User login

Tanning Attitudes and Behaviors in Adolescents and Young Adults

Intentional tanning—through sun exposure and tanning beds—is an easily avoidable contributor to skin cancer development and an important area for public education. Since the advent of social media, a correlation between social media use and increased indoor tanning behaviors has been reported.1 In 2010, 11.3% of US adults aged 18 to 29 years reported using a tanning bed in the last 12 months.2 The American Academy of Dermatology first published their “Position Statement on Indoor Tanning” in 1998, endorsing a ban on the sale of indoor tanning equipment for nonmedical purposes.3

Although there has been no outright ban on indoor tanning, regulations have been put in place in many states—including Texas, where (as of 2013) a person younger than 18 years must have written consent from their parent(s) to use a tanning bed. Despite efforts of organizations including the American Academy of Dermatology and the government to educate the public on skin cancer prevention and sun safety, the skin cancer rate has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years.

There is a constant campaign among dermatologists to educate their patients on how to reduce or avoid the risk for skin cancer, including the use of sunscreen and avoidance of tanning. Adolescents and young adults are an especially important demographic to reach and educate because increased UV light exposure during these years leads to a greatly increased risk for skin cancer later in life.4 Data on the overall prevalence of tanning and the demographics of participation in tanning activities are important to capture and can be used to efficiently target higher-risk populations.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults regarding sun protection and tanning. We also aimed to determine which avenues, including social media, would be most effective at educating about skin cancer awareness and sun protection to the higher-risk younger population.

Materials and Methods

We developed an institutional review board–approved protocol for the prospective collection of data from registered patients at the dermatology clinic of the Mays Cancer Center at the University of Texas Health at San Antonio. A paper survey containing 15 rating-scale questions was administered to 60 patients aged 13 to 27 years. Surveys were administered during intake, prior to the patients’ visit with a dermatologist; all visits were of a functional (not cosmetic) nature. Data collection spanned June to August 2018. Survey results were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software for qualitative analysis.

Results

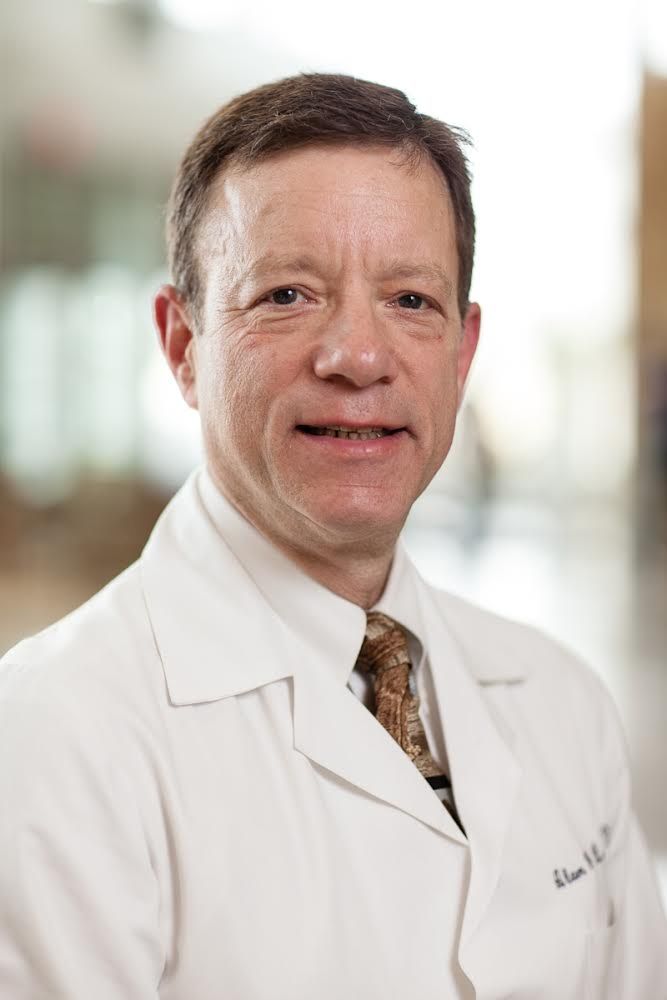

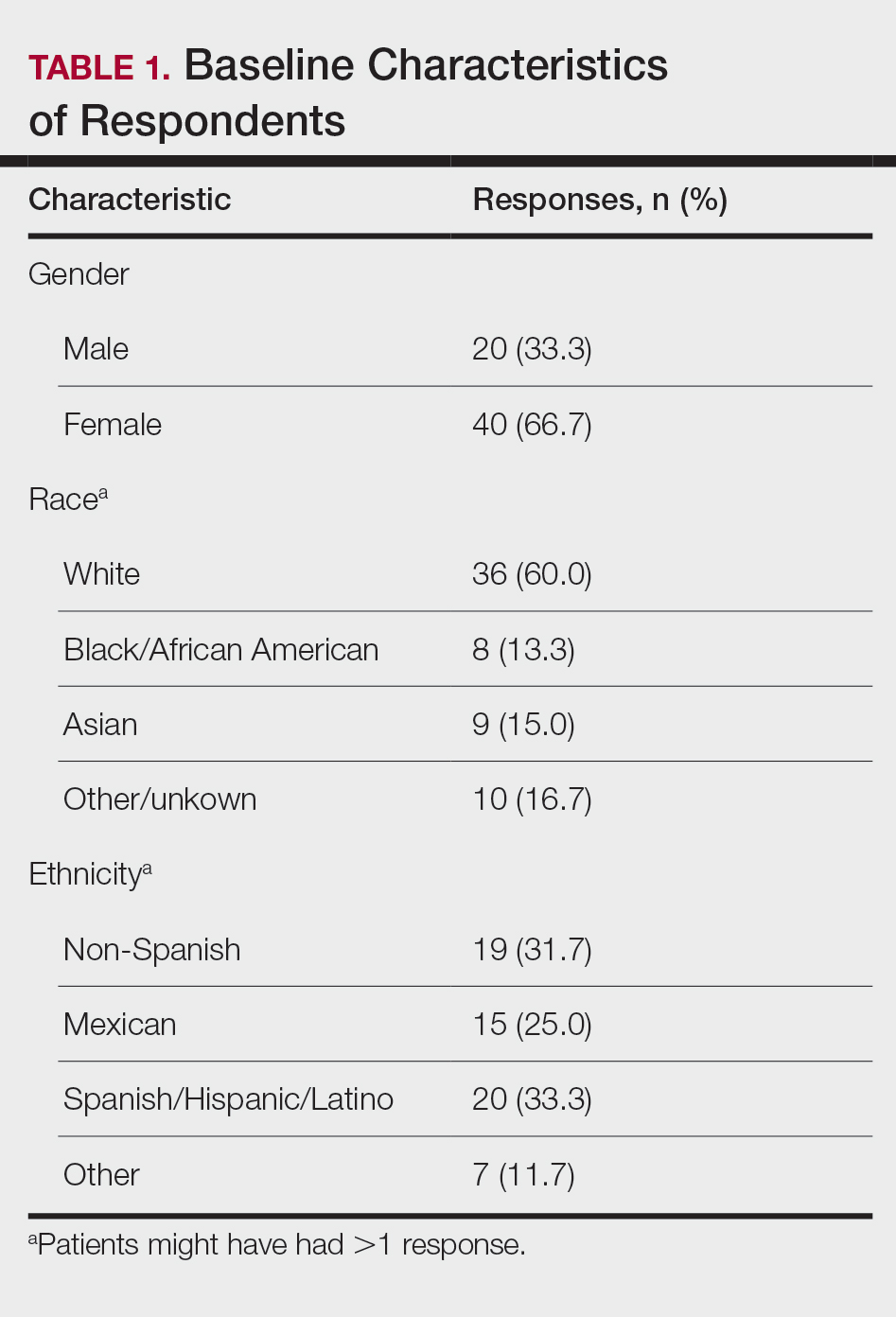

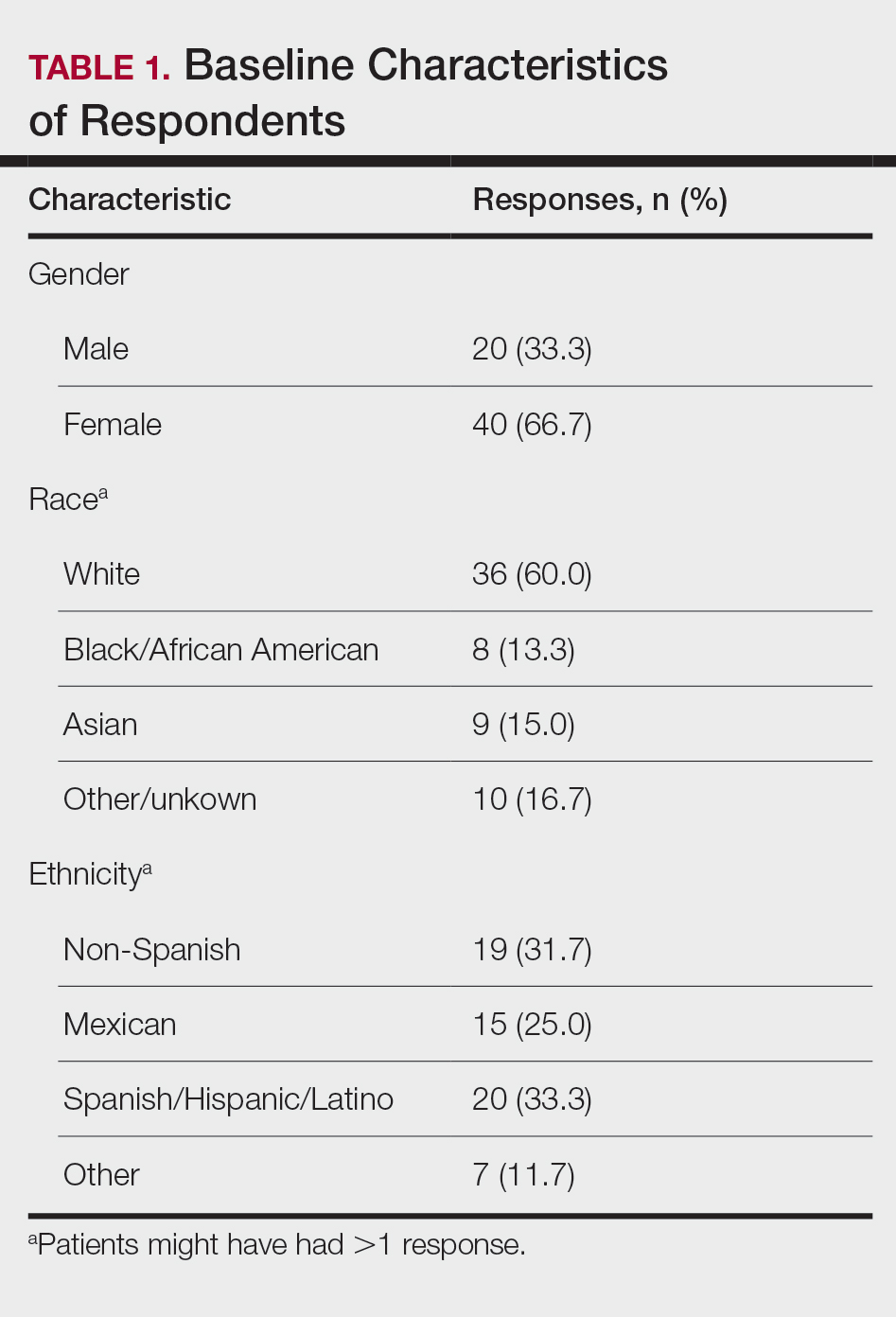

Sixty patients responded to the survey. The mean age of respondents was 19.5 years. No surveys were excluded from the data set. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of respondents. Some respondents left questions unanswered, resulting in questions with fewer than 60 responses.

Among respondents to the survey, 70% (42/60) reported it is very important to protect their skin from sun exposure, and 30% (18/60) reported it is somewhat important. Regarding sunscreen use, 70% (42/60) indicated they use sunscreen only before outdoor activities, 12% (7/60) use sunscreen daily, and 17% (10/60) never use sunscreen. Of those who use sunscreen, 52% (28/54) do so to prevent skin damage and aging and 44% (24/54) to prevent skin cancer. Twenty-three percent (13/56) of respondents reported finding tanned skin attractive; 26% (14/55) reported wanting to be tan. Looking at race, 28% (10/36) of Whites, 25% (5/20) of Spanish/Hispanic/Latinos, and 22% (2/9) of Asians found tanned skin attractive; no Black respondents found tanned skin attractive.

