User login

Petrolatum Is Effective as a Moisturizer, But There Are More Uses for It

Petrolatum recently has received substantial social media attention. In the last year, the number of TikTok and Instagram videos mentioning petrolatum increased by 46% and 93%, respectively. According to Unilever, the company that manufactures Vaseline, mentions of the product have gone up by 327% on social media compared to last year largely due to a trend known as “slugging,” or the practice of slathering on petrolatum overnight to improve skin hydration.1 However, petrolatum has a variety of other uses. Given its increase in popularity, we review the many uses of petrolatum within dermatology.

The main reason for petrolatum’s presence on social media is its effectiveness as a moisturizer, which is due to its occlusive property. Its oil-based nature allows it to seal water in the skin by creating a hydrophobic barrier that decreases transepidermal water loss (TEWL). Among available oil-based moisturizers, petrolatum is the most effective in reducing TEWL by 98%, while others only provide reductions of 20% to 30%,2 which makes it ideal for soothing itch and irritation in several skin conditions, including dry skin, cheilitis, chafing, and diaper rash. Petrolatum is particularly helpful in sensitive areas where the skin is thinner, such as the eyelids or lips, as it is less irritating than lotions.

Petrolatum also may be used to treat dry skin and mild atopic dermatitis with the soak-and-smear technique,3 which entails soaking the affected skin—or the entire body, if needed—in a plain water bath for 20 minutes and then immediately smearing the skin with petrolatum. Soaking hydrates the damaged stratum corneum and enhances desquamation. The moist stratum corneum absorbs topical treatments more effectively, and desquamation leaves a thinner stratum corneum for the product to traverse. Smearing with petrolatum then traps the moisture in the skin and thus has a dual function by both delivering the petrolatum to the skin and trapping the moisture from the soak. The result is decreased TEWL, improved hydration, and increased penetration, thereby enhancing skin barrier repair.3,4

Smearing solely with petrolatum is effective in cases not accompanied by considerable inflammation. In cases involving notable inflammation or severe xerosis, a steroidal ointment may be required.3 This generally is done for several nights to 2 weeks before conversion to maintenance therapy. In these cases, petrolatum may then be used as maintenance therapy or bridge therapy for maintenance with simple moisturizers, which decreases recurrence and flares of dermatitis and also prevents continuous exposure to steroidal agents that can result in atrophy and purpura at application sites. The soak-and-smear technique has been found to be effective, with 90% of patients having 90% to 100% clearance.3

Petrolatum also is particularly useful for wound healing. A study on the molecular responses induced by petrolatum found that it significantly upregulated innate immune genes (P<.01), increased antimicrobial peptides (P<.001), and improved epidermal differentiation.5 Additionally, it keeps wound edges moist, which enhances angiogenesis, improves collagen synthesis, and increases the breakdown of dead tissue and fibrin.6 It also prevents scab formation, which can prolong healing time.7

Petrolatum is superior to antibiotic use after clean cutaneous surgery given its excellent safety profile. In one randomized controlled trial comparing petrolatum to bacitracin, petrolatum was found to be just as effective for wound healing with a similar infection rate. Although 4 patients developed allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) with bacitracin use, no patients who used petrolatum developed ACD.8 There are numerous other reports of bacitracin causing ACD,9,10 with a prevalence as high as 22% in chronic leg ulcer patients.10 There are even multiple reports of bacitracin causing contact urticaria and life-threatening anaphylaxis.11 In the most recent report from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group’s list of top allergens, bacitracin placed 11th with an ACD prevalence of 5.5%. Neomycin, another common postwound emollient, has similar adverse effects and ranked 12th with an ACD prevalence of 5.4%.12 Despite the risk for ACD with antibiotics, one study on wound care handouts from dermatologists (N=169) found that nearly half (43%) still advocated for the use of antibiotics.13 Likewise, another study among nondermatologists found that 40% (10/25) recommended the use of antibiotics for wound care14 despite strong evidence that topical antibiotics in clean dermatologic procedures offer no additional benefit compared with petrolatum. Additionally, topical antibiotics carry a risk of antibiotic resistance, adverse reactions such as ACD and anaphylaxis, and higher health care costs.9 Thus, petrolatum should be used as standard care after clean cutaneous procedures, and the application of antibiotics should be abandoned.

Petrolatum also is an effective treatment for pruritus scroti.15 It is particularly helpful for recalcitrant disease when several topical medications have failed or ACD or irritant contact dermatitis to medications or cleansing products is suspected. Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, severe burning or redness may occur with prolonged use of these medications, thus it often is useful to discontinue topical medications and treat with plain water sitz baths at night followed by petrolatum immediately applied over wet skin. This approach has several benefits, including soothing the area, providing an occlusive barrier, retaining moisture, and eliminating contact with steroids and potential allergens and irritants. This may be followed with patch testing to determine if ACD from cleansing products or medications is the culprit. This treatment also may be used in pruritus ani or pruritus vulvae.15

Finally, petrolatum may even be used to treat parasitic skin infections such as cutaneous furuncular myiasis,16 a condition most commonly caused by the human botfly (Dermatobia hominis) or the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). The larvae infest the skin by penetrating the dermis and burrowing into the subdermal layer. It is characterized by furuncular nodules with a central black punctum formed by larvae burrowed underneath the skin. An inflammatory reaction occurs in the sites surrounding the larvae with erythematous, edematous, and tender skin. Symptoms range from mild pruritus and a prickly heat sensation to intense cutaneous pain, agitation, and insomnia. Occluding the punctum, or breathing hole, of the infectious organism with petrolatum will asphyxiate the larvae, causing it to emerge within and leading to definitive diagnosis and treatment. This permits rapid removal and avoids extensive incision and extraction.16

The increased social media attention of petrolatum has raised the awareness of its utility as a moisturizer; however, it has many other uses, including soothing itch and irritation, improving wound healing, alleviating scrotal itch, and treating parasitic skin infections. It not only is an effective product but also is a particularly safe one. Petrolatum is well deserving of its positive reputation in dermatology and its current popularity among the general public

- Cramer M. A staple of grandma’s medicine cabinet gets hot on TikTok. New York Times. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed September 15, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/11/business/vaseline-slugging-tiktok.html

- Sethi A, Kaur T, Malhotra SK, et al. Moisturizers: the slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-287. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182427

- Gutman AB, Kligman AM, Sciacca J, et al. Soak and smear: a standard technique revisited. 2005;141:1556-1559. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.12.1556

- Ghadially R, Halkier-Sorensen L, Elias PM. Effects of petrolatum on stratum corneum structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:387-396. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70060-S

- Czarnowicki T, Malajian D, Khattri S, et al. Petrolatum: barrier repair and antimicrobial responses underlying this “inert” moisturizer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1091-1102.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.013

- Field CK, Kerstein MD. Overview of wound healing in a moist environment. Am J Surg. 1994;167:2S-6S.

- Winter GD. Some factors affecting skin and wound healing. J Tissue Viability. 2006;16:20-23. doi:10.1016/S0965-206X(06)62006-8

- Smack DP, Harrington AC, Dunn C, et al. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:972-977.

- Jacob SE, James WD. From road rash to top allergen in a flash: bacitracin. 2004;30(4 pt 1):521-524. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30168.x..

- Zaki I, Shall L, Dalziel KL. Bacitracin: a significant sensitizer in leg ulcer patients? Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:92-94. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01924.x

- Farley M, Pak H, Carregal V, et al. Anaphylaxis to topically applied bacitracin. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1995;6:28-31. doi:10.1016/1046-199X(95)90066-7

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Nguyen JK, Huang A, Siegel DM, et al. Variability in wound care recommendations following dermatologic procedures. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:186-191. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001952

- Fathy R, Chu B, Singh P, et al. Variation in topical antibiotics recommendations in wound care instructions by non-dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:238-239. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05689-2

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Ockenhouse CF, Samlaska CP, Benson PM, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:199-202.

Petrolatum recently has received substantial social media attention. In the last year, the number of TikTok and Instagram videos mentioning petrolatum increased by 46% and 93%, respectively. According to Unilever, the company that manufactures Vaseline, mentions of the product have gone up by 327% on social media compared to last year largely due to a trend known as “slugging,” or the practice of slathering on petrolatum overnight to improve skin hydration.1 However, petrolatum has a variety of other uses. Given its increase in popularity, we review the many uses of petrolatum within dermatology.

The main reason for petrolatum’s presence on social media is its effectiveness as a moisturizer, which is due to its occlusive property. Its oil-based nature allows it to seal water in the skin by creating a hydrophobic barrier that decreases transepidermal water loss (TEWL). Among available oil-based moisturizers, petrolatum is the most effective in reducing TEWL by 98%, while others only provide reductions of 20% to 30%,2 which makes it ideal for soothing itch and irritation in several skin conditions, including dry skin, cheilitis, chafing, and diaper rash. Petrolatum is particularly helpful in sensitive areas where the skin is thinner, such as the eyelids or lips, as it is less irritating than lotions.

