User login

COMMENTARY—EXPEDITION3: A Winding Path to Nowhere

This new phase III trial of solanezumab reveals that the drug is not effective for patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, despite the hint that it was possibly effective based on post hoc analyses of earlier studies with this drug.

The findings expose the hazards of such post hoc analyses, typically done when the desired results are not observed, in the hope of squeezing lemonade from lemons. Although the subanalysis of patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease in the earlier studies suggested a 34% slowing of cognitive decline, as assessed by ADAS-Cog, an incremental slowing of 11% was seen in the new study that was not even statistically significant. While some secondary end points reached statistical significance, the slowing was so modest as to make no practical difference clinically.

I cannot emphasize enough that such equivocal results as seen in EXPEDITION3 do absolutely nothing to either confirm or deny the amyloid hypothesis. By now, there have been so many of these studies with antiamyloid agents, with little or no hint of efficacy, that we have long passed the definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over in the hope of getting a different result.

The combination of all these clinical trial failures with the result of imaging studies that have shown amyloid deposition some 20 years before the expected onset of symptoms clearly tells us that antiamyloid agents should only be considered as potential prophylactics. By the time symptoms appear, disease progression is largely independent of amyloid and may be primarily tau-driven, spreading from neuron to neuron even when amyloid is effectively targeted by therapeutics. Even the A4 and DIAN studies are likely initiating treatment too late to make anything more than a modest effect with little practical value clinically. I am not suggesting that we drop amyloid as a target, only that we stop making these incremental changes in clinical trial design in the hope of getting a different result.

—Michael S. Wolfe, PhD

Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry

University of Kansas, Lawrence

This new phase III trial of solanezumab reveals that the drug is not effective for patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, despite the hint that it was possibly effective based on post hoc analyses of earlier studies with this drug.

The findings expose the hazards of such post hoc analyses, typically done when the desired results are not observed, in the hope of squeezing lemonade from lemons. Although the subanalysis of patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease in the earlier studies suggested a 34% slowing of cognitive decline, as assessed by ADAS-Cog, an incremental slowing of 11% was seen in the new study that was not even statistically significant. While some secondary end points reached statistical significance, the slowing was so modest as to make no practical difference clinically.

I cannot emphasize enough that such equivocal results as seen in EXPEDITION3 do absolutely nothing to either confirm or deny the amyloid hypothesis. By now, there have been so many of these studies with antiamyloid agents, with little or no hint of efficacy, that we have long passed the definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over in the hope of getting a different result.

The combination of all these clinical trial failures with the result of imaging studies that have shown amyloid deposition some 20 years before the expected onset of symptoms clearly tells us that antiamyloid agents should only be considered as potential prophylactics. By the time symptoms appear, disease progression is largely independent of amyloid and may be primarily tau-driven, spreading from neuron to neuron even when amyloid is effectively targeted by therapeutics. Even the A4 and DIAN studies are likely initiating treatment too late to make anything more than a modest effect with little practical value clinically. I am not suggesting that we drop amyloid as a target, only that we stop making these incremental changes in clinical trial design in the hope of getting a different result.

—Michael S. Wolfe, PhD

Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry

University of Kansas, Lawrence

This new phase III trial of solanezumab reveals that the drug is not effective for patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, despite the hint that it was possibly effective based on post hoc analyses of earlier studies with this drug.

The findings expose the hazards of such post hoc analyses, typically done when the desired results are not observed, in the hope of squeezing lemonade from lemons. Although the subanalysis of patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease in the earlier studies suggested a 34% slowing of cognitive decline, as assessed by ADAS-Cog, an incremental slowing of 11% was seen in the new study that was not even statistically significant. While some secondary end points reached statistical significance, the slowing was so modest as to make no practical difference clinically.

I cannot emphasize enough that such equivocal results as seen in EXPEDITION3 do absolutely nothing to either confirm or deny the amyloid hypothesis. By now, there have been so many of these studies with antiamyloid agents, with little or no hint of efficacy, that we have long passed the definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over in the hope of getting a different result.

The combination of all these clinical trial failures with the result of imaging studies that have shown amyloid deposition some 20 years before the expected onset of symptoms clearly tells us that antiamyloid agents should only be considered as potential prophylactics. By the time symptoms appear, disease progression is largely independent of amyloid and may be primarily tau-driven, spreading from neuron to neuron even when amyloid is effectively targeted by therapeutics. Even the A4 and DIAN studies are likely initiating treatment too late to make anything more than a modest effect with little practical value clinically. I am not suggesting that we drop amyloid as a target, only that we stop making these incremental changes in clinical trial design in the hope of getting a different result.

