User login

Fibromyalgia-PTSD Link Shows Bidirectional Relationship With Exposure to Combat Environments

Fibromyalgia-PTSD Link Shows Bidirectional Relationship With Exposure to Combat Environments

Spending time in a war zone can lead to chronic mental and physical pain. Now, research points to a link between two common disorders that can leave service members struggling.

Published in the journal Arthritis Care & Research, a longitudinal cohort study of 1761 US military service members found that those who had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before deployment were nearly 3times more likely to develop fibromyalgia after returning home (odds ratio, 2.96; 95% CI, 2.08-4.22). Those with fibromyalgia before deployment had more than threefold greater likelihood of developing PTSD after deployment (odds ratio, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.63-5.95).

This is the largest prospective study to date linking the stress of combat deployment to the onset of fibromyalgia.

“We had the advantage of observing a large population before and after exposure to an environment that often involves significant stress,” said lead study author Jay Higgs, MD, a retired rheumatologist with Brooke Army Medical Center and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Here’s what the team found and why it matters.

Significant Increase in Fibromyalgia After Development

Service members were checked for fibromyalgia using the 2011 questionnaire modification of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. They were assessed for PTSD using the PTSD Checklist Stressor-Specific Version.

Before deployment, service members had similar rates of fibromyalgia as the general population: 2.2% in men and 2.0% in women. After deployment, fibromyalgia rates increased significantly to 8.0% in men and 11.1% in women.

While fibromyalgia tends to be underreported in men, the findings suggest it should not be overlooked in this population. “Our results are consistent with the notion that there should be no gender bias when considering the possibility of fibromyalgia in an individual patient,” Higgs said.

Before deployment, 20.7% of men and 18.3% of women had PTSD symptoms. After deployment, the PTSD rate increased slightly to 22.7% in men and 25.5% in women.

The Link Between Fibromyalgia and PTSD

The researchers said the results suggest that PTSD and fibromyalgia might be linked through central nervous system mechanisms such as central sensitization, elevated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, elevated cortisol, and proinflammatory cytokines. However, shared causation, associated risk factors, selection bias, or alternative mechanisms within the central and peripheral neuroendocrine and cytokine systems could also be part of the story.

“What we do not know is how much of what we see clinically represents central nervous system pathology, peripheral problems, or a combination of the 2,” Higgs said. “Neurotransmission in the central nervous system is highly complex, and may not only involve specific structures, but a web of communications between them.”

Loci in the midbrain appear especially important, he said.

Elizabeth Hoge, MD, professor and director of the Anxiety Disorders Research Program at Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, said that patients with PTSD often have pain, headaches, sleep disturbances, and other symptoms that are part of the picture of fibromyalgia. It’s plausible that pain syndromes could be manifestations of PTSD or groupings of symptoms that suggest a subtype.

“Pain is one way that people experience distress, and we know that in PTSD, sometimes the trauma memories are encoded too strongly, more stressful and more alarming to the body system,” she said.

When patients have symptoms such as chronic pain, headaches, fatigue, or cognitive brain fog, clinicians should remember to ask about trauma exposure, Hoge said. You might be the first to broach the subject.

“I’ve certainly seen patients in clinic who never get asked about the exposure to trauma, including sexual trauma, so sometimes that can be the first pathway to helping people feel better is just to have their trauma recognized,” Hoge said.

If a patient has experienced or witnessed violence, consider a referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist to evaluate them for PTSD. Higgs said he collaborated closely with a psychologist to complement his treatment plans for active duty and retired military service members and families.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense (DoD) recommend trauma-focused psychotherapy as the first line of treatment for PTSD. This form of therapy deliberately focuses on bringing trauma memories into the open, Hoge said.

“When a person talks about their trauma, and it comes into direct consciousness, somehow it’s malleable, and so when it goes back down into the memory banks, it’s changed somewhat,” she said.

This study was supported by the DoD through awards from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, and Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program. The funding organizations played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Higgs’s comments are his own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Health Agency, Brooke Army Medical Center, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, the DoD, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or any agencies under the US government. Hoge had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Spending time in a war zone can lead to chronic mental and physical pain. Now, research points to a link between two common disorders that can leave service members struggling.

Published in the journal Arthritis Care & Research, a longitudinal cohort study of 1761 US military service members found that those who had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before deployment were nearly 3times more likely to develop fibromyalgia after returning home (odds ratio, 2.96; 95% CI, 2.08-4.22). Those with fibromyalgia before deployment had more than threefold greater likelihood of developing PTSD after deployment (odds ratio, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.63-5.95).

This is the largest prospective study to date linking the stress of combat deployment to the onset of fibromyalgia.

“We had the advantage of observing a large population before and after exposure to an environment that often involves significant stress,” said lead study author Jay Higgs, MD, a retired rheumatologist with Brooke Army Medical Center and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Here’s what the team found and why it matters.

Significant Increase in Fibromyalgia After Development

Service members were checked for fibromyalgia using the 2011 questionnaire modification of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. They were assessed for PTSD using the PTSD Checklist Stressor-Specific Version.

Before deployment, service members had similar rates of fibromyalgia as the general population: 2.2% in men and 2.0% in women. After deployment, fibromyalgia rates increased significantly to 8.0% in men and 11.1% in women.

While fibromyalgia tends to be underreported in men, the findings suggest it should not be overlooked in this population. “Our results are consistent with the notion that there should be no gender bias when considering the possibility of fibromyalgia in an individual patient,” Higgs said.

Before deployment, 20.7% of men and 18.3% of women had PTSD symptoms. After deployment, the PTSD rate increased slightly to 22.7% in men and 25.5% in women.

The Link Between Fibromyalgia and PTSD

The researchers said the results suggest that PTSD and fibromyalgia might be linked through central nervous system mechanisms such as central sensitization, elevated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, elevated cortisol, and proinflammatory cytokines. However, shared causation, associated risk factors, selection bias, or alternative mechanisms within the central and peripheral neuroendocrine and cytokine systems could also be part of the story.

“What we do not know is how much of what we see clinically represents central nervous system pathology, peripheral problems, or a combination of the 2,” Higgs said. “Neurotransmission in the central nervous system is highly complex, and may not only involve specific structures, but a web of communications between them.”

Loci in the midbrain appear especially important, he said.

Elizabeth Hoge, MD, professor and director of the Anxiety Disorders Research Program at Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, said that patients with PTSD often have pain, headaches, sleep disturbances, and other symptoms that are part of the picture of fibromyalgia. It’s plausible that pain syndromes could be manifestations of PTSD or groupings of symptoms that suggest a subtype.

“Pain is one way that people experience distress, and we know that in PTSD, sometimes the trauma memories are encoded too strongly, more stressful and more alarming to the body system,” she said.

When patients have symptoms such as chronic pain, headaches, fatigue, or cognitive brain fog, clinicians should remember to ask about trauma exposure, Hoge said. You might be the first to broach the subject.

“I’ve certainly seen patients in clinic who never get asked about the exposure to trauma, including sexual trauma, so sometimes that can be the first pathway to helping people feel better is just to have their trauma recognized,” Hoge said.

