User login

Dupilumab hits the mark for severe AD in younger children

The monoclonal antibody , according to new clinical trial results.

In a cohort of children with severe AD, 33% achieved clear or nearly clear skin after 16 weeks of treatment with every 4-week dosing of the injectable medication, while 30% also achieved that mark when receiving a weight-based dose every 2 weeks. Both groups had results that were significantly better than those receiving placebo, with 11% of these children had clear or nearly clear skin by 16 weeks of dupilumab (Dupixent) therapy (P less than .0001 for both therapy arms versus placebo).

“Dupilumab with a topical corticosteroid showed clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in the atopic dermatitis signs and symptoms in children aged 6 to less than 12 years of age with severe atopic dermatitis,” said Amy Paller, MD, the Walter J. Hamlin professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presenting the results at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. Portions of the conference, which has been rescheduled to December 2020, in Chicago, were presented virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The phase 3 trial of subcutaneously injected dupilumab for atopic dermatitis, dubbed LIBERTY AD PEDS, included children aged 6-11 years with severe AD. The study’s primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale by study week 16.

For the purposes of reporting results to the European Medicines Agency, the investigators added a coprimary endpoint of patients reaching 75% clearing on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) by week 16.

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled 367 children with IGA scores of 4, denoting severe AD. The EASI score had to be at least 21 and patients had to endorse peak pruritus of at least 4 on a 0-10 numeric rating scale; body surface involvement had to be at least 15%. Patients went through a washout period of any systemic therapies before beginning the trial, which randomized patients 1:1:1 to receive placebo, dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks, or dupilumab every 2 weeks with weight-dependent dosing. All participants were also permitted topical corticosteroids.

Patients were an average of aged 8 years, about half were female, and about two-thirds were white. Most participants had developed AD within their first year of life. Patients were about evenly divided between weighing over and under 30 kg, which was the cutoff for 100 mcg versus 200 mcg dupilumab for the every-2-week dosing group.

Over 90% of patients had other atopic comorbidities, and the mean EASI score was about 38 with average weekly peak pruritus averaging 7.8 on the numeric rating scale.

“When we’re talking about how severe this population is, it’s interesting to note that about 30 to 35% were all that had been previously treated with either systemic steroids or some systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressants,” Dr. Paller pointed out. “I think that reflects the fact that so many of these very severely affected children are not put on a systemic therapy, but are still staying on topical therapies to try to control their disease.”

Looking at the proportion of patients reaching EASI-75, both dosing strategies for dupilumab out-performed placebo, with 70% of the every 4-week group and 67% of the every 2-week group reaching EASI-75 at 16 weeks, compared with 27% of those on placebo (P less than .0001 for both active arms). “These differences were seen very early on; by 2 weeks already, we can see that we’re starting to see a difference in both of these arms,” noted Dr. Paller, adding that the difference was statistically significant by 4 weeks into the study.

The overall group of dupilumab participants saw their EASI scores drop by about 80%, while those taking placebo saw a 49% drop in EASI scores.

For the group of participants weighing less than 30 kg, the every 4-week strategy resulted in better clearing as measured by both IGA and EASI-75. This effect wasn’t seen for heavier patients. Trough dupilumab concentrations at 16 weeks were higher for lighter patients with every 4-week dosing and for heavier patients with the biweekly strategy, noted Dr. Paller.

In terms of itch, 60% to 68% of participants receiving dupilumab had a drop of at least 3 points in peak pruritus on the numeric rating scale, compared with 21% of those receiving placebo (P less than .001), while about half of the dupilumab groups and 12% of the placebo group saw pruritus improvements of 4 points or more (P less than .001). Pruritus improved early in the active arms of the study, becoming statistically significant at the 2 to 4 week range.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were numerically higher in patients in the placebo group, including infections and adjudicated skin infections. Conjunctivitis occurred more frequently in the dupilumab group, as did injection-site reactions.

“Overall, dupilumab was well tolerated, and data were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile observed in adults and adolescents,” Dr. Paller said.

Dupilumab has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat moderate to severe AD in those aged 12 years and older whose disease can’t be adequately controlled with topical prescription medications, or when those treatments are not advisable.

The fully human monoclonal antibody blocks a shared receptor component for interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, which contribute to inflammation in AD, as well as asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Dr. Paller reported receiving support from multiple pharmaceutical companies including Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study.

The monoclonal antibody , according to new clinical trial results.

