User login

Derms in survey say climate change is impacting their patients

in which the majority of participants said their patients are already being impacted.

Almost 80% of the 148 participants who responded to an electronic survey reported this belief.

The survey was designed and distributed to the membership of various dermatological organizations by Misha Rosenbach, MD, and coauthors. The results were published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Asked also about specific types of climate-driven phenomena with a current – or future – impact on their patients, 80.1% reported that they believed that increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is impactful, or will be. Changes in temporal or geographic patterns of vector-borne illnesses were affirmed by 78.7%, and an increase in social displacement caused by extreme weather or other events was affirmed by 67.1% as having an impact on their patients currently or in the future.

Other phenomena affirmed by respondents as already having an impact or impacting patients in the future were an increased incidence of heat exposure or heat-related illness (58.2%); an increase in rates of inflammatory skin disease flares (43.2%); increased incidence of waterborne infections (42.5%); and increased rates of allergic contact dermatitis (29.5%).

The survey was sent to the membership of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s Climate Change Expert Resource Group (ERG), among other organizations.

The study design and membership overlap made it impossible to calculate a response rate, the authors said, but they estimated it to be about 10%.

Almost all respondents were from the United States, and most (86.3%) practiced in an academic setting. The findings are similar to those of an online survey of members of the International Society of Dermatology (ISD), published in 2020, which found that 89% of 158 respondents believed climate change will impact the incidence of skin diseases in their area.

“Physicians, including dermatologists, are starting to understand the impact of the climate crisis on both their patients and themselves ... both through lived experiences and [issues raised] more in the scientific literature and in meetings,” Dr. Rosenbach, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

A majority of participants in the U.S. survey agreed they have a responsibility to bring awareness of the health effects of climate change to patients (77.2%) and to policymakers (88.6%). (In the ISD survey, 88% said they believed that dermatologists should play an advocacy role in climate change-related issues).

Only a minority of respondents in the U.S. survey said that they would feel comfortable discussing climate change with their patients (37.2%). Almost one-third of the respondents said they would like to be better informed about climate change before doing so. And 81.8% said they would like to read more about the dermatological effects of climate change in scientific journals.

“There continues to be unfilled interest in education and advocacy regarding climate change, suggesting a ‘practice gap’ even among dermatologists,” Dr. Rosenbach and his colleagues wrote, noting opportunities for professional organizations and journals to provide more resources and “actionable items” regarding climate change.

Some dermatologists have been taking action, in the meantime, to reduce the carbon footprint of their practices and institutions. Reductions in facility energy consumption, and reductions in medical waste/optimization of recycling, were each reported by more than one-third of survey respondents.

And almost half indicated that their practice or institution had increased capacity for telemedicine or telecommuting in response to climate change. Only 8% said their practice or institution had divested from fossil fuel stocks and/or bonds.

“There are a lot of sustainability-in-medicine solutions that are actually cost-neutral or cost-saving for practices,” said Dr. Rosenbach, who is a founder and co-chair of the AAD’s ERG on Climate Change and Environmental Issues.

Research in dermatology is starting to quantify the environmental impact of some of these changes. In a research letter also published in the British Journal of Dermatology, researchers from Cardiff University and the department of dermatology at University Hospital of Wales, described how they determined that reusable surgical packs used for skin surgery are more sustainable than single-use packs because of their reduced cost and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Such single-site reports are “early feeders” into what will become a stream of larger studies quantifying the impact of measures taken in dermatology, Dr. Rosenbach said.

Across medicine, there is evidence that health care professionals are now seeing climate change as a threat to their patients. In a multinational survey published last year in The Lancet Planetary Health, 77% of 3,977 participants said that climate change will cause a moderate or great deal of harm for their patients.

Climate change will be discussed at the AAD’s annual meeting in late March in a session devoted to the topic, and as part of a broader session on controversies in dermatology.

Dr. Rosenbach and two of the five authors of the dermatology research letter are members of the AAD’s ERG on climate change, but in the publication they noted that they were not writing on behalf of the AAD. None of the authors reported any disclosures, and there was no funding source for the survey.

in which the majority of participants said their patients are already being impacted.

Almost 80% of the 148 participants who responded to an electronic survey reported this belief.

The survey was designed and distributed to the membership of various dermatological organizations by Misha Rosenbach, MD, and coauthors. The results were published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Asked also about specific types of climate-driven phenomena with a current – or future – impact on their patients, 80.1% reported that they believed that increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is impactful, or will be. Changes in temporal or geographic patterns of vector-borne illnesses were affirmed by 78.7%, and an increase in social displacement caused by extreme weather or other events was affirmed by 67.1% as having an impact on their patients currently or in the future.

Other phenomena affirmed by respondents as already having an impact or impacting patients in the future were an increased incidence of heat exposure or heat-related illness (58.2%); an increase in rates of inflammatory skin disease flares (43.2%); increased incidence of waterborne infections (42.5%); and increased rates of allergic contact dermatitis (29.5%).

The survey was sent to the membership of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s Climate Change Expert Resource Group (ERG), among other organizations.

The study design and membership overlap made it impossible to calculate a response rate, the authors said, but they estimated it to be about 10%.

Almost all respondents were from the United States, and most (86.3%) practiced in an academic setting. The findings are similar to those of an online survey of members of the International Society of Dermatology (ISD), published in 2020, which found that 89% of 158 respondents believed climate change will impact the incidence of skin diseases in their area.

“Physicians, including dermatologists, are starting to understand the impact of the climate crisis on both their patients and themselves ... both through lived experiences and [issues raised] more in the scientific literature and in meetings,” Dr. Rosenbach, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

A majority of participants in the U.S. survey agreed they have a responsibility to bring awareness of the health effects of climate change to patients (77.2%) and to policymakers (88.6%). (In the ISD survey, 88% said they believed that dermatologists should play an advocacy role in climate change-related issues).

Only a minority of respondents in the U.S. survey said that they would feel comfortable discussing climate change with their patients (37.2%). Almost one-third of the respondents said they would like to be better informed about climate change before doing so. And 81.8% said they would like to read more about the dermatological effects of climate change in scientific journals.

“There continues to be unfilled interest in education and advocacy regarding climate change, suggesting a ‘practice gap’ even among dermatologists,” Dr. Rosenbach and his colleagues wrote, noting opportunities for professional organizations and journals to provide more resources and “actionable items” regarding climate change.

Some dermatologists have been taking action, in the meantime, to reduce the carbon footprint of their practices and institutions. Reductions in facility energy consumption, and reductions in medical waste/optimization of recycling, were each reported by more than one-third of survey respondents.

And almost half indicated that their practice or institution had increased capacity for telemedicine or telecommuting in response to climate change. Only 8% said their practice or institution had divested from fossil fuel stocks and/or bonds.

“There are a lot of sustainability-in-medicine solutions that are actually cost-neutral or cost-saving for practices,” said Dr. Rosenbach, who is a founder and co-chair of the AAD’s ERG on Climate Change and Environmental Issues.

Research in dermatology is starting to quantify the environmental impact of some of these changes. In a research letter also published in the British Journal of Dermatology, researchers from Cardiff University and the department of dermatology at University Hospital of Wales, described how they determined that reusable surgical packs used for skin surgery are more sustainable than single-use packs because of their reduced cost and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Such single-site reports are “early feeders” into what will become a stream of larger studies quantifying the impact of measures taken in dermatology, Dr. Rosenbach said.

Across medicine, there is evidence that health care professionals are now seeing climate change as a threat to their patients. In a multinational survey published last year in The Lancet Planetary Health, 77% of 3,977 participants said that climate change will cause a moderate or great deal of harm for their patients.

Climate change will be discussed at the AAD’s annual meeting in late March in a session devoted to the topic, and as part of a broader session on controversies in dermatology.

Dr. Rosenbach and two of the five authors of the dermatology research letter are members of the AAD’s ERG on climate change, but in the publication they noted that they were not writing on behalf of the AAD. None of the authors reported any disclosures, and there was no funding source for the survey.

in which the majority of participants said their patients are already being impacted.

Almost 80% of the 148 participants who responded to an electronic survey reported this belief.

The survey was designed and distributed to the membership of various dermatological organizations by Misha Rosenbach, MD, and coauthors. The results were published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Asked also about specific types of climate-driven phenomena with a current – or future – impact on their patients, 80.1% reported that they believed that increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is impactful, or will be. Changes in temporal or geographic patterns of vector-borne illnesses were affirmed by 78.7%, and an increase in social displacement caused by extreme weather or other events was affirmed by 67.1% as having an impact on their patients currently or in the future.

Other phenomena affirmed by respondents as already having an impact or impacting patients in the future were an increased incidence of heat exposure or heat-related illness (58.2%); an increase in rates of inflammatory skin disease flares (43.2%); increased incidence of waterborne infections (42.5%); and increased rates of allergic contact dermatitis (29.5%).

The survey was sent to the membership of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s Climate Change Expert Resource Group (ERG), among other organizations.

The study design and membership overlap made it impossible to calculate a response rate, the authors said, but they estimated it to be about 10%.

Almost all respondents were from the United States, and most (86.3%) practiced in an academic setting. The findings are similar to those of an online survey of members of the International Society of Dermatology (ISD), published in 2020, which found that 89% of 158 respondents believed climate change will impact the incidence of skin diseases in their area.

“Physicians, including dermatologists, are starting to understand the impact of the climate crisis on both their patients and themselves ... both through lived experiences and [issues raised] more in the scientific literature and in meetings,” Dr. Rosenbach, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

A majority of participants in the U.S. survey agreed they have a responsibility to bring awareness of the health effects of climate change to patients (77.2%) and to policymakers (88.6%). (In the ISD survey, 88% said they believed that dermatologists should play an advocacy role in climate change-related issues).

Only a minority of respondents in the U.S. survey said that they would feel comfortable discussing climate change with their patients (37.2%). Almost one-third of the respondents said they would like to be better informed about climate change before doing so. And 81.8% said they would like to read more about the dermatological effects of climate change in scientific journals.

“There continues to be unfilled interest in education and advocacy regarding climate change, suggesting a ‘practice gap’ even among dermatologists,” Dr. Rosenbach and his colleagues wrote, noting opportunities for professional organizations and journals to provide more resources and “actionable items” regarding climate change.

Some dermatologists have been taking action, in the meantime, to reduce the carbon footprint of their practices and institutions. Reductions in facility energy consumption, and reductions in medical waste/optimization of recycling, were each reported by more than one-third of survey respondents.

And almost half indicated that their practice or institution had increased capacity for telemedicine or telecommuting in response to climate change. Only 8% said their practice or institution had divested from fossil fuel stocks and/or bonds.

“There are a lot of sustainability-in-medicine solutions that are actually cost-neutral or cost-saving for practices,” said Dr. Rosenbach, who is a founder and co-chair of the AAD’s ERG on Climate Change and Environmental Issues.

Research in dermatology is starting to quantify the environmental impact of some of these changes. In a research letter also published in the British Journal of Dermatology, researchers from Cardiff University and the department of dermatology at University Hospital of Wales, described how they determined that reusable surgical packs used for skin surgery are more sustainable than single-use packs because of their reduced cost and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Such single-site reports are “early feeders” into what will become a stream of larger studies quantifying the impact of measures taken in dermatology, Dr. Rosenbach said.

Across medicine, there is evidence that health care professionals are now seeing climate change as a threat to their patients. In a multinational survey published last year in The Lancet Planetary Health, 77% of 3,977 participants said that climate change will cause a moderate or great deal of harm for their patients.

Climate change will be discussed at the AAD’s annual meeting in late March in a session devoted to the topic, and as part of a broader session on controversies in dermatology.

Dr. Rosenbach and two of the five authors of the dermatology research letter are members of the AAD’s ERG on climate change, but in the publication they noted that they were not writing on behalf of the AAD. None of the authors reported any disclosures, and there was no funding source for the survey.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Phototoxic Contact Dermatitis From Over-the-counter 8-Methoxypsoralen

To the Editor:

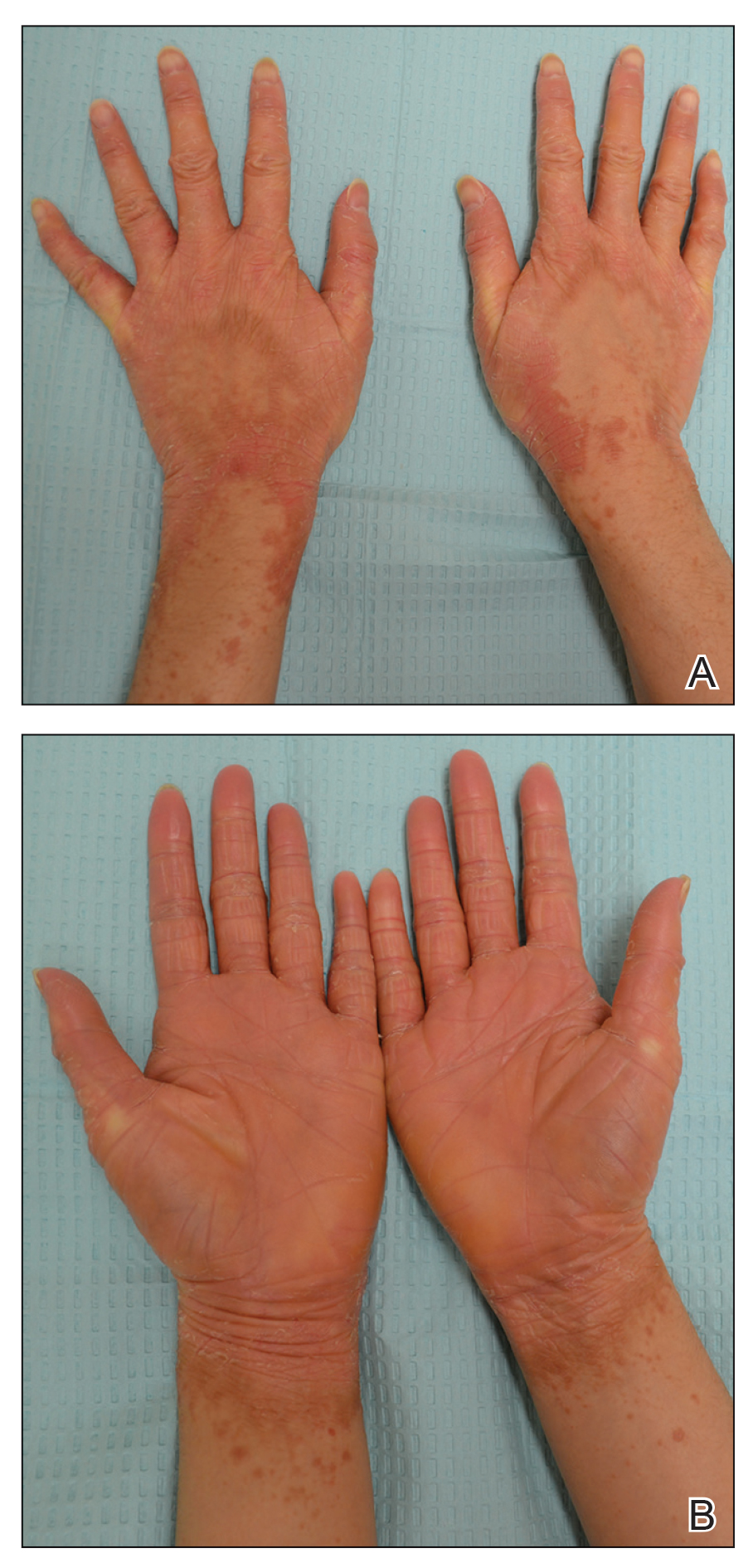

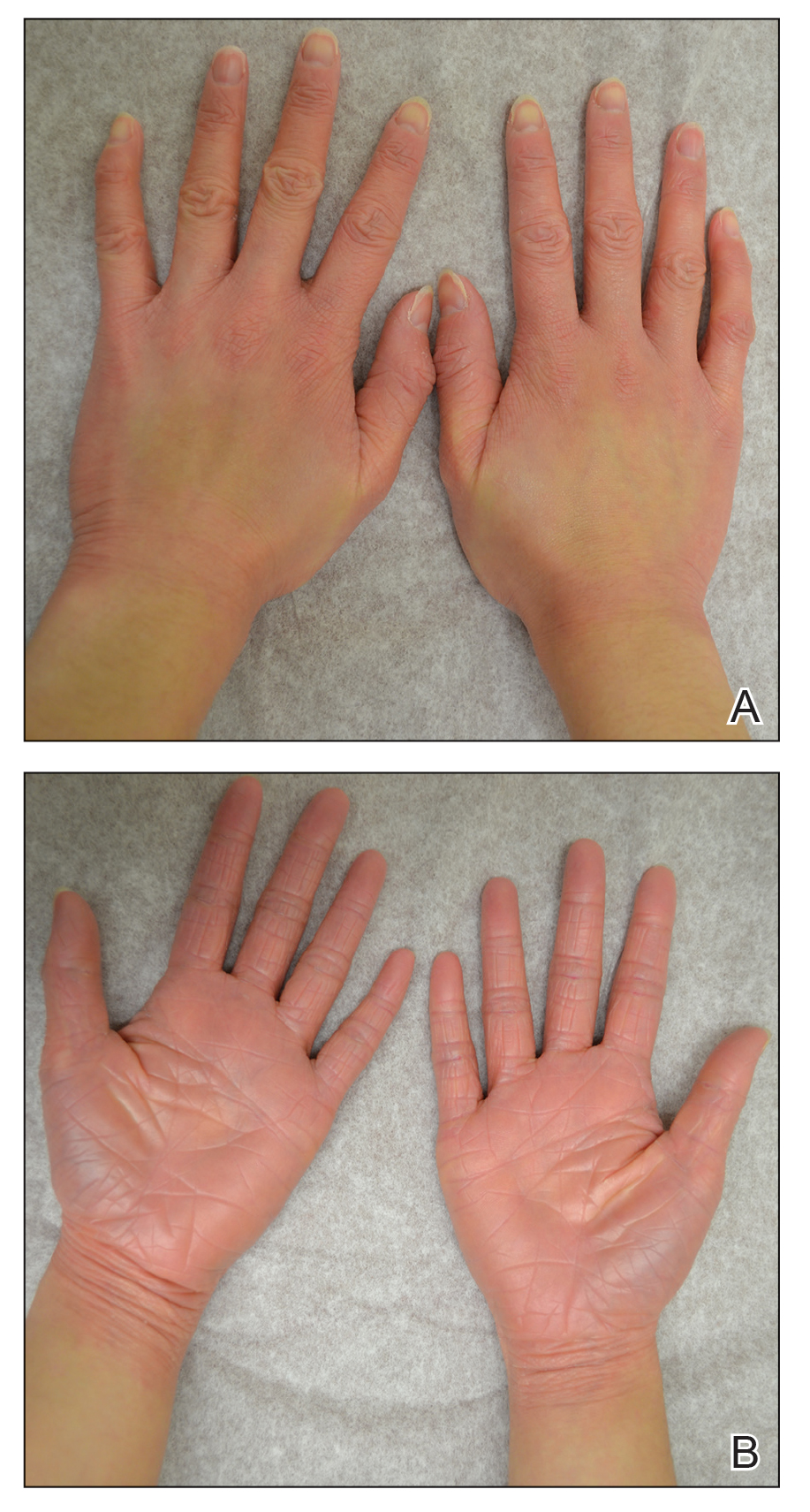

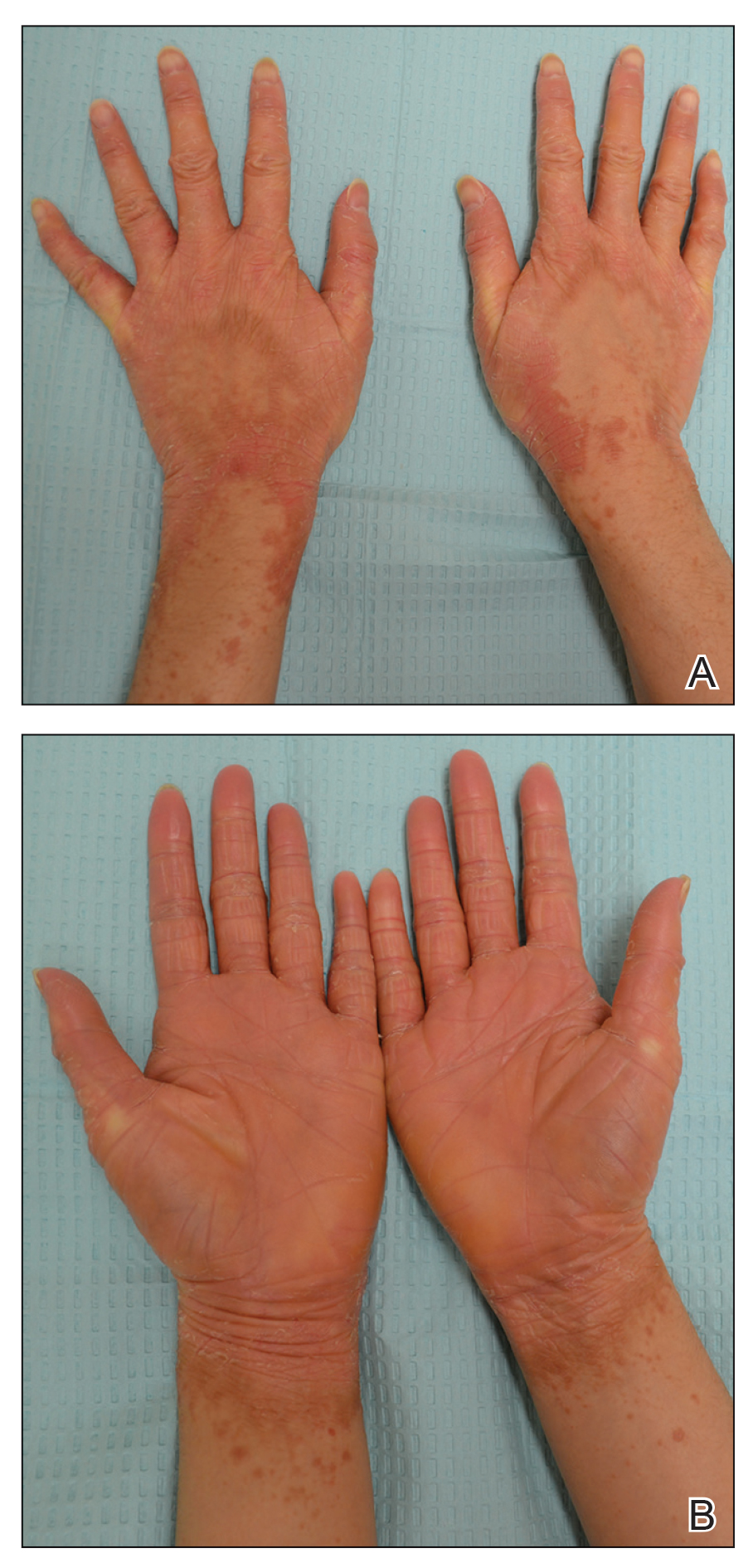

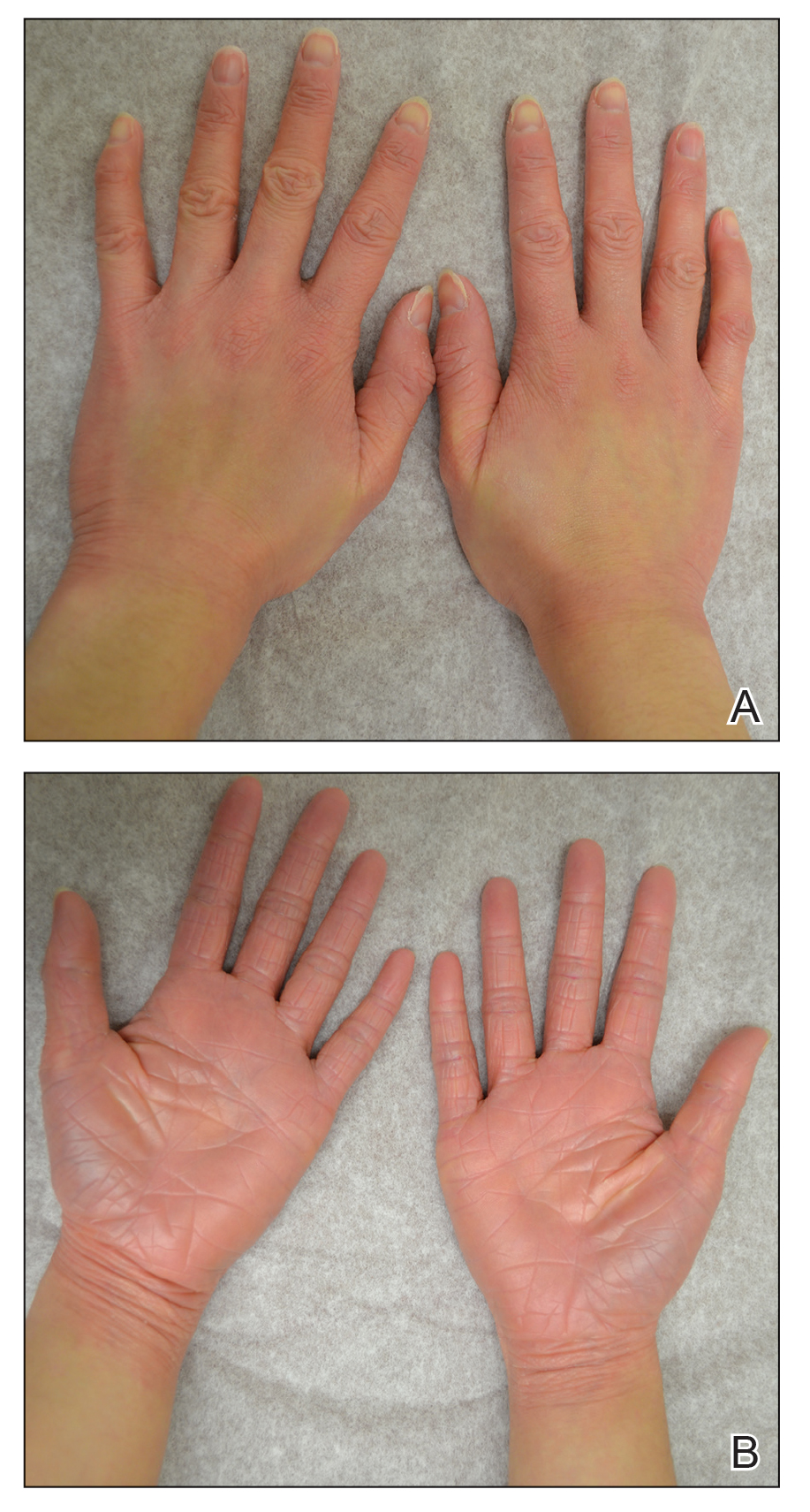

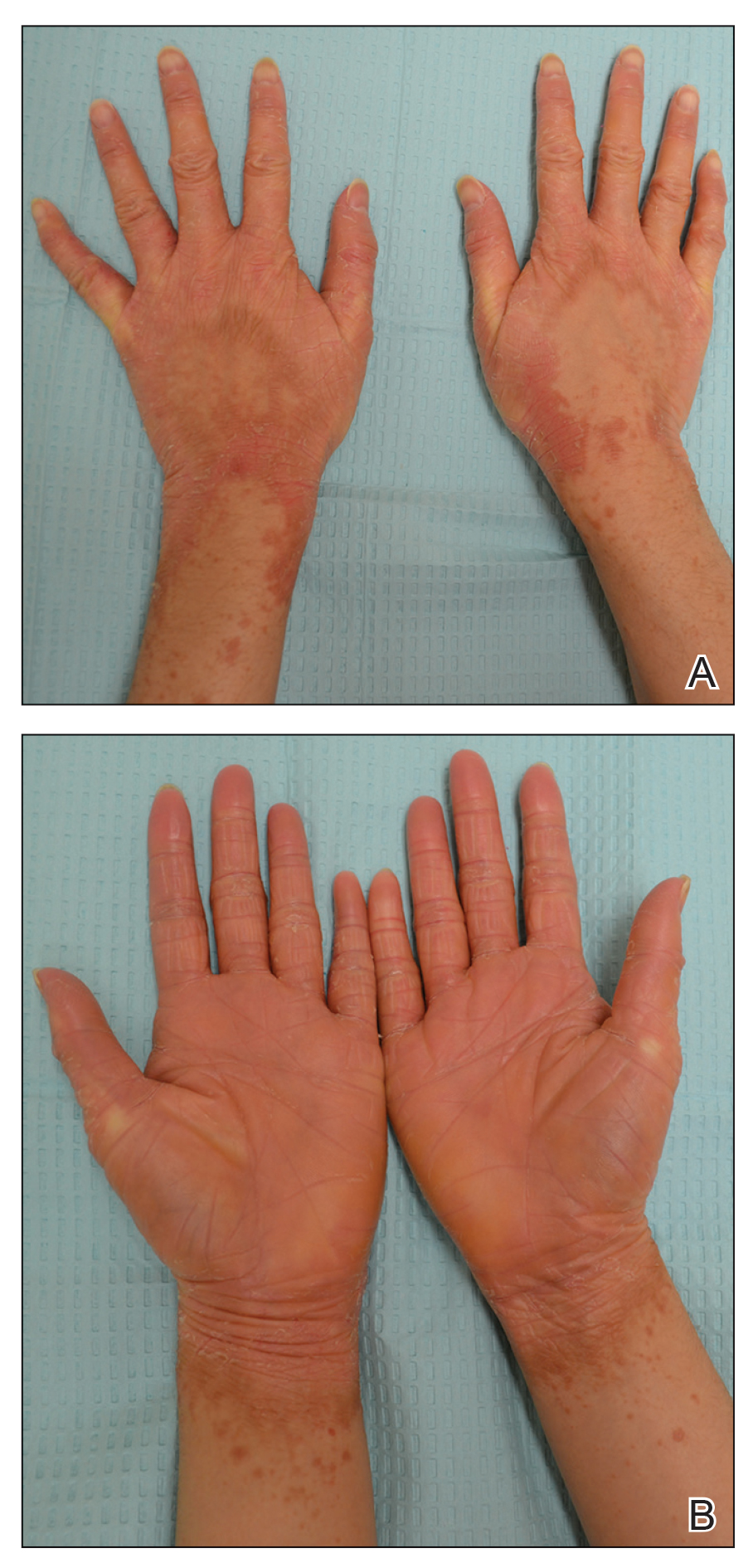

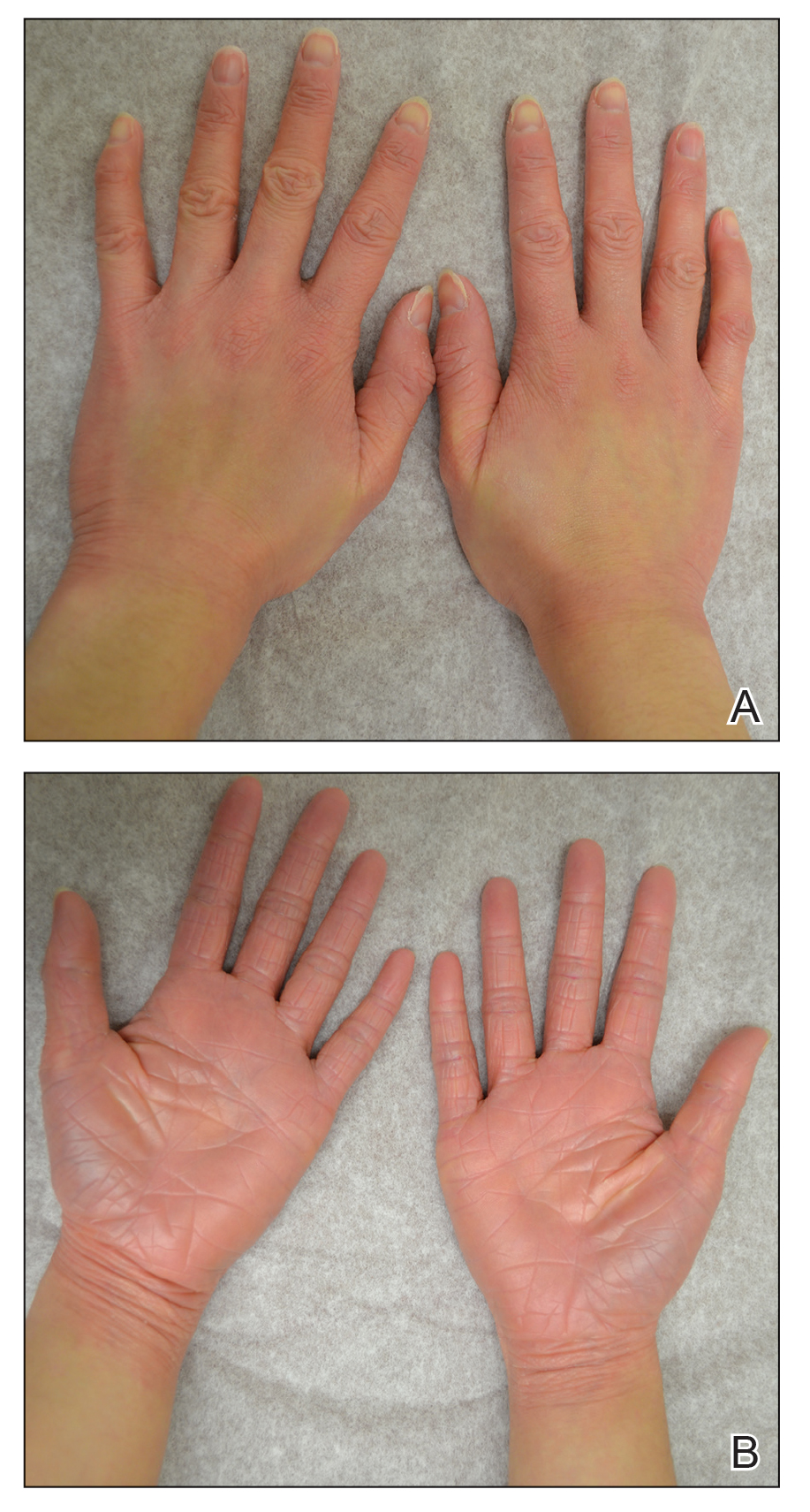

A 71-year-old Hispanic man with a history of vitiligo presented with an acute-onset blistering rash on the face, arms, and hands. Physical examination demonstrated photodistributed erythematous plaques with overlying vesicles and erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands, and wrists (Figure). Further history revealed that the patient applied a new cream that was recommended to treat vitiligo the night before the rash onset; he obtained the cream from a Central American market without a prescription. He had gone running in the park without any form of sun protection and then developed the rash within several hours. He denied taking any other medications or supplements. The involvement of sun-protected areas (ie, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds, submental area) was explained when the patient further elaborated that he had performed supine exercises during his outdoor recreation. He brought his new cream into the clinic, which was found to contain prescription-strength methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen), confirming the diagnosis of acute phototoxic contact dermatitis. The acute reaction had subsided, and the patient already had discontinued the causative agent. He was counseled on further avoidance of the cream and sun-protective measures.

The photosensitizing properties of certain compounds have been harnessed for therapeutic purposes. For example, psoralen plus UVA therapy has been used for psoriasis and vitiligo and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers.1 However, these agents can induce severe phototoxicity if UV light exposure is not carefully monitored, as seen in our patient. This case is a classic example of phototoxic contact dermatitis and highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history to allow for proper diagnosis and identification of the causative agent. Importantly, because prescription-strength topical medications are readily available over-the-counter, particularly in stores specializing in international goods, patients should be questioned about the use of all topical and systemic medications, both prescription and nonprescription.2

- Richard EG. The science and (lost) art of psoralen plus UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:11-23. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.08.002

- Kimyon RS, Schlarbaum JP, Liou YL, et al. Prescription-strengthtopical corticosteroids available over the counter: cross-sectional study of 80 stores in 13 United States cities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:524-525. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.035

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old Hispanic man with a history of vitiligo presented with an acute-onset blistering rash on the face, arms, and hands. Physical examination demonstrated photodistributed erythematous plaques with overlying vesicles and erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands, and wrists (Figure). Further history revealed that the patient applied a new cream that was recommended to treat vitiligo the night before the rash onset; he obtained the cream from a Central American market without a prescription. He had gone running in the park without any form of sun protection and then developed the rash within several hours. He denied taking any other medications or supplements. The involvement of sun-protected areas (ie, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds, submental area) was explained when the patient further elaborated that he had performed supine exercises during his outdoor recreation. He brought his new cream into the clinic, which was found to contain prescription-strength methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen), confirming the diagnosis of acute phototoxic contact dermatitis. The acute reaction had subsided, and the patient already had discontinued the causative agent. He was counseled on further avoidance of the cream and sun-protective measures.

The photosensitizing properties of certain compounds have been harnessed for therapeutic purposes. For example, psoralen plus UVA therapy has been used for psoriasis and vitiligo and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers.1 However, these agents can induce severe phototoxicity if UV light exposure is not carefully monitored, as seen in our patient. This case is a classic example of phototoxic contact dermatitis and highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history to allow for proper diagnosis and identification of the causative agent. Importantly, because prescription-strength topical medications are readily available over-the-counter, particularly in stores specializing in international goods, patients should be questioned about the use of all topical and systemic medications, both prescription and nonprescription.2

