User login

Cerliponase alfa continues to impress for CLN2 disease

BANGKOK – Biweekly cerliponase alfa continued to show durable and clinically important therapeutic benefit in children with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2) disease at the 3-year mark in an ongoing international study, Marina Trivisano, MD, reported at the International Epilepsy Congress.

Cerliponase alfa, approved under the trade name Brineura by the Food and Drug Administration and European Commission, is a recombinant human tripeptidyl peptidase 1 designed as enzyme replacement therapy delivered by a surgically implanted intraventricular infusion device in children with this rare lysosomal storage disease, a form of Batten disease, she explained at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

When both healthy parents carry one defective gene, each of their children has a one in four chance of inheriting this devastating disease that causes rapidly progressive dementia. CLN2 disease typically reveals itself when a child reaches about 3 years of age, with seizures, language delay, or loss of acquired language being the most common first indications.

Of 23 patients enrolled in the open-label study, 21 remained participants at 3 years of follow-up. The two dropouts weren’t caused by treatment-related adverse events, but rather by the formidable logistic challenges posed because the treatment – 300 mg of cerliponase alfa delivered by intraventricular infusion over a 4-hour period every 2 weeks – was available only at five medical centers located in Rome; London; New York; Hamburg, Germany; and Columbus, Ohio.

At 3 years of follow-up, 83% of patients met the primary study endpoint, defined as the absence of a 2-point or greater decline in the motor-language score on the 0-6 CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale. This was a success rate 12 times greater than in 42 historical controls. Indeed, at 3 years the cerliponase alfa–treated patients had an average CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale motor-language score 3.8 points better than the historical controls, reported Dr. Trivisano, a pediatric neurologist at Bambino Gesu Children’s Hospital in Rome.

Side effects included several cases of device failure, infection, and hypersensitivity reactions.

In an earlier report based upon 96 weeks of follow-up, the mean rate of decline in the motor-language score was 0.27 points per 48 weeks in treated patients, compared with 2.12 points in the historical controls (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17;378[20]:1898-1907).

The study was funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical, which markets Brineura. Dr. Trivisano was a subinvestigator in the trial.

SOURCE: Trivisano M et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P333.

BANGKOK – Biweekly cerliponase alfa continued to show durable and clinically important therapeutic benefit in children with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2) disease at the 3-year mark in an ongoing international study, Marina Trivisano, MD, reported at the International Epilepsy Congress.

Cerliponase alfa, approved under the trade name Brineura by the Food and Drug Administration and European Commission, is a recombinant human tripeptidyl peptidase 1 designed as enzyme replacement therapy delivered by a surgically implanted intraventricular infusion device in children with this rare lysosomal storage disease, a form of Batten disease, she explained at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

When both healthy parents carry one defective gene, each of their children has a one in four chance of inheriting this devastating disease that causes rapidly progressive dementia. CLN2 disease typically reveals itself when a child reaches about 3 years of age, with seizures, language delay, or loss of acquired language being the most common first indications.

Of 23 patients enrolled in the open-label study, 21 remained participants at 3 years of follow-up. The two dropouts weren’t caused by treatment-related adverse events, but rather by the formidable logistic challenges posed because the treatment – 300 mg of cerliponase alfa delivered by intraventricular infusion over a 4-hour period every 2 weeks – was available only at five medical centers located in Rome; London; New York; Hamburg, Germany; and Columbus, Ohio.

At 3 years of follow-up, 83% of patients met the primary study endpoint, defined as the absence of a 2-point or greater decline in the motor-language score on the 0-6 CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale. This was a success rate 12 times greater than in 42 historical controls. Indeed, at 3 years the cerliponase alfa–treated patients had an average CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale motor-language score 3.8 points better than the historical controls, reported Dr. Trivisano, a pediatric neurologist at Bambino Gesu Children’s Hospital in Rome.

Side effects included several cases of device failure, infection, and hypersensitivity reactions.

In an earlier report based upon 96 weeks of follow-up, the mean rate of decline in the motor-language score was 0.27 points per 48 weeks in treated patients, compared with 2.12 points in the historical controls (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17;378[20]:1898-1907).

The study was funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical, which markets Brineura. Dr. Trivisano was a subinvestigator in the trial.

SOURCE: Trivisano M et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P333.

BANGKOK – Biweekly cerliponase alfa continued to show durable and clinically important therapeutic benefit in children with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2) disease at the 3-year mark in an ongoing international study, Marina Trivisano, MD, reported at the International Epilepsy Congress.

Cerliponase alfa, approved under the trade name Brineura by the Food and Drug Administration and European Commission, is a recombinant human tripeptidyl peptidase 1 designed as enzyme replacement therapy delivered by a surgically implanted intraventricular infusion device in children with this rare lysosomal storage disease, a form of Batten disease, she explained at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

When both healthy parents carry one defective gene, each of their children has a one in four chance of inheriting this devastating disease that causes rapidly progressive dementia. CLN2 disease typically reveals itself when a child reaches about 3 years of age, with seizures, language delay, or loss of acquired language being the most common first indications.

Of 23 patients enrolled in the open-label study, 21 remained participants at 3 years of follow-up. The two dropouts weren’t caused by treatment-related adverse events, but rather by the formidable logistic challenges posed because the treatment – 300 mg of cerliponase alfa delivered by intraventricular infusion over a 4-hour period every 2 weeks – was available only at five medical centers located in Rome; London; New York; Hamburg, Germany; and Columbus, Ohio.

At 3 years of follow-up, 83% of patients met the primary study endpoint, defined as the absence of a 2-point or greater decline in the motor-language score on the 0-6 CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale. This was a success rate 12 times greater than in 42 historical controls. Indeed, at 3 years the cerliponase alfa–treated patients had an average CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale motor-language score 3.8 points better than the historical controls, reported Dr. Trivisano, a pediatric neurologist at Bambino Gesu Children’s Hospital in Rome.

Side effects included several cases of device failure, infection, and hypersensitivity reactions.

In an earlier report based upon 96 weeks of follow-up, the mean rate of decline in the motor-language score was 0.27 points per 48 weeks in treated patients, compared with 2.12 points in the historical controls (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17;378[20]:1898-1907).

The study was funded by BioMarin Pharmaceutical, which markets Brineura. Dr. Trivisano was a subinvestigator in the trial.

SOURCE: Trivisano M et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P333.

REPORTING FROM IEC 2019

Dapagliflozin-Induced Sweet Syndrome

To the Editor:

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, gout, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus was started on dapagliflozin (5 mg) for glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c, 7.9 [reference range, 4–7]). Within 1 week of starting the medication, she developed a fine papular eruption in a photodistributed area on the neck and chest with associated malaise. The rash progressed over the next 2 weeks, evolving into edematous papules and plaques, some with vesicles involving the neck, chest, postauricular areas, and nose. Approximately 3 weeks after starting dapagliflozin, the patient also developed bilateral painful, hemorrhagic, bullous plaques (10×3 cm overall) without satellite lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands. The borders of the bullae had rapidly expanding geographic margins and were extremely painful. The patient’s primary care physician advised to discontinue dapagliflozin, as this medication was thought to be triggering the eruption. She was administered triamcinolone (40 mg intramuscularly) and advised to take ibuprofen as needed. She had malaise and reported that she felt hot but had no known fever. No laboratory tests were ordered.

