User login

Do Clonal Hematopoiesis and Mosaic Chromosomal Alterations Increase Solid Tumor Risk?

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) and mosaic chromosomal alterations (mCAs) are associated with an increased risk for breast cancer, and CHIP is associated with increased mortality in patients with colon cancer, according to the authors of new research.

These findings, drawn from almost 11,000 patients in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, add further evidence that CHIP and mCA drive solid tumor risk, alongside known associations with hematologic malignancies, reported lead author Pinkal Desai, MD, associate professor of medicine and clinical director of molecular aging at Englander Institute for Precision Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City, and colleagues.

How This Study Differs From Others of Breast Cancer Risk Factors

“The independent effect of CHIP and mCA on risk and mortality from solid tumors has not been elucidated due to lack of detailed data on mortality outcomes and risk factors,” the investigators wrote in Cancer, although some previous studies have suggested a link.

In particular, the investigators highlighted a 2022 UK Biobank study, which reported an association between CHIP and lung cancer and a borderline association with breast cancer that did not quite reach statistical significance.

But the UK Biobank study was confined to a UK population, Dr. Desai noted in an interview, and the data were less detailed than those in the present investigation.

“In terms of risk, the part that was lacking in previous studies was a comprehensive assessment of risk factors that increase risk for all these cancers,” Dr. Desai said. “For example, for breast cancer, we had very detailed data on [participants’] Gail risk score, which is known to impact breast cancer risk. We also had mammogram data and colonoscopy data.”

In an accompanying editorial, Koichi Takahashi, MD, PhD , and Nehali Shah, BS, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, pointed out the same UK Biobank findings, then noted that CHIP has also been linked with worse overall survival in unselected cancer patients. Still, they wrote, “the impact of CH on cancer risk and mortality remains controversial due to conflicting data and context‐dependent effects,” necessitating studies like this one by Dr. Desai and colleagues.

How Was the Relationship Between CHIP, MCA, and Solid Tumor Risk Assessed?

To explore possible associations between CHIP, mCA, and solid tumors, the investigators analyzed whole genome sequencing data from 10,866 women in the WHI, a multi-study program that began in 1992 and involved 161,808 women in both observational and clinical trial cohorts.

In 2002, the first big data release from the WHI suggested that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increased breast cancer risk, leading to widespread reduction in HRT use.

More recent reports continue to shape our understanding of these risks, suggesting differences across cancer types. For breast cancer, the WHI data suggested that HRT-associated risk was largely driven by formulations involving progesterone and estrogen, whereas estrogen-only formulations, now more common, are generally considered to present an acceptable risk profile for suitable patients.

The new study accounted for this potential HRT-associated risk, including by adjusting for patients who received HRT, type of HRT received, and duration of HRT received. According to Desai, this approach is commonly used when analyzing data from the WHI, nullifying concerns about the potentially deleterious effects of the hormones used in the study.

“Our question was not ‘does HRT cause cancer?’ ” Dr. Desai said in an interview. “But HRT can be linked to breast cancer risk and has a potential to be a confounder, and hence the above methodology.

“So I can say that the confounding/effect modification that HRT would have contributed to in the relationship between exposure (CH and mCA) and outcome (cancer) is well adjusted for as described above. This is standard in WHI analyses,” she continued.

“Every Women’s Health Initiative analysis that comes out — not just for our study — uses a standard method ... where you account for hormonal therapy,” Dr. Desai added, again noting that many other potential risk factors were considered, enabling a “detailed, robust” analysis.

Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah agreed. “A notable strength of this study is its adjustment for many confounding factors,” they wrote. “The cohort’s well‐annotated data on other known cancer risk factors allowed for a robust assessment of CH’s independent risk.”

How Do Findings Compare With Those of the UK Biobank Study?

CHIP was associated with a 30% increased risk for breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.30; 95% CI, 1.03-1.64; P = .02), strengthening the borderline association reported by the UK Biobank study.

In contrast with the UK Biobank study, CHIP was not associated with lung cancer risk, although this may have been caused by fewer cases of lung cancer and a lack of male patients, Dr. Desai suggested.

“The discrepancy between the studies lies in the risk of lung cancer, although the point estimate in the current study suggested a positive association,” wrote Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah.

As in the UK Biobank study, CHIP was not associated with increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Mortality analysis, however, which was not conducted in the UK Biobank study, offered a new insight: Patients with existing colorectal cancer and CHIP had a significantly higher mortality risk than those without CHIP. Before stage adjustment, risk for mortality among those with colorectal cancer and CHIP was fourfold higher than those without CHIP (HR, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.41-6.62; P < .001). After stage adjustment, CHIP was still associated with a twofold higher mortality risk (HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.32-4.72; P = .004).

The investigators’ first mCA analyses, which employed a cell fraction cutoff greater than 3%, were unfruitful. But raising the cell fraction threshold to 5% in an exploratory analysis showed that autosomal mCA was associated with a 39% increased risk for breast cancer (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.06-1.83; P = .01). No such associations were found between mCA and colorectal or lung cancer, regardless of cell fraction threshold.

The original 3% cell fraction threshold was selected on the basis of previous studies reporting a link between mCA and hematologic malignancies at this cutoff, Dr. Desai said.

She and her colleagues said a higher 5% cutoff might be needed, as they suspected that the link between mCA and solid tumors may not be causal, requiring a higher mutation rate.

