User login

PPI use linked with increased fracture risk in children

under 18 years.

The fracture incidence rates among 115,933 pairs of children under age 18 years matched based on propensity score and age were 20.2 versus 18.3 per 1,000 person-years among those who did and did not receive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.11), Yun-Han Wang of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm and colleagues reported in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increases in risk with PPI use were seen for upper-limb fracture (HR, 1.08), lower-limb fracture (HR, 1.19) and other fractures (HR, 1.51), but not head fractures (HR, 0.93). The risks increased nominally in tandem with cumulative duration of PPI use (HR, 1.08, 1.14, and 1.34 for 30 days or less, 31-364 days, and 365 days or more, respectively), the investigators found.

After subgroup and sensitivity analyses, Mr. Wang and associates stated that PPI use in children “was associated with a statistically significant 11% relative increase in risk of any fracture. The association was driven by fractures of upper limbs, lower limbs, and other sites; appeared to be mainly restricted to children 6 years and older; and seemed to be somewhat more pronounced with a longer cumulative duration of PPI use.”

“Risk of fracture should be taken into account when weighing the benefits and risks of PPI treatment in children, they concluded.

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation; one coauthor was supported by a grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology program at Karolinska Institutet. Two coauthors reported associations with pharmaceutical companies, and one of them with a health care data company. Dr. Wang and the remaining coauthors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 101001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007.

under 18 years.

The fracture incidence rates among 115,933 pairs of children under age 18 years matched based on propensity score and age were 20.2 versus 18.3 per 1,000 person-years among those who did and did not receive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.11), Yun-Han Wang of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm and colleagues reported in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increases in risk with PPI use were seen for upper-limb fracture (HR, 1.08), lower-limb fracture (HR, 1.19) and other fractures (HR, 1.51), but not head fractures (HR, 0.93). The risks increased nominally in tandem with cumulative duration of PPI use (HR, 1.08, 1.14, and 1.34 for 30 days or less, 31-364 days, and 365 days or more, respectively), the investigators found.

After subgroup and sensitivity analyses, Mr. Wang and associates stated that PPI use in children “was associated with a statistically significant 11% relative increase in risk of any fracture. The association was driven by fractures of upper limbs, lower limbs, and other sites; appeared to be mainly restricted to children 6 years and older; and seemed to be somewhat more pronounced with a longer cumulative duration of PPI use.”

“Risk of fracture should be taken into account when weighing the benefits and risks of PPI treatment in children, they concluded.

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation; one coauthor was supported by a grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology program at Karolinska Institutet. Two coauthors reported associations with pharmaceutical companies, and one of them with a health care data company. Dr. Wang and the remaining coauthors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 101001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007.

under 18 years.

The fracture incidence rates among 115,933 pairs of children under age 18 years matched based on propensity score and age were 20.2 versus 18.3 per 1,000 person-years among those who did and did not receive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.11), Yun-Han Wang of Karolinska Institute, Stockholm and colleagues reported in JAMA Pediatrics.

Increases in risk with PPI use were seen for upper-limb fracture (HR, 1.08), lower-limb fracture (HR, 1.19) and other fractures (HR, 1.51), but not head fractures (HR, 0.93). The risks increased nominally in tandem with cumulative duration of PPI use (HR, 1.08, 1.14, and 1.34 for 30 days or less, 31-364 days, and 365 days or more, respectively), the investigators found.

After subgroup and sensitivity analyses, Mr. Wang and associates stated that PPI use in children “was associated with a statistically significant 11% relative increase in risk of any fracture. The association was driven by fractures of upper limbs, lower limbs, and other sites; appeared to be mainly restricted to children 6 years and older; and seemed to be somewhat more pronounced with a longer cumulative duration of PPI use.”

“Risk of fracture should be taken into account when weighing the benefits and risks of PPI treatment in children, they concluded.