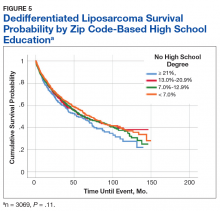

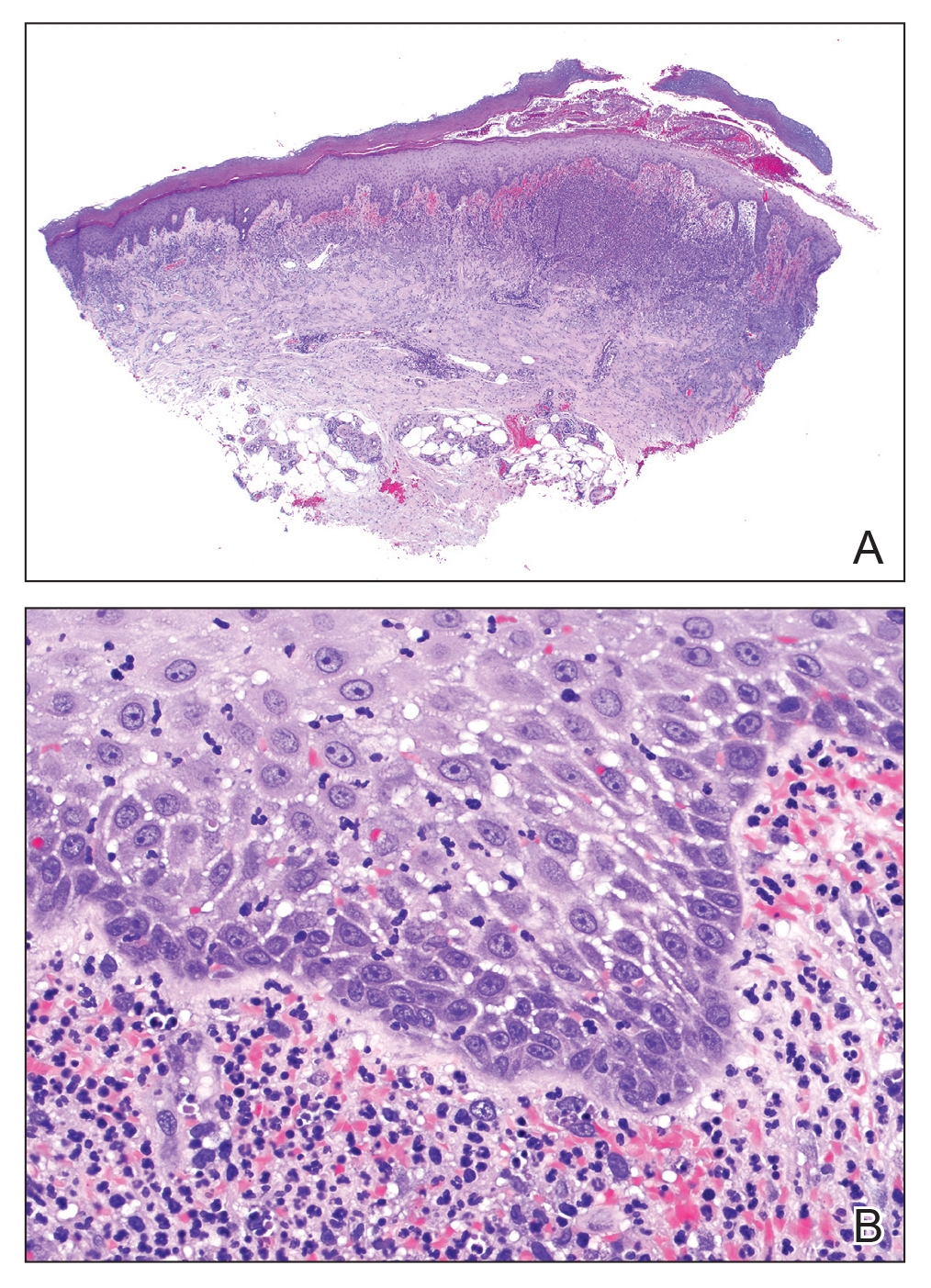

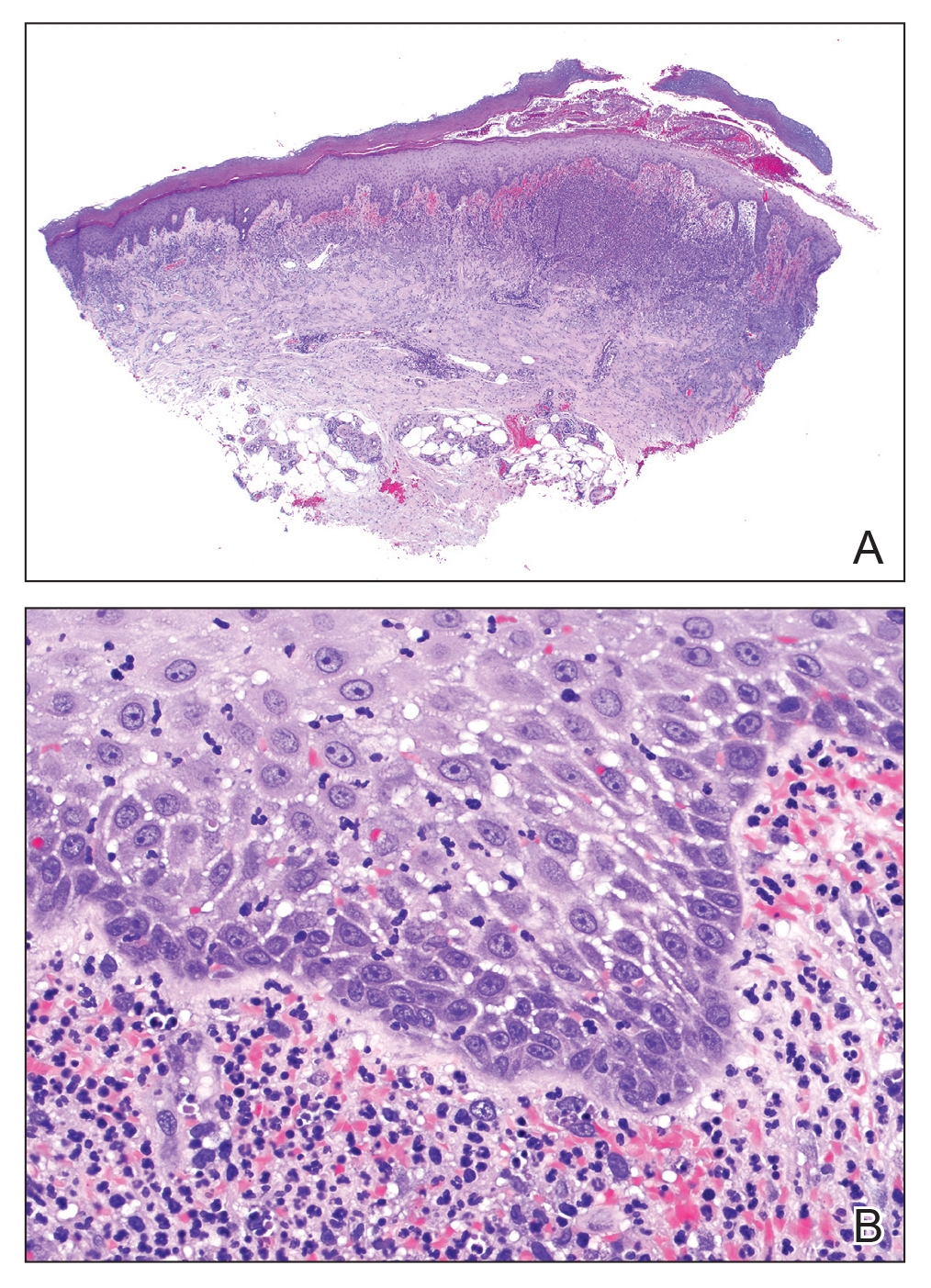

The lesions on the neck and chest began to fade within 1 week of stopping the medication and administering corticosteroids; however, the hand lesions continued to progress and began to involve the base of the digits (Figure 1). The patient was then seen by a dermatologist who biopsied the hand lesions. Histopathology was characteristic of Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis and Gomm-Button disease. Notably, there was a dense nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris without leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

The following therapies in addition to gentle wound care were prescribed: betamethasone injectable suspension (9 mg intramuscularly), oral prednisone (60 mg daily for 5 days, tapering off over 2 months), clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily, and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily. The patient responded well to therapy, with complete resolution and healing of the skin lesions except for mild postinflammatory pigment alteration. The systemic steroids were slowly tapered over 2 months, and the patient remained free of symptoms or recurrences more than 3 years after discontinuation of the medication.

Dapagliflozin is a member of a new class of medications (gliflozins) used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.3,4 The medication lowers blood glucose by inhibiting the sodium-glucose cotransport protein 2, thus lowering the blood glucose levels by increasing urinary excretion of glucose. Because many patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are overweight, these medications are poised to gain popularity for weight loss and decreased blood pressure side effects. Three other medications in this class also have been approved by US Food and Drug Administration: empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and ertugliflozin.

