User login

Home Treatment of Presumed Melanocytic Nevus With Frankincense

To the Editor:

Melanocytic nevi are ubiquitous, and although they are benign, patients often desire to have them removed. We report a patient who presented to our clinic after attempting home removal of a concerning mole on the back with frankincense, a remedy that she found online.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a worrisome mole on the back. She had no personal history of skin cancer, but her father had a history of melanoma in situ in his 60s. The patient reported that she had the mole for years, but approximately 1 month prior to her visit she noticed that it began to bleed and crust, causing concern for melanoma. She read online that the lesion could be removed with topical application of the essential oil frankincense; she applied it directly to the lesion on the back. Within hours she developed a burn where it was applied with associated blistering.

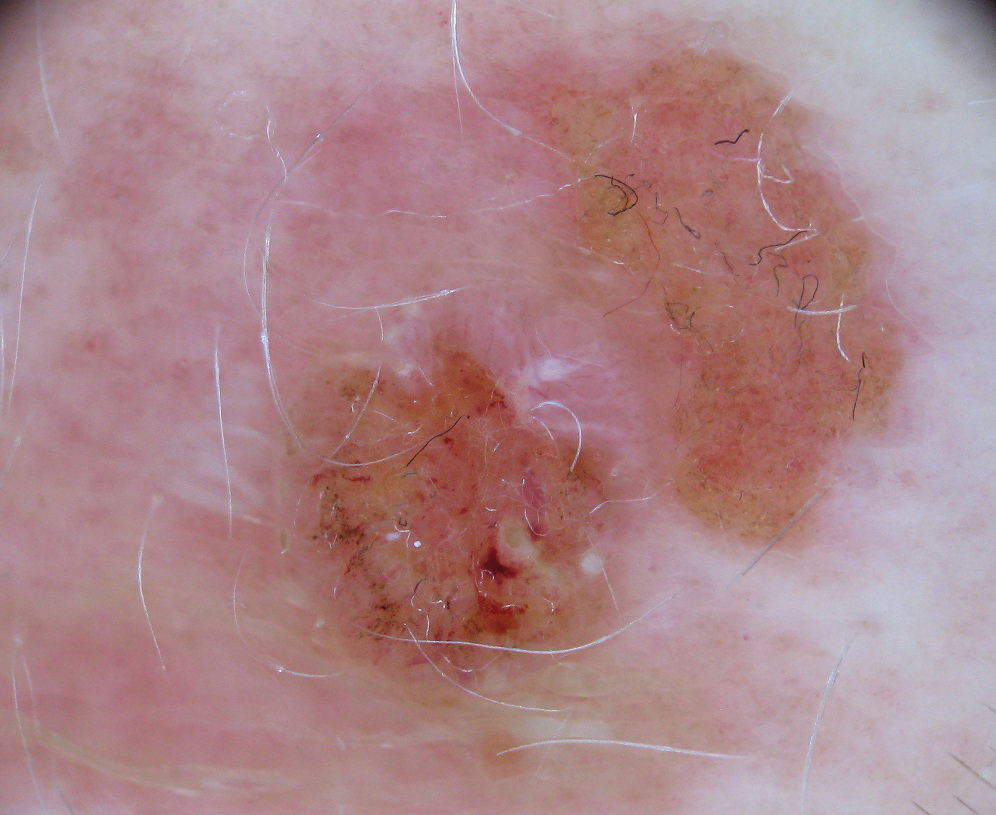

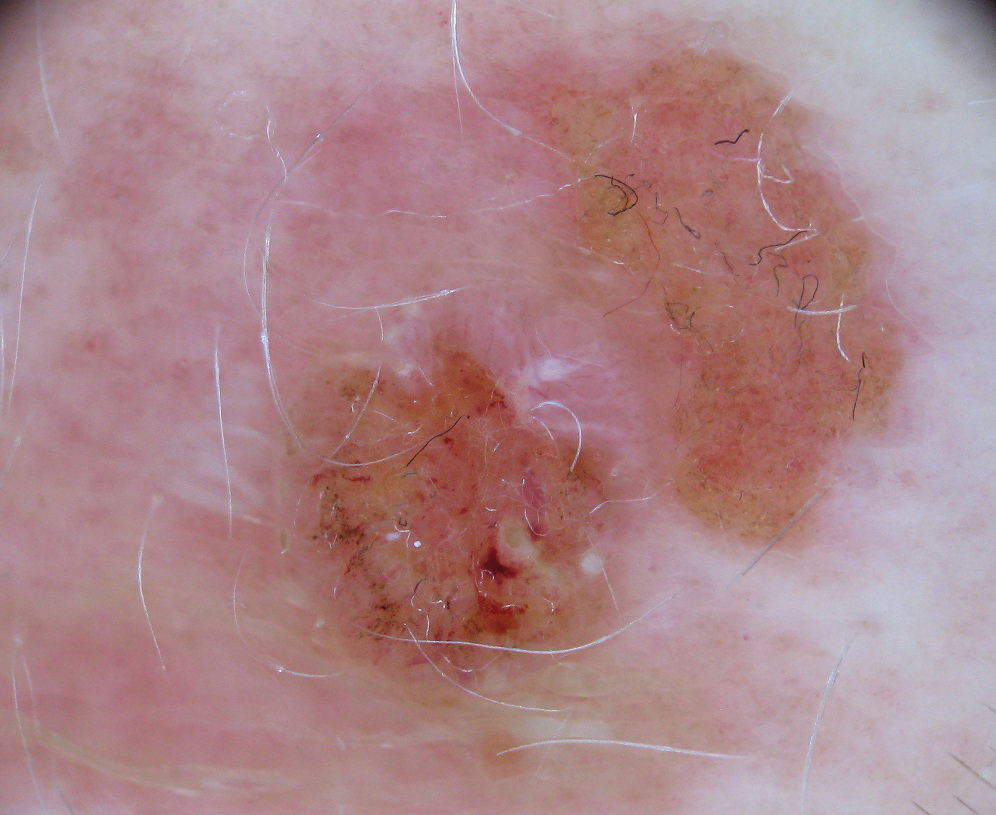

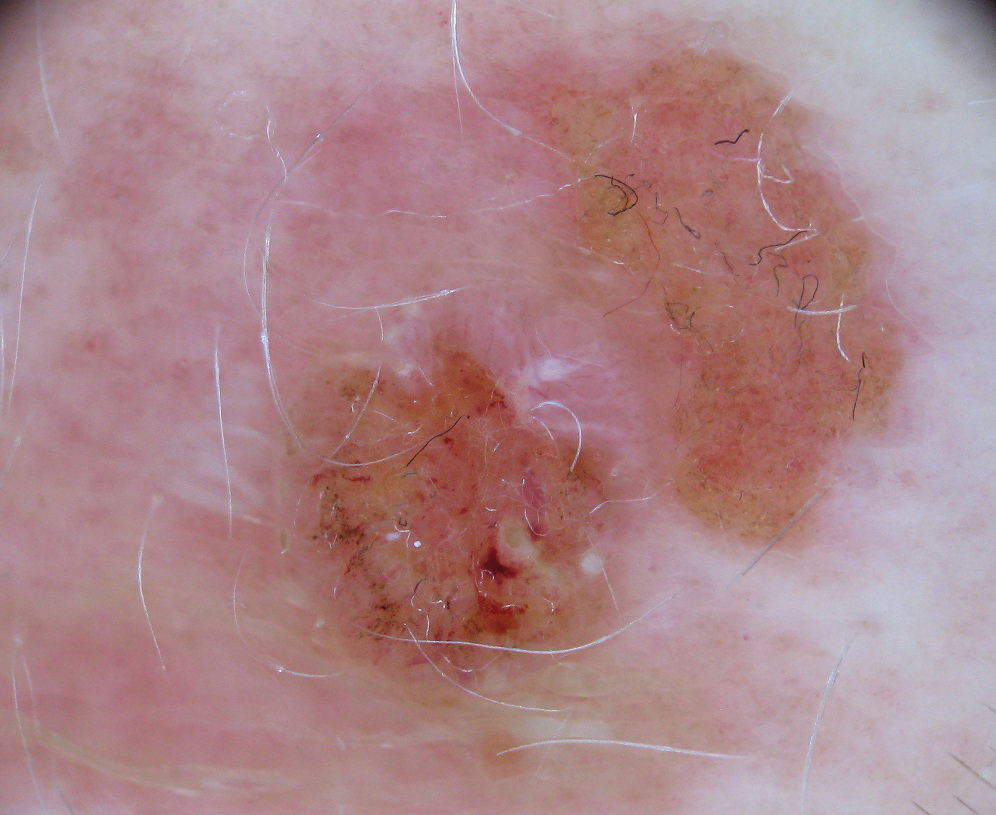

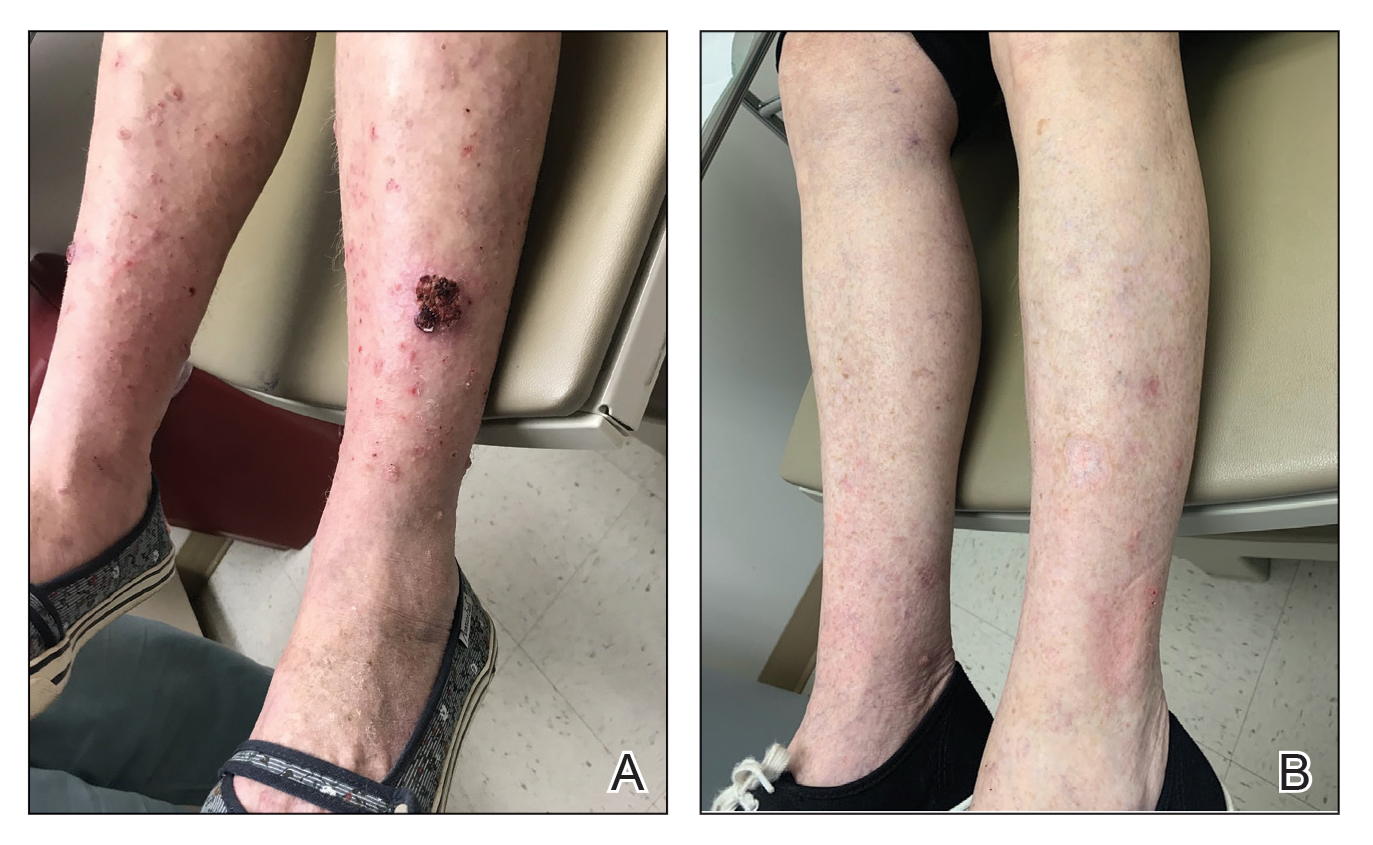

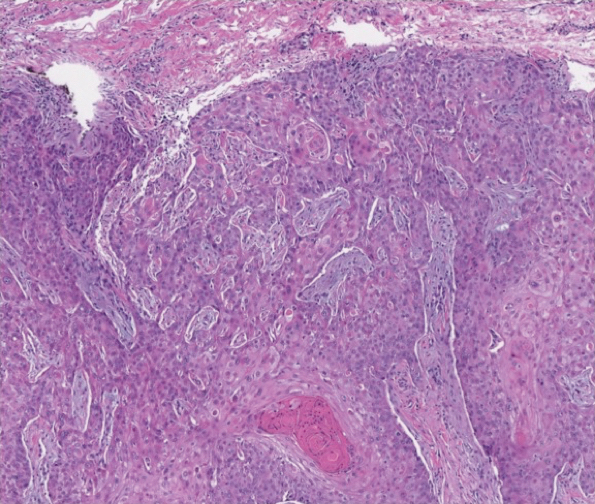

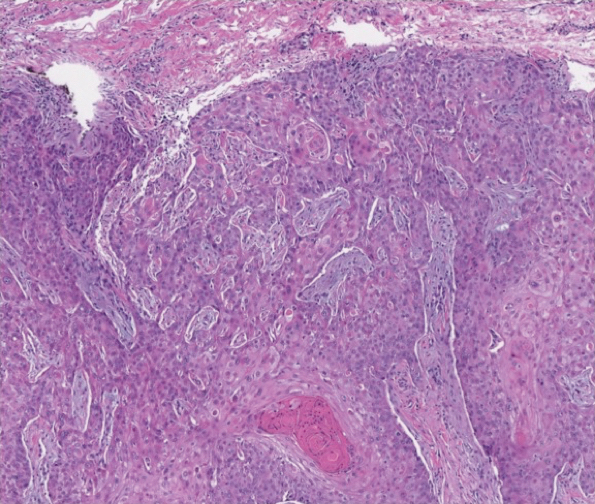

Clinically, the lesion appeared as a darkly pigmented, well-circumscribed papule with hemorrhagic crust overlying a well-demarcated pink plaque (Figure 1). Dermatoscopically, the lesion lacked a pigment network and demonstrated 2 distinct pink papules with peripheral telangiectasia and a pink background with white streaks (Figure 2). A shave biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a nodular basal cell carcinoma extending to the base and margin.

Frankincense is the common name given to oleo-gum-resins of Boswellia species.1 It has been studied extensively for anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of its active component, boswellic acid, can have a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on certain malignant cell lines, such as melanoma, in vitro.2,3 It also has been shown to be antitumoral in mouse models.4 There are limited in vivo studies in the literature assessing the effects of boswellic acid or frankincense on cutaneous melanocytic lesions or other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma.

A Google search of home remedy mole removal yielded more than 1,000,000 results. At the time of submission, the top 5 results all listed frankincense as a potential treatment along with garlic, iodine, castor oil, onion juice, pineapple juice, banana peels, honey, and aloe vera. None of the results cited evidence for their treatments. Although all recommended dilution of the frankincense prior to application, none warned of potential risks or side effects of its use.