If a patient has experienced or witnessed violence, consider a referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist to evaluate them for PTSD. Higgs said he collaborated closely with a psychologist to complement his treatment plans for active duty and retired military service members and families.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense (DoD) recommend trauma-focused psychotherapy as the first line of treatment for PTSD. This form of therapy deliberately focuses on bringing trauma memories into the open, Hoge said.

“When a person talks about their trauma, and it comes into direct consciousness, somehow it’s malleable, and so when it goes back down into the memory banks, it’s changed somewhat,” she said.

This study was supported by the DoD through awards from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, and Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program. The funding organizations played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Higgs’s comments are his own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Health Agency, Brooke Army Medical Center, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, the DoD, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or any agencies under the US government. Hoge had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Spending time in a war zone can lead to chronic mental and physical pain. Now, research points to a link between two common disorders that can leave service members struggling.

Published in the journal Arthritis Care & Research, a longitudinal cohort study of 1761 US military service members found that those who had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before deployment were nearly 3times more likely to develop fibromyalgia after returning home (odds ratio, 2.96; 95% CI, 2.08-4.22). Those with fibromyalgia before deployment had more than threefold greater likelihood of developing PTSD after deployment (odds ratio, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.63-5.95).

This is the largest prospective study to date linking the stress of combat deployment to the onset of fibromyalgia.

“We had the advantage of observing a large population before and after exposure to an environment that often involves significant stress,” said lead study author Jay Higgs, MD, a retired rheumatologist with Brooke Army Medical Center and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Here’s what the team found and why it matters.

Significant Increase in Fibromyalgia After Development

Service members were checked for fibromyalgia using the 2011 questionnaire modification of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. They were assessed for PTSD using the PTSD Checklist Stressor-Specific Version.

Before deployment, service members had similar rates of fibromyalgia as the general population: 2.2% in men and 2.0% in women. After deployment, fibromyalgia rates increased significantly to 8.0% in men and 11.1% in women.

While fibromyalgia tends to be underreported in men, the findings suggest it should not be overlooked in this population. “Our results are consistent with the notion that there should be no gender bias when considering the possibility of fibromyalgia in an individual patient,” Higgs said.

Before deployment, 20.7% of men and 18.3% of women had PTSD symptoms. After deployment, the PTSD rate increased slightly to 22.7% in men and 25.5% in women.

The Link Between Fibromyalgia and PTSD

The researchers said the results suggest that PTSD and fibromyalgia might be linked through central nervous system mechanisms such as central sensitization, elevated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, elevated cortisol, and proinflammatory cytokines. However, shared causation, associated risk factors, selection bias, or alternative mechanisms within the central and peripheral neuroendocrine and cytokine systems could also be part of the story.

“What we do not know is how much of what we see clinically represents central nervous system pathology, peripheral problems, or a combination of the 2,” Higgs said. “Neurotransmission in the central nervous system is highly complex, and may not only involve specific structures, but a web of communications between them.”

Loci in the midbrain appear especially important, he said.

Elizabeth Hoge, MD, professor and director of the Anxiety Disorders Research Program at Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, said that patients with PTSD often have pain, headaches, sleep disturbances, and other symptoms that are part of the picture of fibromyalgia. It’s plausible that pain syndromes could be manifestations of PTSD or groupings of symptoms that suggest a subtype.

“Pain is one way that people experience distress, and we know that in PTSD, sometimes the trauma memories are encoded too strongly, more stressful and more alarming to the body system,” she said.

When patients have symptoms such as chronic pain, headaches, fatigue, or cognitive brain fog, clinicians should remember to ask about trauma exposure, Hoge said. You might be the first to broach the subject.

“I’ve certainly seen patients in clinic who never get asked about the exposure to trauma, including sexual trauma, so sometimes that can be the first pathway to helping people feel better is just to have their trauma recognized,” Hoge said.

If a patient has experienced or witnessed violence, consider a referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist to evaluate them for PTSD. Higgs said he collaborated closely with a psychologist to complement his treatment plans for active duty and retired military service members and families.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense (DoD) recommend trauma-focused psychotherapy as the first line of treatment for PTSD. This form of therapy deliberately focuses on bringing trauma memories into the open, Hoge said.

“When a person talks about their trauma, and it comes into direct consciousness, somehow it’s malleable, and so when it goes back down into the memory banks, it’s changed somewhat,” she said.

This study was supported by the DoD through awards from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, and Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program. The funding organizations played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Higgs’s comments are his own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Health Agency, Brooke Army Medical Center, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, the DoD, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or any agencies under the US government. Hoge had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fibromyalgia-PTSD Link Shows Bidirectional Relationship With Exposure to Combat Environments

Fibromyalgia-PTSD Link Shows Bidirectional Relationship With Exposure to Combat Environments

Vasculitis Patients Need Multiple COVID Vaccine Boosters

People with vasculitis may need at least three or four vaccinations for COVID-19 before they start to show an immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection, new research has suggested.

In a longitudinal retrospective study, serum antibody neutralization against the Omicron variant of the virus and its descendants was found to be “largely absent” after the first two doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been given to patients. But increasing neutralizing antibody titers were seen after both the third and fourth vaccine boosters had been administered.

Results also showed that the more recently people had been treated with the B cell–depleting therapy rituximab, the lower the levels of immunogenicity that were achieved, and thus protection against SARS-CoV-2.

“Our results have significant implications for individuals treated with rituximab in the post-Omicron era, highlighting the value of additive boosters in affirming increasing protection in clinically vulnerable populations,” the team behind the work at the University of Cambridge in England, has reported in Science Advances.

Moreover, because the use of rituximab reduced the neutralization of not just wild-type (WT) Omicron but also the Omicron-descendant variants BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB, this highlights “the urgent need for additional adjunctive strategies to enhance vaccine-induced immunity as well as preferential access for such patients to updated vaccines using spike from now circulating Omicron lineages,” the team added.

Studying Humoral Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

Corresponding author Ravindra K. Gupta, BMBCh, MA, MPH, PhD, told this news organization that studying humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunocompromised individuals such as those with vasculitis was important for two main reasons.

“It is really important at individual level for their own health, of course, but also because we know that variants of concern have often evolved and developed within patients and can then spread in wider populations,” he said.

Gupta, who is professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute for Therapeutic Immunology & Infectious Disease added: “We believe that the variants of concern that we’re having to deal with right now, including Omicron, have come from such [immunocompromised] individuals.”

Omicron “was a big shift,” Gupta noted. “It had a lot of new mutations on it, so it was almost like a new strain of the virus.” Few studies have looked at the longitudinal immunogenicity proffered by COVID vaccines in the post-Omicron era, particularly in those with vasculitis who are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including rituximab.

Two-Pronged Study Approach

For the study, a population of immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with vasculitis who had been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years was identified. Just over half (58%) had received adenovirus-based AZD1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca-Oxford; AZN) and 37% BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech; mRNA) as their primary vaccines. Patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis comprised the majority of those who received rituximab (83%), compared with less than half of those who did not take rituximab (48%).

A two-pronged approach was taken with the researchers first measuring neutralizing antibody titers before and 30 days after four successive COVID vaccinations in a group of 32 individuals with available samples. They then performed a cross-sectional, case-control study in 95 individuals to look at neutralizing antibody titers and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) in individuals who had (n = 64) and had not (n = 31) been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years and had samples available after their third and fourth COVID vaccinations.

