User login

Painful blue fingers

A 48-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented to the emergency department from the rheumatology clinic for digital ischemia. The clinical manifestations of her SLE consisted predominantly of arthralgias, which had been previously well controlled on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d PO. On presentation, she denied oral ulcers, alopecia, shortness of breath, chest pain/pressure, and history of blood clots or miscarriages.

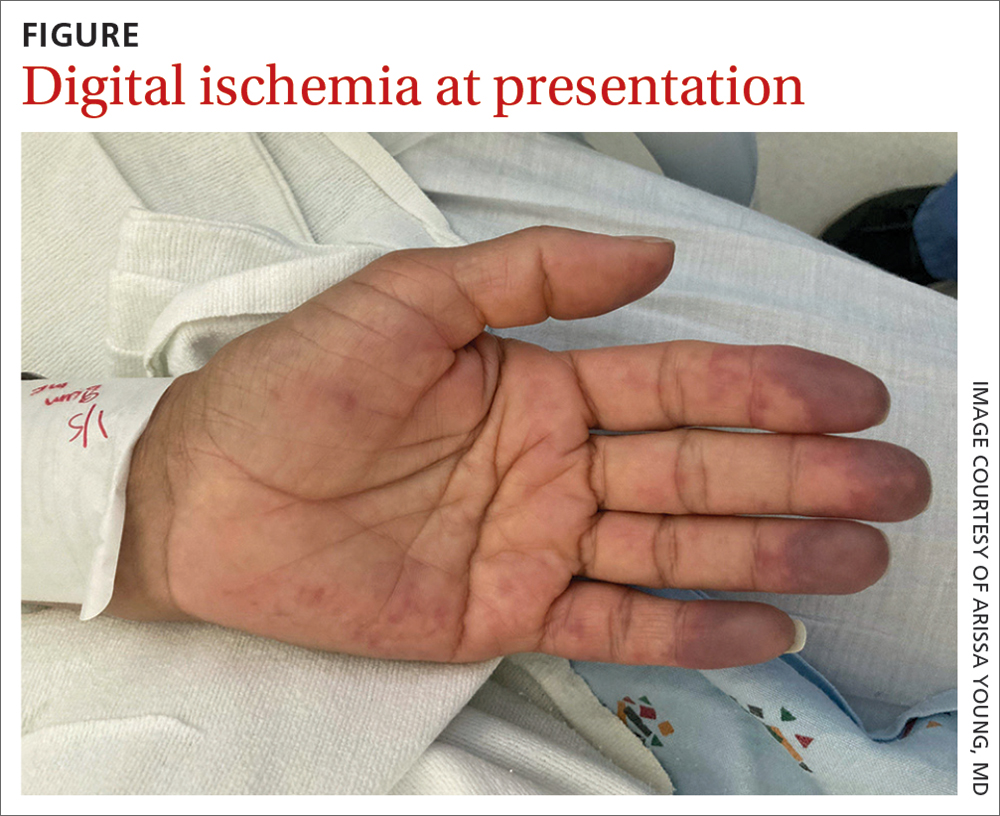

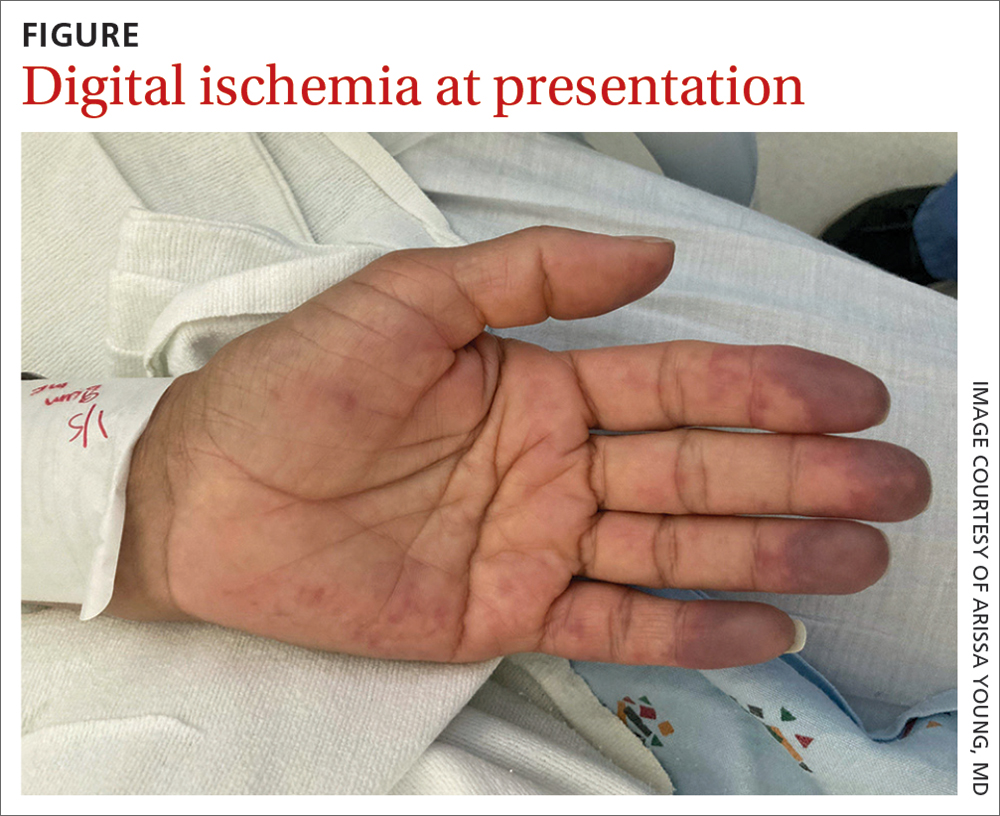

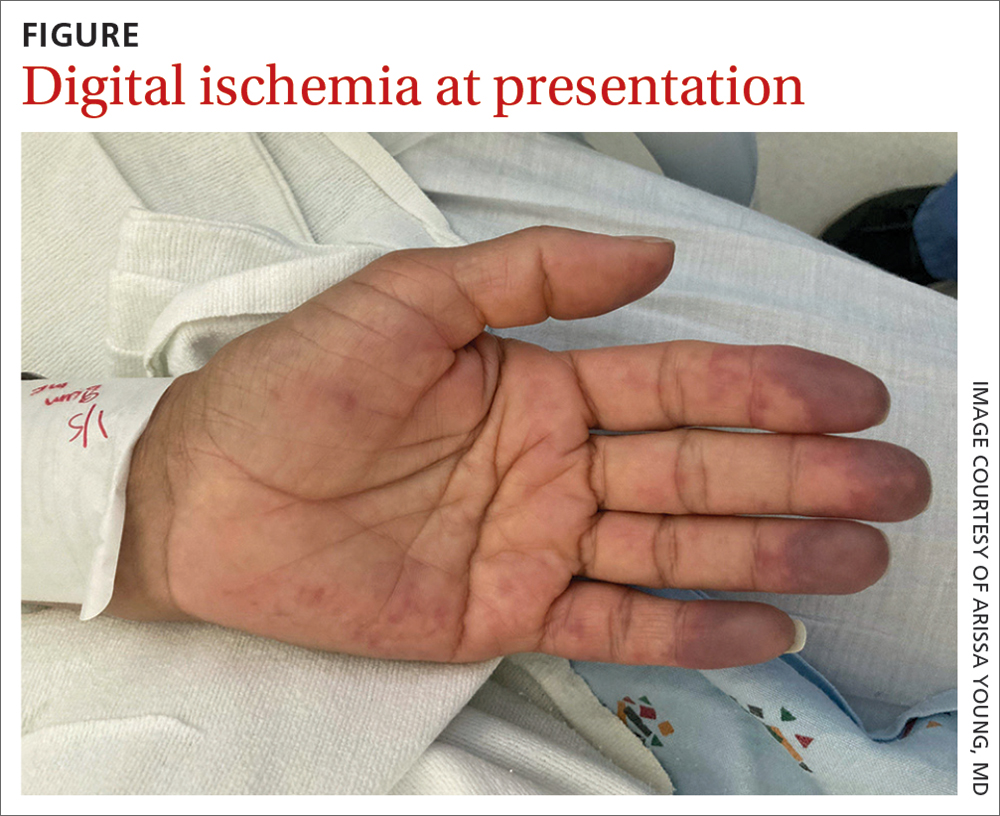

On exam, the patient was afebrile and had a heart rate of 74 bpm; blood pressure, 140/77 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The fingertips on her left hand were tender and cool to the touch, and the fingertips of her second through fifth digits were blue (FIGURE).

Laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL (normal range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 44 mm/h (normal range, ≤ 25 mm/h). Double-stranded DNA and complement levels were normal.

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations, and blood cultures from admission were negative. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast of her left upper extremity showed a filling defect in the origin of the left subclavian artery. Digital plethysmography showed dampened flow signals in the second through fifth digits of the left hand.

Tests for antiphospholipid antibodies were positive for lupus anticoagulant; there were also high titers of anti-β-2-glycoprotein immunoglobulin (Ig) G (58 SGU; normal, ≤ 20 SGU) and anticardiolipin IgG (242.4 CU; normal, ≤ 20 CU).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid syndrome

Given our patient’s SLE, left subclavian artery thrombosis, digital ischemia, and high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies, we had significant concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). The diagnosis of APS is most often based on the fulfillment of the revised Sapporo classification criteria. These criteria include both clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and laboratory criteria (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies on at least 2 separate occasions separated by 12 weeks).1 Our patient met clinical criteria given the evidence of subclavian artery thrombosis on CTA as well as digital plethysmography findings consistent with digital emboli. To meet laboratory criteria, she would have needed to have persistent high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies 12 weeks apart.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with thrombosis; it can be divided into primary and secondary APS. The estimated prevalence of APS is 50 per 100,000 people in the United States.2 Primary APS occurs in the absence of an underlying autoimmune disease, while secondary APS occurs in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune disease most often associated with APS is SLE.3 Among patients with SLE, 15% to 34% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 12% to 30% have anticardiolipin antibodies.4-6 This is compared with young healthy subjects among whom only 1% to 4% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 1% to 5% have anticardiolipin antibodies.7 Previous studies have estimated that 30% to 50% of patients with SLE who test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies will develop thrombosis.5,7

Differential includes Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis

The differential diagnosis for digital ischemia in a patient with SLE includes APS, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, and septic emboli.

Raynaud phenomenon can manifest in patients with SLE, but the presence of thrombosis on CTA and high-titer positive antiphospholipid antibodies make the diagnosis of APS more likely. Additionally, Raynaud phenomenon is typically temperature dependent with vasospasm in the digital arteries, occurring in cold temperatures and resolving with warming.

Systemic vasculitis may develop in patients with SLE, but in our case was less likely given the patient did not have any evidence of vasculitis on CTA, such as blood vessel wall thickening and/or enhancement.8

Septic emboli from endocarditis can cause digital ischemia but is typically associated with positive blood cultures, fever, and other systemic signs of infection, and/or vegetations on an echocardiogram.

Continue to: Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong antiocagulation Tx

Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong anticoagulation Tx

The mainstay of therapy for patients with APS is lifelong anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. The intensity of anticoagulation is determined based on the presence of venous or arterial thrombosis. In patients who present with arterial thrombosis, a higher intensity vitamin K antagonist (ie, international normalized ratio [INR] goal > 3) or the addition of low-dose aspirin should be considered.9,10

Factor Xa inhibitors are generally not recommended at this time due to the lack of evidence to support their use.10 Additionally, a randomized clinical trial comparing rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity was terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic events in the rivaroxaban arm.11

For patients with secondary APS in the setting of SLE, hydroxychloroquine in combination with a vitamin K antagonist has been shown to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombosis compared with treatment with a vitamin K antagonist alone.12

Our patient was started on a heparin drip and transitioned to an oral vitamin K antagonist with an INR goal of 2 to 3. Lifelong anticoagulation was planned. The pain and discoloration in her hands improved on anticoagulation and had nearly resolved by the time of discharge. Given her history of arterial thrombosis, the addition of aspirin was also considered, but this decision was ultimately deferred to her outpatient rheumatologist and hematologist.

1. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

2. Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1545-1552. doi: 10.1002/art.40901

3. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752-763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974

4. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113-124.

5. Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:682-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682

6. Merkel PA, Chang YC, Pierangeli SS, et al. The prevalence and clinical associations of anticardiolipin antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue diseases. Am J Med. 1996;101:576-583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00335-x

7. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:145-151. doi: 10.1006/jaut. 2000.0409

8. Bozlar U, Ogur T, Khaja MS, et al. CT angiography of the upper extremity arterial system: Part 2—Clinical applications beyond trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:753-763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11208

9. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Hunt BJ, Khamashta MA. A systematic review of secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;7:1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23109

10. Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: rationale and design of the Trial on Rivaroxaban in AntiPhospholipid Syndrome (TRAPS) trial. Lupus. 2016;25:301-306. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611495

12. Schmidt-Tanguy A, Voswinkel J, Henrion D, et al. Antithrombotic effects of hydroxychloroquine in primary antiphospholipid syndrome patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1927-1929. doi: 10.1111/jth.12363

A 48-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented to the emergency department from the rheumatology clinic for digital ischemia. The clinical manifestations of her SLE consisted predominantly of arthralgias, which had been previously well controlled on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d PO. On presentation, she denied oral ulcers, alopecia, shortness of breath, chest pain/pressure, and history of blood clots or miscarriages.

On exam, the patient was afebrile and had a heart rate of 74 bpm; blood pressure, 140/77 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The fingertips on her left hand were tender and cool to the touch, and the fingertips of her second through fifth digits were blue (FIGURE).

Laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL (normal range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 44 mm/h (normal range, ≤ 25 mm/h). Double-stranded DNA and complement levels were normal.

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations, and blood cultures from admission were negative. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast of her left upper extremity showed a filling defect in the origin of the left subclavian artery. Digital plethysmography showed dampened flow signals in the second through fifth digits of the left hand.

