User login

Ordering and Interpreting Precision Oncology Studies for Adults With Advanced Solid Tumors: A Primer

The ability to find and target specific biomarkers in the DNA of advanced cancers is rapidly changing options and outcomes for patients with locally advanced and metastatic solid tumors. This strategy is the basis for precision oncology, defined here as using predictive biomarkers from tumor and/or germline sequencing to guide therapies. This article focuses specifically on the use of DNA sequencing to find those biomarkers and provides guidance about which test is optimal in a specific situation, as well as interpretation of the results. We emphasize the identification of biomarkers that provide adult patients with advanced solid tumors access to therapies that would not be an option had sequencing not been performed and that have the potential for significant clinical benefit. The best approach is to have an expert team with experience in precision oncology to assist in the interpretation of results.

Which test?

Deciding what test of the array of assays available to use and which tissue to test can be overwhelming, and uncertainty may prevent oncology practitioners from ordering germline or somatic sequencing. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on DNA sequencing for inherited/germline alterations (including mutations, copy number changes, or fusions), which may inform treatment, or alterations that arise in the process of carcinogenesis and tumor evolution (somatic alterations in tumor DNA). This focus is not meant to exclude any specific test but to focus on DNA-based tests in patients with locally advanced or metastatic malignancy.

Germline Testing

Germline testing is the sequencing of inherited DNA in noncancerous cells to find alterations that may play a role in the development of cancers and are actionable in some cases. Germline alterations can inform therapeutic decisions, predict future cancer risk, and provide information that can help family members to better manage their risks of malignancy. Detailed discussions of the importance of germline testing to inform cancer surveillance, risk-reducing interventions, and the testing of relatives to determine who carries inherited alterations (cascade testing) is extremely important with several advantages and is covered in a number of excellent reviews elsewhere.1-3 Testing of germline DNA in patients with a metastatic malignancy can provide treatment options otherwise not available for patients, particularly for BRCA1/2 and Lynch syndrome–related cancers. Recent studies have shown that 10 to 15% of patients with advanced malignancies of many types have a pathogenic germline alteration.4,5

Germline DNA is usually acquired from peripheral blood, a buccal swab, or saliva collection and is therefore readily available. This is advantageous because it does not require a biopsy to identify relevant alterations. Germline testing is also less susceptible to the rare situations in which artifacts occur in formalin-fixed tissues and obscure relevant alterations.

The cost of germline testing varies, but most commercial vendor assays for germline testing are significantly less expensive than the cost of somatic testing. The disadvantages include the inability of germline testing to find any alterations that arise solely in tumor tissue and the smaller gene panels included in germline testing as compared to somatic testing panels. Other considerations relate to the inherited nature of pathogenic germline variants and its implications for family members that may affect the patient’s psychosocial health and potentially change the family dynamics.

Deciding who is appropriate for germline testing and when to perform the testing should be individualized to the patient’s wishes and disease status. Treatment planning may be less complicated if testing has been performed and germline status is known. In some cases urgent germline testing is indicated to inform pending procedures and/or surgical decisions for risk reduction, including more extensive tissue resection, such as the removal of additional organs or contralateral tissue. A minor point regarding germline testing is that the DNA of patients with hematologic malignancies may be difficult to sequence because of sample contamination by the circulating malignancy. For this reason, most laboratories will not accept peripheral blood or saliva samples for germline testing in patients with active hematologic malignancies; they often require DNA from another source such as fibroblasts from a skin biopsy or cells from a muscle biopsy. Germline testing is recommended for all patients with metastatic prostate cancer, as well as any patient with any stage of pancreatic cancer or ovarian cancer and patients with breast cancer diagnosed at age ≤ 45 years. More detailed criteria for who is appropriate for germline testing outside of these groups can be found in the appropriate National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.6-8 In patients with some malignancies such as prostate and pancreatic cancer, approximately half of patients who have a BRCA-related cancer developed that malignancy because of a germline BRCA alteration.9-11 Testing germline DNA is therefore an easy way to quickly find almost half of all targetable alterations with a treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and at low cost, with the added benefit of providing critical information for families who may be unaware that members carry a relevant pathogenic germline alteration. In those families, cascade testing can provide surveillance and intervention strategies that can be lifesaving.

A related and particularly relevant question is when should a result found on a somatic testing panel prompt follow-up germline testing? Some institutions have algorithms in place to automate referral for germline testing based on specific genetic criteria.12 Excellent reviews are available that outline the following considerations in more detail.13 Typically, somatic testing results that would trigger follow-up germline testing would be truncating or deleterious or likely deleterious mutations per germline datasets in high-risk genes associated with highly penetrant autosomal dominant conditions (BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6), selected moderate-risk genes (BRIP1, RAD51C, and RAD51D), and specific variants with a high probability of being germline because they are common germline founder mutations. Although the actionability and significance of specific genes remains a matter of some discussion, generally finding a somatic pathogenic sequencing result included in the 59-gene list of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines would be an indication for germline testing. Another indication for germline testing would be finding genes with germline mutations for which the NCCN has specific management guidelines, or the presence of alterations consistent with known founder mutations.14 When a patient’s tumor has microsatellite instability or is hypermutated (defined as > 10 mutations per megabase), a search for germline alterations is warranted given that about 15% of these patients with these tumors carry a Lynch syndrome gene.15 Genes that are commonly found as somatic alterations alone (eg, TP53 or APC) are generally not an indication for germline testing unless family history is compelling.

Although some clinicians use the variant allele fraction in the somatic sequencing report to decide whether to conduct germline testing, this approach is suboptimal, as allele fraction may be confounded by assay conditions and a high allele fraction may be found in pure tumors with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the other allele. There is also evidence that for a variety of reasons, somatic sequencing panels do not always detect germline alterations in somatic tissues.16 Reasons for this may include discordance between the genes being tested in the germline vs the somatic panel, technical differences such as interference of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) artifact with detecting the germline variant, lack of expertise in germline variant interpretation among laboratories doing tumor-only sequencing, and, in rare cases, large deletions in tumor tissue masking a germline point mutation.

Variant Interpretation of Germline Testing

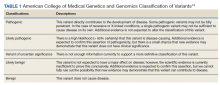

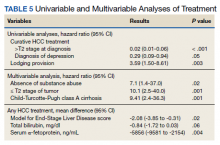

A general understanding of the terminology used for germline variant interpretation allows for the ordering health care practitioner (HCP) to provide the best quality care and an appreciation for the limitations of current molecular testing. Not all variants are associated with disease; the clinical significance of a genetic variant falls on a spectrum. The criteria for determining pathogenicity differ between molecular laboratories, but most are influenced by the standards and guidelines set forth by the ACMG.14 The clinical molecular laboratory determines variant classification, and a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this primer. In brief, variant classification is based on evidence of varying strength in different categories including population data, computational and predictive data, functional data, segregation data, de novo data, allelic data, and information from various databases. The ACMG has proposed a 5-tiered classification system, by which most molecular laboratories adhere to in their genetic test reports (Table 1).14

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are clinically actionable, whereas variants of uncertain significance (VUS) require additional data and/or functional studies before making clinical decisions. Depending on the clinical context and existing supporting evidence, it may be prudent to continue monitoring for worsening or new signs of disease in patients with one or more VUS while additional efforts are underway to understand the variant’s significance.