—Michael S. Wolfe, PhD

Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry

University of Kansas, Lawrence

Preventing surgical site infections in hysterectomy

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

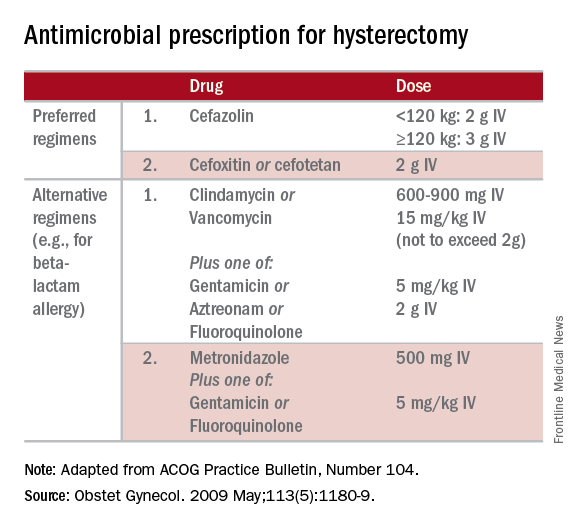

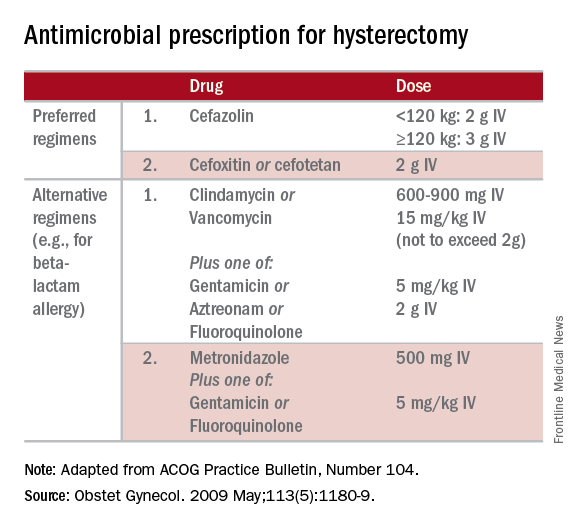

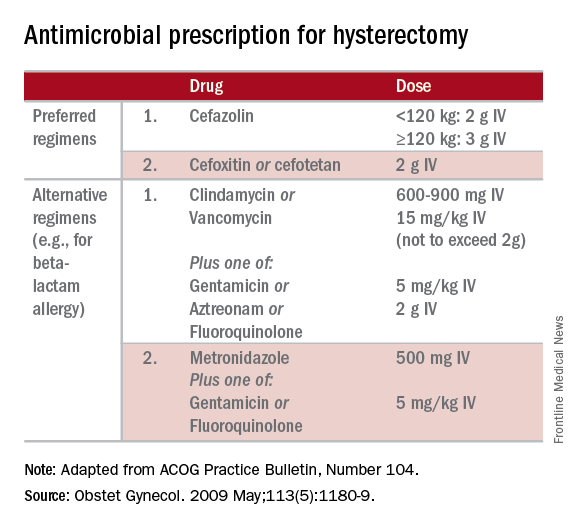

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Letters to the Editor: Benefit of self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel in IUD placement

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Letters to the Editor: Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

“DO YOU UTILIZE VASOPRESSIN IN YOUR DIFFICULT CESAREAN DELIVERY SURGERIES?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; NOVEMBER 2016)

Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

Thank you for your recent editorial discussing using vasopressin in difficult cesarean deliveries. I am very interested in using vasopressin for our placenta previa cases.

I reviewed the Kato et al article that Dr. Barbieri referenced, and the authors note a risk of injecting vasopressin into a vessel.1 If you are injecting into the placental bed, how can you confirm you are not in a vessel? (When you withdraw, you will get some blood regardless.)

Sara Garmel, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

REFERENCE

- Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1249–1256.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Garmel that we should avoid the intravascular injection of vasopressin. As I noted in the editorial, “I prefer to inject vasopressin in the subserosa of the uterus rather than inject it in a highly vascular area such as the subendometrium or near the uterine artery and vein.” Subserosal injection creates a depot bleb of vasopressin that is absorbed over a few minutes. You can visualize the reduced blood flow to the uterus following vasopressin injection because the uterus blanches and the diameter of the uterine vessels decreases significantly.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“DO YOU UTILIZE VASOPRESSIN IN YOUR DIFFICULT CESAREAN DELIVERY SURGERIES?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; NOVEMBER 2016)

Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

Thank you for your recent editorial discussing using vasopressin in difficult cesarean deliveries. I am very interested in using vasopressin for our placenta previa cases.

I reviewed the Kato et al article that Dr. Barbieri referenced, and the authors note a risk of injecting vasopressin into a vessel.1 If you are injecting into the placental bed, how can you confirm you are not in a vessel? (When you withdraw, you will get some blood regardless.)

Sara Garmel, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

REFERENCE

- Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1249–1256.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Garmel that we should avoid the intravascular injection of vasopressin. As I noted in the editorial, “I prefer to inject vasopressin in the subserosa of the uterus rather than inject it in a highly vascular area such as the subendometrium or near the uterine artery and vein.” Subserosal injection creates a depot bleb of vasopressin that is absorbed over a few minutes. You can visualize the reduced blood flow to the uterus following vasopressin injection because the uterus blanches and the diameter of the uterine vessels decreases significantly.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“DO YOU UTILIZE VASOPRESSIN IN YOUR DIFFICULT CESAREAN DELIVERY SURGERIES?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; NOVEMBER 2016)

Avoid uterine vessels when injecting vasopressin

Thank you for your recent editorial discussing using vasopressin in difficult cesarean deliveries. I am very interested in using vasopressin for our placenta previa cases.

I reviewed the Kato et al article that Dr. Barbieri referenced, and the authors note a risk of injecting vasopressin into a vessel.1 If you are injecting into the placental bed, how can you confirm you are not in a vessel? (When you withdraw, you will get some blood regardless.)

