User login

Psychiatry resident’s viral posts reveal his own mental health battle

First-year psychiatry resident Jake Goodman, MD, knew he was taking a chance when he opened up on his popular social media platforms about his personal mental health battle. He mulled over the decision for several weeks before deciding to take the plunge.

As he voiced recently on his TikTok page, his biggest social media fanbase, with 1.3 million followers, it felt freeing to get his personal struggle off his chest.

“I’m a doctor in training, and most doctors would advise me not to post this,” the 29-year-old from Miami said in the video last month, which garnered 1.2 million views on TikTok alone. “They would say it’s risky for my career. But I didn’t join the medical field to continue the toxic status quo. I’m part of a new generation of health care professionals that are not afraid to be vulnerable and talk about mental health.”

“Dr. Jake,” as he calls himself on social media, admitted he was a physician who treats mental illness and also takes medication for it. “It felt good to say that. And by the way, I’m proud of it,” he said in the TikTok post.

A champion of mental health throughout the pandemic, Dr. Goodman called attention to the illness in the medical field. In a message on Instagram, he stated, “Opening up about your mental health as a medical professional, especially as a doctor who treats mental illness, can be taboo ... So here’s me leading by example.”

He also cited statistics on the challenge: “1 in 2 people will be diagnosed with a mental health illness at some point in their life. Yet many of us will never take medication that can help correct the chemical imbalance in our brains due to medication stigma: the fear that taking medications for our mental health somehow makes us weak.”

Mental health remains an issue among residents. Nearly 70% of residents polled by Medscape in its 2021 Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report said they strongly or somewhat agree there’s a stigma against seeking mental health help. And nearly half, or 47% of those polled, said they sometimes (36%) or always/most of the time (11%) were depressed. The latter category rose in the past year.

Dr. Goodman told this news organization that he became passionate about mental health when he lost a college friend to suicide. “It really exposed the stigma” of mental health, he said. “I always knew it was there, but it took me seeing someone lose his life and [asking] why didn’t he feel comfortable talking to us, and why didn’t I feel comfortable talking to him?”

Stress of medical training

The decision to pursue psychiatry as his specialty came after a rotation in a clinic for people struggling with substance use disorders. “I was enthralled to see people change their life ... just by mental health care.” It’s why he went into medicine, he tells this news organization. “I always wanted to be in a field to help people [before they hit] rock bottom, when no one else could be there for them.”

Dr. Goodman’s personal battle with mental health didn’t arise until he started residency. “I was not really myself.” He said he felt numb and burned out. “I was not getting as much enjoyment out of things.” A friend pointed out that he might be depressed, so he went to see a therapist and then a psychiatrist and started on medication. “It had a profound impact on how I felt.”

Still, it took a while before Dr. Goodman was comfortable sharing his story with the 1.6 million followers he had already built across his social media platforms.

“I started on social media in 2020 with the goal of advocating for mental health and inspiring future doctors.” He said the message seemed to resonate with people struggling during the early part of the pandemic. On his social media accounts, he also talks about medical school, residency, and being a health care provider. His fiancé is also a resident doctor, in internal medicine.

Dr. Goodman is also trying to create a more realistic image of doctors than the superheroes he believed they were growing up. He wants those who grow up wanting to be doctors and who look up to him to see him as a human being with vulnerabilities, such as mental health.

“You can be a doctor and have mental health issues. Seeking treatment for mental health makes you a better doctor, and for other health care workers suffering in the midst of the pandemic, I want to let them know they are not alone.”

He pointed to the statistic that doctors have one of the highest suicide rates of any professions. “It’s better to talk about that in the early stages of training.”

Students, residents, or attending physicians who have mental health challenges shouldn’t allow their symptoms to go untreated, Dr. Goodman added. “Holding in all the stress and anxiety and feelings in a very traumatic field may be dangerous. ”

One of his goals is to campaign for the removal of a question on state medical licensing forms requiring doctors to report any mental health diagnosis. It’s why doctors may be afraid to admit that they are struggling. “I’m still here. It didn’t ruin my career.”

Doctors who seek treatment for mental health are theoretically protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act from being refused a license on the basis of that diagnosis. Dr. Goodman hopes to advocate at the state level to reduce discrimination and increase accessibility for doctors to seek mental health care.

Still, Dr. Goodman concedes he was initially fearful of the repercussions. “I opened up about it because this post could save lives. I was doing what I believed in.”

So if he runs into barriers to receive his medical license because of his admission, “that’s a serious problem,” he said. “There is already a shortage of doctors. We’ll see what happens in a few years. I am not the only one who will answer ‘yes’ to having sought treatment for a mental illness. The questions do not really need to be there.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First-year psychiatry resident Jake Goodman, MD, knew he was taking a chance when he opened up on his popular social media platforms about his personal mental health battle. He mulled over the decision for several weeks before deciding to take the plunge.

As he voiced recently on his TikTok page, his biggest social media fanbase, with 1.3 million followers, it felt freeing to get his personal struggle off his chest.

“I’m a doctor in training, and most doctors would advise me not to post this,” the 29-year-old from Miami said in the video last month, which garnered 1.2 million views on TikTok alone. “They would say it’s risky for my career. But I didn’t join the medical field to continue the toxic status quo. I’m part of a new generation of health care professionals that are not afraid to be vulnerable and talk about mental health.”

“Dr. Jake,” as he calls himself on social media, admitted he was a physician who treats mental illness and also takes medication for it. “It felt good to say that. And by the way, I’m proud of it,” he said in the TikTok post.

A champion of mental health throughout the pandemic, Dr. Goodman called attention to the illness in the medical field. In a message on Instagram, he stated, “Opening up about your mental health as a medical professional, especially as a doctor who treats mental illness, can be taboo ... So here’s me leading by example.”

He also cited statistics on the challenge: “1 in 2 people will be diagnosed with a mental health illness at some point in their life. Yet many of us will never take medication that can help correct the chemical imbalance in our brains due to medication stigma: the fear that taking medications for our mental health somehow makes us weak.”

Mental health remains an issue among residents. Nearly 70% of residents polled by Medscape in its 2021 Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report said they strongly or somewhat agree there’s a stigma against seeking mental health help. And nearly half, or 47% of those polled, said they sometimes (36%) or always/most of the time (11%) were depressed. The latter category rose in the past year.

