User login

The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: A Novel Interactive Database Within the Veterans Health Administration (FULL)

The VA MS Surveillance Registry combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US.

A number of large registries exist for multiple sclerosis (MS) in North America and Europe. The Scandinavian countries have some of the longest running and integrated MS registries to date. The Danish MS Registry was initiated in 1948 and has been consistently maintained to track MS epidemiologic trends.2 Similar databases exist in Swedenand Norway that were created in the later 20th century.3,4 The Rochester Epidemiology Project, launched by Len Kurland at the Mayo Clinic, has tracked the morbidity of MS and many other conditions in Olmsted county Minnesota for > 60 years.5

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba also have long standing MS registries.6-8 Other North American MS registries have gathered state-wide cases, such as the New York State MS Consortium.9 Some registries have gathered a population-based sample throughout the US, such as the Sonya Slifka MS Study.10 The North American Research Consortium on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a patient-driven registry within the US that has enrolled > 30,000 cases.11 The MSBase is the largest online registry to date utilizing data from several countries.12 The MS Bioscreen, based at the University of California San Francisco, is a recent effort to create a longitudinal clinical dataset.13 This electronic registry integrates clinical disease morbidity scales, neuroimaging, genetics and laboratory data for individual patients with the goal of providing predictive tools.

The US military provides a unique population to study MS and has the oldest and largest nation-wide MS cohort in existence starting with World War I service members and continuing through the recent Gulf War Era.14 With the advent of EHRs in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the mid-1990s and large clinical databases, the possibility of an integrated registry for chronic conditions was created. In this report, we describe the creation of the VA MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR) and the initial roll out to several VA medical centers within the MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE). The MSSR is a unique platform with potential for improving MS patient care and clinical research.

Methods

The MSSR was designed by MSCoE health care providers in conjunction with IT specialists from the VA Northwest Innovation Center. Between 2012 and 2013, the team developed and tested a core template for data entry and refined an efficient data dashboard display to optimize clinical decisions. IT programmers created data entry templates that were tested by 4 to 5 clinicians who provided feedback in biweekly meetings. Technical problems were addressed and enhancements added and the trial process was repeated.

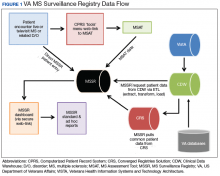

After creation of the prototype MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) data entry template that fed into the prototype MSSR, our team received a grant in 2013 for national development and sustainment. The MSSR was established on the VA Converged Registries Solution (CRS) platform, which is a hardware and software architecture designed to host individual clinical registries and eliminate duplicative development effort while maximizing the ability to create new patient registries. The common platform includes a relational database, Health Level 7 messaging, software classes, security modules, extraction services, and other components. The CR obtains data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), directly from the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) and via direct user input using MSAT.

From 2016 to 2019, data from patients with MS followed in several VA MS regional programs were inputted into MSSR. A roll-out process to start patient data entry at VA medical centers began in 2017 that included an orientation, technical support, and quality assurance review. Twelve sites from Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN) 5 (mid-Atlantic) and VISN 20 (Pacific Northwest) were included in the initial roll-out.

Results

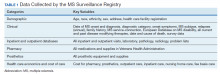

After a live or remote telehealth or telephone visit, a clinician can access MSAT from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or directly from the MSSR online portal (Figure 1). The tool uses radio buttons and pull-down menus and takes about 5 to 15 minutes to complete with a list of required variables. Data is auto-saved for efficiency, and the key variables that are collected in MSAT are noted in Table 1. The MSAT subsequently creates a text integration utility progress note with health factors that is processed through an integration engine and eventually transmitted to VISTA and becomes part of the EHR and available to all health care providers involved in that patient’s care. Additionally, data from VA outpatient and inpatient utilization files, pharmacy, prosthetics, laboratory, and radiology databases are included in the CDW and are included in MSSR. With data from 1998 to the present, the MSAT and CDW databases can provide longitudinal data analysis.

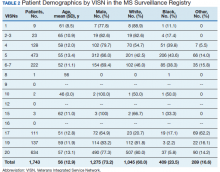

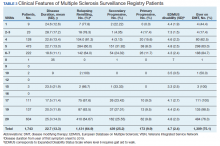

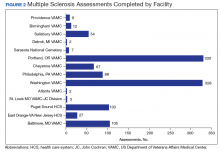

Between 18,000 and 20,000 patients with MS are evaluated in the VHA annually, and 56,000 unique patients have been assessed since 1998. From 2016 to 2019, 1,743 patients with MS or related disorders were enrolled in MSSR (Table 2 and Figure 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 56.0 (12.9) years and the male:female ratio was 2.7. Racial minorities make up 40% of the cohort. Among those with definite and possible MS, the mean disease duration was 22.7 years and the mean (SD) European Database for MS disability score was 4.7 (2.4) (Table 3). Three-quarters of the MSSR cohort have used ≥ 1 MS disease modifying therapy and 65% were classified as relapsing-remitting MS. An electronic dashboard was developed for health care providers to easily access demographic and clinical data for individuals and groups of patients (Figure 3). Standard and ad hoc reports can be generated from the MSSR. Larger longitudinal analyses can be performed with MSAT and clinical data from CDW. Data on comorbid conditions, pharmacy, radiology and prosthetics utilization, outpatient clinic and inpatient admission can be accessed for each patient or a group of patients.

In 2015, MSCoE published a larger national survey of the VA MS population.15 This study revealed that the majority of clinical features and demographics of the MSSR were not significantly different from other major US MS registries including the North American Research Committee on MS, the New York State MS Consortium, and the Sonya Slifka Study.16-18

Discussion

The MSSR is novel in that it combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US. This new registry leverages the existing databases related to cost of care, utilization, and pharmacy services to provide surveillance tools for longitudinal follow-up of the MS population within the VHA. Because the structure of the MSAT and MSSR were developed in a partnership between IT developers and clinicians, there has been mutual buy-in for those who use it and maintain it. This registry can be a test bed for standardized patient outcomes including the recently released MS Quality measures from the American Academy of Neurology.19

To achieve greater numbers across populations, there has been efforts in Europe to combine registries into a common European Register for MS. A recent survey found that although many European registries were heterogeneous, it would be possible to have a minimum common data set for limited epidemiologic studies.20 Still many registries do not have environmental or genetic data to evaluate etiologic questions.21 Additionally, most registries are not set up to evaluate cost or quality of care within a health care system.

Recommendations for maximizing the impact of existing MS registries were recently released by a panel of MS clinicians and researchers.22 The first recommendation was to create a broad network of registries that would communicate and collaborate. This group of MS registries would have strategic oversight and direction that would greatly streamline and leverage existing and future efforts. Second, registries should standardize data collection and management thereby enhancing the ability to share data and perform meta-analyses with aggregated data. Third, the collection of physician- and patient-reported outcomes should be encouraged to provide a more complete picture of MS. Finally, registries should prioritize research questions and utilize new technologies for data collection. These recommendations would help to coordinate existing registries and accelerate knowledge discovery.