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old Hispanic man with a history of vitiligo presented with an acute-onset blistering rash on the face, arms, and hands. Physical examination demonstrated photodistributed erythematous plaques with overlying vesicles and erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands, and wrists (Figure). Further history revealed that the patient applied a new cream that was recommended to treat vitiligo the night before the rash onset; he obtained the cream from a Central American market without a prescription. He had gone running in the park without any form of sun protection and then developed the rash within several hours. He denied taking any other medications or supplements. The involvement of sun-protected areas (ie, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds, submental area) was explained when the patient further elaborated that he had performed supine exercises during his outdoor recreation. He brought his new cream into the clinic, which was found to contain prescription-strength methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen), confirming the diagnosis of acute phototoxic contact dermatitis. The acute reaction had subsided, and the patient already had discontinued the causative agent. He was counseled on further avoidance of the cream and sun-protective measures.

The photosensitizing properties of certain compounds have been harnessed for therapeutic purposes. For example, psoralen plus UVA therapy has been used for psoriasis and vitiligo and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers.1 However, these agents can induce severe phototoxicity if UV light exposure is not carefully monitored, as seen in our patient. This case is a classic example of phototoxic contact dermatitis and highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history to allow for proper diagnosis and identification of the causative agent. Importantly, because prescription-strength topical medications are readily available over-the-counter, particularly in stores specializing in international goods, patients should be questioned about the use of all topical and systemic medications, both prescription and nonprescription.2

- Richard EG. The science and (lost) art of psoralen plus UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:11-23. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.08.002

- Kimyon RS, Schlarbaum JP, Liou YL, et al. Prescription-strengthtopical corticosteroids available over the counter: cross-sectional study of 80 stores in 13 United States cities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:524-525. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.035

- Richard EG. The science and (lost) art of psoralen plus UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:11-23. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.08.002

- Kimyon RS, Schlarbaum JP, Liou YL, et al. Prescription-strengthtopical corticosteroids available over the counter: cross-sectional study of 80 stores in 13 United States cities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:524-525. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.035

Practice Points

- Phototoxic contact dermatitis is an irritant reaction resembling an exaggerated sunburn that occurs with the use of a photosensitizing agent and UV light exposure.

- A range of topical and systemic medications, plants, and natural products can elicit phototoxic reactions.

- With the wide availability of prescription-strength over-the-counter medications, a detailed history often is necessary to identify the causative agents of phototoxic contact dermatitis and ensure future avoidance.

Contact Allergy to Topical Medicaments, Part 2: Steroids, Immunomodulators, and Anesthetics, Oh My!

In the first part of this 2-part series (Cutis. 2021;108:271-275), we discussed topical medicament allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) from acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations. In part 2 of this series, we focus on topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetics.

Corticosteroids

Given their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, topical corticosteroids are utilized for the treatment of contact dermatitis and yet also are frequent culprits of ACD. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) demonstrated a 4% frequency of positive patch tests to at least one corticosteroid from 2007 to 2014; the relevant allergens were tixocortol pivalate (TP)(2.3%), budesonide (0.9%), hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (0.4%), clobetasol-17-propionate (0.3%), and desoximetasone (0.2%).1 Corticosteroid contact allergy can be difficult to recognize and may present as a flare of the underlying condition being treated. Clinically, these rashes may demonstrate an edge effect, characterized by pronounced dermatitis adjacent to and surrounding the treatment area due to concentrated anti-inflammatory effects in the center.

