User login

A 60-year-old man with forehead swelling

A 60-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 4-day history of frontal headaches he described as “stinging.” He had also had a large swollen area on his forehead for the past 8 weeks.

He denied fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, blurry vision, tinnitus, and neck pain, as well as any recent sinus infection, intransanal cocaine use, rhinorrhea, or head trauma. A month ago, he had presented to our emergency department with forehead swelling but no headaches. At that time, the swelling was thought to be an allergic reaction to lisinopril or metformin, medications he takes for hypertension and type 2 diabetes. He had been discharged home with a prescription for a course of prednisone in tapering doses, but that had failed to resolve the swelling.

Physical examination revealed a well-circumscribed area of swelling, 3 by 4 cm, in the central forehead (Figure 1). The area was warm, erythematous, fluctuant, and tender to palpation. The nasal septum was intact and the nasal mucosa appeared pink and healthy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

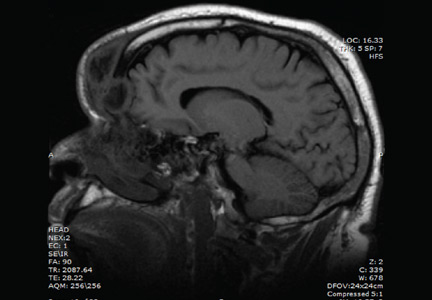

He was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. His peripheral white blood cell count was mildly elevated at 11.1 × 109. Computed tomography of the brain and sinuses revealed a fluid collection in the frontal scalp associated with erosion of the anterior frontal sinus with posterior extension and enhancement of the adjacent meninges. Magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed similar findings. A diagnosis of Pott puffy tumor was made based on the imaging findings.

The name of this condition is misleading, as it is not a neoplasm but an infection. It requires urgent antibiotic therapy and surgical management because of the high risk of the infection spreading to the brain. Our patient was started on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of intravenous vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole pending tissue culture to identify the causative organism.

POTT PUFFY TUMOR: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

First described in 1760 by Sir Percivall Pott,1 the same English surgeon who first described tuberculosis of the spine, Pott puffy tumor is a well-demarcated area of swelling that occurs when a frontal sinus infection breaks through the anterior portion of the frontal sinus and forms an abscess between the frontal bone and periosteum with associated osteomyelitis.2 Though rare in adults (it is more common in children and adolescents),3 Pott puffy tumor is caused by conditions often encountered in internal medicine practice, such as bacterial sinusitis, head trauma, and intranasal cocaine use.

The infection can spread to the brain either directly by destruction of the posterior frontal sinus (as in our patient) or by way of the veins that drain the frontal sinus. Meningitis, epidural empyema, frontal lobe abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombosis2 have all been described. Intracranial complications are seen in nearly 100% of children and adolescents with Pott puffy tumor. The rate in adults is 30%,4,5 which is much lower but is nevertheless worrisome because patients can be initially misdiagnosed with scalp abscess,3 cellulitis, or epidermoid cyst,4 and then sent home from the emergency department or physician’s office. In a case series of 32 adult patients with Pott puffy tumor, nearly 45% were initially misdiagnosed, most often by an internist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, or emergency room physician.4

The most common infective organisms are streptococci, staphylococci, and anaerobes,4 but Haemophilus, Aspergillus species, and invasive mucormycosis have also been described.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

Because of the risk of spread of the infection to the brain, rapid initiation of a broad-spectrum antibiotic is warranted in all patients with Pott puffy tumor pending results of tissue culture. Antibiotics may be necessary for at least 4 to 6 weeks to resolve osteomyelitis of the frontal bone and to decrease inflammation before surgery.6

Endoscopic sinus surgery is routinely done to drain the infected sinus and to remove or debride infected bone. Patients with intracranial extension of infection may require a combined endoscopic and neurosurgical approach.

OUTCOME

Our patient’s puffy tumor spontaneously ruptured externally on hospital day 3, and the purulent fluid was sent for culture that grew Streptococcus anginosus. His headaches improved almost immediately after this occurred. The antibiotic regimen was narrowed to ceftriaxone and metronidazole, and 1 week later he was discharged home with instructions to complete a 6-week course of antibiotics. Three weeks after he was discharged, he returned for outpatient endoscopic sinus surgery. At a follow-up visit 2 weeks after surgery, the forehead swelling had resolved, and he was well.

- Tattersall R, Tattersall R. Pott’s puffy tumor. Lancet 2002; 359:1060–1063.

- Forgie SE, Marrie TJ. Pott’s puffy tumor. Am J Med 2008; 121:1041–1042.

- Grewal HS, Dangaych NS, Esposito A. A tumor that is not a tumor but it sure can kill! Am J Case Rep 2012; 13:133–136.

- Akiyama K, Karaki M, Mori N. Evaluation of adult Pott’s puffy tumor: our five cases and 27 literature cases. Laryngoscope 2012; 122:2382–2388.

- Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott’s puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr 2012; 2012:386104.

- Lauria RA, Laffitte Fernandes F, Brito TP, Pereira PS, Chone CT. Extensive frontoparietal abscess: complication of frontal sinusitis (Pott’s puffy tumor). Case Rep Otolaryngol 2014; 2014:632464.

A 60-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 4-day history of frontal headaches he described as “stinging.” He had also had a large swollen area on his forehead for the past 8 weeks.

He denied fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, blurry vision, tinnitus, and neck pain, as well as any recent sinus infection, intransanal cocaine use, rhinorrhea, or head trauma. A month ago, he had presented to our emergency department with forehead swelling but no headaches. At that time, the swelling was thought to be an allergic reaction to lisinopril or metformin, medications he takes for hypertension and type 2 diabetes. He had been discharged home with a prescription for a course of prednisone in tapering doses, but that had failed to resolve the swelling.

Physical examination revealed a well-circumscribed area of swelling, 3 by 4 cm, in the central forehead (Figure 1). The area was warm, erythematous, fluctuant, and tender to palpation. The nasal septum was intact and the nasal mucosa appeared pink and healthy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

He was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. His peripheral white blood cell count was mildly elevated at 11.1 × 109. Computed tomography of the brain and sinuses revealed a fluid collection in the frontal scalp associated with erosion of the anterior frontal sinus with posterior extension and enhancement of the adjacent meninges. Magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed similar findings. A diagnosis of Pott puffy tumor was made based on the imaging findings.

The name of this condition is misleading, as it is not a neoplasm but an infection. It requires urgent antibiotic therapy and surgical management because of the high risk of the infection spreading to the brain. Our patient was started on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of intravenous vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole pending tissue culture to identify the causative organism.

POTT PUFFY TUMOR: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

First described in 1760 by Sir Percivall Pott,1 the same English surgeon who first described tuberculosis of the spine, Pott puffy tumor is a well-demarcated area of swelling that occurs when a frontal sinus infection breaks through the anterior portion of the frontal sinus and forms an abscess between the frontal bone and periosteum with associated osteomyelitis.2 Though rare in adults (it is more common in children and adolescents),3 Pott puffy tumor is caused by conditions often encountered in internal medicine practice, such as bacterial sinusitis, head trauma, and intranasal cocaine use.

The infection can spread to the brain either directly by destruction of the posterior frontal sinus (as in our patient) or by way of the veins that drain the frontal sinus. Meningitis, epidural empyema, frontal lobe abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombosis2 have all been described. Intracranial complications are seen in nearly 100% of children and adolescents with Pott puffy tumor. The rate in adults is 30%,4,5 which is much lower but is nevertheless worrisome because patients can be initially misdiagnosed with scalp abscess,3 cellulitis, or epidermoid cyst,4 and then sent home from the emergency department or physician’s office. In a case series of 32 adult patients with Pott puffy tumor, nearly 45% were initially misdiagnosed, most often by an internist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, or emergency room physician.4

The most common infective organisms are streptococci, staphylococci, and anaerobes,4 but Haemophilus, Aspergillus species, and invasive mucormycosis have also been described.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

Because of the risk of spread of the infection to the brain, rapid initiation of a broad-spectrum antibiotic is warranted in all patients with Pott puffy tumor pending results of tissue culture. Antibiotics may be necessary for at least 4 to 6 weeks to resolve osteomyelitis of the frontal bone and to decrease inflammation before surgery.6

Endoscopic sinus surgery is routinely done to drain the infected sinus and to remove or debride infected bone. Patients with intracranial extension of infection may require a combined endoscopic and neurosurgical approach.

