User login

The Power of a Multidisciplinary Tumor Board: Managing Unresectable and/or High-Risk Skin Cancers

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

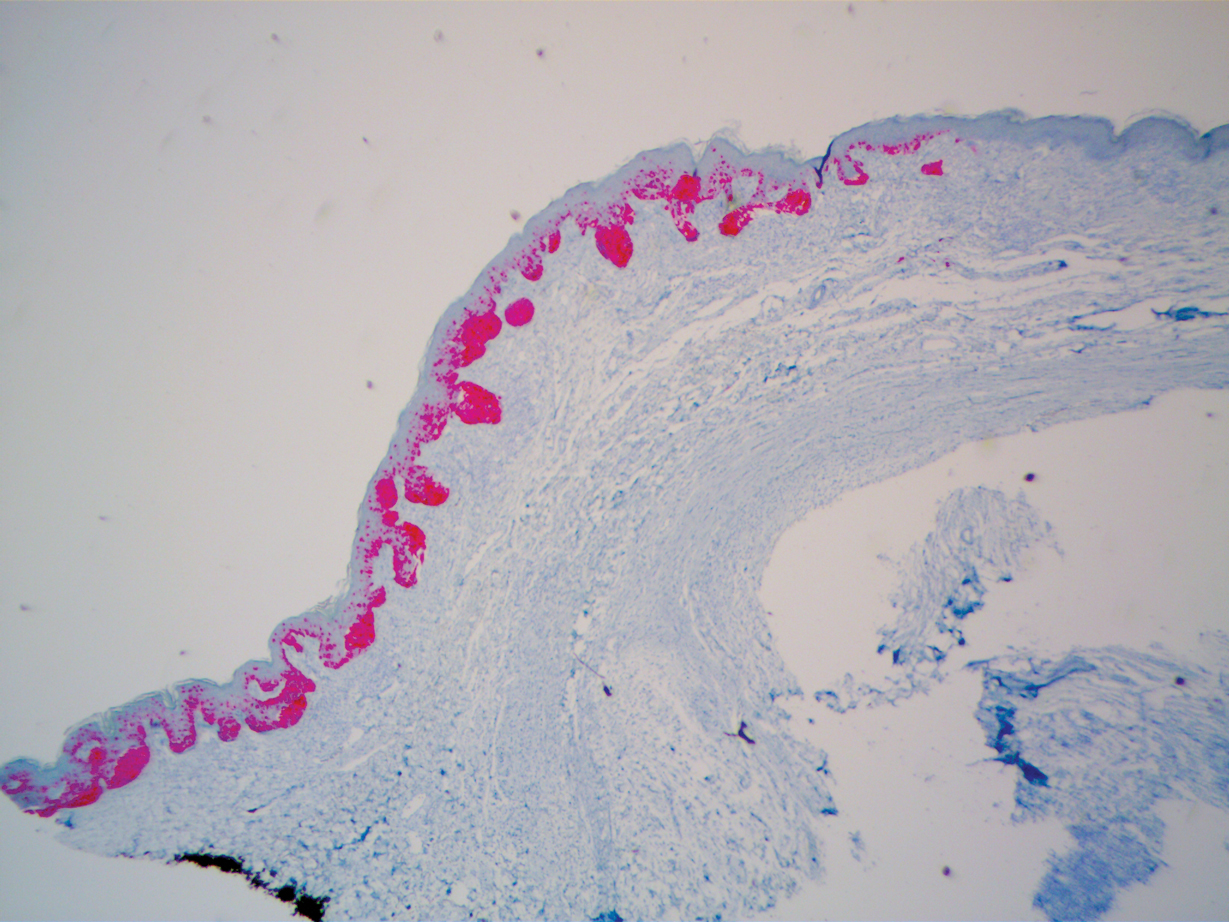

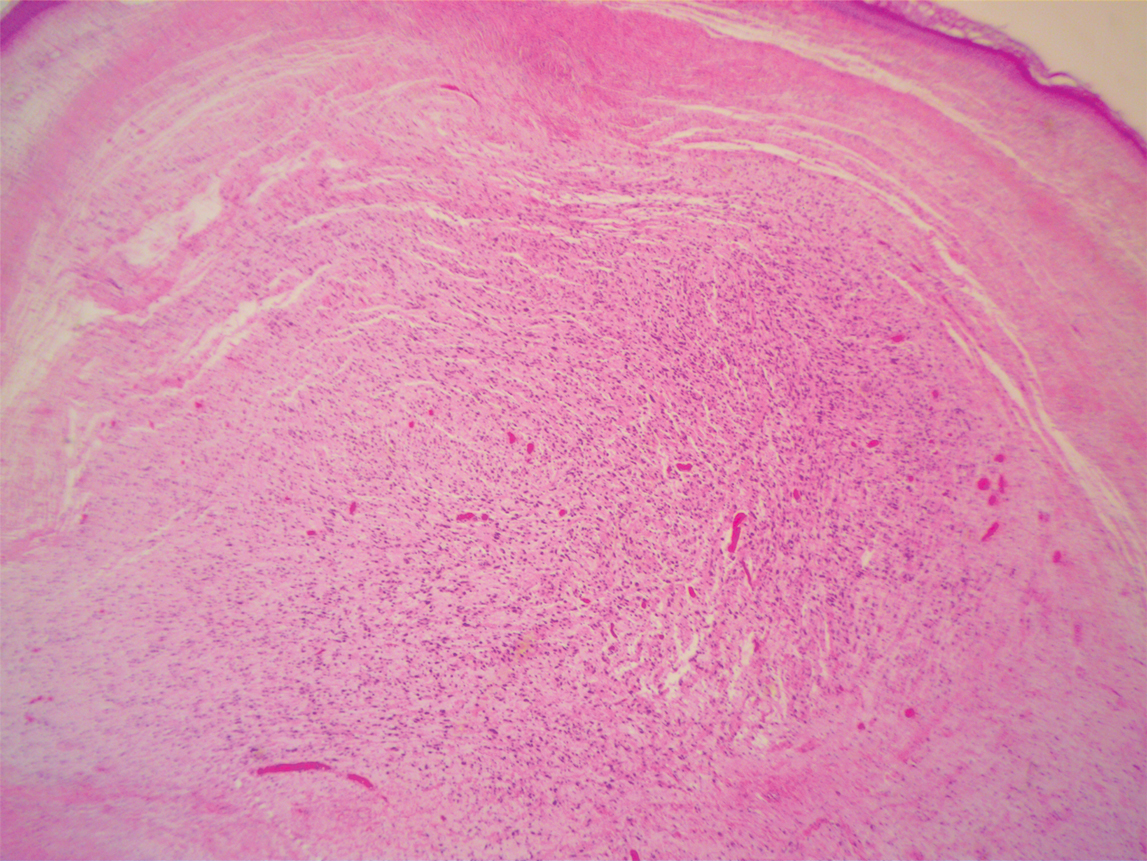

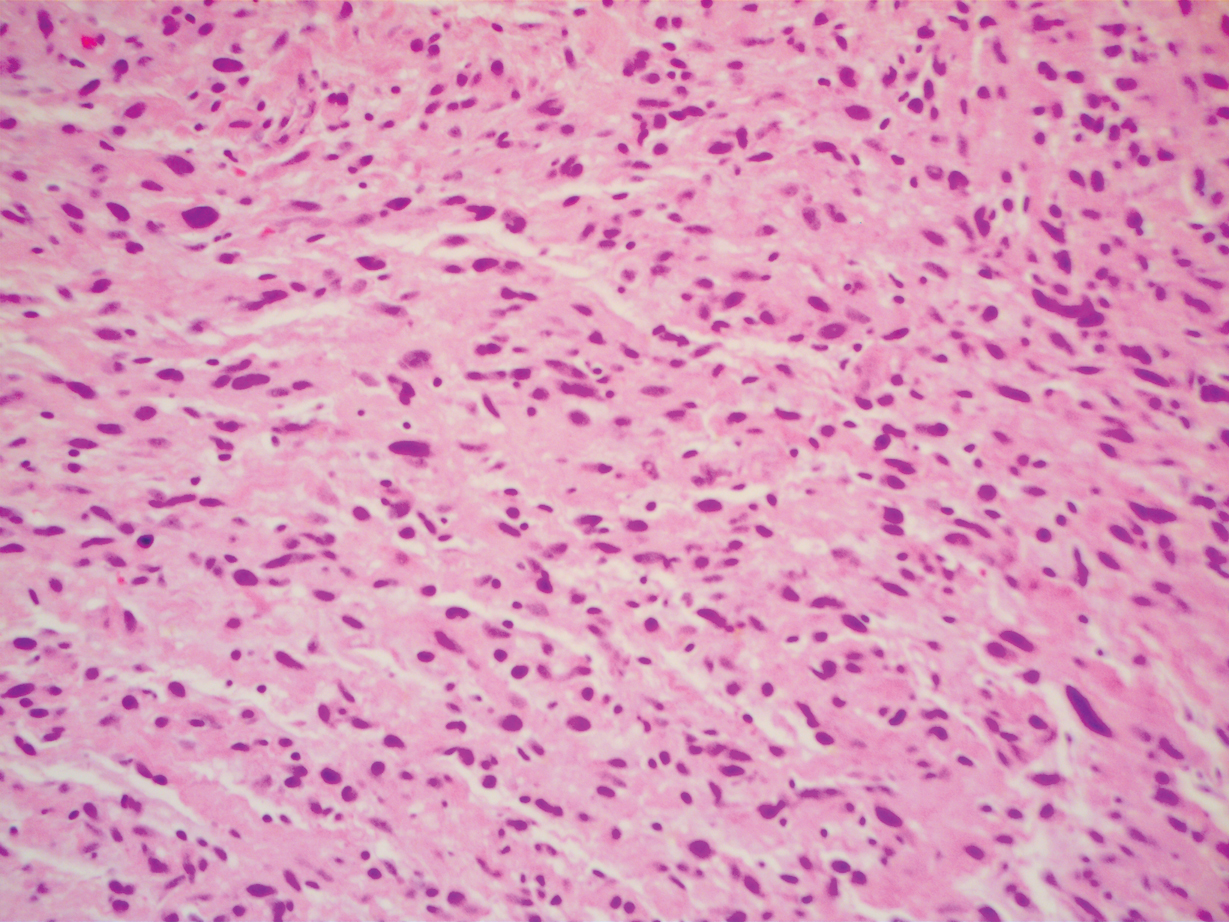

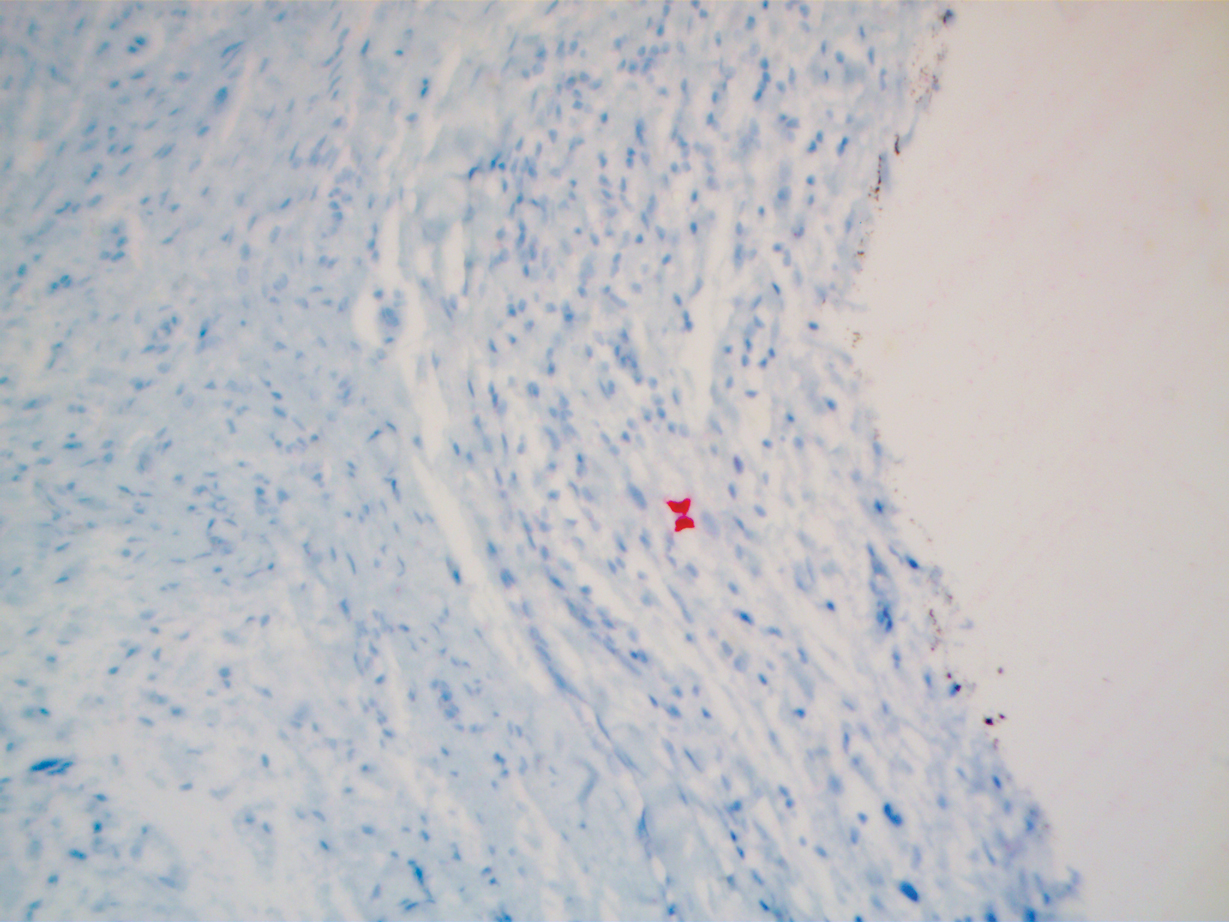

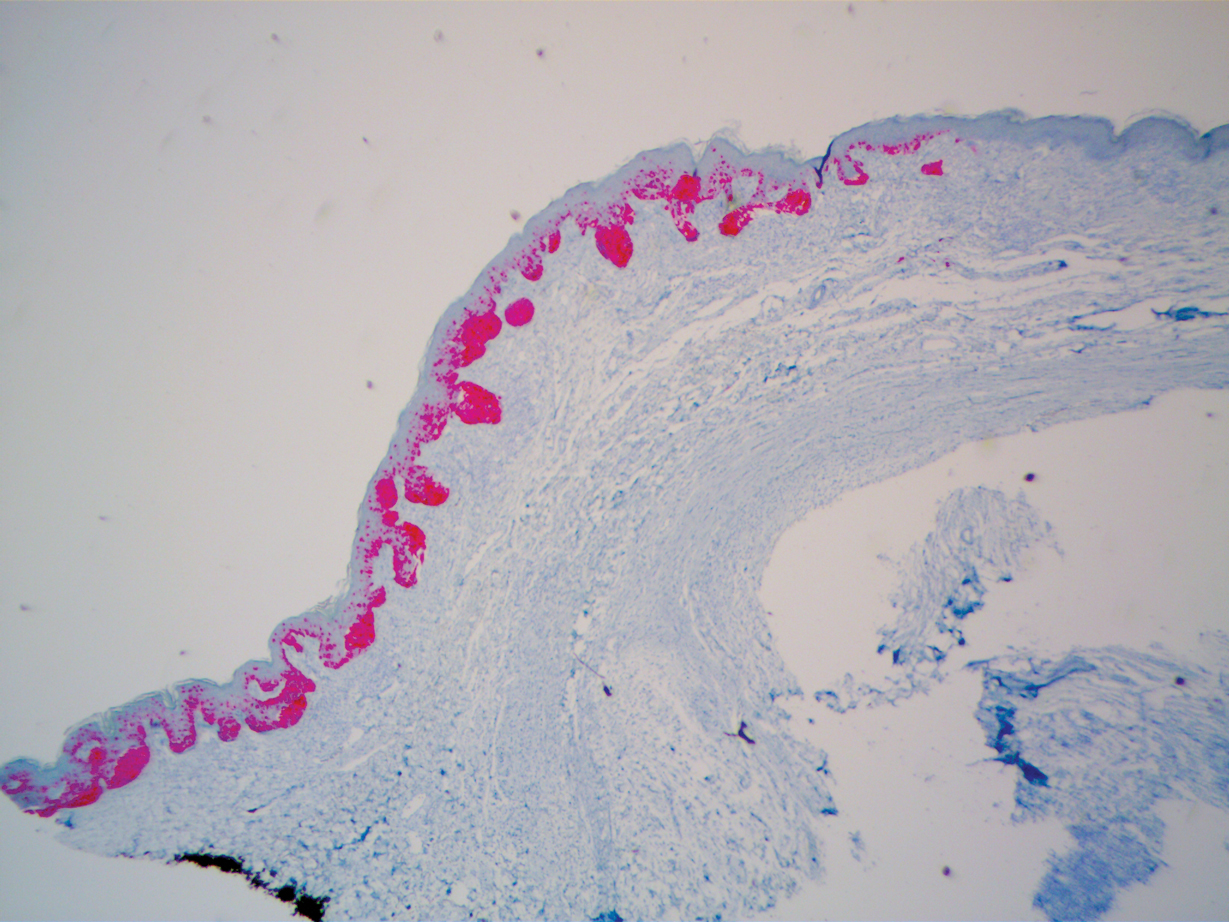

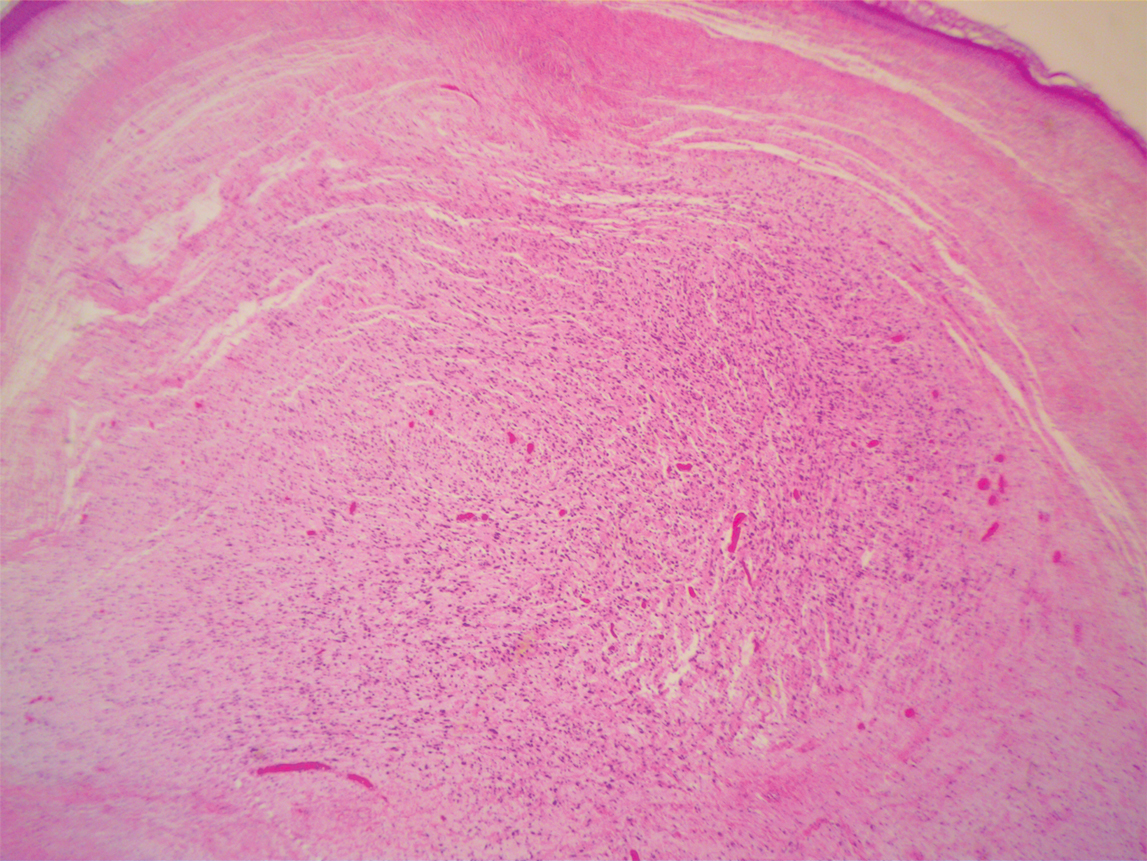

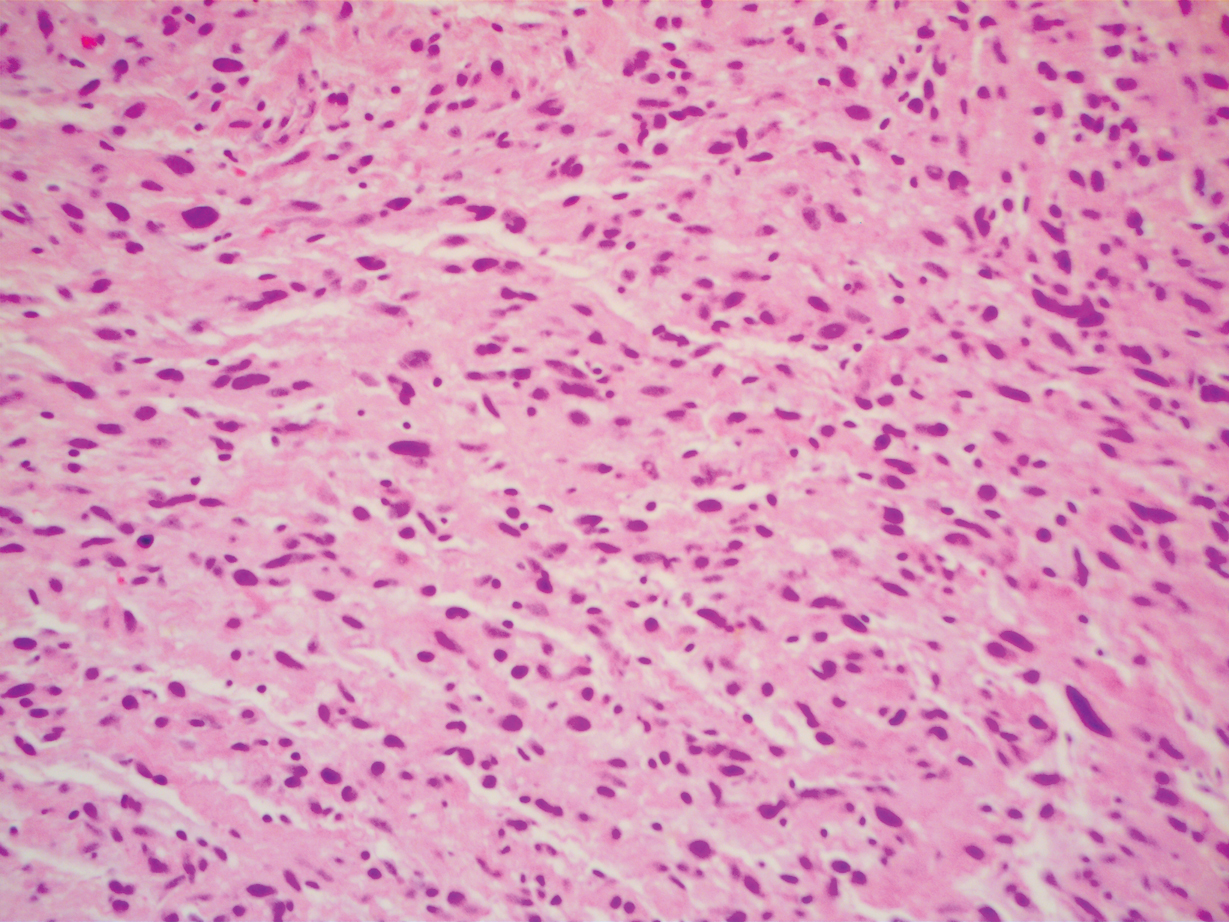

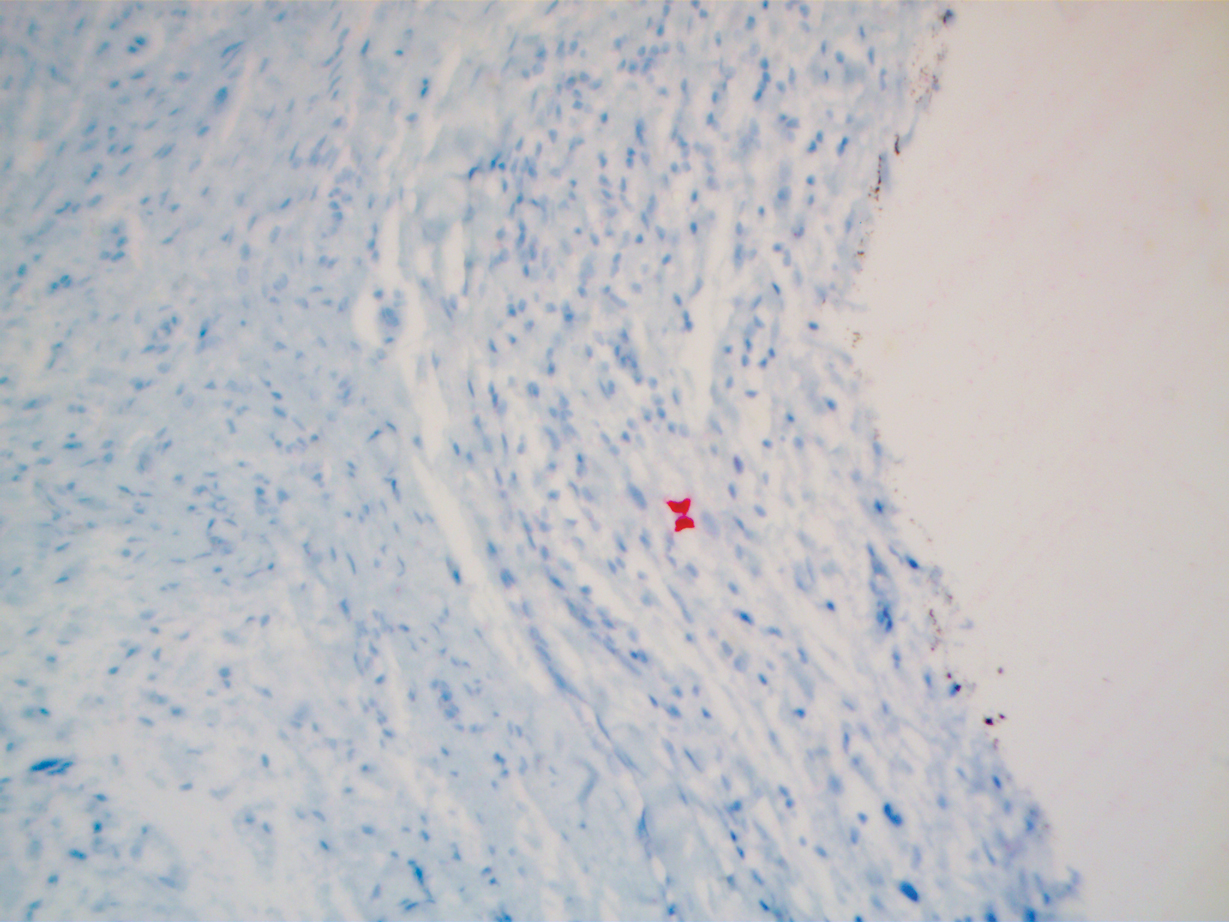

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

Resident Pearl

- Participating in a multidisciplinary tumor board allows residents to learn more about how to manage and treat high-risk skin cancers. The multidisciplinary team approach provides high-quality care for challenging patients.

Benzene found in some sunscreen products, online pharmacy says

Valisure, an online pharmacy known for testing every batch of medication it sells, announced that it has

The company tested 294 batches from 69 companies and found benzene in 27% – many in major national brands like Neutrogena and Banana Boat. Some batches contained as much as three times the emergency FDA limit of 2 parts per million.

Long-term exposure to benzene is known to cause cancer in humans.

“This is especially concerning with sunscreen because multiple FDA studies have shown that sunscreen ingredients absorb through the skin and end up in the blood at high levels,” said David Light, CEO of Valisure.

The FDA is seeking more information about the potential risks from common sunscreen ingredients.

“There is not a safe level of benzene that can exist in sunscreen products,” Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in Valisure’s FDA petition. “The total mass of sunscreen required to cover and protect the human body, in single daily application or repeated applications daily, means that even benzene at 0.1 ppm in a sunscreen could expose people to excessively high nanogram amounts of benzene.”

Valisure’s testing previously led to FDA recalls of heartburn medications and hand sanitizers.

Examining sunscreen’s environmental impact

Chemicals in sunscreen may be harmful to other forms of life, too. For years, scientists have been examining whether certain chemicals in sunscreen could be causing damage to marine life, in particular the world’s coral reefs. Specific ingredients, including oxybenzone, benzophenone-1, benzophenone-8, OD-PABA, 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 3-benzylidene camphor, nano-titanium dioxide, nano-zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octocrylene, have been identified as potential risks.