The first analysis was done to see how people were responding to vaccination over time. “That told us that there was a problem with the first two doses and that we got some response after doses three and four, but the response was uniformly quite poor against the new variants of concern,” Gupta said.

A human embryonic kidney cell model had been used to determine individuals’ neutralizing antibody titers in response to WT, BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB pseudotyped viruses. After the first and second COVID vaccinations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) against each variant barely increased from a baseline of 40.0. The greatest increases in GMT was seen with the WT virus, at 43.7, 90.7, 256.3, and 394.2, after the first, second, third and fourth doses, respectively. The lowest increases in GMT were seen with the XBB variant, with respective values of 40.0, 40.8, 45.7, and 53.9.

Incremental Benefit Offers Some ‘Reassurance’

Vasculitis specialist Rona Smith, MA, MB BChir, MD, who was one of the authors of the paper, told this news organization separately that the results showed there was “an incremental benefit of having COVID vaccinations,” which “offers a little bit of reassurance” that there can be an immune response in people with vasculitis.

Although results of the cross-sectional study showed that there was a significant dampening effect of rituximab treatment on the immune response, “I don’t think it’s an isolated effect in our [vasculitis] patients,” Smith suggested, adding the results were “probably still relevant to patients who receive routine dosing of rituximab for other conditions.”

Neutralizing antibody titers were consistently lower among individuals who had been treated with rituximab vs those who had not, with treatment in the past 18 months found to significantly impair immunogenicity.

The ADCC response was better preserved than the neutralizing antibody response, Gupta said, although it was still significantly lower in the rituximab-treated than in the non–rituximab-treated patients.

When to Vaccinate in Vasculitis?

Regarding when to give vaccines to people with vasculitis, Smith said: “Current recommendations are that patients should receive any vaccines that they’re offered routinely, whether that be COVID vaccines, flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccines.”

As for the timing of those vaccinations, she observed that the current thinking was that vaccinations should “ideally be at least 1 month before a rituximab treatment, and ideally 3-4 [months] after their last dose. However, as many patients are on a 6-month dosing cycle, it can be difficult for some of them to find a suitable time window to have the COVID vaccine when it is offered.”

Additional precautions, such as wearing masks in crowded places and avoiding visits to acutely unwell friends or relatives, may still be prudent, Smith acknowledged, but he was clear that people should not be locking themselves away as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When advising patients, “our general recommendation is that it is better to have a vaccine than not, but we can’t guarantee how well you will respond to it, but some response is better than none,” Smith said.

The study was independently supported. Gupta had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Smith was a coauthor of the paper and has received research grant funding from Union Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline/Vir Biotechnology, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, and Vasculitis UK. Another coauthor reported receiving research grants from CSL Vifor, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board, consultancy, and lecture fees from Roche and CSL Vifor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with vasculitis may need at least three or four vaccinations for COVID-19 before they start to show an immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection, new research has suggested.

In a longitudinal retrospective study, serum antibody neutralization against the Omicron variant of the virus and its descendants was found to be “largely absent” after the first two doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been given to patients. But increasing neutralizing antibody titers were seen after both the third and fourth vaccine boosters had been administered.

Results also showed that the more recently people had been treated with the B cell–depleting therapy rituximab, the lower the levels of immunogenicity that were achieved, and thus protection against SARS-CoV-2.

“Our results have significant implications for individuals treated with rituximab in the post-Omicron era, highlighting the value of additive boosters in affirming increasing protection in clinically vulnerable populations,” the team behind the work at the University of Cambridge in England, has reported in Science Advances.

Moreover, because the use of rituximab reduced the neutralization of not just wild-type (WT) Omicron but also the Omicron-descendant variants BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB, this highlights “the urgent need for additional adjunctive strategies to enhance vaccine-induced immunity as well as preferential access for such patients to updated vaccines using spike from now circulating Omicron lineages,” the team added.

Studying Humoral Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

Corresponding author Ravindra K. Gupta, BMBCh, MA, MPH, PhD, told this news organization that studying humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunocompromised individuals such as those with vasculitis was important for two main reasons.

“It is really important at individual level for their own health, of course, but also because we know that variants of concern have often evolved and developed within patients and can then spread in wider populations,” he said.

Gupta, who is professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute for Therapeutic Immunology & Infectious Disease added: “We believe that the variants of concern that we’re having to deal with right now, including Omicron, have come from such [immunocompromised] individuals.”

Omicron “was a big shift,” Gupta noted. “It had a lot of new mutations on it, so it was almost like a new strain of the virus.” Few studies have looked at the longitudinal immunogenicity proffered by COVID vaccines in the post-Omicron era, particularly in those with vasculitis who are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including rituximab.

Two-Pronged Study Approach

For the study, a population of immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with vasculitis who had been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years was identified. Just over half (58%) had received adenovirus-based AZD1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca-Oxford; AZN) and 37% BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech; mRNA) as their primary vaccines. Patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis comprised the majority of those who received rituximab (83%), compared with less than half of those who did not take rituximab (48%).

A two-pronged approach was taken with the researchers first measuring neutralizing antibody titers before and 30 days after four successive COVID vaccinations in a group of 32 individuals with available samples. They then performed a cross-sectional, case-control study in 95 individuals to look at neutralizing antibody titers and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) in individuals who had (n = 64) and had not (n = 31) been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years and had samples available after their third and fourth COVID vaccinations.

The first analysis was done to see how people were responding to vaccination over time. “That told us that there was a problem with the first two doses and that we got some response after doses three and four, but the response was uniformly quite poor against the new variants of concern,” Gupta said.

A human embryonic kidney cell model had been used to determine individuals’ neutralizing antibody titers in response to WT, BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB pseudotyped viruses. After the first and second COVID vaccinations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) against each variant barely increased from a baseline of 40.0. The greatest increases in GMT was seen with the WT virus, at 43.7, 90.7, 256.3, and 394.2, after the first, second, third and fourth doses, respectively. The lowest increases in GMT were seen with the XBB variant, with respective values of 40.0, 40.8, 45.7, and 53.9.

Incremental Benefit Offers Some ‘Reassurance’

Vasculitis specialist Rona Smith, MA, MB BChir, MD, who was one of the authors of the paper, told this news organization separately that the results showed there was “an incremental benefit of having COVID vaccinations,” which “offers a little bit of reassurance” that there can be an immune response in people with vasculitis.

Although results of the cross-sectional study showed that there was a significant dampening effect of rituximab treatment on the immune response, “I don’t think it’s an isolated effect in our [vasculitis] patients,” Smith suggested, adding the results were “probably still relevant to patients who receive routine dosing of rituximab for other conditions.”

Neutralizing antibody titers were consistently lower among individuals who had been treated with rituximab vs those who had not, with treatment in the past 18 months found to significantly impair immunogenicity.

The ADCC response was better preserved than the neutralizing antibody response, Gupta said, although it was still significantly lower in the rituximab-treated than in the non–rituximab-treated patients.

When to Vaccinate in Vasculitis?

Regarding when to give vaccines to people with vasculitis, Smith said: “Current recommendations are that patients should receive any vaccines that they’re offered routinely, whether that be COVID vaccines, flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccines.”