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and Frimurare Barnhuset Foundation; one coauthor was supported by a grant from the Strategic Research Area Epidemiology program at Karolinska Institutet. Two coauthors reported associations with pharmaceutical companies, and one of them with a health care data company. Dr. Wang and the remaining coauthors reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang Y et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 101001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Nearly half of STI events go without HIV testing

according to Danielle Petsis, MPH, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 1,816 acute STI events from 1,313 patients aged 13-24 years admitted between July 2014 and Dec. 2017 at two urban health care clinics. The most common STIs in the analysis were Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis; the mean age at diagnosis was 17 years, 71% of episodes occurred in females, and 97% occurred in African American patients.

Of the 1,816 events, HIV testing was completed within 90 days of the STI diagnosis for only 55%; there was 1 confirmed HIV diagnosis among the completed tests. When HIV testing did occur, in 38% of cases it was completed concurrently with STI testing or HIV testing was performed in 35% of the 872 follow-up cases. Of the 815 events where HIV testing was not performed, 27% had a test ordered by the provider but not completed by the patient; the patient leaving the laboratory before the test could be performed was the most common reason for test noncompletion (67%), followed by not showing up at all (18%) and errors in the medical record or laboratory (5%); the remaining patients gave as reasons for test noncompletion: declining an HIV test, a closed lab, or no reason.

Logistic regression showed that participants who were female and those with a previous history of STIs had significantly lower adjusted odds of HIV test completion, compared with males and those with no previous history of STIs, respectively, the investigators said. In addition, having insurance and having a family planning visit were associated with decreased odds of HIV testing, compared with not having insurance or a family planning visit.

“As we enter the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, it remains clear that missed opportunities for diagnosis have the potential to delay HIV diagnosis and linkage to antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and prevention services, thus increasing the population risk of HIV transmission. Our data underscore the need for improved HIV testing education for providers of all levels of training and the need for public health agencies to clearly communicate the need for testing at the time of STI infection to reduce the number of missed opportunities for testing,” Ms. Petsis and colleagues concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute K-Readiness Award. One coauthor reported receiving funding from Bayer Healthcare, the Templeton Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Janssen Biotech. She also serves on expert advisory boards for Mylan Pharmaceuticals and Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wood S et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2265.

according to Danielle Petsis, MPH, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 1,816 acute STI events from 1,313 patients aged 13-24 years admitted between July 2014 and Dec. 2017 at two urban health care clinics. The most common STIs in the analysis were Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis; the mean age at diagnosis was 17 years, 71% of episodes occurred in females, and 97% occurred in African American patients.

Of the 1,816 events, HIV testing was completed within 90 days of the STI diagnosis for only 55%; there was 1 confirmed HIV diagnosis among the completed tests. When HIV testing did occur, in 38% of cases it was completed concurrently with STI testing or HIV testing was performed in 35% of the 872 follow-up cases. Of the 815 events where HIV testing was not performed, 27% had a test ordered by the provider but not completed by the patient; the patient leaving the laboratory before the test could be performed was the most common reason for test noncompletion (67%), followed by not showing up at all (18%) and errors in the medical record or laboratory (5%); the remaining patients gave as reasons for test noncompletion: declining an HIV test, a closed lab, or no reason.

Logistic regression showed that participants who were female and those with a previous history of STIs had significantly lower adjusted odds of HIV test completion, compared with males and those with no previous history of STIs, respectively, the investigators said. In addition, having insurance and having a family planning visit were associated with decreased odds of HIV testing, compared with not having insurance or a family planning visit.

