User login

U.S. health system ranks last among 11 high-income countries

The U.S. health care system ranked last overall among 11 high-income countries in an analysis by the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund, according to a report released on Aug. 4.

The report is the seventh international comparison of countries’ health systems by the Commonwealth Fund since 2004, and the United States has ranked last in every edition, David Blumenthal, MD, president of the Commonwealth Fund, told reporters during a press briefing.

Researchers analyzed survey answers from tens of thousands of patients and physicians in 11 countries. They analyzed performance on 71 measures across five categories – access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. Administrative data were gathered from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Health Organization.

Among contributors to the poor showing by the United States is that half (50%) of lower-income U.S. adults and 27% of higher-income U.S. adults say costs keep them from getting needed health care.

“In no other country does income inequality so profoundly limit access to care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

In the United Kingdom, only 12% with lower incomes and 7% with higher incomes said costs kept them from care.

In a stark comparison, the researchers found that “a high-income person in the U.S. was more likely to report financial barriers than a low-income person in nearly all the other countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.”

Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia were ranked at the top overall in that order. Rounding out the 11 in overall ranking were the U.K., Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, France, Switzerland, Canada, and the United States.

“What this report tells us is that our health care system is not working for Americans, particularly those with lower incomes, who are at a severe disadvantage compared to citizens of other countries. And they are paying the price with their health and their lives,” Dr. Blumenthal said in a press release.

“To catch up with other high-income countries, the administration and Congress would have to expand access to health care, equitably, to all Americans, act aggressively to control costs, and invest in the social services we know can lead to a healthier population.”

High infant mortality, low life expectancy in U.S.

Several factors contributed to the U.S. ranking at the bottom of the outcomes category. Among them are that the United States has the highest infant mortality rate (5.7 deaths per 1,000 live births) and lowest life expectancy at age 60 (living on average 23.1 years after age 60), compared with the other countries surveyed. The U.S. rate of preventable mortality (177 deaths per 100,000 population) is more than double that of the best-performing country, Switzerland.

Lead author Eric Schneider, MD, senior vice president for policy and research at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that, in terms of the change in avoidable mortality over a decade, not only did the United States have the highest rate, compared with the other countries surveyed, “it also experienced the smallest decline in avoidable mortality over that 10-year period.”

The U.S. maternal mortality rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births is twice that of France, the country with the next-highest rate (7.6 deaths per 100,000 live births).

U.S. excelled in only one category

The only category in which the United States did not rank last was in “care process,” where it ranked second behind only New Zealand.

The care process category combines preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient engagement and preferences. The category includes indicators such as mammography screening and influenza vaccination for older adults as well as the percentage of adults counseled by a health care provider about nutrition, smoking, or alcohol use.

The United States and Germany performed best on engagement and patient preferences, although U.S. adults have the lowest rates of continuity with the same doctor.

New Zealand and the United States ranked highest in the safe care category, with higher reported use of computerized alerts and routine review of medications.

‘Too little, too late’: Key recommendations for U.S. to improve

Reginald Williams, vice president of International Health Policy and Practice Innovations at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that the U.S. shortcomings in health care come despite spending more than twice as much of its GDP (17% in 2019) as the average OECD country.

“It appears that the US delivers too little of the care that is most needed and often delivers that care too late, especially for people with chronic illnesses,” he said.

He then summarized the team’s recommendations on how the United States can change course.

First is expanding insurance coverage, he said, noting that the United States is the only one of the 11 countries that lacks universal coverage and nearly 30 million people remain uninsured.

Top-performing countries in the survey have universal coverage, annual out-of-pocket caps on covered benefits, and full coverage for primary care and treatment for chronic conditions, he said.

The United States must also improve access to care, he said.

“Top-ranking countries like the Netherlands and Norway ensure timely availability to care by telephone on nights and weekends, and in-person follow-up at home, if needed,” he said.

Mr. Williams said reducing administrative burdens is also critical to free up resources for improving health. He gave an example: “Norway determines patient copayments or physician fees on a regional basis, applying standardized copayments to all physicians within a specialty in a geographic area.”

Reducing income-related barriers is important as well, he said.

The fear of unpredictably high bills and other issues prevent people in the United States from getting the care they ultimately need, he said, adding that top-performing countries invest more in social services to reduce health risks.

That could have implications for the COVID-19 response.

Responding effectively to COVID-19 requires that patients can access affordable health care services, Mr. Williams noted.

“We know from our research that more than two-thirds of U.S. adults say their potential out-of-pocket costs would figure prominently in their decisions to get care if they had coronavirus symptoms,” he said.

Dr. Schneider summed up in the press release: “This study makes clear that higher U.S. spending on health care is not producing better health especially as the U.S. continues on a path of deepening inequality. A country that spends as much as we do should have the best health system in the world. We should adapt what works in other high-income countries to build a better health care system that provides affordable, high-quality health care for everyone.”

Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Schneider, and Mr. Williams reported no relevant financial relationships outside their employment with the Commonwealth Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. health care system ranked last overall among 11 high-income countries in an analysis by the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund, according to a report released on Aug. 4.

The report is the seventh international comparison of countries’ health systems by the Commonwealth Fund since 2004, and the United States has ranked last in every edition, David Blumenthal, MD, president of the Commonwealth Fund, told reporters during a press briefing.

Researchers analyzed survey answers from tens of thousands of patients and physicians in 11 countries. They analyzed performance on 71 measures across five categories – access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. Administrative data were gathered from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Health Organization.

Among contributors to the poor showing by the United States is that half (50%) of lower-income U.S. adults and 27% of higher-income U.S. adults say costs keep them from getting needed health care.

“In no other country does income inequality so profoundly limit access to care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

In the United Kingdom, only 12% with lower incomes and 7% with higher incomes said costs kept them from care.

In a stark comparison, the researchers found that “a high-income person in the U.S. was more likely to report financial barriers than a low-income person in nearly all the other countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.”

Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia were ranked at the top overall in that order. Rounding out the 11 in overall ranking were the U.K., Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, France, Switzerland, Canada, and the United States.

“What this report tells us is that our health care system is not working for Americans, particularly those with lower incomes, who are at a severe disadvantage compared to citizens of other countries. And they are paying the price with their health and their lives,” Dr. Blumenthal said in a press release.

“To catch up with other high-income countries, the administration and Congress would have to expand access to health care, equitably, to all Americans, act aggressively to control costs, and invest in the social services we know can lead to a healthier population.”

High infant mortality, low life expectancy in U.S.

Several factors contributed to the U.S. ranking at the bottom of the outcomes category. Among them are that the United States has the highest infant mortality rate (5.7 deaths per 1,000 live births) and lowest life expectancy at age 60 (living on average 23.1 years after age 60), compared with the other countries surveyed. The U.S. rate of preventable mortality (177 deaths per 100,000 population) is more than double that of the best-performing country, Switzerland.

Lead author Eric Schneider, MD, senior vice president for policy and research at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that, in terms of the change in avoidable mortality over a decade, not only did the United States have the highest rate, compared with the other countries surveyed, “it also experienced the smallest decline in avoidable mortality over that 10-year period.”

The U.S. maternal mortality rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births is twice that of France, the country with the next-highest rate (7.6 deaths per 100,000 live births).

U.S. excelled in only one category

The only category in which the United States did not rank last was in “care process,” where it ranked second behind only New Zealand.

The care process category combines preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient engagement and preferences. The category includes indicators such as mammography screening and influenza vaccination for older adults as well as the percentage of adults counseled by a health care provider about nutrition, smoking, or alcohol use.

The United States and Germany performed best on engagement and patient preferences, although U.S. adults have the lowest rates of continuity with the same doctor.

New Zealand and the United States ranked highest in the safe care category, with higher reported use of computerized alerts and routine review of medications.

‘Too little, too late’: Key recommendations for U.S. to improve

Reginald Williams, vice president of International Health Policy and Practice Innovations at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that the U.S. shortcomings in health care come despite spending more than twice as much of its GDP (17% in 2019) as the average OECD country.

“It appears that the US delivers too little of the care that is most needed and often delivers that care too late, especially for people with chronic illnesses,” he said.

He then summarized the team’s recommendations on how the United States can change course.

First is expanding insurance coverage, he said, noting that the United States is the only one of the 11 countries that lacks universal coverage and nearly 30 million people remain uninsured.

Top-performing countries in the survey have universal coverage, annual out-of-pocket caps on covered benefits, and full coverage for primary care and treatment for chronic conditions, he said.

The United States must also improve access to care, he said.

“Top-ranking countries like the Netherlands and Norway ensure timely availability to care by telephone on nights and weekends, and in-person follow-up at home, if needed,” he said.

Mr. Williams said reducing administrative burdens is also critical to free up resources for improving health. He gave an example: “Norway determines patient copayments or physician fees on a regional basis, applying standardized copayments to all physicians within a specialty in a geographic area.”

Reducing income-related barriers is important as well, he said.

The fear of unpredictably high bills and other issues prevent people in the United States from getting the care they ultimately need, he said, adding that top-performing countries invest more in social services to reduce health risks.

That could have implications for the COVID-19 response.

Responding effectively to COVID-19 requires that patients can access affordable health care services, Mr. Williams noted.

“We know from our research that more than two-thirds of U.S. adults say their potential out-of-pocket costs would figure prominently in their decisions to get care if they had coronavirus symptoms,” he said.

Dr. Schneider summed up in the press release: “This study makes clear that higher U.S. spending on health care is not producing better health especially as the U.S. continues on a path of deepening inequality. A country that spends as much as we do should have the best health system in the world. We should adapt what works in other high-income countries to build a better health care system that provides affordable, high-quality health care for everyone.”

Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Schneider, and Mr. Williams reported no relevant financial relationships outside their employment with the Commonwealth Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. health care system ranked last overall among 11 high-income countries in an analysis by the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund, according to a report released on Aug. 4.

The report is the seventh international comparison of countries’ health systems by the Commonwealth Fund since 2004, and the United States has ranked last in every edition, David Blumenthal, MD, president of the Commonwealth Fund, told reporters during a press briefing.

Researchers analyzed survey answers from tens of thousands of patients and physicians in 11 countries. They analyzed performance on 71 measures across five categories – access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. Administrative data were gathered from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Health Organization.

Among contributors to the poor showing by the United States is that half (50%) of lower-income U.S. adults and 27% of higher-income U.S. adults say costs keep them from getting needed health care.

“In no other country does income inequality so profoundly limit access to care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

In the United Kingdom, only 12% with lower incomes and 7% with higher incomes said costs kept them from care.

In a stark comparison, the researchers found that “a high-income person in the U.S. was more likely to report financial barriers than a low-income person in nearly all the other countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.”

Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia were ranked at the top overall in that order. Rounding out the 11 in overall ranking were the U.K., Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, France, Switzerland, Canada, and the United States.

“What this report tells us is that our health care system is not working for Americans, particularly those with lower incomes, who are at a severe disadvantage compared to citizens of other countries. And they are paying the price with their health and their lives,” Dr. Blumenthal said in a press release.

“To catch up with other high-income countries, the administration and Congress would have to expand access to health care, equitably, to all Americans, act aggressively to control costs, and invest in the social services we know can lead to a healthier population.”

High infant mortality, low life expectancy in U.S.

