User login

COVID-19 pandemic brings unexpected pediatric consequences

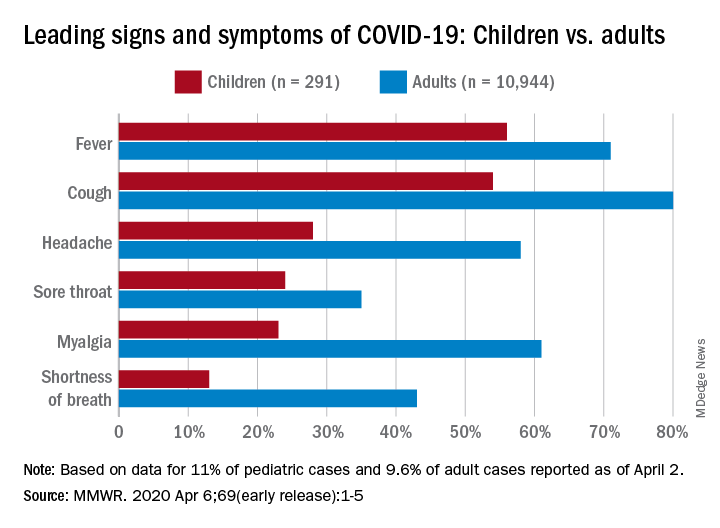

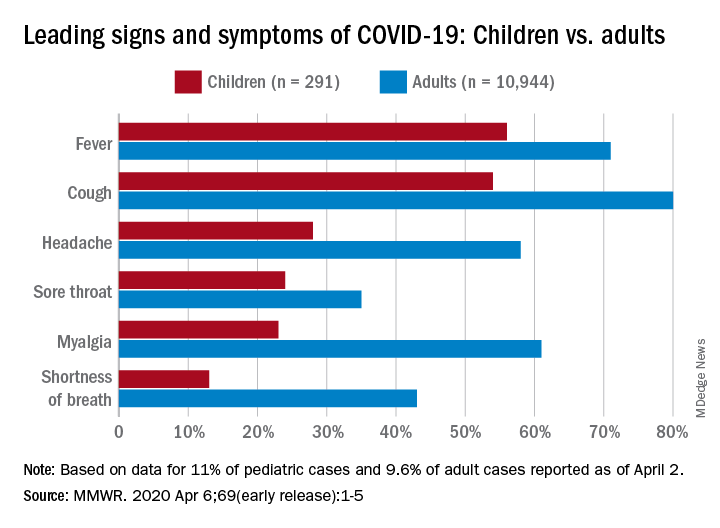

As physicians and advanced practitioners, we have been preparing to face COVID-19 – anticipating increasing volumes of patients with fevers, cough, and shortness of breath, and potential surges in emergency departments (EDs) and primary care offices. Fortunately, while COVID-19 has demonstrated more mild symptoms in pediatric patients, the heightened public health fears and mandated social isolation have created some unforeseen consequences for pediatric patients. This article presents cases encountered over the course of 2 weeks in our ED that shed light on the unexpected ramifications of living in the time of a pandemic. These encounters should remind us as providers to be diligent and thorough in giving guidance to families during a time when face-to-face medicine has become increasingly difficult and limited.

These stories have been modified to protect patient confidentiality.

Case 1

A 2-week-old full-term infant arrived in the ED after having a fever for 48 hours. The patient’s mother reported that she had called the pediatrician yesterday to ask for advice on treating the fever and was instructed to give acetaminophen and bring the infant into the ED for testing.

When we asked mom why she did not bring the infant in yesterday, she stated that the fever went down with acetaminophen, and the baby was drinking well and urinating normally. Mostly, she was afraid to bring the child into the ED given concern for COVID-19; however, when the fever persisted today, she came in. During the work-up, the infant was noted to have focal seizures and was ultimately diagnosed with bacterial meningitis.

Takeaway: Families may be hesitant to follow pediatrician’s advice to seek medical attention at an ED or doctor’s office because of the fear of being exposed to COVID-19.

- If something is urgent or emergent, be sure to stress the importance to families that the advice is non-negotiable for their child’s health.

- Attempt to call ahead for patients who might be more vulnerable in waiting rooms or overcrowded hospitals.

Case 2

A 5-month-old baby presented to the ED with new-onset seizures. Immediate bedside blood work performed demonstrated a normal blood glucose, but the baby was profoundly hyponatremic. Upon asking the mother if the baby has had any vomiting, diarrhea, or difficulty tolerating feeds, she says that she has been diluting formula because all the stores were out of formula. Today, she gave the baby plain water because they were completely out of formula.

Takeaway: With economists estimating unemployment rates in the United States at 13% at press time (the worst since the Great Depression), many families may lack resources to purchase necessities.

- Even if families have the ability to purchase necessities, they may be difficult to find or unavailable (e.g., formula, medications, diapers).

- Consider reaching out to patients in your practice to ask about their ability to find essentials and with advice on what to do if they run out of formula or diapers, or who they should contact if they cannot refill a medication.

- Are you in a position to speak with your mayor or local council to ensure there are regulations on the hoarding of essential items?

- In a time when breast milk or formula is not available for children younger than 1 year of age, what will you recommend for families? There are no current American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines.

Case 3

A school-aged girl was helping her mother sanitize the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. She had her gloves on, her commercial antiseptic cleaner ready to go, but it was not spraying. She turned the bottle around to check the nozzle and sprayed herself in the eyes. The family presented to the ED for alkaline burn to her eyes, which required copious irrigation.

Takeaway: Children are spending more time in the house with access to button batteries, choking hazards, and cleaning supplies.

- Cleaning products can cause chemical burns. These products should not be used by young children.

Case 4

A school-aged boy arrived via emergency medical services (EMS) for altered mental status. He told his father he was feeling dizzy and then lost consciousness. EMS noticed that he had some tonic movements of his lower extremities, and when he arrived in the ED, he had eye deviation and was unresponsive.

Work-up ultimately demonstrated that this patient had a seizure and a dangerously elevated ethanol level from drinking an entire bottle of hand sanitizer. Hand sanitizer may contain high concentrations of ethyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol, which when ingested can cause intoxication or poisoning.

Takeaway: Many products that we may view as harmless can be toxic if ingested in large amounts.

- Consider making a list of products that families may have acquired and have around the home during this COVID-19 pandemic and instruct families to make sure dangerous items (e.g., acetaminophen, aspirin, hand sanitizer, lighters, firearms, batteries) are locked up and/or out of reach of children.

- Make sure families know the Poison Control phone number (800-222-1222).

Case 5

An adolescent female currently being treated with immunosuppressants arrived from home with fever. Her medical history revealed that the patient’s guardian recently passed away from suspected COVID-19. The patient was tested and is herself found to be positive for COVID-19. The patient is currently being cared for by relatives who also live in the same home. They require extensive education and teaching regarding the patient’s medication regimen, while also dealing with the loss of their loved one and the fear of personal exposure.

Takeaway: Communicate with families – especially those with special health care needs – about issues of guardianship in case a child’s primary caretaker falls ill.

- Discuss with families about having easily accessible lists of medications and medical conditions.

- Involve social work and child life specialists to help children and their families deal with life-altering changes and losses suffered during this time, as well as fears related to mortality and exposure.

Case 6

A 3-year-old boy arrived covered in bruises and complaining of stomachache. While the mother denies any known abuse, she states that her significant other has been getting more and more “worked up having to deal with the child’s behavior all day every day.” The preschool the child previously attended has closed due to the pandemic.

