User login

Flu activity measures continue COVID-19–related divergence

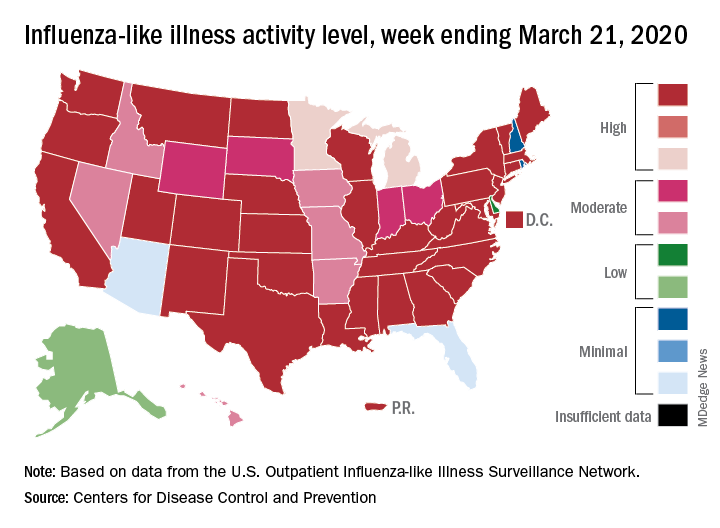

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

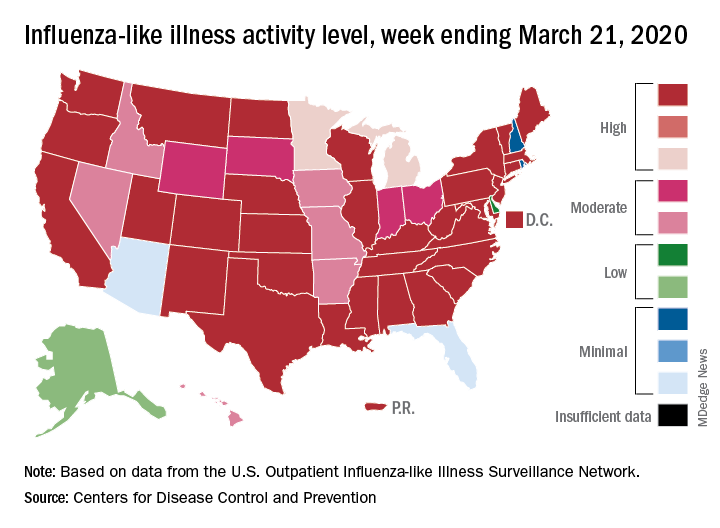

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

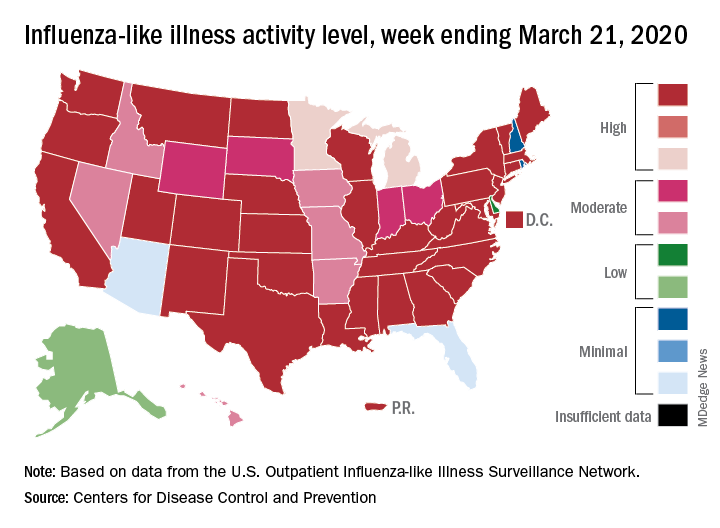

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

Do we need another vital sign?

If you haven’t already found out that activity is a critical component in the physical and mental health of your patients, or if you’re trying to convince an influential person or group it deserves their attention and investment, I suggest you chase down this clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Representing the AAP’s Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Section on Obesity, the authors quite thoroughly make the case that anyone concerned about the health of this nation and its children should make promotion of physical activity a top priority.

I suspect that, like many of the position papers that come from the AAP, this clinical report is another example of preaching to the choir. However, I understand that the academy also hopes to convince a broader audience of nonphysician decision makers by laying out all of the evidence they can muster.

With their voluminous supporting evidence on the table, the authors move on to getting those of us in clinical practice to make our approach to this more systematic – including the addition of a Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) in our patients’ health records. And here is where the authors begin to drift into the hazy dream world of unreality. They admit that “pediatricians will need efficient workflows to incorporate physical activity assessment, counseling and referral in the clinical visit.” Although there is no pediatrician more convinced of the importance of physical activity, I would find it very difficult to include a detailed assessment of my patients’ daily activity in their charts in the manner that the council members envision. Clunky EHRs, limited support staff, and a crowd of advocates already clamoring for my attention on their favorite health issue (nutrition, gun safety, parental depression, dental health to name just a few) all make creating an “efficient workflow” difficult on a good day and impossible on many days.

But, as I have said, I am a strong advocate of physical activity. So here’s a more nuanced suggestion based on a combination of my practical experience and the council’s recommendations.

If you provide good continuity of care to the families in your practice and have been asking good “getting to know you” questions at each visit, you probably already know which of your patients are sufficiently active. You don’t need to ask them how many hours a week they are doing something active. You should be able to just check a box that says “active.”

For patients that you haven’t seen before or suspect are too sedentary from looking at their biometrics and listening to their complaints you need only ask “What do you and your family like to do for fun?” The simple follow-up question of how many hours are spent watching TV, looking at smart phones or tablets, and playing video games in each day completes the survey. You don’t need to chart the depressing details because, as we know, relying on patient or parental recall is unlikely to provide the actual numbers. Just simply check the box that says “not active enough.” What you do with this crude assessment activity is another story and will be the topic for the next Letters from Maine.

