User login

Cutaneous Manifestation as Initial Presentation of Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

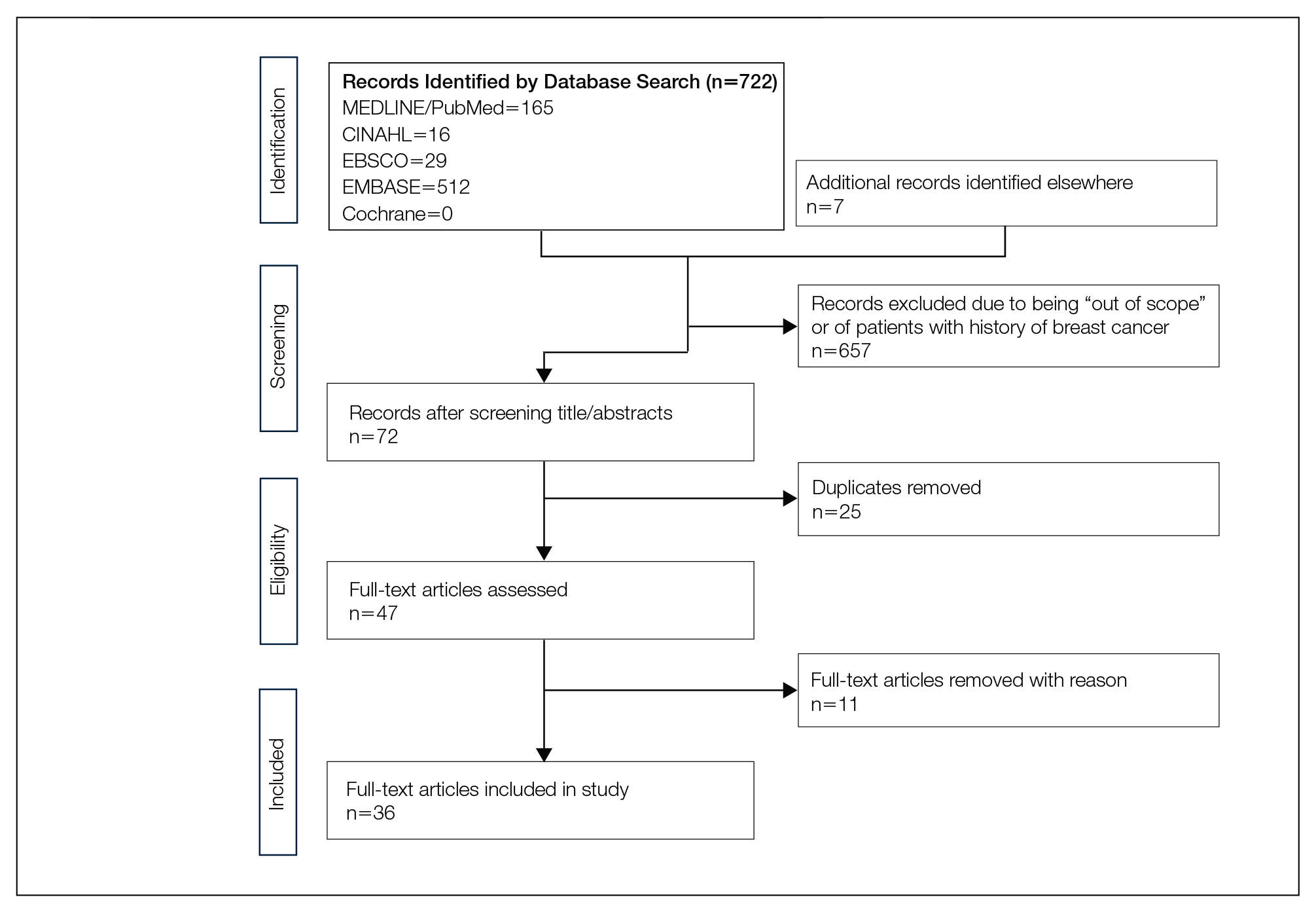

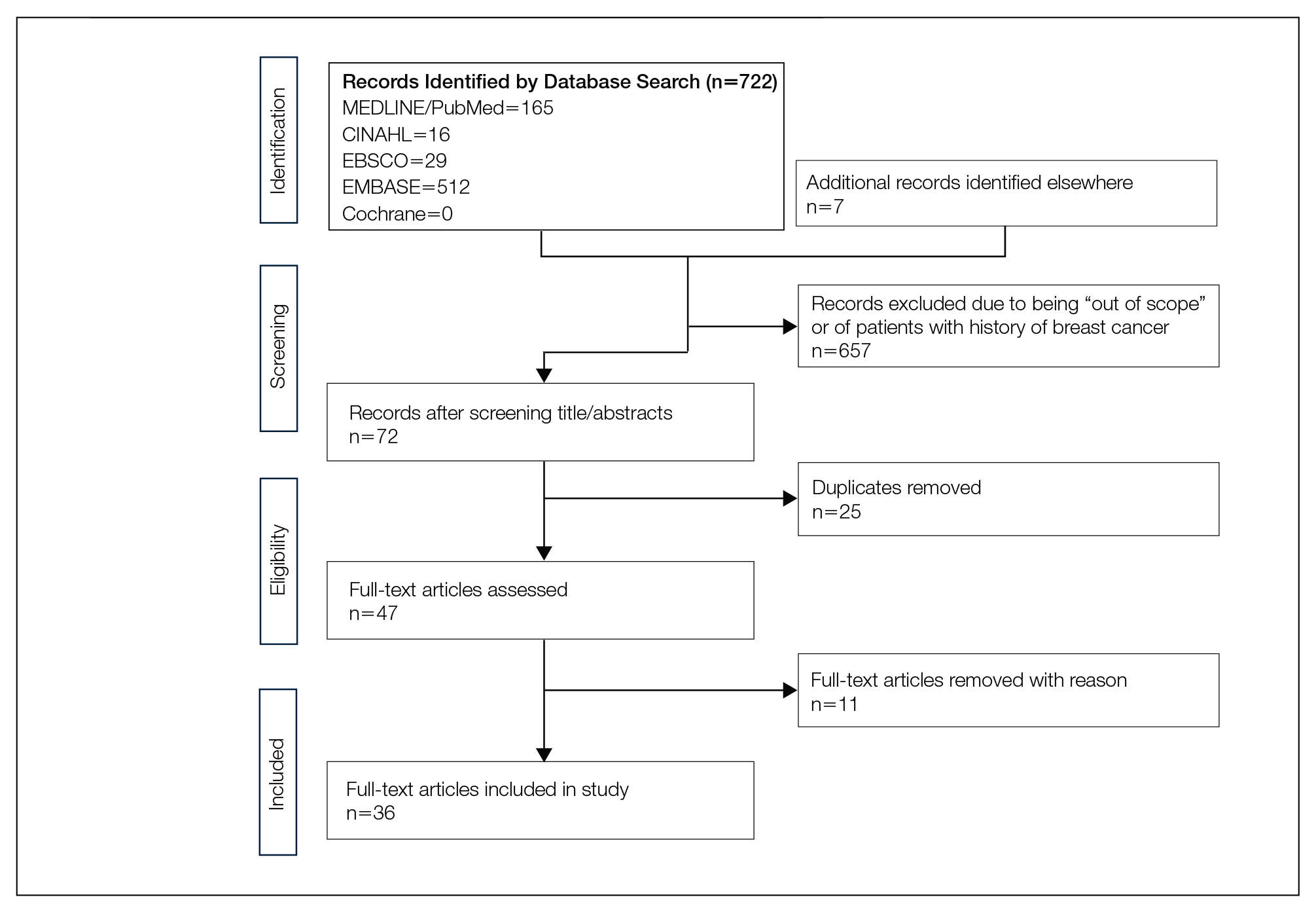

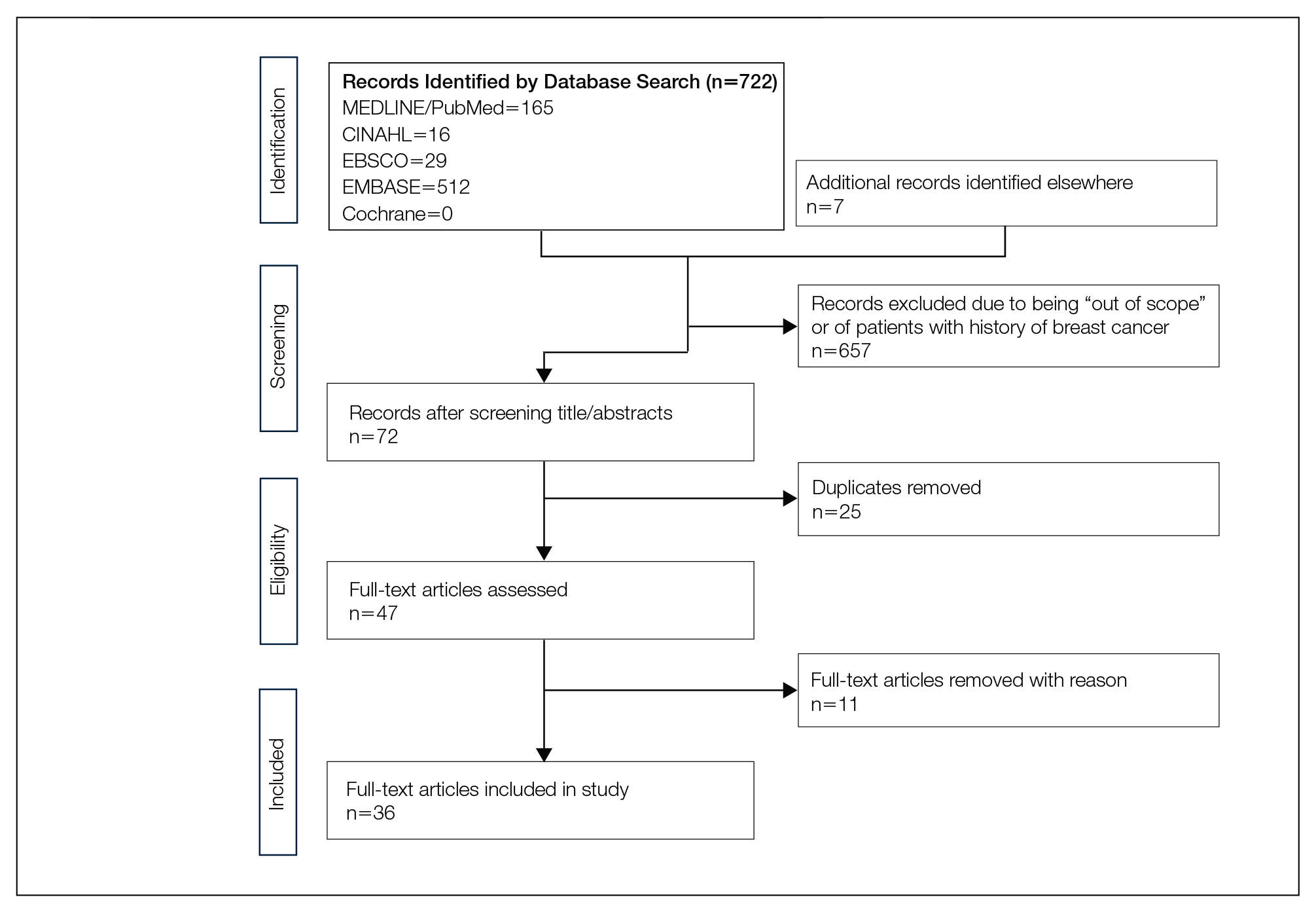

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

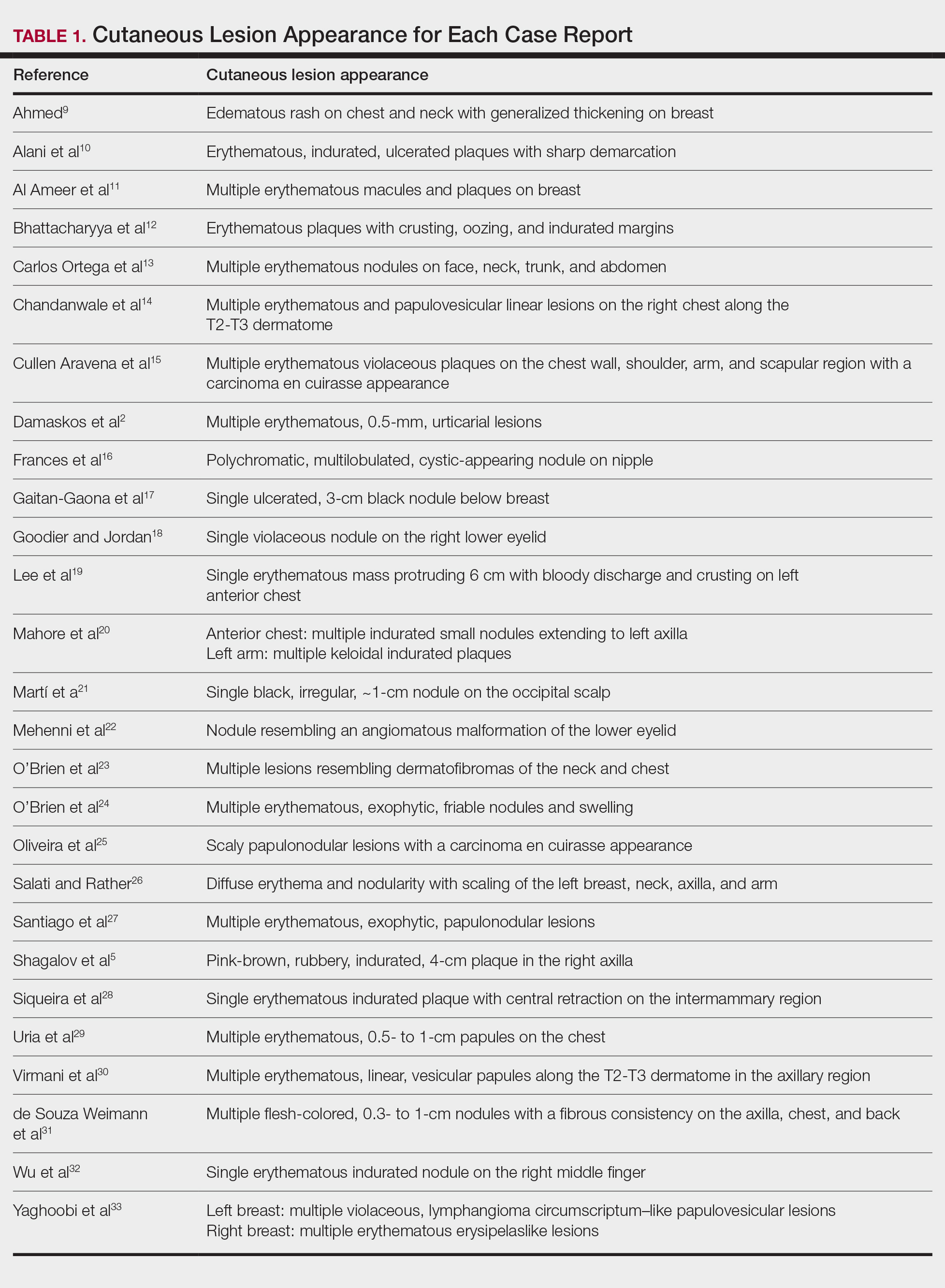

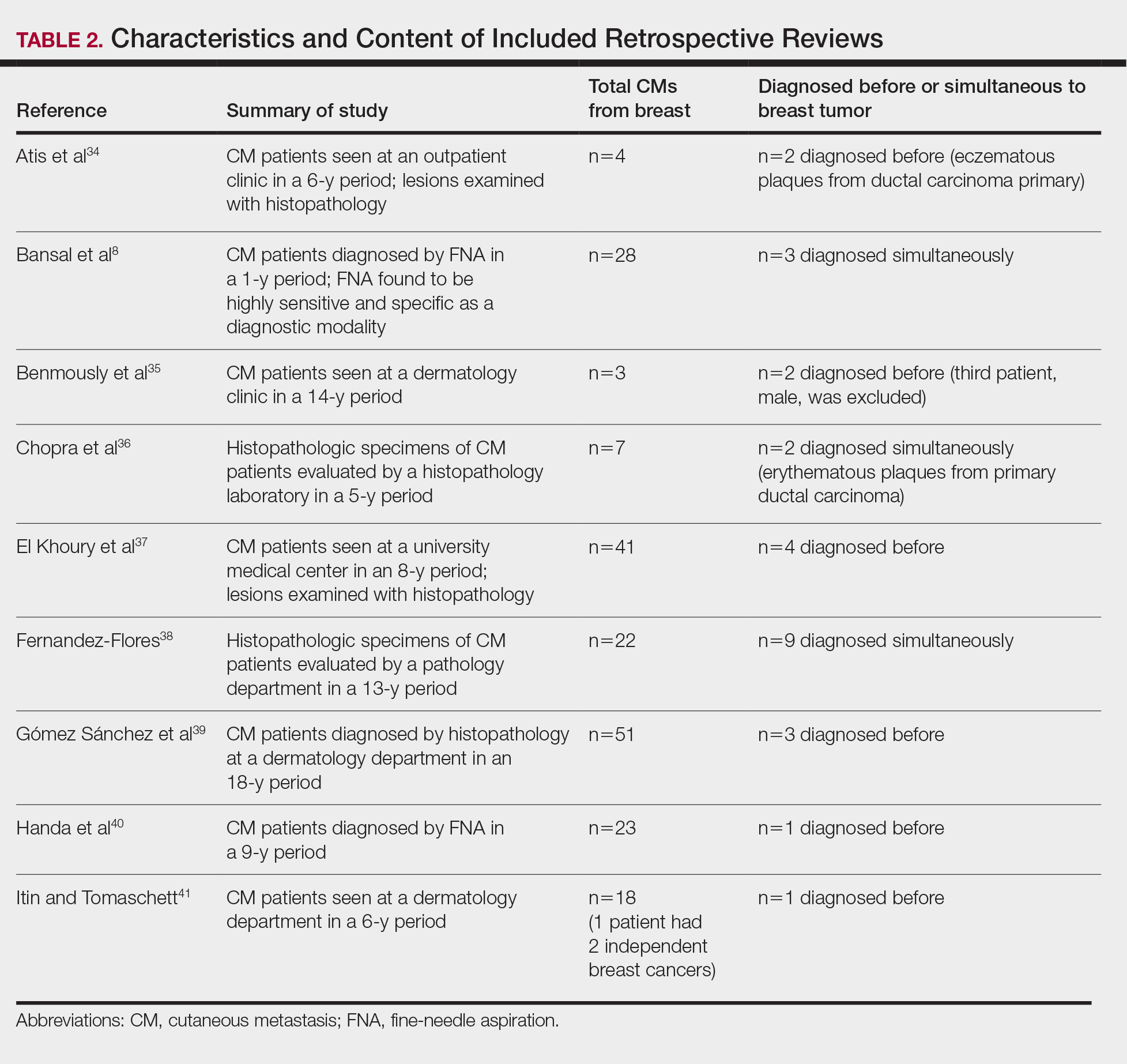

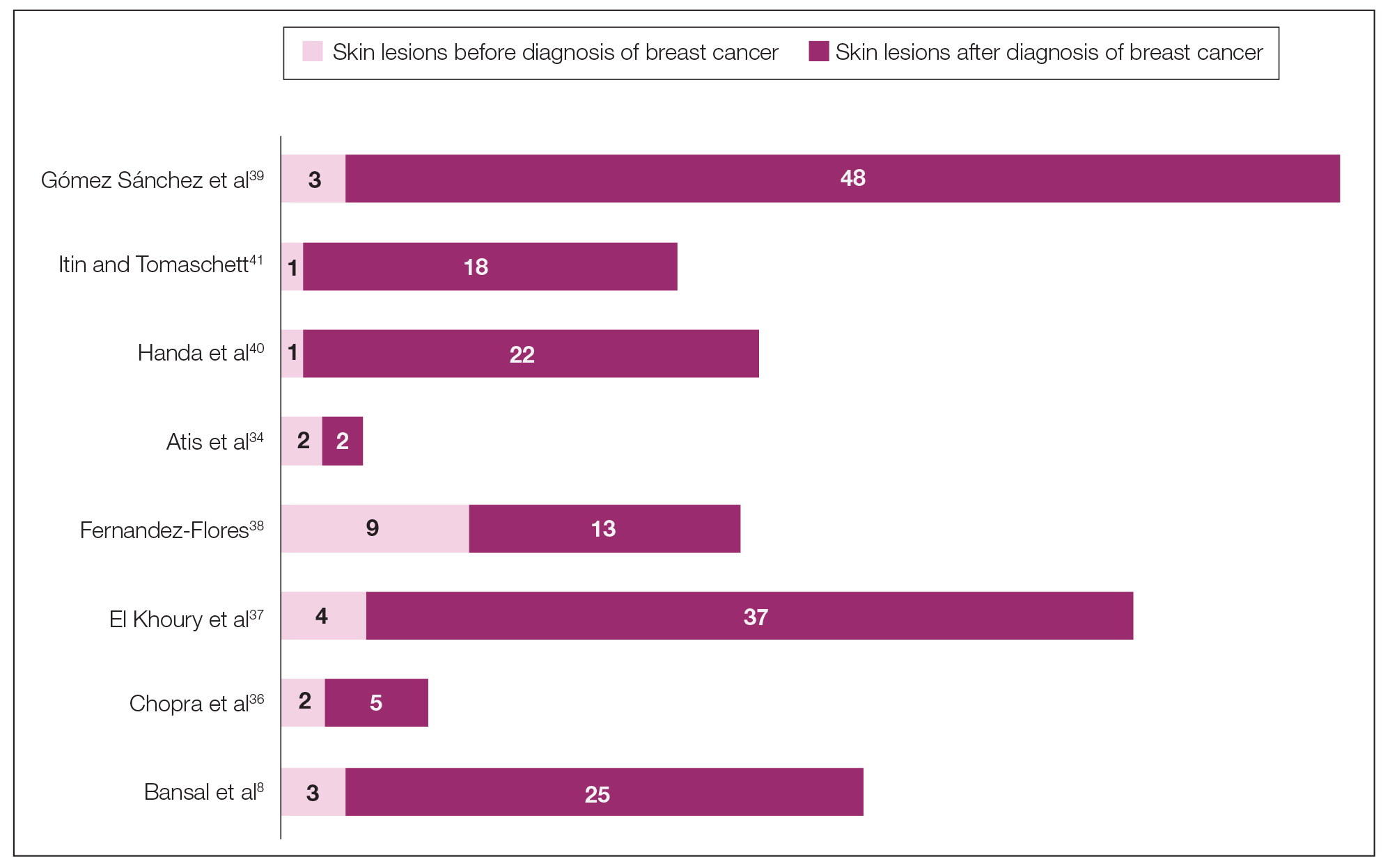

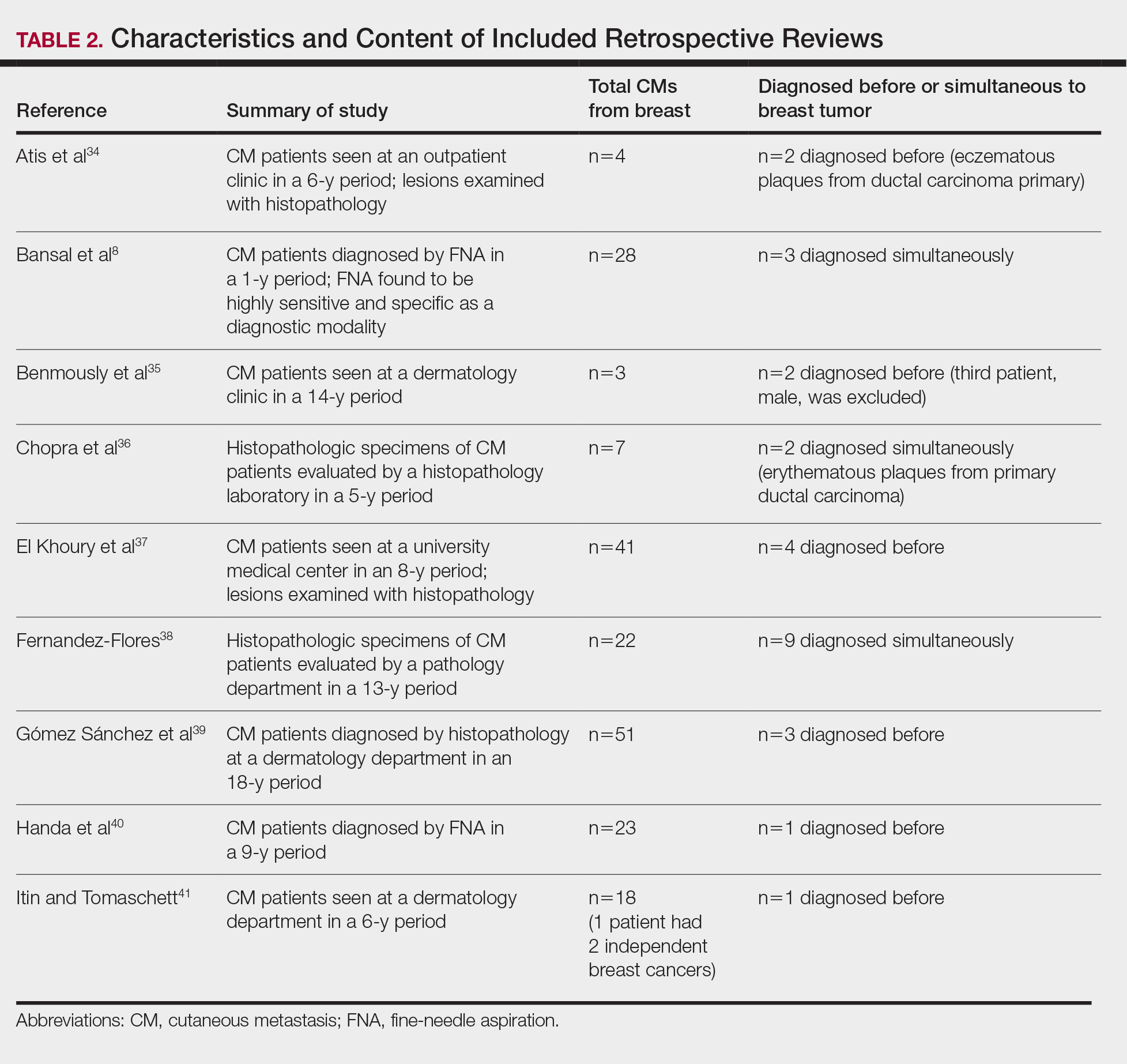

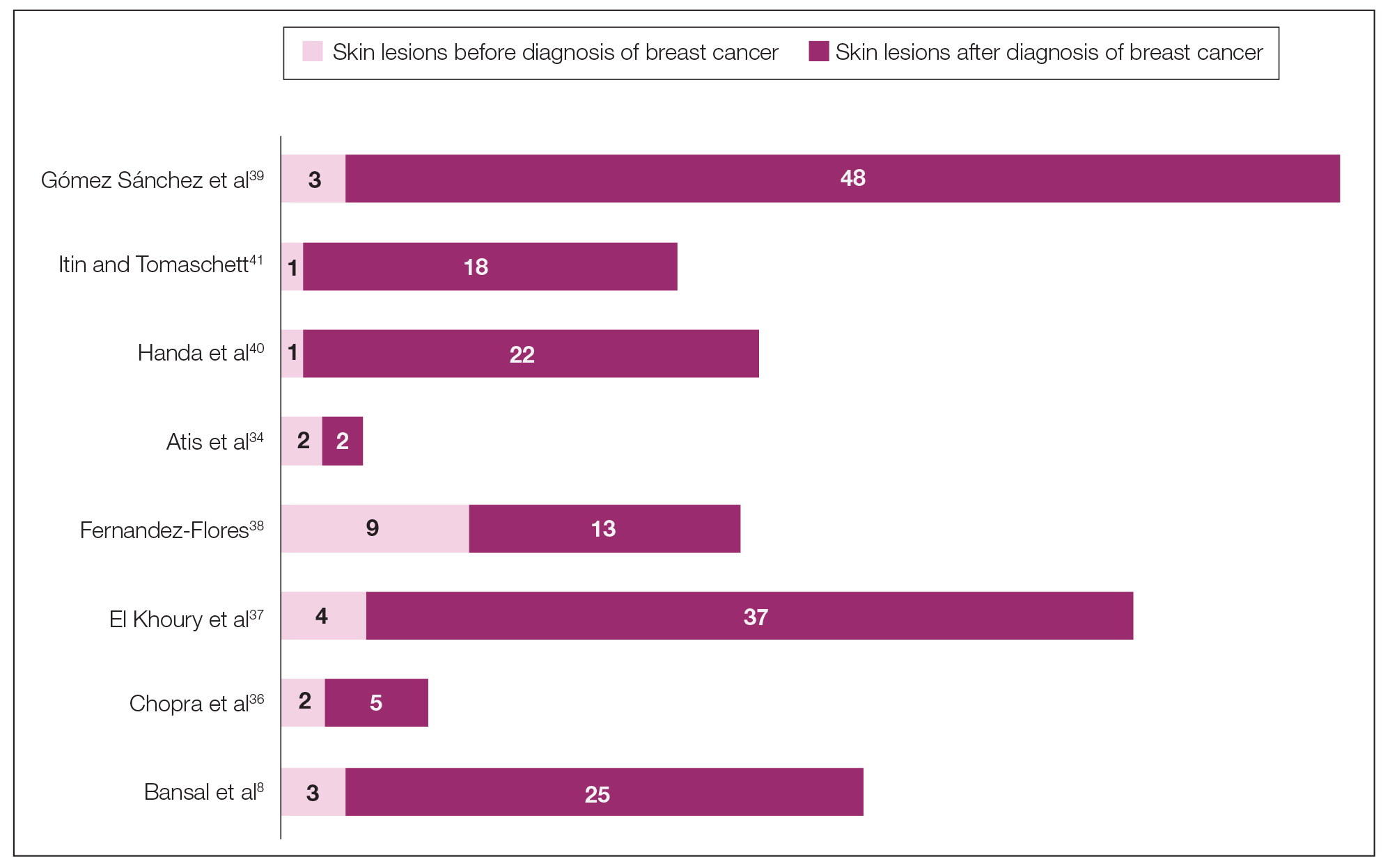

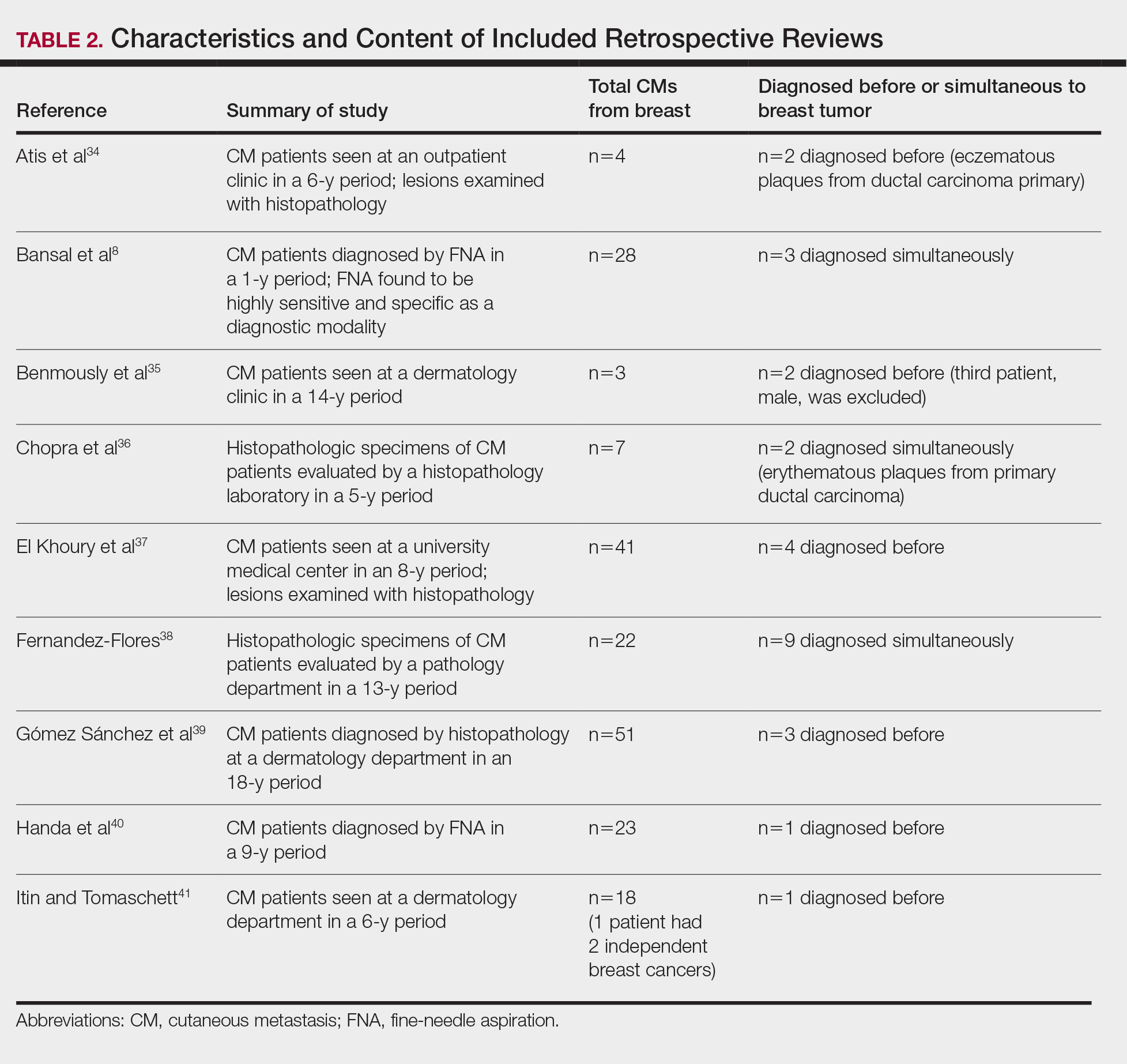

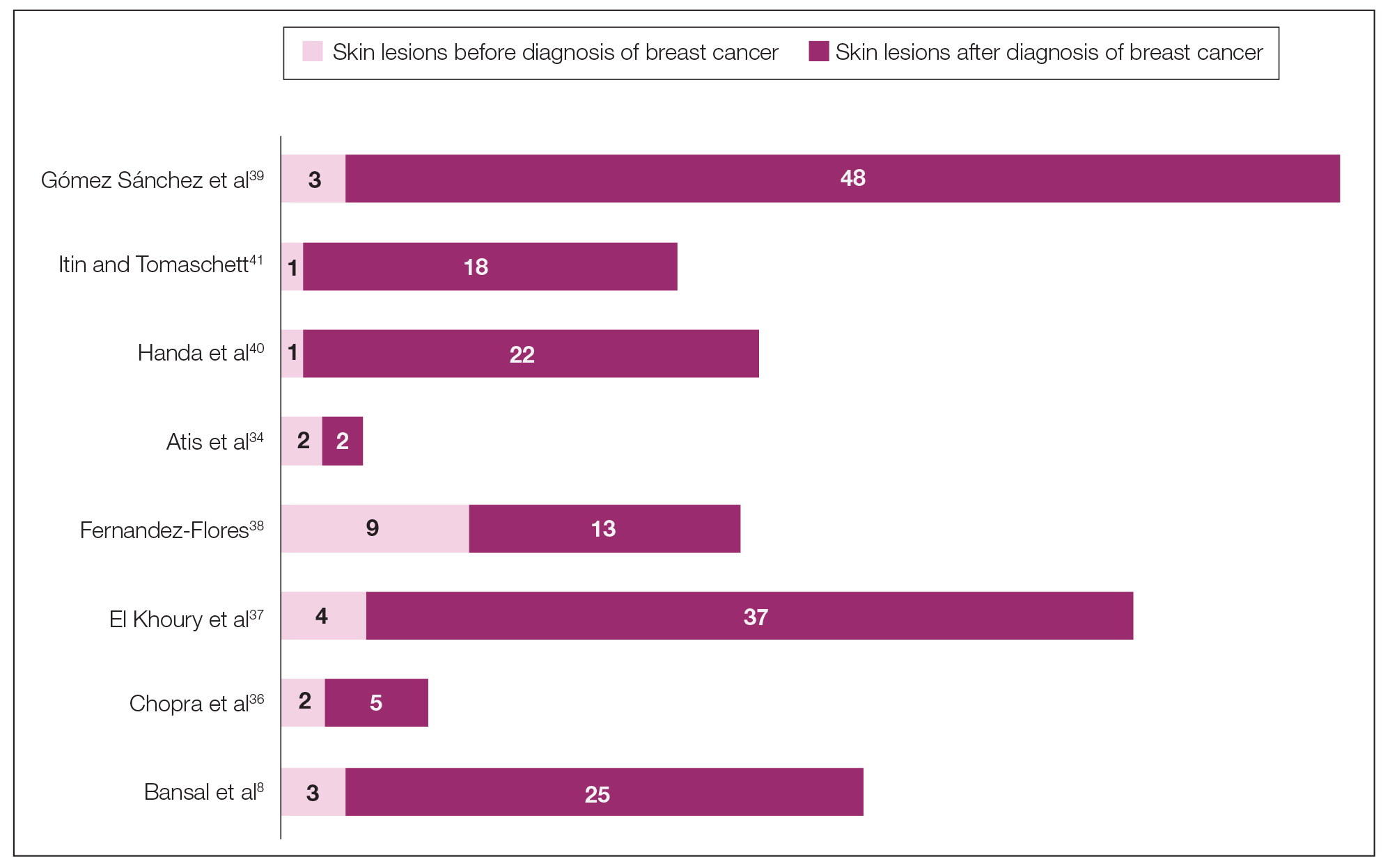

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

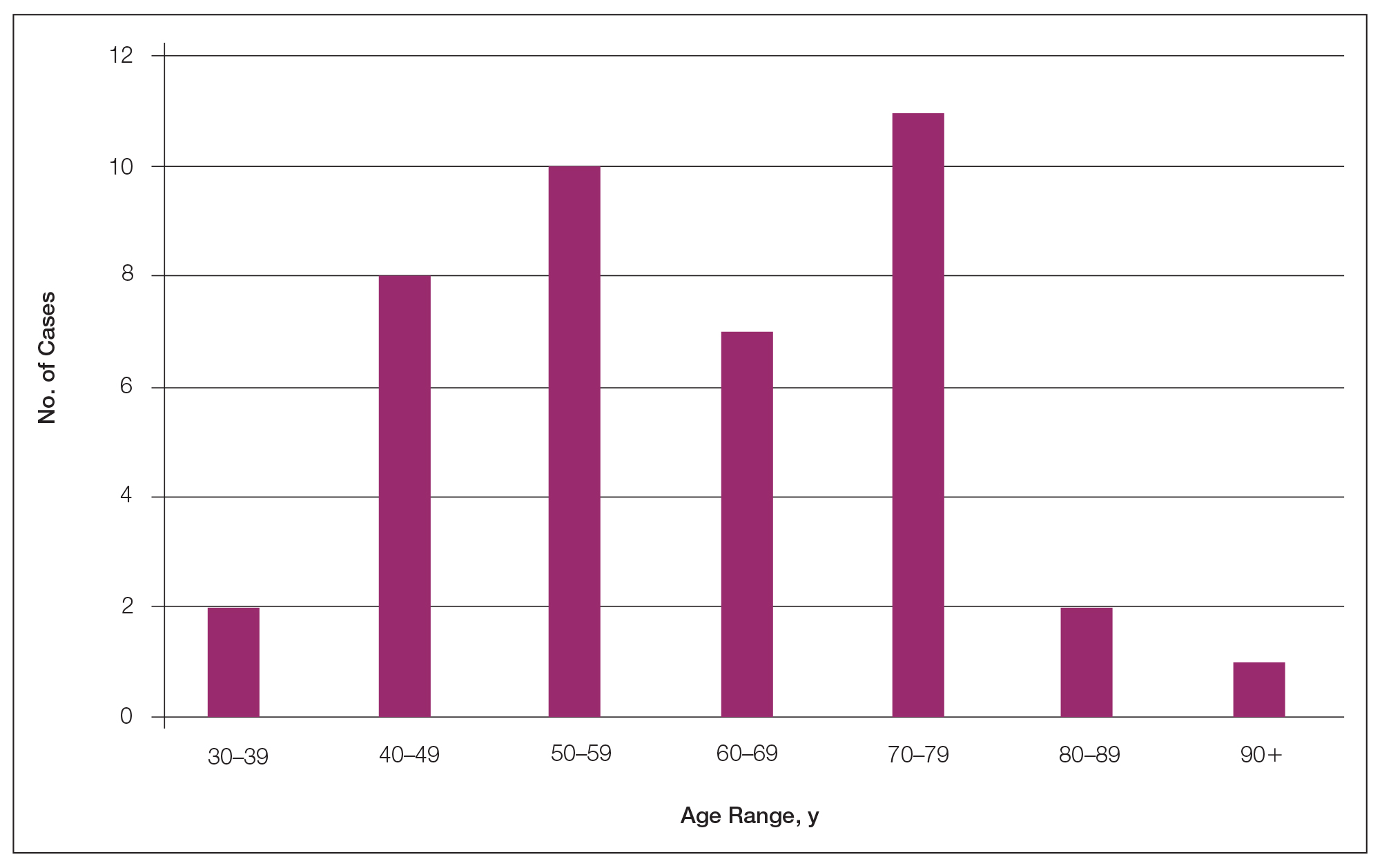

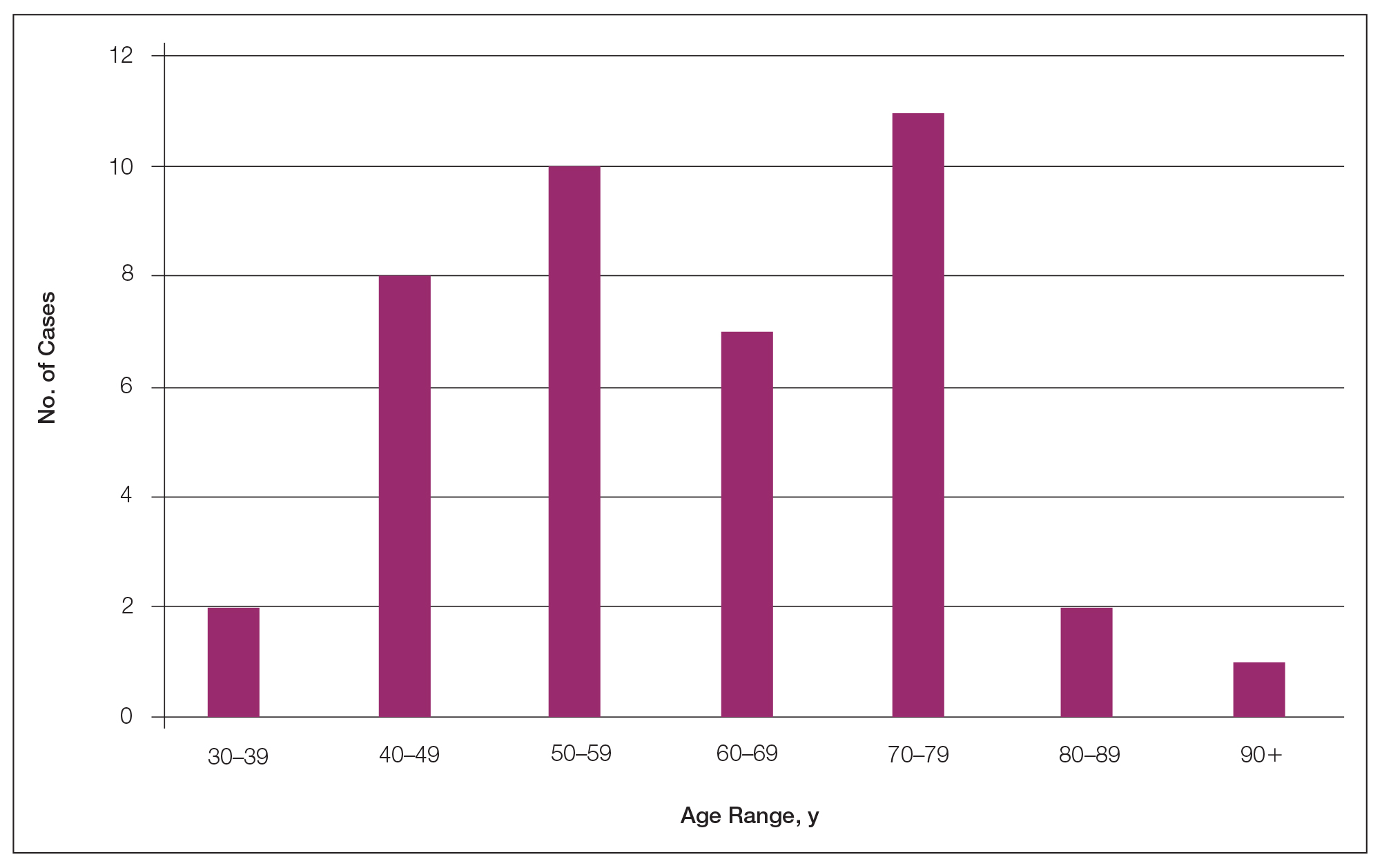

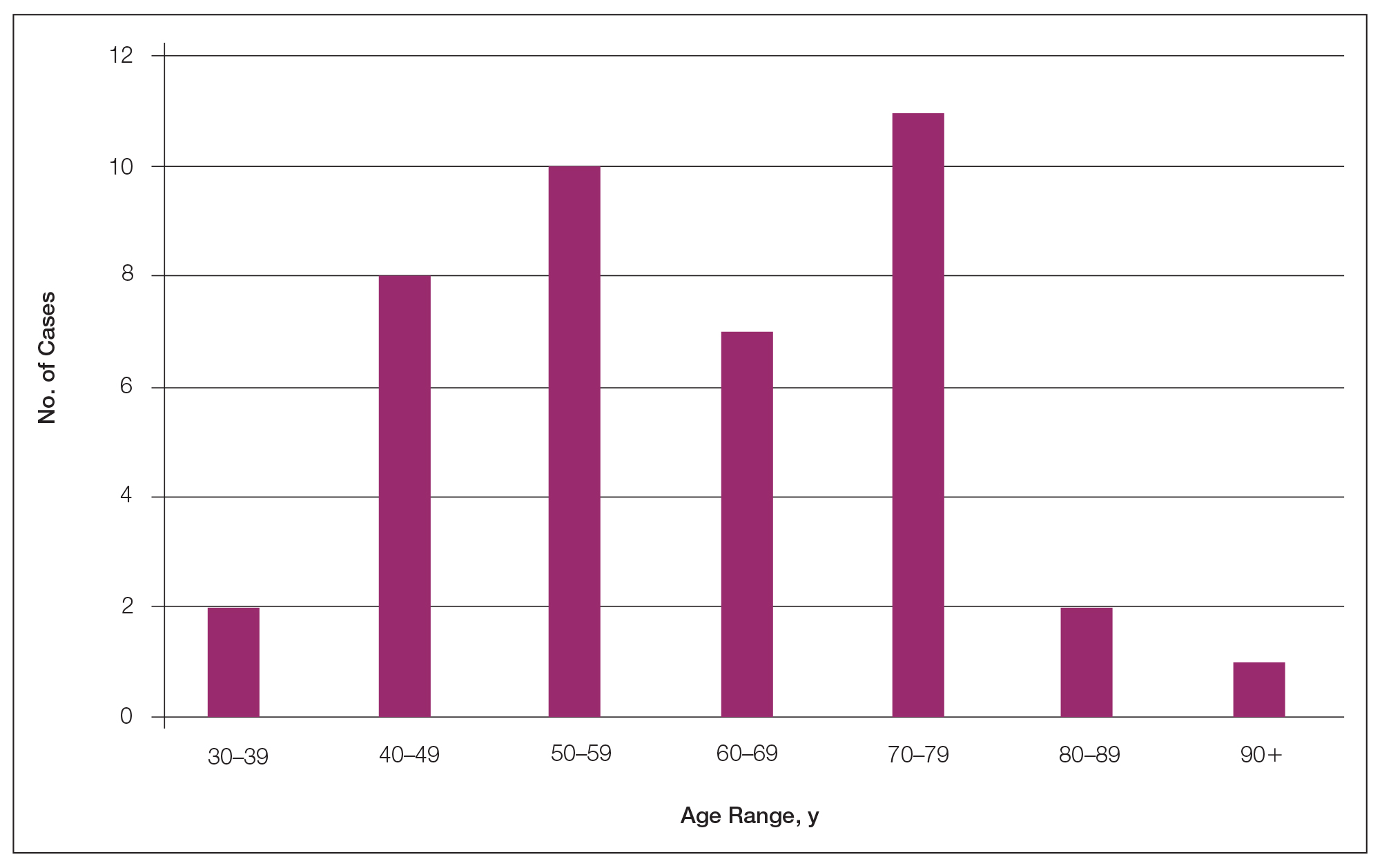

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

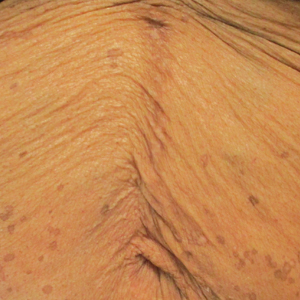

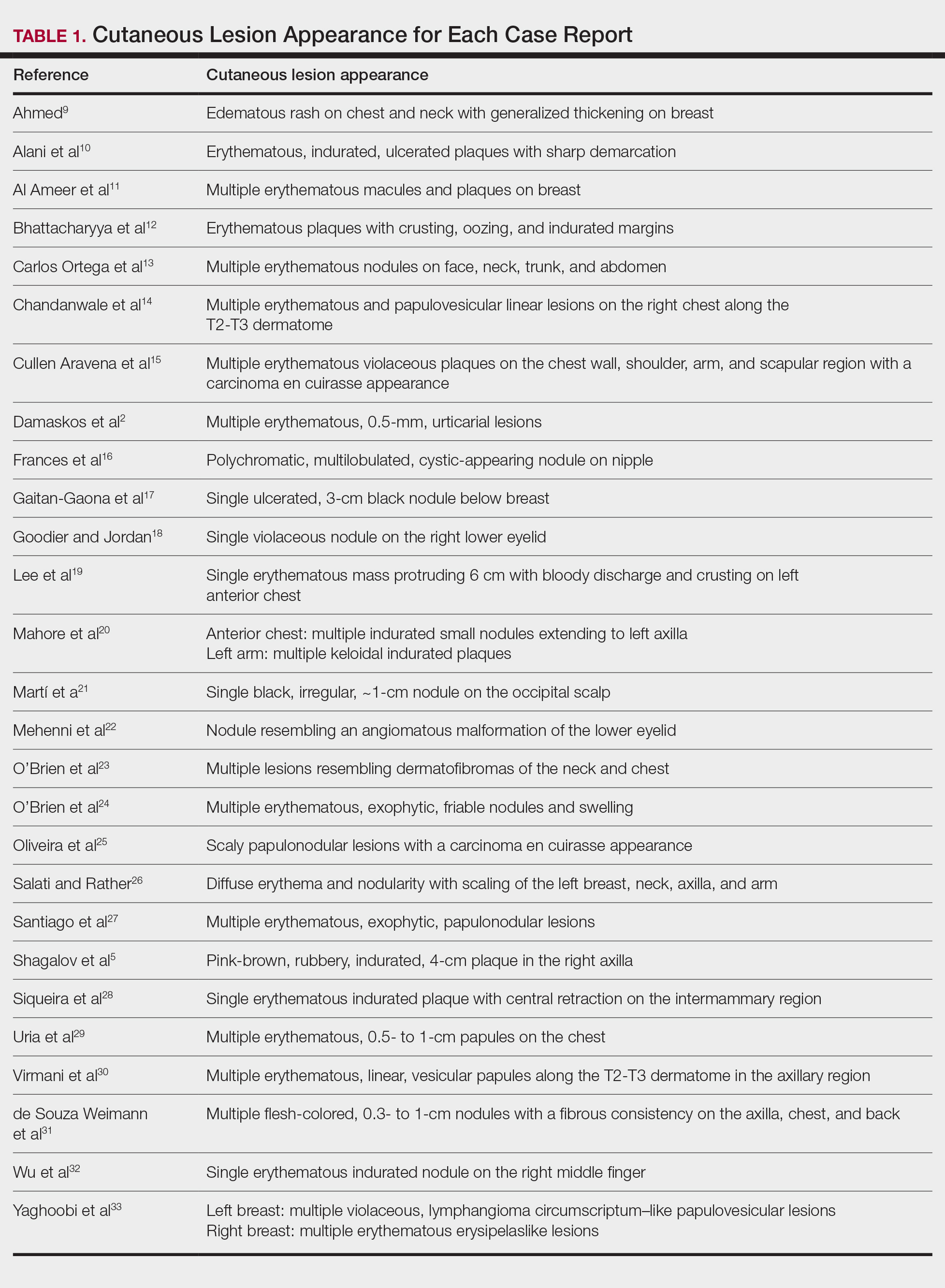

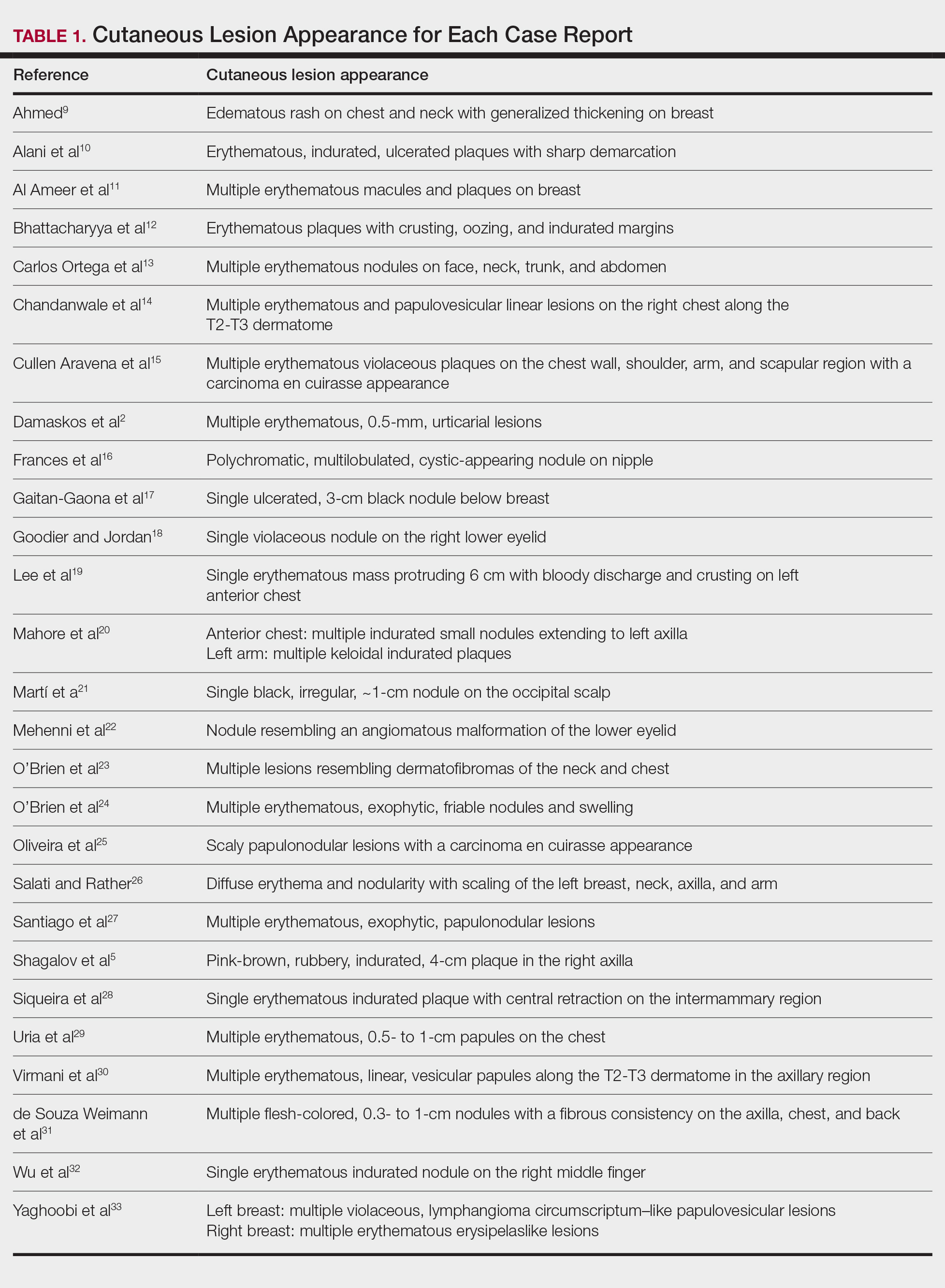

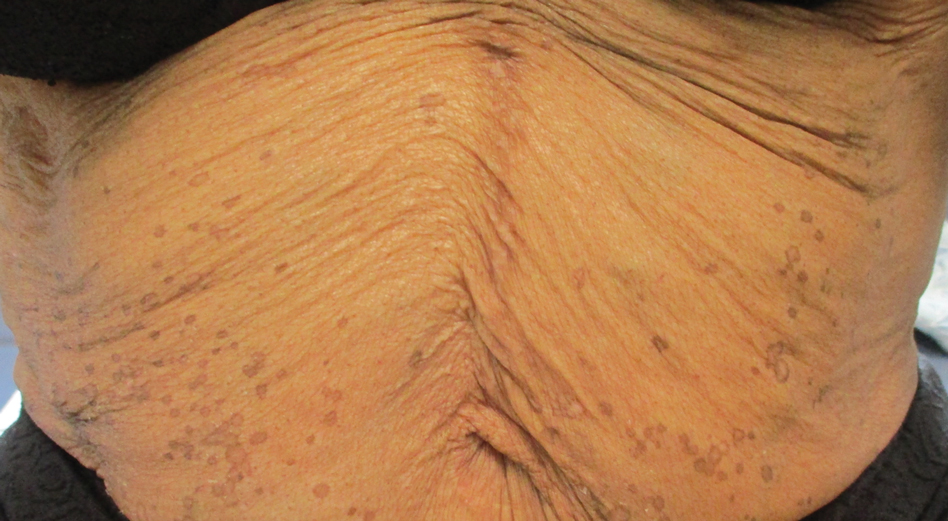

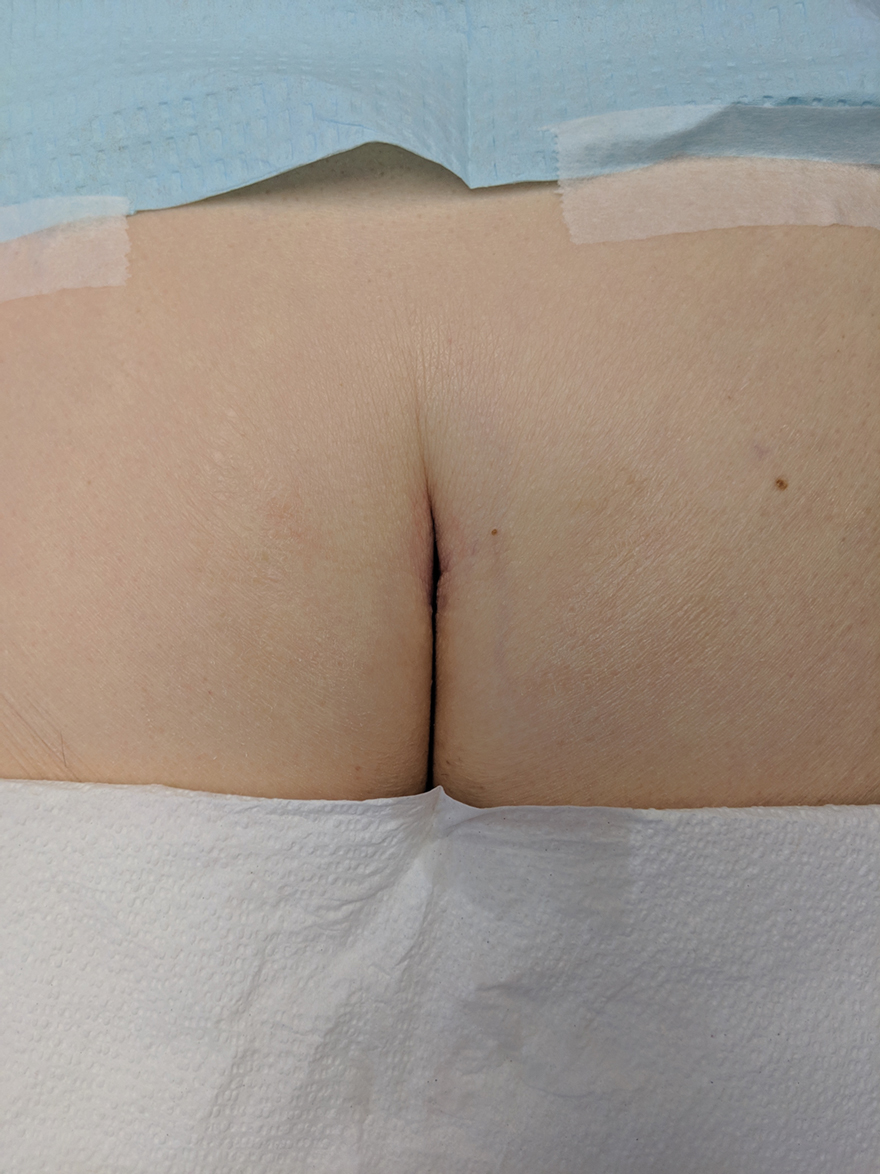

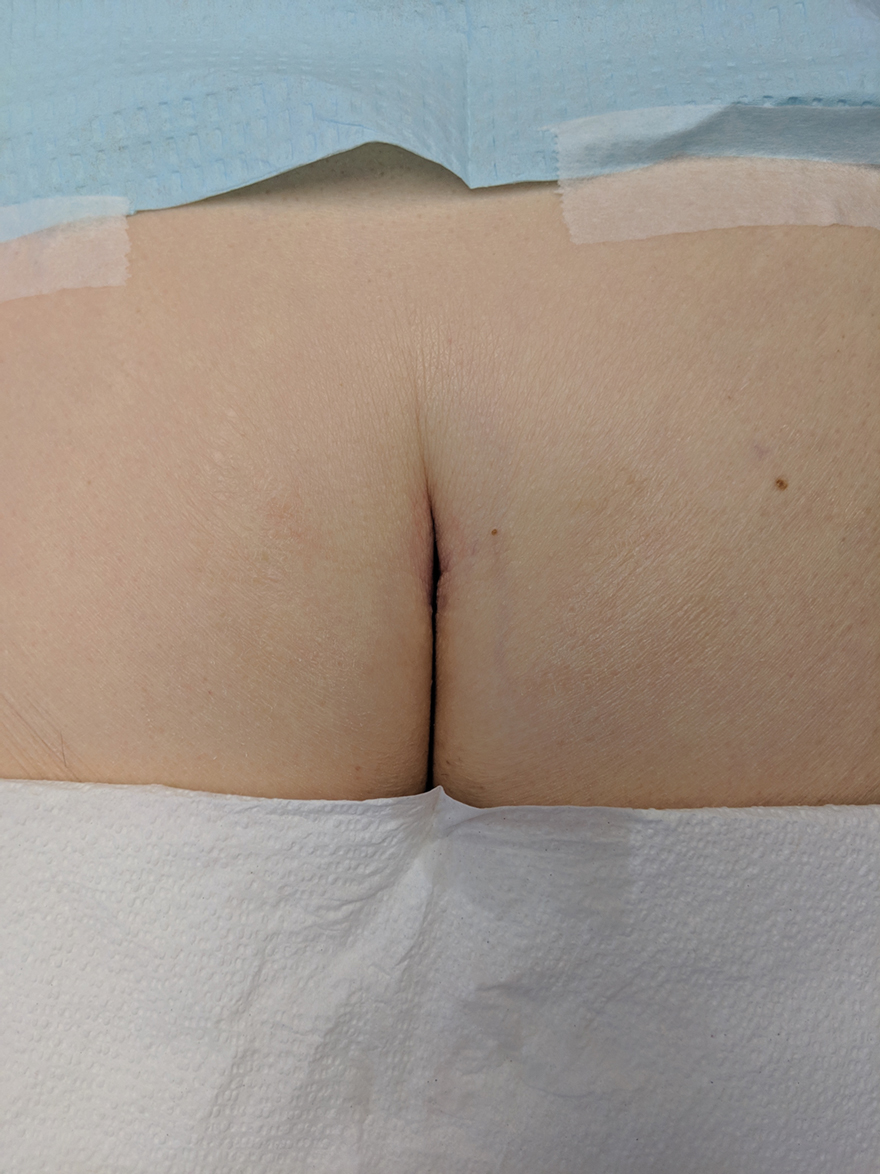

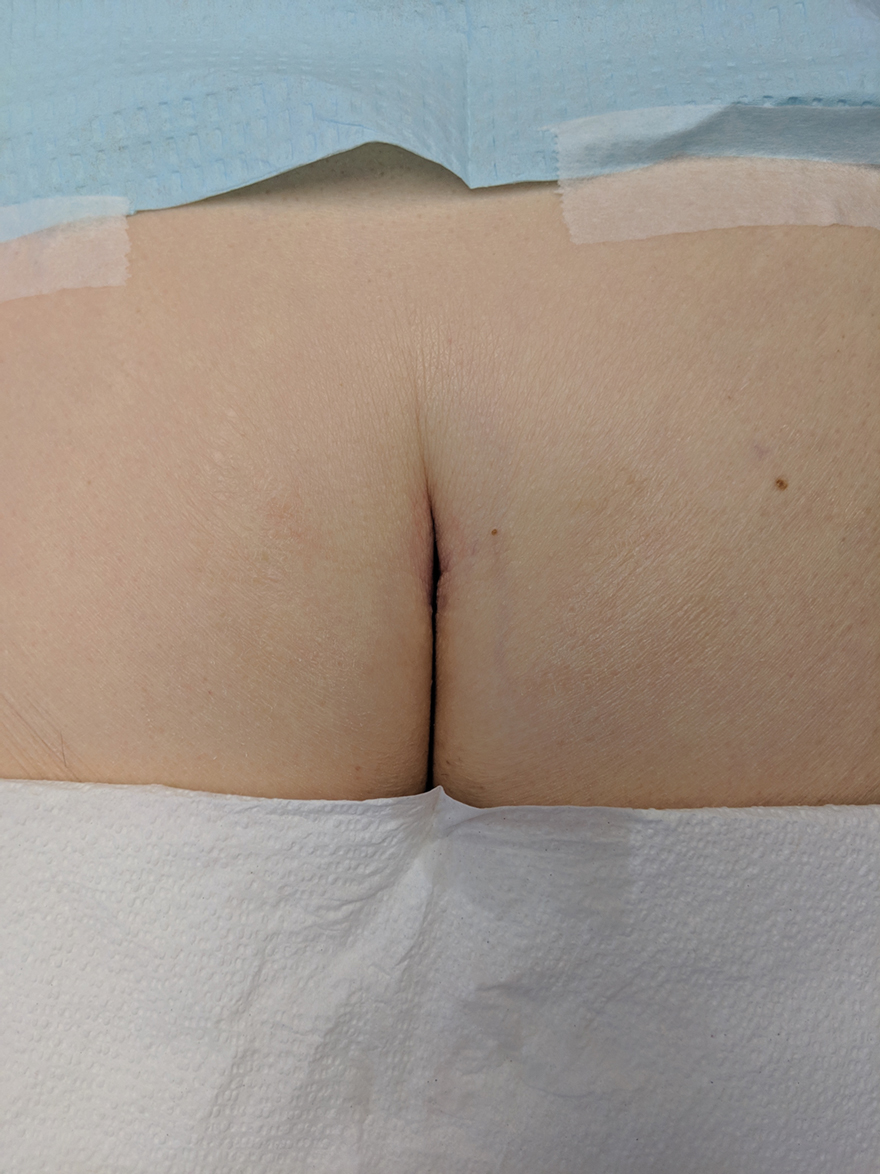

Lesion Characteristics

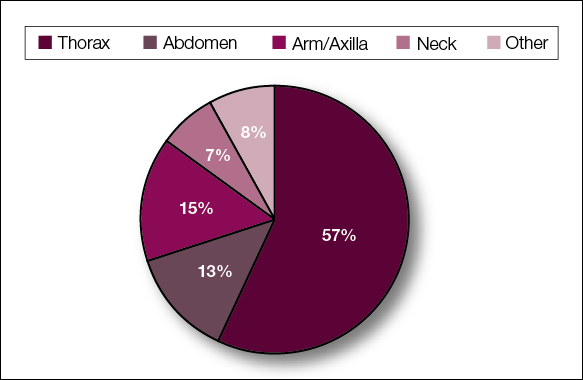

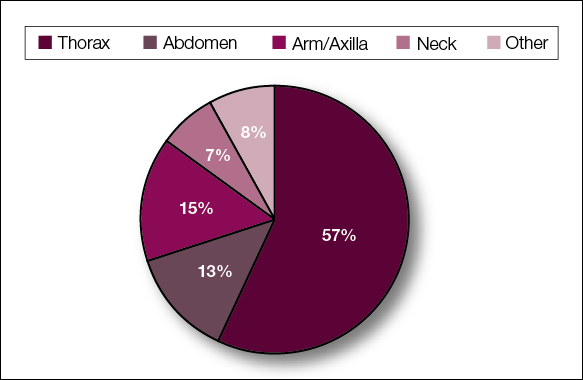

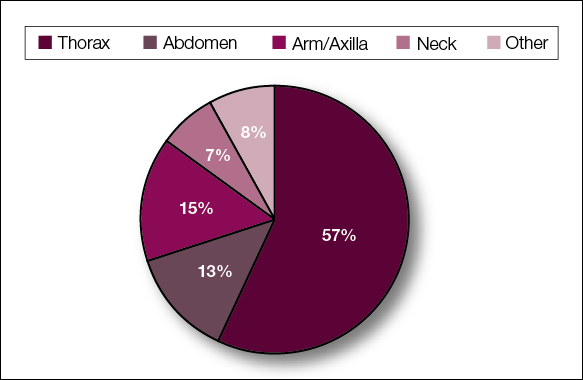

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

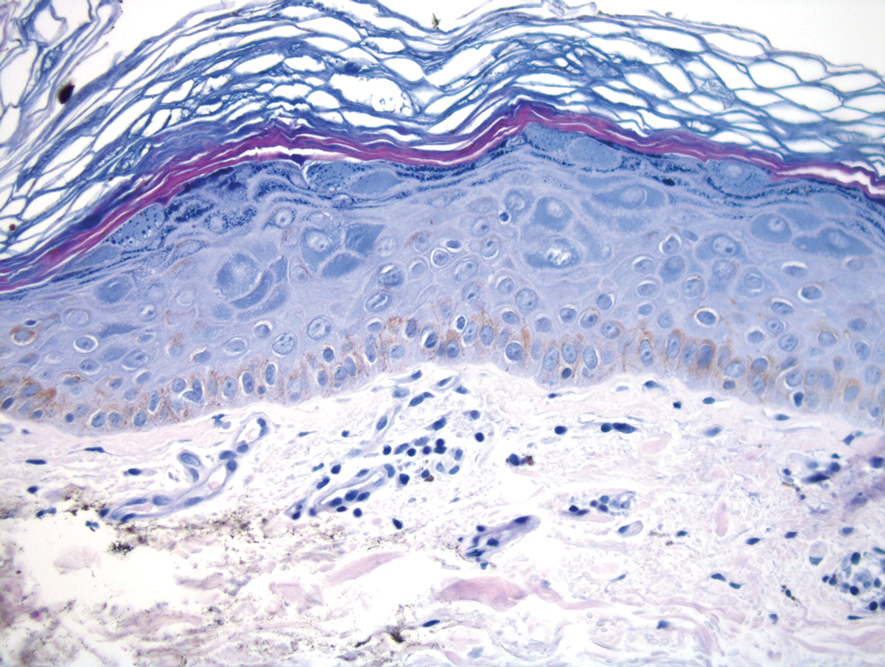

