User login

Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: A hypothesis (Part 3)

Optimal diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illness requires clinicians to be able to connect mental and physical symptoms. Direct brain neurotransmitter testing is presently in its infancy and the science of defining the underlying mechanisms of psychiatric disorders lags behind the obvious clinical needs. We are not yet equipped to clearly recognize which neurotransmitters cause which symptoms. In this article series, we suggest an indirect way of judging neurotransmitter activity by recognizing specific mental and physical symptoms connected by common biology. Here we present hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms in order to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. The descriptions we present in this series do not reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by the neurotransmitters we discuss; we created them based on what is presently known (or suspected). Additional research is needed to confirm or disprove the hypothesis we present. We argue that in cases of multiple psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, the development and approval of medications currently is based on an umbrella descriptive diagnoses, and disregards the various underlying causes of such conditions. Similar to how the many types of pneumonias are treated differently depending on the infective agent, we suggested the same possible causative approach to various types of depression and pain.

Part 1 of this series (

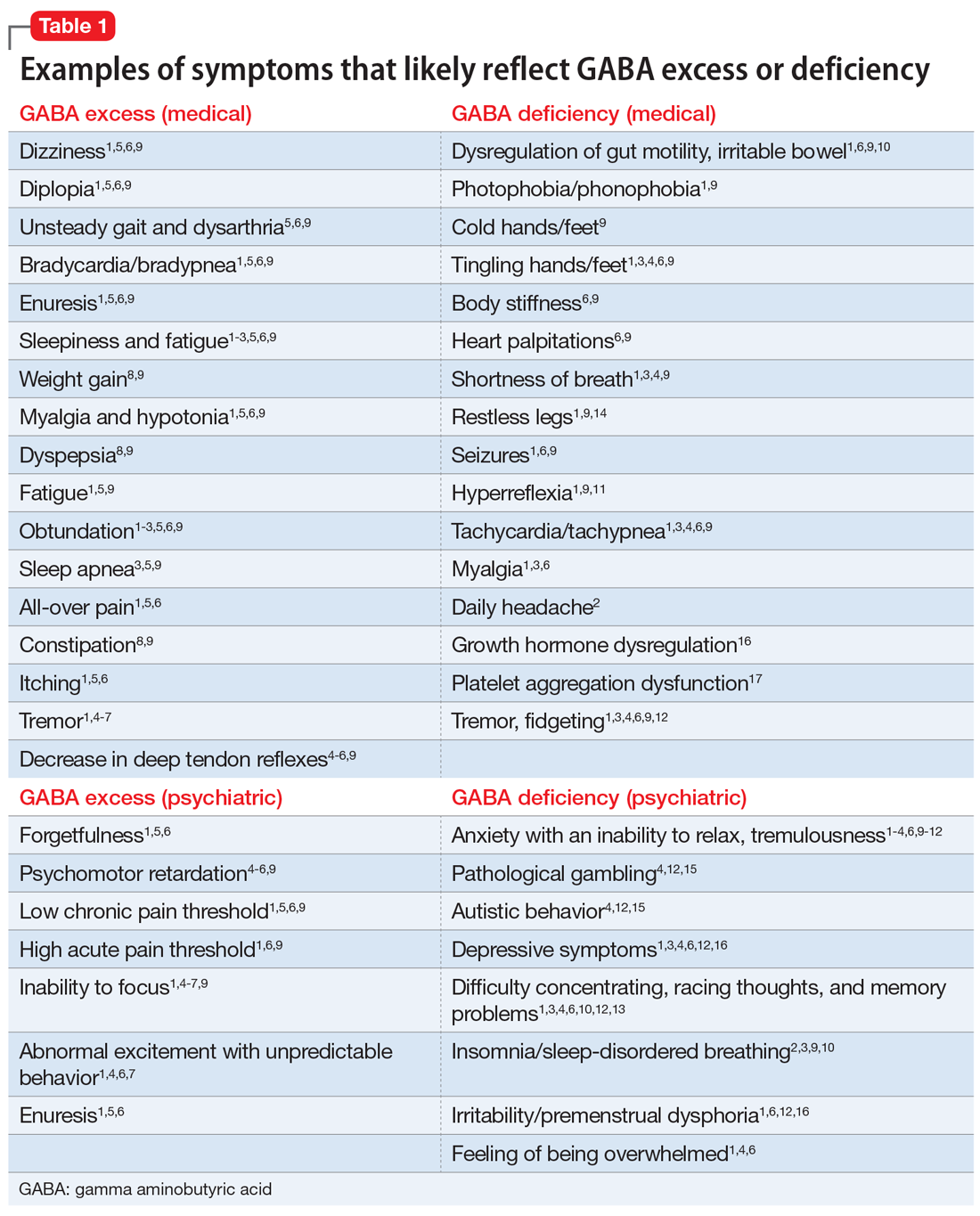

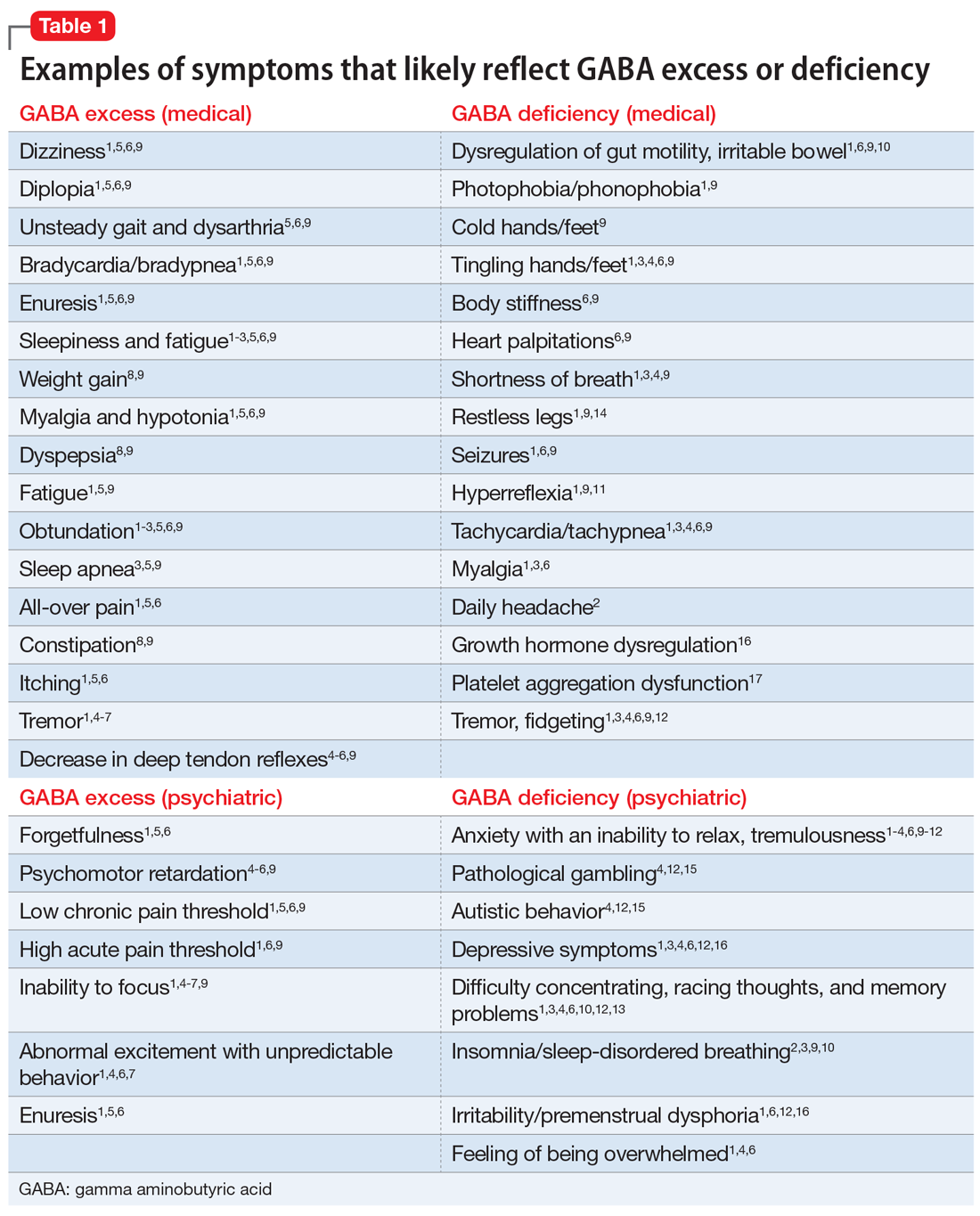

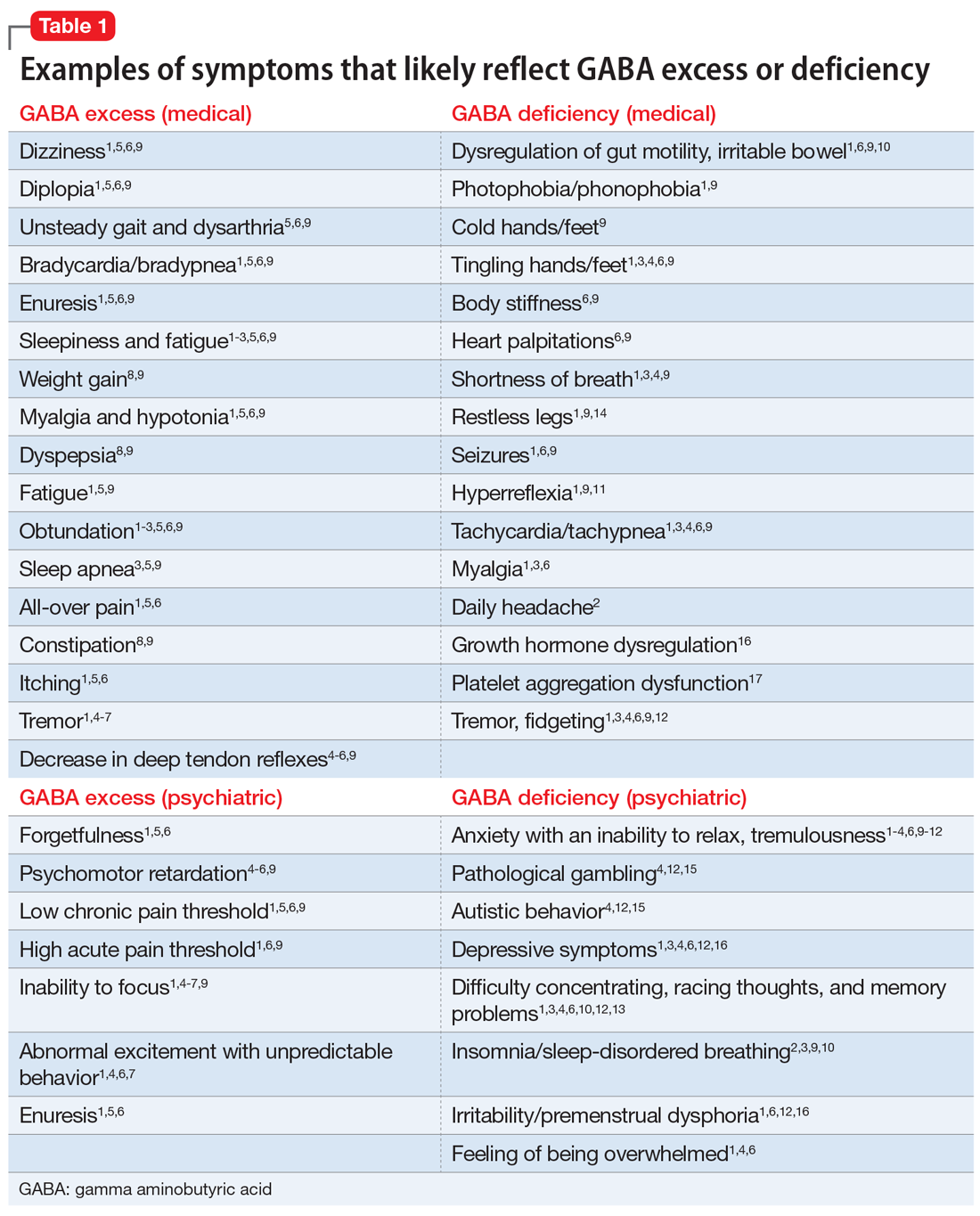

GABA excess (Table 11-9)

Ms. V is brought to your office by a friend. She complains of pain all over her body, itchiness, inability to focus, and dizziness.1,5,6,9 She is puzzled by how little pain she feels when she cuts her finger but by how much pain she is in every day, though her clinicians have not discovered a reason for her pain.1,6,9 She states that her fatigue is so severe that she can sleep 15 hours a day.1-6,9 Her obstructive and central sleep apnea have been treated, but this did not improve her fatigue.3,5,9 She is forgetful and has been diagnosed with depression, though she says she does not feel depressed.1,5,6 Nothing is pleasant to her, but she is prone to abnormal excitement and unpredictable behavior.1,4,6,7

A physical exam shows slow breathing, bradycardia, decreased deep tendon reflexes, and decreased muscle tone.1,5,6,9 Ms. V complains of double vision1,5,6,9 and problems with gait and balance,5,6,9 as well as tremors.1,4-7 She experienced enuresis well into adulthood1,5,6,9 and is prone to weight gain, dyspepsia, and constipation.8,9 She cannot understand people who have anxiety, and is prone to melancholy.4-6,9 Ms. V had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy in the past but states that she “had to have so much electricity, they gave up on me.”

Impression. Ms. V exhibits multiple symptoms associated with GABA excess. Dopaminergic medications such as methylphenidate or amphetamines may be helpful, as they suppress GABA. GABAergic medications and supplements should be avoided in such a patient. Noradrenergic medications including antidepressants with corresponding activity or vasopressors may be beneficial. Suppression of glutamate increases GABA, which is why ketamine in any formulation should be avoided in a patient such as Ms. V.

