User login

HIV, HBV, and HCV Increase Risks After Joint Replacement

As patients with HIV, hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV) live longer, more active lives with the help of antiviral treatments, they are now more often having joint replacement surgeries. But HIV, HBV, and HCV can increase the risk of postoperative complications, say researchers from Duke University in North Carolina.

The researchers studied 16,338 patients in 4 cohorts: those with HIV, HBV, HCV, and HIV plus HBV or HCV. They evaluated the patients at 30 days, 90 days, and 2 years after total joint arthroplasty (TJA), comparing their progress with that of a control group.

Patients with HBV and HCV were at risk of both acute and long-term medical and surgical complications. At 90 days and 2 years, the participants had increased risk of pneumonia, sepsis, joint infection, and revision surgery. They also had a greater risk of complications than did patients with HIV, especially for infection, within the first 90 days postsurgery.

Notably, after TJA, patients with HCV had increased risk of acute kidney injury, sepsis, and transfusion at 30 and 90 days. After hip replacement, patients with HBV had a higher risk of acute kidney injury, pneumonia, and transfusion at 30 and 90 days.

Only 364 patients in the study had both HIV and HBV or HBC, but they did have a greater risk of transfusion at 30 and 90 days following both knee and hip surgery.

Following total hip arthroplasty, patients with HIV were more at risk for deep vein thrombosis and transfusion rather than infection. The lower incidence of infection is likely to be related to effective highly active antiretroviral therapy, the researchers say. HIV patients also were more likely to have mechanical complications, such as loosening, periprosthetic fracture, and revision at 90 days, but not at 2 years. Patients with HIV who underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) had a higher risk of death at 30 days and medical complications at 90 days. At 2 years, they had a higher risk of periprosthetic joint infection, irrigation and debridement, and revision. The researchers say the higher incidence of mechanical complications can be explained by the younger, more active, and healthy HIV patients in the cohort—the majority were aged younger than 65 years. They also emphasize that the only risk of infection following TJA in their study was 2 years after TKA.

The researchers suggest that their findings could help prompt future guidelines supporting routine screening prior to elective TJA.

Source:

Kildow BJ, Politzer CS, DiLallo M, Bolognesi MP, Seyler TM. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(suppl 7):S86-S92.

doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.061.

As patients with HIV, hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV) live longer, more active lives with the help of antiviral treatments, they are now more often having joint replacement surgeries. But HIV, HBV, and HCV can increase the risk of postoperative complications, say researchers from Duke University in North Carolina.

The researchers studied 16,338 patients in 4 cohorts: those with HIV, HBV, HCV, and HIV plus HBV or HCV. They evaluated the patients at 30 days, 90 days, and 2 years after total joint arthroplasty (TJA), comparing their progress with that of a control group.

Patients with HBV and HCV were at risk of both acute and long-term medical and surgical complications. At 90 days and 2 years, the participants had increased risk of pneumonia, sepsis, joint infection, and revision surgery. They also had a greater risk of complications than did patients with HIV, especially for infection, within the first 90 days postsurgery.

Notably, after TJA, patients with HCV had increased risk of acute kidney injury, sepsis, and transfusion at 30 and 90 days. After hip replacement, patients with HBV had a higher risk of acute kidney injury, pneumonia, and transfusion at 30 and 90 days.

Only 364 patients in the study had both HIV and HBV or HBC, but they did have a greater risk of transfusion at 30 and 90 days following both knee and hip surgery.

Following total hip arthroplasty, patients with HIV were more at risk for deep vein thrombosis and transfusion rather than infection. The lower incidence of infection is likely to be related to effective highly active antiretroviral therapy, the researchers say. HIV patients also were more likely to have mechanical complications, such as loosening, periprosthetic fracture, and revision at 90 days, but not at 2 years. Patients with HIV who underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) had a higher risk of death at 30 days and medical complications at 90 days. At 2 years, they had a higher risk of periprosthetic joint infection, irrigation and debridement, and revision. The researchers say the higher incidence of mechanical complications can be explained by the younger, more active, and healthy HIV patients in the cohort—the majority were aged younger than 65 years. They also emphasize that the only risk of infection following TJA in their study was 2 years after TKA.

The researchers suggest that their findings could help prompt future guidelines supporting routine screening prior to elective TJA.

Source:

Kildow BJ, Politzer CS, DiLallo M, Bolognesi MP, Seyler TM. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(suppl 7):S86-S92.

doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.061.

As patients with HIV, hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV) live longer, more active lives with the help of antiviral treatments, they are now more often having joint replacement surgeries. But HIV, HBV, and HCV can increase the risk of postoperative complications, say researchers from Duke University in North Carolina.

The researchers studied 16,338 patients in 4 cohorts: those with HIV, HBV, HCV, and HIV plus HBV or HCV. They evaluated the patients at 30 days, 90 days, and 2 years after total joint arthroplasty (TJA), comparing their progress with that of a control group.

Patients with HBV and HCV were at risk of both acute and long-term medical and surgical complications. At 90 days and 2 years, the participants had increased risk of pneumonia, sepsis, joint infection, and revision surgery. They also had a greater risk of complications than did patients with HIV, especially for infection, within the first 90 days postsurgery.

Notably, after TJA, patients with HCV had increased risk of acute kidney injury, sepsis, and transfusion at 30 and 90 days. After hip replacement, patients with HBV had a higher risk of acute kidney injury, pneumonia, and transfusion at 30 and 90 days.

Only 364 patients in the study had both HIV and HBV or HBC, but they did have a greater risk of transfusion at 30 and 90 days following both knee and hip surgery.

Following total hip arthroplasty, patients with HIV were more at risk for deep vein thrombosis and transfusion rather than infection. The lower incidence of infection is likely to be related to effective highly active antiretroviral therapy, the researchers say. HIV patients also were more likely to have mechanical complications, such as loosening, periprosthetic fracture, and revision at 90 days, but not at 2 years. Patients with HIV who underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) had a higher risk of death at 30 days and medical complications at 90 days. At 2 years, they had a higher risk of periprosthetic joint infection, irrigation and debridement, and revision. The researchers say the higher incidence of mechanical complications can be explained by the younger, more active, and healthy HIV patients in the cohort—the majority were aged younger than 65 years. They also emphasize that the only risk of infection following TJA in their study was 2 years after TKA.

The researchers suggest that their findings could help prompt future guidelines supporting routine screening prior to elective TJA.

Source:

Kildow BJ, Politzer CS, DiLallo M, Bolognesi MP, Seyler TM. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(suppl 7):S86-S92.

doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.061.

Acute Aortic Occlusion With Spinal Cord Infarction

Acute aortic occlusion (AAO) is a relatively rare vascular emergency. The actual incidence of AAO is unknown but has been variously reported to be 1% to 4%, and the incidence of AAO secondary to infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm is reported to be about 2%.1 Acute aortic occlusion may present with acute onset of neurologic deficits as a consequence of spinal cord ischemia from thrombotic or embolic etiology. Risk factors for thrombosis include hypertension, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus; heart disease and female gender are associated with embolism.2 Spinal cord infarction accounts for only 1% to 2% of all strokes and is characterized by acute onset of paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of pain and temperature perception. Proprioception and vibratory sense are typically preserved.3 The authors present the case of a patient with acute onset of lower limb paralysis and urinary incontinence who was later found to have AAO due to thrombosis and consequent spinal cord infarction.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department of Jefferson Regional Medical Center in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with the sudden onset of severe lower back pain, bilateral leg paralysis and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. The patient stated that she had been watching television when her legs began to tingle and feel numb. Within 10 to 20 minutes she was unable to move her legs and became incontinent of urine. She reported no injury or previous history of back pain. Her medical history was significant for “irregular heartbeat my whole life,” hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bladder cancer. She was not receiving systemic anticoagulation therapy. She reported a previous 15 pack-year smoking history but reported that she had quit cigarette smoking and usually drank 1 glass of wine daily. She had previously completed 3 rounds of chemotherapy for bladder cancer and received her first radiation treatment earlier that day. The symptoms began about 8 hours later that evening.

On examination the patient was noted to be in acute distress due to pain. Her vital signs in triage were blood pressure (BP) 122/71 mm Hg, pulse 54 beats per min (BPM), respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 90% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable only for serum sodium 132 mEq/L, potassium 2.8 mEq/L, and thrombocytosis with platelets 697 × 103/μL. A neurologic examination showed normal motor function, strength of the upper extremities, and paralysis of the lower extremities, which were insensate to blunt or sharp touch and with decreased skin temperature from the groin distally. Pedal pulses were absent bilaterally. She was incontinent of urine and had anal sphincter laxity.