In some cases, variants are reclassified, which may alter the management and treatment of patients. Reclassification can occur with VUS, and in rare instances, can also occur with variants previously classified as pathogenic/likely pathogenic or benign/likely benign. In such a case, the reporting laboratory will typically make concerted efforts to alert the ordering HCP. However, variant reclassifications are not always communicated to the care team. Thus, it is important to periodically contact the molecular laboratory of interest to obtain updated test interpretations.

Somatic Testing

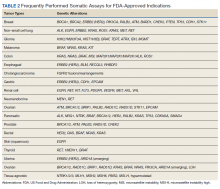

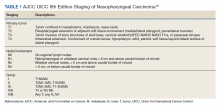

Testing of somatic (tumor) tissue is critical and is the approach most commonly taken in medical oncology (Table 2).

The advantages of primary tumor are that it is usually in hand as a diagnostic biopsy, acquisition is standard of care, and several targetable alterations are truncal, defined as driver mutations present at the time of tumor development. Also, the potential that the tumor arose in the background of a predisposing germline alteration can be suggested by sequencing primary tumor as discussed above. Moreover, sequencing the primary tumor can be done at any time unless the biopsy sample is considered too old or degraded (per specific platform requirements). The information gained can be used to anticipate additional treatment options that are relevant when patients experience disease progression. Disadvantages include the problem that primary specimens may be old or have limited tumor content, both of which increase the likelihood that sequencing will not be technically successful.

Alterations that are targetable and arise as a result of either treatment pressure or clonal evolution are considered evolutionary. If evolutionary alterations are the main focus for sequencing, then metastasis biopsy or ctDNA are better choices. The advantages of a metastasis biopsy are that tissue is contemporary, tumor content may be higher than in primary tumor, and both truncal and evolutionary alterations can be detected.

For specific tumors, continued analysis of evolving genomic alterations can play a critical role in management. In non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), somatic testing is conducted again at progression on repeat biopsies to evaluate for emerging resistance mutations. In epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–mutated lung cancer, the resistance mutation, exon 20 p.T790M (point mutation), can present in patients after treatment with first- or second-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). Even in patients who are treated with the third-generation EGFR TKI osimertinib that can treat T790M-mutated lung cancer, multiple possible evolutionary mutations can occur at progression, including other EGFR mutations, MET/HER2 amplification, and BRAF V600E, to name a few.20 Resistance mechanisms develop due to treatment selection pressure and the molecular heterogeneity seen in lung cancer.

Disadvantages for metastatic biopsy include the inability to safely access a metastatic site, the time considerations for preauthorization and arrangement of biopsy, and a lower-than-average likelihood of successful sequencing from sites such as bone.21,22 In addition, there is some concern that a single metastatic site may not capture all relevant alterations for multiple reasons, including tumor heterogeneity.

Significant advances in the past decade have dramatically improved the ability to use ctDNA to guide therapy. Advantages include ease of acquisition as acquiring a sample requires only a blood draw, and the potential that the pool of ctDNA is a better reflection of the relevant biology as it potentially reflects all metastatic tissues. Disadvantages are that sequencing attempts may not be productive if the sample is acquired at a time when the tumor is either quiescent or tumor burden is so low that only limited amounts of DNA are being shed. Performing ctDNA analysis when a tumor is not progressing is less likely to be productive for a number of tumor types.23,24 Sequencing ctDNA is also more susceptible than sequencing tumor biopsies to detection of alterations that are not from the tumor of interest but from clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) or other clonal hematopoietic disorders (see Confounders section below).

Selecting the Tissue

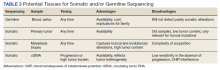

Deciding on the tissue to analyze is a critical part of the decision process (Table 3). If the primary tumor tissue is old the likelihood of productive sequencing is lower, although age alone is not the only consideration and the methods of fixation may be just as relevant.

For prostate cancer in particular, the ability to successfully sequence primary tumor tissue decreases as the amount of tumor decreases in low-volume biopsies such as prostate needle biopsies. Generally, if tumor content is < 10% of the biopsy specimen, then sequencing is less likely to be productive.25 Also, if the alteration of interest is not known to be truncal, then a relevant target might be missed by sequencing tissue that does not reflect current biology. Metastasis biopsy may be the most appropriate tissue, particularly if this specimen has already been acquired. As above, a metastasis biopsy may have a higher tumor content, and it should reflect relevant biology if it is recent. However, bone biopsies have a relatively low yield for successful sequencing, so a soft tissue lesion (eg, liver or lymph node metastasis) is generally preferred.

The inability to safely access tissue is often a consideration. Proximity to vital structures such as large blood vessels or the potential for significant morbidity in the event of a complication (liver or lung biopsies, particularly in patients on anticoagulation medications) may make the risk/benefit ratio too high. The inability to conduct somatic testing has been reported to often be due to inadequate tissue sampling.26 ctDNA is an attractive alternative but should typically be drawn when a tumor is progressing with a reasonable tumor burden that is more likely to be shedding DNA. Performing ctDNA analysis in patients without obvious radiographic metastasis or in patients whose tumor is under good control is unlikely to produce interpretable results.

Interpreting the Results

The intent of sequencing tumor tissue is to identify alterations that are biologically important and may provide a point of therapeutic leverage. However, deciding which alterations are relevant is not always straightforward. For example, any normal individual genome contains around 10,000 missense variants, hundreds of insertion/deletion variants, and dozens of protein-truncating variants. Distinguishing these alterations, which are part of the individual, from those that are tumor-specific and have functional significance can be difficult in the absence of paired sequencing of both normal and tissue samples.

Specific Alterations

Although most commercial vendors provide important information in sequencing reports to assist oncology HCPs in deciding which alterations are relevant, the reports are not always clear. In many cases the report will specifically indicate whether the alteration has been reported previously as pathogenic or benign. However, some platforms will report alterations that are not known to be drivers of tumor biology. It is critical to be aware that if variants are not reported as pathogenic, they should not be assumed to be pathogenic simply because they are included in the report. Alterations more likely to be drivers of relevant biology are those that change gene and protein structure and include frameshift (fs*), nonsense (denoted by sequence ending in “X” or “*”), or specific fusions or insertions/deletions (indel) that occur in important domains of the gene.

For some genes, only specific alterations are targetable and not all alterations have the same effect on protein function. Although overexpression of certain genes and proteins are actionable (eg, HER2), amplification of a gene does not necessarily indicate that it is targetable. In NSCLC, specific alterations convey sensitivity to targeted therapies. For example, in EGFR-mutated NSCLC, the sensitizing mutations to EGFR TKIs are exon19 deletions and exon 21 L858R point mutations (the most common mutations), as well as less common mutations found in exon 18-21. Exon 20 mutations, however, are not responsive to EGFR TKIs with a few exceptions.27 Patients who have tumors that do not harbor a sensitizing EGFR mutation should not be treated with an EGFR TKI. In a variety of solid tumors, gene fusions of the NTRK 1/2/3, act as oncogenic drivers. The chromosomal fusion events involving the carboxy-terminal kinase domain of TRK and upstream amino-terminal partners lead to overexpression of the chimeric proteins tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) A/B/C, resulting in constitutively active, ligand-independent downstream signaling. In patients with NTRK 1/2/3 gene fusions, larotrectinib and entrectinib, small molecule inhibitors to TRK, have shown antitumor activity.28,29 No alterations beyond these fusions are known to be targetable.

