User login

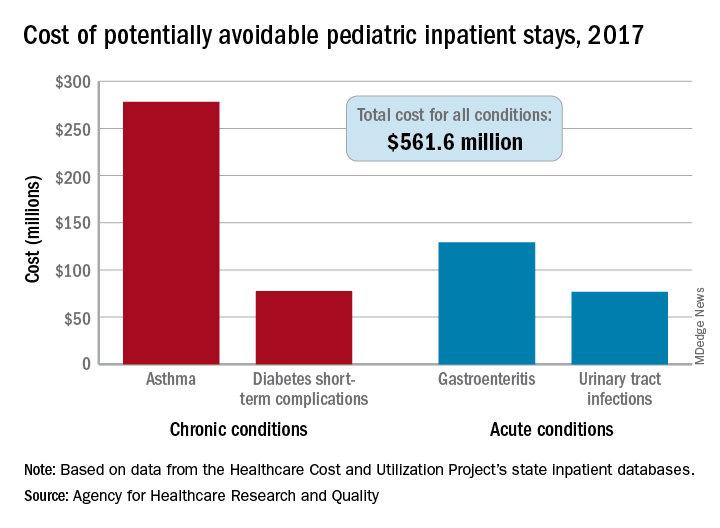

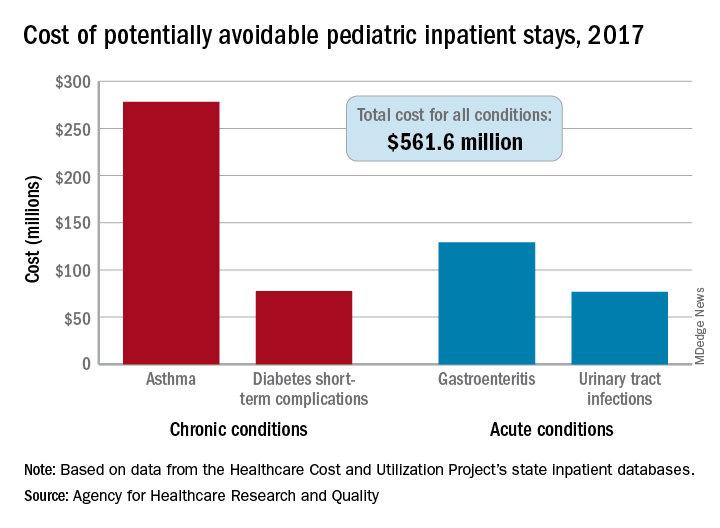

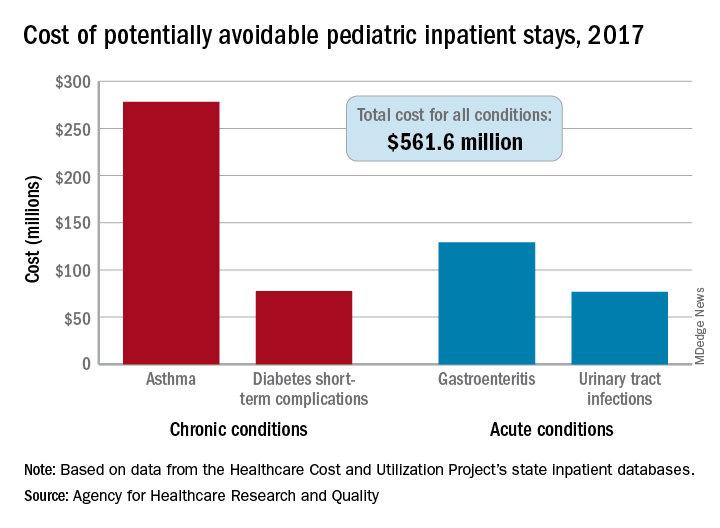

Asthma leads spending on avoidable pediatric inpatient stays

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The cost of potentially avoidable visits for asthma that year was $278 million, versus $284 million combined for the other three conditions “that evidence suggests may be avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Those three other conditions are diabetes short-term complications, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Neonatal stays were excluded from the analysis, Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ noted.

The state inpatient databases of the AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project included 1.4 million inpatient stays among children aged 3 months to 17 years in 2017, of which 8% (108,300) were deemed potentially preventable. Hospital charges for the preventable stays came to $561.6 million, or 3% of the $20 billion in total costs for all nonneonatal stays, they said.

Rates of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (159 per 100,000 population), gastroenteritis (90 per 100,000), and UTIs (41 per 100,000) were highest for children aged 0-4 years and generally decreased with age, but diabetes stays increased with age, rising from 12 per 100,000 in children aged 5-9 years to 38 per 100,000 for those 15-17 years old, the researchers said.

Black children had a much higher rate of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (218 per 100,000) than did Hispanic children (74), Asian/Pacific Islander children (46), or white children (43), but children classified as other race/ethnicity were higher still: 380 per 100,000. Rates for children classified as other race/ethnicity were highest for the other three conditions as well, they reported.

Comparisons by sex for the four conditions ended up in a 2-2 tie: Girls had higher rates for diabetes (28 vs. 23) and UTIs (35 vs. 8), and boys had higher rates for asthma (96 vs. 67) and gastroenteritis (38 vs. 35), Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang reported.

SOURCE: McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The cost of potentially avoidable visits for asthma that year was $278 million, versus $284 million combined for the other three conditions “that evidence suggests may be avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Those three other conditions are diabetes short-term complications, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Neonatal stays were excluded from the analysis, Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ noted.

The state inpatient databases of the AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project included 1.4 million inpatient stays among children aged 3 months to 17 years in 2017, of which 8% (108,300) were deemed potentially preventable. Hospital charges for the preventable stays came to $561.6 million, or 3% of the $20 billion in total costs for all nonneonatal stays, they said.

Rates of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (159 per 100,000 population), gastroenteritis (90 per 100,000), and UTIs (41 per 100,000) were highest for children aged 0-4 years and generally decreased with age, but diabetes stays increased with age, rising from 12 per 100,000 in children aged 5-9 years to 38 per 100,000 for those 15-17 years old, the researchers said.

Black children had a much higher rate of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (218 per 100,000) than did Hispanic children (74), Asian/Pacific Islander children (46), or white children (43), but children classified as other race/ethnicity were higher still: 380 per 100,000. Rates for children classified as other race/ethnicity were highest for the other three conditions as well, they reported.

Comparisons by sex for the four conditions ended up in a 2-2 tie: Girls had higher rates for diabetes (28 vs. 23) and UTIs (35 vs. 8), and boys had higher rates for asthma (96 vs. 67) and gastroenteritis (38 vs. 35), Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang reported.

SOURCE: McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The cost of potentially avoidable visits for asthma that year was $278 million, versus $284 million combined for the other three conditions “that evidence suggests may be avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Those three other conditions are diabetes short-term complications, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Neonatal stays were excluded from the analysis, Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ noted.

The state inpatient databases of the AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project included 1.4 million inpatient stays among children aged 3 months to 17 years in 2017, of which 8% (108,300) were deemed potentially preventable. Hospital charges for the preventable stays came to $561.6 million, or 3% of the $20 billion in total costs for all nonneonatal stays, they said.

Rates of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (159 per 100,000 population), gastroenteritis (90 per 100,000), and UTIs (41 per 100,000) were highest for children aged 0-4 years and generally decreased with age, but diabetes stays increased with age, rising from 12 per 100,000 in children aged 5-9 years to 38 per 100,000 for those 15-17 years old, the researchers said.