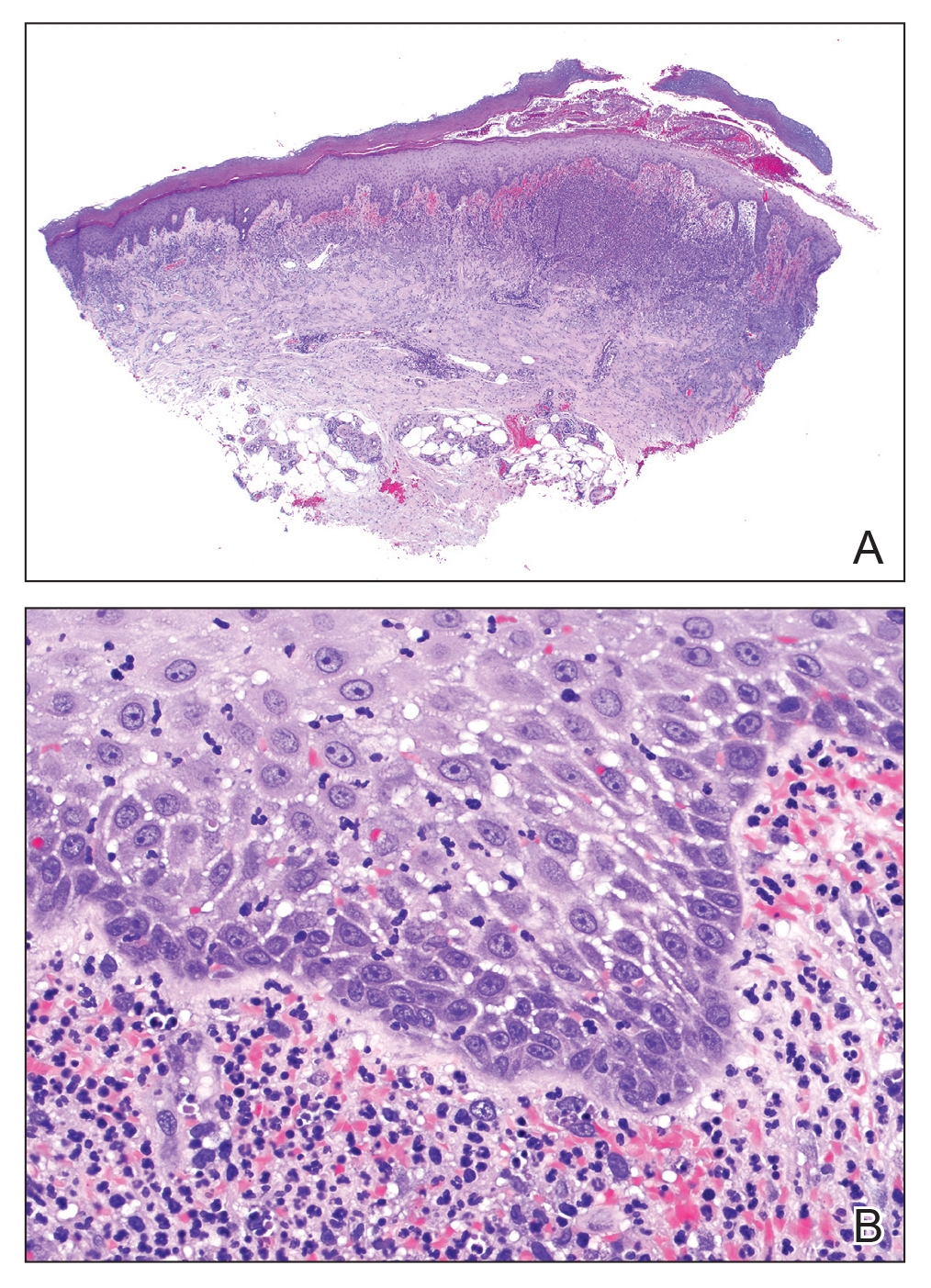

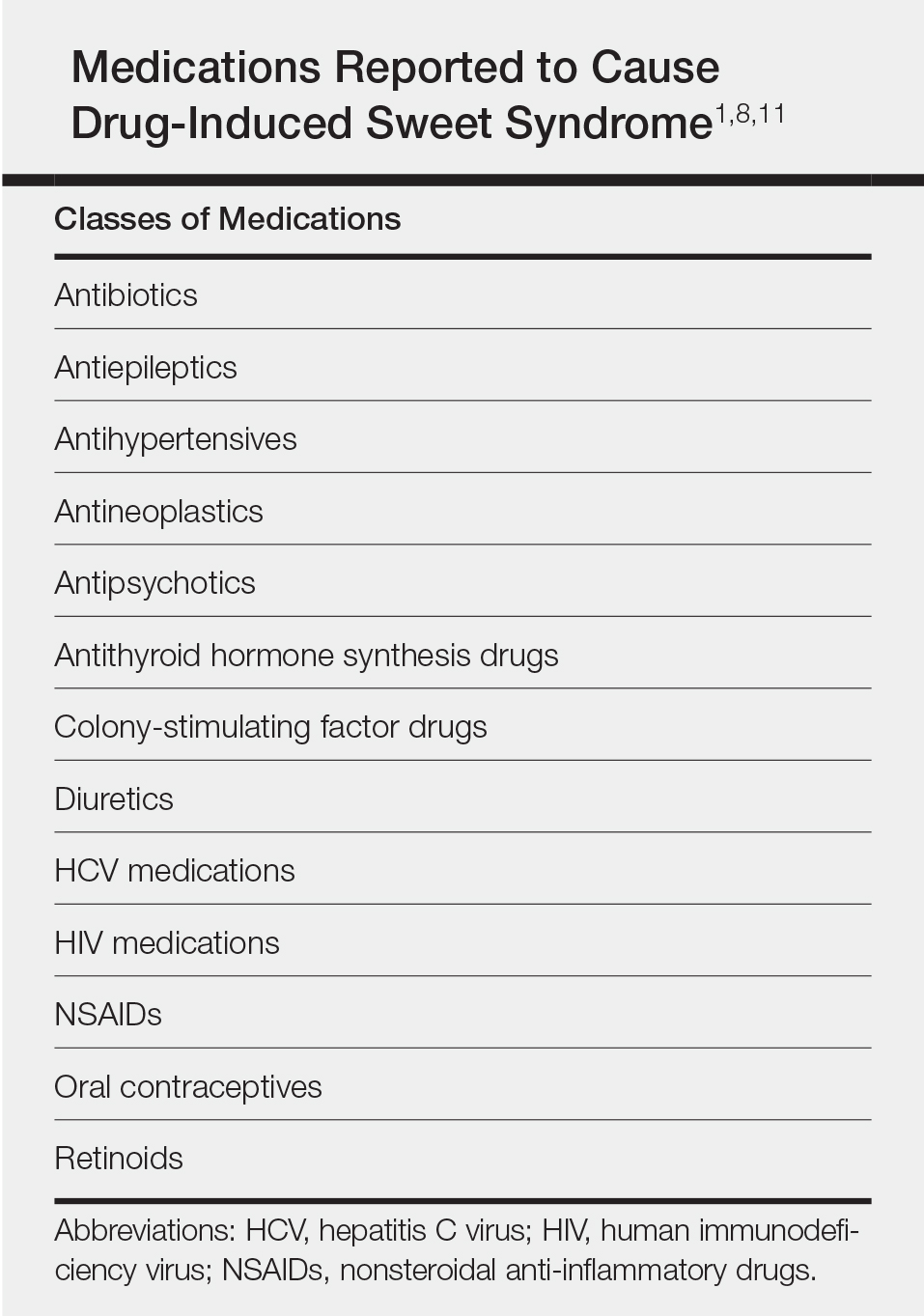

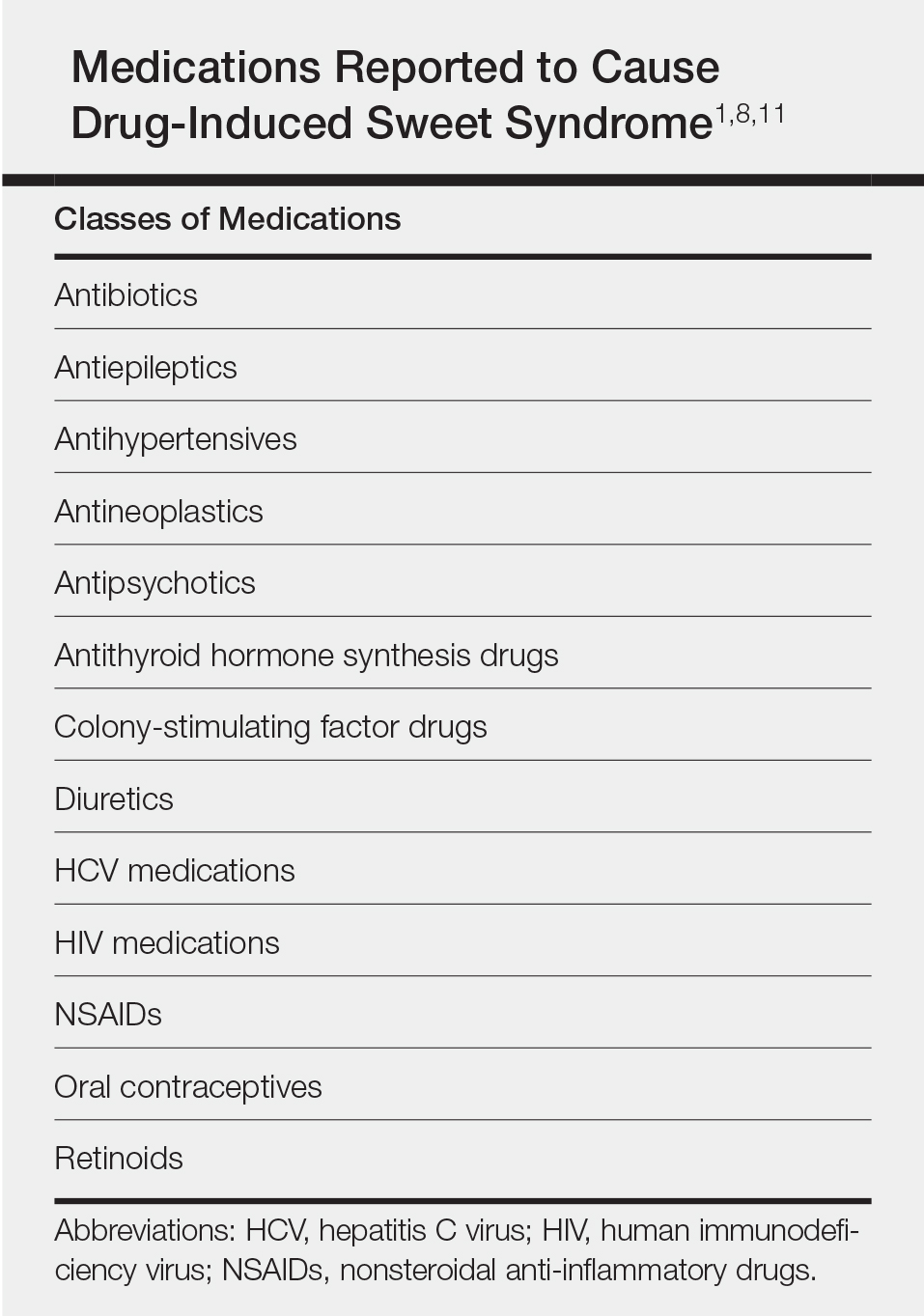

Sweet syndrome consists of 4 cardinal features that were first described in 1964: fever, leukocytosis, tender red plaques, and a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.5 Since then, Su and Liu6 proposed guidelines consisting of major and minor criteria. In 1996, Walker and Cohen7 suggested a set of diagnostic criteria specifically for drug-induced Sweet syndrome, including painful erythematous plaques, histopathologic neutrophilic infiltrate, and fever. Additional criteria included a temporal relationship between drug ingestion and clinical presentation as well as resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids.7 The lesions of drug-induced Sweet syndrome often are described as painful red papules that can form plaques, may appear vesicular, and are more common in women. These lesions classically appear on the upper extremities, as well as the head, neck, trunk, and back.8 Clinically, symptoms most commonly include fever and musculoskeletal involvement, both of which were experienced by the patient who described herself as feeling feverish when the lesions first appeared and reported malaise. Our patient experienced all of these features, and although a fever was not measured in the acute stage of presentation, she reported feeling hot. Other symptoms that may occur include arthralgia, headache, and myalgia.9 Microscopically, there is a nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris. The pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome remains unclear but can be associated with malignancy, pregnancy, autoimmune disorders, and drug reactions.10 Many different classes of medications have been reported to cause drug-induced Sweet syndrome and are listed in the Table.1,8,11 The recommended treatment of Sweet syndrome is systemic corticosteroids.12

The temporal use of dapagliflozin and appearance of the hand lesions, along with the histology, favored drug-induced Sweet syndrome to dapagliflozin as the cause of the plaques. Our patient did not seek medical attention at the onset of the initial chest and neck rash but did so several weeks after the painful hand lesions that were consistent with Sweet syndrome had appeared. Discontinuation of dapagliflozin and treatment with immunosuppressive medications resulted in resolution of the skin lesions on the hands. This scenario raises the question whether or not she would have developed the inflammatory hand lesions if she had stopped the medication earlier. Because dapagliflozin is a relatively new medication and boasts the potentially beneficial side effects of reducing body weight and blood pressure in addition to glucose control, we expect additional cases may occur, especially if use of this medication notably increases. Furthermore, this reaction may be a drug-class side effect and not one specific to dapagliflozin.

- Weedon D. The vasculopathic reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:218-225.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) for type 2 diabetes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56:13-15.

- Aylsworth A, Dean Z, VanNorman C, et al. Dapagliflozin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus [published online June 20, 2014]. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1202-1208.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(5 pt 2):918-923.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome. a neutrophilic dermatosis classically associated with acute onset and fever. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:265-282.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- Thompson DF, Montarella KE. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:802-811.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

To the Editor:

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, gout, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus was started on dapagliflozin (5 mg) for glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c, 7.9 [reference range, 4–7]). Within 1 week of starting the medication, she developed a fine papular eruption in a photodistributed area on the neck and chest with associated malaise. The rash progressed over the next 2 weeks, evolving into edematous papules and plaques, some with vesicles involving the neck, chest, postauricular areas, and nose. Approximately 3 weeks after starting dapagliflozin, the patient also developed bilateral painful, hemorrhagic, bullous plaques (10×3 cm overall) without satellite lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands. The borders of the bullae had rapidly expanding geographic margins and were extremely painful. The patient’s primary care physician advised to discontinue dapagliflozin, as this medication was thought to be triggering the eruption. She was administered triamcinolone (40 mg intramuscularly) and advised to take ibuprofen as needed. She had malaise and reported that she felt hot but had no known fever. No laboratory tests were ordered.

