User login

A Call for More Autopsies

In the past 50 years, the number of autopsies at most U.S. hospitals has dropped drastically. The decline is due in part to a “widespread perception” that new imaging techniques and laboratory tests have improved diagnostic accuracy to the extent that an autopsy is considered obsolete, say researchers from Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. But the researchers claim that autopsies are still relevant and “a valuable tool to evaluate diagnostic accuracy.”

According to the researchers, autopsy studies continue to show that the proportions of clinical misdiagnosis have remained largely unchanged. They also found that autopsies performed over 10 years of 821 adults showed 8% had clinically undiagnosed malignancies—similar to the numbers found in studies done 10 years earlier. Out of 66 cases, 26 revealed undiagnosed malignancies directly related to the primary cause of death. In 16 autopsies, there was no clinical suspicion of malignancy, but the primary cause of death (such as acute bronchopneumonia and gastrointestinal perforation) was directly related to an undiagnosed neoplasm. In 10 cases, there was clinical suspicion of malignancy based on history, radiologic studies, and laboratory tests but without definite tissue diagnosis.

The researchers note that some studies have suggested a link between short hospital stays and missed diagnoses. But in the current study, length of stay had no bearing on a patient’s having an unsuspected malignancy. “Ironically,” the cases with no clinical suspicion involved longer hospital stays. In at least 5 cases the hospital stay was for more than 5 days. Moreover, CT scans of the thorax/abdomen raised no suspicion of cancer.

The researchers say their findings make a “strong case for a vigorous hospital autopsy program,” and for using autopsy data to improve performance in clinical, radiologic, and laboratory services. Their study “reiterates the value of the hospital autopsy as an auditing tool for diagnostic accuracy.”

Source: Parajuli S, Aneja A, Mukherjee A. Hum Pathol. 2016; 48:32-36.

doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.040.

In the past 50 years, the number of autopsies at most U.S. hospitals has dropped drastically. The decline is due in part to a “widespread perception” that new imaging techniques and laboratory tests have improved diagnostic accuracy to the extent that an autopsy is considered obsolete, say researchers from Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. But the researchers claim that autopsies are still relevant and “a valuable tool to evaluate diagnostic accuracy.”

According to the researchers, autopsy studies continue to show that the proportions of clinical misdiagnosis have remained largely unchanged. They also found that autopsies performed over 10 years of 821 adults showed 8% had clinically undiagnosed malignancies—similar to the numbers found in studies done 10 years earlier. Out of 66 cases, 26 revealed undiagnosed malignancies directly related to the primary cause of death. In 16 autopsies, there was no clinical suspicion of malignancy, but the primary cause of death (such as acute bronchopneumonia and gastrointestinal perforation) was directly related to an undiagnosed neoplasm. In 10 cases, there was clinical suspicion of malignancy based on history, radiologic studies, and laboratory tests but without definite tissue diagnosis.

The researchers note that some studies have suggested a link between short hospital stays and missed diagnoses. But in the current study, length of stay had no bearing on a patient’s having an unsuspected malignancy. “Ironically,” the cases with no clinical suspicion involved longer hospital stays. In at least 5 cases the hospital stay was for more than 5 days. Moreover, CT scans of the thorax/abdomen raised no suspicion of cancer.

The researchers say their findings make a “strong case for a vigorous hospital autopsy program,” and for using autopsy data to improve performance in clinical, radiologic, and laboratory services. Their study “reiterates the value of the hospital autopsy as an auditing tool for diagnostic accuracy.”

Source: Parajuli S, Aneja A, Mukherjee A. Hum Pathol. 2016; 48:32-36.

doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.040.

In the past 50 years, the number of autopsies at most U.S. hospitals has dropped drastically. The decline is due in part to a “widespread perception” that new imaging techniques and laboratory tests have improved diagnostic accuracy to the extent that an autopsy is considered obsolete, say researchers from Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. But the researchers claim that autopsies are still relevant and “a valuable tool to evaluate diagnostic accuracy.”

According to the researchers, autopsy studies continue to show that the proportions of clinical misdiagnosis have remained largely unchanged. They also found that autopsies performed over 10 years of 821 adults showed 8% had clinically undiagnosed malignancies—similar to the numbers found in studies done 10 years earlier. Out of 66 cases, 26 revealed undiagnosed malignancies directly related to the primary cause of death. In 16 autopsies, there was no clinical suspicion of malignancy, but the primary cause of death (such as acute bronchopneumonia and gastrointestinal perforation) was directly related to an undiagnosed neoplasm. In 10 cases, there was clinical suspicion of malignancy based on history, radiologic studies, and laboratory tests but without definite tissue diagnosis.

The researchers note that some studies have suggested a link between short hospital stays and missed diagnoses. But in the current study, length of stay had no bearing on a patient’s having an unsuspected malignancy. “Ironically,” the cases with no clinical suspicion involved longer hospital stays. In at least 5 cases the hospital stay was for more than 5 days. Moreover, CT scans of the thorax/abdomen raised no suspicion of cancer.

The researchers say their findings make a “strong case for a vigorous hospital autopsy program,” and for using autopsy data to improve performance in clinical, radiologic, and laboratory services. Their study “reiterates the value of the hospital autopsy as an auditing tool for diagnostic accuracy.”

Source: Parajuli S, Aneja A, Mukherjee A. Hum Pathol. 2016; 48:32-36.

doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.040.

Zika virus: Counseling considerations for this emerging perinatal threat

Zika virus infection in the news

- CDC: Zika virus disease cases by US state or territory, updated periodically

- CDC: Q&As for ObGyns on pregnant women and Zika virus, 2/9/16

- CDC: Zika virus infection among US pregnant travelers, 2/26/16

- CDC: Interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection, 2/19/16

- SMFM statement: Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure, 2/16/16

- FDA approves first Zika diagnostic test for commercial use. Newsweek, 2/26/16

- NIH accelerates timeline for human trials of Zika vaccine. The Washington Post, 2/17/16

- Patient resource: Zika virus and pregnancy fact sheet from MotherToBaby.org

- Zika virus article collection from New England Journal of Medicine

- Zika infection diagnosed in 18 pregnant US women who traveled to Zika-affected areas

- FDA grants emergency approval to new 3-in-1 lab test for Zika

- ACOG Practice Advisory: Updated interim guidance for care of women of reproductive age during a Zika virus outbreak, 3/31/16

- MMWR: Patterns in Zika virus testing and infection, 4/22/16

- What insect repellents are safe during pregnancy? 5/19/16

- Zika virus and complications: Q&A from WHO, 5/31/16

- WHO strengthens guidelines to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus, 5/31/16

- Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure (from AJOG), 6/1/16

- CDC: Interim guidance for interpretation of Zika virus antibody test results, 6/3/16

- First Zika vaccine to begin testing in human trials, The Washington Post, 6/20/16

- NIH launches the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) international study, 6/21/16

CASE 1: Pregnant traveler asks: Should I be tested for Zika virus?

A 28-year-old Hispanic woman (G3P2) at 15 weeks’ gestation visits your office for a routine prenatal care appointment. She reports having returned from a 3-week holiday in Brazil 2 days ago, and she is concerned about having experienced fever, malaise, arthralgias, and a disseminated erythematous rash. She has since heard about the Zika virus and asks you if she and her baby are in danger and whether she should be tested for the disease.

