User login

First EDition: A-Fib Management Pathway in the ED, more

Atrial Fibrillation Management Pathway in the ED May Lower Hospital Admissions

TED BOSWORTH

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

An atrial fibrillation (AF) treatment pathway designed specifically to reduce the proportion of patients with this complaint who are admitted to the hospital from the ED was remarkably effective, according to a pilot study presented at the annual International AF Symposium.

“In this single-center observational study, a multidisciplinary AF pathway was associated with 5-fold reduction in admission rate and 2.5-fold reduction in length-of-stay [LOS] for those who were admitted,” reported Jeremy N. Ruskin, MD.

Relative to many other countries, admission rates for AF in the United States are “extremely high,” according to Dr Ruskin, director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Citing 2013 figures from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database, rates ranged between 60% and 80% by geographic region, with an average of about 66%. In contrast, and as an example of lower rates elsewhere, fewer than 40% of AF patients with similar characteristics presenting at EDs in Ontario, Canada were admitted. Similarly low admission rates have been reported in Europe.

The AF pathway tested in the study at Massachusetts General was developed through collaboration between electrophysiologists and emergency physicians (EPs). It is suitable for patients presenting with a primary complaint of AF without concomitant diseases, such as sepsis or myocardial infarction. Patients were entered into this study after it was shown that AF was the chief complaint. The first step was to determine whether participants were best suited to a rhythm-control or rate-control strategy.

“The rhythm-control group was anticoagulated and then underwent expedited cardioversion with TEE [transesophageal echocardiogram] if necessary. The rate-control group was anticoagulated and then given appropriate pharmacologic therapy,” Dr Ruskin explained. Once patients were on treatment, an electrophysiologist and an EP evaluated the patients’ response. For both groups, stable patients were discharged and unstable patients were admitted.

In this nonrandomized observational study conducted over a 1-year period, 94 patients were managed with the AF pathway. Admissions and outcomes in this group were compared with 265 patients who received usual care.

Only 16% of those managed through the AF pathway were admitted versus 80% (P < .001) in the usual care group. Among those admitted, LOS was shorter in patients managed along the AF pathway relative to usual care (32 vs 85 hours; P = .002). Dr Ruskin reported that both the cardioversion rate and the proportion of patients discharged on novel oral anticoagulation drugs were higher in the AF pathway group.

The reductions in hospital admissions would be expected to translate into large reductions in costs, particularly as follow-up showed no difference in return visits to the hospital between those entered into the AF pathway relative to those who received routine care, according to Dr Ruskin. Emphasizing the cost burden of AF admissions, he noted that the estimated charges for the more than 300,000 AF admissions in US hospitals in 2013 exceeded $7 billion.

Currently, there are no uniform guidelines for managing AF in the ED, and there is wide variation in practice among centers, according to Dr Ruskin. He provided data from the NEDS database demonstrating highly significant variations in rates of admission by geographic region (eg, rates were >10% higher in the northeast vs the west) and hospital type (eg, rates were twice as high in metropolitan than nonmetropolitan hospitals).

In the NEDS database, various patient characteristics were associated with increased odds ratios (ORs) for admission. These included hypertension (OR, 2.3), valvular disease (OR, 3.6), and congestive heart failure (OR, 3.7). However, Dr Ruskin indicated that patients with these or other characteristics associated with increased likelihood of admission, such as older age, have better outcomes with hospitalization.

The data from this initial observational study were recently published, and a larger prospective study of this AF pathway is already underway at both Massachusetts General and at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. If the data confirm that AF admissions can be safely reduced through this pathway, Dr Ruskin anticipates that implementation will be adopted at other hospitals in the Harvard system.

Ptaszek LM, White B, Lubitz SA, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary approach for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation in the emergency department on hospital admission rate and length of stay. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(1):64-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.04.014.

Understanding SSTI Admission, Treatment Crucial to Reducing Disease Burden

DEEPAK CHITNIS

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Connecticut) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average LOS and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion.

“Patients were categorized into two groups based on disposition of care, inpatient or outpatient, on index presentation,” the authors explained. “Economic data were collected using reports from hospital finance databases and included reports of total billed costs.”

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall (22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients; P > .05) or for SSTI-related re-presentation (10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients; P > .05). For those patients who were admitted, the mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of 0 were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of 1, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of 2 or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high-frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

Linder KE, Nicolau DP, Nailor MD. Epidemiology, treatment, and economics of patients presenting to the emergency department for skin and soft tissue infections. Hosp Pract (1995). 2017;16:1-7. doi:10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519.

Adolescents, Boys, Black Children Most Likely To Be Hospitalized for SJS and TEN

WHITNEY MCKNIGHT

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Annual hospitalization rates in the United States for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were shown to be higher in adolescents, boys, and black children, in a cross-sectional analysis of discharge records from more than 4,100 hospitals.

Using relevant ICD-9 codes, researchers at Harvard University identified 1,571 patients hospitalized for SJS, TEN, or both in 2009 and 2012, as listed in the Kids Inpatient Database from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The highest hospitalization rates per 100,000 in each year were for adolescents between ages 15 and 19 years (P = .01), boys (P = .03), and black children (P = .82). The overall risk of death from these conditions was 1.5% in 2009 and 0.3% in 2012. The data were published online in a brief report.

Although the difference in the number of hospitalizations for black children was not significant when compared with other ethnic and racial groups, at 1.03 hospitalizations per 100,000 children (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80-1.31) in 2009 and 1.06 hospitalizations per 100,000 children (95% CI, 0.86-1.30) in 2012, the rate was greatest in this group. The next highest ratio was in white children at 0.82 hospitalizations per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.74-0.91) in 2009, and 0.95 hospitalizations per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.86-1.05) in 2012.

With the number of SJS- and TEN-related hospitalizations between 0.1 and 1.0 per 100,000, lead author Yusuke Okubo, MD, MPH, and colleagues wrote that their data aligned with previous studies; however, regarding the emphasis on demographic differences, theirs was, to the best of their knowledge, “the first study to reveal these disparities.” Compared with adults, they added, mortality was “remarkably lower” in children.

Okubo Y, Nochioka K, Testa MA. Nationwide survey of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Dec 19. doi:10.1111/pde.13050. [Epub ahead of print]

Guidelines Released for Diagnosing TB in Adults, Children

MARY ANN MOON

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

A clinical practice guideline for diagnosing pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and latent tuberculosis (TB) in adults and children has been released jointly by the American Thoracic Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The American Academy of Pediatrics also provided input to the guideline, which includes 23 evidence-based recommendations. The document is intended to assist clinicians in high-resource countries with a low incidence of TB disease and latent TB infection, such as the United States, said David M. Lewinsohn, MD, PhD, and his associates on the joint task force that wrote the guideline.

There were 9,412 cases of TB disease reported in the United States in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available. This translates to a rate of 3.0 cases per 100,000 persons. Two-thirds of the cases in the United States developed in foreign-born persons. “The rate of disease was 13.4 times higher in foreign-born persons than in US-born individuals [15.3 vs 1.1 per 100,000, respectively],” wrote Dr Lewinsohn of pulmonary and critical care medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues.

