User login

Surgical Specimens and Margins

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

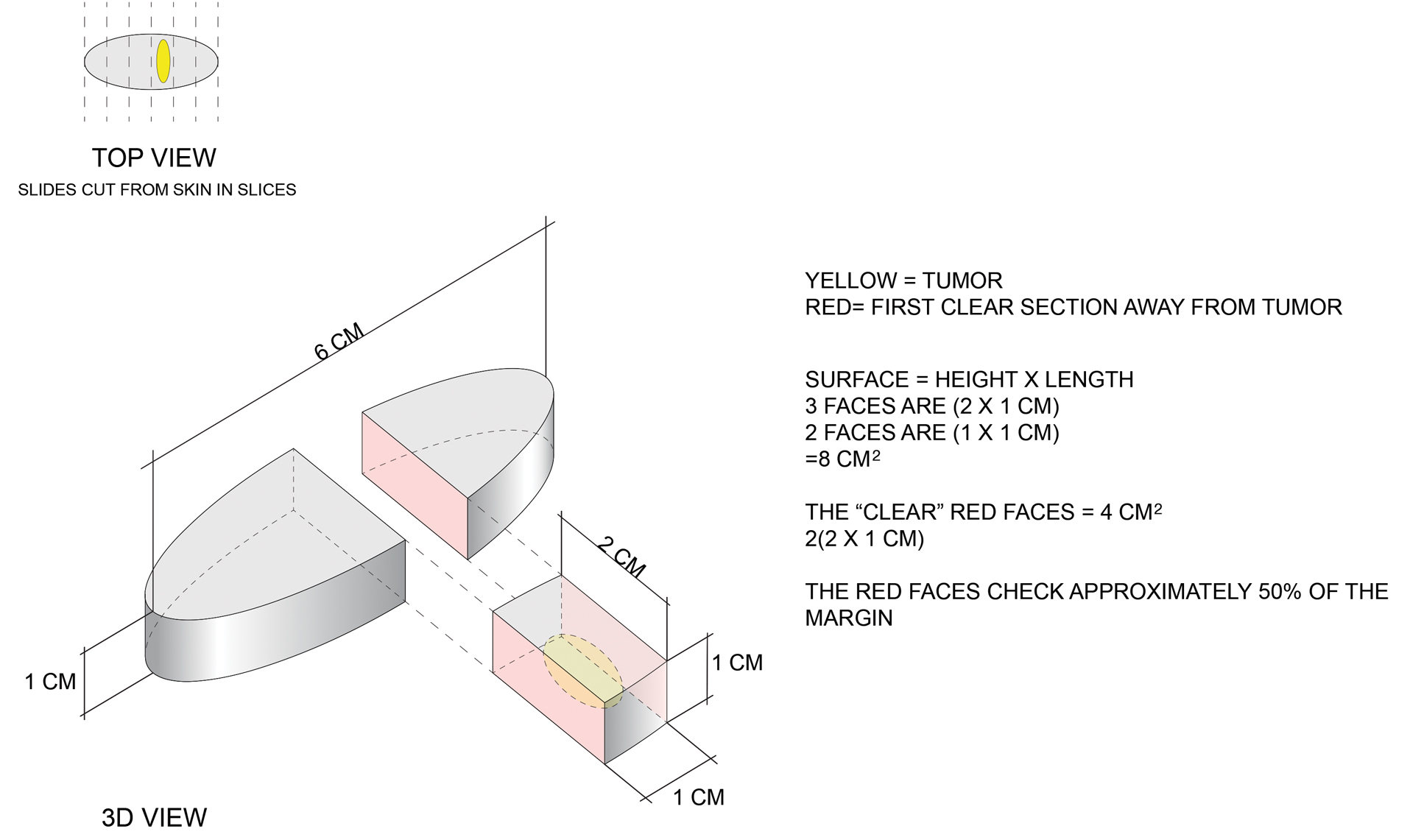

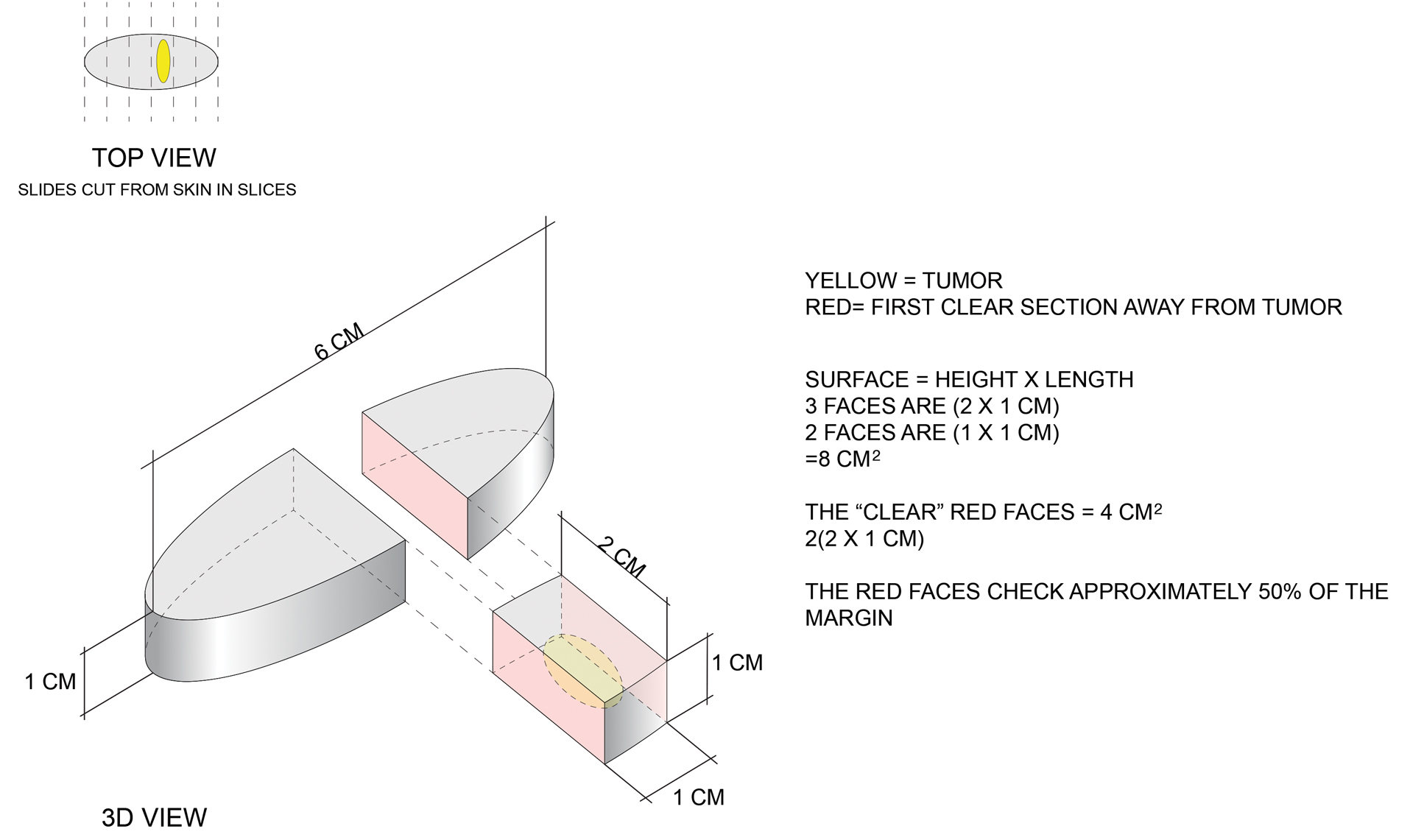

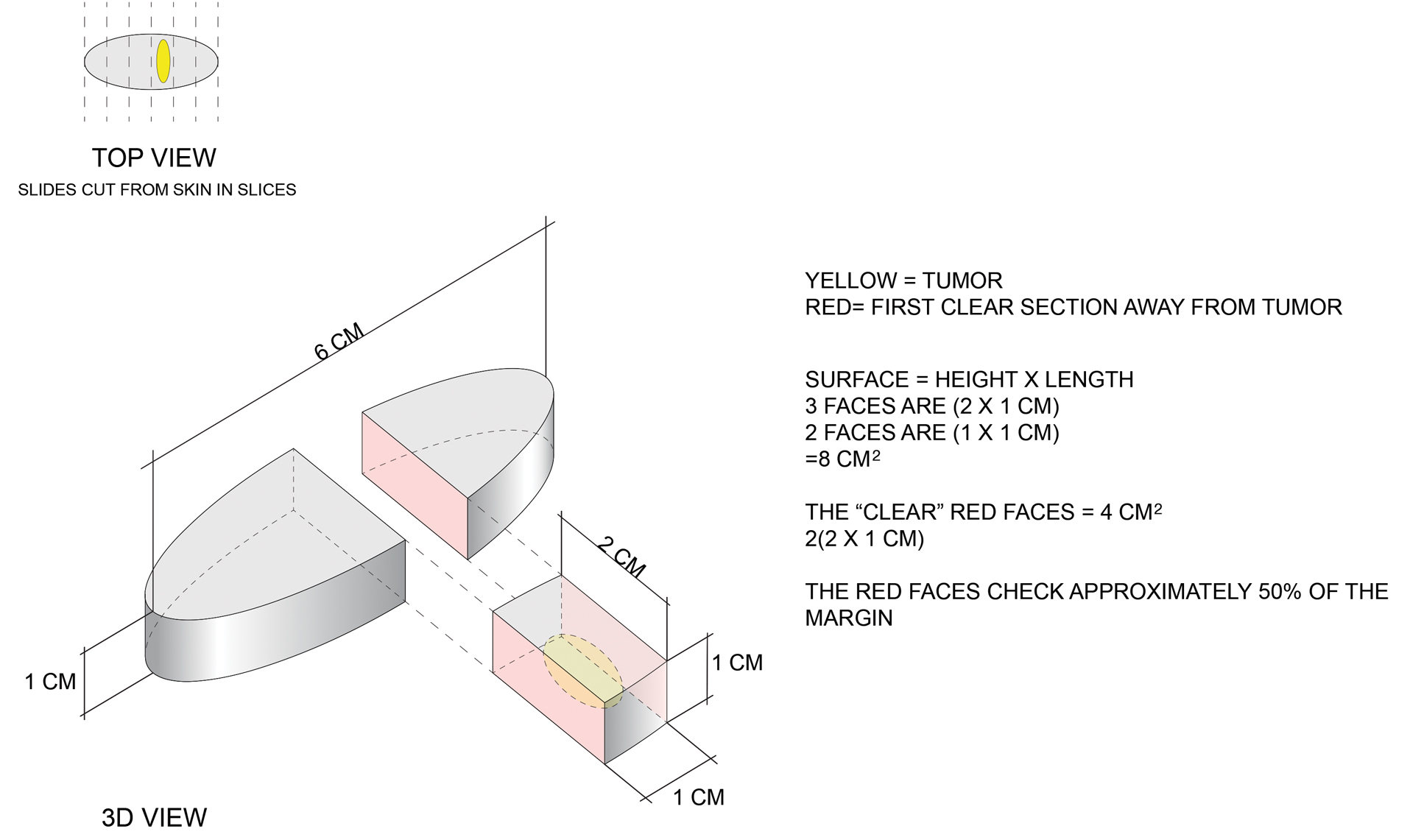

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

Practice Points

- Margin analysis in simple excisions can provide useful information by proxy about more than the 1% of the margin often quoted in the literature.

- Simple excisions of uncomplicated keratinocytic carcinomas are associated with high cure rates.

‘Not their fault:’ Obesity warrants long-term management

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s important to remember and to think about the first time when patients with obesity come to see us: What have they faced? What have been their struggles? What shame and blame and bias have they faced?

One of the first things that I do when a patient comes to see me is invite them to share their weight journey with me. I ask them to tell me about their struggles, about what’s worked and what hasn’t worked, what they would like, and what their health goals are.

As they share their stories, I look for the opportunity to share with them that obesity is not their fault, but that it’s biology driving their body to carry extra weight and their body is super smart. Neither their body nor their brain want them to starve.

Our bodies evolved during a time where there was food scarcity and the potential of famine. We have a complex system that was designed to make sure that we always held on to extra weight, specifically extra fat, because that’s how we store energy. In the current obesogenic environment, what happens is our bodies carry extra weight, or specifically, extra fat.

Again, I say to them, this is biology. Your body’s doing exactly what it was designed to do. Your body’s very smart, but now we have to figure out how to help your body want to carry less fat because it is impacting your health. This is not your fault. Having obesity is not your fault any more than having diabetes or hypertension is anyone’s fault. Now it’s time for all of us to use highly effective tools that target the pathophysiology of obesity.

When a patient comes to me for weight management or to help them treat their obesity, I listen to them, and I look for clues as to what might help that specific patient. Every patient deserves to have individualized treatment. One medicine may be right for one person, another medicine may be right for another, and surgery may be right for another patient. I really try to listen and hear what that patient is telling me.