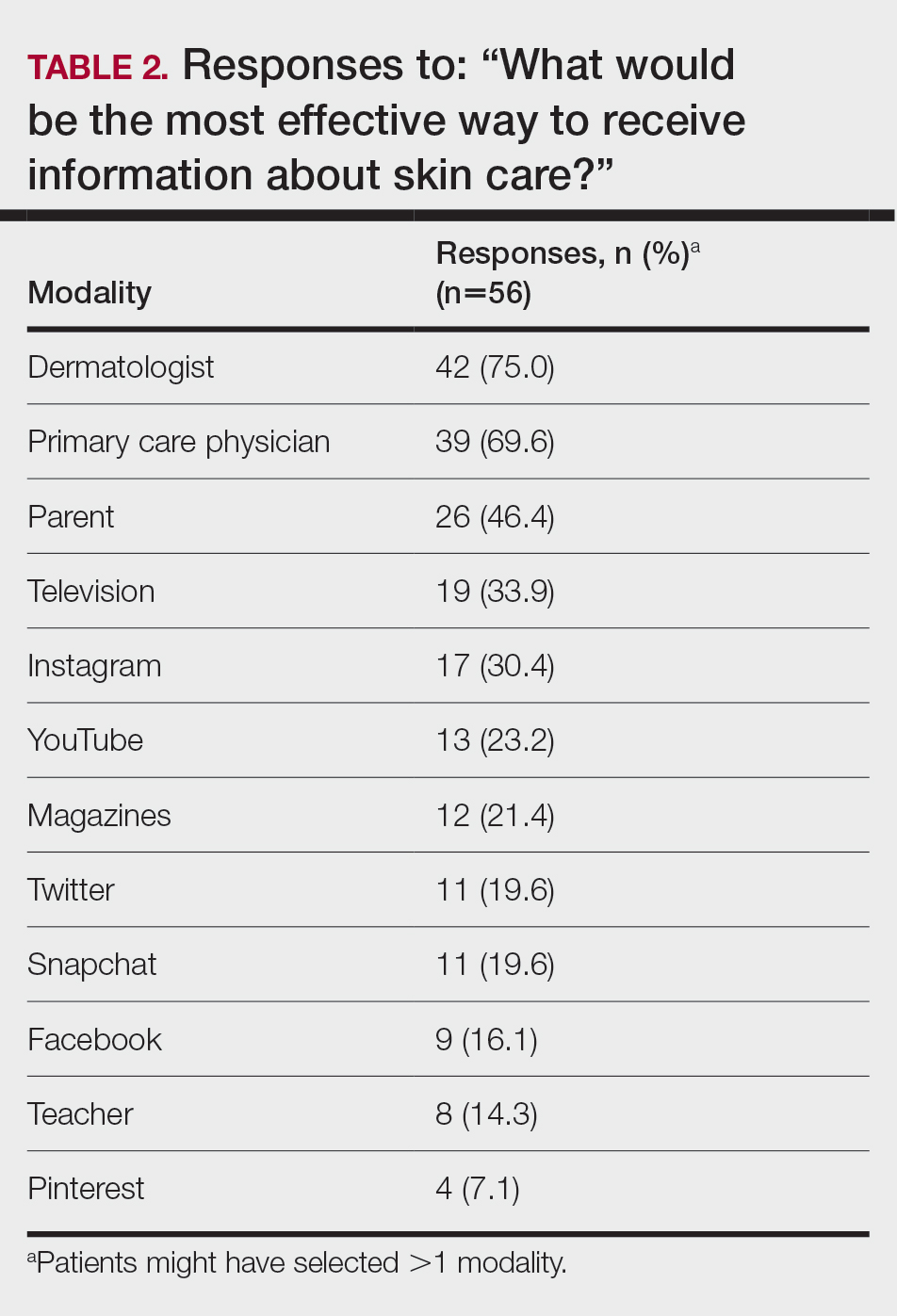

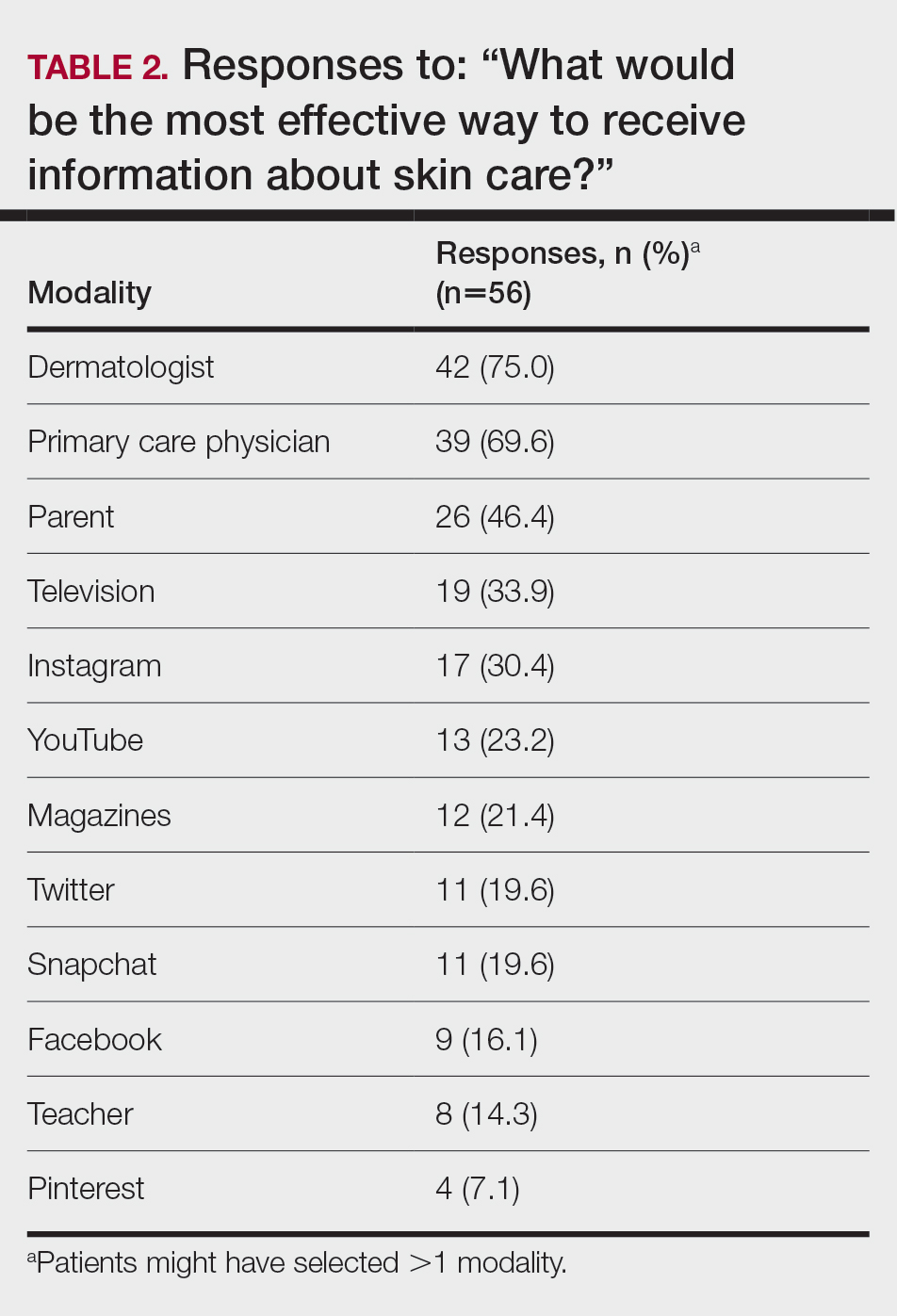

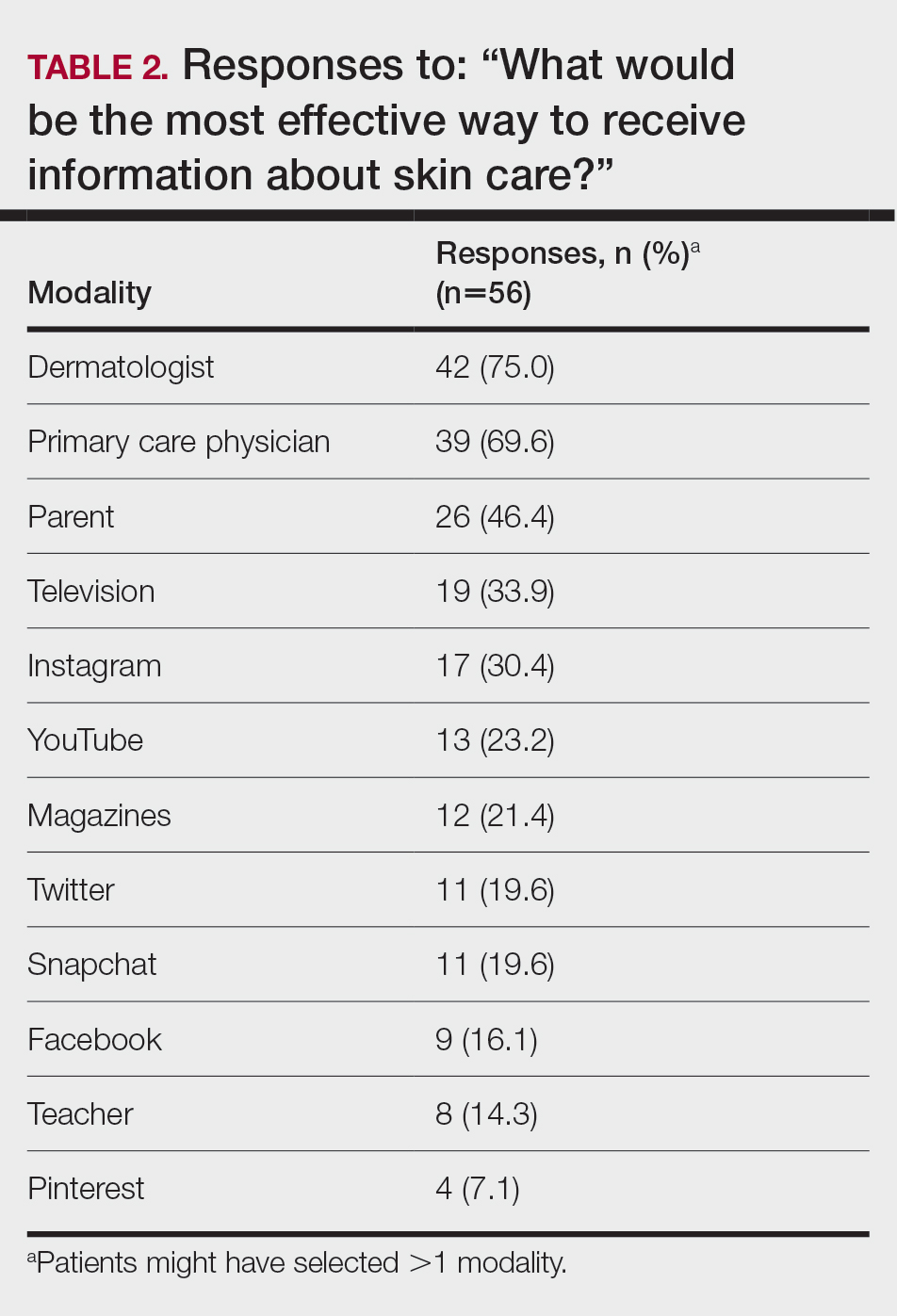

Regarding tanning, 12% (7/57) reported using a tanning bed in their lifetime and 4% (2/57) in the last year; 34% (19/56) reported deliberately tanning outdoors; and 9% (5/56) reported using sunless or spray-on tanning. Dermatologists (75% [42/56]), primary care physicians (69.6% [39/56]), and parents (46.4% [26/56]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education; among media modalities, television (33.9% [19/56]), Instagram (30.4% [17/60]), and YouTube (23.2% [13/60]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education (Table 2).

Comment

Perceptions of Tanning

Almost one-quarter of respondents found tanned skin attractive, which might reflect a shift from prior generations. Compared to the 11% of respondents in the 2010 survey,2 only 3.5% (2/57) of our respondents reported using a tanning bed in the last year, which could reflect the results of recent Texas legislation restricting the use of tanning beds by adolescents.

An alarming number of respondents reported going outdoors with the intention of tanning; although it appears that indoor tanning education has been successful, this finding shows that there is still a need for sun protection education because outdoor tanning is not a suitable alternative. A small number of respondents reported getting a sunless or spray-on tan, which is a risk-free alternative to indoor tanning.

Despite all respondents stating that protecting skin from the sun is important, most respondents surveyed do not use sunscreen daily. More respondents use sunscreen to prevent damage and aging than to prevent skin cancer. Young people might be more alarmed by the threat of early aging and losing their “youthful appearance” than by the possibility of developing skin cancer in the distant future. This discrepancy might indicate a lack of knowledge and be an important focus for future education efforts.

Perceptions of Trustworthiness of Education Sources

Our findings show dermatologists and primary care physicians are important educators on skin protection. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant to recognize at-risk patients who would benefit from skin protection education, especially those who do not see a dermatologist. Education of young people focusing on their concern over maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Although education provided by a physician is effective, using media—particularly social media—might be more efficient. Television, Instagram, and YouTube were listed by respondents as the 3 most preferred media outlets for skin health education, which shows important areas of focus for future advertising. Facebook was listed at a surprisingly low level, possibly showing the change in use of certain social media websites among this age group. According to the Pew Research Center, the most widely used social media apps among young adults aged 18 to 29 years are YouTube (91%), Facebook (63%), Instagram (67%), and Snapchat (62%). More than half of the same demographic visit Facebook (74%), Instagram (63%), Snapchat (61%), and YouTube (51%) daily.5 Although respondents to our survey were not specifically asked about the frequency of their use of social media and our data set includes patients younger than 18 years, we know that social media use has been increasing over the last decade among adolescents.1 Therefore, we assume that more than one-half of respondents to our survey use their reported social media platforms daily.

Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist. Unlike printed pamphlets and posters, advertisements through social media can use metrics such as age, race, gender, and interests to target high-risk individuals.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study of currently enrolled dermatology patients who might be more aware of skin protection than the general population because they are being treated by a dermatologist. Survey questions regarding demographics, required by our institution, could not effectively differentiate Hispanic and White patients. Respondents could have been subject to the Hawthorne effect—awareness that their behavior is being observed—when responding to the survey because it was administered in the office prior to being seen by a dermatologist.

- Falzone AE, Brindis CD, Chren M-M, et al. Teens, tweets, and tanning beds: rethinking the use of social media for skin cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S86-S94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on indoor tanning. Amended November 14, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Indoor%20Tanning%2011-16-09.pdf?

- American Academy of Dermatology. Indoor tanning. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-indoor-tanning

- Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center; April 10, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

Intentional tanning—through sun exposure and tanning beds—is an easily avoidable contributor to skin cancer development and an important area for public education. Since the advent of social media, a correlation between social media use and increased indoor tanning behaviors has been reported.1 In 2010, 11.3% of US adults aged 18 to 29 years reported using a tanning bed in the last 12 months.2 The American Academy of Dermatology first published their “Position Statement on Indoor Tanning” in 1998, endorsing a ban on the sale of indoor tanning equipment for nonmedical purposes.3

Although there has been no outright ban on indoor tanning, regulations have been put in place in many states—including Texas, where (as of 2013) a person younger than 18 years must have written consent from their parent(s) to use a tanning bed. Despite efforts of organizations including the American Academy of Dermatology and the government to educate the public on skin cancer prevention and sun safety, the skin cancer rate has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years.

There is a constant campaign among dermatologists to educate their patients on how to reduce or avoid the risk for skin cancer, including the use of sunscreen and avoidance of tanning. Adolescents and young adults are an especially important demographic to reach and educate because increased UV light exposure during these years leads to a greatly increased risk for skin cancer later in life.4 Data on the overall prevalence of tanning and the demographics of participation in tanning activities are important to capture and can be used to efficiently target higher-risk populations.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults regarding sun protection and tanning. We also aimed to determine which avenues, including social media, would be most effective at educating about skin cancer awareness and sun protection to the higher-risk younger population.

Materials and Methods

We developed an institutional review board–approved protocol for the prospective collection of data from registered patients at the dermatology clinic of the Mays Cancer Center at the University of Texas Health at San Antonio. A paper survey containing 15 rating-scale questions was administered to 60 patients aged 13 to 27 years. Surveys were administered during intake, prior to the patients’ visit with a dermatologist; all visits were of a functional (not cosmetic) nature. Data collection spanned June to August 2018. Survey results were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software for qualitative analysis.

Results

Sixty patients responded to the survey. The mean age of respondents was 19.5 years. No surveys were excluded from the data set. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of respondents. Some respondents left questions unanswered, resulting in questions with fewer than 60 responses.

Among respondents to the survey, 70% (42/60) reported it is very important to protect their skin from sun exposure, and 30% (18/60) reported it is somewhat important. Regarding sunscreen use, 70% (42/60) indicated they use sunscreen only before outdoor activities, 12% (7/60) use sunscreen daily, and 17% (10/60) never use sunscreen. Of those who use sunscreen, 52% (28/54) do so to prevent skin damage and aging and 44% (24/54) to prevent skin cancer. Twenty-three percent (13/56) of respondents reported finding tanned skin attractive; 26% (14/55) reported wanting to be tan. Looking at race, 28% (10/36) of Whites, 25% (5/20) of Spanish/Hispanic/Latinos, and 22% (2/9) of Asians found tanned skin attractive; no Black respondents found tanned skin attractive.

Regarding tanning, 12% (7/57) reported using a tanning bed in their lifetime and 4% (2/57) in the last year; 34% (19/56) reported deliberately tanning outdoors; and 9% (5/56) reported using sunless or spray-on tanning. Dermatologists (75% [42/56]), primary care physicians (69.6% [39/56]), and parents (46.4% [26/56]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education; among media modalities, television (33.9% [19/56]), Instagram (30.4% [17/60]), and YouTube (23.2% [13/60]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education (Table 2).

Comment

Perceptions of Tanning

Almost one-quarter of respondents found tanned skin attractive, which might reflect a shift from prior generations. Compared to the 11% of respondents in the 2010 survey,2 only 3.5% (2/57) of our respondents reported using a tanning bed in the last year, which could reflect the results of recent Texas legislation restricting the use of tanning beds by adolescents.

An alarming number of respondents reported going outdoors with the intention of tanning; although it appears that indoor tanning education has been successful, this finding shows that there is still a need for sun protection education because outdoor tanning is not a suitable alternative. A small number of respondents reported getting a sunless or spray-on tan, which is a risk-free alternative to indoor tanning.

Despite all respondents stating that protecting skin from the sun is important, most respondents surveyed do not use sunscreen daily. More respondents use sunscreen to prevent damage and aging than to prevent skin cancer. Young people might be more alarmed by the threat of early aging and losing their “youthful appearance” than by the possibility of developing skin cancer in the distant future. This discrepancy might indicate a lack of knowledge and be an important focus for future education efforts.

Perceptions of Trustworthiness of Education Sources

Our findings show dermatologists and primary care physicians are important educators on skin protection. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant to recognize at-risk patients who would benefit from skin protection education, especially those who do not see a dermatologist. Education of young people focusing on their concern over maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Although education provided by a physician is effective, using media—particularly social media—might be more efficient. Television, Instagram, and YouTube were listed by respondents as the 3 most preferred media outlets for skin health education, which shows important areas of focus for future advertising. Facebook was listed at a surprisingly low level, possibly showing the change in use of certain social media websites among this age group. According to the Pew Research Center, the most widely used social media apps among young adults aged 18 to 29 years are YouTube (91%), Facebook (63%), Instagram (67%), and Snapchat (62%). More than half of the same demographic visit Facebook (74%), Instagram (63%), Snapchat (61%), and YouTube (51%) daily.5 Although respondents to our survey were not specifically asked about the frequency of their use of social media and our data set includes patients younger than 18 years, we know that social media use has been increasing over the last decade among adolescents.1 Therefore, we assume that more than one-half of respondents to our survey use their reported social media platforms daily.

Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist. Unlike printed pamphlets and posters, advertisements through social media can use metrics such as age, race, gender, and interests to target high-risk individuals.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study of currently enrolled dermatology patients who might be more aware of skin protection than the general population because they are being treated by a dermatologist. Survey questions regarding demographics, required by our institution, could not effectively differentiate Hispanic and White patients. Respondents could have been subject to the Hawthorne effect—awareness that their behavior is being observed—when responding to the survey because it was administered in the office prior to being seen by a dermatologist.

Intentional tanning—through sun exposure and tanning beds—is an easily avoidable contributor to skin cancer development and an important area for public education. Since the advent of social media, a correlation between social media use and increased indoor tanning behaviors has been reported.1 In 2010, 11.3% of US adults aged 18 to 29 years reported using a tanning bed in the last 12 months.2 The American Academy of Dermatology first published their “Position Statement on Indoor Tanning” in 1998, endorsing a ban on the sale of indoor tanning equipment for nonmedical purposes.3

Although there has been no outright ban on indoor tanning, regulations have been put in place in many states—including Texas, where (as of 2013) a person younger than 18 years must have written consent from their parent(s) to use a tanning bed. Despite efforts of organizations including the American Academy of Dermatology and the government to educate the public on skin cancer prevention and sun safety, the skin cancer rate has been steadily increasing over the last 20 years.