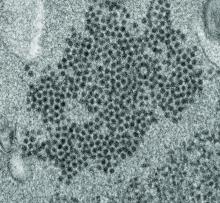

The lesions on the neck and chest began to fade within 1 week of stopping the medication and administering corticosteroids; however, the hand lesions continued to progress and began to involve the base of the digits (Figure 1). The patient was then seen by a dermatologist who biopsied the hand lesions. Histopathology was characteristic of Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis and Gomm-Button disease. Notably, there was a dense nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris without leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

The following therapies in addition to gentle wound care were prescribed: betamethasone injectable suspension (9 mg intramuscularly), oral prednisone (60 mg daily for 5 days, tapering off over 2 months), clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily, and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily. The patient responded well to therapy, with complete resolution and healing of the skin lesions except for mild postinflammatory pigment alteration. The systemic steroids were slowly tapered over 2 months, and the patient remained free of symptoms or recurrences more than 3 years after discontinuation of the medication.

Dapagliflozin is a member of a new class of medications (gliflozins) used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.3,4 The medication lowers blood glucose by inhibiting the sodium-glucose cotransport protein 2, thus lowering the blood glucose levels by increasing urinary excretion of glucose. Because many patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are overweight, these medications are poised to gain popularity for weight loss and decreased blood pressure side effects. Three other medications in this class also have been approved by US Food and Drug Administration: empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and ertugliflozin.

Sweet syndrome consists of 4 cardinal features that were first described in 1964: fever, leukocytosis, tender red plaques, and a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.5 Since then, Su and Liu6 proposed guidelines consisting of major and minor criteria. In 1996, Walker and Cohen7 suggested a set of diagnostic criteria specifically for drug-induced Sweet syndrome, including painful erythematous plaques, histopathologic neutrophilic infiltrate, and fever. Additional criteria included a temporal relationship between drug ingestion and clinical presentation as well as resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids.7 The lesions of drug-induced Sweet syndrome often are described as painful red papules that can form plaques, may appear vesicular, and are more common in women. These lesions classically appear on the upper extremities, as well as the head, neck, trunk, and back.8 Clinically, symptoms most commonly include fever and musculoskeletal involvement, both of which were experienced by the patient who described herself as feeling feverish when the lesions first appeared and reported malaise. Our patient experienced all of these features, and although a fever was not measured in the acute stage of presentation, she reported feeling hot. Other symptoms that may occur include arthralgia, headache, and myalgia.9 Microscopically, there is a nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris. The pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome remains unclear but can be associated with malignancy, pregnancy, autoimmune disorders, and drug reactions.10 Many different classes of medications have been reported to cause drug-induced Sweet syndrome and are listed in the Table.1,8,11 The recommended treatment of Sweet syndrome is systemic corticosteroids.12

The temporal use of dapagliflozin and appearance of the hand lesions, along with the histology, favored drug-induced Sweet syndrome to dapagliflozin as the cause of the plaques. Our patient did not seek medical attention at the onset of the initial chest and neck rash but did so several weeks after the painful hand lesions that were consistent with Sweet syndrome had appeared. Discontinuation of dapagliflozin and treatment with immunosuppressive medications resulted in resolution of the skin lesions on the hands. This scenario raises the question whether or not she would have developed the inflammatory hand lesions if she had stopped the medication earlier. Because dapagliflozin is a relatively new medication and boasts the potentially beneficial side effects of reducing body weight and blood pressure in addition to glucose control, we expect additional cases may occur, especially if use of this medication notably increases. Furthermore, this reaction may be a drug-class side effect and not one specific to dapagliflozin.

