User login

Severe maternal morbidity increasing in California

The according to a study covering almost 8.3 million births in California.

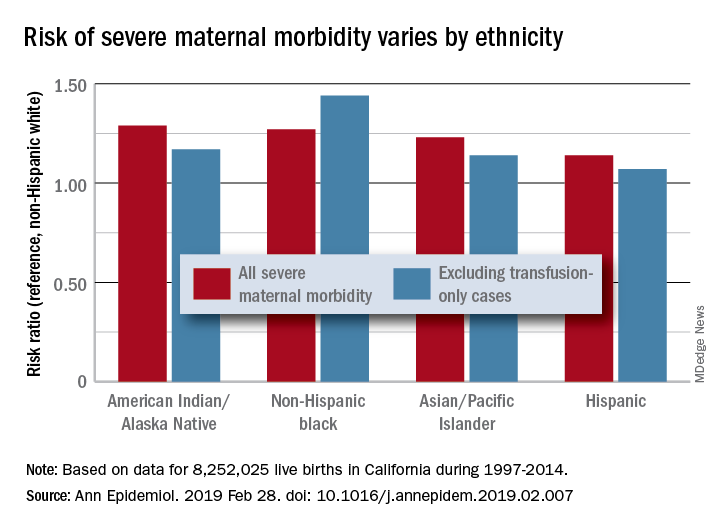

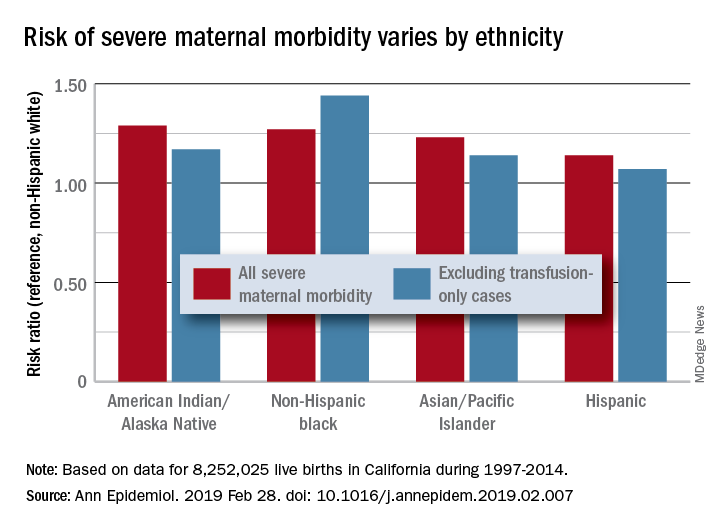

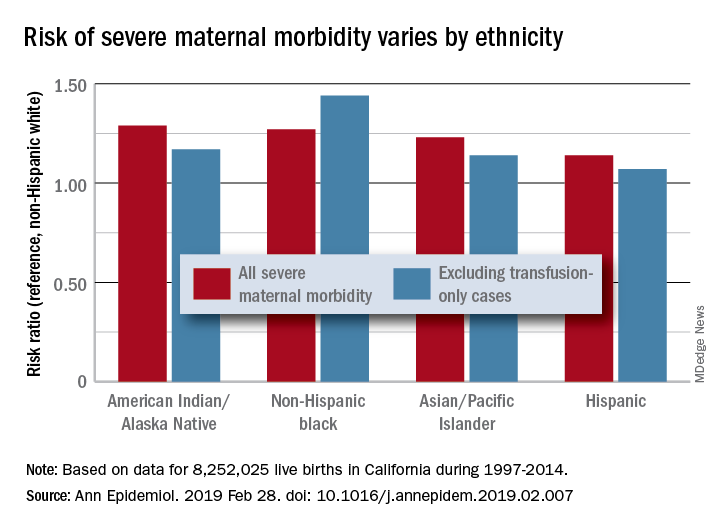

Changes in severe maternal morbidity (SMM) prevalence from 1997 to 2014 were fairly consistent by race/ethnicity, although increases for black (179%), Asian/Pacific Islander (175%), and Hispanic (173%) women were somewhat larger than for whites (163%), Stephanie A. Leonard, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates reported in Annals of Epidemiology.

Differences between races/ethnicities over the entire study period were seen for SMM with and without transfusion-only cases. Individual-level factors such as cesarean birth, comorbidities, and anemia “contribute to, but do not fully explain, these disparities. Additionally, changes in the characteristics of pregnant women – including increases in comorbidities – have not affected racial/ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity over time,” the investigators wrote.

The cohort study used data for 8,252,025 live births with birth certificates that were previously linked to delivery discharge records. SMM was measured using the Severe Maternity Morbidity Index. Because “blood transfusion is the only qualifying indicator for approximately half of SMM cases … we also studied a subset of SMM that excluded those cases for which the only indication was a blood transfusion,” they noted.

SOURCE: Leonard SA et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.007.

The according to a study covering almost 8.3 million births in California.

Changes in severe maternal morbidity (SMM) prevalence from 1997 to 2014 were fairly consistent by race/ethnicity, although increases for black (179%), Asian/Pacific Islander (175%), and Hispanic (173%) women were somewhat larger than for whites (163%), Stephanie A. Leonard, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates reported in Annals of Epidemiology.

Differences between races/ethnicities over the entire study period were seen for SMM with and without transfusion-only cases. Individual-level factors such as cesarean birth, comorbidities, and anemia “contribute to, but do not fully explain, these disparities. Additionally, changes in the characteristics of pregnant women – including increases in comorbidities – have not affected racial/ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity over time,” the investigators wrote.

The cohort study used data for 8,252,025 live births with birth certificates that were previously linked to delivery discharge records. SMM was measured using the Severe Maternity Morbidity Index. Because “blood transfusion is the only qualifying indicator for approximately half of SMM cases … we also studied a subset of SMM that excluded those cases for which the only indication was a blood transfusion,” they noted.

SOURCE: Leonard SA et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.007.

The according to a study covering almost 8.3 million births in California.

Changes in severe maternal morbidity (SMM) prevalence from 1997 to 2014 were fairly consistent by race/ethnicity, although increases for black (179%), Asian/Pacific Islander (175%), and Hispanic (173%) women were somewhat larger than for whites (163%), Stephanie A. Leonard, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her associates reported in Annals of Epidemiology.

Differences between races/ethnicities over the entire study period were seen for SMM with and without transfusion-only cases. Individual-level factors such as cesarean birth, comorbidities, and anemia “contribute to, but do not fully explain, these disparities. Additionally, changes in the characteristics of pregnant women – including increases in comorbidities – have not affected racial/ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity over time,” the investigators wrote.

The cohort study used data for 8,252,025 live births with birth certificates that were previously linked to delivery discharge records. SMM was measured using the Severe Maternity Morbidity Index. Because “blood transfusion is the only qualifying indicator for approximately half of SMM cases … we also studied a subset of SMM that excluded those cases for which the only indication was a blood transfusion,” they noted.

SOURCE: Leonard SA et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2019 Feb 28. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.007.

FROM ANNALS OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

New SOFA version could streamline outcomes research

SAN DIEGO – The new method replaces some of SOFA’s more subjective criteria with objective measures.

eSOFA relies on electronic health records to reduce reliance on administrative records, which suffer from cross-hospital variability in diagnosis and coding practices, as well as changes in these practices over time. The diagnosis of sepsis itself is also highly subjective. Instead, eSOFA determines dysfunction in six organ systems, indicated by use of vasopressors and mechanical ventilation, and the presence of abnormal laboratory values.

“The SOFA score includes measures like the Glasgow Coma Scale, which undoubtedly at the bedside is a very important clinical sign, but when trying to implement something that is objective for purposes of retrospective case counting and standardization, it can be problematic. The measures we chose [for eSOFA] are concrete, important maneuvers that were initiated by clinicians,” Chanu Rhee, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Rhee is assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. He presented the results of the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the work was simultaneously published online in Critical Care Medicine.

