lower than 40%, Black or non-Black race, and ischemic or nonischemic etiology.

Patient access to data considered a plus

If lack of randomization is a weakness of this study, the decision to unblind the data for both investigators and patients might not be, according to Lynne Stevenson, MD, director of the cardiomyopathy program, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

“You might be criticized for this [allowing patients to monitor their data], but I actually think this is a strength of the study,” said Dr. Stevenson, who believes the growing trend to involve heart failure patients in self-management has been a positive direction in clinical care.

She indicated that, despite the potential bias derived from being aware of fluid fluctuations, this information might also be contributing to patient motivation for adherence and appropriate lifestyle modifications.

Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, chair of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, made a similar point but for a different reason. She expressed concern about the work that monitoring the wearable device creates for clinicians. Despite the positive data generated by this study, Dr. Bozkurt said the device as used in the study demanded “a lot of clinical time and effort” when these are both in short supply.

While she called for a larger and randomized study to corroborate the results of this investigation, she also thinks that it would make sense to compare the clinical value of this device against alternative methods for monitoring heart failure, including other wearable devices. Dr. Bozkurt asserted that some of the most helpful devices from a clinical perspective might be those that patients monitor themselves.

“Hopefully in the future, we will be offering tools that provide patients information they can use without the immediate need of a clinician,” she said.

Dr. Boehmer reports financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical Corporation, which provided the funding for this study. Dr. Stevenson reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Bozkurt reports financial relationships with Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardurion, LivaNova, Relypsa, Renovacor, Sanofi-Aventis, and Vifor.

NEW ORLEANS – A wearable device that monitors thoracic fluid and can signal elevated levels can improve outcomes after heart failure hospitalization, according to a comparative but nonrandomized trial.

In this study, management adjustments made in response to a threshold alert from the device led to several improvements in outcome at 90 days, including a significant 38% reduction in the primary outcome of rehospitalization, relative to controls (P = .02), reported John P. Boehmer, MD, at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

The same relative risk reduction at 90 days was observed for a composite outcome of time to first hospitalization, visit to an emergency room, or death (hazard ratio, 0.62; P = .03).

Quality of life, as measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), improved steadily in both the experimental and control arm over the 90-day study, but the curves separated at about 30 days, Dr. Boehmer reported. By the end of the study, the mean KCCQ difference was 12 points favoring the experimental arm on a scale in which 5 points is considered clinically meaningful.

70% report improved quality of life

“Responder analysis revealed that nearly 70% of patients in the arm managed with the monitor reported a clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life, compared to 50% of patients in the control arm,” said Dr. Boehmer, professor of medicine and surgery at Penn State Health, Hershey.

Fluid overload is an indication of worsening disease and a frequent cause of heart failure hospitalization. The Zoll Heart Failure Monitoring System (HFMS) that was tested in this study already has regulatory approval. It is equipped to monitor several biomarkers, including heart rate and respiration rate, but its ability to measure lung fluid through low electromagnetic radiofrequency pulses was the function of interest for this study.

In this nonrandomized study, called Benefits of Microcor in Ambulatory

Decompensated Heart Failure (BMAD), a control arm was enrolled first. By monitoring the initial patients enrolled in the control arm, the investigators established a threshold of thoracic fluid that would be used to trigger an alert in the intervention arm. This ultimately was defined as 3 standard deviations from the population mean.

Patients were eligible for this study if they were discharged from a hospital with heart failure in the previous 10 days. Of exclusion criteria, a short life expectancy (< 1 year) and a wearable cardiac defibrillator were notable. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was not considered for inclusion or exclusion.

All subjects participated in weekly phone calls and monthly office visits. However, both investigators and patients were blinded to the device data in the control arm. Conversely, subjects and investigators in the intervention arm were able to access data generated by the device through a secure website.

Of the 245 eligible patients in the control arm, 168 were available for evaluation at 90 days. Among the 249 eligible patients in the intervention arm, 176 were included in the 90-day evaluation. Of those who were not available, the most common reason was study withdrawal. About 20% died before the 90-day evaluation.

The majority of patients in both arms were in class III or IV heart failure. About half had LVEF less than 40%, and more than 40% of patients in each group had chronic kidney disease (CKD). Roughly 55% of patients were at least 65 years of age.

At 90 days, the absolute risk reduction in rehospitalization was 7%, producing a number to treat with the device of 14.3 to prevent one rehospitalization. In a subgroup stratification, the benefit was similar by age, sex, presence or absence of CKD, LVEF greater or lower than 40%, Black or non-Black race, and ischemic or nonischemic etiology.

Patient access to data considered a plus

If lack of randomization is a weakness of this study, the decision to unblind the data for both investigators and patients might not be, according to Lynne Stevenson, MD, director of the cardiomyopathy program, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

“You might be criticized for this [allowing patients to monitor their data], but I actually think this is a strength of the study,” said Dr. Stevenson, who believes the growing trend to involve heart failure patients in self-management has been a positive direction in clinical care.

She indicated that, despite the potential bias derived from being aware of fluid fluctuations, this information might also be contributing to patient motivation for adherence and appropriate lifestyle modifications.

Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, chair of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, made a similar point but for a different reason. She expressed concern about the work that monitoring the wearable device creates for clinicians. Despite the positive data generated by this study, Dr. Bozkurt said the device as used in the study demanded “a lot of clinical time and effort” when these are both in short supply.

