User login

Hidden Risks of Formaldehyde in Hair-Straightening Products

Hidden Risks of Formaldehyde in Hair-Straightening Products

Formaldehyde (FA) is a colorless, flammable, highly pungent gas that remains ubiquitous in the environment despite being a known carcinogen and allergen.1 In the cosmetic industry, FA commonly is used as both a preservative and active ingredient in hairstraightening products. Due to its toxicity and the thermal instability of FA releasers (ie, the release of FA at high temperatures), the US Food and Drug Administration has proposed a ban on formaldehyde and other FA-releasing chemicals (eg, methylene glycol) as an ingredient in hairsmoothing or hair-straightening products marketed in the United States.2 However, the implementation of this ban is not yet in effect.

Hair-straightening products that are referred to as chemical relaxers typically contain alkaline derivatives. Alkaline hair straighteners—which include lye relaxers (active ingredient: sodium hydroxide), nolye relaxers (active ingredients: potassium hydroxide, lithium hydroxide, calcium hydroxide, guanidine hydroxide, or ammonium thioglycolate), and the Japanese hair straightening process (active ingredient: ammonium thioglycolate)—do not contain FA or FA-derivatives as active ingredients.3 Alternatively, acidic hair straighteners—popularly known as keratin treatments—contain either FA or FA-releasers and will be the primary focus of this discussion. As many patients are exposed to these products, we aim to highlight the cutaneous and systemic manifestations of acute and chronic exposure.

How Hair-Straightening Products Work

Hair straighteners that include FA or its derivatives generally contain high and low molecular weights of keratin peptides. The keratin peptides with high molecular weights diffuse into the cuticle while the low-molecular-weight peptides can penetrate further into the cortex of the hair shaft.4 Formaldehyde forms cross-links with the keratin amino acids (eg, tyrosine, arginine), and the application of heat via blow-drying enhances its ability to cross-link the hydrolyzed keratin from the straightening product to the natural keratin in the hair fibers; the use of a heated flat iron further enhances the cross-linking and seals the cuticle.5 The same mechanism of action applies for “safe keratin” (marketing terminology used for FA releasers) treatments, whereby the hydrogen and salt bonds of the hair are weakened, allowing for interconversion of the cysteine bonds of the hair fibers. This chemical conversion allows for the hair shafts to have a stable straight configuration. Of note, this mechanism of action differs from the action of chemical relaxers, which have a high pH and straighten the hair by opening the cuticles and permanently breaking the disulfide bonds in the cortex of the hair shaft—a process that restructures the keratin bonds without requiring heat application.5

The outcome of a keratin treatment, as seen on light microscopy, is the replenishment of gaps in the hair’s cuticle, therefore increasing its mechanical and thermal properties.6 This can give the appearance of increased shine, softness, and tensile strength. However, Sanad et al6 report that, as viewed on transmission electron microscopy, these keratin treatments do not repair lost cuticles, cuticle splitting, or detached cuticle layers from damaged strands.

Lastly, some patients notice lightening of their hair color after a hair-straightening treatment, which is possibly due to inhibition of the enzymatic synthesis of melanin, decomposition of melanin granules, or a direct reaction from chemical neutralizers with a high pH.6 Knowledge of the mechanism of action of hair-straightening treatments will aid dermatologists in educating patients about their immediate and long-term effects. This education subsequently will help patients avoid inappropriate hair care techniques that further damage the hair.

Environmental Distribution and Systemic Absorption of Formaldehyde

Atmospheric FA is absorbed via cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. Atmospheric FA concentrations produced when hair-straightening products are used cannot routinely be predicted because the amount generated depends on factors such as the pH of the preparation, the temperature to which the product is heated during straightening, duration of storage, and aeration and size of the environment in which the product is being used, among others.7

Peteffi et al7 and Aglan et al8 detected a moderate positive correlation between environmental FA concentrations and those in cosmetic products, particularly after blow-drying the hair or using other heat applications; however, the products examined by Peteffi et al7 contained exceedingly high concentrations of FA (up to 5.9%, which is higher than the legal limit of 0.1% in the United States).9 Of note, some products in this study were labelled as “formaldehyde free” but still contained high concentrations of FA.7 This is consistent with data published by the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, which citied salons with exposure limits outside the national recommendations (2.0 FA ppm/air).10 These findings highlight the inadvertent exposure that consumers face from products that are not regulated consistently.

Interestingly, Henault et al11 observed that products with a high concentration of FA dispersed more airborne particles during hair brushing than hair straightening/ironing.11 Further studies are needed to clarify the different routes and methods contributing to FA dispersion and the molecular instability of FA-releasers.

Clinical Correlation

Products that contain low (ie, less than the legal limit) levels of FA are not mandated to declare its presence on the product label; however, many products are contaminated with FA or inappropriately omit FA from the ingredient list, even at elevated concentrations. Consumers therefore may be inadvertently exposed to FA particles. Additionally, occupations with frequent exposure to FA include hairdressers, barbers, beauticians and related workers (33.6% exposure rate); sewers and embroiderers (26.1%); and cooks (19.1%).12

Adverse health effects associated with acute FA exposure include but are not limited to headache, eye irritation, allergic/irritant contact dermatitis, psoriasiform reactions, and acute kidney and respiratory tract injuries. Frontal fibrosing alopecia; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; and cancers of the upper digestive tract, lungs, and bladder also have been associated with chronic FA exposure.7,13 In a cohort of female hairdressers, a longer duration of FA exposure (>8 years) as well as cumulative exposure were associated with an increase in ovarian cancer (OR, 1.48 [0.88 to 2.51]).12 Formalin, the aqueous derivative of FA, also contains phenolic products that can mediate inflammatory response, DNA methylation, and carcinogenesis even with chronic low-level exposure.14 However, evidence supporting a direct correlation of FA exposure with breast carcinoma in both hairstylists and consumers remains controversial.7

Sanchez-Duenas et al15 described a case series of patients who were found to have psoriasiform scalp reactions after exposure to keratin treatments containing FA. The time to development of the lesions was inversely correlated with the number of treatments received, although the mean time to development was 12 months postprocedure.15 These researchers also identified no allergies to the substance on contact testing, which suggests an alternate pathogenesis as a consequence of FA exposure, resulting in the development of a psoriasiform reaction.15

Following adjustment for sex, age, menopause status, and skin color, frontal fibrosing alopecia also has been associated with the use of formalin and FA in hair straighteners.14 This is possibly related to the ability of FA and many phenolic products to induce chronic inflammation; however, a cumulative effect has not been noted consistently across the literature.

Future Directives

Continuous industry regulation is needed to ensure that use of FA is reduced and it is eventually eliminated from consumer products. Additionally, strict regulations are required to ensure products containing FA and FA-releasers are accurately labeled. Physicians and consumers should be aware of the potential health hazards associated with FA and advocate for effective legislation. While there is controversy regarding the level of absorption from environmental exposure and the subsequent biologic effects of absorption, both consumers and workers in industries such as hairdressing and barbering should reduce exposure time to FA and limit the application of heat and contact with products containing FA and FA releasers.

- González-Muñoz P, Conde-Salazar L, Vañó-Galván S. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by cosmetic products. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:822-832. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2013.12.018

- Department of Health and Human Services. Use of formaldehyde and formaldehyde-releasing chemicals as an ingredient in hair smoothing products or hair straightening products (RIN: 0910-AI83). Spring 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202304&RIN=0910-AI83

- Velasco MVR, de Sá-Dias TC, Dario MF, et al. Impact of acid (“progressive brush”) and alkaline straightening on the hair fiber: differential effects on the cuticle and cortex properties. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:197-203. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_158_20

- Malinauskyte E, Shrestha R, Cornwell P, et al. Penetration of different molecular weight hydrolysed keratins into hair fibres and their effects on the physical properties of textured hair. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2021;43:26-37. doi:10.1111/ics.12663

- Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. doi:10.1111/jocd.12030

- Sanad EM, El]Esawy FM, Mustafa AI, et al. Structural changes of hair shaft after application of chemical hair straighteners: clinical and histopathological study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:929-935. doi:10.1111/jocd.12752

- Peteffi GP, Antunes MV, Carrer C, et al. Environmental and biological monitoring of occupational formaldehyde exposure resulting from the use of products for hair straightening. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:908-917. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5343-4

- Aglan MA, Mansour GN. Hair straightening products and the risk of occupational formaldehyde exposure in hairstylists. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;43:488-495. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2018 .1508215

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hair smoothing products that could release formaldehyde. Hazard Alert Update. September 2011. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/hazard_alert.pdf

- US Department of Labor. US Department of Labor continues to cite beauty salons and manufacturers for formaldehyde exposure from hair smoothing products. December 8, 2011. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20111208