Key elements of SOFA that pose challenges for administrative data include: PaO2/FiO2, which are not routinely measured, and can be difficult to assign to arterial or venous samples; inconsistency in blood pressure and transient increases in vasopressor dose; the subjectivity of the Glasgow Coma Scale, which is also difficult to assess in sedated patients; and inconsistent urine output.

eSOFA introduced new measures for various organ functions, including cardiovascular (vasopressor initiation), pulmonary (mechanical ventilation initiation), renal (doubling of creatinine levels or a 50% or greater decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate, compared with baseline), hepatic (bilirubin levels greater than or equal to 2.0 mg/dL and at least doubled from baseline), coagulation (platelet count less than 100 cells/mcL and at least a 50% decrease from a baseline of at least 100 cells/mcL), and neurological (lactate greater than or equal to 2.0 mmol/L).

“[eSOFA] opens a window into inter-facility comparisons that has not been possible to do. It’s really critical to ask, ‘How am I doing compared to my peer institutions?’ If you’re doing worse, you can look at the whole spectrum of things to try to drive improvements in care,” said Dr. Rhee.

The new tool isn’t just limited to quality improvement research. Shaeesta Khan, MD, assistant professor of critical care medicine at Geisinger Medical Center,Danville, Pa., has found eSOFA to be useful in her research into how genetic polymorphisms play a role in sepsis outcomes. Geisinger has a large population of patients with completed whole genome sequencing, and Dr. Khan began by trying to glean sepsis outcomes from administrative data.

“I explained SOFA scores to our data broker, and he pulled up 3,000 patients and gave everybody a SOFA score based on the algorithm he created, and it was all over the chart. Once I started doing chart review and phenotype verification, it was just a nightmare,” Dr. Khan said in an interview.

After struggling with the project, one of her mentors put her in touch with one of Dr. Rhee’s colleagues, and she asked the data broker to modify the eSOFA algorithm to fit her specific criteria. “It was a blessing,” she said.

Now, she has data from 5,000 patients with sepsis and sequenced DNA, and can begin comparing outcomes and genetic variants. About 20 candidate genes for sepsis outcomes have been identified to date, but she has a particular interest in PCSK9, which is an innate immune system regulator. She hopes to present results at CCC49 in 2020.

Validating mortality prediction

The researchers compared eSOFA and SOFA in a sample from 111 U.S. acute care hospitals to see if eSOFA had a comparable predictive validity for mortality. The analysis included 942,360 adults seen between 2013 and 2015. A total of 11.1% (104,903) had a presumed serious infection based on a blood culture order and at least 4 consecutive days of antibiotic use.

The analysis showed that 6.1% of those with infections had a sepsis event based on at least a 2-point increase in SOFA score from baseline (Sepsis-3 criteria), compared with 4.4% identified by at least a 1-point increase in eSOFA score. A total of 34,174 patients (3.6%) overlapped between SOFA and eSOFA, which represented good agreement (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.81). Compared with SOFA/Sepsis-3, eSOFA had a sensitivity of 60%, and a positive predictive value of 82%.

Patients identified by eSOFA were slightly more ill, with more requiring ICU admission (41% vs. 35%), and a greater frequency of in-hospital mortality (17% vs. 14%). Those patients who were identified by SOFA/Sepsis-3, but missed by eSOFA, had an overall lower mortality (6%).

There was a similar risk of mortality across deciles between SOFA- and eSOFA-identified sepsis patients. In an independent analysis of four hospitals from the Emory system, the area under the receiver operating characteristics was 0.77 for eSOFA and 0.76 for SOFA (P less than .001).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the study. Dr. Rhee and Dr. Khan have no relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(3):307-14.

SAN DIEGO – The new method replaces some of SOFA’s more subjective criteria with objective measures.

eSOFA relies on electronic health records to reduce reliance on administrative records, which suffer from cross-hospital variability in diagnosis and coding practices, as well as changes in these practices over time. The diagnosis of sepsis itself is also highly subjective. Instead, eSOFA determines dysfunction in six organ systems, indicated by use of vasopressors and mechanical ventilation, and the presence of abnormal laboratory values.

“The SOFA score includes measures like the Glasgow Coma Scale, which undoubtedly at the bedside is a very important clinical sign, but when trying to implement something that is objective for purposes of retrospective case counting and standardization, it can be problematic. The measures we chose [for eSOFA] are concrete, important maneuvers that were initiated by clinicians,” Chanu Rhee, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Rhee is assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. He presented the results of the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the work was simultaneously published online in Critical Care Medicine.

Key elements of SOFA that pose challenges for administrative data include: PaO2/FiO2, which are not routinely measured, and can be difficult to assign to arterial or venous samples; inconsistency in blood pressure and transient increases in vasopressor dose; the subjectivity of the Glasgow Coma Scale, which is also difficult to assess in sedated patients; and inconsistent urine output.

eSOFA introduced new measures for various organ functions, including cardiovascular (vasopressor initiation), pulmonary (mechanical ventilation initiation), renal (doubling of creatinine levels or a 50% or greater decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate, compared with baseline), hepatic (bilirubin levels greater than or equal to 2.0 mg/dL and at least doubled from baseline), coagulation (platelet count less than 100 cells/mcL and at least a 50% decrease from a baseline of at least 100 cells/mcL), and neurological (lactate greater than or equal to 2.0 mmol/L).

“[eSOFA] opens a window into inter-facility comparisons that has not been possible to do. It’s really critical to ask, ‘How am I doing compared to my peer institutions?’ If you’re doing worse, you can look at the whole spectrum of things to try to drive improvements in care,” said Dr. Rhee.

The new tool isn’t just limited to quality improvement research. Shaeesta Khan, MD, assistant professor of critical care medicine at Geisinger Medical Center,Danville, Pa., has found eSOFA to be useful in her research into how genetic polymorphisms play a role in sepsis outcomes. Geisinger has a large population of patients with completed whole genome sequencing, and Dr. Khan began by trying to glean sepsis outcomes from administrative data.

“I explained SOFA scores to our data broker, and he pulled up 3,000 patients and gave everybody a SOFA score based on the algorithm he created, and it was all over the chart. Once I started doing chart review and phenotype verification, it was just a nightmare,” Dr. Khan said in an interview.

After struggling with the project, one of her mentors put her in touch with one of Dr. Rhee’s colleagues, and she asked the data broker to modify the eSOFA algorithm to fit her specific criteria. “It was a blessing,” she said.

Now, she has data from 5,000 patients with sepsis and sequenced DNA, and can begin comparing outcomes and genetic variants. About 20 candidate genes for sepsis outcomes have been identified to date, but she has a particular interest in PCSK9, which is an innate immune system regulator. She hopes to present results at CCC49 in 2020.

Validating mortality prediction

The researchers compared eSOFA and SOFA in a sample from 111 U.S. acute care hospitals to see if eSOFA had a comparable predictive validity for mortality. The analysis included 942,360 adults seen between 2013 and 2015. A total of 11.1% (104,903) had a presumed serious infection based on a blood culture order and at least 4 consecutive days of antibiotic use.

The analysis showed that 6.1% of those with infections had a sepsis event based on at least a 2-point increase in SOFA score from baseline (Sepsis-3 criteria), compared with 4.4% identified by at least a 1-point increase in eSOFA score. A total of 34,174 patients (3.6%) overlapped between SOFA and eSOFA, which represented good agreement (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.81). Compared with SOFA/Sepsis-3, eSOFA had a sensitivity of 60%, and a positive predictive value of 82%.

Patients identified by eSOFA were slightly more ill, with more requiring ICU admission (41% vs. 35%), and a greater frequency of in-hospital mortality (17% vs. 14%). Those patients who were identified by SOFA/Sepsis-3, but missed by eSOFA, had an overall lower mortality (6%).

There was a similar risk of mortality across deciles between SOFA- and eSOFA-identified sepsis patients. In an independent analysis of four hospitals from the Emory system, the area under the receiver operating characteristics was 0.77 for eSOFA and 0.76 for SOFA (P less than .001).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the study. Dr. Rhee and Dr. Khan have no relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(3):307-14.