As for the timing of those vaccinations, she observed that the current thinking was that vaccinations should “ideally be at least 1 month before a rituximab treatment, and ideally 3-4 [months] after their last dose. However, as many patients are on a 6-month dosing cycle, it can be difficult for some of them to find a suitable time window to have the COVID vaccine when it is offered.”

Additional precautions, such as wearing masks in crowded places and avoiding visits to acutely unwell friends or relatives, may still be prudent, Smith acknowledged, but he was clear that people should not be locking themselves away as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When advising patients, “our general recommendation is that it is better to have a vaccine than not, but we can’t guarantee how well you will respond to it, but some response is better than none,” Smith said.

The study was independently supported. Gupta had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Smith was a coauthor of the paper and has received research grant funding from Union Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline/Vir Biotechnology, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, and Vasculitis UK. Another coauthor reported receiving research grants from CSL Vifor, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board, consultancy, and lecture fees from Roche and CSL Vifor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with vasculitis may need at least three or four vaccinations for COVID-19 before they start to show an immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection, new research has suggested.

In a longitudinal retrospective study, serum antibody neutralization against the Omicron variant of the virus and its descendants was found to be “largely absent” after the first two doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been given to patients. But increasing neutralizing antibody titers were seen after both the third and fourth vaccine boosters had been administered.

Results also showed that the more recently people had been treated with the B cell–depleting therapy rituximab, the lower the levels of immunogenicity that were achieved, and thus protection against SARS-CoV-2.

“Our results have significant implications for individuals treated with rituximab in the post-Omicron era, highlighting the value of additive boosters in affirming increasing protection in clinically vulnerable populations,” the team behind the work at the University of Cambridge in England, has reported in Science Advances.

Moreover, because the use of rituximab reduced the neutralization of not just wild-type (WT) Omicron but also the Omicron-descendant variants BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB, this highlights “the urgent need for additional adjunctive strategies to enhance vaccine-induced immunity as well as preferential access for such patients to updated vaccines using spike from now circulating Omicron lineages,” the team added.

Studying Humoral Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines

Corresponding author Ravindra K. Gupta, BMBCh, MA, MPH, PhD, told this news organization that studying humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in immunocompromised individuals such as those with vasculitis was important for two main reasons.

“It is really important at individual level for their own health, of course, but also because we know that variants of concern have often evolved and developed within patients and can then spread in wider populations,” he said.

Gupta, who is professor of clinical microbiology at the Cambridge Institute for Therapeutic Immunology & Infectious Disease added: “We believe that the variants of concern that we’re having to deal with right now, including Omicron, have come from such [immunocompromised] individuals.”

Omicron “was a big shift,” Gupta noted. “It had a lot of new mutations on it, so it was almost like a new strain of the virus.” Few studies have looked at the longitudinal immunogenicity proffered by COVID vaccines in the post-Omicron era, particularly in those with vasculitis who are often treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including rituximab.

Two-Pronged Study Approach

For the study, a population of immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with vasculitis who had been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years was identified. Just over half (58%) had received adenovirus-based AZD1222/ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca-Oxford; AZN) and 37% BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech; mRNA) as their primary vaccines. Patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis comprised the majority of those who received rituximab (83%), compared with less than half of those who did not take rituximab (48%).

A two-pronged approach was taken with the researchers first measuring neutralizing antibody titers before and 30 days after four successive COVID vaccinations in a group of 32 individuals with available samples. They then performed a cross-sectional, case-control study in 95 individuals to look at neutralizing antibody titers and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) in individuals who had (n = 64) and had not (n = 31) been treated with rituximab in the past 5 years and had samples available after their third and fourth COVID vaccinations.

The first analysis was done to see how people were responding to vaccination over time. “That told us that there was a problem with the first two doses and that we got some response after doses three and four, but the response was uniformly quite poor against the new variants of concern,” Gupta said.

A human embryonic kidney cell model had been used to determine individuals’ neutralizing antibody titers in response to WT, BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and XBB pseudotyped viruses. After the first and second COVID vaccinations, the geometric mean titer (GMT) against each variant barely increased from a baseline of 40.0. The greatest increases in GMT was seen with the WT virus, at 43.7, 90.7, 256.3, and 394.2, after the first, second, third and fourth doses, respectively. The lowest increases in GMT were seen with the XBB variant, with respective values of 40.0, 40.8, 45.7, and 53.9.

Incremental Benefit Offers Some ‘Reassurance’

Vasculitis specialist Rona Smith, MA, MB BChir, MD, who was one of the authors of the paper, told this news organization separately that the results showed there was “an incremental benefit of having COVID vaccinations,” which “offers a little bit of reassurance” that there can be an immune response in people with vasculitis.

Although results of the cross-sectional study showed that there was a significant dampening effect of rituximab treatment on the immune response, “I don’t think it’s an isolated effect in our [vasculitis] patients,” Smith suggested, adding the results were “probably still relevant to patients who receive routine dosing of rituximab for other conditions.”

Neutralizing antibody titers were consistently lower among individuals who had been treated with rituximab vs those who had not, with treatment in the past 18 months found to significantly impair immunogenicity.

The ADCC response was better preserved than the neutralizing antibody response, Gupta said, although it was still significantly lower in the rituximab-treated than in the non–rituximab-treated patients.

When to Vaccinate in Vasculitis?

Regarding when to give vaccines to people with vasculitis, Smith said: “Current recommendations are that patients should receive any vaccines that they’re offered routinely, whether that be COVID vaccines, flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccines.”

As for the timing of those vaccinations, she observed that the current thinking was that vaccinations should “ideally be at least 1 month before a rituximab treatment, and ideally 3-4 [months] after their last dose. However, as many patients are on a 6-month dosing cycle, it can be difficult for some of them to find a suitable time window to have the COVID vaccine when it is offered.”

Additional precautions, such as wearing masks in crowded places and avoiding visits to acutely unwell friends or relatives, may still be prudent, Smith acknowledged, but he was clear that people should not be locking themselves away as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When advising patients, “our general recommendation is that it is better to have a vaccine than not, but we can’t guarantee how well you will respond to it, but some response is better than none,” Smith said.

The study was independently supported. Gupta had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Smith was a coauthor of the paper and has received research grant funding from Union Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline/Vir Biotechnology, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, and Vasculitis UK. Another coauthor reported receiving research grants from CSL Vifor, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board, consultancy, and lecture fees from Roche and CSL Vifor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SCIENCE ADVANCES

Around 5% of US Population Diagnosed With Autoimmune Disease

TOPLINE:

In 2022, autoimmune diseases affected over 15 million individuals in the United States, with women nearly twice as likely to be affected as men and more than one third of affected individuals having more than one autoimmune condition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used electronic health record (EHR) data from six healthcare systems in the United States between 2011 and 2022 to estimate the prevalence of autoimmune diseases according to sex and age.

- They selected 105 autoimmune diseases from the textbook The Autoimmune Diseases and estimated their prevalence in more than 10 million individuals from these healthcare systems; these statistics were subsequently extrapolated to an estimated US population of 333.3 million.

- An individual was considered to have a diagnosis of an autoimmune disease if they had at least two diagnosis codes for the condition, with the codes being at least 30 days apart.

- A software program was developed to compute the prevalence of autoimmune diseases alone and in aggregate, enabling other researchers to replicate or modify the analysis over time.