What we as providers really need is tools – different options – to be able to provide for our patients and basically present them with different options, and then guide them toward the best therapy for them. Whether it’s semaglutide or tirzepatide potentially in the future, these types of medications are excellent options for our patients. They’re highly effective tools with safe profiles.

A question that I often get from providers or patients is, “Well, Doctor, I’ve lost the weight now. How long should I take this medicine? Can I stop it now?”

Then, we have a conversation, and we actually usually have this conversation even before we start the medicine. Basically, we talk about the fact that obesity is a chronic disease. There’s no cure for obesity. Because it’s a chronic disease, we need to treat it like we would treat any other chronic disease.

The example that I often use is, if you have a patient who has hypertension and you start them on an antihypertensive medication, what happens? Their blood pressure goes down. It improves. Now, if their blood pressure is improved with a specific antihypertensive, would you stop that medicine? What would happen if you stopped that antihypertensive? Well, their blood pressure would go up, and we wouldn’t be surprised.

In the same way, if you have a patient who has obesity and you start that patient on an antiobesity medication, and their weight decreases, and their body fat mass at that point decreases, what would happen if you stop that medicine? They lost the weight, but you stop the medicine. Well, their weight gain comes back. They regain the weight.

We should not be surprised that weight gain occurs when we stop the treatment. That really underscores the fact that treatment needs to be continued. If a patient is started on an antiobesity medication and they lose weight, that medication needs to be continued to maintain that weight loss.

Basically, we eat food and our body responds by releasing these hormones. The hormones are made in our gut and in our pancreas and these hormones inform our brain. Are we hungry? Are we full? Where are we with our homeostatic set point of fat mass? Based on that, our brain is like the sensor or the thermostat.

Obesity is a chronic, treatable disease. We should treat obesity as we treat any other chronic disease, with effective and safe approaches that target underlying disease mechanisms. These results in the SURMOUNT-1 trial underscore that tirzepatide may be doing just that. Remarkably, 9 in 10 individuals with obesity lost weight while taking tirzepatide. These results are impressive. They’re an important step forward in potentially expanding effective therapeutic options for people with obesity.

Dr. Jastreboff is an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and director of weight management and obesity prevention at Yale Stress Center. She reported conducting trials with Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals; serving on scientific advisory boards for Ely Lilly, Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, and WW; and consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim and Scholar Rock.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s important to remember and to think about the first time when patients with obesity come to see us: What have they faced? What have been their struggles? What shame and blame and bias have they faced?

One of the first things that I do when a patient comes to see me is invite them to share their weight journey with me. I ask them to tell me about their struggles, about what’s worked and what hasn’t worked, what they would like, and what their health goals are.

As they share their stories, I look for the opportunity to share with them that obesity is not their fault, but that it’s biology driving their body to carry extra weight and their body is super smart. Neither their body nor their brain want them to starve.

Our bodies evolved during a time where there was food scarcity and the potential of famine. We have a complex system that was designed to make sure that we always held on to extra weight, specifically extra fat, because that’s how we store energy. In the current obesogenic environment, what happens is our bodies carry extra weight, or specifically, extra fat.

Again, I say to them, this is biology. Your body’s doing exactly what it was designed to do. Your body’s very smart, but now we have to figure out how to help your body want to carry less fat because it is impacting your health. This is not your fault. Having obesity is not your fault any more than having diabetes or hypertension is anyone’s fault. Now it’s time for all of us to use highly effective tools that target the pathophysiology of obesity.

When a patient comes to me for weight management or to help them treat their obesity, I listen to them, and I look for clues as to what might help that specific patient. Every patient deserves to have individualized treatment. One medicine may be right for one person, another medicine may be right for another, and surgery may be right for another patient. I really try to listen and hear what that patient is telling me.

What we as providers really need is tools – different options – to be able to provide for our patients and basically present them with different options, and then guide them toward the best therapy for them. Whether it’s semaglutide or tirzepatide potentially in the future, these types of medications are excellent options for our patients. They’re highly effective tools with safe profiles.

A question that I often get from providers or patients is, “Well, Doctor, I’ve lost the weight now. How long should I take this medicine? Can I stop it now?”

Then, we have a conversation, and we actually usually have this conversation even before we start the medicine. Basically, we talk about the fact that obesity is a chronic disease. There’s no cure for obesity. Because it’s a chronic disease, we need to treat it like we would treat any other chronic disease.