GABA deficiency (Table 11-4,6,9-17)

Mr. N complains of depression,1,3,4,6,12,16 pain all over his body, tingling in his hands and feet,1,6,9 a constant dull headache,2 and severe insomnia.2,3,9,10 He cannot control his anxiety and, in general, has problems relaxing. In the office, he is jumpy, tremulous, and fidgety during the interview and examination.1,3,4,6,9,12 His muscle tone is high1,9,11 and he feels stiff.6,9 Mr. N’s pupils are narrow1,9; he is hyper-reflexive1,9,11 and reports “Klonopin withdrawal seizures.”1,6,9 He loves alcohol because “it makes me feel good” and helps with his mind, which otherwise “never stops.”1,6,13 Mr. N is frequently anxious and very sensitive to pain, especially when he is upset. He was diagnosed with fibromyalgia by his primary care doctor, who says that irritable bowel is common in patients like him.1,6 His anxiety disables him.1-4,6,9-12 His sister reports that in addition to having difficulty relaxing, Mr. N is easily frustrated and sleeps poorly because he says he has racing thoughts.10 She mentions that her brother’s gambling addiction endangered his finances on several occasions4,12,15 and he was suspected of having autism spectrum disorder.4,12 Mr. N is frequently overwhelmed, including during your interview.1,3,4,6 He is sensitive to light and noise1,9 and complains of palpitations1,3,4,6,9 and frequent shortness of breath.1,3,4,9 He mentions his hands and feet often are cold, especially when he is anxious.1,3,4,6,9 Not eating at regular times makes his symptoms even worse. Mr. N commonly feels depressed, but his anxiety is more bothersome.1,3,4,6,12,16 His ongoing complaints include difficulty concentrating and memory problems,3,4,12,13 as well as a constant feeling of being overwhelmed.1,3,4,6 His restless leg syndrome requires ongoing treatment.1,9,14 Though uncommon, Mr. N has episodes of slowing and weakness, which are associated with growth hormone problems.16 In the past, he experienced gut motility dysregulation9,10 and prolonged bleeding that worried his doctors.17

Impression. Mr. N shows multiple symptoms associated with GABA deficiency. The deficiency of GABA activity ultimately causes an increase in norepinephrine and dopamine firing; therefore, symptoms of GABA deficiency are partially aligned with symptoms of dopamine and norepinephrine excess. GABAergic medications would be most beneficial for such patients. Anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) are preferable. Acamprostate may be considered. For long-term use, benzodiapines are as problematic as opioids and should be avoided, if possible. The use of opioids in such patients is especially counterproductive. Some supplements and vitamins may enhance GABA activity. Avoiding bupropion and stimulants would be wise. Ketamine in any formulation would be a good choice in this scenario. Sedating antipsychotic medications have a promise for patients such as Mr. N. The muscle relaxant baclofen frequently helps with these patients’ pain, anxiety, and sleep.