Takeaway: Abuse is more common when the parents perceive that there is little community support and when families feel a lack of connection to the community.1 Huang et al. examined the relationship between the economy and nonaccidental trauma, showing a doubling in the rate of nonaccidental head trauma during economic recession.2

- Allow families to know that they are not alone and that child care is difficult

- Offer advice on what caretakers can do if they feel alone or at their mental or physical limit.

- Provide strategies on your practice’s website if a situation at home becomes tense and strained.

Case 7

An adolescent female arrived to the ED with increased suicidality. She normally follows with her psychiatrist once a month and her therapist once a week. Since the beginning of COVID-19 restrictions, she has been using telemedicine for her therapy visits. While previously doing well, she reports that her suicidal ideations have worsened because of feeling isolated from her friends now that school is out and she is not allowed to see them. Although compliant with her medications, her thoughts have increased to the point where she has to be admitted to inpatient psychiatry.

Takeaway: Anxiety, depression, and suicide may increase in a down economy. After the 2008 global economic crisis, rates of suicide drastically increased.3

- Recognize the limitations of telemedicine (technology limitations, patient cooperation, etc.)

- Social isolation may contribute to worsening mental health

- Know when to advise patients to seek in-person evaluation and care for medical and mental health concerns.

Pediatricians are at the forefront of preventative medicine. Families rely on pediatricians for trustworthy and accurate anticipatory guidance, a need that is only heightened during times of local and national stress. The social isolation, fear, and lack of resources accompanying this pandemic have serious consequences for our families. What can you and your practice do to keep children safe in the time of COVID-19?

Dr. Angelica DesPain is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital in Washington. Dr. Rachel Hatcliffe is an attending physician at the hospital. Neither physician had any relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. DesPain and/or Dr. Hatcliffe at [email protected].

References

1. Child Dev. 1978;49:604-16.

2. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011 Aug;8(2):171-6.

3. BMJ 2013;347:f5239.

As physicians and advanced practitioners, we have been preparing to face COVID-19 – anticipating increasing volumes of patients with fevers, cough, and shortness of breath, and potential surges in emergency departments (EDs) and primary care offices. Fortunately, while COVID-19 has demonstrated more mild symptoms in pediatric patients, the heightened public health fears and mandated social isolation have created some unforeseen consequences for pediatric patients. This article presents cases encountered over the course of 2 weeks in our ED that shed light on the unexpected ramifications of living in the time of a pandemic. These encounters should remind us as providers to be diligent and thorough in giving guidance to families during a time when face-to-face medicine has become increasingly difficult and limited.

These stories have been modified to protect patient confidentiality.

Case 1

A 2-week-old full-term infant arrived in the ED after having a fever for 48 hours. The patient’s mother reported that she had called the pediatrician yesterday to ask for advice on treating the fever and was instructed to give acetaminophen and bring the infant into the ED for testing.

When we asked mom why she did not bring the infant in yesterday, she stated that the fever went down with acetaminophen, and the baby was drinking well and urinating normally. Mostly, she was afraid to bring the child into the ED given concern for COVID-19; however, when the fever persisted today, she came in. During the work-up, the infant was noted to have focal seizures and was ultimately diagnosed with bacterial meningitis.

Takeaway: Families may be hesitant to follow pediatrician’s advice to seek medical attention at an ED or doctor’s office because of the fear of being exposed to COVID-19.

- If something is urgent or emergent, be sure to stress the importance to families that the advice is non-negotiable for their child’s health.

- Attempt to call ahead for patients who might be more vulnerable in waiting rooms or overcrowded hospitals.

Case 2

A 5-month-old baby presented to the ED with new-onset seizures. Immediate bedside blood work performed demonstrated a normal blood glucose, but the baby was profoundly hyponatremic. Upon asking the mother if the baby has had any vomiting, diarrhea, or difficulty tolerating feeds, she says that she has been diluting formula because all the stores were out of formula. Today, she gave the baby plain water because they were completely out of formula.

Takeaway: With economists estimating unemployment rates in the United States at 13% at press time (the worst since the Great Depression), many families may lack resources to purchase necessities.

- Even if families have the ability to purchase necessities, they may be difficult to find or unavailable (e.g., formula, medications, diapers).

- Consider reaching out to patients in your practice to ask about their ability to find essentials and with advice on what to do if they run out of formula or diapers, or who they should contact if they cannot refill a medication.

- Are you in a position to speak with your mayor or local council to ensure there are regulations on the hoarding of essential items?

- In a time when breast milk or formula is not available for children younger than 1 year of age, what will you recommend for families? There are no current American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines.

Case 3

A school-aged girl was helping her mother sanitize the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. She had her gloves on, her commercial antiseptic cleaner ready to go, but it was not spraying. She turned the bottle around to check the nozzle and sprayed herself in the eyes. The family presented to the ED for alkaline burn to her eyes, which required copious irrigation.

Takeaway: Children are spending more time in the house with access to button batteries, choking hazards, and cleaning supplies.

- Cleaning products can cause chemical burns. These products should not be used by young children.

Case 4

A school-aged boy arrived via emergency medical services (EMS) for altered mental status. He told his father he was feeling dizzy and then lost consciousness. EMS noticed that he had some tonic movements of his lower extremities, and when he arrived in the ED, he had eye deviation and was unresponsive.

Work-up ultimately demonstrated that this patient had a seizure and a dangerously elevated ethanol level from drinking an entire bottle of hand sanitizer. Hand sanitizer may contain high concentrations of ethyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol, which when ingested can cause intoxication or poisoning.

Takeaway: Many products that we may view as harmless can be toxic if ingested in large amounts.

- Consider making a list of products that families may have acquired and have around the home during this COVID-19 pandemic and instruct families to make sure dangerous items (e.g., acetaminophen, aspirin, hand sanitizer, lighters, firearms, batteries) are locked up and/or out of reach of children.

- Make sure families know the Poison Control phone number (800-222-1222).

Case 5

An adolescent female currently being treated with immunosuppressants arrived from home with fever. Her medical history revealed that the patient’s guardian recently passed away from suspected COVID-19. The patient was tested and is herself found to be positive for COVID-19. The patient is currently being cared for by relatives who also live in the same home. They require extensive education and teaching regarding the patient’s medication regimen, while also dealing with the loss of their loved one and the fear of personal exposure.

Takeaway: Communicate with families – especially those with special health care needs – about issues of guardianship in case a child’s primary caretaker falls ill.

- Discuss with families about having easily accessible lists of medications and medical conditions.

- Involve social work and child life specialists to help children and their families deal with life-altering changes and losses suffered during this time, as well as fears related to mortality and exposure.

Case 6

A 3-year-old boy arrived covered in bruises and complaining of stomachache. While the mother denies any known abuse, she states that her significant other has been getting more and more “worked up having to deal with the child’s behavior all day every day.” The preschool the child previously attended has closed due to the pandemic.

Takeaway: Abuse is more common when the parents perceive that there is little community support and when families feel a lack of connection to the community.1 Huang et al. examined the relationship between the economy and nonaccidental trauma, showing a doubling in the rate of nonaccidental head trauma during economic recession.2

- Allow families to know that they are not alone and that child care is difficult

- Offer advice on what caretakers can do if they feel alone or at their mental or physical limit.

- Provide strategies on your practice’s website if a situation at home becomes tense and strained.

Case 7

An adolescent female arrived to the ED with increased suicidality. She normally follows with her psychiatrist once a month and her therapist once a week. Since the beginning of COVID-19 restrictions, she has been using telemedicine for her therapy visits. While previously doing well, she reports that her suicidal ideations have worsened because of feeling isolated from her friends now that school is out and she is not allowed to see them. Although compliant with her medications, her thoughts have increased to the point where she has to be admitted to inpatient psychiatry.

