User login

Video-Based Coaching for Dermatology Resident Surgical Education

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

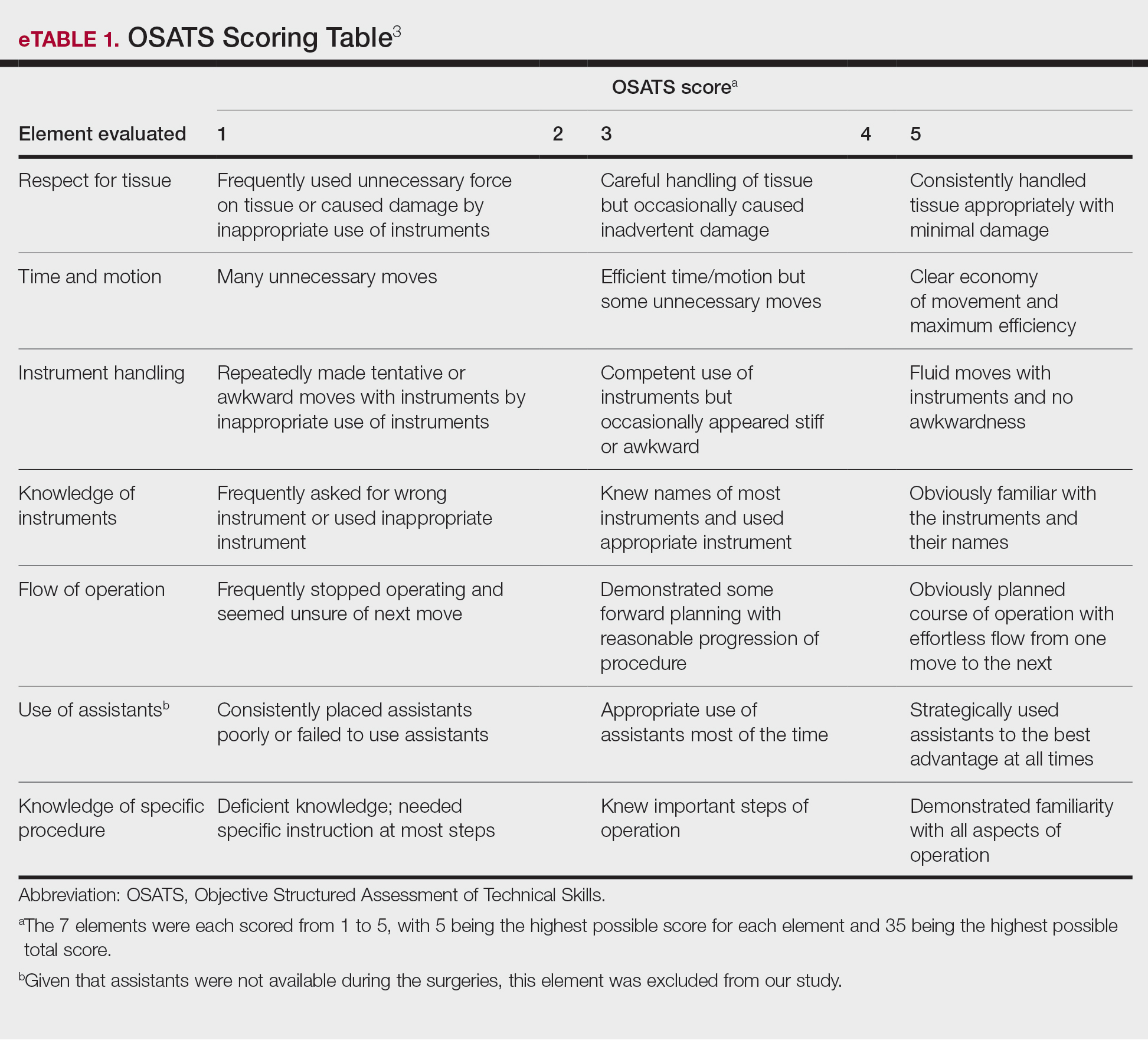

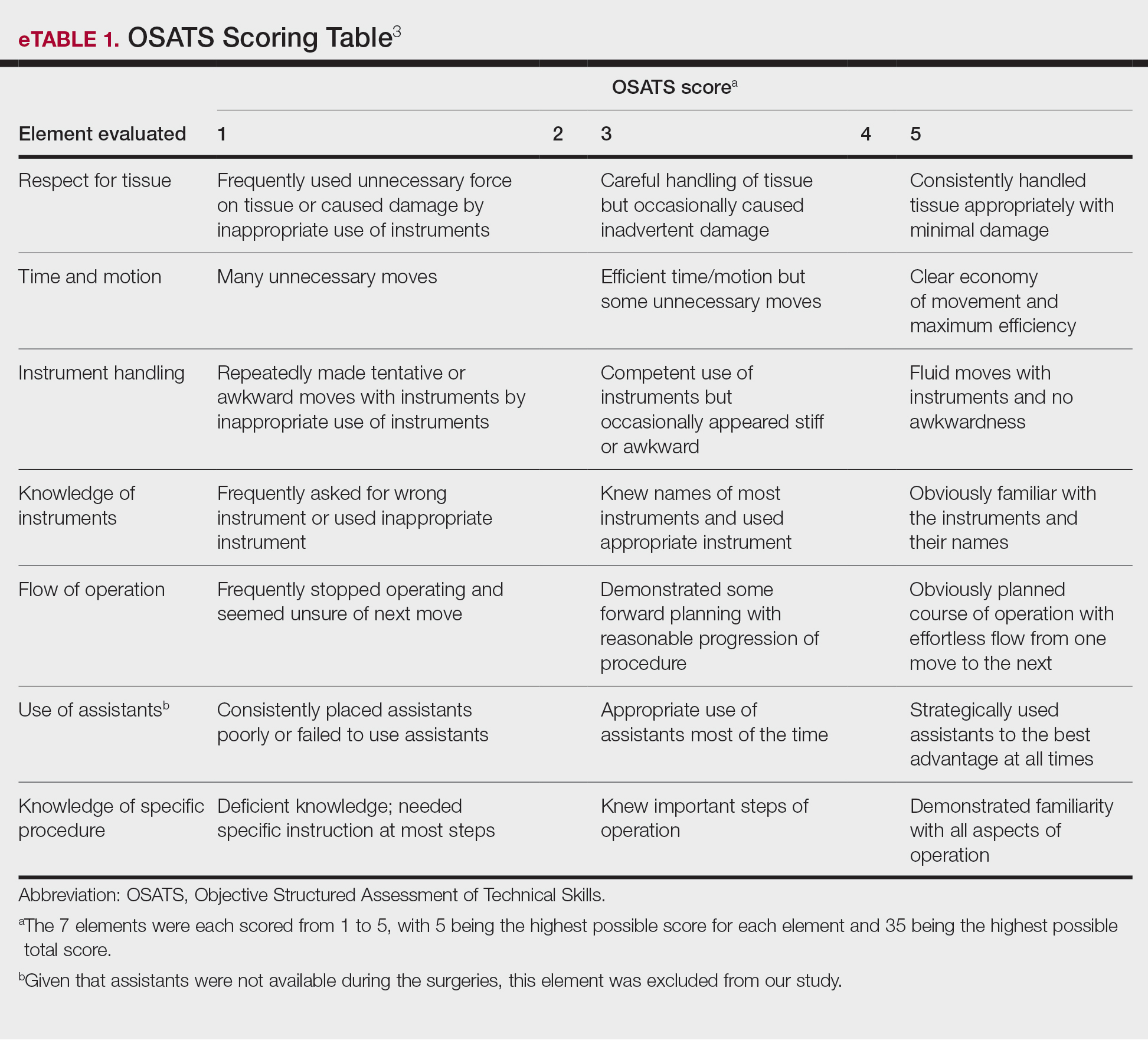

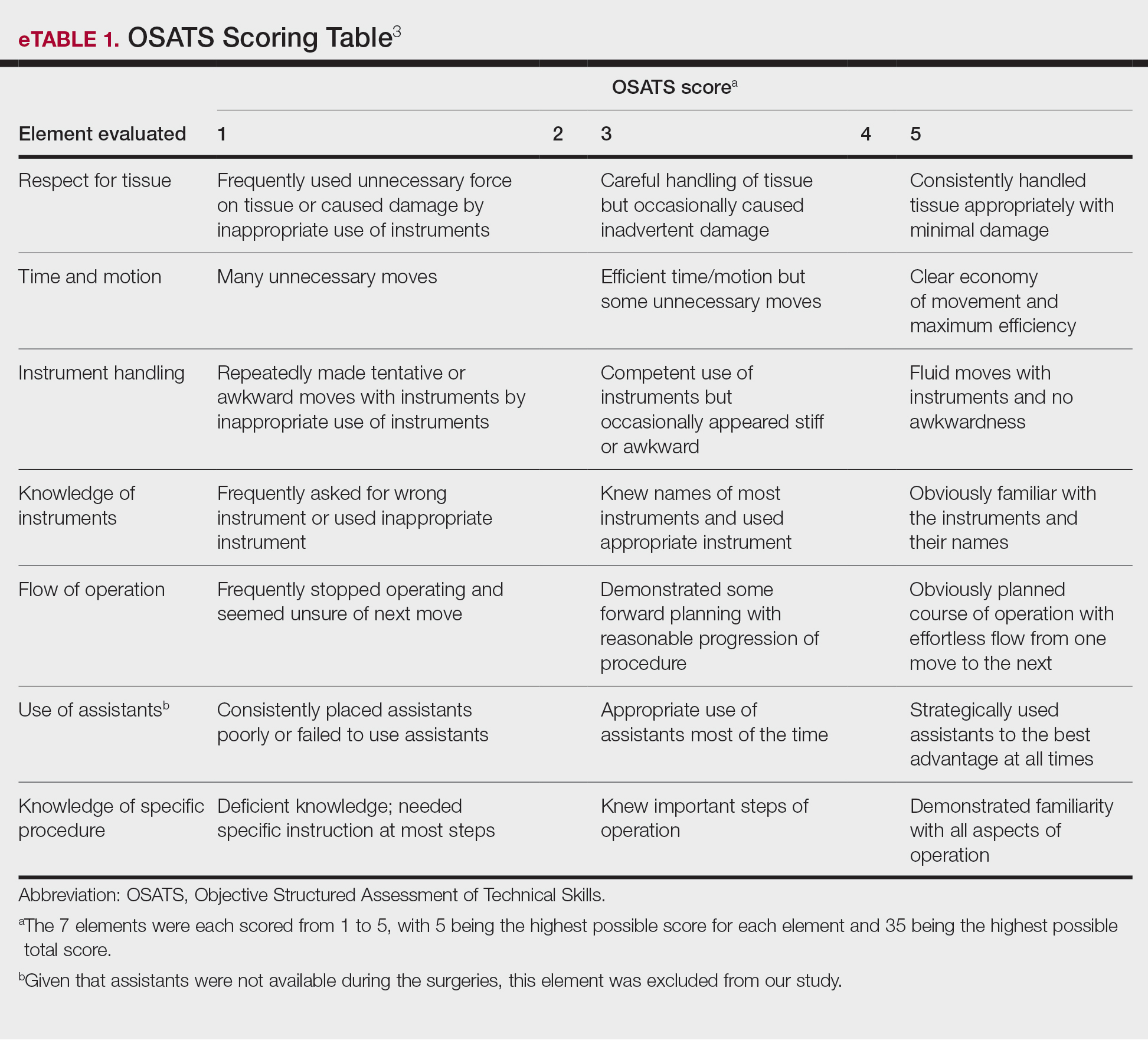

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

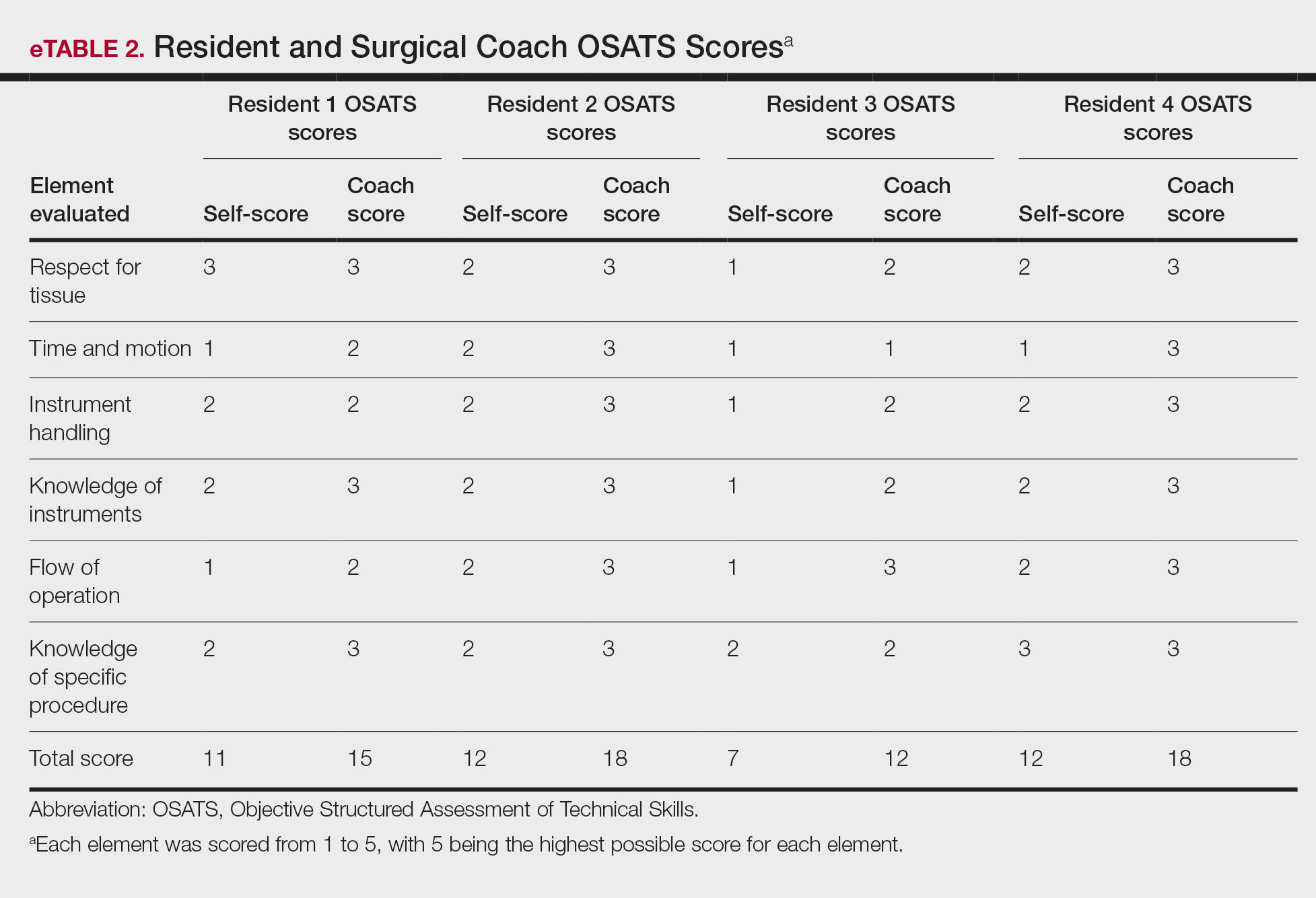

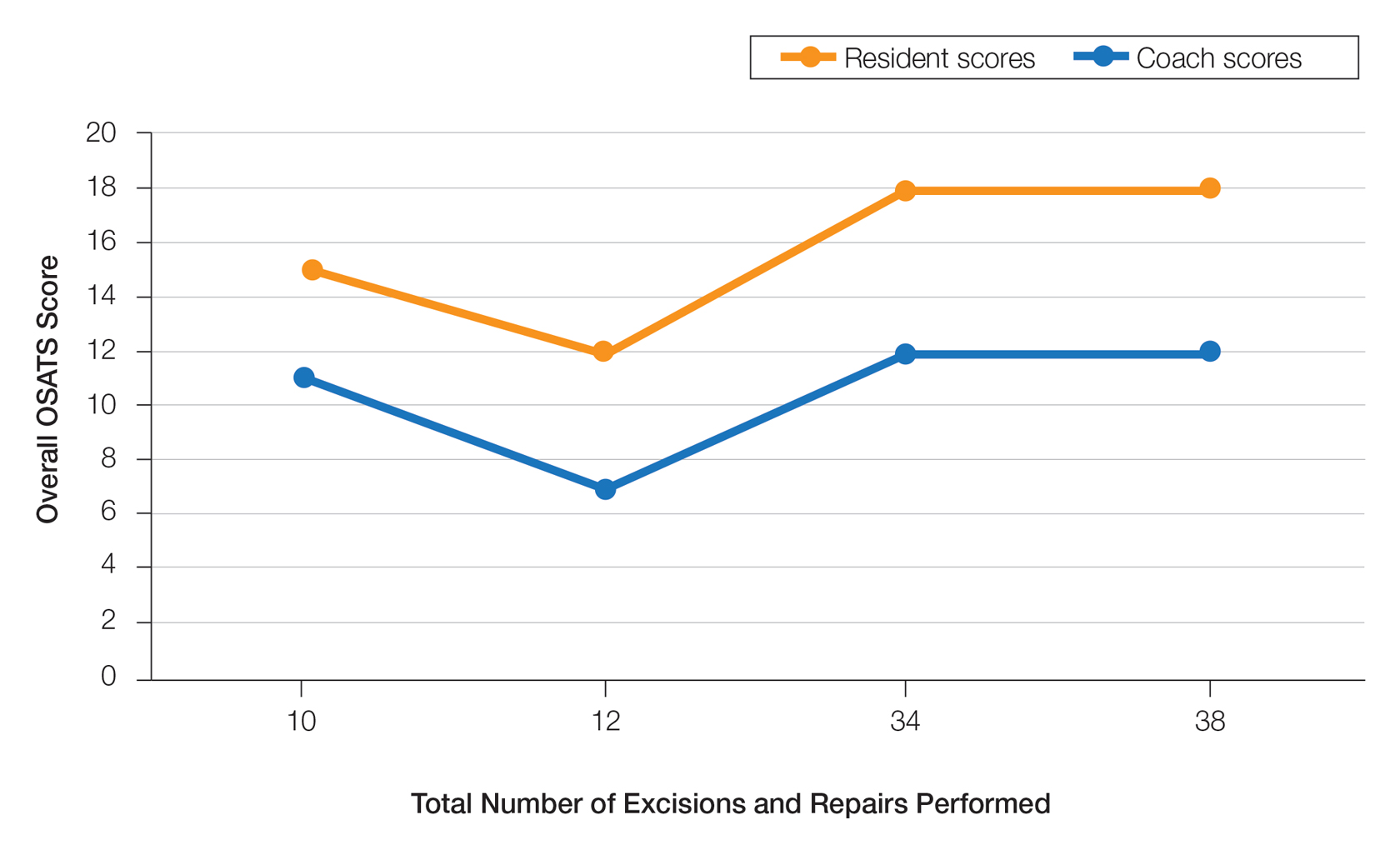

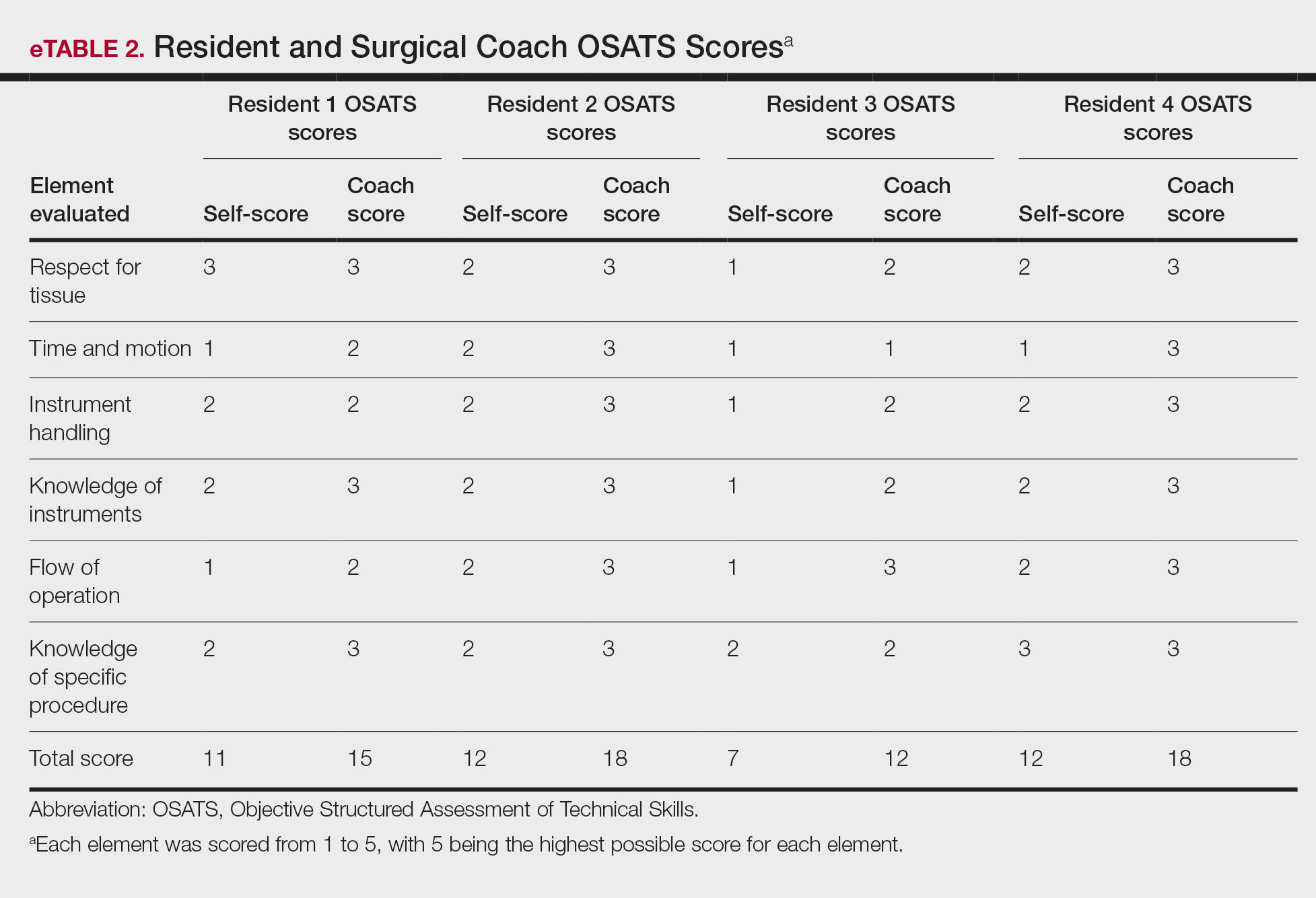

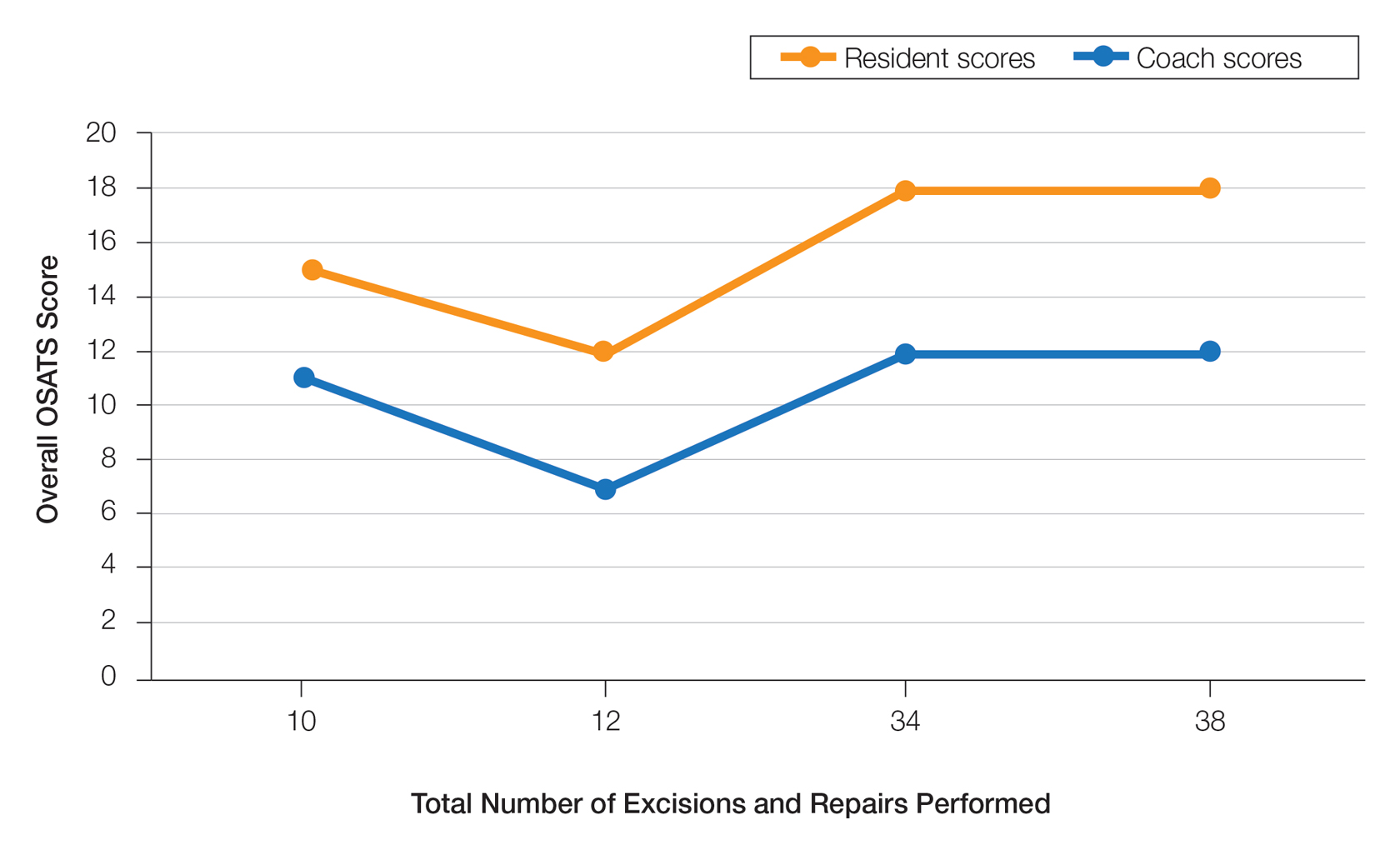

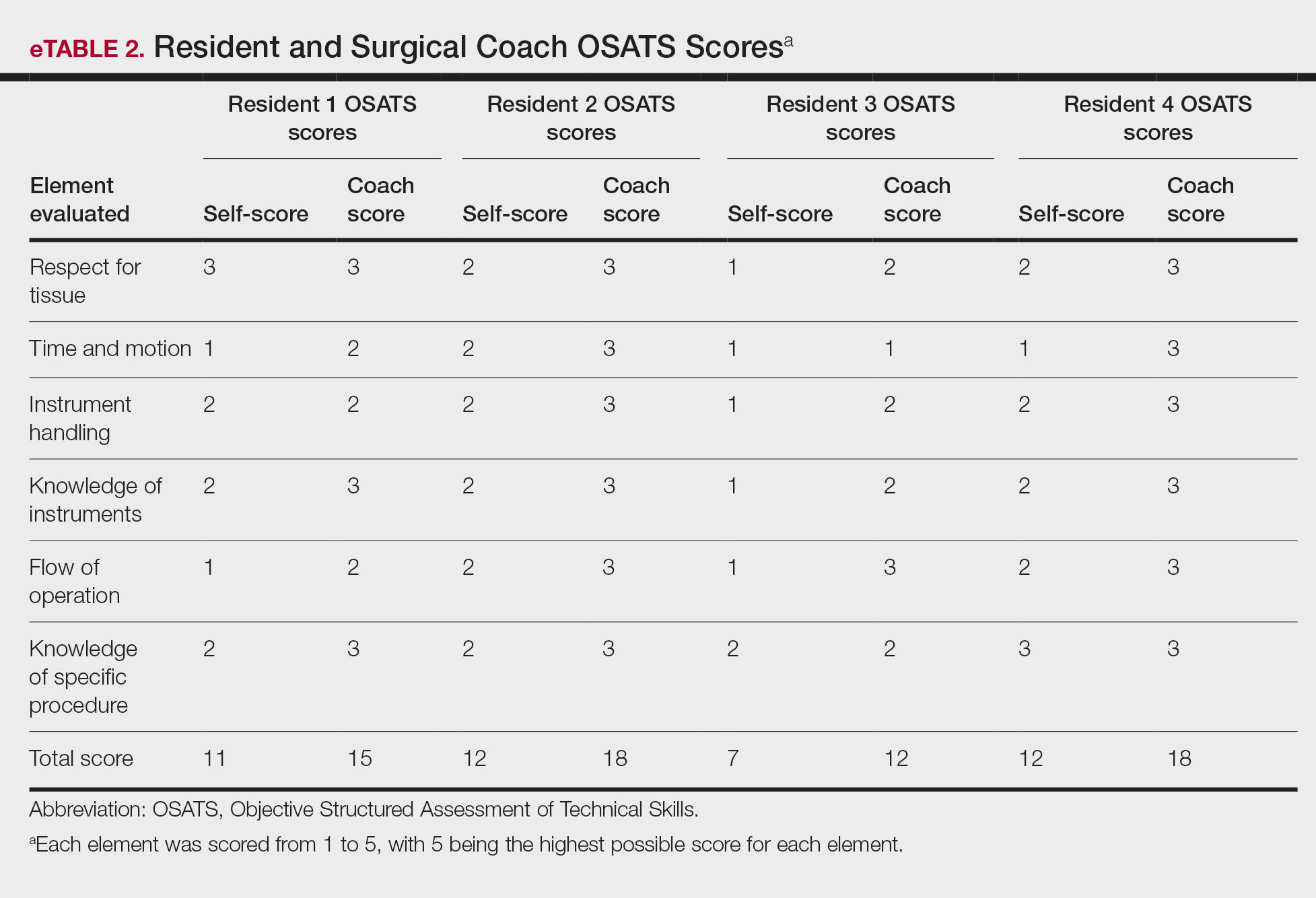

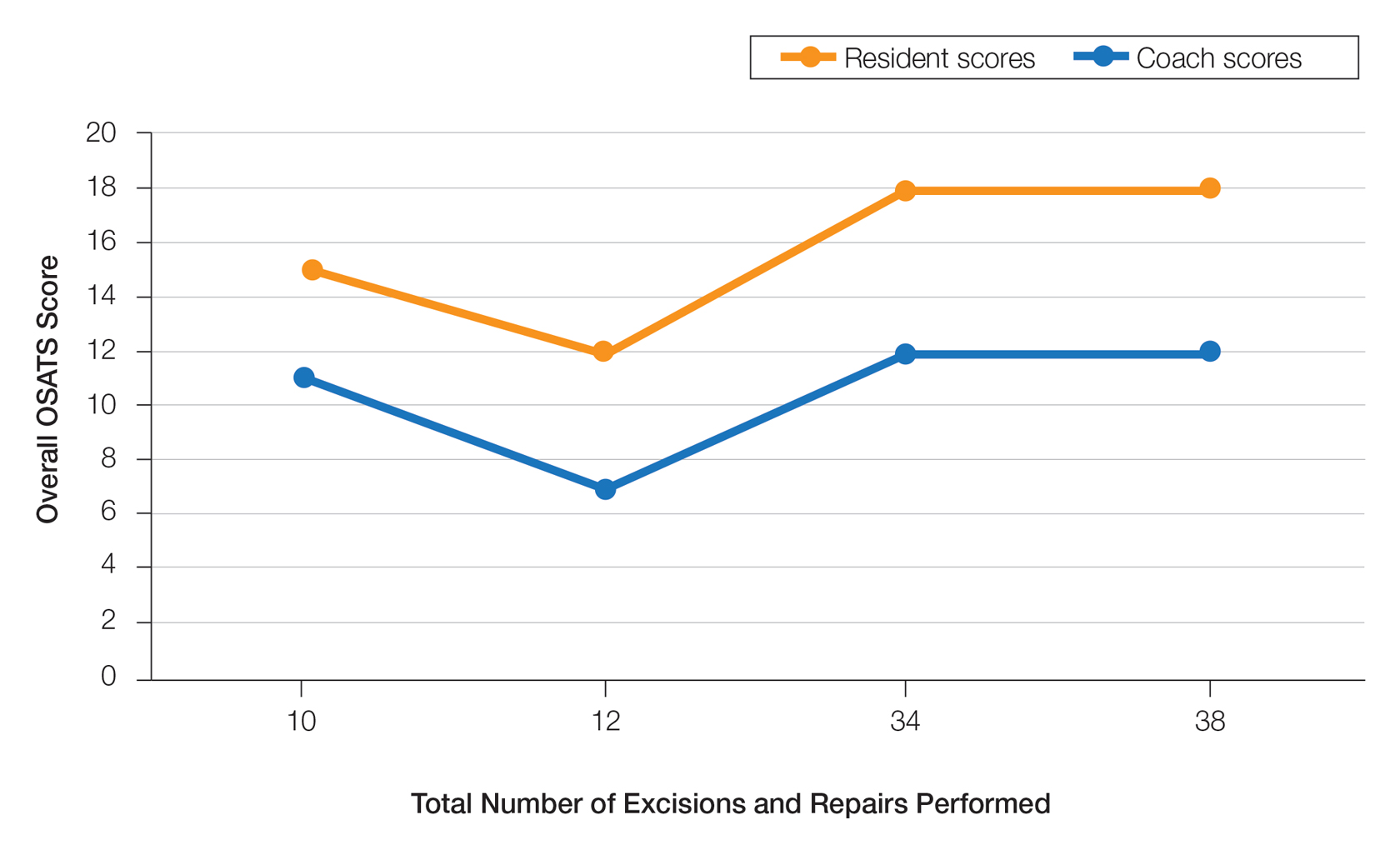

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Video-based coaching (VBC) for surgical procedures is an up-and-coming form of medical education that allows a “coach” to provide thoughtful and in-depth feedback while reviewing a recording with the surgeon in a private setting. This format has potential utility in teaching dermatology resident surgeons being coached by a dermatology faculty member.

- We performed a pilot study demonstrating that VBC can be performed easily with a minimal time investment for both the surgeon and the coach. Dermatology residents not only felt that VBC was an effective teaching method but also should become a formal part of their education.

Perceived Benefits of a Research Fellowship for Dermatology Residency Applicants: Outcomes of a Faculty-Reported Survey