Petrolatum also may be used to treat dry skin and mild atopic dermatitis with the soak-and-smear technique,3 which entails soaking the affected skin—or the entire body, if needed—in a plain water bath for 20 minutes and then immediately smearing the skin with petrolatum. Soaking hydrates the damaged stratum corneum and enhances desquamation. The moist stratum corneum absorbs topical treatments more effectively, and desquamation leaves a thinner stratum corneum for the product to traverse. Smearing with petrolatum then traps the moisture in the skin and thus has a dual function by both delivering the petrolatum to the skin and trapping the moisture from the soak. The result is decreased TEWL, improved hydration, and increased penetration, thereby enhancing skin barrier repair.3,4

Smearing solely with petrolatum is effective in cases not accompanied by considerable inflammation. In cases involving notable inflammation or severe xerosis, a steroidal ointment may be required.3 This generally is done for several nights to 2 weeks before conversion to maintenance therapy. In these cases, petrolatum may then be used as maintenance therapy or bridge therapy for maintenance with simple moisturizers, which decreases recurrence and flares of dermatitis and also prevents continuous exposure to steroidal agents that can result in atrophy and purpura at application sites. The soak-and-smear technique has been found to be effective, with 90% of patients having 90% to 100% clearance.3

Petrolatum also is particularly useful for wound healing. A study on the molecular responses induced by petrolatum found that it significantly upregulated innate immune genes (P<.01), increased antimicrobial peptides (P<.001), and improved epidermal differentiation.5 Additionally, it keeps wound edges moist, which enhances angiogenesis, improves collagen synthesis, and increases the breakdown of dead tissue and fibrin.6 It also prevents scab formation, which can prolong healing time.7

Petrolatum is superior to antibiotic use after clean cutaneous surgery given its excellent safety profile. In one randomized controlled trial comparing petrolatum to bacitracin, petrolatum was found to be just as effective for wound healing with a similar infection rate. Although 4 patients developed allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) with bacitracin use, no patients who used petrolatum developed ACD.8 There are numerous other reports of bacitracin causing ACD,9,10 with a prevalence as high as 22% in chronic leg ulcer patients.10 There are even multiple reports of bacitracin causing contact urticaria and life-threatening anaphylaxis.11 In the most recent report from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group’s list of top allergens, bacitracin placed 11th with an ACD prevalence of 5.5%. Neomycin, another common postwound emollient, has similar adverse effects and ranked 12th with an ACD prevalence of 5.4%.12 Despite the risk for ACD with antibiotics, one study on wound care handouts from dermatologists (N=169) found that nearly half (43%) still advocated for the use of antibiotics.13 Likewise, another study among nondermatologists found that 40% (10/25) recommended the use of antibiotics for wound care14 despite strong evidence that topical antibiotics in clean dermatologic procedures offer no additional benefit compared with petrolatum. Additionally, topical antibiotics carry a risk of antibiotic resistance, adverse reactions such as ACD and anaphylaxis, and higher health care costs.9 Thus, petrolatum should be used as standard care after clean cutaneous procedures, and the application of antibiotics should be abandoned.

Petrolatum also is an effective treatment for pruritus scroti.15 It is particularly helpful for recalcitrant disease when several topical medications have failed or ACD or irritant contact dermatitis to medications or cleansing products is suspected. Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, severe burning or redness may occur with prolonged use of these medications, thus it often is useful to discontinue topical medications and treat with plain water sitz baths at night followed by petrolatum immediately applied over wet skin. This approach has several benefits, including soothing the area, providing an occlusive barrier, retaining moisture, and eliminating contact with steroids and potential allergens and irritants. This may be followed with patch testing to determine if ACD from cleansing products or medications is the culprit. This treatment also may be used in pruritus ani or pruritus vulvae.15

Finally, petrolatum may even be used to treat parasitic skin infections such as cutaneous furuncular myiasis,16 a condition most commonly caused by the human botfly (Dermatobia hominis) or the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). The larvae infest the skin by penetrating the dermis and burrowing into the subdermal layer. It is characterized by furuncular nodules with a central black punctum formed by larvae burrowed underneath the skin. An inflammatory reaction occurs in the sites surrounding the larvae with erythematous, edematous, and tender skin. Symptoms range from mild pruritus and a prickly heat sensation to intense cutaneous pain, agitation, and insomnia. Occluding the punctum, or breathing hole, of the infectious organism with petrolatum will asphyxiate the larvae, causing it to emerge within and leading to definitive diagnosis and treatment. This permits rapid removal and avoids extensive incision and extraction.16

The increased social media attention of petrolatum has raised the awareness of its utility as a moisturizer; however, it has many other uses, including soothing itch and irritation, improving wound healing, alleviating scrotal itch, and treating parasitic skin infections. It not only is an effective product but also is a particularly safe one. Petrolatum is well deserving of its positive reputation in dermatology and its current popularity among the general public

Petrolatum recently has received substantial social media attention. In the last year, the number of TikTok and Instagram videos mentioning petrolatum increased by 46% and 93%, respectively. According to Unilever, the company that manufactures Vaseline, mentions of the product have gone up by 327% on social media compared to last year largely due to a trend known as “slugging,” or the practice of slathering on petrolatum overnight to improve skin hydration.1 However, petrolatum has a variety of other uses. Given its increase in popularity, we review the many uses of petrolatum within dermatology.

The main reason for petrolatum’s presence on social media is its effectiveness as a moisturizer, which is due to its occlusive property. Its oil-based nature allows it to seal water in the skin by creating a hydrophobic barrier that decreases transepidermal water loss (TEWL). Among available oil-based moisturizers, petrolatum is the most effective in reducing TEWL by 98%, while others only provide reductions of 20% to 30%,2 which makes it ideal for soothing itch and irritation in several skin conditions, including dry skin, cheilitis, chafing, and diaper rash. Petrolatum is particularly helpful in sensitive areas where the skin is thinner, such as the eyelids or lips, as it is less irritating than lotions.

Petrolatum also may be used to treat dry skin and mild atopic dermatitis with the soak-and-smear technique,3 which entails soaking the affected skin—or the entire body, if needed—in a plain water bath for 20 minutes and then immediately smearing the skin with petrolatum. Soaking hydrates the damaged stratum corneum and enhances desquamation. The moist stratum corneum absorbs topical treatments more effectively, and desquamation leaves a thinner stratum corneum for the product to traverse. Smearing with petrolatum then traps the moisture in the skin and thus has a dual function by both delivering the petrolatum to the skin and trapping the moisture from the soak. The result is decreased TEWL, improved hydration, and increased penetration, thereby enhancing skin barrier repair.3,4

Smearing solely with petrolatum is effective in cases not accompanied by considerable inflammation. In cases involving notable inflammation or severe xerosis, a steroidal ointment may be required.3 This generally is done for several nights to 2 weeks before conversion to maintenance therapy. In these cases, petrolatum may then be used as maintenance therapy or bridge therapy for maintenance with simple moisturizers, which decreases recurrence and flares of dermatitis and also prevents continuous exposure to steroidal agents that can result in atrophy and purpura at application sites. The soak-and-smear technique has been found to be effective, with 90% of patients having 90% to 100% clearance.3

Petrolatum also is particularly useful for wound healing. A study on the molecular responses induced by petrolatum found that it significantly upregulated innate immune genes (P<.01), increased antimicrobial peptides (P<.001), and improved epidermal differentiation.5 Additionally, it keeps wound edges moist, which enhances angiogenesis, improves collagen synthesis, and increases the breakdown of dead tissue and fibrin.6 It also prevents scab formation, which can prolong healing time.7

Petrolatum is superior to antibiotic use after clean cutaneous surgery given its excellent safety profile. In one randomized controlled trial comparing petrolatum to bacitracin, petrolatum was found to be just as effective for wound healing with a similar infection rate. Although 4 patients developed allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) with bacitracin use, no patients who used petrolatum developed ACD.8 There are numerous other reports of bacitracin causing ACD,9,10 with a prevalence as high as 22% in chronic leg ulcer patients.10 There are even multiple reports of bacitracin causing contact urticaria and life-threatening anaphylaxis.11 In the most recent report from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group’s list of top allergens, bacitracin placed 11th with an ACD prevalence of 5.5%. Neomycin, another common postwound emollient, has similar adverse effects and ranked 12th with an ACD prevalence of 5.4%.12 Despite the risk for ACD with antibiotics, one study on wound care handouts from dermatologists (N=169) found that nearly half (43%) still advocated for the use of antibiotics.13 Likewise, another study among nondermatologists found that 40% (10/25) recommended the use of antibiotics for wound care14 despite strong evidence that topical antibiotics in clean dermatologic procedures offer no additional benefit compared with petrolatum. Additionally, topical antibiotics carry a risk of antibiotic resistance, adverse reactions such as ACD and anaphylaxis, and higher health care costs.9 Thus, petrolatum should be used as standard care after clean cutaneous procedures, and the application of antibiotics should be abandoned.

Petrolatum also is an effective treatment for pruritus scroti.15 It is particularly helpful for recalcitrant disease when several topical medications have failed or ACD or irritant contact dermatitis to medications or cleansing products is suspected. Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, severe burning or redness may occur with prolonged use of these medications, thus it often is useful to discontinue topical medications and treat with plain water sitz baths at night followed by petrolatum immediately applied over wet skin. This approach has several benefits, including soothing the area, providing an occlusive barrier, retaining moisture, and eliminating contact with steroids and potential allergens and irritants. This may be followed with patch testing to determine if ACD from cleansing products or medications is the culprit. This treatment also may be used in pruritus ani or pruritus vulvae.15

Finally, petrolatum may even be used to treat parasitic skin infections such as cutaneous furuncular myiasis,16 a condition most commonly caused by the human botfly (Dermatobia hominis) or the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). The larvae infest the skin by penetrating the dermis and burrowing into the subdermal layer. It is characterized by furuncular nodules with a central black punctum formed by larvae burrowed underneath the skin. An inflammatory reaction occurs in the sites surrounding the larvae with erythematous, edematous, and tender skin. Symptoms range from mild pruritus and a prickly heat sensation to intense cutaneous pain, agitation, and insomnia. Occluding the punctum, or breathing hole, of the infectious organism with petrolatum will asphyxiate the larvae, causing it to emerge within and leading to definitive diagnosis and treatment. This permits rapid removal and avoids extensive incision and extraction.16

The increased social media attention of petrolatum has raised the awareness of its utility as a moisturizer; however, it has many other uses, including soothing itch and irritation, improving wound healing, alleviating scrotal itch, and treating parasitic skin infections. It not only is an effective product but also is a particularly safe one. Petrolatum is well deserving of its positive reputation in dermatology and its current popularity among the general public

- Cramer M. A staple of grandma’s medicine cabinet gets hot on TikTok. New York Times. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed September 15, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/11/business/vaseline-slugging-tiktok.html

- Sethi A, Kaur T, Malhotra SK, et al. Moisturizers: the slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-287. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182427

- Gutman AB, Kligman AM, Sciacca J, et al. Soak and smear: a standard technique revisited. 2005;141:1556-1559. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.12.1556

- Ghadially R, Halkier-Sorensen L, Elias PM. Effects of petrolatum on stratum corneum structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:387-396. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70060-S

- Czarnowicki T, Malajian D, Khattri S, et al. Petrolatum: barrier repair and antimicrobial responses underlying this “inert” moisturizer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1091-1102.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.013

- Field CK, Kerstein MD. Overview of wound healing in a moist environment. Am J Surg. 1994;167:2S-6S.

- Winter GD. Some factors affecting skin and wound healing. J Tissue Viability. 2006;16:20-23. doi:10.1016/S0965-206X(06)62006-8

- Smack DP, Harrington AC, Dunn C, et al. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:972-977.