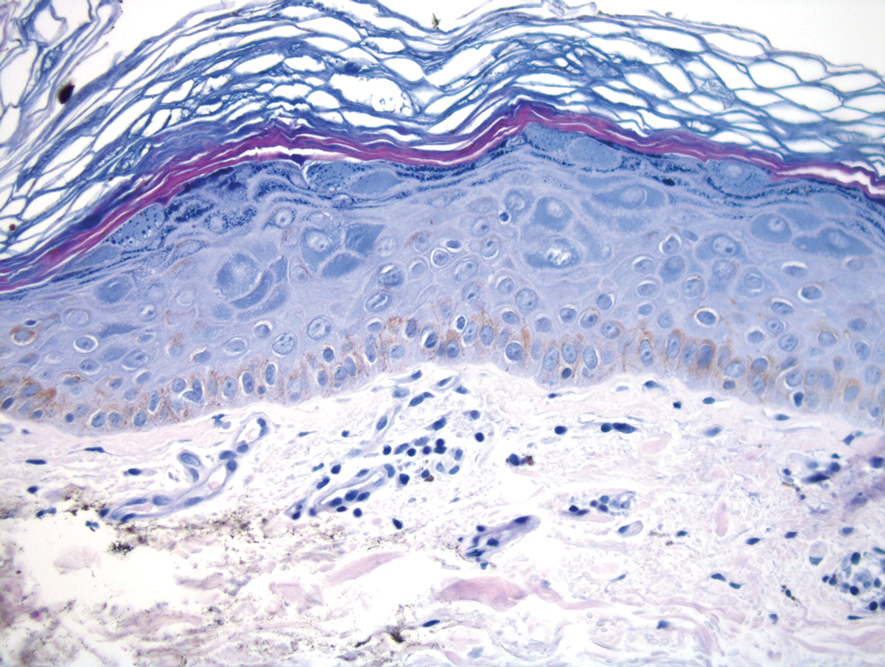

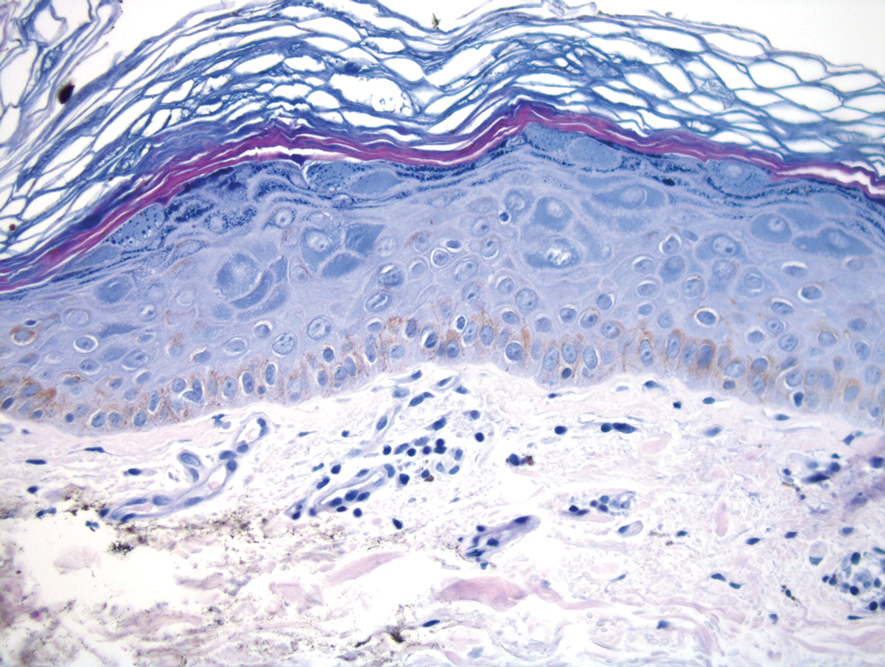

Diagnostic Data

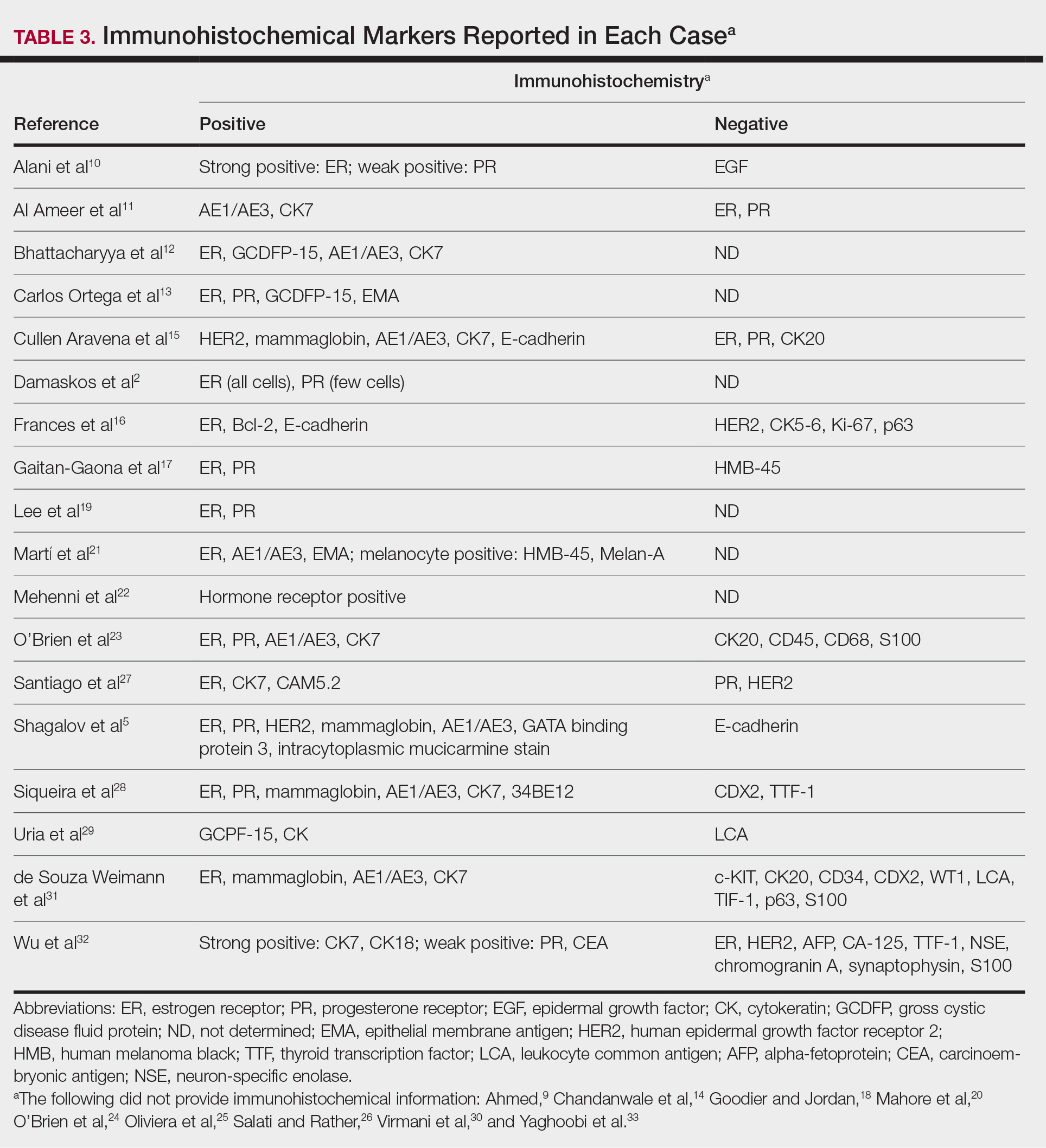

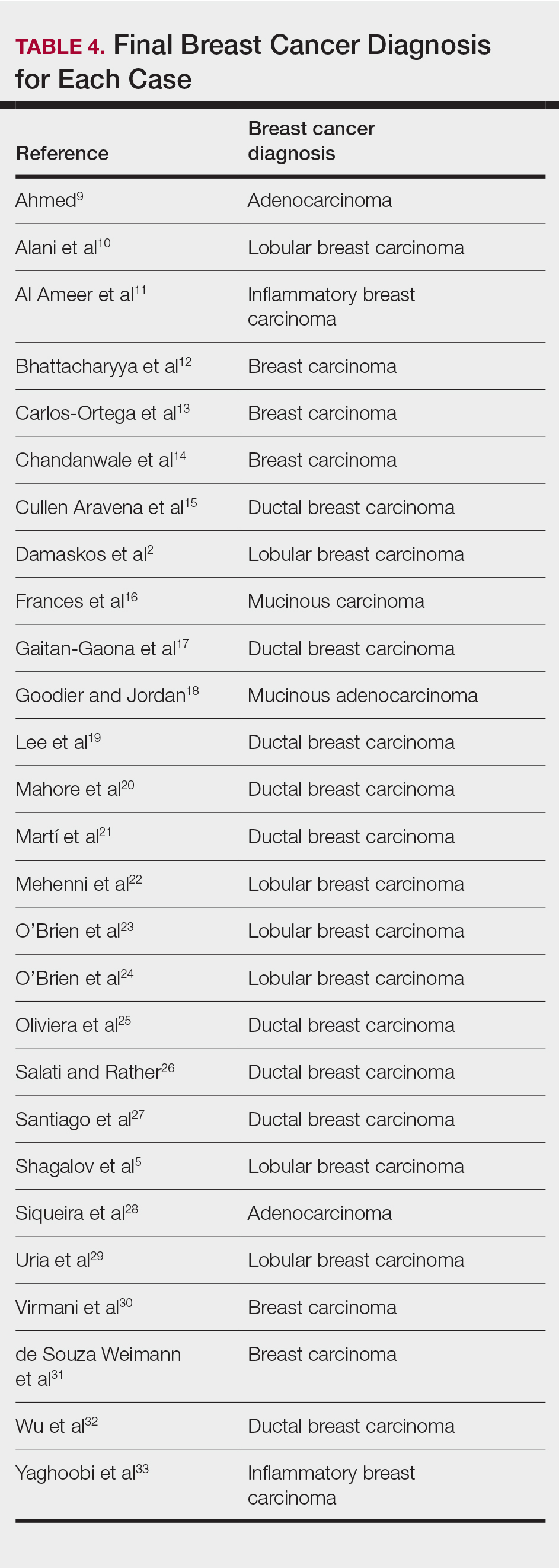

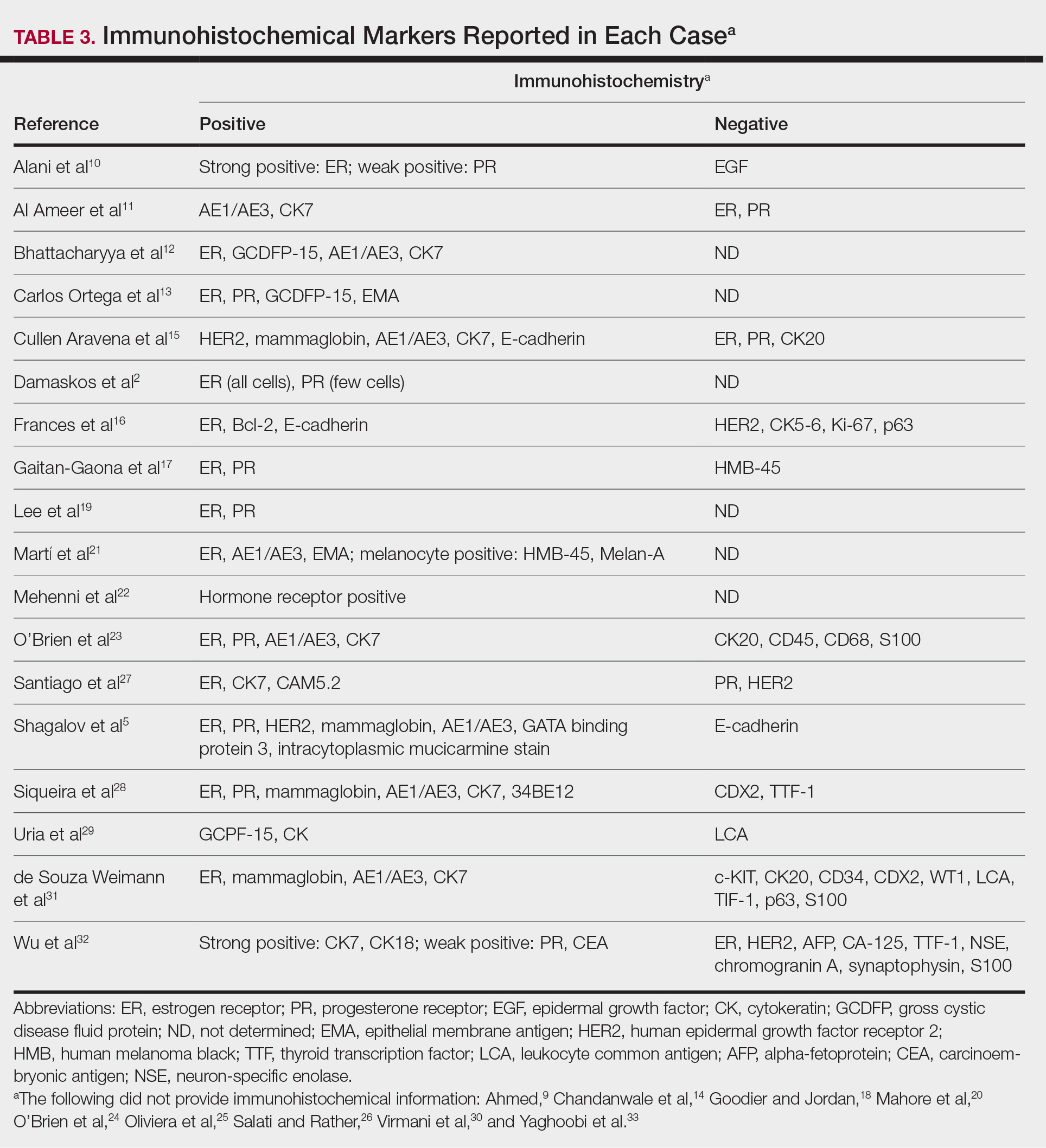

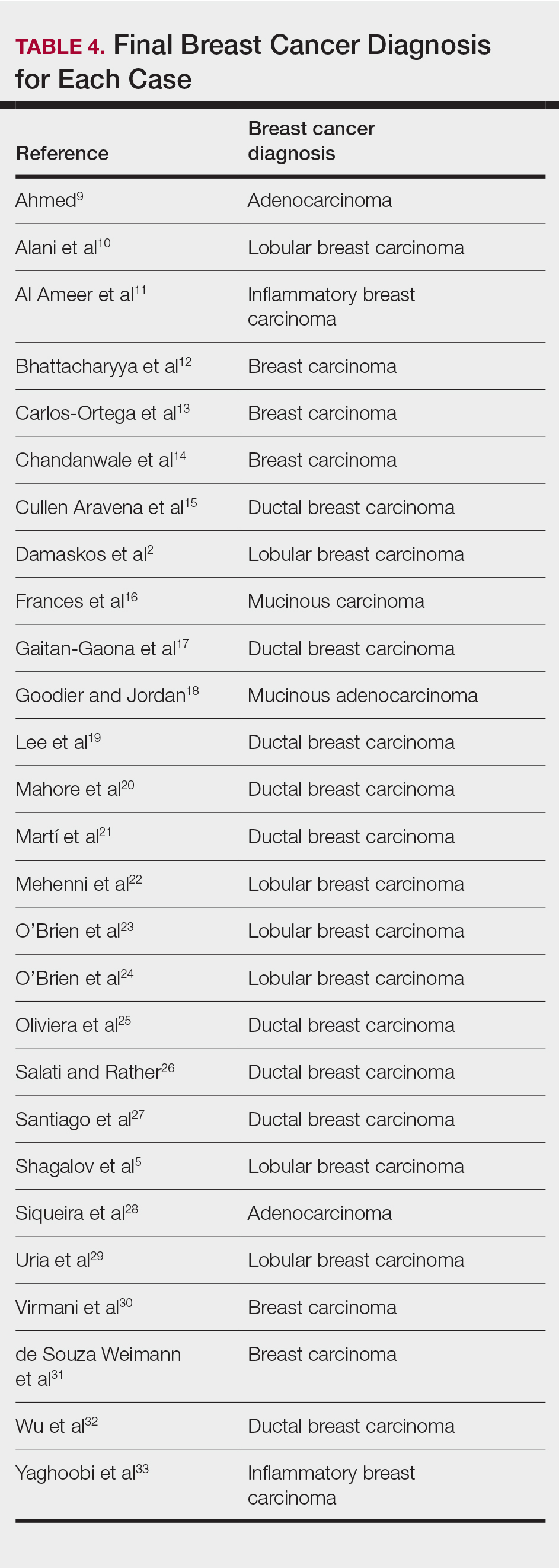

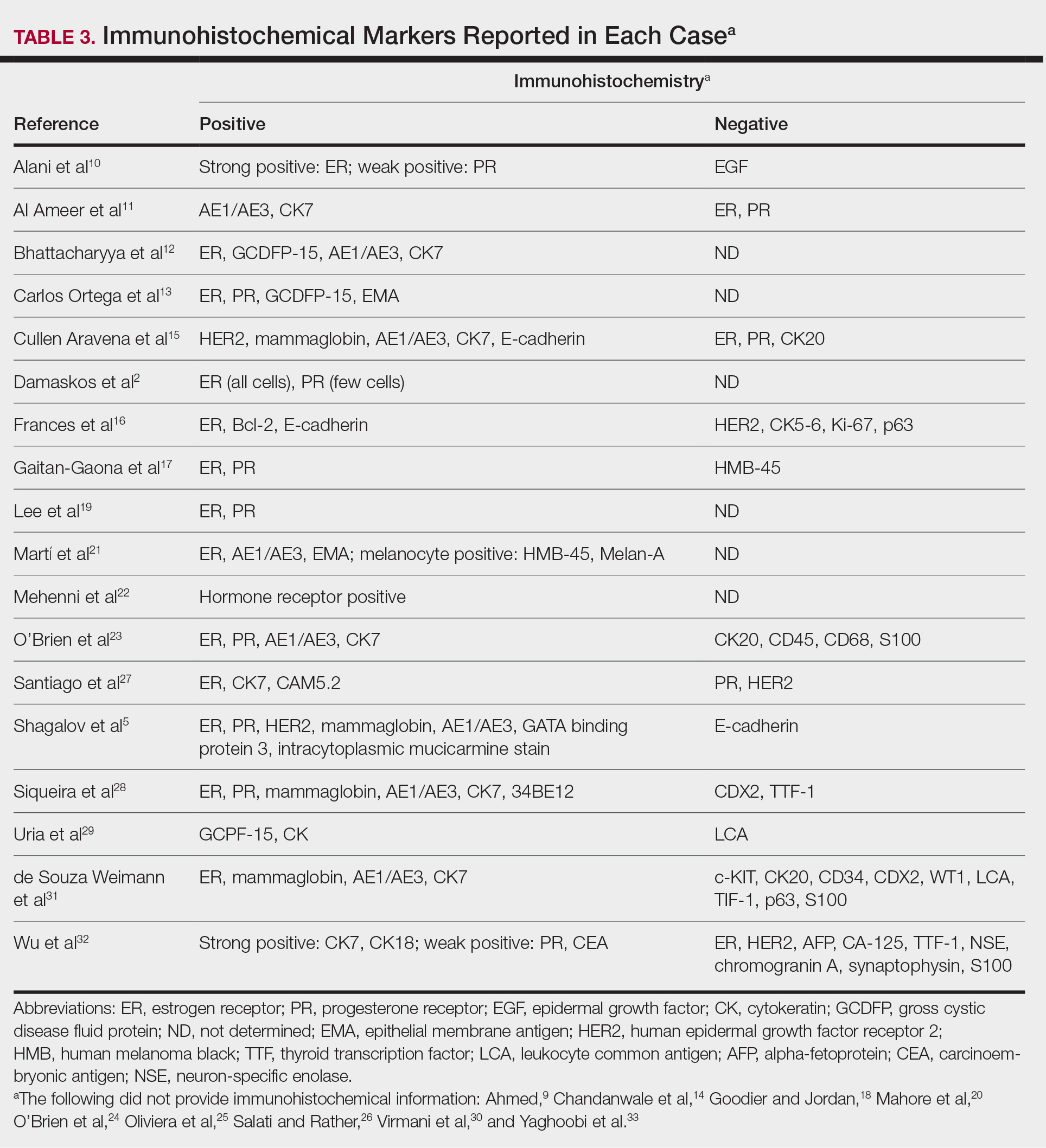

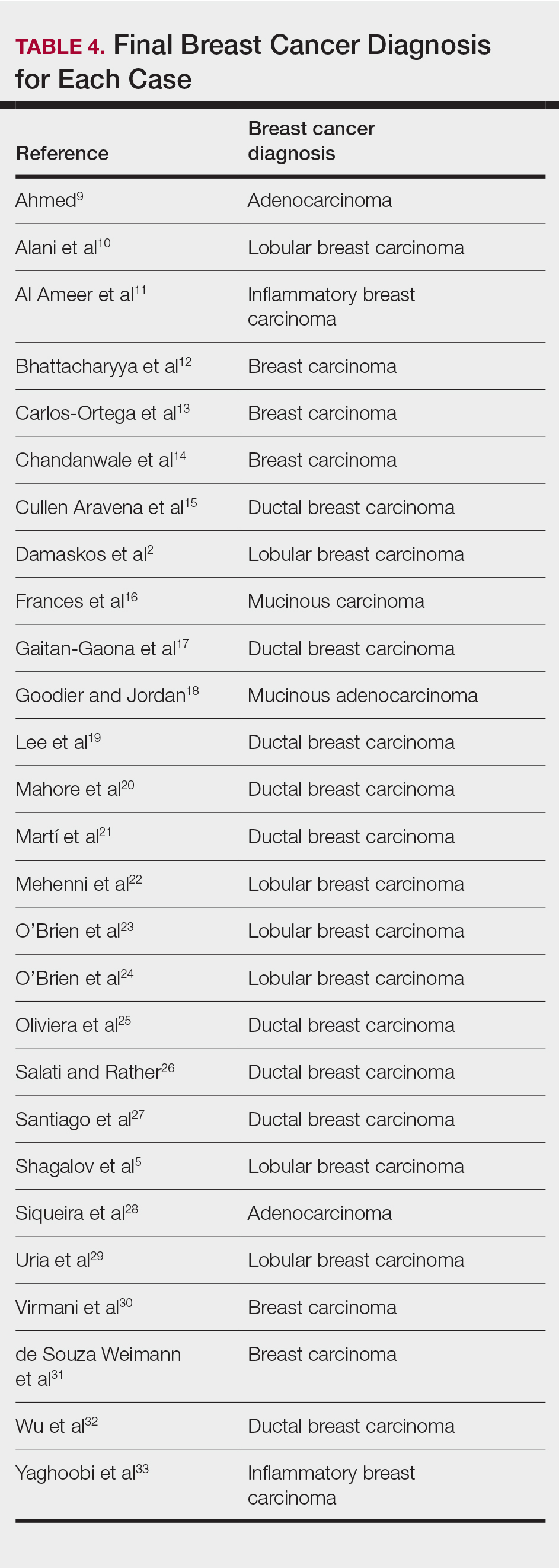

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists may play a role in diagnosing breast cancer through cutaneous metastasis, even in patients without a history of breast cancer.

- Clinicians should consider breast cancer metastasis in the differential for any erythematous lesion on the trunk.

Don’t delay: Cancer patients need both doses of COVID vaccine

The new findings, which are soon to be published as a preprint, cast doubt on the current U.K. policy of delaying the second dose of the vaccine.

Delaying the second dose can leave most patients with cancer wholly or partially unprotected, according to the researchers. Moreover, such a delay has implications for transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the cancer patient’s environs as well as for the evolution of virus variants that could be of concern, the researchers concluded.

The data come from a British study that included 151 patients with cancer and 54 healthy control persons. All participants received the COVID-19 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech).