In a cohort of children with severe AD, 33% achieved clear or nearly clear skin after 16 weeks of treatment with every 4-week dosing of the injectable medication, while 30% also achieved that mark when receiving a weight-based dose every 2 weeks. Both groups had results that were significantly better than those receiving placebo, with 11% of these children had clear or nearly clear skin by 16 weeks of dupilumab (Dupixent) therapy (P less than .0001 for both therapy arms versus placebo).

“Dupilumab with a topical corticosteroid showed clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in the atopic dermatitis signs and symptoms in children aged 6 to less than 12 years of age with severe atopic dermatitis,” said Amy Paller, MD, the Walter J. Hamlin professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presenting the results at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. Portions of the conference, which has been rescheduled to December 2020, in Chicago, were presented virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The phase 3 trial of subcutaneously injected dupilumab for atopic dermatitis, dubbed LIBERTY AD PEDS, included children aged 6-11 years with severe AD. The study’s primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale by study week 16.

For the purposes of reporting results to the European Medicines Agency, the investigators added a coprimary endpoint of patients reaching 75% clearing on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) by week 16.

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled 367 children with IGA scores of 4, denoting severe AD. The EASI score had to be at least 21 and patients had to endorse peak pruritus of at least 4 on a 0-10 numeric rating scale; body surface involvement had to be at least 15%. Patients went through a washout period of any systemic therapies before beginning the trial, which randomized patients 1:1:1 to receive placebo, dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks, or dupilumab every 2 weeks with weight-dependent dosing. All participants were also permitted topical corticosteroids.

Patients were an average of aged 8 years, about half were female, and about two-thirds were white. Most participants had developed AD within their first year of life. Patients were about evenly divided between weighing over and under 30 kg, which was the cutoff for 100 mcg versus 200 mcg dupilumab for the every-2-week dosing group.

Over 90% of patients had other atopic comorbidities, and the mean EASI score was about 38 with average weekly peak pruritus averaging 7.8 on the numeric rating scale.

“When we’re talking about how severe this population is, it’s interesting to note that about 30 to 35% were all that had been previously treated with either systemic steroids or some systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressants,” Dr. Paller pointed out. “I think that reflects the fact that so many of these very severely affected children are not put on a systemic therapy, but are still staying on topical therapies to try to control their disease.”

Looking at the proportion of patients reaching EASI-75, both dosing strategies for dupilumab out-performed placebo, with 70% of the every 4-week group and 67% of the every 2-week group reaching EASI-75 at 16 weeks, compared with 27% of those on placebo (P less than .0001 for both active arms). “These differences were seen very early on; by 2 weeks already, we can see that we’re starting to see a difference in both of these arms,” noted Dr. Paller, adding that the difference was statistically significant by 4 weeks into the study.

The overall group of dupilumab participants saw their EASI scores drop by about 80%, while those taking placebo saw a 49% drop in EASI scores.

For the group of participants weighing less than 30 kg, the every 4-week strategy resulted in better clearing as measured by both IGA and EASI-75. This effect wasn’t seen for heavier patients. Trough dupilumab concentrations at 16 weeks were higher for lighter patients with every 4-week dosing and for heavier patients with the biweekly strategy, noted Dr. Paller.

In terms of itch, 60% to 68% of participants receiving dupilumab had a drop of at least 3 points in peak pruritus on the numeric rating scale, compared with 21% of those receiving placebo (P less than .001), while about half of the dupilumab groups and 12% of the placebo group saw pruritus improvements of 4 points or more (P less than .001). Pruritus improved early in the active arms of the study, becoming statistically significant at the 2 to 4 week range.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were numerically higher in patients in the placebo group, including infections and adjudicated skin infections. Conjunctivitis occurred more frequently in the dupilumab group, as did injection-site reactions.

“Overall, dupilumab was well tolerated, and data were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile observed in adults and adolescents,” Dr. Paller said.

Dupilumab has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat moderate to severe AD in those aged 12 years and older whose disease can’t be adequately controlled with topical prescription medications, or when those treatments are not advisable.

The fully human monoclonal antibody blocks a shared receptor component for interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, which contribute to inflammation in AD, as well as asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Dr. Paller reported receiving support from multiple pharmaceutical companies including Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study.

The monoclonal antibody , according to new clinical trial results.

In a cohort of children with severe AD, 33% achieved clear or nearly clear skin after 16 weeks of treatment with every 4-week dosing of the injectable medication, while 30% also achieved that mark when receiving a weight-based dose every 2 weeks. Both groups had results that were significantly better than those receiving placebo, with 11% of these children had clear or nearly clear skin by 16 weeks of dupilumab (Dupixent) therapy (P less than .0001 for both therapy arms versus placebo).