This clinical report from the AAP is an excellent and exhaustive discussion of the importance of physical activity, but I hope that it doesn’t spark further cluttering of our already challenged EHR systems. Most of us don’t have the time to be data collectors and quantifiers. Let’s leave that to the clinical researchers. We already know activity is important and that most of our sedentary families aren’t going to be impressed by more science. Our challenge is to get them moving.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

If you haven’t already found out that activity is a critical component in the physical and mental health of your patients, or if you’re trying to convince an influential person or group it deserves their attention and investment, I suggest you chase down this clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Representing the AAP’s Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Section on Obesity, the authors quite thoroughly make the case that anyone concerned about the health of this nation and its children should make promotion of physical activity a top priority.

I suspect that, like many of the position papers that come from the AAP, this clinical report is another example of preaching to the choir. However, I understand that the academy also hopes to convince a broader audience of nonphysician decision makers by laying out all of the evidence they can muster.

With their voluminous supporting evidence on the table, the authors move on to getting those of us in clinical practice to make our approach to this more systematic – including the addition of a Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) in our patients’ health records. And here is where the authors begin to drift into the hazy dream world of unreality. They admit that “pediatricians will need efficient workflows to incorporate physical activity assessment, counseling and referral in the clinical visit.” Although there is no pediatrician more convinced of the importance of physical activity, I would find it very difficult to include a detailed assessment of my patients’ daily activity in their charts in the manner that the council members envision. Clunky EHRs, limited support staff, and a crowd of advocates already clamoring for my attention on their favorite health issue (nutrition, gun safety, parental depression, dental health to name just a few) all make creating an “efficient workflow” difficult on a good day and impossible on many days.

But, as I have said, I am a strong advocate of physical activity. So here’s a more nuanced suggestion based on a combination of my practical experience and the council’s recommendations.

If you provide good continuity of care to the families in your practice and have been asking good “getting to know you” questions at each visit, you probably already know which of your patients are sufficiently active. You don’t need to ask them how many hours a week they are doing something active. You should be able to just check a box that says “active.”

For patients that you haven’t seen before or suspect are too sedentary from looking at their biometrics and listening to their complaints you need only ask “What do you and your family like to do for fun?” The simple follow-up question of how many hours are spent watching TV, looking at smart phones or tablets, and playing video games in each day completes the survey. You don’t need to chart the depressing details because, as we know, relying on patient or parental recall is unlikely to provide the actual numbers. Just simply check the box that says “not active enough.” What you do with this crude assessment activity is another story and will be the topic for the next Letters from Maine.

This clinical report from the AAP is an excellent and exhaustive discussion of the importance of physical activity, but I hope that it doesn’t spark further cluttering of our already challenged EHR systems. Most of us don’t have the time to be data collectors and quantifiers. Let’s leave that to the clinical researchers. We already know activity is important and that most of our sedentary families aren’t going to be impressed by more science. Our challenge is to get them moving.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

If you haven’t already found out that activity is a critical component in the physical and mental health of your patients, or if you’re trying to convince an influential person or group it deserves their attention and investment, I suggest you chase down this clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Representing the AAP’s Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Section on Obesity, the authors quite thoroughly make the case that anyone concerned about the health of this nation and its children should make promotion of physical activity a top priority.

I suspect that, like many of the position papers that come from the AAP, this clinical report is another example of preaching to the choir. However, I understand that the academy also hopes to convince a broader audience of nonphysician decision makers by laying out all of the evidence they can muster.

With their voluminous supporting evidence on the table, the authors move on to getting those of us in clinical practice to make our approach to this more systematic – including the addition of a Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) in our patients’ health records. And here is where the authors begin to drift into the hazy dream world of unreality. They admit that “pediatricians will need efficient workflows to incorporate physical activity assessment, counseling and referral in the clinical visit.” Although there is no pediatrician more convinced of the importance of physical activity, I would find it very difficult to include a detailed assessment of my patients’ daily activity in their charts in the manner that the council members envision. Clunky EHRs, limited support staff, and a crowd of advocates already clamoring for my attention on their favorite health issue (nutrition, gun safety, parental depression, dental health to name just a few) all make creating an “efficient workflow” difficult on a good day and impossible on many days.

But, as I have said, I am a strong advocate of physical activity. So here’s a more nuanced suggestion based on a combination of my practical experience and the council’s recommendations.

If you provide good continuity of care to the families in your practice and have been asking good “getting to know you” questions at each visit, you probably already know which of your patients are sufficiently active. You don’t need to ask them how many hours a week they are doing something active. You should be able to just check a box that says “active.”

For patients that you haven’t seen before or suspect are too sedentary from looking at their biometrics and listening to their complaints you need only ask “What do you and your family like to do for fun?” The simple follow-up question of how many hours are spent watching TV, looking at smart phones or tablets, and playing video games in each day completes the survey. You don’t need to chart the depressing details because, as we know, relying on patient or parental recall is unlikely to provide the actual numbers. Just simply check the box that says “not active enough.” What you do with this crude assessment activity is another story and will be the topic for the next Letters from Maine.

This clinical report from the AAP is an excellent and exhaustive discussion of the importance of physical activity, but I hope that it doesn’t spark further cluttering of our already challenged EHR systems. Most of us don’t have the time to be data collectors and quantifiers. Let’s leave that to the clinical researchers. We already know activity is important and that most of our sedentary families aren’t going to be impressed by more science. Our challenge is to get them moving.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Reports suggest possible in utero transmission of novel coronavirus 2019

Reports of three neonates with elevated IgM antibody concentrations whose mothers had COVID-19 in two articles raise questions about whether the infants may have been infected with the virus in utero.

The data, while provocative, “are not conclusive and do not prove in utero transmission” of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), editorialists cautioned.

“The suggestion of in utero transmission rests on IgM detection in these 3 neonates, and IgM is a challenging way to diagnose many congenital infections,” David W. Kimberlin, MD, and Sergio Stagno, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in their editorial. “IgM antibodies are too large to cross the placenta and so detection in a newborn reasonably could be assumed to reflect fetal production following in utero infection. However, most congenital infections are not diagnosed based on IgM detection because IgM assays can be prone to false-positive and false-negative results, along with cross-reactivity and testing challenges.”

None of the three infants had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, “so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission,” the editorialists noted.