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

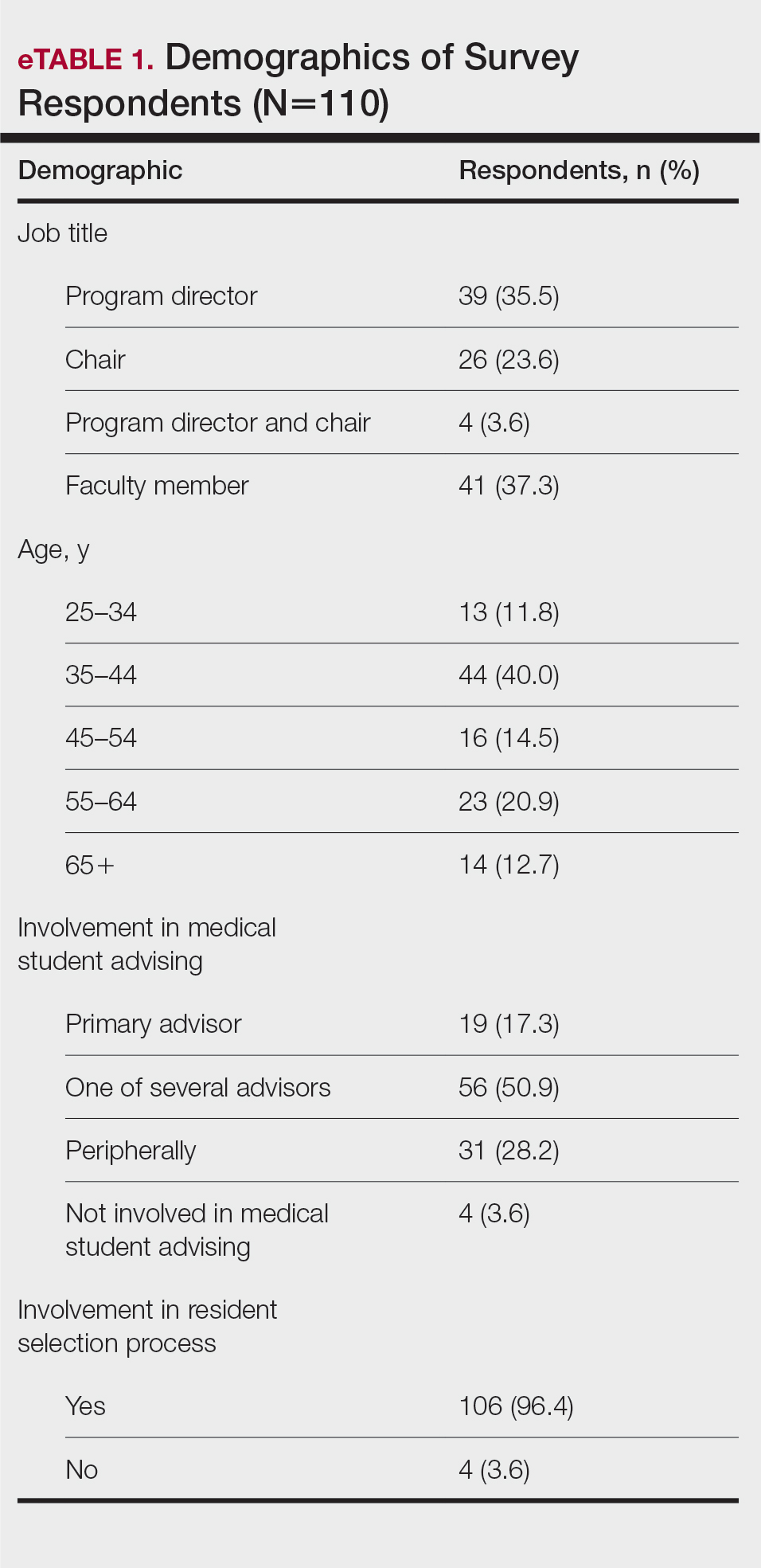

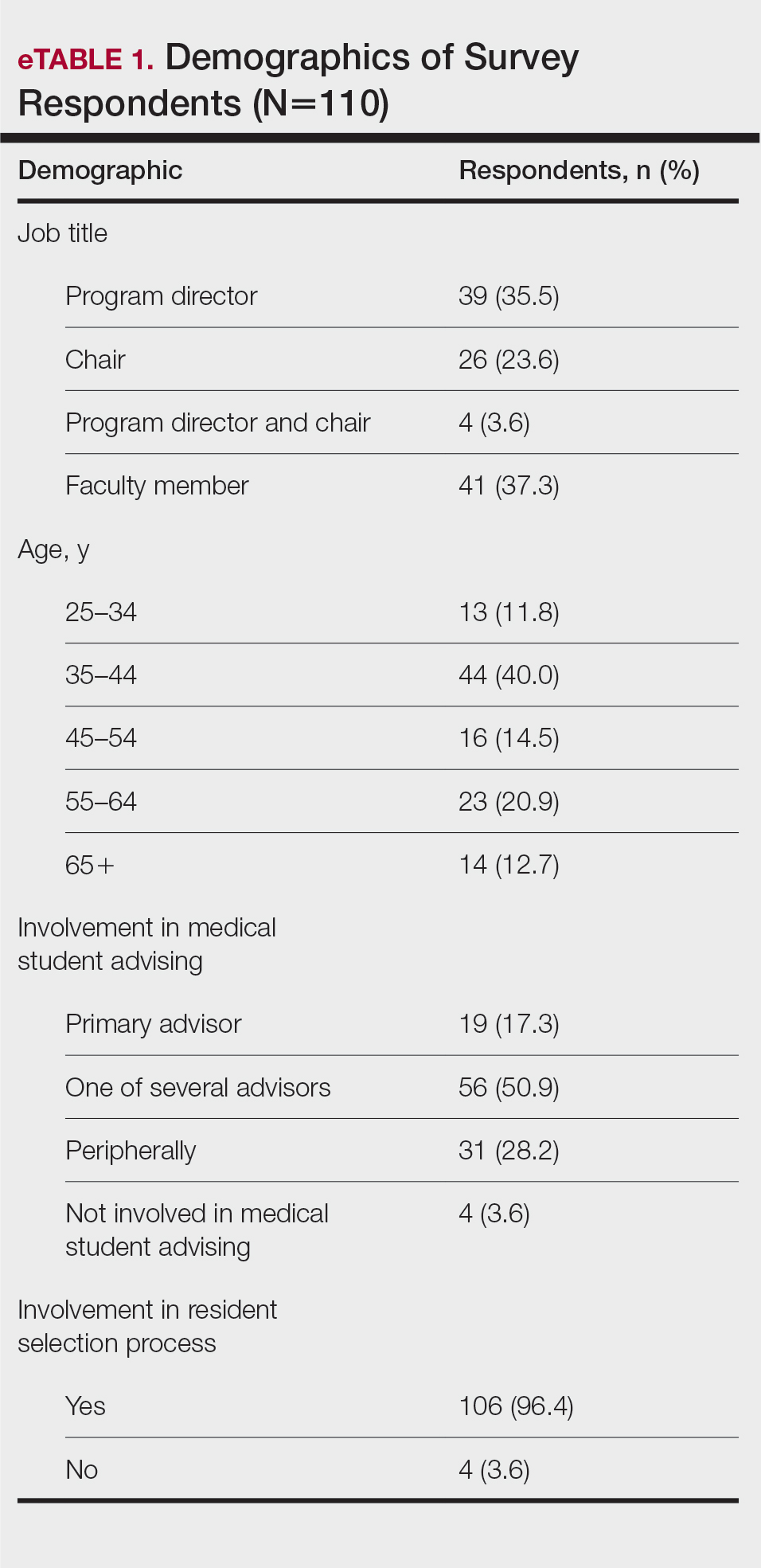

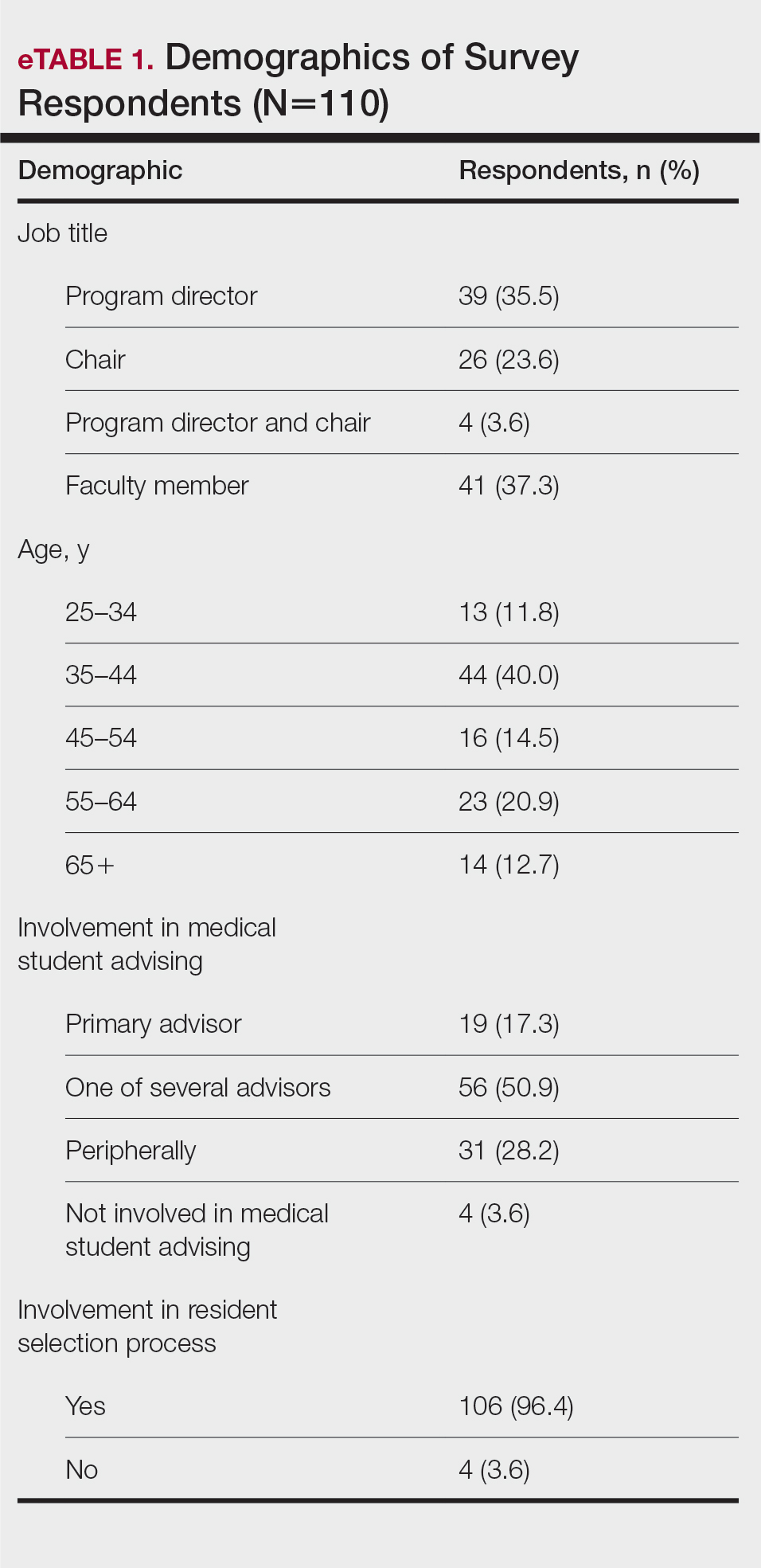

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

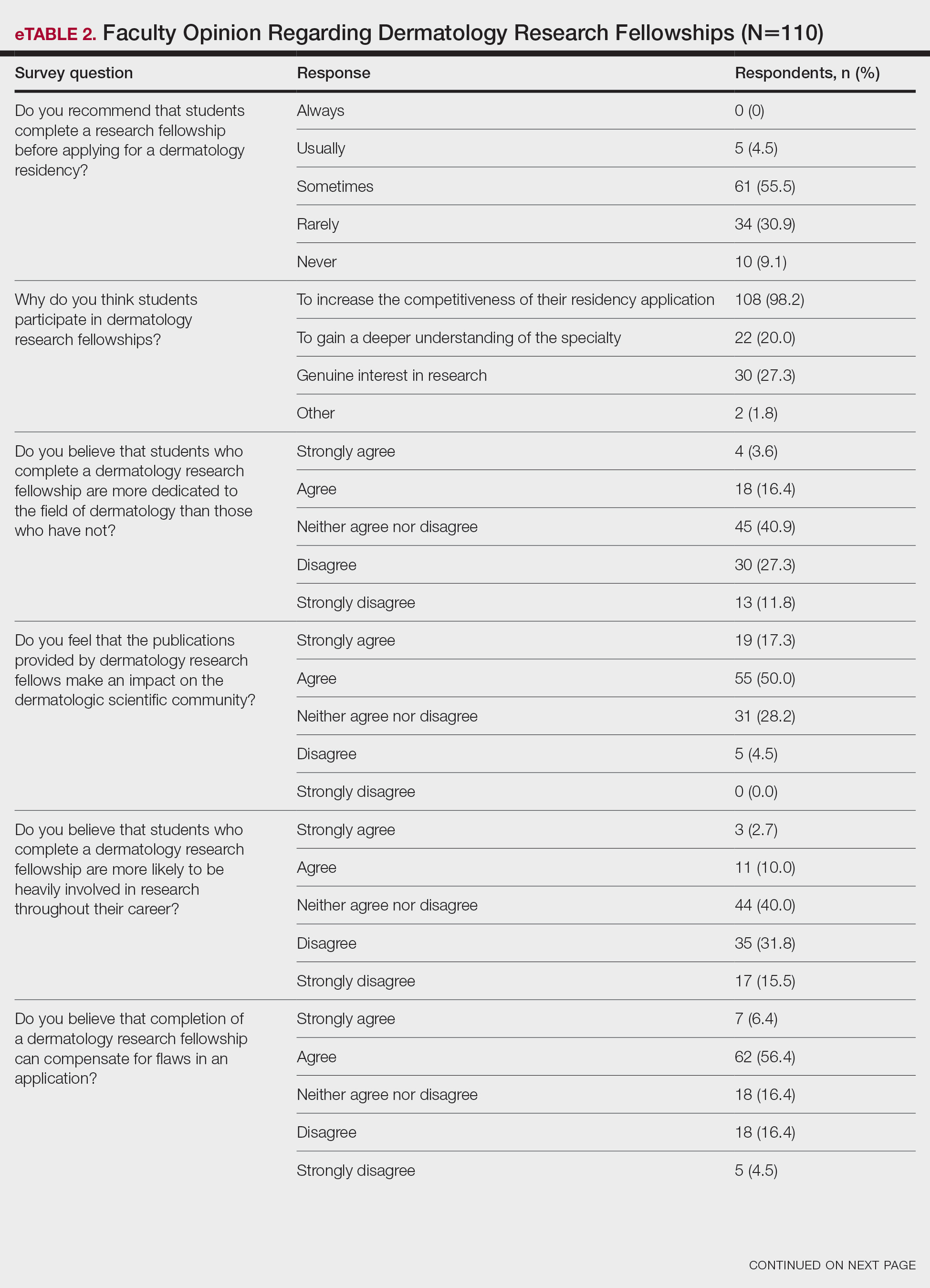

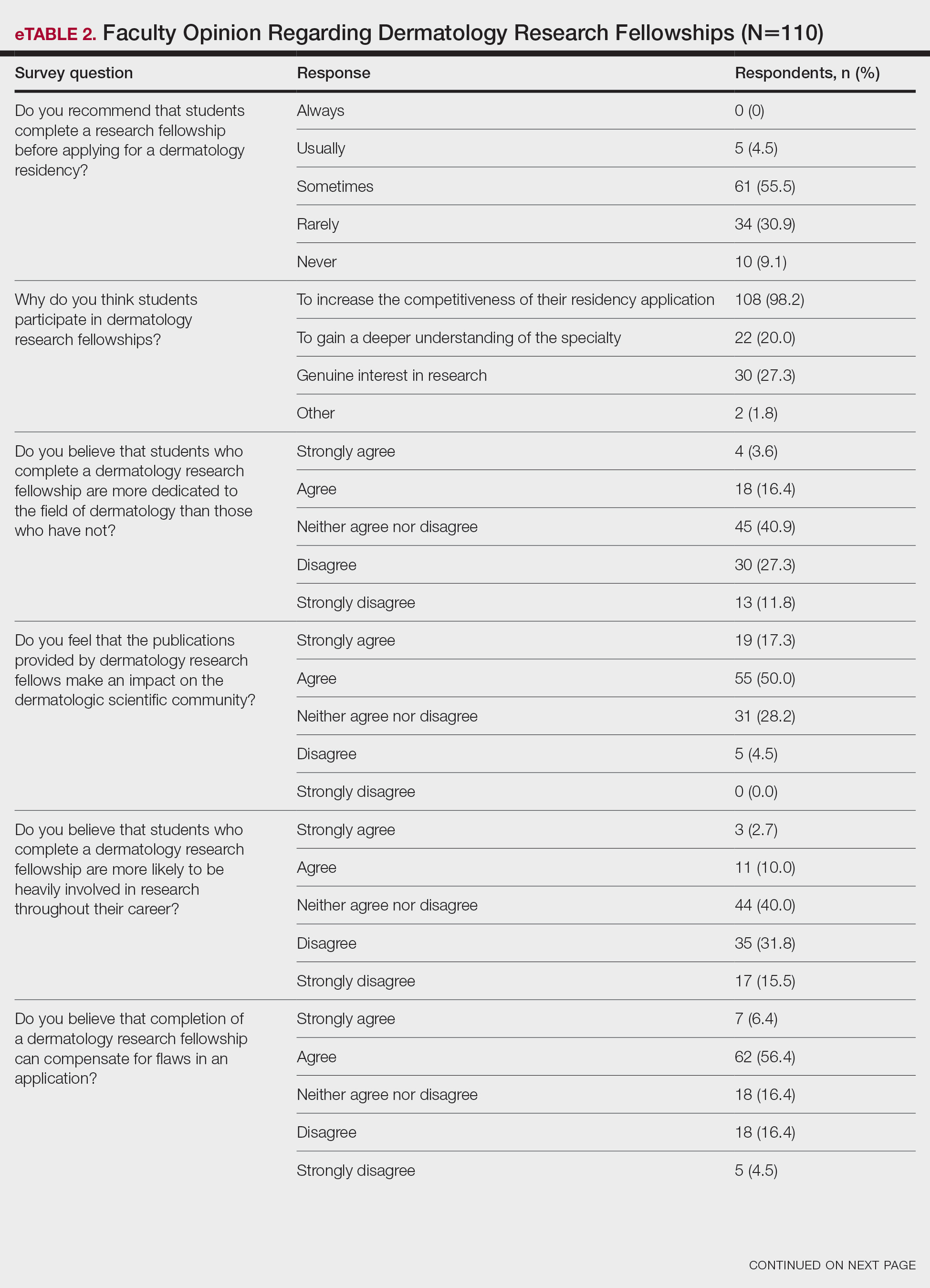

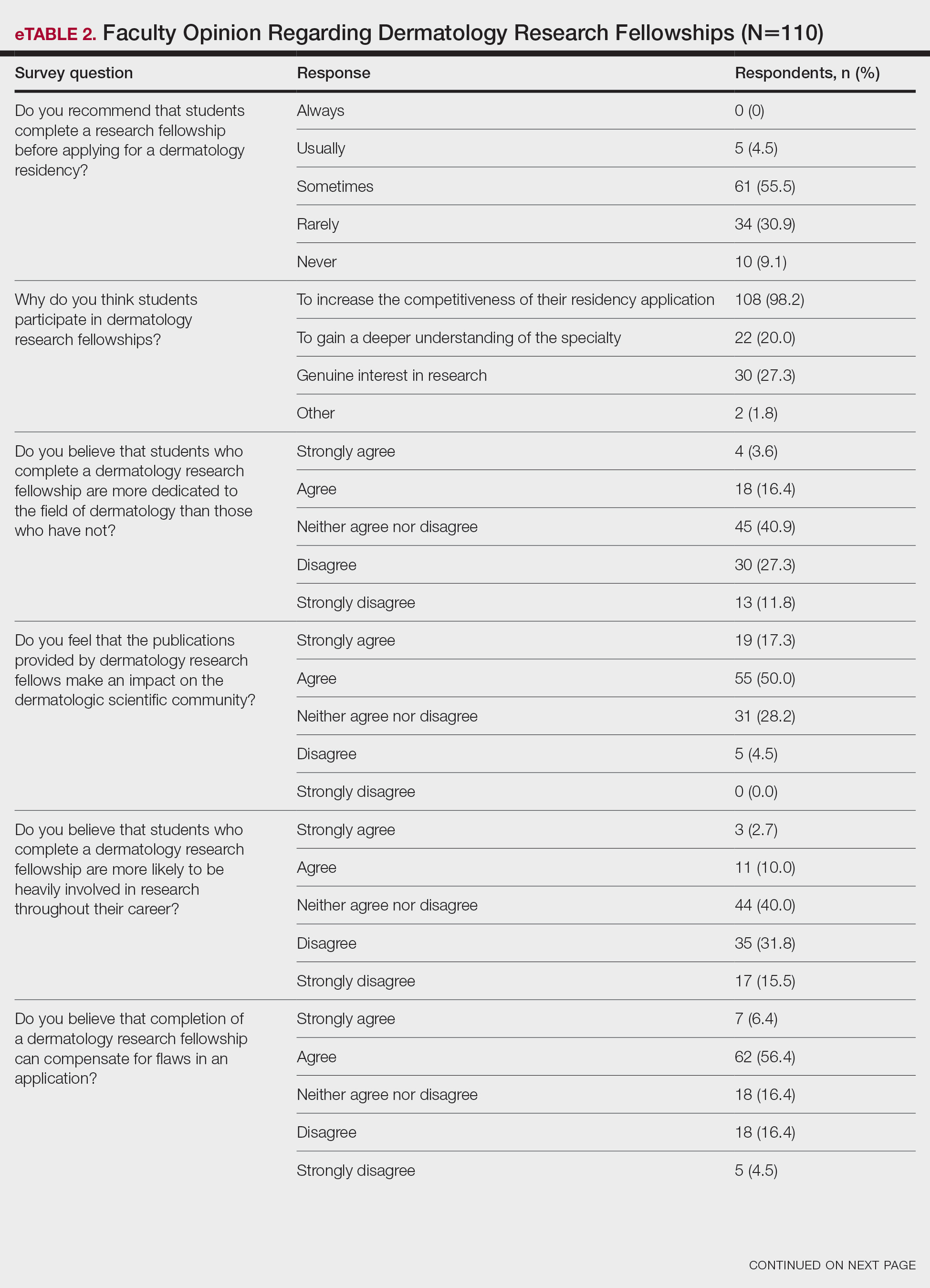

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

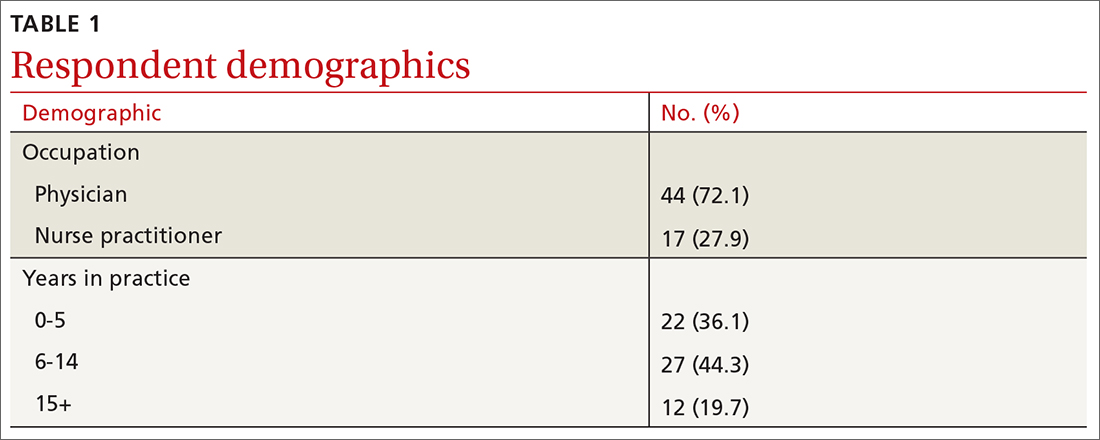

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Many medical students seeking to match into a dermatology residency program complete a research fellowship (RF).

- Completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants even though most advisors acknowledge that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their career, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

- The decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic and should be tailored to each individual applicant.

Assessment of the Efficacy of Tranexamic Acid Solution 5% in the Treatment of Melasma in Patients of South Asian Descent

Melasma is a complex, long-lasting, acquired dermatologic pigmentation disorder resulting in grey-brown patches that last for more than 3 months. Sun-exposed areas including the nose, cheeks, forehead, and forearms are most likely to be affected.1 In Southeast Asia, 0.25% to 4% of the population affected by melasma is aged 30 to 40 years.2 In particular, melasma is a concern among pregnant women due to increased levels of melanocyte-stimulating hormones (MSHs) and is impacted by genetics, hormonal influence, and exposure to UV light.3,4 In Pakistan, approximately 46% of women are affected by melasma during pregnancy.2,5 Although few studies have focused on the clinical approaches to melasma in darker skin types, it continues to disproportionately affect the skin of color population.4

The areas of hyperpigmentation seen in melasma exhibit increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis and dermis, but melanocytes are not elevated. However, in areas of hyperpigmentation, the melanocytes are larger and more dendritic and demonstrate an increased level of melanogenesis.6 During pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, elevated levels of estrogen, progesterone, and MSH often are found in association with melasma.7 Tyrosinase (TYR) activity increases and cellular proliferation is reduced after treatment of melanocytes in culture with β-estradiol.8 Sex steroids increase transcription of genes encoding melanogenic enzymes in normal human melanocytes, especially TYR.9 These results are consistent with the notable increases in melanin synthesis and TYR activity reported for normal human melanocytes under similar conditions in culture.10 Because melanocytes contain both cytosolic and nuclear estrogen receptors, melanocytes in patients with melasma may be inherently more sensitive to the stimulatory effects of estrogens and possibly other steroid hormones.11

The current treatment options for melasma have varying levels of success and include topical depigmenting agents such as hydroquinone, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, and corticosteroids; dermabrasion; and chemical peels.12-14 Chemical peels with glycolic acid, salicylic acid, lactic acid, trichloroacetic acid, and phenol, as well as laser therapy, are reliable management options.13,14 Traditionally, melasma has been treated with a combination of modalities along with photoprotection and trigger avoidance.12