- Jacob SE, James WD. From road rash to top allergen in a flash: bacitracin. 2004;30(4 pt 1):521-524. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30168.x..

- Zaki I, Shall L, Dalziel KL. Bacitracin: a significant sensitizer in leg ulcer patients? Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:92-94. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01924.x

- Farley M, Pak H, Carregal V, et al. Anaphylaxis to topically applied bacitracin. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1995;6:28-31. doi:10.1016/1046-199X(95)90066-7

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Nguyen JK, Huang A, Siegel DM, et al. Variability in wound care recommendations following dermatologic procedures. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:186-191. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001952

- Fathy R, Chu B, Singh P, et al. Variation in topical antibiotics recommendations in wound care instructions by non-dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:238-239. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05689-2

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Ockenhouse CF, Samlaska CP, Benson PM, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:199-202.

- Cramer M. A staple of grandma’s medicine cabinet gets hot on TikTok. New York Times. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed September 15, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/11/business/vaseline-slugging-tiktok.html

- Sethi A, Kaur T, Malhotra SK, et al. Moisturizers: the slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-287. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182427

- Gutman AB, Kligman AM, Sciacca J, et al. Soak and smear: a standard technique revisited. 2005;141:1556-1559. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.12.1556

- Ghadially R, Halkier-Sorensen L, Elias PM. Effects of petrolatum on stratum corneum structure and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:387-396. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70060-S

- Czarnowicki T, Malajian D, Khattri S, et al. Petrolatum: barrier repair and antimicrobial responses underlying this “inert” moisturizer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1091-1102.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.013

- Field CK, Kerstein MD. Overview of wound healing in a moist environment. Am J Surg. 1994;167:2S-6S.

- Winter GD. Some factors affecting skin and wound healing. J Tissue Viability. 2006;16:20-23. doi:10.1016/S0965-206X(06)62006-8

- Smack DP, Harrington AC, Dunn C, et al. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:972-977.

- Jacob SE, James WD. From road rash to top allergen in a flash: bacitracin. 2004;30(4 pt 1):521-524. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30168.x..

- Zaki I, Shall L, Dalziel KL. Bacitracin: a significant sensitizer in leg ulcer patients? Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:92-94. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01924.x

- Farley M, Pak H, Carregal V, et al. Anaphylaxis to topically applied bacitracin. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 1995;6:28-31. doi:10.1016/1046-199X(95)90066-7

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Nguyen JK, Huang A, Siegel DM, et al. Variability in wound care recommendations following dermatologic procedures. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:186-191. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001952

- Fathy R, Chu B, Singh P, et al. Variation in topical antibiotics recommendations in wound care instructions by non-dermatologists. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:238-239. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05689-2

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Ockenhouse CF, Samlaska CP, Benson PM, et al. Cutaneous myiasis caused by the African tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:199-202.

‘Amazing’ data for cheap beta-blocker gel for diabetic foot ulcers

STOCKHOLM – Esmolol hydrochloride gel (Galnobax, NovoLead) appears to be a safe and effective novel topical treatment option for diabetic foot ulcers, according to results from a new trial of the drug, which is widely available as a generic and is inexpensive.

Of note, the proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure at 12 weeks with esmolol (plus standard of care) was around 60% compared with just over 40% in patients who received standard of care alone.

Presenting the findings at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes was Ashu Rastogi, MD, a professor of endocrinology at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India.

“Esmolol can be given topically as a 14% gel and is a novel treatment option in diabetic foot ulcer,” said Dr. Rastogi.

Esmolol, a short-acting beta-adrenergic blocker, is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for cardiac indications only, such as short-term use for controlling supraventricular tachycardia. Beta-blockers are also used to treat hypertension.

However, esmolol has also been repurposed and formulated as a topical gel for the treatment of hard-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers (mainly neuropathic grade 1).

Audience member Ketan Dhatariya, MBBS, MD, PhD, a National Health Service consultant in diabetes, endocrinology, and general medicine and honorary senior lecturer at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, England, enthused about the findings.

“This is an amazing study. I’m part of a working group looking at the updating of a guideline for the International Working Group of the Diabetic Foot, reviewing all the studies on wound healing, specifically pharmacological interventions. This is way beyond anything shown to date in terms of medical intervention. [The authors] should be congratulated; this is really astounding,” he told this news organization.

“Right now, there is very little out there in terms of pharmacological interventions that have shown benefit,” he added. “Once this study has been peer-reviewed and is published properly, it is potentially game-changing because it is a generic, worldwide, cheap, and freely available medication.”

Study across 27 sites in India

Prior phase 1/2 data have shown that 60% of ulcers completely closed with esmolol (14% gel) compared with 39% with standard of care. Encouraged by these findings, a phase 3 randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study was conducted across 27 sites in India.

Patients were a mean age of 56 years, and had a body mass index (BMI) of 25-26 kg/m2 and mean hemoglobin A1c of 8.4%-8.7%. Around 70% of participants were men. Mean ulcer area was approximately 460-500 mm2, two-thirds of the ulcers were plantar, and mean ulcer duration was 40-50 weeks.

After screening and discontinuations (39 participants), a 12-week treatment phase began with patients randomized to one of three groups: esmolol (14% gel) along with standard of care administered twice daily (57 completers); standard of care only (63 completers); or vehicle gel (placebo) along with standard of care administered twice daily (17 completers).

Standard of care comprised wound cleaning, debridement, maintenance of moist wound environment, twice-daily fresh bandages, and off-loading footwear as needed, and was provided to all participants irrespective of study group.

The 12-week treatment period was followed by an observation period of 12 weeks up to the 24-week study endpoint.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure (100% re-epithelialization without drainage or dressing requirement) within the 12-week treatment phase.

Secondary endpoints included time to target ulcer closure during the 12-week treatment phase and proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure by 24 weeks (end of study). Investigators were blinded throughout.

Subanalyses were conducted based on ulcer location, size, and age, as well as estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 90 mL/min and ankle-brachial index under 0.9 but greater than 0.7.

50% more patients on esmolol had complete ulcer closure

The proportion of participants with complete ulcer closure at 12 weeks was 60.3% in the esmolol plus standard of care group, compared with 41.7% with standard of care only, a difference of 18.6% (odds ratio, 2.13; P = .0276).

“The 24-week end-of-study data show what happened in the 12 weeks following end of treatment,” said Dr. Rastogi, turning to results showing that by 24 weeks the proportion of participants with complete ulcer closure was 77.2% versus 55.6%, respectively, with a difference of 21.6% (OR, 2.71; P = .013).

Time to ulcer closure (a secondary endpoint) was similar between the esmolol plus standard of care vs. standard of care groups (74.3 vs. 72.5 days).

The impact of ulcer location on complete ulcer closure, a subanalysis, showed a higher proportion of patients experienced complete ulcer closure with esmolol plus standard of care versus standard of care. For example, in plantar-based ulcers, esmolol led to complete closure in 58.7% vs. 43.1%, while for nonplantar ulcers, complete closure was found in 63.6% vs. 38.1%.

In wounds less than 5 cm2, the proportion of complete closures was 66.0% vs. 50.0% for esmolol compared with standard of care alone, while in wounds over 5 cm2, these proportions were 47.6% vs. 26.9%.

Subanalyses also showed that esmolol was substantially better in patients with BMI greater than 25, ulcer duration over 12 weeks, and A1c above 8%.

Also, a subanalysis stratified by “real-life” situations favored esmolol, showing a 50.9% difference in the proportion of patients with diabetic foot ulcer healing in those with a history of hypertension and a 31.8% difference favoring esmolol in those with an abnormal electrocardiogram.

Overall, the proportions of patients who had an adverse event were 13.2%, 18.4%, and 37.5% in the esmolol plus standard of care, standard of care alone, and vehicle plus standard of care groups, respectively, and the vast majority were unrelated to study drug. There were no serious adverse events in the esmolol plus standard of care group.

A class effect of beta blockers?

The proposed mechanism of action of esmolol relates to a sequence of reducing inflammation (via vasodilation, fibroblast migration, and cytokine reduction); proliferation by beta-blockade (improves keratinocyte migration and epithelialization); and remodeling (increases collagen turnover).

Asked by an audience member if the observations were a class effect and systemic effect of beta-blockers, Dr. Rastogi said he could not say for sure that it was a class effect, but they deliberately used a beta-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist.

“It may not be a systemic effect because we have some patients who use beta-blockers systemically and they still have diabetic foot ulcers,” he said.

Dr. Rastogi and Dr. Dhatariya have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Esmolol hydrochloride gel (Galnobax, NovoLead) appears to be a safe and effective novel topical treatment option for diabetic foot ulcers, according to results from a new trial of the drug, which is widely available as a generic and is inexpensive.

Of note, the proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure at 12 weeks with esmolol (plus standard of care) was around 60% compared with just over 40% in patients who received standard of care alone.

Presenting the findings at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes was Ashu Rastogi, MD, a professor of endocrinology at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India.

“Esmolol can be given topically as a 14% gel and is a novel treatment option in diabetic foot ulcer,” said Dr. Rastogi.

Esmolol, a short-acting beta-adrenergic blocker, is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for cardiac indications only, such as short-term use for controlling supraventricular tachycardia. Beta-blockers are also used to treat hypertension.

However, esmolol has also been repurposed and formulated as a topical gel for the treatment of hard-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers (mainly neuropathic grade 1).

Audience member Ketan Dhatariya, MBBS, MD, PhD, a National Health Service consultant in diabetes, endocrinology, and general medicine and honorary senior lecturer at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, England, enthused about the findings.

“This is an amazing study. I’m part of a working group looking at the updating of a guideline for the International Working Group of the Diabetic Foot, reviewing all the studies on wound healing, specifically pharmacological interventions. This is way beyond anything shown to date in terms of medical intervention. [The authors] should be congratulated; this is really astounding,” he told this news organization.

“Right now, there is very little out there in terms of pharmacological interventions that have shown benefit,” he added. “Once this study has been peer-reviewed and is published properly, it is potentially game-changing because it is a generic, worldwide, cheap, and freely available medication.”

Study across 27 sites in India

Prior phase 1/2 data have shown that 60% of ulcers completely closed with esmolol (14% gel) compared with 39% with standard of care. Encouraged by these findings, a phase 3 randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study was conducted across 27 sites in India.