Examining the possibility of vertical transmission

A prior case series of nine pregnant women found no transmission of the virus from mother to child, but the question of in utero transmission is not settled, said Lan Dong, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues. In their research letter, the investigators described a newborn with elevated IgM antibodies to novel coronavirus 2019 born to a mother with COVID-19. The infant was delivered by cesarean section February 22, 2020, at Renmin Hospital in a negative-pressure isolation room.

“The mother wore an N95 mask and did not hold the infant,” the researchers said. “The neonate had no symptoms and was immediately quarantined in the neonatal intensive care unit. At 2 hours of age, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG level was 140.32 AU/mL and the IgM level was 45.83 AU/mL.” Although the infant may have been infected at delivery, IgM antibodies usually take days to appear, Dr. Dong and colleagues wrote. “The infant’s repeatedly negative RT-PCR test results on nasopharyngeal swabs are difficult to explain, although these tests are not always positive with infection. ... Additional examination of maternal and newborn samples should be done to confirm this preliminary observation.”

A review of infants’ serologic characteristics

Hui Zeng, MD, of the department of laboratory medicine at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues retrospectively reviewed clinical records and laboratory results for six pregnant women with COVID-19, according to a study in JAMA. The women had mild clinical manifestations and were admitted to Zhongnan Hospital between February 16 and March 6. “All had cesarean deliveries in their third trimester in negative pressure isolation rooms,” the investigators said. “All mothers wore masks, and all medical staff wore protective suits and double masks. The infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after delivery.”

Two of the infants had elevated IgG and IgM concentrations. IgM “is not usually transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure. ... Whether the placentas of women in this study were damaged and abnormal is unknown,” Dr. Zeng and colleagues said. “Alternatively, IgM could have been produced by the infant if the virus crossed the placenta.”

“Although these 2 studies deserve careful evaluation, more definitive evidence is needed” before physicians can “counsel pregnant women that their fetuses are at risk from congenital infection with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno concluded.

Dr. Dong and associates had no conflicts of interest. Their work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project and others. Dr. Zeng and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Their study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Zhongnan Hospital. Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dong L et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621; Zeng H et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

Reports of three neonates with elevated IgM antibody concentrations whose mothers had COVID-19 in two articles raise questions about whether the infants may have been infected with the virus in utero.

The data, while provocative, “are not conclusive and do not prove in utero transmission” of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), editorialists cautioned.

“The suggestion of in utero transmission rests on IgM detection in these 3 neonates, and IgM is a challenging way to diagnose many congenital infections,” David W. Kimberlin, MD, and Sergio Stagno, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in their editorial. “IgM antibodies are too large to cross the placenta and so detection in a newborn reasonably could be assumed to reflect fetal production following in utero infection. However, most congenital infections are not diagnosed based on IgM detection because IgM assays can be prone to false-positive and false-negative results, along with cross-reactivity and testing challenges.”

None of the three infants had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, “so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission,” the editorialists noted.

Examining the possibility of vertical transmission

A prior case series of nine pregnant women found no transmission of the virus from mother to child, but the question of in utero transmission is not settled, said Lan Dong, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues. In their research letter, the investigators described a newborn with elevated IgM antibodies to novel coronavirus 2019 born to a mother with COVID-19. The infant was delivered by cesarean section February 22, 2020, at Renmin Hospital in a negative-pressure isolation room.

“The mother wore an N95 mask and did not hold the infant,” the researchers said. “The neonate had no symptoms and was immediately quarantined in the neonatal intensive care unit. At 2 hours of age, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG level was 140.32 AU/mL and the IgM level was 45.83 AU/mL.” Although the infant may have been infected at delivery, IgM antibodies usually take days to appear, Dr. Dong and colleagues wrote. “The infant’s repeatedly negative RT-PCR test results on nasopharyngeal swabs are difficult to explain, although these tests are not always positive with infection. ... Additional examination of maternal and newborn samples should be done to confirm this preliminary observation.”

A review of infants’ serologic characteristics

Hui Zeng, MD, of the department of laboratory medicine at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues retrospectively reviewed clinical records and laboratory results for six pregnant women with COVID-19, according to a study in JAMA. The women had mild clinical manifestations and were admitted to Zhongnan Hospital between February 16 and March 6. “All had cesarean deliveries in their third trimester in negative pressure isolation rooms,” the investigators said. “All mothers wore masks, and all medical staff wore protective suits and double masks. The infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after delivery.”

Two of the infants had elevated IgG and IgM concentrations. IgM “is not usually transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure. ... Whether the placentas of women in this study were damaged and abnormal is unknown,” Dr. Zeng and colleagues said. “Alternatively, IgM could have been produced by the infant if the virus crossed the placenta.”

“Although these 2 studies deserve careful evaluation, more definitive evidence is needed” before physicians can “counsel pregnant women that their fetuses are at risk from congenital infection with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno concluded.

Dr. Dong and associates had no conflicts of interest. Their work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project and others. Dr. Zeng and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Their study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Zhongnan Hospital. Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dong L et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621; Zeng H et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

Reports of three neonates with elevated IgM antibody concentrations whose mothers had COVID-19 in two articles raise questions about whether the infants may have been infected with the virus in utero.

The data, while provocative, “are not conclusive and do not prove in utero transmission” of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), editorialists cautioned.

“The suggestion of in utero transmission rests on IgM detection in these 3 neonates, and IgM is a challenging way to diagnose many congenital infections,” David W. Kimberlin, MD, and Sergio Stagno, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in their editorial. “IgM antibodies are too large to cross the placenta and so detection in a newborn reasonably could be assumed to reflect fetal production following in utero infection. However, most congenital infections are not diagnosed based on IgM detection because IgM assays can be prone to false-positive and false-negative results, along with cross-reactivity and testing challenges.”

None of the three infants had a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, “so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission,” the editorialists noted.

Examining the possibility of vertical transmission

A prior case series of nine pregnant women found no transmission of the virus from mother to child, but the question of in utero transmission is not settled, said Lan Dong, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues. In their research letter, the investigators described a newborn with elevated IgM antibodies to novel coronavirus 2019 born to a mother with COVID-19. The infant was delivered by cesarean section February 22, 2020, at Renmin Hospital in a negative-pressure isolation room.