“Dupilumab with a topical corticosteroid showed clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in the atopic dermatitis signs and symptoms in children aged 6 to less than 12 years of age with severe atopic dermatitis,” said Amy Paller, MD, the Walter J. Hamlin professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, presenting the results at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. Portions of the conference, which has been rescheduled to December 2020, in Chicago, were presented virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The phase 3 trial of subcutaneously injected dupilumab for atopic dermatitis, dubbed LIBERTY AD PEDS, included children aged 6-11 years with severe AD. The study’s primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving a score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale by study week 16.

For the purposes of reporting results to the European Medicines Agency, the investigators added a coprimary endpoint of patients reaching 75% clearing on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) by week 16.

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled 367 children with IGA scores of 4, denoting severe AD. The EASI score had to be at least 21 and patients had to endorse peak pruritus of at least 4 on a 0-10 numeric rating scale; body surface involvement had to be at least 15%. Patients went through a washout period of any systemic therapies before beginning the trial, which randomized patients 1:1:1 to receive placebo, dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks, or dupilumab every 2 weeks with weight-dependent dosing. All participants were also permitted topical corticosteroids.

Patients were an average of aged 8 years, about half were female, and about two-thirds were white. Most participants had developed AD within their first year of life. Patients were about evenly divided between weighing over and under 30 kg, which was the cutoff for 100 mcg versus 200 mcg dupilumab for the every-2-week dosing group.

Over 90% of patients had other atopic comorbidities, and the mean EASI score was about 38 with average weekly peak pruritus averaging 7.8 on the numeric rating scale.

“When we’re talking about how severe this population is, it’s interesting to note that about 30 to 35% were all that had been previously treated with either systemic steroids or some systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressants,” Dr. Paller pointed out. “I think that reflects the fact that so many of these very severely affected children are not put on a systemic therapy, but are still staying on topical therapies to try to control their disease.”

Looking at the proportion of patients reaching EASI-75, both dosing strategies for dupilumab out-performed placebo, with 70% of the every 4-week group and 67% of the every 2-week group reaching EASI-75 at 16 weeks, compared with 27% of those on placebo (P less than .0001 for both active arms). “These differences were seen very early on; by 2 weeks already, we can see that we’re starting to see a difference in both of these arms,” noted Dr. Paller, adding that the difference was statistically significant by 4 weeks into the study.

The overall group of dupilumab participants saw their EASI scores drop by about 80%, while those taking placebo saw a 49% drop in EASI scores.

For the group of participants weighing less than 30 kg, the every 4-week strategy resulted in better clearing as measured by both IGA and EASI-75. This effect wasn’t seen for heavier patients. Trough dupilumab concentrations at 16 weeks were higher for lighter patients with every 4-week dosing and for heavier patients with the biweekly strategy, noted Dr. Paller.

In terms of itch, 60% to 68% of participants receiving dupilumab had a drop of at least 3 points in peak pruritus on the numeric rating scale, compared with 21% of those receiving placebo (P less than .001), while about half of the dupilumab groups and 12% of the placebo group saw pruritus improvements of 4 points or more (P less than .001). Pruritus improved early in the active arms of the study, becoming statistically significant at the 2 to 4 week range.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were numerically higher in patients in the placebo group, including infections and adjudicated skin infections. Conjunctivitis occurred more frequently in the dupilumab group, as did injection-site reactions.

“Overall, dupilumab was well tolerated, and data were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile observed in adults and adolescents,” Dr. Paller said.

Dupilumab has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat moderate to severe AD in those aged 12 years and older whose disease can’t be adequately controlled with topical prescription medications, or when those treatments are not advisable.

The fully human monoclonal antibody blocks a shared receptor component for interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, which contribute to inflammation in AD, as well as asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Dr. Paller reported receiving support from multiple pharmaceutical companies including Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2020