This vaccine requires two doses. The first few participants in this study were given the second dose 21 days after they had received the first dose, but then national guidelines changed, and the remaining participants had to wait 12 weeks to receive their second dose.

The researchers reported that, among health controls, the immune efficacy of the first dose was very high (97% efficacious). By contrast, among patients with solid tumors, the immune efficacy of a single dose was strikingly low (39%), and it was even lower in patients with hematologic malignancies (13%).

The second dose of vaccine greatly and rapidly increased the immune efficacy in patients with solid tumors (95% within 2 weeks of receiving the second dose), the researchers added.

Too few patients with hematologic cancers had received the second dose before the study ended for clear conclusions to be drawn. Nevertheless, the available data suggest that 50% of patients with hematologic cancers who had received the booster at day 21 were seropositive at 5 weeks vs. only 8% of those who had not received the booster.

“Our data provide the first real-world evidence of immune efficacy following one dose of the Pfizer vaccine in immunocompromised patient populations [and] clearly show that the poor one-dose efficacy in cancer patients can be rescued with an early booster at day 21,” commented senior author Sheeba Irshad, MD, senior clinical lecturer, King’s College London.

“Based on our findings, we would recommend an urgent review of the vaccine strategy for clinically extremely vulnerable groups. Until then, it is important that cancer patients continue to observe all public health measures in place, such as social distancing and shielding when attending hospitals, even after vaccination,” Dr. Irshad added.

The paper, with first author Leticia Monin-Aldama, PhD, is scheduled to appear on the preprint server medRxiv. It has not undergone peer review. The paper was distributed to journalists, with comments from experts not involved in the study, by the UK Science Media Centre.

These data are “of immediate importance” to patients with cancer, commented Shoba Amarnath, PhD, Newcastle University research fellow, Laboratory of T-cell Regulation, Newcastle University Center for Cancer, Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

“These findings are consistent with our understanding. … We know that the immune system within cancer patients is compromised as compared to healthy controls,” Dr. Amarnath said. “The data in the study support the notion that, in solid cancer patients, a considerable delay in second dose will extend the period when cancer patients are at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Although more