There is a constant campaign among dermatologists to educate their patients on how to reduce or avoid the risk for skin cancer, including the use of sunscreen and avoidance of tanning. Adolescents and young adults are an especially important demographic to reach and educate because increased UV light exposure during these years leads to a greatly increased risk for skin cancer later in life.4 Data on the overall prevalence of tanning and the demographics of participation in tanning activities are important to capture and can be used to efficiently target higher-risk populations.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults regarding sun protection and tanning. We also aimed to determine which avenues, including social media, would be most effective at educating about skin cancer awareness and sun protection to the higher-risk younger population.

Materials and Methods

We developed an institutional review board–approved protocol for the prospective collection of data from registered patients at the dermatology clinic of the Mays Cancer Center at the University of Texas Health at San Antonio. A paper survey containing 15 rating-scale questions was administered to 60 patients aged 13 to 27 years. Surveys were administered during intake, prior to the patients’ visit with a dermatologist; all visits were of a functional (not cosmetic) nature. Data collection spanned June to August 2018. Survey results were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software for qualitative analysis.

Results

Sixty patients responded to the survey. The mean age of respondents was 19.5 years. No surveys were excluded from the data set. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of respondents. Some respondents left questions unanswered, resulting in questions with fewer than 60 responses.

Among respondents to the survey, 70% (42/60) reported it is very important to protect their skin from sun exposure, and 30% (18/60) reported it is somewhat important. Regarding sunscreen use, 70% (42/60) indicated they use sunscreen only before outdoor activities, 12% (7/60) use sunscreen daily, and 17% (10/60) never use sunscreen. Of those who use sunscreen, 52% (28/54) do so to prevent skin damage and aging and 44% (24/54) to prevent skin cancer. Twenty-three percent (13/56) of respondents reported finding tanned skin attractive; 26% (14/55) reported wanting to be tan. Looking at race, 28% (10/36) of Whites, 25% (5/20) of Spanish/Hispanic/Latinos, and 22% (2/9) of Asians found tanned skin attractive; no Black respondents found tanned skin attractive.

Regarding tanning, 12% (7/57) reported using a tanning bed in their lifetime and 4% (2/57) in the last year; 34% (19/56) reported deliberately tanning outdoors; and 9% (5/56) reported using sunless or spray-on tanning. Dermatologists (75% [42/56]), primary care physicians (69.6% [39/56]), and parents (46.4% [26/56]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education; among media modalities, television (33.9% [19/56]), Instagram (30.4% [17/60]), and YouTube (23.2% [13/60]) were perceived as more effective sources of skin care education (Table 2).

Comment

Perceptions of Tanning

Almost one-quarter of respondents found tanned skin attractive, which might reflect a shift from prior generations. Compared to the 11% of respondents in the 2010 survey,2 only 3.5% (2/57) of our respondents reported using a tanning bed in the last year, which could reflect the results of recent Texas legislation restricting the use of tanning beds by adolescents.

An alarming number of respondents reported going outdoors with the intention of tanning; although it appears that indoor tanning education has been successful, this finding shows that there is still a need for sun protection education because outdoor tanning is not a suitable alternative. A small number of respondents reported getting a sunless or spray-on tan, which is a risk-free alternative to indoor tanning.

Despite all respondents stating that protecting skin from the sun is important, most respondents surveyed do not use sunscreen daily. More respondents use sunscreen to prevent damage and aging than to prevent skin cancer. Young people might be more alarmed by the threat of early aging and losing their “youthful appearance” than by the possibility of developing skin cancer in the distant future. This discrepancy might indicate a lack of knowledge and be an important focus for future education efforts.

Perceptions of Trustworthiness of Education Sources

Our findings show dermatologists and primary care physicians are important educators on skin protection. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant to recognize at-risk patients who would benefit from skin protection education, especially those who do not see a dermatologist. Education of young people focusing on their concern over maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Although education provided by a physician is effective, using media—particularly social media—might be more efficient. Television, Instagram, and YouTube were listed by respondents as the 3 most preferred media outlets for skin health education, which shows important areas of focus for future advertising. Facebook was listed at a surprisingly low level, possibly showing the change in use of certain social media websites among this age group. According to the Pew Research Center, the most widely used social media apps among young adults aged 18 to 29 years are YouTube (91%), Facebook (63%), Instagram (67%), and Snapchat (62%). More than half of the same demographic visit Facebook (74%), Instagram (63%), Snapchat (61%), and YouTube (51%) daily.5 Although respondents to our survey were not specifically asked about the frequency of their use of social media and our data set includes patients younger than 18 years, we know that social media use has been increasing over the last decade among adolescents.1 Therefore, we assume that more than one-half of respondents to our survey use their reported social media platforms daily.

Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist. Unlike printed pamphlets and posters, advertisements through social media can use metrics such as age, race, gender, and interests to target high-risk individuals.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study of currently enrolled dermatology patients who might be more aware of skin protection than the general population because they are being treated by a dermatologist. Survey questions regarding demographics, required by our institution, could not effectively differentiate Hispanic and White patients. Respondents could have been subject to the Hawthorne effect—awareness that their behavior is being observed—when responding to the survey because it was administered in the office prior to being seen by a dermatologist.

- Falzone AE, Brindis CD, Chren M-M, et al. Teens, tweets, and tanning beds: rethinking the use of social media for skin cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S86-S94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on indoor tanning. Amended November 14, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Indoor%20Tanning%2011-16-09.pdf?

- American Academy of Dermatology. Indoor tanning. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-indoor-tanning

- Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center; April 10, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

- Falzone AE, Brindis CD, Chren M-M, et al. Teens, tweets, and tanning beds: rethinking the use of social media for skin cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3 suppl 1):S86-S94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of indoor tanning devices by adults—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:323-326.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on indoor tanning. Amended November 14, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Indoor%20Tanning%2011-16-09.pdf?

- American Academy of Dermatology. Indoor tanning. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-indoor-tanning

- Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center; April 10, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists are the preferred educators of skin care for adolescents and young adults.

- Social media is an underused medium for skin cancer prevention education and can reach those who do not regularly see a dermatologist.

- Education of young people focusing on their concerns about maintaining a youthful appearance instead of the possibility of developing skin cancer in the future might be more effective.

Communication Strategies in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Methods, Time Savings, and Perceived Patient Satisfaction