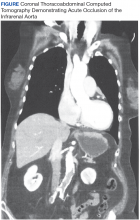

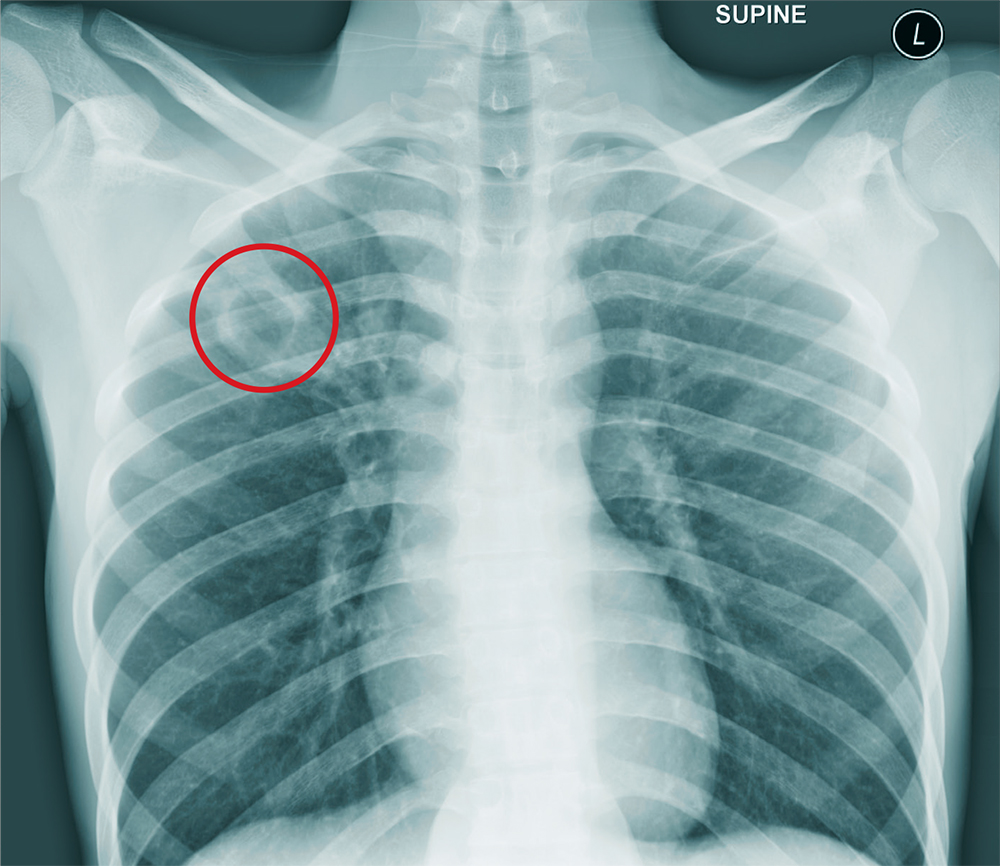

Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulging lumbar intervertebral discs and foraminal narrowing, which the consulting neurosurgeon did not feel explained her presentation and suggested that a vascular etiology was more likely. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta, bilateral common, and external iliac arteries. The proximal inferior mesenteric artery was occluded, and there was 90% stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric artery with noncalcified plaque. There was no abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection demonstrated. A chest CT was unremarkable.

The patient was started on IV heparin 800 U/h and transferred via ambulance to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas, for vascular surgery. On arrival her vital signs were BP 108/69 mm Hg, pulse 123 BPM, respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 94% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. The patient’s electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with premature ventricular complexes. On examination the bilateral lower extremities were cyanotic and cold to the touch. The pedal pulses were nonpalpable, and decreased distal sensation with dense paralysis was noted.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for left axillary bifemoral bypass. Severe atherosclerotic disease was noted at surgery. She was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for postoperative hemodynamic monitoring. Her clinical course became complicated by mesenteric ischemia from chronic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. On postoperative day 2, she became progressively more hypotensive, and she was placed on vasopressin 0.04 U/min and amiodarone 0.5 mg/min infusions.

Bedside echocardiography showed diffuse ventricular hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 30% but no mural thrombus. The patient developed altered mental status and respiratory distress, and her serum lactate increased to 6.1 mg/dL. She was emergently intubated and taken to the OR to attempt recanalization of the SMA occlusion, which was unsuccessful. She was returned to the SICU for continued resuscitation and monitoring. She continued to decline with hypotensive pressures, increasing serum creatinine and lactate, and worsening metabolic acidosis. Management options and goals of care were discussed with the family, and it was decided to honor her do not resuscitate status and pursue comfort care. She was extubated and expired a short time after this was done.

Discussion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency with a mortality rate that approaches 75%.4-6 It results from numerous etiologies, including saddle embolism at the aortic bifurcation, acute thrombus formation, subsequent to aortic dissection, or other causes related to severe atherosclerotic disease or hypercoagulable states.4,7

A recent retrospective series of 29 cases of AAO found that thrombosis was the cause for 76% of cases, and > 40% of patients had a hypercoagulable state either because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (17%) or malignancy (24%).6 The most common presentation of AAO is the abrupt onset of painful bilateral paresis or paraplegia.5,6 While some studies have suggested that the major determinant of mortality is time elapsed until revascularization,7 other studies have reported that the neurologic status of the extremities is more closely related with mortality.2

The anterior spinal artery is the major independent provider of blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, including the anterior horns, the anterior commissure, the anterior funiculi, and to a variable extent, the lateral funiculi. The largest segmental posterior radicular branch of the anterior spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz, which arises from the T9 to T12 level on the left in 75% of cases and provides perfusion to the lumbar spinal cord and the conus medullaris. Obstruction of blood flow in this region has been implicated in the clinical picture of anterior cord syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of radicular pain, flaccid paresis or paralysis, sphincter dysfunction with urinary and fecal incontinence, and decreased pain and temperature sensation below a sensory level with spared proprioception and vibratory sensation.3, 8-10

Aortography is the gold standard procedure for diagnosis of AAO, but it is a time-consuming procedure, and preoperative testing is controversial. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for evaluation as it can be quickly accomplished and is more available in general hospitals. Moreover, CT scanning may reveal aortic dissections or aneurysms as the cause of occlusion. Deep Doppler ultrasonography also has demonstrated utility as a noninvasive and rapidly performed diagnostic procedure. Magnetic resonance angiography or CT should be performed for all cases unless the patient’s clinical condition prevents this evaluation. Imaging not only confirms diagnosis, but also is valuable for assessment and planning management.11-14

Once the diagnosis of AAO is made, management with IV fluid hydration, heparin administration, and optimizing cardiac function are essential. However, conservative management with anticoagulation alone is associated with high mortality, and unless the ischemia is irreversible or unless the patient is in a dying state, surgery is appropriate.5,7 Depending on the etiology of the AAO, anatomic considerations, and other patient factors, urgent revascularization with thrombo-embolectomy, direct aortic reconstruction, or anatomic or extra-anatomic bypass procedures may be employed. Aortic reconstruction has been advocated for all patients with infrarenal aortic occlusion given the concern for propagation of thrombosis at the distal aorta proximally to the renal and mesenteric arteries.7 Axillary-bifemoral bypass has been advocated as a rapid revascularization strategy with good patency and less physiologic strain for critically ill AAO patients.6

The patient in this study had a constellation of risk factors for developing AAO due to thrombosis and consequently sustaining spinal cord infarction. Echocardiography ruled out embolism of a mural thrombus. She had cardiac dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation and left ventricular failure causing a low-flow state (LVEF 30%). She also had a hypercoagulable state due to bladder malignancy in addition to severe atherosclerotic disease. She was not on systemic anticoagulation therapy because of her high fall risk. Hence, her risk for thrombosis was quite high. Despite expedient revascularization surgery, her postoperative course was complicated as a result of severe mesenteric ischemia due to chronic SMA occlusion, which caused her death.

Conclusion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency. The patient presenting with the abrupt onset of bilateral leg pain, neurologic deficits of paresis/paralysis, sensory disturbance, and/or sphincter dysfunction, and stigmata of vascular compromise with lower extremity mottling should alert the physician to AAO. Acute aortic occlusion continues to have high morbidity and mortality, and prompt recognition and appropriate transfer for surgical intervention are essential for improving outcomes.

1. de Varona Frolov SR, Acosta Silva MP, Volvo Pérez G, Fiuza Pérez MD. Outcomes after treatment of acute aortic occlusion. [Article in English, Spanish] Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):573-579.

2. Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al. Acute aortic occlusion: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):603-608.

3. Sandson TA, Friedman JH. Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68(5):282-292.

4. Yamamoto H, Yamamoto F, Tanaka F, et al. Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta with concomitant internal iliac artery occlusion. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):422-427.

5. Zainal AA, Oommen G, Chew LG, Yusha AW. Acute aortic occlusion: the need to be aware. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(1):29-32.

6. Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

7. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J. Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(4):567-572.

8. Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):321-330.

9. Rosenthal D. Spinal cord ischemia after abdominal aortic operation: is it preventable? J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):391-397.

10. Triantafyllopoulos GK, Athanassacopoulos M, Maltezos C, Pneumaticos SG. Acute infrarenal aortic thrombosis presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(15):E1042-E1045.

11. Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):15-23.

12. Bollinger B, Strandberg C, Baekgaard N, Mantoni M, Helweg-Larsen S. Diagnosis of acute aortic occlusion by computer tomography. Vasa. 1995;24(2):199-201.

13. Bertucci B, Rotundo A, Perri G, Sessa E, Tamburrini O. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta: its diagnosis with spiral computed tomography in a case [Article in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1997;94(5):541-543.

14. Battaglia S, Danesino GM, Danesino V, Castellani S. Color doppler ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta. J Ultrasound. 2010;13(3):107-117.

Acute aortic occlusion (AAO) is a relatively rare vascular emergency. The actual incidence of AAO is unknown but has been variously reported to be 1% to 4%, and the incidence of AAO secondary to infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm is reported to be about 2%.1 Acute aortic occlusion may present with acute onset of neurologic deficits as a consequence of spinal cord ischemia from thrombotic or embolic etiology. Risk factors for thrombosis include hypertension, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus; heart disease and female gender are associated with embolism.2 Spinal cord infarction accounts for only 1% to 2% of all strokes and is characterized by acute onset of paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of pain and temperature perception. Proprioception and vibratory sense are typically preserved.3 The authors present the case of a patient with acute onset of lower limb paralysis and urinary incontinence who was later found to have AAO due to thrombosis and consequent spinal cord infarction.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department of Jefferson Regional Medical Center in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with the sudden onset of severe lower back pain, bilateral leg paralysis and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. The patient stated that she had been watching television when her legs began to tingle and feel numb. Within 10 to 20 minutes she was unable to move her legs and became incontinent of urine. She reported no injury or previous history of back pain. Her medical history was significant for “irregular heartbeat my whole life,” hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bladder cancer. She was not receiving systemic anticoagulation therapy. She reported a previous 15 pack-year smoking history but reported that she had quit cigarette smoking and usually drank 1 glass of wine daily. She had previously completed 3 rounds of chemotherapy for bladder cancer and received her first radiation treatment earlier that day. The symptoms began about 8 hours later that evening.

On examination the patient was noted to be in acute distress due to pain. Her vital signs in triage were blood pressure (BP) 122/71 mm Hg, pulse 54 beats per min (BPM), respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 90% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable only for serum sodium 132 mEq/L, potassium 2.8 mEq/L, and thrombocytosis with platelets 697 × 103/μL. A neurologic examination showed normal motor function, strength of the upper extremities, and paralysis of the lower extremities, which were insensate to blunt or sharp touch and with decreased skin temperature from the groin distally. Pedal pulses were absent bilaterally. She was incontinent of urine and had anal sphincter laxity.

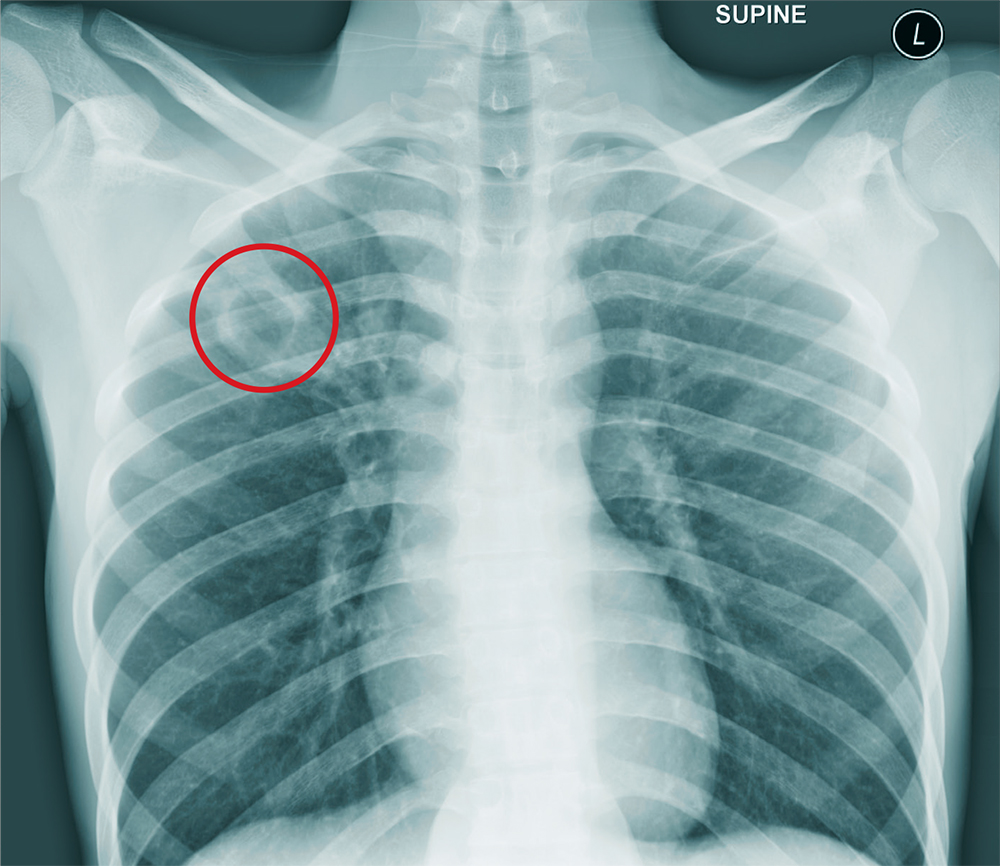

Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulging lumbar intervertebral discs and foraminal narrowing, which the consulting neurosurgeon did not feel explained her presentation and suggested that a vascular etiology was more likely. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta, bilateral common, and external iliac arteries. The proximal inferior mesenteric artery was occluded, and there was 90% stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric artery with noncalcified plaque. There was no abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection demonstrated. A chest CT was unremarkable.

The patient was started on IV heparin 800 U/h and transferred via ambulance to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas, for vascular surgery. On arrival her vital signs were BP 108/69 mm Hg, pulse 123 BPM, respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 94% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. The patient’s electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with premature ventricular complexes. On examination the bilateral lower extremities were cyanotic and cold to the touch. The pedal pulses were nonpalpable, and decreased distal sensation with dense paralysis was noted.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for left axillary bifemoral bypass. Severe atherosclerotic disease was noted at surgery. She was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for postoperative hemodynamic monitoring. Her clinical course became complicated by mesenteric ischemia from chronic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. On postoperative day 2, she became progressively more hypotensive, and she was placed on vasopressin 0.04 U/min and amiodarone 0.5 mg/min infusions.

Bedside echocardiography showed diffuse ventricular hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 30% but no mural thrombus. The patient developed altered mental status and respiratory distress, and her serum lactate increased to 6.1 mg/dL. She was emergently intubated and taken to the OR to attempt recanalization of the SMA occlusion, which was unsuccessful. She was returned to the SICU for continued resuscitation and monitoring. She continued to decline with hypotensive pressures, increasing serum creatinine and lactate, and worsening metabolic acidosis. Management options and goals of care were discussed with the family, and it was decided to honor her do not resuscitate status and pursue comfort care. She was extubated and expired a short time after this was done.