Allele Fraction

Knowing the fraction (or proportion) of the alteration of interest in the sequenced tissue relative to the estimated tumor content can assist in decision making. Not all platforms will provide this information, which is referred to as mutation allele fraction (MAF) or variant allele fraction (VAF), but sometimes will provide it on request. Platforms will usually provide an estimate of the percent tumor in the tissue being sampled if it is from a biopsy. If the MAF is around 50% in the sequenced tissue (including ctDNA), then there is a reasonable chance that it is a germline variant. However, there are nuances as germline alterations in some genes, such as BRCA1/2, can be accompanied by loss of the other allele of the gene (LOH). In that case, if most of the circulating DNA is from tumor, then the MAF can be > 50%.

If there are 2 alterations of the same gene with MAF percentages that are each half of the total percent tumor, there is a high likelihood of biallelic alteration. These sorts of paired alterations or one mutation with apparent LOH or copy loss would again indicate a high likelihood that the alteration is in fact pathogenic and a relevant driver. Not all pathogenic alterations have to be biallelic to be driver mutations but in BRCA1/2, or mismatch repair deficiency genes, the presence of biallelic alterations increases the likelihood of their being pathogenic.

Tumors that are hypermutated—containing sometimes hundreds of mutations per megabyte of DNA—can be particularly complicated to interpret, because the likelihood increases that many of the alterations are a function of the hypermutation and not a driver mutation. This is particularly important when there are concurrent mutations in mismatch repair genes and genes, such as BRCA1/2. If the tumor is

Confounders

In some situations, interpretation can be particularly challenging. For example, several alterations for which there are FDA on-label indications (such as ATM or BRCA2) can be detected in ctDNA that may not be due to the tumor but to CHIP. CHIP represents hematopoietic clones that are dysplastic as a result of exposure to DNA-damaging agents (eg, platinum chemotherapy) or as a result of aging and arise when mutations in hematopoietic stem cells provide a competitive advantage.31 The most common CHIP clones that can be detected are DNMT3A, ASXL1, or TET2; because these alterations are not targetable, their importance lies primarily in whether patients have evidence of hematologic abnormality, which might represent an evolving hematopoietic disorder. Because CHIP alterations can overlap with somatic alterations for which FDA-approved drugs exist, such as ATM or CHEK2 (olaparib for prostate cancer) and BRCA2 (poly-ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors in a range of indications) there is concern that CHIP might result in patient harm from inappropriate treatment of CHIP rather than the tumor, with no likelihood that the treatment would affect the tumor, causing treatment delays.32 General considerations for deciding whether an alteration represents CHIP include excluding alteration in which the VAF is < 1% and when the VAF in the alteration of interest is < 20% of the estimated tumor fraction in the sample. Exceptions to this are found in patients with true myelodysplasia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in whom the VAF can be well over 50% because of circulating tumor burden. The only way to be certain that an alteration detected on ctDNA reflects tumor rather than CHIP is to utilize an assay with matched tumor-normal sequencing.

Resources for Assistance

For oncology HCPs, perhaps the best resource to help in selecting and interpreting the appropriate testing is through a dedicated molecular oncology tumor board and subject matter experts who contribute to those tumor boards. In the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the national precision oncology program and its affiliated clinical services, such as the option to order a national consultation and molecular tumor board education, are easily accessible to all HCPs (www.cancer.va.gov). Many commercial vendors provide support to assist with questions of interpretation and to inform clinical decision-making. Other resources that can assist with deciding whether an alteration is pathogenic include extensive curated databases such as ClinVar (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar) and the Human Genetic Mutation Database (www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php) for germline alterations or COSMIC (cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) for somatic alterations. OncoKB (www.oncokb.org) is a resource for assistance in defining levels of evidence for the use of agents to target specific alterations and to assist in assigning pathogenicity to specific alterations. Additional educational resources for training in genomics and genetics are also included in the Appendix.

The rapid growth in technology and ability to enhance understanding of relevant tumor biology continues to improve the therapeutic landscape for men and women dealing with malignancy and our ability to find targetable genetic alterations with the potential for meaningful clinical benefit.

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to Neil Spector.

1. Domchek SM, Mardis E, Carlisle JW, Owonikoko TK. Integrating genetic and genomic testing into oncology practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:e259-e263. doi:10.1200/EDBK_280607

2. Stoffel EM, Carethers JM. Current approaches to germline cancer genetic testing. Annu Rev Med. 2020;71:85-102. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-052318-101009

3. Lappalainen T, Scott AJ, Brandt M, Hall IM. Genomic analysis in the age of human genome sequencing. Cell. 2019;177(1):70-84. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.032

4. Samadder NJ, Riegert-Johnson D, Boardman L, et al. Comparison of universal genetic testing vs guideline-directed targeted testing for patients with hereditary cancer syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252

5. Schneider BP, Stout L, Philips S, et al. Implications of incidental germline findings identified in the context of clinical whole exome sequencing for guiding cancer therapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4:1109-1121. doi:10.1200/PO.19.00354

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Pancreatic cancer (Version 1.2022). Updated February 24, 2022. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf

7. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate cancer (Version 3.2022). Updated January 10, 2022. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf

8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic (Version 2.2022). Updated March 9, 2022. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf

9. Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215-1228. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001

10. Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):443-453. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603144

11. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(2):185-203.e13. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.007

12. Clark DF, Maxwell KN, Powers J, et al. Identification and confirmation of potentially actionable germline mutations in tumor-only genomic sequencing. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:PO.19.00076. doi:10.1200/PO.19.00076

13. DeLeonardis K, Hogan L, Cannistra SA, Rangachari D, Tung N. When should tumor genomic profiling prompt consideration of germline testing? J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(9):465-473. doi:10.1200/JOP.19.00201

14. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30

15. Latham A, Srinivasan P, Kemel Y, et al. Microsatellite instability is associated with the presence of Lynch syndrome pan-cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4):286-295. doi:10.1200/JCO.18.00283

16. Lincoln SE, Nussbaum RL, Kurian AW, et al. Yield and utility of germline testing following tumor sequencing in patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019452. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19452

17. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non-small cell lung cancer (Version: 3.2022). Updated March 16, 2022. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Colon cancer (Version 1.2022). February 25, 2022. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf

19. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Melanoma: cutaneous (Version 3.2022). April 11, 2022. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf

20. Leonetti A, Sharma S, Minari R, Perego P, Giovannetti E, Tiseo M. Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(9):725-737. doi:10.1038/s41416-019-0573-8

21. Zheng G, Lin MT, Lokhandwala PM, et al. Clinical mutational profiling of bone metastases of lung and colon carcinoma and malignant melanoma using next-generation sequencing. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124(10):744-753. doi:10.1002/cncy.21743

22. Spritzer CE, Afonso PD, Vinson EN, et al. Bone marrow biopsy: RNA isolation with expression profiling in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer—factors affecting diagnostic success. Radiology. 2013;269(3):816-823. doi:10.1148/radiol.13121782

23. Schweizer MT, Gulati R, Beightol M, et al. Clinical determinants for successful circulating tumor DNA analysis in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2019;79(7):701-708. doi:10.1002/pros.23778

24. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra224. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094

25. Pritchard CC, Salipante SJ, Koehler K, et al. Validation and implementation of targeted capture and sequencing for the detection of actionable mutation, copy number variation, and gene rearrangement in clinical cancer specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16(1):56-67. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.08.004

26. Gutierrez ME, Choi K, Lanman RB, et al. Genomic profiling of advanced non-small cell lung cancer in community settings: gaps and opportunities. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(6):651-659. doi:10.1016/j.cllc.2017.04.004