Why Do Results Differ Between These Types of Studies?

Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah suggested that one possible limitation of the new study, and an obstacle to comparing results with the UK Biobank study and others like it, goes beyond population heterogeneity; incongruent findings could also be explained by differences in whole genome sequencing (WGS) technique.

“Although WGS allows sensitive detection of mCA through broad genomic coverage, it is less effective at detecting CHIP with low variant allele frequency (VAF) due to its relatively shallow depth (30x),” they wrote. “Consequently, the prevalence of mCA (18.8%) was much higher than that of CHIP (8.3%) in this cohort, contrasting with other studies using deeper sequencing.” As a result, the present study may have underestimated CHIP prevalence because of shallow sequencing depth.

“This inconsistency is a common challenge in CH population studies due to the lack of standardized methodologies and the frequent reliance on preexisting data not originally intended for CH detection,” Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah said.

Even so, despite the “heavily context-dependent” nature of these reported risks, the body of evidence to date now offers a convincing biological rationale linking CH with cancer development and outcomes, they added.

How Do the CHIP- and mCA-associated Risks Differ Between Solid Tumors and Blood Cancers?

“[These solid tumor risks are] not causal in the way CHIP mutations are causal for blood cancers,” Dr. Desai said. “Here we are talking about solid tumor risk, and it’s kind of scattered. It’s not just breast cancer ... there’s also increased colon cancer mortality. So I feel these mutations are doing something different ... they are sort of an added factor.”

Specific mechanisms remain unclear, Dr. Desai said, although she speculated about possible impacts on the inflammatory state or alterations to the tumor microenvironment.

“These are blood cells, right?” Dr. Desai asked. “They’re everywhere, and they’re changing something inherently in these tumors.”

Future research and therapeutic development

Siddhartha Jaiswal, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Pathology at Stanford University in California, whose lab focuses on clonal hematopoiesis, said the causality question is central to future research.

“The key question is, are these mutations acting because they alter the function of blood cells in some way to promote cancer risk, or is it reflective of some sort of shared etiology that’s not causal?” Dr. Jaiswal said in an interview.

Available data support both possibilities.

On one side, “reasonable evidence” supports the noncausal view, Dr. Jaiswal noted, because telomere length is one of the most common genetic risk factors for clonal hematopoiesis and also for solid tumors, suggesting a shared genetic factor. On the other hand, CHIP and mCA could be directly protumorigenic via conferred disturbances of immune cell function.

When asked if both causal and noncausal factors could be at play, Dr. Jaiswal said, “yeah, absolutely.”

The presence of a causal association could be promising from a therapeutic standpoint.

“If it turns out that this association is driven by a direct causal effect of the mutations, perhaps related to immune cell function or dysfunction, then targeting that dysfunction could be a therapeutic path to improve outcomes in people, and there’s a lot of interest in this,” Dr. Jaiswal said. He went on to explain how a trial exploring this approach via interleukin-8 inhibition in lung cancer fell short.

Yet earlier intervention may still hold promise, according to experts.

“[This study] provokes the hypothesis that CH‐targeted interventions could potentially reduce cancer risk in the future,” Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah said in their editorial.

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The investigators disclosed relationships with Eli Lilly, AbbVie, Celgene, and others. Dr. Jaiswal reported stock equity in a company that has an interest in clonal hematopoiesis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) and mosaic chromosomal alterations (mCAs) are associated with an increased risk for breast cancer, and CHIP is associated with increased mortality in patients with colon cancer, according to the authors of new research.

These findings, drawn from almost 11,000 patients in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, add further evidence that CHIP and mCA drive solid tumor risk, alongside known associations with hematologic malignancies, reported lead author Pinkal Desai, MD, associate professor of medicine and clinical director of molecular aging at Englander Institute for Precision Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City, and colleagues.

How This Study Differs From Others of Breast Cancer Risk Factors

“The independent effect of CHIP and mCA on risk and mortality from solid tumors has not been elucidated due to lack of detailed data on mortality outcomes and risk factors,” the investigators wrote in Cancer, although some previous studies have suggested a link.

In particular, the investigators highlighted a 2022 UK Biobank study, which reported an association between CHIP and lung cancer and a borderline association with breast cancer that did not quite reach statistical significance.

But the UK Biobank study was confined to a UK population, Dr. Desai noted in an interview, and the data were less detailed than those in the present investigation.

“In terms of risk, the part that was lacking in previous studies was a comprehensive assessment of risk factors that increase risk for all these cancers,” Dr. Desai said. “For example, for breast cancer, we had very detailed data on [participants’] Gail risk score, which is known to impact breast cancer risk. We also had mammogram data and colonoscopy data.”

In an accompanying editorial, Koichi Takahashi, MD, PhD , and Nehali Shah, BS, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, pointed out the same UK Biobank findings, then noted that CHIP has also been linked with worse overall survival in unselected cancer patients. Still, they wrote, “the impact of CH on cancer risk and mortality remains controversial due to conflicting data and context‐dependent effects,” necessitating studies like this one by Dr. Desai and colleagues.

How Was the Relationship Between CHIP, MCA, and Solid Tumor Risk Assessed?

To explore possible associations between CHIP, mCA, and solid tumors, the investigators analyzed whole genome sequencing data from 10,866 women in the WHI, a multi-study program that began in 1992 and involved 161,808 women in both observational and clinical trial cohorts.

