User login

‘Profound human toll’ in excess deaths from COVID-19 calculated in two studies

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in LGBTQ Patients: The Need for Dermatologists on the Front Lines

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the United States. It is the causative agent of genital warts, as well as cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, vaginal, and some head and neck cancers.1 Development of the HPV vaccine and its introduction into the scheduled vaccine series recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) represented a major public health milestone. The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for all children beginning at 11 or 12 years of age, even as early as 9 years, regardless of gender identity or sexuality. As of late 2016, the 9-valent formulation (Gardasil 9 [Merck]) is the only HPV vaccine distributed in the United States, and the vaccination schedule depends specifically on age. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC revised its recommendations in 2019 to include “shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination . . . for some adults aged 27 through 45 years.”2 This change in policy has notable implications for sexual and gender minority populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) patients, especially in the context of dermatologic care. Herein, we discuss HPV-related conditions for LGBTQ patients, barriers to vaccine administration, and the role of dermatologists in promoting an increased vaccination rate in the LGBTQ community.

HPV-Related Conditions

A 2019 review of dermatologic care for LGBTQ patients identified many specific health disparities of HPV.3 Specifically, men who have sex with men (MSM) are more likely than heterosexual men to have oral, anal, and penile HPV infections, including high-risk HPV types.3 From 2011 to 2014, 18% and 13% of MSM had oral HPV infection and high-risk oral HPV infection, respectively, compared to only 11% and 7%, respectively, of men who reported never having had a same-sex sexual partner.4

Similarly, despite the CDC’s position that patients with perianal warts might benefit from digital anal examination or referral for standard or high-resolution anoscopy to detect intra-anal warts, improvements in morbidity have not yet been realized. In 2017, anal cancer incidence was 45.9 cases for every 100,000 person-years among human immunodeficiency (HIV)–positive MSM and 5.1 cases for every 100,000 person-years among HIV-negative MSM vs only 1.5 cases for every 100,000 person-years among men in the United States overall.3 Yet the CDC states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine anal cancer screening among MSM, even when a patient is HIV positive. Therefore, current screening practices and treatments are insufficient as MSM continue to have a disproportionately higher rate of HPV-associated disease compared to other populations.

Barriers to HPV Vaccine Administration

The HPV vaccination rate among MSM in adolescent populations varies across reports.5-7 Interestingly, a 2016 survey study found that MSM had approximately 2-times greater odds of initiating the HPV vaccine than heterosexual men.8 However, a study specifically sampling young gay and bisexual men (N=428) found that only 13% had received any doses of the HPV vaccine.6

Regardless, HPV vaccination is much less common among all males than it is among all females, and the low rate of vaccination among sexual minority men has a disproportionate impact, given their higher risk for HPV infection.4 Although the HPV vaccination rate increased from 2014 to 2017, the HPV vaccination rate in MSM overall is less than half of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%.9 A 2018 review determined that HPV vaccination is a cost-effective strategy for preventing anal cancer in MSM10; yet male patients might still view the HPV vaccine as a “women’s issue” and are less likely to be vaccinated if they are not prompted by health care providers. Additionally, HPV vaccination is remarkably less likely in MSM when patients are older, uninsured, of lower socioeconomic status, or have not disclosed their sexual identity to their health care provider.9 Dermatologists should be mindful of these barriers to promote HPV vaccination in MSM before, or soon after, sexual debut.

Other members of the LGBTQ community, such as women who have sex with women, face notable HPV-related health disparities and would benefit from increased vaccination efforts by dermatologists. Adolescent and young adult women who have sex with women are less likely than heterosexual adolescent and young adult women to receive routine Papanicolaou tests and initiate HPV vaccination, despite having a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and a higher risk for HPV exposure.11 A 2015 survey study (N=3253) found that after adjusting for covariates, only 8.5% of lesbians and 33.2% of bisexual women and girls who had heard of the HPV vaccine had initiated vaccination compared to 28.4% of their heterosexual counterparts.11 The HPV vaccine is an effective public health tool for the prevention of cervical cancer in these populations. A study of women aged 15 to 19 years in the HPV vaccination era (2007-2014) found significant (P<.05) observed population-level decreases in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence across all grades.12

Transgender women also face a high rate of HPV infection, HIV infection, and other structural and financial disparities, such as low insurance coverage, that can limit their access to vaccination. Transgender men have a higher rate of HPV infection than cisgender men, and those with female internal reproductive organs are less likely to receive routine Papanicolaou tests. A 2018 survey study found that approximately one-third of transgender men and women reported initiating the HPV vaccination series,13 but further investigation is required to make balanced comparisons to cisgender patients.

The Role of the Dermatologist

Collectively, these disparities emphasize the need for increased involvement by dermatologists in HPV vaccination efforts for all LGBTQ patients. Adult patients may have concerns about ties of the HPV vaccine to drug manufacturers and the general safety of vaccination. For pediatric patients, parents/guardians also may be concerned about an assumed but not evidence-based increase in sexual promiscuity following HPV vaccination.14 These topics can be challenging to discuss, but dermatologists have the duty to be proactive and initiate conversation about HPV vaccination, as opposed to waiting for patients to express interest. Dermatologists should stress the safety of the vaccine as well as its potential to protect against multiple, even life-threatening diseases. Providers also can explain that the ACIP recommends catch-up vaccination for all individuals through 26 years of age, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

With the ACIP having recently expanded the appropriate age range for HPV vaccination, we encourage dermatologists to engage in education and shared decision-making to ensure that adult patients with specific risk factors receive the HPV vaccine. Because the expanded ACIP recommendations are aimed at vaccination before HPV exposure, vaccination might not be appropriate for all LGBTQ patients. However, eliciting a sexual history with routine patient intake forms or during the clinical encounter ensures equal access to the HPV vaccine.

Greater awareness of HPV-related disparities and barriers to vaccination in LGBTQ populations has the potential to notably decrease HPV-associated mortality and morbidity. Increased involvement by dermatologists contributes to the efforts of other specialties in universal HPV vaccination, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity—ideally in younger age groups, such that patients receive the vaccine prior to coitarche.

There are many ways that dermatologists can advocate for HPV vaccination. Those in a multispecialty or academic practice can readily refer patients to an associated internist, primary care physician, or vaccination clinic in the same building or institution. Dermatologists in private practice might be able to administer the HPV vaccine themselves or can advocate for patients to receive the vaccine at a local facility of the Department of Health or at a nonprofit organization, such as a Planned Parenthood center. Although pediatricians and family physicians remain front-line providers of these services, dermatologists represent an additional member of a patient’s care team, capable of advocating for this important intervention.

- Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40:80-85.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Sonawane K, Suk R, Chiao EY, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection: differences in prevalence between sexes and concordance with genital human papillomavirus infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:714-724.

- Kosche C, Mansh M, Luskus M, et al. Dermatologic care of sexual and gender minority/LGBTQIA youth, part 2: recognition and management of the unique dermatologic needs of SGM adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;35:587-593.

- Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Katz ML, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult gay and bisexual men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:96-102.

- Charlton BM, Reisner SL, Ag

énor M, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination in a longitudinal cohort of U.S. males and females. LGBT Health. 2017;4:202-209. - Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination initiation and completion among young adult US women and men. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:1187-1196.

- Loretan C, Chamberlain AT, Sanchez T, et al. Trends and characteristics associated with human papillomavirus vaccination uptake among men who have sex with men in the United States, 2014-2017. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:465-473.

- Setiawan D, Wondimu A, Ong K, et al. Cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination for men who have sex with men; reviewing the available evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:929-939.

- Agénor M, Peitzmeier S, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in awareness and initiation of the human papillomavirus vaccine among U.S. women and girls: a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:99-106.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:833-837.

- McRee A-L, Gower AL, Reiter PL. Preventive healthcare services use among transgender young adults. Int J Transgend. 2018;19:417-423.

- Trinidad J. Policy focus: promoting human papilloma virus vaccine to prevent genital warts and cancer. Boston, MA: The Fenway Institute; 2012. https://fenwayhealth.org/documents/the-fenway-institute/policy-briefs/PolicyFocus_HPV_v4_10.09.12.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the United States. It is the causative agent of genital warts, as well as cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, vaginal, and some head and neck cancers.1 Development of the HPV vaccine and its introduction into the scheduled vaccine series recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) represented a major public health milestone. The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for all children beginning at 11 or 12 years of age, even as early as 9 years, regardless of gender identity or sexuality. As of late 2016, the 9-valent formulation (Gardasil 9 [Merck]) is the only HPV vaccine distributed in the United States, and the vaccination schedule depends specifically on age. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC revised its recommendations in 2019 to include “shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination . . . for some adults aged 27 through 45 years.”2 This change in policy has notable implications for sexual and gender minority populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) patients, especially in the context of dermatologic care. Herein, we discuss HPV-related conditions for LGBTQ patients, barriers to vaccine administration, and the role of dermatologists in promoting an increased vaccination rate in the LGBTQ community.

HPV-Related Conditions

A 2019 review of dermatologic care for LGBTQ patients identified many specific health disparities of HPV.3 Specifically, men who have sex with men (MSM) are more likely than heterosexual men to have oral, anal, and penile HPV infections, including high-risk HPV types.3 From 2011 to 2014, 18% and 13% of MSM had oral HPV infection and high-risk oral HPV infection, respectively, compared to only 11% and 7%, respectively, of men who reported never having had a same-sex sexual partner.4

Similarly, despite the CDC’s position that patients with perianal warts might benefit from digital anal examination or referral for standard or high-resolution anoscopy to detect intra-anal warts, improvements in morbidity have not yet been realized. In 2017, anal cancer incidence was 45.9 cases for every 100,000 person-years among human immunodeficiency (HIV)–positive MSM and 5.1 cases for every 100,000 person-years among HIV-negative MSM vs only 1.5 cases for every 100,000 person-years among men in the United States overall.3 Yet the CDC states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine anal cancer screening among MSM, even when a patient is HIV positive. Therefore, current screening practices and treatments are insufficient as MSM continue to have a disproportionately higher rate of HPV-associated disease compared to other populations.