Autism prevalence: ‘Diminishing disparity’ between black and white children

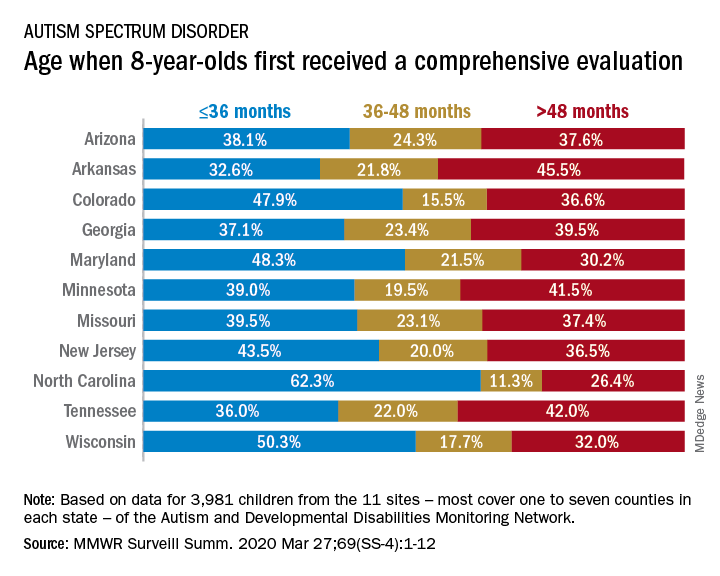

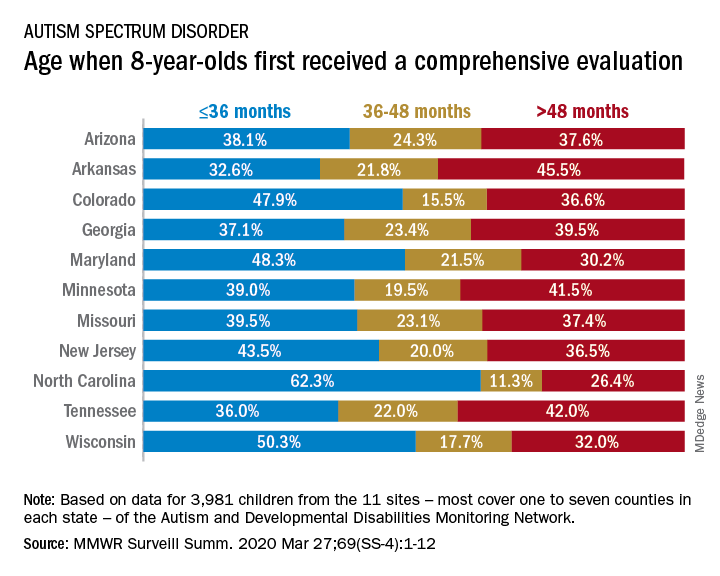

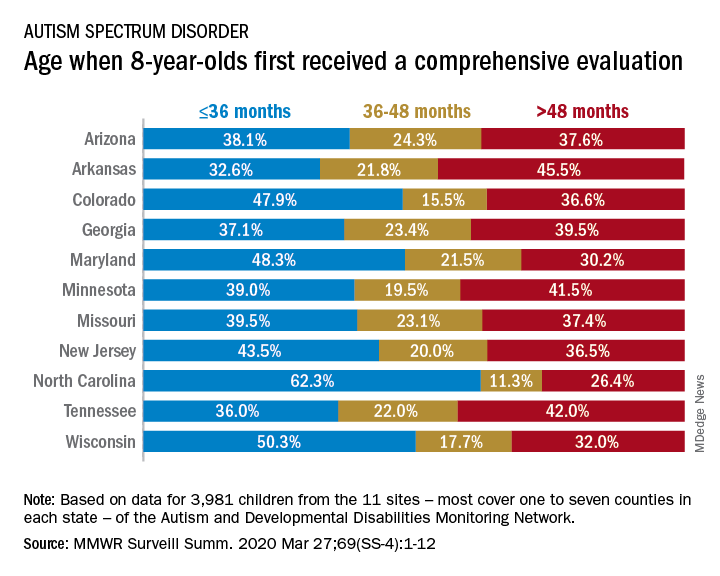

For the first time since detailed measurement began in 2000, there was no significant difference in autism prevalence between black and white 8-year-olds in 2016, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The latest analysis from the CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network puts the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at 18.3 per 1,000 children aged 8 years among black children and 18.5 per 1,000 in white children, Matthew J. Maenner, PhD, and associates said in MMWR Surveillance Summaries. Overall prevalence was 18.5 per 1,000 children, or 1 in 54 children, aged 8 years.

“This diminishing disparity in ASD prevalence might signify progress toward earlier and more equitable identification of ASD,” they wrote, while also noting that “black children with ASD were more likely than white children to have an intellectual disability” and were less likely to undergo evaluation by age 36 months.

and 42.9% of Hispanic children, said Dr. Maenner of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

The overall rate of early evaluation was 44% for the cohort of 3,981 children who were born in 2008 and included in the 2016 analysis of the 11 ADDM Network sites, they reported.