27. Malapelle U, Pilotto S, Passiglia F, et al. Dealing with NSCLC EGFR mutation testing and treatment: a comprehensive review with an Italian real-world perspective. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;160:103300. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103300

28. Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731-739. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

29. Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):271-282. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

30. Jonsson P, Bandlamudi C, Cheng ML, et al. Tumour lineage shapes BRCA-mediated phenotypes. Nature. 2019;571(7766):576-579. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1382-1

31. Steensma DP. Clinical consequences of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018(1):264-269. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.264

32. Jensen K, Konnick EQ, Schweizer MT, et al. Association of clonal hematopoiesis in DNA repair genes with prostate cancer plasma cell-free DNA testing interference. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(1):107-110. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5161

The ability to find and target specific biomarkers in the DNA of advanced cancers is rapidly changing options and outcomes for patients with locally advanced and metastatic solid tumors. This strategy is the basis for precision oncology, defined here as using predictive biomarkers from tumor and/or germline sequencing to guide therapies. This article focuses specifically on the use of DNA sequencing to find those biomarkers and provides guidance about which test is optimal in a specific situation, as well as interpretation of the results. We emphasize the identification of biomarkers that provide adult patients with advanced solid tumors access to therapies that would not be an option had sequencing not been performed and that have the potential for significant clinical benefit. The best approach is to have an expert team with experience in precision oncology to assist in the interpretation of results.

Which test?

Deciding what test of the array of assays available to use and which tissue to test can be overwhelming, and uncertainty may prevent oncology practitioners from ordering germline or somatic sequencing. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on DNA sequencing for inherited/germline alterations (including mutations, copy number changes, or fusions), which may inform treatment, or alterations that arise in the process of carcinogenesis and tumor evolution (somatic alterations in tumor DNA). This focus is not meant to exclude any specific test but to focus on DNA-based tests in patients with locally advanced or metastatic malignancy.

Germline Testing

Germline testing is the sequencing of inherited DNA in noncancerous cells to find alterations that may play a role in the development of cancers and are actionable in some cases. Germline alterations can inform therapeutic decisions, predict future cancer risk, and provide information that can help family members to better manage their risks of malignancy. Detailed discussions of the importance of germline testing to inform cancer surveillance, risk-reducing interventions, and the testing of relatives to determine who carries inherited alterations (cascade testing) is extremely important with several advantages and is covered in a number of excellent reviews elsewhere.1-3 Testing of germline DNA in patients with a metastatic malignancy can provide treatment options otherwise not available for patients, particularly for BRCA1/2 and Lynch syndrome–related cancers. Recent studies have shown that 10 to 15% of patients with advanced malignancies of many types have a pathogenic germline alteration.4,5

Germline DNA is usually acquired from peripheral blood, a buccal swab, or saliva collection and is therefore readily available. This is advantageous because it does not require a biopsy to identify relevant alterations. Germline testing is also less susceptible to the rare situations in which artifacts occur in formalin-fixed tissues and obscure relevant alterations.

The cost of germline testing varies, but most commercial vendor assays for germline testing are significantly less expensive than the cost of somatic testing. The disadvantages include the inability of germline testing to find any alterations that arise solely in tumor tissue and the smaller gene panels included in germline testing as compared to somatic testing panels. Other considerations relate to the inherited nature of pathogenic germline variants and its implications for family members that may affect the patient’s psychosocial health and potentially change the family dynamics.

Deciding who is appropriate for germline testing and when to perform the testing should be individualized to the patient’s wishes and disease status. Treatment planning may be less complicated if testing has been performed and germline status is known. In some cases urgent germline testing is indicated to inform pending procedures and/or surgical decisions for risk reduction, including more extensive tissue resection, such as the removal of additional organs or contralateral tissue. A minor point regarding germline testing is that the DNA of patients with hematologic malignancies may be difficult to sequence because of sample contamination by the circulating malignancy. For this reason, most laboratories will not accept peripheral blood or saliva samples for germline testing in patients with active hematologic malignancies; they often require DNA from another source such as fibroblasts from a skin biopsy or cells from a muscle biopsy. Germline testing is recommended for all patients with metastatic prostate cancer, as well as any patient with any stage of pancreatic cancer or ovarian cancer and patients with breast cancer diagnosed at age ≤ 45 years. More detailed criteria for who is appropriate for germline testing outside of these groups can be found in the appropriate National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.6-8 In patients with some malignancies such as prostate and pancreatic cancer, approximately half of patients who have a BRCA-related cancer developed that malignancy because of a germline BRCA alteration.9-11 Testing germline DNA is therefore an easy way to quickly find almost half of all targetable alterations with a treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and at low cost, with the added benefit of providing critical information for families who may be unaware that members carry a relevant pathogenic germline alteration. In those families, cascade testing can provide surveillance and intervention strategies that can be lifesaving.

A related and particularly relevant question is when should a result found on a somatic testing panel prompt follow-up germline testing? Some institutions have algorithms in place to automate referral for germline testing based on specific genetic criteria.12 Excellent reviews are available that outline the following considerations in more detail.13 Typically, somatic testing results that would trigger follow-up germline testing would be truncating or deleterious or likely deleterious mutations per germline datasets in high-risk genes associated with highly penetrant autosomal dominant conditions (BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6), selected moderate-risk genes (BRIP1, RAD51C, and RAD51D), and specific variants with a high probability of being germline because they are common germline founder mutations. Although the actionability and significance of specific genes remains a matter of some discussion, generally finding a somatic pathogenic sequencing result included in the 59-gene list of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines would be an indication for germline testing. Another indication for germline testing would be finding genes with germline mutations for which the NCCN has specific management guidelines, or the presence of alterations consistent with known founder mutations.14 When a patient’s tumor has microsatellite instability or is hypermutated (defined as > 10 mutations per megabase), a search for germline alterations is warranted given that about 15% of these patients with these tumors carry a Lynch syndrome gene.15 Genes that are commonly found as somatic alterations alone (eg, TP53 or APC) are generally not an indication for germline testing unless family history is compelling.

Although some clinicians use the variant allele fraction in the somatic sequencing report to decide whether to conduct germline testing, this approach is suboptimal, as allele fraction may be confounded by assay conditions and a high allele fraction may be found in pure tumors with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the other allele. There is also evidence that for a variety of reasons, somatic sequencing panels do not always detect germline alterations in somatic tissues.16 Reasons for this may include discordance between the genes being tested in the germline vs the somatic panel, technical differences such as interference of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) artifact with detecting the germline variant, lack of expertise in germline variant interpretation among laboratories doing tumor-only sequencing, and, in rare cases, large deletions in tumor tissue masking a germline point mutation.

Variant Interpretation of Germline Testing

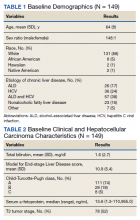

A general understanding of the terminology used for germline variant interpretation allows for the ordering health care practitioner (HCP) to provide the best quality care and an appreciation for the limitations of current molecular testing. Not all variants are associated with disease; the clinical significance of a genetic variant falls on a spectrum. The criteria for determining pathogenicity differ between molecular laboratories, but most are influenced by the standards and guidelines set forth by the ACMG.14 The clinical molecular laboratory determines variant classification, and a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this primer. In brief, variant classification is based on evidence of varying strength in different categories including population data, computational and predictive data, functional data, segregation data, de novo data, allelic data, and information from various databases. The ACMG has proposed a 5-tiered classification system, by which most molecular laboratories adhere to in their genetic test reports (Table 1).14

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are clinically actionable, whereas variants of uncertain significance (VUS) require additional data and/or functional studies before making clinical decisions. Depending on the clinical context and existing supporting evidence, it may be prudent to continue monitoring for worsening or new signs of disease in patients with one or more VUS while additional efforts are underway to understand the variant’s significance.