Tests for antiphospholipid antibodies were positive for lupus anticoagulant; there were also high titers of anti-β-2-glycoprotein immunoglobulin (Ig) G (58 SGU; normal, ≤ 20 SGU) and anticardiolipin IgG (242.4 CU; normal, ≤ 20 CU).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid syndrome

Given our patient’s SLE, left subclavian artery thrombosis, digital ischemia, and high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies, we had significant concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). The diagnosis of APS is most often based on the fulfillment of the revised Sapporo classification criteria. These criteria include both clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and laboratory criteria (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies on at least 2 separate occasions separated by 12 weeks).1 Our patient met clinical criteria given the evidence of subclavian artery thrombosis on CTA as well as digital plethysmography findings consistent with digital emboli. To meet laboratory criteria, she would have needed to have persistent high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies 12 weeks apart.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with thrombosis; it can be divided into primary and secondary APS. The estimated prevalence of APS is 50 per 100,000 people in the United States.2 Primary APS occurs in the absence of an underlying autoimmune disease, while secondary APS occurs in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune disease most often associated with APS is SLE.3 Among patients with SLE, 15% to 34% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 12% to 30% have anticardiolipin antibodies.4-6 This is compared with young healthy subjects among whom only 1% to 4% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 1% to 5% have anticardiolipin antibodies.7 Previous studies have estimated that 30% to 50% of patients with SLE who test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies will develop thrombosis.5,7

Differential includes Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis

The differential diagnosis for digital ischemia in a patient with SLE includes APS, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, and septic emboli.

Raynaud phenomenon can manifest in patients with SLE, but the presence of thrombosis on CTA and high-titer positive antiphospholipid antibodies make the diagnosis of APS more likely. Additionally, Raynaud phenomenon is typically temperature dependent with vasospasm in the digital arteries, occurring in cold temperatures and resolving with warming.

Systemic vasculitis may develop in patients with SLE, but in our case was less likely given the patient did not have any evidence of vasculitis on CTA, such as blood vessel wall thickening and/or enhancement.8

Septic emboli from endocarditis can cause digital ischemia but is typically associated with positive blood cultures, fever, and other systemic signs of infection, and/or vegetations on an echocardiogram.

Continue to: Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong antiocagulation Tx

Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong anticoagulation Tx

The mainstay of therapy for patients with APS is lifelong anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. The intensity of anticoagulation is determined based on the presence of venous or arterial thrombosis. In patients who present with arterial thrombosis, a higher intensity vitamin K antagonist (ie, international normalized ratio [INR] goal > 3) or the addition of low-dose aspirin should be considered.9,10

Factor Xa inhibitors are generally not recommended at this time due to the lack of evidence to support their use.10 Additionally, a randomized clinical trial comparing rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity was terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic events in the rivaroxaban arm.11

For patients with secondary APS in the setting of SLE, hydroxychloroquine in combination with a vitamin K antagonist has been shown to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombosis compared with treatment with a vitamin K antagonist alone.12

Our patient was started on a heparin drip and transitioned to an oral vitamin K antagonist with an INR goal of 2 to 3. Lifelong anticoagulation was planned. The pain and discoloration in her hands improved on anticoagulation and had nearly resolved by the time of discharge. Given her history of arterial thrombosis, the addition of aspirin was also considered, but this decision was ultimately deferred to her outpatient rheumatologist and hematologist.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented to the emergency department from the rheumatology clinic for digital ischemia. The clinical manifestations of her SLE consisted predominantly of arthralgias, which had been previously well controlled on hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/d PO. On presentation, she denied oral ulcers, alopecia, shortness of breath, chest pain/pressure, and history of blood clots or miscarriages.

On exam, the patient was afebrile and had a heart rate of 74 bpm; blood pressure, 140/77 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The fingertips on her left hand were tender and cool to the touch, and the fingertips of her second through fifth digits were blue (FIGURE).

Laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin, 9.3 g/dL (normal range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 44 mm/h (normal range, ≤ 25 mm/h). Double-stranded DNA and complement levels were normal.

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations, and blood cultures from admission were negative. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) with contrast of her left upper extremity showed a filling defect in the origin of the left subclavian artery. Digital plethysmography showed dampened flow signals in the second through fifth digits of the left hand.

Tests for antiphospholipid antibodies were positive for lupus anticoagulant; there were also high titers of anti-β-2-glycoprotein immunoglobulin (Ig) G (58 SGU; normal, ≤ 20 SGU) and anticardiolipin IgG (242.4 CU; normal, ≤ 20 CU).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Antiphospholipid syndrome

Given our patient’s SLE, left subclavian artery thrombosis, digital ischemia, and high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies, we had significant concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). The diagnosis of APS is most often based on the fulfillment of the revised Sapporo classification criteria. These criteria include both clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and laboratory criteria (the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies on at least 2 separate occasions separated by 12 weeks).1 Our patient met clinical criteria given the evidence of subclavian artery thrombosis on CTA as well as digital plethysmography findings consistent with digital emboli. To meet laboratory criteria, she would have needed to have persistent high-titer antiphospholipid antibodies 12 weeks apart.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with thrombosis; it can be divided into primary and secondary APS. The estimated prevalence of APS is 50 per 100,000 people in the United States.2 Primary APS occurs in the absence of an underlying autoimmune disease, while secondary APS occurs in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disease.

The autoimmune disease most often associated with APS is SLE.3 Among patients with SLE, 15% to 34% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 12% to 30% have anticardiolipin antibodies.4-6 This is compared with young healthy subjects among whom only 1% to 4% have positive lupus anticoagulant and 1% to 5% have anticardiolipin antibodies.7 Previous studies have estimated that 30% to 50% of patients with SLE who test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies will develop thrombosis.5,7

Differential includes Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis

The differential diagnosis for digital ischemia in a patient with SLE includes APS, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, and septic emboli.

Raynaud phenomenon can manifest in patients with SLE, but the presence of thrombosis on CTA and high-titer positive antiphospholipid antibodies make the diagnosis of APS more likely. Additionally, Raynaud phenomenon is typically temperature dependent with vasospasm in the digital arteries, occurring in cold temperatures and resolving with warming.

Systemic vasculitis may develop in patients with SLE, but in our case was less likely given the patient did not have any evidence of vasculitis on CTA, such as blood vessel wall thickening and/or enhancement.8

Septic emboli from endocarditis can cause digital ischemia but is typically associated with positive blood cultures, fever, and other systemic signs of infection, and/or vegetations on an echocardiogram.

Continue to: Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong antiocagulation Tx

Thrombosis determines intensity of lifelong anticoagulation Tx

The mainstay of therapy for patients with APS is lifelong anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist. The intensity of anticoagulation is determined based on the presence of venous or arterial thrombosis. In patients who present with arterial thrombosis, a higher intensity vitamin K antagonist (ie, international normalized ratio [INR] goal > 3) or the addition of low-dose aspirin should be considered.9,10

Factor Xa inhibitors are generally not recommended at this time due to the lack of evidence to support their use.10 Additionally, a randomized clinical trial comparing rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients with triple antiphospholipid antibody positivity was terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic events in the rivaroxaban arm.11

For patients with secondary APS in the setting of SLE, hydroxychloroquine in combination with a vitamin K antagonist has been shown to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombosis compared with treatment with a vitamin K antagonist alone.12

Our patient was started on a heparin drip and transitioned to an oral vitamin K antagonist with an INR goal of 2 to 3. Lifelong anticoagulation was planned. The pain and discoloration in her hands improved on anticoagulation and had nearly resolved by the time of discharge. Given her history of arterial thrombosis, the addition of aspirin was also considered, but this decision was ultimately deferred to her outpatient rheumatologist and hematologist.

1. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

2. Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1545-1552. doi: 10.1002/art.40901

3. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752-763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974

4. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113-124.

5. Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:682-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682

6. Merkel PA, Chang YC, Pierangeli SS, et al. The prevalence and clinical associations of anticardiolipin antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue diseases. Am J Med. 1996;101:576-583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00335-x

7. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:145-151. doi: 10.1006/jaut. 2000.0409

8. Bozlar U, Ogur T, Khaja MS, et al. CT angiography of the upper extremity arterial system: Part 2—Clinical applications beyond trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:753-763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11208

9. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Hunt BJ, Khamashta MA. A systematic review of secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;7:1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23109

10. Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: rationale and design of the Trial on Rivaroxaban in AntiPhospholipid Syndrome (TRAPS) trial. Lupus. 2016;25:301-306. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611495

12. Schmidt-Tanguy A, Voswinkel J, Henrion D, et al. Antithrombotic effects of hydroxychloroquine in primary antiphospholipid syndrome patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1927-1929. doi: 10.1111/jth.12363

1. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

2. Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1545-1552. doi: 10.1002/art.40901

3. Levine JS, Branch DW, Rauch J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:752-763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974

4. Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993;72:113-124.

5. Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:682-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682

6. Merkel PA, Chang YC, Pierangeli SS, et al. The prevalence and clinical associations of anticardiolipin antibodies in a large inception cohort of patients with connective tissue diseases. Am J Med. 1996;101:576-583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00335-x

7. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:145-151. doi: 10.1006/jaut. 2000.0409

8. Bozlar U, Ogur T, Khaja MS, et al. CT angiography of the upper extremity arterial system: Part 2—Clinical applications beyond trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:753-763. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11208

9. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Hunt BJ, Khamashta MA. A systematic review of secondary thromboprophylaxis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;7:1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/art.23109

10. Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213

Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: rationale and design of the Trial on Rivaroxaban in AntiPhospholipid Syndrome (TRAPS) trial. Lupus. 2016;25:301-306. doi: 10.1177/0961203315611495

12. Schmidt-Tanguy A, Voswinkel J, Henrion D, et al. Antithrombotic effects of hydroxychloroquine in primary antiphospholipid syndrome patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1927-1929. doi: 10.1111/jth.12363

Should antenatal testing be performed in patients with a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 35?

Evidence summary

Association between higher maternal BMI and increased risk for stillbirth

The purpose of antenatal testing is to decrease the risk for stillbirth between visits. Because of the resources involved and the risk for false-positives when testing low-risk patients, antenatal testing is reserved for pregnant people with higher risk for stillbirth.

In a retrospective cohort study of more than 2.8 million singleton births including 9030 stillbirths, pregnant people with an elevated BMI had an increased risk for stillbirth compared to those with a normal BMI. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.71 (95% CI, 1.62-1.83) for those with a BMI of 30.0 to 34.9; 2.04 (95% CI, 1.8-2.21) for those with a BMI of 35.0 to 39.9; and 2.50 (95% CI, 2.28-2.74) for those with a BMI ≥ 40.1

A meta-analysis of 38 studies, which included data on 16,274 stillbirths, found that a 5-unit increase in BMI was associated with an increased risk for stillbirth (relative risk, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.18-1.30).2

Another meta-analysis included 6 cohort studies involving more than 1 million pregnancies and 3 case-control studies involving 2530 stillbirths and 2837 controls from 1980-2005. There was an association between increasing BMI and stillbirth: the odds ratio (OR) was 1.47 (95% CI, 1.08-1.94) for those with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 and 2.07 (95% CI, 1.59-2.74) for those with a BMI ≥ 30.0, compared to those with a normal BMI.3

However, a retrospective cohort study of 182,362 singleton births including 442 stillbirths found no association between stillbirth and increasing BMI. The OR was 1.10 (95% CI, 0.90-1.36) for those with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.87-1.37) for those with a BMI ≥ 30.0, compared to those with a normal BMI.4 However, this cohort study may have been underpowered to detect an association between stillbirth and BMI.

Recommendations from others

In 2021, ACOG suggested that weekly antenatal testing may be considered from 34w0d for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40.0 and from 37w0d for pregnant people with a BMI between 35.0 and 39.9.5 The 2021 ACOG Practice Bulletin on Obesity in Pregnancy rates this recommendation as Level C—based primarily on consensus and expert opinion.6

A 2018 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Green-top Guideline recognizes “definitive recommendations for fetal surveillance are hampered by the lack of randomized controlled trials demonstrating that antepartum fetal surveillance decreases perinatal morbidity or mortality in late-term and post-term gestations…. There are no definitive studies determining the optimal type or frequency of such testing and no evidence specific for women with obesity.”7

A 2019 Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada practice guideline states “stillbirth is more common with maternal obesity” and recommends “increased fetal surveillance … in the third trimester if reduced fetal movements are reported.” The guideline notes “the role for non-stress tests … in surveillance of well-being in this population is uncertain.” Also, for pregnant people with a BMI > 30, “assessment of fetal well-being is … recommended weekly from 37 weeks until delivery.” Finally, increased fetal surveillance is recommended in the setting of increased BMI and an abnormal pulsatility index of the umbilical artery and/or maternal uterine artery.8

Editor’s takeaway

Evidence demonstrates that increased maternal BMI is associated with increased stillbirths. However, evidence has not shown that third-trimester antenatal testing decreases this morbidity and mortality. Expert opinion varies, with ACOG recommending weekly antenatal testing from 34 and 37 weeks for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40 and of 35 to 39.9, respectively.

1. Yao R, Ananth C, Park B, et al; Perinatal Research Consortium. Obesity and the risk of stillbirth: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:e1-e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog. 2014.01.044

2. Aune D, Saugstad O, Henriksen T, et al. Maternal body mass index and the risk of fetal death, stillbirth, and infant death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1536-1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2269

3. Chu S, Kim S, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:223-228. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.027

4. Mahomed K, Chan G, Norton M. Obesity and the risk of stillbirth—a reappraisal—a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:25-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb. 2020.09.044

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal fetal surveillance: ACOG committee opinion, number 828. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004407

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Obesity in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, number 230. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e128-e144. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004395

7. Denison F, Aedla N, Keag O, et al; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Care of women with obesity in pregnancy: Green-top Guideline No. 72. BJOG. 2019;126:e62-e106. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15386

8. Maxwell C, Gaudet L, Cassir G, et al. Guideline No. 391–Pregnancy and maternal obesity part 1: pre-conception and prenatal care. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:1623-1640. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc. 2019.03.026

Evidence summary

Association between higher maternal BMI and increased risk for stillbirth

The purpose of antenatal testing is to decrease the risk for stillbirth between visits. Because of the resources involved and the risk for false-positives when testing low-risk patients, antenatal testing is reserved for pregnant people with higher risk for stillbirth.

