User login

Manual vacuum aspiration: A safe and effective treatment for early miscarriage

Case Miscarriage in a 29-year-old woman

A woman (G0P0) presents to her gynecologist with amenorrhea for 3 months and a positive home urine pregnancy test. She is 29 years of age. She denies any bleeding or pain and intends to continue the pregnancy, though it was unplanned. Results of office ultrasonography to assess fetal viability reveal an intrauterine gestation with an 8-mm fetal pole but no heartbeat. The diagnosis is miscarriage.

This case illustrates a typical miscarriage diagnosis; most women with miscarriage are asymptomatic and without serious bleeding requiring emergency intervention. The management options include surgical, medical, and expectant. Women should be offered all 3 of these, and clinicians should explain the risks and benefits of each approach. But while each strategy can be safe, effective, and acceptable, many women, as well as their health care providers, will benefit from office-based uterine aspiration. In this article, we present the data available on office-based manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) as well as procedure pointers and urge you to consider MVA in your practice for your patients.

Surgical management

Surgical management of miscarriage offers several clear advantages over medical and expectant management. Perhaps the most important advantage to patients is that surgery offers rapid resolution of miscarriage with the shortest duration of bleeding.1,2 When skilled providers perform electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) or MVA in outpatient or emergency department settings, successful uterine evacuation is completed in a single medical encounter 99% of the time.1 By comparison, several follow-up visits and additional ultrasounds may be required during medical or expectant management. Uterine aspiration rarely requires an operating room (OR). Such a setting should be limited to cases in which the clinical picture reflects:

- hemodynamic instability with active uterine bleeding

- serious uterine infection

- the presence of medical comorbidities in patients who may benefit from additional blood bank and anesthesia resources.

Office-based MVA

Office-based MVA is well tolerated when performed using a combination of verbal distraction and reassurance, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and a paracervical block with or without intravenous sedation.

Evidence on managing pain at MVA. Multiple studies have assessed preprocedure and postprocedure pain using NSAIDs, oral anxiolytics, and local anesthesia at the time of EVA or MVA.3,4 Renner and colleagues found that women who received a paracervical block prior to MVA or EVA reported moderate levels of pain, according to a 100-point visual analogue scale (VAS), at the time of cervical dilation (mean, 42) and uterine aspiration (mean, 63).4 In this same study, patients’ willingness to treat a future pregnancy with EVA or MVA using local anesthesia and their overall satisfaction with the procedure was high (mean, 90 on 100-point VAS).

In-office advantages over the OR. Women and clinicians can avoid the extensive scheduling delays associated with ORs, as well as the complications associated with medical and expectant management, if office-based EVA and MVA services are readily available. Compared with surgical management of miscarriage in an OR, office-based EVA and MVA are faster to complete. For example, Dalton and colleagues compared patients undergoing first-trimester procedures in an office setting with those undergoing a procedure in an OR. The mean procedure time for women treated in an office was 10 minutes, compared with 19 minutes for women treated in the OR. In addition, women treated in an office setting spent a mean total of 97 minutes at the office; women treated in an OR spent a mean total of 290 minutes at the hospital.5

Patients’ satisfaction with care provided in the OR was comparable to patients’ satisfaction with care provided in a medical office. In fact, the median total satisfaction score was high among women who had a procedure in either setting (office score, 19 of 20; OR score, 20 of 20).

Cost and equipment for in-office MVA

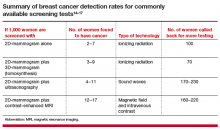

Office-based surgical management of miscarriage is more cost-effective than OR-based management. In 2006, Dalton and colleagues conducted a cost analysis and found that average charges for office-based MVA were less than half the cost of charges for a dilation and curettage (D&C) in the OR ($968 vs $1,965, respectively).5

More recently, these researchers found that usual care (expectant or OR management) was more costly than a model that also included medical and office-based surgical options. They found that the expanded care model—with use of the OR only when needed—cost $1,033.29 per case. This was compared with $1,247.58 per case when management options did not include medical and office-based surgical treatments.6

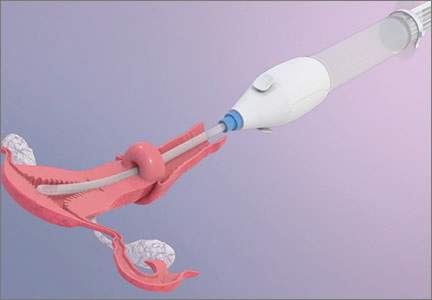

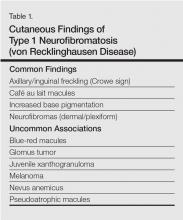

The cost of supplies needed to initiate MVA services within an established outpatient gynecologist’s office is modest. Equipment includes manual vacuum aspirators; disposable cannulae of various sizes; reusable plastic or metal dilators; supplies for disinfection, allowing reuse of MVA aspirators; and supplies for examination of products of conception (POC; FIGURE 1).

According to WomanCare Global, manufacturer of the IPAS MVA Plus, equipment should be sterilized after each use with soap and water, medical cleaning solution (such as Cidex, SPOROX II, etc.), or autoclaving.7 If 2 reusable aspirators are purchased along with dilators, disposable cannulae, and tools for tissue assessment, the price of supplies is estimated at US $500.8 WomanCare Global also offers prepackaged, single-use aspirator kits, which may be ideal for the emergency department setting.9

The procedure

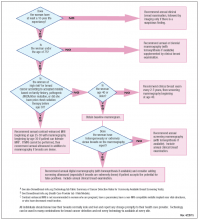

To view a video on the MVA device and procedure, including step-by-step technique (FIGURE 2), local anesthesia administration, choosing cannula size, and cervical dilation, visit the Managing Early Pregnancy Loss Web site (http://www.earlypregnancylossresources.org) and access “Videos.” The video “Uterine aspiration for EPL” is available under password protection and broken into chapters for viewing ease.

The risk of endometritis after surgical management of miscarriage is low. Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to MVA or EVA should be considered. Experts recommend giving a single dose of doxycycline 200 mg orally at least 1 hour prior to uterine aspiration.2,10

Use of EVA or MVA for outpatient management of miscarriage yields the opportunity to conduct immediate gross examination of the evacuated tissue and to verify the presence of complete POC. The process is simple: rinse the specimen through a sieve with water or saline, placed in a clear glass container under a small water bath and backlit on a light box. This allows clinicians to separate uterine decidua and pregnancy tissues. “Floating” tissue in this manner is especially useful in patients with pregnancy of unknown location, as immediate confirmation of a gestational sac rules out ectopic pregnancy.

Examine evacuated tissue for macroscopic evidence of pregnancy. Chorionic villi, which arise from syncytiotrophoblasts, can be seen with the naked eye. Immediate evaluation of POC is also useful for patients who desire diagnostic testing to ascertain a cause of their miscarriage because evacuated tissue stored in saline may be sent to a laboratory for cytogenetic analysis.

Medical management

Management of miscarriage with misoprostol is also safe and acceptable to women, though it has a lower success rate than surgical management.

Comparing efficacy: Medical vs surgical management. The Management of Early Pregnancy Failure Trial (MEPF) is the largest randomized controlled trial comparing medical management of miscarriage to surgical management. This multicenter study compared treatment with office-based EVA or MVA to vaginal misoprostol 800 µg. A repeat dose of vaginal misoprostol was offered 48 hours after the initial dose if a gestational sac was present on ultrasound.

Findings from the MEPF trial revealed a 71% complete uterine evacuation rate after 1 dose of misoprostol and an 84% rate after 2 doses.1 The average (SD) reported pain score documented within 48 hours of treatment with misoprostol or MVA/EVA was moderate (5.7 cm [2.4] on 10-cm VAS). The rate of infection or hospitalization was less than 1% in both treatment groups.

These data should provide patients who are clinically stable and who wish to avoid an invasive procedure reassurance that using medication for the management of miscarriage is a reasonable option.

