User login

Spikes out: A COVID mystery

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

To date, it has been a mystery, like “Glass Onion.” And in the spirit of all the great mysteries, to get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to round up the usual suspects.

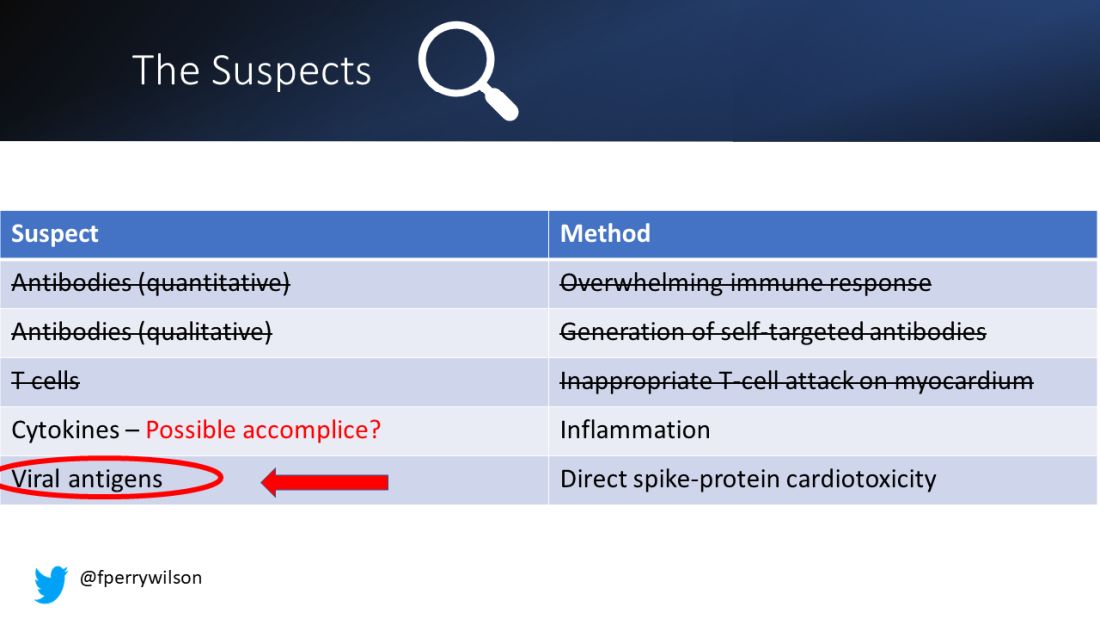

Appearing in Circulation, a new study does a great job of systematically evaluating multiple hypotheses linking vaccination to myocarditis, and eliminating them, Poirot-style, one by one until only one remains. We’ll get there.

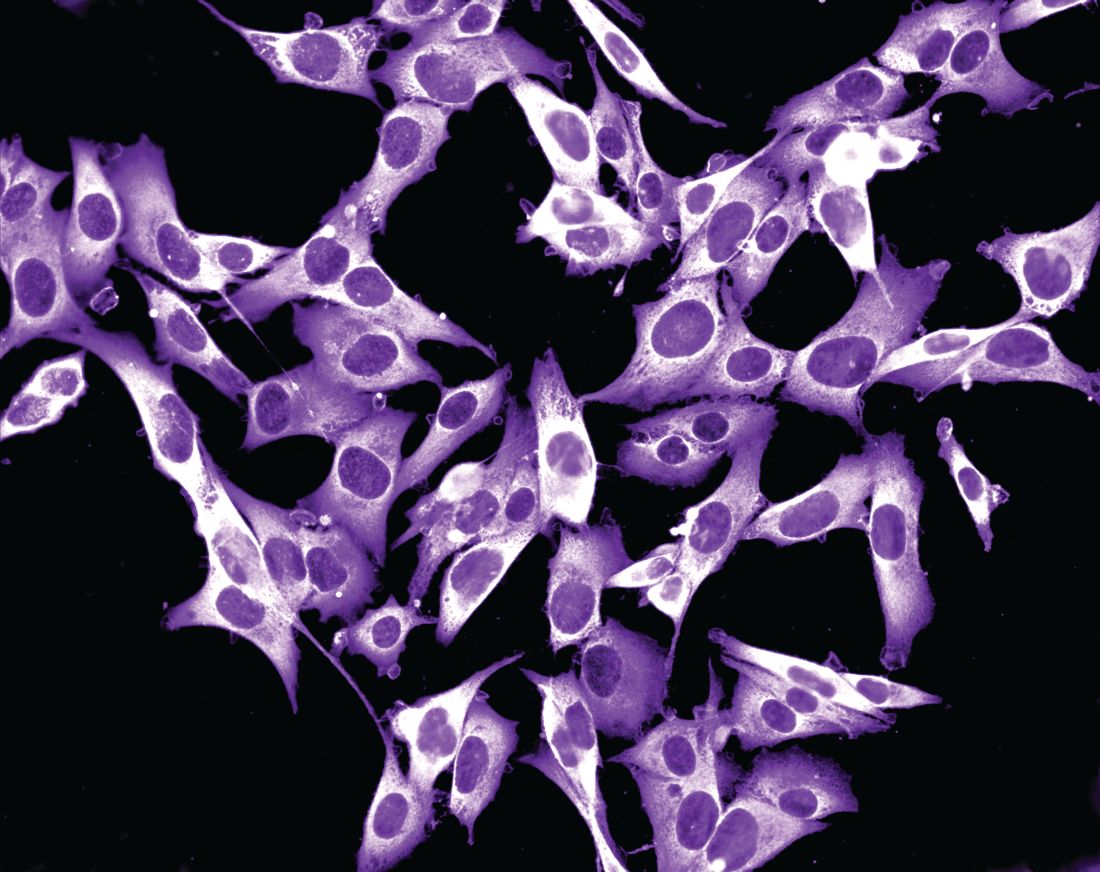

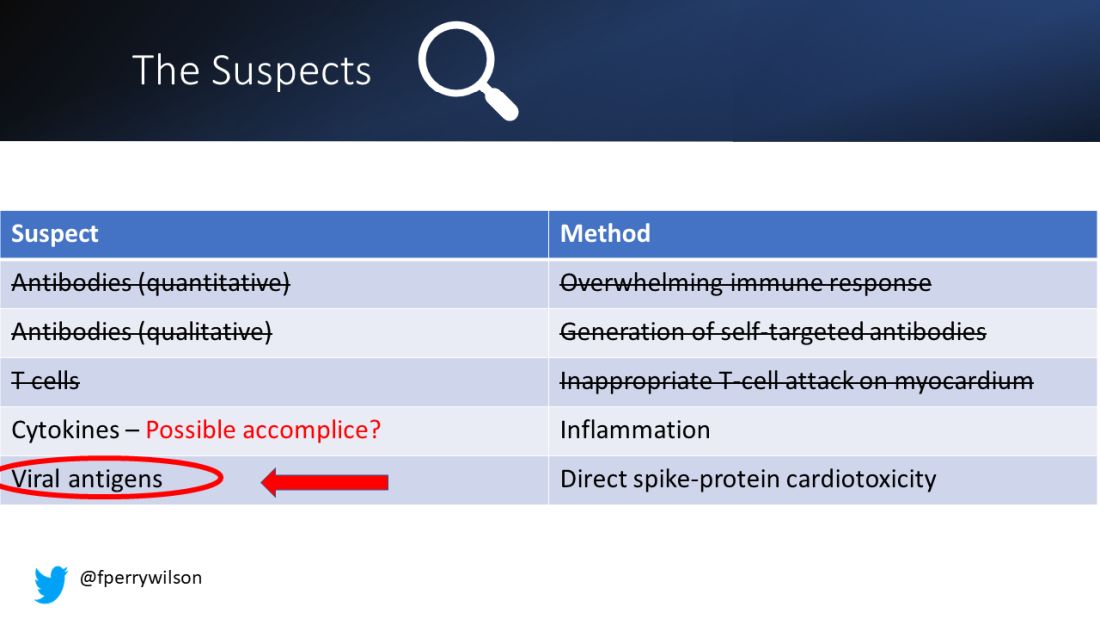

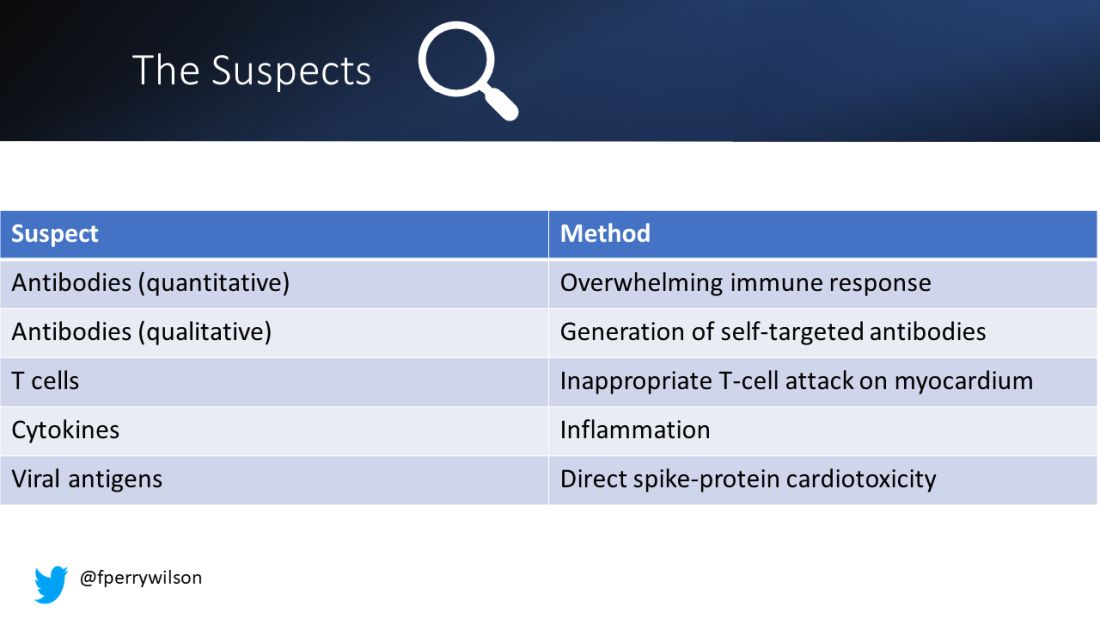

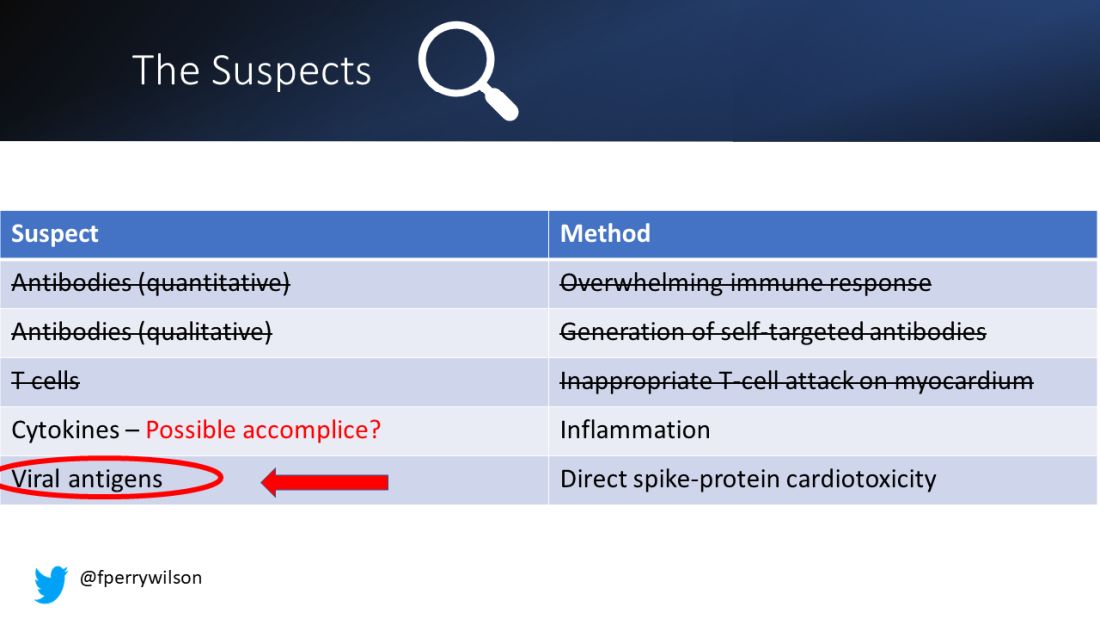

But first, let’s review the suspects. Why do the mRNA vaccines cause myocarditis in a small subset of people?

There are a few leading candidates.

Number one: antibody responses. There are two flavors here. The quantitative hypothesis suggests that some people simply generate too many antibodies to the vaccine, leading to increased inflammation and heart damage.

The qualitative hypothesis suggests that maybe it’s the nature of the antibodies generated rather than the amount; they might cross-react with some protein on the surface of heart cells for instance.

Or maybe it is driven by T-cell responses, which, of course, are independent of antibody levels.

There’s the idea that myocarditis is due to excessive cytokine release – sort of like what we see in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Or it could be due to the viral antigens themselves – the spike protein the mRNA codes for that is generated after vaccination.