The example that I often use is, if you have a patient who has hypertension and you start them on an antihypertensive medication, what happens? Their blood pressure goes down. It improves. Now, if their blood pressure is improved with a specific antihypertensive, would you stop that medicine? What would happen if you stopped that antihypertensive? Well, their blood pressure would go up, and we wouldn’t be surprised.

In the same way, if you have a patient who has obesity and you start that patient on an antiobesity medication, and their weight decreases, and their body fat mass at that point decreases, what would happen if you stop that medicine? They lost the weight, but you stop the medicine. Well, their weight gain comes back. They regain the weight.

We should not be surprised that weight gain occurs when we stop the treatment. That really underscores the fact that treatment needs to be continued. If a patient is started on an antiobesity medication and they lose weight, that medication needs to be continued to maintain that weight loss.

Basically, we eat food and our body responds by releasing these hormones. The hormones are made in our gut and in our pancreas and these hormones inform our brain. Are we hungry? Are we full? Where are we with our homeostatic set point of fat mass? Based on that, our brain is like the sensor or the thermostat.

Obesity is a chronic, treatable disease. We should treat obesity as we treat any other chronic disease, with effective and safe approaches that target underlying disease mechanisms. These results in the SURMOUNT-1 trial underscore that tirzepatide may be doing just that. Remarkably, 9 in 10 individuals with obesity lost weight while taking tirzepatide. These results are impressive. They’re an important step forward in potentially expanding effective therapeutic options for people with obesity.

Dr. Jastreboff is an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and director of weight management and obesity prevention at Yale Stress Center. She reported conducting trials with Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals; serving on scientific advisory boards for Ely Lilly, Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, and WW; and consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim and Scholar Rock.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s important to remember and to think about the first time when patients with obesity come to see us: What have they faced? What have been their struggles? What shame and blame and bias have they faced?

One of the first things that I do when a patient comes to see me is invite them to share their weight journey with me. I ask them to tell me about their struggles, about what’s worked and what hasn’t worked, what they would like, and what their health goals are.

As they share their stories, I look for the opportunity to share with them that obesity is not their fault, but that it’s biology driving their body to carry extra weight and their body is super smart. Neither their body nor their brain want them to starve.

Our bodies evolved during a time where there was food scarcity and the potential of famine. We have a complex system that was designed to make sure that we always held on to extra weight, specifically extra fat, because that’s how we store energy. In the current obesogenic environment, what happens is our bodies carry extra weight, or specifically, extra fat.

Again, I say to them, this is biology. Your body’s doing exactly what it was designed to do. Your body’s very smart, but now we have to figure out how to help your body want to carry less fat because it is impacting your health. This is not your fault. Having obesity is not your fault any more than having diabetes or hypertension is anyone’s fault. Now it’s time for all of us to use highly effective tools that target the pathophysiology of obesity.

When a patient comes to me for weight management or to help them treat their obesity, I listen to them, and I look for clues as to what might help that specific patient. Every patient deserves to have individualized treatment. One medicine may be right for one person, another medicine may be right for another, and surgery may be right for another patient. I really try to listen and hear what that patient is telling me.

What we as providers really need is tools – different options – to be able to provide for our patients and basically present them with different options, and then guide them toward the best therapy for them. Whether it’s semaglutide or tirzepatide potentially in the future, these types of medications are excellent options for our patients. They’re highly effective tools with safe profiles.

A question that I often get from providers or patients is, “Well, Doctor, I’ve lost the weight now. How long should I take this medicine? Can I stop it now?”

Then, we have a conversation, and we actually usually have this conversation even before we start the medicine. Basically, we talk about the fact that obesity is a chronic disease. There’s no cure for obesity. Because it’s a chronic disease, we need to treat it like we would treat any other chronic disease.

The example that I often use is, if you have a patient who has hypertension and you start them on an antihypertensive medication, what happens? Their blood pressure goes down. It improves. Now, if their blood pressure is improved with a specific antihypertensive, would you stop that medicine? What would happen if you stopped that antihypertensive? Well, their blood pressure would go up, and we wouldn’t be surprised.

In the same way, if you have a patient who has obesity and you start that patient on an antiobesity medication, and their weight decreases, and their body fat mass at that point decreases, what would happen if you stop that medicine? They lost the weight, but you stop the medicine. Well, their weight gain comes back. They regain the weight.

We should not be surprised that weight gain occurs when we stop the treatment. That really underscores the fact that treatment needs to be continued. If a patient is started on an antiobesity medication and they lose weight, that medication needs to be continued to maintain that weight loss.

