User login

A serpiginous, itchy rash on the foot

A 22-year-old woman presented with a serpiginous, erythematous, itchy lesion on her left foot (Figure 1), 10 days after returning from a beach holiday in Tanzania. She noted that the site of the lesion kept changing. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s recent travel, the pattern of the lesion, the intense pruritus, and the lack of other symptoms, the lesion was diagnosed as cutaneous larva migrans. We applied cryosurgery and prescribed thiabendazole 10% cream twice daily for 2 weeks. The lesions resolved completely after 2 weeks.

BEACH WORM

Cutaneous larva migrans—also known as migrant linear epidermitis, beach worm, migrant helminthiasis, dermatitis serpiginosa, creeping eruption, or sand worm—is a zoodermatosis caused by cutaneous penetration of helminth larvae, usually parasites of the small intestines of cats and dogs.1–3 This eruption is usually seen in tropical and subtropical climates, such as Central America, South America, Africa, and even the southeastern parts of the United States, although with the ease of travel to the tropics its incidence could well be increasing on return to the home countries.1,2 The disease is endemic along the southeastern Atlantic coast of North America, in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean, and on the coast of Uruguay.

Common species

The most common cause is Ancylostoma braziliense, with less common species being Ancylostoma caninum, Uncinaria stenocephala, and Bunostomum phlebotomum.4 The larvae may cause a nonspecific dermatitis at the site of penetration where the skin has been in contact with infected soil, commonly the feet, hands, or buttocks. From the point where larvae penetrate, they gradually form linear tunnels with an irregular and capricious path, advancing at a rate of a few millimeters a day.3 There may be a single path, as in our patient, or hundreds or even a thousand in cases of massive infection.

The larvae rarely affect other organs, and systemic manifestations such as migratory pulmonary infiltrates and peripheral eosinophilia (Loeffler syndrome) are rarely seen. Larva currens, caused by the rapid-moving parasitic roundworm Strongyloides stercoralis, generally manifests on the buttocks or the perianal region and lasts only a few hours.

Key diagnostic features

The diagnosis of cutaneous larva migrans is based on the clinical history and on the serpiginous and migratory pattern of the lesions. However, eczematization and secondary infection may make recognition of these features more difficult.3 Biopsy of the lesions usually does not help identify the larvae, since they advance in front of the path.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Although the disease is self-limiting, treatment is usually recommended because of intense pruritus and the risk of bacterial infection. With no treatment, the number of lesions falls by 33% after 1 week, 54% after 2 weeks, 71% after 3 weeks, and 81% after 4 weeks according to Katz et al.5 Other reports mention that 25% to 33% of the larvae die every 4 weeks.5

Treatment is topical or systemic, depending on the extent and location of the lesions. Systemic treatment is preferred for widespread or multiple lesions or lesions located near the eye, but use is limited due to a high incidence of adverse effects.

The drugs of choice are albendazole 400 mg/day for 3 days, ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg in a single dose, or thiabendazole 25 mg/kg/day, divided into two doses for 5 days. If there are few lesions, as in our patient, thiabendazole ointment or 10% cream may be applied to the entire lesion, slightly in front of the leading point of advance of the lesion.1,6 However, thiabendazole is not available in the United States.

Adverse effects of ivermectin include fever, pruritus, and skin rash. Albendazole may cause abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, bone marrow suppression, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, or elevation of liver enzyme levels. Thiabendazole may cause delirium, diarrhea, hallucinations, loss of appetite, numbness, nausea, and central nervous system toxicity.

- Kalil CLPV, Webber A. Zoodermatoses. In: Ramos e Silva M, Castro MCR, editors. Fundamentos de Dermatologia. Rio de Janeiro: Atheneu; 2010:1055–1057.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol 2001; 145:434–437.

- Meotti CD, Plates G, Nogueira LL, et al. Cutaneous larva migrans on the scalp: atypical presentation of a common disease. An Bras Dermatol 2014; 89:332–333.

- Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002; 68:252–258.

- Katz R, Ziegler J, Blank H. The natural course of creeping eruption and treatment with thiabendazole. Arch Dermatol 1965; 91:420–424.

- Upendra Y, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS, Chander B. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013; 79:418–419.

A 22-year-old woman presented with a serpiginous, erythematous, itchy lesion on her left foot (Figure 1), 10 days after returning from a beach holiday in Tanzania. She noted that the site of the lesion kept changing. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s recent travel, the pattern of the lesion, the intense pruritus, and the lack of other symptoms, the lesion was diagnosed as cutaneous larva migrans. We applied cryosurgery and prescribed thiabendazole 10% cream twice daily for 2 weeks. The lesions resolved completely after 2 weeks.

BEACH WORM

Cutaneous larva migrans—also known as migrant linear epidermitis, beach worm, migrant helminthiasis, dermatitis serpiginosa, creeping eruption, or sand worm—is a zoodermatosis caused by cutaneous penetration of helminth larvae, usually parasites of the small intestines of cats and dogs.1–3 This eruption is usually seen in tropical and subtropical climates, such as Central America, South America, Africa, and even the southeastern parts of the United States, although with the ease of travel to the tropics its incidence could well be increasing on return to the home countries.1,2 The disease is endemic along the southeastern Atlantic coast of North America, in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean, and on the coast of Uruguay.

Common species

The most common cause is Ancylostoma braziliense, with less common species being Ancylostoma caninum, Uncinaria stenocephala, and Bunostomum phlebotomum.4 The larvae may cause a nonspecific dermatitis at the site of penetration where the skin has been in contact with infected soil, commonly the feet, hands, or buttocks. From the point where larvae penetrate, they gradually form linear tunnels with an irregular and capricious path, advancing at a rate of a few millimeters a day.3 There may be a single path, as in our patient, or hundreds or even a thousand in cases of massive infection.

The larvae rarely affect other organs, and systemic manifestations such as migratory pulmonary infiltrates and peripheral eosinophilia (Loeffler syndrome) are rarely seen. Larva currens, caused by the rapid-moving parasitic roundworm Strongyloides stercoralis, generally manifests on the buttocks or the perianal region and lasts only a few hours.

Key diagnostic features

The diagnosis of cutaneous larva migrans is based on the clinical history and on the serpiginous and migratory pattern of the lesions. However, eczematization and secondary infection may make recognition of these features more difficult.3 Biopsy of the lesions usually does not help identify the larvae, since they advance in front of the path.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Although the disease is self-limiting, treatment is usually recommended because of intense pruritus and the risk of bacterial infection. With no treatment, the number of lesions falls by 33% after 1 week, 54% after 2 weeks, 71% after 3 weeks, and 81% after 4 weeks according to Katz et al.5 Other reports mention that 25% to 33% of the larvae die every 4 weeks.5

Treatment is topical or systemic, depending on the extent and location of the lesions. Systemic treatment is preferred for widespread or multiple lesions or lesions located near the eye, but use is limited due to a high incidence of adverse effects.

The drugs of choice are albendazole 400 mg/day for 3 days, ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg in a single dose, or thiabendazole 25 mg/kg/day, divided into two doses for 5 days. If there are few lesions, as in our patient, thiabendazole ointment or 10% cream may be applied to the entire lesion, slightly in front of the leading point of advance of the lesion.1,6 However, thiabendazole is not available in the United States.

Adverse effects of ivermectin include fever, pruritus, and skin rash. Albendazole may cause abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, bone marrow suppression, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, or elevation of liver enzyme levels. Thiabendazole may cause delirium, diarrhea, hallucinations, loss of appetite, numbness, nausea, and central nervous system toxicity.