Sara Garmel, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

REFERENCE

- Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(5):1249–1256.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Garmel that we should avoid the intravascular injection of vasopressin. As I noted in the editorial, “I prefer to inject vasopressin in the subserosa of the uterus rather than inject it in a highly vascular area such as the subendometrium or near the uterine artery and vein.” Subserosal injection creates a depot bleb of vasopressin that is absorbed over a few minutes. You can visualize the reduced blood flow to the uterus following vasopressin injection because the uterus blanches and the diameter of the uterine vessels decreases significantly.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Letters to the Editor: Patient with a breast mass: Why did she pursue litigation?

“PATIENT WITH A BREAST MASS: WHY DID SHE PURSUE LITIGATION?”

JOSEPH S. SANFILIPPO, MD, MBA, AND STEVEN R. SMITH, JD (WHAT'S THE VERDICT?; DECEMBER 2016)

Clear communication is often key to avoiding litigation

Thank you for the article concerning the patient who commenced action for delay in diagnosis of her breast lesion. In my opinion the gynecologist lost control of the situation because of inadequate communication with the patient either on his or her part and/or on the part of the staff.

J. S. Calabrese, MD, JD

Buffalo, New York

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“PATIENT WITH A BREAST MASS: WHY DID SHE PURSUE LITIGATION?”

JOSEPH S. SANFILIPPO, MD, MBA, AND STEVEN R. SMITH, JD (WHAT'S THE VERDICT?; DECEMBER 2016)

Clear communication is often key to avoiding litigation

Thank you for the article concerning the patient who commenced action for delay in diagnosis of her breast lesion. In my opinion the gynecologist lost control of the situation because of inadequate communication with the patient either on his or her part and/or on the part of the staff.

J. S. Calabrese, MD, JD

Buffalo, New York

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“PATIENT WITH A BREAST MASS: WHY DID SHE PURSUE LITIGATION?”

JOSEPH S. SANFILIPPO, MD, MBA, AND STEVEN R. SMITH, JD (WHAT'S THE VERDICT?; DECEMBER 2016)

Clear communication is often key to avoiding litigation

Thank you for the article concerning the patient who commenced action for delay in diagnosis of her breast lesion. In my opinion the gynecologist lost control of the situation because of inadequate communication with the patient either on his or her part and/or on the part of the staff.

J. S. Calabrese, MD, JD

Buffalo, New York

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Point/Counterpoint: Is limb salvage always best in diabetes?

Salvage limbs at all costs

Aggressive limb salvage in people with diabetes leads to an overall reduction in cost not only economically, but also from the patient’s perspective. The vast majority of diabetic patients with critical ischemia are actually good candidates for limb salvage. Tragically, many of these patients are never referred for evaluation for limb salvage because of misconceptions about the pathophysiology of the disease.

An argument against limb salvage is that primary amputation prevents or shortens the course of wound care and enables patients to become ambulatory, albeit with a prosthesis, faster. However, in the modern era of vascular surgery, revascularization can be performed successfully with minimal mortality and excellent rates of limb salvage, especially when it’s done within a team-based approach.

The mortality in primary amputation is shockingly high, anywhere from 5% to 23% higher than revascularization alone, and the major complication rate of amputation associated with diabetes is also unacceptably high – up to 37%. This is in contrast to a 17% rate in major nonamputation vascular surgery and 1%-5% in endovascular procedures (BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:3).

We can’t ignore the economic burden this places on the country. In 2014, primary amputations cost the health care system $11 billion annually, and that is expected to grow to more than $25 billion in the next several years, according to the SAGE Group. It’s important to keep in mind that Medicare covers over 80% of this cost.

A number of studies have shown that conservative management with wound care and amputation is more cost effective than primary amputation in ambulatory, independent adults. Data can be difficult to interpret because of different recording strategies for all the costs associated with amputation, but a single-institution study concluded that revascularization costs almost $5,280 more than expectant management, but $33,900 less than primary amputation alone (Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7;62-9).

We must also consider the costs of revision after primary amputation; above-the-knee amputation has a 12% in-hospital revision rate, and below-the-knee amputation about 20%. Endovascular interventions, on the other hand, have a 1%-9% in-hospital revision rate, and only 2%-4% of these patients will go on to require an amputation during the same admission (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:484-90; Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:480-6).This does not include the costs of those complications as well as other indirect costs of amputation, such as nursing home care and living situation modification (Int J Behav Med. 2016;23:714-21; Pak J Med Sci. 2014; 30:1044-9). They quickly add up to that $25 billion.

The proponents of primary amputation tell us that it leads to quicker recovery time and an earlier time to ambulation. However, only 47% of patients will actually ambulate after amputation, in contrast to 97% who will ambulate after limb salvage as a primary procedure. In a nonambulatory cohort, 21% of those patients go on to regain functional status that was lost prior to surgery (J Vasc Surg. 1997;25;287-95).

Many question if our success with vascular surgery over the past few decades can translate to helping the most difficult subset of patients. An Italian study reported on a cohort of diabetic vs. nondiabetic patients and determined both groups have similar amputation-free rates after infrainguinal arterial reconstruction for critical limb ischemia, with excellent primary and secondary patency rates and a limb salvage rate of 88% at 5 years (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:708-19). This tells us that we do have the skill set necessary to save these limbs.