SAN DIEGO – The new method replaces some of SOFA’s more subjective criteria with objective measures.

eSOFA relies on electronic health records to reduce reliance on administrative records, which suffer from cross-hospital variability in diagnosis and coding practices, as well as changes in these practices over time. The diagnosis of sepsis itself is also highly subjective. Instead, eSOFA determines dysfunction in six organ systems, indicated by use of vasopressors and mechanical ventilation, and the presence of abnormal laboratory values.

“The SOFA score includes measures like the Glasgow Coma Scale, which undoubtedly at the bedside is a very important clinical sign, but when trying to implement something that is objective for purposes of retrospective case counting and standardization, it can be problematic. The measures we chose [for eSOFA] are concrete, important maneuvers that were initiated by clinicians,” Chanu Rhee, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Rhee is assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. He presented the results of the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the work was simultaneously published online in Critical Care Medicine.

Key elements of SOFA that pose challenges for administrative data include: PaO2/FiO2, which are not routinely measured, and can be difficult to assign to arterial or venous samples; inconsistency in blood pressure and transient increases in vasopressor dose; the subjectivity of the Glasgow Coma Scale, which is also difficult to assess in sedated patients; and inconsistent urine output.

eSOFA introduced new measures for various organ functions, including cardiovascular (vasopressor initiation), pulmonary (mechanical ventilation initiation), renal (doubling of creatinine levels or a 50% or greater decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate, compared with baseline), hepatic (bilirubin levels greater than or equal to 2.0 mg/dL and at least doubled from baseline), coagulation (platelet count less than 100 cells/mcL and at least a 50% decrease from a baseline of at least 100 cells/mcL), and neurological (lactate greater than or equal to 2.0 mmol/L).

“[eSOFA] opens a window into inter-facility comparisons that has not been possible to do. It’s really critical to ask, ‘How am I doing compared to my peer institutions?’ If you’re doing worse, you can look at the whole spectrum of things to try to drive improvements in care,” said Dr. Rhee.

The new tool isn’t just limited to quality improvement research. Shaeesta Khan, MD, assistant professor of critical care medicine at Geisinger Medical Center,Danville, Pa., has found eSOFA to be useful in her research into how genetic polymorphisms play a role in sepsis outcomes. Geisinger has a large population of patients with completed whole genome sequencing, and Dr. Khan began by trying to glean sepsis outcomes from administrative data.

“I explained SOFA scores to our data broker, and he pulled up 3,000 patients and gave everybody a SOFA score based on the algorithm he created, and it was all over the chart. Once I started doing chart review and phenotype verification, it was just a nightmare,” Dr. Khan said in an interview.

After struggling with the project, one of her mentors put her in touch with one of Dr. Rhee’s colleagues, and she asked the data broker to modify the eSOFA algorithm to fit her specific criteria. “It was a blessing,” she said.

Now, she has data from 5,000 patients with sepsis and sequenced DNA, and can begin comparing outcomes and genetic variants. About 20 candidate genes for sepsis outcomes have been identified to date, but she has a particular interest in PCSK9, which is an innate immune system regulator. She hopes to present results at CCC49 in 2020.

Validating mortality prediction

The researchers compared eSOFA and SOFA in a sample from 111 U.S. acute care hospitals to see if eSOFA had a comparable predictive validity for mortality. The analysis included 942,360 adults seen between 2013 and 2015. A total of 11.1% (104,903) had a presumed serious infection based on a blood culture order and at least 4 consecutive days of antibiotic use.

The analysis showed that 6.1% of those with infections had a sepsis event based on at least a 2-point increase in SOFA score from baseline (Sepsis-3 criteria), compared with 4.4% identified by at least a 1-point increase in eSOFA score. A total of 34,174 patients (3.6%) overlapped between SOFA and eSOFA, which represented good agreement (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.81). Compared with SOFA/Sepsis-3, eSOFA had a sensitivity of 60%, and a positive predictive value of 82%.

Patients identified by eSOFA were slightly more ill, with more requiring ICU admission (41% vs. 35%), and a greater frequency of in-hospital mortality (17% vs. 14%). Those patients who were identified by SOFA/Sepsis-3, but missed by eSOFA, had an overall lower mortality (6%).

There was a similar risk of mortality across deciles between SOFA- and eSOFA-identified sepsis patients. In an independent analysis of four hospitals from the Emory system, the area under the receiver operating characteristics was 0.77 for eSOFA and 0.76 for SOFA (P less than .001).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the study. Dr. Rhee and Dr. Khan have no relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(3):307-14.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Risk for Appendicitis, Cholecystitis, or Diverticulitis in Patients With Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