Misoprostol. Use of misoprostol is associated with a longer median duration of bleeding compared with suction aspiration. After misoprostol, bleeding usually begins after several hours and may continue for weeks.11 Based on 2-week prospective bleeding diary entries from the MEPF trial, women who used misoprostol for management of miscarriage were more likely to have any bleeding during the 2 weeks after initiation of treatment, compared with women who had suction aspiration.12

Clinically significant changes in hemoglobin levels are more common in women treated with misoprostol than in those who choose EVA or MVA; however, these differences rarely require hospitalization or transfusion.1 Women who are considering use of misoprostol should be aware of common adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and low-grade temperature.

Medical management of miscarriage requires multiple office visits with repeat ultrasounds or serum beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels to confirm treatment success. In cases of medication failure (persistent gestational sac with or without bleeding) or suspected retained POC (endometrial stripe greater than 30 mm measured on ultrasound or persistent vaginal bleeding remote from treatment), women should be prepared for surgical resolution of pregnancy and clinicians should be able to perform an office-based procedure.

Expectant management

Women who choose the “watch and wait” approach should be advised that the process is unpredictable and occasionally requires urgent surgical intervention. Successful resolution of pregnancies that are expectantly managed depends on the type of miscarriage diagnosed at initial presentation. Luise and colleagues conducted a prospective study of 451 women with miscarriage who declined medical and surgical management. They found that the watch-and-wait approach was successful in 91% of women with an incomplete abortion, 76% of women with missed abortion, and 66% of women with anembryonic pregnancies.13 Success was defined by the absence of vaginal bleeding and an anterior-posterior endometrial stripe measuring less than 15 mm 4 weeks after initial diagnosis of miscarriage.

Like medical management for miscarriage, expectant management requires multiple office visits plus repeat ultrasounds or β-hCG measurement trends to confirm treatment success. Women who fail expectant management will require medical or surgical intervention to resolve the pregnancy. For those who are seeking pregnancy right away, the unpredictability and longer time to resolution of miscarriage may render expectant management anxiety provoking and unacceptable.

Etiology: Do true and perceived causes match?

Miscarriage during the first 13 weeks of gestation occurs in at least 10% of all clinically diagnosed pregnancies.10 A recent survey administered by Bardos and colleagues

assessed perceived prevalence and causes of miscarriage in more than 1,000 US men and women.14 The majority of respondents believed miscarriage is uncommon, occurring in less than 5% of pregnancies. Respondents also believed stressful events, lifting heavy objects, and prior use of intrauterine or hormonal contraception are often to blame for pregnancy loss.

Despite more than 3 decades of data confirming that more than 60% of early losses are associated with chromosomal abnormalities and that an additional 18% may be associated with fetal anomalies, women often blame themselves.15 Bardos and colleagues found that 47% of women felt guilty about the experience of miscarriage.

Diagnosis: Updated ultrasonography criteria issued

When miscarriage is suspected based on symptoms of pain and bleeding in preg-

nancy, obtain a thorough history and conduct a limited physical examination. If an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) was previously identified, a repeat ultrasound can confirm the presence or absence of the gestational sac. If an IUP has not been documented, then additional studies, including serial serum β-hCG examinations and ultrasonography, are essential to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Rh status should be determined and a 50-µg dose of Rh(D)-immune globulin administered to Rh(D)-unsensitized women within 72 hours of documented bleeding.

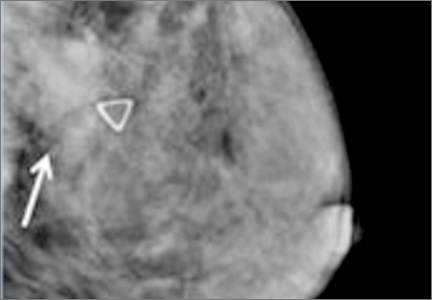

Ultrasonography is often used to diagnose miscarriage. Many gynecologists use ultrasound criteria based on studies conducted in the early 1990s that define nonviability by an empty gestational sac with mean gestational sac diameter greater than 16 mm or a crown-rump length (CRL) without evidence of fetal cardiac activity greater than 5 mm.10 In 2012, members of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy developed more conservative criteria for the diagnosis of miscarriage.16

Doubilet and colleagues suggested new cutoffs, based on their reanalysis of 2 large prospective studies conducted in the United Kingdom.17 Calculations for these new cut-offs are based on mathematical adjustments for interobserver variability. Strict adherence to these more conservative criteria is sensible when a pregnancy is desired. For women who do not want to continue the pregnancy there is no medical justification for using this diagnostic process. Indeed, delays can lead to stress and poor outcomes including emergent surgical management for spontaneous and heavy bleeding.

Culture change is needed

Patients’ beliefs and scientific evidence about miscarriage are incongruous. By making simple changes in practice and providing straightforward patient education, ObGyns

can demystify the causes of miscarriage and improve its management. In particular, providing office-based MVA when requested can streamline treatment for many women. For too long, patients have blamed themselves for miscarriage and physicians have relied on D&C in the OR. Changes in culture surrounding miscarriage are

long overdue.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, Creinin MD, Westhoff C, Frederick MM. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Eng J Med. 2005;353(8):761−769.

2. Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD, eds. Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

3. Edelman A, Nichols MD, Jensen J. Comparison of pain and time of procedures with two first-trimester abortion techniques performed by residents and faculty. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1564−1567.

4. Renner RM, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Li H, Edelman AB. Paracervical block for pain control in first-trimester surgical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1030−1037.

5. Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, Guire K, Castleman L, Lebovic D. Patient p, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):103−110.

6. Dalton VK, Liang A, Hutton DW, Zochowski MK, Fendrick AM. Beyond usual care: the economic consequences of expanding treatment options in early pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):177.e171−177.e176.

7. Ipas. Ipas start-up kit for integrating manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) for early pregnancy loss into women’s reproductive healthcare services. Chapel Hill, NC: Ipas; 2009.

8. MVA Products page. HPSRx Web site. http://www.hpsrx.com/mva-products.html. Accessed October 13, 2015.

9. Kinariwala M, Quinley KE, Datner EM, Schreiber CA. Manual vacuum aspiration in the emergency department for management of early pregnancy failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):244−247.

10. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 150: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1258−1267.

11. Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, Goldberg AB, Darney PD. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes: drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Part 1):582−590.

12. Davis AR, Hendlish SK, Westhoff C, et al. Bleeding patterns after misoprostol vs surgical treatment of early pregnancy failure: results from a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):31.e31−31.e37.

13. Luise C, Jermy K, May C, Costello G, Collins WP, Bourne TH. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324(7342):873−875.

14. Bardos J, Hercz D, Friedenthal J, Missmer SA, Williams Z. A national survey on public perceptions of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1313−1320.

15. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(5):1103−1111.

16. Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, Blaivas M. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Eng JMed. 2013;369(15):1443−1451.

17. Abdallah Y, Daemen A, Kirk E, et al. Limitations of current definitions of miscarriage using mean gestational sac diameter and crown–rump length measurements: a multicenter observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(5):497−502.

Case Miscarriage in a 29-year-old woman

A woman (G0P0) presents to her gynecologist with amenorrhea for 3 months and a positive home urine pregnancy test. She is 29 years of age. She denies any bleeding or pain and intends to continue the pregnancy, though it was unplanned. Results of office ultrasonography to assess fetal viability reveal an intrauterine gestation with an 8-mm fetal pole but no heartbeat. The diagnosis is miscarriage.

This case illustrates a typical miscarriage diagnosis; most women with miscarriage are asymptomatic and without serious bleeding requiring emergency intervention. The management options include surgical, medical, and expectant. Women should be offered all 3 of these, and clinicians should explain the risks and benefits of each approach. But while each strategy can be safe, effective, and acceptable, many women, as well as their health care providers, will benefit from office-based uterine aspiration. In this article, we present the data available on office-based manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) as well as procedure pointers and urge you to consider MVA in your practice for your patients.

