User login

Hyaluronidase for Skin Necrosis Induced by Amiodarone

To the Editor:

Amiodarone is an oral or intravenous (IV) drug commonly used to treat supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia as well as atrial fibrillation.1 Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of amiodarone include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, thyroid, ocular, neurologic, and cutaneous reactions.1 Long-term use of amiodarone—typically more than 4 months—can lead to slate-gray skin discoloration and photosensitivity, both of which can be reversed with drug withdrawal.2,3 Phlebitis also has been described in less than 3% of patients who receive peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.4

Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis due to extravasation is a rare complication of this antiarrhythmic medication, with only 3 reported cases in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiodarone and skin and (necrosis or ischemia or extravasation or reaction).5–7 Although hyaluronidase is a known therapy for extravasation of fluids, including parenteral nutrition and chemotherapy, its use for the treatment of extravasation from amiodarone is not well documented.6 We report a case of skin necrosis of the left dorsal forearm and the left dorsal and ventral hand following infusion of amiodarone through a peripheral IV line, which was treated with injections of hyaluronidase.

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for sepsis secondary to cholangitis in the setting of an obstructive gallbladder stone. His medical history was notable for multivessel coronary artery disease and atrial flutter treated with ablation. One day after admission, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was attempted and aborted due to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography attempt was made 4 days later, during which the patient underwent cardiac arrest. During this event, amiodarone was administered in a 200-mL solution (1.8 mg/mL) in 5% dextrose through a peripheral IV line in the left forearm. The patient was stabilized and transferred to the intensive care unit.

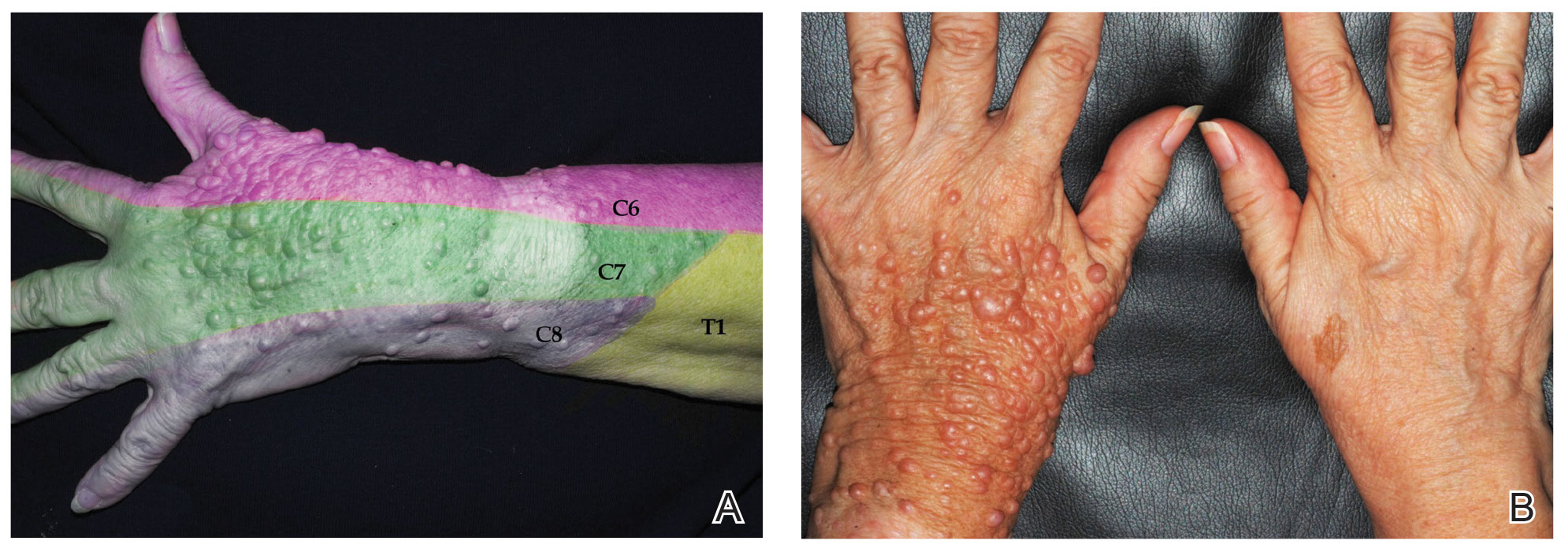

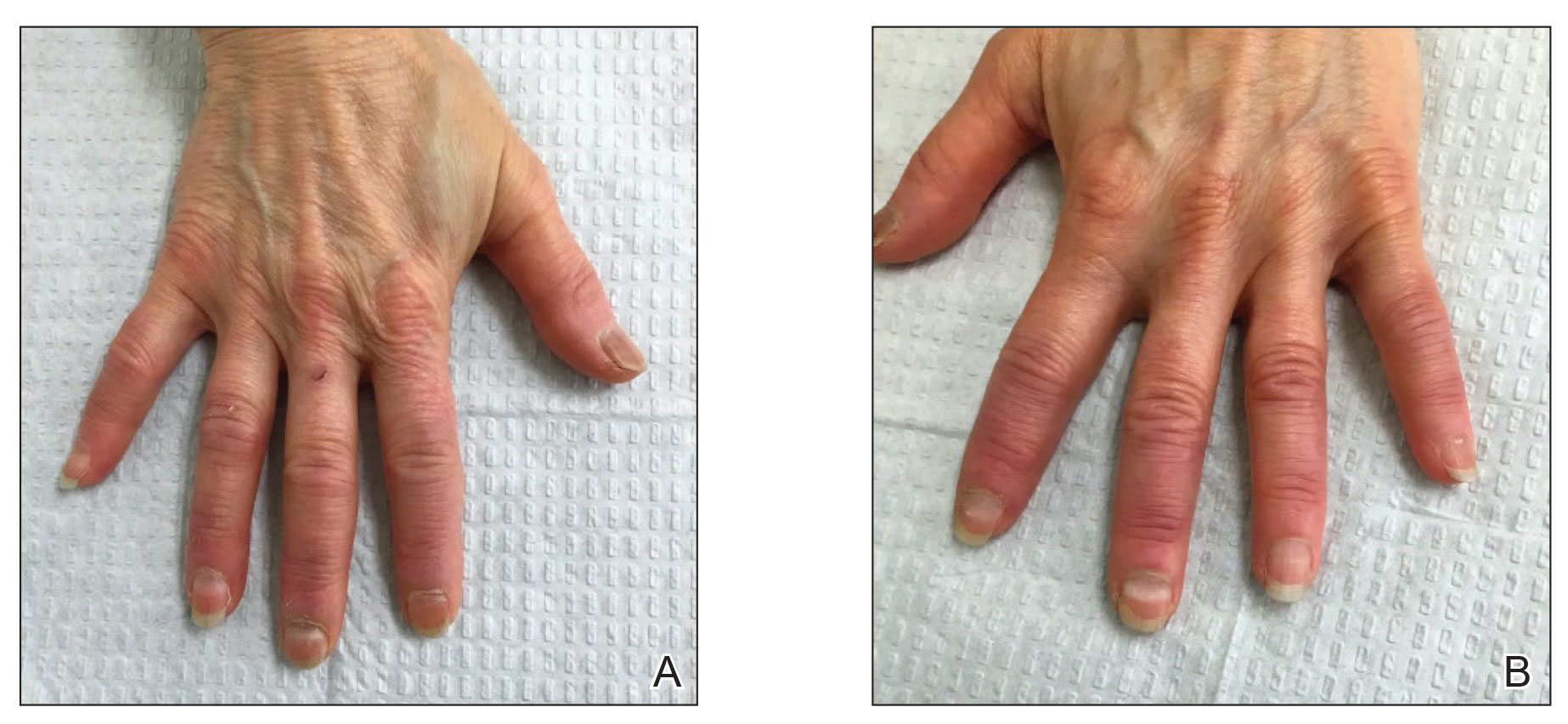

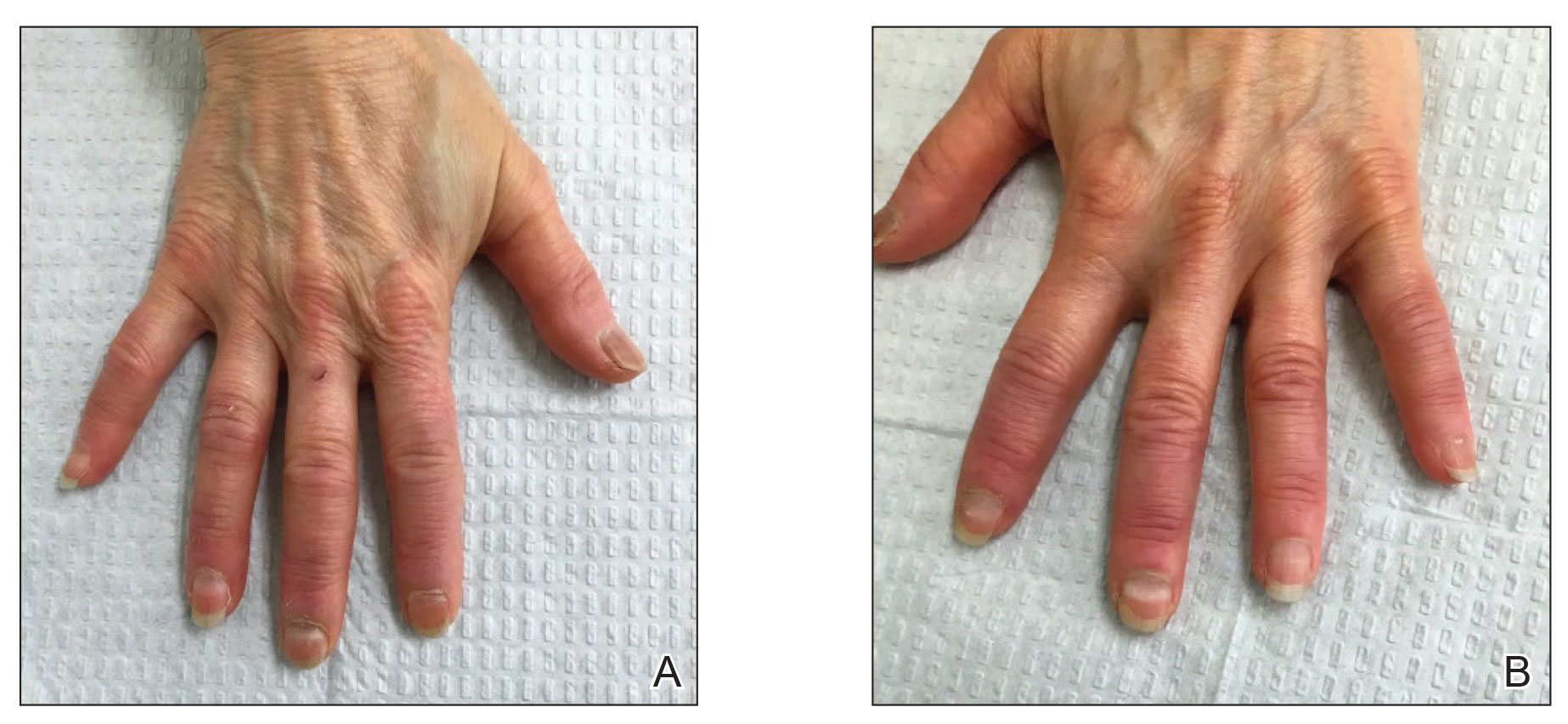

Twenty-four hours after amiodarone administration, erythema was noted on the left dorsal forearm. Within hours, the digits of the hand became a dark, dusky color, which spread to involve the forearm. Surgical debridement was not deemed necessary; the left arm was elevated, and warm compresses were applied regularly. Within the next week, the skin of the left hand and dorsal forearm had progressively worsened and took on a well-demarcated, dusky blue hue surrounded by an erythematous border involving the proximal forearm and upper arm (Figure 1A). The skin was fragile and had overlying bullae (Figure 1B).