Even though the case rate is relatively low in the United States and has declined in recent years, “an estimated 11 million persons are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Thus…there remains a large reservoir of individuals who are infected. Without the application of improved diagnosis and effective treatment for latent [disease], new cases of TB will develop from within this group,” they noted.

Among the guideline’s strongest recommendations are the following:

- Acid-fast bacilli smear microscopy should be performed in all patients suspected of having pulmonary TB, using at least three sputum samples. A sputum volume of at least 3 mL is needed, but 5 to 10 mL would be better.

- Both liquid and solid mycobacterial cultures should be performed on every specimen from patients suspected of having TB disease, rather than either type alone.

- A diagnostic nucleic acid amplification test should be performed on the initial specimen from patients suspected of having pulmonary TB.

- Rapid molecular drug-susceptibility testing of respiratory specimens is advised for certain patients, with a focus on testing for rifampin susceptibility with or without isoniazid.

- Patients suspected of having extrapulmonary TB also should have mycobacterial cultures performed on all specimens.

- For all mycobacterial cultures that are positive for TB, a culture isolate should be submitted for genotyping to a regional genotyping laboratory.

- For patients aged 5 and older who are suspected of having latent TB infection, an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) is advised rather than a tuberculin skin test, especially if the patient is not likely to return to have the test result read. A tuberculin skin test is an acceptable alternative if IGRA is not available, is too expensive, or is too burdensome.

The guideline also addresses bronchoscopic sampling, cell counts and chemistries from fluid specimens collected from sites suspected of harboring extrapulmonary TB (such as pleural, cerebrospinal, ascetic, or joint fluids), and measurement of adenosine deaminase levels.

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):e1-e33. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw694.

Atrial Fibrillation Management Pathway in the ED May Lower Hospital Admissions

TED BOSWORTH

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

An atrial fibrillation (AF) treatment pathway designed specifically to reduce the proportion of patients with this complaint who are admitted to the hospital from the ED was remarkably effective, according to a pilot study presented at the annual International AF Symposium.

“In this single-center observational study, a multidisciplinary AF pathway was associated with 5-fold reduction in admission rate and 2.5-fold reduction in length-of-stay [LOS] for those who were admitted,” reported Jeremy N. Ruskin, MD.

Relative to many other countries, admission rates for AF in the United States are “extremely high,” according to Dr Ruskin, director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Citing 2013 figures from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database, rates ranged between 60% and 80% by geographic region, with an average of about 66%. In contrast, and as an example of lower rates elsewhere, fewer than 40% of AF patients with similar characteristics presenting at EDs in Ontario, Canada were admitted. Similarly low admission rates have been reported in Europe.

The AF pathway tested in the study at Massachusetts General was developed through collaboration between electrophysiologists and emergency physicians (EPs). It is suitable for patients presenting with a primary complaint of AF without concomitant diseases, such as sepsis or myocardial infarction. Patients were entered into this study after it was shown that AF was the chief complaint. The first step was to determine whether participants were best suited to a rhythm-control or rate-control strategy.

“The rhythm-control group was anticoagulated and then underwent expedited cardioversion with TEE [transesophageal echocardiogram] if necessary. The rate-control group was anticoagulated and then given appropriate pharmacologic therapy,” Dr Ruskin explained. Once patients were on treatment, an electrophysiologist and an EP evaluated the patients’ response. For both groups, stable patients were discharged and unstable patients were admitted.

In this nonrandomized observational study conducted over a 1-year period, 94 patients were managed with the AF pathway. Admissions and outcomes in this group were compared with 265 patients who received usual care.

Only 16% of those managed through the AF pathway were admitted versus 80% (P < .001) in the usual care group. Among those admitted, LOS was shorter in patients managed along the AF pathway relative to usual care (32 vs 85 hours; P = .002). Dr Ruskin reported that both the cardioversion rate and the proportion of patients discharged on novel oral anticoagulation drugs were higher in the AF pathway group.

The reductions in hospital admissions would be expected to translate into large reductions in costs, particularly as follow-up showed no difference in return visits to the hospital between those entered into the AF pathway relative to those who received routine care, according to Dr Ruskin. Emphasizing the cost burden of AF admissions, he noted that the estimated charges for the more than 300,000 AF admissions in US hospitals in 2013 exceeded $7 billion.

Currently, there are no uniform guidelines for managing AF in the ED, and there is wide variation in practice among centers, according to Dr Ruskin. He provided data from the NEDS database demonstrating highly significant variations in rates of admission by geographic region (eg, rates were >10% higher in the northeast vs the west) and hospital type (eg, rates were twice as high in metropolitan than nonmetropolitan hospitals).

In the NEDS database, various patient characteristics were associated with increased odds ratios (ORs) for admission. These included hypertension (OR, 2.3), valvular disease (OR, 3.6), and congestive heart failure (OR, 3.7). However, Dr Ruskin indicated that patients with these or other characteristics associated with increased likelihood of admission, such as older age, have better outcomes with hospitalization.

The data from this initial observational study were recently published, and a larger prospective study of this AF pathway is already underway at both Massachusetts General and at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. If the data confirm that AF admissions can be safely reduced through this pathway, Dr Ruskin anticipates that implementation will be adopted at other hospitals in the Harvard system.

Ptaszek LM, White B, Lubitz SA, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary approach for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation in the emergency department on hospital admission rate and length of stay. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(1):64-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.04.014.

Understanding SSTI Admission, Treatment Crucial to Reducing Disease Burden

DEEPAK CHITNIS

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Connecticut) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average LOS and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion.

“Patients were categorized into two groups based on disposition of care, inpatient or outpatient, on index presentation,” the authors explained. “Economic data were collected using reports from hospital finance databases and included reports of total billed costs.”

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall (22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients; P > .05) or for SSTI-related re-presentation (10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients; P > .05). For those patients who were admitted, the mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of 0 were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of 1, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of 2 or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high-frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

Linder KE, Nicolau DP, Nailor MD. Epidemiology, treatment, and economics of patients presenting to the emergency department for skin and soft tissue infections. Hosp Pract (1995). 2017;16:1-7. doi:10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519.

Adolescents, Boys, Black Children Most Likely To Be Hospitalized for SJS and TEN

WHITNEY MCKNIGHT

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Annual hospitalization rates in the United States for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were shown to be higher in adolescents, boys, and black children, in a cross-sectional analysis of discharge records from more than 4,100 hospitals.

Using relevant ICD-9 codes, researchers at Harvard University identified 1,571 patients hospitalized for SJS, TEN, or both in 2009 and 2012, as listed in the Kids Inpatient Database from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The highest hospitalization rates per 100,000 in each year were for adolescents between ages 15 and 19 years (P = .01), boys (P = .03), and black children (P = .82). The overall risk of death from these conditions was 1.5% in 2009 and 0.3% in 2012. The data were published online in a brief report.

