User login

Resident Participation Impact on Operative Time and Outcomes in Veterans Undergoing Total Laryngectomy

Resident Participation Impact on Operative Time and Outcomes in Veterans Undergoing Total Laryngectomy

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been integral in resident training. Resident surgical training requires a balance of supervision and autonomy, along with procedure repetition and appropriate feedback.1-3 Non-VA research has found that resident participation across various otolaryngology procedures, including thyroidectomy, neck dissection, and laryngectomy, does not increase patient morbidity.4-7 However, resident involvement in private and academic settings that included nonhead and neck procedures was linked to increased operative time and reduced productivity, as determined by work relative value units (wRVUs).7-13 This has also been identified in other specialties, including general surgery, orthopedics, and ophthalmology.14-16

Unlike the private sector, surgeon compensation at the VA is not as closely linked to operative productivity, offering a unique setting for resident training. While VA integration in otolaryngology residency programs increases resident case numbers, particularly in head and neck cases, the impact on VA patient outcomes and productivity is unknown.17 The use of larynxpreserving treatment modalities for laryngeal cancer has led to a decline in the number of total laryngectomies performed, which could potentially impact resident operative training for laryngectomies.18-20

This study sought to determine the impact of resident participation on operative time, wRVUs, and patient outcomes in veterans who underwent a total laryngectomy. This study was reviewed and approved by the MedStar Georgetown University Hospital Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee (#1595672).

Methods

A retrospective cohort of veterans nationwide who underwent total laryngectomy between 2001 and 2021, with or without neck dissection, was identified from the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP). Data were extracted via the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure and patients were included based on Current Procedural Terminology codes for total laryngectomy, with or without neck dissection (31320, 31360, 31365). Laryngopharyngectomies, partial laryngectomies, and minimally invasive laryngectomies were excluded. VASQIP nurse data managers reviewed patient data for operative data, postoperative outcomes (including 30- day morbidity and mortality), and preoperative risk factors (Appendix).21

The VASQIP data provide the highest resident or postgraduate year (PGY) per surgery. PGY 1, 2, and 3 were considered junior residents and PGY ≥4, surgical fellows, and individuals who took research years during residency were considered senior residents. Cases performed by attending physicians alone were compared with those involving junior or senior residents.

Patient demographic data included age, body mass index, smoking and alcohol use, weight loss, and functional status. Consumption of any tobacco products within 12 months of surgery was considered tobacco use. Drinking on average ≥2 alcoholic beverages daily was considered alcohol use. Weight loss was defined as a 10% reduction in body weight within the 6 months before surgery, excluding patients enrolled in a weight loss program. Functional status was categorized as independent, partially dependent, totally dependent, and unknown.

Primary outcomes included operative time, wRVUs generated, and wRVUs generated per hour of operative time. Postoperative complications were recorded both as a continuous variable and as a binary variable for presence or absence of a complication. Additional outcome variables included length of postoperative hospital stay, return to the operating room (OR), and death within 30 days of surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and median with IQR for continuous variables. Data were also summarized based on resident involvement in the surgery and the PGY level of the residents involved. The occurrence of total laryngectomy, rate of complications, and patient return to the OR were summarized by year.

Univariate associations between resident involvement and surgical outcomes were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the ÷2 test for categorical variables. A Fisher exact test was used when the cell count in the contingency table was < 5. The univariate associations between surgical outcomes and demographic/preoperative variables were examined using 2-sided Wilcoxon ranksum tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests between continuous variables and categorical variables, X2 or Fisher exact test between 2 categorical variables, and 2-sided Spearman correlation test between 2 continuous variables. A false-discovery rate approach was used for simultaneous posthoc tests to determine the adjusted P values for wRVUs generated/operative time for attending physicians alone vs with junior residents and for attending physicians alone vs with senior residents. Models were used to evaluate the effects of resident involvement on surgical outcomes, adjusting for variables that showed significant univariate associations. Linear regression models were used for operative time, wRVUs generated, wRVUs generated/operative time, and length of postoperative stay. A logistic regression model was used for death within 30 days. Models were not built for postoperative complications or patient return to the OR, as these were only statistically significantly associated with the patient’s preoperative functional status. A finding was considered significant if P < .05. All analyses were performed using statistical software RStudio Version 2023.03.0.