The efficacy and safety of the available therapies for melasma are still controversial and require further exploration. In recent years, off-label tranexamic acid (TA) has emerged as a potential therapy for melasma. Although the mechanism of action remains unclear, TA may inhibit melanin synthesis by blocking the interaction between melanocytes and keratinocytes.15 Tranexamic acid also may reverse the abnormal dermal changes associated with melasma by inhibiting melanogenesis and angiogenesis.16

Although various therapeutic options exist for melasma, the search for a reliable option in patients with darker skin types continues.13 We sought to evaluate the efficacy of TA solution 5% in reducing the severity of melasma in South Asian patients, thereby improving patient outcomes and maximizing patient satisfaction. Topical TA is inexpensive and readily accessible and does not cause systemic side effects. These qualities make it a promising treatment compared to traditional therapies.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial at Rawalpindi Medical Institute (Punjab, Pakistan). The researchers obtained informed consent for all enrolled patients. Cases were sampled from the original patient population seen at the office using nonprobability consecutive sampling. The sample size was calculated with a 95% CI, margin of error of 9%, and expected percentage of efficacy of 86.1% by using TA solution 5%. South Asian male and female patients aged 20 to 45 years with melasma were included in the analysis. Patients were excluded if they were already taking TA, oral contraceptive pills, or photosensitizing drugs (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tetracyclines, phenytoin, carbamazepine); were pregnant; had chronic kidney disease (creatinine >2.0 mg/dL); had cardiac abnormalities (abnormal electrocardiogram); had hematologic disorders (international normalized ratio >2); or had received another melasma treatment within the last 3 to 6 months.

All enrolled patients underwent a detailed history and physical examination. Patient demographics were subsequently noted, including age, sex, history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension, and duration of melasma. The melasma area and severity index (MASI) score of each patient was calculated at baseline, and a corresponding photograph was taken.

The topical solution was prepared with 5 g of TA dissolved in 10 cc of ethanol at 96 °F, 10 cc of 1,3-butanediol, and distilled water up to 100 cc. The TA solution was applied to the affected areas once daily by the patient for 12 weeks. Each application covered the affected areas completely. Patients were instructed to apply sunscreen with sun protection factor 60 to those same areas for UV protection after 15 minutes of TA application. Biweekly follow-ups were scheduled during the trial, and the MASI score was recorded at these visits. If the mean MASI score was reduced by half after 12 weeks of treatment, then the treatment was considered efficacious with a 95% CI.

The percentage reduction from baseline was calculated as follows: percentage reduction=(baseline score– follow-up score)/baseline score×100.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed in SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM). The quantitative variables of age, duration of melasma, and body mass index were presented as mean (SD). Qualitative variables such as sex, history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension, site of melasma, and efficacy were presented as frequencies and percentages. Mean MASI scores at baseline and 12 weeks posttreatment were compared using a paired t test (P≤.05). Data were stratified for age, sex, history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension, site of melasma, and duration of melasma, and a χ2 test was applied to compare efficacy in stratified groups (P≤.05).