Earlier this year, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine created a committee to review the existing science about the potential environmental hazards. Over the next 2 years, they’ll also consider the public health implications if people stopped using sunscreen.

Valisure’s announcement included this message: “It is important to note that not all sunscreen products contain benzene and that uncontaminated products are available, should continue to be used, and are important for protecting against potentially harmful solar radiation.”

Using sunscreen with SPF 15 every day can lower risk of squamous cell carcinoma by around 40% and melanoma by 50%. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Valisure, an online pharmacy known for testing every batch of medication it sells, announced that it has

The company tested 294 batches from 69 companies and found benzene in 27% – many in major national brands like Neutrogena and Banana Boat. Some batches contained as much as three times the emergency FDA limit of 2 parts per million.

Long-term exposure to benzene is known to cause cancer in humans.

“This is especially concerning with sunscreen because multiple FDA studies have shown that sunscreen ingredients absorb through the skin and end up in the blood at high levels,” said David Light, CEO of Valisure.

The FDA is seeking more information about the potential risks from common sunscreen ingredients.

“There is not a safe level of benzene that can exist in sunscreen products,” Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in Valisure’s FDA petition. “The total mass of sunscreen required to cover and protect the human body, in single daily application or repeated applications daily, means that even benzene at 0.1 ppm in a sunscreen could expose people to excessively high nanogram amounts of benzene.”

Valisure’s testing previously led to FDA recalls of heartburn medications and hand sanitizers.

Examining sunscreen’s environmental impact

Chemicals in sunscreen may be harmful to other forms of life, too. For years, scientists have been examining whether certain chemicals in sunscreen could be causing damage to marine life, in particular the world’s coral reefs. Specific ingredients, including oxybenzone, benzophenone-1, benzophenone-8, OD-PABA, 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 3-benzylidene camphor, nano-titanium dioxide, nano-zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octocrylene, have been identified as potential risks.

