User login

How ObGyns can best work with radiologists to optimize screening for patients with dense breasts

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

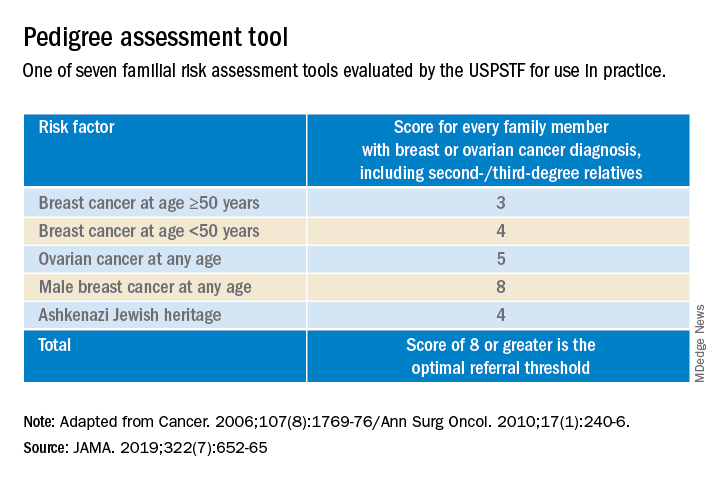

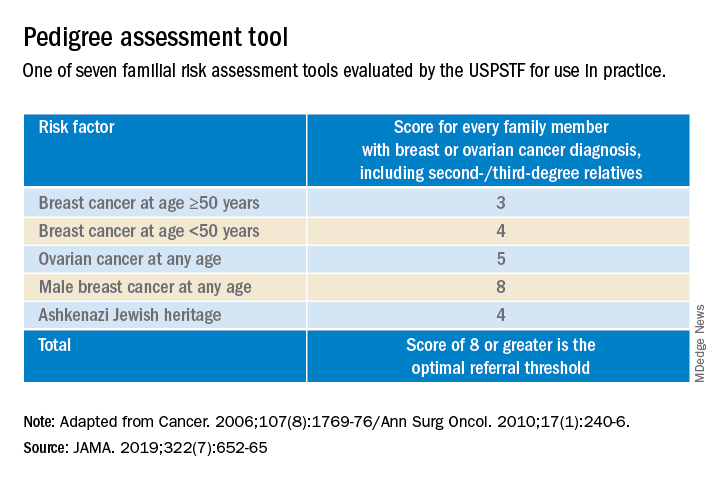

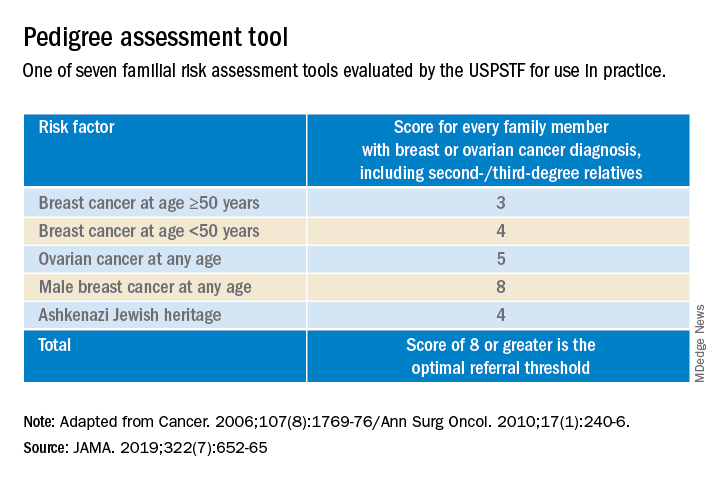

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

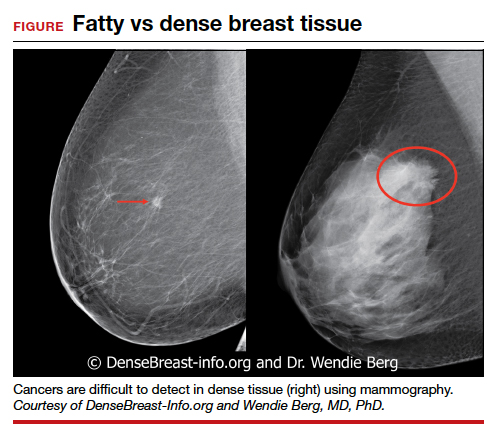

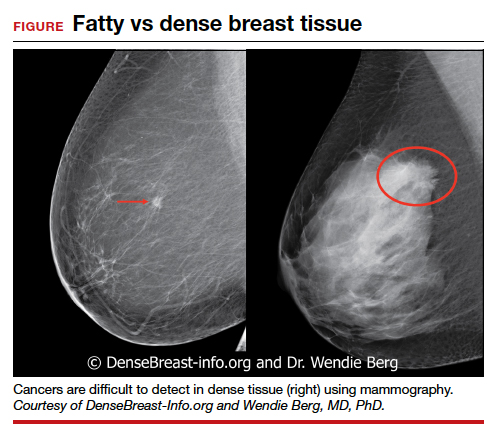

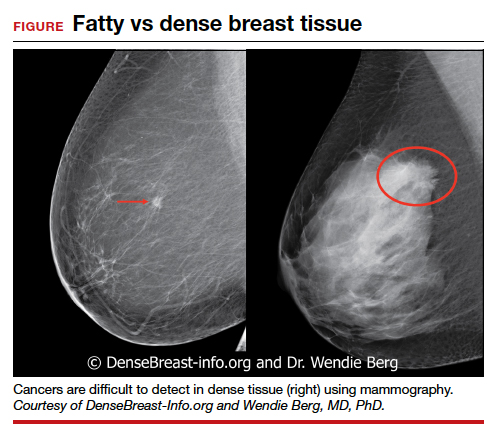

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

Restarting breast cancer screening after disruption not so simple

according to a modeling study reported at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Fallout of the pandemic has included reductions in cancer screening and diagnosis, said study investigator Lindy M. Kregting, a PhD student in the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands, new breast cancer diagnoses fell dramatically from historical levels starting in February. The number in April was less than half of that expected.

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used modeling to assess the impact of four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. The strategies differed regarding the population affected, the duration of the effects, and changes in stopping age. The usual situation, without any disruption, served as the comparator.

Results showed wide variation across strategies with respect to the increase in screening capacity needed during the latter half of this year – from 0% to 100% – and the excess breast cancer mortality occurring during 2020-2030 – from as many as 181 excess breast cancer deaths to as few as 14.

“The effects of the disruption are dependent on the chosen restart strategy,” Ms. Kregting summarized. “It would be preferred to immediately catch up because this minimizes the impact, but it also requires a very high capacity, so it may not always be possible. A proper alternative would be to increase the stopping age, so no screens are omitted, because this requires a rather normal capacity, and it will result in only small effects on incidence and mortality.”

As screening programs restart in some countries, there are still a lot of unknowns that could affect outcomes, including how many women will attend given that some may stay away out of fear, Ms. Kregting cautioned.