- Henault P, Lemaire R, Salzedo A, et al. A methodological approach for quantifying aerial formaldehyde released by some hair treatmentsmodeling a hair-salon environment. J Air Waste Manage. 2021;71: 754-760. doi:10.1080/10962247.2021.1893238

- Leung L, Lavoué J, Siemiatycki J, et al. Occupational environment and ovarian cancer risk. Occup Environ Med. 2023;80:489-497. doi:10.1136/oemed-2022-108557

- Bnaya A, Abu-Amer N, Beckerman P, et al. Acute kidney injury and hair-straightening products: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;82:43-52.E1. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.11.016

- Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case-control study in a multiracial population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:712-718. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.076

- Sanchez-Duenas LE, Ruiz-Dueñas A, Guevara-Gutiérrez E, et al. Psoriasiform skin reaction due to Brazilian keratin treatment: a clinicaldermatoscopic study of 43 patients. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:103-108. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_62_21

Formaldehyde (FA) is a colorless, flammable, highly pungent gas that remains ubiquitous in the environment despite being a known carcinogen and allergen.1 In the cosmetic industry, FA commonly is used as both a preservative and active ingredient in hairstraightening products. Due to its toxicity and the thermal instability of FA releasers (ie, the release of FA at high temperatures), the US Food and Drug Administration has proposed a ban on formaldehyde and other FA-releasing chemicals (eg, methylene glycol) as an ingredient in hairsmoothing or hair-straightening products marketed in the United States.2 However, the implementation of this ban is not yet in effect.

Hair-straightening products that are referred to as chemical relaxers typically contain alkaline derivatives. Alkaline hair straighteners—which include lye relaxers (active ingredient: sodium hydroxide), nolye relaxers (active ingredients: potassium hydroxide, lithium hydroxide, calcium hydroxide, guanidine hydroxide, or ammonium thioglycolate), and the Japanese hair straightening process (active ingredient: ammonium thioglycolate)—do not contain FA or FA-derivatives as active ingredients.3 Alternatively, acidic hair straighteners—popularly known as keratin treatments—contain either FA or FA-releasers and will be the primary focus of this discussion. As many patients are exposed to these products, we aim to highlight the cutaneous and systemic manifestations of acute and chronic exposure.

How Hair-Straightening Products Work

Hair straighteners that include FA or its derivatives generally contain high and low molecular weights of keratin peptides. The keratin peptides with high molecular weights diffuse into the cuticle while the low-molecular-weight peptides can penetrate further into the cortex of the hair shaft.4 Formaldehyde forms cross-links with the keratin amino acids (eg, tyrosine, arginine), and the application of heat via blow-drying enhances its ability to cross-link the hydrolyzed keratin from the straightening product to the natural keratin in the hair fibers; the use of a heated flat iron further enhances the cross-linking and seals the cuticle.5 The same mechanism of action applies for “safe keratin” (marketing terminology used for FA releasers) treatments, whereby the hydrogen and salt bonds of the hair are weakened, allowing for interconversion of the cysteine bonds of the hair fibers. This chemical conversion allows for the hair shafts to have a stable straight configuration. Of note, this mechanism of action differs from the action of chemical relaxers, which have a high pH and straighten the hair by opening the cuticles and permanently breaking the disulfide bonds in the cortex of the hair shaft—a process that restructures the keratin bonds without requiring heat application.5

The outcome of a keratin treatment, as seen on light microscopy, is the replenishment of gaps in the hair’s cuticle, therefore increasing its mechanical and thermal properties.6 This can give the appearance of increased shine, softness, and tensile strength. However, Sanad et al6 report that, as viewed on transmission electron microscopy, these keratin treatments do not repair lost cuticles, cuticle splitting, or detached cuticle layers from damaged strands.

Lastly, some patients notice lightening of their hair color after a hair-straightening treatment, which is possibly due to inhibition of the enzymatic synthesis of melanin, decomposition of melanin granules, or a direct reaction from chemical neutralizers with a high pH.6 Knowledge of the mechanism of action of hair-straightening treatments will aid dermatologists in educating patients about their immediate and long-term effects. This education subsequently will help patients avoid inappropriate hair care techniques that further damage the hair.

Environmental Distribution and Systemic Absorption of Formaldehyde

Atmospheric FA is absorbed via cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. Atmospheric FA concentrations produced when hair-straightening products are used cannot routinely be predicted because the amount generated depends on factors such as the pH of the preparation, the temperature to which the product is heated during straightening, duration of storage, and aeration and size of the environment in which the product is being used, among others.7

Peteffi et al7 and Aglan et al8 detected a moderate positive correlation between environmental FA concentrations and those in cosmetic products, particularly after blow-drying the hair or using other heat applications; however, the products examined by Peteffi et al7 contained exceedingly high concentrations of FA (up to 5.9%, which is higher than the legal limit of 0.1% in the United States).9 Of note, some products in this study were labelled as “formaldehyde free” but still contained high concentrations of FA.7 This is consistent with data published by the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, which citied salons with exposure limits outside the national recommendations (2.0 FA ppm/air).10 These findings highlight the inadvertent exposure that consumers face from products that are not regulated consistently.

Interestingly, Henault et al11 observed that products with a high concentration of FA dispersed more airborne particles during hair brushing than hair straightening/ironing.11 Further studies are needed to clarify the different routes and methods contributing to FA dispersion and the molecular instability of FA-releasers.

Clinical Correlation

Products that contain low (ie, less than the legal limit) levels of FA are not mandated to declare its presence on the product label; however, many products are contaminated with FA or inappropriately omit FA from the ingredient list, even at elevated concentrations. Consumers therefore may be inadvertently exposed to FA particles. Additionally, occupations with frequent exposure to FA include hairdressers, barbers, beauticians and related workers (33.6% exposure rate); sewers and embroiderers (26.1%); and cooks (19.1%).12

Adverse health effects associated with acute FA exposure include but are not limited to headache, eye irritation, allergic/irritant contact dermatitis, psoriasiform reactions, and acute kidney and respiratory tract injuries. Frontal fibrosing alopecia; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; and cancers of the upper digestive tract, lungs, and bladder also have been associated with chronic FA exposure.7,13 In a cohort of female hairdressers, a longer duration of FA exposure (>8 years) as well as cumulative exposure were associated with an increase in ovarian cancer (OR, 1.48 [0.88 to 2.51]).12 Formalin, the aqueous derivative of FA, also contains phenolic products that can mediate inflammatory response, DNA methylation, and carcinogenesis even with chronic low-level exposure.14 However, evidence supporting a direct correlation of FA exposure with breast carcinoma in both hairstylists and consumers remains controversial.7

Sanchez-Duenas et al15 described a case series of patients who were found to have psoriasiform scalp reactions after exposure to keratin treatments containing FA. The time to development of the lesions was inversely correlated with the number of treatments received, although the mean time to development was 12 months postprocedure.15 These researchers also identified no allergies to the substance on contact testing, which suggests an alternate pathogenesis as a consequence of FA exposure, resulting in the development of a psoriasiform reaction.15

Following adjustment for sex, age, menopause status, and skin color, frontal fibrosing alopecia also has been associated with the use of formalin and FA in hair straighteners.14 This is possibly related to the ability of FA and many phenolic products to induce chronic inflammation; however, a cumulative effect has not been noted consistently across the literature.

Future Directives

Continuous industry regulation is needed to ensure that use of FA is reduced and it is eventually eliminated from consumer products. Additionally, strict regulations are required to ensure products containing FA and FA-releasers are accurately labeled. Physicians and consumers should be aware of the potential health hazards associated with FA and advocate for effective legislation. While there is controversy regarding the level of absorption from environmental exposure and the subsequent biologic effects of absorption, both consumers and workers in industries such as hairdressing and barbering should reduce exposure time to FA and limit the application of heat and contact with products containing FA and FA releasers.

Formaldehyde (FA) is a colorless, flammable, highly pungent gas that remains ubiquitous in the environment despite being a known carcinogen and allergen.1 In the cosmetic industry, FA commonly is used as both a preservative and active ingredient in hairstraightening products. Due to its toxicity and the thermal instability of FA releasers (ie, the release of FA at high temperatures), the US Food and Drug Administration has proposed a ban on formaldehyde and other FA-releasing chemicals (eg, methylene glycol) as an ingredient in hairsmoothing or hair-straightening products marketed in the United States.2 However, the implementation of this ban is not yet in effect.