“As we enter the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, it remains clear that missed opportunities for diagnosis have the potential to delay HIV diagnosis and linkage to antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and prevention services, thus increasing the population risk of HIV transmission. Our data underscore the need for improved HIV testing education for providers of all levels of training and the need for public health agencies to clearly communicate the need for testing at the time of STI infection to reduce the number of missed opportunities for testing,” Ms. Petsis and colleagues concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute K-Readiness Award. One coauthor reported receiving funding from Bayer Healthcare, the Templeton Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Janssen Biotech. She also serves on expert advisory boards for Mylan Pharmaceuticals and Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wood S et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2265.

according to Danielle Petsis, MPH, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 1,816 acute STI events from 1,313 patients aged 13-24 years admitted between July 2014 and Dec. 2017 at two urban health care clinics. The most common STIs in the analysis were Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis; the mean age at diagnosis was 17 years, 71% of episodes occurred in females, and 97% occurred in African American patients.

Of the 1,816 events, HIV testing was completed within 90 days of the STI diagnosis for only 55%; there was 1 confirmed HIV diagnosis among the completed tests. When HIV testing did occur, in 38% of cases it was completed concurrently with STI testing or HIV testing was performed in 35% of the 872 follow-up cases. Of the 815 events where HIV testing was not performed, 27% had a test ordered by the provider but not completed by the patient; the patient leaving the laboratory before the test could be performed was the most common reason for test noncompletion (67%), followed by not showing up at all (18%) and errors in the medical record or laboratory (5%); the remaining patients gave as reasons for test noncompletion: declining an HIV test, a closed lab, or no reason.

Logistic regression showed that participants who were female and those with a previous history of STIs had significantly lower adjusted odds of HIV test completion, compared with males and those with no previous history of STIs, respectively, the investigators said. In addition, having insurance and having a family planning visit were associated with decreased odds of HIV testing, compared with not having insurance or a family planning visit.

“As we enter the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, it remains clear that missed opportunities for diagnosis have the potential to delay HIV diagnosis and linkage to antiretroviral therapy or PrEP and prevention services, thus increasing the population risk of HIV transmission. Our data underscore the need for improved HIV testing education for providers of all levels of training and the need for public health agencies to clearly communicate the need for testing at the time of STI infection to reduce the number of missed opportunities for testing,” Ms. Petsis and colleagues concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute K-Readiness Award. One coauthor reported receiving funding from Bayer Healthcare, the Templeton Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and Janssen Biotech. She also serves on expert advisory boards for Mylan Pharmaceuticals and Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wood S et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2265.

FROM PEDIATRICS

COVID-19 in children, pregnant women: What do we know?

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Detection of COVID-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