The MSSR will contribute to the growing registry network of data. The MSSR can address questions about clinical outcomes, cost, quality with a growing data repository and linked biobank. Based on the CR platform, the MSSR allows for integration with other VA clinical registries, including registries for traumatic brain injuries, oncology, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and eye injuries. Identifying case outcomes related to other registries is optimized with the CR common structure.

Conclusion

The MSSR has been a useful tool for clinicians managing individual patients and their regional referral populations with real-time access to clinical and utilization data. It will also be a useful research tool in tracking epidemiological trends for the military population. The MSSR has enhanced clinical management of MS and serves as a national source for clinical outcomes.

1. Flachenecker P. Multiple sclerosis databases: present and future. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(suppl 1):29-31.

2. Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M, Laursen B. Registers of multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):4-10.

3. Alping P, Piehl F, Langer-Gould A, Frisell T; COMBAT-MS Study Group. Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):230-233.

4. Benjaminsen E, Myhr KM, Grytten N, Alstadhaug KB. Validation of the multiple sclerosis diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2019;9(11):e01422.

5. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202-1213.

6. Kingwell E, Zhu F, Marrie RA, et al. High incidence and increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in British Columbia, Canada: findings from over two decades (1991-2010). J Neurol. 2015;262(10):2352-2363.

7. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914-1929.

8. Mahmud SM, Bozat-Emre S, Mostaço-Guidolin LC, Marrie RA. Registry cohort study to determine risk for multiple sclerosis after vaccination for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with Arepanrix, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1267-1274.

9. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Cutter G, Herbert J; New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Trend for decreasing Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MSSS) with increasing calendar year of enrollment into the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):725-733.

10. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12(1):24-38.

11. Fox RJ, Salter A, Alster JM, et al. Risk tolerance to MS therapies: survey results from the NARCOMS registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):241-249.

12. Kalincik T, Butzkueven H. The MSBase registry: Informing clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2019;25(14):1828-1834.

13. Gourraud PA, Henry RG, Cree BA, et al. Precision medicine in chronic disease management: the multiple sclerosis BioScreen. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):633-642.

14. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1778-1785.

15. Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT, Magder LS, et al. VHA Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry and its similarities to other contemporary multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):263-272.

16. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 12]. Mult Scler. 2020;1352458520910499.

17. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2020;26(1):99-108.

18. Minden SL, Kinkel RP, Machado HT, et al. Use and cost of disease-modifying therapies by Sonya Slifka Study participants: has anything really changed since 2000 and 2009? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(1):2055217318820888.

19. Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C. Quality improvement in neurology: multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary [published correction appears in Neurology. 2016;86(15):1465]. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1904-1908.

20. Flachenecker P, Buckow K, Pugliatti M, et al; EUReMS Consortium. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - results of a systematic survey. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1523-1532.

21. Traboulsee A, McMullen K. How useful are MS registries?. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1423-1424.

22. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, Utz U, Thompson AJ. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler. 2018;24(5):579-586.

The VA MS Surveillance Registry combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US.

The VA MS Surveillance Registry combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US.

A number of large registries exist for multiple sclerosis (MS) in North America and Europe. The Scandinavian countries have some of the longest running and integrated MS registries to date. The Danish MS Registry was initiated in 1948 and has been consistently maintained to track MS epidemiologic trends.2 Similar databases exist in Swedenand Norway that were created in the later 20th century.3,4 The Rochester Epidemiology Project, launched by Len Kurland at the Mayo Clinic, has tracked the morbidity of MS and many other conditions in Olmsted county Minnesota for > 60 years.5

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba also have long standing MS registries.6-8 Other North American MS registries have gathered state-wide cases, such as the New York State MS Consortium.9 Some registries have gathered a population-based sample throughout the US, such as the Sonya Slifka MS Study.10 The North American Research Consortium on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a patient-driven registry within the US that has enrolled > 30,000 cases.11 The MSBase is the largest online registry to date utilizing data from several countries.12 The MS Bioscreen, based at the University of California San Francisco, is a recent effort to create a longitudinal clinical dataset.13 This electronic registry integrates clinical disease morbidity scales, neuroimaging, genetics and laboratory data for individual patients with the goal of providing predictive tools.

The US military provides a unique population to study MS and has the oldest and largest nation-wide MS cohort in existence starting with World War I service members and continuing through the recent Gulf War Era.14 With the advent of EHRs in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the mid-1990s and large clinical databases, the possibility of an integrated registry for chronic conditions was created. In this report, we describe the creation of the VA MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR) and the initial roll out to several VA medical centers within the MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE). The MSSR is a unique platform with potential for improving MS patient care and clinical research.

Methods

The MSSR was designed by MSCoE health care providers in conjunction with IT specialists from the VA Northwest Innovation Center. Between 2012 and 2013, the team developed and tested a core template for data entry and refined an efficient data dashboard display to optimize clinical decisions. IT programmers created data entry templates that were tested by 4 to 5 clinicians who provided feedback in biweekly meetings. Technical problems were addressed and enhancements added and the trial process was repeated.

After creation of the prototype MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) data entry template that fed into the prototype MSSR, our team received a grant in 2013 for national development and sustainment. The MSSR was established on the VA Converged Registries Solution (CRS) platform, which is a hardware and software architecture designed to host individual clinical registries and eliminate duplicative development effort while maximizing the ability to create new patient registries. The common platform includes a relational database, Health Level 7 messaging, software classes, security modules, extraction services, and other components. The CR obtains data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), directly from the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) and via direct user input using MSAT.

From 2016 to 2019, data from patients with MS followed in several VA MS regional programs were inputted into MSSR. A roll-out process to start patient data entry at VA medical centers began in 2017 that included an orientation, technical support, and quality assurance review. Twelve sites from Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN) 5 (mid-Atlantic) and VISN 20 (Pacific Northwest) were included in the initial roll-out.

Results

After a live or remote telehealth or telephone visit, a clinician can access MSAT from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or directly from the MSSR online portal (Figure 1). The tool uses radio buttons and pull-down menus and takes about 5 to 15 minutes to complete with a list of required variables. Data is auto-saved for efficiency, and the key variables that are collected in MSAT are noted in Table 1. The MSAT subsequently creates a text integration utility progress note with health factors that is processed through an integration engine and eventually transmitted to VISTA and becomes part of the EHR and available to all health care providers involved in that patient’s care. Additionally, data from VA outpatient and inpatient utilization files, pharmacy, prosthetics, laboratory, and radiology databases are included in the CDW and are included in MSSR. With data from 1998 to the present, the MSAT and CDW databases can provide longitudinal data analysis.