Natural methods of home mole removal have long been sought after. Escharotics are most commonly utilized, including bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), zinc chloride, Chelidonium majus, and Solanum sodomaeum. Many formulations are commercially available online, despite the fact that they can be mutilating and potentially dangerous when used without appropriate supervision.5 This case and an online search demonstrated that these agents are not only potentially harmful home remedies but also are currently falsely advertised as effective therapeutic management for melanocytic nevi.

Approximately 6 million individuals in the United States search the internet for health information daily, and as many as 41% of those do so to learn about alternative medicine.5,6 Although information gleaned from search engines can be useful, it is unregulated and often can be inaccurate. Clinicians generally are unaware of the erroneous material presented online and, therefore, cannot appropriately combat patient misinformation. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain an awareness of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

- Du Z, Liu Z, Ning Z, et al. Prospects of boswellic acids as potential pharmaceutics. Planta Med. 2015;81:259-271.

- Eichhorn T, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Molecular determinants of the response of tumor cells to boswellic acids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4:1171-1182.

- Zhao W, Entschladen F, Liu H, et al. Boswellic acid acetate induces differentiation and apoptosis in highly metastatic melanoma and fibrosarcoma cell. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

- Huang MT, Badmaev V, Ding Y, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-carcinogenic activities of triterpenoid, beta-boswellic acid. Biofactors. 2000;13:225-230.

- Adler BL, Friedman AJ. Safety & efficacy of agents used for home mole removal and skin cancer treatment in the internet age, and analysis of cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1058-1063.

- Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to health questions: internet search results versus online health community responses. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:E95.

To the Editor:

Melanocytic nevi are ubiquitous, and although they are benign, patients often desire to have them removed. We report a patient who presented to our clinic after attempting home removal of a concerning mole on the back with frankincense, a remedy that she found online.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a worrisome mole on the back. She had no personal history of skin cancer, but her father had a history of melanoma in situ in his 60s. The patient reported that she had the mole for years, but approximately 1 month prior to her visit she noticed that it began to bleed and crust, causing concern for melanoma. She read online that the lesion could be removed with topical application of the essential oil frankincense; she applied it directly to the lesion on the back. Within hours she developed a burn where it was applied with associated blistering.

Clinically, the lesion appeared as a darkly pigmented, well-circumscribed papule with hemorrhagic crust overlying a well-demarcated pink plaque (Figure 1). Dermatoscopically, the lesion lacked a pigment network and demonstrated 2 distinct pink papules with peripheral telangiectasia and a pink background with white streaks (Figure 2). A shave biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a nodular basal cell carcinoma extending to the base and margin.

Frankincense is the common name given to oleo-gum-resins of Boswellia species.1 It has been studied extensively for anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of its active component, boswellic acid, can have a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on certain malignant cell lines, such as melanoma, in vitro.2,3 It also has been shown to be antitumoral in mouse models.4 There are limited in vivo studies in the literature assessing the effects of boswellic acid or frankincense on cutaneous melanocytic lesions or other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma.

A Google search of home remedy mole removal yielded more than 1,000,000 results. At the time of submission, the top 5 results all listed frankincense as a potential treatment along with garlic, iodine, castor oil, onion juice, pineapple juice, banana peels, honey, and aloe vera. None of the results cited evidence for their treatments. Although all recommended dilution of the frankincense prior to application, none warned of potential risks or side effects of its use.

Natural methods of home mole removal have long been sought after. Escharotics are most commonly utilized, including bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), zinc chloride, Chelidonium majus, and Solanum sodomaeum. Many formulations are commercially available online, despite the fact that they can be mutilating and potentially dangerous when used without appropriate supervision.5 This case and an online search demonstrated that these agents are not only potentially harmful home remedies but also are currently falsely advertised as effective therapeutic management for melanocytic nevi.