Continue to: Glutamate excess

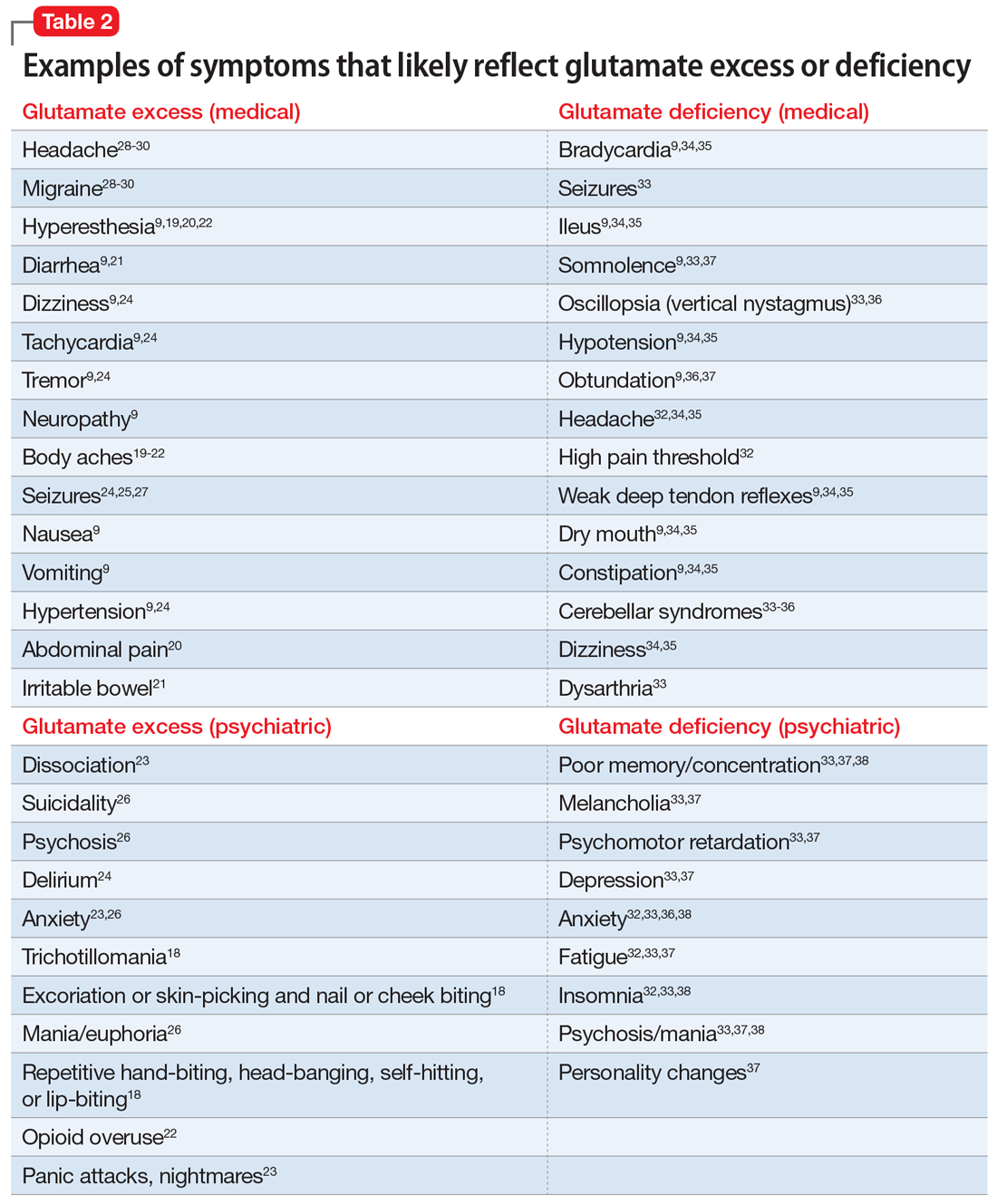

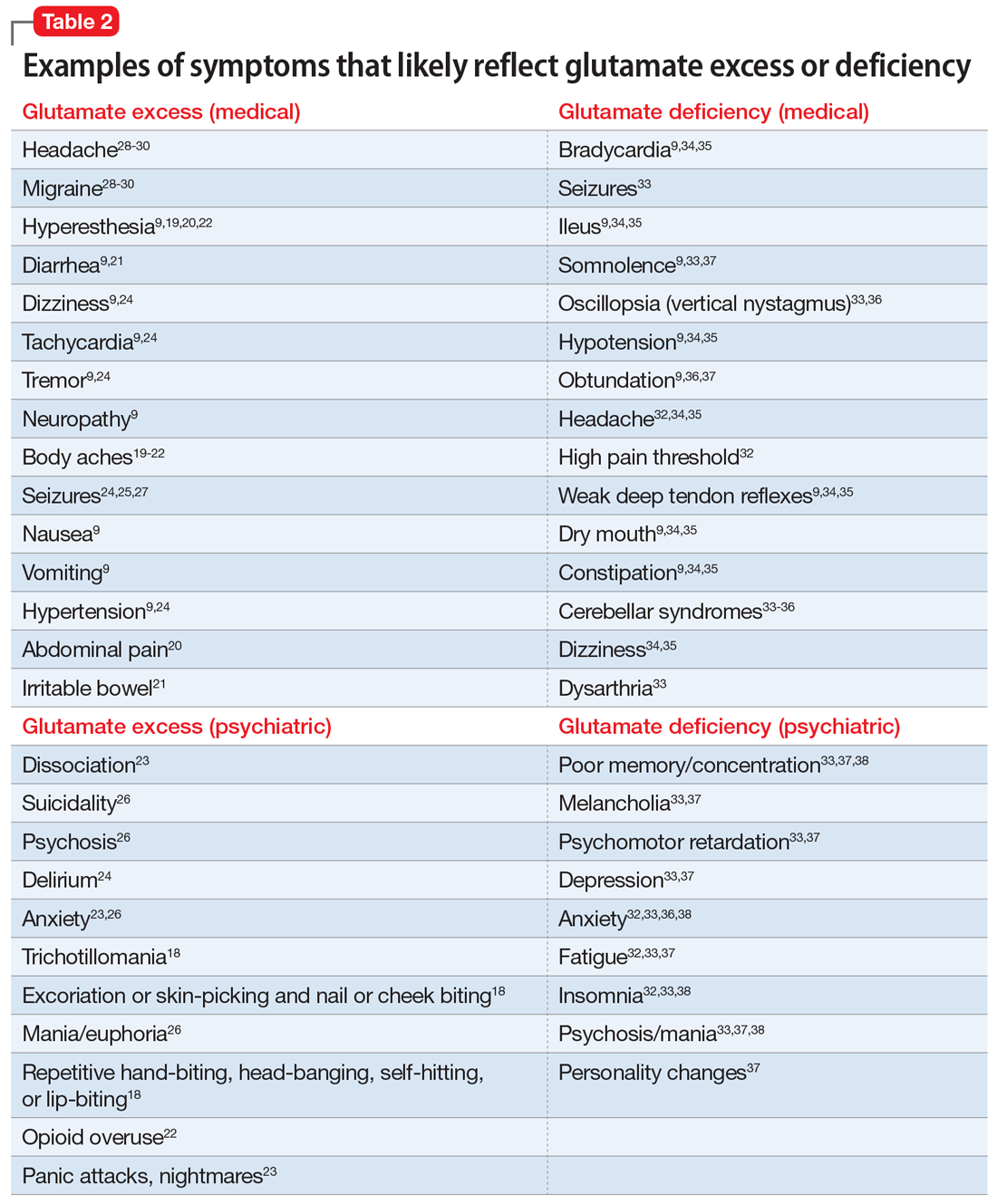

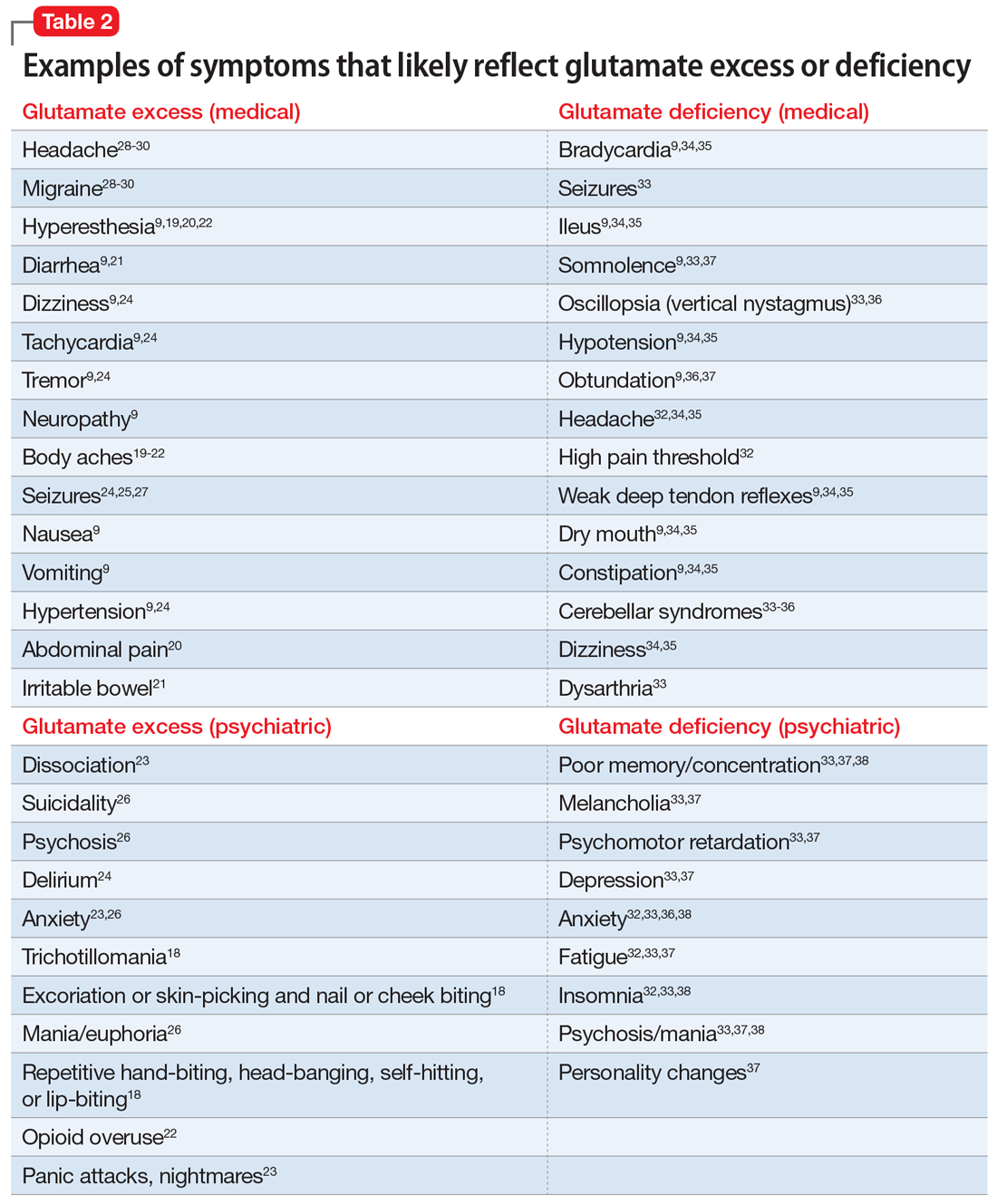

Glutamate excess (Table 29,18-30)

Mr. B is anxious and bites his fingernails and cheek while you interview him.18 He has scars on his lower arms that were caused by years of picking his skin.18 He complains of headache28-30 and deep muscle, whole body,19-23 and abdominal pain.20 Both hyperesthesia (he calls it “fibromyalgia”)9,19,20,22 and irritable bowel syndrome flare up if he eats Chinese food that contains monosodium glutamate.21 This also increases nausea, vomiting, and hypertensive episodes.9,19,20,22,24,26 Mr. B developed and received treatment for opioid use disorder after being prescribed morphine for the treatment of fibromyalgia.22 He is being treated for posttraumatic stress disorder at the VA hospital and is bitter that his flashbacks are not controlled.23 Once, he experienced a frank psychosis.26 He commonly experiences dissociative symptoms and suicidality.23,26 The sensations of crawling skin,18 panic attacks, and nightmares complicate his life.23 Mr. B is angry that his “incompetent” psychiatrist stopped his diazepam and that it “almost killed him” by causing delirium.24 He suffers from severe neuropathic pain in his feet and says that his pain, depression, and anxiety respond especially well to ketamine treatment.9,23,26 He is prone to euphoria and has had several manic episodes.26 In childhood, his parents brought him to a psychiatrist to address episodes of head-banging and self-hitting.18 Mr. B developed seizures; presently, they are controlled, but he remains chronically dizzy.9,24,25,27 He claims that his headaches and migraines respond only to methadone and that sumatriptan makes them worse, especially in prolonged treatment.28-30 He is tachycardic, tremulous, and makes you feel deeply uneasy.9,24