Several factors contributed to the U.S. ranking at the bottom of the outcomes category. Among them are that the United States has the highest infant mortality rate (5.7 deaths per 1,000 live births) and lowest life expectancy at age 60 (living on average 23.1 years after age 60), compared with the other countries surveyed. The U.S. rate of preventable mortality (177 deaths per 100,000 population) is more than double that of the best-performing country, Switzerland.

Lead author Eric Schneider, MD, senior vice president for policy and research at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that, in terms of the change in avoidable mortality over a decade, not only did the United States have the highest rate, compared with the other countries surveyed, “it also experienced the smallest decline in avoidable mortality over that 10-year period.”

The U.S. maternal mortality rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births is twice that of France, the country with the next-highest rate (7.6 deaths per 100,000 live births).

U.S. excelled in only one category

The only category in which the United States did not rank last was in “care process,” where it ranked second behind only New Zealand.

The care process category combines preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient engagement and preferences. The category includes indicators such as mammography screening and influenza vaccination for older adults as well as the percentage of adults counseled by a health care provider about nutrition, smoking, or alcohol use.

The United States and Germany performed best on engagement and patient preferences, although U.S. adults have the lowest rates of continuity with the same doctor.

New Zealand and the United States ranked highest in the safe care category, with higher reported use of computerized alerts and routine review of medications.

‘Too little, too late’: Key recommendations for U.S. to improve

Reginald Williams, vice president of International Health Policy and Practice Innovations at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that the U.S. shortcomings in health care come despite spending more than twice as much of its GDP (17% in 2019) as the average OECD country.

“It appears that the US delivers too little of the care that is most needed and often delivers that care too late, especially for people with chronic illnesses,” he said.

He then summarized the team’s recommendations on how the United States can change course.

First is expanding insurance coverage, he said, noting that the United States is the only one of the 11 countries that lacks universal coverage and nearly 30 million people remain uninsured.

Top-performing countries in the survey have universal coverage, annual out-of-pocket caps on covered benefits, and full coverage for primary care and treatment for chronic conditions, he said.

The United States must also improve access to care, he said.

“Top-ranking countries like the Netherlands and Norway ensure timely availability to care by telephone on nights and weekends, and in-person follow-up at home, if needed,” he said.

Mr. Williams said reducing administrative burdens is also critical to free up resources for improving health. He gave an example: “Norway determines patient copayments or physician fees on a regional basis, applying standardized copayments to all physicians within a specialty in a geographic area.”

Reducing income-related barriers is important as well, he said.

The fear of unpredictably high bills and other issues prevent people in the United States from getting the care they ultimately need, he said, adding that top-performing countries invest more in social services to reduce health risks.

That could have implications for the COVID-19 response.

Responding effectively to COVID-19 requires that patients can access affordable health care services, Mr. Williams noted.

“We know from our research that more than two-thirds of U.S. adults say their potential out-of-pocket costs would figure prominently in their decisions to get care if they had coronavirus symptoms,” he said.

Dr. Schneider summed up in the press release: “This study makes clear that higher U.S. spending on health care is not producing better health especially as the U.S. continues on a path of deepening inequality. A country that spends as much as we do should have the best health system in the world. We should adapt what works in other high-income countries to build a better health care system that provides affordable, high-quality health care for everyone.”

Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Schneider, and Mr. Williams reported no relevant financial relationships outside their employment with the Commonwealth Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oncologists face nightmares every day with prior authorization

Editor’s note: Prior authorization has been flagged as the biggest payer-related cause of stress for U.S. oncologists. In one survey, 75% said prior authorization was their biggest burden, followed by coverage denials and appeals (62%). Another survey found that practices spent on average 16.4 hours a week dealing with prior authorizations.

Around 5% of my emails every day are from insurance companies denying my patients the treatments I have recommended. A part of every day is spent worrying about how I’m going to cover my patients’ therapy and what I need to order to make sure it doesn’t get delayed.

Many doctors are retiring because they don’t want to deal with this anymore. There are many times that I have thought about quitting for this reason. A partner of mine had a heart attack last year. He’s a few years older than I am – in his mid-50s – and that scared me. I actually had a CT angiogram just to make sure. They told me my heart is fine, but I worry because of all these frustrations every day. And I’m not alone. For every doctor I work with, it’s the same story, and it’s just ridiculous.

For example, I had a patient with a huge breast mass. My nurse got me the prior authorization for an emergency biopsy. I got back the results for estrogen and progesterone receptor status, but not the HER2-neu results because that test required another authorization.

Authorization shouldn’t be required for every single step. I understand if maybe you need to get an authorization to do something outside the standard of care or something that is unique or unheard of, but HER2-neu biopsy is standard of care and should not require additional authorization.

And the sad part is, that patient turned out to be HER2-neu positive. She lost 4 weeks just waiting for an authorization of a test that should be a no-brainer.

We cannot even do a blood count in our office before getting authorization from some insurances. This is a very important test when we give chemotherapy, and it’s very cheap.

And then another nightmare is if you want to give a patient growth factors when you see their blood count is going down. Sometimes the insurance company will say, “When they get neutropenic fever, we’ll allow it with the next cycle.” Why do I have to wait until the patient develops such a problem to start with a treatment that could avoid it? They may end up in the hospital.

I think I’m one of the more conservative doctors; I try to do everything scientifically and only order a test or a treatment if it’s indicated. But sometimes this guidance costs more money. For example, an insurance company may say to order a CT scan first and if you don’t find your answer, then get a PET scan.

So I order a CT scan, knowing it’s not going to help, and then I tell them, “Now I need a PET scan.” That’s another week delay and an extra cost that I don’t want the system to incur.

I’ve even had some issues with lung screening scans for smokers. This screening has reduced mortality by 20%; it should be a no-brainer to encourage smokers to do it because many of them may not even need chemotherapy if you find early-stage lung cancer. And the screening is not expensive, you can do it for $90 to $100. So why do we have to get authorization for that?

Sometimes I push back and request a “peer-to-peer,” where you challenge the decision of the insurance company and speak to one of their doctors. Out of 10 doctors, maybe three or four will do the peer-to-peer. The rest will give up because it’s so frustrating.

In one case, I wanted to modify a standard regimen and give only two out of three drugs because I thought the third would be too toxic. But the insurance company wouldn’t approve the regimen because the guidelines say you have to give three drugs.

Guidelines are guidance, they should not dictate how you treat an individual patient – there should be some allowance in there for a doctor’s discretion. If not, why do we even need doctors? We could just follow treatment regimens dictated by computers. They have to allow me to personalize the care that my patient deserves and make changes so that the treatment can be tolerated.

But then, I get that one patient whom I feel I really helped and I realize, “Okay, I can help more people.”

I had this one patient, a young, 40-year-old nurse with breast cancer – also HER2-neu positive. She’d had her surgery and finished her adjuvant chemotherapy. One of the things that you do as standard of care, after a year of trastuzumab, is you start them on neratinib. There are studies that show it improves progression-free survival if you give them an extra year of this drug as an adjuvant.

I prescribed the neratinib, but the insurance company denied it because the patient “did not have positive lymph nodes and was not considered high risk.” I told them, “That’s BS, that’s not what the indication is for.” I asked for a peer-to-peer and they said the policy did not allow for peer-to-peer. So, I made a big fuss about it. We appealed, and I finally spoke to a pharmacist who worked for the insurance company. I told him, “Why did you guys deny this? It’s standard of care.” He said, “Oh, I agree with you, this will be approved. And actually, we’re going to change the policy now.”

When that pharmacist told me they were going to change the policy, it was like someone gave me 1 million dollars. Because, you know what? I didn’t just help my patient; now other patients will also get it. The hope is that if you keep fighting for something, they will change it.

I think every doctor wants to do the best for their patients. It’s not like they don’t want to, but really, I am fortunate that I have the means to do it. We’re a big practice and we have dedicated staff who can help.

If you’re a small practice, it’s almost impossible to deal with this. I have two nurse practitioners, and a lot of their work is filling out paperwork for insurance companies.

We had a colleague, a solo practitioner, who would send us his patients with complicated therapies, because he couldn’t afford the time or the effort or the risk of not getting reimbursed. His practice could have paid out $100,000 for drugs and not get a reimbursement for a few months.

Even when an insurance company does give the preauthorization, there’s always this disclaimer that it doesn’t guarantee payment. If they find in the future that your patient didn’t meet the criteria, they can still deny payment.

If the insurers refuse coverage, we really work hard at getting patients free drugs, and most of the time, we manage to do that. We either look to charitable organizations, like the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, or we look for rare disease societies or we go to the pharmaceutical company.

For really expensive drugs, pharmaceutical companies have a program where you can enroll the patient and they can help copay or even cover the drug. For less expensive drugs, it might not be a big problem, but for a drug that can cost $18,000 to $20,000 a month, that’s a big risk to take.

It’s confusing for patients, too. They get angry and frustrated, and that’s not good for their treatment, because attitude and psychology are very important. Sometimes they yell at us because they think it’s our fault. I encourage them to call their insurance companies themselves, and some of them do.

I don’t do it with every patient, but there are some more educated patients who are advocates, and if their condition is stable, I do encourage them to call their senators or congressmen or congresswomen to complain.

I don’t mind treating complicated patients. I don’t want to say I enjoy it, but I like challenges. That’s my field, that’s medicine, that’s what I’m supposed to do. But it’s really sad and frustrating that, when you want to treat a patient, you first have to look at their insurance to see how much care you can actually give them.

Maen Hussein, MD, is physician director of finance at Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute, Fort Myers. He is a board member of the Florida Cancer Specialists Foundation and sits on the board of directors for the Florida Society of Clinical Oncology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Prior authorization has been flagged as the biggest payer-related cause of stress for U.S. oncologists. In one survey, 75% said prior authorization was their biggest burden, followed by coverage denials and appeals (62%). Another survey found that practices spent on average 16.4 hours a week dealing with prior authorizations.

Around 5% of my emails every day are from insurance companies denying my patients the treatments I have recommended. A part of every day is spent worrying about how I’m going to cover my patients’ therapy and what I need to order to make sure it doesn’t get delayed.

Many doctors are retiring because they don’t want to deal with this anymore. There are many times that I have thought about quitting for this reason. A partner of mine had a heart attack last year. He’s a few years older than I am – in his mid-50s – and that scared me. I actually had a CT angiogram just to make sure. They told me my heart is fine, but I worry because of all these frustrations every day. And I’m not alone. For every doctor I work with, it’s the same story, and it’s just ridiculous.

For example, I had a patient with a huge breast mass. My nurse got me the prior authorization for an emergency biopsy. I got back the results for estrogen and progesterone receptor status, but not the HER2-neu results because that test required another authorization.

Authorization shouldn’t be required for every single step. I understand if maybe you need to get an authorization to do something outside the standard of care or something that is unique or unheard of, but HER2-neu biopsy is standard of care and should not require additional authorization.

And the sad part is, that patient turned out to be HER2-neu positive. She lost 4 weeks just waiting for an authorization of a test that should be a no-brainer.

We cannot even do a blood count in our office before getting authorization from some insurances. This is a very important test when we give chemotherapy, and it’s very cheap.

And then another nightmare is if you want to give a patient growth factors when you see their blood count is going down. Sometimes the insurance company will say, “When they get neutropenic fever, we’ll allow it with the next cycle.” Why do I have to wait until the patient develops such a problem to start with a treatment that could avoid it? They may end up in the hospital.

I think I’m one of the more conservative doctors; I try to do everything scientifically and only order a test or a treatment if it’s indicated. But sometimes this guidance costs more money. For example, an insurance company may say to order a CT scan first and if you don’t find your answer, then get a PET scan.