What should you tell this patient?

The Zika virus is an RNA Flavivirus, transmitted primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.1 This virus is closely related to the organisms that cause dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya infection, and West Nile infection. By feeding on infected prey, mosquitoes can transmit the virus to humans through bites. They breed near pools of stagnant water, can survive both indoors and outdoors, and prefer to be near people. These mosquitoes bite mostly during daylight hours, so it is essential that people use insect repellent throughout the day while in endemic areas.2 These mosquitoes live only in tropical regions; however, the Aedes albopictus mosquito, also known as the Asian tiger mosquito, lives in temperate regions and can transmit the Zika virus as well3 (FIGURE 1).

| FIGURE 1 Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes | ||

|

| |

Aedes aegypti (left) and Aedes albopictus (right) mosquitoes. Aedes mosquitoes are the main transmission vector for the Zika virus. | ||

|

The Zika virus was first discovered in 1947 when it was isolated from a rhesus monkey in Uganda. It subsequently spread to Southeast Asia and eventually caused major outbreaks in the Yap Islands of Micronesia (2007)4 and French Polynesia (2013).5 In 2015, local transmission of the Zika virus infection was noted in Brazil, and, most recently, a pandemic of Zika virus infection has occurred throughout South America, Central America, and the Caribbean islands. To date, local mosquito-borne virus transmission has not occurred in the continental United States, although at least 82 cases acquired during travel to infected areas have been reported.6

Additionally, there have been rare cases involving spread of this virus from infected blood transfusions and through sexual contact.7 In February 2016, the first case of locally acquired Zika virus infection was reported in Texas following sexual transmission of the disease.8

Clinical manifestations of Zika virus infection

Eighty percent of patients infected with Zika virus remain asymptomatic. The illness is short-lived, occurring 2 to 12 days following the mosquito bite, and infected individuals usually do not require hospitalization or experience serious morbidity. When symptoms are present, they typically include low-grade fever (37.8° to 38.5°C), maculopapular rash, arthralgias of the hands and feet, and nonpurulent conjunctivitis. Patients also may experience headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, and, rarely, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ulcerations of mucous membranes, and pruritus.9 Guillain-Barré syndrome has been reported in association with Zika virus infection10; however, a definitive cause-effect relationship has not been proven.

If a pregnant woman is infected with the Zika virus, perinatal transmission can occur, either through uteroplacental transmission or vertically from mother to child at the time of delivery. Zika virus RNA has been detected in blood, amniotic fluid, semen, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and breast milk. Although the virus has been shown to be present in breast milk, there has been no evidence of viral replication in milk or reported transmission in breastfed infants.11 Pregnant women are not known to have increased susceptibility to Zika virus infection when compared with the general population, and there is no evidence to suggest pregnant women will have a more serious illness if infected.

The Zika virus has been strongly associated with congenital microcephaly and fetal loss among women infected during pregnancy.12 Following the recent large outbreak in Brazil, an alarmingly high number of Brazilian newborns with microcephaly have been observed. The total now exceeds 4,000. Because of these ominous findings, fetuses and neonates born to women with a history of infection should be evaluated for adverse effects of congenital infection.

Management strategies for Zika virus exposure during pregnancy

The incidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy remains unknown. However, a pregnant woman may be infected in any trimester, and maternal-fetal transmission of the virus can occur throughout pregnancy. If a patient is pregnant and has travelled to areas of Zika virus transmission, or has had unprotected sexual contact with a partner who has had exposure, she should be carefully screened with a detailed review of systems and ultrasonography to evaluate for fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initially recommended that, if a patient exhibited 2 or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection within 2 weeks of exposure or if sonographic evidence revealed fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, she should be tested for Zika virus infection.11

More recently, the CDC issued new guidelines recommending that even asymptomatic women with exposure have serologic testing for infection and that all exposed women undergo serial ultrasound assessments.13 The CDC also recommends offering retesting in the mid second trimester for women who were exposed very early in gestation.

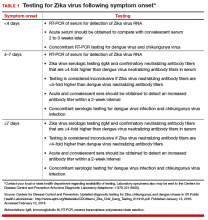

The best diagnostic test for infection is reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and, ideally, it should be completed within 4 days of symptom onset. Beyond 4 days after symptom onset, testing for Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibody and neutralizing antibody should be performed in addition to the RT-PCR test. At times, interpretation of antibody testing can be problematic because cross-reaction with related arboviruses is common. Moreover, Zika viremia decreases rapidly over time; therefore, if serum is collected even 5 to 7 days after symptom onset, a negative test does not definitively exclude infection (TABLE 1).

In the United States, local health departments should be contacted to facilitate testing, as the tests described above are not currently commercially available. If the local health department is unable to perform this testing, clinicians should contact the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (telephone: 1-970-221-6400) or visit their website (http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/specimensub/arboviral-shipping.html) for detailed instructions on specimen submission.

Testing is not indicated for women without a history of travel to areas where Zika virus infection is endemic or without a history of unprotected sexual contact with someone who has been exposed to the infection.

Following the delivery of a live infant to an infected or exposed mother, detailed histopathologic evaluation of the placenta and umbilical cord should be performed. Frozen sections of placental and cord tissue should be tested for Zika virus RNA, and cord serum should be tested for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. In cases of fetal loss in the setting of relevant travel history or exposure (particularly maternal symptoms or sonographic evidence of microcephaly), RT-PCR testing and immunohistochemistry should be completed on fetal tissues, umbilical cord, and placenta.2

Treatment is supportive

At present, there is no vaccine for the Zika virus, and no hyperimmune globulin or anti‑ viral chemotherapy is available. Treatment is therefore supportive. Patients should be encouraged to rest and maintain hydration. The preferred antipyretic and analgesic is acetaminophen (650 mg orally every 6 hours or 1,000 mg orally every 8 hours). Aspirin should be avoided until dengue infection has been ruled out because of the related risk of bleeding with hemorrhagic fever. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in the second half of pregnancy because of their effect on fetal renal blood flow (oligohydramnios) and stricture of the ductus arteriosus.

CASE 1 Continued

Given this patient’s recent travel, exposure to mosquito-borne illness, and clinical manifestations of malaise, rash, and joint pain, you proceed with serologic testing. The RT-PCR test is positive for Zika virus.

What should be the next step in the management of this patient?