Earlier this year, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine created a committee to review the existing science about the potential environmental hazards. Over the next 2 years, they’ll also consider the public health implications if people stopped using sunscreen.

Valisure’s announcement included this message: “It is important to note that not all sunscreen products contain benzene and that uncontaminated products are available, should continue to be used, and are important for protecting against potentially harmful solar radiation.”

Using sunscreen with SPF 15 every day can lower risk of squamous cell carcinoma by around 40% and melanoma by 50%. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Valisure, an online pharmacy known for testing every batch of medication it sells, announced that it has

The company tested 294 batches from 69 companies and found benzene in 27% – many in major national brands like Neutrogena and Banana Boat. Some batches contained as much as three times the emergency FDA limit of 2 parts per million.

Long-term exposure to benzene is known to cause cancer in humans.

“This is especially concerning with sunscreen because multiple FDA studies have shown that sunscreen ingredients absorb through the skin and end up in the blood at high levels,” said David Light, CEO of Valisure.

The FDA is seeking more information about the potential risks from common sunscreen ingredients.

“There is not a safe level of benzene that can exist in sunscreen products,” Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in Valisure’s FDA petition. “The total mass of sunscreen required to cover and protect the human body, in single daily application or repeated applications daily, means that even benzene at 0.1 ppm in a sunscreen could expose people to excessively high nanogram amounts of benzene.”

Valisure’s testing previously led to FDA recalls of heartburn medications and hand sanitizers.

Examining sunscreen’s environmental impact

Chemicals in sunscreen may be harmful to other forms of life, too. For years, scientists have been examining whether certain chemicals in sunscreen could be causing damage to marine life, in particular the world’s coral reefs. Specific ingredients, including oxybenzone, benzophenone-1, benzophenone-8, OD-PABA, 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 3-benzylidene camphor, nano-titanium dioxide, nano-zinc oxide, octinoxate, and octocrylene, have been identified as potential risks.

