User login

When to use mesh in laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair

LAS VEGAS – Routine use of mesh reinforcement when performing laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia defects 5 cm or larger in diameter is associated with a low recurrence rate, Dr. Chetan V. Aher reported at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

His coinvestigators had shown in an earlier randomized controlled trial that mesh reinforcement of primary cruroplasty in patients with a hernia of 8 cm or greater was associated with no recurrences. Repair with simple cruroplasty was associated with a 22% recurrence rate (Arch. Surg. 2002;137:649-52).

However, Dr. Aher and his coinvestigators subsequently observed a high recurrence rate following mesh-free simple cruroplasty for defects in the 5- to 8-cm range. He presented a case series involving 1,094 laparoscopic hiatal hernia repairs performed since he and his colleagues changed their practice by lowering their threshold for polytetrafluoroethylene mesh reinforcement to defects of at least 5 cm from their prior standard of 8 cm or more.

Hernias were less than 5 cm in diameter in 84% of the patients, so mesh wasn’t used for those repairs. In the remaining 178 patients – those with hernias of at least 5 cm – PTFE mesh was utilized to circumferentially reinforce the cruroplasty.

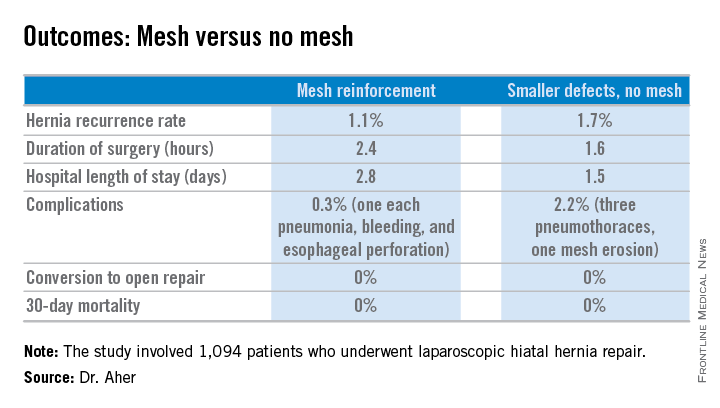

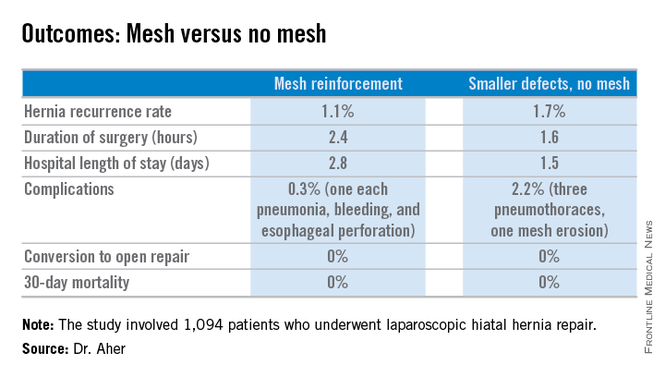

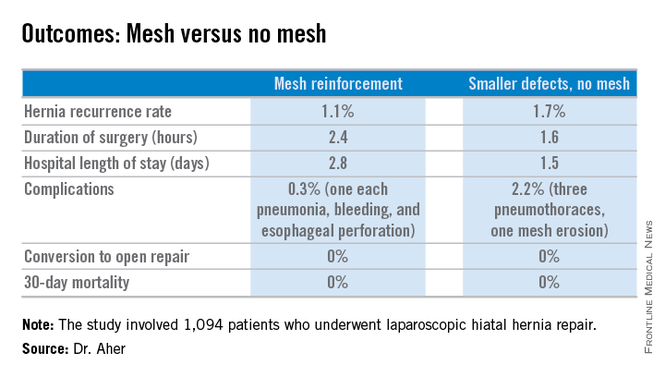

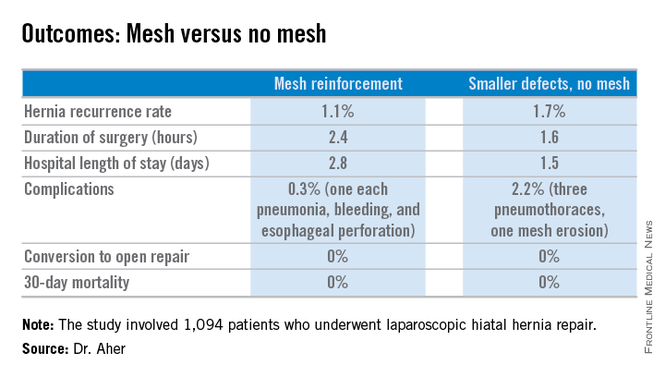

During a mean follow-up of 3.1 years, the hernia recurrence rate was 1.7% in the group with hernia defects of less than 5 cm and similar at 1.1% in those who received mesh reinforcement because their hernias were larger, reported Dr. Aher of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Operative time and length of stay were longer in the mesh reinforcement group (see chart).

“There’s more dissection when using mesh, and obviously the placement of the mesh takes a little longer,” he noted at the meeting presented by the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons and affiliated societies.

All repairs were performed using cruroplasty with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures approximating the right and left bundles of the right crura.

Laparoscopic repair has become the standard approach in the primary repair of hiatal hernias. In a 2010 survey of members of the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons conducted by Dr. Aher’s colleagues, respondents indicated they laparoscopically performed 77% of their mesh-reinforced repairs. However, the survey results underscored a lack of consensus within the surgical community regarding mesh usage. Biologic mesh was used by 28% of surgeons; 25% used PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene), and 21% polypropylene. Mesh placement practices also varied widely: 14% of surgeons utilized anterior placement, 34% posterior, and only 10% circumferential (Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1017-24).

Asked how he counsels patients about the competing risks of mesh erosion and hernia recurrence in the absence of mesh reinforcement, Dr. Aher pointed to the 22% recurrence risk with large hernias in the earlier randomized trial.

“I would counsel my own family that if you have a large hernia, the risk of mesh erosion is very low and the risk of undergoing a recurrent operation if there is no mesh reinforcement is, I think, overall higher. So I would say they should get the mesh reinforcement,” he concluded.

Dr. Aher reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

LAS VEGAS – Routine use of mesh reinforcement when performing laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia defects 5 cm or larger in diameter is associated with a low recurrence rate, Dr. Chetan V. Aher reported at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

His coinvestigators had shown in an earlier randomized controlled trial that mesh reinforcement of primary cruroplasty in patients with a hernia of 8 cm or greater was associated with no recurrences. Repair with simple cruroplasty was associated with a 22% recurrence rate (Arch. Surg. 2002;137:649-52).

However, Dr. Aher and his coinvestigators subsequently observed a high recurrence rate following mesh-free simple cruroplasty for defects in the 5- to 8-cm range. He presented a case series involving 1,094 laparoscopic hiatal hernia repairs performed since he and his colleagues changed their practice by lowering their threshold for polytetrafluoroethylene mesh reinforcement to defects of at least 5 cm from their prior standard of 8 cm or more.

Hernias were less than 5 cm in diameter in 84% of the patients, so mesh wasn’t used for those repairs. In the remaining 178 patients – those with hernias of at least 5 cm – PTFE mesh was utilized to circumferentially reinforce the cruroplasty.

During a mean follow-up of 3.1 years, the hernia recurrence rate was 1.7% in the group with hernia defects of less than 5 cm and similar at 1.1% in those who received mesh reinforcement because their hernias were larger, reported Dr. Aher of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Operative time and length of stay were longer in the mesh reinforcement group (see chart).

“There’s more dissection when using mesh, and obviously the placement of the mesh takes a little longer,” he noted at the meeting presented by the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons and affiliated societies.

All repairs were performed using cruroplasty with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures approximating the right and left bundles of the right crura.