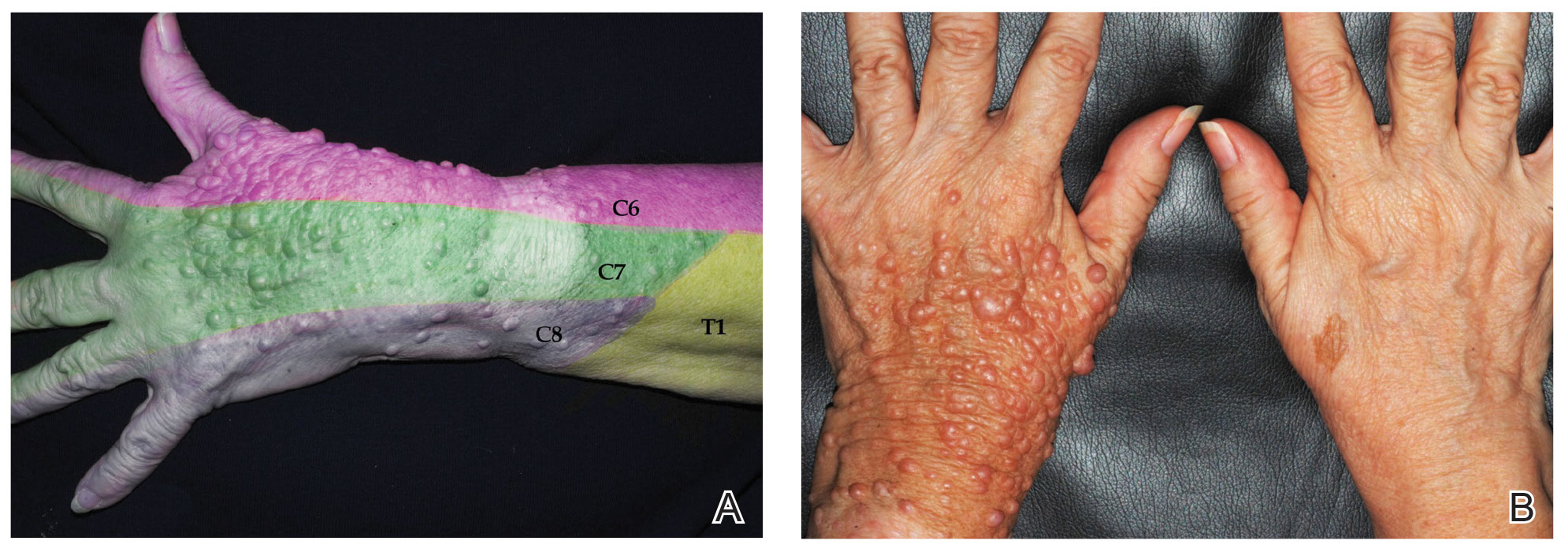

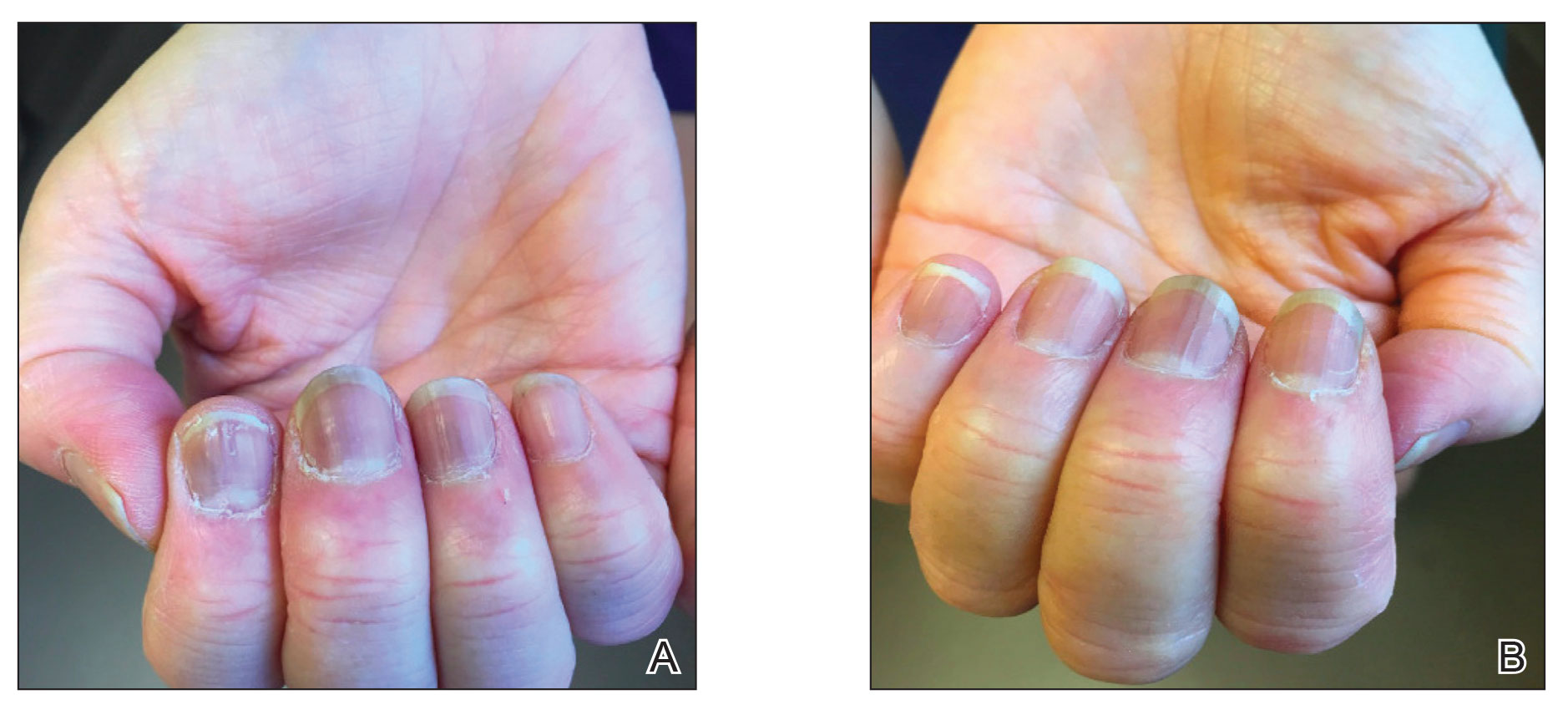

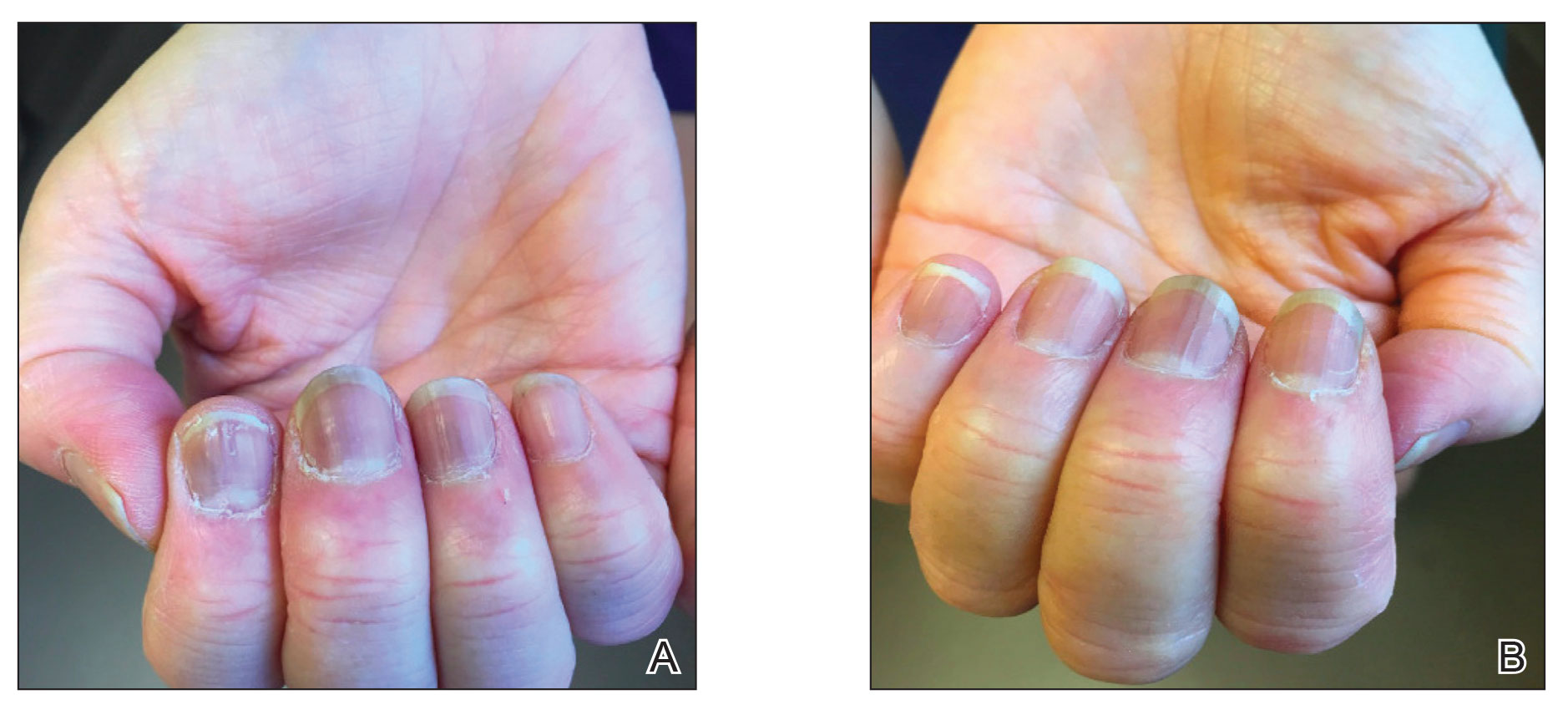

Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into the surrounding areas of erythema, which resolved from the left proximal forearm to the elbow within 2 days after injection (Figure 2). The dusky violaceous patches were persistent, and the necrotic bullae were unchanged. Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into necrotic skin of the left dorsal forearm and dorsal and ventral hand. No improvement was noted on subsequent evaluations of this area. While still an inpatient, he received wound care and twice-daily Doppler ultrasounds in the areas of necrosis. The patient lost sensation in the left hand with increased soft tissue necrosis and developed an eschar on the left dorsal forearm. Due to the progressive loss of function and necrosis, a partial forearm amputation was performed that healed well, and the patient experienced improvement in range of motion of the left upper extremity.