There was, however, considerable variation in the timing of that initial evaluation for ASD among the sites, which largely consisted of one to seven counties in most states, except for Arkansas (all 75 counties), Tennessee (11 counties), and Wisconsin (10 counties), Dr. Maenner and associates noted.

The two ADDM Network sites at the extremes of that variation were North Carolina and Arkansas. In North Carolina, almost twice as many children (62.3%) had an evaluation by 36 months than in Arkansas (32.6%), although Arkansas closed the gap a bit by evaluating 21.8% of children aged 37-48 months, compared with 11.3% in North Carolina, the investigators said.

“ASD continues to be a public health concern; the latest data from the ADDM Network underscore the ongoing need for timely and accessible developmental assessments, educational supports, and services for persons with ASD and their families,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Maenner MJ et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Mar 27;69(SS-4):1-12.

For the first time since detailed measurement began in 2000, there was no significant difference in autism prevalence between black and white 8-year-olds in 2016, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The latest analysis from the CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network puts the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at 18.3 per 1,000 children aged 8 years among black children and 18.5 per 1,000 in white children, Matthew J. Maenner, PhD, and associates said in MMWR Surveillance Summaries. Overall prevalence was 18.5 per 1,000 children, or 1 in 54 children, aged 8 years.

“This diminishing disparity in ASD prevalence might signify progress toward earlier and more equitable identification of ASD,” they wrote, while also noting that “black children with ASD were more likely than white children to have an intellectual disability” and were less likely to undergo evaluation by age 36 months.

and 42.9% of Hispanic children, said Dr. Maenner of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

The overall rate of early evaluation was 44% for the cohort of 3,981 children who were born in 2008 and included in the 2016 analysis of the 11 ADDM Network sites, they reported.

There was, however, considerable variation in the timing of that initial evaluation for ASD among the sites, which largely consisted of one to seven counties in most states, except for Arkansas (all 75 counties), Tennessee (11 counties), and Wisconsin (10 counties), Dr. Maenner and associates noted.

The two ADDM Network sites at the extremes of that variation were North Carolina and Arkansas. In North Carolina, almost twice as many children (62.3%) had an evaluation by 36 months than in Arkansas (32.6%), although Arkansas closed the gap a bit by evaluating 21.8% of children aged 37-48 months, compared with 11.3% in North Carolina, the investigators said.

“ASD continues to be a public health concern; the latest data from the ADDM Network underscore the ongoing need for timely and accessible developmental assessments, educational supports, and services for persons with ASD and their families,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Maenner MJ et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Mar 27;69(SS-4):1-12.

For the first time since detailed measurement began in 2000, there was no significant difference in autism prevalence between black and white 8-year-olds in 2016, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The latest analysis from the CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network puts the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at 18.3 per 1,000 children aged 8 years among black children and 18.5 per 1,000 in white children, Matthew J. Maenner, PhD, and associates said in MMWR Surveillance Summaries. Overall prevalence was 18.5 per 1,000 children, or 1 in 54 children, aged 8 years.

“This diminishing disparity in ASD prevalence might signify progress toward earlier and more equitable identification of ASD,” they wrote, while also noting that “black children with ASD were more likely than white children to have an intellectual disability” and were less likely to undergo evaluation by age 36 months.

and 42.9% of Hispanic children, said Dr. Maenner of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

The overall rate of early evaluation was 44% for the cohort of 3,981 children who were born in 2008 and included in the 2016 analysis of the 11 ADDM Network sites, they reported.

There was, however, considerable variation in the timing of that initial evaluation for ASD among the sites, which largely consisted of one to seven counties in most states, except for Arkansas (all 75 counties), Tennessee (11 counties), and Wisconsin (10 counties), Dr. Maenner and associates noted.

The two ADDM Network sites at the extremes of that variation were North Carolina and Arkansas. In North Carolina, almost twice as many children (62.3%) had an evaluation by 36 months than in Arkansas (32.6%), although Arkansas closed the gap a bit by evaluating 21.8% of children aged 37-48 months, compared with 11.3% in North Carolina, the investigators said.

“ASD continues to be a public health concern; the latest data from the ADDM Network underscore the ongoing need for timely and accessible developmental assessments, educational supports, and services for persons with ASD and their families,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Maenner MJ et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Mar 27;69(SS-4):1-12.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

Conducting cancer trials amid the COVID-19 pandemic

More than three-quarters of cancer clinical research programs have experienced operational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) during a recent webinar.