data are required, “this study does raise the issue of whether patients with cancer, other diseases, or those undergoing therapies that affect the body’s immune response should be fast-tracked for their second vaccine dose,” commented Lawrence Young, PhD, professor of molecular oncology and director of the Warwick Cancer Research Center, University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

Stephen Evans, MSc, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, underlined that the study is “essentially” observational and “inevitable limitations must be taken into account.

“Nevertheless, these results do suggest that the vaccines may well not protect those patients with cancer as well as those without cancer,” Mr. Evans said. He added that it is “important that this population continues to observe all COVID-19–associated measures, such as social distancing and shielding when attending hospitals, even after vaccination.”

Study details

Previous studies have shown that some patients with cancer have prolonged responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection, with ongoing immune dysregulation, inefficient seroconversion, and prolonged viral shedding.

There are few data, however, on how these patients respond to COVID-19 vaccination. The authors point out that, among the 18,860 individuals who received the Pfizer vaccine during its development trials, “none with an active oncological diagnosis was included.”

To investigate this issue, they launched the SARS-CoV-2 for Cancer Patients (SOAP-02) study.

The 151 patients with cancer who participated in this study were mostly elderly, the authors noted (75% were older than 65 years; the median age was 73 years). The majority (63%) had solid-tumor malignancies. Of those, 8% had late-stage disease and had been living with their cancer for more than 24 months.

The healthy control persons were vaccine-eligible primary health care workers who were not age matched to the cancer patients.

All participants received the first dose of vaccine; 31 (of 151) patients with cancer and 16 (of 54) healthy control persons received the second dose on day 21.

The remaining participants were scheduled to receive their second dose 12 weeks later (after the study ended), in line with the changes in the national guidelines.

The team reported that, approximately 21 days after receiving the first vaccine dose, the immune efficacy of the vaccine was estimated to be 97% among healthy control persons vs. 39% for patients with solid tumors and only 13% for those with hematologic malignancies (P < .0001 for both).

T-cell responses, as assessed via interferon-gamma and/or interleukin-2 production, were observed in 82% of healthy control persons, 71% of patients with solid tumors, and 50% of those with hematologic cancers.

Vaccine boosting at day 21 resulted in immune efficacy of 100% for healthy control persons and 95% for patients with solid tumors. In contrast, only 43% of those who did not receive the second dose were seropositive 2 weeks later.

Further analysis suggested that participants who did not have a serologic response were “spread evenly” across different cancer types, but the reduced responses were more frequent among patients who had received the vaccine within 15 days of cancer treatment, especially chemotherapy, and had undergone intensive treatments.

The SOAP study is sponsored by King’s College London and Guy’s and St. Thomas Trust Foundation NHS Trust. It is funded from grants from the KCL Charity, Cancer Research UK, and program grants from Breast Cancer Now. The investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new findings, which are soon to be published as a preprint, cast doubt on the current U.K. policy of delaying the second dose of the vaccine.

Delaying the second dose can leave most patients with cancer wholly or partially unprotected, according to the researchers. Moreover, such a delay has implications for transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the cancer patient’s environs as well as for the evolution of virus variants that could be of concern, the researchers concluded.