Laparoscopic repair has become the standard approach in the primary repair of hiatal hernias. In a 2010 survey of members of the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons conducted by Dr. Aher’s colleagues, respondents indicated they laparoscopically performed 77% of their mesh-reinforced repairs. However, the survey results underscored a lack of consensus within the surgical community regarding mesh usage. Biologic mesh was used by 28% of surgeons; 25% used PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene), and 21% polypropylene. Mesh placement practices also varied widely: 14% of surgeons utilized anterior placement, 34% posterior, and only 10% circumferential (Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1017-24).

Asked how he counsels patients about the competing risks of mesh erosion and hernia recurrence in the absence of mesh reinforcement, Dr. Aher pointed to the 22% recurrence risk with large hernias in the earlier randomized trial.

“I would counsel my own family that if you have a large hernia, the risk of mesh erosion is very low and the risk of undergoing a recurrent operation if there is no mesh reinforcement is, I think, overall higher. So I would say they should get the mesh reinforcement,” he concluded.

Dr. Aher reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

LAS VEGAS – Routine use of mesh reinforcement when performing laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia defects 5 cm or larger in diameter is associated with a low recurrence rate, Dr. Chetan V. Aher reported at the annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Week.

His coinvestigators had shown in an earlier randomized controlled trial that mesh reinforcement of primary cruroplasty in patients with a hernia of 8 cm or greater was associated with no recurrences. Repair with simple cruroplasty was associated with a 22% recurrence rate (Arch. Surg. 2002;137:649-52).

However, Dr. Aher and his coinvestigators subsequently observed a high recurrence rate following mesh-free simple cruroplasty for defects in the 5- to 8-cm range. He presented a case series involving 1,094 laparoscopic hiatal hernia repairs performed since he and his colleagues changed their practice by lowering their threshold for polytetrafluoroethylene mesh reinforcement to defects of at least 5 cm from their prior standard of 8 cm or more.

Hernias were less than 5 cm in diameter in 84% of the patients, so mesh wasn’t used for those repairs. In the remaining 178 patients – those with hernias of at least 5 cm – PTFE mesh was utilized to circumferentially reinforce the cruroplasty.

During a mean follow-up of 3.1 years, the hernia recurrence rate was 1.7% in the group with hernia defects of less than 5 cm and similar at 1.1% in those who received mesh reinforcement because their hernias were larger, reported Dr. Aher of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Operative time and length of stay were longer in the mesh reinforcement group (see chart).

“There’s more dissection when using mesh, and obviously the placement of the mesh takes a little longer,” he noted at the meeting presented by the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons and affiliated societies.

All repairs were performed using cruroplasty with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures approximating the right and left bundles of the right crura.

Laparoscopic repair has become the standard approach in the primary repair of hiatal hernias. In a 2010 survey of members of the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons conducted by Dr. Aher’s colleagues, respondents indicated they laparoscopically performed 77% of their mesh-reinforced repairs. However, the survey results underscored a lack of consensus within the surgical community regarding mesh usage. Biologic mesh was used by 28% of surgeons; 25% used PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene), and 21% polypropylene. Mesh placement practices also varied widely: 14% of surgeons utilized anterior placement, 34% posterior, and only 10% circumferential (Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1017-24).

Asked how he counsels patients about the competing risks of mesh erosion and hernia recurrence in the absence of mesh reinforcement, Dr. Aher pointed to the 22% recurrence risk with large hernias in the earlier randomized trial.

“I would counsel my own family that if you have a large hernia, the risk of mesh erosion is very low and the risk of undergoing a recurrent operation if there is no mesh reinforcement is, I think, overall higher. So I would say they should get the mesh reinforcement,” he concluded.

Dr. Aher reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

AT MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY WEEK

Key clinical point: Using hernia defect size to guide selective use of mesh reinforcement in laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair results in a low recurrence rate and excellent safety.

Major finding: The hernia recurrence rate was 1.7% in patients who underwent primary cruroplasty for hernias less than 5 cm in diameter and 1.1% in those who received mesh reinforcement because their hernias exceeded that size.

Data source: This was a retrospective study of 1,094 patients who underwent laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair since the investigators changed their threshold for utilizing mesh reinforcement from 8- to 5-cm hernia defects.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

More docs need to use available Rx-monitoring programs to help curb opioid abuse

WASHINGTON – The prescription drug–monitoring programs that exist in every state are not going to make a dent in opioid abuse unless physicians use them.

Because each state governs its own prescription drug–monitoring program (PDMP), the efficiency and effectiveness of each varies widely from the others. In the ideal, a PDMP collects information on which prescriptions are being filled by what patients as well as which physicians are prescribing the drugs. Information from the databases is used to help determine which patients might be doctor shopping for opioids as well as identify physicians who might be operating “pill mills” and contributing to the availability of narcotic pain medication that is used for other than clinical purposes.

Data from several studies have shown that in many instances, doctors do not realize the detail and usefulness of data from PDMPs, Allan Coukell, senior director for drugs and medical devices at Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, said at a panel discussion on prescription drug abuse hosted by the Alliance for Health Reform and the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the industry lobby for pharmacy benefit managers.

When shown data on a specific patient, a physician was often “surprised to know how many other physicians that patient was seeing, and having that information changed their prescribing,” Mr. Coukell said, noting that in some cases, the information led to physicians refusing to prescribe pain medication and in others, it eased fears that a patient might be doctor shopping, giving the physician some peace of mind about writing a prescription for a narcotic.

Panelist Dr. Sarah Chouinard, medical director of Community Care of West Virginia, noted that physicians often are surprised when presented with data collected by PDMPs about their own individual prescribing habits.

“Eight out of 10 people were very surprised at the number of hydrocodone prescriptions they had written in the last 3 months,” Dr. Chouinard said.

In addition, the culture of administering pain medicine has gone through a shift in the last 10 years that is contributing to the problem of how many pills are available.

“About 10 years ago, there were doctors wandering around with buttons that said ‘No Pain’ with a red circle and a line through it because we were accused of under treating pain,” she observed. “Now, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. They used to say, ‘Hey, we’ll get sued if we don’t write pain medicine for these people,’ and now it’s, ‘Gosh, don’t write anything, or we will be a pill mill.’ I think the real answer is getting back to the middle and allowing the word to be out there that you don’t have to use a narcotic for every bump.”

To that end, Dr. Chouinard shared a solution her community organization has implemented. She said that “none of the [family physicians] are equipped, myself included, to treat chronic pain. Chronic pain is a specialty. ... It requires special training. The training that we as family doctors get now, after residency, is a mandatory 3 hours every 2 years.”

So Community Health of West Virgina hired an anesthetist who is not interested in family medicine but rather has a special interest in addictions medicine and outpatient pain medicine.

“Every one of our patients who has chronic pain [is sent] to this physician first,” Dr. Chouinard explained. “He does the work-up. He looks to see if the patients are amenable to any kind of alternatives and then sends those patients back to us as primary care doctors.”

After that, every patient gets a pain contract that essentially provides consent to have urine tested on a regular basis to track adherence, as well as provide pill counts and office visits as required by the doctors. The physicians also are required to regularly check the PDMP database.

Patients who need this kind of treatment do not complain that the requirements are burdensome, said Dr. Chouinard, who described the program as successful overall. She said 30% have stayed properly adherent to their prescription narcotics and are living within the agreements of their contracts, while another 20% were taken off their medication because they were able to be placed on alternate, nonopioid therapies. About 30% ended up recommended for or enrolled in an addiction program, while 20% failed to maintain their contracts, and thus were unable to get their prescriptions.

Dr. Chouinard said a program like this could easily be rolled out across the country to help address the opioid abuse problem, as well as help remove primary care doctors from the prescribing loop.

“None of these people went into medicine because they had an interest in treating chronic pain,” she said.

In keeping with the overall message of getting doctors to use PDMPs more, Mr. Coukell said that getting this information integrated into electronic health records is “the Holy Grail,” though he added that getting practice alerts are a good short-term fix. He also said that getting consistency of reporting practice uniform across states and getting more states to trade information also was key, as is getting rules in place to allow someone in the office other than the doctor to have access to the PDMP databases (which some states do allow).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director of the Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention Grant Baldwin, Ph.D., concurred.