Discussion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency with a mortality rate that approaches 75%.4-6 It results from numerous etiologies, including saddle embolism at the aortic bifurcation, acute thrombus formation, subsequent to aortic dissection, or other causes related to severe atherosclerotic disease or hypercoagulable states.4,7

A recent retrospective series of 29 cases of AAO found that thrombosis was the cause for 76% of cases, and > 40% of patients had a hypercoagulable state either because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (17%) or malignancy (24%).6 The most common presentation of AAO is the abrupt onset of painful bilateral paresis or paraplegia.5,6 While some studies have suggested that the major determinant of mortality is time elapsed until revascularization,7 other studies have reported that the neurologic status of the extremities is more closely related with mortality.2

The anterior spinal artery is the major independent provider of blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, including the anterior horns, the anterior commissure, the anterior funiculi, and to a variable extent, the lateral funiculi. The largest segmental posterior radicular branch of the anterior spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz, which arises from the T9 to T12 level on the left in 75% of cases and provides perfusion to the lumbar spinal cord and the conus medullaris. Obstruction of blood flow in this region has been implicated in the clinical picture of anterior cord syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of radicular pain, flaccid paresis or paralysis, sphincter dysfunction with urinary and fecal incontinence, and decreased pain and temperature sensation below a sensory level with spared proprioception and vibratory sensation.3, 8-10

Aortography is the gold standard procedure for diagnosis of AAO, but it is a time-consuming procedure, and preoperative testing is controversial. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for evaluation as it can be quickly accomplished and is more available in general hospitals. Moreover, CT scanning may reveal aortic dissections or aneurysms as the cause of occlusion. Deep Doppler ultrasonography also has demonstrated utility as a noninvasive and rapidly performed diagnostic procedure. Magnetic resonance angiography or CT should be performed for all cases unless the patient’s clinical condition prevents this evaluation. Imaging not only confirms diagnosis, but also is valuable for assessment and planning management.11-14

Once the diagnosis of AAO is made, management with IV fluid hydration, heparin administration, and optimizing cardiac function are essential. However, conservative management with anticoagulation alone is associated with high mortality, and unless the ischemia is irreversible or unless the patient is in a dying state, surgery is appropriate.5,7 Depending on the etiology of the AAO, anatomic considerations, and other patient factors, urgent revascularization with thrombo-embolectomy, direct aortic reconstruction, or anatomic or extra-anatomic bypass procedures may be employed. Aortic reconstruction has been advocated for all patients with infrarenal aortic occlusion given the concern for propagation of thrombosis at the distal aorta proximally to the renal and mesenteric arteries.7 Axillary-bifemoral bypass has been advocated as a rapid revascularization strategy with good patency and less physiologic strain for critically ill AAO patients.6

The patient in this study had a constellation of risk factors for developing AAO due to thrombosis and consequently sustaining spinal cord infarction. Echocardiography ruled out embolism of a mural thrombus. She had cardiac dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation and left ventricular failure causing a low-flow state (LVEF 30%). She also had a hypercoagulable state due to bladder malignancy in addition to severe atherosclerotic disease. She was not on systemic anticoagulation therapy because of her high fall risk. Hence, her risk for thrombosis was quite high. Despite expedient revascularization surgery, her postoperative course was complicated as a result of severe mesenteric ischemia due to chronic SMA occlusion, which caused her death.

Conclusion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency. The patient presenting with the abrupt onset of bilateral leg pain, neurologic deficits of paresis/paralysis, sensory disturbance, and/or sphincter dysfunction, and stigmata of vascular compromise with lower extremity mottling should alert the physician to AAO. Acute aortic occlusion continues to have high morbidity and mortality, and prompt recognition and appropriate transfer for surgical intervention are essential for improving outcomes.

Acute aortic occlusion (AAO) is a relatively rare vascular emergency. The actual incidence of AAO is unknown but has been variously reported to be 1% to 4%, and the incidence of AAO secondary to infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm is reported to be about 2%.1 Acute aortic occlusion may present with acute onset of neurologic deficits as a consequence of spinal cord ischemia from thrombotic or embolic etiology. Risk factors for thrombosis include hypertension, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus; heart disease and female gender are associated with embolism.2 Spinal cord infarction accounts for only 1% to 2% of all strokes and is characterized by acute onset of paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of pain and temperature perception. Proprioception and vibratory sense are typically preserved.3 The authors present the case of a patient with acute onset of lower limb paralysis and urinary incontinence who was later found to have AAO due to thrombosis and consequent spinal cord infarction.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department of Jefferson Regional Medical Center in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with the sudden onset of severe lower back pain, bilateral leg paralysis and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. The patient stated that she had been watching television when her legs began to tingle and feel numb. Within 10 to 20 minutes she was unable to move her legs and became incontinent of urine. She reported no injury or previous history of back pain. Her medical history was significant for “irregular heartbeat my whole life,” hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bladder cancer. She was not receiving systemic anticoagulation therapy. She reported a previous 15 pack-year smoking history but reported that she had quit cigarette smoking and usually drank 1 glass of wine daily. She had previously completed 3 rounds of chemotherapy for bladder cancer and received her first radiation treatment earlier that day. The symptoms began about 8 hours later that evening.

On examination the patient was noted to be in acute distress due to pain. Her vital signs in triage were blood pressure (BP) 122/71 mm Hg, pulse 54 beats per min (BPM), respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 90% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable only for serum sodium 132 mEq/L, potassium 2.8 mEq/L, and thrombocytosis with platelets 697 × 103/μL. A neurologic examination showed normal motor function, strength of the upper extremities, and paralysis of the lower extremities, which were insensate to blunt or sharp touch and with decreased skin temperature from the groin distally. Pedal pulses were absent bilaterally. She was incontinent of urine and had anal sphincter laxity.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulging lumbar intervertebral discs and foraminal narrowing, which the consulting neurosurgeon did not feel explained her presentation and suggested that a vascular etiology was more likely. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta, bilateral common, and external iliac arteries. The proximal inferior mesenteric artery was occluded, and there was 90% stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric artery with noncalcified plaque. There was no abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection demonstrated. A chest CT was unremarkable.

The patient was started on IV heparin 800 U/h and transferred via ambulance to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas, for vascular surgery. On arrival her vital signs were BP 108/69 mm Hg, pulse 123 BPM, respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 94% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. The patient’s electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with premature ventricular complexes. On examination the bilateral lower extremities were cyanotic and cold to the touch. The pedal pulses were nonpalpable, and decreased distal sensation with dense paralysis was noted.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for left axillary bifemoral bypass. Severe atherosclerotic disease was noted at surgery. She was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for postoperative hemodynamic monitoring. Her clinical course became complicated by mesenteric ischemia from chronic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. On postoperative day 2, she became progressively more hypotensive, and she was placed on vasopressin 0.04 U/min and amiodarone 0.5 mg/min infusions.

Bedside echocardiography showed diffuse ventricular hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 30% but no mural thrombus. The patient developed altered mental status and respiratory distress, and her serum lactate increased to 6.1 mg/dL. She was emergently intubated and taken to the OR to attempt recanalization of the SMA occlusion, which was unsuccessful. She was returned to the SICU for continued resuscitation and monitoring. She continued to decline with hypotensive pressures, increasing serum creatinine and lactate, and worsening metabolic acidosis. Management options and goals of care were discussed with the family, and it was decided to honor her do not resuscitate status and pursue comfort care. She was extubated and expired a short time after this was done.

Discussion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency with a mortality rate that approaches 75%.4-6 It results from numerous etiologies, including saddle embolism at the aortic bifurcation, acute thrombus formation, subsequent to aortic dissection, or other causes related to severe atherosclerotic disease or hypercoagulable states.4,7

A recent retrospective series of 29 cases of AAO found that thrombosis was the cause for 76% of cases, and > 40% of patients had a hypercoagulable state either because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (17%) or malignancy (24%).6 The most common presentation of AAO is the abrupt onset of painful bilateral paresis or paraplegia.5,6 While some studies have suggested that the major determinant of mortality is time elapsed until revascularization,7 other studies have reported that the neurologic status of the extremities is more closely related with mortality.2

The anterior spinal artery is the major independent provider of blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, including the anterior horns, the anterior commissure, the anterior funiculi, and to a variable extent, the lateral funiculi. The largest segmental posterior radicular branch of the anterior spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz, which arises from the T9 to T12 level on the left in 75% of cases and provides perfusion to the lumbar spinal cord and the conus medullaris. Obstruction of blood flow in this region has been implicated in the clinical picture of anterior cord syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of radicular pain, flaccid paresis or paralysis, sphincter dysfunction with urinary and fecal incontinence, and decreased pain and temperature sensation below a sensory level with spared proprioception and vibratory sensation.3, 8-10

Aortography is the gold standard procedure for diagnosis of AAO, but it is a time-consuming procedure, and preoperative testing is controversial. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for evaluation as it can be quickly accomplished and is more available in general hospitals. Moreover, CT scanning may reveal aortic dissections or aneurysms as the cause of occlusion. Deep Doppler ultrasonography also has demonstrated utility as a noninvasive and rapidly performed diagnostic procedure. Magnetic resonance angiography or CT should be performed for all cases unless the patient’s clinical condition prevents this evaluation. Imaging not only confirms diagnosis, but also is valuable for assessment and planning management.11-14

