User login

COMFORT mnemonic can help guide malignant wound care

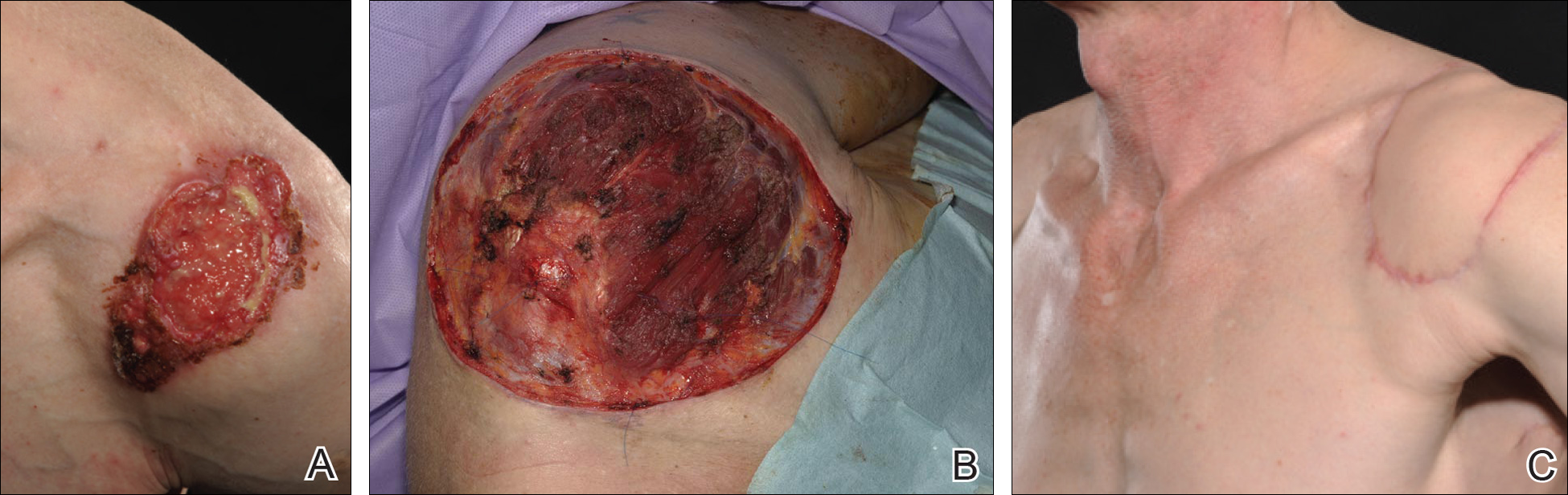

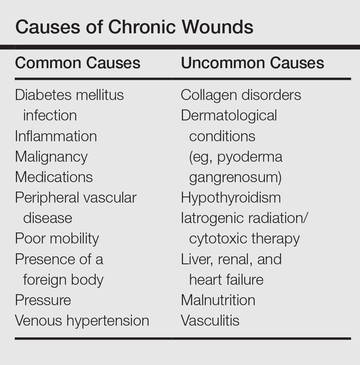

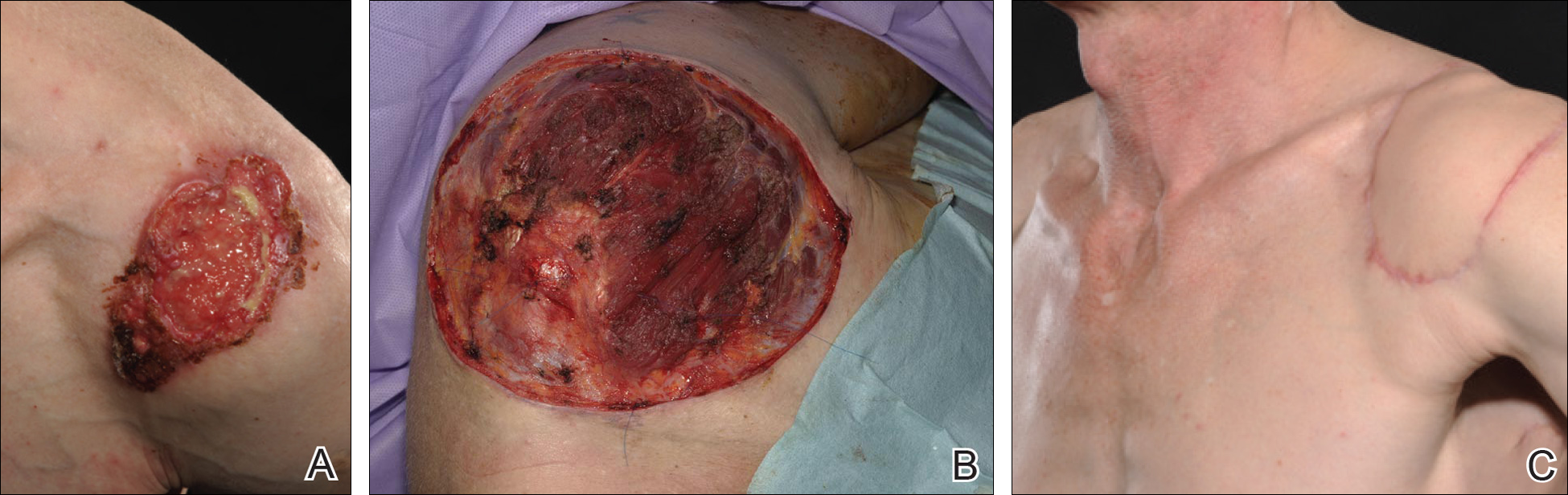

BOSTON – Malignancy in a chronic leg wound can be very aggressive, and multidisciplinary care is a must – particularly in those who oppose amputation, according to Tania J. Phillips, MD.

“When you get a more advanced, malignant, ulcerated wound, this is really a complex situation that requires multidisciplinary care,” she said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

In addition to dermatologic care, patients may need medical oncology, surgery, radiation, and good nursing care, she explained.

For patients with malignancy who oppose amputation, a palliative care team may also be a necessity, said Dr. Phillips, professor of dermatology at Boston University. She described one patient she cared for who had an ulcerated wound with squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was treated daily 5 days per week for 2 months. The wound did not heal.

“In these kinds of patients you may not heal the wound; you may just have to try to keep the wound clean, free of pain, and free of infection, she said.

COMFORT is a valuable mnemonic device for caring for such patients, she said: Care for pain and itching, use Odor control, Manage exudate and bleeding, Fight infection, Optimize peri-wound skin integrity, use Reparative and aesthetic wound dressings, Treat the cancer.

Pain is a major issue in patients with such wounds. It is important assess the wound etiology and treat the underlying disease, but it is also important to assess the pain and try to manage it, Dr. Phillips said. Often, addressing local wound management will help with the pain. Appropriate dressing selection is particularly important, as dressing changes can be very painful, she said, recommending the use of non-stick dressings that keep the wound moist. Local and systemic treatment may also be necessary to control pain and itching, she said.

Odor control is another concern. Necrotic tissue has a lot of odor, so debridement can help.

“Use a 19-guage needle to cleanse the wound,” she suggested, noting that this provides higher pressure that can be effective for cleansing.

Dressings that contain nanocrystalline silver or activated charcoal can also help.

As for managing exudate and bleeding, dressing choice is again an important consideration. More absorbent dressings like alginates are useful and have hemostatic properties that can also help with bleeding. Frequent dressing changes are also important.