Approximately 6 million individuals in the United States search the internet for health information daily, and as many as 41% of those do so to learn about alternative medicine.5,6 Although information gleaned from search engines can be useful, it is unregulated and often can be inaccurate. Clinicians generally are unaware of the erroneous material presented online and, therefore, cannot appropriately combat patient misinformation. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain an awareness of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

To the Editor:

Melanocytic nevi are ubiquitous, and although they are benign, patients often desire to have them removed. We report a patient who presented to our clinic after attempting home removal of a concerning mole on the back with frankincense, a remedy that she found online.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a worrisome mole on the back. She had no personal history of skin cancer, but her father had a history of melanoma in situ in his 60s. The patient reported that she had the mole for years, but approximately 1 month prior to her visit she noticed that it began to bleed and crust, causing concern for melanoma. She read online that the lesion could be removed with topical application of the essential oil frankincense; she applied it directly to the lesion on the back. Within hours she developed a burn where it was applied with associated blistering.

Clinically, the lesion appeared as a darkly pigmented, well-circumscribed papule with hemorrhagic crust overlying a well-demarcated pink plaque (Figure 1). Dermatoscopically, the lesion lacked a pigment network and demonstrated 2 distinct pink papules with peripheral telangiectasia and a pink background with white streaks (Figure 2). A shave biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a nodular basal cell carcinoma extending to the base and margin.

Frankincense is the common name given to oleo-gum-resins of Boswellia species.1 It has been studied extensively for anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of its active component, boswellic acid, can have a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on certain malignant cell lines, such as melanoma, in vitro.2,3 It also has been shown to be antitumoral in mouse models.4 There are limited in vivo studies in the literature assessing the effects of boswellic acid or frankincense on cutaneous melanocytic lesions or other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma.

A Google search of home remedy mole removal yielded more than 1,000,000 results. At the time of submission, the top 5 results all listed frankincense as a potential treatment along with garlic, iodine, castor oil, onion juice, pineapple juice, banana peels, honey, and aloe vera. None of the results cited evidence for their treatments. Although all recommended dilution of the frankincense prior to application, none warned of potential risks or side effects of its use.

Natural methods of home mole removal have long been sought after. Escharotics are most commonly utilized, including bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), zinc chloride, Chelidonium majus, and Solanum sodomaeum. Many formulations are commercially available online, despite the fact that they can be mutilating and potentially dangerous when used without appropriate supervision.5 This case and an online search demonstrated that these agents are not only potentially harmful home remedies but also are currently falsely advertised as effective therapeutic management for melanocytic nevi.

Approximately 6 million individuals in the United States search the internet for health information daily, and as many as 41% of those do so to learn about alternative medicine.5,6 Although information gleaned from search engines can be useful, it is unregulated and often can be inaccurate. Clinicians generally are unaware of the erroneous material presented online and, therefore, cannot appropriately combat patient misinformation. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain an awareness of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

- Du Z, Liu Z, Ning Z, et al. Prospects of boswellic acids as potential pharmaceutics. Planta Med. 2015;81:259-271.

- Eichhorn T, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Molecular determinants of the response of tumor cells to boswellic acids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4:1171-1182.

- Zhao W, Entschladen F, Liu H, et al. Boswellic acid acetate induces differentiation and apoptosis in highly metastatic melanoma and fibrosarcoma cell. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

- Huang MT, Badmaev V, Ding Y, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-carcinogenic activities of triterpenoid, beta-boswellic acid. Biofactors. 2000;13:225-230.

- Adler BL, Friedman AJ. Safety & efficacy of agents used for home mole removal and skin cancer treatment in the internet age, and analysis of cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1058-1063.

- Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to health questions: internet search results versus online health community responses. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:E95.

- Du Z, Liu Z, Ning Z, et al. Prospects of boswellic acids as potential pharmaceutics. Planta Med. 2015;81:259-271.

- Eichhorn T, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Molecular determinants of the response of tumor cells to boswellic acids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4:1171-1182.

- Zhao W, Entschladen F, Liu H, et al. Boswellic acid acetate induces differentiation and apoptosis in highly metastatic melanoma and fibrosarcoma cell. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

- Huang MT, Badmaev V, Ding Y, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-carcinogenic activities of triterpenoid, beta-boswellic acid. Biofactors. 2000;13:225-230.

- Adler BL, Friedman AJ. Safety & efficacy of agents used for home mole removal and skin cancer treatment in the internet age, and analysis of cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1058-1063.

- Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to health questions: internet search results versus online health community responses. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:E95.

Practice Points

- Many patients seek natural methods of home mole removal online, including topical application of essential oils such as frankincense.

- These agents often are unregulated and can be potentially harmful when used without appropriate supervision.

- Dermatologists should be aware of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

For diagnosing skin lesions, AI risks failing in skin of color

In the analysis of images for detecting potential pathology, if training does not specifically address these skin types, according to Adewole S. Adamson, MD, who outlined this issue at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

“Machine learning algorithms are only as good as the inputs through which they learn. Without representation from individuals with skin of color, we are at risk of creating a new source of racial disparity in patient care,” Dr. Adamson, assistant professor in the division of dermatology, department of internal medicine, University of Texas at Austin, said at the meeting.

Diagnostic algorithms using AI are typically based on deep learning, a subset of machine learning that depends on artificial neural networks. In the case of image processing, neural networks can “learn” to recognize objects, faces, or, in the realm of health care, disease, from exposure to multiple images.

There are many other variables that affect the accuracy of deep learning for diagnostic algorithms, including the depth of the layering through which the process distills multiple inputs of information, but the number of inputs is critical. In the case of skin lesions, machines cannot learn to recognize features of different skin types without exposure.

“There are studies demonstrating that dermatologists can be outperformed for detection of skin cancers by AI, so this is going to be an increasingly powerful tool,” Dr. Adamson said. The problem is that “there has been very little representation in darker skin types” in the algorithms developed so far.

The risk is that AI will exacerbate an existing problem. Skin cancer in darker skin is less common but already underdiagnosed, independent of AI. Per 100,000 males in the United States, the rate of melanoma is about 30-fold greater in White men than in Black men (33.0 vs. 1.0). Among females, the racial difference is smaller but still enormous (20.2 vs. 1.2 per 100,000 females), according to U.S. data.

For the low representation of darker skin in studies so far with AI, “one of the arguments is that skin cancer is not a big deal in darker skin types,” Dr. Adamson said.

It might be the other way around. The relative infrequency with which skin cancer occurs in the Black population in the United States might explain a low level of suspicion and ultimately delays in diagnosis, which, in turn, leads to worse outcomes. According to one analysis drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Result (SEER) database (1998-2011), the proportion of patients with regionally advanced or distant disease was nearly twice as great (11.6% vs. 6.0%; P < .05) in Black patients, relative to White patients.