Dr. Goodman told this news organization that he became passionate about mental health when he lost a college friend to suicide. “It really exposed the stigma” of mental health, he said. “I always knew it was there, but it took me seeing someone lose his life and [asking] why didn’t he feel comfortable talking to us, and why didn’t I feel comfortable talking to him?”

Stress of medical training

The decision to pursue psychiatry as his specialty came after a rotation in a clinic for people struggling with substance use disorders. “I was enthralled to see people change their life ... just by mental health care.” It’s why he went into medicine, he tells this news organization. “I always wanted to be in a field to help people [before they hit] rock bottom, when no one else could be there for them.”

Dr. Goodman’s personal battle with mental health didn’t arise until he started residency. “I was not really myself.” He said he felt numb and burned out. “I was not getting as much enjoyment out of things.” A friend pointed out that he might be depressed, so he went to see a therapist and then a psychiatrist and started on medication. “It had a profound impact on how I felt.”

Still, it took a while before Dr. Goodman was comfortable sharing his story with the 1.6 million followers he had already built across his social media platforms.

“I started on social media in 2020 with the goal of advocating for mental health and inspiring future doctors.” He said the message seemed to resonate with people struggling during the early part of the pandemic. On his social media accounts, he also talks about medical school, residency, and being a health care provider. His fiancé is also a resident doctor, in internal medicine.

Dr. Goodman is also trying to create a more realistic image of doctors than the superheroes he believed they were growing up. He wants those who grow up wanting to be doctors and who look up to him to see him as a human being with vulnerabilities, such as mental health.

“You can be a doctor and have mental health issues. Seeking treatment for mental health makes you a better doctor, and for other health care workers suffering in the midst of the pandemic, I want to let them know they are not alone.”

He pointed to the statistic that doctors have one of the highest suicide rates of any professions. “It’s better to talk about that in the early stages of training.”

Students, residents, or attending physicians who have mental health challenges shouldn’t allow their symptoms to go untreated, Dr. Goodman added. “Holding in all the stress and anxiety and feelings in a very traumatic field may be dangerous. ”

One of his goals is to campaign for the removal of a question on state medical licensing forms requiring doctors to report any mental health diagnosis. It’s why doctors may be afraid to admit that they are struggling. “I’m still here. It didn’t ruin my career.”

Doctors who seek treatment for mental health are theoretically protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act from being refused a license on the basis of that diagnosis. Dr. Goodman hopes to advocate at the state level to reduce discrimination and increase accessibility for doctors to seek mental health care.

Still, Dr. Goodman concedes he was initially fearful of the repercussions. “I opened up about it because this post could save lives. I was doing what I believed in.”

So if he runs into barriers to receive his medical license because of his admission, “that’s a serious problem,” he said. “There is already a shortage of doctors. We’ll see what happens in a few years. I am not the only one who will answer ‘yes’ to having sought treatment for a mental illness. The questions do not really need to be there.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First-year psychiatry resident Jake Goodman, MD, knew he was taking a chance when he opened up on his popular social media platforms about his personal mental health battle. He mulled over the decision for several weeks before deciding to take the plunge.

As he voiced recently on his TikTok page, his biggest social media fanbase, with 1.3 million followers, it felt freeing to get his personal struggle off his chest.

“I’m a doctor in training, and most doctors would advise me not to post this,” the 29-year-old from Miami said in the video last month, which garnered 1.2 million views on TikTok alone. “They would say it’s risky for my career. But I didn’t join the medical field to continue the toxic status quo. I’m part of a new generation of health care professionals that are not afraid to be vulnerable and talk about mental health.”

“Dr. Jake,” as he calls himself on social media, admitted he was a physician who treats mental illness and also takes medication for it. “It felt good to say that. And by the way, I’m proud of it,” he said in the TikTok post.

A champion of mental health throughout the pandemic, Dr. Goodman called attention to the illness in the medical field. In a message on Instagram, he stated, “Opening up about your mental health as a medical professional, especially as a doctor who treats mental illness, can be taboo ... So here’s me leading by example.”

He also cited statistics on the challenge: “1 in 2 people will be diagnosed with a mental health illness at some point in their life. Yet many of us will never take medication that can help correct the chemical imbalance in our brains due to medication stigma: the fear that taking medications for our mental health somehow makes us weak.”

Mental health remains an issue among residents. Nearly 70% of residents polled by Medscape in its 2021 Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report said they strongly or somewhat agree there’s a stigma against seeking mental health help. And nearly half, or 47% of those polled, said they sometimes (36%) or always/most of the time (11%) were depressed. The latter category rose in the past year.

Dr. Goodman told this news organization that he became passionate about mental health when he lost a college friend to suicide. “It really exposed the stigma” of mental health, he said. “I always knew it was there, but it took me seeing someone lose his life and [asking] why didn’t he feel comfortable talking to us, and why didn’t I feel comfortable talking to him?”

Stress of medical training

The decision to pursue psychiatry as his specialty came after a rotation in a clinic for people struggling with substance use disorders. “I was enthralled to see people change their life ... just by mental health care.” It’s why he went into medicine, he tells this news organization. “I always wanted to be in a field to help people [before they hit] rock bottom, when no one else could be there for them.”

Dr. Goodman’s personal battle with mental health didn’t arise until he started residency. “I was not really myself.” He said he felt numb and burned out. “I was not getting as much enjoyment out of things.” A friend pointed out that he might be depressed, so he went to see a therapist and then a psychiatrist and started on medication. “It had a profound impact on how I felt.”

Still, it took a while before Dr. Goodman was comfortable sharing his story with the 1.6 million followers he had already built across his social media platforms.

“I started on social media in 2020 with the goal of advocating for mental health and inspiring future doctors.” He said the message seemed to resonate with people struggling during the early part of the pandemic. On his social media accounts, he also talks about medical school, residency, and being a health care provider. His fiancé is also a resident doctor, in internal medicine.

Dr. Goodman is also trying to create a more realistic image of doctors than the superheroes he believed they were growing up. He wants those who grow up wanting to be doctors and who look up to him to see him as a human being with vulnerabilities, such as mental health.

“You can be a doctor and have mental health issues. Seeking treatment for mental health makes you a better doctor, and for other health care workers suffering in the midst of the pandemic, I want to let them know they are not alone.”