Well-known adverse reactions of amiodarone treatment include pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, and corneal deposits.1 Cutaneous adverse reactions include photosensitivity (phototoxic and photoallergic reactions), hyperpigmentation, pseudoporphyria, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Less commonly, it also can cause urticaria, pruritus, erythema nodosum, purpura, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.3 Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis is rare, first described by Russell and Saltissi5 in 2006 in a 60-year-old man who developed dark discoloration and edema of the forearm 24 hours after initiation of an amiodarone peripheral IV. The patient was treated with hot or cold packs and steroid cream per the pharmaceutical company’s recommendations; however, patient outcomes were not discussed.5 A 77-year-old man who received subcutaneous amiodarone due to misplaced vascular access developed edema and bullae of the forearm followed by tissue necrosis, resulting in notably reduced mobility.6 Fox et al7 described a 60-year-old man who developed atrial fibrillation after emergent spinal fusion and laminectomy. He received intradermal hyaluronidase administration within 24 hours of developing severe pain from extravasation induced by amiodarone with no adverse outcomes and full recovery.7

There are numerous properties of amiodarone that may have resulted in the skin necrosis seen in these cases. The acidic pH (3.5–4.5) of amiodarone can contribute to coagulative necrosis, cellular desiccation, eschar formation, and edema.8 It also can contain additives such as polysorbate and benzyl alcohol, which may contribute to the drug’s vesicant properties.9

Current recommendations for IV administration of amiodarone include delivery through a central vein with high concentrations (>2 mg/mL) because peripheral infusion is slower and may cause phlebitis.4 In-line filters also may be a potential method of preventing phlebitis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.10 Extravasation of amiodarone can be treated nonpharmacologically with limb elevation and warm compresses, as these methods may promote vasodilation and enhance drug removal.5-7 However, when extravasation leads to progressive erythema and skin necrosis or is refractory to these therapies, intradermal injection of hyaluronidase should be considered. Hyaluronidase mediates the degradation of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix, allowing for increased permeability of injected fluids into tissues and diluting the concentration of toxins at the site of exposure.9,11 It has been used to treat extravasation of fluids such as parenteral nutrition, electrolyte infusion, antibiotics, aminophylline, mannitol, and chemotherapy.11 Although hyaluronidase has been recognized as therapeutic for extravasation, there is no established consistent dosing or proper technique. In the setting of infiltration of chemotherapy, doses of hyaluronidase ranging from 150 to 1500 U/mL can be subcutaneously or intradermally injected into the site within 1 hour of extravasation. Side effects of using hyaluronidase are rare, including local pruritus, allergic reactions, urticaria, and angioedema.12

The patient described by Fox et al7 who fully recovered from amiodarone extravasation after hyaluronidase injections likely benefited from quick intervention, as he received amiodarone within 24 hours of the care team identifying initial erythema. Although our patient did have improvement of the areas of erythema on the forearm, evidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis on the left hand and proximal forearm was already apparent and not reversible, most likely caused by late intervention of intradermal hyaluronidase almost a week after the extravasation event. It is important to identify amiodarone as the source of extravasation and administer intradermal hyaluronidase in a timely fashion for extravasation refractory to conventional measurements to prevent progression to severe tissue damage.

Our case draws attention to the risk for skin necrosis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone. Interventions include limb elevation, warm compresses, and consideration of intradermal hyaluronidase within 24 hours of extravasation, as this may reduce the severity of subsequent tissue damage with minimal side effects.

- Epstein AE, Olshansky B, Naccarelli GV, et al. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am J Med. 2016;129:468-475. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039

- Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, et al. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45-51. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45

- Jaworski K, Walecka I, Rudnicka L, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions of amiodarone. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2369-2372. doi:10.12659/MSM.890881

- Kowey Peter R, Marinchak Roger A, Rials Seth J, et al. Intravenous amiodarone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1190-1198. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00069-7

- Russell SJ, Saltissi S. Amiodarone induced skin necrosis. Heart. 2006;92:1395. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.086157

- Grove EL. Skin necrosis and consequences of accidental subcutaneous administration of amiodarone. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V66928.

- Fox AN, Villanueva R, Miller JL. Management of amiodarone extravasation with intradermal hyaluronidase. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1545-1548. doi:10.2146/ajhp160737

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1396

- Le A, Patel S. Extravasation of noncytotoxic drugs: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:870-886. doi:10.1177/1060028014527820

- Slim AM, Roth JE, Duffy B, et al. The incidence of phlebitis with intravenous amiodarone at guideline dose recommendations. Mil Med. 2007;172:1279-1283.

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921-1943. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037

- Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47:297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

To the Editor:

Amiodarone is an oral or intravenous (IV) drug commonly used to treat supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia as well as atrial fibrillation.1 Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of amiodarone include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, thyroid, ocular, neurologic, and cutaneous reactions.1 Long-term use of amiodarone—typically more than 4 months—can lead to slate-gray skin discoloration and photosensitivity, both of which can be reversed with drug withdrawal.2,3 Phlebitis also has been described in less than 3% of patients who receive peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.4

Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis due to extravasation is a rare complication of this antiarrhythmic medication, with only 3 reported cases in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiodarone and skin and (necrosis or ischemia or extravasation or reaction).5–7 Although hyaluronidase is a known therapy for extravasation of fluids, including parenteral nutrition and chemotherapy, its use for the treatment of extravasation from amiodarone is not well documented.6 We report a case of skin necrosis of the left dorsal forearm and the left dorsal and ventral hand following infusion of amiodarone through a peripheral IV line, which was treated with injections of hyaluronidase.

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for sepsis secondary to cholangitis in the setting of an obstructive gallbladder stone. His medical history was notable for multivessel coronary artery disease and atrial flutter treated with ablation. One day after admission, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was attempted and aborted due to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography attempt was made 4 days later, during which the patient underwent cardiac arrest. During this event, amiodarone was administered in a 200-mL solution (1.8 mg/mL) in 5% dextrose through a peripheral IV line in the left forearm. The patient was stabilized and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Twenty-four hours after amiodarone administration, erythema was noted on the left dorsal forearm. Within hours, the digits of the hand became a dark, dusky color, which spread to involve the forearm. Surgical debridement was not deemed necessary; the left arm was elevated, and warm compresses were applied regularly. Within the next week, the skin of the left hand and dorsal forearm had progressively worsened and took on a well-demarcated, dusky blue hue surrounded by an erythematous border involving the proximal forearm and upper arm (Figure 1A). The skin was fragile and had overlying bullae (Figure 1B).

Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into the surrounding areas of erythema, which resolved from the left proximal forearm to the elbow within 2 days after injection (Figure 2). The dusky violaceous patches were persistent, and the necrotic bullae were unchanged. Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into necrotic skin of the left dorsal forearm and dorsal and ventral hand. No improvement was noted on subsequent evaluations of this area. While still an inpatient, he received wound care and twice-daily Doppler ultrasounds in the areas of necrosis. The patient lost sensation in the left hand with increased soft tissue necrosis and developed an eschar on the left dorsal forearm. Due to the progressive loss of function and necrosis, a partial forearm amputation was performed that healed well, and the patient experienced improvement in range of motion of the left upper extremity.

Well-known adverse reactions of amiodarone treatment include pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, and corneal deposits.1 Cutaneous adverse reactions include photosensitivity (phototoxic and photoallergic reactions), hyperpigmentation, pseudoporphyria, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Less commonly, it also can cause urticaria, pruritus, erythema nodosum, purpura, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.3 Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis is rare, first described by Russell and Saltissi5 in 2006 in a 60-year-old man who developed dark discoloration and edema of the forearm 24 hours after initiation of an amiodarone peripheral IV. The patient was treated with hot or cold packs and steroid cream per the pharmaceutical company’s recommendations; however, patient outcomes were not discussed.5 A 77-year-old man who received subcutaneous amiodarone due to misplaced vascular access developed edema and bullae of the forearm followed by tissue necrosis, resulting in notably reduced mobility.6 Fox et al7 described a 60-year-old man who developed atrial fibrillation after emergent spinal fusion and laminectomy. He received intradermal hyaluronidase administration within 24 hours of developing severe pain from extravasation induced by amiodarone with no adverse outcomes and full recovery.7

There are numerous properties of amiodarone that may have resulted in the skin necrosis seen in these cases. The acidic pH (3.5–4.5) of amiodarone can contribute to coagulative necrosis, cellular desiccation, eschar formation, and edema.8 It also can contain additives such as polysorbate and benzyl alcohol, which may contribute to the drug’s vesicant properties.9

Current recommendations for IV administration of amiodarone include delivery through a central vein with high concentrations (>2 mg/mL) because peripheral infusion is slower and may cause phlebitis.4 In-line filters also may be a potential method of preventing phlebitis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.10 Extravasation of amiodarone can be treated nonpharmacologically with limb elevation and warm compresses, as these methods may promote vasodilation and enhance drug removal.5-7 However, when extravasation leads to progressive erythema and skin necrosis or is refractory to these therapies, intradermal injection of hyaluronidase should be considered. Hyaluronidase mediates the degradation of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix, allowing for increased permeability of injected fluids into tissues and diluting the concentration of toxins at the site of exposure.9,11 It has been used to treat extravasation of fluids such as parenteral nutrition, electrolyte infusion, antibiotics, aminophylline, mannitol, and chemotherapy.11 Although hyaluronidase has been recognized as therapeutic for extravasation, there is no established consistent dosing or proper technique. In the setting of infiltration of chemotherapy, doses of hyaluronidase ranging from 150 to 1500 U/mL can be subcutaneously or intradermally injected into the site within 1 hour of extravasation. Side effects of using hyaluronidase are rare, including local pruritus, allergic reactions, urticaria, and angioedema.12

The patient described by Fox et al7 who fully recovered from amiodarone extravasation after hyaluronidase injections likely benefited from quick intervention, as he received amiodarone within 24 hours of the care team identifying initial erythema. Although our patient did have improvement of the areas of erythema on the forearm, evidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis on the left hand and proximal forearm was already apparent and not reversible, most likely caused by late intervention of intradermal hyaluronidase almost a week after the extravasation event. It is important to identify amiodarone as the source of extravasation and administer intradermal hyaluronidase in a timely fashion for extravasation refractory to conventional measurements to prevent progression to severe tissue damage.

Our case draws attention to the risk for skin necrosis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone. Interventions include limb elevation, warm compresses, and consideration of intradermal hyaluronidase within 24 hours of extravasation, as this may reduce the severity of subsequent tissue damage with minimal side effects.

To the Editor:

Amiodarone is an oral or intravenous (IV) drug commonly used to treat supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia as well as atrial fibrillation.1 Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of amiodarone include pulmonary, gastrointestinal, thyroid, ocular, neurologic, and cutaneous reactions.1 Long-term use of amiodarone—typically more than 4 months—can lead to slate-gray skin discoloration and photosensitivity, both of which can be reversed with drug withdrawal.2,3 Phlebitis also has been described in less than 3% of patients who receive peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.4

Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis due to extravasation is a rare complication of this antiarrhythmic medication, with only 3 reported cases in the literature according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms amiodarone and skin and (necrosis or ischemia or extravasation or reaction).5–7 Although hyaluronidase is a known therapy for extravasation of fluids, including parenteral nutrition and chemotherapy, its use for the treatment of extravasation from amiodarone is not well documented.6 We report a case of skin necrosis of the left dorsal forearm and the left dorsal and ventral hand following infusion of amiodarone through a peripheral IV line, which was treated with injections of hyaluronidase.

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department for sepsis secondary to cholangitis in the setting of an obstructive gallbladder stone. His medical history was notable for multivessel coronary artery disease and atrial flutter treated with ablation. One day after admission, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was attempted and aborted due to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. A second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography attempt was made 4 days later, during which the patient underwent cardiac arrest. During this event, amiodarone was administered in a 200-mL solution (1.8 mg/mL) in 5% dextrose through a peripheral IV line in the left forearm. The patient was stabilized and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Twenty-four hours after amiodarone administration, erythema was noted on the left dorsal forearm. Within hours, the digits of the hand became a dark, dusky color, which spread to involve the forearm. Surgical debridement was not deemed necessary; the left arm was elevated, and warm compresses were applied regularly. Within the next week, the skin of the left hand and dorsal forearm had progressively worsened and took on a well-demarcated, dusky blue hue surrounded by an erythematous border involving the proximal forearm and upper arm (Figure 1A). The skin was fragile and had overlying bullae (Figure 1B).

Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into the surrounding areas of erythema, which resolved from the left proximal forearm to the elbow within 2 days after injection (Figure 2). The dusky violaceous patches were persistent, and the necrotic bullae were unchanged. Hyaluronidase (1000 U) was injected into necrotic skin of the left dorsal forearm and dorsal and ventral hand. No improvement was noted on subsequent evaluations of this area. While still an inpatient, he received wound care and twice-daily Doppler ultrasounds in the areas of necrosis. The patient lost sensation in the left hand with increased soft tissue necrosis and developed an eschar on the left dorsal forearm. Due to the progressive loss of function and necrosis, a partial forearm amputation was performed that healed well, and the patient experienced improvement in range of motion of the left upper extremity.