Not surprisingly, given the importance of early diagnosis of cancers overall and skin cancer specifically, the mean survival for malignant melanoma in Black patients was almost 4 years lower than in White patients (10.8 vs. 14.6 years; P < .001) for nodular melanoma, the same study found.

In humans, bias is reasonably attributed in many cases to judgments made on a small sample size. The problem in AI is analogous. Dr. Adamson, who has published research on the potential for machine learning to contribute to health care disparities in dermatology, cited work done by Joy Buolamwini, a graduate researcher in the media lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In one study she conducted, the rate of AI facial recognition failure was 1% in White males, 7% in White females, 12% in skin-of-color males, and 35% in skin-of-color females. Fewer inputs of skin of color is the likely explanation, Dr. Adamson said.

The potential for racial bias from AI in the diagnosis of disease increases and becomes more complex when inputs beyond imaging, such as past medical history, are included. Dr. Adamson warned of the potential for “bias to creep in” when there is failure to account for societal, cultural, or other differences that distinguish one patient group from another. However, for skin cancer or other diseases based on images alone, he said there are solutions.

“We are in the early days, and there is time to change this,” Dr. Adamson said, referring to the low representation of skin of color in AI training sets. In addition to including more skin types to train recognition, creating AI algorithms specifically for dark skin is another potential approach.

However, his key point was the importance of recognizing the need for solutions.

“AI is the future, but we must apply the same rigor to AI as to other medical interventions to ensure that the technology is not applied in a biased fashion,” he said.

Susan M. Swetter, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the pigmented lesion and melanoma program at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center and Cancer Institute, agreed. As someone who has been following the progress of AI in the diagnosis of skin cancer, Dr. Swetter recognizes the potential for this technology to increase diagnostic efficiency and accuracy, but she also called for studies specific to skin of color.

The algorithms “have not yet been adequately evaluated in people of color, particularly Black patients in whom dermoscopic criteria for benign versus malignant melanocytic neoplasms differ from those with lighter skin types,” Dr. Swetter said in an interview.

She sees the same fix as that proposed by Dr. Adamson.

“Efforts to include skin of color in AI algorithms for validation and further training are needed to prevent potential harms of over- or underdiagnosis in darker skin patients,” she pointed out.

Dr. Adamson reports no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this topic. Dr. Swetter had no relevant disclosures.

In the analysis of images for detecting potential pathology, if training does not specifically address these skin types, according to Adewole S. Adamson, MD, who outlined this issue at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

“Machine learning algorithms are only as good as the inputs through which they learn. Without representation from individuals with skin of color, we are at risk of creating a new source of racial disparity in patient care,” Dr. Adamson, assistant professor in the division of dermatology, department of internal medicine, University of Texas at Austin, said at the meeting.

Diagnostic algorithms using AI are typically based on deep learning, a subset of machine learning that depends on artificial neural networks. In the case of image processing, neural networks can “learn” to recognize objects, faces, or, in the realm of health care, disease, from exposure to multiple images.

There are many other variables that affect the accuracy of deep learning for diagnostic algorithms, including the depth of the layering through which the process distills multiple inputs of information, but the number of inputs is critical. In the case of skin lesions, machines cannot learn to recognize features of different skin types without exposure.

“There are studies demonstrating that dermatologists can be outperformed for detection of skin cancers by AI, so this is going to be an increasingly powerful tool,” Dr. Adamson said. The problem is that “there has been very little representation in darker skin types” in the algorithms developed so far.

The risk is that AI will exacerbate an existing problem. Skin cancer in darker skin is less common but already underdiagnosed, independent of AI. Per 100,000 males in the United States, the rate of melanoma is about 30-fold greater in White men than in Black men (33.0 vs. 1.0). Among females, the racial difference is smaller but still enormous (20.2 vs. 1.2 per 100,000 females), according to U.S. data.

For the low representation of darker skin in studies so far with AI, “one of the arguments is that skin cancer is not a big deal in darker skin types,” Dr. Adamson said.

It might be the other way around. The relative infrequency with which skin cancer occurs in the Black population in the United States might explain a low level of suspicion and ultimately delays in diagnosis, which, in turn, leads to worse outcomes. According to one analysis drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Result (SEER) database (1998-2011), the proportion of patients with regionally advanced or distant disease was nearly twice as great (11.6% vs. 6.0%; P < .05) in Black patients, relative to White patients.

Not surprisingly, given the importance of early diagnosis of cancers overall and skin cancer specifically, the mean survival for malignant melanoma in Black patients was almost 4 years lower than in White patients (10.8 vs. 14.6 years; P < .001) for nodular melanoma, the same study found.

In humans, bias is reasonably attributed in many cases to judgments made on a small sample size. The problem in AI is analogous. Dr. Adamson, who has published research on the potential for machine learning to contribute to health care disparities in dermatology, cited work done by Joy Buolamwini, a graduate researcher in the media lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In one study she conducted, the rate of AI facial recognition failure was 1% in White males, 7% in White females, 12% in skin-of-color males, and 35% in skin-of-color females. Fewer inputs of skin of color is the likely explanation, Dr. Adamson said.

The potential for racial bias from AI in the diagnosis of disease increases and becomes more complex when inputs beyond imaging, such as past medical history, are included. Dr. Adamson warned of the potential for “bias to creep in” when there is failure to account for societal, cultural, or other differences that distinguish one patient group from another. However, for skin cancer or other diseases based on images alone, he said there are solutions.

“We are in the early days, and there is time to change this,” Dr. Adamson said, referring to the low representation of skin of color in AI training sets. In addition to including more skin types to train recognition, creating AI algorithms specifically for dark skin is another potential approach.

However, his key point was the importance of recognizing the need for solutions.

“AI is the future, but we must apply the same rigor to AI as to other medical interventions to ensure that the technology is not applied in a biased fashion,” he said.

Susan M. Swetter, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the pigmented lesion and melanoma program at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center and Cancer Institute, agreed. As someone who has been following the progress of AI in the diagnosis of skin cancer, Dr. Swetter recognizes the potential for this technology to increase diagnostic efficiency and accuracy, but she also called for studies specific to skin of color.

The algorithms “have not yet been adequately evaluated in people of color, particularly Black patients in whom dermoscopic criteria for benign versus malignant melanocytic neoplasms differ from those with lighter skin types,” Dr. Swetter said in an interview.

She sees the same fix as that proposed by Dr. Adamson.