Black children had a much higher rate of potentially avoidable stays for asthma (218 per 100,000) than did Hispanic children (74), Asian/Pacific Islander children (46), or white children (43), but children classified as other race/ethnicity were higher still: 380 per 100,000. Rates for children classified as other race/ethnicity were highest for the other three conditions as well, they reported.

Comparisons by sex for the four conditions ended up in a 2-2 tie: Girls had higher rates for diabetes (28 vs. 23) and UTIs (35 vs. 8), and boys had higher rates for asthma (96 vs. 67) and gastroenteritis (38 vs. 35), Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang reported.

SOURCE: McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

First-episode psychosis in the time of COVID-19

Patients may need more than weekly teletherapy

In response to COVID-19, we have seen a rapid transformation to virtually delivered mental health care, essential for the prevention and treatment of various mental health conditions during an isolating and stress-inducing pandemic. Yet teletherapy and virtual medication management alone may not adequately address the needs of some of the populations we serve.

Take Jackson, whose name and details have been changed for privacy. A year ago, Jackson, in his last year of high school, began hearing voices that others could not hear. After becoming increasingly withdrawn, his father sought out treatment for him and learned that Jackson was experiencing his first episode of psychosis.

Psychosis involves disruptions in the way one processes thoughts and feelings or behaves, and includes delusions – or unusual beliefs – and hallucinations, meaning seeing and hearing things that others cannot. “First-episode psychosis” (FEP) simply refers to the first time an individual experiences this. It typically occurs between one’s teenage years and their 20s. Whereas some individuals recover from their first episode and may not experience another, others go on to experience recurrence, and sometimes a waxing and waning illness course.

Jackson enrolled in a comprehensive mental health program that not only includes a psychiatrist, but also therapists who provide case management services, as well as a peer specialist; this is someone with lived experience navigating mental illness. The program also includes an employment and education specialist and family and group therapy sessions. His team helped him identify and work toward his personal recovery goals: graduating from high school, obtaining a job, and maintaining a strong relationship with his father.

One hundred thousand adolescents and young adults like Jackson experience FEP each year, and now, in the wake of COVID-19, they probably have more limited access to the kind of support that can be vital to recovery.

Studies have shown that untreated psychosis can detrimentally affect quality of life in several ways, including by negatively affecting interpersonal relationships, interfering with obtaining or maintaining employment, and increasing the risk for problematic substance use. The psychosocial effects of COVID-19 could compound problems that individuals navigating psychosis already face, such as stigmatization, social isolation, and unemployment. On top of this, individuals who experience additional marginalization and downstream effects of systematic discriminatory practices by virtue of their race or ethnicity, immigration status, or language bear the brunt of some of this pandemic’s worst health inequities.

Early and efficacious treatment is critically important for individuals experiencing psychosis. Evidence shows that engagement in coordinated specialty care (CSC) specifically can improve outcomes, including the likelihood of being engaged in school or work and lower rates of hospitalization. CSC is a team-based approach that utilizes the unique skills of every team member to support an individual in reaching their recovery goals, whether it’s starting or finishing college or building a new relationship.

Unlike traditional treatment goals, which often focus on “symptom reduction,” recovery-oriented care is about supporting an individual in obtaining a sense of satisfaction, meaning, and purpose in life. It also supports navigating such experiences as a job interview or a date. These key, multifaceted components must be made accessible and adapted during these times.

For individuals like Jackson, it is crucial to be able to continue accessing quality CSC, even during our current pandemic. Lisa Dixon, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, leads ONTrackNY, a statewide FEP program. She states that “effective, recovery-oriented treatment can make such a huge difference in the lives of these young people who are at a potential inflection point in their lives. Creative, collaborative clinicians can maintain connection and support.”

So how can we adapt CSC during this time? In addition to virtualized medication management and individual therapy, other components of CSC can be creatively adapted for online platforms. Group sessions can be completed virtually, from family to peer-led. Though the unemployment rate continues to rise, we can still help participants with a desire to work find employers that are offering remote work or navigate the risks of potential COVID-19 work exposures if remote options aren’t available. We can also support their developing skills to be used once other employers that pose less risk reopen.

For those in school, virtual education support can provide study skills, ways to cope with transition to an online classroom, or help with obtaining tutoring. Nutritionists can work remotely to provide support and creatively use online platforms for real-time feedback in a participant’s kitchen. Virtual case management is even more essential in the wake of COVID-19, from assistance with applying for unemployment insurance and financial aid to obtaining health insurance or determining eligibility.

For those without access to virtual platforms, individual and group telephone sessions and text check-ins can provide meaningful opportunities for continued engagement. For those who are unstably housed or have limited privacy in housing, teams must generate ideas of where to have remote sessions, such as a nearby park.

In a world now dominated by virtual care, it is critically important that individuals needing to see a clinician in person still be able to do so. Whether it is due to an acute crisis or to administer a long-acting injection medication, it is our responsibility to thoughtfully and judiciously remain available to patients, using appropriate personal protective equipment and precautions.

Jackson is one of many young people in recovery from psychosis. He is not defined by or limited by his experiences, but rather is navigating the possibilities that lie ahead of him, defining for himself who he wants to be in this world as it evolves. In the midst of COVID-19, as we seek to innovate – from how we exercise to how we throw birthday parties – let’s also be innovative in how we provide care and support for individuals experiencing psychosis.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients may need more than weekly teletherapy

Patients may need more than weekly teletherapy

In response to COVID-19, we have seen a rapid transformation to virtually delivered mental health care, essential for the prevention and treatment of various mental health conditions during an isolating and stress-inducing pandemic. Yet teletherapy and virtual medication management alone may not adequately address the needs of some of the populations we serve.

Take Jackson, whose name and details have been changed for privacy. A year ago, Jackson, in his last year of high school, began hearing voices that others could not hear. After becoming increasingly withdrawn, his father sought out treatment for him and learned that Jackson was experiencing his first episode of psychosis.

Psychosis involves disruptions in the way one processes thoughts and feelings or behaves, and includes delusions – or unusual beliefs – and hallucinations, meaning seeing and hearing things that others cannot. “First-episode psychosis” (FEP) simply refers to the first time an individual experiences this. It typically occurs between one’s teenage years and their 20s. Whereas some individuals recover from their first episode and may not experience another, others go on to experience recurrence, and sometimes a waxing and waning illness course.

Jackson enrolled in a comprehensive mental health program that not only includes a psychiatrist, but also therapists who provide case management services, as well as a peer specialist; this is someone with lived experience navigating mental illness. The program also includes an employment and education specialist and family and group therapy sessions. His team helped him identify and work toward his personal recovery goals: graduating from high school, obtaining a job, and maintaining a strong relationship with his father.

One hundred thousand adolescents and young adults like Jackson experience FEP each year, and now, in the wake of COVID-19, they probably have more limited access to the kind of support that can be vital to recovery.

Studies have shown that untreated psychosis can detrimentally affect quality of life in several ways, including by negatively affecting interpersonal relationships, interfering with obtaining or maintaining employment, and increasing the risk for problematic substance use. The psychosocial effects of COVID-19 could compound problems that individuals navigating psychosis already face, such as stigmatization, social isolation, and unemployment. On top of this, individuals who experience additional marginalization and downstream effects of systematic discriminatory practices by virtue of their race or ethnicity, immigration status, or language bear the brunt of some of this pandemic’s worst health inequities.

Early and efficacious treatment is critically important for individuals experiencing psychosis. Evidence shows that engagement in coordinated specialty care (CSC) specifically can improve outcomes, including the likelihood of being engaged in school or work and lower rates of hospitalization. CSC is a team-based approach that utilizes the unique skills of every team member to support an individual in reaching their recovery goals, whether it’s starting or finishing college or building a new relationship.