Once the diagnosis of AAO is made, management with IV fluid hydration, heparin administration, and optimizing cardiac function are essential. However, conservative management with anticoagulation alone is associated with high mortality, and unless the ischemia is irreversible or unless the patient is in a dying state, surgery is appropriate.5,7 Depending on the etiology of the AAO, anatomic considerations, and other patient factors, urgent revascularization with thrombo-embolectomy, direct aortic reconstruction, or anatomic or extra-anatomic bypass procedures may be employed. Aortic reconstruction has been advocated for all patients with infrarenal aortic occlusion given the concern for propagation of thrombosis at the distal aorta proximally to the renal and mesenteric arteries.7 Axillary-bifemoral bypass has been advocated as a rapid revascularization strategy with good patency and less physiologic strain for critically ill AAO patients.6

The patient in this study had a constellation of risk factors for developing AAO due to thrombosis and consequently sustaining spinal cord infarction. Echocardiography ruled out embolism of a mural thrombus. She had cardiac dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation and left ventricular failure causing a low-flow state (LVEF 30%). She also had a hypercoagulable state due to bladder malignancy in addition to severe atherosclerotic disease. She was not on systemic anticoagulation therapy because of her high fall risk. Hence, her risk for thrombosis was quite high. Despite expedient revascularization surgery, her postoperative course was complicated as a result of severe mesenteric ischemia due to chronic SMA occlusion, which caused her death.

Conclusion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency. The patient presenting with the abrupt onset of bilateral leg pain, neurologic deficits of paresis/paralysis, sensory disturbance, and/or sphincter dysfunction, and stigmata of vascular compromise with lower extremity mottling should alert the physician to AAO. Acute aortic occlusion continues to have high morbidity and mortality, and prompt recognition and appropriate transfer for surgical intervention are essential for improving outcomes.

1. de Varona Frolov SR, Acosta Silva MP, Volvo Pérez G, Fiuza Pérez MD. Outcomes after treatment of acute aortic occlusion. [Article in English, Spanish] Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):573-579.

2. Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al. Acute aortic occlusion: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):603-608.

3. Sandson TA, Friedman JH. Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68(5):282-292.

4. Yamamoto H, Yamamoto F, Tanaka F, et al. Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta with concomitant internal iliac artery occlusion. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):422-427.

5. Zainal AA, Oommen G, Chew LG, Yusha AW. Acute aortic occlusion: the need to be aware. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(1):29-32.

6. Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

7. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J. Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(4):567-572.

8. Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):321-330.

9. Rosenthal D. Spinal cord ischemia after abdominal aortic operation: is it preventable? J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):391-397.

10. Triantafyllopoulos GK, Athanassacopoulos M, Maltezos C, Pneumaticos SG. Acute infrarenal aortic thrombosis presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(15):E1042-E1045.

11. Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):15-23.

12. Bollinger B, Strandberg C, Baekgaard N, Mantoni M, Helweg-Larsen S. Diagnosis of acute aortic occlusion by computer tomography. Vasa. 1995;24(2):199-201.

13. Bertucci B, Rotundo A, Perri G, Sessa E, Tamburrini O. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta: its diagnosis with spiral computed tomography in a case [Article in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1997;94(5):541-543.

14. Battaglia S, Danesino GM, Danesino V, Castellani S. Color doppler ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta. J Ultrasound. 2010;13(3):107-117.

1. de Varona Frolov SR, Acosta Silva MP, Volvo Pérez G, Fiuza Pérez MD. Outcomes after treatment of acute aortic occlusion. [Article in English, Spanish] Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):573-579.

2. Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al. Acute aortic occlusion: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):603-608.

3. Sandson TA, Friedman JH. Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68(5):282-292.

4. Yamamoto H, Yamamoto F, Tanaka F, et al. Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta with concomitant internal iliac artery occlusion. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):422-427.

5. Zainal AA, Oommen G, Chew LG, Yusha AW. Acute aortic occlusion: the need to be aware. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(1):29-32.

6. Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

7. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J. Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(4):567-572.

8. Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):321-330.

9. Rosenthal D. Spinal cord ischemia after abdominal aortic operation: is it preventable? J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):391-397.

10. Triantafyllopoulos GK, Athanassacopoulos M, Maltezos C, Pneumaticos SG. Acute infrarenal aortic thrombosis presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(15):E1042-E1045.

11. Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):15-23.

12. Bollinger B, Strandberg C, Baekgaard N, Mantoni M, Helweg-Larsen S. Diagnosis of acute aortic occlusion by computer tomography. Vasa. 1995;24(2):199-201.

13. Bertucci B, Rotundo A, Perri G, Sessa E, Tamburrini O. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta: its diagnosis with spiral computed tomography in a case [Article in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1997;94(5):541-543.

14. Battaglia S, Danesino GM, Danesino V, Castellani S. Color doppler ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta. J Ultrasound. 2010;13(3):107-117.

High Body Mass Index is Related to Increased Perioperative Complications After Periacetabular Osteotomy

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to determine the relationship of body mass index (BMI), age, smoking status, and other comorbid conditions to the rate and type of complications occurring in the perioperative period following periacetabular osteotomy. A retrospective review was performed on 80 hips to determine demographic information as well as pre- and postoperative pain scores, center-edge angle, Tönnis angle, intraoperative blood loss, and perioperative complications within 90 days of surgery. Patients were placed into high- (>30) and low- (<30) BMI groups to determine any correlation between complications and BMI. The high-BMI group had a significantly greater rate of perioperative complications than the low-BMI group (30% vs 8%) and, correspondingly, patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). Center-edge angle and Tönnis angle were corrected in both groups. Improvement in postoperative pain scores and radiographically measured acetabular correction can be achieved in high- and low-BMI patients. High-BMI patients have a higher rate of perioperative wound complications.

Continue to: The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy...

The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) has become a widely used procedure for hip preservation in adolescent and young adult patients with symptomatic anatomic aberrancies of the acetabulum due to developmental hip dysplasia, trauma, infection, femoroacetabular impingement, and other causes.1-6 Acetabular dysplasia is one of the most common causes of secondary osteoarthritis, and the goal of PAO is to slow or halt the progression of arthrosis to prolong or potentially eliminate the need for total hip arthroplasty while relieving pain and increasing function and activity.1,7,8

The PAO involves realigning the acetabulum to improve anterior and lateral coverage of the femoral head, acetabular anteversion, and medicalization of the joint.5,6 It is preferred over other described acetabular osteotomies due to its inherent stability given that the posterior column is not violated.3,5,6,9 Since its initial description in 1988,5 short-, medium- and long-term outcomes have been reported with excellent patient satisfaction and function.2,7,10-15 The radiographic, functional, and patient satisfaction outcomes are excellent; therefore, this has become an accepted form of treatment for acetabular dysplasia.16 Additional procedures, such as hip arthroscopy, have also been combined with PAO to treat intra-articular pathologies without open arthrotomy.17 Several studies have evaluated preoperative radiographic factors, such as Tönnis grade, previous surgeries, and morphology of the hip; as well as demographic factors, such as age, body mass index (BMI), comorbid diseases, and activity level, which seem to play a role in the final outcome.11,18,19 This work has advanced our understanding and allowed surgeons to apply selection criteria to improve patient outcomes.

There are multiple reported complications of the PAO procedure, including infection,2 wound dehiscence,20 periacetabular fracture,21 intra-articular extension of the osteotomy,22 excessive acetabular retroversion,23,24 hardware failure, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy,25 heterotopic ossification, prominent hardware, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism,26 osteonecrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum,24 non-union,24 intrapelvic bleeding,24 incisional hernia,27 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy,20,28 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,2,29 There are also several studies reporting a learning curve phenomenon, in which the proportion of complications is higher in the initial series of surgeries performed by each specific surgeon.22,20,29

Despite the widely reported short-, medium-, and long-term results of this treatment, no study thus far has attempted to correlate preoperative patient factors with early perioperative outcomes and complications. This information would be useful in patient counseling and decision making in the early postoperative period. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze data from the perioperative period in patients who have undergone the PAO performed by a single surgeon at our institution to determine any correlation between patient characteristics such as age, comorbid disease, hip pathologic diagnosis, BMI, or previous procedures and perioperative complications occurring within the first 90 days.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a search was performed on the basis of operative report Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for all patients who underwent PAO performed by a single surgeon between 2005 and 2013. Patients were included if they had PAO surgery with at least 90 days of follow-up. There was no exclusion for age, previous surgery, or underlying hip or medical diagnosis. A retrospective review of electronic medical records and radiographic imaging was undertaken to determine pre- and postoperative demographic information, pain scores, center-edge angle of Weiberg and Tönnis angles, intraoperative estimated blood loss, and all perioperative complications. Weight and height were recorded from the immediate preoperative visit and measured in kilograms (kg) and meters (m), respectively. BMI was derived from these measurements. Pain was assessed via visual analog scale at the preoperative visit as well as at 12 weeks postoperatively. Preoperative and 12-week postoperative Tönnis and center-edge angles were measured by a single orthopedic surgeon. All radiographs were deemed adequate in position and penetration for measurement of these parameters. Evidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head was evaluated on all postoperative radiographs within this perioperative period. Estimated blood loss was established by review of operative records and anesthesia notes.