“Efforts to include skin of color in AI algorithms for validation and further training are needed to prevent potential harms of over- or underdiagnosis in darker skin patients,” she pointed out.

Dr. Adamson reports no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this topic. Dr. Swetter had no relevant disclosures.

In the analysis of images for detecting potential pathology, if training does not specifically address these skin types, according to Adewole S. Adamson, MD, who outlined this issue at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

“Machine learning algorithms are only as good as the inputs through which they learn. Without representation from individuals with skin of color, we are at risk of creating a new source of racial disparity in patient care,” Dr. Adamson, assistant professor in the division of dermatology, department of internal medicine, University of Texas at Austin, said at the meeting.

Diagnostic algorithms using AI are typically based on deep learning, a subset of machine learning that depends on artificial neural networks. In the case of image processing, neural networks can “learn” to recognize objects, faces, or, in the realm of health care, disease, from exposure to multiple images.

There are many other variables that affect the accuracy of deep learning for diagnostic algorithms, including the depth of the layering through which the process distills multiple inputs of information, but the number of inputs is critical. In the case of skin lesions, machines cannot learn to recognize features of different skin types without exposure.

“There are studies demonstrating that dermatologists can be outperformed for detection of skin cancers by AI, so this is going to be an increasingly powerful tool,” Dr. Adamson said. The problem is that “there has been very little representation in darker skin types” in the algorithms developed so far.

The risk is that AI will exacerbate an existing problem. Skin cancer in darker skin is less common but already underdiagnosed, independent of AI. Per 100,000 males in the United States, the rate of melanoma is about 30-fold greater in White men than in Black men (33.0 vs. 1.0). Among females, the racial difference is smaller but still enormous (20.2 vs. 1.2 per 100,000 females), according to U.S. data.

For the low representation of darker skin in studies so far with AI, “one of the arguments is that skin cancer is not a big deal in darker skin types,” Dr. Adamson said.

It might be the other way around. The relative infrequency with which skin cancer occurs in the Black population in the United States might explain a low level of suspicion and ultimately delays in diagnosis, which, in turn, leads to worse outcomes. According to one analysis drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Result (SEER) database (1998-2011), the proportion of patients with regionally advanced or distant disease was nearly twice as great (11.6% vs. 6.0%; P < .05) in Black patients, relative to White patients.

Not surprisingly, given the importance of early diagnosis of cancers overall and skin cancer specifically, the mean survival for malignant melanoma in Black patients was almost 4 years lower than in White patients (10.8 vs. 14.6 years; P < .001) for nodular melanoma, the same study found.

In humans, bias is reasonably attributed in many cases to judgments made on a small sample size. The problem in AI is analogous. Dr. Adamson, who has published research on the potential for machine learning to contribute to health care disparities in dermatology, cited work done by Joy Buolamwini, a graduate researcher in the media lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In one study she conducted, the rate of AI facial recognition failure was 1% in White males, 7% in White females, 12% in skin-of-color males, and 35% in skin-of-color females. Fewer inputs of skin of color is the likely explanation, Dr. Adamson said.

The potential for racial bias from AI in the diagnosis of disease increases and becomes more complex when inputs beyond imaging, such as past medical history, are included. Dr. Adamson warned of the potential for “bias to creep in” when there is failure to account for societal, cultural, or other differences that distinguish one patient group from another. However, for skin cancer or other diseases based on images alone, he said there are solutions.

“We are in the early days, and there is time to change this,” Dr. Adamson said, referring to the low representation of skin of color in AI training sets. In addition to including more skin types to train recognition, creating AI algorithms specifically for dark skin is another potential approach.

However, his key point was the importance of recognizing the need for solutions.

“AI is the future, but we must apply the same rigor to AI as to other medical interventions to ensure that the technology is not applied in a biased fashion,” he said.

Susan M. Swetter, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the pigmented lesion and melanoma program at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center and Cancer Institute, agreed. As someone who has been following the progress of AI in the diagnosis of skin cancer, Dr. Swetter recognizes the potential for this technology to increase diagnostic efficiency and accuracy, but she also called for studies specific to skin of color.

The algorithms “have not yet been adequately evaluated in people of color, particularly Black patients in whom dermoscopic criteria for benign versus malignant melanocytic neoplasms differ from those with lighter skin types,” Dr. Swetter said in an interview.

She sees the same fix as that proposed by Dr. Adamson.

“Efforts to include skin of color in AI algorithms for validation and further training are needed to prevent potential harms of over- or underdiagnosis in darker skin patients,” she pointed out.

Dr. Adamson reports no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this topic. Dr. Swetter had no relevant disclosures.

FROM AAD VMX 2021

The power and promise of social media in oncology

Mark A. Lewis, MD, explained to the COSMO meeting audience how storytelling on social media can educate and engage patients, advocates, and professional colleagues – advancing knowledge, dispelling misinformation, and promoting clinical research.

Dr. Lewis, an oncologist at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, reflected on the bifid roles of oncologists as scientists engaged in life-long learning and humanists who can internalize and appreciate the unique character and circumstances of their patients.

Patients who have serious illnesses are necessarily aggregated by statistics. However, in an essay published in 2011, Dr. Lewis noted that “each individual patient partakes in a unique, irreproducible experiment where n = 1” (J Clin Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;29[22]:3103-4).

Dr. Lewis highlighted the duality of individual data points on a survival curve as descriptors of common disease trajectories and treatment effects. However, those data points also conceal important narratives regarding the most highly valued aspects of the doctor-patient relationship and the impact of cancer treatment on patients’ lives.

In referring to the futuristic essay “Ars Brevis,” Dr. Lewis contrasted the humanism of oncology specialists in the present day with the fictional image of data-regurgitating robots programmed to maximize the efficiency of each patient encounter (J Clin Oncol. 2013 May 10;31[14]:1792-4).

Dr. Lewis reminded attendees that to practice medicine without using both “head and heart” undermines the inherent nature of medical care.

Unfortunately, that perspective may not match the public perception of oncologists. Dr. Lewis described his experience of typing “oncologists are” into an Internet search engine and seeing the auto-complete function prompt words such as “criminals,” “evil,” “murderers,” and “confused.”

Obviously, it is hard to establish a trusting patient-doctor relationship if that is the prima facie perception of the oncology specialty.

Dispelling myths and creating community via social media

A primary goal of consultation with a newly-diagnosed cancer patient is for the patient to feel that the oncologist will be there to take care of them, regardless of what the future holds.

Dr. Lewis has found that social media can potentially extend that feeling to a global community of patients, caregivers, and others seeking information relevant to a cancer diagnosis. He believes that oncologists have an opportunity to dispel myths and fears by being attentive to the real-life concerns of patients.