Earlier this year, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine created a committee to review the existing science about the potential environmental hazards. Over the next 2 years, they’ll also consider the public health implications if people stopped using sunscreen.

Valisure’s announcement included this message: “It is important to note that not all sunscreen products contain benzene and that uncontaminated products are available, should continue to be used, and are important for protecting against potentially harmful solar radiation.”

Using sunscreen with SPF 15 every day can lower risk of squamous cell carcinoma by around 40% and melanoma by 50%. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Survey: Many Mohs surgeons are struggling on the job

.

In a measurement of well-being, 40% of members of the American College of Mohs

Surgery (ACMS) who responded to the survey – and 52% of women – scored at a level considered “at-risk” for adverse outcomes, such as poor quality of life.

“I didn’t think the numbers were going to be that high,” said study author Kemi O. Awe, MD, PhD, a dermatology resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, especially in light of Mohs surgery’s reputation as being an especially desirable field in dermatology. She presented the findings at the annual meeting of the ACMS.

Dr. Awe, who hopes to become a Mohs surgeon herself, said in an interview that she launched the study in part to understand how colleagues are faring. “Dermatology is known as a specialty that has a good lifestyle and less stress, but the rate of burnout is actually going up.”

For the study, Dr. Awe and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members between October and December 2020. The 91 respondents had an average age of 46, and 58% were male. Most practiced in academic facilities (56%), while the rest worked in private practice (39%) or multispecialty (4%) practices. Almost all (89%) were married or in partnerships.

The survey calculated scores on the expanded Physician Well Being Index, a validated tool for measuring physician distress. Forty percent of 68 respondents to this part of the survey got a score of 3 or higher, which the study describes as “a threshold for respondents who are ‘at-risk’ of adverse outcomes such as poor quality of life, depression, and a high level of fatigue.”

Women were more likely to be considered at risk (52%) than men (28%). “This isn’t different than what’s already out there: Female physicians are more likely to be burned out compared to men,” Dr. Awe said.