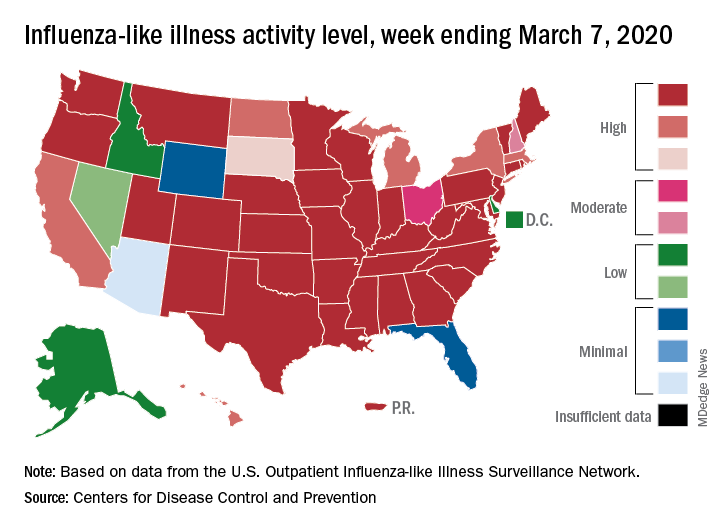

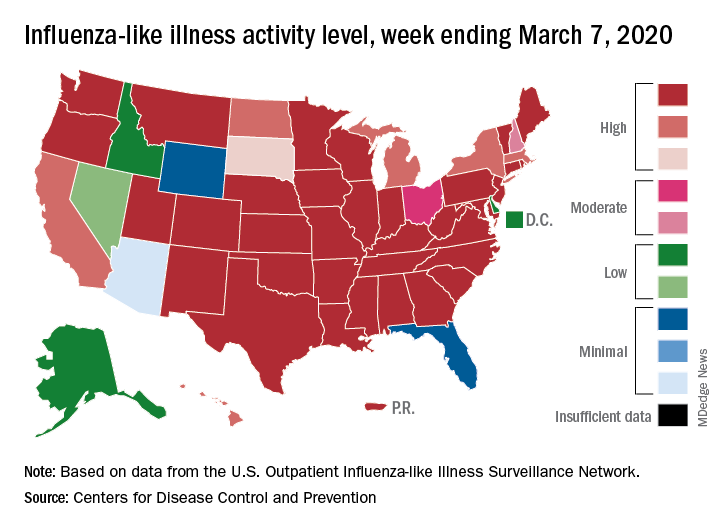

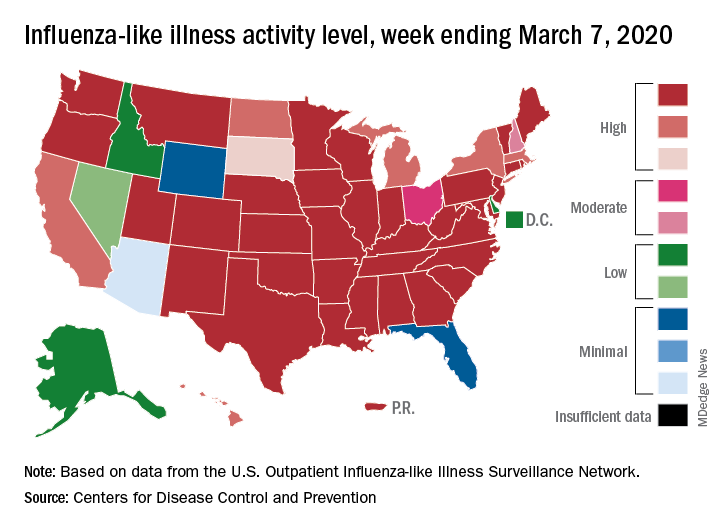

After weeks of decline, influenza activity increases slightly

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

Expert says progress in gut-brain research requires an open mind

A growing body of research links the gut with the brain and behavior, but compartmentalization within the medical community may be slowing investigation of the gut-brain axis, according to a leading expert.

Studies have shown that the microbiome may influence a diverse range of behavioral and neurological processes, from acute and chronic stress responses to development of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, reported John F. Cryan, PhD, of University College Cork, Ireland.

Dr. Cryan began his presentation at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit by citing Hippocrates, who is thought to have stated that all diseases begin in the gut.

“That can be quite strange when I talk to my neurology or psychiatry colleagues,” Dr. Cryan said. “They sometimes look at me like I have two heads. Because in medicine we compartmentalize, and if you are studying neurology or psychiatry or [you are] in clinical practice, you are focusing on everything from the neck upwards.”

For more than a decade, Dr. Cryan and colleagues have been investigating the gut-brain axis, predominantly in mouse models, but also across animal species and in humans.

At the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Dr. Cryan reviewed a variety of representative studies.

For instance, in both mice and humans, research has shown that C-section, which is associated with poorer microbiome diversity than vaginal delivery, has also been linked with social deficits and elevated stress responses. And in the case of mice, coprophagia, in which cesarean-delivered mice eat the feces of vaginally born mice, has been shown to ameliorate these psychiatric effects.

Dr. Cryan likened this process to an “artificial fecal transplant.”

“You know, co-housing and eating each other’s poo is not the translational approach that we were advocating by any means,” Dr. Cryan said. “But at least it tells us – in a proof-of-concept way – that if we change the microbiome, then we can reverse what’s going on.”