Surgical management

Surgical management of miscarriage offers several clear advantages over medical and expectant management. Perhaps the most important advantage to patients is that surgery offers rapid resolution of miscarriage with the shortest duration of bleeding.1,2 When skilled providers perform electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) or MVA in outpatient or emergency department settings, successful uterine evacuation is completed in a single medical encounter 99% of the time.1 By comparison, several follow-up visits and additional ultrasounds may be required during medical or expectant management. Uterine aspiration rarely requires an operating room (OR). Such a setting should be limited to cases in which the clinical picture reflects:

- hemodynamic instability with active uterine bleeding

- serious uterine infection

- the presence of medical comorbidities in patients who may benefit from additional blood bank and anesthesia resources.

Office-based MVA

Office-based MVA is well tolerated when performed using a combination of verbal distraction and reassurance, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and a paracervical block with or without intravenous sedation.

Evidence on managing pain at MVA. Multiple studies have assessed preprocedure and postprocedure pain using NSAIDs, oral anxiolytics, and local anesthesia at the time of EVA or MVA.3,4 Renner and colleagues found that women who received a paracervical block prior to MVA or EVA reported moderate levels of pain, according to a 100-point visual analogue scale (VAS), at the time of cervical dilation (mean, 42) and uterine aspiration (mean, 63).4 In this same study, patients’ willingness to treat a future pregnancy with EVA or MVA using local anesthesia and their overall satisfaction with the procedure was high (mean, 90 on 100-point VAS).

In-office advantages over the OR. Women and clinicians can avoid the extensive scheduling delays associated with ORs, as well as the complications associated with medical and expectant management, if office-based EVA and MVA services are readily available. Compared with surgical management of miscarriage in an OR, office-based EVA and MVA are faster to complete. For example, Dalton and colleagues compared patients undergoing first-trimester procedures in an office setting with those undergoing a procedure in an OR. The mean procedure time for women treated in an office was 10 minutes, compared with 19 minutes for women treated in the OR. In addition, women treated in an office setting spent a mean total of 97 minutes at the office; women treated in an OR spent a mean total of 290 minutes at the hospital.5

Patients’ satisfaction with care provided in the OR was comparable to patients’ satisfaction with care provided in a medical office. In fact, the median total satisfaction score was high among women who had a procedure in either setting (office score, 19 of 20; OR score, 20 of 20).

Cost and equipment for in-office MVA

Office-based surgical management of miscarriage is more cost-effective than OR-based management. In 2006, Dalton and colleagues conducted a cost analysis and found that average charges for office-based MVA were less than half the cost of charges for a dilation and curettage (D&C) in the OR ($968 vs $1,965, respectively).5

More recently, these researchers found that usual care (expectant or OR management) was more costly than a model that also included medical and office-based surgical options. They found that the expanded care model—with use of the OR only when needed—cost $1,033.29 per case. This was compared with $1,247.58 per case when management options did not include medical and office-based surgical treatments.6

The cost of supplies needed to initiate MVA services within an established outpatient gynecologist’s office is modest. Equipment includes manual vacuum aspirators; disposable cannulae of various sizes; reusable plastic or metal dilators; supplies for disinfection, allowing reuse of MVA aspirators; and supplies for examination of products of conception (POC; FIGURE 1).

According to WomanCare Global, manufacturer of the IPAS MVA Plus, equipment should be sterilized after each use with soap and water, medical cleaning solution (such as Cidex, SPOROX II, etc.), or autoclaving.7 If 2 reusable aspirators are purchased along with dilators, disposable cannulae, and tools for tissue assessment, the price of supplies is estimated at US $500.8 WomanCare Global also offers prepackaged, single-use aspirator kits, which may be ideal for the emergency department setting.9

The procedure

To view a video on the MVA device and procedure, including step-by-step technique (FIGURE 2), local anesthesia administration, choosing cannula size, and cervical dilation, visit the Managing Early Pregnancy Loss Web site (http://www.earlypregnancylossresources.org) and access “Videos.” The video “Uterine aspiration for EPL” is available under password protection and broken into chapters for viewing ease.

The risk of endometritis after surgical management of miscarriage is low. Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to MVA or EVA should be considered. Experts recommend giving a single dose of doxycycline 200 mg orally at least 1 hour prior to uterine aspiration.2,10

Use of EVA or MVA for outpatient management of miscarriage yields the opportunity to conduct immediate gross examination of the evacuated tissue and to verify the presence of complete POC. The process is simple: rinse the specimen through a sieve with water or saline, placed in a clear glass container under a small water bath and backlit on a light box. This allows clinicians to separate uterine decidua and pregnancy tissues. “Floating” tissue in this manner is especially useful in patients with pregnancy of unknown location, as immediate confirmation of a gestational sac rules out ectopic pregnancy.

Examine evacuated tissue for macroscopic evidence of pregnancy. Chorionic villi, which arise from syncytiotrophoblasts, can be seen with the naked eye. Immediate evaluation of POC is also useful for patients who desire diagnostic testing to ascertain a cause of their miscarriage because evacuated tissue stored in saline may be sent to a laboratory for cytogenetic analysis.

Medical management

Management of miscarriage with misoprostol is also safe and acceptable to women, though it has a lower success rate than surgical management.

Comparing efficacy: Medical vs surgical management. The Management of Early Pregnancy Failure Trial (MEPF) is the largest randomized controlled trial comparing medical management of miscarriage to surgical management. This multicenter study compared treatment with office-based EVA or MVA to vaginal misoprostol 800 µg. A repeat dose of vaginal misoprostol was offered 48 hours after the initial dose if a gestational sac was present on ultrasound.

Findings from the MEPF trial revealed a 71% complete uterine evacuation rate after 1 dose of misoprostol and an 84% rate after 2 doses.1 The average (SD) reported pain score documented within 48 hours of treatment with misoprostol or MVA/EVA was moderate (5.7 cm [2.4] on 10-cm VAS). The rate of infection or hospitalization was less than 1% in both treatment groups.

These data should provide patients who are clinically stable and who wish to avoid an invasive procedure reassurance that using medication for the management of miscarriage is a reasonable option.

Misoprostol. Use of misoprostol is associated with a longer median duration of bleeding compared with suction aspiration. After misoprostol, bleeding usually begins after several hours and may continue for weeks.11 Based on 2-week prospective bleeding diary entries from the MEPF trial, women who used misoprostol for management of miscarriage were more likely to have any bleeding during the 2 weeks after initiation of treatment, compared with women who had suction aspiration.12

Clinically significant changes in hemoglobin levels are more common in women treated with misoprostol than in those who choose EVA or MVA; however, these differences rarely require hospitalization or transfusion.1 Women who are considering use of misoprostol should be aware of common adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and low-grade temperature.

Medical management of miscarriage requires multiple office visits with repeat ultrasounds or serum beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels to confirm treatment success. In cases of medication failure (persistent gestational sac with or without bleeding) or suspected retained POC (endometrial stripe greater than 30 mm measured on ultrasound or persistent vaginal bleeding remote from treatment), women should be prepared for surgical resolution of pregnancy and clinicians should be able to perform an office-based procedure.

Expectant management

Women who choose the “watch and wait” approach should be advised that the process is unpredictable and occasionally requires urgent surgical intervention. Successful resolution of pregnancies that are expectantly managed depends on the type of miscarriage diagnosed at initial presentation. Luise and colleagues conducted a prospective study of 451 women with miscarriage who declined medical and surgical management. They found that the watch-and-wait approach was successful in 91% of women with an incomplete abortion, 76% of women with missed abortion, and 66% of women with anembryonic pregnancies.13 Success was defined by the absence of vaginal bleeding and an anterior-posterior endometrial stripe measuring less than 15 mm 4 weeks after initial diagnosis of miscarriage.