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

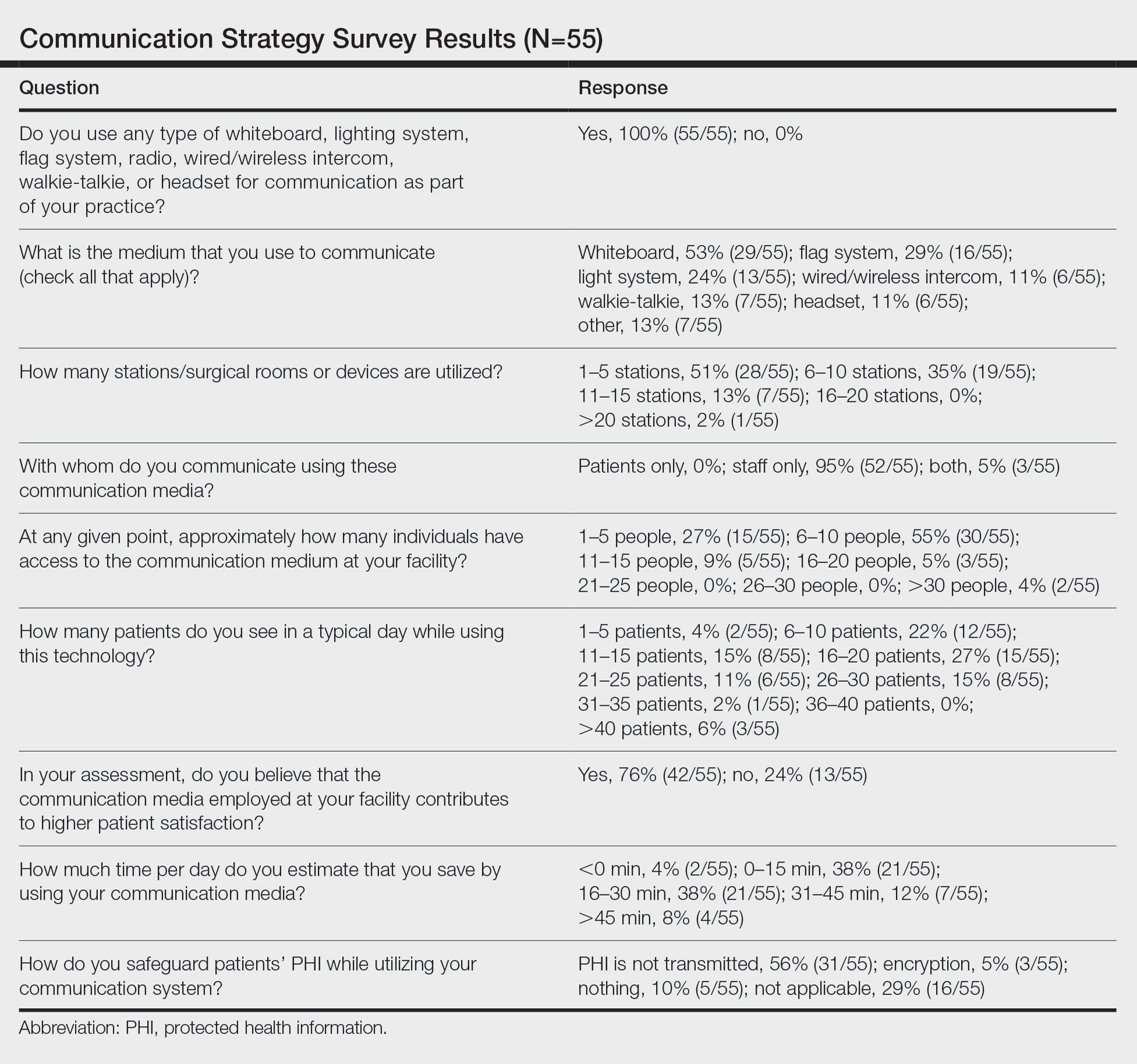

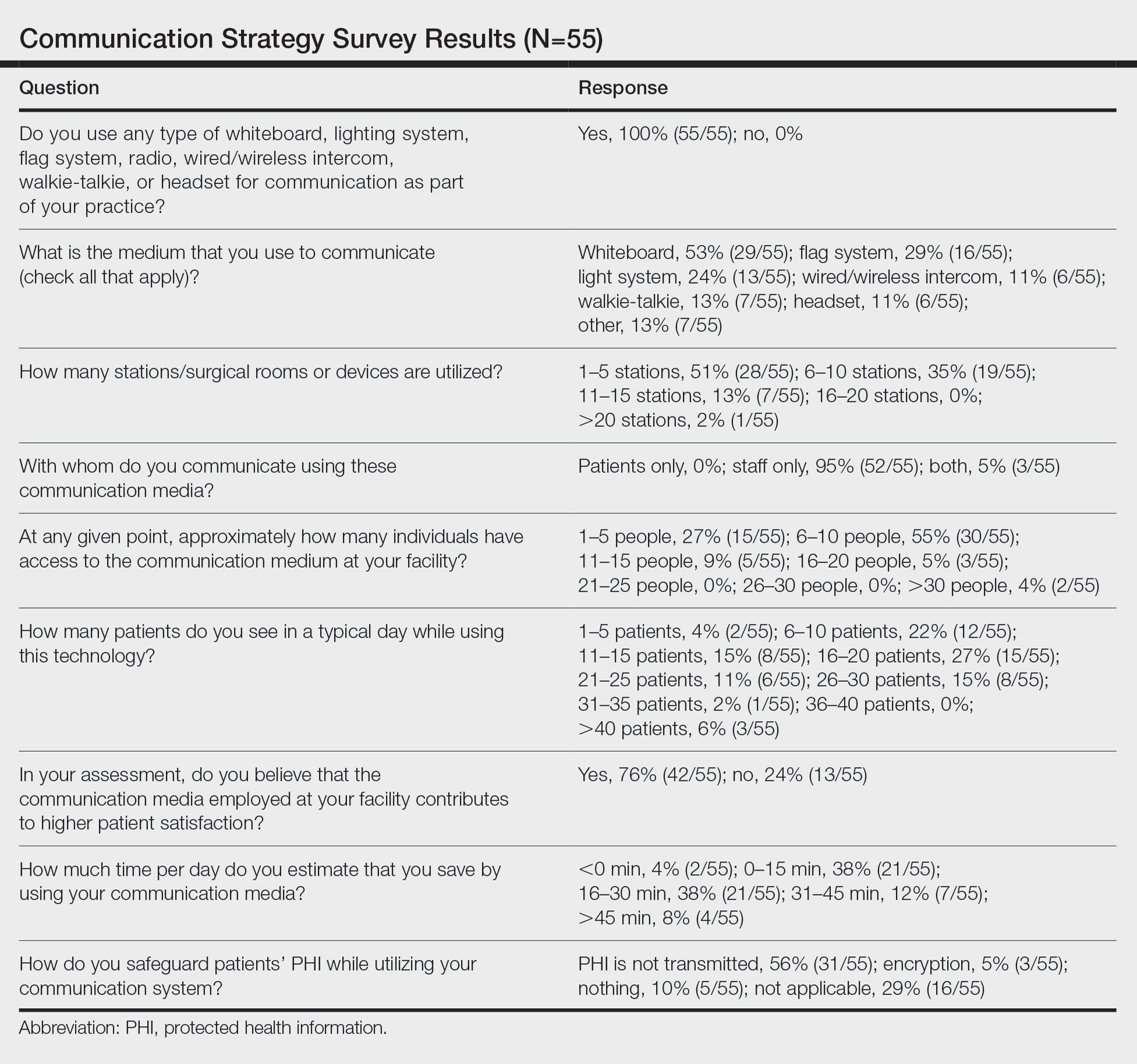

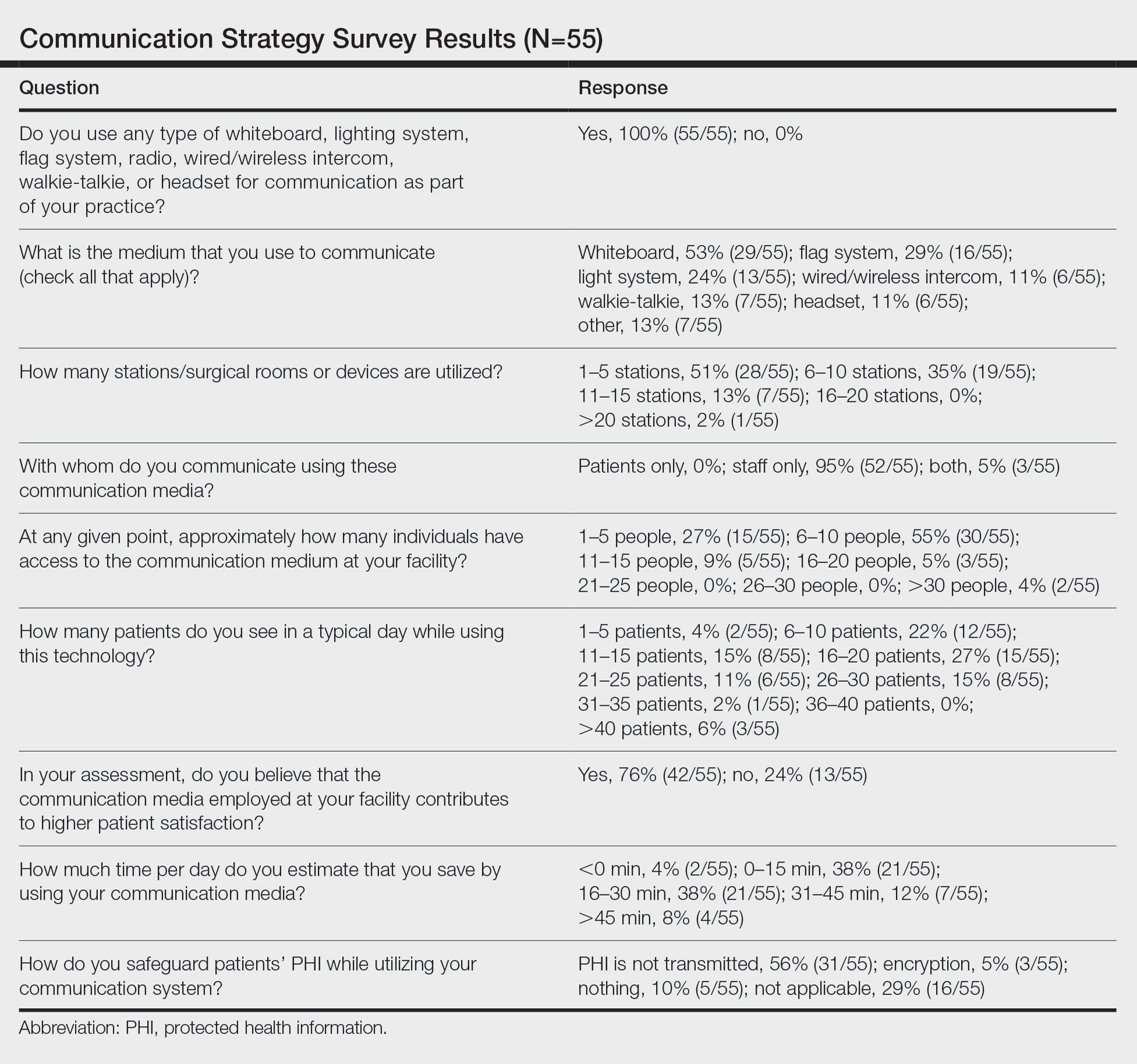

Results

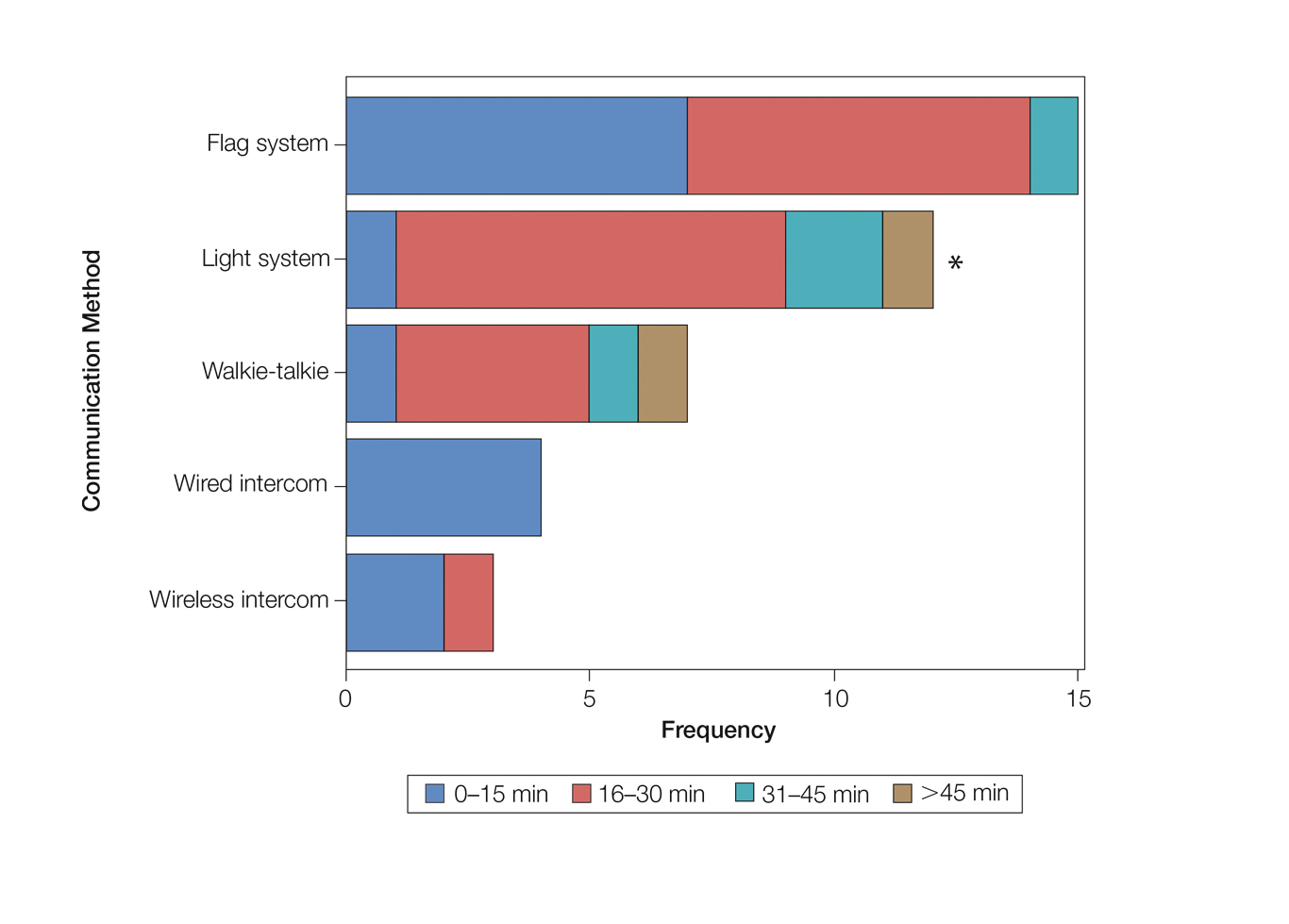

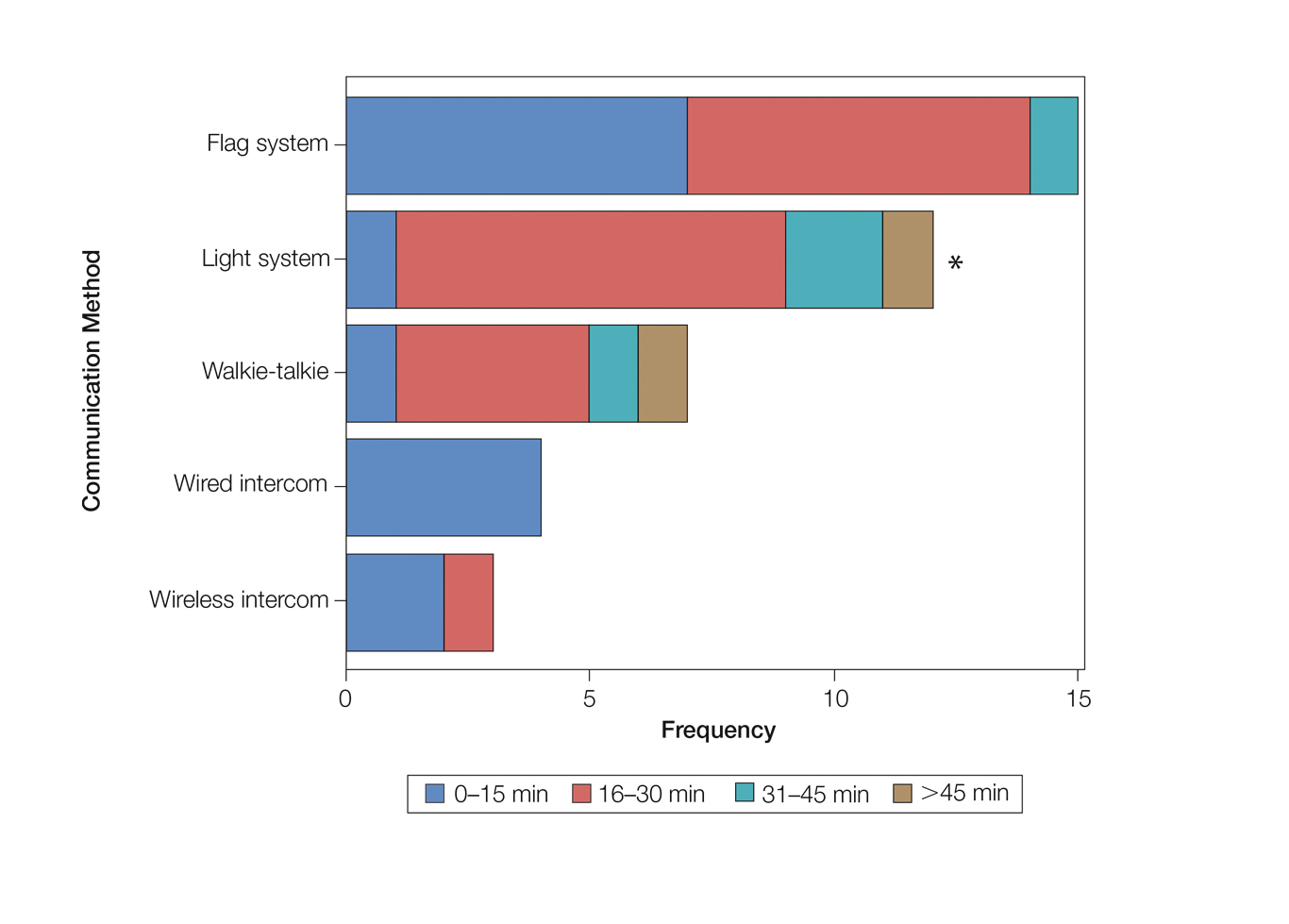

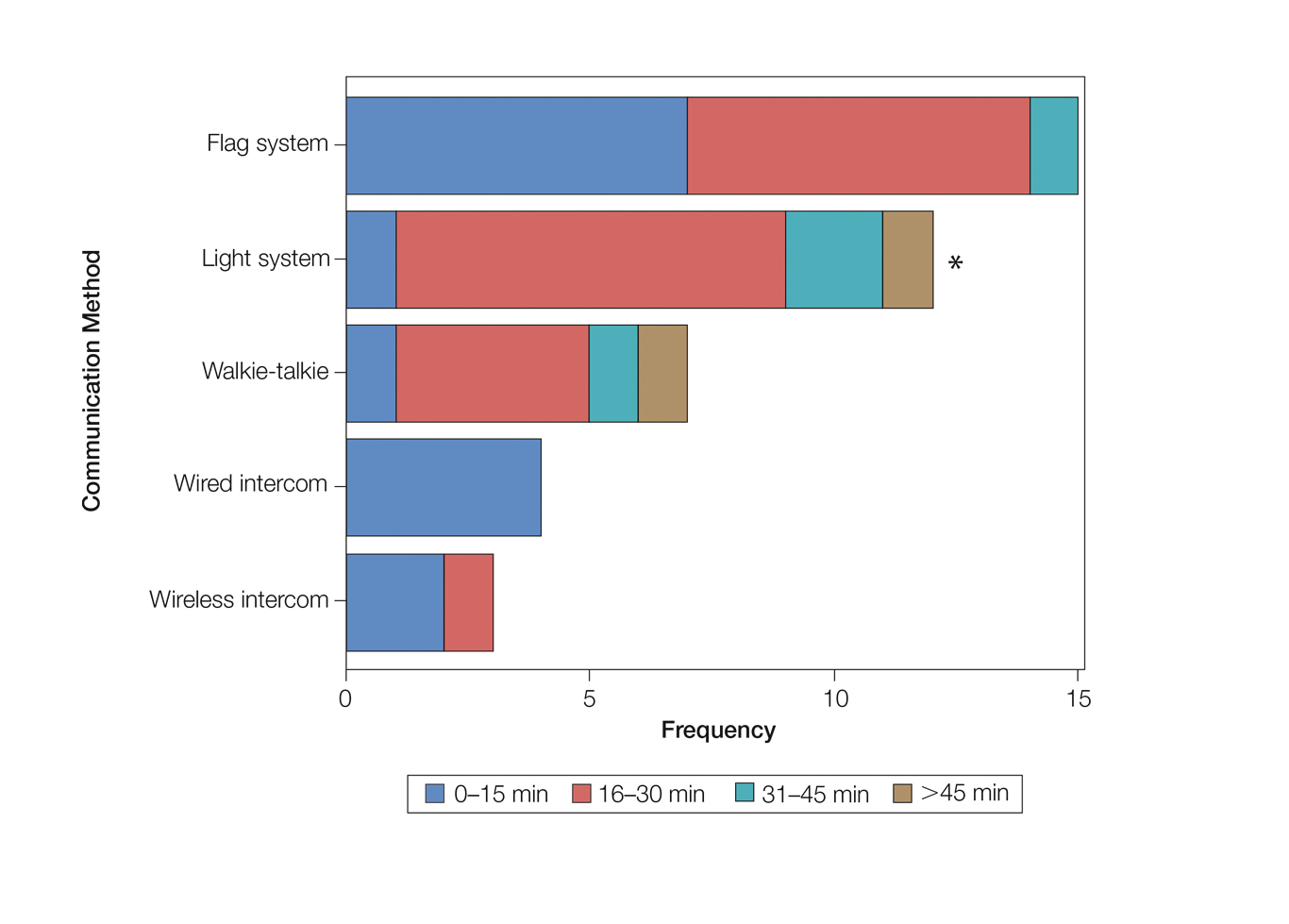

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

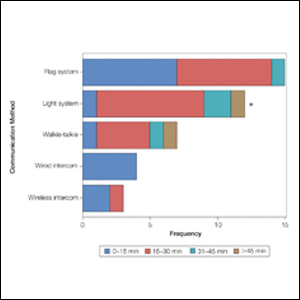

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

Results

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) entails multiple time-consuming surgical and histological examinations for each patient. As surgical stages are performed and histological sections are processed, an efficient communication method among providers, medical assistants, histotechnologists, and patients is necessary to avoid delays. To address these and other communication issues, providers have focused on ways to increase clinic efficiency and improve patient-reported outcomes by utilizing new or repurposed communication technologies in their Mohs practice.

Prior reports have highlighted the utility of hands-free headsets that allow real-time communication among staff members as a means of increasing clinic efficiency and decreasing patient wait times.1-4 These systems may mediate a more rapid turnover between stages by mitigating the need for surgeons and support staff to assemble within a designated workspace.1,3,4 However, there is no single or standardized communication method that best suits all surgical suites and MMS practices. Our study aimed to identify the current communication strategies employed by Mohs surgeons and thereby ascertain which method(s) portend(s) the highest benefit in average daily time savings and provider-perceived patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

A new 10-question electronic survey was published on the SurveyMonkey website, and a link to the survey was provided in a quarterly email that originated from the American College of Mohs Surgery and was distributed to all 1735 active members. Responses were obtained from January 2019 to February 2019.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was done to determine any significant associations among the providers’ responses. P<.05 was used to determine statistical significance. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to identify significant associations between the number of rooms and the communication systems that were used. Thus, 7 total tests—1 for each device (whiteboard, light system, flag system, wired intercom, wireless intercom, walkie-talkie, or headset)—were conducted. The Cochran-Armitage test also was used to determine whether the probability of using the device was affected by the number of stations/surgical rooms that were attended by the Mohs surgeons. To determine whether the communication devices used were associated with higher patient satisfaction, a χ2 test was conducted for each device (7 total tests), testing the categories of using that device (yes/no) and patient satisfaction (yes/no). A Fisher exact test of independence was used in any case where the proportion for the device and patient satisfaction was 25% or higher. To determine whether the communication method was associated with increased time savings, 7 total Cochran-Armitage tests were conducted, 1 for each device. A logistic regression model was used to determine whether there was a significant association between the number of stations and the likelihood of reporting patient satisfaction.

Results

Eighty-eight surgeons responded to the survey, with a response rate of 5% (88/1735). A total of 55 surgeons completed the survey in its entirety and were included in the data analysis. The most commonly used communication mediums were whiteboards (29/55 [53%]), followed by a flag system (16/55 [29%]) and a light system (13/55 [24%]). Most Mohs surgeons (52/55 [95%]) used the communication media to communicate with their staff only, and 76% (42/55) of Mohs surgeons believed that their communication media contributed to higher patient satisfaction. Overall, 58% (32/55) of Mohs surgeons stated that their communication media saved more than 15 minutes (on average) per day. The use of a whiteboard and/or flag system was reported as the least efficient method, with average daily time savings of 13 minutes. With the introduction of newer technology (wired or wireless intercoms, headsets, walkie-talkies, or internal messaging systems such as Skype) to the whiteboard and/or flag system, the time savings increased by 10 minutes per day. Nearly 25% (14/55) of surgeons utilized more than 1 communication system.

As the number of stations in an MMS suite increased, the probability of using a whiteboard to track the progress of the cases decreased. There were no statistically significant associations identified between the number of stations and the use of other communication devices (ie, flag system, light system, wireless intercom, wired intercom, walkie-talkie, headset). The stratified percentages of the amount of time savings for each communication modality are presented in the Figure (whiteboards and headsets were excluded because they did not increase time savings). The use of a light system was the only communication modality found to be statistically associated with an increase in provider-reported time savings (P=.0482; Figure). In addition, our analysis did not show an improvement in provider-reported patient satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics.

Comment

The process of transmitting information among the medical team during MMS is a complex interplay involving the relay of crucial information, with many opportunities for the introduction of distraction and error. Despite numerous improvements in the efficiency of the preparation of histological specimens and implementation of various time-saving and tissue-saving surgical interventions, relatively little attention has been given to address the sometimes chaotic and challenging process of organizing results from each stage of multiple patients in an MMS surgical suite.5

As demonstrated by our survey, incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic may improve workplace efficiency by decreasing the redundant use of support staff and allowing Mohs surgeons to transition from one station to the next seamlessly. Light-based communication systems provide an immediate notification for support staff via color-coded and/or numerically coded indicators on input switches located outside and inside the examination/surgery rooms. The switch indicators can be depressed with minimal disruption from station to station, thereby foregoing the need to interrupt an ongoing excision or closure to convey the status of the case. These systems may then permit enhanced clinic and workflow efficiency, which may help to shorten patient wait times.