“The mother wore an N95 mask and did not hold the infant,” the researchers said. “The neonate had no symptoms and was immediately quarantined in the neonatal intensive care unit. At 2 hours of age, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG level was 140.32 AU/mL and the IgM level was 45.83 AU/mL.” Although the infant may have been infected at delivery, IgM antibodies usually take days to appear, Dr. Dong and colleagues wrote. “The infant’s repeatedly negative RT-PCR test results on nasopharyngeal swabs are difficult to explain, although these tests are not always positive with infection. ... Additional examination of maternal and newborn samples should be done to confirm this preliminary observation.”

A review of infants’ serologic characteristics

Hui Zeng, MD, of the department of laboratory medicine at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in China and colleagues retrospectively reviewed clinical records and laboratory results for six pregnant women with COVID-19, according to a study in JAMA. The women had mild clinical manifestations and were admitted to Zhongnan Hospital between February 16 and March 6. “All had cesarean deliveries in their third trimester in negative pressure isolation rooms,” the investigators said. “All mothers wore masks, and all medical staff wore protective suits and double masks. The infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after delivery.”

Two of the infants had elevated IgG and IgM concentrations. IgM “is not usually transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure. ... Whether the placentas of women in this study were damaged and abnormal is unknown,” Dr. Zeng and colleagues said. “Alternatively, IgM could have been produced by the infant if the virus crossed the placenta.”

“Although these 2 studies deserve careful evaluation, more definitive evidence is needed” before physicians can “counsel pregnant women that their fetuses are at risk from congenital infection with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno concluded.

Dr. Dong and associates had no conflicts of interest. Their work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project and others. Dr. Zeng and colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures. Their study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Zhongnan Hospital. Dr. Kimberlin and Dr. Stagno had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dong L et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621; Zeng H et al. JAMA. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

FROM JAMA

Hormone therapy boosts body image in transgender youth

based on data from 148 individuals.

“Understanding the impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the mental health of transgender youth is critical given the health disparities documented in this population,” wrote Laura E. Kuper, PhD, of Children’s Health Systems of Texas, Dallas, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 148 youth aged 9-18 years who underwent gender-affirming hormone therapy in a multidisciplinary program. The average age of the patients was 15 years; 25 were receiving puberty suppression hormones only, 93 were receiving just feminizing or masculinizing hormones, and 30 were receiving both treatments.

At baseline and at approximately 1 year follow-up, all patients completed the Body Image Scale, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, and Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. In addition, clinicians collected information on patients’ suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury.

Overall, the average scores on the Body Image Scale on body dissatisfaction decreased from 70 to 52, and average scores on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms decreased from 9 to 7; both were statistically significant (P less than .001), as were changes from baseline on the anxiety subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, which decreased from 32 to 29 (P less than .01). No change occurred in the average overall clinician-reported depressive symptoms.

During the follow-up period, the rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury were 38%, 5%, and 17%, respectively. Of patients who reported these experiences, the lifetime histories of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury were 81%, 15%, and 52%, respectively.

The findings were limited by several factors including some missing data and the relatively small sample size, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results suggest “that youth receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy experience meaningful short-term improvements in body dissatisfaction, and no participants discontinued feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy.” These results support the use of such therapy, Dr. Kuper and associates wrote.

The study is important because of the need for evidence that hormones actually improve patient outcomes, said Shauna M. Lawlis, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Medical Center, Oklahoma City.

“Especially given the rash of legislation across the country aimed at blocking care for transgender youth, it is helpful to show that these treatments really do decrease patients’ anxiety and depressive symptoms,” she said in an interview. “In addition, previous research has been focused on those who have undergone puberty suppression followed by gender-affirming hormone therapy, but many patients are too far along in puberty for puberty suppression to be effective and providers often go straight to gender-affirming hormones in those cases.”

Dr. Lawlis said she was not at all surprised by the study findings. “In my own practice, I have seen patients improve greatly on gender-affirming hormones with overall improvement in anxiety and depression. As a patient’s outward appearance more closely matches their gender identity, they feel more comfortable in their own bodies and their interactions with the world around them, thus improving these symptoms.”

Dr. Lawlis added that the message for pediatricians who treat transgender youth is simple: Gender-affirming hormones improve patient outcomes. “They are essential for the mental health of this vulnerable population.”

She noted that long-term follow-up studies would be useful. “There is still a lot of concern about regret and detransitioning among health care providers and the general population – showing that patients maintain satisfaction in the long-term would be helpful.

“In addition, long-term studies about other health outcomes (cardiovascular disease, cancer risk, etc.) would also be helpful,” said Dr. Lawlis, who was asked to comment on this study, with which she had no involvement.

The study was supported in part by Children’s Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lawlis had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kuper LE et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3006.

based on data from 148 individuals.

“Understanding the impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the mental health of transgender youth is critical given the health disparities documented in this population,” wrote Laura E. Kuper, PhD, of Children’s Health Systems of Texas, Dallas, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 148 youth aged 9-18 years who underwent gender-affirming hormone therapy in a multidisciplinary program. The average age of the patients was 15 years; 25 were receiving puberty suppression hormones only, 93 were receiving just feminizing or masculinizing hormones, and 30 were receiving both treatments.

At baseline and at approximately 1 year follow-up, all patients completed the Body Image Scale, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, and Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. In addition, clinicians collected information on patients’ suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury.

Overall, the average scores on the Body Image Scale on body dissatisfaction decreased from 70 to 52, and average scores on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms decreased from 9 to 7; both were statistically significant (P less than .001), as were changes from baseline on the anxiety subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, which decreased from 32 to 29 (P less than .01). No change occurred in the average overall clinician-reported depressive symptoms.

During the follow-up period, the rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury were 38%, 5%, and 17%, respectively. Of patients who reported these experiences, the lifetime histories of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury were 81%, 15%, and 52%, respectively.

The findings were limited by several factors including some missing data and the relatively small sample size, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results suggest “that youth receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy experience meaningful short-term improvements in body dissatisfaction, and no participants discontinued feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy.” These results support the use of such therapy, Dr. Kuper and associates wrote.

The study is important because of the need for evidence that hormones actually improve patient outcomes, said Shauna M. Lawlis, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Medical Center, Oklahoma City.