Although the difference in the number of hospitalizations for black children was not significant when compared with other ethnic and racial groups, at 1.03 hospitalizations per 100,000 children (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80-1.31) in 2009 and 1.06 hospitalizations per 100,000 children (95% CI, 0.86-1.30) in 2012, the rate was greatest in this group. The next highest ratio was in white children at 0.82 hospitalizations per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.74-0.91) in 2009, and 0.95 hospitalizations per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.86-1.05) in 2012.

With the number of SJS- and TEN-related hospitalizations between 0.1 and 1.0 per 100,000, lead author Yusuke Okubo, MD, MPH, and colleagues wrote that their data aligned with previous studies; however, regarding the emphasis on demographic differences, theirs was, to the best of their knowledge, “the first study to reveal these disparities.” Compared with adults, they added, mortality was “remarkably lower” in children.

Okubo Y, Nochioka K, Testa MA. Nationwide survey of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Dec 19. doi:10.1111/pde.13050. [Epub ahead of print]

Guidelines Released for Diagnosing TB in Adults, Children

MARY ANN MOON

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

A clinical practice guideline for diagnosing pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and latent tuberculosis (TB) in adults and children has been released jointly by the American Thoracic Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The American Academy of Pediatrics also provided input to the guideline, which includes 23 evidence-based recommendations. The document is intended to assist clinicians in high-resource countries with a low incidence of TB disease and latent TB infection, such as the United States, said David M. Lewinsohn, MD, PhD, and his associates on the joint task force that wrote the guideline.

There were 9,412 cases of TB disease reported in the United States in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available. This translates to a rate of 3.0 cases per 100,000 persons. Two-thirds of the cases in the United States developed in foreign-born persons. “The rate of disease was 13.4 times higher in foreign-born persons than in US-born individuals [15.3 vs 1.1 per 100,000, respectively],” wrote Dr Lewinsohn of pulmonary and critical care medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues.

Even though the case rate is relatively low in the United States and has declined in recent years, “an estimated 11 million persons are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Thus…there remains a large reservoir of individuals who are infected. Without the application of improved diagnosis and effective treatment for latent [disease], new cases of TB will develop from within this group,” they noted.

Among the guideline’s strongest recommendations are the following:

- Acid-fast bacilli smear microscopy should be performed in all patients suspected of having pulmonary TB, using at least three sputum samples. A sputum volume of at least 3 mL is needed, but 5 to 10 mL would be better.

- Both liquid and solid mycobacterial cultures should be performed on every specimen from patients suspected of having TB disease, rather than either type alone.

- A diagnostic nucleic acid amplification test should be performed on the initial specimen from patients suspected of having pulmonary TB.

- Rapid molecular drug-susceptibility testing of respiratory specimens is advised for certain patients, with a focus on testing for rifampin susceptibility with or without isoniazid.

- Patients suspected of having extrapulmonary TB also should have mycobacterial cultures performed on all specimens.

- For all mycobacterial cultures that are positive for TB, a culture isolate should be submitted for genotyping to a regional genotyping laboratory.

- For patients aged 5 and older who are suspected of having latent TB infection, an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) is advised rather than a tuberculin skin test, especially if the patient is not likely to return to have the test result read. A tuberculin skin test is an acceptable alternative if IGRA is not available, is too expensive, or is too burdensome.

The guideline also addresses bronchoscopic sampling, cell counts and chemistries from fluid specimens collected from sites suspected of harboring extrapulmonary TB (such as pleural, cerebrospinal, ascetic, or joint fluids), and measurement of adenosine deaminase levels.

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):e1-e33. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw694.

Atrial Fibrillation Management Pathway in the ED May Lower Hospital Admissions

TED BOSWORTH

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

An atrial fibrillation (AF) treatment pathway designed specifically to reduce the proportion of patients with this complaint who are admitted to the hospital from the ED was remarkably effective, according to a pilot study presented at the annual International AF Symposium.

“In this single-center observational study, a multidisciplinary AF pathway was associated with 5-fold reduction in admission rate and 2.5-fold reduction in length-of-stay [LOS] for those who were admitted,” reported Jeremy N. Ruskin, MD.

Relative to many other countries, admission rates for AF in the United States are “extremely high,” according to Dr Ruskin, director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Citing 2013 figures from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) database, rates ranged between 60% and 80% by geographic region, with an average of about 66%. In contrast, and as an example of lower rates elsewhere, fewer than 40% of AF patients with similar characteristics presenting at EDs in Ontario, Canada were admitted. Similarly low admission rates have been reported in Europe.

The AF pathway tested in the study at Massachusetts General was developed through collaboration between electrophysiologists and emergency physicians (EPs). It is suitable for patients presenting with a primary complaint of AF without concomitant diseases, such as sepsis or myocardial infarction. Patients were entered into this study after it was shown that AF was the chief complaint. The first step was to determine whether participants were best suited to a rhythm-control or rate-control strategy.

“The rhythm-control group was anticoagulated and then underwent expedited cardioversion with TEE [transesophageal echocardiogram] if necessary. The rate-control group was anticoagulated and then given appropriate pharmacologic therapy,” Dr Ruskin explained. Once patients were on treatment, an electrophysiologist and an EP evaluated the patients’ response. For both groups, stable patients were discharged and unstable patients were admitted.

In this nonrandomized observational study conducted over a 1-year period, 94 patients were managed with the AF pathway. Admissions and outcomes in this group were compared with 265 patients who received usual care.

Only 16% of those managed through the AF pathway were admitted versus 80% (P < .001) in the usual care group. Among those admitted, LOS was shorter in patients managed along the AF pathway relative to usual care (32 vs 85 hours; P = .002). Dr Ruskin reported that both the cardioversion rate and the proportion of patients discharged on novel oral anticoagulation drugs were higher in the AF pathway group.

The reductions in hospital admissions would be expected to translate into large reductions in costs, particularly as follow-up showed no difference in return visits to the hospital between those entered into the AF pathway relative to those who received routine care, according to Dr Ruskin. Emphasizing the cost burden of AF admissions, he noted that the estimated charges for the more than 300,000 AF admissions in US hospitals in 2013 exceeded $7 billion.

Currently, there are no uniform guidelines for managing AF in the ED, and there is wide variation in practice among centers, according to Dr Ruskin. He provided data from the NEDS database demonstrating highly significant variations in rates of admission by geographic region (eg, rates were >10% higher in the northeast vs the west) and hospital type (eg, rates were twice as high in metropolitan than nonmetropolitan hospitals).

In the NEDS database, various patient characteristics were associated with increased odds ratios (ORs) for admission. These included hypertension (OR, 2.3), valvular disease (OR, 3.6), and congestive heart failure (OR, 3.7). However, Dr Ruskin indicated that patients with these or other characteristics associated with increased likelihood of admission, such as older age, have better outcomes with hospitalization.

The data from this initial observational study were recently published, and a larger prospective study of this AF pathway is already underway at both Massachusetts General and at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. If the data confirm that AF admissions can be safely reduced through this pathway, Dr Ruskin anticipates that implementation will be adopted at other hospitals in the Harvard system.