He pointed to the statistic that doctors have one of the highest suicide rates of any professions. “It’s better to talk about that in the early stages of training.”

Students, residents, or attending physicians who have mental health challenges shouldn’t allow their symptoms to go untreated, Dr. Goodman added. “Holding in all the stress and anxiety and feelings in a very traumatic field may be dangerous. ”

One of his goals is to campaign for the removal of a question on state medical licensing forms requiring doctors to report any mental health diagnosis. It’s why doctors may be afraid to admit that they are struggling. “I’m still here. It didn’t ruin my career.”

Doctors who seek treatment for mental health are theoretically protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act from being refused a license on the basis of that diagnosis. Dr. Goodman hopes to advocate at the state level to reduce discrimination and increase accessibility for doctors to seek mental health care.

Still, Dr. Goodman concedes he was initially fearful of the repercussions. “I opened up about it because this post could save lives. I was doing what I believed in.”

So if he runs into barriers to receive his medical license because of his admission, “that’s a serious problem,” he said. “There is already a shortage of doctors. We’ll see what happens in a few years. I am not the only one who will answer ‘yes’ to having sought treatment for a mental illness. The questions do not really need to be there.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What’s in a White Coat? The Changing Trends in Physician Attire and What it Means for Dermatology

The White Coat Ceremony is an enduring memory from my medical school years. Amidst the tumult of memories of seemingly endless sleepless nights spent in libraries and cramming for clerkship examinations between surgical cases, I recall a sunny spring day in 2016 where I gathered with my classmates, family, and friends in the medical school campus courtyard. There were several short, mostly forgotten speeches after which proud fathers and mothers, partners, or siblings slipped the all-important white coat onto the shoulders of the physicians-to-be. At that moment, I felt the weight of tradition centuries in the making resting on my shoulders. Of course, the pomp of the ceremony might have felt a tad overblown had I known that the whole thing had fewer years under its belt than the movie Die Hard.

That’s right, the first White Coat Ceremony was held 5 years after the release of that Bruce Willis classic. Dr. Arnold Gold, a pediatric neurologist on faculty at Columbia University, conceived the ceremony in 1993, and it spread rapidly to medical schools—and later nursing schools—across the United States.1 Although the values highlighted by the White Coat Ceremony—humanism and compassion in medicine—are timeless, the ceremony itself is a more modern undertaking. What, then, of the white coat itself? Is it the timeless symbol of doctoring—of medicine—that we all presume it to be? Or is it a symbol of modern marketing, just a trend that caught on? And is it encountering its twilight—as trends often do—in the face of changing fashion and, more fundamentally, in changes to who our physicians are and to their roles in our society?

The Cleanliness of the White Coat

Until the end of the 19th century, physicians in the Western world most frequently dressed in black formal wear. The rationale behind this attire seems to have been twofold. First, society as a whole perceived the physician’s work as a serious and formal matter, and any medical encounter had to reflect the gravity of the occasion. Additionally, physicians’ visits often were a portent of impending demise, as physicians in the era prior to antibiotics and antisepsis frequently had little to offer their patients outside of—at best—anecdotal treatments and—at worst—sheer quackery.2 Black may have seemed a respectful choice for patients who likely faced dire outcomes regardless of the treatment afforded.3

With the turn of the century came a new understanding of the concepts of antisepsis and disease transmission. While Joseph Lister first published on the use of antisepsis in 1867, his practices did not become commonplace until the early 1900s.4 Around the same time came the Flexner report,5 the publication of William Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,6 and the establishment of the modern medical residency, all of which contributed to the shift from the patient’s own bedside and to the hospital as the house of medicine, with cleanliness and antisepsis as part of its core principles.7 The white coat arose as a symbol of purity and freedom from disease. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, it has remained the predominant symbol of cleanliness and professionalism for the medical practitioner.

Patient Preference of Physician Attire

Although the white coat may serve as a professional symbol and is well respected medicine, it also plays an important role in the layperson’s perception of their health care providers.8 There is little denying that patients prefer their physicians, almost uniformly, to wear a white coat. A systematic review of physician attire that included 30 studies mainly from North America, Europe, and the United Kingdom found that patient preference for formal attire and white coats is near universal.9 Patients routinely rate physicians wearing a white coat as more intelligent and trustworthy and feel more confident in the care they will receive.10-13 They also freely admit that a physician’s appearance influences their satisfaction with their care.14 The recent adoption of the fleece, or softshell, jacket has not yet pervaded patients’ perceptions of what is considered appropriate physician attire. A 500-respondent survey found that patients were more likely to rate a model wearing a white coat as more professional and experienced compared to the same model wearing a fleece or softshell jacket or other formal attire sans white coat.15

Closer examination of the same data, however, reveals results reproduced with startling consistency across several studies, which suggest those of us adopting other attire need not dig those white coats out of the closet just yet. First, while many studies point to patient preference for white coats, this preference is uniformly strongest in older patients, beginning around age 40 years and becoming an entrenched preference in those older than 65 years.9,14,16-18 On the other hand, younger patient populations display little to no such preference, and some studies indicate that younger patients actually prefer scrubs over formal attire in specific settings such as surgical offices, procedural spaces, or the emergency department.12,14,19 This suggests that bias in favor of traditional physician garb may be more linked to age demographics and may continue to shift as the overall population ages. Additionally, although patients might profess a strong preference for physician attire in theory, it often does not translate into any impact on the patient’s perception of the physician following a clinic visit. The large systematic review on the topic noted that only 25% of studies that surveyed patients about a clinical visit following the encounter reported that physician attire influenced their satisfaction with that visit, suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the real-world context of receiving care.9 In fact, a prospective study of patient perception of medical staff and interactions found that staff style of dress not only had no bearing on the perception of staff or visit satisfaction but that patients often failed to even accurately recall physician attire when surveyed.20 Another survey study echoed these conclusions, finding that physician attire had no effect on the perception of a proposed treatment plan.21