“We plan to do further model calculations when we know exactly what has happened. ... For now, we just assumed some reasonable disruption periods, and we assumed that capacity would be back to the original, before COVID-19, but I think we can say this is probably not the case,” she added.

Study details

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used Dutch breast cancer screening program parameters (biennial digital mammography for women aged 50-75 years) and a microsimulation screening analysis model to simulate four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening after a 6-month disruption:

- “Everyone delay,” a strategy in which all screening continues in the order planned with no change in the stopping age of 75 years (so that one in four women ultimately miss a screening during their lifetime)

- “First rounds no delay,” in which there is a delay in screening except for women having their first screening

- “Continue after stopping age,” in which there is a delay in screening but temporary increasing of the stopping age (to 76.5 years) to ensure all women get their final screen

- “Catch-up after stop,” in which capacity is increased to ensure full catch-up, with all delayed screens caught up in a 6-month period (the second half of 2020).

Results showed that 5,872 women would be screened in the latter half of 2020 if screening proceeded as usual without disruption. The necessary capacity was essentially the same with all of the restarting strategies, except for the catch-up-after-stop strategy, which would require a doubling of that number.

The temporal pattern of breast cancer incidence varied according to restart strategy early on, but incidence essentially returned to that expected with undisrupted screening by 2025 for all four strategies, with some small fluctuations thereafter.

The impact on breast cancer mortality differed considerably long term. It increased slightly and transiently above the expected level with the catch-up-after-stop strategy, but there were sizable, long-lasting increases with the other strategies, with excess deaths still seen in 2060 for the everyone-delay strategy.

In absolute terms, the excess number of breast cancer deaths during 2020-2030, compared with undisrupted screening, was 181 with the everyone-delay strategy, 155 with the first-rounds-no-delay strategy, 145 with the continue-after-stopping-age strategy, and just 14 with the catch-up-after-stop strategy. Ms. Kregting declined to provide numbers for other countries, given that the model is based on the Dutch population and screening program.