A 22-year-old woman presented with a serpiginous, erythematous, itchy lesion on her left foot (Figure 1), 10 days after returning from a beach holiday in Tanzania. She noted that the site of the lesion kept changing. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s recent travel, the pattern of the lesion, the intense pruritus, and the lack of other symptoms, the lesion was diagnosed as cutaneous larva migrans. We applied cryosurgery and prescribed thiabendazole 10% cream twice daily for 2 weeks. The lesions resolved completely after 2 weeks.

BEACH WORM

Cutaneous larva migrans—also known as migrant linear epidermitis, beach worm, migrant helminthiasis, dermatitis serpiginosa, creeping eruption, or sand worm—is a zoodermatosis caused by cutaneous penetration of helminth larvae, usually parasites of the small intestines of cats and dogs.1–3 This eruption is usually seen in tropical and subtropical climates, such as Central America, South America, Africa, and even the southeastern parts of the United States, although with the ease of travel to the tropics its incidence could well be increasing on return to the home countries.1,2 The disease is endemic along the southeastern Atlantic coast of North America, in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean, and on the coast of Uruguay.

Common species

The most common cause is Ancylostoma braziliense, with less common species being Ancylostoma caninum, Uncinaria stenocephala, and Bunostomum phlebotomum.4 The larvae may cause a nonspecific dermatitis at the site of penetration where the skin has been in contact with infected soil, commonly the feet, hands, or buttocks. From the point where larvae penetrate, they gradually form linear tunnels with an irregular and capricious path, advancing at a rate of a few millimeters a day.3 There may be a single path, as in our patient, or hundreds or even a thousand in cases of massive infection.

The larvae rarely affect other organs, and systemic manifestations such as migratory pulmonary infiltrates and peripheral eosinophilia (Loeffler syndrome) are rarely seen. Larva currens, caused by the rapid-moving parasitic roundworm Strongyloides stercoralis, generally manifests on the buttocks or the perianal region and lasts only a few hours.

Key diagnostic features

The diagnosis of cutaneous larva migrans is based on the clinical history and on the serpiginous and migratory pattern of the lesions. However, eczematization and secondary infection may make recognition of these features more difficult.3 Biopsy of the lesions usually does not help identify the larvae, since they advance in front of the path.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Although the disease is self-limiting, treatment is usually recommended because of intense pruritus and the risk of bacterial infection. With no treatment, the number of lesions falls by 33% after 1 week, 54% after 2 weeks, 71% after 3 weeks, and 81% after 4 weeks according to Katz et al.5 Other reports mention that 25% to 33% of the larvae die every 4 weeks.5

Treatment is topical or systemic, depending on the extent and location of the lesions. Systemic treatment is preferred for widespread or multiple lesions or lesions located near the eye, but use is limited due to a high incidence of adverse effects.

The drugs of choice are albendazole 400 mg/day for 3 days, ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg in a single dose, or thiabendazole 25 mg/kg/day, divided into two doses for 5 days. If there are few lesions, as in our patient, thiabendazole ointment or 10% cream may be applied to the entire lesion, slightly in front of the leading point of advance of the lesion.1,6 However, thiabendazole is not available in the United States.

Adverse effects of ivermectin include fever, pruritus, and skin rash. Albendazole may cause abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, bone marrow suppression, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, or elevation of liver enzyme levels. Thiabendazole may cause delirium, diarrhea, hallucinations, loss of appetite, numbness, nausea, and central nervous system toxicity.

- Kalil CLPV, Webber A. Zoodermatoses. In: Ramos e Silva M, Castro MCR, editors. Fundamentos de Dermatologia. Rio de Janeiro: Atheneu; 2010:1055–1057.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol 2001; 145:434–437.

- Meotti CD, Plates G, Nogueira LL, et al. Cutaneous larva migrans on the scalp: atypical presentation of a common disease. An Bras Dermatol 2014; 89:332–333.

- Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002; 68:252–258.

- Katz R, Ziegler J, Blank H. The natural course of creeping eruption and treatment with thiabendazole. Arch Dermatol 1965; 91:420–424.

- Upendra Y, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS, Chander B. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013; 79:418–419.

- Kalil CLPV, Webber A. Zoodermatoses. In: Ramos e Silva M, Castro MCR, editors. Fundamentos de Dermatologia. Rio de Janeiro: Atheneu; 2010:1055–1057.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol 2001; 145:434–437.

- Meotti CD, Plates G, Nogueira LL, et al. Cutaneous larva migrans on the scalp: atypical presentation of a common disease. An Bras Dermatol 2014; 89:332–333.

- Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002; 68:252–258.

- Katz R, Ziegler J, Blank H. The natural course of creeping eruption and treatment with thiabendazole. Arch Dermatol 1965; 91:420–424.

- Upendra Y, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS, Chander B. Cutaneous larva migrans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013; 79:418–419.

Whiplash-shaped acute rash

A previously healthy 32-year-old man presented to the emergency room with a persistent, nonpruritic rash on his trunk, which had suddenly appeared 2 days after he ate Chinese food.

Physical examination revealed multiple crosslinked linear plaques that appeared like scratches over his chest, back, and shoulders (Figures 1 and 2). He had no dermatographism, and his scalp, nails, palms, and soles were not affected. He had no signs of lymphadenopathy or systemic involvement.

Basic blood and urinary laboratory testing, blood cultures, and serologic studies showed normal or negative results.

Given the presentation and results of initial testing, his rash was diagnosed as flagellate erythema, likely due to shiitake mushroom intake. The diagnosis does not require histopathologic confirmation.

The rash resolved spontaneously over the next 2 weeks with use of a topical emollient and without scarring or residual hyperpigmentation.

FLAGELLATE ERYTHEMA

Flagellate erythema is a peculiar cutaneous eruption characterized by the progressive or sudden onset of parallel linear or curvilinear plaques, most commonly on the trunk. The plaques are typically arranged in a scratch pattern resembling marks left by the lashes of a whip.1 In contrast to other itchy dermatoses and neurotic excoriations that may present with self-induced linear marks, flagellate erythema appears spontaneously.

Drug-related causes, disease associations

Originally described in association with bleomycin treatment, flagellate erythema is currently considered a distinct feature of several dermatologic and systemic disorders, and therefore the ability to recognize it is valuable in daily practice.2 In addition to bleomycin analogues and anticancer agents such as peplomycin,1 bendamustine,3 and docetaxel,4 physicians should consider shiitake dermatitis5 and other less commonly reported associations such as dermatomyositis,6 lupus,7 Still disease,8 and parvovirus infection.9

Diagnostic features

The diagnosis of flagellate erythema is mainly based on the morphologic features of the clinical lesions.1 Shiitake dermatitis and flagellate erythema related to rheumatologic disease usually present with more inflammatory and erythematous plaques. Chemotherapy-induced flagellate rash typically has a violaceous or purpuric coloration, which tends to leave noticeable hyperpigmentation for several months.2

Skin biopsy may be necessary to distinguish it from similar-looking dermatoses with different histologic findings, such as dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, erythema gyratum repens, and factitious dermatoses, which may require specific treatments or be related to important underlying pathology.1,2

Treatment

Treatment includes both specific treatment of the underlying cause and symptomatic care of the skin with topical emollients and, in cases of associated pruritus, oral antihistamines. The patient should also be reassured about the self-healing nature of shiitake dermatitis rash.5

- Yamamoto T, Nishioka K. Flagellate erythema. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45:627–631.

- Bhushan P, Manjul P, Baliyan V. Flagellate dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014; 80:149–152.

- Mahmoud BH, Eide MJ. Bendamustine-induced “flagellate dermatitis.” Dermatol Online J 2012; 18:12.

- Tallon B, Lamb S. Flagellate erythema induced by docetaxel. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008; 33:276–277.

- Adler MJ, Larsen WG. Clinical variability of shiitake dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67:140–141.

- Jara M, Amérigo J, Duce S, Borbujo J. Dermatomyositis and flagellate erythema. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21:440–441.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K. Systemic lupus erythematosus with flagellate erythema. Eur J Dermatol 2012; 22:808–809.