Impression. Mr. B has many symptoms of glutamate hyperactivity. The use of N-methyl-

Glutamate deficiency (Table 29,32-38)

Mr. Z feels dull, fatigued, and unhappy.32,33,37 He is overweight and moves slowly. Sometimes he is so slow and clumsy that he seems obtunded.9,36,37 He states that his peripheral neuropathy does not cause him pain, though his neurodiagnostic results are unfavorable.32 Mr. Z’s overall pain threshold is high, and he is unhappy with people who complain about pain because “who cares?”32 His memory and concentration were never good.33,37,38 He suffers from insomnia and is frequently miserable and disheartened.32,33,38 People view him as melancholic.33,37 Mr. Z is mildly depressed, but he experiences aggressive outbursts37,38 and bouts of anxiety,32,33,36,38 psychosis, and mania.33,37,38 He is visibly confused37 and says it is easy for him to get disoriented and lost.37,38 His medical history includes long-term constipation and several episodes of ileus.9,34,35 His childhood-onset seizures are controlled presently.33 He complains of frequent bouts of dizziness and headache.32,34,35 On physical exam, Mr. Z has dry mouth, hypotension, diminished deep tendon reflexes, and bradycardia.9,34,35 He sought a consultation from an ophthalmologist to evaluate an eye movement problem.33,36 No cause was found, but the ophthalmologist thought this problem might have the same underlying mechanism as his dysarthria.33 Mr. Z’s balance is bothersome, but his podiatrist was unable to help him to correct his abnormal gait.33-36 A friend who came with Mr. Z mentioned she had noticed personality changes in him over the last several months.37

Impression. Mr. Z exhibits multiple signs of low glutamatergic function. Amino acid taurine has been shown in rodents to increase brain levels of both GABA and glutamate. Glutamate is metabolized into GABA, so low glutamate and low GABA symptoms overlap. Glutamine, which is present in meat, fish, eggs, dairy, wheat, and some vegetables, is converted in the body into glutamate and may be considered for a patient with low glutamate function. The medication approach to such a patient would be similar to the treatment of a low GABA patient and includes glutamate-enhancing magnesium and dextromethorphan.

Rarely is just 1 neurotransmitter involved

Most real-world patients have mixed presentations with more than 1 neurotransmitter implicated in the pathology of their symptoms. A clinician’s ability to dissect the clinical picture and select an appropriate treatment must be based on history and observed behavior because no lab results or reliable tests are presently available.

Continue to: The most studied...

The most studied neurotransmitter in depression and anxiety is serotonin, and for many years psychiatrists have paid too much attention to it. Similarly, pain physicians have been overly focused on the opioid system. Excessive attention to these neurochemicals has overshadowed multiple other (no less impactful) neurotransmitters. Dopamine is frequently not attended to by many physicians who treat chronic pain. Psychiatrists also may overlook underlying endorphin or glutamate dysfunction in patients with psychiatric illness.

Nonpharmacologic approaches can affect neurotransmitters

With all the emphasis on pharmacologic treatments, it is important to remember that nonpharmacologic modalities such as exercise, diet, hydrotherapy, acupuncture, and psychotherapy can help normalize neurotransmitter function in the brain and ultimately help patients with chronic conditions. Careful use of nutritional supplements and vitamins may also be beneficial.

A hypothesis for future research

Multiple peripheral and central mechanisms define various chronic pain and psychiatric symptoms and disorders, including depression, anxiety, and fibromyalgia. The variety of mechanisms of pathologic mood and pain perception may be expressed to a different extent and in countless combinations in individual patients. This, in part, explains the variable responses to the same treatment observed in similar patients, or even in the same patient.

Clinicians should always remember that depression and anxiety as well as chronic pain (including fibromyalgia and chronic headache) are not a representation of a single condition but are the result of an assembly of different syndromes; therefore, 1 treatment does not fit all patients. Pain is ultimately recognized and comprehended centrally, making it very much a neuropsychiatric field. The optimal treatment for 2 patients with similar pain or psychiatric symptoms may be drastically different due to different underlying mechanisms that can be distinguished by looking at the symptoms other than “pain” or “depression.”

Remembering that every neurotransmitter deficiency or excess has an identifiable clinical correlation is important. Basing a treatment approach on a specific clinical presentation in a particular depressed or chronic pain patient would assure a more successful and reliable outcome.

Continue to: This 3-part series...

This 3-part series was designed to bring attention to a notion that diagnosis and treatment of diverse conditions such as “depression,” “anxiety,” or “chronic pain” should be based on clinically identifiable symptoms that may suggest specific neurotransmitter(s) involved in a specific type of each of these conditions. However, there are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in this series. The collection of symptoms associated with the various neurotransmitters described in this series is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for future research.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Arbuck DM, Salmerón JM, Mueller R. Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: a hypothesis (part 1). Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(5):30-36. doi:10.12788/cp.0242

- Arbuck DM, Salmerón JM, Mueller R. Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: a hypothesis (part 2). Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):28-33. doi:10.12788/cp.0253

Drug Brand Names

Acamprostate • Campral

Amantadine • Gocovri

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clonidine • Catapres

Diazepam • Valium

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Ketamine • Ketalar

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Concerta

Morphine • Kadian

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Tizanidine • Zanaflex

1. Petroff OA. GABA and glutamate in the human brain. Neuroscientist. 2002;8(6):562-573.

2. Winkelman JW, Buxton OM, Jensen JE, et al. Reduced brain GABA in primary insomnia: preliminary data from 4T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Sleep. 2008;31(11):1499-1506.

3. Pereira AC, Mao X, Jiang CS, et al. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex GABA deficit in older adults with sleep-disordered breathing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(38):10250-10255.

4. Schür RR, Draisma LW, Wijnen JP, et al. Brain GABA levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of (1) H-MRS studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(9):3337-3352.

5. Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR. Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin. Drugs. 2017;77(4):403-426.

6. Mersfelder TL, Nichols WH. Gabapentin: abuse, dependence, and withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(3):229-233.

7. Bremner JD. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):445-461.

8. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, et al. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability, and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392.

9. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2011:550-551,692-693.

10. Evrensel A, Ceylan ME. The gut-brain axis: the missing link in depression. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(3):239-244.

11. Vianello M, Tavolato B, Giometto B. Glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibodies and neurological disorders. Neurol Sci. 2002;23(4):145-151.

12. Marin O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(2):107-120.

13. Huang D, Liu D, Yin J, et al. Glutamate-glutamine and GABA in the brain of normal aged and patients with cognitive impairment. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(7):2698-2705.

14. Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, García-Martín E, et al. Neurochemical features of idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;45:70-87.

15. Mick I, Ramos AC, Myers J, et al. Evidence for GABA-A receptor dysregulation in gambling disorder: correlation with impulsivity. Addict Biol. 2017;22(6):1601-1609.

16. Brambilla P, Perez J, Barale F, et al. Gabaergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:721-737.

17. Kaneez FS, Saeed SA. Investigating GABA and its function in platelets as compared to neurons. Platelets. 2009;20(5):328-333.

18. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702.

19. Miranda A, Peles S, Rudolph C, et al. Altered visceral sensation in response to somatic pain in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1082-1089.

20. Skyba DA, King EW, Sluka KA. Effects of NMDA and non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on the development and maintenance of hyperalgesia induced by repeated intramuscular injection of acidic saline. Pain. 2002;98(1-2):69-78.

21. Holton KF, Taren DL, Thomson CA, et al. The effect of dietary glutamate on fibromyalgia and irritable bowel symptoms. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(6 Suppl 74):10-70.

22. Sekiya Y, Nakagawa T, Ozawa T, et al. Facilitation of morphine withdrawal symptoms and morphine-induced conditioned place preference by a glutamate transporter inhibitor DL-threo-beta-benzyloxy aspartate in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;485(1-3):201-210.

23. Bestha D, Soliman L, Blankenship K. et al. The walking wounded: emerging treatments for PTSD. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(10):94.

24. Tsuda M, Shimizu N, Suzuki T. Contribution of glutamate receptors to benzodiazepine withdrawal signs. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1999;81(1):1-6.

25. Spravato [package insert]. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2019.

26. Mattingly GW, Anderson RH. Intranasal ketamine. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(5):31-38.

27. Buckingham SC, Campbell SL, Haas BR, et al. Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1269-1275.

28. Ferrari A, Spaccapelo L, Pinetti D, et al. Effective prophylactic treatment of migraines lower plasma glutamate levels. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(4):423-429.

29. Vieira DS, Naffah-Mazzacoratti Mda G, Zukerman E, et al. Glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid and triptans overuse in chronic migraine. Headache. 2007;47(6):842-847.

30. Chan K, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Glutamate receptor antagonists in the management of migraine. Drugs. 2014;74:1165-1176.

31. Pappa S, Tsouli S, Apostolou G, et al. Effects of amantadine on tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):271-275.

32. Kraal AZ, Arvanitis NR, Jaeger AP, et al. Could dietary glutamate play a role in psychiatric distress? Neuro Psych. 2020;79:13-19.

33. Levite M. Glutamate receptor antibodies in neurological diseases: anti-AMPA-GluR3 antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR1 antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR2A/B antibodies, Anti-mGluR1 antibodies or Anti-mGluR5 antibodies are present in subpopulations of patients with either: epilepsy, encephalitis, cerebellar ataxia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and neuropsychiatric SLE, Sjogren’s syndrome, schizophrenia, mania or stroke. These autoimmune anti-glutamate receptor antibodies can bind neurons in few brain regions, activate glutamate receptors, decrease glutamate receptor’s expression, impair glutamate-induced signaling and function, activate blood brain barrier endothelial cells, kill neurons, damage the brain, induce behavioral/psychiatric/cognitive abnormalities and ataxia in animal models, and can be removed or silenced in some patients by immunotherapy. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2014;121(8):1029-1075.