So I order a CT scan, knowing it’s not going to help, and then I tell them, “Now I need a PET scan.” That’s another week delay and an extra cost that I don’t want the system to incur.

I’ve even had some issues with lung screening scans for smokers. This screening has reduced mortality by 20%; it should be a no-brainer to encourage smokers to do it because many of them may not even need chemotherapy if you find early-stage lung cancer. And the screening is not expensive, you can do it for $90 to $100. So why do we have to get authorization for that?

Sometimes I push back and request a “peer-to-peer,” where you challenge the decision of the insurance company and speak to one of their doctors. Out of 10 doctors, maybe three or four will do the peer-to-peer. The rest will give up because it’s so frustrating.

In one case, I wanted to modify a standard regimen and give only two out of three drugs because I thought the third would be too toxic. But the insurance company wouldn’t approve the regimen because the guidelines say you have to give three drugs.

Guidelines are guidance, they should not dictate how you treat an individual patient – there should be some allowance in there for a doctor’s discretion. If not, why do we even need doctors? We could just follow treatment regimens dictated by computers. They have to allow me to personalize the care that my patient deserves and make changes so that the treatment can be tolerated.

But then, I get that one patient whom I feel I really helped and I realize, “Okay, I can help more people.”

I had this one patient, a young, 40-year-old nurse with breast cancer – also HER2-neu positive. She’d had her surgery and finished her adjuvant chemotherapy. One of the things that you do as standard of care, after a year of trastuzumab, is you start them on neratinib. There are studies that show it improves progression-free survival if you give them an extra year of this drug as an adjuvant.

I prescribed the neratinib, but the insurance company denied it because the patient “did not have positive lymph nodes and was not considered high risk.” I told them, “That’s BS, that’s not what the indication is for.” I asked for a peer-to-peer and they said the policy did not allow for peer-to-peer. So, I made a big fuss about it. We appealed, and I finally spoke to a pharmacist who worked for the insurance company. I told him, “Why did you guys deny this? It’s standard of care.” He said, “Oh, I agree with you, this will be approved. And actually, we’re going to change the policy now.”

When that pharmacist told me they were going to change the policy, it was like someone gave me 1 million dollars. Because, you know what? I didn’t just help my patient; now other patients will also get it. The hope is that if you keep fighting for something, they will change it.

I think every doctor wants to do the best for their patients. It’s not like they don’t want to, but really, I am fortunate that I have the means to do it. We’re a big practice and we have dedicated staff who can help.

If you’re a small practice, it’s almost impossible to deal with this. I have two nurse practitioners, and a lot of their work is filling out paperwork for insurance companies.

We had a colleague, a solo practitioner, who would send us his patients with complicated therapies, because he couldn’t afford the time or the effort or the risk of not getting reimbursed. His practice could have paid out $100,000 for drugs and not get a reimbursement for a few months.

Even when an insurance company does give the preauthorization, there’s always this disclaimer that it doesn’t guarantee payment. If they find in the future that your patient didn’t meet the criteria, they can still deny payment.

If the insurers refuse coverage, we really work hard at getting patients free drugs, and most of the time, we manage to do that. We either look to charitable organizations, like the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, or we look for rare disease societies or we go to the pharmaceutical company.

For really expensive drugs, pharmaceutical companies have a program where you can enroll the patient and they can help copay or even cover the drug. For less expensive drugs, it might not be a big problem, but for a drug that can cost $18,000 to $20,000 a month, that’s a big risk to take.

It’s confusing for patients, too. They get angry and frustrated, and that’s not good for their treatment, because attitude and psychology are very important. Sometimes they yell at us because they think it’s our fault. I encourage them to call their insurance companies themselves, and some of them do.

I don’t do it with every patient, but there are some more educated patients who are advocates, and if their condition is stable, I do encourage them to call their senators or congressmen or congresswomen to complain.

I don’t mind treating complicated patients. I don’t want to say I enjoy it, but I like challenges. That’s my field, that’s medicine, that’s what I’m supposed to do. But it’s really sad and frustrating that, when you want to treat a patient, you first have to look at their insurance to see how much care you can actually give them.

Maen Hussein, MD, is physician director of finance at Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute, Fort Myers. He is a board member of the Florida Cancer Specialists Foundation and sits on the board of directors for the Florida Society of Clinical Oncology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Prior authorization has been flagged as the biggest payer-related cause of stress for U.S. oncologists. In one survey, 75% said prior authorization was their biggest burden, followed by coverage denials and appeals (62%). Another survey found that practices spent on average 16.4 hours a week dealing with prior authorizations.

Around 5% of my emails every day are from insurance companies denying my patients the treatments I have recommended. A part of every day is spent worrying about how I’m going to cover my patients’ therapy and what I need to order to make sure it doesn’t get delayed.

Many doctors are retiring because they don’t want to deal with this anymore. There are many times that I have thought about quitting for this reason. A partner of mine had a heart attack last year. He’s a few years older than I am – in his mid-50s – and that scared me. I actually had a CT angiogram just to make sure. They told me my heart is fine, but I worry because of all these frustrations every day. And I’m not alone. For every doctor I work with, it’s the same story, and it’s just ridiculous.

For example, I had a patient with a huge breast mass. My nurse got me the prior authorization for an emergency biopsy. I got back the results for estrogen and progesterone receptor status, but not the HER2-neu results because that test required another authorization.

Authorization shouldn’t be required for every single step. I understand if maybe you need to get an authorization to do something outside the standard of care or something that is unique or unheard of, but HER2-neu biopsy is standard of care and should not require additional authorization.

And the sad part is, that patient turned out to be HER2-neu positive. She lost 4 weeks just waiting for an authorization of a test that should be a no-brainer.

We cannot even do a blood count in our office before getting authorization from some insurances. This is a very important test when we give chemotherapy, and it’s very cheap.

And then another nightmare is if you want to give a patient growth factors when you see their blood count is going down. Sometimes the insurance company will say, “When they get neutropenic fever, we’ll allow it with the next cycle.” Why do I have to wait until the patient develops such a problem to start with a treatment that could avoid it? They may end up in the hospital.

I think I’m one of the more conservative doctors; I try to do everything scientifically and only order a test or a treatment if it’s indicated. But sometimes this guidance costs more money. For example, an insurance company may say to order a CT scan first and if you don’t find your answer, then get a PET scan.

So I order a CT scan, knowing it’s not going to help, and then I tell them, “Now I need a PET scan.” That’s another week delay and an extra cost that I don’t want the system to incur.

I’ve even had some issues with lung screening scans for smokers. This screening has reduced mortality by 20%; it should be a no-brainer to encourage smokers to do it because many of them may not even need chemotherapy if you find early-stage lung cancer. And the screening is not expensive, you can do it for $90 to $100. So why do we have to get authorization for that?

Sometimes I push back and request a “peer-to-peer,” where you challenge the decision of the insurance company and speak to one of their doctors. Out of 10 doctors, maybe three or four will do the peer-to-peer. The rest will give up because it’s so frustrating.

In one case, I wanted to modify a standard regimen and give only two out of three drugs because I thought the third would be too toxic. But the insurance company wouldn’t approve the regimen because the guidelines say you have to give three drugs.

Guidelines are guidance, they should not dictate how you treat an individual patient – there should be some allowance in there for a doctor’s discretion. If not, why do we even need doctors? We could just follow treatment regimens dictated by computers. They have to allow me to personalize the care that my patient deserves and make changes so that the treatment can be tolerated.

But then, I get that one patient whom I feel I really helped and I realize, “Okay, I can help more people.”

I had this one patient, a young, 40-year-old nurse with breast cancer – also HER2-neu positive. She’d had her surgery and finished her adjuvant chemotherapy. One of the things that you do as standard of care, after a year of trastuzumab, is you start them on neratinib. There are studies that show it improves progression-free survival if you give them an extra year of this drug as an adjuvant.

I prescribed the neratinib, but the insurance company denied it because the patient “did not have positive lymph nodes and was not considered high risk.” I told them, “That’s BS, that’s not what the indication is for.” I asked for a peer-to-peer and they said the policy did not allow for peer-to-peer. So, I made a big fuss about it. We appealed, and I finally spoke to a pharmacist who worked for the insurance company. I told him, “Why did you guys deny this? It’s standard of care.” He said, “Oh, I agree with you, this will be approved. And actually, we’re going to change the policy now.”

When that pharmacist told me they were going to change the policy, it was like someone gave me 1 million dollars. Because, you know what? I didn’t just help my patient; now other patients will also get it. The hope is that if you keep fighting for something, they will change it.

I think every doctor wants to do the best for their patients. It’s not like they don’t want to, but really, I am fortunate that I have the means to do it. We’re a big practice and we have dedicated staff who can help.

If you’re a small practice, it’s almost impossible to deal with this. I have two nurse practitioners, and a lot of their work is filling out paperwork for insurance companies.

We had a colleague, a solo practitioner, who would send us his patients with complicated therapies, because he couldn’t afford the time or the effort or the risk of not getting reimbursed. His practice could have paid out $100,000 for drugs and not get a reimbursement for a few months.

Even when an insurance company does give the preauthorization, there’s always this disclaimer that it doesn’t guarantee payment. If they find in the future that your patient didn’t meet the criteria, they can still deny payment.

If the insurers refuse coverage, we really work hard at getting patients free drugs, and most of the time, we manage to do that. We either look to charitable organizations, like the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, or we look for rare disease societies or we go to the pharmaceutical company.

For really expensive drugs, pharmaceutical companies have a program where you can enroll the patient and they can help copay or even cover the drug. For less expensive drugs, it might not be a big problem, but for a drug that can cost $18,000 to $20,000 a month, that’s a big risk to take.

It’s confusing for patients, too. They get angry and frustrated, and that’s not good for their treatment, because attitude and psychology are very important. Sometimes they yell at us because they think it’s our fault. I encourage them to call their insurance companies themselves, and some of them do.

I don’t do it with every patient, but there are some more educated patients who are advocates, and if their condition is stable, I do encourage them to call their senators or congressmen or congresswomen to complain.

I don’t mind treating complicated patients. I don’t want to say I enjoy it, but I like challenges. That’s my field, that’s medicine, that’s what I’m supposed to do. But it’s really sad and frustrating that, when you want to treat a patient, you first have to look at their insurance to see how much care you can actually give them.

Maen Hussein, MD, is physician director of finance at Florida Cancer Specialists and Research Institute, Fort Myers. He is a board member of the Florida Cancer Specialists Foundation and sits on the board of directors for the Florida Society of Clinical Oncology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feasibility of Risk Stratification of Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Chest Pain Using HEART Score

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Dr. Gandhi), and the School of Medicine, Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College, and King Edward Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India (Drs. Gandhi and Tiwari).

Objective: Calculation of HEART score to (1) stratify patients as low-risk, intermediate-risk, high-risk, and to predict the short-term incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and (2) demonstrate feasibility of HEART score in our local settings.

Design: A prospective cohort study of patients with a chief complaint of chest pain concerning for acute coronary syndrome.

Setting: Participants were recruited from the emergency department (ED) of King Edward Memorial Hospital, a tertiary care academic medical center and a resource-limited setting in Mumbai, India.