Results

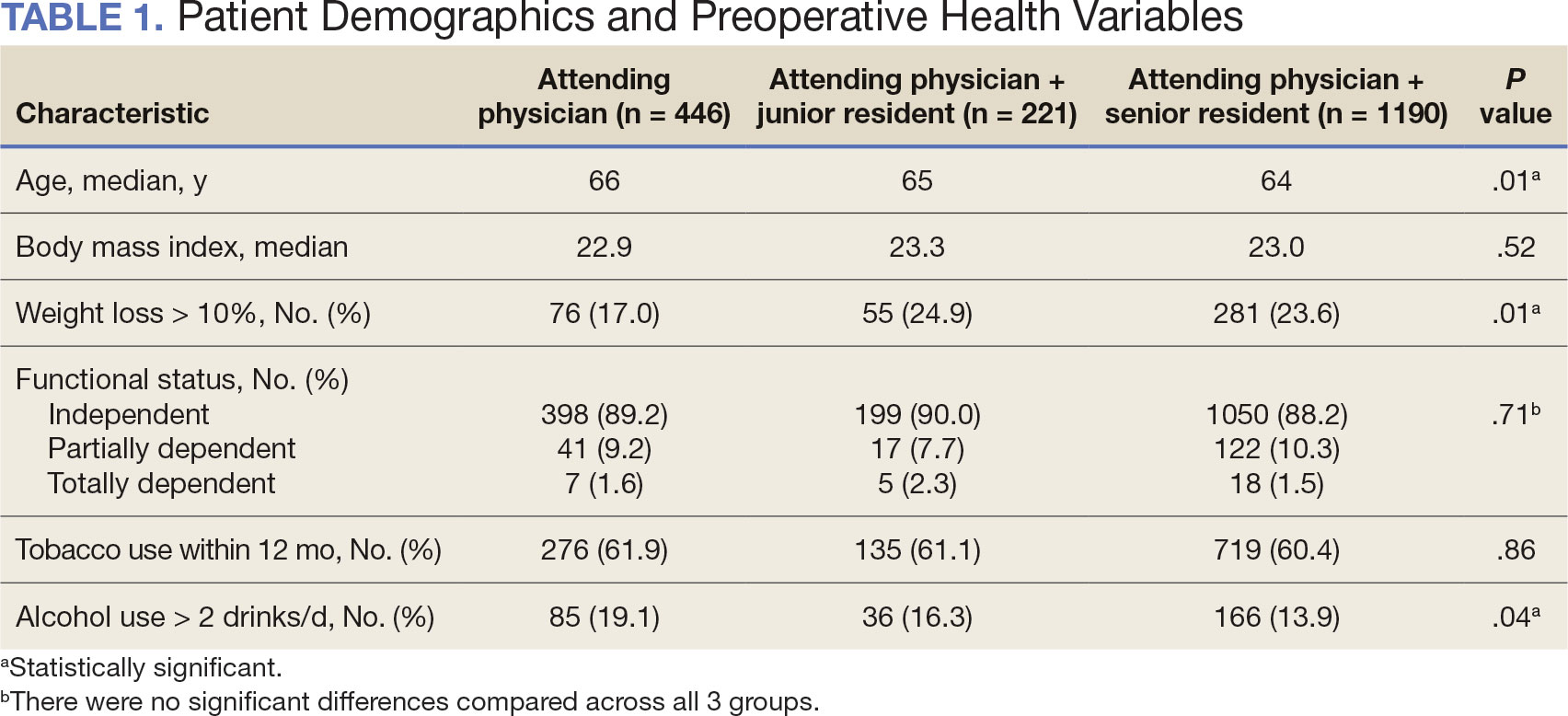

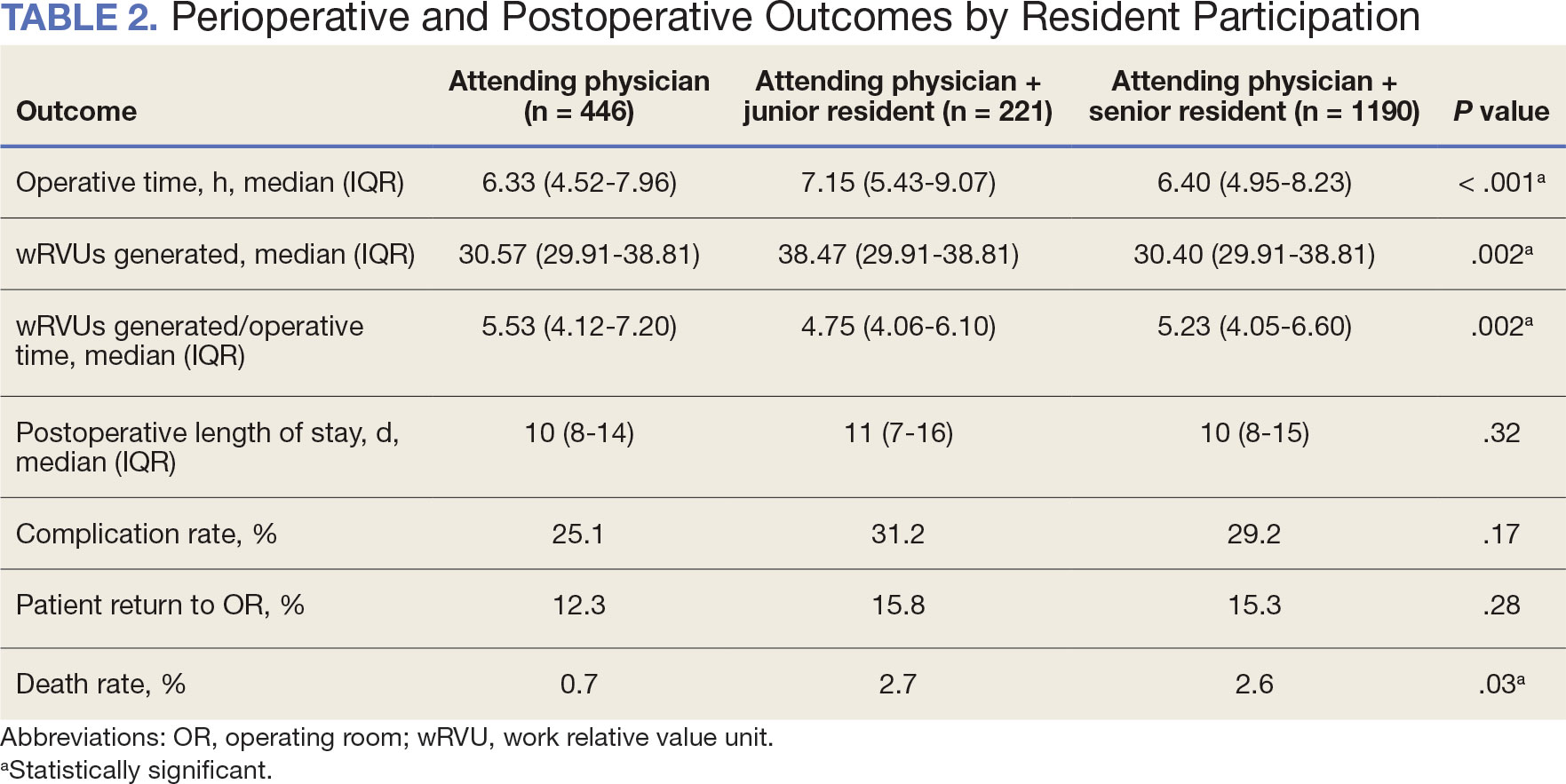

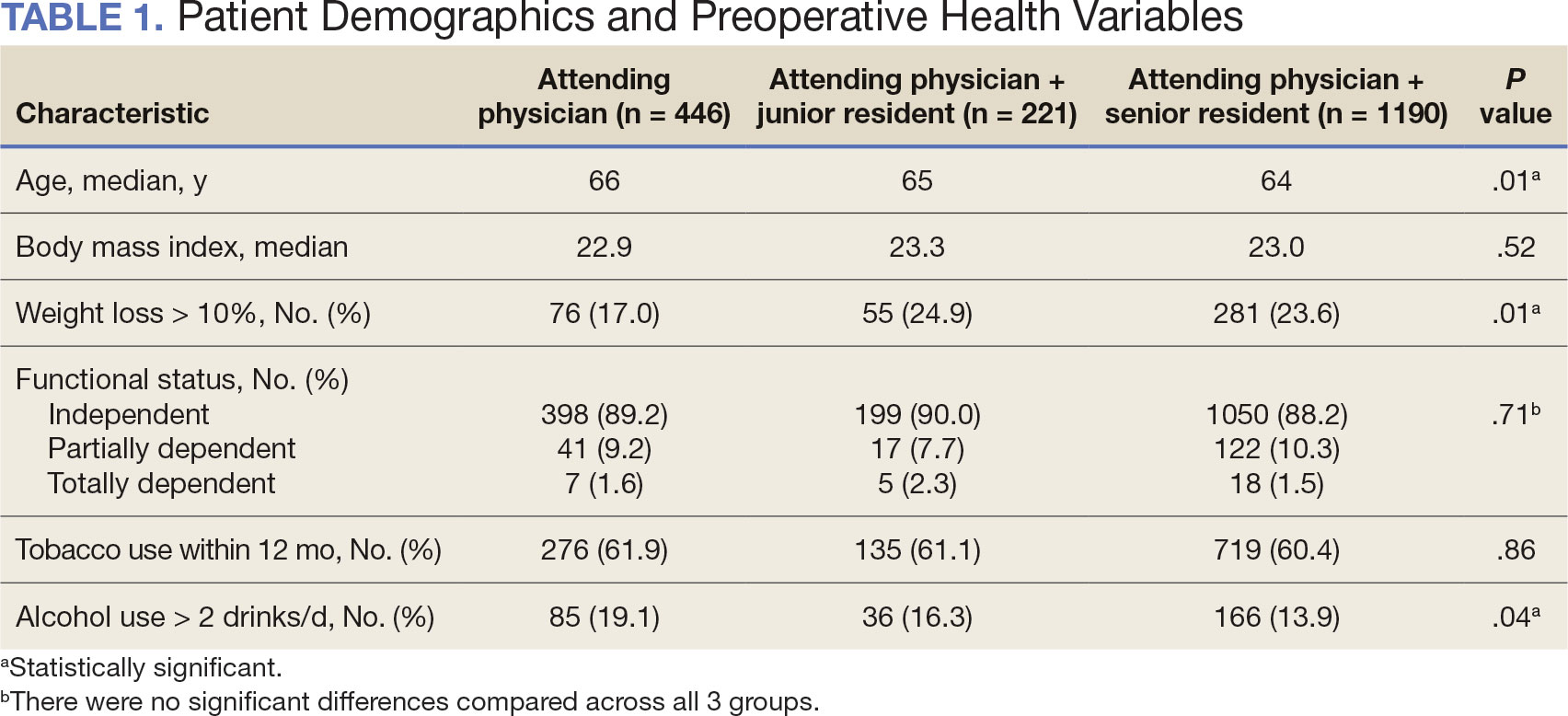

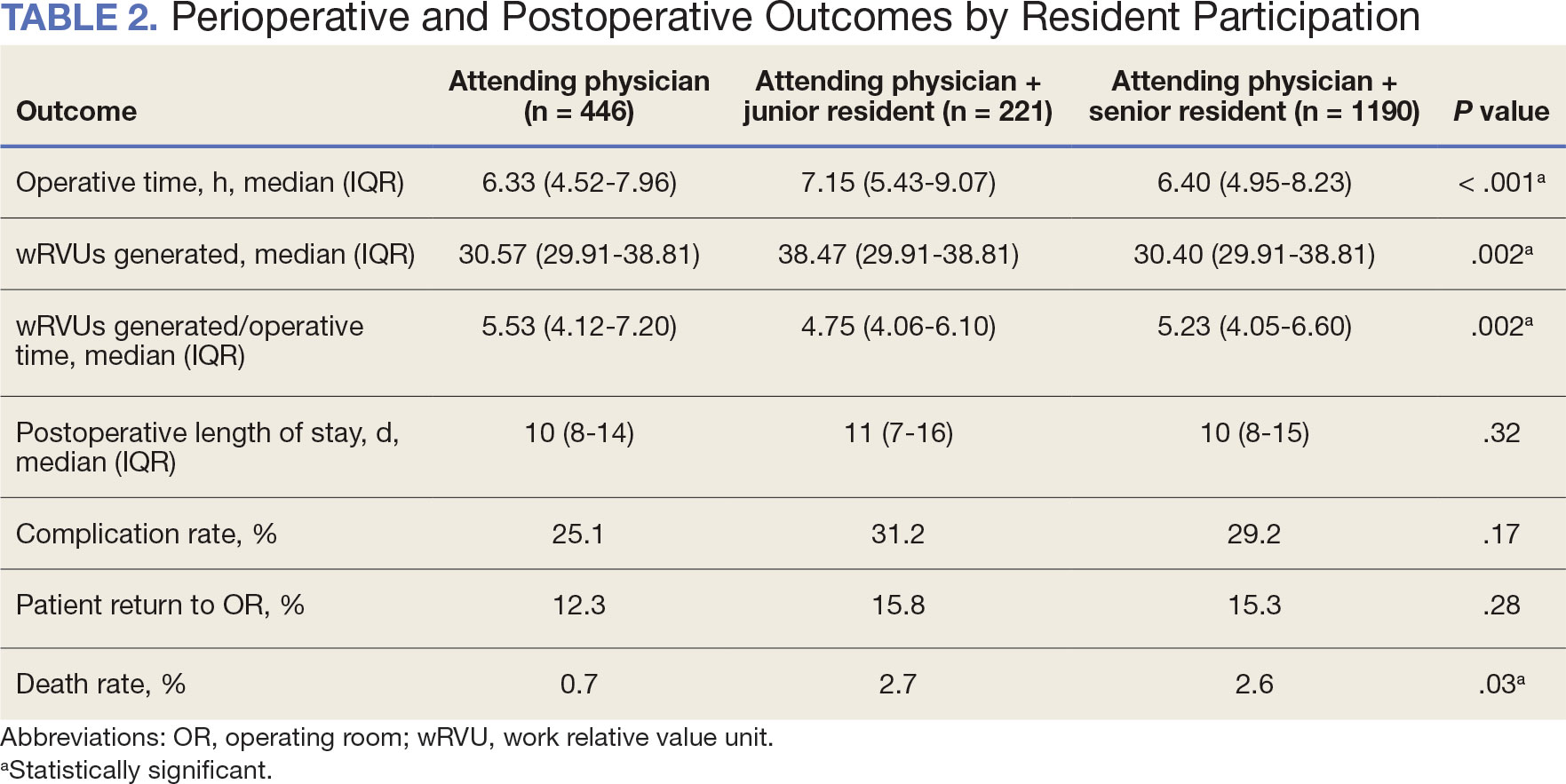

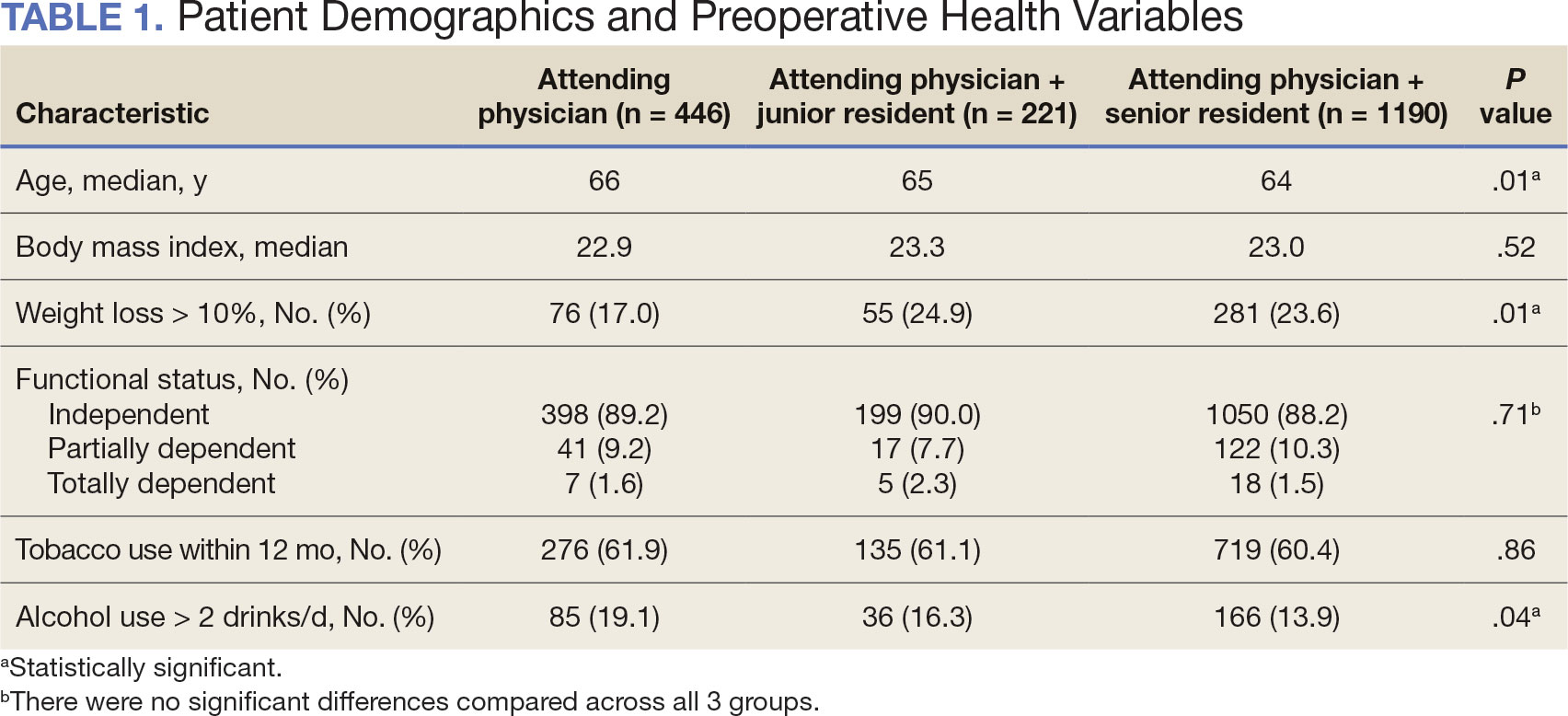

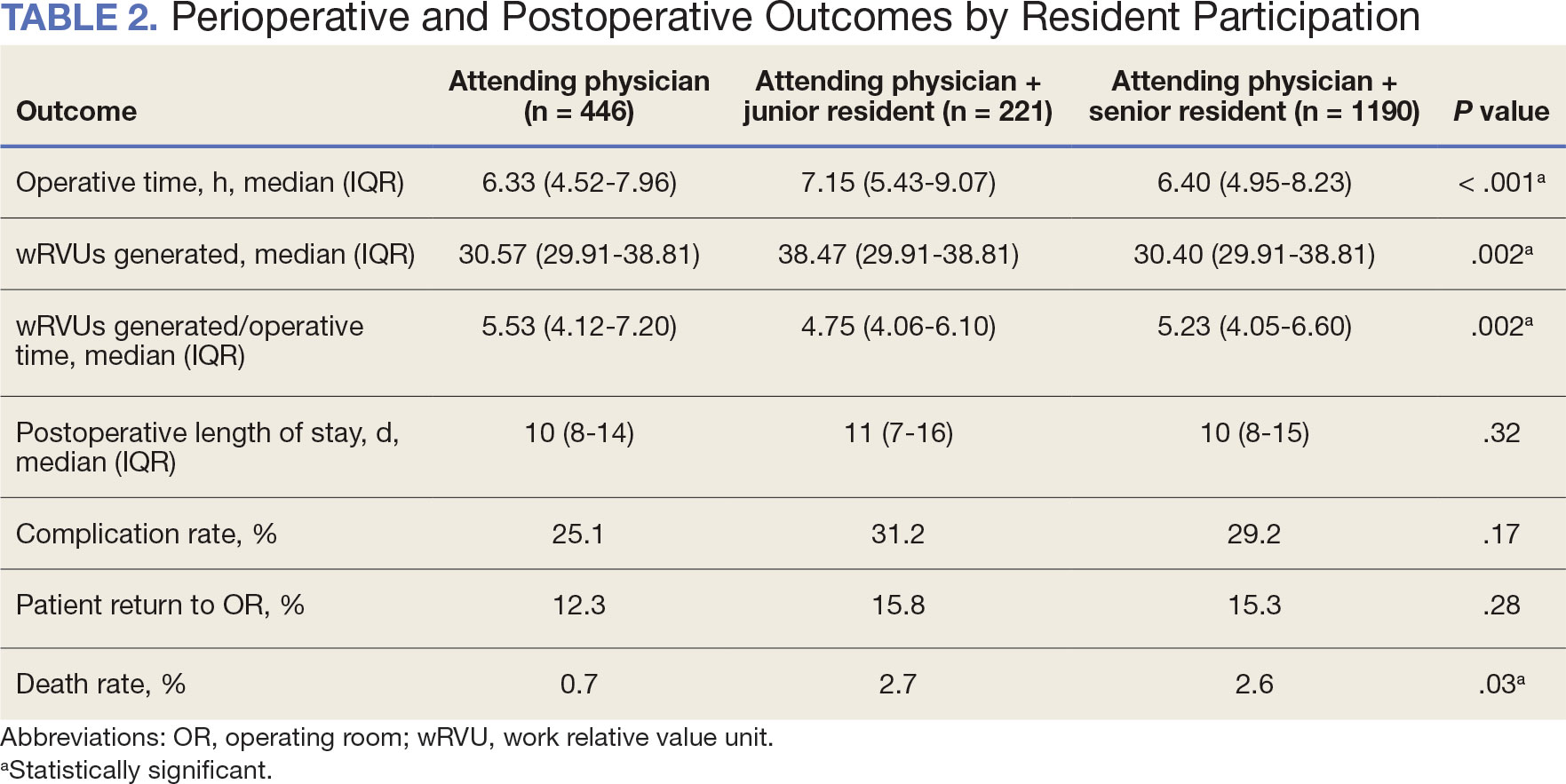

Between 2001 and 2021, 1857 patients who underwent total laryngectomy were identified from the VASQIP database nationwide. Most of the total laryngectomies were staffed by an attending physician with a senior resident (n = 1190, 64%), 446 (24%) were conducted by the attending physician alone, and 221 (12%) by an attending physician with a junior resident (Table 1). The mean operating time for an attending physician alone was 378 minutes, 384 minutes for an attending physician with a senior resident, and 432 minutes for an attending physician with a junior resident (Table 2). There was a statistically significant increase in operating time for laryngectomies with resident participation compared to attending physicians operating alone (P < .001).