- Ciliberto H, Kumar MG, Musiek A. Flagellate erythema in a patient with fever. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149:1425–1426.

- Miguélez A, Dueñas J, Hervás D, Hervás JA, Salva F, Martín-Santiago A. Flagellate erythema in parvovirus B19 infection. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53:e583–e585.

A previously healthy 32-year-old man presented to the emergency room with a persistent, nonpruritic rash on his trunk, which had suddenly appeared 2 days after he ate Chinese food.

Physical examination revealed multiple crosslinked linear plaques that appeared like scratches over his chest, back, and shoulders (Figures 1 and 2). He had no dermatographism, and his scalp, nails, palms, and soles were not affected. He had no signs of lymphadenopathy or systemic involvement.

Basic blood and urinary laboratory testing, blood cultures, and serologic studies showed normal or negative results.

Given the presentation and results of initial testing, his rash was diagnosed as flagellate erythema, likely due to shiitake mushroom intake. The diagnosis does not require histopathologic confirmation.

The rash resolved spontaneously over the next 2 weeks with use of a topical emollient and without scarring or residual hyperpigmentation.

FLAGELLATE ERYTHEMA

Flagellate erythema is a peculiar cutaneous eruption characterized by the progressive or sudden onset of parallel linear or curvilinear plaques, most commonly on the trunk. The plaques are typically arranged in a scratch pattern resembling marks left by the lashes of a whip.1 In contrast to other itchy dermatoses and neurotic excoriations that may present with self-induced linear marks, flagellate erythema appears spontaneously.

Drug-related causes, disease associations

Originally described in association with bleomycin treatment, flagellate erythema is currently considered a distinct feature of several dermatologic and systemic disorders, and therefore the ability to recognize it is valuable in daily practice.2 In addition to bleomycin analogues and anticancer agents such as peplomycin,1 bendamustine,3 and docetaxel,4 physicians should consider shiitake dermatitis5 and other less commonly reported associations such as dermatomyositis,6 lupus,7 Still disease,8 and parvovirus infection.9

Diagnostic features

The diagnosis of flagellate erythema is mainly based on the morphologic features of the clinical lesions.1 Shiitake dermatitis and flagellate erythema related to rheumatologic disease usually present with more inflammatory and erythematous plaques. Chemotherapy-induced flagellate rash typically has a violaceous or purpuric coloration, which tends to leave noticeable hyperpigmentation for several months.2

Skin biopsy may be necessary to distinguish it from similar-looking dermatoses with different histologic findings, such as dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, erythema gyratum repens, and factitious dermatoses, which may require specific treatments or be related to important underlying pathology.1,2

Treatment

Treatment includes both specific treatment of the underlying cause and symptomatic care of the skin with topical emollients and, in cases of associated pruritus, oral antihistamines. The patient should also be reassured about the self-healing nature of shiitake dermatitis rash.5

A previously healthy 32-year-old man presented to the emergency room with a persistent, nonpruritic rash on his trunk, which had suddenly appeared 2 days after he ate Chinese food.

Physical examination revealed multiple crosslinked linear plaques that appeared like scratches over his chest, back, and shoulders (Figures 1 and 2). He had no dermatographism, and his scalp, nails, palms, and soles were not affected. He had no signs of lymphadenopathy or systemic involvement.

Basic blood and urinary laboratory testing, blood cultures, and serologic studies showed normal or negative results.

Given the presentation and results of initial testing, his rash was diagnosed as flagellate erythema, likely due to shiitake mushroom intake. The diagnosis does not require histopathologic confirmation.

The rash resolved spontaneously over the next 2 weeks with use of a topical emollient and without scarring or residual hyperpigmentation.

FLAGELLATE ERYTHEMA

Flagellate erythema is a peculiar cutaneous eruption characterized by the progressive or sudden onset of parallel linear or curvilinear plaques, most commonly on the trunk. The plaques are typically arranged in a scratch pattern resembling marks left by the lashes of a whip.1 In contrast to other itchy dermatoses and neurotic excoriations that may present with self-induced linear marks, flagellate erythema appears spontaneously.

Drug-related causes, disease associations

Originally described in association with bleomycin treatment, flagellate erythema is currently considered a distinct feature of several dermatologic and systemic disorders, and therefore the ability to recognize it is valuable in daily practice.2 In addition to bleomycin analogues and anticancer agents such as peplomycin,1 bendamustine,3 and docetaxel,4 physicians should consider shiitake dermatitis5 and other less commonly reported associations such as dermatomyositis,6 lupus,7 Still disease,8 and parvovirus infection.9

Diagnostic features

The diagnosis of flagellate erythema is mainly based on the morphologic features of the clinical lesions.1 Shiitake dermatitis and flagellate erythema related to rheumatologic disease usually present with more inflammatory and erythematous plaques. Chemotherapy-induced flagellate rash typically has a violaceous or purpuric coloration, which tends to leave noticeable hyperpigmentation for several months.2

Skin biopsy may be necessary to distinguish it from similar-looking dermatoses with different histologic findings, such as dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, erythema gyratum repens, and factitious dermatoses, which may require specific treatments or be related to important underlying pathology.1,2

Treatment

Treatment includes both specific treatment of the underlying cause and symptomatic care of the skin with topical emollients and, in cases of associated pruritus, oral antihistamines. The patient should also be reassured about the self-healing nature of shiitake dermatitis rash.5

- Yamamoto T, Nishioka K. Flagellate erythema. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45:627–631.

- Bhushan P, Manjul P, Baliyan V. Flagellate dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014; 80:149–152.

- Mahmoud BH, Eide MJ. Bendamustine-induced “flagellate dermatitis.” Dermatol Online J 2012; 18:12.

- Tallon B, Lamb S. Flagellate erythema induced by docetaxel. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008; 33:276–277.

- Adler MJ, Larsen WG. Clinical variability of shiitake dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67:140–141.

- Jara M, Amérigo J, Duce S, Borbujo J. Dermatomyositis and flagellate erythema. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21:440–441.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K. Systemic lupus erythematosus with flagellate erythema. Eur J Dermatol 2012; 22:808–809.

- Ciliberto H, Kumar MG, Musiek A. Flagellate erythema in a patient with fever. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149:1425–1426.

- Miguélez A, Dueñas J, Hervás D, Hervás JA, Salva F, Martín-Santiago A. Flagellate erythema in parvovirus B19 infection. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53:e583–e585.

- Yamamoto T, Nishioka K. Flagellate erythema. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45:627–631.

- Bhushan P, Manjul P, Baliyan V. Flagellate dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014; 80:149–152.

- Mahmoud BH, Eide MJ. Bendamustine-induced “flagellate dermatitis.” Dermatol Online J 2012; 18:12.

- Tallon B, Lamb S. Flagellate erythema induced by docetaxel. Clin Exp Dermatol 2008; 33:276–277.

- Adler MJ, Larsen WG. Clinical variability of shiitake dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67:140–141.

- Jara M, Amérigo J, Duce S, Borbujo J. Dermatomyositis and flagellate erythema. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21:440–441.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K. Systemic lupus erythematosus with flagellate erythema. Eur J Dermatol 2012; 22:808–809.

- Ciliberto H, Kumar MG, Musiek A. Flagellate erythema in a patient with fever. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149:1425–1426.

- Miguélez A, Dueñas J, Hervás D, Hervás JA, Salva F, Martín-Santiago A. Flagellate erythema in parvovirus B19 infection. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53:e583–e585.

Multiple linear subcutaneous nodules

A 34-year-old woman sought consultation at our clinic for an asymptomatic swelling on her right foot that had been growing very slowly over the last 15 years. She said she had presented to other healthcare facilities, but no diagnosis had been made and no treatment had been offered.