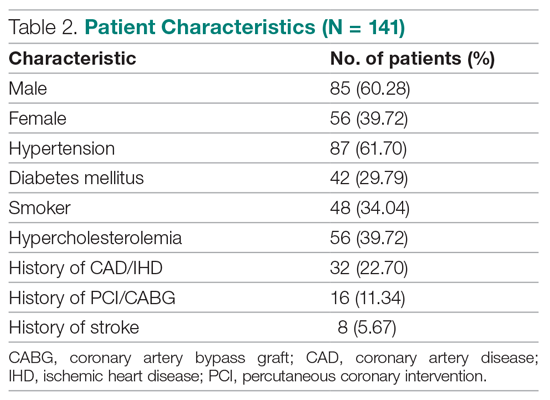

Participants: We evaluated 141 patients aged 18 years and older presenting to the ED and stratified them using the HEART score. To assess patients’ progress, a follow-up phone call was made within 6 weeks after presentation to the ED.

Measurements: The primary outcomes were a risk stratification, 6-week occurrence of MACE, and performance of unscheduled revascularization or stress testing. The secondary outcomes were discharge or death.

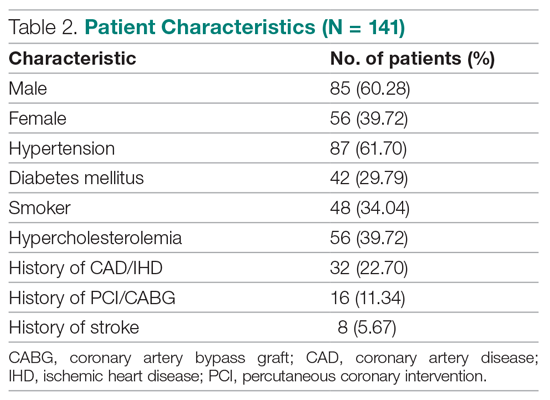

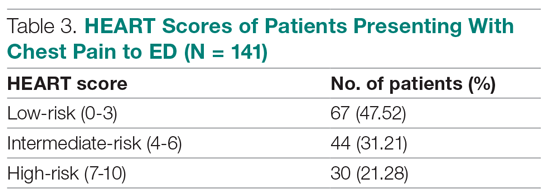

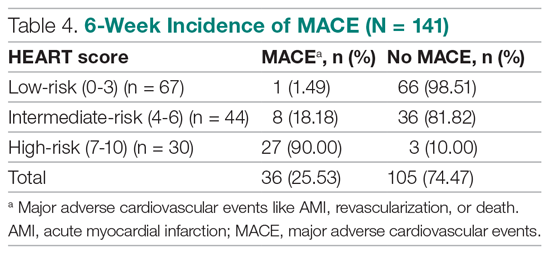

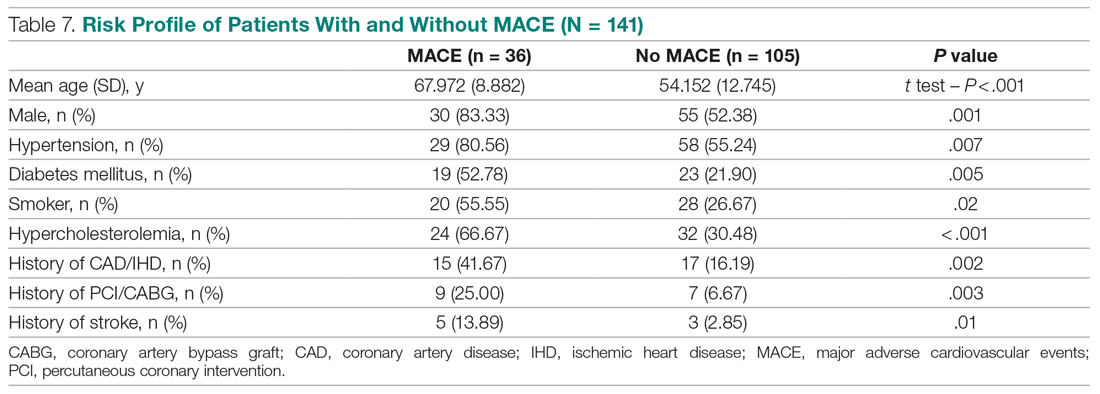

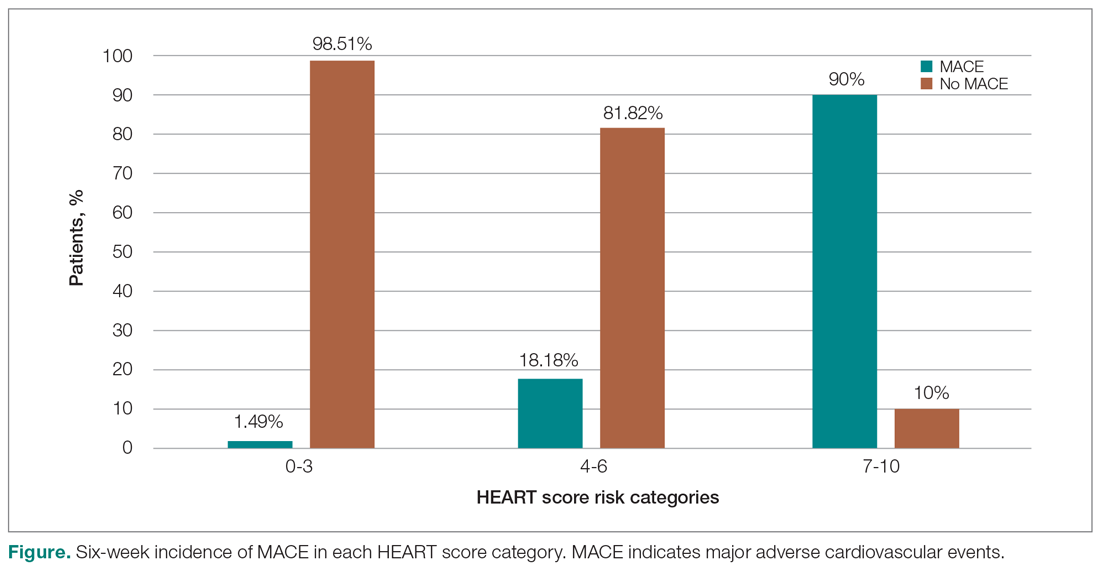

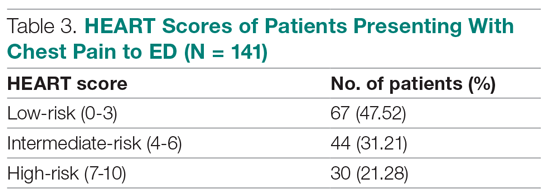

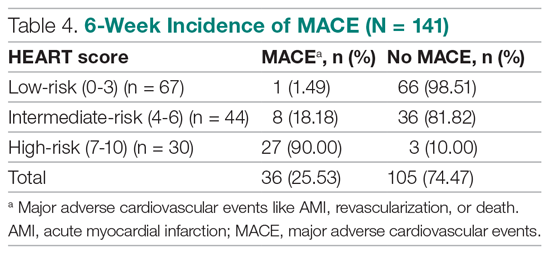

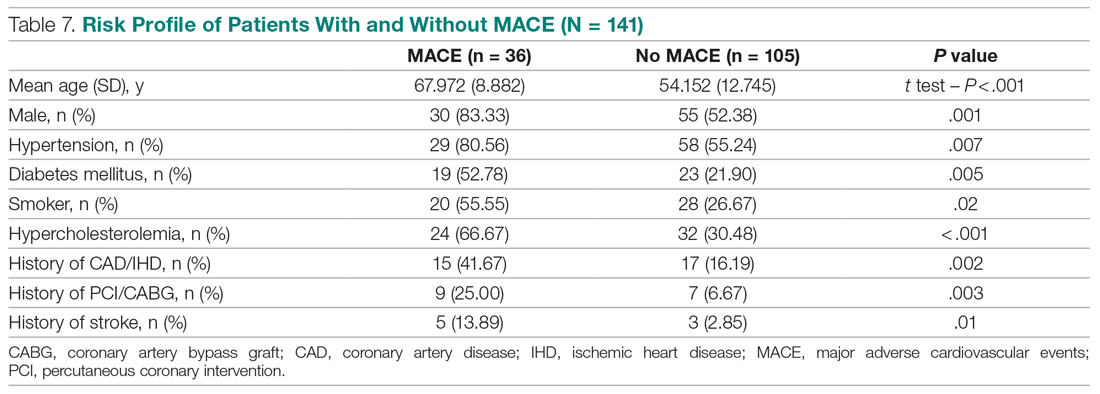

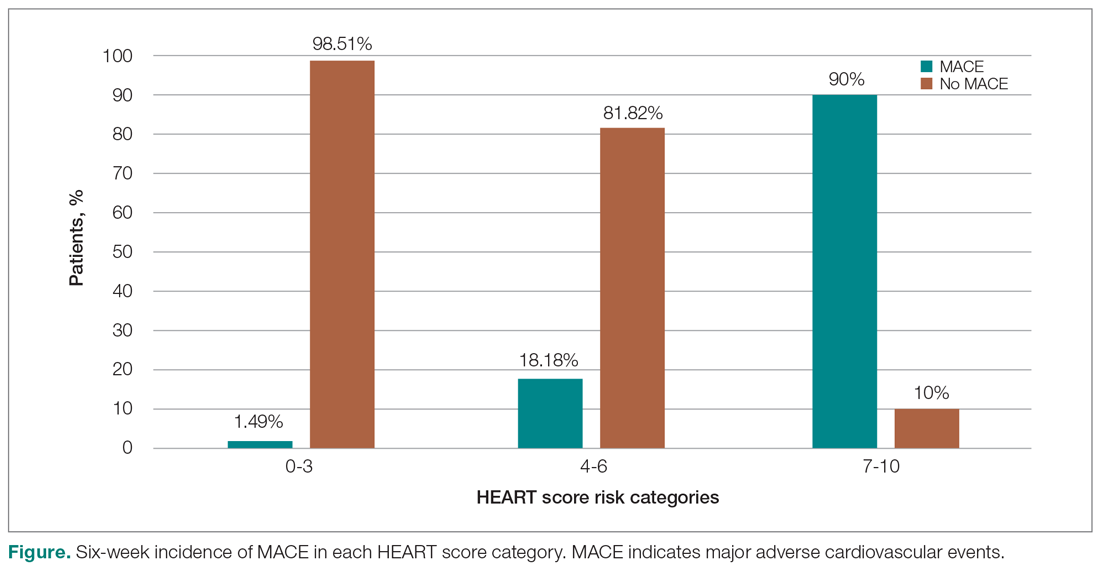

Results: The 141 participants were stratified into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups: 67 (47.52%), 44 (31.21%), and 30 (21.28%), respectively. The 6-week incidence of MACE in each category was 1.49%, 18.18%, and 90%, respectively. An acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed in 24 patients (17.02%), 15 patients (10.64%) underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and 4 patients (2.84%) underwent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). Overall, 98.5% of low-risk patients and 93.33% of high-risk patients had an uneventful recovery following discharge; therefore, extrapolation based on results demonstrated reduced health care utilization. All the survey respondents found the HEART score to be feasible. The patient characteristics and risk profile of the patients with and without MACE demonstrated that: patients with MACE were older and had a higher proportion of males, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, prior history of PCI/CABG, and history of stroke.

Conclusion: The HEART score seems to be a useful tool for risk stratification and a reliable predictor of outcomes in chest pain patients and can therefore be used for triage.