In 2002, the first big data release from the WHI suggested that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increased breast cancer risk, leading to widespread reduction in HRT use.

More recent reports continue to shape our understanding of these risks, suggesting differences across cancer types. For breast cancer, the WHI data suggested that HRT-associated risk was largely driven by formulations involving progesterone and estrogen, whereas estrogen-only formulations, now more common, are generally considered to present an acceptable risk profile for suitable patients.

The new study accounted for this potential HRT-associated risk, including by adjusting for patients who received HRT, type of HRT received, and duration of HRT received. According to Desai, this approach is commonly used when analyzing data from the WHI, nullifying concerns about the potentially deleterious effects of the hormones used in the study.

“Our question was not ‘does HRT cause cancer?’ ” Dr. Desai said in an interview. “But HRT can be linked to breast cancer risk and has a potential to be a confounder, and hence the above methodology.

“So I can say that the confounding/effect modification that HRT would have contributed to in the relationship between exposure (CH and mCA) and outcome (cancer) is well adjusted for as described above. This is standard in WHI analyses,” she continued.

“Every Women’s Health Initiative analysis that comes out — not just for our study — uses a standard method ... where you account for hormonal therapy,” Dr. Desai added, again noting that many other potential risk factors were considered, enabling a “detailed, robust” analysis.

Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah agreed. “A notable strength of this study is its adjustment for many confounding factors,” they wrote. “The cohort’s well‐annotated data on other known cancer risk factors allowed for a robust assessment of CH’s independent risk.”

How Do Findings Compare With Those of the UK Biobank Study?

CHIP was associated with a 30% increased risk for breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.30; 95% CI, 1.03-1.64; P = .02), strengthening the borderline association reported by the UK Biobank study.

In contrast with the UK Biobank study, CHIP was not associated with lung cancer risk, although this may have been caused by fewer cases of lung cancer and a lack of male patients, Dr. Desai suggested.

“The discrepancy between the studies lies in the risk of lung cancer, although the point estimate in the current study suggested a positive association,” wrote Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah.

As in the UK Biobank study, CHIP was not associated with increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Mortality analysis, however, which was not conducted in the UK Biobank study, offered a new insight: Patients with existing colorectal cancer and CHIP had a significantly higher mortality risk than those without CHIP. Before stage adjustment, risk for mortality among those with colorectal cancer and CHIP was fourfold higher than those without CHIP (HR, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.41-6.62; P < .001). After stage adjustment, CHIP was still associated with a twofold higher mortality risk (HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.32-4.72; P = .004).

The investigators’ first mCA analyses, which employed a cell fraction cutoff greater than 3%, were unfruitful. But raising the cell fraction threshold to 5% in an exploratory analysis showed that autosomal mCA was associated with a 39% increased risk for breast cancer (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.06-1.83; P = .01). No such associations were found between mCA and colorectal or lung cancer, regardless of cell fraction threshold.

The original 3% cell fraction threshold was selected on the basis of previous studies reporting a link between mCA and hematologic malignancies at this cutoff, Dr. Desai said.

She and her colleagues said a higher 5% cutoff might be needed, as they suspected that the link between mCA and solid tumors may not be causal, requiring a higher mutation rate.

Why Do Results Differ Between These Types of Studies?

Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah suggested that one possible limitation of the new study, and an obstacle to comparing results with the UK Biobank study and others like it, goes beyond population heterogeneity; incongruent findings could also be explained by differences in whole genome sequencing (WGS) technique.

“Although WGS allows sensitive detection of mCA through broad genomic coverage, it is less effective at detecting CHIP with low variant allele frequency (VAF) due to its relatively shallow depth (30x),” they wrote. “Consequently, the prevalence of mCA (18.8%) was much higher than that of CHIP (8.3%) in this cohort, contrasting with other studies using deeper sequencing.” As a result, the present study may have underestimated CHIP prevalence because of shallow sequencing depth.

“This inconsistency is a common challenge in CH population studies due to the lack of standardized methodologies and the frequent reliance on preexisting data not originally intended for CH detection,” Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah said.

Even so, despite the “heavily context-dependent” nature of these reported risks, the body of evidence to date now offers a convincing biological rationale linking CH with cancer development and outcomes, they added.

How Do the CHIP- and mCA-associated Risks Differ Between Solid Tumors and Blood Cancers?

“[These solid tumor risks are] not causal in the way CHIP mutations are causal for blood cancers,” Dr. Desai said. “Here we are talking about solid tumor risk, and it’s kind of scattered. It’s not just breast cancer ... there’s also increased colon cancer mortality. So I feel these mutations are doing something different ... they are sort of an added factor.”

Specific mechanisms remain unclear, Dr. Desai said, although she speculated about possible impacts on the inflammatory state or alterations to the tumor microenvironment.

“These are blood cells, right?” Dr. Desai asked. “They’re everywhere, and they’re changing something inherently in these tumors.”

Future research and therapeutic development

Siddhartha Jaiswal, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Pathology at Stanford University in California, whose lab focuses on clonal hematopoiesis, said the causality question is central to future research.

“The key question is, are these mutations acting because they alter the function of blood cells in some way to promote cancer risk, or is it reflective of some sort of shared etiology that’s not causal?” Dr. Jaiswal said in an interview.

Available data support both possibilities.