Takeaway: Anxiety, depression, and suicide may increase in a down economy. After the 2008 global economic crisis, rates of suicide drastically increased.3

- Recognize the limitations of telemedicine (technology limitations, patient cooperation, etc.)

- Social isolation may contribute to worsening mental health

- Know when to advise patients to seek in-person evaluation and care for medical and mental health concerns.

Pediatricians are at the forefront of preventative medicine. Families rely on pediatricians for trustworthy and accurate anticipatory guidance, a need that is only heightened during times of local and national stress. The social isolation, fear, and lack of resources accompanying this pandemic have serious consequences for our families. What can you and your practice do to keep children safe in the time of COVID-19?

Dr. Angelica DesPain is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital in Washington. Dr. Rachel Hatcliffe is an attending physician at the hospital. Neither physician had any relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. DesPain and/or Dr. Hatcliffe at [email protected].

References

1. Child Dev. 1978;49:604-16.

2. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011 Aug;8(2):171-6.

3. BMJ 2013;347:f5239.

As physicians and advanced practitioners, we have been preparing to face COVID-19 – anticipating increasing volumes of patients with fevers, cough, and shortness of breath, and potential surges in emergency departments (EDs) and primary care offices. Fortunately, while COVID-19 has demonstrated more mild symptoms in pediatric patients, the heightened public health fears and mandated social isolation have created some unforeseen consequences for pediatric patients. This article presents cases encountered over the course of 2 weeks in our ED that shed light on the unexpected ramifications of living in the time of a pandemic. These encounters should remind us as providers to be diligent and thorough in giving guidance to families during a time when face-to-face medicine has become increasingly difficult and limited.

These stories have been modified to protect patient confidentiality.

Case 1

A 2-week-old full-term infant arrived in the ED after having a fever for 48 hours. The patient’s mother reported that she had called the pediatrician yesterday to ask for advice on treating the fever and was instructed to give acetaminophen and bring the infant into the ED for testing.

When we asked mom why she did not bring the infant in yesterday, she stated that the fever went down with acetaminophen, and the baby was drinking well and urinating normally. Mostly, she was afraid to bring the child into the ED given concern for COVID-19; however, when the fever persisted today, she came in. During the work-up, the infant was noted to have focal seizures and was ultimately diagnosed with bacterial meningitis.

Takeaway: Families may be hesitant to follow pediatrician’s advice to seek medical attention at an ED or doctor’s office because of the fear of being exposed to COVID-19.

- If something is urgent or emergent, be sure to stress the importance to families that the advice is non-negotiable for their child’s health.

- Attempt to call ahead for patients who might be more vulnerable in waiting rooms or overcrowded hospitals.

Case 2

A 5-month-old baby presented to the ED with new-onset seizures. Immediate bedside blood work performed demonstrated a normal blood glucose, but the baby was profoundly hyponatremic. Upon asking the mother if the baby has had any vomiting, diarrhea, or difficulty tolerating feeds, she says that she has been diluting formula because all the stores were out of formula. Today, she gave the baby plain water because they were completely out of formula.

Takeaway: With economists estimating unemployment rates in the United States at 13% at press time (the worst since the Great Depression), many families may lack resources to purchase necessities.

- Even if families have the ability to purchase necessities, they may be difficult to find or unavailable (e.g., formula, medications, diapers).

- Consider reaching out to patients in your practice to ask about their ability to find essentials and with advice on what to do if they run out of formula or diapers, or who they should contact if they cannot refill a medication.

- Are you in a position to speak with your mayor or local council to ensure there are regulations on the hoarding of essential items?

- In a time when breast milk or formula is not available for children younger than 1 year of age, what will you recommend for families? There are no current American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines.

Case 3

A school-aged girl was helping her mother sanitize the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. She had her gloves on, her commercial antiseptic cleaner ready to go, but it was not spraying. She turned the bottle around to check the nozzle and sprayed herself in the eyes. The family presented to the ED for alkaline burn to her eyes, which required copious irrigation.

Takeaway: Children are spending more time in the house with access to button batteries, choking hazards, and cleaning supplies.

- Cleaning products can cause chemical burns. These products should not be used by young children.

Case 4

A school-aged boy arrived via emergency medical services (EMS) for altered mental status. He told his father he was feeling dizzy and then lost consciousness. EMS noticed that he had some tonic movements of his lower extremities, and when he arrived in the ED, he had eye deviation and was unresponsive.

Work-up ultimately demonstrated that this patient had a seizure and a dangerously elevated ethanol level from drinking an entire bottle of hand sanitizer. Hand sanitizer may contain high concentrations of ethyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol, which when ingested can cause intoxication or poisoning.

Takeaway: Many products that we may view as harmless can be toxic if ingested in large amounts.

- Consider making a list of products that families may have acquired and have around the home during this COVID-19 pandemic and instruct families to make sure dangerous items (e.g., acetaminophen, aspirin, hand sanitizer, lighters, firearms, batteries) are locked up and/or out of reach of children.

- Make sure families know the Poison Control phone number (800-222-1222).

Case 5

An adolescent female currently being treated with immunosuppressants arrived from home with fever. Her medical history revealed that the patient’s guardian recently passed away from suspected COVID-19. The patient was tested and is herself found to be positive for COVID-19. The patient is currently being cared for by relatives who also live in the same home. They require extensive education and teaching regarding the patient’s medication regimen, while also dealing with the loss of their loved one and the fear of personal exposure.

Takeaway: Communicate with families – especially those with special health care needs – about issues of guardianship in case a child’s primary caretaker falls ill.

- Discuss with families about having easily accessible lists of medications and medical conditions.

- Involve social work and child life specialists to help children and their families deal with life-altering changes and losses suffered during this time, as well as fears related to mortality and exposure.

Case 6

A 3-year-old boy arrived covered in bruises and complaining of stomachache. While the mother denies any known abuse, she states that her significant other has been getting more and more “worked up having to deal with the child’s behavior all day every day.” The preschool the child previously attended has closed due to the pandemic.

Takeaway: Abuse is more common when the parents perceive that there is little community support and when families feel a lack of connection to the community.1 Huang et al. examined the relationship between the economy and nonaccidental trauma, showing a doubling in the rate of nonaccidental head trauma during economic recession.2

- Allow families to know that they are not alone and that child care is difficult

- Offer advice on what caretakers can do if they feel alone or at their mental or physical limit.

- Provide strategies on your practice’s website if a situation at home becomes tense and strained.

Case 7

An adolescent female arrived to the ED with increased suicidality. She normally follows with her psychiatrist once a month and her therapist once a week. Since the beginning of COVID-19 restrictions, she has been using telemedicine for her therapy visits. While previously doing well, she reports that her suicidal ideations have worsened because of feeling isolated from her friends now that school is out and she is not allowed to see them. Although compliant with her medications, her thoughts have increased to the point where she has to be admitted to inpatient psychiatry.

Takeaway: Anxiety, depression, and suicide may increase in a down economy. After the 2008 global economic crisis, rates of suicide drastically increased.3

- Recognize the limitations of telemedicine (technology limitations, patient cooperation, etc.)

- Social isolation may contribute to worsening mental health

- Know when to advise patients to seek in-person evaluation and care for medical and mental health concerns.

Pediatricians are at the forefront of preventative medicine. Families rely on pediatricians for trustworthy and accurate anticipatory guidance, a need that is only heightened during times of local and national stress. The social isolation, fear, and lack of resources accompanying this pandemic have serious consequences for our families. What can you and your practice do to keep children safe in the time of COVID-19?

Dr. Angelica DesPain is a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Hospital in Washington. Dr. Rachel Hatcliffe is an attending physician at the hospital. Neither physician had any relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. DesPain and/or Dr. Hatcliffe at [email protected].