Patients were a mean age of 56 years, and had a body mass index (BMI) of 25-26 kg/m2 and mean hemoglobin A1c of 8.4%-8.7%. Around 70% of participants were men. Mean ulcer area was approximately 460-500 mm2, two-thirds of the ulcers were plantar, and mean ulcer duration was 40-50 weeks.

After screening and discontinuations (39 participants), a 12-week treatment phase began with patients randomized to one of three groups: esmolol (14% gel) along with standard of care administered twice daily (57 completers); standard of care only (63 completers); or vehicle gel (placebo) along with standard of care administered twice daily (17 completers).

Standard of care comprised wound cleaning, debridement, maintenance of moist wound environment, twice-daily fresh bandages, and off-loading footwear as needed, and was provided to all participants irrespective of study group.

The 12-week treatment period was followed by an observation period of 12 weeks up to the 24-week study endpoint.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure (100% re-epithelialization without drainage or dressing requirement) within the 12-week treatment phase.

Secondary endpoints included time to target ulcer closure during the 12-week treatment phase and proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure by 24 weeks (end of study). Investigators were blinded throughout.

Subanalyses were conducted based on ulcer location, size, and age, as well as estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 90 mL/min and ankle-brachial index under 0.9 but greater than 0.7.

50% more patients on esmolol had complete ulcer closure

The proportion of participants with complete ulcer closure at 12 weeks was 60.3% in the esmolol plus standard of care group, compared with 41.7% with standard of care only, a difference of 18.6% (odds ratio, 2.13; P = .0276).

“The 24-week end-of-study data show what happened in the 12 weeks following end of treatment,” said Dr. Rastogi, turning to results showing that by 24 weeks the proportion of participants with complete ulcer closure was 77.2% versus 55.6%, respectively, with a difference of 21.6% (OR, 2.71; P = .013).

Time to ulcer closure (a secondary endpoint) was similar between the esmolol plus standard of care vs. standard of care groups (74.3 vs. 72.5 days).

The impact of ulcer location on complete ulcer closure, a subanalysis, showed a higher proportion of patients experienced complete ulcer closure with esmolol plus standard of care versus standard of care. For example, in plantar-based ulcers, esmolol led to complete closure in 58.7% vs. 43.1%, while for nonplantar ulcers, complete closure was found in 63.6% vs. 38.1%.

In wounds less than 5 cm2, the proportion of complete closures was 66.0% vs. 50.0% for esmolol compared with standard of care alone, while in wounds over 5 cm2, these proportions were 47.6% vs. 26.9%.

Subanalyses also showed that esmolol was substantially better in patients with BMI greater than 25, ulcer duration over 12 weeks, and A1c above 8%.

Also, a subanalysis stratified by “real-life” situations favored esmolol, showing a 50.9% difference in the proportion of patients with diabetic foot ulcer healing in those with a history of hypertension and a 31.8% difference favoring esmolol in those with an abnormal electrocardiogram.

Overall, the proportions of patients who had an adverse event were 13.2%, 18.4%, and 37.5% in the esmolol plus standard of care, standard of care alone, and vehicle plus standard of care groups, respectively, and the vast majority were unrelated to study drug. There were no serious adverse events in the esmolol plus standard of care group.

A class effect of beta blockers?

The proposed mechanism of action of esmolol relates to a sequence of reducing inflammation (via vasodilation, fibroblast migration, and cytokine reduction); proliferation by beta-blockade (improves keratinocyte migration and epithelialization); and remodeling (increases collagen turnover).

Asked by an audience member if the observations were a class effect and systemic effect of beta-blockers, Dr. Rastogi said he could not say for sure that it was a class effect, but they deliberately used a beta-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist.

“It may not be a systemic effect because we have some patients who use beta-blockers systemically and they still have diabetic foot ulcers,” he said.

Dr. Rastogi and Dr. Dhatariya have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Esmolol hydrochloride gel (Galnobax, NovoLead) appears to be a safe and effective novel topical treatment option for diabetic foot ulcers, according to results from a new trial of the drug, which is widely available as a generic and is inexpensive.

Of note, the proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure at 12 weeks with esmolol (plus standard of care) was around 60% compared with just over 40% in patients who received standard of care alone.

Presenting the findings at this year’s annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes was Ashu Rastogi, MD, a professor of endocrinology at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India.

“Esmolol can be given topically as a 14% gel and is a novel treatment option in diabetic foot ulcer,” said Dr. Rastogi.

Esmolol, a short-acting beta-adrenergic blocker, is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for cardiac indications only, such as short-term use for controlling supraventricular tachycardia. Beta-blockers are also used to treat hypertension.

However, esmolol has also been repurposed and formulated as a topical gel for the treatment of hard-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers (mainly neuropathic grade 1).

Audience member Ketan Dhatariya, MBBS, MD, PhD, a National Health Service consultant in diabetes, endocrinology, and general medicine and honorary senior lecturer at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, England, enthused about the findings.

“This is an amazing study. I’m part of a working group looking at the updating of a guideline for the International Working Group of the Diabetic Foot, reviewing all the studies on wound healing, specifically pharmacological interventions. This is way beyond anything shown to date in terms of medical intervention. [The authors] should be congratulated; this is really astounding,” he told this news organization.

“Right now, there is very little out there in terms of pharmacological interventions that have shown benefit,” he added. “Once this study has been peer-reviewed and is published properly, it is potentially game-changing because it is a generic, worldwide, cheap, and freely available medication.”

Study across 27 sites in India

Prior phase 1/2 data have shown that 60% of ulcers completely closed with esmolol (14% gel) compared with 39% with standard of care. Encouraged by these findings, a phase 3 randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study was conducted across 27 sites in India.

Patients were a mean age of 56 years, and had a body mass index (BMI) of 25-26 kg/m2 and mean hemoglobin A1c of 8.4%-8.7%. Around 70% of participants were men. Mean ulcer area was approximately 460-500 mm2, two-thirds of the ulcers were plantar, and mean ulcer duration was 40-50 weeks.

After screening and discontinuations (39 participants), a 12-week treatment phase began with patients randomized to one of three groups: esmolol (14% gel) along with standard of care administered twice daily (57 completers); standard of care only (63 completers); or vehicle gel (placebo) along with standard of care administered twice daily (17 completers).

Standard of care comprised wound cleaning, debridement, maintenance of moist wound environment, twice-daily fresh bandages, and off-loading footwear as needed, and was provided to all participants irrespective of study group.

The 12-week treatment period was followed by an observation period of 12 weeks up to the 24-week study endpoint.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure (100% re-epithelialization without drainage or dressing requirement) within the 12-week treatment phase.

Secondary endpoints included time to target ulcer closure during the 12-week treatment phase and proportion of participants achieving target ulcer closure by 24 weeks (end of study). Investigators were blinded throughout.

Subanalyses were conducted based on ulcer location, size, and age, as well as estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 90 mL/min and ankle-brachial index under 0.9 but greater than 0.7.

50% more patients on esmolol had complete ulcer closure

The proportion of participants with complete ulcer closure at 12 weeks was 60.3% in the esmolol plus standard of care group, compared with 41.7% with standard of care only, a difference of 18.6% (odds ratio, 2.13; P = .0276).

“The 24-week end-of-study data show what happened in the 12 weeks following end of treatment,” said Dr. Rastogi, turning to results showing that by 24 weeks the proportion of participants with complete ulcer closure was 77.2% versus 55.6%, respectively, with a difference of 21.6% (OR, 2.71; P = .013).

Time to ulcer closure (a secondary endpoint) was similar between the esmolol plus standard of care vs. standard of care groups (74.3 vs. 72.5 days).

The impact of ulcer location on complete ulcer closure, a subanalysis, showed a higher proportion of patients experienced complete ulcer closure with esmolol plus standard of care versus standard of care. For example, in plantar-based ulcers, esmolol led to complete closure in 58.7% vs. 43.1%, while for nonplantar ulcers, complete closure was found in 63.6% vs. 38.1%.

In wounds less than 5 cm2, the proportion of complete closures was 66.0% vs. 50.0% for esmolol compared with standard of care alone, while in wounds over 5 cm2, these proportions were 47.6% vs. 26.9%.

Subanalyses also showed that esmolol was substantially better in patients with BMI greater than 25, ulcer duration over 12 weeks, and A1c above 8%.

Also, a subanalysis stratified by “real-life” situations favored esmolol, showing a 50.9% difference in the proportion of patients with diabetic foot ulcer healing in those with a history of hypertension and a 31.8% difference favoring esmolol in those with an abnormal electrocardiogram.

Overall, the proportions of patients who had an adverse event were 13.2%, 18.4%, and 37.5% in the esmolol plus standard of care, standard of care alone, and vehicle plus standard of care groups, respectively, and the vast majority were unrelated to study drug. There were no serious adverse events in the esmolol plus standard of care group.

A class effect of beta blockers?

The proposed mechanism of action of esmolol relates to a sequence of reducing inflammation (via vasodilation, fibroblast migration, and cytokine reduction); proliferation by beta-blockade (improves keratinocyte migration and epithelialization); and remodeling (increases collagen turnover).

Asked by an audience member if the observations were a class effect and systemic effect of beta-blockers, Dr. Rastogi said he could not say for sure that it was a class effect, but they deliberately used a beta-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist.

“It may not be a systemic effect because we have some patients who use beta-blockers systemically and they still have diabetic foot ulcers,” he said.