Basically, we eat food and our body responds by releasing these hormones. The hormones are made in our gut and in our pancreas and these hormones inform our brain. Are we hungry? Are we full? Where are we with our homeostatic set point of fat mass? Based on that, our brain is like the sensor or the thermostat.

Obesity is a chronic, treatable disease. We should treat obesity as we treat any other chronic disease, with effective and safe approaches that target underlying disease mechanisms. These results in the SURMOUNT-1 trial underscore that tirzepatide may be doing just that. Remarkably, 9 in 10 individuals with obesity lost weight while taking tirzepatide. These results are impressive. They’re an important step forward in potentially expanding effective therapeutic options for people with obesity.

Dr. Jastreboff is an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and director of weight management and obesity prevention at Yale Stress Center. She reported conducting trials with Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals; serving on scientific advisory boards for Ely Lilly, Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, and WW; and consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim and Scholar Rock.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bored? Change the world or read a book

A weekend, for most of us in solo practice, doesn’t really signify time off from work. It just means we’re not seeing patients at the office.

There’s always business stuff to do (like payroll and paying bills), legal cases to review, the never-ending forms for a million things, and all the other stuff there never seems to be enough time to do on weekdays.

So this weekend I started attacking the pile after dinner on Friday and found myself done by Saturday afternoon. Which is rare, usually I spend the better part of a weekend at my desk.

And then, unexpectedly faced with an empty desk, I found myself wondering what to do.

Boredom is one of the odder human conditions. Certainly, there are more ways to waste time now than there ever have been. TV, Netflix, phone games, TikTok, books, just to name a few.

But do we always have to be entertained? Many great scientists have said that world-changing ideas have come to them when they weren’t working, such as while showering or riding to work. Leo Szilard was crossing a London street in 1933 when he suddenly saw how a nuclear chain reaction would be self-sustaining once initiated. (Fortunately, he wasn’t hit by a car in the process.)

But I’m not Szilard. So I rationalized a reason not to exercise and sat on the couch with a book.

The remarkable human brain doesn’t shut down easily. With nothing else to do, most other mammals tend to doze off. But not us. It’s always on, trying to think of the next goal, the next move, the next whatever.

Having nothing to do sounds like a great idea, until you have nothing to do. It may be fine for a few days, but after a while you realize there’s only so long you can stare at the waves or mountains before your mind turns back to “what’s next.”

This isn’t a bad thing. Being bored is probably constructive. Without realizing it we use it to form new ideas and start new plans.

Maybe this is why we’re here. The mind that keeps working is a powerful tool, driving us forward in all walks of life. Perhaps it’s this feature that pushed the development of intelligence further and led us to form civilizations.

Perhaps it’s the real reason we keep moving forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A weekend, for most of us in solo practice, doesn’t really signify time off from work. It just means we’re not seeing patients at the office.

There’s always business stuff to do (like payroll and paying bills), legal cases to review, the never-ending forms for a million things, and all the other stuff there never seems to be enough time to do on weekdays.

So this weekend I started attacking the pile after dinner on Friday and found myself done by Saturday afternoon. Which is rare, usually I spend the better part of a weekend at my desk.

And then, unexpectedly faced with an empty desk, I found myself wondering what to do.

Boredom is one of the odder human conditions. Certainly, there are more ways to waste time now than there ever have been. TV, Netflix, phone games, TikTok, books, just to name a few.

But do we always have to be entertained? Many great scientists have said that world-changing ideas have come to them when they weren’t working, such as while showering or riding to work. Leo Szilard was crossing a London street in 1933 when he suddenly saw how a nuclear chain reaction would be self-sustaining once initiated. (Fortunately, he wasn’t hit by a car in the process.)

But I’m not Szilard. So I rationalized a reason not to exercise and sat on the couch with a book.

The remarkable human brain doesn’t shut down easily. With nothing else to do, most other mammals tend to doze off. But not us. It’s always on, trying to think of the next goal, the next move, the next whatever.

Having nothing to do sounds like a great idea, until you have nothing to do. It may be fine for a few days, but after a while you realize there’s only so long you can stare at the waves or mountains before your mind turns back to “what’s next.”

This isn’t a bad thing. Being bored is probably constructive. Without realizing it we use it to form new ideas and start new plans.

Maybe this is why we’re here. The mind that keeps working is a powerful tool, driving us forward in all walks of life. Perhaps it’s this feature that pushed the development of intelligence further and led us to form civilizations.