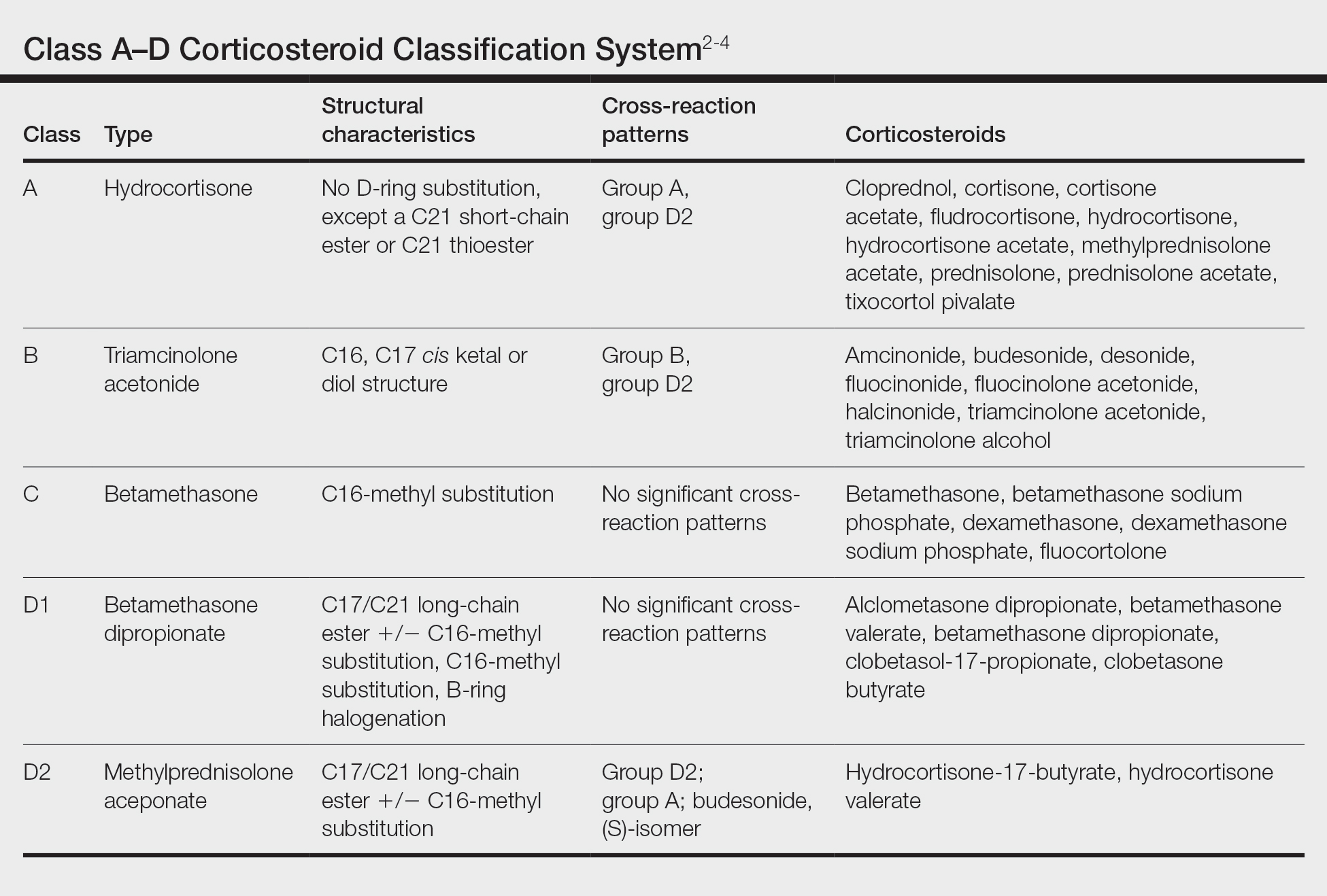

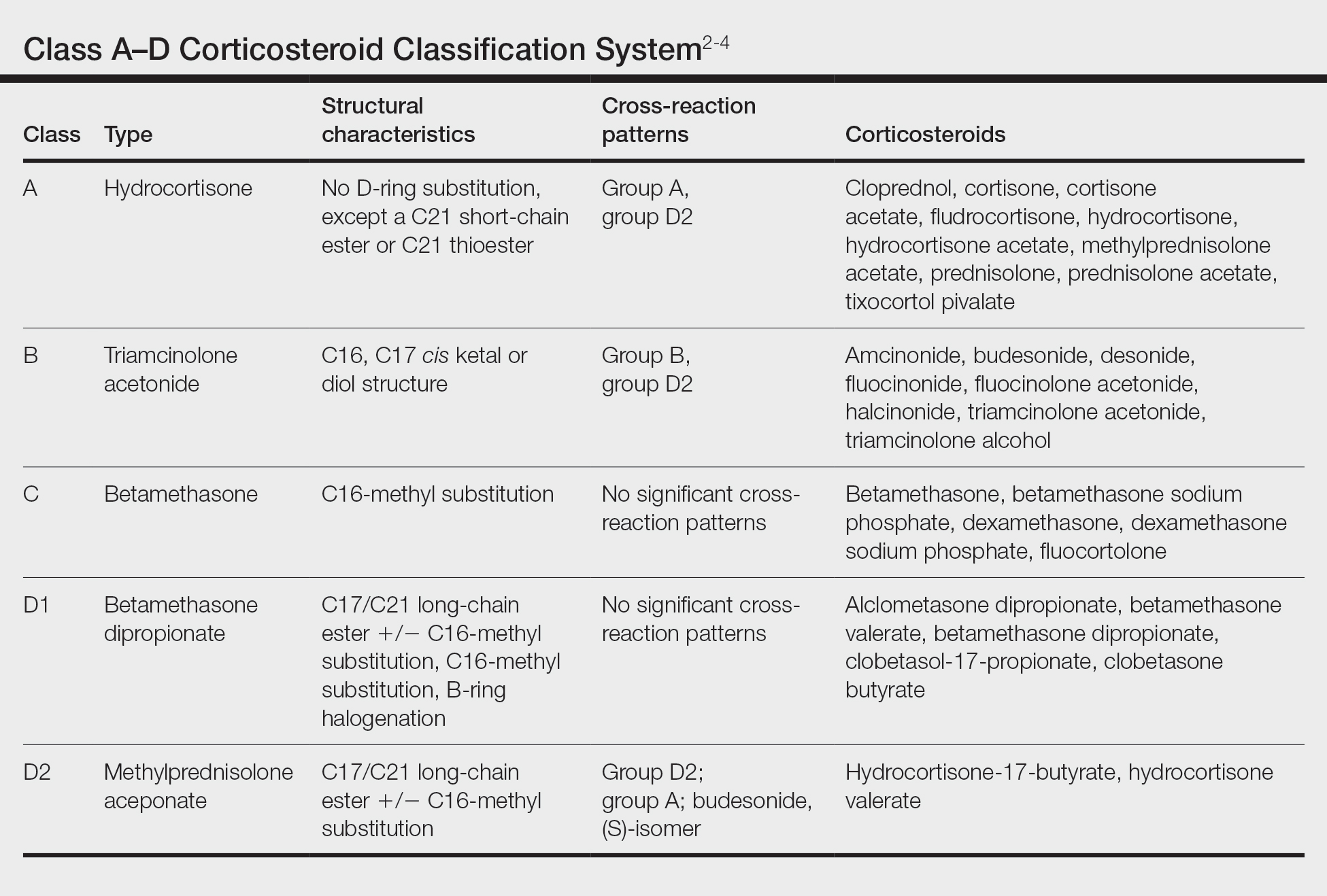

Traditionally, corticosteroids are divided into 4 basic structural groups—classes A, B, C, and D—based on the Coopman et al2 classification (Table). The class D corticosteroids were further subdivided into classes D1, defined by C16-methyl substitution and halogenation of the B ring, and D2, which lacks the aforementioned substitutions.4 However, more recently Baeck et al5 simplified this classification into 3 main groups of steroids based on molecular modeling in combination with patch test results. Group 1 combines the nonmethylated and (mostly) nonhalogenated class A and D2 molecules plus budesonide; group 2 accounts for some halogenated class B molecules with the C16, C17 cis ketal or diol structure; and group 3 includes halogenated and C16-methylated molecules from classes C and D1.4 For the purposes of this review, discussion of classes A through D refers to the Coopman et al2 classification, and groups 1 through 3 refers to Baeck et al.5

Tixocortol pivalate is used as a surrogate marker for hydrocortisone allergy and other class A corticosteroids and is part of the group 1 steroid classification. Interestingly, patients with TP-positive patch tests may not exhibit signs or symptoms of ACD from the use of hydrocortisone products. Repeat open application testing (ROAT) or provocative use testing may elicit a positive response in these patients, especially with the use of hydrocortisone cream (vs ointment), likely due to greater transepidermal penetration.6 There is little consensus on the optimal concentration of TP for patch testing. Although TP 1% often is recommended, studies have shown mixed findings of notable differences between high (1% petrolatum) and low (0.1% petrolatum) concentrations of TP.7,8

Budesonide also is part of group 1 and is a marker for contact allergy to class B corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and fluocinonide. Cross-reactions between budesonide and other corticosteroids traditionally classified as group B may be explained by structural similarities, whereas cross-reactions with certain class D corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone-17-butyrate, may be better explained by the diastereomer composition of budesonide.9,10 In a European study, budesonide 0.01% and TP 0.1% included in the European Baseline Series detected 85% (23/27) of cases of corticosteroid allergies.11 Use of inhaled budesonide can provoke recall dermatitis and therefore should be avoided in allergic patients.12

Testing for ACD to topical steroids is complex, as the potent anti-inflammatory properties of these medications can complicate results. Selecting the appropriate test, vehicle, and concentration can help avoid false negatives. Although intradermal testing previously was thought to be superior to patch testing in detecting topical corticosteroid contact allergy, newer data have demonstrated strong concordance between the two methods.13,14 The risk for skin atrophy, particularly with the use of suspensions, limits the use of intradermal testing.14 An ethanol vehicle is recommended for patch testing, except when testing with TP or budesonide when petrolatum provides greater corticosteroid stability.14-16 An irritant pattern or a rim effect on patch testing often is considered positive when testing corticosteroids, as the effect of the steroid itself can diminish a positive reaction. As a result, 0.1% dilutions sometimes are favored over 1% test concentrations.14,15,17 Late readings (>7 days) may be necessary to detect positive reactions in both adults and children.18,19

The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) find these varied classifications of steroids daunting (and somewhat confusing!). In general, when ACD to topical steroids is suspected, in addition to standard patch testing with a corticosteroid series, ROAT of the suspected steroid may be necessary, as the rules of steroid classification may not be reproducible in the real world. For patients with only corticosteroid allergy, calcineurin inhibitors are a safe alternative.

Immunomodulators

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue commonly used to treat psoriasis. Although it is a well-known irritant, ACD to topical calcipotriol rarely has been reported.20-23 Topical calcipotriol does not seem to cross-react with other vitamin D analogues, including tacalcitol and calcitriol.21,24 Based on the literature and the nonirritant reactive thresholds described by Fullerton et al,25 recommended patch test concentrations of calcipotriol in isopropanol are 2 to 10 µg/mL. Given its immunomodulating effects, calcipotriol may suppress contact hypersensitization from other allergens, similar to the effects seen with UV radiation.26

Calcineurin inhibitors act on the nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling pathway, resulting in downstream suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Contact allergy to these topical medications is rare and mainly has involved pimecrolimus.27-30 In one case, a patient with a previously documented topical tacrolimus contact allergy demonstrated cross-reactivity with pimecrolimus on a double-blinded, right-vs-left ROAT, as well as by patch testing with pimecrolimus cream 1%, which was only weakly positive (+).27 Patch test concentrations of 2.5% or higher may be required to elicit positive reactions to tacrolimus, as shown in one case where this was attributed to high molecular weight and poor extrafacial skin absorption of tacrolimus.30 In an unusual case, a patient reacted positively to patch testing and ROAT using pimecrolimus cream 1% but not pimecrolimus 1% to 5% in petrolatum or alcohol nor the individual excipients, illustrating the importance of testing with both active and inactive ingredients.29

Anesthetics

Local anesthetics can be separated into 2 main groups—amides and esters—based on their chemical structures. From 2001 to 2004, the NACDG patch tested 10,061 patients and found 344 (3.4%) with a positive reaction to at least one topical anesthetic.31 We will discuss some of the allergic cutaneous reactions associated with topical benzocaine (an ester) and lidocaine and prilocaine (amides).

According to the NACDG, the estimated prevalence of topical benzocaine allergy from 2001 to 2018 was roughly 3%.32 Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in patients who used topical benzocaine to treat localized pain disorders, including herpes zoster and dental pain.33,34 Benzocaine may be used in the anogenital region in the form of antihemorrhoidal creams and in condoms and is a considerably more common allergen in those with anogenital dermatitis compared to those without.35-38 Although cross-reactions within the same anesthetic group are common, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for concomitant sensitivity between unrelated local anesthetics.39-41

From 2001 to 2018, the prevalence of ACD to topical lidocaine was estimated to be 7.9%, according to the NACDG.32 A topical anesthetic containing both lidocaine and prilocaine often is used preprocedurally and can be a source of ACD. Interestingly, several cases of ACD to combination lidocaine/prilocaine cream demonstrated positive patch tests to prilocaine but not lidocaine, despite their structural similarities.42-44 One case report described simultaneous positive reactions to both prilocaine 5% and lidocaine 1%.45

There are a few key points to consider when working up contact allergy to local anesthetics. Patients who develop positive patch test reactions to a local anesthetic should undergo further testing to better understand alternatives and future use. As previously mentioned, ACD to one anesthetic does not necessarily preclude the use of other related anesthetics. Intradermal testing may help differentiate immediate and delayed-type allergic reactions to local anesthetics and should therefore follow positive patch tests.46 Importantly, a delayed reading (ie, after day 6 or 7) also should be performed as part of intradermal testing. Patients with positive patch tests but negative intradermal test results may be able to tolerate systemic anesthetic use.47