34. Lancaster E. CNS syndromes associated with antibodies against metabotropic receptors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:354-360.

35. Sillevis Smitt P, Kinoshita A, De Leeuw B, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia due to autoantibodies against a glutamate receptor. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(1):21-27.

36. Marignier R, Chenevier F, Rogemond V, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1 autoantibody-associated cerebellitis: a primary autoimmune disease? Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):627-630.

37. Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Titulaer MJ, et al. Antibodies to metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the Ophelia syndrome. Neurology. 2011;77:1698-1701.

38. Mat A, Adler H, Merwick A, et al. Ophelia syndrome with metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antibodies in CSF. Neurology. 2013;80(14):1349-1350.

Optimal diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illness requires clinicians to be able to connect mental and physical symptoms. Direct brain neurotransmitter testing is presently in its infancy and the science of defining the underlying mechanisms of psychiatric disorders lags behind the obvious clinical needs. We are not yet equipped to clearly recognize which neurotransmitters cause which symptoms. In this article series, we suggest an indirect way of judging neurotransmitter activity by recognizing specific mental and physical symptoms connected by common biology. Here we present hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms in order to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. The descriptions we present in this series do not reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by the neurotransmitters we discuss; we created them based on what is presently known (or suspected). Additional research is needed to confirm or disprove the hypothesis we present. We argue that in cases of multiple psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, the development and approval of medications currently is based on an umbrella descriptive diagnoses, and disregards the various underlying causes of such conditions. Similar to how the many types of pneumonias are treated differently depending on the infective agent, we suggested the same possible causative approach to various types of depression and pain.

Part 1 of this series (

GABA excess (Table 11-9)

Ms. V is brought to your office by a friend. She complains of pain all over her body, itchiness, inability to focus, and dizziness.1,5,6,9 She is puzzled by how little pain she feels when she cuts her finger but by how much pain she is in every day, though her clinicians have not discovered a reason for her pain.1,6,9 She states that her fatigue is so severe that she can sleep 15 hours a day.1-6,9 Her obstructive and central sleep apnea have been treated, but this did not improve her fatigue.3,5,9 She is forgetful and has been diagnosed with depression, though she says she does not feel depressed.1,5,6 Nothing is pleasant to her, but she is prone to abnormal excitement and unpredictable behavior.1,4,6,7

A physical exam shows slow breathing, bradycardia, decreased deep tendon reflexes, and decreased muscle tone.1,5,6,9 Ms. V complains of double vision1,5,6,9 and problems with gait and balance,5,6,9 as well as tremors.1,4-7 She experienced enuresis well into adulthood1,5,6,9 and is prone to weight gain, dyspepsia, and constipation.8,9 She cannot understand people who have anxiety, and is prone to melancholy.4-6,9 Ms. V had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy in the past but states that she “had to have so much electricity, they gave up on me.”

Impression. Ms. V exhibits multiple symptoms associated with GABA excess. Dopaminergic medications such as methylphenidate or amphetamines may be helpful, as they suppress GABA. GABAergic medications and supplements should be avoided in such a patient. Noradrenergic medications including antidepressants with corresponding activity or vasopressors may be beneficial. Suppression of glutamate increases GABA, which is why ketamine in any formulation should be avoided in a patient such as Ms. V.

GABA deficiency (Table 11-4,6,9-17)

Mr. N complains of depression,1,3,4,6,12,16 pain all over his body, tingling in his hands and feet,1,6,9 a constant dull headache,2 and severe insomnia.2,3,9,10 He cannot control his anxiety and, in general, has problems relaxing. In the office, he is jumpy, tremulous, and fidgety during the interview and examination.1,3,4,6,9,12 His muscle tone is high1,9,11 and he feels stiff.6,9 Mr. N’s pupils are narrow1,9; he is hyper-reflexive1,9,11 and reports “Klonopin withdrawal seizures.”1,6,9 He loves alcohol because “it makes me feel good” and helps with his mind, which otherwise “never stops.”1,6,13 Mr. N is frequently anxious and very sensitive to pain, especially when he is upset. He was diagnosed with fibromyalgia by his primary care doctor, who says that irritable bowel is common in patients like him.1,6 His anxiety disables him.1-4,6,9-12 His sister reports that in addition to having difficulty relaxing, Mr. N is easily frustrated and sleeps poorly because he says he has racing thoughts.10 She mentions that her brother’s gambling addiction endangered his finances on several occasions4,12,15 and he was suspected of having autism spectrum disorder.4,12 Mr. N is frequently overwhelmed, including during your interview.1,3,4,6 He is sensitive to light and noise1,9 and complains of palpitations1,3,4,6,9 and frequent shortness of breath.1,3,4,9 He mentions his hands and feet often are cold, especially when he is anxious.1,3,4,6,9 Not eating at regular times makes his symptoms even worse. Mr. N commonly feels depressed, but his anxiety is more bothersome.1,3,4,6,12,16 His ongoing complaints include difficulty concentrating and memory problems,3,4,12,13 as well as a constant feeling of being overwhelmed.1,3,4,6 His restless leg syndrome requires ongoing treatment.1,9,14 Though uncommon, Mr. N has episodes of slowing and weakness, which are associated with growth hormone problems.16 In the past, he experienced gut motility dysregulation9,10 and prolonged bleeding that worried his doctors.17

Impression. Mr. N shows multiple symptoms associated with GABA deficiency. The deficiency of GABA activity ultimately causes an increase in norepinephrine and dopamine firing; therefore, symptoms of GABA deficiency are partially aligned with symptoms of dopamine and norepinephrine excess. GABAergic medications would be most beneficial for such patients. Anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) are preferable. Acamprostate may be considered. For long-term use, benzodiapines are as problematic as opioids and should be avoided, if possible. The use of opioids in such patients is especially counterproductive. Some supplements and vitamins may enhance GABA activity. Avoiding bupropion and stimulants would be wise. Ketamine in any formulation would be a good choice in this scenario. Sedating antipsychotic medications have a promise for patients such as Mr. N. The muscle relaxant baclofen frequently helps with these patients’ pain, anxiety, and sleep.

Continue to: Glutamate excess

Glutamate excess (Table 29,18-30)

Mr. B is anxious and bites his fingernails and cheek while you interview him.18 He has scars on his lower arms that were caused by years of picking his skin.18 He complains of headache28-30 and deep muscle, whole body,19-23 and abdominal pain.20 Both hyperesthesia (he calls it “fibromyalgia”)9,19,20,22 and irritable bowel syndrome flare up if he eats Chinese food that contains monosodium glutamate.21 This also increases nausea, vomiting, and hypertensive episodes.9,19,20,22,24,26 Mr. B developed and received treatment for opioid use disorder after being prescribed morphine for the treatment of fibromyalgia.22 He is being treated for posttraumatic stress disorder at the VA hospital and is bitter that his flashbacks are not controlled.23 Once, he experienced a frank psychosis.26 He commonly experiences dissociative symptoms and suicidality.23,26 The sensations of crawling skin,18 panic attacks, and nightmares complicate his life.23 Mr. B is angry that his “incompetent” psychiatrist stopped his diazepam and that it “almost killed him” by causing delirium.24 He suffers from severe neuropathic pain in his feet and says that his pain, depression, and anxiety respond especially well to ketamine treatment.9,23,26 He is prone to euphoria and has had several manic episodes.26 In childhood, his parents brought him to a psychiatrist to address episodes of head-banging and self-hitting.18 Mr. B developed seizures; presently, they are controlled, but he remains chronically dizzy.9,24,25,27 He claims that his headaches and migraines respond only to methadone and that sumatriptan makes them worse, especially in prolonged treatment.28-30 He is tachycardic, tremulous, and makes you feel deeply uneasy.9,24

Impression. Mr. B has many symptoms of glutamate hyperactivity. The use of N-methyl-

Glutamate deficiency (Table 29,32-38)

Mr. Z feels dull, fatigued, and unhappy.32,33,37 He is overweight and moves slowly. Sometimes he is so slow and clumsy that he seems obtunded.9,36,37 He states that his peripheral neuropathy does not cause him pain, though his neurodiagnostic results are unfavorable.32 Mr. Z’s overall pain threshold is high, and he is unhappy with people who complain about pain because “who cares?”32 His memory and concentration were never good.33,37,38 He suffers from insomnia and is frequently miserable and disheartened.32,33,38 People view him as melancholic.33,37 Mr. Z is mildly depressed, but he experiences aggressive outbursts37,38 and bouts of anxiety,32,33,36,38 psychosis, and mania.33,37,38 He is visibly confused37 and says it is easy for him to get disoriented and lost.37,38 His medical history includes long-term constipation and several episodes of ileus.9,34,35 His childhood-onset seizures are controlled presently.33 He complains of frequent bouts of dizziness and headache.32,34,35 On physical exam, Mr. Z has dry mouth, hypotension, diminished deep tendon reflexes, and bradycardia.9,34,35 He sought a consultation from an ophthalmologist to evaluate an eye movement problem.33,36 No cause was found, but the ophthalmologist thought this problem might have the same underlying mechanism as his dysarthria.33 Mr. Z’s balance is bothersome, but his podiatrist was unable to help him to correct his abnormal gait.33-36 A friend who came with Mr. Z mentioned she had noticed personality changes in him over the last several months.37

Impression. Mr. Z exhibits multiple signs of low glutamatergic function. Amino acid taurine has been shown in rodents to increase brain levels of both GABA and glutamate. Glutamate is metabolized into GABA, so low glutamate and low GABA symptoms overlap. Glutamine, which is present in meat, fish, eggs, dairy, wheat, and some vegetables, is converted in the body into glutamate and may be considered for a patient with low glutamate function. The medication approach to such a patient would be similar to the treatment of a low GABA patient and includes glutamate-enhancing magnesium and dextromethorphan.

Rarely is just 1 neurotransmitter involved

Most real-world patients have mixed presentations with more than 1 neurotransmitter implicated in the pathology of their symptoms. A clinician’s ability to dissect the clinical picture and select an appropriate treatment must be based on history and observed behavior because no lab results or reliable tests are presently available.