“Providers have a limited amount of time to see patients,” Dr. Baldwin said. “Integrating all of these fixes will not necessarily extend the amount of time, but it actually makes it easier for the health care team to do their job in an efficient manner in that same 10-15 minute time."

WASHINGTON – The prescription drug–monitoring programs that exist in every state are not going to make a dent in opioid abuse unless physicians use them.

Because each state governs its own prescription drug–monitoring program (PDMP), the efficiency and effectiveness of each varies widely from the others. In the ideal, a PDMP collects information on which prescriptions are being filled by what patients as well as which physicians are prescribing the drugs. Information from the databases is used to help determine which patients might be doctor shopping for opioids as well as identify physicians who might be operating “pill mills” and contributing to the availability of narcotic pain medication that is used for other than clinical purposes.

Data from several studies have shown that in many instances, doctors do not realize the detail and usefulness of data from PDMPs, Allan Coukell, senior director for drugs and medical devices at Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, said at a panel discussion on prescription drug abuse hosted by the Alliance for Health Reform and the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the industry lobby for pharmacy benefit managers.

When shown data on a specific patient, a physician was often “surprised to know how many other physicians that patient was seeing, and having that information changed their prescribing,” Mr. Coukell said, noting that in some cases, the information led to physicians refusing to prescribe pain medication and in others, it eased fears that a patient might be doctor shopping, giving the physician some peace of mind about writing a prescription for a narcotic.

Panelist Dr. Sarah Chouinard, medical director of Community Care of West Virginia, noted that physicians often are surprised when presented with data collected by PDMPs about their own individual prescribing habits.

“Eight out of 10 people were very surprised at the number of hydrocodone prescriptions they had written in the last 3 months,” Dr. Chouinard said.

In addition, the culture of administering pain medicine has gone through a shift in the last 10 years that is contributing to the problem of how many pills are available.

“About 10 years ago, there were doctors wandering around with buttons that said ‘No Pain’ with a red circle and a line through it because we were accused of under treating pain,” she observed. “Now, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. They used to say, ‘Hey, we’ll get sued if we don’t write pain medicine for these people,’ and now it’s, ‘Gosh, don’t write anything, or we will be a pill mill.’ I think the real answer is getting back to the middle and allowing the word to be out there that you don’t have to use a narcotic for every bump.”

To that end, Dr. Chouinard shared a solution her community organization has implemented. She said that “none of the [family physicians] are equipped, myself included, to treat chronic pain. Chronic pain is a specialty. ... It requires special training. The training that we as family doctors get now, after residency, is a mandatory 3 hours every 2 years.”

So Community Health of West Virgina hired an anesthetist who is not interested in family medicine but rather has a special interest in addictions medicine and outpatient pain medicine.

“Every one of our patients who has chronic pain [is sent] to this physician first,” Dr. Chouinard explained. “He does the work-up. He looks to see if the patients are amenable to any kind of alternatives and then sends those patients back to us as primary care doctors.”

After that, every patient gets a pain contract that essentially provides consent to have urine tested on a regular basis to track adherence, as well as provide pill counts and office visits as required by the doctors. The physicians also are required to regularly check the PDMP database.

Patients who need this kind of treatment do not complain that the requirements are burdensome, said Dr. Chouinard, who described the program as successful overall. She said 30% have stayed properly adherent to their prescription narcotics and are living within the agreements of their contracts, while another 20% were taken off their medication because they were able to be placed on alternate, nonopioid therapies. About 30% ended up recommended for or enrolled in an addiction program, while 20% failed to maintain their contracts, and thus were unable to get their prescriptions.

Dr. Chouinard said a program like this could easily be rolled out across the country to help address the opioid abuse problem, as well as help remove primary care doctors from the prescribing loop.

“None of these people went into medicine because they had an interest in treating chronic pain,” she said.

In keeping with the overall message of getting doctors to use PDMPs more, Mr. Coukell said that getting this information integrated into electronic health records is “the Holy Grail,” though he added that getting practice alerts are a good short-term fix. He also said that getting consistency of reporting practice uniform across states and getting more states to trade information also was key, as is getting rules in place to allow someone in the office other than the doctor to have access to the PDMP databases (which some states do allow).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director of the Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention Grant Baldwin, Ph.D., concurred.

“Providers have a limited amount of time to see patients,” Dr. Baldwin said. “Integrating all of these fixes will not necessarily extend the amount of time, but it actually makes it easier for the health care team to do their job in an efficient manner in that same 10-15 minute time."

WASHINGTON – The prescription drug–monitoring programs that exist in every state are not going to make a dent in opioid abuse unless physicians use them.

Because each state governs its own prescription drug–monitoring program (PDMP), the efficiency and effectiveness of each varies widely from the others. In the ideal, a PDMP collects information on which prescriptions are being filled by what patients as well as which physicians are prescribing the drugs. Information from the databases is used to help determine which patients might be doctor shopping for opioids as well as identify physicians who might be operating “pill mills” and contributing to the availability of narcotic pain medication that is used for other than clinical purposes.

Data from several studies have shown that in many instances, doctors do not realize the detail and usefulness of data from PDMPs, Allan Coukell, senior director for drugs and medical devices at Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, said at a panel discussion on prescription drug abuse hosted by the Alliance for Health Reform and the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the industry lobby for pharmacy benefit managers.

When shown data on a specific patient, a physician was often “surprised to know how many other physicians that patient was seeing, and having that information changed their prescribing,” Mr. Coukell said, noting that in some cases, the information led to physicians refusing to prescribe pain medication and in others, it eased fears that a patient might be doctor shopping, giving the physician some peace of mind about writing a prescription for a narcotic.

Panelist Dr. Sarah Chouinard, medical director of Community Care of West Virginia, noted that physicians often are surprised when presented with data collected by PDMPs about their own individual prescribing habits.

“Eight out of 10 people were very surprised at the number of hydrocodone prescriptions they had written in the last 3 months,” Dr. Chouinard said.

In addition, the culture of administering pain medicine has gone through a shift in the last 10 years that is contributing to the problem of how many pills are available.

“About 10 years ago, there were doctors wandering around with buttons that said ‘No Pain’ with a red circle and a line through it because we were accused of under treating pain,” she observed. “Now, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. They used to say, ‘Hey, we’ll get sued if we don’t write pain medicine for these people,’ and now it’s, ‘Gosh, don’t write anything, or we will be a pill mill.’ I think the real answer is getting back to the middle and allowing the word to be out there that you don’t have to use a narcotic for every bump.”

To that end, Dr. Chouinard shared a solution her community organization has implemented. She said that “none of the [family physicians] are equipped, myself included, to treat chronic pain. Chronic pain is a specialty. ... It requires special training. The training that we as family doctors get now, after residency, is a mandatory 3 hours every 2 years.”

So Community Health of West Virgina hired an anesthetist who is not interested in family medicine but rather has a special interest in addictions medicine and outpatient pain medicine.

“Every one of our patients who has chronic pain [is sent] to this physician first,” Dr. Chouinard explained. “He does the work-up. He looks to see if the patients are amenable to any kind of alternatives and then sends those patients back to us as primary care doctors.”

After that, every patient gets a pain contract that essentially provides consent to have urine tested on a regular basis to track adherence, as well as provide pill counts and office visits as required by the doctors. The physicians also are required to regularly check the PDMP database.

Patients who need this kind of treatment do not complain that the requirements are burdensome, said Dr. Chouinard, who described the program as successful overall. She said 30% have stayed properly adherent to their prescription narcotics and are living within the agreements of their contracts, while another 20% were taken off their medication because they were able to be placed on alternate, nonopioid therapies. About 30% ended up recommended for or enrolled in an addiction program, while 20% failed to maintain their contracts, and thus were unable to get their prescriptions.

Dr. Chouinard said a program like this could easily be rolled out across the country to help address the opioid abuse problem, as well as help remove primary care doctors from the prescribing loop.

“None of these people went into medicine because they had an interest in treating chronic pain,” she said.