Results in context

“The unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide has important implications for cancer care,” said invited discussant Alessandra Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Eastern Piedmont and Maggiore della Carità Hospital, both in Novara, Italy.

“There is a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that screening programs and diagnostic programs have been decreased or suspended in many Western countries where this is standard of care. Patients also are more reluctant to present to health care services, delaying their diagnosis,” Dr. Gennari said.

Findings of this new study add to those of similar studies undertaken in Italy (published in In Vivo) and the United Kingdom (published in The Lancet Oncology) showing the likely marked toll of the pandemic on cancer diagnosis and mortality, Dr. Gennari noted. Taken together, the findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate this impact.

“These interventions should focus on increasing routine diagnostic capacity, through which up to 40% of patients with cancer are diagnosed,” Dr. Gennari recommended. “Public health messaging is needed that accurately conveys the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 versus the risks of not seeking health care advice if patients are symptomatic. Finally, there is a need for provision of evidence-based data on which clinicians can adequately base their decision on how to manage the risks of cancer patients and the risks and benefits of procedures during the pandemic.”

The current study did not have any specific funding, and Ms. Kregting disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gennari disclosed relationships with Roche, Eisai, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kregting L et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Conference, Abstract 24.

according to a modeling study reported at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Fallout of the pandemic has included reductions in cancer screening and diagnosis, said study investigator Lindy M. Kregting, a PhD student in the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands, new breast cancer diagnoses fell dramatically from historical levels starting in February. The number in April was less than half of that expected.

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used modeling to assess the impact of four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. The strategies differed regarding the population affected, the duration of the effects, and changes in stopping age. The usual situation, without any disruption, served as the comparator.

Results showed wide variation across strategies with respect to the increase in screening capacity needed during the latter half of this year – from 0% to 100% – and the excess breast cancer mortality occurring during 2020-2030 – from as many as 181 excess breast cancer deaths to as few as 14.

“The effects of the disruption are dependent on the chosen restart strategy,” Ms. Kregting summarized. “It would be preferred to immediately catch up because this minimizes the impact, but it also requires a very high capacity, so it may not always be possible. A proper alternative would be to increase the stopping age, so no screens are omitted, because this requires a rather normal capacity, and it will result in only small effects on incidence and mortality.”

As screening programs restart in some countries, there are still a lot of unknowns that could affect outcomes, including how many women will attend given that some may stay away out of fear, Ms. Kregting cautioned.

“We plan to do further model calculations when we know exactly what has happened. ... For now, we just assumed some reasonable disruption periods, and we assumed that capacity would be back to the original, before COVID-19, but I think we can say this is probably not the case,” she added.

Study details

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used Dutch breast cancer screening program parameters (biennial digital mammography for women aged 50-75 years) and a microsimulation screening analysis model to simulate four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening after a 6-month disruption:

- “Everyone delay,” a strategy in which all screening continues in the order planned with no change in the stopping age of 75 years (so that one in four women ultimately miss a screening during their lifetime)

- “First rounds no delay,” in which there is a delay in screening except for women having their first screening

- “Continue after stopping age,” in which there is a delay in screening but temporary increasing of the stopping age (to 76.5 years) to ensure all women get their final screen

- “Catch-up after stop,” in which capacity is increased to ensure full catch-up, with all delayed screens caught up in a 6-month period (the second half of 2020).

Results showed that 5,872 women would be screened in the latter half of 2020 if screening proceeded as usual without disruption. The necessary capacity was essentially the same with all of the restarting strategies, except for the catch-up-after-stop strategy, which would require a doubling of that number.

The temporal pattern of breast cancer incidence varied according to restart strategy early on, but incidence essentially returned to that expected with undisrupted screening by 2025 for all four strategies, with some small fluctuations thereafter.

The impact on breast cancer mortality differed considerably long term. It increased slightly and transiently above the expected level with the catch-up-after-stop strategy, but there were sizable, long-lasting increases with the other strategies, with excess deaths still seen in 2060 for the everyone-delay strategy.

In absolute terms, the excess number of breast cancer deaths during 2020-2030, compared with undisrupted screening, was 181 with the everyone-delay strategy, 155 with the first-rounds-no-delay strategy, 145 with the continue-after-stopping-age strategy, and just 14 with the catch-up-after-stop strategy. Ms. Kregting declined to provide numbers for other countries, given that the model is based on the Dutch population and screening program.