What do we know about patient perception of physician attire in the dermatology setting specifically, where visits can be unique in their tendency to transition from medical to procedural in the span of a 15-minute encounter depending on the patient’s chief concern? A survey study of dermatology patients at the general, surgical, and wound care dermatology clinics of an academic medical center (Miami, Florida) found that professional attire with a white coat was strongly preferred across a litany of scenarios assessing many aspects of dermatologic care.21 Similarly, a study of patients visiting a single institution’s dermatology and pediatric dermatology clinics surveyed patients and parents regarding attire prior to an appointment and specifically asked if a white coat should be worn.13 Fifty-four percent of the adult patients (n=176) surveyed professed a preference for physicians in white coats, with a stronger preference for white coats reported by those 50 years and older (55%; n=113). Parents or guardians presenting to the pediatric dermatology clinic, on the other hand, favored less formal attire.13 A recent, real-world study performed at an outpatient dermatology clinic examined the influence of changing physician attire on a patient’s perceptions of care received during clinic encounters. They found no substantial difference in patient satisfaction scores before and following the adoption of a new clinic uniform that transitioned from formal attire to fitted scrubs.22

Racial and Gender Bias Affecting Attire Preference

With any study of preference, there is the underlying concern over respondent bias. Many of the studies discussed here have found secondarily that a patient’s implicit bias does not end at the clothes their physician is wearing. The survey study of dermatology patients from the academic medical center in Miami, Florida, found that patients preferred that Black physicians of either sex be garbed in professional attire at all times but generally were more accepting of White physicians in less formal attire.21 Adamson et al23 published a response to the study’s findings urging dermatologists to recognize that a physician’s race and gender influence patients’ perceptions in much the same way that physician attire seems to and encouraged the development of a more diverse dermatologic workforce to help combat this prejudice. The issue of bias is not limited to the specialty of dermatology; the recent survey study by Xun et al15 found that respondents consistently rated female models garbed in physician attire as less professional than male model counterparts. Additionally, female models wearing white coats were mistakenly identified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses with substantially more frequency than males, despite being clothed in the traditional physician garb. Several other publications on the subject have uncovered implicit bias, though it is rarely, if ever, the principle focus of the study.10,24,25 As is unfortunately true in many professions, female physicians and physicians from ethnic minorities face barriers to being perceived as fully competent physicians.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Finally, of course, there is the ever-present question of the effect of the pandemic. Although the exact role of the white coat as a fomite for infection—and especially for the spread of viral illness—remains controversial, the perception nonetheless has helped catalyze the movement to alternatives such as short-sleeved white coats, technical jackets, and more recently, fitted scrubs.26-29 As with much in this realm, facts seem less important than perceptions; Zahrina et al30 found that when patients were presented with information regarding the risk for microbial contamination associated with white coats, preference for physicians in professional garb plummeted from 72% to only 22%. To date no articles have examined patient perceptions of the white coat in the context of microbial transmission in the age of COVID-19, but future articles on this topic are likely and may serve to further the demise of the white coat.

Final Thoughts

From my vantage point, it seems the white coat will be claimed by the outgoing tide. During this most recent residency interview season, I do not recall a single medical student wearing a short white coat. The closest I came was a quick glimpse of a crumpled white jacket slung over an arm or stuffed in a shoulder bag. Rotating interns and residents from other services on rotation in our department present in softshell or fleece jackets. Fitted scrubs in the newest trendy colors speckle a previously all-white canvas. I, for one, have not donned my own white coat in at least a year, and perhaps it is all for the best. Physician attire is one small aspect of the practice of medicine and likely bears little, if any, relation to the wearer’s qualifications. Our focus should be on building rapport with our patients, providing high-quality care, reducing the risk for nosocomial infection, and developing a health care system that is fair and equitable for patients and health care workers alike, not on who is wearing what. Perhaps the introduction of new physician attire is a small part of the disruption we need to help address persistent gender and racial biases in our field and help shepherd our patients and colleagues to a worldview that is more open and accepting of physicians of diverse backgrounds.

- White Coat Ceremony. Gold Foundation website. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/white-coat-ceremony/

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2017.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—an historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Lister J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. Lancet. 1867;90:353-356.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

- Osler W. Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton & Company; 1892.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:111-116.

- Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Jadhav N, et al. Physician attire: physicians’ perspectives on attire in a community hospital setting among non-surgical specialties. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:1-5.

- Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature—targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006678.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279-1286.

- Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, et al. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908-1918.

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, et al. Are we dressed to impress? a descriptive survey assessing patients preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med (Lond). 2009;9:519-524.

- Thomas MW, Burkhart CN, Lugo-Somolinos A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of physician attire in dermatology clinics. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:505-506.

- Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8:E021239.

- Xun H, Chen J, Sun AH, et al. Public perceptions of physician attire and professionalism in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:E2117779.

- Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan [published online February 11, 2020]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204-210.

- Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, et al. The physician’s attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006;96:132-138.

- Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. Br Med J. 2005;331:1524-1527.

- Hossler EW, Shipp D, Palmer M, et al. Impact of provider attire on patient satisfaction in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Cutis. 2018;102:127-129.

- Boon D, Wardrope J. What should doctors wear in the accident and emergency department? patients’ perception. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994;11:175-177.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Bray JK, Porter C, Feldman SR. The effect of physician appearance on patient perceptions of treatment plans. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553611

- Adamson AS, Wright SW, Pandya AG. A missed opportunity to discuss racial and gender bias in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:110-111.

- Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, et al. The doctor’s new clothes: professional or fashionable? Primary Health Care. 2013;3:135.

- Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:2.

- Treakle AM, Thom KA, Furuno JP, et al. Bacterial contamination of health care workers’ white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101-105.

- Banu A, Anand M, Nagi N, et al. White coats as a vehicle for bacterial dissemination. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1381-1384.

- Haun N, Hooper-Lane C, Safdar N. Healthcare personnel attire and devices as fomites: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1367-1373.

- Tse G, Withey S, Yeo JM, et al. Bare below the elbows: was the target the white coat? J Hosp Infect. 2015;91:299-301.

- Zahrina AZ, Haymond P, Rosanna P, et al. Does the attire of a primary care physician affect patients’ perceptions and their levels of trust in the doctor? Malays Fam Physician. 2018;13:3-11.

The White Coat Ceremony is an enduring memory from my medical school years. Amidst the tumult of memories of seemingly endless sleepless nights spent in libraries and cramming for clerkship examinations between surgical cases, I recall a sunny spring day in 2016 where I gathered with my classmates, family, and friends in the medical school campus courtyard. There were several short, mostly forgotten speeches after which proud fathers and mothers, partners, or siblings slipped the all-important white coat onto the shoulders of the physicians-to-be. At that moment, I felt the weight of tradition centuries in the making resting on my shoulders. Of course, the pomp of the ceremony might have felt a tad overblown had I known that the whole thing had fewer years under its belt than the movie Die Hard.