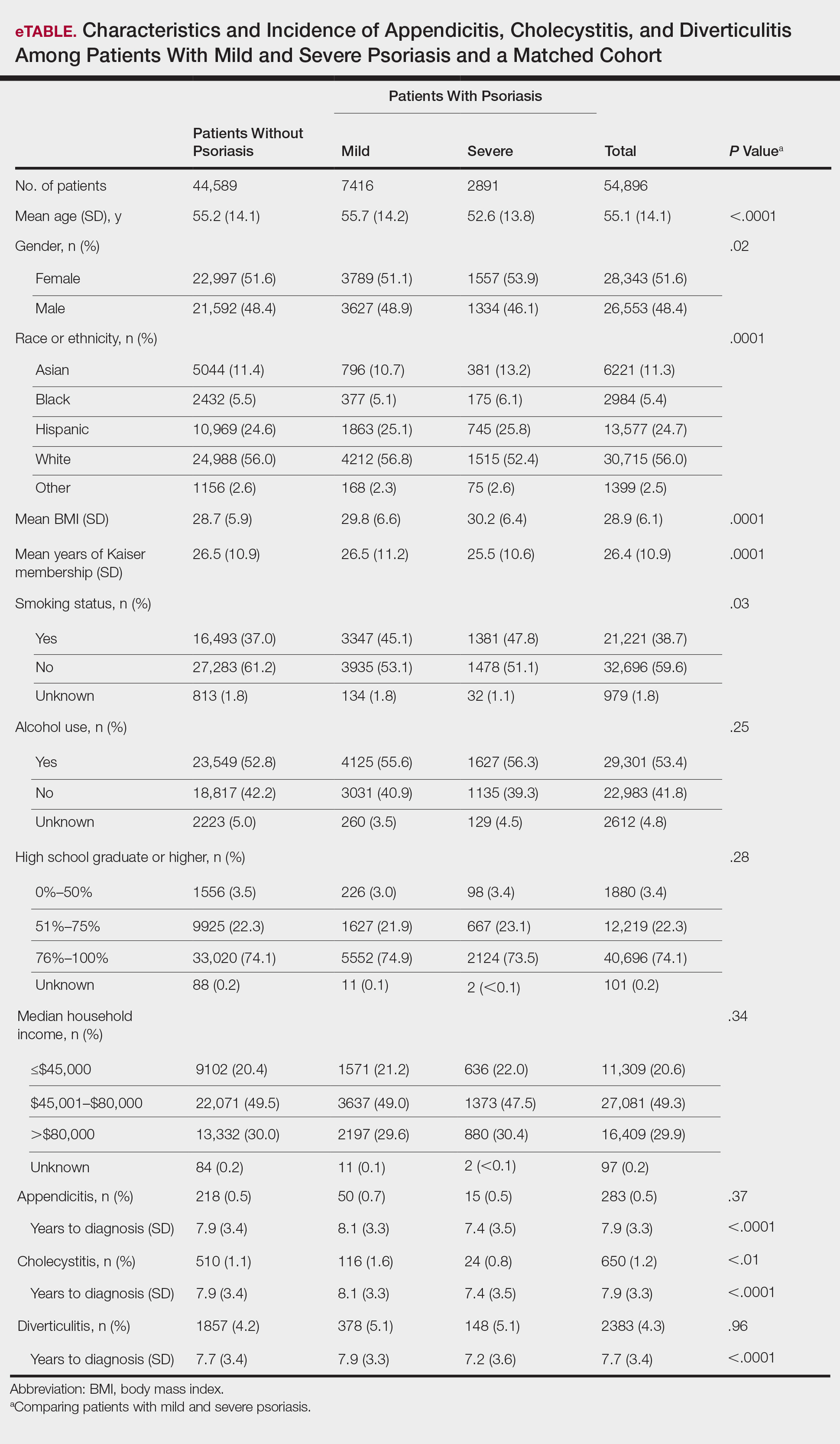

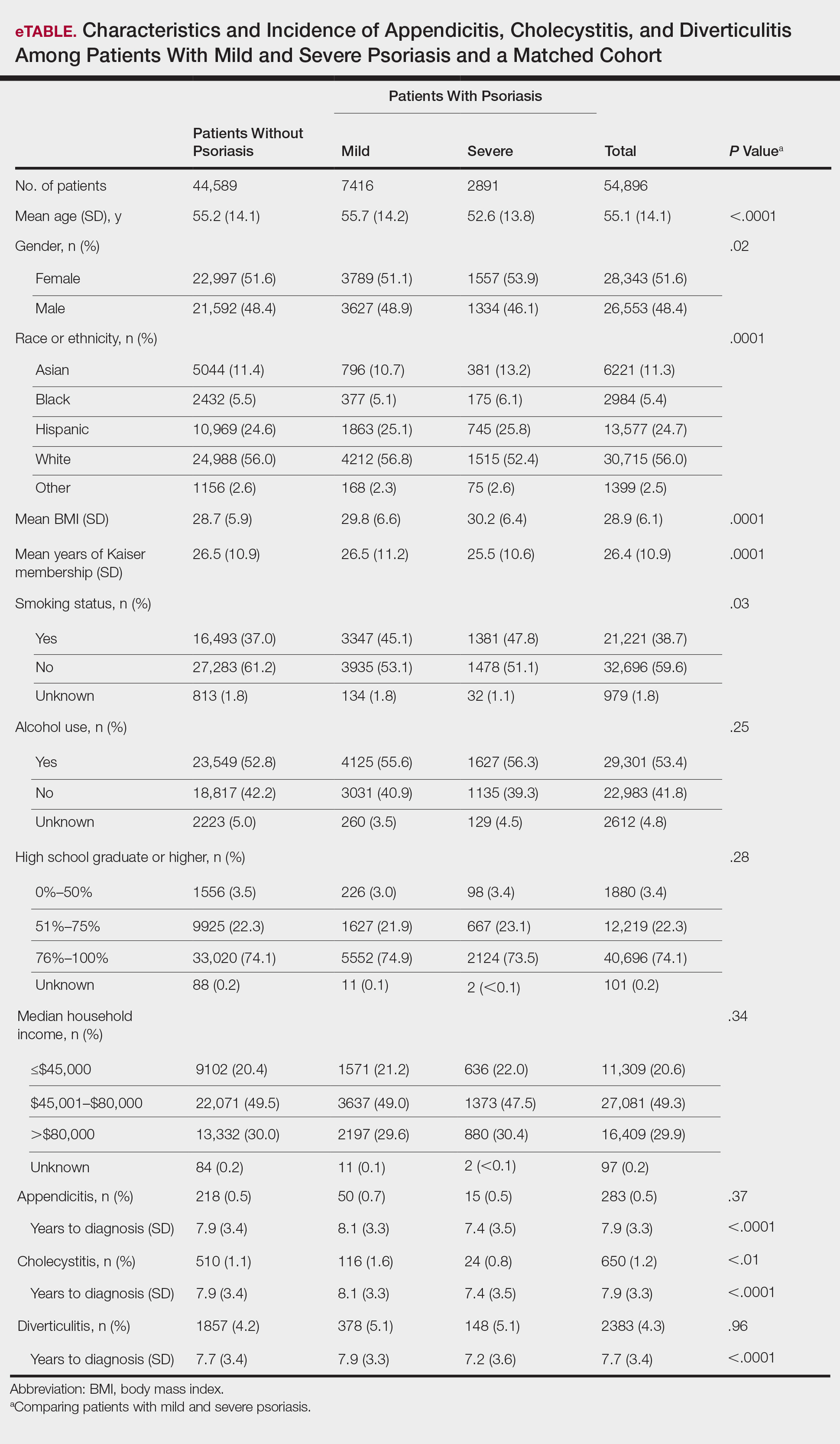

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