Examination revealed a linear swelling extending from the lower third to the mid-dorsal surface of the right foot (Figure 1). Palpation revealed multiple, closely set nodules arranged in a linear fashion. This finding along with the history raised the suspicion of neurofibroma and other conditions in the differential diagnosis, eg, pure neuritic Hansen disease, phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination results were normal. No café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or other swelling suggestive of neurofibroma was seen. She had no family history of mucocutaneous disease or other systemic disorder.

Because of the suspicion of neurofibromatosis, slit-lamp examination of the eyes was done to rule out Lisch nodules, a common feature of neurofibromatosis; the results were normal. Plain radiography of the right foot showed only soft-tissue swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, done to determine the extent of the lesions, revealed multiple dumbbell-shaped lesions with homogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). Histopathologic study of a biopsy specimen of the lesions showed tumor cells in the dermis. The cells were long, with elongated nuclei with pointed ends, arranged in long and short fascicles—an appearance characteristic of neurofibroma. Areas of hypocellularity and hypercellularity were seen, and on S100 protein immunostaining, the tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Figure 3).

The histologic evaluation confirmed neurofibroma. The specific diagnosis of sporadic solitary neurofibroma was made based on the onset of the lesions, the number of lesions (one in this patient), and the absence of features suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

SPORADIC SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibroma is a common tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath and, when present with features such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, and characteristic bone changes, it is pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type 1.1 But solitary neurofibromas can occur sporadically in the absence of other features of neurofibromatosis.

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma arises from small nerves, is benign in nature, and carries a lower rate of malignant transformation than its counterpart that occurs in the setting of neurofibromatosis.2 Though sporadic solitary neurofibroma can occur in any part of the body, it is commonly seen on the head and neck, and occasionally on the presacral and parasacral space, thigh, intrascrotal area,3 the ankle and foot,4,5 and the subungual region.6 A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors examined over 30 years showed 55 sporadic solitary neurofibromas occurring in the brachial plexus region, 45 in the upper extremities, 10 in the pelvic plexus, and 31 in the lower extremities.7

Management of sporadic solitary neurofibroma depends on the patient’s discomfort. For asymptomatic lesions, serial observation is all that is required. Complete surgical excision including the parent nerve is the treatment for large lesions. More research is needed to define the potential role of drugs such as pirfenidone and tipifarnib.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma can masquerade as pure neuritic Hansen disease (leprosy), phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The absence of neural symptoms and no evidence of trophic changes exclude pure neuritic Hansen disease. Phaeohyphomycosis clinically presents as a single cyst that may evolve into pigmented plaques,8 and the diagnosis relies on the presence of fungus in tissue. The absence of cystic changes clinically and fungi histopathologically in this patient did not favor phaeohyphomycosis. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is characterized clinically by cordlike skin lesions (the “rope sign”) and is accompanied by extracutaneous, mostly articular features. Histopathologically, it shows intense neutrophilic infiltrate and interstitial histiocytic infiltrate along with collagen degeneration. The absence of extracutaneous and classical histologic features negated this possibility in this patient.

Though sporotrichosis and cutaneous atypical mycobacterial infections may present in linear fashion following the course of the lymphatic vessels, the absence of epidermal changes after a disease course of 15 years and the absence of granulomatous infiltrate in histopathology excluded these possibilities in this patient.

The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, and the lesions were successfully resected. She did not return for additional review after that.

- Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:834–843.

- Pulathan Z, Imamoglu M, Cay A, Guven YK. Intermittent claudication due to right common femoral artery compression by a solitary neurofibroma. Eur J Pediatr 2005; 164:463–465.

- Hosseini MM, Geramizadeh B, Shakeri S, Karimi MH. Intrascrotal solitary neurofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Ann 2012; 4:119–121.

- Carvajal JA, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Levi AD, Temple HT. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32:163–167.

- Tahririan MA, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Heidarpour M, Hekmatnia F. Solitary giant neurofibroma of thigh. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3:158.

- Huajun J, Wei Q, Ming L, Chongyang F, Weiguo Z, Decheng L. Solitary subungual neurofibroma in the right first finger. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51:335–338.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102:246–255.

- Garnica M, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F. Difficult mycoses of the skin: advances in the epidemiology and management of eumycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22:559–563.

A 34-year-old woman sought consultation at our clinic for an asymptomatic swelling on her right foot that had been growing very slowly over the last 15 years. She said she had presented to other healthcare facilities, but no diagnosis had been made and no treatment had been offered.

Examination revealed a linear swelling extending from the lower third to the mid-dorsal surface of the right foot (Figure 1). Palpation revealed multiple, closely set nodules arranged in a linear fashion. This finding along with the history raised the suspicion of neurofibroma and other conditions in the differential diagnosis, eg, pure neuritic Hansen disease, phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination results were normal. No café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or other swelling suggestive of neurofibroma was seen. She had no family history of mucocutaneous disease or other systemic disorder.

Because of the suspicion of neurofibromatosis, slit-lamp examination of the eyes was done to rule out Lisch nodules, a common feature of neurofibromatosis; the results were normal. Plain radiography of the right foot showed only soft-tissue swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, done to determine the extent of the lesions, revealed multiple dumbbell-shaped lesions with homogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). Histopathologic study of a biopsy specimen of the lesions showed tumor cells in the dermis. The cells were long, with elongated nuclei with pointed ends, arranged in long and short fascicles—an appearance characteristic of neurofibroma. Areas of hypocellularity and hypercellularity were seen, and on S100 protein immunostaining, the tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Figure 3).

The histologic evaluation confirmed neurofibroma. The specific diagnosis of sporadic solitary neurofibroma was made based on the onset of the lesions, the number of lesions (one in this patient), and the absence of features suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

SPORADIC SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibroma is a common tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath and, when present with features such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, and characteristic bone changes, it is pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type 1.1 But solitary neurofibromas can occur sporadically in the absence of other features of neurofibromatosis.

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma arises from small nerves, is benign in nature, and carries a lower rate of malignant transformation than its counterpart that occurs in the setting of neurofibromatosis.2 Though sporadic solitary neurofibroma can occur in any part of the body, it is commonly seen on the head and neck, and occasionally on the presacral and parasacral space, thigh, intrascrotal area,3 the ankle and foot,4,5 and the subungual region.6 A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors examined over 30 years showed 55 sporadic solitary neurofibromas occurring in the brachial plexus region, 45 in the upper extremities, 10 in the pelvic plexus, and 31 in the lower extremities.7

Management of sporadic solitary neurofibroma depends on the patient’s discomfort. For asymptomatic lesions, serial observation is all that is required. Complete surgical excision including the parent nerve is the treatment for large lesions. More research is needed to define the potential role of drugs such as pirfenidone and tipifarnib.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma can masquerade as pure neuritic Hansen disease (leprosy), phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The absence of neural symptoms and no evidence of trophic changes exclude pure neuritic Hansen disease. Phaeohyphomycosis clinically presents as a single cyst that may evolve into pigmented plaques,8 and the diagnosis relies on the presence of fungus in tissue. The absence of cystic changes clinically and fungi histopathologically in this patient did not favor phaeohyphomycosis. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is characterized clinically by cordlike skin lesions (the “rope sign”) and is accompanied by extracutaneous, mostly articular features. Histopathologically, it shows intense neutrophilic infiltrate and interstitial histiocytic infiltrate along with collagen degeneration. The absence of extracutaneous and classical histologic features negated this possibility in this patient.

Though sporotrichosis and cutaneous atypical mycobacterial infections may present in linear fashion following the course of the lymphatic vessels, the absence of epidermal changes after a disease course of 15 years and the absence of granulomatous infiltrate in histopathology excluded these possibilities in this patient.

The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, and the lesions were successfully resected. She did not return for additional review after that.