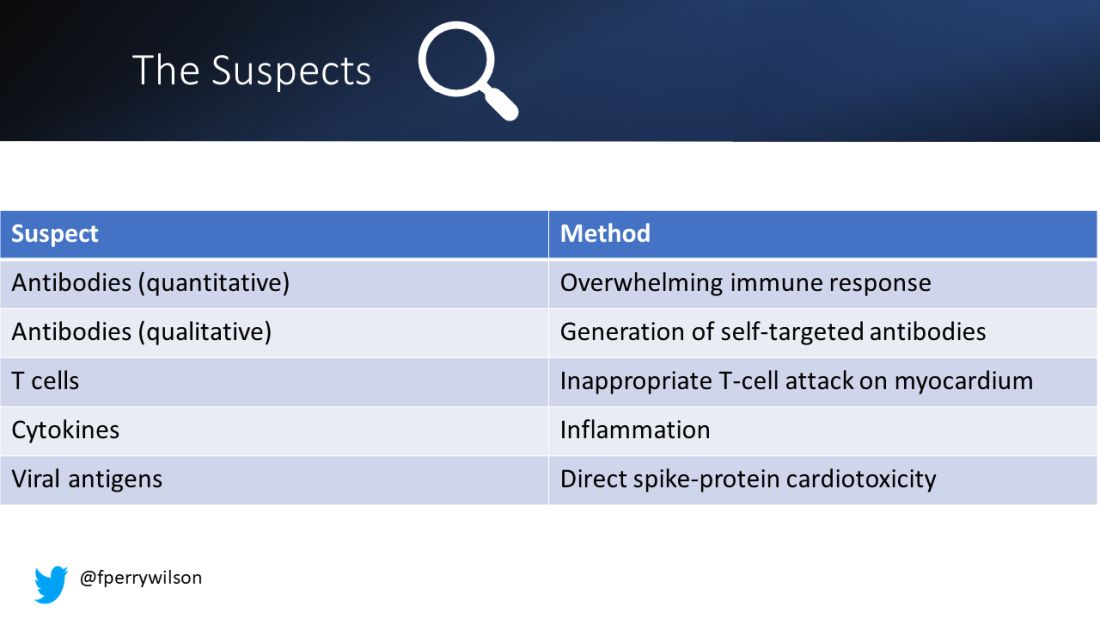

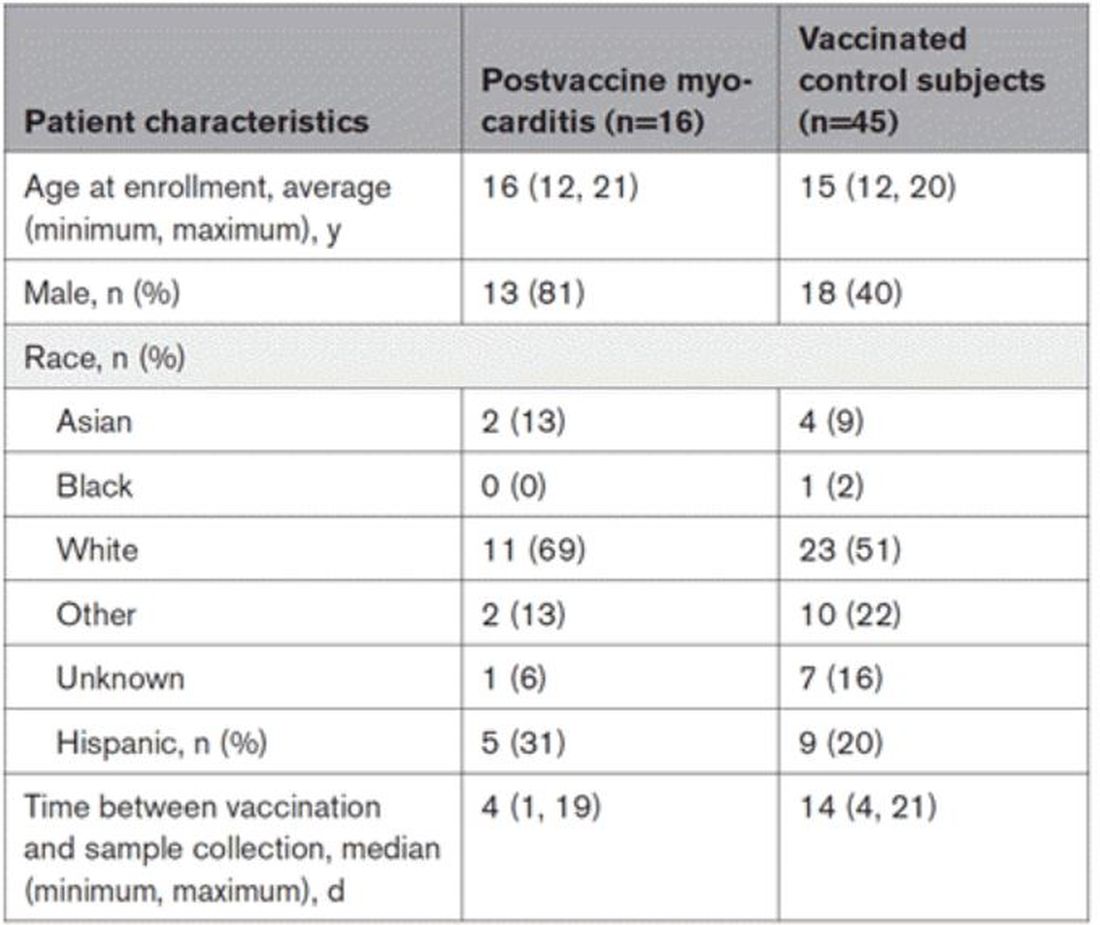

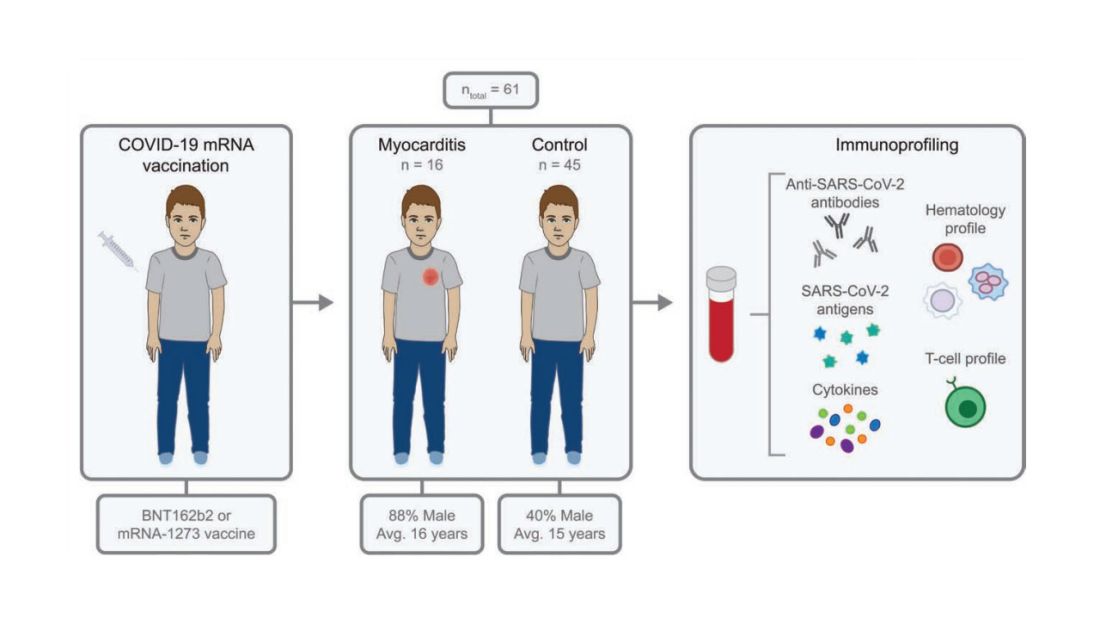

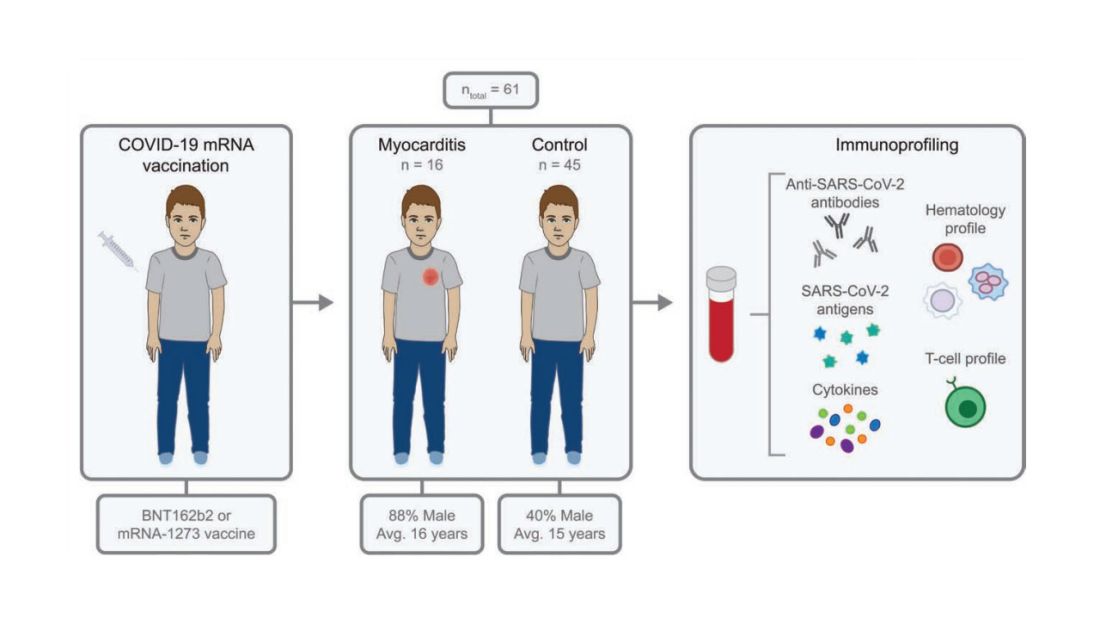

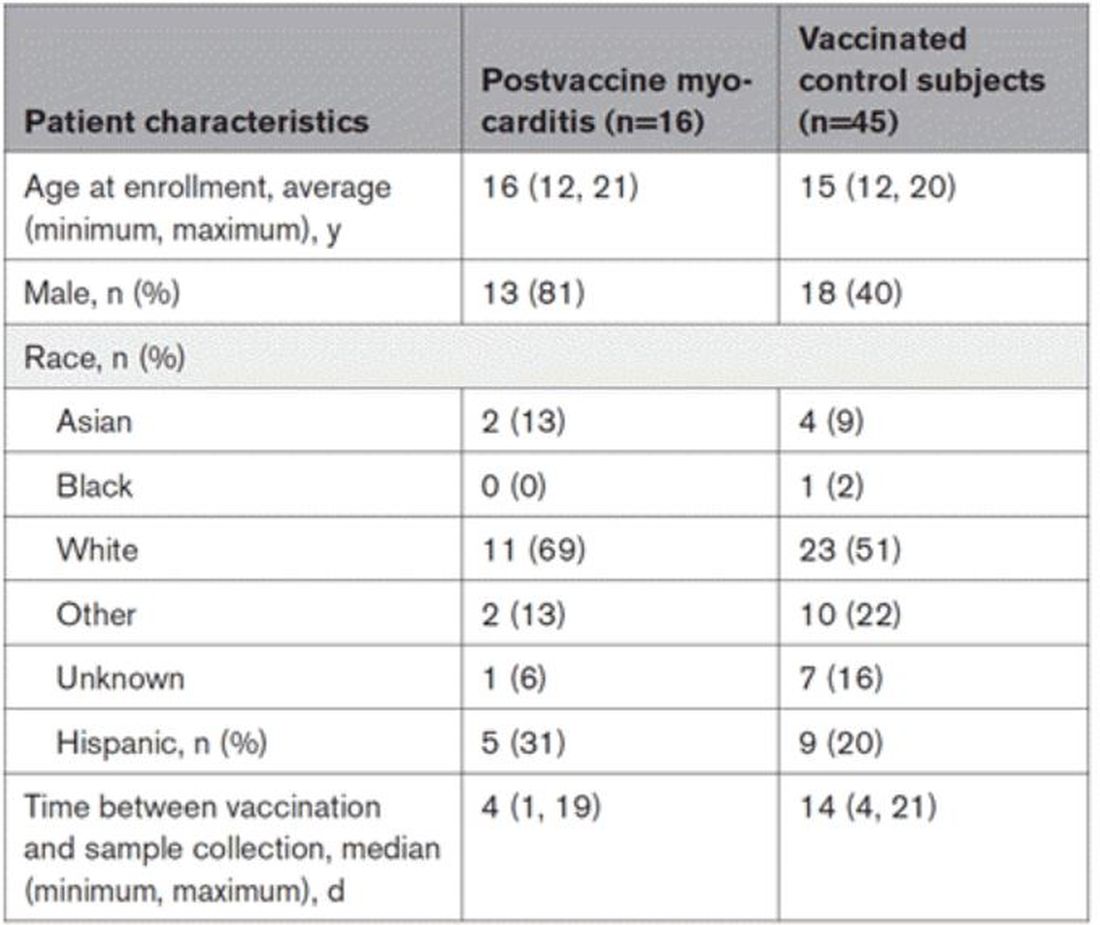

To tease all these possibilities apart, researchers led by Lael Yonker at Mass General performed a case-control study. Sixteen children with postvaccine myocarditis were matched by age to 45 control children who had been vaccinated without complications.

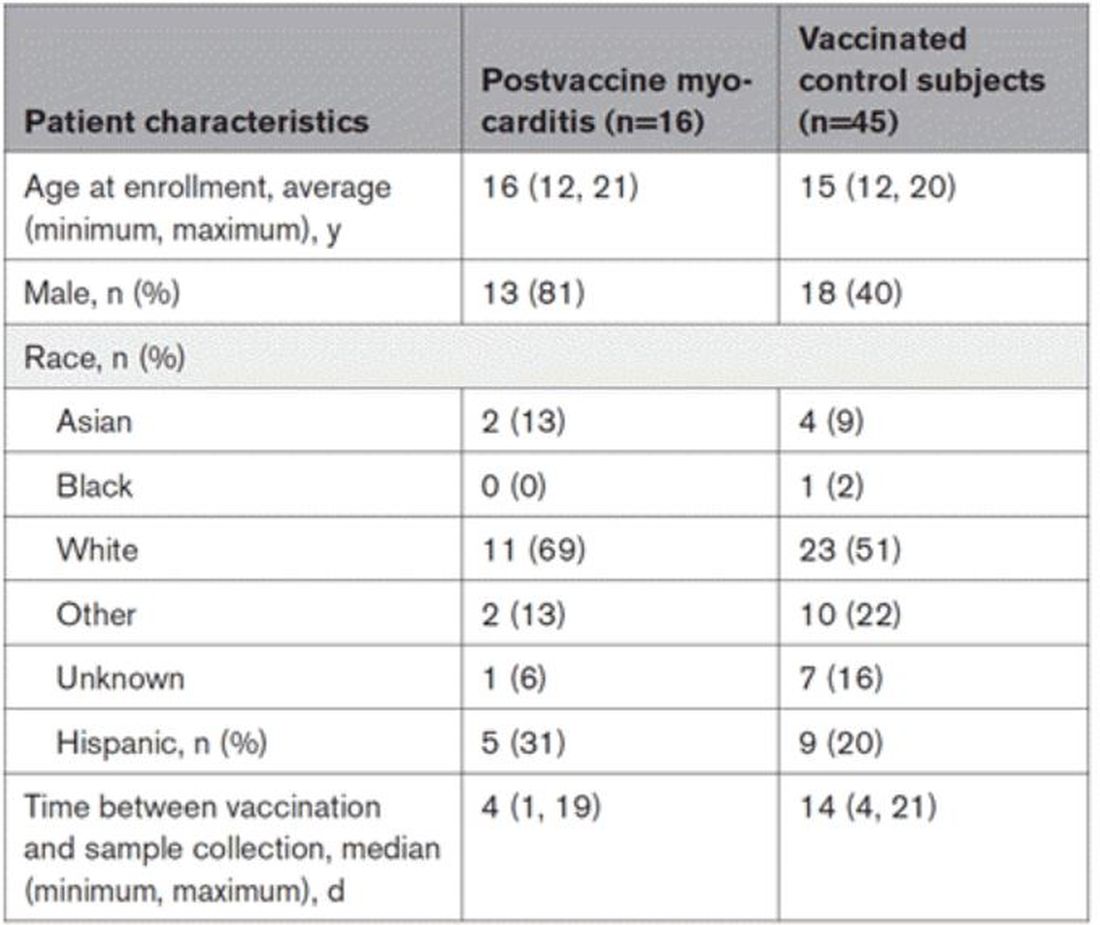

The matching was OK, but as you can see here, there were more boys in the myocarditis group, and the time from vaccination was a bit shorter in that group as well. We’ll keep that in mind as we go through the results.