Compared with their male counterparts, female Mohs surgeons were more likely to say that time at work, malpractice concerns, insurance reimbursement, and compensation structure negatively affected their well-being (P ≤ .05).

It’s unclear whether there’s a well-being gender gap among dermatologists overall, however. Dr. Awe highlighted a 2019 survey of 108 dermatologists that found no significant difference in overall burnout between men and women – about 42% of both genders reported symptoms. But the survey did find that “dermatologists with children living at home had significantly higher levels of burnout,” with a P value of .03.

Dr. Awe said the findings offer insight into what to look out for when pursuing a career as a Mohs surgeon. “There’s potentially excess stress about being a Mohs surgeon,” she said, although the field also has a reputation as being fulfilling and rewarding.

In an interview, Stanford (Calif.) University dermatologist Zakia Rahman, MD, praised the study and said it “certainly provides a framework to address professional fulfillment amongst Mohs surgeons.”

It was especially surprising, she said, that female surgeons didn’t rate their compensation structure as positively as did their male colleagues. “It is possible that there is still a significant amount of gender-based difference in compensation between male and female Mohs surgeons. This is an area that can be further explored.”

Moving forward, she said, “our professional dermatology societies must examine the increase in burnout within our specialty. Further funding and research in this area is needed.”

For now, dermatologists can focus on strategies that can reduce burnout in the field, Sailesh Konda, MD, a Mohs surgeon at the Univeristy of Florida, Gainesville, said in an interview. Dr. Konda highlighted a report published in 2020 that, he said, "recommended focusing on incremental changes that help restore autonomy and control over work, connecting with colleagues within dermatology and the broader medical community, developing self-awareness and recognition of a perfectionist mindset, and restoring meaning and joy to patient care.”*

No funding is reported for the study. Dr. Awe, Dr. Rahman, and Dr. Konda have no relevant disclosures.

*This story was updated on June 2 for clarity.

.

In a measurement of well-being, 40% of members of the American College of Mohs

Surgery (ACMS) who responded to the survey – and 52% of women – scored at a level considered “at-risk” for adverse outcomes, such as poor quality of life.

“I didn’t think the numbers were going to be that high,” said study author Kemi O. Awe, MD, PhD, a dermatology resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, especially in light of Mohs surgery’s reputation as being an especially desirable field in dermatology. She presented the findings at the annual meeting of the ACMS.

Dr. Awe, who hopes to become a Mohs surgeon herself, said in an interview that she launched the study in part to understand how colleagues are faring. “Dermatology is known as a specialty that has a good lifestyle and less stress, but the rate of burnout is actually going up.”

For the study, Dr. Awe and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members between October and December 2020. The 91 respondents had an average age of 46, and 58% were male. Most practiced in academic facilities (56%), while the rest worked in private practice (39%) or multispecialty (4%) practices. Almost all (89%) were married or in partnerships.

The survey calculated scores on the expanded Physician Well Being Index, a validated tool for measuring physician distress. Forty percent of 68 respondents to this part of the survey got a score of 3 or higher, which the study describes as “a threshold for respondents who are ‘at-risk’ of adverse outcomes such as poor quality of life, depression, and a high level of fatigue.”

Women were more likely to be considered at risk (52%) than men (28%). “This isn’t different than what’s already out there: Female physicians are more likely to be burned out compared to men,” Dr. Awe said.

Compared with their male counterparts, female Mohs surgeons were more likely to say that time at work, malpractice concerns, insurance reimbursement, and compensation structure negatively affected their well-being (P ≤ .05).

It’s unclear whether there’s a well-being gender gap among dermatologists overall, however. Dr. Awe highlighted a 2019 survey of 108 dermatologists that found no significant difference in overall burnout between men and women – about 42% of both genders reported symptoms. But the survey did find that “dermatologists with children living at home had significantly higher levels of burnout,” with a P value of .03.

Dr. Awe said the findings offer insight into what to look out for when pursuing a career as a Mohs surgeon. “There’s potentially excess stress about being a Mohs surgeon,” she said, although the field also has a reputation as being fulfilling and rewarding.

In an interview, Stanford (Calif.) University dermatologist Zakia Rahman, MD, praised the study and said it “certainly provides a framework to address professional fulfillment amongst Mohs surgeons.”

It was especially surprising, she said, that female surgeons didn’t rate their compensation structure as positively as did their male colleagues. “It is possible that there is still a significant amount of gender-based difference in compensation between male and female Mohs surgeons. This is an area that can be further explored.”

Moving forward, she said, “our professional dermatology societies must examine the increase in burnout within our specialty. Further funding and research in this area is needed.”

For now, dermatologists can focus on strategies that can reduce burnout in the field, Sailesh Konda, MD, a Mohs surgeon at the Univeristy of Florida, Gainesville, said in an interview. Dr. Konda highlighted a report published in 2020 that, he said, "recommended focusing on incremental changes that help restore autonomy and control over work, connecting with colleagues within dermatology and the broader medical community, developing self-awareness and recognition of a perfectionist mindset, and restoring meaning and joy to patient care.”*

No funding is reported for the study. Dr. Awe, Dr. Rahman, and Dr. Konda have no relevant disclosures.

*This story was updated on June 2 for clarity.

.

In a measurement of well-being, 40% of members of the American College of Mohs

Surgery (ACMS) who responded to the survey – and 52% of women – scored at a level considered “at-risk” for adverse outcomes, such as poor quality of life.

“I didn’t think the numbers were going to be that high,” said study author Kemi O. Awe, MD, PhD, a dermatology resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, especially in light of Mohs surgery’s reputation as being an especially desirable field in dermatology. She presented the findings at the annual meeting of the ACMS.

Dr. Awe, who hopes to become a Mohs surgeon herself, said in an interview that she launched the study in part to understand how colleagues are faring. “Dermatology is known as a specialty that has a good lifestyle and less stress, but the rate of burnout is actually going up.”

For the study, Dr. Awe and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members between October and December 2020. The 91 respondents had an average age of 46, and 58% were male. Most practiced in academic facilities (56%), while the rest worked in private practice (39%) or multispecialty (4%) practices. Almost all (89%) were married or in partnerships.

The survey calculated scores on the expanded Physician Well Being Index, a validated tool for measuring physician distress. Forty percent of 68 respondents to this part of the survey got a score of 3 or higher, which the study describes as “a threshold for respondents who are ‘at-risk’ of adverse outcomes such as poor quality of life, depression, and a high level of fatigue.”

Women were more likely to be considered at risk (52%) than men (28%). “This isn’t different than what’s already out there: Female physicians are more likely to be burned out compared to men,” Dr. Awe said.

Compared with their male counterparts, female Mohs surgeons were more likely to say that time at work, malpractice concerns, insurance reimbursement, and compensation structure negatively affected their well-being (P ≤ .05).

It’s unclear whether there’s a well-being gender gap among dermatologists overall, however. Dr. Awe highlighted a 2019 survey of 108 dermatologists that found no significant difference in overall burnout between men and women – about 42% of both genders reported symptoms. But the survey did find that “dermatologists with children living at home had significantly higher levels of burnout,” with a P value of .03.

Dr. Awe said the findings offer insight into what to look out for when pursuing a career as a Mohs surgeon. “There’s potentially excess stress about being a Mohs surgeon,” she said, although the field also has a reputation as being fulfilling and rewarding.

In an interview, Stanford (Calif.) University dermatologist Zakia Rahman, MD, praised the study and said it “certainly provides a framework to address professional fulfillment amongst Mohs surgeons.”

It was especially surprising, she said, that female surgeons didn’t rate their compensation structure as positively as did their male colleagues. “It is possible that there is still a significant amount of gender-based difference in compensation between male and female Mohs surgeons. This is an area that can be further explored.”

Moving forward, she said, “our professional dermatology societies must examine the increase in burnout within our specialty. Further funding and research in this area is needed.”

For now, dermatologists can focus on strategies that can reduce burnout in the field, Sailesh Konda, MD, a Mohs surgeon at the Univeristy of Florida, Gainesville, said in an interview. Dr. Konda highlighted a report published in 2020 that, he said, "recommended focusing on incremental changes that help restore autonomy and control over work, connecting with colleagues within dermatology and the broader medical community, developing self-awareness and recognition of a perfectionist mindset, and restoring meaning and joy to patient care.”*

No funding is reported for the study. Dr. Awe, Dr. Rahman, and Dr. Konda have no relevant disclosures.

*This story was updated on June 2 for clarity.

FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Novel immunotherapy relatlimab in advanced melanoma

Adding the novel immune checkpoint inhibitor relatlimab to the more established nivolumab (Opdivo) significantly extended the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with previously untreated advanced melanoma in comparison with nivolumab alone in the phase 3 RELATIVITY-047 trial.

Both drugs are from Bristol-Myers Squibb, which funded the study.