Prenatal diagnosis and fetal surveillance

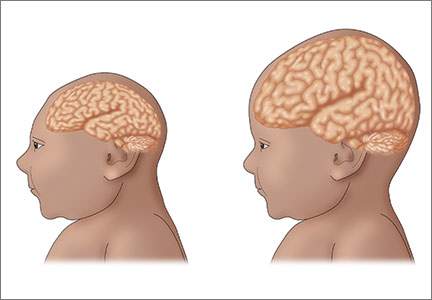

The recent epidemic of microcephaly and poor pregnancy outcomes reported in Brazil has been alarming and demonstrates an almost 20-fold increase in incidence of this condition between 2014–2015.14 Careful surveillance is needed for this birth defect and other poor pregnancy outcomes in association with the Zika virus. To date, a direct causal relationship between Zika virus infection and microcephaly has not been unequivocally established15; however; these microcephaly cases have yet to be attributed to any other cause (FIGURE 2)

| FIGURE 2 Microcephaly: associated with Zika virus infection in pregnancy |

|

Illustration depicts a child with congenital microcephaly (left) and one with head circumference within the mean SD (right). |

Following the outbreak in Brazil, a task force and registry were established to investigate microcephaly and other birth defects associated with Zika virus infection. In one small investigation, 35 cases of microcephaly were reported, and 71% of the infants were seriously affected (head circumference >3 SD below the mean). Fifty percent of babies had at least one neurologic abnormality, and, of the 27 patients who had neuroimaging studies, all had distinct abnormalities, including widespread brain calcifications and cell migration abnormalities, such as lissencephaly, pachgyria, and ventriculomegaly due to cortical atrophy.16

In addition to microcephaly, fetal ultrasound monitoring has revealed focal brain abnormalities, such as asymmetric cerebral hemispheres, ventriculomegaly, displacement of the midline, failure to visualize the corpus callosum, failure of thalamic development, and the presence of intraocular and brain calcifications.17

In collaboration with the CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal Fetal-Medicine have developed guidelines to monitor fetal growth in women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection.18 Recommendations include having a detailed anatomy ultrasound and serial growth sonograms every 3 to 4 weeks, along with referral to a maternal-fetal medicine or infectious disease specialist.

If the pregnancy is beyond 15 weeks’ gestational age, an amniocentesis should be performed in symptomatic patients and in those with abnormal ultrasound findings. Amniotic fluid should be tested for Zika virus with RT-PCR (FIGURE 3).12 The sensitivity and specificity of amniotic fluid RT-PCR in detecting congenital infection, as well as the predictive value of a fetal anomaly, remain unknown at this time. For this reason, a patient must be counseled carefully regarding the benefits of confirming intrauterine infection versus the slight risks of premature rupture of membranes, infection, and pregnancy loss related to amniocentesis.

Once diagnosed, microcephaly cannot be “fixed.” However, pregnancy termination is an option that some parents may choose once they are aware of the diagnosis and prognosis of microcephaly. Moreover, even for parents who would not choose abortion, there may be considerable value in being prepared for the care of a severely disabled child. Microcephaly has many possible causes, Zika virus infection being just one. Others include genetic syndromes and other congenital infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and toxoplasmosis. Amniocentesis therefore may help the clinician sort through these causes. For both CMV infection and toxoplasmosis, certain antenatal treatments may be helpful in lessening the severity of fetal injury.

CASE 2 Pregnant patient has travel plans

A 34-year-old woman (G1P0) presents to you for her first prenatal visit. She mentions she plans to take a cruise through the Eastern Caribbean in 2 weeks. Following the history and physical examination, what should you tell this patient?

Perinatal counseling: Limiting exposure is best

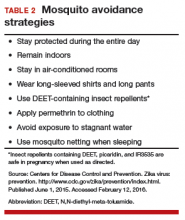

As mentioned, there is currently no treatment, prophylactic medication, or vaccination for Zika virus infection. Because of the virus’s significant associations with adverse pregnancy outcomes, birth defects, and fetal loss, the CDC has issued a travel advisory urging pregnant women to avoid travel to areas when Zika virus infection is prevalent. Currently, Zika virus outbreaks are occurring throughout South and Central America, the Pacific Islands, and Africa, and the infection is expected to spread, mainly due to international air travel. If travel to these areas is inevitable, women should take rigorous precautions to avoid exposure to mosquito bites and infection (TABLE 2).

If a woman was infected with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection in a prior pregnancy, she should not be at risk for congenital infection during her next pregnancy. This is mainly because the period of viremia is short-lived and lasts approximately 5 to 7 days.2

Further, based on documented sexual transmission of the virus, pregnant women should abstain from sexual activity or should consistently and correctly use condoms with partners who have Zika virus infection or exposure to the virus until further evidence is available.

Stay informed

Zika virus infection is now pandemic; it has evolved from an isolated disease of the tropics to one that is sweeping the Western hemisphere. It is being reported daily in new locations around the world. Given the unsettling association of Zika virus infection with birth defects, careful obstetric surveillance of exposed or symptomatic patients is imperative. Clinicians must carefully screen patients with potential risk of exposure and be prepared to offer appropriate perinatal counseling and diagnostic testing during pregnancy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dyer O. Zika virus spreads across Americas as concerns mount over birth defects. BMJ. 2015;351:h6983.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Bogoch II, Brady OJ, Kraemer MU, et al. Anticipating the international spread of Zika virus from Brazil. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):335–336.

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2536–2543.

- Besnard M, Lastere S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V, Musso D. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(13):pii:20751.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, et al. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(5):880–882.

- Dallas County Health and Human Services. DCHHS reports first Zika virus case in Dallas County acquired through sexual transmission. http://www.dallascounty.org/department/hhs /press/documents/PR2-2-16DCHHSReportsFirstCaseofZikaVirusThroughSexualTransmission.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Ministry of Health, Manuatu Hauora. Zika virus. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/zika -virus. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Oehler E, Watrin L, Larre P, et al. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barre syndrome—case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:4–6.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus: transmission. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/transmission/index.html. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delamn, D et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30–33.

- Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5):122–127.

- Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Epidemiological alert: neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications for public health in the Americas. December 1,2015. http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_doc man&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32405&lang=en. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential associations with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. December 10, 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association -with-microcephaly-rapid-risk-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, et al; Brazilian Medical Genetics Society—Zika Embryopathy Task Force. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):59–62.

- Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis AM. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):6–7.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential associations with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. December 10, 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association.

Zika virus infection in the news

- CDC: Zika virus disease cases by US state or territory, updated periodically

- CDC: Q&As for ObGyns on pregnant women and Zika virus, 2/9/16

- CDC: Zika virus infection among US pregnant travelers, 2/26/16

- CDC: Interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection, 2/19/16

- SMFM statement: Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure, 2/16/16

- FDA approves first Zika diagnostic test for commercial use. Newsweek, 2/26/16

- NIH accelerates timeline for human trials of Zika vaccine. The Washington Post, 2/17/16

- Patient resource: Zika virus and pregnancy fact sheet from MotherToBaby.org

- Zika virus article collection from New England Journal of Medicine

- Zika infection diagnosed in 18 pregnant US women who traveled to Zika-affected areas

- FDA grants emergency approval to new 3-in-1 lab test for Zika

- ACOG Practice Advisory: Updated interim guidance for care of women of reproductive age during a Zika virus outbreak, 3/31/16

- MMWR: Patterns in Zika virus testing and infection, 4/22/16

- What insect repellents are safe during pregnancy? 5/19/16

- Zika virus and complications: Q&A from WHO, 5/31/16

- WHO strengthens guidelines to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus, 5/31/16

- Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure (from AJOG), 6/1/16

- CDC: Interim guidance for interpretation of Zika virus antibody test results, 6/3/16

- First Zika vaccine to begin testing in human trials, The Washington Post, 6/20/16

- NIH launches the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) international study, 6/21/16

CASE 1: Pregnant traveler asks: Should I be tested for Zika virus?