Barriers to HPV Vaccine Administration

The HPV vaccination rate among MSM in adolescent populations varies across reports.5-7 Interestingly, a 2016 survey study found that MSM had approximately 2-times greater odds of initiating the HPV vaccine than heterosexual men.8 However, a study specifically sampling young gay and bisexual men (N=428) found that only 13% had received any doses of the HPV vaccine.6

Regardless, HPV vaccination is much less common among all males than it is among all females, and the low rate of vaccination among sexual minority men has a disproportionate impact, given their higher risk for HPV infection.4 Although the HPV vaccination rate increased from 2014 to 2017, the HPV vaccination rate in MSM overall is less than half of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%.9 A 2018 review determined that HPV vaccination is a cost-effective strategy for preventing anal cancer in MSM10; yet male patients might still view the HPV vaccine as a “women’s issue” and are less likely to be vaccinated if they are not prompted by health care providers. Additionally, HPV vaccination is remarkably less likely in MSM when patients are older, uninsured, of lower socioeconomic status, or have not disclosed their sexual identity to their health care provider.9 Dermatologists should be mindful of these barriers to promote HPV vaccination in MSM before, or soon after, sexual debut.

Other members of the LGBTQ community, such as women who have sex with women, face notable HPV-related health disparities and would benefit from increased vaccination efforts by dermatologists. Adolescent and young adult women who have sex with women are less likely than heterosexual adolescent and young adult women to receive routine Papanicolaou tests and initiate HPV vaccination, despite having a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and a higher risk for HPV exposure.11 A 2015 survey study (N=3253) found that after adjusting for covariates, only 8.5% of lesbians and 33.2% of bisexual women and girls who had heard of the HPV vaccine had initiated vaccination compared to 28.4% of their heterosexual counterparts.11 The HPV vaccine is an effective public health tool for the prevention of cervical cancer in these populations. A study of women aged 15 to 19 years in the HPV vaccination era (2007-2014) found significant (P<.05) observed population-level decreases in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence across all grades.12

Transgender women also face a high rate of HPV infection, HIV infection, and other structural and financial disparities, such as low insurance coverage, that can limit their access to vaccination. Transgender men have a higher rate of HPV infection than cisgender men, and those with female internal reproductive organs are less likely to receive routine Papanicolaou tests. A 2018 survey study found that approximately one-third of transgender men and women reported initiating the HPV vaccination series,13 but further investigation is required to make balanced comparisons to cisgender patients.

The Role of the Dermatologist

Collectively, these disparities emphasize the need for increased involvement by dermatologists in HPV vaccination efforts for all LGBTQ patients. Adult patients may have concerns about ties of the HPV vaccine to drug manufacturers and the general safety of vaccination. For pediatric patients, parents/guardians also may be concerned about an assumed but not evidence-based increase in sexual promiscuity following HPV vaccination.14 These topics can be challenging to discuss, but dermatologists have the duty to be proactive and initiate conversation about HPV vaccination, as opposed to waiting for patients to express interest. Dermatologists should stress the safety of the vaccine as well as its potential to protect against multiple, even life-threatening diseases. Providers also can explain that the ACIP recommends catch-up vaccination for all individuals through 26 years of age, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

With the ACIP having recently expanded the appropriate age range for HPV vaccination, we encourage dermatologists to engage in education and shared decision-making to ensure that adult patients with specific risk factors receive the HPV vaccine. Because the expanded ACIP recommendations are aimed at vaccination before HPV exposure, vaccination might not be appropriate for all LGBTQ patients. However, eliciting a sexual history with routine patient intake forms or during the clinical encounter ensures equal access to the HPV vaccine.

Greater awareness of HPV-related disparities and barriers to vaccination in LGBTQ populations has the potential to notably decrease HPV-associated mortality and morbidity. Increased involvement by dermatologists contributes to the efforts of other specialties in universal HPV vaccination, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity—ideally in younger age groups, such that patients receive the vaccine prior to coitarche.

There are many ways that dermatologists can advocate for HPV vaccination. Those in a multispecialty or academic practice can readily refer patients to an associated internist, primary care physician, or vaccination clinic in the same building or institution. Dermatologists in private practice might be able to administer the HPV vaccine themselves or can advocate for patients to receive the vaccine at a local facility of the Department of Health or at a nonprofit organization, such as a Planned Parenthood center. Although pediatricians and family physicians remain front-line providers of these services, dermatologists represent an additional member of a patient’s care team, capable of advocating for this important intervention.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the United States. It is the causative agent of genital warts, as well as cervical, anal, penile, vulvar, vaginal, and some head and neck cancers.1 Development of the HPV vaccine and its introduction into the scheduled vaccine series recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) represented a major public health milestone. The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for all children beginning at 11 or 12 years of age, even as early as 9 years, regardless of gender identity or sexuality. As of late 2016, the 9-valent formulation (Gardasil 9 [Merck]) is the only HPV vaccine distributed in the United States, and the vaccination schedule depends specifically on age. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the CDC revised its recommendations in 2019 to include “shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination . . . for some adults aged 27 through 45 years.”2 This change in policy has notable implications for sexual and gender minority populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) patients, especially in the context of dermatologic care. Herein, we discuss HPV-related conditions for LGBTQ patients, barriers to vaccine administration, and the role of dermatologists in promoting an increased vaccination rate in the LGBTQ community.

HPV-Related Conditions

A 2019 review of dermatologic care for LGBTQ patients identified many specific health disparities of HPV.3 Specifically, men who have sex with men (MSM) are more likely than heterosexual men to have oral, anal, and penile HPV infections, including high-risk HPV types.3 From 2011 to 2014, 18% and 13% of MSM had oral HPV infection and high-risk oral HPV infection, respectively, compared to only 11% and 7%, respectively, of men who reported never having had a same-sex sexual partner.4

Similarly, despite the CDC’s position that patients with perianal warts might benefit from digital anal examination or referral for standard or high-resolution anoscopy to detect intra-anal warts, improvements in morbidity have not yet been realized. In 2017, anal cancer incidence was 45.9 cases for every 100,000 person-years among human immunodeficiency (HIV)–positive MSM and 5.1 cases for every 100,000 person-years among HIV-negative MSM vs only 1.5 cases for every 100,000 person-years among men in the United States overall.3 Yet the CDC states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine anal cancer screening among MSM, even when a patient is HIV positive. Therefore, current screening practices and treatments are insufficient as MSM continue to have a disproportionately higher rate of HPV-associated disease compared to other populations.

Barriers to HPV Vaccine Administration

The HPV vaccination rate among MSM in adolescent populations varies across reports.5-7 Interestingly, a 2016 survey study found that MSM had approximately 2-times greater odds of initiating the HPV vaccine than heterosexual men.8 However, a study specifically sampling young gay and bisexual men (N=428) found that only 13% had received any doses of the HPV vaccine.6

Regardless, HPV vaccination is much less common among all males than it is among all females, and the low rate of vaccination among sexual minority men has a disproportionate impact, given their higher risk for HPV infection.4 Although the HPV vaccination rate increased from 2014 to 2017, the HPV vaccination rate in MSM overall is less than half of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%.9 A 2018 review determined that HPV vaccination is a cost-effective strategy for preventing anal cancer in MSM10; yet male patients might still view the HPV vaccine as a “women’s issue” and are less likely to be vaccinated if they are not prompted by health care providers. Additionally, HPV vaccination is remarkably less likely in MSM when patients are older, uninsured, of lower socioeconomic status, or have not disclosed their sexual identity to their health care provider.9 Dermatologists should be mindful of these barriers to promote HPV vaccination in MSM before, or soon after, sexual debut.

Other members of the LGBTQ community, such as women who have sex with women, face notable HPV-related health disparities and would benefit from increased vaccination efforts by dermatologists. Adolescent and young adult women who have sex with women are less likely than heterosexual adolescent and young adult women to receive routine Papanicolaou tests and initiate HPV vaccination, despite having a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and a higher risk for HPV exposure.11 A 2015 survey study (N=3253) found that after adjusting for covariates, only 8.5% of lesbians and 33.2% of bisexual women and girls who had heard of the HPV vaccine had initiated vaccination compared to 28.4% of their heterosexual counterparts.11 The HPV vaccine is an effective public health tool for the prevention of cervical cancer in these populations. A study of women aged 15 to 19 years in the HPV vaccination era (2007-2014) found significant (P<.05) observed population-level decreases in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence across all grades.12

Transgender women also face a high rate of HPV infection, HIV infection, and other structural and financial disparities, such as low insurance coverage, that can limit their access to vaccination. Transgender men have a higher rate of HPV infection than cisgender men, and those with female internal reproductive organs are less likely to receive routine Papanicolaou tests. A 2018 survey study found that approximately one-third of transgender men and women reported initiating the HPV vaccination series,13 but further investigation is required to make balanced comparisons to cisgender patients.

The Role of the Dermatologist

Collectively, these disparities emphasize the need for increased involvement by dermatologists in HPV vaccination efforts for all LGBTQ patients. Adult patients may have concerns about ties of the HPV vaccine to drug manufacturers and the general safety of vaccination. For pediatric patients, parents/guardians also may be concerned about an assumed but not evidence-based increase in sexual promiscuity following HPV vaccination.14 These topics can be challenging to discuss, but dermatologists have the duty to be proactive and initiate conversation about HPV vaccination, as opposed to waiting for patients to express interest. Dermatologists should stress the safety of the vaccine as well as its potential to protect against multiple, even life-threatening diseases. Providers also can explain that the ACIP recommends catch-up vaccination for all individuals through 26 years of age, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

With the ACIP having recently expanded the appropriate age range for HPV vaccination, we encourage dermatologists to engage in education and shared decision-making to ensure that adult patients with specific risk factors receive the HPV vaccine. Because the expanded ACIP recommendations are aimed at vaccination before HPV exposure, vaccination might not be appropriate for all LGBTQ patients. However, eliciting a sexual history with routine patient intake forms or during the clinical encounter ensures equal access to the HPV vaccine.

Greater awareness of HPV-related disparities and barriers to vaccination in LGBTQ populations has the potential to notably decrease HPV-associated mortality and morbidity. Increased involvement by dermatologists contributes to the efforts of other specialties in universal HPV vaccination, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity—ideally in younger age groups, such that patients receive the vaccine prior to coitarche.