Keywords: chest pain; emergency department; HEART score; acute coronary syndrome; major adverse cardiac events; myocardial infarction; revascularization.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), especially coronary heart disease (CHD), have epidemic proportions worldwide. Globally, in 2012, CVD led to 17.5 million deaths,1,2 with more than 75% of them occurring in developing countries. In contrast to developed countries, where mortality from CHD is rapidly declining, it is increasing in developing countries.1,3 Current estimates from epidemiologic studies from various parts of India indicate the prevalence of CHD in India to be between 7% and 13% in urban populations and 2% and 7% in rural populations.4

Premature mortality in terms of years of life lost because of CVD in India increased by 59% over a 20-year span, from 23.2 million in 1990 to 37 million in 2010.5 Studies conducted in Mumbai (Mumbai Cohort Study) reported very high CVD mortality rates, approaching 500 per 100 000 for men and 250 per 100 000 for women.6,7 However, to the best of our knowledge, in the Indian population, there are minimal data on utilization of a triage score, such as the HEART score, in chest pain patients in the emergency department (ED) in a resource-limited setting.

The most common reason for admitting patients to the ED is chest pain.8 There are various cardiac and noncardiac etiologies of chest pain presentation. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) needs to be ruled out first in every patient presenting with chest pain. However, 80% of patients with ACS have no clear diagnostic features on presentation.9 The timely diagnosis and treatment of patients with ACS improves their prognosis. Therefore, clinicians tend to start each patient on ACS treatment to reduce the risk, which often leads to increased costs due to unnecessary, time-consuming diagnostic procedures that may place burdens on both the health care system and the patient.10

Several risk-stratifying tools have been developed in the last few years. Both the GRACE and TIMI risk scores have been designed for risk stratification of patients with proven ACS and not for the chest pain population at the ED.11 Some of these tools are applicable to patients with all types of chest pain presenting to the ED, such as the Manchester Triage System. Other, more selective systems are devoted to the risk stratification of suspected ACS in the ED. One is the HEART score.12

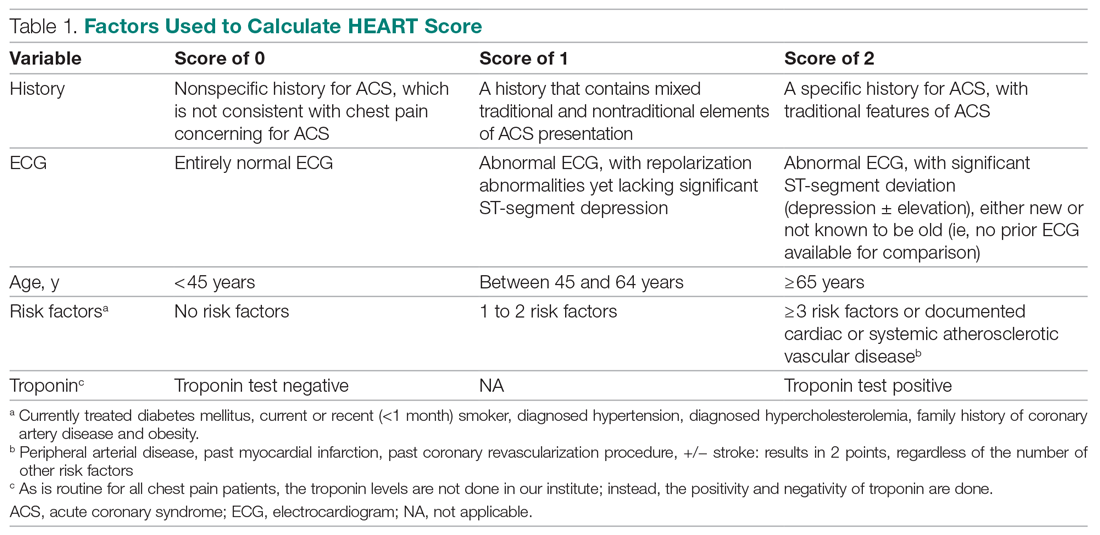

The first study on the HEART score—an acronym that stands for History, Electrocardiogram, Age, Risk factors, and Troponin—was done by Backus et al, who proved that the HEART score is an easy, quick, and reliable predictor of outcomes in chest pain patients.10 The HEART score predicts the short-term incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), which allows clinicians to stratify patients as low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk and to guide their clinical decision-making accordingly. It was developed to provide clinicians with a simple, reliable predictor of cardiac risk on the basis of the lowest score of 0 (very low-risk) up to a score of 10 (very high-risk).

We studied the clinical performance of the HEART score in patients with chest pain, focusing on the efficacy and safety of rapidly identifying patients at risk of MACE. We aimed to determine (1) whether the HEART score is a reliable predictor of outcomes of chest pain patients presenting to the ED; (2) whether the score is feasible in our local settings; and (3) whether it describes the risk profile of patients with and without MACE.

Methods

Setting

Participants were recruited from the ED of King Edward Memorial Hospital, a municipal teaching hospital in Mumbai. The study institute is a tertiary care academic medical center located in Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, and is a resource-limited setting serving urban, suburban, and rural populations. Participants requiring urgent attention are first seen by a casualty officer and then referred to the emergency ward. Here, the physician on duty evaluates them and decides on admission to the various wards, like the general ward, medical intensive care unit (ICU), coronary care unit (CCU), etc. The specialist’s opinion may also be obtained before admission. Critically ill patients are initially admitted to the emergency ward and stabilized before being shifted to other areas of the hospital.

Participants

Patients aged 18 years and older presenting with symptoms of acute chest pain or suspected ACS were stratified by priority using the chest pain scoring system—the HEART score. Only patients presenting to the ED were eligible for the study. Informed consent from the patient or next of kin was mandatory for participation in the study.

Patients were determined ineligible for the following reasons: a clear cause for chest pain other than ACS (eg, trauma, diagnosed aortic dissection), persisting or recurrent chest pain caused by rheumatic diseases or cancer (a terminal illness), pregnancy, unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, or incomplete data.

Study design

We conducted a

We conducted our study to determine the importance of calculating the HEART score in each patient, which will help to correctly place them into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups for clinically important, irreversible adverse cardiac events and guide the clinical decision-making. Patients with low risk will avoid costly tests and hospital admissions, thus decreasing the cost of treatment and ensuring timely discharge from the ED. Patients with high risk will be treated immediately, to possibly prevent a life-threatening, ACS-related incident. Thus, the HEART score will serve as a quick and reliable predictor of outcomes in chest pain patients and help clinicians to make accurate diagnostic and therapeutic choices in uncertain situations.

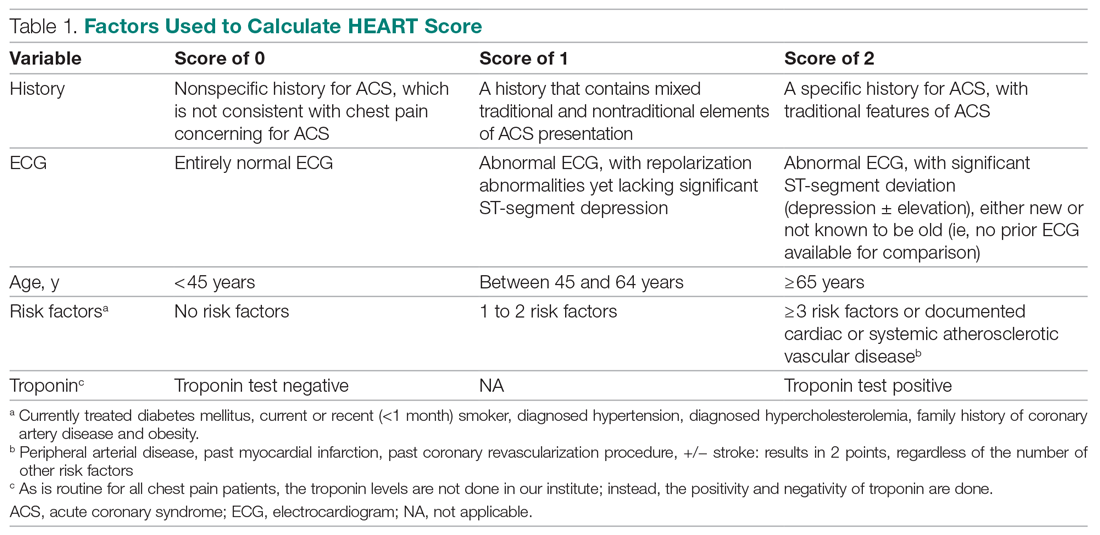

HEART score

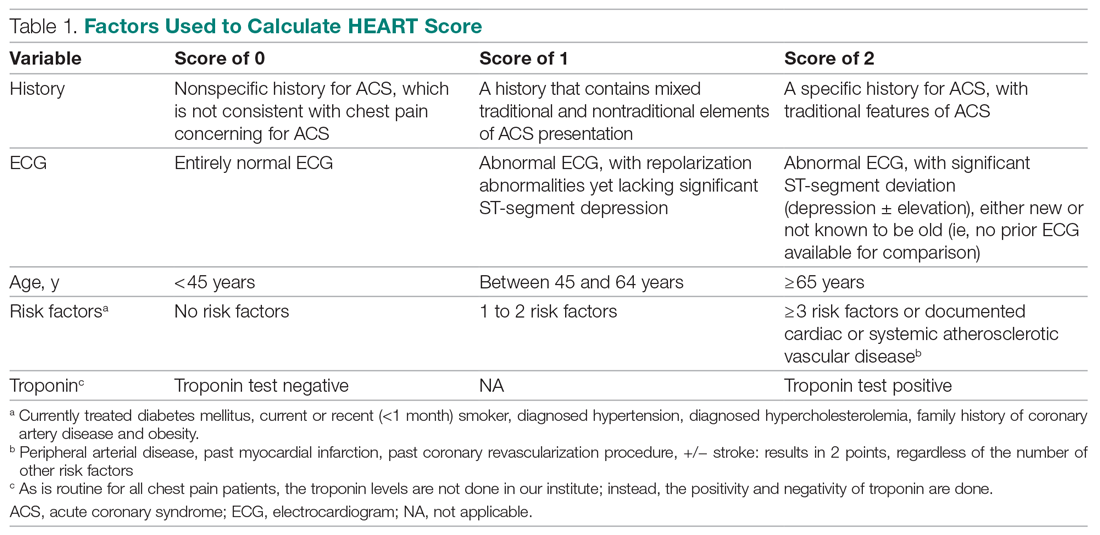

The total number of points for History, Electrocardiogram (ECG), Age, Risk factors, and Troponin was noted as the HEART score (Table 1).

For this study, the patient’s history and ECGs were interpreted by internal medicine attending physicians in the ED. The ECG taken in the emergency room was reviewed and classified, and a copy of the admission ECG was added to the file. The recommendation for patients with a HEART score in a particular range was evaluated. Notably, those with a score of 3 or lower led to a recommendation of reassurance and early discharge. Those with a HEART score in the intermediate range (4-6) were admitted to the hospital for further clinical observation and testing, whereas a high HEART score (7-10) led to admission for intensive monitoring and early intervention. In the analysis of HEART score data, we only used those patients having records for all 5 parameters, excluding patients without an ECG or troponin test.

Results

Myocardial infarction (MI) was defined based on Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.13 Coronary revascularization was defined as angioplasty with or without stent placement or coronary artery bypass surgery.14 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was defined as any therapeutic catheter intervention in the coronary arteries. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery was defined as any cardiac surgery in which coronary arteries were operated on.