Results in context

“The unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide has important implications for cancer care,” said invited discussant Alessandra Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Eastern Piedmont and Maggiore della Carità Hospital, both in Novara, Italy.

“There is a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that screening programs and diagnostic programs have been decreased or suspended in many Western countries where this is standard of care. Patients also are more reluctant to present to health care services, delaying their diagnosis,” Dr. Gennari said.

Findings of this new study add to those of similar studies undertaken in Italy (published in In Vivo) and the United Kingdom (published in The Lancet Oncology) showing the likely marked toll of the pandemic on cancer diagnosis and mortality, Dr. Gennari noted. Taken together, the findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate this impact.

“These interventions should focus on increasing routine diagnostic capacity, through which up to 40% of patients with cancer are diagnosed,” Dr. Gennari recommended. “Public health messaging is needed that accurately conveys the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 versus the risks of not seeking health care advice if patients are symptomatic. Finally, there is a need for provision of evidence-based data on which clinicians can adequately base their decision on how to manage the risks of cancer patients and the risks and benefits of procedures during the pandemic.”

The current study did not have any specific funding, and Ms. Kregting disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gennari disclosed relationships with Roche, Eisai, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kregting L et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Conference, Abstract 24.

according to a modeling study reported at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Fallout of the pandemic has included reductions in cancer screening and diagnosis, said study investigator Lindy M. Kregting, a PhD student in the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands, new breast cancer diagnoses fell dramatically from historical levels starting in February. The number in April was less than half of that expected.

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used modeling to assess the impact of four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. The strategies differed regarding the population affected, the duration of the effects, and changes in stopping age. The usual situation, without any disruption, served as the comparator.

Results showed wide variation across strategies with respect to the increase in screening capacity needed during the latter half of this year – from 0% to 100% – and the excess breast cancer mortality occurring during 2020-2030 – from as many as 181 excess breast cancer deaths to as few as 14.

“The effects of the disruption are dependent on the chosen restart strategy,” Ms. Kregting summarized. “It would be preferred to immediately catch up because this minimizes the impact, but it also requires a very high capacity, so it may not always be possible. A proper alternative would be to increase the stopping age, so no screens are omitted, because this requires a rather normal capacity, and it will result in only small effects on incidence and mortality.”

As screening programs restart in some countries, there are still a lot of unknowns that could affect outcomes, including how many women will attend given that some may stay away out of fear, Ms. Kregting cautioned.

“We plan to do further model calculations when we know exactly what has happened. ... For now, we just assumed some reasonable disruption periods, and we assumed that capacity would be back to the original, before COVID-19, but I think we can say this is probably not the case,” she added.

Study details

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used Dutch breast cancer screening program parameters (biennial digital mammography for women aged 50-75 years) and a microsimulation screening analysis model to simulate four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening after a 6-month disruption:

- “Everyone delay,” a strategy in which all screening continues in the order planned with no change in the stopping age of 75 years (so that one in four women ultimately miss a screening during their lifetime)

- “First rounds no delay,” in which there is a delay in screening except for women having their first screening

- “Continue after stopping age,” in which there is a delay in screening but temporary increasing of the stopping age (to 76.5 years) to ensure all women get their final screen

- “Catch-up after stop,” in which capacity is increased to ensure full catch-up, with all delayed screens caught up in a 6-month period (the second half of 2020).

Results showed that 5,872 women would be screened in the latter half of 2020 if screening proceeded as usual without disruption. The necessary capacity was essentially the same with all of the restarting strategies, except for the catch-up-after-stop strategy, which would require a doubling of that number.

The temporal pattern of breast cancer incidence varied according to restart strategy early on, but incidence essentially returned to that expected with undisrupted screening by 2025 for all four strategies, with some small fluctuations thereafter.

The impact on breast cancer mortality differed considerably long term. It increased slightly and transiently above the expected level with the catch-up-after-stop strategy, but there were sizable, long-lasting increases with the other strategies, with excess deaths still seen in 2060 for the everyone-delay strategy.

In absolute terms, the excess number of breast cancer deaths during 2020-2030, compared with undisrupted screening, was 181 with the everyone-delay strategy, 155 with the first-rounds-no-delay strategy, 145 with the continue-after-stopping-age strategy, and just 14 with the catch-up-after-stop strategy. Ms. Kregting declined to provide numbers for other countries, given that the model is based on the Dutch population and screening program.