TAKEAWAY:

- More than 15 million people, accounting for 4.6% of the US population, were diagnosed with at least one autoimmune disease from January 2011 to June 2022; 34% were diagnosed with more than one autoimmune disease.

- Sex-stratified analysis revealed that 63% of patients diagnosed with autoimmune disease were women, and only 37% were men, establishing a female-to-male ratio of 1.7:1; age-stratified analysis revealed increasing prevalence of autoimmune conditions with age, peaking in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.

- Among individuals with autoimmune diseases, 65% of patients had one condition, whereas 24% had two, 8% had three, and 2% had four or more autoimmune diseases (does not add to 100% due to rounding).

- Rheumatoid arthritis emerged as the most prevalent autoimmune disease, followed by psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, Grave’s disease, and autoimmune thyroiditis; 19 of the top 20 most prevalent autoimmune diseases occurred more frequently in women.

IN PRACTICE:

“Accurate data on the prevalence of autoimmune diseases as a category of disease and for individual autoimmune diseases are needed to further clinical and basic research to improve diagnosis, biomarkers, and therapies for these diseases, which significantly impact the US population,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Aaron H. Abend, Autoimmune Registry, Guilford, Connecticut, and was published online in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of EHR data presented several challenges, including potential inaccuracies in diagnosis codes and the possibility of missing patients with single diagnosis codes because of the two-code requirement. Certain autoimmune diseases evolve over time and involve nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms that can mimic other diseases, potentially resulting in underdiagnosis. Moreover, rare diseases lacking specific diagnosis codes may have been underrepresented.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from Autoimmune Registry; the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and other sources. Information on potential conflicts of interest was not disclosed.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In 2022, autoimmune diseases affected over 15 million individuals in the United States, with women nearly twice as likely to be affected as men and more than one third of affected individuals having more than one autoimmune condition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used electronic health record (EHR) data from six healthcare systems in the United States between 2011 and 2022 to estimate the prevalence of autoimmune diseases according to sex and age.

- They selected 105 autoimmune diseases from the textbook The Autoimmune Diseases and estimated their prevalence in more than 10 million individuals from these healthcare systems; these statistics were subsequently extrapolated to an estimated US population of 333.3 million.

- An individual was considered to have a diagnosis of an autoimmune disease if they had at least two diagnosis codes for the condition, with the codes being at least 30 days apart.

- A software program was developed to compute the prevalence of autoimmune diseases alone and in aggregate, enabling other researchers to replicate or modify the analysis over time.

TAKEAWAY:

- More than 15 million people, accounting for 4.6% of the US population, were diagnosed with at least one autoimmune disease from January 2011 to June 2022; 34% were diagnosed with more than one autoimmune disease.

- Sex-stratified analysis revealed that 63% of patients diagnosed with autoimmune disease were women, and only 37% were men, establishing a female-to-male ratio of 1.7:1; age-stratified analysis revealed increasing prevalence of autoimmune conditions with age, peaking in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.

- Among individuals with autoimmune diseases, 65% of patients had one condition, whereas 24% had two, 8% had three, and 2% had four or more autoimmune diseases (does not add to 100% due to rounding).

- Rheumatoid arthritis emerged as the most prevalent autoimmune disease, followed by psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, Grave’s disease, and autoimmune thyroiditis; 19 of the top 20 most prevalent autoimmune diseases occurred more frequently in women.

IN PRACTICE:

“Accurate data on the prevalence of autoimmune diseases as a category of disease and for individual autoimmune diseases are needed to further clinical and basic research to improve diagnosis, biomarkers, and therapies for these diseases, which significantly impact the US population,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Aaron H. Abend, Autoimmune Registry, Guilford, Connecticut, and was published online in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of EHR data presented several challenges, including potential inaccuracies in diagnosis codes and the possibility of missing patients with single diagnosis codes because of the two-code requirement. Certain autoimmune diseases evolve over time and involve nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms that can mimic other diseases, potentially resulting in underdiagnosis. Moreover, rare diseases lacking specific diagnosis codes may have been underrepresented.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from Autoimmune Registry; the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and other sources. Information on potential conflicts of interest was not disclosed.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In 2022, autoimmune diseases affected over 15 million individuals in the United States, with women nearly twice as likely to be affected as men and more than one third of affected individuals having more than one autoimmune condition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used electronic health record (EHR) data from six healthcare systems in the United States between 2011 and 2022 to estimate the prevalence of autoimmune diseases according to sex and age.

- They selected 105 autoimmune diseases from the textbook The Autoimmune Diseases and estimated their prevalence in more than 10 million individuals from these healthcare systems; these statistics were subsequently extrapolated to an estimated US population of 333.3 million.

- An individual was considered to have a diagnosis of an autoimmune disease if they had at least two diagnosis codes for the condition, with the codes being at least 30 days apart.

- A software program was developed to compute the prevalence of autoimmune diseases alone and in aggregate, enabling other researchers to replicate or modify the analysis over time.

TAKEAWAY:

- More than 15 million people, accounting for 4.6% of the US population, were diagnosed with at least one autoimmune disease from January 2011 to June 2022; 34% were diagnosed with more than one autoimmune disease.

- Sex-stratified analysis revealed that 63% of patients diagnosed with autoimmune disease were women, and only 37% were men, establishing a female-to-male ratio of 1.7:1; age-stratified analysis revealed increasing prevalence of autoimmune conditions with age, peaking in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.

- Among individuals with autoimmune diseases, 65% of patients had one condition, whereas 24% had two, 8% had three, and 2% had four or more autoimmune diseases (does not add to 100% due to rounding).

- Rheumatoid arthritis emerged as the most prevalent autoimmune disease, followed by psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, Grave’s disease, and autoimmune thyroiditis; 19 of the top 20 most prevalent autoimmune diseases occurred more frequently in women.

IN PRACTICE:

“Accurate data on the prevalence of autoimmune diseases as a category of disease and for individual autoimmune diseases are needed to further clinical and basic research to improve diagnosis, biomarkers, and therapies for these diseases, which significantly impact the US population,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Aaron H. Abend, Autoimmune Registry, Guilford, Connecticut, and was published online in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of EHR data presented several challenges, including potential inaccuracies in diagnosis codes and the possibility of missing patients with single diagnosis codes because of the two-code requirement. Certain autoimmune diseases evolve over time and involve nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms that can mimic other diseases, potentially resulting in underdiagnosis. Moreover, rare diseases lacking specific diagnosis codes may have been underrepresented.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from Autoimmune Registry; the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and other sources. Information on potential conflicts of interest was not disclosed.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TNF Inhibitors Show Comparable Safety With Non-TNF Inhibitors in US Veterans With RA-ILD

TOPLINE:

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors led to no significant difference in survival or respiratory-related hospitalizations, compared with non-TNF inhibitors, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD).

METHODOLOGY:

- Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the American College of Chest Physicians conditionally advise against the use of TNF inhibitors for treating ILD in patients with RA-ILD, with persisting uncertainty about the safety of TNF inhibitors.

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, with a focus on comparing outcomes in patients with RA-ILD who initiated TNF or non-TNF inhibitors between 2006 and 2018.

- A total of 1047 US veterans with RA-ILD were included, with 237 who initiated TNF inhibitors propensity matched in a 1:1 ratio with 237 who initiated non-TNF inhibitors (mean age, 68 years; 92% men).