Dr. Rastogi and Dr. Dhatariya have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2022

Pink Nodule Behind the Ear

The Diagnosis: Acanthoma Fissuratum

Acanthoma fissuratum is a skin lesion that results from consistent pressure, typically from ill-fitting eyeglass frames.1 The chronic irritation leads to collagen deposition and inflammation that gradually creates the lesion. Many patients never seek care, making incidence figures undeterminable.2 It usually presents as a firm, tender, flesh-colored or pink nodule or plaque with a central indentation from where the frame rests. This indentation splits the lesion in half and classically gives the appearance of a coffee bean.1 The repeated minor trauma at this point of contact also may lead to centralized ulceration, which further blurs the diagnosis to include basal cell carcinoma (BCC).3,4 Although the postauricular groove is the most cited location, lesions also may occur at other contact points of the glasses, such as the lateral aspect of the bridge of the nose and the superior auricular sulcus.5 Acanthoma fissuratum is not limited to the external head. Other etiologies of local trauma and pressure have led to its diagnosis in the upper labioalveolar fold, posterior fourchette of the vulva, penis, and external auditory canal.6-9

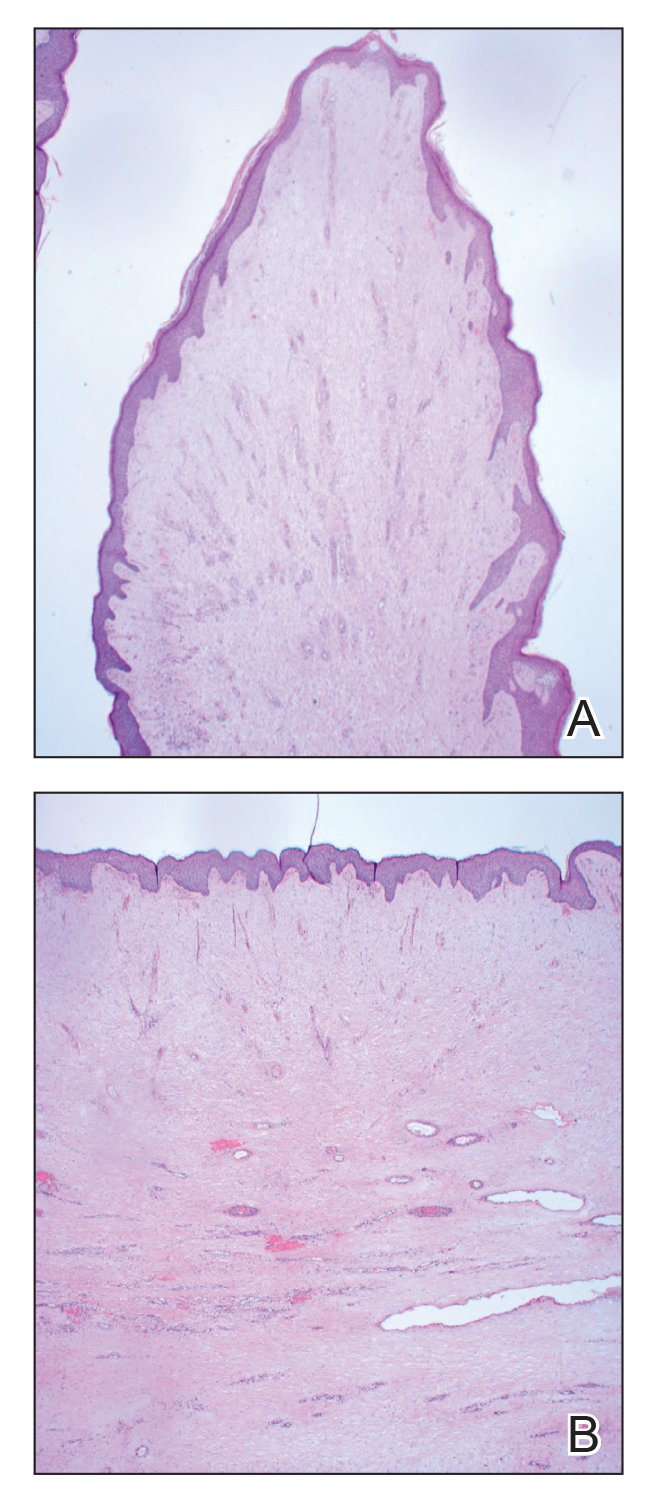

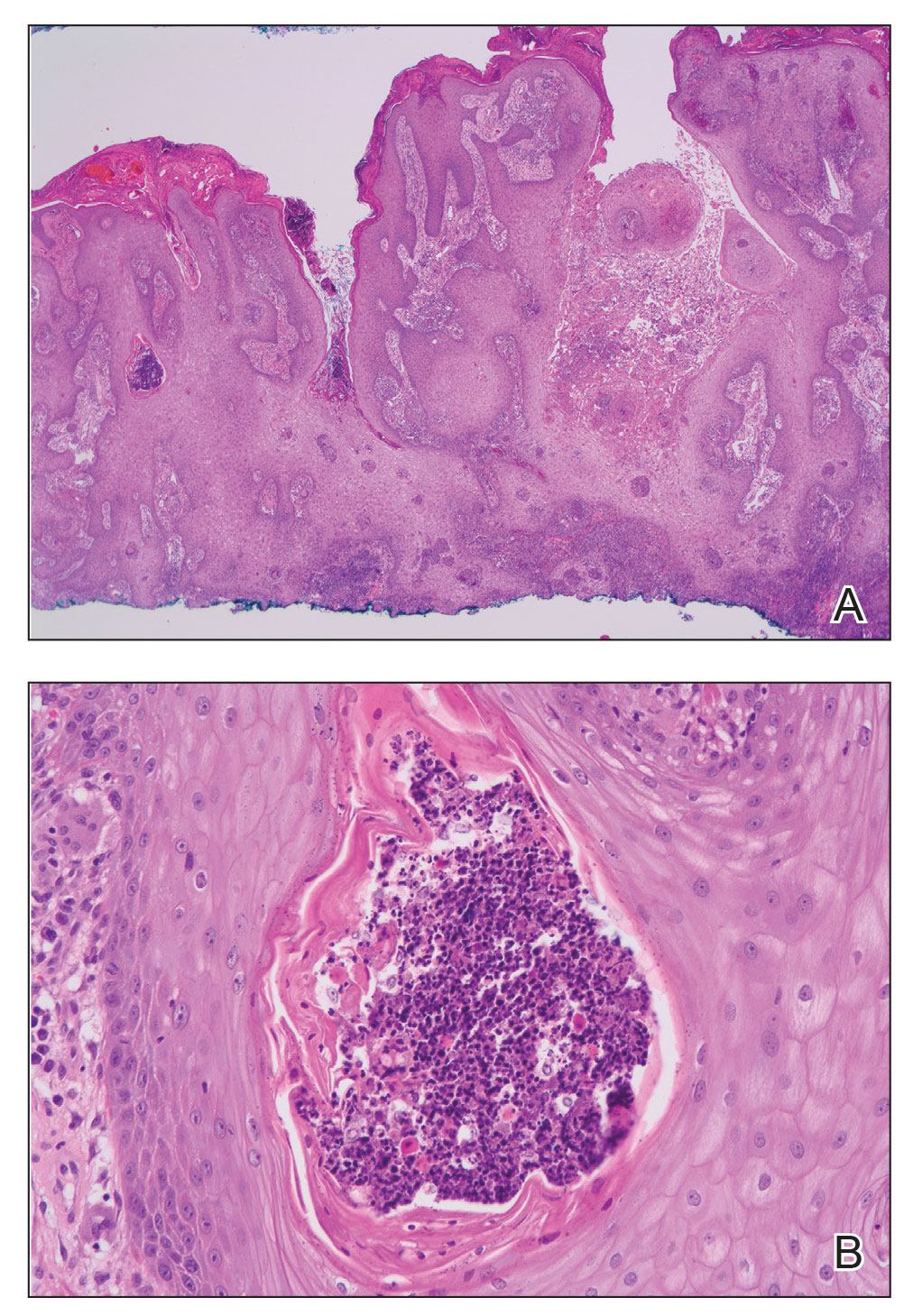

The diagnosis of acanthoma fissuratum mainly is clinical; however, due to its similar appearance to BCC and other lesions, a biopsy can be taken to support the diagnosis; a biopsy was not performed in our patient. The main features seen on histopathology include acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, variable parakeratosis, and perivascular nonspecific inflammatory infiltration. The epidermis may reflect the macroscopic frame indentation with central attenuation of the epidermis, which potentially is filled with inflammatory cells or keratin.5

Treatment normally encompasses removing the illfitting frames or fixing the fit, which gradually leads to reduction of the lesion.4,5 This occurred in our patient, who changed eyeglasses and saw an 80% resolution of the lesion in 8 months. Such improvement after removal of a trauma-inducing stimulus would not be seen in malignancies (eg, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]), keloids, or cylindromas. If the granulation tissue does not regress or recurs, other potential treatments include excision, intralesional corticosteroids, and electrosurgery.5

Basal cell carcinoma is a common nonmelanoma skin cancer that most often presents on the sun-exposed areas of the head and neck, especially the cheeks, nasolabial folds, and forehead. Although the nodular subtype may clinically appear similar to acanthoma fissuratum, it more typically presents as a pearly papule or nodule with a sharp border, small telangiectases, and potential ulceration.10 Squamous cell carcinoma is another common nonmelanoma skin cancer that often arises in sun-exposed areas, which can include the postauricular area. Although the lesion can be associated with chronic wounds and also can grow vertically, SCC typically has a scalier and more hyperkeratotic surface that can ulcerate.1 A cylindroma is a benign sweat gland tumor that most commonly presents on the head and neck (also known as the turban tumor), though it can develop on the ear. It appears as solitary or multiple nodules that often are flesh colored, red, or blue with a shiny surface.1 Cylindromas are not known to be associated with chronic local trauma or irritation,11 such as wearing ill-fitting eyeglasses. Unlike acanthoma fissuratum, the treatment of cylindromas, BCC, and SCC most often involves excision.1 A keloid presents as a flesh-colored, red, or purple exophytic plaque that is composed of dense dermal tissue and progressively forms after local trauma. Although keloids can spontaneously develop, they commonly form on the ears in susceptible individuals after skin excisions including prior keloid removal, piercings, repairment of auricular traumas, or infections.1 The patient’s coffee bean–like lesion that coincided with wearing new eyeglasses better fits the diagnosis of acanthoma fissuratum than a keloid. Additionally, keloids typically do not regress without treatment. Keloid treatment consists of intralesional steroid injections, occlusive silicone dressings, compression, cryotherapy, radiation, and excisional surgery.1

- Sand M, Sand D, Brors D, et al. Cutaneous lesions of the external ear. Head Face Med. 2008;4. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-4-2

- Orengo I, Robbins K, Marsch A. Pathology of the ear. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:279-287. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1288920

- Ramroop S. Successful treatment of acanthoma fissuratum with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:702-703. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2708

- Delaney TJ, Stewart TW. Granuloma fissuratum. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:373-375. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14235.x

- Deshpande NS, Sen A, Vasudevan B, et al. Acanthoma fissuratum: lest we forget. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:141-143. doi:10.4103/2229- 5178.202267

- Surron RL Jr. A fissured granulomatous lesion of the upper labioalveolar fold. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1932;26:425. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1932.01450030423004

- Kennedy CM, Dewdney S, Galask RP. Vulvar granuloma fissuratum: a description of fissuring of the posterior fourchette and the repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1018-1023. doi:10.1097/01. AOG.0000158863.70819.53

- Lee JL, Lee YB, Cho BK, et al. Acanthoma fissuratum on the penis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:382-384. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04903.x

- Gonzalez SA, Moore AGN. Acanthoma fissuratum of the outer auditory canal from a hearing aid. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:304.