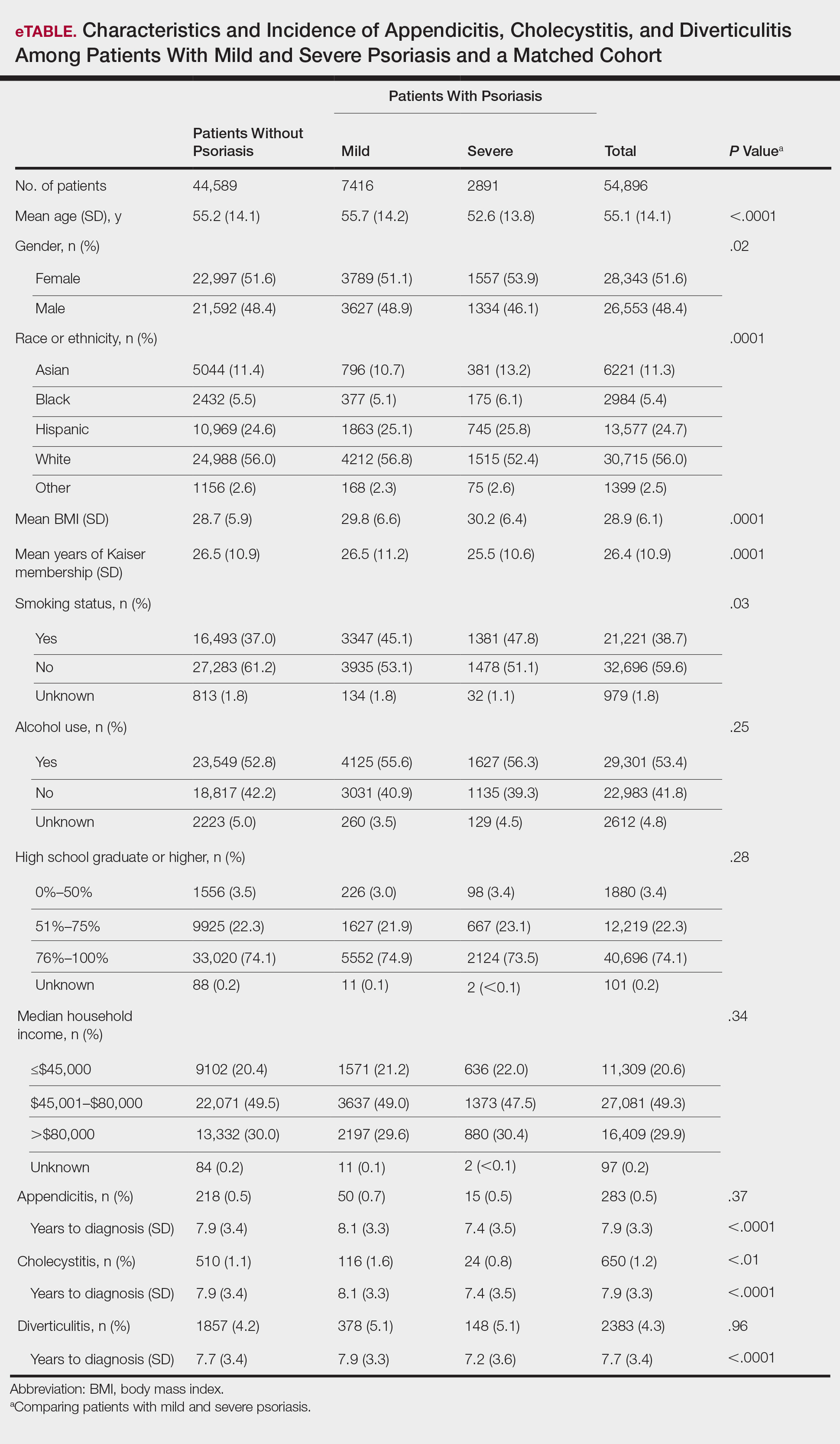

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

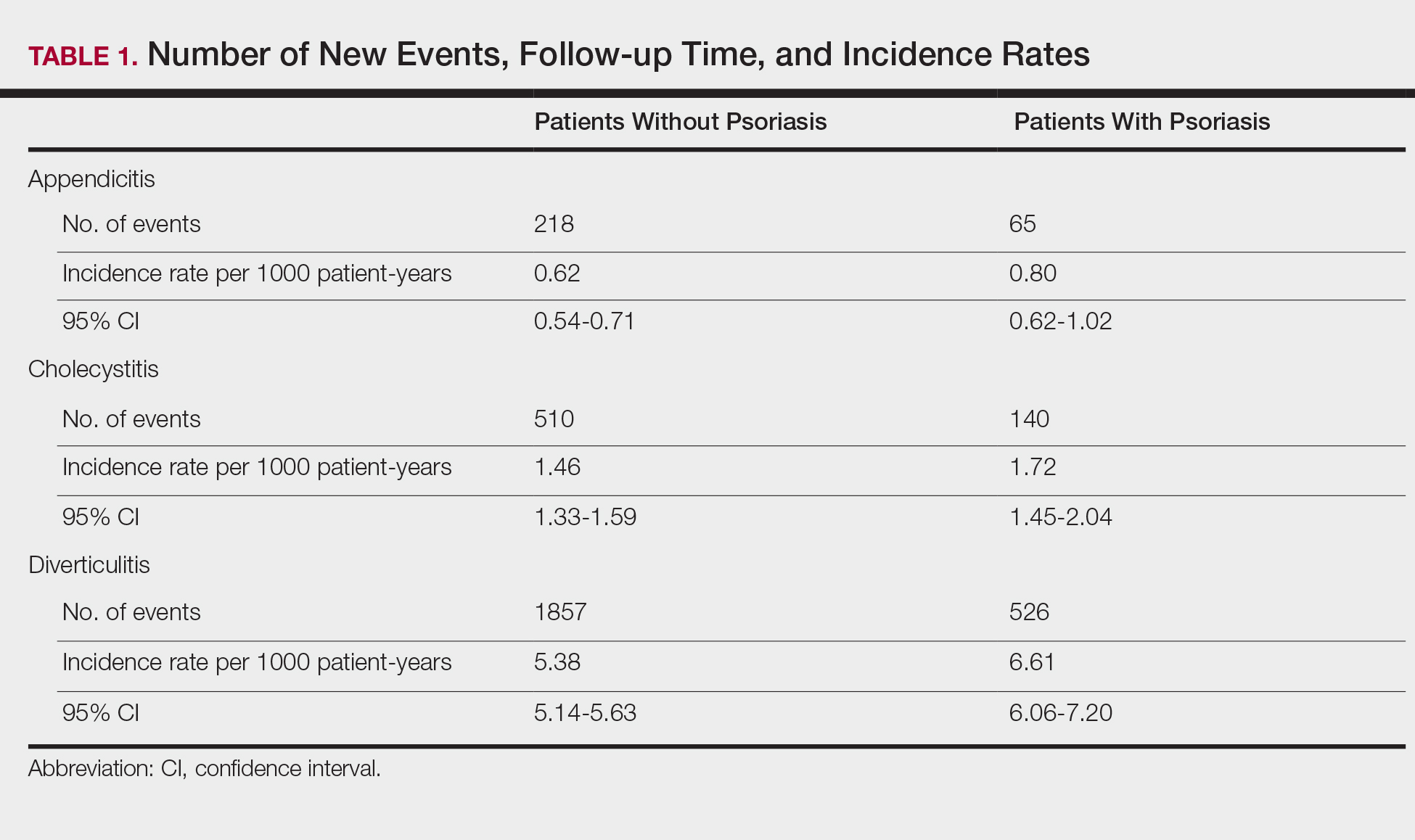