Like medical management for miscarriage, expectant management requires multiple office visits plus repeat ultrasounds or β-hCG measurement trends to confirm treatment success. Women who fail expectant management will require medical or surgical intervention to resolve the pregnancy. For those who are seeking pregnancy right away, the unpredictability and longer time to resolution of miscarriage may render expectant management anxiety provoking and unacceptable.

Etiology: Do true and perceived causes match?

Miscarriage during the first 13 weeks of gestation occurs in at least 10% of all clinically diagnosed pregnancies.10 A recent survey administered by Bardos and colleagues

assessed perceived prevalence and causes of miscarriage in more than 1,000 US men and women.14 The majority of respondents believed miscarriage is uncommon, occurring in less than 5% of pregnancies. Respondents also believed stressful events, lifting heavy objects, and prior use of intrauterine or hormonal contraception are often to blame for pregnancy loss.

Despite more than 3 decades of data confirming that more than 60% of early losses are associated with chromosomal abnormalities and that an additional 18% may be associated with fetal anomalies, women often blame themselves.15 Bardos and colleagues found that 47% of women felt guilty about the experience of miscarriage.

Diagnosis: Updated ultrasonography criteria issued

When miscarriage is suspected based on symptoms of pain and bleeding in preg-

nancy, obtain a thorough history and conduct a limited physical examination. If an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) was previously identified, a repeat ultrasound can confirm the presence or absence of the gestational sac. If an IUP has not been documented, then additional studies, including serial serum β-hCG examinations and ultrasonography, are essential to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Rh status should be determined and a 50-µg dose of Rh(D)-immune globulin administered to Rh(D)-unsensitized women within 72 hours of documented bleeding.

Ultrasonography is often used to diagnose miscarriage. Many gynecologists use ultrasound criteria based on studies conducted in the early 1990s that define nonviability by an empty gestational sac with mean gestational sac diameter greater than 16 mm or a crown-rump length (CRL) without evidence of fetal cardiac activity greater than 5 mm.10 In 2012, members of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy developed more conservative criteria for the diagnosis of miscarriage.16

Doubilet and colleagues suggested new cutoffs, based on their reanalysis of 2 large prospective studies conducted in the United Kingdom.17 Calculations for these new cut-offs are based on mathematical adjustments for interobserver variability. Strict adherence to these more conservative criteria is sensible when a pregnancy is desired. For women who do not want to continue the pregnancy there is no medical justification for using this diagnostic process. Indeed, delays can lead to stress and poor outcomes including emergent surgical management for spontaneous and heavy bleeding.

Culture change is needed

Patients’ beliefs and scientific evidence about miscarriage are incongruous. By making simple changes in practice and providing straightforward patient education, ObGyns

can demystify the causes of miscarriage and improve its management. In particular, providing office-based MVA when requested can streamline treatment for many women. For too long, patients have blamed themselves for miscarriage and physicians have relied on D&C in the OR. Changes in culture surrounding miscarriage are

long overdue.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Case Miscarriage in a 29-year-old woman

A woman (G0P0) presents to her gynecologist with amenorrhea for 3 months and a positive home urine pregnancy test. She is 29 years of age. She denies any bleeding or pain and intends to continue the pregnancy, though it was unplanned. Results of office ultrasonography to assess fetal viability reveal an intrauterine gestation with an 8-mm fetal pole but no heartbeat. The diagnosis is miscarriage.

This case illustrates a typical miscarriage diagnosis; most women with miscarriage are asymptomatic and without serious bleeding requiring emergency intervention. The management options include surgical, medical, and expectant. Women should be offered all 3 of these, and clinicians should explain the risks and benefits of each approach. But while each strategy can be safe, effective, and acceptable, many women, as well as their health care providers, will benefit from office-based uterine aspiration. In this article, we present the data available on office-based manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) as well as procedure pointers and urge you to consider MVA in your practice for your patients.

Surgical management

Surgical management of miscarriage offers several clear advantages over medical and expectant management. Perhaps the most important advantage to patients is that surgery offers rapid resolution of miscarriage with the shortest duration of bleeding.1,2 When skilled providers perform electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) or MVA in outpatient or emergency department settings, successful uterine evacuation is completed in a single medical encounter 99% of the time.1 By comparison, several follow-up visits and additional ultrasounds may be required during medical or expectant management. Uterine aspiration rarely requires an operating room (OR). Such a setting should be limited to cases in which the clinical picture reflects:

- hemodynamic instability with active uterine bleeding

- serious uterine infection

- the presence of medical comorbidities in patients who may benefit from additional blood bank and anesthesia resources.

Office-based MVA

Office-based MVA is well tolerated when performed using a combination of verbal distraction and reassurance, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and a paracervical block with or without intravenous sedation.

Evidence on managing pain at MVA. Multiple studies have assessed preprocedure and postprocedure pain using NSAIDs, oral anxiolytics, and local anesthesia at the time of EVA or MVA.3,4 Renner and colleagues found that women who received a paracervical block prior to MVA or EVA reported moderate levels of pain, according to a 100-point visual analogue scale (VAS), at the time of cervical dilation (mean, 42) and uterine aspiration (mean, 63).4 In this same study, patients’ willingness to treat a future pregnancy with EVA or MVA using local anesthesia and their overall satisfaction with the procedure was high (mean, 90 on 100-point VAS).

In-office advantages over the OR. Women and clinicians can avoid the extensive scheduling delays associated with ORs, as well as the complications associated with medical and expectant management, if office-based EVA and MVA services are readily available. Compared with surgical management of miscarriage in an OR, office-based EVA and MVA are faster to complete. For example, Dalton and colleagues compared patients undergoing first-trimester procedures in an office setting with those undergoing a procedure in an OR. The mean procedure time for women treated in an office was 10 minutes, compared with 19 minutes for women treated in the OR. In addition, women treated in an office setting spent a mean total of 97 minutes at the office; women treated in an OR spent a mean total of 290 minutes at the hospital.5

Patients’ satisfaction with care provided in the OR was comparable to patients’ satisfaction with care provided in a medical office. In fact, the median total satisfaction score was high among women who had a procedure in either setting (office score, 19 of 20; OR score, 20 of 20).

Cost and equipment for in-office MVA

Office-based surgical management of miscarriage is more cost-effective than OR-based management. In 2006, Dalton and colleagues conducted a cost analysis and found that average charges for office-based MVA were less than half the cost of charges for a dilation and curettage (D&C) in the OR ($968 vs $1,965, respectively).5

More recently, these researchers found that usual care (expectant or OR management) was more costly than a model that also included medical and office-based surgical options. They found that the expanded care model—with use of the OR only when needed—cost $1,033.29 per case. This was compared with $1,247.58 per case when management options did not include medical and office-based surgical treatments.6

The cost of supplies needed to initiate MVA services within an established outpatient gynecologist’s office is modest. Equipment includes manual vacuum aspirators; disposable cannulae of various sizes; reusable plastic or metal dilators; supplies for disinfection, allowing reuse of MVA aspirators; and supplies for examination of products of conception (POC; FIGURE 1).

According to WomanCare Global, manufacturer of the IPAS MVA Plus, equipment should be sterilized after each use with soap and water, medical cleaning solution (such as Cidex, SPOROX II, etc.), or autoclaving.7 If 2 reusable aspirators are purchased along with dilators, disposable cannulae, and tools for tissue assessment, the price of supplies is estimated at US $500.8 WomanCare Global also offers prepackaged, single-use aspirator kits, which may be ideal for the emergency department setting.9

The procedure

To view a video on the MVA device and procedure, including step-by-step technique (FIGURE 2), local anesthesia administration, choosing cannula size, and cervical dilation, visit the Managing Early Pregnancy Loss Web site (http://www.earlypregnancylossresources.org) and access “Videos.” The video “Uterine aspiration for EPL” is available under password protection and broken into chapters for viewing ease.