“And obviously, you want to treat infection,” Dr. Phillips added. Metronidazole gel or powder can help with both infection and odor, she noted.

Peri-wound skin can be very fragile, so it is important to provide protection. In some cases, this can be addressed simply with zinc oxide or petrolatum. Various skin sealants are also available, and can be used to form a barrier to dressings that can be damaging to the skin.

Silicone dressings are very powerful because they don’t stick to the skin, and are not painful or damaging when removed, she said.

The use of a window with hydrocolloid dressing, which allows for changing only the inside of the dressing, is another useful approach, and using mesh rather than tape to hold the dressing in place can help to protect peri-wound skin.

Dr. Phillips reported a financial relationship with Hygeia.

BOSTON – Malignancy in a chronic leg wound can be very aggressive, and multidisciplinary care is a must – particularly in those who oppose amputation, according to Tania J. Phillips, MD.

“When you get a more advanced, malignant, ulcerated wound, this is really a complex situation that requires multidisciplinary care,” she said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

In addition to dermatologic care, patients may need medical oncology, surgery, radiation, and good nursing care, she explained.

For patients with malignancy who oppose amputation, a palliative care team may also be a necessity, said Dr. Phillips, professor of dermatology at Boston University. She described one patient she cared for who had an ulcerated wound with squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was treated daily 5 days per week for 2 months. The wound did not heal.

“In these kinds of patients you may not heal the wound; you may just have to try to keep the wound clean, free of pain, and free of infection, she said.

COMFORT is a valuable mnemonic device for caring for such patients, she said: Care for pain and itching, use Odor control, Manage exudate and bleeding, Fight infection, Optimize peri-wound skin integrity, use Reparative and aesthetic wound dressings, Treat the cancer.

Pain is a major issue in patients with such wounds. It is important assess the wound etiology and treat the underlying disease, but it is also important to assess the pain and try to manage it, Dr. Phillips said. Often, addressing local wound management will help with the pain. Appropriate dressing selection is particularly important, as dressing changes can be very painful, she said, recommending the use of non-stick dressings that keep the wound moist. Local and systemic treatment may also be necessary to control pain and itching, she said.

Odor control is another concern. Necrotic tissue has a lot of odor, so debridement can help.

“Use a 19-guage needle to cleanse the wound,” she suggested, noting that this provides higher pressure that can be effective for cleansing.

Dressings that contain nanocrystalline silver or activated charcoal can also help.

As for managing exudate and bleeding, dressing choice is again an important consideration. More absorbent dressings like alginates are useful and have hemostatic properties that can also help with bleeding. Frequent dressing changes are also important.

“And obviously, you want to treat infection,” Dr. Phillips added. Metronidazole gel or powder can help with both infection and odor, she noted.

Peri-wound skin can be very fragile, so it is important to provide protection. In some cases, this can be addressed simply with zinc oxide or petrolatum. Various skin sealants are also available, and can be used to form a barrier to dressings that can be damaging to the skin.

Silicone dressings are very powerful because they don’t stick to the skin, and are not painful or damaging when removed, she said.

The use of a window with hydrocolloid dressing, which allows for changing only the inside of the dressing, is another useful approach, and using mesh rather than tape to hold the dressing in place can help to protect peri-wound skin.

Dr. Phillips reported a financial relationship with Hygeia.

BOSTON – Malignancy in a chronic leg wound can be very aggressive, and multidisciplinary care is a must – particularly in those who oppose amputation, according to Tania J. Phillips, MD.

“When you get a more advanced, malignant, ulcerated wound, this is really a complex situation that requires multidisciplinary care,” she said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

In addition to dermatologic care, patients may need medical oncology, surgery, radiation, and good nursing care, she explained.

For patients with malignancy who oppose amputation, a palliative care team may also be a necessity, said Dr. Phillips, professor of dermatology at Boston University. She described one patient she cared for who had an ulcerated wound with squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was treated daily 5 days per week for 2 months. The wound did not heal.

“In these kinds of patients you may not heal the wound; you may just have to try to keep the wound clean, free of pain, and free of infection, she said.

COMFORT is a valuable mnemonic device for caring for such patients, she said: Care for pain and itching, use Odor control, Manage exudate and bleeding, Fight infection, Optimize peri-wound skin integrity, use Reparative and aesthetic wound dressings, Treat the cancer.

Pain is a major issue in patients with such wounds. It is important assess the wound etiology and treat the underlying disease, but it is also important to assess the pain and try to manage it, Dr. Phillips said. Often, addressing local wound management will help with the pain. Appropriate dressing selection is particularly important, as dressing changes can be very painful, she said, recommending the use of non-stick dressings that keep the wound moist. Local and systemic treatment may also be necessary to control pain and itching, she said.

Odor control is another concern. Necrotic tissue has a lot of odor, so debridement can help.

“Use a 19-guage needle to cleanse the wound,” she suggested, noting that this provides higher pressure that can be effective for cleansing.

Dressings that contain nanocrystalline silver or activated charcoal can also help.

As for managing exudate and bleeding, dressing choice is again an important consideration. More absorbent dressings like alginates are useful and have hemostatic properties that can also help with bleeding. Frequent dressing changes are also important.

“And obviously, you want to treat infection,” Dr. Phillips added. Metronidazole gel or powder can help with both infection and odor, she noted.

Peri-wound skin can be very fragile, so it is important to provide protection. In some cases, this can be addressed simply with zinc oxide or petrolatum. Various skin sealants are also available, and can be used to form a barrier to dressings that can be damaging to the skin.

Silicone dressings are very powerful because they don’t stick to the skin, and are not painful or damaging when removed, she said.

The use of a window with hydrocolloid dressing, which allows for changing only the inside of the dressing, is another useful approach, and using mesh rather than tape to hold the dressing in place can help to protect peri-wound skin.

Dr. Phillips reported a financial relationship with Hygeia.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2016