Results in context

“The unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide has important implications for cancer care,” said invited discussant Alessandra Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Eastern Piedmont and Maggiore della Carità Hospital, both in Novara, Italy.

“There is a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that screening programs and diagnostic programs have been decreased or suspended in many Western countries where this is standard of care. Patients also are more reluctant to present to health care services, delaying their diagnosis,” Dr. Gennari said.

Findings of this new study add to those of similar studies undertaken in Italy (published in In Vivo) and the United Kingdom (published in The Lancet Oncology) showing the likely marked toll of the pandemic on cancer diagnosis and mortality, Dr. Gennari noted. Taken together, the findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate this impact.

“These interventions should focus on increasing routine diagnostic capacity, through which up to 40% of patients with cancer are diagnosed,” Dr. Gennari recommended. “Public health messaging is needed that accurately conveys the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 versus the risks of not seeking health care advice if patients are symptomatic. Finally, there is a need for provision of evidence-based data on which clinicians can adequately base their decision on how to manage the risks of cancer patients and the risks and benefits of procedures during the pandemic.”

The current study did not have any specific funding, and Ms. Kregting disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gennari disclosed relationships with Roche, Eisai, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kregting L et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Conference, Abstract 24.

FROM EBCC-12 VIRTUAL CONFERENCE

Radiotherapy planning scans reveal breast cancer patients’ CVD risk

Radiotherapy planning scans may be a rich untapped source of information for estimating the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in breast cancer patients, a large study suggests.

Researchers found that breast cancer patients with a coronary artery calcifications (CAC) score exceeding 400 had nearly four times the adjusted risk of fatal and nonfatal CVD events when compared with patients who had a CAC score of 0.

Patients with scores exceeding 400 also had more than eight times the risk of coronary heart disease events. The associations were especially strong in the subset of patients who received anthracycline-containing chemotherapy.

Helena Verkooijen, MD, PhD, of University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands) presented these findings at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Dr. Verkooijen noted that, over the past 50 years, breast cancer has dramatically declined as a cause of death among breast cancer survivors, while CVD has continued to account for about 20% of the total deaths in this population.

CACs are sometimes incidentally seen in radiotherapy planning CT scans. “Right now, this information is not often used for patient stratification or informing patients about their cardiovascular risk, and this is a pity, because we know that it is an independent risk factor, and, often, the presence of calcifications can occur in the absence of other cardiovascular risk factors,” Dr. Verkooijen said.

Study details

Dr. Verkooijen and and colleagues from the Bragataston Study Group retrospectively studied 15,919 breast cancer patients who had radiotherapy planning CT scans during 2004-2016 at three Dutch institutions.

The researchers used an automated deep-learning algorithm (described in Radiology) to detect and quantify coronary calcium in planning CT scans and calculate CAC scores, classifying them into five categories.

The median follow-up was 51.6 months. Most women (70%) did not have any calcium detected in their coronary arteries (CAC score of 0), while 3% fell into the highest category (CAC score of >400).

The incidence of nonfatal and fatal CVD events increased with CAC score:

- 5.1% with a score of 0.

- 8.5% with a score of 1-10.

- 13.5% with a score of 11-100.

- 17.6% with a score of 101-400.

- 28.0% with a score greater than 400.

In analyses adjusted for age, laterality of radiation, and receipt of cardiotoxic agents – anthracyclines and trastuzumab – women with a score exceeding 400 had sharply elevated adjusted risks of CVD events (hazard ratio, 3.7), of coronary heart disease events specifically (HR, 8.2), and of death from any cause (HR, 2.8), when compared with peers who had a CAC score of 0.

On further scrutiny of CVD events, the pattern was similar regardless of whether radiation was left- or right-sided. However, the association was stronger among women who received anthracyclines as compared with counterparts who did not, with a nearly six-fold higher risk for those with highest versus lowest CAC scores.

When the women were surveyed, nearly 90% said they wanted to be informed about their CAC score and associated CVD risk, even in the absence of evidence-based risk reduction strategies.

Applying the results

“We believe that this is the first time that anyone has conducted a study on this topic on a scale like this, and we show that it is possible to relatively easily identify women at a very high risk of CVD,” Dr. Verkooijen said. “But what do we do with this information, because these scans are not made to answer this question. … This is information that we get that we haven’t really requested. I think we should only use this information when we have really shown that we can help patients reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease.”