References

1. Child Dev. 1978;49:604-16.

2. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011 Aug;8(2):171-6.

3. BMJ 2013;347:f5239.

Managing gynecologic cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic

To manage patients with gynecologic cancers, oncologists in the United States and Europe are recommending reducing outpatient visits, delaying surgeries, prolonging chemotherapy regimens, and generally trying to keep cancer patients away from those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

“We recognize that, in this special situation, we must continue to provide our gynecologic oncology patients with the highest quality of medical services,” Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and associates wrote in an editorial published in the International Journal of Gynecological Cancer.

At the same time, the authors added, the safety of patients, their families, and medical staff needs to be assured.

Dr. Ramirez and colleagues’ editorial includes recommendations on how to optimize the care of patients with gynecologic cancers while prioritizing safety and minimizing the burden to the healthcare system. The group’s recommendations outline when surgery, radiotherapy, and other treatments might be safely postponed and when they need to proceed out of urgency.

Some authors of the editorial also described their experiences with COVID-19 during a webinar on managing patients with advanced ovarian cancer, which was hosted by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO).

A lack of resources

In Spain, health resources “are collapsed” by the pandemic, editorial author Luis Chiva, MD, said during the webinar.

At his institution, the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, 98% of the 1,500 intensive care beds were occupied by COVID-19 patients at the end of March. So the hope was to be able to refer their patients to other communities where there may still be some capacity.

Another problem in Spain is the high percentage of health workers infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. More than 15,000 health workers were recently reported to be sick or self-isolating, which is around 14% of the health care workforce in the country.

Dr. Chiva noted that this puts those treating gynecologic cancers in a difficult position. On the one hand, surgery to remove a high-risk ovarian mass should not be delayed, but the majority of hospitals in Spain simply cannot perform this type of surgery during the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, due to this specific situation, almost, I would say in 80%-90% of hospitals, we are only able to carry out emergency surgical procedures,” Dr. Chiva said. That’s general emergency procedures such as appendectomies, removing blockages, and dealing with hemorrhages, not gynecologic surgeries. “It’s almost impossible to schedule the typical oncological cases,” he said.

Even with the Hospital IFEMA now set up at the Feria de Madrid, which is usually used to host large-scale events, there are “minimal options for performing standard oncological surgery,” Dr. Chiva said. He estimated that just 5% of hospitals in Spain are able to perform oncologic surgeries as normal, with maybe 15% able to offer surgery without the backup of postsurgical intensive care.

‘Ring-fencing’

“This is really an unusual time for us,” commented Jonathan Ledermann, MD, vice president of ESGO and a professor of medical oncology at University College London, who moderated the webinar.

“This is affecting the way in which we diagnose our patients and have access to care,” he said. “It compromises the way in which we treat patients. We have to adjust our treatment pathways. We have to look at the risks of coronavirus infection in cancer patients and how we manage patients in a socially distancing environment. We also need to think about managing gynecological oncology departments in the face of disease amongst staff, the risks of transmission, and the reduced clinical service.”

Dr. Ledermann noted that “ring-fencing” a few hospitals to deal only with patients free of COVID-19 might be a way forward. This approach has been used in Northern Italy and was recently started in London.

“We try to divide and have separate access between COVID-positive and -negative patients,” said Anna Fagotti, MD, an assistant professor at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome and another coauthor of the editorial.

“We are trying to divide the work flow of patients and try to ensure treatment to cancer patients as much as we can,” she explained. “This means that it’s a very difficult situation, and, every time, you have to deal with the number of places available as some places have been taken by other patients from the emergency room. We are still trying to have a number of beds and intensive care unit beds available for our patients.”

Setting up dedicated hospitals is a good idea, but it has to be done before the “tsunami” of cases hits and there are no more intensive care beds or ventilators, according to Antonio González-Martín, MD, of Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, another coauthor of the editorial.

Limiting hospital visits

Strategies to limit the number of times patients need to come into hospital for appointments and treatment is key to getting through the pandemic, Sandro Pignata, MD, of Instituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale in Naples, Italy, said during the webinar.

“It will be imperative to explore options that reduce the number of procedures or surgical interventions that may be associated with prolonged operative time, risk of major blood loss, necessitating blood products, risk of infection to the medical personnel, or admission to intensive care units,” Dr. Ramirez and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

“In considering management of disease, we must recognize that, in many centers, access to routine visits and surgery may be either completely restricted or significantly reduced. We must, therefore, consider options that may still offer our patients a treatment plan that addresses their disease while at the same time limiting risk of exposure,” the authors wrote.

The authors declared no competing interests or specific funding in relation to their work, and the webinar participants had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ramirez PT et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001419.

To manage patients with gynecologic cancers, oncologists in the United States and Europe are recommending reducing outpatient visits, delaying surgeries, prolonging chemotherapy regimens, and generally trying to keep cancer patients away from those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

“We recognize that, in this special situation, we must continue to provide our gynecologic oncology patients with the highest quality of medical services,” Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and associates wrote in an editorial published in the International Journal of Gynecological Cancer.

At the same time, the authors added, the safety of patients, their families, and medical staff needs to be assured.

Dr. Ramirez and colleagues’ editorial includes recommendations on how to optimize the care of patients with gynecologic cancers while prioritizing safety and minimizing the burden to the healthcare system. The group’s recommendations outline when surgery, radiotherapy, and other treatments might be safely postponed and when they need to proceed out of urgency.

Some authors of the editorial also described their experiences with COVID-19 during a webinar on managing patients with advanced ovarian cancer, which was hosted by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO).

A lack of resources

In Spain, health resources “are collapsed” by the pandemic, editorial author Luis Chiva, MD, said during the webinar.

At his institution, the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, 98% of the 1,500 intensive care beds were occupied by COVID-19 patients at the end of March. So the hope was to be able to refer their patients to other communities where there may still be some capacity.

Another problem in Spain is the high percentage of health workers infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. More than 15,000 health workers were recently reported to be sick or self-isolating, which is around 14% of the health care workforce in the country.

Dr. Chiva noted that this puts those treating gynecologic cancers in a difficult position. On the one hand, surgery to remove a high-risk ovarian mass should not be delayed, but the majority of hospitals in Spain simply cannot perform this type of surgery during the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, due to this specific situation, almost, I would say in 80%-90% of hospitals, we are only able to carry out emergency surgical procedures,” Dr. Chiva said. That’s general emergency procedures such as appendectomies, removing blockages, and dealing with hemorrhages, not gynecologic surgeries. “It’s almost impossible to schedule the typical oncological cases,” he said.

Even with the Hospital IFEMA now set up at the Feria de Madrid, which is usually used to host large-scale events, there are “minimal options for performing standard oncological surgery,” Dr. Chiva said. He estimated that just 5% of hospitals in Spain are able to perform oncologic surgeries as normal, with maybe 15% able to offer surgery without the backup of postsurgical intensive care.

‘Ring-fencing’

“This is really an unusual time for us,” commented Jonathan Ledermann, MD, vice president of ESGO and a professor of medical oncology at University College London, who moderated the webinar.

“This is affecting the way in which we diagnose our patients and have access to care,” he said. “It compromises the way in which we treat patients. We have to adjust our treatment pathways. We have to look at the risks of coronavirus infection in cancer patients and how we manage patients in a socially distancing environment. We also need to think about managing gynecological oncology departments in the face of disease amongst staff, the risks of transmission, and the reduced clinical service.”

Dr. Ledermann noted that “ring-fencing” a few hospitals to deal only with patients free of COVID-19 might be a way forward. This approach has been used in Northern Italy and was recently started in London.