In keeping with the overall message of getting doctors to use PDMPs more, Mr. Coukell said that getting this information integrated into electronic health records is “the Holy Grail,” though he added that getting practice alerts are a good short-term fix. He also said that getting consistency of reporting practice uniform across states and getting more states to trade information also was key, as is getting rules in place to allow someone in the office other than the doctor to have access to the PDMP databases (which some states do allow).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director of the Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention Grant Baldwin, Ph.D., concurred.

“Providers have a limited amount of time to see patients,” Dr. Baldwin said. “Integrating all of these fixes will not necessarily extend the amount of time, but it actually makes it easier for the health care team to do their job in an efficient manner in that same 10-15 minute time."

AT A PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS–HOSTED PANEL

High-dose treatment did not benefit ICU patients with vitamin D deficiency

High-dose vitamin D did not improve outcomes in critically ill, vitamin D–deficient patients, compared with placebo, researchers reported in JAMA and at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Although the study was adequately powered, length of stay did not differ between the vitamin D and placebo groups, said Dr. Karin Amrein of the Medical University of Graz, Austria, and her associates. “In the overall cohort, hospital and 6-month mortality rates were numerically lower in the vitamin D3 group, but these differences were not significant,” the researchers said.

A subgroup of patients with severe vitamin D deficiency did have significantly lower hospital mortality when treated with vitamin D, compared with placebo, but the effect “should be considered hypothesis generating and requires further study,” the investigators concluded (JAMA 2014 Sept. 29 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13204]).

The randomized, double-blind, single-center trial enrolled 492 critically ill medical and surgical patients with serum vitamin D levels of 20 ng/mL or less. Patients received placebo or vitamin D3 at a loading dose of 540,000 IU, followed by a monthly maintenance dose of 90,000 IU for 5 months, the researchers said.

Length of hospital stay averaged 20.1 days for patients who received vitamin D and 19.3 days for the placebo group, the investigators reported.

Among patients who received vitamin D3, 28.3% died in the hospital, compared with 35.3% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 1.11), they said. Six-month mortality was 35.0% for the vitamin D3 group, compared with 42.9% for the placebo group (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.58-1.04), they said.

Among 200 patients with severe vitamin D deficiencies of 12 ng/mL or less, vitamin D3 treatment was linked to a 44% drop in risk of dying in the hospital, the researchers said (28.6% vs. 46.1% for placebo; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.90; P = .04).But length of hospital stay and 6-month mortality rates were similar between the two groups, they reported.

Drug maker Fresenius Kabi provided study medication and a grant to support the research. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism and the Austrian National Bank also funded the study.

Dr Amrein reported and one coauthor reported receiving lecture fees from Fresenius Kabi. The authors reported no other relevant financial conflicts of interest.

High-dose vitamin D did not improve outcomes in critically ill, vitamin D–deficient patients, compared with placebo, researchers reported in JAMA and at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Although the study was adequately powered, length of stay did not differ between the vitamin D and placebo groups, said Dr. Karin Amrein of the Medical University of Graz, Austria, and her associates. “In the overall cohort, hospital and 6-month mortality rates were numerically lower in the vitamin D3 group, but these differences were not significant,” the researchers said.

A subgroup of patients with severe vitamin D deficiency did have significantly lower hospital mortality when treated with vitamin D, compared with placebo, but the effect “should be considered hypothesis generating and requires further study,” the investigators concluded (JAMA 2014 Sept. 29 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13204]).

The randomized, double-blind, single-center trial enrolled 492 critically ill medical and surgical patients with serum vitamin D levels of 20 ng/mL or less. Patients received placebo or vitamin D3 at a loading dose of 540,000 IU, followed by a monthly maintenance dose of 90,000 IU for 5 months, the researchers said.

Length of hospital stay averaged 20.1 days for patients who received vitamin D and 19.3 days for the placebo group, the investigators reported.

Among patients who received vitamin D3, 28.3% died in the hospital, compared with 35.3% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 1.11), they said. Six-month mortality was 35.0% for the vitamin D3 group, compared with 42.9% for the placebo group (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.58-1.04), they said.

Among 200 patients with severe vitamin D deficiencies of 12 ng/mL or less, vitamin D3 treatment was linked to a 44% drop in risk of dying in the hospital, the researchers said (28.6% vs. 46.1% for placebo; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.90; P = .04).But length of hospital stay and 6-month mortality rates were similar between the two groups, they reported.

Drug maker Fresenius Kabi provided study medication and a grant to support the research. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism and the Austrian National Bank also funded the study.

Dr Amrein reported and one coauthor reported receiving lecture fees from Fresenius Kabi. The authors reported no other relevant financial conflicts of interest.

High-dose vitamin D did not improve outcomes in critically ill, vitamin D–deficient patients, compared with placebo, researchers reported in JAMA and at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Although the study was adequately powered, length of stay did not differ between the vitamin D and placebo groups, said Dr. Karin Amrein of the Medical University of Graz, Austria, and her associates. “In the overall cohort, hospital and 6-month mortality rates were numerically lower in the vitamin D3 group, but these differences were not significant,” the researchers said.

A subgroup of patients with severe vitamin D deficiency did have significantly lower hospital mortality when treated with vitamin D, compared with placebo, but the effect “should be considered hypothesis generating and requires further study,” the investigators concluded (JAMA 2014 Sept. 29 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13204]).

The randomized, double-blind, single-center trial enrolled 492 critically ill medical and surgical patients with serum vitamin D levels of 20 ng/mL or less. Patients received placebo or vitamin D3 at a loading dose of 540,000 IU, followed by a monthly maintenance dose of 90,000 IU for 5 months, the researchers said.

Length of hospital stay averaged 20.1 days for patients who received vitamin D and 19.3 days for the placebo group, the investigators reported.

Among patients who received vitamin D3, 28.3% died in the hospital, compared with 35.3% of the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 1.11), they said. Six-month mortality was 35.0% for the vitamin D3 group, compared with 42.9% for the placebo group (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.58-1.04), they said.

Among 200 patients with severe vitamin D deficiencies of 12 ng/mL or less, vitamin D3 treatment was linked to a 44% drop in risk of dying in the hospital, the researchers said (28.6% vs. 46.1% for placebo; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.90; P = .04).But length of hospital stay and 6-month mortality rates were similar between the two groups, they reported.

Drug maker Fresenius Kabi provided study medication and a grant to support the research. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism and the Austrian National Bank also funded the study.

Dr Amrein reported and one coauthor reported receiving lecture fees from Fresenius Kabi. The authors reported no other relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Vitamin D3 treatment did not reduce hospital length of stay or mortality in critically ill patients with vitamin D deficiency.

Major finding: Length of hospital stay averaged 20.1 days for patients who received vitamin D and 19.3 days for the placebo group (P = 0.98).

Data source: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center trial of 492 critically ill medical and surgical patients with vitamin D deficiency of 20 ng per mL or less.

Disclosures: Drug maker Fresenius Kabi provided study medication and a grant to support the research. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism and the Austrian National Bank also funded the study. Dr Amrein reported and one coauthor reported receiving lecture fees from Fresenius Kabi. The authors reported no other relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Hydrocodone rescheduling takes effect Oct. 6

Physicians should ready themselves now for the new set of rules expected when hydrocodone-containing products become subject to tighter regulation on Oct. 6, according to various physician groups.

After a years-long process, the Drug Enforcement Administration announced in late August that it would be moving hydrocodone-containing products from schedule III to schedule II.

That rule takes effect on Oct. 6.

After that date, physicians who want to prescribe HCPs will have to use tamper-proof prescription forms, or use e-prescribing programs. They can call in a 72-hour supply, but must follow that up by mailing the prescription to the pharmacy. Refills by fax or phone are otherwise prohibited.

Patients who are on long term HCP therapy can get up to a 90-day supply through three separate, no-refill prescriptions.

The American Medical Association, which campaigned against the rescheduling of HCPs, is now urging its members to be prepared for the changes in prescribing and work flow that will come with the new landscape.

In a fact sheet, the AMA says that physicians should try to refill prescriptions before Oct. 6, noting that these prescriptions will essentially be grandfathered in under the old rules until Apr. 2015.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology in early September also notified its members of the coming changes, and said that it, too, had opposed rescheduling of HCPs.