A multidisciplinary limb preservation team is paramount to the success of any limb salvage program. A revascularization team should be in place which uses early intervention to achieve the highest limb salvage rates possible. Wound care needs to be an integrated part of it. Advanced podiatric reconstructive surgery also is key because this can provide complex foot reconstructions and help ambulatory patients return home.

Dr. Trissa A. Babrowski is an assistant professor of surgery, specializing in vascular surgery and endovascular therapy, at the University of Chicago Heart and Vascular Center. She had no financial relationships to disclose.

Primary amputation can be OK

I am not an amputationalist. I do practice limb salvage. In fact I’m probably the most aggressive limb salvage surgeon in my hospital. But primary amputation is a completely acceptable option for a selected group of patients with diabetes. We should not try to do limb salvage “at all costs.”

I do not find this to be a contradictory position. In fact, I think it adds credence to my support of limb salvage that I think primary amputation can be OK. In all honesty, there are very few things in life that should be done at all costs.

A study out of Loma Linda University involving patients with CLI compared primary amputation vs. revascularization; 43% of patients had a primary amputation (Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:458-63). A multivariate analysis showed that patients with major tissue loss, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), diabetes and nonambulatory status were more likely to undergo primary amputation rather than revascularization.

While major tissue loss (Rutherford category 6) is certainly an indication for primary amputation, ambulatory status can represent a gray area in determining the best course. ESRD and diabetes are much more nonspecific factors; probably more than 10% of the patients that we see with CLI have ESRD. Also, 50%-70% of these patients with CLI, and in some series even higher percentages, have diabetes. Thus, these factors by themselves do not assist us in determining which patients potentially should be offered primary amputation vs. revascularization.

In general, we know that we can get good results in limb bypass or revascularization in patients with CLI: The PREVENT III multicenter trial, with the use of the vein as the conduit, showed 1-year limb salvage rates of 88% in these high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:742-51). However, one of the major risk factors that adversely affected outcome was ESRD.

We know that ESRD is a significant predictor of lowering our chances of saving a limb successfully. Knowing the cost of multiple continued episodes of revascularization in these patients prior to proceeding with an amputation, it’s intuitive that these patients would benefit from a more precise process in their treatment from the beginning. A number of papers have concluded that a primary amputation may be the preferred approach in patients with ESRD.

Can we preoperatively predict which patients with CLI will fail operative revascularization? Data from the New England Vascular Quality Initiative identified eight variables associated with failure of revascularization, among them age younger than 59, ESRD, diabetes, CLI, conduit requiring venovenostomy, tarsal target, and nursing home residence (Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:57-68). The presence of three or more risk factors has a 27.7% risk of limb loss and/or graft thrombosis within 1 year.

Postponing amputation is a major cost issue. Direct costs of bypass for critical limb ischemia were $3.6 billion in 2004 (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1021-31), and we know that a functional outcome can be problematic in this patient group. Factors associated with a poor functional outcome include dementia, dependent-living situation preoperatively and nonambulatory status.

Unfortunately, there are not a lot of data that deal with quality of life outcomes for patients with CLI who have undergone bypass. Using a point system comprised of dialysis (4 points), tissue loss (3 points), age above 75 (2 points), hematocrit less than or equal to 30 (2 points), and coronary artery disease (1 point), a follow-up study of patients in the PREVENT III trial found that a high-risk group (greater than or equal to 8 points) had an amputation-free survival of only 45% (J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:769-75). Again, these results do not justify the effort and costs of limb salvage in this high-risk patient group.

We should consider the following options carefully in selecting a cost-effective patient-focused approach in patients with CLI: wound care, primary amputation, bypass revascularization, or endovascular revascularization. I would argue that the vascular surgeon who is qualified as an expert in all of the above is best positioned to select an appropriate plan of treatment based upon the patient’s risk factors, wound factors, ambulatory ability, pattern of disease, severity of ischemia, and living status.

Thus, upon presentation, a patient with CLI should undergo confirmatory tests and optimize his or her risk factors. The vascular surgeon then has the option, in discussion with the patient and family, to pursue an appropriate treatment plan inclusive of primary amputation – not one of limb salvage “at all costs.”

Primary amputation should be used in situations where there is dementia and nonambulatory status, and in patients who are poor candidates for revascularization because of high risk of failure and limited life expectancy. The recently developed WIfI (wound, ischemia, and foot infection) classification can also be utilized, as stage 4 WIfI classification is associated with high risk of limb loss – 38%-40% at 1 year.

Primary amputation is an option that can result in better care overall, and it is a cost-effective approach for a selected group of patients. We should not try to do limb salvage at all cost. Primary amputation, in selected patients, is OK.

Dr. Timothy J. Nypaver is head of vascular surgery at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Salvage limbs at all costs

Aggressive limb salvage in people with diabetes leads to an overall reduction in cost not only economically, but also from the patient’s perspective. The vast majority of diabetic patients with critical ischemia are actually good candidates for limb salvage. Tragically, many of these patients are never referred for evaluation for limb salvage because of misconceptions about the pathophysiology of the disease.

An argument against limb salvage is that primary amputation prevents or shortens the course of wound care and enables patients to become ambulatory, albeit with a prosthesis, faster. However, in the modern era of vascular surgery, revascularization can be performed successfully with minimal mortality and excellent rates of limb salvage, especially when it’s done within a team-based approach.