Perform biopsy in non-healing ulcers

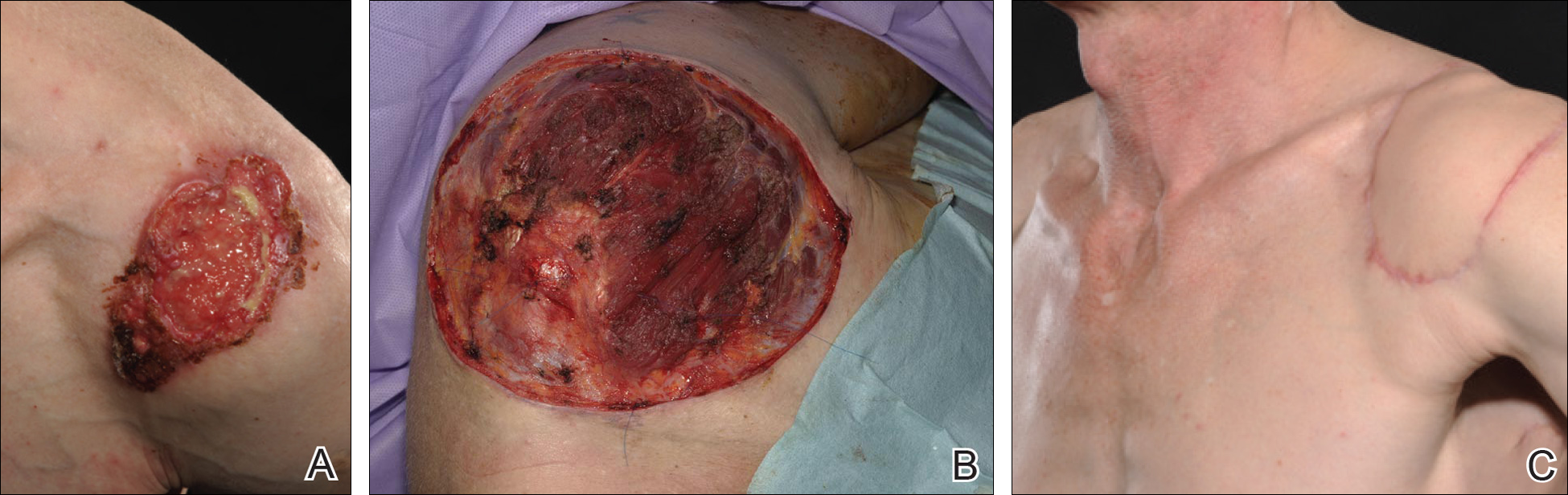

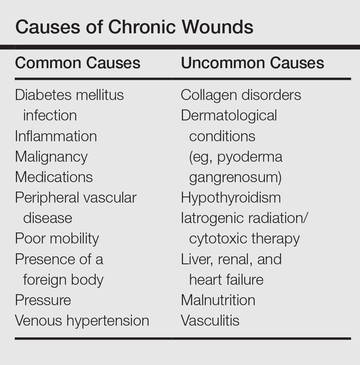

BOSTON – Most ulcers seen in the clinic setting are venous, arterial, or neuropathic, but about 10% are tied to “more unusual causes” and require biopsy, according to Tania J. Phillips, MD.

A particular concern is malignancy, Dr. Phillips, professor of dermatology at Boston University, said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“We do need to have a low threshold for biopsying wounds – particularly if they are wounds of long duration and are not healing,”

A rule of thumb for performing biopsy is 3 months of non-healing, she said.

“If you have a non-healing wound and you’re doing good wound care, you have to re-evaluate. Do you have the right diagnosis? You may need several biopsies on several different occasions to get the right diagnosis,” she said.

Other reasons to biopsy include suspected infection – whether bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial; atypical appearance; suspected vasculitis; and recent travel history.

Ideally, the biopsy will include a deep wedge containing wound margin and the wound bed.

“Failing that, [take] multiple punch biopsies from the wound bed and the margins,” she said.

While many people are nervous about biopsying an ulcer, most biopsy sites heal very well with no complications, she noted.

As for what to do with the tissue, it can be sent in formalin.

“But if you’re going to do immunofluorescence, you will need Michel’s medium. And if you want to culture, just check with your microbiology lab, because often they will take your piece of tissue and they’ll mix it up, and they’ll divide it and will send it out for bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial culture and you won’t have to do that yourself,” she said.

Dr. Phillips noted that she doesn’t usually suture an ulcer biopsy site.

“The skin around ulcers is usually very friable, the sutures often pull out, and you can usually just pack the biopsy site with gel foam or with an alginate, and then just apply firm compression like a wrap over the biopsy site and you’ll do just fine,” she said.

Dr. Phillips reported a financial relationship with Hygeia.

BOSTON – Most ulcers seen in the clinic setting are venous, arterial, or neuropathic, but about 10% are tied to “more unusual causes” and require biopsy, according to Tania J. Phillips, MD.

A particular concern is malignancy, Dr. Phillips, professor of dermatology at Boston University, said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“We do need to have a low threshold for biopsying wounds – particularly if they are wounds of long duration and are not healing,”

A rule of thumb for performing biopsy is 3 months of non-healing, she said.

“If you have a non-healing wound and you’re doing good wound care, you have to re-evaluate. Do you have the right diagnosis? You may need several biopsies on several different occasions to get the right diagnosis,” she said.

Other reasons to biopsy include suspected infection – whether bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial; atypical appearance; suspected vasculitis; and recent travel history.

Ideally, the biopsy will include a deep wedge containing wound margin and the wound bed.

“Failing that, [take] multiple punch biopsies from the wound bed and the margins,” she said.

While many people are nervous about biopsying an ulcer, most biopsy sites heal very well with no complications, she noted.

As for what to do with the tissue, it can be sent in formalin.

“But if you’re going to do immunofluorescence, you will need Michel’s medium. And if you want to culture, just check with your microbiology lab, because often they will take your piece of tissue and they’ll mix it up, and they’ll divide it and will send it out for bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial culture and you won’t have to do that yourself,” she said.

Dr. Phillips noted that she doesn’t usually suture an ulcer biopsy site.

“The skin around ulcers is usually very friable, the sutures often pull out, and you can usually just pack the biopsy site with gel foam or with an alginate, and then just apply firm compression like a wrap over the biopsy site and you’ll do just fine,” she said.

Dr. Phillips reported a financial relationship with Hygeia.

BOSTON – Most ulcers seen in the clinic setting are venous, arterial, or neuropathic, but about 10% are tied to “more unusual causes” and require biopsy, according to Tania J. Phillips, MD.

A particular concern is malignancy, Dr. Phillips, professor of dermatology at Boston University, said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“We do need to have a low threshold for biopsying wounds – particularly if they are wounds of long duration and are not healing,”

A rule of thumb for performing biopsy is 3 months of non-healing, she said.

“If you have a non-healing wound and you’re doing good wound care, you have to re-evaluate. Do you have the right diagnosis? You may need several biopsies on several different occasions to get the right diagnosis,” she said.

Other reasons to biopsy include suspected infection – whether bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial; atypical appearance; suspected vasculitis; and recent travel history.

Ideally, the biopsy will include a deep wedge containing wound margin and the wound bed.

“Failing that, [take] multiple punch biopsies from the wound bed and the margins,” she said.

While many people are nervous about biopsying an ulcer, most biopsy sites heal very well with no complications, she noted.

As for what to do with the tissue, it can be sent in formalin.

“But if you’re going to do immunofluorescence, you will need Michel’s medium. And if you want to culture, just check with your microbiology lab, because often they will take your piece of tissue and they’ll mix it up, and they’ll divide it and will send it out for bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial culture and you won’t have to do that yourself,” she said.

Dr. Phillips noted that she doesn’t usually suture an ulcer biopsy site.

“The skin around ulcers is usually very friable, the sutures often pull out, and you can usually just pack the biopsy site with gel foam or with an alginate, and then just apply firm compression like a wrap over the biopsy site and you’ll do just fine,” she said.

Dr. Phillips reported a financial relationship with Hygeia.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2016

Nonpainful Ulcerations on the Nose and Forehead

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

A 57-year-old man with a history of multiple cerebrovascular accidents was transferred from an outside hospital to our inpatient rheumatology service with nonpainful erosions of the forehead and nasal ala of 6 months’ duration. The patient reported that he initially developed a sore on the nose months prior to presentation with worsening sensations of itching and tingling on the forehead and nose. He also noted a headache and gradual loss of vision in the right eye. The patient was immunocompetent and denied arthralgia or any other skin lesions.

Preventing, Identifying, and Managing Cosmetic Procedure Complications, Part 1: Soft-Tissue Augmentation and Botulinum Toxin Injections

The primary cosmetic procedures that dermatology residents will perform or assist in performing during their training are soft-tissue augmentation, botulinum toxin injections, chemical peels, and laser therapy. Because complications can occur from these procedures, it is important for residents to learn how to prevent, identify, and manage them for optimal patient outcomes. In part 1 of this 2-part series, soft-tissue augmentation and botulinum toxin injections are discussed. Chemical peels and laser therapy will be addressed in part 2.