Ptaszek LM, White B, Lubitz SA, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary approach for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation in the emergency department on hospital admission rate and length of stay. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(1):64-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.04.014.

Understanding SSTI Admission, Treatment Crucial to Reducing Disease Burden

DEEPAK CHITNIS

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Connecticut) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average LOS and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion.

“Patients were categorized into two groups based on disposition of care, inpatient or outpatient, on index presentation,” the authors explained. “Economic data were collected using reports from hospital finance databases and included reports of total billed costs.”

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall (22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients; P > .05) or for SSTI-related re-presentation (10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients; P > .05). For those patients who were admitted, the mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of 0 were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of 1, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of 2 or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high-frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

Linder KE, Nicolau DP, Nailor MD. Epidemiology, treatment, and economics of patients presenting to the emergency department for skin and soft tissue infections. Hosp Pract (1995). 2017;16:1-7. doi:10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519.

Adolescents, Boys, Black Children Most Likely To Be Hospitalized for SJS and TEN

WHITNEY MCKNIGHT

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

Annual hospitalization rates in the United States for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were shown to be higher in adolescents, boys, and black children, in a cross-sectional analysis of discharge records from more than 4,100 hospitals.

Using relevant ICD-9 codes, researchers at Harvard University identified 1,571 patients hospitalized for SJS, TEN, or both in 2009 and 2012, as listed in the Kids Inpatient Database from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The highest hospitalization rates per 100,000 in each year were for adolescents between ages 15 and 19 years (P = .01), boys (P = .03), and black children (P = .82). The overall risk of death from these conditions was 1.5% in 2009 and 0.3% in 2012. The data were published online in a brief report.

Although the difference in the number of hospitalizations for black children was not significant when compared with other ethnic and racial groups, at 1.03 hospitalizations per 100,000 children (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80-1.31) in 2009 and 1.06 hospitalizations per 100,000 children (95% CI, 0.86-1.30) in 2012, the rate was greatest in this group. The next highest ratio was in white children at 0.82 hospitalizations per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.74-0.91) in 2009, and 0.95 hospitalizations per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.86-1.05) in 2012.

With the number of SJS- and TEN-related hospitalizations between 0.1 and 1.0 per 100,000, lead author Yusuke Okubo, MD, MPH, and colleagues wrote that their data aligned with previous studies; however, regarding the emphasis on demographic differences, theirs was, to the best of their knowledge, “the first study to reveal these disparities.” Compared with adults, they added, mortality was “remarkably lower” in children.

Okubo Y, Nochioka K, Testa MA. Nationwide survey of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Dec 19. doi:10.1111/pde.13050. [Epub ahead of print]

Guidelines Released for Diagnosing TB in Adults, Children

MARY ANN MOON

FRONTLINE MEDICAL NEWS

A clinical practice guideline for diagnosing pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and latent tuberculosis (TB) in adults and children has been released jointly by the American Thoracic Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The American Academy of Pediatrics also provided input to the guideline, which includes 23 evidence-based recommendations. The document is intended to assist clinicians in high-resource countries with a low incidence of TB disease and latent TB infection, such as the United States, said David M. Lewinsohn, MD, PhD, and his associates on the joint task force that wrote the guideline.

There were 9,412 cases of TB disease reported in the United States in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available. This translates to a rate of 3.0 cases per 100,000 persons. Two-thirds of the cases in the United States developed in foreign-born persons. “The rate of disease was 13.4 times higher in foreign-born persons than in US-born individuals [15.3 vs 1.1 per 100,000, respectively],” wrote Dr Lewinsohn of pulmonary and critical care medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues.

Even though the case rate is relatively low in the United States and has declined in recent years, “an estimated 11 million persons are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Thus…there remains a large reservoir of individuals who are infected. Without the application of improved diagnosis and effective treatment for latent [disease], new cases of TB will develop from within this group,” they noted.

Among the guideline’s strongest recommendations are the following:

- Acid-fast bacilli smear microscopy should be performed in all patients suspected of having pulmonary TB, using at least three sputum samples. A sputum volume of at least 3 mL is needed, but 5 to 10 mL would be better.

- Both liquid and solid mycobacterial cultures should be performed on every specimen from patients suspected of having TB disease, rather than either type alone.

- A diagnostic nucleic acid amplification test should be performed on the initial specimen from patients suspected of having pulmonary TB.

- Rapid molecular drug-susceptibility testing of respiratory specimens is advised for certain patients, with a focus on testing for rifampin susceptibility with or without isoniazid.

- Patients suspected of having extrapulmonary TB also should have mycobacterial cultures performed on all specimens.

- For all mycobacterial cultures that are positive for TB, a culture isolate should be submitted for genotyping to a regional genotyping laboratory.

- For patients aged 5 and older who are suspected of having latent TB infection, an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) is advised rather than a tuberculin skin test, especially if the patient is not likely to return to have the test result read. A tuberculin skin test is an acceptable alternative if IGRA is not available, is too expensive, or is too burdensome.

The guideline also addresses bronchoscopic sampling, cell counts and chemistries from fluid specimens collected from sites suspected of harboring extrapulmonary TB (such as pleural, cerebrospinal, ascetic, or joint fluids), and measurement of adenosine deaminase levels.

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):e1-e33. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw694.

2017 Update on fertility

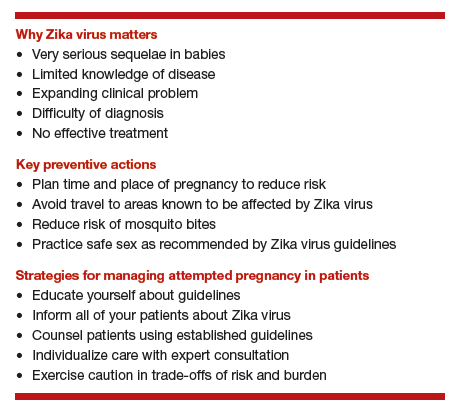

Zika virus is a serious problem. Education and infection prevention are critical to effective management, and why we chose to include Zika virus as a topic for this year’s Update. We also discuss obesity’s effects on reproduction—a very relevant concern for all ObGyns and patients alike as about half of reproductive-age women are obese. Finally, subclinical hypothyroidism can present unique management challenges, such as determining when it is present and when treatment is indicated.

Read about counseling patients about Zika virus

Managing attempted pregnancy in the era of Zika virus

Oduyebo T, Igbinosa I, Petersen EE, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers caring for pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, July 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(29):739-744.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

US Food and Drug Administration. Donor Screening Recommendations to Reduce the Risk of Transmission of Zika Virus by Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Tissue/UCM488582.pdf. Published March 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

National Institutes of Health. Zika: Overview. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/zika/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2017.

World Health Organization. Prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus interim guidance. WHO reference number: WHO/ZIKV/MOC/16. 1 Rev. 3, September 6, 2016.

Zika Virus Guidance Task Force of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Rev. 13, September 2016.