OK, let’s start eliminating suspects.

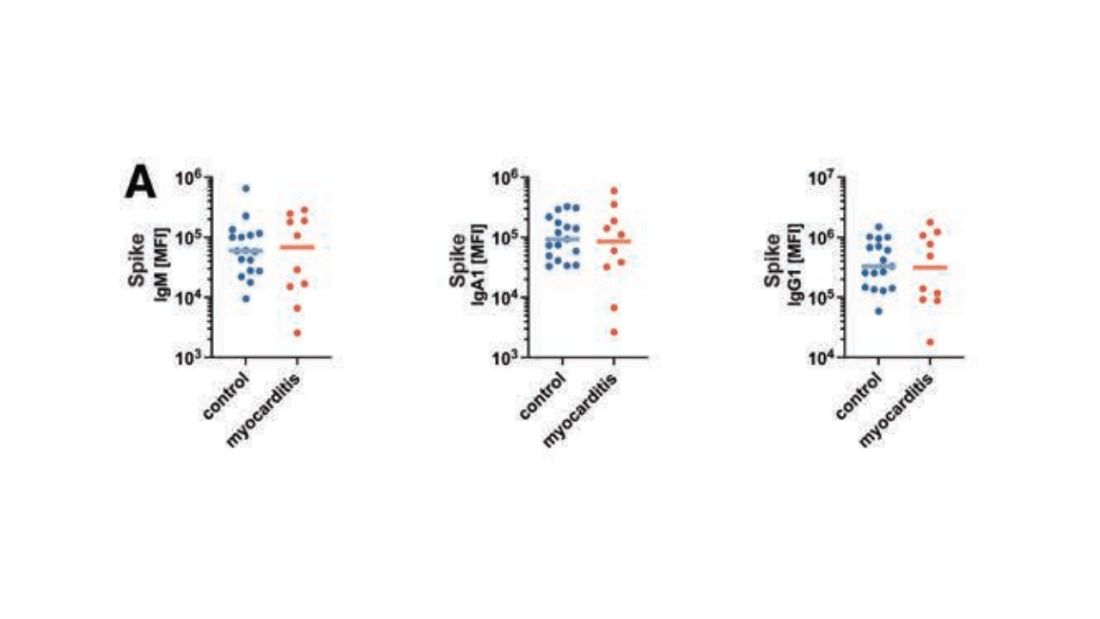

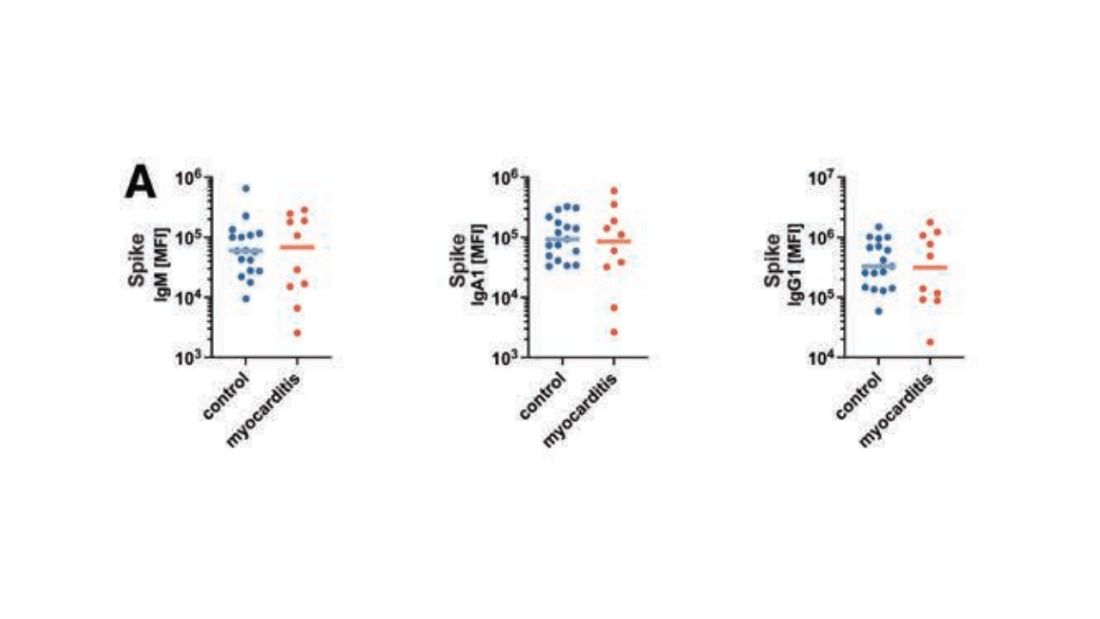

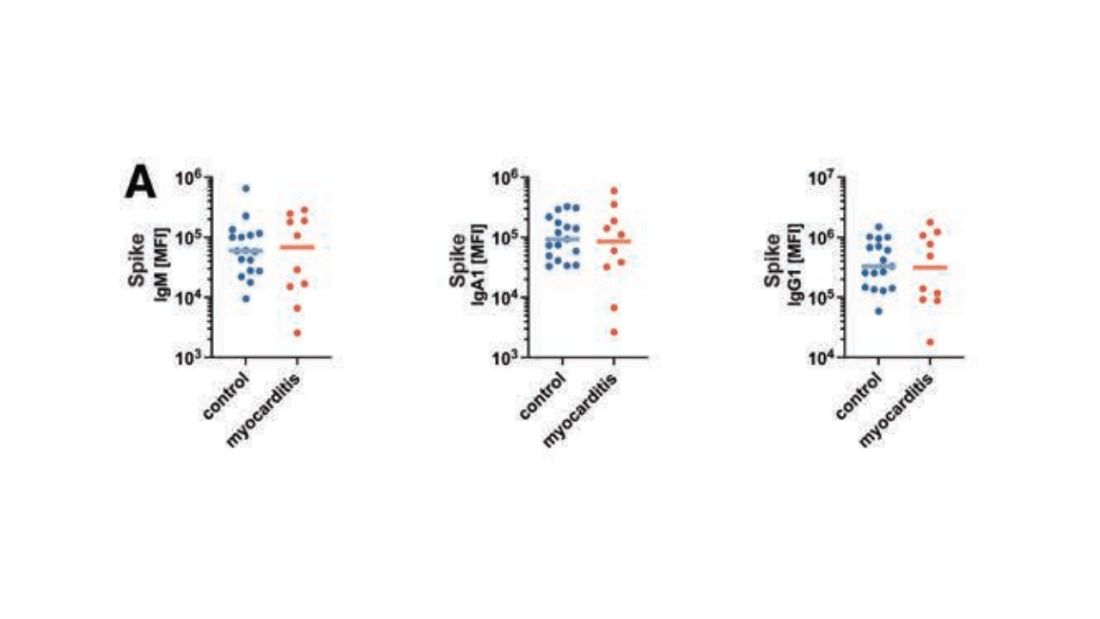

First, quantitative antibodies. Seems unlikely. Absolute antibody titers were really no different in the myocarditis vs. the control group.

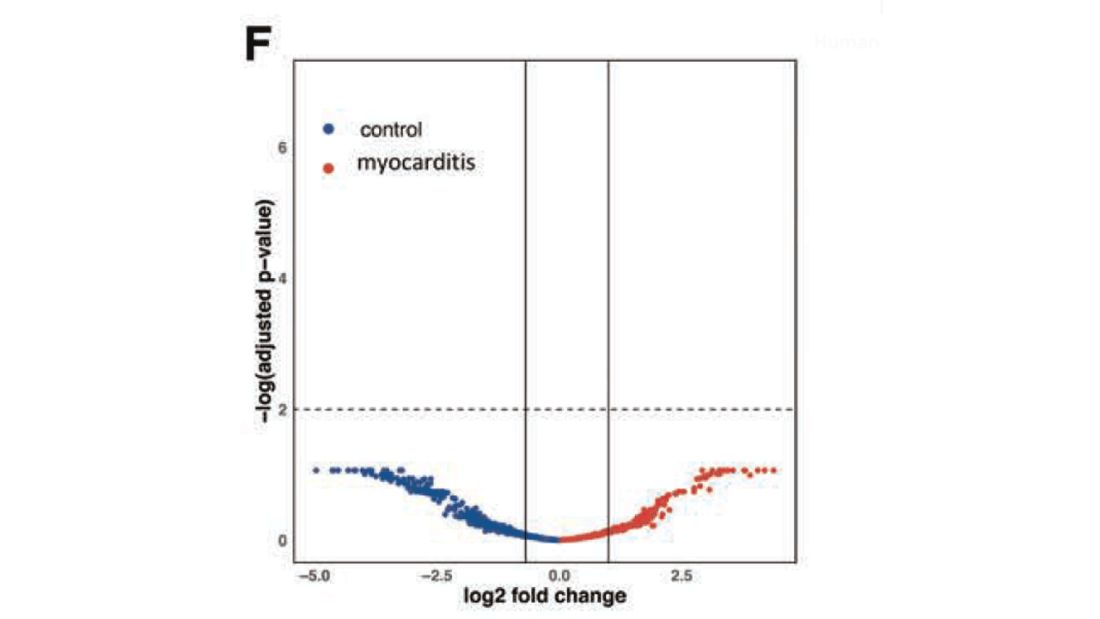

What about the quality of the antibodies? Would the kids with myocarditis have more self-recognizing antibodies present? It doesn’t appear so. Autoantibody levels were similar in the two groups.

Take antibodies off the list.