While she called for a larger and randomized study to corroborate the results of this investigation, she also thinks that it would make sense to compare the clinical value of this device against alternative methods for monitoring heart failure, including other wearable devices. Dr. Bozkurt asserted that some of the most helpful devices from a clinical perspective might be those that patients monitor themselves.

“Hopefully in the future, we will be offering tools that provide patients information they can use without the immediate need of a clinician,” she said.

Dr. Boehmer reports financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical Corporation, which provided the funding for this study. Dr. Stevenson reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Bozkurt reports financial relationships with Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardurion, LivaNova, Relypsa, Renovacor, Sanofi-Aventis, and Vifor.

NEW ORLEANS – A wearable device that monitors thoracic fluid and can signal elevated levels can improve outcomes after heart failure hospitalization, according to a comparative but nonrandomized trial.

In this study, management adjustments made in response to a threshold alert from the device led to several improvements in outcome at 90 days, including a significant 38% reduction in the primary outcome of rehospitalization, relative to controls (P = .02), reported John P. Boehmer, MD, at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

The same relative risk reduction at 90 days was observed for a composite outcome of time to first hospitalization, visit to an emergency room, or death (hazard ratio, 0.62; P = .03).

Quality of life, as measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), improved steadily in both the experimental and control arm over the 90-day study, but the curves separated at about 30 days, Dr. Boehmer reported. By the end of the study, the mean KCCQ difference was 12 points favoring the experimental arm on a scale in which 5 points is considered clinically meaningful.

70% report improved quality of life

“Responder analysis revealed that nearly 70% of patients in the arm managed with the monitor reported a clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life, compared to 50% of patients in the control arm,” said Dr. Boehmer, professor of medicine and surgery at Penn State Health, Hershey.

Fluid overload is an indication of worsening disease and a frequent cause of heart failure hospitalization. The Zoll Heart Failure Monitoring System (HFMS) that was tested in this study already has regulatory approval. It is equipped to monitor several biomarkers, including heart rate and respiration rate, but its ability to measure lung fluid through low electromagnetic radiofrequency pulses was the function of interest for this study.

In this nonrandomized study, called Benefits of Microcor in Ambulatory

Decompensated Heart Failure (BMAD), a control arm was enrolled first. By monitoring the initial patients enrolled in the control arm, the investigators established a threshold of thoracic fluid that would be used to trigger an alert in the intervention arm. This ultimately was defined as 3 standard deviations from the population mean.

Patients were eligible for this study if they were discharged from a hospital with heart failure in the previous 10 days. Of exclusion criteria, a short life expectancy (< 1 year) and a wearable cardiac defibrillator were notable. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was not considered for inclusion or exclusion.

All subjects participated in weekly phone calls and monthly office visits. However, both investigators and patients were blinded to the device data in the control arm. Conversely, subjects and investigators in the intervention arm were able to access data generated by the device through a secure website.

Of the 245 eligible patients in the control arm, 168 were available for evaluation at 90 days. Among the 249 eligible patients in the intervention arm, 176 were included in the 90-day evaluation. Of those who were not available, the most common reason was study withdrawal. About 20% died before the 90-day evaluation.

The majority of patients in both arms were in class III or IV heart failure. About half had LVEF less than 40%, and more than 40% of patients in each group had chronic kidney disease (CKD). Roughly 55% of patients were at least 65 years of age.

At 90 days, the absolute risk reduction in rehospitalization was 7%, producing a number to treat with the device of 14.3 to prevent one rehospitalization. In a subgroup stratification, the benefit was similar by age, sex, presence or absence of CKD, LVEF greater or lower than 40%, Black or non-Black race, and ischemic or nonischemic etiology.

Patient access to data considered a plus

If lack of randomization is a weakness of this study, the decision to unblind the data for both investigators and patients might not be, according to Lynne Stevenson, MD, director of the cardiomyopathy program, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

“You might be criticized for this [allowing patients to monitor their data], but I actually think this is a strength of the study,” said Dr. Stevenson, who believes the growing trend to involve heart failure patients in self-management has been a positive direction in clinical care.

She indicated that, despite the potential bias derived from being aware of fluid fluctuations, this information might also be contributing to patient motivation for adherence and appropriate lifestyle modifications.

Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, chair of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, made a similar point but for a different reason. She expressed concern about the work that monitoring the wearable device creates for clinicians. Despite the positive data generated by this study, Dr. Bozkurt said the device as used in the study demanded “a lot of clinical time and effort” when these are both in short supply.

While she called for a larger and randomized study to corroborate the results of this investigation, she also thinks that it would make sense to compare the clinical value of this device against alternative methods for monitoring heart failure, including other wearable devices. Dr. Bozkurt asserted that some of the most helpful devices from a clinical perspective might be those that patients monitor themselves.

“Hopefully in the future, we will be offering tools that provide patients information they can use without the immediate need of a clinician,” she said.

Dr. Boehmer reports financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical Corporation, which provided the funding for this study. Dr. Stevenson reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Bozkurt reports financial relationships with Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardurion, LivaNova, Relypsa, Renovacor, Sanofi-Aventis, and Vifor.

AT ACC 2023

FREEDOM COVID: Full-dose anticoagulation cut mortality but missed primary endpoint

Study conducted in noncritically ill

NEW ORLEANS – In the international FREEDOM COVID trial that randomized non–critically ill hospitalized patients, a therapeutic dose of anticoagulation relative to a prophylactic dose significantly reduced death from COVID-19 at 30 days, even as a larger composite primary endpoint was missed.