Many physician groups have said that moving HCPs to schedule II will not stop abuse or diversion and may hurt patients who have a legitimate need. Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that “it’s hard to say,” whether upscheduling will make a dent in inappropriate or unnecessary prescribing.

He said in an interview that his practice already requires patients on long-term opioid therapy to come in at least every 3 months for refills and an evaluation. Although physicians may have to change their practice schedules to accommodate refill visits, those visits are good opportunities for education and follow-up, said Dr. Blackwelder.

Requiring face-to-face visits “creates more opportunities to review a treatment plan and make sure it still makes sense,” he said, noting that for many patients, short-acting opioids are the wrong medication.

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, for one, is applauding the rescheduling of HCPs, saying that the explosion in prescriptions for HCPs such as Vicodin (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) has been the single biggest contributor to the rise in opioid addiction.

“I think this is going to have an enormous impact on bringing the epidemic to an end,” Dr. Kolodny, chief medical officer at the Phoenix House Foundation and director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, said in an interview.

He noted that many opioid addicts get their start with HCPs, in part because they are ubiquitous.

The schedule change will bring “a sharp reduction in prescribing of hydrocodone-containing products,” because “it will communicate to prescribers that this drug is every bit as addictive as the other opioids, and needs to be prescribed cautiously,” said Dr. Kolodny.

Dr. Kolodny disclosed that Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing does not accept any industry funding. It is a financed as a Phoenix House program.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Physicians should ready themselves now for the new set of rules expected when hydrocodone-containing products become subject to tighter regulation on Oct. 6, according to various physician groups.

After a years-long process, the Drug Enforcement Administration announced in late August that it would be moving hydrocodone-containing products from schedule III to schedule II.

That rule takes effect on Oct. 6.

After that date, physicians who want to prescribe HCPs will have to use tamper-proof prescription forms, or use e-prescribing programs. They can call in a 72-hour supply, but must follow that up by mailing the prescription to the pharmacy. Refills by fax or phone are otherwise prohibited.

Patients who are on long term HCP therapy can get up to a 90-day supply through three separate, no-refill prescriptions.

The American Medical Association, which campaigned against the rescheduling of HCPs, is now urging its members to be prepared for the changes in prescribing and work flow that will come with the new landscape.

In a fact sheet, the AMA says that physicians should try to refill prescriptions before Oct. 6, noting that these prescriptions will essentially be grandfathered in under the old rules until Apr. 2015.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology in early September also notified its members of the coming changes, and said that it, too, had opposed rescheduling of HCPs.

Many physician groups have said that moving HCPs to schedule II will not stop abuse or diversion and may hurt patients who have a legitimate need. Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that “it’s hard to say,” whether upscheduling will make a dent in inappropriate or unnecessary prescribing.

He said in an interview that his practice already requires patients on long-term opioid therapy to come in at least every 3 months for refills and an evaluation. Although physicians may have to change their practice schedules to accommodate refill visits, those visits are good opportunities for education and follow-up, said Dr. Blackwelder.

Requiring face-to-face visits “creates more opportunities to review a treatment plan and make sure it still makes sense,” he said, noting that for many patients, short-acting opioids are the wrong medication.

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, for one, is applauding the rescheduling of HCPs, saying that the explosion in prescriptions for HCPs such as Vicodin (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) has been the single biggest contributor to the rise in opioid addiction.

“I think this is going to have an enormous impact on bringing the epidemic to an end,” Dr. Kolodny, chief medical officer at the Phoenix House Foundation and director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, said in an interview.

He noted that many opioid addicts get their start with HCPs, in part because they are ubiquitous.

The schedule change will bring “a sharp reduction in prescribing of hydrocodone-containing products,” because “it will communicate to prescribers that this drug is every bit as addictive as the other opioids, and needs to be prescribed cautiously,” said Dr. Kolodny.

Dr. Kolodny disclosed that Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing does not accept any industry funding. It is a financed as a Phoenix House program.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Physicians should ready themselves now for the new set of rules expected when hydrocodone-containing products become subject to tighter regulation on Oct. 6, according to various physician groups.

After a years-long process, the Drug Enforcement Administration announced in late August that it would be moving hydrocodone-containing products from schedule III to schedule II.

That rule takes effect on Oct. 6.

After that date, physicians who want to prescribe HCPs will have to use tamper-proof prescription forms, or use e-prescribing programs. They can call in a 72-hour supply, but must follow that up by mailing the prescription to the pharmacy. Refills by fax or phone are otherwise prohibited.

Patients who are on long term HCP therapy can get up to a 90-day supply through three separate, no-refill prescriptions.

The American Medical Association, which campaigned against the rescheduling of HCPs, is now urging its members to be prepared for the changes in prescribing and work flow that will come with the new landscape.

In a fact sheet, the AMA says that physicians should try to refill prescriptions before Oct. 6, noting that these prescriptions will essentially be grandfathered in under the old rules until Apr. 2015.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology in early September also notified its members of the coming changes, and said that it, too, had opposed rescheduling of HCPs.

Many physician groups have said that moving HCPs to schedule II will not stop abuse or diversion and may hurt patients who have a legitimate need. Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that “it’s hard to say,” whether upscheduling will make a dent in inappropriate or unnecessary prescribing.

He said in an interview that his practice already requires patients on long-term opioid therapy to come in at least every 3 months for refills and an evaluation. Although physicians may have to change their practice schedules to accommodate refill visits, those visits are good opportunities for education and follow-up, said Dr. Blackwelder.

Requiring face-to-face visits “creates more opportunities to review a treatment plan and make sure it still makes sense,” he said, noting that for many patients, short-acting opioids are the wrong medication.

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, for one, is applauding the rescheduling of HCPs, saying that the explosion in prescriptions for HCPs such as Vicodin (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) has been the single biggest contributor to the rise in opioid addiction.

“I think this is going to have an enormous impact on bringing the epidemic to an end,” Dr. Kolodny, chief medical officer at the Phoenix House Foundation and director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, said in an interview.

He noted that many opioid addicts get their start with HCPs, in part because they are ubiquitous.

The schedule change will bring “a sharp reduction in prescribing of hydrocodone-containing products,” because “it will communicate to prescribers that this drug is every bit as addictive as the other opioids, and needs to be prescribed cautiously,” said Dr. Kolodny.

Dr. Kolodny disclosed that Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing does not accept any industry funding. It is a financed as a Phoenix House program.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Laparoscopic resection improved short-term outcomes in patients with cirrhotic liver cancer

Patients with liver cancer and cirrhosis who underwent laparoscopic hepatic resection had fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, no port site recurrences, and no significant difference in survival, compared with patients who had open resections, according to a single-center, 10-year study published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study is the first to report long-term favorable results of laparoscopic hepatic resection for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, said Dr. Yo-ichi Yamashita and associates at Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan. Based on the data, laparoscopic instead of open resection should be considered for patients with cirrhosis whose hepatocellular carcinomas fall within the Milan criteria, the investigators said (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014 Sept. 9 [doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.09.003]).

The retrospective study included 162 patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. In all, 99 patients had open hepatic resections, while 63 underwent laparoscopic resections, the investigators said. Only 10% of laparoscopy patients had complications of grade 2 or higher, compared with 26% of open surgery cases (P = .0459), they reported. And while 7% of the open surgery patients developed ascites after surgery, none of the laparoscopy patients did (P = .0077), possibly because they experienced less tissue damage and because the deliberate induction of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopy can reduce local inflammatory responses, the researchers said. Laparoscopy patients also averaged 6 fewer days in the hospital after their procedures, Dr. Yamashita and associates reported (median length of stay, 10 vs. 16 days; P = .0008).

The laparoscopy group had no port site recurrences or peritoneal seeding of hepatocellular carcinoma, the investigators noted. Rates of disease-free and overall survival were similar between the two groups (P = .5196 and P = .6791, respectively), they added. Five-year and 10-year overall survival rates were 78% and 69% for laparoscopy patients, and were 77% and 57% for open resection patients, they said.