Well-known adverse reactions of amiodarone treatment include pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic dysfunction, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, peripheral neuropathy, and corneal deposits.1 Cutaneous adverse reactions include photosensitivity (phototoxic and photoallergic reactions), hyperpigmentation, pseudoporphyria, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Less commonly, it also can cause urticaria, pruritus, erythema nodosum, purpura, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.3 Amiodarone-induced skin necrosis is rare, first described by Russell and Saltissi5 in 2006 in a 60-year-old man who developed dark discoloration and edema of the forearm 24 hours after initiation of an amiodarone peripheral IV. The patient was treated with hot or cold packs and steroid cream per the pharmaceutical company’s recommendations; however, patient outcomes were not discussed.5 A 77-year-old man who received subcutaneous amiodarone due to misplaced vascular access developed edema and bullae of the forearm followed by tissue necrosis, resulting in notably reduced mobility.6 Fox et al7 described a 60-year-old man who developed atrial fibrillation after emergent spinal fusion and laminectomy. He received intradermal hyaluronidase administration within 24 hours of developing severe pain from extravasation induced by amiodarone with no adverse outcomes and full recovery.7

There are numerous properties of amiodarone that may have resulted in the skin necrosis seen in these cases. The acidic pH (3.5–4.5) of amiodarone can contribute to coagulative necrosis, cellular desiccation, eschar formation, and edema.8 It also can contain additives such as polysorbate and benzyl alcohol, which may contribute to the drug’s vesicant properties.9

Current recommendations for IV administration of amiodarone include delivery through a central vein with high concentrations (>2 mg/mL) because peripheral infusion is slower and may cause phlebitis.4 In-line filters also may be a potential method of preventing phlebitis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone.10 Extravasation of amiodarone can be treated nonpharmacologically with limb elevation and warm compresses, as these methods may promote vasodilation and enhance drug removal.5-7 However, when extravasation leads to progressive erythema and skin necrosis or is refractory to these therapies, intradermal injection of hyaluronidase should be considered. Hyaluronidase mediates the degradation of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix, allowing for increased permeability of injected fluids into tissues and diluting the concentration of toxins at the site of exposure.9,11 It has been used to treat extravasation of fluids such as parenteral nutrition, electrolyte infusion, antibiotics, aminophylline, mannitol, and chemotherapy.11 Although hyaluronidase has been recognized as therapeutic for extravasation, there is no established consistent dosing or proper technique. In the setting of infiltration of chemotherapy, doses of hyaluronidase ranging from 150 to 1500 U/mL can be subcutaneously or intradermally injected into the site within 1 hour of extravasation. Side effects of using hyaluronidase are rare, including local pruritus, allergic reactions, urticaria, and angioedema.12

The patient described by Fox et al7 who fully recovered from amiodarone extravasation after hyaluronidase injections likely benefited from quick intervention, as he received amiodarone within 24 hours of the care team identifying initial erythema. Although our patient did have improvement of the areas of erythema on the forearm, evidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis on the left hand and proximal forearm was already apparent and not reversible, most likely caused by late intervention of intradermal hyaluronidase almost a week after the extravasation event. It is important to identify amiodarone as the source of extravasation and administer intradermal hyaluronidase in a timely fashion for extravasation refractory to conventional measurements to prevent progression to severe tissue damage.

Our case draws attention to the risk for skin necrosis with peripheral IV administration of amiodarone. Interventions include limb elevation, warm compresses, and consideration of intradermal hyaluronidase within 24 hours of extravasation, as this may reduce the severity of subsequent tissue damage with minimal side effects.

- Epstein AE, Olshansky B, Naccarelli GV, et al. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am J Med. 2016;129:468-475. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039

- Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, et al. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45-51. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45

- Jaworski K, Walecka I, Rudnicka L, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions of amiodarone. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2369-2372. doi:10.12659/MSM.890881

- Kowey Peter R, Marinchak Roger A, Rials Seth J, et al. Intravenous amiodarone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1190-1198. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00069-7

- Russell SJ, Saltissi S. Amiodarone induced skin necrosis. Heart. 2006;92:1395. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.086157

- Grove EL. Skin necrosis and consequences of accidental subcutaneous administration of amiodarone. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V66928.

- Fox AN, Villanueva R, Miller JL. Management of amiodarone extravasation with intradermal hyaluronidase. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1545-1548. doi:10.2146/ajhp160737

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1396

- Le A, Patel S. Extravasation of noncytotoxic drugs: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:870-886. doi:10.1177/1060028014527820

- Slim AM, Roth JE, Duffy B, et al. The incidence of phlebitis with intravenous amiodarone at guideline dose recommendations. Mil Med. 2007;172:1279-1283.

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921-1943. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037

- Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47:297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

- Epstein AE, Olshansky B, Naccarelli GV, et al. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am J Med. 2016;129:468-475. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039

- Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, et al. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45-51. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45

- Jaworski K, Walecka I, Rudnicka L, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions of amiodarone. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2369-2372. doi:10.12659/MSM.890881

- Kowey Peter R, Marinchak Roger A, Rials Seth J, et al. Intravenous amiodarone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1190-1198. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00069-7

- Russell SJ, Saltissi S. Amiodarone induced skin necrosis. Heart. 2006;92:1395. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.086157

- Grove EL. Skin necrosis and consequences of accidental subcutaneous administration of amiodarone. Ugeskr Laeger. 2015;177:V66928.

- Fox AN, Villanueva R, Miller JL. Management of amiodarone extravasation with intradermal hyaluronidase. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1545-1548. doi:10.2146/ajhp160737

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1396

- Le A, Patel S. Extravasation of noncytotoxic drugs: a review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:870-886. doi:10.1177/1060028014527820

- Slim AM, Roth JE, Duffy B, et al. The incidence of phlebitis with intravenous amiodarone at guideline dose recommendations. Mil Med. 2007;172:1279-1283.

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921-1943. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037

- Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47:297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

Practice Points

- Intravenous amiodarone administered peripherally can induce skin extravasation, leading to necrosis.

- Dermatologists should be aware that early intervention with intradermal hyaluronidase may reduce the severity of tissue damage caused by amiodarone-induced skin necrosis.

Genital Lentiginosis: A Benign Pigmentary Abnormality Often Raising Concern for Melanoma

To the Editor:

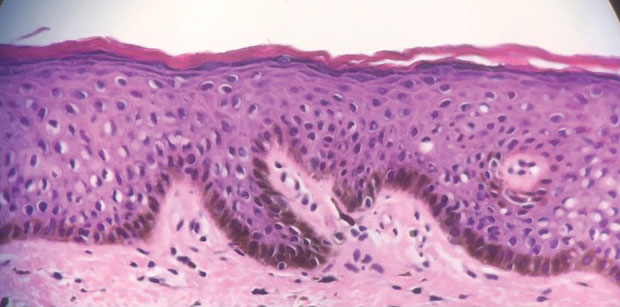

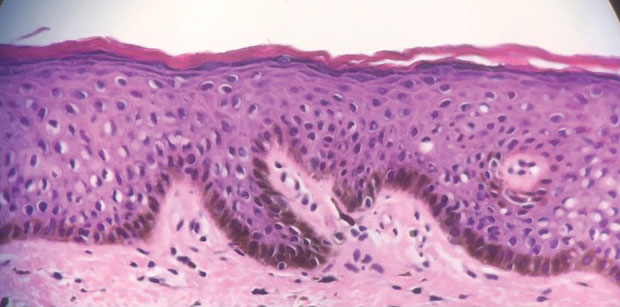

Genital lentiginosis (also known as mucosal melanotic macules, vulvar melanosis, penile melanosis, and penile lentigines) occurs in men and women.1 Lesions present in adult life as multifocal, asymmetrical, pigmented patches that can have a mottled appearance or exhibit skip areas. The irregular appearance of the pigmented areas often raises concern for melanoma. Biopsy reveals increased pigmentation along the basal layer of the epidermis; the irregular distribution of single melanocytes and pagetoid spread typical of melanoma in situ is not identified.

Genital lentiginosis usually occurs as an isolated finding; however, the condition can be a manifestation of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Carney complex, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.1-3 When it occurs as an isolated finding, the patient can be reassured and treatment is unnecessary. Because genital lentiginosis may mimic the appearance of melanoma, it is important for physicians to differentiate the two and make a correct diagnosis. We present a case of genital lentiginosis that mimicked vulvar melanoma.