“Our findings demonstrate that relatlimab plus nivolumab is a potential novel treatment option for this patient population,” said lead researcher Evan J. Lipson, MD, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Relatlimab has a different mechanism of action from currently available immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab and similar agents, which act as inhibitors of the programmed cell death protein–1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death–ligand-1 (PD-L1). In contrast, relatlimab acts as an antibody that targets lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), which inhibits T cells and thus helps cancer cells evade immune attack.

“This is the first phase 3 study to validate inhibition of the LAG-3 immune checkpoint as a therapeutic strategy for patients with cancer, and it establishes the LAG-3 pathway as the third immune checkpoint pathway in history, after CLTA-4 and PD-1, for which blockade appears to have clinical benefit,” Dr. Lipson said at a press briefing ahead of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), where this study will be presented (abstract 9503).

Commenting for ASCO, Julie R. Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president, agreed that “these results provide validation of the LAG-3 immune checkpoint as a therapeutic target ... and they also support combination treatment with immunotherapies that act on different parts of the immune system.”

When Dr. Lipson was asked whether he would recommend the combination of relatlimab plus nivolumab as a first-line treatment for this patient population, he said that “for many patients,” the first-line treatment choice is made on a “case-by-case” basis.

“We are fortunate in melanoma that we have an ever-expanding list of seemingly effective options, and I think we’ll find at some point this will be added to that list,” he said. “Whether this is the first-line choice for any given patient really depends on a lot of factors,” he added.

Dr. Gralow added a note of caution. “The combination was clearly more toxic, and so I think there will be a lot of discussion” as to when it would be used and for which patients, she said.

In the absence of head-to-head comparisons, “I’m not sure that we have one answer” as to which treatment to choose, she added. With the ever-increasing number of options available in melanoma, the individual treatment choice is “getting more complicated,” she said.

Study details

The global RELATIVITY-047 study was conducted in 714 patients with previously untreated unresectable or metastatic melanoma. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either relatlimab plus nivolumab or nivolumab alone.

Dr. Lipson explained that the treatments were given as a fixed-dosed combination, meaning the preparation of relatlimab and nivolumab was given in the “same medication phial and administered as a single intravenous infusion in order to reduce preparation and infusion times and minimize the risk of administration errors.”

PFS, as determined on blinded independent central review, was significantly longer with the combination therapy than with nivolumab alone, at a median of 10.12 months vs. 4.63 months (hazard ratio, 0.75; P = .0055).

At 12 months, the PFS rate among patients given relatlimab plus nivolumab was 47.7%, versus 36.0% among those given nivolumab alone.

“This significant improvement meant that the study met its primary endpoint,” Dr. Lipson said, adding that the PFS benefit “appeared relatively early in the course of therapy.” The curves separated at 12 weeks, and benefit was “sustained” over the course of follow-up.

He added that the performance of nivolumab alone was “in the range” of that seen in previous studies, although he underlined that cross-trial comparison is difficult, given the differences in study design.

“In general, treatment-related adverse events” associated with the combination therapy were “manageable and reflected the safety profile that we typically see with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” he noted.

The results showed that 40.3% of patients who received the combination therapy experienced a grade 3-4 adverse event, compared with 33.4% of those given nivolumab alone. Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 8.5% and 3.1% of patients, respectively.

Three treatment-related deaths occurred in the relatlimab and nivolumab arm. Two such deaths occurred in the nivolumab-alone group.

The study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Lipson has relationships with Array BioPharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Genentech, Macrogenics, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Sanofi/Regeneron, and Sysmex (inst). Dr. Gralow has relationships with AstraZeneca, Genentech, Sandoz, and Immunomedics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding the novel immune checkpoint inhibitor relatlimab to the more established nivolumab (Opdivo) significantly extended the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with previously untreated advanced melanoma in comparison with nivolumab alone in the phase 3 RELATIVITY-047 trial.

Both drugs are from Bristol-Myers Squibb, which funded the study.

“Our findings demonstrate that relatlimab plus nivolumab is a potential novel treatment option for this patient population,” said lead researcher Evan J. Lipson, MD, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Relatlimab has a different mechanism of action from currently available immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab and similar agents, which act as inhibitors of the programmed cell death protein–1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death–ligand-1 (PD-L1). In contrast, relatlimab acts as an antibody that targets lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), which inhibits T cells and thus helps cancer cells evade immune attack.

“This is the first phase 3 study to validate inhibition of the LAG-3 immune checkpoint as a therapeutic strategy for patients with cancer, and it establishes the LAG-3 pathway as the third immune checkpoint pathway in history, after CLTA-4 and PD-1, for which blockade appears to have clinical benefit,” Dr. Lipson said at a press briefing ahead of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), where this study will be presented (abstract 9503).

Commenting for ASCO, Julie R. Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president, agreed that “these results provide validation of the LAG-3 immune checkpoint as a therapeutic target ... and they also support combination treatment with immunotherapies that act on different parts of the immune system.”

When Dr. Lipson was asked whether he would recommend the combination of relatlimab plus nivolumab as a first-line treatment for this patient population, he said that “for many patients,” the first-line treatment choice is made on a “case-by-case” basis.

“We are fortunate in melanoma that we have an ever-expanding list of seemingly effective options, and I think we’ll find at some point this will be added to that list,” he said. “Whether this is the first-line choice for any given patient really depends on a lot of factors,” he added.

Dr. Gralow added a note of caution. “The combination was clearly more toxic, and so I think there will be a lot of discussion” as to when it would be used and for which patients, she said.

In the absence of head-to-head comparisons, “I’m not sure that we have one answer” as to which treatment to choose, she added. With the ever-increasing number of options available in melanoma, the individual treatment choice is “getting more complicated,” she said.

Study details

The global RELATIVITY-047 study was conducted in 714 patients with previously untreated unresectable or metastatic melanoma. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either relatlimab plus nivolumab or nivolumab alone.

Dr. Lipson explained that the treatments were given as a fixed-dosed combination, meaning the preparation of relatlimab and nivolumab was given in the “same medication phial and administered as a single intravenous infusion in order to reduce preparation and infusion times and minimize the risk of administration errors.”

PFS, as determined on blinded independent central review, was significantly longer with the combination therapy than with nivolumab alone, at a median of 10.12 months vs. 4.63 months (hazard ratio, 0.75; P = .0055).

At 12 months, the PFS rate among patients given relatlimab plus nivolumab was 47.7%, versus 36.0% among those given nivolumab alone.

“This significant improvement meant that the study met its primary endpoint,” Dr. Lipson said, adding that the PFS benefit “appeared relatively early in the course of therapy.” The curves separated at 12 weeks, and benefit was “sustained” over the course of follow-up.

He added that the performance of nivolumab alone was “in the range” of that seen in previous studies, although he underlined that cross-trial comparison is difficult, given the differences in study design.

“In general, treatment-related adverse events” associated with the combination therapy were “manageable and reflected the safety profile that we typically see with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” he noted.

The results showed that 40.3% of patients who received the combination therapy experienced a grade 3-4 adverse event, compared with 33.4% of those given nivolumab alone. Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 8.5% and 3.1% of patients, respectively.

Three treatment-related deaths occurred in the relatlimab and nivolumab arm. Two such deaths occurred in the nivolumab-alone group.

The study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Lipson has relationships with Array BioPharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Genentech, Macrogenics, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Sanofi/Regeneron, and Sysmex (inst). Dr. Gralow has relationships with AstraZeneca, Genentech, Sandoz, and Immunomedics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding the novel immune checkpoint inhibitor relatlimab to the more established nivolumab (Opdivo) significantly extended the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with previously untreated advanced melanoma in comparison with nivolumab alone in the phase 3 RELATIVITY-047 trial.

Both drugs are from Bristol-Myers Squibb, which funded the study.

“Our findings demonstrate that relatlimab plus nivolumab is a potential novel treatment option for this patient population,” said lead researcher Evan J. Lipson, MD, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Relatlimab has a different mechanism of action from currently available immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab and similar agents, which act as inhibitors of the programmed cell death protein–1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death–ligand-1 (PD-L1). In contrast, relatlimab acts as an antibody that targets lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), which inhibits T cells and thus helps cancer cells evade immune attack.

“This is the first phase 3 study to validate inhibition of the LAG-3 immune checkpoint as a therapeutic strategy for patients with cancer, and it establishes the LAG-3 pathway as the third immune checkpoint pathway in history, after CLTA-4 and PD-1, for which blockade appears to have clinical benefit,” Dr. Lipson said at a press briefing ahead of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), where this study will be presented (abstract 9503).

Commenting for ASCO, Julie R. Gralow, MD, chief medical officer and executive vice president, agreed that “these results provide validation of the LAG-3 immune checkpoint as a therapeutic target ... and they also support combination treatment with immunotherapies that act on different parts of the immune system.”