- The primary composite outcome was time to death or respiratory-related hospitalization over a follow-up period of up to 3 years.

- The secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, respiratory-related mortality, and respiratory-related hospitalization, with additional assessments over a 1-year period.

TAKEAWAY:

- No significant difference was observed in the composite outcome of death or respiratory-related hospitalization between the TNF and non-TNF inhibitor groups (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.92-1.58).

- No significant differences in the risk for respiratory-related hospitalization and all-cause or respiratory-related mortality were found between the TNF and non-TNF inhibitor groups. Similar findings were observed for all the outcomes during 1 year of follow-up.

- The mean duration of medication use prior to discontinuation, the time to discontinuation, and the mean predicted forced vital capacity percentage were similar for both groups.

- In a subgroup analysis of patients aged ≥ 65 years, those treated with non-TNF inhibitors had a higher risk for the composite outcome and all-cause and respiratory-related mortality than those treated with TNF inhibitors. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between the two treatment groups among patients aged < 65 years.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results do not suggest that systematic avoidance of TNF inhibitors is required in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD. However, given disease heterogeneity and imprecision of our estimates, some subpopulations of patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD might benefit from specific biological or targeted synthetic DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] treatment strategies,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha It was published online on January 7, 2025, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Administrative algorithms were used for identifying RA-ILD, potentially leading to misclassification and limiting phenotyping accuracy. Even with the use of propensity score methods, there might still be residual selection bias or unmeasured confounding. The study lacked comprehensive measures of posttreatment forced vital capacity and other indicators of ILD severity. The study population, predominantly men and those with a smoking history, may limit the generalizability of the findings to other groups.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was primarily funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Some authors reported having financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors led to no significant difference in survival or respiratory-related hospitalizations, compared with non-TNF inhibitors, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD).

METHODOLOGY:

- Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the American College of Chest Physicians conditionally advise against the use of TNF inhibitors for treating ILD in patients with RA-ILD, with persisting uncertainty about the safety of TNF inhibitors.

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, with a focus on comparing outcomes in patients with RA-ILD who initiated TNF or non-TNF inhibitors between 2006 and 2018.

- A total of 1047 US veterans with RA-ILD were included, with 237 who initiated TNF inhibitors propensity matched in a 1:1 ratio with 237 who initiated non-TNF inhibitors (mean age, 68 years; 92% men).

- The primary composite outcome was time to death or respiratory-related hospitalization over a follow-up period of up to 3 years.

- The secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, respiratory-related mortality, and respiratory-related hospitalization, with additional assessments over a 1-year period.

TAKEAWAY:

- No significant difference was observed in the composite outcome of death or respiratory-related hospitalization between the TNF and non-TNF inhibitor groups (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.92-1.58).

- No significant differences in the risk for respiratory-related hospitalization and all-cause or respiratory-related mortality were found between the TNF and non-TNF inhibitor groups. Similar findings were observed for all the outcomes during 1 year of follow-up.

- The mean duration of medication use prior to discontinuation, the time to discontinuation, and the mean predicted forced vital capacity percentage were similar for both groups.

- In a subgroup analysis of patients aged ≥ 65 years, those treated with non-TNF inhibitors had a higher risk for the composite outcome and all-cause and respiratory-related mortality than those treated with TNF inhibitors. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between the two treatment groups among patients aged < 65 years.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results do not suggest that systematic avoidance of TNF inhibitors is required in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD. However, given disease heterogeneity and imprecision of our estimates, some subpopulations of patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD might benefit from specific biological or targeted synthetic DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] treatment strategies,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha It was published online on January 7, 2025, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Administrative algorithms were used for identifying RA-ILD, potentially leading to misclassification and limiting phenotyping accuracy. Even with the use of propensity score methods, there might still be residual selection bias or unmeasured confounding. The study lacked comprehensive measures of posttreatment forced vital capacity and other indicators of ILD severity. The study population, predominantly men and those with a smoking history, may limit the generalizability of the findings to other groups.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was primarily funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Some authors reported having financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors led to no significant difference in survival or respiratory-related hospitalizations, compared with non-TNF inhibitors, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD).

METHODOLOGY:

- Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the American College of Chest Physicians conditionally advise against the use of TNF inhibitors for treating ILD in patients with RA-ILD, with persisting uncertainty about the safety of TNF inhibitors.

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, with a focus on comparing outcomes in patients with RA-ILD who initiated TNF or non-TNF inhibitors between 2006 and 2018.

- A total of 1047 US veterans with RA-ILD were included, with 237 who initiated TNF inhibitors propensity matched in a 1:1 ratio with 237 who initiated non-TNF inhibitors (mean age, 68 years; 92% men).

- The primary composite outcome was time to death or respiratory-related hospitalization over a follow-up period of up to 3 years.

- The secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, respiratory-related mortality, and respiratory-related hospitalization, with additional assessments over a 1-year period.

TAKEAWAY:

- No significant difference was observed in the composite outcome of death or respiratory-related hospitalization between the TNF and non-TNF inhibitor groups (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.92-1.58).

- No significant differences in the risk for respiratory-related hospitalization and all-cause or respiratory-related mortality were found between the TNF and non-TNF inhibitor groups. Similar findings were observed for all the outcomes during 1 year of follow-up.

- The mean duration of medication use prior to discontinuation, the time to discontinuation, and the mean predicted forced vital capacity percentage were similar for both groups.

- In a subgroup analysis of patients aged ≥ 65 years, those treated with non-TNF inhibitors had a higher risk for the composite outcome and all-cause and respiratory-related mortality than those treated with TNF inhibitors. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between the two treatment groups among patients aged < 65 years.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our results do not suggest that systematic avoidance of TNF inhibitors is required in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD. However, given disease heterogeneity and imprecision of our estimates, some subpopulations of patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD might benefit from specific biological or targeted synthetic DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] treatment strategies,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha It was published online on January 7, 2025, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Administrative algorithms were used for identifying RA-ILD, potentially leading to misclassification and limiting phenotyping accuracy. Even with the use of propensity score methods, there might still be residual selection bias or unmeasured confounding. The study lacked comprehensive measures of posttreatment forced vital capacity and other indicators of ILD severity. The study population, predominantly men and those with a smoking history, may limit the generalizability of the findings to other groups.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was primarily funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Some authors reported having financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most Kids With COVID-Linked MIS-C Recover by 6 Months

Children who were severely ill with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) related to COVID-19 infection appear to show excellent cardiovascular and noncardiovascular outcomes by 6 months, according to data published in JAMA Pediatrics.

MIS-C is a life-threatening complication of COVID-19 infection and data on outcomes are limited, wrote the authors, led by Dongngan T. Truong, MD, MSSI, with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Cardiology, Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia. These 6-month results are from the Long-Term Outcomes After the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MUSIC) study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Researchers found in this cohort study of 1204 participants that by 6 months after hospital discharge, 99% had normalization of left ventricular systolic function, and 92.3% had normalized coronary artery dimensions. More than 95% reported being more than 90% back to baseline health.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems (PROMIS) Global Health scores were at least equivalent to prepandemic population normative values. PROMIS Global Health parent/guardian proxy median T scores for fatigue, global health, and pain interference improved significantly from 2 weeks to 6 months: fatigue, 56.1 vs 48.9; global health, 48.8 vs 51.3; pain interference, 53.0 vs 43.3 (P < .001).