To the Editor:

A 75-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, gout, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus was started on dapagliflozin (5 mg) for glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c, 7.9 [reference range, 4–7]). Within 1 week of starting the medication, she developed a fine papular eruption in a photodistributed area on the neck and chest with associated malaise. The rash progressed over the next 2 weeks, evolving into edematous papules and plaques, some with vesicles involving the neck, chest, postauricular areas, and nose. Approximately 3 weeks after starting dapagliflozin, the patient also developed bilateral painful, hemorrhagic, bullous plaques (10×3 cm overall) without satellite lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands. The borders of the bullae had rapidly expanding geographic margins and were extremely painful. The patient’s primary care physician advised to discontinue dapagliflozin, as this medication was thought to be triggering the eruption. She was administered triamcinolone (40 mg intramuscularly) and advised to take ibuprofen as needed. She had malaise and reported that she felt hot but had no known fever. No laboratory tests were ordered.

The lesions on the neck and chest began to fade within 1 week of stopping the medication and administering corticosteroids; however, the hand lesions continued to progress and began to involve the base of the digits (Figure 1). The patient was then seen by a dermatologist who biopsied the hand lesions. Histopathology was characteristic of Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis and Gomm-Button disease. Notably, there was a dense nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris without leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

The following therapies in addition to gentle wound care were prescribed: betamethasone injectable suspension (9 mg intramuscularly), oral prednisone (60 mg daily for 5 days, tapering off over 2 months), clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily, and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% twice daily. The patient responded well to therapy, with complete resolution and healing of the skin lesions except for mild postinflammatory pigment alteration. The systemic steroids were slowly tapered over 2 months, and the patient remained free of symptoms or recurrences more than 3 years after discontinuation of the medication.

Dapagliflozin is a member of a new class of medications (gliflozins) used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.3,4 The medication lowers blood glucose by inhibiting the sodium-glucose cotransport protein 2, thus lowering the blood glucose levels by increasing urinary excretion of glucose. Because many patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are overweight, these medications are poised to gain popularity for weight loss and decreased blood pressure side effects. Three other medications in this class also have been approved by US Food and Drug Administration: empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and ertugliflozin.

Sweet syndrome consists of 4 cardinal features that were first described in 1964: fever, leukocytosis, tender red plaques, and a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.5 Since then, Su and Liu6 proposed guidelines consisting of major and minor criteria. In 1996, Walker and Cohen7 suggested a set of diagnostic criteria specifically for drug-induced Sweet syndrome, including painful erythematous plaques, histopathologic neutrophilic infiltrate, and fever. Additional criteria included a temporal relationship between drug ingestion and clinical presentation as well as resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids.7 The lesions of drug-induced Sweet syndrome often are described as painful red papules that can form plaques, may appear vesicular, and are more common in women. These lesions classically appear on the upper extremities, as well as the head, neck, trunk, and back.8 Clinically, symptoms most commonly include fever and musculoskeletal involvement, both of which were experienced by the patient who described herself as feeling feverish when the lesions first appeared and reported malaise. Our patient experienced all of these features, and although a fever was not measured in the acute stage of presentation, she reported feeling hot. Other symptoms that may occur include arthralgia, headache, and myalgia.9 Microscopically, there is a nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris. The pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome remains unclear but can be associated with malignancy, pregnancy, autoimmune disorders, and drug reactions.10 Many different classes of medications have been reported to cause drug-induced Sweet syndrome and are listed in the Table.1,8,11 The recommended treatment of Sweet syndrome is systemic corticosteroids.12

The temporal use of dapagliflozin and appearance of the hand lesions, along with the histology, favored drug-induced Sweet syndrome to dapagliflozin as the cause of the plaques. Our patient did not seek medical attention at the onset of the initial chest and neck rash but did so several weeks after the painful hand lesions that were consistent with Sweet syndrome had appeared. Discontinuation of dapagliflozin and treatment with immunosuppressive medications resulted in resolution of the skin lesions on the hands. This scenario raises the question whether or not she would have developed the inflammatory hand lesions if she had stopped the medication earlier. Because dapagliflozin is a relatively new medication and boasts the potentially beneficial side effects of reducing body weight and blood pressure in addition to glucose control, we expect additional cases may occur, especially if use of this medication notably increases. Furthermore, this reaction may be a drug-class side effect and not one specific to dapagliflozin.

- Weedon D. The vasculopathic reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:218-225.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) for type 2 diabetes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56:13-15.

- Aylsworth A, Dean Z, VanNorman C, et al. Dapagliflozin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus [published online June 20, 2014]. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1202-1208.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(5 pt 2):918-923.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome. a neutrophilic dermatosis classically associated with acute onset and fever. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:265-282.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- Thompson DF, Montarella KE. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:802-811.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Weedon D. The vasculopathic reaction pattern. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:218-225.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) for type 2 diabetes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56:13-15.

- Aylsworth A, Dean Z, VanNorman C, et al. Dapagliflozin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus [published online June 20, 2014]. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1202-1208.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(5 pt 2):918-923.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome. a neutrophilic dermatosis classically associated with acute onset and fever. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:265-282.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- Thompson DF, Montarella KE. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:802-811.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

Practice Points

- Sweet syndrome consists of 4 cardinal features: fever, leukocytosis, tender red plaques, and a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate.

- In drug-induced Sweet syndrome, there is a temporal relationship between drug ingestion and clinical presentation as well as resolution of lesions after drug withdrawal or treatment with systemic corticosteroids.

- Microscopic findings of Sweet syndrome include a nodular infiltrate of neutrophils, papillary dermal edema, and leukocytoclastic debris.

- Dapagliflozin is a member of a new class of medications (gliflozins) used for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which may cause drug-induced Sweet syndrome.