The risk of endometritis after surgical management of miscarriage is low. Antibiotic prophylaxis prior to MVA or EVA should be considered. Experts recommend giving a single dose of doxycycline 200 mg orally at least 1 hour prior to uterine aspiration.2,10

Use of EVA or MVA for outpatient management of miscarriage yields the opportunity to conduct immediate gross examination of the evacuated tissue and to verify the presence of complete POC. The process is simple: rinse the specimen through a sieve with water or saline, placed in a clear glass container under a small water bath and backlit on a light box. This allows clinicians to separate uterine decidua and pregnancy tissues. “Floating” tissue in this manner is especially useful in patients with pregnancy of unknown location, as immediate confirmation of a gestational sac rules out ectopic pregnancy.

Examine evacuated tissue for macroscopic evidence of pregnancy. Chorionic villi, which arise from syncytiotrophoblasts, can be seen with the naked eye. Immediate evaluation of POC is also useful for patients who desire diagnostic testing to ascertain a cause of their miscarriage because evacuated tissue stored in saline may be sent to a laboratory for cytogenetic analysis.

Medical management

Management of miscarriage with misoprostol is also safe and acceptable to women, though it has a lower success rate than surgical management.

Comparing efficacy: Medical vs surgical management. The Management of Early Pregnancy Failure Trial (MEPF) is the largest randomized controlled trial comparing medical management of miscarriage to surgical management. This multicenter study compared treatment with office-based EVA or MVA to vaginal misoprostol 800 µg. A repeat dose of vaginal misoprostol was offered 48 hours after the initial dose if a gestational sac was present on ultrasound.

Findings from the MEPF trial revealed a 71% complete uterine evacuation rate after 1 dose of misoprostol and an 84% rate after 2 doses.1 The average (SD) reported pain score documented within 48 hours of treatment with misoprostol or MVA/EVA was moderate (5.7 cm [2.4] on 10-cm VAS). The rate of infection or hospitalization was less than 1% in both treatment groups.

These data should provide patients who are clinically stable and who wish to avoid an invasive procedure reassurance that using medication for the management of miscarriage is a reasonable option.

Misoprostol. Use of misoprostol is associated with a longer median duration of bleeding compared with suction aspiration. After misoprostol, bleeding usually begins after several hours and may continue for weeks.11 Based on 2-week prospective bleeding diary entries from the MEPF trial, women who used misoprostol for management of miscarriage were more likely to have any bleeding during the 2 weeks after initiation of treatment, compared with women who had suction aspiration.12

Clinically significant changes in hemoglobin levels are more common in women treated with misoprostol than in those who choose EVA or MVA; however, these differences rarely require hospitalization or transfusion.1 Women who are considering use of misoprostol should be aware of common adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and low-grade temperature.

Medical management of miscarriage requires multiple office visits with repeat ultrasounds or serum beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels to confirm treatment success. In cases of medication failure (persistent gestational sac with or without bleeding) or suspected retained POC (endometrial stripe greater than 30 mm measured on ultrasound or persistent vaginal bleeding remote from treatment), women should be prepared for surgical resolution of pregnancy and clinicians should be able to perform an office-based procedure.

Expectant management

Women who choose the “watch and wait” approach should be advised that the process is unpredictable and occasionally requires urgent surgical intervention. Successful resolution of pregnancies that are expectantly managed depends on the type of miscarriage diagnosed at initial presentation. Luise and colleagues conducted a prospective study of 451 women with miscarriage who declined medical and surgical management. They found that the watch-and-wait approach was successful in 91% of women with an incomplete abortion, 76% of women with missed abortion, and 66% of women with anembryonic pregnancies.13 Success was defined by the absence of vaginal bleeding and an anterior-posterior endometrial stripe measuring less than 15 mm 4 weeks after initial diagnosis of miscarriage.

Like medical management for miscarriage, expectant management requires multiple office visits plus repeat ultrasounds or β-hCG measurement trends to confirm treatment success. Women who fail expectant management will require medical or surgical intervention to resolve the pregnancy. For those who are seeking pregnancy right away, the unpredictability and longer time to resolution of miscarriage may render expectant management anxiety provoking and unacceptable.

Etiology: Do true and perceived causes match?

Miscarriage during the first 13 weeks of gestation occurs in at least 10% of all clinically diagnosed pregnancies.10 A recent survey administered by Bardos and colleagues

assessed perceived prevalence and causes of miscarriage in more than 1,000 US men and women.14 The majority of respondents believed miscarriage is uncommon, occurring in less than 5% of pregnancies. Respondents also believed stressful events, lifting heavy objects, and prior use of intrauterine or hormonal contraception are often to blame for pregnancy loss.

Despite more than 3 decades of data confirming that more than 60% of early losses are associated with chromosomal abnormalities and that an additional 18% may be associated with fetal anomalies, women often blame themselves.15 Bardos and colleagues found that 47% of women felt guilty about the experience of miscarriage.

Diagnosis: Updated ultrasonography criteria issued

When miscarriage is suspected based on symptoms of pain and bleeding in preg-

nancy, obtain a thorough history and conduct a limited physical examination. If an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) was previously identified, a repeat ultrasound can confirm the presence or absence of the gestational sac. If an IUP has not been documented, then additional studies, including serial serum β-hCG examinations and ultrasonography, are essential to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Rh status should be determined and a 50-µg dose of Rh(D)-immune globulin administered to Rh(D)-unsensitized women within 72 hours of documented bleeding.

Ultrasonography is often used to diagnose miscarriage. Many gynecologists use ultrasound criteria based on studies conducted in the early 1990s that define nonviability by an empty gestational sac with mean gestational sac diameter greater than 16 mm or a crown-rump length (CRL) without evidence of fetal cardiac activity greater than 5 mm.10 In 2012, members of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy developed more conservative criteria for the diagnosis of miscarriage.16

Doubilet and colleagues suggested new cutoffs, based on their reanalysis of 2 large prospective studies conducted in the United Kingdom.17 Calculations for these new cut-offs are based on mathematical adjustments for interobserver variability. Strict adherence to these more conservative criteria is sensible when a pregnancy is desired. For women who do not want to continue the pregnancy there is no medical justification for using this diagnostic process. Indeed, delays can lead to stress and poor outcomes including emergent surgical management for spontaneous and heavy bleeding.

Culture change is needed

Patients’ beliefs and scientific evidence about miscarriage are incongruous. By making simple changes in practice and providing straightforward patient education, ObGyns

can demystify the causes of miscarriage and improve its management. In particular, providing office-based MVA when requested can streamline treatment for many women. For too long, patients have blamed themselves for miscarriage and physicians have relied on D&C in the OR. Changes in culture surrounding miscarriage are

long overdue.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, Creinin MD, Westhoff C, Frederick MM. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Eng J Med. 2005;353(8):761−769.

2. Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD, eds. Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

3. Edelman A, Nichols MD, Jensen J. Comparison of pain and time of procedures with two first-trimester abortion techniques performed by residents and faculty. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1564−1567.

4. Renner RM, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Li H, Edelman AB. Paracervical block for pain control in first-trimester surgical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1030−1037.

5. Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, Guire K, Castleman L, Lebovic D. Patient p, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):103−110.

6. Dalton VK, Liang A, Hutton DW, Zochowski MK, Fendrick AM. Beyond usual care: the economic consequences of expanding treatment options in early pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):177.e171−177.e176.

7. Ipas. Ipas start-up kit for integrating manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) for early pregnancy loss into women’s reproductive healthcare services. Chapel Hill, NC: Ipas; 2009.

8. MVA Products page. HPSRx Web site. http://www.hpsrx.com/mva-products.html. Accessed October 13, 2015.

9. Kinariwala M, Quinley KE, Datner EM, Schreiber CA. Manual vacuum aspiration in the emergency department for management of early pregnancy failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):244−247.

10. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 150: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1258−1267.

11. Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, Goldberg AB, Darney PD. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes: drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Part 1):582−590.

12. Davis AR, Hendlish SK, Westhoff C, et al. Bleeding patterns after misoprostol vs surgical treatment of early pregnancy failure: results from a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):31.e31−31.e37.