While the mechanisms behind the gut-brain axis remain incompletely understood, Dr. Cryan noted that the vagus nerve, which travels from the gut to the brain, plays a central role, and that transecting this nerve in mice stops the microbiome from affecting the brain.

“What happens in vagus doesn’t just stay in vagus, but will actually affect our emotions in different ways,” Dr. Cryan said.

He emphasized that communication travels both ways along the gut-brain axis, and went on to describe how this phenomenon has been demonstrated across a wide array of animals.

“From insects all the way through to primates, if you start to interfere with social behavior, you change the microbiome,” Dr. Cryan said. “But the opposite is also true; if you start to change the microbiome you can start to have widespread effects on social behavior.”

In humans, manipulating the microbiome could open up new psychiatric frontiers, Dr. Cryan said.

“[In the past 30 years], there really have been no real advances in how we manage mental health,” he said. “That’s very sobering when we are having such a mental health problem across all ages right now. And so perhaps it’s time for what we’ve coined the ‘psychobiotic revolution’ – time for a new way of thinking about mental health.”

According to Dr. Cryan, psychobiotics are interventions that target the microbiome for mental health purposes, including fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, parabiotics, and postbiotics.

Among these, probiotics have been a focal point of interventional research. Although results have been mixed, Dr. Cryan suggested that negative probiotic studies are more likely due to bacterial strain than a failure of the concept as a whole.

“Most strains of bacteria will do absolutely nothing,” Dr. Cryan said. “Strain is really important.”

In demonstration of this concept, he recounted a 2017 study conducted at University College Cork in which 22 healthy volunteers were given Bifidobacterium longum 1714, and then subjected to a social stress test. The results, published in Translational Psychiatry, showed that the probiotic, compared with placebo, was associated with attenuated stress responses, reduced daily stress, and enhanced visuospatial memory.

In contrast, a similar study by Dr. Cryan and colleagues, which tested Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1), fell short.

“You [could not have gotten] more negative data into one paper if you tried,” Dr. Cryan said, referring to the study. “It did absolutely nothing.”

To find out which psychobiotics may have an impact, and how, Dr. Cryan called for more research.

“It’s still early days,” he said. “We probably have more meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the field than we have primary research papers.

Dr. Cryan concluded his presentation on an optimistic note.

“Neurology is waking up ... to understand that the microbiome could be playing a key role in many, many other disorders. ... Overall, what we’re beginning to see is that our state of gut markedly affects our state of mind.”

Dr. Cryan disclosed relationships with Abbott Nutrition, Roche Pharma, Nutricia, and others.

A growing body of research links the gut with the brain and behavior, but compartmentalization within the medical community may be slowing investigation of the gut-brain axis, according to a leading expert.

Studies have shown that the microbiome may influence a diverse range of behavioral and neurological processes, from acute and chronic stress responses to development of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, reported John F. Cryan, PhD, of University College Cork, Ireland.

Dr. Cryan began his presentation at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit by citing Hippocrates, who is thought to have stated that all diseases begin in the gut.

“That can be quite strange when I talk to my neurology or psychiatry colleagues,” Dr. Cryan said. “They sometimes look at me like I have two heads. Because in medicine we compartmentalize, and if you are studying neurology or psychiatry or [you are] in clinical practice, you are focusing on everything from the neck upwards.”

For more than a decade, Dr. Cryan and colleagues have been investigating the gut-brain axis, predominantly in mouse models, but also across animal species and in humans.

At the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Dr. Cryan reviewed a variety of representative studies.

For instance, in both mice and humans, research has shown that C-section, which is associated with poorer microbiome diversity than vaginal delivery, has also been linked with social deficits and elevated stress responses. And in the case of mice, coprophagia, in which cesarean-delivered mice eat the feces of vaginally born mice, has been shown to ameliorate these psychiatric effects.

Dr. Cryan likened this process to an “artificial fecal transplant.”