Perhaps it’s the real reason we keep moving forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A weekend, for most of us in solo practice, doesn’t really signify time off from work. It just means we’re not seeing patients at the office.

There’s always business stuff to do (like payroll and paying bills), legal cases to review, the never-ending forms for a million things, and all the other stuff there never seems to be enough time to do on weekdays.

So this weekend I started attacking the pile after dinner on Friday and found myself done by Saturday afternoon. Which is rare, usually I spend the better part of a weekend at my desk.

And then, unexpectedly faced with an empty desk, I found myself wondering what to do.

Boredom is one of the odder human conditions. Certainly, there are more ways to waste time now than there ever have been. TV, Netflix, phone games, TikTok, books, just to name a few.

But do we always have to be entertained? Many great scientists have said that world-changing ideas have come to them when they weren’t working, such as while showering or riding to work. Leo Szilard was crossing a London street in 1933 when he suddenly saw how a nuclear chain reaction would be self-sustaining once initiated. (Fortunately, he wasn’t hit by a car in the process.)

But I’m not Szilard. So I rationalized a reason not to exercise and sat on the couch with a book.

The remarkable human brain doesn’t shut down easily. With nothing else to do, most other mammals tend to doze off. But not us. It’s always on, trying to think of the next goal, the next move, the next whatever.

Having nothing to do sounds like a great idea, until you have nothing to do. It may be fine for a few days, but after a while you realize there’s only so long you can stare at the waves or mountains before your mind turns back to “what’s next.”

This isn’t a bad thing. Being bored is probably constructive. Without realizing it we use it to form new ideas and start new plans.

Maybe this is why we’re here. The mind that keeps working is a powerful tool, driving us forward in all walks of life. Perhaps it’s this feature that pushed the development of intelligence further and led us to form civilizations.

Perhaps it’s the real reason we keep moving forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Book Review: Quality improvement in mental health care

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Adapting to Changes in Acne Management: Take One Step at a Time

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

What is palliative care and what’s new in practicing this type of medicine?

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.”1

The common misperception is that palliative care is only for those at end of life or only in the advanced stages of their illness. However, palliative care is ideally most helpful following individuals from diagnosis through their illness trajectory. Another misperception is that palliative care and hospice are the same thing. Though all hospice is palliative care, all palliative care is not hospice. Both palliative care and hospice provide care for individuals facing a serious illness and focus on the same philosophy of care, but palliative care can be initiated at any stage of illness, even if the goal is to pursue curative and life-prolonging therapies/interventions.

In contrast, hospice is considered for those who are at the end of life and are usually not pursuing life-prolonging therapies or interventions, instead focusing on comfort, symptom management, and optimization of quality of life.

Though there is a growing need for palliative care, there is a shortage of specialist palliative care providers. Much of the palliative care needs can be met by all providers who can offer basic symptom management, identification surrounding goals of care and discussions of advance care planning, and understanding of illness/prognosis and treatment options, which is called primary palliative care.2 In fact, two-thirds of patients with a serious illness other than cancer prefer discussion of end-of-life care or advance care planning with their primary care providers.3

Referral to specialty palliative care should be considered when there are more complexities to symptom/pain management and goals of care/end of life, transition to hospice, or complex communication dynamics.4

Though specialty palliative care was shown to be more comprehensive, both primary palliative care and specialty palliative care have led to improvements in the quality of life in individuals living with serious illness.5 Early integration of palliative care into routine care has been shown to improve symptom burden, mood, quality of life, survival, and health care costs.6

Updates in alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care

There are several alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care, including cannabis and psychedelics. These therapies are becoming or may become a familiar part of medical therapies that are listed in a patient’s history as part of their medical regimen, especially as more states continue to legalize and/or decriminalize the use of these alternative therapies for recreational or medicinal use.

Both cannabis and psychedelics have a longstanding history of therapeutic and holistic use. Cannabis has been used to manage symptoms such as pain since the 16th and 17th century.7 In palliative care, more patients may turn to various forms of cannabis as a source of relief from symptoms and suffering as their focus shifts more to quality of life.

Even with the increasing popularity of the use of cannabis among seriously ill patients, there is still a lack of evidence of the benefits of medical cannabis use in palliative care, and there is a lack of standardization of type of cannabis used and state regulations regarding their use.7

A recent systematic review found that despite the reported positive treatment effects of cannabis in palliative care, the results of the studies were conflicting. This highlights the need for further high-quality research to determine whether cannabis products are an effective treatment in palliative care patients.8

One limitation to note is that the majority of the included studies focused on cannabis use in patients with cancer for cancer-related symptoms. Few studies included patients with other serious conditions.