13. Luise C, Jermy K, May C, Costello G, Collins WP, Bourne TH. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324(7342):873−875.

14. Bardos J, Hercz D, Friedenthal J, Missmer SA, Williams Z. A national survey on public perceptions of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1313−1320.

15. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(5):1103−1111.

16. Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, Blaivas M. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Eng JMed. 2013;369(15):1443−1451.

17. Abdallah Y, Daemen A, Kirk E, et al. Limitations of current definitions of miscarriage using mean gestational sac diameter and crown–rump length measurements: a multicenter observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(5):497−502.

1. Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, Creinin MD, Westhoff C, Frederick MM. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Eng J Med. 2005;353(8):761−769.

2. Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD, eds. Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

3. Edelman A, Nichols MD, Jensen J. Comparison of pain and time of procedures with two first-trimester abortion techniques performed by residents and faculty. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1564−1567.

4. Renner RM, Nichols MD, Jensen JT, Li H, Edelman AB. Paracervical block for pain control in first-trimester surgical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1030−1037.

5. Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, Guire K, Castleman L, Lebovic D. Patient p, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):103−110.

6. Dalton VK, Liang A, Hutton DW, Zochowski MK, Fendrick AM. Beyond usual care: the economic consequences of expanding treatment options in early pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):177.e171−177.e176.

7. Ipas. Ipas start-up kit for integrating manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) for early pregnancy loss into women’s reproductive healthcare services. Chapel Hill, NC: Ipas; 2009.

8. MVA Products page. HPSRx Web site. http://www.hpsrx.com/mva-products.html. Accessed October 13, 2015.

9. Kinariwala M, Quinley KE, Datner EM, Schreiber CA. Manual vacuum aspiration in the emergency department for management of early pregnancy failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):244−247.

10. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 150: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1258−1267.

11. Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, Goldberg AB, Darney PD. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes: drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Part 1):582−590.

12. Davis AR, Hendlish SK, Westhoff C, et al. Bleeding patterns after misoprostol vs surgical treatment of early pregnancy failure: results from a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):31.e31−31.e37.

13. Luise C, Jermy K, May C, Costello G, Collins WP, Bourne TH. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324(7342):873−875.

14. Bardos J, Hercz D, Friedenthal J, Missmer SA, Williams Z. A national survey on public perceptions of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1313−1320.

15. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(5):1103−1111.

16. Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, Blaivas M. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Eng JMed. 2013;369(15):1443−1451.

17. Abdallah Y, Daemen A, Kirk E, et al. Limitations of current definitions of miscarriage using mean gestational sac diameter and crown–rump length measurements: a multicenter observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(5):497−502.

In this Article

- Advantages of office-based manual vacuum aspiration

- Medical management

- Current diagnostic criteria

Medial Patellar Subluxation: Diagnosis and Treatment

Medial patellar subluxation (MPS) is a disabling condition caused by an imbalance in the medial and lateral forces in the normal knee, allowing the patella to displace medially. Normally, the patella glides appropriately in the femoral trochlea, but alteration in this medial–lateral equilibrium can lead to pain and instability.1 MPS was first described in 1987 by Betz and colleagues2 as a complication of lateral retinacular release. Since then, multiple cases of iatrogenic, traumatic, and isolated medial subluxation have been reported.3–15 However, MPS after lateral release is the most common cause, accounting for the majority of published cases, whereas only 8 cases of isolated MPS have been reported to date.

Optimal treatment for MPS is not well understood. To better comprehend and manage MPS, we must fully appreciate the pathoanatomy, biomechanics, and current research. In this review, we focus on the anatomy of the lateral retinaculum, diagnosis and treatment of MPS, and outcomes of current treatment techniques.

Anatomy

In 1980, Fulkerson and Gossling16 delineated the anatomy of the knee joint lateral retinaculum. They described a 2-layered system with separate distinct anatomical structures. The lateral retinaculum is oriented longitudinally with the knee extended but exerts a posterolateral force on the lateral aspect of the patella as the knee is flexed. The superficial layer is composed of oblique fibers of the lateral retinaculum originating from the iliotibial band and the vastus lateralis fascia and inserting into the lateral margin of the patella and the patella tendon. The deep layer of the retinaculum consists of several structures, including the deep transverse retinaculum, lateral patellofemoral ligament (LPFL), and the patellotibial band.

Over the years, several studies have described the importance of the lateral retinaculum and, in particular, the LPFL. Examining the functional anatomy of the knee in 1962, Kaplan17 first described the lateral epicondylopatellar ligament as a palpable thickening of the joint capsule. Reider and colleagues18 later named this structure the lateral patellofemoral ligament in their anatomical study of 21 fresh cadaver knees. They described its width as ranging from 3 to 10 mm. In a comprehensive cadaveric study of the LPFL, Navarro and colleagues19,20 found it to be a distinct structure present in all 20 of their dissected specimens. They found its femoral insertion at the lateral epicondyle with a fanlike expansion of the fibers predominantly in the posterior region proximal to the lateral epicondyle. The patellar insertion was found in the posterior half and upper lateral aspect, also with expanded fibers. Mean length of the LPFL is 42.1 mm, and mean width is 16.1 mm.

Medial and lateral forces are balanced in a normal knee, and the patella glides appropriately in the femoral trochlea. Alteration in this medial–lateral equilibrium can lead to pain and instability.1 Normally, the patella lies laterally with the knee extended, but in early flexion the patella moves medially as it engages in the trochlea. As the knee continues to flex, the patella flexes and translates distally.21 By 45°, the patella is fully engaged in the trochlear groove throughout the remainder of the knee’s range of motion (ROM).

Lateral release procedures, as described in the literature, result in sectioning of both layers of the lateral retinaculum. In a biomechanical study, Merican and colleagues22 found that staged release of the lateral retinaculum reduced the medial stability of the patellofemoral joint progressively, making it easier to push the patella medially. At 30° of flexion, the transverse fibers of the midsection of the lateral retinaculum were found to be the main contributor to the lateral restraint of the patella. When the release extends too far proximally, the transverse fibers that anchor the lateral patella and the vastus lateralis oblique tendon to the iliotibial band are disrupted. Subsequent loss of a dynamic muscular pull in the orientation of the lateral stabilizing structures results in medial subluxation in a range from full knee extension to about 30° of flexion.

Furthermore, the attachments of the LPFL and the orientation of its fibers suggest that the LPFL may have a significant role in limiting medial excursion of the patella. Vieira and colleagues23 resected the LPFL in 10 fresh cadaver knees. They noticed that, after resection, the patella spontaneously traveled medially, demonstrating the importance of this ligament in patellar stability. In cases of isolated MPS, there have been no reports of associated pathology, such as muscular imbalance or coronal/rotational malalignment of the lower extremity. With an intact lateral retinaculum, medial subluxation is likely caused by pathology in the normal histologic structure of the LPFL and lateral retinaculum. However, the histologic structure of the LPFL and its contribution to the understanding of the pathoetiology of MPS have not been documented.

Diagnosis

MPS diagnosis can be challenging. Often, clinical examination findings are subtle, and radiographs may not show significant pathology. The most accurate diagnosis is obtained by combining patient history, physical examination findings, imaging studies, and diagnostic arthroscopy.

Patient History

Patients with MPS report chronic pain localized to the inferior medial patella and anterior-medial joint line. Occasionally, they complain of crepitus and intermittent swelling. Other symptoms include pain with knee flexion activity, such as squatting and climbing or descending stairs. Some patients describe episodes of giving way and feelings of instability. Often, they are aware the direction of instability is medial. The pain typically is not relieved by medication, physical therapy, or bracing.

Physical Examination

MPS must be identified by clinical examination. Peripatellar tenderness is typically noted. There is often no effusion or crepitus, but the patella is unstable in early flexion. Active and passive ROM is painful through the first 30° of knee flexion. The patient may have a positive medial apprehension test7 in which he or she experiences apprehension of the patella being subluxated with a medially directed force on the lateral border of the patella.