The most common symptoms reported at 2 weeks were fatigue (15.9%) and low stamina/energy (9.2%); both decreased to 3.4% and 3.3%, respectively, by 6 months. The most common cardiovascular symptom at 2 weeks was palpitations (1.5%), which decreased to 0.6%.

Chest Pain Increased Over Time

Reports of chest pain, however, reportedly increased over time, with 1.3% reporting chest pain at rest at 2 weeks and 2.2% at 6 months. Although gastrointestinal symptoms were common during the acute MIS-C, only 5.3% of respondents reported those symptoms at 2 weeks.

Children in the cohort had a median age of 9 years, and 60% were men. They self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: American Indian or Alaska Native (0.1%), Asian (3.3%), Black (27.0%), Hawaiian Native or Other Pacific Islander (0.2%), Hispanic or Latino (26.9%), multiracial (2.7%), White (31.2%), other (1.0%), and unknown or refused to specify (7.6%). Authors wrote that the cohort was followed-up to 2 years after illness onset and long-term results are not yet known.

Time to Exhale

David J. Goldberg, MD, with the Cardiac Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and colleagues, wrote in an accompanying editorial that “the decreased frequency of the disease along (with) the reassuring reports on midterm outcomes can allow the pediatric community a moment of collective exhale.”

The editorialists note that of those who initially presented with myocardial dysfunction, all but one patient evaluated had a normal ejection fraction at follow-up. Energy, sleep, appetite, cognition, and mood also normalized by midterm.

“The results of the MUSIC study add to the emerging midterm outcomes data suggesting a near-complete cardiovascular recovery in the overwhelming majority of patients who develop MIS-C,” Goldberg and colleagues wrote. “Despite initial concerns, driven by the severity of acute presentation at diagnosis and longer-term questions that remain (for example, does coronary microvascular dysfunction persist even after normalization of coronary artery z score?), these data suggest an encouraging outlook for the long-term health of affected children.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies have reported a declining overall incidence of MIS-C and highlighted the protective value of vaccination.

The editorialists add, however, that while the drop in MIS-C cases is encouraging, cases are still reported, especially amid high viral activity periods, “and nearly half of affected children continue to require intensive care in the acute phase of illness.”

Truong reported grants from the National Institutes of Health and serving as coprincipal investigator for Pfizer for research on COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis funded by Pfizer and occurring through the framework of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Pediatric Heart Network outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported grants from Pfizer and Boston Scientific outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving grants from Additional Ventures Foundation outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving consultant fees from Amryt Pharma, Chiesi, Esperion, and Ultragenyx outside the submitted work. A coauthor reported receiving consultant fees from Larimar Therapeutics for mitochondrial therapies outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported being an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals since July 2023. One editorialist reported grants from Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and the Arthritis Foundation, Academy Health, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who were severely ill with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) related to COVID-19 infection appear to show excellent cardiovascular and noncardiovascular outcomes by 6 months, according to data published in JAMA Pediatrics.

MIS-C is a life-threatening complication of COVID-19 infection and data on outcomes are limited, wrote the authors, led by Dongngan T. Truong, MD, MSSI, with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Cardiology, Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia. These 6-month results are from the Long-Term Outcomes After the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MUSIC) study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Researchers found in this cohort study of 1204 participants that by 6 months after hospital discharge, 99% had normalization of left ventricular systolic function, and 92.3% had normalized coronary artery dimensions. More than 95% reported being more than 90% back to baseline health.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems (PROMIS) Global Health scores were at least equivalent to prepandemic population normative values. PROMIS Global Health parent/guardian proxy median T scores for fatigue, global health, and pain interference improved significantly from 2 weeks to 6 months: fatigue, 56.1 vs 48.9; global health, 48.8 vs 51.3; pain interference, 53.0 vs 43.3 (P < .001).

The most common symptoms reported at 2 weeks were fatigue (15.9%) and low stamina/energy (9.2%); both decreased to 3.4% and 3.3%, respectively, by 6 months. The most common cardiovascular symptom at 2 weeks was palpitations (1.5%), which decreased to 0.6%.

Chest Pain Increased Over Time

Reports of chest pain, however, reportedly increased over time, with 1.3% reporting chest pain at rest at 2 weeks and 2.2% at 6 months. Although gastrointestinal symptoms were common during the acute MIS-C, only 5.3% of respondents reported those symptoms at 2 weeks.

Children in the cohort had a median age of 9 years, and 60% were men. They self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: American Indian or Alaska Native (0.1%), Asian (3.3%), Black (27.0%), Hawaiian Native or Other Pacific Islander (0.2%), Hispanic or Latino (26.9%), multiracial (2.7%), White (31.2%), other (1.0%), and unknown or refused to specify (7.6%). Authors wrote that the cohort was followed-up to 2 years after illness onset and long-term results are not yet known.

Time to Exhale

David J. Goldberg, MD, with the Cardiac Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and colleagues, wrote in an accompanying editorial that “the decreased frequency of the disease along (with) the reassuring reports on midterm outcomes can allow the pediatric community a moment of collective exhale.”

The editorialists note that of those who initially presented with myocardial dysfunction, all but one patient evaluated had a normal ejection fraction at follow-up. Energy, sleep, appetite, cognition, and mood also normalized by midterm.

“The results of the MUSIC study add to the emerging midterm outcomes data suggesting a near-complete cardiovascular recovery in the overwhelming majority of patients who develop MIS-C,” Goldberg and colleagues wrote. “Despite initial concerns, driven by the severity of acute presentation at diagnosis and longer-term questions that remain (for example, does coronary microvascular dysfunction persist even after normalization of coronary artery z score?), these data suggest an encouraging outlook for the long-term health of affected children.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies have reported a declining overall incidence of MIS-C and highlighted the protective value of vaccination.

The editorialists add, however, that while the drop in MIS-C cases is encouraging, cases are still reported, especially amid high viral activity periods, “and nearly half of affected children continue to require intensive care in the acute phase of illness.”

Truong reported grants from the National Institutes of Health and serving as coprincipal investigator for Pfizer for research on COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis funded by Pfizer and occurring through the framework of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Pediatric Heart Network outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported grants from Pfizer and Boston Scientific outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving grants from Additional Ventures Foundation outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving consultant fees from Amryt Pharma, Chiesi, Esperion, and Ultragenyx outside the submitted work. A coauthor reported receiving consultant fees from Larimar Therapeutics for mitochondrial therapies outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported being an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals since July 2023. One editorialist reported grants from Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and the Arthritis Foundation, Academy Health, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who were severely ill with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) related to COVID-19 infection appear to show excellent cardiovascular and noncardiovascular outcomes by 6 months, according to data published in JAMA Pediatrics.