Violaceous Patches on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

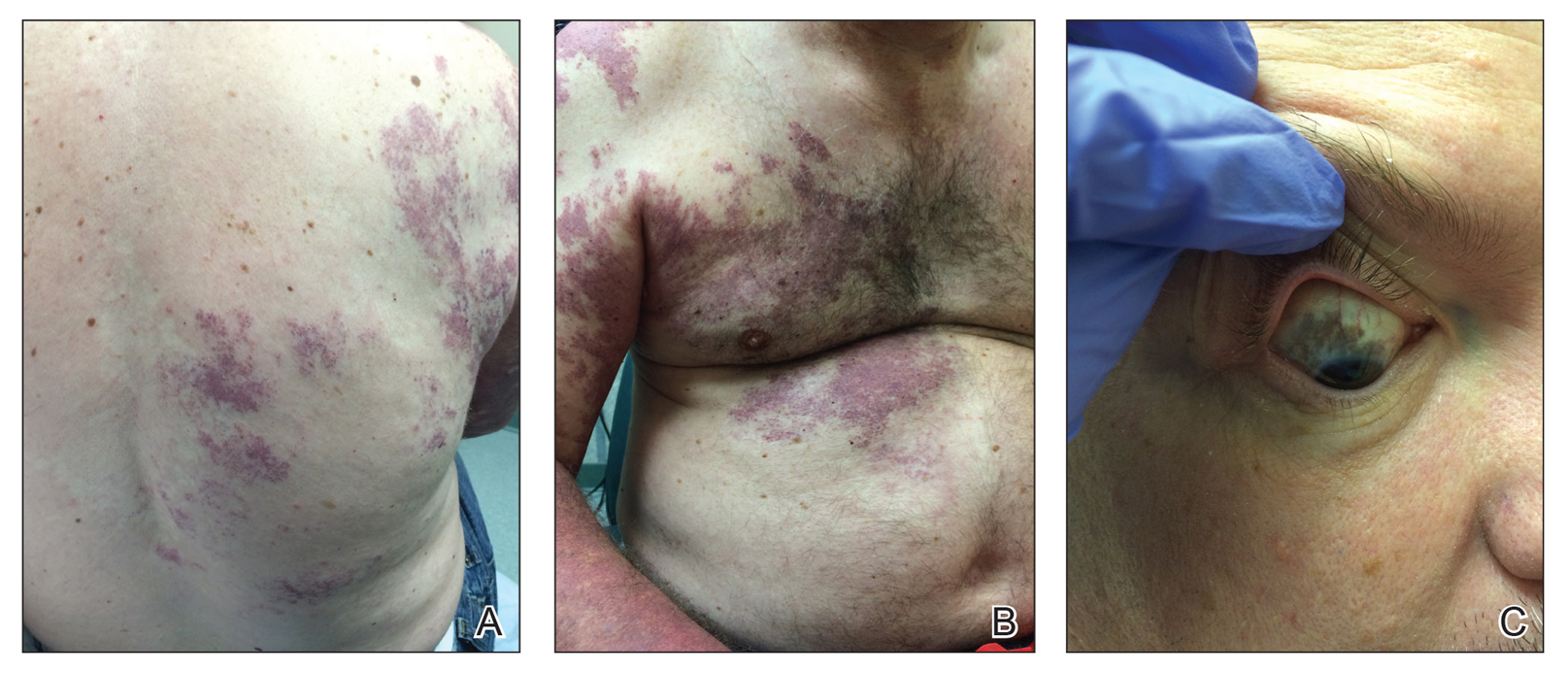

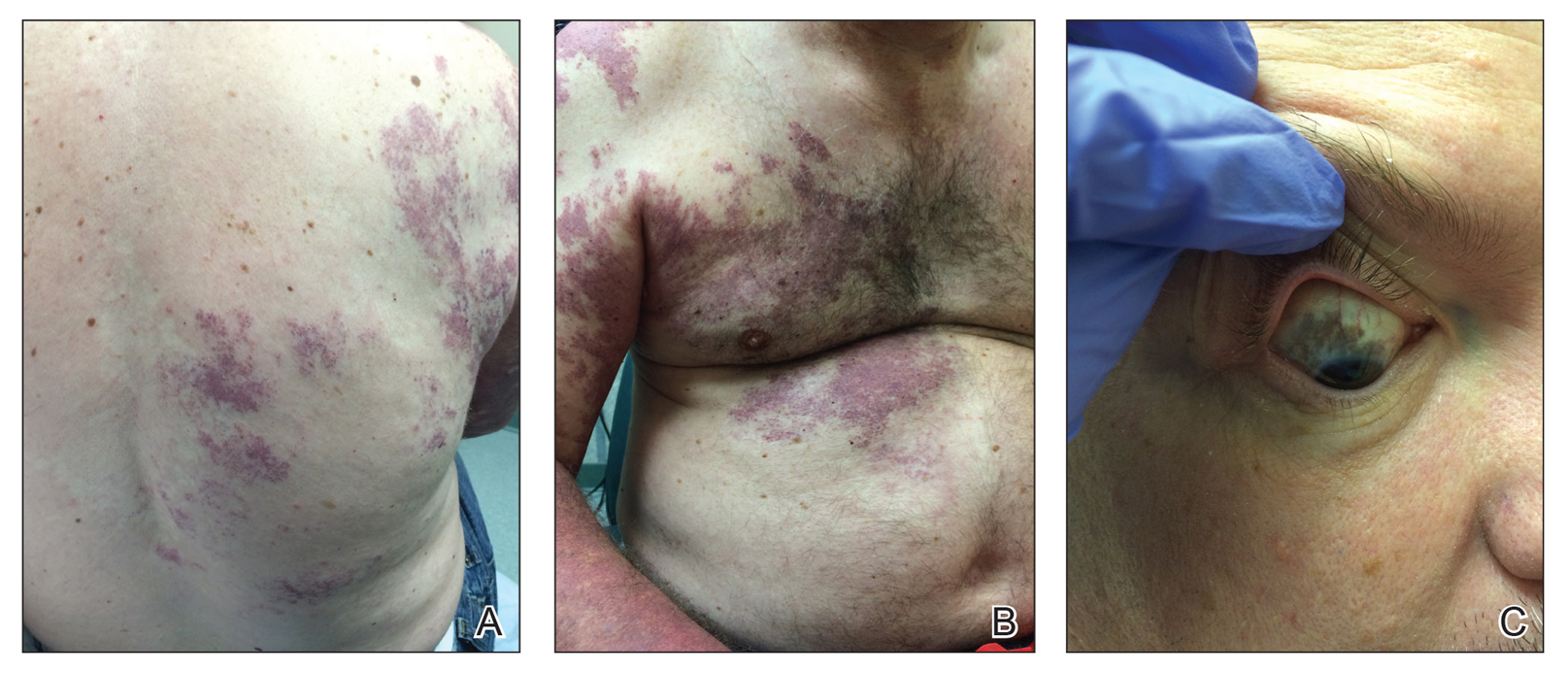

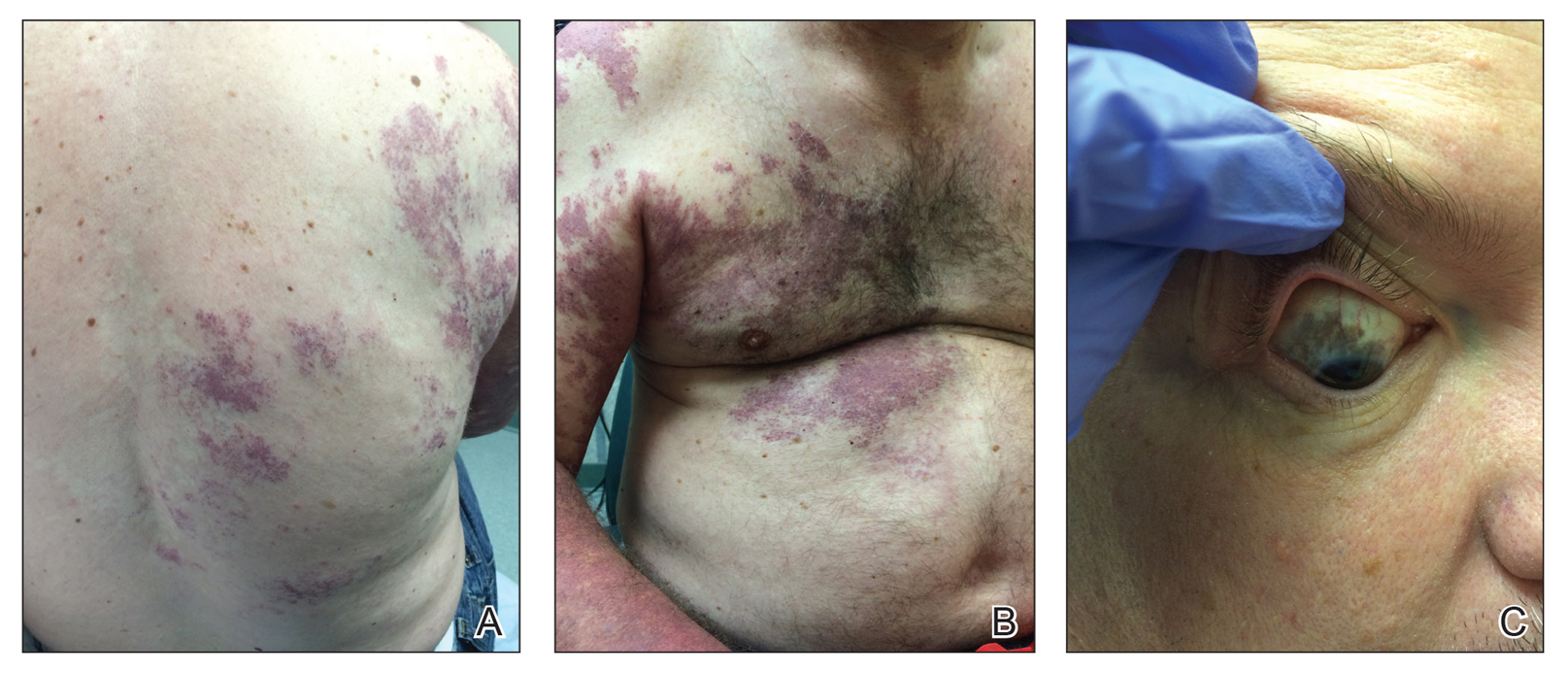

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

A 55-year-old man presented with red-violet patches on the right arm and chest that had been present since birth. The patches were asymptomatic and stable in size and shape. He denied any personal or family history of glaucoma or epilepsy. Physical examination demonstrated nonblanchable, violaceous to red patches on the right arm, back, and chest. No thrills or bruits were appreciable, and the right and left arms were of equal circumference and length. Further examination revealed hyperpigmented patches on the bilateral conjunctivae.