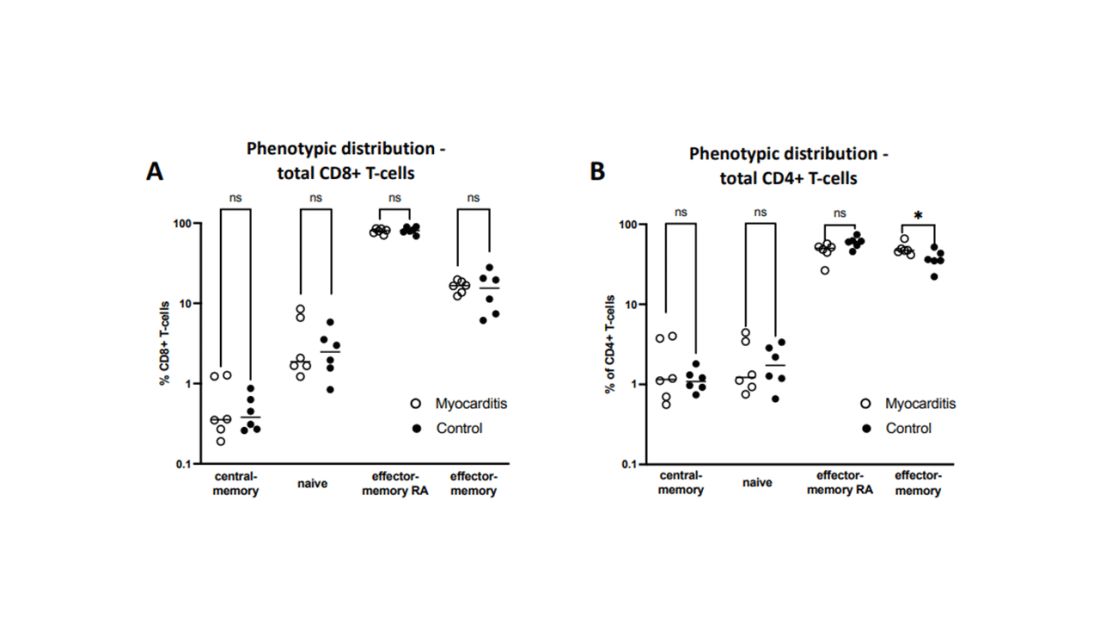

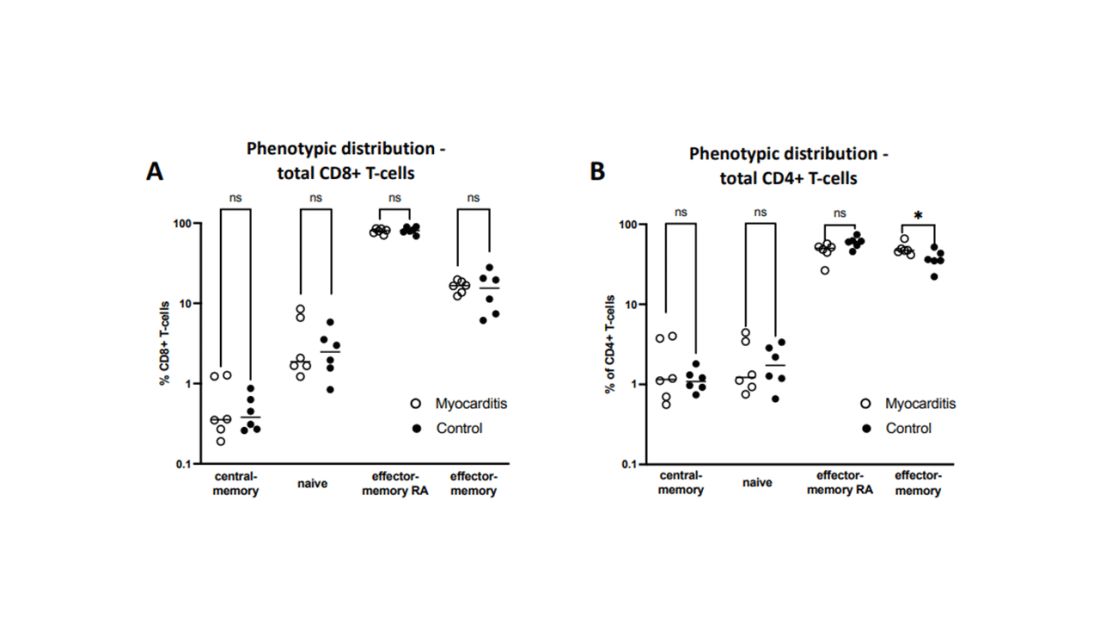

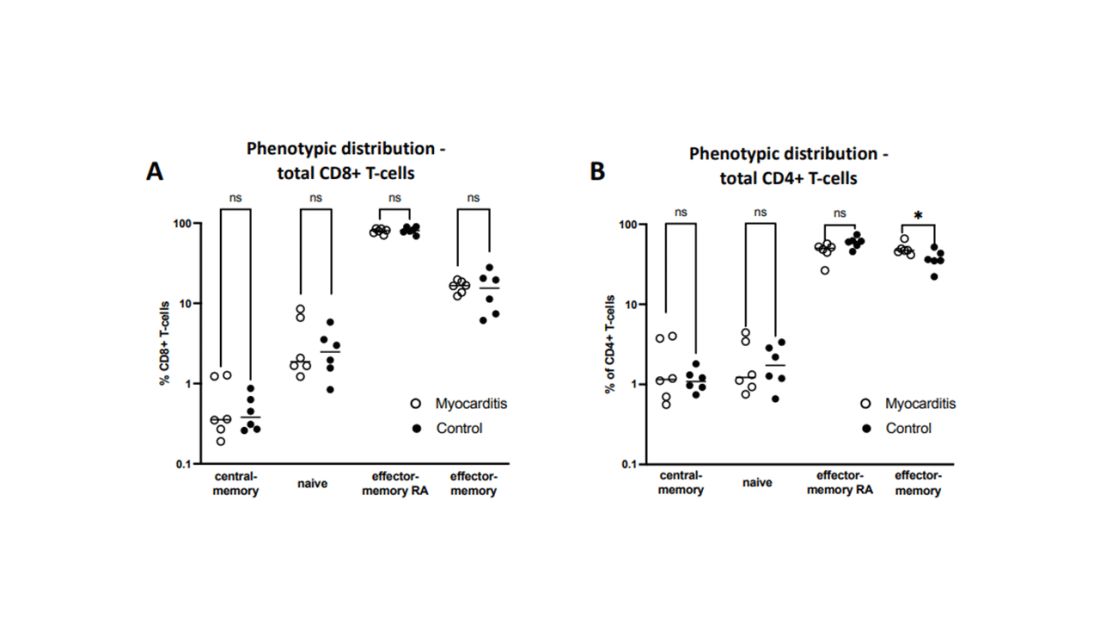

T-cell responses come next, and, again, no major differences here, save for one specific T-cell subtype that was moderately elevated in the myocarditis group. Not what I would call a smoking gun, frankly.

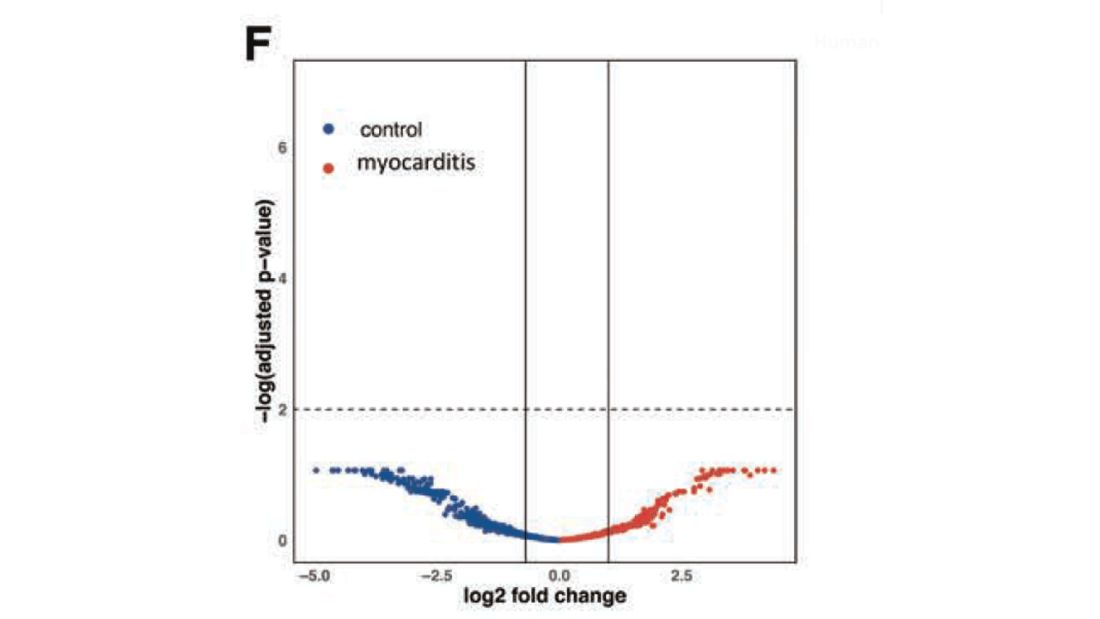

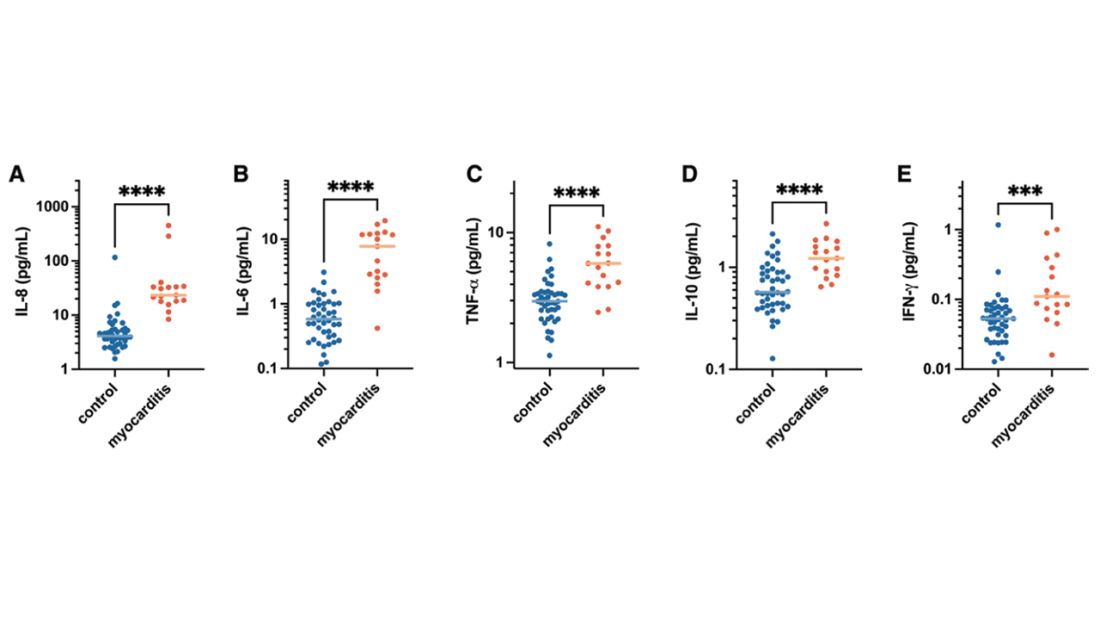

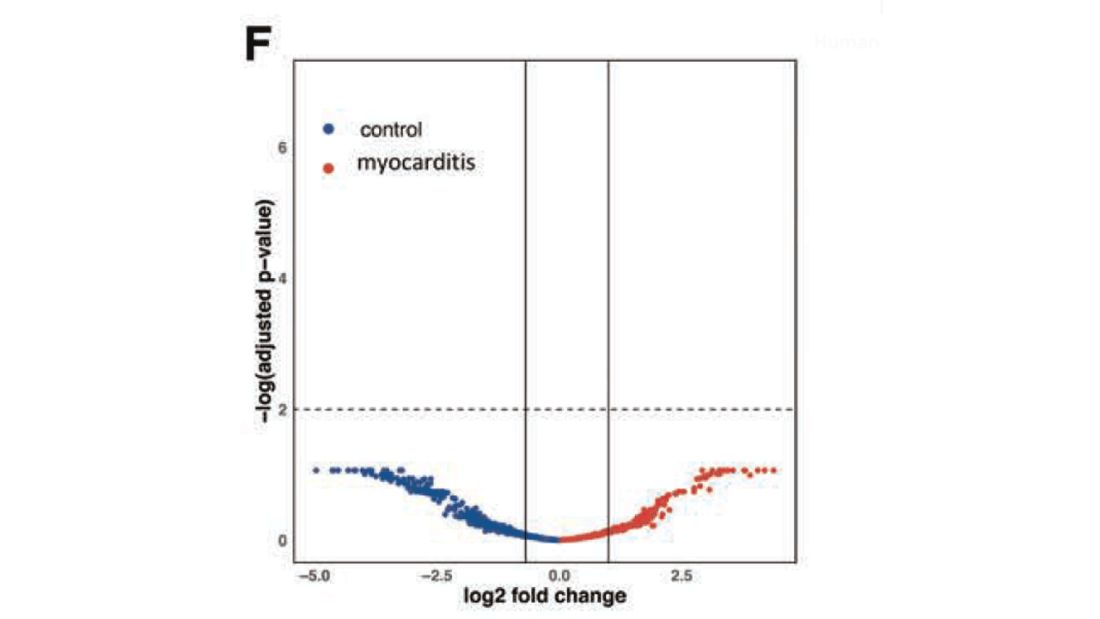

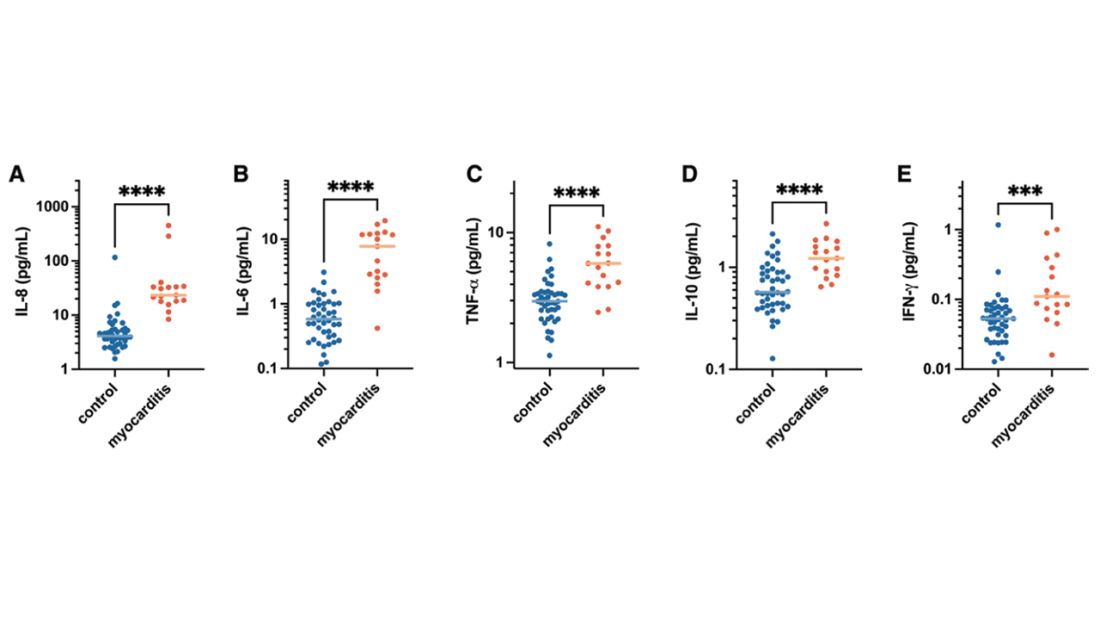

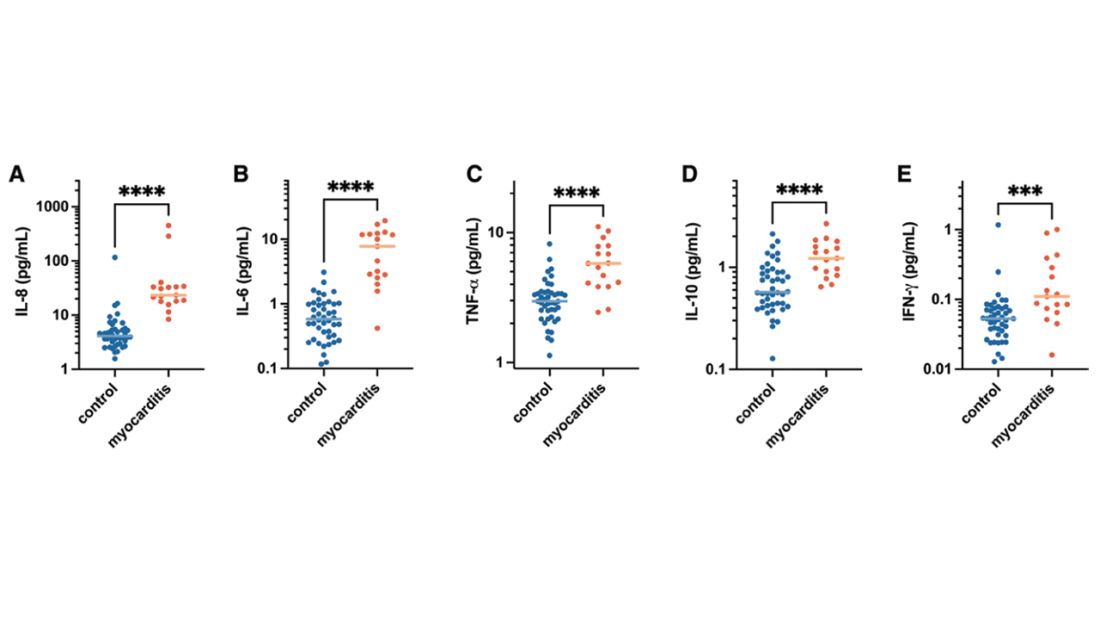

Cytokines give us a bit more to chew on. Levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-10 were all substantially higher in the kids with myocarditis.

But the thing about cytokines is that they are not particularly specific. OK, kids with myocarditis have more systemic inflammation than kids without; that’s not really surprising. It still leaves us with the question of what is causing all this inflammation? Who is the arch-villain? The kingpin? The don?