The mortality reduction suggests therapeutic-dose anticoagulation “may improve outcomes in non–critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who are at increased risk for adverse events but do not yet require ICU-level of care,” reported Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

These data provide a suggestion rather than a demonstration of benefit because the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, intubation requiring mechanical ventilation, systemic thromboembolism or ischemic stroke at 30 days was not met. Although this 30-day outcome was lower on the therapeutic dose (11.3% vs. 13.2%), the difference was only a trend (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .11), said Dr. Fuster, physician-in-chief, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Missed primary endpoint blamed on low events

The declining severity of more recent COVID-19 variants (the trial was conducted from August 2022 to September 2022) might be one explanation that the primary endpoint was not met, but the more likely explanation is the relatively good health status – and therefore a low risk of events – among patients randomized in India, 1 of 10 participating countries.

India accounted for roughly 40% of the total number of 3,398 patients in the intention-to-treat population. In India, the rates of events were 0.7 and 1.3 in the prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulation arms, respectively. In contrast, they were 17.5 and 9.5, respectively in the United States. In combined data from the other eight countries, the rates were 22.78 and 20.4, respectively.

“These results emphasize that varying country-specific thresholds for hospitalization may affect patient prognosis and the potential utility of advanced therapies” Dr. Fuster said.

In fact, the therapeutic anticoagulation was linked to a nonsignificant twofold increase in the risk of the primary outcome in India (HR, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-7.13) when outcomes were stratified by country. In the United States, where there was a much higher incidence of events, therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a nearly 50% reduction (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.91).

In the remaining countries, which included those in Latin America and Europe as well as the city of Hong Kong, the primary outcome was reduced numerically but not statistically by therapeutic relative to prophylactic anticoagulation (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.71-1.11).

Enoxaparin and apixaban are studied

In FREEDOM COVID, patients were randomized to a therapeutic dose of the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin (1 mg/kg every 12 hours), a prophylactic dose of enoxaparin (40 mg once daily), or a therapeutic dose of the direct factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (5 mg every 12 hours). Lower doses of enoxaparin and apixaban were used for those with renal impairment, and lower doses of apixaban were employed for elderly patients (≥ 80 years) and those with low body weight (≤ 60 kg).

The major inclusion criteria were confirmed COVID-19 infection with symptomatic systemic involvement. The major exclusion criteria were need for ICU level of care or active bleeding.

The therapeutic anticoagulation arms performed similarly and were combined for comparison to the prophylactic arm. Despite the failure to show a difference in the primary outcome, the rate of 30-day mortality was substantially lower in the therapeutic arm (4.9% vs. 7.0%), translating into a 30% risk reduction (HR, 0.70; P = .01).

Therapeutic anticoagulation was also associated with a lower rate of intubation/mechanical ventilation (6.4% vs. 8.4%) that reached statistical significance (HR, 0.75; P = .03). The risk reduction was also significant for a combination of these endpoints (HR, 0.77; P = .03).

The lower proportion of patients who eventually required ICU-level of care (9.9% vs. 11.7%) showed a trend in favor of therapeutic anticoagulation (HR, 0.84; P = .11).

Bleeding rates did not differ between arms

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium major bleeding types 3 and 5 were slightly numerically higher in the group randomized to therapeutic enoxaparin (0.5%) than prophylactic enoxaparin (0.1%) and therapeutic apixaban (0.3%), but the differences between any groups were not significant.

Numerous anticoagulation trials in patients with COVID-19 have been published previously. One 2021 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine also suggested benefit from a therapeutic relative to prophylactic anticoagulation. In that trial, which compared heparin to usual-care thromboprophylaxis, benefits were derived from a Bayesian analysis. Significant differences were not shown for death or other major outcome assessed individually.

Even though this more recent trial missed its primary endpoint, Gregg Stone, MD, a coauthor of this study and a colleague of Dr. Fuster at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, reiterated that these results support routine anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“These are robust reductions in mortality and intubation rates, which are the most serious outcomes,” said Dr. Stone, who is first author of the paper, which was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology immediately after Dr. Fuster’s presentation.

COVID-19 has proven to be a very thrombogenic virus, but the literature has not been wholly consistent on which anticoagulation treatment provides the best balance of benefits and risks, according to Julia Grapsa, MD, PhD, attending cardiologist, Guys and St. Thomas Hospital, London. She said that this randomized trial, despite its failure to meet the primary endpoint, is useful.

“This demonstrates that a therapeutic dose of enoxaparin is likely to improve outcomes over a prophylactic dose with a low risk of bleeding,” Dr. Grapsa said. On the basis of the randomized study, “I feel more confident with this approach.”

Dr. Fuster reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Stone has financial relationships with more than 30 companies that make pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Dr. Grapsa reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Study conducted in noncritically ill

Study conducted in noncritically ill

NEW ORLEANS – In the international FREEDOM COVID trial that randomized non–critically ill hospitalized patients, a therapeutic dose of anticoagulation relative to a prophylactic dose significantly reduced death from COVID-19 at 30 days, even as a larger composite primary endpoint was missed.

The mortality reduction suggests therapeutic-dose anticoagulation “may improve outcomes in non–critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who are at increased risk for adverse events but do not yet require ICU-level of care,” reported Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

These data provide a suggestion rather than a demonstration of benefit because the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, intubation requiring mechanical ventilation, systemic thromboembolism or ischemic stroke at 30 days was not met. Although this 30-day outcome was lower on the therapeutic dose (11.3% vs. 13.2%), the difference was only a trend (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .11), said Dr. Fuster, physician-in-chief, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Missed primary endpoint blamed on low events

The declining severity of more recent COVID-19 variants (the trial was conducted from August 2022 to September 2022) might be one explanation that the primary endpoint was not met, but the more likely explanation is the relatively good health status – and therefore a low risk of events – among patients randomized in India, 1 of 10 participating countries.