- Fania L, Didona D, Morese R, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Biomedicines. 2020;8:449. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8110449

- Chauhan DS, Guruprasad Y. Dermal cylindroma of the scalp. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3:59-61. doi:10.4103/0975-5950.102163

The Diagnosis: Acanthoma Fissuratum

Acanthoma fissuratum is a skin lesion that results from consistent pressure, typically from ill-fitting eyeglass frames.1 The chronic irritation leads to collagen deposition and inflammation that gradually creates the lesion. Many patients never seek care, making incidence figures undeterminable.2 It usually presents as a firm, tender, flesh-colored or pink nodule or plaque with a central indentation from where the frame rests. This indentation splits the lesion in half and classically gives the appearance of a coffee bean.1 The repeated minor trauma at this point of contact also may lead to centralized ulceration, which further blurs the diagnosis to include basal cell carcinoma (BCC).3,4 Although the postauricular groove is the most cited location, lesions also may occur at other contact points of the glasses, such as the lateral aspect of the bridge of the nose and the superior auricular sulcus.5 Acanthoma fissuratum is not limited to the external head. Other etiologies of local trauma and pressure have led to its diagnosis in the upper labioalveolar fold, posterior fourchette of the vulva, penis, and external auditory canal.6-9

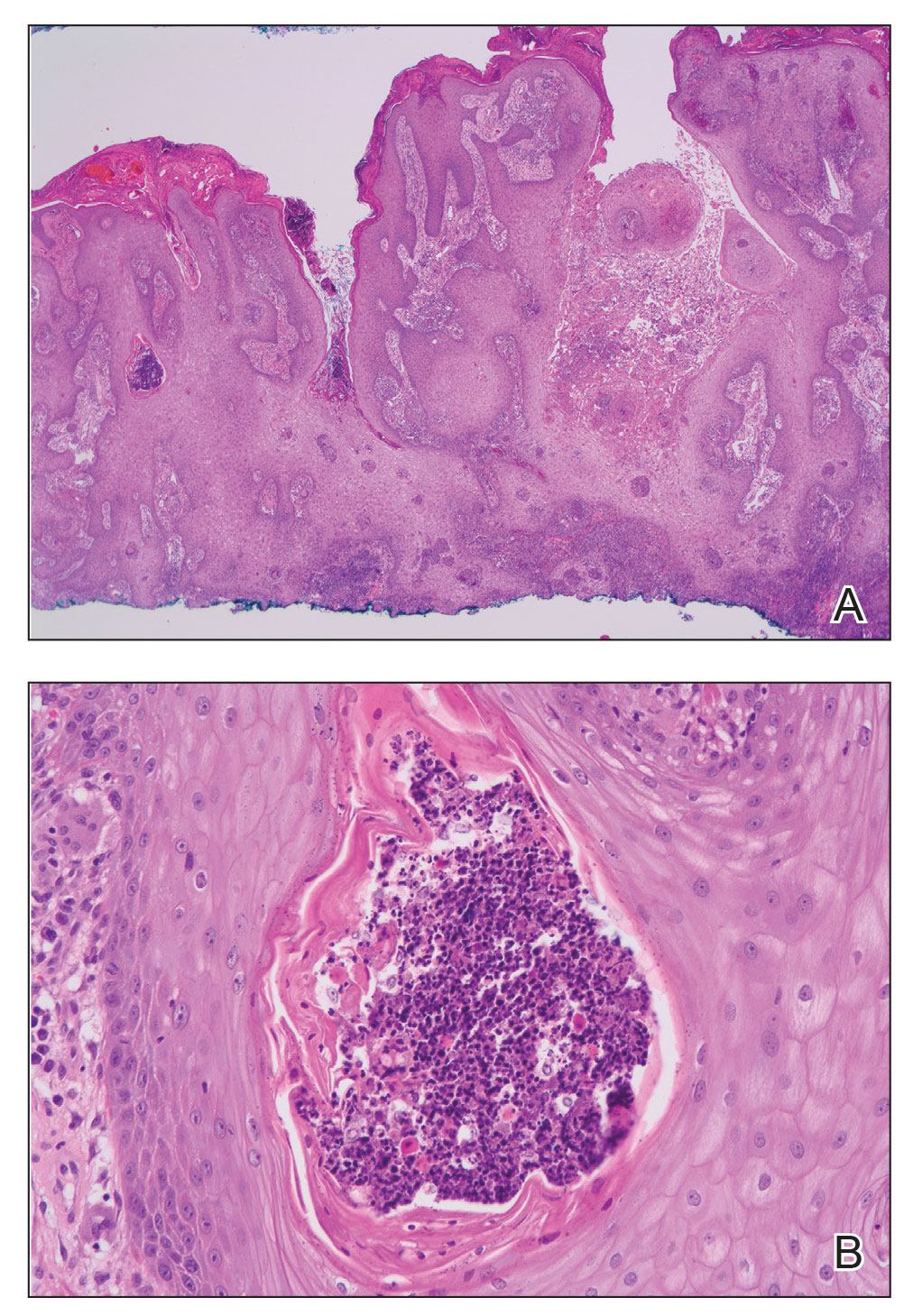

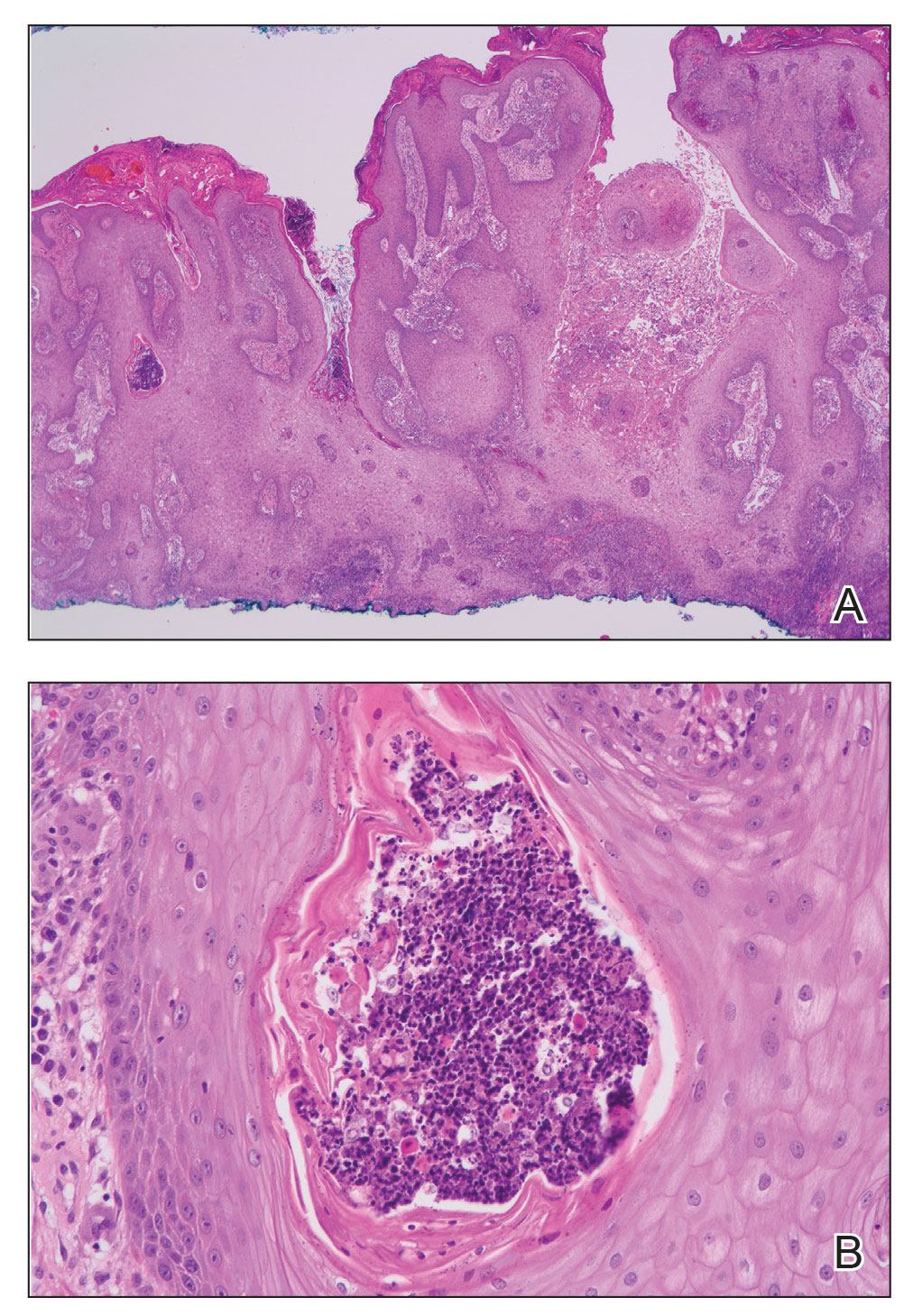

The diagnosis of acanthoma fissuratum mainly is clinical; however, due to its similar appearance to BCC and other lesions, a biopsy can be taken to support the diagnosis; a biopsy was not performed in our patient. The main features seen on histopathology include acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, variable parakeratosis, and perivascular nonspecific inflammatory infiltration. The epidermis may reflect the macroscopic frame indentation with central attenuation of the epidermis, which potentially is filled with inflammatory cells or keratin.5

Treatment normally encompasses removing the illfitting frames or fixing the fit, which gradually leads to reduction of the lesion.4,5 This occurred in our patient, who changed eyeglasses and saw an 80% resolution of the lesion in 8 months. Such improvement after removal of a trauma-inducing stimulus would not be seen in malignancies (eg, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]), keloids, or cylindromas. If the granulation tissue does not regress or recurs, other potential treatments include excision, intralesional corticosteroids, and electrosurgery.5