‘Pot’ is still hot for Dravet, Lennox-Gastaut

BANGKOK – Interim results of long-term, open-label extension trials of add-on prescription cannabidiol in patients with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome show sustained, clinically meaningful seizure reductions with no new safety concerns, Anup D. Patel, MD, reported at the International Epilepsy Congress.

“Overall, this is a very promising and sustainable result that we were happy to see,” said Dr. Patel, chief of child neurology at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

Epidiolex is the brand name for the plant-derived, highly purified cannabidiol (CBD) in an oil-based oral solution at 100 mg/mL. Dr. Patel has been involved in the medication’s development program since the earliest open-label compassionate use study, which was followed by rigorous phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trials, eventually leading to Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the treatment of Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in patients 2 years of age or older.

“On June 25th, 2018, history was made: for the first time in United States history, a plant-based derivative of marijuana was approved for use as a medication, and it was also the first FDA-approved treatment for Dravet syndrome,” Dr. Patel noted at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

A total of 96% of the 289 children with Dravet syndrome who completed the 14-week, double-blind, controlled randomized trials enrolled in the open-label, long-term extension study, during which they were on a median of three concurrent antiepileptic drugs along with a mean modal dose of CBD at 22 mg/kg/day. Although the target maintenance dose of CBD was 20 mg/kg/day, as advised in the product labeling, physicians could reduce or increase the dose up to 30 mg/kg/day.

“In the initial compassionate-use study, our site could go up to 50 mg/kg/day,” according to Dr. Patel. “We have plenty of data showing efficacy and continued safety beyond the FDA-recommended dose.”

In the open-label extension study, the median reduction from baseline in monthly seizure frequency assessed in 12-week intervals up to a maximum of week 72 was 44%-57% for convulsive seizures and 49%-67% for total seizures. More than 80% of patients and/or caregivers reported improvement in the patient’s overall condition as assessed on the Subject/Caregiver Global Impression of Change scale.

The pattern of adverse events associated with CBD has been consistent across all of the studies. The most common side effects are diarrhea in about one-third of patients, sleepiness in one-quarter, and decreased appetite in about one-quarter. Seven percent of patients discontinued the long-term extension trial because of adverse events.

Seventy percent of patients remained in the long-term extension study at 1 year.

Twenty-six patients developed liver transaminase levels greater than three times the upper limit of normal, and of note, 23 of the 26 were on concomitant valproic acid. None met criteria for severe drug-induced liver injury, and all recovered either spontaneously or after a reduction in the dose of CBD or valproic acid. But this association between CBD, valproic acid, and increased risk of mild liver injury has been a consistent finding across the clinical trials program.

“This is a very important clinical pearl to take away,” commented Dr. Patel, who is also a pediatric neurologist at Ohio State University.

The interim results of the long-term, open-label extension study of add-on CBD in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome are similar to the Dravet syndrome study. Overall, 99% of the 368 patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome who completed the 14-week, double-blind, randomized trials signed up for the open-label extension. During a median follow-up of 61 weeks, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency as assessed in serial 12-week windows was 48%-70% for drop seizures and 48%-63% for total seizures. Twenty-four percent of patients withdrew from the study. Eighty-eight percent of patients or caregivers reported an improvement in overall condition when assessed at weeks 24 and 48. Forty-seven patients developed elevated transaminase levels – typically within the first 2 months on CBD – and 35 of them were on concomitant valproic acid.

More on drug-drug interactions

Elsewhere at IEC 2019, Gilmour Morrison of GW Pharmaceuticals, the Cambridge, England, company that markets Epidiolex, presented the findings of a series of drug-drug interaction studies involving coadministration of their CBD with clobazam (Sympazan and Onfi), valproate, stiripentol (Diacomit), or midazolam (Versed) in adult epilepsy patients and healthy volunteers. The researchers reported a bidirectional drug-drug interaction between Epidiolex and clobazam resulting in increased levels of the active metabolites of both drugs. The mechanism is believed to involve inhibition of cytochrome P450 2C19. However, there were no interactions with midazolam or valproate, and the slight bump in stiripentol levels when given with CBD didn’t reach the level of a clinically meaningful drug-drug interaction, according to the investigators.

On the horizon, Canadian researchers are investigating the possibility that since both the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and CBD components of marijuana have been shown to have anticonvulsant effects, adding a bit of THC to CBD will result in even better seizure control than with pure CBD in patients with Dravet syndrome. Investigators at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children have conducted a prospective, open-label study of a product containing CBD and THC in a 50:1 ratio as add-on therapy in 20 children with Dravet syndrome. The dose was 2-16 mg/kg/day of CBD and 0.04-0.32 mg/kg/day of THC. The cannabis plant extract used in the study was produced by Tilray, a Canadian pharmaceutical company.

Nineteen of the 20 patients completed the 20-week study. The sole noncompleter died of SUDEP (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy) deemed treatment unrelated. Patients experienced a median 71% reduction in motor seizures, compared with baseline. Sixty-three percent of patients had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Elevated liver transaminases occurred in patients on concomitant valproic acid, as did platelet abnormalities, which have not been seen in the Epidiolex studies, noted Dr. Patel, who was not involved in the Canadian study (Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018 Aug 1;5[9]:1077-88).

Dr. Patel reported serving as a consultant to Greenwich Biosciences, a U.S. offshoot of GW Pharmaceuticals. He receives research grants from that company as well as from the National Institutes of Health and the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation.

BANGKOK – Interim results of long-term, open-label extension trials of add-on prescription cannabidiol in patients with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome show sustained, clinically meaningful seizure reductions with no new safety concerns, Anup D. Patel, MD, reported at the International Epilepsy Congress.

“Overall, this is a very promising and sustainable result that we were happy to see,” said Dr. Patel, chief of child neurology at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

Epidiolex is the brand name for the plant-derived, highly purified cannabidiol (CBD) in an oil-based oral solution at 100 mg/mL. Dr. Patel has been involved in the medication’s development program since the earliest open-label compassionate use study, which was followed by rigorous phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trials, eventually leading to Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the treatment of Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in patients 2 years of age or older.

“On June 25th, 2018, history was made: for the first time in United States history, a plant-based derivative of marijuana was approved for use as a medication, and it was also the first FDA-approved treatment for Dravet syndrome,” Dr. Patel noted at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

A total of 96% of the 289 children with Dravet syndrome who completed the 14-week, double-blind, controlled randomized trials enrolled in the open-label, long-term extension study, during which they were on a median of three concurrent antiepileptic drugs along with a mean modal dose of CBD at 22 mg/kg/day. Although the target maintenance dose of CBD was 20 mg/kg/day, as advised in the product labeling, physicians could reduce or increase the dose up to 30 mg/kg/day.

“In the initial compassionate-use study, our site could go up to 50 mg/kg/day,” according to Dr. Patel. “We have plenty of data showing efficacy and continued safety beyond the FDA-recommended dose.”

In the open-label extension study, the median reduction from baseline in monthly seizure frequency assessed in 12-week intervals up to a maximum of week 72 was 44%-57% for convulsive seizures and 49%-67% for total seizures. More than 80% of patients and/or caregivers reported improvement in the patient’s overall condition as assessed on the Subject/Caregiver Global Impression of Change scale.

The pattern of adverse events associated with CBD has been consistent across all of the studies. The most common side effects are diarrhea in about one-third of patients, sleepiness in one-quarter, and decreased appetite in about one-quarter. Seven percent of patients discontinued the long-term extension trial because of adverse events.

Seventy percent of patients remained in the long-term extension study at 1 year.

Twenty-six patients developed liver transaminase levels greater than three times the upper limit of normal, and of note, 23 of the 26 were on concomitant valproic acid. None met criteria for severe drug-induced liver injury, and all recovered either spontaneously or after a reduction in the dose of CBD or valproic acid. But this association between CBD, valproic acid, and increased risk of mild liver injury has been a consistent finding across the clinical trials program.

“This is a very important clinical pearl to take away,” commented Dr. Patel, who is also a pediatric neurologist at Ohio State University.

The interim results of the long-term, open-label extension study of add-on CBD in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome are similar to the Dravet syndrome study. Overall, 99% of the 368 patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome who completed the 14-week, double-blind, randomized trials signed up for the open-label extension. During a median follow-up of 61 weeks, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency as assessed in serial 12-week windows was 48%-70% for drop seizures and 48%-63% for total seizures. Twenty-four percent of patients withdrew from the study. Eighty-eight percent of patients or caregivers reported an improvement in overall condition when assessed at weeks 24 and 48. Forty-seven patients developed elevated transaminase levels – typically within the first 2 months on CBD – and 35 of them were on concomitant valproic acid.