A 28-year-old Hispanic woman (G3P2) at 15 weeks’ gestation visits your office for a routine prenatal care appointment. She reports having returned from a 3-week holiday in Brazil 2 days ago, and she is concerned about having experienced fever, malaise, arthralgias, and a disseminated erythematous rash. She has since heard about the Zika virus and asks you if she and her baby are in danger and whether she should be tested for the disease.

What should you tell this patient?

The Zika virus is an RNA Flavivirus, transmitted primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.1 This virus is closely related to the organisms that cause dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya infection, and West Nile infection. By feeding on infected prey, mosquitoes can transmit the virus to humans through bites. They breed near pools of stagnant water, can survive both indoors and outdoors, and prefer to be near people. These mosquitoes bite mostly during daylight hours, so it is essential that people use insect repellent throughout the day while in endemic areas.2 These mosquitoes live only in tropical regions; however, the Aedes albopictus mosquito, also known as the Asian tiger mosquito, lives in temperate regions and can transmit the Zika virus as well3 (FIGURE 1).

| FIGURE 1 Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes | ||

|

| |

Aedes aegypti (left) and Aedes albopictus (right) mosquitoes. Aedes mosquitoes are the main transmission vector for the Zika virus. | ||

|

The Zika virus was first discovered in 1947 when it was isolated from a rhesus monkey in Uganda. It subsequently spread to Southeast Asia and eventually caused major outbreaks in the Yap Islands of Micronesia (2007)4 and French Polynesia (2013).5 In 2015, local transmission of the Zika virus infection was noted in Brazil, and, most recently, a pandemic of Zika virus infection has occurred throughout South America, Central America, and the Caribbean islands. To date, local mosquito-borne virus transmission has not occurred in the continental United States, although at least 82 cases acquired during travel to infected areas have been reported.6

Additionally, there have been rare cases involving spread of this virus from infected blood transfusions and through sexual contact.7 In February 2016, the first case of locally acquired Zika virus infection was reported in Texas following sexual transmission of the disease.8

Clinical manifestations of Zika virus infection

Eighty percent of patients infected with Zika virus remain asymptomatic. The illness is short-lived, occurring 2 to 12 days following the mosquito bite, and infected individuals usually do not require hospitalization or experience serious morbidity. When symptoms are present, they typically include low-grade fever (37.8° to 38.5°C), maculopapular rash, arthralgias of the hands and feet, and nonpurulent conjunctivitis. Patients also may experience headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, and, rarely, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ulcerations of mucous membranes, and pruritus.9 Guillain-Barré syndrome has been reported in association with Zika virus infection10; however, a definitive cause-effect relationship has not been proven.

If a pregnant woman is infected with the Zika virus, perinatal transmission can occur, either through uteroplacental transmission or vertically from mother to child at the time of delivery. Zika virus RNA has been detected in blood, amniotic fluid, semen, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and breast milk. Although the virus has been shown to be present in breast milk, there has been no evidence of viral replication in milk or reported transmission in breastfed infants.11 Pregnant women are not known to have increased susceptibility to Zika virus infection when compared with the general population, and there is no evidence to suggest pregnant women will have a more serious illness if infected.

The Zika virus has been strongly associated with congenital microcephaly and fetal loss among women infected during pregnancy.12 Following the recent large outbreak in Brazil, an alarmingly high number of Brazilian newborns with microcephaly have been observed. The total now exceeds 4,000. Because of these ominous findings, fetuses and neonates born to women with a history of infection should be evaluated for adverse effects of congenital infection.

Management strategies for Zika virus exposure during pregnancy

The incidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy remains unknown. However, a pregnant woman may be infected in any trimester, and maternal-fetal transmission of the virus can occur throughout pregnancy. If a patient is pregnant and has travelled to areas of Zika virus transmission, or has had unprotected sexual contact with a partner who has had exposure, she should be carefully screened with a detailed review of systems and ultrasonography to evaluate for fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initially recommended that, if a patient exhibited 2 or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection within 2 weeks of exposure or if sonographic evidence revealed fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, she should be tested for Zika virus infection.11

More recently, the CDC issued new guidelines recommending that even asymptomatic women with exposure have serologic testing for infection and that all exposed women undergo serial ultrasound assessments.13 The CDC also recommends offering retesting in the mid second trimester for women who were exposed very early in gestation.

The best diagnostic test for infection is reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and, ideally, it should be completed within 4 days of symptom onset. Beyond 4 days after symptom onset, testing for Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibody and neutralizing antibody should be performed in addition to the RT-PCR test. At times, interpretation of antibody testing can be problematic because cross-reaction with related arboviruses is common. Moreover, Zika viremia decreases rapidly over time; therefore, if serum is collected even 5 to 7 days after symptom onset, a negative test does not definitively exclude infection (TABLE 1).

In the United States, local health departments should be contacted to facilitate testing, as the tests described above are not currently commercially available. If the local health department is unable to perform this testing, clinicians should contact the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (telephone: 1-970-221-6400) or visit their website (http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/specimensub/arboviral-shipping.html) for detailed instructions on specimen submission.

Testing is not indicated for women without a history of travel to areas where Zika virus infection is endemic or without a history of unprotected sexual contact with someone who has been exposed to the infection.

Following the delivery of a live infant to an infected or exposed mother, detailed histopathologic evaluation of the placenta and umbilical cord should be performed. Frozen sections of placental and cord tissue should be tested for Zika virus RNA, and cord serum should be tested for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. In cases of fetal loss in the setting of relevant travel history or exposure (particularly maternal symptoms or sonographic evidence of microcephaly), RT-PCR testing and immunohistochemistry should be completed on fetal tissues, umbilical cord, and placenta.2

Treatment is supportive

At present, there is no vaccine for the Zika virus, and no hyperimmune globulin or anti‑ viral chemotherapy is available. Treatment is therefore supportive. Patients should be encouraged to rest and maintain hydration. The preferred antipyretic and analgesic is acetaminophen (650 mg orally every 6 hours or 1,000 mg orally every 8 hours). Aspirin should be avoided until dengue infection has been ruled out because of the related risk of bleeding with hemorrhagic fever. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in the second half of pregnancy because of their effect on fetal renal blood flow (oligohydramnios) and stricture of the ductus arteriosus.

CASE 1 Continued

Given this patient’s recent travel, exposure to mosquito-borne illness, and clinical manifestations of malaise, rash, and joint pain, you proceed with serologic testing. The RT-PCR test is positive for Zika virus.

What should be the next step in the management of this patient?

Prenatal diagnosis and fetal surveillance

The recent epidemic of microcephaly and poor pregnancy outcomes reported in Brazil has been alarming and demonstrates an almost 20-fold increase in incidence of this condition between 2014–2015.14 Careful surveillance is needed for this birth defect and other poor pregnancy outcomes in association with the Zika virus. To date, a direct causal relationship between Zika virus infection and microcephaly has not been unequivocally established15; however; these microcephaly cases have yet to be attributed to any other cause (FIGURE 2)

| FIGURE 2 Microcephaly: associated with Zika virus infection in pregnancy |

|

Illustration depicts a child with congenital microcephaly (left) and one with head circumference within the mean SD (right). |

Following the outbreak in Brazil, a task force and registry were established to investigate microcephaly and other birth defects associated with Zika virus infection. In one small investigation, 35 cases of microcephaly were reported, and 71% of the infants were seriously affected (head circumference >3 SD below the mean). Fifty percent of babies had at least one neurologic abnormality, and, of the 27 patients who had neuroimaging studies, all had distinct abnormalities, including widespread brain calcifications and cell migration abnormalities, such as lissencephaly, pachgyria, and ventriculomegaly due to cortical atrophy.16

In addition to microcephaly, fetal ultrasound monitoring has revealed focal brain abnormalities, such as asymmetric cerebral hemispheres, ventriculomegaly, displacement of the midline, failure to visualize the corpus callosum, failure of thalamic development, and the presence of intraocular and brain calcifications.17

In collaboration with the CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal Fetal-Medicine have developed guidelines to monitor fetal growth in women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection.18 Recommendations include having a detailed anatomy ultrasound and serial growth sonograms every 3 to 4 weeks, along with referral to a maternal-fetal medicine or infectious disease specialist.