India accounted for roughly 40% of the total number of 3,398 patients in the intention-to-treat population. In India, the rates of events were 0.7 and 1.3 in the prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulation arms, respectively. In contrast, they were 17.5 and 9.5, respectively in the United States. In combined data from the other eight countries, the rates were 22.78 and 20.4, respectively.

“These results emphasize that varying country-specific thresholds for hospitalization may affect patient prognosis and the potential utility of advanced therapies” Dr. Fuster said.

In fact, the therapeutic anticoagulation was linked to a nonsignificant twofold increase in the risk of the primary outcome in India (HR, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-7.13) when outcomes were stratified by country. In the United States, where there was a much higher incidence of events, therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a nearly 50% reduction (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.91).

In the remaining countries, which included those in Latin America and Europe as well as the city of Hong Kong, the primary outcome was reduced numerically but not statistically by therapeutic relative to prophylactic anticoagulation (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.71-1.11).

Enoxaparin and apixaban are studied

In FREEDOM COVID, patients were randomized to a therapeutic dose of the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin (1 mg/kg every 12 hours), a prophylactic dose of enoxaparin (40 mg once daily), or a therapeutic dose of the direct factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (5 mg every 12 hours). Lower doses of enoxaparin and apixaban were used for those with renal impairment, and lower doses of apixaban were employed for elderly patients (≥ 80 years) and those with low body weight (≤ 60 kg).

The major inclusion criteria were confirmed COVID-19 infection with symptomatic systemic involvement. The major exclusion criteria were need for ICU level of care or active bleeding.

The therapeutic anticoagulation arms performed similarly and were combined for comparison to the prophylactic arm. Despite the failure to show a difference in the primary outcome, the rate of 30-day mortality was substantially lower in the therapeutic arm (4.9% vs. 7.0%), translating into a 30% risk reduction (HR, 0.70; P = .01).

Therapeutic anticoagulation was also associated with a lower rate of intubation/mechanical ventilation (6.4% vs. 8.4%) that reached statistical significance (HR, 0.75; P = .03). The risk reduction was also significant for a combination of these endpoints (HR, 0.77; P = .03).

The lower proportion of patients who eventually required ICU-level of care (9.9% vs. 11.7%) showed a trend in favor of therapeutic anticoagulation (HR, 0.84; P = .11).

Bleeding rates did not differ between arms

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium major bleeding types 3 and 5 were slightly numerically higher in the group randomized to therapeutic enoxaparin (0.5%) than prophylactic enoxaparin (0.1%) and therapeutic apixaban (0.3%), but the differences between any groups were not significant.

Numerous anticoagulation trials in patients with COVID-19 have been published previously. One 2021 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine also suggested benefit from a therapeutic relative to prophylactic anticoagulation. In that trial, which compared heparin to usual-care thromboprophylaxis, benefits were derived from a Bayesian analysis. Significant differences were not shown for death or other major outcome assessed individually.

Even though this more recent trial missed its primary endpoint, Gregg Stone, MD, a coauthor of this study and a colleague of Dr. Fuster at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, reiterated that these results support routine anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“These are robust reductions in mortality and intubation rates, which are the most serious outcomes,” said Dr. Stone, who is first author of the paper, which was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology immediately after Dr. Fuster’s presentation.

COVID-19 has proven to be a very thrombogenic virus, but the literature has not been wholly consistent on which anticoagulation treatment provides the best balance of benefits and risks, according to Julia Grapsa, MD, PhD, attending cardiologist, Guys and St. Thomas Hospital, London. She said that this randomized trial, despite its failure to meet the primary endpoint, is useful.

“This demonstrates that a therapeutic dose of enoxaparin is likely to improve outcomes over a prophylactic dose with a low risk of bleeding,” Dr. Grapsa said. On the basis of the randomized study, “I feel more confident with this approach.”

Dr. Fuster reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Stone has financial relationships with more than 30 companies that make pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Dr. Grapsa reported no potential conflicts of interest.

NEW ORLEANS – In the international FREEDOM COVID trial that randomized non–critically ill hospitalized patients, a therapeutic dose of anticoagulation relative to a prophylactic dose significantly reduced death from COVID-19 at 30 days, even as a larger composite primary endpoint was missed.

The mortality reduction suggests therapeutic-dose anticoagulation “may improve outcomes in non–critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who are at increased risk for adverse events but do not yet require ICU-level of care,” reported Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

These data provide a suggestion rather than a demonstration of benefit because the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, intubation requiring mechanical ventilation, systemic thromboembolism or ischemic stroke at 30 days was not met. Although this 30-day outcome was lower on the therapeutic dose (11.3% vs. 13.2%), the difference was only a trend (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .11), said Dr. Fuster, physician-in-chief, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Missed primary endpoint blamed on low events

The declining severity of more recent COVID-19 variants (the trial was conducted from August 2022 to September 2022) might be one explanation that the primary endpoint was not met, but the more likely explanation is the relatively good health status – and therefore a low risk of events – among patients randomized in India, 1 of 10 participating countries.