More on drug-drug interactions

Elsewhere at IEC 2019, Gilmour Morrison of GW Pharmaceuticals, the Cambridge, England, company that markets Epidiolex, presented the findings of a series of drug-drug interaction studies involving coadministration of their CBD with clobazam (Sympazan and Onfi), valproate, stiripentol (Diacomit), or midazolam (Versed) in adult epilepsy patients and healthy volunteers. The researchers reported a bidirectional drug-drug interaction between Epidiolex and clobazam resulting in increased levels of the active metabolites of both drugs. The mechanism is believed to involve inhibition of cytochrome P450 2C19. However, there were no interactions with midazolam or valproate, and the slight bump in stiripentol levels when given with CBD didn’t reach the level of a clinically meaningful drug-drug interaction, according to the investigators.

On the horizon, Canadian researchers are investigating the possibility that since both the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and CBD components of marijuana have been shown to have anticonvulsant effects, adding a bit of THC to CBD will result in even better seizure control than with pure CBD in patients with Dravet syndrome. Investigators at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children have conducted a prospective, open-label study of a product containing CBD and THC in a 50:1 ratio as add-on therapy in 20 children with Dravet syndrome. The dose was 2-16 mg/kg/day of CBD and 0.04-0.32 mg/kg/day of THC. The cannabis plant extract used in the study was produced by Tilray, a Canadian pharmaceutical company.

Nineteen of the 20 patients completed the 20-week study. The sole noncompleter died of SUDEP (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy) deemed treatment unrelated. Patients experienced a median 71% reduction in motor seizures, compared with baseline. Sixty-three percent of patients had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Elevated liver transaminases occurred in patients on concomitant valproic acid, as did platelet abnormalities, which have not been seen in the Epidiolex studies, noted Dr. Patel, who was not involved in the Canadian study (Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018 Aug 1;5[9]:1077-88).

Dr. Patel reported serving as a consultant to Greenwich Biosciences, a U.S. offshoot of GW Pharmaceuticals. He receives research grants from that company as well as from the National Institutes of Health and the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation.

BANGKOK – Interim results of long-term, open-label extension trials of add-on prescription cannabidiol in patients with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome show sustained, clinically meaningful seizure reductions with no new safety concerns, Anup D. Patel, MD, reported at the International Epilepsy Congress.

“Overall, this is a very promising and sustainable result that we were happy to see,” said Dr. Patel, chief of child neurology at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

Epidiolex is the brand name for the plant-derived, highly purified cannabidiol (CBD) in an oil-based oral solution at 100 mg/mL. Dr. Patel has been involved in the medication’s development program since the earliest open-label compassionate use study, which was followed by rigorous phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trials, eventually leading to Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the treatment of Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in patients 2 years of age or older.

“On June 25th, 2018, history was made: for the first time in United States history, a plant-based derivative of marijuana was approved for use as a medication, and it was also the first FDA-approved treatment for Dravet syndrome,” Dr. Patel noted at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

A total of 96% of the 289 children with Dravet syndrome who completed the 14-week, double-blind, controlled randomized trials enrolled in the open-label, long-term extension study, during which they were on a median of three concurrent antiepileptic drugs along with a mean modal dose of CBD at 22 mg/kg/day. Although the target maintenance dose of CBD was 20 mg/kg/day, as advised in the product labeling, physicians could reduce or increase the dose up to 30 mg/kg/day.

“In the initial compassionate-use study, our site could go up to 50 mg/kg/day,” according to Dr. Patel. “We have plenty of data showing efficacy and continued safety beyond the FDA-recommended dose.”

In the open-label extension study, the median reduction from baseline in monthly seizure frequency assessed in 12-week intervals up to a maximum of week 72 was 44%-57% for convulsive seizures and 49%-67% for total seizures. More than 80% of patients and/or caregivers reported improvement in the patient’s overall condition as assessed on the Subject/Caregiver Global Impression of Change scale.

The pattern of adverse events associated with CBD has been consistent across all of the studies. The most common side effects are diarrhea in about one-third of patients, sleepiness in one-quarter, and decreased appetite in about one-quarter. Seven percent of patients discontinued the long-term extension trial because of adverse events.

Seventy percent of patients remained in the long-term extension study at 1 year.

Twenty-six patients developed liver transaminase levels greater than three times the upper limit of normal, and of note, 23 of the 26 were on concomitant valproic acid. None met criteria for severe drug-induced liver injury, and all recovered either spontaneously or after a reduction in the dose of CBD or valproic acid. But this association between CBD, valproic acid, and increased risk of mild liver injury has been a consistent finding across the clinical trials program.

“This is a very important clinical pearl to take away,” commented Dr. Patel, who is also a pediatric neurologist at Ohio State University.

The interim results of the long-term, open-label extension study of add-on CBD in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome are similar to the Dravet syndrome study. Overall, 99% of the 368 patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome who completed the 14-week, double-blind, randomized trials signed up for the open-label extension. During a median follow-up of 61 weeks, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency as assessed in serial 12-week windows was 48%-70% for drop seizures and 48%-63% for total seizures. Twenty-four percent of patients withdrew from the study. Eighty-eight percent of patients or caregivers reported an improvement in overall condition when assessed at weeks 24 and 48. Forty-seven patients developed elevated transaminase levels – typically within the first 2 months on CBD – and 35 of them were on concomitant valproic acid.

More on drug-drug interactions

Elsewhere at IEC 2019, Gilmour Morrison of GW Pharmaceuticals, the Cambridge, England, company that markets Epidiolex, presented the findings of a series of drug-drug interaction studies involving coadministration of their CBD with clobazam (Sympazan and Onfi), valproate, stiripentol (Diacomit), or midazolam (Versed) in adult epilepsy patients and healthy volunteers. The researchers reported a bidirectional drug-drug interaction between Epidiolex and clobazam resulting in increased levels of the active metabolites of both drugs. The mechanism is believed to involve inhibition of cytochrome P450 2C19. However, there were no interactions with midazolam or valproate, and the slight bump in stiripentol levels when given with CBD didn’t reach the level of a clinically meaningful drug-drug interaction, according to the investigators.

On the horizon, Canadian researchers are investigating the possibility that since both the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and CBD components of marijuana have been shown to have anticonvulsant effects, adding a bit of THC to CBD will result in even better seizure control than with pure CBD in patients with Dravet syndrome. Investigators at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children have conducted a prospective, open-label study of a product containing CBD and THC in a 50:1 ratio as add-on therapy in 20 children with Dravet syndrome. The dose was 2-16 mg/kg/day of CBD and 0.04-0.32 mg/kg/day of THC. The cannabis plant extract used in the study was produced by Tilray, a Canadian pharmaceutical company.

Nineteen of the 20 patients completed the 20-week study. The sole noncompleter died of SUDEP (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy) deemed treatment unrelated. Patients experienced a median 71% reduction in motor seizures, compared with baseline. Sixty-three percent of patients had at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Elevated liver transaminases occurred in patients on concomitant valproic acid, as did platelet abnormalities, which have not been seen in the Epidiolex studies, noted Dr. Patel, who was not involved in the Canadian study (Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018 Aug 1;5[9]:1077-88).

Dr. Patel reported serving as a consultant to Greenwich Biosciences, a U.S. offshoot of GW Pharmaceuticals. He receives research grants from that company as well as from the National Institutes of Health and the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation.

REPORTING FROM IEC 2019

Possible role of enterovirus infection in acute flaccid myelitis cases detected

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

FROM MBIO

Key clinical point:

Major finding: EV peptide antibodies were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), significantly higher than in controls.

Study details: A peptide microarray analysis was performed on CSF and sera from 14 AFM patients, as well as three control groups of 5 pediatric and adult patients with a non-AFM CNS diseases, 10 children with Kawasaki disease, and 10 adult patients with non-AFM CNS diseases.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

Favorable Ebola results lead to drug trial termination, new focus

An investigational agent known as REGN-EB3 has met an early stopping criterion in the protocol of an Ebola therapeutics trial, according to a National Institutes of Health media advisory.

Preliminary results in 499 study participants showed that individuals receiving either of two treatments, REGN-EB3 or mAb114, had a greater chance of survival, compared with participants in the other two study arms.

The randomized, controlled Pamoja Tulinde Maisha (PALM) study, which began Nov. 20, 2018, was designed to evaluate four investigational agents (ZMapp, remdesivir, mAb114, and REGN-EB3) for the treatment of patients with Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as part of the emergency response to an ongoing outbreak in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces.

As of Aug. 9, 2019, the trial had enrolled 681 patients at four Ebola treatment centers in live outbreak regions of the DRC, with the goal of enrolling 725 patients in total.