In a retrospective cohort study of more than 2.8 million singleton births including 9030 stillbirths, pregnant people with an elevated BMI had an increased risk for stillbirth compared to those with a normal BMI. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.71 (95% CI, 1.62-1.83) for those with a BMI of 30.0 to 34.9; 2.04 (95% CI, 1.8-2.21) for those with a BMI of 35.0 to 39.9; and 2.50 (95% CI, 2.28-2.74) for those with a BMI ≥ 40.1

A meta-analysis of 38 studies, which included data on 16,274 stillbirths, found that a 5-unit increase in BMI was associated with an increased risk for stillbirth (relative risk, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.18-1.30).2

Another meta-analysis included 6 cohort studies involving more than 1 million pregnancies and 3 case-control studies involving 2530 stillbirths and 2837 controls from 1980-2005. There was an association between increasing BMI and stillbirth: the odds ratio (OR) was 1.47 (95% CI, 1.08-1.94) for those with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 and 2.07 (95% CI, 1.59-2.74) for those with a BMI ≥ 30.0, compared to those with a normal BMI.3

However, a retrospective cohort study of 182,362 singleton births including 442 stillbirths found no association between stillbirth and increasing BMI. The OR was 1.10 (95% CI, 0.90-1.36) for those with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.87-1.37) for those with a BMI ≥ 30.0, compared to those with a normal BMI.4 However, this cohort study may have been underpowered to detect an association between stillbirth and BMI.

Recommendations from others

In 2021, ACOG suggested that weekly antenatal testing may be considered from 34w0d for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40.0 and from 37w0d for pregnant people with a BMI between 35.0 and 39.9.5 The 2021 ACOG Practice Bulletin on Obesity in Pregnancy rates this recommendation as Level C—based primarily on consensus and expert opinion.6

A 2018 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Green-top Guideline recognizes “definitive recommendations for fetal surveillance are hampered by the lack of randomized controlled trials demonstrating that antepartum fetal surveillance decreases perinatal morbidity or mortality in late-term and post-term gestations…. There are no definitive studies determining the optimal type or frequency of such testing and no evidence specific for women with obesity.”7

A 2019 Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada practice guideline states “stillbirth is more common with maternal obesity” and recommends “increased fetal surveillance … in the third trimester if reduced fetal movements are reported.” The guideline notes “the role for non-stress tests … in surveillance of well-being in this population is uncertain.” Also, for pregnant people with a BMI > 30, “assessment of fetal well-being is … recommended weekly from 37 weeks until delivery.” Finally, increased fetal surveillance is recommended in the setting of increased BMI and an abnormal pulsatility index of the umbilical artery and/or maternal uterine artery.8

Editor’s takeaway

Evidence demonstrates that increased maternal BMI is associated with increased stillbirths. However, evidence has not shown that third-trimester antenatal testing decreases this morbidity and mortality. Expert opinion varies, with ACOG recommending weekly antenatal testing from 34 and 37 weeks for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40 and of 35 to 39.9, respectively.

Evidence summary

Association between higher maternal BMI and increased risk for stillbirth

The purpose of antenatal testing is to decrease the risk for stillbirth between visits. Because of the resources involved and the risk for false-positives when testing low-risk patients, antenatal testing is reserved for pregnant people with higher risk for stillbirth.

In a retrospective cohort study of more than 2.8 million singleton births including 9030 stillbirths, pregnant people with an elevated BMI had an increased risk for stillbirth compared to those with a normal BMI. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.71 (95% CI, 1.62-1.83) for those with a BMI of 30.0 to 34.9; 2.04 (95% CI, 1.8-2.21) for those with a BMI of 35.0 to 39.9; and 2.50 (95% CI, 2.28-2.74) for those with a BMI ≥ 40.1

A meta-analysis of 38 studies, which included data on 16,274 stillbirths, found that a 5-unit increase in BMI was associated with an increased risk for stillbirth (relative risk, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.18-1.30).2

Another meta-analysis included 6 cohort studies involving more than 1 million pregnancies and 3 case-control studies involving 2530 stillbirths and 2837 controls from 1980-2005. There was an association between increasing BMI and stillbirth: the odds ratio (OR) was 1.47 (95% CI, 1.08-1.94) for those with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 and 2.07 (95% CI, 1.59-2.74) for those with a BMI ≥ 30.0, compared to those with a normal BMI.3

However, a retrospective cohort study of 182,362 singleton births including 442 stillbirths found no association between stillbirth and increasing BMI. The OR was 1.10 (95% CI, 0.90-1.36) for those with a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.87-1.37) for those with a BMI ≥ 30.0, compared to those with a normal BMI.4 However, this cohort study may have been underpowered to detect an association between stillbirth and BMI.

Recommendations from others

In 2021, ACOG suggested that weekly antenatal testing may be considered from 34w0d for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40.0 and from 37w0d for pregnant people with a BMI between 35.0 and 39.9.5 The 2021 ACOG Practice Bulletin on Obesity in Pregnancy rates this recommendation as Level C—based primarily on consensus and expert opinion.6

A 2018 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Green-top Guideline recognizes “definitive recommendations for fetal surveillance are hampered by the lack of randomized controlled trials demonstrating that antepartum fetal surveillance decreases perinatal morbidity or mortality in late-term and post-term gestations…. There are no definitive studies determining the optimal type or frequency of such testing and no evidence specific for women with obesity.”7

A 2019 Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada practice guideline states “stillbirth is more common with maternal obesity” and recommends “increased fetal surveillance … in the third trimester if reduced fetal movements are reported.” The guideline notes “the role for non-stress tests … in surveillance of well-being in this population is uncertain.” Also, for pregnant people with a BMI > 30, “assessment of fetal well-being is … recommended weekly from 37 weeks until delivery.” Finally, increased fetal surveillance is recommended in the setting of increased BMI and an abnormal pulsatility index of the umbilical artery and/or maternal uterine artery.8

Editor’s takeaway

Evidence demonstrates that increased maternal BMI is associated with increased stillbirths. However, evidence has not shown that third-trimester antenatal testing decreases this morbidity and mortality. Expert opinion varies, with ACOG recommending weekly antenatal testing from 34 and 37 weeks for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40 and of 35 to 39.9, respectively.

1. Yao R, Ananth C, Park B, et al; Perinatal Research Consortium. Obesity and the risk of stillbirth: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:e1-e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog. 2014.01.044

2. Aune D, Saugstad O, Henriksen T, et al. Maternal body mass index and the risk of fetal death, stillbirth, and infant death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1536-1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2269

3. Chu S, Kim S, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:223-228. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.027

4. Mahomed K, Chan G, Norton M. Obesity and the risk of stillbirth—a reappraisal—a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:25-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb. 2020.09.044

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal fetal surveillance: ACOG committee opinion, number 828. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004407

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Obesity in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, number 230. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e128-e144. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004395

7. Denison F, Aedla N, Keag O, et al; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Care of women with obesity in pregnancy: Green-top Guideline No. 72. BJOG. 2019;126:e62-e106. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15386

8. Maxwell C, Gaudet L, Cassir G, et al. Guideline No. 391–Pregnancy and maternal obesity part 1: pre-conception and prenatal care. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:1623-1640. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc. 2019.03.026

1. Yao R, Ananth C, Park B, et al; Perinatal Research Consortium. Obesity and the risk of stillbirth: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:e1-e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog. 2014.01.044

2. Aune D, Saugstad O, Henriksen T, et al. Maternal body mass index and the risk of fetal death, stillbirth, and infant death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1536-1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2269

3. Chu S, Kim S, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:223-228. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.027

4. Mahomed K, Chan G, Norton M. Obesity and the risk of stillbirth—a reappraisal—a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:25-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb. 2020.09.044

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal fetal surveillance: ACOG committee opinion, number 828. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e177-e197. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004407

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Obesity in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, number 230. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e128-e144. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004395

7. Denison F, Aedla N, Keag O, et al; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Care of women with obesity in pregnancy: Green-top Guideline No. 72. BJOG. 2019;126:e62-e106. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15386

8. Maxwell C, Gaudet L, Cassir G, et al. Guideline No. 391–Pregnancy and maternal obesity part 1: pre-conception and prenatal care. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:1623-1640. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc. 2019.03.026

EVIDENCE-BASED REVIEW:

Possibly. Elevated BMI is associated with an increased risk for stillbirth (strength of recommendation [SOR], B; cohort studies and meta-analysis of cohort studies). Three studies found an association between elevated BMI and stillbirth and one did not. However, no studies demonstrate that antenatal testing in pregnant people with higher BMIs decreases stillbirth rates, or that no harm is caused by unnecessary testing or resultant interventions.

Still, in 2021, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) suggested weekly antenatal testing may be considered from 34w0d for pregnant people with a BMI ≥ 40.0 and from 37w0d for pregnant people with a BMI between 35.0 and 39.9 (SOR, C; consensus guideline). Thus, doing the antenatal testing recommended in the ACOG guideline in an attempt to prevent stillbirth is reasonable, given evidence that elevated BMI is associated with stillbirth.

Isolated third nerve palsy: Lessons from the literature and 4 case studies

Of all the cranial nerve (CN) palsies that affect the eye, the third (oculomotor) nerve palsy (TNP) requires the most urgent evaluation.1 Third nerve dysfunction may signal an underlying neurologic emergency, such as ruptured cerebral aneurysm or giant cell arteritis. Early recognition and prompt treatment choices are key to reversing clinical and visual defects. The classic presentation of isolated TNP is a “down and out eye” deviation and ptosis with or without pupillary involvement.1

Recognize varying clinical presentations. TNPs, isolated or not, may be partial or complete, congenital or acquired, pupil involving or pupil sparing. In many cases, patients may have additional constitutional, ocular, or neurologic symptoms or signs, such as ataxia or hemiplegia.2 Recognition of these clinical findings, which at times can be subtle, is crucial. Appropriate clinical diagnosis and management rely on distinguishing isolated TNP from TNP that involves other CNs.2

Further clues to underlying pathology. Disruption of the third nerve can occur anywhere along its course from the oculomotor nucleus in the brain to its terminus at the extraocular muscles in the orbit.2 TNP’s effect on the pupil can often aid in diagnosis.3 Pupil-sparing TNP is usually due to microvascular ischemia, as may occur with diabetes or hypertension. Pupil involvement, though, may be the first sign of a compressive lesion.

Influence of age. Among individuals older than 60 years, the annual incidence of isolated TNP has been shown to be 12.5 per 100,000, compared with 1.7 per 100,000 in those younger than 60 years.4 In those older than 50 years, microvascular ischemia tends to be the dominant cause.4 Other possible causes include aneurysm, trauma, and neoplasm, particularly pituitary adenoma and metastatic tumor. In childhood and young adulthood, the most common cause of TNP is trauma.5

Use of vascular imaging is influenced by an individual’s age and clinical risk for an aneurysm. Isolated partial TNP or TNP with pupil involvement suggest compression of the third nerve and the need for immediate imaging. Given the dire implications of intracranial aneurysm, most physicians will focus their initial evaluation on vascular imaging, if available.2 If clinical findings instead suggest underlying microvascular ischemia, a delay of imaging may be possible.

In the text that follows, we present 4 patient cases describing the clinical investigative process and treatment determinations based on an individual’s history, clinical presentation, and neurologic findings.