When Dr. Lipson was asked whether he would recommend the combination of relatlimab plus nivolumab as a first-line treatment for this patient population, he said that “for many patients,” the first-line treatment choice is made on a “case-by-case” basis.

“We are fortunate in melanoma that we have an ever-expanding list of seemingly effective options, and I think we’ll find at some point this will be added to that list,” he said. “Whether this is the first-line choice for any given patient really depends on a lot of factors,” he added.

Dr. Gralow added a note of caution. “The combination was clearly more toxic, and so I think there will be a lot of discussion” as to when it would be used and for which patients, she said.

In the absence of head-to-head comparisons, “I’m not sure that we have one answer” as to which treatment to choose, she added. With the ever-increasing number of options available in melanoma, the individual treatment choice is “getting more complicated,” she said.

Study details

The global RELATIVITY-047 study was conducted in 714 patients with previously untreated unresectable or metastatic melanoma. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either relatlimab plus nivolumab or nivolumab alone.

Dr. Lipson explained that the treatments were given as a fixed-dosed combination, meaning the preparation of relatlimab and nivolumab was given in the “same medication phial and administered as a single intravenous infusion in order to reduce preparation and infusion times and minimize the risk of administration errors.”

PFS, as determined on blinded independent central review, was significantly longer with the combination therapy than with nivolumab alone, at a median of 10.12 months vs. 4.63 months (hazard ratio, 0.75; P = .0055).

At 12 months, the PFS rate among patients given relatlimab plus nivolumab was 47.7%, versus 36.0% among those given nivolumab alone.

“This significant improvement meant that the study met its primary endpoint,” Dr. Lipson said, adding that the PFS benefit “appeared relatively early in the course of therapy.” The curves separated at 12 weeks, and benefit was “sustained” over the course of follow-up.

He added that the performance of nivolumab alone was “in the range” of that seen in previous studies, although he underlined that cross-trial comparison is difficult, given the differences in study design.

“In general, treatment-related adverse events” associated with the combination therapy were “manageable and reflected the safety profile that we typically see with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” he noted.

The results showed that 40.3% of patients who received the combination therapy experienced a grade 3-4 adverse event, compared with 33.4% of those given nivolumab alone. Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 8.5% and 3.1% of patients, respectively.

Three treatment-related deaths occurred in the relatlimab and nivolumab arm. Two such deaths occurred in the nivolumab-alone group.

The study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Lipson has relationships with Array BioPharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Genentech, Macrogenics, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Sanofi/Regeneron, and Sysmex (inst). Dr. Gralow has relationships with AstraZeneca, Genentech, Sandoz, and Immunomedics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Telemedicine is popular among Mohs surgeons – for now

A majority of

A variety of factors combine to make it “very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices,” said Mario Maruthur, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “Telemedicine likely has a role in Mohs practices, particularly with postop follow-up visits. However, postpandemic reimbursement and regulatory issues need to be formally laid out before Mohs surgeons are able to incorporate it into their permanent work flow.”

Dr. Maruthur, a Mohs surgery and dermatologic oncology fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members in September and October 2020. “We saw first-hand in our surgical practice that telemedicine quickly became an important tool when the pandemic surged in the spring of 2020,” he said. Considering that surgical practices are highly dependent on in-person visits, the impetus for this study was to assess to what degree Mohs practices from across the spectrum, including academic and private practices, embraced telemedicine during the pandemic, and “what these surgical practices used telemedicine for, how it was received by their patients, which telemedicine platforms were most often utilized, and lastly, what are their plans if any for incorporating telemedicine into their surgical practices after the pandemic subsides.”

The researchers received responses from 115 surgeons representing all regions of the country (40% Northeast, 21% South, 21% Midwest, and 18% West). Half practiced in urban areas (37%) and large cities (13%), and 40% were in an academic setting versus 36% in a single-specialty private practice.

More than 70% of the respondents said their case load fell by at least 75% during the initial surge of the pandemic; 80% turned to telemedicine, compared with just 23% who relied on the technology prior to the pandemic. The most commonly used telemedicine technologies were FaceTime, Zoom, Doximity, and Epic.

Mohs surgeons reported most commonly using telemedicine for postsurgery management (77% of the total 115 responses). “Telemedicine is a great fit for this category of visits as they allow the surgeon to view the surgical site and answer any questions they patient may have,” Dr. Maruthur said. “If the surgeon does suspect a postop infection or other concern based on a patient’s signs or symptoms, they can easily schedule the patient for an in-person assessment. We suspect that postop follow-up visits may be the best candidate for long-term use of telemedicine in Mohs surgery practices.”

Surgeons also reported using telemedicine for “spot checks” (61%) and surgical consultations (59%).

However, Dr. Maruther noted that preoperative assessments and spot checks can be difficult to perform using telemedicine. “The quality of the video image is not always great, patients can have a difficult time pointing the camera at the right spot and at the right distance. Even appreciating the actual size of the lesion are all difficult over a video encounter. And there is a lot of information gleaned from in-person physical examination, such as whether the lesion is fixed to a deeper structure and whether there are any nearby scars or other suspicious lesions.”

Nearly three-quarters of the surgeons using the technology said most or all patients were receptive to telemedicine.

However, the surgeons reported multiple barriers to the use of telemedicine: Limitations when compared with physical exams (88%), fitting it into the work flow (58%), patient response and training (57%), reimbursement concerns (50%), implementation of the technology (37%), regulations such as HIPAA (24%), training of staff (17%), and licensing (8%).

In an interview, Sumaira Z. Aasi, MD, director of Mohs and dermatologic surgery, Stanford University, agreed that there are many obstacles to routine use of telemedicine by Mohs surgeons. “As surgeons, we rely on the physical and tactile exam to get a sense of the size and extent of the cancer and characteristics such as the laxity of the surrounding tissue whether the tumor is fixed,” she said. “It is very difficult to access this on a telemedicine visit.”

In addition, she said, “many of our patients are in the elderly population, and some may not be comfortable using this technology. Also, it’s not a work flow that we are comfortable or familiar with. And I think that the technology has to improve to allow for better resolution of images as we ‘examine’ patients through a telemedicine visit.”

She added that “another con is there is a reliance on having the patient point out lesions of concern. Many cancers are picked by a careful in-person examination by a qualified physician/dermatologist/Mohs surgeon when the lesion is quite small or subtle and not even noticed by the patient themselves. This approach invariably leads to earlier biopsies and earlier treatments that can prevent morbidity and save health care money.”

On the other hand, she said, telemedicine “may save patients some time and money in terms of the effort and cost of transportation to come in for simpler postoperative medical visits that are often short in their very nature, such as postop check-ups.”

Most of the surgeons surveyed (69%) said telemedicine probably or definitely deserves a place in the practice Mohs surgery, but only 50% said they’d like to or would definitely pursue giving telemedicine a role in their practices once the pandemic is over.

“At the start of the pandemic, many regulations in areas such as HIPAA were eased, and reimbursements were increased, which allowed telemedicine to be quickly adopted,” Dr. Maruther said. “The government and payers have yet to decide which regulations and reimbursements will be in place after the pandemic. That makes it very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices.”

Dr. Aasi predicted that telemedicine will become more appealing to patients and physicians as it its technology and usability improves. More familiarity with its use will also be helpful, she said, and surgeons will be more receptive as it’s incorporated into efficient daily work flow.

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

A majority of

A variety of factors combine to make it “very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices,” said Mario Maruthur, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “Telemedicine likely has a role in Mohs practices, particularly with postop follow-up visits. However, postpandemic reimbursement and regulatory issues need to be formally laid out before Mohs surgeons are able to incorporate it into their permanent work flow.”

Dr. Maruthur, a Mohs surgery and dermatologic oncology fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members in September and October 2020. “We saw first-hand in our surgical practice that telemedicine quickly became an important tool when the pandemic surged in the spring of 2020,” he said. Considering that surgical practices are highly dependent on in-person visits, the impetus for this study was to assess to what degree Mohs practices from across the spectrum, including academic and private practices, embraced telemedicine during the pandemic, and “what these surgical practices used telemedicine for, how it was received by their patients, which telemedicine platforms were most often utilized, and lastly, what are their plans if any for incorporating telemedicine into their surgical practices after the pandemic subsides.”

The researchers received responses from 115 surgeons representing all regions of the country (40% Northeast, 21% South, 21% Midwest, and 18% West). Half practiced in urban areas (37%) and large cities (13%), and 40% were in an academic setting versus 36% in a single-specialty private practice.

More than 70% of the respondents said their case load fell by at least 75% during the initial surge of the pandemic; 80% turned to telemedicine, compared with just 23% who relied on the technology prior to the pandemic. The most commonly used telemedicine technologies were FaceTime, Zoom, Doximity, and Epic.