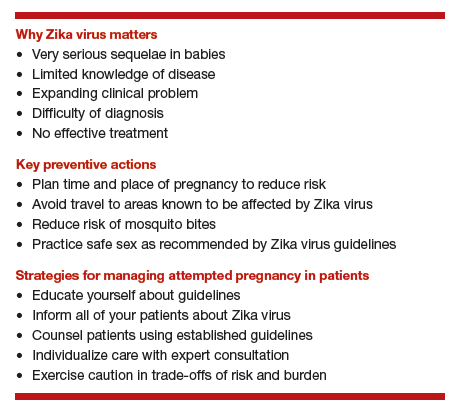

Zika virus presents unique challenges to physicians managing the care of patients attempting pregnancy, with or without fertility treatment. Neonatal Zika virus infection sequelae only recently have been appreciated; microcephaly was associated with Zika virus in October 2015, followed by other neurologic conditions including brain abnormalities, neural tube defects, and eye abnormalities. Results of recent studies involving the US Zika Pregnancy Registry show that 6% of women with Zika at any time in pregnancy had affected babies, but 11% of those who contracted the disease in the first trimester were affected.

Diagnosis is difficult because symptoms are generally mild, with 80% of affected patients asymptomatic. Possible Zika virus exposure is defined as travel to or residence in an area of active Zika virus transmission, or sex without a condom with a partner who traveled to or lived in an area of active transmission. Much is unknown about the interval from exposure to symptoms. Testing availability is limited and variable, and much is unknown about sensitivity and specificity of direct viral RNA testing, appearance and disappearance of detectable immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG antibodies that affect false positive and false negative test results, duration of infectious phase, risk of transmission, and numerous other factors.

Positive serum viral testing likely indicates virus in semen or other bodily fluids, but a negative serum viral test cannot definitively preclude virus in other bodily fluids. Zika virus likely can be passed from any combination of semen and vaginal and cervical fluids, but validating tests for these fluids are not yet available. It is not known if sperm preparation and assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures that minimize risk of HIV transmission are effective against Zika virus or whether or not cryopreservation can destroy the virus.

Pregnancy timing

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends that all men with possible Zika virus exposure who are considering attempting pregnancy with their partner wait to get pregnant until at least 6 months after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible Zika virus exposure (if asymptomatic). Women with possible Zika virus exposure are recommended to wait to get pregnant until at least 8 weeks after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible Zika virus exposure (if asymptomatic).

Women and men with possible exposure to Zika virus but without clinical symptoms of illness should consider testing for Zika viral RNA within 2 weeks of suspected exposure and wait at least 8 weeks after the last date of exposure before being re-tested. If direct viral testing (using rRT-PCR) results initially are negative, ideally, antibody testing would be obtained, if available, at 8 weeks. However, no testing paradigm will absolutely guarantee lack of Zika virus infectivity.

Virus management problems are dramatically compounded in areas endemic for Zika. Women and men who have had Zika virus disease should wait at least 6 months after illness onset to attempt reproduction. The temporal relationship between the presence of viral RNA and infectivity is not known definitively, and so the absolute duration of time to wait before attempting pregnancy is unknown. Male and female partners who become infected should avoid all forms of intimate sexual conduct or use condoms for the same 6 months. There is no evidence Zika will cause congenital infection in pregnancies initiated after resolution of maternal Zika viremia. However, any testing performed at a time other than the time of treatment might not reflect true viral status, particularly in areas of active Zika virus transmission.

Prevention

Women and men, especially those residing in areas of active Zika virus transmission, should talk with their physicians regarding pregnancy plans and avoid mosquito bites using the usual precautions: avoid mosquito areas, drain standing water, use mosquito repellent containing DEET, and use mosquito netting. Some people have gone so far as to relocate to nonendemic areas.

Those contemplating pregnancy should be advised to consider what they would do if they become exposed to or have suspected or confirmed Zika virus during pregnancy. Additional considerations are gamete or embryo cryopreservation and quarantine until a subsequent rRT-PCR test result is negative in both the male and female and at least 8 weeks have passed from gamete collection.

Patient counseling essentials

Counsel patients considering reproduction about:

- Zika virus as a new reproductive hazard

- the significance of the hazard to the fetus if infected

- the areas of active transmission, and that they are constantly changing

- avoidance of Zika areas if possible

- methods of transmission through mosquito bites or sex

- avoidance of mosquito bites

- symptoms of Zika infection

- safe sex practices

- testing limitations and knowledge deficiency about Zika.

Not uncommonly, clinical situations require complex individualized management decisions regarding trade-offs of risks, especially in older patients with decreased ovarian reserve. Consultation with infectious disease and reproductive specialists should be obtained when complicated and consequential decisions have to be made.

All practitioners should inform their patients, especially those undergoing fertility treatments, about Zika, and develop language in their informed consent that conveys the gap in knowledge to these patients.

Read how obesity specifically affects reproduction in an adverse way

Obesity adversely affects reproduction, but how specifically?

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Obesity and Reproduction: A committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(5):1116-1126.

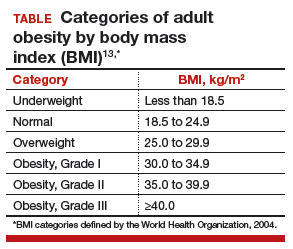

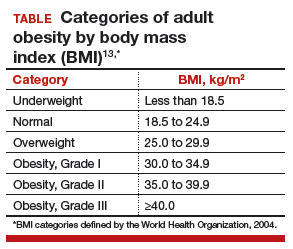

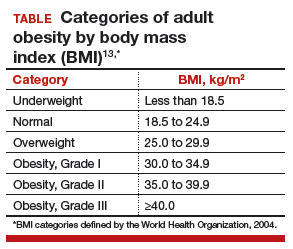

The prevalence of obesity has increased substantially over the past 2 decades. Almost two-thirds of women and three-fourths of men in the United States are overweight or obese (defined as a body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2 and BMI ≥30 kg/m2, respectively; TABLE). Nearly 50% of reproductive-age women are obese.

A disease of excess body fat and insulin resistance, obesity increases the risks of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, respiratory problems, and cancer as well as other serious health problems. While not all individuals with obesity will have infertility, obesity is associated with impaired reproduction in both women and men, adverse obstetric outcomes, and health problems in offspring. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) reviewed this important issue in a recent practice committee opinion.