CASE 1

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

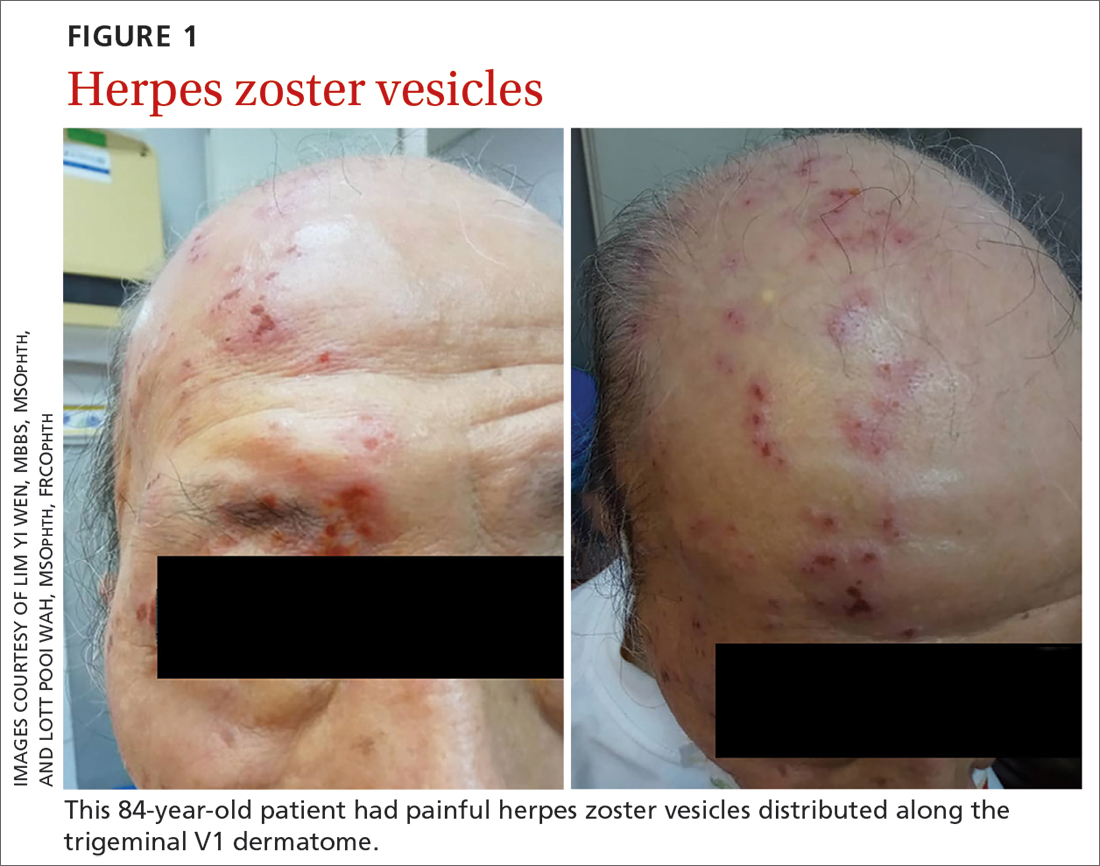

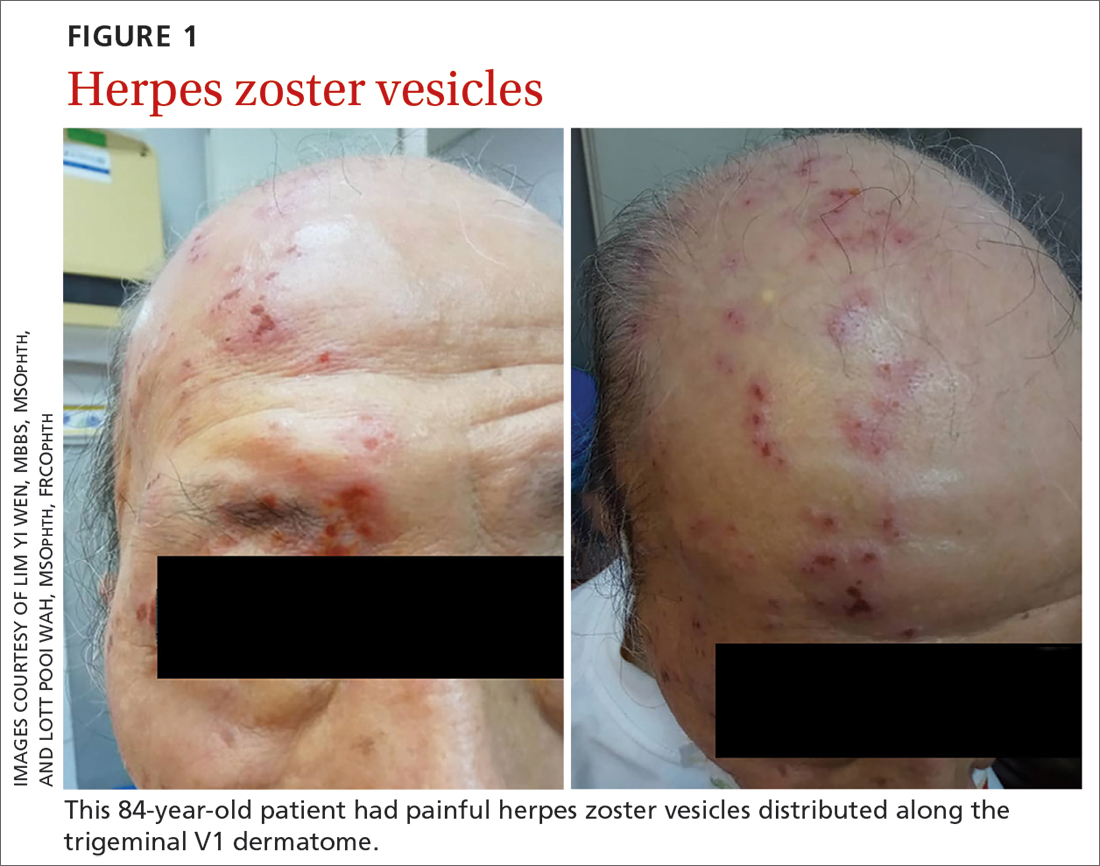

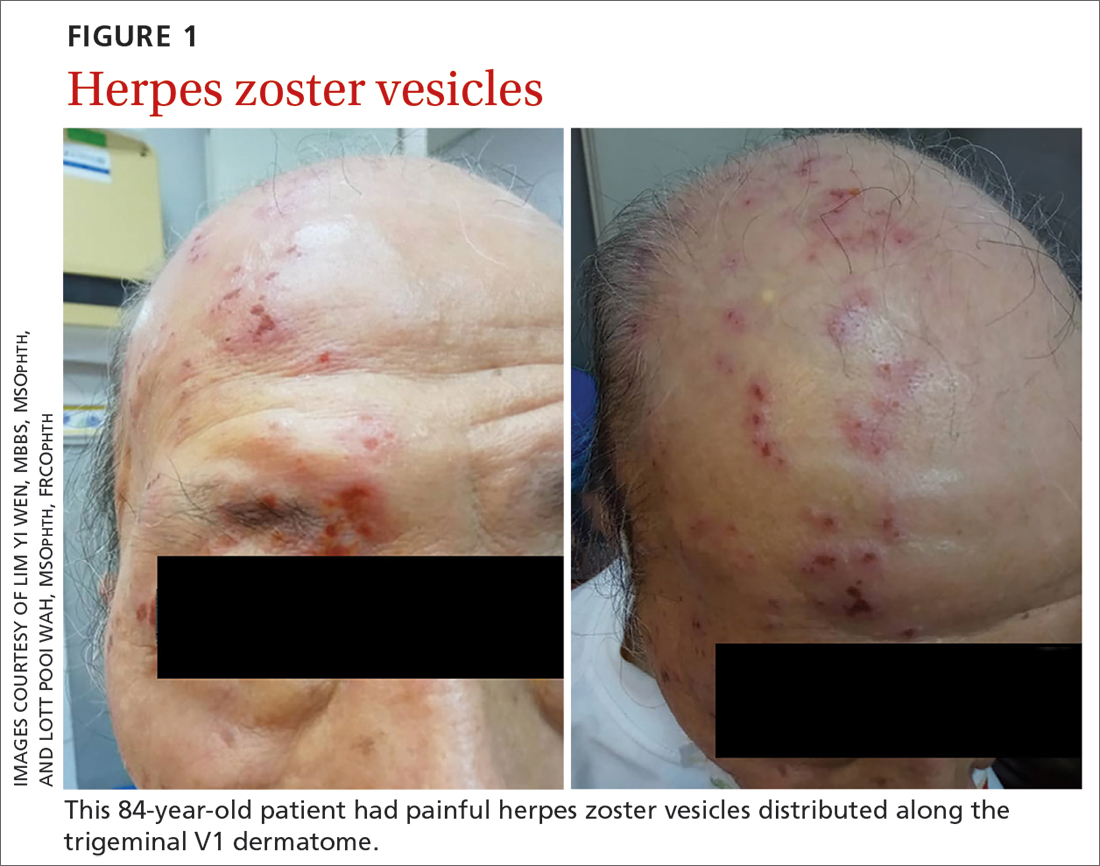

An 84-year-old man with no known medical illness presented to the emergency department (ED) with vesicular skin lesions that had appeared 4 days earlier over his scalp, right forehead, and periorbital region. The vesicles followed the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (FIGURE 1). The patient was given a diagnosis of shingles. The only notable ocular features were the swollen right upper eyelid, injected conjunctiva, and reduced corneal sensation with otherwise normal right eye vision at 6/6. For right eye herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), he was prescribed oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day for 2 weeks.

Continue to: Two days later...

Two days later, he returned after experiencing a sudden onset of binocular diplopia and ptosis of the right eye. Partial ptosis was noted, with restricted adduction and elevation. Pupils were reactive and equal bilaterally. Hutchinson sign, which would indicate an impaired nasociliary nerve and increased risk for corneal and ocular sequelae,6 was absent. Relative afferent pupillary defect also was absent. All other CN functions were intact, with no systemic neurologic deficit. Contrast CT of the brain and orbit showed no radiologic evidence of meningitis, space-occupying lesion, or cerebral aneurysm.

Given the unremarkable imaging findings and lack of symptoms of meningism (eg, headache, vomiting, neck stiffness, or fever), we diagnosed right eye pupil-sparing partial TNP secondary to HZO. The patient continued taking oral acyclovir, which was tapered over 6 weeks. After 4 weeks of antiviral treatment, he recovered full extraocular movement and the ptosis subsided.

CASE 2

Posterior communicating artery aneurysm

A 71-year-old woman with hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease presented to the ED with a 4-day history of headache, vomiting, and neck pain and a 2-day history of a drooping left eyelid. When asked if she had double vision, she said “No.” She had no other neurologic symptoms. Her blood pressure (BP) was 199/88 mm Hg. An initial plain CT of the brain ruled out ischemia, intracranial hemorrhage, and space-occupying lesion.

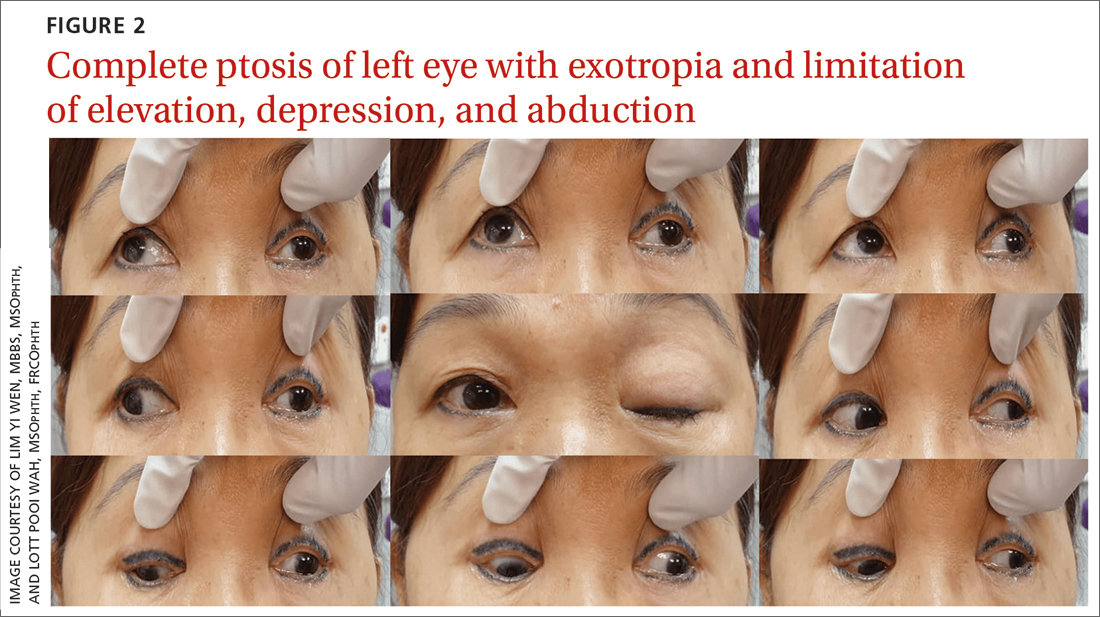

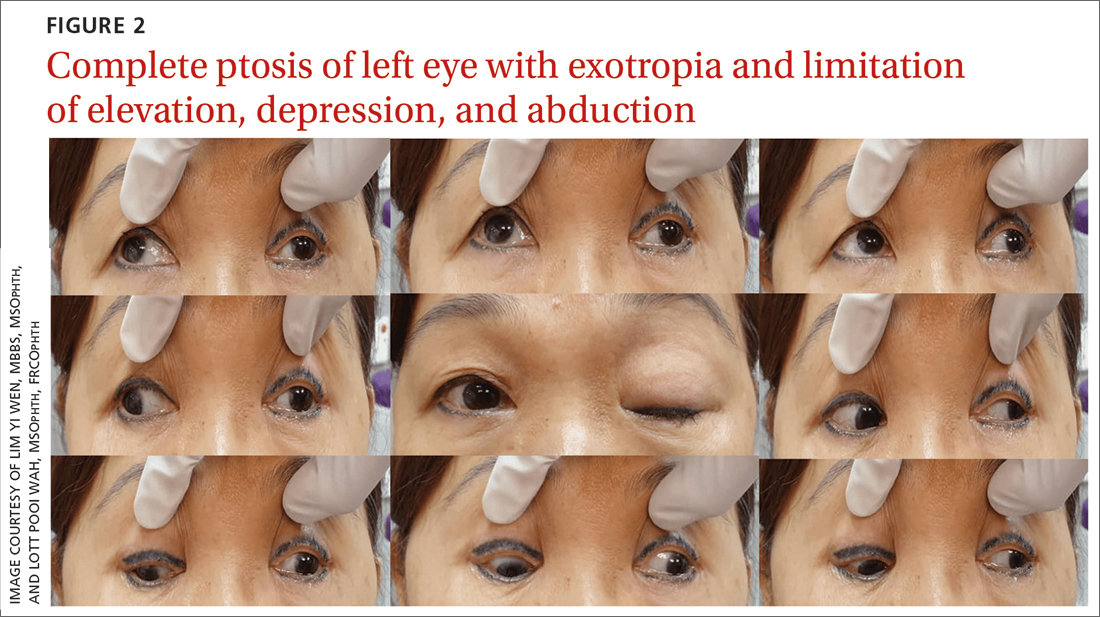

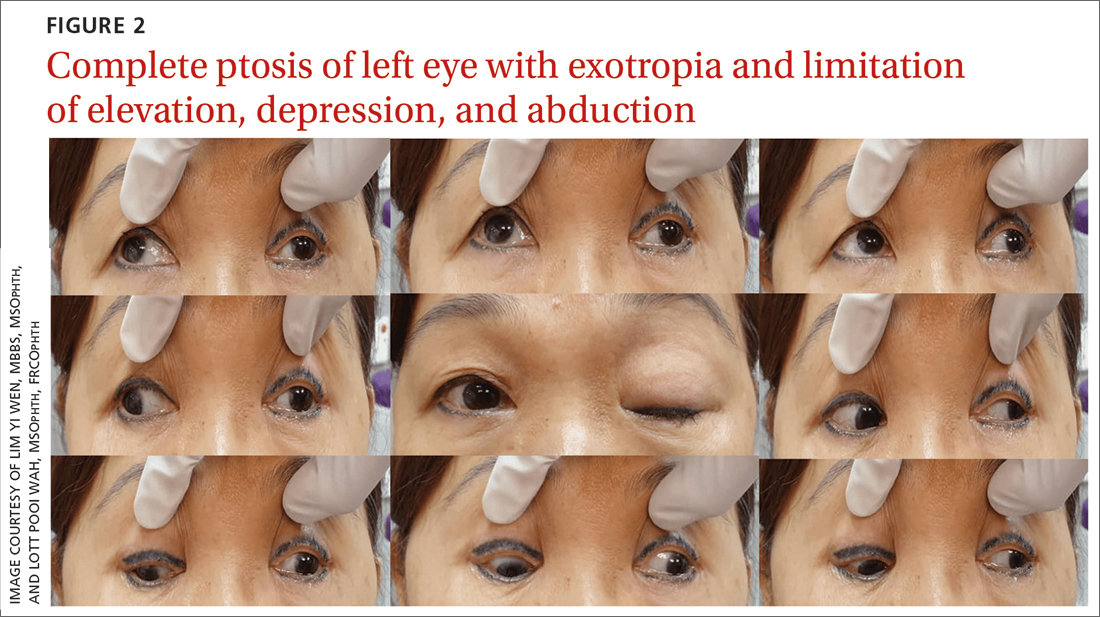

Once her BP was stabilized, she was referred to us for detailed eye assessment. Her best corrected visual acuity was 6/12 bilaterally. In contrast to her right eye pupil, which was 4 mm in diameter and reactive, her left eye pupil was 7 mm and poorly reactive to light. Optic nerve functions were preserved. There was complete ptosis of the left eye, with exotropia and total limitation of elevation, depression, and abduction (FIGURE 2). There was no proptosis; intraocular pressure was normal. Fundus examination of the left eye was unremarkable. All other CN and neurologic examinations were normal. We diagnosed left eye pupil-involving TNP.