“Especially given the rash of legislation across the country aimed at blocking care for transgender youth, it is helpful to show that these treatments really do decrease patients’ anxiety and depressive symptoms,” she said in an interview. “In addition, previous research has been focused on those who have undergone puberty suppression followed by gender-affirming hormone therapy, but many patients are too far along in puberty for puberty suppression to be effective and providers often go straight to gender-affirming hormones in those cases.”

Dr. Lawlis said she was not at all surprised by the study findings. “In my own practice, I have seen patients improve greatly on gender-affirming hormones with overall improvement in anxiety and depression. As a patient’s outward appearance more closely matches their gender identity, they feel more comfortable in their own bodies and their interactions with the world around them, thus improving these symptoms.”

Dr. Lawlis added that the message for pediatricians who treat transgender youth is simple: Gender-affirming hormones improve patient outcomes. “They are essential for the mental health of this vulnerable population.”

She noted that long-term follow-up studies would be useful. “There is still a lot of concern about regret and detransitioning among health care providers and the general population – showing that patients maintain satisfaction in the long-term would be helpful.

“In addition, long-term studies about other health outcomes (cardiovascular disease, cancer risk, etc.) would also be helpful,” said Dr. Lawlis, who was asked to comment on this study, with which she had no involvement.

The study was supported in part by Children’s Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lawlis had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kuper LE et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3006.

based on data from 148 individuals.

“Understanding the impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the mental health of transgender youth is critical given the health disparities documented in this population,” wrote Laura E. Kuper, PhD, of Children’s Health Systems of Texas, Dallas, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 148 youth aged 9-18 years who underwent gender-affirming hormone therapy in a multidisciplinary program. The average age of the patients was 15 years; 25 were receiving puberty suppression hormones only, 93 were receiving just feminizing or masculinizing hormones, and 30 were receiving both treatments.

At baseline and at approximately 1 year follow-up, all patients completed the Body Image Scale, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, and Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. In addition, clinicians collected information on patients’ suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury.

Overall, the average scores on the Body Image Scale on body dissatisfaction decreased from 70 to 52, and average scores on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms decreased from 9 to 7; both were statistically significant (P less than .001), as were changes from baseline on the anxiety subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, which decreased from 32 to 29 (P less than .01). No change occurred in the average overall clinician-reported depressive symptoms.

During the follow-up period, the rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury were 38%, 5%, and 17%, respectively. Of patients who reported these experiences, the lifetime histories of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and nonsuicidal self-injury were 81%, 15%, and 52%, respectively.

The findings were limited by several factors including some missing data and the relatively small sample size, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results suggest “that youth receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy experience meaningful short-term improvements in body dissatisfaction, and no participants discontinued feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy.” These results support the use of such therapy, Dr. Kuper and associates wrote.

The study is important because of the need for evidence that hormones actually improve patient outcomes, said Shauna M. Lawlis, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Medical Center, Oklahoma City.

“Especially given the rash of legislation across the country aimed at blocking care for transgender youth, it is helpful to show that these treatments really do decrease patients’ anxiety and depressive symptoms,” she said in an interview. “In addition, previous research has been focused on those who have undergone puberty suppression followed by gender-affirming hormone therapy, but many patients are too far along in puberty for puberty suppression to be effective and providers often go straight to gender-affirming hormones in those cases.”

Dr. Lawlis said she was not at all surprised by the study findings. “In my own practice, I have seen patients improve greatly on gender-affirming hormones with overall improvement in anxiety and depression. As a patient’s outward appearance more closely matches their gender identity, they feel more comfortable in their own bodies and their interactions with the world around them, thus improving these symptoms.”

Dr. Lawlis added that the message for pediatricians who treat transgender youth is simple: Gender-affirming hormones improve patient outcomes. “They are essential for the mental health of this vulnerable population.”

She noted that long-term follow-up studies would be useful. “There is still a lot of concern about regret and detransitioning among health care providers and the general population – showing that patients maintain satisfaction in the long-term would be helpful.

“In addition, long-term studies about other health outcomes (cardiovascular disease, cancer risk, etc.) would also be helpful,” said Dr. Lawlis, who was asked to comment on this study, with which she had no involvement.

The study was supported in part by Children’s Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lawlis had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kuper LE et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3006.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Despite strict controls, some infants born to mothers with COVID-19 appear infected

Despite implementation of strict infection control and prevention procedures in a hospital in Wuhan, China, according to Lingkong Zeng, MD, of the department of neonatology at Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and associates.

Thirty-three neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 were included in the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. Of this group, three neonates (9%) were confirmed to be infected with the novel coronavirus 2019 at 2 and 4 days of life through nasopharyngeal and anal swabs.

Of the three infected neonates, two were born at 40 weeks’ gestation and the third was born at 31 weeks. The two full-term infants had mild symptoms such as lethargy and fever and were negative for the virus at 6 days of life. The preterm infant had somewhat worse symptoms, but the investigators acknowledged that “the most seriously ill neonate may have been symptomatic from prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis, rather than [the novel coronavirus 2019] infection.” They added that outcomes for all three neonates were favorable, consistent with past research.

“Because strict infection control and prevention procedures were implemented during the delivery, it is likely that the sources of [novel coronavirus 2019] in the neonates’ upper respiratory tracts or anuses were maternal in origin,” Dr. Zeng and associates surmised.

While previous studies have shown no evidence of COVID-19 transmission between mothers and neonates, and all samples, including amniotic fluid, cord blood, and breast milk, were negative for the novel coronavirus 2019, “vertical maternal-fetal transmission cannot be ruled out in the current cohort. Therefore, it is crucial to screen pregnant women and implement strict infection control measures, quarantine of infected mothers, and close monitoring of neonates at risk of COVID-19,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zeng L et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

Despite implementation of strict infection control and prevention procedures in a hospital in Wuhan, China, according to Lingkong Zeng, MD, of the department of neonatology at Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and associates.

Thirty-three neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 were included in the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. Of this group, three neonates (9%) were confirmed to be infected with the novel coronavirus 2019 at 2 and 4 days of life through nasopharyngeal and anal swabs.