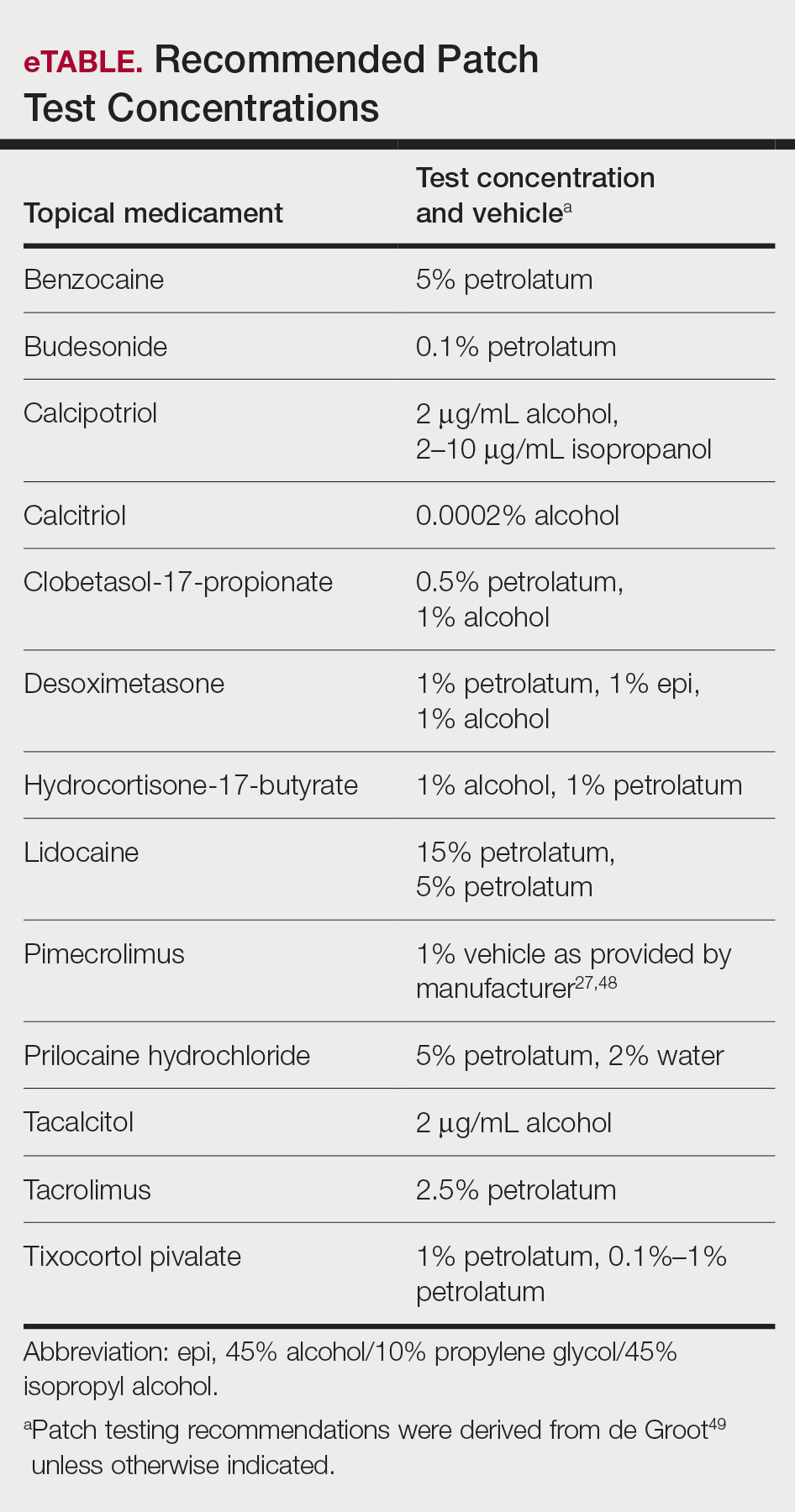

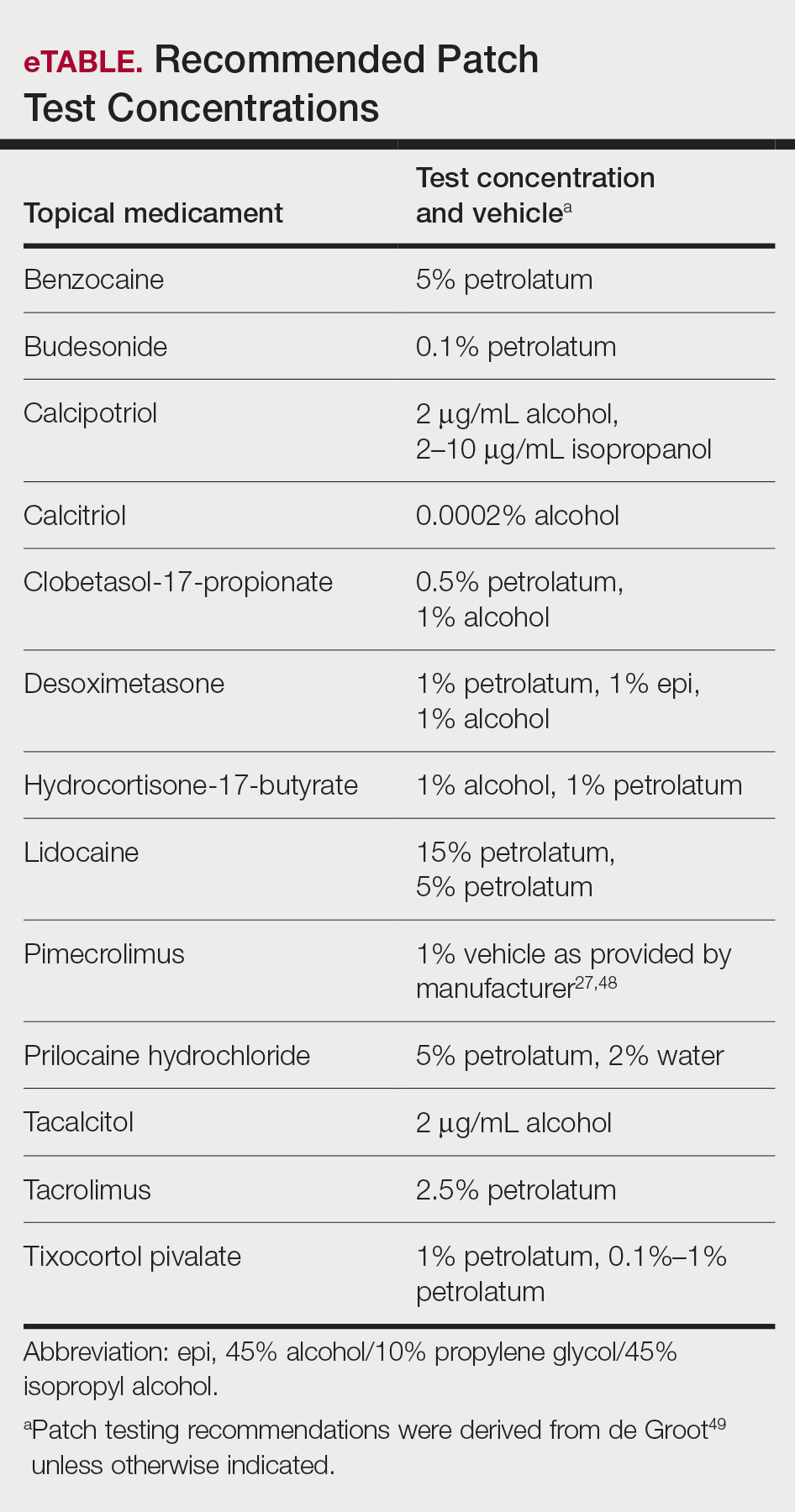

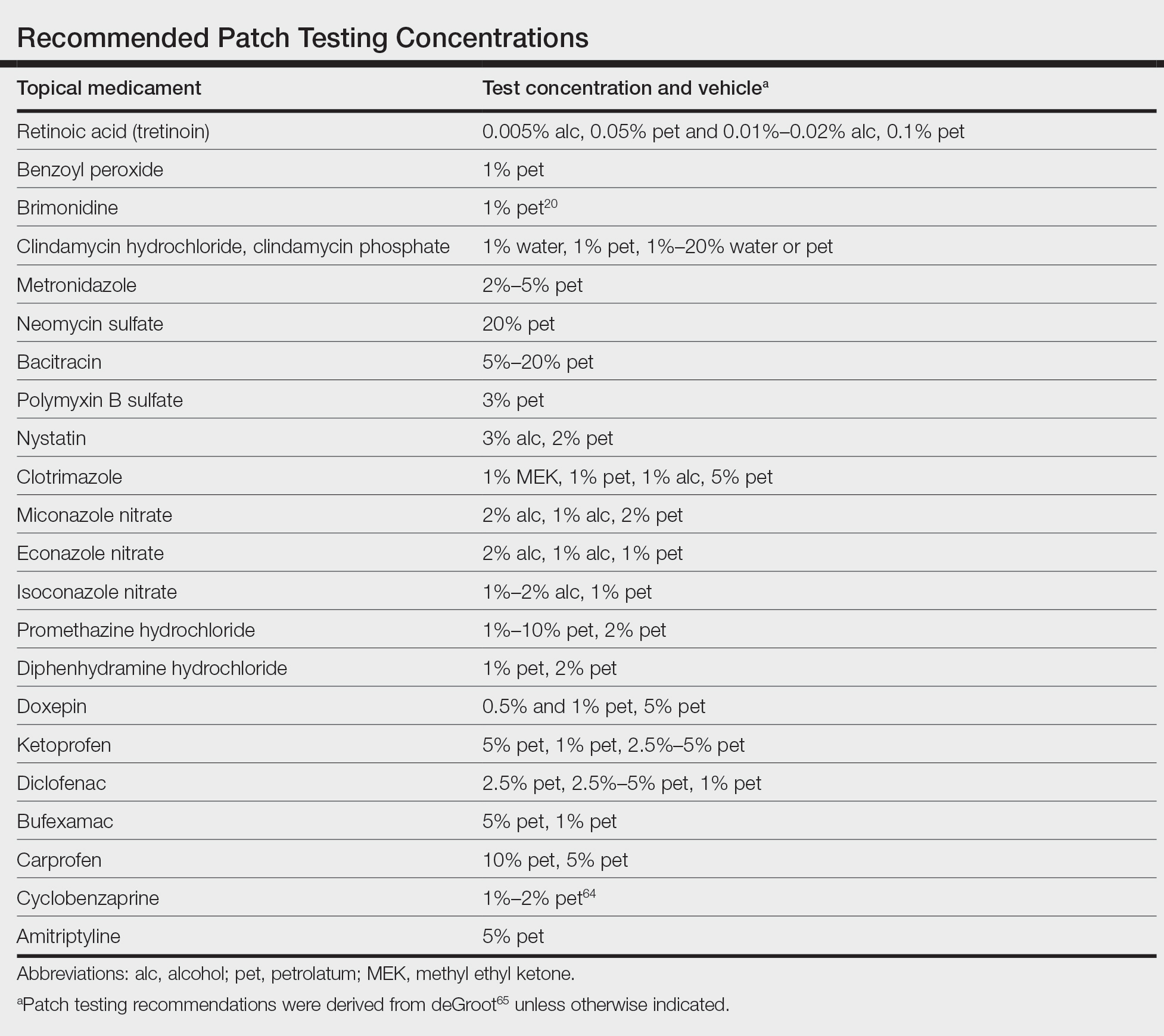

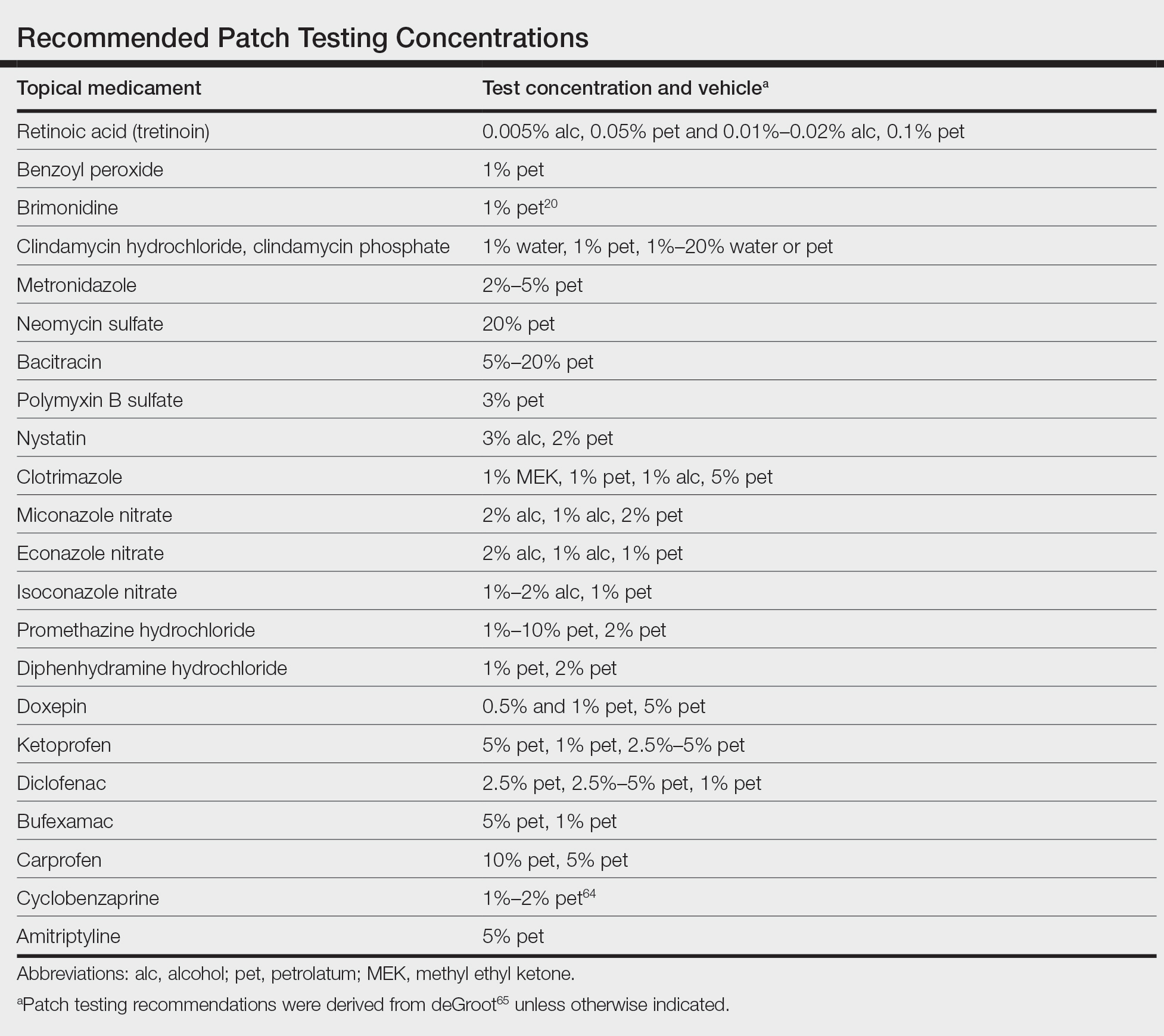

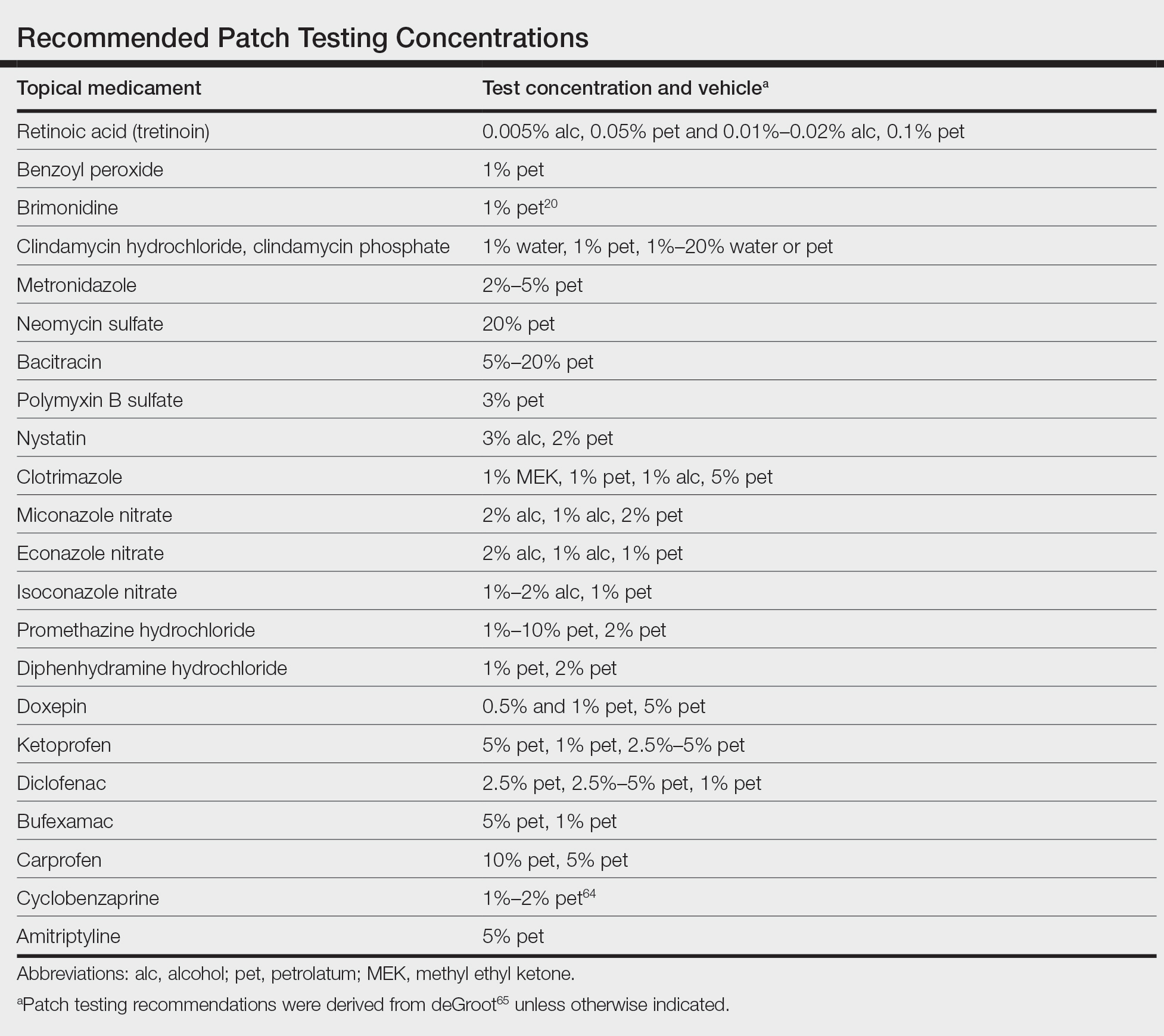

Patch Testing for Potential Medicament ACD

In this article, we touched on several topical medications that have nuanced patch testing specifications given their immunomodulating effects. A simplified outline of recommended patch test concentrations is provided in the eTable, and we encourage you to revisit these useful resources as needed. In many cases, referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be necessary. Although they are not reviewed in this article, always consider inactive ingredients such as preservatives, softening agents, and emulsifiers in the setting of medicament dermatitis, as they also may be culprits of ACD.

Final Interpretation

In this 2-part series, we covered ACD to several common topical drugs with a focus on active ingredients as the source of allergy, and yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Topical medicaments are prevalent in the field of dermatology, and associated cases of ACD have been reported proportionately. Consider ACD when topical medication efficacy plateaus, triggers new-onset dermatitis, or seems to exacerbate an underlying dermatitis.

- Pratt MD, Mufti A, Lipson J, et al. Patch test reactions to corticosteroids: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2007-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:58-63. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000251

- Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A. Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:27-34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028

- Matura M, Goossens A. Contact allergy to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2000;55:698-704. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00121.x

- Baeck M, Chemelle JA, Goossens A, et al. Corticosteroid cross-reactivity: clinical and molecular modelling tools. Allergy. 2011;66:1367-1374. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02666.x

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI. Clinical relevance of tixocortol pivalate-positive patch tests and questionable bioequivalence of different hydrocortisone preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:369-375. doi:10.1111/cod.12066

- Kalavala M, Statham BN, Green CM, et al. Tixocortol pivalate: what is the right concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:44-46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01136.x

- Chowdhury MM, Statham BN, Sansom JE, et al. Patch testing for corticosteroid allergy with low and high concentrations of tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:311-312. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460519.x

- Isaksson M, Bruze M, Lepoittevin JP, et al. Patch testing with serial dilutions of budesonide, its R and S diastereomers, and potentially cross-reacting substances. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:170-176.

- Ferguson AD, Emerson RM, English JS. Cross-reactivity patterns to budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:337-340. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470604.x

- Kot M, Bogaczewicz J, Kre˛cisz B, et al. Contact allergy in the population of patients with chronic inflammatory dermatoses and contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:253-259. doi:10.5114/ada.2017.67848

- Isaksson M, Bruze M. Allergic contact dermatitis in response to budesonide reactivated by inhalation of the allergen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:880-885. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120464

- Mimesh S, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis from corticosteroids: reproducibility of patch testing and correlation with intradermal testing. Dermatitis. 2006;17:137-142. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05048

- Soria A, Baeck M, Goossens A, et al. Patch, prick or intradermal tests to detect delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids?. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:313-324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01888.x

- Wilkinson SM, Beck MH. Corticosteroid contact hypersensitivity: what vehicle and concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:305-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02212.x

- Isaksson M, Beck MH, Wilkinson SM. Comparative testing with budesonide in petrolatum and ethanol in a standard series. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:123-124. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_16.x

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01967.x

- Isaksson M. Corticosteroid contact allergy—the importance of late readings and testing with corticosteroids used by the patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:56-57. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00959.x

- Tam I, Yu J. Delayed patch test reaction to budesonide in an 8-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:690-691. doi:10.1111/pde.14168

- Garcia-Bravo B, Camacho F. Two cases of contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol cream. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:118-119.

- Zollner TM, Ochsendorf FR, Hensel O, et al. Delayed-type reactivity to calcipotriol without cross-sensitization to tacalcitol. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:251. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb02457.x

- Frosch PJ, Rustemeyer T. Contact allergy to calcipotriol does exist. report of an unequivocal case and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:66-71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb05993.x

- Gilissen L, Huygens S, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:139-142. doi:10.1111/cod.12910

- Foti C, Carnimeo L, Bonamonte D, et al. Tolerance to calcitriol and tacalcitol in three patients with allergic contact dermatitis to calcipotriol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:756-759.

- Fullerton A, Benfeldt E, Petersen JR, et al. The calcipotriol dose-irritation relationship: 48-hour occlusive testing in healthy volunteers using Finn Chambers. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:259-265. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02071.x

- Hanneman KK, Scull HM, Cooper KD, et al. Effect of topical vitamin D analogue on in vivo contact sensitization. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1332-1334. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1332

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI, Eichenfield LF. Allergic contact dermatitis from pimecrolimus in a patient with tacrolimus allergy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.033