Psychedelics

There is evidence that psychedelic assisted therapy (PAT) is a safe and effective treatment for individuals with refractory depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder.9 Plus, there have been ample studies providing support that PAT improves symptoms such as refractory anxiety/depression, demoralization, and existential distress in seriously ill patients, thus improving their quality of life and overall well-being.9

Nine U.S. cities and the State of Oregon have decriminalized or legalized the psychedelic psilocybin, based on the medical benefits patients have experienced evidenced from using it.10

In light of the increasing interest in PAT, Dr. Ira Byock provided the following points on what “all clinicians should know as they enter this uncharted territory”:

- Psychedelics have been around for a long time.

- Psychedelic-assisted therapies’ therapeutic effects are experiential.

- There are a variety of terms for specific categories of psychedelic compounds.

- Some palliative care teams are already caring for patients who undergo psychedelic experiences.

- Use of psychedelics should be well-observed by a skilled clinician with expertise.

I am hoping this provides a general refresher on palliative care and an overview of updates to alternative and complementary therapies for patients living with serious illness.9

Dr. Kang is a geriatrician and palliative care provider at the University of Washington, Seattle in the division of geriatrics and gerontology. She has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2020 Aug 5..

2. Weissman DE and Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting a consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

3. Sherry D et al. Is primary care physician involvement associated with earlier advance care planning? A study of patients in an academic primary care setting. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(1):75-80.

4. Quill TE and Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173-75.

5. Ernecoff NC et al. Comparing specialty and primary palliative care interventions: Analysis of a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(3):389-96.

6. Temmel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;363:733-42.

7. Kogan M and Sexton M. Medical cannabis: A new old tool for palliative care. J Altern Complement Med . 2020 Sep;26(9):776-8.

8. Doppen M et al. Cannabis in palliative care: A systematic review of the current evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022 Jun 12;S0885-3924(22)00760-6.

9. Byock I. Psychedelics for serious illness: Five things clinicians need to know. The Center to Advance Palliative Care. Psychedelics for Serious Illness, Palliative in Practice, Center to Advance Palliative Care (capc.org). June 13, 2022.

10. Marks M. A strategy for rescheduling psilocybin. Scientific American. Oct. 11, 2021.

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.”1

The common misperception is that palliative care is only for those at end of life or only in the advanced stages of their illness. However, palliative care is ideally most helpful following individuals from diagnosis through their illness trajectory. Another misperception is that palliative care and hospice are the same thing. Though all hospice is palliative care, all palliative care is not hospice. Both palliative care and hospice provide care for individuals facing a serious illness and focus on the same philosophy of care, but palliative care can be initiated at any stage of illness, even if the goal is to pursue curative and life-prolonging therapies/interventions.

In contrast, hospice is considered for those who are at the end of life and are usually not pursuing life-prolonging therapies or interventions, instead focusing on comfort, symptom management, and optimization of quality of life.

Though there is a growing need for palliative care, there is a shortage of specialist palliative care providers. Much of the palliative care needs can be met by all providers who can offer basic symptom management, identification surrounding goals of care and discussions of advance care planning, and understanding of illness/prognosis and treatment options, which is called primary palliative care.2 In fact, two-thirds of patients with a serious illness other than cancer prefer discussion of end-of-life care or advance care planning with their primary care providers.3

Referral to specialty palliative care should be considered when there are more complexities to symptom/pain management and goals of care/end of life, transition to hospice, or complex communication dynamics.4

Though specialty palliative care was shown to be more comprehensive, both primary palliative care and specialty palliative care have led to improvements in the quality of life in individuals living with serious illness.5 Early integration of palliative care into routine care has been shown to improve symptom burden, mood, quality of life, survival, and health care costs.6

Updates in alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care

There are several alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care, including cannabis and psychedelics. These therapies are becoming or may become a familiar part of medical therapies that are listed in a patient’s history as part of their medical regimen, especially as more states continue to legalize and/or decriminalize the use of these alternative therapies for recreational or medicinal use.

Both cannabis and psychedelics have a longstanding history of therapeutic and holistic use. Cannabis has been used to manage symptoms such as pain since the 16th and 17th century.7 In palliative care, more patients may turn to various forms of cannabis as a source of relief from symptoms and suffering as their focus shifts more to quality of life.