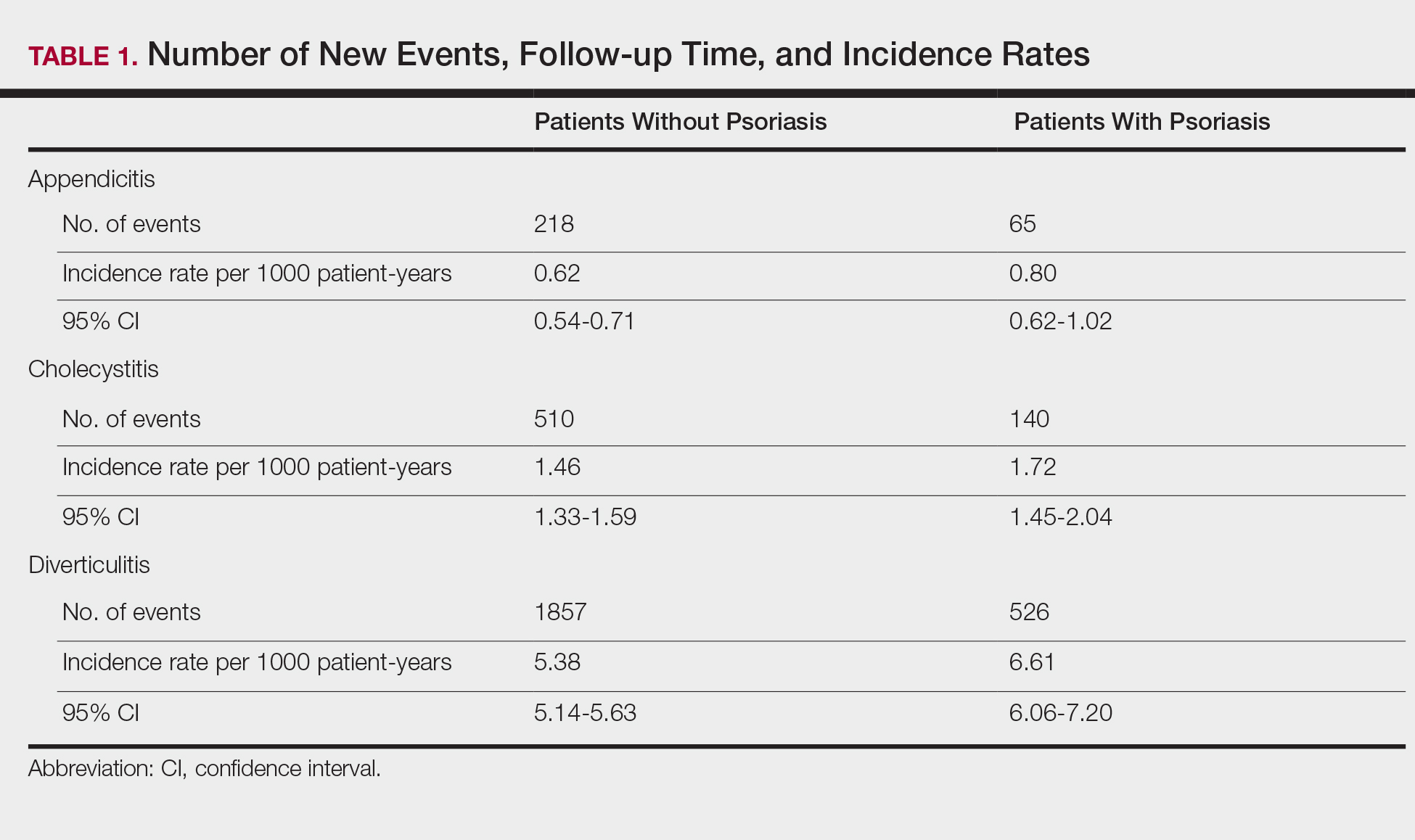

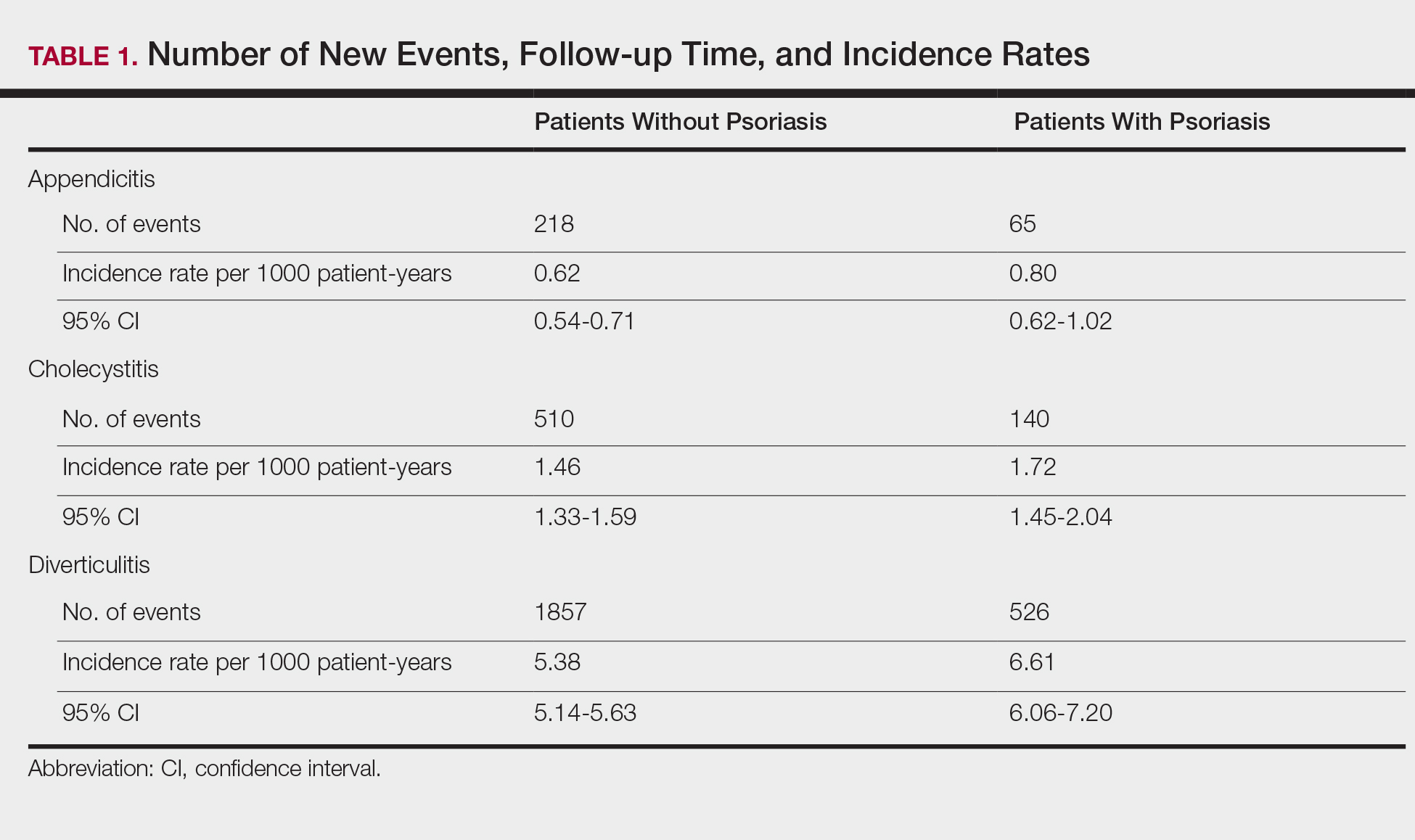

Appendicitis

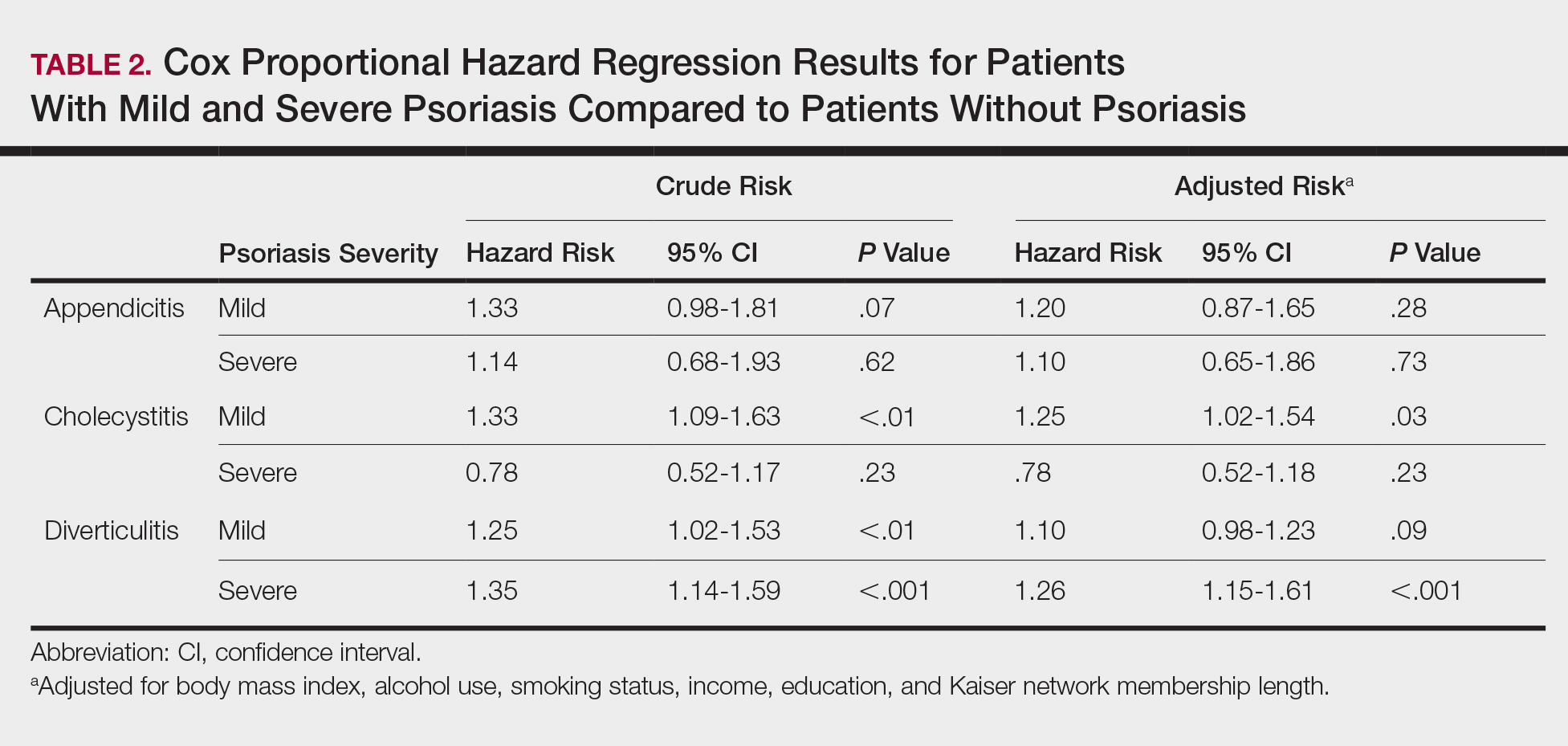

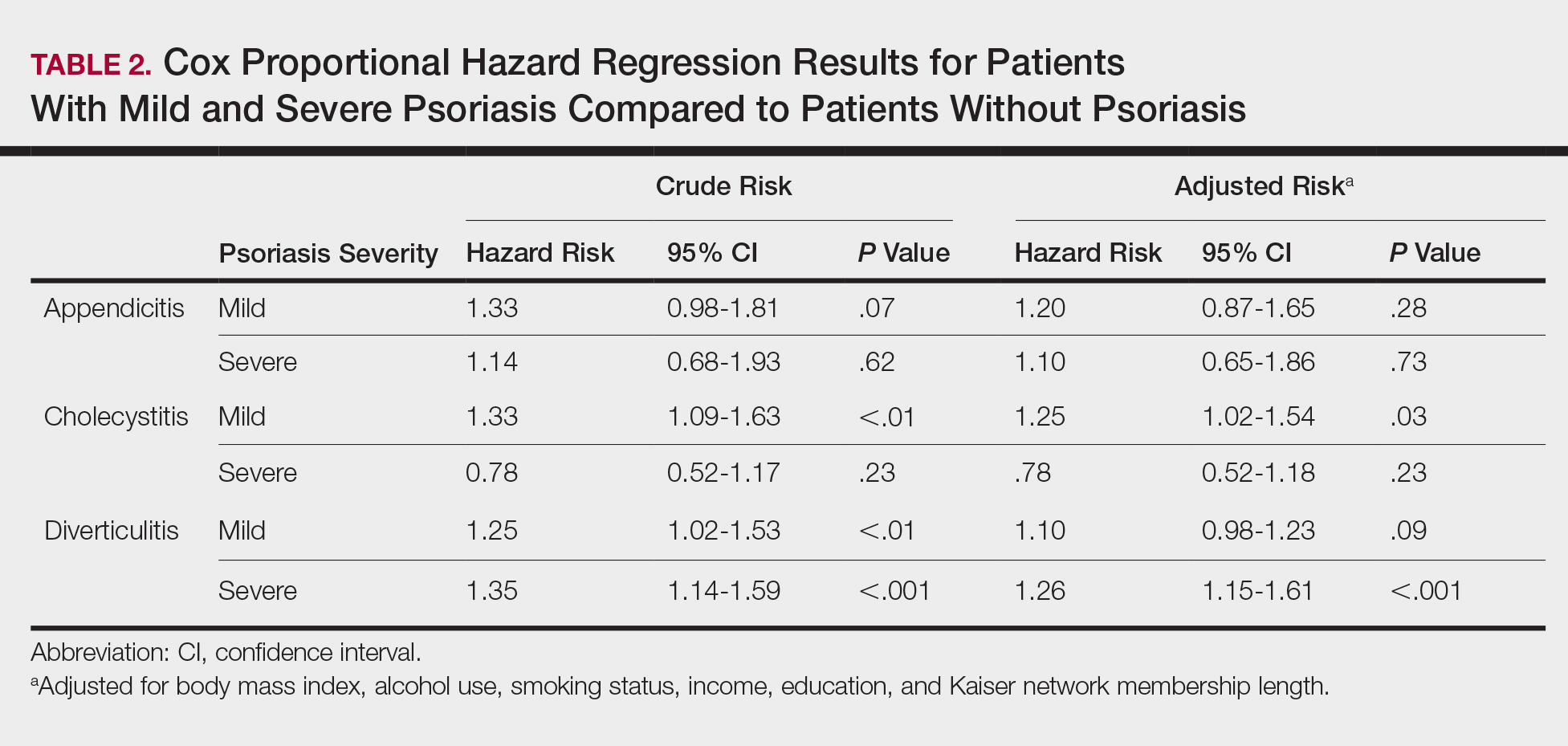