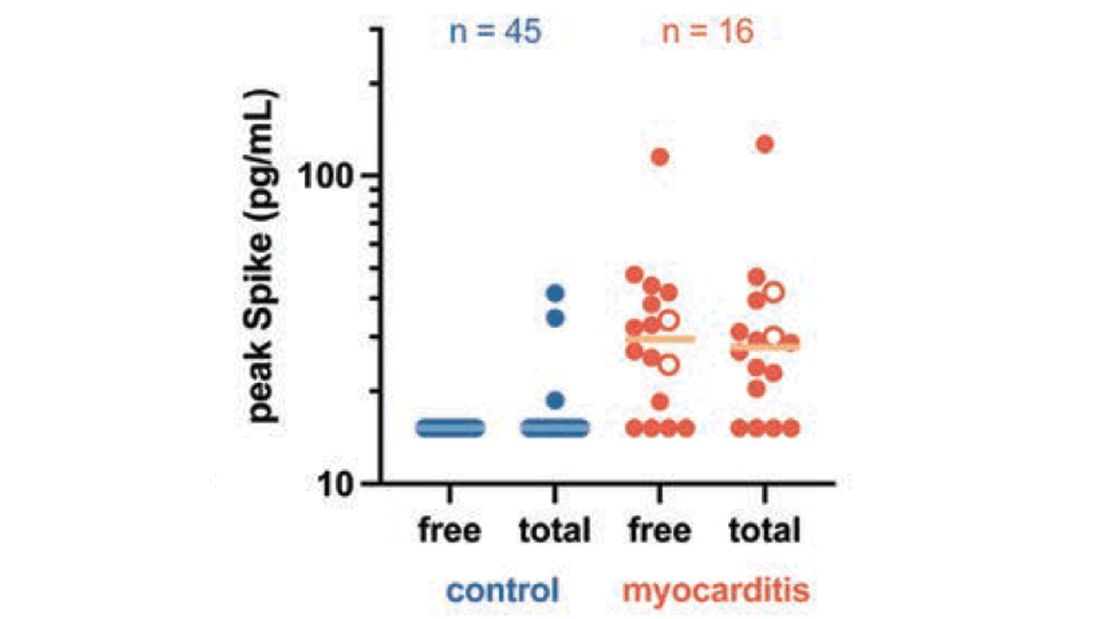

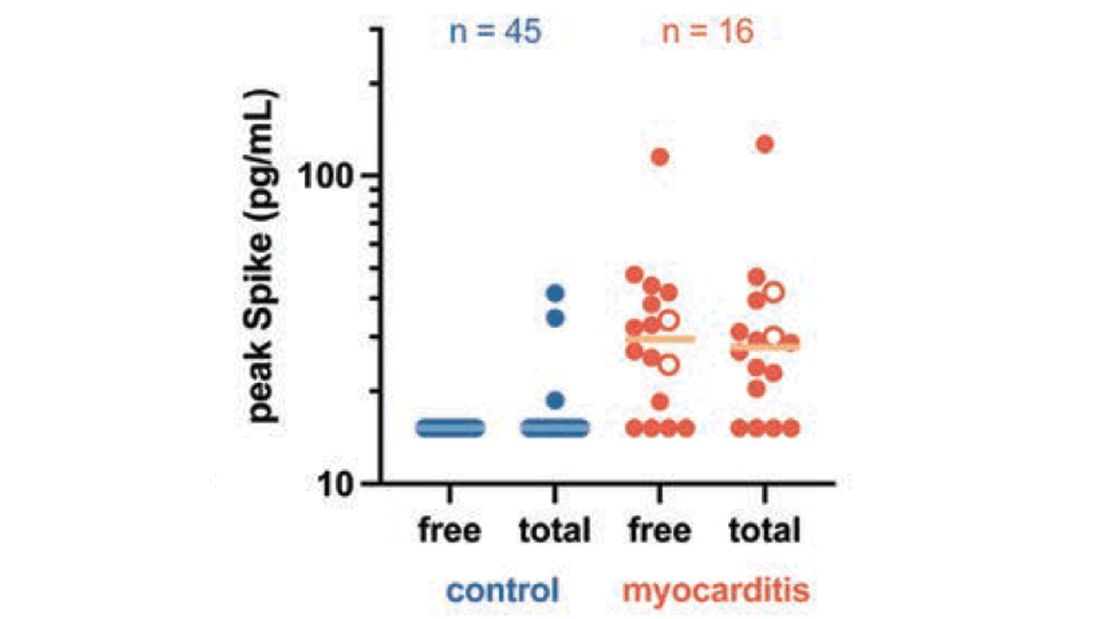

It’s the analyses of antigens – the protein products of vaccination – that may hold the key here.

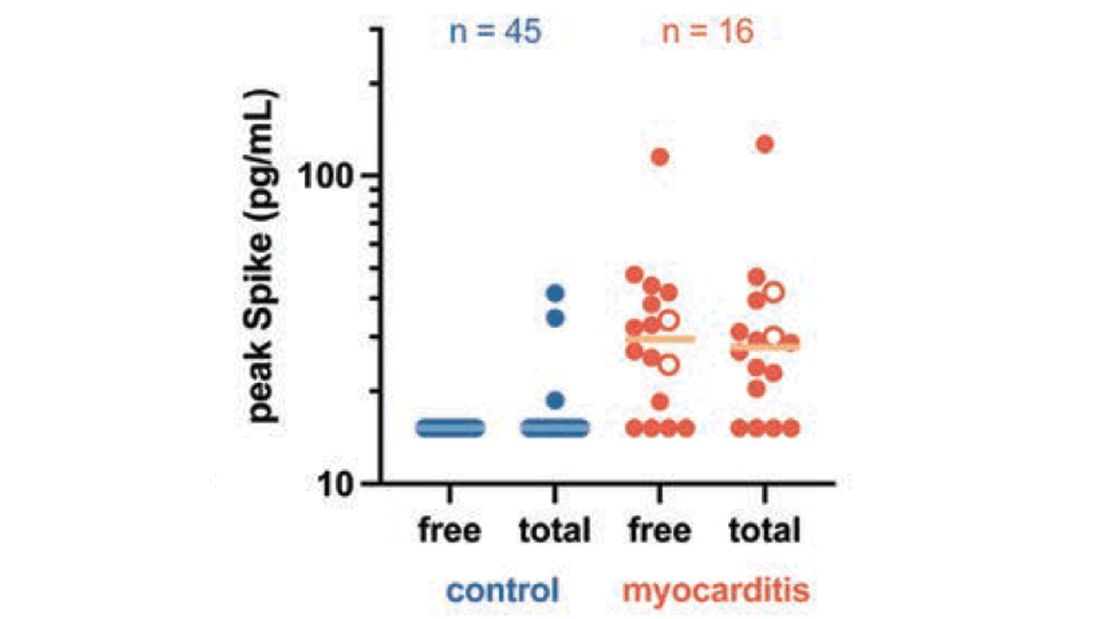

In 12 out of 16 kids with myocarditis, the researchers were able to measure free spike protein in the blood – that is to say spike protein, not bound by antispike antibodies.

These free spikes were present in – wait for it – zero of the 45 control patients. That makes spike protein itself our prime suspect. J’accuse free spike protein!

Of course, all good detectives need to wrap up the case with a good story: How was it all done?

And here’s where we could use Agatha Christie’s help. How could this all work? The vaccine gets injected; mRNA is taken up into cells, where spike protein is generated and released, generating antibody and T-cell responses all the while. Those responses rapidly clear that spike protein from the system – this has been demonstrated in multiple studies – in adults, at least. But in some small number of people, apparently, spike protein is not cleared. Why? It makes no damn sense. Compels me, though. Some have suggested that inadvertent intravenous injection of vaccine, compared with the appropriate intramuscular route, might distribute the vaccine to sites with less immune surveillance. But that is definitely not proven yet.

We are on the path for sure, but this is, as Benoit Blanc would say, a twisted web – and we are not finished untangling it. Not yet.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available for preorder now. He reports no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

To date, it has been a mystery, like “Glass Onion.” And in the spirit of all the great mysteries, to get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to round up the usual suspects.

Appearing in Circulation, a new study does a great job of systematically evaluating multiple hypotheses linking vaccination to myocarditis, and eliminating them, Poirot-style, one by one until only one remains. We’ll get there.

But first, let’s review the suspects. Why do the mRNA vaccines cause myocarditis in a small subset of people?

There are a few leading candidates.

Number one: antibody responses. There are two flavors here. The quantitative hypothesis suggests that some people simply generate too many antibodies to the vaccine, leading to increased inflammation and heart damage.

The qualitative hypothesis suggests that maybe it’s the nature of the antibodies generated rather than the amount; they might cross-react with some protein on the surface of heart cells for instance.

Or maybe it is driven by T-cell responses, which, of course, are independent of antibody levels.

There’s the idea that myocarditis is due to excessive cytokine release – sort of like what we see in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Or it could be due to the viral antigens themselves – the spike protein the mRNA codes for that is generated after vaccination.

To tease all these possibilities apart, researchers led by Lael Yonker at Mass General performed a case-control study. Sixteen children with postvaccine myocarditis were matched by age to 45 control children who had been vaccinated without complications.

The matching was OK, but as you can see here, there were more boys in the myocarditis group, and the time from vaccination was a bit shorter in that group as well. We’ll keep that in mind as we go through the results.

OK, let’s start eliminating suspects.

First, quantitative antibodies. Seems unlikely. Absolute antibody titers were really no different in the myocarditis vs. the control group.

What about the quality of the antibodies? Would the kids with myocarditis have more self-recognizing antibodies present? It doesn’t appear so. Autoantibody levels were similar in the two groups.

Take antibodies off the list.

T-cell responses come next, and, again, no major differences here, save for one specific T-cell subtype that was moderately elevated in the myocarditis group. Not what I would call a smoking gun, frankly.

Cytokines give us a bit more to chew on. Levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-10 were all substantially higher in the kids with myocarditis.

But the thing about cytokines is that they are not particularly specific. OK, kids with myocarditis have more systemic inflammation than kids without; that’s not really surprising. It still leaves us with the question of what is causing all this inflammation? Who is the arch-villain? The kingpin? The don?

It’s the analyses of antigens – the protein products of vaccination – that may hold the key here.

In 12 out of 16 kids with myocarditis, the researchers were able to measure free spike protein in the blood – that is to say spike protein, not bound by antispike antibodies.

These free spikes were present in – wait for it – zero of the 45 control patients. That makes spike protein itself our prime suspect. J’accuse free spike protein!

Of course, all good detectives need to wrap up the case with a good story: How was it all done?

And here’s where we could use Agatha Christie’s help. How could this all work? The vaccine gets injected; mRNA is taken up into cells, where spike protein is generated and released, generating antibody and T-cell responses all the while. Those responses rapidly clear that spike protein from the system – this has been demonstrated in multiple studies – in adults, at least. But in some small number of people, apparently, spike protein is not cleared. Why? It makes no damn sense. Compels me, though. Some have suggested that inadvertent intravenous injection of vaccine, compared with the appropriate intramuscular route, might distribute the vaccine to sites with less immune surveillance. But that is definitely not proven yet.

We are on the path for sure, but this is, as Benoit Blanc would say, a twisted web – and we are not finished untangling it. Not yet.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available for preorder now. He reports no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

To date, it has been a mystery, like “Glass Onion.” And in the spirit of all the great mysteries, to get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to round up the usual suspects.

Appearing in Circulation, a new study does a great job of systematically evaluating multiple hypotheses linking vaccination to myocarditis, and eliminating them, Poirot-style, one by one until only one remains. We’ll get there.

But first, let’s review the suspects. Why do the mRNA vaccines cause myocarditis in a small subset of people?

There are a few leading candidates.

Number one: antibody responses. There are two flavors here. The quantitative hypothesis suggests that some people simply generate too many antibodies to the vaccine, leading to increased inflammation and heart damage.

The qualitative hypothesis suggests that maybe it’s the nature of the antibodies generated rather than the amount; they might cross-react with some protein on the surface of heart cells for instance.

Or maybe it is driven by T-cell responses, which, of course, are independent of antibody levels.

There’s the idea that myocarditis is due to excessive cytokine release – sort of like what we see in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Or it could be due to the viral antigens themselves – the spike protein the mRNA codes for that is generated after vaccination.

To tease all these possibilities apart, researchers led by Lael Yonker at Mass General performed a case-control study. Sixteen children with postvaccine myocarditis were matched by age to 45 control children who had been vaccinated without complications.

The matching was OK, but as you can see here, there were more boys in the myocarditis group, and the time from vaccination was a bit shorter in that group as well. We’ll keep that in mind as we go through the results.

OK, let’s start eliminating suspects.

First, quantitative antibodies. Seems unlikely. Absolute antibody titers were really no different in the myocarditis vs. the control group.

What about the quality of the antibodies? Would the kids with myocarditis have more self-recognizing antibodies present? It doesn’t appear so. Autoantibody levels were similar in the two groups.

Take antibodies off the list.

T-cell responses come next, and, again, no major differences here, save for one specific T-cell subtype that was moderately elevated in the myocarditis group. Not what I would call a smoking gun, frankly.

Cytokines give us a bit more to chew on. Levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and IL-10 were all substantially higher in the kids with myocarditis.

But the thing about cytokines is that they are not particularly specific. OK, kids with myocarditis have more systemic inflammation than kids without; that’s not really surprising. It still leaves us with the question of what is causing all this inflammation? Who is the arch-villain? The kingpin? The don?

It’s the analyses of antigens – the protein products of vaccination – that may hold the key here.

In 12 out of 16 kids with myocarditis, the researchers were able to measure free spike protein in the blood – that is to say spike protein, not bound by antispike antibodies.

These free spikes were present in – wait for it – zero of the 45 control patients. That makes spike protein itself our prime suspect. J’accuse free spike protein!

Of course, all good detectives need to wrap up the case with a good story: How was it all done?

And here’s where we could use Agatha Christie’s help. How could this all work? The vaccine gets injected; mRNA is taken up into cells, where spike protein is generated and released, generating antibody and T-cell responses all the while. Those responses rapidly clear that spike protein from the system – this has been demonstrated in multiple studies – in adults, at least. But in some small number of people, apparently, spike protein is not cleared. Why? It makes no damn sense. Compels me, though. Some have suggested that inadvertent intravenous injection of vaccine, compared with the appropriate intramuscular route, might distribute the vaccine to sites with less immune surveillance. But that is definitely not proven yet.

We are on the path for sure, but this is, as Benoit Blanc would say, a twisted web – and we are not finished untangling it. Not yet.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t,” is available for preorder now. He reports no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Measles

I received a call late one night from a colleague in the emergency department of the children’s hospital. “This 2-year-old has a fever, cough, red eyes, and an impressive rash. I’ve personally never seen a case of measles, but I’m worried given that this child has never received the MMR vaccine.”