Hair-straightening products that are referred to as chemical relaxers typically contain alkaline derivatives. Alkaline hair straighteners—which include lye relaxers (active ingredient: sodium hydroxide), nolye relaxers (active ingredients: potassium hydroxide, lithium hydroxide, calcium hydroxide, guanidine hydroxide, or ammonium thioglycolate), and the Japanese hair straightening process (active ingredient: ammonium thioglycolate)—do not contain FA or FA-derivatives as active ingredients.3 Alternatively, acidic hair straighteners—popularly known as keratin treatments—contain either FA or FA-releasers and will be the primary focus of this discussion. As many patients are exposed to these products, we aim to highlight the cutaneous and systemic manifestations of acute and chronic exposure.

How Hair-Straightening Products Work

Hair straighteners that include FA or its derivatives generally contain high and low molecular weights of keratin peptides. The keratin peptides with high molecular weights diffuse into the cuticle while the low-molecular-weight peptides can penetrate further into the cortex of the hair shaft.4 Formaldehyde forms cross-links with the keratin amino acids (eg, tyrosine, arginine), and the application of heat via blow-drying enhances its ability to cross-link the hydrolyzed keratin from the straightening product to the natural keratin in the hair fibers; the use of a heated flat iron further enhances the cross-linking and seals the cuticle.5 The same mechanism of action applies for “safe keratin” (marketing terminology used for FA releasers) treatments, whereby the hydrogen and salt bonds of the hair are weakened, allowing for interconversion of the cysteine bonds of the hair fibers. This chemical conversion allows for the hair shafts to have a stable straight configuration. Of note, this mechanism of action differs from the action of chemical relaxers, which have a high pH and straighten the hair by opening the cuticles and permanently breaking the disulfide bonds in the cortex of the hair shaft—a process that restructures the keratin bonds without requiring heat application.5

The outcome of a keratin treatment, as seen on light microscopy, is the replenishment of gaps in the hair’s cuticle, therefore increasing its mechanical and thermal properties.6 This can give the appearance of increased shine, softness, and tensile strength. However, Sanad et al6 report that, as viewed on transmission electron microscopy, these keratin treatments do not repair lost cuticles, cuticle splitting, or detached cuticle layers from damaged strands.

Lastly, some patients notice lightening of their hair color after a hair-straightening treatment, which is possibly due to inhibition of the enzymatic synthesis of melanin, decomposition of melanin granules, or a direct reaction from chemical neutralizers with a high pH.6 Knowledge of the mechanism of action of hair-straightening treatments will aid dermatologists in educating patients about their immediate and long-term effects. This education subsequently will help patients avoid inappropriate hair care techniques that further damage the hair.

Environmental Distribution and Systemic Absorption of Formaldehyde

Atmospheric FA is absorbed via cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. Atmospheric FA concentrations produced when hair-straightening products are used cannot routinely be predicted because the amount generated depends on factors such as the pH of the preparation, the temperature to which the product is heated during straightening, duration of storage, and aeration and size of the environment in which the product is being used, among others.7

Peteffi et al7 and Aglan et al8 detected a moderate positive correlation between environmental FA concentrations and those in cosmetic products, particularly after blow-drying the hair or using other heat applications; however, the products examined by Peteffi et al7 contained exceedingly high concentrations of FA (up to 5.9%, which is higher than the legal limit of 0.1% in the United States).9 Of note, some products in this study were labelled as “formaldehyde free” but still contained high concentrations of FA.7 This is consistent with data published by the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, which citied salons with exposure limits outside the national recommendations (2.0 FA ppm/air).10 These findings highlight the inadvertent exposure that consumers face from products that are not regulated consistently.

Interestingly, Henault et al11 observed that products with a high concentration of FA dispersed more airborne particles during hair brushing than hair straightening/ironing.11 Further studies are needed to clarify the different routes and methods contributing to FA dispersion and the molecular instability of FA-releasers.

Clinical Correlation

Products that contain low (ie, less than the legal limit) levels of FA are not mandated to declare its presence on the product label; however, many products are contaminated with FA or inappropriately omit FA from the ingredient list, even at elevated concentrations. Consumers therefore may be inadvertently exposed to FA particles. Additionally, occupations with frequent exposure to FA include hairdressers, barbers, beauticians and related workers (33.6% exposure rate); sewers and embroiderers (26.1%); and cooks (19.1%).12

Adverse health effects associated with acute FA exposure include but are not limited to headache, eye irritation, allergic/irritant contact dermatitis, psoriasiform reactions, and acute kidney and respiratory tract injuries. Frontal fibrosing alopecia; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; and cancers of the upper digestive tract, lungs, and bladder also have been associated with chronic FA exposure.7,13 In a cohort of female hairdressers, a longer duration of FA exposure (>8 years) as well as cumulative exposure were associated with an increase in ovarian cancer (OR, 1.48 [0.88 to 2.51]).12 Formalin, the aqueous derivative of FA, also contains phenolic products that can mediate inflammatory response, DNA methylation, and carcinogenesis even with chronic low-level exposure.14 However, evidence supporting a direct correlation of FA exposure with breast carcinoma in both hairstylists and consumers remains controversial.7

Sanchez-Duenas et al15 described a case series of patients who were found to have psoriasiform scalp reactions after exposure to keratin treatments containing FA. The time to development of the lesions was inversely correlated with the number of treatments received, although the mean time to development was 12 months postprocedure.15 These researchers also identified no allergies to the substance on contact testing, which suggests an alternate pathogenesis as a consequence of FA exposure, resulting in the development of a psoriasiform reaction.15

Following adjustment for sex, age, menopause status, and skin color, frontal fibrosing alopecia also has been associated with the use of formalin and FA in hair straighteners.14 This is possibly related to the ability of FA and many phenolic products to induce chronic inflammation; however, a cumulative effect has not been noted consistently across the literature.

Future Directives

Continuous industry regulation is needed to ensure that use of FA is reduced and it is eventually eliminated from consumer products. Additionally, strict regulations are required to ensure products containing FA and FA-releasers are accurately labeled. Physicians and consumers should be aware of the potential health hazards associated with FA and advocate for effective legislation. While there is controversy regarding the level of absorption from environmental exposure and the subsequent biologic effects of absorption, both consumers and workers in industries such as hairdressing and barbering should reduce exposure time to FA and limit the application of heat and contact with products containing FA and FA releasers.

- González-Muñoz P, Conde-Salazar L, Vañó-Galván S. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by cosmetic products. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:822-832. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2013.12.018

- Department of Health and Human Services. Use of formaldehyde and formaldehyde-releasing chemicals as an ingredient in hair smoothing products or hair straightening products (RIN: 0910-AI83). Spring 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202304&RIN=0910-AI83

- Velasco MVR, de Sá-Dias TC, Dario MF, et al. Impact of acid (“progressive brush”) and alkaline straightening on the hair fiber: differential effects on the cuticle and cortex properties. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:197-203. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_158_20

- Malinauskyte E, Shrestha R, Cornwell P, et al. Penetration of different molecular weight hydrolysed keratins into hair fibres and their effects on the physical properties of textured hair. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2021;43:26-37. doi:10.1111/ics.12663

- Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. doi:10.1111/jocd.12030

- Sanad EM, El]Esawy FM, Mustafa AI, et al. Structural changes of hair shaft after application of chemical hair straighteners: clinical and histopathological study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:929-935. doi:10.1111/jocd.12752

- Peteffi GP, Antunes MV, Carrer C, et al. Environmental and biological monitoring of occupational formaldehyde exposure resulting from the use of products for hair straightening. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:908-917. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5343-4

- Aglan MA, Mansour GN. Hair straightening products and the risk of occupational formaldehyde exposure in hairstylists. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;43:488-495. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2018 .1508215

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hair smoothing products that could release formaldehyde. Hazard Alert Update. September 2011. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/hazard_alert.pdf

- US Department of Labor. US Department of Labor continues to cite beauty salons and manufacturers for formaldehyde exposure from hair smoothing products. December 8, 2011. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20111208

- Henault P, Lemaire R, Salzedo A, et al. A methodological approach for quantifying aerial formaldehyde released by some hair treatmentsmodeling a hair-salon environment. J Air Waste Manage. 2021;71: 754-760. doi:10.1080/10962247.2021.1893238

- Leung L, Lavoué J, Siemiatycki J, et al. Occupational environment and ovarian cancer risk. Occup Environ Med. 2023;80:489-497. doi:10.1136/oemed-2022-108557

- Bnaya A, Abu-Amer N, Beckerman P, et al. Acute kidney injury and hair-straightening products: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;82:43-52.E1. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.11.016

- Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case-control study in a multiracial population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:712-718. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.076

- Sanchez-Duenas LE, Ruiz-Dueñas A, Guevara-Gutiérrez E, et al. Psoriasiform skin reaction due to Brazilian keratin treatment: a clinicaldermatoscopic study of 43 patients. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:103-108. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_62_21