The mortality in primary amputation is shockingly high, anywhere from 5% to 23% higher than revascularization alone, and the major complication rate of amputation associated with diabetes is also unacceptably high – up to 37%. This is in contrast to a 17% rate in major nonamputation vascular surgery and 1%-5% in endovascular procedures (BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:3).

We can’t ignore the economic burden this places on the country. In 2014, primary amputations cost the health care system $11 billion annually, and that is expected to grow to more than $25 billion in the next several years, according to the SAGE Group. It’s important to keep in mind that Medicare covers over 80% of this cost.

A number of studies have shown that conservative management with wound care and amputation is more cost effective than primary amputation in ambulatory, independent adults. Data can be difficult to interpret because of different recording strategies for all the costs associated with amputation, but a single-institution study concluded that revascularization costs almost $5,280 more than expectant management, but $33,900 less than primary amputation alone (Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7;62-9).

We must also consider the costs of revision after primary amputation; above-the-knee amputation has a 12% in-hospital revision rate, and below-the-knee amputation about 20%. Endovascular interventions, on the other hand, have a 1%-9% in-hospital revision rate, and only 2%-4% of these patients will go on to require an amputation during the same admission (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:484-90; Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:480-6).This does not include the costs of those complications as well as other indirect costs of amputation, such as nursing home care and living situation modification (Int J Behav Med. 2016;23:714-21; Pak J Med Sci. 2014; 30:1044-9). They quickly add up to that $25 billion.

The proponents of primary amputation tell us that it leads to quicker recovery time and an earlier time to ambulation. However, only 47% of patients will actually ambulate after amputation, in contrast to 97% who will ambulate after limb salvage as a primary procedure. In a nonambulatory cohort, 21% of those patients go on to regain functional status that was lost prior to surgery (J Vasc Surg. 1997;25;287-95).

Many question if our success with vascular surgery over the past few decades can translate to helping the most difficult subset of patients. An Italian study reported on a cohort of diabetic vs. nondiabetic patients and determined both groups have similar amputation-free rates after infrainguinal arterial reconstruction for critical limb ischemia, with excellent primary and secondary patency rates and a limb salvage rate of 88% at 5 years (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:708-19). This tells us that we do have the skill set necessary to save these limbs.

A multidisciplinary limb preservation team is paramount to the success of any limb salvage program. A revascularization team should be in place which uses early intervention to achieve the highest limb salvage rates possible. Wound care needs to be an integrated part of it. Advanced podiatric reconstructive surgery also is key because this can provide complex foot reconstructions and help ambulatory patients return home.

Dr. Trissa A. Babrowski is an assistant professor of surgery, specializing in vascular surgery and endovascular therapy, at the University of Chicago Heart and Vascular Center. She had no financial relationships to disclose.

Primary amputation can be OK

I am not an amputationalist. I do practice limb salvage. In fact I’m probably the most aggressive limb salvage surgeon in my hospital. But primary amputation is a completely acceptable option for a selected group of patients with diabetes. We should not try to do limb salvage “at all costs.”

I do not find this to be a contradictory position. In fact, I think it adds credence to my support of limb salvage that I think primary amputation can be OK. In all honesty, there are very few things in life that should be done at all costs.

A study out of Loma Linda University involving patients with CLI compared primary amputation vs. revascularization; 43% of patients had a primary amputation (Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:458-63). A multivariate analysis showed that patients with major tissue loss, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), diabetes and nonambulatory status were more likely to undergo primary amputation rather than revascularization.

While major tissue loss (Rutherford category 6) is certainly an indication for primary amputation, ambulatory status can represent a gray area in determining the best course. ESRD and diabetes are much more nonspecific factors; probably more than 10% of the patients that we see with CLI have ESRD. Also, 50%-70% of these patients with CLI, and in some series even higher percentages, have diabetes. Thus, these factors by themselves do not assist us in determining which patients potentially should be offered primary amputation vs. revascularization.

In general, we know that we can get good results in limb bypass or revascularization in patients with CLI: The PREVENT III multicenter trial, with the use of the vein as the conduit, showed 1-year limb salvage rates of 88% in these high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:742-51). However, one of the major risk factors that adversely affected outcome was ESRD.

We know that ESRD is a significant predictor of lowering our chances of saving a limb successfully. Knowing the cost of multiple continued episodes of revascularization in these patients prior to proceeding with an amputation, it’s intuitive that these patients would benefit from a more precise process in their treatment from the beginning. A number of papers have concluded that a primary amputation may be the preferred approach in patients with ESRD.

Can we preoperatively predict which patients with CLI will fail operative revascularization? Data from the New England Vascular Quality Initiative identified eight variables associated with failure of revascularization, among them age younger than 59, ESRD, diabetes, CLI, conduit requiring venovenostomy, tarsal target, and nursing home residence (Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:57-68). The presence of three or more risk factors has a 27.7% risk of limb loss and/or graft thrombosis within 1 year.

Postponing amputation is a major cost issue. Direct costs of bypass for critical limb ischemia were $3.6 billion in 2004 (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1021-31), and we know that a functional outcome can be problematic in this patient group. Factors associated with a poor functional outcome include dementia, dependent-living situation preoperatively and nonambulatory status.