Perioperative complications were classified using the Clavien-Dindo system, which has previously been validated for use in hip preservation surgery.30 This includes 5 grades of complications based on the treatment needed and severity of resulting long-term disability. Grade I complications do not require any change in the postoperative course and were therefore left out of our statistical analysis. Examples include symptomatic hardware, mild heterotopic ossification, and iliopsoas tendonitis. Grade II complications are those that require a change in outpatient management, such as delayed wound healing, superficial infection, transient nerve palsy, violation of the posterior column, and intra-articular osteotomy. Grade III complications require invasive or surgical treatment but leave the patient with no long-term disability. Examples include wound dehiscence, hematoma or infection necessitating surgical débridement and irrigation, and revision of the osteotomy due to hardware malposition or hip instability. Grade IV complications involve both surgery and long-term disability. Grade IV complications applicable to hip preservation surgery are osteonecrosis, permanent nerve injury, major vascular injury, or pulmonary embolism. A grade V complication is death.

For analysis and correlation between demographics and perioperative outcomes and complications, patients were grouped into several groups for comparison. Low (<30) vs high (>30) BMI, smokers vs non-smokers, diabetic vs non-diabetic patients, and those who had previous surgery vs those who did not were compared. A two-tailed t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables and a Mann-Whitney U test, for non-parametric data to compare postoperative radiographic correction, pain scores, and complication rates between each of these groups.

The operative technique for PAO as described by Ganz and colleagues5 in 1988 was utilized in all patients. When preoperative imaging showed evidence of labral pathology, a Cam lesion of the femoral head and neck junction, abnormal proximal femoral anatomy, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, or an os acetabulum, a concomitant procedure was performed. Seventeen patients underwent débridement of a Cam lesion noted to be impinging following PAO. Seventeen patients underwent labral débridement and 4 underwent labral repair. Four patients underwent intertrochanteric osteotomy and 1 underwent greater trochanteric slide. Two patients underwent free-vascularized fibular grafting to the ipsilateral femoral head and 5 underwent fixation of an os acetabulum.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

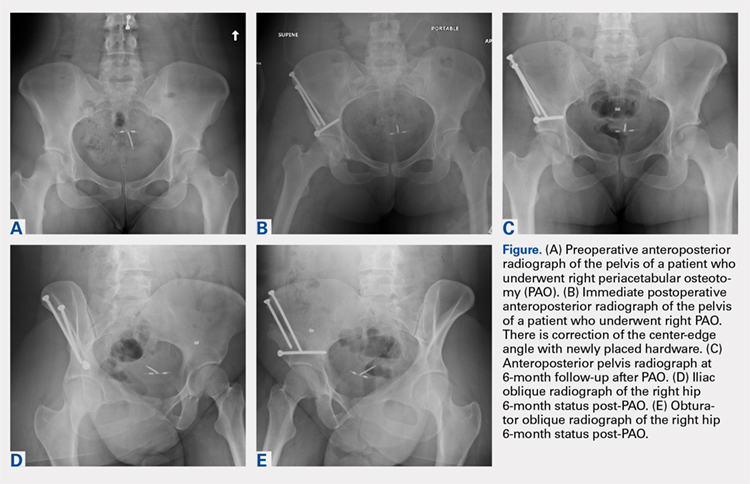

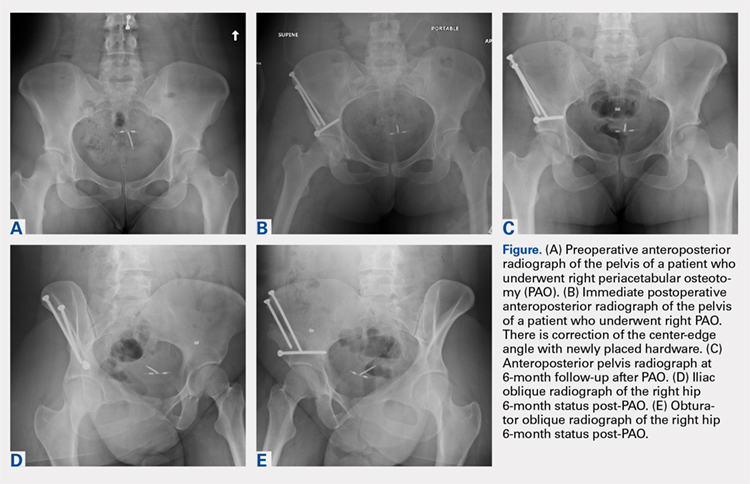

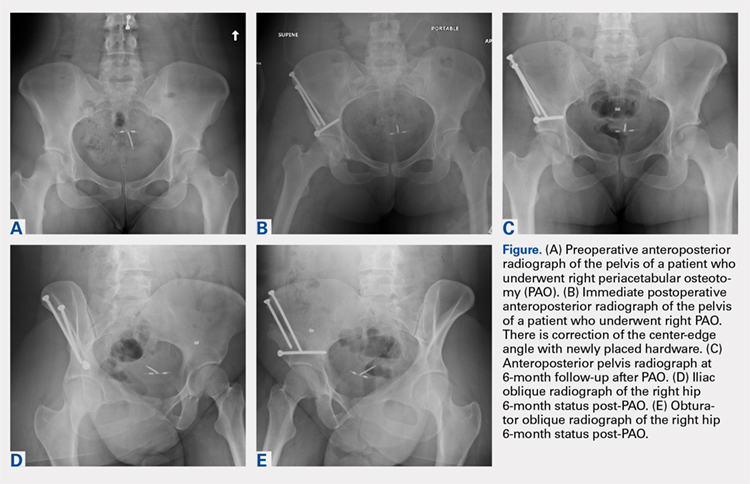

A total of 80 hips in 73 patients underwent PAO with adequate perioperative follow-up and records in the inclusion period. Figures A-E represent a patient pre-procedure, immediately post procedure, and 6 months after successful PAO. The average age was 27.5 years (12.8-43.6 years), and the average BMI was 26.8 (18.7-52.2). Four patients had diabetes, 8 were smokers, and 10 had undergone previous surgeries including arthroscopic labral débridement, 3 open reduction with Salter osteotomy, 3 open reduction with internal fixation of a femoral neck fracture, 1 core decompression for femoral head osteonecrosis, 3 subtrochanteric osteotomy and subsequent non-union treated with cephalomedullary nailing, and 1 previous PAO requiring revision.1

There were 11 perioperative complications in 10 patients (12.5%). The majority of these were infection (n = 10). Overall complications categorized by BMI are summarized in Table 1. Age was similar in patients with complications (27.4 ± 8.8 years) and those without (27.5 ± 8.2 years) (P = .99). Patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9.3 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). There was no effect of concomitant procedures on the complication rate. Of the patients who had complications, 60% (6/10) had concomitant procedures, vs 63% (44/70) of those who had no complications (P = .86) Two of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed complications, both of which were wound infections. One of these required incision and débridement. There were no perioperative complications in any of the 7 smokers.

Table 1. Complications in Low- and High-BMI Patients | ||||

Complications | Total | BMI <30 | BMI >30 | |

Infection | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Superficial | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Deep | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Long screw | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Total | 13 | 5 | 6 | |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Twenty hips were in the high-BMI (>30) and 60 were in the low-BMI (<30) patient groups. There were 6 total perioperative complications in the high-BMI group (30%) and 5 in the low-BMI group (8%). The most common complications in the low-BMI group were superficial infections.4 There were 6 total complications in the high-BMI group: 2 deep and 4 superficial infections. There were 3 reoperations (5%) in the low-BMI group during the perioperative period. Two patients underwent successful débridement and irrigation of a superficial wound, and 1 patient required removal of a prominent screw. There were 3 reoperations in the high-BMI group, all of which were débridement and irrigations for wound infections. The rate of wound dehiscence and wound infection was significantly higher in high-BMI patients (30% [6/20]) than in low-BMI patients (8.3% [4/60]) (P = .006). The mean estimated blood loss in the high-BMI group was greater at 923.75 mL vs 779.25 mL in the low-BMI patients; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = .350). Seventy percent (14/20) of patients who were obese had concomitant procedures vs 60% (36/60) of those who had normal BMI (P = .42 by chi-square analysis). There was no difference in estimated blood loss in patients who underwent concomitant procedures (Table 2).