The primary outcomes in this study were the (1) risk stratification of chest pain patients into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk categories; (2) incidence of a MACE within 6 weeks of initial presentation. MACE consists of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), PCI, CABG, coronary angiography revealing procedurally correctable stenosis managed conservatively, and death due to any cause.

Our secondary outcomes were discharge or death due to any cause within 6 weeks after presentation.

Follow-up

Within 6 weeks after presentation to the ED, a follow-up phone call was placed to assess the patient’s progress. The follow-up focused on the endpoint of MACE, comprising all-cause death, MI, and revascularization. No patient was lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We aimed to find a difference in the 6-week MACE between low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories of the HEART score. The prevalence of CHD in India is 10%,4 and assuming an α of 0.05, we needed a sample of 141 patients from the ED patient population. Continuous variables were presented by mean (SD), and categorical variables as percentages. We used t test and the Mann-Whitney U test for comparison of means for continuous variables, χ2 for categorical variables, and Fisher’s exact test for comparison of the categorical variables. Results with P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

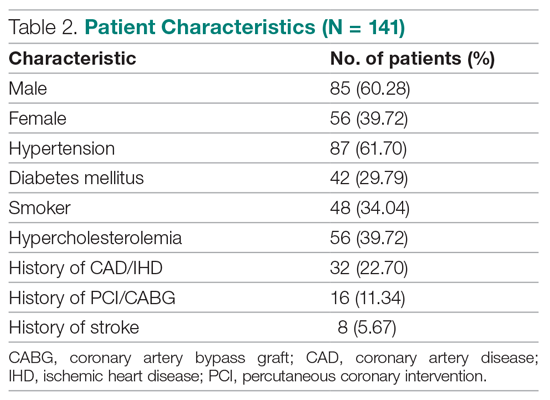

We evaluated 141 patients presenting to the ED with chest pain concerning for ACS during the study period, from July 2019 to October 2019.

Primary outcomes

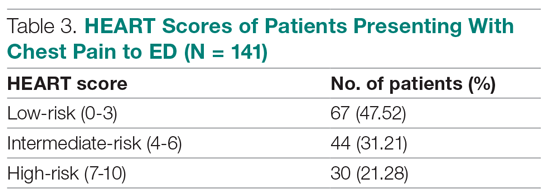

The risk stratification of the HEART score in chest pain patients and the incidence of 6-week MACE are outlined in Table 3

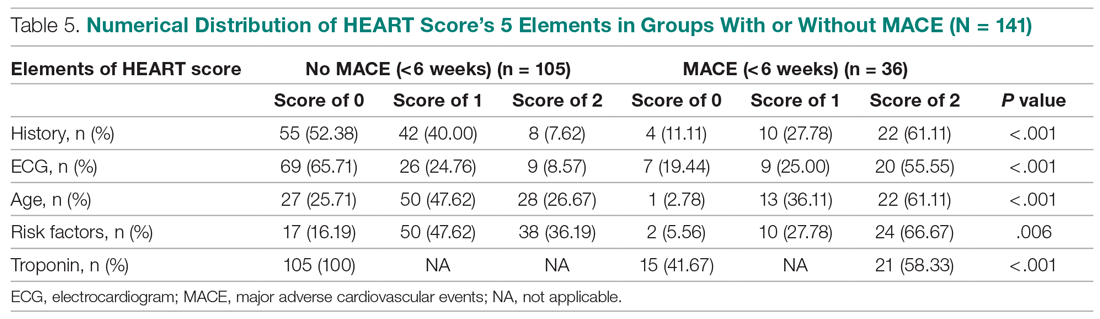

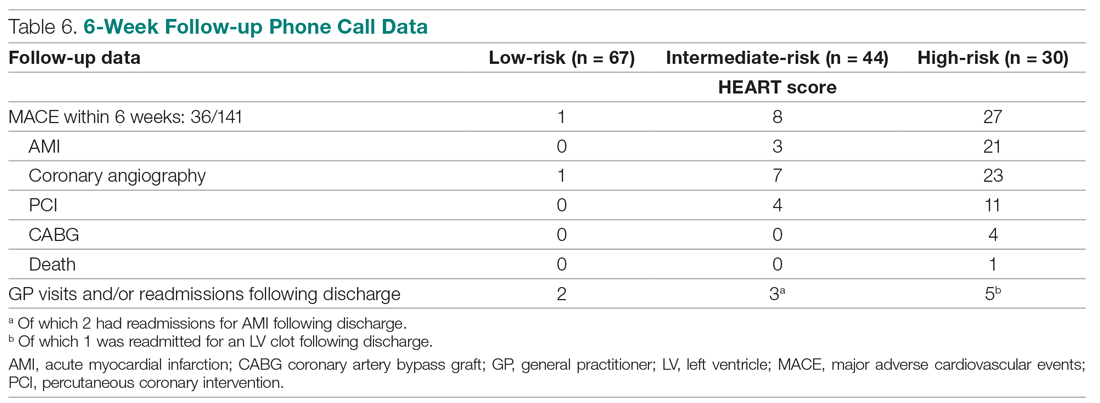

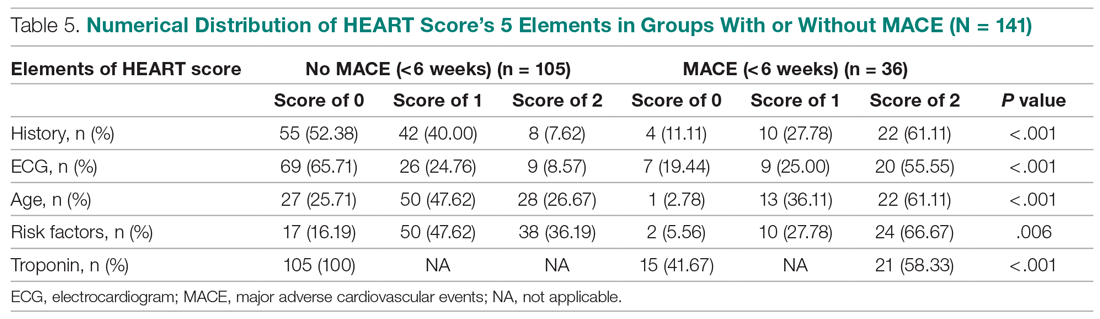

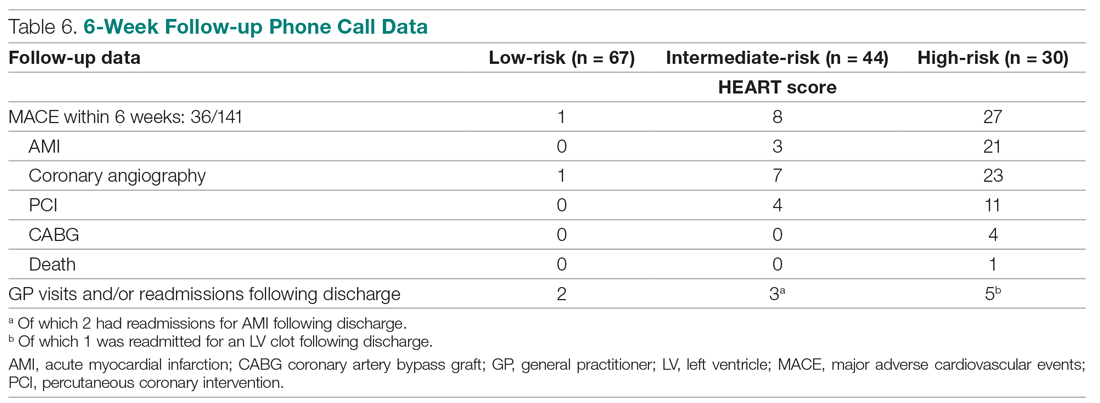

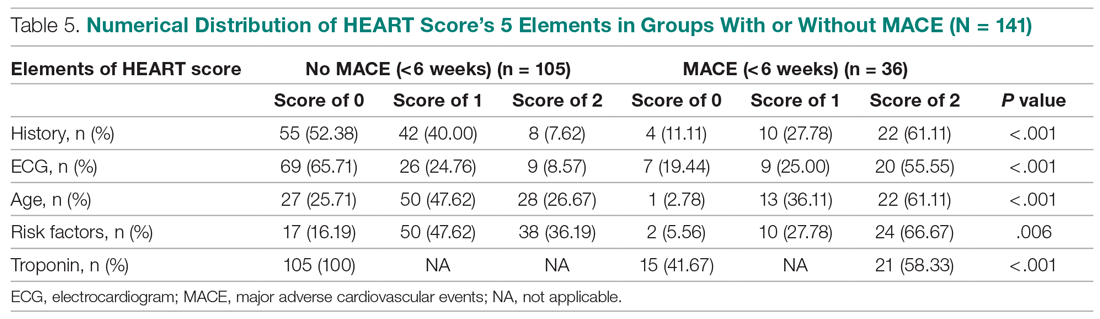

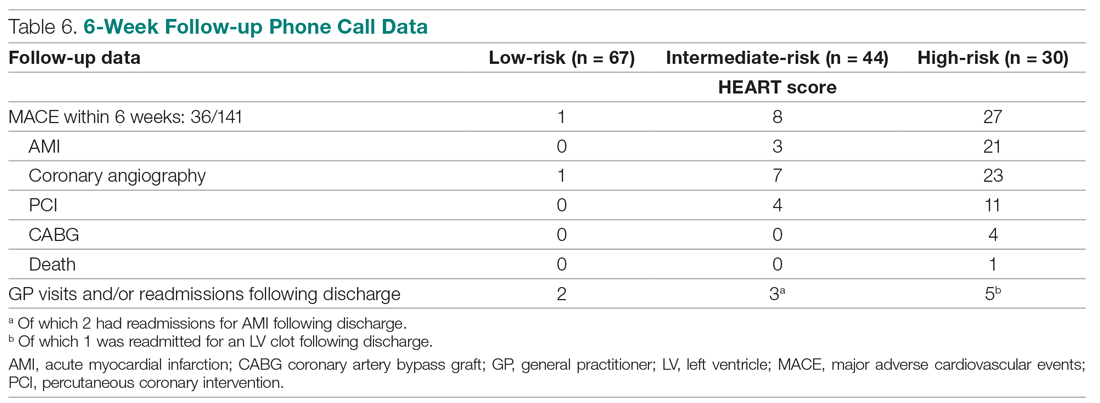

The distribution of the HEART score’s 5 elements in the groups with or without MACE endpoints is shown in Table 5. Notice the significant differences between the groups. A follow-up phone call was made within 6 weeks after the presentation to the ED to assess the patient’s progress. The 6-week follow-up call data are included in Table 6.

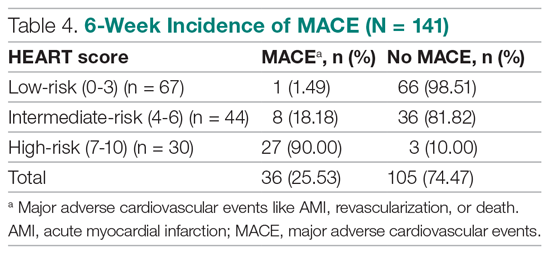

Of 141 patients, 36 patients (25.53%) were diagnosed with MACE within 6 weeks of presentation.