Unfortunately, there are not a lot of data that deal with quality of life outcomes for patients with CLI who have undergone bypass. Using a point system comprised of dialysis (4 points), tissue loss (3 points), age above 75 (2 points), hematocrit less than or equal to 30 (2 points), and coronary artery disease (1 point), a follow-up study of patients in the PREVENT III trial found that a high-risk group (greater than or equal to 8 points) had an amputation-free survival of only 45% (J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:769-75). Again, these results do not justify the effort and costs of limb salvage in this high-risk patient group.

We should consider the following options carefully in selecting a cost-effective patient-focused approach in patients with CLI: wound care, primary amputation, bypass revascularization, or endovascular revascularization. I would argue that the vascular surgeon who is qualified as an expert in all of the above is best positioned to select an appropriate plan of treatment based upon the patient’s risk factors, wound factors, ambulatory ability, pattern of disease, severity of ischemia, and living status.

Thus, upon presentation, a patient with CLI should undergo confirmatory tests and optimize his or her risk factors. The vascular surgeon then has the option, in discussion with the patient and family, to pursue an appropriate treatment plan inclusive of primary amputation – not one of limb salvage “at all costs.”

Primary amputation should be used in situations where there is dementia and nonambulatory status, and in patients who are poor candidates for revascularization because of high risk of failure and limited life expectancy. The recently developed WIfI (wound, ischemia, and foot infection) classification can also be utilized, as stage 4 WIfI classification is associated with high risk of limb loss – 38%-40% at 1 year.

Primary amputation is an option that can result in better care overall, and it is a cost-effective approach for a selected group of patients. We should not try to do limb salvage at all cost. Primary amputation, in selected patients, is OK.

Dr. Timothy J. Nypaver is head of vascular surgery at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Salvage limbs at all costs

Aggressive limb salvage in people with diabetes leads to an overall reduction in cost not only economically, but also from the patient’s perspective. The vast majority of diabetic patients with critical ischemia are actually good candidates for limb salvage. Tragically, many of these patients are never referred for evaluation for limb salvage because of misconceptions about the pathophysiology of the disease.

An argument against limb salvage is that primary amputation prevents or shortens the course of wound care and enables patients to become ambulatory, albeit with a prosthesis, faster. However, in the modern era of vascular surgery, revascularization can be performed successfully with minimal mortality and excellent rates of limb salvage, especially when it’s done within a team-based approach.

The mortality in primary amputation is shockingly high, anywhere from 5% to 23% higher than revascularization alone, and the major complication rate of amputation associated with diabetes is also unacceptably high – up to 37%. This is in contrast to a 17% rate in major nonamputation vascular surgery and 1%-5% in endovascular procedures (BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:3).

We can’t ignore the economic burden this places on the country. In 2014, primary amputations cost the health care system $11 billion annually, and that is expected to grow to more than $25 billion in the next several years, according to the SAGE Group. It’s important to keep in mind that Medicare covers over 80% of this cost.

A number of studies have shown that conservative management with wound care and amputation is more cost effective than primary amputation in ambulatory, independent adults. Data can be difficult to interpret because of different recording strategies for all the costs associated with amputation, but a single-institution study concluded that revascularization costs almost $5,280 more than expectant management, but $33,900 less than primary amputation alone (Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7;62-9).

We must also consider the costs of revision after primary amputation; above-the-knee amputation has a 12% in-hospital revision rate, and below-the-knee amputation about 20%. Endovascular interventions, on the other hand, have a 1%-9% in-hospital revision rate, and only 2%-4% of these patients will go on to require an amputation during the same admission (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:484-90; Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:480-6).This does not include the costs of those complications as well as other indirect costs of amputation, such as nursing home care and living situation modification (Int J Behav Med. 2016;23:714-21; Pak J Med Sci. 2014; 30:1044-9). They quickly add up to that $25 billion.

The proponents of primary amputation tell us that it leads to quicker recovery time and an earlier time to ambulation. However, only 47% of patients will actually ambulate after amputation, in contrast to 97% who will ambulate after limb salvage as a primary procedure. In a nonambulatory cohort, 21% of those patients go on to regain functional status that was lost prior to surgery (J Vasc Surg. 1997;25;287-95).

Many question if our success with vascular surgery over the past few decades can translate to helping the most difficult subset of patients. An Italian study reported on a cohort of diabetic vs. nondiabetic patients and determined both groups have similar amputation-free rates after infrainguinal arterial reconstruction for critical limb ischemia, with excellent primary and secondary patency rates and a limb salvage rate of 88% at 5 years (J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:708-19). This tells us that we do have the skill set necessary to save these limbs.

A multidisciplinary limb preservation team is paramount to the success of any limb salvage program. A revascularization team should be in place which uses early intervention to achieve the highest limb salvage rates possible. Wound care needs to be an integrated part of it. Advanced podiatric reconstructive surgery also is key because this can provide complex foot reconstructions and help ambulatory patients return home.

Dr. Trissa A. Babrowski is an assistant professor of surgery, specializing in vascular surgery and endovascular therapy, at the University of Chicago Heart and Vascular Center. She had no financial relationships to disclose.

Primary amputation can be OK

I am not an amputationalist. I do practice limb salvage. In fact I’m probably the most aggressive limb salvage surgeon in my hospital. But primary amputation is a completely acceptable option for a selected group of patients with diabetes. We should not try to do limb salvage “at all costs.”