“You know, co-housing and eating each other’s poo is not the translational approach that we were advocating by any means,” Dr. Cryan said. “But at least it tells us – in a proof-of-concept way – that if we change the microbiome, then we can reverse what’s going on.”

While the mechanisms behind the gut-brain axis remain incompletely understood, Dr. Cryan noted that the vagus nerve, which travels from the gut to the brain, plays a central role, and that transecting this nerve in mice stops the microbiome from affecting the brain.

“What happens in vagus doesn’t just stay in vagus, but will actually affect our emotions in different ways,” Dr. Cryan said.

He emphasized that communication travels both ways along the gut-brain axis, and went on to describe how this phenomenon has been demonstrated across a wide array of animals.

“From insects all the way through to primates, if you start to interfere with social behavior, you change the microbiome,” Dr. Cryan said. “But the opposite is also true; if you start to change the microbiome you can start to have widespread effects on social behavior.”

In humans, manipulating the microbiome could open up new psychiatric frontiers, Dr. Cryan said.

“[In the past 30 years], there really have been no real advances in how we manage mental health,” he said. “That’s very sobering when we are having such a mental health problem across all ages right now. And so perhaps it’s time for what we’ve coined the ‘psychobiotic revolution’ – time for a new way of thinking about mental health.”

According to Dr. Cryan, psychobiotics are interventions that target the microbiome for mental health purposes, including fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, parabiotics, and postbiotics.

Among these, probiotics have been a focal point of interventional research. Although results have been mixed, Dr. Cryan suggested that negative probiotic studies are more likely due to bacterial strain than a failure of the concept as a whole.

“Most strains of bacteria will do absolutely nothing,” Dr. Cryan said. “Strain is really important.”

In demonstration of this concept, he recounted a 2017 study conducted at University College Cork in which 22 healthy volunteers were given Bifidobacterium longum 1714, and then subjected to a social stress test. The results, published in Translational Psychiatry, showed that the probiotic, compared with placebo, was associated with attenuated stress responses, reduced daily stress, and enhanced visuospatial memory.

In contrast, a similar study by Dr. Cryan and colleagues, which tested Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1), fell short.

“You [could not have gotten] more negative data into one paper if you tried,” Dr. Cryan said, referring to the study. “It did absolutely nothing.”

To find out which psychobiotics may have an impact, and how, Dr. Cryan called for more research.

“It’s still early days,” he said. “We probably have more meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the field than we have primary research papers.

Dr. Cryan concluded his presentation on an optimistic note.

“Neurology is waking up ... to understand that the microbiome could be playing a key role in many, many other disorders. ... Overall, what we’re beginning to see is that our state of gut markedly affects our state of mind.”

Dr. Cryan disclosed relationships with Abbott Nutrition, Roche Pharma, Nutricia, and others.

A growing body of research links the gut with the brain and behavior, but compartmentalization within the medical community may be slowing investigation of the gut-brain axis, according to a leading expert.

Studies have shown that the microbiome may influence a diverse range of behavioral and neurological processes, from acute and chronic stress responses to development of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, reported John F. Cryan, PhD, of University College Cork, Ireland.

Dr. Cryan began his presentation at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit by citing Hippocrates, who is thought to have stated that all diseases begin in the gut.

“That can be quite strange when I talk to my neurology or psychiatry colleagues,” Dr. Cryan said. “They sometimes look at me like I have two heads. Because in medicine we compartmentalize, and if you are studying neurology or psychiatry or [you are] in clinical practice, you are focusing on everything from the neck upwards.”

For more than a decade, Dr. Cryan and colleagues have been investigating the gut-brain axis, predominantly in mouse models, but also across animal species and in humans.

At the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Dr. Cryan reviewed a variety of representative studies.

For instance, in both mice and humans, research has shown that C-section, which is associated with poorer microbiome diversity than vaginal delivery, has also been linked with social deficits and elevated stress responses. And in the case of mice, coprophagia, in which cesarean-delivered mice eat the feces of vaginally born mice, has been shown to ameliorate these psychiatric effects.