Results

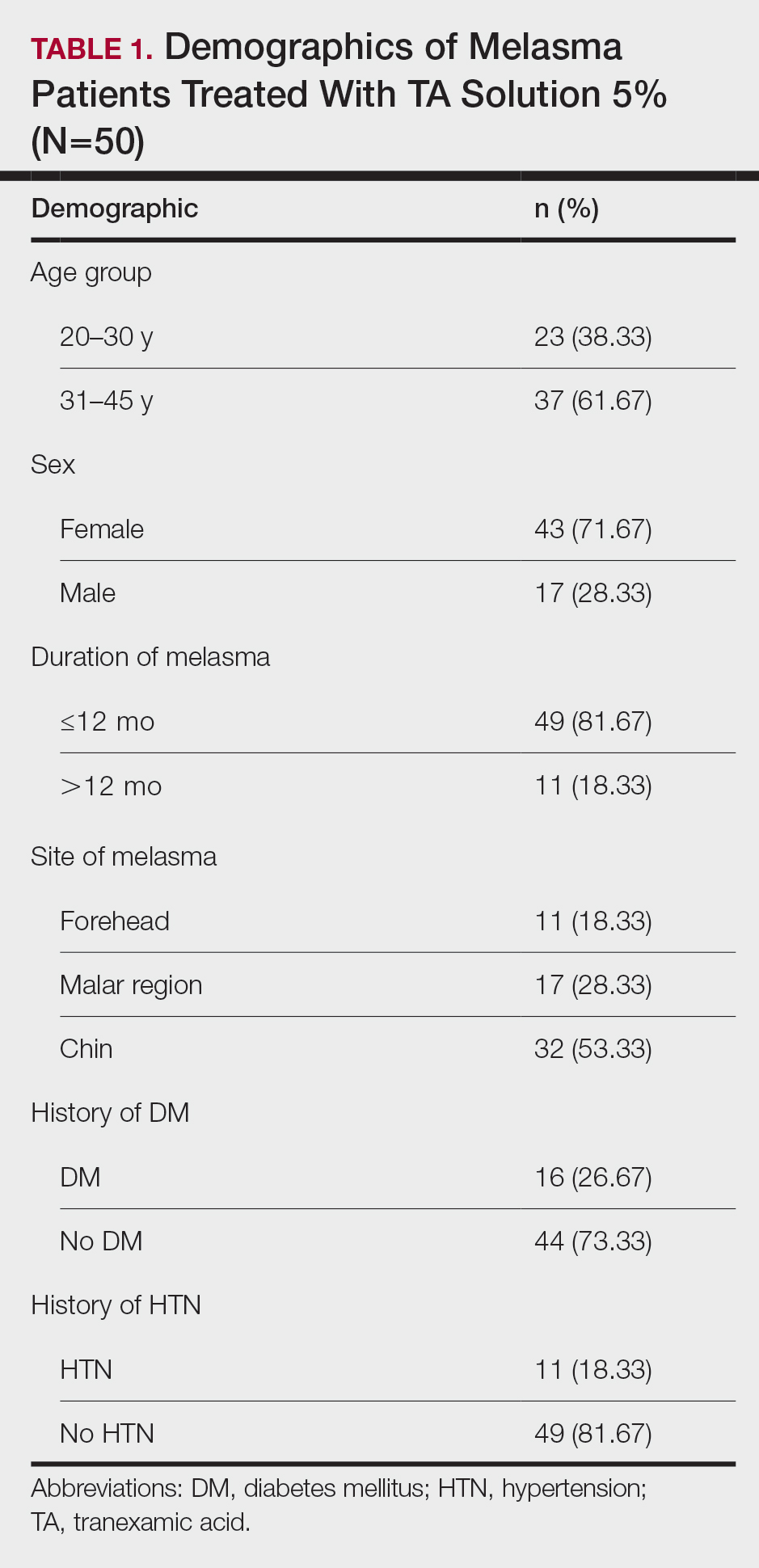

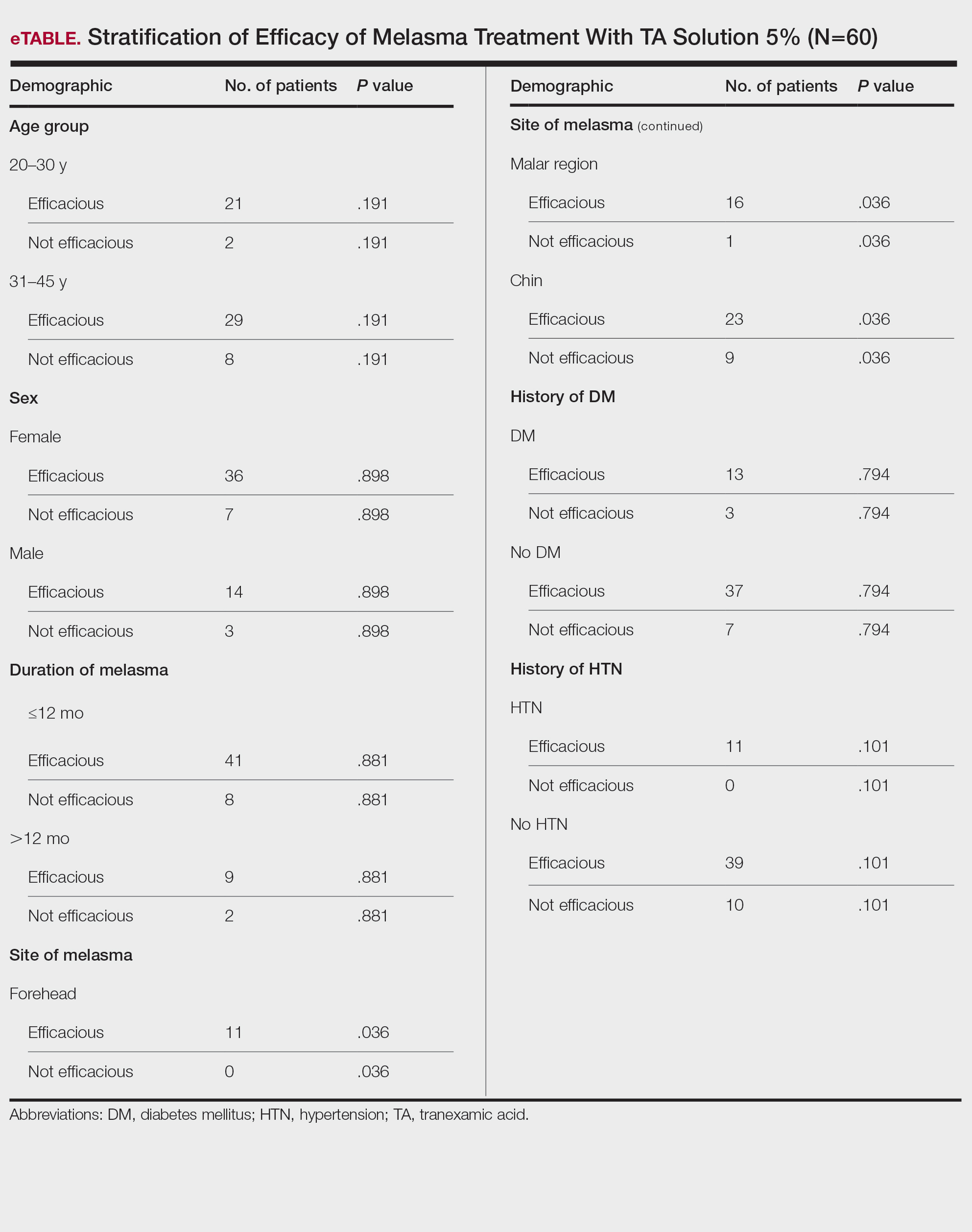

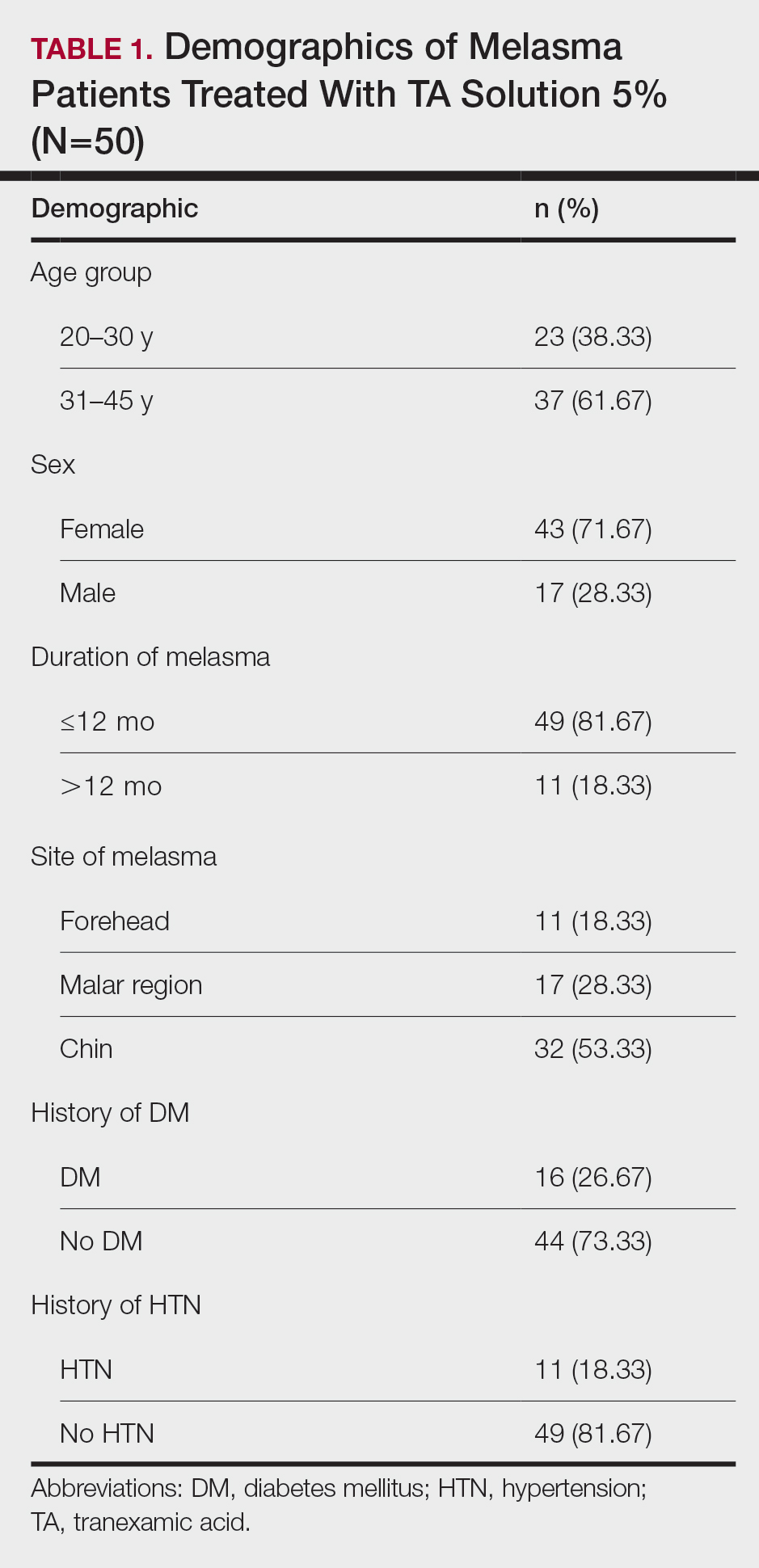

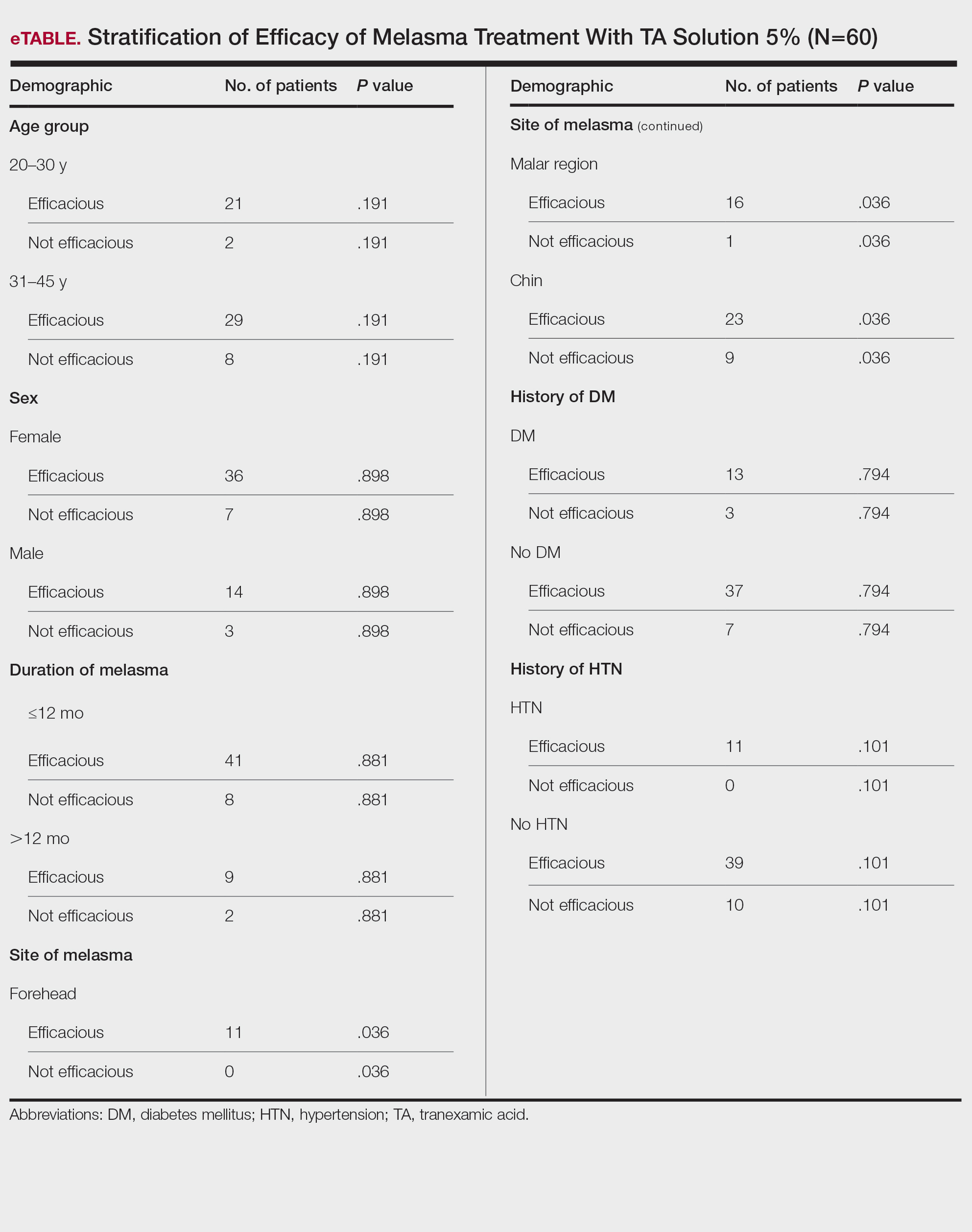

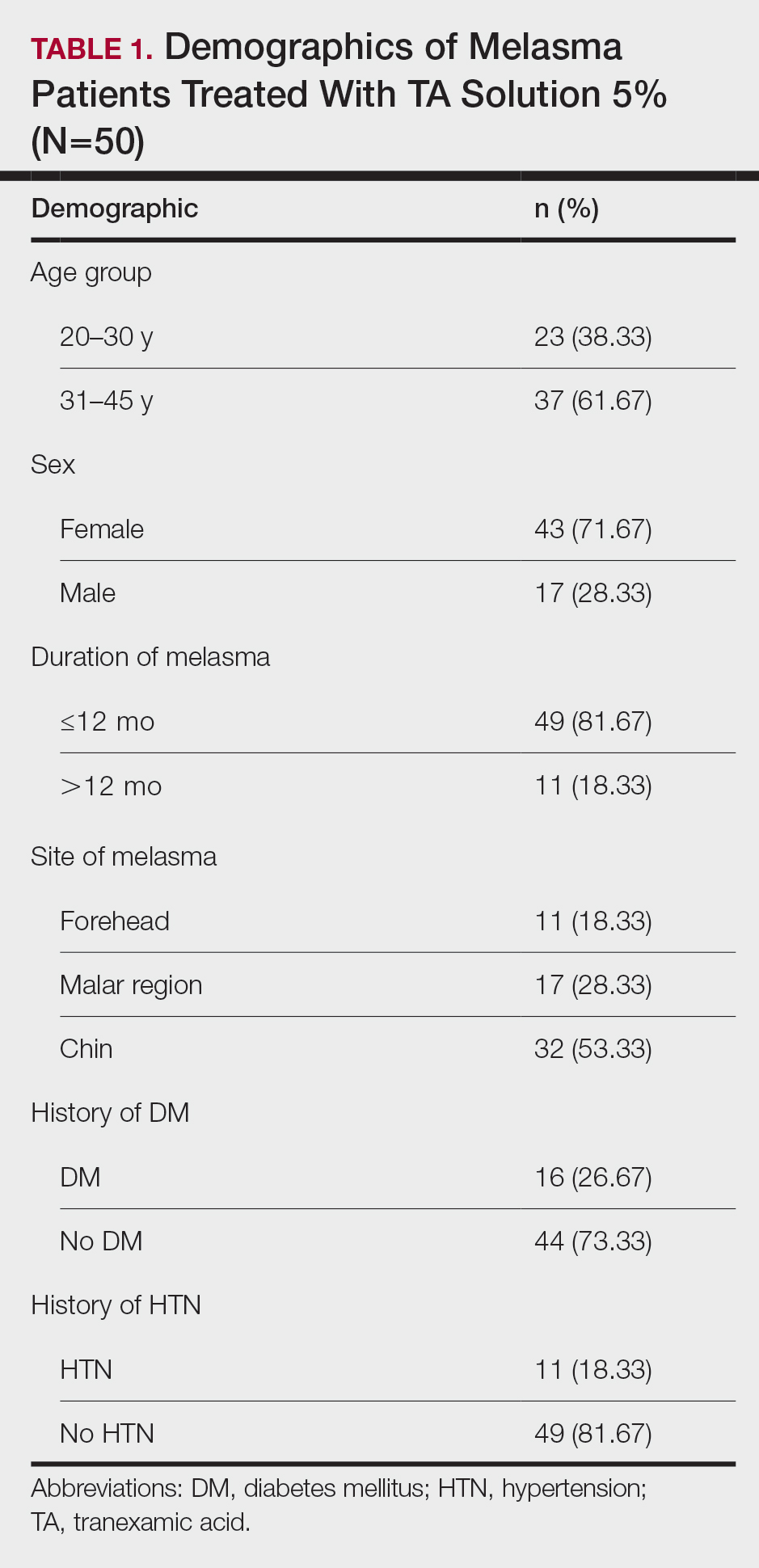

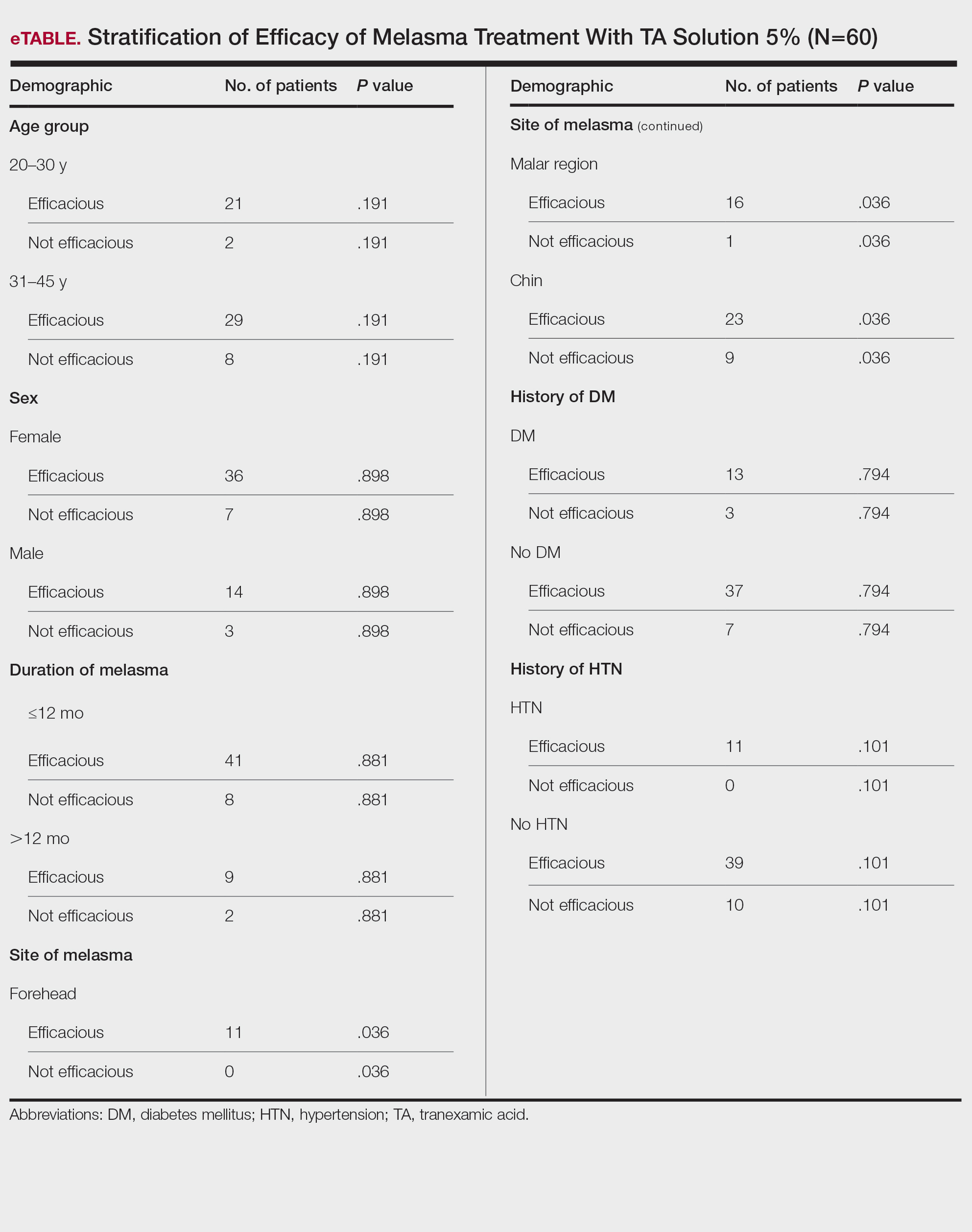

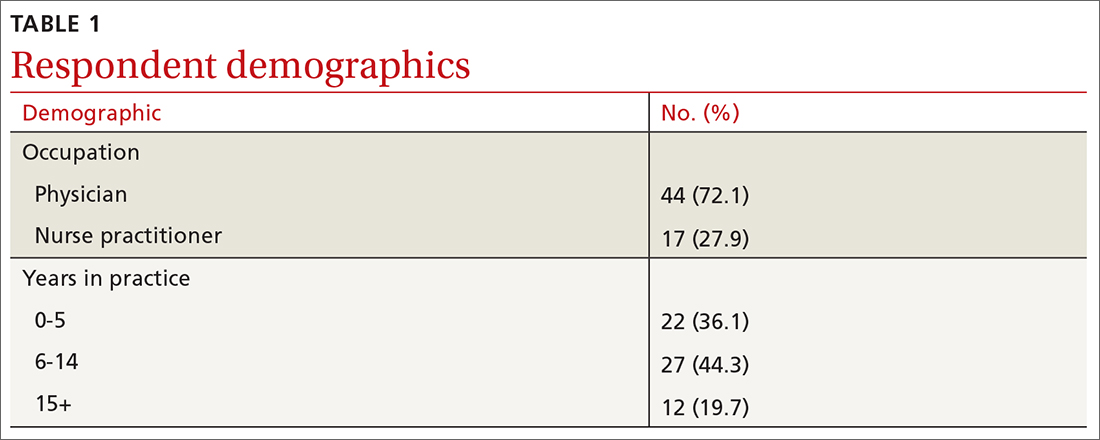

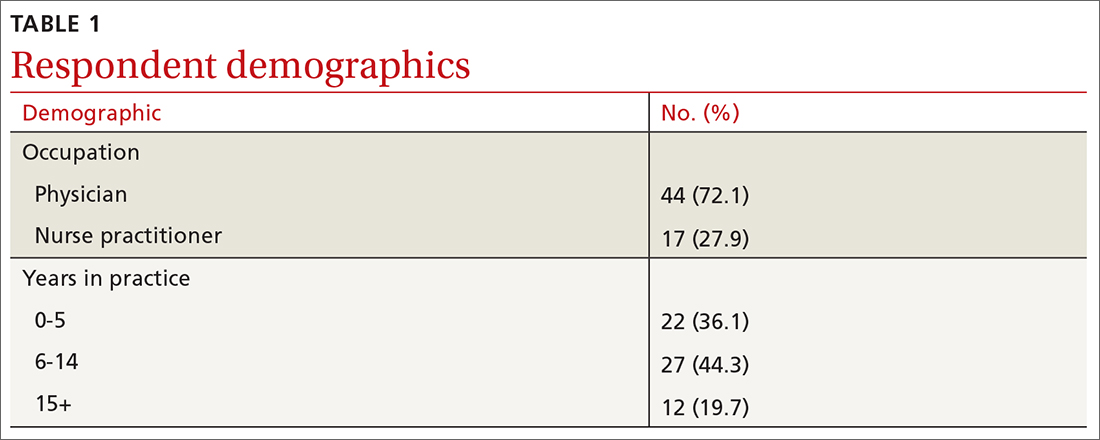

Sixty patients were enrolled in the study. Of them, 17 (28.33%) were male, and 43 (71.67%) were female (2:5 ratio). They ranged in age from 20 to 45 years (mean [SD], 31.93 [6.26] years). Thirty-seven patients (61.67%) were aged 31 to 45 years of age (Table 1). The mean (SD) duration of disease was 10.18 (2.10) months. The response to TA was recorded based on patient distribution according to the site of melasma as well as history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