Soft-Tissue Augmentation

Soft-tissue fillers include those that are made from collagen (bovine or human), hyaluronic acid (HA), poly-L-lactic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, silicone, and polymethylmethacrylate. In general, acute complications of soft-tissue filler injections include erythema, swelling, and bruising.1-3 Patients who take blood thinners or supplements (eg, vitamin E, ginseng, garlic, ginger) should be asked to discontinue use 1 week prior to the procedure. Patients who take blood thinners also should be counseled to expect some bruising. Prior to injection, the skin should be thoroughly cleansed to avoid introducing skin bacteria into the injection site and to reduce infection risk. Postinjection erythema may be related to mast cell activation, which is temporary and should resolve after a few days.1-3

If you find yourself injecting the filler too superficially, you may notice that the skin begins to take on a blue-gray hue1-3 that is known as the Tyndall effect and can be prevented by injecting the filler at the proper level. For example, collagen-based fillers should be placed at the mid dermis, thicker HA fillers should be placed in the deep dermis, and calcium hydroxylapatite should be placed at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Polymethylmethacrylate and poly-L-lactic acid should both be placed subdermally.1-3

The gravest immediate complications associated with soft-tissue filler injections are occlusion of the central retinal artery and/or skin necrosis.1-4 Residents should never inject filler to the glabella or to the nose.1-3 Injections at these sites are sometimes performed but should only be performed by experienced dermatologists. The perioral and tear trough regions also are high-risk injection areas that require a high degree of experience and should only be injected with proper supervision by an experienced dermatologist.1-3 Residents generally can avoid these complications, though not with a 100% guarantee, by avoiding injections in high-risk areas, aspirating to check for blood, and slowly injecting a small amount of filler into the treatment area.1-3 A consensus statement on management of injection-induced necrosis advises to apply a nitropaste ointment 2% to the treatment site or administer an oral aspirin if the patient develops severe pain; vision loss; or acute skin discoloration, especially blanching.4 For HA-based fillers, at least 200 U of hyaluronidase should be injected. It has been suggested that saline can be injected to flush out calcium hydroxylapatite fillers.3 Warm compresses should be placed on the involved area. Following these interventions, any patient with vision loss or orbital pain should immediately undergo ophthalmologic evaluation.3 The most important intervention occurs in the first 24 hours.3,4 After 24 hours, careful wound care, oral anticoagulants, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy have been suggested as management options.3

There are 2 major chronic complications of soft-tissue filler injection, including delayed-onset infection, which occurs 2 weeks or more postinjection, and granuloma formation.1-3 Chronic low-grade infection at the injection site may be indicative of biofilm formation. If an HA filler was used, it should be dissolved with hyaluronidase to help break up the biofilm nidus.3 A course of oral antibiotics also may be indicated.1-3 Intralesional steroids may be used but only after antibiotics have been administered. A biofilm that develops from more permanent fillers may be more difficult to manage. Atypical mycobacterial infections have been known to develop at injection sites, which should be considered in refractory cases.1-3,5

Calcium hydroxylapatite, polymethylmethacrylate, and silicone can stimulate chronic immune system activation, which makes them more prone to granuloma formation.1-3 Once infection is ruled out, granulomas may be treated with intralesional steroids, surgical excision (if the results would be cosmetically acceptable), laser therapy, or potentially local injection of an immunosuppressant (eg, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil).3

Botulinum Toxin Injections

Patients who are pregnant, lactating, or have neuromuscular disease are not candidates for botulinum toxin injections. There also is a risk that patients taking calcium channel blockers or aminoglycoside antibiotics may experience potentiated effects of the botulinum toxin.6

Patients should be informed that a postinjection headache may occur and should be treated with over-the-counter medications.6 Complication-free botulinum toxin procedures depend heavily on the physician’s knowledge of facial anatomy.1,6 The diagrams provided by Hirsch and Stier1 offer an excellent guide on where to place the injections. Brow droop, eyelid ptosis, and “Spock brow” (eyebrows that are overarched) largely can be avoided by proper injection point placement. A Spock brow may be corrected by injecting the lateral upper forehead with a few units to correct the exaggerated arch.6,7 For eyelid ptosis, apraclonidine 0.05% drops (1–2 drops 3 times daily) should be used until the ptosis resolves.6 Phenylephrine hydrochloride drops may be used should a patient have a documented sensitivity to apraclonidine but should not be used in a patient with acute angle-closure glaucoma or aneurysms.6

Final Thoughts

Learning to perform soft-tissue augmentation and botulinum toxin injections can be a satisfying and fun part of dermatology residency. Preventing, identifying, and managing any complications that may occur is an integral part of performing these procedures.

- Hirsch R, Stier M. Complications and their management in cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:507-520.

- Gladstone HB, Cohen JL. Adverse effects when injecting facial fillers. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:34-39.

- Boulle K, Heydenrych I. Patient factors influencing dermal filler complications: prevention, assessment, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:205-214.

- Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of hyaluronic acid filler–induced impending necrosis with hyaluronidase: consensus recommendations [published online May 10, 2015]. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:844-849.

- Rodriguez JM, Xie YL, Winthrop KL, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae facial infections following injection of dermal filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:265-269.

- Nigam PK, Nigam A. Botulinum toxin. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:8-14.

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Update on the botulinum neurotoxins. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-2.

The primary cosmetic procedures that dermatology residents will perform or assist in performing during their training are soft-tissue augmentation, botulinum toxin injections, chemical peels, and laser therapy. Because complications can occur from these procedures, it is important for residents to learn how to prevent, identify, and manage them for optimal patient outcomes. In part 1 of this 2-part series, soft-tissue augmentation and botulinum toxin injections are discussed. Chemical peels and laser therapy will be addressed in part 2.

Soft-Tissue Augmentation

Soft-tissue fillers include those that are made from collagen (bovine or human), hyaluronic acid (HA), poly-L-lactic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, silicone, and polymethylmethacrylate. In general, acute complications of soft-tissue filler injections include erythema, swelling, and bruising.1-3 Patients who take blood thinners or supplements (eg, vitamin E, ginseng, garlic, ginger) should be asked to discontinue use 1 week prior to the procedure. Patients who take blood thinners also should be counseled to expect some bruising. Prior to injection, the skin should be thoroughly cleansed to avoid introducing skin bacteria into the injection site and to reduce infection risk. Postinjection erythema may be related to mast cell activation, which is temporary and should resolve after a few days.1-3

If you find yourself injecting the filler too superficially, you may notice that the skin begins to take on a blue-gray hue1-3 that is known as the Tyndall effect and can be prevented by injecting the filler at the proper level. For example, collagen-based fillers should be placed at the mid dermis, thicker HA fillers should be placed in the deep dermis, and calcium hydroxylapatite should be placed at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Polymethylmethacrylate and poly-L-lactic acid should both be placed subdermally.1-3