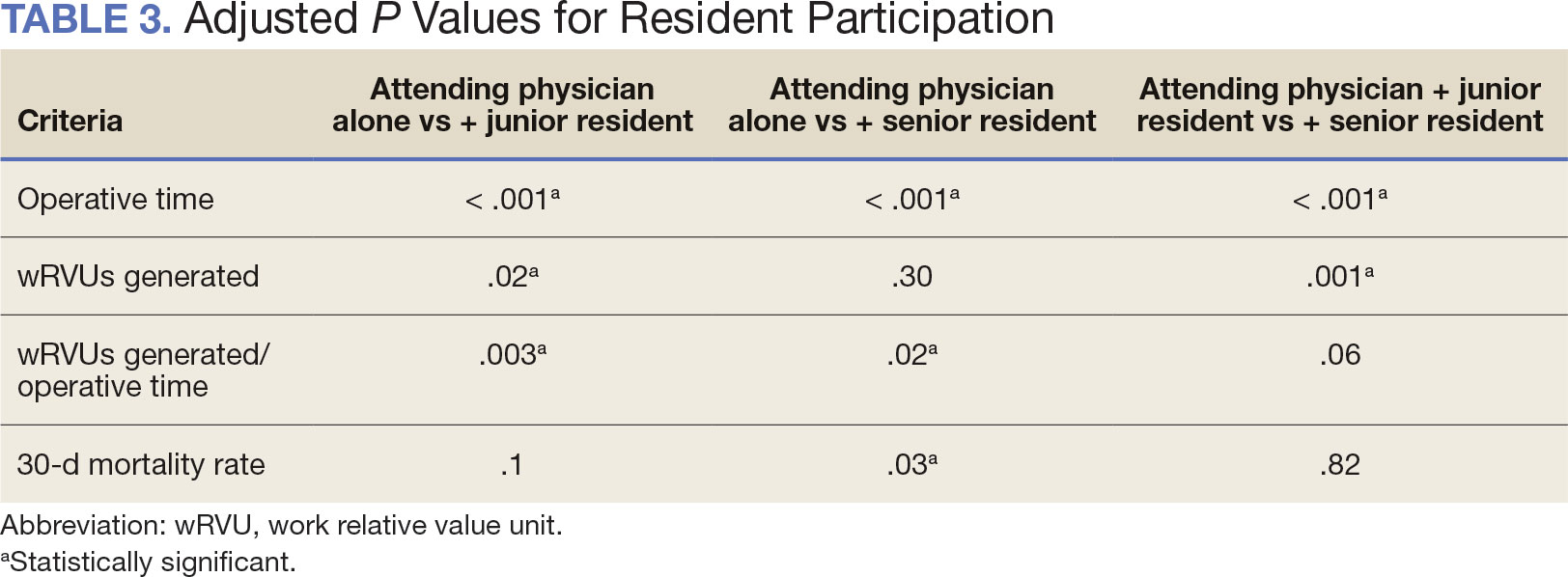

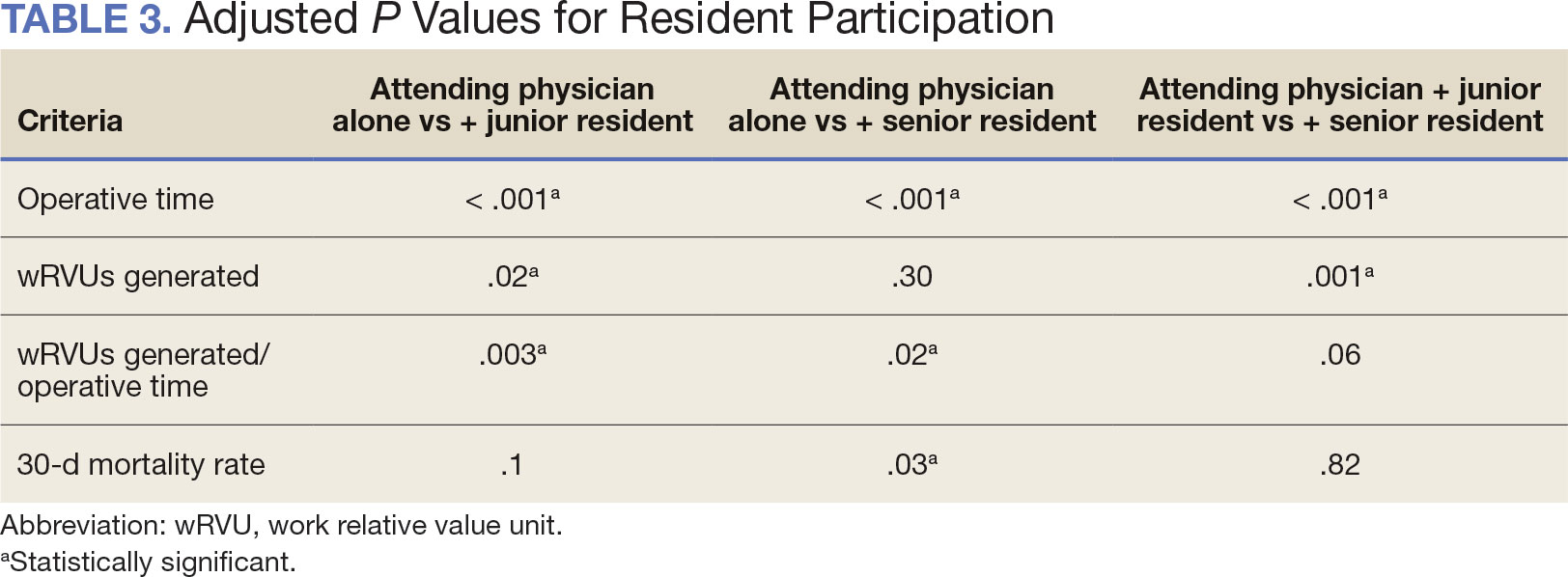

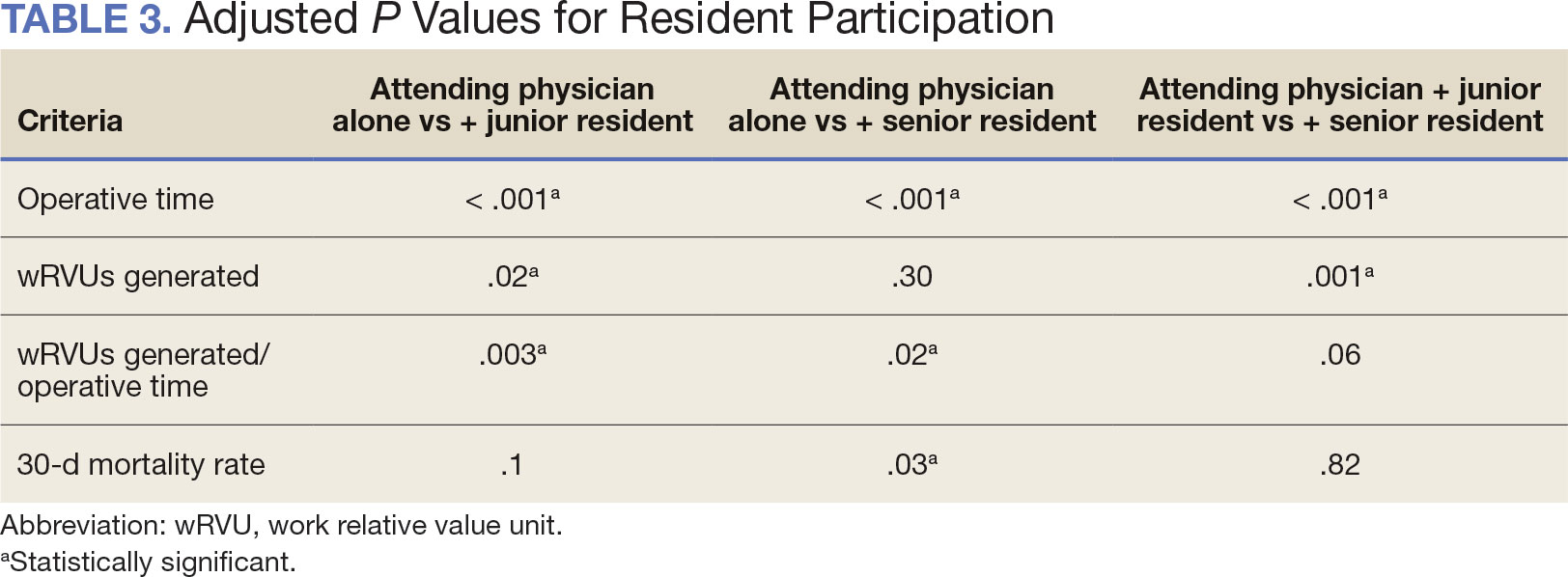

When the wRVUs generated/operative time was analyzed, there was a statistically significant difference between comparison groups. Total laryngectomies performed by attending physicians alone had the highest wRVUs generated/operative time (5.5), followed by laryngectomies performed by attending physicians with senior residents and laryngectomies performed by attending physicians with junior residents (5.2 and 4.8, respectively; P = .002). Table 3 describes adjusted P values for wRVUs generated/ operative time for total laryngectomies performed by attending physicians alone vs with junior residents (P = .003) and for attending physicians alone vs with senior residents (P = .02). Resident participation in total laryngectomies did not significantly impact the development or number of postoperative complications or the rate of return to the OR.