There are many ways that dermatologists can advocate for HPV vaccination. Those in a multispecialty or academic practice can readily refer patients to an associated internist, primary care physician, or vaccination clinic in the same building or institution. Dermatologists in private practice might be able to administer the HPV vaccine themselves or can advocate for patients to receive the vaccine at a local facility of the Department of Health or at a nonprofit organization, such as a Planned Parenthood center. Although pediatricians and family physicians remain front-line providers of these services, dermatologists represent an additional member of a patient’s care team, capable of advocating for this important intervention.

- Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40:80-85.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Sonawane K, Suk R, Chiao EY, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection: differences in prevalence between sexes and concordance with genital human papillomavirus infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:714-724.

- Kosche C, Mansh M, Luskus M, et al. Dermatologic care of sexual and gender minority/LGBTQIA youth, part 2: recognition and management of the unique dermatologic needs of SGM adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;35:587-593.

- Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Katz ML, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult gay and bisexual men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:96-102.

- Charlton BM, Reisner SL, Ag

énor M, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination in a longitudinal cohort of U.S. males and females. LGBT Health. 2017;4:202-209. - Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination initiation and completion among young adult US women and men. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:1187-1196.

- Loretan C, Chamberlain AT, Sanchez T, et al. Trends and characteristics associated with human papillomavirus vaccination uptake among men who have sex with men in the United States, 2014-2017. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:465-473.

- Setiawan D, Wondimu A, Ong K, et al. Cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination for men who have sex with men; reviewing the available evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:929-939.

- Agénor M, Peitzmeier S, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in awareness and initiation of the human papillomavirus vaccine among U.S. women and girls: a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:99-106.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:833-837.

- McRee A-L, Gower AL, Reiter PL. Preventive healthcare services use among transgender young adults. Int J Transgend. 2018;19:417-423.

- Trinidad J. Policy focus: promoting human papilloma virus vaccine to prevent genital warts and cancer. Boston, MA: The Fenway Institute; 2012. https://fenwayhealth.org/documents/the-fenway-institute/policy-briefs/PolicyFocus_HPV_v4_10.09.12.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40:80-85.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Sonawane K, Suk R, Chiao EY, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection: differences in prevalence between sexes and concordance with genital human papillomavirus infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:714-724.

- Kosche C, Mansh M, Luskus M, et al. Dermatologic care of sexual and gender minority/LGBTQIA youth, part 2: recognition and management of the unique dermatologic needs of SGM adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;35:587-593.

- Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Katz ML, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult gay and bisexual men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:96-102.

- Charlton BM, Reisner SL, Ag

énor M, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination in a longitudinal cohort of U.S. males and females. LGBT Health. 2017;4:202-209. - Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination initiation and completion among young adult US women and men. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:1187-1196.

- Loretan C, Chamberlain AT, Sanchez T, et al. Trends and characteristics associated with human papillomavirus vaccination uptake among men who have sex with men in the United States, 2014-2017. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:465-473.

- Setiawan D, Wondimu A, Ong K, et al. Cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination for men who have sex with men; reviewing the available evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36:929-939.

- Agénor M, Peitzmeier S, Gordon AR, et al. Sexual orientation identity disparities in awareness and initiation of the human papillomavirus vaccine among U.S. women and girls: a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:99-106.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:833-837.

- McRee A-L, Gower AL, Reiter PL. Preventive healthcare services use among transgender young adults. Int J Transgend. 2018;19:417-423.

- Trinidad J. Policy focus: promoting human papilloma virus vaccine to prevent genital warts and cancer. Boston, MA: The Fenway Institute; 2012. https://fenwayhealth.org/documents/the-fenway-institute/policy-briefs/PolicyFocus_HPV_v4_10.09.12.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2020.

An Unusual Skin Infection With Achromobacter xylosoxidans

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with a sore, tender, red lump on the right superior buttock of 5 months’ duration. Five months prior to presentation the patient used this area to attach the infusion set for an insulin pump, which was left in place for 7 days as opposed to the 2 or 3 days recommended by the device manufacturer. A firm, slightly tender lump formed, similar to prior scars that had developed from use of the insulin pump. However, the lump began to grow and get softer. It was intermittently warm and red. Although the area was sore and tender, she never had any major pain. She also denied any fever, malaise, or other systemic symptoms.

The patient indicated a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 9 years of age; hypertension; asthma; gastroesophageal reflux disease; allergic rhinitis; migraine headaches; depression; hidradenitis suppurativa that resolved after surgical excision; and recurrent vaginal yeast infections, especially when taking antibiotics. She had a surgical history of hidradenitis suppurativa excision at the inguinal folds, bilateral carpal tunnel release, tubal ligation, abdominoplasty, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s current medications included insulin aspart, mometasone furoate, inhaled fluticasone, pantoprazole, cetirizine, spironolactone, duloxetine, sumatriptan, fluconazole, topiramate, and enalapril.