That’s right, the first White Coat Ceremony was held 5 years after the release of that Bruce Willis classic. Dr. Arnold Gold, a pediatric neurologist on faculty at Columbia University, conceived the ceremony in 1993, and it spread rapidly to medical schools—and later nursing schools—across the United States.1 Although the values highlighted by the White Coat Ceremony—humanism and compassion in medicine—are timeless, the ceremony itself is a more modern undertaking. What, then, of the white coat itself? Is it the timeless symbol of doctoring—of medicine—that we all presume it to be? Or is it a symbol of modern marketing, just a trend that caught on? And is it encountering its twilight—as trends often do—in the face of changing fashion and, more fundamentally, in changes to who our physicians are and to their roles in our society?

The Cleanliness of the White Coat

Until the end of the 19th century, physicians in the Western world most frequently dressed in black formal wear. The rationale behind this attire seems to have been twofold. First, society as a whole perceived the physician’s work as a serious and formal matter, and any medical encounter had to reflect the gravity of the occasion. Additionally, physicians’ visits often were a portent of impending demise, as physicians in the era prior to antibiotics and antisepsis frequently had little to offer their patients outside of—at best—anecdotal treatments and—at worst—sheer quackery.2 Black may have seemed a respectful choice for patients who likely faced dire outcomes regardless of the treatment afforded.3

With the turn of the century came a new understanding of the concepts of antisepsis and disease transmission. While Joseph Lister first published on the use of antisepsis in 1867, his practices did not become commonplace until the early 1900s.4 Around the same time came the Flexner report,5 the publication of William Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,6 and the establishment of the modern medical residency, all of which contributed to the shift from the patient’s own bedside and to the hospital as the house of medicine, with cleanliness and antisepsis as part of its core principles.7 The white coat arose as a symbol of purity and freedom from disease. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, it has remained the predominant symbol of cleanliness and professionalism for the medical practitioner.

Patient Preference of Physician Attire

Although the white coat may serve as a professional symbol and is well respected medicine, it also plays an important role in the layperson’s perception of their health care providers.8 There is little denying that patients prefer their physicians, almost uniformly, to wear a white coat. A systematic review of physician attire that included 30 studies mainly from North America, Europe, and the United Kingdom found that patient preference for formal attire and white coats is near universal.9 Patients routinely rate physicians wearing a white coat as more intelligent and trustworthy and feel more confident in the care they will receive.10-13 They also freely admit that a physician’s appearance influences their satisfaction with their care.14 The recent adoption of the fleece, or softshell, jacket has not yet pervaded patients’ perceptions of what is considered appropriate physician attire. A 500-respondent survey found that patients were more likely to rate a model wearing a white coat as more professional and experienced compared to the same model wearing a fleece or softshell jacket or other formal attire sans white coat.15

Closer examination of the same data, however, reveals results reproduced with startling consistency across several studies, which suggest those of us adopting other attire need not dig those white coats out of the closet just yet. First, while many studies point to patient preference for white coats, this preference is uniformly strongest in older patients, beginning around age 40 years and becoming an entrenched preference in those older than 65 years.9,14,16-18 On the other hand, younger patient populations display little to no such preference, and some studies indicate that younger patients actually prefer scrubs over formal attire in specific settings such as surgical offices, procedural spaces, or the emergency department.12,14,19 This suggests that bias in favor of traditional physician garb may be more linked to age demographics and may continue to shift as the overall population ages. Additionally, although patients might profess a strong preference for physician attire in theory, it often does not translate into any impact on the patient’s perception of the physician following a clinic visit. The large systematic review on the topic noted that only 25% of studies that surveyed patients about a clinical visit following the encounter reported that physician attire influenced their satisfaction with that visit, suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the real-world context of receiving care.9 In fact, a prospective study of patient perception of medical staff and interactions found that staff style of dress not only had no bearing on the perception of staff or visit satisfaction but that patients often failed to even accurately recall physician attire when surveyed.20 Another survey study echoed these conclusions, finding that physician attire had no effect on the perception of a proposed treatment plan.21

What do we know about patient perception of physician attire in the dermatology setting specifically, where visits can be unique in their tendency to transition from medical to procedural in the span of a 15-minute encounter depending on the patient’s chief concern? A survey study of dermatology patients at the general, surgical, and wound care dermatology clinics of an academic medical center (Miami, Florida) found that professional attire with a white coat was strongly preferred across a litany of scenarios assessing many aspects of dermatologic care.21 Similarly, a study of patients visiting a single institution’s dermatology and pediatric dermatology clinics surveyed patients and parents regarding attire prior to an appointment and specifically asked if a white coat should be worn.13 Fifty-four percent of the adult patients (n=176) surveyed professed a preference for physicians in white coats, with a stronger preference for white coats reported by those 50 years and older (55%; n=113). Parents or guardians presenting to the pediatric dermatology clinic, on the other hand, favored less formal attire.13 A recent, real-world study performed at an outpatient dermatology clinic examined the influence of changing physician attire on a patient’s perceptions of care received during clinic encounters. They found no substantial difference in patient satisfaction scores before and following the adoption of a new clinic uniform that transitioned from formal attire to fitted scrubs.22

Racial and Gender Bias Affecting Attire Preference

With any study of preference, there is the underlying concern over respondent bias. Many of the studies discussed here have found secondarily that a patient’s implicit bias does not end at the clothes their physician is wearing. The survey study of dermatology patients from the academic medical center in Miami, Florida, found that patients preferred that Black physicians of either sex be garbed in professional attire at all times but generally were more accepting of White physicians in less formal attire.21 Adamson et al23 published a response to the study’s findings urging dermatologists to recognize that a physician’s race and gender influence patients’ perceptions in much the same way that physician attire seems to and encouraged the development of a more diverse dermatologic workforce to help combat this prejudice. The issue of bias is not limited to the specialty of dermatology; the recent survey study by Xun et al15 found that respondents consistently rated female models garbed in physician attire as less professional than male model counterparts. Additionally, female models wearing white coats were mistakenly identified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses with substantially more frequency than males, despite being clothed in the traditional physician garb. Several other publications on the subject have uncovered implicit bias, though it is rarely, if ever, the principle focus of the study.10,24,25 As is unfortunately true in many professions, female physicians and physicians from ethnic minorities face barriers to being perceived as fully competent physicians.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Finally, of course, there is the ever-present question of the effect of the pandemic. Although the exact role of the white coat as a fomite for infection—and especially for the spread of viral illness—remains controversial, the perception nonetheless has helped catalyze the movement to alternatives such as short-sleeved white coats, technical jackets, and more recently, fitted scrubs.26-29 As with much in this realm, facts seem less important than perceptions; Zahrina et al30 found that when patients were presented with information regarding the risk for microbial contamination associated with white coats, preference for physicians in professional garb plummeted from 72% to only 22%. To date no articles have examined patient perceptions of the white coat in the context of microbial transmission in the age of COVID-19, but future articles on this topic are likely and may serve to further the demise of the white coat.