The authors disclosed no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

Patients with liver cancer and cirrhosis who underwent laparoscopic hepatic resection had fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, no port site recurrences, and no significant difference in survival, compared with patients who had open resections, according to a single-center, 10-year study published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study is the first to report long-term favorable results of laparoscopic hepatic resection for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, said Dr. Yo-ichi Yamashita and associates at Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan. Based on the data, laparoscopic instead of open resection should be considered for patients with cirrhosis whose hepatocellular carcinomas fall within the Milan criteria, the investigators said (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014 Sept. 9 [doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.09.003]).

The retrospective study included 162 patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. In all, 99 patients had open hepatic resections, while 63 underwent laparoscopic resections, the investigators said. Only 10% of laparoscopy patients had complications of grade 2 or higher, compared with 26% of open surgery cases (P = .0459), they reported. And while 7% of the open surgery patients developed ascites after surgery, none of the laparoscopy patients did (P = .0077), possibly because they experienced less tissue damage and because the deliberate induction of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopy can reduce local inflammatory responses, the researchers said. Laparoscopy patients also averaged 6 fewer days in the hospital after their procedures, Dr. Yamashita and associates reported (median length of stay, 10 vs. 16 days; P = .0008).

The laparoscopy group had no port site recurrences or peritoneal seeding of hepatocellular carcinoma, the investigators noted. Rates of disease-free and overall survival were similar between the two groups (P = .5196 and P = .6791, respectively), they added. Five-year and 10-year overall survival rates were 78% and 69% for laparoscopy patients, and were 77% and 57% for open resection patients, they said.

The authors disclosed no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

Patients with liver cancer and cirrhosis who underwent laparoscopic hepatic resection had fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, no port site recurrences, and no significant difference in survival, compared with patients who had open resections, according to a single-center, 10-year study published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study is the first to report long-term favorable results of laparoscopic hepatic resection for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, said Dr. Yo-ichi Yamashita and associates at Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan. Based on the data, laparoscopic instead of open resection should be considered for patients with cirrhosis whose hepatocellular carcinomas fall within the Milan criteria, the investigators said (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014 Sept. 9 [doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.09.003]).

The retrospective study included 162 patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. In all, 99 patients had open hepatic resections, while 63 underwent laparoscopic resections, the investigators said. Only 10% of laparoscopy patients had complications of grade 2 or higher, compared with 26% of open surgery cases (P = .0459), they reported. And while 7% of the open surgery patients developed ascites after surgery, none of the laparoscopy patients did (P = .0077), possibly because they experienced less tissue damage and because the deliberate induction of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopy can reduce local inflammatory responses, the researchers said. Laparoscopy patients also averaged 6 fewer days in the hospital after their procedures, Dr. Yamashita and associates reported (median length of stay, 10 vs. 16 days; P = .0008).

The laparoscopy group had no port site recurrences or peritoneal seeding of hepatocellular carcinoma, the investigators noted. Rates of disease-free and overall survival were similar between the two groups (P = .5196 and P = .6791, respectively), they added. Five-year and 10-year overall survival rates were 78% and 69% for laparoscopy patients, and were 77% and 57% for open resection patients, they said.

The authors disclosed no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Patients with liver cancer and cirrhosis who underwent laparoscopic hepatic resections had lower postoperative morbidity and shorter hospital stays than patients who had open resections.

Major finding: Laparoscopy patients had significantly less postoperative morbidity (10% vs. 26%; P = .0459) and shorter hospital stays (10 vs. 16 days; P = .0008), compared with patients who underwent open resection, with no port site recurrences and no significant differences in long-term survival.

Data source:Retrospective, single-center study of 162 patients with cirrhosis and primary hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent curative hepatic resections, of whom 99 underwent open procedures and 63 underwent laparoscopies.

Disclosures: The authors disclosed no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

Closing large dermal defects much like a Victorian corset

EDINBURGH – Barbed absorbable sutures are a useful new tool to facilitate dermal closure of facial and nonfacial defects following tumor resection.

“These are not the bad old sutures that you might of heard about before, that were nonabsorbable sutures and attempted for use in cosmetic procedures,” Dr. John Strasswimmer said at the 15th World Congress on Cancers of the Skin.

Last year, Dr. Strasswimmer, medical director of melanoma and cutaneous oncology at the Lynn Cancer Institute in Boca Raton, Fla., reported his initial experience using a procedure he calls “Corseta” to close a large Mohs defect on the trunk of an 83-year-old man (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:853-4).

The procedure employs a barbed, bioabsorbable suture (Ethicon’s Stratafix and Covidien’s V-Loc) that is run in a continuous vertical looping manner in the subcutaneous layer, with minimal to no undermining of the wound. Undermining is typically used in cutaneous surgery to relieve tension or provide structure around anatomical landmarks, but it can increase the risk of bleeding, swelling, and patient discomfort, he said.

Instead, the first suture pass is placed in the deepest portion of the subcutaneous tissue and brought out within the more superficial subcutaneous layer. Each bite of the barbed suture extends peripherally at least 2.0 cm from the edge of the wound, so the point of tension is lateral to the wound margins. At every two passes, tension is placed evenly across the sutures to close the deepest layer of tissue and to engage the barbs, much like closing of a Victorian corset, Dr. Strasswimmer said.

The second arm of the suture is passed in a similar manner in the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the first pass.

“This is a lacing, not a suturing technique,” he said. “You get tissue approximation, but more importantly, because we’re bringing in all that deep tissue, you automatically get beautiful wound-edge eversion and very nice cosmetic results.”

Because the sutures have barbs cut into them, however, a 0-0 weight polydioxane or other absorbable material suture can have a breaking strength of a #2-0 suture. “You have to look very carefully at the manufacturer’s sizing and strength requirements,” Dr. Strasswimmer cautioned.

Since their initial case report, Dr. Strasswimmer and his colleagues have expanded use of the Corseta technique to more than 600 facial and nonfacial reconstructions. The Corseta procedure is not as helpful for curved topography such as the central face or scalp, he said in an interview. Still, of the 600 or so cases, none required conversion to another closure technique.

“The traditional closure technique would not have worked in those challenging cases,” Dr. Strasswimmer said. “In the most difficult situations, such as older patients with severely atrophic skin, even the best suturing won’t work. In that case, the Corseta at least produces a partial closure, thereby reducing the wound and accelerating healing.” The Corseta procedure is often coupled with tumescent anesthesia to decrease the risk of bleeding, particularly in patients on anticoagulation, he noted.

The conference was sponsored by the Skin Cancer Foundation.

EDINBURGH – Barbed absorbable sutures are a useful new tool to facilitate dermal closure of facial and nonfacial defects following tumor resection.

“These are not the bad old sutures that you might of heard about before, that were nonabsorbable sutures and attempted for use in cosmetic procedures,” Dr. John Strasswimmer said at the 15th World Congress on Cancers of the Skin.

Last year, Dr. Strasswimmer, medical director of melanoma and cutaneous oncology at the Lynn Cancer Institute in Boca Raton, Fla., reported his initial experience using a procedure he calls “Corseta” to close a large Mohs defect on the trunk of an 83-year-old man (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:853-4).

The procedure employs a barbed, bioabsorbable suture (Ethicon’s Stratafix and Covidien’s V-Loc) that is run in a continuous vertical looping manner in the subcutaneous layer, with minimal to no undermining of the wound. Undermining is typically used in cutaneous surgery to relieve tension or provide structure around anatomical landmarks, but it can increase the risk of bleeding, swelling, and patient discomfort, he said.

Instead, the first suture pass is placed in the deepest portion of the subcutaneous tissue and brought out within the more superficial subcutaneous layer. Each bite of the barbed suture extends peripherally at least 2.0 cm from the edge of the wound, so the point of tension is lateral to the wound margins. At every two passes, tension is placed evenly across the sutures to close the deepest layer of tissue and to engage the barbs, much like closing of a Victorian corset, Dr. Strasswimmer said.

The second arm of the suture is passed in a similar manner in the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the first pass.