Continue to: The most studied...

The most studied neurotransmitter in depression and anxiety is serotonin, and for many years psychiatrists have paid too much attention to it. Similarly, pain physicians have been overly focused on the opioid system. Excessive attention to these neurochemicals has overshadowed multiple other (no less impactful) neurotransmitters. Dopamine is frequently not attended to by many physicians who treat chronic pain. Psychiatrists also may overlook underlying endorphin or glutamate dysfunction in patients with psychiatric illness.

Nonpharmacologic approaches can affect neurotransmitters

With all the emphasis on pharmacologic treatments, it is important to remember that nonpharmacologic modalities such as exercise, diet, hydrotherapy, acupuncture, and psychotherapy can help normalize neurotransmitter function in the brain and ultimately help patients with chronic conditions. Careful use of nutritional supplements and vitamins may also be beneficial.

A hypothesis for future research

Multiple peripheral and central mechanisms define various chronic pain and psychiatric symptoms and disorders, including depression, anxiety, and fibromyalgia. The variety of mechanisms of pathologic mood and pain perception may be expressed to a different extent and in countless combinations in individual patients. This, in part, explains the variable responses to the same treatment observed in similar patients, or even in the same patient.

Clinicians should always remember that depression and anxiety as well as chronic pain (including fibromyalgia and chronic headache) are not a representation of a single condition but are the result of an assembly of different syndromes; therefore, 1 treatment does not fit all patients. Pain is ultimately recognized and comprehended centrally, making it very much a neuropsychiatric field. The optimal treatment for 2 patients with similar pain or psychiatric symptoms may be drastically different due to different underlying mechanisms that can be distinguished by looking at the symptoms other than “pain” or “depression.”

Remembering that every neurotransmitter deficiency or excess has an identifiable clinical correlation is important. Basing a treatment approach on a specific clinical presentation in a particular depressed or chronic pain patient would assure a more successful and reliable outcome.

Continue to: This 3-part series...

This 3-part series was designed to bring attention to a notion that diagnosis and treatment of diverse conditions such as “depression,” “anxiety,” or “chronic pain” should be based on clinically identifiable symptoms that may suggest specific neurotransmitter(s) involved in a specific type of each of these conditions. However, there are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in this series. The collection of symptoms associated with the various neurotransmitters described in this series is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for future research.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Arbuck DM, Salmerón JM, Mueller R. Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: a hypothesis (part 1). Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(5):30-36. doi:10.12788/cp.0242

- Arbuck DM, Salmerón JM, Mueller R. Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: a hypothesis (part 2). Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):28-33. doi:10.12788/cp.0253

Drug Brand Names

Acamprostate • Campral

Amantadine • Gocovri

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clonidine • Catapres

Diazepam • Valium

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Ketamine • Ketalar

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Concerta

Morphine • Kadian

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Tizanidine • Zanaflex

Optimal diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illness requires clinicians to be able to connect mental and physical symptoms. Direct brain neurotransmitter testing is presently in its infancy and the science of defining the underlying mechanisms of psychiatric disorders lags behind the obvious clinical needs. We are not yet equipped to clearly recognize which neurotransmitters cause which symptoms. In this article series, we suggest an indirect way of judging neurotransmitter activity by recognizing specific mental and physical symptoms connected by common biology. Here we present hypothetical clinical cases to emphasize a possible way of analyzing symptoms in order to identify underlying pathology and guide more effective treatment. The descriptions we present in this series do not reflect the entire set of symptoms caused by the neurotransmitters we discuss; we created them based on what is presently known (or suspected). Additional research is needed to confirm or disprove the hypothesis we present. We argue that in cases of multiple psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, the development and approval of medications currently is based on an umbrella descriptive diagnoses, and disregards the various underlying causes of such conditions. Similar to how the many types of pneumonias are treated differently depending on the infective agent, we suggested the same possible causative approach to various types of depression and pain.

Part 1 of this series (

GABA excess (Table 11-9)

Ms. V is brought to your office by a friend. She complains of pain all over her body, itchiness, inability to focus, and dizziness.1,5,6,9 She is puzzled by how little pain she feels when she cuts her finger but by how much pain she is in every day, though her clinicians have not discovered a reason for her pain.1,6,9 She states that her fatigue is so severe that she can sleep 15 hours a day.1-6,9 Her obstructive and central sleep apnea have been treated, but this did not improve her fatigue.3,5,9 She is forgetful and has been diagnosed with depression, though she says she does not feel depressed.1,5,6 Nothing is pleasant to her, but she is prone to abnormal excitement and unpredictable behavior.1,4,6,7

A physical exam shows slow breathing, bradycardia, decreased deep tendon reflexes, and decreased muscle tone.1,5,6,9 Ms. V complains of double vision1,5,6,9 and problems with gait and balance,5,6,9 as well as tremors.1,4-7 She experienced enuresis well into adulthood1,5,6,9 and is prone to weight gain, dyspepsia, and constipation.8,9 She cannot understand people who have anxiety, and is prone to melancholy.4-6,9 Ms. V had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy in the past but states that she “had to have so much electricity, they gave up on me.”

Impression. Ms. V exhibits multiple symptoms associated with GABA excess. Dopaminergic medications such as methylphenidate or amphetamines may be helpful, as they suppress GABA. GABAergic medications and supplements should be avoided in such a patient. Noradrenergic medications including antidepressants with corresponding activity or vasopressors may be beneficial. Suppression of glutamate increases GABA, which is why ketamine in any formulation should be avoided in a patient such as Ms. V.

GABA deficiency (Table 11-4,6,9-17)

Mr. N complains of depression,1,3,4,6,12,16 pain all over his body, tingling in his hands and feet,1,6,9 a constant dull headache,2 and severe insomnia.2,3,9,10 He cannot control his anxiety and, in general, has problems relaxing. In the office, he is jumpy, tremulous, and fidgety during the interview and examination.1,3,4,6,9,12 His muscle tone is high1,9,11 and he feels stiff.6,9 Mr. N’s pupils are narrow1,9; he is hyper-reflexive1,9,11 and reports “Klonopin withdrawal seizures.”1,6,9 He loves alcohol because “it makes me feel good” and helps with his mind, which otherwise “never stops.”1,6,13 Mr. N is frequently anxious and very sensitive to pain, especially when he is upset. He was diagnosed with fibromyalgia by his primary care doctor, who says that irritable bowel is common in patients like him.1,6 His anxiety disables him.1-4,6,9-12 His sister reports that in addition to having difficulty relaxing, Mr. N is easily frustrated and sleeps poorly because he says he has racing thoughts.10 She mentions that her brother’s gambling addiction endangered his finances on several occasions4,12,15 and he was suspected of having autism spectrum disorder.4,12 Mr. N is frequently overwhelmed, including during your interview.1,3,4,6 He is sensitive to light and noise1,9 and complains of palpitations1,3,4,6,9 and frequent shortness of breath.1,3,4,9 He mentions his hands and feet often are cold, especially when he is anxious.1,3,4,6,9 Not eating at regular times makes his symptoms even worse. Mr. N commonly feels depressed, but his anxiety is more bothersome.1,3,4,6,12,16 His ongoing complaints include difficulty concentrating and memory problems,3,4,12,13 as well as a constant feeling of being overwhelmed.1,3,4,6 His restless leg syndrome requires ongoing treatment.1,9,14 Though uncommon, Mr. N has episodes of slowing and weakness, which are associated with growth hormone problems.16 In the past, he experienced gut motility dysregulation9,10 and prolonged bleeding that worried his doctors.17

Impression. Mr. N shows multiple symptoms associated with GABA deficiency. The deficiency of GABA activity ultimately causes an increase in norepinephrine and dopamine firing; therefore, symptoms of GABA deficiency are partially aligned with symptoms of dopamine and norepinephrine excess. GABAergic medications would be most beneficial for such patients. Anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) are preferable. Acamprostate may be considered. For long-term use, benzodiapines are as problematic as opioids and should be avoided, if possible. The use of opioids in such patients is especially counterproductive. Some supplements and vitamins may enhance GABA activity. Avoiding bupropion and stimulants would be wise. Ketamine in any formulation would be a good choice in this scenario. Sedating antipsychotic medications have a promise for patients such as Mr. N. The muscle relaxant baclofen frequently helps with these patients’ pain, anxiety, and sleep.

Continue to: Glutamate excess

Glutamate excess (Table 29,18-30)

Mr. B is anxious and bites his fingernails and cheek while you interview him.18 He has scars on his lower arms that were caused by years of picking his skin.18 He complains of headache28-30 and deep muscle, whole body,19-23 and abdominal pain.20 Both hyperesthesia (he calls it “fibromyalgia”)9,19,20,22 and irritable bowel syndrome flare up if he eats Chinese food that contains monosodium glutamate.21 This also increases nausea, vomiting, and hypertensive episodes.9,19,20,22,24,26 Mr. B developed and received treatment for opioid use disorder after being prescribed morphine for the treatment of fibromyalgia.22 He is being treated for posttraumatic stress disorder at the VA hospital and is bitter that his flashbacks are not controlled.23 Once, he experienced a frank psychosis.26 He commonly experiences dissociative symptoms and suicidality.23,26 The sensations of crawling skin,18 panic attacks, and nightmares complicate his life.23 Mr. B is angry that his “incompetent” psychiatrist stopped his diazepam and that it “almost killed him” by causing delirium.24 He suffers from severe neuropathic pain in his feet and says that his pain, depression, and anxiety respond especially well to ketamine treatment.9,23,26 He is prone to euphoria and has had several manic episodes.26 In childhood, his parents brought him to a psychiatrist to address episodes of head-banging and self-hitting.18 Mr. B developed seizures; presently, they are controlled, but he remains chronically dizzy.9,24,25,27 He claims that his headaches and migraines respond only to methadone and that sumatriptan makes them worse, especially in prolonged treatment.28-30 He is tachycardic, tremulous, and makes you feel deeply uneasy.9,24