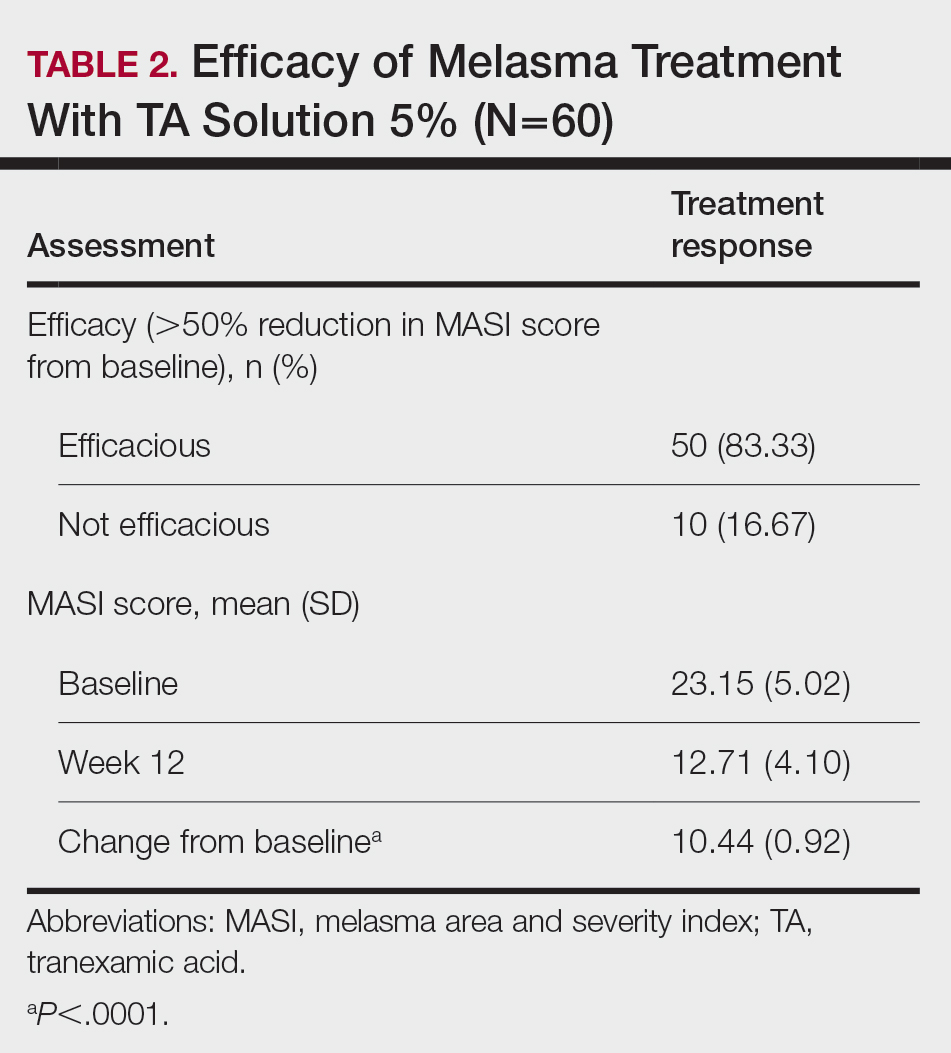

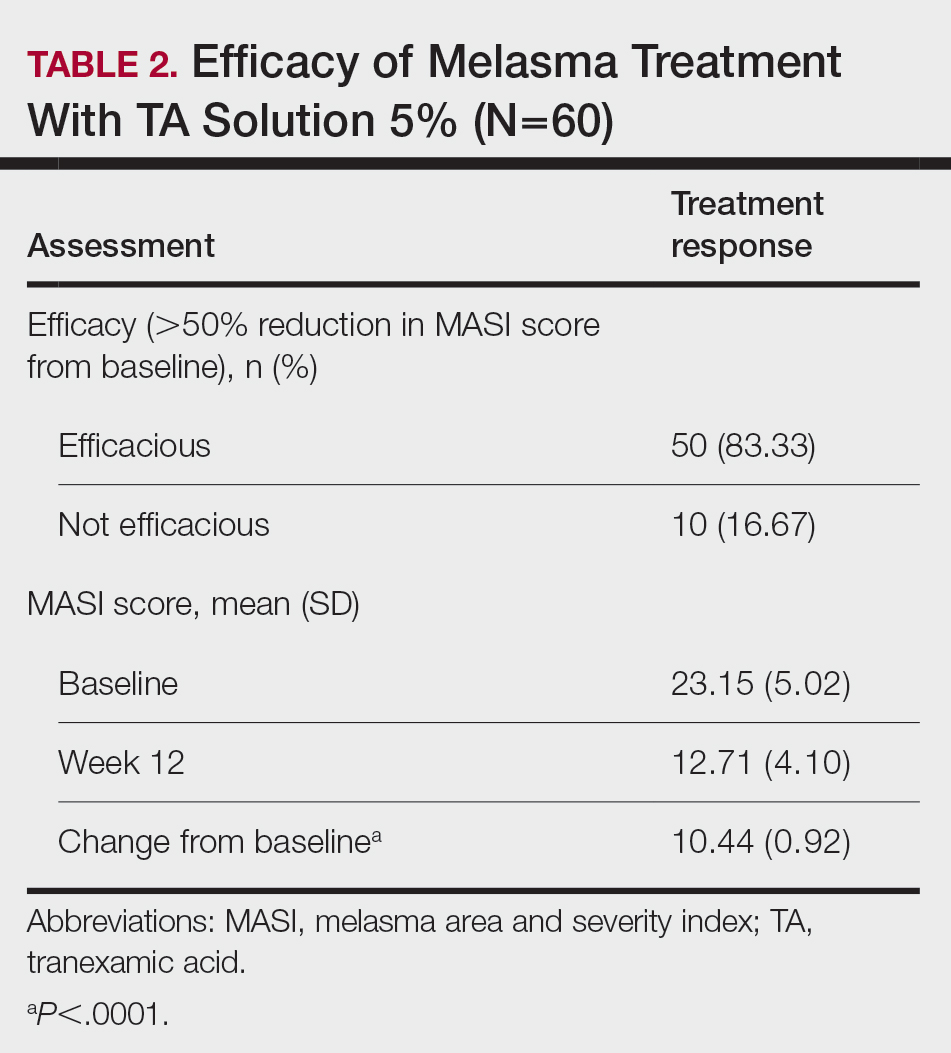

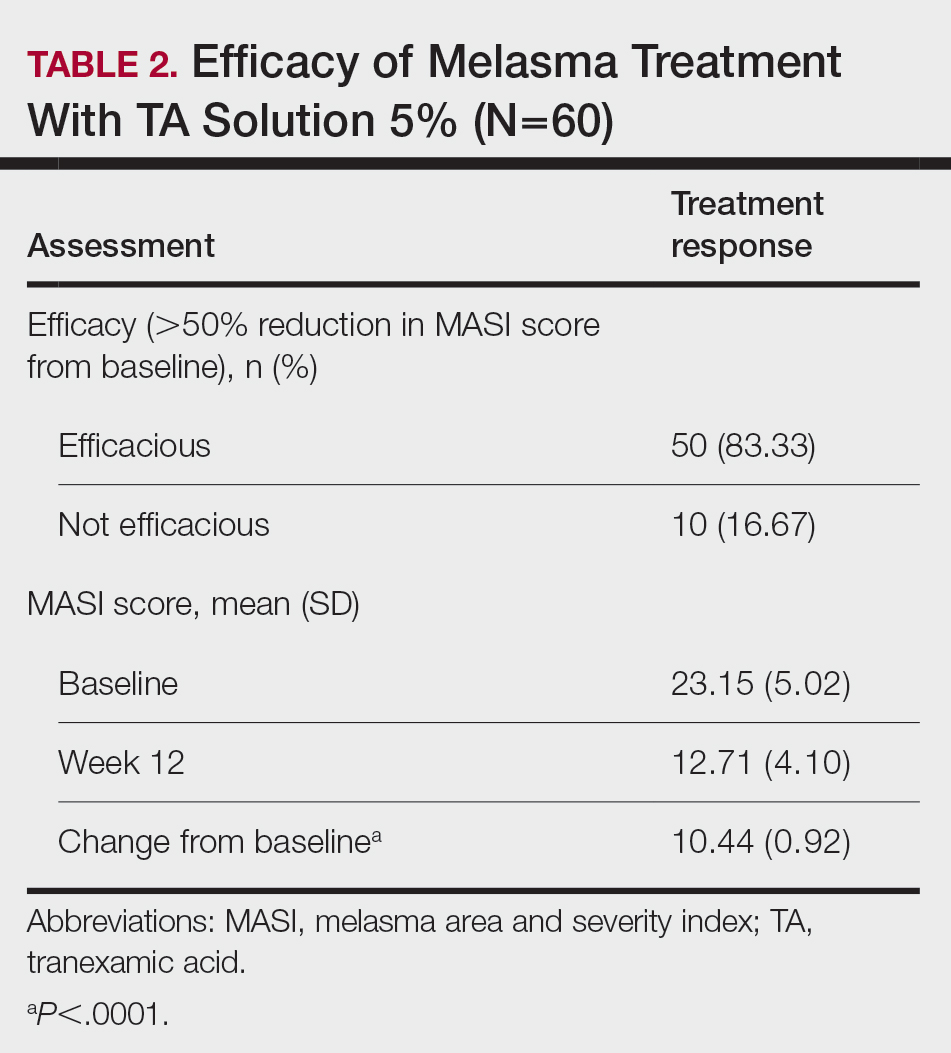

Topical TA was found to be efficacious for melasma in 50 (83.33%) patients. The mean (SD) baseline and week 12 MASI scores were 23.15 (5.02) and 12.71 (4.10)(P<.0001), respectively (Table 2). The stratification of efficacy with respect to age, sex, duration of melasma, site of melasma, and history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension is shown in the eTable. The site of melasma was significant with respect to stratification of efficacy. On the forehead, TA was found to be efficacious in 11 patients and nonefficacious in 0 patients (P=.036). In the malar region, it was efficacious in 16 patients and nonefficacious in 1 patient (P=.036). Finally, on the chin, it was efficacious in 23 patients and nonefficacious in 9 patients (P=.036).

Comment

Melasma Presentation and Development—Melasma is a chronic skin condition that more often affects patients with darker skin types. This condition is characterized by hyperpigmentation of skin that is directly exposed to the sun, such as the cheek, nose, forehead, and above the upper lip.17 Although the mechanism behind how melasma develops is unknown, one theory suggests that UV light can lead to increased plasmin in keratinocytes.18 This increased plasmin will thereby increase the arachidonic acid and α-MSH, leading to the observed uneven hyperpigmentation that is notable in melasma. Melasma is common in patients using oral contraceptives or expired cosmetic drugs; in those who are pregnant; and in those with liver dysfunction.18 Melasma has a negative impact on patients’ quality of life because of substantial psychological and social distress. Thus, finding an accessible treatment is imperative.19

Melasma Management—The most common treatments for melasma have been topical bleaching agents and photoprotection. Combination therapy options include chemical peels, dermabrasion, and laser treatments, though they present with limited efficacy.17,20 Because melasma focuses on pigmentation correction, topical treatments work to disturb melanocyte pigment production at the enzymatic level.21 Tyrosinase is rate limiting in melanin production, as it converts L-tyrosinase to L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, using copper to interact with L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine as a cofactor in the active site.22 Therefore, tyrosine is a major target for many drugs that have been developed for melasma to decrease melaninization.21

Recently, research has focused on the effects of topical, intradermal, and oral TA for melasma.17 Tranexamic acid most commonly has been used in medicine as a fibrinolytic agent because of its antiplasmin properties. It has been hypothesized that TA can inhibit the release of paracrine melanogenic factors that normally act to stimulate melanocytes.17 Although studies have supported the safety and efficacy of TA, there remains a lack of clinical studies that are sufficiently powered. No definitive consensus on the use of TA for melasma currently exists, which indicates the need for large-scale, randomized, controlled trials.23

One trial (N=25) found that TA solution 5% achieved efficacy (>50% reduction in MASI score from baseline) in 86.1% of patients with melasma.24 In another study (N=18), topical TA 5% achieved efficacy (>50% reduction in MASI score) in 86% of patients with melasma.25

Melasma Comorbidities—To determine if certain comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension, influenced the progression of melasma, we stratified the efficacy results for patients with these 2 comorbidities, which showed no significant difference (P=.794 and P=.101, respectively). Thus, the relatively higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (16 patients) and hypertension (11 patients) did not contribute to the efficacy of TA in lowering MASI scores over the 12-week period, which supports the findings of Doolan and Gupta,26 who investigated the endocrinologic conditions associated with melasma and found no such association with diabetes mellitus or hypertension.

TA Formulations for Melasma—The efficacy of topical TA has been explored in several studies. Six studies with sample sizes of 13 to 50 patients each showed statistically significant differences in MASI scores between baseline and following TA treatment (P<.001).27-32 Several formulations and regimens were utilized, including TA cream 3% for 12 weeks, TA gel 5% for 12 weeks, TA solution 3% for 12 weeks, TA liposome 5% for 12 weeks, and TA solution 2% for 12 weeks.18 Additionally, these studies found TA to be effective in limiting dyschromia and decreasing MASI scores. There were no statistically significant differences between formulations and method of application. Topical TA has been found to be just as effective as other treatments for melasma, including intradermal TA injections, topical hydroquinone, and a combination of topical hydroquinone and dexamethasone.18

Further study of the efficacy of intradermal TA is necessary because many human trials have lacked statistical significance or a control group. Lee et al32 conducted a trial of 100 female patients who received weekly intradermal TA microinjections for 12 weeks. After 8 and 12 weeks, MASI scores decreased significantly (P<.01).32 Similarly, Badran et al33 observed 60 female patients in 3 trial groups: group A received TA (4 mg/mL) intradermal injections every 2 weeks, group B received TA (10 mg/mL) intradermal injections every 2 weeks, and group C received TA cream 10% twice daily. Although all groups showed improvement in MASI, group B, which had the highest intradermal TA concentration, exhibited the most improvement. Thus, it was determined that intradermal application led to better results, but the cream was still effective.33

Saki et al34 conducted a randomized, split-face trial of 37 patients comparing the efficacy of intradermal TA and topical hydroquinone. Each group was treated with either monthly intradermal TA injections or nightly hydroquinone for 3 months. After 4 weeks of treatment, TA initially had a greater improvement. However, after 20 weeks, the overall changes were not significant between the 2 groups.34 Pazyar et al35 conducted a randomized, split-face trial of 49 patients comparing the efficacy of intradermal TA and hydroquinone cream. After 24 weeks of biweekly TA injections or twice-daily hydroquinone, there were no statistically significant differences in the decreased MASI scores between treatments.35 Additional large, double-blind, controlled trials are needed to thoroughly assess the role of intradermal TA in comparison to its treatment counterpart of hydroquinone.

Ebrahimi and Naeini29 conducted a 12-week, double-blind, split-phase trial of 50 Iranian melasma patients, which showed that 27.3% of patients rated the improvement in melasma as excellent, 42.4% as good, and 30.3% as fair after using TA solution 3%. Wu et al36 also showed a total melasma improvement rate of 80.9% in 256 patients with long-term oral use of TA. In a study by Kim et al31 (N=245), the mean MASI score considerably decreased after topical TA use, with a total response rate of 95.6%. In another study, Atefi et al37 presented significantly increased levels of satisfaction in patients treated with topical TA 5% vs hydroquinone (P=.015).