On one side, “reasonable evidence” supports the noncausal view, Dr. Jaiswal noted, because telomere length is one of the most common genetic risk factors for clonal hematopoiesis and also for solid tumors, suggesting a shared genetic factor. On the other hand, CHIP and mCA could be directly protumorigenic via conferred disturbances of immune cell function.

When asked if both causal and noncausal factors could be at play, Dr. Jaiswal said, “yeah, absolutely.”

The presence of a causal association could be promising from a therapeutic standpoint.

“If it turns out that this association is driven by a direct causal effect of the mutations, perhaps related to immune cell function or dysfunction, then targeting that dysfunction could be a therapeutic path to improve outcomes in people, and there’s a lot of interest in this,” Dr. Jaiswal said. He went on to explain how a trial exploring this approach via interleukin-8 inhibition in lung cancer fell short.

Yet earlier intervention may still hold promise, according to experts.

“[This study] provokes the hypothesis that CH‐targeted interventions could potentially reduce cancer risk in the future,” Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah said in their editorial.

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The investigators disclosed relationships with Eli Lilly, AbbVie, Celgene, and others. Dr. Jaiswal reported stock equity in a company that has an interest in clonal hematopoiesis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) and mosaic chromosomal alterations (mCAs) are associated with an increased risk for breast cancer, and CHIP is associated with increased mortality in patients with colon cancer, according to the authors of new research.

These findings, drawn from almost 11,000 patients in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, add further evidence that CHIP and mCA drive solid tumor risk, alongside known associations with hematologic malignancies, reported lead author Pinkal Desai, MD, associate professor of medicine and clinical director of molecular aging at Englander Institute for Precision Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City, and colleagues.

How This Study Differs From Others of Breast Cancer Risk Factors

“The independent effect of CHIP and mCA on risk and mortality from solid tumors has not been elucidated due to lack of detailed data on mortality outcomes and risk factors,” the investigators wrote in Cancer, although some previous studies have suggested a link.

In particular, the investigators highlighted a 2022 UK Biobank study, which reported an association between CHIP and lung cancer and a borderline association with breast cancer that did not quite reach statistical significance.

But the UK Biobank study was confined to a UK population, Dr. Desai noted in an interview, and the data were less detailed than those in the present investigation.

“In terms of risk, the part that was lacking in previous studies was a comprehensive assessment of risk factors that increase risk for all these cancers,” Dr. Desai said. “For example, for breast cancer, we had very detailed data on [participants’] Gail risk score, which is known to impact breast cancer risk. We also had mammogram data and colonoscopy data.”

In an accompanying editorial, Koichi Takahashi, MD, PhD , and Nehali Shah, BS, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, pointed out the same UK Biobank findings, then noted that CHIP has also been linked with worse overall survival in unselected cancer patients. Still, they wrote, “the impact of CH on cancer risk and mortality remains controversial due to conflicting data and context‐dependent effects,” necessitating studies like this one by Dr. Desai and colleagues.

How Was the Relationship Between CHIP, MCA, and Solid Tumor Risk Assessed?

To explore possible associations between CHIP, mCA, and solid tumors, the investigators analyzed whole genome sequencing data from 10,866 women in the WHI, a multi-study program that began in 1992 and involved 161,808 women in both observational and clinical trial cohorts.

In 2002, the first big data release from the WHI suggested that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increased breast cancer risk, leading to widespread reduction in HRT use.

More recent reports continue to shape our understanding of these risks, suggesting differences across cancer types. For breast cancer, the WHI data suggested that HRT-associated risk was largely driven by formulations involving progesterone and estrogen, whereas estrogen-only formulations, now more common, are generally considered to present an acceptable risk profile for suitable patients.

The new study accounted for this potential HRT-associated risk, including by adjusting for patients who received HRT, type of HRT received, and duration of HRT received. According to Desai, this approach is commonly used when analyzing data from the WHI, nullifying concerns about the potentially deleterious effects of the hormones used in the study.

“Our question was not ‘does HRT cause cancer?’ ” Dr. Desai said in an interview. “But HRT can be linked to breast cancer risk and has a potential to be a confounder, and hence the above methodology.

“So I can say that the confounding/effect modification that HRT would have contributed to in the relationship between exposure (CH and mCA) and outcome (cancer) is well adjusted for as described above. This is standard in WHI analyses,” she continued.

“Every Women’s Health Initiative analysis that comes out — not just for our study — uses a standard method ... where you account for hormonal therapy,” Dr. Desai added, again noting that many other potential risk factors were considered, enabling a “detailed, robust” analysis.

Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah agreed. “A notable strength of this study is its adjustment for many confounding factors,” they wrote. “The cohort’s well‐annotated data on other known cancer risk factors allowed for a robust assessment of CH’s independent risk.”

How Do Findings Compare With Those of the UK Biobank Study?

CHIP was associated with a 30% increased risk for breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.30; 95% CI, 1.03-1.64; P = .02), strengthening the borderline association reported by the UK Biobank study.

In contrast with the UK Biobank study, CHIP was not associated with lung cancer risk, although this may have been caused by fewer cases of lung cancer and a lack of male patients, Dr. Desai suggested.

“The discrepancy between the studies lies in the risk of lung cancer, although the point estimate in the current study suggested a positive association,” wrote Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah.