MIS-C is a life-threatening complication of COVID-19 infection and data on outcomes are limited, wrote the authors, led by Dongngan T. Truong, MD, MSSI, with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Cardiology, Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia. These 6-month results are from the Long-Term Outcomes After the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MUSIC) study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Researchers found in this cohort study of 1204 participants that by 6 months after hospital discharge, 99% had normalization of left ventricular systolic function, and 92.3% had normalized coronary artery dimensions. More than 95% reported being more than 90% back to baseline health.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems (PROMIS) Global Health scores were at least equivalent to prepandemic population normative values. PROMIS Global Health parent/guardian proxy median T scores for fatigue, global health, and pain interference improved significantly from 2 weeks to 6 months: fatigue, 56.1 vs 48.9; global health, 48.8 vs 51.3; pain interference, 53.0 vs 43.3 (P < .001).

The most common symptoms reported at 2 weeks were fatigue (15.9%) and low stamina/energy (9.2%); both decreased to 3.4% and 3.3%, respectively, by 6 months. The most common cardiovascular symptom at 2 weeks was palpitations (1.5%), which decreased to 0.6%.

Chest Pain Increased Over Time

Reports of chest pain, however, reportedly increased over time, with 1.3% reporting chest pain at rest at 2 weeks and 2.2% at 6 months. Although gastrointestinal symptoms were common during the acute MIS-C, only 5.3% of respondents reported those symptoms at 2 weeks.

Children in the cohort had a median age of 9 years, and 60% were men. They self-identified with the following races and ethnicities: American Indian or Alaska Native (0.1%), Asian (3.3%), Black (27.0%), Hawaiian Native or Other Pacific Islander (0.2%), Hispanic or Latino (26.9%), multiracial (2.7%), White (31.2%), other (1.0%), and unknown or refused to specify (7.6%). Authors wrote that the cohort was followed-up to 2 years after illness onset and long-term results are not yet known.

Time to Exhale

David J. Goldberg, MD, with the Cardiac Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and colleagues, wrote in an accompanying editorial that “the decreased frequency of the disease along (with) the reassuring reports on midterm outcomes can allow the pediatric community a moment of collective exhale.”

The editorialists note that of those who initially presented with myocardial dysfunction, all but one patient evaluated had a normal ejection fraction at follow-up. Energy, sleep, appetite, cognition, and mood also normalized by midterm.

“The results of the MUSIC study add to the emerging midterm outcomes data suggesting a near-complete cardiovascular recovery in the overwhelming majority of patients who develop MIS-C,” Goldberg and colleagues wrote. “Despite initial concerns, driven by the severity of acute presentation at diagnosis and longer-term questions that remain (for example, does coronary microvascular dysfunction persist even after normalization of coronary artery z score?), these data suggest an encouraging outlook for the long-term health of affected children.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies have reported a declining overall incidence of MIS-C and highlighted the protective value of vaccination.

The editorialists add, however, that while the drop in MIS-C cases is encouraging, cases are still reported, especially amid high viral activity periods, “and nearly half of affected children continue to require intensive care in the acute phase of illness.”

Truong reported grants from the National Institutes of Health and serving as coprincipal investigator for Pfizer for research on COVID-19 vaccine-associated myocarditis funded by Pfizer and occurring through the framework of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Pediatric Heart Network outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported grants from Pfizer and Boston Scientific outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving grants from Additional Ventures Foundation outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported receiving consultant fees from Amryt Pharma, Chiesi, Esperion, and Ultragenyx outside the submitted work. A coauthor reported receiving consultant fees from Larimar Therapeutics for mitochondrial therapies outside the submitted work. One coauthor reported being an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals since July 2023. One editorialist reported grants from Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and the Arthritis Foundation, Academy Health, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

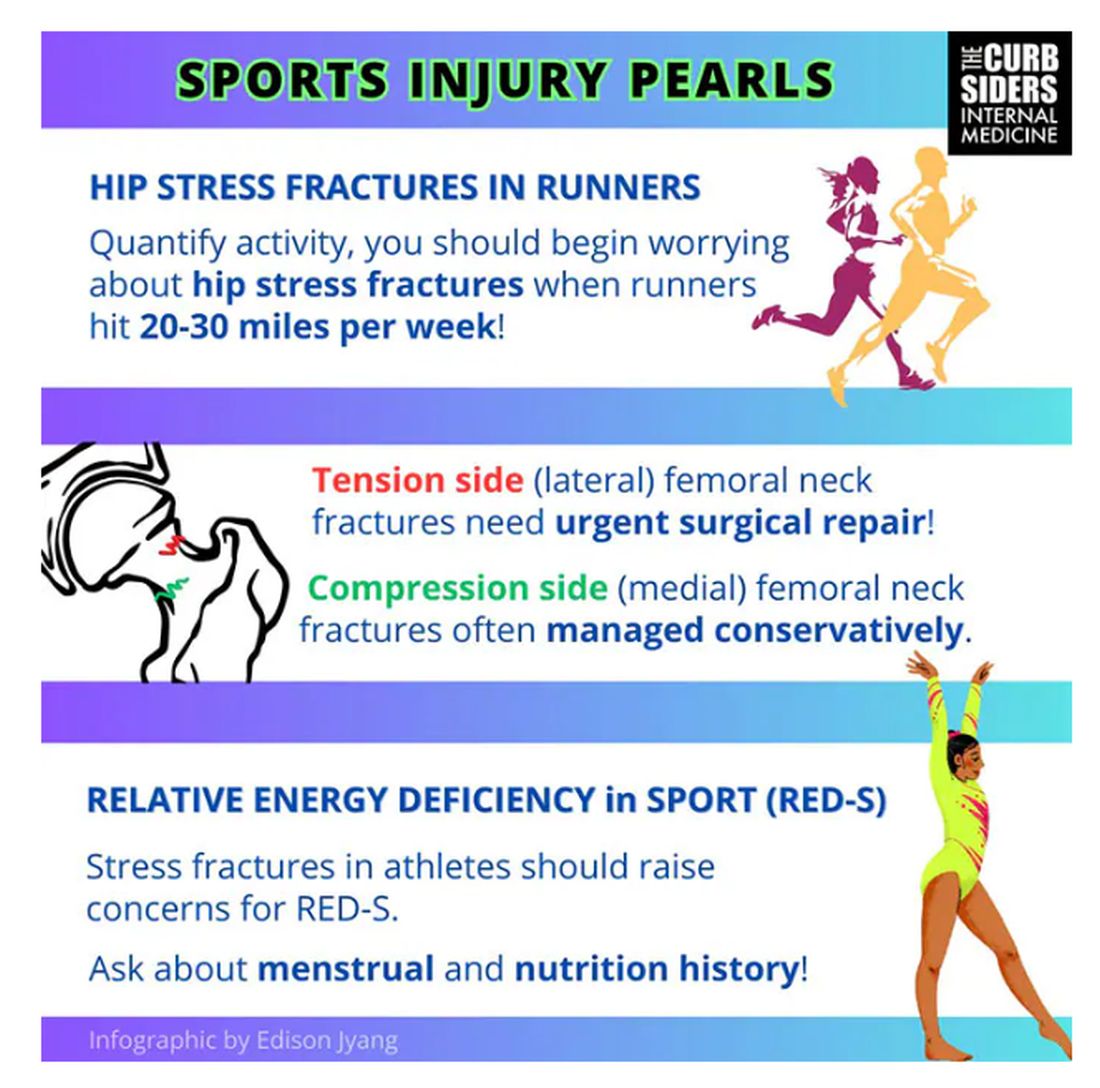

Sports Injuries of the Hip in Primary Care

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.