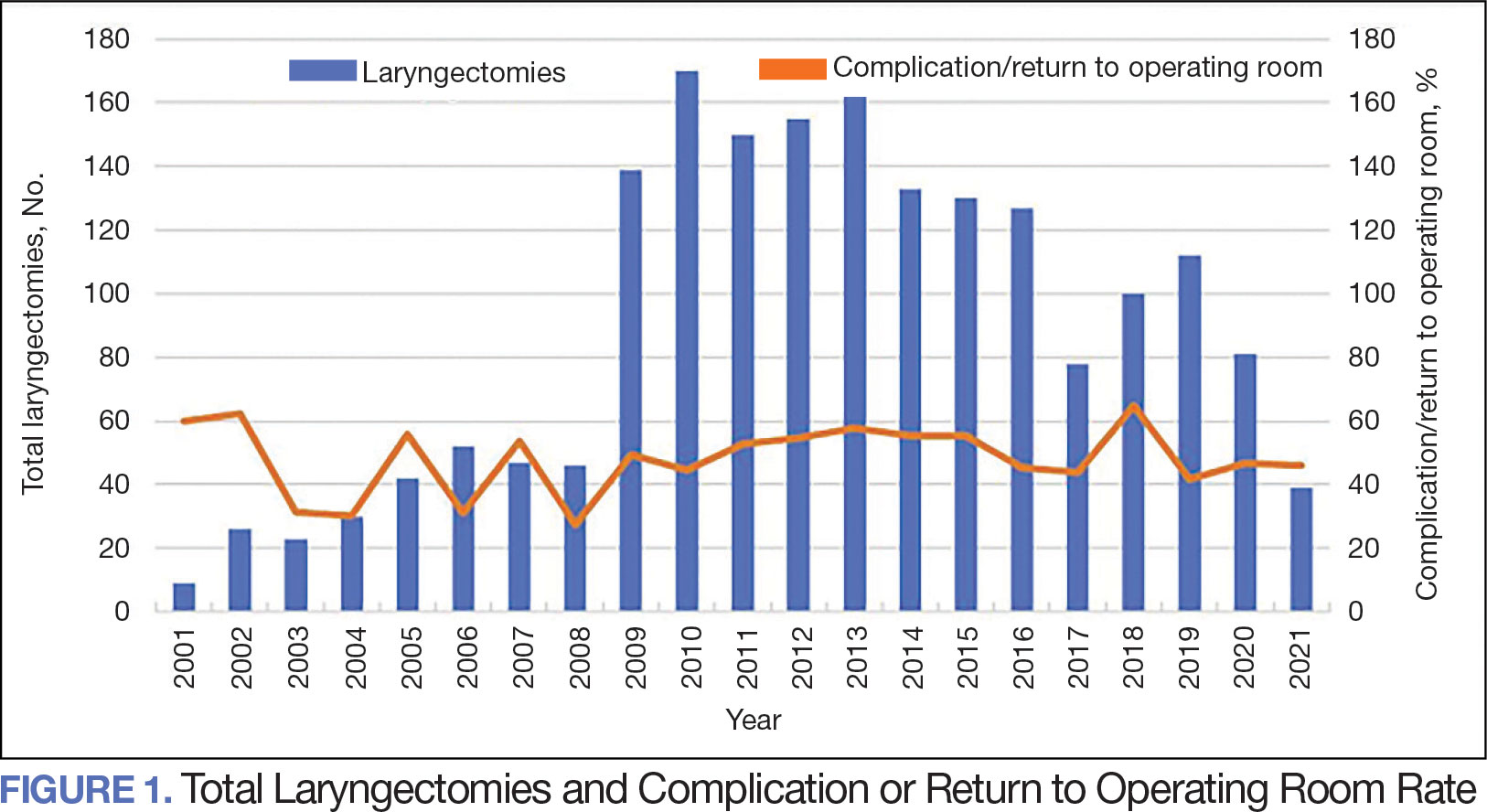

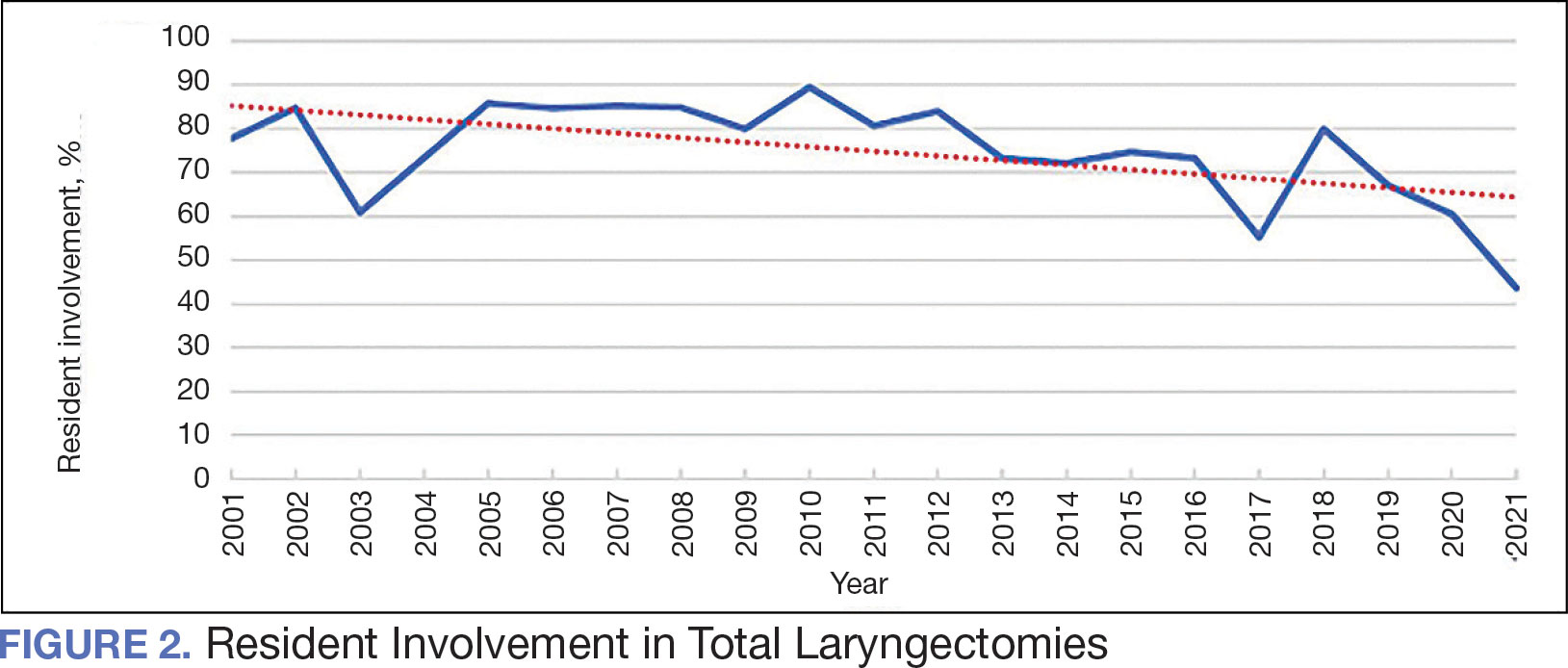

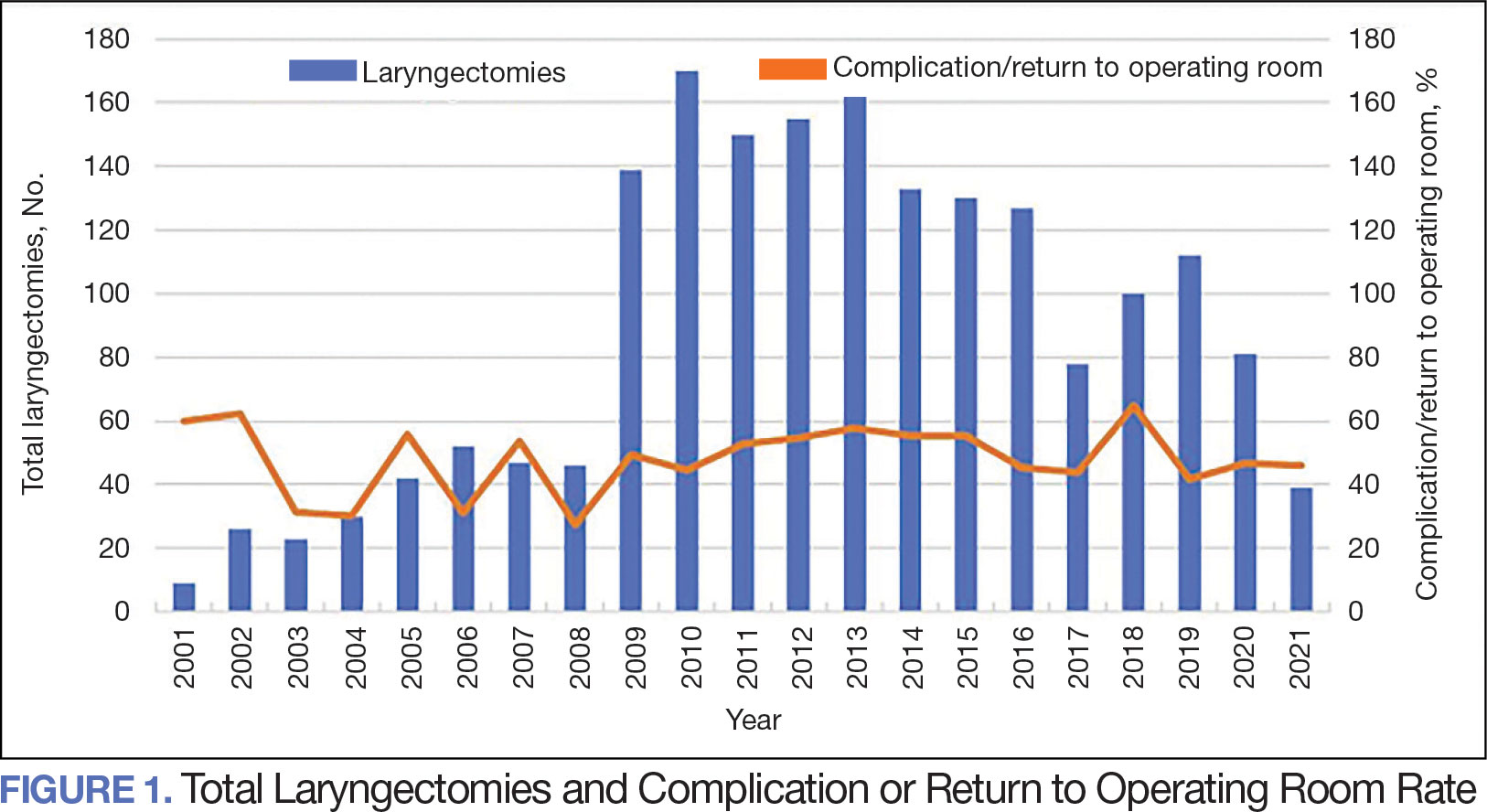

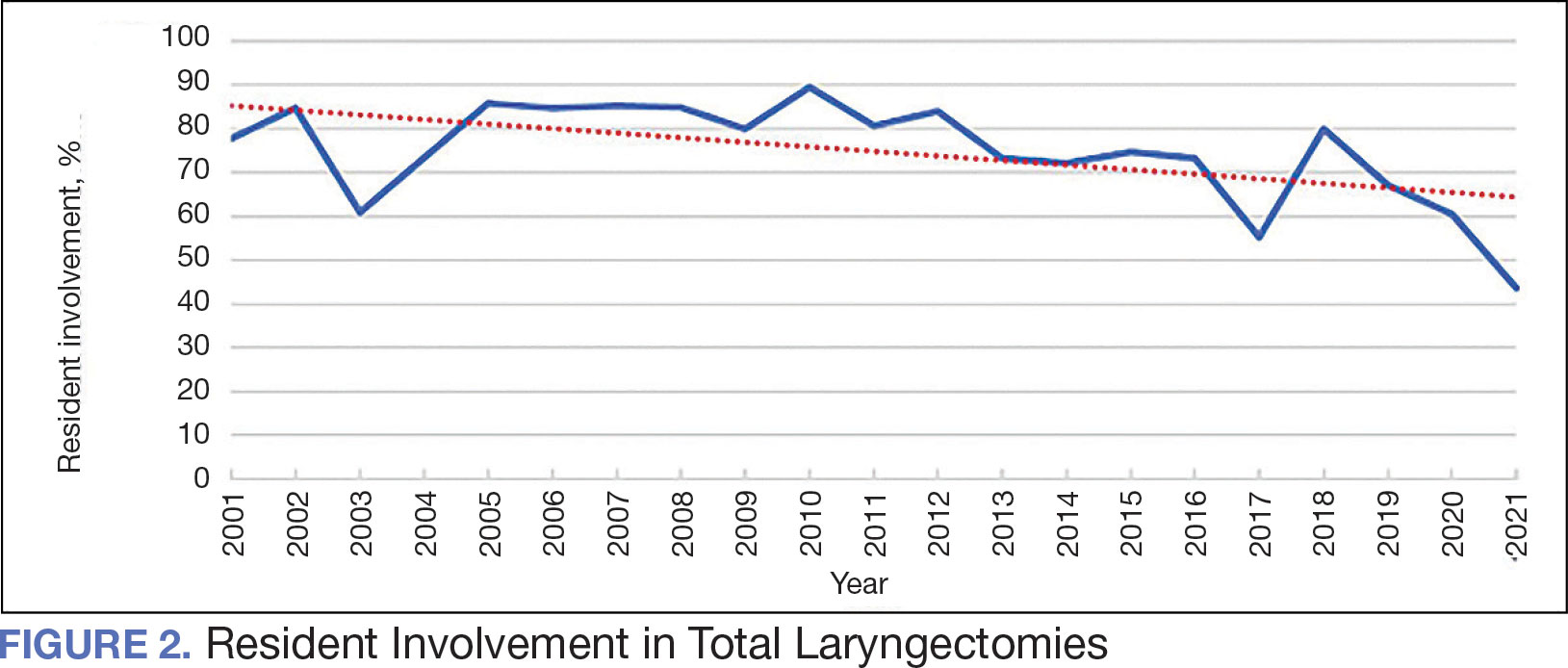

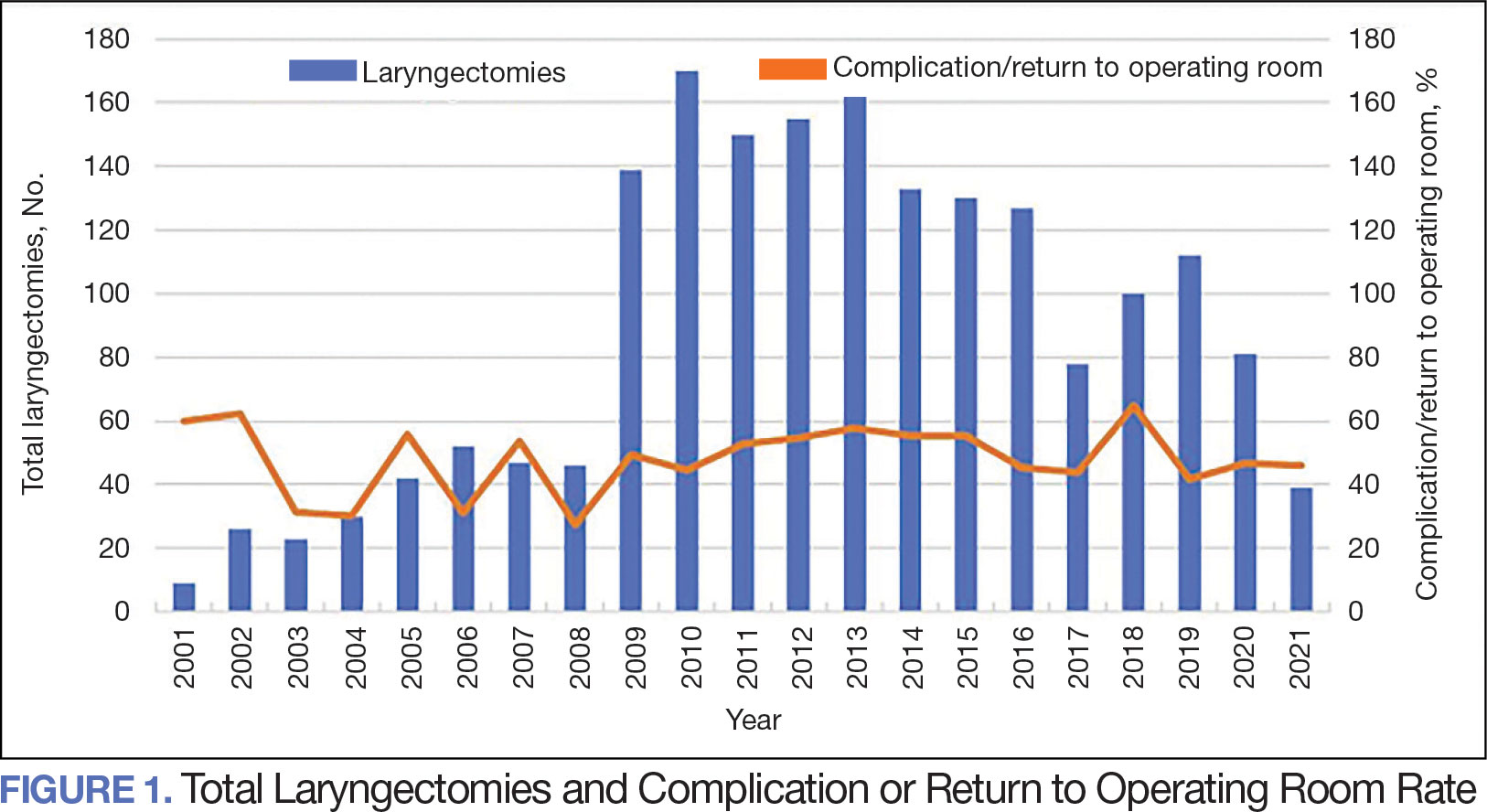

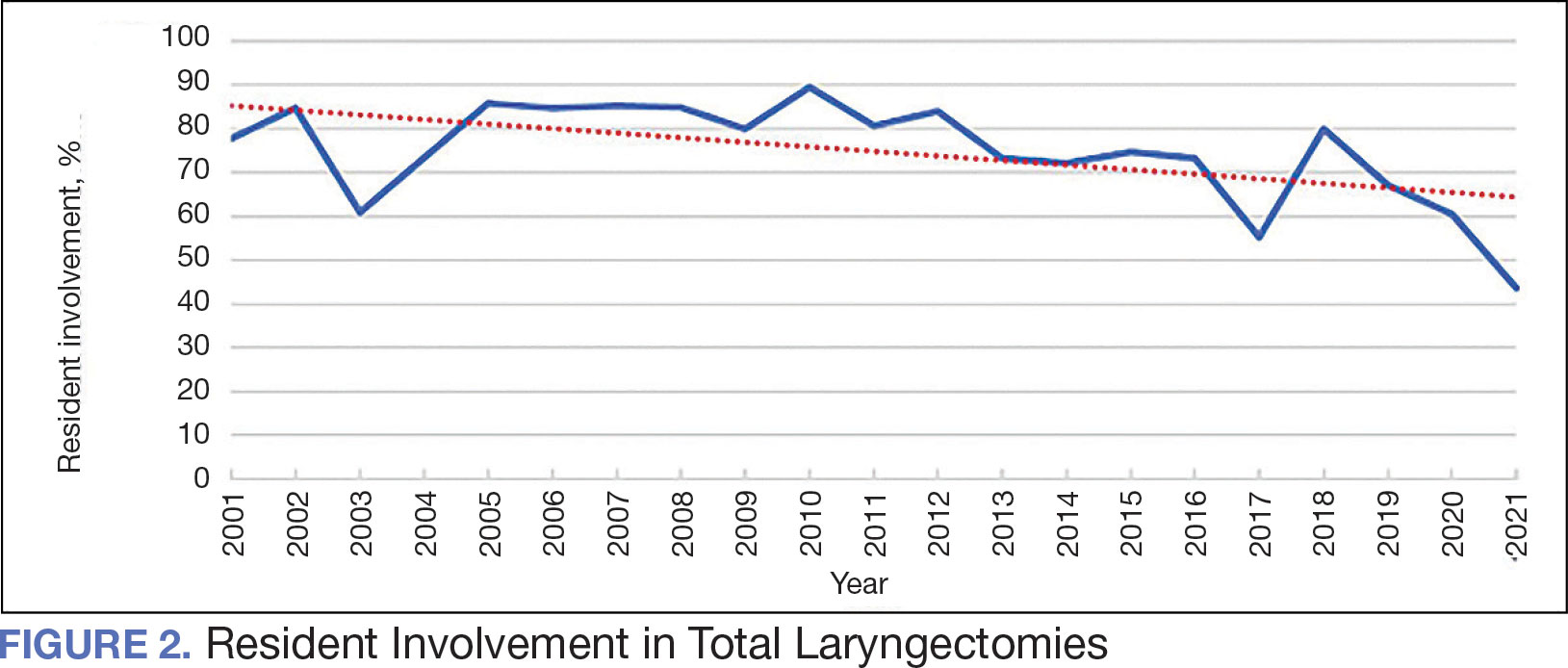

The number of laryngectomies performed in a single fiscal year peaked in 2010 at 170 cases (Figure 1). Between 2001 and 2021, the mean rates of postoperative complications (21.3%) and patient return to the OR (14.6%) did not significantly change. Resident participation in total laryngectomies also peaked in 2010 at 89.0% but has significantly declined, falling to a low of 43.6% in 2021 (Figure 2). From 2001 to 2011, the mean resident participation rate in total laryngectomies was 80.6%, compared with 68.3% from 2012 to 2021 (P < .001).