Final Thoughts

From my vantage point, it seems the white coat will be claimed by the outgoing tide. During this most recent residency interview season, I do not recall a single medical student wearing a short white coat. The closest I came was a quick glimpse of a crumpled white jacket slung over an arm or stuffed in a shoulder bag. Rotating interns and residents from other services on rotation in our department present in softshell or fleece jackets. Fitted scrubs in the newest trendy colors speckle a previously all-white canvas. I, for one, have not donned my own white coat in at least a year, and perhaps it is all for the best. Physician attire is one small aspect of the practice of medicine and likely bears little, if any, relation to the wearer’s qualifications. Our focus should be on building rapport with our patients, providing high-quality care, reducing the risk for nosocomial infection, and developing a health care system that is fair and equitable for patients and health care workers alike, not on who is wearing what. Perhaps the introduction of new physician attire is a small part of the disruption we need to help address persistent gender and racial biases in our field and help shepherd our patients and colleagues to a worldview that is more open and accepting of physicians of diverse backgrounds.

The White Coat Ceremony is an enduring memory from my medical school years. Amidst the tumult of memories of seemingly endless sleepless nights spent in libraries and cramming for clerkship examinations between surgical cases, I recall a sunny spring day in 2016 where I gathered with my classmates, family, and friends in the medical school campus courtyard. There were several short, mostly forgotten speeches after which proud fathers and mothers, partners, or siblings slipped the all-important white coat onto the shoulders of the physicians-to-be. At that moment, I felt the weight of tradition centuries in the making resting on my shoulders. Of course, the pomp of the ceremony might have felt a tad overblown had I known that the whole thing had fewer years under its belt than the movie Die Hard.

That’s right, the first White Coat Ceremony was held 5 years after the release of that Bruce Willis classic. Dr. Arnold Gold, a pediatric neurologist on faculty at Columbia University, conceived the ceremony in 1993, and it spread rapidly to medical schools—and later nursing schools—across the United States.1 Although the values highlighted by the White Coat Ceremony—humanism and compassion in medicine—are timeless, the ceremony itself is a more modern undertaking. What, then, of the white coat itself? Is it the timeless symbol of doctoring—of medicine—that we all presume it to be? Or is it a symbol of modern marketing, just a trend that caught on? And is it encountering its twilight—as trends often do—in the face of changing fashion and, more fundamentally, in changes to who our physicians are and to their roles in our society?

The Cleanliness of the White Coat

Until the end of the 19th century, physicians in the Western world most frequently dressed in black formal wear. The rationale behind this attire seems to have been twofold. First, society as a whole perceived the physician’s work as a serious and formal matter, and any medical encounter had to reflect the gravity of the occasion. Additionally, physicians’ visits often were a portent of impending demise, as physicians in the era prior to antibiotics and antisepsis frequently had little to offer their patients outside of—at best—anecdotal treatments and—at worst—sheer quackery.2 Black may have seemed a respectful choice for patients who likely faced dire outcomes regardless of the treatment afforded.3

With the turn of the century came a new understanding of the concepts of antisepsis and disease transmission. While Joseph Lister first published on the use of antisepsis in 1867, his practices did not become commonplace until the early 1900s.4 Around the same time came the Flexner report,5 the publication of William Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,6 and the establishment of the modern medical residency, all of which contributed to the shift from the patient’s own bedside and to the hospital as the house of medicine, with cleanliness and antisepsis as part of its core principles.7 The white coat arose as a symbol of purity and freedom from disease. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, it has remained the predominant symbol of cleanliness and professionalism for the medical practitioner.

Patient Preference of Physician Attire

Although the white coat may serve as a professional symbol and is well respected medicine, it also plays an important role in the layperson’s perception of their health care providers.8 There is little denying that patients prefer their physicians, almost uniformly, to wear a white coat. A systematic review of physician attire that included 30 studies mainly from North America, Europe, and the United Kingdom found that patient preference for formal attire and white coats is near universal.9 Patients routinely rate physicians wearing a white coat as more intelligent and trustworthy and feel more confident in the care they will receive.10-13 They also freely admit that a physician’s appearance influences their satisfaction with their care.14 The recent adoption of the fleece, or softshell, jacket has not yet pervaded patients’ perceptions of what is considered appropriate physician attire. A 500-respondent survey found that patients were more likely to rate a model wearing a white coat as more professional and experienced compared to the same model wearing a fleece or softshell jacket or other formal attire sans white coat.15

Closer examination of the same data, however, reveals results reproduced with startling consistency across several studies, which suggest those of us adopting other attire need not dig those white coats out of the closet just yet. First, while many studies point to patient preference for white coats, this preference is uniformly strongest in older patients, beginning around age 40 years and becoming an entrenched preference in those older than 65 years.9,14,16-18 On the other hand, younger patient populations display little to no such preference, and some studies indicate that younger patients actually prefer scrubs over formal attire in specific settings such as surgical offices, procedural spaces, or the emergency department.12,14,19 This suggests that bias in favor of traditional physician garb may be more linked to age demographics and may continue to shift as the overall population ages. Additionally, although patients might profess a strong preference for physician attire in theory, it often does not translate into any impact on the patient’s perception of the physician following a clinic visit. The large systematic review on the topic noted that only 25% of studies that surveyed patients about a clinical visit following the encounter reported that physician attire influenced their satisfaction with that visit, suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the real-world context of receiving care.9 In fact, a prospective study of patient perception of medical staff and interactions found that staff style of dress not only had no bearing on the perception of staff or visit satisfaction but that patients often failed to even accurately recall physician attire when surveyed.20 Another survey study echoed these conclusions, finding that physician attire had no effect on the perception of a proposed treatment plan.21