The gravest immediate complications associated with soft-tissue filler injections are occlusion of the central retinal artery and/or skin necrosis.1-4 Residents should never inject filler to the glabella or to the nose.1-3 Injections at these sites are sometimes performed but should only be performed by experienced dermatologists. The perioral and tear trough regions also are high-risk injection areas that require a high degree of experience and should only be injected with proper supervision by an experienced dermatologist.1-3 Residents generally can avoid these complications, though not with a 100% guarantee, by avoiding injections in high-risk areas, aspirating to check for blood, and slowly injecting a small amount of filler into the treatment area.1-3 A consensus statement on management of injection-induced necrosis advises to apply a nitropaste ointment 2% to the treatment site or administer an oral aspirin if the patient develops severe pain; vision loss; or acute skin discoloration, especially blanching.4 For HA-based fillers, at least 200 U of hyaluronidase should be injected. It has been suggested that saline can be injected to flush out calcium hydroxylapatite fillers.3 Warm compresses should be placed on the involved area. Following these interventions, any patient with vision loss or orbital pain should immediately undergo ophthalmologic evaluation.3 The most important intervention occurs in the first 24 hours.3,4 After 24 hours, careful wound care, oral anticoagulants, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy have been suggested as management options.3

There are 2 major chronic complications of soft-tissue filler injection, including delayed-onset infection, which occurs 2 weeks or more postinjection, and granuloma formation.1-3 Chronic low-grade infection at the injection site may be indicative of biofilm formation. If an HA filler was used, it should be dissolved with hyaluronidase to help break up the biofilm nidus.3 A course of oral antibiotics also may be indicated.1-3 Intralesional steroids may be used but only after antibiotics have been administered. A biofilm that develops from more permanent fillers may be more difficult to manage. Atypical mycobacterial infections have been known to develop at injection sites, which should be considered in refractory cases.1-3,5

Calcium hydroxylapatite, polymethylmethacrylate, and silicone can stimulate chronic immune system activation, which makes them more prone to granuloma formation.1-3 Once infection is ruled out, granulomas may be treated with intralesional steroids, surgical excision (if the results would be cosmetically acceptable), laser therapy, or potentially local injection of an immunosuppressant (eg, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil).3

Botulinum Toxin Injections

Patients who are pregnant, lactating, or have neuromuscular disease are not candidates for botulinum toxin injections. There also is a risk that patients taking calcium channel blockers or aminoglycoside antibiotics may experience potentiated effects of the botulinum toxin.6

Patients should be informed that a postinjection headache may occur and should be treated with over-the-counter medications.6 Complication-free botulinum toxin procedures depend heavily on the physician’s knowledge of facial anatomy.1,6 The diagrams provided by Hirsch and Stier1 offer an excellent guide on where to place the injections. Brow droop, eyelid ptosis, and “Spock brow” (eyebrows that are overarched) largely can be avoided by proper injection point placement. A Spock brow may be corrected by injecting the lateral upper forehead with a few units to correct the exaggerated arch.6,7 For eyelid ptosis, apraclonidine 0.05% drops (1–2 drops 3 times daily) should be used until the ptosis resolves.6 Phenylephrine hydrochloride drops may be used should a patient have a documented sensitivity to apraclonidine but should not be used in a patient with acute angle-closure glaucoma or aneurysms.6

Final Thoughts

Learning to perform soft-tissue augmentation and botulinum toxin injections can be a satisfying and fun part of dermatology residency. Preventing, identifying, and managing any complications that may occur is an integral part of performing these procedures.

The primary cosmetic procedures that dermatology residents will perform or assist in performing during their training are soft-tissue augmentation, botulinum toxin injections, chemical peels, and laser therapy. Because complications can occur from these procedures, it is important for residents to learn how to prevent, identify, and manage them for optimal patient outcomes. In part 1 of this 2-part series, soft-tissue augmentation and botulinum toxin injections are discussed. Chemical peels and laser therapy will be addressed in part 2.

Soft-Tissue Augmentation

Soft-tissue fillers include those that are made from collagen (bovine or human), hyaluronic acid (HA), poly-L-lactic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, silicone, and polymethylmethacrylate. In general, acute complications of soft-tissue filler injections include erythema, swelling, and bruising.1-3 Patients who take blood thinners or supplements (eg, vitamin E, ginseng, garlic, ginger) should be asked to discontinue use 1 week prior to the procedure. Patients who take blood thinners also should be counseled to expect some bruising. Prior to injection, the skin should be thoroughly cleansed to avoid introducing skin bacteria into the injection site and to reduce infection risk. Postinjection erythema may be related to mast cell activation, which is temporary and should resolve after a few days.1-3

If you find yourself injecting the filler too superficially, you may notice that the skin begins to take on a blue-gray hue1-3 that is known as the Tyndall effect and can be prevented by injecting the filler at the proper level. For example, collagen-based fillers should be placed at the mid dermis, thicker HA fillers should be placed in the deep dermis, and calcium hydroxylapatite should be placed at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Polymethylmethacrylate and poly-L-lactic acid should both be placed subdermally.1-3

The gravest immediate complications associated with soft-tissue filler injections are occlusion of the central retinal artery and/or skin necrosis.1-4 Residents should never inject filler to the glabella or to the nose.1-3 Injections at these sites are sometimes performed but should only be performed by experienced dermatologists. The perioral and tear trough regions also are high-risk injection areas that require a high degree of experience and should only be injected with proper supervision by an experienced dermatologist.1-3 Residents generally can avoid these complications, though not with a 100% guarantee, by avoiding injections in high-risk areas, aspirating to check for blood, and slowly injecting a small amount of filler into the treatment area.1-3 A consensus statement on management of injection-induced necrosis advises to apply a nitropaste ointment 2% to the treatment site or administer an oral aspirin if the patient develops severe pain; vision loss; or acute skin discoloration, especially blanching.4 For HA-based fillers, at least 200 U of hyaluronidase should be injected. It has been suggested that saline can be injected to flush out calcium hydroxylapatite fillers.3 Warm compresses should be placed on the involved area. Following these interventions, any patient with vision loss or orbital pain should immediately undergo ophthalmologic evaluation.3 The most important intervention occurs in the first 24 hours.3,4 After 24 hours, careful wound care, oral anticoagulants, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy have been suggested as management options.3

There are 2 major chronic complications of soft-tissue filler injection, including delayed-onset infection, which occurs 2 weeks or more postinjection, and granuloma formation.1-3 Chronic low-grade infection at the injection site may be indicative of biofilm formation. If an HA filler was used, it should be dissolved with hyaluronidase to help break up the biofilm nidus.3 A course of oral antibiotics also may be indicated.1-3 Intralesional steroids may be used but only after antibiotics have been administered. A biofilm that develops from more permanent fillers may be more difficult to manage. Atypical mycobacterial infections have been known to develop at injection sites, which should be considered in refractory cases.1-3,5

Calcium hydroxylapatite, polymethylmethacrylate, and silicone can stimulate chronic immune system activation, which makes them more prone to granuloma formation.1-3 Once infection is ruled out, granulomas may be treated with intralesional steroids, surgical excision (if the results would be cosmetically acceptable), laser therapy, or potentially local injection of an immunosuppressant (eg, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil).3

Botulinum Toxin Injections

Patients who are pregnant, lactating, or have neuromuscular disease are not candidates for botulinum toxin injections. There also is a risk that patients taking calcium channel blockers or aminoglycoside antibiotics may experience potentiated effects of the botulinum toxin.6

Patients should be informed that a postinjection headache may occur and should be treated with over-the-counter medications.6 Complication-free botulinum toxin procedures depend heavily on the physician’s knowledge of facial anatomy.1,6 The diagrams provided by Hirsch and Stier1 offer an excellent guide on where to place the injections. Brow droop, eyelid ptosis, and “Spock brow” (eyebrows that are overarched) largely can be avoided by proper injection point placement. A Spock brow may be corrected by injecting the lateral upper forehead with a few units to correct the exaggerated arch.6,7 For eyelid ptosis, apraclonidine 0.05% drops (1–2 drops 3 times daily) should be used until the ptosis resolves.6 Phenylephrine hydrochloride drops may be used should a patient have a documented sensitivity to apraclonidine but should not be used in a patient with acute angle-closure glaucoma or aneurysms.6

Final Thoughts

Learning to perform soft-tissue augmentation and botulinum toxin injections can be a satisfying and fun part of dermatology residency. Preventing, identifying, and managing any complications that may occur is an integral part of performing these procedures.