OUTCOME

Our patient’s puffy tumor spontaneously ruptured externally on hospital day 3, and the purulent fluid was sent for culture that grew Streptococcus anginosus. His headaches improved almost immediately after this occurred. The antibiotic regimen was narrowed to ceftriaxone and metronidazole, and 1 week later he was discharged home with instructions to complete a 6-week course of antibiotics. Three weeks after he was discharged, he returned for outpatient endoscopic sinus surgery. At a follow-up visit 2 weeks after surgery, the forehead swelling had resolved, and he was well.

A 60-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 4-day history of frontal headaches he described as “stinging.” He had also had a large swollen area on his forehead for the past 8 weeks.

He denied fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, blurry vision, tinnitus, and neck pain, as well as any recent sinus infection, intransanal cocaine use, rhinorrhea, or head trauma. A month ago, he had presented to our emergency department with forehead swelling but no headaches. At that time, the swelling was thought to be an allergic reaction to lisinopril or metformin, medications he takes for hypertension and type 2 diabetes. He had been discharged home with a prescription for a course of prednisone in tapering doses, but that had failed to resolve the swelling.

Physical examination revealed a well-circumscribed area of swelling, 3 by 4 cm, in the central forehead (Figure 1). The area was warm, erythematous, fluctuant, and tender to palpation. The nasal septum was intact and the nasal mucosa appeared pink and healthy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

He was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. His peripheral white blood cell count was mildly elevated at 11.1 × 109. Computed tomography of the brain and sinuses revealed a fluid collection in the frontal scalp associated with erosion of the anterior frontal sinus with posterior extension and enhancement of the adjacent meninges. Magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed similar findings. A diagnosis of Pott puffy tumor was made based on the imaging findings.

The name of this condition is misleading, as it is not a neoplasm but an infection. It requires urgent antibiotic therapy and surgical management because of the high risk of the infection spreading to the brain. Our patient was started on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of intravenous vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole pending tissue culture to identify the causative organism.

POTT PUFFY TUMOR: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

First described in 1760 by Sir Percivall Pott,1 the same English surgeon who first described tuberculosis of the spine, Pott puffy tumor is a well-demarcated area of swelling that occurs when a frontal sinus infection breaks through the anterior portion of the frontal sinus and forms an abscess between the frontal bone and periosteum with associated osteomyelitis.2 Though rare in adults (it is more common in children and adolescents),3 Pott puffy tumor is caused by conditions often encountered in internal medicine practice, such as bacterial sinusitis, head trauma, and intranasal cocaine use.

The infection can spread to the brain either directly by destruction of the posterior frontal sinus (as in our patient) or by way of the veins that drain the frontal sinus. Meningitis, epidural empyema, frontal lobe abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombosis2 have all been described. Intracranial complications are seen in nearly 100% of children and adolescents with Pott puffy tumor. The rate in adults is 30%,4,5 which is much lower but is nevertheless worrisome because patients can be initially misdiagnosed with scalp abscess,3 cellulitis, or epidermoid cyst,4 and then sent home from the emergency department or physician’s office. In a case series of 32 adult patients with Pott puffy tumor, nearly 45% were initially misdiagnosed, most often by an internist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, or emergency room physician.4

The most common infective organisms are streptococci, staphylococci, and anaerobes,4 but Haemophilus, Aspergillus species, and invasive mucormycosis have also been described.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

Because of the risk of spread of the infection to the brain, rapid initiation of a broad-spectrum antibiotic is warranted in all patients with Pott puffy tumor pending results of tissue culture. Antibiotics may be necessary for at least 4 to 6 weeks to resolve osteomyelitis of the frontal bone and to decrease inflammation before surgery.6

Endoscopic sinus surgery is routinely done to drain the infected sinus and to remove or debride infected bone. Patients with intracranial extension of infection may require a combined endoscopic and neurosurgical approach.

OUTCOME

Our patient’s puffy tumor spontaneously ruptured externally on hospital day 3, and the purulent fluid was sent for culture that grew Streptococcus anginosus. His headaches improved almost immediately after this occurred. The antibiotic regimen was narrowed to ceftriaxone and metronidazole, and 1 week later he was discharged home with instructions to complete a 6-week course of antibiotics. Three weeks after he was discharged, he returned for outpatient endoscopic sinus surgery. At a follow-up visit 2 weeks after surgery, the forehead swelling had resolved, and he was well.

- Tattersall R, Tattersall R. Pott’s puffy tumor. Lancet 2002; 359:1060–1063.

- Forgie SE, Marrie TJ. Pott’s puffy tumor. Am J Med 2008; 121:1041–1042.

- Grewal HS, Dangaych NS, Esposito A. A tumor that is not a tumor but it sure can kill! Am J Case Rep 2012; 13:133–136.

- Akiyama K, Karaki M, Mori N. Evaluation of adult Pott’s puffy tumor: our five cases and 27 literature cases. Laryngoscope 2012; 122:2382–2388.

- Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott’s puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr 2012; 2012:386104.

- Lauria RA, Laffitte Fernandes F, Brito TP, Pereira PS, Chone CT. Extensive frontoparietal abscess: complication of frontal sinusitis (Pott’s puffy tumor). Case Rep Otolaryngol 2014; 2014:632464.

- Tattersall R, Tattersall R. Pott’s puffy tumor. Lancet 2002; 359:1060–1063.

- Forgie SE, Marrie TJ. Pott’s puffy tumor. Am J Med 2008; 121:1041–1042.

- Grewal HS, Dangaych NS, Esposito A. A tumor that is not a tumor but it sure can kill! Am J Case Rep 2012; 13:133–136.

- Akiyama K, Karaki M, Mori N. Evaluation of adult Pott’s puffy tumor: our five cases and 27 literature cases. Laryngoscope 2012; 122:2382–2388.

- Suwan PT, Mogal S, Chaudhary S. Pott’s puffy tumor: an uncommon clinical entity. Case Rep Pediatr 2012; 2012:386104.

- Lauria RA, Laffitte Fernandes F, Brito TP, Pereira PS, Chone CT. Extensive frontoparietal abscess: complication of frontal sinusitis (Pott’s puffy tumor). Case Rep Otolaryngol 2014; 2014:632464.

Eventration of the diaphragm presenting as spontaneous pneumothorax

A 25-year-old man with a 2-day history of upper respiratory tract infection presents to the emergency department with the sudden onset of right-sided back and chest pain and shortness of breath after a severe coughing fit.

He is morbidly obese, is a long-time smoker, and has had recurrent exacerbations of asthma with frequent upper respiratory tract infections. He has no history of recent trauma.

A review of systems reveals no significant impairment in exercise tolerance. He has been able to continue doing manual labor at his job as a railroad worker.

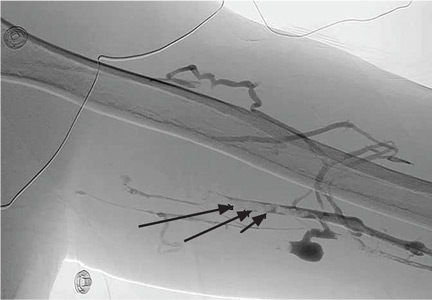

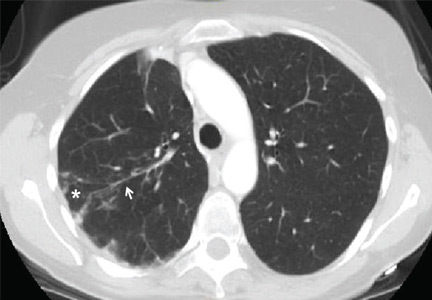

Radiography shows a large right pneumothorax and an elevated right diaphragm (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2) reveals a right anterior apical pneumothorax with hypoplastic lung and significant elevation of the right diaphragm with fat, bowel, and kidney within the right thorax. He is hemodynamically stable and shows no signs of bowel obstruction.

The physical examination is normal except for diminished breath sounds on the right side. He is diagnosed with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and spontaneous pneumothorax. A 10-F locking pigtail catheter is inserted under CT guidance, leading to complete resolution of the pneumothorax. He is discharged home the next day with a plan for elective repair of the hernia.