Study Limitation

Although all members of the American College of Mohs Surgery were invited to participate in this online survey, only a small number (N=55) completed it in its entirety. Moreover, sample sizes for some of the communication devices were small. As a result, many of the tests might be lacking sufficient power to detect possible relationships, which might be identified in future larger-scale studies.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of light-based communication systems in MMS suites to improve efficiency in the clinic. Based on our analysis, light-based communication methods were significantly associated with improved time savings (P=.0482). Our study did not show an improvement in provider-reported satisfaction with any of the current systems used in MMS clinics. We hope that this information will help guide providers in implementing new communication techniques to improve clinic efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kathy Kyler (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) for her assistance in preparing this manuscript. Support for Dr. Chen and Mr. Stubblefield was provided through National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant 2U54GM104938-06, PI Judith James].

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

- Chen T, Vines L, Wanitphakdeedecha R, et al. Electronically linked: wireless, discrete, hands-free communication to improve surgical workflow in Mohs and dermasurgery clinic. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:248-252.

- Lanto AB, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Anatomy of an outpatient visit. An evaluation of clinic efficiency in general and subspecialty clinics. Med Group Manage J. 1995;42:18-25.

- Kantor J. Application of Google Glass to Mohs micrographic surgery: a pilot study in 120 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:288-289.

- Spurk PA, Mohr ML, Seroka AM, et al. The impact of a wireless telecommunication system on efficiency. J Nurs Admin. 1995;25:21-26.

- Dietert JB, MacFarlane DF. A survey of Mohs tissue tracking practices. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:514-518.

Practice Points

- There are limited studies evaluating the efficacy of different communication methods in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) clinics.

- This study suggests that incorporation of a light-based system into an MMS clinic improves workplace efficiency.

Checkpoint inhibitor skin side effects more common in women

of 235 patients at Dana Farber Cancer Center, Boston.

Overall, 62.4% of the 93 women in the review and 48.6% of the 142 men experienced confirmed skin reactions, for an odds ratio (OR) of 2.11 for women compared with men (P = .01).

“Clinicians should consider these results in counseling female patients regarding an elevated risk of dermatologic adverse events” when taking checkpoint inhibitors, said investigators led by Harvard University medical student Jordan Said, who presented the results at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

Autoimmune-like adverse events are common with checkpoint inhibitors. Dermatologic side effects occur in about half of people receiving monotherapy and more than that among patients receiving combination therapy.

Skin reactions can include psoriasiform dermatitis, lichenoid reactions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid and may require hospitalization and prolonged steroid treatment.

Not much is known about risk factors for these reactions. A higher incidence among women has been previously reported. A 2019 study found a higher risk for pneumonitis and endocrinopathy, including hypophysitis, among women who underwent treatment for non–small cell lung cancer or metastatic melanoma.

The 2019 study found that the risk was higher among premenopausal women than postmenopausal women, which led some to suggest that estrogen may play a role.

The results of the Dana Farber review argue against that notion. In their review, the investigators found that the risk was similarly elevated among the 27 premenopausal women (OR, 1.97; P = .40) and the 66 postmenopausal women (OR, 2.17, P = .05). In the study, women who were aged 52 years or older at the start of treatment were considered to be postmenopausal.

“This suggests that factors beyond sex hormones are likely contributory” to the difference in risk between men and women. It’s known that women are at higher risk for autoimmune disease overall, which might be related to the increased odds of autoimmune-like reactions, and it may be that sex-related differences in innate and adoptive immunity are at work, Mr. Said noted.

When asked for comment, Douglas Johnson, MD, assistant professor of hematology/oncology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said that although some studies have reported a greater risk for side effects among women, others have not. “Additional research is needed to determine the interactions between sex and effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as many other possible triggers of immune-related adverse events,” he said.

“Continued work in this area will be so important to help determine how to best counsel women and to ensure early recognition and intervention for dermatologic side effects,” said Bernice Kwong, MD, director of the Supportive Dermato-Oncology Program at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The patients in the review were treated from 2011 to 2016 and underwent at least monthly evaluations by their medical teams. They were taking either nivolumab, pembrolizumab, or ipilimumab or a nivolumab/ipilimumab combination.

The median age of the men in the study was 65 years; the median age of women was 60 years. Almost 98% of the participants were White. The majority received one to three infusions, most commonly with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

No funding for the study was reported. Mr. Said has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

of 235 patients at Dana Farber Cancer Center, Boston.

Overall, 62.4% of the 93 women in the review and 48.6% of the 142 men experienced confirmed skin reactions, for an odds ratio (OR) of 2.11 for women compared with men (P = .01).

“Clinicians should consider these results in counseling female patients regarding an elevated risk of dermatologic adverse events” when taking checkpoint inhibitors, said investigators led by Harvard University medical student Jordan Said, who presented the results at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

Autoimmune-like adverse events are common with checkpoint inhibitors. Dermatologic side effects occur in about half of people receiving monotherapy and more than that among patients receiving combination therapy.

Skin reactions can include psoriasiform dermatitis, lichenoid reactions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid and may require hospitalization and prolonged steroid treatment.

Not much is known about risk factors for these reactions. A higher incidence among women has been previously reported. A 2019 study found a higher risk for pneumonitis and endocrinopathy, including hypophysitis, among women who underwent treatment for non–small cell lung cancer or metastatic melanoma.

The 2019 study found that the risk was higher among premenopausal women than postmenopausal women, which led some to suggest that estrogen may play a role.

The results of the Dana Farber review argue against that notion. In their review, the investigators found that the risk was similarly elevated among the 27 premenopausal women (OR, 1.97; P = .40) and the 66 postmenopausal women (OR, 2.17, P = .05). In the study, women who were aged 52 years or older at the start of treatment were considered to be postmenopausal.

“This suggests that factors beyond sex hormones are likely contributory” to the difference in risk between men and women. It’s known that women are at higher risk for autoimmune disease overall, which might be related to the increased odds of autoimmune-like reactions, and it may be that sex-related differences in innate and adoptive immunity are at work, Mr. Said noted.

When asked for comment, Douglas Johnson, MD, assistant professor of hematology/oncology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said that although some studies have reported a greater risk for side effects among women, others have not. “Additional research is needed to determine the interactions between sex and effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as many other possible triggers of immune-related adverse events,” he said.

“Continued work in this area will be so important to help determine how to best counsel women and to ensure early recognition and intervention for dermatologic side effects,” said Bernice Kwong, MD, director of the Supportive Dermato-Oncology Program at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The patients in the review were treated from 2011 to 2016 and underwent at least monthly evaluations by their medical teams. They were taking either nivolumab, pembrolizumab, or ipilimumab or a nivolumab/ipilimumab combination.

The median age of the men in the study was 65 years; the median age of women was 60 years. Almost 98% of the participants were White. The majority received one to three infusions, most commonly with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

No funding for the study was reported. Mr. Said has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

of 235 patients at Dana Farber Cancer Center, Boston.

Overall, 62.4% of the 93 women in the review and 48.6% of the 142 men experienced confirmed skin reactions, for an odds ratio (OR) of 2.11 for women compared with men (P = .01).

“Clinicians should consider these results in counseling female patients regarding an elevated risk of dermatologic adverse events” when taking checkpoint inhibitors, said investigators led by Harvard University medical student Jordan Said, who presented the results at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

Autoimmune-like adverse events are common with checkpoint inhibitors. Dermatologic side effects occur in about half of people receiving monotherapy and more than that among patients receiving combination therapy.

Skin reactions can include psoriasiform dermatitis, lichenoid reactions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid and may require hospitalization and prolonged steroid treatment.

Not much is known about risk factors for these reactions. A higher incidence among women has been previously reported. A 2019 study found a higher risk for pneumonitis and endocrinopathy, including hypophysitis, among women who underwent treatment for non–small cell lung cancer or metastatic melanoma.

The 2019 study found that the risk was higher among premenopausal women than postmenopausal women, which led some to suggest that estrogen may play a role.

The results of the Dana Farber review argue against that notion. In their review, the investigators found that the risk was similarly elevated among the 27 premenopausal women (OR, 1.97; P = .40) and the 66 postmenopausal women (OR, 2.17, P = .05). In the study, women who were aged 52 years or older at the start of treatment were considered to be postmenopausal.

“This suggests that factors beyond sex hormones are likely contributory” to the difference in risk between men and women. It’s known that women are at higher risk for autoimmune disease overall, which might be related to the increased odds of autoimmune-like reactions, and it may be that sex-related differences in innate and adoptive immunity are at work, Mr. Said noted.

When asked for comment, Douglas Johnson, MD, assistant professor of hematology/oncology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said that although some studies have reported a greater risk for side effects among women, others have not. “Additional research is needed to determine the interactions between sex and effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as many other possible triggers of immune-related adverse events,” he said.

“Continued work in this area will be so important to help determine how to best counsel women and to ensure early recognition and intervention for dermatologic side effects,” said Bernice Kwong, MD, director of the Supportive Dermato-Oncology Program at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The patients in the review were treated from 2011 to 2016 and underwent at least monthly evaluations by their medical teams. They were taking either nivolumab, pembrolizumab, or ipilimumab or a nivolumab/ipilimumab combination.

The median age of the men in the study was 65 years; the median age of women was 60 years. Almost 98% of the participants were White. The majority received one to three infusions, most commonly with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

No funding for the study was reported. Mr. Said has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment Delay in Melanoma: A Risk Factor Analysis of an Impending Crisis

Melanoma is the most lethal skin cancer and is the second most common cancer in adolescents and young adults.1 It is the fifth most common cancer in the United States based on incidence, which has steadily risen for the last 2 decades.2,3 For melanoma management, delayed initial diagnosis has been associated with more advanced lesions at presentation and poorer outcomes.4 However, the prognostic implications of delaying melanoma management after diagnosis merits further scrutiny.

This study investigates the associations between melanoma treatment delay (MTD) and patient and tumor characteristics. Although most cases undergo surgical treatment first, more advanced stages may require initiating chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy. In addition, patients who are poor surgical candidates may opt for topical field therapy, such as imiquimod for superficial lesions, prior to more definitive treatment.5 In the Medicaid population, patients who are older than 85 years, married, and previously diagnosed with another melanoma and who also have an increased comorbidity burden have a higher likelihood of MTD.6 For nonmelanoma skin cancers, patient denial is the most common patient-specific factor accounting for treatment delay.7 For this study, our aim was to further evaluate the independent risk factors associated with MTD.

Methods

Case Selection

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was queried for all cutaneous melanoma cases from 2004 to 2015 (N=525,271). The NCDB is an oncology database sourced from more than 1500 accredited cancer facilities in the United States and Puerto Rico. It receives cases from academic hospitals, Veterans Health Administration hospitals, and community centers.8 Annually, the database collects approximately 70% of cancer diagnoses and 48% of melanoma diagnoses in the United States.9,10 Per institutional guidelines, this analysis was determined to be exempt from institutional review board approval due to the deidentified nature of the dataset.

The selection scheme is illustrated in Table 1. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems histology codes 8720/3 through 8780/3 combined with the site and morphology primary codes C44.0 through C44.9 identified all patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. Primary site was established with the histology codes in the following manner: C44.0 through C44.4 for head/neck primary, C44.5 for trunk primary, C44.6 through C44.7 for extremity primary, and C44.8 through C44.9 for not otherwise specified. Because the NCDB does not specify cause of death, any cases in which the melanoma diagnosis was not the patient’s primary (or first) cancer diagnosis were excluded because of potential ambiguity. Cases lacking histologic confirmation of the diagnosis after primary site biopsy or cases diagnosed from autopsy reports also were excluded. Reports missing staging data or undergoing palliative management were removed. In total, 104,118 cases met the inclusion criteria.

Variables of Interest

The NCDB database codes for a variable “Treatment Started, Days from Dx” are defined as the number of days between the date of diagnosis and the date on which treatment—surgery, radiation, systemic, or other therapy—of the patient began at any facility.11 Treatment delays were classified as more than 45 days or more than 90 days. These thresholds were chosen based on previous studies citing a 45-day recommendation as the timeframe in which primary site excision of melanoma should occur for improved outcomes.1,6,12 Additionally, the postponement cutoffs were aligned with prior studies on surgical delay in melanoma for the Medicaid population.6 Delays of 45 days were labeled as moderate MTD (mMTD), whereas postponements more than 90 days were designated as severe MTD (sMTD).