I do not find this to be a contradictory position. In fact, I think it adds credence to my support of limb salvage that I think primary amputation can be OK. In all honesty, there are very few things in life that should be done at all costs.

A study out of Loma Linda University involving patients with CLI compared primary amputation vs. revascularization; 43% of patients had a primary amputation (Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:458-63). A multivariate analysis showed that patients with major tissue loss, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), diabetes and nonambulatory status were more likely to undergo primary amputation rather than revascularization.

While major tissue loss (Rutherford category 6) is certainly an indication for primary amputation, ambulatory status can represent a gray area in determining the best course. ESRD and diabetes are much more nonspecific factors; probably more than 10% of the patients that we see with CLI have ESRD. Also, 50%-70% of these patients with CLI, and in some series even higher percentages, have diabetes. Thus, these factors by themselves do not assist us in determining which patients potentially should be offered primary amputation vs. revascularization.

In general, we know that we can get good results in limb bypass or revascularization in patients with CLI: The PREVENT III multicenter trial, with the use of the vein as the conduit, showed 1-year limb salvage rates of 88% in these high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:742-51). However, one of the major risk factors that adversely affected outcome was ESRD.

We know that ESRD is a significant predictor of lowering our chances of saving a limb successfully. Knowing the cost of multiple continued episodes of revascularization in these patients prior to proceeding with an amputation, it’s intuitive that these patients would benefit from a more precise process in their treatment from the beginning. A number of papers have concluded that a primary amputation may be the preferred approach in patients with ESRD.

Can we preoperatively predict which patients with CLI will fail operative revascularization? Data from the New England Vascular Quality Initiative identified eight variables associated with failure of revascularization, among them age younger than 59, ESRD, diabetes, CLI, conduit requiring venovenostomy, tarsal target, and nursing home residence (Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:57-68). The presence of three or more risk factors has a 27.7% risk of limb loss and/or graft thrombosis within 1 year.

Postponing amputation is a major cost issue. Direct costs of bypass for critical limb ischemia were $3.6 billion in 2004 (J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1021-31), and we know that a functional outcome can be problematic in this patient group. Factors associated with a poor functional outcome include dementia, dependent-living situation preoperatively and nonambulatory status.

Unfortunately, there are not a lot of data that deal with quality of life outcomes for patients with CLI who have undergone bypass. Using a point system comprised of dialysis (4 points), tissue loss (3 points), age above 75 (2 points), hematocrit less than or equal to 30 (2 points), and coronary artery disease (1 point), a follow-up study of patients in the PREVENT III trial found that a high-risk group (greater than or equal to 8 points) had an amputation-free survival of only 45% (J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:769-75). Again, these results do not justify the effort and costs of limb salvage in this high-risk patient group.

We should consider the following options carefully in selecting a cost-effective patient-focused approach in patients with CLI: wound care, primary amputation, bypass revascularization, or endovascular revascularization. I would argue that the vascular surgeon who is qualified as an expert in all of the above is best positioned to select an appropriate plan of treatment based upon the patient’s risk factors, wound factors, ambulatory ability, pattern of disease, severity of ischemia, and living status.

Thus, upon presentation, a patient with CLI should undergo confirmatory tests and optimize his or her risk factors. The vascular surgeon then has the option, in discussion with the patient and family, to pursue an appropriate treatment plan inclusive of primary amputation – not one of limb salvage “at all costs.”

Primary amputation should be used in situations where there is dementia and nonambulatory status, and in patients who are poor candidates for revascularization because of high risk of failure and limited life expectancy. The recently developed WIfI (wound, ischemia, and foot infection) classification can also be utilized, as stage 4 WIfI classification is associated with high risk of limb loss – 38%-40% at 1 year.

Primary amputation is an option that can result in better care overall, and it is a cost-effective approach for a selected group of patients. We should not try to do limb salvage at all cost. Primary amputation, in selected patients, is OK.

Dr. Timothy J. Nypaver is head of vascular surgery at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Transition to adult epilepsy care done right

Has this ever happened to you? You are an adult neurologist who has been asked to take on the care of a pediatric neurology patient. The patient who comes to your clinic is a 20-year-old young woman with a history of moderate developmental delay and intractable epilepsy. She is on numerous medications including valproic acid with a previous trial of the ketogenic diet. You receive a report that she has focal epilepsy and is having frequent seizures and last had an MRI at age 2 years. Prior notes talk about her summer vacations but not much about the future plans for her epilepsy. You see the patient in clinic, and the family is not happy to be in the adult clinic. They are disappointed that you don’t spend more time with them or fill out myriad forms. You find out that they have not obtained legal guardianship for their daughter and have no plan for work placement after school. She also has various other medical comorbidities that were previously addressed by the pediatric neurologist.

There is a not much evidence on the right way to do this. In 2013, the American Epilepsy Society approved a Transition Tool that is helpful in outlining the steps for a successful transition, and in 2016, the Child Neurology Foundation put forth a consensus statement with eight principles to guide a successful transition. Transitions are an expectation of good care and they recommend that a written policy be present for all offices.