India accounted for roughly 40% of the total number of 3,398 patients in the intention-to-treat population. In India, the rates of events were 0.7 and 1.3 in the prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulation arms, respectively. In contrast, they were 17.5 and 9.5, respectively in the United States. In combined data from the other eight countries, the rates were 22.78 and 20.4, respectively.

“These results emphasize that varying country-specific thresholds for hospitalization may affect patient prognosis and the potential utility of advanced therapies” Dr. Fuster said.

In fact, the therapeutic anticoagulation was linked to a nonsignificant twofold increase in the risk of the primary outcome in India (HR, 2.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-7.13) when outcomes were stratified by country. In the United States, where there was a much higher incidence of events, therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a nearly 50% reduction (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.91).

In the remaining countries, which included those in Latin America and Europe as well as the city of Hong Kong, the primary outcome was reduced numerically but not statistically by therapeutic relative to prophylactic anticoagulation (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.71-1.11).

Enoxaparin and apixaban are studied

In FREEDOM COVID, patients were randomized to a therapeutic dose of the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin (1 mg/kg every 12 hours), a prophylactic dose of enoxaparin (40 mg once daily), or a therapeutic dose of the direct factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (5 mg every 12 hours). Lower doses of enoxaparin and apixaban were used for those with renal impairment, and lower doses of apixaban were employed for elderly patients (≥ 80 years) and those with low body weight (≤ 60 kg).

The major inclusion criteria were confirmed COVID-19 infection with symptomatic systemic involvement. The major exclusion criteria were need for ICU level of care or active bleeding.

The therapeutic anticoagulation arms performed similarly and were combined for comparison to the prophylactic arm. Despite the failure to show a difference in the primary outcome, the rate of 30-day mortality was substantially lower in the therapeutic arm (4.9% vs. 7.0%), translating into a 30% risk reduction (HR, 0.70; P = .01).

Therapeutic anticoagulation was also associated with a lower rate of intubation/mechanical ventilation (6.4% vs. 8.4%) that reached statistical significance (HR, 0.75; P = .03). The risk reduction was also significant for a combination of these endpoints (HR, 0.77; P = .03).

The lower proportion of patients who eventually required ICU-level of care (9.9% vs. 11.7%) showed a trend in favor of therapeutic anticoagulation (HR, 0.84; P = .11).

Bleeding rates did not differ between arms

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium major bleeding types 3 and 5 were slightly numerically higher in the group randomized to therapeutic enoxaparin (0.5%) than prophylactic enoxaparin (0.1%) and therapeutic apixaban (0.3%), but the differences between any groups were not significant.

Numerous anticoagulation trials in patients with COVID-19 have been published previously. One 2021 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine also suggested benefit from a therapeutic relative to prophylactic anticoagulation. In that trial, which compared heparin to usual-care thromboprophylaxis, benefits were derived from a Bayesian analysis. Significant differences were not shown for death or other major outcome assessed individually.

Even though this more recent trial missed its primary endpoint, Gregg Stone, MD, a coauthor of this study and a colleague of Dr. Fuster at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, reiterated that these results support routine anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

“These are robust reductions in mortality and intubation rates, which are the most serious outcomes,” said Dr. Stone, who is first author of the paper, which was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology immediately after Dr. Fuster’s presentation.

COVID-19 has proven to be a very thrombogenic virus, but the literature has not been wholly consistent on which anticoagulation treatment provides the best balance of benefits and risks, according to Julia Grapsa, MD, PhD, attending cardiologist, Guys and St. Thomas Hospital, London. She said that this randomized trial, despite its failure to meet the primary endpoint, is useful.

“This demonstrates that a therapeutic dose of enoxaparin is likely to improve outcomes over a prophylactic dose with a low risk of bleeding,” Dr. Grapsa said. On the basis of the randomized study, “I feel more confident with this approach.”

Dr. Fuster reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Stone has financial relationships with more than 30 companies that make pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Dr. Grapsa reported no potential conflicts of interest.

AT ACC 2023

Inspector General Finds Security Vulnerabilities and Risks at VA Medical Facilities

In 2022, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) received 36 separate serious incident reports involving 32 medical facilities—including a bomb threat. In response to those reports, OIG teams of auditors and criminal investigators visited 70 VA medical facilities in September 2022 to assess security and to issue a formal report.

Noting that VA policy includes an “extensive list of security safeguards” for medical facilities to implement, the OIG focused its review on those that “a person with a reasonable level of security knowledge could assess.” According to their report, released in February, they identified a variety of security vulnerabilities and deficiencies, ranging from shortages of police officers to radios with poor signal strength.

For one, the OIG says, the facilities were designed to provide a welcoming environment, which means the public can enter the grounds freely at many different points. But the open-campus design makes it more difficult to balance security with easy and prompt access for patients. Consequently, the OIG says, “threats may originate from many locations within the medical facility campus itself or in the nearby community.”

Walking around the perimeters of the facility buildings, the OIG teams assessed the security level of 2960 public and nonpublic access doors. They found that 87% of public doors did not have an active security presence, and of those, 23% also did not have a security camera. Moreover, 17% of nonpublic doors were unlocked; 97% of those did not have a security presence, and 43% did not have a security camera. Even more concerning: Some of those doors led to sensitive or restricted facility areas. For example, at one midwestern facility, an unlocked nonpublic access door led to the surgical intensive care unit.

The OIG teams also assessed training records for 170 police officers across the 70 facilities and found that nearly all officers were compliant with training requirements. Most respondents also reported they received adequate training to perform their job duties and provided numerous positive indicators. Well trained or not, though, a notable problem in maintaining security, the OIG teams found, was there simply weren’t enough officers.