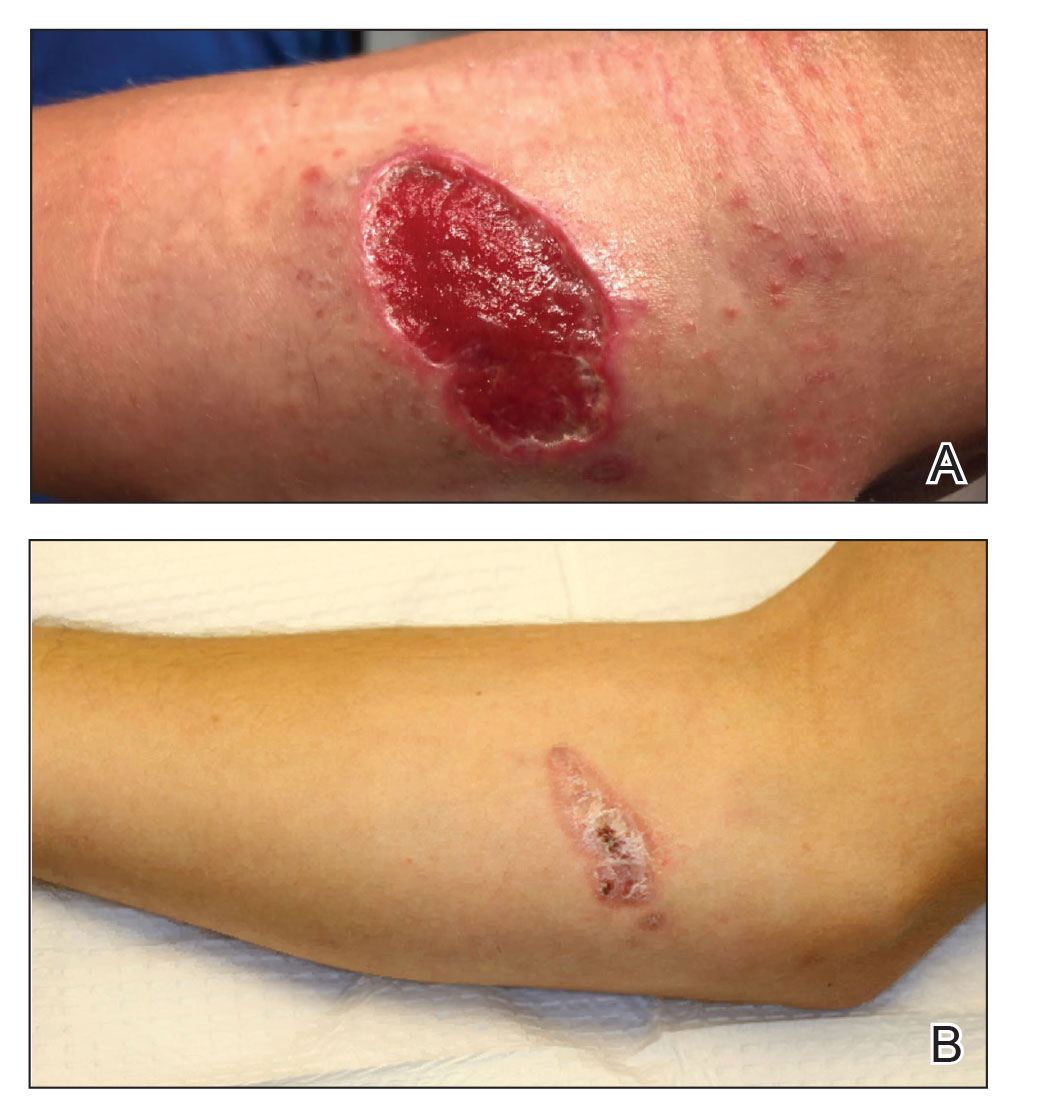

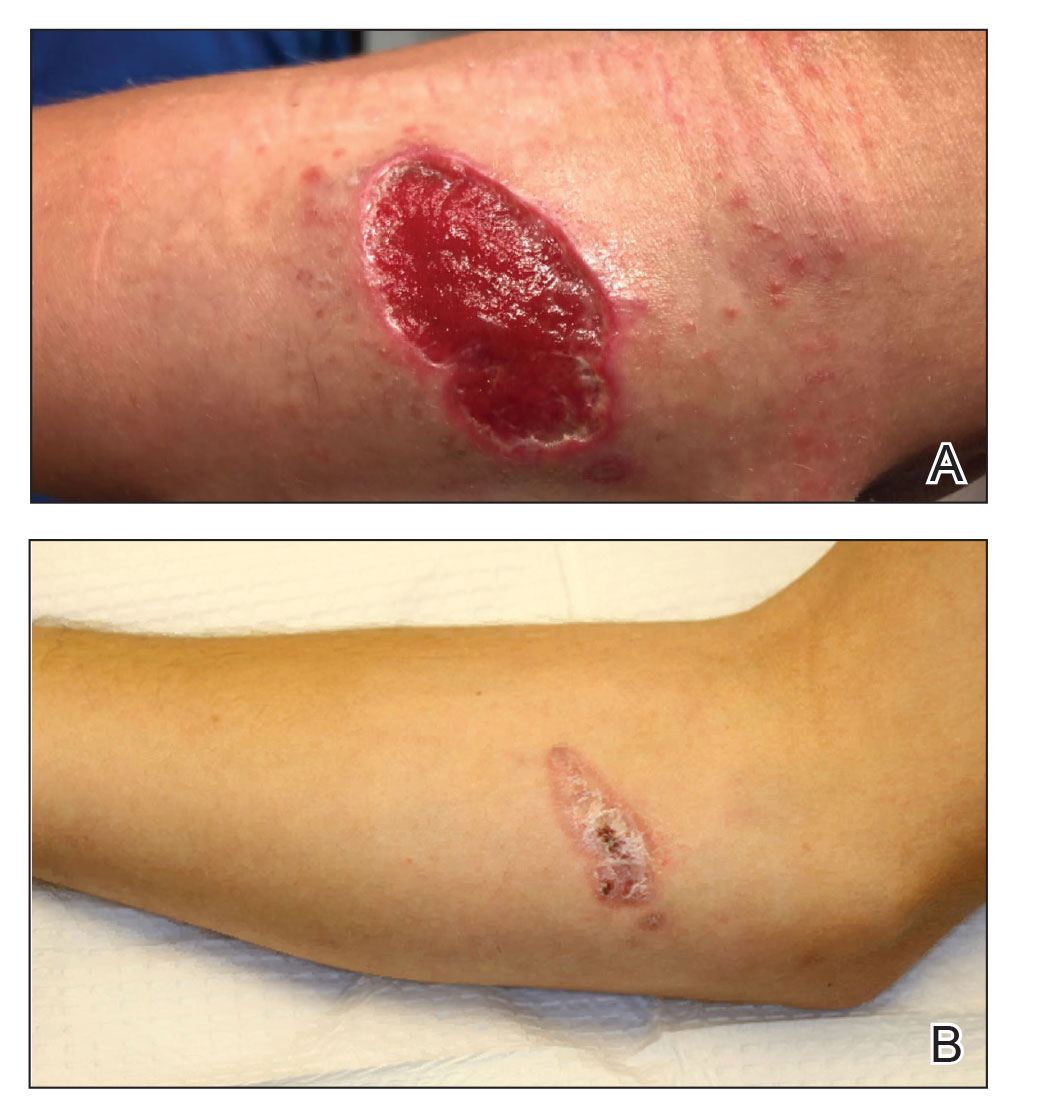

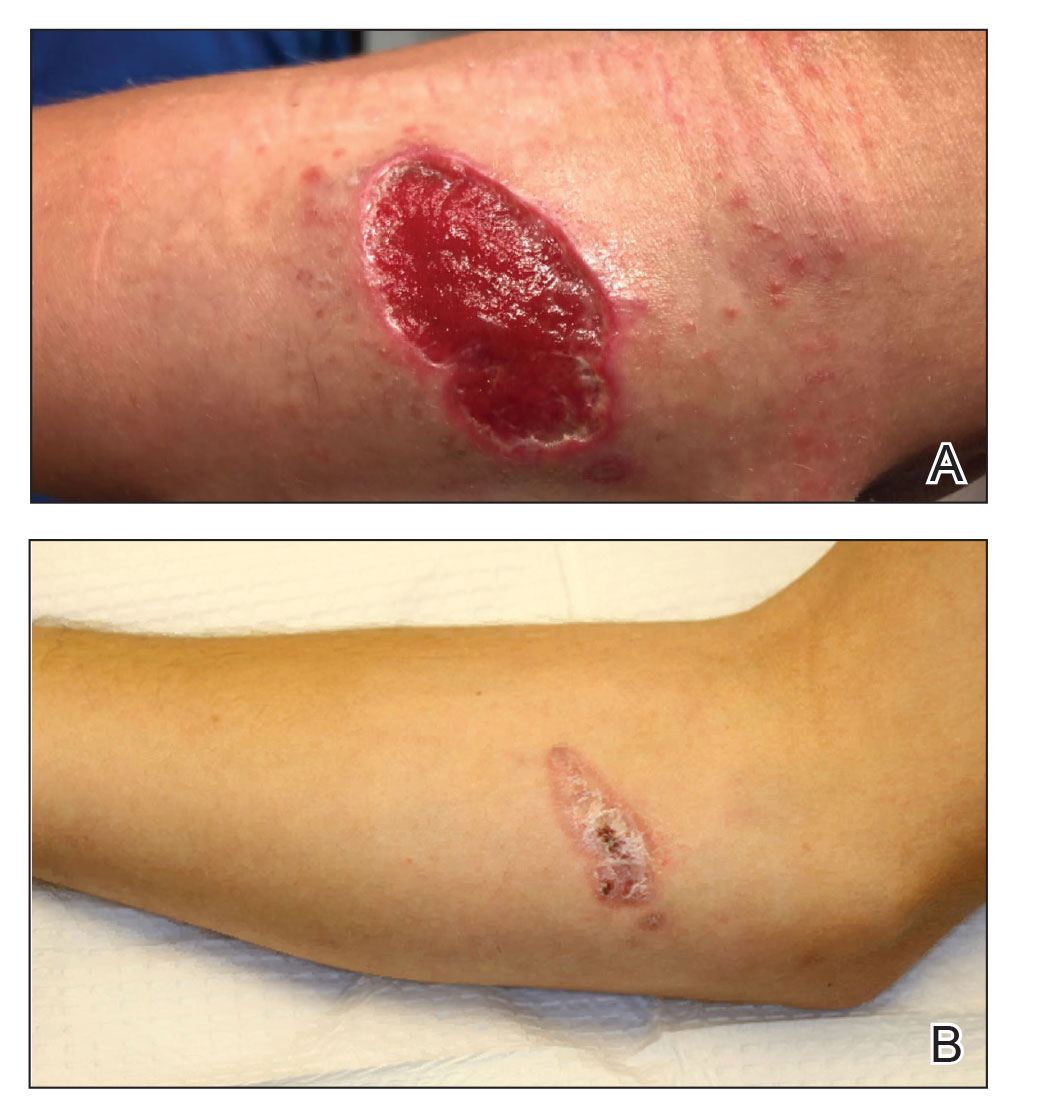

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and the patient was afebrile. She had no swollen or tender lymph nodes. There was a 5.5×7.0-cm, soft, tender, erythematous subcutaneous mass with no visible punctum or overlying epidermal change on the right superior buttock (Figure 1). Based on the history and physical examination, the differential diagnosis included subcutaneous fat necrosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, and an abscess.

The patient was scheduled for excision of the mass the day after presenting to the clinic. During excision, 10 mL of thick purulent liquid was drained. A sample of the liquid was sent for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and antibiotic sensitivities. Necrotic-appearing adipose and fibrotic tissues were dissected and extirpated through an elliptical incision and submitted for pathologic evaluation.