Unlike traditional treatment goals, which often focus on “symptom reduction,” recovery-oriented care is about supporting an individual in obtaining a sense of satisfaction, meaning, and purpose in life. It also supports navigating such experiences as a job interview or a date. These key, multifaceted components must be made accessible and adapted during these times.

For individuals like Jackson, it is crucial to be able to continue accessing quality CSC, even during our current pandemic. Lisa Dixon, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, leads ONTrackNY, a statewide FEP program. She states that “effective, recovery-oriented treatment can make such a huge difference in the lives of these young people who are at a potential inflection point in their lives. Creative, collaborative clinicians can maintain connection and support.”

So how can we adapt CSC during this time? In addition to virtualized medication management and individual therapy, other components of CSC can be creatively adapted for online platforms. Group sessions can be completed virtually, from family to peer-led. Though the unemployment rate continues to rise, we can still help participants with a desire to work find employers that are offering remote work or navigate the risks of potential COVID-19 work exposures if remote options aren’t available. We can also support their developing skills to be used once other employers that pose less risk reopen.

For those in school, virtual education support can provide study skills, ways to cope with transition to an online classroom, or help with obtaining tutoring. Nutritionists can work remotely to provide support and creatively use online platforms for real-time feedback in a participant’s kitchen. Virtual case management is even more essential in the wake of COVID-19, from assistance with applying for unemployment insurance and financial aid to obtaining health insurance or determining eligibility.

For those without access to virtual platforms, individual and group telephone sessions and text check-ins can provide meaningful opportunities for continued engagement. For those who are unstably housed or have limited privacy in housing, teams must generate ideas of where to have remote sessions, such as a nearby park.

In a world now dominated by virtual care, it is critically important that individuals needing to see a clinician in person still be able to do so. Whether it is due to an acute crisis or to administer a long-acting injection medication, it is our responsibility to thoughtfully and judiciously remain available to patients, using appropriate personal protective equipment and precautions.

Jackson is one of many young people in recovery from psychosis. He is not defined by or limited by his experiences, but rather is navigating the possibilities that lie ahead of him, defining for himself who he wants to be in this world as it evolves. In the midst of COVID-19, as we seek to innovate – from how we exercise to how we throw birthday parties – let’s also be innovative in how we provide care and support for individuals experiencing psychosis.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In response to COVID-19, we have seen a rapid transformation to virtually delivered mental health care, essential for the prevention and treatment of various mental health conditions during an isolating and stress-inducing pandemic. Yet teletherapy and virtual medication management alone may not adequately address the needs of some of the populations we serve.

Take Jackson, whose name and details have been changed for privacy. A year ago, Jackson, in his last year of high school, began hearing voices that others could not hear. After becoming increasingly withdrawn, his father sought out treatment for him and learned that Jackson was experiencing his first episode of psychosis.

Psychosis involves disruptions in the way one processes thoughts and feelings or behaves, and includes delusions – or unusual beliefs – and hallucinations, meaning seeing and hearing things that others cannot. “First-episode psychosis” (FEP) simply refers to the first time an individual experiences this. It typically occurs between one’s teenage years and their 20s. Whereas some individuals recover from their first episode and may not experience another, others go on to experience recurrence, and sometimes a waxing and waning illness course.

Jackson enrolled in a comprehensive mental health program that not only includes a psychiatrist, but also therapists who provide case management services, as well as a peer specialist; this is someone with lived experience navigating mental illness. The program also includes an employment and education specialist and family and group therapy sessions. His team helped him identify and work toward his personal recovery goals: graduating from high school, obtaining a job, and maintaining a strong relationship with his father.

One hundred thousand adolescents and young adults like Jackson experience FEP each year, and now, in the wake of COVID-19, they probably have more limited access to the kind of support that can be vital to recovery.

Studies have shown that untreated psychosis can detrimentally affect quality of life in several ways, including by negatively affecting interpersonal relationships, interfering with obtaining or maintaining employment, and increasing the risk for problematic substance use. The psychosocial effects of COVID-19 could compound problems that individuals navigating psychosis already face, such as stigmatization, social isolation, and unemployment. On top of this, individuals who experience additional marginalization and downstream effects of systematic discriminatory practices by virtue of their race or ethnicity, immigration status, or language bear the brunt of some of this pandemic’s worst health inequities.

Early and efficacious treatment is critically important for individuals experiencing psychosis. Evidence shows that engagement in coordinated specialty care (CSC) specifically can improve outcomes, including the likelihood of being engaged in school or work and lower rates of hospitalization. CSC is a team-based approach that utilizes the unique skills of every team member to support an individual in reaching their recovery goals, whether it’s starting or finishing college or building a new relationship.

Unlike traditional treatment goals, which often focus on “symptom reduction,” recovery-oriented care is about supporting an individual in obtaining a sense of satisfaction, meaning, and purpose in life. It also supports navigating such experiences as a job interview or a date. These key, multifaceted components must be made accessible and adapted during these times.

For individuals like Jackson, it is crucial to be able to continue accessing quality CSC, even during our current pandemic. Lisa Dixon, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, leads ONTrackNY, a statewide FEP program. She states that “effective, recovery-oriented treatment can make such a huge difference in the lives of these young people who are at a potential inflection point in their lives. Creative, collaborative clinicians can maintain connection and support.”

So how can we adapt CSC during this time? In addition to virtualized medication management and individual therapy, other components of CSC can be creatively adapted for online platforms. Group sessions can be completed virtually, from family to peer-led. Though the unemployment rate continues to rise, we can still help participants with a desire to work find employers that are offering remote work or navigate the risks of potential COVID-19 work exposures if remote options aren’t available. We can also support their developing skills to be used once other employers that pose less risk reopen.

For those in school, virtual education support can provide study skills, ways to cope with transition to an online classroom, or help with obtaining tutoring. Nutritionists can work remotely to provide support and creatively use online platforms for real-time feedback in a participant’s kitchen. Virtual case management is even more essential in the wake of COVID-19, from assistance with applying for unemployment insurance and financial aid to obtaining health insurance or determining eligibility.

For those without access to virtual platforms, individual and group telephone sessions and text check-ins can provide meaningful opportunities for continued engagement. For those who are unstably housed or have limited privacy in housing, teams must generate ideas of where to have remote sessions, such as a nearby park.

In a world now dominated by virtual care, it is critically important that individuals needing to see a clinician in person still be able to do so. Whether it is due to an acute crisis or to administer a long-acting injection medication, it is our responsibility to thoughtfully and judiciously remain available to patients, using appropriate personal protective equipment and precautions.

Jackson is one of many young people in recovery from psychosis. He is not defined by or limited by his experiences, but rather is navigating the possibilities that lie ahead of him, defining for himself who he wants to be in this world as it evolves. In the midst of COVID-19, as we seek to innovate – from how we exercise to how we throw birthday parties – let’s also be innovative in how we provide care and support for individuals experiencing psychosis.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lung ultrasound works well in children with COVID-19

researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

They also noted the benefits that modality provides over other imaging techniques.

Marco Denina, MD, and colleagues from the pediatric infectious diseases unit at Regina Margherita Children’s Hospital in Turin, Italy, performed an observational study of eight children aged 0-17 years who were admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 between March 8 and 26, 2020. In seven of eight patients, the findings were concordant between imaging modalities; in the remaining patient, lung ultrasound (LUS) found an interstitial B-lines pattern that was not seen on radiography. In seven patients with pathologic ultrasound findings at baseline, the improvement or resolution of the subpleural consolidations or interstitial patterns was consistent with concomitant radiologic findings.