The gravity subluxation test described by Nonweiler and DeLee6 is useful in detecting MPS after lateral release and indicates that the vastus lateralis muscle has been detached from the patella and that the lateral retinaculum is lax. In this test, the patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position with the involved knee farthest from the table. In this position, gravity causes the patella to subluxate out of the trochlea. The test is positive for MPS when a voluntary contraction of the quadriceps does not center the patella into the trochlear groove. Patients with MPS without previous lateral release can have the patella subluxate medially in the lateral decubitus position, but it is pulled back into the trochlea with active quadriceps contraction (Figure 1).

Patients with MPS often have lateral patellar laxity (LPL), which allows the patella to rotate upward on the lateral side and skid across the medial facet of the femoral trochlea. A physical examination sign combining lateral patellar glide and tilt was described by Shneider24 to identify LPL. This “lateral patellar float” sign is present when the patella translates laterally and rotates or tilts upward with medial pressure on the patella (Figure 2). Another maneuver to test for subtle MPS involves manually centering the patella in the trochlea during active knee flexion and extension. The involved knee is examined in the seated position. The examiner attempts to center the patella in the trochlea with a laterally directed force from the examiner’s thumb on the medial border of the patella. This will usually provide immediate relief as the patient actively ranges the knee.

Imaging Studies

Diagnostic imaging is a crucial component of the evaluation and treatment decision process. Plain radiographs often are not helpful in diagnosing MPS but may provide additional information.5 A variety of radiographic measurements have been described as indicators of structural disease, but there is a lack of comprehensive information recommending radiographic evaluation and interpretation of patients with patellofemoral dysfunction. It is crucial that orthopedic surgeons have common and consistent radiographic views for plain radiographic assessment that can serve as a basis for accurate diagnosis and surgical decision-making.

Standard knee radiographs should include a standing anteroposterior view of bilateral knees, a standing lateral view of the symptomatic knee in 30° of flexion, a patellar axial view, and a tunnel view. These views, occasionally combined with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can yield information vital to surgical decision-making. Image quality is highly technique-dependent, and variability in patient positioning can substantially affect the ability to properly diagnose structural abnormalities. For improved diagnostic accuracy and disease classification, radiographs must be obtained with use of the same standardized imaging protocol.

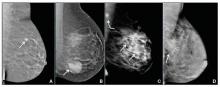

Kinetic MRI was shown by Shellock and colleagues25 to provide diagnostic information related to patellar malalignment. As kinetic MRI can image the patellofemoral joint within the initial 20° to 30° of flexion, it is useful in detecting some of the more subtle patellar tracking problems. In their study of 43 knees (40 patients) with symptoms after lateral release, Shellock and colleagues25 found that 27 knees (63%) had medial subluxation of the patella as the knee moved from extension to flexion. Furthermore, MPS was noted on the contralateral, unoperated knee in 17 (43%) of the 40 patients.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

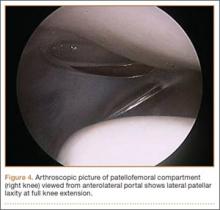

Once MPS is suspected after a thorough history and physical examination, examination under anesthesia accompanied by diagnostic arthroscopy confirms the diagnosis. Lateral forces are applied to the patella in full knee extension and 30° of flexion (Figure 3). During arthroscopy, the patellofemoral compartment is viewed from the anterolateral portal. With the knee at full extension, the lateral laxity and medial tilt of the patella can be identified (Figure 4). As the knee is flexed to 30°, the patella moves medially and can subluxate over the edge of the medial facet of the trochlea (Figure 5).

Treatment

Nonsurgical Management

Treatment of MPS depends entirely on making an accurate diagnosis and determining the degree of impairment. Patients with symptomatic MPS should initially undergo supervised rehabilitation focusing on balancing the medial and lateral forces that influence patellar tracking. Patients should be evaluated for specific muscle tightness, weakness, and biomechanical abnormalities. Each problem should be addressed with an individualized rehabilitation prescription. Emphasis is placed on balance, proprioception, and strengthening of the quadriceps, hip abductors/external rotators, and abdominal core muscle groups.

In some patients, symptomatic MPS may be reduced with a patella-stabilizing brace with a medial buttress.3,5,26 Although bracing should be regarded as an adjuvant to a structured physical therapy program, it can also be helpful in confirming the diagnosis of MPS. Shannon and Keene3 reported that all patients in their study experienced significant pain relief and decreased medial patellar subluxations when they wore a medial patella–stabilizing brace. Shellock and colleagues25 used kinematic MRI to investigate the effect of a patella-realignment brace and found that bracing counteracted patellar subluxation in the majority of knees studied.

Surgical Management

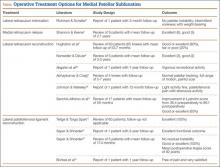

When conservative management fails and patients continue to experience pain and instability, surgical intervention is often required. Although various surgical techniques have been used (Table),3–6,8–10,14,15,27,28 the optimal surgical treatment for MPS has not been identified.

Lateral Retinaculum Imbrication. Lateral retinaculum imbrication has been used to centralize patella tracking and stabilize the patella. Richman and Scheller5 reported on a 17-year-old patient who had isolated medial subluxation of the patella without having undergone a previous lateral release. At 3-month follow-up, there was no recurrent instability; there was only intermittent medial knee soreness with weight-bearing activity.

Lateral Retinaculum Repair/Reconstruction. Hughston and colleagues8 treated 65 knees for MPS. Most had undergone lateral release. Of the 65 knees, 39 were treated with direct repair of the lateral retinaculum, and 26 with reconstruction of the lateral patellotibial ligament using locally available tissue, such as strips of iliotibial band or patellar tendon. Results were good to excellent in 80% of patients at a mean follow-up of 53.7 months. Nonweiler and DeLee6 reconstructed the lateral retinaculum in 5 patients with MPS that developed after isolated lateral retinacular release. Four (80%) of the 5 patients had no symptoms or physical signs of instability at a mean follow-up of 3.3 years. Results were excellent (3 knees) and good (2 knees) according to the Merchant and Mercer rating scale. Akşahin and colleagues28 reported on a single case of spontaneous medial patellar instability. At surgery, imbrication of the lateral structures failed to prevent the medial subluxation. Lateral patellotibial ligament augmentation was performed using an iliotibial band flap that effectively corrected the instability. At 1 year, the patient was characterized as engaging in vigorous recreational activity, according to the clinical score defined by Hughston and colleagues.8 He had mild pain with competitive sports but no pain with daily activity. Abhaykumar and Craig9 reported on 4 surgically treated knees with medial instability. They reconstructed the lateral retinaculum using a strip of fascia lata. By follow-up (5-7 years), each knee had its instability resolved and full ROM restored. Johnson and Wakeley26 reported on a case of iatrogenic MPS after lateral release. Treatment consisted of mobilization and direct repair of the lateral retinaculum. At 12-month follow-up, there was no instability. Although symptom-free with light activity, the patient had patellofemoral pain with strenuous activity. Sanchis-Alfonso and colleagues14 reported the results of isolated lateral retinacular reconstruction for iatrogenic MPS in 17 patients. At mean follow-up of 56 months, results were good or excellent in 65% of patients, and the Lysholm score improved from 36.4 preoperatively to 86.1 postoperatively.

Medial Retinaculum Release. Medial retinaculum release has been used as an alternative to open reconstruction. Shannon and Keene3 reported the results of medial retinacular release procedures on 9 knees. Four (44%) of the 9 patients had either spontaneous or traumatic onset of instability. All cases were treated with arthroscopic medial retinacular release, extending 2 cm medial to the superior pole of the patella down to the anteromedial portal. This avoided releasing the attachment of the vastus medialis oblique muscle to the patella and removing its dynamic medial stabilizing force. At a mean follow-up of 2.7 years, both medial subluxation and knee pain were relieved in all 9 knees without complications or further realignment surgery. Results were excellent in 6 knees (66.7%) and good in 3 knees (33.3%). Shannon and Keene3 emphasized that the procedure should not be used in patients with hypermobile patellae or in cases of failed lateral retinacular releases in which MPS is not clearly and carefully documented.