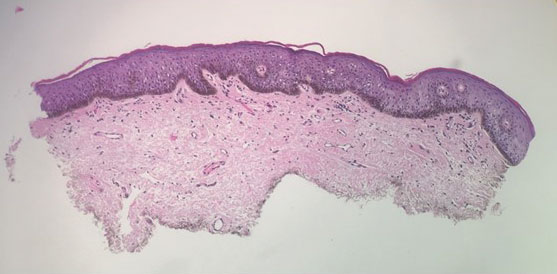

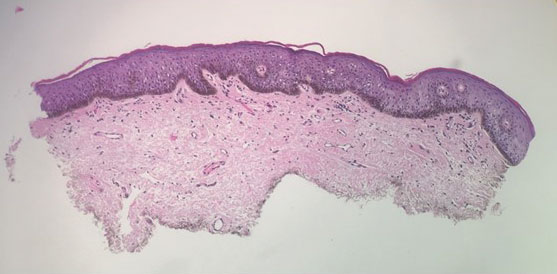

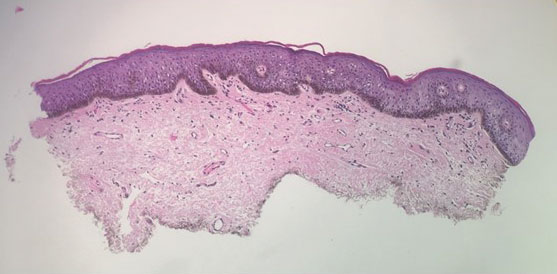

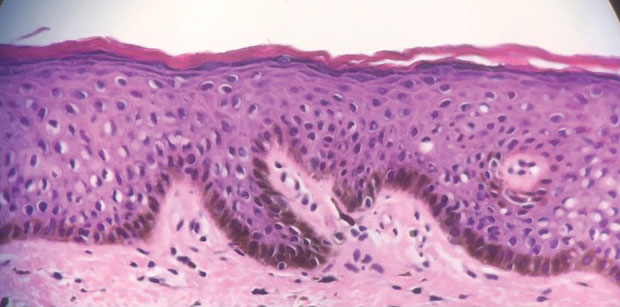

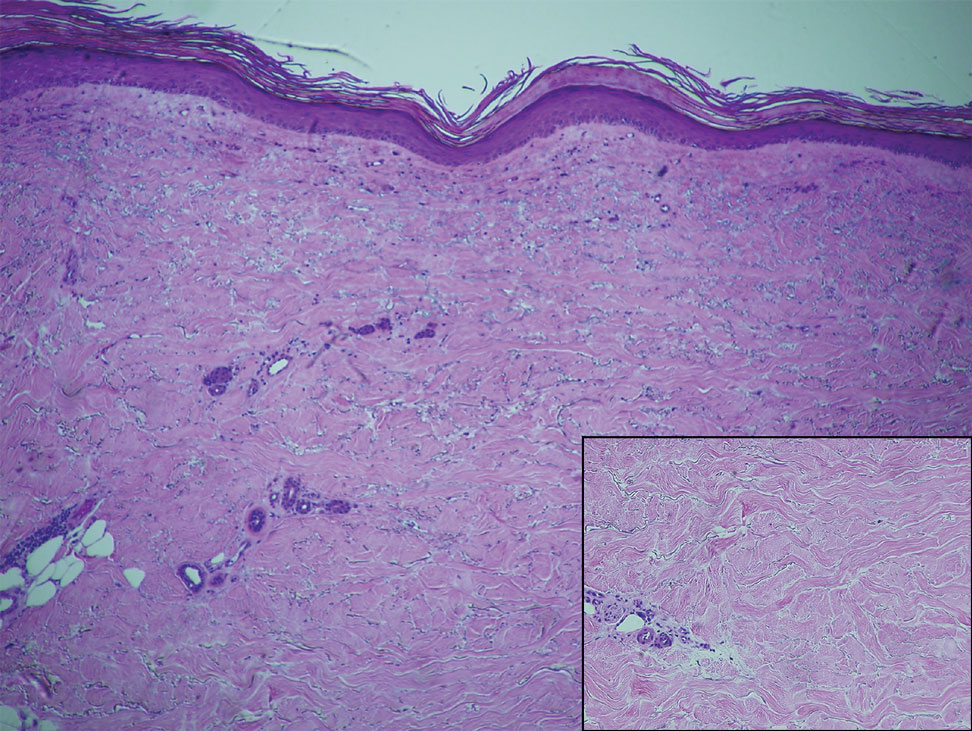

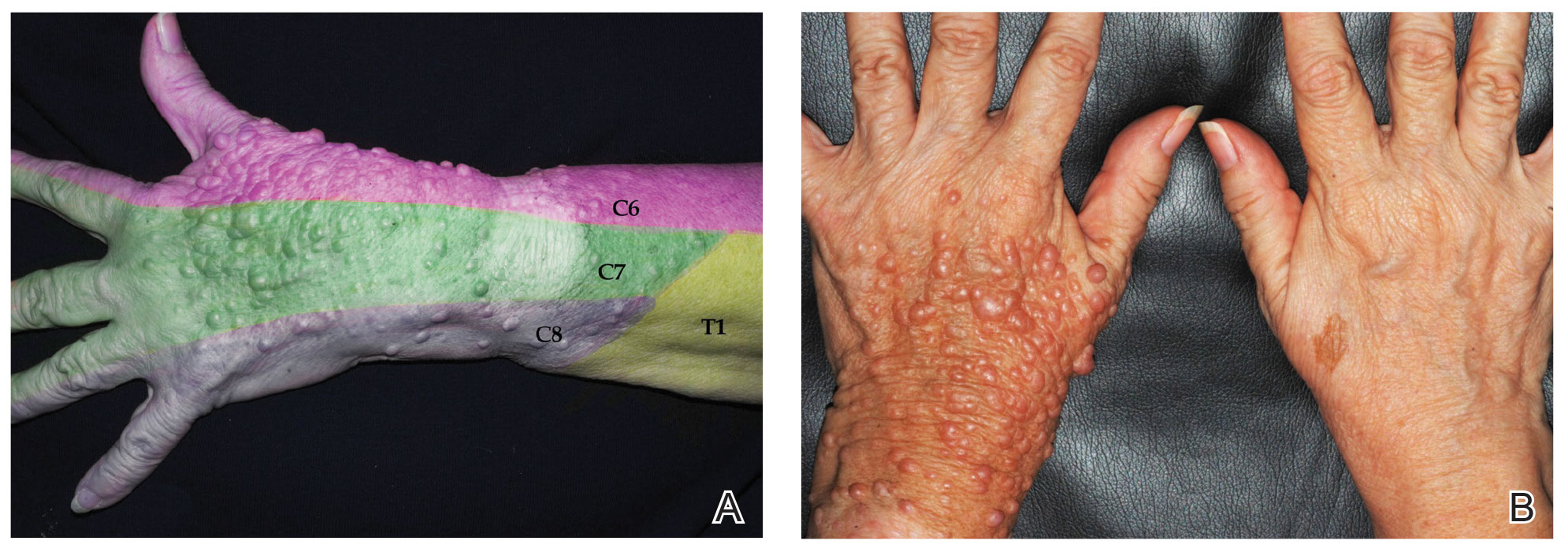

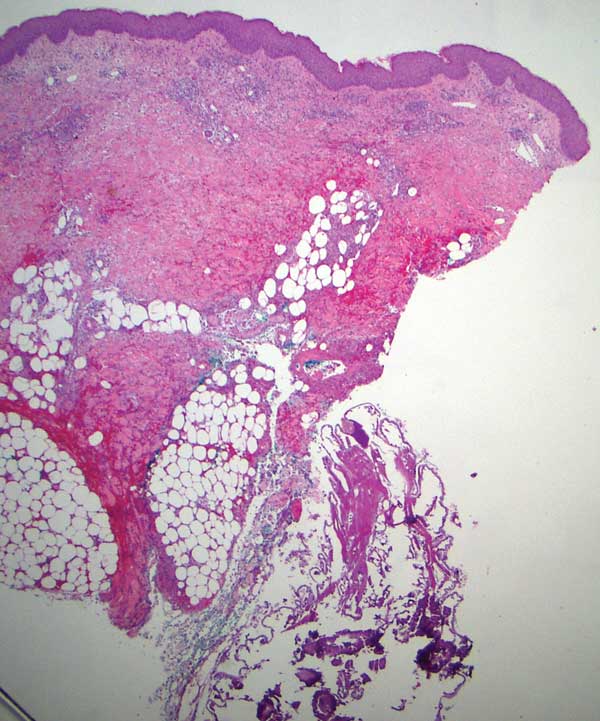

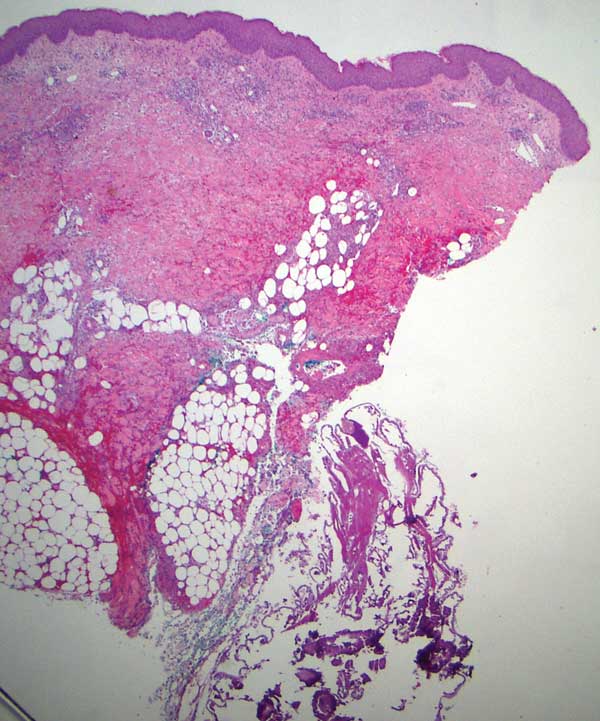

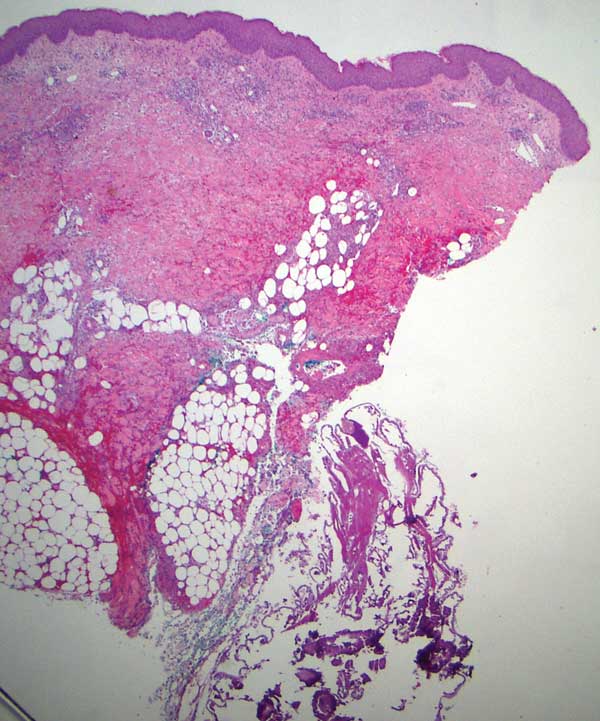

A 64-year-old woman was referred by her gynecologist to dermatology to rule out vulvar melanoma. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism and hypercholesterolemia but was otherwise in good health. Genital examination revealed asymptomatic pigmented macules and patches of unknown duration (Figure 1). Specimens were taken from 3 areas by punch biopsy to clarify the diagnosis. All 3 specimens showed identical features including basilar pigmentation, occasional melanophages in the papillary dermis, and no evidence of nests or pagetoid spread of atypical melanocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Histologic findings were diagnostic for genital lentiginosis. The patient was reassured, and no treatment was provided. At 6-month follow-up there was no change in clinical appearance.

Genital lentiginosis is characterized by brown lesions that can have a mottled appearance and often are associated with skip areas.1 Lesions can be strikingly irregular and darkly pigmented.

Although the lesions of genital lentiginosis most often are isolated findings, they can be a clue to several uncommon syndromes such as autosomal-dominant Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which is associated with genital lentiginosis, intestinal polyposis, and macrocephaly.3 Vascular malformations, lipomatosis, verrucal keratoses, and acrochordons can occur. Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden syndrome may share genetic linkage; mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) has been implicated in both syndromes.4 Underlying Carney complex should be excluded when genital lentiginosis is encountered.

Genital lentiginosis is idiopathic in most instances, but reports of lesions occurring after annular lichen planus suggest a possible mechanism.5 The disappearance of lentigines after imatinib therapy suggests a role for c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in intracellular signaling, in some cases.6 At times, lesions can simulate trichrome vitiligo or have a reticulate pattern.7

Men and women present at different points in the course of disease. Men often present with penile lesions 14 years after onset, on average; they notice a gradual increase in the size of lesions. Because women can have greater difficulty self-examining the genital region, they tend to present much later in the course but often within a few months after initial inspection.1,8

Genital lentiginosis can mimic melanoma with nonhomogeneous pigmentation, asymmetry, and unilateral distribution, which makes dermoscopic assessment of colors helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Melanoma is associated with combinations of gray, red, blue, and white, which are not found in genital lentiginosis.9

Biopsy of a genital lentigo is diagnostic, distinguishing the lesion from melanoma—failing to reveal the atypical melanocytes and pagetoid spread characteristic of melanoma in situ. Histologic findings can cause diagnostic difficulties when concurrent lichen sclerosus is associated with genital lentigines or nevi.10

Lentigines on sun-damaged skin or in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum have been associated with melanoma,11-13 but genital lentigines are not considered a form of precancerous melanosis. In women, early diagnosis is important when there is concern for melanoma because the prognosis for vulvar melanoma is improved in thin lesions.14

Other entities in the differential include secondary syphilis, which commonly presents as macules and scaly papules and can be found on mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity,15 as well as Kaposi sarcoma, which is characterized by purplish, brown, or black macules, plaques, and nodules, more commonly in immunosuppressed patients.16

To avoid unwarranted concern and unnecessary surgery, dermatologists should be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adults.