What do we know about patient perception of physician attire in the dermatology setting specifically, where visits can be unique in their tendency to transition from medical to procedural in the span of a 15-minute encounter depending on the patient’s chief concern? A survey study of dermatology patients at the general, surgical, and wound care dermatology clinics of an academic medical center (Miami, Florida) found that professional attire with a white coat was strongly preferred across a litany of scenarios assessing many aspects of dermatologic care.21 Similarly, a study of patients visiting a single institution’s dermatology and pediatric dermatology clinics surveyed patients and parents regarding attire prior to an appointment and specifically asked if a white coat should be worn.13 Fifty-four percent of the adult patients (n=176) surveyed professed a preference for physicians in white coats, with a stronger preference for white coats reported by those 50 years and older (55%; n=113). Parents or guardians presenting to the pediatric dermatology clinic, on the other hand, favored less formal attire.13 A recent, real-world study performed at an outpatient dermatology clinic examined the influence of changing physician attire on a patient’s perceptions of care received during clinic encounters. They found no substantial difference in patient satisfaction scores before and following the adoption of a new clinic uniform that transitioned from formal attire to fitted scrubs.22

Racial and Gender Bias Affecting Attire Preference

With any study of preference, there is the underlying concern over respondent bias. Many of the studies discussed here have found secondarily that a patient’s implicit bias does not end at the clothes their physician is wearing. The survey study of dermatology patients from the academic medical center in Miami, Florida, found that patients preferred that Black physicians of either sex be garbed in professional attire at all times but generally were more accepting of White physicians in less formal attire.21 Adamson et al23 published a response to the study’s findings urging dermatologists to recognize that a physician’s race and gender influence patients’ perceptions in much the same way that physician attire seems to and encouraged the development of a more diverse dermatologic workforce to help combat this prejudice. The issue of bias is not limited to the specialty of dermatology; the recent survey study by Xun et al15 found that respondents consistently rated female models garbed in physician attire as less professional than male model counterparts. Additionally, female models wearing white coats were mistakenly identified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses with substantially more frequency than males, despite being clothed in the traditional physician garb. Several other publications on the subject have uncovered implicit bias, though it is rarely, if ever, the principle focus of the study.10,24,25 As is unfortunately true in many professions, female physicians and physicians from ethnic minorities face barriers to being perceived as fully competent physicians.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Finally, of course, there is the ever-present question of the effect of the pandemic. Although the exact role of the white coat as a fomite for infection—and especially for the spread of viral illness—remains controversial, the perception nonetheless has helped catalyze the movement to alternatives such as short-sleeved white coats, technical jackets, and more recently, fitted scrubs.26-29 As with much in this realm, facts seem less important than perceptions; Zahrina et al30 found that when patients were presented with information regarding the risk for microbial contamination associated with white coats, preference for physicians in professional garb plummeted from 72% to only 22%. To date no articles have examined patient perceptions of the white coat in the context of microbial transmission in the age of COVID-19, but future articles on this topic are likely and may serve to further the demise of the white coat.

Final Thoughts

From my vantage point, it seems the white coat will be claimed by the outgoing tide. During this most recent residency interview season, I do not recall a single medical student wearing a short white coat. The closest I came was a quick glimpse of a crumpled white jacket slung over an arm or stuffed in a shoulder bag. Rotating interns and residents from other services on rotation in our department present in softshell or fleece jackets. Fitted scrubs in the newest trendy colors speckle a previously all-white canvas. I, for one, have not donned my own white coat in at least a year, and perhaps it is all for the best. Physician attire is one small aspect of the practice of medicine and likely bears little, if any, relation to the wearer’s qualifications. Our focus should be on building rapport with our patients, providing high-quality care, reducing the risk for nosocomial infection, and developing a health care system that is fair and equitable for patients and health care workers alike, not on who is wearing what. Perhaps the introduction of new physician attire is a small part of the disruption we need to help address persistent gender and racial biases in our field and help shepherd our patients and colleagues to a worldview that is more open and accepting of physicians of diverse backgrounds.

- White Coat Ceremony. Gold Foundation website. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/white-coat-ceremony/

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2017.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—an historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Lister J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. Lancet. 1867;90:353-356.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

- Osler W. Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton & Company; 1892.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:111-116.

- Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Jadhav N, et al. Physician attire: physicians’ perspectives on attire in a community hospital setting among non-surgical specialties. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:1-5.

- Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature—targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006678.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279-1286.

- Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, et al. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908-1918.

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, et al. Are we dressed to impress? a descriptive survey assessing patients preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med (Lond). 2009;9:519-524.

- Thomas MW, Burkhart CN, Lugo-Somolinos A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of physician attire in dermatology clinics. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:505-506.

- Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8:E021239.

- Xun H, Chen J, Sun AH, et al. Public perceptions of physician attire and professionalism in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:E2117779.

- Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan [published online February 11, 2020]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204-210.

- Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, et al. The physician’s attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006;96:132-138.

- Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. Br Med J. 2005;331:1524-1527.

- Hossler EW, Shipp D, Palmer M, et al. Impact of provider attire on patient satisfaction in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Cutis. 2018;102:127-129.

- Boon D, Wardrope J. What should doctors wear in the accident and emergency department? patients’ perception. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994;11:175-177.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Bray JK, Porter C, Feldman SR. The effect of physician appearance on patient perceptions of treatment plans. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553611

- Adamson AS, Wright SW, Pandya AG. A missed opportunity to discuss racial and gender bias in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:110-111.

- Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, et al. The doctor’s new clothes: professional or fashionable? Primary Health Care. 2013;3:135.

- Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:2.

- Treakle AM, Thom KA, Furuno JP, et al. Bacterial contamination of health care workers’ white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101-105.

- Banu A, Anand M, Nagi N, et al. White coats as a vehicle for bacterial dissemination. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1381-1384.

- Haun N, Hooper-Lane C, Safdar N. Healthcare personnel attire and devices as fomites: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1367-1373.

- Tse G, Withey S, Yeo JM, et al. Bare below the elbows: was the target the white coat? J Hosp Infect. 2015;91:299-301.