If the pregnancy is beyond 15 weeks’ gestational age, an amniocentesis should be performed in symptomatic patients and in those with abnormal ultrasound findings. Amniotic fluid should be tested for Zika virus with RT-PCR (FIGURE 3).12 The sensitivity and specificity of amniotic fluid RT-PCR in detecting congenital infection, as well as the predictive value of a fetal anomaly, remain unknown at this time. For this reason, a patient must be counseled carefully regarding the benefits of confirming intrauterine infection versus the slight risks of premature rupture of membranes, infection, and pregnancy loss related to amniocentesis.

Once diagnosed, microcephaly cannot be “fixed.” However, pregnancy termination is an option that some parents may choose once they are aware of the diagnosis and prognosis of microcephaly. Moreover, even for parents who would not choose abortion, there may be considerable value in being prepared for the care of a severely disabled child. Microcephaly has many possible causes, Zika virus infection being just one. Others include genetic syndromes and other congenital infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and toxoplasmosis. Amniocentesis therefore may help the clinician sort through these causes. For both CMV infection and toxoplasmosis, certain antenatal treatments may be helpful in lessening the severity of fetal injury.

CASE 2 Pregnant patient has travel plans

A 34-year-old woman (G1P0) presents to you for her first prenatal visit. She mentions she plans to take a cruise through the Eastern Caribbean in 2 weeks. Following the history and physical examination, what should you tell this patient?

Perinatal counseling: Limiting exposure is best

As mentioned, there is currently no treatment, prophylactic medication, or vaccination for Zika virus infection. Because of the virus’s significant associations with adverse pregnancy outcomes, birth defects, and fetal loss, the CDC has issued a travel advisory urging pregnant women to avoid travel to areas when Zika virus infection is prevalent. Currently, Zika virus outbreaks are occurring throughout South and Central America, the Pacific Islands, and Africa, and the infection is expected to spread, mainly due to international air travel. If travel to these areas is inevitable, women should take rigorous precautions to avoid exposure to mosquito bites and infection (TABLE 2).

If a woman was infected with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection in a prior pregnancy, she should not be at risk for congenital infection during her next pregnancy. This is mainly because the period of viremia is short-lived and lasts approximately 5 to 7 days.2

Further, based on documented sexual transmission of the virus, pregnant women should abstain from sexual activity or should consistently and correctly use condoms with partners who have Zika virus infection or exposure to the virus until further evidence is available.

Stay informed

Zika virus infection is now pandemic; it has evolved from an isolated disease of the tropics to one that is sweeping the Western hemisphere. It is being reported daily in new locations around the world. Given the unsettling association of Zika virus infection with birth defects, careful obstetric surveillance of exposed or symptomatic patients is imperative. Clinicians must carefully screen patients with potential risk of exposure and be prepared to offer appropriate perinatal counseling and diagnostic testing during pregnancy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Zika virus infection in the news

- CDC: Zika virus disease cases by US state or territory, updated periodically

- CDC: Q&As for ObGyns on pregnant women and Zika virus, 2/9/16

- CDC: Zika virus infection among US pregnant travelers, 2/26/16

- CDC: Interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection, 2/19/16

- SMFM statement: Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure, 2/16/16

- FDA approves first Zika diagnostic test for commercial use. Newsweek, 2/26/16

- NIH accelerates timeline for human trials of Zika vaccine. The Washington Post, 2/17/16

- Patient resource: Zika virus and pregnancy fact sheet from MotherToBaby.org

- Zika virus article collection from New England Journal of Medicine

- Zika infection diagnosed in 18 pregnant US women who traveled to Zika-affected areas

- FDA grants emergency approval to new 3-in-1 lab test for Zika

- ACOG Practice Advisory: Updated interim guidance for care of women of reproductive age during a Zika virus outbreak, 3/31/16

- MMWR: Patterns in Zika virus testing and infection, 4/22/16

- What insect repellents are safe during pregnancy? 5/19/16

- Zika virus and complications: Q&A from WHO, 5/31/16

- WHO strengthens guidelines to prevent sexual transmission of Zika virus, 5/31/16

- Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure (from AJOG), 6/1/16

- CDC: Interim guidance for interpretation of Zika virus antibody test results, 6/3/16

- First Zika vaccine to begin testing in human trials, The Washington Post, 6/20/16

- NIH launches the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) international study, 6/21/16

CASE 1: Pregnant traveler asks: Should I be tested for Zika virus?

A 28-year-old Hispanic woman (G3P2) at 15 weeks’ gestation visits your office for a routine prenatal care appointment. She reports having returned from a 3-week holiday in Brazil 2 days ago, and she is concerned about having experienced fever, malaise, arthralgias, and a disseminated erythematous rash. She has since heard about the Zika virus and asks you if she and her baby are in danger and whether she should be tested for the disease.

What should you tell this patient?

The Zika virus is an RNA Flavivirus, transmitted primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.1 This virus is closely related to the organisms that cause dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya infection, and West Nile infection. By feeding on infected prey, mosquitoes can transmit the virus to humans through bites. They breed near pools of stagnant water, can survive both indoors and outdoors, and prefer to be near people. These mosquitoes bite mostly during daylight hours, so it is essential that people use insect repellent throughout the day while in endemic areas.2 These mosquitoes live only in tropical regions; however, the Aedes albopictus mosquito, also known as the Asian tiger mosquito, lives in temperate regions and can transmit the Zika virus as well3 (FIGURE 1).

| FIGURE 1 Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes | ||

|

| |

Aedes aegypti (left) and Aedes albopictus (right) mosquitoes. Aedes mosquitoes are the main transmission vector for the Zika virus. | ||

|

The Zika virus was first discovered in 1947 when it was isolated from a rhesus monkey in Uganda. It subsequently spread to Southeast Asia and eventually caused major outbreaks in the Yap Islands of Micronesia (2007)4 and French Polynesia (2013).5 In 2015, local transmission of the Zika virus infection was noted in Brazil, and, most recently, a pandemic of Zika virus infection has occurred throughout South America, Central America, and the Caribbean islands. To date, local mosquito-borne virus transmission has not occurred in the continental United States, although at least 82 cases acquired during travel to infected areas have been reported.6

Additionally, there have been rare cases involving spread of this virus from infected blood transfusions and through sexual contact.7 In February 2016, the first case of locally acquired Zika virus infection was reported in Texas following sexual transmission of the disease.8

Clinical manifestations of Zika virus infection

Eighty percent of patients infected with Zika virus remain asymptomatic. The illness is short-lived, occurring 2 to 12 days following the mosquito bite, and infected individuals usually do not require hospitalization or experience serious morbidity. When symptoms are present, they typically include low-grade fever (37.8° to 38.5°C), maculopapular rash, arthralgias of the hands and feet, and nonpurulent conjunctivitis. Patients also may experience headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, and, rarely, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ulcerations of mucous membranes, and pruritus.9 Guillain-Barré syndrome has been reported in association with Zika virus infection10; however, a definitive cause-effect relationship has not been proven.