- Saitta P, Brancaccio R. Allergic contact dermatitis to pimecrolimus. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:43-44. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00822.x

- Neczyporenko F, Blondeel A. Allergic contact dermatitis to Elidel cream itself? Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:171-172. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01764.x

- Shaw DW, Eichenfield LF, Shainhouse T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:962-965. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.013

- Warshaw EM, Schram SE, Belsito DV, et al. Patch-test reactions to topical anesthetics: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data, 2001 to 2004. Dermatitis. 2008;19:81-85.

- Warshaw EM, Shaver RL, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch test reactions associated with topical medications: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data (2001-2018)[published online September 1, 2021]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000777

- Roos TC, Merk HF. Allergic contact dermatitis from benzocaine ointment during treatment of herpes zoster. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:104. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.4402097.x

- González-Rodríguez AJ, Gutiérrez-Paredes EM, Revert Fernández Á, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to benzocaine: the importance of concomitant positive patch test results. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:156-158. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2011.07.023

- Muratore L, Calogiuri G, Foti C, et al. Contact allergy to benzocaine in a condom. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:173-174. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01359.x

- Sharma A, Agarwal S, Garg G, et al. Desire for lasting long in bed led to contact allergic dermatitis and subsequent superficial penile gangrene: a dreadful complication of benzocaine-containing extended-pleasure condom [published online September 27, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018227351. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227351

- Bauer A, Geier J, Elsner P. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with anogenital complaints. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:649-654.

- Warshaw EM, Kimyon RS, Silverberg JI, et al. Evaluation of patch test findings in patients with anogenital dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:85-91. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3844

- Weightman W, Turner T. Allergic contact dermatitis from lignocaine: report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:265-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05928.x

- Jovanovic´ M, Karadaglic´ D, Brkic´ S. Contact urticaria and allergic contact dermatitis to lidocaine in a patient sensitive to benzocaine and propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:124-126. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0560f.x

- Carazo JL, Morera BS, Colom LP, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from ethyl chloride and benzocaine. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E13-E15.

- le Coz CJ, Cribier BJ, Heid E. Patch testing in suspected allergic contact dermatitis due to EMLA cream in haemodialyzed patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:316-317. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02407.x

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00498e.x

- Pérez-Pérez LC, Fernández-Redondo V, Ginarte-Val M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream in a hemodialyzed patient. Dermatitis. 2006;17:85-87.

- Timmermans MW, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream: concomitant sensitization to both local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:237-238. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06932.x

- Fuzier R, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Mertes PM, et al. Immediate- and delayed-type allergic reactions to amide local anesthetics: clinical features and skin testing. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:595-601. doi:10.1002/pds.1758

- Ruzicka T, Gerstmeier M, Przybilla B, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics: comparison of patch test with prick and intradermal test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1202-1208. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70158-3

- Fowler JF Jr, Fowler L, Douglas JL, et al. Skin reactions to pimecrolimus cream 1% in patients allergic to propylene glycol: a double-blind randomized study. Dermatitis. 2007;18:134-139. doi:10.2310/6620.2007.06028

- de Groot A. Patch Testing. 3rd ed. acdegroot publishing; 2008.

In the first part of this 2-part series (Cutis. 2021;108:271-275), we discussed topical medicament allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) from acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations. In part 2 of this series, we focus on topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetics.

Corticosteroids

Given their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, topical corticosteroids are utilized for the treatment of contact dermatitis and yet also are frequent culprits of ACD. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) demonstrated a 4% frequency of positive patch tests to at least one corticosteroid from 2007 to 2014; the relevant allergens were tixocortol pivalate (TP)(2.3%), budesonide (0.9%), hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (0.4%), clobetasol-17-propionate (0.3%), and desoximetasone (0.2%).1 Corticosteroid contact allergy can be difficult to recognize and may present as a flare of the underlying condition being treated. Clinically, these rashes may demonstrate an edge effect, characterized by pronounced dermatitis adjacent to and surrounding the treatment area due to concentrated anti-inflammatory effects in the center.

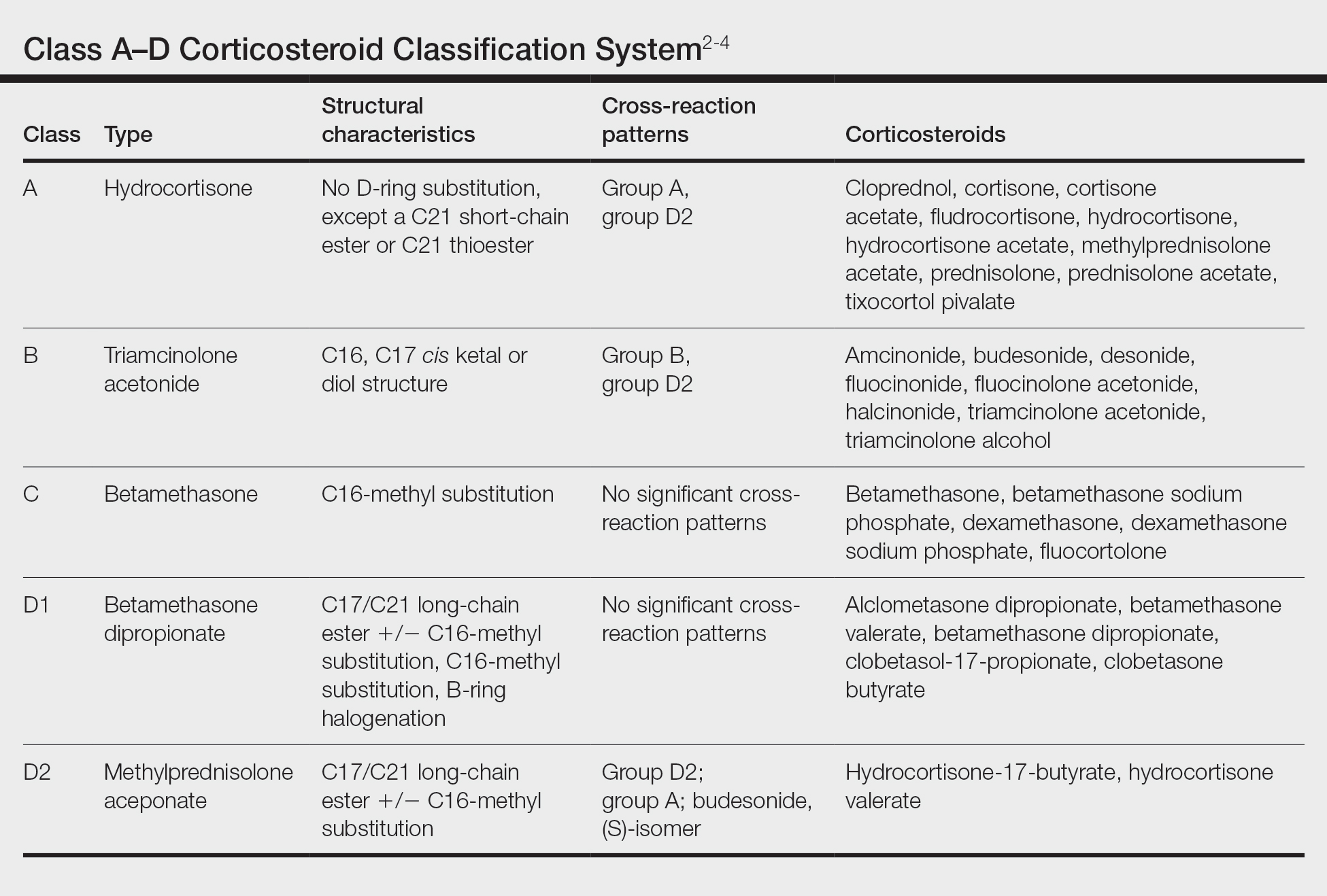

Traditionally, corticosteroids are divided into 4 basic structural groups—classes A, B, C, and D—based on the Coopman et al2 classification (Table). The class D corticosteroids were further subdivided into classes D1, defined by C16-methyl substitution and halogenation of the B ring, and D2, which lacks the aforementioned substitutions.4 However, more recently Baeck et al5 simplified this classification into 3 main groups of steroids based on molecular modeling in combination with patch test results. Group 1 combines the nonmethylated and (mostly) nonhalogenated class A and D2 molecules plus budesonide; group 2 accounts for some halogenated class B molecules with the C16, C17 cis ketal or diol structure; and group 3 includes halogenated and C16-methylated molecules from classes C and D1.4 For the purposes of this review, discussion of classes A through D refers to the Coopman et al2 classification, and groups 1 through 3 refers to Baeck et al.5