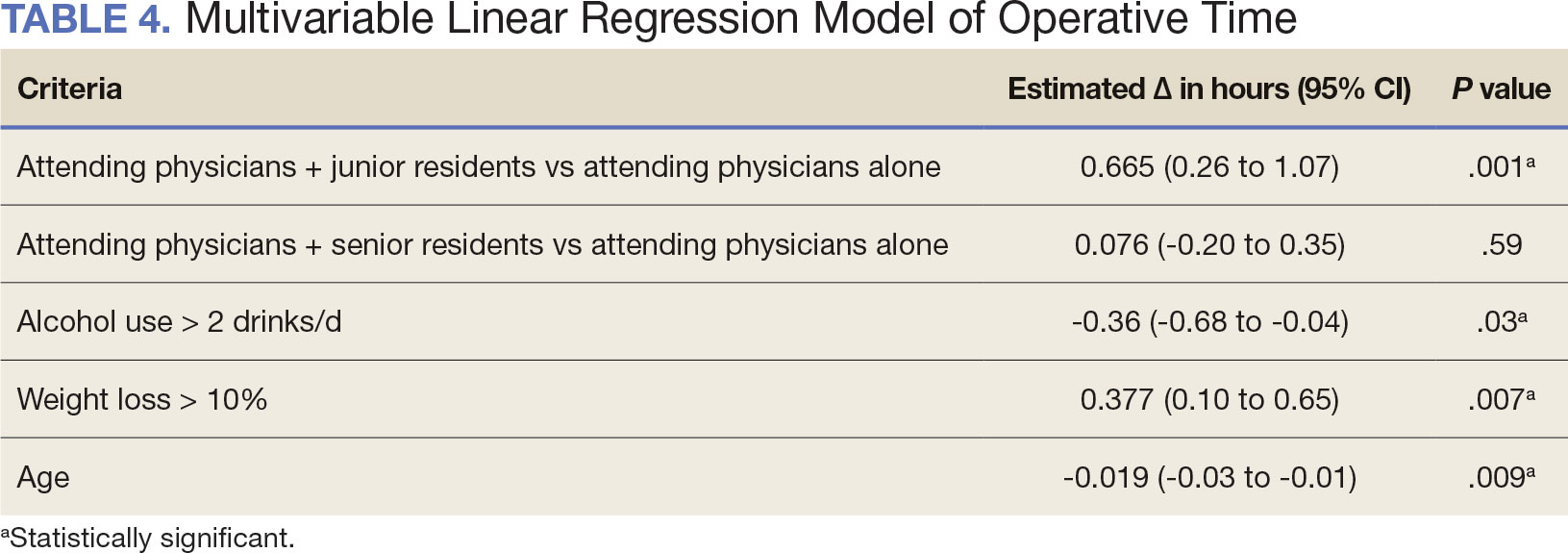

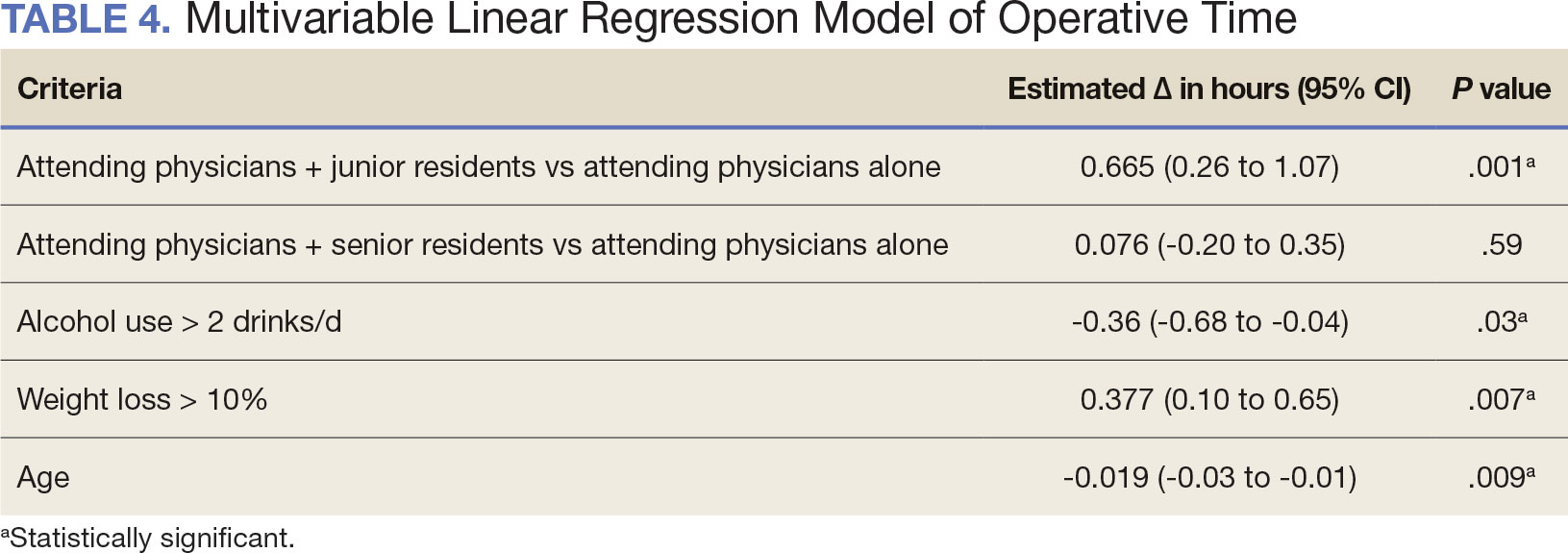

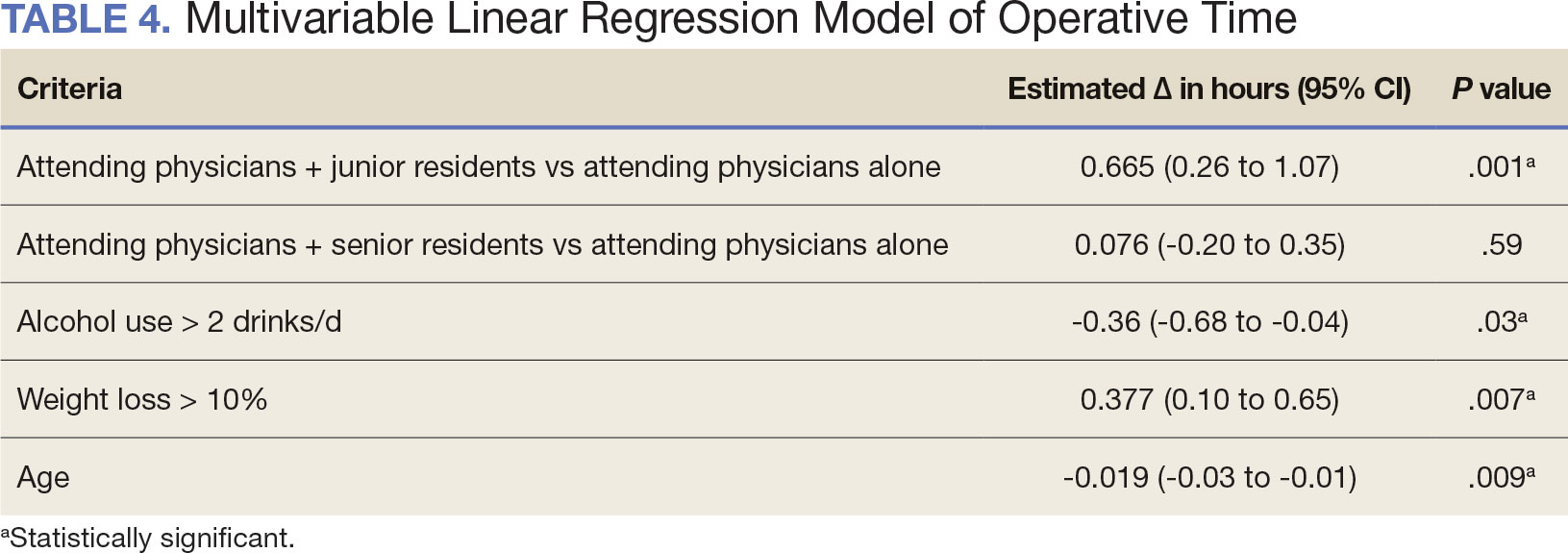

The effect of various demographic and preoperative characteristics on surgical outcomes was also analyzed. A linear regression model accounted for each variable significantly associated with operative time. On multivariable analysis, when all other variables were held constant, Table 4 shows the estimated change in operative time based on certain criteria. For instance, the operative time for attendings with junior residents surgeries was 40 minutes longer (95% CI, 16 to 64) than that of attending alone surgeries (P = .001). Furthermore, operative time decreased by 1.1 minutes (95% CI, 0.30 to 2.04) for each 1-year increase in patient age (P = .009).

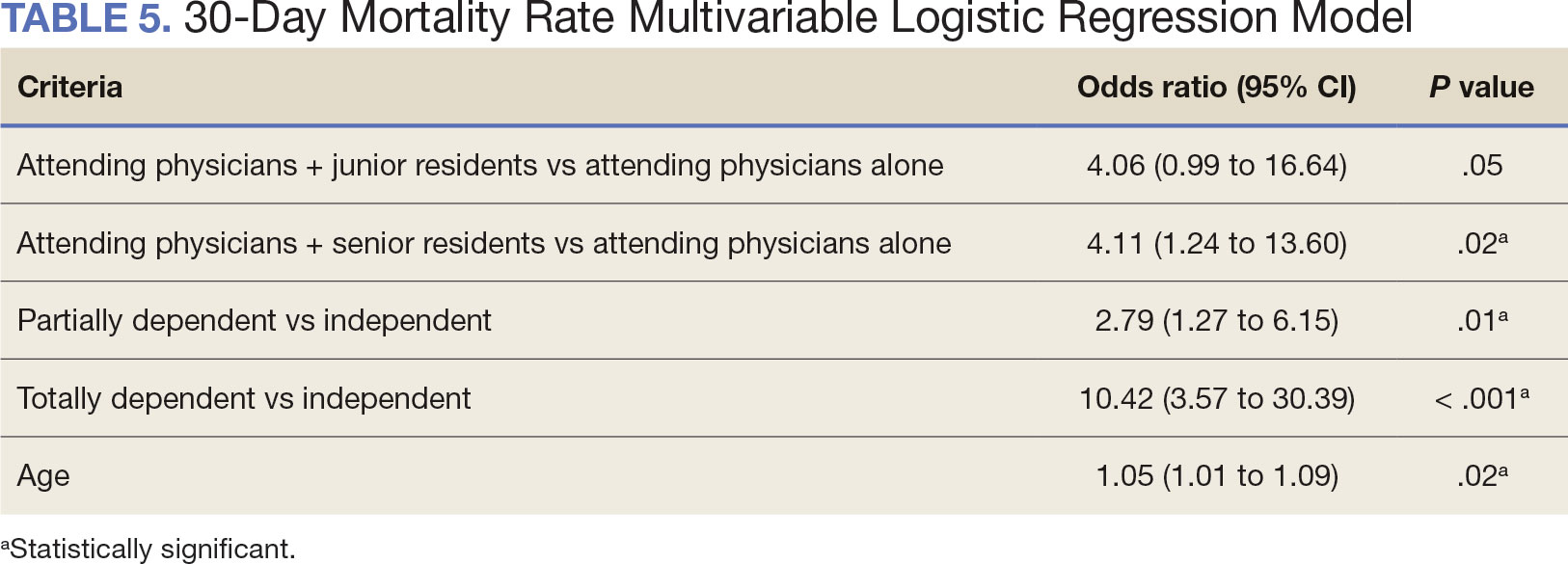

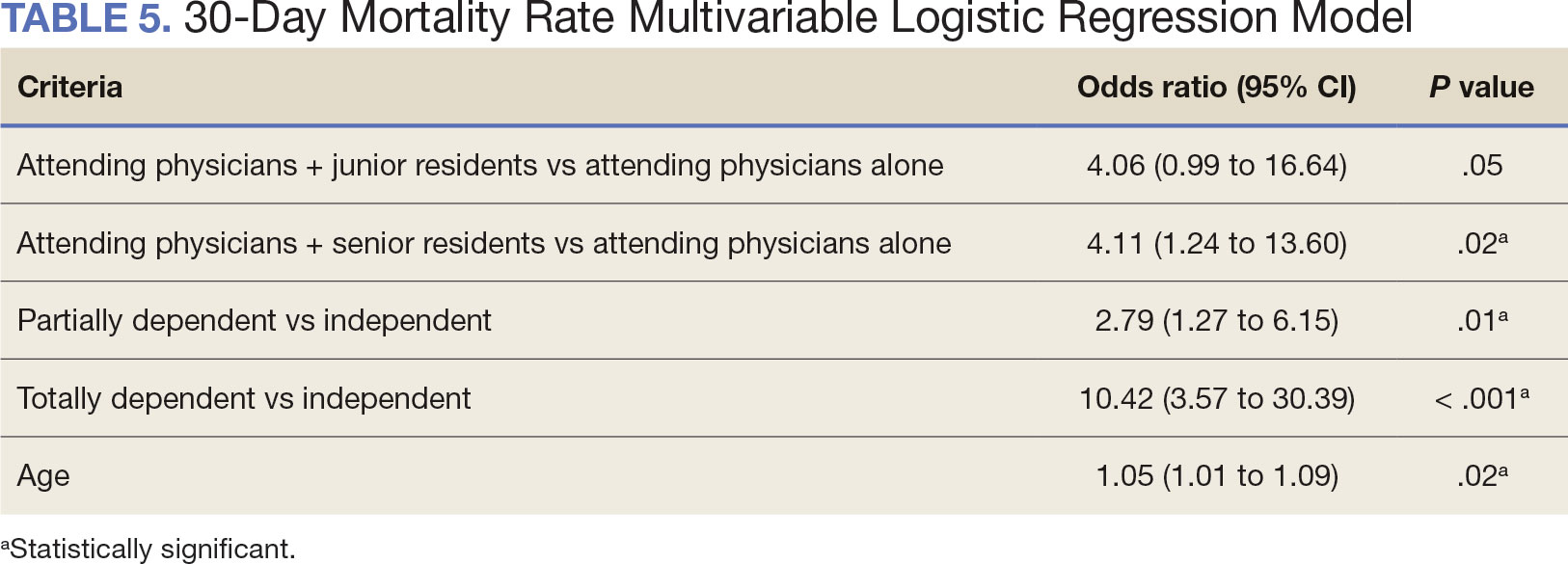

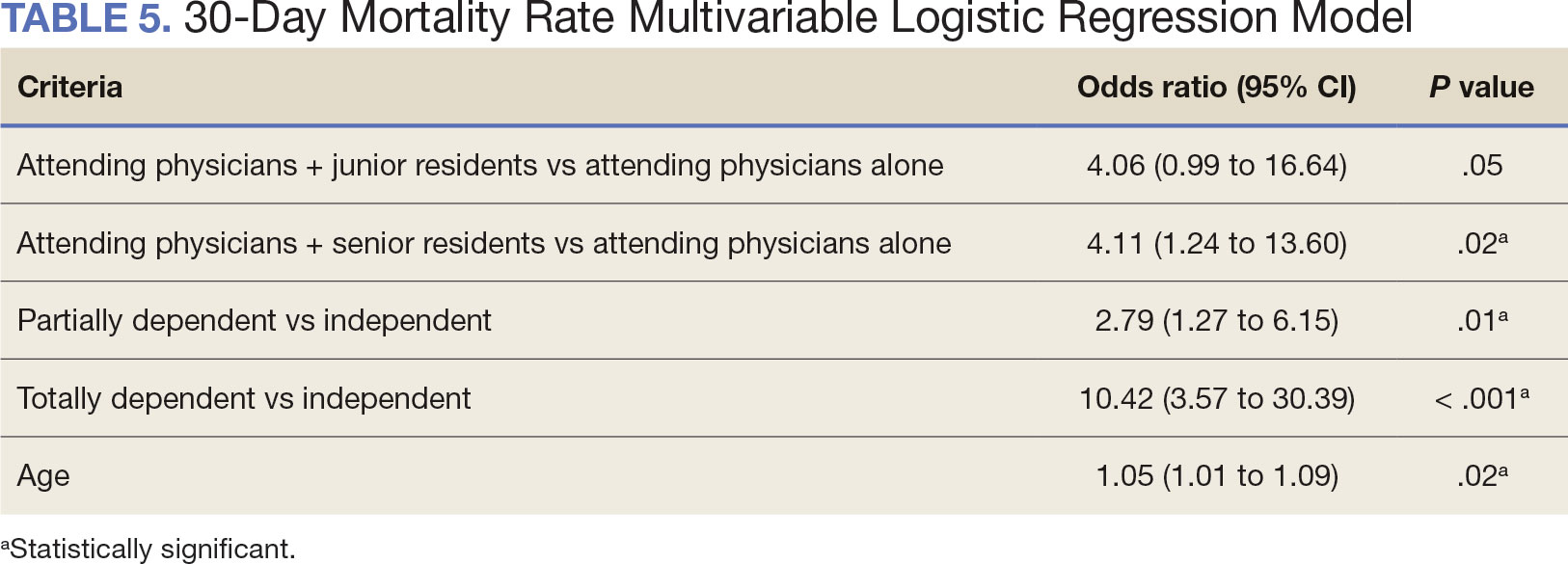

A multivariable logistic regression model evaluated the effect of resident involvement on 30-day mortality rates. Senior resident involvement (P = .02), partially dependent functional status (P = .01), totally dependent functional status (P < .001), and advanced age (P = .02) all were significantly associated with 30-day mortality (Table 5). When other variables remained constant, the odds of death for totally dependent patients were 10.4 times higher than that of patients with independent functional status. Thus, totally dependent functional status appeared to have a greater impact on this outcome than resident participation. The linear regression model for postoperative length of stay demonstrated that senior resident involvement (P = .04), functional status (partially dependent vs independent P < .001), and age (P = .03) were significantly associated with prolonged length of stay.

Discussion

Otolaryngology residency training is designed to educate future otolaryngologists through hands-on learning, adequate feedback, and supervision.1 Although this exposure is paramount for resident education, balancing appropriate supervision and autonomy while mitigating patient risk has been difficult. Numerous non-VA studies have reviewed the impact of resident participation on patient outcomes in various specialties, ranging from a single institution to the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).4,5,7,22 This study is the first to describe the nationwide impact of resident participation on outcomes in veterans undergoing total laryngectomy.

This study found that resident participation increases operative time and decreases wRVUs generated/operative time without impacting complication rates or patient return to the OR. This reinforces the notion that under close supervision, resident participation does not negatively impact patient outcomes. Resident operative training requires time and dedication by the attending physician and surgical team, thereby increasing operative time. Because VA physician compensation is not linked with productivity as closely as it is in other private and academic settings, surgeons can dedicate more time to operative teaching. This study found that a total laryngectomy involving a junior resident took about 45 minutes longer than an attending physician working alone.

As expected, with longer operative times, the wRVUs generated/operative time ratio was lower in cases with resident participation. Even though resident participation leads to lower OR efficiency, their participation may not significantly impact ancillary costs.23 However, a recent study from NSQIP found an opportunity cost of $60.44 per hour for surgeons operating with a resident in head and neck cases.13

Postoperative complications and mortality are key measures of surgical outcomes in addition to operative time and efficiency. This study found that neither junior nor senior resident participation significantly increased complication rates or patient return to the OR. Despite declining resident involvement and the number of total laryngectomy surgeries in the VA, the complication rate has remained steady. The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in cases involving senior residents compared to cases with attending physicians alone. This could be a result of senior resident participation in more challenging cases, such as laryngectomies performed as salvage surgery following radiation. Residents are more often involved in cases with greater complexity at teaching institutions.24-26 Therefore, the higher mortality seen among laryngectomies with senior resident involvement is likely due to the higher complexity of those cases.

The proportion of resident involvement in laryngectomies at VA medical centers has been decreasing over time. Due to the single payer nature of the VA health care system and the number of complex and comorbid patients, the VA offers an invaluable space for resident education in the OR. The fact that less than half of laryngectomies in 2021 involved resident participation is noteworthy for residency training programs. As wRVU compensation models evolve, VA attending surgeons may face less pressure to move the case along, leading to a high potential for operative teaching. Therefore, complex cases, such as laryngectomies, are often ideal for resident participation in the VA.

The steady decline in total laryngectomies at the VA parallels the recent decrease seen in non-VA settings.20 This is due in part to the use of larynx-preserving treatment modalities for laryngeal cancer as well as decreases in the incidence of laryngeal cancer due to population level changes in smoking behaviors. 18,19 Although a laryngectomy is not a key indicator case as determined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, it is important for otolaryngology residents to be exposed to these cases and have a thorough understanding of the operative technique.27 Total laryngectomy was selected for this study because it is a complex and time-consuming surgery with somewhat standardized surgical steps. Unlike microvascular surgery that is very rarely performed by an attending physician alone, laryngectomies can be performed by attending physicians alone or with a resident.28

Limitations

Since this was a retrospective study, it was susceptible to errors in data entry and data extraction from the VASQIP database. Another limitation is the lack of preoperative treatment data on tumor stage and prior nonoperative treatment. For example, a salvage laryngectomy after treatment with radiation and/or chemoradiation is a higher risk procedure than an upfront laryngectomy. Senior resident involvement may be more common in patients undergoing salvage laryngectomy due to the high risk of postoperative fistula and other complications. This may have contributed to the association identified between senior resident participation and 30-day mortality.

Since we could not account for residents who took research years or were fellows, a senior resident may have been mislabeled as a junior resident or vice versa. However, because most research years occur following the third year of residency. We are confident that PGY-1, PGY-2, and PGY-3 is likely to capture junior residents. Other factors, such as coattending surgeon cases, medical student assistance, and fellow involvement may have also impacted the results of this study.