Two months later, he returns for scheduled right thoracotomy to repair the hernia. However, while preparing the chest cavity, the surgeon finds no diaphragmatic hernia and no intra-abdominal content—but rather, a severely elevated and thinned-out diaphragm with uninterrupted continuity. The diagnosis is changed to congenital diaphragmatic eventration, and plication of the diaphragm is performed with a series of interrupted, pledgeted polypropylene sutures.

CONGENITAL EVENTRATION OF THE DIAPHRAGM

Congenital diaphragmatic eventration is a rare developmental defect of the central, muscular portion of the diaphragm. The true prevalence is not known, but early reports identified this condition in less than 0.1% of adult.1

Symptomatic patients usually experience dyspnea secondary to ventilation-perfusion mismatch resulting from chronic atelectasis and lung hypoplasia, as well as impaired ventilation resulting from the limited caudal migration of the diaphragm.2,3 Increased susceptibility to recurrent upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia is also a common feature.

Although rare, spontaneous pneumothorax can develop in patients such as ours, whose lengthy history of smoking and asthma predisposed him to the development of emphysema-like blebs and bullae and to subsequent rupture of blebs brought on by vigorous coughing that caused an involuntary Valsalva maneuver.4

As in our patient, distinguishing congenital diaphragmatic eventration from hernia preoperatively can be difficult with plain chest radiography. Spiral CT with multiplanar reconstruction or with magnetic resonance imaging can help establish the diagnosis.3 However, a severely attenuated diaphragm can be difficult to visualize on CT, as in our patient, leading to a presumptive diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. In such situations, the diagnosis of eventration can only be made intraoperatively.

Surgical repair is indicated only for patients with symptoms. Other potential causes of the symptoms should first be ruled out, however, including primary pulmonary disease, cardiac dysfunction, and morbid obesity.

- Chin EF, Lynn RB. Surgery of eventration of the diaphragm. J Thorac Surg 1956; 32:6–14.

- Ridyard JB, Stewart RM. Regional lung function in unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Thorax 1976; 31:438–442.

- Shen C, Che G. Congenital eventration of hemidiaphragm in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 94:e137–e139.

- Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Spyratos D, et al. Pneumothorax and asthma. J Thorac Dis 2014; 6(suppl 1):S152–S161.

A 25-year-old man with a 2-day history of upper respiratory tract infection presents to the emergency department with the sudden onset of right-sided back and chest pain and shortness of breath after a severe coughing fit.

He is morbidly obese, is a long-time smoker, and has had recurrent exacerbations of asthma with frequent upper respiratory tract infections. He has no history of recent trauma.

A review of systems reveals no significant impairment in exercise tolerance. He has been able to continue doing manual labor at his job as a railroad worker.

Radiography shows a large right pneumothorax and an elevated right diaphragm (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2) reveals a right anterior apical pneumothorax with hypoplastic lung and significant elevation of the right diaphragm with fat, bowel, and kidney within the right thorax. He is hemodynamically stable and shows no signs of bowel obstruction.

The physical examination is normal except for diminished breath sounds on the right side. He is diagnosed with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and spontaneous pneumothorax. A 10-F locking pigtail catheter is inserted under CT guidance, leading to complete resolution of the pneumothorax. He is discharged home the next day with a plan for elective repair of the hernia.

Two months later, he returns for scheduled right thoracotomy to repair the hernia. However, while preparing the chest cavity, the surgeon finds no diaphragmatic hernia and no intra-abdominal content—but rather, a severely elevated and thinned-out diaphragm with uninterrupted continuity. The diagnosis is changed to congenital diaphragmatic eventration, and plication of the diaphragm is performed with a series of interrupted, pledgeted polypropylene sutures.

CONGENITAL EVENTRATION OF THE DIAPHRAGM

Congenital diaphragmatic eventration is a rare developmental defect of the central, muscular portion of the diaphragm. The true prevalence is not known, but early reports identified this condition in less than 0.1% of adult.1

Symptomatic patients usually experience dyspnea secondary to ventilation-perfusion mismatch resulting from chronic atelectasis and lung hypoplasia, as well as impaired ventilation resulting from the limited caudal migration of the diaphragm.2,3 Increased susceptibility to recurrent upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia is also a common feature.

Although rare, spontaneous pneumothorax can develop in patients such as ours, whose lengthy history of smoking and asthma predisposed him to the development of emphysema-like blebs and bullae and to subsequent rupture of blebs brought on by vigorous coughing that caused an involuntary Valsalva maneuver.4

As in our patient, distinguishing congenital diaphragmatic eventration from hernia preoperatively can be difficult with plain chest radiography. Spiral CT with multiplanar reconstruction or with magnetic resonance imaging can help establish the diagnosis.3 However, a severely attenuated diaphragm can be difficult to visualize on CT, as in our patient, leading to a presumptive diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. In such situations, the diagnosis of eventration can only be made intraoperatively.

Surgical repair is indicated only for patients with symptoms. Other potential causes of the symptoms should first be ruled out, however, including primary pulmonary disease, cardiac dysfunction, and morbid obesity.

A 25-year-old man with a 2-day history of upper respiratory tract infection presents to the emergency department with the sudden onset of right-sided back and chest pain and shortness of breath after a severe coughing fit.

He is morbidly obese, is a long-time smoker, and has had recurrent exacerbations of asthma with frequent upper respiratory tract infections. He has no history of recent trauma.

A review of systems reveals no significant impairment in exercise tolerance. He has been able to continue doing manual labor at his job as a railroad worker.

Radiography shows a large right pneumothorax and an elevated right diaphragm (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2) reveals a right anterior apical pneumothorax with hypoplastic lung and significant elevation of the right diaphragm with fat, bowel, and kidney within the right thorax. He is hemodynamically stable and shows no signs of bowel obstruction.

The physical examination is normal except for diminished breath sounds on the right side. He is diagnosed with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and spontaneous pneumothorax. A 10-F locking pigtail catheter is inserted under CT guidance, leading to complete resolution of the pneumothorax. He is discharged home the next day with a plan for elective repair of the hernia.

Two months later, he returns for scheduled right thoracotomy to repair the hernia. However, while preparing the chest cavity, the surgeon finds no diaphragmatic hernia and no intra-abdominal content—but rather, a severely elevated and thinned-out diaphragm with uninterrupted continuity. The diagnosis is changed to congenital diaphragmatic eventration, and plication of the diaphragm is performed with a series of interrupted, pledgeted polypropylene sutures.

CONGENITAL EVENTRATION OF THE DIAPHRAGM

Congenital diaphragmatic eventration is a rare developmental defect of the central, muscular portion of the diaphragm. The true prevalence is not known, but early reports identified this condition in less than 0.1% of adult.1

Symptomatic patients usually experience dyspnea secondary to ventilation-perfusion mismatch resulting from chronic atelectasis and lung hypoplasia, as well as impaired ventilation resulting from the limited caudal migration of the diaphragm.2,3 Increased susceptibility to recurrent upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia is also a common feature.

Although rare, spontaneous pneumothorax can develop in patients such as ours, whose lengthy history of smoking and asthma predisposed him to the development of emphysema-like blebs and bullae and to subsequent rupture of blebs brought on by vigorous coughing that caused an involuntary Valsalva maneuver.4

As in our patient, distinguishing congenital diaphragmatic eventration from hernia preoperatively can be difficult with plain chest radiography. Spiral CT with multiplanar reconstruction or with magnetic resonance imaging can help establish the diagnosis.3 However, a severely attenuated diaphragm can be difficult to visualize on CT, as in our patient, leading to a presumptive diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. In such situations, the diagnosis of eventration can only be made intraoperatively.

Surgical repair is indicated only for patients with symptoms. Other potential causes of the symptoms should first be ruled out, however, including primary pulmonary disease, cardiac dysfunction, and morbid obesity.

- Chin EF, Lynn RB. Surgery of eventration of the diaphragm. J Thorac Surg 1956; 32:6–14.

- Ridyard JB, Stewart RM. Regional lung function in unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Thorax 1976; 31:438–442.

- Shen C, Che G. Congenital eventration of hemidiaphragm in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 94:e137–e139.

- Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Spyratos D, et al. Pneumothorax and asthma. J Thorac Dis 2014; 6(suppl 1):S152–S161.

- Chin EF, Lynn RB. Surgery of eventration of the diaphragm. J Thorac Surg 1956; 32:6–14.

- Ridyard JB, Stewart RM. Regional lung function in unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Thorax 1976; 31:438–442.

- Shen C, Che G. Congenital eventration of hemidiaphragm in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 94:e137–e139.

- Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Spyratos D, et al. Pneumothorax and asthma. J Thorac Dis 2014; 6(suppl 1):S152–S161.

Bony bumps in the mouth

A 79-year-old woman with a long history of limited scleroderma was being evaluated in the rheumatology clinic. During routine examination of the oral cavity, masses were noted on her hard palate and on the lingual surface of both sides of the mandible (Figure 1). The masses had a bony consistency. The patient said that she had had these lumps for as long as she could remember, and that they were painless and had never caused any discomfort.

The masses were diagnosed as torus palatinus and torus mandibularis, localized benign overgrowths of cortical bone. The patient was reassured about the benign nature of these masses, and as they were asymptomatic, no further action was considered necessary.

TORUS PALATINUS AND TORUS MANDIBULARIS

Torus palatinus and torus mandibularis are common exostoses of the mouth, ie, localized benign bony overgrowths arising from cortical bone.1 They are occasionally found incidentally during routine examination of the oral cavity. Patients should be reassured about the nonpathologic nature of this condition.

The condition is thought to be multifactorial, with causal factors including autosomal dominant inheritance, trauma, and lifestyle factors2 such as vitamin deficiency,3 a calcium-rich diet,3 fish consumption,4,5 and chewing on dry, raw, or frozen meat (as in Eskimo cultures).3 Masticatory hyperfunction and bruxism are thought to be risk factors.2,3

Epidemiologic studies indicate that oral tori are more common in women, and the prevalence varies considerably between geographic areas and ethnic groups.3 It is more common in Native Americans, Eskimos, Norwegians, and Thais.4

Torus palatinus is the most prevalent oral torus, occurring in 20% of the US population.6 It arises from the median raphe of the palatine bone and can vary in shape and size. Torus mandibularis is a protuberance arising in the premolar area of the lingual surface of the mandible.3 This form is much less common than torus palatinus, with a prevalence of 6%, and is bilateral in about 80% of cases.

Microscopic examination of tori reveal a mass of dense, lamellar, cortical bone with a small amount of fibrofatty marrow.1 An inner zone of trabecular bone may also be present.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Oral tori must be differentiated from other growths in the mouth including fibromas, mucoceles, osteomas, osteochondromas, and osteoid osteomas.4 However, oral tori can usually be distinguished from other conditions on the basis of clinical findings alone. Biopsy may be warranted if there is doubt.4

Tori tend to grow gradually throughout life and do not have potential for malignant transformation.4 Although they are typically asymptomatic, removal is sometimes warranted for proper fitting of prostheses or for use in autogenous cortical bone grafting.5

- Neville BW, Douglas DD, Carl MA, Bouquot J. Developmental defects of the oral and maxillofacial region. In: Neville BW, Douglas DD, Carl MA, Bouquot J, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: WB Saunders; 2009:1–53.

- Eggen S. Torus mandibularis: an estimation of the degree of genetic determination. Acta Odontol Scand 1989; 47:409–415.

- Loukas M, Hulsberg P, Tubbs RS, et al. The tori of the mouth and ear: a review. Clin Anat 2013; 26:953–960.

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. A nodular protuberance on the hard palate. JAMA 2014; 311:1558–1559.

- García-García AS, Martínez-González JM, Gómez-Font R, Soto-Rivadeneira A, Oviedo-Roldán L. Current status of the torus palatinus and torus mandibularis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2010; 15:e353–e360.

- Larheim TA, Westesson PL. Facial growth disturbances. In: Maxillofacial Imaging. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2008:231.

A 79-year-old woman with a long history of limited scleroderma was being evaluated in the rheumatology clinic. During routine examination of the oral cavity, masses were noted on her hard palate and on the lingual surface of both sides of the mandible (Figure 1). The masses had a bony consistency. The patient said that she had had these lumps for as long as she could remember, and that they were painless and had never caused any discomfort.

The masses were diagnosed as torus palatinus and torus mandibularis, localized benign overgrowths of cortical bone. The patient was reassured about the benign nature of these masses, and as they were asymptomatic, no further action was considered necessary.

TORUS PALATINUS AND TORUS MANDIBULARIS

Torus palatinus and torus mandibularis are common exostoses of the mouth, ie, localized benign bony overgrowths arising from cortical bone.1 They are occasionally found incidentally during routine examination of the oral cavity. Patients should be reassured about the nonpathologic nature of this condition.

The condition is thought to be multifactorial, with causal factors including autosomal dominant inheritance, trauma, and lifestyle factors2 such as vitamin deficiency,3 a calcium-rich diet,3 fish consumption,4,5 and chewing on dry, raw, or frozen meat (as in Eskimo cultures).3 Masticatory hyperfunction and bruxism are thought to be risk factors.2,3

Epidemiologic studies indicate that oral tori are more common in women, and the prevalence varies considerably between geographic areas and ethnic groups.3 It is more common in Native Americans, Eskimos, Norwegians, and Thais.4

Torus palatinus is the most prevalent oral torus, occurring in 20% of the US population.6 It arises from the median raphe of the palatine bone and can vary in shape and size. Torus mandibularis is a protuberance arising in the premolar area of the lingual surface of the mandible.3 This form is much less common than torus palatinus, with a prevalence of 6%, and is bilateral in about 80% of cases.

Microscopic examination of tori reveal a mass of dense, lamellar, cortical bone with a small amount of fibrofatty marrow.1 An inner zone of trabecular bone may also be present.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Oral tori must be differentiated from other growths in the mouth including fibromas, mucoceles, osteomas, osteochondromas, and osteoid osteomas.4 However, oral tori can usually be distinguished from other conditions on the basis of clinical findings alone. Biopsy may be warranted if there is doubt.4

Tori tend to grow gradually throughout life and do not have potential for malignant transformation.4 Although they are typically asymptomatic, removal is sometimes warranted for proper fitting of prostheses or for use in autogenous cortical bone grafting.5

A 79-year-old woman with a long history of limited scleroderma was being evaluated in the rheumatology clinic. During routine examination of the oral cavity, masses were noted on her hard palate and on the lingual surface of both sides of the mandible (Figure 1). The masses had a bony consistency. The patient said that she had had these lumps for as long as she could remember, and that they were painless and had never caused any discomfort.

The masses were diagnosed as torus palatinus and torus mandibularis, localized benign overgrowths of cortical bone. The patient was reassured about the benign nature of these masses, and as they were asymptomatic, no further action was considered necessary.

TORUS PALATINUS AND TORUS MANDIBULARIS

Torus palatinus and torus mandibularis are common exostoses of the mouth, ie, localized benign bony overgrowths arising from cortical bone.1 They are occasionally found incidentally during routine examination of the oral cavity. Patients should be reassured about the nonpathologic nature of this condition.

The condition is thought to be multifactorial, with causal factors including autosomal dominant inheritance, trauma, and lifestyle factors2 such as vitamin deficiency,3 a calcium-rich diet,3 fish consumption,4,5 and chewing on dry, raw, or frozen meat (as in Eskimo cultures).3 Masticatory hyperfunction and bruxism are thought to be risk factors.2,3

Epidemiologic studies indicate that oral tori are more common in women, and the prevalence varies considerably between geographic areas and ethnic groups.3 It is more common in Native Americans, Eskimos, Norwegians, and Thais.4

Torus palatinus is the most prevalent oral torus, occurring in 20% of the US population.6 It arises from the median raphe of the palatine bone and can vary in shape and size. Torus mandibularis is a protuberance arising in the premolar area of the lingual surface of the mandible.3 This form is much less common than torus palatinus, with a prevalence of 6%, and is bilateral in about 80% of cases.