Between 18,000 and 20,000 patients with MS are evaluated in the VHA annually, and 56,000 unique patients have been assessed since 1998. From 2016 to 2019, 1,743 patients with MS or related disorders were enrolled in MSSR (Table 2 and Figure 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 56.0 (12.9) years and the male:female ratio was 2.7. Racial minorities make up 40% of the cohort. Among those with definite and possible MS, the mean disease duration was 22.7 years and the mean (SD) European Database for MS disability score was 4.7 (2.4) (Table 3). Three-quarters of the MSSR cohort have used ≥ 1 MS disease modifying therapy and 65% were classified as relapsing-remitting MS. An electronic dashboard was developed for health care providers to easily access demographic and clinical data for individuals and groups of patients (Figure 3). Standard and ad hoc reports can be generated from the MSSR. Larger longitudinal analyses can be performed with MSAT and clinical data from CDW. Data on comorbid conditions, pharmacy, radiology and prosthetics utilization, outpatient clinic and inpatient admission can be accessed for each patient or a group of patients.

In 2015, MSCoE published a larger national survey of the VA MS population.15 This study revealed that the majority of clinical features and demographics of the MSSR were not significantly different from other major US MS registries including the North American Research Committee on MS, the New York State MS Consortium, and the Sonya Slifka Study.16-18

Discussion

The MSSR is novel in that it combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US. This new registry leverages the existing databases related to cost of care, utilization, and pharmacy services to provide surveillance tools for longitudinal follow-up of the MS population within the VHA. Because the structure of the MSAT and MSSR were developed in a partnership between IT developers and clinicians, there has been mutual buy-in for those who use it and maintain it. This registry can be a test bed for standardized patient outcomes including the recently released MS Quality measures from the American Academy of Neurology.19

To achieve greater numbers across populations, there has been efforts in Europe to combine registries into a common European Register for MS. A recent survey found that although many European registries were heterogeneous, it would be possible to have a minimum common data set for limited epidemiologic studies.20 Still many registries do not have environmental or genetic data to evaluate etiologic questions.21 Additionally, most registries are not set up to evaluate cost or quality of care within a health care system.

Recommendations for maximizing the impact of existing MS registries were recently released by a panel of MS clinicians and researchers.22 The first recommendation was to create a broad network of registries that would communicate and collaborate. This group of MS registries would have strategic oversight and direction that would greatly streamline and leverage existing and future efforts. Second, registries should standardize data collection and management thereby enhancing the ability to share data and perform meta-analyses with aggregated data. Third, the collection of physician- and patient-reported outcomes should be encouraged to provide a more complete picture of MS. Finally, registries should prioritize research questions and utilize new technologies for data collection. These recommendations would help to coordinate existing registries and accelerate knowledge discovery.

The MSSR will contribute to the growing registry network of data. The MSSR can address questions about clinical outcomes, cost, quality with a growing data repository and linked biobank. Based on the CR platform, the MSSR allows for integration with other VA clinical registries, including registries for traumatic brain injuries, oncology, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and eye injuries. Identifying case outcomes related to other registries is optimized with the CR common structure.

Conclusion

The MSSR has been a useful tool for clinicians managing individual patients and their regional referral populations with real-time access to clinical and utilization data. It will also be a useful research tool in tracking epidemiological trends for the military population. The MSSR has enhanced clinical management of MS and serves as a national source for clinical outcomes.

A number of large registries exist for multiple sclerosis (MS) in North America and Europe. The Scandinavian countries have some of the longest running and integrated MS registries to date. The Danish MS Registry was initiated in 1948 and has been consistently maintained to track MS epidemiologic trends.2 Similar databases exist in Swedenand Norway that were created in the later 20th century.3,4 The Rochester Epidemiology Project, launched by Len Kurland at the Mayo Clinic, has tracked the morbidity of MS and many other conditions in Olmsted county Minnesota for > 60 years.5

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba also have long standing MS registries.6-8 Other North American MS registries have gathered state-wide cases, such as the New York State MS Consortium.9 Some registries have gathered a population-based sample throughout the US, such as the Sonya Slifka MS Study.10 The North American Research Consortium on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a patient-driven registry within the US that has enrolled > 30,000 cases.11 The MSBase is the largest online registry to date utilizing data from several countries.12 The MS Bioscreen, based at the University of California San Francisco, is a recent effort to create a longitudinal clinical dataset.13 This electronic registry integrates clinical disease morbidity scales, neuroimaging, genetics and laboratory data for individual patients with the goal of providing predictive tools.

The US military provides a unique population to study MS and has the oldest and largest nation-wide MS cohort in existence starting with World War I service members and continuing through the recent Gulf War Era.14 With the advent of EHRs in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the mid-1990s and large clinical databases, the possibility of an integrated registry for chronic conditions was created. In this report, we describe the creation of the VA MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR) and the initial roll out to several VA medical centers within the MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE). The MSSR is a unique platform with potential for improving MS patient care and clinical research.

Methods

The MSSR was designed by MSCoE health care providers in conjunction with IT specialists from the VA Northwest Innovation Center. Between 2012 and 2013, the team developed and tested a core template for data entry and refined an efficient data dashboard display to optimize clinical decisions. IT programmers created data entry templates that were tested by 4 to 5 clinicians who provided feedback in biweekly meetings. Technical problems were addressed and enhancements added and the trial process was repeated.

After creation of the prototype MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) data entry template that fed into the prototype MSSR, our team received a grant in 2013 for national development and sustainment. The MSSR was established on the VA Converged Registries Solution (CRS) platform, which is a hardware and software architecture designed to host individual clinical registries and eliminate duplicative development effort while maximizing the ability to create new patient registries. The common platform includes a relational database, Health Level 7 messaging, software classes, security modules, extraction services, and other components. The CR obtains data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), directly from the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) and via direct user input using MSAT.

From 2016 to 2019, data from patients with MS followed in several VA MS regional programs were inputted into MSSR. A roll-out process to start patient data entry at VA medical centers began in 2017 that included an orientation, technical support, and quality assurance review. Twelve sites from Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN) 5 (mid-Atlantic) and VISN 20 (Pacific Northwest) were included in the initial roll-out.

Results

After a live or remote telehealth or telephone visit, a clinician can access MSAT from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or directly from the MSSR online portal (Figure 1). The tool uses radio buttons and pull-down menus and takes about 5 to 15 minutes to complete with a list of required variables. Data is auto-saved for efficiency, and the key variables that are collected in MSAT are noted in Table 1. The MSAT subsequently creates a text integration utility progress note with health factors that is processed through an integration engine and eventually transmitted to VISTA and becomes part of the EHR and available to all health care providers involved in that patient’s care. Additionally, data from VA outpatient and inpatient utilization files, pharmacy, prosthetics, laboratory, and radiology databases are included in the CDW and are included in MSSR. With data from 1998 to the present, the MSAT and CDW databases can provide longitudinal data analysis.