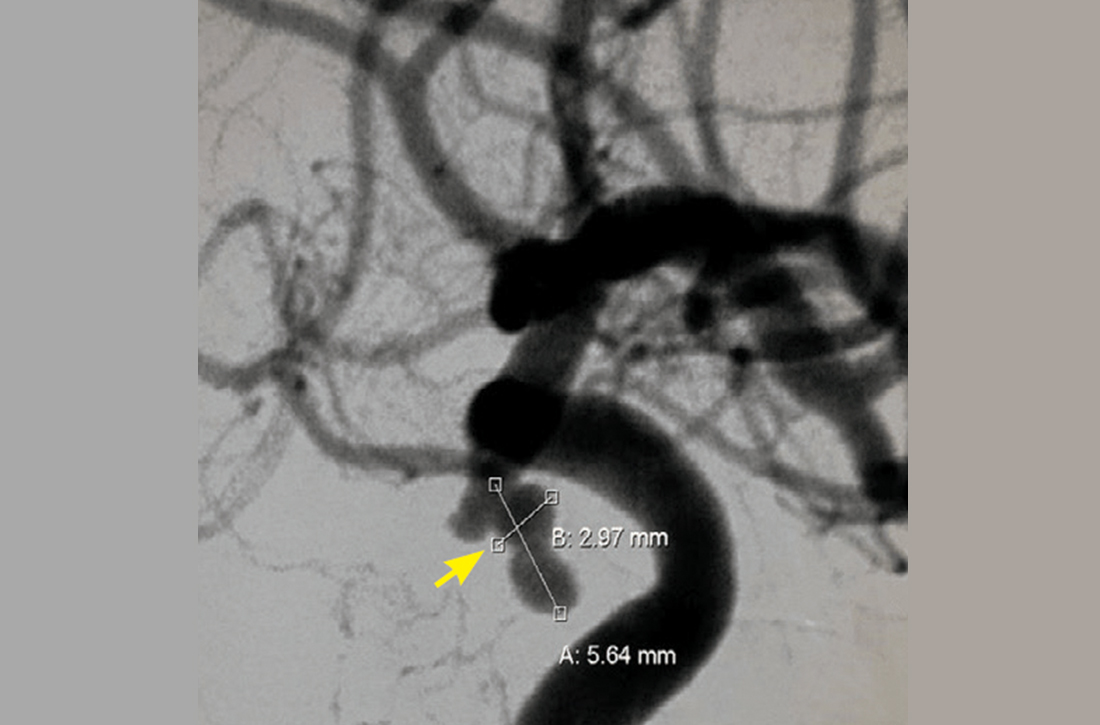

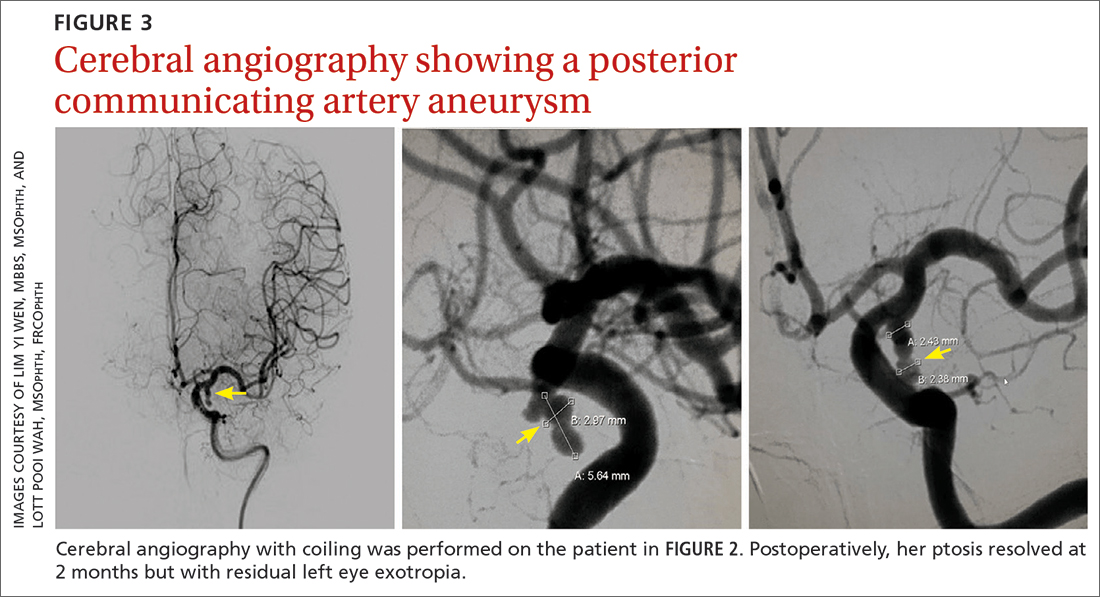

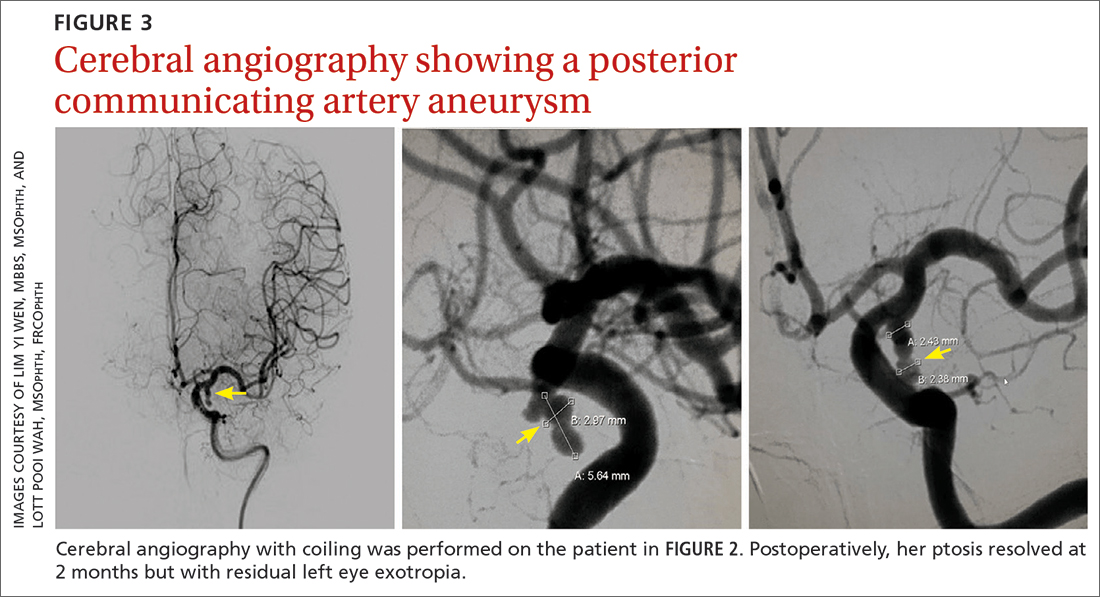

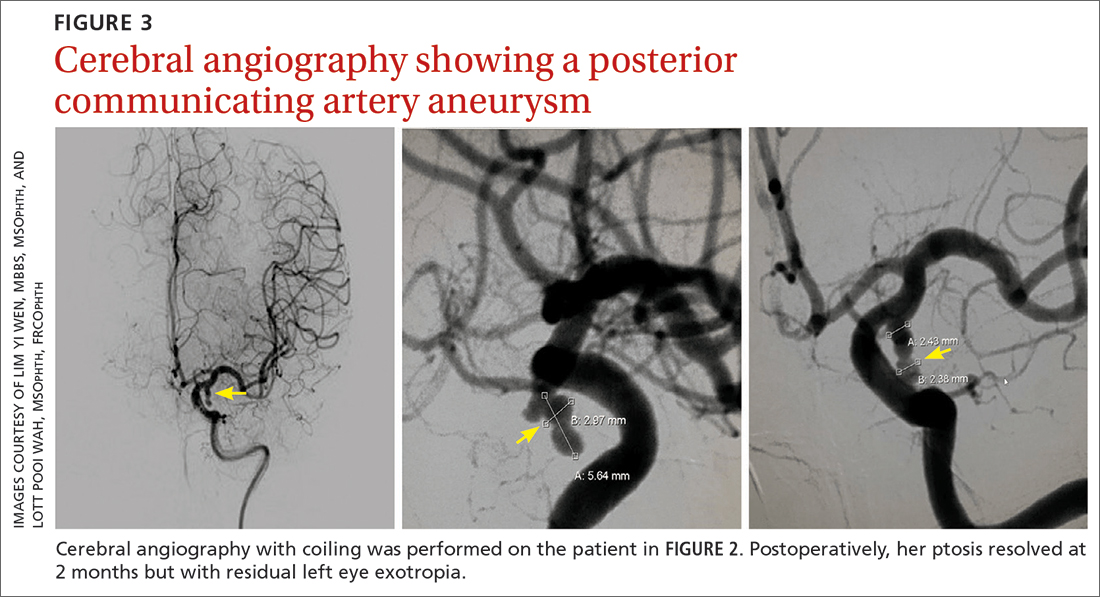

Further assessment of the brain with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a left posterior communicating artery aneurysm. We performed cerebral angiography (FIGURE 3) with coiling. Postoperatively, her ptosis resolved at 2 months but with residual left eye exotropia.