Dr. Cryan likened this process to an “artificial fecal transplant.”

“You know, co-housing and eating each other’s poo is not the translational approach that we were advocating by any means,” Dr. Cryan said. “But at least it tells us – in a proof-of-concept way – that if we change the microbiome, then we can reverse what’s going on.”

While the mechanisms behind the gut-brain axis remain incompletely understood, Dr. Cryan noted that the vagus nerve, which travels from the gut to the brain, plays a central role, and that transecting this nerve in mice stops the microbiome from affecting the brain.

“What happens in vagus doesn’t just stay in vagus, but will actually affect our emotions in different ways,” Dr. Cryan said.

He emphasized that communication travels both ways along the gut-brain axis, and went on to describe how this phenomenon has been demonstrated across a wide array of animals.

“From insects all the way through to primates, if you start to interfere with social behavior, you change the microbiome,” Dr. Cryan said. “But the opposite is also true; if you start to change the microbiome you can start to have widespread effects on social behavior.”

In humans, manipulating the microbiome could open up new psychiatric frontiers, Dr. Cryan said.

“[In the past 30 years], there really have been no real advances in how we manage mental health,” he said. “That’s very sobering when we are having such a mental health problem across all ages right now. And so perhaps it’s time for what we’ve coined the ‘psychobiotic revolution’ – time for a new way of thinking about mental health.”

According to Dr. Cryan, psychobiotics are interventions that target the microbiome for mental health purposes, including fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, parabiotics, and postbiotics.

Among these, probiotics have been a focal point of interventional research. Although results have been mixed, Dr. Cryan suggested that negative probiotic studies are more likely due to bacterial strain than a failure of the concept as a whole.

“Most strains of bacteria will do absolutely nothing,” Dr. Cryan said. “Strain is really important.”

In demonstration of this concept, he recounted a 2017 study conducted at University College Cork in which 22 healthy volunteers were given Bifidobacterium longum 1714, and then subjected to a social stress test. The results, published in Translational Psychiatry, showed that the probiotic, compared with placebo, was associated with attenuated stress responses, reduced daily stress, and enhanced visuospatial memory.

In contrast, a similar study by Dr. Cryan and colleagues, which tested Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1), fell short.

“You [could not have gotten] more negative data into one paper if you tried,” Dr. Cryan said, referring to the study. “It did absolutely nothing.”

To find out which psychobiotics may have an impact, and how, Dr. Cryan called for more research.

“It’s still early days,” he said. “We probably have more meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the field than we have primary research papers.

Dr. Cryan concluded his presentation on an optimistic note.

“Neurology is waking up ... to understand that the microbiome could be playing a key role in many, many other disorders. ... Overall, what we’re beginning to see is that our state of gut markedly affects our state of mind.”

Dr. Cryan disclosed relationships with Abbott Nutrition, Roche Pharma, Nutricia, and others.

FROM GMFH 2020

Wuhan case review: COVID-19 characteristics differ in children vs. adults

Pediatric cases of COVID-19 infection are typically mild, but underlying coinfection may be more common in children than in adults, according to an analysis of clinical, laboratory, and chest CT features of pediatric inpatients in Wuhan, China.

The findings point toward a need for early chest CT with corresponding pathogen detection in children with suspected COVID-19 infection, Wei Xia, MD, of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, and colleagues reported in Pediatric Pulmonology.

The most common symptoms in 20 pediatric patients hospitalized between Jan. 23 and Feb. 8, 2020, with COVID-19 infection confirmed by the pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test were fever and cough, which occurred in 60% and 65% of patients, respectively. Coinfection was detected in eight patients (40%), they noted.

Clinical manifestations were similar to those seen in adults, but overall symptoms were relatively mild and overall prognosis was good. Of particular note, 7 of the 20 (35%) patients had a previously diagnosed congenital or acquired diseases, suggesting that children with underlying conditions may be more susceptible, Dr. Xia and colleagues wrote.