- González-Muñoz P, Conde-Salazar L, Vañó-Galván S. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by cosmetic products. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:822-832. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2013.12.018

- Department of Health and Human Services. Use of formaldehyde and formaldehyde-releasing chemicals as an ingredient in hair smoothing products or hair straightening products (RIN: 0910-AI83). Spring 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202304&RIN=0910-AI83

- Velasco MVR, de Sá-Dias TC, Dario MF, et al. Impact of acid (“progressive brush”) and alkaline straightening on the hair fiber: differential effects on the cuticle and cortex properties. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:197-203. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_158_20

- Malinauskyte E, Shrestha R, Cornwell P, et al. Penetration of different molecular weight hydrolysed keratins into hair fibres and their effects on the physical properties of textured hair. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2021;43:26-37. doi:10.1111/ics.12663

- Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. doi:10.1111/jocd.12030

- Sanad EM, El]Esawy FM, Mustafa AI, et al. Structural changes of hair shaft after application of chemical hair straighteners: clinical and histopathological study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:929-935. doi:10.1111/jocd.12752

- Peteffi GP, Antunes MV, Carrer C, et al. Environmental and biological monitoring of occupational formaldehyde exposure resulting from the use of products for hair straightening. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:908-917. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5343-4

- Aglan MA, Mansour GN. Hair straightening products and the risk of occupational formaldehyde exposure in hairstylists. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;43:488-495. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2018 .1508215

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hair smoothing products that could release formaldehyde. Hazard Alert Update. September 2011. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/hazard_alert.pdf

- US Department of Labor. US Department of Labor continues to cite beauty salons and manufacturers for formaldehyde exposure from hair smoothing products. December 8, 2011. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20111208

- Henault P, Lemaire R, Salzedo A, et al. A methodological approach for quantifying aerial formaldehyde released by some hair treatmentsmodeling a hair-salon environment. J Air Waste Manage. 2021;71: 754-760. doi:10.1080/10962247.2021.1893238

- Leung L, Lavoué J, Siemiatycki J, et al. Occupational environment and ovarian cancer risk. Occup Environ Med. 2023;80:489-497. doi:10.1136/oemed-2022-108557

- Bnaya A, Abu-Amer N, Beckerman P, et al. Acute kidney injury and hair-straightening products: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;82:43-52.E1. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.11.016

- Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case-control study in a multiracial population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:712-718. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.076

- Sanchez-Duenas LE, Ruiz-Dueñas A, Guevara-Gutiérrez E, et al. Psoriasiform skin reaction due to Brazilian keratin treatment: a clinicaldermatoscopic study of 43 patients. Int J Trichology. 2022;14:103-108. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_62_21

Hidden Risks of Formaldehyde in Hair-Straightening Products

Hidden Risks of Formaldehyde in Hair-Straightening Products

Focus on Nutrient Density Instead of Limiting Certain Foods

The word “malnutrition” probably brings to mind images of very thin patients with catabolic illness. But it really just means “poor nutrition,” which can — and often does — apply to patients with overweight or obesity.

That’s because malnutrition doesn’t occur simply because of a lack of calories, but rather because there is a gap in the nutrition the body requires and the nutrition it receives.

Each day, clinicians see patients with chronic conditions related to malnutrition. That list includes diabetes and hypertension, which can be promoted by excess intake of certain nutrients (carbohydrates and sodium) or inadequate intake of others (fiber, protein, potassium, magnesium, and calcium).

Diet Education Is Vital in Chronic Disease Management

Diet education is without a doubt a core pillar of chronic disease management. Nutrition therapy is recommended in treatment guidelines for the management of some of the most commonly seen chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and kidney disease. But in one study, only 58% of physicians, nurses and other health professionals surveyed had received formal nutrition education and only 40% were confident in their ability to provide nutrition education to patients.

As a registered dietitian, I welcome referrals for both prevention and management of chronic diseases with open arms. But medical nutrition therapy with a registered dietitian may not be realistic for all patients owing to financial, geographic, or other constraints. So, their best option may be the few minutes that a physician or physician extender has to spare at the end of their appointment.

But time constraints may result in clinicians turning to short, easy-to-remember messages such as “Don’t eat anything white” or “Only shop the edges of the grocery store.” Although catchy, this type of advice can inadvertently encourage patients to skip over foods that are actually very nutrient dense. For example, white foods such as onions, turnips, mushrooms, cauliflower, and even popcorn are low in calories and high in nutritional value. The center aisles of the grocery store may harbor high-carbohydrate breakfast cereals and potato chips, but they are also home to legumes, nuts, and canned and frozen fruits and vegetables.

What may be more effective is educating the patient on the importance of focusing on the nutrient density of foods, rather than simply limiting certain food groups or colors.

How to Work Nutrient Density into the Conversation

Nutrient density is a concept that refers to the proportion of nutrients to calories in a food item: essentially, a food’s qualitative nutritional value. It provides more depth than simply referring to foods as being high or low in calories, healthy or unhealthy, or good or bad.

Educating patients about nutrition density and encouraging a focus on foods that are low in calories and high in vitamins and minerals can help address micronutrient deficiencies, which may be more common than previously thought and linked to the chronic diseases that we see daily. It is worth noting that some foods that are not low in calories are still nutrient dense. Avocados, liver, and nuts come to mind as foods that are high in calories, but they have additional nutrients such as fiber, potassium, antioxidants, vitamin A, iron, and selenium that can still make them an excellent choice if they are part of a well-balanced diet.

I fear that we often underestimate our patients. We worry that not providing them with a list of acceptable foods will set them up for failure. But, in my experience, that list of “good” and “bad” foods may be useful for a week or so but will eventually become lost on the fridge under children’s artwork and save-the-dates.

Patients know that potato chips offer little more than fat, carbs, and salt and that they’re a poor choice for long-term health. What they might not know is that cocktail peanuts can also satisfy the craving for a salty snack, with more than four times the protein, twice the fiber, and just over half of the sodium found in the same serving size of regular salted potato chips. Peanuts have the added bonus of being high in heart-healthy monounsaturated fatty acids.

The best thing that clinicians can do with just a few minutes of time for diet education is to talk to patients about the nutrient density of whole foods and caution patients against highly processed foods, because processing can decrease nutritional content. Our most effective option is to explain why a varied diet with focus on fruits, vegetables, lean protein, nuts, legumes, and healthy fats is beneficial for cardiovascular and metabolic health. After that, all that is left is to trust the patient to make the right choices for their health.

Brandy Winfree Root, a renal dietitian in private practice in Mary Esther, Florida, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The word “malnutrition” probably brings to mind images of very thin patients with catabolic illness. But it really just means “poor nutrition,” which can — and often does — apply to patients with overweight or obesity.

That’s because malnutrition doesn’t occur simply because of a lack of calories, but rather because there is a gap in the nutrition the body requires and the nutrition it receives.

Each day, clinicians see patients with chronic conditions related to malnutrition. That list includes diabetes and hypertension, which can be promoted by excess intake of certain nutrients (carbohydrates and sodium) or inadequate intake of others (fiber, protein, potassium, magnesium, and calcium).

Diet Education Is Vital in Chronic Disease Management

Diet education is without a doubt a core pillar of chronic disease management. Nutrition therapy is recommended in treatment guidelines for the management of some of the most commonly seen chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and kidney disease. But in one study, only 58% of physicians, nurses and other health professionals surveyed had received formal nutrition education and only 40% were confident in their ability to provide nutrition education to patients.

As a registered dietitian, I welcome referrals for both prevention and management of chronic diseases with open arms. But medical nutrition therapy with a registered dietitian may not be realistic for all patients owing to financial, geographic, or other constraints. So, their best option may be the few minutes that a physician or physician extender has to spare at the end of their appointment.

But time constraints may result in clinicians turning to short, easy-to-remember messages such as “Don’t eat anything white” or “Only shop the edges of the grocery store.” Although catchy, this type of advice can inadvertently encourage patients to skip over foods that are actually very nutrient dense. For example, white foods such as onions, turnips, mushrooms, cauliflower, and even popcorn are low in calories and high in nutritional value. The center aisles of the grocery store may harbor high-carbohydrate breakfast cereals and potato chips, but they are also home to legumes, nuts, and canned and frozen fruits and vegetables.

What may be more effective is educating the patient on the importance of focusing on the nutrient density of foods, rather than simply limiting certain food groups or colors.

How to Work Nutrient Density into the Conversation

Nutrient density is a concept that refers to the proportion of nutrients to calories in a food item: essentially, a food’s qualitative nutritional value. It provides more depth than simply referring to foods as being high or low in calories, healthy or unhealthy, or good or bad.