Mohs surgeons reported most commonly using telemedicine for postsurgery management (77% of the total 115 responses). “Telemedicine is a great fit for this category of visits as they allow the surgeon to view the surgical site and answer any questions they patient may have,” Dr. Maruthur said. “If the surgeon does suspect a postop infection or other concern based on a patient’s signs or symptoms, they can easily schedule the patient for an in-person assessment. We suspect that postop follow-up visits may be the best candidate for long-term use of telemedicine in Mohs surgery practices.”

Surgeons also reported using telemedicine for “spot checks” (61%) and surgical consultations (59%).

However, Dr. Maruther noted that preoperative assessments and spot checks can be difficult to perform using telemedicine. “The quality of the video image is not always great, patients can have a difficult time pointing the camera at the right spot and at the right distance. Even appreciating the actual size of the lesion are all difficult over a video encounter. And there is a lot of information gleaned from in-person physical examination, such as whether the lesion is fixed to a deeper structure and whether there are any nearby scars or other suspicious lesions.”

Nearly three-quarters of the surgeons using the technology said most or all patients were receptive to telemedicine.

However, the surgeons reported multiple barriers to the use of telemedicine: Limitations when compared with physical exams (88%), fitting it into the work flow (58%), patient response and training (57%), reimbursement concerns (50%), implementation of the technology (37%), regulations such as HIPAA (24%), training of staff (17%), and licensing (8%).

In an interview, Sumaira Z. Aasi, MD, director of Mohs and dermatologic surgery, Stanford University, agreed that there are many obstacles to routine use of telemedicine by Mohs surgeons. “As surgeons, we rely on the physical and tactile exam to get a sense of the size and extent of the cancer and characteristics such as the laxity of the surrounding tissue whether the tumor is fixed,” she said. “It is very difficult to access this on a telemedicine visit.”

In addition, she said, “many of our patients are in the elderly population, and some may not be comfortable using this technology. Also, it’s not a work flow that we are comfortable or familiar with. And I think that the technology has to improve to allow for better resolution of images as we ‘examine’ patients through a telemedicine visit.”

She added that “another con is there is a reliance on having the patient point out lesions of concern. Many cancers are picked by a careful in-person examination by a qualified physician/dermatologist/Mohs surgeon when the lesion is quite small or subtle and not even noticed by the patient themselves. This approach invariably leads to earlier biopsies and earlier treatments that can prevent morbidity and save health care money.”

On the other hand, she said, telemedicine “may save patients some time and money in terms of the effort and cost of transportation to come in for simpler postoperative medical visits that are often short in their very nature, such as postop check-ups.”

Most of the surgeons surveyed (69%) said telemedicine probably or definitely deserves a place in the practice Mohs surgery, but only 50% said they’d like to or would definitely pursue giving telemedicine a role in their practices once the pandemic is over.

“At the start of the pandemic, many regulations in areas such as HIPAA were eased, and reimbursements were increased, which allowed telemedicine to be quickly adopted,” Dr. Maruther said. “The government and payers have yet to decide which regulations and reimbursements will be in place after the pandemic. That makes it very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices.”

Dr. Aasi predicted that telemedicine will become more appealing to patients and physicians as it its technology and usability improves. More familiarity with its use will also be helpful, she said, and surgeons will be more receptive as it’s incorporated into efficient daily work flow.

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

A majority of

A variety of factors combine to make it “very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices,” said Mario Maruthur, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery. “Telemedicine likely has a role in Mohs practices, particularly with postop follow-up visits. However, postpandemic reimbursement and regulatory issues need to be formally laid out before Mohs surgeons are able to incorporate it into their permanent work flow.”

Dr. Maruthur, a Mohs surgery and dermatologic oncology fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues sent a survey to ACMS members in September and October 2020. “We saw first-hand in our surgical practice that telemedicine quickly became an important tool when the pandemic surged in the spring of 2020,” he said. Considering that surgical practices are highly dependent on in-person visits, the impetus for this study was to assess to what degree Mohs practices from across the spectrum, including academic and private practices, embraced telemedicine during the pandemic, and “what these surgical practices used telemedicine for, how it was received by their patients, which telemedicine platforms were most often utilized, and lastly, what are their plans if any for incorporating telemedicine into their surgical practices after the pandemic subsides.”

The researchers received responses from 115 surgeons representing all regions of the country (40% Northeast, 21% South, 21% Midwest, and 18% West). Half practiced in urban areas (37%) and large cities (13%), and 40% were in an academic setting versus 36% in a single-specialty private practice.

More than 70% of the respondents said their case load fell by at least 75% during the initial surge of the pandemic; 80% turned to telemedicine, compared with just 23% who relied on the technology prior to the pandemic. The most commonly used telemedicine technologies were FaceTime, Zoom, Doximity, and Epic.

Mohs surgeons reported most commonly using telemedicine for postsurgery management (77% of the total 115 responses). “Telemedicine is a great fit for this category of visits as they allow the surgeon to view the surgical site and answer any questions they patient may have,” Dr. Maruthur said. “If the surgeon does suspect a postop infection or other concern based on a patient’s signs or symptoms, they can easily schedule the patient for an in-person assessment. We suspect that postop follow-up visits may be the best candidate for long-term use of telemedicine in Mohs surgery practices.”

Surgeons also reported using telemedicine for “spot checks” (61%) and surgical consultations (59%).

However, Dr. Maruther noted that preoperative assessments and spot checks can be difficult to perform using telemedicine. “The quality of the video image is not always great, patients can have a difficult time pointing the camera at the right spot and at the right distance. Even appreciating the actual size of the lesion are all difficult over a video encounter. And there is a lot of information gleaned from in-person physical examination, such as whether the lesion is fixed to a deeper structure and whether there are any nearby scars or other suspicious lesions.”

Nearly three-quarters of the surgeons using the technology said most or all patients were receptive to telemedicine.

However, the surgeons reported multiple barriers to the use of telemedicine: Limitations when compared with physical exams (88%), fitting it into the work flow (58%), patient response and training (57%), reimbursement concerns (50%), implementation of the technology (37%), regulations such as HIPAA (24%), training of staff (17%), and licensing (8%).

In an interview, Sumaira Z. Aasi, MD, director of Mohs and dermatologic surgery, Stanford University, agreed that there are many obstacles to routine use of telemedicine by Mohs surgeons. “As surgeons, we rely on the physical and tactile exam to get a sense of the size and extent of the cancer and characteristics such as the laxity of the surrounding tissue whether the tumor is fixed,” she said. “It is very difficult to access this on a telemedicine visit.”

In addition, she said, “many of our patients are in the elderly population, and some may not be comfortable using this technology. Also, it’s not a work flow that we are comfortable or familiar with. And I think that the technology has to improve to allow for better resolution of images as we ‘examine’ patients through a telemedicine visit.”

She added that “another con is there is a reliance on having the patient point out lesions of concern. Many cancers are picked by a careful in-person examination by a qualified physician/dermatologist/Mohs surgeon when the lesion is quite small or subtle and not even noticed by the patient themselves. This approach invariably leads to earlier biopsies and earlier treatments that can prevent morbidity and save health care money.”

On the other hand, she said, telemedicine “may save patients some time and money in terms of the effort and cost of transportation to come in for simpler postoperative medical visits that are often short in their very nature, such as postop check-ups.”

Most of the surgeons surveyed (69%) said telemedicine probably or definitely deserves a place in the practice Mohs surgery, but only 50% said they’d like to or would definitely pursue giving telemedicine a role in their practices once the pandemic is over.

“At the start of the pandemic, many regulations in areas such as HIPAA were eased, and reimbursements were increased, which allowed telemedicine to be quickly adopted,” Dr. Maruther said. “The government and payers have yet to decide which regulations and reimbursements will be in place after the pandemic. That makes it very difficult for surgeons to make long-term plans for implementing telemedicine in their practices.”

Dr. Aasi predicted that telemedicine will become more appealing to patients and physicians as it its technology and usability improves. More familiarity with its use will also be helpful, she said, and surgeons will be more receptive as it’s incorporated into efficient daily work flow.

The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

New guideline provides recommendations on reconstruction after skin cancer resection

You’ve successfully resected a skin cancer lesion, leaving clear margins. Now what?

That’s

The guideline – a joint effort of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, American Academy of Dermatology, American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Mohs Surgery, and American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

From the outset, the panel members realized that to keep the guideline manageable they had to limit recommendations to the practice of reconstruction defined as “cutaneous closure that requires a flap, graft, or tissue rearrangement.”

Other wound closure methods, such as secondary intention healing; simple closures; and complex closures that do not involve flaps, grafts, muscle, or bone, were not covered in the recommendations.

As with similar guidelines, the developers selected seven clinical questions to be addressed, and attempted to find consensus through literature searches, appraisal of the evidence, grading of recommendations, peer review, and public comment.

“We had a very heterogeneous set of things that we were trying to comment on, so we had to keep things somewhat generic,” lead author Andrew Chen, MD, chief of the division of plastic surgery, at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, said in an interview.