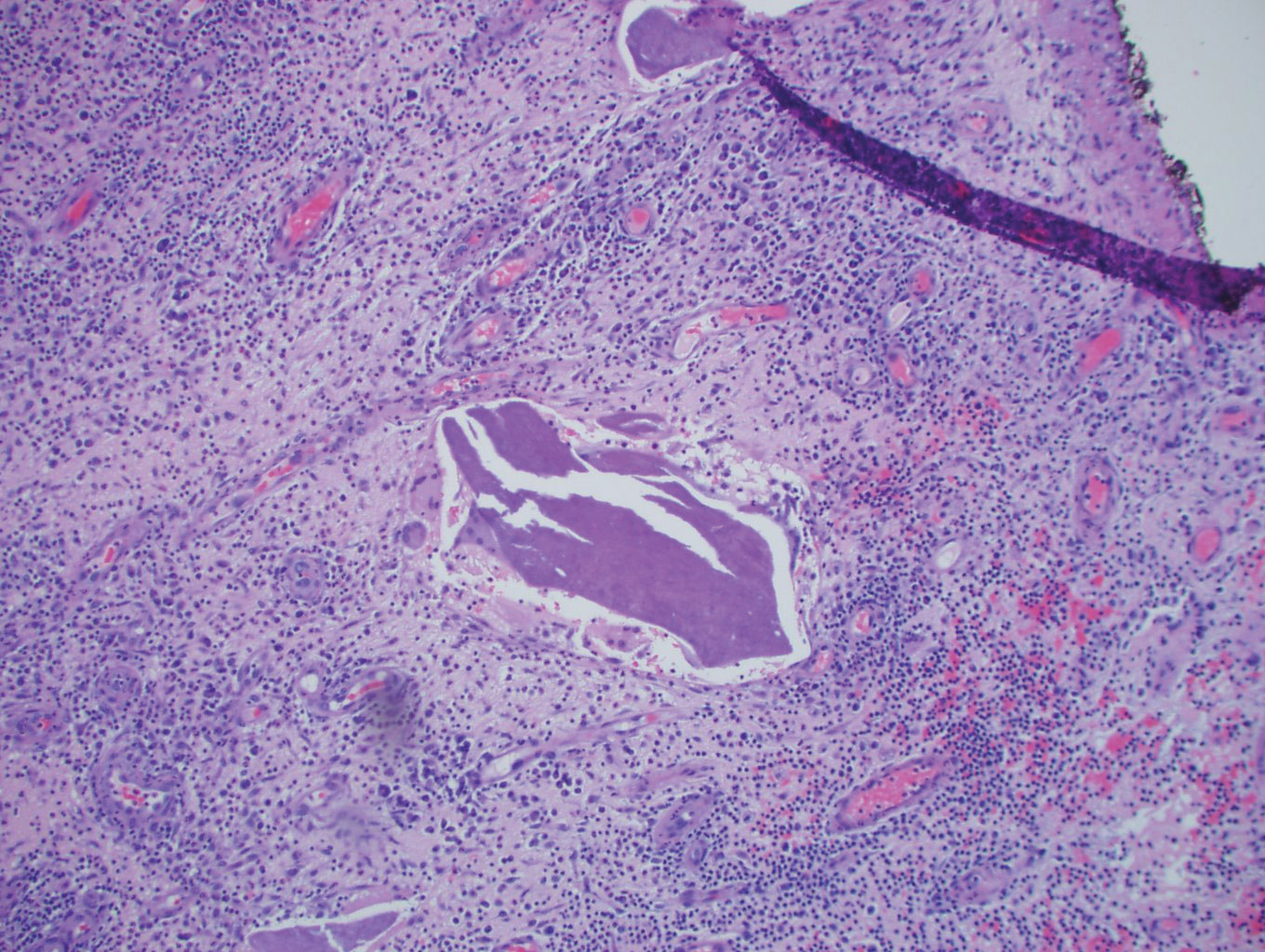

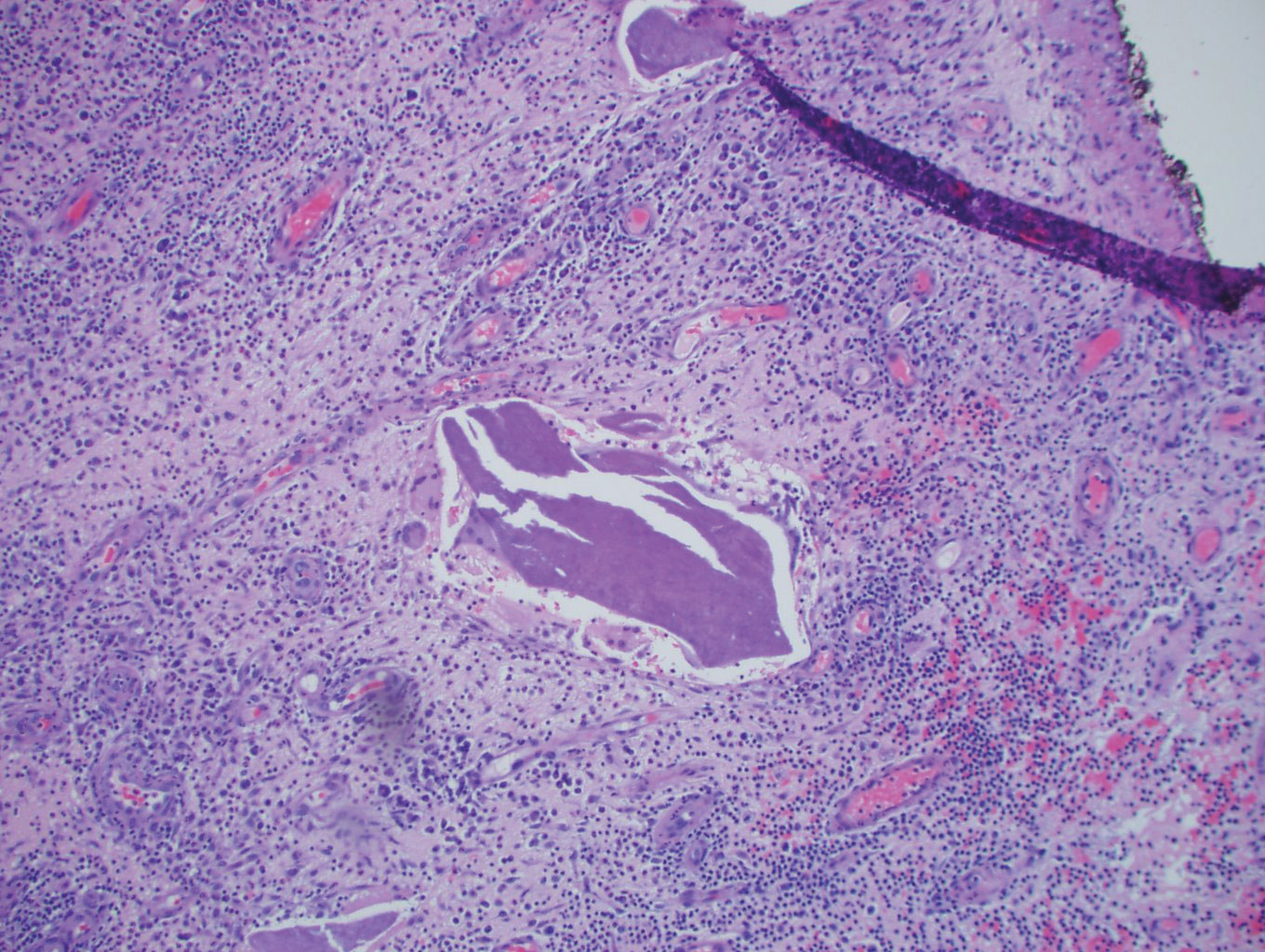

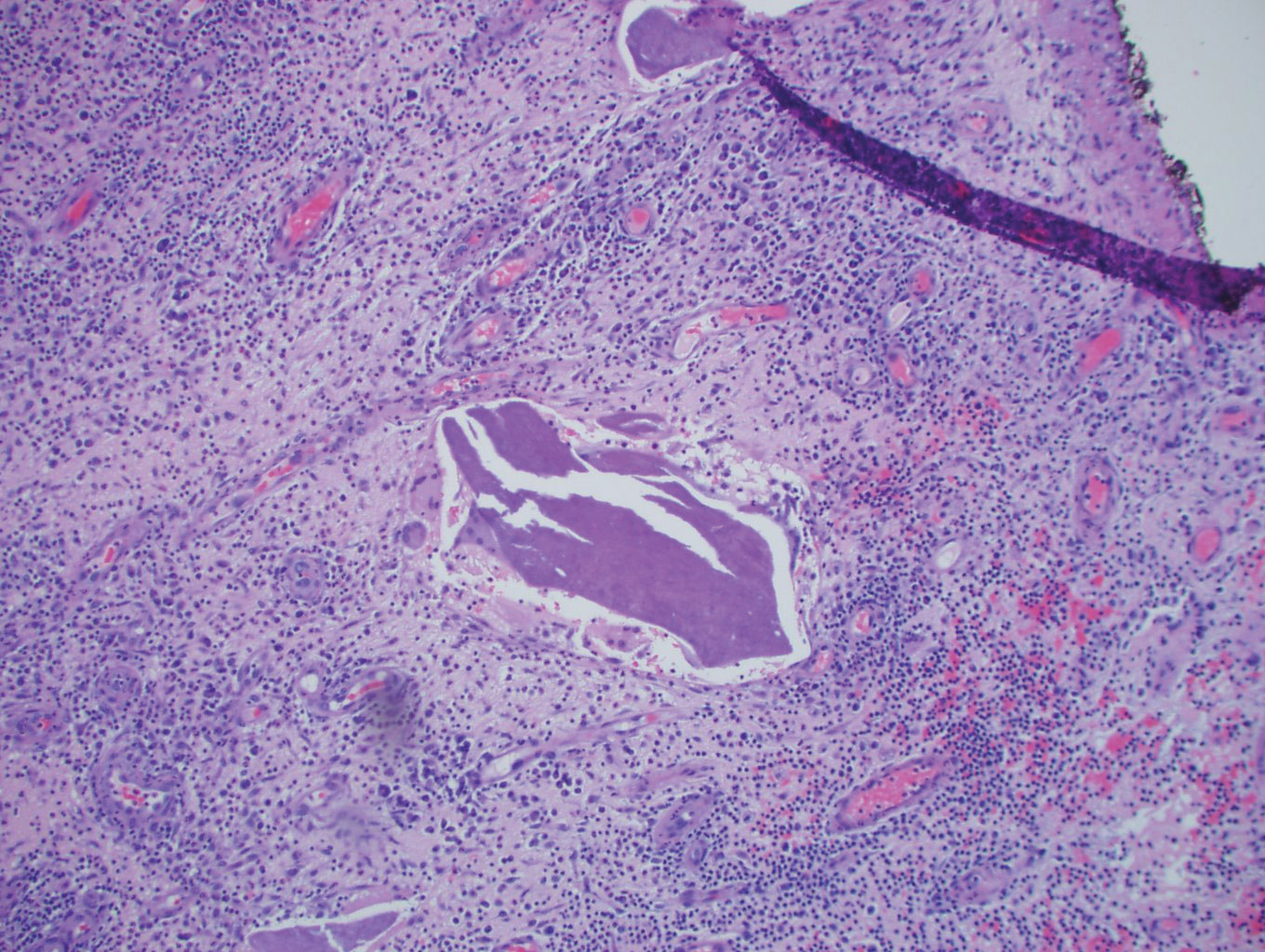

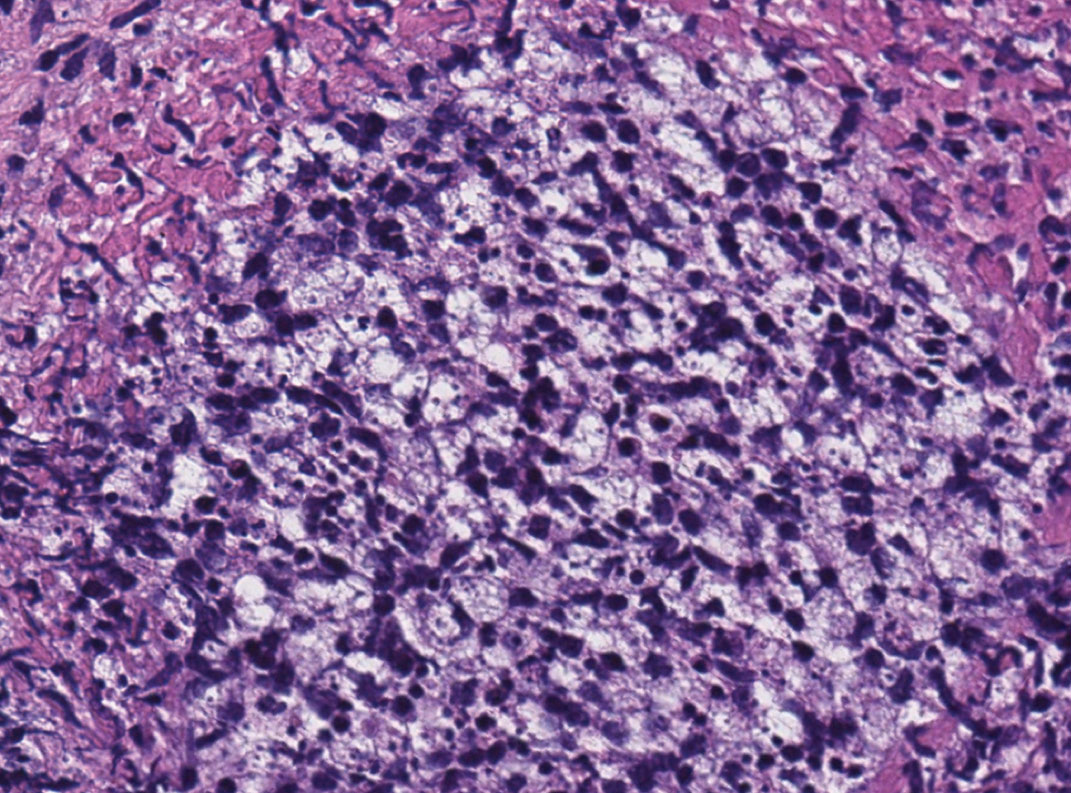

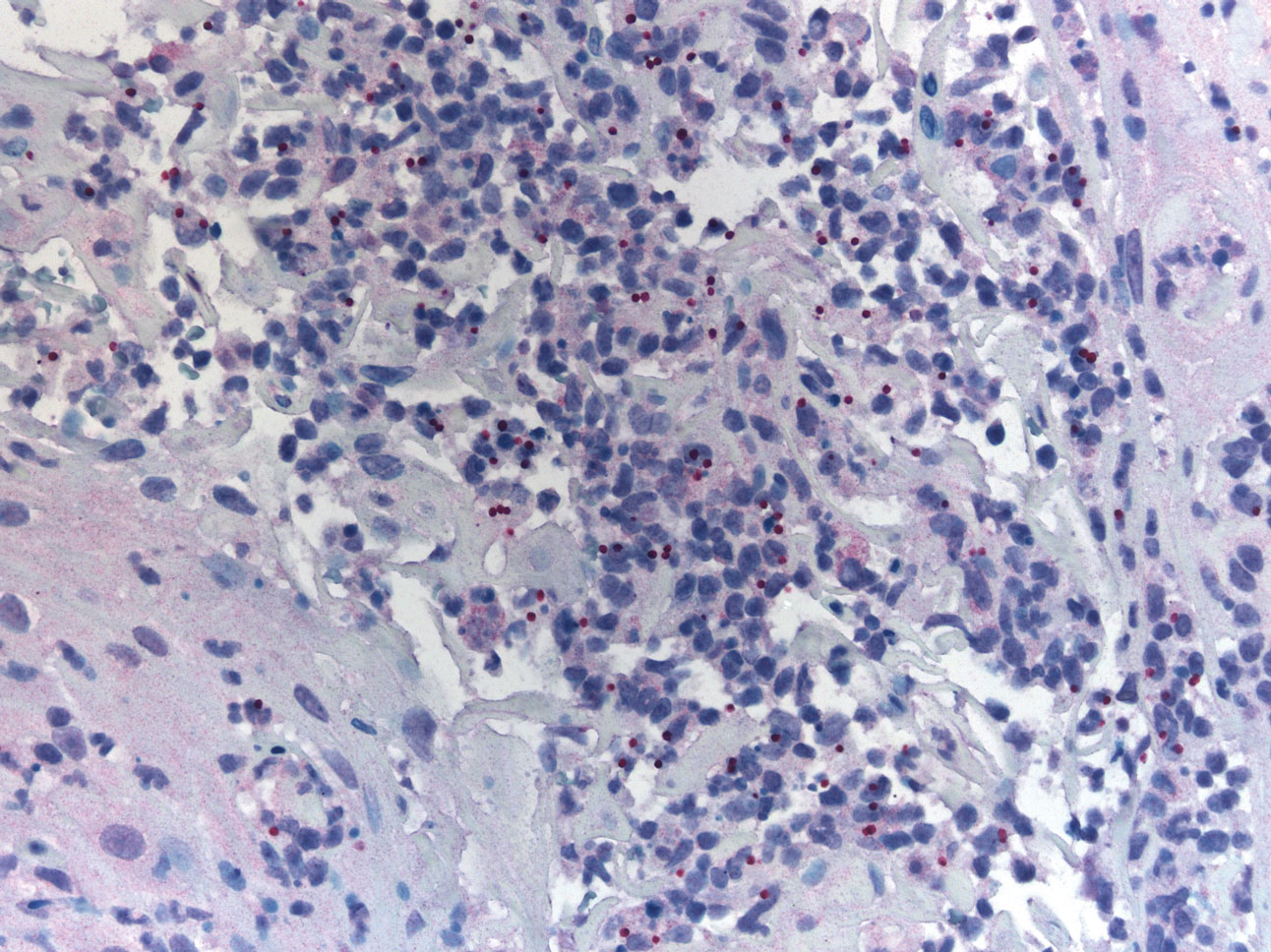

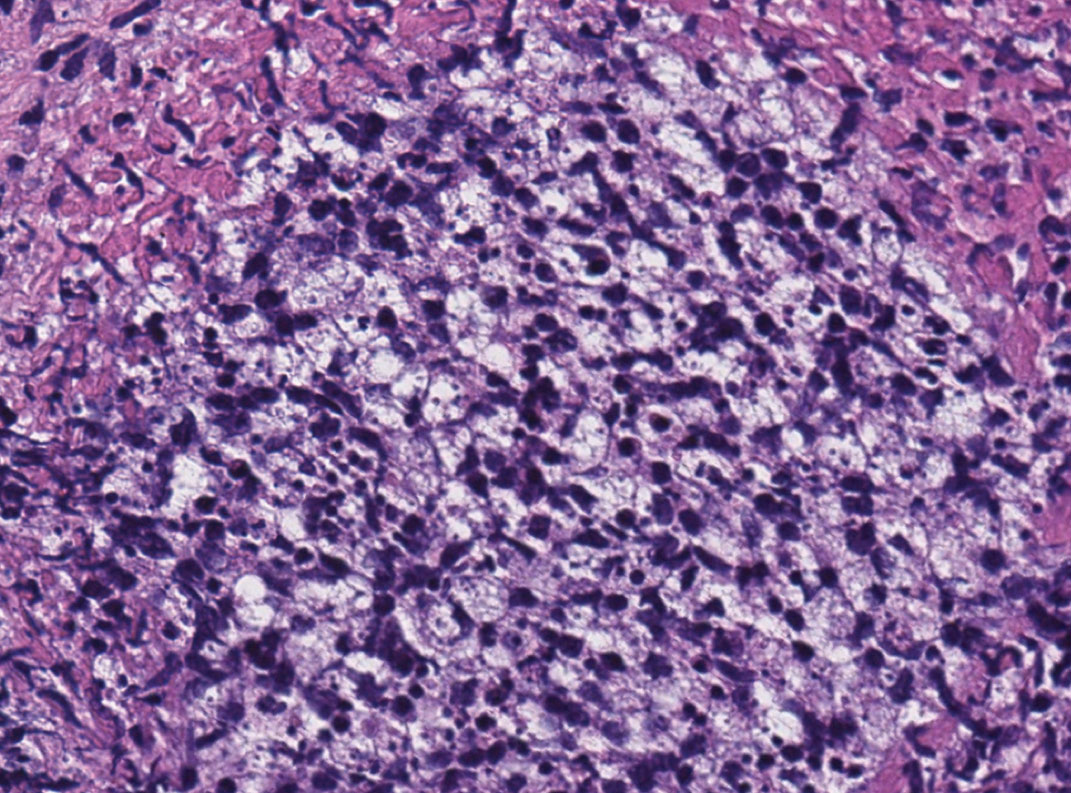

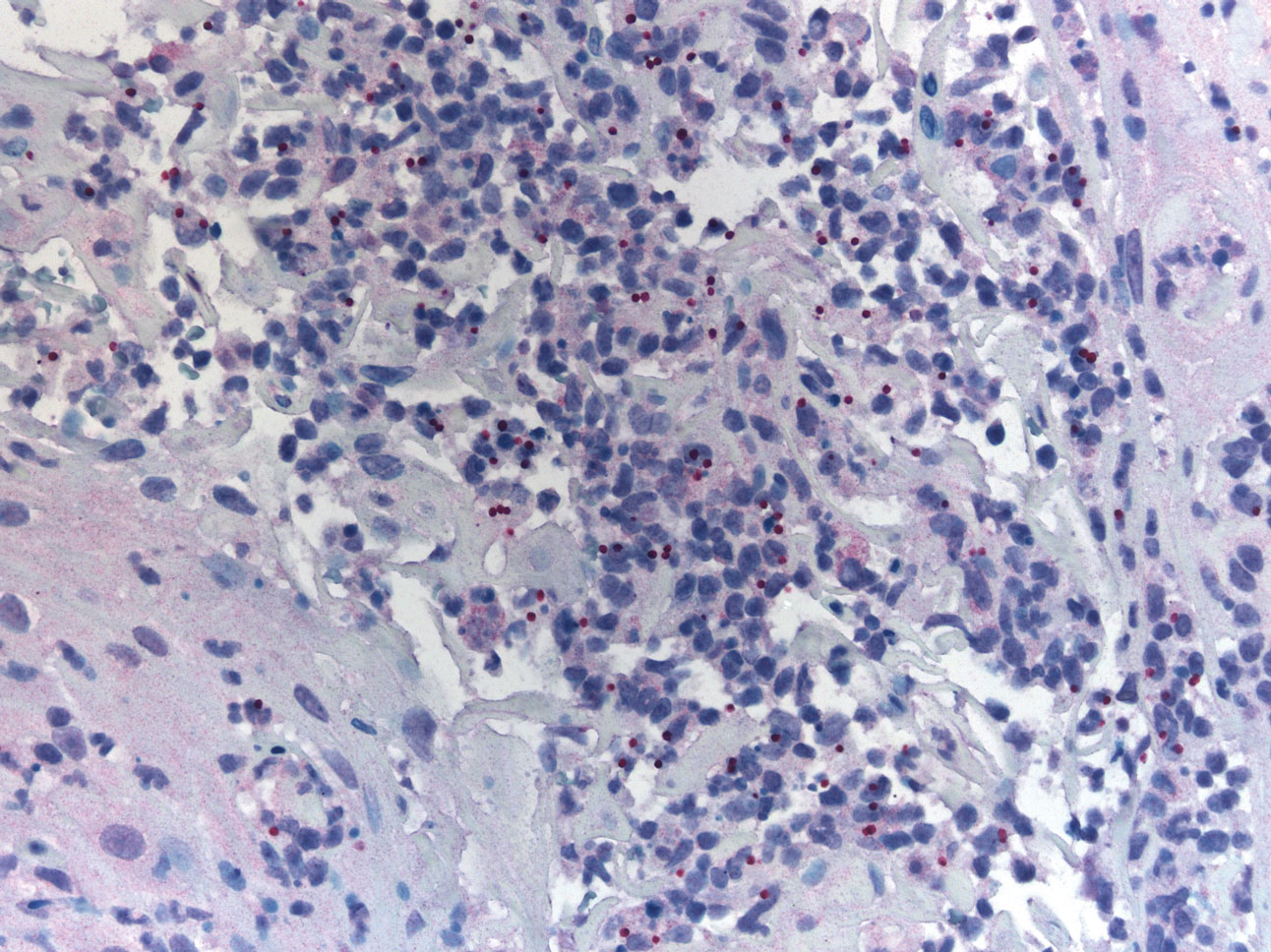

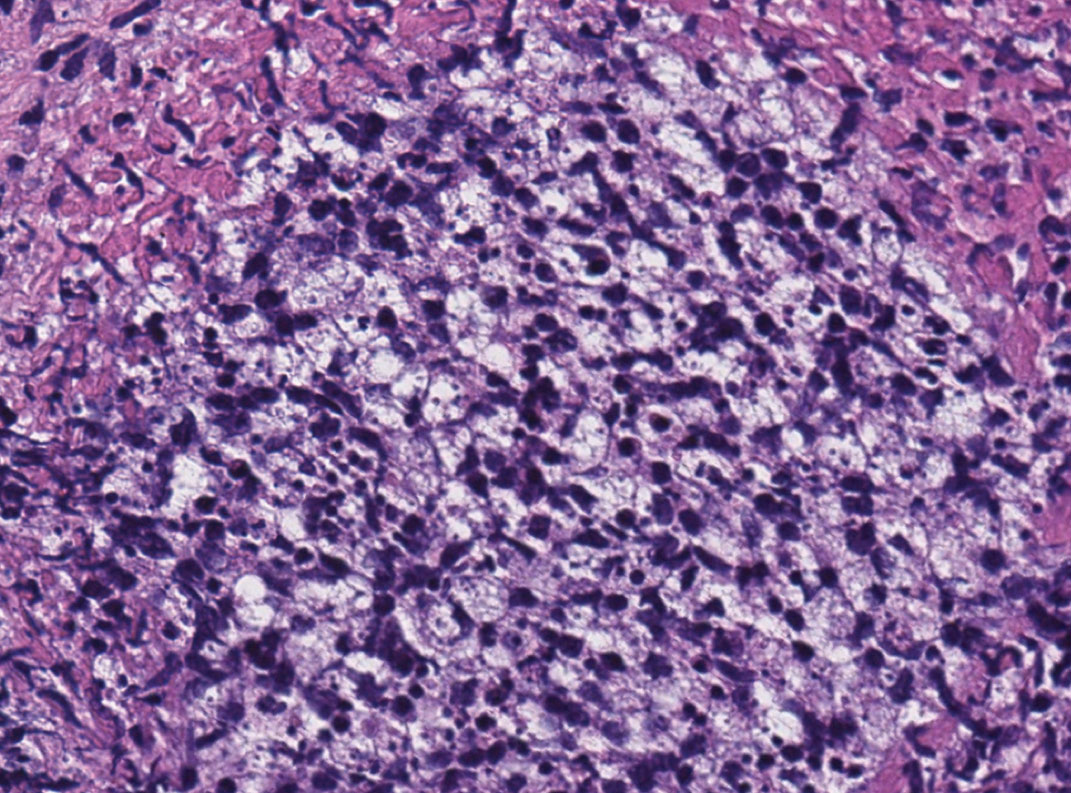

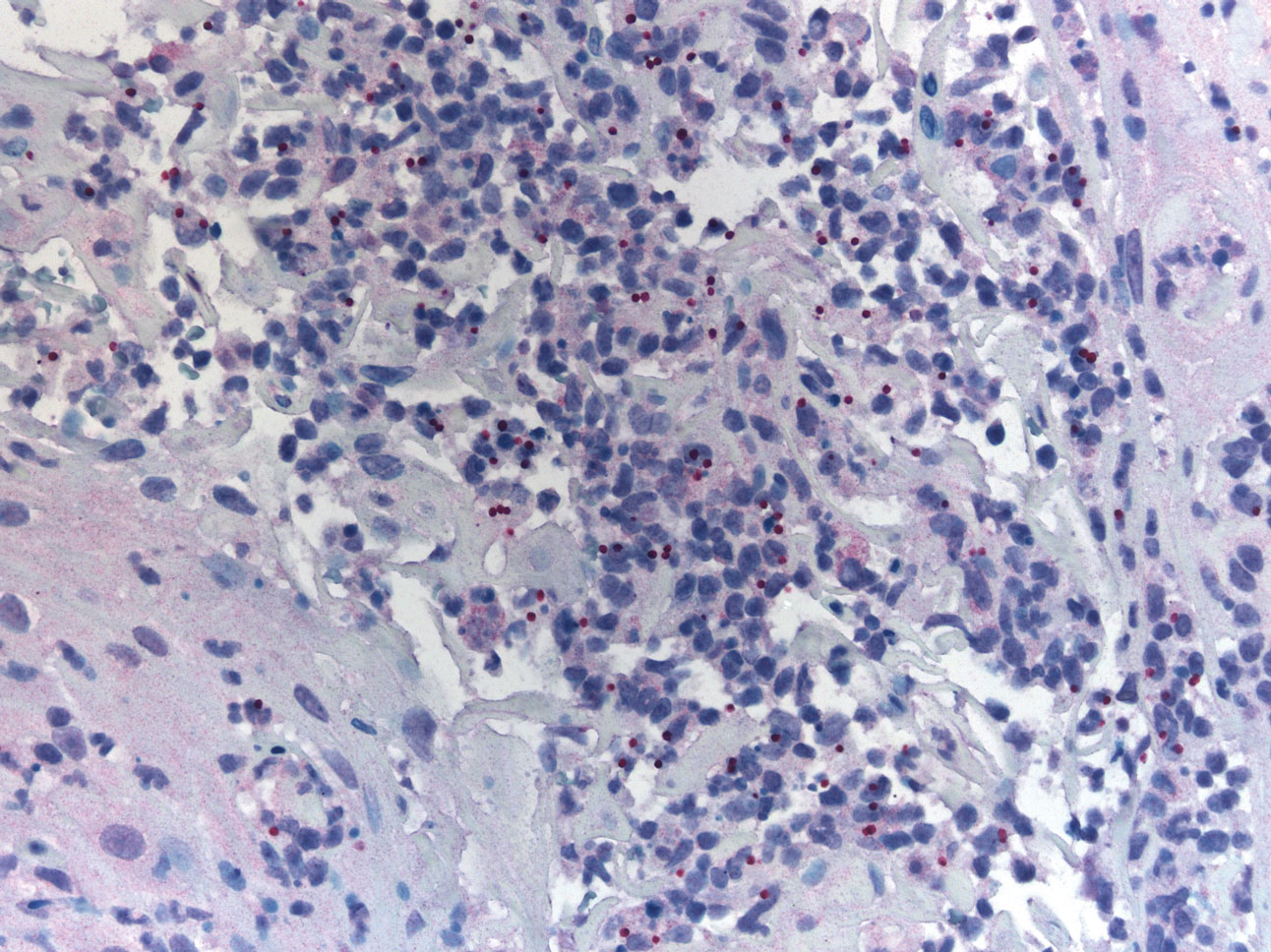

Histopathology showed a subcutaneous defect with palisaded granulomatous inflammation and sclerosis (Figure 2). There was no detection of microorganisms with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, tissue Gram, or acid-fast stains. There was a focus of acellular material embedded within the inflammation (Figure 3). The Gram stain of the purulent material showed few white blood cells and rare gram-negative bacilli. Culture grew moderate Achromobacter xylosoxidans resistant to cefepime, cefotaxime, and gentamicin. The culture was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, levofloxacin, piperacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The patient was prescribed oral TMP-SMX (160 mg of TMP and 800 mg of SMX) twice daily for 10 days. The patient tolerated the procedure and the subsequent antibiotics well. The patient had normal levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as a negative screening test for human immunodeficiency virus. She healed well from the surgical procedure and has had no recurrence of symptoms.

Comment