Educating patients about nutrition density and encouraging a focus on foods that are low in calories and high in vitamins and minerals can help address micronutrient deficiencies, which may be more common than previously thought and linked to the chronic diseases that we see daily. It is worth noting that some foods that are not low in calories are still nutrient dense. Avocados, liver, and nuts come to mind as foods that are high in calories, but they have additional nutrients such as fiber, potassium, antioxidants, vitamin A, iron, and selenium that can still make them an excellent choice if they are part of a well-balanced diet.

I fear that we often underestimate our patients. We worry that not providing them with a list of acceptable foods will set them up for failure. But, in my experience, that list of “good” and “bad” foods may be useful for a week or so but will eventually become lost on the fridge under children’s artwork and save-the-dates.

Patients know that potato chips offer little more than fat, carbs, and salt and that they’re a poor choice for long-term health. What they might not know is that cocktail peanuts can also satisfy the craving for a salty snack, with more than four times the protein, twice the fiber, and just over half of the sodium found in the same serving size of regular salted potato chips. Peanuts have the added bonus of being high in heart-healthy monounsaturated fatty acids.

The best thing that clinicians can do with just a few minutes of time for diet education is to talk to patients about the nutrient density of whole foods and caution patients against highly processed foods, because processing can decrease nutritional content. Our most effective option is to explain why a varied diet with focus on fruits, vegetables, lean protein, nuts, legumes, and healthy fats is beneficial for cardiovascular and metabolic health. After that, all that is left is to trust the patient to make the right choices for their health.

Brandy Winfree Root, a renal dietitian in private practice in Mary Esther, Florida, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The word “malnutrition” probably brings to mind images of very thin patients with catabolic illness. But it really just means “poor nutrition,” which can — and often does — apply to patients with overweight or obesity.

That’s because malnutrition doesn’t occur simply because of a lack of calories, but rather because there is a gap in the nutrition the body requires and the nutrition it receives.

Each day, clinicians see patients with chronic conditions related to malnutrition. That list includes diabetes and hypertension, which can be promoted by excess intake of certain nutrients (carbohydrates and sodium) or inadequate intake of others (fiber, protein, potassium, magnesium, and calcium).

Diet Education Is Vital in Chronic Disease Management

Diet education is without a doubt a core pillar of chronic disease management. Nutrition therapy is recommended in treatment guidelines for the management of some of the most commonly seen chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and kidney disease. But in one study, only 58% of physicians, nurses and other health professionals surveyed had received formal nutrition education and only 40% were confident in their ability to provide nutrition education to patients.

As a registered dietitian, I welcome referrals for both prevention and management of chronic diseases with open arms. But medical nutrition therapy with a registered dietitian may not be realistic for all patients owing to financial, geographic, or other constraints. So, their best option may be the few minutes that a physician or physician extender has to spare at the end of their appointment.

But time constraints may result in clinicians turning to short, easy-to-remember messages such as “Don’t eat anything white” or “Only shop the edges of the grocery store.” Although catchy, this type of advice can inadvertently encourage patients to skip over foods that are actually very nutrient dense. For example, white foods such as onions, turnips, mushrooms, cauliflower, and even popcorn are low in calories and high in nutritional value. The center aisles of the grocery store may harbor high-carbohydrate breakfast cereals and potato chips, but they are also home to legumes, nuts, and canned and frozen fruits and vegetables.

What may be more effective is educating the patient on the importance of focusing on the nutrient density of foods, rather than simply limiting certain food groups or colors.

How to Work Nutrient Density into the Conversation

Nutrient density is a concept that refers to the proportion of nutrients to calories in a food item: essentially, a food’s qualitative nutritional value. It provides more depth than simply referring to foods as being high or low in calories, healthy or unhealthy, or good or bad.

Educating patients about nutrition density and encouraging a focus on foods that are low in calories and high in vitamins and minerals can help address micronutrient deficiencies, which may be more common than previously thought and linked to the chronic diseases that we see daily. It is worth noting that some foods that are not low in calories are still nutrient dense. Avocados, liver, and nuts come to mind as foods that are high in calories, but they have additional nutrients such as fiber, potassium, antioxidants, vitamin A, iron, and selenium that can still make them an excellent choice if they are part of a well-balanced diet.

I fear that we often underestimate our patients. We worry that not providing them with a list of acceptable foods will set them up for failure. But, in my experience, that list of “good” and “bad” foods may be useful for a week or so but will eventually become lost on the fridge under children’s artwork and save-the-dates.

Patients know that potato chips offer little more than fat, carbs, and salt and that they’re a poor choice for long-term health. What they might not know is that cocktail peanuts can also satisfy the craving for a salty snack, with more than four times the protein, twice the fiber, and just over half of the sodium found in the same serving size of regular salted potato chips. Peanuts have the added bonus of being high in heart-healthy monounsaturated fatty acids.

The best thing that clinicians can do with just a few minutes of time for diet education is to talk to patients about the nutrient density of whole foods and caution patients against highly processed foods, because processing can decrease nutritional content. Our most effective option is to explain why a varied diet with focus on fruits, vegetables, lean protein, nuts, legumes, and healthy fats is beneficial for cardiovascular and metabolic health. After that, all that is left is to trust the patient to make the right choices for their health.

Brandy Winfree Root, a renal dietitian in private practice in Mary Esther, Florida, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Maintaining Weight Loss With GLP-1s Needs Lifestyle Changes

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Nearly every patient I start on incretin therapy for weight loss asks me the same question, which is, will I have to stay on this forever? The answer is probably yes, but I think it’s much more nuanced than that because A) forever is a long time and B) I think there are various ways to approach this.

I want people to start just saying, let’s see how this works, because not everyone’s going to lose the same amount of weight or respond in the same way. I say let’s try it, but don’t stop it suddenly. If we decide at some point you don’t need quite the same dose, we can reduce the dose and maybe even reduce the frequency of giving it, but you don’t want to stop cold turkey because you may well regain the weight, and that’s obviously not our desired outcome.

There have been multiple clinical trials in which people started on an incretin hormone, either a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a dual hormone, and they’ve actually shown that stopping it and then continuing patients on a placebo vs active drug results in continued weight gain over time vs either weight maintenance or weight loss when they remain on the incretin hormone. Clearly, on average, people will regain the weight, but that isn’t always true.

One of the things I think is really important is that, from the get-go on starting on these hormones, people start working with a lifestyle plan, whether it’s working with a coach or an online program. However they approach this, it’s important to start changing habits and increasing exercise.

I can’t say how important this is enough, because people need to increase their physical activity to enhance the benefits of these agents and also to help retain lean body mass. I don’t want people losing a large amount of lean body mass as they go through the process of weight loss.

I set the stage for the fact that I expect people to adhere to a lifestyle program, and maybe losing weight with the medications is going to help them do even better because they’re going to see positive outcomes.

When they get to the point of weight maintenance, I think we need to reinforce lifestyle. I either go down on the dose given weekly or I start having patients take the dose every other week, for instance, as opposed to every week, and then sometimes every month. Depending on the patient, I get them potentially to a lower dose, and then they’re able to maintain the weight as long as they improved their lifestyle along with the changes in the medication.

I tell people we’ll work with the drug, we’ll work with their metabolic needs, that there are many benefits to being on incretin hormone therapy, but I think it’s important that we can do this on an individualized basis. The thing I don’t want to happen, though, is for people to start on it and then stop it, and then start on it and stop it because they may lose weight, regain weight, get side effects, get used to the side effects, stop it, and start it.

As we know, that’s not the best way to do this, and I think it’s not healthy for people to do that either. I know it’s been somewhat problematic with supply chain issues, but hopefully we’ll be able to start these agents, reach the desired outcome in terms of weight loss, and then help patients maintain that weight with a combination of both medication and lifestyle.

Dr. Peters, professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Keck School of Medicine; Director, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, Los Angeles, disclosed ties with Abbott Diabetes Care, Becton Dickinson; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo; Medscape; Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, Zafgen, Dexcom, MannKind, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Nearly every patient I start on incretin therapy for weight loss asks me the same question, which is, will I have to stay on this forever? The answer is probably yes, but I think it’s much more nuanced than that because A) forever is a long time and B) I think there are various ways to approach this.

I want people to start just saying, let’s see how this works, because not everyone’s going to lose the same amount of weight or respond in the same way. I say let’s try it, but don’t stop it suddenly. If we decide at some point you don’t need quite the same dose, we can reduce the dose and maybe even reduce the frequency of giving it, but you don’t want to stop cold turkey because you may well regain the weight, and that’s obviously not our desired outcome.