As in the UK Biobank study, CHIP was not associated with increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Mortality analysis, however, which was not conducted in the UK Biobank study, offered a new insight: Patients with existing colorectal cancer and CHIP had a significantly higher mortality risk than those without CHIP. Before stage adjustment, risk for mortality among those with colorectal cancer and CHIP was fourfold higher than those without CHIP (HR, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.41-6.62; P < .001). After stage adjustment, CHIP was still associated with a twofold higher mortality risk (HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.32-4.72; P = .004).

The investigators’ first mCA analyses, which employed a cell fraction cutoff greater than 3%, were unfruitful. But raising the cell fraction threshold to 5% in an exploratory analysis showed that autosomal mCA was associated with a 39% increased risk for breast cancer (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.06-1.83; P = .01). No such associations were found between mCA and colorectal or lung cancer, regardless of cell fraction threshold.

The original 3% cell fraction threshold was selected on the basis of previous studies reporting a link between mCA and hematologic malignancies at this cutoff, Dr. Desai said.

She and her colleagues said a higher 5% cutoff might be needed, as they suspected that the link between mCA and solid tumors may not be causal, requiring a higher mutation rate.

Why Do Results Differ Between These Types of Studies?

Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah suggested that one possible limitation of the new study, and an obstacle to comparing results with the UK Biobank study and others like it, goes beyond population heterogeneity; incongruent findings could also be explained by differences in whole genome sequencing (WGS) technique.

“Although WGS allows sensitive detection of mCA through broad genomic coverage, it is less effective at detecting CHIP with low variant allele frequency (VAF) due to its relatively shallow depth (30x),” they wrote. “Consequently, the prevalence of mCA (18.8%) was much higher than that of CHIP (8.3%) in this cohort, contrasting with other studies using deeper sequencing.” As a result, the present study may have underestimated CHIP prevalence because of shallow sequencing depth.

“This inconsistency is a common challenge in CH population studies due to the lack of standardized methodologies and the frequent reliance on preexisting data not originally intended for CH detection,” Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah said.

Even so, despite the “heavily context-dependent” nature of these reported risks, the body of evidence to date now offers a convincing biological rationale linking CH with cancer development and outcomes, they added.

How Do the CHIP- and mCA-associated Risks Differ Between Solid Tumors and Blood Cancers?

“[These solid tumor risks are] not causal in the way CHIP mutations are causal for blood cancers,” Dr. Desai said. “Here we are talking about solid tumor risk, and it’s kind of scattered. It’s not just breast cancer ... there’s also increased colon cancer mortality. So I feel these mutations are doing something different ... they are sort of an added factor.”

Specific mechanisms remain unclear, Dr. Desai said, although she speculated about possible impacts on the inflammatory state or alterations to the tumor microenvironment.

“These are blood cells, right?” Dr. Desai asked. “They’re everywhere, and they’re changing something inherently in these tumors.”

Future research and therapeutic development

Siddhartha Jaiswal, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Pathology at Stanford University in California, whose lab focuses on clonal hematopoiesis, said the causality question is central to future research.

“The key question is, are these mutations acting because they alter the function of blood cells in some way to promote cancer risk, or is it reflective of some sort of shared etiology that’s not causal?” Dr. Jaiswal said in an interview.

Available data support both possibilities.

On one side, “reasonable evidence” supports the noncausal view, Dr. Jaiswal noted, because telomere length is one of the most common genetic risk factors for clonal hematopoiesis and also for solid tumors, suggesting a shared genetic factor. On the other hand, CHIP and mCA could be directly protumorigenic via conferred disturbances of immune cell function.

When asked if both causal and noncausal factors could be at play, Dr. Jaiswal said, “yeah, absolutely.”

The presence of a causal association could be promising from a therapeutic standpoint.

“If it turns out that this association is driven by a direct causal effect of the mutations, perhaps related to immune cell function or dysfunction, then targeting that dysfunction could be a therapeutic path to improve outcomes in people, and there’s a lot of interest in this,” Dr. Jaiswal said. He went on to explain how a trial exploring this approach via interleukin-8 inhibition in lung cancer fell short.

Yet earlier intervention may still hold promise, according to experts.

“[This study] provokes the hypothesis that CH‐targeted interventions could potentially reduce cancer risk in the future,” Dr. Takahashi and Ms. Shah said in their editorial.

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The investigators disclosed relationships with Eli Lilly, AbbVie, Celgene, and others. Dr. Jaiswal reported stock equity in a company that has an interest in clonal hematopoiesis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANCER

Cancer Cases, Deaths in Men Predicted to Surge by 2050

TOPLINE:

— with substantial disparities in cancer cases and deaths by age and region of the world, a recent analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overall, men have higher cancer incidence and mortality rates, which can be largely attributed to a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational carcinogens, as well as the underuse of cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services.

- To assess the burden of cancer in men of different ages and from different regions of the world, researchers analyzed data from the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), which provides national-level estimates for cancer cases and deaths.

- Study outcomes included the incidence, mortality, and prevalence of cancer among men in 2022, along with projections for 2050. Estimates were stratified by several factors, including age; region; and Human Development Index (HDI), a composite score for health, education, and standard of living.

- Researchers also calculated mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) for various cancer types, where higher values indicate worse survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers reported an estimated 10.3 million cancer cases and 5.4 million deaths globally in 2022, with almost two thirds of cases and deaths occurring in men aged 65 years or older.