The webinar included insights into how some cancer research programs have adapted to the pandemic, a review of guidance for conducting cancer trials during this time, and a discussion of how the cancer research landscape may be affected by COVID-19 going forward.

The webinar was led by Randall A. Oyer, MD, president of the ACCC and medical director of the oncology program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health in Pennsylvania.

The impact of COVID-19 on cancer research

Dr. Oyer observed that planning and implementation for COVID-19–related illness at U.S. health care institutions has had a predictable effect of limiting patient access and staff availability for nonessential services.

Coronavirus-related exposure and/or illness has relegated cancer research to a lower-level priority. As a result, ACCC institutions have made adjustments in their cancer research programs, including moving clinical research coordinators off-campus and deploying them in clinical areas.

New clinical trials have not been opened. In some cases, new accruals have been halted, particularly for registry, prevention, and symptom control trials.

Standards that have changed and those that have not

Guidance documents for conducting clinical trials during the pandemic have been developed by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Central Institutional Review Board, and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Extramural Research. Industry sponsors and parent institutions of research programs have also disseminated guidance.

Among other topics, guidance documents have addressed:

- How COVID-19-related protocol deviations will be judged at monitoring visits and audits

- Missed office visits and endpoint evaluations

- Providing investigational oral medications to patients via mail and potential issues of medication unavailability

- Processes for patients to have interim visits with providers at external institutions, including providers who may not be personally engaged in or credentialed for the research trial

- Potential delays in submitting protocol amendments for institutional review board (IRB) review

- Recommendations for patients confirmed or suspected of having a coronavirus infection.

Dr. Oyer emphasized that patient safety must remain the highest priority for patient management, on or off study. He advised continuing investigational therapy when potential benefit from treatment is anticipated and identifying alternative methods to face-to-face visits for monitoring and access to treatment.

Dr. Oyer urged programs to:

- Maintain good clinical practice standards

- Consult with sponsors and IRBs when questions arise but implement changes that affect patient safety prior to IRB review if necessary

- Document all deviations and COVID-19 related adaptations in a log or spreadsheet in anticipation of future questions from sponsors, monitors, and other entities.

New questions and considerations

In the short-term, Dr. Oyer predicts fewer available trials and a decreased rate of accrual to existing studies. This may result in delays in trial completion and the possibility of redesign for some trials.

He predicts the emergence of COVID-19-focused research questions, including those assessing the course of coronavirus infection in various malignant settings and the impact of cancer-directed treatments and supportive care interventions (e.g., treatment for graft-versus-host disease) on response to COVID-19.

To facilitate developing a clinically and research-relevant database, Dr. Oyer stressed the importance of documentation in the research record, reporting infections as serious adverse events. Documentation should specify whether the infection was confirmed or suspected coronavirus or related to another organism.

In general, when coronavirus infection is strongly suspected, Dr. Oyer said investigational treatments should be interrupted, but study-specific criteria will be forthcoming on that issue.

Looking to the future

For patients with advanced cancers, clinical trials provide an important option for hope and clinical benefit. Disrupting the conduct of clinical trials could endanger the lives of participants and delay the emergence of promising treatments and diagnostic tests.

When the coronavirus pandemic recedes, advancing knowledge and treatments for cancer will demand renewed commitment across the oncology care community.

Going forward, Dr. Oyer advised that clinical research staff protect their own health and the safety of trial participants. He encouraged programs to work with sponsors and IRBs to solve logistical problems and clarify individual issues.

He was optimistic that resumption of more normal conduct of studies will enable the successful completion of ongoing trials, enhanced by the creative solutions that were devised during the crisis and by additional prospective, clinically annotated, carefully recorded data from academic and community research sites.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

More than three-quarters of cancer clinical research programs have experienced operational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) during a recent webinar.

The webinar included insights into how some cancer research programs have adapted to the pandemic, a review of guidance for conducting cancer trials during this time, and a discussion of how the cancer research landscape may be affected by COVID-19 going forward.

The webinar was led by Randall A. Oyer, MD, president of the ACCC and medical director of the oncology program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health in Pennsylvania.

The impact of COVID-19 on cancer research

Dr. Oyer observed that planning and implementation for COVID-19–related illness at U.S. health care institutions has had a predictable effect of limiting patient access and staff availability for nonessential services.

Coronavirus-related exposure and/or illness has relegated cancer research to a lower-level priority. As a result, ACCC institutions have made adjustments in their cancer research programs, including moving clinical research coordinators off-campus and deploying them in clinical areas.