The authors cited the benefits of using point-of-care ultrasound instead of other modalities, such as CT. “First, it may reduce the number of radiologic examinations, lowering the radiation exposure of the patients,” they wrote. “Secondly, when performed at the bedside, LUS allows for the reduction of the patient’s movement within the hospital; thus, it lowers the number of health care workers and medical devices exposed to [SARS-CoV-2].”

One limitation of the study is the small sample size; however, the researchers felt the high concordance still suggests LUS is a reasonable method for COVID-19 patients.

There was no external funding for this study and the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Denina M et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157.

researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

They also noted the benefits that modality provides over other imaging techniques.

Marco Denina, MD, and colleagues from the pediatric infectious diseases unit at Regina Margherita Children’s Hospital in Turin, Italy, performed an observational study of eight children aged 0-17 years who were admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 between March 8 and 26, 2020. In seven of eight patients, the findings were concordant between imaging modalities; in the remaining patient, lung ultrasound (LUS) found an interstitial B-lines pattern that was not seen on radiography. In seven patients with pathologic ultrasound findings at baseline, the improvement or resolution of the subpleural consolidations or interstitial patterns was consistent with concomitant radiologic findings.

The authors cited the benefits of using point-of-care ultrasound instead of other modalities, such as CT. “First, it may reduce the number of radiologic examinations, lowering the radiation exposure of the patients,” they wrote. “Secondly, when performed at the bedside, LUS allows for the reduction of the patient’s movement within the hospital; thus, it lowers the number of health care workers and medical devices exposed to [SARS-CoV-2].”

One limitation of the study is the small sample size; however, the researchers felt the high concordance still suggests LUS is a reasonable method for COVID-19 patients.

There was no external funding for this study and the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Denina M et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157.

researchers wrote in Pediatrics.

They also noted the benefits that modality provides over other imaging techniques.

Marco Denina, MD, and colleagues from the pediatric infectious diseases unit at Regina Margherita Children’s Hospital in Turin, Italy, performed an observational study of eight children aged 0-17 years who were admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 between March 8 and 26, 2020. In seven of eight patients, the findings were concordant between imaging modalities; in the remaining patient, lung ultrasound (LUS) found an interstitial B-lines pattern that was not seen on radiography. In seven patients with pathologic ultrasound findings at baseline, the improvement or resolution of the subpleural consolidations or interstitial patterns was consistent with concomitant radiologic findings.

The authors cited the benefits of using point-of-care ultrasound instead of other modalities, such as CT. “First, it may reduce the number of radiologic examinations, lowering the radiation exposure of the patients,” they wrote. “Secondly, when performed at the bedside, LUS allows for the reduction of the patient’s movement within the hospital; thus, it lowers the number of health care workers and medical devices exposed to [SARS-CoV-2].”

One limitation of the study is the small sample size; however, the researchers felt the high concordance still suggests LUS is a reasonable method for COVID-19 patients.

There was no external funding for this study and the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Denina M et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157.

FROM PEDIATRICS

What presents as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque?

Scrapings of the child’s rash were analyzed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) under microscopy which revealed multiple septate hyphae.

She was diagnosed with Majocchi’s granuloma. The fungal culture was positive for Trichophyton rubrum.

Majocchi’s granuloma (MG) is cutaneous mycosis in which the fungal infection goes deeper into the hair follicle causing granulomatous folliculitis and perifolliculitis.1 It was first described by Domenico Majocchi in 1883, and he named the condition “granuloma tricofitico.”2

It is commonly caused by T. rubrum but also can be caused by T. mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans, T. verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Epidermophyton floccosum.2,3 Patients at risk for developing this infection include those previously treated with topical corticosteroids, immunosuppressed patients, patients with areas under occlusion, and those with areas traumatized by shaving. This infection is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, but can happen anywhere in the body. The lesions present as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque as seen on our patient.

A KOH test of skin scrapings and hair extractions often can reveal fungal hyphae. Identification of the pathogen can be performed with culture or polymerase chain reaction of skin samples. If the diagnosis is uncertain or the KOH is negative, a skin biopsy can be performed. Histopathologic examination reveals perifollicular granulomas with associated dermal abscesses. Giant cells may be observed. MG is associated with chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.2,3

The differential diagnosis for these lesions in children includes other granulomatous conditions such as granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, and granuloma faciale, as well as bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

Treatment of MG requires systemic treatment with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine for at least 4-8 weeks or until all the lesions have resolved. Our patient was treated with 6 weeks of high-dose griseofulvin with resolution of her lesions.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Dec 15;24(12):13030/qt89k4t6wj.

2. Med Mycol. 2012 Jul;50(5):449-57.

3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80.

Scrapings of the child’s rash were analyzed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) under microscopy which revealed multiple septate hyphae.

She was diagnosed with Majocchi’s granuloma. The fungal culture was positive for Trichophyton rubrum.

Majocchi’s granuloma (MG) is cutaneous mycosis in which the fungal infection goes deeper into the hair follicle causing granulomatous folliculitis and perifolliculitis.1 It was first described by Domenico Majocchi in 1883, and he named the condition “granuloma tricofitico.”2

It is commonly caused by T. rubrum but also can be caused by T. mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans, T. verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Epidermophyton floccosum.2,3 Patients at risk for developing this infection include those previously treated with topical corticosteroids, immunosuppressed patients, patients with areas under occlusion, and those with areas traumatized by shaving. This infection is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, but can happen anywhere in the body. The lesions present as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque as seen on our patient.

A KOH test of skin scrapings and hair extractions often can reveal fungal hyphae. Identification of the pathogen can be performed with culture or polymerase chain reaction of skin samples. If the diagnosis is uncertain or the KOH is negative, a skin biopsy can be performed. Histopathologic examination reveals perifollicular granulomas with associated dermal abscesses. Giant cells may be observed. MG is associated with chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.2,3

The differential diagnosis for these lesions in children includes other granulomatous conditions such as granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, and granuloma faciale, as well as bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

Treatment of MG requires systemic treatment with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine for at least 4-8 weeks or until all the lesions have resolved. Our patient was treated with 6 weeks of high-dose griseofulvin with resolution of her lesions.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Dec 15;24(12):13030/qt89k4t6wj.

2. Med Mycol. 2012 Jul;50(5):449-57.

3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80.

Scrapings of the child’s rash were analyzed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) under microscopy which revealed multiple septate hyphae.

She was diagnosed with Majocchi’s granuloma. The fungal culture was positive for Trichophyton rubrum.

Majocchi’s granuloma (MG) is cutaneous mycosis in which the fungal infection goes deeper into the hair follicle causing granulomatous folliculitis and perifolliculitis.1 It was first described by Domenico Majocchi in 1883, and he named the condition “granuloma tricofitico.”2

It is commonly caused by T. rubrum but also can be caused by T. mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans, T. verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Epidermophyton floccosum.2,3 Patients at risk for developing this infection include those previously treated with topical corticosteroids, immunosuppressed patients, patients with areas under occlusion, and those with areas traumatized by shaving. This infection is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, but can happen anywhere in the body. The lesions present as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque as seen on our patient.