- By 2050, cancer cases and deaths were projected to increase by 84.3% (to 19 million) and 93.2% (to 10.5 million), respectively. The increase from 2022 to 2050 was more than twofold higher for older men and countries with low and medium HDI.

- In 2022, the estimated global cancer MIR among men was nearly 55%, with variations by cancer types, age, and HDI. The MIR was lowest for thyroid cancer (7.6%) and highest for pancreatic cancer (90.9%); among World Health Organization regions, Africa had the highest MIR (72.6%), while the Americas had the lowest MIR (39.1%); countries with the lowest HDI had the highest MIR (73.5% vs 41.1% for very high HDI).

- Lung cancer was the leading cause for cases and deaths in 2022 and was projected to remain the leading cause in 2050.

IN PRACTICE:

“Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among men were observed across age groups, countries/territories, and HDI in 2022, with these disparities projected to widen further by 2050,” according to the authors, who called for efforts to “reduce disparities in cancer burden and ensure equity in cancer prevention and care for men across the globe.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu, PhD, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, was published online in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may be influenced by the quality of GLOBOCAN data. Interpretation should be cautious as MIR may not fully reflect cancer outcome inequalities. The study did not include other measures of cancer burden, such as years of life lost or years lived with disability, which were unavailable from the data source.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not disclose any funding information. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

— with substantial disparities in cancer cases and deaths by age and region of the world, a recent analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overall, men have higher cancer incidence and mortality rates, which can be largely attributed to a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational carcinogens, as well as the underuse of cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services.

- To assess the burden of cancer in men of different ages and from different regions of the world, researchers analyzed data from the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), which provides national-level estimates for cancer cases and deaths.

- Study outcomes included the incidence, mortality, and prevalence of cancer among men in 2022, along with projections for 2050. Estimates were stratified by several factors, including age; region; and Human Development Index (HDI), a composite score for health, education, and standard of living.

- Researchers also calculated mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) for various cancer types, where higher values indicate worse survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers reported an estimated 10.3 million cancer cases and 5.4 million deaths globally in 2022, with almost two thirds of cases and deaths occurring in men aged 65 years or older.

- By 2050, cancer cases and deaths were projected to increase by 84.3% (to 19 million) and 93.2% (to 10.5 million), respectively. The increase from 2022 to 2050 was more than twofold higher for older men and countries with low and medium HDI.

- In 2022, the estimated global cancer MIR among men was nearly 55%, with variations by cancer types, age, and HDI. The MIR was lowest for thyroid cancer (7.6%) and highest for pancreatic cancer (90.9%); among World Health Organization regions, Africa had the highest MIR (72.6%), while the Americas had the lowest MIR (39.1%); countries with the lowest HDI had the highest MIR (73.5% vs 41.1% for very high HDI).

- Lung cancer was the leading cause for cases and deaths in 2022 and was projected to remain the leading cause in 2050.

IN PRACTICE:

“Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among men were observed across age groups, countries/territories, and HDI in 2022, with these disparities projected to widen further by 2050,” according to the authors, who called for efforts to “reduce disparities in cancer burden and ensure equity in cancer prevention and care for men across the globe.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu, PhD, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, was published online in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may be influenced by the quality of GLOBOCAN data. Interpretation should be cautious as MIR may not fully reflect cancer outcome inequalities. The study did not include other measures of cancer burden, such as years of life lost or years lived with disability, which were unavailable from the data source.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not disclose any funding information. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

— with substantial disparities in cancer cases and deaths by age and region of the world, a recent analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overall, men have higher cancer incidence and mortality rates, which can be largely attributed to a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational carcinogens, as well as the underuse of cancer prevention, screening, and treatment services.

- To assess the burden of cancer in men of different ages and from different regions of the world, researchers analyzed data from the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), which provides national-level estimates for cancer cases and deaths.

- Study outcomes included the incidence, mortality, and prevalence of cancer among men in 2022, along with projections for 2050. Estimates were stratified by several factors, including age; region; and Human Development Index (HDI), a composite score for health, education, and standard of living.

- Researchers also calculated mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) for various cancer types, where higher values indicate worse survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers reported an estimated 10.3 million cancer cases and 5.4 million deaths globally in 2022, with almost two thirds of cases and deaths occurring in men aged 65 years or older.

- By 2050, cancer cases and deaths were projected to increase by 84.3% (to 19 million) and 93.2% (to 10.5 million), respectively. The increase from 2022 to 2050 was more than twofold higher for older men and countries with low and medium HDI.

- In 2022, the estimated global cancer MIR among men was nearly 55%, with variations by cancer types, age, and HDI. The MIR was lowest for thyroid cancer (7.6%) and highest for pancreatic cancer (90.9%); among World Health Organization regions, Africa had the highest MIR (72.6%), while the Americas had the lowest MIR (39.1%); countries with the lowest HDI had the highest MIR (73.5% vs 41.1% for very high HDI).

- Lung cancer was the leading cause for cases and deaths in 2022 and was projected to remain the leading cause in 2050.