- Zahrina AZ, Haymond P, Rosanna P, et al. Does the attire of a primary care physician affect patients’ perceptions and their levels of trust in the doctor? Malays Fam Physician. 2018;13:3-11.

- White Coat Ceremony. Gold Foundation website. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/white-coat-ceremony/

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2017.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—an historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Lister J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. Lancet. 1867;90:353-356.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

- Osler W. Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton & Company; 1892.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:111-116.

- Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Jadhav N, et al. Physician attire: physicians’ perspectives on attire in a community hospital setting among non-surgical specialties. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:1-5.

- Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature—targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006678.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279-1286.

- Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, et al. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908-1918.

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, et al. Are we dressed to impress? a descriptive survey assessing patients preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med (Lond). 2009;9:519-524.

- Thomas MW, Burkhart CN, Lugo-Somolinos A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of physician attire in dermatology clinics. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:505-506.

- Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8:E021239.

- Xun H, Chen J, Sun AH, et al. Public perceptions of physician attire and professionalism in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:E2117779.

- Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan [published online February 11, 2020]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204-210.

- Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, et al. The physician’s attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006;96:132-138.

- Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. Br Med J. 2005;331:1524-1527.

- Hossler EW, Shipp D, Palmer M, et al. Impact of provider attire on patient satisfaction in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Cutis. 2018;102:127-129.

- Boon D, Wardrope J. What should doctors wear in the accident and emergency department? patients’ perception. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994;11:175-177.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Bray JK, Porter C, Feldman SR. The effect of physician appearance on patient perceptions of treatment plans. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553611

- Adamson AS, Wright SW, Pandya AG. A missed opportunity to discuss racial and gender bias in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:110-111.

- Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, et al. The doctor’s new clothes: professional or fashionable? Primary Health Care. 2013;3:135.

- Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:2.

- Treakle AM, Thom KA, Furuno JP, et al. Bacterial contamination of health care workers’ white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101-105.

- Banu A, Anand M, Nagi N, et al. White coats as a vehicle for bacterial dissemination. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1381-1384.

- Haun N, Hooper-Lane C, Safdar N. Healthcare personnel attire and devices as fomites: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1367-1373.

- Tse G, Withey S, Yeo JM, et al. Bare below the elbows: was the target the white coat? J Hosp Infect. 2015;91:299-301.

- Zahrina AZ, Haymond P, Rosanna P, et al. Does the attire of a primary care physician affect patients’ perceptions and their levels of trust in the doctor? Malays Fam Physician. 2018;13:3-11.

Resident Pearls

- Until the end of the 19th century, Western physicians most commonly wore black formal wear. The rise of the physician’s white coat occurred in conjunction with the shift to hospital medicine.

- Patient surveys repeatedly have demonstrated a preference for physicians to wear white coats; whether or not this has any bearing on patient satisfaction in real-world scenarios is less clear.

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on trends in white coat wear has not yet been elucidated.

Pursuit of a Research Year or Dual Degree by Dermatology Residency Applicants: A Cross-Sectional Study

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

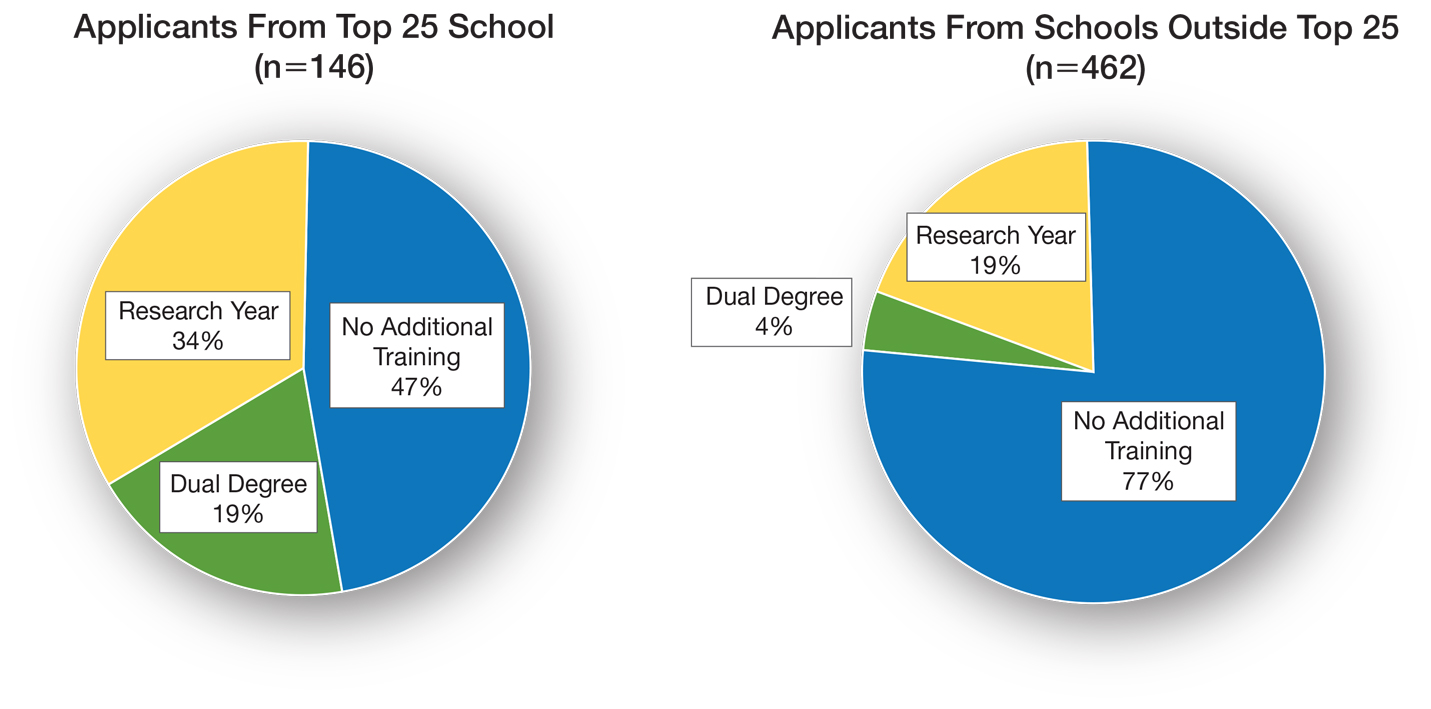

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.