The OIG has repeatedly issued reports on significant police officer staffing shortages since at least 2018. VA police officers are not only empowered to make arrests, carry firearms while on duty, and investigate criminal activity within VA’s jurisdiction, but also assist individuals on medical campuses “in myriad ways,” the OIG notes. Staffing shortages are likely to compromise overall facility security, morale, and staff retention and underscore the need for maintaining communication with local law enforcement agencies for assistance, the OIG report points out.

In the OIG surveys, security personnel often noted they were understaffed. Although VA guidance calls for at least 2 VA police officers on duty at all times, 21% of respondents said they were aware of a duty shift during which minimum police staffing requirements were not met. About 37% of respondents expressed concerns about the physical security at their facilities. Some pointed out that the lack of VA police on duty could make it difficult to respond to threats like an active shooter.

In May 2022, the VA issued a directive that established minimum police coverage at medical facilities, as well as a police officer staffing decision tool to help determine appropriate officer levels. It required facilities to have an active security presence in their emergency departments around-the-clock by May 2023. As of September 2022, 58% of the facilities’ emergency departments did not yet have a visible security presence.

The teams also found issues with security devices: 19% of all cameras were not functional; at 24 facilities, more than 20% of the cameras were not working. A few facilities had “highly functional” systems that allowed personnel to monitor the campus thoroughly and even search for specific individuals—but they weren’t always operable.

At one western facility, it came down to a problem that would be frustrating at any time, but alarming for security management: Security personnel could not access the monitoring system because the required security certificates had expired, and no one knew the administrative password. If the system went offline, the OIG team was told, no one could fix the problem without password access. Neither VA’s Office of Information and Technology nor the contractor for the facility’s cameras could override the administrative password.

On the bright side, the OIG teams found that camera video feeds were being actively surveilled by security personnel at 60 of 70 facilities. All but 1 site kept camera footage for an average of 2 weeks or more.

VA policy states that, in addition to at least 2 intermediate weapons (such as batons and pepper spray) uniformed officers must always be issued radios for use while on duty. Survey respondents generally indicated they received their equipment and that it was adequate, but 15% said theirs lacked functionality, such as battery life and signal strength.

Based on the teams’ findings, the OIG made 6 recommendations: (1) delegating a responsible official to monitor and report monthly on facilities’ security-related vacancies; (2) authorizing sufficient staff to inspect VA police forces per the OIG’s 2018 unimplemented recommendation; (3) ensuring medical facility directors appropriately assess VA police staffing needs, authorize associated positions, and leverage available mechanisms to fill vacancies; (4) committing sufficient resources to ensure that facility security measures are adequate, current, and operational; (5) directing Veterans Integrated Services Network police chiefs, in coordination with medical facility directors, facility police chiefs, and facility emergency management leaders, to present a plan to remedy identified security weaknesses; and (6) establishing policy that standardizes the review and retention requirements for facility security camera footage.

The VA concurred with all recommendations and submitted corrective action plans.

In 2022, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) received 36 separate serious incident reports involving 32 medical facilities—including a bomb threat. In response to those reports, OIG teams of auditors and criminal investigators visited 70 VA medical facilities in September 2022 to assess security and to issue a formal report.

Noting that VA policy includes an “extensive list of security safeguards” for medical facilities to implement, the OIG focused its review on those that “a person with a reasonable level of security knowledge could assess.” According to their report, released in February, they identified a variety of security vulnerabilities and deficiencies, ranging from shortages of police officers to radios with poor signal strength.

For one, the OIG says, the facilities were designed to provide a welcoming environment, which means the public can enter the grounds freely at many different points. But the open-campus design makes it more difficult to balance security with easy and prompt access for patients. Consequently, the OIG says, “threats may originate from many locations within the medical facility campus itself or in the nearby community.”

Walking around the perimeters of the facility buildings, the OIG teams assessed the security level of 2960 public and nonpublic access doors. They found that 87% of public doors did not have an active security presence, and of those, 23% also did not have a security camera. Moreover, 17% of nonpublic doors were unlocked; 97% of those did not have a security presence, and 43% did not have a security camera. Even more concerning: Some of those doors led to sensitive or restricted facility areas. For example, at one midwestern facility, an unlocked nonpublic access door led to the surgical intensive care unit.

The OIG teams also assessed training records for 170 police officers across the 70 facilities and found that nearly all officers were compliant with training requirements. Most respondents also reported they received adequate training to perform their job duties and provided numerous positive indicators. Well trained or not, though, a notable problem in maintaining security, the OIG teams found, was there simply weren’t enough officers.

The OIG has repeatedly issued reports on significant police officer staffing shortages since at least 2018. VA police officers are not only empowered to make arrests, carry firearms while on duty, and investigate criminal activity within VA’s jurisdiction, but also assist individuals on medical campuses “in myriad ways,” the OIG notes. Staffing shortages are likely to compromise overall facility security, morale, and staff retention and underscore the need for maintaining communication with local law enforcement agencies for assistance, the OIG report points out.

In the OIG surveys, security personnel often noted they were understaffed. Although VA guidance calls for at least 2 VA police officers on duty at all times, 21% of respondents said they were aware of a duty shift during which minimum police staffing requirements were not met. About 37% of respondents expressed concerns about the physical security at their facilities. Some pointed out that the lack of VA police on duty could make it difficult to respond to threats like an active shooter.