Table 2. Average Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | |||

| Average EBL | BMI <30 | BMI >30 |

Concomitant procedure | 765 | 759 | 779 |

No concomitant procedure | 900 | 810 | 1263 |

Total | 815 | 779 | 924 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EBL, estimated blood loss.

Preoperative pain scores improved from 4.9 (range, 0-10) to 1.9 (range, 0-6) in the high-BMI group and 4.2 (range, 0-10) to 1.2 (range, 0-6) in the low-BMI group (P = .260). The preoperative center-edge angle in the high-BMI group improved from 6.63° ± 6.5° to 28.53° ± 6.7°, and the Tönnis angle from 24.96° ± 6.3° to 10.06° ± 7.7°. In the low-BMI group the center-edge angle improved from 10.53° ± 11.77° to 27.07° ± 13.9°, and the Tönnis angle from 19.00° ± 10.3° to 2.79° ± 8.3°. There was no difference in postoperative center-edge angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .66). There was a trend toward significance in the postoperative Tönnis angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .051).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

There have been 4 previously published articles specifically on complications following PAO. Each of these encompassed follow-up visits including both the perioperative period and at least 2 years of follow-up.20,22,24,29 Davey and Santore29 reported an overall rate of complications of 10% in a series of 70 patients. These authors classified complications into minor, moderate, and major for purposes of research and discussion, and this classification system has been utilized or modified within the literature to discuss complications in most other articles. Complications within the perioperative period included 2 cases of excessive intraoperative bleeding, 2 cases of reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and 1 case each of unresolved sciatic nerve palsy and deep vein thrombosis.29 Hussell and colleagues22 reported on a large series of 508 PAOs and analyzed the technical complications that occurred during the procedure and caused either immediate or longer-term problems for the patients. Notably, they concluded that 85% of the technical complications occurred with the initial 50 PAOs performed, signifying a steep learning curve for this technically demanding procedure. Perioperative complications reported were intra-articular osteotomy in 2.2%, femoral nerve palsy in 0.6%, sciatic nerve palsy in 1.0%, posterior column insufficiency in 1.2%, and symptomatic hardware in 3.0%.22 Biedermann and colleagues20 found that 47 out of 60 PAOs in their series had at least 1 minor complication. The most common perioperative complications were lateral femoral cutaneous nerve dysesthesia in 33%, delayed wound healing infection in 15%, major blood loss in 8.3%, sciatic or peroneal nerve palsy in 10%, posterior column discontinuity in 6.7%, and intra-articular osteotomy in 1.6%.20 Most recently, complications of PAO in an adolescent population were evaluated.24 The overall rate of complications was 37%. Major perioperative complications included 1 patient with excessive bleeding due to an aberrant artery at the medial wall of the pelvis thought to be due to revascularization following a previous Dega osteotomy. Two patients required immediate revision of the osteotomy due to excessive anterior coverage noted on postoperative radiographs. There were 5% with superficial stitch abscess causing minor infection, 5% with transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy, and 15 patients with symptomatic hardware.24

At 12.5%, our overall complication rate is slightly lower than that previously reported in the literature. This may be due to the difference in the scope of this study, which reported only perioperative complications. We also chose to utilize the modified Clavien-Dindo classification system for reporting our complications rather than classifying them as minor or major as in the above studies. This classification system has been validated for use in reporting complications of hip preservation surgery. We considered only Grade II complications and higher for statistical analysis as these required a change in postoperative management, which may have artificially lowered our complication rate.

The data in this study indicate that, compared with patients with a BMI of <30, obese patients have a higher rate of perioperative complications and reoperations. Additionally, the proportion of Grade II and higher complications, importantly deep infection, was higher in obese patients. We did not have any reported incidence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, intra-articular osteotomy, acetabular or pelvic fracture, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy, or long-term lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy in this series of patients. The most common complication in the low-BMI group was symptomatic hardware. Sixteen patients had this complaint; however, this was not considered a Grade II complication as there would be no change in management during the study period, including the perioperative time frame. Two out of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed wound infections, both of which required reoperation. However, the number of patients with diabetes mellitus was not large enough to draw any conclusions from this information. There were no perioperative complications in smokers. We hypothesized that there may be a higher rate of wound complications in this population, and although the data in our patients did not support this hypothesis, a larger cohort of smokers is needed to make this determination. Another potential complication in smokers is non-union, which was not reported in this study on perioperative complications. Although it did not reach statistical significance, the intraoperative blood loss was almost 150 mL greater in high-BMI patients (924 mL vs 779 mL). Additionally, there appears to be no effect of concomitant procedure on estimated blood loss in either low- or high-BMI groups. Age was not a risk factor for the development of perioperative complications in this cohort. Pain was reliably improved in both the high- and low-BMI groups at the 12-week follow-up visit. The center-edge angle could be normalized in both groups to 28.53° in the high-BMI group and 27.07° in the low-BMI group, with a similar final correction between groups. The Tönnis angle was also improved in both groups, but the final Tönnis angle strongly trended toward statistical significance (2.79° in the low-BMI group vs 10.06° in the high-BMI group).

This study has limitations in that it is a retrospective review of patient information based on medical records and therefore relied on documentation performed at the time of service. There also may have been a difference in the intraoperative or postoperative protocol for wound monitoring or rehabilitation among patients based on body habitus, which we are not able to detect from the medical records. Although the overall number of patients in this cohort is comparable to other studies on the outcomes of patients after PAO, the number of patients in each BMI group was not evenly matched. Without randomization, selection bias occurred at the time of the procedure as some obese patients were not offered this procedure based on the senior surgeon’s discretion. Additionally, when subgroups such as patients with diabetes mellitus or smokers were analyzed, the number of subjects was too small for statistical analysis; therefore, no conclusions could be made as to the risk of perioperative complications in these populations.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations in this study, based on the data from this cohort, we concluded that the goal of PAO of restoring more normal hip joint anatomy can be achieved in both low- and high-BMI patients. However, patients with a BMI >30 should be counseled on their increased risk of major perioperative complications, specifically wound dehiscence and infection, and the higher likelihood of reoperation for treatment of these complications. Diabetic patients can be counseled that they may have a higher risk of infection as well, but future studies with larger numbers will be needed to confirm this. Patients with low BMI should be counseled about the potential for prominent or symptomatic hardware, which may necessitate removal following osteotomy union.

1. Clohisy JC, Barrett SE, Gordon JE, Delgado ED, Schoenecker PL. Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):254-259. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00887.

2. Clohisy JC, Schutz AL, St John L, Schoenecker PL, Wright RW. Periacetabular osteotomy: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(8):2041-2052. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0842-6.

3. Gillingham BL, Sanchez AA, Wenger DR. Pelvic osteotomies for the treatment of hip dysplasia in children and young adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(5):325-337. doi:10.5435/00124635-199909000-00005.

4. Siebenrock KA, Schoeniger R, Ganz R. Anterior femoro-acetabular impingement due to acetabular retroversion. Treatment with periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):278-286. doi:10.2106/00004623-200302000-00015.

5. Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(232):26-36. doi:10.1097/00003086-198807000-00006.

6. Tibor LM, Sink EL. Periacetabular osteotomy for hip preservation. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(3):343-357. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2012.05.011.

7. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B6.18805.

8. Novais EN, Heyworth B, Murray K, Johnson VM, Kim YJ, Millis MB. Physical activity level improves after periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of symptomatic hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(3):981-988. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2578-y.

9. Clohisy JC, Barrett SE, Gordon JE, Delgado ED, Schoenecker PL. Periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 1 Pt 1:65-83. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00887.

10. Badra MI, Anand A, Straight JJ, Sala DA, Ruchelsman DE, Feldman DS. Functional outcome in adult patients following Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Orthopedics 2008;31(1):69. doi:10.3928/01477447-20080101-03.

11. Hartig-Andreasen C, Troelsen A, Thillemann TM, Soballe K. What factors predict failure 4 to 12 years after periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(11):2978-2987. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2386-4.