Between 18,000 and 20,000 patients with MS are evaluated in the VHA annually, and 56,000 unique patients have been assessed since 1998. From 2016 to 2019, 1,743 patients with MS or related disorders were enrolled in MSSR (Table 2 and Figure 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 56.0 (12.9) years and the male:female ratio was 2.7. Racial minorities make up 40% of the cohort. Among those with definite and possible MS, the mean disease duration was 22.7 years and the mean (SD) European Database for MS disability score was 4.7 (2.4) (Table 3). Three-quarters of the MSSR cohort have used ≥ 1 MS disease modifying therapy and 65% were classified as relapsing-remitting MS. An electronic dashboard was developed for health care providers to easily access demographic and clinical data for individuals and groups of patients (Figure 3). Standard and ad hoc reports can be generated from the MSSR. Larger longitudinal analyses can be performed with MSAT and clinical data from CDW. Data on comorbid conditions, pharmacy, radiology and prosthetics utilization, outpatient clinic and inpatient admission can be accessed for each patient or a group of patients.

In 2015, MSCoE published a larger national survey of the VA MS population.15 This study revealed that the majority of clinical features and demographics of the MSSR were not significantly different from other major US MS registries including the North American Research Committee on MS, the New York State MS Consortium, and the Sonya Slifka Study.16-18

Discussion

The MSSR is novel in that it combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US. This new registry leverages the existing databases related to cost of care, utilization, and pharmacy services to provide surveillance tools for longitudinal follow-up of the MS population within the VHA. Because the structure of the MSAT and MSSR were developed in a partnership between IT developers and clinicians, there has been mutual buy-in for those who use it and maintain it. This registry can be a test bed for standardized patient outcomes including the recently released MS Quality measures from the American Academy of Neurology.19

To achieve greater numbers across populations, there has been efforts in Europe to combine registries into a common European Register for MS. A recent survey found that although many European registries were heterogeneous, it would be possible to have a minimum common data set for limited epidemiologic studies.20 Still many registries do not have environmental or genetic data to evaluate etiologic questions.21 Additionally, most registries are not set up to evaluate cost or quality of care within a health care system.

Recommendations for maximizing the impact of existing MS registries were recently released by a panel of MS clinicians and researchers.22 The first recommendation was to create a broad network of registries that would communicate and collaborate. This group of MS registries would have strategic oversight and direction that would greatly streamline and leverage existing and future efforts. Second, registries should standardize data collection and management thereby enhancing the ability to share data and perform meta-analyses with aggregated data. Third, the collection of physician- and patient-reported outcomes should be encouraged to provide a more complete picture of MS. Finally, registries should prioritize research questions and utilize new technologies for data collection. These recommendations would help to coordinate existing registries and accelerate knowledge discovery.

The MSSR will contribute to the growing registry network of data. The MSSR can address questions about clinical outcomes, cost, quality with a growing data repository and linked biobank. Based on the CR platform, the MSSR allows for integration with other VA clinical registries, including registries for traumatic brain injuries, oncology, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and eye injuries. Identifying case outcomes related to other registries is optimized with the CR common structure.

Conclusion

The MSSR has been a useful tool for clinicians managing individual patients and their regional referral populations with real-time access to clinical and utilization data. It will also be a useful research tool in tracking epidemiological trends for the military population. The MSSR has enhanced clinical management of MS and serves as a national source for clinical outcomes.

1. Flachenecker P. Multiple sclerosis databases: present and future. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(suppl 1):29-31.

2. Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M, Laursen B. Registers of multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):4-10.

3. Alping P, Piehl F, Langer-Gould A, Frisell T; COMBAT-MS Study Group. Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):230-233.

4. Benjaminsen E, Myhr KM, Grytten N, Alstadhaug KB. Validation of the multiple sclerosis diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2019;9(11):e01422.

5. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202-1213.

6. Kingwell E, Zhu F, Marrie RA, et al. High incidence and increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in British Columbia, Canada: findings from over two decades (1991-2010). J Neurol. 2015;262(10):2352-2363.

7. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914-1929.

8. Mahmud SM, Bozat-Emre S, Mostaço-Guidolin LC, Marrie RA. Registry cohort study to determine risk for multiple sclerosis after vaccination for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with Arepanrix, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1267-1274.

9. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Cutter G, Herbert J; New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Trend for decreasing Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MSSS) with increasing calendar year of enrollment into the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):725-733.

10. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12(1):24-38.

11. Fox RJ, Salter A, Alster JM, et al. Risk tolerance to MS therapies: survey results from the NARCOMS registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):241-249.

12. Kalincik T, Butzkueven H. The MSBase registry: Informing clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2019;25(14):1828-1834.

13. Gourraud PA, Henry RG, Cree BA, et al. Precision medicine in chronic disease management: the multiple sclerosis BioScreen. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):633-642.

14. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1778-1785.

15. Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT, Magder LS, et al. VHA Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry and its similarities to other contemporary multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):263-272.

16. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 12]. Mult Scler. 2020;1352458520910499.

17. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2020;26(1):99-108.

18. Minden SL, Kinkel RP, Machado HT, et al. Use and cost of disease-modifying therapies by Sonya Slifka Study participants: has anything really changed since 2000 and 2009? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(1):2055217318820888.

19. Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C. Quality improvement in neurology: multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary [published correction appears in Neurology. 2016;86(15):1465]. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1904-1908.

20. Flachenecker P, Buckow K, Pugliatti M, et al; EUReMS Consortium. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - results of a systematic survey. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1523-1532.

21. Traboulsee A, McMullen K. How useful are MS registries?. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1423-1424.

22. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, Utz U, Thompson AJ. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler. 2018;24(5):579-586.

1. Flachenecker P. Multiple sclerosis databases: present and future. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(suppl 1):29-31.

2. Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M, Laursen B. Registers of multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):4-10.

3. Alping P, Piehl F, Langer-Gould A, Frisell T; COMBAT-MS Study Group. Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):230-233.

4. Benjaminsen E, Myhr KM, Grytten N, Alstadhaug KB. Validation of the multiple sclerosis diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2019;9(11):e01422.

5. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202-1213.

6. Kingwell E, Zhu F, Marrie RA, et al. High incidence and increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in British Columbia, Canada: findings from over two decades (1991-2010). J Neurol. 2015;262(10):2352-2363.

7. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914-1929.

8. Mahmud SM, Bozat-Emre S, Mostaço-Guidolin LC, Marrie RA. Registry cohort study to determine risk for multiple sclerosis after vaccination for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with Arepanrix, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1267-1274.

9. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Cutter G, Herbert J; New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Trend for decreasing Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MSSS) with increasing calendar year of enrollment into the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):725-733.

10. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12(1):24-38.

11. Fox RJ, Salter A, Alster JM, et al. Risk tolerance to MS therapies: survey results from the NARCOMS registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):241-249.

12. Kalincik T, Butzkueven H. The MSBase registry: Informing clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2019;25(14):1828-1834.

13. Gourraud PA, Henry RG, Cree BA, et al. Precision medicine in chronic disease management: the multiple sclerosis BioScreen. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):633-642.

14. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1778-1785.

15. Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT, Magder LS, et al. VHA Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry and its similarities to other contemporary multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):263-272.

16. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 12]. Mult Scler. 2020;1352458520910499.

17. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2020;26(1):99-108.

18. Minden SL, Kinkel RP, Machado HT, et al. Use and cost of disease-modifying therapies by Sonya Slifka Study participants: has anything really changed since 2000 and 2009? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(1):2055217318820888.

19. Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C. Quality improvement in neurology: multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary [published correction appears in Neurology. 2016;86(15):1465]. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1904-1908.

20. Flachenecker P, Buckow K, Pugliatti M, et al; EUReMS Consortium. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - results of a systematic survey. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1523-1532.

21. Traboulsee A, McMullen K. How useful are MS registries?. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1423-1424.

22. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, Utz U, Thompson AJ. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler. 2018;24(5):579-586.

Cutaneous Manifestation as Initial Presentation of Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

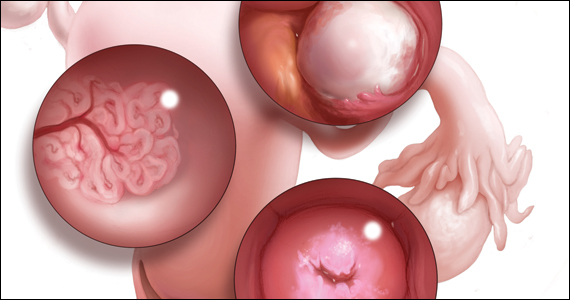

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

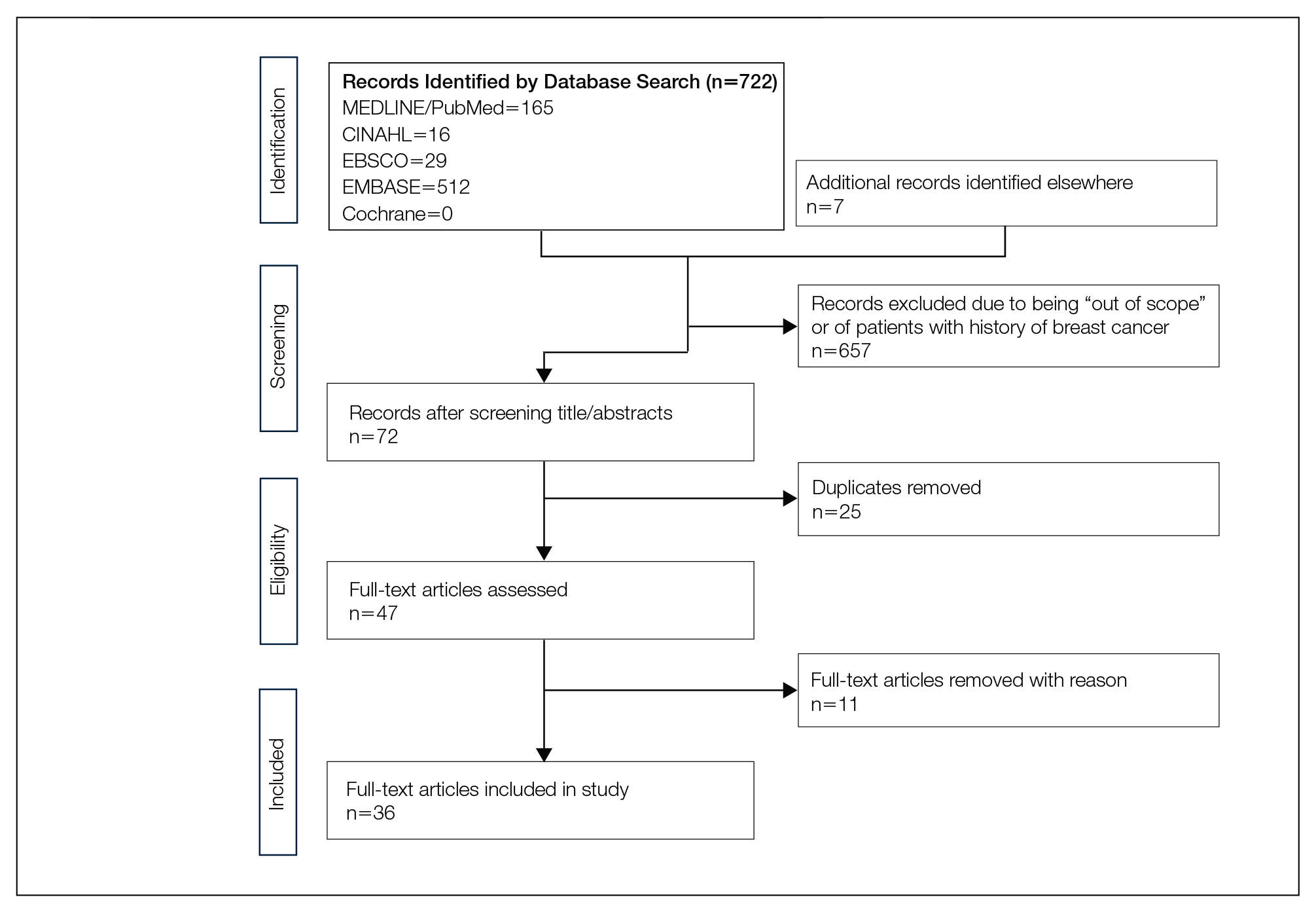

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

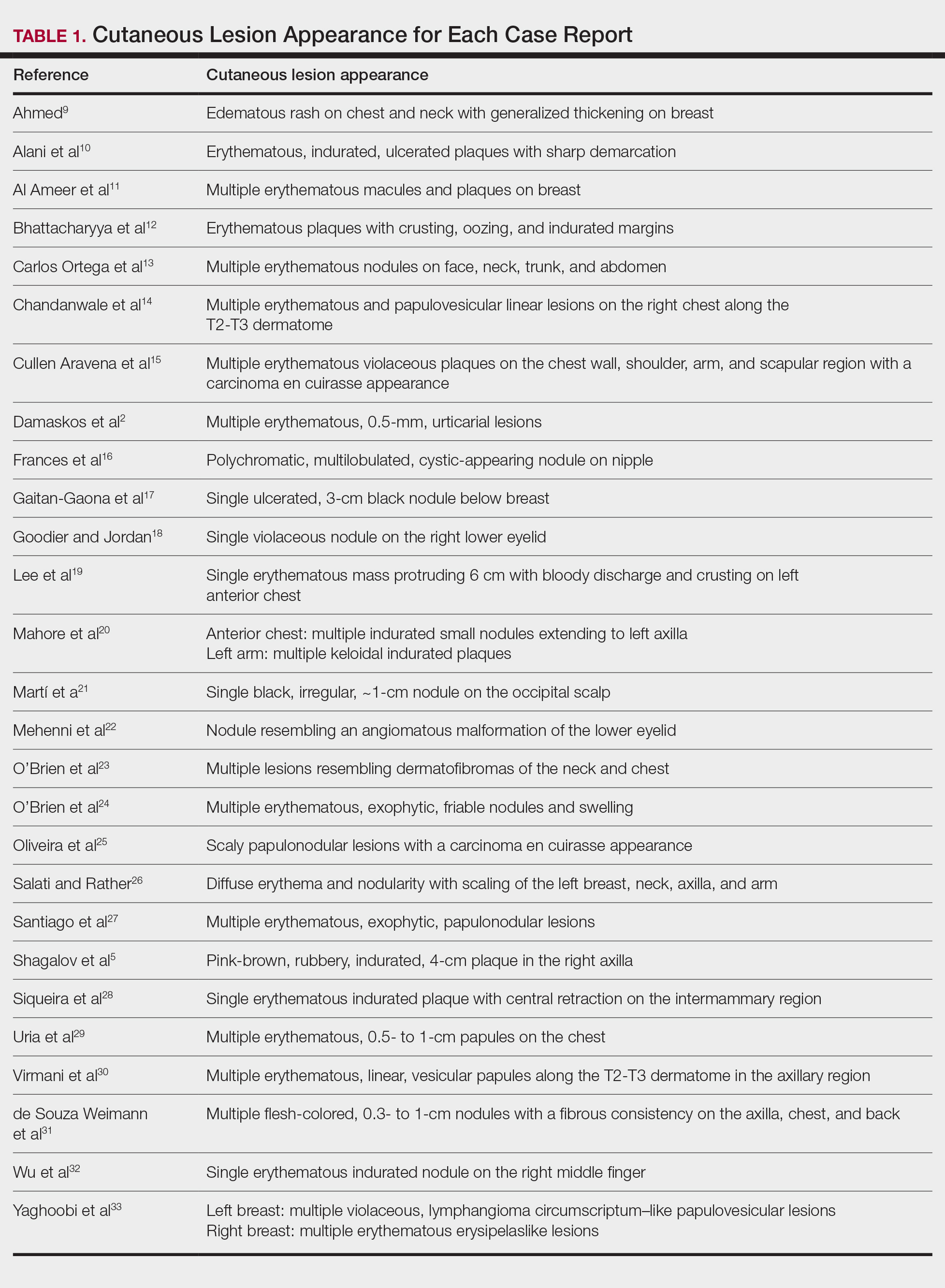

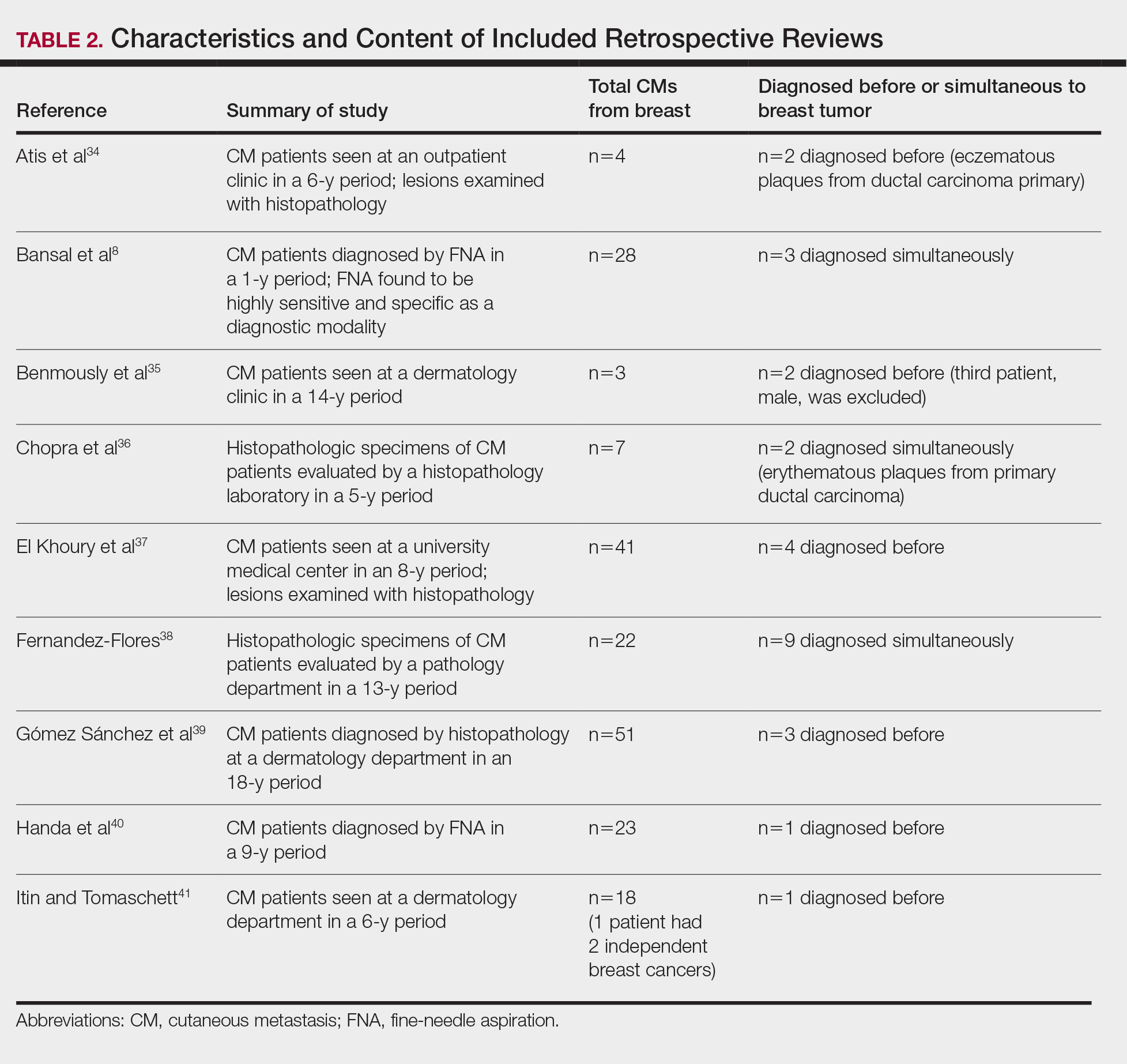

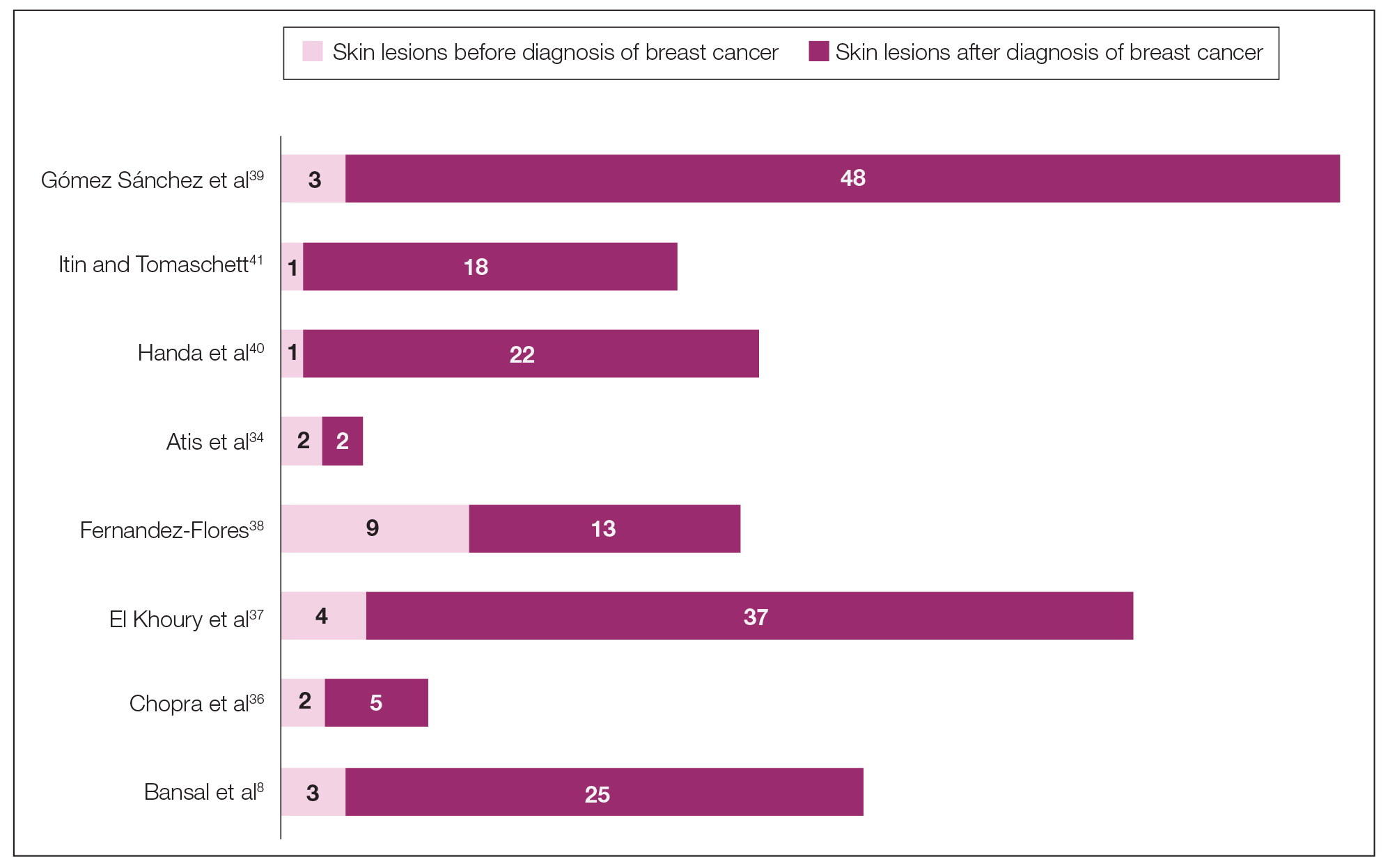