In May 2022, the VA issued a directive that established minimum police coverage at medical facilities, as well as a police officer staffing decision tool to help determine appropriate officer levels. It required facilities to have an active security presence in their emergency departments around-the-clock by May 2023. As of September 2022, 58% of the facilities’ emergency departments did not yet have a visible security presence.

The teams also found issues with security devices: 19% of all cameras were not functional; at 24 facilities, more than 20% of the cameras were not working. A few facilities had “highly functional” systems that allowed personnel to monitor the campus thoroughly and even search for specific individuals—but they weren’t always operable.

At one western facility, it came down to a problem that would be frustrating at any time, but alarming for security management: Security personnel could not access the monitoring system because the required security certificates had expired, and no one knew the administrative password. If the system went offline, the OIG team was told, no one could fix the problem without password access. Neither VA’s Office of Information and Technology nor the contractor for the facility’s cameras could override the administrative password.

On the bright side, the OIG teams found that camera video feeds were being actively surveilled by security personnel at 60 of 70 facilities. All but 1 site kept camera footage for an average of 2 weeks or more.

VA policy states that, in addition to at least 2 intermediate weapons (such as batons and pepper spray) uniformed officers must always be issued radios for use while on duty. Survey respondents generally indicated they received their equipment and that it was adequate, but 15% said theirs lacked functionality, such as battery life and signal strength.

Based on the teams’ findings, the OIG made 6 recommendations: (1) delegating a responsible official to monitor and report monthly on facilities’ security-related vacancies; (2) authorizing sufficient staff to inspect VA police forces per the OIG’s 2018 unimplemented recommendation; (3) ensuring medical facility directors appropriately assess VA police staffing needs, authorize associated positions, and leverage available mechanisms to fill vacancies; (4) committing sufficient resources to ensure that facility security measures are adequate, current, and operational; (5) directing Veterans Integrated Services Network police chiefs, in coordination with medical facility directors, facility police chiefs, and facility emergency management leaders, to present a plan to remedy identified security weaknesses; and (6) establishing policy that standardizes the review and retention requirements for facility security camera footage.

The VA concurred with all recommendations and submitted corrective action plans.

In 2022, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) received 36 separate serious incident reports involving 32 medical facilities—including a bomb threat. In response to those reports, OIG teams of auditors and criminal investigators visited 70 VA medical facilities in September 2022 to assess security and to issue a formal report.

Noting that VA policy includes an “extensive list of security safeguards” for medical facilities to implement, the OIG focused its review on those that “a person with a reasonable level of security knowledge could assess.” According to their report, released in February, they identified a variety of security vulnerabilities and deficiencies, ranging from shortages of police officers to radios with poor signal strength.

For one, the OIG says, the facilities were designed to provide a welcoming environment, which means the public can enter the grounds freely at many different points. But the open-campus design makes it more difficult to balance security with easy and prompt access for patients. Consequently, the OIG says, “threats may originate from many locations within the medical facility campus itself or in the nearby community.”

Walking around the perimeters of the facility buildings, the OIG teams assessed the security level of 2960 public and nonpublic access doors. They found that 87% of public doors did not have an active security presence, and of those, 23% also did not have a security camera. Moreover, 17% of nonpublic doors were unlocked; 97% of those did not have a security presence, and 43% did not have a security camera. Even more concerning: Some of those doors led to sensitive or restricted facility areas. For example, at one midwestern facility, an unlocked nonpublic access door led to the surgical intensive care unit.

The OIG teams also assessed training records for 170 police officers across the 70 facilities and found that nearly all officers were compliant with training requirements. Most respondents also reported they received adequate training to perform their job duties and provided numerous positive indicators. Well trained or not, though, a notable problem in maintaining security, the OIG teams found, was there simply weren’t enough officers.

The OIG has repeatedly issued reports on significant police officer staffing shortages since at least 2018. VA police officers are not only empowered to make arrests, carry firearms while on duty, and investigate criminal activity within VA’s jurisdiction, but also assist individuals on medical campuses “in myriad ways,” the OIG notes. Staffing shortages are likely to compromise overall facility security, morale, and staff retention and underscore the need for maintaining communication with local law enforcement agencies for assistance, the OIG report points out.

In the OIG surveys, security personnel often noted they were understaffed. Although VA guidance calls for at least 2 VA police officers on duty at all times, 21% of respondents said they were aware of a duty shift during which minimum police staffing requirements were not met. About 37% of respondents expressed concerns about the physical security at their facilities. Some pointed out that the lack of VA police on duty could make it difficult to respond to threats like an active shooter.

In May 2022, the VA issued a directive that established minimum police coverage at medical facilities, as well as a police officer staffing decision tool to help determine appropriate officer levels. It required facilities to have an active security presence in their emergency departments around-the-clock by May 2023. As of September 2022, 58% of the facilities’ emergency departments did not yet have a visible security presence.

The teams also found issues with security devices: 19% of all cameras were not functional; at 24 facilities, more than 20% of the cameras were not working. A few facilities had “highly functional” systems that allowed personnel to monitor the campus thoroughly and even search for specific individuals—but they weren’t always operable.

At one western facility, it came down to a problem that would be frustrating at any time, but alarming for security management: Security personnel could not access the monitoring system because the required security certificates had expired, and no one knew the administrative password. If the system went offline, the OIG team was told, no one could fix the problem without password access. Neither VA’s Office of Information and Technology nor the contractor for the facility’s cameras could override the administrative password.

On the bright side, the OIG teams found that camera video feeds were being actively surveilled by security personnel at 60 of 70 facilities. All but 1 site kept camera footage for an average of 2 weeks or more.