Microscopic examination of tori reveal a mass of dense, lamellar, cortical bone with a small amount of fibrofatty marrow.1 An inner zone of trabecular bone may also be present.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Oral tori must be differentiated from other growths in the mouth including fibromas, mucoceles, osteomas, osteochondromas, and osteoid osteomas.4 However, oral tori can usually be distinguished from other conditions on the basis of clinical findings alone. Biopsy may be warranted if there is doubt.4

Tori tend to grow gradually throughout life and do not have potential for malignant transformation.4 Although they are typically asymptomatic, removal is sometimes warranted for proper fitting of prostheses or for use in autogenous cortical bone grafting.5

- Neville BW, Douglas DD, Carl MA, Bouquot J. Developmental defects of the oral and maxillofacial region. In: Neville BW, Douglas DD, Carl MA, Bouquot J, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: WB Saunders; 2009:1–53.

- Eggen S. Torus mandibularis: an estimation of the degree of genetic determination. Acta Odontol Scand 1989; 47:409–415.

- Loukas M, Hulsberg P, Tubbs RS, et al. The tori of the mouth and ear: a review. Clin Anat 2013; 26:953–960.

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. A nodular protuberance on the hard palate. JAMA 2014; 311:1558–1559.

- García-García AS, Martínez-González JM, Gómez-Font R, Soto-Rivadeneira A, Oviedo-Roldán L. Current status of the torus palatinus and torus mandibularis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2010; 15:e353–e360.

- Larheim TA, Westesson PL. Facial growth disturbances. In: Maxillofacial Imaging. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2008:231.

- Neville BW, Douglas DD, Carl MA, Bouquot J. Developmental defects of the oral and maxillofacial region. In: Neville BW, Douglas DD, Carl MA, Bouquot J, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: WB Saunders; 2009:1–53.

- Eggen S. Torus mandibularis: an estimation of the degree of genetic determination. Acta Odontol Scand 1989; 47:409–415.

- Loukas M, Hulsberg P, Tubbs RS, et al. The tori of the mouth and ear: a review. Clin Anat 2013; 26:953–960.

- Ladizinski B, Lee KC. A nodular protuberance on the hard palate. JAMA 2014; 311:1558–1559.

- García-García AS, Martínez-González JM, Gómez-Font R, Soto-Rivadeneira A, Oviedo-Roldán L. Current status of the torus palatinus and torus mandibularis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2010; 15:e353–e360.

- Larheim TA, Westesson PL. Facial growth disturbances. In: Maxillofacial Imaging. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2008:231.

An alerting sign: Enlarged cardiac silhouette

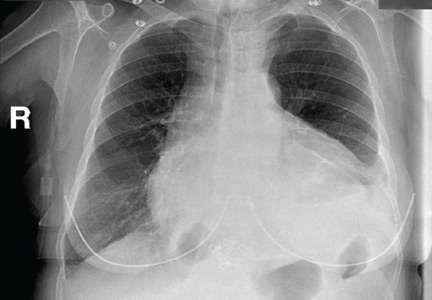

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and left-lung lobectomy for a carcinoid tumor 10 years ago presented with a 2-week history of progressive cough, dyspnea, and fatigue. Her heart rate was 159 beats per minute with an irregularly irregular rhythm, and her respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. Examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness on percussion at the left lung base, jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux sign, and an enlarged liver. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography (Figure 1) revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, with a disproportionately increased transverse diameter, and an obscured left costophrenic angle. A radiograph taken 13 months earlier (Figure 1) had shown a normal cardiothoracic ratio.

EVALUATION OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial effusion should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms of impaired cardiac function such as fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, palpitations, lightheadedness, cough, and hoarseness. Patients may also present with chest pain, often decreased by sitting up and leaning forward and exacerbated by lying supine.

Physical examination may reveal distant heart sounds, an absent or displaced apical impulse, dullness and increased fremitus beneath the angle of the left scapula (the Ewart sign), pulsus paradoxus, and nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and hypotension. Jugular venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, and peripheral edema suggest impaired cardiac function.

A chest radiograph showing unexplained new symmetric cardiomegaly (which is often globe-shaped) without signs of pulmonary congestion1 or with a left dominant pleural effusion is an indicator of pericardial effusion, as in our patient. Pericardial fluid may be seen outlining the heart between the epicardial and mediastinal fat, posterior to the sternum in a lateral view.

Other common causes of cardiomegaly include hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and pulmonary disease.

Once pericardial effusion is suspected, the next step is to confirm its presence and determine its hemodynamic significance. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging test of choice to confirm effusion, as it can be done rapidly and in unstable patients.2

If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic but suspicion is high, further evaluation may include transesophageal echocardiography,3 computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Pericardial effusion can occur as part of various diseases involving the pericardium, eg, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, autoimmune disease, postmyocardial infarction, malignancy, aortic dissection, and chest trauma. It can also be associated with certain drugs.

In our patient, echocardiography (Figure 2, Figure 3) demonstrated a large amount of pericardial fluid, and 820 mL of red fluid was aspirated by pericardiocentesis, resulting in relief of her respiratory symptoms. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated rocking of the heart and intermittent right-ventricular collapse (watch video at www.ccjm.org). Flow cytometry demonstrated 10% kappa+ monoclonal cells. Bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical staining revealed infiltration by CD20+, CD5+, CD23+, and BCL1– cells, compatible with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial disease can be the first manifestation of malignancy,4 more often when the patient presents with a large pericardial effusion or tamponade. Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, and esophagus—as well as lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma—often spread to the pericardium directly or through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream.4 In our patient, corticosteroid treatment was initiated, and echocardiography at a follow-up visit 2 months later showed no pericardial fluid.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:572–593.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society of Echocardiography. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3:333–343.

- Burazor I, Imazio M, Markel G, Adler Y. Malignant pericardial effusion. Cardiology 2013; 124:224–232.

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and left-lung lobectomy for a carcinoid tumor 10 years ago presented with a 2-week history of progressive cough, dyspnea, and fatigue. Her heart rate was 159 beats per minute with an irregularly irregular rhythm, and her respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. Examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness on percussion at the left lung base, jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux sign, and an enlarged liver. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography (Figure 1) revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, with a disproportionately increased transverse diameter, and an obscured left costophrenic angle. A radiograph taken 13 months earlier (Figure 1) had shown a normal cardiothoracic ratio.

EVALUATION OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial effusion should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms of impaired cardiac function such as fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, palpitations, lightheadedness, cough, and hoarseness. Patients may also present with chest pain, often decreased by sitting up and leaning forward and exacerbated by lying supine.

Physical examination may reveal distant heart sounds, an absent or displaced apical impulse, dullness and increased fremitus beneath the angle of the left scapula (the Ewart sign), pulsus paradoxus, and nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and hypotension. Jugular venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, and peripheral edema suggest impaired cardiac function.

A chest radiograph showing unexplained new symmetric cardiomegaly (which is often globe-shaped) without signs of pulmonary congestion1 or with a left dominant pleural effusion is an indicator of pericardial effusion, as in our patient. Pericardial fluid may be seen outlining the heart between the epicardial and mediastinal fat, posterior to the sternum in a lateral view.

Other common causes of cardiomegaly include hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and pulmonary disease.

Once pericardial effusion is suspected, the next step is to confirm its presence and determine its hemodynamic significance. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging test of choice to confirm effusion, as it can be done rapidly and in unstable patients.2

If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic but suspicion is high, further evaluation may include transesophageal echocardiography,3 computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Pericardial effusion can occur as part of various diseases involving the pericardium, eg, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, autoimmune disease, postmyocardial infarction, malignancy, aortic dissection, and chest trauma. It can also be associated with certain drugs.

In our patient, echocardiography (Figure 2, Figure 3) demonstrated a large amount of pericardial fluid, and 820 mL of red fluid was aspirated by pericardiocentesis, resulting in relief of her respiratory symptoms. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated rocking of the heart and intermittent right-ventricular collapse (watch video at www.ccjm.org). Flow cytometry demonstrated 10% kappa+ monoclonal cells. Bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical staining revealed infiltration by CD20+, CD5+, CD23+, and BCL1– cells, compatible with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial disease can be the first manifestation of malignancy,4 more often when the patient presents with a large pericardial effusion or tamponade. Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, and esophagus—as well as lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma—often spread to the pericardium directly or through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream.4 In our patient, corticosteroid treatment was initiated, and echocardiography at a follow-up visit 2 months later showed no pericardial fluid.