A 34-year-old woman sought consultation at our clinic for an asymptomatic swelling on her right foot that had been growing very slowly over the last 15 years. She said she had presented to other healthcare facilities, but no diagnosis had been made and no treatment had been offered.

Examination revealed a linear swelling extending from the lower third to the mid-dorsal surface of the right foot (Figure 1). Palpation revealed multiple, closely set nodules arranged in a linear fashion. This finding along with the history raised the suspicion of neurofibroma and other conditions in the differential diagnosis, eg, pure neuritic Hansen disease, phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination results were normal. No café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or other swelling suggestive of neurofibroma was seen. She had no family history of mucocutaneous disease or other systemic disorder.

Because of the suspicion of neurofibromatosis, slit-lamp examination of the eyes was done to rule out Lisch nodules, a common feature of neurofibromatosis; the results were normal. Plain radiography of the right foot showed only soft-tissue swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, done to determine the extent of the lesions, revealed multiple dumbbell-shaped lesions with homogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). Histopathologic study of a biopsy specimen of the lesions showed tumor cells in the dermis. The cells were long, with elongated nuclei with pointed ends, arranged in long and short fascicles—an appearance characteristic of neurofibroma. Areas of hypocellularity and hypercellularity were seen, and on S100 protein immunostaining, the tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Figure 3).

The histologic evaluation confirmed neurofibroma. The specific diagnosis of sporadic solitary neurofibroma was made based on the onset of the lesions, the number of lesions (one in this patient), and the absence of features suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

SPORADIC SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibroma is a common tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath and, when present with features such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, and characteristic bone changes, it is pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type 1.1 But solitary neurofibromas can occur sporadically in the absence of other features of neurofibromatosis.

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma arises from small nerves, is benign in nature, and carries a lower rate of malignant transformation than its counterpart that occurs in the setting of neurofibromatosis.2 Though sporadic solitary neurofibroma can occur in any part of the body, it is commonly seen on the head and neck, and occasionally on the presacral and parasacral space, thigh, intrascrotal area,3 the ankle and foot,4,5 and the subungual region.6 A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors examined over 30 years showed 55 sporadic solitary neurofibromas occurring in the brachial plexus region, 45 in the upper extremities, 10 in the pelvic plexus, and 31 in the lower extremities.7

Management of sporadic solitary neurofibroma depends on the patient’s discomfort. For asymptomatic lesions, serial observation is all that is required. Complete surgical excision including the parent nerve is the treatment for large lesions. More research is needed to define the potential role of drugs such as pirfenidone and tipifarnib.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma can masquerade as pure neuritic Hansen disease (leprosy), phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The absence of neural symptoms and no evidence of trophic changes exclude pure neuritic Hansen disease. Phaeohyphomycosis clinically presents as a single cyst that may evolve into pigmented plaques,8 and the diagnosis relies on the presence of fungus in tissue. The absence of cystic changes clinically and fungi histopathologically in this patient did not favor phaeohyphomycosis. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is characterized clinically by cordlike skin lesions (the “rope sign”) and is accompanied by extracutaneous, mostly articular features. Histopathologically, it shows intense neutrophilic infiltrate and interstitial histiocytic infiltrate along with collagen degeneration. The absence of extracutaneous and classical histologic features negated this possibility in this patient.

Though sporotrichosis and cutaneous atypical mycobacterial infections may present in linear fashion following the course of the lymphatic vessels, the absence of epidermal changes after a disease course of 15 years and the absence of granulomatous infiltrate in histopathology excluded these possibilities in this patient.

The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, and the lesions were successfully resected. She did not return for additional review after that.

- Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:834–843.

- Pulathan Z, Imamoglu M, Cay A, Guven YK. Intermittent claudication due to right common femoral artery compression by a solitary neurofibroma. Eur J Pediatr 2005; 164:463–465.

- Hosseini MM, Geramizadeh B, Shakeri S, Karimi MH. Intrascrotal solitary neurofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Ann 2012; 4:119–121.

- Carvajal JA, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Levi AD, Temple HT. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32:163–167.

- Tahririan MA, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Heidarpour M, Hekmatnia F. Solitary giant neurofibroma of thigh. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3:158.

- Huajun J, Wei Q, Ming L, Chongyang F, Weiguo Z, Decheng L. Solitary subungual neurofibroma in the right first finger. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51:335–338.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102:246–255.

- Garnica M, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F. Difficult mycoses of the skin: advances in the epidemiology and management of eumycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22:559–563.

- Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:834–843.

- Pulathan Z, Imamoglu M, Cay A, Guven YK. Intermittent claudication due to right common femoral artery compression by a solitary neurofibroma. Eur J Pediatr 2005; 164:463–465.

- Hosseini MM, Geramizadeh B, Shakeri S, Karimi MH. Intrascrotal solitary neurofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Ann 2012; 4:119–121.

- Carvajal JA, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Levi AD, Temple HT. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32:163–167.

- Tahririan MA, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Heidarpour M, Hekmatnia F. Solitary giant neurofibroma of thigh. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3:158.

- Huajun J, Wei Q, Ming L, Chongyang F, Weiguo Z, Decheng L. Solitary subungual neurofibroma in the right first finger. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51:335–338.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102:246–255.

- Garnica M, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F. Difficult mycoses of the skin: advances in the epidemiology and management of eumycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22:559–563.

Epiglottic cysts in clinical practice

A 50-year-old man presented to the otolaryngology clinic, complaining of throat discomfort for the past 3 months that worsened in the supine position. The clinical examination revealed one cystic lesion on either side of the epiglottis (Figure 1). The larger cyst measured 23 × 13 × 12 mm. The man’s symptoms resolved completely after endoscopic removal of the cysts under general anesthesia (Figure 2).

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Epiglottic cysts are benign lesions on the lingual or laryngeal aspect of the epiglottis and are often a result of mucus retention. Otolaryngologists, anesthesiologists, and endoscopists are usually the first to discover them. Because the cysts are usually asymptomatic, it is difficult to calculate their prevalence in the general population.

If the cysts are symptomatic, patients usually describe nonspecific complaints such as pharyngeal discomfort and foreign-body sensation. Voluminous cysts discovered incidentally in patients requiring general anesthesia pose a challenge to intubation and increase the risk of airway obstruction.

In addition, epiglottic cysts have been reported in a proportion of adult patients with acute epiglottitis (25% in one series)1; They may be discovered either during the acute infection or when inflammation subsides.2 These patients have been reported to have a higher risk of acute airway obstruction, with a sixfold increase in the need for acute airway management in one series.1 Moreover, epiglottitis was reported to recur in 12.5% and 17% of patients with cysts in two different series,1,2 corresponding to a recurrence rate 15 times higher than in patients with no cysts.1 Hence, it would be useful to rule out their presence after any episode of acute epiglottitis.

Once an epiglottic cyst is discovered in a symptomatic patient, it can be managed either by elective endoscopic resection or by marsupialization. Either procedure is safe, with good long-term results. Simple evacuation of the cyst should be considered in cases of acute airway management.

- Yoon TM, Choi JO, Lim SC, Lee JK. The incidence of epiglottic cysts in a cohort of adults with acute epiglottitis. Clin Otolaryngol 2010; 35:18–24.

- Berger G, Averbuch E, Zilka K, Berger R, Ophir D. Adult vallecular cyst: thirteen-year experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 138:321–327.

A 50-year-old man presented to the otolaryngology clinic, complaining of throat discomfort for the past 3 months that worsened in the supine position. The clinical examination revealed one cystic lesion on either side of the epiglottis (Figure 1). The larger cyst measured 23 × 13 × 12 mm. The man’s symptoms resolved completely after endoscopic removal of the cysts under general anesthesia (Figure 2).