12. Ito H, Tanino H, Yamanaka Y, Minami A, Matsuno T. Intermediate to long-term results of periacetabular osteotomy in patients younger and older than forty years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(14):1347-1354. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01059.

13. Matheney T, Kim YJ, Zurakowski D, Matero C, Millis M. Intermediate to long-term results following the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy and predictors of clinical outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2113-2123. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00143.

14. Pogliacomi F, Stark A, Wallensten R. Periacetabular osteotomy. Good pain relief in symptomatic hip dysplasia, 32 patients followed for 4 years. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(1):67-74. doi:10.1080/00016470510030346.

15. Zhu J, Chen X, Cui Y, Shen C, Cai G. Mid-term results of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy for developmental dysplasia of hip in middle aged patients. Int Orthop. 2013;37(4):589-594. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-1790-z.

16. Lehmann CL, Nepple JJ, Baca G, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Do fluoroscopy and postoperative radiographs correlate for periacetabular osteotomy corrections? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3508-3514. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2483-4.

17. Nakayama H, Fukunishi S, Fukui T, Yoshiya S. Arthroscopic labral repair concomitantly performed with curved periacetabular osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):938-941. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2362-x.

18. Sambandam SN, Hull J, Jiranek WA. Factors predicting the failure of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: a meta-regression analysis. Int Orthop. 2009;33(6):1483-1488. doi:10.1007/s00264-008-0643-7.

19. Yasunaga Y, Yamasaki T, Ochi M. Patient selection criteria for periacetabular osteotomy or rotational acetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3342-3354. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2516-z.

20. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):611-617. doi:10.1007/s00264-007-0372-3.

21. Espinosa N, Strassberg J, Belzile EL, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Extraarticular fractures after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1645-1651. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0280-x.

22. Hussell JG, Rodriguez JA, Ganz R. Technical complications of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(363):81-92.

23. Tannast M, Pfander G, Steppacher SD, Mast JW, Ganz R. Total acetabular retroversion following pelvic osteotomy: presentation, management, and outcome. Hip Int. 2013;23 Suppl 9:S14-S26. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000089.

24. Thawrani D, Sucato DJ, Podeszwa DA, DeLaRocha A. Complications associated with the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(8):1707-1714. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00829.

25. Sierra RJ, Beaule P, Zaltz I, Millis MB, Clohisy JC, Trousdale RT; ANCHOR Group. Prevention of nerve injury after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(8):2209-2219. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2409-1.

26. Zaltz I, Beaulé P, Clohisy J, et al. Incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus following periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93 Suppl 2:62-65. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01769.

27. Burmeister H, Kaiser B, Siebenrock KA, Ganz R. Incisional hernia after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(425):177-179. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000130203.28818.da.

28. Kiyama T, Naito M, Shiramizu K, Shinoda T, Maeyama A. Ischemia of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve during periacetabular osteotomy using Smith-Petersen approach. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(3):123-126. doi:10.1007/s10195-009-0055-5.

29. Davey JP, Santore RF. Complications of periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(363):33-37. doi:10.1097/00003086-199906000-00005.

30. Sink EL, Leunig M, Zaltz I, Gilbert JC, Clohisy J; Academic Network for Conservational Hip Outcomes Research Group. Reliability of a complication classification system for orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(8):2220-2226. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2343-2.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to determine the relationship of body mass index (BMI), age, smoking status, and other comorbid conditions to the rate and type of complications occurring in the perioperative period following periacetabular osteotomy. A retrospective review was performed on 80 hips to determine demographic information as well as pre- and postoperative pain scores, center-edge angle, Tönnis angle, intraoperative blood loss, and perioperative complications within 90 days of surgery. Patients were placed into high- (>30) and low- (<30) BMI groups to determine any correlation between complications and BMI. The high-BMI group had a significantly greater rate of perioperative complications than the low-BMI group (30% vs 8%) and, correspondingly, patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). Center-edge angle and Tönnis angle were corrected in both groups. Improvement in postoperative pain scores and radiographically measured acetabular correction can be achieved in high- and low-BMI patients. High-BMI patients have a higher rate of perioperative wound complications.

Continue to: The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy...

The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) has become a widely used procedure for hip preservation in adolescent and young adult patients with symptomatic anatomic aberrancies of the acetabulum due to developmental hip dysplasia, trauma, infection, femoroacetabular impingement, and other causes.1-6 Acetabular dysplasia is one of the most common causes of secondary osteoarthritis, and the goal of PAO is to slow or halt the progression of arthrosis to prolong or potentially eliminate the need for total hip arthroplasty while relieving pain and increasing function and activity.1,7,8

The PAO involves realigning the acetabulum to improve anterior and lateral coverage of the femoral head, acetabular anteversion, and medicalization of the joint.5,6 It is preferred over other described acetabular osteotomies due to its inherent stability given that the posterior column is not violated.3,5,6,9 Since its initial description in 1988,5 short-, medium- and long-term outcomes have been reported with excellent patient satisfaction and function.2,7,10-15 The radiographic, functional, and patient satisfaction outcomes are excellent; therefore, this has become an accepted form of treatment for acetabular dysplasia.16 Additional procedures, such as hip arthroscopy, have also been combined with PAO to treat intra-articular pathologies without open arthrotomy.17 Several studies have evaluated preoperative radiographic factors, such as Tönnis grade, previous surgeries, and morphology of the hip; as well as demographic factors, such as age, body mass index (BMI), comorbid diseases, and activity level, which seem to play a role in the final outcome.11,18,19 This work has advanced our understanding and allowed surgeons to apply selection criteria to improve patient outcomes.

There are multiple reported complications of the PAO procedure, including infection,2 wound dehiscence,20 periacetabular fracture,21 intra-articular extension of the osteotomy,22 excessive acetabular retroversion,23,24 hardware failure, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy,25 heterotopic ossification, prominent hardware, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism,26 osteonecrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum,24 non-union,24 intrapelvic bleeding,24 incisional hernia,27 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy,20,28 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,2,29 There are also several studies reporting a learning curve phenomenon, in which the proportion of complications is higher in the initial series of surgeries performed by each specific surgeon.22,20,29

Despite the widely reported short-, medium-, and long-term results of this treatment, no study thus far has attempted to correlate preoperative patient factors with early perioperative outcomes and complications. This information would be useful in patient counseling and decision making in the early postoperative period. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze data from the perioperative period in patients who have undergone the PAO performed by a single surgeon at our institution to determine any correlation between patient characteristics such as age, comorbid disease, hip pathologic diagnosis, BMI, or previous procedures and perioperative complications occurring within the first 90 days.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a search was performed on the basis of operative report Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for all patients who underwent PAO performed by a single surgeon between 2005 and 2013. Patients were included if they had PAO surgery with at least 90 days of follow-up. There was no exclusion for age, previous surgery, or underlying hip or medical diagnosis. A retrospective review of electronic medical records and radiographic imaging was undertaken to determine pre- and postoperative demographic information, pain scores, center-edge angle of Weiberg and Tönnis angles, intraoperative estimated blood loss, and all perioperative complications. Weight and height were recorded from the immediate preoperative visit and measured in kilograms (kg) and meters (m), respectively. BMI was derived from these measurements. Pain was assessed via visual analog scale at the preoperative visit as well as at 12 weeks postoperatively. Preoperative and 12-week postoperative Tönnis and center-edge angles were measured by a single orthopedic surgeon. All radiographs were deemed adequate in position and penetration for measurement of these parameters. Evidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head was evaluated on all postoperative radiographs within this perioperative period. Estimated blood loss was established by review of operative records and anesthesia notes.

Perioperative complications were classified using the Clavien-Dindo system, which has previously been validated for use in hip preservation surgery.30 This includes 5 grades of complications based on the treatment needed and severity of resulting long-term disability. Grade I complications do not require any change in the postoperative course and were therefore left out of our statistical analysis. Examples include symptomatic hardware, mild heterotopic ossification, and iliopsoas tendonitis. Grade II complications are those that require a change in outpatient management, such as delayed wound healing, superficial infection, transient nerve palsy, violation of the posterior column, and intra-articular osteotomy. Grade III complications require invasive or surgical treatment but leave the patient with no long-term disability. Examples include wound dehiscence, hematoma or infection necessitating surgical débridement and irrigation, and revision of the osteotomy due to hardware malposition or hip instability. Grade IV complications involve both surgery and long-term disability. Grade IV complications applicable to hip preservation surgery are osteonecrosis, permanent nerve injury, major vascular injury, or pulmonary embolism. A grade V complication is death.