Menstrual cycle and ovulatory dysfunction

Menstrual cycle abnormalities are more common in women with obesity. Elevated levels of insulin in obese women suppress sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG) which in turn reduces gonadotropin secretion due to increased production of estrogen from conversion of androgens by adipose aromatase.1 Adipose tissue produces adipokines, which directly can suppress ovarian function.2

Ovulatory dysfunction is common among obese women; the relative risk of such dysfunction is 3.1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2−4.4) among women with BMI levels >27 kg/m2 versus BMI levels 20.0 to 24.9 kg/m2.3,4 Obesity decreases fecundity even in women with normal menstrual cycles.5 This may in part be due to altered ovulatory dynamics with reduced early follicular luteinizing hormone pulse amplitude accompanied by prolonged folliculogenesis and reduced luteal progesterone levels.6

Compared with normal-weight women, obese women have a lower chance of conception within 1 year of stopping contraception; about 66% of obese women conceive within 1 year of stopping contraception, compared with about 81% of women with normal weight.7 Results of a Dutch study of 3,029 women with regular ovulation, at least one patent tube, and a partner with a normal semen analysis indicated a direct correlation between obesity and delayed conception, with a 4% lower spontaneous pregnancy rate per kg/m2 increase in women with a BMI >29 kg/m2 versus a BMI of 21 to 29 kg/m2 (hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91−0.99).8

Assisted reproduction

Assisted reproduction in women with obesity is associated with lower success rates than in women with normal weight. A systematic review of 27 in vitro fertilization (IVF) studies (23 of which were retrospective) reveals 10% lower live-birth rate in overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) versus normal-weight women (BMI <25 kg/m2) undergoing IVF (odds ratio [OR], 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82−1.0).9 Data from a meta-analysis of 33 IVF studies, including 47,967 cycles, show that, compared with women with a BMI <25 kg/m2, overweight or obese women have significantly reduced rates of clinical pregnancy (relative risk [RR], 0.90; P<.0001) and live birth (RR, 0.84; P = .0002).10

Results of a retrospective study of 4,609 women undergoing first IVF or IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles revealed impaired embryo implantation (controlling for embryo quality and transfer day), reducing the age-adjusted odds of live birth in a BMI-dependent manner by 37% (BMI, 30.0−34.9 kg/m2), 61% (BMI, 35.0−39.9 kg/m2), and 68% (BMI, >40 kg/m2) compared with women with a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2.11 In a study of 12,566 Danish couples undergoing assisted reproduction, overweight and obese ovulatory women had a 12% (95% CI, 0.79−0.99) and 25% (95% CI, 0.63−0.90) reduction in IVF-related live birth rate, respectively (referent BMI, 18.5−24.9 kg/m2), with a 2% (95% CI, 0.97−0.99) decrease in live-birth rate for every one-unit increase in BMI.12 Putative mechanisms for these findings include altered oocyte morphology and reduced fertilization in eggs from obese women,13 and impaired embryo quality in women less than age 35.14 Oocytes from women with a BMI >25 kg/m2 are smaller and less likely to complete development postfertilization, with embryos arrested prior to blastulation containing more triglyceride than those forming blastocysts.15

Blastocysts developed from oocytes of high-BMI women are smaller, contain fewer cells and have a higher content of triglycerides, lower glucose consumption, and altered amino acid metabolism compared with embryos of normal-weight women (BMI <24.9 kg/m2).15 Obesity may alter endometrial receptivity during IVF given the finding that third-party surrogate women with a BMI >35 kg/m2 have a lower live-birth rate (25%) compared with women with a BMI <35 kg/m2 (49%; P<.05).16

Pregnancy outcomes

Obesity is linked to an increased risk of miscarriage. Results of a meta-analysis of 33 IVF studies including 47,967 cycles indicated that overweight or obese women have a higher rate of miscarriage (RR, 1.31; P<.0001) than normal-weight women (BMI <25 kg/m2).17 Maternal and perinatal morbid obesity are strongly associated with obstetric and perinatal complications, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, preterm delivery, shoulder dystocia, fetal distress, early neonatal death, and small- as well as large-for-gestational age infants.

Obese women who conceive by IVF are at increased risk for preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery, and cesarean delivery.13 Authors of a meta-analysis of 18 observational studies concluded that obese mothers were at increased odds of pregnancies affected by such birth defects as neural tube defects, cardiovascular anomalies, and cleft lip and palate, among others.18

In addition to being the cause of these fetal abnormalities, maternal metabolic dysfunction is linked to promoting obesity in offspring, thereby perpetuating a cycle of obesity and adverse health outcomes that include an increased risk of premature death in adult offspring in subsequent generations.13

Treatment for obesity

Lifestyle modification is the first-line treatment for obesity.

Pre-fertility therapy and pregnancy goals. Targets for pregnancy should include:

- preconception weight loss to a BMI of 35 kg/m2

- prevention of excess weight gain in pregnancy

- long-term reduction in weight.

For all obese individuals, lifestyle modifications should include a weight loss of 7% of body weight and increased physical activity to at least 150 minutes of moderate activity, such as walking, per week. Calorie restriction should be emphasized. A 500 to 1,000 kcal/day decrease from usual dietary intake is expected to result in a 1- to 2-lb weight loss per week. A low-calorie diet of 1,000 to 1,200 kcal/day can lead to an average 10% decrease in total body weight over 6 months.

Adjunct supervised medical therapy or bariatric surgery can play an important role in successful weight loss prepregnancy but are not appropriate for women actively attempting conception. Importantly, pregnancy should be deferred for a minimum of 1 year after bariatric surgery. The decision to postpone pregnancy to achieve weight loss must be balanced against the risk of declining fertility with advancing age of the woman.

Read about when to treat subclinical hypothyroidism

Optimal management of subclinical hypothyroidism in women with infertility

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the infertile female population: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(3):545-553.

Thyroid disorders long have been associated with the potential for adverse reproductive outcomes. While overt hypothyroidism has been linked to infertility, increased miscarriage risk, and poor maternal and fetal outcomes, controversy has existed regarding the association between subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) and reproductive problems. The ASRM recently published a guideline on the role of SCH in the infertile female population.

How is subclinical hypothyroidism defined?

SCH is classically defined as a thyrotropin (TSH) level above the upper limit of normal range (4.5−5.0 mIU/L) with normal free thyroxine (FT4) levels. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) population has been used to establish normative data for TSH for a disease-free population. These include a median serum level for TSH of 1.5 mIU/L, with the corresponding 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of 0.41 and 6.10, respectively.19 Data from the National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry, however, reveal that 95% of individuals without evidence of thyroid disease have a TSH level <2.5 mIU/L, and that the normal reference range is skewed to the right.20 Adjusting the upper limit of the normal range to 2.5 mIU/L would result in an additional 11.8% to 14.2% of the United States population (22 to 28 million individuals) being diagnosed with hypothyroidism.

This information raises several important questions.

1. Should nonpregnant women be treated for SCH?

No. There is no benefit from the standpoint of lipid profile or alteration of cardiovascular risk in the treatment of TSH levels between 5 and 10 mIU/L and, therefore, treatment of individuals with TSH <5 mIU/L is questionable. Furthermore, the risk of overtreatment resulting in bone loss is a concern. The Endocrine Society does not recommend changing the current normal TSH range for nonpregnant women.

2. What are normal TSH levels in pregnant women?

Because human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can bind to and affect the TSH receptor, thereby influencing TSH values, the normal range for TSH is modified in pregnancy. The Endocrine Society recommends the following pregnancy trimester guidelines for TSH levels: 2.5 mIU/L is the recommended upper limit of normal in the first trimester, 3.0 mIU/L in the second trimester, and 3.5 mIU/L in the third trimester.

3. Is untreated SCH associated with miscarriage?

There is fair evidence that SCH, defined as a TSH level >4 mIU/L during pregnancy, is associated with miscarriage, but there is insufficient evidence that TSH levels between 2.5 and 4 mIU/L are associated with miscarriage.