“We try to divide and have separate access between COVID-positive and -negative patients,” said Anna Fagotti, MD, an assistant professor at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome and another coauthor of the editorial.

“We are trying to divide the work flow of patients and try to ensure treatment to cancer patients as much as we can,” she explained. “This means that it’s a very difficult situation, and, every time, you have to deal with the number of places available as some places have been taken by other patients from the emergency room. We are still trying to have a number of beds and intensive care unit beds available for our patients.”

Setting up dedicated hospitals is a good idea, but it has to be done before the “tsunami” of cases hits and there are no more intensive care beds or ventilators, according to Antonio González-Martín, MD, of Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, another coauthor of the editorial.

Limiting hospital visits

Strategies to limit the number of times patients need to come into hospital for appointments and treatment is key to getting through the pandemic, Sandro Pignata, MD, of Instituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale in Naples, Italy, said during the webinar.

“It will be imperative to explore options that reduce the number of procedures or surgical interventions that may be associated with prolonged operative time, risk of major blood loss, necessitating blood products, risk of infection to the medical personnel, or admission to intensive care units,” Dr. Ramirez and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

“In considering management of disease, we must recognize that, in many centers, access to routine visits and surgery may be either completely restricted or significantly reduced. We must, therefore, consider options that may still offer our patients a treatment plan that addresses their disease while at the same time limiting risk of exposure,” the authors wrote.

The authors declared no competing interests or specific funding in relation to their work, and the webinar participants had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ramirez PT et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001419.

To manage patients with gynecologic cancers, oncologists in the United States and Europe are recommending reducing outpatient visits, delaying surgeries, prolonging chemotherapy regimens, and generally trying to keep cancer patients away from those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

“We recognize that, in this special situation, we must continue to provide our gynecologic oncology patients with the highest quality of medical services,” Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and associates wrote in an editorial published in the International Journal of Gynecological Cancer.

At the same time, the authors added, the safety of patients, their families, and medical staff needs to be assured.

Dr. Ramirez and colleagues’ editorial includes recommendations on how to optimize the care of patients with gynecologic cancers while prioritizing safety and minimizing the burden to the healthcare system. The group’s recommendations outline when surgery, radiotherapy, and other treatments might be safely postponed and when they need to proceed out of urgency.

Some authors of the editorial also described their experiences with COVID-19 during a webinar on managing patients with advanced ovarian cancer, which was hosted by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO).

A lack of resources

In Spain, health resources “are collapsed” by the pandemic, editorial author Luis Chiva, MD, said during the webinar.

At his institution, the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, 98% of the 1,500 intensive care beds were occupied by COVID-19 patients at the end of March. So the hope was to be able to refer their patients to other communities where there may still be some capacity.

Another problem in Spain is the high percentage of health workers infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. More than 15,000 health workers were recently reported to be sick or self-isolating, which is around 14% of the health care workforce in the country.

Dr. Chiva noted that this puts those treating gynecologic cancers in a difficult position. On the one hand, surgery to remove a high-risk ovarian mass should not be delayed, but the majority of hospitals in Spain simply cannot perform this type of surgery during the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, due to this specific situation, almost, I would say in 80%-90% of hospitals, we are only able to carry out emergency surgical procedures,” Dr. Chiva said. That’s general emergency procedures such as appendectomies, removing blockages, and dealing with hemorrhages, not gynecologic surgeries. “It’s almost impossible to schedule the typical oncological cases,” he said.

Even with the Hospital IFEMA now set up at the Feria de Madrid, which is usually used to host large-scale events, there are “minimal options for performing standard oncological surgery,” Dr. Chiva said. He estimated that just 5% of hospitals in Spain are able to perform oncologic surgeries as normal, with maybe 15% able to offer surgery without the backup of postsurgical intensive care.

‘Ring-fencing’

“This is really an unusual time for us,” commented Jonathan Ledermann, MD, vice president of ESGO and a professor of medical oncology at University College London, who moderated the webinar.

“This is affecting the way in which we diagnose our patients and have access to care,” he said. “It compromises the way in which we treat patients. We have to adjust our treatment pathways. We have to look at the risks of coronavirus infection in cancer patients and how we manage patients in a socially distancing environment. We also need to think about managing gynecological oncology departments in the face of disease amongst staff, the risks of transmission, and the reduced clinical service.”

Dr. Ledermann noted that “ring-fencing” a few hospitals to deal only with patients free of COVID-19 might be a way forward. This approach has been used in Northern Italy and was recently started in London.

“We try to divide and have separate access between COVID-positive and -negative patients,” said Anna Fagotti, MD, an assistant professor at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome and another coauthor of the editorial.

“We are trying to divide the work flow of patients and try to ensure treatment to cancer patients as much as we can,” she explained. “This means that it’s a very difficult situation, and, every time, you have to deal with the number of places available as some places have been taken by other patients from the emergency room. We are still trying to have a number of beds and intensive care unit beds available for our patients.”

Setting up dedicated hospitals is a good idea, but it has to be done before the “tsunami” of cases hits and there are no more intensive care beds or ventilators, according to Antonio González-Martín, MD, of Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, another coauthor of the editorial.

Limiting hospital visits

Strategies to limit the number of times patients need to come into hospital for appointments and treatment is key to getting through the pandemic, Sandro Pignata, MD, of Instituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale in Naples, Italy, said during the webinar.

“It will be imperative to explore options that reduce the number of procedures or surgical interventions that may be associated with prolonged operative time, risk of major blood loss, necessitating blood products, risk of infection to the medical personnel, or admission to intensive care units,” Dr. Ramirez and colleagues wrote in their editorial.

“In considering management of disease, we must recognize that, in many centers, access to routine visits and surgery may be either completely restricted or significantly reduced. We must, therefore, consider options that may still offer our patients a treatment plan that addresses their disease while at the same time limiting risk of exposure,” the authors wrote.

The authors declared no competing interests or specific funding in relation to their work, and the webinar participants had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ramirez PT et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001419.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGICAL CANCER

Most endometrial cancers treated with minimally invasive procedures

Of 3,730 women with endometrial cancer in the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Clinical Outcomes Registry (SGO-COR), 88.8% underwent minimally invasive procedures, reported Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“When you have surgery with a gyn-oncologist who is specially trained in this type of surgery, we see that women have a very high likelihood of having the appropriate surgery, the minimally invasive surgery, and we thought that this benchmark of an 80% rate of minimally invasive surgery in these patients is very feasible and should be recognized as the standard of care,” Dr. Nickles Fader said in an interview.

Coinvestigator Summer B. Dewdney, MD, of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was instrumental in creating and running the SGO-COR registry, said these findings are encouraging.

“We’re happy to see that rate. It’s the rate that it should be because minimally invasive surgery is the standard of care for endometrial cancer,” Dr. Dewdney said. She added, however, that data supplied to the registry come from gynecologic oncologists who are highly motivated to participate and follow best practice guidelines, which could skew the results slightly toward more favorable outcomes.

Results of the registry-based study are detailed in an abstract that was slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Assessing adherence to guidelines

In 2015, the SGO Clinical Practice Committee and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a practice bulletin, which stated that “minimally invasive surgery should be embraced as the standard surgical approach for comprehensive surgical staging in women with endometrial cancer.”

Similarly, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for uterine cancer state that “minimally invasive surgery is the preferred approach when technically feasible” for treatment of endometrial cancer confined to the uterus.

Despite these recommendations, the overall rate of minimally invasive endometrial cancer surgery in the United States is reported be around to 60%, Dr. Nickles Fader and colleagues wrote.

With this in mind, the investigators set out to determine the rate of minimally invasive surgery in women with apparent stage I, II, or III endometrial cancer who underwent hysterectomy with or without staging from 2012 to 2017 at a center reporting to SGO-COR.