Of the three infected neonates, two were born at 40 weeks’ gestation and the third was born at 31 weeks. The two full-term infants had mild symptoms such as lethargy and fever and were negative for the virus at 6 days of life. The preterm infant had somewhat worse symptoms, but the investigators acknowledged that “the most seriously ill neonate may have been symptomatic from prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis, rather than [the novel coronavirus 2019] infection.” They added that outcomes for all three neonates were favorable, consistent with past research.

“Because strict infection control and prevention procedures were implemented during the delivery, it is likely that the sources of [novel coronavirus 2019] in the neonates’ upper respiratory tracts or anuses were maternal in origin,” Dr. Zeng and associates surmised.

While previous studies have shown no evidence of COVID-19 transmission between mothers and neonates, and all samples, including amniotic fluid, cord blood, and breast milk, were negative for the novel coronavirus 2019, “vertical maternal-fetal transmission cannot be ruled out in the current cohort. Therefore, it is crucial to screen pregnant women and implement strict infection control measures, quarantine of infected mothers, and close monitoring of neonates at risk of COVID-19,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zeng L et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

Despite implementation of strict infection control and prevention procedures in a hospital in Wuhan, China, according to Lingkong Zeng, MD, of the department of neonatology at Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and associates.

Thirty-three neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 were included in the study, published as a research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. Of this group, three neonates (9%) were confirmed to be infected with the novel coronavirus 2019 at 2 and 4 days of life through nasopharyngeal and anal swabs.

Of the three infected neonates, two were born at 40 weeks’ gestation and the third was born at 31 weeks. The two full-term infants had mild symptoms such as lethargy and fever and were negative for the virus at 6 days of life. The preterm infant had somewhat worse symptoms, but the investigators acknowledged that “the most seriously ill neonate may have been symptomatic from prematurity, asphyxia, and sepsis, rather than [the novel coronavirus 2019] infection.” They added that outcomes for all three neonates were favorable, consistent with past research.

“Because strict infection control and prevention procedures were implemented during the delivery, it is likely that the sources of [novel coronavirus 2019] in the neonates’ upper respiratory tracts or anuses were maternal in origin,” Dr. Zeng and associates surmised.

While previous studies have shown no evidence of COVID-19 transmission between mothers and neonates, and all samples, including amniotic fluid, cord blood, and breast milk, were negative for the novel coronavirus 2019, “vertical maternal-fetal transmission cannot be ruled out in the current cohort. Therefore, it is crucial to screen pregnant women and implement strict infection control measures, quarantine of infected mothers, and close monitoring of neonates at risk of COVID-19,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zeng L et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Oral propranolol shown safe in PHACE

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Reassuring evidence of the safety of oral propranolol for treatment of complicated infantile hemangiomas in patients with PHACE syndrome comes from a recent multicenter study.

Oral propranolol is now well-ensconced as first-line therapy for complicated infantile hemangiomas in otherwise healthy children. However, the beta-blocker’s use in PHACE (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, and Eye abnormalities) syndrome has been controversial, with concerns raised by some that it might raise the risk for arterial ischemic stroke. Not so, Moise L. Levy, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“I’m not suggesting you use propranolol with reckless abandon in this population, but this stroke concern is something that should be put to bed based on this study,” advised Dr. Levy, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Dell Medical School in Austin, Tex., and physician-in-chief at Dell Children’s Medical Center.

PHACE syndrome is characterized by large, thick, plaque-like hemangiomas greater than 5 cm in size, most commonly on the face, although they can be located elsewhere.

“There was concern that if you found severely altered cerebrovascular arterial flow and you put a kid on a beta-blocker you might be causing some harm. But what I will tell you is that in this recently published paper this was not in fact an issue,” he said.

Dr. Levy was not an investigator in the multicenter retrospective study, which included 76 patients with PHACE syndrome treated for infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol at 0.3 mg/kg per dose or more at 11 academic tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinics. Treatment started at a median age of 56 days.

There were no strokes, TIAs, cardiovascular events, or other significant problems associated with treatment. Twenty-nine children experienced mild adverse events: minor gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and sleep disturbances were threefold more frequent than reported with placebo in another study. The investigators noted that the safety experience in their PHACE syndrome population compared favorably with that in 726 infants without PHACE syndrome who received oral propranolol for hemangiomas, where the incidence of serious adverse events on treatment was 0.4% (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839).

‘Hemangiomas – but we were taught that they go away’

Dr. Levy gave a shout-out to the American Academy of Pediatrics for publishing interdisciplinary expert consensus-based practice guidelines for the management of infantile hemangiomas, which he praised as “quite well done” (Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143[1]. pii: e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475).

Following release of the guidelines last year, he and other pediatric vascular anomalies experts saw an uptick in referrals from general pediatricians, which has since tapered off.

“It’s probably like for all of us: We read an article, it’s fresh on the mind, then you forget about the article and what you’ve read. So we need a little reinforcement from a learning perspective. This is a great article,” he said.

The guidelines debunk as myth the classic teaching that infantile hemangiomas go away. Explicit information is provided about the high-risk anatomic sites warranting consideration for early referral, including the periocular, lumbosacral, and perineal areas, the lip, and lower face.

“The major point is early identification of those lesions requiring evaluation and intervention. Hemangiomas generally speaking are at their ultimate size by 3-5 months of age. The bottom line is if you think something needs to be done, please send that patient, or act upon that patient, sooner rather than later. I can’t tell you how many cases of hemangiomas I’ve seen when the kid is 18 months of age, 3 years of age, 5 years, with a large area of redundant skin, scarring, or something of that sort, and it would have been really nice to have seen them earlier and acted upon them then,” the pediatric dermatologist said.

The guidelines recommend intervention or referral by 1 month of age, ideally. Guidance is provided about the use of oral propranolol as first-line therapy.

“Propranolol is something that has been a real game changer for us,” he noted. “Many people continue to be worried about side effects in using this, particularly in the young childhood population, but this paper shows pretty clearly that hypotension or bradycardia is not a real concern. I never hospitalize these patients for propranolol therapy except in high-risk populations: very preemie, any history of breathing problems. We check the blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, again at 7-10 days, and at every visit. We’ve never found any significant drop in blood pressure.”

Dr. Levy reported financial relationships with half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, none relevant to his presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Reassuring evidence of the safety of oral propranolol for treatment of complicated infantile hemangiomas in patients with PHACE syndrome comes from a recent multicenter study.