By the end of the call, I was worried too. Measles is a febrile respiratory illness classically accompanied by cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and a characteristic maculopapular rash that begins on the face and spreads to the trunk and limbs. It is also highly contagious: 90% percent of susceptible, exposed individuals become infected.

Admittedly, measles is rare. Just 118 cases were reported in the United States in 2022, but 83 of those were in Columbus just 3 hours from where my colleague and I live and work. According to City of Columbus officials, the outbreak occurred almost exclusively in unimmunized children, the majority of whom were 5 years and younger. An unexpectedly high number of children were hospitalized. Typically, one in five people with measles will require hospitalization. In this outbreak, 33 children have been hospitalized as of Jan. 10.

Public health experts warn that 2023 could be much worse unless we increase measles immunization rates in the United States and globally. Immunization of around 95% of eligible people with two doses of measles-containing vaccine is associated with herd immunity. Globally, we’re falling short. Only 81% of the world’s children have received their first measle vaccine dose and only 71% have received the second dose. These are the lowest coverage rates for measles vaccine since 2008.

A 2022 joint press release from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization noted that “measles anywhere is a threat everywhere, as the virus can quickly spread to multiple communities and across international borders.” Some prior measles outbreaks in the United States have started with a case in an international traveler or a U.S. resident who contracted measles during travel abroad.

In the United States, the number of children immunized with multiple routine vaccines has fallen in the last couple of years, in part because of pandemic-related disruptions in health care delivery. Increasing vaccine hesitancy, fueled by debates over the COVID-19 vaccine, may be slowing catch-up immunization in kids who fell behind.

Investigators from Emory University, Atlanta, and Marshfield Clinic Research Institute recently estimated that 9,145,026 U.S. children are susceptible to measles. If pandemic-level immunization rates continue without effective catch-up immunization, that number could rise to more than 15 million.

School vaccination requirements support efforts to ensure that kids are protected against vaccine-preventable diseases, but some data suggest that opposition to requiring MMR vaccine to attend public school is growing. According to a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation Vaccine Monitor survey, 28% of U.S. adults – and 35% of parents of children under 18 – now say that parents should be able to decide to not vaccinate their children for measles, mumps, and rubella. That’s up from 16% of adults and 23% of parents in a 2019 Pew Research Center poll.

Public confidence in the benefits of MMR has also dropped modestly. About 85% of adults surveyed said that the benefits of MMR vaccine outweigh the risk, down from 88% in 2019. Among adults not vaccinated against COVID-19, only 70% said that benefits of these vaccines outweigh the risks.

While the WHO ramps up efforts to improve measles vaccination globally, pediatric clinicians can take steps now to mitigate the risk of measles outbreaks in their own communities. Query health records to understand how many eligible children in your practice have not yet received MMR vaccine. Notify families that vaccination is strongly recommended and make scheduling an appointment to receive vaccine easy. Some practices may have the bandwidth to offer evening and weekend hours for vaccine catch-up visits.

Curious about immunization rates in your state? The American Academy of Pediatrics has an interactive map that reports immunization coverage levels by state and provides comparisons to national rates and goals.

Prompt recognition and isolation of individuals with measles, along with prophylaxis of susceptible contacts, can limit community transmission. Measles can resemble other illnesses associated with fever and rash. Washington state has developed a screening tool to assist with recognition of measles. The CDC also has a measles outbreak toolkit that includes resources that outline clinical features and diagnoses, as well as strategies for talking to parents about vaccines.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected].

I received a call late one night from a colleague in the emergency department of the children’s hospital. “This 2-year-old has a fever, cough, red eyes, and an impressive rash. I’ve personally never seen a case of measles, but I’m worried given that this child has never received the MMR vaccine.”

By the end of the call, I was worried too. Measles is a febrile respiratory illness classically accompanied by cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and a characteristic maculopapular rash that begins on the face and spreads to the trunk and limbs. It is also highly contagious: 90% percent of susceptible, exposed individuals become infected.

Admittedly, measles is rare. Just 118 cases were reported in the United States in 2022, but 83 of those were in Columbus just 3 hours from where my colleague and I live and work. According to City of Columbus officials, the outbreak occurred almost exclusively in unimmunized children, the majority of whom were 5 years and younger. An unexpectedly high number of children were hospitalized. Typically, one in five people with measles will require hospitalization. In this outbreak, 33 children have been hospitalized as of Jan. 10.

Public health experts warn that 2023 could be much worse unless we increase measles immunization rates in the United States and globally. Immunization of around 95% of eligible people with two doses of measles-containing vaccine is associated with herd immunity. Globally, we’re falling short. Only 81% of the world’s children have received their first measle vaccine dose and only 71% have received the second dose. These are the lowest coverage rates for measles vaccine since 2008.

A 2022 joint press release from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization noted that “measles anywhere is a threat everywhere, as the virus can quickly spread to multiple communities and across international borders.” Some prior measles outbreaks in the United States have started with a case in an international traveler or a U.S. resident who contracted measles during travel abroad.

In the United States, the number of children immunized with multiple routine vaccines has fallen in the last couple of years, in part because of pandemic-related disruptions in health care delivery. Increasing vaccine hesitancy, fueled by debates over the COVID-19 vaccine, may be slowing catch-up immunization in kids who fell behind.

Investigators from Emory University, Atlanta, and Marshfield Clinic Research Institute recently estimated that 9,145,026 U.S. children are susceptible to measles. If pandemic-level immunization rates continue without effective catch-up immunization, that number could rise to more than 15 million.

School vaccination requirements support efforts to ensure that kids are protected against vaccine-preventable diseases, but some data suggest that opposition to requiring MMR vaccine to attend public school is growing. According to a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation Vaccine Monitor survey, 28% of U.S. adults – and 35% of parents of children under 18 – now say that parents should be able to decide to not vaccinate their children for measles, mumps, and rubella. That’s up from 16% of adults and 23% of parents in a 2019 Pew Research Center poll.

Public confidence in the benefits of MMR has also dropped modestly. About 85% of adults surveyed said that the benefits of MMR vaccine outweigh the risk, down from 88% in 2019. Among adults not vaccinated against COVID-19, only 70% said that benefits of these vaccines outweigh the risks.

While the WHO ramps up efforts to improve measles vaccination globally, pediatric clinicians can take steps now to mitigate the risk of measles outbreaks in their own communities. Query health records to understand how many eligible children in your practice have not yet received MMR vaccine. Notify families that vaccination is strongly recommended and make scheduling an appointment to receive vaccine easy. Some practices may have the bandwidth to offer evening and weekend hours for vaccine catch-up visits.

Curious about immunization rates in your state? The American Academy of Pediatrics has an interactive map that reports immunization coverage levels by state and provides comparisons to national rates and goals.

Prompt recognition and isolation of individuals with measles, along with prophylaxis of susceptible contacts, can limit community transmission. Measles can resemble other illnesses associated with fever and rash. Washington state has developed a screening tool to assist with recognition of measles. The CDC also has a measles outbreak toolkit that includes resources that outline clinical features and diagnoses, as well as strategies for talking to parents about vaccines.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected].

I received a call late one night from a colleague in the emergency department of the children’s hospital. “This 2-year-old has a fever, cough, red eyes, and an impressive rash. I’ve personally never seen a case of measles, but I’m worried given that this child has never received the MMR vaccine.”

By the end of the call, I was worried too. Measles is a febrile respiratory illness classically accompanied by cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and a characteristic maculopapular rash that begins on the face and spreads to the trunk and limbs. It is also highly contagious: 90% percent of susceptible, exposed individuals become infected.

Admittedly, measles is rare. Just 118 cases were reported in the United States in 2022, but 83 of those were in Columbus just 3 hours from where my colleague and I live and work. According to City of Columbus officials, the outbreak occurred almost exclusively in unimmunized children, the majority of whom were 5 years and younger. An unexpectedly high number of children were hospitalized. Typically, one in five people with measles will require hospitalization. In this outbreak, 33 children have been hospitalized as of Jan. 10.

Public health experts warn that 2023 could be much worse unless we increase measles immunization rates in the United States and globally. Immunization of around 95% of eligible people with two doses of measles-containing vaccine is associated with herd immunity. Globally, we’re falling short. Only 81% of the world’s children have received their first measle vaccine dose and only 71% have received the second dose. These are the lowest coverage rates for measles vaccine since 2008.

A 2022 joint press release from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization noted that “measles anywhere is a threat everywhere, as the virus can quickly spread to multiple communities and across international borders.” Some prior measles outbreaks in the United States have started with a case in an international traveler or a U.S. resident who contracted measles during travel abroad.

In the United States, the number of children immunized with multiple routine vaccines has fallen in the last couple of years, in part because of pandemic-related disruptions in health care delivery. Increasing vaccine hesitancy, fueled by debates over the COVID-19 vaccine, may be slowing catch-up immunization in kids who fell behind.

Investigators from Emory University, Atlanta, and Marshfield Clinic Research Institute recently estimated that 9,145,026 U.S. children are susceptible to measles. If pandemic-level immunization rates continue without effective catch-up immunization, that number could rise to more than 15 million.

School vaccination requirements support efforts to ensure that kids are protected against vaccine-preventable diseases, but some data suggest that opposition to requiring MMR vaccine to attend public school is growing. According to a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation Vaccine Monitor survey, 28% of U.S. adults – and 35% of parents of children under 18 – now say that parents should be able to decide to not vaccinate their children for measles, mumps, and rubella. That’s up from 16% of adults and 23% of parents in a 2019 Pew Research Center poll.

Public confidence in the benefits of MMR has also dropped modestly. About 85% of adults surveyed said that the benefits of MMR vaccine outweigh the risk, down from 88% in 2019. Among adults not vaccinated against COVID-19, only 70% said that benefits of these vaccines outweigh the risks.

While the WHO ramps up efforts to improve measles vaccination globally, pediatric clinicians can take steps now to mitigate the risk of measles outbreaks in their own communities. Query health records to understand how many eligible children in your practice have not yet received MMR vaccine. Notify families that vaccination is strongly recommended and make scheduling an appointment to receive vaccine easy. Some practices may have the bandwidth to offer evening and weekend hours for vaccine catch-up visits.

Curious about immunization rates in your state? The American Academy of Pediatrics has an interactive map that reports immunization coverage levels by state and provides comparisons to national rates and goals.

Prompt recognition and isolation of individuals with measles, along with prophylaxis of susceptible contacts, can limit community transmission. Measles can resemble other illnesses associated with fever and rash. Washington state has developed a screening tool to assist with recognition of measles. The CDC also has a measles outbreak toolkit that includes resources that outline clinical features and diagnoses, as well as strategies for talking to parents about vaccines.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant disclosed that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected].

Study spotlights clinicopathologic features, survival outcomes of pediatric melanoma

.

“Cutaneous melanomas are rare in children and much less common in adolescents than in later life,” researchers led by Mary-Ann El Sharouni, PhD, wrote in the study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Management of these young patients currently follows guidelines developed for adults. Better understanding of melanoma occurring in the first 2 decades of life is, therefore, warranted.”

Drawing from two datasets – one from the Netherlands and the other from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) at the University of Sydney – Dr. El Sharouni of the MIA and of the department of dermatology at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues, evaluated all patients younger than 20 years of age who were diagnosed with invasive melanoma between January 2000 and December 2014. The pooled cohort included 397 Dutch and 117 Australian individuals. Of these, 62 were children and 452 were adolescents. To determine melanoma subtypes, the researchers reevaluated pathology reports and used multivariate Cox models to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The median Breslow thickness was 2.7 mm in children and 1.0 mm in adolescents. Most patients (83%) had conventional melanoma, which consisted of superficial spreading, nodular, desmoplastic, and acral lentiginous forms, while 78 had spitzoid melanoma and 8 had melanoma associated with a congenital nevus. The 10-year RFS was 91.5% in children and 86.4% in adolescents (P =.32), while the 10-year OS was 100% in children and 92.7% in adolescents (P = .09).

On multivariable analysis, which was possible only for the adolescent cohort because of the small number of children, ulceration status and anatomic site were associated with RFS and OS, whereas age, sex, mitotic index, sentinel node status, and melanoma subtype were not. Breslow thickness > 4 mm was associated with worse RFS. As for affected anatomic site, those with melanomas located on the upper and lower limbs had a better overall RFS and OS compared with those who had head or neck melanomas.

The authors acknowledged certain limitation of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the small number of children. “Our data suggest that adolescent melanomas are often similar to adult-type melanomas, whilst those which occur in young children frequently occur via different molecular mechanisms,” they concluded. “In the future it is likely that further understanding of these molecular mechanisms and ability to classify melanomas based on their molecular characteristics will assist in further refining prognostic estimates and possible guiding treatment for young patients with melanoma.”

Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, assistant program director of the division of dermatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the analysis “greatly contributes to dermatology, as we are still learning the differences between melanoma in children and adolescents versus adults.

This study found that adolescents with melanoma had worse survival if mitosis were present and/or located on head/neck, which could aid in aggressiveness of treatment.”

A key strength of analysis, she continued, is the large sample size of 514 patients, “given that melanoma in this population is very rare. A limitation which [the researchers] brought up is the discrepancy of diagnosis via histopathology of melanoma in children versus adults. The study relied on the pathology report given the retrospective nature of this [analysis, and it] was based on Australian and Dutch populations, which may limit its scope in other countries.”

Dr. El Sharouni was supported by a research fellowship grant from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), while two of her coauthors, Richard A. Scolyer, MD, and John F. Thompson, MD, were recipients of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant. The study was also supported by a research program grant from Cancer Institute New South Wales. Dr. Thiede reported having no financial disclosures.

.

“Cutaneous melanomas are rare in children and much less common in adolescents than in later life,” researchers led by Mary-Ann El Sharouni, PhD, wrote in the study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Management of these young patients currently follows guidelines developed for adults. Better understanding of melanoma occurring in the first 2 decades of life is, therefore, warranted.”

Drawing from two datasets – one from the Netherlands and the other from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) at the University of Sydney – Dr. El Sharouni of the MIA and of the department of dermatology at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues, evaluated all patients younger than 20 years of age who were diagnosed with invasive melanoma between January 2000 and December 2014. The pooled cohort included 397 Dutch and 117 Australian individuals. Of these, 62 were children and 452 were adolescents. To determine melanoma subtypes, the researchers reevaluated pathology reports and used multivariate Cox models to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The median Breslow thickness was 2.7 mm in children and 1.0 mm in adolescents. Most patients (83%) had conventional melanoma, which consisted of superficial spreading, nodular, desmoplastic, and acral lentiginous forms, while 78 had spitzoid melanoma and 8 had melanoma associated with a congenital nevus. The 10-year RFS was 91.5% in children and 86.4% in adolescents (P =.32), while the 10-year OS was 100% in children and 92.7% in adolescents (P = .09).