Basal cell carcinoma is a common nonmelanoma skin cancer that most often presents on the sun-exposed areas of the head and neck, especially the cheeks, nasolabial folds, and forehead. Although the nodular subtype may clinically appear similar to acanthoma fissuratum, it more typically presents as a pearly papule or nodule with a sharp border, small telangiectases, and potential ulceration.10 Squamous cell carcinoma is another common nonmelanoma skin cancer that often arises in sun-exposed areas, which can include the postauricular area. Although the lesion can be associated with chronic wounds and also can grow vertically, SCC typically has a scalier and more hyperkeratotic surface that can ulcerate.1 A cylindroma is a benign sweat gland tumor that most commonly presents on the head and neck (also known as the turban tumor), though it can develop on the ear. It appears as solitary or multiple nodules that often are flesh colored, red, or blue with a shiny surface.1 Cylindromas are not known to be associated with chronic local trauma or irritation,11 such as wearing ill-fitting eyeglasses. Unlike acanthoma fissuratum, the treatment of cylindromas, BCC, and SCC most often involves excision.1 A keloid presents as a flesh-colored, red, or purple exophytic plaque that is composed of dense dermal tissue and progressively forms after local trauma. Although keloids can spontaneously develop, they commonly form on the ears in susceptible individuals after skin excisions including prior keloid removal, piercings, repairment of auricular traumas, or infections.1 The patient’s coffee bean–like lesion that coincided with wearing new eyeglasses better fits the diagnosis of acanthoma fissuratum than a keloid. Additionally, keloids typically do not regress without treatment. Keloid treatment consists of intralesional steroid injections, occlusive silicone dressings, compression, cryotherapy, radiation, and excisional surgery.1

The Diagnosis: Acanthoma Fissuratum

Acanthoma fissuratum is a skin lesion that results from consistent pressure, typically from ill-fitting eyeglass frames.1 The chronic irritation leads to collagen deposition and inflammation that gradually creates the lesion. Many patients never seek care, making incidence figures undeterminable.2 It usually presents as a firm, tender, flesh-colored or pink nodule or plaque with a central indentation from where the frame rests. This indentation splits the lesion in half and classically gives the appearance of a coffee bean.1 The repeated minor trauma at this point of contact also may lead to centralized ulceration, which further blurs the diagnosis to include basal cell carcinoma (BCC).3,4 Although the postauricular groove is the most cited location, lesions also may occur at other contact points of the glasses, such as the lateral aspect of the bridge of the nose and the superior auricular sulcus.5 Acanthoma fissuratum is not limited to the external head. Other etiologies of local trauma and pressure have led to its diagnosis in the upper labioalveolar fold, posterior fourchette of the vulva, penis, and external auditory canal.6-9

The diagnosis of acanthoma fissuratum mainly is clinical; however, due to its similar appearance to BCC and other lesions, a biopsy can be taken to support the diagnosis; a biopsy was not performed in our patient. The main features seen on histopathology include acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, variable parakeratosis, and perivascular nonspecific inflammatory infiltration. The epidermis may reflect the macroscopic frame indentation with central attenuation of the epidermis, which potentially is filled with inflammatory cells or keratin.5

Treatment normally encompasses removing the illfitting frames or fixing the fit, which gradually leads to reduction of the lesion.4,5 This occurred in our patient, who changed eyeglasses and saw an 80% resolution of the lesion in 8 months. Such improvement after removal of a trauma-inducing stimulus would not be seen in malignancies (eg, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]), keloids, or cylindromas. If the granulation tissue does not regress or recurs, other potential treatments include excision, intralesional corticosteroids, and electrosurgery.5

Basal cell carcinoma is a common nonmelanoma skin cancer that most often presents on the sun-exposed areas of the head and neck, especially the cheeks, nasolabial folds, and forehead. Although the nodular subtype may clinically appear similar to acanthoma fissuratum, it more typically presents as a pearly papule or nodule with a sharp border, small telangiectases, and potential ulceration.10 Squamous cell carcinoma is another common nonmelanoma skin cancer that often arises in sun-exposed areas, which can include the postauricular area. Although the lesion can be associated with chronic wounds and also can grow vertically, SCC typically has a scalier and more hyperkeratotic surface that can ulcerate.1 A cylindroma is a benign sweat gland tumor that most commonly presents on the head and neck (also known as the turban tumor), though it can develop on the ear. It appears as solitary or multiple nodules that often are flesh colored, red, or blue with a shiny surface.1 Cylindromas are not known to be associated with chronic local trauma or irritation,11 such as wearing ill-fitting eyeglasses. Unlike acanthoma fissuratum, the treatment of cylindromas, BCC, and SCC most often involves excision.1 A keloid presents as a flesh-colored, red, or purple exophytic plaque that is composed of dense dermal tissue and progressively forms after local trauma. Although keloids can spontaneously develop, they commonly form on the ears in susceptible individuals after skin excisions including prior keloid removal, piercings, repairment of auricular traumas, or infections.1 The patient’s coffee bean–like lesion that coincided with wearing new eyeglasses better fits the diagnosis of acanthoma fissuratum than a keloid. Additionally, keloids typically do not regress without treatment. Keloid treatment consists of intralesional steroid injections, occlusive silicone dressings, compression, cryotherapy, radiation, and excisional surgery.1

- Sand M, Sand D, Brors D, et al. Cutaneous lesions of the external ear. Head Face Med. 2008;4. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-4-2

- Orengo I, Robbins K, Marsch A. Pathology of the ear. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:279-287. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1288920

- Ramroop S. Successful treatment of acanthoma fissuratum with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:702-703. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2708

- Delaney TJ, Stewart TW. Granuloma fissuratum. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:373-375. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14235.x

- Deshpande NS, Sen A, Vasudevan B, et al. Acanthoma fissuratum: lest we forget. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:141-143. doi:10.4103/2229- 5178.202267

- Surron RL Jr. A fissured granulomatous lesion of the upper labioalveolar fold. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1932;26:425. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1932.01450030423004

- Kennedy CM, Dewdney S, Galask RP. Vulvar granuloma fissuratum: a description of fissuring of the posterior fourchette and the repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1018-1023. doi:10.1097/01. AOG.0000158863.70819.53

- Lee JL, Lee YB, Cho BK, et al. Acanthoma fissuratum on the penis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:382-384. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04903.x

- Gonzalez SA, Moore AGN. Acanthoma fissuratum of the outer auditory canal from a hearing aid. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:304.

- Fania L, Didona D, Morese R, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Biomedicines. 2020;8:449. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8110449

- Chauhan DS, Guruprasad Y. Dermal cylindroma of the scalp. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3:59-61. doi:10.4103/0975-5950.102163

- Sand M, Sand D, Brors D, et al. Cutaneous lesions of the external ear. Head Face Med. 2008;4. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-4-2

- Orengo I, Robbins K, Marsch A. Pathology of the ear. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:279-287. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1288920

- Ramroop S. Successful treatment of acanthoma fissuratum with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:702-703. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2708

- Delaney TJ, Stewart TW. Granuloma fissuratum. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:373-375. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14235.x

- Deshpande NS, Sen A, Vasudevan B, et al. Acanthoma fissuratum: lest we forget. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:141-143. doi:10.4103/2229- 5178.202267

- Surron RL Jr. A fissured granulomatous lesion of the upper labioalveolar fold. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1932;26:425. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1932.01450030423004

- Kennedy CM, Dewdney S, Galask RP. Vulvar granuloma fissuratum: a description of fissuring of the posterior fourchette and the repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1018-1023. doi:10.1097/01. AOG.0000158863.70819.53

- Lee JL, Lee YB, Cho BK, et al. Acanthoma fissuratum on the penis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:382-384. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04903.x

- Gonzalez SA, Moore AGN. Acanthoma fissuratum of the outer auditory canal from a hearing aid. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:304.

- Fania L, Didona D, Morese R, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Biomedicines. 2020;8:449. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8110449

- Chauhan DS, Guruprasad Y. Dermal cylindroma of the scalp. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3:59-61. doi:10.4103/0975-5950.102163

A 62-year-old man presented to the dermatology office with a 1.5-cm, pink, rubbery nodule behind the left ear that sometimes was tender. He stated that the lesion gradually grew in size over the last 2 years, and it developed after he was fitted for new glasses.

Multiple Fingerlike Projections on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