4. Is untreated SCH associated with infertility?

Limited data are available to assess the effect of SCH on infertility. While a few studies show an association between SCH on unexplained infertility and ovulatory disorders, SCH does not appear to be increased in other causes of infertility.

5. Is SCH associated with adverse obstetric outcomes?

Available data reveal that SCH with TSH levels outside the normal pregnancy range are associated with an increased risk of such obstetric complications as placental abruption, preterm birth, fetal death, and preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM). However, it is unclear if prepregnancy TSH levels between 2.5 and 4 mIU/L are associated with adverse obstetric outcomes.

6. Does untreated SCH affect developmental outcomes in children?

The fetus is solely dependent on maternal thyroid hormone in early pregnancy because the fetal thyroid does not produce thyroid hormone before 10 to 13 weeks of gestation. Significant evidence has associated untreated maternal hypothyroidism with delayed fetal neurologic development, impaired school performance, and lower intelligence quotient (IQ) among offspring.21 There is fair evidence that SCH diagnosed in pregnancy is associated with adverse neurologic development. There is no evidence that SCH prior to pregnancy is associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. It should be noted that only one study has examined whether treatment of SCH improves developmental outcomes (measured by IQ scored at age 3 years) and no significant differences were observed in women with SCH who were treated with levothyroxine versus those who were not.22

7. Does treatment of SCH improve miscarriage rates, live-birth rates, and/or clinical pregnancy rates?

Small randomized controlled studies of women undergoing infertility treatment and a few observational studies in the general population yield good evidence that levothyroxine treatment in women with SCH defined as TSH >4.0 mIU/L is associated with improvement in pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates. There are no randomized trials assessing whether levothyroxine treatment in women with TSH levels between 2.5 and 4 mIU/L would yield similar benefits to those observed in women with TSH levels above 4 mIU/L.

8. Are thyroid antibodies associated with infertility or adverse reproductive outcomes?

There is good evidence that the thyroid autoimmunity, or the presence of TPO-Ab, is associated with miscarriage and fair evidence that it is associated with infertility. Treatment with levothyroxine may improve pregnancy outcomes especially if the TSH level is above 2.5 mIU/L.

9. Should there be universal screening for hypothyroidism in the first trimester of pregnancy?

Current evidence does not reveal a benefit of universal screening at this time. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend routine screening for hypothyroidism in pregnancy unless women have risk factors for thyroid disease, including a personal or family history of thyroid disease, physical findings or symptoms of goiter or hypothyroidism, type 1 diabetes mellitus, infertility, history of miscarriage or preterm delivery, and/or personal or family history of autoimmune disease.

The bottom line

SCH, defined as a TSH level greater than the upper limit of normal range (4.5−5.0 mIU/L)with normal FT4 levels, is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes including miscarriage, pregnancy complications, and delayed fetal neurodevelopment. Thyroid supplementation is beneficial; however, treatment has not been shown to improve long-term neurologic developmental outcomes in offspring. Data are limited on whether TSH values between 2.5 mIU/L and the upper range of normal are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes and therefore treatment in this group remains controversial. Although available evidence is weak, there may be a benefit in some subgroups, and because risk is minimal, it may be reasonable to treat or to monitor levels and treat above nonpregnant and pregnancy ranges. There is fair evidence that thyroid autoimmunity (positive thyroid antibody) is associated with miscarriage and infertility. Levothyroxine therapy may improve pregnancy outcomes especially if the TSH level is above 2.5 mIU/L. While universal screening of thyroid function in pregnancy is not recommended, women at high risk for thyroid disease should be screened.23

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Pasquali R, Pelusi C, Genghini S, Cacciari M, Gambineri A. Obesity and reproductive disorders in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9(4):359-372.

- Greisen S, Ledet T, Møller N, et al. Effects of leptin on basal and FSH stimulated steroidogenesis in human granulosa luteal cells. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(11):931-935.

- Rich-Edwards JW, Goldman MB, Willett WC, et al. Adolescent body mass index and infertility caused by ovulatory disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(1):171-177.

- Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Cramer DW. Body mass index and ovulatory infertility. Epidemiology. 1994;5(2):247-250.

- Gesink Law DC, Maclehose RF, Longnecker MP. Obesity and time to pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(2):414-420.

- Jain A, Polotsky AJ, Rochester D, et al. Pulsatile luteinizing hormone amplitude and progesterone metabolite excretion are reduced in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2468-2473.

- Lake JK, Power C, Cole TJ. Women's reproductive health: the role of body mass index in early and adult life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(6):432-438.

- van der Steeg JW, Steures P, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Obesity affects spontaneous pregnancy chances in subfertile, ovulatory women. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(2):324-328.

- Koning AM, Mutsaerts MA, Kuchenbecker WK, et al. Complications and outcome of assisted reproduction technologies in overweight and obese women [Published correction appears in Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2570.] Hum Reprod. 2012;27(2):457-467.

- Rittenberg V, Seshadri S, Sunkara SK, Sobaleva S, Oteng-Ntim E, El-Toukhy T. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23(4):421-439.

- Moragianni VA, Jones SM, Ryley DA. The effect of body mass index on the outcomes of first assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(1):102-108.

- Petersen GL, Schmidt L, Pinborg A, Kamper-Jørgensen M. The influence of female and male body mass index on live births after assisted reproductive technology treatment: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(6):1654-1662.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Obesity and Reproduction: A committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(5):1116-1126.

- Metwally M, Cutting R, Tipton A, Skull J, Ledger WL, Li TC. Effect of increased body mass index on oocyte and embryo quality in IVF patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15(5):532-538.

- Leary C, Leese HJ, Sturmey RG. Human embryos from overweight and obese women display phenotypic and metabolic abnormalities. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(1):122-132.

- Deugarte D, Deugarte C, Sahakian V. Surrogate obesity negatively impacts pregnancy rates in third-party reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):1008-1010.

- Rittenberg V, Seshadri S, Sunkara SK, Sobaleva S, Oteng-Ntim E, El-Toukhy T. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23(4):421-439.

- Stothard KJ, Tennant PWG, Bell R, Rankin J. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(6):636-650.

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):489-499.

- Baloch Z, Carayon P, Conte-Devolx B, et al. Laboratory medicine practice guidelines. Laboratory support for the diagnosis and monitoring of thyroid disease. Thyroid. 2003;13(1):3-126.

- Pop VJ, Kuijpens JL, van Baar AL, et al. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;50(2):149-155.

- Lazarus JH, Bestwick JP, Channon S, et al. Antenatal thyroid screening and childhood cognitive function. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):493-501.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the infertile female population: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(3):545-553.