There have been multiple clinical trials in which people started on an incretin hormone, either a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a dual hormone, and they’ve actually shown that stopping it and then continuing patients on a placebo vs active drug results in continued weight gain over time vs either weight maintenance or weight loss when they remain on the incretin hormone. Clearly, on average, people will regain the weight, but that isn’t always true.

One of the things I think is really important is that, from the get-go on starting on these hormones, people start working with a lifestyle plan, whether it’s working with a coach or an online program. However they approach this, it’s important to start changing habits and increasing exercise.

I can’t say how important this is enough, because people need to increase their physical activity to enhance the benefits of these agents and also to help retain lean body mass. I don’t want people losing a large amount of lean body mass as they go through the process of weight loss.

I set the stage for the fact that I expect people to adhere to a lifestyle program, and maybe losing weight with the medications is going to help them do even better because they’re going to see positive outcomes.

When they get to the point of weight maintenance, I think we need to reinforce lifestyle. I either go down on the dose given weekly or I start having patients take the dose every other week, for instance, as opposed to every week, and then sometimes every month. Depending on the patient, I get them potentially to a lower dose, and then they’re able to maintain the weight as long as they improved their lifestyle along with the changes in the medication.

I tell people we’ll work with the drug, we’ll work with their metabolic needs, that there are many benefits to being on incretin hormone therapy, but I think it’s important that we can do this on an individualized basis. The thing I don’t want to happen, though, is for people to start on it and then stop it, and then start on it and stop it because they may lose weight, regain weight, get side effects, get used to the side effects, stop it, and start it.

As we know, that’s not the best way to do this, and I think it’s not healthy for people to do that either. I know it’s been somewhat problematic with supply chain issues, but hopefully we’ll be able to start these agents, reach the desired outcome in terms of weight loss, and then help patients maintain that weight with a combination of both medication and lifestyle.

Dr. Peters, professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Keck School of Medicine; Director, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, Los Angeles, disclosed ties with Abbott Diabetes Care, Becton Dickinson; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo; Medscape; Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, Zafgen, Dexcom, MannKind, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Nearly every patient I start on incretin therapy for weight loss asks me the same question, which is, will I have to stay on this forever? The answer is probably yes, but I think it’s much more nuanced than that because A) forever is a long time and B) I think there are various ways to approach this.

I want people to start just saying, let’s see how this works, because not everyone’s going to lose the same amount of weight or respond in the same way. I say let’s try it, but don’t stop it suddenly. If we decide at some point you don’t need quite the same dose, we can reduce the dose and maybe even reduce the frequency of giving it, but you don’t want to stop cold turkey because you may well regain the weight, and that’s obviously not our desired outcome.

There have been multiple clinical trials in which people started on an incretin hormone, either a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a dual hormone, and they’ve actually shown that stopping it and then continuing patients on a placebo vs active drug results in continued weight gain over time vs either weight maintenance or weight loss when they remain on the incretin hormone. Clearly, on average, people will regain the weight, but that isn’t always true.

One of the things I think is really important is that, from the get-go on starting on these hormones, people start working with a lifestyle plan, whether it’s working with a coach or an online program. However they approach this, it’s important to start changing habits and increasing exercise.

I can’t say how important this is enough, because people need to increase their physical activity to enhance the benefits of these agents and also to help retain lean body mass. I don’t want people losing a large amount of lean body mass as they go through the process of weight loss.

I set the stage for the fact that I expect people to adhere to a lifestyle program, and maybe losing weight with the medications is going to help them do even better because they’re going to see positive outcomes.

When they get to the point of weight maintenance, I think we need to reinforce lifestyle. I either go down on the dose given weekly or I start having patients take the dose every other week, for instance, as opposed to every week, and then sometimes every month. Depending on the patient, I get them potentially to a lower dose, and then they’re able to maintain the weight as long as they improved their lifestyle along with the changes in the medication.

I tell people we’ll work with the drug, we’ll work with their metabolic needs, that there are many benefits to being on incretin hormone therapy, but I think it’s important that we can do this on an individualized basis. The thing I don’t want to happen, though, is for people to start on it and then stop it, and then start on it and stop it because they may lose weight, regain weight, get side effects, get used to the side effects, stop it, and start it.

As we know, that’s not the best way to do this, and I think it’s not healthy for people to do that either. I know it’s been somewhat problematic with supply chain issues, but hopefully we’ll be able to start these agents, reach the desired outcome in terms of weight loss, and then help patients maintain that weight with a combination of both medication and lifestyle.

Dr. Peters, professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Keck School of Medicine; Director, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, Los Angeles, disclosed ties with Abbott Diabetes Care, Becton Dickinson; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo; Medscape; Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, Zafgen, Dexcom, MannKind, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New Approaches to Research Beyond Massive Clinical Trials

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly present a fascinating effort, one that needs to be applauded and applauded again, and then we need to scratch our collective heads and ask, why did we do it and what did we learn?

I’m referring to a report recently published in Annals of Internal Medicine, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women: Postintervention Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial.” The title of this report does not do it justice. This was a massive effort — one could, I believe, even use the term Herculean — to ask an important question that was asked more than 20 years ago.

This was a national women’s health initiative to answer these questions. The study looked at 36,282 postmenopausal women who, at the time of agreeing to be randomized in this trial, had no history of breast or colorectal cancer. This was a 7-year randomized intervention effort, and 40 centers across the United States participated, obviously funded by the government. Randomization was one-to-one to placebo or 1000 mg calcium and 400 international units of vitamin D3 daily.

They looked at the incidence of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and total cancer, and importantly as an endpoint, total cardiovascular disease and hip fractures. They didn’t comment on hip fractures in this particular analysis. Obviously, hip fractures relate to this question of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Here’s the bottom line: With a median follow-up now of 22.3 years — that’s not 2 years, but 22.3 years — there was a 7% decrease in cancer mortality in the population that received the calcium and vitamin D3. This is nothing to snicker at, and nothing at which to say, “Wow. That’s not important.”

However, in this analysis involving several tens of thousands of women, there was a 6% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality noted and reported. Overall, there was no effect on all-cause mortality of this intervention, with a hazard ratio — you rarely see this — of 1.00.

There is much that can be said, but I will summarize my comments very briefly. Criticize this if you want. It’s not inappropriate to criticize, but what was the individual impact of the calcium vs vitamin D? If they had only used one vs the other, or used both but in separate arms of the trial, and you could have separated what might have caused the decrease in cancer mortality and not the increased cardiovascular disease… This was designed more than 20 years ago. That’s one point.

The second is, how many more tens of thousands of patients would they have had to add to do this, and at what cost? This was a massive study, a national study, and a simple study in terms of the intervention. It was low risk except if you look at the long-term outcome. You can only imagine how much it would cost to do that study today — not the cost of the calcium, the vitamin D3, but the cost of doing the trial that was concluded to have no impact.

From a societal perspective, this was an important question to answer, certainly then. What did we learn and at what cost? The bottom line is that we have to figure out a way of answering these kinds of questions.

Perhaps now they should be from real-world data, looking at electronic medical records or at a variety of other population-based data so that we can get the answer — not in 20 years but in perhaps 2 months, because we’ve looked at the data using artificial intelligence to help us to answer these questions; and maybe not 36,000 patients but 360,000 individuals looked at over this period of time.

Again, I’m proposing an alternative solution because the questions that were asked 20 years ago remain important today. This cannot be the way that we, in the future, try to answer them, certainly from the perspective of cost and also the perspective of time to get the answers.

Let me conclude by, again, applauding these researchers because of the quality of the work they started out doing and ended up doing and reporting. Also, I think we’ve learned that we have to come up with alternative ways to answer what were important questions then and are important questions today.

Dr. Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly present a fascinating effort, one that needs to be applauded and applauded again, and then we need to scratch our collective heads and ask, why did we do it and what did we learn?

I’m referring to a report recently published in Annals of Internal Medicine, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women: Postintervention Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial.” The title of this report does not do it justice. This was a massive effort — one could, I believe, even use the term Herculean — to ask an important question that was asked more than 20 years ago.

This was a national women’s health initiative to answer these questions. The study looked at 36,282 postmenopausal women who, at the time of agreeing to be randomized in this trial, had no history of breast or colorectal cancer. This was a 7-year randomized intervention effort, and 40 centers across the United States participated, obviously funded by the government. Randomization was one-to-one to placebo or 1000 mg calcium and 400 international units of vitamin D3 daily.

They looked at the incidence of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and total cancer, and importantly as an endpoint, total cardiovascular disease and hip fractures. They didn’t comment on hip fractures in this particular analysis. Obviously, hip fractures relate to this question of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Here’s the bottom line: With a median follow-up now of 22.3 years — that’s not 2 years, but 22.3 years — there was a 7% decrease in cancer mortality in the population that received the calcium and vitamin D3. This is nothing to snicker at, and nothing at which to say, “Wow. That’s not important.”