In some cases, variants are reclassified, which may alter the management and treatment of patients. Reclassification can occur with VUS, and in rare instances, can also occur with variants previously classified as pathogenic/likely pathogenic or benign/likely benign. In such a case, the reporting laboratory will typically make concerted efforts to alert the ordering HCP. However, variant reclassifications are not always communicated to the care team. Thus, it is important to periodically contact the molecular laboratory of interest to obtain updated test interpretations.

Somatic Testing

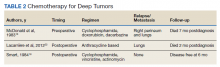

Testing of somatic (tumor) tissue is critical and is the approach most commonly taken in medical oncology (Table 2).

The advantages of primary tumor are that it is usually in hand as a diagnostic biopsy, acquisition is standard of care, and several targetable alterations are truncal, defined as driver mutations present at the time of tumor development. Also, the potential that the tumor arose in the background of a predisposing germline alteration can be suggested by sequencing primary tumor as discussed above. Moreover, sequencing the primary tumor can be done at any time unless the biopsy sample is considered too old or degraded (per specific platform requirements). The information gained can be used to anticipate additional treatment options that are relevant when patients experience disease progression. Disadvantages include the problem that primary specimens may be old or have limited tumor content, both of which increase the likelihood that sequencing will not be technically successful.

Alterations that are targetable and arise as a result of either treatment pressure or clonal evolution are considered evolutionary. If evolutionary alterations are the main focus for sequencing, then metastasis biopsy or ctDNA are better choices. The advantages of a metastasis biopsy are that tissue is contemporary, tumor content may be higher than in primary tumor, and both truncal and evolutionary alterations can be detected.

For specific tumors, continued analysis of evolving genomic alterations can play a critical role in management. In non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), somatic testing is conducted again at progression on repeat biopsies to evaluate for emerging resistance mutations. In epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–mutated lung cancer, the resistance mutation, exon 20 p.T790M (point mutation), can present in patients after treatment with first- or second-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). Even in patients who are treated with the third-generation EGFR TKI osimertinib that can treat T790M-mutated lung cancer, multiple possible evolutionary mutations can occur at progression, including other EGFR mutations, MET/HER2 amplification, and BRAF V600E, to name a few.20 Resistance mechanisms develop due to treatment selection pressure and the molecular heterogeneity seen in lung cancer.

Disadvantages for metastatic biopsy include the inability to safely access a metastatic site, the time considerations for preauthorization and arrangement of biopsy, and a lower-than-average likelihood of successful sequencing from sites such as bone.21,22 In addition, there is some concern that a single metastatic site may not capture all relevant alterations for multiple reasons, including tumor heterogeneity.

Significant advances in the past decade have dramatically improved the ability to use ctDNA to guide therapy. Advantages include ease of acquisition as acquiring a sample requires only a blood draw, and the potential that the pool of ctDNA is a better reflection of the relevant biology as it potentially reflects all metastatic tissues. Disadvantages are that sequencing attempts may not be productive if the sample is acquired at a time when the tumor is either quiescent or tumor burden is so low that only limited amounts of DNA are being shed. Performing ctDNA analysis when a tumor is not progressing is less likely to be productive for a number of tumor types.23,24 Sequencing ctDNA is also more susceptible than sequencing tumor biopsies to detection of alterations that are not from the tumor of interest but from clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) or other clonal hematopoietic disorders (see Confounders section below).

Selecting the Tissue

Deciding on the tissue to analyze is a critical part of the decision process (Table 3). If the primary tumor tissue is old the likelihood of productive sequencing is lower, although age alone is not the only consideration and the methods of fixation may be just as relevant.

For prostate cancer in particular, the ability to successfully sequence primary tumor tissue decreases as the amount of tumor decreases in low-volume biopsies such as prostate needle biopsies. Generally, if tumor content is < 10% of the biopsy specimen, then sequencing is less likely to be productive.25 Also, if the alteration of interest is not known to be truncal, then a relevant target might be missed by sequencing tissue that does not reflect current biology. Metastasis biopsy may be the most appropriate tissue, particularly if this specimen has already been acquired. As above, a metastasis biopsy may have a higher tumor content, and it should reflect relevant biology if it is recent. However, bone biopsies have a relatively low yield for successful sequencing, so a soft tissue lesion (eg, liver or lymph node metastasis) is generally preferred.

The inability to safely access tissue is often a consideration. Proximity to vital structures such as large blood vessels or the potential for significant morbidity in the event of a complication (liver or lung biopsies, particularly in patients on anticoagulation medications) may make the risk/benefit ratio too high. The inability to conduct somatic testing has been reported to often be due to inadequate tissue sampling.26 ctDNA is an attractive alternative but should typically be drawn when a tumor is progressing with a reasonable tumor burden that is more likely to be shedding DNA. Performing ctDNA analysis in patients without obvious radiographic metastasis or in patients whose tumor is under good control is unlikely to produce interpretable results.

Interpreting the Results

The intent of sequencing tumor tissue is to identify alterations that are biologically important and may provide a point of therapeutic leverage. However, deciding which alterations are relevant is not always straightforward. For example, any normal individual genome contains around 10,000 missense variants, hundreds of insertion/deletion variants, and dozens of protein-truncating variants. Distinguishing these alterations, which are part of the individual, from those that are tumor-specific and have functional significance can be difficult in the absence of paired sequencing of both normal and tissue samples.

Specific Alterations

Although most commercial vendors provide important information in sequencing reports to assist oncology HCPs in deciding which alterations are relevant, the reports are not always clear. In many cases the report will specifically indicate whether the alteration has been reported previously as pathogenic or benign. However, some platforms will report alterations that are not known to be drivers of tumor biology. It is critical to be aware that if variants are not reported as pathogenic, they should not be assumed to be pathogenic simply because they are included in the report. Alterations more likely to be drivers of relevant biology are those that change gene and protein structure and include frameshift (fs*), nonsense (denoted by sequence ending in “X” or “*”), or specific fusions or insertions/deletions (indel) that occur in important domains of the gene.

For some genes, only specific alterations are targetable and not all alterations have the same effect on protein function. Although overexpression of certain genes and proteins are actionable (eg, HER2), amplification of a gene does not necessarily indicate that it is targetable. In NSCLC, specific alterations convey sensitivity to targeted therapies. For example, in EGFR-mutated NSCLC, the sensitizing mutations to EGFR TKIs are exon19 deletions and exon 21 L858R point mutations (the most common mutations), as well as less common mutations found in exon 18-21. Exon 20 mutations, however, are not responsive to EGFR TKIs with a few exceptions.27 Patients who have tumors that do not harbor a sensitizing EGFR mutation should not be treated with an EGFR TKI. In a variety of solid tumors, gene fusions of the NTRK 1/2/3, act as oncogenic drivers. The chromosomal fusion events involving the carboxy-terminal kinase domain of TRK and upstream amino-terminal partners lead to overexpression of the chimeric proteins tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) A/B/C, resulting in constitutively active, ligand-independent downstream signaling. In patients with NTRK 1/2/3 gene fusions, larotrectinib and entrectinib, small molecule inhibitors to TRK, have shown antitumor activity.28,29 No alterations beyond these fusions are known to be targetable.