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is a nonfermentative, non–spore-forming, motile, gram-negative, aerobic, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive flagellate bacterium. It is an emerging pathogen that was first isolated in 1971 from patients with chronic otitis media.1 Since its recognition, it has been documented to cause a variety of infections, including pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as abdominal, urinary tract, ocular, and skin and soft tissue infections.2,3 Those affected usually are immunocompromised, have hematologic disorders, or have indwelling catheters.4 Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown resistance to multiple antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and TMP-SMX. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been documented to form biofilms on plastics, including on contact lenses, urinary and intravenous catheters, and reusable tissue dispensers treated with disinfectant solution.4-6 One study demonstrated that A xylosoxidans is even capable of biodegradation of plastic, using the plastic as its sole source of carbon.7

Our case illustrates an indolent infection with A xylosoxidans forming a granulomatous abscess at the site of an insulin pump that was left in place for 7 days in an immunocompetent patient. Although infections with A xylosoxidans in patients with urinary or intravenous catheters have been reported,4 our case is unique, as the insulin pump was the source of such an infection. It is possible that the subcutaneous focus of acellular material described on the pathology report represented a partially biodegraded piece of the insulin pump catheter that broke off and was serving as a nidus of infection for A xylosoxidans. Although multidrug resistance is common, the culture grown from our patient was susceptible to TMP-SMX, among other antibiotics. Our patient was treated successfully with surgical excision, drainage, and a 10-day course of TMP-SMX.

Conclusion

Health care providers should recognize A xylosoxidans as an emerging pathogen that is capable of forming biofilms on “disinfected” surfaces and medical products, especially plastics. Achromobacter xylosoxidans may be resistant to multiple antibiotics and can cause infections with various presentations.

- Yabuuchi E, Oyama A. Achromobacter xylosoxidans n. sp. from human ear discharge. Jpn J Microbiol. 1971;15:477-481.

- Rodrigues CG, Rays J, Kanegae MY. Native-valve endocarditis caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: a case report and review of literature. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:50-55.

- Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:130-135.

- Pérez Barragán E, Sandino Pérez J, Corbella L, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans bacteremia: clinical and microbiological features in a 10-year case series. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:268-273.

- Konstantinović N, Ćirković I, Đukić S, et al. Biofilm formation of Achromobacter xylosoxidans on contact lens. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:293-300.

- Günther F, Merle U, Frank U, et al. Pseudobacteremia outbreak of biofilm-forming Achromobacter xylosoxidans—environmental transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:584.