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Epiglottic cysts are benign lesions on the lingual or laryngeal aspect of the epiglottis and are often a result of mucus retention. Otolaryngologists, anesthesiologists, and endoscopists are usually the first to discover them. Because the cysts are usually asymptomatic, it is difficult to calculate their prevalence in the general population.

If the cysts are symptomatic, patients usually describe nonspecific complaints such as pharyngeal discomfort and foreign-body sensation. Voluminous cysts discovered incidentally in patients requiring general anesthesia pose a challenge to intubation and increase the risk of airway obstruction.

In addition, epiglottic cysts have been reported in a proportion of adult patients with acute epiglottitis (25% in one series)1; They may be discovered either during the acute infection or when inflammation subsides.2 These patients have been reported to have a higher risk of acute airway obstruction, with a sixfold increase in the need for acute airway management in one series.1 Moreover, epiglottitis was reported to recur in 12.5% and 17% of patients with cysts in two different series,1,2 corresponding to a recurrence rate 15 times higher than in patients with no cysts.1 Hence, it would be useful to rule out their presence after any episode of acute epiglottitis.

Once an epiglottic cyst is discovered in a symptomatic patient, it can be managed either by elective endoscopic resection or by marsupialization. Either procedure is safe, with good long-term results. Simple evacuation of the cyst should be considered in cases of acute airway management.

A 50-year-old man presented to the otolaryngology clinic, complaining of throat discomfort for the past 3 months that worsened in the supine position. The clinical examination revealed one cystic lesion on either side of the epiglottis (Figure 1). The larger cyst measured 23 × 13 × 12 mm. The man’s symptoms resolved completely after endoscopic removal of the cysts under general anesthesia (Figure 2).

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Epiglottic cysts are benign lesions on the lingual or laryngeal aspect of the epiglottis and are often a result of mucus retention. Otolaryngologists, anesthesiologists, and endoscopists are usually the first to discover them. Because the cysts are usually asymptomatic, it is difficult to calculate their prevalence in the general population.

If the cysts are symptomatic, patients usually describe nonspecific complaints such as pharyngeal discomfort and foreign-body sensation. Voluminous cysts discovered incidentally in patients requiring general anesthesia pose a challenge to intubation and increase the risk of airway obstruction.

In addition, epiglottic cysts have been reported in a proportion of adult patients with acute epiglottitis (25% in one series)1; They may be discovered either during the acute infection or when inflammation subsides.2 These patients have been reported to have a higher risk of acute airway obstruction, with a sixfold increase in the need for acute airway management in one series.1 Moreover, epiglottitis was reported to recur in 12.5% and 17% of patients with cysts in two different series,1,2 corresponding to a recurrence rate 15 times higher than in patients with no cysts.1 Hence, it would be useful to rule out their presence after any episode of acute epiglottitis.

Once an epiglottic cyst is discovered in a symptomatic patient, it can be managed either by elective endoscopic resection or by marsupialization. Either procedure is safe, with good long-term results. Simple evacuation of the cyst should be considered in cases of acute airway management.

- Yoon TM, Choi JO, Lim SC, Lee JK. The incidence of epiglottic cysts in a cohort of adults with acute epiglottitis. Clin Otolaryngol 2010; 35:18–24.

- Berger G, Averbuch E, Zilka K, Berger R, Ophir D. Adult vallecular cyst: thirteen-year experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 138:321–327.

- Yoon TM, Choi JO, Lim SC, Lee JK. The incidence of epiglottic cysts in a cohort of adults with acute epiglottitis. Clin Otolaryngol 2010; 35:18–24.

- Berger G, Averbuch E, Zilka K, Berger R, Ophir D. Adult vallecular cyst: thirteen-year experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 138:321–327.

This is not an acute coronary syndrome

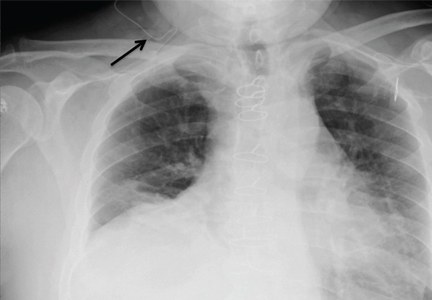

A 72-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with persistent substernal chest discomfort. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed 2.0-mm ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, and 1.0-mm ST-segment elevation in lead V6 (Figure 1). The index troponin T level was 1.5 ng/mL (reference range < 0.01). ST-elevation myocardial infarction protocols were activated, and she was taken for urgent catheterization.

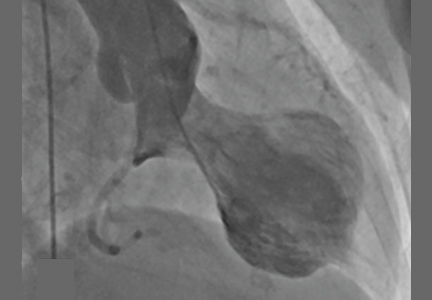

Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries. However, intraprocedural left ventriculography identified circumferential midventricular and apical akinesis with compensatory basal hyperkinesis (Figure 2).

Further inquiry into the patient’s medical history revealed that she had been experiencing psychological distress brought on by the failure of businesses she owned.

Transthoracic echocardiography subsequently verified a depressed ejection fraction (30%) with prominent apical and midventricular wall akinesis, thus confirming the diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy. She was discharged home on a low-dose beta-blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and within 6 weeks her systolic function had completely returned to normal.

STRESS CARDIOMYOPATHY: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS, PROGNOSIS

Stress cardiomyopathy—also called broken heart syndrome, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and apical ballooning syndrome—is an increasingly recognized acquired cardiomyopathy that typically affects older postmenopausal women exposed to a triggering stressor such as severe medical illness, major surgery, or a psychologically stressful life event.1,2

Our patient’s acute presentation is a classic example of how stress cardiomyopathy can be indistinguishable from acute coronary syndrome. It has been estimated that 1% to 2% of patients presenting with an initial diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome actually have stress cardiomyopathy.2

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy can be established when coronary angiography reveals nonobstructive coronary arteries in patients with abnormal ventricular wall motion identified on echocardiography or ventriculography, or both. These findings are part of the proposed diagnostic criteria2:

- Transient hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis of the left ventricle midsegments, with or without apical involvement; regional wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; usually, a psychological or physiologic stressor is present

- No obstructive coronary disease or no angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture

- New abnormalities on ECG, or modest elevation in cardiac enzymes

- No evidence of pheochromocytoma or myocarditis.2

Other characteristics that help to differentiate stress cardiomyopathy from acute coronary syndrome include a prolonged QTc interval, attenuation of the QRS amplitude, and a decreased troponin-ejection fraction product.3–5

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally excellent, with most patients achieving full recovery of myocardial function within several weeks.2 However, in the acute setting, there are relatively high rates of acute heart failure (44% to 46%), left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (19%), and unstable ventricular arrhythmias (3.4%), including torsades de pointes.1,2,6,7

Stress cardiomyopathy recurs in approximately 11% of patients within 4 years.8 Death is considered a rare complication but has occurred in as many as 8% of reported cases.1

- Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:858–865.

- Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 155:408–417.

- Bennett J, Ferdinande B, Kayaert P, et al. Time course of electrocardiographic changes in transient left ventricular ballooning syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2013; 169:276–280.

- Madias JE. Transient attenuation of the amplitude of the QRS complexes in the diagnosis of takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014; 3:28–36.

- Nascimento FO, Yang S, Larrauri-Reyes M, et al. Usefulness of the troponin-ejection fraction product to differentiate stress cardiomyopathy from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:429–433.

- De Backer O, Debonnaire P, Gevaert S, Missault L, Gheeraert P, Muyldermans L. Prevalence, associated factors and management implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a two-year, two-center experience. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014; 14:147.