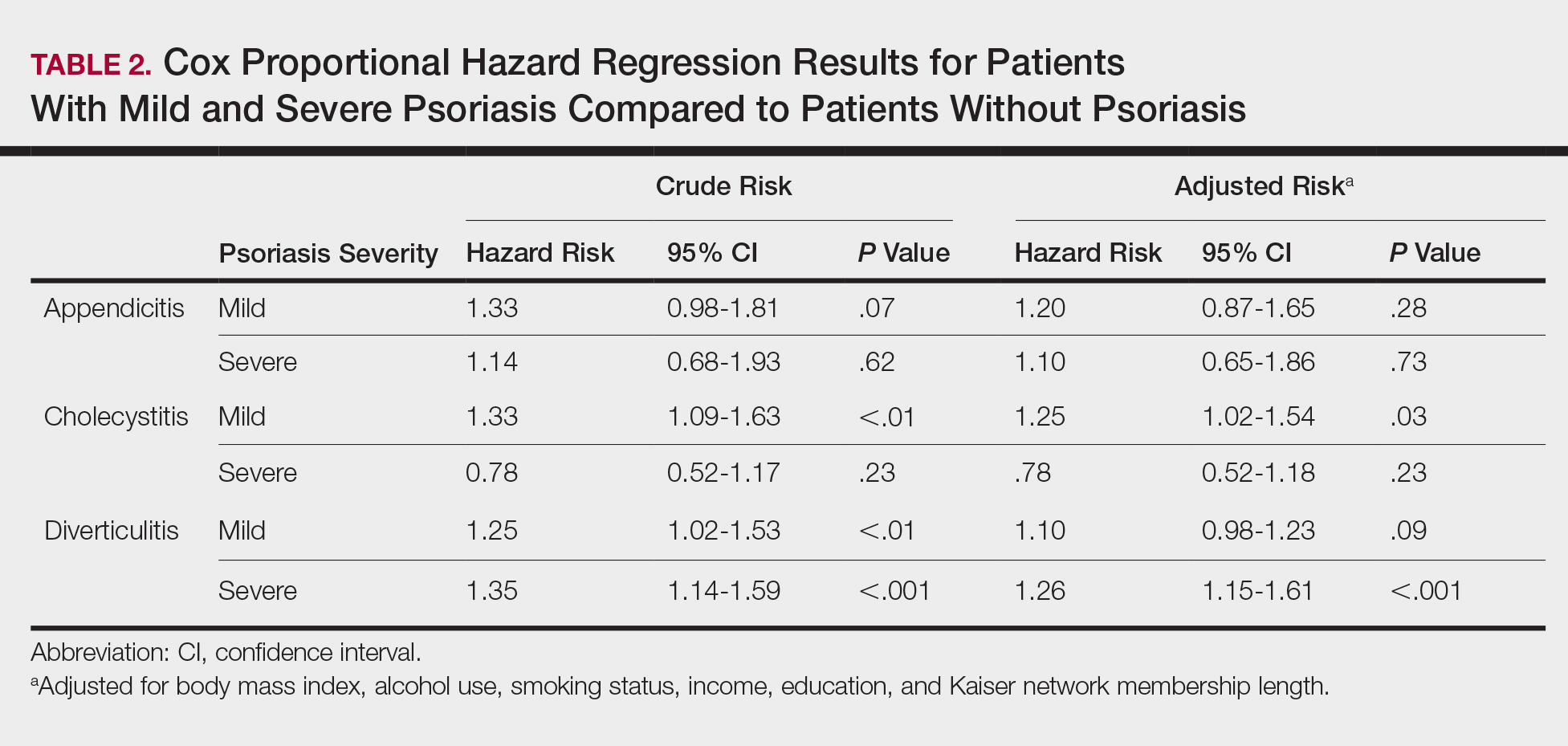

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

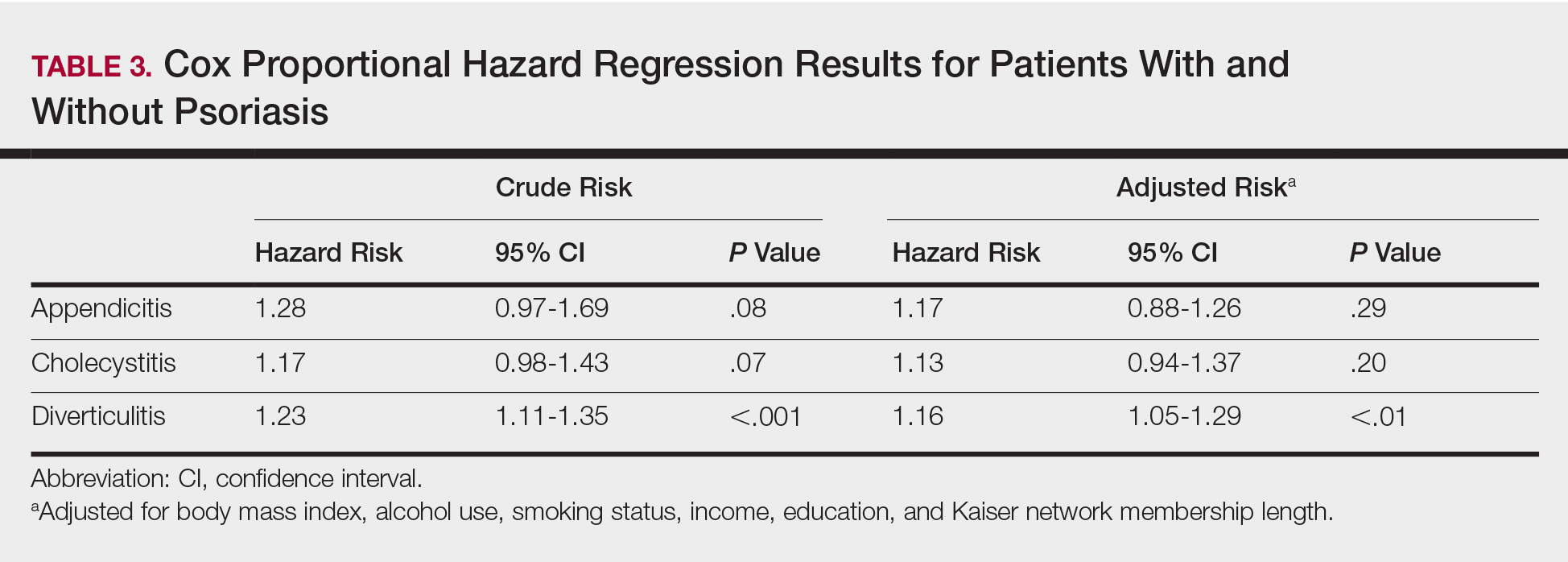