Myocardial infarction—An AMI was diagnosed in 24 of the 141 patients (17.02%). Twenty-one of those already had positive markers on admission (apparently, these AMI had started before their arrival to the emergency room). One AMI occurred 2 days after admission in a 66-year-old male, and another occurred 10 days after discharge. A further AMI occurred 2 weeks after discharge. All 3 patients belonged to the intermediate-risk group.

Revascularization—Coronary angiography was performed in 31 of 141 patients (21.99%). Revascularization was performed in 19 patients (13.48%), of which 15 were PCIs (10.64%) and 4 were CABGs (2.84%).

Mortality—One patient died from the study population. He was a 72-year-old male who died 14 days after admission. He had a HEART score of 8.

Among the 67 low-risk patients:

- MACE: Coronary angiography was performed in 1 patient (1.49%). Among the 67 patients in the low-risk category, there was no cases of AMI or deaths. The remaining 66 patients (98.51%) had an uneventful recovery following discharge.

- General practitioner (GP) visits/readmissions following discharge: Two of 67 patients (2.99%) had GP visits following discharge, of which 1 was uneventful. The other patient, a 64-year-old male, was readmitted due to a recurrent history of chest pain and underwent coronary angiography.

Among the 44 intermediate-risk patients:

- MACE: Of the 7 of 44 patients (15.91%) who had coronary angiography, 3 patients (6.82%) had AMI, of which 1 occurred 2 days after admission in a 66-year-old male. Two patients had AMI following discharge. There were no deaths. Overall, 42 of 44 patients (95.55%) had an uneventful recovery following discharge.

- GP visits/readmissions following discharge: Three of 44 patients (6.82%) had repeated visits following discharge. One was a GP visit that was uneventful. The remaining 2 patients were diagnosed with AMI and readmitted following discharge. One AMI occurred 10 days after discharge in a patient with a HEART score of 6; another occurred 2 weeks after discharge in a patient with a HEART score of 5.

Among the 30 high-risk patients:

- MACE: Twenty-three of 30 patients (76.67%) underwent coronary angiography. One patient died 5 days after discharge. The patient had a HEART score of 8. Most patients however, had an uneventful recovery following discharge (28, 93.33%).

- GP visits/readmissions following discharge: Five of 30 patients (16.67%) had repeated visits following discharge. Two were uneventful. Two patients had a history of recurrent chest pain that resolved on Sorbitrate. One patient was readmitted 2 weeks following discharge due to a complication: a left ventricular clot was found. The patient had a HEART score of 10.

Secondary outcome—Overall, 140 of 141 patients were discharged. One patient died: a 72-year-old male with a HEART score of 8.

Feasibility—To determine the ease and feasibility of performing a HEART score in chest pain patients presenting to the ED, a survey was distributed to the internal medicine physicians in the ED. In the survey, the Likert scale was used to rate the ease of utilizing the HEART score and whether the physicians found it feasible to use it for risk stratification of their chest pain patients. A total of 12 of 15 respondents (80%) found it “easy” to use. Of the remaining 3 respondents, 2 (13.33%) rated the HEART score “very easy” to use, while 1 (6.66%) considered it “difficult” to work with. None of the respondents said that it was not feasible to perform a HEART score in the ED.

Risk factors for reaching an endpoint:

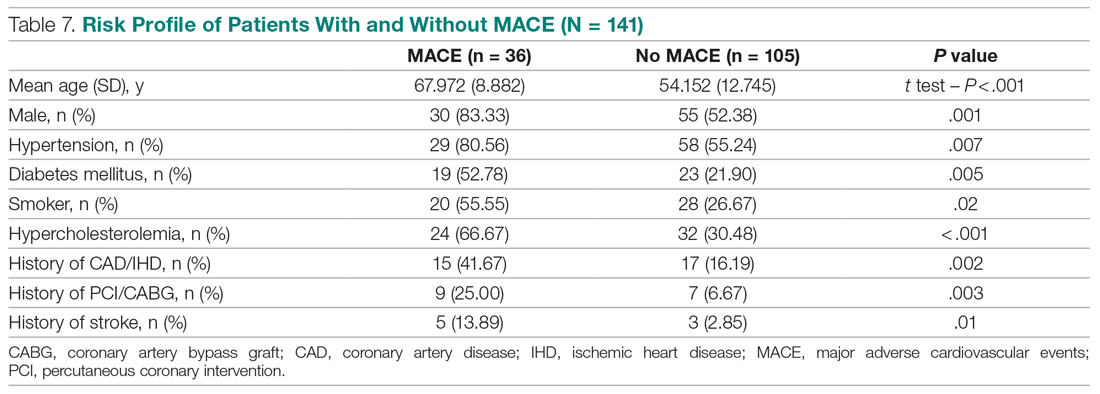

We compared risk profiles between the patient groups with and without an endpoint. The group of patients with MACE were older and had a higher proportion of males than the group of patients without MACE. Moreover, they also had a higher prevalence of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, prior history of PCI/CABG, and history of stroke. These also showed a significant association with MACE. Obesity was not included in our risk factors as we did not have data collected to measure body mass index. Results are represented in Table 7.

Discussion

Our study described a patient population presenting to an ED with chest pain as their primary complaint. The results of this prospective study confirm that the HEART score is an excellent system to triage chest pain patients. It provides the clinician with a reliable predictor of the outcome (MACE) after the patient’s arrival, based on available clinical data and in a resource-limited setting like ours.

Cardiovascular epidemiology studies indicate that this has become a significant public health problem in India.1 Several risk scores for ACS have been published in European and American guidelines. However, in the Indian population, minimal data are available on utilization of such a triage score (HEART score) in chest pain patients in the ED in a resource-limited setting, to the best of our knowledge. In India, only 1 such study is reported,15 at the Sundaram Medical Foundation, a 170-bed community hospital in Chennai. In this study, 13 of 14 patients (92.86%) with a high HEART score had MACE, indicating a sensitivity of 92.86%; in the 44 patients with a low HEART score, 1 patient (2.22%) had MACE, indicating a specificity of 97.78%; and in the 28 patients with a moderate HEART score, 12 patients (42.86%) had MACE.

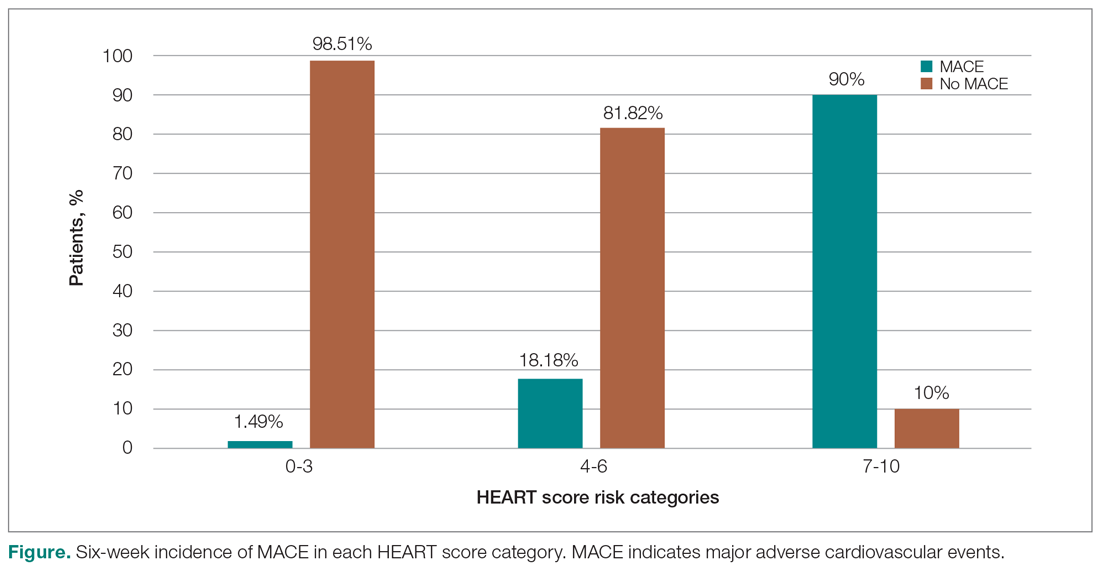

In looking for the optimal risk-stratifying system for chest pain patients, we analyzed the HEART score. The first study on the HEART score was done Backus et al, proving that the HEART score is an easy, quick, and reliable predictor of outcomes in chest pain patients.10 The HEART score had good discriminatory power, too. The C statistic for the HEART score for ACS occurrence shows a value of 0.83. This signifies a good-to-excellent ability to stratify all-cause chest pain patients in the ED for their risk of MACE. The application of the HEART score to our patient population demonstrated that the majority of the patients belonged to the low-risk category, as reported in the first cohort study that applied the HEART score.8 The relationship between the HEART score category and occurrence of MACE within 6 weeks showed a curve with 3 different patterns, corresponding to the 3 risk categories defined in the literature.11,12 The risk stratification of chest pain patients using the 3 categories (0-3, 4-6, 7-10) identified MACE with an incidence similar to the multicenter study of Backus et al,10,11 but with a greater risk of MACE in the high-risk category (Figure).

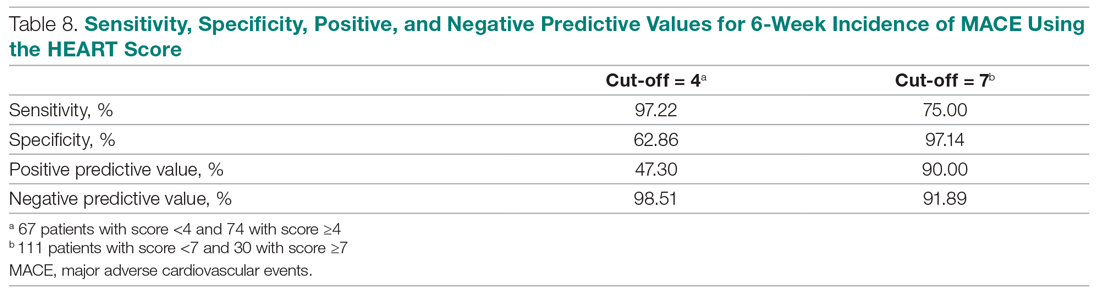

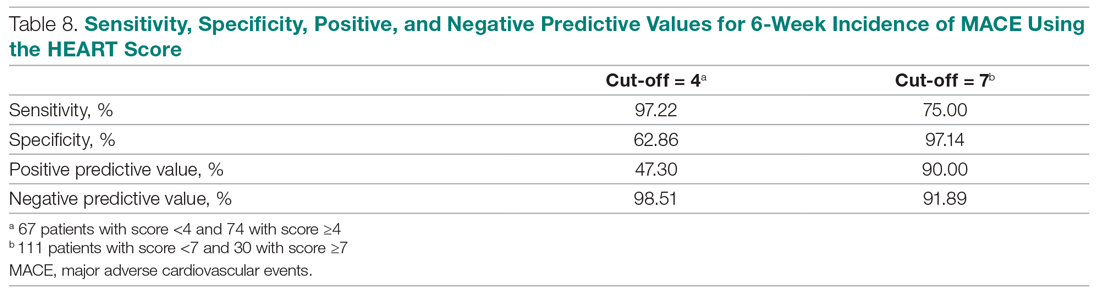

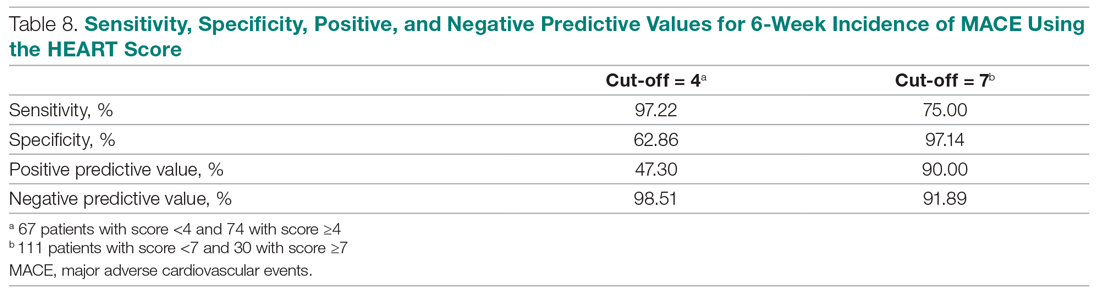

Thus, our study confirmed the utility of the HEART score categories to predict the 6-week incidence of MACE. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for the established cut-off scores of 4 and 7 are shown in Table 8. The patients in the low-risk category, corresponding to a score < 4, had a very high negative predictive value, thus identifying a small-risk population. The patients in the high-risk category (score ≥ 7) showed a high positive predictive value, allowing the identification of a high-risk population, even in patients with more atypical presentations. Therefore, the HEART score may help clinicians to make accurate management choices by being a strong predictor of both event-free survival and potentially life-threatening cardiac events.11,12