“This is a lacing, not a suturing technique,” he said. “You get tissue approximation, but more importantly, because we’re bringing in all that deep tissue, you automatically get beautiful wound-edge eversion and very nice cosmetic results.”

Because the sutures have barbs cut into them, however, a 0-0 weight polydioxane or other absorbable material suture can have a breaking strength of a #2-0 suture. “You have to look very carefully at the manufacturer’s sizing and strength requirements,” Dr. Strasswimmer cautioned.

Since their initial case report, Dr. Strasswimmer and his colleagues have expanded use of the Corseta technique to more than 600 facial and nonfacial reconstructions. The Corseta procedure is not as helpful for curved topography such as the central face or scalp, he said in an interview. Still, of the 600 or so cases, none required conversion to another closure technique.

“The traditional closure technique would not have worked in those challenging cases,” Dr. Strasswimmer said. “In the most difficult situations, such as older patients with severely atrophic skin, even the best suturing won’t work. In that case, the Corseta at least produces a partial closure, thereby reducing the wound and accelerating healing.” The Corseta procedure is often coupled with tumescent anesthesia to decrease the risk of bleeding, particularly in patients on anticoagulation, he noted.

The conference was sponsored by the Skin Cancer Foundation.

EDINBURGH – Barbed absorbable sutures are a useful new tool to facilitate dermal closure of facial and nonfacial defects following tumor resection.

“These are not the bad old sutures that you might of heard about before, that were nonabsorbable sutures and attempted for use in cosmetic procedures,” Dr. John Strasswimmer said at the 15th World Congress on Cancers of the Skin.

Last year, Dr. Strasswimmer, medical director of melanoma and cutaneous oncology at the Lynn Cancer Institute in Boca Raton, Fla., reported his initial experience using a procedure he calls “Corseta” to close a large Mohs defect on the trunk of an 83-year-old man (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:853-4).

The procedure employs a barbed, bioabsorbable suture (Ethicon’s Stratafix and Covidien’s V-Loc) that is run in a continuous vertical looping manner in the subcutaneous layer, with minimal to no undermining of the wound. Undermining is typically used in cutaneous surgery to relieve tension or provide structure around anatomical landmarks, but it can increase the risk of bleeding, swelling, and patient discomfort, he said.

Instead, the first suture pass is placed in the deepest portion of the subcutaneous tissue and brought out within the more superficial subcutaneous layer. Each bite of the barbed suture extends peripherally at least 2.0 cm from the edge of the wound, so the point of tension is lateral to the wound margins. At every two passes, tension is placed evenly across the sutures to close the deepest layer of tissue and to engage the barbs, much like closing of a Victorian corset, Dr. Strasswimmer said.

The second arm of the suture is passed in a similar manner in the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the first pass.

“This is a lacing, not a suturing technique,” he said. “You get tissue approximation, but more importantly, because we’re bringing in all that deep tissue, you automatically get beautiful wound-edge eversion and very nice cosmetic results.”

Because the sutures have barbs cut into them, however, a 0-0 weight polydioxane or other absorbable material suture can have a breaking strength of a #2-0 suture. “You have to look very carefully at the manufacturer’s sizing and strength requirements,” Dr. Strasswimmer cautioned.

Since their initial case report, Dr. Strasswimmer and his colleagues have expanded use of the Corseta technique to more than 600 facial and nonfacial reconstructions. The Corseta procedure is not as helpful for curved topography such as the central face or scalp, he said in an interview. Still, of the 600 or so cases, none required conversion to another closure technique.

“The traditional closure technique would not have worked in those challenging cases,” Dr. Strasswimmer said. “In the most difficult situations, such as older patients with severely atrophic skin, even the best suturing won’t work. In that case, the Corseta at least produces a partial closure, thereby reducing the wound and accelerating healing.” The Corseta procedure is often coupled with tumescent anesthesia to decrease the risk of bleeding, particularly in patients on anticoagulation, he noted.

The conference was sponsored by the Skin Cancer Foundation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCCS 2014

Same-day combined ERCP and cholecystectomy: achievable and cost effective

“Same-day procedures decreased length of stay by 2 days and led to an approximately $30,000 cost savings with no difference in conversion rates or complications between the two cohorts. The success rate of operative ERCP was 100%,” Dr. Jeffrey Wild, of Geisinger Health System in Northeastern Pennsylvania, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

The Geisinger study validated the findings of two previous European studies (Endoscopy 2006;38:779-86; Am. Surg. 2013;79:1243-7). “These studies found decreased length of stay by 2 to 3 days, they found no difference in the incidence of retained stones, no difference in conversion rates to open cholecystectomy, and there was no difference in complications between the two groups,” Dr. Wild said.

The Geisinger investigators conducted the single-center, retrospective study of 240 patients from 2010 to 2014 comparing same-day and separate-day approaches for patients with choledocholithiasis and cholecystitis. In all, 65 patients had same-day procedures, with an average length of stay of 3 days vs. 5 days for patients who had ERCP and cholecystectomy on separate days, Dr. Wild said.

Like the European studies, the Geisinger experience found no statistical difference in conversion rates to open operation (12% for same-day vs. 14% for separate-day procedures) while the rate of discharge to a skilled nursing facility was half in the same-day cohort: 10% vs. 20% for separate-day patients, Dr. Wild said.

The goal of the Geisinger gallbladder pathway is to facilitate early operations in patients with cholecystitis. “Patients who present with cholecystitis should undergo cholecystectomy within 24 hours of presentation, if appropriate,” Dr. Wild said. “If there is evidence of biliary obstruction and the need for further work-up, our goal is to have gastroenterology work-up and management of the patient and have cholecystectomy done within the first 48 hours.”

The study noted some slight variations between the same-day and separate-day approaches, Dr. Wild said. The success rate of the endoscopist to cannulate the ampulla and perform ERCP was 95% in the same-day group and 100% in the separate-day cohort. ERCP was positive in identifying common bile duct stones or sludge in 97% of the same-day group vs. 91% in separate-day patients. More patients in the separate-day cohort required a second ERCP, usually 3 or 4 weeks after discharge and for removal of biliary stents, Dr. Wild said. Demographics in both groups were similar.

Operating room times varied between the two groups, and even within the same-day group depending on the setting for the ERCP, according to Dr. Wild. For patients in the separate-day group, average operative time was 1 hour, 42 minutes; same-day patients who had ERCP in the endoscopy suite and then transferred to the OR for cholecystectomy averaged 1 hour, 34 minutes; while the same-day cohort who had both ERCP and cholecystectomy done in the OR averaged 2 hours, 12 minutes.

Same-day care required coordination between different departments, Dr. Wild said. “Patients in the same-day group required coordination between the acute care surgical service, anesthesia, and gastroenterology to make sure both procedures could be performed under the same general anesthesia,” he said. The same-day group was almost evenly split between having ERCP in endoscopy before moving to the OR and having both done in the OR, Dr. Wild said.

“The findings of this study are, Number 1, intuitively obvious and easily predicted; and, Number 2, why didn’t I think of that myself?” said discussant Dr. Michael Chang of Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Chang also noted that the study provides an example of how to restructure care organizations. “Grouping practitioners by disease process, as opposed to what board they’re certified by or what department they live in, is thought to be a more patient-centered approach to provide cost-effective care,” he said.

Dr. Chang and others asked how the Geisinger surgeons overcame institutional barriers in creating their care model. “Most institutions are still dependent on the gastroenterologists, and lining up that procedure with another service can be difficult,” Dr. Donald Reed Jr. of Lutheran Medical Group in Fort Wayne, Ind., noted.

Dr. Wild acknowledged at first the pathway encountered some resistance. “But what really started this process was that the endoscopy suite was closed on weekends and all the ERCPs were performed in OR,” he said. “And then we were taking patients the following morning back to the OR to take out their gallbladder. Some of my senior partners questioned why aren’t we doing these at the same time.”

At this point, gastroenterology is “very willing” to embrace ERCP in the OR before gallbladder removal, Dr. Wild said.