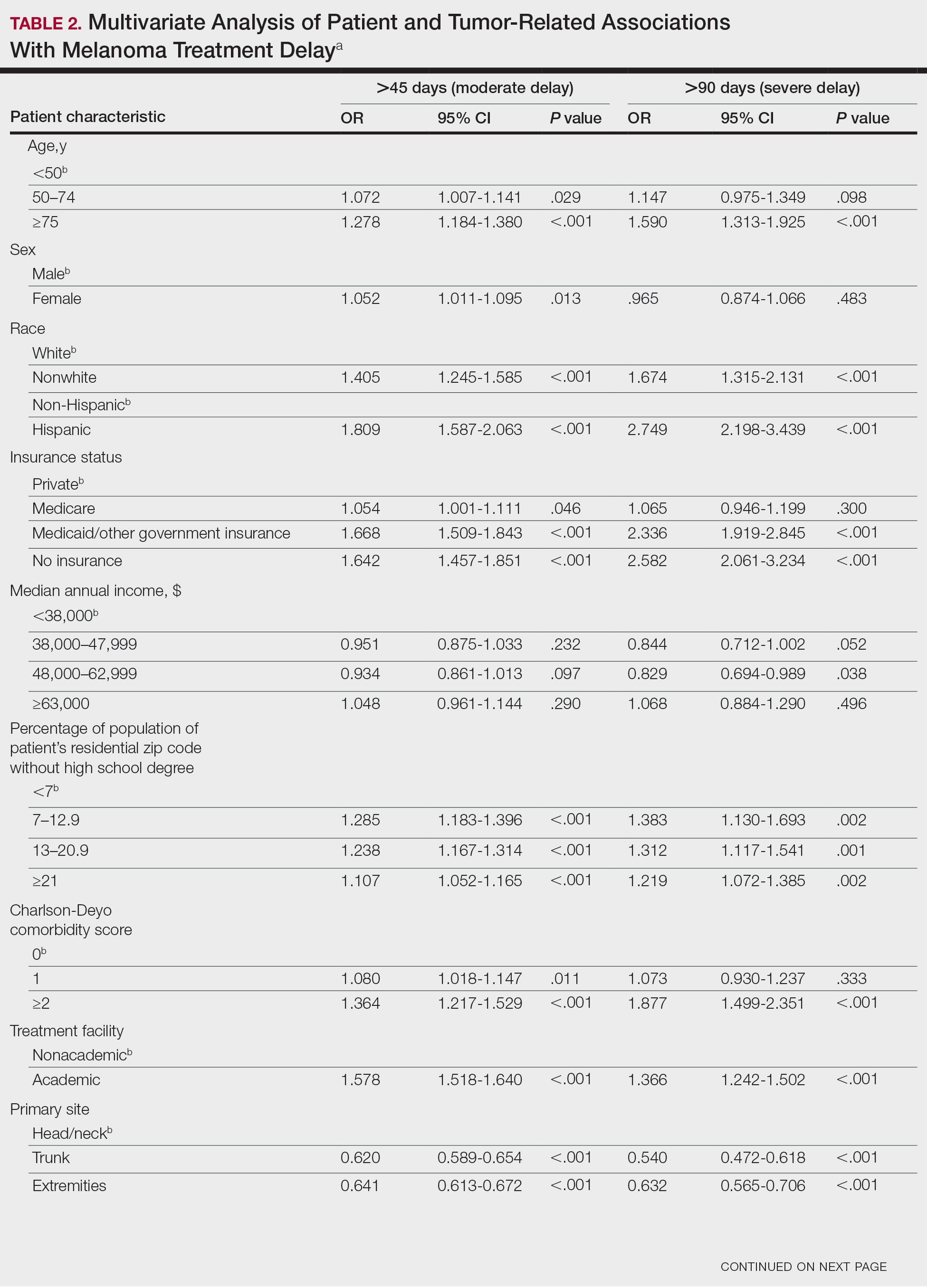

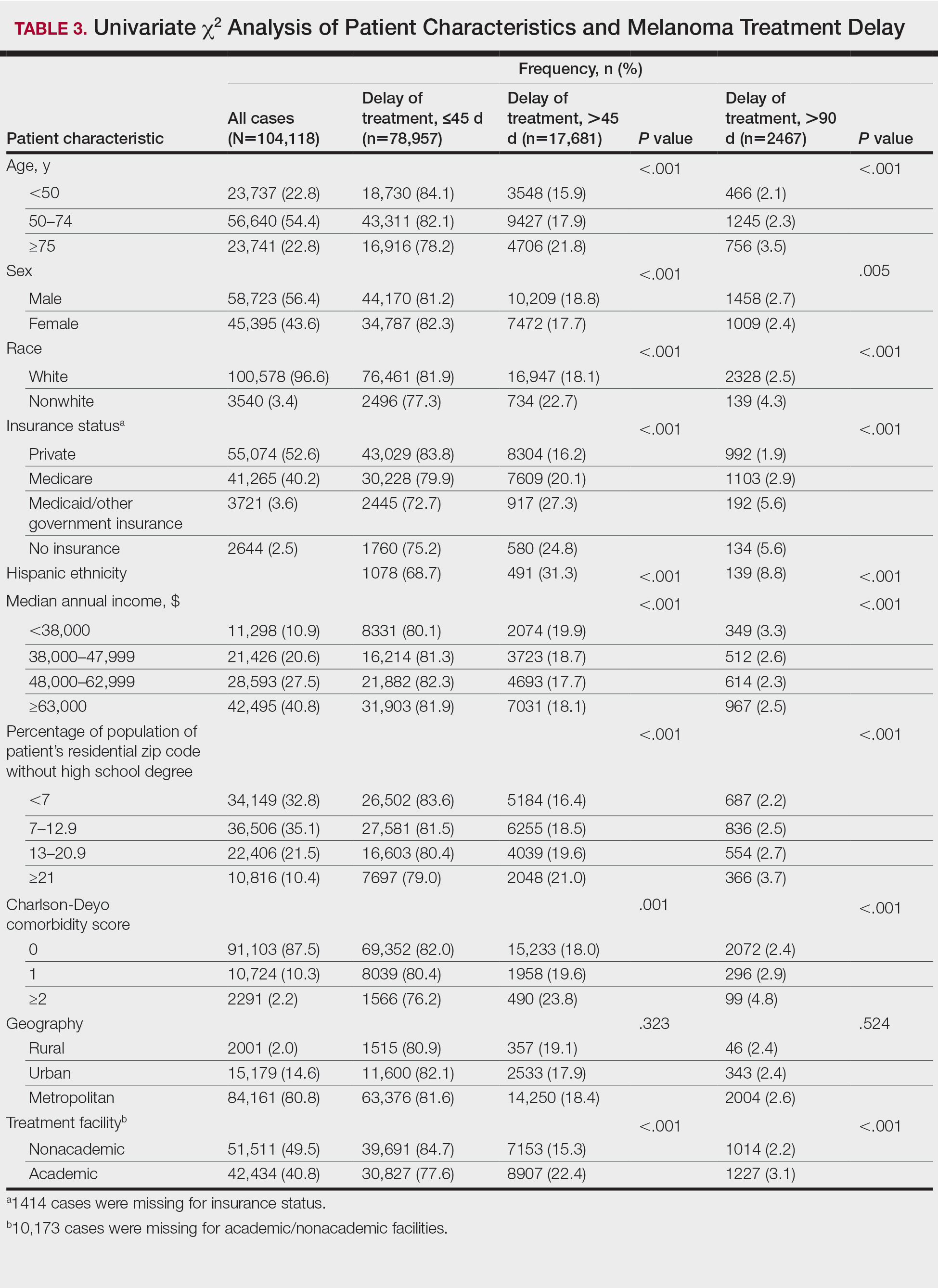

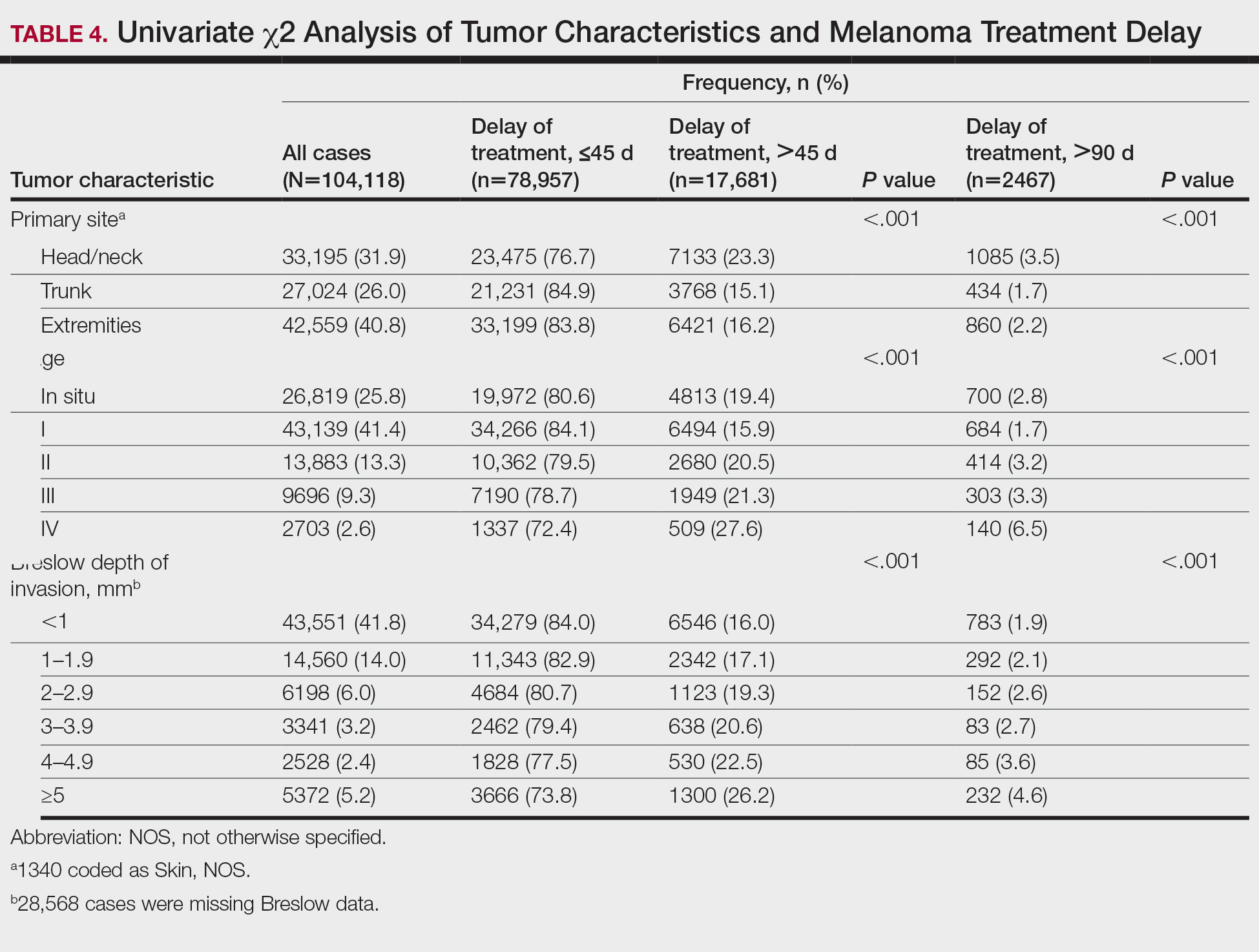

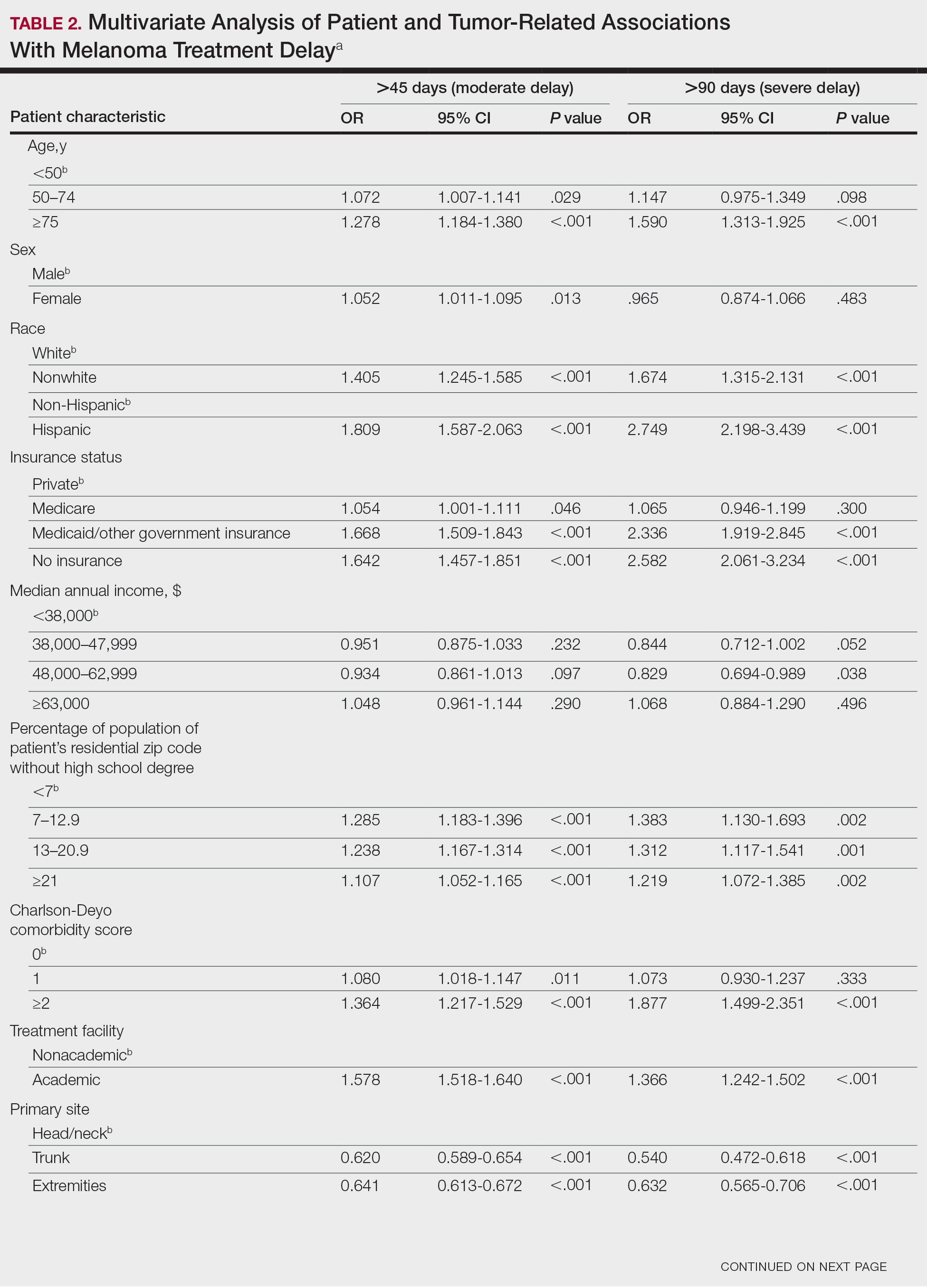

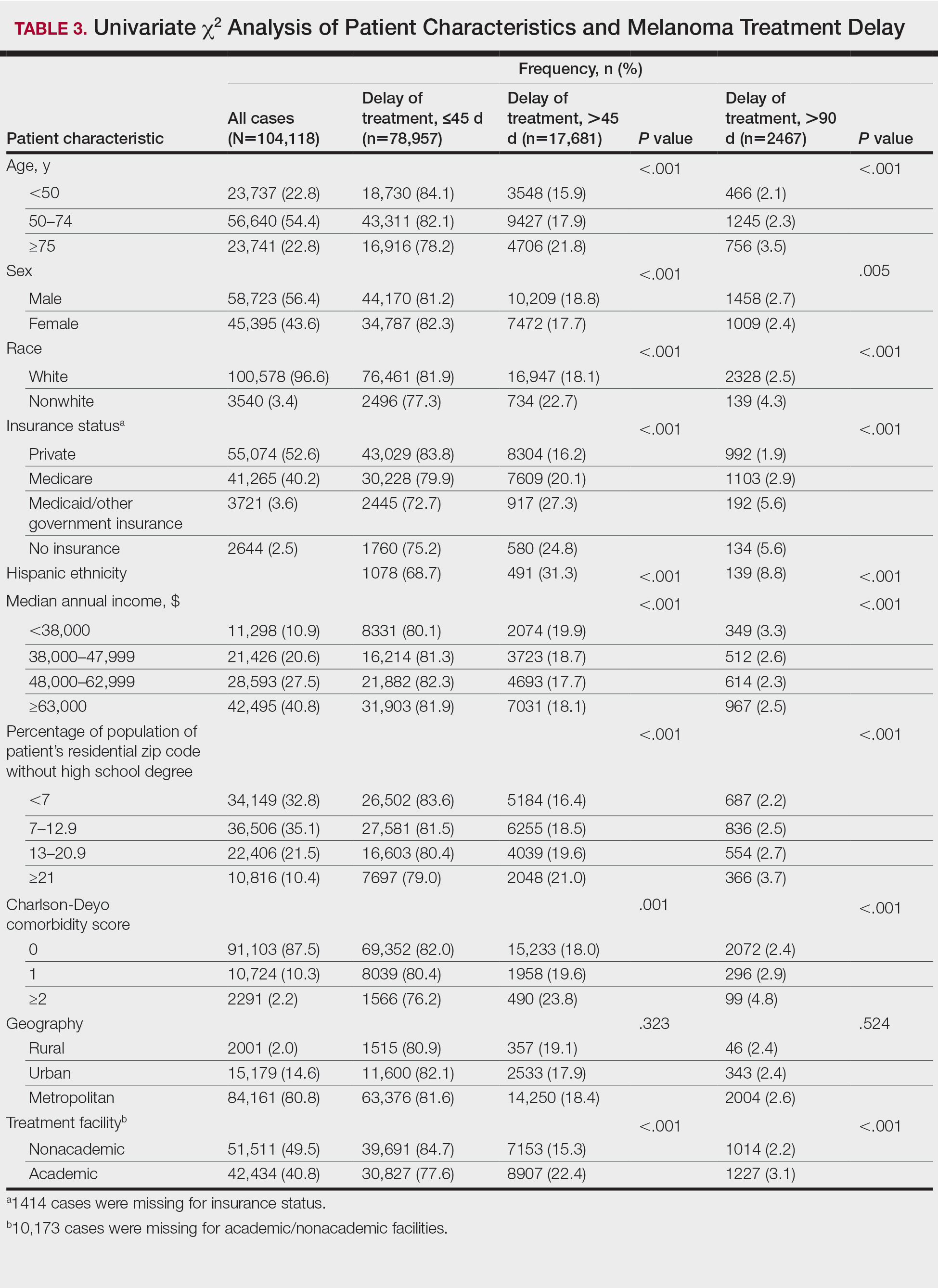

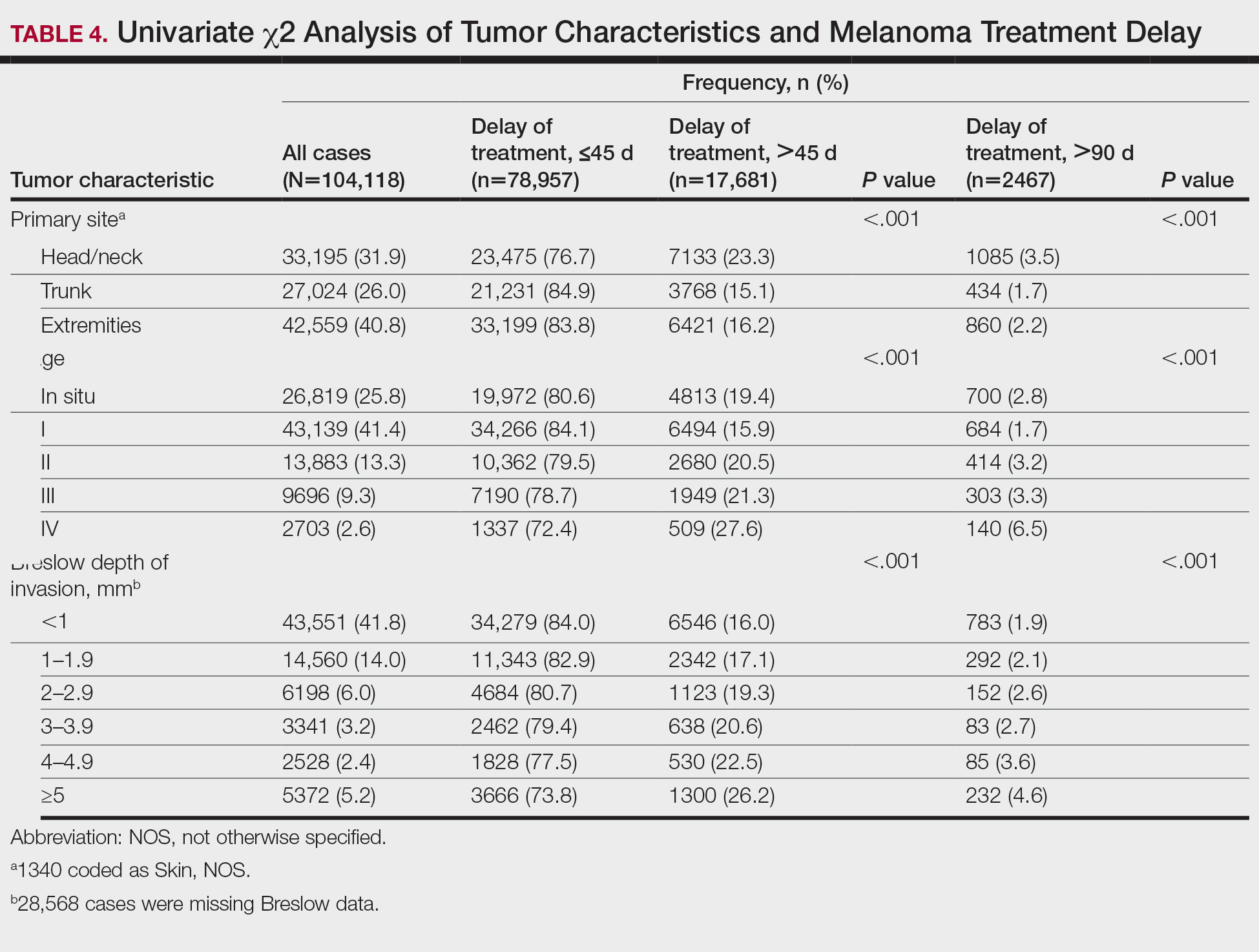

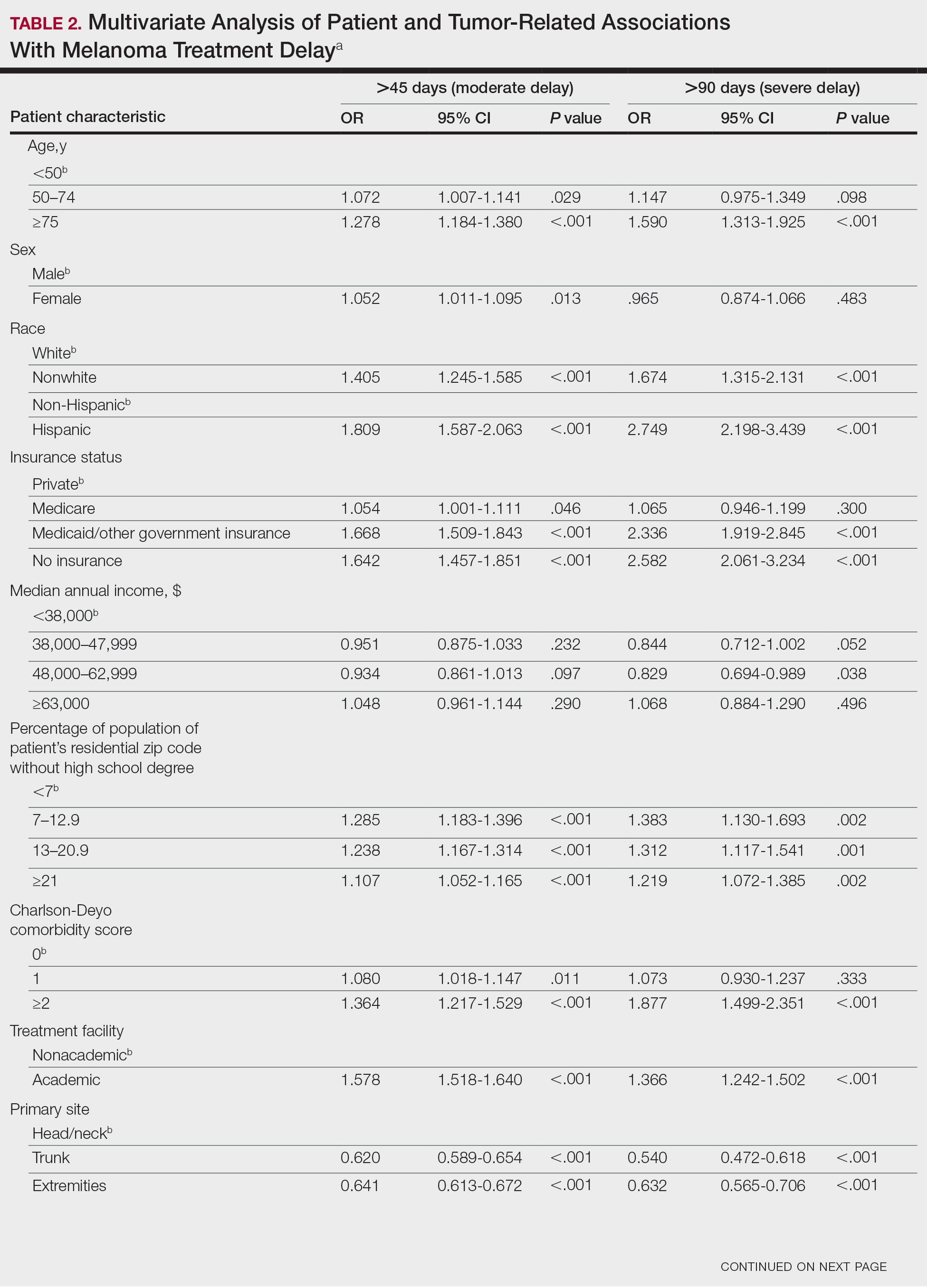

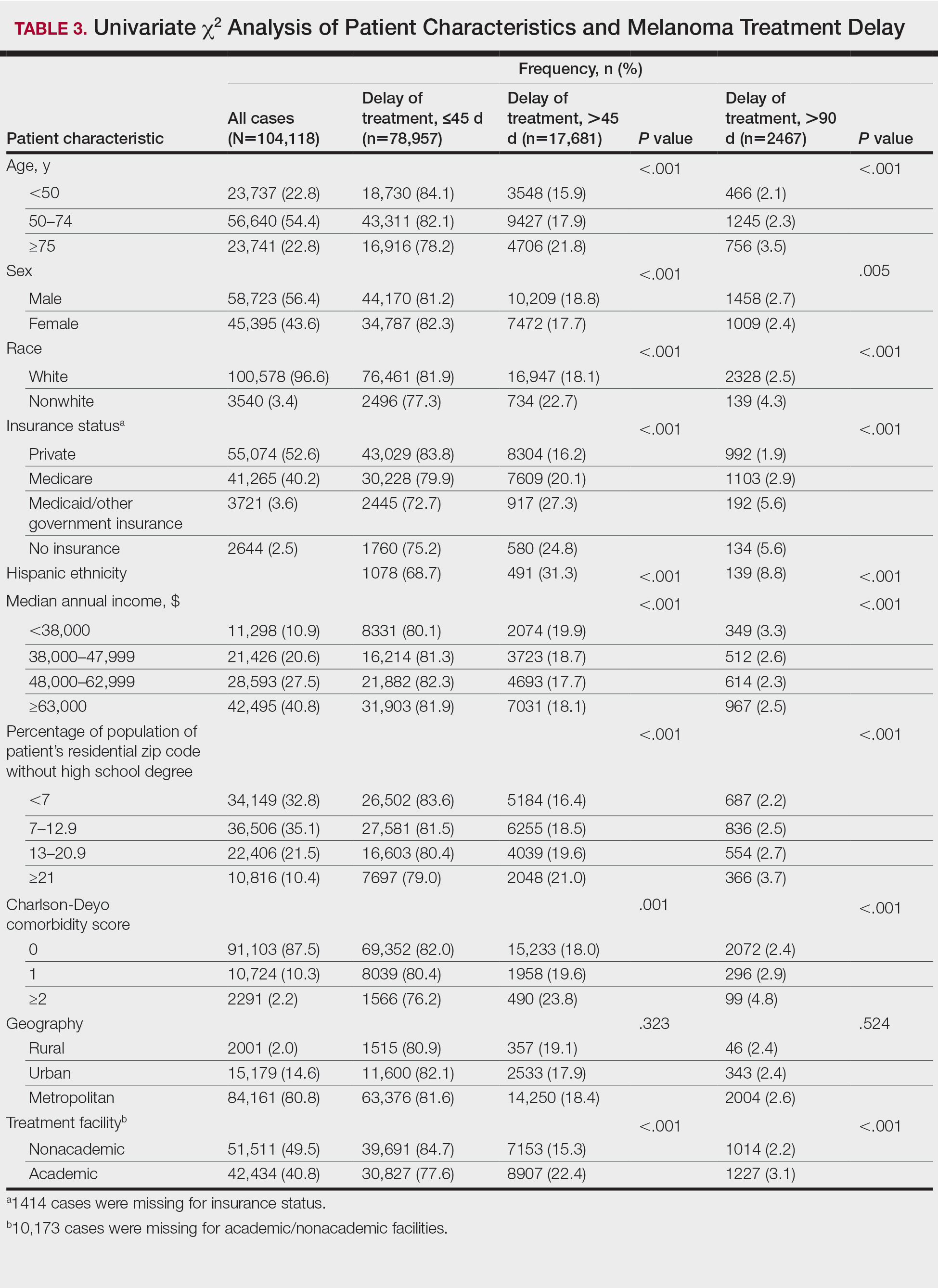

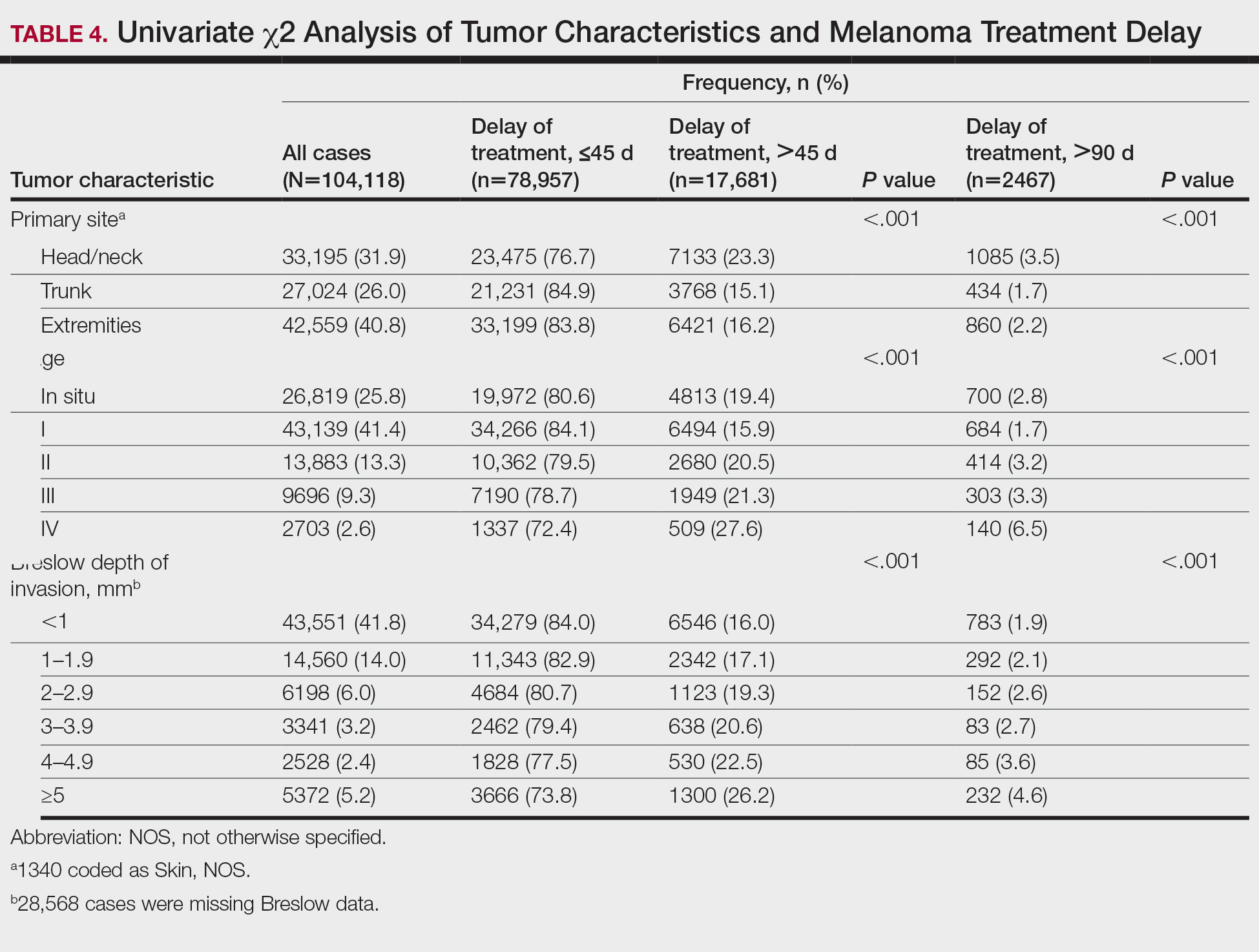

Patient and tumor characteristics were analyzed for associations with MTD (Table 2). Covariates included age, sex, race (white vs nonwhite), Hispanic ethnicity, insurance status (private; Medicare, Medicaid or other government insurance; and no insurance), median annual income of the patient’s residential zip code (based on 2008-2012 census data), percentage of the population of the patient’s residential zip code without a high school degree (based on 2008-2012 census data), Charlson-Deyo (CD) comorbidity score (a weighted score derived from the sum scores for comorbid conditions), geographic location (rural, urban, and metropolitan), and treatment facility (academic vs nonacademic). Tumor characteristics included