- Hwang L, Wilson H, Orengo I. Off-center fold: irregular, pigmented genital macules. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1559-1564. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1559-b

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, et al. Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:72-82. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80047-x

- Erkek E, Hizel S, Sanl C, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:639-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.022

- Blum RR, Rahimizadeh A, Kardon N, et al. Genital lentigines in a 6-year-old boy with a family history of Cowden’s disease: clinical and genetic evidence of the linkage between Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:228-230. doi:10.1177/120347540100500307

- Isbary G, Dyall-Smith D, Coras-Stepanek B, et al. Penile lentigo (genital mucosal macule) following annular lichen planus: a possible association? Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:159-161. doi:10.1111/ajd.12169

- Campbell T, Felsten L, Moore J. Disappearance of lentigines in a patient receiving imatinib treatment for familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1313-1316. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.263

- Romero- A, R, , et al. Reticulate genital pigmentation associated with localized vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:574-575. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.69

- Barnhill RL, Albert LS, Shama SK, et al. Genital lentiginosis: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:453-460. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70064-o

- De Giorgi V, Gori A, Salvati L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1185–1191. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2528

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi H, et al. Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:690-694. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.034

- Shatkin M, Helm MF, Muhlbauer A, et al. Solar lentigo evolving into fatal metastatic melanoma in a patient who initially refused surgery. N A J Med Sci. 2020;1:28-31. doi:10.7156/najms.2020.1301028

- Stern JB, Peck GL, Haupt HM, et al. Malignant melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum: search for a precursor lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:591-594. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70079-9

- Byrom L, Barksdale S, Weedon D, et al. Unstable solar lentigo: a defined separate entity. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:229-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.12447

- Panizzon RG. Vulvar melanoma. Semin Dermatol. 1996;15:67-70. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80021-6

- Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164. doi:10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151. doi:10.1002/jso.20090

To the Editor:

Genital lentiginosis (also known as mucosal melanotic macules, vulvar melanosis, penile melanosis, and penile lentigines) occurs in men and women.1 Lesions present in adult life as multifocal, asymmetrical, pigmented patches that can have a mottled appearance or exhibit skip areas. The irregular appearance of the pigmented areas often raises concern for melanoma. Biopsy reveals increased pigmentation along the basal layer of the epidermis; the irregular distribution of single melanocytes and pagetoid spread typical of melanoma in situ is not identified.

Genital lentiginosis usually occurs as an isolated finding; however, the condition can be a manifestation of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Carney complex, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.1-3 When it occurs as an isolated finding, the patient can be reassured and treatment is unnecessary. Because genital lentiginosis may mimic the appearance of melanoma, it is important for physicians to differentiate the two and make a correct diagnosis. We present a case of genital lentiginosis that mimicked vulvar melanoma.

A 64-year-old woman was referred by her gynecologist to dermatology to rule out vulvar melanoma. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism and hypercholesterolemia but was otherwise in good health. Genital examination revealed asymptomatic pigmented macules and patches of unknown duration (Figure 1). Specimens were taken from 3 areas by punch biopsy to clarify the diagnosis. All 3 specimens showed identical features including basilar pigmentation, occasional melanophages in the papillary dermis, and no evidence of nests or pagetoid spread of atypical melanocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Histologic findings were diagnostic for genital lentiginosis. The patient was reassured, and no treatment was provided. At 6-month follow-up there was no change in clinical appearance.

Genital lentiginosis is characterized by brown lesions that can have a mottled appearance and often are associated with skip areas.1 Lesions can be strikingly irregular and darkly pigmented.

Although the lesions of genital lentiginosis most often are isolated findings, they can be a clue to several uncommon syndromes such as autosomal-dominant Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which is associated with genital lentiginosis, intestinal polyposis, and macrocephaly.3 Vascular malformations, lipomatosis, verrucal keratoses, and acrochordons can occur. Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden syndrome may share genetic linkage; mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) has been implicated in both syndromes.4 Underlying Carney complex should be excluded when genital lentiginosis is encountered.

Genital lentiginosis is idiopathic in most instances, but reports of lesions occurring after annular lichen planus suggest a possible mechanism.5 The disappearance of lentigines after imatinib therapy suggests a role for c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in intracellular signaling, in some cases.6 At times, lesions can simulate trichrome vitiligo or have a reticulate pattern.7

Men and women present at different points in the course of disease. Men often present with penile lesions 14 years after onset, on average; they notice a gradual increase in the size of lesions. Because women can have greater difficulty self-examining the genital region, they tend to present much later in the course but often within a few months after initial inspection.1,8

Genital lentiginosis can mimic melanoma with nonhomogeneous pigmentation, asymmetry, and unilateral distribution, which makes dermoscopic assessment of colors helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Melanoma is associated with combinations of gray, red, blue, and white, which are not found in genital lentiginosis.9

Biopsy of a genital lentigo is diagnostic, distinguishing the lesion from melanoma—failing to reveal the atypical melanocytes and pagetoid spread characteristic of melanoma in situ. Histologic findings can cause diagnostic difficulties when concurrent lichen sclerosus is associated with genital lentigines or nevi.10

Lentigines on sun-damaged skin or in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum have been associated with melanoma,11-13 but genital lentigines are not considered a form of precancerous melanosis. In women, early diagnosis is important when there is concern for melanoma because the prognosis for vulvar melanoma is improved in thin lesions.14

Other entities in the differential include secondary syphilis, which commonly presents as macules and scaly papules and can be found on mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity,15 as well as Kaposi sarcoma, which is characterized by purplish, brown, or black macules, plaques, and nodules, more commonly in immunosuppressed patients.16

To avoid unwarranted concern and unnecessary surgery, dermatologists should be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adults.

To the Editor:

Genital lentiginosis (also known as mucosal melanotic macules, vulvar melanosis, penile melanosis, and penile lentigines) occurs in men and women.1 Lesions present in adult life as multifocal, asymmetrical, pigmented patches that can have a mottled appearance or exhibit skip areas. The irregular appearance of the pigmented areas often raises concern for melanoma. Biopsy reveals increased pigmentation along the basal layer of the epidermis; the irregular distribution of single melanocytes and pagetoid spread typical of melanoma in situ is not identified.

Genital lentiginosis usually occurs as an isolated finding; however, the condition can be a manifestation of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Carney complex, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.1-3 When it occurs as an isolated finding, the patient can be reassured and treatment is unnecessary. Because genital lentiginosis may mimic the appearance of melanoma, it is important for physicians to differentiate the two and make a correct diagnosis. We present a case of genital lentiginosis that mimicked vulvar melanoma.

A 64-year-old woman was referred by her gynecologist to dermatology to rule out vulvar melanoma. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism and hypercholesterolemia but was otherwise in good health. Genital examination revealed asymptomatic pigmented macules and patches of unknown duration (Figure 1). Specimens were taken from 3 areas by punch biopsy to clarify the diagnosis. All 3 specimens showed identical features including basilar pigmentation, occasional melanophages in the papillary dermis, and no evidence of nests or pagetoid spread of atypical melanocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Histologic findings were diagnostic for genital lentiginosis. The patient was reassured, and no treatment was provided. At 6-month follow-up there was no change in clinical appearance.

Genital lentiginosis is characterized by brown lesions that can have a mottled appearance and often are associated with skip areas.1 Lesions can be strikingly irregular and darkly pigmented.

Although the lesions of genital lentiginosis most often are isolated findings, they can be a clue to several uncommon syndromes such as autosomal-dominant Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which is associated with genital lentiginosis, intestinal polyposis, and macrocephaly.3 Vascular malformations, lipomatosis, verrucal keratoses, and acrochordons can occur. Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden syndrome may share genetic linkage; mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) has been implicated in both syndromes.4 Underlying Carney complex should be excluded when genital lentiginosis is encountered.

Genital lentiginosis is idiopathic in most instances, but reports of lesions occurring after annular lichen planus suggest a possible mechanism.5 The disappearance of lentigines after imatinib therapy suggests a role for c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in intracellular signaling, in some cases.6 At times, lesions can simulate trichrome vitiligo or have a reticulate pattern.7

Men and women present at different points in the course of disease. Men often present with penile lesions 14 years after onset, on average; they notice a gradual increase in the size of lesions. Because women can have greater difficulty self-examining the genital region, they tend to present much later in the course but often within a few months after initial inspection.1,8

Genital lentiginosis can mimic melanoma with nonhomogeneous pigmentation, asymmetry, and unilateral distribution, which makes dermoscopic assessment of colors helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Melanoma is associated with combinations of gray, red, blue, and white, which are not found in genital lentiginosis.9

Biopsy of a genital lentigo is diagnostic, distinguishing the lesion from melanoma—failing to reveal the atypical melanocytes and pagetoid spread characteristic of melanoma in situ. Histologic findings can cause diagnostic difficulties when concurrent lichen sclerosus is associated with genital lentigines or nevi.10

Lentigines on sun-damaged skin or in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum have been associated with melanoma,11-13 but genital lentigines are not considered a form of precancerous melanosis. In women, early diagnosis is important when there is concern for melanoma because the prognosis for vulvar melanoma is improved in thin lesions.14

Other entities in the differential include secondary syphilis, which commonly presents as macules and scaly papules and can be found on mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity,15 as well as Kaposi sarcoma, which is characterized by purplish, brown, or black macules, plaques, and nodules, more commonly in immunosuppressed patients.16

To avoid unwarranted concern and unnecessary surgery, dermatologists should be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adults.

- Hwang L, Wilson H, Orengo I. Off-center fold: irregular, pigmented genital macules. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1559-1564. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1559-b

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, et al. Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:72-82. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80047-x

- Erkek E, Hizel S, Sanl C, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:639-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.022

- Blum RR, Rahimizadeh A, Kardon N, et al. Genital lentigines in a 6-year-old boy with a family history of Cowden’s disease: clinical and genetic evidence of the linkage between Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:228-230. doi:10.1177/120347540100500307

- Isbary G, Dyall-Smith D, Coras-Stepanek B, et al. Penile lentigo (genital mucosal macule) following annular lichen planus: a possible association? Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:159-161. doi:10.1111/ajd.12169

- Campbell T, Felsten L, Moore J. Disappearance of lentigines in a patient receiving imatinib treatment for familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1313-1316. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.263

- Romero- A, R, , et al. Reticulate genital pigmentation associated with localized vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:574-575. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.69

- Barnhill RL, Albert LS, Shama SK, et al. Genital lentiginosis: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:453-460. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70064-o

- De Giorgi V, Gori A, Salvati L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1185–1191. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2528

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi H, et al. Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:690-694. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.034

- Shatkin M, Helm MF, Muhlbauer A, et al. Solar lentigo evolving into fatal metastatic melanoma in a patient who initially refused surgery. N A J Med Sci. 2020;1:28-31. doi:10.7156/najms.2020.1301028

- Stern JB, Peck GL, Haupt HM, et al. Malignant melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum: search for a precursor lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:591-594. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70079-9

- Byrom L, Barksdale S, Weedon D, et al. Unstable solar lentigo: a defined separate entity. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:229-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.12447

- Panizzon RG. Vulvar melanoma. Semin Dermatol. 1996;15:67-70. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80021-6

- Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164. doi:10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151. doi:10.1002/jso.20090

- Hwang L, Wilson H, Orengo I. Off-center fold: irregular, pigmented genital macules. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1559-1564. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1559-b

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, et al. Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:72-82. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80047-x

- Erkek E, Hizel S, Sanl C, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:639-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.022

- Blum RR, Rahimizadeh A, Kardon N, et al. Genital lentigines in a 6-year-old boy with a family history of Cowden’s disease: clinical and genetic evidence of the linkage between Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:228-230. doi:10.1177/120347540100500307

- Isbary G, Dyall-Smith D, Coras-Stepanek B, et al. Penile lentigo (genital mucosal macule) following annular lichen planus: a possible association? Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:159-161. doi:10.1111/ajd.12169

- Campbell T, Felsten L, Moore J. Disappearance of lentigines in a patient receiving imatinib treatment for familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1313-1316. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.263

- Romero- A, R, , et al. Reticulate genital pigmentation associated with localized vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:574-575. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.69

- Barnhill RL, Albert LS, Shama SK, et al. Genital lentiginosis: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:453-460. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70064-o

- De Giorgi V, Gori A, Salvati L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1185–1191. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2528

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi H, et al. Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:690-694. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.034

- Shatkin M, Helm MF, Muhlbauer A, et al. Solar lentigo evolving into fatal metastatic melanoma in a patient who initially refused surgery. N A J Med Sci. 2020;1:28-31. doi:10.7156/najms.2020.1301028

- Stern JB, Peck GL, Haupt HM, et al. Malignant melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum: search for a precursor lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:591-594. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70079-9

- Byrom L, Barksdale S, Weedon D, et al. Unstable solar lentigo: a defined separate entity. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:229-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.12447

- Panizzon RG. Vulvar melanoma. Semin Dermatol. 1996;15:67-70. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80021-6

- Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164. doi:10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151. doi:10.1002/jso.20090

Practice Points

- The irregular appearance of genital lentiginosis—multifocal, asymmetric, irregular, and darkly pigmented patches—often raises concern for melanoma but is benign.