Dr. Lewis took advantage of this opportunity when he underwent a Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) for a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. He and the hospital’s media services staff “live-tweeted” his surgery and recovery.

With those tweets, Dr. Lewis demystified each step of a major surgical procedure. From messages he received on social media, Dr. Lewis knows he made the decision to have a Whipple procedure more acceptable to other patients.

His personal medical experience notwithstanding, Dr. Lewis acknowledged that every patient’s circumstances are unique.

Oncologists cannot possibly empathize with every circumstance. However, when they show sensitivity to personal elements of the cancer experience, they shed light on the complicated role they play in patient care and can facilitate good decision-making among patients across the globe.

Social media for professional development and patient care

The publication of his 2011 essay was gratifying for Dr. Lewis, but the finite number of comments he received thereafter illustrated the rather limited audience that traditional academic publications have and the laborious process for subsequent interaction (J Clin Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;29[22]:3103-4).

First as an observer and later as a participant on social media, Dr. Lewis appreciated that teaching points and publications can be amplified by global distribution and the potential for informal bidirectional communication.

Social media platforms enable physicians to connect with a larger audience through participative communication, in which users develop, share, and react to content (N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 13;361[7]:649-51).

Dr. Lewis reflected on how oncologists are challenged to sort through the thousands of oncology-focused publications annually. Through social media, one can see the studies on which the experts are commenting and appreciate the nuances that contextualize the results. Focused interactions with renowned doctors, at regular intervals, require little formality.

Online journal clubs enable the sharing of ideas, opinions, multimedia resources, and references across institutional and international borders (J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Oct;29[10]:1317-8).

Social media in oncology: Accomplishments and promise

The development of broadband Internet, wireless connectivity, and social media for peer-to-peer and general communication are among the major technological advances that have transformed medical communication.

As an organization, COSMO aims to describe, understand, and improve the use of social media to increase the penetration of evidence-based guidelines and research insights into clinical practice (Future Oncol. 2017 Jun;13[15]:1281-5).

At the inaugural COSMO meeting, areas of progress since COSMO’s inception in 2015 were highlighted, including:

- The involvement of cancer professionals and advocates in multiple distinctive platforms.

- The development of hashtag libraries to aggregate interest groups and topics.

- The refinement of strategies for engaging advocates with attention to inclusiveness.

- A steady trajectory of growth in tweeting at scientific conferences.

An overarching theme of the COSMO meeting was “authenticity,” a virtue that is easy to admire but requires conscious, consistent effort to achieve.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest and avoiding using social media simply as a recruitment tool for clinical trials are basic components of accurate self-representation.

In addition, Dr. Lewis advocated for sharing personal experiences in a component of social media posts so oncologists can show humanity as a feature of their professional online identity and inherent nature.

Dr. Lewis disclosed consultancy with Medscape/WebMD, which are owned by the same parent company as MDedge. He also disclosed relationships with Foundation Medicine, Natera, Exelixis, QED, HalioDX, and Ipsen.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Mark A. Lewis, MD, explained to the COSMO meeting audience how storytelling on social media can educate and engage patients, advocates, and professional colleagues – advancing knowledge, dispelling misinformation, and promoting clinical research.

Dr. Lewis, an oncologist at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, reflected on the bifid roles of oncologists as scientists engaged in life-long learning and humanists who can internalize and appreciate the unique character and circumstances of their patients.

Patients who have serious illnesses are necessarily aggregated by statistics. However, in an essay published in 2011, Dr. Lewis noted that “each individual patient partakes in a unique, irreproducible experiment where n = 1” (J Clin Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;29[22]:3103-4).

Dr. Lewis highlighted the duality of individual data points on a survival curve as descriptors of common disease trajectories and treatment effects. However, those data points also conceal important narratives regarding the most highly valued aspects of the doctor-patient relationship and the impact of cancer treatment on patients’ lives.

In referring to the futuristic essay “Ars Brevis,” Dr. Lewis contrasted the humanism of oncology specialists in the present day with the fictional image of data-regurgitating robots programmed to maximize the efficiency of each patient encounter (J Clin Oncol. 2013 May 10;31[14]:1792-4).

Dr. Lewis reminded attendees that to practice medicine without using both “head and heart” undermines the inherent nature of medical care.

Unfortunately, that perspective may not match the public perception of oncologists. Dr. Lewis described his experience of typing “oncologists are” into an Internet search engine and seeing the auto-complete function prompt words such as “criminals,” “evil,” “murderers,” and “confused.”

Obviously, it is hard to establish a trusting patient-doctor relationship if that is the prima facie perception of the oncology specialty.

Dispelling myths and creating community via social media

A primary goal of consultation with a newly-diagnosed cancer patient is for the patient to feel that the oncologist will be there to take care of them, regardless of what the future holds.

Dr. Lewis has found that social media can potentially extend that feeling to a global community of patients, caregivers, and others seeking information relevant to a cancer diagnosis. He believes that oncologists have an opportunity to dispel myths and fears by being attentive to the real-life concerns of patients.

Dr. Lewis took advantage of this opportunity when he underwent a Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) for a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. He and the hospital’s media services staff “live-tweeted” his surgery and recovery.

With those tweets, Dr. Lewis demystified each step of a major surgical procedure. From messages he received on social media, Dr. Lewis knows he made the decision to have a Whipple procedure more acceptable to other patients.

His personal medical experience notwithstanding, Dr. Lewis acknowledged that every patient’s circumstances are unique.

Oncologists cannot possibly empathize with every circumstance. However, when they show sensitivity to personal elements of the cancer experience, they shed light on the complicated role they play in patient care and can facilitate good decision-making among patients across the globe.

Social media for professional development and patient care

The publication of his 2011 essay was gratifying for Dr. Lewis, but the finite number of comments he received thereafter illustrated the rather limited audience that traditional academic publications have and the laborious process for subsequent interaction (J Clin Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;29[22]:3103-4).

First as an observer and later as a participant on social media, Dr. Lewis appreciated that teaching points and publications can be amplified by global distribution and the potential for informal bidirectional communication.

Social media platforms enable physicians to connect with a larger audience through participative communication, in which users develop, share, and react to content (N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 13;361[7]:649-51).

Dr. Lewis reflected on how oncologists are challenged to sort through the thousands of oncology-focused publications annually. Through social media, one can see the studies on which the experts are commenting and appreciate the nuances that contextualize the results. Focused interactions with renowned doctors, at regular intervals, require little formality.