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and left-lung lobectomy for a carcinoid tumor 10 years ago presented with a 2-week history of progressive cough, dyspnea, and fatigue. Her heart rate was 159 beats per minute with an irregularly irregular rhythm, and her respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute. Her blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg. Examination revealed decreased breath sounds and dullness on percussion at the left lung base, jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux sign, and an enlarged liver. Electrocardiography showed atrial fibrillation. Chest radiography (Figure 1) revealed enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, with a disproportionately increased transverse diameter, and an obscured left costophrenic angle. A radiograph taken 13 months earlier (Figure 1) had shown a normal cardiothoracic ratio.

EVALUATION OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial effusion should be suspected in patients presenting with symptoms of impaired cardiac function such as fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, palpitations, lightheadedness, cough, and hoarseness. Patients may also present with chest pain, often decreased by sitting up and leaning forward and exacerbated by lying supine.

Physical examination may reveal distant heart sounds, an absent or displaced apical impulse, dullness and increased fremitus beneath the angle of the left scapula (the Ewart sign), pulsus paradoxus, and nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and hypotension. Jugular venous distention, hepatojugular reflux, and peripheral edema suggest impaired cardiac function.

A chest radiograph showing unexplained new symmetric cardiomegaly (which is often globe-shaped) without signs of pulmonary congestion1 or with a left dominant pleural effusion is an indicator of pericardial effusion, as in our patient. Pericardial fluid may be seen outlining the heart between the epicardial and mediastinal fat, posterior to the sternum in a lateral view.

Other common causes of cardiomegaly include hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, and pulmonary disease.

Once pericardial effusion is suspected, the next step is to confirm its presence and determine its hemodynamic significance. Transthoracic echocardiography is the imaging test of choice to confirm effusion, as it can be done rapidly and in unstable patients.2

If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic but suspicion is high, further evaluation may include transesophageal echocardiography,3 computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Pericardial effusion can occur as part of various diseases involving the pericardium, eg, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, autoimmune disease, postmyocardial infarction, malignancy, aortic dissection, and chest trauma. It can also be associated with certain drugs.

In our patient, echocardiography (Figure 2, Figure 3) demonstrated a large amount of pericardial fluid, and 820 mL of red fluid was aspirated by pericardiocentesis, resulting in relief of her respiratory symptoms. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated rocking of the heart and intermittent right-ventricular collapse (watch video at www.ccjm.org). Flow cytometry demonstrated 10% kappa+ monoclonal cells. Bone marrow biopsy with immunohistochemical staining revealed infiltration by CD20+, CD5+, CD23+, and BCL1– cells, compatible with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

Pericardial disease can be the first manifestation of malignancy,4 more often when the patient presents with a large pericardial effusion or tamponade. Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, and esophagus—as well as lymphoma, leukemia, and melanoma—often spread to the pericardium directly or through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream.4 In our patient, corticosteroid treatment was initiated, and echocardiography at a follow-up visit 2 months later showed no pericardial fluid.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:572–593.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society of Echocardiography. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3:333–343.

- Burazor I, Imazio M, Markel G, Adler Y. Malignant pericardial effusion. Cardiology 2013; 124:224–232.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:572–593.

- Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; American Society of Echocardiography. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovascular Imaging 2010; 3:333–343.

- Burazor I, Imazio M, Markel G, Adler Y. Malignant pericardial effusion. Cardiology 2013; 124:224–232.

Brown tumor of the pelvis

A 39-year-old man presented with acute left hip pain and inability to bear weight following a minor trauma. The patient had a history of polycystic kidney disease and was on dialysis. Five years ago he had undergone bilateral nephrectomy and a renal transplantation that subsequently failed.

On examination, the active and passive range of motion of the left hip were limited due to pain. His serum laboratory values were:

- Parathyroid hormone 259.7 pmol/L (reference range 1.5–9.3)

- Calcium 2.32 mmol/L (1.15–1.32)

- Phosphate 3.26 mmol/L (0.8–1.45).

Computed tomography of the pelvis revealed an exophytic calcified lesion with multiple cystic spaces and fluid-fluid levels centered on the left pubis, extending medially into the right pubis and laterally into the left adductor muscle group. An acute pathologic fracture was documented in the left inferior pubic ramus (Figure 1). Other radiographic signs of long-standing hyperparathyroidism were present, including subperiosteal bone resorption at the radial side of the middle phalanges and the clavicle epiphysis.

The differential diagnosis of the pelvic lesion included giant cell tumor of bone with aneurysmal bone-cyst-like changes, osteitis fibrosa cystica, and, less likely, metastatic bone disease. Biopsy of the lesion showed clusters of osteoclast-type giant cells on a background of spindle cells and fibrous stroma that in this clinical context was consistent with the diagnosis of brown tumor (Figure 2).1

BROWN TUMOR

Brown tumor has been reported in fewer than 2% of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and in 1.5% to 1.7% of those with secondary hyperparathyroidism (ie, from chronic renal failure, malabsorption, vitamin D deficiency, or hypocalcemia).2–4 An excess of parathyroid hormone increases the number and activity of osteoclasts, which are responsible for the lytic lesions. Brown tumor is the localized form of osteitis fibrosa cystica and is the most characteristic of the many skeletal changes that accompany secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Brown tumor is named for its color, which results from hemorrhages with accumulation of hemosiderin within the vascularized fibrous tissue. The tumor most commonly affects the pelvis, ribs, long-bone shafts, clavicle, and mandible.5 Clinical symptoms are nonspecific and depend on the size and location of the lesion.

Medical management of secondary hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients involves some combination of phosphate binders (either calcium-containing or non-calcium-containing binders), calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs, and a calcimimetic. Parathyroidectomy is required if drug therapy is ineffective. Surgical excision of brown tumor should be considered in patients who have large bone defects with spontaneous fracture risk or increasing pain. Our patient declined surgical intervention.

- Davies AM, Evans N, Mangham DC, Grimer RJ. MR imaging of brown tumour with fluid-fluid levels: a report of three cases. Eur Radiol 2001; 11:1445–1449.

- Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Evaluation and management of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:2036–2040.

- Bohlman ME, Kim YC, Eagan J, Spees EK. Brown tumor in secondary hyperparathyroidism causing acute paraplegia. Am J Med 1986; 81:545–547.

- Demay MB, Rosenthal DI, Deshpande V. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 16-2008. A 46-year-old woman with bone pain. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2266–2274.

- Perlman JS, Pletcher SD, Schmidt BL, Eisele DW. Pathology quiz case 2. Giant cell lesion (brown tumor) of the mandible, associated with primary hyperparathyroidism (HPT). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:793–794.

A 39-year-old man presented with acute left hip pain and inability to bear weight following a minor trauma. The patient had a history of polycystic kidney disease and was on dialysis. Five years ago he had undergone bilateral nephrectomy and a renal transplantation that subsequently failed.

On examination, the active and passive range of motion of the left hip were limited due to pain. His serum laboratory values were:

- Parathyroid hormone 259.7 pmol/L (reference range 1.5–9.3)

- Calcium 2.32 mmol/L (1.15–1.32)

- Phosphate 3.26 mmol/L (0.8–1.45).

Computed tomography of the pelvis revealed an exophytic calcified lesion with multiple cystic spaces and fluid-fluid levels centered on the left pubis, extending medially into the right pubis and laterally into the left adductor muscle group. An acute pathologic fracture was documented in the left inferior pubic ramus (Figure 1). Other radiographic signs of long-standing hyperparathyroidism were present, including subperiosteal bone resorption at the radial side of the middle phalanges and the clavicle epiphysis.

The differential diagnosis of the pelvic lesion included giant cell tumor of bone with aneurysmal bone-cyst-like changes, osteitis fibrosa cystica, and, less likely, metastatic bone disease. Biopsy of the lesion showed clusters of osteoclast-type giant cells on a background of spindle cells and fibrous stroma that in this clinical context was consistent with the diagnosis of brown tumor (Figure 2).1

BROWN TUMOR

Brown tumor has been reported in fewer than 2% of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and in 1.5% to 1.7% of those with secondary hyperparathyroidism (ie, from chronic renal failure, malabsorption, vitamin D deficiency, or hypocalcemia).2–4 An excess of parathyroid hormone increases the number and activity of osteoclasts, which are responsible for the lytic lesions. Brown tumor is the localized form of osteitis fibrosa cystica and is the most characteristic of the many skeletal changes that accompany secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Brown tumor is named for its color, which results from hemorrhages with accumulation of hemosiderin within the vascularized fibrous tissue. The tumor most commonly affects the pelvis, ribs, long-bone shafts, clavicle, and mandible.5 Clinical symptoms are nonspecific and depend on the size and location of the lesion.