Talking about transitioning should start as early as 10-12 years of age and should be discussed every year. Thinking about prognosis and a realistic plan for each child as they enter adult life is important. Patients and families should be able to understand how the disease affects them, what their medications are and how to independently obtain them, what comorbidities are associated with their disease, how to stay healthy, how to improve their quality of life, and how to advocate for themselves. As children become teenagers they should have a concrete plan for ongoing education, work, women’s issues, and an understanding of decision-making capacity and whether legal guardianship or a power of attorney needs to be implemented.

, even if they are still seen in the pediatric setting. A transition packet should be created that includes a summary of the diagnosis, work-up, previous treatments, and considerations for future treatments and emergency care. Also included is a plan for who will continue to address any non–seizure-related diagnoses the pediatric neurologist may have been managing. The patient and family also have an opportunity to review and contribute to this. This packet enables the adult neurologist to easily understand all issues and assume care of the patient, easing this aspect of the transition.

An advance meeting of the patient and family with the adult provider should be arranged whenever possible. To address this, some centers are now creating a transition clinic staffed by both pediatric and adult neurologists and/or nurses. This ideally takes place in the adult setting and is an excellent way to smooth the transition for the patient, family, and providers. Good transition is important to help prevent gaps in care, avoid reinventing the wheel, and improve satisfaction for everyone involved (patient, family, nurses, and neurologists). The key points are that transition discussions start early, patients and families should be involved and empowered in the process, and the creation of a transition packet for the adult provider is very helpful. Care transitions are something we will be hearing a lot more about in the upcoming years. And, hopefully, next time, the patient scenario seen above will go more smoothly!

Dr. Felton is an epilepsy specialist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and Dr. Kelley is director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Monitoring Unit at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. This editorial reflects the content of a presentation given by Dr. Felton and Dr. Kelley at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society in Houston. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Has this ever happened to you? You are an adult neurologist who has been asked to take on the care of a pediatric neurology patient. The patient who comes to your clinic is a 20-year-old young woman with a history of moderate developmental delay and intractable epilepsy. She is on numerous medications including valproic acid with a previous trial of the ketogenic diet. You receive a report that she has focal epilepsy and is having frequent seizures and last had an MRI at age 2 years. Prior notes talk about her summer vacations but not much about the future plans for her epilepsy. You see the patient in clinic, and the family is not happy to be in the adult clinic. They are disappointed that you don’t spend more time with them or fill out myriad forms. You find out that they have not obtained legal guardianship for their daughter and have no plan for work placement after school. She also has various other medical comorbidities that were previously addressed by the pediatric neurologist.

There is a not much evidence on the right way to do this. In 2013, the American Epilepsy Society approved a Transition Tool that is helpful in outlining the steps for a successful transition, and in 2016, the Child Neurology Foundation put forth a consensus statement with eight principles to guide a successful transition. Transitions are an expectation of good care and they recommend that a written policy be present for all offices.

Talking about transitioning should start as early as 10-12 years of age and should be discussed every year. Thinking about prognosis and a realistic plan for each child as they enter adult life is important. Patients and families should be able to understand how the disease affects them, what their medications are and how to independently obtain them, what comorbidities are associated with their disease, how to stay healthy, how to improve their quality of life, and how to advocate for themselves. As children become teenagers they should have a concrete plan for ongoing education, work, women’s issues, and an understanding of decision-making capacity and whether legal guardianship or a power of attorney needs to be implemented.

, even if they are still seen in the pediatric setting. A transition packet should be created that includes a summary of the diagnosis, work-up, previous treatments, and considerations for future treatments and emergency care. Also included is a plan for who will continue to address any non–seizure-related diagnoses the pediatric neurologist may have been managing. The patient and family also have an opportunity to review and contribute to this. This packet enables the adult neurologist to easily understand all issues and assume care of the patient, easing this aspect of the transition.

An advance meeting of the patient and family with the adult provider should be arranged whenever possible. To address this, some centers are now creating a transition clinic staffed by both pediatric and adult neurologists and/or nurses. This ideally takes place in the adult setting and is an excellent way to smooth the transition for the patient, family, and providers. Good transition is important to help prevent gaps in care, avoid reinventing the wheel, and improve satisfaction for everyone involved (patient, family, nurses, and neurologists). The key points are that transition discussions start early, patients and families should be involved and empowered in the process, and the creation of a transition packet for the adult provider is very helpful. Care transitions are something we will be hearing a lot more about in the upcoming years. And, hopefully, next time, the patient scenario seen above will go more smoothly!

Dr. Felton is an epilepsy specialist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and Dr. Kelley is director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Monitoring Unit at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. This editorial reflects the content of a presentation given by Dr. Felton and Dr. Kelley at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society in Houston. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Has this ever happened to you? You are an adult neurologist who has been asked to take on the care of a pediatric neurology patient. The patient who comes to your clinic is a 20-year-old young woman with a history of moderate developmental delay and intractable epilepsy. She is on numerous medications including valproic acid with a previous trial of the ketogenic diet. You receive a report that she has focal epilepsy and is having frequent seizures and last had an MRI at age 2 years. Prior notes talk about her summer vacations but not much about the future plans for her epilepsy. You see the patient in clinic, and the family is not happy to be in the adult clinic. They are disappointed that you don’t spend more time with them or fill out myriad forms. You find out that they have not obtained legal guardianship for their daughter and have no plan for work placement after school. She also has various other medical comorbidities that were previously addressed by the pediatric neurologist.