Impression. Mr. B has many symptoms of glutamate hyperactivity. The use of N-methyl-

Glutamate deficiency (Table 29,32-38)

Mr. Z feels dull, fatigued, and unhappy.32,33,37 He is overweight and moves slowly. Sometimes he is so slow and clumsy that he seems obtunded.9,36,37 He states that his peripheral neuropathy does not cause him pain, though his neurodiagnostic results are unfavorable.32 Mr. Z’s overall pain threshold is high, and he is unhappy with people who complain about pain because “who cares?”32 His memory and concentration were never good.33,37,38 He suffers from insomnia and is frequently miserable and disheartened.32,33,38 People view him as melancholic.33,37 Mr. Z is mildly depressed, but he experiences aggressive outbursts37,38 and bouts of anxiety,32,33,36,38 psychosis, and mania.33,37,38 He is visibly confused37 and says it is easy for him to get disoriented and lost.37,38 His medical history includes long-term constipation and several episodes of ileus.9,34,35 His childhood-onset seizures are controlled presently.33 He complains of frequent bouts of dizziness and headache.32,34,35 On physical exam, Mr. Z has dry mouth, hypotension, diminished deep tendon reflexes, and bradycardia.9,34,35 He sought a consultation from an ophthalmologist to evaluate an eye movement problem.33,36 No cause was found, but the ophthalmologist thought this problem might have the same underlying mechanism as his dysarthria.33 Mr. Z’s balance is bothersome, but his podiatrist was unable to help him to correct his abnormal gait.33-36 A friend who came with Mr. Z mentioned she had noticed personality changes in him over the last several months.37

Impression. Mr. Z exhibits multiple signs of low glutamatergic function. Amino acid taurine has been shown in rodents to increase brain levels of both GABA and glutamate. Glutamate is metabolized into GABA, so low glutamate and low GABA symptoms overlap. Glutamine, which is present in meat, fish, eggs, dairy, wheat, and some vegetables, is converted in the body into glutamate and may be considered for a patient with low glutamate function. The medication approach to such a patient would be similar to the treatment of a low GABA patient and includes glutamate-enhancing magnesium and dextromethorphan.

Rarely is just 1 neurotransmitter involved

Most real-world patients have mixed presentations with more than 1 neurotransmitter implicated in the pathology of their symptoms. A clinician’s ability to dissect the clinical picture and select an appropriate treatment must be based on history and observed behavior because no lab results or reliable tests are presently available.

Continue to: The most studied...

The most studied neurotransmitter in depression and anxiety is serotonin, and for many years psychiatrists have paid too much attention to it. Similarly, pain physicians have been overly focused on the opioid system. Excessive attention to these neurochemicals has overshadowed multiple other (no less impactful) neurotransmitters. Dopamine is frequently not attended to by many physicians who treat chronic pain. Psychiatrists also may overlook underlying endorphin or glutamate dysfunction in patients with psychiatric illness.

Nonpharmacologic approaches can affect neurotransmitters

With all the emphasis on pharmacologic treatments, it is important to remember that nonpharmacologic modalities such as exercise, diet, hydrotherapy, acupuncture, and psychotherapy can help normalize neurotransmitter function in the brain and ultimately help patients with chronic conditions. Careful use of nutritional supplements and vitamins may also be beneficial.

A hypothesis for future research

Multiple peripheral and central mechanisms define various chronic pain and psychiatric symptoms and disorders, including depression, anxiety, and fibromyalgia. The variety of mechanisms of pathologic mood and pain perception may be expressed to a different extent and in countless combinations in individual patients. This, in part, explains the variable responses to the same treatment observed in similar patients, or even in the same patient.

Clinicians should always remember that depression and anxiety as well as chronic pain (including fibromyalgia and chronic headache) are not a representation of a single condition but are the result of an assembly of different syndromes; therefore, 1 treatment does not fit all patients. Pain is ultimately recognized and comprehended centrally, making it very much a neuropsychiatric field. The optimal treatment for 2 patients with similar pain or psychiatric symptoms may be drastically different due to different underlying mechanisms that can be distinguished by looking at the symptoms other than “pain” or “depression.”

Remembering that every neurotransmitter deficiency or excess has an identifiable clinical correlation is important. Basing a treatment approach on a specific clinical presentation in a particular depressed or chronic pain patient would assure a more successful and reliable outcome.

Continue to: This 3-part series...

This 3-part series was designed to bring attention to a notion that diagnosis and treatment of diverse conditions such as “depression,” “anxiety,” or “chronic pain” should be based on clinically identifiable symptoms that may suggest specific neurotransmitter(s) involved in a specific type of each of these conditions. However, there are no well-recognized, well-established, reliable, or validated syndromes described in this series. The collection of symptoms associated with the various neurotransmitters described in this series is not complete. We have assembled what is described in the literature as a suggestion for future research.

Bottom Line

Both high and low levels of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate may be associated with certain psychiatric and medical symptoms and disorders. An astute clinician may judge which neurotransmitter is dysfunctional based on the patient’s presentation, and tailor treatment accordingly.

Related Resources

- Arbuck DM, Salmerón JM, Mueller R. Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: a hypothesis (part 1). Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(5):30-36. doi:10.12788/cp.0242

- Arbuck DM, Salmerón JM, Mueller R. Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: a hypothesis (part 2). Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):28-33. doi:10.12788/cp.0253

Drug Brand Names

Acamprostate • Campral

Amantadine • Gocovri

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clonidine • Catapres

Diazepam • Valium

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Ketamine • Ketalar

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Concerta

Morphine • Kadian

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Tizanidine • Zanaflex

1. Petroff OA. GABA and glutamate in the human brain. Neuroscientist. 2002;8(6):562-573.

2. Winkelman JW, Buxton OM, Jensen JE, et al. Reduced brain GABA in primary insomnia: preliminary data from 4T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Sleep. 2008;31(11):1499-1506.

3. Pereira AC, Mao X, Jiang CS, et al. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex GABA deficit in older adults with sleep-disordered breathing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(38):10250-10255.

4. Schür RR, Draisma LW, Wijnen JP, et al. Brain GABA levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of (1) H-MRS studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(9):3337-3352.

5. Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR. Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin. Drugs. 2017;77(4):403-426.

6. Mersfelder TL, Nichols WH. Gabapentin: abuse, dependence, and withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(3):229-233.

7. Bremner JD. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):445-461.

8. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, et al. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability, and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392.

9. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2011:550-551,692-693.

10. Evrensel A, Ceylan ME. The gut-brain axis: the missing link in depression. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(3):239-244.

11. Vianello M, Tavolato B, Giometto B. Glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibodies and neurological disorders. Neurol Sci. 2002;23(4):145-151.

12. Marin O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(2):107-120.

13. Huang D, Liu D, Yin J, et al. Glutamate-glutamine and GABA in the brain of normal aged and patients with cognitive impairment. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(7):2698-2705.

14. Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, García-Martín E, et al. Neurochemical features of idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;45:70-87.

15. Mick I, Ramos AC, Myers J, et al. Evidence for GABA-A receptor dysregulation in gambling disorder: correlation with impulsivity. Addict Biol. 2017;22(6):1601-1609.

16. Brambilla P, Perez J, Barale F, et al. Gabaergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:721-737.

17. Kaneez FS, Saeed SA. Investigating GABA and its function in platelets as compared to neurons. Platelets. 2009;20(5):328-333.

18. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702.

19. Miranda A, Peles S, Rudolph C, et al. Altered visceral sensation in response to somatic pain in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1082-1089.

20. Skyba DA, King EW, Sluka KA. Effects of NMDA and non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on the development and maintenance of hyperalgesia induced by repeated intramuscular injection of acidic saline. Pain. 2002;98(1-2):69-78.

21. Holton KF, Taren DL, Thomson CA, et al. The effect of dietary glutamate on fibromyalgia and irritable bowel symptoms. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(6 Suppl 74):10-70.

22. Sekiya Y, Nakagawa T, Ozawa T, et al. Facilitation of morphine withdrawal symptoms and morphine-induced conditioned place preference by a glutamate transporter inhibitor DL-threo-beta-benzyloxy aspartate in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;485(1-3):201-210.

23. Bestha D, Soliman L, Blankenship K. et al. The walking wounded: emerging treatments for PTSD. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(10):94.

24. Tsuda M, Shimizu N, Suzuki T. Contribution of glutamate receptors to benzodiazepine withdrawal signs. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1999;81(1):1-6.

25. Spravato [package insert]. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2019.

26. Mattingly GW, Anderson RH. Intranasal ketamine. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(5):31-38.

27. Buckingham SC, Campbell SL, Haas BR, et al. Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1269-1275.

28. Ferrari A, Spaccapelo L, Pinetti D, et al. Effective prophylactic treatment of migraines lower plasma glutamate levels. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(4):423-429.

29. Vieira DS, Naffah-Mazzacoratti Mda G, Zukerman E, et al. Glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid and triptans overuse in chronic migraine. Headache. 2007;47(6):842-847.

30. Chan K, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Glutamate receptor antagonists in the management of migraine. Drugs. 2014;74:1165-1176.

31. Pappa S, Tsouli S, Apostolou G, et al. Effects of amantadine on tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):271-275.

32. Kraal AZ, Arvanitis NR, Jaeger AP, et al. Could dietary glutamate play a role in psychiatric distress? Neuro Psych. 2020;79:13-19.

33. Levite M. Glutamate receptor antibodies in neurological diseases: anti-AMPA-GluR3 antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR1 antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR2A/B antibodies, Anti-mGluR1 antibodies or Anti-mGluR5 antibodies are present in subpopulations of patients with either: epilepsy, encephalitis, cerebellar ataxia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and neuropsychiatric SLE, Sjogren’s syndrome, schizophrenia, mania or stroke. These autoimmune anti-glutamate receptor antibodies can bind neurons in few brain regions, activate glutamate receptors, decrease glutamate receptor’s expression, impair glutamate-induced signaling and function, activate blood brain barrier endothelial cells, kill neurons, damage the brain, induce behavioral/psychiatric/cognitive abnormalities and ataxia in animal models, and can be removed or silenced in some patients by immunotherapy. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2014;121(8):1029-1075.