Conclusions

This study is the first to investigate the impact of resident participation on operative time, wRVUs generated, and complication rates in head and neck surgery at VA medical centers. It found that resident participation in total laryngectomies among veterans increased operative time and reduced wRVUs generated per hour but did not impact complication rate or patient return to the OR. The VA offers a unique and invaluable space for resident education and operative training, and the recent decline in resident participation among laryngectomies is important for residency programs to acknowledge and potentially address moving forward.

In contrast to oral cavity resections which can vary from partial glossectomies to composite resections, laryngectomy represents a homogenous procedure from which to draw meaningful conclusions about complication rates, operative time, and outcome. Future directions should include studying other types of head and neck surgery in the VA to determine whether the impact of resident participation mirrors the findings of this study.

- Chung RS. How much time do surgical residents need to learn operative surgery? Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):351-353. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.035

- S, Darzi A. Defining quality in surgical training: perceptions of the profession. Am J Surg. 2014;207(4):628-636. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.044

- Bhatti NI, Ahmed A, Choi SS. Identifying quality indicators of surgical of surgical training: a national survey. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(12):2685-2689. doi:10.1002/lary.25262

- Abt NB, Reh DD, Eisele DW, Francis HW, Gourin CG. Does resident participation influence otolaryngology-head and neck surgery morbidity and mortality? Laryngoscope. 2016;126(10):2263-2269. doi:10.1002/lary.25973

- Jubbal KT, Chang D, Izaddoost SA, Pederson W, Zavlin D, Echo A. Resident involvement in microsurgery: an American College of Surgeons national surgical quality improvement program analysis. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):1124-1132. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.05.017

- Kshirsagar RS, Chandy Z, Mahboubi H, Verma SP. Does resident involvement in thyroid surgery lead to increased postoperative complications? Laryngoscope. 2017;127(5):1242-1246. doi:10.1002/lary.26176

- Vieira BL, Hernandez DJ, Qin C, Smith SS, Kim JY, Dutra JC. The impact of resident involvement on otolaryngology surgical outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(3):602-607. doi:10.1002/lary.25046

- Advani V, Ahad S, Gonczy C, Markwell S, Hassan I. Does resident involvement effect surgical times and complication rates during laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis? An analysis of 16,849 cases from the ACS-NSQIP. Am J Surg. 2012;203(3):347-352. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.015

- Quinn NA, Alt JA, Ashby S, Orlandi RR. Time, resident involvement, and supply drive cost variability in septoplasty with turbinate reduction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(2):310-314. doi:10.1177/0194599818765099

- Leader BA, Wiebracht ND, Meinzen-Derr J, Ishman SL. The impact of resident involvement on tonsillectomy outcomes and surgical time. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2481-2486. doi:10.1002/lary.28427

- Muelleman T, Shew M, Muelleman RJ, et al. Impact of resident participation on operative time and outcomes in otologic surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(1):151-154. doi:10.1177/0194599817737270

- Puram SV, Kozin ED, Sethi R, et al. Impact of resident surgeons on procedure length based on common pediatric otolaryngology cases. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(4):991 -997. doi:10.1002/lary.24912

- Chow MS, Gordon AJ, Talwar A, Lydiatt WM, Yueh B, Givi B. The RVU compensation model and head and neck surgical education. Laryngoscope. 2024;134(1):113-119. doi:10.1002/lary.30807

- Papandria D, Rhee D, Ortega G, et al. Assessing trainee impact on operative time for common general surgical procedures in ACS-NSQIP. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(2):149-155. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.08.003

- Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Martin CT, Callagh JJ, Weinstein SL, Marsh JL. The effect of resident participation on short-term outcomes after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(7):2290-2300. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3567-0

- Hosler MR, Scott IU, Kunselman AR, Wolford KR, Oltra EZ, Murray WB. Impact of resident participation in cataract surgery on operative time and cost. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(1):95-98. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.026

- Lanigan A, Spaw M, Donaghe C, Brennan J. The impact of the Veteran’s Affairs medical system on an otolaryngology residency training program. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e671-e675. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy041

- American Society of Clinical Oncology, Pfister DG, Laurie SA, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline for the use of larynx-preservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(22):3693-3704. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4559

- Forastiere AA, Ismaila N, Lewin JS, et al. Use of larynxpreservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1143-1169. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7385

- Verma SP, Mahboubi H. The changing landscape of total laryngectomy surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):413-418. doi:10.1177/0194599813514515

- Habermann EB, Harris AHS, Giori NJ. Large surgical databases with direct data abstraction: VASQIP and ACSNSQIP. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104(suppl 3):9-14. doi:10.2106/JBJS.22.00596

- Benito DA, Mamidi I, Pasick LJ, et al. Evaluating resident involvement and the ‘July effect’ in parotidectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135(5):452-457. doi:10.1017/S0022215121000578

- Hwang CS, Wichterman KA, Alfrey EJ. The cost of resident education. J Surg Res. 2010;163(1):18-23. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.013

- Saliba AN, Taher AT, Tamim H, et al. Impact of resident involvement in surgery (IRIS-NSQIP): looking at the bigger picture based on the American College of Surgeons- NSQIP database. J Am Coll Surg. 2016; 222(1):30-40. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.10.011

- Khuri SF, Najjar SF, Daley J, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between teaching and nonteaching hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):370-383. doi:10.1097/00000658-200109000-00011

- Relles DM, Burkhart RA, Pucci MJ et al. Does resident experience affect outcomes in complex abdominal surgery? Pancreaticoduodenectomy as an example. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(2):279-285. doi:10.1007/s11605-013-2372-5

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Required minimum number of key indicator procedures for graduating residents. June 2019. Accessed January 2, 2025. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programresources/280_core_case_log_minimums.pdf

- Brady JS, Crippen MM, Filimonov A, et al. The effect of training level on complications after free flap surgery of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38(5):560-564. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2017.06.001

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been integral in resident training. Resident surgical training requires a balance of supervision and autonomy, along with procedure repetition and appropriate feedback.1-3 Non-VA research has found that resident participation across various otolaryngology procedures, including thyroidectomy, neck dissection, and laryngectomy, does not increase patient morbidity.4-7 However, resident involvement in private and academic settings that included nonhead and neck procedures was linked to increased operative time and reduced productivity, as determined by work relative value units (wRVUs).7-13 This has also been identified in other specialties, including general surgery, orthopedics, and ophthalmology.14-16

Unlike the private sector, surgeon compensation at the VA is not as closely linked to operative productivity, offering a unique setting for resident training. While VA integration in otolaryngology residency programs increases resident case numbers, particularly in head and neck cases, the impact on VA patient outcomes and productivity is unknown.17 The use of larynxpreserving treatment modalities for laryngeal cancer has led to a decline in the number of total laryngectomies performed, which could potentially impact resident operative training for laryngectomies.18-20

This study sought to determine the impact of resident participation on operative time, wRVUs, and patient outcomes in veterans who underwent a total laryngectomy. This study was reviewed and approved by the MedStar Georgetown University Hospital Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee (#1595672).

Methods

A retrospective cohort of veterans nationwide who underwent total laryngectomy between 2001 and 2021, with or without neck dissection, was identified from the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP). Data were extracted via the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure and patients were included based on Current Procedural Terminology codes for total laryngectomy, with or without neck dissection (31320, 31360, 31365). Laryngopharyngectomies, partial laryngectomies, and minimally invasive laryngectomies were excluded. VASQIP nurse data managers reviewed patient data for operative data, postoperative outcomes (including 30- day morbidity and mortality), and preoperative risk factors (Appendix).21

The VASQIP data provide the highest resident or postgraduate year (PGY) per surgery. PGY 1, 2, and 3 were considered junior residents and PGY ≥4, surgical fellows, and individuals who took research years during residency were considered senior residents. Cases performed by attending physicians alone were compared with those involving junior or senior residents.

Patient demographic data included age, body mass index, smoking and alcohol use, weight loss, and functional status. Consumption of any tobacco products within 12 months of surgery was considered tobacco use. Drinking on average ≥2 alcoholic beverages daily was considered alcohol use. Weight loss was defined as a 10% reduction in body weight within the 6 months before surgery, excluding patients enrolled in a weight loss program. Functional status was categorized as independent, partially dependent, totally dependent, and unknown.

Primary outcomes included operative time, wRVUs generated, and wRVUs generated per hour of operative time. Postoperative complications were recorded both as a continuous variable and as a binary variable for presence or absence of a complication. Additional outcome variables included length of postoperative hospital stay, return to the operating room (OR), and death within 30 days of surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and median with IQR for continuous variables. Data were also summarized based on resident involvement in the surgery and the PGY level of the residents involved. The occurrence of total laryngectomy, rate of complications, and patient return to the OR were summarized by year.

Univariate associations between resident involvement and surgical outcomes were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the ÷2 test for categorical variables. A Fisher exact test was used when the cell count in the contingency table was < 5. The univariate associations between surgical outcomes and demographic/preoperative variables were examined using 2-sided Wilcoxon ranksum tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests between continuous variables and categorical variables, X2 or Fisher exact test between 2 categorical variables, and 2-sided Spearman correlation test between 2 continuous variables. A false-discovery rate approach was used for simultaneous posthoc tests to determine the adjusted P values for wRVUs generated/operative time for attending physicians alone vs with junior residents and for attending physicians alone vs with senior residents. Models were used to evaluate the effects of resident involvement on surgical outcomes, adjusting for variables that showed significant univariate associations. Linear regression models were used for operative time, wRVUs generated, wRVUs generated/operative time, and length of postoperative stay. A logistic regression model was used for death within 30 days. Models were not built for postoperative complications or patient return to the OR, as these were only statistically significantly associated with the patient’s preoperative functional status. A finding was considered significant if P < .05. All analyses were performed using statistical software RStudio Version 2023.03.0.

Results

Between 2001 and 2021, 1857 patients who underwent total laryngectomy were identified from the VASQIP database nationwide. Most of the total laryngectomies were staffed by an attending physician with a senior resident (n = 1190, 64%), 446 (24%) were conducted by the attending physician alone, and 221 (12%) by an attending physician with a junior resident (Table 1). The mean operating time for an attending physician alone was 378 minutes, 384 minutes for an attending physician with a senior resident, and 432 minutes for an attending physician with a junior resident (Table 2). There was a statistically significant increase in operating time for laryngectomies with resident participation compared to attending physicians operating alone (P < .001).

When the wRVUs generated/operative time was analyzed, there was a statistically significant difference between comparison groups. Total laryngectomies performed by attending physicians alone had the highest wRVUs generated/operative time (5.5), followed by laryngectomies performed by attending physicians with senior residents and laryngectomies performed by attending physicians with junior residents (5.2 and 4.8, respectively; P = .002). Table 3 describes adjusted P values for wRVUs generated/ operative time for total laryngectomies performed by attending physicians alone vs with junior residents (P = .003) and for attending physicians alone vs with senior residents (P = .02). Resident participation in total laryngectomies did not significantly impact the development or number of postoperative complications or the rate of return to the OR.

The number of laryngectomies performed in a single fiscal year peaked in 2010 at 170 cases (Figure 1). Between 2001 and 2021, the mean rates of postoperative complications (21.3%) and patient return to the OR (14.6%) did not significantly change. Resident participation in total laryngectomies also peaked in 2010 at 89.0% but has significantly declined, falling to a low of 43.6% in 2021 (Figure 2). From 2001 to 2011, the mean resident participation rate in total laryngectomies was 80.6%, compared with 68.3% from 2012 to 2021 (P < .001).

The effect of various demographic and preoperative characteristics on surgical outcomes was also analyzed. A linear regression model accounted for each variable significantly associated with operative time. On multivariable analysis, when all other variables were held constant, Table 4 shows the estimated change in operative time based on certain criteria. For instance, the operative time for attendings with junior residents surgeries was 40 minutes longer (95% CI, 16 to 64) than that of attending alone surgeries (P = .001). Furthermore, operative time decreased by 1.1 minutes (95% CI, 0.30 to 2.04) for each 1-year increase in patient age (P = .009).

A multivariable logistic regression model evaluated the effect of resident involvement on 30-day mortality rates. Senior resident involvement (P = .02), partially dependent functional status (P = .01), totally dependent functional status (P < .001), and advanced age (P = .02) all were significantly associated with 30-day mortality (Table 5). When other variables remained constant, the odds of death for totally dependent patients were 10.4 times higher than that of patients with independent functional status. Thus, totally dependent functional status appeared to have a greater impact on this outcome than resident participation. The linear regression model for postoperative length of stay demonstrated that senior resident involvement (P = .04), functional status (partially dependent vs independent P < .001), and age (P = .03) were significantly associated with prolonged length of stay.

Discussion

Otolaryngology residency training is designed to educate future otolaryngologists through hands-on learning, adequate feedback, and supervision.1 Although this exposure is paramount for resident education, balancing appropriate supervision and autonomy while mitigating patient risk has been difficult. Numerous non-VA studies have reviewed the impact of resident participation on patient outcomes in various specialties, ranging from a single institution to the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).4,5,7,22 This study is the first to describe the nationwide impact of resident participation on outcomes in veterans undergoing total laryngectomy.

This study found that resident participation increases operative time and decreases wRVUs generated/operative time without impacting complication rates or patient return to the OR. This reinforces the notion that under close supervision, resident participation does not negatively impact patient outcomes. Resident operative training requires time and dedication by the attending physician and surgical team, thereby increasing operative time. Because VA physician compensation is not linked with productivity as closely as it is in other private and academic settings, surgeons can dedicate more time to operative teaching. This study found that a total laryngectomy involving a junior resident took about 45 minutes longer than an attending physician working alone.

As expected, with longer operative times, the wRVUs generated/operative time ratio was lower in cases with resident participation. Even though resident participation leads to lower OR efficiency, their participation may not significantly impact ancillary costs.23 However, a recent study from NSQIP found an opportunity cost of $60.44 per hour for surgeons operating with a resident in head and neck cases.13

Postoperative complications and mortality are key measures of surgical outcomes in addition to operative time and efficiency. This study found that neither junior nor senior resident participation significantly increased complication rates or patient return to the OR. Despite declining resident involvement and the number of total laryngectomy surgeries in the VA, the complication rate has remained steady. The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in cases involving senior residents compared to cases with attending physicians alone. This could be a result of senior resident participation in more challenging cases, such as laryngectomies performed as salvage surgery following radiation. Residents are more often involved in cases with greater complexity at teaching institutions.24-26 Therefore, the higher mortality seen among laryngectomies with senior resident involvement is likely due to the higher complexity of those cases.

The proportion of resident involvement in laryngectomies at VA medical centers has been decreasing over time. Due to the single payer nature of the VA health care system and the number of complex and comorbid patients, the VA offers an invaluable space for resident education in the OR. The fact that less than half of laryngectomies in 2021 involved resident participation is noteworthy for residency training programs. As wRVU compensation models evolve, VA attending surgeons may face less pressure to move the case along, leading to a high potential for operative teaching. Therefore, complex cases, such as laryngectomies, are often ideal for resident participation in the VA.

The steady decline in total laryngectomies at the VA parallels the recent decrease seen in non-VA settings.20 This is due in part to the use of larynx-preserving treatment modalities for laryngeal cancer as well as decreases in the incidence of laryngeal cancer due to population level changes in smoking behaviors. 18,19 Although a laryngectomy is not a key indicator case as determined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, it is important for otolaryngology residents to be exposed to these cases and have a thorough understanding of the operative technique.27 Total laryngectomy was selected for this study because it is a complex and time-consuming surgery with somewhat standardized surgical steps. Unlike microvascular surgery that is very rarely performed by an attending physician alone, laryngectomies can be performed by attending physicians alone or with a resident.28

Limitations

Since this was a retrospective study, it was susceptible to errors in data entry and data extraction from the VASQIP database. Another limitation is the lack of preoperative treatment data on tumor stage and prior nonoperative treatment. For example, a salvage laryngectomy after treatment with radiation and/or chemoradiation is a higher risk procedure than an upfront laryngectomy. Senior resident involvement may be more common in patients undergoing salvage laryngectomy due to the high risk of postoperative fistula and other complications. This may have contributed to the association identified between senior resident participation and 30-day mortality.