The team identified 3,730 women treated at 25 SGO-COR centers; 12 of which were university-affiliated centers and 13 of which were nonuniversity based. Most patients (83.2%) had stage I disease, 4.7% had stage II cancer, and 12.1% had stage III disease. The median patient age was 57 years. Most patients (88%) were white, and two-thirds (67.1%) were obese. In all, 80.4% of samples had endometrioid histology, and 77.7% were either grade 1 or 2.

Factors associated with minimally invasive surgery

The data showed that 88.8% of patients underwent a minimally invasive hysterectomy, composed of robotic-assisted procedures in 73.9% of cases, laparoscopy in 13.4%, and vaginal access in 1.6%.

The proportion of patients who underwent a minimally invasive procedure was significantly higher at nonuniversity centers, compared with academic centers (92.6% vs. 82.7%; P < .0001), but rates of minimally invasive procedures did not differ significantly across U.S. geographic regions.

Dr. Dewdney said that the higher proportion of open surgeries performed at university centers may be attributable to those centers treating patients with more advanced disease or rare aggressive cancers that may not be amenable to a minimally invasive approach.

In a multivariate analysis, factors associated with a failure to perform minimally invasive surgery were black race of the patient (adjusted odds ratio, 0.57), body mass index over 35 kg/m2 (aOR, 1.40), stage II disease (aOR, 0.49), stage III disease (aOR, 0.36), carcinosarcoma/leiomyosarcoma (aOR, 0.58), and university hospital (aOR, 3.46).

Looking at perioperative complications, the investigators found that laparotomy was associated with more in-hospital complications than minimally invasive procedures, including more unscheduled ICU stays (P < .001) and prolonged hospital stays (P = .0002).

Dr. Dewdney said that investigators are planning further registry-based studies focusing on ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, and cervical cancer.

Dr. Nickles Fader and Dr. Dewdney reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nickles Fader A et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 63.

Of 3,730 women with endometrial cancer in the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Clinical Outcomes Registry (SGO-COR), 88.8% underwent minimally invasive procedures, reported Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“When you have surgery with a gyn-oncologist who is specially trained in this type of surgery, we see that women have a very high likelihood of having the appropriate surgery, the minimally invasive surgery, and we thought that this benchmark of an 80% rate of minimally invasive surgery in these patients is very feasible and should be recognized as the standard of care,” Dr. Nickles Fader said in an interview.

Coinvestigator Summer B. Dewdney, MD, of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was instrumental in creating and running the SGO-COR registry, said these findings are encouraging.

“We’re happy to see that rate. It’s the rate that it should be because minimally invasive surgery is the standard of care for endometrial cancer,” Dr. Dewdney said. She added, however, that data supplied to the registry come from gynecologic oncologists who are highly motivated to participate and follow best practice guidelines, which could skew the results slightly toward more favorable outcomes.

Results of the registry-based study are detailed in an abstract that was slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Assessing adherence to guidelines

In 2015, the SGO Clinical Practice Committee and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a practice bulletin, which stated that “minimally invasive surgery should be embraced as the standard surgical approach for comprehensive surgical staging in women with endometrial cancer.”

Similarly, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for uterine cancer state that “minimally invasive surgery is the preferred approach when technically feasible” for treatment of endometrial cancer confined to the uterus.

Despite these recommendations, the overall rate of minimally invasive endometrial cancer surgery in the United States is reported be around to 60%, Dr. Nickles Fader and colleagues wrote.

With this in mind, the investigators set out to determine the rate of minimally invasive surgery in women with apparent stage I, II, or III endometrial cancer who underwent hysterectomy with or without staging from 2012 to 2017 at a center reporting to SGO-COR.

The team identified 3,730 women treated at 25 SGO-COR centers; 12 of which were university-affiliated centers and 13 of which were nonuniversity based. Most patients (83.2%) had stage I disease, 4.7% had stage II cancer, and 12.1% had stage III disease. The median patient age was 57 years. Most patients (88%) were white, and two-thirds (67.1%) were obese. In all, 80.4% of samples had endometrioid histology, and 77.7% were either grade 1 or 2.

Factors associated with minimally invasive surgery

The data showed that 88.8% of patients underwent a minimally invasive hysterectomy, composed of robotic-assisted procedures in 73.9% of cases, laparoscopy in 13.4%, and vaginal access in 1.6%.

The proportion of patients who underwent a minimally invasive procedure was significantly higher at nonuniversity centers, compared with academic centers (92.6% vs. 82.7%; P < .0001), but rates of minimally invasive procedures did not differ significantly across U.S. geographic regions.

Dr. Dewdney said that the higher proportion of open surgeries performed at university centers may be attributable to those centers treating patients with more advanced disease or rare aggressive cancers that may not be amenable to a minimally invasive approach.

In a multivariate analysis, factors associated with a failure to perform minimally invasive surgery were black race of the patient (adjusted odds ratio, 0.57), body mass index over 35 kg/m2 (aOR, 1.40), stage II disease (aOR, 0.49), stage III disease (aOR, 0.36), carcinosarcoma/leiomyosarcoma (aOR, 0.58), and university hospital (aOR, 3.46).

Looking at perioperative complications, the investigators found that laparotomy was associated with more in-hospital complications than minimally invasive procedures, including more unscheduled ICU stays (P < .001) and prolonged hospital stays (P = .0002).

Dr. Dewdney said that investigators are planning further registry-based studies focusing on ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, and cervical cancer.

Dr. Nickles Fader and Dr. Dewdney reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nickles Fader A et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 63.

Of 3,730 women with endometrial cancer in the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Clinical Outcomes Registry (SGO-COR), 88.8% underwent minimally invasive procedures, reported Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“When you have surgery with a gyn-oncologist who is specially trained in this type of surgery, we see that women have a very high likelihood of having the appropriate surgery, the minimally invasive surgery, and we thought that this benchmark of an 80% rate of minimally invasive surgery in these patients is very feasible and should be recognized as the standard of care,” Dr. Nickles Fader said in an interview.

Coinvestigator Summer B. Dewdney, MD, of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was instrumental in creating and running the SGO-COR registry, said these findings are encouraging.

“We’re happy to see that rate. It’s the rate that it should be because minimally invasive surgery is the standard of care for endometrial cancer,” Dr. Dewdney said. She added, however, that data supplied to the registry come from gynecologic oncologists who are highly motivated to participate and follow best practice guidelines, which could skew the results slightly toward more favorable outcomes.

Results of the registry-based study are detailed in an abstract that was slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Assessing adherence to guidelines

In 2015, the SGO Clinical Practice Committee and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a practice bulletin, which stated that “minimally invasive surgery should be embraced as the standard surgical approach for comprehensive surgical staging in women with endometrial cancer.”

Similarly, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for uterine cancer state that “minimally invasive surgery is the preferred approach when technically feasible” for treatment of endometrial cancer confined to the uterus.

Despite these recommendations, the overall rate of minimally invasive endometrial cancer surgery in the United States is reported be around to 60%, Dr. Nickles Fader and colleagues wrote.

With this in mind, the investigators set out to determine the rate of minimally invasive surgery in women with apparent stage I, II, or III endometrial cancer who underwent hysterectomy with or without staging from 2012 to 2017 at a center reporting to SGO-COR.

The team identified 3,730 women treated at 25 SGO-COR centers; 12 of which were university-affiliated centers and 13 of which were nonuniversity based. Most patients (83.2%) had stage I disease, 4.7% had stage II cancer, and 12.1% had stage III disease. The median patient age was 57 years. Most patients (88%) were white, and two-thirds (67.1%) were obese. In all, 80.4% of samples had endometrioid histology, and 77.7% were either grade 1 or 2.