Laboratory findings also were notable in that 80% of the children had procalcitonin (PCT) elevations not typically seen in adults with COVID-19. PCT is a marker for bacterial infection and “[this finding] may suggest that routine antibacterial treatment should be considered in pediatric patients,” the investigators wrote.

As for imaging results, chest CT findings in children were similar to those in adults.“The typical manifestations were unilateral or bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities, and consolidations with surrounding halo signs,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote, adding that consolidations with surrounding halo sign accounted for about half the pediatric cases and should be considered as “typical signs in pediatric patients.”

Pediatric cases were “rather rare” in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, where the first cases of infection were reported.

“As a pediatric group is usually susceptible to upper respiratory tract infection, because of their developing immune system, the delayed presence of pediatric patients is confusing,” the investigators wrote, noting that a low detection rate of pharyngeal swab COVID-19 nucleic acid test, distinguishing the virus from other common respiratory tract infectious pathogens in pediatric patients, “is still a problem.”

To better characterize the clinical and imaging features in children versus adults with COVID-19, Dr. Xia and associates reviewed these 20 pediatric cases, including 13 boys and 7 girls with ages ranging from less than 1 month to 14 years, 7 months (median 2 years, 1.5 months). Thirteen had an identified close contact with a COVID-19–diagnosed family member, and all were treated in an isolation ward. A total of 18 children were cured and discharged after an average stay of 13 days, and 2 neonates remained under observation because of positive swab results with negative CT findings. The investigators speculated that the different findings in neonates were perhaps caused by the influence of delivery on sampling or the specific CT manifestations for neonates, adding that more samples are needed for further clarification.

Based on these findings, “the CT imaging of COVID-19 infection should be differentiated with other virus pneumonias such as influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus,” they concluded. It also should “be differentiated from bacterial pneumonia, mycoplasma pneumonia, and chlamydia pneumonia ... the density of pneumonia lesions caused by the latter pathogens is relatively higher.”

However, Dr. Xia and colleagues noted that chest CT manifestations of pneumonia caused by different pathogens overlap, and COVID-19 pneumonia “can be superimposed with serious and complex imaging manifestations, so epidemiological and etiological examinations should be combined.”

The investigators concluded that COVID-19 virus pneumonia in children is generally mild, and that the characteristic changes of subpleural ground-glass opacities and consolidations with surrounding halo on chest CT provide an “effective means for follow-up and evaluating the changes of lung lesions.”

“In the case that the positive rate of COVID-19 nucleic acid test from pharyngeal swab samples is not high, the early detection of lesions by CT is conducive to reasonable management and early treatment for pediatric patients. However, the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia by CT imaging alone is not sufficient enough, especially in the case of coinfection with other pathogens,” Dr. Xia and associates wrote. “Therefore, early chest CT screening and timely follow-up, combined with corresponding pathogen detection, is a feasible clinical protocol in children.”

An early study

In a separate retrospective analysis described in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, Weiyong Liu, PhD, of Tongji Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and colleagues found that the most frequently detected pathogens in 366 children under the age of 16 years hospitalized with respiratory infections in Wuhan during Jan. 7-15, 2020, were influenza A virus (6.3% of cases) and influenza B virus (5.5% of cases), whereas COVID-19 was detected in 1.6% of cases.

The median age of the COVID-19 patients in that series was 3 years (range 1-7 years), and in contrast to the findings of Xia et al., all previously had been “completely healthy.” Common characteristics were high fever and cough in all six patients, and vomiting in four patients. Five had pneumonia as assessed by X-ray, and CTs showed typical viral pneumonia patterns.

One patient was admitted to a pediatric ICU. All patients received antiviral agents, antibiotic agents, and supportive therapies; all recovered after a median hospital stay of 7.5 days (median range, 5-13 days).