However, in this analysis involving several tens of thousands of women, there was a 6% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality noted and reported. Overall, there was no effect on all-cause mortality of this intervention, with a hazard ratio — you rarely see this — of 1.00.

There is much that can be said, but I will summarize my comments very briefly. Criticize this if you want. It’s not inappropriate to criticize, but what was the individual impact of the calcium vs vitamin D? If they had only used one vs the other, or used both but in separate arms of the trial, and you could have separated what might have caused the decrease in cancer mortality and not the increased cardiovascular disease… This was designed more than 20 years ago. That’s one point.

The second is, how many more tens of thousands of patients would they have had to add to do this, and at what cost? This was a massive study, a national study, and a simple study in terms of the intervention. It was low risk except if you look at the long-term outcome. You can only imagine how much it would cost to do that study today — not the cost of the calcium, the vitamin D3, but the cost of doing the trial that was concluded to have no impact.

From a societal perspective, this was an important question to answer, certainly then. What did we learn and at what cost? The bottom line is that we have to figure out a way of answering these kinds of questions.

Perhaps now they should be from real-world data, looking at electronic medical records or at a variety of other population-based data so that we can get the answer — not in 20 years but in perhaps 2 months, because we’ve looked at the data using artificial intelligence to help us to answer these questions; and maybe not 36,000 patients but 360,000 individuals looked at over this period of time.

Again, I’m proposing an alternative solution because the questions that were asked 20 years ago remain important today. This cannot be the way that we, in the future, try to answer them, certainly from the perspective of cost and also the perspective of time to get the answers.

Let me conclude by, again, applauding these researchers because of the quality of the work they started out doing and ended up doing and reporting. Also, I think we’ve learned that we have to come up with alternative ways to answer what were important questions then and are important questions today.

Dr. Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly present a fascinating effort, one that needs to be applauded and applauded again, and then we need to scratch our collective heads and ask, why did we do it and what did we learn?

I’m referring to a report recently published in Annals of Internal Medicine, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women: Postintervention Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial.” The title of this report does not do it justice. This was a massive effort — one could, I believe, even use the term Herculean — to ask an important question that was asked more than 20 years ago.

This was a national women’s health initiative to answer these questions. The study looked at 36,282 postmenopausal women who, at the time of agreeing to be randomized in this trial, had no history of breast or colorectal cancer. This was a 7-year randomized intervention effort, and 40 centers across the United States participated, obviously funded by the government. Randomization was one-to-one to placebo or 1000 mg calcium and 400 international units of vitamin D3 daily.

They looked at the incidence of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and total cancer, and importantly as an endpoint, total cardiovascular disease and hip fractures. They didn’t comment on hip fractures in this particular analysis. Obviously, hip fractures relate to this question of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Here’s the bottom line: With a median follow-up now of 22.3 years — that’s not 2 years, but 22.3 years — there was a 7% decrease in cancer mortality in the population that received the calcium and vitamin D3. This is nothing to snicker at, and nothing at which to say, “Wow. That’s not important.”

However, in this analysis involving several tens of thousands of women, there was a 6% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality noted and reported. Overall, there was no effect on all-cause mortality of this intervention, with a hazard ratio — you rarely see this — of 1.00.

There is much that can be said, but I will summarize my comments very briefly. Criticize this if you want. It’s not inappropriate to criticize, but what was the individual impact of the calcium vs vitamin D? If they had only used one vs the other, or used both but in separate arms of the trial, and you could have separated what might have caused the decrease in cancer mortality and not the increased cardiovascular disease… This was designed more than 20 years ago. That’s one point.

The second is, how many more tens of thousands of patients would they have had to add to do this, and at what cost? This was a massive study, a national study, and a simple study in terms of the intervention. It was low risk except if you look at the long-term outcome. You can only imagine how much it would cost to do that study today — not the cost of the calcium, the vitamin D3, but the cost of doing the trial that was concluded to have no impact.

From a societal perspective, this was an important question to answer, certainly then. What did we learn and at what cost? The bottom line is that we have to figure out a way of answering these kinds of questions.

Perhaps now they should be from real-world data, looking at electronic medical records or at a variety of other population-based data so that we can get the answer — not in 20 years but in perhaps 2 months, because we’ve looked at the data using artificial intelligence to help us to answer these questions; and maybe not 36,000 patients but 360,000 individuals looked at over this period of time.

Again, I’m proposing an alternative solution because the questions that were asked 20 years ago remain important today. This cannot be the way that we, in the future, try to answer them, certainly from the perspective of cost and also the perspective of time to get the answers.

Let me conclude by, again, applauding these researchers because of the quality of the work they started out doing and ended up doing and reporting. Also, I think we’ve learned that we have to come up with alternative ways to answer what were important questions then and are important questions today.

Dr. Markman, Professor of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center; President, Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, Phoenix, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How Metals Affect the Brain

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

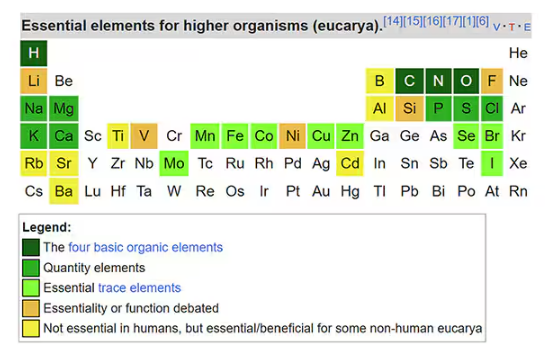

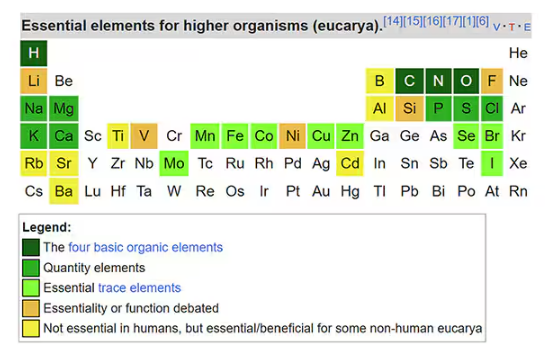

It has always amazed me that our bodies require these tiny amounts of incredibly rare substances to function. Sure, we need oxygen. We need water. But we also need molybdenum, which makes up just 1.2 parts per million of the Earth’s crust.

Without adequate molybdenum intake, we develop seizures, developmental delays, death. Fortunately, we need so little molybdenum that true molybdenum deficiency is incredibly rare — seen only in people on total parenteral nutrition without supplementation or those with certain rare genetic conditions. But still, molybdenum is necessary for life.

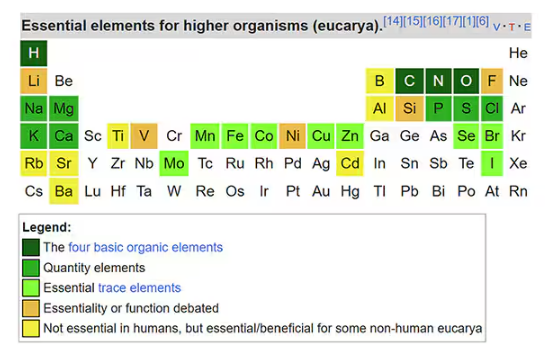

Many metals are. Figure 1 colors the essential minerals on the periodic table. You can see that to stay alive, we humans need not only things like sodium, but selenium, bromine, zinc, copper, and cobalt.

Some metals are very clearly not essential; we can all do without lead and mercury, and probably should.

But just because something is essential for life does not mean that more is better. The dose is the poison, as they say. And this week, we explore whether metals — even essential metals — might be adversely affecting our brains.

It’s not a stretch to think that metal intake could have weird effects on our nervous system. Lead exposure, primarily due to leaded gasoline, has been blamed for an average reduction of about 3 points in our national IQ, for example . But not all metals are created equal. Researchers set out to find out which might be more strongly associated with performance on cognitive tests and dementia, and reported their results in this study in JAMA Network Open.