Medical management of secondary hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients involves some combination of phosphate binders (either calcium-containing or non-calcium-containing binders), calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs, and a calcimimetic. Parathyroidectomy is required if drug therapy is ineffective. Surgical excision of brown tumor should be considered in patients who have large bone defects with spontaneous fracture risk or increasing pain. Our patient declined surgical intervention.

A 39-year-old man presented with acute left hip pain and inability to bear weight following a minor trauma. The patient had a history of polycystic kidney disease and was on dialysis. Five years ago he had undergone bilateral nephrectomy and a renal transplantation that subsequently failed.

On examination, the active and passive range of motion of the left hip were limited due to pain. His serum laboratory values were:

- Parathyroid hormone 259.7 pmol/L (reference range 1.5–9.3)

- Calcium 2.32 mmol/L (1.15–1.32)

- Phosphate 3.26 mmol/L (0.8–1.45).

Computed tomography of the pelvis revealed an exophytic calcified lesion with multiple cystic spaces and fluid-fluid levels centered on the left pubis, extending medially into the right pubis and laterally into the left adductor muscle group. An acute pathologic fracture was documented in the left inferior pubic ramus (Figure 1). Other radiographic signs of long-standing hyperparathyroidism were present, including subperiosteal bone resorption at the radial side of the middle phalanges and the clavicle epiphysis.

The differential diagnosis of the pelvic lesion included giant cell tumor of bone with aneurysmal bone-cyst-like changes, osteitis fibrosa cystica, and, less likely, metastatic bone disease. Biopsy of the lesion showed clusters of osteoclast-type giant cells on a background of spindle cells and fibrous stroma that in this clinical context was consistent with the diagnosis of brown tumor (Figure 2).1

BROWN TUMOR

Brown tumor has been reported in fewer than 2% of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and in 1.5% to 1.7% of those with secondary hyperparathyroidism (ie, from chronic renal failure, malabsorption, vitamin D deficiency, or hypocalcemia).2–4 An excess of parathyroid hormone increases the number and activity of osteoclasts, which are responsible for the lytic lesions. Brown tumor is the localized form of osteitis fibrosa cystica and is the most characteristic of the many skeletal changes that accompany secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Brown tumor is named for its color, which results from hemorrhages with accumulation of hemosiderin within the vascularized fibrous tissue. The tumor most commonly affects the pelvis, ribs, long-bone shafts, clavicle, and mandible.5 Clinical symptoms are nonspecific and depend on the size and location of the lesion.

Medical management of secondary hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients involves some combination of phosphate binders (either calcium-containing or non-calcium-containing binders), calcitriol or synthetic vitamin D analogs, and a calcimimetic. Parathyroidectomy is required if drug therapy is ineffective. Surgical excision of brown tumor should be considered in patients who have large bone defects with spontaneous fracture risk or increasing pain. Our patient declined surgical intervention.

- Davies AM, Evans N, Mangham DC, Grimer RJ. MR imaging of brown tumour with fluid-fluid levels: a report of three cases. Eur Radiol 2001; 11:1445–1449.

- Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Evaluation and management of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:2036–2040.

- Bohlman ME, Kim YC, Eagan J, Spees EK. Brown tumor in secondary hyperparathyroidism causing acute paraplegia. Am J Med 1986; 81:545–547.

- Demay MB, Rosenthal DI, Deshpande V. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 16-2008. A 46-year-old woman with bone pain. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2266–2274.

- Perlman JS, Pletcher SD, Schmidt BL, Eisele DW. Pathology quiz case 2. Giant cell lesion (brown tumor) of the mandible, associated with primary hyperparathyroidism (HPT). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:793–794.

- Davies AM, Evans N, Mangham DC, Grimer RJ. MR imaging of brown tumour with fluid-fluid levels: a report of three cases. Eur Radiol 2001; 11:1445–1449.

- Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Evaluation and management of primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:2036–2040.

- Bohlman ME, Kim YC, Eagan J, Spees EK. Brown tumor in secondary hyperparathyroidism causing acute paraplegia. Am J Med 1986; 81:545–547.

- Demay MB, Rosenthal DI, Deshpande V. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 16-2008. A 46-year-old woman with bone pain. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2266–2274.

- Perlman JS, Pletcher SD, Schmidt BL, Eisele DW. Pathology quiz case 2. Giant cell lesion (brown tumor) of the mandible, associated with primary hyperparathyroidism (HPT). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:793–794.

The color purple

A 58-year-old man with a history of cystoprostatectomy for prostate cancer, end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, and distal ureteral obstruction requiring bilateral nephrostomy tubes noticed that one of the nephrostomy bags looked “purple” (Figure 1). A specimen collected from one bag was reddish purple (Figure 2). The urine in the other bag was normal. The condition was diagnosed as purple urine bag syndrome.

PURPLE URINE BAG SYNDROME

Purple urine bag syndrome, a relatively rare condition that appears after 2 to 3 months of indwelling urinary catheterization, is usually asymptomatic, the only signs being the purplish urine and staining of the urinary bags and catheters. However, it should be considered a sign of underlying urinary tract infection, which can disseminate causing local complications (Fournier gangrene), systemic complications (septicemia), and death.1–3

The syndrome, first described in 1978 in children with spina bifida and urinary diversion,4 is more prevalent in women than in men, possibly because of the shorter urethra and closer proximity to the anus, which predispose women to bacterial colonization of the urinary tract. Predisposing conditions include dementia,5 female sex, increased dietary tryptophan, bacteriuria, urinary tract infection, constipation, older age, immobility, and alkaline urine.6–8

The cause of the discoloration

The purple color is from indigo and indirubin compounds in the urine, the result of the breakdown of dietary tryptophan. The color varies depending on the proportions of the two pigments.

Dietary tryptophan is broken down into indole by colonic bacteria. After reaching the portal circulation, it is excreted into the urine as indoxyl sulfate, which is broken down to indoxyl by sulfatase-producing bacteria (eg, Klebsiella pneumonia, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Providencia species, Morganella morganii). Indoxyl is then oxidized to indigo and indirubin.

These compounds do not discolor the urine directly, but rather precipitate after interacting with the lining of the urinary catheter and bags, thereby imparting a purple color.1,9–13

Management

Effective initial measures are improved urinary hygiene (eg, frequent, careful changing of the urinary catheter) and management of constipation, as constipation leads to increased colonization of the intestine by bacteria that metabolize dietary tryptophan into indoxyl. Antibiotics should be given for symptomatic urinary tract infection (fever, increased urinary frequency, dysuria, abdominal pain) but not for color change alone. Coverage should be for gram-negative bacilli, although methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, which is gram-positive, has also been reported to cause purple urine bag syndrome.

In most cases, purple urine bag syndrome is benign and requires no therapy other than that mentioned above.3,13–15 However, in rare cases, immunocompromised patients (eg, people with diabetes) can develop local complications and sepsis from dissemination of bacterial infection, requiring aggressive therapy.14 Therefore, purple urine bag syndrome should be recognized as an indicator of an underlying urinary tract infection and should be treated if symptomatic. Nevertheless, the long-term prognosis is generally good.

OUR PATIENT’S MANAGEMENT

Our patient was confirmed to have urinary colonization with P aeruginosa and E coli, and alkaline urine. He underwent replacement of the nephrostomy tubes and urinary bag during his hospital stay (he was already in the hospital for another indication), but he continued to produce purple-colored urine from his right side and normal-colored urine from his left side. The unilateral involvement was likely from selective colonization of the right-sided nephrostomy tube with gram-negative bacteria.

- Kang KH, Jeong KH, Baik SK, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome: case report and literature review. Clin Nephrol 2011; 75:557–559.

- Ribeiro JP, Marcelino P, Marum S, Fernandes AP, Grilo A. Case report: purple urine bag syndrome. Crit Care 2004; 8:R137.