- Hirsch R, Stier M. Complications and their management in cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:507-520.

- Gladstone HB, Cohen JL. Adverse effects when injecting facial fillers. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:34-39.

- Boulle K, Heydenrych I. Patient factors influencing dermal filler complications: prevention, assessment, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:205-214.

- Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of hyaluronic acid filler–induced impending necrosis with hyaluronidase: consensus recommendations [published online May 10, 2015]. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:844-849.

- Rodriguez JM, Xie YL, Winthrop KL, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae facial infections following injection of dermal filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:265-269.

- Nigam PK, Nigam A. Botulinum toxin. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:8-14.

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Update on the botulinum neurotoxins. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-2.

- Hirsch R, Stier M. Complications and their management in cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:507-520.

- Gladstone HB, Cohen JL. Adverse effects when injecting facial fillers. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:34-39.

- Boulle K, Heydenrych I. Patient factors influencing dermal filler complications: prevention, assessment, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:205-214.

- Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of hyaluronic acid filler–induced impending necrosis with hyaluronidase: consensus recommendations [published online May 10, 2015]. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:844-849.

- Rodriguez JM, Xie YL, Winthrop KL, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae facial infections following injection of dermal filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:265-269.

- Nigam PK, Nigam A. Botulinum toxin. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:8-14.

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Update on the botulinum neurotoxins. Skin Therapy Lett. 2001;6:1-2.

VIDEO: Smart insole system helped reduce reulceration risk

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy who used a smart watch and specially designed smart insoles equipped with an alert system minimized their reulceration risk, results from a proof-of-concept study demonstrated.

The findings suggest that mobile health “could be an effective method to educate patients to change their harmful activity behavior, could enhance adherence to regularly inspect their feet and seek for care in a timely manner, and ultimately may assist in prevention of recurrence of ulcers,” lead author Bijan Najafi, Ph.D., said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Najafi, professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said that in 2015, approximately one-third of all diabetes-related costs in the United States were spent on diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). “Unfortunately, many DFUs end up in amputation, which could devastate patients and their families,” he said. “On the same note, persons within the lowest income brackets are estimated to have 38% higher amputation rate, compared with those in the highest income bracket. All these highlight an important gap in effective management of DFUs, in particular among poor working-class people.”

He also noted that DFU recurrence rates are 30%-40% in the first year, compared with 7.5% annual incidence for patients with peripheral neuropathy and no ulcer history. “The good news is that 75% of recurrent foot ulcers are preventable,” said Dr. Najafi, who is also director of clinical research in Baylor’s division of vascular surgery and endovascular therapy and director of the Interdisciplinary Consortium on Advanced Motion Performance. “An effective method is empowering patients to take care of their own health via regular self-inspection of their feet as well as providing timely and personalized foot care. The big challenge is adherence to prevention and regular foot inspection.”

In a study supported in part by Orpyx Medical Technologies, the investigators used a smart watch and smart insoles to enhance adherence to footwear and effective offloading by providing real-time feedback to 19 patients at high risk of DFUs about a harmful plantar pressure event. The patients wore the insole system for 3 months and were alerted through a smart watch if their plantar pressure exceeded 50 mm Hg over 95% of a moving 15-minute window. A successful response to an alert was recorded when offloading occurred within 20 minutes.

Dr. Najafi reported that by the third month, patients who received a higher number of alerts were more likely to use devices and technique to offload weight from their foot, compared with those who received a lower number of alerts (55% vs. 17%, respectively; P less than .01). In addition, patients whose wear time increased during the study tended to have more alerts, compared with other participants (a mean of .82 vs. .36 alerts per hour; P = .09). The best results occurred when patients received at least one alert every 2 hours. “We found that those who frequently received alerts about harmful plantar pressure events improved their adherence to the prescribed footwear and were more responsive to alerts,” he said. At the same time, those patients who received fewer alerts per day, “started to neglect alerts and adherence to footwear over time, despite having initially good adherence at the first month.”

Going forward, Dr. Najafi said, a key challenge is to continue engaging patients to use such technologies on a daily basis. “This could be addressable by providing frequent and comprehensive alerts which not only address harmful plantar pressure during walking but also any harmful foot-loading conditions, including prolonged harmful foot-loading pressure during standing as well as sitting,” he said.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Najafi discussed the study and the challenges of encouraging treatment adherence.

Orpyx Medical Technologies provided partial funding support for the study. Dr. Najafi reported having no financial disclosures. The other authors of this study are Eyal Ron, Ana Enriquez, Ivan Marin, Jacqueline Lee-Eng, Javad Razjouyan, Ph.D., and Dr. David Armstrong. All subjects were recruited at the University of Arizona, College of Medicine, Tucson.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy who used a smart watch and specially designed smart insoles equipped with an alert system minimized their reulceration risk, results from a proof-of-concept study demonstrated.

The findings suggest that mobile health “could be an effective method to educate patients to change their harmful activity behavior, could enhance adherence to regularly inspect their feet and seek for care in a timely manner, and ultimately may assist in prevention of recurrence of ulcers,” lead author Bijan Najafi, Ph.D., said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Najafi, professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said that in 2015, approximately one-third of all diabetes-related costs in the United States were spent on diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). “Unfortunately, many DFUs end up in amputation, which could devastate patients and their families,” he said. “On the same note, persons within the lowest income brackets are estimated to have 38% higher amputation rate, compared with those in the highest income bracket. All these highlight an important gap in effective management of DFUs, in particular among poor working-class people.”

He also noted that DFU recurrence rates are 30%-40% in the first year, compared with 7.5% annual incidence for patients with peripheral neuropathy and no ulcer history. “The good news is that 75% of recurrent foot ulcers are preventable,” said Dr. Najafi, who is also director of clinical research in Baylor’s division of vascular surgery and endovascular therapy and director of the Interdisciplinary Consortium on Advanced Motion Performance. “An effective method is empowering patients to take care of their own health via regular self-inspection of their feet as well as providing timely and personalized foot care. The big challenge is adherence to prevention and regular foot inspection.”

In a study supported in part by Orpyx Medical Technologies, the investigators used a smart watch and smart insoles to enhance adherence to footwear and effective offloading by providing real-time feedback to 19 patients at high risk of DFUs about a harmful plantar pressure event. The patients wore the insole system for 3 months and were alerted through a smart watch if their plantar pressure exceeded 50 mm Hg over 95% of a moving 15-minute window. A successful response to an alert was recorded when offloading occurred within 20 minutes.

Dr. Najafi reported that by the third month, patients who received a higher number of alerts were more likely to use devices and technique to offload weight from their foot, compared with those who received a lower number of alerts (55% vs. 17%, respectively; P less than .01). In addition, patients whose wear time increased during the study tended to have more alerts, compared with other participants (a mean of .82 vs. .36 alerts per hour; P = .09). The best results occurred when patients received at least one alert every 2 hours. “We found that those who frequently received alerts about harmful plantar pressure events improved their adherence to the prescribed footwear and were more responsive to alerts,” he said. At the same time, those patients who received fewer alerts per day, “started to neglect alerts and adherence to footwear over time, despite having initially good adherence at the first month.”