Tixocortol pivalate is used as a surrogate marker for hydrocortisone allergy and other class A corticosteroids and is part of the group 1 steroid classification. Interestingly, patients with TP-positive patch tests may not exhibit signs or symptoms of ACD from the use of hydrocortisone products. Repeat open application testing (ROAT) or provocative use testing may elicit a positive response in these patients, especially with the use of hydrocortisone cream (vs ointment), likely due to greater transepidermal penetration.6 There is little consensus on the optimal concentration of TP for patch testing. Although TP 1% often is recommended, studies have shown mixed findings of notable differences between high (1% petrolatum) and low (0.1% petrolatum) concentrations of TP.7,8

Budesonide also is part of group 1 and is a marker for contact allergy to class B corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and fluocinonide. Cross-reactions between budesonide and other corticosteroids traditionally classified as group B may be explained by structural similarities, whereas cross-reactions with certain class D corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone-17-butyrate, may be better explained by the diastereomer composition of budesonide.9,10 In a European study, budesonide 0.01% and TP 0.1% included in the European Baseline Series detected 85% (23/27) of cases of corticosteroid allergies.11 Use of inhaled budesonide can provoke recall dermatitis and therefore should be avoided in allergic patients.12

Testing for ACD to topical steroids is complex, as the potent anti-inflammatory properties of these medications can complicate results. Selecting the appropriate test, vehicle, and concentration can help avoid false negatives. Although intradermal testing previously was thought to be superior to patch testing in detecting topical corticosteroid contact allergy, newer data have demonstrated strong concordance between the two methods.13,14 The risk for skin atrophy, particularly with the use of suspensions, limits the use of intradermal testing.14 An ethanol vehicle is recommended for patch testing, except when testing with TP or budesonide when petrolatum provides greater corticosteroid stability.14-16 An irritant pattern or a rim effect on patch testing often is considered positive when testing corticosteroids, as the effect of the steroid itself can diminish a positive reaction. As a result, 0.1% dilutions sometimes are favored over 1% test concentrations.14,15,17 Late readings (>7 days) may be necessary to detect positive reactions in both adults and children.18,19

The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) find these varied classifications of steroids daunting (and somewhat confusing!). In general, when ACD to topical steroids is suspected, in addition to standard patch testing with a corticosteroid series, ROAT of the suspected steroid may be necessary, as the rules of steroid classification may not be reproducible in the real world. For patients with only corticosteroid allergy, calcineurin inhibitors are a safe alternative.

Immunomodulators

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue commonly used to treat psoriasis. Although it is a well-known irritant, ACD to topical calcipotriol rarely has been reported.20-23 Topical calcipotriol does not seem to cross-react with other vitamin D analogues, including tacalcitol and calcitriol.21,24 Based on the literature and the nonirritant reactive thresholds described by Fullerton et al,25 recommended patch test concentrations of calcipotriol in isopropanol are 2 to 10 µg/mL. Given its immunomodulating effects, calcipotriol may suppress contact hypersensitization from other allergens, similar to the effects seen with UV radiation.26

Calcineurin inhibitors act on the nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling pathway, resulting in downstream suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Contact allergy to these topical medications is rare and mainly has involved pimecrolimus.27-30 In one case, a patient with a previously documented topical tacrolimus contact allergy demonstrated cross-reactivity with pimecrolimus on a double-blinded, right-vs-left ROAT, as well as by patch testing with pimecrolimus cream 1%, which was only weakly positive (+).27 Patch test concentrations of 2.5% or higher may be required to elicit positive reactions to tacrolimus, as shown in one case where this was attributed to high molecular weight and poor extrafacial skin absorption of tacrolimus.30 In an unusual case, a patient reacted positively to patch testing and ROAT using pimecrolimus cream 1% but not pimecrolimus 1% to 5% in petrolatum or alcohol nor the individual excipients, illustrating the importance of testing with both active and inactive ingredients.29

Anesthetics

Local anesthetics can be separated into 2 main groups—amides and esters—based on their chemical structures. From 2001 to 2004, the NACDG patch tested 10,061 patients and found 344 (3.4%) with a positive reaction to at least one topical anesthetic.31 We will discuss some of the allergic cutaneous reactions associated with topical benzocaine (an ester) and lidocaine and prilocaine (amides).

According to the NACDG, the estimated prevalence of topical benzocaine allergy from 2001 to 2018 was roughly 3%.32 Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in patients who used topical benzocaine to treat localized pain disorders, including herpes zoster and dental pain.33,34 Benzocaine may be used in the anogenital region in the form of antihemorrhoidal creams and in condoms and is a considerably more common allergen in those with anogenital dermatitis compared to those without.35-38 Although cross-reactions within the same anesthetic group are common, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for concomitant sensitivity between unrelated local anesthetics.39-41

From 2001 to 2018, the prevalence of ACD to topical lidocaine was estimated to be 7.9%, according to the NACDG.32 A topical anesthetic containing both lidocaine and prilocaine often is used preprocedurally and can be a source of ACD. Interestingly, several cases of ACD to combination lidocaine/prilocaine cream demonstrated positive patch tests to prilocaine but not lidocaine, despite their structural similarities.42-44 One case report described simultaneous positive reactions to both prilocaine 5% and lidocaine 1%.45

There are a few key points to consider when working up contact allergy to local anesthetics. Patients who develop positive patch test reactions to a local anesthetic should undergo further testing to better understand alternatives and future use. As previously mentioned, ACD to one anesthetic does not necessarily preclude the use of other related anesthetics. Intradermal testing may help differentiate immediate and delayed-type allergic reactions to local anesthetics and should therefore follow positive patch tests.46 Importantly, a delayed reading (ie, after day 6 or 7) also should be performed as part of intradermal testing. Patients with positive patch tests but negative intradermal test results may be able to tolerate systemic anesthetic use.47

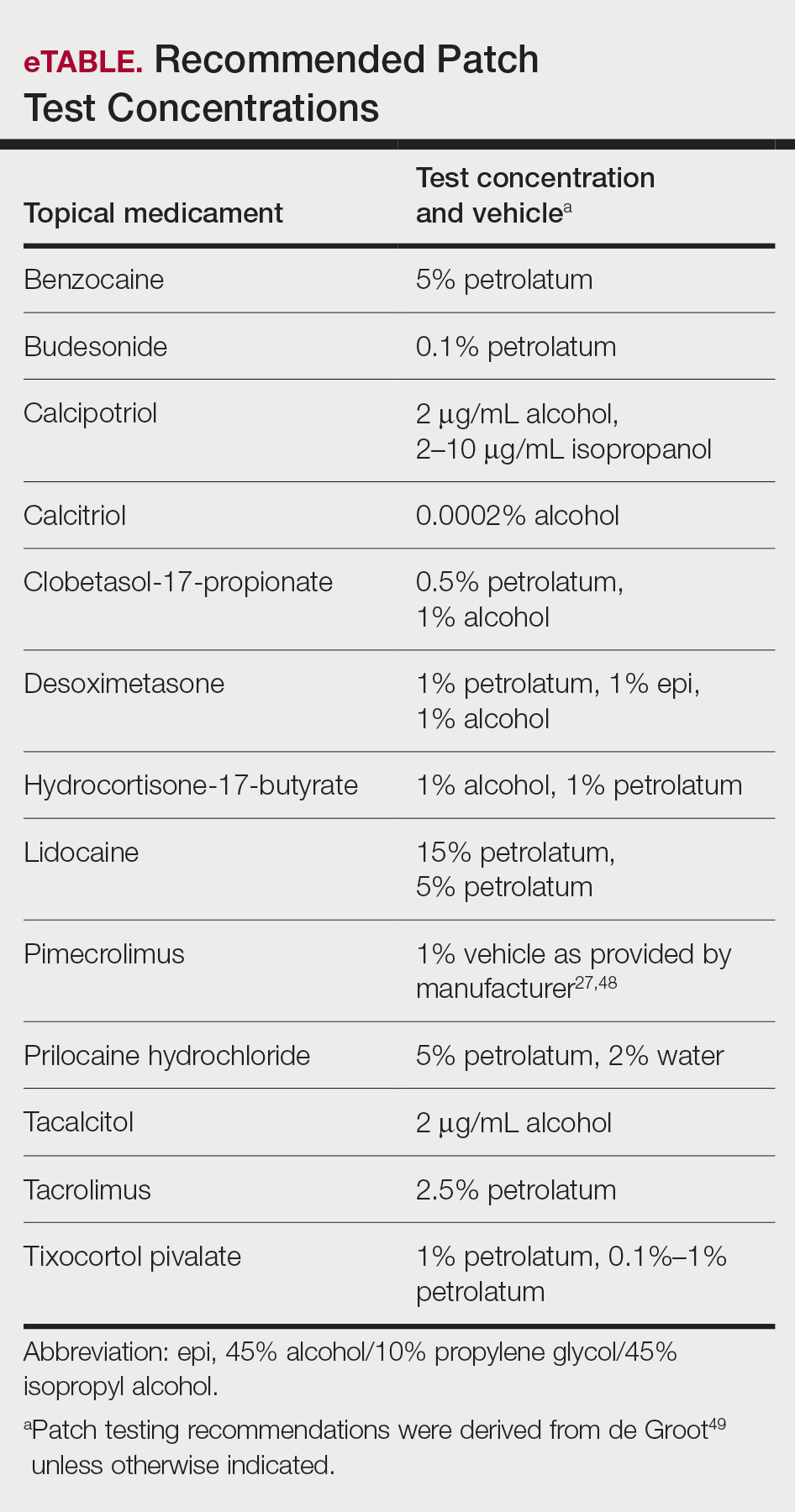

Patch Testing for Potential Medicament ACD

In this article, we touched on several topical medications that have nuanced patch testing specifications given their immunomodulating effects. A simplified outline of recommended patch test concentrations is provided in the eTable, and we encourage you to revisit these useful resources as needed. In many cases, referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be necessary. Although they are not reviewed in this article, always consider inactive ingredients such as preservatives, softening agents, and emulsifiers in the setting of medicament dermatitis, as they also may be culprits of ACD.

Final Interpretation

In this 2-part series, we covered ACD to several common topical drugs with a focus on active ingredients as the source of allergy, and yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Topical medicaments are prevalent in the field of dermatology, and associated cases of ACD have been reported proportionately. Consider ACD when topical medication efficacy plateaus, triggers new-onset dermatitis, or seems to exacerbate an underlying dermatitis.

In the first part of this 2-part series (Cutis. 2021;108:271-275), we discussed topical medicament allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) from acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations. In part 2 of this series, we focus on topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetics.

Corticosteroids

Given their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, topical corticosteroids are utilized for the treatment of contact dermatitis and yet also are frequent culprits of ACD. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) demonstrated a 4% frequency of positive patch tests to at least one corticosteroid from 2007 to 2014; the relevant allergens were tixocortol pivalate (TP)(2.3%), budesonide (0.9%), hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (0.4%), clobetasol-17-propionate (0.3%), and desoximetasone (0.2%).1 Corticosteroid contact allergy can be difficult to recognize and may present as a flare of the underlying condition being treated. Clinically, these rashes may demonstrate an edge effect, characterized by pronounced dermatitis adjacent to and surrounding the treatment area due to concentrated anti-inflammatory effects in the center.

Traditionally, corticosteroids are divided into 4 basic structural groups—classes A, B, C, and D—based on the Coopman et al2 classification (Table). The class D corticosteroids were further subdivided into classes D1, defined by C16-methyl substitution and halogenation of the B ring, and D2, which lacks the aforementioned substitutions.4 However, more recently Baeck et al5 simplified this classification into 3 main groups of steroids based on molecular modeling in combination with patch test results. Group 1 combines the nonmethylated and (mostly) nonhalogenated class A and D2 molecules plus budesonide; group 2 accounts for some halogenated class B molecules with the C16, C17 cis ketal or diol structure; and group 3 includes halogenated and C16-methylated molecules from classes C and D1.4 For the purposes of this review, discussion of classes A through D refers to the Coopman et al2 classification, and groups 1 through 3 refers to Baeck et al.5

Tixocortol pivalate is used as a surrogate marker for hydrocortisone allergy and other class A corticosteroids and is part of the group 1 steroid classification. Interestingly, patients with TP-positive patch tests may not exhibit signs or symptoms of ACD from the use of hydrocortisone products. Repeat open application testing (ROAT) or provocative use testing may elicit a positive response in these patients, especially with the use of hydrocortisone cream (vs ointment), likely due to greater transepidermal penetration.6 There is little consensus on the optimal concentration of TP for patch testing. Although TP 1% often is recommended, studies have shown mixed findings of notable differences between high (1% petrolatum) and low (0.1% petrolatum) concentrations of TP.7,8

Budesonide also is part of group 1 and is a marker for contact allergy to class B corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and fluocinonide. Cross-reactions between budesonide and other corticosteroids traditionally classified as group B may be explained by structural similarities, whereas cross-reactions with certain class D corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone-17-butyrate, may be better explained by the diastereomer composition of budesonide.9,10 In a European study, budesonide 0.01% and TP 0.1% included in the European Baseline Series detected 85% (23/27) of cases of corticosteroid allergies.11 Use of inhaled budesonide can provoke recall dermatitis and therefore should be avoided in allergic patients.12

Testing for ACD to topical steroids is complex, as the potent anti-inflammatory properties of these medications can complicate results. Selecting the appropriate test, vehicle, and concentration can help avoid false negatives. Although intradermal testing previously was thought to be superior to patch testing in detecting topical corticosteroid contact allergy, newer data have demonstrated strong concordance between the two methods.13,14 The risk for skin atrophy, particularly with the use of suspensions, limits the use of intradermal testing.14 An ethanol vehicle is recommended for patch testing, except when testing with TP or budesonide when petrolatum provides greater corticosteroid stability.14-16 An irritant pattern or a rim effect on patch testing often is considered positive when testing corticosteroids, as the effect of the steroid itself can diminish a positive reaction. As a result, 0.1% dilutions sometimes are favored over 1% test concentrations.14,15,17 Late readings (>7 days) may be necessary to detect positive reactions in both adults and children.18,19

The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) find these varied classifications of steroids daunting (and somewhat confusing!). In general, when ACD to topical steroids is suspected, in addition to standard patch testing with a corticosteroid series, ROAT of the suspected steroid may be necessary, as the rules of steroid classification may not be reproducible in the real world. For patients with only corticosteroid allergy, calcineurin inhibitors are a safe alternative.