Allele Fraction

Knowing the fraction (or proportion) of the alteration of interest in the sequenced tissue relative to the estimated tumor content can assist in decision making. Not all platforms will provide this information, which is referred to as mutation allele fraction (MAF) or variant allele fraction (VAF), but sometimes will provide it on request. Platforms will usually provide an estimate of the percent tumor in the tissue being sampled if it is from a biopsy. If the MAF is around 50% in the sequenced tissue (including ctDNA), then there is a reasonable chance that it is a germline variant. However, there are nuances as germline alterations in some genes, such as BRCA1/2, can be accompanied by loss of the other allele of the gene (LOH). In that case, if most of the circulating DNA is from tumor, then the MAF can be > 50%.

If there are 2 alterations of the same gene with MAF percentages that are each half of the total percent tumor, there is a high likelihood of biallelic alteration. These sorts of paired alterations or one mutation with apparent LOH or copy loss would again indicate a high likelihood that the alteration is in fact pathogenic and a relevant driver. Not all pathogenic alterations have to be biallelic to be driver mutations but in BRCA1/2, or mismatch repair deficiency genes, the presence of biallelic alterations increases the likelihood of their being pathogenic.

Tumors that are hypermutated—containing sometimes hundreds of mutations per megabyte of DNA—can be particularly complicated to interpret, because the likelihood increases that many of the alterations are a function of the hypermutation and not a driver mutation. This is particularly important when there are concurrent mutations in mismatch repair genes and genes, such as BRCA1/2. If the tumor is

Confounders

In some situations, interpretation can be particularly challenging. For example, several alterations for which there are FDA on-label indications (such as ATM or BRCA2) can be detected in ctDNA that may not be due to the tumor but to CHIP. CHIP represents hematopoietic clones that are dysplastic as a result of exposure to DNA-damaging agents (eg, platinum chemotherapy) or as a result of aging and arise when mutations in hematopoietic stem cells provide a competitive advantage.31 The most common CHIP clones that can be detected are DNMT3A, ASXL1, or TET2; because these alterations are not targetable, their importance lies primarily in whether patients have evidence of hematologic abnormality, which might represent an evolving hematopoietic disorder. Because CHIP alterations can overlap with somatic alterations for which FDA-approved drugs exist, such as ATM or CHEK2 (olaparib for prostate cancer) and BRCA2 (poly-ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors in a range of indications) there is concern that CHIP might result in patient harm from inappropriate treatment of CHIP rather than the tumor, with no likelihood that the treatment would affect the tumor, causing treatment delays.32 General considerations for deciding whether an alteration represents CHIP include excluding alteration in which the VAF is < 1% and when the VAF in the alteration of interest is < 20% of the estimated tumor fraction in the sample. Exceptions to this are found in patients with true myelodysplasia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in whom the VAF can be well over 50% because of circulating tumor burden. The only way to be certain that an alteration detected on ctDNA reflects tumor rather than CHIP is to utilize an assay with matched tumor-normal sequencing.

Resources for Assistance

For oncology HCPs, perhaps the best resource to help in selecting and interpreting the appropriate testing is through a dedicated molecular oncology tumor board and subject matter experts who contribute to those tumor boards. In the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the national precision oncology program and its affiliated clinical services, such as the option to order a national consultation and molecular tumor board education, are easily accessible to all HCPs (www.cancer.va.gov). Many commercial vendors provide support to assist with questions of interpretation and to inform clinical decision-making. Other resources that can assist with deciding whether an alteration is pathogenic include extensive curated databases such as ClinVar (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar) and the Human Genetic Mutation Database (www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php) for germline alterations or COSMIC (cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) for somatic alterations. OncoKB (www.oncokb.org) is a resource for assistance in defining levels of evidence for the use of agents to target specific alterations and to assist in assigning pathogenicity to specific alterations. Additional educational resources for training in genomics and genetics are also included in the Appendix.

The rapid growth in technology and ability to enhance understanding of relevant tumor biology continues to improve the therapeutic landscape for men and women dealing with malignancy and our ability to find targetable genetic alterations with the potential for meaningful clinical benefit.

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to Neil Spector.

The ability to find and target specific biomarkers in the DNA of advanced cancers is rapidly changing options and outcomes for patients with locally advanced and metastatic solid tumors. This strategy is the basis for precision oncology, defined here as using predictive biomarkers from tumor and/or germline sequencing to guide therapies. This article focuses specifically on the use of DNA sequencing to find those biomarkers and provides guidance about which test is optimal in a specific situation, as well as interpretation of the results. We emphasize the identification of biomarkers that provide adult patients with advanced solid tumors access to therapies that would not be an option had sequencing not been performed and that have the potential for significant clinical benefit. The best approach is to have an expert team with experience in precision oncology to assist in the interpretation of results.

Which test?

Deciding what test of the array of assays available to use and which tissue to test can be overwhelming, and uncertainty may prevent oncology practitioners from ordering germline or somatic sequencing. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on DNA sequencing for inherited/germline alterations (including mutations, copy number changes, or fusions), which may inform treatment, or alterations that arise in the process of carcinogenesis and tumor evolution (somatic alterations in tumor DNA). This focus is not meant to exclude any specific test but to focus on DNA-based tests in patients with locally advanced or metastatic malignancy.

Germline Testing

Germline testing is the sequencing of inherited DNA in noncancerous cells to find alterations that may play a role in the development of cancers and are actionable in some cases. Germline alterations can inform therapeutic decisions, predict future cancer risk, and provide information that can help family members to better manage their risks of malignancy. Detailed discussions of the importance of germline testing to inform cancer surveillance, risk-reducing interventions, and the testing of relatives to determine who carries inherited alterations (cascade testing) is extremely important with several advantages and is covered in a number of excellent reviews elsewhere.1-3 Testing of germline DNA in patients with a metastatic malignancy can provide treatment options otherwise not available for patients, particularly for BRCA1/2 and Lynch syndrome–related cancers. Recent studies have shown that 10 to 15% of patients with advanced malignancies of many types have a pathogenic germline alteration.4,5

Germline DNA is usually acquired from peripheral blood, a buccal swab, or saliva collection and is therefore readily available. This is advantageous because it does not require a biopsy to identify relevant alterations. Germline testing is also less susceptible to the rare situations in which artifacts occur in formalin-fixed tissues and obscure relevant alterations.

The cost of germline testing varies, but most commercial vendor assays for germline testing are significantly less expensive than the cost of somatic testing. The disadvantages include the inability of germline testing to find any alterations that arise solely in tumor tissue and the smaller gene panels included in germline testing as compared to somatic testing panels. Other considerations relate to the inherited nature of pathogenic germline variants and its implications for family members that may affect the patient’s psychosocial health and potentially change the family dynamics.