On multivariable analysis, which was possible only for the adolescent cohort because of the small number of children, ulceration status and anatomic site were associated with RFS and OS, whereas age, sex, mitotic index, sentinel node status, and melanoma subtype were not. Breslow thickness > 4 mm was associated with worse RFS. As for affected anatomic site, those with melanomas located on the upper and lower limbs had a better overall RFS and OS compared with those who had head or neck melanomas.

The authors acknowledged certain limitation of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the small number of children. “Our data suggest that adolescent melanomas are often similar to adult-type melanomas, whilst those which occur in young children frequently occur via different molecular mechanisms,” they concluded. “In the future it is likely that further understanding of these molecular mechanisms and ability to classify melanomas based on their molecular characteristics will assist in further refining prognostic estimates and possible guiding treatment for young patients with melanoma.”

Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, assistant program director of the division of dermatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the analysis “greatly contributes to dermatology, as we are still learning the differences between melanoma in children and adolescents versus adults.

This study found that adolescents with melanoma had worse survival if mitosis were present and/or located on head/neck, which could aid in aggressiveness of treatment.”

A key strength of analysis, she continued, is the large sample size of 514 patients, “given that melanoma in this population is very rare. A limitation which [the researchers] brought up is the discrepancy of diagnosis via histopathology of melanoma in children versus adults. The study relied on the pathology report given the retrospective nature of this [analysis, and it] was based on Australian and Dutch populations, which may limit its scope in other countries.”

Dr. El Sharouni was supported by a research fellowship grant from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), while two of her coauthors, Richard A. Scolyer, MD, and John F. Thompson, MD, were recipients of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant. The study was also supported by a research program grant from Cancer Institute New South Wales. Dr. Thiede reported having no financial disclosures.

.

“Cutaneous melanomas are rare in children and much less common in adolescents than in later life,” researchers led by Mary-Ann El Sharouni, PhD, wrote in the study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “Management of these young patients currently follows guidelines developed for adults. Better understanding of melanoma occurring in the first 2 decades of life is, therefore, warranted.”

Drawing from two datasets – one from the Netherlands and the other from Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA) at the University of Sydney – Dr. El Sharouni of the MIA and of the department of dermatology at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and colleagues, evaluated all patients younger than 20 years of age who were diagnosed with invasive melanoma between January 2000 and December 2014. The pooled cohort included 397 Dutch and 117 Australian individuals. Of these, 62 were children and 452 were adolescents. To determine melanoma subtypes, the researchers reevaluated pathology reports and used multivariate Cox models to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The median Breslow thickness was 2.7 mm in children and 1.0 mm in adolescents. Most patients (83%) had conventional melanoma, which consisted of superficial spreading, nodular, desmoplastic, and acral lentiginous forms, while 78 had spitzoid melanoma and 8 had melanoma associated with a congenital nevus. The 10-year RFS was 91.5% in children and 86.4% in adolescents (P =.32), while the 10-year OS was 100% in children and 92.7% in adolescents (P = .09).

On multivariable analysis, which was possible only for the adolescent cohort because of the small number of children, ulceration status and anatomic site were associated with RFS and OS, whereas age, sex, mitotic index, sentinel node status, and melanoma subtype were not. Breslow thickness > 4 mm was associated with worse RFS. As for affected anatomic site, those with melanomas located on the upper and lower limbs had a better overall RFS and OS compared with those who had head or neck melanomas.

The authors acknowledged certain limitation of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the small number of children. “Our data suggest that adolescent melanomas are often similar to adult-type melanomas, whilst those which occur in young children frequently occur via different molecular mechanisms,” they concluded. “In the future it is likely that further understanding of these molecular mechanisms and ability to classify melanomas based on their molecular characteristics will assist in further refining prognostic estimates and possible guiding treatment for young patients with melanoma.”

Rebecca M. Thiede, MD, assistant program director of the division of dermatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the analysis “greatly contributes to dermatology, as we are still learning the differences between melanoma in children and adolescents versus adults.

This study found that adolescents with melanoma had worse survival if mitosis were present and/or located on head/neck, which could aid in aggressiveness of treatment.”

A key strength of analysis, she continued, is the large sample size of 514 patients, “given that melanoma in this population is very rare. A limitation which [the researchers] brought up is the discrepancy of diagnosis via histopathology of melanoma in children versus adults. The study relied on the pathology report given the retrospective nature of this [analysis, and it] was based on Australian and Dutch populations, which may limit its scope in other countries.”

Dr. El Sharouni was supported by a research fellowship grant from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), while two of her coauthors, Richard A. Scolyer, MD, and John F. Thompson, MD, were recipients of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant. The study was also supported by a research program grant from Cancer Institute New South Wales. Dr. Thiede reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

ADHD beyond medications

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is often a very challenging condition for parents to manage, both because of the “gleeful mayhem” children with ADHD manifest and because of the nature of effective treatments. Multiple randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that stimulant medication with behavioral interventions is the optimal first-line treatment for children with both subtypes of ADHD, and that medications alone are superior to behavioral interventions alone. By improving attention and impulse control, the medications effectively decrease the many negative interactions with teachers, peers, and parents, aiding development and healthy self-esteem.

But many parents feel anxious about treating their young children with stimulants. Importantly, how children with ADHD will fare as adults is not predicted by their symptom level, but instead by the quality of their relationships with their parents, their ability to perform at school, and their social skills. Bring this framework to parents as you listen to their questions and help them decide on the best approach for their family. To assist you in these conversations, we will review the evidence for (or against) several of the most common alternatives to medication that parents are likely to ask about.

Diets and supplements

Dietary modifications are among the most popular “natural” approaches to managing ADHD in children. Diets that eliminate processed sugars or food additives (particularly artificial food coloring) are among the most common approaches discussed in the lay press. These diets are usually very time-consuming and disruptive for families to follow, and there is no evidence to support their general use in ADHD management. Those studies that rigorously examined them suggest that, for children with severe impairment who have failed to respond to medications for ADHD, a workup for food intolerance or nutritional deficits may reveal a different problem underlying their behavioral difficulties.1

Similarly, supplementation with high-dose omega-3 fatty acids is modestly helpful only in a subset of children with ADHD symptoms, and not nearly as effective as medications or behavioral interventions. Spending time on an exacting diet or buying expensive supplements is very unlikely to relieve the children’s symptoms and may only add to their stress at home. The “sugar high” parents note may be the rare joy of eating a candy bar and not sugar causing ADHD. Offer parents the guidance to focus on a healthy diet, high in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and healthy protein, and on meals that emphasize family time instead of struggles around food.

Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is an approach that grew out of the observation that many adults with ADHD had resting patterns of brain wave activity different from those of neurotypical adults. In neurofeedback, patients learn strategies that amplify the brain waves associated with focused mental activity, rather than listless or hyperactive states. Businesses market this service for all sorts of illnesses and challenges, ADHD chief among them. Despite the marketing, there are very few randomized controlled studies of this intervention for ADHD in youth, and those have shown only the possibility of a benefit.

While there is no evidence of serious side effects, these treatments are time-consuming and expensive and unlikely to be covered by any insurance. You might suggest to parents that they could achieve some of the same theoretical benefits by looking for hobbies that invite sustained focus in their children. That is, they should think about activities that interest the children, such as music lessons or karate, that they could practice in classes and at home. If the children find these activities even somewhat interesting (or just enjoy the reward of their parents’ or teachers’ attention), regular practice will be supporting their developing attention while building social skills and authentic self-confidence, rather than the activities feeling like a treatment for an illness or condition.

Sleep and exercise

There are not many businesses or books selling worried and exhausted parents a quick nonmedication solution for their children’s ADHD in the form of healthy sleep and exercise habits. But these are safe and healthy ways to reduce symptoms and support development. Children with ADHD often enjoy and benefit from participating in a sport, and daily exercise can help with sleep and regulating their energy. They also often have difficulty with sleep initiation, and commonly do not get adequate or restful sleep. Inadequate sleep exacerbates inattention, distractibility, and irritability. Children with untreated ADHD also often spend a lot of time on screens, as it is difficult for them to shift away from rewarding activities, and parents can find screen time to be a welcome break from hyperactivity and negative interactions. But excessive screen time, especially close to bedtime, can worsen irritability and make sleep more difficult. Talk with parents about the value of establishing a routine around screen time, modest daily physical activity, and sleep that everyone can follow. If their family life is currently marked by late bedtimes and long hours in front of video games, this change will take effort. But within a few weeks, it could lead to significant improvements in energy, attention, and interactions at home.

Behavioral treatments

Effective behavioral treatments for ADHD do not change ADHD symptoms, but they do help children learn how to manage them. In “parent management training,” younger children and parents learn together how to avoid negative cycles of behavior (i.e., temper outbursts) by focusing on consistent routines and consequences that support children calmly learning to manage their impulses. The only other evidence-based treatment focuses on helping school age and older children develop executive functions – their planning, organization, and time management skills – with a range of age-appropriate tools. Both of these therapies may be more effective if the children are also receiving medication, but medication is not necessary for them to be helpful. It is important to note that play therapy and other evidence-based psychotherapies are not effective for management of ADHD, although they may treat comorbid problems.

Parent treatment

You may have diagnosed children with ADHD only to hear their parents respond by saying that they suspect (or know) that they (or their spouses) also have ADHD. This would not be surprising, as ADHD has one of the highest rates of heritability of psychiatric disorders, at 80%. Somewhere between 25% and 50% of parents of children with ADHD have ADHD themselves.2 Screening for adults with ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is widely available and free. Speak with parents about the fact that behavioral treatments for their children’s ADHD are demanding. Such treatments require patience, calm, organization, and consistency.

If parents have ADHD, it may be very helpful for them to prioritize their own effective treatments, so that their attention and impulse control will support their parenting. They may be interested in learning about how treatment might also improve their performance at work and even the quality of their relationships. While there is some evidence that their children’s treatment outcome will hinge on the parents’ treatment,3 they deserve good care independent of the expectations of parenting.

Families benefit from a comprehensive “ADHD plan” for their children. This would start with an assessment of the severity of their children’s symptoms, specifying their impairment at home, school, and in social relationships. It would include their nonacademic performance, exploration of interests, and developing self-confidence. All of these considerations lead to setting reasonable expectations so the children can feel successful. Parents should think about how best to structure their children’s schedules to promote healthy sleep, exercise, and nutrition, and to expand opportunities for building their frustration tolerance, social skills, and executive function.

Parents will need to consider what kind of supports they themselves need to offer this structure. There are good resources available online for information and support, including Children and Adults with ADHD (chadd.org) and the ADHD Resource Center from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (aacap.org). This approach may help parents to evaluate the potential risks and benefits of medications as a component of treatment. Most of the quick fixes for childhood ADHD on the market will take a family’s time and money without providing meaningful improvement. Parents should focus instead on the tried-and-true routines and supports that will help them to create the setting at home that will enable their children to flourish.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Millichap JG and Yee MM. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb;129(2):330-7.

2. Grimm O et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020 Feb 27;22(4):18.

3. Chronis-Tuscano A et al. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017 Apr;45(3):501-7.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is often a very challenging condition for parents to manage, both because of the “gleeful mayhem” children with ADHD manifest and because of the nature of effective treatments. Multiple randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that stimulant medication with behavioral interventions is the optimal first-line treatment for children with both subtypes of ADHD, and that medications alone are superior to behavioral interventions alone. By improving attention and impulse control, the medications effectively decrease the many negative interactions with teachers, peers, and parents, aiding development and healthy self-esteem.

But many parents feel anxious about treating their young children with stimulants. Importantly, how children with ADHD will fare as adults is not predicted by their symptom level, but instead by the quality of their relationships with their parents, their ability to perform at school, and their social skills. Bring this framework to parents as you listen to their questions and help them decide on the best approach for their family. To assist you in these conversations, we will review the evidence for (or against) several of the most common alternatives to medication that parents are likely to ask about.

Diets and supplements

Dietary modifications are among the most popular “natural” approaches to managing ADHD in children. Diets that eliminate processed sugars or food additives (particularly artificial food coloring) are among the most common approaches discussed in the lay press. These diets are usually very time-consuming and disruptive for families to follow, and there is no evidence to support their general use in ADHD management. Those studies that rigorously examined them suggest that, for children with severe impairment who have failed to respond to medications for ADHD, a workup for food intolerance or nutritional deficits may reveal a different problem underlying their behavioral difficulties.1

Similarly, supplementation with high-dose omega-3 fatty acids is modestly helpful only in a subset of children with ADHD symptoms, and not nearly as effective as medications or behavioral interventions. Spending time on an exacting diet or buying expensive supplements is very unlikely to relieve the children’s symptoms and may only add to their stress at home. The “sugar high” parents note may be the rare joy of eating a candy bar and not sugar causing ADHD. Offer parents the guidance to focus on a healthy diet, high in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and healthy protein, and on meals that emphasize family time instead of struggles around food.

Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is an approach that grew out of the observation that many adults with ADHD had resting patterns of brain wave activity different from those of neurotypical adults. In neurofeedback, patients learn strategies that amplify the brain waves associated with focused mental activity, rather than listless or hyperactive states. Businesses market this service for all sorts of illnesses and challenges, ADHD chief among them. Despite the marketing, there are very few randomized controlled studies of this intervention for ADHD in youth, and those have shown only the possibility of a benefit.

While there is no evidence of serious side effects, these treatments are time-consuming and expensive and unlikely to be covered by any insurance. You might suggest to parents that they could achieve some of the same theoretical benefits by looking for hobbies that invite sustained focus in their children. That is, they should think about activities that interest the children, such as music lessons or karate, that they could practice in classes and at home. If the children find these activities even somewhat interesting (or just enjoy the reward of their parents’ or teachers’ attention), regular practice will be supporting their developing attention while building social skills and authentic self-confidence, rather than the activities feeling like a treatment for an illness or condition.

Sleep and exercise

There are not many businesses or books selling worried and exhausted parents a quick nonmedication solution for their children’s ADHD in the form of healthy sleep and exercise habits. But these are safe and healthy ways to reduce symptoms and support development. Children with ADHD often enjoy and benefit from participating in a sport, and daily exercise can help with sleep and regulating their energy. They also often have difficulty with sleep initiation, and commonly do not get adequate or restful sleep. Inadequate sleep exacerbates inattention, distractibility, and irritability. Children with untreated ADHD also often spend a lot of time on screens, as it is difficult for them to shift away from rewarding activities, and parents can find screen time to be a welcome break from hyperactivity and negative interactions. But excessive screen time, especially close to bedtime, can worsen irritability and make sleep more difficult. Talk with parents about the value of establishing a routine around screen time, modest daily physical activity, and sleep that everyone can follow. If their family life is currently marked by late bedtimes and long hours in front of video games, this change will take effort. But within a few weeks, it could lead to significant improvements in energy, attention, and interactions at home.