New clinical trials have not been opened. In some cases, new accruals have been halted, particularly for registry, prevention, and symptom control trials.

Standards that have changed and those that have not

Guidance documents for conducting clinical trials during the pandemic have been developed by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Central Institutional Review Board, and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Extramural Research. Industry sponsors and parent institutions of research programs have also disseminated guidance.

Among other topics, guidance documents have addressed:

- How COVID-19-related protocol deviations will be judged at monitoring visits and audits

- Missed office visits and endpoint evaluations

- Providing investigational oral medications to patients via mail and potential issues of medication unavailability

- Processes for patients to have interim visits with providers at external institutions, including providers who may not be personally engaged in or credentialed for the research trial

- Potential delays in submitting protocol amendments for institutional review board (IRB) review

- Recommendations for patients confirmed or suspected of having a coronavirus infection.

Dr. Oyer emphasized that patient safety must remain the highest priority for patient management, on or off study. He advised continuing investigational therapy when potential benefit from treatment is anticipated and identifying alternative methods to face-to-face visits for monitoring and access to treatment.

Dr. Oyer urged programs to:

- Maintain good clinical practice standards

- Consult with sponsors and IRBs when questions arise but implement changes that affect patient safety prior to IRB review if necessary

- Document all deviations and COVID-19 related adaptations in a log or spreadsheet in anticipation of future questions from sponsors, monitors, and other entities.

New questions and considerations

In the short-term, Dr. Oyer predicts fewer available trials and a decreased rate of accrual to existing studies. This may result in delays in trial completion and the possibility of redesign for some trials.

He predicts the emergence of COVID-19-focused research questions, including those assessing the course of coronavirus infection in various malignant settings and the impact of cancer-directed treatments and supportive care interventions (e.g., treatment for graft-versus-host disease) on response to COVID-19.

To facilitate developing a clinically and research-relevant database, Dr. Oyer stressed the importance of documentation in the research record, reporting infections as serious adverse events. Documentation should specify whether the infection was confirmed or suspected coronavirus or related to another organism.

In general, when coronavirus infection is strongly suspected, Dr. Oyer said investigational treatments should be interrupted, but study-specific criteria will be forthcoming on that issue.

Looking to the future

For patients with advanced cancers, clinical trials provide an important option for hope and clinical benefit. Disrupting the conduct of clinical trials could endanger the lives of participants and delay the emergence of promising treatments and diagnostic tests.

When the coronavirus pandemic recedes, advancing knowledge and treatments for cancer will demand renewed commitment across the oncology care community.

Going forward, Dr. Oyer advised that clinical research staff protect their own health and the safety of trial participants. He encouraged programs to work with sponsors and IRBs to solve logistical problems and clarify individual issues.

He was optimistic that resumption of more normal conduct of studies will enable the successful completion of ongoing trials, enhanced by the creative solutions that were devised during the crisis and by additional prospective, clinically annotated, carefully recorded data from academic and community research sites.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

More than three-quarters of cancer clinical research programs have experienced operational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) during a recent webinar.

The webinar included insights into how some cancer research programs have adapted to the pandemic, a review of guidance for conducting cancer trials during this time, and a discussion of how the cancer research landscape may be affected by COVID-19 going forward.

The webinar was led by Randall A. Oyer, MD, president of the ACCC and medical director of the oncology program at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health in Pennsylvania.

The impact of COVID-19 on cancer research

Dr. Oyer observed that planning and implementation for COVID-19–related illness at U.S. health care institutions has had a predictable effect of limiting patient access and staff availability for nonessential services.

Coronavirus-related exposure and/or illness has relegated cancer research to a lower-level priority. As a result, ACCC institutions have made adjustments in their cancer research programs, including moving clinical research coordinators off-campus and deploying them in clinical areas.

New clinical trials have not been opened. In some cases, new accruals have been halted, particularly for registry, prevention, and symptom control trials.

Standards that have changed and those that have not

Guidance documents for conducting clinical trials during the pandemic have been developed by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Central Institutional Review Board, and the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Extramural Research. Industry sponsors and parent institutions of research programs have also disseminated guidance.

Among other topics, guidance documents have addressed:

- How COVID-19-related protocol deviations will be judged at monitoring visits and audits

- Missed office visits and endpoint evaluations

- Providing investigational oral medications to patients via mail and potential issues of medication unavailability

- Processes for patients to have interim visits with providers at external institutions, including providers who may not be personally engaged in or credentialed for the research trial

- Potential delays in submitting protocol amendments for institutional review board (IRB) review

- Recommendations for patients confirmed or suspected of having a coronavirus infection.