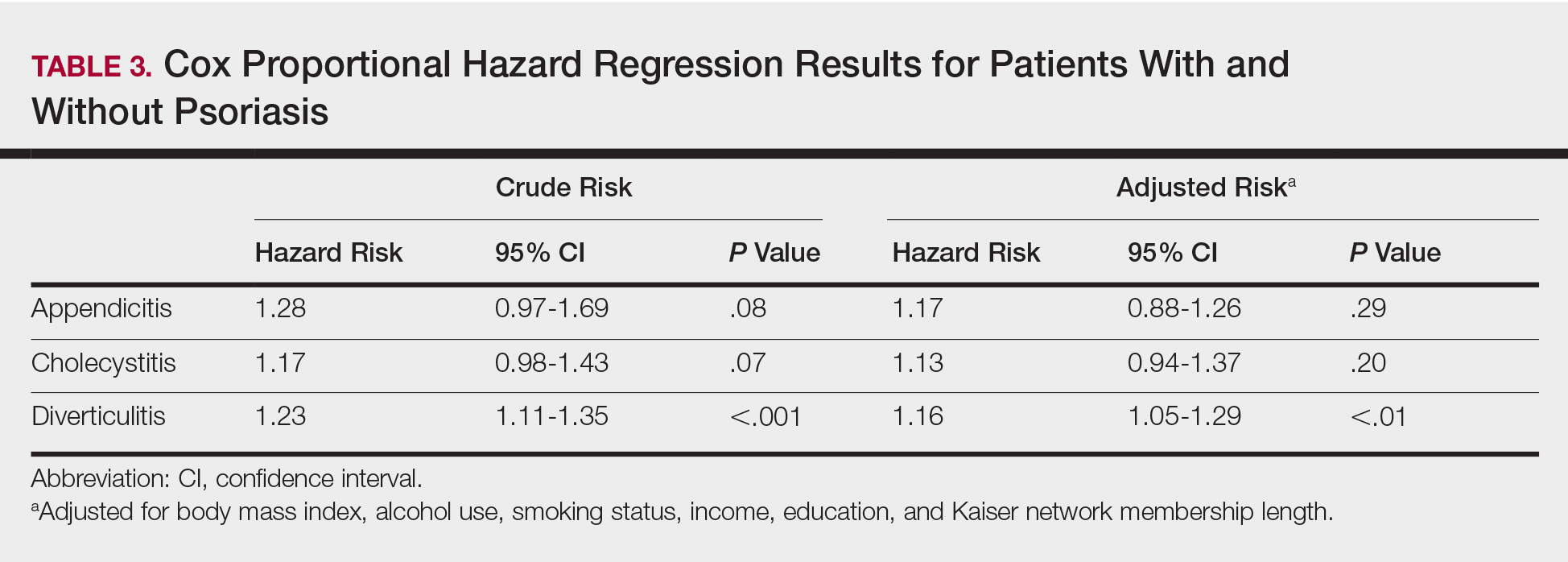

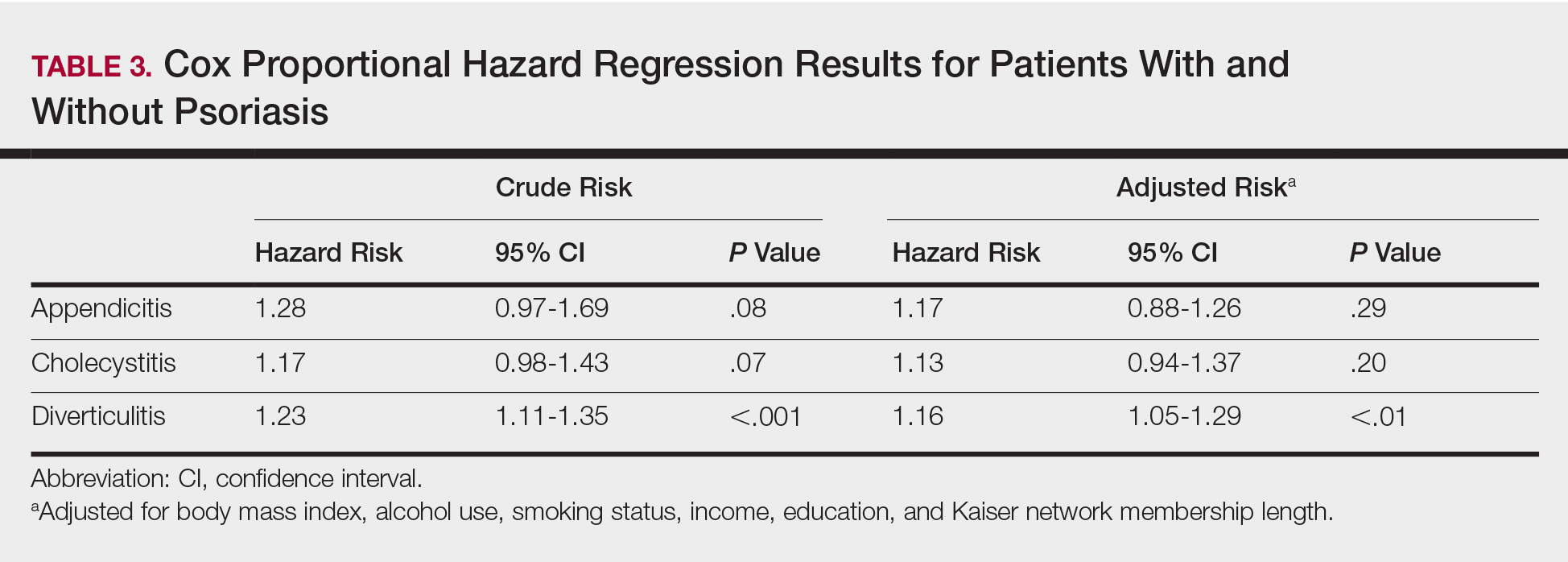

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.