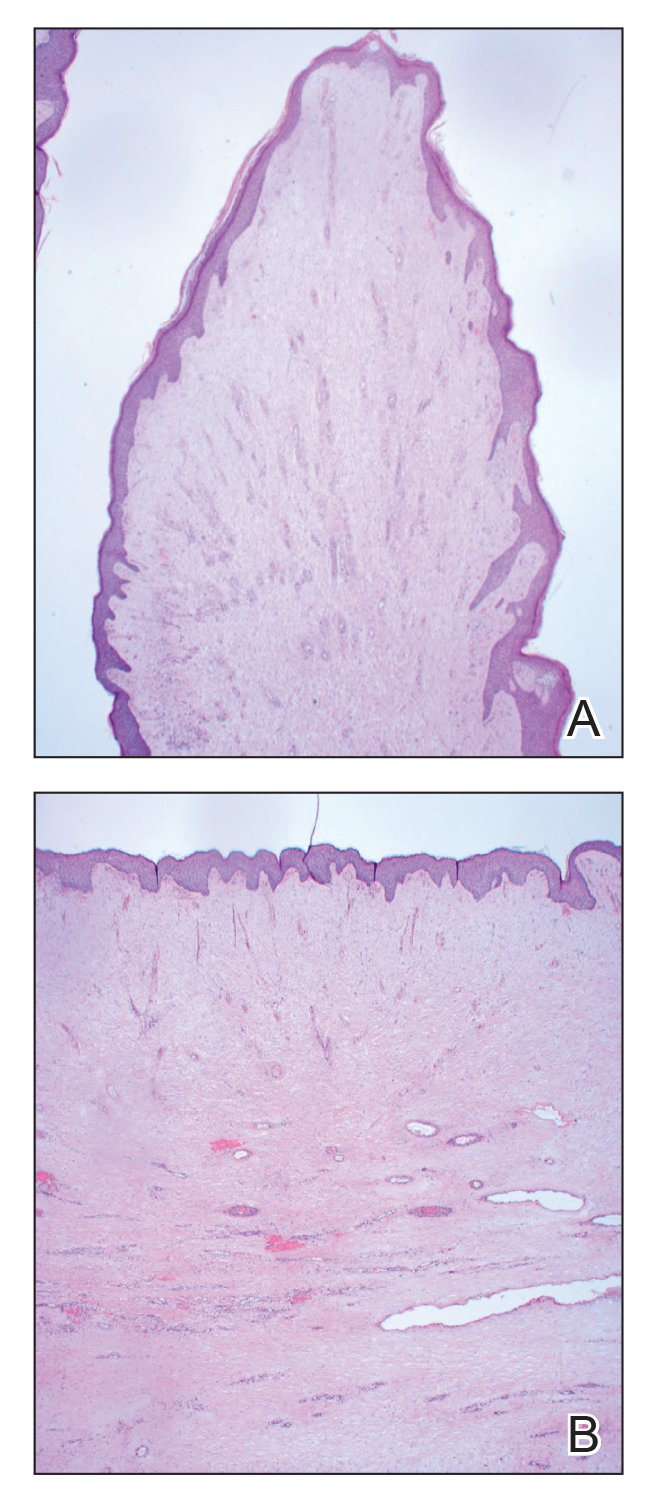

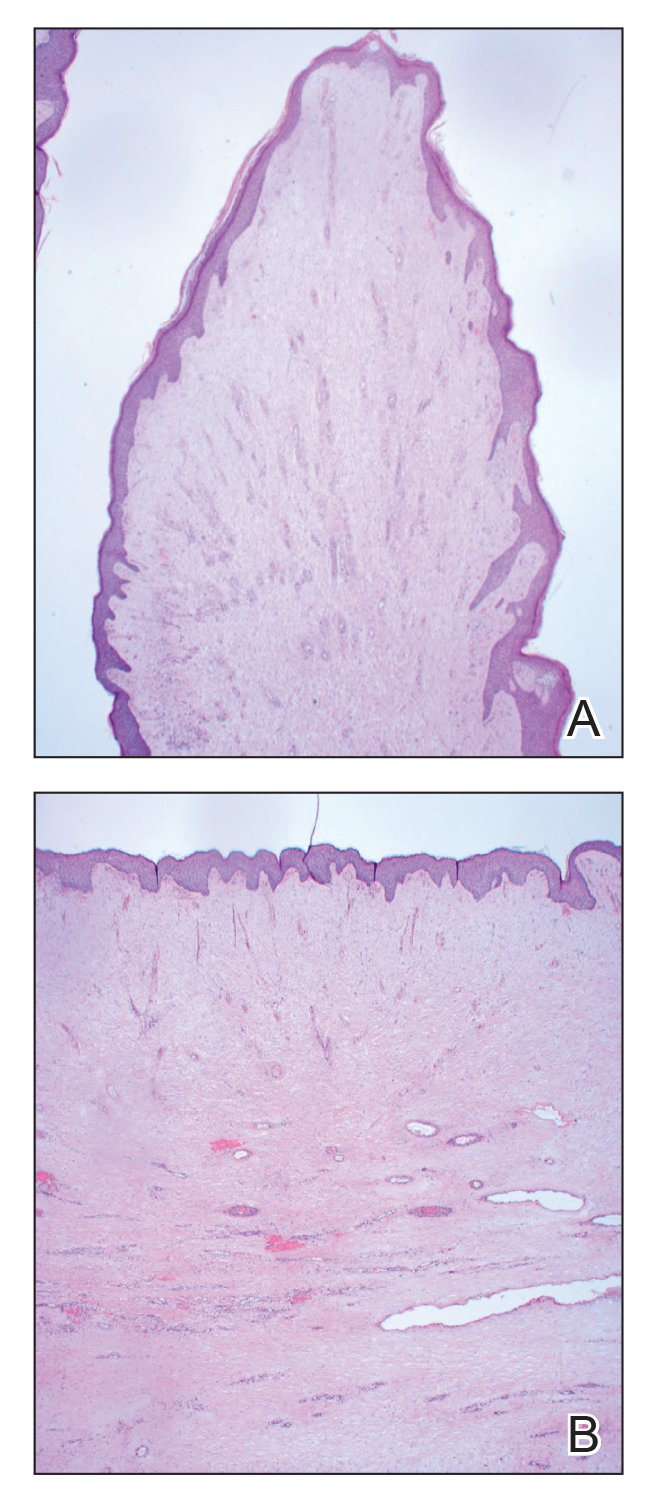

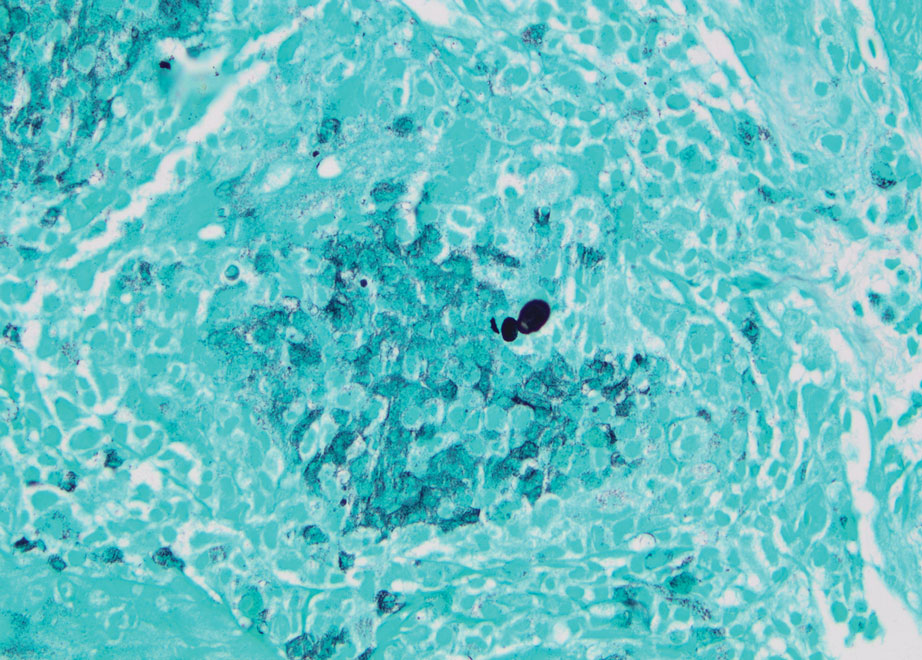

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

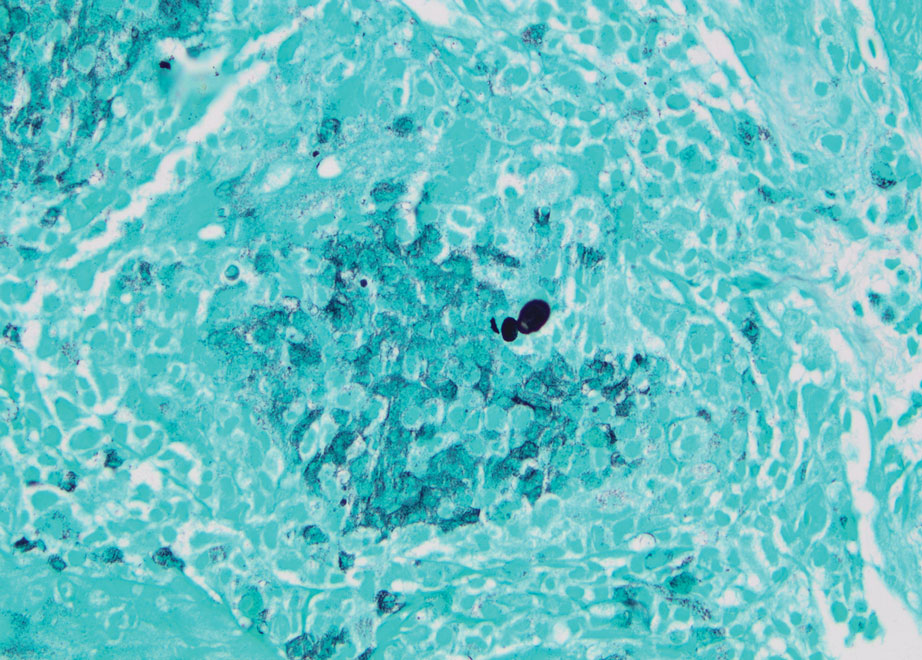

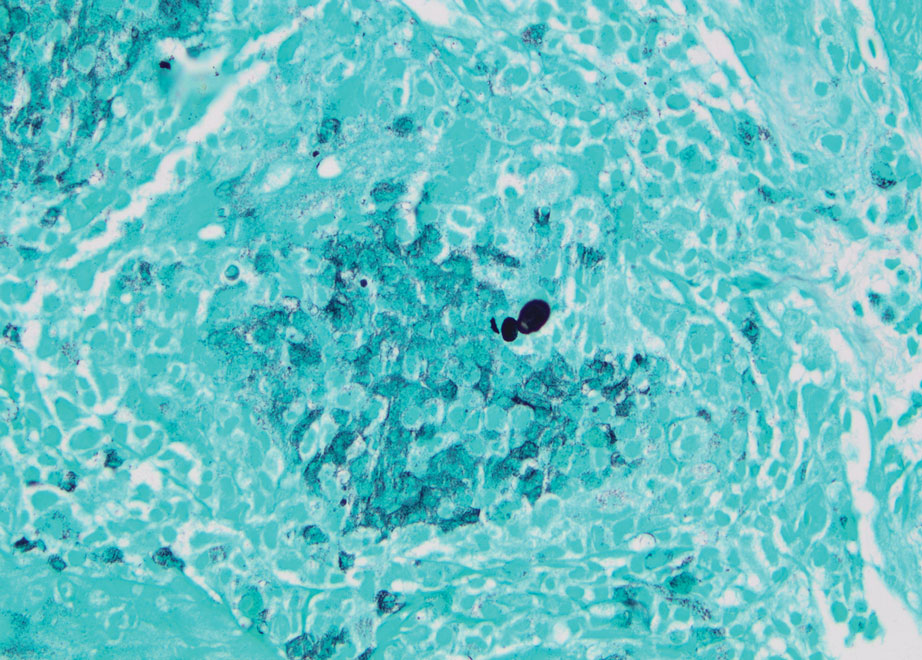

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5