Factors associated with minimally invasive surgery

The data showed that 88.8% of patients underwent a minimally invasive hysterectomy, composed of robotic-assisted procedures in 73.9% of cases, laparoscopy in 13.4%, and vaginal access in 1.6%.

The proportion of patients who underwent a minimally invasive procedure was significantly higher at nonuniversity centers, compared with academic centers (92.6% vs. 82.7%; P < .0001), but rates of minimally invasive procedures did not differ significantly across U.S. geographic regions.

Dr. Dewdney said that the higher proportion of open surgeries performed at university centers may be attributable to those centers treating patients with more advanced disease or rare aggressive cancers that may not be amenable to a minimally invasive approach.

In a multivariate analysis, factors associated with a failure to perform minimally invasive surgery were black race of the patient (adjusted odds ratio, 0.57), body mass index over 35 kg/m2 (aOR, 1.40), stage II disease (aOR, 0.49), stage III disease (aOR, 0.36), carcinosarcoma/leiomyosarcoma (aOR, 0.58), and university hospital (aOR, 3.46).

Looking at perioperative complications, the investigators found that laparotomy was associated with more in-hospital complications than minimally invasive procedures, including more unscheduled ICU stays (P < .001) and prolonged hospital stays (P = .0002).

Dr. Dewdney said that investigators are planning further registry-based studies focusing on ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, and cervical cancer.

Dr. Nickles Fader and Dr. Dewdney reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Nickles Fader A et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 63.

FROM SGO 2020

Learning to live with COVID-19: Postpandemic life will be reflected in how effectively we leverage this crisis

While often compared with the Spanish influenza contagion of 1918, the current COVID-19 pandemic is arguably unprecedented in scale and scope, global reach, and the rate at which it has spread across the world.

Unprecedented times

The United States now has the greatest burden of COVID-19 disease worldwide.1 Although Boston has thus far been spared the full force of the disease’s impact, it is likely only a matter of time before it reaches here. To prepare for the imminent surge, we at Tufts Medical Center defined 4 short-term strategic imperatives to help guide our COVID-19 preparedness. Having a single unified strategy across our organization has helped to maintain focus and consistency in the messaging amidst all of the uncertainty. Our focus areas are outlined below.

1 Flatten the curve

This term refers to the use of “social distancing” and community isolation measures to keep the number of disease cases at a manageable level. COVID-19 is spread almost exclusively through contact with contaminated respiratory droplets. While several categories of risk have been described, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines disease “exposure” as face-to-face contact within 6 feet of an infected individual for more than 15 minutes without wearing a mask.2 Intervening at all 3 of these touchpoints effectively reduces transmission. Interventions include limiting in-person meetings, increasing the space between individuals (both providers and patients), and routinely using personal protective equipment (PPE).

Another effective strategy is to divide frontline providers into smaller units or teams to limit cross-contamination: the inpatient team versus the outpatient team, the day team versus the night team, the “on” team versus the “off” team. If the infection lays one team low, other providers can step in until they recover and return to work.

Visitor policies should be developed and strictly implemented. Many institutions do allow one support person in labor and delivery (L&D) regardless of the patient’s COVID-19 status, although that person should not be symptomatic or COVID-19 positive. Whether to test all patients and support persons for COVID-19 on arrival at L&D remains controversial.3 At a minimum, these individuals should be screened for symptoms. Although it was a major focus of initial preventative efforts, taking a travel and exposure history is no longer informative as the virus is now endemic and community spread is common.

Initial preventative efforts focused also on high-risk patients, but routine use of PPE for all encounters clearly is more effective because of the high rate of asymptomatic shedding. The virus can survive suspended in the air for up to 2 hours following an aerosol-generating procedure (AGP) and on surfaces for several hours or even days. Practices such as regular handwashing, cleaning of exposed work surfaces, and avoiding face touching should by now be part of our everyday routine.

Institutions throughout the United States have established inpatient COVID-19 units—so-called “dirty” units—with mixed success. As the pandemic spreads and the number of patients with asymptomatic shedding increases, it is harder to determine who is and who is not infected. Cross-contamination has rendered this approach largely ineffective. Whether this will change with the introduction of rapid point-of-care testing remains to be seen.

Continue to: 2 Preserve PPE...

2 Preserve PPE

PPE use is effective in reducing transmission. This includes tier 1 PPE with or without enhanced droplet precaution (surgical mask, eye protection, gloves, yellow gown) and tier 2 PPE (tier 1 plus N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators [PAPR]). Given the acute PPE shortage in many parts of the country, appropriate use of PPE is critical to maintain an adequate supply. For example, tier 2 PPE is required only in the setting of an AGP. This includes intubation and, in our determination, the second stage of labor for COVID-19–positive patients and patients under investigation (PUIs); we do not employ tier 2 PPE for all patients in the second stage of labor, although some hospitals endorse this practice.

Creative solutions to the impending PPE shortage abound, such as the use of 3D printers to make face shields and novel techniques to sterilize and reuse N95 respirators.

3 Create capacity

In the absence of effective treatment for COVID-19 and with a vaccine still many months away, supportive care is critical. The pulmonary sequelae with cytokine storm and acute hypoxemia can come on quickly, require urgent mechanical ventilatory support, and take several weeks to resolve.

Our ability to create inpatient capacity to accommodate ill patients, monitor them closely, and intubate early will likely be the most critical driver of the case fatality rate. This requires deferring outpatient visits (or doing them via telemedicine), expanding intensive care unit capabilities (especially ventilator beds), and canceling elective surgeries. What constitutes “elective surgery” is not always clear. Our institution, for example, regards abortion services as essential and not elective, but this is not the case throughout the United States.

Creating capacity also refers to staffing. Where necessary, providers should be retrained and redeployed. This may require emergency credentialing of providers in areas outside their usual clinical practice and permission may be needed from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to engage trainees outside their usual duty hours.

4 Support and protect your workforce

Everyone is anxious, and people convey their anxiety in different ways. I have found it helpful to acknowledge those feelings and provide a forum for staff to express and share their anxieties. That said, hospitals are not a democracy. While staff members should be encouraged to ask questions and voice their opinions, everyone is expected to follow protocol regarding patient care.

Celebrating small successes and finding creative ways to alleviate the stress and inject humor can help. Most institutions are using electronic conferencing platforms (such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams) to stay in touch and to continue education initiatives through interactive didactic sessions, grand rounds, morbidity and mortality conferences, and e-journal clubs. These are also a great platform for social events, such as w(h)ine and book clubs and virtual karaoke.

Since many ObGyn providers are women, the closure of day-care centers and schools is particularly challenging. Share best practices among your staff on how to address this problem, such as alternating on-call shifts or matching providers needing day care with ‘furloughed’ college students who are looking to keep busy and make a little money.

Continue to: Avoid overcommunicating...

Avoid overcommunicating

Clear, concise, and timely communication is key. This can be challenging given the rapidly evolving science of COVID-19 and the daily barrage of information from both reliable and unreliable sources. Setting up regular online meetings with your faculty 2 or 3 times per week can keep people informed, promote engagement, and boost morale.

If an urgent e-mail announcement is needed, keep the message focused. Highlight only updated information and changes to existing policies and guidelines. And consider adding a brief anecdote to illustrate the staff’s creativity and resilience: a “best catch” story, for example, or a staff member who started a “commit to sit” program (spending time in the room with patients who want company but are not able to have their family in attendance).

Look to the future

COVID-19 will pass. Herd immunity will inevitably develop. The question is how quickly and at what cost. Children delivered today are being born into a society already profoundly altered by COVID-19. Some have started to call them Generation C.