A KOH test of skin scrapings and hair extractions often can reveal fungal hyphae. Identification of the pathogen can be performed with culture or polymerase chain reaction of skin samples. If the diagnosis is uncertain or the KOH is negative, a skin biopsy can be performed. Histopathologic examination reveals perifollicular granulomas with associated dermal abscesses. Giant cells may be observed. MG is associated with chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.2,3

The differential diagnosis for these lesions in children includes other granulomatous conditions such as granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, and granuloma faciale, as well as bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

Treatment of MG requires systemic treatment with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine for at least 4-8 weeks or until all the lesions have resolved. Our patient was treated with 6 weeks of high-dose griseofulvin with resolution of her lesions.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Dec 15;24(12):13030/qt89k4t6wj.

2. Med Mycol. 2012 Jul;50(5):449-57.

3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80.

A 3-year-old girl with a known history of eczema presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent rash for about a year on the right cheek.

The mother reported she was treating the lesions with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% as instructed previously for her eczema. Initially the rash got partially better but then started getting worse again. The area was itchy.

The child was later seen in the emergency department, where she was recommended to treat the area with a combination cream of terbinafine 1% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%. The mother applied this cream as instructed for 3 weeks with some improvement of the lesions on the cheek.

A few weeks later, pimples started coming back. The mother tried the medication again but this time it was not helpful and the rash continued to expand.

The mother reported having a rash on her hand months back, which she successfully treated with the combination cream provided at the emergency department. They have no pets at home.

The child has a little sister who also has mild eczema.

She goes to day care and dances ballet.

FDA makes Ilaris the first approved treatment for adult-onset Still’s disease

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indications for canakinumab (Ilaris) to include all patients with active Still’s disease older than 2 years, adding adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) to a previous approval for juvenile-onset Still’s disease, also known as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), making it the first approved treatment for AOSD, according to an FDA announcement.

The approval comes under a Priority Review designation that used “comparable pharmacokinetic exposure and extrapolation of established efficacy of canakinumab in patients with sJIA, as well as the safety of canakinumab in patients with AOSD and other diseases,” the FDA said.

The results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 36 patients with AOSD aged 22-70 years showed that the efficacy and safety data in AOSD were generally consistent with the results of a pooled analysis of sJIA patients, according to Novartis, which markets canakinumab.

AOSD and sJIA share certain similarities, such as fever, arthritis, rash, and elevated markers of inflammation, which has led to suspicion that they are part of a continuum rather than wholly distinct, according to the agency. In addition, the role of interleukin-1 is well established in both diseases and is blocked by canakinumab.

The most common side effects (occurring in greater than 10% of patients) in sJIA studies included infections, abdominal pain, and injection-site reactions. Serious infections (e.g., pneumonia, varicella, gastroenteritis, measles, sepsis, otitis media, sinusitis, adenovirus, lymph node abscess, pharyngitis) were observed in approximately 4%-5%, according to the full prescribing information.

Canakinumab is also approved for the periodic fever syndromes of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes in adults and children aged 4 years and older (including familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome), tumor necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome in adult and pediatric patients, hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome/mevalonate kinase deficiency in adult and pediatric patients, and familial Mediterranean fever in adult and pediatric patients.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indications for canakinumab (Ilaris) to include all patients with active Still’s disease older than 2 years, adding adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) to a previous approval for juvenile-onset Still’s disease, also known as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), making it the first approved treatment for AOSD, according to an FDA announcement.

The approval comes under a Priority Review designation that used “comparable pharmacokinetic exposure and extrapolation of established efficacy of canakinumab in patients with sJIA, as well as the safety of canakinumab in patients with AOSD and other diseases,” the FDA said.

The results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 36 patients with AOSD aged 22-70 years showed that the efficacy and safety data in AOSD were generally consistent with the results of a pooled analysis of sJIA patients, according to Novartis, which markets canakinumab.

AOSD and sJIA share certain similarities, such as fever, arthritis, rash, and elevated markers of inflammation, which has led to suspicion that they are part of a continuum rather than wholly distinct, according to the agency. In addition, the role of interleukin-1 is well established in both diseases and is blocked by canakinumab.

The most common side effects (occurring in greater than 10% of patients) in sJIA studies included infections, abdominal pain, and injection-site reactions. Serious infections (e.g., pneumonia, varicella, gastroenteritis, measles, sepsis, otitis media, sinusitis, adenovirus, lymph node abscess, pharyngitis) were observed in approximately 4%-5%, according to the full prescribing information.

Canakinumab is also approved for the periodic fever syndromes of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes in adults and children aged 4 years and older (including familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome), tumor necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome in adult and pediatric patients, hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome/mevalonate kinase deficiency in adult and pediatric patients, and familial Mediterranean fever in adult and pediatric patients.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indications for canakinumab (Ilaris) to include all patients with active Still’s disease older than 2 years, adding adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) to a previous approval for juvenile-onset Still’s disease, also known as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), making it the first approved treatment for AOSD, according to an FDA announcement.

The approval comes under a Priority Review designation that used “comparable pharmacokinetic exposure and extrapolation of established efficacy of canakinumab in patients with sJIA, as well as the safety of canakinumab in patients with AOSD and other diseases,” the FDA said.

The results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 36 patients with AOSD aged 22-70 years showed that the efficacy and safety data in AOSD were generally consistent with the results of a pooled analysis of sJIA patients, according to Novartis, which markets canakinumab.

AOSD and sJIA share certain similarities, such as fever, arthritis, rash, and elevated markers of inflammation, which has led to suspicion that they are part of a continuum rather than wholly distinct, according to the agency. In addition, the role of interleukin-1 is well established in both diseases and is blocked by canakinumab.

The most common side effects (occurring in greater than 10% of patients) in sJIA studies included infections, abdominal pain, and injection-site reactions. Serious infections (e.g., pneumonia, varicella, gastroenteritis, measles, sepsis, otitis media, sinusitis, adenovirus, lymph node abscess, pharyngitis) were observed in approximately 4%-5%, according to the full prescribing information.

Canakinumab is also approved for the periodic fever syndromes of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes in adults and children aged 4 years and older (including familial cold auto-inflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome), tumor necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome in adult and pediatric patients, hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome/mevalonate kinase deficiency in adult and pediatric patients, and familial Mediterranean fever in adult and pediatric patients.

Getting unstuck: Helping patients with behavior change

Kyle is a 14-year-old cisgender male who just moved to your town. At his first well-check, his single father brings him in reluctantly, stating, “We’ve never liked doctors.” Kyle has a history of asthma and obesity that have been relatively unchanged over time. He is an average student, an avid gamer, and seems somewhat shy. Privately he admits to occasional cannabis use. His father has no concerns, lamenting, “He’s always been pretty healthy for a fat kid.” Next patient?

Of course there is a lot to work with here. You might be concerned with Kyle’s asthma; his weight, sedentary nature, and body image; the criticism from his father and concerns about self-esteem; the possibility of anxiety in relation to his shyness; and the health effects of his cannabis use. In the end, recommendations for behavior change seem likely. These might take the form of tips on exercise, nutrition, substance use, study habits, parenting, social activities, or mental health support; the literature on behavior change would suggest that any success will be predicated on trust. How can we learn from someone we do not trust?1

To build trust is no easy task, and yet is perhaps the foundation on which the entire clinical relationship rests. Guidance from decades of evidence supporting the use of motivational interviewing2 suggests that the process of building rapport can be neatly summed up in an acronym as PACE. This represents Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation. Almost too clichéd to repeat, the most powerful change agent is the person making the change. In the setting of pediatric health care, we sometimes lean on caregivers to initiate or promote change because they are an intimate part of the patient’s microsystem, and thus moving one gear (the parents) inevitably shifts something in connected gears (the children).