If a pregnant woman is infected with the Zika virus, perinatal transmission can occur, either through uteroplacental transmission or vertically from mother to child at the time of delivery. Zika virus RNA has been detected in blood, amniotic fluid, semen, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and breast milk. Although the virus has been shown to be present in breast milk, there has been no evidence of viral replication in milk or reported transmission in breastfed infants.11 Pregnant women are not known to have increased susceptibility to Zika virus infection when compared with the general population, and there is no evidence to suggest pregnant women will have a more serious illness if infected.

The Zika virus has been strongly associated with congenital microcephaly and fetal loss among women infected during pregnancy.12 Following the recent large outbreak in Brazil, an alarmingly high number of Brazilian newborns with microcephaly have been observed. The total now exceeds 4,000. Because of these ominous findings, fetuses and neonates born to women with a history of infection should be evaluated for adverse effects of congenital infection.

Management strategies for Zika virus exposure during pregnancy

The incidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy remains unknown. However, a pregnant woman may be infected in any trimester, and maternal-fetal transmission of the virus can occur throughout pregnancy. If a patient is pregnant and has travelled to areas of Zika virus transmission, or has had unprotected sexual contact with a partner who has had exposure, she should be carefully screened with a detailed review of systems and ultrasonography to evaluate for fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initially recommended that, if a patient exhibited 2 or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection within 2 weeks of exposure or if sonographic evidence revealed fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, she should be tested for Zika virus infection.11

More recently, the CDC issued new guidelines recommending that even asymptomatic women with exposure have serologic testing for infection and that all exposed women undergo serial ultrasound assessments.13 The CDC also recommends offering retesting in the mid second trimester for women who were exposed very early in gestation.

The best diagnostic test for infection is reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and, ideally, it should be completed within 4 days of symptom onset. Beyond 4 days after symptom onset, testing for Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibody and neutralizing antibody should be performed in addition to the RT-PCR test. At times, interpretation of antibody testing can be problematic because cross-reaction with related arboviruses is common. Moreover, Zika viremia decreases rapidly over time; therefore, if serum is collected even 5 to 7 days after symptom onset, a negative test does not definitively exclude infection (TABLE 1).

In the United States, local health departments should be contacted to facilitate testing, as the tests described above are not currently commercially available. If the local health department is unable to perform this testing, clinicians should contact the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (telephone: 1-970-221-6400) or visit their website (http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/specimensub/arboviral-shipping.html) for detailed instructions on specimen submission.

Testing is not indicated for women without a history of travel to areas where Zika virus infection is endemic or without a history of unprotected sexual contact with someone who has been exposed to the infection.

Following the delivery of a live infant to an infected or exposed mother, detailed histopathologic evaluation of the placenta and umbilical cord should be performed. Frozen sections of placental and cord tissue should be tested for Zika virus RNA, and cord serum should be tested for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. In cases of fetal loss in the setting of relevant travel history or exposure (particularly maternal symptoms or sonographic evidence of microcephaly), RT-PCR testing and immunohistochemistry should be completed on fetal tissues, umbilical cord, and placenta.2

Treatment is supportive

At present, there is no vaccine for the Zika virus, and no hyperimmune globulin or anti‑ viral chemotherapy is available. Treatment is therefore supportive. Patients should be encouraged to rest and maintain hydration. The preferred antipyretic and analgesic is acetaminophen (650 mg orally every 6 hours or 1,000 mg orally every 8 hours). Aspirin should be avoided until dengue infection has been ruled out because of the related risk of bleeding with hemorrhagic fever. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in the second half of pregnancy because of their effect on fetal renal blood flow (oligohydramnios) and stricture of the ductus arteriosus.

CASE 1 Continued

Given this patient’s recent travel, exposure to mosquito-borne illness, and clinical manifestations of malaise, rash, and joint pain, you proceed with serologic testing. The RT-PCR test is positive for Zika virus.

What should be the next step in the management of this patient?

Prenatal diagnosis and fetal surveillance

The recent epidemic of microcephaly and poor pregnancy outcomes reported in Brazil has been alarming and demonstrates an almost 20-fold increase in incidence of this condition between 2014–2015.14 Careful surveillance is needed for this birth defect and other poor pregnancy outcomes in association with the Zika virus. To date, a direct causal relationship between Zika virus infection and microcephaly has not been unequivocally established15; however; these microcephaly cases have yet to be attributed to any other cause (FIGURE 2)

| FIGURE 2 Microcephaly: associated with Zika virus infection in pregnancy |

|

Illustration depicts a child with congenital microcephaly (left) and one with head circumference within the mean SD (right). |

Following the outbreak in Brazil, a task force and registry were established to investigate microcephaly and other birth defects associated with Zika virus infection. In one small investigation, 35 cases of microcephaly were reported, and 71% of the infants were seriously affected (head circumference >3 SD below the mean). Fifty percent of babies had at least one neurologic abnormality, and, of the 27 patients who had neuroimaging studies, all had distinct abnormalities, including widespread brain calcifications and cell migration abnormalities, such as lissencephaly, pachgyria, and ventriculomegaly due to cortical atrophy.16

In addition to microcephaly, fetal ultrasound monitoring has revealed focal brain abnormalities, such as asymmetric cerebral hemispheres, ventriculomegaly, displacement of the midline, failure to visualize the corpus callosum, failure of thalamic development, and the presence of intraocular and brain calcifications.17

In collaboration with the CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal Fetal-Medicine have developed guidelines to monitor fetal growth in women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection.18 Recommendations include having a detailed anatomy ultrasound and serial growth sonograms every 3 to 4 weeks, along with referral to a maternal-fetal medicine or infectious disease specialist.

If the pregnancy is beyond 15 weeks’ gestational age, an amniocentesis should be performed in symptomatic patients and in those with abnormal ultrasound findings. Amniotic fluid should be tested for Zika virus with RT-PCR (FIGURE 3).12 The sensitivity and specificity of amniotic fluid RT-PCR in detecting congenital infection, as well as the predictive value of a fetal anomaly, remain unknown at this time. For this reason, a patient must be counseled carefully regarding the benefits of confirming intrauterine infection versus the slight risks of premature rupture of membranes, infection, and pregnancy loss related to amniocentesis.

Once diagnosed, microcephaly cannot be “fixed.” However, pregnancy termination is an option that some parents may choose once they are aware of the diagnosis and prognosis of microcephaly. Moreover, even for parents who would not choose abortion, there may be considerable value in being prepared for the care of a severely disabled child. Microcephaly has many possible causes, Zika virus infection being just one. Others include genetic syndromes and other congenital infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and toxoplasmosis. Amniocentesis therefore may help the clinician sort through these causes. For both CMV infection and toxoplasmosis, certain antenatal treatments may be helpful in lessening the severity of fetal injury.