34. Lancaster E. CNS syndromes associated with antibodies against metabotropic receptors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:354-360.

35. Sillevis Smitt P, Kinoshita A, De Leeuw B, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia due to autoantibodies against a glutamate receptor. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(1):21-27.

36. Marignier R, Chenevier F, Rogemond V, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1 autoantibody-associated cerebellitis: a primary autoimmune disease? Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):627-630.

37. Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Titulaer MJ, et al. Antibodies to metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the Ophelia syndrome. Neurology. 2011;77:1698-1701.

38. Mat A, Adler H, Merwick A, et al. Ophelia syndrome with metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antibodies in CSF. Neurology. 2013;80(14):1349-1350.

1. Petroff OA. GABA and glutamate in the human brain. Neuroscientist. 2002;8(6):562-573.

2. Winkelman JW, Buxton OM, Jensen JE, et al. Reduced brain GABA in primary insomnia: preliminary data from 4T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Sleep. 2008;31(11):1499-1506.

3. Pereira AC, Mao X, Jiang CS, et al. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex GABA deficit in older adults with sleep-disordered breathing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(38):10250-10255.

4. Schür RR, Draisma LW, Wijnen JP, et al. Brain GABA levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of (1) H-MRS studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(9):3337-3352.

5. Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR. Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin. Drugs. 2017;77(4):403-426.

6. Mersfelder TL, Nichols WH. Gabapentin: abuse, dependence, and withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(3):229-233.

7. Bremner JD. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):445-461.

8. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, et al. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability, and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392.

9. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2011:550-551,692-693.

10. Evrensel A, Ceylan ME. The gut-brain axis: the missing link in depression. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(3):239-244.

11. Vianello M, Tavolato B, Giometto B. Glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibodies and neurological disorders. Neurol Sci. 2002;23(4):145-151.

12. Marin O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(2):107-120.

13. Huang D, Liu D, Yin J, et al. Glutamate-glutamine and GABA in the brain of normal aged and patients with cognitive impairment. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(7):2698-2705.

14. Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, García-Martín E, et al. Neurochemical features of idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;45:70-87.

15. Mick I, Ramos AC, Myers J, et al. Evidence for GABA-A receptor dysregulation in gambling disorder: correlation with impulsivity. Addict Biol. 2017;22(6):1601-1609.

16. Brambilla P, Perez J, Barale F, et al. Gabaergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:721-737.

17. Kaneez FS, Saeed SA. Investigating GABA and its function in platelets as compared to neurons. Platelets. 2009;20(5):328-333.

18. Paholpak P, Mendez MF. Trichotillomania as a manifestation of dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2016;2016:9782702.

19. Miranda A, Peles S, Rudolph C, et al. Altered visceral sensation in response to somatic pain in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1082-1089.

20. Skyba DA, King EW, Sluka KA. Effects of NMDA and non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on the development and maintenance of hyperalgesia induced by repeated intramuscular injection of acidic saline. Pain. 2002;98(1-2):69-78.

21. Holton KF, Taren DL, Thomson CA, et al. The effect of dietary glutamate on fibromyalgia and irritable bowel symptoms. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(6 Suppl 74):10-70.

22. Sekiya Y, Nakagawa T, Ozawa T, et al. Facilitation of morphine withdrawal symptoms and morphine-induced conditioned place preference by a glutamate transporter inhibitor DL-threo-beta-benzyloxy aspartate in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;485(1-3):201-210.

23. Bestha D, Soliman L, Blankenship K. et al. The walking wounded: emerging treatments for PTSD. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(10):94.

24. Tsuda M, Shimizu N, Suzuki T. Contribution of glutamate receptors to benzodiazepine withdrawal signs. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1999;81(1):1-6.

25. Spravato [package insert]. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2019.

26. Mattingly GW, Anderson RH. Intranasal ketamine. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(5):31-38.

27. Buckingham SC, Campbell SL, Haas BR, et al. Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1269-1275.

28. Ferrari A, Spaccapelo L, Pinetti D, et al. Effective prophylactic treatment of migraines lower plasma glutamate levels. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(4):423-429.

29. Vieira DS, Naffah-Mazzacoratti Mda G, Zukerman E, et al. Glutamate levels in cerebrospinal fluid and triptans overuse in chronic migraine. Headache. 2007;47(6):842-847.

30. Chan K, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Glutamate receptor antagonists in the management of migraine. Drugs. 2014;74:1165-1176.

31. Pappa S, Tsouli S, Apostolou G, et al. Effects of amantadine on tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):271-275.

32. Kraal AZ, Arvanitis NR, Jaeger AP, et al. Could dietary glutamate play a role in psychiatric distress? Neuro Psych. 2020;79:13-19.

33. Levite M. Glutamate receptor antibodies in neurological diseases: anti-AMPA-GluR3 antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR1 antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR2A/B antibodies, Anti-mGluR1 antibodies or Anti-mGluR5 antibodies are present in subpopulations of patients with either: epilepsy, encephalitis, cerebellar ataxia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and neuropsychiatric SLE, Sjogren’s syndrome, schizophrenia, mania or stroke. These autoimmune anti-glutamate receptor antibodies can bind neurons in few brain regions, activate glutamate receptors, decrease glutamate receptor’s expression, impair glutamate-induced signaling and function, activate blood brain barrier endothelial cells, kill neurons, damage the brain, induce behavioral/psychiatric/cognitive abnormalities and ataxia in animal models, and can be removed or silenced in some patients by immunotherapy. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2014;121(8):1029-1075.

34. Lancaster E. CNS syndromes associated with antibodies against metabotropic receptors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:354-360.

35. Sillevis Smitt P, Kinoshita A, De Leeuw B, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia due to autoantibodies against a glutamate receptor. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(1):21-27.

36. Marignier R, Chenevier F, Rogemond V, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1 autoantibody-associated cerebellitis: a primary autoimmune disease? Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):627-630.

37. Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Titulaer MJ, et al. Antibodies to metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the Ophelia syndrome. Neurology. 2011;77:1698-1701.

38. Mat A, Adler H, Merwick A, et al. Ophelia syndrome with metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antibodies in CSF. Neurology. 2013;80(14):1349-1350.

3 steps to bend the curve of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

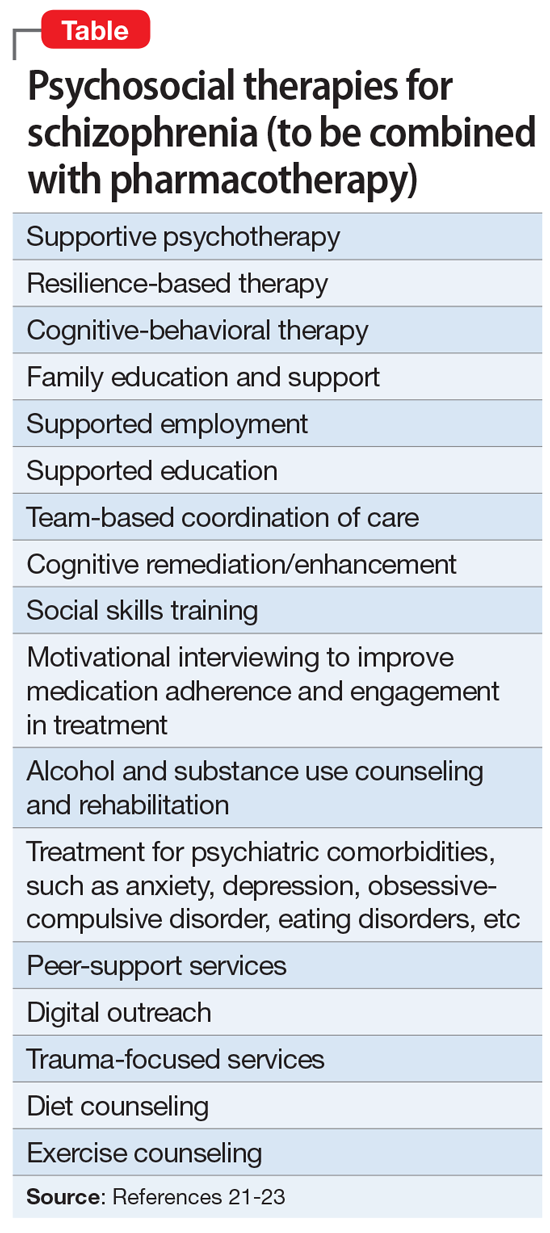

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

1. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

2. Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95.

3. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372.

4. Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057

5. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

6. Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Primary nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):665-663.

7. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

8. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

9. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

10. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic doses for relapse prevention in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in Finland: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):271-279.

11. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):38-45,e3.

12. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

13. Feigenson KA, Kusnecov AW, Silverstein SM. Inflammation and the two-hit hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:72-93.

14. Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):400-409.

15. Lavoie S, Polari AR, Goldstone S, et al. Staging model in psychiatry: review of the evolution of electroencephalography abnormalities in major psychiatric disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(6):1319-1328.

16. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

17. Lin YH, Wu CS, Liu CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in preventing readmission for first-admission schizophrenia patients in national cohorts from 2001 to 2017 in Taiwan. Schizophr Bull. 2022;sbac046. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbac046

18. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

21. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

22. Keshavan MS, Ongur D, Srihari VH. Toward an expanded and personalized approach to coordinated specialty care in early course psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:119-121.

23. Srihari VH, Keshavan MS. Early intervention services for schizophrenia: looking back and looking ahead. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):544-550.

24. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

25. Nasrallah HA. Clozapine is a vastly underutilized, unique agent with multiple applications. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(10):21,24-25.

26. CureSZ Foundation. Clozapine success stories. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://curesz.org/clozapine-success-stories/

27. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.