primary site (head/neck, trunk, and extremities), stage, and Breslow depth of invasion. Tumor stage was determined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer 6th and 7th editions, depending on the patient’s year of diagnosis.

Statistical Methods

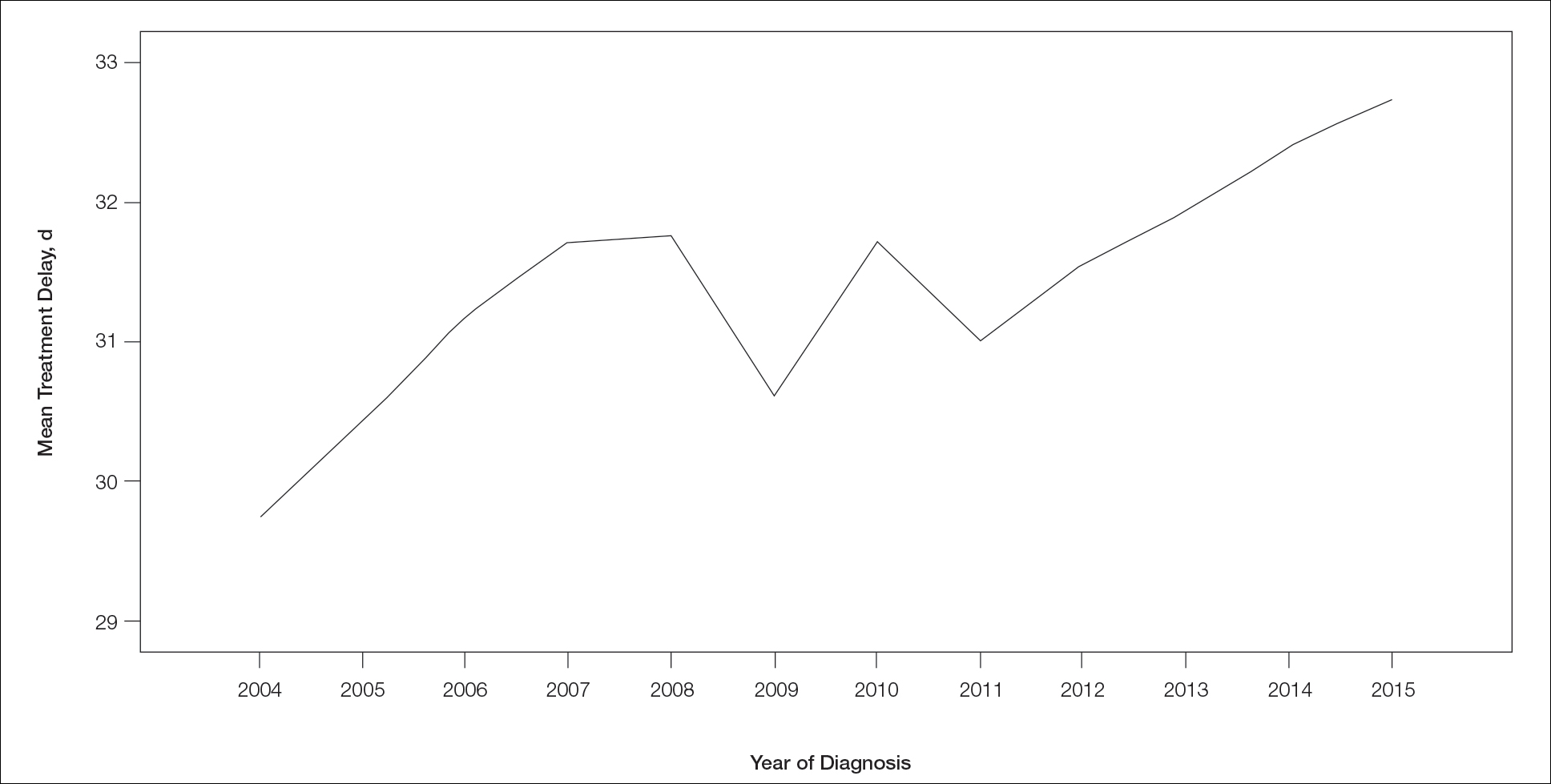

χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to analyze categorical variables involving patient demographics and tumor characteristics by bivariate analysis (Tables 3 and 4). Multivariate analysis determined the relative impact on MTD by including variables that significantly differed on bivariate χ2 analysis (Table 2). Multivariate modeling determined odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% CI for the risk-adjusted associations of the variables with MTD. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM). P<.05 was considered statistically significant, and all statistical tests were 2-tailed. Line graph figures by year of diagnosis were modeled by SPSS using the mean days of delay per year. Independent sample t tests assessed for differences in mean values.