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

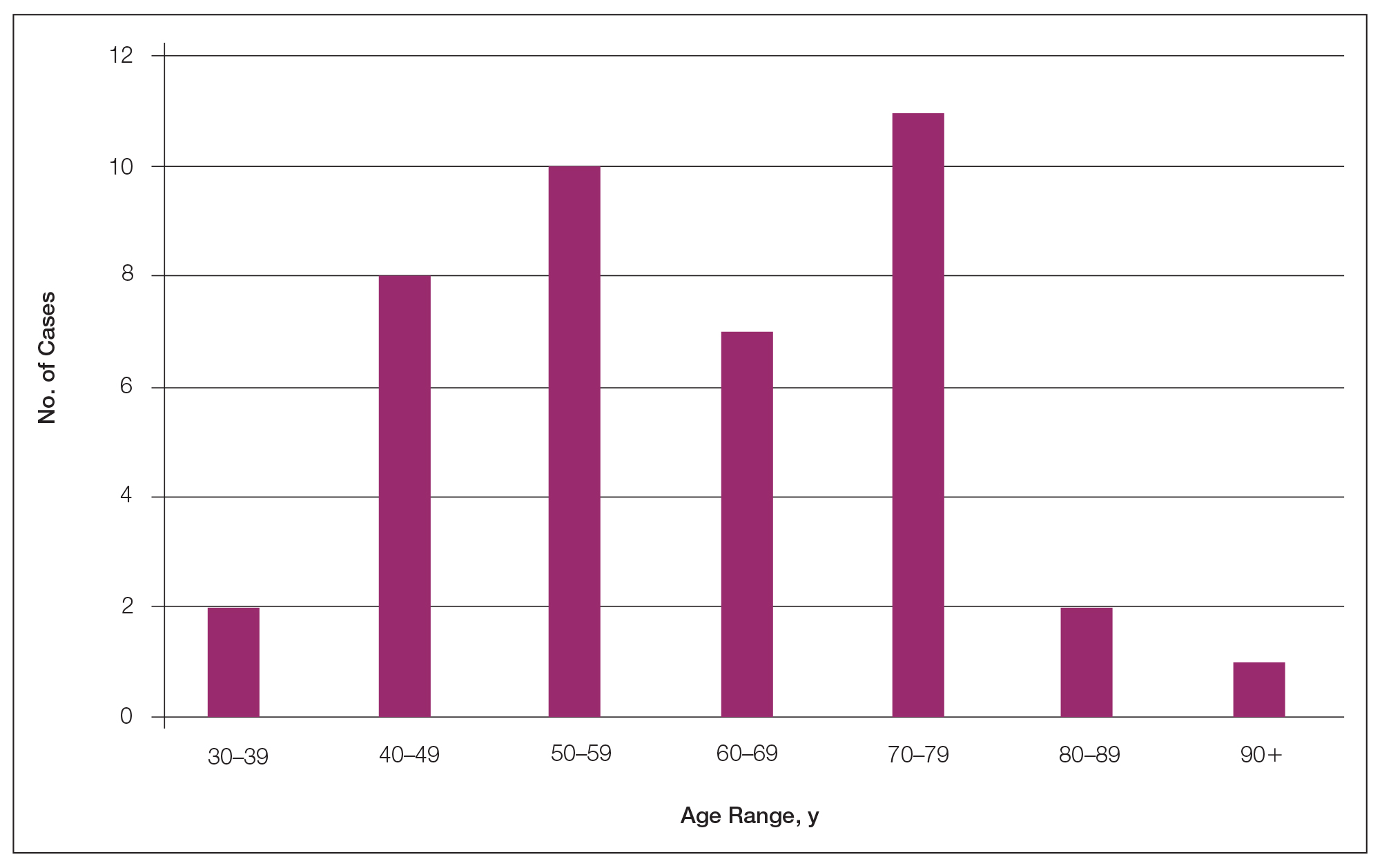

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

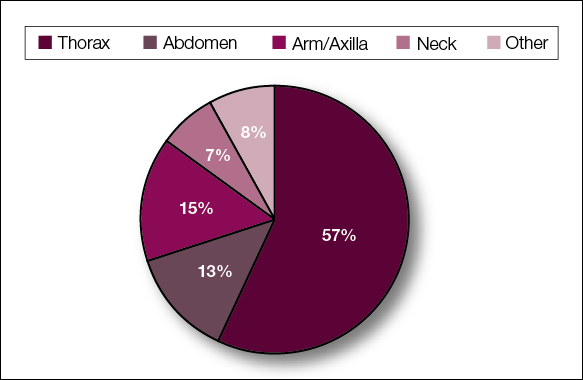

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

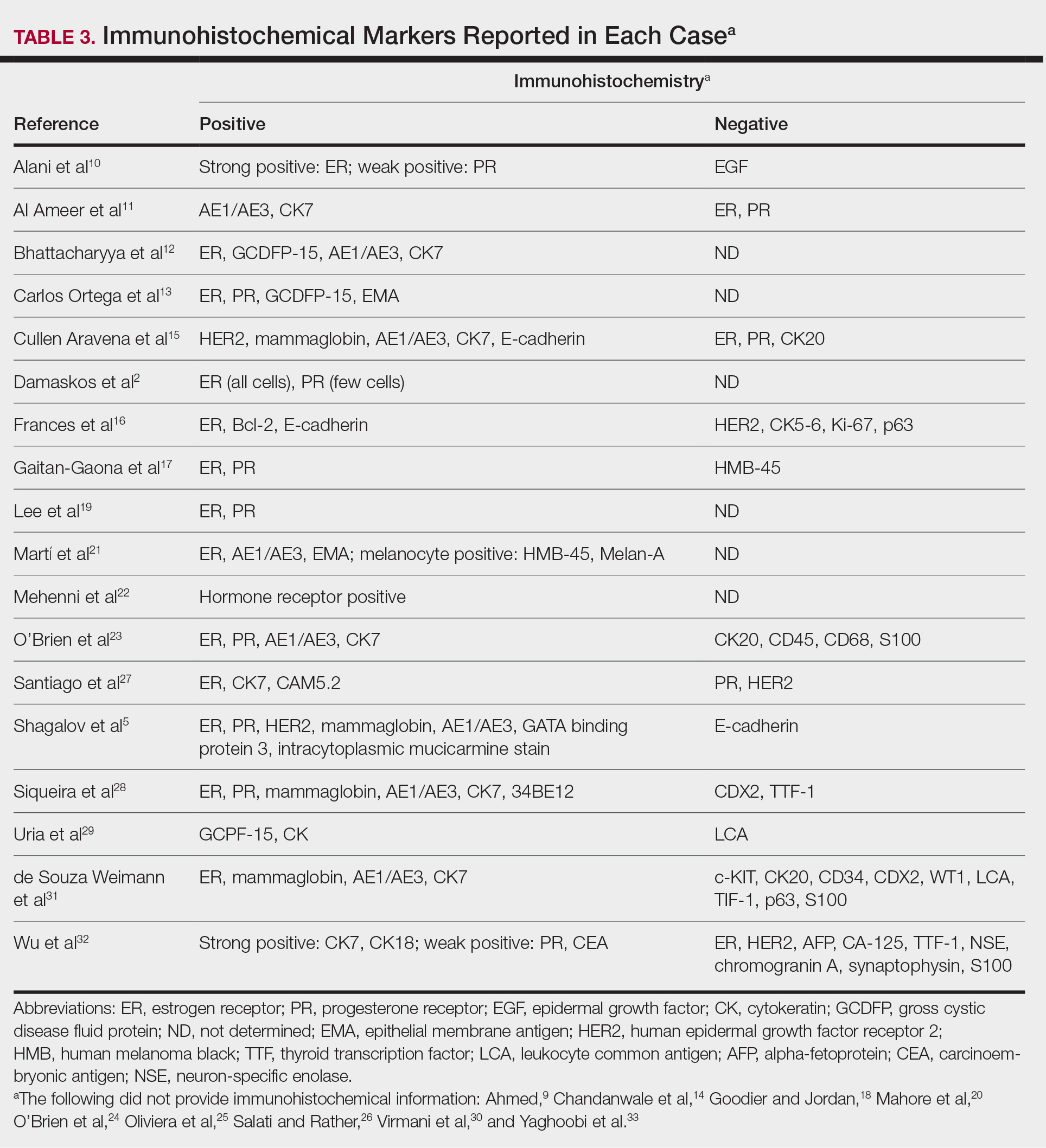

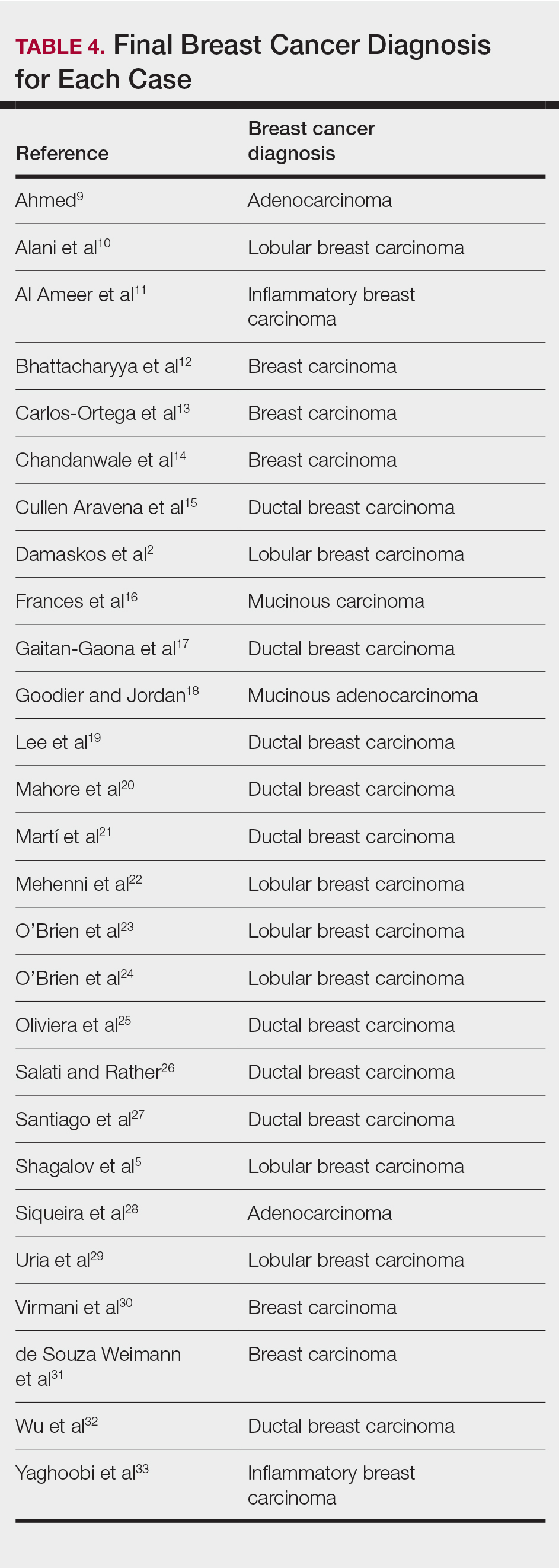

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14