So Partnership is centered on the patient, but inclusive of any important person in the patient’s sphere. In a family-based approach, this might show up as leveraging Kyle’s father’s motivation for behavior change by having the father start an exercise routine. This role models behavior change, shifts the home environment around the behavior, and builds empathy in the parent for the inherent challenges of change processes.

Acceptance can be distilled into knowing that the patient and family are doing the best they can. This does not preclude the possibility of change, but it seats this possibility in an attitude of assumed adequacy. There is nothing wrong with the patient, nothing to be fixed, just the possibility for change.

Similarly, Compassion takes a nonjudgmental viewpoint. With the stance of “this could happen to anybody,” the patient can feel responsible without feeling blamed. Noting the patient’s suffering without blame allows the clinician to be motivated not just to empathize, but to help.

And from this basis of compassionate partnership, the work of Evocation begins. What is happening in the patient’s life and relationships? What are their own goals and values? Where are the discrepancies between what the patient wants and what the patient does? For teenagers, this often brings into conflict developmentally appropriate wishes for autonomy – wanting to drive or get a car or stay out later or have more privacy – with developmentally typical challenges regarding responsibility.3 For example:

Clinician: “You want to use the car, and your parents want you to pay for the gas, but you’re out of money from buying weed. I see how you’re stuck.”

Teen: “Yeah, they really need to give me more allowance. It’s not like we’re living in the 1990s anymore!”

Clinician: “So you could ask for more allowance to get more money for gas. Any other ideas?”

Teen: “I could give up smoking pot and just be miserable all the time.”

Clinician: “Yeah, that sounds too difficult right now; if anything it sounds like you’d like to smoke more pot if you had more money.”

Teen: “Nah, I’m not that hooked on it. ... I could probably smoke a bit less each week and save some gas money.”

The PACE acronym also serves as a reminder of the patience required to grow connection where none has previously existed – pace yourself. Here are some skills-based tips to foster the spirit of motivational interviewing to help balance patience with the time frame of a pediatric check-in. The OARS skills represent the fundamental building blocks of motivational interviewing in practice. Taking the case of Kyle as an example, an Open-Ended Question makes space for the child or parent to express their views with less interviewer bias. Reflections expand this space by underscoring and, in the case of complex Reflections, adding some nuance to what the patient has to say.

Clinician: “How do you feel about your body?”

Teen: “Well, I’m fat. Nobody really wants to be fat. It sucks. But what can I do?”

Clinician: “You feel fat and kind of hopeless.”

Teen: “Yeah, I know you’re going to tell me to go on a diet and start exercising. Doesn’t work. My dad says I was born fat; I guess I’m going to stay that way.”

Clinician: “Sounds like you and your dad can get down on you for your weight. That must feel terrible.”

Teen: “Ah, it’s not that bad. I’m kind of used to it. Fat kid at home, fat kid at school.”

Affirmations are statements focusing on positive actions or attributes of the patient. They tend to build rapport by demonstrating that the clinician sees the strengths of the patient, not just the problems.

Clinician: “I’m pretty impressed that you’re able to show up here and talk about this. It can’t be easy when it sounds like your family and friends have put you down so much that you’re even putting yourself down about your body.”

Teen: “I didn’t really want to come, but then I thought, maybe this new doctor will have some new ideas. I actually want to do something about it, I just don’t know if anything will help. Plus my dad said if I showed up, we could go to McDonald’s afterward.”

Summaries are multipurpose. They demonstrate that you have been listening closely, which builds rapport. They provide a chance to put information together so that both clinician and patient can reflect on the sum of the data and notice what may be missing. And they provide a pause to consider where to go next.

Clinician: “So if I’m getting it right, you’ve been worried about your weight for a long time now. Your dad and your friends give you a hard time about it, which makes you feel down and hopeless, but somehow you stay brave and keep trying to figure it out. You feel ready to do something, you just don’t know what, and you were hoping maybe coming here could give you a place to work on your health. Does that sound about right?”

Teen: “I think that’s pretty much it. Plus the McDonald’s.”

Clinician: “Right, that’s important too – we have to consider your motivation! I wonder if we could talk about this more at our next visit – would that be alright?”

Offices with additional resources might be able to offer some of those as well, if timing seems appropriate; for example, referral to a wellness coach or social worker or nutritionist could be helpful int his case. With the spirit of PACE and the skills of OARS, you can be well on your way to fostering behavior changes that could last a lifetime! Check out the resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics with video and narrative demonstrations of motivational interviewing in pediatrics.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center and the university’s Robert Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. He reported no relevant disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “Engagement and disengagement,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

2. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “The spirit of motivational interviewing,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

3. Naar S, Suarez M. “Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A brief review of development,” in “Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults” (New York: Guilford, 2011).

Kyle is a 14-year-old cisgender male who just moved to your town. At his first well-check, his single father brings him in reluctantly, stating, “We’ve never liked doctors.” Kyle has a history of asthma and obesity that have been relatively unchanged over time. He is an average student, an avid gamer, and seems somewhat shy. Privately he admits to occasional cannabis use. His father has no concerns, lamenting, “He’s always been pretty healthy for a fat kid.” Next patient?

Of course there is a lot to work with here. You might be concerned with Kyle’s asthma; his weight, sedentary nature, and body image; the criticism from his father and concerns about self-esteem; the possibility of anxiety in relation to his shyness; and the health effects of his cannabis use. In the end, recommendations for behavior change seem likely. These might take the form of tips on exercise, nutrition, substance use, study habits, parenting, social activities, or mental health support; the literature on behavior change would suggest that any success will be predicated on trust. How can we learn from someone we do not trust?1

To build trust is no easy task, and yet is perhaps the foundation on which the entire clinical relationship rests. Guidance from decades of evidence supporting the use of motivational interviewing2 suggests that the process of building rapport can be neatly summed up in an acronym as PACE. This represents Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation. Almost too clichéd to repeat, the most powerful change agent is the person making the change. In the setting of pediatric health care, we sometimes lean on caregivers to initiate or promote change because they are an intimate part of the patient’s microsystem, and thus moving one gear (the parents) inevitably shifts something in connected gears (the children).

So Partnership is centered on the patient, but inclusive of any important person in the patient’s sphere. In a family-based approach, this might show up as leveraging Kyle’s father’s motivation for behavior change by having the father start an exercise routine. This role models behavior change, shifts the home environment around the behavior, and builds empathy in the parent for the inherent challenges of change processes.

Acceptance can be distilled into knowing that the patient and family are doing the best they can. This does not preclude the possibility of change, but it seats this possibility in an attitude of assumed adequacy. There is nothing wrong with the patient, nothing to be fixed, just the possibility for change.

Similarly, Compassion takes a nonjudgmental viewpoint. With the stance of “this could happen to anybody,” the patient can feel responsible without feeling blamed. Noting the patient’s suffering without blame allows the clinician to be motivated not just to empathize, but to help.

And from this basis of compassionate partnership, the work of Evocation begins. What is happening in the patient’s life and relationships? What are their own goals and values? Where are the discrepancies between what the patient wants and what the patient does? For teenagers, this often brings into conflict developmentally appropriate wishes for autonomy – wanting to drive or get a car or stay out later or have more privacy – with developmentally typical challenges regarding responsibility.3 For example:

Clinician: “You want to use the car, and your parents want you to pay for the gas, but you’re out of money from buying weed. I see how you’re stuck.”

Teen: “Yeah, they really need to give me more allowance. It’s not like we’re living in the 1990s anymore!”

Clinician: “So you could ask for more allowance to get more money for gas. Any other ideas?”

Teen: “I could give up smoking pot and just be miserable all the time.”