Since we could not account for residents who took research years or were fellows, a senior resident may have been mislabeled as a junior resident or vice versa. However, because most research years occur following the third year of residency. We are confident that PGY-1, PGY-2, and PGY-3 is likely to capture junior residents. Other factors, such as coattending surgeon cases, medical student assistance, and fellow involvement may have also impacted the results of this study.

Conclusions

This study is the first to investigate the impact of resident participation on operative time, wRVUs generated, and complication rates in head and neck surgery at VA medical centers. It found that resident participation in total laryngectomies among veterans increased operative time and reduced wRVUs generated per hour but did not impact complication rate or patient return to the OR. The VA offers a unique and invaluable space for resident education and operative training, and the recent decline in resident participation among laryngectomies is important for residency programs to acknowledge and potentially address moving forward.

In contrast to oral cavity resections which can vary from partial glossectomies to composite resections, laryngectomy represents a homogenous procedure from which to draw meaningful conclusions about complication rates, operative time, and outcome. Future directions should include studying other types of head and neck surgery in the VA to determine whether the impact of resident participation mirrors the findings of this study.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been integral in resident training. Resident surgical training requires a balance of supervision and autonomy, along with procedure repetition and appropriate feedback.1-3 Non-VA research has found that resident participation across various otolaryngology procedures, including thyroidectomy, neck dissection, and laryngectomy, does not increase patient morbidity.4-7 However, resident involvement in private and academic settings that included nonhead and neck procedures was linked to increased operative time and reduced productivity, as determined by work relative value units (wRVUs).7-13 This has also been identified in other specialties, including general surgery, orthopedics, and ophthalmology.14-16

Unlike the private sector, surgeon compensation at the VA is not as closely linked to operative productivity, offering a unique setting for resident training. While VA integration in otolaryngology residency programs increases resident case numbers, particularly in head and neck cases, the impact on VA patient outcomes and productivity is unknown.17 The use of larynxpreserving treatment modalities for laryngeal cancer has led to a decline in the number of total laryngectomies performed, which could potentially impact resident operative training for laryngectomies.18-20

This study sought to determine the impact of resident participation on operative time, wRVUs, and patient outcomes in veterans who underwent a total laryngectomy. This study was reviewed and approved by the MedStar Georgetown University Hospital Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee (#1595672).

Methods

A retrospective cohort of veterans nationwide who underwent total laryngectomy between 2001 and 2021, with or without neck dissection, was identified from the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP). Data were extracted via the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure and patients were included based on Current Procedural Terminology codes for total laryngectomy, with or without neck dissection (31320, 31360, 31365). Laryngopharyngectomies, partial laryngectomies, and minimally invasive laryngectomies were excluded. VASQIP nurse data managers reviewed patient data for operative data, postoperative outcomes (including 30- day morbidity and mortality), and preoperative risk factors (Appendix).21

The VASQIP data provide the highest resident or postgraduate year (PGY) per surgery. PGY 1, 2, and 3 were considered junior residents and PGY ≥4, surgical fellows, and individuals who took research years during residency were considered senior residents. Cases performed by attending physicians alone were compared with those involving junior or senior residents.

Patient demographic data included age, body mass index, smoking and alcohol use, weight loss, and functional status. Consumption of any tobacco products within 12 months of surgery was considered tobacco use. Drinking on average ≥2 alcoholic beverages daily was considered alcohol use. Weight loss was defined as a 10% reduction in body weight within the 6 months before surgery, excluding patients enrolled in a weight loss program. Functional status was categorized as independent, partially dependent, totally dependent, and unknown.

Primary outcomes included operative time, wRVUs generated, and wRVUs generated per hour of operative time. Postoperative complications were recorded both as a continuous variable and as a binary variable for presence or absence of a complication. Additional outcome variables included length of postoperative hospital stay, return to the operating room (OR), and death within 30 days of surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and median with IQR for continuous variables. Data were also summarized based on resident involvement in the surgery and the PGY level of the residents involved. The occurrence of total laryngectomy, rate of complications, and patient return to the OR were summarized by year.

Univariate associations between resident involvement and surgical outcomes were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the ÷2 test for categorical variables. A Fisher exact test was used when the cell count in the contingency table was < 5. The univariate associations between surgical outcomes and demographic/preoperative variables were examined using 2-sided Wilcoxon ranksum tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests between continuous variables and categorical variables, X2 or Fisher exact test between 2 categorical variables, and 2-sided Spearman correlation test between 2 continuous variables. A false-discovery rate approach was used for simultaneous posthoc tests to determine the adjusted P values for wRVUs generated/operative time for attending physicians alone vs with junior residents and for attending physicians alone vs with senior residents. Models were used to evaluate the effects of resident involvement on surgical outcomes, adjusting for variables that showed significant univariate associations. Linear regression models were used for operative time, wRVUs generated, wRVUs generated/operative time, and length of postoperative stay. A logistic regression model was used for death within 30 days. Models were not built for postoperative complications or patient return to the OR, as these were only statistically significantly associated with the patient’s preoperative functional status. A finding was considered significant if P < .05. All analyses were performed using statistical software RStudio Version 2023.03.0.

Results

Between 2001 and 2021, 1857 patients who underwent total laryngectomy were identified from the VASQIP database nationwide. Most of the total laryngectomies were staffed by an attending physician with a senior resident (n = 1190, 64%), 446 (24%) were conducted by the attending physician alone, and 221 (12%) by an attending physician with a junior resident (Table 1). The mean operating time for an attending physician alone was 378 minutes, 384 minutes for an attending physician with a senior resident, and 432 minutes for an attending physician with a junior resident (Table 2). There was a statistically significant increase in operating time for laryngectomies with resident participation compared to attending physicians operating alone (P < .001).

When the wRVUs generated/operative time was analyzed, there was a statistically significant difference between comparison groups. Total laryngectomies performed by attending physicians alone had the highest wRVUs generated/operative time (5.5), followed by laryngectomies performed by attending physicians with senior residents and laryngectomies performed by attending physicians with junior residents (5.2 and 4.8, respectively; P = .002). Table 3 describes adjusted P values for wRVUs generated/ operative time for total laryngectomies performed by attending physicians alone vs with junior residents (P = .003) and for attending physicians alone vs with senior residents (P = .02). Resident participation in total laryngectomies did not significantly impact the development or number of postoperative complications or the rate of return to the OR.

The number of laryngectomies performed in a single fiscal year peaked in 2010 at 170 cases (Figure 1). Between 2001 and 2021, the mean rates of postoperative complications (21.3%) and patient return to the OR (14.6%) did not significantly change. Resident participation in total laryngectomies also peaked in 2010 at 89.0% but has significantly declined, falling to a low of 43.6% in 2021 (Figure 2). From 2001 to 2011, the mean resident participation rate in total laryngectomies was 80.6%, compared with 68.3% from 2012 to 2021 (P < .001).

The effect of various demographic and preoperative characteristics on surgical outcomes was also analyzed. A linear regression model accounted for each variable significantly associated with operative time. On multivariable analysis, when all other variables were held constant, Table 4 shows the estimated change in operative time based on certain criteria. For instance, the operative time for attendings with junior residents surgeries was 40 minutes longer (95% CI, 16 to 64) than that of attending alone surgeries (P = .001). Furthermore, operative time decreased by 1.1 minutes (95% CI, 0.30 to 2.04) for each 1-year increase in patient age (P = .009).

A multivariable logistic regression model evaluated the effect of resident involvement on 30-day mortality rates. Senior resident involvement (P = .02), partially dependent functional status (P = .01), totally dependent functional status (P < .001), and advanced age (P = .02) all were significantly associated with 30-day mortality (Table 5). When other variables remained constant, the odds of death for totally dependent patients were 10.4 times higher than that of patients with independent functional status. Thus, totally dependent functional status appeared to have a greater impact on this outcome than resident participation. The linear regression model for postoperative length of stay demonstrated that senior resident involvement (P = .04), functional status (partially dependent vs independent P < .001), and age (P = .03) were significantly associated with prolonged length of stay.

Discussion

Otolaryngology residency training is designed to educate future otolaryngologists through hands-on learning, adequate feedback, and supervision.1 Although this exposure is paramount for resident education, balancing appropriate supervision and autonomy while mitigating patient risk has been difficult. Numerous non-VA studies have reviewed the impact of resident participation on patient outcomes in various specialties, ranging from a single institution to the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).4,5,7,22 This study is the first to describe the nationwide impact of resident participation on outcomes in veterans undergoing total laryngectomy.

This study found that resident participation increases operative time and decreases wRVUs generated/operative time without impacting complication rates or patient return to the OR. This reinforces the notion that under close supervision, resident participation does not negatively impact patient outcomes. Resident operative training requires time and dedication by the attending physician and surgical team, thereby increasing operative time. Because VA physician compensation is not linked with productivity as closely as it is in other private and academic settings, surgeons can dedicate more time to operative teaching. This study found that a total laryngectomy involving a junior resident took about 45 minutes longer than an attending physician working alone.

As expected, with longer operative times, the wRVUs generated/operative time ratio was lower in cases with resident participation. Even though resident participation leads to lower OR efficiency, their participation may not significantly impact ancillary costs.23 However, a recent study from NSQIP found an opportunity cost of $60.44 per hour for surgeons operating with a resident in head and neck cases.13

Postoperative complications and mortality are key measures of surgical outcomes in addition to operative time and efficiency. This study found that neither junior nor senior resident participation significantly increased complication rates or patient return to the OR. Despite declining resident involvement and the number of total laryngectomy surgeries in the VA, the complication rate has remained steady. The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in cases involving senior residents compared to cases with attending physicians alone. This could be a result of senior resident participation in more challenging cases, such as laryngectomies performed as salvage surgery following radiation. Residents are more often involved in cases with greater complexity at teaching institutions.24-26 Therefore, the higher mortality seen among laryngectomies with senior resident involvement is likely due to the higher complexity of those cases.

The proportion of resident involvement in laryngectomies at VA medical centers has been decreasing over time. Due to the single payer nature of the VA health care system and the number of complex and comorbid patients, the VA offers an invaluable space for resident education in the OR. The fact that less than half of laryngectomies in 2021 involved resident participation is noteworthy for residency training programs. As wRVU compensation models evolve, VA attending surgeons may face less pressure to move the case along, leading to a high potential for operative teaching. Therefore, complex cases, such as laryngectomies, are often ideal for resident participation in the VA.

The steady decline in total laryngectomies at the VA parallels the recent decrease seen in non-VA settings.20 This is due in part to the use of larynx-preserving treatment modalities for laryngeal cancer as well as decreases in the incidence of laryngeal cancer due to population level changes in smoking behaviors. 18,19 Although a laryngectomy is not a key indicator case as determined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, it is important for otolaryngology residents to be exposed to these cases and have a thorough understanding of the operative technique.27 Total laryngectomy was selected for this study because it is a complex and time-consuming surgery with somewhat standardized surgical steps. Unlike microvascular surgery that is very rarely performed by an attending physician alone, laryngectomies can be performed by attending physicians alone or with a resident.28

Limitations

Since this was a retrospective study, it was susceptible to errors in data entry and data extraction from the VASQIP database. Another limitation is the lack of preoperative treatment data on tumor stage and prior nonoperative treatment. For example, a salvage laryngectomy after treatment with radiation and/or chemoradiation is a higher risk procedure than an upfront laryngectomy. Senior resident involvement may be more common in patients undergoing salvage laryngectomy due to the high risk of postoperative fistula and other complications. This may have contributed to the association identified between senior resident participation and 30-day mortality.

Since we could not account for residents who took research years or were fellows, a senior resident may have been mislabeled as a junior resident or vice versa. However, because most research years occur following the third year of residency. We are confident that PGY-1, PGY-2, and PGY-3 is likely to capture junior residents. Other factors, such as coattending surgeon cases, medical student assistance, and fellow involvement may have also impacted the results of this study.

Conclusions

This study is the first to investigate the impact of resident participation on operative time, wRVUs generated, and complication rates in head and neck surgery at VA medical centers. It found that resident participation in total laryngectomies among veterans increased operative time and reduced wRVUs generated per hour but did not impact complication rate or patient return to the OR. The VA offers a unique and invaluable space for resident education and operative training, and the recent decline in resident participation among laryngectomies is important for residency programs to acknowledge and potentially address moving forward.

In contrast to oral cavity resections which can vary from partial glossectomies to composite resections, laryngectomy represents a homogenous procedure from which to draw meaningful conclusions about complication rates, operative time, and outcome. Future directions should include studying other types of head and neck surgery in the VA to determine whether the impact of resident participation mirrors the findings of this study.

- Chung RS. How much time do surgical residents need to learn operative surgery? Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):351-353. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.035

- S, Darzi A. Defining quality in surgical training: perceptions of the profession. Am J Surg. 2014;207(4):628-636. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.044

- Bhatti NI, Ahmed A, Choi SS. Identifying quality indicators of surgical of surgical training: a national survey. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(12):2685-2689. doi:10.1002/lary.25262

- Abt NB, Reh DD, Eisele DW, Francis HW, Gourin CG. Does resident participation influence otolaryngology-head and neck surgery morbidity and mortality? Laryngoscope. 2016;126(10):2263-2269. doi:10.1002/lary.25973

- Jubbal KT, Chang D, Izaddoost SA, Pederson W, Zavlin D, Echo A. Resident involvement in microsurgery: an American College of Surgeons national surgical quality improvement program analysis. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):1124-1132. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.05.017

- Kshirsagar RS, Chandy Z, Mahboubi H, Verma SP. Does resident involvement in thyroid surgery lead to increased postoperative complications? Laryngoscope. 2017;127(5):1242-1246. doi:10.1002/lary.26176

- Vieira BL, Hernandez DJ, Qin C, Smith SS, Kim JY, Dutra JC. The impact of resident involvement on otolaryngology surgical outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(3):602-607. doi:10.1002/lary.25046

- Advani V, Ahad S, Gonczy C, Markwell S, Hassan I. Does resident involvement effect surgical times and complication rates during laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis? An analysis of 16,849 cases from the ACS-NSQIP. Am J Surg. 2012;203(3):347-352. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.015

- Quinn NA, Alt JA, Ashby S, Orlandi RR. Time, resident involvement, and supply drive cost variability in septoplasty with turbinate reduction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(2):310-314. doi:10.1177/0194599818765099

- Leader BA, Wiebracht ND, Meinzen-Derr J, Ishman SL. The impact of resident involvement on tonsillectomy outcomes and surgical time. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2481-2486. doi:10.1002/lary.28427

- Muelleman T, Shew M, Muelleman RJ, et al. Impact of resident participation on operative time and outcomes in otologic surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(1):151-154. doi:10.1177/0194599817737270

- Puram SV, Kozin ED, Sethi R, et al. Impact of resident surgeons on procedure length based on common pediatric otolaryngology cases. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(4):991 -997. doi:10.1002/lary.24912

- Chow MS, Gordon AJ, Talwar A, Lydiatt WM, Yueh B, Givi B. The RVU compensation model and head and neck surgical education. Laryngoscope. 2024;134(1):113-119. doi:10.1002/lary.30807

- Papandria D, Rhee D, Ortega G, et al. Assessing trainee impact on operative time for common general surgical procedures in ACS-NSQIP. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(2):149-155. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.08.003

- Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Martin CT, Callagh JJ, Weinstein SL, Marsh JL. The effect of resident participation on short-term outcomes after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(7):2290-2300. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3567-0

- Hosler MR, Scott IU, Kunselman AR, Wolford KR, Oltra EZ, Murray WB. Impact of resident participation in cataract surgery on operative time and cost. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(1):95-98. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.026

- Lanigan A, Spaw M, Donaghe C, Brennan J. The impact of the Veteran’s Affairs medical system on an otolaryngology residency training program. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e671-e675. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy041

- American Society of Clinical Oncology, Pfister DG, Laurie SA, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline for the use of larynx-preservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(22):3693-3704. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4559

- Forastiere AA, Ismaila N, Lewin JS, et al. Use of larynxpreservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1143-1169. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7385