Deciding who is appropriate for germline testing and when to perform the testing should be individualized to the patient’s wishes and disease status. Treatment planning may be less complicated if testing has been performed and germline status is known. In some cases urgent germline testing is indicated to inform pending procedures and/or surgical decisions for risk reduction, including more extensive tissue resection, such as the removal of additional organs or contralateral tissue. A minor point regarding germline testing is that the DNA of patients with hematologic malignancies may be difficult to sequence because of sample contamination by the circulating malignancy. For this reason, most laboratories will not accept peripheral blood or saliva samples for germline testing in patients with active hematologic malignancies; they often require DNA from another source such as fibroblasts from a skin biopsy or cells from a muscle biopsy. Germline testing is recommended for all patients with metastatic prostate cancer, as well as any patient with any stage of pancreatic cancer or ovarian cancer and patients with breast cancer diagnosed at age ≤ 45 years. More detailed criteria for who is appropriate for germline testing outside of these groups can be found in the appropriate National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.6-8 In patients with some malignancies such as prostate and pancreatic cancer, approximately half of patients who have a BRCA-related cancer developed that malignancy because of a germline BRCA alteration.9-11 Testing germline DNA is therefore an easy way to quickly find almost half of all targetable alterations with a treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and at low cost, with the added benefit of providing critical information for families who may be unaware that members carry a relevant pathogenic germline alteration. In those families, cascade testing can provide surveillance and intervention strategies that can be lifesaving.

A related and particularly relevant question is when should a result found on a somatic testing panel prompt follow-up germline testing? Some institutions have algorithms in place to automate referral for germline testing based on specific genetic criteria.12 Excellent reviews are available that outline the following considerations in more detail.13 Typically, somatic testing results that would trigger follow-up germline testing would be truncating or deleterious or likely deleterious mutations per germline datasets in high-risk genes associated with highly penetrant autosomal dominant conditions (BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6), selected moderate-risk genes (BRIP1, RAD51C, and RAD51D), and specific variants with a high probability of being germline because they are common germline founder mutations. Although the actionability and significance of specific genes remains a matter of some discussion, generally finding a somatic pathogenic sequencing result included in the 59-gene list of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines would be an indication for germline testing. Another indication for germline testing would be finding genes with germline mutations for which the NCCN has specific management guidelines, or the presence of alterations consistent with known founder mutations.14 When a patient’s tumor has microsatellite instability or is hypermutated (defined as > 10 mutations per megabase), a search for germline alterations is warranted given that about 15% of these patients with these tumors carry a Lynch syndrome gene.15 Genes that are commonly found as somatic alterations alone (eg, TP53 or APC) are generally not an indication for germline testing unless family history is compelling.

Although some clinicians use the variant allele fraction in the somatic sequencing report to decide whether to conduct germline testing, this approach is suboptimal, as allele fraction may be confounded by assay conditions and a high allele fraction may be found in pure tumors with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the other allele. There is also evidence that for a variety of reasons, somatic sequencing panels do not always detect germline alterations in somatic tissues.16 Reasons for this may include discordance between the genes being tested in the germline vs the somatic panel, technical differences such as interference of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) artifact with detecting the germline variant, lack of expertise in germline variant interpretation among laboratories doing tumor-only sequencing, and, in rare cases, large deletions in tumor tissue masking a germline point mutation.

Variant Interpretation of Germline Testing

A general understanding of the terminology used for germline variant interpretation allows for the ordering health care practitioner (HCP) to provide the best quality care and an appreciation for the limitations of current molecular testing. Not all variants are associated with disease; the clinical significance of a genetic variant falls on a spectrum. The criteria for determining pathogenicity differ between molecular laboratories, but most are influenced by the standards and guidelines set forth by the ACMG.14 The clinical molecular laboratory determines variant classification, and a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this primer. In brief, variant classification is based on evidence of varying strength in different categories including population data, computational and predictive data, functional data, segregation data, de novo data, allelic data, and information from various databases. The ACMG has proposed a 5-tiered classification system, by which most molecular laboratories adhere to in their genetic test reports (Table 1).14

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are clinically actionable, whereas variants of uncertain significance (VUS) require additional data and/or functional studies before making clinical decisions. Depending on the clinical context and existing supporting evidence, it may be prudent to continue monitoring for worsening or new signs of disease in patients with one or more VUS while additional efforts are underway to understand the variant’s significance.

In some cases, variants are reclassified, which may alter the management and treatment of patients. Reclassification can occur with VUS, and in rare instances, can also occur with variants previously classified as pathogenic/likely pathogenic or benign/likely benign. In such a case, the reporting laboratory will typically make concerted efforts to alert the ordering HCP. However, variant reclassifications are not always communicated to the care team. Thus, it is important to periodically contact the molecular laboratory of interest to obtain updated test interpretations.

Somatic Testing

Testing of somatic (tumor) tissue is critical and is the approach most commonly taken in medical oncology (Table 2).

The advantages of primary tumor are that it is usually in hand as a diagnostic biopsy, acquisition is standard of care, and several targetable alterations are truncal, defined as driver mutations present at the time of tumor development. Also, the potential that the tumor arose in the background of a predisposing germline alteration can be suggested by sequencing primary tumor as discussed above. Moreover, sequencing the primary tumor can be done at any time unless the biopsy sample is considered too old or degraded (per specific platform requirements). The information gained can be used to anticipate additional treatment options that are relevant when patients experience disease progression. Disadvantages include the problem that primary specimens may be old or have limited tumor content, both of which increase the likelihood that sequencing will not be technically successful.

Alterations that are targetable and arise as a result of either treatment pressure or clonal evolution are considered evolutionary. If evolutionary alterations are the main focus for sequencing, then metastasis biopsy or ctDNA are better choices. The advantages of a metastasis biopsy are that tissue is contemporary, tumor content may be higher than in primary tumor, and both truncal and evolutionary alterations can be detected.

For specific tumors, continued analysis of evolving genomic alterations can play a critical role in management. In non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), somatic testing is conducted again at progression on repeat biopsies to evaluate for emerging resistance mutations. In epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–mutated lung cancer, the resistance mutation, exon 20 p.T790M (point mutation), can present in patients after treatment with first- or second-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). Even in patients who are treated with the third-generation EGFR TKI osimertinib that can treat T790M-mutated lung cancer, multiple possible evolutionary mutations can occur at progression, including other EGFR mutations, MET/HER2 amplification, and BRAF V600E, to name a few.20 Resistance mechanisms develop due to treatment selection pressure and the molecular heterogeneity seen in lung cancer.

Disadvantages for metastatic biopsy include the inability to safely access a metastatic site, the time considerations for preauthorization and arrangement of biopsy, and a lower-than-average likelihood of successful sequencing from sites such as bone.21,22 In addition, there is some concern that a single metastatic site may not capture all relevant alterations for multiple reasons, including tumor heterogeneity.

Significant advances in the past decade have dramatically improved the ability to use ctDNA to guide therapy. Advantages include ease of acquisition as acquiring a sample requires only a blood draw, and the potential that the pool of ctDNA is a better reflection of the relevant biology as it potentially reflects all metastatic tissues. Disadvantages are that sequencing attempts may not be productive if the sample is acquired at a time when the tumor is either quiescent or tumor burden is so low that only limited amounts of DNA are being shed. Performing ctDNA analysis when a tumor is not progressing is less likely to be productive for a number of tumor types.23,24 Sequencing ctDNA is also more susceptible than sequencing tumor biopsies to detection of alterations that are not from the tumor of interest but from clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) or other clonal hematopoietic disorders (see Confounders section below).

Selecting the Tissue

Deciding on the tissue to analyze is a critical part of the decision process (Table 3). If the primary tumor tissue is old the likelihood of productive sequencing is lower, although age alone is not the only consideration and the methods of fixation may be just as relevant.