Online journal clubs enable the sharing of ideas, opinions, multimedia resources, and references across institutional and international borders (J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Oct;29[10]:1317-8).

Social media in oncology: Accomplishments and promise

The development of broadband Internet, wireless connectivity, and social media for peer-to-peer and general communication are among the major technological advances that have transformed medical communication.

As an organization, COSMO aims to describe, understand, and improve the use of social media to increase the penetration of evidence-based guidelines and research insights into clinical practice (Future Oncol. 2017 Jun;13[15]:1281-5).

At the inaugural COSMO meeting, areas of progress since COSMO’s inception in 2015 were highlighted, including:

- The involvement of cancer professionals and advocates in multiple distinctive platforms.

- The development of hashtag libraries to aggregate interest groups and topics.

- The refinement of strategies for engaging advocates with attention to inclusiveness.

- A steady trajectory of growth in tweeting at scientific conferences.

An overarching theme of the COSMO meeting was “authenticity,” a virtue that is easy to admire but requires conscious, consistent effort to achieve.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest and avoiding using social media simply as a recruitment tool for clinical trials are basic components of accurate self-representation.

In addition, Dr. Lewis advocated for sharing personal experiences in a component of social media posts so oncologists can show humanity as a feature of their professional online identity and inherent nature.

Dr. Lewis disclosed consultancy with Medscape/WebMD, which are owned by the same parent company as MDedge. He also disclosed relationships with Foundation Medicine, Natera, Exelixis, QED, HalioDX, and Ipsen.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Mark A. Lewis, MD, explained to the COSMO meeting audience how storytelling on social media can educate and engage patients, advocates, and professional colleagues – advancing knowledge, dispelling misinformation, and promoting clinical research.

Dr. Lewis, an oncologist at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, reflected on the bifid roles of oncologists as scientists engaged in life-long learning and humanists who can internalize and appreciate the unique character and circumstances of their patients.

Patients who have serious illnesses are necessarily aggregated by statistics. However, in an essay published in 2011, Dr. Lewis noted that “each individual patient partakes in a unique, irreproducible experiment where n = 1” (J Clin Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;29[22]:3103-4).

Dr. Lewis highlighted the duality of individual data points on a survival curve as descriptors of common disease trajectories and treatment effects. However, those data points also conceal important narratives regarding the most highly valued aspects of the doctor-patient relationship and the impact of cancer treatment on patients’ lives.

In referring to the futuristic essay “Ars Brevis,” Dr. Lewis contrasted the humanism of oncology specialists in the present day with the fictional image of data-regurgitating robots programmed to maximize the efficiency of each patient encounter (J Clin Oncol. 2013 May 10;31[14]:1792-4).

Dr. Lewis reminded attendees that to practice medicine without using both “head and heart” undermines the inherent nature of medical care.

Unfortunately, that perspective may not match the public perception of oncologists. Dr. Lewis described his experience of typing “oncologists are” into an Internet search engine and seeing the auto-complete function prompt words such as “criminals,” “evil,” “murderers,” and “confused.”

Obviously, it is hard to establish a trusting patient-doctor relationship if that is the prima facie perception of the oncology specialty.

Dispelling myths and creating community via social media

A primary goal of consultation with a newly-diagnosed cancer patient is for the patient to feel that the oncologist will be there to take care of them, regardless of what the future holds.

Dr. Lewis has found that social media can potentially extend that feeling to a global community of patients, caregivers, and others seeking information relevant to a cancer diagnosis. He believes that oncologists have an opportunity to dispel myths and fears by being attentive to the real-life concerns of patients.

Dr. Lewis took advantage of this opportunity when he underwent a Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) for a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. He and the hospital’s media services staff “live-tweeted” his surgery and recovery.

With those tweets, Dr. Lewis demystified each step of a major surgical procedure. From messages he received on social media, Dr. Lewis knows he made the decision to have a Whipple procedure more acceptable to other patients.

His personal medical experience notwithstanding, Dr. Lewis acknowledged that every patient’s circumstances are unique.

Oncologists cannot possibly empathize with every circumstance. However, when they show sensitivity to personal elements of the cancer experience, they shed light on the complicated role they play in patient care and can facilitate good decision-making among patients across the globe.

Social media for professional development and patient care

The publication of his 2011 essay was gratifying for Dr. Lewis, but the finite number of comments he received thereafter illustrated the rather limited audience that traditional academic publications have and the laborious process for subsequent interaction (J Clin Oncol. 2011 Aug 1;29[22]:3103-4).

First as an observer and later as a participant on social media, Dr. Lewis appreciated that teaching points and publications can be amplified by global distribution and the potential for informal bidirectional communication.

Social media platforms enable physicians to connect with a larger audience through participative communication, in which users develop, share, and react to content (N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 13;361[7]:649-51).

Dr. Lewis reflected on how oncologists are challenged to sort through the thousands of oncology-focused publications annually. Through social media, one can see the studies on which the experts are commenting and appreciate the nuances that contextualize the results. Focused interactions with renowned doctors, at regular intervals, require little formality.

Online journal clubs enable the sharing of ideas, opinions, multimedia resources, and references across institutional and international borders (J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Oct;29[10]:1317-8).

Social media in oncology: Accomplishments and promise

The development of broadband Internet, wireless connectivity, and social media for peer-to-peer and general communication are among the major technological advances that have transformed medical communication.

As an organization, COSMO aims to describe, understand, and improve the use of social media to increase the penetration of evidence-based guidelines and research insights into clinical practice (Future Oncol. 2017 Jun;13[15]:1281-5).

At the inaugural COSMO meeting, areas of progress since COSMO’s inception in 2015 were highlighted, including:

- The involvement of cancer professionals and advocates in multiple distinctive platforms.

- The development of hashtag libraries to aggregate interest groups and topics.

- The refinement of strategies for engaging advocates with attention to inclusiveness.

- A steady trajectory of growth in tweeting at scientific conferences.

An overarching theme of the COSMO meeting was “authenticity,” a virtue that is easy to admire but requires conscious, consistent effort to achieve.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest and avoiding using social media simply as a recruitment tool for clinical trials are basic components of accurate self-representation.

In addition, Dr. Lewis advocated for sharing personal experiences in a component of social media posts so oncologists can show humanity as a feature of their professional online identity and inherent nature.

Dr. Lewis disclosed consultancy with Medscape/WebMD, which are owned by the same parent company as MDedge. He also disclosed relationships with Foundation Medicine, Natera, Exelixis, QED, HalioDX, and Ipsen.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM COSMO 2021

Hyperprogression on immunotherapy: When outcomes are much worse

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making