Oral propranolol is now well-ensconced as first-line therapy for complicated infantile hemangiomas in otherwise healthy children. However, the beta-blocker’s use in PHACE (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, and Eye abnormalities) syndrome has been controversial, with concerns raised by some that it might raise the risk for arterial ischemic stroke. Not so, Moise L. Levy, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“I’m not suggesting you use propranolol with reckless abandon in this population, but this stroke concern is something that should be put to bed based on this study,” advised Dr. Levy, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Dell Medical School in Austin, Tex., and physician-in-chief at Dell Children’s Medical Center.

PHACE syndrome is characterized by large, thick, plaque-like hemangiomas greater than 5 cm in size, most commonly on the face, although they can be located elsewhere.

“There was concern that if you found severely altered cerebrovascular arterial flow and you put a kid on a beta-blocker you might be causing some harm. But what I will tell you is that in this recently published paper this was not in fact an issue,” he said.

Dr. Levy was not an investigator in the multicenter retrospective study, which included 76 patients with PHACE syndrome treated for infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol at 0.3 mg/kg per dose or more at 11 academic tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinics. Treatment started at a median age of 56 days.

There were no strokes, TIAs, cardiovascular events, or other significant problems associated with treatment. Twenty-nine children experienced mild adverse events: minor gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and sleep disturbances were threefold more frequent than reported with placebo in another study. The investigators noted that the safety experience in their PHACE syndrome population compared favorably with that in 726 infants without PHACE syndrome who received oral propranolol for hemangiomas, where the incidence of serious adverse events on treatment was 0.4% (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839).

‘Hemangiomas – but we were taught that they go away’

Dr. Levy gave a shout-out to the American Academy of Pediatrics for publishing interdisciplinary expert consensus-based practice guidelines for the management of infantile hemangiomas, which he praised as “quite well done” (Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143[1]. pii: e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475).

Following release of the guidelines last year, he and other pediatric vascular anomalies experts saw an uptick in referrals from general pediatricians, which has since tapered off.

“It’s probably like for all of us: We read an article, it’s fresh on the mind, then you forget about the article and what you’ve read. So we need a little reinforcement from a learning perspective. This is a great article,” he said.

The guidelines debunk as myth the classic teaching that infantile hemangiomas go away. Explicit information is provided about the high-risk anatomic sites warranting consideration for early referral, including the periocular, lumbosacral, and perineal areas, the lip, and lower face.

“The major point is early identification of those lesions requiring evaluation and intervention. Hemangiomas generally speaking are at their ultimate size by 3-5 months of age. The bottom line is if you think something needs to be done, please send that patient, or act upon that patient, sooner rather than later. I can’t tell you how many cases of hemangiomas I’ve seen when the kid is 18 months of age, 3 years of age, 5 years, with a large area of redundant skin, scarring, or something of that sort, and it would have been really nice to have seen them earlier and acted upon them then,” the pediatric dermatologist said.

The guidelines recommend intervention or referral by 1 month of age, ideally. Guidance is provided about the use of oral propranolol as first-line therapy.

“Propranolol is something that has been a real game changer for us,” he noted. “Many people continue to be worried about side effects in using this, particularly in the young childhood population, but this paper shows pretty clearly that hypotension or bradycardia is not a real concern. I never hospitalize these patients for propranolol therapy except in high-risk populations: very preemie, any history of breathing problems. We check the blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, again at 7-10 days, and at every visit. We’ve never found any significant drop in blood pressure.”

Dr. Levy reported financial relationships with half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, none relevant to his presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Reassuring evidence of the safety of oral propranolol for treatment of complicated infantile hemangiomas in patients with PHACE syndrome comes from a recent multicenter study.

Oral propranolol is now well-ensconced as first-line therapy for complicated infantile hemangiomas in otherwise healthy children. However, the beta-blocker’s use in PHACE (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, and Eye abnormalities) syndrome has been controversial, with concerns raised by some that it might raise the risk for arterial ischemic stroke. Not so, Moise L. Levy, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“I’m not suggesting you use propranolol with reckless abandon in this population, but this stroke concern is something that should be put to bed based on this study,” advised Dr. Levy, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Dell Medical School in Austin, Tex., and physician-in-chief at Dell Children’s Medical Center.

PHACE syndrome is characterized by large, thick, plaque-like hemangiomas greater than 5 cm in size, most commonly on the face, although they can be located elsewhere.

“There was concern that if you found severely altered cerebrovascular arterial flow and you put a kid on a beta-blocker you might be causing some harm. But what I will tell you is that in this recently published paper this was not in fact an issue,” he said.

Dr. Levy was not an investigator in the multicenter retrospective study, which included 76 patients with PHACE syndrome treated for infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol at 0.3 mg/kg per dose or more at 11 academic tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinics. Treatment started at a median age of 56 days.

There were no strokes, TIAs, cardiovascular events, or other significant problems associated with treatment. Twenty-nine children experienced mild adverse events: minor gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and sleep disturbances were threefold more frequent than reported with placebo in another study. The investigators noted that the safety experience in their PHACE syndrome population compared favorably with that in 726 infants without PHACE syndrome who received oral propranolol for hemangiomas, where the incidence of serious adverse events on treatment was 0.4% (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839).

‘Hemangiomas – but we were taught that they go away’

Dr. Levy gave a shout-out to the American Academy of Pediatrics for publishing interdisciplinary expert consensus-based practice guidelines for the management of infantile hemangiomas, which he praised as “quite well done” (Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143[1]. pii: e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475).

Following release of the guidelines last year, he and other pediatric vascular anomalies experts saw an uptick in referrals from general pediatricians, which has since tapered off.

“It’s probably like for all of us: We read an article, it’s fresh on the mind, then you forget about the article and what you’ve read. So we need a little reinforcement from a learning perspective. This is a great article,” he said.

The guidelines debunk as myth the classic teaching that infantile hemangiomas go away. Explicit information is provided about the high-risk anatomic sites warranting consideration for early referral, including the periocular, lumbosacral, and perineal areas, the lip, and lower face.