For prostate cancer in particular, the ability to successfully sequence primary tumor tissue decreases as the amount of tumor decreases in low-volume biopsies such as prostate needle biopsies. Generally, if tumor content is < 10% of the biopsy specimen, then sequencing is less likely to be productive.25 Also, if the alteration of interest is not known to be truncal, then a relevant target might be missed by sequencing tissue that does not reflect current biology. Metastasis biopsy may be the most appropriate tissue, particularly if this specimen has already been acquired. As above, a metastasis biopsy may have a higher tumor content, and it should reflect relevant biology if it is recent. However, bone biopsies have a relatively low yield for successful sequencing, so a soft tissue lesion (eg, liver or lymph node metastasis) is generally preferred.

The inability to safely access tissue is often a consideration. Proximity to vital structures such as large blood vessels or the potential for significant morbidity in the event of a complication (liver or lung biopsies, particularly in patients on anticoagulation medications) may make the risk/benefit ratio too high. The inability to conduct somatic testing has been reported to often be due to inadequate tissue sampling.26 ctDNA is an attractive alternative but should typically be drawn when a tumor is progressing with a reasonable tumor burden that is more likely to be shedding DNA. Performing ctDNA analysis in patients without obvious radiographic metastasis or in patients whose tumor is under good control is unlikely to produce interpretable results.

Interpreting the Results

The intent of sequencing tumor tissue is to identify alterations that are biologically important and may provide a point of therapeutic leverage. However, deciding which alterations are relevant is not always straightforward. For example, any normal individual genome contains around 10,000 missense variants, hundreds of insertion/deletion variants, and dozens of protein-truncating variants. Distinguishing these alterations, which are part of the individual, from those that are tumor-specific and have functional significance can be difficult in the absence of paired sequencing of both normal and tissue samples.

Specific Alterations

Although most commercial vendors provide important information in sequencing reports to assist oncology HCPs in deciding which alterations are relevant, the reports are not always clear. In many cases the report will specifically indicate whether the alteration has been reported previously as pathogenic or benign. However, some platforms will report alterations that are not known to be drivers of tumor biology. It is critical to be aware that if variants are not reported as pathogenic, they should not be assumed to be pathogenic simply because they are included in the report. Alterations more likely to be drivers of relevant biology are those that change gene and protein structure and include frameshift (fs*), nonsense (denoted by sequence ending in “X” or “*”), or specific fusions or insertions/deletions (indel) that occur in important domains of the gene.

For some genes, only specific alterations are targetable and not all alterations have the same effect on protein function. Although overexpression of certain genes and proteins are actionable (eg, HER2), amplification of a gene does not necessarily indicate that it is targetable. In NSCLC, specific alterations convey sensitivity to targeted therapies. For example, in EGFR-mutated NSCLC, the sensitizing mutations to EGFR TKIs are exon19 deletions and exon 21 L858R point mutations (the most common mutations), as well as less common mutations found in exon 18-21. Exon 20 mutations, however, are not responsive to EGFR TKIs with a few exceptions.27 Patients who have tumors that do not harbor a sensitizing EGFR mutation should not be treated with an EGFR TKI. In a variety of solid tumors, gene fusions of the NTRK 1/2/3, act as oncogenic drivers. The chromosomal fusion events involving the carboxy-terminal kinase domain of TRK and upstream amino-terminal partners lead to overexpression of the chimeric proteins tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) A/B/C, resulting in constitutively active, ligand-independent downstream signaling. In patients with NTRK 1/2/3 gene fusions, larotrectinib and entrectinib, small molecule inhibitors to TRK, have shown antitumor activity.28,29 No alterations beyond these fusions are known to be targetable.

Allele Fraction

Knowing the fraction (or proportion) of the alteration of interest in the sequenced tissue relative to the estimated tumor content can assist in decision making. Not all platforms will provide this information, which is referred to as mutation allele fraction (MAF) or variant allele fraction (VAF), but sometimes will provide it on request. Platforms will usually provide an estimate of the percent tumor in the tissue being sampled if it is from a biopsy. If the MAF is around 50% in the sequenced tissue (including ctDNA), then there is a reasonable chance that it is a germline variant. However, there are nuances as germline alterations in some genes, such as BRCA1/2, can be accompanied by loss of the other allele of the gene (LOH). In that case, if most of the circulating DNA is from tumor, then the MAF can be > 50%.

If there are 2 alterations of the same gene with MAF percentages that are each half of the total percent tumor, there is a high likelihood of biallelic alteration. These sorts of paired alterations or one mutation with apparent LOH or copy loss would again indicate a high likelihood that the alteration is in fact pathogenic and a relevant driver. Not all pathogenic alterations have to be biallelic to be driver mutations but in BRCA1/2, or mismatch repair deficiency genes, the presence of biallelic alterations increases the likelihood of their being pathogenic.

Tumors that are hypermutated—containing sometimes hundreds of mutations per megabyte of DNA—can be particularly complicated to interpret, because the likelihood increases that many of the alterations are a function of the hypermutation and not a driver mutation. This is particularly important when there are concurrent mutations in mismatch repair genes and genes, such as BRCA1/2. If the tumor is

Confounders

In some situations, interpretation can be particularly challenging. For example, several alterations for which there are FDA on-label indications (such as ATM or BRCA2) can be detected in ctDNA that may not be due to the tumor but to CHIP. CHIP represents hematopoietic clones that are dysplastic as a result of exposure to DNA-damaging agents (eg, platinum chemotherapy) or as a result of aging and arise when mutations in hematopoietic stem cells provide a competitive advantage.31 The most common CHIP clones that can be detected are DNMT3A, ASXL1, or TET2; because these alterations are not targetable, their importance lies primarily in whether patients have evidence of hematologic abnormality, which might represent an evolving hematopoietic disorder. Because CHIP alterations can overlap with somatic alterations for which FDA-approved drugs exist, such as ATM or CHEK2 (olaparib for prostate cancer) and BRCA2 (poly-ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors in a range of indications) there is concern that CHIP might result in patient harm from inappropriate treatment of CHIP rather than the tumor, with no likelihood that the treatment would affect the tumor, causing treatment delays.32 General considerations for deciding whether an alteration represents CHIP include excluding alteration in which the VAF is < 1% and when the VAF in the alteration of interest is < 20% of the estimated tumor fraction in the sample. Exceptions to this are found in patients with true myelodysplasia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in whom the VAF can be well over 50% because of circulating tumor burden. The only way to be certain that an alteration detected on ctDNA reflects tumor rather than CHIP is to utilize an assay with matched tumor-normal sequencing.

Resources for Assistance

For oncology HCPs, perhaps the best resource to help in selecting and interpreting the appropriate testing is through a dedicated molecular oncology tumor board and subject matter experts who contribute to those tumor boards. In the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the national precision oncology program and its affiliated clinical services, such as the option to order a national consultation and molecular tumor board education, are easily accessible to all HCPs (www.cancer.va.gov). Many commercial vendors provide support to assist with questions of interpretation and to inform clinical decision-making. Other resources that can assist with deciding whether an alteration is pathogenic include extensive curated databases such as ClinVar (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar) and the Human Genetic Mutation Database (www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php) for germline alterations or COSMIC (cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) for somatic alterations. OncoKB (www.oncokb.org) is a resource for assistance in defining levels of evidence for the use of agents to target specific alterations and to assist in assigning pathogenicity to specific alterations. Additional educational resources for training in genomics and genetics are also included in the Appendix.

The rapid growth in technology and ability to enhance understanding of relevant tumor biology continues to improve the therapeutic landscape for men and women dealing with malignancy and our ability to find targetable genetic alterations with the potential for meaningful clinical benefit.

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to Neil Spector.