CASE 3

Viral infection

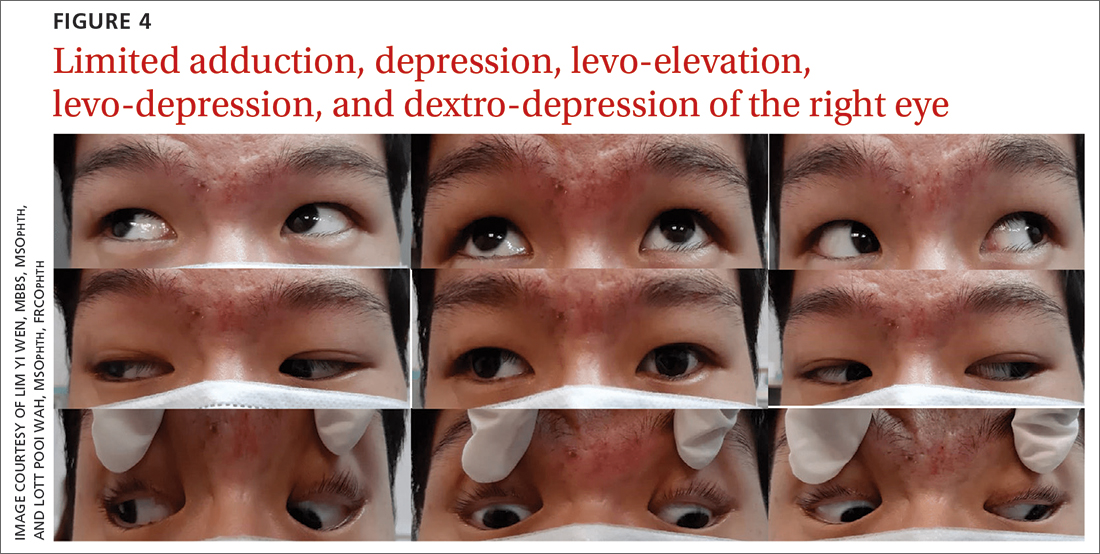

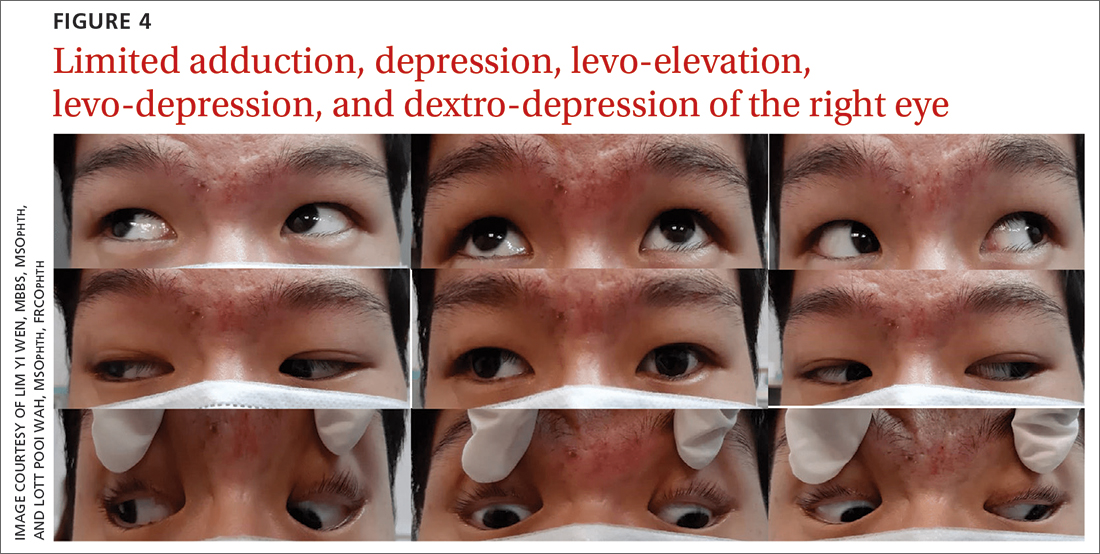

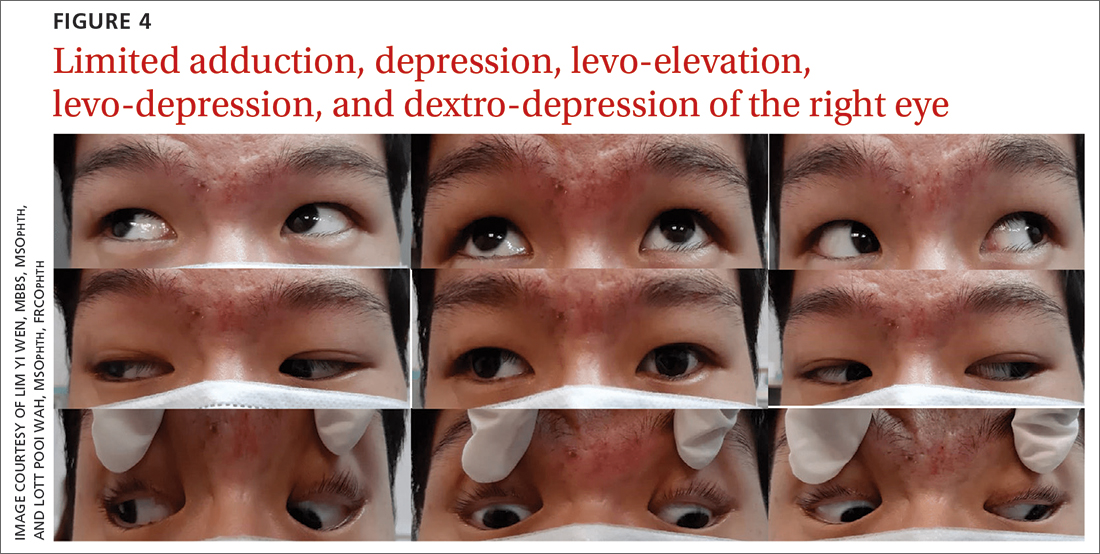

A 20-year-old male student presented to the ED for evaluation of acute-onset diplopia that was present upon awakening from sleep 4 days earlier. There was no ptosis or other neurologic symptoms. He had no history of trauma or viral illness. Examination revealed limited adduction, depression, levo-elevation, levo-depression, and dextro-depression in the right eye (FIGURE 4). Both pupils were reactive. There was no sign of aberrant third nerve regeneration. The optic nerve and other CN functions were intact. A systemic neurologic examination was unremarkable, and the fundus was normal, with no optic disc swelling. All blood work was negative for diabetes, hypercoagulability, and hyperlipidemia.

CT angiography (CTA) and MR angiography (MRA) did not reveal any vascular abnormalities such as intracranial aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, or berry aneurysm. We treated the patient for right eye partial TNP secondary to presumed prior viral infection that led to an immune-mediated palsy of the third nerve. He was given a short course of low-dose oral prednisolone (30 mg/d for 5 days). He achieved full recovery of his ocular motility after 2 weeks.

Continue to: CASE 4

CASE 4

Trauma

A 33-year-old woman was brought to the ED after she was knocked off her motorbike by a car. A passerby found her unconscious and still wearing her helmet. En route to the hospital, the patient regained consciousness but had retrograde amnesia.

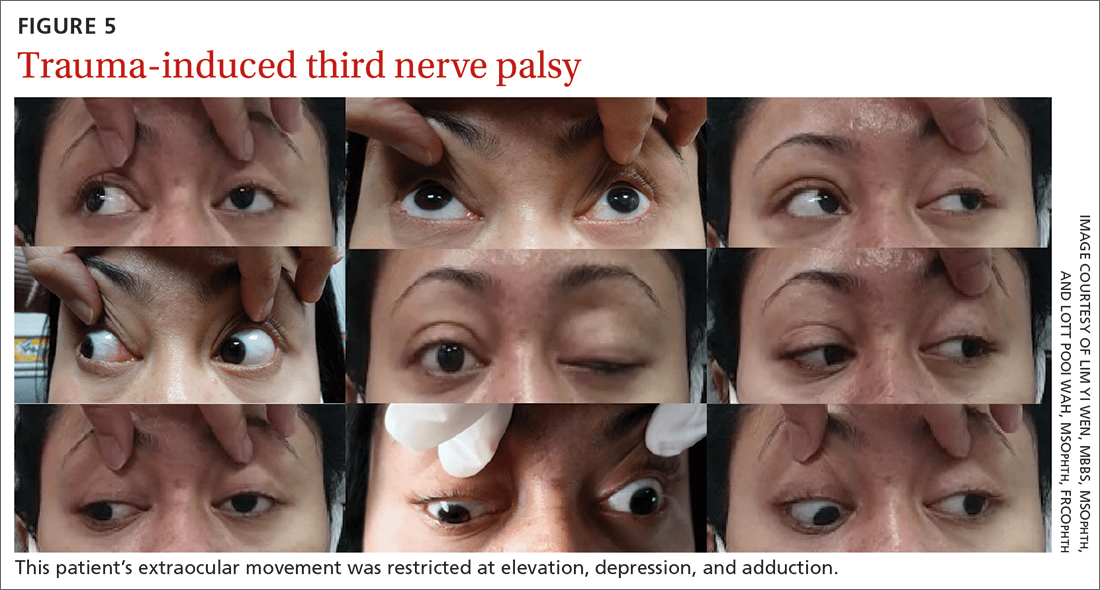

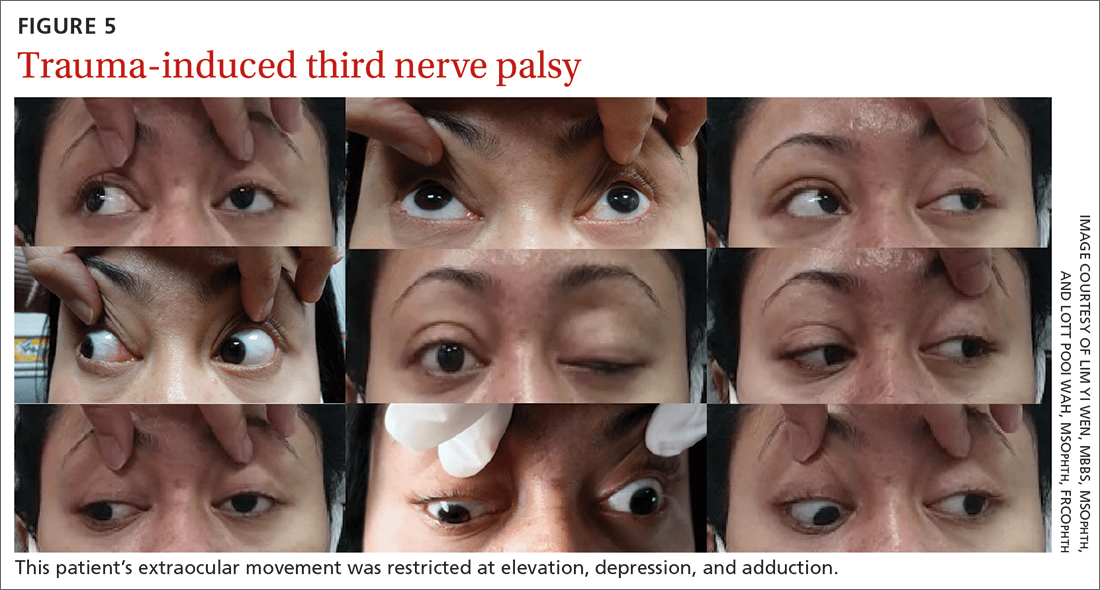

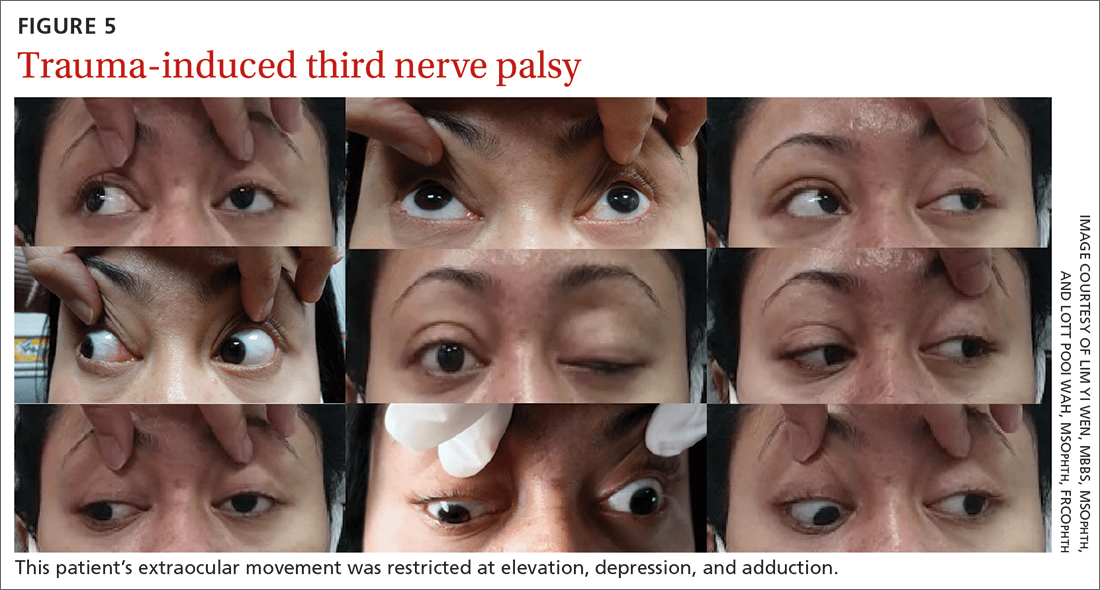

She was referred to us for evaluation of complete ptosis of her left eye. She was fully conscious during the examination. Her left eye vision was 6/9. Complete ptosis with exotropia was noted. Pupillary examination revealed a sluggish dilated left eye pupil of 7 mm with no reverse relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular movement was restricted at elevation, depression, and adduction with diplopia (FIGURE 5). All other CN functions were preserved.