LPFL Reconstruction. Before coming to our practice, most patients have tried several months of formal physical rehabilitation, medications, and bracing. Many have already had surgical procedures, including arthroscopy, lateral release, and tibial tubercle transfer. When the diagnosis of MPS is suspected after a thorough history and physical examination, LPFL reconstruction is offered. Management of MPS with LPFL reconstruction has yielded excellent and reliable clinical results. Teitge and Torga Spak10 described an LPFL reconstruction technique that is used as a salvage procedure in managing medial iatrogenic patellar instability (the patient’s own quadriceps tendon is used). In their experience, direct repair or imbrication of the lateral retinaculum failed to provide long-term stability because medial excursion usually appeared after 1 year. The 60 patients’ outcomes were excellent with respect to patellar stability, and there were no cases of recurrent subluxation. Borbas and colleagues15 reported a case of LPFL reconstruction in a symptomatic medial subluxated patella resulting from TKA and extended lateral release. Using a free gracilis autograft through patellar bone tunnels to reconstruct the LPFL, the patient was free of pain and very satisfied with the result at 1 year postoperatively. Our current strategy is anatomical reconstruction of the LPFL using a quadriceps tendon graft and no bone tunnels, screws, or anchors in the patella.27 We previously reported a single case of isolated medial instability.4 At 2-year follow-up, there was no recurrent instability, and the functional outcome was excellent. This LPFL reconstruction method has been used in 10 patients with isolated MPS. There has been no residual medial subluxation on follow-up ranging from 3 months to 2 years. Outcome studies are in progress.

Rehabilitation. The initial goal of rehabilitation after surgical reconstruction of the lateral retinaculum or LPFL is to protect the healing soft tissues, restore normal knee ROM, and normalize gait. The knee is immobilized in a brace for weight-bearing activity for 4 to 6 weeks, until limb control is sufficient to prevent rotational stress on the knee. Gradual increase to full weight-bearing without bracing is permitted as quadriceps strength is restored. As motion is regained, strength, balance, and proprioception are emphasized for the entire lower extremity and core.

Functional limb training, including rotational activity, begins at 12 weeks. As strength and neuromuscular control progress, single-leg activity may be started with particular attention to proper alignment of the pelvis and the entire lower extremity. For competitive or recreational athletes, the final stages of rehabilitation focus on dynamic lower extremity control during sport-specific movements. Patients return to unrestricted activity by 6 months to 1 year after surgery.

Summary

MPS is a disabling condition that can limit daily functional activity because of apprehension and pain. Initially described as a complication of lateral retinacular release, isolated MPS can occur in the absence of a previous lateral release. Thorough physical examination and identification during arthroscopy are crucial for proper MPS diagnosis and management. When nonsurgical measures fail, LPFL reconstruction can provide patellofemoral stability and excellent functional outcomes.

1. Marumoto JM, Jordan C, Akins R. A biomechanical comparison of lateral retinacular releases. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):151-155.

2. Betz RR, Magill JT, Lonergan RP. The percutaneous lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(5):477-482.

3. Shannon BD, Keene JS. Results of arthroscopic medial retinacular release for treatment of medial subluxation of the patella. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1180-1187.

4. Saper MG, Shneider DA. Medial patellar subluxation without previous lateral release: a case report. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23(4):350-353.

5. Richman NM, Scheller AD Jr. Medial subluxation of the patella without previous lateral retinacular release. Orthopedics. 1998;21(7):810-813.

6. Nonweiler DE, DeLee JC. The diagnosis and treatment of medial subluxation of the patella after lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(5):680-686.

7. Hughston JC, Deese M. Medial subluxation of the patella as a complication of lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):383-388.

8. Hughston JC, Flandry F, Brinker MR, Terry GC, Mills JC 3rd. Surgical correction of medial subluxation of the patella. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(4):486-491.

9. Abhaykumar S, Craig DM. Fascia lata sling reconstruction for recurrent medial dislocation of the patella. The Knee. 1999;6(1):55-57.

10. Teitge RA, Torga Spak R. Lateral patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(9):998-1002.

11. Kusano M, Horibe S, Tanaka Y, et al. Simultaneous MPFL and LPFL reconstruction for recurrent lateral patellar dislocation with medial patellofemoral instability. Asia-Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2014;1:42-46.

12. Saper MG, Shneider DA. Simultaneous medial and lateral patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for combined medial and lateral patellar subluxation. Arthrosc Tech. 2014,3(2):e227-e231.

13. Udagawa K, Niki Y, Matsumoto H, et al. Lateral patellar retinaculum reconstruction for medial patellar instability following lateral retinacular release: a case report. Knee. 2014;21(1):336-339.

14. Sanchis-Alfonso V, Montesinos-Berry E, Monllau JC, Merchant AC. Results of isolated lateral retinacular reconstruction for iatrogenic medial patellar instability. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(3):422-427.

15. Borbas P, Koch PP, Fucentese SF. Lateral patellofemoral ligament reconstruction using a free gracilis autograft. Orthopedics. 2014;37(7):e665-e668.

16. Fulkerson JP, Gossling H. Anatomy of the knee joint lateral retinaculum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;153:183-188.

17. Kaplan E. Some aspects of functional anatomy of the human knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1962;23:18-29.

18. Reider B, Marshall J, Koslin B, Ring B, Girgis F. The anterior aspect of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(3):351-356.

19. Navarro MS, Navarro RD, Akita Junior J, Cohen M. Anatomical study of the lateral patellofemoral ligament in cadaver knees. Rev Bras Ortop. 2008;43(7):300-307.

20. Navarro MS, Beltrani Filho CA, Akita Junior J, Navarro RD, Cohen M. Relationship between the lateral patellofemoral ligament and the width of the lateral patellar facet. Acta Ortop Bras. 2010;18(1):19-22.

21. Salsich GB, Ward SR, Terk MR, Powers CM. In vivo assessment of patellofemoral joint contact area in individuals who are pain free. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:277-284.

22. Merican AM, Kondo E, Amis AA. The effect on patellofemoral joint stability of selective cutting of lateral retinacular and capsular structures. J Biomech. 2009;42(3):291-296.

23. Vieira EL, Vieira EÁ, da Silva RT, Berlfein PA, Abdalla RJ, Cohen M. An anatomic study of the iliotibial tract. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(3):269-274.

24. Shneider DA. Lateral patellar laxity—identification, significance, treatment. Poster session presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; February 25-28, 2009; Las Vegas, NV.

25. Shellock FG, Mink JH, Deutsch A, Fox JM, Ferkel RD. Evaluation of patients with persistent symptoms after lateral retinacular release by kinematic magnetic resonance imaging of the patellofemoral joint. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(3):226-234.

26. Johnson DP, Wakeley C. Reconstruction of the lateral patellar retinaculum following lateral release: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10(6):361-363.

27. Saper MG, Shneider DA. Lateral patellofemoral ligament reconstruction using a quadriceps tendon graft. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e445-e448.

28. Akşahin E, Yumrukçal F, Yüksel HY, Doğruyol D, Celebi L. Role of pathophysiology of patellofemoral instability in the treatment of spontaneous medial patellofemoral subluxation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:148.

Medial patellar subluxation (MPS) is a disabling condition caused by an imbalance in the medial and lateral forces in the normal knee, allowing the patella to displace medially. Normally, the patella glides appropriately in the femoral trochlea, but alteration in this medial–lateral equilibrium can lead to pain and instability.1 MPS was first described in 1987 by Betz and colleagues2 as a complication of lateral retinacular release. Since then, multiple cases of iatrogenic, traumatic, and isolated medial subluxation have been reported.3–15 However, MPS after lateral release is the most common cause, accounting for the majority of published cases, whereas only 8 cases of isolated MPS have been reported to date.