- Syed FF, Asirvatham SJ, Francis J. Arrhythmia occurrence with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a literature review. Europace 2011; 13:780–788.

- Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Wright RS, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Four-year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:448–452.

A 72-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with persistent substernal chest discomfort. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed 2.0-mm ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, and 1.0-mm ST-segment elevation in lead V6 (Figure 1). The index troponin T level was 1.5 ng/mL (reference range < 0.01). ST-elevation myocardial infarction protocols were activated, and she was taken for urgent catheterization.

Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries. However, intraprocedural left ventriculography identified circumferential midventricular and apical akinesis with compensatory basal hyperkinesis (Figure 2).

Further inquiry into the patient’s medical history revealed that she had been experiencing psychological distress brought on by the failure of businesses she owned.

Transthoracic echocardiography subsequently verified a depressed ejection fraction (30%) with prominent apical and midventricular wall akinesis, thus confirming the diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy. She was discharged home on a low-dose beta-blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and within 6 weeks her systolic function had completely returned to normal.

STRESS CARDIOMYOPATHY: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS, PROGNOSIS

Stress cardiomyopathy—also called broken heart syndrome, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and apical ballooning syndrome—is an increasingly recognized acquired cardiomyopathy that typically affects older postmenopausal women exposed to a triggering stressor such as severe medical illness, major surgery, or a psychologically stressful life event.1,2

Our patient’s acute presentation is a classic example of how stress cardiomyopathy can be indistinguishable from acute coronary syndrome. It has been estimated that 1% to 2% of patients presenting with an initial diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome actually have stress cardiomyopathy.2

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy can be established when coronary angiography reveals nonobstructive coronary arteries in patients with abnormal ventricular wall motion identified on echocardiography or ventriculography, or both. These findings are part of the proposed diagnostic criteria2:

- Transient hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis of the left ventricle midsegments, with or without apical involvement; regional wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; usually, a psychological or physiologic stressor is present

- No obstructive coronary disease or no angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture

- New abnormalities on ECG, or modest elevation in cardiac enzymes

- No evidence of pheochromocytoma or myocarditis.2

Other characteristics that help to differentiate stress cardiomyopathy from acute coronary syndrome include a prolonged QTc interval, attenuation of the QRS amplitude, and a decreased troponin-ejection fraction product.3–5

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally excellent, with most patients achieving full recovery of myocardial function within several weeks.2 However, in the acute setting, there are relatively high rates of acute heart failure (44% to 46%), left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (19%), and unstable ventricular arrhythmias (3.4%), including torsades de pointes.1,2,6,7

Stress cardiomyopathy recurs in approximately 11% of patients within 4 years.8 Death is considered a rare complication but has occurred in as many as 8% of reported cases.1

A 72-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with persistent substernal chest discomfort. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed 2.0-mm ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, and 1.0-mm ST-segment elevation in lead V6 (Figure 1). The index troponin T level was 1.5 ng/mL (reference range < 0.01). ST-elevation myocardial infarction protocols were activated, and she was taken for urgent catheterization.

Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries. However, intraprocedural left ventriculography identified circumferential midventricular and apical akinesis with compensatory basal hyperkinesis (Figure 2).

Further inquiry into the patient’s medical history revealed that she had been experiencing psychological distress brought on by the failure of businesses she owned.

Transthoracic echocardiography subsequently verified a depressed ejection fraction (30%) with prominent apical and midventricular wall akinesis, thus confirming the diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy. She was discharged home on a low-dose beta-blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and within 6 weeks her systolic function had completely returned to normal.

STRESS CARDIOMYOPATHY: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS, PROGNOSIS

Stress cardiomyopathy—also called broken heart syndrome, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and apical ballooning syndrome—is an increasingly recognized acquired cardiomyopathy that typically affects older postmenopausal women exposed to a triggering stressor such as severe medical illness, major surgery, or a psychologically stressful life event.1,2

Our patient’s acute presentation is a classic example of how stress cardiomyopathy can be indistinguishable from acute coronary syndrome. It has been estimated that 1% to 2% of patients presenting with an initial diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome actually have stress cardiomyopathy.2

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy can be established when coronary angiography reveals nonobstructive coronary arteries in patients with abnormal ventricular wall motion identified on echocardiography or ventriculography, or both. These findings are part of the proposed diagnostic criteria2:

- Transient hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis of the left ventricle midsegments, with or without apical involvement; regional wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; usually, a psychological or physiologic stressor is present

- No obstructive coronary disease or no angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture

- New abnormalities on ECG, or modest elevation in cardiac enzymes

- No evidence of pheochromocytoma or myocarditis.2

Other characteristics that help to differentiate stress cardiomyopathy from acute coronary syndrome include a prolonged QTc interval, attenuation of the QRS amplitude, and a decreased troponin-ejection fraction product.3–5

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally excellent, with most patients achieving full recovery of myocardial function within several weeks.2 However, in the acute setting, there are relatively high rates of acute heart failure (44% to 46%), left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (19%), and unstable ventricular arrhythmias (3.4%), including torsades de pointes.1,2,6,7

Stress cardiomyopathy recurs in approximately 11% of patients within 4 years.8 Death is considered a rare complication but has occurred in as many as 8% of reported cases.1

- Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:858–865.

- Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 155:408–417.

- Bennett J, Ferdinande B, Kayaert P, et al. Time course of electrocardiographic changes in transient left ventricular ballooning syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2013; 169:276–280.

- Madias JE. Transient attenuation of the amplitude of the QRS complexes in the diagnosis of takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014; 3:28–36.

- Nascimento FO, Yang S, Larrauri-Reyes M, et al. Usefulness of the troponin-ejection fraction product to differentiate stress cardiomyopathy from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:429–433.

- De Backer O, Debonnaire P, Gevaert S, Missault L, Gheeraert P, Muyldermans L. Prevalence, associated factors and management implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a two-year, two-center experience. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014; 14:147.

- Syed FF, Asirvatham SJ, Francis J. Arrhythmia occurrence with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a literature review. Europace 2011; 13:780–788.

- Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Wright RS, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Four-year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:448–452.

- Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:858–865.

- Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 155:408–417.

- Bennett J, Ferdinande B, Kayaert P, et al. Time course of electrocardiographic changes in transient left ventricular ballooning syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2013; 169:276–280.

- Madias JE. Transient attenuation of the amplitude of the QRS complexes in the diagnosis of takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014; 3:28–36.

- Nascimento FO, Yang S, Larrauri-Reyes M, et al. Usefulness of the troponin-ejection fraction product to differentiate stress cardiomyopathy from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:429–433.

- De Backer O, Debonnaire P, Gevaert S, Missault L, Gheeraert P, Muyldermans L. Prevalence, associated factors and management implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a two-year, two-center experience. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2014; 14:147.

- Syed FF, Asirvatham SJ, Francis J. Arrhythmia occurrence with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a literature review. Europace 2011; 13:780–788.

- Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Wright RS, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Four-year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:448–452.

Hordeolum: Acute abscess within an eyelid sebaceous gland

An 89-year-old man presented complaining of a tender, painful lump in the right lower eyelid that spontaneously appeared 3 days previously. There was no discharge, bleeding, or reduced vision. He had a history of hypertension and macular degeneration. There was no history of a pre-existing eyelid lesion, ocular malignancy, rosacea, or seborrheic dermatitis. Examination of the right lower lid revealed a roundish raised abscess with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). The raised area was tender on palpation; there was no discharge. The palpebral conjunctiva was normal. A diagnosis of a hordeolum was made, and conservative treatment was prescribed, ie, warm compresses and massage for 10 minutes four times a day. The lesion improved gradually and resolved over 3 weeks.