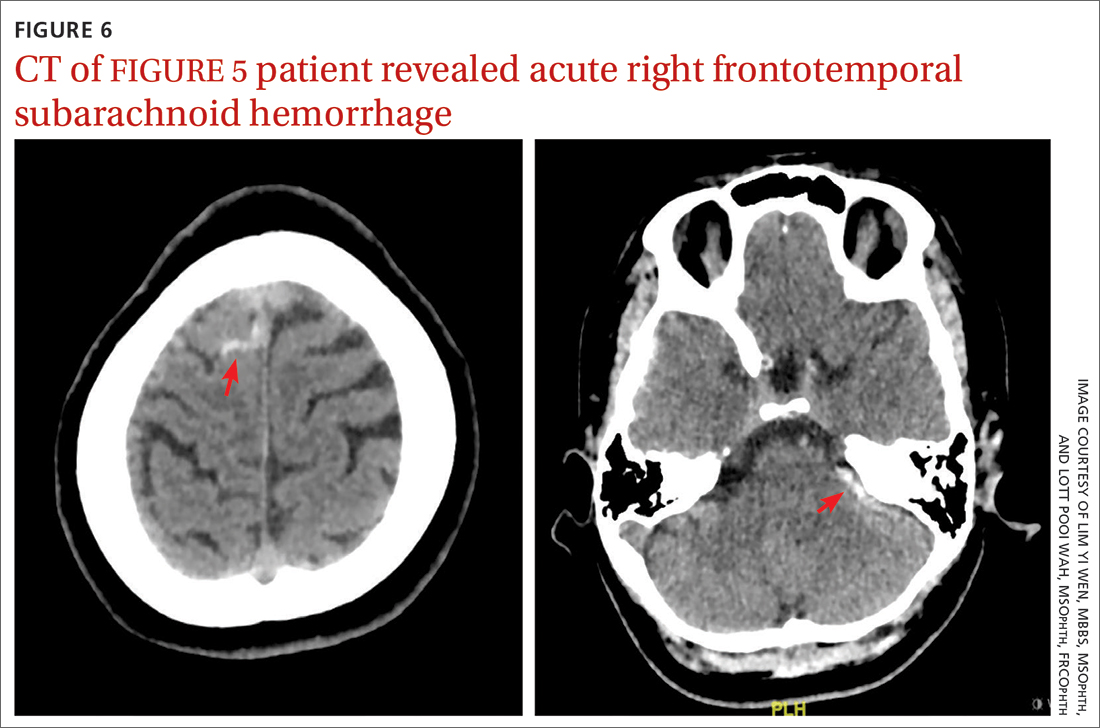

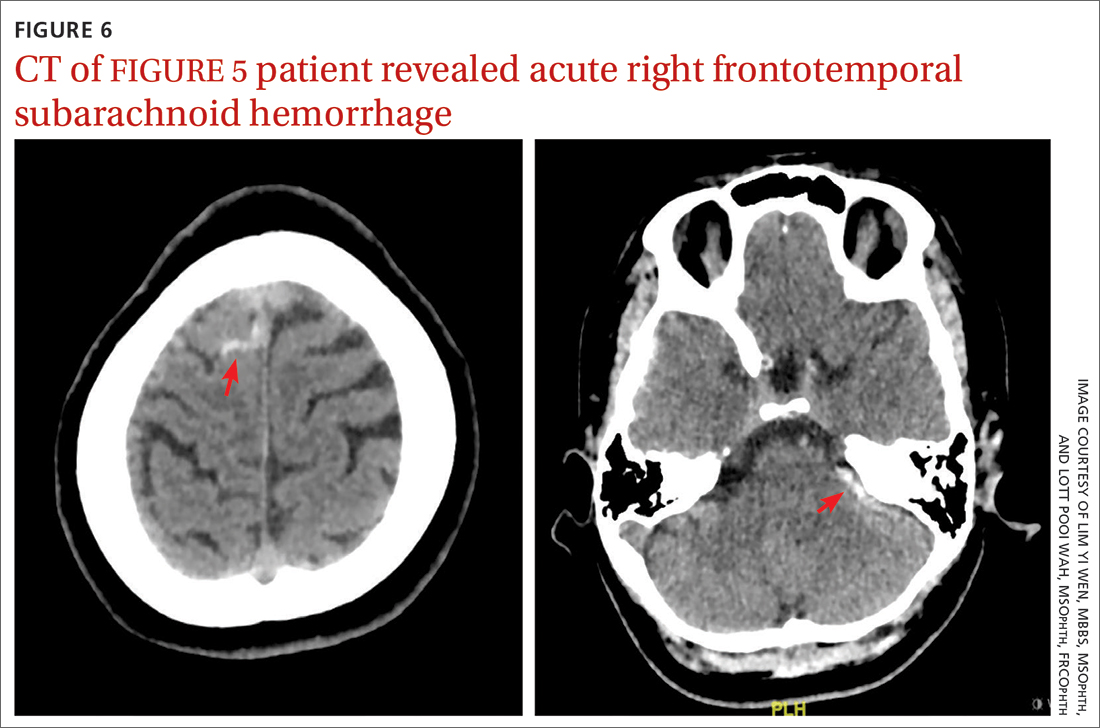

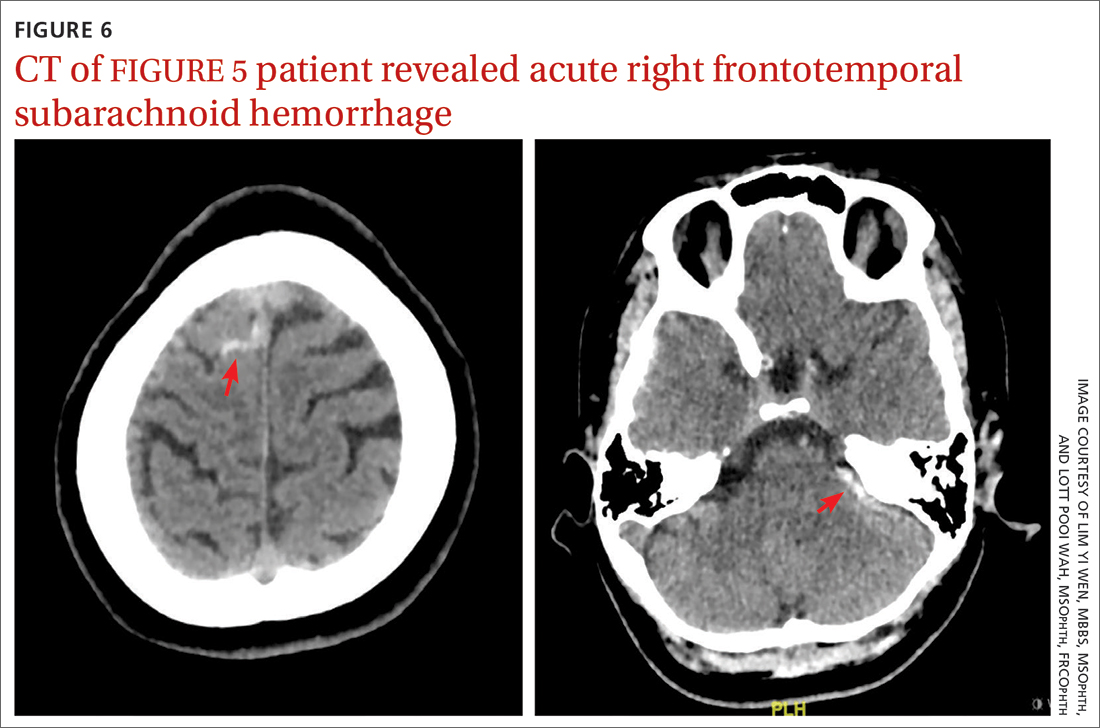

CT of the brain and orbit revealed acute right frontotemporal subarachnoid hemorrhage (FIGURE 6). There was no radiologic evidence of orbital wall fractures or extraocular muscle entrapment. She remained stable during the first 24 hours of monitoring and was given a diagnosis of

Repeat CT of the brain 5 days later revealed complete resolution of the subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient's clinical condition improved 2 weeks later and included resolution of ptosis and recovery of ocular motility.

Key takeaways from the cases

Case 1: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Clinical diagnosis of HZO is straightforward, with painful vesicular lesions occurring along the trigeminal nerve (V1) dermatome, as was seen in this case. The oculomotor nerve is the CN most commonly involved; the trochlear nerve is the least-often affected.6 In a report from the Mayo Clinic, 3 of 86 patients with HZO had oculomotor nerve palsies (3.4%).7 A separate review from an eye hospital study stated that 9.8% (n = 133) of 1356 patients with HZO had extraocular muscle palsy, with TNP in 4 of the patients.8

Ocular complications such as blepharitis, keratoconjunctivits, or iritis occur in 20% to 70% of HZO cases.9 Ophthalmoplegia, which most often involves the oculomotor nerve, is seen in 7% to 31% of HZO cases (mostly in the elderly) and usually occurs within 1 to 3 weeks of the onset of rash.6 Our patient immediately underwent contrast CT of the brain to rule out meningitis and nerve compression.

Treatment with a systemic antiviral agent is crucial. Acyclovir, valaciclovir, and famciclovir are available treatment options, used for treating the skin lesions, reducing the viral load, and reducing the risk for ocular involvement or its progression. Our patient started a 2-week course of oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day. Ophthalmoplegia is usually self-limiting and has a good prognosis. Time to resolution varies from 2 to 18 months. Diplopia, if present, resolves within 1 year.6 Our patient achieved full recovery of his extraocular movement after completing 4 weeks of antiviral treatment.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2: Posterior communicating artery aneurysm

Given the patient’s high BP, ruling out a hypertensive emergency with CT was the first priority. TNP caused by microvascular ischemia is not uncommon in the elderly. However, her pupil involvement and persistent headache called for an MRI to better evaluate the soft tissues and to rule out possible vascular pathologies. Left posterior communicating artery aneurysm was discovered with MRI, and urgent cerebral angiography and coiling was performed successfully.

Incidence. One report of 1400 patients with TNP confirmed that aneurysm was the cause in 10% of cases, with posterior communicating artery aneurysm accounting for the greatest number, 119 (25.7%).10 Of these cases of posterior communicating artery aneurysm, pupillary involvement was detected in 108 (90.8%). The oculomotor nerve lies adjacent to the posterior communicating artery as it passes through the subarachnoid space of the basal cisterns, where it is susceptible to compression.3

A high index of suspicion for posterior communicating artery aneurysm is crucial for early detection and lifesaving treatment. The patient in this case did well after the coiling. Her ptosis resolved at 2 months, although she had residual left eye exotropia.

Case 3: Viral infection

We chose CTA of the brain instead of contrast CT to rule out the possibility of intracranial aneurysm. CTA has been shown to be an adequate first-line study to detect aneurysms, particularly those greater than 4 mm in diameter.2,11 One study demonstrated an 81.8% sensitivity for aneurysms smaller than 3 mm when performed on a 320-slice CT.12

Additional imaging selection. We also selected MRA to rule out berry aneurysm, which is often asymptomatic. We decided against MRI because of its higher cost and longer acquisition time. It is usually reserved for patients with a negative initial work-up with CT or cerebral angiography if suspicion of a possible aneurysm remains.11 The MRA finding in this case was negative, and we made a presumptive diagnosis of TNP secondary to viral infection.

Isolated TNP following viral infection is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. In 1 reported case, a 39-year-old man developed a superior division palsy after a common cold without fever, underwent no serologic study, and recovered spontaneously 6 weeks later.13 A 5-year-old boy who experienced a superior division palsy immediately after a common cold with fever was found on serologic examination to have an increased titre of influenza A virus. His palsy resolved in 4 months.14

The exact mechanism of viral-induced palsy is unknown. The possibility of postinfectious cranial neuropathy has been postulated, as most reported cases following a flu-like illness resolved within a few months.15 Although the pathogenesis remains speculative, an autoimmune process might have been involved.16 Our patient recovered fully in 1 month following a short course of oral prednisolone 30 mg/d for 5 days.

Case 4: Trauma

Trauma accounts for approximately 12% of all TNP cases.17 Traumatic TNPs are usually sustained in severe, high-speed, closed-head injuries, and are often associated with other CN injuries and neurologic deficits. The damage may be caused indirectly by compression, hemorrhage, or ischemia, or directly at certain vulnerable points including the nerve’s exit from the brainstem and the point at which it crosses the petroclinoid ligament.17 In our case, despite the patient having complete TNP, there was no sign of localized orbital trauma on the CT other than the presence of subarachnoid hemorrhage at the right frontotemporal region.

In a similar reported case, the patient had a right traumatic isolated TNP and was found to have left frontal subarachnoid hemorrhage with no sign of orbital trauma.18 However, the mechanisms of isolated TNP caused by traumatic brain injury are not clear. Possible causes include rootlet avulsion, distal fascicular damage, stretching of the nerve (including the parasellar segment), and decreased blood supply.18

It has been suggested that TNP is more frequently observed in cases of frontal region injury. As orbitofrontal regions are predominantly affected by cortical contusions, the risk for ocular involvement increases.19

Keep these fundamentals in mind

The diagnosis and management of isolated TNP are guided by the patient’s age, by the degree to which each of the oculomotor nerve’s 2 major functions—pupillomotor and oculomotor—are affected, and by the circumstances preceding the onset of TNP.2 Cases 1 and 3 in our series presented with partial TNP, while Cases 2 and 4 exhibited complete TNP. Pupillary involvement was detected only in Case 2. Nevertheless, radiologic imaging was ordered for all 4 cases after the diagnosis of TNP was made, to exclude the most worrying neurologic emergencies. The choice of imaging modality depends on not only the availability of the services but also the clinical signs and symptoms and presumptive clinical diagnosis. A tailored and thoughtful approach with consideration of the anatomy and varied pathologies help clinicians to skillfully discern emergencies from nonurgent cases.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lott Pooi Wah, MSOphth, FRCOphth, Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected] Orcid no: 0000-0001-8746-1528

1. Radia M, Stahl M, Arunakirinathan M, et al. Examination of a third nerve palsy. Brit J Hosp Med. 2017;78:188-192. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2017.78.12.C188

2. Bruce BB, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Third nerve palsies. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:257-268. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979681

3. Motoyama Y, Nonaka J, Hironaka Y, et al. Pupil-sparing oculomotor nerve palsy caused by upward compression of a large posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2012;52:202-205. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.202

4. Fang C, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, et al. Incidence and etiologies of acquired third nerve palsy using a population-based method. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:23-28. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthal mol.2016.4456

5. Wyatt K. Three common ophthalmic emergencies. JAAPA. 2014;27:32-37. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000447004.96714.34

6. Daswani M, Bhosale N, Shah VM. Rare case of herpes zoster ophthalmicus with orbital myositis, oculomotor nerve palsy and anterior uveitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:365-367. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.199582

7. Womack LW, Liesegang TJ. Complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:42-45. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010044004

8. Marsh RJ, Dulley B, Kelly V. External ocular motor palsies in ophthalmic zoster: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:667-682. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.11.677

9. Lim JJ, Ong YM, Zalina MCW, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with orbital apex syndrome – difference in outcomes and literature review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;26:187-193. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1327604

10. Keane JR. Third nerve palsy: analysis of 1400 personally-examined patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:662-670. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100010866

11. Yoon NK, McNally S, Taussky P, et al. Imaging of cerebral aneurysms: a clinical perspective. Neurovasc Imaging. 2016;2:6. doi: 10.1186/s40809-016-0016-3

12. Wang H, Li W, He H, et al. 320-detector row CT angiography for detection and evaluation of intracranial aneurysms: comparison with conventional digital subtraction angiography. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:e15-20. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.09.001

13. Derakhshan I. Superior branch palsy with spontaneous recovery. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:478-479. doi: 10.1002/ana.410040519

14. Engelhardt A, Credzich C, Kompf D. Isolated superior branch palsy of the oculomotor nerve in influenza A. Neuroophthalmol. 1989;9:233-235. doi: 10.3109/01658108908997359

15. Knox DL, Clark DB, Schuster FF. Benign VI nerve palsies in children. Pediatrics. 1967;40:560-564.

16. Saeki N, Yotsukura J, Adachi E, et al. Isolated superior division oculomotor palsy in a child with spontaneous recovery. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7:62-64. doi: 10.1054/jocn.1998.0152

17. Nagendran ST, Lee V, Perry M. Traumatic orbital third nerve palsy. Brit J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57:578-581. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.01.029

18. Kim T, Nam K, Kwon BS. Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy in mild traumatic brain injury: a literature review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99:430-435. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001316

19. Sharma B, Gupta R, Anand R, et al. Ocular manifestations of head injury and incidence of post-traumatic ocular motor nerve involvement in cases of head injury: a clinical review. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:893-900. doi: 10.1007/s10792-014-9898-8

Of all the cranial nerve (CN) palsies that affect the eye, the third (oculomotor) nerve palsy (TNP) requires the most urgent evaluation.1 Third nerve dysfunction may signal an underlying neurologic emergency, such as ruptured cerebral aneurysm or giant cell arteritis. Early recognition and prompt treatment choices are key to reversing clinical and visual defects. The classic presentation of isolated TNP is a “down and out eye” deviation and ptosis with or without pupillary involvement.1

Recognize varying clinical presentations. TNPs, isolated or not, may be partial or complete, congenital or acquired, pupil involving or pupil sparing. In many cases, patients may have additional constitutional, ocular, or neurologic symptoms or signs, such as ataxia or hemiplegia.2 Recognition of these clinical findings, which at times can be subtle, is crucial. Appropriate clinical diagnosis and management rely on distinguishing isolated TNP from TNP that involves other CNs.2

Further clues to underlying pathology. Disruption of the third nerve can occur anywhere along its course from the oculomotor nucleus in the brain to its terminus at the extraocular muscles in the orbit.2 TNP’s effect on the pupil can often aid in diagnosis.3 Pupil-sparing TNP is usually due to microvascular ischemia, as may occur with diabetes or hypertension. Pupil involvement, though, may be the first sign of a compressive lesion.