- Verma SP, Mahboubi H. The changing landscape of total laryngectomy surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):413-418. doi:10.1177/0194599813514515

- Habermann EB, Harris AHS, Giori NJ. Large surgical databases with direct data abstraction: VASQIP and ACSNSQIP. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104(suppl 3):9-14. doi:10.2106/JBJS.22.00596

- Benito DA, Mamidi I, Pasick LJ, et al. Evaluating resident involvement and the ‘July effect’ in parotidectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135(5):452-457. doi:10.1017/S0022215121000578

- Hwang CS, Wichterman KA, Alfrey EJ. The cost of resident education. J Surg Res. 2010;163(1):18-23. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.013

- Saliba AN, Taher AT, Tamim H, et al. Impact of resident involvement in surgery (IRIS-NSQIP): looking at the bigger picture based on the American College of Surgeons- NSQIP database. J Am Coll Surg. 2016; 222(1):30-40. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.10.011

- Khuri SF, Najjar SF, Daley J, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between teaching and nonteaching hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):370-383. doi:10.1097/00000658-200109000-00011

- Relles DM, Burkhart RA, Pucci MJ et al. Does resident experience affect outcomes in complex abdominal surgery? Pancreaticoduodenectomy as an example. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(2):279-285. doi:10.1007/s11605-013-2372-5

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Required minimum number of key indicator procedures for graduating residents. June 2019. Accessed January 2, 2025. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programresources/280_core_case_log_minimums.pdf

- Brady JS, Crippen MM, Filimonov A, et al. The effect of training level on complications after free flap surgery of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38(5):560-564. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2017.06.001

- Chung RS. How much time do surgical residents need to learn operative surgery? Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):351-353. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.035

- S, Darzi A. Defining quality in surgical training: perceptions of the profession. Am J Surg. 2014;207(4):628-636. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.044

- Bhatti NI, Ahmed A, Choi SS. Identifying quality indicators of surgical of surgical training: a national survey. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(12):2685-2689. doi:10.1002/lary.25262

- Abt NB, Reh DD, Eisele DW, Francis HW, Gourin CG. Does resident participation influence otolaryngology-head and neck surgery morbidity and mortality? Laryngoscope. 2016;126(10):2263-2269. doi:10.1002/lary.25973

- Jubbal KT, Chang D, Izaddoost SA, Pederson W, Zavlin D, Echo A. Resident involvement in microsurgery: an American College of Surgeons national surgical quality improvement program analysis. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):1124-1132. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.05.017

- Kshirsagar RS, Chandy Z, Mahboubi H, Verma SP. Does resident involvement in thyroid surgery lead to increased postoperative complications? Laryngoscope. 2017;127(5):1242-1246. doi:10.1002/lary.26176

- Vieira BL, Hernandez DJ, Qin C, Smith SS, Kim JY, Dutra JC. The impact of resident involvement on otolaryngology surgical outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(3):602-607. doi:10.1002/lary.25046

- Advani V, Ahad S, Gonczy C, Markwell S, Hassan I. Does resident involvement effect surgical times and complication rates during laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis? An analysis of 16,849 cases from the ACS-NSQIP. Am J Surg. 2012;203(3):347-352. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.015

- Quinn NA, Alt JA, Ashby S, Orlandi RR. Time, resident involvement, and supply drive cost variability in septoplasty with turbinate reduction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(2):310-314. doi:10.1177/0194599818765099

- Leader BA, Wiebracht ND, Meinzen-Derr J, Ishman SL. The impact of resident involvement on tonsillectomy outcomes and surgical time. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2481-2486. doi:10.1002/lary.28427

- Muelleman T, Shew M, Muelleman RJ, et al. Impact of resident participation on operative time and outcomes in otologic surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(1):151-154. doi:10.1177/0194599817737270

- Puram SV, Kozin ED, Sethi R, et al. Impact of resident surgeons on procedure length based on common pediatric otolaryngology cases. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(4):991 -997. doi:10.1002/lary.24912

- Chow MS, Gordon AJ, Talwar A, Lydiatt WM, Yueh B, Givi B. The RVU compensation model and head and neck surgical education. Laryngoscope. 2024;134(1):113-119. doi:10.1002/lary.30807

- Papandria D, Rhee D, Ortega G, et al. Assessing trainee impact on operative time for common general surgical procedures in ACS-NSQIP. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(2):149-155. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.08.003

- Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Martin CT, Callagh JJ, Weinstein SL, Marsh JL. The effect of resident participation on short-term outcomes after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(7):2290-2300. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3567-0

- Hosler MR, Scott IU, Kunselman AR, Wolford KR, Oltra EZ, Murray WB. Impact of resident participation in cataract surgery on operative time and cost. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(1):95-98. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.026

- Lanigan A, Spaw M, Donaghe C, Brennan J. The impact of the Veteran’s Affairs medical system on an otolaryngology residency training program. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e671-e675. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy041

- American Society of Clinical Oncology, Pfister DG, Laurie SA, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline for the use of larynx-preservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(22):3693-3704. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4559

- Forastiere AA, Ismaila N, Lewin JS, et al. Use of larynxpreservation strategies in the treatment of laryngeal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1143-1169. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7385

- Verma SP, Mahboubi H. The changing landscape of total laryngectomy surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):413-418. doi:10.1177/0194599813514515

- Habermann EB, Harris AHS, Giori NJ. Large surgical databases with direct data abstraction: VASQIP and ACSNSQIP. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104(suppl 3):9-14. doi:10.2106/JBJS.22.00596

- Benito DA, Mamidi I, Pasick LJ, et al. Evaluating resident involvement and the ‘July effect’ in parotidectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135(5):452-457. doi:10.1017/S0022215121000578

- Hwang CS, Wichterman KA, Alfrey EJ. The cost of resident education. J Surg Res. 2010;163(1):18-23. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.013

- Saliba AN, Taher AT, Tamim H, et al. Impact of resident involvement in surgery (IRIS-NSQIP): looking at the bigger picture based on the American College of Surgeons- NSQIP database. J Am Coll Surg. 2016; 222(1):30-40. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.10.011

- Khuri SF, Najjar SF, Daley J, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between teaching and nonteaching hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):370-383. doi:10.1097/00000658-200109000-00011

- Relles DM, Burkhart RA, Pucci MJ et al. Does resident experience affect outcomes in complex abdominal surgery? Pancreaticoduodenectomy as an example. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(2):279-285. doi:10.1007/s11605-013-2372-5

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Required minimum number of key indicator procedures for graduating residents. June 2019. Accessed January 2, 2025. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programresources/280_core_case_log_minimums.pdf

- Brady JS, Crippen MM, Filimonov A, et al. The effect of training level on complications after free flap surgery of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38(5):560-564. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2017.06.001

Resident Participation Impact on Operative Time and Outcomes in Veterans Undergoing Total Laryngectomy

Resident Participation Impact on Operative Time and Outcomes in Veterans Undergoing Total Laryngectomy

Total Intravenous Anesthesia Enables Earlier Facial Nerve Monitoring Than Sevoflurane in Ear Surgery

TOPLINE:

Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) enables earlier intraoperative monitoring of facial nerve activity than sevoflurane anesthesia during ear surgery, with reduced patient-ventilator dyssynchrony and fewer requirements for postoperative antiemetics.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the difference in the timeliness of intraoperative monitoring of facial nerve activity during ear surgery with TIVA vs sevoflurane anesthesia.

- They included 98 patients aged 18-74 years undergoing ear surgery between November 2021 and November 2022; patients were randomly assigned to receive either TIVA or sevoflurane during the procedure. Of these, 92 were included in the final analysis.

- Neuromuscular function was monitored quantitatively throughout anesthesia with train-of-four counts and train-of-four ratios.

- The time from the administration of rocuronium to the start of facial nerve monitoring was recorded.

- The primary outcome measure focused on the recovery index, defined as the time interval between a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 and 0.75; the key secondary outcome was the time to reach a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 from rocuronium administration.

TAKEAWAY:

- The time to reach a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 was achieved earlier with TIVA than with sevoflurane (34 minutes vs 51 minutes; P < .001).

- Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony occurred less frequently in the TIVA group than in the sevoflurane group (15% vs 39%; P = .01).

- Postoperative requests for antiemetics were less frequent in the TIVA group than in the sevoflurane group (2% vs 17%; P = .03).

IN PRACTICE:

“We suggest that TIVA may be a better choice than sevoflurane anesthesia to meet an earlier request” for intraoperative facial nerve monitoring by surgeons, the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yu Jeong Bang, MD, of the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, in Seoul, Republic of Korea. It was published online on November 27, 2024, in The Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

LIMITATIONS:

A careful interpretation of results may be necessary when clinicians use balanced anesthesia, such as sevoflurane with adjuvants like opioids or nonopioids. The feasibility of intraoperative facial nerve monitoring was decided by the surgeon during surgery, and the lowest stimulation intensity threshold for electromyography amplitude was not detected, as it was not the focus of this study. Although patients requiring intraoperative facial nerve monitoring during ear surgery were enrolled, some did not undergo the procedure based on the surgeon’s judgment.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) enables earlier intraoperative monitoring of facial nerve activity than sevoflurane anesthesia during ear surgery, with reduced patient-ventilator dyssynchrony and fewer requirements for postoperative antiemetics.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the difference in the timeliness of intraoperative monitoring of facial nerve activity during ear surgery with TIVA vs sevoflurane anesthesia.

- They included 98 patients aged 18-74 years undergoing ear surgery between November 2021 and November 2022; patients were randomly assigned to receive either TIVA or sevoflurane during the procedure. Of these, 92 were included in the final analysis.

- Neuromuscular function was monitored quantitatively throughout anesthesia with train-of-four counts and train-of-four ratios.

- The time from the administration of rocuronium to the start of facial nerve monitoring was recorded.

- The primary outcome measure focused on the recovery index, defined as the time interval between a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 and 0.75; the key secondary outcome was the time to reach a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 from rocuronium administration.

TAKEAWAY:

- The time to reach a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 was achieved earlier with TIVA than with sevoflurane (34 minutes vs 51 minutes; P < .001).

- Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony occurred less frequently in the TIVA group than in the sevoflurane group (15% vs 39%; P = .01).

- Postoperative requests for antiemetics were less frequent in the TIVA group than in the sevoflurane group (2% vs 17%; P = .03).

IN PRACTICE:

“We suggest that TIVA may be a better choice than sevoflurane anesthesia to meet an earlier request” for intraoperative facial nerve monitoring by surgeons, the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yu Jeong Bang, MD, of the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, in Seoul, Republic of Korea. It was published online on November 27, 2024, in The Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

LIMITATIONS:

A careful interpretation of results may be necessary when clinicians use balanced anesthesia, such as sevoflurane with adjuvants like opioids or nonopioids. The feasibility of intraoperative facial nerve monitoring was decided by the surgeon during surgery, and the lowest stimulation intensity threshold for electromyography amplitude was not detected, as it was not the focus of this study. Although patients requiring intraoperative facial nerve monitoring during ear surgery were enrolled, some did not undergo the procedure based on the surgeon’s judgment.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) enables earlier intraoperative monitoring of facial nerve activity than sevoflurane anesthesia during ear surgery, with reduced patient-ventilator dyssynchrony and fewer requirements for postoperative antiemetics.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated the difference in the timeliness of intraoperative monitoring of facial nerve activity during ear surgery with TIVA vs sevoflurane anesthesia.

- They included 98 patients aged 18-74 years undergoing ear surgery between November 2021 and November 2022; patients were randomly assigned to receive either TIVA or sevoflurane during the procedure. Of these, 92 were included in the final analysis.

- Neuromuscular function was monitored quantitatively throughout anesthesia with train-of-four counts and train-of-four ratios.

- The time from the administration of rocuronium to the start of facial nerve monitoring was recorded.

- The primary outcome measure focused on the recovery index, defined as the time interval between a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 and 0.75; the key secondary outcome was the time to reach a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 from rocuronium administration.

TAKEAWAY:

- The time to reach a train-of-four ratio of 0.25 was achieved earlier with TIVA than with sevoflurane (34 minutes vs 51 minutes; P < .001).

- Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony occurred less frequently in the TIVA group than in the sevoflurane group (15% vs 39%; P = .01).

- Postoperative requests for antiemetics were less frequent in the TIVA group than in the sevoflurane group (2% vs 17%; P = .03).

IN PRACTICE:

“We suggest that TIVA may be a better choice than sevoflurane anesthesia to meet an earlier request” for intraoperative facial nerve monitoring by surgeons, the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yu Jeong Bang, MD, of the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, in Seoul, Republic of Korea. It was published online on November 27, 2024, in The Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

LIMITATIONS:

A careful interpretation of results may be necessary when clinicians use balanced anesthesia, such as sevoflurane with adjuvants like opioids or nonopioids. The feasibility of intraoperative facial nerve monitoring was decided by the surgeon during surgery, and the lowest stimulation intensity threshold for electromyography amplitude was not detected, as it was not the focus of this study. Although patients requiring intraoperative facial nerve monitoring during ear surgery were enrolled, some did not undergo the procedure based on the surgeon’s judgment.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not receive any funding. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thyroidectomy Beneficial but Risky for Hashimoto Disease

TOPLINE:

In patients with Hashimoto disease and persistent symptoms despite adequate medical treatment, total thyroidectomy had a beneficial effect up to 5 years but with a substantially higher risk for complications than initially anticipated.

METHODOLOGY:

- The 5-year follow-up of 65 participants in a randomized, open-label trial of thyroidectomy plus medical management vs medical management alone aimed at testing the hypothesis that persistent symptoms despite adequate thyroxine replacement may be related to extrathyroidal autoimmune reactions and that complete removal of thyroid tissues may attenuate autoimmune responses and relieve symptoms.

- Patients in the control group were given the option of having surgery 18 months after enrollment, depending on trial results.

- The primary outcome was patient-reported health-related quality of life measured by the dimensional general health score in the generic Short Form-36 Health Survey questionnaire.

TAKEAWAY:

- The positive treatment effect seen after 18 months was maintained throughout the 3-year follow-up.

- In the intervention group, the improved general health score remained at the same level during the 5-year follow-up.

- Results were similar for the other Short Form-36 Health Survey domains and for total fatigue and chronic fatigue.

- Short-term (<12 months) or longer-lasting complications occurred in 23 patients, including 6 with recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis (4 were long-term) and 12 with hypoparathyroidism (6 long-term, including 3 permanent).

- Five patients had postoperative hematoma and/or infection requiring intervention.

IN PRACTICE:

“The improvements in patient-reported outcome measures reported at 18 months after surgery were maintained at 5 years after surgery in the intervention group. In contrast, no spontaneous improvement was seen during 3 years in the control group.”

“Long-term complications in 10 of 73 (14%) patients despite use of meticulous dissection to achieve total thyroidectomy is unacceptably high. Medication and compensatory mechanisms for hypoparathyroidism and unilateral recurrent nerve injury, respectively, did alleviate symptoms.”

SOURCE:

This study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine, by Geir Hoff, MD, PhD, of the Department of Research, Telemark Hospital, Skien, and the Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and colleagues.

LIMITATIONS:

None listed.

DISCLOSURES:

None.

TOPLINE:

In patients with Hashimoto disease and persistent symptoms despite adequate medical treatment, total thyroidectomy had a beneficial effect up to 5 years but with a substantially higher risk for complications than initially anticipated.

METHODOLOGY:

- The 5-year follow-up of 65 participants in a randomized, open-label trial of thyroidectomy plus medical management vs medical management alone aimed at testing the hypothesis that persistent symptoms despite adequate thyroxine replacement may be related to extrathyroidal autoimmune reactions and that complete removal of thyroid tissues may attenuate autoimmune responses and relieve symptoms.

- Patients in the control group were given the option of having surgery 18 months after enrollment, depending on trial results.

- The primary outcome was patient-reported health-related quality of life measured by the dimensional general health score in the generic Short Form-36 Health Survey questionnaire.

TAKEAWAY:

- The positive treatment effect seen after 18 months was maintained throughout the 3-year follow-up.