The data come from a British study that included 151 patients with cancer and 54 healthy control persons. All participants received the COVID-19 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech).

This vaccine requires two doses. The first few participants in this study were given the second dose 21 days after they had received the first dose, but then national guidelines changed, and the remaining participants had to wait 12 weeks to receive their second dose.

The researchers reported that, among health controls, the immune efficacy of the first dose was very high (97% efficacious). By contrast, among patients with solid tumors, the immune efficacy of a single dose was strikingly low (39%), and it was even lower in patients with hematologic malignancies (13%).

The second dose of vaccine greatly and rapidly increased the immune efficacy in patients with solid tumors (95% within 2 weeks of receiving the second dose), the researchers added.

Too few patients with hematologic cancers had received the second dose before the study ended for clear conclusions to be drawn. Nevertheless, the available data suggest that 50% of patients with hematologic cancers who had received the booster at day 21 were seropositive at 5 weeks vs. only 8% of those who had not received the booster.

“Our data provide the first real-world evidence of immune efficacy following one dose of the Pfizer vaccine in immunocompromised patient populations [and] clearly show that the poor one-dose efficacy in cancer patients can be rescued with an early booster at day 21,” commented senior author Sheeba Irshad, MD, senior clinical lecturer, King’s College London.

“Based on our findings, we would recommend an urgent review of the vaccine strategy for clinically extremely vulnerable groups. Until then, it is important that cancer patients continue to observe all public health measures in place, such as social distancing and shielding when attending hospitals, even after vaccination,” Dr. Irshad added.

The paper, with first author Leticia Monin-Aldama, PhD, is scheduled to appear on the preprint server medRxiv. It has not undergone peer review. The paper was distributed to journalists, with comments from experts not involved in the study, by the UK Science Media Centre.

These data are “of immediate importance” to patients with cancer, commented Shoba Amarnath, PhD, Newcastle University research fellow, Laboratory of T-cell Regulation, Newcastle University Center for Cancer, Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

“These findings are consistent with our understanding. … We know that the immune system within cancer patients is compromised as compared to healthy controls,” Dr. Amarnath said. “The data in the study support the notion that, in solid cancer patients, a considerable delay in second dose will extend the period when cancer patients are at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Although more data are required, “this study does raise the issue of whether patients with cancer, other diseases, or those undergoing therapies that affect the body’s immune response should be fast-tracked for their second vaccine dose,” commented Lawrence Young, PhD, professor of molecular oncology and director of the Warwick Cancer Research Center, University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

Stephen Evans, MSc, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, underlined that the study is “essentially” observational and “inevitable limitations must be taken into account.

“Nevertheless, these results do suggest that the vaccines may well not protect those patients with cancer as well as those without cancer,” Mr. Evans said. He added that it is “important that this population continues to observe all COVID-19–associated measures, such as social distancing and shielding when attending hospitals, even after vaccination.”

Study details

Previous studies have shown that some patients with cancer have prolonged responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection, with ongoing immune dysregulation, inefficient seroconversion, and prolonged viral shedding.

There are few data, however, on how these patients respond to COVID-19 vaccination. The authors point out that, among the 18,860 individuals who received the Pfizer vaccine during its development trials, “none with an active oncological diagnosis was included.”

To investigate this issue, they launched the SARS-CoV-2 for Cancer Patients (SOAP-02) study.

The 151 patients with cancer who participated in this study were mostly elderly, the authors noted (75% were older than 65 years; the median age was 73 years). The majority (63%) had solid-tumor malignancies. Of those, 8% had late-stage disease and had been living with their cancer for more than 24 months.

The healthy control persons were vaccine-eligible primary health care workers who were not age matched to the cancer patients.

All participants received the first dose of vaccine; 31 (of 151) patients with cancer and 16 (of 54) healthy control persons received the second dose on day 21.

The remaining participants were scheduled to receive their second dose 12 weeks later (after the study ended), in line with the changes in the national guidelines.

The team reported that, approximately 21 days after receiving the first vaccine dose, the immune efficacy of the vaccine was estimated to be 97% among healthy control persons vs. 39% for patients with solid tumors and only 13% for those with hematologic malignancies (P < .0001 for both).

T-cell responses, as assessed via interferon-gamma and/or interleukin-2 production, were observed in 82% of healthy control persons, 71% of patients with solid tumors, and 50% of those with hematologic cancers.

Vaccine boosting at day 21 resulted in immune efficacy of 100% for healthy control persons and 95% for patients with solid tumors. In contrast, only 43% of those who did not receive the second dose were seropositive 2 weeks later.

Further analysis suggested that participants who did not have a serologic response were “spread evenly” across different cancer types, but the reduced responses were more frequent among patients who had received the vaccine within 15 days of cancer treatment, especially chemotherapy, and had undergone intensive treatments.

The SOAP study is sponsored by King’s College London and Guy’s and St. Thomas Trust Foundation NHS Trust. It is funded from grants from the KCL Charity, Cancer Research UK, and program grants from Breast Cancer Now. The investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new findings, which are soon to be published as a preprint, cast doubt on the current U.K. policy of delaying the second dose of the vaccine.

Delaying the second dose can leave most patients with cancer wholly or partially unprotected, according to the researchers. Moreover, such a delay has implications for transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the cancer patient’s environs as well as for the evolution of virus variants that could be of concern, the researchers concluded.

The data come from a British study that included 151 patients with cancer and 54 healthy control persons. All participants received the COVID-19 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech).

This vaccine requires two doses. The first few participants in this study were given the second dose 21 days after they had received the first dose, but then national guidelines changed, and the remaining participants had to wait 12 weeks to receive their second dose.

The researchers reported that, among health controls, the immune efficacy of the first dose was very high (97% efficacious). By contrast, among patients with solid tumors, the immune efficacy of a single dose was strikingly low (39%), and it was even lower in patients with hematologic malignancies (13%).

The second dose of vaccine greatly and rapidly increased the immune efficacy in patients with solid tumors (95% within 2 weeks of receiving the second dose), the researchers added.

Too few patients with hematologic cancers had received the second dose before the study ended for clear conclusions to be drawn. Nevertheless, the available data suggest that 50% of patients with hematologic cancers who had received the booster at day 21 were seropositive at 5 weeks vs. only 8% of those who had not received the booster.

“Our data provide the first real-world evidence of immune efficacy following one dose of the Pfizer vaccine in immunocompromised patient populations [and] clearly show that the poor one-dose efficacy in cancer patients can be rescued with an early booster at day 21,” commented senior author Sheeba Irshad, MD, senior clinical lecturer, King’s College London.

“Based on our findings, we would recommend an urgent review of the vaccine strategy for clinically extremely vulnerable groups. Until then, it is important that cancer patients continue to observe all public health measures in place, such as social distancing and shielding when attending hospitals, even after vaccination,” Dr. Irshad added.

The paper, with first author Leticia Monin-Aldama, PhD, is scheduled to appear on the preprint server medRxiv. It has not undergone peer review. The paper was distributed to journalists, with comments from experts not involved in the study, by the UK Science Media Centre.

These data are “of immediate importance” to patients with cancer, commented Shoba Amarnath, PhD, Newcastle University research fellow, Laboratory of T-cell Regulation, Newcastle University Center for Cancer, Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

“These findings are consistent with our understanding. … We know that the immune system within cancer patients is compromised as compared to healthy controls,” Dr. Amarnath said. “The data in the study support the notion that, in solid cancer patients, a considerable delay in second dose will extend the period when cancer patients are at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Although more data are required, “this study does raise the issue of whether patients with cancer, other diseases, or those undergoing therapies that affect the body’s immune response should be fast-tracked for their second vaccine dose,” commented Lawrence Young, PhD, professor of molecular oncology and director of the Warwick Cancer Research Center, University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

Stephen Evans, MSc, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, underlined that the study is “essentially” observational and “inevitable limitations must be taken into account.

“Nevertheless, these results do suggest that the vaccines may well not protect those patients with cancer as well as those without cancer,” Mr. Evans said. He added that it is “important that this population continues to observe all COVID-19–associated measures, such as social distancing and shielding when attending hospitals, even after vaccination.”

Study details

Previous studies have shown that some patients with cancer have prolonged responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection, with ongoing immune dysregulation, inefficient seroconversion, and prolonged viral shedding.

There are few data, however, on how these patients respond to COVID-19 vaccination. The authors point out that, among the 18,860 individuals who received the Pfizer vaccine during its development trials, “none with an active oncological diagnosis was included.”

To investigate this issue, they launched the SARS-CoV-2 for Cancer Patients (SOAP-02) study.

The 151 patients with cancer who participated in this study were mostly elderly, the authors noted (75% were older than 65 years; the median age was 73 years). The majority (63%) had solid-tumor malignancies. Of those, 8% had late-stage disease and had been living with their cancer for more than 24 months.

The healthy control persons were vaccine-eligible primary health care workers who were not age matched to the cancer patients.

All participants received the first dose of vaccine; 31 (of 151) patients with cancer and 16 (of 54) healthy control persons received the second dose on day 21.

The remaining participants were scheduled to receive their second dose 12 weeks later (after the study ended), in line with the changes in the national guidelines.

The team reported that, approximately 21 days after receiving the first vaccine dose, the immune efficacy of the vaccine was estimated to be 97% among healthy control persons vs. 39% for patients with solid tumors and only 13% for those with hematologic malignancies (P < .0001 for both).

T-cell responses, as assessed via interferon-gamma and/or interleukin-2 production, were observed in 82% of healthy control persons, 71% of patients with solid tumors, and 50% of those with hematologic cancers.

Vaccine boosting at day 21 resulted in immune efficacy of 100% for healthy control persons and 95% for patients with solid tumors. In contrast, only 43% of those who did not receive the second dose were seropositive 2 weeks later.

Further analysis suggested that participants who did not have a serologic response were “spread evenly” across different cancer types, but the reduced responses were more frequent among patients who had received the vaccine within 15 days of cancer treatment, especially chemotherapy, and had undergone intensive treatments.

The SOAP study is sponsored by King’s College London and Guy’s and St. Thomas Trust Foundation NHS Trust. It is funded from grants from the KCL Charity, Cancer Research UK, and program grants from Breast Cancer Now. The investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The cutaneous benefits of bee venom, Part II: Acupuncture, wound healing, and various potential indications

A wide range of products derived from bees, including honey, propolis, bee pollen, bee bread, royal jelly, beeswax, and bee venom, have been used since ancient times for medical purposes.1 Specifically, bee venom has been used in traditional medicine to treat multiple disorders, including arthritis, cancer, pain, rheumatism, and skin diseases.2,3 The primary active constituent of bee venom is melittin, an amphiphilic peptide containing 26 amino acid residues and known to impart anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic, and anticancer effects.4-7 Additional anti-inflammatory compounds found in bee venom include adolapin, apamin, and phospholipase A2; melittin and phospholipase A2 are also capable of delivering pro-inflammatory activity.8,9

The anti-aging, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties of bee venom have been cited as justification for its use as a cosmetic ingredient.10 In experimental studies, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects have been reported.11 Bee venom phospholipase A2 has also demonstrated notable success in vitro and in vivo in conferring immunomodulatory effects and is a key component in past and continuing use of bee venom therapy for immune-related disorders, such as arthritis.12

A recent review of the biomedical literature by Nguyen et al. reveals that bee venom is one of the key ingredients in the booming Korean cosmeceuticals industry.13 Kim et al. reviewed the therapeutic applications of bee venom in 2019, noting that anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antifibrotic, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties have been cited in experimental and clinical reports, with cutaneous treatments ranging from acne, alopecia, and atopic dermatitis to melanoma, morphea, photoaging, psoriasis, vitiligo, wounds, and wrinkles.14 This column focuses on the use of bee venom in acupuncture and wound healing, as well as some other potential applications of this bee product used for millennia.

Acupuncture

Bee venom acupuncture entails the application of bee venom to the tips of acupuncture needles, which are then applied to acupoints on the skin. Cherniack and Govorushko state that several small studies in humans show that bee venom acupuncture has been used effectively to treat various musculoskeletal and neurological conditions.8

In 2016, Sur et al. explored the effects of bee venom acupuncture on atopic dermatitis in a mouse model with lesions induced by trimellitic anhydride. Bee venom treatment was found to significantly ease inflammation, lesion thickness, and lymph node weight. Suppression of T-cell proliferation and infiltration, Th1 and Th2 cytokine synthesis, and interleukin (IL)-4 and immunoglobulin E (IgE) production was also noted.15

A case report by Hwang and Kim in 2018 described the successful use of bee venom acupuncture in the treatment of a 64-year-old Korean woman with circumscribed morphea resulting from systemic sclerosis. Subcutaneous bee venom acupuncture along the margins resolved pruritus through 2 months of follow-up.11

Wound healing

A study by Hozzein et al. in 2018 on protecting functional macrophages from apoptosis and improving Nrf2, Ang-1, and Tie-2 signaling in diabetic wound healing in mice revealed that bee venom supports immune function, thus promoting healing from diabetic wounds.(16) Previously, this team had shown that bee venom facilitates wound healing in diabetic mice by inhibiting the activation of transcription factor-3 and inducible nitric oxide synthase-mediated stress.17

In early 2020, Nakashima et al. reported their results showing that bee venom-derived phospholipase A2 augmented poly(I:C)-induced activation in human keratinocytes, suggesting that it could play a role in wound healing promotion through enhanced TLR3 responses.18

Alopecia

A 2016 study on the effect of bee venom on alopecia in C57BL/6 mice by Park et al. showed that the bee toxin dose-dependently stimulated proliferation of several growth factors, including fibroblast growth factors 2 and 7, as compared with the control group. Bee venom also suppressed transition from the anagen to catagen phases, nurtured hair growth, and presented the potential as a strong 5α-reductase inhibitor.19

Anticancer and anti-arthritic activity

In 2007, Son et al. reported that the various peptides (melittin, apamin, adolapin, the mast-cell-degranulating peptide), enzymes (i.e., phospholipase A2), as well as biologically active amines (i.e., histamine and epinephrine) and nonpeptide components in bee venom are thought to account for multiple pharmaceutical properties that yield anti-arthritis, antinociceptive, and anticancer effects.2

In 2019, Lim et al. determined that bee venom and melittin inhibited the growth and migration of melanoma cells (B16F10, A375SM, and SK-MEL-28) by downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. They concluded that melittin has the potential for use in preventing and treating malignant melanoma.4

Phototoxicity

Heo et al. conducted phototoxicity and skin sensitization studies of bee venom, as well as a bee venom from which they removed phospholipase A2, and determined that both were nonphototoxic substances and did not act as sensitizers.20