Influence of age. Among individuals older than 60 years, the annual incidence of isolated TNP has been shown to be 12.5 per 100,000, compared with 1.7 per 100,000 in those younger than 60 years.4 In those older than 50 years, microvascular ischemia tends to be the dominant cause.4 Other possible causes include aneurysm, trauma, and neoplasm, particularly pituitary adenoma and metastatic tumor. In childhood and young adulthood, the most common cause of TNP is trauma.5

Use of vascular imaging is influenced by an individual’s age and clinical risk for an aneurysm. Isolated partial TNP or TNP with pupil involvement suggest compression of the third nerve and the need for immediate imaging. Given the dire implications of intracranial aneurysm, most physicians will focus their initial evaluation on vascular imaging, if available.2 If clinical findings instead suggest underlying microvascular ischemia, a delay of imaging may be possible.

In the text that follows, we present 4 patient cases describing the clinical investigative process and treatment determinations based on an individual’s history, clinical presentation, and neurologic findings.

CASE 1

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An 84-year-old man with no known medical illness presented to the emergency department (ED) with vesicular skin lesions that had appeared 4 days earlier over his scalp, right forehead, and periorbital region. The vesicles followed the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (FIGURE 1). The patient was given a diagnosis of shingles. The only notable ocular features were the swollen right upper eyelid, injected conjunctiva, and reduced corneal sensation with otherwise normal right eye vision at 6/6. For right eye herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), he was prescribed oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day for 2 weeks.

Continue to: Two days later...

Two days later, he returned after experiencing a sudden onset of binocular diplopia and ptosis of the right eye. Partial ptosis was noted, with restricted adduction and elevation. Pupils were reactive and equal bilaterally. Hutchinson sign, which would indicate an impaired nasociliary nerve and increased risk for corneal and ocular sequelae,6 was absent. Relative afferent pupillary defect also was absent. All other CN functions were intact, with no systemic neurologic deficit. Contrast CT of the brain and orbit showed no radiologic evidence of meningitis, space-occupying lesion, or cerebral aneurysm.

Given the unremarkable imaging findings and lack of symptoms of meningism (eg, headache, vomiting, neck stiffness, or fever), we diagnosed right eye pupil-sparing partial TNP secondary to HZO. The patient continued taking oral acyclovir, which was tapered over 6 weeks. After 4 weeks of antiviral treatment, he recovered full extraocular movement and the ptosis subsided.

CASE 2

Posterior communicating artery aneurysm

A 71-year-old woman with hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease presented to the ED with a 4-day history of headache, vomiting, and neck pain and a 2-day history of a drooping left eyelid. When asked if she had double vision, she said “No.” She had no other neurologic symptoms. Her blood pressure (BP) was 199/88 mm Hg. An initial plain CT of the brain ruled out ischemia, intracranial hemorrhage, and space-occupying lesion.

Once her BP was stabilized, she was referred to us for detailed eye assessment. Her best corrected visual acuity was 6/12 bilaterally. In contrast to her right eye pupil, which was 4 mm in diameter and reactive, her left eye pupil was 7 mm and poorly reactive to light. Optic nerve functions were preserved. There was complete ptosis of the left eye, with exotropia and total limitation of elevation, depression, and abduction (FIGURE 2). There was no proptosis; intraocular pressure was normal. Fundus examination of the left eye was unremarkable. All other CN and neurologic examinations were normal. We diagnosed left eye pupil-involving TNP.

Further assessment of the brain with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a left posterior communicating artery aneurysm. We performed cerebral angiography (FIGURE 3) with coiling. Postoperatively, her ptosis resolved at 2 months but with residual left eye exotropia.

CASE 3

Viral infection

A 20-year-old male student presented to the ED for evaluation of acute-onset diplopia that was present upon awakening from sleep 4 days earlier. There was no ptosis or other neurologic symptoms. He had no history of trauma or viral illness. Examination revealed limited adduction, depression, levo-elevation, levo-depression, and dextro-depression in the right eye (FIGURE 4). Both pupils were reactive. There was no sign of aberrant third nerve regeneration. The optic nerve and other CN functions were intact. A systemic neurologic examination was unremarkable, and the fundus was normal, with no optic disc swelling. All blood work was negative for diabetes, hypercoagulability, and hyperlipidemia.

CT angiography (CTA) and MR angiography (MRA) did not reveal any vascular abnormalities such as intracranial aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, or berry aneurysm. We treated the patient for right eye partial TNP secondary to presumed prior viral infection that led to an immune-mediated palsy of the third nerve. He was given a short course of low-dose oral prednisolone (30 mg/d for 5 days). He achieved full recovery of his ocular motility after 2 weeks.

Continue to: CASE 4

CASE 4

Trauma

A 33-year-old woman was brought to the ED after she was knocked off her motorbike by a car. A passerby found her unconscious and still wearing her helmet. En route to the hospital, the patient regained consciousness but had retrograde amnesia.

She was referred to us for evaluation of complete ptosis of her left eye. She was fully conscious during the examination. Her left eye vision was 6/9. Complete ptosis with exotropia was noted. Pupillary examination revealed a sluggish dilated left eye pupil of 7 mm with no reverse relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular movement was restricted at elevation, depression, and adduction with diplopia (FIGURE 5). All other CN functions were preserved.

CT of the brain and orbit revealed acute right frontotemporal subarachnoid hemorrhage (FIGURE 6). There was no radiologic evidence of orbital wall fractures or extraocular muscle entrapment. She remained stable during the first 24 hours of monitoring and was given a diagnosis of

Repeat CT of the brain 5 days later revealed complete resolution of the subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient's clinical condition improved 2 weeks later and included resolution of ptosis and recovery of ocular motility.

Key takeaways from the cases

Case 1: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Clinical diagnosis of HZO is straightforward, with painful vesicular lesions occurring along the trigeminal nerve (V1) dermatome, as was seen in this case. The oculomotor nerve is the CN most commonly involved; the trochlear nerve is the least-often affected.6 In a report from the Mayo Clinic, 3 of 86 patients with HZO had oculomotor nerve palsies (3.4%).7 A separate review from an eye hospital study stated that 9.8% (n = 133) of 1356 patients with HZO had extraocular muscle palsy, with TNP in 4 of the patients.8

Ocular complications such as blepharitis, keratoconjunctivits, or iritis occur in 20% to 70% of HZO cases.9 Ophthalmoplegia, which most often involves the oculomotor nerve, is seen in 7% to 31% of HZO cases (mostly in the elderly) and usually occurs within 1 to 3 weeks of the onset of rash.6 Our patient immediately underwent contrast CT of the brain to rule out meningitis and nerve compression.

Treatment with a systemic antiviral agent is crucial. Acyclovir, valaciclovir, and famciclovir are available treatment options, used for treating the skin lesions, reducing the viral load, and reducing the risk for ocular involvement or its progression. Our patient started a 2-week course of oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day. Ophthalmoplegia is usually self-limiting and has a good prognosis. Time to resolution varies from 2 to 18 months. Diplopia, if present, resolves within 1 year.6 Our patient achieved full recovery of his extraocular movement after completing 4 weeks of antiviral treatment.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2: Posterior communicating artery aneurysm

Given the patient’s high BP, ruling out a hypertensive emergency with CT was the first priority. TNP caused by microvascular ischemia is not uncommon in the elderly. However, her pupil involvement and persistent headache called for an MRI to better evaluate the soft tissues and to rule out possible vascular pathologies. Left posterior communicating artery aneurysm was discovered with MRI, and urgent cerebral angiography and coiling was performed successfully.

Incidence. One report of 1400 patients with TNP confirmed that aneurysm was the cause in 10% of cases, with posterior communicating artery aneurysm accounting for the greatest number, 119 (25.7%).10 Of these cases of posterior communicating artery aneurysm, pupillary involvement was detected in 108 (90.8%). The oculomotor nerve lies adjacent to the posterior communicating artery as it passes through the subarachnoid space of the basal cisterns, where it is susceptible to compression.3

A high index of suspicion for posterior communicating artery aneurysm is crucial for early detection and lifesaving treatment. The patient in this case did well after the coiling. Her ptosis resolved at 2 months, although she had residual left eye exotropia.

Case 3: Viral infection

We chose CTA of the brain instead of contrast CT to rule out the possibility of intracranial aneurysm. CTA has been shown to be an adequate first-line study to detect aneurysms, particularly those greater than 4 mm in diameter.2,11 One study demonstrated an 81.8% sensitivity for aneurysms smaller than 3 mm when performed on a 320-slice CT.12

Additional imaging selection. We also selected MRA to rule out berry aneurysm, which is often asymptomatic. We decided against MRI because of its higher cost and longer acquisition time. It is usually reserved for patients with a negative initial work-up with CT or cerebral angiography if suspicion of a possible aneurysm remains.11 The MRA finding in this case was negative, and we made a presumptive diagnosis of TNP secondary to viral infection.

Isolated TNP following viral infection is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion. In 1 reported case, a 39-year-old man developed a superior division palsy after a common cold without fever, underwent no serologic study, and recovered spontaneously 6 weeks later.13 A 5-year-old boy who experienced a superior division palsy immediately after a common cold with fever was found on serologic examination to have an increased titre of influenza A virus. His palsy resolved in 4 months.14

The exact mechanism of viral-induced palsy is unknown. The possibility of postinfectious cranial neuropathy has been postulated, as most reported cases following a flu-like illness resolved within a few months.15 Although the pathogenesis remains speculative, an autoimmune process might have been involved.16 Our patient recovered fully in 1 month following a short course of oral prednisolone 30 mg/d for 5 days.

Case 4: Trauma

Trauma accounts for approximately 12% of all TNP cases.17 Traumatic TNPs are usually sustained in severe, high-speed, closed-head injuries, and are often associated with other CN injuries and neurologic deficits. The damage may be caused indirectly by compression, hemorrhage, or ischemia, or directly at certain vulnerable points including the nerve’s exit from the brainstem and the point at which it crosses the petroclinoid ligament.17 In our case, despite the patient having complete TNP, there was no sign of localized orbital trauma on the CT other than the presence of subarachnoid hemorrhage at the right frontotemporal region.

In a similar reported case, the patient had a right traumatic isolated TNP and was found to have left frontal subarachnoid hemorrhage with no sign of orbital trauma.18 However, the mechanisms of isolated TNP caused by traumatic brain injury are not clear. Possible causes include rootlet avulsion, distal fascicular damage, stretching of the nerve (including the parasellar segment), and decreased blood supply.18

It has been suggested that TNP is more frequently observed in cases of frontal region injury. As orbitofrontal regions are predominantly affected by cortical contusions, the risk for ocular involvement increases.19

Keep these fundamentals in mind

The diagnosis and management of isolated TNP are guided by the patient’s age, by the degree to which each of the oculomotor nerve’s 2 major functions—pupillomotor and oculomotor—are affected, and by the circumstances preceding the onset of TNP.2 Cases 1 and 3 in our series presented with partial TNP, while Cases 2 and 4 exhibited complete TNP. Pupillary involvement was detected only in Case 2. Nevertheless, radiologic imaging was ordered for all 4 cases after the diagnosis of TNP was made, to exclude the most worrying neurologic emergencies. The choice of imaging modality depends on not only the availability of the services but also the clinical signs and symptoms and presumptive clinical diagnosis. A tailored and thoughtful approach with consideration of the anatomy and varied pathologies help clinicians to skillfully discern emergencies from nonurgent cases.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lott Pooi Wah, MSOphth, FRCOphth, Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected] Orcid no: 0000-0001-8746-1528

Of all the cranial nerve (CN) palsies that affect the eye, the third (oculomotor) nerve palsy (TNP) requires the most urgent evaluation.1 Third nerve dysfunction may signal an underlying neurologic emergency, such as ruptured cerebral aneurysm or giant cell arteritis. Early recognition and prompt treatment choices are key to reversing clinical and visual defects. The classic presentation of isolated TNP is a “down and out eye” deviation and ptosis with or without pupillary involvement.1

Recognize varying clinical presentations. TNPs, isolated or not, may be partial or complete, congenital or acquired, pupil involving or pupil sparing. In many cases, patients may have additional constitutional, ocular, or neurologic symptoms or signs, such as ataxia or hemiplegia.2 Recognition of these clinical findings, which at times can be subtle, is crucial. Appropriate clinical diagnosis and management rely on distinguishing isolated TNP from TNP that involves other CNs.2

Further clues to underlying pathology. Disruption of the third nerve can occur anywhere along its course from the oculomotor nucleus in the brain to its terminus at the extraocular muscles in the orbit.2 TNP’s effect on the pupil can often aid in diagnosis.3 Pupil-sparing TNP is usually due to microvascular ischemia, as may occur with diabetes or hypertension. Pupil involvement, though, may be the first sign of a compressive lesion.

Influence of age. Among individuals older than 60 years, the annual incidence of isolated TNP has been shown to be 12.5 per 100,000, compared with 1.7 per 100,000 in those younger than 60 years.4 In those older than 50 years, microvascular ischemia tends to be the dominant cause.4 Other possible causes include aneurysm, trauma, and neoplasm, particularly pituitary adenoma and metastatic tumor. In childhood and young adulthood, the most common cause of TNP is trauma.5

Use of vascular imaging is influenced by an individual’s age and clinical risk for an aneurysm. Isolated partial TNP or TNP with pupil involvement suggest compression of the third nerve and the need for immediate imaging. Given the dire implications of intracranial aneurysm, most physicians will focus their initial evaluation on vascular imaging, if available.2 If clinical findings instead suggest underlying microvascular ischemia, a delay of imaging may be possible.