VA policy states that, in addition to at least 2 intermediate weapons (such as batons and pepper spray) uniformed officers must always be issued radios for use while on duty. Survey respondents generally indicated they received their equipment and that it was adequate, but 15% said theirs lacked functionality, such as battery life and signal strength.

Based on the teams’ findings, the OIG made 6 recommendations: (1) delegating a responsible official to monitor and report monthly on facilities’ security-related vacancies; (2) authorizing sufficient staff to inspect VA police forces per the OIG’s 2018 unimplemented recommendation; (3) ensuring medical facility directors appropriately assess VA police staffing needs, authorize associated positions, and leverage available mechanisms to fill vacancies; (4) committing sufficient resources to ensure that facility security measures are adequate, current, and operational; (5) directing Veterans Integrated Services Network police chiefs, in coordination with medical facility directors, facility police chiefs, and facility emergency management leaders, to present a plan to remedy identified security weaknesses; and (6) establishing policy that standardizes the review and retention requirements for facility security camera footage.

The VA concurred with all recommendations and submitted corrective action plans.

History of nonproductive cough

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of eosinophilic asthma.

Asthma is a common, chronic, and heterogeneous respiratory disease, most often characterized by chronic airway inflammation. Affected individuals experience respiratory symptoms (ie, wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and cough) that may fluctuate over time and in intensity, as well as variable expiratory airflow limitation, which may become persistent. For many patients, asthma has a significant impact on quality of life. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people and caused 455,000 deaths. Currently, approximately 334 million people worldwide are believed to be affected by asthma.

Asthma frequently begins in childhood, but adult-onset asthma can occur and often presents as a nonatopic and eosinophilic condition. In fact, asthma is an umbrella diagnosis that encompasses several diseases with distinct mechanistic pathways (endotypes) and variable clinical presentations (phenotypes), all of which manifest with respiratory symptoms and are accompanied by variable airflow obstruction.

Broadly, asthma endotypes are categorized as type 2 (T2)-high or T2-low. Eosinophilic asthma falls under the T2-high endotype and comprises three phenotypes: atopic, late-onset, and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Late-onset T2-high asthma is characterized by prominent blood and sputum eosinophilia and is refractory to inhaled/oral corticosteroid treatment. Patients in this subgroup tend to be older and have more severe asthma with fixed airflow obstruction and more frequent exacerbations; patients may also have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, which usually precedes asthma development. High FeNO levels and normal or elevated serum total IgE levels are also often seen in this subgroup.

The late-onset eosinophilic asthma phenotype accounts for 20%-40% of severe asthma cases and is associated with rapid decline of respiratory functions. Thus, earlier escalation of therapy may be indicated in patients with this phenotype.

According to a 2022 report from the Global Initiative for Asthma, the possibility of refractory T2 asthma should be considered when any of the following is found in patients taking high-dose ICS or daily oral corticosteroids:

• Blood eosinophils ≥ 150/μL, and/or

• FeNO ≥ 20 ppb, and/or

• Sputum eosinophils ≥ 2%, and/or

• Asthma is clinically allergen driven

Biologic T2-targeted therapies are available as add-on therapies for patients with T2 airway inflammation and severe asthma despite taking at least a high-dose ICS-LABA, and who have eosinophilic or allergic biomarkers or need maintenance oral corticosteroids. Available options for eosinophilic asthma include anti-interleukin (IL)-5/anti-IL-5R therapies (benralizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab) and anti-IL-4R therapy (dupilumab).

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of eosinophilic asthma.

Asthma is a common, chronic, and heterogeneous respiratory disease, most often characterized by chronic airway inflammation. Affected individuals experience respiratory symptoms (ie, wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and cough) that may fluctuate over time and in intensity, as well as variable expiratory airflow limitation, which may become persistent. For many patients, asthma has a significant impact on quality of life. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people and caused 455,000 deaths. Currently, approximately 334 million people worldwide are believed to be affected by asthma.

Asthma frequently begins in childhood, but adult-onset asthma can occur and often presents as a nonatopic and eosinophilic condition. In fact, asthma is an umbrella diagnosis that encompasses several diseases with distinct mechanistic pathways (endotypes) and variable clinical presentations (phenotypes), all of which manifest with respiratory symptoms and are accompanied by variable airflow obstruction.

Broadly, asthma endotypes are categorized as type 2 (T2)-high or T2-low. Eosinophilic asthma falls under the T2-high endotype and comprises three phenotypes: atopic, late-onset, and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Late-onset T2-high asthma is characterized by prominent blood and sputum eosinophilia and is refractory to inhaled/oral corticosteroid treatment. Patients in this subgroup tend to be older and have more severe asthma with fixed airflow obstruction and more frequent exacerbations; patients may also have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, which usually precedes asthma development. High FeNO levels and normal or elevated serum total IgE levels are also often seen in this subgroup.

The late-onset eosinophilic asthma phenotype accounts for 20%-40% of severe asthma cases and is associated with rapid decline of respiratory functions. Thus, earlier escalation of therapy may be indicated in patients with this phenotype.

According to a 2022 report from the Global Initiative for Asthma, the possibility of refractory T2 asthma should be considered when any of the following is found in patients taking high-dose ICS or daily oral corticosteroids:

• Blood eosinophils ≥ 150/μL, and/or

• FeNO ≥ 20 ppb, and/or

• Sputum eosinophils ≥ 2%, and/or

• Asthma is clinically allergen driven