Going forward, Dr. Najafi said, a key challenge is to continue engaging patients to use such technologies on a daily basis. “This could be addressable by providing frequent and comprehensive alerts which not only address harmful plantar pressure during walking but also any harmful foot-loading conditions, including prolonged harmful foot-loading pressure during standing as well as sitting,” he said.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Najafi discussed the study and the challenges of encouraging treatment adherence.

Orpyx Medical Technologies provided partial funding support for the study. Dr. Najafi reported having no financial disclosures. The other authors of this study are Eyal Ron, Ana Enriquez, Ivan Marin, Jacqueline Lee-Eng, Javad Razjouyan, Ph.D., and Dr. David Armstrong. All subjects were recruited at the University of Arizona, College of Medicine, Tucson.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy who used a smart watch and specially designed smart insoles equipped with an alert system minimized their reulceration risk, results from a proof-of-concept study demonstrated.

The findings suggest that mobile health “could be an effective method to educate patients to change their harmful activity behavior, could enhance adherence to regularly inspect their feet and seek for care in a timely manner, and ultimately may assist in prevention of recurrence of ulcers,” lead author Bijan Najafi, Ph.D., said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Dr. Najafi, professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said that in 2015, approximately one-third of all diabetes-related costs in the United States were spent on diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). “Unfortunately, many DFUs end up in amputation, which could devastate patients and their families,” he said. “On the same note, persons within the lowest income brackets are estimated to have 38% higher amputation rate, compared with those in the highest income bracket. All these highlight an important gap in effective management of DFUs, in particular among poor working-class people.”

He also noted that DFU recurrence rates are 30%-40% in the first year, compared with 7.5% annual incidence for patients with peripheral neuropathy and no ulcer history. “The good news is that 75% of recurrent foot ulcers are preventable,” said Dr. Najafi, who is also director of clinical research in Baylor’s division of vascular surgery and endovascular therapy and director of the Interdisciplinary Consortium on Advanced Motion Performance. “An effective method is empowering patients to take care of their own health via regular self-inspection of their feet as well as providing timely and personalized foot care. The big challenge is adherence to prevention and regular foot inspection.”

In a study supported in part by Orpyx Medical Technologies, the investigators used a smart watch and smart insoles to enhance adherence to footwear and effective offloading by providing real-time feedback to 19 patients at high risk of DFUs about a harmful plantar pressure event. The patients wore the insole system for 3 months and were alerted through a smart watch if their plantar pressure exceeded 50 mm Hg over 95% of a moving 15-minute window. A successful response to an alert was recorded when offloading occurred within 20 minutes.

Dr. Najafi reported that by the third month, patients who received a higher number of alerts were more likely to use devices and technique to offload weight from their foot, compared with those who received a lower number of alerts (55% vs. 17%, respectively; P less than .01). In addition, patients whose wear time increased during the study tended to have more alerts, compared with other participants (a mean of .82 vs. .36 alerts per hour; P = .09). The best results occurred when patients received at least one alert every 2 hours. “We found that those who frequently received alerts about harmful plantar pressure events improved their adherence to the prescribed footwear and were more responsive to alerts,” he said. At the same time, those patients who received fewer alerts per day, “started to neglect alerts and adherence to footwear over time, despite having initially good adherence at the first month.”

Going forward, Dr. Najafi said, a key challenge is to continue engaging patients to use such technologies on a daily basis. “This could be addressable by providing frequent and comprehensive alerts which not only address harmful plantar pressure during walking but also any harmful foot-loading conditions, including prolonged harmful foot-loading pressure during standing as well as sitting,” he said.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Najafi discussed the study and the challenges of encouraging treatment adherence.

Orpyx Medical Technologies provided partial funding support for the study. Dr. Najafi reported having no financial disclosures. The other authors of this study are Eyal Ron, Ana Enriquez, Ivan Marin, Jacqueline Lee-Eng, Javad Razjouyan, Ph.D., and Dr. David Armstrong. All subjects were recruited at the University of Arizona, College of Medicine, Tucson.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A smart insole system helped to minimize reulceration risk among patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy.

Major finding: By the third month, patients who received a higher number of alerts were more likely to use devices to reduce pressure on the foot, compared with those who received a lower number of alerts (55% vs. 17%, respectively; P less than .01).

Data source: A proof-of-concept study conducted with 19 patients at high risk of diabetic foot ulcers that used a smart watch and smart insole device.

Disclosures: Orpyx Medical Technologies provided partial funding support for the study. Dr. Najafi reported having no financial disclosures.

Managing Residual Limb Hyperhidrosis in Wounded Warriors

We live in a time when young, otherwise healthy, active-duty individuals are undergoing traumatic amputations at an exceedingly high rate due to ongoing military engagements. According to US military casualty statistics through September 1, 2014, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation New Dawn veterans have undergone a total of 1573 amputations.1 Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) is one of several military facilities that has managed the care of these unique patients returning from the many ongoing conflicts around the globe. Multidisciplinary teams composed of surgeons, anesthesiologists, physical therapists, prosthetists, and others have joined forces to provide extraordinary emergency and recovery care for these patients. Even in the best hands, however, these traumatic amputee patients often experience long-term and lifelong sequelae of their injuries. As dermatologists at this facility (S.P. was at WRNMMC for 3 years before transferring to Madigan Army Medical Center), we are often asked to assist in the management of a subset of these sequelae: residual limb dermatoses. Residual limb dermatoses such as recurrent bacterial and fungal infections, cysts, abrasions, blistering, irritant and allergic dermatitis, pressure ulcers, acroangiodermatitis, stump edema, and many others have a high prevalence in our wounded warrior population and impact both amputee quality of life and utilization of medical resources. As many as 73% of amputees will experience a variety of residual limb dermatoses at some point in their life, with the highest prevalence in younger, more active patients.2,3 We have observed that many, if not most, of these cutaneous problems can be attributed to or are exacerbated by hyperhidrosis of the residual limb. Hyperhidrosis in this population of patients can be related to excessive sweat production, but more commonly, it is attributed to the lack of evaporation of normal perspiration.

Excess Sweat and the Prosthesis

To understand hyperhidrosis in amputee patients, it is important to understand the anatomy of the prosthesis. There are a variety of materials that are used to create prosthetic limbs. The most commonly used materials are a combination of plastic and carbon graphite/carbon fiber. The modern prosthetic limb uses a suspension system that attaches the prosthetic limb to the residual limb by creating a vacuum. There are several mechanisms to create this vacuum; however, they all depend on a liner that fits snugly over the residual limb. This liner-limb interface is responsible for protection, mitigation of sheering forces, and comfort, and it is the anchor for a good fit in the prosthesis. Unfortunately, this liner is the primary factor contributing to residual limb dermatologic problems. The liner usually is made of silicone or polyurethane and is designed to be water and sweat resistant; any excess water that finds its way into the liner-prosthetic interface will affect the seal of the device and cause slippage of the prosthesis.4 This water-resistant barrier is what induces the hyperhidrotic environment over the residual limb that is covered. These patients sweat with exertion, and because of the water-resistant liner, there is no mechanism for sweat evaporation. This leads to a localized environment of hyperhidrosis, increasing patients’ susceptibility to chronic skin conditions. In addition to the dermatologic pathology of the residual limb, there are notable functional concerns caused by excessive sweating. Increased moisture due to sweating not only leads to pathologic dermatoses but also to impaired fit and loss of suction by leaking into the prosthetic-limb interface, which in turn can lead to decreased stamina in the prosthesis, falls, and in severe cases even prosthetic abandonment.5

Treating Hyperhidrosis

While working with wounded warriors in the dermatology, prosthetics, and wound care clinics at WRNMMC, it repeatedly became clear that our current treatment options for hyperhidrosis in this population were not routinely tolerated or efficacious. Although hyperhidrosis of the axillary or palmoplantar region is a commonly encountered problem with clear treatment algorithms and management strategies, hyperhidrosis in the setting of a residual limb following amputation is somewhat unique and without definitive permanent cure. In approaching this problem, our institution has implemented a variety of therapies to the residual limb that have been well described and effective in the treatment in the axillary region.