IN PRACTICE:

“Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among men were observed across age groups, countries/territories, and HDI in 2022, with these disparities projected to widen further by 2050,” according to the authors, who called for efforts to “reduce disparities in cancer burden and ensure equity in cancer prevention and care for men across the globe.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu, PhD, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, was published online in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may be influenced by the quality of GLOBOCAN data. Interpretation should be cautious as MIR may not fully reflect cancer outcome inequalities. The study did not include other measures of cancer burden, such as years of life lost or years lived with disability, which were unavailable from the data source.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not disclose any funding information. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

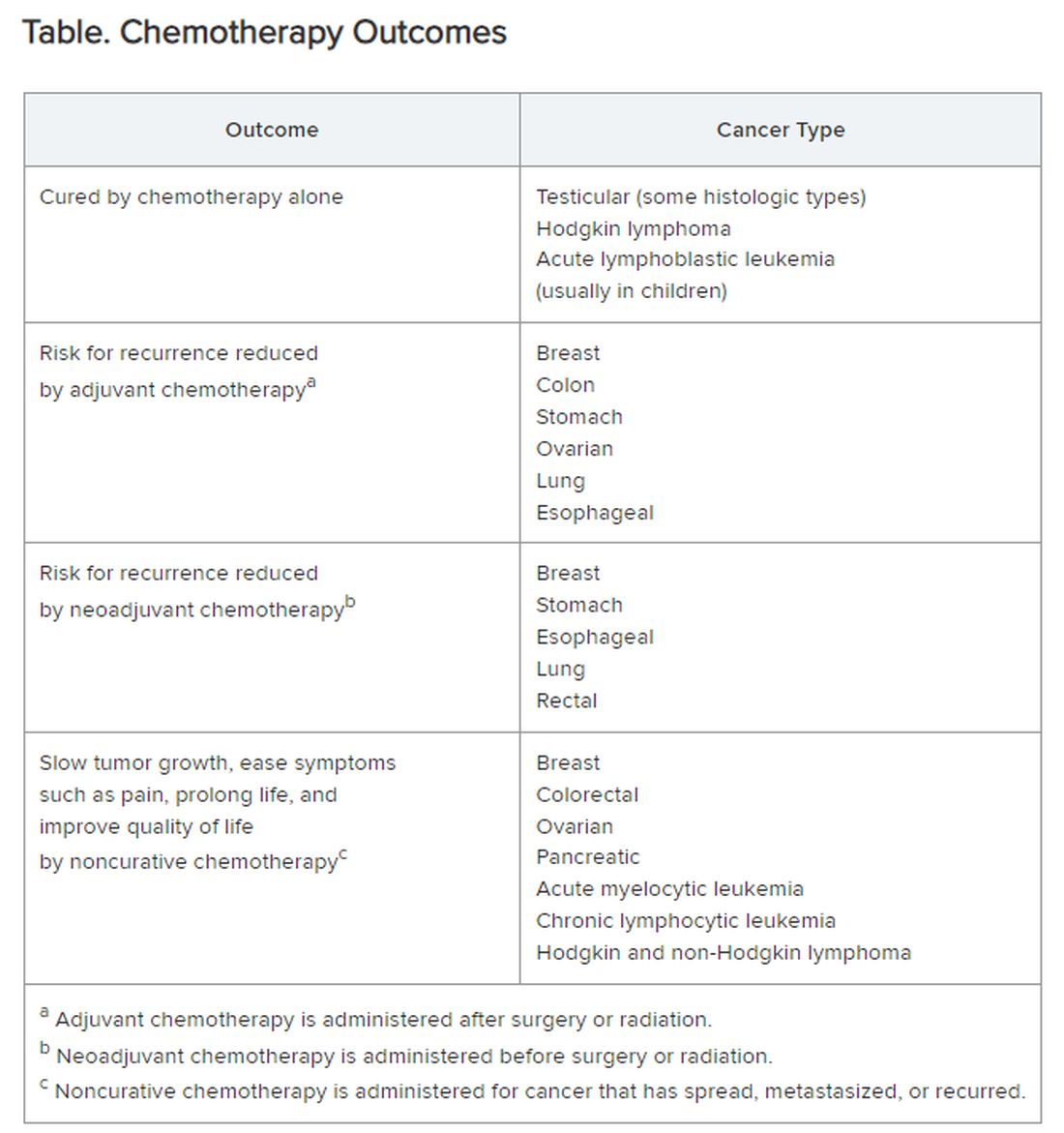

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When Childhood Cancer Survivors Face Sexual Challenges

Childhood cancers represent a diverse group of neoplasms, and thanks to advances in treatment, survival rates have improved significantly. Today, more than 80%-85% of children diagnosed with cancer in developed countries survive into adulthood.

This increase in survival has brought new challenges, however. Compared with the general population, childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at a notably higher risk for early mortality, developing secondary cancers, and experiencing various long-term clinical and psychosocial issues stemming from their disease or its treatment.

Long-term follow-up care for CCS is a complex and evolving field. Despite ongoing efforts to establish global and national guidelines, current evidence indicates that the care and management of these patients remain suboptimal.

The disruptions caused by cancer and its treatment can interfere with normal physiological and psychological development, leading to issues with sexual function. This aspect of health is critical as it influences not just physical well-being but also psychosocial, developmental, and emotional health.

Characteristics and Mechanisms

Sexual functioning encompasses the physiological and psychological aspects of sexual behavior, including desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, and overall satisfaction.

As CCS reach adolescence or adulthood, they often face sexual and reproductive issues, particularly as they enter romantic relationships.

Sexual functioning is a complex process that relies on the interaction of various factors, including physiological health, psychosexual development, romantic relationships, body image, and desire.