Melasma in Patients With Darker Skin Types—Special attention must be given to choosing the appropriate medication in melasma patients with darker skin types, as there is an increased risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Currently, few randomized controlled trials exist that fulfill the criteria of evaluating pharmacologic options for patients with melasma, and even fewer studies solely focus on patients with darker skin types.38 In addition to treatment advances, patients must be educated on the need to avoid sun exposure when possible or to use photoprotection, especially in the South Asian region, where these practices rarely are taught. Our study provided a unique analysis regarding the efficacy of TA solution 5% for the treatment of melasma in patients of South Asian descent. Clinicians can use these findings as a foundation for treating all patients with melasma but particularly those with darker skin types.

Study Limitations—Our study consisted of 60 patients; although our study had more patients than similar trials, larger studies are needed. Additionally, other variables were excluded from our analysis, such as comorbidities beyond diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the growing field of melasma therapeutics by evaluating the efficacy of using TA solution 5% for the treatment of melasma in South Asian patients with darker skin types. Clinicians may use our study to broaden their treatment options for a common condition while also addressing the lack of clinical options for patients with darker skin types. Further studies investigating the effectiveness of TA in large clinical trials in humans are warranted to understand the efficacy and the risk for any complications.

- Espósito ACC, Brianezi G, De Souza NP, et al. Exploratory study of epidermis, basement membrane zone, upper dermis alterations and Wnt pathway activation in melasma compared to adjacent and retroauricular skin. Ann Dermatol. 2020;32:101-108.

- Janney MS, Subramaniyan R, Dabas R, et al. A randomized controlled study comparing the efficacy of topical 5% tranexamic acid solution versus 3% hydroquinone cream in melasma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2019;12:63-67.

- Chalermchai T, Rummaneethorn P. Effects of a fractional picosecond 1,064 nm laser for the treatment of dermal and mixed type melasmaJ Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:134-139.

- Grimes PE, Ijaz S, Nashawati R, et al. New oral and topical approaches for the treatment of melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:30-36.

- Handel AC, Miot LDB, Miot HA. Melasma: a clinical and epidemiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:771-782.

- Barankin B, Silver SG, Carruthers A. The skin in pregnancy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:236-240.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Smith AG, Shuster S, Thody AJ, et al. Chloasma, oral contraceptives, and plasma immunoreactive beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. J Invest Dermatol. 1977;68:169-170.

- Ranson M, Posen S, Mason RS. Human melanocytes as a target tissue for hormones: in vitro studies with 1 alpha-25, dihydroxyvitamin D3, alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone, and beta-estradiol. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:593-598.

- Kippenberger S, Loitsch S, Solano F, et al. Quantification of tyrosinase, TRP-1, and Trp-2 transcripts in human melanocytes by reverse transcriptase-competitive multiplex PCR—regulation by steroid hormones. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:364-367.

- McLeod SD, Ranson M, Mason RS. Effects of estrogens on human melanocytes in vitro. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;49:9-14.

- Chalermchai T, Rummaneethorn P. Effects of a fractional picosecond 1,064 nm laser for the treatment of dermal and mixed type melasma. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:134-139.

- Sheu SL. Treatment of melasma using tranexamic acid: what’s known and what’s next. Cutis. 2018;101:E7-E8.

- Tian B. The Asian problem of frequent laser toning for melasma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:40-42.

- Zhang L, Tan WQ, Fang QQ, et al. Tranexamic acid for adults with melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1683414.

- Zhu JW, Ni YJ, Tong XY, et al. Tranexamic acid inhibits angiogenesis and melanogenesis in vitro by targeting VEGF receptors. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:903-911.

- Colferai MMT, Miquelin GM, Steiner D. Evaluation of oral tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:1495-1501.

- Taraz M, Niknam S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:19-26.

- Yalamanchili R, Shastry V, Betkerur J. Clinico-epidemiological study and quality of life assessment in melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:519.

- Kim HJ, Moon SH, Cho SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in melasma: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:776-781.

- Kim YJ, Kim MJ, Kweon DK, et al. Quantification of hypopigmentation activity in vitro. J Vis Exp. 2019;145:20-25.

- Cardoso R, Valente R, Souza da Costa CH, et al. Analysis of kojic acid derivatives as competitive inhibitors of tyrosinase: a molecular modeling approach. Molecules. 2021;26:2875.

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Khuraiya S, Kachhawa D, Chouhan B, et al. A comparative study of topical 5% tranexamic acid and triple combination therapy for the treatment of melasma in Indian population. Pigment International. 2019;6:18-23.

- Steiner D, Feola C, Bialeski N, et al. Study evaluating the efficacy of topical and injected tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;1:174-177.

- Doolan B, Gupta M. Melasma. Aust J Gen Pract. 2021;50:880-885.

- Banihashemi M, Zabolinejad N, Jaafari MR, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects of liposomal tranexamic acid and conventional hydroquinone on melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:174-177.

- Chung JY, Lee JH, Lee JH. Topical tranexamic acid as an adjuvant treatment in melasma: side-by-side comparison clinical study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:373-377.

- Ebrahimi B, Naeini FF. Topical tranexamic acid as a promising treatment for melasma. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:753-757.

- Kanechorn Na Ayuthaya P, Niumphradit N, Manosroi A, et al. Topical 5% tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma in Asians: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14:150-154.

- Kim SJ, Park JY, Shibata T, et al. Efficacy and possible mechanisms of topical tranexamic acid in melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:480-485.

- Lee JH, Park JG, Lim SH, et al. Localized intradermal microinjection of tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma in Asian patients: a preliminary clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:626-631.

- Badran AY, Ali AU, Gomaa AS. Efficacy of topical versus intradermal injection of tranexamic acid in Egyptian melasma patients: a randomised clinical trial. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E373-E379.