Behavioral treatments

Effective behavioral treatments for ADHD do not change ADHD symptoms, but they do help children learn how to manage them. In “parent management training,” younger children and parents learn together how to avoid negative cycles of behavior (i.e., temper outbursts) by focusing on consistent routines and consequences that support children calmly learning to manage their impulses. The only other evidence-based treatment focuses on helping school age and older children develop executive functions – their planning, organization, and time management skills – with a range of age-appropriate tools. Both of these therapies may be more effective if the children are also receiving medication, but medication is not necessary for them to be helpful. It is important to note that play therapy and other evidence-based psychotherapies are not effective for management of ADHD, although they may treat comorbid problems.

Parent treatment

You may have diagnosed children with ADHD only to hear their parents respond by saying that they suspect (or know) that they (or their spouses) also have ADHD. This would not be surprising, as ADHD has one of the highest rates of heritability of psychiatric disorders, at 80%. Somewhere between 25% and 50% of parents of children with ADHD have ADHD themselves.2 Screening for adults with ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is widely available and free. Speak with parents about the fact that behavioral treatments for their children’s ADHD are demanding. Such treatments require patience, calm, organization, and consistency.

If parents have ADHD, it may be very helpful for them to prioritize their own effective treatments, so that their attention and impulse control will support their parenting. They may be interested in learning about how treatment might also improve their performance at work and even the quality of their relationships. While there is some evidence that their children’s treatment outcome will hinge on the parents’ treatment,3 they deserve good care independent of the expectations of parenting.

Families benefit from a comprehensive “ADHD plan” for their children. This would start with an assessment of the severity of their children’s symptoms, specifying their impairment at home, school, and in social relationships. It would include their nonacademic performance, exploration of interests, and developing self-confidence. All of these considerations lead to setting reasonable expectations so the children can feel successful. Parents should think about how best to structure their children’s schedules to promote healthy sleep, exercise, and nutrition, and to expand opportunities for building their frustration tolerance, social skills, and executive function.

Parents will need to consider what kind of supports they themselves need to offer this structure. There are good resources available online for information and support, including Children and Adults with ADHD (chadd.org) and the ADHD Resource Center from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (aacap.org). This approach may help parents to evaluate the potential risks and benefits of medications as a component of treatment. Most of the quick fixes for childhood ADHD on the market will take a family’s time and money without providing meaningful improvement. Parents should focus instead on the tried-and-true routines and supports that will help them to create the setting at home that will enable their children to flourish.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Millichap JG and Yee MM. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb;129(2):330-7.

2. Grimm O et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020 Feb 27;22(4):18.

3. Chronis-Tuscano A et al. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017 Apr;45(3):501-7.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is often a very challenging condition for parents to manage, both because of the “gleeful mayhem” children with ADHD manifest and because of the nature of effective treatments. Multiple randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that stimulant medication with behavioral interventions is the optimal first-line treatment for children with both subtypes of ADHD, and that medications alone are superior to behavioral interventions alone. By improving attention and impulse control, the medications effectively decrease the many negative interactions with teachers, peers, and parents, aiding development and healthy self-esteem.

But many parents feel anxious about treating their young children with stimulants. Importantly, how children with ADHD will fare as adults is not predicted by their symptom level, but instead by the quality of their relationships with their parents, their ability to perform at school, and their social skills. Bring this framework to parents as you listen to their questions and help them decide on the best approach for their family. To assist you in these conversations, we will review the evidence for (or against) several of the most common alternatives to medication that parents are likely to ask about.

Diets and supplements

Dietary modifications are among the most popular “natural” approaches to managing ADHD in children. Diets that eliminate processed sugars or food additives (particularly artificial food coloring) are among the most common approaches discussed in the lay press. These diets are usually very time-consuming and disruptive for families to follow, and there is no evidence to support their general use in ADHD management. Those studies that rigorously examined them suggest that, for children with severe impairment who have failed to respond to medications for ADHD, a workup for food intolerance or nutritional deficits may reveal a different problem underlying their behavioral difficulties.1

Similarly, supplementation with high-dose omega-3 fatty acids is modestly helpful only in a subset of children with ADHD symptoms, and not nearly as effective as medications or behavioral interventions. Spending time on an exacting diet or buying expensive supplements is very unlikely to relieve the children’s symptoms and may only add to their stress at home. The “sugar high” parents note may be the rare joy of eating a candy bar and not sugar causing ADHD. Offer parents the guidance to focus on a healthy diet, high in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and healthy protein, and on meals that emphasize family time instead of struggles around food.

Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is an approach that grew out of the observation that many adults with ADHD had resting patterns of brain wave activity different from those of neurotypical adults. In neurofeedback, patients learn strategies that amplify the brain waves associated with focused mental activity, rather than listless or hyperactive states. Businesses market this service for all sorts of illnesses and challenges, ADHD chief among them. Despite the marketing, there are very few randomized controlled studies of this intervention for ADHD in youth, and those have shown only the possibility of a benefit.

While there is no evidence of serious side effects, these treatments are time-consuming and expensive and unlikely to be covered by any insurance. You might suggest to parents that they could achieve some of the same theoretical benefits by looking for hobbies that invite sustained focus in their children. That is, they should think about activities that interest the children, such as music lessons or karate, that they could practice in classes and at home. If the children find these activities even somewhat interesting (or just enjoy the reward of their parents’ or teachers’ attention), regular practice will be supporting their developing attention while building social skills and authentic self-confidence, rather than the activities feeling like a treatment for an illness or condition.

Sleep and exercise

There are not many businesses or books selling worried and exhausted parents a quick nonmedication solution for their children’s ADHD in the form of healthy sleep and exercise habits. But these are safe and healthy ways to reduce symptoms and support development. Children with ADHD often enjoy and benefit from participating in a sport, and daily exercise can help with sleep and regulating their energy. They also often have difficulty with sleep initiation, and commonly do not get adequate or restful sleep. Inadequate sleep exacerbates inattention, distractibility, and irritability. Children with untreated ADHD also often spend a lot of time on screens, as it is difficult for them to shift away from rewarding activities, and parents can find screen time to be a welcome break from hyperactivity and negative interactions. But excessive screen time, especially close to bedtime, can worsen irritability and make sleep more difficult. Talk with parents about the value of establishing a routine around screen time, modest daily physical activity, and sleep that everyone can follow. If their family life is currently marked by late bedtimes and long hours in front of video games, this change will take effort. But within a few weeks, it could lead to significant improvements in energy, attention, and interactions at home.

Behavioral treatments

Effective behavioral treatments for ADHD do not change ADHD symptoms, but they do help children learn how to manage them. In “parent management training,” younger children and parents learn together how to avoid negative cycles of behavior (i.e., temper outbursts) by focusing on consistent routines and consequences that support children calmly learning to manage their impulses. The only other evidence-based treatment focuses on helping school age and older children develop executive functions – their planning, organization, and time management skills – with a range of age-appropriate tools. Both of these therapies may be more effective if the children are also receiving medication, but medication is not necessary for them to be helpful. It is important to note that play therapy and other evidence-based psychotherapies are not effective for management of ADHD, although they may treat comorbid problems.

Parent treatment

You may have diagnosed children with ADHD only to hear their parents respond by saying that they suspect (or know) that they (or their spouses) also have ADHD. This would not be surprising, as ADHD has one of the highest rates of heritability of psychiatric disorders, at 80%. Somewhere between 25% and 50% of parents of children with ADHD have ADHD themselves.2 Screening for adults with ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is widely available and free. Speak with parents about the fact that behavioral treatments for their children’s ADHD are demanding. Such treatments require patience, calm, organization, and consistency.

If parents have ADHD, it may be very helpful for them to prioritize their own effective treatments, so that their attention and impulse control will support their parenting. They may be interested in learning about how treatment might also improve their performance at work and even the quality of their relationships. While there is some evidence that their children’s treatment outcome will hinge on the parents’ treatment,3 they deserve good care independent of the expectations of parenting.

Families benefit from a comprehensive “ADHD plan” for their children. This would start with an assessment of the severity of their children’s symptoms, specifying their impairment at home, school, and in social relationships. It would include their nonacademic performance, exploration of interests, and developing self-confidence. All of these considerations lead to setting reasonable expectations so the children can feel successful. Parents should think about how best to structure their children’s schedules to promote healthy sleep, exercise, and nutrition, and to expand opportunities for building their frustration tolerance, social skills, and executive function.

Parents will need to consider what kind of supports they themselves need to offer this structure. There are good resources available online for information and support, including Children and Adults with ADHD (chadd.org) and the ADHD Resource Center from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (aacap.org). This approach may help parents to evaluate the potential risks and benefits of medications as a component of treatment. Most of the quick fixes for childhood ADHD on the market will take a family’s time and money without providing meaningful improvement. Parents should focus instead on the tried-and-true routines and supports that will help them to create the setting at home that will enable their children to flourish.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Millichap JG and Yee MM. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb;129(2):330-7.

2. Grimm O et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020 Feb 27;22(4):18.

3. Chronis-Tuscano A et al. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017 Apr;45(3):501-7.

New study offers details on post-COVID pediatric illness

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is more common than previously thought. This pediatric illness occurs 2-6 weeks after being infected with COVID-19.

a new study found. The illness is rare, but it causes dangerous multiorgan dysfunction and frequently requires a stay in the ICU. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been at least 9,333 cases nationwide and 76 deaths from MIS-C.

Researchers said their findings were in such contrast to previous MIS-C research that it may render the old research “misleading.”

The analysis was powered by improved data extracted from hospital billing systems. Previous analyses of MIS-C were limited to voluntarily reported cases, which is likely the reason for the undercount.

The study reported a mortality rate for people with the most severe cases (affecting six to eight organs) of 5.8%. The authors of a companion editorial to the study said the mortality rate was low when considering the widespread impacts, “reflecting the rapid reversibility of MIS-C” with treatment.

Differences in MIS-C cases were also found based on children’s race and ethnicity. Black patients were more likely to have severe cases affecting more organs, compared to white patients.

The study included 4,107 MIS-C cases, using data from 2021 for patients younger than 21 years old. The median age was 9 years old.

The findings provide direction for further research, the editorial writers suggested.

Questions that need to be answered include asking why Black children with MIS-C are more likely to have a higher number of organ systems affected.

“Identifying patient biological or socioeconomic factors that can be targeted for treatment or prevention should be pursued,” they wrote.

The CDC says symptoms of MIS-C are an ongoing fever plus more than one of the following: stomach pain, bloodshot eyes, diarrhea, dizziness or lightheadedness (signs of low blood pressure), skin rash, or vomiting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is more common than previously thought. This pediatric illness occurs 2-6 weeks after being infected with COVID-19.

a new study found. The illness is rare, but it causes dangerous multiorgan dysfunction and frequently requires a stay in the ICU. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been at least 9,333 cases nationwide and 76 deaths from MIS-C.

Researchers said their findings were in such contrast to previous MIS-C research that it may render the old research “misleading.”

The analysis was powered by improved data extracted from hospital billing systems. Previous analyses of MIS-C were limited to voluntarily reported cases, which is likely the reason for the undercount.

The study reported a mortality rate for people with the most severe cases (affecting six to eight organs) of 5.8%. The authors of a companion editorial to the study said the mortality rate was low when considering the widespread impacts, “reflecting the rapid reversibility of MIS-C” with treatment.

Differences in MIS-C cases were also found based on children’s race and ethnicity. Black patients were more likely to have severe cases affecting more organs, compared to white patients.

The study included 4,107 MIS-C cases, using data from 2021 for patients younger than 21 years old. The median age was 9 years old.

The findings provide direction for further research, the editorial writers suggested.

Questions that need to be answered include asking why Black children with MIS-C are more likely to have a higher number of organ systems affected.

“Identifying patient biological or socioeconomic factors that can be targeted for treatment or prevention should be pursued,” they wrote.

The CDC says symptoms of MIS-C are an ongoing fever plus more than one of the following: stomach pain, bloodshot eyes, diarrhea, dizziness or lightheadedness (signs of low blood pressure), skin rash, or vomiting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is more common than previously thought. This pediatric illness occurs 2-6 weeks after being infected with COVID-19.

a new study found. The illness is rare, but it causes dangerous multiorgan dysfunction and frequently requires a stay in the ICU. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been at least 9,333 cases nationwide and 76 deaths from MIS-C.

Researchers said their findings were in such contrast to previous MIS-C research that it may render the old research “misleading.”

The analysis was powered by improved data extracted from hospital billing systems. Previous analyses of MIS-C were limited to voluntarily reported cases, which is likely the reason for the undercount.

The study reported a mortality rate for people with the most severe cases (affecting six to eight organs) of 5.8%. The authors of a companion editorial to the study said the mortality rate was low when considering the widespread impacts, “reflecting the rapid reversibility of MIS-C” with treatment.

Differences in MIS-C cases were also found based on children’s race and ethnicity. Black patients were more likely to have severe cases affecting more organs, compared to white patients.

The study included 4,107 MIS-C cases, using data from 2021 for patients younger than 21 years old. The median age was 9 years old.

The findings provide direction for further research, the editorial writers suggested.

Questions that need to be answered include asking why Black children with MIS-C are more likely to have a higher number of organ systems affected.

“Identifying patient biological or socioeconomic factors that can be targeted for treatment or prevention should be pursued,” they wrote.

The CDC says symptoms of MIS-C are an ongoing fever plus more than one of the following: stomach pain, bloodshot eyes, diarrhea, dizziness or lightheadedness (signs of low blood pressure), skin rash, or vomiting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Infantile hemangioma: Analysis underscores importance of early propranolol treatment

, results from a post-hoc analysis of phase 2 and 3 clinical trial data showed.

“It is widely accepted that oral propranolol should be started early to improve the success rate, but proposed thresholds have lacked supportive data,” researchers led by Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, of the department of dermatology at Pellegrin Children’s Hospital, Bordeaux, France, wrote in the study, which was published online in Pediatric Dermatology. In the pivotal phase 2/3 trial of propranolol of 460 infants, published in 2015, the mean initiation of treatment was 104 days, they added, but “in real-life studies, most infants are referred later than this.”

In addition, a European expert consensus panel set the ideal age for a patient to be seen by a specialist at between 3 and 5 weeks of age, while an American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline set the ideal age at 1 month.