Despite its importance, the impact of childhood cancer on sexual function is often overlooked, even though cancer and its treatments can have lifelong effects.

Sexual Function in CCS

A recent review aimed to summarize the existing research on sexual function among CCS, highlighting assessment tools, key stages of psychosexual development, common sexual problems, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.

The review study included 22 studies published between 2000 and 2022, comprising two qualitative, six cohort, and 14 cross-sectional studies.

Most CCS reached all key stages of psychosexual development at an average age of 29.8 years. Although some milestones were achieved later than is typical, many survivors felt they reached these stages at the appropriate time. Sexual initiation was less common among those who had undergone intensive neurotoxic treatments, such as those diagnosed with brain tumors or leukemia in childhood.

In a cross-sectional study of CCS aged 17-39 years, about one third had never engaged in sexual intercourse, 41.4% reported never experiencing sexual attraction, 44.8% were dissatisfied with their sex lives, and many rarely felt sexually attractive to others. Another study found that common issues among CCS included a lack of interest in sex (30%), difficulty enjoying sex (24%), and difficulty becoming aroused (23%). However, comparing and analyzing these problems was challenging due to the lack of standardized assessment criteria.

The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among CCS ranged from 12.3% to 46.5%. For males, the prevalence ranged from 12.3% to 54.0%, while for females, it ranged from 19.9% to 57.0%.

Factors Influencing Sexual Function

The review identified the following four categories of factors influencing sexual function in CCS: Demographic, treatment-related, psychological, and physiological.

Demographic factors: Gender, age, education level, relationship status, income level, and race all play roles in sexual function.

Female survivors reported more severe sexual dysfunction and poorer sexual health than did male survivors. Age at cancer diagnosis, age at evaluation, and the time since diagnosis were closely linked to sexual experiences. Patients diagnosed with cancer during childhood tended to report better sexual function than those diagnosed during adolescence.

Treatment-related factors: The type of cancer and intensity of treatment, along with surgical history, were significant factors. Surgeries involving the spinal cord or sympathetic nerves, as well as a history of prostate or pelvic surgery, were strongly associated with erectile dysfunction in men. In women, pelvic surgeries and treatments to the pelvic area were commonly linked to sexual dysfunction.

The association between treatment intensity and sexual function was noted across several studies, although the results were not always consistent. For example, testicular radiation above 10 Gy was positively correlated with sexual dysfunction. Women who underwent more intensive treatments were more likely to report issues in multiple areas of sexual function, while men in this group were less likely to have children.

Among female CCS, certain types of cancer, such as germ cell tumors, renal tumors, and leukemia, present a higher risk for sexual dysfunction. Women who had CNS tumors in childhood frequently reported problems like difficulty in sexual arousal, low sexual satisfaction, infrequent sexual activity, and fewer sexual partners, compared with survivors of other cancers. Survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and those who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) also showed varying degrees of impaired sexual function, compared with the general population. The HSCT group showed significant testicular damage, including reduced testicular volumes, low testosterone levels, and low sperm counts.

Psychological factors: These factors, such as emotional distress, play a significant role in sexual dysfunction among CCS. Symptoms like anxiety, nervousness during sexual activity, and depression are commonly reported by those with sexual dysfunction. The connection between body image and sexual function is complex. Many CCS with sexual dysfunction express concern about how others, particularly their partners, perceived their altered body image due to cancer and its treatment.

Physiological factors: In male CCS, low serum testosterone levels and low lean muscle mass are linked to an increased risk for sexual dysfunction. Treatments involving alkylating agents or testicular radiation, and surgery or radiotherapy targeting the genitourinary organs or the hypothalamic-pituitary region, can lead to various physiological and endocrine disorders, contributing to sexual dysfunction. Despite these risks, there is a lack of research evaluating sexual function through the lens of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and neuroendocrine pathways.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood cancers represent a diverse group of neoplasms, and thanks to advances in treatment, survival rates have improved significantly. Today, more than 80%-85% of children diagnosed with cancer in developed countries survive into adulthood.

This increase in survival has brought new challenges, however. Compared with the general population, childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at a notably higher risk for early mortality, developing secondary cancers, and experiencing various long-term clinical and psychosocial issues stemming from their disease or its treatment.

Long-term follow-up care for CCS is a complex and evolving field. Despite ongoing efforts to establish global and national guidelines, current evidence indicates that the care and management of these patients remain suboptimal.

The disruptions caused by cancer and its treatment can interfere with normal physiological and psychological development, leading to issues with sexual function. This aspect of health is critical as it influences not just physical well-being but also psychosocial, developmental, and emotional health.

Characteristics and Mechanisms

Sexual functioning encompasses the physiological and psychological aspects of sexual behavior, including desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, and overall satisfaction.

As CCS reach adolescence or adulthood, they often face sexual and reproductive issues, particularly as they enter romantic relationships.

Sexual functioning is a complex process that relies on the interaction of various factors, including physiological health, psychosexual development, romantic relationships, body image, and desire.

Despite its importance, the impact of childhood cancer on sexual function is often overlooked, even though cancer and its treatments can have lifelong effects.

Sexual Function in CCS

A recent review aimed to summarize the existing research on sexual function among CCS, highlighting assessment tools, key stages of psychosexual development, common sexual problems, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.

The review study included 22 studies published between 2000 and 2022, comprising two qualitative, six cohort, and 14 cross-sectional studies.