“The major point is early identification of those lesions requiring evaluation and intervention. Hemangiomas generally speaking are at their ultimate size by 3-5 months of age. The bottom line is if you think something needs to be done, please send that patient, or act upon that patient, sooner rather than later. I can’t tell you how many cases of hemangiomas I’ve seen when the kid is 18 months of age, 3 years of age, 5 years, with a large area of redundant skin, scarring, or something of that sort, and it would have been really nice to have seen them earlier and acted upon them then,” the pediatric dermatologist said.

The guidelines recommend intervention or referral by 1 month of age, ideally. Guidance is provided about the use of oral propranolol as first-line therapy.

“Propranolol is something that has been a real game changer for us,” he noted. “Many people continue to be worried about side effects in using this, particularly in the young childhood population, but this paper shows pretty clearly that hypotension or bradycardia is not a real concern. I never hospitalize these patients for propranolol therapy except in high-risk populations: very preemie, any history of breathing problems. We check the blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, again at 7-10 days, and at every visit. We’ve never found any significant drop in blood pressure.”

Dr. Levy reported financial relationships with half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, none relevant to his presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Don’t call it perioral dermatitis

LAHAINA, HAWAII – , according to Jessica Sprague, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Years ago, some of her senior colleagues at the children’s hospital carried out a retrospective study of 79 patients, aged 6 months to 18 years, who were treated for what’s typically called perioral dermatitis. Of note, only 40% of patients had isolated perioral involvement, while 30% of the patients had no perioral lesions at all. Perinasal lesions were present in 43%, and 25% had periocular involvement, she noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The peak incidence of periorificial dermatitis in this series was under age 5 years. At presentation, the rash had been present for an average of 8 months. Seventy-two percent of patients had a history of exposure to corticosteroids, most often in the form of topical steroids, but in some cases inhaled or systemic steroids.

“Obviously you want to discontinue the topical steroid. Sometimes you need to taper them off, or you can switch to a topical calcineurin inhibitor [TCI] because they tend to flare a lot when you stop their topical steroid, although there are cases of TCIs precipitating periorificial dermatitis, so keep that in mind,” Dr. Sprague said.

If a patient is on inhaled steroids by mask for asthma, switching to a tube can sometimes limit the exposure, she continued.

Her first-line therapy for mild to moderate periorificial dermatitis, and the one supported by the strongest evidence base, is metronidazole cream. Other topical agents shown to be effective include azelaic acid, sulfacetamide, clindamycin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Oral therapy is a good option for more extensive or recalcitrant cases.

“If parents are very anxious, like before school photos or holiday photos, sometimes I’ll use oral therapy as well. In younger kids, I prefer erythromycin at 30 mg/kg per day t.i.d. for 3-6 weeks. In kids 8 years old and up you can use doxycycline at 50-100 mg b.i.d., again for 3-6 weeks. And you have to tell them it’s going to take a while for this to go away,” Dr. Sprague said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – , according to Jessica Sprague, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Years ago, some of her senior colleagues at the children’s hospital carried out a retrospective study of 79 patients, aged 6 months to 18 years, who were treated for what’s typically called perioral dermatitis. Of note, only 40% of patients had isolated perioral involvement, while 30% of the patients had no perioral lesions at all. Perinasal lesions were present in 43%, and 25% had periocular involvement, she noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The peak incidence of periorificial dermatitis in this series was under age 5 years. At presentation, the rash had been present for an average of 8 months. Seventy-two percent of patients had a history of exposure to corticosteroids, most often in the form of topical steroids, but in some cases inhaled or systemic steroids.

“Obviously you want to discontinue the topical steroid. Sometimes you need to taper them off, or you can switch to a topical calcineurin inhibitor [TCI] because they tend to flare a lot when you stop their topical steroid, although there are cases of TCIs precipitating periorificial dermatitis, so keep that in mind,” Dr. Sprague said.

If a patient is on inhaled steroids by mask for asthma, switching to a tube can sometimes limit the exposure, she continued.

Her first-line therapy for mild to moderate periorificial dermatitis, and the one supported by the strongest evidence base, is metronidazole cream. Other topical agents shown to be effective include azelaic acid, sulfacetamide, clindamycin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Oral therapy is a good option for more extensive or recalcitrant cases.

“If parents are very anxious, like before school photos or holiday photos, sometimes I’ll use oral therapy as well. In younger kids, I prefer erythromycin at 30 mg/kg per day t.i.d. for 3-6 weeks. In kids 8 years old and up you can use doxycycline at 50-100 mg b.i.d., again for 3-6 weeks. And you have to tell them it’s going to take a while for this to go away,” Dr. Sprague said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – , according to Jessica Sprague, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Years ago, some of her senior colleagues at the children’s hospital carried out a retrospective study of 79 patients, aged 6 months to 18 years, who were treated for what’s typically called perioral dermatitis. Of note, only 40% of patients had isolated perioral involvement, while 30% of the patients had no perioral lesions at all. Perinasal lesions were present in 43%, and 25% had periocular involvement, she noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The peak incidence of periorificial dermatitis in this series was under age 5 years. At presentation, the rash had been present for an average of 8 months. Seventy-two percent of patients had a history of exposure to corticosteroids, most often in the form of topical steroids, but in some cases inhaled or systemic steroids.

“Obviously you want to discontinue the topical steroid. Sometimes you need to taper them off, or you can switch to a topical calcineurin inhibitor [TCI] because they tend to flare a lot when you stop their topical steroid, although there are cases of TCIs precipitating periorificial dermatitis, so keep that in mind,” Dr. Sprague said.

If a patient is on inhaled steroids by mask for asthma, switching to a tube can sometimes limit the exposure, she continued.

Her first-line therapy for mild to moderate periorificial dermatitis, and the one supported by the strongest evidence base, is metronidazole cream. Other topical agents shown to be effective include azelaic acid, sulfacetamide, clindamycin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Oral therapy is a good option for more extensive or recalcitrant cases.

“If parents are very anxious, like before school photos or holiday photos, sometimes I’ll use oral therapy as well. In younger kids, I prefer erythromycin at 30 mg/kg per day t.i.d. for 3-6 weeks. In kids 8 years old and up you can use doxycycline at 50-100 mg b.i.d., again for 3-6 weeks. And you have to tell them it’s going to take a while for this to go away,” Dr. Sprague said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Focus groups seek transgender experience with HIV prevention

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.