To that end, Dr. Verkooijen and colleagues are planning additional research that will look at the potential benefit of referring high-risk patients for cardioprevention strategies and at the role of using the CAC score to personalize treatment strategies.

“This is an interesting and novel approach to predicting cardiac events for patients undergoing breast cancer treatment,” Meena S. Moran, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., commented in an interview.

The approach would likely be feasible in typical practice with widespread availability of the automated algorithm and might even alter treatment planning in real time, she said. “From the standpoint of radiation oncology, it would mean running the software to generate a CAC score, which would allow for modifications in decision-making during treatment planning, such as whether or not to include the internal mammary nodal chain in a patient who may be in the ‘gray zone’ for regional nodal radiation. For example, if a patient has a high CAC score, plus if they have received (or are receiving) cardiotoxic drugs, radiation oncologists can use that information as an additional factor to consider in the decision-making of whether or not to include the internal mammary chain, which inevitably can increase the dose delivered to the heart,” Dr. Moran elaborated.

Dr. Verkooijen’s study was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society, the European Commission, the Dutch Digestive Foundation, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, and Elekta. Dr. Verkooijen and Dr. Moran disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gal R et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Congress, Abstract 7.

Radiotherapy planning scans may be a rich untapped source of information for estimating the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in breast cancer patients, a large study suggests.

Researchers found that breast cancer patients with a coronary artery calcifications (CAC) score exceeding 400 had nearly four times the adjusted risk of fatal and nonfatal CVD events when compared with patients who had a CAC score of 0.

Patients with scores exceeding 400 also had more than eight times the risk of coronary heart disease events. The associations were especially strong in the subset of patients who received anthracycline-containing chemotherapy.

Helena Verkooijen, MD, PhD, of University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands) presented these findings at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Dr. Verkooijen noted that, over the past 50 years, breast cancer has dramatically declined as a cause of death among breast cancer survivors, while CVD has continued to account for about 20% of the total deaths in this population.

CACs are sometimes incidentally seen in radiotherapy planning CT scans. “Right now, this information is not often used for patient stratification or informing patients about their cardiovascular risk, and this is a pity, because we know that it is an independent risk factor, and, often, the presence of calcifications can occur in the absence of other cardiovascular risk factors,” Dr. Verkooijen said.

Study details

Dr. Verkooijen and and colleagues from the Bragataston Study Group retrospectively studied 15,919 breast cancer patients who had radiotherapy planning CT scans during 2004-2016 at three Dutch institutions.

The researchers used an automated deep-learning algorithm (described in Radiology) to detect and quantify coronary calcium in planning CT scans and calculate CAC scores, classifying them into five categories.

The median follow-up was 51.6 months. Most women (70%) did not have any calcium detected in their coronary arteries (CAC score of 0), while 3% fell into the highest category (CAC score of >400).

The incidence of nonfatal and fatal CVD events increased with CAC score:

- 5.1% with a score of 0.

- 8.5% with a score of 1-10.

- 13.5% with a score of 11-100.

- 17.6% with a score of 101-400.

- 28.0% with a score greater than 400.

In analyses adjusted for age, laterality of radiation, and receipt of cardiotoxic agents – anthracyclines and trastuzumab – women with a score exceeding 400 had sharply elevated adjusted risks of CVD events (hazard ratio, 3.7), of coronary heart disease events specifically (HR, 8.2), and of death from any cause (HR, 2.8), when compared with peers who had a CAC score of 0.

On further scrutiny of CVD events, the pattern was similar regardless of whether radiation was left- or right-sided. However, the association was stronger among women who received anthracyclines as compared with counterparts who did not, with a nearly six-fold higher risk for those with highest versus lowest CAC scores.

When the women were surveyed, nearly 90% said they wanted to be informed about their CAC score and associated CVD risk, even in the absence of evidence-based risk reduction strategies.

Applying the results

“We believe that this is the first time that anyone has conducted a study on this topic on a scale like this, and we show that it is possible to relatively easily identify women at a very high risk of CVD,” Dr. Verkooijen said. “But what do we do with this information, because these scans are not made to answer this question. … This is information that we get that we haven’t really requested. I think we should only use this information when we have really shown that we can help patients reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease.”

To that end, Dr. Verkooijen and colleagues are planning additional research that will look at the potential benefit of referring high-risk patients for cardioprevention strategies and at the role of using the CAC score to personalize treatment strategies.

“This is an interesting and novel approach to predicting cardiac events for patients undergoing breast cancer treatment,” Meena S. Moran, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., commented in an interview.