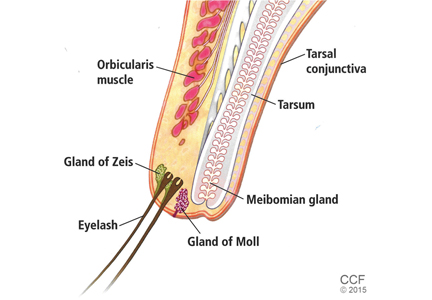

A hordeolum is an acute abscess within an eyelid gland, usually staphylococcal in origin. When it involves a meibomian gland it is termed an internal hordeolum, and when it involves the gland of Zeis or Moll it is termed an external hordeolum (Figure 2).1 Hordeola may be associated with diabetes, blepharitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and high levels of serum lipids. Treatment is with warm compresses and massage. A hordeolum with preseptal cellulitis, signs of bacteremia, or tender preauricular lymph nodes requires systemic antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 250–500 mg four times a day for 1 week).

Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum. The orbital septum is a sheet of fibrous tissue that originates in the orbital periosteum and inserts in the palpebral tissues along the tarsal plates of the eyelid. The orbital septum provides a barrier against the spread of periorbital infection into the orbit (orbital cellulitis). The causes of preseptal cellulitis include skin trauma (eg, lacerations, insect bites), spread from local infections (eg, hordeolum, dacryocystitis), or systemic infections (eg, upper respiratory tract, middle ear). Clinical features include malaise, fever, and painful eyelid with periorbital edema. Any sign of proptosis, chemosis, painful restricted eye movements, diplopia, lagophthalmos, or optic nerve dysfunction warrants further investigation. Chronic or large hordeola may require incision and curettage.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence of the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions (including hot or warm compresses, lid scrubs, antibiotics, and steroids) for hordeolum, and controlled clinical trials would be useful.2

Chalazion and hordeolum are similar in appearance and often confused (Table 1). A chalazion is a chronic lipogranuloma due to leakage of sebum from an obstructed meibomian gland. It may develop from an internal hordeolum. Small chalazia usually resolve with time without any intervention, and hot compresses can be effective at encouraging drainage. Persistent lesions may be surgically removed by incision and curettage. Recurrence warrants biopsy and histologic study to rule out sebaceous gland carcinoma.3

- Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008; 26:57–72.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD007742.

- Denniston AKO, Murray PI: Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2009.

An 89-year-old man presented complaining of a tender, painful lump in the right lower eyelid that spontaneously appeared 3 days previously. There was no discharge, bleeding, or reduced vision. He had a history of hypertension and macular degeneration. There was no history of a pre-existing eyelid lesion, ocular malignancy, rosacea, or seborrheic dermatitis. Examination of the right lower lid revealed a roundish raised abscess with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). The raised area was tender on palpation; there was no discharge. The palpebral conjunctiva was normal. A diagnosis of a hordeolum was made, and conservative treatment was prescribed, ie, warm compresses and massage for 10 minutes four times a day. The lesion improved gradually and resolved over 3 weeks.

A hordeolum is an acute abscess within an eyelid gland, usually staphylococcal in origin. When it involves a meibomian gland it is termed an internal hordeolum, and when it involves the gland of Zeis or Moll it is termed an external hordeolum (Figure 2).1 Hordeola may be associated with diabetes, blepharitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and high levels of serum lipids. Treatment is with warm compresses and massage. A hordeolum with preseptal cellulitis, signs of bacteremia, or tender preauricular lymph nodes requires systemic antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 250–500 mg four times a day for 1 week).

Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum. The orbital septum is a sheet of fibrous tissue that originates in the orbital periosteum and inserts in the palpebral tissues along the tarsal plates of the eyelid. The orbital septum provides a barrier against the spread of periorbital infection into the orbit (orbital cellulitis). The causes of preseptal cellulitis include skin trauma (eg, lacerations, insect bites), spread from local infections (eg, hordeolum, dacryocystitis), or systemic infections (eg, upper respiratory tract, middle ear). Clinical features include malaise, fever, and painful eyelid with periorbital edema. Any sign of proptosis, chemosis, painful restricted eye movements, diplopia, lagophthalmos, or optic nerve dysfunction warrants further investigation. Chronic or large hordeola may require incision and curettage.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence of the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions (including hot or warm compresses, lid scrubs, antibiotics, and steroids) for hordeolum, and controlled clinical trials would be useful.2

Chalazion and hordeolum are similar in appearance and often confused (Table 1). A chalazion is a chronic lipogranuloma due to leakage of sebum from an obstructed meibomian gland. It may develop from an internal hordeolum. Small chalazia usually resolve with time without any intervention, and hot compresses can be effective at encouraging drainage. Persistent lesions may be surgically removed by incision and curettage. Recurrence warrants biopsy and histologic study to rule out sebaceous gland carcinoma.3

An 89-year-old man presented complaining of a tender, painful lump in the right lower eyelid that spontaneously appeared 3 days previously. There was no discharge, bleeding, or reduced vision. He had a history of hypertension and macular degeneration. There was no history of a pre-existing eyelid lesion, ocular malignancy, rosacea, or seborrheic dermatitis. Examination of the right lower lid revealed a roundish raised abscess with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). The raised area was tender on palpation; there was no discharge. The palpebral conjunctiva was normal. A diagnosis of a hordeolum was made, and conservative treatment was prescribed, ie, warm compresses and massage for 10 minutes four times a day. The lesion improved gradually and resolved over 3 weeks.

A hordeolum is an acute abscess within an eyelid gland, usually staphylococcal in origin. When it involves a meibomian gland it is termed an internal hordeolum, and when it involves the gland of Zeis or Moll it is termed an external hordeolum (Figure 2).1 Hordeola may be associated with diabetes, blepharitis, seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, and high levels of serum lipids. Treatment is with warm compresses and massage. A hordeolum with preseptal cellulitis, signs of bacteremia, or tender preauricular lymph nodes requires systemic antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 250–500 mg four times a day for 1 week).

Preseptal cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum. The orbital septum is a sheet of fibrous tissue that originates in the orbital periosteum and inserts in the palpebral tissues along the tarsal plates of the eyelid. The orbital septum provides a barrier against the spread of periorbital infection into the orbit (orbital cellulitis). The causes of preseptal cellulitis include skin trauma (eg, lacerations, insect bites), spread from local infections (eg, hordeolum, dacryocystitis), or systemic infections (eg, upper respiratory tract, middle ear). Clinical features include malaise, fever, and painful eyelid with periorbital edema. Any sign of proptosis, chemosis, painful restricted eye movements, diplopia, lagophthalmos, or optic nerve dysfunction warrants further investigation. Chronic or large hordeola may require incision and curettage.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence of the effectiveness of nonsurgical interventions (including hot or warm compresses, lid scrubs, antibiotics, and steroids) for hordeolum, and controlled clinical trials would be useful.2

Chalazion and hordeolum are similar in appearance and often confused (Table 1). A chalazion is a chronic lipogranuloma due to leakage of sebum from an obstructed meibomian gland. It may develop from an internal hordeolum. Small chalazia usually resolve with time without any intervention, and hot compresses can be effective at encouraging drainage. Persistent lesions may be surgically removed by incision and curettage. Recurrence warrants biopsy and histologic study to rule out sebaceous gland carcinoma.3

- Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008; 26:57–72.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD007742.

- Denniston AKO, Murray PI: Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2008; 26:57–72.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD007742.

- Denniston AKO, Murray PI: Oxford handbook of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Cocaine-induced ecchymotic rash

A 50-year-old man presented with a painful rash over his extremities for the past 2 days (Figure 1). He said he had been in his usual state of health until the day he woke up with the rash. The rash was initially limited to his upper and lower extremities, but the next day he noticed similar lesions over his cheek and hard palate. He was a smoker and was known to have hepatitis C virus infection. He denied recent trauma, fever, or chills. He said he had snorted cocaine about 24 hours before the rash first appeared.