- Robinson J. Purple urinary bag syndrome: a harmless but alarming problem. Br J Community Nurs 2003; 8:263–266.

- Barlow GB, Dickson JAS. Purple urine bags. Lancet 1978; 1:220–221.

- Ga H, Kojima T. Purple urine bag syndrome. JAMA 2012; 307:1912–1913.

- Ishida T, Ogura S, Kawakami Y. Five cases of purple urine bag syndrome in a geriatric ward. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 1999; 36:826–829. Japanese.

- Gautam G, Kothari A, Kumar R, Dogra PN. Purple urine bag syndrome: a rare clinical entity in patients with long term indwelling catheters. Int Urol Nephrol 2007; 39:155–156.

- Shiao CC, Weng CY, Chuang JC, Huang MS, Chen ZY. Purple urine bag syndrome: a community-based study and literature review. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008; 13:554–559.

- Chong VH. Purple urine bag syndrome: it is the urine bag and not the urine that is discolored purple. South Med J 2012; 105:446.

- Chung SD, Liao CH, Sun HD. Purple urine bag syndrome with acidic urine. Int J Infect Dis 2008; 12:526–527.

- Wu HH, Yang WC, Lin CC. Purple urine bag syndrome. Am J Med Sci 2009; 337:368.

- Achtergael W, Michielsen D, Gorus FK, Gerlo E. Indoxyl sulphate and the purple urine bag syndrome: a case report. Acta Clin Belg 2006; 61:38–41.

- Hadano Y, Shimizu T, Takada S, Inoue T, Sorano S. An update on purple urine bag syndrome. Int J Gen Med 2012; 5:707–710.

- Tasi YM, Huang MS, Yang CJ, Yeh SM, Liu CC. Purple urine bag syndrome, not always a benign process. Am J Emerg Med 2009; 27:895–897.

- Ferrara F, D’Angelo G, Costantino G. Monolateral purple urine bag syndrome in bilateral nephrostomy. Postgrad Med J 2010; 86:627.

A 58-year-old man with a history of cystoprostatectomy for prostate cancer, end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, and distal ureteral obstruction requiring bilateral nephrostomy tubes noticed that one of the nephrostomy bags looked “purple” (Figure 1). A specimen collected from one bag was reddish purple (Figure 2). The urine in the other bag was normal. The condition was diagnosed as purple urine bag syndrome.

PURPLE URINE BAG SYNDROME

Purple urine bag syndrome, a relatively rare condition that appears after 2 to 3 months of indwelling urinary catheterization, is usually asymptomatic, the only signs being the purplish urine and staining of the urinary bags and catheters. However, it should be considered a sign of underlying urinary tract infection, which can disseminate causing local complications (Fournier gangrene), systemic complications (septicemia), and death.1–3

The syndrome, first described in 1978 in children with spina bifida and urinary diversion,4 is more prevalent in women than in men, possibly because of the shorter urethra and closer proximity to the anus, which predispose women to bacterial colonization of the urinary tract. Predisposing conditions include dementia,5 female sex, increased dietary tryptophan, bacteriuria, urinary tract infection, constipation, older age, immobility, and alkaline urine.6–8

The cause of the discoloration

The purple color is from indigo and indirubin compounds in the urine, the result of the breakdown of dietary tryptophan. The color varies depending on the proportions of the two pigments.

Dietary tryptophan is broken down into indole by colonic bacteria. After reaching the portal circulation, it is excreted into the urine as indoxyl sulfate, which is broken down to indoxyl by sulfatase-producing bacteria (eg, Klebsiella pneumonia, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Providencia species, Morganella morganii). Indoxyl is then oxidized to indigo and indirubin.

These compounds do not discolor the urine directly, but rather precipitate after interacting with the lining of the urinary catheter and bags, thereby imparting a purple color.1,9–13

Management

Effective initial measures are improved urinary hygiene (eg, frequent, careful changing of the urinary catheter) and management of constipation, as constipation leads to increased colonization of the intestine by bacteria that metabolize dietary tryptophan into indoxyl. Antibiotics should be given for symptomatic urinary tract infection (fever, increased urinary frequency, dysuria, abdominal pain) but not for color change alone. Coverage should be for gram-negative bacilli, although methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, which is gram-positive, has also been reported to cause purple urine bag syndrome.

In most cases, purple urine bag syndrome is benign and requires no therapy other than that mentioned above.3,13–15 However, in rare cases, immunocompromised patients (eg, people with diabetes) can develop local complications and sepsis from dissemination of bacterial infection, requiring aggressive therapy.14 Therefore, purple urine bag syndrome should be recognized as an indicator of an underlying urinary tract infection and should be treated if symptomatic. Nevertheless, the long-term prognosis is generally good.

OUR PATIENT’S MANAGEMENT

Our patient was confirmed to have urinary colonization with P aeruginosa and E coli, and alkaline urine. He underwent replacement of the nephrostomy tubes and urinary bag during his hospital stay (he was already in the hospital for another indication), but he continued to produce purple-colored urine from his right side and normal-colored urine from his left side. The unilateral involvement was likely from selective colonization of the right-sided nephrostomy tube with gram-negative bacteria.

A 58-year-old man with a history of cystoprostatectomy for prostate cancer, end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, and distal ureteral obstruction requiring bilateral nephrostomy tubes noticed that one of the nephrostomy bags looked “purple” (Figure 1). A specimen collected from one bag was reddish purple (Figure 2). The urine in the other bag was normal. The condition was diagnosed as purple urine bag syndrome.

PURPLE URINE BAG SYNDROME

Purple urine bag syndrome, a relatively rare condition that appears after 2 to 3 months of indwelling urinary catheterization, is usually asymptomatic, the only signs being the purplish urine and staining of the urinary bags and catheters. However, it should be considered a sign of underlying urinary tract infection, which can disseminate causing local complications (Fournier gangrene), systemic complications (septicemia), and death.1–3

The syndrome, first described in 1978 in children with spina bifida and urinary diversion,4 is more prevalent in women than in men, possibly because of the shorter urethra and closer proximity to the anus, which predispose women to bacterial colonization of the urinary tract. Predisposing conditions include dementia,5 female sex, increased dietary tryptophan, bacteriuria, urinary tract infection, constipation, older age, immobility, and alkaline urine.6–8

The cause of the discoloration

The purple color is from indigo and indirubin compounds in the urine, the result of the breakdown of dietary tryptophan. The color varies depending on the proportions of the two pigments.

Dietary tryptophan is broken down into indole by colonic bacteria. After reaching the portal circulation, it is excreted into the urine as indoxyl sulfate, which is broken down to indoxyl by sulfatase-producing bacteria (eg, Klebsiella pneumonia, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Providencia species, Morganella morganii). Indoxyl is then oxidized to indigo and indirubin.

These compounds do not discolor the urine directly, but rather precipitate after interacting with the lining of the urinary catheter and bags, thereby imparting a purple color.1,9–13

Management

Effective initial measures are improved urinary hygiene (eg, frequent, careful changing of the urinary catheter) and management of constipation, as constipation leads to increased colonization of the intestine by bacteria that metabolize dietary tryptophan into indoxyl. Antibiotics should be given for symptomatic urinary tract infection (fever, increased urinary frequency, dysuria, abdominal pain) but not for color change alone. Coverage should be for gram-negative bacilli, although methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, which is gram-positive, has also been reported to cause purple urine bag syndrome.

In most cases, purple urine bag syndrome is benign and requires no therapy other than that mentioned above.3,13–15 However, in rare cases, immunocompromised patients (eg, people with diabetes) can develop local complications and sepsis from dissemination of bacterial infection, requiring aggressive therapy.14 Therefore, purple urine bag syndrome should be recognized as an indicator of an underlying urinary tract infection and should be treated if symptomatic. Nevertheless, the long-term prognosis is generally good.

OUR PATIENT’S MANAGEMENT

Our patient was confirmed to have urinary colonization with P aeruginosa and E coli, and alkaline urine. He underwent replacement of the nephrostomy tubes and urinary bag during his hospital stay (he was already in the hospital for another indication), but he continued to produce purple-colored urine from his right side and normal-colored urine from his left side. The unilateral involvement was likely from selective colonization of the right-sided nephrostomy tube with gram-negative bacteria.