Clinician: “Yeah, that sounds too difficult right now; if anything it sounds like you’d like to smoke more pot if you had more money.”

Teen: “Nah, I’m not that hooked on it. ... I could probably smoke a bit less each week and save some gas money.”

The PACE acronym also serves as a reminder of the patience required to grow connection where none has previously existed – pace yourself. Here are some skills-based tips to foster the spirit of motivational interviewing to help balance patience with the time frame of a pediatric check-in. The OARS skills represent the fundamental building blocks of motivational interviewing in practice. Taking the case of Kyle as an example, an Open-Ended Question makes space for the child or parent to express their views with less interviewer bias. Reflections expand this space by underscoring and, in the case of complex Reflections, adding some nuance to what the patient has to say.

Clinician: “How do you feel about your body?”

Teen: “Well, I’m fat. Nobody really wants to be fat. It sucks. But what can I do?”

Clinician: “You feel fat and kind of hopeless.”

Teen: “Yeah, I know you’re going to tell me to go on a diet and start exercising. Doesn’t work. My dad says I was born fat; I guess I’m going to stay that way.”

Clinician: “Sounds like you and your dad can get down on you for your weight. That must feel terrible.”

Teen: “Ah, it’s not that bad. I’m kind of used to it. Fat kid at home, fat kid at school.”

Affirmations are statements focusing on positive actions or attributes of the patient. They tend to build rapport by demonstrating that the clinician sees the strengths of the patient, not just the problems.

Clinician: “I’m pretty impressed that you’re able to show up here and talk about this. It can’t be easy when it sounds like your family and friends have put you down so much that you’re even putting yourself down about your body.”

Teen: “I didn’t really want to come, but then I thought, maybe this new doctor will have some new ideas. I actually want to do something about it, I just don’t know if anything will help. Plus my dad said if I showed up, we could go to McDonald’s afterward.”

Summaries are multipurpose. They demonstrate that you have been listening closely, which builds rapport. They provide a chance to put information together so that both clinician and patient can reflect on the sum of the data and notice what may be missing. And they provide a pause to consider where to go next.

Clinician: “So if I’m getting it right, you’ve been worried about your weight for a long time now. Your dad and your friends give you a hard time about it, which makes you feel down and hopeless, but somehow you stay brave and keep trying to figure it out. You feel ready to do something, you just don’t know what, and you were hoping maybe coming here could give you a place to work on your health. Does that sound about right?”

Teen: “I think that’s pretty much it. Plus the McDonald’s.”

Clinician: “Right, that’s important too – we have to consider your motivation! I wonder if we could talk about this more at our next visit – would that be alright?”

Offices with additional resources might be able to offer some of those as well, if timing seems appropriate; for example, referral to a wellness coach or social worker or nutritionist could be helpful int his case. With the spirit of PACE and the skills of OARS, you can be well on your way to fostering behavior changes that could last a lifetime! Check out the resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics with video and narrative demonstrations of motivational interviewing in pediatrics.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center and the university’s Robert Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. He reported no relevant disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “Engagement and disengagement,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

2. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “The spirit of motivational interviewing,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

3. Naar S, Suarez M. “Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A brief review of development,” in “Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults” (New York: Guilford, 2011).

Kyle is a 14-year-old cisgender male who just moved to your town. At his first well-check, his single father brings him in reluctantly, stating, “We’ve never liked doctors.” Kyle has a history of asthma and obesity that have been relatively unchanged over time. He is an average student, an avid gamer, and seems somewhat shy. Privately he admits to occasional cannabis use. His father has no concerns, lamenting, “He’s always been pretty healthy for a fat kid.” Next patient?

Of course there is a lot to work with here. You might be concerned with Kyle’s asthma; his weight, sedentary nature, and body image; the criticism from his father and concerns about self-esteem; the possibility of anxiety in relation to his shyness; and the health effects of his cannabis use. In the end, recommendations for behavior change seem likely. These might take the form of tips on exercise, nutrition, substance use, study habits, parenting, social activities, or mental health support; the literature on behavior change would suggest that any success will be predicated on trust. How can we learn from someone we do not trust?1

To build trust is no easy task, and yet is perhaps the foundation on which the entire clinical relationship rests. Guidance from decades of evidence supporting the use of motivational interviewing2 suggests that the process of building rapport can be neatly summed up in an acronym as PACE. This represents Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation. Almost too clichéd to repeat, the most powerful change agent is the person making the change. In the setting of pediatric health care, we sometimes lean on caregivers to initiate or promote change because they are an intimate part of the patient’s microsystem, and thus moving one gear (the parents) inevitably shifts something in connected gears (the children).

So Partnership is centered on the patient, but inclusive of any important person in the patient’s sphere. In a family-based approach, this might show up as leveraging Kyle’s father’s motivation for behavior change by having the father start an exercise routine. This role models behavior change, shifts the home environment around the behavior, and builds empathy in the parent for the inherent challenges of change processes.

Acceptance can be distilled into knowing that the patient and family are doing the best they can. This does not preclude the possibility of change, but it seats this possibility in an attitude of assumed adequacy. There is nothing wrong with the patient, nothing to be fixed, just the possibility for change.

Similarly, Compassion takes a nonjudgmental viewpoint. With the stance of “this could happen to anybody,” the patient can feel responsible without feeling blamed. Noting the patient’s suffering without blame allows the clinician to be motivated not just to empathize, but to help.

And from this basis of compassionate partnership, the work of Evocation begins. What is happening in the patient’s life and relationships? What are their own goals and values? Where are the discrepancies between what the patient wants and what the patient does? For teenagers, this often brings into conflict developmentally appropriate wishes for autonomy – wanting to drive or get a car or stay out later or have more privacy – with developmentally typical challenges regarding responsibility.3 For example:

Clinician: “You want to use the car, and your parents want you to pay for the gas, but you’re out of money from buying weed. I see how you’re stuck.”

Teen: “Yeah, they really need to give me more allowance. It’s not like we’re living in the 1990s anymore!”

Clinician: “So you could ask for more allowance to get more money for gas. Any other ideas?”

Teen: “I could give up smoking pot and just be miserable all the time.”

Clinician: “Yeah, that sounds too difficult right now; if anything it sounds like you’d like to smoke more pot if you had more money.”

Teen: “Nah, I’m not that hooked on it. ... I could probably smoke a bit less each week and save some gas money.”

The PACE acronym also serves as a reminder of the patience required to grow connection where none has previously existed – pace yourself. Here are some skills-based tips to foster the spirit of motivational interviewing to help balance patience with the time frame of a pediatric check-in. The OARS skills represent the fundamental building blocks of motivational interviewing in practice. Taking the case of Kyle as an example, an Open-Ended Question makes space for the child or parent to express their views with less interviewer bias. Reflections expand this space by underscoring and, in the case of complex Reflections, adding some nuance to what the patient has to say.

Clinician: “How do you feel about your body?”

Teen: “Well, I’m fat. Nobody really wants to be fat. It sucks. But what can I do?”

Clinician: “You feel fat and kind of hopeless.”

Teen: “Yeah, I know you’re going to tell me to go on a diet and start exercising. Doesn’t work. My dad says I was born fat; I guess I’m going to stay that way.”

Clinician: “Sounds like you and your dad can get down on you for your weight. That must feel terrible.”

Teen: “Ah, it’s not that bad. I’m kind of used to it. Fat kid at home, fat kid at school.”

Affirmations are statements focusing on positive actions or attributes of the patient. They tend to build rapport by demonstrating that the clinician sees the strengths of the patient, not just the problems.