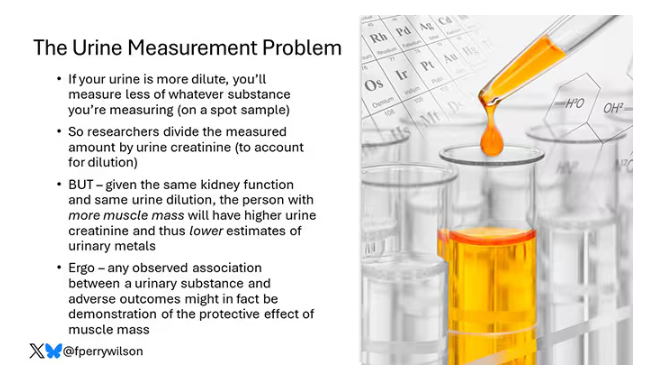

To do this, they leveraged the MESA cohort study. This is a longitudinal study of a relatively diverse group of 6300 adults who were enrolled from 2000 to 2002 around the United States. At enrollment, they gave a urine sample and took a variety of cognitive tests. Important for this study was the digit symbol substitution test, where participants are provided a code and need to replace a list of numbers with symbols as per that code. Performance on this test worsens with age, depression, and cognitive impairment.

Participants were followed for more than a decade, and over that time, 559 (about 9%) were diagnosed with dementia.

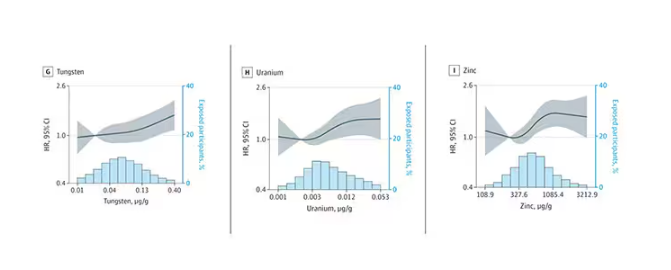

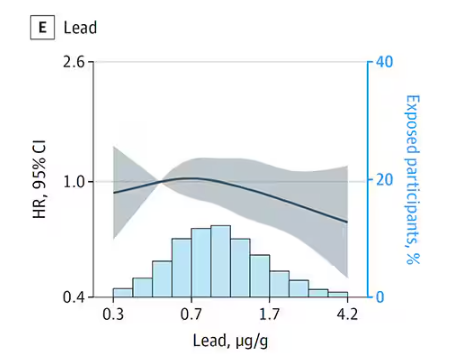

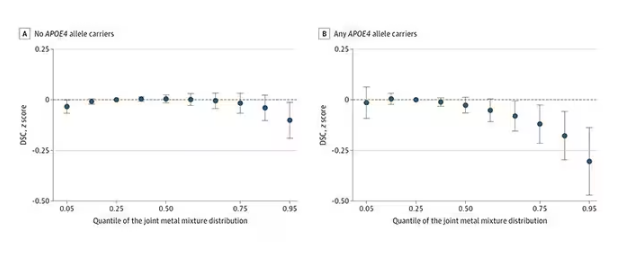

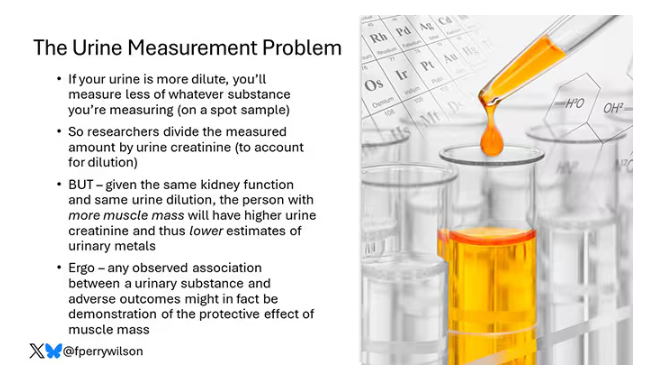

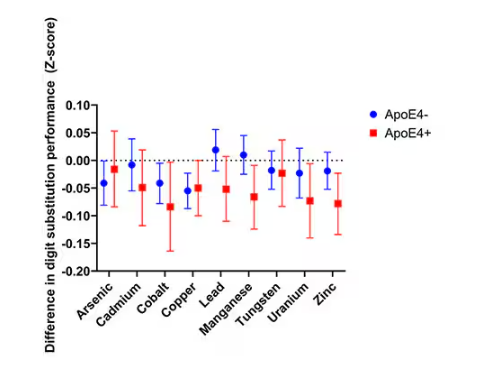

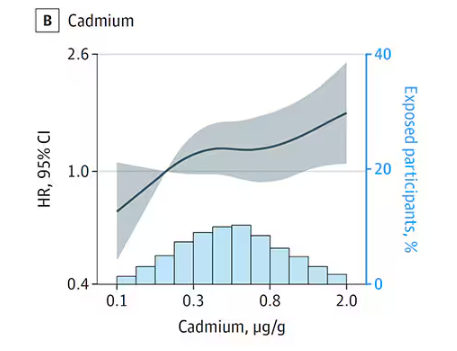

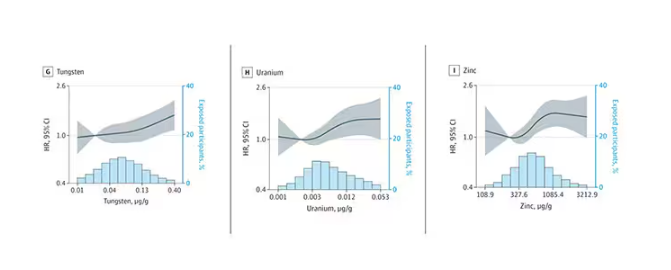

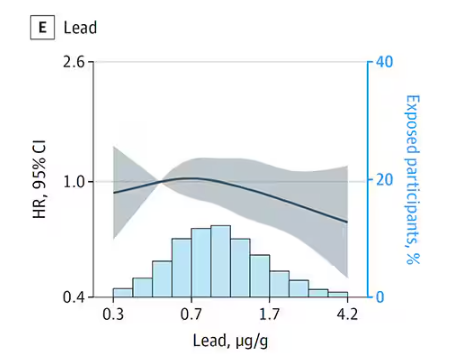

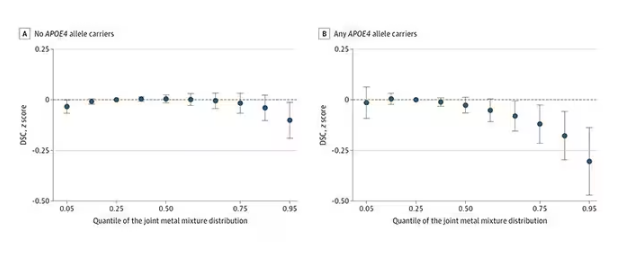

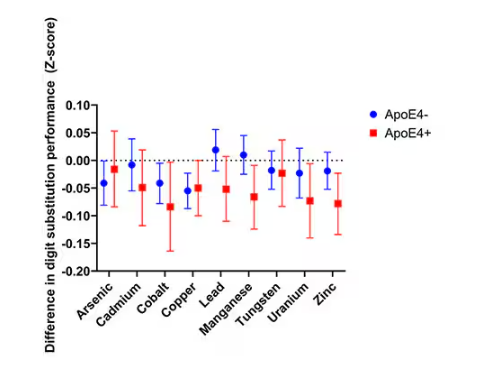

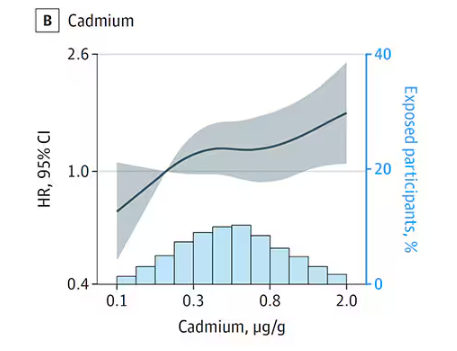

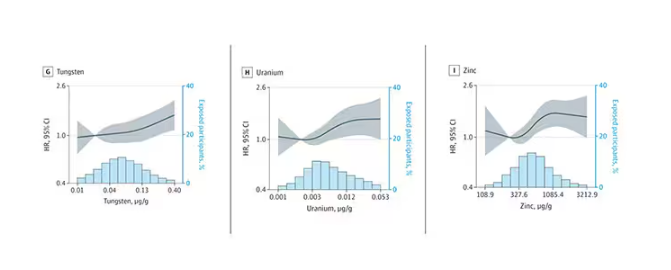

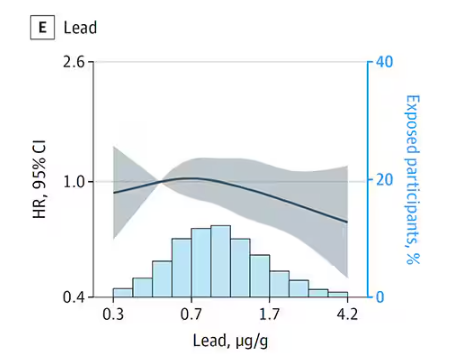

Those baseline urine samples were assayed for a variety of metals — some essential, some very much not, as you can see in Figure 2.