Exactly what life will look like at the back end of this pandemic depends on how effectively we leverage this crisis. There are numerous opportunities to change the way we think about health care and educate the next generation of providers. These include increasing the use of telehealth and remote education, redesigning our traditional prenatal care paradigms, and reinforcing the importance of preventive medicine. This is an opportunity to put the “health” back into “health care.”

Look after yourself

Amid all the chaos and uncertainty, do not forget to take care of yourself and your family. Be calm, be kind, and be flexible. Stay safe.

- Kommenda N, Gutierrez P, Adolphe J. Coronavirus world map: which countries have the most cases and deaths? The Guardian. April 1, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/31/coronavirus-mapped-which-countries-have-the-most-cases-and-deaths. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).Interim US guidance for risk assessment and public health management of healthcare personnel with potential exposure in a healthcare setting to patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Evaluating and testing persons for coronavirus disease 2020 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 1, 2020.

While often compared with the Spanish influenza contagion of 1918, the current COVID-19 pandemic is arguably unprecedented in scale and scope, global reach, and the rate at which it has spread across the world.

Unprecedented times

The United States now has the greatest burden of COVID-19 disease worldwide.1 Although Boston has thus far been spared the full force of the disease’s impact, it is likely only a matter of time before it reaches here. To prepare for the imminent surge, we at Tufts Medical Center defined 4 short-term strategic imperatives to help guide our COVID-19 preparedness. Having a single unified strategy across our organization has helped to maintain focus and consistency in the messaging amidst all of the uncertainty. Our focus areas are outlined below.

1 Flatten the curve

This term refers to the use of “social distancing” and community isolation measures to keep the number of disease cases at a manageable level. COVID-19 is spread almost exclusively through contact with contaminated respiratory droplets. While several categories of risk have been described, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines disease “exposure” as face-to-face contact within 6 feet of an infected individual for more than 15 minutes without wearing a mask.2 Intervening at all 3 of these touchpoints effectively reduces transmission. Interventions include limiting in-person meetings, increasing the space between individuals (both providers and patients), and routinely using personal protective equipment (PPE).

Another effective strategy is to divide frontline providers into smaller units or teams to limit cross-contamination: the inpatient team versus the outpatient team, the day team versus the night team, the “on” team versus the “off” team. If the infection lays one team low, other providers can step in until they recover and return to work.

Visitor policies should be developed and strictly implemented. Many institutions do allow one support person in labor and delivery (L&D) regardless of the patient’s COVID-19 status, although that person should not be symptomatic or COVID-19 positive. Whether to test all patients and support persons for COVID-19 on arrival at L&D remains controversial.3 At a minimum, these individuals should be screened for symptoms. Although it was a major focus of initial preventative efforts, taking a travel and exposure history is no longer informative as the virus is now endemic and community spread is common.

Initial preventative efforts focused also on high-risk patients, but routine use of PPE for all encounters clearly is more effective because of the high rate of asymptomatic shedding. The virus can survive suspended in the air for up to 2 hours following an aerosol-generating procedure (AGP) and on surfaces for several hours or even days. Practices such as regular handwashing, cleaning of exposed work surfaces, and avoiding face touching should by now be part of our everyday routine.

Institutions throughout the United States have established inpatient COVID-19 units—so-called “dirty” units—with mixed success. As the pandemic spreads and the number of patients with asymptomatic shedding increases, it is harder to determine who is and who is not infected. Cross-contamination has rendered this approach largely ineffective. Whether this will change with the introduction of rapid point-of-care testing remains to be seen.

Continue to: 2 Preserve PPE...

2 Preserve PPE

PPE use is effective in reducing transmission. This includes tier 1 PPE with or without enhanced droplet precaution (surgical mask, eye protection, gloves, yellow gown) and tier 2 PPE (tier 1 plus N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators [PAPR]). Given the acute PPE shortage in many parts of the country, appropriate use of PPE is critical to maintain an adequate supply. For example, tier 2 PPE is required only in the setting of an AGP. This includes intubation and, in our determination, the second stage of labor for COVID-19–positive patients and patients under investigation (PUIs); we do not employ tier 2 PPE for all patients in the second stage of labor, although some hospitals endorse this practice.

Creative solutions to the impending PPE shortage abound, such as the use of 3D printers to make face shields and novel techniques to sterilize and reuse N95 respirators.

3 Create capacity

In the absence of effective treatment for COVID-19 and with a vaccine still many months away, supportive care is critical. The pulmonary sequelae with cytokine storm and acute hypoxemia can come on quickly, require urgent mechanical ventilatory support, and take several weeks to resolve.

Our ability to create inpatient capacity to accommodate ill patients, monitor them closely, and intubate early will likely be the most critical driver of the case fatality rate. This requires deferring outpatient visits (or doing them via telemedicine), expanding intensive care unit capabilities (especially ventilator beds), and canceling elective surgeries. What constitutes “elective surgery” is not always clear. Our institution, for example, regards abortion services as essential and not elective, but this is not the case throughout the United States.

Creating capacity also refers to staffing. Where necessary, providers should be retrained and redeployed. This may require emergency credentialing of providers in areas outside their usual clinical practice and permission may be needed from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to engage trainees outside their usual duty hours.

4 Support and protect your workforce

Everyone is anxious, and people convey their anxiety in different ways. I have found it helpful to acknowledge those feelings and provide a forum for staff to express and share their anxieties. That said, hospitals are not a democracy. While staff members should be encouraged to ask questions and voice their opinions, everyone is expected to follow protocol regarding patient care.

Celebrating small successes and finding creative ways to alleviate the stress and inject humor can help. Most institutions are using electronic conferencing platforms (such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams) to stay in touch and to continue education initiatives through interactive didactic sessions, grand rounds, morbidity and mortality conferences, and e-journal clubs. These are also a great platform for social events, such as w(h)ine and book clubs and virtual karaoke.

Since many ObGyn providers are women, the closure of day-care centers and schools is particularly challenging. Share best practices among your staff on how to address this problem, such as alternating on-call shifts or matching providers needing day care with ‘furloughed’ college students who are looking to keep busy and make a little money.

Continue to: Avoid overcommunicating...

Avoid overcommunicating

Clear, concise, and timely communication is key. This can be challenging given the rapidly evolving science of COVID-19 and the daily barrage of information from both reliable and unreliable sources. Setting up regular online meetings with your faculty 2 or 3 times per week can keep people informed, promote engagement, and boost morale.

If an urgent e-mail announcement is needed, keep the message focused. Highlight only updated information and changes to existing policies and guidelines. And consider adding a brief anecdote to illustrate the staff’s creativity and resilience: a “best catch” story, for example, or a staff member who started a “commit to sit” program (spending time in the room with patients who want company but are not able to have their family in attendance).

Look to the future

COVID-19 will pass. Herd immunity will inevitably develop. The question is how quickly and at what cost. Children delivered today are being born into a society already profoundly altered by COVID-19. Some have started to call them Generation C.

Exactly what life will look like at the back end of this pandemic depends on how effectively we leverage this crisis. There are numerous opportunities to change the way we think about health care and educate the next generation of providers. These include increasing the use of telehealth and remote education, redesigning our traditional prenatal care paradigms, and reinforcing the importance of preventive medicine. This is an opportunity to put the “health” back into “health care.”

Look after yourself

Amid all the chaos and uncertainty, do not forget to take care of yourself and your family. Be calm, be kind, and be flexible. Stay safe.

While often compared with the Spanish influenza contagion of 1918, the current COVID-19 pandemic is arguably unprecedented in scale and scope, global reach, and the rate at which it has spread across the world.

Unprecedented times