Results

The final study population included 104,118 patients, most of whom were male (56.4%), white (96.6%), and aged 50 to 74 years (54.4%). Most patients were privately insured (52.6%), had no CD comorbidities (87.5%), and lived in metropolitan cities (80.4%)(Table 3). A large majority (95,473 [91.7%]) of patients received surgery as the first means of treatment, with a smaller portion (863 [0.8%]) having unspecified systemic therapy first. The remaining cases were first treated with chemotherapy (1738 [1.7%]), immunotherapy (382 [0.4%]), or radiation (490 [0.5%]), and the rest did not specify treatment sequence. The tumors were most commonly located on the extremities (40.7%), were stage I (41.2%), and had a Breslow depth of less than 1 mm (41.6%).

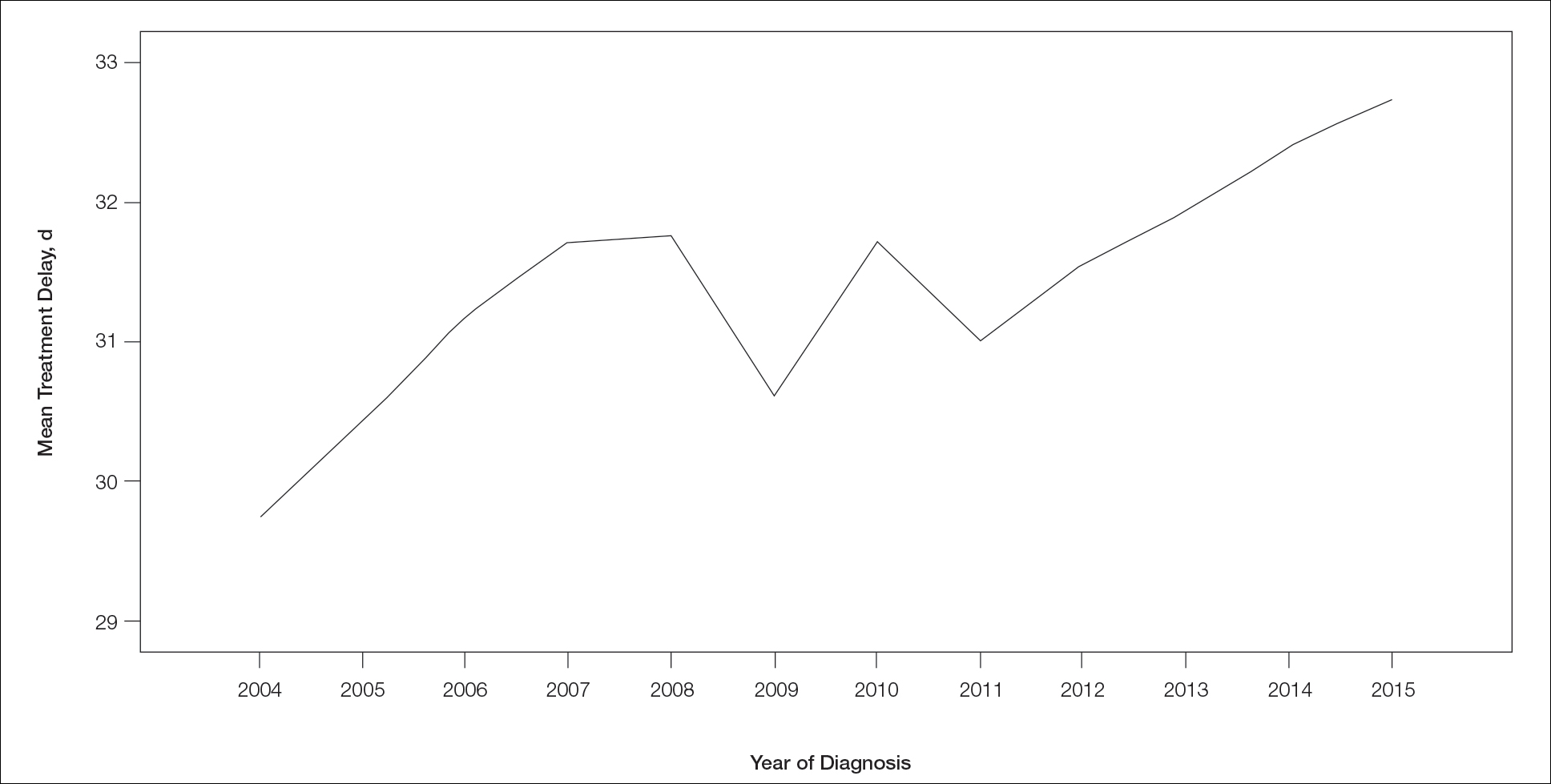

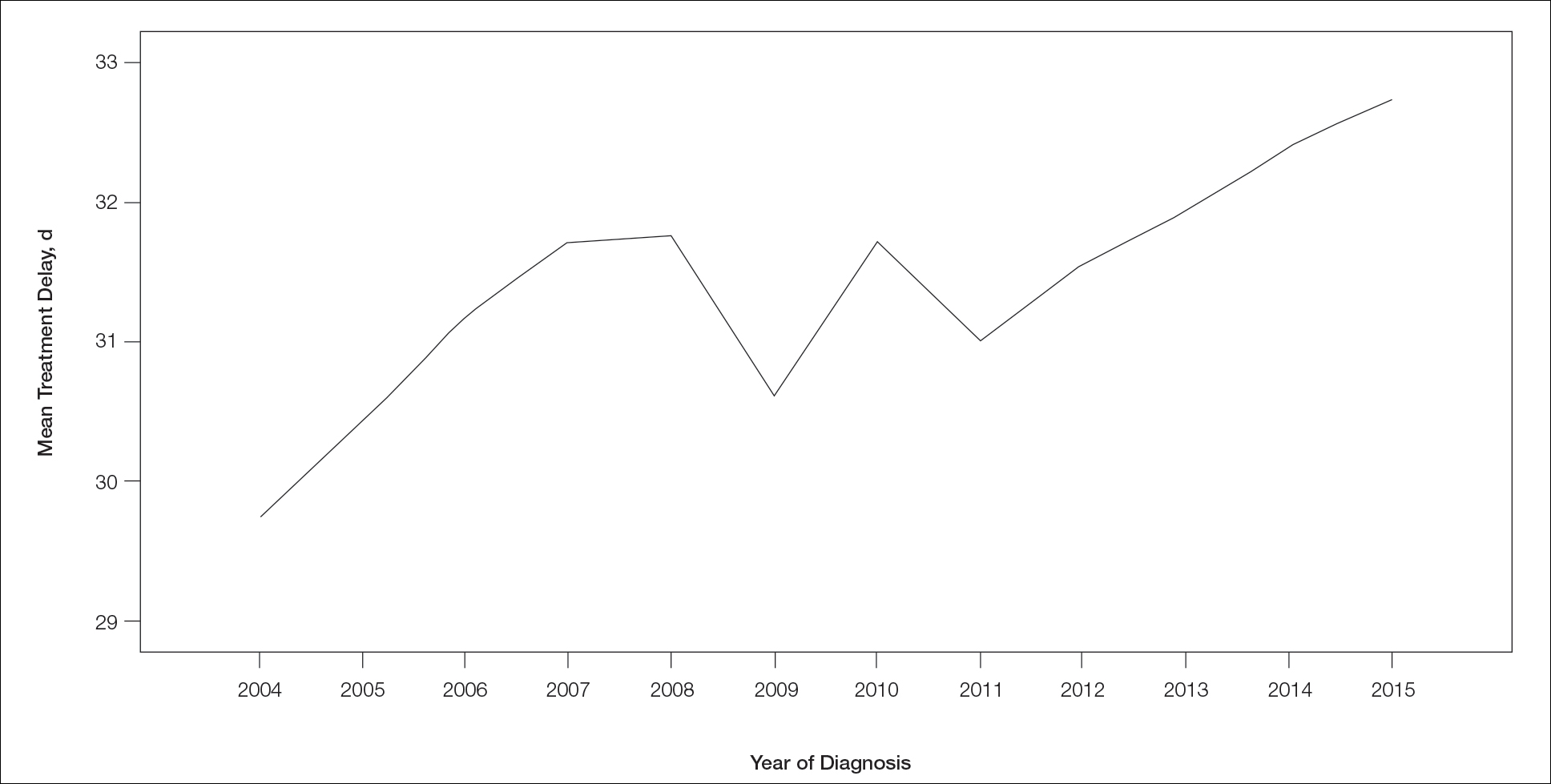

Treatment delay averaged 31.55 days, with a median of 27 days. Overall mean MTD increased significantly from 29.74 days in 2004 to 32.55 days in 2015 (2-tailed t test; P<.001)(Figure). A total of 78,957 cases (75.8%) received treatment within 45 days, whereas 2467 cases (2.5%) were postponed past 90 days. On bivariate analysis, age, sex, race, insurance status, Hispanic ethnicity, median annual income of residential zip code, percentage of the population of the patient’s residential zip code with high school degrees, CD score, and academic treatment facility held significant associations with mMTD and sMTD (P<.05)(Table 3). Analyzing bivariate associations with pertinent tumor characteristics—primary site, stage, and Breslow depth—also held significant associations with mMTD and sMTD (P<.001)(Table 4).

On multivariate analysis, controlling for the variables significant on bivariate analysis, multiple factors showed independent associations with MTD (Table 2). Patients aged 50 to 74 years were more likely to have mMTD (reference: <50 years; P=.029; OR=1.072). Patients 75 years and older showed greater rates of mMTD (reference: <50 years; P<.001; OR=1.278) and sMTD (P<.001; OR=1.590). Women had more mMTD (P=.013; OR=1.052). Nonwhite patients had greater rates of both mMTD (reference: white; P<.001; OR=1.405) and sMTD (P<.001; OR=1.674). Hispanic patients also had greater mMTD (reference: non-Hispanic: P<.001; OR=1.809) and sMTD (P<.001; OR=2.749). Compared to patients with private insurance, those with Medicare were more likely to have mMTD (P=.046; OR=1.054). Patients with no insurance or Medicaid/other government insurance showed more mMTD (no insurance: P<.001, OR=1.642; Medicaid/other: P<.001, OR=1.668) and sMTD (no insurance: P<.001, OR=2.582; Medicaid/other: P<.001, OR=2.336).

With respect to the median annual income of the patient’s residential zip code, patients residing in areas with a median income of $48,000 to $62,999 were less likely to have an sMTD (reference: <$38,000; P=.038; OR=0.829). Compared with patients residing in zip codes where a high percentage of the population had high school degrees, areas with higher nongraduate rates had greater overall rates of MTD (P<.001). Patients with more CD comorbidities also held an association with mMTD (CD1 with reference: CD0; P=.011; OR=1.080)(CD2 with reference: CD0; P<.001; OR=1.364) and sMTD (CD2 with reference: CD0; P<.001; OR=1.877). Academic facilities had greater rates of mMTD (reference: nonacademic facilities; P<.001; OR=1.578) and sMTD (P<.001; OR=1.366). In reference to head/neck primaries, primary sites on the trunk and extremities showed fewer mMTD (trunk: P<.001, OR=0.620; extremities: P<.001, OR=0.641) and sMTD (trunk: P<.001, OR=0.540; extremities: P<.001, OR=0.632). Compared with in situ disease, stage I melanomas were less likely to have treatment delay (mMTD: P<.001, OR=0.902; sMTD: P<.001, OR=0.690), whereas stages II (mMTD: P<.001, OR=1.130), III (mMTD: P<.001, OR=1.196; sMTD: P=.023, OR=1.204), and IV (mMTD: P<.001, OR=1.690; sMTD: P<.001, OR=2.240) were more highly associated with treatments delays.

Comment

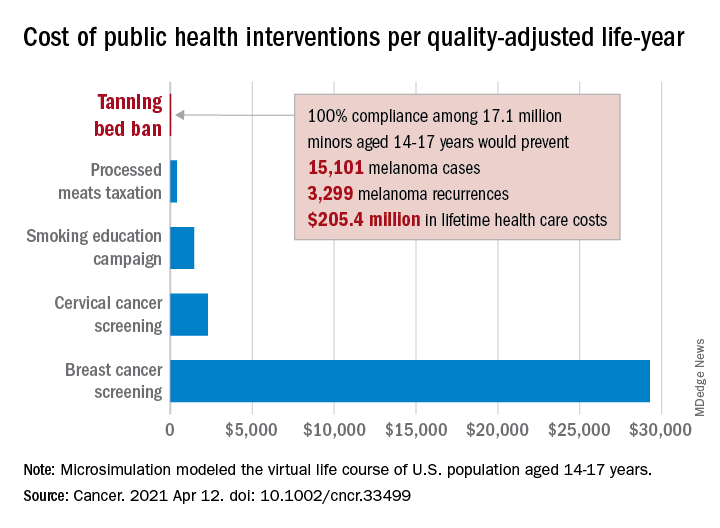

The path to successful melanoma management involves 2 timeframes. One is time to diagnosis and the other is time to treatment. With 24.2% of patients receiving treatment later than 45 days after diagnosis, MTD is common and, according to our results, has increased on average from 2004 to 2015. This delay may be partially explained by a shortage of dermatologists, leading to longer wait times and follow-up.13,14 Melanoma treatment delay also varied based on insurance status. Unsurprisingly, those with private insurance showed the lowest rates of MTD. Those with no insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid/other government insurance likely faced greater socioeconomic barriers to health care, such as coverage issues.15 Transportation, low health literacy, and limited work schedule flexibility have been described as additional hurdles to health care that could contribute to this finding.16,17 Similarly, nonwhite patients, Hispanic patients, and those from zip codes with low high school graduation rates had more MTD. Although these findings may be explained by socioeconomic barriers and heightened distrust of the health care system, it also is important to consider physician accessibility.18,19

Considering the 2011 Affordable Care Act along with the 2014 Medicaid expansion, our study holds implications on the impact of these legislations on melanoma treatment. Studies have supported expected rises in Medicaid coverage.20,21 The overall uninsured rate in the United States declined from 16% in 2010 to 9.1% in 2015.22 In our study, the uninsured population showed the highest average MTD rates, though those with Medicaid also had significant MTD. Another treacherous hurdle for patients is the coordination of care among dermatologists, oncologists, general surgeons, plastic surgeons, and Mohs surgeons as a multidisciplinary team. Lott et al6 found that patients who received both biopsy and excision from a dermatologist had the shortest treatment delays, whereas those who had a dermatologist biopsy the site and a different surgeon—including Mohs surgeons—excise it experienced significantly greater MTDs (probablility of MTD >45 days was 31% [95% CI, 24%-37%]. This discordant care and referrals could explain the surprising finding that treatment at an academic facility was independently associated with more MTD, possibly due to the care transitions and referrals that disproportionately affect academic centers and multidisciplinary teams, as mentioned above, regarding the transition of care to other physicians (eg, plastic surgeon). A total of 70.1% of our cases treated at academic facilities reported a prior diagnosis at another facility. These results should not dissuade the pursuit of multidisciplinary treatment teams but should raise caution to untimely referrals.

Age, sex, and race were all associated with more MTD. Patients older than 50 years likely face more complex decisions regarding treatment burden, quality of life, and functional outcomes of more aggressive treatments. High rates of surgical refusal for a number of malignancies have been documented in the elderly population,23-25 which is of particular concern for the high surgery burden of head and neck melanomas,26 as further supported by the findings of more MTD for head and neck primaries. As with elderly patients, patients with higher comorbidity scores and more advanced tumors face similar family–patient care discussions to guide treatment. Additionally, women were more likely to experience MTD, which may be connected to a greater concern for cosmesis27 and necessitate more complex management options, such as Mohs micrographic surgery (a procedure that has gained some support for melanoma excision with the help of immunostaining).28

There are several limitations to this study. Accurate data rely on precise record keeping, reporting, and coding by the contributing institutions. The NCDB case diagnosis is derived from data entry without a centralized review process by experienced dermatopathologists. We could not assess the effects of tumor diameter, as these data were inadequately recorded within the dataset. The NCDB also does not provide details on specific immunotherapy or chemotherapy agents. The NCDB also is a facility-based data source, potentially biasing the melanoma data toward thicker advanced tumors more readily managed at such institutions. Lastly, it is impossible to distinguish between patient-related (ie, difficult decision-making) and health care–related (ie, health care accessibility) delays. Nonetheless, we maintain that minimizing MTD is important for survival outcomes and for limiting the progression of melanomas, regardless of the underlying rationale. We believe that our study expands on conclusions previously limited to a Medicare population.

Conclusion