Clinician: “I’m pretty impressed that you’re able to show up here and talk about this. It can’t be easy when it sounds like your family and friends have put you down so much that you’re even putting yourself down about your body.”

Teen: “I didn’t really want to come, but then I thought, maybe this new doctor will have some new ideas. I actually want to do something about it, I just don’t know if anything will help. Plus my dad said if I showed up, we could go to McDonald’s afterward.”

Summaries are multipurpose. They demonstrate that you have been listening closely, which builds rapport. They provide a chance to put information together so that both clinician and patient can reflect on the sum of the data and notice what may be missing. And they provide a pause to consider where to go next.

Clinician: “So if I’m getting it right, you’ve been worried about your weight for a long time now. Your dad and your friends give you a hard time about it, which makes you feel down and hopeless, but somehow you stay brave and keep trying to figure it out. You feel ready to do something, you just don’t know what, and you were hoping maybe coming here could give you a place to work on your health. Does that sound about right?”

Teen: “I think that’s pretty much it. Plus the McDonald’s.”

Clinician: “Right, that’s important too – we have to consider your motivation! I wonder if we could talk about this more at our next visit – would that be alright?”

Offices with additional resources might be able to offer some of those as well, if timing seems appropriate; for example, referral to a wellness coach or social worker or nutritionist could be helpful int his case. With the spirit of PACE and the skills of OARS, you can be well on your way to fostering behavior changes that could last a lifetime! Check out the resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics with video and narrative demonstrations of motivational interviewing in pediatrics.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center and the university’s Robert Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. He reported no relevant disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “Engagement and disengagement,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

2. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “The spirit of motivational interviewing,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

3. Naar S, Suarez M. “Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A brief review of development,” in “Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults” (New York: Guilford, 2011).

Racism: Developmental perspective can inform tough conversations

Can we help our pediatric patients with the complicated problems of racism, especially if we are privileged (and even white) professionals? We may not have experienced discrimination, but we can still advise and address it. Racist discrimination, fear, trauma, or distress may produce or exacerbate conditions we are treating.

Three levels of racism impact children’s health and health care: “structural or institutional” policies that influence social determinants of health; “personally mediated” differential treatment based on assumptions about one’s abilities, motives, or intents; and the resulting “internalization” of stereotypes into one’s identity, undermining confidence, self-esteem, and mental health. We can help advocate about structural racism and ensure equity within our offices, but how best to counsel the families and children themselves?

Racism includes actions of “assigning value based on the social interpretation of how a person looks” (Ethn Dis. 2008;18[4]:496-504). “Social interpretations” develop from an early age. Newborns detect differences in appearance and may startle or cry seeing a parent’s drastic haircut or new hat. Parents generally know to use soothing words and tone, bring the difference into view gradually, smile and comfort the child, and explain the change; these are good skills for later, too. Infants notice skin color, which, unlike clothes, is a stable feature by which to recognize parents. Social interpretation of these differences is cued from the parents’ feelings and reactions. Adults naturally transmit biases from their own past unless they work to dampen them. If the parent was taught to regard “other” as negative or is generally fearful, the child mirrors this. Working to reduce racism thus requires parents (and professionals) to examine their prejudices to be able to convey positive or neutral reactions to people who are different. Parents need to show curiosity, positive affect, and comfort about people who are different, and do well to seek contact and friendships with people from other groups and include their children in these relationships. We can encourage this outreach plus ensure diversity and respectful interactions in our offices.

Children from age 3 years value fairness and are upset seeing others treated unfairly – easily understanding “not fair” or “mean.” If the person being hurt is like them in race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexual preference, they also fear for themselves, family, and friends. Balance is needed in discussing racism to avoid increasing fear or overpromising as risks are real and solutions difficult. Children look to adults for understanding and evidence of action to feel safer, rather than helpless. We should state that leaders are working on “making the rules more fair,” ensuring that people “won’t be allowed do it again,” and “teaching that everyone deserves respect.” Even better, parents and children can generate ideas about child actions, giving them some power as an antidote to anxiety. Age-related possibilities might include drawing a picture of people getting along, talking at show-and-tell, writing a note to officials, making a protest sign, posting thoughts on Facebook, or protesting.

With age, the culture increasingly influences a child’s attitudes. Children see lots of teasing and bullying based on differences from being overweight or wearing glasses, to skin color. It is helpful to interpret for children that bullies are insecure, or sometimes have been hurt, and they put other people down to feel better than someone else. Thinking about racist acts this way may reduce the desire for revenge and a cycle of aggression. Effective anti-bullying programs help children recognize bullying, see it as an emergency that requires their action, tell adults, and take action. This action could be surrounding the bully, standing tall, making eye contact, having a dismissive retort, or asking questions that require the bully to think, such as “What do you want to happen by doing this?” We can coach our patients and their parents on these principles as well as advising schools.

Children need to be told that those being put down or held down – especially those like them – have strengths; have made discoveries; have produced writings, art, and music; have shown military bravery, moral leadership, and resistance to discrimination, but it is not the time to show strength when confronted by a gun or police. We can use and arm parents with examples to discuss strengths and accomplishments to help buffer the child from internalization of racist stereotypes. Children need positive role models who look like them; parents can seek out diverse professionals in their children’s lives, such as dentists, doctors, teachers, clergy, mentors, or coaches. We, and parents, can ensure that dolls and books are available, and that the children’s shows, movies, and video games are watched together and include diverse people doing good or brave things. These exposures also are key to all children becoming anti-racist.

Parents can be advised to initiate discussion of racism because children, detecting adult discomfort, may avoid the topic. We can encourage families to give their point of view; otherwise children simply absorb those of peers or the press. Parents should tell their children, “I want you to be able to talk about it if someone is mean or treats you unfairly because of [the color of your skin, your religion, your sex, your disability, etc.]. You might feel helpless, or angry, which is natural. We need to talk about this so you can feel strong. Then we can plan on what we are going to do.” The “sandwich” method of “ask-give information-ask what they think” can encourage discussion and correct misperceptions.

Racist policies have succeeded partly by adult “bullies” dehumanizing the “other.” Most children can consider someone else’s point of view by 4½ years old, shaped with adult help. Parents can begin by telling babies, “That hurts, doesn’t it?” asking toddlers and older, “How would you feel if ... [someone called you a name just because of having red hair]?” or “How do you think she feels when ... [someone pushes her out of line because she wears certain clothes]?” in cases of grabbing, not sharing, hitting, bullying, etc. Older children and teens can analyze more abstract situations when asked, “What if you were the one who ... [got expelled for mumbling about the teacher]?” or “What if that were your sister?” or “How would the world be if everyone ... [got a chance to go to college]?” We can encourage parents to propose these mental exercises to build the child’s perspective-taking while conveying their opinions.

Experiences, including through media, may increase or decrease fear; the child needs to have a supportive person moderating the exposure, providing a positive interpretation, and protecting the child from overwhelm, if needed.

Experiences are insufficient for developing anti-racist attitudes; listening and talking are needed. The first step is to ask children about what they notice, think, and feel about situations reflecting racism, especially as they lack words for these complicated observations. There are television, Internet, and newspaper examples of both racism and anti-racism that can be fruitfully discussed. We can recommend watching or reading together, and asking questions such as, “Why do you think they are shouting [protesting]?” “How do you think the [victim, police] felt?” or “What do you think should be done about this?”

It is important to acknowledge the child’s confusion, fear, anxiety, sadness, or anger as normal and appropriate, not dismissing, too quickly reassuring, or changing the subject, even though it’s uncomfortable.