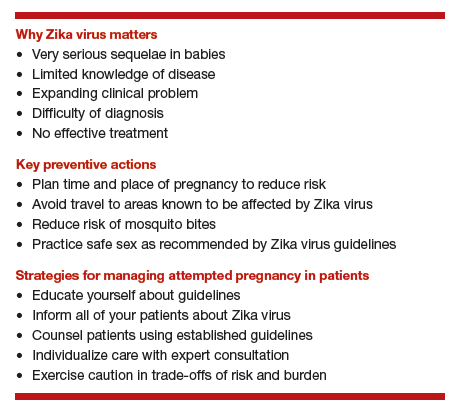

Zika virus is a serious problem. Education and infection prevention are critical to effective management, and why we chose to include Zika virus as a topic for this year’s Update. We also discuss obesity’s effects on reproduction—a very relevant concern for all ObGyns and patients alike as about half of reproductive-age women are obese. Finally, subclinical hypothyroidism can present unique management challenges, such as determining when it is present and when treatment is indicated.

Read about counseling patients about Zika virus

Managing attempted pregnancy in the era of Zika virus

Oduyebo T, Igbinosa I, Petersen EE, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers caring for pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, July 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(29):739-744.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

US Food and Drug Administration. Donor Screening Recommendations to Reduce the Risk of Transmission of Zika Virus by Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Tissue/UCM488582.pdf. Published March 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

National Institutes of Health. Zika: Overview. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/zika/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2017.

World Health Organization. Prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus interim guidance. WHO reference number: WHO/ZIKV/MOC/16. 1 Rev. 3, September 6, 2016.

Zika Virus Guidance Task Force of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Rev. 13, September 2016.

Zika virus presents unique challenges to physicians managing the care of patients attempting pregnancy, with or without fertility treatment. Neonatal Zika virus infection sequelae only recently have been appreciated; microcephaly was associated with Zika virus in October 2015, followed by other neurologic conditions including brain abnormalities, neural tube defects, and eye abnormalities. Results of recent studies involving the US Zika Pregnancy Registry show that 6% of women with Zika at any time in pregnancy had affected babies, but 11% of those who contracted the disease in the first trimester were affected.

Diagnosis is difficult because symptoms are generally mild, with 80% of affected patients asymptomatic. Possible Zika virus exposure is defined as travel to or residence in an area of active Zika virus transmission, or sex without a condom with a partner who traveled to or lived in an area of active transmission. Much is unknown about the interval from exposure to symptoms. Testing availability is limited and variable, and much is unknown about sensitivity and specificity of direct viral RNA testing, appearance and disappearance of detectable immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG antibodies that affect false positive and false negative test results, duration of infectious phase, risk of transmission, and numerous other factors.

Positive serum viral testing likely indicates virus in semen or other bodily fluids, but a negative serum viral test cannot definitively preclude virus in other bodily fluids. Zika virus likely can be passed from any combination of semen and vaginal and cervical fluids, but validating tests for these fluids are not yet available. It is not known if sperm preparation and assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures that minimize risk of HIV transmission are effective against Zika virus or whether or not cryopreservation can destroy the virus.

Pregnancy timing

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends that all men with possible Zika virus exposure who are considering attempting pregnancy with their partner wait to get pregnant until at least 6 months after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible Zika virus exposure (if asymptomatic). Women with possible Zika virus exposure are recommended to wait to get pregnant until at least 8 weeks after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible Zika virus exposure (if asymptomatic).

Women and men with possible exposure to Zika virus but without clinical symptoms of illness should consider testing for Zika viral RNA within 2 weeks of suspected exposure and wait at least 8 weeks after the last date of exposure before being re-tested. If direct viral testing (using rRT-PCR) results initially are negative, ideally, antibody testing would be obtained, if available, at 8 weeks. However, no testing paradigm will absolutely guarantee lack of Zika virus infectivity.

Virus management problems are dramatically compounded in areas endemic for Zika. Women and men who have had Zika virus disease should wait at least 6 months after illness onset to attempt reproduction. The temporal relationship between the presence of viral RNA and infectivity is not known definitively, and so the absolute duration of time to wait before attempting pregnancy is unknown. Male and female partners who become infected should avoid all forms of intimate sexual conduct or use condoms for the same 6 months. There is no evidence Zika will cause congenital infection in pregnancies initiated after resolution of maternal Zika viremia. However, any testing performed at a time other than the time of treatment might not reflect true viral status, particularly in areas of active Zika virus transmission.

Prevention

Women and men, especially those residing in areas of active Zika virus transmission, should talk with their physicians regarding pregnancy plans and avoid mosquito bites using the usual precautions: avoid mosquito areas, drain standing water, use mosquito repellent containing DEET, and use mosquito netting. Some people have gone so far as to relocate to nonendemic areas.

Those contemplating pregnancy should be advised to consider what they would do if they become exposed to or have suspected or confirmed Zika virus during pregnancy. Additional considerations are gamete or embryo cryopreservation and quarantine until a subsequent rRT-PCR test result is negative in both the male and female and at least 8 weeks have passed from gamete collection.

Patient counseling essentials

Counsel patients considering reproduction about:

- Zika virus as a new reproductive hazard

- the significance of the hazard to the fetus if infected

- the areas of active transmission, and that they are constantly changing

- avoidance of Zika areas if possible

- methods of transmission through mosquito bites or sex

- avoidance of mosquito bites

- symptoms of Zika infection

- safe sex practices

- testing limitations and knowledge deficiency about Zika.

Not uncommonly, clinical situations require complex individualized management decisions regarding trade-offs of risks, especially in older patients with decreased ovarian reserve. Consultation with infectious disease and reproductive specialists should be obtained when complicated and consequential decisions have to be made.

All practitioners should inform their patients, especially those undergoing fertility treatments, about Zika, and develop language in their informed consent that conveys the gap in knowledge to these patients.

Read how obesity specifically affects reproduction in an adverse way

Obesity adversely affects reproduction, but how specifically?

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Obesity and Reproduction: A committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(5):1116-1126.

The prevalence of obesity has increased substantially over the past 2 decades. Almost two-thirds of women and three-fourths of men in the United States are overweight or obese (defined as a body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2 and BMI ≥30 kg/m2, respectively; TABLE). Nearly 50% of reproductive-age women are obese.

A disease of excess body fat and insulin resistance, obesity increases the risks of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, respiratory problems, and cancer as well as other serious health problems. While not all individuals with obesity will have infertility, obesity is associated with impaired reproduction in both women and men, adverse obstetric outcomes, and health problems in offspring. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) reviewed this important issue in a recent practice committee opinion.

Menstrual cycle and ovulatory dysfunction

Menstrual cycle abnormalities are more common in women with obesity. Elevated levels of insulin in obese women suppress sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG) which in turn reduces gonadotropin secretion due to increased production of estrogen from conversion of androgens by adipose aromatase.1 Adipose tissue produces adipokines, which directly can suppress ovarian function.2

Ovulatory dysfunction is common among obese women; the relative risk of such dysfunction is 3.1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2−4.4) among women with BMI levels >27 kg/m2 versus BMI levels 20.0 to 24.9 kg/m2.3,4 Obesity decreases fecundity even in women with normal menstrual cycles.5 This may in part be due to altered ovulatory dynamics with reduced early follicular luteinizing hormone pulse amplitude accompanied by prolonged folliculogenesis and reduced luteal progesterone levels.6