CASE 2 Pregnant patient has travel plans

A 34-year-old woman (G1P0) presents to you for her first prenatal visit. She mentions she plans to take a cruise through the Eastern Caribbean in 2 weeks. Following the history and physical examination, what should you tell this patient?

Perinatal counseling: Limiting exposure is best

As mentioned, there is currently no treatment, prophylactic medication, or vaccination for Zika virus infection. Because of the virus’s significant associations with adverse pregnancy outcomes, birth defects, and fetal loss, the CDC has issued a travel advisory urging pregnant women to avoid travel to areas when Zika virus infection is prevalent. Currently, Zika virus outbreaks are occurring throughout South and Central America, the Pacific Islands, and Africa, and the infection is expected to spread, mainly due to international air travel. If travel to these areas is inevitable, women should take rigorous precautions to avoid exposure to mosquito bites and infection (TABLE 2).

If a woman was infected with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection in a prior pregnancy, she should not be at risk for congenital infection during her next pregnancy. This is mainly because the period of viremia is short-lived and lasts approximately 5 to 7 days.2

Further, based on documented sexual transmission of the virus, pregnant women should abstain from sexual activity or should consistently and correctly use condoms with partners who have Zika virus infection or exposure to the virus until further evidence is available.

Stay informed

Zika virus infection is now pandemic; it has evolved from an isolated disease of the tropics to one that is sweeping the Western hemisphere. It is being reported daily in new locations around the world. Given the unsettling association of Zika virus infection with birth defects, careful obstetric surveillance of exposed or symptomatic patients is imperative. Clinicians must carefully screen patients with potential risk of exposure and be prepared to offer appropriate perinatal counseling and diagnostic testing during pregnancy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dyer O. Zika virus spreads across Americas as concerns mount over birth defects. BMJ. 2015;351:h6983.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Bogoch II, Brady OJ, Kraemer MU, et al. Anticipating the international spread of Zika virus from Brazil. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):335–336.

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2536–2543.

- Besnard M, Lastere S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V, Musso D. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(13):pii:20751.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, et al. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(5):880–882.

- Dallas County Health and Human Services. DCHHS reports first Zika virus case in Dallas County acquired through sexual transmission. http://www.dallascounty.org/department/hhs /press/documents/PR2-2-16DCHHSReportsFirstCaseofZikaVirusThroughSexualTransmission.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Ministry of Health, Manuatu Hauora. Zika virus. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/zika -virus. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Oehler E, Watrin L, Larre P, et al. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barre syndrome—case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:4–6.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus: transmission. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/transmission/index.html. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delamn, D et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30–33.

- Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5):122–127.

- Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Epidemiological alert: neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications for public health in the Americas. December 1,2015. http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_doc man&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32405&lang=en. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential associations with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. December 10, 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association -with-microcephaly-rapid-risk-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, et al; Brazilian Medical Genetics Society—Zika Embryopathy Task Force. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):59–62.

- Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis AM. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):6–7.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential associations with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. December 10, 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association.

- Dyer O. Zika virus spreads across Americas as concerns mount over birth defects. BMJ. 2015;351:h6983.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Bogoch II, Brady OJ, Kraemer MU, et al. Anticipating the international spread of Zika virus from Brazil. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):335–336.

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2536–2543.

- Besnard M, Lastere S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau V, Musso D. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(13):pii:20751.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, et al. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(5):880–882.

- Dallas County Health and Human Services. DCHHS reports first Zika virus case in Dallas County acquired through sexual transmission. http://www.dallascounty.org/department/hhs /press/documents/PR2-2-16DCHHSReportsFirstCaseofZikaVirusThroughSexualTransmission.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Ministry of Health, Manuatu Hauora. Zika virus. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/zika -virus. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Oehler E, Watrin L, Larre P, et al. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barre syndrome—case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:4–6.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus: transmission. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/transmission/index.html. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delamn, D et al. Interim guidelines for pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(2):30–33.

- Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5):122–127.

- Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Epidemiological alert: neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications for public health in the Americas. December 1,2015. http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_doc man&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32405&lang=en. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential associations with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. December 10, 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association -with-microcephaly-rapid-risk-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, et al; Brazilian Medical Genetics Society—Zika Embryopathy Task Force. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):59–62.

- Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis AM. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):6–7.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid risk assessment: Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential associations with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. December 10, 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-americas-association.

In this Article

- Management strategies for pregnant patients with Zika virus exposure

- Fetal surveillance

- Perinatal counseling on exposure prevention

- Algorithm for evaluation and management

Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 1: Renal Dysfunction in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

From the Cardiovascular Division, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To present a review of cardiorenal syndrome type 1 (CRS1).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Acute kidney injury occurs in approximately one-third of patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) and the resultant condition was named CRS1. A growing body of literature shows CRS1 patients are at high risk for poor outcomes, and thus there is an urgent need to understand the pathophysiology and subsequently develop effective treatments. In this review we discuss prevalence, proposed pathophysiology including hemodynamic and nonhemodynamic factors, prognosticating variables, data for different treatment strategies, and ongoing clinical trials and highlight questions and problems physicians will face moving forward with this common and challenging condition.

- Conclusion: Further research is needed to understand the pathophysiology of this complex clinical entity and to develop effective treatments.

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is an epidemic facing physicians throughout the world. In the United States alone, ADHF accounts for over 1 million hospitalizations annually, with costs in 2012 reaching $30.7 billion [1]. Despite the advances in chronic heart failure management, ADHF continues to be associated with poor outcomes as exemplified by 30-day readmission rates of over 20% and in-hospital mortality rates of 5% to 6%, both of which have not significantly improved over the past 20 years [2,3]. One of the strongest predictors of adverse outcomes in ADHF is renal dysfunction. An analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) revealed the combination of renal dysfunction (creatinine > 2.75 mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) > 43 mg/dL) and hypotension (systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 115 mm Hg) upon admission was associated with an in-hospital mortality of > 20% [4]. The Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) registry documented a 16.3% in-hospital mortality when patients had a SBP < 100 mm Hg and creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL at admission [5].

The presence of acute kidney injury in the setting of ADHF is a very common occurrence and was termed cardiorenal syndrome type 1 (CRS1) [6]. The prevalence of CRS1 in single-centered studies ranged from 32% to 40% of all ADHF admissions [7,8]. If this estimate holds true throughout the United States, there would be 320,000 to 400,000 hospitalizations for CRS1 annually, highlighting the magnitude of this problem. Moreover, with the number of patients with heart failure expected to continue to rise, CRS1 will only become more prevalent in the future. In this review we discuss the prevalence, proposed pathophysiology including hemodynamic and nonhemodynamic factors, prognosticating variables, data for different treatment strategies, ongoing clinical trials, and highlight questions and problems physicians will face moving forward in this common and challenging condition.