Dr. Wild reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

“Same-day procedures decreased length of stay by 2 days and led to an approximately $30,000 cost savings with no difference in conversion rates or complications between the two cohorts. The success rate of operative ERCP was 100%,” Dr. Jeffrey Wild, of Geisinger Health System in Northeastern Pennsylvania, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

The Geisinger study validated the findings of two previous European studies (Endoscopy 2006;38:779-86; Am. Surg. 2013;79:1243-7). “These studies found decreased length of stay by 2 to 3 days, they found no difference in the incidence of retained stones, no difference in conversion rates to open cholecystectomy, and there was no difference in complications between the two groups,” Dr. Wild said.

The Geisinger investigators conducted the single-center, retrospective study of 240 patients from 2010 to 2014 comparing same-day and separate-day approaches for patients with choledocholithiasis and cholecystitis. In all, 65 patients had same-day procedures, with an average length of stay of 3 days vs. 5 days for patients who had ERCP and cholecystectomy on separate days, Dr. Wild said.

Like the European studies, the Geisinger experience found no statistical difference in conversion rates to open operation (12% for same-day vs. 14% for separate-day procedures) while the rate of discharge to a skilled nursing facility was half in the same-day cohort: 10% vs. 20% for separate-day patients, Dr. Wild said.

The goal of the Geisinger gallbladder pathway is to facilitate early operations in patients with cholecystitis. “Patients who present with cholecystitis should undergo cholecystectomy within 24 hours of presentation, if appropriate,” Dr. Wild said. “If there is evidence of biliary obstruction and the need for further work-up, our goal is to have gastroenterology work-up and management of the patient and have cholecystectomy done within the first 48 hours.”

The study noted some slight variations between the same-day and separate-day approaches, Dr. Wild said. The success rate of the endoscopist to cannulate the ampulla and perform ERCP was 95% in the same-day group and 100% in the separate-day cohort. ERCP was positive in identifying common bile duct stones or sludge in 97% of the same-day group vs. 91% in separate-day patients. More patients in the separate-day cohort required a second ERCP, usually 3 or 4 weeks after discharge and for removal of biliary stents, Dr. Wild said. Demographics in both groups were similar.

Operating room times varied between the two groups, and even within the same-day group depending on the setting for the ERCP, according to Dr. Wild. For patients in the separate-day group, average operative time was 1 hour, 42 minutes; same-day patients who had ERCP in the endoscopy suite and then transferred to the OR for cholecystectomy averaged 1 hour, 34 minutes; while the same-day cohort who had both ERCP and cholecystectomy done in the OR averaged 2 hours, 12 minutes.

Same-day care required coordination between different departments, Dr. Wild said. “Patients in the same-day group required coordination between the acute care surgical service, anesthesia, and gastroenterology to make sure both procedures could be performed under the same general anesthesia,” he said. The same-day group was almost evenly split between having ERCP in endoscopy before moving to the OR and having both done in the OR, Dr. Wild said.

“The findings of this study are, Number 1, intuitively obvious and easily predicted; and, Number 2, why didn’t I think of that myself?” said discussant Dr. Michael Chang of Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Chang also noted that the study provides an example of how to restructure care organizations. “Grouping practitioners by disease process, as opposed to what board they’re certified by or what department they live in, is thought to be a more patient-centered approach to provide cost-effective care,” he said.

Dr. Chang and others asked how the Geisinger surgeons overcame institutional barriers in creating their care model. “Most institutions are still dependent on the gastroenterologists, and lining up that procedure with another service can be difficult,” Dr. Donald Reed Jr. of Lutheran Medical Group in Fort Wayne, Ind., noted.

Dr. Wild acknowledged at first the pathway encountered some resistance. “But what really started this process was that the endoscopy suite was closed on weekends and all the ERCPs were performed in OR,” he said. “And then we were taking patients the following morning back to the OR to take out their gallbladder. Some of my senior partners questioned why aren’t we doing these at the same time.”

At this point, gastroenterology is “very willing” to embrace ERCP in the OR before gallbladder removal, Dr. Wild said.

Dr. Wild reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

“Same-day procedures decreased length of stay by 2 days and led to an approximately $30,000 cost savings with no difference in conversion rates or complications between the two cohorts. The success rate of operative ERCP was 100%,” Dr. Jeffrey Wild, of Geisinger Health System in Northeastern Pennsylvania, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

The Geisinger study validated the findings of two previous European studies (Endoscopy 2006;38:779-86; Am. Surg. 2013;79:1243-7). “These studies found decreased length of stay by 2 to 3 days, they found no difference in the incidence of retained stones, no difference in conversion rates to open cholecystectomy, and there was no difference in complications between the two groups,” Dr. Wild said.

The Geisinger investigators conducted the single-center, retrospective study of 240 patients from 2010 to 2014 comparing same-day and separate-day approaches for patients with choledocholithiasis and cholecystitis. In all, 65 patients had same-day procedures, with an average length of stay of 3 days vs. 5 days for patients who had ERCP and cholecystectomy on separate days, Dr. Wild said.

Like the European studies, the Geisinger experience found no statistical difference in conversion rates to open operation (12% for same-day vs. 14% for separate-day procedures) while the rate of discharge to a skilled nursing facility was half in the same-day cohort: 10% vs. 20% for separate-day patients, Dr. Wild said.

The goal of the Geisinger gallbladder pathway is to facilitate early operations in patients with cholecystitis. “Patients who present with cholecystitis should undergo cholecystectomy within 24 hours of presentation, if appropriate,” Dr. Wild said. “If there is evidence of biliary obstruction and the need for further work-up, our goal is to have gastroenterology work-up and management of the patient and have cholecystectomy done within the first 48 hours.”

The study noted some slight variations between the same-day and separate-day approaches, Dr. Wild said. The success rate of the endoscopist to cannulate the ampulla and perform ERCP was 95% in the same-day group and 100% in the separate-day cohort. ERCP was positive in identifying common bile duct stones or sludge in 97% of the same-day group vs. 91% in separate-day patients. More patients in the separate-day cohort required a second ERCP, usually 3 or 4 weeks after discharge and for removal of biliary stents, Dr. Wild said. Demographics in both groups were similar.

Operating room times varied between the two groups, and even within the same-day group depending on the setting for the ERCP, according to Dr. Wild. For patients in the separate-day group, average operative time was 1 hour, 42 minutes; same-day patients who had ERCP in the endoscopy suite and then transferred to the OR for cholecystectomy averaged 1 hour, 34 minutes; while the same-day cohort who had both ERCP and cholecystectomy done in the OR averaged 2 hours, 12 minutes.

Same-day care required coordination between different departments, Dr. Wild said. “Patients in the same-day group required coordination between the acute care surgical service, anesthesia, and gastroenterology to make sure both procedures could be performed under the same general anesthesia,” he said. The same-day group was almost evenly split between having ERCP in endoscopy before moving to the OR and having both done in the OR, Dr. Wild said.

“The findings of this study are, Number 1, intuitively obvious and easily predicted; and, Number 2, why didn’t I think of that myself?” said discussant Dr. Michael Chang of Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Chang also noted that the study provides an example of how to restructure care organizations. “Grouping practitioners by disease process, as opposed to what board they’re certified by or what department they live in, is thought to be a more patient-centered approach to provide cost-effective care,” he said.

Dr. Chang and others asked how the Geisinger surgeons overcame institutional barriers in creating their care model. “Most institutions are still dependent on the gastroenterologists, and lining up that procedure with another service can be difficult,” Dr. Donald Reed Jr. of Lutheran Medical Group in Fort Wayne, Ind., noted.

Dr. Wild acknowledged at first the pathway encountered some resistance. “But what really started this process was that the endoscopy suite was closed on weekends and all the ERCPs were performed in OR,” he said. “And then we were taking patients the following morning back to the OR to take out their gallbladder. Some of my senior partners questioned why aren’t we doing these at the same time.”

At this point, gastroenterology is “very willing” to embrace ERCP in the OR before gallbladder removal, Dr. Wild said.

Dr. Wild reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE AAST ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Scheduling both ERCP and cholecystectomy on the same day reduces hospital stays and saves money.