Topical antiperspirants (ie, aluminum chloride) are well-documented treatments of hyperhidrosis and work by the formation of a metal iron precipitate when binding with mucopolysaccharides. These complexes cause damage to epithelial cells lining the ostia of eccrine glands, forming a plug in the lumen of the eccrine duct.6 Unfortunately, irritant contact dermatitis has affected the majority of our residual limb patients who have used topical antiperspirants and has led to poor compliance. Glycopyrrolate, an antimuscarinic agent, often is used with varying degrees of success. It works as a competitive antagonist blocking the acetylcholine muscarinic receptors that are responsible for the innervation of eccrine sweat glands. Several of our residual limb patients have a history of global hyperhidrosis and have responded favorably to 1- to 2-mg doses of glycopyrrolate administered twice daily. The side-effect profile headlined by xerostomia, urinary retention, and constipation has, as it often does, limited the dosing. We have observed that with the use of glycopyrrolate, these patients admit to less overall sweating but experience only a mild decrease in the cutaneous problems they experience over the residual limbs, which is likely attributed to the prosthetic liner that induces hyperhidrosis by preventing sweat evaporation from the residual limb. Patients may not be sweating as much, but they are still sweating and that sweat is unable to evaporate from under the liner.

Botulinum toxin is a common treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis and its effects on residual limbs are the same.5,7 Botulinum toxin types A, B, and E specifically cleave soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complexes, which prevents neurosecretory vesicles from fusing with the interior surface of the plasma membrane of the nerve synapse, thereby blocking release of acetylcholine.8 In inhibiting acetylcholine release, the signal for eccrine secretion is blocked. This therapy has been effective in our residual limb patients who tolerate the treatment. It typically involves the injection of 300 to 500 U of botulinum toxin type A diluted with 0.9% saline at 2 to 5 U per 0.1 mL into the residual limb.5 As with the other treatments, there are side effects that complicate compliance. Most residual limb treatments require 150 injections, which can be uncomfortable for this patient cohort. The majority of these wounded warriors have abnormal anatomy because of the traumatic nature of their injuries (ie, improvised explosive device attacks, artillery injury), and they often experience hyperesthesia, phantom limb pain, and notable scarring. These injections can be extremely painful, which often limits their utility. In addition, the therapy only provides 3 to 6 months of symptom relief. Our compliance rate for returning patients has not been good and we suspect that it is likely due to the discomfort associated with the injections.

Other therapies such as laser hair removal and iontophoresis have been attempted but have not yielded great results or compliance. In addition to the limitations of these treatment methods, the residual limbs have presented their own unique set of challenges; complications have included varied anatomy of the residual limbs, scarring, sensitivities, and heterotopic ossification. Temporary remedies such as botulinum toxin injections also present logistical complications because they require repetitive procedural appointments that can be quite burdensome to attend when these patients move back home, often far away from our large military treatment facilities.

A New Therapy With Exciting Potential

With the recent advent of microwave thermal ablation technology, the potential for a different, possibly permanent treatment was discovered. Microwave thermal ablation of the eccrine coils has been proven safe and effective in the prolonged reduction of hyperhidrosis of the axillae and has presented as a potential therapy for our residual limb hyperhidrosis patient population. This technology produces heat that is targeted to a specific depth in the treated tissue while cooling the epidermis. There are various treatment levels that can be used to deliver graded intensities of heat. When the deep dermis is targeted, adnexal structures are denatured and destroyed, causing diminished or eliminated function. Eccrine sweat glands, apocrine glands, and even hair follicles are affected by the therapy. The manufacturer of the only microwave thermal ablation device on the market that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat axillary hyperhidrosis has suggested that these effects are long-term and possibly permanent.9 After several iterations with this technology, we have been able to successfully apply microwave thermal ablation of eccrine coils to 5 residual limbs and are excited about the promise that this technique possesses. A report of our index case will be published soon,10 and we are looking forward to launching our protocol treating traumatic lower extremity amputee patients that have hyperhidrosis with microwave therapy ablation technology here at WRNMMC.

Final Thoughts

Amputation residual limb dermatoses have a high prevalence and impact on amputee quality of life, particularly among young military members who strive to maintain a highly active lifestyle. Many of these dermatoses are directly related to hyperhidrosis of the residual limb that is covered by the prosthetic device and the liner that interfaces with the skin. Although many treatments for residual limb hyperhidrosis have been used with varying efficacy, none have offered a cost-effective or sustained response. Many of our wounded warriors in this amputee population have or will be transitioning out of the military in the coming years. It is imperative to our government, our institution, and most importantly our patients that efforts are made to develop a more permanent and efficacious treatment application to provide relief to these wounded heroes. This amputee population is unique in that they are younger, healthier, and highly motivated to live as “normal” of a life as possible. The ability to ambulate in a prosthetic device can have a huge social and psychological impact, and providing a therapy that minimizes complications associated with prosthetic use is invaluable. We are excited about the results we have seen with the microwave thermal ablation device and feel that there is potential benefit for other amputee populations if the procedure is perfected.

It is an exciting age in medicine where technology and biology have remarkably honed our diagnostic and treatment capabilities. We hope that everyone in the dermatology community shares our enthusiasm and will continue to explore and test these new technologies to improve and better the lives of the patients we treat.

- Fischer H. A guide to U.S. military casualty statistics: Operation Inherent Resolve, Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom. http://ibiblio.org/hyperwar/NHC/CasualtyStats2014Nov/CasualtyStats2014Nov.htm. Congressional Research Service 7-5700; RS22452. Published November 20, 2014. Accessed May 13, 2016.

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286.

- Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, et al. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:463-466.

- Ghoseiri K, Safari MR. Prevalence of heat and perspiration discomfort inside prostheses: literature review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51:855-868.

- Gratrix M, Hivnor C. Botulinum A toxin treatment for hyperhidrosis in patients with prosthetic limbs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1314-1315.

- Hölzle E. Topical pharmacological treatment. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2002;30:30-43.

- Lee KYC, Levell NJ. Turning the tide: a history and review of hyperhidrosis treatment. JRSM Open. 2014;5. doi:10.1177/2042533313505511.

- Dressler D, Adib Saberi F. Botulinum toxin: mechanisms of action. Eur Neurol. 2005;53:3-9.

- Lupin M, Hong HC, O’Shaughnessy KF. Long-term efficacy and quality of life assessment for treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis with a microwave device. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:805-807.

- Mula K, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. In press.