- Kowalczyk A, Chyc M, Ryszka P, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans as a new microorganism strain colonizing high-density polyethylene as a key step to its biodegradation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:11349-11356.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with a sore, tender, red lump on the right superior buttock of 5 months’ duration. Five months prior to presentation the patient used this area to attach the infusion set for an insulin pump, which was left in place for 7 days as opposed to the 2 or 3 days recommended by the device manufacturer. A firm, slightly tender lump formed, similar to prior scars that had developed from use of the insulin pump. However, the lump began to grow and get softer. It was intermittently warm and red. Although the area was sore and tender, she never had any major pain. She also denied any fever, malaise, or other systemic symptoms.

The patient indicated a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 9 years of age; hypertension; asthma; gastroesophageal reflux disease; allergic rhinitis; migraine headaches; depression; hidradenitis suppurativa that resolved after surgical excision; and recurrent vaginal yeast infections, especially when taking antibiotics. She had a surgical history of hidradenitis suppurativa excision at the inguinal folds, bilateral carpal tunnel release, tubal ligation, abdominoplasty, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s current medications included insulin aspart, mometasone furoate, inhaled fluticasone, pantoprazole, cetirizine, spironolactone, duloxetine, sumatriptan, fluconazole, topiramate, and enalapril.

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and the patient was afebrile. She had no swollen or tender lymph nodes. There was a 5.5×7.0-cm, soft, tender, erythematous subcutaneous mass with no visible punctum or overlying epidermal change on the right superior buttock (Figure 1). Based on the history and physical examination, the differential diagnosis included subcutaneous fat necrosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, and an abscess.

The patient was scheduled for excision of the mass the day after presenting to the clinic. During excision, 10 mL of thick purulent liquid was drained. A sample of the liquid was sent for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and antibiotic sensitivities. Necrotic-appearing adipose and fibrotic tissues were dissected and extirpated through an elliptical incision and submitted for pathologic evaluation.

Histopathology showed a subcutaneous defect with palisaded granulomatous inflammation and sclerosis (Figure 2). There was no detection of microorganisms with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, tissue Gram, or acid-fast stains. There was a focus of acellular material embedded within the inflammation (Figure 3). The Gram stain of the purulent material showed few white blood cells and rare gram-negative bacilli. Culture grew moderate Achromobacter xylosoxidans resistant to cefepime, cefotaxime, and gentamicin. The culture was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, levofloxacin, piperacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The patient was prescribed oral TMP-SMX (160 mg of TMP and 800 mg of SMX) twice daily for 10 days. The patient tolerated the procedure and the subsequent antibiotics well. The patient had normal levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as a negative screening test for human immunodeficiency virus. She healed well from the surgical procedure and has had no recurrence of symptoms.

Comment

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is a nonfermentative, non–spore-forming, motile, gram-negative, aerobic, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive flagellate bacterium. It is an emerging pathogen that was first isolated in 1971 from patients with chronic otitis media.1 Since its recognition, it has been documented to cause a variety of infections, including pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as abdominal, urinary tract, ocular, and skin and soft tissue infections.2,3 Those affected usually are immunocompromised, have hematologic disorders, or have indwelling catheters.4 Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown resistance to multiple antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and TMP-SMX. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been documented to form biofilms on plastics, including on contact lenses, urinary and intravenous catheters, and reusable tissue dispensers treated with disinfectant solution.4-6 One study demonstrated that A xylosoxidans is even capable of biodegradation of plastic, using the plastic as its sole source of carbon.7

Our case illustrates an indolent infection with A xylosoxidans forming a granulomatous abscess at the site of an insulin pump that was left in place for 7 days in an immunocompetent patient. Although infections with A xylosoxidans in patients with urinary or intravenous catheters have been reported,4 our case is unique, as the insulin pump was the source of such an infection. It is possible that the subcutaneous focus of acellular material described on the pathology report represented a partially biodegraded piece of the insulin pump catheter that broke off and was serving as a nidus of infection for A xylosoxidans. Although multidrug resistance is common, the culture grown from our patient was susceptible to TMP-SMX, among other antibiotics. Our patient was treated successfully with surgical excision, drainage, and a 10-day course of TMP-SMX.

Conclusion

Health care providers should recognize A xylosoxidans as an emerging pathogen that is capable of forming biofilms on “disinfected” surfaces and medical products, especially plastics. Achromobacter xylosoxidans may be resistant to multiple antibiotics and can cause infections with various presentations.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with a sore, tender, red lump on the right superior buttock of 5 months’ duration. Five months prior to presentation the patient used this area to attach the infusion set for an insulin pump, which was left in place for 7 days as opposed to the 2 or 3 days recommended by the device manufacturer. A firm, slightly tender lump formed, similar to prior scars that had developed from use of the insulin pump. However, the lump began to grow and get softer. It was intermittently warm and red. Although the area was sore and tender, she never had any major pain. She also denied any fever, malaise, or other systemic symptoms.

The patient indicated a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 9 years of age; hypertension; asthma; gastroesophageal reflux disease; allergic rhinitis; migraine headaches; depression; hidradenitis suppurativa that resolved after surgical excision; and recurrent vaginal yeast infections, especially when taking antibiotics. She had a surgical history of hidradenitis suppurativa excision at the inguinal folds, bilateral carpal tunnel release, tubal ligation, abdominoplasty, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s current medications included insulin aspart, mometasone furoate, inhaled fluticasone, pantoprazole, cetirizine, spironolactone, duloxetine, sumatriptan, fluconazole, topiramate, and enalapril.

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and the patient was afebrile. She had no swollen or tender lymph nodes. There was a 5.5×7.0-cm, soft, tender, erythematous subcutaneous mass with no visible punctum or overlying epidermal change on the right superior buttock (Figure 1). Based on the history and physical examination, the differential diagnosis included subcutaneous fat necrosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, and an abscess.

The patient was scheduled for excision of the mass the day after presenting to the clinic. During excision, 10 mL of thick purulent liquid was drained. A sample of the liquid was sent for Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic culture, and antibiotic sensitivities. Necrotic-appearing adipose and fibrotic tissues were dissected and extirpated through an elliptical incision and submitted for pathologic evaluation.

Histopathology showed a subcutaneous defect with palisaded granulomatous inflammation and sclerosis (Figure 2). There was no detection of microorganisms with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, tissue Gram, or acid-fast stains. There was a focus of acellular material embedded within the inflammation (Figure 3). The Gram stain of the purulent material showed few white blood cells and rare gram-negative bacilli. Culture grew moderate Achromobacter xylosoxidans resistant to cefepime, cefotaxime, and gentamicin. The culture was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, levofloxacin, piperacillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The patient was prescribed oral TMP-SMX (160 mg of TMP and 800 mg of SMX) twice daily for 10 days. The patient tolerated the procedure and the subsequent antibiotics well. The patient had normal levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as a negative screening test for human immunodeficiency virus. She healed well from the surgical procedure and has had no recurrence of symptoms.

Comment

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is a nonfermentative, non–spore-forming, motile, gram-negative, aerobic, catalase-positive and oxidase-positive flagellate bacterium. It is an emerging pathogen that was first isolated in 1971 from patients with chronic otitis media.1 Since its recognition, it has been documented to cause a variety of infections, including pneumonia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as abdominal, urinary tract, ocular, and skin and soft tissue infections.2,3 Those affected usually are immunocompromised, have hematologic disorders, or have indwelling catheters.4 Strains of A xylosoxidans have shown resistance to multiple antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and TMP-SMX. Achromobacter xylosoxidans has been documented to form biofilms on plastics, including on contact lenses, urinary and intravenous catheters, and reusable tissue dispensers treated with disinfectant solution.4-6 One study demonstrated that A xylosoxidans is even capable of biodegradation of plastic, using the plastic as its sole source of carbon.7

Our case illustrates an indolent infection with A xylosoxidans forming a granulomatous abscess at the site of an insulin pump that was left in place for 7 days in an immunocompetent patient. Although infections with A xylosoxidans in patients with urinary or intravenous catheters have been reported,4 our case is unique, as the insulin pump was the source of such an infection. It is possible that the subcutaneous focus of acellular material described on the pathology report represented a partially biodegraded piece of the insulin pump catheter that broke off and was serving as a nidus of infection for A xylosoxidans. Although multidrug resistance is common, the culture grown from our patient was susceptible to TMP-SMX, among other antibiotics. Our patient was treated successfully with surgical excision, drainage, and a 10-day course of TMP-SMX.

Conclusion

Health care providers should recognize A xylosoxidans as an emerging pathogen that is capable of forming biofilms on “disinfected” surfaces and medical products, especially plastics. Achromobacter xylosoxidans may be resistant to multiple antibiotics and can cause infections with various presentations.

- Yabuuchi E, Oyama A. Achromobacter xylosoxidans n. sp. from human ear discharge. Jpn J Microbiol. 1971;15:477-481.

- Rodrigues CG, Rays J, Kanegae MY. Native-valve endocarditis caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: a case report and review of literature. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:50-55.

- Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:130-135.

- Pérez Barragán E, Sandino Pérez J, Corbella L, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans bacteremia: clinical and microbiological features in a 10-year case series. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:268-273.

- Konstantinović N, Ćirković I, Đukić S, et al. Biofilm formation of Achromobacter xylosoxidans on contact lens. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:293-300.

- Günther F, Merle U, Frank U, et al. Pseudobacteremia outbreak of biofilm-forming Achromobacter xylosoxidans—environmental transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:584.

- Kowalczyk A, Chyc M, Ryszka P, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans as a new microorganism strain colonizing high-density polyethylene as a key step to its biodegradation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23:11349-11356.

- Yabuuchi E, Oyama A. Achromobacter xylosoxidans n. sp. from human ear discharge. Jpn J Microbiol. 1971;15:477-481.

- Rodrigues CG, Rays J, Kanegae MY. Native-valve endocarditis caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: a case report and review of literature. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:50-55.

- Tena D, Martínez NM, Losa C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infection caused by Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:130-135.

- Pérez Barragán E, Sandino Pérez J, Corbella L, et al. Achromobacter xylosoxidans bacteremia: clinical and microbiological features in a 10-year case series. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:268-273.

- Konstantinović N, Ćirković I, Đukić S, et al. Biofilm formation of Achromobacter xylosoxidans on contact lens. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:293-300.

- Günther F, Merle U, Frank U, et al. Pseudobacteremia outbreak of biofilm-forming Achromobacter xylosoxidans—environmental transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:584.