Pathogenesis of CRS1

Hemodynamic Effects

The early hypothesis for renal dysfunction in ADHF centered on hemodynamics, as reduced cardiac output was believed to decrease renal perfusion. However, analysis of invasive hemodynamics from patients with ADHF suggested that central venous pressure (CVP) was actually a better predictor of the development of CRS1 than cardiac output. In a single-center study conducted at the Cleveland Clinic, hemodynamics from 145 patients with ADHF were evaluated and surprisingly baseline cardiac index was greater in the patients with CRS1 than patients without renal dysfunction (2.0 ± 0.8 L/min/m2 vs 1.8 ± 0.4 L/min/m2; P = 0.008). However, baseline CVP was higher in the CRS1 group (18 ± 7 mm Hg vs 12 ± 6 mm Hg; P = 0.001), and there was a heightened risk of developing CRS1 as CVP increased. In fact, 75% of the patients with a CVP of > 24 mm Hg developed renal impairment [9]. In a retrospective study of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Arterial Catheter Effectiveness (ESCAPE) trial, the only hemodynamic parameter that correlated with baseline creatinine was CVP. However, no invasive measures predicted worsening renal function during hospitalization [10]. Finally, an experiment that used isolated canine kidneys showed increased venous pressure acutely reduced urine production. Interestingly, this relationship was dependent on arterial pressure; as arterial flow decreased smaller increases in CVP were needed to reduce urine output [11]. Together, these data suggest increased CVP plays an important role in CRS1, but imply hemodynamics alone may not fully explain the pathophysiology of CRS1.

Inflammation

As information about how hemodynamics incompletely predict renal dysfunction in ADHF became available, alternative hypotheses were investigated to gain a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology underlying CRS1. A pathological role of inflammation in CRS1 has gained attention due to recent publications. First of all, serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-a and IL-6 were elevated in patients with CRS1 when compared to health controls [12]. Interestingly, Virzi et al showed that the median value of IL-6 was 5 times higher in CRS1 patients when compared to ADHF patients without renal dysfunction [13]. The negative consequences of elevated serum cytokines were demonstrated when incubation of a human cell line of monocytes with serum from CRS1 patients induced apoptosis in 81% of cells compared to just 11% of cells with control serum [12]. It is possible that cytokine-induced apoptosis could occur in other cell types in different organs in patients with CRS1, which may contribute to both cardiac and renal dysfunction. Finally, analysis from a rat model of CRS1 revealed macrophage infiltration into the kidneys and increased numbers of activated monocytes in the peripheral blood. Interestingly, monocyte/macrophage depletion using liposome clodronate prevented chronic renal dysfunction in the rat model [14]. In summary, these data suggest inflammation contributes to CRS1 pathophysiology, but more experimental data is needed to determine if there is a causal relationship.

Oxidative Stress

Very recently, oxidative stress was proposed to play a role in CRS1. Virzi et al analyzed serum levels of markers of oxidative stress and compared ADHF patients without renal impairment to CRS1 patients. The markers of oxidative stress, which included myeloperoxidase, nitric oxide, copper/zinc superoxide dismutase, and endogenous peroxidase, were all significantly higher in CRS1 patients [13]. While provocative, the tissues responsible for the generation of these molecules and the subsequent effects have not yet been fully elucidated.

Prognostication

Severity of Acute Kidney Injury

Initial publications did not document a strong link between kidney injury and poor outcomes in ADHF. Firstly, Ather et al performed a single-centered study that investigated how change in renal function defined by change in creatinine, estimated GFR, and BUN affected outcomes one year post admission for ADHF. Kidney injury defined by a change in creatinine or in estimated GFR was not associated with increased risk of mortality, but a change in BUN was associated with increased mortality in a univariate analysis [15]. Testani et al retrospectively analyzed patients from the ESCAPE trial and found worsening renal function defined by a ≥ 20% reduction in estimated GFR was not significantly associated with 180-day mortality, but there was a trend towards higher mortality (hazard ration 1.4; P = 0.11) [16]. Importantly, neither of 2 these studies assessed how severity of AKI impacted outcomes, which may have contributed to the weak relationships observed.

Diuretic Responsiveness

Voors et al performed a retrospective analysis of diuretic responsiveness in 1161 patients from the Relaxin in Acute Heart Failure (RELAX-AHF) trial. Diuretic responsiveness was defined as weight change (kg) per diuretic dose (IV furosemide and PO furosemide) over 5 days and then patients were separated into tertiles. The lowest tertile group had an approximate 20% incidence of 60-day combined end-point of death, heart failure or renal failure readmission compared to less than 10% incidence in the middle and upper tertiles. Interestingly, when the effects of worsening renal function (WRF), defined as creatinine change of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL, were examined in patients stratified by diuretic response, WRF did not offer additional prognostic information [19].

Finally, Valenete et al analyzed diuretic response in 1745 patients from the PROTECT trial (Placebo-Controlled Randomized Study of the Selective A1-Adenosine Receptor Antagonist Rolofylline for Patients Hospitalized with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure and Volume Overload to Assess Treatment Effect on Congestion and Renal Function). Diuretic response was calculated using the weight change per 40 mg of furosemide, and as diuretic response declined there was increasing risk of 60-day rehospitalization and 180-day mortality rates. In fact, the lowest quintile responders had a 25% mortality rate at 180 days [20].

Emerging Biomarkers

Urine Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin

Because previous studies showed urinary levels of NGAL was an earlier and more reliable marker of renal dysfunction than creatinine in AKI [21], it was studied as a possible biomarker for the development of CRS1 in ADHF. A single-centered study quantified levels of urine NGAL in 100 patients admitted with heart failure and then tracked the rates of acute kidney injury. Urine NGAL was elevated in patients that developed AKI and a cut-off value 12 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 67% for predicting CRS1 [22]. While promising, further studies are needed to better define the role of NGAL in CRS1.

Cystatin C

Cystatin C is a ubiquitously expressed cysteine protease that has a constant production rate and is freely filtered by the glomerulus without being secreted into the tubules, and has effectively prognosticated outcomes in ADHF [23]. Lassus et al showed an adjusted hazard ratio of 3.2 (2.0–5.3) for 12-month mortality when cystatin C levels were elevated. Moreover, patients with the highest tertitle of NT-proBNP and cystatin C had a 48.7% 1-year mortality. Interestingly, patients with an elevated cystatin C but normal creatinine had a 40.6% 1-year mortality compared to 12.6% for those with normal cystatin C and creatinine [24]. Furthermore, Arimoto et al showed elevated cystatin C predicted death or rehospitalization in a small cohort of ADHF patients in Japan [25]. Also, Naruse et al showed cystatin C was a better predictor of cardiac death than estimated GFR by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD) equation [26]. Finally, Manzano-Fernandez et al showed the highest tertile of cystatin C was a significant independent risk factor for 2-year death or rehospitalization while creatinine and MDRD estimates of GFR were not [27]. In agreement with Lassus et al, elevations in either 2 or 3 of cystatin C, troponin, and NT-proBNP predicted death or rehospitalization when compared to those with normal levels of these 3 markers [27]. In conclusion, cystatin C either alone or in combination with other biomarkers identifies high-risk patients.

Kidney Injury Molecule 1

Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) is a type-1 cell membrane glycoprotein expressed in regenerating proximal tubular cells but not under normal conditions [28]. Although associated with increased risk of hospitalization and mortality in chronic heart failure [29,30], elevated levels of urinary KIM-1 did not predict mortality in ADHF [31]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the utility of KIM-1 in CRS1.

Treatment Approaches

Diuretics