- Certain genetic conditions can present with genital lentiginosis.

- Dermoscopic assessment of the lesion color is highly helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis; seeing no gray, red, blue, or white makes melanoma less likely.

- Be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adulthood to avoid unwarranted concern and unneeded surgery.

Atypical Localized Scleroderma Development During Nivolumab Therapy for Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

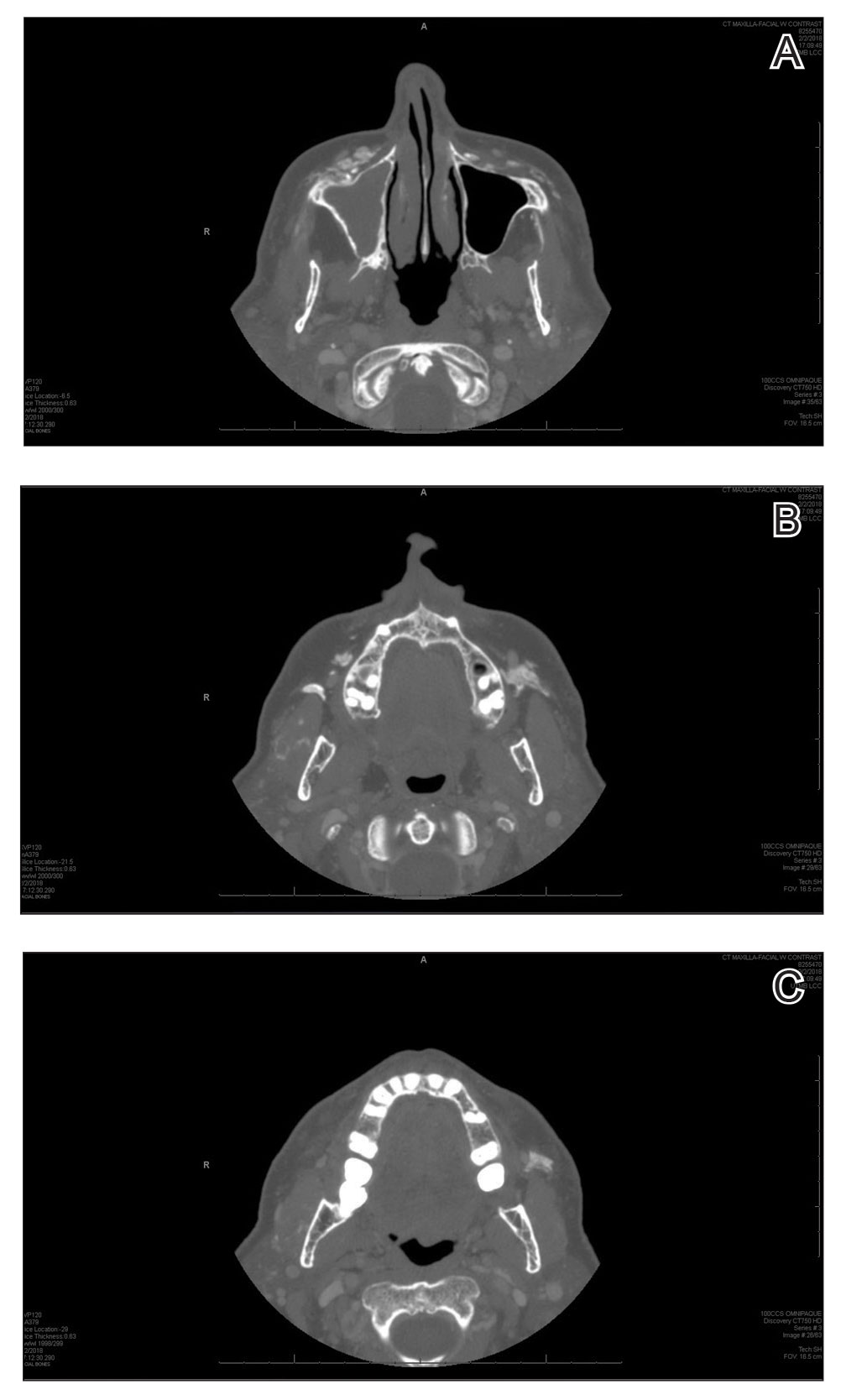

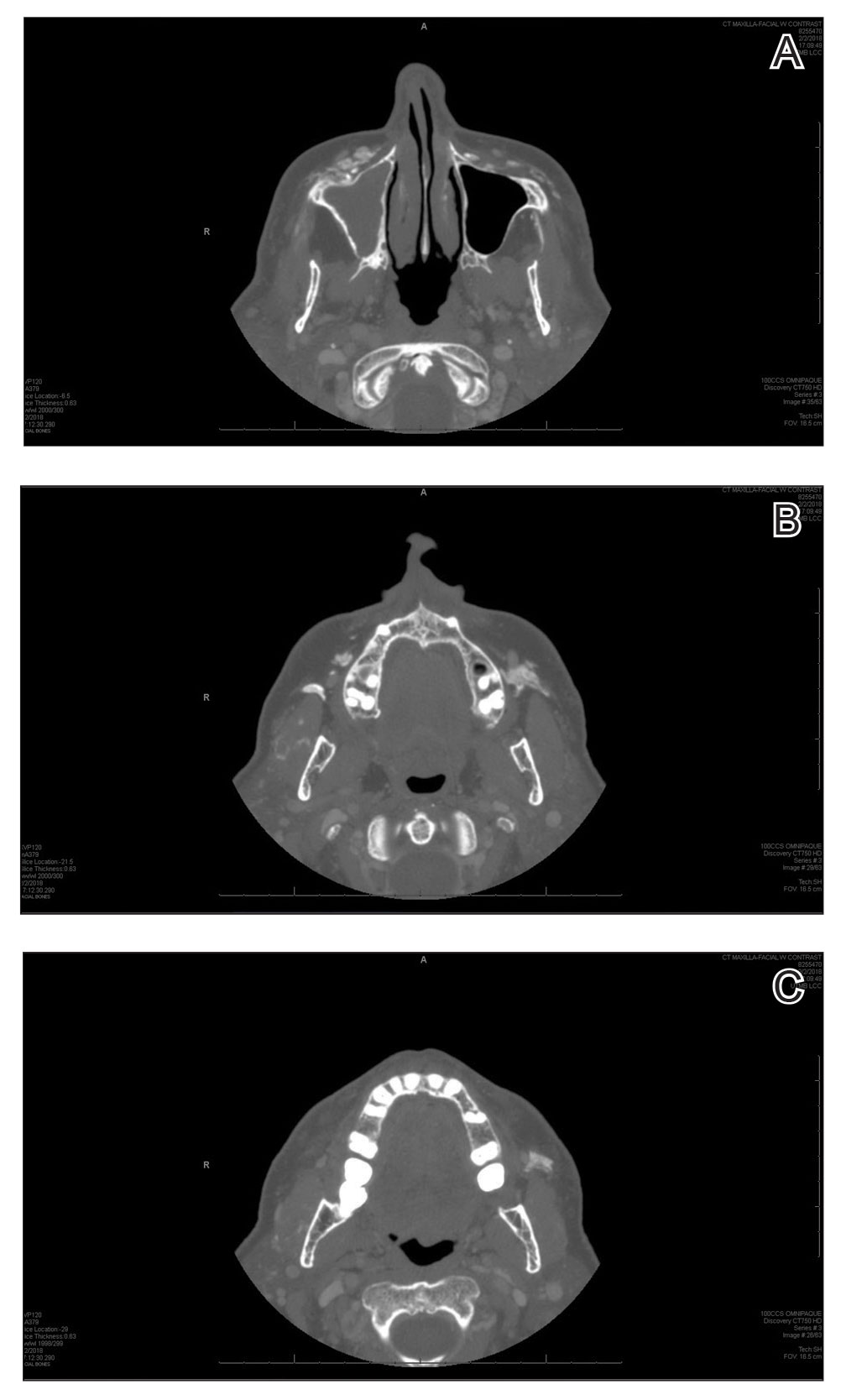

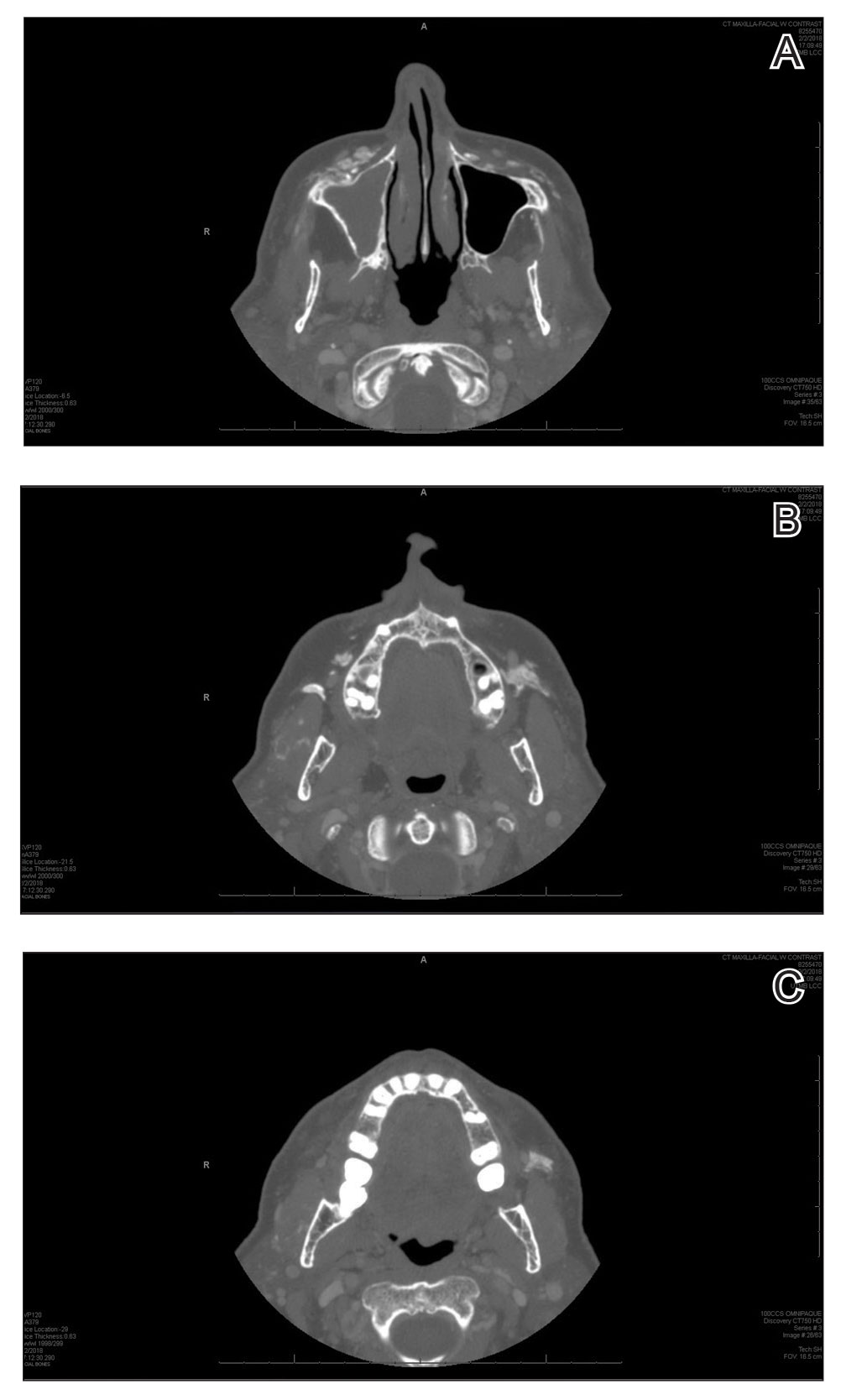

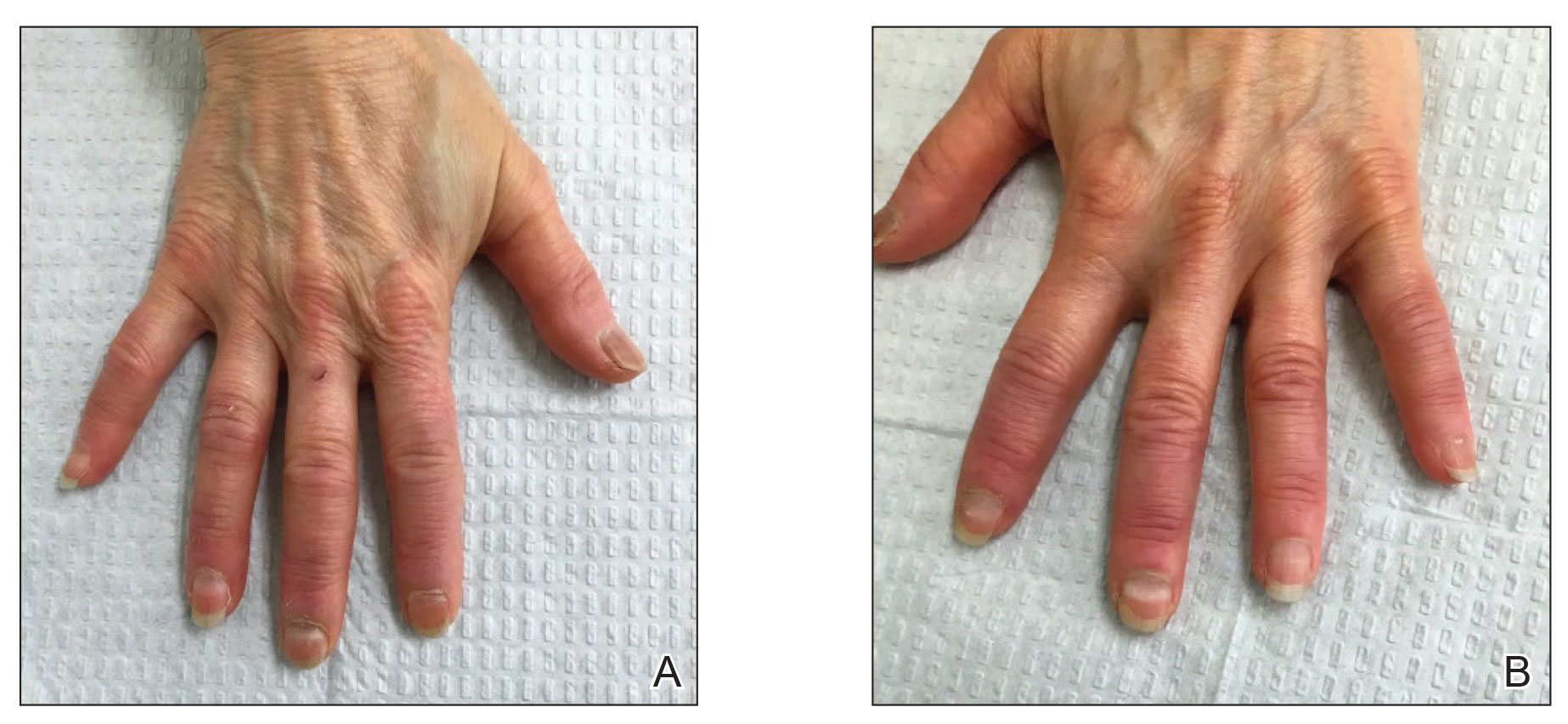

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

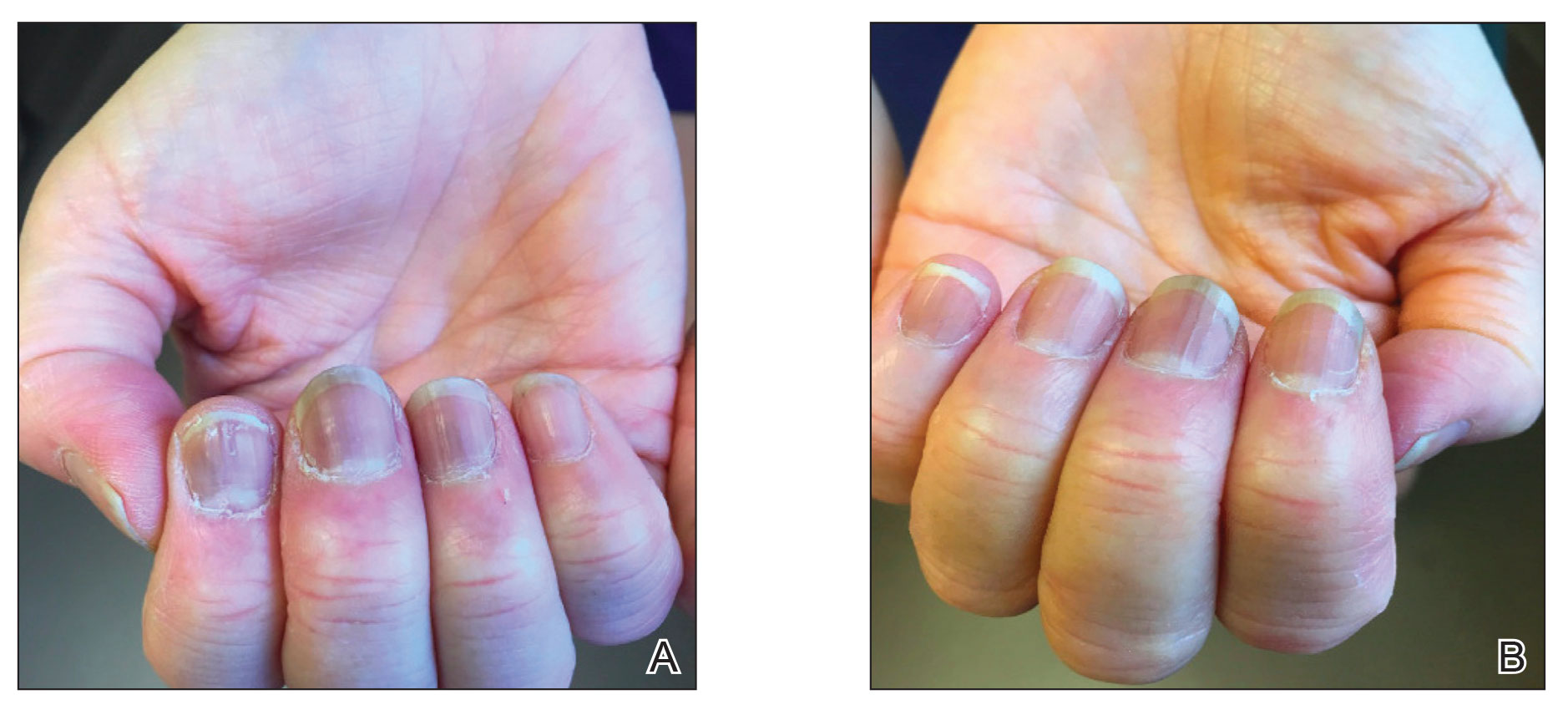

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

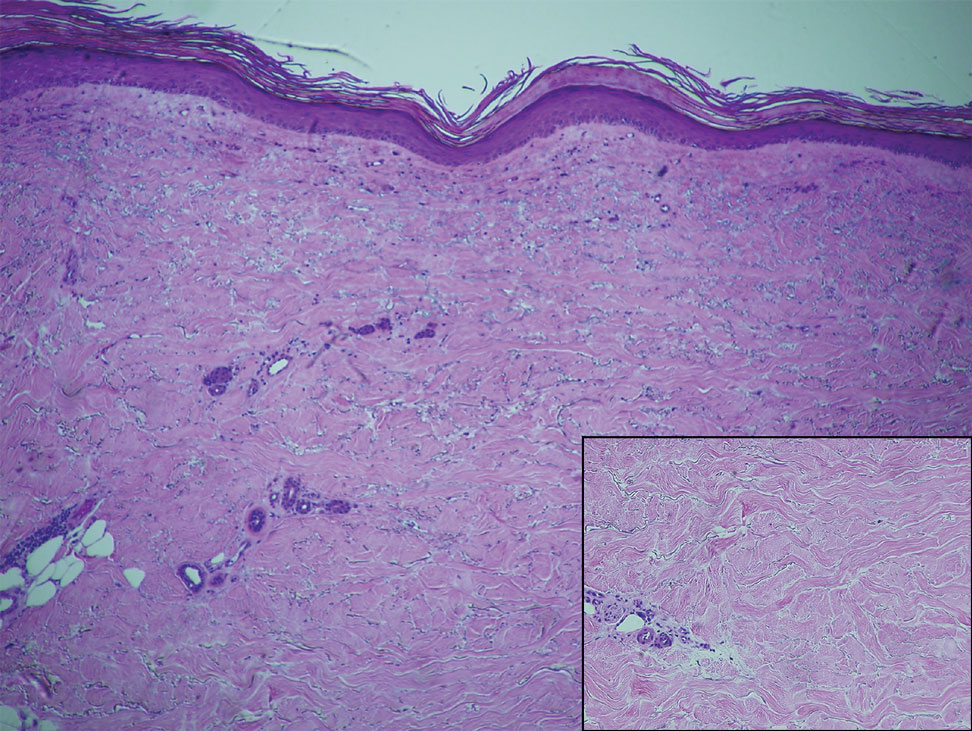

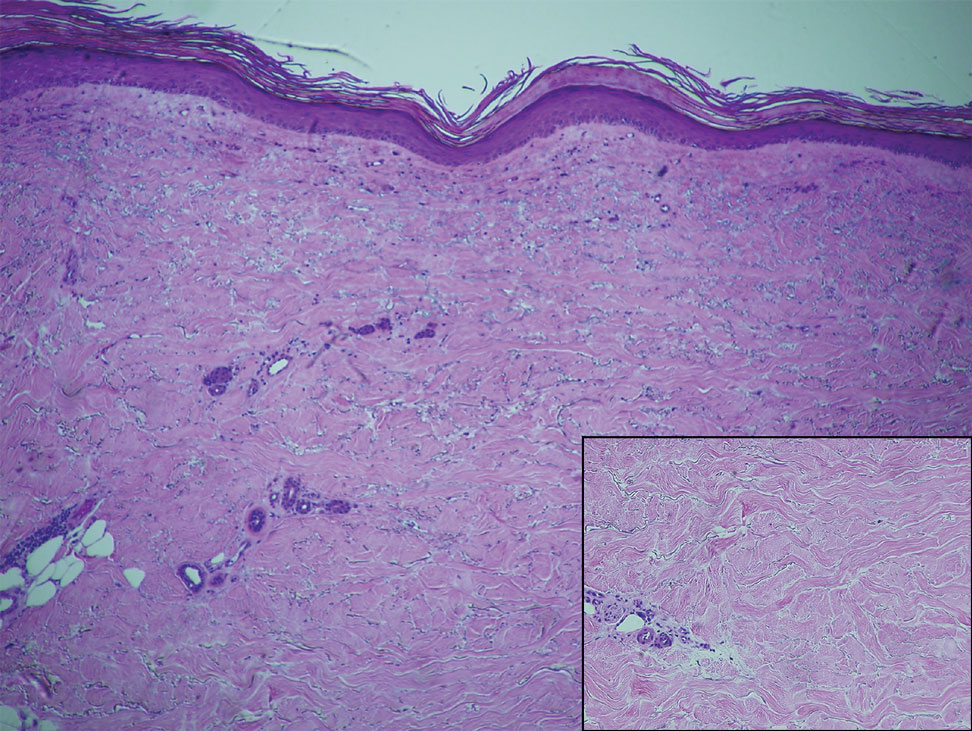

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7