Immunomodulators

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue commonly used to treat psoriasis. Although it is a well-known irritant, ACD to topical calcipotriol rarely has been reported.20-23 Topical calcipotriol does not seem to cross-react with other vitamin D analogues, including tacalcitol and calcitriol.21,24 Based on the literature and the nonirritant reactive thresholds described by Fullerton et al,25 recommended patch test concentrations of calcipotriol in isopropanol are 2 to 10 µg/mL. Given its immunomodulating effects, calcipotriol may suppress contact hypersensitization from other allergens, similar to the effects seen with UV radiation.26

Calcineurin inhibitors act on the nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling pathway, resulting in downstream suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Contact allergy to these topical medications is rare and mainly has involved pimecrolimus.27-30 In one case, a patient with a previously documented topical tacrolimus contact allergy demonstrated cross-reactivity with pimecrolimus on a double-blinded, right-vs-left ROAT, as well as by patch testing with pimecrolimus cream 1%, which was only weakly positive (+).27 Patch test concentrations of 2.5% or higher may be required to elicit positive reactions to tacrolimus, as shown in one case where this was attributed to high molecular weight and poor extrafacial skin absorption of tacrolimus.30 In an unusual case, a patient reacted positively to patch testing and ROAT using pimecrolimus cream 1% but not pimecrolimus 1% to 5% in petrolatum or alcohol nor the individual excipients, illustrating the importance of testing with both active and inactive ingredients.29

Anesthetics

Local anesthetics can be separated into 2 main groups—amides and esters—based on their chemical structures. From 2001 to 2004, the NACDG patch tested 10,061 patients and found 344 (3.4%) with a positive reaction to at least one topical anesthetic.31 We will discuss some of the allergic cutaneous reactions associated with topical benzocaine (an ester) and lidocaine and prilocaine (amides).

According to the NACDG, the estimated prevalence of topical benzocaine allergy from 2001 to 2018 was roughly 3%.32 Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in patients who used topical benzocaine to treat localized pain disorders, including herpes zoster and dental pain.33,34 Benzocaine may be used in the anogenital region in the form of antihemorrhoidal creams and in condoms and is a considerably more common allergen in those with anogenital dermatitis compared to those without.35-38 Although cross-reactions within the same anesthetic group are common, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for concomitant sensitivity between unrelated local anesthetics.39-41

From 2001 to 2018, the prevalence of ACD to topical lidocaine was estimated to be 7.9%, according to the NACDG.32 A topical anesthetic containing both lidocaine and prilocaine often is used preprocedurally and can be a source of ACD. Interestingly, several cases of ACD to combination lidocaine/prilocaine cream demonstrated positive patch tests to prilocaine but not lidocaine, despite their structural similarities.42-44 One case report described simultaneous positive reactions to both prilocaine 5% and lidocaine 1%.45

There are a few key points to consider when working up contact allergy to local anesthetics. Patients who develop positive patch test reactions to a local anesthetic should undergo further testing to better understand alternatives and future use. As previously mentioned, ACD to one anesthetic does not necessarily preclude the use of other related anesthetics. Intradermal testing may help differentiate immediate and delayed-type allergic reactions to local anesthetics and should therefore follow positive patch tests.46 Importantly, a delayed reading (ie, after day 6 or 7) also should be performed as part of intradermal testing. Patients with positive patch tests but negative intradermal test results may be able to tolerate systemic anesthetic use.47

Patch Testing for Potential Medicament ACD

In this article, we touched on several topical medications that have nuanced patch testing specifications given their immunomodulating effects. A simplified outline of recommended patch test concentrations is provided in the eTable, and we encourage you to revisit these useful resources as needed. In many cases, referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be necessary. Although they are not reviewed in this article, always consider inactive ingredients such as preservatives, softening agents, and emulsifiers in the setting of medicament dermatitis, as they also may be culprits of ACD.

Final Interpretation

In this 2-part series, we covered ACD to several common topical drugs with a focus on active ingredients as the source of allergy, and yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Topical medicaments are prevalent in the field of dermatology, and associated cases of ACD have been reported proportionately. Consider ACD when topical medication efficacy plateaus, triggers new-onset dermatitis, or seems to exacerbate an underlying dermatitis.

- Pratt MD, Mufti A, Lipson J, et al. Patch test reactions to corticosteroids: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2007-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:58-63. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000251

- Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A. Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:27-34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028

- Matura M, Goossens A. Contact allergy to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2000;55:698-704. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00121.x

- Baeck M, Chemelle JA, Goossens A, et al. Corticosteroid cross-reactivity: clinical and molecular modelling tools. Allergy. 2011;66:1367-1374. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02666.x

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI. Clinical relevance of tixocortol pivalate-positive patch tests and questionable bioequivalence of different hydrocortisone preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:369-375. doi:10.1111/cod.12066

- Kalavala M, Statham BN, Green CM, et al. Tixocortol pivalate: what is the right concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:44-46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01136.x

- Chowdhury MM, Statham BN, Sansom JE, et al. Patch testing for corticosteroid allergy with low and high concentrations of tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:311-312. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460519.x

- Isaksson M, Bruze M, Lepoittevin JP, et al. Patch testing with serial dilutions of budesonide, its R and S diastereomers, and potentially cross-reacting substances. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:170-176.

- Ferguson AD, Emerson RM, English JS. Cross-reactivity patterns to budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:337-340. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470604.x

- Kot M, Bogaczewicz J, Kre˛cisz B, et al. Contact allergy in the population of patients with chronic inflammatory dermatoses and contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:253-259. doi:10.5114/ada.2017.67848

- Isaksson M, Bruze M. Allergic contact dermatitis in response to budesonide reactivated by inhalation of the allergen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:880-885. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120464

- Mimesh S, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis from corticosteroids: reproducibility of patch testing and correlation with intradermal testing. Dermatitis. 2006;17:137-142. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05048

- Soria A, Baeck M, Goossens A, et al. Patch, prick or intradermal tests to detect delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids?. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:313-324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01888.x

- Wilkinson SM, Beck MH. Corticosteroid contact hypersensitivity: what vehicle and concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:305-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02212.x

- Isaksson M, Beck MH, Wilkinson SM. Comparative testing with budesonide in petrolatum and ethanol in a standard series. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:123-124. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_16.x

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01967.x

- Isaksson M. Corticosteroid contact allergy—the importance of late readings and testing with corticosteroids used by the patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:56-57. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00959.x

- Tam I, Yu J. Delayed patch test reaction to budesonide in an 8-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:690-691. doi:10.1111/pde.14168

- Garcia-Bravo B, Camacho F. Two cases of contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol cream. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:118-119.

- Zollner TM, Ochsendorf FR, Hensel O, et al. Delayed-type reactivity to calcipotriol without cross-sensitization to tacalcitol. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:251. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb02457.x

- Frosch PJ, Rustemeyer T. Contact allergy to calcipotriol does exist. report of an unequivocal case and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:66-71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb05993.x

- Gilissen L, Huygens S, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:139-142. doi:10.1111/cod.12910

- Foti C, Carnimeo L, Bonamonte D, et al. Tolerance to calcitriol and tacalcitol in three patients with allergic contact dermatitis to calcipotriol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:756-759.

- Fullerton A, Benfeldt E, Petersen JR, et al. The calcipotriol dose-irritation relationship: 48-hour occlusive testing in healthy volunteers using Finn Chambers. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:259-265. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02071.x

- Hanneman KK, Scull HM, Cooper KD, et al. Effect of topical vitamin D analogue on in vivo contact sensitization. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1332-1334. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1332

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI, Eichenfield LF. Allergic contact dermatitis from pimecrolimus in a patient with tacrolimus allergy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.033

- Saitta P, Brancaccio R. Allergic contact dermatitis to pimecrolimus. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:43-44. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00822.x

- Neczyporenko F, Blondeel A. Allergic contact dermatitis to Elidel cream itself? Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:171-172. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01764.x

- Shaw DW, Eichenfield LF, Shainhouse T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:962-965. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.013

- Warshaw EM, Schram SE, Belsito DV, et al. Patch-test reactions to topical anesthetics: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data, 2001 to 2004. Dermatitis. 2008;19:81-85.

- Warshaw EM, Shaver RL, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch test reactions associated with topical medications: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data (2001-2018)[published online September 1, 2021]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000777

- Roos TC, Merk HF. Allergic contact dermatitis from benzocaine ointment during treatment of herpes zoster. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:104. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.4402097.x

- González-Rodríguez AJ, Gutiérrez-Paredes EM, Revert Fernández Á, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to benzocaine: the importance of concomitant positive patch test results. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:156-158. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2011.07.023

- Muratore L, Calogiuri G, Foti C, et al. Contact allergy to benzocaine in a condom. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:173-174. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01359.x

- Sharma A, Agarwal S, Garg G, et al. Desire for lasting long in bed led to contact allergic dermatitis and subsequent superficial penile gangrene: a dreadful complication of benzocaine-containing extended-pleasure condom [published online September 27, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018227351. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227351

- Bauer A, Geier J, Elsner P. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with anogenital complaints. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:649-654.

- Warshaw EM, Kimyon RS, Silverberg JI, et al. Evaluation of patch test findings in patients with anogenital dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:85-91. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3844

- Weightman W, Turner T. Allergic contact dermatitis from lignocaine: report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:265-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05928.x

- Jovanovic´ M, Karadaglic´ D, Brkic´ S. Contact urticaria and allergic contact dermatitis to lidocaine in a patient sensitive to benzocaine and propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:124-126. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0560f.x

- Carazo JL, Morera BS, Colom LP, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from ethyl chloride and benzocaine. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E13-E15.

- le Coz CJ, Cribier BJ, Heid E. Patch testing in suspected allergic contact dermatitis due to EMLA cream in haemodialyzed patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:316-317. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02407.x

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00498e.x

- Pérez-Pérez LC, Fernández-Redondo V, Ginarte-Val M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream in a hemodialyzed patient. Dermatitis. 2006;17:85-87.

- Timmermans MW, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream: concomitant sensitization to both local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:237-238. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06932.x

- Fuzier R, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Mertes PM, et al. Immediate- and delayed-type allergic reactions to amide local anesthetics: clinical features and skin testing. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:595-601. doi:10.1002/pds.1758

- Ruzicka T, Gerstmeier M, Przybilla B, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics: comparison of patch test with prick and intradermal test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1202-1208. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70158-3

- Fowler JF Jr, Fowler L, Douglas JL, et al. Skin reactions to pimecrolimus cream 1% in patients allergic to propylene glycol: a double-blind randomized study. Dermatitis. 2007;18:134-139. doi:10.2310/6620.2007.06028

- de Groot A. Patch Testing. 3rd ed. acdegroot publishing; 2008.

- Pratt MD, Mufti A, Lipson J, et al. Patch test reactions to corticosteroids: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2007-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:58-63. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000251

- Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A. Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:27-34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028

- Matura M, Goossens A. Contact allergy to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2000;55:698-704. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00121.x

- Baeck M, Chemelle JA, Goossens A, et al. Corticosteroid cross-reactivity: clinical and molecular modelling tools. Allergy. 2011;66:1367-1374. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02666.x

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI. Clinical relevance of tixocortol pivalate-positive patch tests and questionable bioequivalence of different hydrocortisone preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:369-375. doi:10.1111/cod.12066

- Kalavala M, Statham BN, Green CM, et al. Tixocortol pivalate: what is the right concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:44-46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01136.x

- Chowdhury MM, Statham BN, Sansom JE, et al. Patch testing for corticosteroid allergy with low and high concentrations of tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:311-312. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460519.x

- Isaksson M, Bruze M, Lepoittevin JP, et al. Patch testing with serial dilutions of budesonide, its R and S diastereomers, and potentially cross-reacting substances. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:170-176.

- Ferguson AD, Emerson RM, English JS. Cross-reactivity patterns to budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:337-340. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470604.x

- Kot M, Bogaczewicz J, Kre˛cisz B, et al. Contact allergy in the population of patients with chronic inflammatory dermatoses and contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:253-259. doi:10.5114/ada.2017.67848

- Isaksson M, Bruze M. Allergic contact dermatitis in response to budesonide reactivated by inhalation of the allergen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:880-885. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120464

- Mimesh S, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis from corticosteroids: reproducibility of patch testing and correlation with intradermal testing. Dermatitis. 2006;17:137-142. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05048

- Soria A, Baeck M, Goossens A, et al. Patch, prick or intradermal tests to detect delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids?. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:313-324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01888.x

- Wilkinson SM, Beck MH. Corticosteroid contact hypersensitivity: what vehicle and concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:305-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02212.x

- Isaksson M, Beck MH, Wilkinson SM. Comparative testing with budesonide in petrolatum and ethanol in a standard series. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:123-124. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_16.x

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01967.x