Dr. Oyer emphasized that patient safety must remain the highest priority for patient management, on or off study. He advised continuing investigational therapy when potential benefit from treatment is anticipated and identifying alternative methods to face-to-face visits for monitoring and access to treatment.

Dr. Oyer urged programs to:

- Maintain good clinical practice standards

- Consult with sponsors and IRBs when questions arise but implement changes that affect patient safety prior to IRB review if necessary

- Document all deviations and COVID-19 related adaptations in a log or spreadsheet in anticipation of future questions from sponsors, monitors, and other entities.

New questions and considerations

In the short-term, Dr. Oyer predicts fewer available trials and a decreased rate of accrual to existing studies. This may result in delays in trial completion and the possibility of redesign for some trials.

He predicts the emergence of COVID-19-focused research questions, including those assessing the course of coronavirus infection in various malignant settings and the impact of cancer-directed treatments and supportive care interventions (e.g., treatment for graft-versus-host disease) on response to COVID-19.

To facilitate developing a clinically and research-relevant database, Dr. Oyer stressed the importance of documentation in the research record, reporting infections as serious adverse events. Documentation should specify whether the infection was confirmed or suspected coronavirus or related to another organism.

In general, when coronavirus infection is strongly suspected, Dr. Oyer said investigational treatments should be interrupted, but study-specific criteria will be forthcoming on that issue.

Looking to the future

For patients with advanced cancers, clinical trials provide an important option for hope and clinical benefit. Disrupting the conduct of clinical trials could endanger the lives of participants and delay the emergence of promising treatments and diagnostic tests.

When the coronavirus pandemic recedes, advancing knowledge and treatments for cancer will demand renewed commitment across the oncology care community.

Going forward, Dr. Oyer advised that clinical research staff protect their own health and the safety of trial participants. He encouraged programs to work with sponsors and IRBs to solve logistical problems and clarify individual issues.

He was optimistic that resumption of more normal conduct of studies will enable the successful completion of ongoing trials, enhanced by the creative solutions that were devised during the crisis and by additional prospective, clinically annotated, carefully recorded data from academic and community research sites.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

‘The kids will be all right,’ won’t they?

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

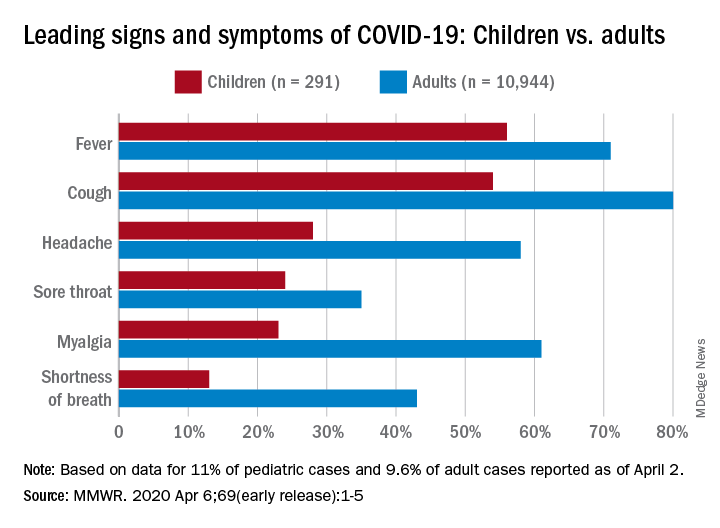

Many children with COVID-19 don’t have cough or fever

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

FROM MMWR

AAP issues guidance on managing infants born to mothers with COVID-19

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

Novel acne drug now under review at the FDA

LAHAINA, HAWAII – by the Food and Drug Administration, is already generating considerable buzz in the patient-advocacy community even though the agency won’t issue its decision until August.

“I’ve actually had a lot of interest in this already from parents, especially regarding girls who have very hormonal acne but the parents are really not interested in starting them on a systemic hormonal therapy at their age,” Jessica Sprague, MD, said at the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Clascoterone targets androgen receptors in the skin in order to reduce cutaneous 5-alpha dihydrotestosterone.

“It’s being developed for use in both males and females, which is great because at this point there’s no hormonal treatment for males,” noted Dr. Sprague, a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego.

The manufacturer’s application for marketing approval of clascoterone cream 1% under FDA review includes evidence from two identical phase-3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials. The two studies included a total of 1,440 patients aged 9 years through adulthood with moderate to severe facial acne vulgaris who were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or its vehicle.