Our study tested the efficacy of the HEART score pathway in helping clinicians make smart diagnostic and therapeutic choices. It confirmed that the HEART score was accurate in predicting the short-term incidence of MACE, thus stratifying patients according to their risk severity. In our study, 67 of 141 patients (47.52%) had low-risk HEART scores, and we found the 6-week incidence of MACE to be 1.49%. We omitted the diagnostic and treatment evaluation for patients in the low-risk category and moved onto discharge. Overall, 66 of 67 patients (98.51%) in the low-risk category had an uneventful recovery following discharge. Only 2 of 67 these patients (2.99%) of patients had health care utilization following discharge. Therefore, extrapolation based on results demonstrates reduced health care utilization. Previous studies have shown similar results.9,12,14,16 For instance, in a prospective study conducted in the Netherlands, low-risk patients representing 36.4% of the total were found to have a low MACE rate (1.7%).9 These low-risk patients were categorized as appropriate and safe for ED discharge without additional cardiac evaluation or inpatient admission.9 Another retrospective study in Portugal,12 and one in Chennai, India,15 found the 6-week incidence of MACE to be 2.00% and 2.22%, respectively. The results of the first HEART Pathway Randomized Control Trial14 showed that the HEART score pathway reduces health care utilization (cardiac testing, hospitalization, and hospital length of stay). The study also showed that these gains occurred without any of the patients that were identified for early discharge, suffering from MACE at 30 days, or secondary increase in cardiac-related hospitalizations. Similar results were obtained by a randomized trial conducted in North Carolina17 that also demonstrated a reduction in objective cardiac testing, a doubling of the rate of early discharge from the ED, and a reduced length of stay by half a day. Another study using a modified HEART score also demonstrated that when low-risk patients are evaluated with cardiac testing, the likelihood for false positives is high.16 Hoffman et al also reported that patients randomized to coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) received > 2.5 times more radiation exposure.16 Thus, low-risk patients may be safely discharged without the need for stress testing or CCTA.

In our study, 30 out of 141 patients (21.28%) had high-risk HEART scores (7-10), and we found the 6-week incidence of MACE to be 90%. Based on the pathway leading to inpatient admission and intensive treatment, 23 of 30 patients (76.67%) patients in our study underwent coronary angiography and further therapeutic treatment. In the high-risk category, 28 of 30 patients (93.33%) patients had an uneventful recovery following discharge. Previous studies have shown similar results. A retrospective study in Portugal showed that 76.9% of the high-risk patients had a 6-week incidence of MACE.12 In a study in the Netherlands,9 72.7% of high-risk patients had a 6-week incidence of MACE. Therefore, a HEART score of ≥ 7 in patients implies early aggressive treatment, including invasive strategies, when necessary, without noninvasive treatment preceding it.8

In terms of intermediate risk, in our study 44 of 141 patients (31.21%) patients had an intermediate-risk HEART score (4-6), and we found the 6-week incidence of MACE to be 18.18%. Based on the pathway, they were kept in the observation ward on admission. In our study, 7 of 44 patients (15.91%) underwent coronary angiography and further treatment; 42 of 44 patients (95.55%) had an uneventful recovery following discharge. In a prospective study in the Netherlands, 46.1% of patients with an intermediate score had a 6-week MACE incidence of 16.6%.10 Similarly, in another retrospective study in Portugal, the incidence of 6-week MACE in intermediate-risk patients (36.7%) was found to be 15.6%.12 Therefore, in patients with a HEART score of 4-6 points, immediate discharge is not an option, as this figure indicates a risk of 18.18% for an adverse outcome. These patients should be admitted for clinical observation, treated as an ACS awaiting final diagnosis, and subjected to noninvasive investigations, such as repeated troponin. Using the HEART score as guidance in the treatment of chest pain patients will benefit patients on both sides of the spectrum.11,12

Our sample presented a male predominance, a wide range of age, and a mean age similar to that of previous studies.12.16 Some risk factors, we found, can increase significantly the odds of chest pain being of cardiovascular origin, such as male gender, smoking, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia. Other studies also reported similar findings.8,12,16 Risk factors for premature CHD have been quantified in the case-control INTERHEART study.1 In the INTERHEART study, 8 common risk factors explained > 90% of AMIs in South Asian and Indian patients. The risk factors include dyslipidemia, smoking or tobacco use, known hypertension, known diabetes, abdominal obesity, physical inactivity, low fruit and vegetable intake, and psychosocial stress.1 Regarding the feasibility of treating physicians using the HEART score in the ED, we observed that, based on the Likert scale, 80% of survey respondents found it easy to use, and 100% found it feasible in the ED.

However, there were certain limitations to our study. It involved a single academic medical center and a small sample size, which limit generalizability of the findings. In addition, troponin levels are not calculated at our institution, as it is a resource-limited setting; therefore, we used a positive and negative as +2 and 0, respectively.

Conclusion

The HEART score provides the clinician with a quick and reliable predictor of outcome of patients with chest pain after arrival to the ED and can be used for triage. For patients with low HEART scores (0-3), short-term MACE can be excluded with greater than 98% certainty. In these patients, one may consider reserved treatment and discharge policies that may also reduce health care utilization. In patients with high HEART scores (7-10), the high risk of MACE (90%) may indicate early aggressive treatment, including invasive strategies, when necessary. Therefore, the HEART score may help clinicians make accurate management choices by being a strong predictor of both event-free survival and potentially life-threatening cardiac events. Age, gender, and cardiovascular risk factors may also be considered in the assessment of patients. This study confirmed the utility of the HEART score categories to predict the 6-week incidence of MACE.

Corresponding author: Smrati Bajpai Tiwari, MD, DNB, FAIMER, Department of Medicine, Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College and King Edward Memorial Hospital, Acharya Donde Marg, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, Maharashtra, India; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gupta R, Mohan I, Narula J. Trends in coronary heart disease epidemiology in India. Ann Glob Health. 2016;82:307-315.

2. World Health Organization. Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf

3. Fuster V, Kelly BB, eds. Promoting Cardiovascular Health in the Developing World: A Critical Challenge to Achieve Global Health. Institutes of Medicine; 2010.

4. Krishnan MN. Coronary heart disease and risk factors in India—on the brink of an epidemic. Indian Heart J. 2012;64:364-367.

5. Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Roy A. Cardiovascular diseases in India: current epidemiology and future directions. Circulation. 2016;133:1605-1620.

6. Aeri B, Chauhan S. The rising incidence of cardiovascular diseases in India: assessing its economic impact. J Prev Cardiol. 2015;4:735-740.

7. Pednekar M, Gupta R, Gupta PC. Illiteracy, low educational status and cardiovascular mortality in India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:567.

8. Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:191-196.

9. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168;2153-2158.

10. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART score. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010;9:164-169.

11. Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JH, et al. Risk scores for patients with chest pain: evaluation in the emergency department. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2011;7:2-8.

12. Leite L, Baptista R, Leitão J, et al. Chest pain in the emergency department: risk stratification with Manchester triage system and HEART score. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:48.

13. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2018;138:e618-e651.

14. Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART Pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:195-203.

15. Natarajan B, Mallick P, Thangalvadi TA, Rajavelu P. Validation of the HEART score in Indian population. Int J Emerg Med. 2015,8(suppl 1):P5.

16. McCord J, Cabrera R, Lindahl B, et al. Prognostic utility of a modified HEART score in chest pain patients in the emergency department. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e003101.

17. Mahler SA, Miller CD, Hollander JE, et al. Identifying patients for early discharge: performance of decision rules among patients with acute chest pain. Int J Cardiol. 2012;168:795-802.

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Dr. Gandhi), and the School of Medicine, Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College, and King Edward Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India (Drs. Gandhi and Tiwari).

Objective: Calculation of HEART score to (1) stratify patients as low-risk, intermediate-risk, high-risk, and to predict the short-term incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and (2) demonstrate feasibility of HEART score in our local settings.

Design: A prospective cohort study of patients with a chief complaint of chest pain concerning for acute coronary syndrome.

Setting: Participants were recruited from the emergency department (ED) of King Edward Memorial Hospital, a tertiary care academic medical center and a resource-limited setting in Mumbai, India.

Participants: We evaluated 141 patients aged 18 years and older presenting to the ED and stratified them using the HEART score. To assess patients’ progress, a follow-up phone call was made within 6 weeks after presentation to the ED.

Measurements: The primary outcomes were a risk stratification, 6-week occurrence of MACE, and performance of unscheduled revascularization or stress testing. The secondary outcomes were discharge or death.

Results: The 141 participants were stratified into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups: 67 (47.52%), 44 (31.21%), and 30 (21.28%), respectively. The 6-week incidence of MACE in each category was 1.49%, 18.18%, and 90%, respectively. An acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed in 24 patients (17.02%), 15 patients (10.64%) underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and 4 patients (2.84%) underwent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). Overall, 98.5% of low-risk patients and 93.33% of high-risk patients had an uneventful recovery following discharge; therefore, extrapolation based on results demonstrated reduced health care utilization. All the survey respondents found the HEART score to be feasible. The patient characteristics and risk profile of the patients with and without MACE demonstrated that: patients with MACE were older and had a higher proportion of males, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, prior history of PCI/CABG, and history of stroke.

Conclusion: The HEART score seems to be a useful tool for risk stratification and a reliable predictor of outcomes in chest pain patients and can therefore be used for triage.

Keywords: chest pain; emergency department; HEART score; acute coronary syndrome; major adverse cardiac events; myocardial infarction; revascularization.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), especially coronary heart disease (CHD), have epidemic proportions worldwide. Globally, in 2012, CVD led to 17.5 million deaths,1,2 with more than 75% of them occurring in developing countries. In contrast to developed countries, where mortality from CHD is rapidly declining, it is increasing in developing countries.1,3 Current estimates from epidemiologic studies from various parts of India indicate the prevalence of CHD in India to be between 7% and 13% in urban populations and 2% and 7% in rural populations.4